User login

A passion for education: Lonika Sood, MD

On top of her role as a hospitalist at the Aurora BayCare Medical Center in Green Bay, Wis., Lonika Sood, MD, FACP, is currently a candidate for a Masters in health professions education.

From her earliest training to the present day, she has maintained her passion for education, both as a student and an educator.

“I am a part of a community of practice, if you will, of other health professionals who do just this – medical education on a higher level.” Dr. Sood said. “Not only on the front lines of care, but also in designing curricula, undertaking medical education research, and holding leadership positions at medical schools and hospitals around the world.”

As one of the eight new members of The Hospitalist editorial advisory board, Dr. Sood is excited to use her role to help inform and to learn. She told us more about herself in a recent interview.

Q: How did you choose a career in medicine?

A: I grew up in India. I come from a family of doctors. When I was in high school, we found that we had close to 60 physicians in our family, and that number has grown quite a bit since then. At home, being around physicians, that was the language that I grew into. It was a big part of who I wanted to become when I grew up. The other part of it was that I’ve always wanted to help people and do something in one of the science fields, so this seemed like a natural choice for me.

Q: What made you choose hospital medicine?

A: I’ll be very honest – when I came to the United States for my residency, I wanted to become a subspecialist. I used to joke with my mentors in my residency program that every month I wanted to be a different subspecialist depending on which rotation I had or which physician really did a great job on the wards. After moving to Green Bay, Wis., I thought, “We’ll keep residency on hold for a couple of years.” Then I realized that I really liked medical education. I knew that I wanted to be a "specialist" in medical education, yet keep practicing internal medicine, which is something that I’ve always wanted to do. Being a hospitalist is like a marriage of those two passions.

Q: What about medical education draws you?

A: I think a large part of it was that my mother is a physician. My dad is in the merchant navy. In their midlife, they kind of fine-tuned their career paths by going into teaching, so both of them are educators, and very well accomplished in their own right. Growing up, that was a big part of what I saw myself becoming. I did not realize until later in my residency that it was my calling. Additionally, my experience of going into medicine and learning from good teachers is, in my mind, one of the things that really makes me comfortable, and happy being a doctor. I want to be able to leave that legacy for the coming generation.

Q: Tell us how your skills as a teacher help you when you’re working with your patients?

A: To give you an example, we have an adult internal medicine hospital, so we frequently have patients who come to the hospital for the first time. Some of our patients have not seen a physician in over 30 or 40 years. There may be many reasons for that, but they’re scared. They’re sick. They’re in a new environment. They are placing their trust in somebody else’s hands. As teachers and as doctors, it’s important for us to be compassionate, kind, and relatable to patients. We must also be able to explain to patients in their own words what is going on with their body, what might happen, and how can we help. We’re not telling patients what to do or forcing them to take our treatment recommendations, but we are helping them make informed choices. I think hospital medicine really is an incredibly powerful field that can help us relate to our patients.

Q: What is the best professional advice you have received in medicine?

A: I think the advice that I try to follow every day is to be humble. Try to be the best that you can be, yet stay humble, because there’s so much more that you can accomplish if you stay grounded. I think that has stuck with me. It’s come from my parents. It’s come from my mentors. And sometimes it comes from my patients, too.

Q: What is the worst advice you have received?

A: That’s a hard question, but an important one as well, I think. Sometimes there is a push – from society or your colleagues – to be as efficient as you can be, which is great, but we have to look at the downside of it. We sometimes don’t stop and think, or stop and be human. We’re kind of mechanical if data are all we follow.

Q: So where do you see yourself in the next 10 years?

A: That’s a question I try to answer daily, and I get a different answer each time. I think I do see myself continuing to provide clinical care for hospitalized patients. I see myself doing a little more in educational leadership, working with medical students and medical residents. I’m just completing my master’s in health professions education, so I’m excited to also start a career in medical education research.

Q: What’s the best book that you’ve read recently, and why was it the best?

A: Oh, well, it’s not a new book, and I’ve read this before, but I keep coming back to it. I don’t know if you’ve heard of Jim Corbett. He was a wildlife enthusiast in the early 20th century. He wrote a lot of books on man-eating tigers and leopards in India. My brother and I and my dad used to read these books growing up. That’s something that I’m going back to and rereading. There is a lot of rich description about Indian wildlife, and it’s something that brings back good memories.

On top of her role as a hospitalist at the Aurora BayCare Medical Center in Green Bay, Wis., Lonika Sood, MD, FACP, is currently a candidate for a Masters in health professions education.

From her earliest training to the present day, she has maintained her passion for education, both as a student and an educator.

“I am a part of a community of practice, if you will, of other health professionals who do just this – medical education on a higher level.” Dr. Sood said. “Not only on the front lines of care, but also in designing curricula, undertaking medical education research, and holding leadership positions at medical schools and hospitals around the world.”

As one of the eight new members of The Hospitalist editorial advisory board, Dr. Sood is excited to use her role to help inform and to learn. She told us more about herself in a recent interview.

Q: How did you choose a career in medicine?

A: I grew up in India. I come from a family of doctors. When I was in high school, we found that we had close to 60 physicians in our family, and that number has grown quite a bit since then. At home, being around physicians, that was the language that I grew into. It was a big part of who I wanted to become when I grew up. The other part of it was that I’ve always wanted to help people and do something in one of the science fields, so this seemed like a natural choice for me.

Q: What made you choose hospital medicine?

A: I’ll be very honest – when I came to the United States for my residency, I wanted to become a subspecialist. I used to joke with my mentors in my residency program that every month I wanted to be a different subspecialist depending on which rotation I had or which physician really did a great job on the wards. After moving to Green Bay, Wis., I thought, “We’ll keep residency on hold for a couple of years.” Then I realized that I really liked medical education. I knew that I wanted to be a "specialist" in medical education, yet keep practicing internal medicine, which is something that I’ve always wanted to do. Being a hospitalist is like a marriage of those two passions.

Q: What about medical education draws you?

A: I think a large part of it was that my mother is a physician. My dad is in the merchant navy. In their midlife, they kind of fine-tuned their career paths by going into teaching, so both of them are educators, and very well accomplished in their own right. Growing up, that was a big part of what I saw myself becoming. I did not realize until later in my residency that it was my calling. Additionally, my experience of going into medicine and learning from good teachers is, in my mind, one of the things that really makes me comfortable, and happy being a doctor. I want to be able to leave that legacy for the coming generation.

Q: Tell us how your skills as a teacher help you when you’re working with your patients?

A: To give you an example, we have an adult internal medicine hospital, so we frequently have patients who come to the hospital for the first time. Some of our patients have not seen a physician in over 30 or 40 years. There may be many reasons for that, but they’re scared. They’re sick. They’re in a new environment. They are placing their trust in somebody else’s hands. As teachers and as doctors, it’s important for us to be compassionate, kind, and relatable to patients. We must also be able to explain to patients in their own words what is going on with their body, what might happen, and how can we help. We’re not telling patients what to do or forcing them to take our treatment recommendations, but we are helping them make informed choices. I think hospital medicine really is an incredibly powerful field that can help us relate to our patients.

Q: What is the best professional advice you have received in medicine?

A: I think the advice that I try to follow every day is to be humble. Try to be the best that you can be, yet stay humble, because there’s so much more that you can accomplish if you stay grounded. I think that has stuck with me. It’s come from my parents. It’s come from my mentors. And sometimes it comes from my patients, too.

Q: What is the worst advice you have received?

A: That’s a hard question, but an important one as well, I think. Sometimes there is a push – from society or your colleagues – to be as efficient as you can be, which is great, but we have to look at the downside of it. We sometimes don’t stop and think, or stop and be human. We’re kind of mechanical if data are all we follow.

Q: So where do you see yourself in the next 10 years?

A: That’s a question I try to answer daily, and I get a different answer each time. I think I do see myself continuing to provide clinical care for hospitalized patients. I see myself doing a little more in educational leadership, working with medical students and medical residents. I’m just completing my master’s in health professions education, so I’m excited to also start a career in medical education research.

Q: What’s the best book that you’ve read recently, and why was it the best?

A: Oh, well, it’s not a new book, and I’ve read this before, but I keep coming back to it. I don’t know if you’ve heard of Jim Corbett. He was a wildlife enthusiast in the early 20th century. He wrote a lot of books on man-eating tigers and leopards in India. My brother and I and my dad used to read these books growing up. That’s something that I’m going back to and rereading. There is a lot of rich description about Indian wildlife, and it’s something that brings back good memories.

On top of her role as a hospitalist at the Aurora BayCare Medical Center in Green Bay, Wis., Lonika Sood, MD, FACP, is currently a candidate for a Masters in health professions education.

From her earliest training to the present day, she has maintained her passion for education, both as a student and an educator.

“I am a part of a community of practice, if you will, of other health professionals who do just this – medical education on a higher level.” Dr. Sood said. “Not only on the front lines of care, but also in designing curricula, undertaking medical education research, and holding leadership positions at medical schools and hospitals around the world.”

As one of the eight new members of The Hospitalist editorial advisory board, Dr. Sood is excited to use her role to help inform and to learn. She told us more about herself in a recent interview.

