User login

Consulting for the dead

As the years roll on, it’s nice to be open to new experiences. Till now, for instance, every patient I’ve examined has been alive.

My local hospital called 2 weeks ago. Although I’m on staff, I haven’t consulted on an inpatient there in 20 years.

I ran their skin clinic years ago. Medical residents came to my office for an elective.

“Did you see the glucagonoma on Sefton 6?” a resident would ask.

“No, they didn’t call me for that. They called me for the seborrheic dermatitis on Sefton 4.”

I no longer visit hospitals; nowadays, the main function of my hospital affiliations is to be able to see patients insured on their referral circles. This year, my hospital made a new rule: All dermatologists must cover consults to stay on staff. I drew 3 weeks in June. For 2½ weeks, nobody called. And then, late one morning …

“Hello, doctor. I’m a nurse in the medical ICU. We need your help.”

“Yes?”

“A 25-year-old man died of a drug overdose. We need to harvest his organs. He has skin changes on his back and a blister in his groin, and we need to know that these pose no bar to transplants.”

“I’m stuck in the office,“ I said. “I could come tonight.”

“Can someone else come?” he asked. “Time is critical.”

I told him I would try.

My morning session ended on time. Patient callbacks and lunch could wait. I dashed over to the hospital, phoning the nurse en route. “On my way,” I said, “but I don’t know where the ICU is, and I don’t know your protocols – what forms to fill out and so on.”

He gave me the name of the building and told me to go to the fourth floor. “We’ll have the paperwork ready,” he said.

The parking garage had a free space near the entrance. Asking directions in the lobby, I blundered my way over to the ICU building, newly built and unfamiliar, where the nurse greeted me.

“We appreciate your coming,” he said. “I’ll ask the family at the bedside to leave.”

He introduced a resident, who told me dermatologists dropped by the ICU from time to time to assess issues of graft-versus-host rashes, that sort of thing.

The nurse gave me a yellow paper gown. The patient had his own room. Back in my day, ICUs had no quiet, private spaces.

A middle-aged woman stood by the bed rail – the stepmother of the deceased. What do you say to a newly bereaved family member in this circumstance? “I am your deceased stepson’s dermatology consultant. Pleased to meet you”?

Instead, I said I was sorry for her loss, which seemed pallid but apt. She withdrew.

In bed, was a young man attached to life support. “No track marks,” the nurse observed. “He must have snorted something.”

The nurse and the resident rolled the body over, and I noted the red marks on his back. “Those are from acne,” I said. “No infection.”

Laying him down, they showed me a 1-mm scab at the base of his scrotum. “Appears to be trauma,” I said, “perhaps a scratch. Not herpes or anything infectious.”

Finding nothing else on his integument, I turned to leave. His stepmother was sitting on a chair near the door, her head in her hands. As I passed, she looked up.

In most life settings, including doctors’ offices, there are protocols of behavior, guidelines for how to act, what to say: “We’re all done.” “This should take care of it.” “I will write up a report.” “Nice to have met you.” “Take care.”

I looked down at her tortured face and said, “There is nothing to say.”

At this, I lost my composure, and left.

“I’m not sure what we were concerned about,” said the nurse, “but we appreciate your coming over.” He handed me a sheet of blank paper. I scribbled my nonfindings. Now the transplant wheels could begin to turn.

I left the ICU to its normal goings-on and returned to my office, where the paths of clinical engagement are well worn – and the patients are still alive.

Dr. Rockoff practices dermatology in Brookline, Mass., and is a longtime contributor to Dermatology News. He serves on the clinical faculty at Tufts University, Boston, and has taught senior medical students and other trainees for 30 years. His second book, “Act Like a Doctor, Think Like a Patient,” is available at amazon.com and barnesandnoble.com. Write to him at [email protected].

As the years roll on, it’s nice to be open to new experiences. Till now, for instance, every patient I’ve examined has been alive.

My local hospital called 2 weeks ago. Although I’m on staff, I haven’t consulted on an inpatient there in 20 years.

I ran their skin clinic years ago. Medical residents came to my office for an elective.

“Did you see the glucagonoma on Sefton 6?” a resident would ask.

“No, they didn’t call me for that. They called me for the seborrheic dermatitis on Sefton 4.”

I no longer visit hospitals; nowadays, the main function of my hospital affiliations is to be able to see patients insured on their referral circles. This year, my hospital made a new rule: All dermatologists must cover consults to stay on staff. I drew 3 weeks in June. For 2½ weeks, nobody called. And then, late one morning …

“Hello, doctor. I’m a nurse in the medical ICU. We need your help.”

“Yes?”

“A 25-year-old man died of a drug overdose. We need to harvest his organs. He has skin changes on his back and a blister in his groin, and we need to know that these pose no bar to transplants.”

“I’m stuck in the office,“ I said. “I could come tonight.”

“Can someone else come?” he asked. “Time is critical.”

I told him I would try.

My morning session ended on time. Patient callbacks and lunch could wait. I dashed over to the hospital, phoning the nurse en route. “On my way,” I said, “but I don’t know where the ICU is, and I don’t know your protocols – what forms to fill out and so on.”

He gave me the name of the building and told me to go to the fourth floor. “We’ll have the paperwork ready,” he said.

The parking garage had a free space near the entrance. Asking directions in the lobby, I blundered my way over to the ICU building, newly built and unfamiliar, where the nurse greeted me.

“We appreciate your coming,” he said. “I’ll ask the family at the bedside to leave.”

He introduced a resident, who told me dermatologists dropped by the ICU from time to time to assess issues of graft-versus-host rashes, that sort of thing.

The nurse gave me a yellow paper gown. The patient had his own room. Back in my day, ICUs had no quiet, private spaces.

A middle-aged woman stood by the bed rail – the stepmother of the deceased. What do you say to a newly bereaved family member in this circumstance? “I am your deceased stepson’s dermatology consultant. Pleased to meet you”?

Instead, I said I was sorry for her loss, which seemed pallid but apt. She withdrew.

In bed, was a young man attached to life support. “No track marks,” the nurse observed. “He must have snorted something.”

The nurse and the resident rolled the body over, and I noted the red marks on his back. “Those are from acne,” I said. “No infection.”

Laying him down, they showed me a 1-mm scab at the base of his scrotum. “Appears to be trauma,” I said, “perhaps a scratch. Not herpes or anything infectious.”

Finding nothing else on his integument, I turned to leave. His stepmother was sitting on a chair near the door, her head in her hands. As I passed, she looked up.

In most life settings, including doctors’ offices, there are protocols of behavior, guidelines for how to act, what to say: “We’re all done.” “This should take care of it.” “I will write up a report.” “Nice to have met you.” “Take care.”

I looked down at her tortured face and said, “There is nothing to say.”

At this, I lost my composure, and left.

“I’m not sure what we were concerned about,” said the nurse, “but we appreciate your coming over.” He handed me a sheet of blank paper. I scribbled my nonfindings. Now the transplant wheels could begin to turn.

I left the ICU to its normal goings-on and returned to my office, where the paths of clinical engagement are well worn – and the patients are still alive.

Dr. Rockoff practices dermatology in Brookline, Mass., and is a longtime contributor to Dermatology News. He serves on the clinical faculty at Tufts University, Boston, and has taught senior medical students and other trainees for 30 years. His second book, “Act Like a Doctor, Think Like a Patient,” is available at amazon.com and barnesandnoble.com. Write to him at [email protected].

As the years roll on, it’s nice to be open to new experiences. Till now, for instance, every patient I’ve examined has been alive.

My local hospital called 2 weeks ago. Although I’m on staff, I haven’t consulted on an inpatient there in 20 years.

I ran their skin clinic years ago. Medical residents came to my office for an elective.

“Did you see the glucagonoma on Sefton 6?” a resident would ask.

“No, they didn’t call me for that. They called me for the seborrheic dermatitis on Sefton 4.”

I no longer visit hospitals; nowadays, the main function of my hospital affiliations is to be able to see patients insured on their referral circles. This year, my hospital made a new rule: All dermatologists must cover consults to stay on staff. I drew 3 weeks in June. For 2½ weeks, nobody called. And then, late one morning …

“Hello, doctor. I’m a nurse in the medical ICU. We need your help.”

“Yes?”

“A 25-year-old man died of a drug overdose. We need to harvest his organs. He has skin changes on his back and a blister in his groin, and we need to know that these pose no bar to transplants.”

“I’m stuck in the office,“ I said. “I could come tonight.”

“Can someone else come?” he asked. “Time is critical.”

I told him I would try.

My morning session ended on time. Patient callbacks and lunch could wait. I dashed over to the hospital, phoning the nurse en route. “On my way,” I said, “but I don’t know where the ICU is, and I don’t know your protocols – what forms to fill out and so on.”

He gave me the name of the building and told me to go to the fourth floor. “We’ll have the paperwork ready,” he said.

The parking garage had a free space near the entrance. Asking directions in the lobby, I blundered my way over to the ICU building, newly built and unfamiliar, where the nurse greeted me.

“We appreciate your coming,” he said. “I’ll ask the family at the bedside to leave.”

He introduced a resident, who told me dermatologists dropped by the ICU from time to time to assess issues of graft-versus-host rashes, that sort of thing.

The nurse gave me a yellow paper gown. The patient had his own room. Back in my day, ICUs had no quiet, private spaces.

A middle-aged woman stood by the bed rail – the stepmother of the deceased. What do you say to a newly bereaved family member in this circumstance? “I am your deceased stepson’s dermatology consultant. Pleased to meet you”?

Instead, I said I was sorry for her loss, which seemed pallid but apt. She withdrew.

In bed, was a young man attached to life support. “No track marks,” the nurse observed. “He must have snorted something.”

The nurse and the resident rolled the body over, and I noted the red marks on his back. “Those are from acne,” I said. “No infection.”

Laying him down, they showed me a 1-mm scab at the base of his scrotum. “Appears to be trauma,” I said, “perhaps a scratch. Not herpes or anything infectious.”

Finding nothing else on his integument, I turned to leave. His stepmother was sitting on a chair near the door, her head in her hands. As I passed, she looked up.

In most life settings, including doctors’ offices, there are protocols of behavior, guidelines for how to act, what to say: “We’re all done.” “This should take care of it.” “I will write up a report.” “Nice to have met you.” “Take care.”

I looked down at her tortured face and said, “There is nothing to say.”

At this, I lost my composure, and left.

“I’m not sure what we were concerned about,” said the nurse, “but we appreciate your coming over.” He handed me a sheet of blank paper. I scribbled my nonfindings. Now the transplant wheels could begin to turn.

I left the ICU to its normal goings-on and returned to my office, where the paths of clinical engagement are well worn – and the patients are still alive.

