User login

Morbo Serpentino

A 58-year-old Danish man presented to an urgent care center due to several months of gradually worsening fatigue, weight loss, abdominal pain, and changes in vision . His abdominal pain was diffuse, constant, and moderate in severity. There was no association with meals, and he reported no nausea, vomiting, or change in bowel movements. He also said his vision in both eyes was blurry, but denied diplopia and said the blurring did not improve when either eye w as closed. He denied dysphagia, headache, focal weakness, or sensitivity to bright lights.

Fatigue and weight loss in a middle-aged man are nonspecific complaints that mainly help to alert the clinician that there may be a serious, systemic process lurking. Constant abdominal pain without nausea, vomiting, or change in bowel movements makes intestinal obstruction or a motility disorder less likely. Given that the pain is diffuse, it raises the possibility of an intraperitoneal process or a process within an organ that is irritating the peritoneum.

Worsening of vision can result from disorders anywhere along the visual pathway, including the cornea (keratitis or corneal edema from glaucoma), anterior chamber (uveitis or hyphema), lens (cataracts, dislocations, hyperglycemia), vitreous humor (uveitis), retina (infections, ischemia, detachment, diabetic retinopathy), macula (degenerative disease), optic nerve (optic neuritis), optic chiasm, and the visual projections through the hemispheres to the occipital lobes. To narrow the differential diagnosis, it would be important to inquire about prior eye problems, to measure visual acuity and intraocular pressure, to perform fundoscopic and slit-lamp exams to detect retinal and anterior chamber disorders, respectively, and to assess visual fields. An afferent pupillary defect would suggest optic nerve pathology.

Disorders that could unify the constitutional, abdominal, and visual symptoms include systemic inflammatory diseases, such as sarcoidosis (which has an increased incidence among Northern Europeans), tuberculosis, or cancer. While diabetes mellitus could explain his visual problems, weight loss, and fatigue, the absence of polyuria, polydipsia, or polyphagia argues against this possibility.

The patient had hypercholesterolemia and type 2 diabetes mellitus. Medications were metformin, atorvastatin, and glimepiride. He was a former smoker with 23 pack-years and had quit over 5 years prior. He had not traveled outside of Denmark in 2 years and had no pets at home. He reported being monogamous with his same-sex partner for the past 25 years. He had no significant family history, and he worked at a local hospital as a nurse. He denied any previous ocular history.

On examination, the pulse was 67 beats per minute, temperature was 36.7 degrees Celsius, respiratory rate was 16 breaths per minute, oxygen saturation was 99% while breathing ambient air, and blood pressure was 132/78. Oropharynx demonstrated no thrush or other lesions. The heart rhythm was regular and there were no murmurs. Lungs were clear to auscultation bilaterally. Abdominal exam was normal except for mild tenderness upon palpation in all quadrants, but no masses, organomegaly, rigidity, or rebound tenderness were present. Skin examination revealed several subcutaneous nodules measuring up to 0.5 cm in diameter overlying the right and left posterolateral chest walls. T he nodules were rubbery, pink, nontender, and not warm nor fluctuant. Visual acuity was reduced in both eyes. Extraocular movements were intact, and the pupils reacted to light and accommodated appropriately. The sclerae were injected bilaterally. The remainder of the cranial nerves and neurologic exam were normal. Due to the vision loss , the patient was referred to an ophthalmologist who diagnosed bilateral anterior uveitis.

Though monogamous with his male partner for many years, it is mandatory to consider complications of human immunodeficiency virus infection (HIV ). The absence of oral lesions indicative of a low CD4 count, such as oral hairy leukoplakia or thrush, does not rule out HIV disease. Additional history about his work as a nurse might shed light on his risk of infection, such as airborne exposure to tuberculosis or acquisition of blood-borne pathogens through a needle stick injury. His unremarkable vital signs support the chronicity of his medical condition.

Uveitis can result from numerous causes. When confined to the eye, uncommon hereditary and acquired causes are less likely . In many patients, uveitis arises in the setting of systemic infection or inflammation. The numerous infectious causes of uveitis include syphilis, tuberculosis, toxoplasmosis, cat scratch disease, and viruses such as HIV, West Nile, and Ebola. Among the inflammatory diseases that can cause uveitis are sarcoidosis, inflammatory bowel disease, systemic lupus erythematosus, Behçet disease, and Sjogren syndrome.

Several of these conditions, including tuberculosis and syphilis, may also cause subcutaneous nodules. Both tuberculosis and syphilis can cause skin and gastrointestinal disease. Sarcoidosis could involve the skin, peritoneum, and uvea, and is a possibility in this patient. The dermatologic conditions associated with sarcoidosis are protean and include granulomatous inflammation and nongranulomatous processes such as erythema nodosum. Usually the nodules of erythema nodosum are tender, red or purple, and located on the lower extremities. The lack of tenderness points away from erythema nodosum in this patient. Metastatic cancer can disseminate to the subcutaneous tissue, and the patient’s smoking history and age mandate we consider malignancy. However, skin metastases tend to be hard, not rubbery.

A cost-effective evaluation at this point would include syphilis serologies, HIV testing, testing for tuberculosis with either a purified protein derivative test or interferon gamma release assay, chest radiography, and biopsy of 1 of the lesions on his back.

Laboratory data showed 12,400 white blood cells per cubic milliliter (64% neutrophils, 24% lymphocytes, 9% monocytes, 2% eosinophils, 1% basophils), hemoglobin 7.9 g/dL, mean corpuscular volume 85 fL, platelets 476,000 per cubic milliliter , C-reactive protein 43 mg/ d L (normal < 8 mg/L), gamma-glutamyl-transferase 554 IU/L (normal range 0-45), alkaline phosphatase 865 U/L (normal range 60-200), and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) 71 mm per hour. International normalized ratio was 1.0, albumin was 3.0 mg/dL, activated partial thromboplastin time was 32 seconds (normal 22 to 35 seconds), and bilirubin was 0.3 mg/dL. Antibodies to HIV , hepatitis C, and hepatitis B surface antigen were not detectable. Electrocardiography ( ECG ) was normal. Plain radiograph of the chest demonstrated multiple nodular lesions bilaterally measuring up to 1 cm with no cavitation. There was a left pleural effusion.

The history and exam findings indicate a serious inflammatory condition affecting his lungs, pleura, eyes, skin, liver, and possibly his peritoneum. In this context, the elevated C-reactive protein and ESR are not helpful in differentiating inflammatory from infectious causes. The constellation of uveitis, pulmonary and cutaneous nodules, and marked abnormalities of liver tests in a middle-aged man of Northern European origin points us toward sarcoidosis. Pleural effusions are not common with sarcoidosis but may occur. However, to avoid premature closure, it is important to consider other possibilities.

Metastatic cancer, including lymphoma, could cause pulmonary and cutaneous nodules and liver involvement, but the chronic time course and uveitis are not consistent with malignancy. Tuberculosis is still a consideration, though one would have expected him to report fevers, night sweats, and, perhaps, exposure to patients with pulmonary tuberculosis in his job as a nurse. Multiple solid pulmonary nodules are also uncommon with pulmonary tuberculosis. Fungal infections such as histoplasmosis can cause skin lesions and pulmonary nodules but do not fit well with uveitis.

At this point, “ tissue is the issue.” A skin nodule would be the easiest site to biopsy. If skin biopsy was not diagnostic, computed tomography (CT) of his chest and abdomen should be performed to identify the next most accessible site for biopsy.

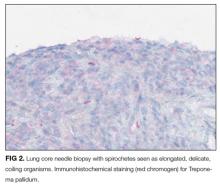

Esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) and colonoscopy showed normal findings, and random biopsies from the stomach and colon were normal. CT of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis performed with the administration of intravenous contrast showed multiple solid opacities in both lung fields up to 1 cm, with enlarged mediastinal and retroperitoneal lymph nodes measuring 1 to 3 cm in diameter, a left pleural effusion, wall thickening in the right colon, and several nonspecific hypodensities in the liver. A punch biopsy taken from the right chest wall lesion demonstrated chronic inflammation without granulomas. The patient underwent CT-guided biopsy of 1 of the right-sided lung nodules, which revealed noncaseating granulomatous inflammation, fibrosis, and necrosis. Neither biopsy contained malignant cells, and additional stains revealed no bacteria, fungi, or acid fast bacilli.

The retroperitoneal and mediastinal adenopathy are indicative of a widely disseminated inflammatory process. Lymphoma continues to be a concern, though uveitis as an initial presenting problem would very unusual. Although biopsy of the chest wall lesion failed to demonstrate granulomatous inflammation, the most parsimonious explanation is that the skin and lung nodules are both related to a single systemic process.

