User login

Association Between Anemia and Fatigue in Hospitalized Patients: Does the Measure of Anemia Matter?

Fatigue is the most common clinical symptom of anemia and is a significant concern to patients.1,2 In ambulatory patients, lower hemoglobin (Hb) concentration is associated with increased fatigue.2,3 Accordingly, therapies that treat anemia by increasing Hb concentration, such as erythropoiesis stimulating agents,4-7 often use fatigue as an outcome measure.

In hospitalized patients, transfusion of red blood cell increases Hb concentration and is the primary treatment for anemia. However, the extent to which transfusion and changes in Hb concentration affect hospitalized patients’ fatigue levels is not well established. Guidelines support transfusing patients with symptoms of anemia, such as fatigue, on the assumption that the increased oxygen delivery will improve the symptoms of anemia. While transfusion studies in hospitalized patients have consistently reported that transfusion at lower or “restrictive” Hb concentrations is safe compared with transfusion at higher Hb concentrations,8-10 these studies have mainly used cardiac events and mortality as outcomes rather than patient symptoms, such as fatigue. Nevertheless, they have resulted in hospitals increasingly adopting restrictive transfusion policies that discourage transfusion at higher Hb levels.11,12 Consequently, the rate of transfusion in hospitalized patients has decreased,13 raising questions of whether some patients with lower Hb concentrations may experience increased fatigue as a result of restrictive transfusion policies. Fatigue among hospitalized patients is important not only because it is an adverse symptom but because it may result in decreased activity levels, deconditioning, and losses in functional status.14,15While the effect of alternative transfusion policies on fatigue in hospitalized patients could be answered by a randomized clinical trial using fatigue and functional status as outcomes, an important first step is to assess whether the Hb concentration of hospitalized patients is associated with their fatigue level during hospitalization. Because hospitalized patients often have acute illnesses that can cause fatigue in and of themselves, it is possible that anemia is not associated with fatigue in hospitalized patients despite anemia’s association with fatigue in ambulatory patients. Additionally, Hb concentration varies during hospitalization,16 raising the question of what measures of Hb during hospitalization might be most associated with anemia-related fatigue.

The objective of this study is to explore multiple Hb measures in hospitalized medical patients with anemia and test whether any of these Hb measures are associated with patients’ fatigue level.

METHODS

Study Design

We performed a prospective, observational study of hospitalized patients with anemia on the general medicine services at The University of Chicago Medical Center (UCMC). The institutional review board approved the study procedures, and all study subjects provided informed consent.

Study Eligibility

Between April 2014 and June 2015, all general medicine inpatients were approached for written consent for The University of Chicago Hospitalist Project,17 a research infrastructure at UCMC. Among patients consenting to participate in the Hospitalist Project, patients were eligible if they had Hb <9 g/dL at any point during their hospitalization and were age ≥50 years. Hb concentration of <9 g/dL was chosen to include the range of Hb values covered by most restrictive transfusion policies.8-10,18 Age ≥50 years was an inclusion criteria because anemia is more strongly associated with poor outcomes, including functional impairment, among older patients compared with younger patients.14,19-21 If patients were not eligible for inclusion at the time of consent for the Hospitalist Project, their Hb values were reviewed twice daily until hospital discharge to assess if their Hb was <9 g/dL. Proxies were sought to answer questions for patients who failed the Short Portable Mental Status Questionnaire.22

Patient Demographic Data Collection

Research assistants abstracted patient age and sex from the electronic health record (EHR), and asked patients to self-identify their race. The individual comorbidities included as part of the Charlson Comorbidity Index were identified using International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision codes from hospital administrative data for each encounter and specifically included the following: myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, peripheral vascular disease, cerebrovascular disease, dementia, chronic pulmonary disease, rheumatic disease, peptic ulcer disease, liver disease, diabetes, hemiplegia and/or paraplegia, renal disease, cancer, and human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome.23 We also used Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/toolssoftware/ccs/ccs.jsp) diagnosis categories to identify whether patients had sickle cell (SC) anemia, gastrointestinal bleeding (GIB), or a depressive disorder (DD) because these conditions are associated with anemia (SC and GIB) and fatigue (DD).24

Measuring Anemia

Hb measures were available only when hospital providers ordered them as part of routine practice. The first Hb concentration <9 g/dL during a patient’s hospitalization, which made them eligible for study participation, was obtained through manual review of the EHR. All additional Hb values during the patient’s hospitalization were obtained from the hospital’s administrative data mart. All Hb values collected for each patient during the hospitalization were used to calculate summary measures of Hb during the hospitalization, including the mean Hb, median Hb, minimum Hb, maximum Hb, admission (first recorded) Hb, and discharge (last recorded) Hb. Hb measures were analyzed both as a continuous variable and as a categorical variable created by dividing the continuous Hb measures into integer ranges of 3 groups of approximately the same size.

Measuring Fatigue

Our primary outcome was patients’ level of fatigue reported during hospitalization, measured using the Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy (FACIT)-Anemia questionnaire. Fatigue was measured using a 13-question fatigue subscale,1,2,25 which measures fatigue within the past 7 days. Scores on the fatigue subscale range from 0 to 52, with lower scores reflecting greater levels of fatigue. As soon as patients met the eligibility criteria for study participation during their hospitalization (age ≥50 years and Hb <9 g/dL), they were approached to answer the FACIT questions. Values for missing data in the fatigue subscale for individual subjects were filled in using a prorated score from their answered questions as long as >50% of the items in the fatigue subscale were answered, in accordance with recommendations for addressing missing data in the FACIT.26 Fatigue was analyzed as a continuous variable and as a dichotomous variable created by dividing the sample into high (FACIT <27) and low (FACIT ≥27) levels of fatigue based on the median FACIT score of the population. Previous literature has shown a FACIT fatigue subscale score between 23 and 26 to be associated with an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG)27 C Performance Status rating of 2 to 33 compared to scores ≥27.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using Stata statistical software (StataCorp, College Station, TX). Descriptive statistics were used to characterize patient demographics. Analysis of variance was used to test for differences in the mean fatigue levels across Hb measures. χ2 tests were performed to test for associations between high fatigue levels and the Hb measures. Multivariable analysis, including both linear and logistic regression models, were used to test the association of Hb concentration and fatigue. P values <0.05 using a 2-tailed test were deemed statistically significant.

RESULTS

Patient Characteristics

During the study period, 8559 patients were admitted to the general medicine service. Of those, 5073 (59%) consented for participation in the Hospitalist Project, and 3670 (72%) completed the Hospitalist Project inpatient interview. Of these patients, 1292 (35%) had Hb <9 g/dL, and 784 (61%) were 50 years or older and completed the FACIT questionnaire.

Table 1 reports the demographic characteristics and comorbidities for the sample, the mean (standard deviation [SD]) for the 6 Hb measures, and mean (SD) and median FACIT scores.

Bivariate Association of Fatigue and Hb

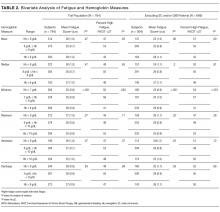

Categorizing patients into low, middle, or high Hb for each of the 6 Hb measures, minimum Hb was strongly associated with fatigue, with a weaker association for mean Hb and no statistically significant association for the other measures.

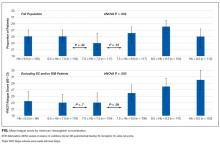

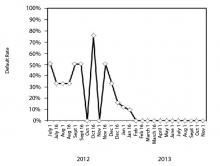

Minimum Hb. Patients with a minimum Hb <7 g/dL and patients with Hb 7-8 g/dL had higher fatigue levels (FACIT = 25 for each) than patients with a minimum Hb ≥8 g/dL (FACIT = 29; P < 0.001; Table 2). When excluding patients with SC and/or GIB because their average minimum Hb differed from the average minimum Hb of the full population (P < 0.001), patients with a minimum Hb <7 g/dL or 7-8 g/dL had even higher fatigue levels (FACIT = 23 and FACIT = 24, respectively), with no change in the fatigue level of patients with a minimum Hb ≥8 g/dL (FACIT = 29; P < 0.001; Table 2). Lower minimum Hb continued to be associated with higher fatigue levels when analyzed in 0.5 g/dL increments (Figure).

Mean Hb and Other Measures. Fatigue levels were high for 47% of patients with a mean Hb <8g /dL and 53% of patients with a mean Hb 8-9 g/dL compared with 43% of patients with a mean Hb ≥9 g/dL (P = 0.05). However, the association between high fatigue and mean Hb was not statistically significant when patients with SC and/or GIB were excluded (Table 2). None of the other 4 Hb measures was significantly associated with fatigue.