Dr. Rockoff practices dermatology in Brookline, Mass., and is a longtime contributor to Dermatology News. He serves on the clinical faculty at Tufts University, Boston, and has taught senior medical students and other trainees for 30 years. His second book, “Act Like a Doctor, Think Like a Patient,” is available at amazon.com and barnesandnoble.com. Write to him at [email protected].

‘Breakthrough’ leukemia drug also portends ‘quantum leap’ in cost

When doctors talk about a new leukemia drug from Novartis, they ooze enthusiasm, using words like “breakthrough,” “revolutionary” and “a watershed moment.”

But when they think about how much the therapy is likely to cost, their tone turns alarmist.

“It’s going to cost a fortune,” said Ivan Borrello, MD, at Johns Hopkins Sidney Kimmel Comprehensive Cancer Center in Baltimore.

“From what we’re hearing, this will be a quantum leap more expensive than other cancer drugs,” said Leonard Saltz, MD, chief of gastrointestinal oncology at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York.

Switzerland-based Novartis hasn’t announced a price for the medicine, but British health authorities have said a price of $649,000 for a one-time treatment would be justified given the significant benefits.

The cancer therapy was unanimously approved by a Food and Drug Administration advisory committee in July, and its approval seems all but certain.

The treatment, CTL019, belongs to a new class of medications called CAR T-cell therapies, which involve harvesting patients’ immune cells and genetically altering them to kill cancer. It’s been tested in patients whose leukemia has relapsed in spite of the best chemotherapy or a bone-marrow transplant.

The prognosis for these patients is normally bleak. But in a clinical trial, 83% of those treated with CAR T-cell therapy – described as a “living drug” because it derives from a patient’s own cells – have gone into remission.

CAR T cells have been successful only in a limited number of cancers, however, and are being suggested for use as a last resort when all else has failed. As a result, only a few hundred patients a year would be eligible for them, at least initially, said J. Leonard Lichtenfeld, MD, deputy chief medical officer for the American Cancer Society.

The FDA is scheduled to decide on approval by Oct. 3. The agency also is considering a CAR T-cell therapy from Kite Pharma.

A third company, Juno Therapeutics, halted the development of one its CAR T-cell therapies after five patients died from complications of the treatment.

Rather than wait for Novartis to announce a price, an advocacy group called Patients for Affordable Drugs has launched a preemptive strike, asking to meet with company officials to discuss a “fair” price for the therapy. The Novartis drug has the potential to be one of the most expensive drugs ever sold, said David Mitchell, the patients group’s president, who has been treated for multiple myeloma, a blood cancer, since 2010. (The Laura and John Arnold Foundation, which provides some funding for Kaiser Health News, supports Patients for Affordable Drugs.)

“Many people with cancer look forward with great hope to the potential of your new drug,” Mr. Mitchell wrote in a letter to Novartis. “But drugs don’t work if patients can’t afford them.”

Cancer drugs today routinely cost more than $100,000 a year. A combination therapy for melanoma sells for $250,000. Such prices are particularly outrageous, given that taxpayers fund many drugs’ early research, Mr. Mitchell said.

The federal government spent more than $200 million over 2 decades to support the basic research into CAR T-cell therapy, long before Novartis bought the rights.

The patients group urged Novartis to charge no more for the drug in the U.S. than in other developed countries.

Novartis has agreed to meet with the patients group. In a statement, Novartis said the company is “carefully considering the appropriate price for CTL019, taking into consideration the value that this treatment represents for patients, society and the healthcare system, both near-term and long-term.”

Novartis made a significant investment in CAR T-cell therapy, according to the statement.

“We employ hundreds of people around the world who work on CAR Ts, we are conducting ongoing U.S. and global clinical trials and have developed a sophisticated, FDA-validated manufacturing site and process for this personalized therapy.”

Soaring prices for cancer drugs have led many patients to cut back on treatment or skip pills, a recent Kaiser Health News analysis showed.

The effect of CAR T-cell therapies on overall health costs would initially be relatively small, because it would be used by relatively few people, Dr. Lichtenfeld said.

Health systems and insurers may struggle to pay for the treatment, however, if the FDA approves it for wider use, Dr. Lichtenfeld said. Researchers are studying CAR T cells in a number of cancers. So far, the technology seems more effective in blood cancers, such as leukemias and lymphomas.

Hidden costs could further add to patients’ financial burdens, Dr. Borrello said.

Beyond the cost of the procedure, patients would need to pay for traditional chemotherapy, which is given before CAR T-cell therapy to improve its odds of success. They would also have to foot the bill for travel and lodging to one of the 30-35 hospitals in the country equipped to provide the high-tech treatment, said Prakash Satwani, MD, a pediatric hematologist at New York-Presbyterian/Columbia University Medical Center, which plans to offer the therapy.

Because patients can develop life-threatening side effects weeks after the procedure, doctors will ask patients to stay within 2 hours of the hospital for up to a month. In New York, even budget hotels cost more than $200 a night – an expense not typically covered by insurance. Patients who develop a dangerous complication, in which the immune system overreacts and attacks vital organs, might need coverage for emergency room care, as well as lengthy stays in the ICU, Dr. Satwani said.

Doctors don’t yet know what the full range of long-term side effects will be. CAR T-cell therapies can damage healthy immune cells, including the cells that produce the antibodies that fight disease. Some patients will need long-term treatments with a product called intravenous immunoglobulin, which provides the antibodies that patients need to prevent infection, Dr. Lichtenfeld said.

Dr. Saltz, an oncologist who has long spoken out about high drug prices, said he applauded the patients group’s efforts. But he said he doubts their efforts will persuade Novartis to set a reasonably affordable price.

“I’m not optimistic that this will have much effect on the company,” said Dr. Saltz. “There’s no market pressure for the company to respond to.”

High drug prices don’t just hurt patients, Dr. Saltz said. They also drive up insurance premiums for everyone.

“They affect each and every one of us,” he said, “because these costs will be paid by anyone who has any kind of insurance coverage.”

KHN’s coverage of prescription drug development, costs and pricing is supported in part by the Laura and John Arnold Foundation. Kaiser Health News is a national health policy news service that is part of the nonpartisan Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation.

When doctors talk about a new leukemia drug from Novartis, they ooze enthusiasm, using words like “breakthrough,” “revolutionary” and “a watershed moment.”

But when they think about how much the therapy is likely to cost, their tone turns alarmist.

“It’s going to cost a fortune,” said Ivan Borrello, MD, at Johns Hopkins Sidney Kimmel Comprehensive Cancer Center in Baltimore.

“From what we’re hearing, this will be a quantum leap more expensive than other cancer drugs,” said Leonard Saltz, MD, chief of gastrointestinal oncology at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York.

Switzerland-based Novartis hasn’t announced a price for the medicine, but British health authorities have said a price of $649,000 for a one-time treatment would be justified given the significant benefits.

The cancer therapy was unanimously approved by a Food and Drug Administration advisory committee in July, and its approval seems all but certain.

The treatment, CTL019, belongs to a new class of medications called CAR T-cell therapies, which involve harvesting patients’ immune cells and genetically altering them to kill cancer. It’s been tested in patients whose leukemia has relapsed in spite of the best chemotherapy or a bone-marrow transplant.

The prognosis for these patients is normally bleak. But in a clinical trial, 83% of those treated with CAR T-cell therapy – described as a “living drug” because it derives from a patient’s own cells – have gone into remission.

CAR T cells have been successful only in a limited number of cancers, however, and are being suggested for use as a last resort when all else has failed. As a result, only a few hundred patients a year would be eligible for them, at least initially, said J. Leonard Lichtenfeld, MD, deputy chief medical officer for the American Cancer Society.

The FDA is scheduled to decide on approval by Oct. 3. The agency also is considering a CAR T-cell therapy from Kite Pharma.

A third company, Juno Therapeutics, halted the development of one its CAR T-cell therapies after five patients died from complications of the treatment.

Rather than wait for Novartis to announce a price, an advocacy group called Patients for Affordable Drugs has launched a preemptive strike, asking to meet with company officials to discuss a “fair” price for the therapy. The Novartis drug has the potential to be one of the most expensive drugs ever sold, said David Mitchell, the patients group’s president, who has been treated for multiple myeloma, a blood cancer, since 2010. (The Laura and John Arnold Foundation, which provides some funding for Kaiser Health News, supports Patients for Affordable Drugs.)

“Many people with cancer look forward with great hope to the potential of your new drug,” Mr. Mitchell wrote in a letter to Novartis. “But drugs don’t work if patients can’t afford them.”

Cancer drugs today routinely cost more than $100,000 a year. A combination therapy for melanoma sells for $250,000. Such prices are particularly outrageous, given that taxpayers fund many drugs’ early research, Mr. Mitchell said.

The federal government spent more than $200 million over 2 decades to support the basic research into CAR T-cell therapy, long before Novartis bought the rights.

The patients group urged Novartis to charge no more for the drug in the U.S. than in other developed countries.

Novartis has agreed to meet with the patients group. In a statement, Novartis said the company is “carefully considering the appropriate price for CTL019, taking into consideration the value that this treatment represents for patients, society and the healthcare system, both near-term and long-term.”

Novartis made a significant investment in CAR T-cell therapy, according to the statement.

“We employ hundreds of people around the world who work on CAR Ts, we are conducting ongoing U.S. and global clinical trials and have developed a sophisticated, FDA-validated manufacturing site and process for this personalized therapy.”

Soaring prices for cancer drugs have led many patients to cut back on treatment or skip pills, a recent Kaiser Health News analysis showed.

The effect of CAR T-cell therapies on overall health costs would initially be relatively small, because it would be used by relatively few people, Dr. Lichtenfeld said.

Health systems and insurers may struggle to pay for the treatment, however, if the FDA approves it for wider use, Dr. Lichtenfeld said. Researchers are studying CAR T cells in a number of cancers. So far, the technology seems more effective in blood cancers, such as leukemias and lymphomas.

Hidden costs could further add to patients’ financial burdens, Dr. Borrello said.

Beyond the cost of the procedure, patients would need to pay for traditional chemotherapy, which is given before CAR T-cell therapy to improve its odds of success. They would also have to foot the bill for travel and lodging to one of the 30-35 hospitals in the country equipped to provide the high-tech treatment, said Prakash Satwani, MD, a pediatric hematologist at New York-Presbyterian/Columbia University Medical Center, which plans to offer the therapy.

Because patients can develop life-threatening side effects weeks after the procedure, doctors will ask patients to stay within 2 hours of the hospital for up to a month. In New York, even budget hotels cost more than $200 a night – an expense not typically covered by insurance. Patients who develop a dangerous complication, in which the immune system overreacts and attacks vital organs, might need coverage for emergency room care, as well as lengthy stays in the ICU, Dr. Satwani said.

