User login

The Effect of Time on Arterial Pressure

We already know quite a lot about how brachial blood pressure (BP) varies by day and time—might chronology also influence arterial occlusion pressure? To their knowledge, say researchers from the University of Mississippi and National Institute of Fitness and Sports in Kanoya, Japan, no study has examined that. They hypothesized that arterial occlusion measurements would oscillate in a pattern that mimicked diurnal variation in brachial systolic blood pressure (bSBP)—specifically, that the measurements would be higher in the evening than in the morning.

In their study of 22 participants, the researchers conducted 4 testing sessions, at 8 am and 6 pm, 48 hours apart. They measured arm circumference, bSBP, and bSBP at rest. They measured arterial occlusion pressure using a cuff inflated on the proximal portion of the upper arm, with a Doppler probe placed over the radial artery.

Pressure varied not only between days but within a day. They found significant difference between morning on day 1 and all other visits, although they say that may have been due to anxiousness during the first visit. But they also found a time effect for morning day 2 compared with all other visits. On day 1 there were no differences from morning to evening; on day 2, occlusion pressure increased from morning to evening.

“The interrelationship between the oscillating nature of different variables is extremely difficult to study,” the researchers say, “and makes it hard to ascertain the rhythm of one physiological variable in the absence of others, due to the inability to isolate variables from temporal progression.” To get the most accurate readings, they advise taking multiple measurements.

We already know quite a lot about how brachial blood pressure (BP) varies by day and time—might chronology also influence arterial occlusion pressure? To their knowledge, say researchers from the University of Mississippi and National Institute of Fitness and Sports in Kanoya, Japan, no study has examined that. They hypothesized that arterial occlusion measurements would oscillate in a pattern that mimicked diurnal variation in brachial systolic blood pressure (bSBP)—specifically, that the measurements would be higher in the evening than in the morning.

In their study of 22 participants, the researchers conducted 4 testing sessions, at 8 am and 6 pm, 48 hours apart. They measured arm circumference, bSBP, and bSBP at rest. They measured arterial occlusion pressure using a cuff inflated on the proximal portion of the upper arm, with a Doppler probe placed over the radial artery.

Pressure varied not only between days but within a day. They found significant difference between morning on day 1 and all other visits, although they say that may have been due to anxiousness during the first visit. But they also found a time effect for morning day 2 compared with all other visits. On day 1 there were no differences from morning to evening; on day 2, occlusion pressure increased from morning to evening.

“The interrelationship between the oscillating nature of different variables is extremely difficult to study,” the researchers say, “and makes it hard to ascertain the rhythm of one physiological variable in the absence of others, due to the inability to isolate variables from temporal progression.” To get the most accurate readings, they advise taking multiple measurements.

We already know quite a lot about how brachial blood pressure (BP) varies by day and time—might chronology also influence arterial occlusion pressure? To their knowledge, say researchers from the University of Mississippi and National Institute of Fitness and Sports in Kanoya, Japan, no study has examined that. They hypothesized that arterial occlusion measurements would oscillate in a pattern that mimicked diurnal variation in brachial systolic blood pressure (bSBP)—specifically, that the measurements would be higher in the evening than in the morning.

In their study of 22 participants, the researchers conducted 4 testing sessions, at 8 am and 6 pm, 48 hours apart. They measured arm circumference, bSBP, and bSBP at rest. They measured arterial occlusion pressure using a cuff inflated on the proximal portion of the upper arm, with a Doppler probe placed over the radial artery.

Pressure varied not only between days but within a day. They found significant difference between morning on day 1 and all other visits, although they say that may have been due to anxiousness during the first visit. But they also found a time effect for morning day 2 compared with all other visits. On day 1 there were no differences from morning to evening; on day 2, occlusion pressure increased from morning to evening.

“The interrelationship between the oscillating nature of different variables is extremely difficult to study,” the researchers say, “and makes it hard to ascertain the rhythm of one physiological variable in the absence of others, due to the inability to isolate variables from temporal progression.” To get the most accurate readings, they advise taking multiple measurements.

Protective Foam Gives Wounded a ‘Fighting Chance for Survival’

Exsanguination—bleeding to death—is the most common cause of potentially survivable death among wounded military. But a caulk gun–like device loaded with foam could extend valuable time to trauma patients and provide a “bridge to surgery,” says Leigh Anne Alexander, product manager for the U.S. Army Medical Materiel Agency (USAMMA). The foam is intended to stop massive intracavitary abdominal bleeding until the patient can get surgical care.

The device contains expandable foam that is injected into the patient. Two separate chemicals, when mixed, cause the foam to swell rapidly to about 35 times its original volume. It expands around the internal organs and can be left inside the patient for up to 3 hours.

The USAMMA, a subordinate organization of the U.S. Army Medical Research and Materiel Command, is supporting a “pivotal” clinical trial to test the safety and effectiveness of the device, which received an Investigational Device Exemption earlier this year from the FDA. The clinical trial will start in 2018.

Exsanguination—bleeding to death—is the most common cause of potentially survivable death among wounded military. But a caulk gun–like device loaded with foam could extend valuable time to trauma patients and provide a “bridge to surgery,” says Leigh Anne Alexander, product manager for the U.S. Army Medical Materiel Agency (USAMMA). The foam is intended to stop massive intracavitary abdominal bleeding until the patient can get surgical care.

The device contains expandable foam that is injected into the patient. Two separate chemicals, when mixed, cause the foam to swell rapidly to about 35 times its original volume. It expands around the internal organs and can be left inside the patient for up to 3 hours.

The USAMMA, a subordinate organization of the U.S. Army Medical Research and Materiel Command, is supporting a “pivotal” clinical trial to test the safety and effectiveness of the device, which received an Investigational Device Exemption earlier this year from the FDA. The clinical trial will start in 2018.

Exsanguination—bleeding to death—is the most common cause of potentially survivable death among wounded military. But a caulk gun–like device loaded with foam could extend valuable time to trauma patients and provide a “bridge to surgery,” says Leigh Anne Alexander, product manager for the U.S. Army Medical Materiel Agency (USAMMA). The foam is intended to stop massive intracavitary abdominal bleeding until the patient can get surgical care.

The device contains expandable foam that is injected into the patient. Two separate chemicals, when mixed, cause the foam to swell rapidly to about 35 times its original volume. It expands around the internal organs and can be left inside the patient for up to 3 hours.

The USAMMA, a subordinate organization of the U.S. Army Medical Research and Materiel Command, is supporting a “pivotal” clinical trial to test the safety and effectiveness of the device, which received an Investigational Device Exemption earlier this year from the FDA. The clinical trial will start in 2018.

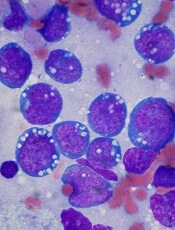

Team uses genetic barcodes to track hematopoiesis

New research suggests the classical yet contested “tree” model of hematopoiesis is accurate.

In this model, the tree trunk is composed of hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs), and the branches consist of various progenitor cells that give rise to a number of distinct cell types.

Because previous research raised doubts about this model, investigators set out to track hematopoiesis more effectively than ever before.

The team used a “random generator” to label HSCs with genetic barcodes, and this allowed them to trace which cell types arise from an HSC.

Hans-Reimer Rodewald, PhD, of the German Cancer Research Center (Deutsches Krebsforschungszentrum, DKFZ) in Heidelberg, and his colleagues described this research in Nature.

“Genetic barcodes have been developed and applied before, but they were based on methods that can also change cellular properties,” Dr Rodewald said. “Our barcodes are different. They can be induced tissue-specifically and directly in the genome of mice–without influencing the animals’ physiological development.”

The basis of the new technology is the Cre/loxP system that is used to rearrange or remove specially labeled DNA segments.

The investigators bred mice whose genomes exhibit the basic elements of the barcode. At a selected site, where no genes are encoded, it contains 9 DNA fragments from a plant called Arabidopsis thaliana. These elements are flanked by 10 genetic cutting sites called IoxP sites.