Granulomas form in an attempt to wall off offending agents, whether foreign antigens (talc, certain medications), infectious agents, or self-antigens. Review of histopathology and microbiologic studies are useful first steps. Stains for bacteria, fungi, or acid-fast organisms may diagnose an infectious cause, such as tuberculosis, leprosy, syphilis, fungi, or cat scratch disease. Granulomas in association with vascular inflammation would indicate vasculitis. Other autoimmune considerations include sarcoidosis and Crohn disease. Noncaseating granulomas are typically found in sarcoidosis, cat scratch disease, syphilis, leprosy, or Crohn disease, but do not entirely exclude tuberculosis.

The negative infectious studies and lack of classic features of Crohn disease or other autoimmune diseases further point to sarcoidosis as the etiology of this patient’s illness. A Norwegian dermatologist first described the pathology of sarcoidosis based upon specimens taken from skin nodules. He thought the lesions were sarcoma and described them as, “ multiple benign sarcoid of the skin,” which is where the name “ sarcoidosis” originated.

Diagnosing sarcoidosis requires excluding other mimickers. Additional testing should include syphilis serologies, rheumatoid factor, and antineutrophilic cytoplasmic antibodies. The latter is associated with granulomatosis with polyangiitis and eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis, either of which may produce granulomatous inflammation of the lungs, skin, and uvea.

At this juncture, PET-CT represents a costly and unnecessary test that does not narrow our diagnostic possibilities sufficiently to justify its use. Osteolytic lesions would be unusual in sarcoidosis and more likely in lymphoma or infectious processes such as tuberculosis. Tests for syphilis and tuberculosis are required, and are a fraction of the cost of a PET-CT.

With the biopsy revealing spirochetes, and the positive results of a nontreponemal test (RPR) and confirmatory treponemal results, the diagnosis of syphilis is firmly established. Uveitis indicates neurosyphilis and warrants a longer course of intravenous penicillin. Lumbar puncture should be performed.

A lumbar puncture was performed. Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) contained 9 white blood cells and 73 red blood cells per cubic milliliter; protein concentration was 73 mg/dL, and glucose was 116 mg/dL. Polymerase chain reaction for T. pallidum was negative. Transthoracic ECG and magnetic resonance imaging of the brain were normal. The patient was treated with intravenous penicillin G at 5 million units 4 times daily for 15 days. A PET-CT scan 3 months later revealed complete resolution of the subcutaneous, pulmonary, liver lesions, lymphadenopathy, and uveitis. Repeat treponemal serologies demonstrated a greater than 4-fold decline in titers.

DISCUSSION

Syphilis is a sexually transmitted disease with increasing incidence worldwide. Untreated infection progresses through 3 stages. The primary stage is characterized by the appearance of a painless chancre after an incubation period of 2 to 3 weeks. Four to 8 weeks later, the secondary stage emerges as a systemic infection, often heralded by a maculopapular rash with desquamation, frequently involving the soles and palms. Hepatitis, iridocyclitis, and early neurosyphilis may also be seen at this stage. Subsequently, syphilis becomes latent. One-third of patients with untreated latent syphilis will develop tertiary syphilis, typified by late neurosyphilis (tabes dorsalis and general paresis), cardiovascular disease (aortitis), or gummatous disease. 1

Gummas are destructive granulomatous lesions that typically present indolently, may occur singly or multiply, and may involve almost any organ. It has been suggested that gummas are the immune system’s defense to slow the bacteria after attempts to kill it have failed. Histologically, gummas are hyalinized nodules with surrounding granulomatous infiltrate of lymphocytes, plasma cells, and multinucleated giant cells with or without necrosis . In the preantibiotic era, gummas were seen in approximately 15% of infected patients, with a latency of 1 to 46 years after primary infection. 2 Penicillin led to a drastic reduction in gummas until the HIV epidemic, which led to the resurgence of gummas at a drastically shortened interval following primary syphilis. 3

Most commonly, gummas affect the skin and bones. In the skin , lesions may be superficial or deep and may progress into ulcerative nodules. In the bones, destructive gummas have a characteristic “moth-eaten” appearance. Less common sequelae of gummas incude gummatous hepatitis, perforated nasal septum (saddle nose deformity), or hard palate erosions. 2,4 R arely, syphilis involves the lungs, appearing as nodules, infiltrates, or pleural effusion. 5

Ocular manifestations occur in approximately 5% of patients with syphilis, more often in secondary and tertiary stages, and are strongly associated with a spread to the central nervous system. Syphilis may affect any structure of the eye, with anterior uveitis as the most frequent manifestation. Partial or complete vision loss is identified in approximately half of the patients with ocular syphilis and may be completely reversed by appropriate treatment. Ophthalmologic findings such as optic neuritis and papilledema imply advanced illness , as do Argyll-Robertson pupils (small pupils that are poorly reactive to light , but with preserved accommodation and convergence). 6,7 The treatment of ocular syphilis is identical to that of neurosyphilis. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends CSF analysis in any patient with ocular syphilis. Abnormal results should prompt repeat lumbar puncture every 3 to 6 months following treatment until the CSF results normalize. 8

The diagnosis of syphilis relies on indirect serologic tests. T. pallidum cannot be cultured in vitro, and techniques to identify spirochetes directly by using darkfield microscopy or DNA amplification via polymerase chain reaction are limited by availability or by poor sensitivity in advanced syphilis. 1 Imaging modalities including PET cannot reliably differentiate syphilis from other infectious and noninfectious mimickers. 9 F ortunately, syphilis infection can be diagnosed accurately based on reactive treponemal and nontreponemal serum tests. Nontreponemal tests, such as the RPR and Venereal Disease Research Laboratory, have traditionally been utilized as first-line evaluation, followed by a confirmatory treponemal test. However, nontreponemal tests may be nonreactive in a few settings: very early or very late in infection, and in individuals previously treated for syphilis. Thus, newer “reverse testing” algorithms utilize more sensitive and less expensive treponemal tests as the first test, followed by nontreponemal tests if the initial treponemal test is reactive. 8 Regardless of the testing sequence, in patients with no prior history of syphilis, reactive results on both treponemal and nontreponemal assays firmly establish a diagnosis of syphilis, obviating the need for more invasive and costly testing.

In patients with unexplained systemic illness, clinicians should have a low threshold to test for syphilis. Testing should be extended to certain asymptomatic individuals at higher risk of infection, including men who have sex with men, sexual partners of patients infected with syphilis, individuals with HIV or sexually-transmitted diseases, and others with high-risk sexual behavior or a history of sexually-transmitted diseases. 8 As the discussant points out, earlier consideration of and testing for syphilis would have spared the patient from unnecessary and costly EGD, colonoscopy, PET-CT scanning, and 3 biopsies.

Syphilis has been known to be a horribly destructive disease for centuries, earning the moniker “morbo serpentino” (serpentine disease) from the Spanish physician Ruiz Diaz de Isla in the 1500s. 10 In the modern era, physicians must remember to consider the diagnosis of syphilis in order to effectively mitigate the harm from this resurgent disease when it attacks our patients.

TEACHING POINTS

- Syphilis, the great imposter, is rising in incidence and should be on the differential diagnosis in all patients with unexplained multisystem inflammatory disease.

- A cost-effective diagnostic approach to syphilis entails serologic testing with treponemal and nontreponemal assays.

- Unexplained granulomas, especially in the skin, bone, or liver, should prompt consideration of gummatous syphilis.

- Ocular syphilis may involve any part of the visual tract and is treated the same as neurosyphilis.

Disclosure

Dr. Weinreich has received payment for lectures from Boehringer er Ingelheim, Astra Zeneca, TEVA and Novartis in 2016. All other contributors have nothing to report.