Linear Regression of Fatigue on Hb

In linear regression models, minimum Hb consistently predicted patient fatigue, mean Hb had a less robust association with fatigue, and the other Hb measures were not associated with patient fatigue. Increases in minimum Hb (analyzed as a continuous variable) were associated with reduced fatigue (higher FACIT score; β = 1.4; P = 0.005). In models in which minimum Hb was a categorical variable, patients with a minimum Hb of <7 g/dL or 7-8 g/dL had greater fatigue (lower FACIT score) than patients whose minimum Hb was ≥8 g/dL (Hb <7 g/dL: β = −4.2; P ≤ 0.001; Hb 7-8 g/dL: β = −4.1; P < 0.001). These results control for patients’ age, sex, individual comorbidities, and whether their minimum Hb occurred before or after the measurement of fatigue during hospitalization (Model 1), and the results are unchanged when also controlling for the number of Hb laboratory draws patients had during their hospitalization (Model 2; Table 3). In a stratified analysis excluding patients with either SC and/or GIB, changes in minimum Hb were associated with larger changes in patient fatigue levels (Supplemental Table 1). We also stratified our analysis to include only patients whose minimum Hb occurred before the measurement of their fatigue level during hospitalization to avoid a spurious association of fatigue with minimum Hb occurring after fatigue was measured. In both Models 1 and 2, minimum Hb remained a predictor of patients’ fatigue levels with similar effect sizes, although in Model 2, the results did not quite reach a statistically significant level, in part due to larger confidence intervals from the smaller sample size of this stratified analysis (Supplemental Table 2a). We further stratified this analysis to include only patients whose transfusion, if they received one, occurred after their minimum Hb and the measurement of their fatigue level to account for the possibility that a transfusion could affect the fatigue level patients report. In this analysis, most of the estimates of the effect of minimum Hb on fatigue were larger than those seen when only analyzing patients whose minimum Hb occurred before the measurement of their fatigue level, although again, the smaller sample size of this additional stratified analysis does produce larger confidence intervals for these estimates (Supplemental Table 2b).

No Hb measure other than minimum or mean had significant association with patient fatigue levels in linear regression models.

Logistic Regression of High Fatigue Level on Hb

Using logistic regression, minimum Hb analyzed as a categorical variable predicted increased odds of a high fatigue level. Patients with a minimum Hb <7 g/dL were 50% (odds ratio [OR] = 1.5; P = 0.03) more likely to have high fatigue and patients with a minimum Hb 7-8 g/dL were 90% (OR = 1.9; P < 0.001) more likely to have high fatigue compared with patients with a minimum Hb ≥8 g/dL in Model 1. These results were similar in Model 2, although the effect was only statistically significant in the 7-8 g/dL Hb group (Table 3). When excluding SC and/or GIB patients, the odds of having high fatigue as minimum Hb decreased were the same or higher for both models compared to the full population of patients. However, again, in Model 2, the effect was only statistically significant in the 7-8 g/dL Hb group (Supplemental Table 1).

Patients with a mean Hb <8 g/dL were 20% to 30% more likely to have high fatigue and patients with mean Hb 8-9 g/dL were 50% more likely to have high fatigue compared with patients with a mean Hb ≥9 g/dL, but the effects were only statistically significant for patients with a mean Hb 8-9 g/dL in both Models 1 and 2 (Table 3). These results were similar when excluding patients with SC and/or GIB, but they were only significant for patients with a mean Hb 8-9 g/dL in Model 1 and patients with a mean Hb <8 g/dL in the Model 2 (Supplemental Table 3).

DISCUSSION

These results demonstrate that minimum Hb during hospitalization is associated with fatigue in hospitalized patients age ≥50 years, and the association is stronger among patients without SC and/or GIB as comorbidities. The analysis of Hb as a continuous and categorical variable and the use of both linear and logistic regression models support the robustness of these associations and illuminate their clinical significance. For example, in linear regression with minimum Hb a continuous variable, the coefficient of 1.4 suggests that an increase of 2 g/dL in Hb, as might be expected from transfusion of 2 units of red blood cells, would be associated with about a 3-point improvement in fatigue. Additionally, as a categorical variable, a minimum Hb ≥8 g/dL compared with a minimum Hb <7 g/dL or 7-8 g/dL is associated with a 3- to 4-point improvement in fatigue. Previous literature suggests that a difference of 3 in the FACIT score is the minimum clinically important difference in fatigue,3 and changes in minimum Hb in either model predict changes in fatigue that are in the range of potential clinical significance.

The clinical significance of the findings is also reflected in the results of the logistic regressions, which may be mapped to potential effects on functional status. Specifically, the odds of having a high fatigue level (FACIT <27) increase 90% for persons with a minimum Hb 7–8 g/dL compared with persons with a minimum Hb ≥8 g/dL. For persons with a minimum Hb <7 g/dL, point estimates suggest a smaller (50%) increase in the odds of high fatigue, but the 95% confidence interval overlaps heavily with the estimate of patients whose minimum Hb is 7-8 g/dL. While it might be expected that patients with a minimum Hb <7 g/dL have greater levels of fatigue compared with patients with a minimum Hb 7-8 g/dL, we did not observe such a pattern. One reason may be that the confidence intervals of our estimated effects are wide enough that we cannot exclude such a pattern. Another possible explanation is that in both groups, the fatigue levels are sufficiently severe, such that the difference in their fatigue levels may not be clinically meaningful. For example, a FACIT score of 23 to 26 has been shown to be associated with an ECOG performance status of 2 to 3, requiring bed rest for at least part of the day.3 Therefore, patients with a minimum Hb 7-8 g/dL (mean FACIT score = 24; Table 2) or a minimum Hb of <7 g/dL (mean FACIT score = 23; Table 2) are already functionally limited to the point of being partially bed bound, such that further decreases in their Hb may not produce additional fatigue in part because they reduce their activity sufficiently to prevent an increase in fatigue. In such cases, the potential benefits of increased Hb may be better assessed by measuring fatigue in response to a specific and provoked activity level, a concept known as fatigability.20

That minimum Hb is more strongly associated with fatigue than any other measure of Hb during hospitalization may not be surprising. Mean, median, maximum, and discharge Hb may all be affected by transfusion during hospitalization that could affect fatigue. Admission Hb may not reflect true oxygen-carrying capacity because of hemoconcentration.

The association between Hb and fatigue in hospitalized patients is important because increased fatigue could contribute to slower clinical recovery in hospitalized patients. Additionally, increased fatigue during hospitalization and at hospital discharge could exacerbate the known deleterious consequences of fatigue on patients and their health outcomes14,15 after hospital discharge. Although one previous study, the Functional Outcomes in Cardiovascular Patients Undergoing Surgical Hip Fracture Repair (FOCUS)8 trial, did not report differences in patients’ fatigue levels at 30 and 60 days postdischarge when transfused at restrictive (8 g/dL) compared with liberal (10 g/dL) Hb thresholds, confidence in the validity of this finding is reduced by the fact that more than half of the patients were lost to follow-up at the 30- and 60-day time points. Further, patients in the restrictive transfusion arm of FOCUS were transfused to maintain Hb levels at or above 8 g/dL. This transfusion threshold of 8 g/dL may have mitigated the high levels of fatigue that are seen in our study when patients’ Hb drops below 8 g/dL, and maintaining a Hb level of 7 g/dL is now the standard of care in stable hospitalized patients. Lastly, FOCUS was limited to postoperative hip fracture patients, and the generalizability of FOCUS to hospitalized medicine patients with anemia is limited.

Therefore, our results support guideline suggestions that practitioners incorporate the presence of patient symptoms such as fatigue into transfusion decisions, particularly if patients’ Hb is <8 g/dL.18 Though reasonable, the suggestion to incorporate symptoms such as fatigue into transfusion decisions has not been strongly supported by evidence so far, and it may often be neglected in practice. Definitive evidence to support such recommendations would benefit from study through an optimal trial18 that incorporates symptoms into decision making. Our findings add support for a study of transfusion strategies that incorporates patients’ fatigue level in addition to Hb concentration.

This study has several limitations. Although our sample size is large and includes patients with a range of comorbidities that we believe are representative of hospitalized general medicine patients, as a single-center, observational study, our results may not be generalizable to other centers. Additionally, although these data support a reliable association between hospitalized patients’ minimum Hb and fatigue level, the observational design of this study cannot prove that this relationship is causal. Also, patients’ Hb values were measured at the discretion of their clinician, and therefore, the measures of Hb were not uniformly measured for participating patients. In addition, fatigue was only measured at one time point during a patient’s hospitalization, and it is possible that patients’ fatigue levels change during hospitalization in relation to variables we did not consider. Finally, our study was not designed to assess the association of Hb with longer-term functional outcomes, which may be of greater concern than fatigue.