Doctors don’t yet know what the full range of long-term side effects will be. CAR T-cell therapies can damage healthy immune cells, including the cells that produce the antibodies that fight disease. Some patients will need long-term treatments with a product called intravenous immunoglobulin, which provides the antibodies that patients need to prevent infection, Dr. Lichtenfeld said.

Dr. Saltz, an oncologist who has long spoken out about high drug prices, said he applauded the patients group’s efforts. But he said he doubts their efforts will persuade Novartis to set a reasonably affordable price.

“I’m not optimistic that this will have much effect on the company,” said Dr. Saltz. “There’s no market pressure for the company to respond to.”

High drug prices don’t just hurt patients, Dr. Saltz said. They also drive up insurance premiums for everyone.

“They affect each and every one of us,” he said, “because these costs will be paid by anyone who has any kind of insurance coverage.”

KHN’s coverage of prescription drug development, costs and pricing is supported in part by the Laura and John Arnold Foundation. Kaiser Health News is a national health policy news service that is part of the nonpartisan Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation.

When doctors talk about a new leukemia drug from Novartis, they ooze enthusiasm, using words like “breakthrough,” “revolutionary” and “a watershed moment.”

But when they think about how much the therapy is likely to cost, their tone turns alarmist.

“It’s going to cost a fortune,” said Ivan Borrello, MD, at Johns Hopkins Sidney Kimmel Comprehensive Cancer Center in Baltimore.

“From what we’re hearing, this will be a quantum leap more expensive than other cancer drugs,” said Leonard Saltz, MD, chief of gastrointestinal oncology at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York.

Switzerland-based Novartis hasn’t announced a price for the medicine, but British health authorities have said a price of $649,000 for a one-time treatment would be justified given the significant benefits.

The cancer therapy was unanimously approved by a Food and Drug Administration advisory committee in July, and its approval seems all but certain.

The treatment, CTL019, belongs to a new class of medications called CAR T-cell therapies, which involve harvesting patients’ immune cells and genetically altering them to kill cancer. It’s been tested in patients whose leukemia has relapsed in spite of the best chemotherapy or a bone-marrow transplant.

The prognosis for these patients is normally bleak. But in a clinical trial, 83% of those treated with CAR T-cell therapy – described as a “living drug” because it derives from a patient’s own cells – have gone into remission.

CAR T cells have been successful only in a limited number of cancers, however, and are being suggested for use as a last resort when all else has failed. As a result, only a few hundred patients a year would be eligible for them, at least initially, said J. Leonard Lichtenfeld, MD, deputy chief medical officer for the American Cancer Society.

The FDA is scheduled to decide on approval by Oct. 3. The agency also is considering a CAR T-cell therapy from Kite Pharma.

A third company, Juno Therapeutics, halted the development of one its CAR T-cell therapies after five patients died from complications of the treatment.

Rather than wait for Novartis to announce a price, an advocacy group called Patients for Affordable Drugs has launched a preemptive strike, asking to meet with company officials to discuss a “fair” price for the therapy. The Novartis drug has the potential to be one of the most expensive drugs ever sold, said David Mitchell, the patients group’s president, who has been treated for multiple myeloma, a blood cancer, since 2010. (The Laura and John Arnold Foundation, which provides some funding for Kaiser Health News, supports Patients for Affordable Drugs.)

“Many people with cancer look forward with great hope to the potential of your new drug,” Mr. Mitchell wrote in a letter to Novartis. “But drugs don’t work if patients can’t afford them.”

Cancer drugs today routinely cost more than $100,000 a year. A combination therapy for melanoma sells for $250,000. Such prices are particularly outrageous, given that taxpayers fund many drugs’ early research, Mr. Mitchell said.

The federal government spent more than $200 million over 2 decades to support the basic research into CAR T-cell therapy, long before Novartis bought the rights.

The patients group urged Novartis to charge no more for the drug in the U.S. than in other developed countries.

Novartis has agreed to meet with the patients group. In a statement, Novartis said the company is “carefully considering the appropriate price for CTL019, taking into consideration the value that this treatment represents for patients, society and the healthcare system, both near-term and long-term.”

Novartis made a significant investment in CAR T-cell therapy, according to the statement.

“We employ hundreds of people around the world who work on CAR Ts, we are conducting ongoing U.S. and global clinical trials and have developed a sophisticated, FDA-validated manufacturing site and process for this personalized therapy.”

Soaring prices for cancer drugs have led many patients to cut back on treatment or skip pills, a recent Kaiser Health News analysis showed.

The effect of CAR T-cell therapies on overall health costs would initially be relatively small, because it would be used by relatively few people, Dr. Lichtenfeld said.

Health systems and insurers may struggle to pay for the treatment, however, if the FDA approves it for wider use, Dr. Lichtenfeld said. Researchers are studying CAR T cells in a number of cancers. So far, the technology seems more effective in blood cancers, such as leukemias and lymphomas.

Hidden costs could further add to patients’ financial burdens, Dr. Borrello said.

Beyond the cost of the procedure, patients would need to pay for traditional chemotherapy, which is given before CAR T-cell therapy to improve its odds of success. They would also have to foot the bill for travel and lodging to one of the 30-35 hospitals in the country equipped to provide the high-tech treatment, said Prakash Satwani, MD, a pediatric hematologist at New York-Presbyterian/Columbia University Medical Center, which plans to offer the therapy.

Because patients can develop life-threatening side effects weeks after the procedure, doctors will ask patients to stay within 2 hours of the hospital for up to a month. In New York, even budget hotels cost more than $200 a night – an expense not typically covered by insurance. Patients who develop a dangerous complication, in which the immune system overreacts and attacks vital organs, might need coverage for emergency room care, as well as lengthy stays in the ICU, Dr. Satwani said.

Doctors don’t yet know what the full range of long-term side effects will be. CAR T-cell therapies can damage healthy immune cells, including the cells that produce the antibodies that fight disease. Some patients will need long-term treatments with a product called intravenous immunoglobulin, which provides the antibodies that patients need to prevent infection, Dr. Lichtenfeld said.

Dr. Saltz, an oncologist who has long spoken out about high drug prices, said he applauded the patients group’s efforts. But he said he doubts their efforts will persuade Novartis to set a reasonably affordable price.

“I’m not optimistic that this will have much effect on the company,” said Dr. Saltz. “There’s no market pressure for the company to respond to.”

High drug prices don’t just hurt patients, Dr. Saltz said. They also drive up insurance premiums for everyone.

“They affect each and every one of us,” he said, “because these costs will be paid by anyone who has any kind of insurance coverage.”

KHN’s coverage of prescription drug development, costs and pricing is supported in part by the Laura and John Arnold Foundation. Kaiser Health News is a national health policy news service that is part of the nonpartisan Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation.

States pass tougher abortion restrictions

A number of states are tightening restrictions for women seeking abortions, while one state – Oregon – has enacted a law that could expand access. Here’s a breakdown of the latest state actions and how they could impact women and physicians.

Texas

Under a new Texas law, insurers are banned from covering abortions in most health plans. House Bill 214, signed into law by Texas Gov. Greg Abbott (R) in August, prohibits private, state-offered, and Affordable Care Act insurance plans from including abortion procedures as part of their general coverage. Women must buy additional policies to get the procedure covered. The only exemption is for abortions performed because of a medical emergency.

Another recently enacted Texas law, House Bill 13, requires doctors to report abortion complications to the state within 3 days, and to report personal information about patients such as their age, race, and marital status.

Missouri

Missouri Gov. Eric Greitens (R) has signed into law a measure that will tighten consent procedures for health providers who offer abortions. Senate Bill 5 requires that all discussions related to abortion risks, methods, and other medical factors be conducted only by the doctor who will perform the abortion. Another part of the bill requires that all tissue removed during an abortion be sent to a pathologist for examination within 72 hours. Current law allows facilities to send just a representative sample of the tissue removed.

Arkansas

A federal judge in Arkansas has temporarily blocked four abortion restrictions that were set to go into effect in August. One of the laws – House Bill 1032 – would bar physicians from performing dilation and evacuation procedures, while House Bill 1566 would require that fetal remains are not used for research. House Bill 1434 would ban abortions performed solely for sex selection and mandates that abortions not be performed until “reasonable time and effort” is spent by health providers to obtain the medical records of the pregnant woman. The fourth law, House Bill 2024, requires physicians who perform abortions on girls under age 17 to preserve fetal tissue in accordance with rules from the Office of the State Crime Laboratory.

Oregon

Oregon meanwhile appears to be moving in the opposite direction when it comes to abortion regulation. A new law signed by Oregon Gov. Kate Brown (D) in August requires that insurers cover abortion procedures and contraception without charging women a copayment. The Reproductive Health Equity Act also dedicates state funds to provide reproductive health care to noncitizens living in Oregon who are excluded from Medicaid.

[email protected]

On Twitter @legal_med

A number of states are tightening restrictions for women seeking abortions, while one state – Oregon – has enacted a law that could expand access. Here’s a breakdown of the latest state actions and how they could impact women and physicians.

Texas

Under a new Texas law, insurers are banned from covering abortions in most health plans. House Bill 214, signed into law by Texas Gov. Greg Abbott (R) in August, prohibits private, state-offered, and Affordable Care Act insurance plans from including abortion procedures as part of their general coverage. Women must buy additional policies to get the procedure covered. The only exemption is for abortions performed because of a medical emergency.

Another recently enacted Texas law, House Bill 13, requires doctors to report abortion complications to the state within 3 days, and to report personal information about patients such as their age, race, and marital status.

Missouri

Missouri Gov. Eric Greitens (R) has signed into law a measure that will tighten consent procedures for health providers who offer abortions. Senate Bill 5 requires that all discussions related to abortion risks, methods, and other medical factors be conducted only by the doctor who will perform the abortion. Another part of the bill requires that all tissue removed during an abortion be sent to a pathologist for examination within 72 hours. Current law allows facilities to send just a representative sample of the tissue removed.

Arkansas

A federal judge in Arkansas has temporarily blocked four abortion restrictions that were set to go into effect in August. One of the laws – House Bill 1032 – would bar physicians from performing dilation and evacuation procedures, while House Bill 1566 would require that fetal remains are not used for research. House Bill 1434 would ban abortions performed solely for sex selection and mandates that abortions not be performed until “reasonable time and effort” is spent by health providers to obtain the medical records of the pregnant woman. The fourth law, House Bill 2024, requires physicians who perform abortions on girls under age 17 to preserve fetal tissue in accordance with rules from the Office of the State Crime Laboratory.

Oregon

Oregon meanwhile appears to be moving in the opposite direction when it comes to abortion regulation. A new law signed by Oregon Gov. Kate Brown (D) in August requires that insurers cover abortion procedures and contraception without charging women a copayment. The Reproductive Health Equity Act also dedicates state funds to provide reproductive health care to noncitizens living in Oregon who are excluded from Medicaid.