By administering a pharmacological agent, the matching molecular scissors, called “Cre,” can be activated in the animals’ HSCs. Then, code elements are randomly rearranged or cut out.

“This genetic, random DNA barcode generator can generate up to 1.8 million genetic barcodes, and we can identify the codes that arise only once in an experiment,” said study author Thomas Höfer, PhD, also of DKFZ.

When these specially labeled HSCs divide and mature, the barcodes are preserved.

The investigators performed comprehensive barcode analyses in order to trace an individual blood cell back to the HSC from which it originated.

These analyses revealed 2 large developmental branches “growing” from the HSC “tree trunk.” In one branch, T cells and B cells develop. In the other, red blood cells and other white blood cells, such as granulocytes and monocytes, form.

“Our findings show that the classical model of a hierarchical developmental tree that starts from multipotent stem cells holds true for hematopoiesis,” Dr Rodewald said.

He and his colleagues believe their genetic barcode system can be used for purposes other than studying blood cell development. In the future, it might be used for experimentally tracing the origin of leukemias and other cancers. ![]()

New research suggests the classical yet contested “tree” model of hematopoiesis is accurate.

In this model, the tree trunk is composed of hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs), and the branches consist of various progenitor cells that give rise to a number of distinct cell types.

Because previous research raised doubts about this model, investigators set out to track hematopoiesis more effectively than ever before.

The team used a “random generator” to label HSCs with genetic barcodes, and this allowed them to trace which cell types arise from an HSC.

Hans-Reimer Rodewald, PhD, of the German Cancer Research Center (Deutsches Krebsforschungszentrum, DKFZ) in Heidelberg, and his colleagues described this research in Nature.

“Genetic barcodes have been developed and applied before, but they were based on methods that can also change cellular properties,” Dr Rodewald said. “Our barcodes are different. They can be induced tissue-specifically and directly in the genome of mice–without influencing the animals’ physiological development.”

The basis of the new technology is the Cre/loxP system that is used to rearrange or remove specially labeled DNA segments.

The investigators bred mice whose genomes exhibit the basic elements of the barcode. At a selected site, where no genes are encoded, it contains 9 DNA fragments from a plant called Arabidopsis thaliana. These elements are flanked by 10 genetic cutting sites called IoxP sites.

By administering a pharmacological agent, the matching molecular scissors, called “Cre,” can be activated in the animals’ HSCs. Then, code elements are randomly rearranged or cut out.

“This genetic, random DNA barcode generator can generate up to 1.8 million genetic barcodes, and we can identify the codes that arise only once in an experiment,” said study author Thomas Höfer, PhD, also of DKFZ.

When these specially labeled HSCs divide and mature, the barcodes are preserved.

The investigators performed comprehensive barcode analyses in order to trace an individual blood cell back to the HSC from which it originated.

These analyses revealed 2 large developmental branches “growing” from the HSC “tree trunk.” In one branch, T cells and B cells develop. In the other, red blood cells and other white blood cells, such as granulocytes and monocytes, form.

“Our findings show that the classical model of a hierarchical developmental tree that starts from multipotent stem cells holds true for hematopoiesis,” Dr Rodewald said.

He and his colleagues believe their genetic barcode system can be used for purposes other than studying blood cell development. In the future, it might be used for experimentally tracing the origin of leukemias and other cancers. ![]()

New research suggests the classical yet contested “tree” model of hematopoiesis is accurate.

In this model, the tree trunk is composed of hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs), and the branches consist of various progenitor cells that give rise to a number of distinct cell types.

Because previous research raised doubts about this model, investigators set out to track hematopoiesis more effectively than ever before.

The team used a “random generator” to label HSCs with genetic barcodes, and this allowed them to trace which cell types arise from an HSC.

Hans-Reimer Rodewald, PhD, of the German Cancer Research Center (Deutsches Krebsforschungszentrum, DKFZ) in Heidelberg, and his colleagues described this research in Nature.

“Genetic barcodes have been developed and applied before, but they were based on methods that can also change cellular properties,” Dr Rodewald said. “Our barcodes are different. They can be induced tissue-specifically and directly in the genome of mice–without influencing the animals’ physiological development.”

The basis of the new technology is the Cre/loxP system that is used to rearrange or remove specially labeled DNA segments.

The investigators bred mice whose genomes exhibit the basic elements of the barcode. At a selected site, where no genes are encoded, it contains 9 DNA fragments from a plant called Arabidopsis thaliana. These elements are flanked by 10 genetic cutting sites called IoxP sites.

By administering a pharmacological agent, the matching molecular scissors, called “Cre,” can be activated in the animals’ HSCs. Then, code elements are randomly rearranged or cut out.

“This genetic, random DNA barcode generator can generate up to 1.8 million genetic barcodes, and we can identify the codes that arise only once in an experiment,” said study author Thomas Höfer, PhD, also of DKFZ.

When these specially labeled HSCs divide and mature, the barcodes are preserved.

The investigators performed comprehensive barcode analyses in order to trace an individual blood cell back to the HSC from which it originated.

These analyses revealed 2 large developmental branches “growing” from the HSC “tree trunk.” In one branch, T cells and B cells develop. In the other, red blood cells and other white blood cells, such as granulocytes and monocytes, form.

“Our findings show that the classical model of a hierarchical developmental tree that starts from multipotent stem cells holds true for hematopoiesis,” Dr Rodewald said.

He and his colleagues believe their genetic barcode system can be used for purposes other than studying blood cell development. In the future, it might be used for experimentally tracing the origin of leukemias and other cancers. ![]()

Antibody could treat AML, MM, and NHL

An investigational antibody has demonstrated activity against acute myeloid leukemia (AML), multiple myeloma (MM), and non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL), according to researchers.

PF-06747143 is a humanized CXCR4 immunoglobulin G1 (IgG1) antibody that binds to CXCR4 and inhibits both CXCL12-mediated signaling pathways and cell migration.

Whether given alone or in combination with chemotherapy, PF-06747143 demonstrated efficacy in mouse models of NHL, MM, and AML.

Treatment involving PF-06747143—alone or in combination—eradicated more cancer cells than did standard treatment options.

These results were published in Blood Advances. The research was sponsored by Pfizer, Inc., the company developing PF-06747143.

“One of the major limitations we see in treating blood cancers is the failure to clear cancer cells from the bone marrow,” said study author Flavia Pernasetti, PhD, of Pfizer Oncology Research and Development.

“Because the bone marrow allows the cancer cells to flourish, removing these cells is an essential step in treating these malignancies effectively.”

With this goal in mind, Dr Pernasetti and her colleagues looked to the mechanisms that control the movement of cells into the bone marrow (BM) in the first place—the chemokine receptor CXCR4 and its ligand CXCL12.

The researchers created PF-06747143, which attacks and kills cancer cells directly but also removes cancer cells from the BM so they can be killed by other treatments.

Results in NHL

The researchers first tested PF-06747143 in an NHL Ramos xenograft model. Mice received PF-06747143 or a control IgG1 antibody at 10 mg/kg on days 1 and 8.

PF-06747143 significantly inhibited tumor growth compared to the control antibody (P<0.0001). Seventy percent of PF-06747143-treated mice had tumor volumes below their initial size at the end of the study.

PF-06747143 produced a dose-dependent response that was sustained until the end of the study, even after treatment was stopped.

Results in MM

The researchers tested PF-06747143 in a disseminated MM model, in which the OPM2-Luc tumor cells were implanted intravenously and migrated spontaneously to the BM.

Mice received PF-06747143 or IgG1 control at 10 mg/kg weekly for 5 doses. Other mice received melphalan at 1 mg/kg twice a week for a total of 4 cycles.

On day 30, PF-06747143 had significantly inhibited BM tumor growth compared to the control antibody or melphalan (P<0.0001).

PF-06747143-treated mice also had a significant survival benefit. The median survival was 33.5 days for mice that received the control antibody and 36 days for mice treated with melphalan. However, there were no deaths in the PF-06747143-treated mice by day 50, which marked the end of the study (P<0.0001).