CONCLUSION

In hospitalized patients ≥50 years old, minimum Hb is reliably associated with patients’ fatigue level. Patients whose minimum Hb is <8 g/dL experience higher fatigue levels compared to patients whose minimum Hb is ≥8 g/dL. Additional studies are warranted to understand if patients may benefit from improved fatigue levels by correcting their anemia through transfusion.

1. Yellen SB, Cella DF, Webster K, Blendowski C, Kaplan E. Measuring fatigue and other anemia-related symptoms with the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy (FACT) measurement system. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1997;13(2):63-74.

2. Cella D, Lai JS, Chang CH, Peterman A, Slavin M. Fatigue in cancer patients compared with fatigue in the general United States population. Cancer. 2002;94(2):528-538. doi:10.1002/cncr.10245.

3. Cella D, Eton DT, Lai J-S, Peterman AH, Merkel DE. Combining anchor and distribution-based methods to derive minimal clinically important differences on the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy (FACT) anemia and fatigue scales. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2002;24(6):547-561.

4. Tonelli M, Hemmelgarn B, Reiman T, et al. Benefits and harms of erythropoiesis-stimulating agents for anemia related to cancer: a meta-analysis. CMAJ Can Med Assoc J J Assoc Medicale Can. 2009;180(11):E62-E71. doi:10.1503/cmaj.090470.

5. Foley RN, Curtis BM, Parfrey PS. Erythropoietin Therapy, Hemoglobin Targets, and Quality of Life in Healthy Hemodialysis Patients: A Randomized Trial. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;4(4):726-733. doi:10.2215/CJN.04950908.

6. Keown PA, Churchill DN, Poulin-Costello M, et al. Dialysis patients treated with Epoetin alfa show improved anemia symptoms: A new analysis of the Canadian Erythropoietin Study Group trial. Hemodial Int Int Symp Home Hemodial. 2010;14(2):168-173. doi:10.1111/j.1542-4758.2009.00422.x.

7. Palmer SC, Saglimbene V, Mavridis D, et al. Erythropoiesis-stimulating agents for anaemia in adults with chronic kidney disease: a network meta-analysis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014:CD010590.

8. Carson JL, Terrin ML, Noveck H, et al. Liberal or Restrictive Transfusion in high-risk patients after hip surgery. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(26):2453-2462. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1012452.

9. Holst LB, Haase N, Wetterslev J, et al. Transfusion requirements in septic shock (TRISS) trial – comparing the effects and safety of liberal versus restrictive red blood cell transfusion in septic shock patients in the ICU: protocol for a randomised controlled trial. Trials. 2013;14:150. doi:10.1186/1745-6215-14-150.

10. Hébert PC, Wells G, Blajchman MA, et al. A multicenter, randomized, controlled clinical trial of transfusion requirements in critical care. N Engl J Med. 1999;340(6):409-417. doi:10.1056/NEJM199902113400601.

11. Corwin HL, Theus JW, Cargile CS, Lang NP. Red blood cell transfusion: Impact of an education program and a clinical guideline on transfusion practice. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(12):745-749. doi:10.1002/jhm.2237.

12. Saxena, S, editor. The Transfusion Committee: Putting Patient Safety First, 2nd Edition. Bethesda (MD): American Association of Blood Banks; 2013.

13. The 2011 National Blood Collection and Utilization Report. http://www.hhs.gov/ash/bloodsafety/2011-nbcus.pdf. Accessed August 16, 2017.

14. Vestergaard S, Nayfield SG, Patel KV, et al. Fatigue in a Representative Population of Older Persons and Its Association With Functional Impairment, Functional Limitation, and Disability. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2009;64A(1):76-82. doi:10.1093/gerona/gln017.

15. Gill TM, Desai MM, Gahbauer EA, Holford TR, Williams CS. Restricted activity among community-living older persons: incidence, precipitants, and health care utilization. Ann Intern Med. 2001;135(5):313-321.

16. Koch CG, Li L, Sun Z, et al. Hospital-acquired anemia: Prevalence, outcomes, and healthcare implications. J Hosp Med. 2013;8(9):506-512. doi:10.1002/jhm.2061.

17. Meltzer D, Manning WG, Morrison J, et al. Effects of Physician Experience on Costs and Outcomes on an Academic General Medicine Service: Results of a Trial of Hospitalists. Ann Intern Med. 2002;137(11):866-874. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-137-11-200212030-00007.

18. Carson JL, Grossman BJ, Kleinman S, et al. Red Blood Cell Transfusion: A Clinical Practice Guideline From the AABB*. Ann Intern Med. 2012;157(1):49-58. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-157-1-201206190-00429.

19. Moreh E, Jacobs JM, Stessman J. Fatigue, function, and mortality in older adults. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2010;65(8):887-895. doi:10.1093/gerona/glq064.

20. Eldadah BA. Fatigue and Fatigability in Older Adults. PM&R. 2010;2(5):406-413. doi:10.1016/j.pmrj.2010.03.022.

21. Hardy SE, Studenski SA. Fatigue Predicts Mortality among Older Adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56(10):1910-1914. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.01957.x.

22. Pfeiffer E. A short portable mental status questionnaire for the assessment of organic brain deficit in elderly patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1975;23(10):433-441.

23. Quan H, Sundararajan V, Halfon P, et al. Coding algorithms for defining comorbidities in ICD-9-CM and ICD-10 administrative data. Med Care. 2005;43(11):1130-1139.

24. HCUP Clinical Classifications Software (CCS) for ICD-9-CM. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP). 2006-2009. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville, MD. https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/toolssoftware/ccs/ccs.jsp. Accessed November 22, 2016.

25. Cella DF, Tulsky DS, Gray G, et al. The Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy scale: development and validation of the general measure. J Clin Oncol Off J Am Soc Clin Oncol. 1993;11(3):570-579.

26. Webster K, Cella D, Yost K. The Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy (FACIT) Measurement System: properties, applications, and interpretation. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2003;1:79. doi:10.1186/1477-7525-1-79.

27. Oken MMMD a, Creech RHMD b, Tormey DCMD, et al. Toxicity and response criteria of the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group. J Clin Oncol. 1982;5(6):649-656.

Fatigue is the most common clinical symptom of anemia and is a significant concern to patients.1,2 In ambulatory patients, lower hemoglobin (Hb) concentration is associated with increased fatigue.2,3 Accordingly, therapies that treat anemia by increasing Hb concentration, such as erythropoiesis stimulating agents,4-7 often use fatigue as an outcome measure.

In hospitalized patients, transfusion of red blood cell increases Hb concentration and is the primary treatment for anemia. However, the extent to which transfusion and changes in Hb concentration affect hospitalized patients’ fatigue levels is not well established. Guidelines support transfusing patients with symptoms of anemia, such as fatigue, on the assumption that the increased oxygen delivery will improve the symptoms of anemia. While transfusion studies in hospitalized patients have consistently reported that transfusion at lower or “restrictive” Hb concentrations is safe compared with transfusion at higher Hb concentrations,8-10 these studies have mainly used cardiac events and mortality as outcomes rather than patient symptoms, such as fatigue. Nevertheless, they have resulted in hospitals increasingly adopting restrictive transfusion policies that discourage transfusion at higher Hb levels.11,12 Consequently, the rate of transfusion in hospitalized patients has decreased,13 raising questions of whether some patients with lower Hb concentrations may experience increased fatigue as a result of restrictive transfusion policies. Fatigue among hospitalized patients is important not only because it is an adverse symptom but because it may result in decreased activity levels, deconditioning, and losses in functional status.14,15While the effect of alternative transfusion policies on fatigue in hospitalized patients could be answered by a randomized clinical trial using fatigue and functional status as outcomes, an important first step is to assess whether the Hb concentration of hospitalized patients is associated with their fatigue level during hospitalization. Because hospitalized patients often have acute illnesses that can cause fatigue in and of themselves, it is possible that anemia is not associated with fatigue in hospitalized patients despite anemia’s association with fatigue in ambulatory patients. Additionally, Hb concentration varies during hospitalization,16 raising the question of what measures of Hb during hospitalization might be most associated with anemia-related fatigue.

The objective of this study is to explore multiple Hb measures in hospitalized medical patients with anemia and test whether any of these Hb measures are associated with patients’ fatigue level.

METHODS

Study Design

We performed a prospective, observational study of hospitalized patients with anemia on the general medicine services at The University of Chicago Medical Center (UCMC). The institutional review board approved the study procedures, and all study subjects provided informed consent.