1. French P. Syphilis. BMJ. 2007;334:143-147. PubMed

2. Singh AE, Romanowski B. Syphilis: Review with emphasis on clinical, epidemiologic, and some biologic features. Clin Micriobio Rev. 1999;12(2):187-209. PubMed

3. Karp G, Schlaeffer F, Jotkowitz A, Riesenberg K. Syphilis and HIV co-infection. Eur J Int Med. 2009; 20:9-13. PubMed

4. Pilozzi-Edmonds L, Kong LY, Szabo J, Birnbaum LM. Rapid progression to gummatous syphilitic hepatitis and neurosyphilis in a patient with newly diagnosed HIV. Int J STD AIDS. 2014;26(13)985-987. PubMed

5. David G, Perpoint T, Boibieux A, et al. Secondary pulmonary syphilis: report of a likely case and literature review. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;42(3):e11-e15. PubMed

6. Moradi A, Salek S, Daniel E, et al. Clinical features and incidence rates of ocular complications in patients with ocular syphilis. Am J Ophthalmol. 2015;159:334-343. PubMed

7. Aldave AJ, King JA, Cunningham ET Jr. Ocular syphilis. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2001;12:433-441. PubMed

8. Workowski KA, Bolan GA. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2015. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2015;64:1-137. PubMed

9. Lin M, Darwish B, Chu J. Neurosyphilitic gumma on F18-2-fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose (FDG) positron emission tomography: An old disease investigated with new technology. J Clin Neurosc. 2009;16:410-412. PubMed

10. de Ricon‐Ferraz A. Early work on syphilis: Diaz de Ysla’s treatise on the serpentine disease of Hispaniola Island. Int J Dermatol. 1999;38(3):222-227. PubMed

A 58-year-old Danish man presented to an urgent care center due to several months of gradually worsening fatigue, weight loss, abdominal pain, and changes in vision . His abdominal pain was diffuse, constant, and moderate in severity. There was no association with meals, and he reported no nausea, vomiting, or change in bowel movements. He also said his vision in both eyes was blurry, but denied diplopia and said the blurring did not improve when either eye w as closed. He denied dysphagia, headache, focal weakness, or sensitivity to bright lights.

Fatigue and weight loss in a middle-aged man are nonspecific complaints that mainly help to alert the clinician that there may be a serious, systemic process lurking. Constant abdominal pain without nausea, vomiting, or change in bowel movements makes intestinal obstruction or a motility disorder less likely. Given that the pain is diffuse, it raises the possibility of an intraperitoneal process or a process within an organ that is irritating the peritoneum.

Worsening of vision can result from disorders anywhere along the visual pathway, including the cornea (keratitis or corneal edema from glaucoma), anterior chamber (uveitis or hyphema), lens (cataracts, dislocations, hyperglycemia), vitreous humor (uveitis), retina (infections, ischemia, detachment, diabetic retinopathy), macula (degenerative disease), optic nerve (optic neuritis), optic chiasm, and the visual projections through the hemispheres to the occipital lobes. To narrow the differential diagnosis, it would be important to inquire about prior eye problems, to measure visual acuity and intraocular pressure, to perform fundoscopic and slit-lamp exams to detect retinal and anterior chamber disorders, respectively, and to assess visual fields. An afferent pupillary defect would suggest optic nerve pathology.

Disorders that could unify the constitutional, abdominal, and visual symptoms include systemic inflammatory diseases, such as sarcoidosis (which has an increased incidence among Northern Europeans), tuberculosis, or cancer. While diabetes mellitus could explain his visual problems, weight loss, and fatigue, the absence of polyuria, polydipsia, or polyphagia argues against this possibility.

The patient had hypercholesterolemia and type 2 diabetes mellitus. Medications were metformin, atorvastatin, and glimepiride. He was a former smoker with 23 pack-years and had quit over 5 years prior. He had not traveled outside of Denmark in 2 years and had no pets at home. He reported being monogamous with his same-sex partner for the past 25 years. He had no significant family history, and he worked at a local hospital as a nurse. He denied any previous ocular history.

On examination, the pulse was 67 beats per minute, temperature was 36.7 degrees Celsius, respiratory rate was 16 breaths per minute, oxygen saturation was 99% while breathing ambient air, and blood pressure was 132/78. Oropharynx demonstrated no thrush or other lesions. The heart rhythm was regular and there were no murmurs. Lungs were clear to auscultation bilaterally. Abdominal exam was normal except for mild tenderness upon palpation in all quadrants, but no masses, organomegaly, rigidity, or rebound tenderness were present. Skin examination revealed several subcutaneous nodules measuring up to 0.5 cm in diameter overlying the right and left posterolateral chest walls. T he nodules were rubbery, pink, nontender, and not warm nor fluctuant. Visual acuity was reduced in both eyes. Extraocular movements were intact, and the pupils reacted to light and accommodated appropriately. The sclerae were injected bilaterally. The remainder of the cranial nerves and neurologic exam were normal. Due to the vision loss , the patient was referred to an ophthalmologist who diagnosed bilateral anterior uveitis.

Though monogamous with his male partner for many years, it is mandatory to consider complications of human immunodeficiency virus infection (HIV ). The absence of oral lesions indicative of a low CD4 count, such as oral hairy leukoplakia or thrush, does not rule out HIV disease. Additional history about his work as a nurse might shed light on his risk of infection, such as airborne exposure to tuberculosis or acquisition of blood-borne pathogens through a needle stick injury. His unremarkable vital signs support the chronicity of his medical condition.

Uveitis can result from numerous causes. When confined to the eye, uncommon hereditary and acquired causes are less likely . In many patients, uveitis arises in the setting of systemic infection or inflammation. The numerous infectious causes of uveitis include syphilis, tuberculosis, toxoplasmosis, cat scratch disease, and viruses such as HIV, West Nile, and Ebola. Among the inflammatory diseases that can cause uveitis are sarcoidosis, inflammatory bowel disease, systemic lupus erythematosus, Behçet disease, and Sjogren syndrome.

Several of these conditions, including tuberculosis and syphilis, may also cause subcutaneous nodules. Both tuberculosis and syphilis can cause skin and gastrointestinal disease. Sarcoidosis could involve the skin, peritoneum, and uvea, and is a possibility in this patient. The dermatologic conditions associated with sarcoidosis are protean and include granulomatous inflammation and nongranulomatous processes such as erythema nodosum. Usually the nodules of erythema nodosum are tender, red or purple, and located on the lower extremities. The lack of tenderness points away from erythema nodosum in this patient. Metastatic cancer can disseminate to the subcutaneous tissue, and the patient’s smoking history and age mandate we consider malignancy. However, skin metastases tend to be hard, not rubbery.

A cost-effective evaluation at this point would include syphilis serologies, HIV testing, testing for tuberculosis with either a purified protein derivative test or interferon gamma release assay, chest radiography, and biopsy of 1 of the lesions on his back.

Laboratory data showed 12,400 white blood cells per cubic milliliter (64% neutrophils, 24% lymphocytes, 9% monocytes, 2% eosinophils, 1% basophils), hemoglobin 7.9 g/dL, mean corpuscular volume 85 fL, platelets 476,000 per cubic milliliter , C-reactive protein 43 mg/ d L (normal < 8 mg/L), gamma-glutamyl-transferase 554 IU/L (normal range 0-45), alkaline phosphatase 865 U/L (normal range 60-200), and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) 71 mm per hour. International normalized ratio was 1.0, albumin was 3.0 mg/dL, activated partial thromboplastin time was 32 seconds (normal 22 to 35 seconds), and bilirubin was 0.3 mg/dL. Antibodies to HIV , hepatitis C, and hepatitis B surface antigen were not detectable. Electrocardiography ( ECG ) was normal. Plain radiograph of the chest demonstrated multiple nodular lesions bilaterally measuring up to 1 cm with no cavitation. There was a left pleural effusion.

The history and exam findings indicate a serious inflammatory condition affecting his lungs, pleura, eyes, skin, liver, and possibly his peritoneum. In this context, the elevated C-reactive protein and ESR are not helpful in differentiating inflammatory from infectious causes. The constellation of uveitis, pulmonary and cutaneous nodules, and marked abnormalities of liver tests in a middle-aged man of Northern European origin points us toward sarcoidosis. Pleural effusions are not common with sarcoidosis but may occur. However, to avoid premature closure, it is important to consider other possibilities.

Metastatic cancer, including lymphoma, could cause pulmonary and cutaneous nodules and liver involvement, but the chronic time course and uveitis are not consistent with malignancy. Tuberculosis is still a consideration, though one would have expected him to report fevers, night sweats, and, perhaps, exposure to patients with pulmonary tuberculosis in his job as a nurse. Multiple solid pulmonary nodules are also uncommon with pulmonary tuberculosis. Fungal infections such as histoplasmosis can cause skin lesions and pulmonary nodules but do not fit well with uveitis.

At this point, “ tissue is the issue.” A skin nodule would be the easiest site to biopsy. If skin biopsy was not diagnostic, computed tomography (CT) of his chest and abdomen should be performed to identify the next most accessible site for biopsy.

Esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) and colonoscopy showed normal findings, and random biopsies from the stomach and colon were normal. CT of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis performed with the administration of intravenous contrast showed multiple solid opacities in both lung fields up to 1 cm, with enlarged mediastinal and retroperitoneal lymph nodes measuring 1 to 3 cm in diameter, a left pleural effusion, wall thickening in the right colon, and several nonspecific hypodensities in the liver. A punch biopsy taken from the right chest wall lesion demonstrated chronic inflammation without granulomas. The patient underwent CT-guided biopsy of 1 of the right-sided lung nodules, which revealed noncaseating granulomatous inflammation, fibrosis, and necrosis. Neither biopsy contained malignant cells, and additional stains revealed no bacteria, fungi, or acid fast bacilli.

