User login

More states require coverage of 1-year supplies of contraception

Each semester, Sarah Prager, MD, runs through a familiar yet arduous routine: trying to prescribe a 6- to 12-month supply of oral contraceptives for her college student patients. For those young women who study abroad for one or two semesters, the usual 1-month or 3-month supply won’t be enough.

“I even had two patients who had unplanned pregnancies while studying abroad for this very reason,” said Dr. Prager, associate professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Washington, Seattle. “It’s previously been a real challenge to write the letters, and it takes an absurd amount of time to even fail at getting them 6 months, or to make a plan for them to travel some place to get them.”

This type of policy has been in effect in California since Jan. 1, 2017, and a new study estimates that the measure will save the state nearly $43 million in health care costs while preventing thousands of unintended pregnancies, miscarriages, and abortions (Contraception. 2017 May;95[5]:449-51).

“Awareness of this change in policy will be key in determining how much of an impact it will have,” said Sara McMenamin, PhD, MPH, assistant professor of public health at the University of California, San Diego, and the study’s lead author.

Dr. McMenamin and her colleagues project that 38% of current users of the contraceptive pill, patch, and ring will begin receiving 12-month prescriptions at a time, leading to 15,000 fewer unintended pregnancies, 2,000 fewer miscarriages, and 7,000 fewer abortions every year. Health care costs would be reduced by 0.03%, translating to approximately $42.8 million annually.

There are potential environmental concerns to pill wastage as well, such as keeping it out of river systems and drinking water, Dr. Prager noted.

The California law’s effects will not happen immediately, so there may be a delay in reaching the study’s projections. “These results likely represent an overestimation in the short term, as it will likely take some time to change provider and patient behavior and increase awareness of the new policy,” Dr. McMenamin said.

But the idea is catching on. In 2016, Oregon, Hawaii, Illinois, Maryland, Vermont, and the District of Columbia enacted legislation requiring insurers to cover extended supplies of contraception. Since then, Washington state, Colorado, Virginia, and Nevada have approved similar laws and more than a dozen other states have introduced similar legislation.

Importantly, the effects of this type of coverage cut across demographics, Dr. Prager said.

“I think there’s this perception by many that these are challenges experienced by women who are underresourced or poor or teenagers, and they’re not,” Dr. Prager said. “People are busy, and it’s rare for working adults to have to think about getting to a pharmacy on a regular basis. Contraception is the exception.”

In addition, some women may experience coverage gaps that prevent refills during a job change or other insurance change. Women who travel a lot, for college or work, can have a harder time getting their refills, as well. And women in rural areas may need to drive up to an hour for a pharmacy.

“These are real-life concerns for people of all socioeconomic strata of all ages,” Dr. Prager said. “If you’re off by even a day, then a woman is at risk of pregnancy.”

The California study was supported by the California Health Benefits Review Program. Dr. Prager reported being an unpaid trainer for Nexplanon (Merck).

Each semester, Sarah Prager, MD, runs through a familiar yet arduous routine: trying to prescribe a 6- to 12-month supply of oral contraceptives for her college student patients. For those young women who study abroad for one or two semesters, the usual 1-month or 3-month supply won’t be enough.

“I even had two patients who had unplanned pregnancies while studying abroad for this very reason,” said Dr. Prager, associate professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Washington, Seattle. “It’s previously been a real challenge to write the letters, and it takes an absurd amount of time to even fail at getting them 6 months, or to make a plan for them to travel some place to get them.”

This type of policy has been in effect in California since Jan. 1, 2017, and a new study estimates that the measure will save the state nearly $43 million in health care costs while preventing thousands of unintended pregnancies, miscarriages, and abortions (Contraception. 2017 May;95[5]:449-51).

“Awareness of this change in policy will be key in determining how much of an impact it will have,” said Sara McMenamin, PhD, MPH, assistant professor of public health at the University of California, San Diego, and the study’s lead author.

Dr. McMenamin and her colleagues project that 38% of current users of the contraceptive pill, patch, and ring will begin receiving 12-month prescriptions at a time, leading to 15,000 fewer unintended pregnancies, 2,000 fewer miscarriages, and 7,000 fewer abortions every year. Health care costs would be reduced by 0.03%, translating to approximately $42.8 million annually.

There are potential environmental concerns to pill wastage as well, such as keeping it out of river systems and drinking water, Dr. Prager noted.

The California law’s effects will not happen immediately, so there may be a delay in reaching the study’s projections. “These results likely represent an overestimation in the short term, as it will likely take some time to change provider and patient behavior and increase awareness of the new policy,” Dr. McMenamin said.

But the idea is catching on. In 2016, Oregon, Hawaii, Illinois, Maryland, Vermont, and the District of Columbia enacted legislation requiring insurers to cover extended supplies of contraception. Since then, Washington state, Colorado, Virginia, and Nevada have approved similar laws and more than a dozen other states have introduced similar legislation.

Importantly, the effects of this type of coverage cut across demographics, Dr. Prager said.

“I think there’s this perception by many that these are challenges experienced by women who are underresourced or poor or teenagers, and they’re not,” Dr. Prager said. “People are busy, and it’s rare for working adults to have to think about getting to a pharmacy on a regular basis. Contraception is the exception.”

In addition, some women may experience coverage gaps that prevent refills during a job change or other insurance change. Women who travel a lot, for college or work, can have a harder time getting their refills, as well. And women in rural areas may need to drive up to an hour for a pharmacy.

“These are real-life concerns for people of all socioeconomic strata of all ages,” Dr. Prager said. “If you’re off by even a day, then a woman is at risk of pregnancy.”

The California study was supported by the California Health Benefits Review Program. Dr. Prager reported being an unpaid trainer for Nexplanon (Merck).

Each semester, Sarah Prager, MD, runs through a familiar yet arduous routine: trying to prescribe a 6- to 12-month supply of oral contraceptives for her college student patients. For those young women who study abroad for one or two semesters, the usual 1-month or 3-month supply won’t be enough.

“I even had two patients who had unplanned pregnancies while studying abroad for this very reason,” said Dr. Prager, associate professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Washington, Seattle. “It’s previously been a real challenge to write the letters, and it takes an absurd amount of time to even fail at getting them 6 months, or to make a plan for them to travel some place to get them.”

This type of policy has been in effect in California since Jan. 1, 2017, and a new study estimates that the measure will save the state nearly $43 million in health care costs while preventing thousands of unintended pregnancies, miscarriages, and abortions (Contraception. 2017 May;95[5]:449-51).

“Awareness of this change in policy will be key in determining how much of an impact it will have,” said Sara McMenamin, PhD, MPH, assistant professor of public health at the University of California, San Diego, and the study’s lead author.

Dr. McMenamin and her colleagues project that 38% of current users of the contraceptive pill, patch, and ring will begin receiving 12-month prescriptions at a time, leading to 15,000 fewer unintended pregnancies, 2,000 fewer miscarriages, and 7,000 fewer abortions every year. Health care costs would be reduced by 0.03%, translating to approximately $42.8 million annually.

There are potential environmental concerns to pill wastage as well, such as keeping it out of river systems and drinking water, Dr. Prager noted.

The California law’s effects will not happen immediately, so there may be a delay in reaching the study’s projections. “These results likely represent an overestimation in the short term, as it will likely take some time to change provider and patient behavior and increase awareness of the new policy,” Dr. McMenamin said.

But the idea is catching on. In 2016, Oregon, Hawaii, Illinois, Maryland, Vermont, and the District of Columbia enacted legislation requiring insurers to cover extended supplies of contraception. Since then, Washington state, Colorado, Virginia, and Nevada have approved similar laws and more than a dozen other states have introduced similar legislation.

Importantly, the effects of this type of coverage cut across demographics, Dr. Prager said.

“I think there’s this perception by many that these are challenges experienced by women who are underresourced or poor or teenagers, and they’re not,” Dr. Prager said. “People are busy, and it’s rare for working adults to have to think about getting to a pharmacy on a regular basis. Contraception is the exception.”

In addition, some women may experience coverage gaps that prevent refills during a job change or other insurance change. Women who travel a lot, for college or work, can have a harder time getting their refills, as well. And women in rural areas may need to drive up to an hour for a pharmacy.

“These are real-life concerns for people of all socioeconomic strata of all ages,” Dr. Prager said. “If you’re off by even a day, then a woman is at risk of pregnancy.”