Q: How did you choose a career in medicine?

A: I grew up in India. I come from a family of doctors. When I was in high school, we found that we had close to 60 physicians in our family, and that number has grown quite a bit since then. At home, being around physicians, that was the language that I grew into. It was a big part of who I wanted to become when I grew up. The other part of it was that I’ve always wanted to help people and do something in one of the science fields, so this seemed like a natural choice for me.

Q: What made you choose hospital medicine?

A: I’ll be very honest – when I came to the United States for my residency, I wanted to become a subspecialist. I used to joke with my mentors in my residency program that every month I wanted to be a different subspecialist depending on which rotation I had or which physician really did a great job on the wards. After moving to Green Bay, Wis., I thought, “We’ll keep residency on hold for a couple of years.” Then I realized that I really liked medical education. I knew that I wanted to be a "specialist" in medical education, yet keep practicing internal medicine, which is something that I’ve always wanted to do. Being a hospitalist is like a marriage of those two passions.

Q: What about medical education draws you?

A: I think a large part of it was that my mother is a physician. My dad is in the merchant navy. In their midlife, they kind of fine-tuned their career paths by going into teaching, so both of them are educators, and very well accomplished in their own right. Growing up, that was a big part of what I saw myself becoming. I did not realize until later in my residency that it was my calling. Additionally, my experience of going into medicine and learning from good teachers is, in my mind, one of the things that really makes me comfortable, and happy being a doctor. I want to be able to leave that legacy for the coming generation.

Q: Tell us how your skills as a teacher help you when you’re working with your patients?

A: To give you an example, we have an adult internal medicine hospital, so we frequently have patients who come to the hospital for the first time. Some of our patients have not seen a physician in over 30 or 40 years. There may be many reasons for that, but they’re scared. They’re sick. They’re in a new environment. They are placing their trust in somebody else’s hands. As teachers and as doctors, it’s important for us to be compassionate, kind, and relatable to patients. We must also be able to explain to patients in their own words what is going on with their body, what might happen, and how can we help. We’re not telling patients what to do or forcing them to take our treatment recommendations, but we are helping them make informed choices. I think hospital medicine really is an incredibly powerful field that can help us relate to our patients.

Q: What is the best professional advice you have received in medicine?

A: I think the advice that I try to follow every day is to be humble. Try to be the best that you can be, yet stay humble, because there’s so much more that you can accomplish if you stay grounded. I think that has stuck with me. It’s come from my parents. It’s come from my mentors. And sometimes it comes from my patients, too.

Q: What is the worst advice you have received?

A: That’s a hard question, but an important one as well, I think. Sometimes there is a push – from society or your colleagues – to be as efficient as you can be, which is great, but we have to look at the downside of it. We sometimes don’t stop and think, or stop and be human. We’re kind of mechanical if data are all we follow.

Q: So where do you see yourself in the next 10 years?

A: That’s a question I try to answer daily, and I get a different answer each time. I think I do see myself continuing to provide clinical care for hospitalized patients. I see myself doing a little more in educational leadership, working with medical students and medical residents. I’m just completing my master’s in health professions education, so I’m excited to also start a career in medical education research.

Q: What’s the best book that you’ve read recently, and why was it the best?

A: Oh, well, it’s not a new book, and I’ve read this before, but I keep coming back to it. I don’t know if you’ve heard of Jim Corbett. He was a wildlife enthusiast in the early 20th century. He wrote a lot of books on man-eating tigers and leopards in India. My brother and I and my dad used to read these books growing up. That’s something that I’m going back to and rereading. There is a lot of rich description about Indian wildlife, and it’s something that brings back good memories.

Legionnaires’ Disease in Health Care Settings

The CDC investigations of 27 outbreaks of Legionnaires’ disease between 2000 and 2014 found health care-associated Legionnaires’ disease accounted for 33% of the outbreaks, 57% of outbreak-associated cases, and 85% of outbreak-associated deaths. Nearly all were attributed to water system exposures that could have been prevented by effective water management programs.

In 2015, CDC researchers analyzed surveillance data from 20 states and the New York City metropolitan area that reported > 90% of confirmed legionellosis cases to the Supplemental Legionnaires’ Disease Surveillance System. Of 2,809 reported cases, 553 were health care associated. Definite cases accounted for 3%, and possible cases accounted for 17% of all the cases reported. Although only a small percentage were definitely related to health care settings, the fatality rate was high at 12%.

Of the 85 definite health care-associated Legionnaires’ disease cases, 80% were associated with long-term care facilities. Of the 468 possible cases, 13% were “possibly” associated with long-term care facilities, 49% with hospitals, and 26% with clinics.

The CDC says the number of definite cases and facilities reported is “likely an underestimate,” in part because of a lack of Legionella-specific testing. Another explanation is that hospital stays are typically shorter than the 10-day period used in the analysis.

One-fourth of patients with definite health care-associated Legionnaires’ disease die. Health care providers play a critical role in prevention and response, the CDC says, by rapidly identifying and reporting cases. Legionnaires’ disease is “clinically indistinguishable” from other causes of pneumonia, the researchers note. The preferred diagnostic method is to concurrently obtain a lower respiratory sputum sample for culture on selective media and a Legionella urinary antigen test.

In health care facilities, the researchers say, “prevention of the first case of Legionnaires’ disease is the ultimate goal.” The best way to do that, they advise, is to have an effective water management program. Guidelines for developing and monitoring programs are available at https://www.cdc.gov/legionella/WMPtoolkit.

The CDC investigations of 27 outbreaks of Legionnaires’ disease between 2000 and 2014 found health care-associated Legionnaires’ disease accounted for 33% of the outbreaks, 57% of outbreak-associated cases, and 85% of outbreak-associated deaths. Nearly all were attributed to water system exposures that could have been prevented by effective water management programs.

In 2015, CDC researchers analyzed surveillance data from 20 states and the New York City metropolitan area that reported > 90% of confirmed legionellosis cases to the Supplemental Legionnaires’ Disease Surveillance System. Of 2,809 reported cases, 553 were health care associated. Definite cases accounted for 3%, and possible cases accounted for 17% of all the cases reported. Although only a small percentage were definitely related to health care settings, the fatality rate was high at 12%.

Of the 85 definite health care-associated Legionnaires’ disease cases, 80% were associated with long-term care facilities. Of the 468 possible cases, 13% were “possibly” associated with long-term care facilities, 49% with hospitals, and 26% with clinics.

The CDC says the number of definite cases and facilities reported is “likely an underestimate,” in part because of a lack of Legionella-specific testing. Another explanation is that hospital stays are typically shorter than the 10-day period used in the analysis.

One-fourth of patients with definite health care-associated Legionnaires’ disease die. Health care providers play a critical role in prevention and response, the CDC says, by rapidly identifying and reporting cases. Legionnaires’ disease is “clinically indistinguishable” from other causes of pneumonia, the researchers note. The preferred diagnostic method is to concurrently obtain a lower respiratory sputum sample for culture on selective media and a Legionella urinary antigen test.

In health care facilities, the researchers say, “prevention of the first case of Legionnaires’ disease is the ultimate goal.” The best way to do that, they advise, is to have an effective water management program. Guidelines for developing and monitoring programs are available at https://www.cdc.gov/legionella/WMPtoolkit.

The CDC investigations of 27 outbreaks of Legionnaires’ disease between 2000 and 2014 found health care-associated Legionnaires’ disease accounted for 33% of the outbreaks, 57% of outbreak-associated cases, and 85% of outbreak-associated deaths. Nearly all were attributed to water system exposures that could have been prevented by effective water management programs.

In 2015, CDC researchers analyzed surveillance data from 20 states and the New York City metropolitan area that reported > 90% of confirmed legionellosis cases to the Supplemental Legionnaires’ Disease Surveillance System. Of 2,809 reported cases, 553 were health care associated. Definite cases accounted for 3%, and possible cases accounted for 17% of all the cases reported. Although only a small percentage were definitely related to health care settings, the fatality rate was high at 12%.

Of the 85 definite health care-associated Legionnaires’ disease cases, 80% were associated with long-term care facilities. Of the 468 possible cases, 13% were “possibly” associated with long-term care facilities, 49% with hospitals, and 26% with clinics.

The CDC says the number of definite cases and facilities reported is “likely an underestimate,” in part because of a lack of Legionella-specific testing. Another explanation is that hospital stays are typically shorter than the 10-day period used in the analysis.

One-fourth of patients with definite health care-associated Legionnaires’ disease die. Health care providers play a critical role in prevention and response, the CDC says, by rapidly identifying and reporting cases. Legionnaires’ disease is “clinically indistinguishable” from other causes of pneumonia, the researchers note. The preferred diagnostic method is to concurrently obtain a lower respiratory sputum sample for culture on selective media and a Legionella urinary antigen test.

In health care facilities, the researchers say, “prevention of the first case of Legionnaires’ disease is the ultimate goal.” The best way to do that, they advise, is to have an effective water management program. Guidelines for developing and monitoring programs are available at https://www.cdc.gov/legionella/WMPtoolkit.