[email protected]

On Twitter @legal_med

A number of states are tightening restrictions for women seeking abortions, while one state – Oregon – has enacted a law that could expand access. Here’s a breakdown of the latest state actions and how they could impact women and physicians.

Texas

Under a new Texas law, insurers are banned from covering abortions in most health plans. House Bill 214, signed into law by Texas Gov. Greg Abbott (R) in August, prohibits private, state-offered, and Affordable Care Act insurance plans from including abortion procedures as part of their general coverage. Women must buy additional policies to get the procedure covered. The only exemption is for abortions performed because of a medical emergency.

Another recently enacted Texas law, House Bill 13, requires doctors to report abortion complications to the state within 3 days, and to report personal information about patients such as their age, race, and marital status.

Missouri

Missouri Gov. Eric Greitens (R) has signed into law a measure that will tighten consent procedures for health providers who offer abortions. Senate Bill 5 requires that all discussions related to abortion risks, methods, and other medical factors be conducted only by the doctor who will perform the abortion. Another part of the bill requires that all tissue removed during an abortion be sent to a pathologist for examination within 72 hours. Current law allows facilities to send just a representative sample of the tissue removed.

Arkansas

A federal judge in Arkansas has temporarily blocked four abortion restrictions that were set to go into effect in August. One of the laws – House Bill 1032 – would bar physicians from performing dilation and evacuation procedures, while House Bill 1566 would require that fetal remains are not used for research. House Bill 1434 would ban abortions performed solely for sex selection and mandates that abortions not be performed until “reasonable time and effort” is spent by health providers to obtain the medical records of the pregnant woman. The fourth law, House Bill 2024, requires physicians who perform abortions on girls under age 17 to preserve fetal tissue in accordance with rules from the Office of the State Crime Laboratory.

Oregon

Oregon meanwhile appears to be moving in the opposite direction when it comes to abortion regulation. A new law signed by Oregon Gov. Kate Brown (D) in August requires that insurers cover abortion procedures and contraception without charging women a copayment. The Reproductive Health Equity Act also dedicates state funds to provide reproductive health care to noncitizens living in Oregon who are excluded from Medicaid.

[email protected]

On Twitter @legal_med

Axial SpA features don’t guarantee its diagnosis in chronic back pain

The manifestation of multiple features of spondyloarthritis (SpA) in patients with chronic back pain is not sufficient for a diagnosis of axial spondyloarthritis, according to a report from Zineb Ez-Zaitouni and associates.

In a group of 250 people with chronic back pain who were not diagnosed with axial SpA, the most common alternative diagnosis was nonspecific back pain, followed by mechanical back pain, degenerative disc disease, and myalgia/fibromyalgia. Sacroiliitis on either radiographs or MRI and HLA-B27 was uncommon, and HLA-B27 positivity was also infrequent.

A total of 18 patients within the study group had at least four features of SpA but did not have axial SpA. Within this group, the most common SpA features were inflammatory back pain, a positive family history of SpA, a good response to nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, elevated C-reactive protein or erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and enthesitis. No patients had positive imaging, and only four were positive for HLA-B27.

“These findings show that rheumatologists in clinical practice rightly dispute a diagnosis of axSpA even when there is a high number of SpA features, especially when imaging is normal and patients are negative for HLA-B27,” the investigators concluded.

Find the full report in Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases (doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2017-212175)

The manifestation of multiple features of spondyloarthritis (SpA) in patients with chronic back pain is not sufficient for a diagnosis of axial spondyloarthritis, according to a report from Zineb Ez-Zaitouni and associates.

In a group of 250 people with chronic back pain who were not diagnosed with axial SpA, the most common alternative diagnosis was nonspecific back pain, followed by mechanical back pain, degenerative disc disease, and myalgia/fibromyalgia. Sacroiliitis on either radiographs or MRI and HLA-B27 was uncommon, and HLA-B27 positivity was also infrequent.

A total of 18 patients within the study group had at least four features of SpA but did not have axial SpA. Within this group, the most common SpA features were inflammatory back pain, a positive family history of SpA, a good response to nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, elevated C-reactive protein or erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and enthesitis. No patients had positive imaging, and only four were positive for HLA-B27.

“These findings show that rheumatologists in clinical practice rightly dispute a diagnosis of axSpA even when there is a high number of SpA features, especially when imaging is normal and patients are negative for HLA-B27,” the investigators concluded.

Find the full report in Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases (doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2017-212175)

The manifestation of multiple features of spondyloarthritis (SpA) in patients with chronic back pain is not sufficient for a diagnosis of axial spondyloarthritis, according to a report from Zineb Ez-Zaitouni and associates.

In a group of 250 people with chronic back pain who were not diagnosed with axial SpA, the most common alternative diagnosis was nonspecific back pain, followed by mechanical back pain, degenerative disc disease, and myalgia/fibromyalgia. Sacroiliitis on either radiographs or MRI and HLA-B27 was uncommon, and HLA-B27 positivity was also infrequent.

A total of 18 patients within the study group had at least four features of SpA but did not have axial SpA. Within this group, the most common SpA features were inflammatory back pain, a positive family history of SpA, a good response to nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, elevated C-reactive protein or erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and enthesitis. No patients had positive imaging, and only four were positive for HLA-B27.

“These findings show that rheumatologists in clinical practice rightly dispute a diagnosis of axSpA even when there is a high number of SpA features, especially when imaging is normal and patients are negative for HLA-B27,” the investigators concluded.

Find the full report in Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases (doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2017-212175)