The California study was supported by the California Health Benefits Review Program. Dr. Prager reported being an unpaid trainer for Nexplanon (Merck).

Narcotic analgesia for breastfeeding women

Editor’s Note: This is the final installment of a six-part series that reviews key concepts and articles that ob.gyns. can use to prepare for the American Board of Obstetrics and Gynecology Maintenance of Certification examination. The series is adapted from Ob/Gyn Board Master (obgynboardmaster.com), an online board review course created by Erudyte. This month’s edition of the Board Corner focuses on narcotic analgesia for breastfeeding women.

The American College of Obstetrics and Gynecologists “Practice Advisories” are released when there is an important clinical issue that needs immediate attention from ob.gyn. clinicians. On April 27, 2017, ACOG joined with the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine and the Academy of Breastfeeding Medicine to issue a new practice advisory with recommendations on opiate analgesia in breastfeeding women.1 These Practice Advisories contain material that may be tested on a board exam. We recommend that you read this Practice Advisory and review it carefully.

A. Morphine IV

B. Butorphanol

C. Acetaminophen with codeine

D. Hydromorphone

E. Morphine (given orally)

The correct answer is C.

Acetaminophen with codeine (aka Tylenol #3 or Tylenol #4) is the least appropriate first-choice narcotic in a breastfeeding postpartum patient after Cesarean delivery as it is the only narcotic among the choices that is metabolized by the enzyme CYP2D6. Morphine, butorphanol, and hydromorphone are all metabolized by CYP450. If a narcotic is indicated, it is better to choose one that is not metabolized by CYP2D6 because of potential side effects in both mothers and infants who may be “CYP2D6 ultrametabolizers” or “CYP2D6 poor metabolizers.”

Key points

The key points to remember are:

1. Do not use codeine or tramadol as a first-line narcotic choice in breastfeeding mothers, if possible, because of variable side effects in mothers and infants.

2. The preferred narcotics to use when breastfeeding are butorphanol, morphine, or hydromorphone.

3. If codeine or tramadol is used in breastfeeding women, the clinician should speak with the patient and family about the possible side effects and the recent labeling changes required by the Food and Drug Administration.

Literature summary

In April, the Food and Drug Administration issued a safety alert and said it is requiring labeling changes for prescription medications containing codeine and tramadol. Specifically, the agency warned against use of codeine and tramadol when breastfeeding. This change is the result of the fact that certain people metabolize codeine and tramadol differently. There are some people – considered CYP2D6 “ultrarapid metabolizers” – who can have levels of the drug in their breast milk that can cause excessive sleepiness and depressed breathing in infants. There is one report of an infant death resulting from codeine use. The frequency of these “rapid metabolizers” is about 4%-5% in the United States.

In addition to the effects on breastfed infants, there are effects on the mother as well. This is because 6% of patients in the United States are “poor metabolizers” who have insufficient pain relief, as well as greater side effects.

Hydrocodone and oxycodone are not addressed in the recent labeling changes. However, “ultrarapid metabolizers” do show more pain relief and pupil restriction.

When comparing codeine with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications (NSAIDs) in abdominal surgery, nine randomized trials failed to show that codeine provided superior pain relief.

Hydromorphone, butorphanol, and morphine are not metabolized by CYP2D6 so the problems faced by “ultrarapid metabolizers” or “poor metabolizers” is not an issue.

Ob.gyns. should utilize regional anesthesia, NSAIDs, and acetaminophen (without codeine) to help decrease the risks of anesthesia while still ensuring adequate pain relief. Ob.gyns. should closely monitor their patients on narcotics for any side effects in both mothers and infants, especially central nervous system depression.

Dr. Kairis is an assistant professor in the department of gynecology and obstetrics at Loma Linda (Calif.) University Health and is the director of the Women’s Sexual Medicine Program there. She is on the editorial committee of the Ob/Gyn Board Master. Dr. Siddighi is editor in chief of the Ob/Gyn Board Master and director of female pelvic medicine and reconstructive surgery and director of grand rounds at Loma Linda University Health. Ob.Gyn. News and Ob/Gyn Board Master are owned by the same parent company, Frontline Medical Communications.

Reference

1. Practice Advisory on Codeine and Tramadol for Breastfeeding Women. April 27, 2017. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

Editor’s Note: This is the final installment of a six-part series that reviews key concepts and articles that ob.gyns. can use to prepare for the American Board of Obstetrics and Gynecology Maintenance of Certification examination. The series is adapted from Ob/Gyn Board Master (obgynboardmaster.com), an online board review course created by Erudyte. This month’s edition of the Board Corner focuses on narcotic analgesia for breastfeeding women.

The American College of Obstetrics and Gynecologists “Practice Advisories” are released when there is an important clinical issue that needs immediate attention from ob.gyn. clinicians. On April 27, 2017, ACOG joined with the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine and the Academy of Breastfeeding Medicine to issue a new practice advisory with recommendations on opiate analgesia in breastfeeding women.1 These Practice Advisories contain material that may be tested on a board exam. We recommend that you read this Practice Advisory and review it carefully.

A. Morphine IV

B. Butorphanol

C. Acetaminophen with codeine

D. Hydromorphone

E. Morphine (given orally)

The correct answer is C.

Acetaminophen with codeine (aka Tylenol #3 or Tylenol #4) is the least appropriate first-choice narcotic in a breastfeeding postpartum patient after Cesarean delivery as it is the only narcotic among the choices that is metabolized by the enzyme CYP2D6. Morphine, butorphanol, and hydromorphone are all metabolized by CYP450. If a narcotic is indicated, it is better to choose one that is not metabolized by CYP2D6 because of potential side effects in both mothers and infants who may be “CYP2D6 ultrametabolizers” or “CYP2D6 poor metabolizers.”

Key points

The key points to remember are:

1. Do not use codeine or tramadol as a first-line narcotic choice in breastfeeding mothers, if possible, because of variable side effects in mothers and infants.

2. The preferred narcotics to use when breastfeeding are butorphanol, morphine, or hydromorphone.

3. If codeine or tramadol is used in breastfeeding women, the clinician should speak with the patient and family about the possible side effects and the recent labeling changes required by the Food and Drug Administration.

Literature summary

In April, the Food and Drug Administration issued a safety alert and said it is requiring labeling changes for prescription medications containing codeine and tramadol. Specifically, the agency warned against use of codeine and tramadol when breastfeeding. This change is the result of the fact that certain people metabolize codeine and tramadol differently. There are some people – considered CYP2D6 “ultrarapid metabolizers” – who can have levels of the drug in their breast milk that can cause excessive sleepiness and depressed breathing in infants. There is one report of an infant death resulting from codeine use. The frequency of these “rapid metabolizers” is about 4%-5% in the United States.

In addition to the effects on breastfed infants, there are effects on the mother as well. This is because 6% of patients in the United States are “poor metabolizers” who have insufficient pain relief, as well as greater side effects.

Hydrocodone and oxycodone are not addressed in the recent labeling changes. However, “ultrarapid metabolizers” do show more pain relief and pupil restriction.

When comparing codeine with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications (NSAIDs) in abdominal surgery, nine randomized trials failed to show that codeine provided superior pain relief.

Hydromorphone, butorphanol, and morphine are not metabolized by CYP2D6 so the problems faced by “ultrarapid metabolizers” or “poor metabolizers” is not an issue.

Ob.gyns. should utilize regional anesthesia, NSAIDs, and acetaminophen (without codeine) to help decrease the risks of anesthesia while still ensuring adequate pain relief. Ob.gyns. should closely monitor their patients on narcotics for any side effects in both mothers and infants, especially central nervous system depression.

Dr. Kairis is an assistant professor in the department of gynecology and obstetrics at Loma Linda (Calif.) University Health and is the director of the Women’s Sexual Medicine Program there. She is on the editorial committee of the Ob/Gyn Board Master. Dr. Siddighi is editor in chief of the Ob/Gyn Board Master and director of female pelvic medicine and reconstructive surgery and director of grand rounds at Loma Linda University Health. Ob.Gyn. News and Ob/Gyn Board Master are owned by the same parent company, Frontline Medical Communications.