New cancer diagnosis linked to arterial thromboembolism

Patients newly diagnosed with cancer may have a short-term increased risk of arterial thromboembolism, according to a new study.

The research showed that, within 6 months of their diagnosis, cancer patients had a rate of arterial thromboembolism that was more than double the rate in matched control patients without cancer.

However, the risk of arterial thromboembolism varied by cancer type.

Babak B. Navi, MD, of Weill Cornell Medicine in New York, New York, and his colleagues reported these findings in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

The researchers used the Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results–Medicare linked database to identify patients with a new primary diagnosis of breast, lung, prostate, colorectal, bladder, pancreatic, or gastric cancer or non-Hodgkin lymphoma from 2002 to 2011.

The team matched these patients (by demographics and comorbidities) to Medicare enrollees without cancer, collecting data on 279,719 pairs of subjects. The subjects were followed through 2012.

Arterial thromboembolism

The study’s primary outcome was the cumulative incidence of arterial thromboembolism, defined as any inpatient or outpatient diagnosis of myocardial infarction or ischemic stroke.

The incidence of arterial thromboembolism at 3 months was 3.4% in cancer patients and 1.1% in controls. At 6 months, it was 4.7% and 2.2%, respectively. At 1 year, it was 6.5% and 4.2%, respectively. And at 2 years, it was 9.1% and 8.1%, respectively.

The hazard ratios (HRs) for arterial thromboembolism among cancer patients were 5.2 at 0 to 1 month, 2.1 at 1 to 3 months, 1.4 at 3 to 6 months, 1.1 at 6 to 9 months, and 1.1 at 9 to 12 months.

The risk of arterial thromboembolism varied by cancer type, with the greatest excess risk observed in lung cancer. The 6-month cumulative incidence was 8.3% in lung cancer patients and 2.4% in matched controls (P<0.001).

In patients with non-Hodgkin lymphoma, the 6-month cumulative incidence of arterial thromboembolism was 5.4%, compared to 2.2% in matched controls (P<0.001).

Myocardial infarction

The cumulative incidence of myocardial infarction at 3 months was 1.4% in cancer patients and 0.3% in controls.

At 6 months, it was 2.0% and 0.7%, respectively. At 1 year, it was 2.6% and 1.4%, respectively. And at 2 years, it was 3.7% and 2.8%, respectively.

The HRs for myocardial infarction among cancer patients were 7.3 at 0 to 1 month, 3.0 at 1 to 3 months, 1.8 at 3 to 6 months, 1.3 at 6 to 9 months, and 1.0 at 9 to 12 months.

Ischemic stroke

The cumulative incidence of ischemic stroke at 3 months was 2.1% in cancer patients and 0.8% in controls.

At 6 months, it was 3.0% and 1.6%, respectively. At 1 year, it was 4.3% and 3.1%, respectively. And at 2 years, it was 6.1% and 5.8%, respectively.

The HRs for ischemic stroke among cancer patients were 4.5 at 0 to 1 month, 1.7 at 1 to 3 months, 1.3 at 3 to 6 months, 1.0 at 6 to 9 months, and 1.1 at 9 to 12 months.

The researchers said these findings raise the question of whether patients with newly diagnosed cancer should be considered for antithrombotic and statin medicines for primary prevention of cardiovascular disease.

The team stressed that because patients with cancer are also prone to bleeding due to frequent coagulopathy and invasive procedures, carefully designed clinical trials are needed to answer these questions. ![]()

Patients newly diagnosed with cancer may have a short-term increased risk of arterial thromboembolism, according to a new study.

The research showed that, within 6 months of their diagnosis, cancer patients had a rate of arterial thromboembolism that was more than double the rate in matched control patients without cancer.

However, the risk of arterial thromboembolism varied by cancer type.

Babak B. Navi, MD, of Weill Cornell Medicine in New York, New York, and his colleagues reported these findings in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

The researchers used the Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results–Medicare linked database to identify patients with a new primary diagnosis of breast, lung, prostate, colorectal, bladder, pancreatic, or gastric cancer or non-Hodgkin lymphoma from 2002 to 2011.

The team matched these patients (by demographics and comorbidities) to Medicare enrollees without cancer, collecting data on 279,719 pairs of subjects. The subjects were followed through 2012.

Arterial thromboembolism

The study’s primary outcome was the cumulative incidence of arterial thromboembolism, defined as any inpatient or outpatient diagnosis of myocardial infarction or ischemic stroke.

The incidence of arterial thromboembolism at 3 months was 3.4% in cancer patients and 1.1% in controls. At 6 months, it was 4.7% and 2.2%, respectively. At 1 year, it was 6.5% and 4.2%, respectively. And at 2 years, it was 9.1% and 8.1%, respectively.

The hazard ratios (HRs) for arterial thromboembolism among cancer patients were 5.2 at 0 to 1 month, 2.1 at 1 to 3 months, 1.4 at 3 to 6 months, 1.1 at 6 to 9 months, and 1.1 at 9 to 12 months.

The risk of arterial thromboembolism varied by cancer type, with the greatest excess risk observed in lung cancer. The 6-month cumulative incidence was 8.3% in lung cancer patients and 2.4% in matched controls (P<0.001).

In patients with non-Hodgkin lymphoma, the 6-month cumulative incidence of arterial thromboembolism was 5.4%, compared to 2.2% in matched controls (P<0.001).

Myocardial infarction

The cumulative incidence of myocardial infarction at 3 months was 1.4% in cancer patients and 0.3% in controls.

At 6 months, it was 2.0% and 0.7%, respectively. At 1 year, it was 2.6% and 1.4%, respectively. And at 2 years, it was 3.7% and 2.8%, respectively.

The HRs for myocardial infarction among cancer patients were 7.3 at 0 to 1 month, 3.0 at 1 to 3 months, 1.8 at 3 to 6 months, 1.3 at 6 to 9 months, and 1.0 at 9 to 12 months.

Ischemic stroke

The cumulative incidence of ischemic stroke at 3 months was 2.1% in cancer patients and 0.8% in controls.

At 6 months, it was 3.0% and 1.6%, respectively. At 1 year, it was 4.3% and 3.1%, respectively. And at 2 years, it was 6.1% and 5.8%, respectively.

The HRs for ischemic stroke among cancer patients were 4.5 at 0 to 1 month, 1.7 at 1 to 3 months, 1.3 at 3 to 6 months, 1.0 at 6 to 9 months, and 1.1 at 9 to 12 months.

The researchers said these findings raise the question of whether patients with newly diagnosed cancer should be considered for antithrombotic and statin medicines for primary prevention of cardiovascular disease.

The team stressed that because patients with cancer are also prone to bleeding due to frequent coagulopathy and invasive procedures, carefully designed clinical trials are needed to answer these questions. ![]()

Patients newly diagnosed with cancer may have a short-term increased risk of arterial thromboembolism, according to a new study.

The research showed that, within 6 months of their diagnosis, cancer patients had a rate of arterial thromboembolism that was more than double the rate in matched control patients without cancer.

However, the risk of arterial thromboembolism varied by cancer type.

Babak B. Navi, MD, of Weill Cornell Medicine in New York, New York, and his colleagues reported these findings in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

The researchers used the Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results–Medicare linked database to identify patients with a new primary diagnosis of breast, lung, prostate, colorectal, bladder, pancreatic, or gastric cancer or non-Hodgkin lymphoma from 2002 to 2011.

The team matched these patients (by demographics and comorbidities) to Medicare enrollees without cancer, collecting data on 279,719 pairs of subjects. The subjects were followed through 2012.

Arterial thromboembolism

The study’s primary outcome was the cumulative incidence of arterial thromboembolism, defined as any inpatient or outpatient diagnosis of myocardial infarction or ischemic stroke.

The incidence of arterial thromboembolism at 3 months was 3.4% in cancer patients and 1.1% in controls. At 6 months, it was 4.7% and 2.2%, respectively. At 1 year, it was 6.5% and 4.2%, respectively. And at 2 years, it was 9.1% and 8.1%, respectively.

The hazard ratios (HRs) for arterial thromboembolism among cancer patients were 5.2 at 0 to 1 month, 2.1 at 1 to 3 months, 1.4 at 3 to 6 months, 1.1 at 6 to 9 months, and 1.1 at 9 to 12 months.

The risk of arterial thromboembolism varied by cancer type, with the greatest excess risk observed in lung cancer. The 6-month cumulative incidence was 8.3% in lung cancer patients and 2.4% in matched controls (P<0.001).

In patients with non-Hodgkin lymphoma, the 6-month cumulative incidence of arterial thromboembolism was 5.4%, compared to 2.2% in matched controls (P<0.001).

Myocardial infarction

The cumulative incidence of myocardial infarction at 3 months was 1.4% in cancer patients and 0.3% in controls.

At 6 months, it was 2.0% and 0.7%, respectively. At 1 year, it was 2.6% and 1.4%, respectively. And at 2 years, it was 3.7% and 2.8%, respectively.

The HRs for myocardial infarction among cancer patients were 7.3 at 0 to 1 month, 3.0 at 1 to 3 months, 1.8 at 3 to 6 months, 1.3 at 6 to 9 months, and 1.0 at 9 to 12 months.