The retroperitoneal and mediastinal adenopathy are indicative of a widely disseminated inflammatory process. Lymphoma continues to be a concern, though uveitis as an initial presenting problem would very unusual. Although biopsy of the chest wall lesion failed to demonstrate granulomatous inflammation, the most parsimonious explanation is that the skin and lung nodules are both related to a single systemic process.

Granulomas form in an attempt to wall off offending agents, whether foreign antigens (talc, certain medications), infectious agents, or self-antigens. Review of histopathology and microbiologic studies are useful first steps. Stains for bacteria, fungi, or acid-fast organisms may diagnose an infectious cause, such as tuberculosis, leprosy, syphilis, fungi, or cat scratch disease. Granulomas in association with vascular inflammation would indicate vasculitis. Other autoimmune considerations include sarcoidosis and Crohn disease. Noncaseating granulomas are typically found in sarcoidosis, cat scratch disease, syphilis, leprosy, or Crohn disease, but do not entirely exclude tuberculosis.

The negative infectious studies and lack of classic features of Crohn disease or other autoimmune diseases further point to sarcoidosis as the etiology of this patient’s illness. A Norwegian dermatologist first described the pathology of sarcoidosis based upon specimens taken from skin nodules. He thought the lesions were sarcoma and described them as, “ multiple benign sarcoid of the skin,” which is where the name “ sarcoidosis” originated.

Diagnosing sarcoidosis requires excluding other mimickers. Additional testing should include syphilis serologies, rheumatoid factor, and antineutrophilic cytoplasmic antibodies. The latter is associated with granulomatosis with polyangiitis and eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis, either of which may produce granulomatous inflammation of the lungs, skin, and uvea.

At this juncture, PET-CT represents a costly and unnecessary test that does not narrow our diagnostic possibilities sufficiently to justify its use. Osteolytic lesions would be unusual in sarcoidosis and more likely in lymphoma or infectious processes such as tuberculosis. Tests for syphilis and tuberculosis are required, and are a fraction of the cost of a PET-CT.

With the biopsy revealing spirochetes, and the positive results of a nontreponemal test (RPR) and confirmatory treponemal results, the diagnosis of syphilis is firmly established. Uveitis indicates neurosyphilis and warrants a longer course of intravenous penicillin. Lumbar puncture should be performed.

A lumbar puncture was performed. Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) contained 9 white blood cells and 73 red blood cells per cubic milliliter; protein concentration was 73 mg/dL, and glucose was 116 mg/dL. Polymerase chain reaction for T. pallidum was negative. Transthoracic ECG and magnetic resonance imaging of the brain were normal. The patient was treated with intravenous penicillin G at 5 million units 4 times daily for 15 days. A PET-CT scan 3 months later revealed complete resolution of the subcutaneous, pulmonary, liver lesions, lymphadenopathy, and uveitis. Repeat treponemal serologies demonstrated a greater than 4-fold decline in titers.

DISCUSSION

Syphilis is a sexually transmitted disease with increasing incidence worldwide. Untreated infection progresses through 3 stages. The primary stage is characterized by the appearance of a painless chancre after an incubation period of 2 to 3 weeks. Four to 8 weeks later, the secondary stage emerges as a systemic infection, often heralded by a maculopapular rash with desquamation, frequently involving the soles and palms. Hepatitis, iridocyclitis, and early neurosyphilis may also be seen at this stage. Subsequently, syphilis becomes latent. One-third of patients with untreated latent syphilis will develop tertiary syphilis, typified by late neurosyphilis (tabes dorsalis and general paresis), cardiovascular disease (aortitis), or gummatous disease. 1

Gummas are destructive granulomatous lesions that typically present indolently, may occur singly or multiply, and may involve almost any organ. It has been suggested that gummas are the immune system’s defense to slow the bacteria after attempts to kill it have failed. Histologically, gummas are hyalinized nodules with surrounding granulomatous infiltrate of lymphocytes, plasma cells, and multinucleated giant cells with or without necrosis . In the preantibiotic era, gummas were seen in approximately 15% of infected patients, with a latency of 1 to 46 years after primary infection. 2 Penicillin led to a drastic reduction in gummas until the HIV epidemic, which led to the resurgence of gummas at a drastically shortened interval following primary syphilis. 3

Most commonly, gummas affect the skin and bones. In the skin , lesions may be superficial or deep and may progress into ulcerative nodules. In the bones, destructive gummas have a characteristic “moth-eaten” appearance. Less common sequelae of gummas incude gummatous hepatitis, perforated nasal septum (saddle nose deformity), or hard palate erosions. 2,4 R arely, syphilis involves the lungs, appearing as nodules, infiltrates, or pleural effusion. 5

Ocular manifestations occur in approximately 5% of patients with syphilis, more often in secondary and tertiary stages, and are strongly associated with a spread to the central nervous system. Syphilis may affect any structure of the eye, with anterior uveitis as the most frequent manifestation. Partial or complete vision loss is identified in approximately half of the patients with ocular syphilis and may be completely reversed by appropriate treatment. Ophthalmologic findings such as optic neuritis and papilledema imply advanced illness , as do Argyll-Robertson pupils (small pupils that are poorly reactive to light , but with preserved accommodation and convergence). 6,7 The treatment of ocular syphilis is identical to that of neurosyphilis. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends CSF analysis in any patient with ocular syphilis. Abnormal results should prompt repeat lumbar puncture every 3 to 6 months following treatment until the CSF results normalize. 8

The diagnosis of syphilis relies on indirect serologic tests. T. pallidum cannot be cultured in vitro, and techniques to identify spirochetes directly by using darkfield microscopy or DNA amplification via polymerase chain reaction are limited by availability or by poor sensitivity in advanced syphilis. 1 Imaging modalities including PET cannot reliably differentiate syphilis from other infectious and noninfectious mimickers. 9 F ortunately, syphilis infection can be diagnosed accurately based on reactive treponemal and nontreponemal serum tests. Nontreponemal tests, such as the RPR and Venereal Disease Research Laboratory, have traditionally been utilized as first-line evaluation, followed by a confirmatory treponemal test. However, nontreponemal tests may be nonreactive in a few settings: very early or very late in infection, and in individuals previously treated for syphilis. Thus, newer “reverse testing” algorithms utilize more sensitive and less expensive treponemal tests as the first test, followed by nontreponemal tests if the initial treponemal test is reactive. 8 Regardless of the testing sequence, in patients with no prior history of syphilis, reactive results on both treponemal and nontreponemal assays firmly establish a diagnosis of syphilis, obviating the need for more invasive and costly testing.

In patients with unexplained systemic illness, clinicians should have a low threshold to test for syphilis. Testing should be extended to certain asymptomatic individuals at higher risk of infection, including men who have sex with men, sexual partners of patients infected with syphilis, individuals with HIV or sexually-transmitted diseases, and others with high-risk sexual behavior or a history of sexually-transmitted diseases. 8 As the discussant points out, earlier consideration of and testing for syphilis would have spared the patient from unnecessary and costly EGD, colonoscopy, PET-CT scanning, and 3 biopsies.

Syphilis has been known to be a horribly destructive disease for centuries, earning the moniker “morbo serpentino” (serpentine disease) from the Spanish physician Ruiz Diaz de Isla in the 1500s. 10 In the modern era, physicians must remember to consider the diagnosis of syphilis in order to effectively mitigate the harm from this resurgent disease when it attacks our patients.

TEACHING POINTS

- Syphilis, the great imposter, is rising in incidence and should be on the differential diagnosis in all patients with unexplained multisystem inflammatory disease.

- A cost-effective diagnostic approach to syphilis entails serologic testing with treponemal and nontreponemal assays.

- Unexplained granulomas, especially in the skin, bone, or liver, should prompt consideration of gummatous syphilis.

- Ocular syphilis may involve any part of the visual tract and is treated the same as neurosyphilis.

Disclosure

Dr. Weinreich has received payment for lectures from Boehringer er Ingelheim, Astra Zeneca, TEVA and Novartis in 2016. All other contributors have nothing to report.

A 58-year-old Danish man presented to an urgent care center due to several months of gradually worsening fatigue, weight loss, abdominal pain, and changes in vision . His abdominal pain was diffuse, constant, and moderate in severity. There was no association with meals, and he reported no nausea, vomiting, or change in bowel movements. He also said his vision in both eyes was blurry, but denied diplopia and said the blurring did not improve when either eye w as closed. He denied dysphagia, headache, focal weakness, or sensitivity to bright lights.