Reference

1. Practice Advisory on Codeine and Tramadol for Breastfeeding Women. April 27, 2017. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

Editor’s Note: This is the final installment of a six-part series that reviews key concepts and articles that ob.gyns. can use to prepare for the American Board of Obstetrics and Gynecology Maintenance of Certification examination. The series is adapted from Ob/Gyn Board Master (obgynboardmaster.com), an online board review course created by Erudyte. This month’s edition of the Board Corner focuses on narcotic analgesia for breastfeeding women.

The American College of Obstetrics and Gynecologists “Practice Advisories” are released when there is an important clinical issue that needs immediate attention from ob.gyn. clinicians. On April 27, 2017, ACOG joined with the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine and the Academy of Breastfeeding Medicine to issue a new practice advisory with recommendations on opiate analgesia in breastfeeding women.1 These Practice Advisories contain material that may be tested on a board exam. We recommend that you read this Practice Advisory and review it carefully.

A. Morphine IV

B. Butorphanol

C. Acetaminophen with codeine

D. Hydromorphone

E. Morphine (given orally)

The correct answer is C.

Acetaminophen with codeine (aka Tylenol #3 or Tylenol #4) is the least appropriate first-choice narcotic in a breastfeeding postpartum patient after Cesarean delivery as it is the only narcotic among the choices that is metabolized by the enzyme CYP2D6. Morphine, butorphanol, and hydromorphone are all metabolized by CYP450. If a narcotic is indicated, it is better to choose one that is not metabolized by CYP2D6 because of potential side effects in both mothers and infants who may be “CYP2D6 ultrametabolizers” or “CYP2D6 poor metabolizers.”

Key points

The key points to remember are:

1. Do not use codeine or tramadol as a first-line narcotic choice in breastfeeding mothers, if possible, because of variable side effects in mothers and infants.

2. The preferred narcotics to use when breastfeeding are butorphanol, morphine, or hydromorphone.

3. If codeine or tramadol is used in breastfeeding women, the clinician should speak with the patient and family about the possible side effects and the recent labeling changes required by the Food and Drug Administration.

Literature summary

In April, the Food and Drug Administration issued a safety alert and said it is requiring labeling changes for prescription medications containing codeine and tramadol. Specifically, the agency warned against use of codeine and tramadol when breastfeeding. This change is the result of the fact that certain people metabolize codeine and tramadol differently. There are some people – considered CYP2D6 “ultrarapid metabolizers” – who can have levels of the drug in their breast milk that can cause excessive sleepiness and depressed breathing in infants. There is one report of an infant death resulting from codeine use. The frequency of these “rapid metabolizers” is about 4%-5% in the United States.

In addition to the effects on breastfed infants, there are effects on the mother as well. This is because 6% of patients in the United States are “poor metabolizers” who have insufficient pain relief, as well as greater side effects.

Hydrocodone and oxycodone are not addressed in the recent labeling changes. However, “ultrarapid metabolizers” do show more pain relief and pupil restriction.

When comparing codeine with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications (NSAIDs) in abdominal surgery, nine randomized trials failed to show that codeine provided superior pain relief.

Hydromorphone, butorphanol, and morphine are not metabolized by CYP2D6 so the problems faced by “ultrarapid metabolizers” or “poor metabolizers” is not an issue.

Ob.gyns. should utilize regional anesthesia, NSAIDs, and acetaminophen (without codeine) to help decrease the risks of anesthesia while still ensuring adequate pain relief. Ob.gyns. should closely monitor their patients on narcotics for any side effects in both mothers and infants, especially central nervous system depression.

Dr. Kairis is an assistant professor in the department of gynecology and obstetrics at Loma Linda (Calif.) University Health and is the director of the Women’s Sexual Medicine Program there. She is on the editorial committee of the Ob/Gyn Board Master. Dr. Siddighi is editor in chief of the Ob/Gyn Board Master and director of female pelvic medicine and reconstructive surgery and director of grand rounds at Loma Linda University Health. Ob.Gyn. News and Ob/Gyn Board Master are owned by the same parent company, Frontline Medical Communications.

Reference

1. Practice Advisory on Codeine and Tramadol for Breastfeeding Women. April 27, 2017. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

CBO: Senate health care proposal marginally better than House-passed bill

The Senate health care proposal is only marginally better in terms of the number of uninsured Americans, compared with the House-passed bill it aims to replace, but it still would leave 22 million more Americans without insurance coverage, according to a June 26 analysis by the Congressional Budget Office.

The analysis raised voices of opposition from the medical community.

BCRA would lower the federal deficit by $321 billion between 2017-2026, driven by the dramatic cuts in spending on Medicaid (estimated to be $772 billion), as well as $408 billion saved from reduced tax credits and other subsidies to help people afford health insurance.

The CBO’s estimate also addresses how the bill could impact access to health care.

Initially, patients can expect another short-term spike in insurance premiums, with average premiums in 2018 increasing by 20%, compared with current law, “mainly because the penalty for not having insurance would be eliminated, inducing fewer comparatively healthy people to sign up.” In 2019, premiums are predicted to be about 10% higher than under current law; however, by 2020, premiums for benchmark plans would be 30% lower than with current law.

However, as premiums come down, deductibles would continue to rise for plans that would offer lower levels of coverage, according to the CBO report. Additionally, “starting in 2020, the premium for a silver plan would typically be a relatively high percentage of income for low income people. The deductible for a plan ... would be a significantly higher percentage of income – also making such a plan unattractive but for a different reason. As a result, despite being eligible for premium tax credits, few low-income people would purchase any plan.”

The report also notes that the Senate proposal would not necessarily reverse current concerns regarding consumer choice in the individual markets, stating that “a small fraction of the population resides in areas which – because of this legislation, for at least some of the years after 2019 – no insurers will participate in the nongroup market or insurance would be offered only with very high premiums.” Additionally, removing the employer mandate could result in employers forgoing offering health insurance to their employees.

The bill faces an uphill battle in the Senate as there seemingly are not enough votes to pass the bill at this time. The measure is using the budget reconciliation process, meaning it will need 50 of the 52 Senate Republicans to pass it (all 48 Democrats are expected to vote against it). At least six GOP senators have said they are not ready to start debate. Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-Ky) will not present the bill to the chamber for consideration until after the July 4 recess in an effort to tweak the language to garner the 50 votes needed to pass.*

Medical societies are pushing back against the bill as well.

The American Medical Association, in a letter to Senate leaders, notes that the first principal that medical professionals operate under is to do no harm. “The draft legislation violates that standard on many levels,” according to the AMA letter.

The American Osteopathic Association reiterated its objections to BCRA in a statement, citing the CBO’s determination that 22 million would lose coverage.

“As patient advocates, we cannot accept that under [BCRA] patients in need will no longer have the coverage they require to access health care services,” the association said in a statement. “The BCRA does nothing to control health costs but instead focuses on reducing federal health care expenditures by cutting coverage of our nation’s most vulnerable individuals and eliminating policies that promote access to preventive care services that can actually drive down expenses while improving patient outcomes.”

The American College of Cardiology noted that CBO analysis “makes it clear that the [BCRA] would lead to loss of coverage for millions of Americans and limit access to care for our most vulnerable populations. ... The ACC opposes the BCRA as it does not align with our Principles for Health Reform, which stress the need for patient access to meaningful insurance coverage and high-quality care.”

*This article was updated on June 27, 2017.

The Senate health care proposal is only marginally better in terms of the number of uninsured Americans, compared with the House-passed bill it aims to replace, but it still would leave 22 million more Americans without insurance coverage, according to a June 26 analysis by the Congressional Budget Office.

The analysis raised voices of opposition from the medical community.

BCRA would lower the federal deficit by $321 billion between 2017-2026, driven by the dramatic cuts in spending on Medicaid (estimated to be $772 billion), as well as $408 billion saved from reduced tax credits and other subsidies to help people afford health insurance.

The CBO’s estimate also addresses how the bill could impact access to health care.

Initially, patients can expect another short-term spike in insurance premiums, with average premiums in 2018 increasing by 20%, compared with current law, “mainly because the penalty for not having insurance would be eliminated, inducing fewer comparatively healthy people to sign up.” In 2019, premiums are predicted to be about 10% higher than under current law; however, by 2020, premiums for benchmark plans would be 30% lower than with current law.

However, as premiums come down, deductibles would continue to rise for plans that would offer lower levels of coverage, according to the CBO report. Additionally, “starting in 2020, the premium for a silver plan would typically be a relatively high percentage of income for low income people. The deductible for a plan ... would be a significantly higher percentage of income – also making such a plan unattractive but for a different reason. As a result, despite being eligible for premium tax credits, few low-income people would purchase any plan.”