Ischemic stroke

The cumulative incidence of ischemic stroke at 3 months was 2.1% in cancer patients and 0.8% in controls.

At 6 months, it was 3.0% and 1.6%, respectively. At 1 year, it was 4.3% and 3.1%, respectively. And at 2 years, it was 6.1% and 5.8%, respectively.

The HRs for ischemic stroke among cancer patients were 4.5 at 0 to 1 month, 1.7 at 1 to 3 months, 1.3 at 3 to 6 months, 1.0 at 6 to 9 months, and 1.1 at 9 to 12 months.

The researchers said these findings raise the question of whether patients with newly diagnosed cancer should be considered for antithrombotic and statin medicines for primary prevention of cardiovascular disease.

The team stressed that because patients with cancer are also prone to bleeding due to frequent coagulopathy and invasive procedures, carefully designed clinical trials are needed to answer these questions. ![]()

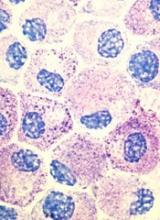

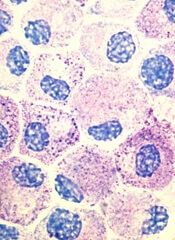

Popular theory of mast cell development is wrong, team says

Stem cell factor (SCF) and KIT signaling are not necessary for early mast cell development, according to research published in Blood.

It has been assumed that the differentiation of hematopoietic progenitors to mast cells requires SCF and KIT signaling.

However, researchers found that mast cell progenitors can survive, mature, and proliferate in the absence of SCF and KIT signaling.

The researchers began this work by analyzing mast cell progenitor populations in samples from healthy subjects, patients with chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) or gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GIST) who were treated with imatinib, and patients with systemic mastocytosis carrying the D816V KIT mutation.

Imatinib inhibits KIT signaling, and the D816V KIT mutation causes KIT signaling to be constitutively active.

The researchers found the imatinib-treated CML and GIST patients and the patients with systemic mastocytosis all had mast cell progenitor populations similar to those observed in healthy subjects.

The team therefore concluded that dysfunctional KIT signaling does not affect the frequency of circulating mast cell progenitors in vivo.

On the other hand, the researchers also found that circulating mast cells were sensitive to imatinib in patients with CML. The patients had higher numbers of peripheral blood mast cells at diagnosis than they did after treatment with imatinib.

“When the patients were treated with the drug imatinib, which blocks the effect of stem cell factor, the number of mature mast cells dropped, while the number of progenitor cells did not change,” said study author Gunnar Nilsson, PhD, of Karolinska Institutet in Stockholm, Sweden.

Subsequent experiments showed that mast cell progenitors can survive in vitro without KIT signaling and without SCF. In addition, mast cell progenitors were able to mature and proliferate in vitro without SCF.

In fact, the researchers said they found that interleukin 3 was sufficient to promote the survival of mast cell progenitors in vitro.

“The study increases our understanding of how mast cells are formed and could be important in the development of new therapies, for example, for mastocytosis . . . ,” said study author Joakim Dahlin, PhD, of the University of Cambridge in the UK.

“One hypothesis that we will now test is whether interleukin 3 can be a new target in the treatment of mast cell-driven diseases.” ![]()

Stem cell factor (SCF) and KIT signaling are not necessary for early mast cell development, according to research published in Blood.

It has been assumed that the differentiation of hematopoietic progenitors to mast cells requires SCF and KIT signaling.

However, researchers found that mast cell progenitors can survive, mature, and proliferate in the absence of SCF and KIT signaling.

The researchers began this work by analyzing mast cell progenitor populations in samples from healthy subjects, patients with chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) or gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GIST) who were treated with imatinib, and patients with systemic mastocytosis carrying the D816V KIT mutation.

Imatinib inhibits KIT signaling, and the D816V KIT mutation causes KIT signaling to be constitutively active.

The researchers found the imatinib-treated CML and GIST patients and the patients with systemic mastocytosis all had mast cell progenitor populations similar to those observed in healthy subjects.

The team therefore concluded that dysfunctional KIT signaling does not affect the frequency of circulating mast cell progenitors in vivo.

On the other hand, the researchers also found that circulating mast cells were sensitive to imatinib in patients with CML. The patients had higher numbers of peripheral blood mast cells at diagnosis than they did after treatment with imatinib.

“When the patients were treated with the drug imatinib, which blocks the effect of stem cell factor, the number of mature mast cells dropped, while the number of progenitor cells did not change,” said study author Gunnar Nilsson, PhD, of Karolinska Institutet in Stockholm, Sweden.

Subsequent experiments showed that mast cell progenitors can survive in vitro without KIT signaling and without SCF. In addition, mast cell progenitors were able to mature and proliferate in vitro without SCF.

In fact, the researchers said they found that interleukin 3 was sufficient to promote the survival of mast cell progenitors in vitro.

“The study increases our understanding of how mast cells are formed and could be important in the development of new therapies, for example, for mastocytosis . . . ,” said study author Joakim Dahlin, PhD, of the University of Cambridge in the UK.

“One hypothesis that we will now test is whether interleukin 3 can be a new target in the treatment of mast cell-driven diseases.” ![]()

Stem cell factor (SCF) and KIT signaling are not necessary for early mast cell development, according to research published in Blood.

It has been assumed that the differentiation of hematopoietic progenitors to mast cells requires SCF and KIT signaling.

However, researchers found that mast cell progenitors can survive, mature, and proliferate in the absence of SCF and KIT signaling.

The researchers began this work by analyzing mast cell progenitor populations in samples from healthy subjects, patients with chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) or gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GIST) who were treated with imatinib, and patients with systemic mastocytosis carrying the D816V KIT mutation.

Imatinib inhibits KIT signaling, and the D816V KIT mutation causes KIT signaling to be constitutively active.

The researchers found the imatinib-treated CML and GIST patients and the patients with systemic mastocytosis all had mast cell progenitor populations similar to those observed in healthy subjects.

The team therefore concluded that dysfunctional KIT signaling does not affect the frequency of circulating mast cell progenitors in vivo.

On the other hand, the researchers also found that circulating mast cells were sensitive to imatinib in patients with CML. The patients had higher numbers of peripheral blood mast cells at diagnosis than they did after treatment with imatinib.

“When the patients were treated with the drug imatinib, which blocks the effect of stem cell factor, the number of mature mast cells dropped, while the number of progenitor cells did not change,” said study author Gunnar Nilsson, PhD, of Karolinska Institutet in Stockholm, Sweden.

Subsequent experiments showed that mast cell progenitors can survive in vitro without KIT signaling and without SCF. In addition, mast cell progenitors were able to mature and proliferate in vitro without SCF.

In fact, the researchers said they found that interleukin 3 was sufficient to promote the survival of mast cell progenitors in vitro.

“The study increases our understanding of how mast cells are formed and could be important in the development of new therapies, for example, for mastocytosis . . . ,” said study author Joakim Dahlin, PhD, of the University of Cambridge in the UK.

“One hypothesis that we will now test is whether interleukin 3 can be a new target in the treatment of mast cell-driven diseases.” ![]()

Cancer patients perceive their abilities differently than caregivers do

New research suggests older cancer patients and their caregivers often differ in their assessment of the patients’ abilities.

In this study, patients generally rated their physical and mental function higher than caregivers did.

The study also showed the differences in assessment of patients’ physical abilities were associated with greater caregiver burden.

This research was published in The Oncologist.

“Caregivers are such an important part of our healthcare system, particularly for older adults with cancer,” said study author Arti Hurria, MD, of City of Hope National Medical Center in Duarte, California.

“We wanted to further understand the factors that are associated with caregiver burden.”

One factor Dr Hurria and her colleagues thought might be important is differences in assessments of patient health and physical abilities between patients and their caregivers.

“In daily practice, we sometimes see a disconnect between what the patient perceives their general health and abilities to be in comparison to what the caregiver thinks,” Dr Hurria said. “We wanted to see whether this disconnect impacted caregiver burden.”

To do this, Dr Hurria and her colleagues questioned 100 older cancer patients and their caregivers.

Subjects were asked about the patients’ general health and physical function, meaning their ability to perform everyday activities. The researchers then compared the answers given by the patients and their respective caregivers.

The researchers also assessed the level of caregiver burden (defined as a subjective feeling of stress caused by being overwhelmed by the demands of caring) by administering a standard questionnaire on topics such as sleep disturbance, physical effort, and patient behavior.

The 100 cancer patients, ages 65 to 91, were suffering from a variety of cancers. The most common were lymphoma (n=26), breast cancer (n=19), and gastrointestinal cancers (n=15). Twelve patients had leukemia, and 10 had myeloma.

The ages of the caregivers ranged from 28 to 85, and the majority were female (73%). They were mainly either the spouse of the patient (68%) or an adult child (18%).

Results

There was no significant difference in patient and caregiver accounts of the patients’ comorbidities (P=0.68), falls in the last 6 months (P=0.71), or percent weight change in the last 6 months (P=0.21).

However, caregivers consistently rated patients as having poorer physical function and mental health and requiring more social support than the patients themselves did.