Study Eligibility

Between April 2014 and June 2015, all general medicine inpatients were approached for written consent for The University of Chicago Hospitalist Project,17 a research infrastructure at UCMC. Among patients consenting to participate in the Hospitalist Project, patients were eligible if they had Hb <9 g/dL at any point during their hospitalization and were age ≥50 years. Hb concentration of <9 g/dL was chosen to include the range of Hb values covered by most restrictive transfusion policies.8-10,18 Age ≥50 years was an inclusion criteria because anemia is more strongly associated with poor outcomes, including functional impairment, among older patients compared with younger patients.14,19-21 If patients were not eligible for inclusion at the time of consent for the Hospitalist Project, their Hb values were reviewed twice daily until hospital discharge to assess if their Hb was <9 g/dL. Proxies were sought to answer questions for patients who failed the Short Portable Mental Status Questionnaire.22

Patient Demographic Data Collection

Research assistants abstracted patient age and sex from the electronic health record (EHR), and asked patients to self-identify their race. The individual comorbidities included as part of the Charlson Comorbidity Index were identified using International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision codes from hospital administrative data for each encounter and specifically included the following: myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, peripheral vascular disease, cerebrovascular disease, dementia, chronic pulmonary disease, rheumatic disease, peptic ulcer disease, liver disease, diabetes, hemiplegia and/or paraplegia, renal disease, cancer, and human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome.23 We also used Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/toolssoftware/ccs/ccs.jsp) diagnosis categories to identify whether patients had sickle cell (SC) anemia, gastrointestinal bleeding (GIB), or a depressive disorder (DD) because these conditions are associated with anemia (SC and GIB) and fatigue (DD).24

Measuring Anemia

Hb measures were available only when hospital providers ordered them as part of routine practice. The first Hb concentration <9 g/dL during a patient’s hospitalization, which made them eligible for study participation, was obtained through manual review of the EHR. All additional Hb values during the patient’s hospitalization were obtained from the hospital’s administrative data mart. All Hb values collected for each patient during the hospitalization were used to calculate summary measures of Hb during the hospitalization, including the mean Hb, median Hb, minimum Hb, maximum Hb, admission (first recorded) Hb, and discharge (last recorded) Hb. Hb measures were analyzed both as a continuous variable and as a categorical variable created by dividing the continuous Hb measures into integer ranges of 3 groups of approximately the same size.

Measuring Fatigue

Our primary outcome was patients’ level of fatigue reported during hospitalization, measured using the Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy (FACIT)-Anemia questionnaire. Fatigue was measured using a 13-question fatigue subscale,1,2,25 which measures fatigue within the past 7 days. Scores on the fatigue subscale range from 0 to 52, with lower scores reflecting greater levels of fatigue. As soon as patients met the eligibility criteria for study participation during their hospitalization (age ≥50 years and Hb <9 g/dL), they were approached to answer the FACIT questions. Values for missing data in the fatigue subscale for individual subjects were filled in using a prorated score from their answered questions as long as >50% of the items in the fatigue subscale were answered, in accordance with recommendations for addressing missing data in the FACIT.26 Fatigue was analyzed as a continuous variable and as a dichotomous variable created by dividing the sample into high (FACIT <27) and low (FACIT ≥27) levels of fatigue based on the median FACIT score of the population. Previous literature has shown a FACIT fatigue subscale score between 23 and 26 to be associated with an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG)27 C Performance Status rating of 2 to 33 compared to scores ≥27.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using Stata statistical software (StataCorp, College Station, TX). Descriptive statistics were used to characterize patient demographics. Analysis of variance was used to test for differences in the mean fatigue levels across Hb measures. χ2 tests were performed to test for associations between high fatigue levels and the Hb measures. Multivariable analysis, including both linear and logistic regression models, were used to test the association of Hb concentration and fatigue. P values <0.05 using a 2-tailed test were deemed statistically significant.

RESULTS

Patient Characteristics

During the study period, 8559 patients were admitted to the general medicine service. Of those, 5073 (59%) consented for participation in the Hospitalist Project, and 3670 (72%) completed the Hospitalist Project inpatient interview. Of these patients, 1292 (35%) had Hb <9 g/dL, and 784 (61%) were 50 years or older and completed the FACIT questionnaire.

Table 1 reports the demographic characteristics and comorbidities for the sample, the mean (standard deviation [SD]) for the 6 Hb measures, and mean (SD) and median FACIT scores.

Bivariate Association of Fatigue and Hb

Categorizing patients into low, middle, or high Hb for each of the 6 Hb measures, minimum Hb was strongly associated with fatigue, with a weaker association for mean Hb and no statistically significant association for the other measures.

Minimum Hb. Patients with a minimum Hb <7 g/dL and patients with Hb 7-8 g/dL had higher fatigue levels (FACIT = 25 for each) than patients with a minimum Hb ≥8 g/dL (FACIT = 29; P < 0.001; Table 2). When excluding patients with SC and/or GIB because their average minimum Hb differed from the average minimum Hb of the full population (P < 0.001), patients with a minimum Hb <7 g/dL or 7-8 g/dL had even higher fatigue levels (FACIT = 23 and FACIT = 24, respectively), with no change in the fatigue level of patients with a minimum Hb ≥8 g/dL (FACIT = 29; P < 0.001; Table 2). Lower minimum Hb continued to be associated with higher fatigue levels when analyzed in 0.5 g/dL increments (Figure).

Mean Hb and Other Measures. Fatigue levels were high for 47% of patients with a mean Hb <8g /dL and 53% of patients with a mean Hb 8-9 g/dL compared with 43% of patients with a mean Hb ≥9 g/dL (P = 0.05). However, the association between high fatigue and mean Hb was not statistically significant when patients with SC and/or GIB were excluded (Table 2). None of the other 4 Hb measures was significantly associated with fatigue.

Linear Regression of Fatigue on Hb

In linear regression models, minimum Hb consistently predicted patient fatigue, mean Hb had a less robust association with fatigue, and the other Hb measures were not associated with patient fatigue. Increases in minimum Hb (analyzed as a continuous variable) were associated with reduced fatigue (higher FACIT score; β = 1.4; P = 0.005). In models in which minimum Hb was a categorical variable, patients with a minimum Hb of <7 g/dL or 7-8 g/dL had greater fatigue (lower FACIT score) than patients whose minimum Hb was ≥8 g/dL (Hb <7 g/dL: β = −4.2; P ≤ 0.001; Hb 7-8 g/dL: β = −4.1; P < 0.001). These results control for patients’ age, sex, individual comorbidities, and whether their minimum Hb occurred before or after the measurement of fatigue during hospitalization (Model 1), and the results are unchanged when also controlling for the number of Hb laboratory draws patients had during their hospitalization (Model 2; Table 3). In a stratified analysis excluding patients with either SC and/or GIB, changes in minimum Hb were associated with larger changes in patient fatigue levels (Supplemental Table 1). We also stratified our analysis to include only patients whose minimum Hb occurred before the measurement of their fatigue level during hospitalization to avoid a spurious association of fatigue with minimum Hb occurring after fatigue was measured. In both Models 1 and 2, minimum Hb remained a predictor of patients’ fatigue levels with similar effect sizes, although in Model 2, the results did not quite reach a statistically significant level, in part due to larger confidence intervals from the smaller sample size of this stratified analysis (Supplemental Table 2a). We further stratified this analysis to include only patients whose transfusion, if they received one, occurred after their minimum Hb and the measurement of their fatigue level to account for the possibility that a transfusion could affect the fatigue level patients report. In this analysis, most of the estimates of the effect of minimum Hb on fatigue were larger than those seen when only analyzing patients whose minimum Hb occurred before the measurement of their fatigue level, although again, the smaller sample size of this additional stratified analysis does produce larger confidence intervals for these estimates (Supplemental Table 2b).

No Hb measure other than minimum or mean had significant association with patient fatigue levels in linear regression models.

Logistic Regression of High Fatigue Level on Hb

Using logistic regression, minimum Hb analyzed as a categorical variable predicted increased odds of a high fatigue level. Patients with a minimum Hb <7 g/dL were 50% (odds ratio [OR] = 1.5; P = 0.03) more likely to have high fatigue and patients with a minimum Hb 7-8 g/dL were 90% (OR = 1.9; P < 0.001) more likely to have high fatigue compared with patients with a minimum Hb ≥8 g/dL in Model 1. These results were similar in Model 2, although the effect was only statistically significant in the 7-8 g/dL Hb group (Table 3). When excluding SC and/or GIB patients, the odds of having high fatigue as minimum Hb decreased were the same or higher for both models compared to the full population of patients. However, again, in Model 2, the effect was only statistically significant in the 7-8 g/dL Hb group (Supplemental Table 1).