FROM ANNALS OF THE RHEUMATIC DISEASES

The microbiota matters: In acne, it’s not us versus them

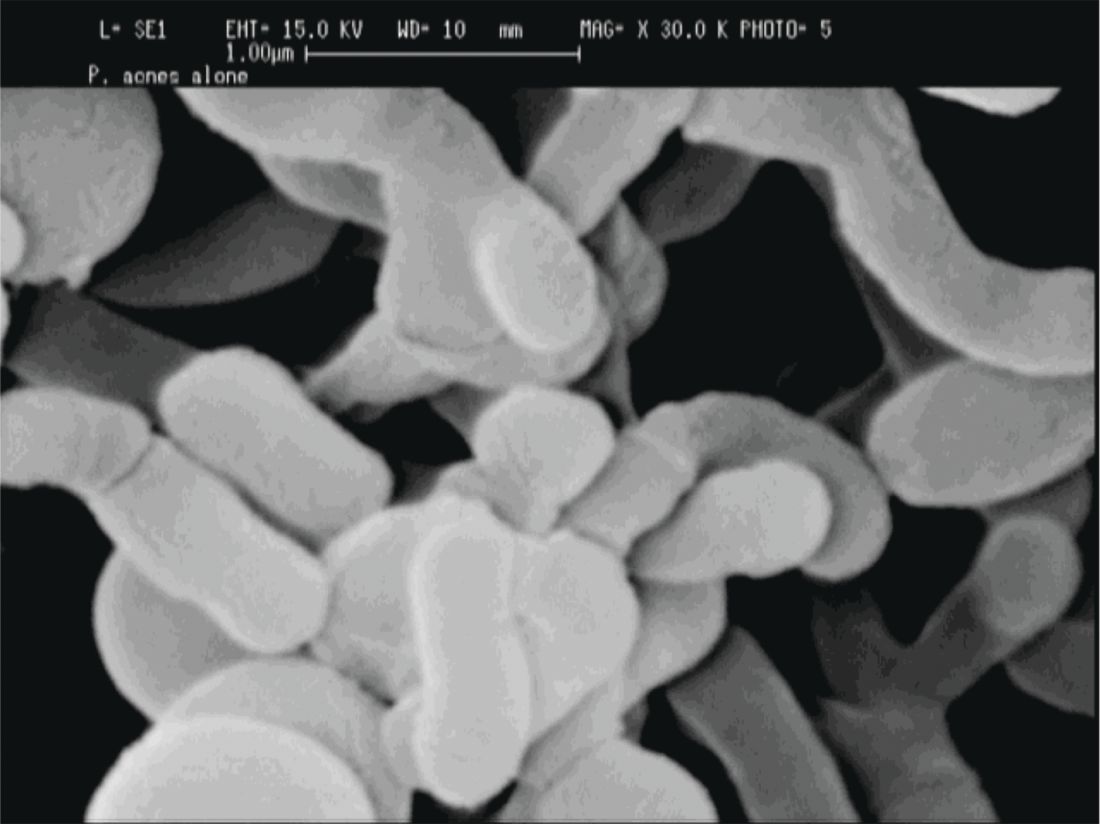

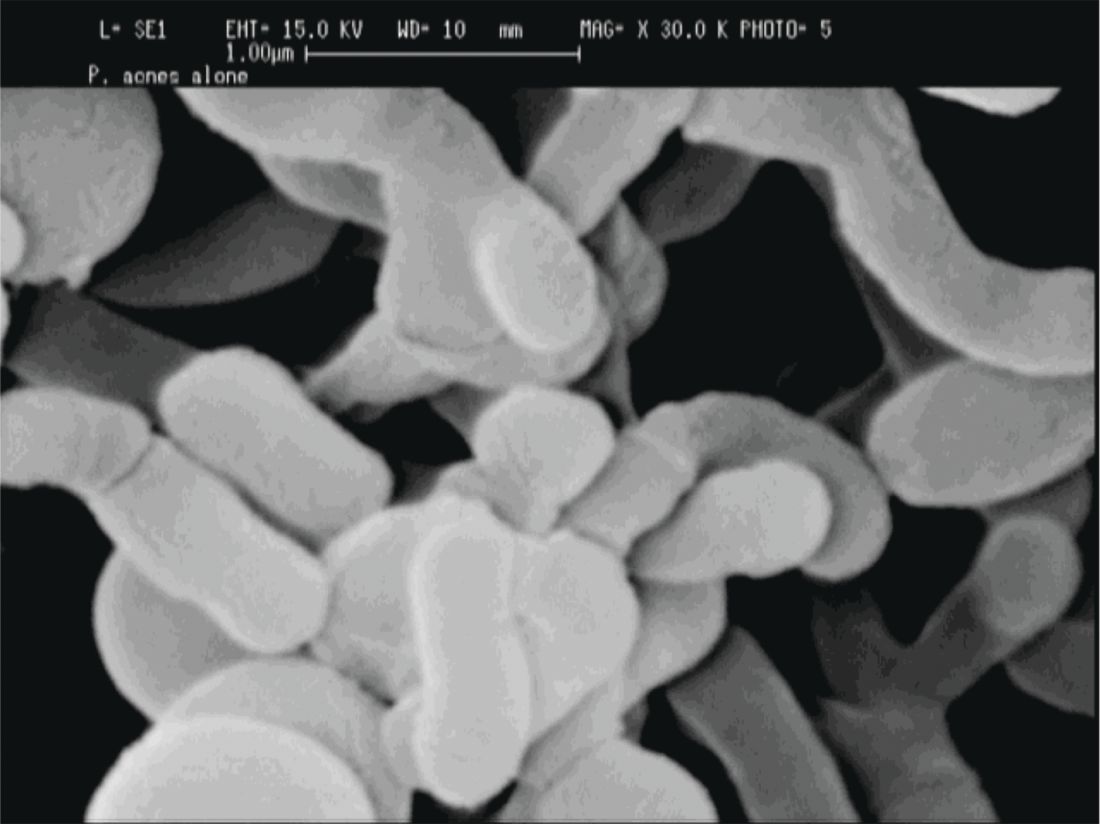

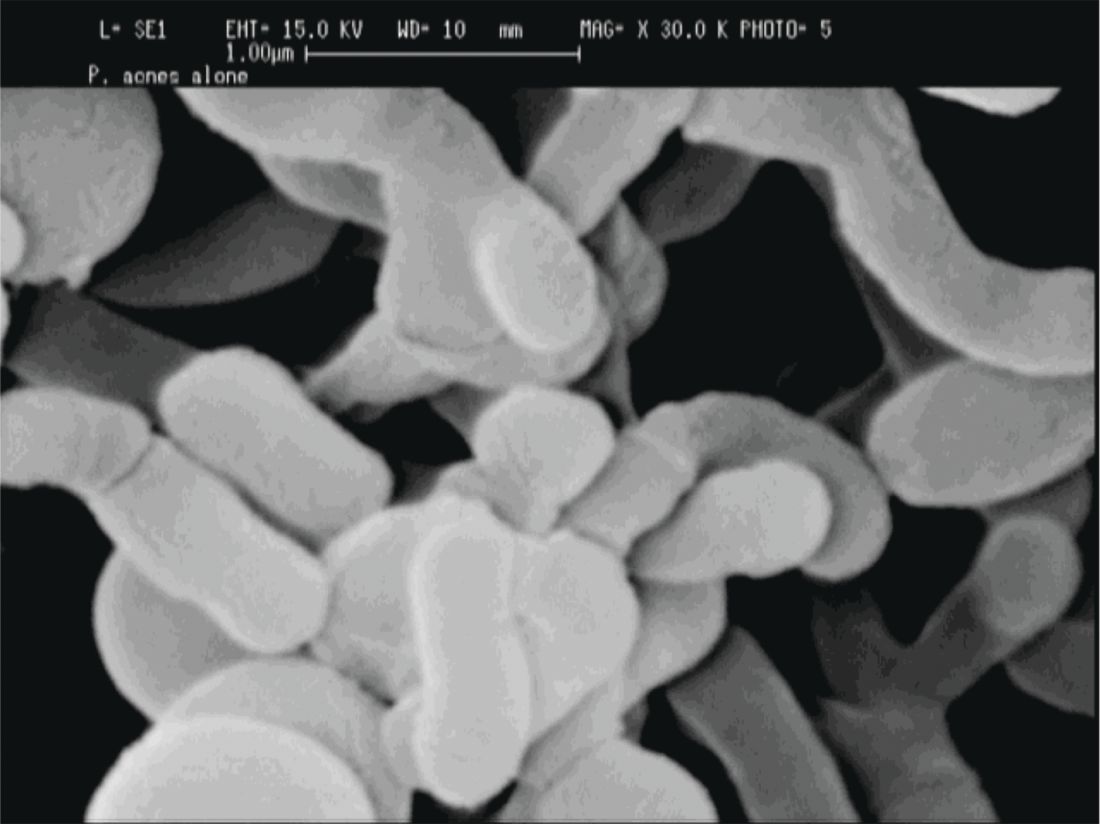

NEW YORK – Just as an imbalance in the intestinal microbiota can disrupt gut function, dysbiosis of the facial skin can allow acne-causing bacteria to flourish.

In acne, said Adam Friedman, MD, “we’ve always been talking about bacteria,” but now the thinking has shifted from just controlling Propionibacterium acnes to a subtler understanding of what’s happening on the skin of individuals with acne. Individuals may have their own unique skin microbiota – the community of organisms resident on the skin – but dysbiosis characterized by a lack of diversity is increasingly understood as a common theme in many skin disorders, and acne is no exception.

As in many other areas of medicine, dermatology’s understanding has been informed by genetic work that moves beyond the human genome. “Using newer technology, we were able to identify that our genome really was overshadowed by the microbial genome that makes up the populations in our skin, in our gut, and what have you,” said Dr. Friedman, speaking at the summer meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology.

The human body is like a planet to the bacteria that live on the human skin, and like a planet, the skin provides multiple “climates” for many bacterial ecosystems, said Dr. Friedman, director of translational research and dermatology residency program director, at George Washington University, Washington, DC.

Some areas are dry, some are moist; some are more oily, and some areas of the skin produce little sebum; while some are mostly dark and some are more likely to be exposed to light.

Considering skin from this perspective, it makes sense that bacterial microbiota for these disparate areas varies widely, with a different mix of bacteria found in the groin than on the forearm, he noted. Further, “each individual has his or her own microbiota fingerprint,” said Dr. Friedman, citing a 2012 study showing that in four healthy volunteers, the microbiota from swabs at four sites (antecubital fossa, back, nare, and plantar heel) varied widely both in diversity and composition (Genome Res. 2012 May;22[5]:850-9).

Multiple factors can contribute to this variability, which can include endogenous factors, such as host genotype, sex, age, immune system, and pathobiology. Exogenous factors, such as climate, geographic location, and occupational exposures, also play a part.

Increasingly, said Dr. Friedman, lack of bacterial diversity in skin microbiota is recognized as an important factor in many disease states, including atopic dermatitis and psoriasis. And bacterial diversity has recently been shown to be reduced on the facial skin of patients with acne, even on areas of clear skin.

When acne treatments work, a healthy facial microbiota is restored. And perhaps counterintuitively, patients with acne who receive isotretinoin and antibiotics have much greater diversity in the microbiota of their facial skin after treatment than before, according to a study recently published online (Exp Dermatol. 2017 Jun 21. doi: 10.1111/exd.13397).

For now, this is still a chicken-and-egg situation, Dr. Friedman said. “Does the disease cause the lack of diversity, or does the lack of diversity cause the disease to develop? We don’t know yet.” (Nat Rev Microbiol. 2011 Apr;9[4]:244-53).

“If we’re going to think about the surface of our skin as a barrier, we must consider the microbiota as part of that barrier.”

P. acnes “is a clear instigator in eliciting a host inflammatory response,” through its recognition by toll-like receptors and the inflammasome to induce inflammation, Dr. Friedman said. However, it can also help prevent the colonization of opportunistic pathogens, including methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus pyogenes by helping maintain an acidic skin pH. “When and how does a commensal [organism] become a pathogen?” he asked.

The fact that P. acnes is a commensal bacterium on healthy skin seems to muddy the picture, until one also recognizes that there are different strains of P. acnes. Only some of these phylotypes cause acne, with an exaggerated host inflammatory response being one possible causative factor, noted Dr. Friedman.

A clue to how this occurs comes from a recent study that found that some types of P. acnes actually convert sebum to short-chain fatty acids that “interfere with how our bodies regulate toll-like receptors, uncoupling them and then laying them loose to create inflammation,” said Dr. Friedman (Sci Immunol. 2016 Oct 28;1[4]. pii: eaah4609).

When considering what to do with the available information, something for dermatologists to consider is the effect moisturizers have on the skin of patients with acne, Dr. Friedman said. A moisturizer contains water; it may also contain a carbon source in the form of a sugar like mannose, nitrogen in the form of amino acids, and some oligoelements such as calcium, magnesium, manganese, strontium, and selenium. All of these ingredients really serve as prebiotics for the skin microbiota, Dr. Friedman noted, adding that products that create a prebiotic environment where acnegenic P. acnes are suppressed and a healthy microbiota can flourish are being developed.

“What does all this mean? We do not know yet,” said Dr. Friedman. But, he added, “clearly, what we’re using is having an effect, and we need to figure it out.”

Dr. Friedman reported financial relationships with several pharmaceutical and skin care companies. He serves on the editorial board of Dermatology News.

[email protected]

On Twitter @karioakes

NEW YORK – Just as an imbalance in the intestinal microbiota can disrupt gut function, dysbiosis of the facial skin can allow acne-causing bacteria to flourish.

In acne, said Adam Friedman, MD, “we’ve always been talking about bacteria,” but now the thinking has shifted from just controlling Propionibacterium acnes to a subtler understanding of what’s happening on the skin of individuals with acne. Individuals may have their own unique skin microbiota – the community of organisms resident on the skin – but dysbiosis characterized by a lack of diversity is increasingly understood as a common theme in many skin disorders, and acne is no exception.

As in many other areas of medicine, dermatology’s understanding has been informed by genetic work that moves beyond the human genome. “Using newer technology, we were able to identify that our genome really was overshadowed by the microbial genome that makes up the populations in our skin, in our gut, and what have you,” said Dr. Friedman, speaking at the summer meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology.

The human body is like a planet to the bacteria that live on the human skin, and like a planet, the skin provides multiple “climates” for many bacterial ecosystems, said Dr. Friedman, director of translational research and dermatology residency program director, at George Washington University, Washington, DC.

Some areas are dry, some are moist; some are more oily, and some areas of the skin produce little sebum; while some are mostly dark and some are more likely to be exposed to light.

Considering skin from this perspective, it makes sense that bacterial microbiota for these disparate areas varies widely, with a different mix of bacteria found in the groin than on the forearm, he noted. Further, “each individual has his or her own microbiota fingerprint,” said Dr. Friedman, citing a 2012 study showing that in four healthy volunteers, the microbiota from swabs at four sites (antecubital fossa, back, nare, and plantar heel) varied widely both in diversity and composition (Genome Res. 2012 May;22[5]:850-9).

Multiple factors can contribute to this variability, which can include endogenous factors, such as host genotype, sex, age, immune system, and pathobiology. Exogenous factors, such as climate, geographic location, and occupational exposures, also play a part.

Increasingly, said Dr. Friedman, lack of bacterial diversity in skin microbiota is recognized as an important factor in many disease states, including atopic dermatitis and psoriasis. And bacterial diversity has recently been shown to be reduced on the facial skin of patients with acne, even on areas of clear skin.

When acne treatments work, a healthy facial microbiota is restored. And perhaps counterintuitively, patients with acne who receive isotretinoin and antibiotics have much greater diversity in the microbiota of their facial skin after treatment than before, according to a study recently published online (Exp Dermatol. 2017 Jun 21. doi: 10.1111/exd.13397).