There was a significant difference (P<0.05) in caregiver and patient accounts when it came to the following measures:

- Need for help with instrumental activities of daily living

- Karnofsky Performance Status

- Medical Outcomes Study-Physical Function

- Medical Outcomes Study-Social Support Survey

- Mental Health Inventory.

Only the disparity in the assessment of physical function was significantly associated with greater caregiver burden (P<0.001). What is still unclear is the cause of this disparity.

“I think there are 2 possible explanations,” said study author Tina Hsu, MD, of the University of Ottawa in Ontario, Canada.

“One is that older adults with cancer either don’t appreciate how much help they require or, more likely, they are able preserve their sense of independence and dignity through a perception that they feel they can do more than they really can.”

“Alternatively, it is possible that caregivers who are more stressed out perceive their loved one to require more help than they actually do need. Most likely, the truth of how much help the patient actually needs lies somewhere between what patients and caregivers report.”

Based on their findings, Drs Hsu and Hurria and their colleagues advise that clinicians consider assessing caregiver burden in those caregivers who report the patient as being more dependent than the patient does themselves.

“Caregivers play an essential role in supporting older adults with cancer,” Dr Hsu said. “We plan to further explore factors associated with caregiver burden in this population, particularly in those who are frailer and thus require even more hands-on support. We also hope to explore what resources caregivers of older adults with cancer feel they need to better help them with their role.” ![]()

New research suggests older cancer patients and their caregivers often differ in their assessment of the patients’ abilities.

In this study, patients generally rated their physical and mental function higher than caregivers did.

The study also showed the differences in assessment of patients’ physical abilities were associated with greater caregiver burden.

This research was published in The Oncologist.

“Caregivers are such an important part of our healthcare system, particularly for older adults with cancer,” said study author Arti Hurria, MD, of City of Hope National Medical Center in Duarte, California.

“We wanted to further understand the factors that are associated with caregiver burden.”

One factor Dr Hurria and her colleagues thought might be important is differences in assessments of patient health and physical abilities between patients and their caregivers.

“In daily practice, we sometimes see a disconnect between what the patient perceives their general health and abilities to be in comparison to what the caregiver thinks,” Dr Hurria said. “We wanted to see whether this disconnect impacted caregiver burden.”

To do this, Dr Hurria and her colleagues questioned 100 older cancer patients and their caregivers.

Subjects were asked about the patients’ general health and physical function, meaning their ability to perform everyday activities. The researchers then compared the answers given by the patients and their respective caregivers.

The researchers also assessed the level of caregiver burden (defined as a subjective feeling of stress caused by being overwhelmed by the demands of caring) by administering a standard questionnaire on topics such as sleep disturbance, physical effort, and patient behavior.

The 100 cancer patients, ages 65 to 91, were suffering from a variety of cancers. The most common were lymphoma (n=26), breast cancer (n=19), and gastrointestinal cancers (n=15). Twelve patients had leukemia, and 10 had myeloma.

The ages of the caregivers ranged from 28 to 85, and the majority were female (73%). They were mainly either the spouse of the patient (68%) or an adult child (18%).

Results

There was no significant difference in patient and caregiver accounts of the patients’ comorbidities (P=0.68), falls in the last 6 months (P=0.71), or percent weight change in the last 6 months (P=0.21).

However, caregivers consistently rated patients as having poorer physical function and mental health and requiring more social support than the patients themselves did.

There was a significant difference (P<0.05) in caregiver and patient accounts when it came to the following measures:

- Need for help with instrumental activities of daily living

- Karnofsky Performance Status

- Medical Outcomes Study-Physical Function

- Medical Outcomes Study-Social Support Survey

- Mental Health Inventory.

Only the disparity in the assessment of physical function was significantly associated with greater caregiver burden (P<0.001). What is still unclear is the cause of this disparity.

“I think there are 2 possible explanations,” said study author Tina Hsu, MD, of the University of Ottawa in Ontario, Canada.

“One is that older adults with cancer either don’t appreciate how much help they require or, more likely, they are able preserve their sense of independence and dignity through a perception that they feel they can do more than they really can.”

“Alternatively, it is possible that caregivers who are more stressed out perceive their loved one to require more help than they actually do need. Most likely, the truth of how much help the patient actually needs lies somewhere between what patients and caregivers report.”

Based on their findings, Drs Hsu and Hurria and their colleagues advise that clinicians consider assessing caregiver burden in those caregivers who report the patient as being more dependent than the patient does themselves.

“Caregivers play an essential role in supporting older adults with cancer,” Dr Hsu said. “We plan to further explore factors associated with caregiver burden in this population, particularly in those who are frailer and thus require even more hands-on support. We also hope to explore what resources caregivers of older adults with cancer feel they need to better help them with their role.” ![]()

New research suggests older cancer patients and their caregivers often differ in their assessment of the patients’ abilities.

In this study, patients generally rated their physical and mental function higher than caregivers did.

The study also showed the differences in assessment of patients’ physical abilities were associated with greater caregiver burden.

This research was published in The Oncologist.

“Caregivers are such an important part of our healthcare system, particularly for older adults with cancer,” said study author Arti Hurria, MD, of City of Hope National Medical Center in Duarte, California.

“We wanted to further understand the factors that are associated with caregiver burden.”

One factor Dr Hurria and her colleagues thought might be important is differences in assessments of patient health and physical abilities between patients and their caregivers.

“In daily practice, we sometimes see a disconnect between what the patient perceives their general health and abilities to be in comparison to what the caregiver thinks,” Dr Hurria said. “We wanted to see whether this disconnect impacted caregiver burden.”

To do this, Dr Hurria and her colleagues questioned 100 older cancer patients and their caregivers.

Subjects were asked about the patients’ general health and physical function, meaning their ability to perform everyday activities. The researchers then compared the answers given by the patients and their respective caregivers.

The researchers also assessed the level of caregiver burden (defined as a subjective feeling of stress caused by being overwhelmed by the demands of caring) by administering a standard questionnaire on topics such as sleep disturbance, physical effort, and patient behavior.

The 100 cancer patients, ages 65 to 91, were suffering from a variety of cancers. The most common were lymphoma (n=26), breast cancer (n=19), and gastrointestinal cancers (n=15). Twelve patients had leukemia, and 10 had myeloma.

The ages of the caregivers ranged from 28 to 85, and the majority were female (73%). They were mainly either the spouse of the patient (68%) or an adult child (18%).

Results

There was no significant difference in patient and caregiver accounts of the patients’ comorbidities (P=0.68), falls in the last 6 months (P=0.71), or percent weight change in the last 6 months (P=0.21).

However, caregivers consistently rated patients as having poorer physical function and mental health and requiring more social support than the patients themselves did.

There was a significant difference (P<0.05) in caregiver and patient accounts when it came to the following measures:

- Need for help with instrumental activities of daily living

- Karnofsky Performance Status

- Medical Outcomes Study-Physical Function

- Medical Outcomes Study-Social Support Survey

- Mental Health Inventory.

Only the disparity in the assessment of physical function was significantly associated with greater caregiver burden (P<0.001). What is still unclear is the cause of this disparity.

“I think there are 2 possible explanations,” said study author Tina Hsu, MD, of the University of Ottawa in Ontario, Canada.

“One is that older adults with cancer either don’t appreciate how much help they require or, more likely, they are able preserve their sense of independence and dignity through a perception that they feel they can do more than they really can.”

“Alternatively, it is possible that caregivers who are more stressed out perceive their loved one to require more help than they actually do need. Most likely, the truth of how much help the patient actually needs lies somewhere between what patients and caregivers report.”

Based on their findings, Drs Hsu and Hurria and their colleagues advise that clinicians consider assessing caregiver burden in those caregivers who report the patient as being more dependent than the patient does themselves.

“Caregivers play an essential role in supporting older adults with cancer,” Dr Hsu said. “We plan to further explore factors associated with caregiver burden in this population, particularly in those who are frailer and thus require even more hands-on support. We also hope to explore what resources caregivers of older adults with cancer feel they need to better help them with their role.” ![]()