Patients with a mean Hb <8 g/dL were 20% to 30% more likely to have high fatigue and patients with mean Hb 8-9 g/dL were 50% more likely to have high fatigue compared with patients with a mean Hb ≥9 g/dL, but the effects were only statistically significant for patients with a mean Hb 8-9 g/dL in both Models 1 and 2 (Table 3). These results were similar when excluding patients with SC and/or GIB, but they were only significant for patients with a mean Hb 8-9 g/dL in Model 1 and patients with a mean Hb <8 g/dL in the Model 2 (Supplemental Table 3).

DISCUSSION

These results demonstrate that minimum Hb during hospitalization is associated with fatigue in hospitalized patients age ≥50 years, and the association is stronger among patients without SC and/or GIB as comorbidities. The analysis of Hb as a continuous and categorical variable and the use of both linear and logistic regression models support the robustness of these associations and illuminate their clinical significance. For example, in linear regression with minimum Hb a continuous variable, the coefficient of 1.4 suggests that an increase of 2 g/dL in Hb, as might be expected from transfusion of 2 units of red blood cells, would be associated with about a 3-point improvement in fatigue. Additionally, as a categorical variable, a minimum Hb ≥8 g/dL compared with a minimum Hb <7 g/dL or 7-8 g/dL is associated with a 3- to 4-point improvement in fatigue. Previous literature suggests that a difference of 3 in the FACIT score is the minimum clinically important difference in fatigue,3 and changes in minimum Hb in either model predict changes in fatigue that are in the range of potential clinical significance.

The clinical significance of the findings is also reflected in the results of the logistic regressions, which may be mapped to potential effects on functional status. Specifically, the odds of having a high fatigue level (FACIT <27) increase 90% for persons with a minimum Hb 7–8 g/dL compared with persons with a minimum Hb ≥8 g/dL. For persons with a minimum Hb <7 g/dL, point estimates suggest a smaller (50%) increase in the odds of high fatigue, but the 95% confidence interval overlaps heavily with the estimate of patients whose minimum Hb is 7-8 g/dL. While it might be expected that patients with a minimum Hb <7 g/dL have greater levels of fatigue compared with patients with a minimum Hb 7-8 g/dL, we did not observe such a pattern. One reason may be that the confidence intervals of our estimated effects are wide enough that we cannot exclude such a pattern. Another possible explanation is that in both groups, the fatigue levels are sufficiently severe, such that the difference in their fatigue levels may not be clinically meaningful. For example, a FACIT score of 23 to 26 has been shown to be associated with an ECOG performance status of 2 to 3, requiring bed rest for at least part of the day.3 Therefore, patients with a minimum Hb 7-8 g/dL (mean FACIT score = 24; Table 2) or a minimum Hb of <7 g/dL (mean FACIT score = 23; Table 2) are already functionally limited to the point of being partially bed bound, such that further decreases in their Hb may not produce additional fatigue in part because they reduce their activity sufficiently to prevent an increase in fatigue. In such cases, the potential benefits of increased Hb may be better assessed by measuring fatigue in response to a specific and provoked activity level, a concept known as fatigability.20

That minimum Hb is more strongly associated with fatigue than any other measure of Hb during hospitalization may not be surprising. Mean, median, maximum, and discharge Hb may all be affected by transfusion during hospitalization that could affect fatigue. Admission Hb may not reflect true oxygen-carrying capacity because of hemoconcentration.

The association between Hb and fatigue in hospitalized patients is important because increased fatigue could contribute to slower clinical recovery in hospitalized patients. Additionally, increased fatigue during hospitalization and at hospital discharge could exacerbate the known deleterious consequences of fatigue on patients and their health outcomes14,15 after hospital discharge. Although one previous study, the Functional Outcomes in Cardiovascular Patients Undergoing Surgical Hip Fracture Repair (FOCUS)8 trial, did not report differences in patients’ fatigue levels at 30 and 60 days postdischarge when transfused at restrictive (8 g/dL) compared with liberal (10 g/dL) Hb thresholds, confidence in the validity of this finding is reduced by the fact that more than half of the patients were lost to follow-up at the 30- and 60-day time points. Further, patients in the restrictive transfusion arm of FOCUS were transfused to maintain Hb levels at or above 8 g/dL. This transfusion threshold of 8 g/dL may have mitigated the high levels of fatigue that are seen in our study when patients’ Hb drops below 8 g/dL, and maintaining a Hb level of 7 g/dL is now the standard of care in stable hospitalized patients. Lastly, FOCUS was limited to postoperative hip fracture patients, and the generalizability of FOCUS to hospitalized medicine patients with anemia is limited.

Therefore, our results support guideline suggestions that practitioners incorporate the presence of patient symptoms such as fatigue into transfusion decisions, particularly if patients’ Hb is <8 g/dL.18 Though reasonable, the suggestion to incorporate symptoms such as fatigue into transfusion decisions has not been strongly supported by evidence so far, and it may often be neglected in practice. Definitive evidence to support such recommendations would benefit from study through an optimal trial18 that incorporates symptoms into decision making. Our findings add support for a study of transfusion strategies that incorporates patients’ fatigue level in addition to Hb concentration.

This study has several limitations. Although our sample size is large and includes patients with a range of comorbidities that we believe are representative of hospitalized general medicine patients, as a single-center, observational study, our results may not be generalizable to other centers. Additionally, although these data support a reliable association between hospitalized patients’ minimum Hb and fatigue level, the observational design of this study cannot prove that this relationship is causal. Also, patients’ Hb values were measured at the discretion of their clinician, and therefore, the measures of Hb were not uniformly measured for participating patients. In addition, fatigue was only measured at one time point during a patient’s hospitalization, and it is possible that patients’ fatigue levels change during hospitalization in relation to variables we did not consider. Finally, our study was not designed to assess the association of Hb with longer-term functional outcomes, which may be of greater concern than fatigue.

CONCLUSION

In hospitalized patients ≥50 years old, minimum Hb is reliably associated with patients’ fatigue level. Patients whose minimum Hb is <8 g/dL experience higher fatigue levels compared to patients whose minimum Hb is ≥8 g/dL. Additional studies are warranted to understand if patients may benefit from improved fatigue levels by correcting their anemia through transfusion.

Fatigue is the most common clinical symptom of anemia and is a significant concern to patients.1,2 In ambulatory patients, lower hemoglobin (Hb) concentration is associated with increased fatigue.2,3 Accordingly, therapies that treat anemia by increasing Hb concentration, such as erythropoiesis stimulating agents,4-7 often use fatigue as an outcome measure.

In hospitalized patients, transfusion of red blood cell increases Hb concentration and is the primary treatment for anemia. However, the extent to which transfusion and changes in Hb concentration affect hospitalized patients’ fatigue levels is not well established. Guidelines support transfusing patients with symptoms of anemia, such as fatigue, on the assumption that the increased oxygen delivery will improve the symptoms of anemia. While transfusion studies in hospitalized patients have consistently reported that transfusion at lower or “restrictive” Hb concentrations is safe compared with transfusion at higher Hb concentrations,8-10 these studies have mainly used cardiac events and mortality as outcomes rather than patient symptoms, such as fatigue. Nevertheless, they have resulted in hospitals increasingly adopting restrictive transfusion policies that discourage transfusion at higher Hb levels.11,12 Consequently, the rate of transfusion in hospitalized patients has decreased,13 raising questions of whether some patients with lower Hb concentrations may experience increased fatigue as a result of restrictive transfusion policies. Fatigue among hospitalized patients is important not only because it is an adverse symptom but because it may result in decreased activity levels, deconditioning, and losses in functional status.14,15While the effect of alternative transfusion policies on fatigue in hospitalized patients could be answered by a randomized clinical trial using fatigue and functional status as outcomes, an important first step is to assess whether the Hb concentration of hospitalized patients is associated with their fatigue level during hospitalization. Because hospitalized patients often have acute illnesses that can cause fatigue in and of themselves, it is possible that anemia is not associated with fatigue in hospitalized patients despite anemia’s association with fatigue in ambulatory patients. Additionally, Hb concentration varies during hospitalization,16 raising the question of what measures of Hb during hospitalization might be most associated with anemia-related fatigue.

The objective of this study is to explore multiple Hb measures in hospitalized medical patients with anemia and test whether any of these Hb measures are associated with patients’ fatigue level.

METHODS

Study Design

We performed a prospective, observational study of hospitalized patients with anemia on the general medicine services at The University of Chicago Medical Center (UCMC). The institutional review board approved the study procedures, and all study subjects provided informed consent.