The researchers also tested PF-06747143 at a lower dose (1 mg/kg weekly for a total of 7 doses), both alone and in combination with bortezomib (0.5 mg/kg twice a week for a total of 4 cycles).

The median survival was 34 days in the control mice, 44 days in mice that received bortezomib alone, and 47 days in mice that received PF-06747143 alone. However, there were no deaths in the combination arm at day 51, which was the end of the study (P<0.0003).

Results in AML

The researchers tested PF-06747143 in an AML disseminated tumor model using MV4-11 cells.

They compared PF-06747143 (given at 0.1, 1, or 10 mg/kg weekly for 4 doses) to the chemotherapeutic agent daunorubicin (2 mg/kg on days 1, 3, and 5), the FLT3 inhibitor crenolanib (7.5 mg/kg twice a day, on days 11-15 and 25-29), and a control IgG1 antibody (10 mg/kg weekly for 4 doses).

PF-06747143 (at 10 mg/kg), daunorubicin, and crenolanib all significantly reduced the number of tumor cells in the peripheral blood and BM when compared with the control antibody (P<0.05).

PF-06746143 treatment (at 10 mg/kg) reduced the number of AML cells in the BM by 95.9%, while daunorubicin reduced them by 84.5% and crenolanib by 80.5%.

The median survival was 36 days for mice that received PF-06747143 at 0.1 mg/kg, 41 days for mice that received the control antibody, 47 days for mice that received PF-06747143 at 1 mg/kg, and 63 days for mice that received PF-06747143 at 10 mg/kg.

The researchers also found that PF-06747143 had a “strong combinatorial effect” with daunorubicin and cytarabine in a chemotherapy-resistant model of AML. The team noted that only 36% of BM cells are positive for CXCR4 in this model.

Treatment with PF-06747143 alone reduced the percentage of AML cells in the BM to 80%, combination daunorubicin and cytarabine reduced it to 27%, and combination PF-06747143, daunorubicin, and cytarabine reduced the percentage of AML cells in the BM to 0.3%.

“Our preliminary preclinical results are encouraging,” Dr Pernasetti said, “and we are very excited to see how our antibody fares in clinical testing.”

PF-06747143 is currently being evaluated in a phase 1 trial of AML patients. ![]()

An investigational antibody has demonstrated activity against acute myeloid leukemia (AML), multiple myeloma (MM), and non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL), according to researchers.

PF-06747143 is a humanized CXCR4 immunoglobulin G1 (IgG1) antibody that binds to CXCR4 and inhibits both CXCL12-mediated signaling pathways and cell migration.

Whether given alone or in combination with chemotherapy, PF-06747143 demonstrated efficacy in mouse models of NHL, MM, and AML.

Treatment involving PF-06747143—alone or in combination—eradicated more cancer cells than did standard treatment options.

These results were published in Blood Advances. The research was sponsored by Pfizer, Inc., the company developing PF-06747143.

“One of the major limitations we see in treating blood cancers is the failure to clear cancer cells from the bone marrow,” said study author Flavia Pernasetti, PhD, of Pfizer Oncology Research and Development.

“Because the bone marrow allows the cancer cells to flourish, removing these cells is an essential step in treating these malignancies effectively.”

With this goal in mind, Dr Pernasetti and her colleagues looked to the mechanisms that control the movement of cells into the bone marrow (BM) in the first place—the chemokine receptor CXCR4 and its ligand CXCL12.

The researchers created PF-06747143, which attacks and kills cancer cells directly but also removes cancer cells from the BM so they can be killed by other treatments.

Results in NHL

The researchers first tested PF-06747143 in an NHL Ramos xenograft model. Mice received PF-06747143 or a control IgG1 antibody at 10 mg/kg on days 1 and 8.

PF-06747143 significantly inhibited tumor growth compared to the control antibody (P<0.0001). Seventy percent of PF-06747143-treated mice had tumor volumes below their initial size at the end of the study.

PF-06747143 produced a dose-dependent response that was sustained until the end of the study, even after treatment was stopped.

Results in MM

The researchers tested PF-06747143 in a disseminated MM model, in which the OPM2-Luc tumor cells were implanted intravenously and migrated spontaneously to the BM.

Mice received PF-06747143 or IgG1 control at 10 mg/kg weekly for 5 doses. Other mice received melphalan at 1 mg/kg twice a week for a total of 4 cycles.

On day 30, PF-06747143 had significantly inhibited BM tumor growth compared to the control antibody or melphalan (P<0.0001).

PF-06747143-treated mice also had a significant survival benefit. The median survival was 33.5 days for mice that received the control antibody and 36 days for mice treated with melphalan. However, there were no deaths in the PF-06747143-treated mice by day 50, which marked the end of the study (P<0.0001).

The researchers also tested PF-06747143 at a lower dose (1 mg/kg weekly for a total of 7 doses), both alone and in combination with bortezomib (0.5 mg/kg twice a week for a total of 4 cycles).

The median survival was 34 days in the control mice, 44 days in mice that received bortezomib alone, and 47 days in mice that received PF-06747143 alone. However, there were no deaths in the combination arm at day 51, which was the end of the study (P<0.0003).

Results in AML

The researchers tested PF-06747143 in an AML disseminated tumor model using MV4-11 cells.

They compared PF-06747143 (given at 0.1, 1, or 10 mg/kg weekly for 4 doses) to the chemotherapeutic agent daunorubicin (2 mg/kg on days 1, 3, and 5), the FLT3 inhibitor crenolanib (7.5 mg/kg twice a day, on days 11-15 and 25-29), and a control IgG1 antibody (10 mg/kg weekly for 4 doses).

PF-06747143 (at 10 mg/kg), daunorubicin, and crenolanib all significantly reduced the number of tumor cells in the peripheral blood and BM when compared with the control antibody (P<0.05).

PF-06746143 treatment (at 10 mg/kg) reduced the number of AML cells in the BM by 95.9%, while daunorubicin reduced them by 84.5% and crenolanib by 80.5%.

The median survival was 36 days for mice that received PF-06747143 at 0.1 mg/kg, 41 days for mice that received the control antibody, 47 days for mice that received PF-06747143 at 1 mg/kg, and 63 days for mice that received PF-06747143 at 10 mg/kg.

The researchers also found that PF-06747143 had a “strong combinatorial effect” with daunorubicin and cytarabine in a chemotherapy-resistant model of AML. The team noted that only 36% of BM cells are positive for CXCR4 in this model.

Treatment with PF-06747143 alone reduced the percentage of AML cells in the BM to 80%, combination daunorubicin and cytarabine reduced it to 27%, and combination PF-06747143, daunorubicin, and cytarabine reduced the percentage of AML cells in the BM to 0.3%.

“Our preliminary preclinical results are encouraging,” Dr Pernasetti said, “and we are very excited to see how our antibody fares in clinical testing.”

PF-06747143 is currently being evaluated in a phase 1 trial of AML patients. ![]()

An investigational antibody has demonstrated activity against acute myeloid leukemia (AML), multiple myeloma (MM), and non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL), according to researchers.

PF-06747143 is a humanized CXCR4 immunoglobulin G1 (IgG1) antibody that binds to CXCR4 and inhibits both CXCL12-mediated signaling pathways and cell migration.

Whether given alone or in combination with chemotherapy, PF-06747143 demonstrated efficacy in mouse models of NHL, MM, and AML.

Treatment involving PF-06747143—alone or in combination—eradicated more cancer cells than did standard treatment options.

These results were published in Blood Advances. The research was sponsored by Pfizer, Inc., the company developing PF-06747143.

“One of the major limitations we see in treating blood cancers is the failure to clear cancer cells from the bone marrow,” said study author Flavia Pernasetti, PhD, of Pfizer Oncology Research and Development.

“Because the bone marrow allows the cancer cells to flourish, removing these cells is an essential step in treating these malignancies effectively.”

With this goal in mind, Dr Pernasetti and her colleagues looked to the mechanisms that control the movement of cells into the bone marrow (BM) in the first place—the chemokine receptor CXCR4 and its ligand CXCL12.