For now, this is still a chicken-and-egg situation, Dr. Friedman said. “Does the disease cause the lack of diversity, or does the lack of diversity cause the disease to develop? We don’t know yet.” (Nat Rev Microbiol. 2011 Apr;9[4]:244-53).

“If we’re going to think about the surface of our skin as a barrier, we must consider the microbiota as part of that barrier.”

P. acnes “is a clear instigator in eliciting a host inflammatory response,” through its recognition by toll-like receptors and the inflammasome to induce inflammation, Dr. Friedman said. However, it can also help prevent the colonization of opportunistic pathogens, including methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus pyogenes by helping maintain an acidic skin pH. “When and how does a commensal [organism] become a pathogen?” he asked.

The fact that P. acnes is a commensal bacterium on healthy skin seems to muddy the picture, until one also recognizes that there are different strains of P. acnes. Only some of these phylotypes cause acne, with an exaggerated host inflammatory response being one possible causative factor, noted Dr. Friedman.

A clue to how this occurs comes from a recent study that found that some types of P. acnes actually convert sebum to short-chain fatty acids that “interfere with how our bodies regulate toll-like receptors, uncoupling them and then laying them loose to create inflammation,” said Dr. Friedman (Sci Immunol. 2016 Oct 28;1[4]. pii: eaah4609).

When considering what to do with the available information, something for dermatologists to consider is the effect moisturizers have on the skin of patients with acne, Dr. Friedman said. A moisturizer contains water; it may also contain a carbon source in the form of a sugar like mannose, nitrogen in the form of amino acids, and some oligoelements such as calcium, magnesium, manganese, strontium, and selenium. All of these ingredients really serve as prebiotics for the skin microbiota, Dr. Friedman noted, adding that products that create a prebiotic environment where acnegenic P. acnes are suppressed and a healthy microbiota can flourish are being developed.

“What does all this mean? We do not know yet,” said Dr. Friedman. But, he added, “clearly, what we’re using is having an effect, and we need to figure it out.”

Dr. Friedman reported financial relationships with several pharmaceutical and skin care companies. He serves on the editorial board of Dermatology News.

[email protected]

On Twitter @karioakes

NEW YORK – Just as an imbalance in the intestinal microbiota can disrupt gut function, dysbiosis of the facial skin can allow acne-causing bacteria to flourish.

In acne, said Adam Friedman, MD, “we’ve always been talking about bacteria,” but now the thinking has shifted from just controlling Propionibacterium acnes to a subtler understanding of what’s happening on the skin of individuals with acne. Individuals may have their own unique skin microbiota – the community of organisms resident on the skin – but dysbiosis characterized by a lack of diversity is increasingly understood as a common theme in many skin disorders, and acne is no exception.

As in many other areas of medicine, dermatology’s understanding has been informed by genetic work that moves beyond the human genome. “Using newer technology, we were able to identify that our genome really was overshadowed by the microbial genome that makes up the populations in our skin, in our gut, and what have you,” said Dr. Friedman, speaking at the summer meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology.

The human body is like a planet to the bacteria that live on the human skin, and like a planet, the skin provides multiple “climates” for many bacterial ecosystems, said Dr. Friedman, director of translational research and dermatology residency program director, at George Washington University, Washington, DC.

Some areas are dry, some are moist; some are more oily, and some areas of the skin produce little sebum; while some are mostly dark and some are more likely to be exposed to light.

Considering skin from this perspective, it makes sense that bacterial microbiota for these disparate areas varies widely, with a different mix of bacteria found in the groin than on the forearm, he noted. Further, “each individual has his or her own microbiota fingerprint,” said Dr. Friedman, citing a 2012 study showing that in four healthy volunteers, the microbiota from swabs at four sites (antecubital fossa, back, nare, and plantar heel) varied widely both in diversity and composition (Genome Res. 2012 May;22[5]:850-9).

Multiple factors can contribute to this variability, which can include endogenous factors, such as host genotype, sex, age, immune system, and pathobiology. Exogenous factors, such as climate, geographic location, and occupational exposures, also play a part.

Increasingly, said Dr. Friedman, lack of bacterial diversity in skin microbiota is recognized as an important factor in many disease states, including atopic dermatitis and psoriasis. And bacterial diversity has recently been shown to be reduced on the facial skin of patients with acne, even on areas of clear skin.

When acne treatments work, a healthy facial microbiota is restored. And perhaps counterintuitively, patients with acne who receive isotretinoin and antibiotics have much greater diversity in the microbiota of their facial skin after treatment than before, according to a study recently published online (Exp Dermatol. 2017 Jun 21. doi: 10.1111/exd.13397).

For now, this is still a chicken-and-egg situation, Dr. Friedman said. “Does the disease cause the lack of diversity, or does the lack of diversity cause the disease to develop? We don’t know yet.” (Nat Rev Microbiol. 2011 Apr;9[4]:244-53).

“If we’re going to think about the surface of our skin as a barrier, we must consider the microbiota as part of that barrier.”

P. acnes “is a clear instigator in eliciting a host inflammatory response,” through its recognition by toll-like receptors and the inflammasome to induce inflammation, Dr. Friedman said. However, it can also help prevent the colonization of opportunistic pathogens, including methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus pyogenes by helping maintain an acidic skin pH. “When and how does a commensal [organism] become a pathogen?” he asked.

The fact that P. acnes is a commensal bacterium on healthy skin seems to muddy the picture, until one also recognizes that there are different strains of P. acnes. Only some of these phylotypes cause acne, with an exaggerated host inflammatory response being one possible causative factor, noted Dr. Friedman.

A clue to how this occurs comes from a recent study that found that some types of P. acnes actually convert sebum to short-chain fatty acids that “interfere with how our bodies regulate toll-like receptors, uncoupling them and then laying them loose to create inflammation,” said Dr. Friedman (Sci Immunol. 2016 Oct 28;1[4]. pii: eaah4609).

When considering what to do with the available information, something for dermatologists to consider is the effect moisturizers have on the skin of patients with acne, Dr. Friedman said. A moisturizer contains water; it may also contain a carbon source in the form of a sugar like mannose, nitrogen in the form of amino acids, and some oligoelements such as calcium, magnesium, manganese, strontium, and selenium. All of these ingredients really serve as prebiotics for the skin microbiota, Dr. Friedman noted, adding that products that create a prebiotic environment where acnegenic P. acnes are suppressed and a healthy microbiota can flourish are being developed.

“What does all this mean? We do not know yet,” said Dr. Friedman. But, he added, “clearly, what we’re using is having an effect, and we need to figure it out.”

Dr. Friedman reported financial relationships with several pharmaceutical and skin care companies. He serves on the editorial board of Dermatology News.

[email protected]

On Twitter @karioakes

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM THE 2017 AAD SUMMER MEETING

Fewer complications, lower mortality with minimally invasive hernia repair

Minimally invasive surgical techniques are now used in nearly 80% of operations for paraesophageal hernia repair (PEH) and are associated with many outcome improvements, in comparison with open surgery, according to a retrospective study of data from nearly 100,000 cases.

“Many studies have shown improved perioperative outcomes in paraesophageal hernia repair with MIS [minimally invasive surgery] approaches, but the optimal approach is still debated,” wrote Patrick J. McLaren, MD, and his colleagues from the division of gastrointestinal and general surgery at Oregon Health & Science University, Portland. “In addition, the extent to which MIS has been adopted on the national level for PEH repair is unknown.” Their research letter was published online Aug. 23 in JAMA Surgery.

They found that the proportion of repair conducted using minimally invasive techniques increased from 9.8% in 2002 to 79.6% in 2012. At the same time, in-hospital mortality associated with paraesophageal hernia repair declined from 3.5% to 1.2%, and the rates of complications dropped from 29.8% to 20.6%.

Compared with open-repair procedures, minimally invasive surgery was associated with significantly lower in-hospital mortality (0.6% vs. 3%; P less than .001); wound complications (0.4% vs. 2.9%; P less than .001); septic complications (0.9% vs. 3.9%; P less than .001); and bleeding complications (0.6% vs. 1.8%; P less than .001), as well as urinary, respiratory, and cardiac complications, and intraoperative injury. No significant differences were seen between the two groups in the incidence of thromboembolic complications.

The mean length of hospital stay was 4.2 days in patients who underwent surgery using minimally invasive techniques, compared with 8.5 days in those who had open surgery.

The authors noted that early research on MIS for PEH raised the question of a possible higher risk of recurrence. While the study did not examine the incidence of hernia recurrence, the authors cited data showing that improvements in minimally invasive surgical techniques have been linked to a reduction in hiatal hernia recurrences.

“Studies have found that recurrences requiring reoperation after MIS repairs are low at 2.2%-6%,” the authors wrote. “Regardless, a role remains for open PEH repairs in cases of multiple prior abdominal operations and acute strangulation and in patients with an unstable condition.”

The study was funded by the Oregon Clinical and Translational Research Institute and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health. No conflicts of interest were declared.

This article was updated August 23, 2017.

Minimally invasive surgical techniques are now used in nearly 80% of operations for paraesophageal hernia repair (PEH) and are associated with many outcome improvements, in comparison with open surgery, according to a retrospective study of data from nearly 100,000 cases.

“Many studies have shown improved perioperative outcomes in paraesophageal hernia repair with MIS [minimally invasive surgery] approaches, but the optimal approach is still debated,” wrote Patrick J. McLaren, MD, and his colleagues from the division of gastrointestinal and general surgery at Oregon Health & Science University, Portland. “In addition, the extent to which MIS has been adopted on the national level for PEH repair is unknown.” Their research letter was published online Aug. 23 in JAMA Surgery.

They found that the proportion of repair conducted using minimally invasive techniques increased from 9.8% in 2002 to 79.6% in 2012. At the same time, in-hospital mortality associated with paraesophageal hernia repair declined from 3.5% to 1.2%, and the rates of complications dropped from 29.8% to 20.6%.

Compared with open-repair procedures, minimally invasive surgery was associated with significantly lower in-hospital mortality (0.6% vs. 3%; P less than .001); wound complications (0.4% vs. 2.9%; P less than .001); septic complications (0.9% vs. 3.9%; P less than .001); and bleeding complications (0.6% vs. 1.8%; P less than .001), as well as urinary, respiratory, and cardiac complications, and intraoperative injury. No significant differences were seen between the two groups in the incidence of thromboembolic complications.

The mean length of hospital stay was 4.2 days in patients who underwent surgery using minimally invasive techniques, compared with 8.5 days in those who had open surgery.

The authors noted that early research on MIS for PEH raised the question of a possible higher risk of recurrence. While the study did not examine the incidence of hernia recurrence, the authors cited data showing that improvements in minimally invasive surgical techniques have been linked to a reduction in hiatal hernia recurrences.