Study Eligibility

Between April 2014 and June 2015, all general medicine inpatients were approached for written consent for The University of Chicago Hospitalist Project,17 a research infrastructure at UCMC. Among patients consenting to participate in the Hospitalist Project, patients were eligible if they had Hb <9 g/dL at any point during their hospitalization and were age ≥50 years. Hb concentration of <9 g/dL was chosen to include the range of Hb values covered by most restrictive transfusion policies.8-10,18 Age ≥50 years was an inclusion criteria because anemia is more strongly associated with poor outcomes, including functional impairment, among older patients compared with younger patients.14,19-21 If patients were not eligible for inclusion at the time of consent for the Hospitalist Project, their Hb values were reviewed twice daily until hospital discharge to assess if their Hb was <9 g/dL. Proxies were sought to answer questions for patients who failed the Short Portable Mental Status Questionnaire.22

Patient Demographic Data Collection

Research assistants abstracted patient age and sex from the electronic health record (EHR), and asked patients to self-identify their race. The individual comorbidities included as part of the Charlson Comorbidity Index were identified using International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision codes from hospital administrative data for each encounter and specifically included the following: myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, peripheral vascular disease, cerebrovascular disease, dementia, chronic pulmonary disease, rheumatic disease, peptic ulcer disease, liver disease, diabetes, hemiplegia and/or paraplegia, renal disease, cancer, and human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome.23 We also used Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/toolssoftware/ccs/ccs.jsp) diagnosis categories to identify whether patients had sickle cell (SC) anemia, gastrointestinal bleeding (GIB), or a depressive disorder (DD) because these conditions are associated with anemia (SC and GIB) and fatigue (DD).24

Measuring Anemia

Hb measures were available only when hospital providers ordered them as part of routine practice. The first Hb concentration <9 g/dL during a patient’s hospitalization, which made them eligible for study participation, was obtained through manual review of the EHR. All additional Hb values during the patient’s hospitalization were obtained from the hospital’s administrative data mart. All Hb values collected for each patient during the hospitalization were used to calculate summary measures of Hb during the hospitalization, including the mean Hb, median Hb, minimum Hb, maximum Hb, admission (first recorded) Hb, and discharge (last recorded) Hb. Hb measures were analyzed both as a continuous variable and as a categorical variable created by dividing the continuous Hb measures into integer ranges of 3 groups of approximately the same size.

Measuring Fatigue

Our primary outcome was patients’ level of fatigue reported during hospitalization, measured using the Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy (FACIT)-Anemia questionnaire. Fatigue was measured using a 13-question fatigue subscale,1,2,25 which measures fatigue within the past 7 days. Scores on the fatigue subscale range from 0 to 52, with lower scores reflecting greater levels of fatigue. As soon as patients met the eligibility criteria for study participation during their hospitalization (age ≥50 years and Hb <9 g/dL), they were approached to answer the FACIT questions. Values for missing data in the fatigue subscale for individual subjects were filled in using a prorated score from their answered questions as long as >50% of the items in the fatigue subscale were answered, in accordance with recommendations for addressing missing data in the FACIT.26 Fatigue was analyzed as a continuous variable and as a dichotomous variable created by dividing the sample into high (FACIT <27) and low (FACIT ≥27) levels of fatigue based on the median FACIT score of the population. Previous literature has shown a FACIT fatigue subscale score between 23 and 26 to be associated with an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG)27 C Performance Status rating of 2 to 33 compared to scores ≥27.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using Stata statistical software (StataCorp, College Station, TX). Descriptive statistics were used to characterize patient demographics. Analysis of variance was used to test for differences in the mean fatigue levels across Hb measures. χ2 tests were performed to test for associations between high fatigue levels and the Hb measures. Multivariable analysis, including both linear and logistic regression models, were used to test the association of Hb concentration and fatigue. P values <0.05 using a 2-tailed test were deemed statistically significant.

RESULTS

Patient Characteristics

During the study period, 8559 patients were admitted to the general medicine service. Of those, 5073 (59%) consented for participation in the Hospitalist Project, and 3670 (72%) completed the Hospitalist Project inpatient interview. Of these patients, 1292 (35%) had Hb <9 g/dL, and 784 (61%) were 50 years or older and completed the FACIT questionnaire.

Table 1 reports the demographic characteristics and comorbidities for the sample, the mean (standard deviation [SD]) for the 6 Hb measures, and mean (SD) and median FACIT scores.

Bivariate Association of Fatigue and Hb

Categorizing patients into low, middle, or high Hb for each of the 6 Hb measures, minimum Hb was strongly associated with fatigue, with a weaker association for mean Hb and no statistically significant association for the other measures.

Minimum Hb. Patients with a minimum Hb <7 g/dL and patients with Hb 7-8 g/dL had higher fatigue levels (FACIT = 25 for each) than patients with a minimum Hb ≥8 g/dL (FACIT = 29; P < 0.001; Table 2). When excluding patients with SC and/or GIB because their average minimum Hb differed from the average minimum Hb of the full population (P < 0.001), patients with a minimum Hb <7 g/dL or 7-8 g/dL had even higher fatigue levels (FACIT = 23 and FACIT = 24, respectively), with no change in the fatigue level of patients with a minimum Hb ≥8 g/dL (FACIT = 29; P < 0.001; Table 2). Lower minimum Hb continued to be associated with higher fatigue levels when analyzed in 0.5 g/dL increments (Figure).

Mean Hb and Other Measures. Fatigue levels were high for 47% of patients with a mean Hb <8g /dL and 53% of patients with a mean Hb 8-9 g/dL compared with 43% of patients with a mean Hb ≥9 g/dL (P = 0.05). However, the association between high fatigue and mean Hb was not statistically significant when patients with SC and/or GIB were excluded (Table 2). None of the other 4 Hb measures was significantly associated with fatigue.

Linear Regression of Fatigue on Hb

In linear regression models, minimum Hb consistently predicted patient fatigue, mean Hb had a less robust association with fatigue, and the other Hb measures were not associated with patient fatigue. Increases in minimum Hb (analyzed as a continuous variable) were associated with reduced fatigue (higher FACIT score; β = 1.4; P = 0.005). In models in which minimum Hb was a categorical variable, patients with a minimum Hb of <7 g/dL or 7-8 g/dL had greater fatigue (lower FACIT score) than patients whose minimum Hb was ≥8 g/dL (Hb <7 g/dL: β = −4.2; P ≤ 0.001; Hb 7-8 g/dL: β = −4.1; P < 0.001). These results control for patients’ age, sex, individual comorbidities, and whether their minimum Hb occurred before or after the measurement of fatigue during hospitalization (Model 1), and the results are unchanged when also controlling for the number of Hb laboratory draws patients had during their hospitalization (Model 2; Table 3). In a stratified analysis excluding patients with either SC and/or GIB, changes in minimum Hb were associated with larger changes in patient fatigue levels (Supplemental Table 1). We also stratified our analysis to include only patients whose minimum Hb occurred before the measurement of their fatigue level during hospitalization to avoid a spurious association of fatigue with minimum Hb occurring after fatigue was measured. In both Models 1 and 2, minimum Hb remained a predictor of patients’ fatigue levels with similar effect sizes, although in Model 2, the results did not quite reach a statistically significant level, in part due to larger confidence intervals from the smaller sample size of this stratified analysis (Supplemental Table 2a). We further stratified this analysis to include only patients whose transfusion, if they received one, occurred after their minimum Hb and the measurement of their fatigue level to account for the possibility that a transfusion could affect the fatigue level patients report. In this analysis, most of the estimates of the effect of minimum Hb on fatigue were larger than those seen when only analyzing patients whose minimum Hb occurred before the measurement of their fatigue level, although again, the smaller sample size of this additional stratified analysis does produce larger confidence intervals for these estimates (Supplemental Table 2b).

No Hb measure other than minimum or mean had significant association with patient fatigue levels in linear regression models.

Logistic Regression of High Fatigue Level on Hb

Using logistic regression, minimum Hb analyzed as a categorical variable predicted increased odds of a high fatigue level. Patients with a minimum Hb <7 g/dL were 50% (odds ratio [OR] = 1.5; P = 0.03) more likely to have high fatigue and patients with a minimum Hb 7-8 g/dL were 90% (OR = 1.9; P < 0.001) more likely to have high fatigue compared with patients with a minimum Hb ≥8 g/dL in Model 1. These results were similar in Model 2, although the effect was only statistically significant in the 7-8 g/dL Hb group (Table 3). When excluding SC and/or GIB patients, the odds of having high fatigue as minimum Hb decreased were the same or higher for both models compared to the full population of patients. However, again, in Model 2, the effect was only statistically significant in the 7-8 g/dL Hb group (Supplemental Table 1).