The researchers created PF-06747143, which attacks and kills cancer cells directly but also removes cancer cells from the BM so they can be killed by other treatments.

Results in NHL

The researchers first tested PF-06747143 in an NHL Ramos xenograft model. Mice received PF-06747143 or a control IgG1 antibody at 10 mg/kg on days 1 and 8.

PF-06747143 significantly inhibited tumor growth compared to the control antibody (P<0.0001). Seventy percent of PF-06747143-treated mice had tumor volumes below their initial size at the end of the study.

PF-06747143 produced a dose-dependent response that was sustained until the end of the study, even after treatment was stopped.

Results in MM

The researchers tested PF-06747143 in a disseminated MM model, in which the OPM2-Luc tumor cells were implanted intravenously and migrated spontaneously to the BM.

Mice received PF-06747143 or IgG1 control at 10 mg/kg weekly for 5 doses. Other mice received melphalan at 1 mg/kg twice a week for a total of 4 cycles.

On day 30, PF-06747143 had significantly inhibited BM tumor growth compared to the control antibody or melphalan (P<0.0001).

PF-06747143-treated mice also had a significant survival benefit. The median survival was 33.5 days for mice that received the control antibody and 36 days for mice treated with melphalan. However, there were no deaths in the PF-06747143-treated mice by day 50, which marked the end of the study (P<0.0001).

The researchers also tested PF-06747143 at a lower dose (1 mg/kg weekly for a total of 7 doses), both alone and in combination with bortezomib (0.5 mg/kg twice a week for a total of 4 cycles).

The median survival was 34 days in the control mice, 44 days in mice that received bortezomib alone, and 47 days in mice that received PF-06747143 alone. However, there were no deaths in the combination arm at day 51, which was the end of the study (P<0.0003).

Results in AML

The researchers tested PF-06747143 in an AML disseminated tumor model using MV4-11 cells.

They compared PF-06747143 (given at 0.1, 1, or 10 mg/kg weekly for 4 doses) to the chemotherapeutic agent daunorubicin (2 mg/kg on days 1, 3, and 5), the FLT3 inhibitor crenolanib (7.5 mg/kg twice a day, on days 11-15 and 25-29), and a control IgG1 antibody (10 mg/kg weekly for 4 doses).

PF-06747143 (at 10 mg/kg), daunorubicin, and crenolanib all significantly reduced the number of tumor cells in the peripheral blood and BM when compared with the control antibody (P<0.05).

PF-06746143 treatment (at 10 mg/kg) reduced the number of AML cells in the BM by 95.9%, while daunorubicin reduced them by 84.5% and crenolanib by 80.5%.

The median survival was 36 days for mice that received PF-06747143 at 0.1 mg/kg, 41 days for mice that received the control antibody, 47 days for mice that received PF-06747143 at 1 mg/kg, and 63 days for mice that received PF-06747143 at 10 mg/kg.

The researchers also found that PF-06747143 had a “strong combinatorial effect” with daunorubicin and cytarabine in a chemotherapy-resistant model of AML. The team noted that only 36% of BM cells are positive for CXCR4 in this model.

Treatment with PF-06747143 alone reduced the percentage of AML cells in the BM to 80%, combination daunorubicin and cytarabine reduced it to 27%, and combination PF-06747143, daunorubicin, and cytarabine reduced the percentage of AML cells in the BM to 0.3%.

“Our preliminary preclinical results are encouraging,” Dr Pernasetti said, “and we are very excited to see how our antibody fares in clinical testing.”

PF-06747143 is currently being evaluated in a phase 1 trial of AML patients. ![]()

FDA grants drug orphan designation for AML

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has granted orphan drug designation to SY-1425 for the treatment of acute myeloid leukemia (AML).

SY-1425 is an oral, first-in-class, selective retinoic acid receptor alpha (RARα) agonist. It is currently under investigation in a phase 2 trial of patients with AML and myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS).

“We believe that SY-1425 may provide a meaningful benefit for subsets of AML patients whose disease is driven by abnormally high expression of the RARA or IRF8 genes,” said David A. Roth, MD, chief medical officer at Syros Pharmaceuticals, the company developing SY-1425.

“Receiving orphan drug designation is an important regulatory milestone in the development of SY-1425. We’re pleased with the continued progress of the ongoing phase 2 clinical trial, and we look forward to presenting initial clinical data in the fourth quarter of this year.”

Using its gene control platform, Syros discovered subsets of AML and MDS patients with super-enhancers associated with RARA or IRF8. These super-enhancers are believed to drive overexpression of the RARA or IRF8 genes, locking cells in an immature, undifferentiated, and proliferative state and leading to disease.

In preclinical studies, SY-1425 promoted differentiation of AML cells with high RARA or IRF8 expression and inhibited tumor growth and prolonged survival in patient-derived xenograft models of AML with high RARA expression.

In the ongoing phase 2 trial, researchers are assessing the safety and efficacy of SY-1425 as a single agent in 4 AML and MDS patient populations, as well as SY-1425 in combination with azacitidine in newly diagnosed AML patients who are not suitable candidates for standard chemotherapy.

All patients are prospectively selected using biomarkers for high expression of RARA or IRF8. Additional details about the trial can be found at https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02807558.

About orphan designation

The FDA grants orphan designation to products intended to treat, diagnose, or prevent diseases/disorders that affect fewer than 200,000 people in the US.

The designation provides incentives for sponsors to develop products for rare diseases. This may include tax credits toward the cost of clinical trials, prescription drug user fee waivers, and 7 years of market exclusivity if the product is approved. ![]()

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has granted orphan drug designation to SY-1425 for the treatment of acute myeloid leukemia (AML).

SY-1425 is an oral, first-in-class, selective retinoic acid receptor alpha (RARα) agonist. It is currently under investigation in a phase 2 trial of patients with AML and myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS).

“We believe that SY-1425 may provide a meaningful benefit for subsets of AML patients whose disease is driven by abnormally high expression of the RARA or IRF8 genes,” said David A. Roth, MD, chief medical officer at Syros Pharmaceuticals, the company developing SY-1425.

“Receiving orphan drug designation is an important regulatory milestone in the development of SY-1425. We’re pleased with the continued progress of the ongoing phase 2 clinical trial, and we look forward to presenting initial clinical data in the fourth quarter of this year.”

Using its gene control platform, Syros discovered subsets of AML and MDS patients with super-enhancers associated with RARA or IRF8. These super-enhancers are believed to drive overexpression of the RARA or IRF8 genes, locking cells in an immature, undifferentiated, and proliferative state and leading to disease.

In preclinical studies, SY-1425 promoted differentiation of AML cells with high RARA or IRF8 expression and inhibited tumor growth and prolonged survival in patient-derived xenograft models of AML with high RARA expression.

In the ongoing phase 2 trial, researchers are assessing the safety and efficacy of SY-1425 as a single agent in 4 AML and MDS patient populations, as well as SY-1425 in combination with azacitidine in newly diagnosed AML patients who are not suitable candidates for standard chemotherapy.

All patients are prospectively selected using biomarkers for high expression of RARA or IRF8. Additional details about the trial can be found at https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02807558.

About orphan designation

The FDA grants orphan designation to products intended to treat, diagnose, or prevent diseases/disorders that affect fewer than 200,000 people in the US.

The designation provides incentives for sponsors to develop products for rare diseases. This may include tax credits toward the cost of clinical trials, prescription drug user fee waivers, and 7 years of market exclusivity if the product is approved. ![]()

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has granted orphan drug designation to SY-1425 for the treatment of acute myeloid leukemia (AML).

SY-1425 is an oral, first-in-class, selective retinoic acid receptor alpha (RARα) agonist. It is currently under investigation in a phase 2 trial of patients with AML and myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS).

“We believe that SY-1425 may provide a meaningful benefit for subsets of AML patients whose disease is driven by abnormally high expression of the RARA or IRF8 genes,” said David A. Roth, MD, chief medical officer at Syros Pharmaceuticals, the company developing SY-1425.