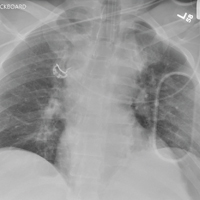

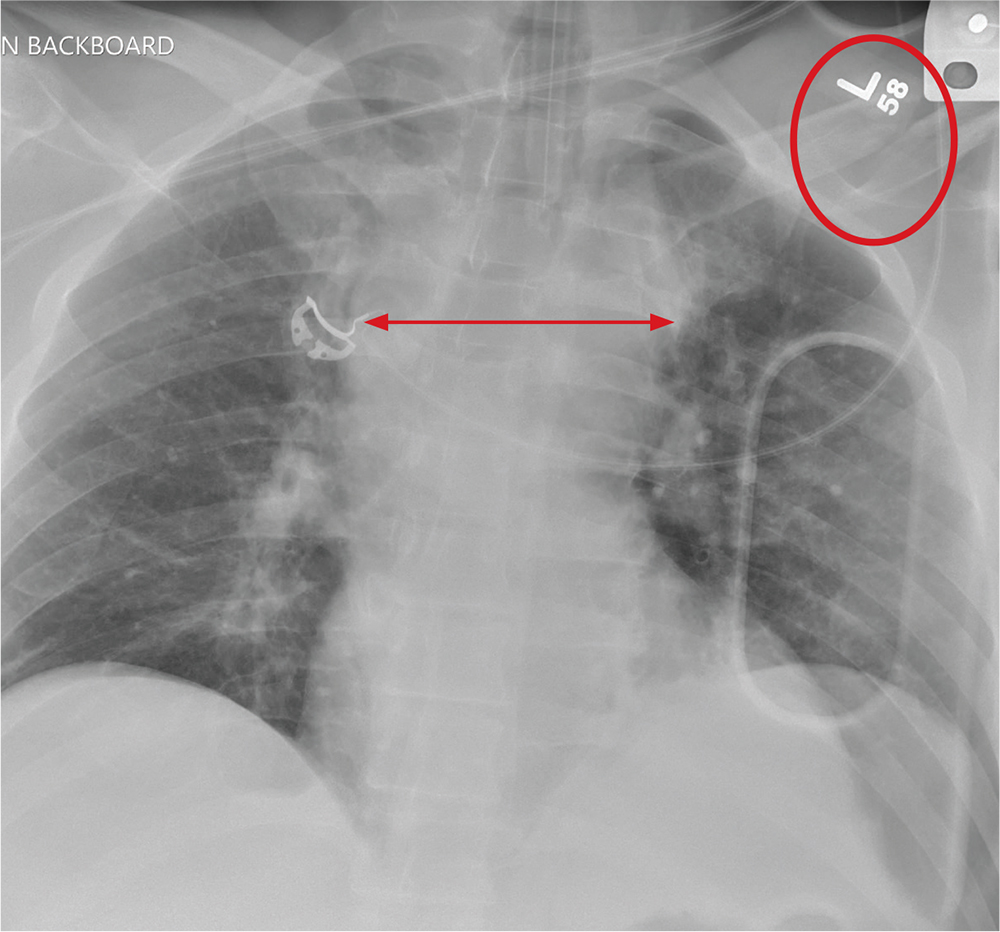

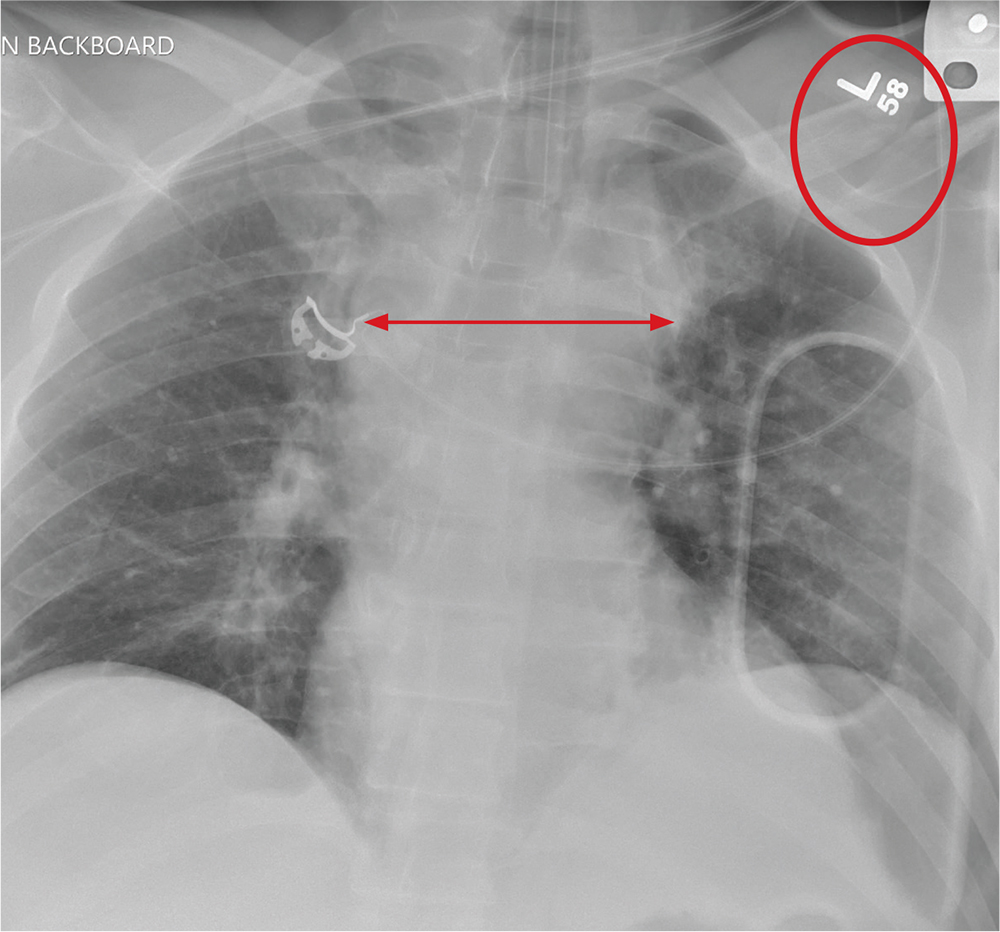

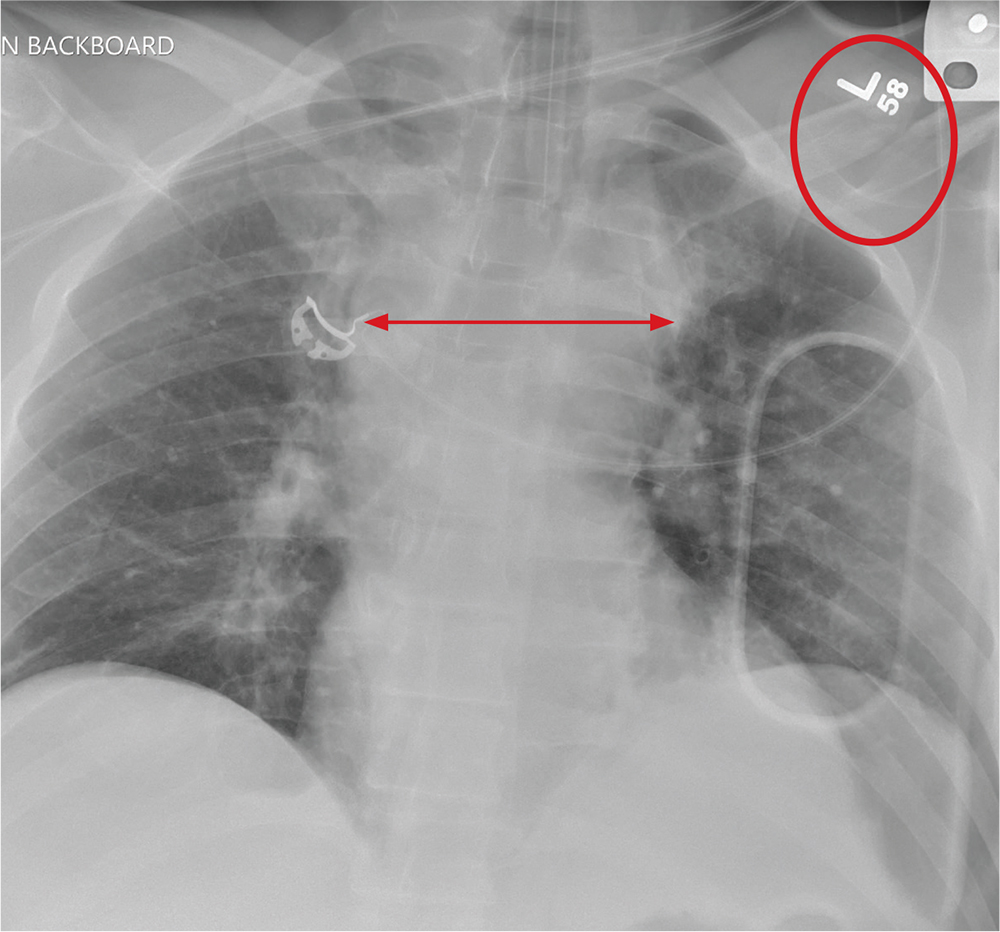

When It All Comes Crashing Down

ANSWER

The radiograph shows that the patient is intubated. The lungs are clear overall. There is a fractured, slightly displaced left clavicle. Of concern, though, is the widened appearance of the mediastinum. In patients with blunt chest trauma, there should be a high index of suspicion for a great vessel injury, warranting a chest CT with contrast for further evaluation. Fortunately, in this patient's case, CT was negative.

ANSWER

The radiograph shows that the patient is intubated. The lungs are clear overall. There is a fractured, slightly displaced left clavicle. Of concern, though, is the widened appearance of the mediastinum. In patients with blunt chest trauma, there should be a high index of suspicion for a great vessel injury, warranting a chest CT with contrast for further evaluation. Fortunately, in this patient's case, CT was negative.