Patients with a mean Hb <8 g/dL were 20% to 30% more likely to have high fatigue and patients with mean Hb 8-9 g/dL were 50% more likely to have high fatigue compared with patients with a mean Hb ≥9 g/dL, but the effects were only statistically significant for patients with a mean Hb 8-9 g/dL in both Models 1 and 2 (Table 3). These results were similar when excluding patients with SC and/or GIB, but they were only significant for patients with a mean Hb 8-9 g/dL in Model 1 and patients with a mean Hb <8 g/dL in the Model 2 (Supplemental Table 3).

DISCUSSION

These results demonstrate that minimum Hb during hospitalization is associated with fatigue in hospitalized patients age ≥50 years, and the association is stronger among patients without SC and/or GIB as comorbidities. The analysis of Hb as a continuous and categorical variable and the use of both linear and logistic regression models support the robustness of these associations and illuminate their clinical significance. For example, in linear regression with minimum Hb a continuous variable, the coefficient of 1.4 suggests that an increase of 2 g/dL in Hb, as might be expected from transfusion of 2 units of red blood cells, would be associated with about a 3-point improvement in fatigue. Additionally, as a categorical variable, a minimum Hb ≥8 g/dL compared with a minimum Hb <7 g/dL or 7-8 g/dL is associated with a 3- to 4-point improvement in fatigue. Previous literature suggests that a difference of 3 in the FACIT score is the minimum clinically important difference in fatigue,3 and changes in minimum Hb in either model predict changes in fatigue that are in the range of potential clinical significance.

The clinical significance of the findings is also reflected in the results of the logistic regressions, which may be mapped to potential effects on functional status. Specifically, the odds of having a high fatigue level (FACIT <27) increase 90% for persons with a minimum Hb 7–8 g/dL compared with persons with a minimum Hb ≥8 g/dL. For persons with a minimum Hb <7 g/dL, point estimates suggest a smaller (50%) increase in the odds of high fatigue, but the 95% confidence interval overlaps heavily with the estimate of patients whose minimum Hb is 7-8 g/dL. While it might be expected that patients with a minimum Hb <7 g/dL have greater levels of fatigue compared with patients with a minimum Hb 7-8 g/dL, we did not observe such a pattern. One reason may be that the confidence intervals of our estimated effects are wide enough that we cannot exclude such a pattern. Another possible explanation is that in both groups, the fatigue levels are sufficiently severe, such that the difference in their fatigue levels may not be clinically meaningful. For example, a FACIT score of 23 to 26 has been shown to be associated with an ECOG performance status of 2 to 3, requiring bed rest for at least part of the day.3 Therefore, patients with a minimum Hb 7-8 g/dL (mean FACIT score = 24; Table 2) or a minimum Hb of <7 g/dL (mean FACIT score = 23; Table 2) are already functionally limited to the point of being partially bed bound, such that further decreases in their Hb may not produce additional fatigue in part because they reduce their activity sufficiently to prevent an increase in fatigue. In such cases, the potential benefits of increased Hb may be better assessed by measuring fatigue in response to a specific and provoked activity level, a concept known as fatigability.20

That minimum Hb is more strongly associated with fatigue than any other measure of Hb during hospitalization may not be surprising. Mean, median, maximum, and discharge Hb may all be affected by transfusion during hospitalization that could affect fatigue. Admission Hb may not reflect true oxygen-carrying capacity because of hemoconcentration.

The association between Hb and fatigue in hospitalized patients is important because increased fatigue could contribute to slower clinical recovery in hospitalized patients. Additionally, increased fatigue during hospitalization and at hospital discharge could exacerbate the known deleterious consequences of fatigue on patients and their health outcomes14,15 after hospital discharge. Although one previous study, the Functional Outcomes in Cardiovascular Patients Undergoing Surgical Hip Fracture Repair (FOCUS)8 trial, did not report differences in patients’ fatigue levels at 30 and 60 days postdischarge when transfused at restrictive (8 g/dL) compared with liberal (10 g/dL) Hb thresholds, confidence in the validity of this finding is reduced by the fact that more than half of the patients were lost to follow-up at the 30- and 60-day time points. Further, patients in the restrictive transfusion arm of FOCUS were transfused to maintain Hb levels at or above 8 g/dL. This transfusion threshold of 8 g/dL may have mitigated the high levels of fatigue that are seen in our study when patients’ Hb drops below 8 g/dL, and maintaining a Hb level of 7 g/dL is now the standard of care in stable hospitalized patients. Lastly, FOCUS was limited to postoperative hip fracture patients, and the generalizability of FOCUS to hospitalized medicine patients with anemia is limited.

Therefore, our results support guideline suggestions that practitioners incorporate the presence of patient symptoms such as fatigue into transfusion decisions, particularly if patients’ Hb is <8 g/dL.18 Though reasonable, the suggestion to incorporate symptoms such as fatigue into transfusion decisions has not been strongly supported by evidence so far, and it may often be neglected in practice. Definitive evidence to support such recommendations would benefit from study through an optimal trial18 that incorporates symptoms into decision making. Our findings add support for a study of transfusion strategies that incorporates patients’ fatigue level in addition to Hb concentration.

This study has several limitations. Although our sample size is large and includes patients with a range of comorbidities that we believe are representative of hospitalized general medicine patients, as a single-center, observational study, our results may not be generalizable to other centers. Additionally, although these data support a reliable association between hospitalized patients’ minimum Hb and fatigue level, the observational design of this study cannot prove that this relationship is causal. Also, patients’ Hb values were measured at the discretion of their clinician, and therefore, the measures of Hb were not uniformly measured for participating patients. In addition, fatigue was only measured at one time point during a patient’s hospitalization, and it is possible that patients’ fatigue levels change during hospitalization in relation to variables we did not consider. Finally, our study was not designed to assess the association of Hb with longer-term functional outcomes, which may be of greater concern than fatigue.

CONCLUSION

In hospitalized patients ≥50 years old, minimum Hb is reliably associated with patients’ fatigue level. Patients whose minimum Hb is <8 g/dL experience higher fatigue levels compared to patients whose minimum Hb is ≥8 g/dL. Additional studies are warranted to understand if patients may benefit from improved fatigue levels by correcting their anemia through transfusion.

1. Yellen SB, Cella DF, Webster K, Blendowski C, Kaplan E. Measuring fatigue and other anemia-related symptoms with the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy (FACT) measurement system. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1997;13(2):63-74.

2. Cella D, Lai JS, Chang CH, Peterman A, Slavin M. Fatigue in cancer patients compared with fatigue in the general United States population. Cancer. 2002;94(2):528-538. doi:10.1002/cncr.10245.

3. Cella D, Eton DT, Lai J-S, Peterman AH, Merkel DE. Combining anchor and distribution-based methods to derive minimal clinically important differences on the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy (FACT) anemia and fatigue scales. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2002;24(6):547-561.

4. Tonelli M, Hemmelgarn B, Reiman T, et al. Benefits and harms of erythropoiesis-stimulating agents for anemia related to cancer: a meta-analysis. CMAJ Can Med Assoc J J Assoc Medicale Can. 2009;180(11):E62-E71. doi:10.1503/cmaj.090470.

5. Foley RN, Curtis BM, Parfrey PS. Erythropoietin Therapy, Hemoglobin Targets, and Quality of Life in Healthy Hemodialysis Patients: A Randomized Trial. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;4(4):726-733. doi:10.2215/CJN.04950908.

6. Keown PA, Churchill DN, Poulin-Costello M, et al. Dialysis patients treated with Epoetin alfa show improved anemia symptoms: A new analysis of the Canadian Erythropoietin Study Group trial. Hemodial Int Int Symp Home Hemodial. 2010;14(2):168-173. doi:10.1111/j.1542-4758.2009.00422.x.

7. Palmer SC, Saglimbene V, Mavridis D, et al. Erythropoiesis-stimulating agents for anaemia in adults with chronic kidney disease: a network meta-analysis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014:CD010590.

8. Carson JL, Terrin ML, Noveck H, et al. Liberal or Restrictive Transfusion in high-risk patients after hip surgery. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(26):2453-2462. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1012452.

9. Holst LB, Haase N, Wetterslev J, et al. Transfusion requirements in septic shock (TRISS) trial – comparing the effects and safety of liberal versus restrictive red blood cell transfusion in septic shock patients in the ICU: protocol for a randomised controlled trial. Trials. 2013;14:150. doi:10.1186/1745-6215-14-150.

10. Hébert PC, Wells G, Blajchman MA, et al. A multicenter, randomized, controlled clinical trial of transfusion requirements in critical care. N Engl J Med. 1999;340(6):409-417. doi:10.1056/NEJM199902113400601.