The report also notes that the Senate proposal would not necessarily reverse current concerns regarding consumer choice in the individual markets, stating that “a small fraction of the population resides in areas which – because of this legislation, for at least some of the years after 2019 – no insurers will participate in the nongroup market or insurance would be offered only with very high premiums.” Additionally, removing the employer mandate could result in employers forgoing offering health insurance to their employees.

The bill faces an uphill battle in the Senate as there seemingly are not enough votes to pass the bill at this time. The measure is using the budget reconciliation process, meaning it will need 50 of the 52 Senate Republicans to pass it (all 48 Democrats are expected to vote against it). At least six GOP senators have said they are not ready to start debate. Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-Ky) will not present the bill to the chamber for consideration until after the July 4 recess in an effort to tweak the language to garner the 50 votes needed to pass.*

Medical societies are pushing back against the bill as well.

The American Medical Association, in a letter to Senate leaders, notes that the first principal that medical professionals operate under is to do no harm. “The draft legislation violates that standard on many levels,” according to the AMA letter.

The American Osteopathic Association reiterated its objections to BCRA in a statement, citing the CBO’s determination that 22 million would lose coverage.

“As patient advocates, we cannot accept that under [BCRA] patients in need will no longer have the coverage they require to access health care services,” the association said in a statement. “The BCRA does nothing to control health costs but instead focuses on reducing federal health care expenditures by cutting coverage of our nation’s most vulnerable individuals and eliminating policies that promote access to preventive care services that can actually drive down expenses while improving patient outcomes.”

The American College of Cardiology noted that CBO analysis “makes it clear that the [BCRA] would lead to loss of coverage for millions of Americans and limit access to care for our most vulnerable populations. ... The ACC opposes the BCRA as it does not align with our Principles for Health Reform, which stress the need for patient access to meaningful insurance coverage and high-quality care.”

*This article was updated on June 27, 2017.

The Senate health care proposal is only marginally better in terms of the number of uninsured Americans, compared with the House-passed bill it aims to replace, but it still would leave 22 million more Americans without insurance coverage, according to a June 26 analysis by the Congressional Budget Office.

The analysis raised voices of opposition from the medical community.

BCRA would lower the federal deficit by $321 billion between 2017-2026, driven by the dramatic cuts in spending on Medicaid (estimated to be $772 billion), as well as $408 billion saved from reduced tax credits and other subsidies to help people afford health insurance.

The CBO’s estimate also addresses how the bill could impact access to health care.

Initially, patients can expect another short-term spike in insurance premiums, with average premiums in 2018 increasing by 20%, compared with current law, “mainly because the penalty for not having insurance would be eliminated, inducing fewer comparatively healthy people to sign up.” In 2019, premiums are predicted to be about 10% higher than under current law; however, by 2020, premiums for benchmark plans would be 30% lower than with current law.

However, as premiums come down, deductibles would continue to rise for plans that would offer lower levels of coverage, according to the CBO report. Additionally, “starting in 2020, the premium for a silver plan would typically be a relatively high percentage of income for low income people. The deductible for a plan ... would be a significantly higher percentage of income – also making such a plan unattractive but for a different reason. As a result, despite being eligible for premium tax credits, few low-income people would purchase any plan.”

The report also notes that the Senate proposal would not necessarily reverse current concerns regarding consumer choice in the individual markets, stating that “a small fraction of the population resides in areas which – because of this legislation, for at least some of the years after 2019 – no insurers will participate in the nongroup market or insurance would be offered only with very high premiums.” Additionally, removing the employer mandate could result in employers forgoing offering health insurance to their employees.

The bill faces an uphill battle in the Senate as there seemingly are not enough votes to pass the bill at this time. The measure is using the budget reconciliation process, meaning it will need 50 of the 52 Senate Republicans to pass it (all 48 Democrats are expected to vote against it). At least six GOP senators have said they are not ready to start debate. Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-Ky) will not present the bill to the chamber for consideration until after the July 4 recess in an effort to tweak the language to garner the 50 votes needed to pass.*

Medical societies are pushing back against the bill as well.

The American Medical Association, in a letter to Senate leaders, notes that the first principal that medical professionals operate under is to do no harm. “The draft legislation violates that standard on many levels,” according to the AMA letter.

The American Osteopathic Association reiterated its objections to BCRA in a statement, citing the CBO’s determination that 22 million would lose coverage.

“As patient advocates, we cannot accept that under [BCRA] patients in need will no longer have the coverage they require to access health care services,” the association said in a statement. “The BCRA does nothing to control health costs but instead focuses on reducing federal health care expenditures by cutting coverage of our nation’s most vulnerable individuals and eliminating policies that promote access to preventive care services that can actually drive down expenses while improving patient outcomes.”

The American College of Cardiology noted that CBO analysis “makes it clear that the [BCRA] would lead to loss of coverage for millions of Americans and limit access to care for our most vulnerable populations. ... The ACC opposes the BCRA as it does not align with our Principles for Health Reform, which stress the need for patient access to meaningful insurance coverage and high-quality care.”

*This article was updated on June 27, 2017.

Impact of an inspirational training director on a resident’s life

The term psychiatry is derived from the Greek words “pskhe” and “iatreia” which mean “healing of the soul.”1 The desire to heal souls from different ethnicities, religions, and languages can be overwhelming for a trainee resident who is new to U.S. culture. The fear of having difficulty in building rapport with patients because of cultural bias and the dread of not understanding accents, slang, jokes, and nonverbal communication can be so frustrating that it overrides the intense desire of becoming an empathetic and successful physician.2 Du