ANSWER

The radiograph shows that the patient is intubated. The lungs are clear overall. There is a fractured, slightly displaced left clavicle. Of concern, though, is the widened appearance of the mediastinum. In patients with blunt chest trauma, there should be a high index of suspicion for a great vessel injury, warranting a chest CT with contrast for further evaluation. Fortunately, in this patient's case, CT was negative.

A 40-year-old construction worker was remodeling a home when the roof collapsed. The patient’s head, face, and chest were reportedly struck by a large metal support beam. He was taken to a local facility, where he was found to have decreased level of consciousness and was combative. He was intubated for airway protection and sent to your facility for tertiary level of care.

History is limited. On arrival, you note a male patient who is intubated and sedated. His blood pressure is 90/60 mm Hg and his heart rate, 130 beats/min. A large laceration on his forehead and scalp has been primarily closed. His pupils are unequal, but both react. Neurologic exam is limited secondary to sedation.

As you complete your primary and secondary surveys, a portable chest radiograph is obtained (shown). What is your impression?

Alternative birthing practices increase risk of infection

All three have been associated with sporadic, serious neonatal infections.

The U.S. prevalence of water births – delivering a baby underwater – is currently unknown, but in the United Kingdom the practice is common. According to a 2015 National Health Service maternity survey, approximately 9% of women who underwent vaginal delivery opted for water birth (Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2016 Jul;101[4]:F357-65). Both the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists and the Royal College of Midwives endorse this practice for healthy women with uncomplicated term pregnancies. According to a 2009 Cochrane Review, immersion during the first phase of labor reduces the use of epidural/spinal analgesia (Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000111.pub3). The maternal benefits of delivery under water, though, have not been clearly defined.

Legionella pneumophila is an uncommon pathogen in children, but cases of neonatal Legionnaires’ disease have been reported after water birth. Two affected babies born in Arizona in 2016 were successfully treated and survived (MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6622a4). A baby born in Texas in 2014 died of sepsis and respiratory failure (Emerg Infect Dis. 2015. doi: 10.3201/eid2101.140846). Canadian investigators have reported fatal disseminated herpes simplex virus infection in an infant after water birth; the mother had herpetic whitlow and a recent blister concerning for HSV on her thigh (J Pediatric Infect Dis Soc. 2017 May 16. doi: 10.1093/jpids/pix035).

Admittedly, each of these cases might have been prevented by adherence to recommended infection control practices, and the absolute risk of infection after water birth is unknown and likely to be small. Still, neither the American Academy of Pediatrics nor the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists currently recommend the practice. ACOG suggests that “births occur on land, not in water” and has called for well-designed, prospective studies of the maternal and perinatal benefits and risks associated with immersion during labor and delivery (Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128:1198-9).

Placentophagia – consuming the placenta after birth – has been promoted by celebrity moms, including Katherine Heigl and Kourtney Kardashian. Placenta can be cooked, blended raw into a smoothie, or dehydrated and encapsulated.

Proponents of placentophagia claim health benefits of this practice, including improved mood and energy, and increased breast milk production. There are few published data to support these claims. A recent case report suggests the practice has the potential to harm the baby. In June 2017, Oregon public health authorities described a neonate with recurrent episodes of group B streptococcal (GBS) bacteremia. An identical strain of GBS was cultured from capsules containing the mother’s dehydrated placenta – she had consumed six of the capsules daily beginning a few days after the baby’s birth. According to the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report communication, “no standards exist for processing placenta for consumption” and the “placenta encapsulation process does not eradicate infectious pathogens per se. … Placenta capsule ingestion should be avoided”(MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66:677-8. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6625a4).

Finally, the ritual practice of umbilical cord nonseverance or lotus birth deserves a mention. In a lotus birth, the umbilical cord is left uncut, allowing the placenta to remain attached to the baby until the cord dries and naturally separates, generally 3-10 days after delivery. Describing a spiritual connection between the baby and the placenta, proponents claim lotus birth promotes bonding and allows for a gentler transition between intra- and extrauterine life.

A review of PubMed turned up no formal studies of this practice, but case reports describe complications such as neonatal idiopathic hepatitis and neonatal sepsis. The Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists has issued a warning about lotus births, advising that babies be monitored closely for infection. RCOG spokesperson Dr. Patrick O’Brien said in a 2008 statement, “If left for a period of time after the birth, there is a risk of infection in the placenta which can consequently spread to the baby. The placenta is particularly prone to infection as it contains blood. Within a short time after birth, once the umbilical cord has stopped pulsating, the placenta has no circulation and is essentially dead tissue.”

Interestingly, a quick scan of Etsy, the popular e-commerce website, turned up a number of lotus birth kits for sale. These generally contain a decorative cloth bag as well as an herb mix containing lavender and eucalyptus to promote drying and mask the smell of the decomposing placenta.

In contrast, many pediatricians, me included, are not well informed about these practices and don’t routinely ask expectant moms about their plans. I propose that we can advocate for our patients-to-be by learning about these practices so that we can engage in an honest, respectful discussion about potential risks and benefits. For me, for now, the risks outweigh the benefits.

Dr. Bryant is a pediatrician specializing in infectious diseases at the University of Louisville (Ky.) and Norton Children’s Hospital, also in Louisville. She said she had no relevant financial disclosures. Email her at [email protected].

All three have been associated with sporadic, serious neonatal infections.

The U.S. prevalence of water births – delivering a baby underwater – is currently unknown, but in the United Kingdom the practice is common. According to a 2015 National Health Service maternity survey, approximately 9% of women who underwent vaginal delivery opted for water birth (Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2016 Jul;101[4]:F357-65). Both the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists and the Royal College of Midwives endorse this practice for healthy women with uncomplicated term pregnancies. According to a 2009 Cochrane Review, immersion during the first phase of labor reduces the use of epidural/spinal analgesia (Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000111.pub3). The maternal benefits of delivery under water, though, have not been clearly defined.

Legionella pneumophila is an uncommon pathogen in children, but cases of neonatal Legionnaires’ disease have been reported after water birth. Two affected babies born in Arizona in 2016 were successfully treated and survived (MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6622a4). A baby born in Texas in 2014 died of sepsis and respiratory failure (Emerg Infect Dis. 2015. doi: 10.3201/eid2101.140846). Canadian investigators have reported fatal disseminated herpes simplex virus infection in an infant after water birth; the mother had herpetic whitlow and a recent blister concerning for HSV on her thigh (J Pediatric Infect Dis Soc. 2017 May 16. doi: 10.1093/jpids/pix035).

Admittedly, each of these cases might have been prevented by adherence to recommended infection control practices, and the absolute risk of infection after water birth is unknown and likely to be small. Still, neither the American Academy of Pediatrics nor the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists currently recommend the practice. ACOG suggests that “births occur on land, not in water” and has called for well-designed, prospective studies of the maternal and perinatal benefits and risks associated with immersion during labor and delivery (Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128:1198-9).

Placentophagia – consuming the placenta after birth – has been promoted by celebrity moms, including Katherine Heigl and Kourtney Kardashian. Placenta can be cooked, blended raw into a smoothie, or dehydrated and encapsulated.

Proponents of placentophagia claim health benefits of this practice, including improved mood and energy, and increased breast milk production. There are few published data to support these claims. A recent case report suggests the practice has the potential to harm the baby. In June 2017, Oregon public health authorities described a neonate with recurrent episodes of group B streptococcal (GBS) bacteremia. An identical strain of GBS was cultured from capsules containing the mother’s dehydrated placenta – she had consumed six of the capsules daily beginning a few days after the baby’s birth. According to the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report communication, “no standards exist for processing placenta for consumption” and the “placenta encapsulation process does not eradicate infectious pathogens per se. … Placenta capsule ingestion should be avoided”(MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66:677-8. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6625a4).

Finally, the ritual practice of umbilical cord nonseverance or lotus birth deserves a mention. In a lotus birth, the umbilical cord is left uncut, allowing the placenta to remain attached to the baby until the cord dries and naturally separates, generally 3-10 days after delivery. Describing a spiritual connection between the baby and the placenta, proponents claim lotus birth promotes bonding and allows for a gentler transition between intra- and extrauterine life.

A review of PubMed turned up no formal studies of this practice, but case reports describe complications such as neonatal idiopathic hepatitis and neonatal sepsis. The Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists has issued a warning about lotus births, advising that babies be monitored closely for infection. RCOG spokesperson Dr. Patrick O’Brien said in a 2008 statement, “If left for a period of time after the birth, there is a risk of infection in the placenta which can consequently spread to the baby. The placenta is particularly prone to infection as it contains blood. Within a short time after birth, once the umbilical cord has stopped pulsating, the placenta has no circulation and is essentially dead tissue.”

Interestingly, a quick scan of Etsy, the popular e-commerce website, turned up a number of lotus birth kits for sale. These generally contain a decorative cloth bag as well as an herb mix containing lavender and eucalyptus to promote drying and mask the smell of the decomposing placenta.

In contrast, many pediatricians, me included, are not well informed about these practices and don’t routinely ask expectant moms about their plans. I propose that we can advocate for our patients-to-be by learning about these practices so that we can engage in an honest, respectful discussion about potential risks and benefits. For me, for now, the risks outweigh the benefits.