“Receiving orphan drug designation is an important regulatory milestone in the development of SY-1425. We’re pleased with the continued progress of the ongoing phase 2 clinical trial, and we look forward to presenting initial clinical data in the fourth quarter of this year.”

Using its gene control platform, Syros discovered subsets of AML and MDS patients with super-enhancers associated with RARA or IRF8. These super-enhancers are believed to drive overexpression of the RARA or IRF8 genes, locking cells in an immature, undifferentiated, and proliferative state and leading to disease.

In preclinical studies, SY-1425 promoted differentiation of AML cells with high RARA or IRF8 expression and inhibited tumor growth and prolonged survival in patient-derived xenograft models of AML with high RARA expression.

In the ongoing phase 2 trial, researchers are assessing the safety and efficacy of SY-1425 as a single agent in 4 AML and MDS patient populations, as well as SY-1425 in combination with azacitidine in newly diagnosed AML patients who are not suitable candidates for standard chemotherapy.

All patients are prospectively selected using biomarkers for high expression of RARA or IRF8. Additional details about the trial can be found at https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02807558.

About orphan designation

The FDA grants orphan designation to products intended to treat, diagnose, or prevent diseases/disorders that affect fewer than 200,000 people in the US.

The designation provides incentives for sponsors to develop products for rare diseases. This may include tax credits toward the cost of clinical trials, prescription drug user fee waivers, and 7 years of market exclusivity if the product is approved. ![]()

BMI z scores fall short for tracking severe obesity

, based on data from nearly 7,000 children in the Bogalusa Heart Study.

The current parameters used in the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention growth charts for children with high body mass index (BMI) “can result in estimates that differ substantially from those that are observed and constrains the maximum BMI z that is attainable at a given sex and age,” wrote David S. Freedman, PhD, of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in Atlanta, and Gerald S. Berenson, MD, of Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center, New Orleans, (Pediatrics. 2017;140:e20171072).

The BMI adjusted z score (BMIaz) or the BMI expressed as a percentage of the 95th percentile (%BMIp95) “will provide more accurate information on body size over time among children with very high BMIs,” they said.

In children with severe obesity, BMI z was a weaker measure (r = 0.46) than were measures of %BMIp95 (r = 0.61) or BMIaz scores with no upper boundary (r = 0.65).

BMI z scores were weakest when applied to children younger than 10 years, with correlations of r = 0.36 for BMI z vs. correlations of 0.60 and 0.57 for BMIaz and %BMIp95, respectively.

The results were limited by several factors including the age of the data (40 years ago, when the prevalence of severe obesity was lower, 2% compared with approximately 6% now) and long intervals between exams in some cases (5 years or more), the researchers noted. However, the results suggest that BMI z values “can differ substantially from empirical estimates, have an effective upper limit, and are strongly influenced by sex and age,” they said. As an alternative, the researchers recommended that “very high BMIs should be should expressed as z scores on the basis of linear extrapolations of a fixed SD or as percentage of the CDC 95th percentile,” or using multilevel models that adjust for age and sex.

The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose. The National Institute on Aging, the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, and the National Institutes of Health funded the study.

The use of BMI z scores to assess and track severe obesity in children should be abandoned.

In the study by Freedman et al., BMI z scores, which are extrapolations of BMI measurements, did not correlate well with other measures of adiposity. Their use to assess severe obesity is problematic because large changes in weight and BMI are linked to small changes in BMI z or BMI percentiles.

William H. Dietz, MD, PhD, is at the Sumner M. Redstone Global Center for Prevention and Wellness, Milken Institute School of Public Health at George Washington University in Washington. He had no relevant financial disclosures, but disclosed that he serves on the scientific advisory board for Weight Watchers and is on the board of directors for the Partnership for a Healthier America. He discussed the article by Freedman et al. in an editorial (Pediatrics. 2017;140:e20172148).

The use of BMI z scores to assess and track severe obesity in children should be abandoned.

In the study by Freedman et al., BMI z scores, which are extrapolations of BMI measurements, did not correlate well with other measures of adiposity. Their use to assess severe obesity is problematic because large changes in weight and BMI are linked to small changes in BMI z or BMI percentiles.

William H. Dietz, MD, PhD, is at the Sumner M. Redstone Global Center for Prevention and Wellness, Milken Institute School of Public Health at George Washington University in Washington. He had no relevant financial disclosures, but disclosed that he serves on the scientific advisory board for Weight Watchers and is on the board of directors for the Partnership for a Healthier America. He discussed the article by Freedman et al. in an editorial (Pediatrics. 2017;140:e20172148).

The use of BMI z scores to assess and track severe obesity in children should be abandoned.

In the study by Freedman et al., BMI z scores, which are extrapolations of BMI measurements, did not correlate well with other measures of adiposity. Their use to assess severe obesity is problematic because large changes in weight and BMI are linked to small changes in BMI z or BMI percentiles.

William H. Dietz, MD, PhD, is at the Sumner M. Redstone Global Center for Prevention and Wellness, Milken Institute School of Public Health at George Washington University in Washington. He had no relevant financial disclosures, but disclosed that he serves on the scientific advisory board for Weight Watchers and is on the board of directors for the Partnership for a Healthier America. He discussed the article by Freedman et al. in an editorial (Pediatrics. 2017;140:e20172148).

, based on data from nearly 7,000 children in the Bogalusa Heart Study.

The current parameters used in the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention growth charts for children with high body mass index (BMI) “can result in estimates that differ substantially from those that are observed and constrains the maximum BMI z that is attainable at a given sex and age,” wrote David S. Freedman, PhD, of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in Atlanta, and Gerald S. Berenson, MD, of Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center, New Orleans, (Pediatrics. 2017;140:e20171072).

The BMI adjusted z score (BMIaz) or the BMI expressed as a percentage of the 95th percentile (%BMIp95) “will provide more accurate information on body size over time among children with very high BMIs,” they said.

In children with severe obesity, BMI z was a weaker measure (r = 0.46) than were measures of %BMIp95 (r = 0.61) or BMIaz scores with no upper boundary (r = 0.65).

BMI z scores were weakest when applied to children younger than 10 years, with correlations of r = 0.36 for BMI z vs. correlations of 0.60 and 0.57 for BMIaz and %BMIp95, respectively.

The results were limited by several factors including the age of the data (40 years ago, when the prevalence of severe obesity was lower, 2% compared with approximately 6% now) and long intervals between exams in some cases (5 years or more), the researchers noted. However, the results suggest that BMI z values “can differ substantially from empirical estimates, have an effective upper limit, and are strongly influenced by sex and age,” they said. As an alternative, the researchers recommended that “very high BMIs should be should expressed as z scores on the basis of linear extrapolations of a fixed SD or as percentage of the CDC 95th percentile,” or using multilevel models that adjust for age and sex.

The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose. The National Institute on Aging, the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, and the National Institutes of Health funded the study.

, based on data from nearly 7,000 children in the Bogalusa Heart Study.

The current parameters used in the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention growth charts for children with high body mass index (BMI) “can result in estimates that differ substantially from those that are observed and constrains the maximum BMI z that is attainable at a given sex and age,” wrote David S. Freedman, PhD, of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in Atlanta, and Gerald S. Berenson, MD, of Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center, New Orleans, (Pediatrics. 2017;140:e20171072).

The BMI adjusted z score (BMIaz) or the BMI expressed as a percentage of the 95th percentile (%BMIp95) “will provide more accurate information on body size over time among children with very high BMIs,” they said.

In children with severe obesity, BMI z was a weaker measure (r = 0.46) than were measures of %BMIp95 (r = 0.61) or BMIaz scores with no upper boundary (r = 0.65).

BMI z scores were weakest when applied to children younger than 10 years, with correlations of r = 0.36 for BMI z vs. correlations of 0.60 and 0.57 for BMIaz and %BMIp95, respectively.