Fatigue and weight loss in a middle-aged man are nonspecific complaints that mainly help to alert the clinician that there may be a serious, systemic process lurking. Constant abdominal pain without nausea, vomiting, or change in bowel movements makes intestinal obstruction or a motility disorder less likely. Given that the pain is diffuse, it raises the possibility of an intraperitoneal process or a process within an organ that is irritating the peritoneum.

Worsening of vision can result from disorders anywhere along the visual pathway, including the cornea (keratitis or corneal edema from glaucoma), anterior chamber (uveitis or hyphema), lens (cataracts, dislocations, hyperglycemia), vitreous humor (uveitis), retina (infections, ischemia, detachment, diabetic retinopathy), macula (degenerative disease), optic nerve (optic neuritis), optic chiasm, and the visual projections through the hemispheres to the occipital lobes. To narrow the differential diagnosis, it would be important to inquire about prior eye problems, to measure visual acuity and intraocular pressure, to perform fundoscopic and slit-lamp exams to detect retinal and anterior chamber disorders, respectively, and to assess visual fields. An afferent pupillary defect would suggest optic nerve pathology.

Disorders that could unify the constitutional, abdominal, and visual symptoms include systemic inflammatory diseases, such as sarcoidosis (which has an increased incidence among Northern Europeans), tuberculosis, or cancer. While diabetes mellitus could explain his visual problems, weight loss, and fatigue, the absence of polyuria, polydipsia, or polyphagia argues against this possibility.

The patient had hypercholesterolemia and type 2 diabetes mellitus. Medications were metformin, atorvastatin, and glimepiride. He was a former smoker with 23 pack-years and had quit over 5 years prior. He had not traveled outside of Denmark in 2 years and had no pets at home. He reported being monogamous with his same-sex partner for the past 25 years. He had no significant family history, and he worked at a local hospital as a nurse. He denied any previous ocular history.

On examination, the pulse was 67 beats per minute, temperature was 36.7 degrees Celsius, respiratory rate was 16 breaths per minute, oxygen saturation was 99% while breathing ambient air, and blood pressure was 132/78. Oropharynx demonstrated no thrush or other lesions. The heart rhythm was regular and there were no murmurs. Lungs were clear to auscultation bilaterally. Abdominal exam was normal except for mild tenderness upon palpation in all quadrants, but no masses, organomegaly, rigidity, or rebound tenderness were present. Skin examination revealed several subcutaneous nodules measuring up to 0.5 cm in diameter overlying the right and left posterolateral chest walls. T he nodules were rubbery, pink, nontender, and not warm nor fluctuant. Visual acuity was reduced in both eyes. Extraocular movements were intact, and the pupils reacted to light and accommodated appropriately. The sclerae were injected bilaterally. The remainder of the cranial nerves and neurologic exam were normal. Due to the vision loss , the patient was referred to an ophthalmologist who diagnosed bilateral anterior uveitis.

Though monogamous with his male partner for many years, it is mandatory to consider complications of human immunodeficiency virus infection (HIV ). The absence of oral lesions indicative of a low CD4 count, such as oral hairy leukoplakia or thrush, does not rule out HIV disease. Additional history about his work as a nurse might shed light on his risk of infection, such as airborne exposure to tuberculosis or acquisition of blood-borne pathogens through a needle stick injury. His unremarkable vital signs support the chronicity of his medical condition.

Uveitis can result from numerous causes. When confined to the eye, uncommon hereditary and acquired causes are less likely . In many patients, uveitis arises in the setting of systemic infection or inflammation. The numerous infectious causes of uveitis include syphilis, tuberculosis, toxoplasmosis, cat scratch disease, and viruses such as HIV, West Nile, and Ebola. Among the inflammatory diseases that can cause uveitis are sarcoidosis, inflammatory bowel disease, systemic lupus erythematosus, Behçet disease, and Sjogren syndrome.

Several of these conditions, including tuberculosis and syphilis, may also cause subcutaneous nodules. Both tuberculosis and syphilis can cause skin and gastrointestinal disease. Sarcoidosis could involve the skin, peritoneum, and uvea, and is a possibility in this patient. The dermatologic conditions associated with sarcoidosis are protean and include granulomatous inflammation and nongranulomatous processes such as erythema nodosum. Usually the nodules of erythema nodosum are tender, red or purple, and located on the lower extremities. The lack of tenderness points away from erythema nodosum in this patient. Metastatic cancer can disseminate to the subcutaneous tissue, and the patient’s smoking history and age mandate we consider malignancy. However, skin metastases tend to be hard, not rubbery.

A cost-effective evaluation at this point would include syphilis serologies, HIV testing, testing for tuberculosis with either a purified protein derivative test or interferon gamma release assay, chest radiography, and biopsy of 1 of the lesions on his back.

Laboratory data showed 12,400 white blood cells per cubic milliliter (64% neutrophils, 24% lymphocytes, 9% monocytes, 2% eosinophils, 1% basophils), hemoglobin 7.9 g/dL, mean corpuscular volume 85 fL, platelets 476,000 per cubic milliliter , C-reactive protein 43 mg/ d L (normal < 8 mg/L), gamma-glutamyl-transferase 554 IU/L (normal range 0-45), alkaline phosphatase 865 U/L (normal range 60-200), and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) 71 mm per hour. International normalized ratio was 1.0, albumin was 3.0 mg/dL, activated partial thromboplastin time was 32 seconds (normal 22 to 35 seconds), and bilirubin was 0.3 mg/dL. Antibodies to HIV , hepatitis C, and hepatitis B surface antigen were not detectable. Electrocardiography ( ECG ) was normal. Plain radiograph of the chest demonstrated multiple nodular lesions bilaterally measuring up to 1 cm with no cavitation. There was a left pleural effusion.

The history and exam findings indicate a serious inflammatory condition affecting his lungs, pleura, eyes, skin, liver, and possibly his peritoneum. In this context, the elevated C-reactive protein and ESR are not helpful in differentiating inflammatory from infectious causes. The constellation of uveitis, pulmonary and cutaneous nodules, and marked abnormalities of liver tests in a middle-aged man of Northern European origin points us toward sarcoidosis. Pleural effusions are not common with sarcoidosis but may occur. However, to avoid premature closure, it is important to consider other possibilities.

Metastatic cancer, including lymphoma, could cause pulmonary and cutaneous nodules and liver involvement, but the chronic time course and uveitis are not consistent with malignancy. Tuberculosis is still a consideration, though one would have expected him to report fevers, night sweats, and, perhaps, exposure to patients with pulmonary tuberculosis in his job as a nurse. Multiple solid pulmonary nodules are also uncommon with pulmonary tuberculosis. Fungal infections such as histoplasmosis can cause skin lesions and pulmonary nodules but do not fit well with uveitis.

At this point, “ tissue is the issue.” A skin nodule would be the easiest site to biopsy. If skin biopsy was not diagnostic, computed tomography (CT) of his chest and abdomen should be performed to identify the next most accessible site for biopsy.

Esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) and colonoscopy showed normal findings, and random biopsies from the stomach and colon were normal. CT of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis performed with the administration of intravenous contrast showed multiple solid opacities in both lung fields up to 1 cm, with enlarged mediastinal and retroperitoneal lymph nodes measuring 1 to 3 cm in diameter, a left pleural effusion, wall thickening in the right colon, and several nonspecific hypodensities in the liver. A punch biopsy taken from the right chest wall lesion demonstrated chronic inflammation without granulomas. The patient underwent CT-guided biopsy of 1 of the right-sided lung nodules, which revealed noncaseating granulomatous inflammation, fibrosis, and necrosis. Neither biopsy contained malignant cells, and additional stains revealed no bacteria, fungi, or acid fast bacilli.

The retroperitoneal and mediastinal adenopathy are indicative of a widely disseminated inflammatory process. Lymphoma continues to be a concern, though uveitis as an initial presenting problem would very unusual. Although biopsy of the chest wall lesion failed to demonstrate granulomatous inflammation, the most parsimonious explanation is that the skin and lung nodules are both related to a single systemic process.

Granulomas form in an attempt to wall off offending agents, whether foreign antigens (talc, certain medications), infectious agents, or self-antigens. Review of histopathology and microbiologic studies are useful first steps. Stains for bacteria, fungi, or acid-fast organisms may diagnose an infectious cause, such as tuberculosis, leprosy, syphilis, fungi, or cat scratch disease. Granulomas in association with vascular inflammation would indicate vasculitis. Other autoimmune considerations include sarcoidosis and Crohn disease. Noncaseating granulomas are typically found in sarcoidosis, cat scratch disease, syphilis, leprosy, or Crohn disease, but do not entirely exclude tuberculosis.