“Studies have found that recurrences requiring reoperation after MIS repairs are low at 2.2%-6%,” the authors wrote. “Regardless, a role remains for open PEH repairs in cases of multiple prior abdominal operations and acute strangulation and in patients with an unstable condition.”

The study was funded by the Oregon Clinical and Translational Research Institute and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health. No conflicts of interest were declared.

This article was updated August 23, 2017.

Minimally invasive surgical techniques are now used in nearly 80% of operations for paraesophageal hernia repair (PEH) and are associated with many outcome improvements, in comparison with open surgery, according to a retrospective study of data from nearly 100,000 cases.

“Many studies have shown improved perioperative outcomes in paraesophageal hernia repair with MIS [minimally invasive surgery] approaches, but the optimal approach is still debated,” wrote Patrick J. McLaren, MD, and his colleagues from the division of gastrointestinal and general surgery at Oregon Health & Science University, Portland. “In addition, the extent to which MIS has been adopted on the national level for PEH repair is unknown.” Their research letter was published online Aug. 23 in JAMA Surgery.

They found that the proportion of repair conducted using minimally invasive techniques increased from 9.8% in 2002 to 79.6% in 2012. At the same time, in-hospital mortality associated with paraesophageal hernia repair declined from 3.5% to 1.2%, and the rates of complications dropped from 29.8% to 20.6%.

Compared with open-repair procedures, minimally invasive surgery was associated with significantly lower in-hospital mortality (0.6% vs. 3%; P less than .001); wound complications (0.4% vs. 2.9%; P less than .001); septic complications (0.9% vs. 3.9%; P less than .001); and bleeding complications (0.6% vs. 1.8%; P less than .001), as well as urinary, respiratory, and cardiac complications, and intraoperative injury. No significant differences were seen between the two groups in the incidence of thromboembolic complications.

The mean length of hospital stay was 4.2 days in patients who underwent surgery using minimally invasive techniques, compared with 8.5 days in those who had open surgery.

The authors noted that early research on MIS for PEH raised the question of a possible higher risk of recurrence. While the study did not examine the incidence of hernia recurrence, the authors cited data showing that improvements in minimally invasive surgical techniques have been linked to a reduction in hiatal hernia recurrences.

“Studies have found that recurrences requiring reoperation after MIS repairs are low at 2.2%-6%,” the authors wrote. “Regardless, a role remains for open PEH repairs in cases of multiple prior abdominal operations and acute strangulation and in patients with an unstable condition.”

The study was funded by the Oregon Clinical and Translational Research Institute and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health. No conflicts of interest were declared.

This article was updated August 23, 2017.

FROM JAMA SURGERY

Key clinical point: Minimally invasive surgery for paraesophageal hernia repair is associated with significantly lower in-hospital mortality and complication rates than open repair.

Major finding: Compared with open-repair procedures, minimally invasive paraesophageal hernia repair was associated with significantly lower in-hospital mortality, wound, septic, bleeding, urinary, respiratory, and cardiac complications, and intraoperative injury.

Data source: A retrospective review of 97,393 inpatient admissions for paraesophageal hernia repair between 2002 and 2012.

Disclosures: The study was funded by the Oregon Clinical and Translational Research Institute and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health. No conflicts of interest were declared.

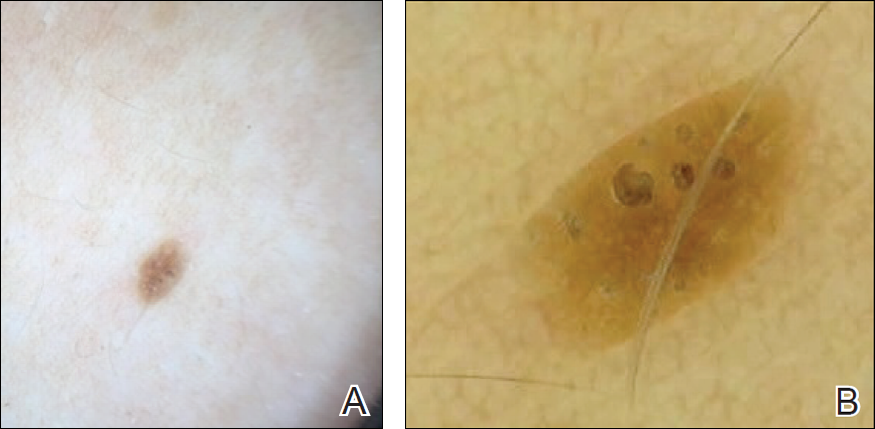

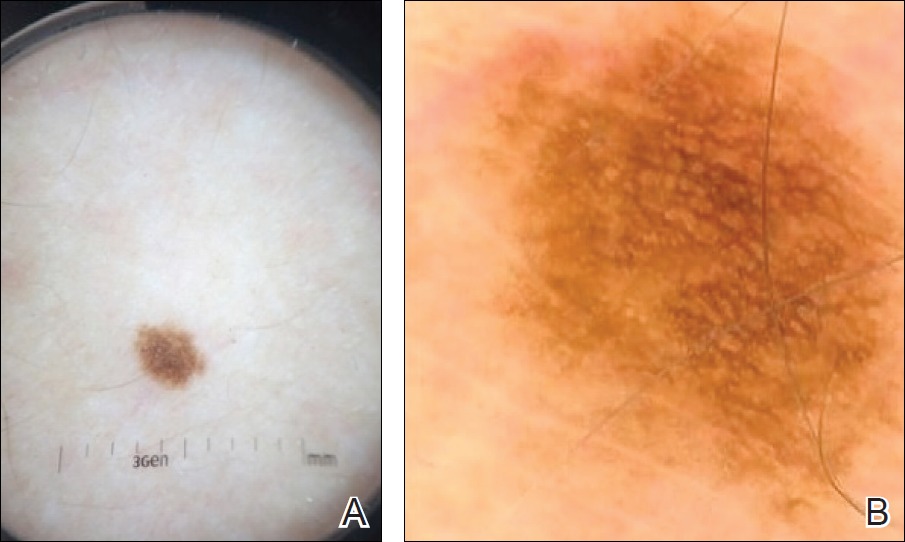

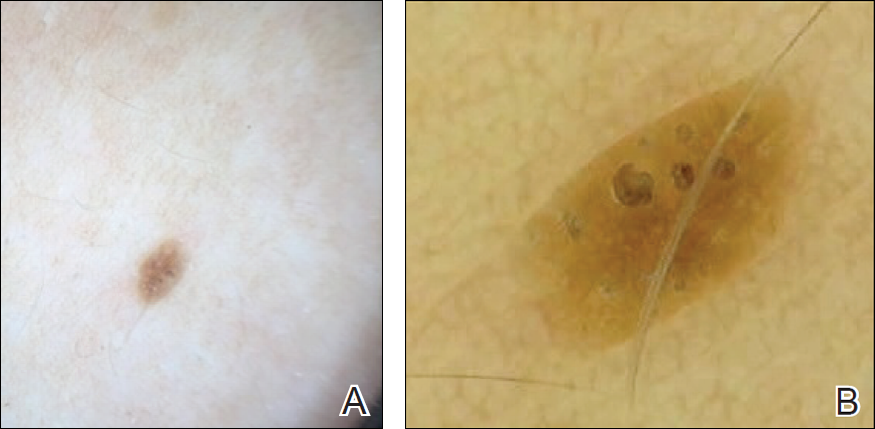

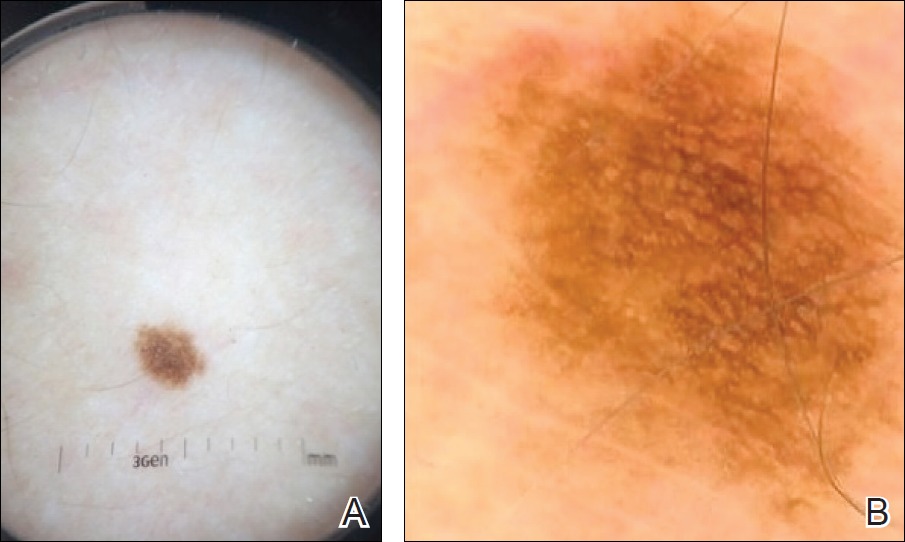

Videodermoscopy as a Novel Tool for Dermatologic Education

Dermoscopy, or the noninvasive in vivo examination of the epidermis and superficial dermis using magnification, facilitates the diagnosis of pigmented and nonpigmented skin lesions.1 Despite the benefit of dermoscopy in making early and accurate diagnoses of potentially life-limiting skin cancers, only 48% of dermatologists in the United States use dermoscopy in their practices.2 The most commonly cited reason for not using dermoscopy is lack of training.

Although the use of dermoscopy is associated with younger age and more recent graduation from residency compared to nonusers, dermatology resident physicians continue to receive limited training in dermoscopy.2 In a survey of 139 dermatology chief residents, 48% were not satisfied with the dermoscopy training that they had received during residency. Residents who received bedside instruction in dermoscopy reported greater satisfaction with their dermoscopy training compared to those who did not receive bedside instruction.3 This article provides a brief comparison of standard dermoscopy versus videodermoscopy for the instruction of trainees on common dermatologic diagnoses.