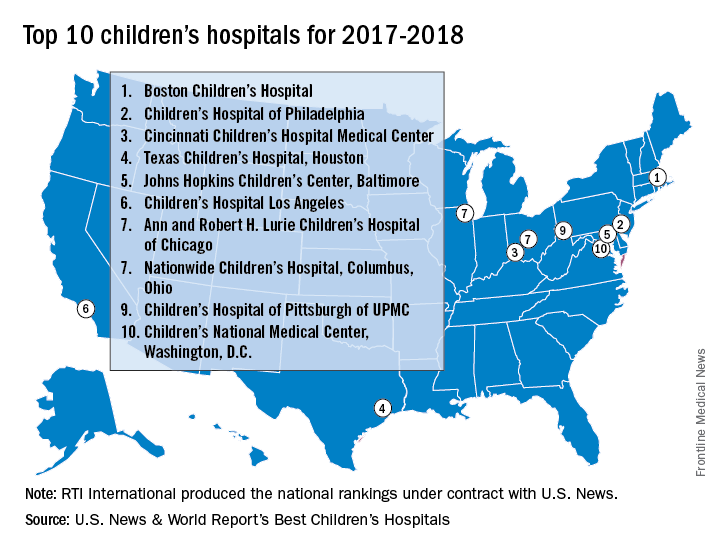

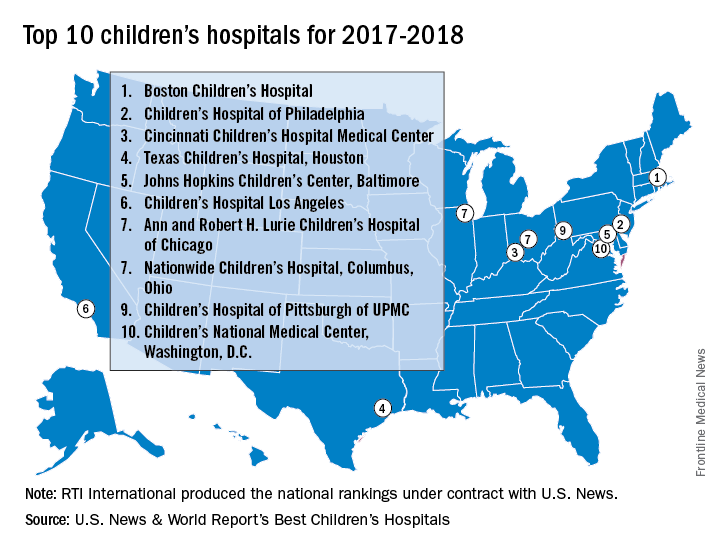

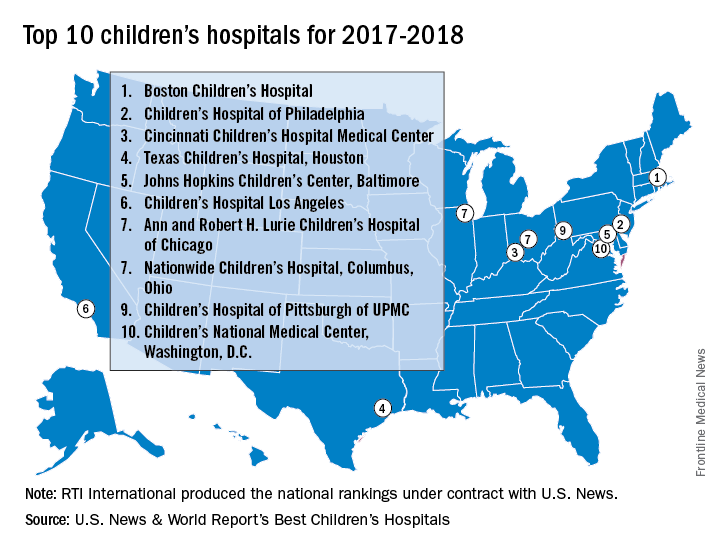

I started my residency training in 2014 without any substantial scholarly work in my background or clinical experience in the United States. However, I had a great learning experience at my training program and would like to express my gratitude by recognizing my program director’s (Panagiota Korenis, MD) role in helping me accomplish my career goals. She believed in me when I was not able to believe in myself, and helped me overcome a helpless feeling of isolation and desperation during my intern year. Because of her mentorship and supervision, I presented 20 posters and oral presentations; published 5 works; drafted guidelines for training residents, including course material on the health care disparities faced by the Lesbian, Gay Bisexual, Transgender, Queer community; created a tool to predict readmissions in an inpatient psychiatric setting; received many prestigious awards, including Resident of the Year, a Certificate of Academic Excellence, a Young Scholar Award, and an American Psychiatric Association Diversity Leadership Fellowship for 2017-2019; and was accepted for a child and adolescent psychiatry fellowship in one of my dream programs, Boston Children’s Hospital.

I strongly believe that the impact of an inspiring, motivating, and encouraging program director on a resident’s life is monumental. Here are some of the qualities I believe make a great program director who can significantly transform a trainee’s life:

A positive attitude.

- Encourage trainees to believe in their abilities, even if they stumble.

- Unleash and nurture their talents, and help them recognize their strengths and confidence.

- Foster a warm, welcoming, and supportive environment that enables residents to strive to reach their potential and goals.

- Boost confidence, acknowledge genuine efforts, and praise achievements.

- Encourage involvement in future projects.

Empathy and generosity.

- Treat residents with respect and care, while recognizing their strengths and weaknesses.

- Understand them at both a professional and personal level.

- Support meaningful and suitable projects that residents are passionate about and at which they excel.

- Influence residents by helping them understand the impact they have on patients and the program.

- Demonstrate sensitivity to the individual needs of each resident and provide constructive feedback.

Easy accessibility.

- Build good rapport with residents.

- Listen carefully to the residents’ ideas and feedback.

- Reassure residents that they can ask any questions or raise any issues they want to address.

Leadership.

- Color/BlackUndertake a leadership role within multidisciplinary teams, and collaborate effectively with other medical specialties for continuity of care, mutual support, Color/Blackand interdisciplinary education and communication.

- Assert authority when needed, and make important decisions for the program.

- Manage conflicts effectively and timely.

- Strictly monitor duty hours.3

Education.

- Design an educational curriculum relevant to all clinical settings.

- Provide protected time for didactics and scholarlyColor/Black activities.

- Ensure that residents develop a comprehensive understanding of the field.

- Actively involve residents in teaching, and modify the curriculum based on residents’ input and feedback.

- Schedule classes for in-service exams (eg, Psychiatry Residency In-Service Training Exam) and for the board exam preparation.4

- Promote residents’ autonomy and sense of competence.

Promote residents well-being.

- Encourage a work–life balance.

- Focus on team building and communication, and organize process groups.

- Adopt innovative ways to enable residents in managing stress.

- Organize social events and group activities, and provide support groups.

- Ensure adequate sleep hours and time away from work to prevent burnout.

Career development.

- Provide career guidance, and connect residents to appropriate resources for further professional development.

- Recognize that mentoring is a lifelong activity that does not end with the completion of residency training.

1. Gilman DC, Peck HT, Colby FM, eds. The new international encyclopedia. Vol 16. New York, NY: Dodd, Mead and Company; 2000:505.

2. Saeed F, Majeed MH, Kousar N. Easing international medical graduates’ entry into US training. J Grad Med Educ. 2011;3(2):269.

3. Johnson V. A resitern’s reflection on duty-hours reform. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(24):2278-2279.

4. Association of American Medical Colleges. Defining the key elements of an optimal residency program. https://www.aamc.org/download/84544/data/definekeyelements.pdf. Published May 2001. Accessed June 7, 2017.

The term psychiatry is derived from the Greek words “pskhe” and “iatreia” which mean “healing of the soul.”1 The desire to heal souls from different ethnicities, religions, and languages can be overwhelming for a trainee resident who is new to U.S. culture. The fear of having difficulty in building rapport with patients because of cultural bias and the dread of not understanding accents, slang, jokes, and nonverbal communication can be so frustrating that it overrides the intense desire of becoming an empathetic and successful physician.2 Du

I started my residency training in 2014 without any substantial scholarly work in my background or clinical experience in the United States. However, I had a great learning experience at my training program and would like to express my gratitude by recognizing my program director’s (Panagiota Korenis, MD) role in helping me accomplish my career goals. She believed in me when I was not able to believe in myself, and helped me overcome a helpless feeling of isolation and desperation during my intern year. Because of her mentorship and supervision, I presented 20 posters and oral presentations; published 5 works; drafted guidelines for training residents, including course material on the health care disparities faced by the Lesbian, Gay Bisexual, Transgender, Queer community; created a tool to predict readmissions in an inpatient psychiatric setting; received many prestigious awards, including Resident of the Year, a Certificate of Academic Excellence, a Young Scholar Award, and an American Psychiatric Association Diversity Leadership Fellowship for 2017-2019; and was accepted for a child and adolescent psychiatry fellowship in one of my dream programs, Boston Children’s Hospital.

I strongly believe that the impact of an inspiring, motivating, and encouraging program director on a resident’s life is monumental. Here are some of the qualities I believe make a great program director who can significantly transform a trainee’s life:

A positive attitude.

- Encourage trainees to believe in their abilities, even if they stumble.

- Unleash and nurture their talents, and help them recognize their strengths and confidence.

- Foster a warm, welcoming, and supportive environment that enables residents to strive to reach their potential and goals.

- Boost confidence, acknowledge genuine efforts, and praise achievements.

- Encourage involvement in future projects.

Empathy and generosity.

- Treat residents with respect and care, while recognizing their strengths and weaknesses.

- Understand them at both a professional and personal level.

- Support meaningful and suitable projects that residents are passionate about and at which they excel.

- Influence residents by helping them understand the impact they have on patients and the program.

- Demonstrate sensitivity to the individual needs of each resident and provide constructive feedback.

Easy accessibility.

- Build good rapport with residents.

- Listen carefully to the residents’ ideas and feedback.

- Reassure residents that they can ask any questions or raise any issues they want to address.

Leadership.

- Color/BlackUndertake a leadership role within multidisciplinary teams, and collaborate effectively with other medical specialties for continuity of care, mutual support, Color/Blackand interdisciplinary education and communication.

- Assert authority when needed, and make important decisions for the program.

- Manage conflicts effectively and timely.

- Strictly monitor duty hours.3

Education.

- Design an educational curriculum relevant to all clinical settings.

- Provide protected time for didactics and scholarlyColor/Black activities.

- Ensure that residents develop a comprehensive understanding of the field.

- Actively involve residents in teaching, and modify the curriculum based on residents’ input and feedback.

- Schedule classes for in-service exams (eg, Psychiatry Residency In-Service Training Exam) and for the board exam preparation.4

- Promote residents’ autonomy and sense of competence.

Promote residents well-being.

- Encourage a work–life balance.

- Focus on team building and communication, and organize process groups.