The negative infectious studies and lack of classic features of Crohn disease or other autoimmune diseases further point to sarcoidosis as the etiology of this patient’s illness. A Norwegian dermatologist first described the pathology of sarcoidosis based upon specimens taken from skin nodules. He thought the lesions were sarcoma and described them as, “ multiple benign sarcoid of the skin,” which is where the name “ sarcoidosis” originated.

Diagnosing sarcoidosis requires excluding other mimickers. Additional testing should include syphilis serologies, rheumatoid factor, and antineutrophilic cytoplasmic antibodies. The latter is associated with granulomatosis with polyangiitis and eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis, either of which may produce granulomatous inflammation of the lungs, skin, and uvea.

At this juncture, PET-CT represents a costly and unnecessary test that does not narrow our diagnostic possibilities sufficiently to justify its use. Osteolytic lesions would be unusual in sarcoidosis and more likely in lymphoma or infectious processes such as tuberculosis. Tests for syphilis and tuberculosis are required, and are a fraction of the cost of a PET-CT.

With the biopsy revealing spirochetes, and the positive results of a nontreponemal test (RPR) and confirmatory treponemal results, the diagnosis of syphilis is firmly established. Uveitis indicates neurosyphilis and warrants a longer course of intravenous penicillin. Lumbar puncture should be performed.

A lumbar puncture was performed. Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) contained 9 white blood cells and 73 red blood cells per cubic milliliter; protein concentration was 73 mg/dL, and glucose was 116 mg/dL. Polymerase chain reaction for T. pallidum was negative. Transthoracic ECG and magnetic resonance imaging of the brain were normal. The patient was treated with intravenous penicillin G at 5 million units 4 times daily for 15 days. A PET-CT scan 3 months later revealed complete resolution of the subcutaneous, pulmonary, liver lesions, lymphadenopathy, and uveitis. Repeat treponemal serologies demonstrated a greater than 4-fold decline in titers.

DISCUSSION

Syphilis is a sexually transmitted disease with increasing incidence worldwide. Untreated infection progresses through 3 stages. The primary stage is characterized by the appearance of a painless chancre after an incubation period of 2 to 3 weeks. Four to 8 weeks later, the secondary stage emerges as a systemic infection, often heralded by a maculopapular rash with desquamation, frequently involving the soles and palms. Hepatitis, iridocyclitis, and early neurosyphilis may also be seen at this stage. Subsequently, syphilis becomes latent. One-third of patients with untreated latent syphilis will develop tertiary syphilis, typified by late neurosyphilis (tabes dorsalis and general paresis), cardiovascular disease (aortitis), or gummatous disease. 1

Gummas are destructive granulomatous lesions that typically present indolently, may occur singly or multiply, and may involve almost any organ. It has been suggested that gummas are the immune system’s defense to slow the bacteria after attempts to kill it have failed. Histologically, gummas are hyalinized nodules with surrounding granulomatous infiltrate of lymphocytes, plasma cells, and multinucleated giant cells with or without necrosis . In the preantibiotic era, gummas were seen in approximately 15% of infected patients, with a latency of 1 to 46 years after primary infection. 2 Penicillin led to a drastic reduction in gummas until the HIV epidemic, which led to the resurgence of gummas at a drastically shortened interval following primary syphilis. 3

Most commonly, gummas affect the skin and bones. In the skin , lesions may be superficial or deep and may progress into ulcerative nodules. In the bones, destructive gummas have a characteristic “moth-eaten” appearance. Less common sequelae of gummas incude gummatous hepatitis, perforated nasal septum (saddle nose deformity), or hard palate erosions. 2,4 R arely, syphilis involves the lungs, appearing as nodules, infiltrates, or pleural effusion. 5

Ocular manifestations occur in approximately 5% of patients with syphilis, more often in secondary and tertiary stages, and are strongly associated with a spread to the central nervous system. Syphilis may affect any structure of the eye, with anterior uveitis as the most frequent manifestation. Partial or complete vision loss is identified in approximately half of the patients with ocular syphilis and may be completely reversed by appropriate treatment. Ophthalmologic findings such as optic neuritis and papilledema imply advanced illness , as do Argyll-Robertson pupils (small pupils that are poorly reactive to light , but with preserved accommodation and convergence). 6,7 The treatment of ocular syphilis is identical to that of neurosyphilis. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends CSF analysis in any patient with ocular syphilis. Abnormal results should prompt repeat lumbar puncture every 3 to 6 months following treatment until the CSF results normalize. 8

The diagnosis of syphilis relies on indirect serologic tests. T. pallidum cannot be cultured in vitro, and techniques to identify spirochetes directly by using darkfield microscopy or DNA amplification via polymerase chain reaction are limited by availability or by poor sensitivity in advanced syphilis. 1 Imaging modalities including PET cannot reliably differentiate syphilis from other infectious and noninfectious mimickers. 9 F ortunately, syphilis infection can be diagnosed accurately based on reactive treponemal and nontreponemal serum tests. Nontreponemal tests, such as the RPR and Venereal Disease Research Laboratory, have traditionally been utilized as first-line evaluation, followed by a confirmatory treponemal test. However, nontreponemal tests may be nonreactive in a few settings: very early or very late in infection, and in individuals previously treated for syphilis. Thus, newer “reverse testing” algorithms utilize more sensitive and less expensive treponemal tests as the first test, followed by nontreponemal tests if the initial treponemal test is reactive. 8 Regardless of the testing sequence, in patients with no prior history of syphilis, reactive results on both treponemal and nontreponemal assays firmly establish a diagnosis of syphilis, obviating the need for more invasive and costly testing.

In patients with unexplained systemic illness, clinicians should have a low threshold to test for syphilis. Testing should be extended to certain asymptomatic individuals at higher risk of infection, including men who have sex with men, sexual partners of patients infected with syphilis, individuals with HIV or sexually-transmitted diseases, and others with high-risk sexual behavior or a history of sexually-transmitted diseases. 8 As the discussant points out, earlier consideration of and testing for syphilis would have spared the patient from unnecessary and costly EGD, colonoscopy, PET-CT scanning, and 3 biopsies.

Syphilis has been known to be a horribly destructive disease for centuries, earning the moniker “morbo serpentino” (serpentine disease) from the Spanish physician Ruiz Diaz de Isla in the 1500s. 10 In the modern era, physicians must remember to consider the diagnosis of syphilis in order to effectively mitigate the harm from this resurgent disease when it attacks our patients.

TEACHING POINTS

- Syphilis, the great imposter, is rising in incidence and should be on the differential diagnosis in all patients with unexplained multisystem inflammatory disease.

- A cost-effective diagnostic approach to syphilis entails serologic testing with treponemal and nontreponemal assays.

- Unexplained granulomas, especially in the skin, bone, or liver, should prompt consideration of gummatous syphilis.

- Ocular syphilis may involve any part of the visual tract and is treated the same as neurosyphilis.

Disclosure

Dr. Weinreich has received payment for lectures from Boehringer er Ingelheim, Astra Zeneca, TEVA and Novartis in 2016. All other contributors have nothing to report.

1. French P. Syphilis. BMJ. 2007;334:143-147. PubMed

2. Singh AE, Romanowski B. Syphilis: Review with emphasis on clinical, epidemiologic, and some biologic features. Clin Micriobio Rev. 1999;12(2):187-209. PubMed

3. Karp G, Schlaeffer F, Jotkowitz A, Riesenberg K. Syphilis and HIV co-infection. Eur J Int Med. 2009; 20:9-13. PubMed

4. Pilozzi-Edmonds L, Kong LY, Szabo J, Birnbaum LM. Rapid progression to gummatous syphilitic hepatitis and neurosyphilis in a patient with newly diagnosed HIV. Int J STD AIDS. 2014;26(13)985-987. PubMed

5. David G, Perpoint T, Boibieux A, et al. Secondary pulmonary syphilis: report of a likely case and literature review. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;42(3):e11-e15. PubMed

6. Moradi A, Salek S, Daniel E, et al. Clinical features and incidence rates of ocular complications in patients with ocular syphilis. Am J Ophthalmol. 2015;159:334-343. PubMed

7. Aldave AJ, King JA, Cunningham ET Jr. Ocular syphilis. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2001;12:433-441. PubMed

8. Workowski KA, Bolan GA. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2015. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2015;64:1-137. PubMed

9. Lin M, Darwish B, Chu J. Neurosyphilitic gumma on F18-2-fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose (FDG) positron emission tomography: An old disease investigated with new technology. J Clin Neurosc. 2009;16:410-412. PubMed