Bedside Dermoscopy

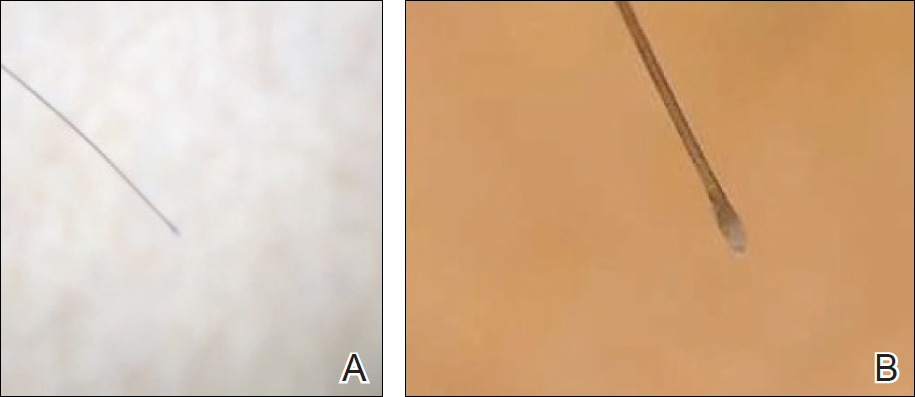

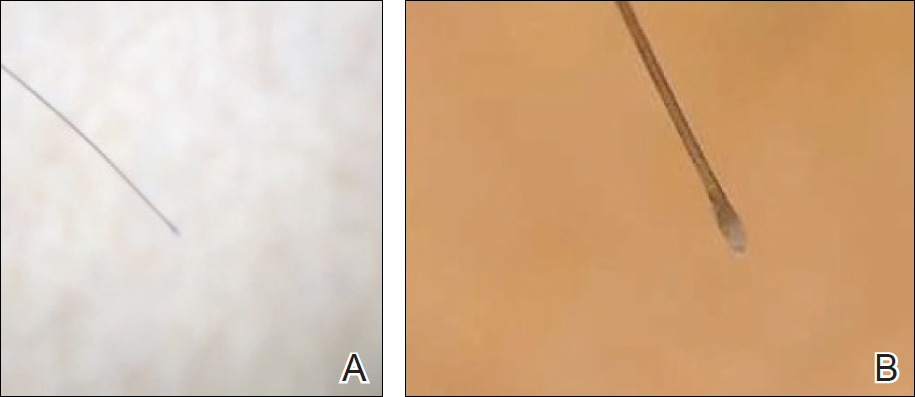

Standard optical dermatoscopes used for patient care and educational purposes typically incorporate 10-fold magnification and permit examination by a single viewer through a lens. With standard dermatoscopes, bedside dermoscopy instruction consists of the independent sequential viewing of skin lesions by instructors and trainees. Trainees must independently search for dermoscopic features noted by the instructor, which may be difficult for novice users. Simultaneous viewing of lesions would allow instructors to clearly indicate in real time pertinent dermoscopic features to their trainees.

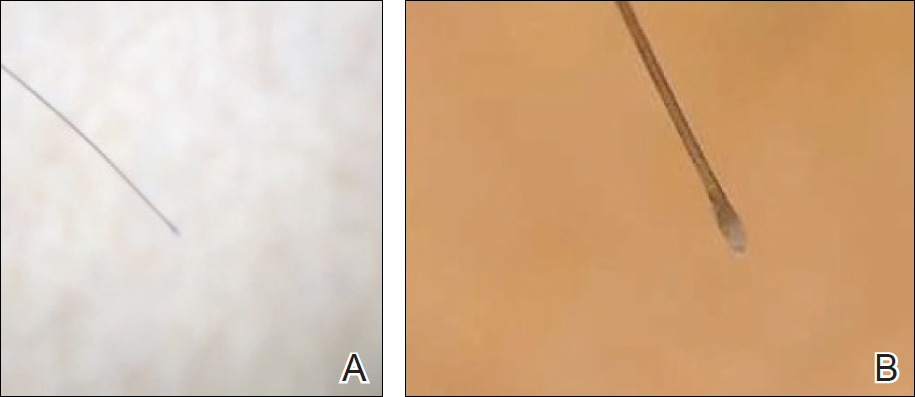

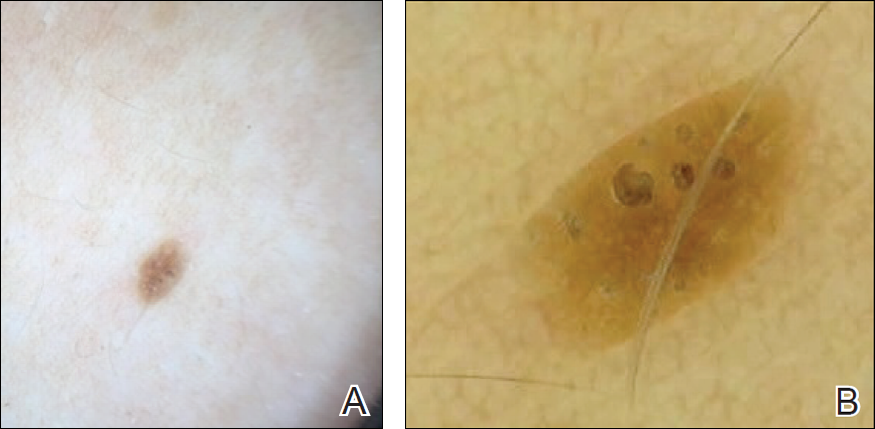

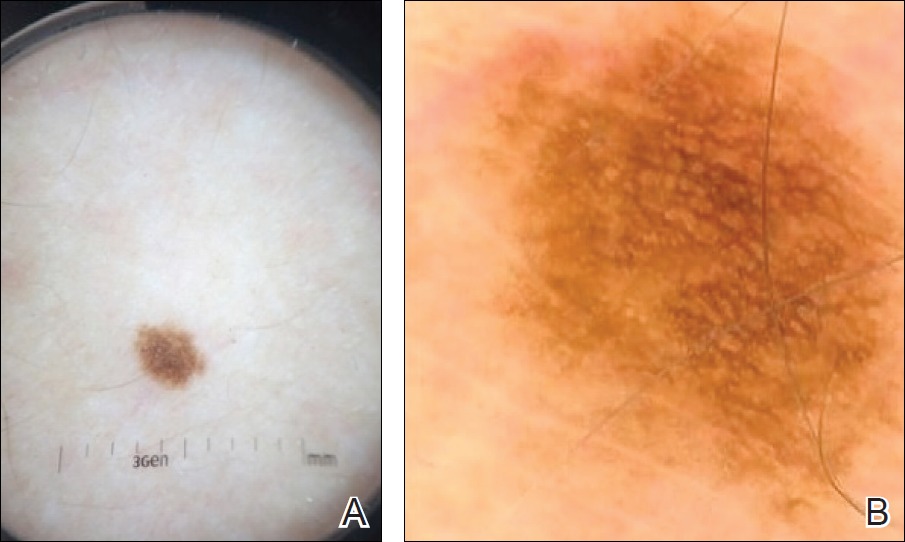

Videodermatoscopes facilitate the simultaneous examination of cutaneous lesions by projecting the dermoscopic image onto a digital screen. Furthermore, these devices can incorporate magnifications of up to 200-fold or greater. In recent years, research pertaining to videodermoscopy has focused on the high magnification capabilities of these devices, specifically dermoscopic features that are visualized at magnifications greater than 10-fold, including the light brown nests of basal cell carcinomas that are seen at 50- to 70-fold magnification, twisted red capillary loops seen in active scalp psoriasis at 50-fold magnification, and longitudinal white indentations seen on nail plates affected by onychomycosis at 20-fold magnification.4-6 The potential value of videodermoscopy in medical education lies not only in the high magnification potential, which may make subtle dermoscopic findings more apparent to novice dermoscopists, but also in the ability to facilitate simultaneous dermoscopic examinations by instructors and trainees.

Educational Applications for Videodermoscopy

To illustrate the educational potential of videodermoscopy, images taken with a standard dermatoscope at 10-fold magnification are presented with videodermoscopic images taken at magnifications ranging from 60- to 185-fold (Figures 1–3). These examples demonstrate the potential for videodermoscopy to facilitate the visualization of subtle dermoscopic features by novice dermoscopists, relating to both the enhanced magnification potential and the potential for simultaneous rather than sequential examination.

Final Thoughts

High-magnification videodermoscopy may be a useful tool to further dermoscopic education. Videodermatoscopes vary in functionality and cost but are available at price points comparable to those of standard optical dermatoscopes. Owners of standard dermatoscopes can approximate some of the benefits of a digital videodermatoscope by using the standard dermatoscope in conjunction with a camera, including those integrated into mobile phones and tablets. By attaching the standard dermatoscope to a camera with a digital display, the digital zoom of the camera can be used to magnify the standard dermoscopic image, enhancing the ability of novice dermoscopists to visualize subtle findings. By presenting this magnified image on a digital display, dermoscopy instructors and trainees would be able to simultaneously view dermoscopic images of lesions, sometimes with magnifications comparable to videodermatoscopes.

In the setting of a dermatology residency program, videodermoscopy can be incorporated into bedside teaching with experienced dermoscopists and for the live presentation of dermoscopic features at departmental grand rounds. By facilitating the simultaneous, high-magnification and live viewing of skin lesions by dermoscopy instructors and trainees, digital videodermoscopy has the potential to address an area of weakness in dermatologic training.

- Vestergaard ME, Macaskill P, Holt PE, et al. Dermoscopy compared with naked eye examination for the diagnosis of primary melanoma: a meta-analysis of studies performed in a clinical setting. Br J Dermatol. 2008;159:669-676.

- Engasser HC, Warshaw EM. Dermatoscopy use by US dermatologists: a cross-sectional survey [published online July 8, 2010]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:412-419, 419.e1-419.e2.

- Wu TP, Newlove T, Smith L, et al. The importance of dedicated dermoscopy training during residency: a survey of US dermatology chief residents. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:1000-1005.

- Seidenari S, Bellucci C, Bassoli S, et al. High magnification digital dermoscopy of basal cell carcinoma: a single-centre study on 400 cases. Acta Derm Venereol. 2014;94:677-682.

- Ross EK, Vincenzi C, Tosti A. Videodermoscopy in the evaluation of hair and scalp disorders. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55:799-806.

- Piraccini BM, Balestri R, Starace M, et al. Nail digital dermoscopy (onychoscopy) in the diagnosis of onychomycosis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27:509-513.

Dermoscopy, or the noninvasive in vivo examination of the epidermis and superficial dermis using magnification, facilitates the diagnosis of pigmented and nonpigmented skin lesions.1 Despite the benefit of dermoscopy in making early and accurate diagnoses of potentially life-limiting skin cancers, only 48% of dermatologists in the United States use dermoscopy in their practices.2 The most commonly cited reason for not using dermoscopy is lack of training.

Although the use of dermoscopy is associated with younger age and more recent graduation from residency compared to nonusers, dermatology resident physicians continue to receive limited training in dermoscopy.2 In a survey of 139 dermatology chief residents, 48% were not satisfied with the dermoscopy training that they had received during residency. Residents who received bedside instruction in dermoscopy reported greater satisfaction with their dermoscopy training compared to those who did not receive bedside instruction.3 This article provides a brief comparison of standard dermoscopy versus videodermoscopy for the instruction of trainees on common dermatologic diagnoses.