The results were limited by several factors including the age of the data (40 years ago, when the prevalence of severe obesity was lower, 2% compared with approximately 6% now) and long intervals between exams in some cases (5 years or more), the researchers noted. However, the results suggest that BMI z values “can differ substantially from empirical estimates, have an effective upper limit, and are strongly influenced by sex and age,” they said. As an alternative, the researchers recommended that “very high BMIs should be should expressed as z scores on the basis of linear extrapolations of a fixed SD or as percentage of the CDC 95th percentile,” or using multilevel models that adjust for age and sex.

The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose. The National Institute on Aging, the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, and the National Institutes of Health funded the study.

FROM PEDIATRICS

Key clinical point: BMI z scores are weak trackers of severe obesity in children.

Major finding: Correlations were weaker for BMI z scores (r = 0.46) than for metrics of BMI using the 95th percentile or z scores with no upper bound (r = approximately 0.6) over 2.8 years.

Data source: The study is based on longitudinal data from 6,994 children participating in the Bogalusa Heart study, including 247 children with severe obesity.

Disclosures: The researchers had no relevant financial conflicts to disclose. The National Institute on Aging, the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, and the National Institutes of Health funded the study.

PVC phlebitis rates varied widely, depending on assessment tool

Rates of phlebitis associated with peripheral venous catheters (PVC) ranged from less than 1% to 34% depending on which assessment tool researchers used in a large cross-sectional study.

Rates also varied within individual instruments because they included several possible case definitions, Katarina Göransson, PhD, and her associates reported in Lancet Haematology. “We find it concerning that our study shows variation of the proportion of PVCs causing phlebitis both within and across the instruments investigated,” they wrote. “How to best measure phlebitis outcomes is still unclear, since no universally accepted instrument exists that has had rigorous testing. From a work environment and patient safety perspective, clinical staff engaged in PVC management should be aware of the absence of adequately validated instruments for phlebitis assessment.”

There are many tools to measure PVC-related phlebitis, but no consensus on which to use, and past studies have reported rates of anywhere from 2% to 62%. Hypothesizing that instrument variability contributed to this discrepancy, the researchers tested 17 instruments in 1,032 patients who had 1,175 PVCs placed at 12 inpatient units in Sweden. Eight tools used clinical definitions, seven used severity rating systems, and two used scoring systems (Lancet Haematol. 2017 doi: 10.1016/S2352-3026[17]30122-9).

Rates of PVC-induced phlebitis reached 12% (137 cases) when the researchers used case definition tools, up to 31% when they used scoring systems (P less than .0001), and up to 34% when they used severity rating systems (P less than .0001, compared with the 12% rate). “The proportion within instruments ranged from less than 1% to 28%,” they added. “We [also] identified face validity issues, such as use of indistinct or complex measurements and inconsistent measurements or definitions.”

The investigators did not perform a systematic review to identify these instruments, and they did not necessarily use the most recent versions, they noted. Nevertheless, the findings have direct implications for hospital quality control measures, which require using a single validated instrument over time to generate meaningful results, they said. Hence, the investigators recommended developing a joint research program to develop reliable measures of PVC-related adverse events and better support clinicians who are trying to decide whether to remove PVCs.

The investigators reported having no funding sources and no competing interests.

Rates of phlebitis associated with peripheral venous catheters (PVC) ranged from less than 1% to 34% depending on which assessment tool researchers used in a large cross-sectional study.

Rates also varied within individual instruments because they included several possible case definitions, Katarina Göransson, PhD, and her associates reported in Lancet Haematology. “We find it concerning that our study shows variation of the proportion of PVCs causing phlebitis both within and across the instruments investigated,” they wrote. “How to best measure phlebitis outcomes is still unclear, since no universally accepted instrument exists that has had rigorous testing. From a work environment and patient safety perspective, clinical staff engaged in PVC management should be aware of the absence of adequately validated instruments for phlebitis assessment.”

There are many tools to measure PVC-related phlebitis, but no consensus on which to use, and past studies have reported rates of anywhere from 2% to 62%. Hypothesizing that instrument variability contributed to this discrepancy, the researchers tested 17 instruments in 1,032 patients who had 1,175 PVCs placed at 12 inpatient units in Sweden. Eight tools used clinical definitions, seven used severity rating systems, and two used scoring systems (Lancet Haematol. 2017 doi: 10.1016/S2352-3026[17]30122-9).

Rates of PVC-induced phlebitis reached 12% (137 cases) when the researchers used case definition tools, up to 31% when they used scoring systems (P less than .0001), and up to 34% when they used severity rating systems (P less than .0001, compared with the 12% rate). “The proportion within instruments ranged from less than 1% to 28%,” they added. “We [also] identified face validity issues, such as use of indistinct or complex measurements and inconsistent measurements or definitions.”

The investigators did not perform a systematic review to identify these instruments, and they did not necessarily use the most recent versions, they noted. Nevertheless, the findings have direct implications for hospital quality control measures, which require using a single validated instrument over time to generate meaningful results, they said. Hence, the investigators recommended developing a joint research program to develop reliable measures of PVC-related adverse events and better support clinicians who are trying to decide whether to remove PVCs.

The investigators reported having no funding sources and no competing interests.

Rates of phlebitis associated with peripheral venous catheters (PVC) ranged from less than 1% to 34% depending on which assessment tool researchers used in a large cross-sectional study.

Rates also varied within individual instruments because they included several possible case definitions, Katarina Göransson, PhD, and her associates reported in Lancet Haematology. “We find it concerning that our study shows variation of the proportion of PVCs causing phlebitis both within and across the instruments investigated,” they wrote. “How to best measure phlebitis outcomes is still unclear, since no universally accepted instrument exists that has had rigorous testing. From a work environment and patient safety perspective, clinical staff engaged in PVC management should be aware of the absence of adequately validated instruments for phlebitis assessment.”

There are many tools to measure PVC-related phlebitis, but no consensus on which to use, and past studies have reported rates of anywhere from 2% to 62%. Hypothesizing that instrument variability contributed to this discrepancy, the researchers tested 17 instruments in 1,032 patients who had 1,175 PVCs placed at 12 inpatient units in Sweden. Eight tools used clinical definitions, seven used severity rating systems, and two used scoring systems (Lancet Haematol. 2017 doi: 10.1016/S2352-3026[17]30122-9).

Rates of PVC-induced phlebitis reached 12% (137 cases) when the researchers used case definition tools, up to 31% when they used scoring systems (P less than .0001), and up to 34% when they used severity rating systems (P less than .0001, compared with the 12% rate). “The proportion within instruments ranged from less than 1% to 28%,” they added. “We [also] identified face validity issues, such as use of indistinct or complex measurements and inconsistent measurements or definitions.”

The investigators did not perform a systematic review to identify these instruments, and they did not necessarily use the most recent versions, they noted. Nevertheless, the findings have direct implications for hospital quality control measures, which require using a single validated instrument over time to generate meaningful results, they said. Hence, the investigators recommended developing a joint research program to develop reliable measures of PVC-related adverse events and better support clinicians who are trying to decide whether to remove PVCs.

The investigators reported having no funding sources and no competing interests.

FROM LANCET HAEMATOLOGY

Key clinical point: Rates of PVC-induced phlebitis varied widely within and between assessment instruments.

Major finding: Rates were as high as 12% (137 cases) based on the case definition tools, up to 31% based on the scoring systems (P less than .0001), and up to 34% based on the severity rating systems (P less than .0001, compared with the case definition rate).

Data source: A cross-sectional study of 17 instruments used to identify phlebitis associated with peripheral venous catheters.

Disclosures: The investigators reported having no funding sources and no competing interests.

Cognitive decline not seen with lower BP treatment targets

Tighter blood pressure control is not linked to cognitive decline among older adults and may instead be associated with preservation of cognitive function, according to a new analysis.

Further, the cognitive benefits of tighter control are even more pronounced among black patients.