10. de Ricon‐Ferraz A. Early work on syphilis: Diaz de Ysla’s treatise on the serpentine disease of Hispaniola Island. Int J Dermatol. 1999;38(3):222-227. PubMed

1. French P. Syphilis. BMJ. 2007;334:143-147. PubMed

2. Singh AE, Romanowski B. Syphilis: Review with emphasis on clinical, epidemiologic, and some biologic features. Clin Micriobio Rev. 1999;12(2):187-209. PubMed

3. Karp G, Schlaeffer F, Jotkowitz A, Riesenberg K. Syphilis and HIV co-infection. Eur J Int Med. 2009; 20:9-13. PubMed

4. Pilozzi-Edmonds L, Kong LY, Szabo J, Birnbaum LM. Rapid progression to gummatous syphilitic hepatitis and neurosyphilis in a patient with newly diagnosed HIV. Int J STD AIDS. 2014;26(13)985-987. PubMed

5. David G, Perpoint T, Boibieux A, et al. Secondary pulmonary syphilis: report of a likely case and literature review. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;42(3):e11-e15. PubMed

6. Moradi A, Salek S, Daniel E, et al. Clinical features and incidence rates of ocular complications in patients with ocular syphilis. Am J Ophthalmol. 2015;159:334-343. PubMed

7. Aldave AJ, King JA, Cunningham ET Jr. Ocular syphilis. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2001;12:433-441. PubMed

8. Workowski KA, Bolan GA. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2015. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2015;64:1-137. PubMed

9. Lin M, Darwish B, Chu J. Neurosyphilitic gumma on F18-2-fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose (FDG) positron emission tomography: An old disease investigated with new technology. J Clin Neurosc. 2009;16:410-412. PubMed

10. de Ricon‐Ferraz A. Early work on syphilis: Diaz de Ysla’s treatise on the serpentine disease of Hispaniola Island. Int J Dermatol. 1999;38(3):222-227. PubMed

© 2017 Society of Hospital Medicine

The cost of experimental medicine

It has been a remarkable summer of milestones and crises for high-technology medicine.

An FDA panel has unanimously approved a gene therapy: The patient’s own immune cells are taken from his or her body, genetically modified, and reinfused to attack cancer. While the treatment has some dangers, it can be worth trying when conventional therapy has failed, and it appears to be curative when it works. Final FDA approval is expected in September.

While those breakthroughs were occurring, the parents of Charlie Gard, an infant in England with a very rare and devastating mitochondrial disease, were seeking experimental therapy for their child. The medical staff disagreed with the parents: They recommended that the best thing for Charlie would be to stop the ventilator and allow him to die, rather than let him to continue to suffer. Three British courts reviewed Charlie’s case and concurred with the medical staff; on appeal, the European Court of Human Rights also denied the parents’ wishes.

End of life cases similar to Charlie’s are not rare. In modern medicine, parents sometimes must make the heart-wrenching decision to stop aggressive therapies and accept that death is imminent and unavoidable. Many factors go into making that decision. Both the courts and medical staff presume that parents are the best decision makers. Generally, medical staff provide emotional and spiritual support to the parents, along with a tincture of time. In the vast majority of cases, parents and physicians come to agree on the course of care, but sometimes, there are irreconcilable disagreements.

It is rare for courts to overrule parents. The government typically intervenes only when the harm from a parent’s choice exceeds some threshold. For instance, it is not in a child’s best interest to be put in a car during a blizzard and driven to the store to get cigarettes. But neither is it wise to have an intrusive government reviewing every choice a parent makes. The potential harm must be large enough, likely enough, and imminent enough before most judges will intervene. The law will insist the child be in a car seat at least.

In Charlie’s case, the medical staff and the judges all explicitly said that the cost of therapy did not factor into their decision making; they looked solely at what was best for Charlie. The focus was on whether the unproven potential benefits of experimental therapy outweighed the risk of suffering caused by the therapy and continued intensive medical care.

Even when a bedside decision ignores the financial impact, money often structures which therapeutic choices are available. There are also issues of equitable access to be raised and weighed. Expenditures impact other social choices.

Money influenced the actions of Martin Shkreli, who is best known as the pharmacy company executive who markedly increased the price of a drug. Mr. Shkreli was recently convicted on three of eight charges for securities fraud, and sentencing is pending; the convictions were not related to the price increase.

The United States has created some amazing technologies to save individual, identifiable lives, but they come at a high price that often costs lives in ways more subtle than the incident in India. At some point, the government and the public are responsible for either financing or rationing care, but that doesn’t absolve the scientists completely. The Russell-Einstein (Pugwash) Manifesto established that scientists have a moral accountability for the negative consequences of creating new technology, and that includes the financial aspects.

Dr. Powell is a pediatric hospitalist and clinical ethics consultant living in St. Louis. Email him at [email protected]

It has been a remarkable summer of milestones and crises for high-technology medicine.

An FDA panel has unanimously approved a gene therapy: The patient’s own immune cells are taken from his or her body, genetically modified, and reinfused to attack cancer. While the treatment has some dangers, it can be worth trying when conventional therapy has failed, and it appears to be curative when it works. Final FDA approval is expected in September.

While those breakthroughs were occurring, the parents of Charlie Gard, an infant in England with a very rare and devastating mitochondrial disease, were seeking experimental therapy for their child. The medical staff disagreed with the parents: They recommended that the best thing for Charlie would be to stop the ventilator and allow him to die, rather than let him to continue to suffer. Three British courts reviewed Charlie’s case and concurred with the medical staff; on appeal, the European Court of Human Rights also denied the parents’ wishes.

End of life cases similar to Charlie’s are not rare. In modern medicine, parents sometimes must make the heart-wrenching decision to stop aggressive therapies and accept that death is imminent and unavoidable. Many factors go into making that decision. Both the courts and medical staff presume that parents are the best decision makers. Generally, medical staff provide emotional and spiritual support to the parents, along with a tincture of time. In the vast majority of cases, parents and physicians come to agree on the course of care, but sometimes, there are irreconcilable disagreements.

It is rare for courts to overrule parents. The government typically intervenes only when the harm from a parent’s choice exceeds some threshold. For instance, it is not in a child’s best interest to be put in a car during a blizzard and driven to the store to get cigarettes. But neither is it wise to have an intrusive government reviewing every choice a parent makes. The potential harm must be large enough, likely enough, and imminent enough before most judges will intervene. The law will insist the child be in a car seat at least.

In Charlie’s case, the medical staff and the judges all explicitly said that the cost of therapy did not factor into their decision making; they looked solely at what was best for Charlie. The focus was on whether the unproven potential benefits of experimental therapy outweighed the risk of suffering caused by the therapy and continued intensive medical care.

Even when a bedside decision ignores the financial impact, money often structures which therapeutic choices are available. There are also issues of equitable access to be raised and weighed. Expenditures impact other social choices.

Money influenced the actions of Martin Shkreli, who is best known as the pharmacy company executive who markedly increased the price of a drug. Mr. Shkreli was recently convicted on three of eight charges for securities fraud, and sentencing is pending; the convictions were not related to the price increase.

The United States has created some amazing technologies to save individual, identifiable lives, but they come at a high price that often costs lives in ways more subtle than the incident in India. At some point, the government and the public are responsible for either financing or rationing care, but that doesn’t absolve the scientists completely. The Russell-Einstein (Pugwash) Manifesto established that scientists have a moral accountability for the negative consequences of creating new technology, and that includes the financial aspects.

Dr. Powell is a pediatric hospitalist and clinical ethics consultant living in St. Louis. Email him at [email protected]

It has been a remarkable summer of milestones and crises for high-technology medicine.

An FDA panel has unanimously approved a gene therapy: The patient’s own immune cells are taken from his or her body, genetically modified, and reinfused to attack cancer. While the treatment has some dangers, it can be worth trying when conventional therapy has failed, and it appears to be curative when it works. Final FDA approval is expected in September.

While those breakthroughs were occurring, the parents of Charlie Gard, an infant in England with a very rare and devastating mitochondrial disease, were seeking experimental therapy for their child. The medical staff disagreed with the parents: They recommended that the best thing for Charlie would be to stop the ventilator and allow him to die, rather than let him to continue to suffer. Three British courts reviewed Charlie’s case and concurred with the medical staff; on appeal, the European Court of Human Rights also denied the parents’ wishes.

End of life cases similar to Charlie’s are not rare. In modern medicine, parents sometimes must make the heart-wrenching decision to stop aggressive therapies and accept that death is imminent and unavoidable. Many factors go into making that decision. Both the courts and medical staff presume that parents are the best decision makers. Generally, medical staff provide emotional and spiritual support to the parents, along with a tincture of time. In the vast majority of cases, parents and physicians come to agree on the course of care, but sometimes, there are irreconcilable disagreements.