- Adopt innovative ways to enable residents in managing stress.

- Organize social events and group activities, and provide support groups.

- Ensure adequate sleep hours and time away from work to prevent burnout.

Career development.

- Provide career guidance, and connect residents to appropriate resources for further professional development.

- Recognize that mentoring is a lifelong activity that does not end with the completion of residency training.

The term psychiatry is derived from the Greek words “pskhe” and “iatreia” which mean “healing of the soul.”1 The desire to heal souls from different ethnicities, religions, and languages can be overwhelming for a trainee resident who is new to U.S. culture. The fear of having difficulty in building rapport with patients because of cultural bias and the dread of not understanding accents, slang, jokes, and nonverbal communication can be so frustrating that it overrides the intense desire of becoming an empathetic and successful physician.2 Du

I started my residency training in 2014 without any substantial scholarly work in my background or clinical experience in the United States. However, I had a great learning experience at my training program and would like to express my gratitude by recognizing my program director’s (Panagiota Korenis, MD) role in helping me accomplish my career goals. She believed in me when I was not able to believe in myself, and helped me overcome a helpless feeling of isolation and desperation during my intern year. Because of her mentorship and supervision, I presented 20 posters and oral presentations; published 5 works; drafted guidelines for training residents, including course material on the health care disparities faced by the Lesbian, Gay Bisexual, Transgender, Queer community; created a tool to predict readmissions in an inpatient psychiatric setting; received many prestigious awards, including Resident of the Year, a Certificate of Academic Excellence, a Young Scholar Award, and an American Psychiatric Association Diversity Leadership Fellowship for 2017-2019; and was accepted for a child and adolescent psychiatry fellowship in one of my dream programs, Boston Children’s Hospital.

I strongly believe that the impact of an inspiring, motivating, and encouraging program director on a resident’s life is monumental. Here are some of the qualities I believe make a great program director who can significantly transform a trainee’s life:

A positive attitude.

- Encourage trainees to believe in their abilities, even if they stumble.

- Unleash and nurture their talents, and help them recognize their strengths and confidence.

- Foster a warm, welcoming, and supportive environment that enables residents to strive to reach their potential and goals.

- Boost confidence, acknowledge genuine efforts, and praise achievements.

- Encourage involvement in future projects.

Empathy and generosity.

- Treat residents with respect and care, while recognizing their strengths and weaknesses.

- Understand them at both a professional and personal level.

- Support meaningful and suitable projects that residents are passionate about and at which they excel.

- Influence residents by helping them understand the impact they have on patients and the program.

- Demonstrate sensitivity to the individual needs of each resident and provide constructive feedback.

Easy accessibility.

- Build good rapport with residents.

- Listen carefully to the residents’ ideas and feedback.

- Reassure residents that they can ask any questions or raise any issues they want to address.

Leadership.

- Color/BlackUndertake a leadership role within multidisciplinary teams, and collaborate effectively with other medical specialties for continuity of care, mutual support, Color/Blackand interdisciplinary education and communication.

- Assert authority when needed, and make important decisions for the program.

- Manage conflicts effectively and timely.

- Strictly monitor duty hours.3

Education.

- Design an educational curriculum relevant to all clinical settings.

- Provide protected time for didactics and scholarlyColor/Black activities.

- Ensure that residents develop a comprehensive understanding of the field.

- Actively involve residents in teaching, and modify the curriculum based on residents’ input and feedback.

- Schedule classes for in-service exams (eg, Psychiatry Residency In-Service Training Exam) and for the board exam preparation.4

- Promote residents’ autonomy and sense of competence.

Promote residents well-being.

- Encourage a work–life balance.

- Focus on team building and communication, and organize process groups.

- Adopt innovative ways to enable residents in managing stress.

- Organize social events and group activities, and provide support groups.

- Ensure adequate sleep hours and time away from work to prevent burnout.

Career development.

- Provide career guidance, and connect residents to appropriate resources for further professional development.

- Recognize that mentoring is a lifelong activity that does not end with the completion of residency training.

1. Gilman DC, Peck HT, Colby FM, eds. The new international encyclopedia. Vol 16. New York, NY: Dodd, Mead and Company; 2000:505.

2. Saeed F, Majeed MH, Kousar N. Easing international medical graduates’ entry into US training. J Grad Med Educ. 2011;3(2):269.

3. Johnson V. A resitern’s reflection on duty-hours reform. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(24):2278-2279.

4. Association of American Medical Colleges. Defining the key elements of an optimal residency program. https://www.aamc.org/download/84544/data/definekeyelements.pdf. Published May 2001. Accessed June 7, 2017.

1. Gilman DC, Peck HT, Colby FM, eds. The new international encyclopedia. Vol 16. New York, NY: Dodd, Mead and Company; 2000:505.

2. Saeed F, Majeed MH, Kousar N. Easing international medical graduates’ entry into US training. J Grad Med Educ. 2011;3(2):269.

3. Johnson V. A resitern’s reflection on duty-hours reform. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(24):2278-2279.

4. Association of American Medical Colleges. Defining the key elements of an optimal residency program. https://www.aamc.org/download/84544/data/definekeyelements.pdf. Published May 2001. Accessed June 7, 2017.

Peer Support for Whistleblowers

Whistleblowers report illegalities, improprieties, or injustices. They step forward wittingly or unwittingly to report perceived wrongdoing. But when a whistleblower takes on powerful and entrenched systems or people, retribution and retaliation often ensue, endangering their career and reputation. These negative consequences can have longterm impacts on the lives of those who believed they were acting in the public interest especially when patient care or public safety was at risk.

The following account is based on personal and professional experiences, conversations with more than a dozen other whistleblowers at the DoD, VA, several other organizations, and a literature review. This documentation of those informal peer conversations, combined with the research, is meant to provide insight into the experiences of a whistleblower and the need for peer support so that employees can remain resilient.

Adverse Whistleblower Experiences

Most employees do not set out to be whistleblowers. The process begins when the whistleblower perceives wrongdoing or harm that is being committed in their workplace. At a health care organization, whistleblowing often is focused on individual or organizational illegal or unethical activities, such as funding or contracting fraud, corruption, theft, discrimination, sexual harassment, public health safety or security violations, persistent medical errors, nepotism, or other violations of workplace rules and regulations. VA employees who experience, witness, or discover wrongdoing may choose to disclose their concerns to a supervisor, senior leader, the Office of the Inspector General (OIG), Human Resources or Equal Employment Opportunity (EEO) Office, Employee Assistance Program (EAP), Office of Special Counsel (OSC), Congress, or to a news organization.

According to the 2013 National Business Ethics Survey, more than 6 million American workers who reported misconduct experienced some form of retaliation.1,2 Retribution can manifest in various overt or covert ways, ranging from outright retaliation and further discrimination to other forms of marginalization. For example, a VA physician alleged that he was detailed to an empty office with no patients after reporting patient wait list mismanagement at his hospital. Other whistleblowers report having misconduct charges levied against them, demotions or loss of position, obstruction from promotion, poor performance evaluations, details to more minor assignments, relocation to more meager office space, or pressure to resign or retire.3

Whistleblowers are rarely rewarded for reporting misconduct within their organization. The Joint Commission describes barriers to reporting sentinel events by medical professionals fearing humiliation, litigation, peer pressure, and oversight investigations if they identify medical errors.4

Once allegations are made, the information often is conveyed to a supervisor or leader. For example, some whistleblowers who have reported a hostile work environment to the DoD EAP have noted that the EAP representative contacted the whistleblower’s manager to mediate the situation. This process can take months or years to resolve. In those instances, the managers are rarely relocated. The whistleblower usually is the one forced to move or take another job, which is not always consistent with their job description, and in turn, may impact their performance rating and opportunities for promotion.

Often, OIG and OSC investigations at the VA and other federal agencies can take as long as 2 years. During that time the whistleblower may remain in a lesser or unwanted position or leave the agency. However, even when OIG substantiates claims of wrongdoing, the agency can make recommendations only to leadership, which may or may not be enacted. Whistleblowers report having to submit Freedom of Information Act requests to learn of the outcome of an OIG investigation when leadership chooses to ignore the recommendation.