Dr. Hajjar and colleagues report that subjects whose systolic blood pressure (SBP) was maintained at 150 mm Hg or higher during the study period saw significantly greater cognitive decline over 10 years, compared with those treated to levels of 120 mm Hg or lower (JAMA Neurol. 2017 Aug 21; doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2017.1863). Furthermore, the investigators noted a differential decrease by blood pressure levels for both cognitive scoring systems, with the greatest decline seen in the group with SBP of 150 mm/Hg or higher and the lowest decrease in the group with 120 mm/Hg or lower (P less than .001 for both).

Black patients saw a greater difference, compared with white patients, between the higher and lower SBP levels in the decrease in cognition. Adjusted differences between the group with 150 mm Hg or higher and those with 120 mm Hg or lower were –0.05 in white patients and –0.08 in black patients for the 3MSE test (P = .03), and –0.07 in white patients and –0.13 in black patients for the DSST (P = .05).

“Almost all guidelines have recommended that target blood pressures be similar for black and white patients,” the investigators wrote in their analysis, adding that “future recommendations for the management of hypertension and cognitive outcomes need to take this racial disparity into consideration.”

The study was funded by the National Institutes on Health and National Institute on Aging. Dr. Hajjar and his colleagues disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Although unanswered questions remain, the data presented by Dr. Hajjar and colleagues add to the existing literature by emphasizing that tight blood pressure control does not appear to lead to poorer cognitive trajectories in older adults and may even be associated with improved cognitive trajectories. An important and unique feature of the data is the diverse population included, with nearly half of the enrollment composed of black individuals. The finding that lower systolic BP was especially protective for black individuals is important, given a noted disparity in rates of dementia among black and white persons. Adding to that the finding that hypertension is more common and more severe in black than in white persons (also supported by the data in this study), and that black persons tend to have more poorly controlled hypertension than do white persons, this outcome points to an important opportunity from a public health standpoint. BP reduction might actually reduce the rates of dementia and reduce the disparities by race with regard to dementia rates; the fact that BP control may require more medications for black than for white patients needs to be considered when monitoring blood pressure levels.

Rebecca F. Gottesman, MD, PhD, of Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, made these comments in an accompanying editorial (JAMA Neurol. 2017 Aug. 21; doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2017.1869). She is an associate editor at JAMA Neurology, and reports no other conflicts of interest.

Although unanswered questions remain, the data presented by Dr. Hajjar and colleagues add to the existing literature by emphasizing that tight blood pressure control does not appear to lead to poorer cognitive trajectories in older adults and may even be associated with improved cognitive trajectories. An important and unique feature of the data is the diverse population included, with nearly half of the enrollment composed of black individuals. The finding that lower systolic BP was especially protective for black individuals is important, given a noted disparity in rates of dementia among black and white persons. Adding to that the finding that hypertension is more common and more severe in black than in white persons (also supported by the data in this study), and that black persons tend to have more poorly controlled hypertension than do white persons, this outcome points to an important opportunity from a public health standpoint. BP reduction might actually reduce the rates of dementia and reduce the disparities by race with regard to dementia rates; the fact that BP control may require more medications for black than for white patients needs to be considered when monitoring blood pressure levels.

Rebecca F. Gottesman, MD, PhD, of Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, made these comments in an accompanying editorial (JAMA Neurol. 2017 Aug. 21; doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2017.1869). She is an associate editor at JAMA Neurology, and reports no other conflicts of interest.

Although unanswered questions remain, the data presented by Dr. Hajjar and colleagues add to the existing literature by emphasizing that tight blood pressure control does not appear to lead to poorer cognitive trajectories in older adults and may even be associated with improved cognitive trajectories. An important and unique feature of the data is the diverse population included, with nearly half of the enrollment composed of black individuals. The finding that lower systolic BP was especially protective for black individuals is important, given a noted disparity in rates of dementia among black and white persons. Adding to that the finding that hypertension is more common and more severe in black than in white persons (also supported by the data in this study), and that black persons tend to have more poorly controlled hypertension than do white persons, this outcome points to an important opportunity from a public health standpoint. BP reduction might actually reduce the rates of dementia and reduce the disparities by race with regard to dementia rates; the fact that BP control may require more medications for black than for white patients needs to be considered when monitoring blood pressure levels.

Rebecca F. Gottesman, MD, PhD, of Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, made these comments in an accompanying editorial (JAMA Neurol. 2017 Aug. 21; doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2017.1869). She is an associate editor at JAMA Neurology, and reports no other conflicts of interest.

Tighter blood pressure control is not linked to cognitive decline among older adults and may instead be associated with preservation of cognitive function, according to a new analysis.

Further, the cognitive benefits of tighter control are even more pronounced among black patients.

Dr. Hajjar and colleagues report that subjects whose systolic blood pressure (SBP) was maintained at 150 mm Hg or higher during the study period saw significantly greater cognitive decline over 10 years, compared with those treated to levels of 120 mm Hg or lower (JAMA Neurol. 2017 Aug 21; doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2017.1863). Furthermore, the investigators noted a differential decrease by blood pressure levels for both cognitive scoring systems, with the greatest decline seen in the group with SBP of 150 mm/Hg or higher and the lowest decrease in the group with 120 mm/Hg or lower (P less than .001 for both).

Black patients saw a greater difference, compared with white patients, between the higher and lower SBP levels in the decrease in cognition. Adjusted differences between the group with 150 mm Hg or higher and those with 120 mm Hg or lower were –0.05 in white patients and –0.08 in black patients for the 3MSE test (P = .03), and –0.07 in white patients and –0.13 in black patients for the DSST (P = .05).

“Almost all guidelines have recommended that target blood pressures be similar for black and white patients,” the investigators wrote in their analysis, adding that “future recommendations for the management of hypertension and cognitive outcomes need to take this racial disparity into consideration.”

The study was funded by the National Institutes on Health and National Institute on Aging. Dr. Hajjar and his colleagues disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Tighter blood pressure control is not linked to cognitive decline among older adults and may instead be associated with preservation of cognitive function, according to a new analysis.

Further, the cognitive benefits of tighter control are even more pronounced among black patients.

Dr. Hajjar and colleagues report that subjects whose systolic blood pressure (SBP) was maintained at 150 mm Hg or higher during the study period saw significantly greater cognitive decline over 10 years, compared with those treated to levels of 120 mm Hg or lower (JAMA Neurol. 2017 Aug 21; doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2017.1863). Furthermore, the investigators noted a differential decrease by blood pressure levels for both cognitive scoring systems, with the greatest decline seen in the group with SBP of 150 mm/Hg or higher and the lowest decrease in the group with 120 mm/Hg or lower (P less than .001 for both).

Black patients saw a greater difference, compared with white patients, between the higher and lower SBP levels in the decrease in cognition. Adjusted differences between the group with 150 mm Hg or higher and those with 120 mm Hg or lower were –0.05 in white patients and –0.08 in black patients for the 3MSE test (P = .03), and –0.07 in white patients and –0.13 in black patients for the DSST (P = .05).

“Almost all guidelines have recommended that target blood pressures be similar for black and white patients,” the investigators wrote in their analysis, adding that “future recommendations for the management of hypertension and cognitive outcomes need to take this racial disparity into consideration.”

The study was funded by the National Institutes on Health and National Institute on Aging. Dr. Hajjar and his colleagues disclosed no conflicts of interest.

FROM JAMA NEUROLOGY

Key clinical point: Treating to more aggressive blood pressure targets does not promote cognitive decline and may help stem it, particularly among black patients.

Major finding: Black patients saw significantly greater decline in cognition over time associated with systolic BP control to 150 mm Hg vs. 120 mm Hg.

Data source: A cohort of 1,700 hypertension-treated patients aged 70-79, about half of them black, drawn from a 10-year observational study of 3,000 patients.

Disclosures: Both the larger cohort and this study were funded by the National Institutes of Health and the National Institute on Aging. None of the investigators declared conflicts of interest.

L-glutamine to prevent sickle cell complications featured in FDA podcast

The recent approval of L-glutamine, marketed as Endari, to reduce the acute complications of sickle cell disease in adult and pediatric patients 5 years of age and older is discussed in the Drug Information Soundcast in Clinical Oncology (DISCO) from a Food and Drug Adminstration podcast series that provides information about new product approvals, emerging safety information for cancer treatments, and other current topics in cancer drug development.