It is rare for courts to overrule parents. The government typically intervenes only when the harm from a parent’s choice exceeds some threshold. For instance, it is not in a child’s best interest to be put in a car during a blizzard and driven to the store to get cigarettes. But neither is it wise to have an intrusive government reviewing every choice a parent makes. The potential harm must be large enough, likely enough, and imminent enough before most judges will intervene. The law will insist the child be in a car seat at least.

In Charlie’s case, the medical staff and the judges all explicitly said that the cost of therapy did not factor into their decision making; they looked solely at what was best for Charlie. The focus was on whether the unproven potential benefits of experimental therapy outweighed the risk of suffering caused by the therapy and continued intensive medical care.

Even when a bedside decision ignores the financial impact, money often structures which therapeutic choices are available. There are also issues of equitable access to be raised and weighed. Expenditures impact other social choices.

Money influenced the actions of Martin Shkreli, who is best known as the pharmacy company executive who markedly increased the price of a drug. Mr. Shkreli was recently convicted on three of eight charges for securities fraud, and sentencing is pending; the convictions were not related to the price increase.

The United States has created some amazing technologies to save individual, identifiable lives, but they come at a high price that often costs lives in ways more subtle than the incident in India. At some point, the government and the public are responsible for either financing or rationing care, but that doesn’t absolve the scientists completely. The Russell-Einstein (Pugwash) Manifesto established that scientists have a moral accountability for the negative consequences of creating new technology, and that includes the financial aspects.

Dr. Powell is a pediatric hospitalist and clinical ethics consultant living in St. Louis. Email him at [email protected]

Mass Confusion

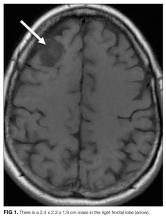

A 57-year-old woman presented to the emergency department of a community hospital with a 2-week history of dizziness, blurred vision, and poor coordination following a flu-like illness. Symptoms were initially attributed to complications from a presumed viral illness, but when they persisted for 2 weeks, she underwent magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain, which was reported as showing a 2.4 x 2.3 x 1.9 cm right frontal lobe mass with mild mass effect and contrast enhancement (Figure 1). She was discharged home at her request with plans for outpatient follow-up.

Brain masses are usually neoplastic, infectious, or less commonly, inflammatory. The isolated lesion in the right frontal lobe is unlikely to explain her symptoms, which are more suggestive of multifocal disease or elevated intracranial pressure. Although the frontal eye fields could be affected by the mass, such lesions usually cause tonic eye deviation, not blurry vision; furthermore, coordination, which is impaired here, is not governed by the frontal lobe.

Two weeks later, she returned to the same emergency department with worsening symptoms and new bilateral upper extremity dystonia, confusion, and visual hallucinations. Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis revealed clear, nonxanthochromic fluid with 4 nucleated cells (a differential was not performed), 113 red blood cells, glucose of 80 mg/dL (normal range, 50-80 mg/dL), and protein of 52 mg/dL (normal range, 15-45 mg/dL).

Confusion is generally caused by a metabolic, infectious, structural, or toxic etiology. Standard CSF test results are usually normal with most toxic or metabolic encephalopathies. The absence of significant CSF inflammation argues against infectious encephalitis; paraneoplastic and autoimmune encephalitis, however, are still possible. The CSF red blood cells were likely due to a mildly traumatic tap, but also may have arisen from the frontal lobe mass or a more diffuse invasive process, although the lack of xanthochromia argues against this. Delirium and red blood cells in the CSF should trigger consideration of herpes simplex virus (HSV) encephalitis, although the time course is a bit too protracted and the reported MRI findings do not suggest typical medial temporal lobe involvement.

The disparate neurologic findings suggest a multifocal process, perhaps embolic (eg, endocarditis), ischemic (eg, intravascular lymphoma), infiltrative (eg, malignancy, neurosarcoidosis), or demyelinating (eg, postinfectious acute disseminated encephalomyelitis, multiple sclerosis). However, most of these would have been detected on the initial MRI. Upper extremity dystonia would likely localize to the basal ganglia, whereas confusion and visual hallucinations are more global. The combination of a movement disorder and visual hallucinations is seen in Lewy body dementia, but this tempo is not typical.

Although the CSF does not have pleocytosis, her original symptoms were flu-like; therefore, CSF testing for viruses (eg, enterovirus) is reasonable. Bacterial, mycobacteria, and fungal studies are apt to be unrevealing, but CSF cytology, IgG index, and oligoclonal bands may be useful. Should the encephalopathy progress further and the general medical evaluation prove to be normal, then tests for autoimmune disorders (eg, antinuclear antibodies, NMDAR, paraneoplastic disorders) and rare causes of rapidly progressive dementias (eg, prion diseases) should be sent.

Additional CSF studies including HSV polymerase chain reaction (PCR), West Nile PCR, Lyme antibody, paraneoplastic antibodies, and cytology were sent. Intravenous acyclovir was administered. The above studies, as well as Gram stain, acid-fast bacillus stain, fungal stain, and cultures, were negative. She was started on levetiracetam for seizure prevention due to the mass lesion. An electroencephalogram (EEG) was reported as showing diffuse background slowing with superimposed semiperiodic sharp waves with a right hemispheric emphasis. Intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) 0.4 mg/kg/day over 5 days was administered with no improvement. The patient was transferred to an academic medical center for further evaluation.

The EEG reflects encephalopathy without pointing to a specific diagnosis. Prophylactic antiepileptic medications are not indicated for CNS mass lesions without clinical or electrophysiologic seizure activity. IVIG is often administered when an autoimmune encephalitis is suspected, but the lack of response does not rule out an autoimmune condition.

Her medical history included bilateral cataract extraction, right leg fracture, tonsillectomy, and total abdominal hysterectomy. She had a 25-year smoking history and a family history of lung cancer. She had no history of drug or alcohol use. On examination, her temperature was 37.9°C, blood pressure of 144/98 mm Hg, respiratory rate of 18 breaths per minute, a heart rate of 121 beats per minute, and oxygen saturation of 97% on ambient air. Her eyes were open but she was nonverbal. Her chest was clear to auscultation. Heart sounds were distinct and rhythm was regular. Abdomen was soft and nontender with no organomegaly. Skin examination revealed no rash. Her pupils were equal, round, and reactive to light. She did not follow verbal or gestural commands and intermittently tracked with her eyes, but not consistently enough to characterize extraocular movements. Her face was symmetric. She had a normal gag and blink reflex and an increased jaw jerk reflex. Her arms were flexed with increased tone. She had a positive palmo-mental reflex. She had spontaneous movement of all extremities. She had symmetric, 3+ reflexes of the patella and Achilles tendon with a bilateral Babinski’s sign. Sensation was intact only to withdrawal from noxious stimuli.

The physical exam does not localize to a specific brain region, but suggests a diffuse brain process. There are multiple signs of upper motor neuron involvement, including increased tone, hyperreflexia, and Babinski (plantar flexion) reflexes. A palmo-mental reflex signifies pathology in the cerebrum. Although cranial nerve testing is limited, there are no features of cranial neuropathy; similarly, no pyramidal weakness or sensory deficit has been demonstrated on limited testing. The differential diagnosis of her rapidly progressive encephalopathy includes autoimmune or paraneoplastic encephalitis, diffuse infiltrative malignancy, metabolic diseases (eg, porphyria, heavy metal intoxication), and prion disease.

Her family history of lung cancer and her smoking increases the possibility of paraneoplastic encephalitis, which often has subacute behavioral changes that precede complete neurologic impairment. Inflammatory or hemorrhagic CSF is seen with Balamuthia amoebic infection, which causes a granulomatous encephalitis and is characteristically associated with a mass lesion. Toxoplasmosis causes encephalitis that can be profound, but patients are usually immunocompromised and there are typically multiple lesions.

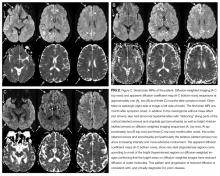

Laboratory results showed a normal white blood cell count and differential, basic metabolic profile and liver function tests, and C-reactive protein. Human immunodeficiency virus antibody testing was negative. Chest radiography and computed tomography of chest, abdomen, and pelvis were normal. A repeat MRI of the brain with contrast was reported as showing a 2.4 x 2.3 x 1.9 cm heterogeneously enhancing mass in the right frontal lobe with an enhancing dural tail and underlying hyperostosis consistent with a meningioma, and blooming within the mass consistent with prior hemorrhage. No mass effect was present.