Dr. Bryant is a pediatrician specializing in infectious diseases at the University of Louisville (Ky.) and Norton Children’s Hospital, also in Louisville. She said she had no relevant financial disclosures. Email her at [email protected].

All three have been associated with sporadic, serious neonatal infections.

The U.S. prevalence of water births – delivering a baby underwater – is currently unknown, but in the United Kingdom the practice is common. According to a 2015 National Health Service maternity survey, approximately 9% of women who underwent vaginal delivery opted for water birth (Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2016 Jul;101[4]:F357-65). Both the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists and the Royal College of Midwives endorse this practice for healthy women with uncomplicated term pregnancies. According to a 2009 Cochrane Review, immersion during the first phase of labor reduces the use of epidural/spinal analgesia (Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000111.pub3). The maternal benefits of delivery under water, though, have not been clearly defined.

Legionella pneumophila is an uncommon pathogen in children, but cases of neonatal Legionnaires’ disease have been reported after water birth. Two affected babies born in Arizona in 2016 were successfully treated and survived (MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6622a4). A baby born in Texas in 2014 died of sepsis and respiratory failure (Emerg Infect Dis. 2015. doi: 10.3201/eid2101.140846). Canadian investigators have reported fatal disseminated herpes simplex virus infection in an infant after water birth; the mother had herpetic whitlow and a recent blister concerning for HSV on her thigh (J Pediatric Infect Dis Soc. 2017 May 16. doi: 10.1093/jpids/pix035).

Admittedly, each of these cases might have been prevented by adherence to recommended infection control practices, and the absolute risk of infection after water birth is unknown and likely to be small. Still, neither the American Academy of Pediatrics nor the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists currently recommend the practice. ACOG suggests that “births occur on land, not in water” and has called for well-designed, prospective studies of the maternal and perinatal benefits and risks associated with immersion during labor and delivery (Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128:1198-9).

Placentophagia – consuming the placenta after birth – has been promoted by celebrity moms, including Katherine Heigl and Kourtney Kardashian. Placenta can be cooked, blended raw into a smoothie, or dehydrated and encapsulated.

Proponents of placentophagia claim health benefits of this practice, including improved mood and energy, and increased breast milk production. There are few published data to support these claims. A recent case report suggests the practice has the potential to harm the baby. In June 2017, Oregon public health authorities described a neonate with recurrent episodes of group B streptococcal (GBS) bacteremia. An identical strain of GBS was cultured from capsules containing the mother’s dehydrated placenta – she had consumed six of the capsules daily beginning a few days after the baby’s birth. According to the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report communication, “no standards exist for processing placenta for consumption” and the “placenta encapsulation process does not eradicate infectious pathogens per se. … Placenta capsule ingestion should be avoided”(MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66:677-8. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6625a4).

Finally, the ritual practice of umbilical cord nonseverance or lotus birth deserves a mention. In a lotus birth, the umbilical cord is left uncut, allowing the placenta to remain attached to the baby until the cord dries and naturally separates, generally 3-10 days after delivery. Describing a spiritual connection between the baby and the placenta, proponents claim lotus birth promotes bonding and allows for a gentler transition between intra- and extrauterine life.

A review of PubMed turned up no formal studies of this practice, but case reports describe complications such as neonatal idiopathic hepatitis and neonatal sepsis. The Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists has issued a warning about lotus births, advising that babies be monitored closely for infection. RCOG spokesperson Dr. Patrick O’Brien said in a 2008 statement, “If left for a period of time after the birth, there is a risk of infection in the placenta which can consequently spread to the baby. The placenta is particularly prone to infection as it contains blood. Within a short time after birth, once the umbilical cord has stopped pulsating, the placenta has no circulation and is essentially dead tissue.”

Interestingly, a quick scan of Etsy, the popular e-commerce website, turned up a number of lotus birth kits for sale. These generally contain a decorative cloth bag as well as an herb mix containing lavender and eucalyptus to promote drying and mask the smell of the decomposing placenta.

In contrast, many pediatricians, me included, are not well informed about these practices and don’t routinely ask expectant moms about their plans. I propose that we can advocate for our patients-to-be by learning about these practices so that we can engage in an honest, respectful discussion about potential risks and benefits. For me, for now, the risks outweigh the benefits.

Dr. Bryant is a pediatrician specializing in infectious diseases at the University of Louisville (Ky.) and Norton Children’s Hospital, also in Louisville. She said she had no relevant financial disclosures. Email her at [email protected].

Cannabis shows inconsistent benefits for pain, PTSD

Chronic pain and posttraumatic stress disorder are among the top reasons given by patients seeking medical marijuana in states where it is legal, but there is little scientific evidence to support its value for treating either condition, based on the results of a pair of systemic evidence reviews conducted by the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs.

The findings were published online Aug. 14 in the Annals of Internal Medicine.

In the PTSD study, Maya E. O’Neil, PhD, of the VA Portland (Ore.) Health Care System, and colleagues found no significant evidence to support the effectiveness of cannabis for relieving symptoms (Ann Intern Med. 2017 Aug 14. doi: 10.7326/M17-0477). The researchers reviewed data from two systematic reviews and three primary studies.

One of the larger studies (included in one of the systematic reviews) included 47,000 veterans in VA intensive PTSD programs during 1992-2011. In fact, after controlling for demographic factors and other confounding variables, individuals who continued to use cannabis or started using cannabis showed worse PTSD symptoms than did nonusers after 4 months.

“Findings from [randomized, controlled trials] are needed to help determine whether and to what extent cannabis may improve PTSD symptoms, and further studies also are needed to clarify harms in patients with PTSD,” the researchers noted.

In the review of chronic pain literature, Shannon M. Nugent, PhD, also of the VA Portland (Ore.) Health Care System, and her colleagues examined 27 trials, 11 reviews, and 32 primary studies (Ann Intern Med. 2017 Aug 14. doi: 10.7326/M17-0155).

“Across nine studies, intervention patients were more likely to report at least 30% improvement in pain,” the investigators said. But this finding was specific to tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), the researchers said, and evidence of the ability of cannabis to relieve other types of pain, such as cancer pain and multiple sclerosis pain, was insufficient.

In addition, the researchers found a low strength of evidence association between cannabis use and the development of psychotic symptoms, and a moderate strength of evidence association between cannabis use and impaired cognitive function in the general population. “However, our confidence in the findings is limited by inconsistent findings among included studies, inadequate assessment of exposure, and inadequate adjustment for confounding among the studies” they said.

Although no significant differences were noted in rates of adverse events between cannabis users and nonusers, some data suggested users had an increased risk for short-term adverse events that ranged from dizziness to paranoia and suicide attempts.

Other potential harms associated with cannabis use included decreased lung function, increased risk of complications from infectious diseases, cannabis hyperemesis syndrome, and increased risk of violent behavior.

“Even though we did not find strong, consistent evidence of benefit, clinicians will still need to engage in evidence-based discussions with patients managing chronic pain who are using or requesting to use cannabis,” the researchers wrote.

The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose. The study was commissioned by the Veterans Health Administration.

“The systematic reviews highlight an alarming lack of high-quality data from which to draw firm conclusions about the efficacy of cannabis for these conditions, for which cannabis is both sanctioned and commonly used,” wrote Sachin Patel, MD, PhD, in an accompanying editorial (Ann Intern Med. 2017 Aug 14. doi: 10.7326/M17-1713).

“Even if future studies reveal a clear lack of substantial benefit of cannabis for pain or PTSD, legislation is unlikely to remove these conditions from the lists of indications for medical cannabis,” he cautioned. “It will be up to front-line practicing physicians to learn about the harms and benefits of cannabis, educate their patients on these topics, and make evidence-based recommendations about using cannabis and related products for various health conditions.

“In parallel, the research community must pursue high-quality studies and disseminate the results to clinicians and the public. In this context, these reviews are must-reads for all physicians, especially those practicing in states where medical cannabis is legal,” Dr. Patel added.

Dr. Patel is affiliated with Vanderbilt Psychiatric Hospital in Nashville, Tenn. He had no relevant financial conflicts to disclose, but reported receiving grants from Lundbeck.

“The systematic reviews highlight an alarming lack of high-quality data from which to draw firm conclusions about the efficacy of cannabis for these conditions, for which cannabis is both sanctioned and commonly used,” wrote Sachin Patel, MD, PhD, in an accompanying editorial (Ann Intern Med. 2017 Aug 14. doi: 10.7326/M17-1713).

“Even if future studies reveal a clear lack of substantial benefit of cannabis for pain or PTSD, legislation is unlikely to remove these conditions from the lists of indications for medical cannabis,” he cautioned. “It will be up to front-line practicing physicians to learn about the harms and benefits of cannabis, educate their patients on these topics, and make evidence-based recommendations about using cannabis and related products for various health conditions.

“In parallel, the research community must pursue high-quality studies and disseminate the results to clinicians and the public. In this context, these reviews are must-reads for all physicians, especially those practicing in states where medical cannabis is legal,” Dr. Patel added.

Dr. Patel is affiliated with Vanderbilt Psychiatric Hospital in Nashville, Tenn. He had no relevant financial conflicts to disclose, but reported receiving grants from Lundbeck.