The basis for the approval was discussed in our coverage of the FDA’s Oncologic Drugs Advisory Committee meeting.

This episode of DISCO is hosted by Sanjeeve Bala, MD, and was developed by Abhilasha Nair, MD; Dr. Bala; Kathy M. Robie Suh, MD; Ann T. Farrell, MD; Kirsten B. Goldberg, and Richard Pazdur, MD. All are with the FDA’s Oncology Center of Excellence and the Office of Hematology and Oncology Products. Steven Jackson of the FDA’s Division of Drug Information was the sound producer.

The recent approval of L-glutamine, marketed as Endari, to reduce the acute complications of sickle cell disease in adult and pediatric patients 5 years of age and older is discussed in the Drug Information Soundcast in Clinical Oncology (DISCO) from a Food and Drug Adminstration podcast series that provides information about new product approvals, emerging safety information for cancer treatments, and other current topics in cancer drug development.

The basis for the approval was discussed in our coverage of the FDA’s Oncologic Drugs Advisory Committee meeting.

This episode of DISCO is hosted by Sanjeeve Bala, MD, and was developed by Abhilasha Nair, MD; Dr. Bala; Kathy M. Robie Suh, MD; Ann T. Farrell, MD; Kirsten B. Goldberg, and Richard Pazdur, MD. All are with the FDA’s Oncology Center of Excellence and the Office of Hematology and Oncology Products. Steven Jackson of the FDA’s Division of Drug Information was the sound producer.

The recent approval of L-glutamine, marketed as Endari, to reduce the acute complications of sickle cell disease in adult and pediatric patients 5 years of age and older is discussed in the Drug Information Soundcast in Clinical Oncology (DISCO) from a Food and Drug Adminstration podcast series that provides information about new product approvals, emerging safety information for cancer treatments, and other current topics in cancer drug development.

The basis for the approval was discussed in our coverage of the FDA’s Oncologic Drugs Advisory Committee meeting.

This episode of DISCO is hosted by Sanjeeve Bala, MD, and was developed by Abhilasha Nair, MD; Dr. Bala; Kathy M. Robie Suh, MD; Ann T. Farrell, MD; Kirsten B. Goldberg, and Richard Pazdur, MD. All are with the FDA’s Oncology Center of Excellence and the Office of Hematology and Oncology Products. Steven Jackson of the FDA’s Division of Drug Information was the sound producer.

Acute lobar nephronia often has misleading presentation

MADRID – Acute lobar nephronia needs to be considered in children with high fever, abdominal pain, and markedly elevated acute-phase reactants, even if their urinalysis and ultrasound results are negative, Paula Sanchez-Marcos, MD, reported at the annual meeting of the European Society for Paediatric Infectious Diseases.

She presented a retrospective study of 18 episodes of acute lobar nephronia (ALN) in 16 children seen at the hospital, a tertiary referral center. Six of the children had vesicoureteral reflux or another underlying uropathy. Mean age at diagnosis was 79 months, with a range of 5 to 180 months.

All patients had a fever greater than 38.5° C when they presented with a mean 6-day history of illness. Of the 16 children, 14 had abdominal pain. The mean C-reactive protein level was 197 mg/L, with a WBC count of 21,962 cells/mcL and a neutrophil count of 17,372 cells/mcL.

Urine dipstick was negative in five episodes. However, urine culture was eventually productive in 10 episodes, with Escherichia coli the most commonly isolated microorganism, found in five of these cases.

All patients underwent ultrasound imaging a mean of 1.7 days into their hospital admission, although it established the diagnosis of ALN in only two episodes. Additional imaging with CT had a 91% sensitivity, showing positive results in 10 of 11 cases, while MRI had 100% sensitivity.

Patients received IV antibiotics for a median of 14 days before switching to sequential oral antibiotics for a median of 8.7 days.

Three patients developed renal abscesses, with percutaneous drainage required in two instances. Unilateral renal scarring occurred in 7 of 16 patients.

Dr. Sanchez-Marcos recommended technetium-99m dimercaptosuccinic acid renal scintigraphy as a tool to confirm improvement in response to antimicrobial therapy.

She reported having no financial conflicts regarding her presentation.

MADRID – Acute lobar nephronia needs to be considered in children with high fever, abdominal pain, and markedly elevated acute-phase reactants, even if their urinalysis and ultrasound results are negative, Paula Sanchez-Marcos, MD, reported at the annual meeting of the European Society for Paediatric Infectious Diseases.

She presented a retrospective study of 18 episodes of acute lobar nephronia (ALN) in 16 children seen at the hospital, a tertiary referral center. Six of the children had vesicoureteral reflux or another underlying uropathy. Mean age at diagnosis was 79 months, with a range of 5 to 180 months.

All patients had a fever greater than 38.5° C when they presented with a mean 6-day history of illness. Of the 16 children, 14 had abdominal pain. The mean C-reactive protein level was 197 mg/L, with a WBC count of 21,962 cells/mcL and a neutrophil count of 17,372 cells/mcL.

Urine dipstick was negative in five episodes. However, urine culture was eventually productive in 10 episodes, with Escherichia coli the most commonly isolated microorganism, found in five of these cases.

All patients underwent ultrasound imaging a mean of 1.7 days into their hospital admission, although it established the diagnosis of ALN in only two episodes. Additional imaging with CT had a 91% sensitivity, showing positive results in 10 of 11 cases, while MRI had 100% sensitivity.

Patients received IV antibiotics for a median of 14 days before switching to sequential oral antibiotics for a median of 8.7 days.

Three patients developed renal abscesses, with percutaneous drainage required in two instances. Unilateral renal scarring occurred in 7 of 16 patients.

Dr. Sanchez-Marcos recommended technetium-99m dimercaptosuccinic acid renal scintigraphy as a tool to confirm improvement in response to antimicrobial therapy.

She reported having no financial conflicts regarding her presentation.

MADRID – Acute lobar nephronia needs to be considered in children with high fever, abdominal pain, and markedly elevated acute-phase reactants, even if their urinalysis and ultrasound results are negative, Paula Sanchez-Marcos, MD, reported at the annual meeting of the European Society for Paediatric Infectious Diseases.

She presented a retrospective study of 18 episodes of acute lobar nephronia (ALN) in 16 children seen at the hospital, a tertiary referral center. Six of the children had vesicoureteral reflux or another underlying uropathy. Mean age at diagnosis was 79 months, with a range of 5 to 180 months.

All patients had a fever greater than 38.5° C when they presented with a mean 6-day history of illness. Of the 16 children, 14 had abdominal pain. The mean C-reactive protein level was 197 mg/L, with a WBC count of 21,962 cells/mcL and a neutrophil count of 17,372 cells/mcL.

Urine dipstick was negative in five episodes. However, urine culture was eventually productive in 10 episodes, with Escherichia coli the most commonly isolated microorganism, found in five of these cases.

All patients underwent ultrasound imaging a mean of 1.7 days into their hospital admission, although it established the diagnosis of ALN in only two episodes. Additional imaging with CT had a 91% sensitivity, showing positive results in 10 of 11 cases, while MRI had 100% sensitivity.

Patients received IV antibiotics for a median of 14 days before switching to sequential oral antibiotics for a median of 8.7 days.

Three patients developed renal abscesses, with percutaneous drainage required in two instances. Unilateral renal scarring occurred in 7 of 16 patients.

Dr. Sanchez-Marcos recommended technetium-99m dimercaptosuccinic acid renal scintigraphy as a tool to confirm improvement in response to antimicrobial therapy.

She reported having no financial conflicts regarding her presentation.

AT ESPID 2017

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Urine dipstick results were negative in 5 instances, and ultrasound was negative in 16 cases.

Data source: This was a single-center, retrospective, descriptive study of 18 episodes of acute lobar nephronia in 16 children.

Disclosures: Dr. Sanchez-Marcos reported having no financial conflicts of interest.