Civilian government employees are undervalued by society in general, and the negative stereotypes of lazy, shiftless workers abound, even though many civil servants work to protect the nation’s health, welfare, and safety. Civil servants are familiar with derogatory expressions, such as “bureaucratic bean-counter,” and “good enough for government work.” Even President Trump stated that he would come to Washington, DC, and “drain the swamp.” Yet civil servants can go years without a cost of living increase, a promotion, or a bonus but still be asked to perform additional duties or work long hours to the sacrifice of a work/life balance.

In the Federal Employee Viewpoints Survey and other employee environmental climate scans, high levels of workforce stress often are related to the number of grievances filed, the level of morale, the rates of absenteeism and retention, recruitment shortages, and lost productivity.5 Success in toxic environments usually is based on trying to maintain a “go along to get along” status quo, which means looking the other way when contracts are fraudulently awarded or employee discrimination occurs. If leadership is antagonistic to reform, then identifying wrongdoing may come at significant personal risk.

Retaliatory Practices

Once a whistleblower has stepped forward, retaliatory practices may follow. There are tangible legal, financial, social, emotional, and physical tolls to whistleblowing. “Be in for a penny. Be in for a pound,” an OIG official advised one whistleblower. Once a disclosure is made, the process may become arduous for the whistleblower and require individual resilience to face adversity.

Keeping in mind that OIG, EEO, EAP, and OSC are government agencies that investigate, police, and monitor the system, they do not represent the civil servants who document and identify much of the evidence of wrongdoing on their own. Most civil service employees are not subject matter experts on the U.S. legal code that outlines prohibited personal practices or the Federal Acquisition Regulation.

The Notification and Federal Employee Antidiscrimination and Retaliation (NO FEAR) Act authorized in 2002 (U.S. Code § 2301) is designed to inform and protect those who file grievances or disclosures, but operationalizing those protections can be overwhelming and confusing. If a whistleblower wants advice, he or she must retain legal counsel often at a substantial personal cost. Whistleblowers report spending from $10,000 to more than $100,000 in legal fees for a 1- to 2-year investigation.

These legal fees may force whistleblowers to use family finances or borrow money while hoping for justice along with remuneration in the end. In some cases, the financial impact is compounded when the whistleblower has been demoted, denied a promotion, or fired. For medical professionals, the impact might result in the loss of hospital privileges, professional credentials, or state licensure. The loss of income also can lead to loss of health insurance. The legal and financial burdens impact marriages, spousal job options, retirement, and other family choices (eg, vacations, children’s schools, and caregiving obligations).

During investigations, social status and the reputation of the whistleblower are often impugned. For example, whistleblowers are sometimes depicted as snitches, moles, spies, or tattletales and may be categorized as paranoid, disloyal, or disgruntled by leadership. Rarely are whistleblowers labeled protectors, patriots, or heroes, despite the few high profile cases that come to light, such as Karen Silkwood, Erin Brockovich, or Frank Serpico.

More often, whistleblowers’ reputations, especially in civil sectors, are damaged through acts of discrimination, such as bullying; mobbing (asking other employees to monitor and report on the activities of the whistleblower); ostracizing the employee from the team; devaluing the contributions or the performance of the whistleblower; blackballing from other jobs or opportunities; doublebinding with difficult tasks to complete; gaslighting by calling into question the memory of the whistleblower, the reality of the accusation, or its scope; and marginalization. Accusations of misusing funds, inaccurately recording time and attendance, and disputing their judgement are all tactics used to socially isolate and harass whistleblowers into dropping their case or leaving the organization.3

Furthermore, this level of ostracism has documented impact on the psychological and physical well-being of the employee and negative consequences to the overall functioning of the organization.6 Consequences, such as physical violence and property damage at the time of termination and at other betrayals have occurred.3,7 Other whistleblowers have reported being threatened in person or on social media, harassed, and assaulted, especially in the military.

Whistleblowers, similar to others who are bullied in the workplace often described feelings such as fear, depression, anxiety, loneliness, and humiliation.8 These feelings can lead to whistleblowers needing treatment for substance abuse, depression, anxiety, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and suicidal ideation.9 Multiple studies on depression and PTSD show a correlation to increased morbidity and mortality.10 However, whistleblowing retaliation is not clearly established as a traumatic stressor in relation to PTSD.11

Insomnia and other sleep disturbances are not uncommon among whistleblowers who also note they have resorted to smoking, overeating, alcohol misuse, or medication to manage their distress. Health consequences also include migraines, muscle tension, gastrointestinal conditions, increased blood pressure, and cardiovascular disease.12

Peer Support Models

Studies of peer-to-peer programs for veterans, law enforcement officers, widows, cancer patients, disaster victims, and others bound by survivorship suggest that peer groups can be an effective means of support, even though the model may vary or be adapted to a specific population. In general, peer support is centered on a common experience, shared credibility, confidentiality, and trust. The approach is meant to provide nonjudgmental support that assists with decision making and resilience and provides comfort and hope. Most peer support or mentorship models require some level of peer counselor screening, competency training on an intervention model, supervision, monitoring, and case management by a more senior or credentialed mental health professional.13

The Defense Centers of Excellence for Psychological Health and Traumatic Brain Injury (DCoE) recognized that health care systems that support civil servants, military members, and veterans can benefit from partnerships with internal (eg, human resources, unions, or dedicated EAP) or external (eg, nonprofit and service organizations) employee peer support programs. The DCoE noted that peer networks facilitate referrals to medical care when threats of suicide or harm to others exists, offer additional case management support, and assist professionals in understanding the patient experience.13

Peer support offered at VA hospitals is conducted by peers who are supervised by mental health clinic staff (usually social workers).14 Law enforcement EAP is another example of peer support within an organization to augment mental health and resilience among officers who have experienced first-responder trauma.

External peer support resources can be accessed through partnerships or referrals. For example, the Tragedy Assistance Program for Survivors (TAPS) relies on survivors of military deaths to support each other through bereavement. Although the DoD offers casualty assistance and mental health care to grieving families, the level of peer support differs from TAPS.15 In another example, Castellano documented the benefits of a reciprocal peer support model implemented across 10 peer-based call center programs that manage high risk-populations.16 Core training was consistent across all programs, and mental health professionals supervised call center peer support providers. This peer/clinician collaboration enhances the overall community mental health efforts.

Temple University documented the patient care benefits for behavioral health services that augmented treatment with evidence-based peer support interventions.17 The researchers found that hospitals that used a peer model improved patient outcomes as demonstrated by fewer hospitalizations, increased life satisfaction and enhanced coping skills, increased medication adherence, and reduced substance abuse or suicidal ideation. Additionally, the peer providers themselves experienced positive health benefits based on their ability to help others, improved their own self-efficacy and gained social and economic growth based on their employment satisfaction.17

Peer Support Interventions

Peer support interventions have been effective with various populations and may be effective for whistleblowers as well. Since whistleblowing tends to involve legal processes that call for privacy and the confidentiality of all parties, whistleblowers experience isolation and alienation. Other whistleblowers can better understand the retaliation, discrimination, and isolation that results. In some instances, whistleblowers discovered years later that other employees had similar experiences. An organized, structured program dedicated to peer support can help employees within a health care system or EAP manage the impacts of identifying wrongdoing.18 Peers may be able to break down this isolation and help establish a new network of support for those involved in whistleblowing cases. Restoring a sense of purpose, meaning, and belonging in the workplace is of significant value for the whistleblower.19 Peers can mentor a whistleblower through the investigative process and help determine next steps. Peers can address building, maintaining, and sustaining resilience to overcome adversity.

Peers who already have experienced their own legal, financial, social, emotional, and physical risks and have developed the necessary resiliency skills to survive make ideal peer counselors.20 These peers have faced similar challenges but have perservered.21

Although peer counselors cannot replace an attorney or mental health provider, they can provide background information on the roles and functions of EEO, EAP, OIG, OSC, and the MSPB and how to navigate those systems. Peers can assist whistleblowers in preparing testimony before congressional hearings or for press interviews. Peer supporters also can encourage whistleblowers to seek care for mental and physical health care and to remain adherent to treatment regimens. They case manage a team effort to enable the whistleblower to overcome the adversity of retaliation.

Creating A New Normal

After the Civil War, the False Claims Act, known as the Lincoln Law, served to protect federal reconstruction activities in the South from individuals who attempted to defraud the federal government.22 Today, most Americans are familiar with WikiLeaks. For generations, whistleblowers have exposed wrongdoing in order to protect or reform governmen programs. Whistleblowers have exposed graft and corruption at the highest levels and in daily operations. They have fought for diversity and inclusion and a workplace free of sexual harassment and assault. They have protected taxpayer dollars from waste, fraud, and abuse.

Despite the personal sacrifices often required, most whistleblowers’ spirits are bolstered by the positive outcomes that their disclosures may produce. However, whistleblowers need compassionate and competent assistance throughout the process. Peers can foster the resilience needed to survive the adversarial nature of the whistleblowing process. Therefore, whistleblowers need to be viewed in a new light that involves advocacy, transparency, and peer support so that positive outcomes in government can be realized for all Americans.

1. Ethics and Compliance Initiative. National Business Ethics Survey (NBES) 2013. http://www.ethics.org/ecihome/research/nbes/nbes-reports/nbes-2013. Published 2013. Accessed June 5, 2017.

2. Schnell G. Whistleblower retaliation on the rise—bad news for whistleblowers and their employers alike. http://constantinecannon.com/whistleblower/whistleblower-retaliation-on-the-rise-bad-news-for-whistleblowers-and-their-employers-alike/#.WNJ1s4WcEYh. Published January 18, 2013. Accessed June 5, 2017.

3. Devine T, Maassarani T. The Corporate Whistleblower’s Survival Guide: A Handbook for Committing the Truth. San Francisco, CA. Berrett-Koehler Publishers; 2011:19-40.

4. The Joint Commission. What Every Hospital Should Know About Sentinel Events. Oakbrook Terrace, IL: Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations; 2000.

5. Reed GE. Tarnished: Toxic Leadership in the U.S. Military. Lincoln, NE; University of Nebraska Press, Potomac Books; 2015:60.

6. McGraw K. Mental health of women warriors: the power of belonging. In: Ritchie EC, Naclerio AL, eds. Women at War. New York, NY. Oxford University Press; 2015:311-320.

7. Blythe B. Blindsided: A Manager’s Guide to Catastrophic Incidents in the Workplace. New York, NY: Penguin Group; 2002:136-145.

8. Dehue F, Bolman C, Völlink T, Pouwelse M. Coping with bullying at work and health related problems. Int J Stress Manage. 2012;19(3):175-197.

9. Panagioti M, Gooding PA, Dunn G, Tarrier N. Pathways to suicidal behavior in posttraumatic stress disorder. J Trauma Stress. 2011;24(2):137-145.

10. World Health Organization. Meeting report on excess mortality in persons with severe mental disorders. November 18-20, 2015. https://www.fountainhouse.org/sites/default/files/ExcessMortalityMeetingReport.pdf. Accessed June 6, 2017.

11. American Psychiatric Association. Trauma- and Stressor-Related Disorders. In: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th Edition. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association;2013:265-268, 749-750.

12. Ford DE. Depression, trauma, and cardiovascular health. In: Schnurr PP, Green BL, eds. Trauma and Health: Physical Health Consequences of Exposure to Extreme Stress. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2004:chap 4.

13. Defense Centers of Excellence for Psychological Health and Traumatic Brain Injury. Best practices identified for peer support programs. http://www.dcoe.mil/file/Best_Practices_Identified_for_Peer_Support_Programs_Jan_2011.pdf. Published January 2011. Accessed June 6, 2017.

14. O’Brian-Mazza D, Zimmerman J. The power of peer support: VHA mental health services. https://www.mentalhealth.va.gov/docs/peersupport.pdf. Published September 21, 2012. Accessed June 6, 2017.

15. Bartone PT. Peer support for bereaved survivors: systematic review of evidence and identification of best practices. https://www.taps.org/globalassets/pdf/about-taps/tapspeersupportreport2016.pdf. Published January 2017. Accessed June 6, 2017.

16. Castellano C. Reciprocal peer support (RPS): a decade of not so random acts of kindness. Int J Emerg Ment Health. 2012;14(2):105-110.

17. Salzer M. Consumer-delivered services as a best practice in mental health care delivery and the development of practice guidelines. http://www.cdsdirectory.org/SalzeretalBPPS2002.pdf. Published 2002. Accessed June 14, 2017.

18. Robinson R, Murdoch P. Establishing and Maintaining Peer Support Programs in the Workplace. 3rd ed. Ellicott City, MD: Chevron Publishing Corporation; 2003:1-24.

19. Baron SA. Violence in the Workplace: A Prevention and Management Guide for Businesses. Ventura, CA: Pathfinding Publishing; 1995:99-106.

20. Southwick SM, Charney DS. Social support: learning the Tap Code. In: Resilience: The Science of Mastering Life’s Greatest Challenges. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press; 2012:100-114.

21. Creamer MC, Varker T, Bisson J, et al. Guidelines for peer support in high-risk organizations: an international consensus study using Delphi method. J Trauma Stress. 2012;25(2):134-141.

22. Downs RB. Afterword. In: Sinclair U. The Jungle. New York, NY. Signet Classics; 1906:343-350.

Whistleblowers report illegalities, improprieties, or injustices. They step forward wittingly or unwittingly to report perceived wrongdoing. But when a whistleblower takes on powerful and entrenched systems or people, retribution and retaliation often ensue, endangering their career and reputation. These negative consequences can have longterm impacts on the lives of those who believed they were acting in the public interest especially when patient care or public safety was at risk.

The following account is based on personal and professional experiences, conversations with more than a dozen other whistleblowers at the DoD, VA, several other organizations, and a literature review. This documentation of those informal peer conversations, combined with the research, is meant to provide insight into the experiences of a whistleblower and the need for peer support so that employees can remain resilient.

Adverse Whistleblower Experiences

Most employees do not set out to be whistleblowers. The process begins when the whistleblower perceives wrongdoing or harm that is being committed in their workplace. At a health care organization, whistleblowing often is focused on individual or organizational illegal or unethical activities, such as funding or contracting fraud, corruption, theft, discrimination, sexual harassment, public health safety or security violations, persistent medical errors, nepotism, or other violations of workplace rules and regulations. VA employees who experience, witness, or discover wrongdoing may choose to disclose their concerns to a supervisor, senior leader, the Office of the Inspector General (OIG), Human Resources or Equal Employment Opportunity (EEO) Office, Employee Assistance Program (EAP), Office of Special Counsel (OSC), Congress, or to a news organization.

According to the 2013 National Business Ethics Survey, more than 6 million American workers who reported misconduct experienced some form of retaliation.1,2 Retribution can manifest in various overt or covert ways, ranging from outright retaliation and further discrimination to other forms of marginalization. For example, a VA physician alleged that he was detailed to an empty office with no patients after reporting patient wait list mismanagement at his hospital. Other whistleblowers report having misconduct charges levied against them, demotions or loss of position, obstruction from promotion, poor performance evaluations, details to more minor assignments, relocation to more meager office space, or pressure to resign or retire.3

Whistleblowers are rarely rewarded for reporting misconduct within their organization. The Joint Commission describes barriers to reporting sentinel events by medical professionals fearing humiliation, litigation, peer pressure, and oversight investigations if they identify medical errors.4

Once allegations are made, the information often is conveyed to a supervisor or leader. For example, some whistleblowers who have reported a hostile work environment to the DoD EAP have noted that the EAP representative contacted the whistleblower’s manager to mediate the situation. This process can take months or years to resolve. In those instances, the managers are rarely relocated. The whistleblower usually is the one forced to move or take another job, which is not always consistent with their job description, and in turn, may impact their performance rating and opportunities for promotion.

Often, OIG and OSC investigations at the VA and other federal agencies can take as long as 2 years. During that time the whistleblower may remain in a lesser or unwanted position or leave the agency. However, even when OIG substantiates claims of wrongdoing, the agency can make recommendations only to leadership, which may or may not be enacted. Whistleblowers report having to submit Freedom of Information Act requests to learn of the outcome of an OIG investigation when leadership chooses to ignore the recommendation.

Civilian government employees are undervalued by society in general, and the negative stereotypes of lazy, shiftless workers abound, even though many civil servants work to protect the nation’s health, welfare, and safety. Civil servants are familiar with derogatory expressions, such as “bureaucratic bean-counter,” and “good enough for government work.” Even President Trump stated that he would come to Washington, DC, and “drain the swamp.” Yet civil servants can go years without a cost of living increase, a promotion, or a bonus but still be asked to perform additional duties or work long hours to the sacrifice of a work/life balance.