11. Corwin HL, Theus JW, Cargile CS, Lang NP. Red blood cell transfusion: Impact of an education program and a clinical guideline on transfusion practice. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(12):745-749. doi:10.1002/jhm.2237.

12. Saxena, S, editor. The Transfusion Committee: Putting Patient Safety First, 2nd Edition. Bethesda (MD): American Association of Blood Banks; 2013.

13. The 2011 National Blood Collection and Utilization Report. http://www.hhs.gov/ash/bloodsafety/2011-nbcus.pdf. Accessed August 16, 2017.

14. Vestergaard S, Nayfield SG, Patel KV, et al. Fatigue in a Representative Population of Older Persons and Its Association With Functional Impairment, Functional Limitation, and Disability. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2009;64A(1):76-82. doi:10.1093/gerona/gln017.

15. Gill TM, Desai MM, Gahbauer EA, Holford TR, Williams CS. Restricted activity among community-living older persons: incidence, precipitants, and health care utilization. Ann Intern Med. 2001;135(5):313-321.

16. Koch CG, Li L, Sun Z, et al. Hospital-acquired anemia: Prevalence, outcomes, and healthcare implications. J Hosp Med. 2013;8(9):506-512. doi:10.1002/jhm.2061.

17. Meltzer D, Manning WG, Morrison J, et al. Effects of Physician Experience on Costs and Outcomes on an Academic General Medicine Service: Results of a Trial of Hospitalists. Ann Intern Med. 2002;137(11):866-874. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-137-11-200212030-00007.

18. Carson JL, Grossman BJ, Kleinman S, et al. Red Blood Cell Transfusion: A Clinical Practice Guideline From the AABB*. Ann Intern Med. 2012;157(1):49-58. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-157-1-201206190-00429.

19. Moreh E, Jacobs JM, Stessman J. Fatigue, function, and mortality in older adults. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2010;65(8):887-895. doi:10.1093/gerona/glq064.

20. Eldadah BA. Fatigue and Fatigability in Older Adults. PM&R. 2010;2(5):406-413. doi:10.1016/j.pmrj.2010.03.022.

21. Hardy SE, Studenski SA. Fatigue Predicts Mortality among Older Adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56(10):1910-1914. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.01957.x.

22. Pfeiffer E. A short portable mental status questionnaire for the assessment of organic brain deficit in elderly patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1975;23(10):433-441.

23. Quan H, Sundararajan V, Halfon P, et al. Coding algorithms for defining comorbidities in ICD-9-CM and ICD-10 administrative data. Med Care. 2005;43(11):1130-1139.

24. HCUP Clinical Classifications Software (CCS) for ICD-9-CM. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP). 2006-2009. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville, MD. https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/toolssoftware/ccs/ccs.jsp. Accessed November 22, 2016.

25. Cella DF, Tulsky DS, Gray G, et al. The Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy scale: development and validation of the general measure. J Clin Oncol Off J Am Soc Clin Oncol. 1993;11(3):570-579.

26. Webster K, Cella D, Yost K. The Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy (FACIT) Measurement System: properties, applications, and interpretation. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2003;1:79. doi:10.1186/1477-7525-1-79.

27. Oken MMMD a, Creech RHMD b, Tormey DCMD, et al. Toxicity and response criteria of the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group. J Clin Oncol. 1982;5(6):649-656.

1. Yellen SB, Cella DF, Webster K, Blendowski C, Kaplan E. Measuring fatigue and other anemia-related symptoms with the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy (FACT) measurement system. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1997;13(2):63-74.

2. Cella D, Lai JS, Chang CH, Peterman A, Slavin M. Fatigue in cancer patients compared with fatigue in the general United States population. Cancer. 2002;94(2):528-538. doi:10.1002/cncr.10245.

3. Cella D, Eton DT, Lai J-S, Peterman AH, Merkel DE. Combining anchor and distribution-based methods to derive minimal clinically important differences on the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy (FACT) anemia and fatigue scales. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2002;24(6):547-561.

4. Tonelli M, Hemmelgarn B, Reiman T, et al. Benefits and harms of erythropoiesis-stimulating agents for anemia related to cancer: a meta-analysis. CMAJ Can Med Assoc J J Assoc Medicale Can. 2009;180(11):E62-E71. doi:10.1503/cmaj.090470.

5. Foley RN, Curtis BM, Parfrey PS. Erythropoietin Therapy, Hemoglobin Targets, and Quality of Life in Healthy Hemodialysis Patients: A Randomized Trial. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;4(4):726-733. doi:10.2215/CJN.04950908.

6. Keown PA, Churchill DN, Poulin-Costello M, et al. Dialysis patients treated with Epoetin alfa show improved anemia symptoms: A new analysis of the Canadian Erythropoietin Study Group trial. Hemodial Int Int Symp Home Hemodial. 2010;14(2):168-173. doi:10.1111/j.1542-4758.2009.00422.x.

7. Palmer SC, Saglimbene V, Mavridis D, et al. Erythropoiesis-stimulating agents for anaemia in adults with chronic kidney disease: a network meta-analysis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014:CD010590.

8. Carson JL, Terrin ML, Noveck H, et al. Liberal or Restrictive Transfusion in high-risk patients after hip surgery. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(26):2453-2462. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1012452.

9. Holst LB, Haase N, Wetterslev J, et al. Transfusion requirements in septic shock (TRISS) trial – comparing the effects and safety of liberal versus restrictive red blood cell transfusion in septic shock patients in the ICU: protocol for a randomised controlled trial. Trials. 2013;14:150. doi:10.1186/1745-6215-14-150.

10. Hébert PC, Wells G, Blajchman MA, et al. A multicenter, randomized, controlled clinical trial of transfusion requirements in critical care. N Engl J Med. 1999;340(6):409-417. doi:10.1056/NEJM199902113400601.

11. Corwin HL, Theus JW, Cargile CS, Lang NP. Red blood cell transfusion: Impact of an education program and a clinical guideline on transfusion practice. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(12):745-749. doi:10.1002/jhm.2237.

12. Saxena, S, editor. The Transfusion Committee: Putting Patient Safety First, 2nd Edition. Bethesda (MD): American Association of Blood Banks; 2013.

13. The 2011 National Blood Collection and Utilization Report. http://www.hhs.gov/ash/bloodsafety/2011-nbcus.pdf. Accessed August 16, 2017.

14. Vestergaard S, Nayfield SG, Patel KV, et al. Fatigue in a Representative Population of Older Persons and Its Association With Functional Impairment, Functional Limitation, and Disability. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2009;64A(1):76-82. doi:10.1093/gerona/gln017.

15. Gill TM, Desai MM, Gahbauer EA, Holford TR, Williams CS. Restricted activity among community-living older persons: incidence, precipitants, and health care utilization. Ann Intern Med. 2001;135(5):313-321.

16. Koch CG, Li L, Sun Z, et al. Hospital-acquired anemia: Prevalence, outcomes, and healthcare implications. J Hosp Med. 2013;8(9):506-512. doi:10.1002/jhm.2061.

17. Meltzer D, Manning WG, Morrison J, et al. Effects of Physician Experience on Costs and Outcomes on an Academic General Medicine Service: Results of a Trial of Hospitalists. Ann Intern Med. 2002;137(11):866-874. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-137-11-200212030-00007.

18. Carson JL, Grossman BJ, Kleinman S, et al. Red Blood Cell Transfusion: A Clinical Practice Guideline From the AABB*. Ann Intern Med. 2012;157(1):49-58. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-157-1-201206190-00429.

19. Moreh E, Jacobs JM, Stessman J. Fatigue, function, and mortality in older adults. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2010;65(8):887-895. doi:10.1093/gerona/glq064.

20. Eldadah BA. Fatigue and Fatigability in Older Adults. PM&R. 2010;2(5):406-413. doi:10.1016/j.pmrj.2010.03.022.

21. Hardy SE, Studenski SA. Fatigue Predicts Mortality among Older Adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56(10):1910-1914. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.01957.x.

22. Pfeiffer E. A short portable mental status questionnaire for the assessment of organic brain deficit in elderly patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1975;23(10):433-441.

23. Quan H, Sundararajan V, Halfon P, et al. Coding algorithms for defining comorbidities in ICD-9-CM and ICD-10 administrative data. Med Care. 2005;43(11):1130-1139.

24. HCUP Clinical Classifications Software (CCS) for ICD-9-CM. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP). 2006-2009. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville, MD. https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/toolssoftware/ccs/ccs.jsp. Accessed November 22, 2016.

25. Cella DF, Tulsky DS, Gray G, et al. The Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy scale: development and validation of the general measure. J Clin Oncol Off J Am Soc Clin Oncol. 1993;11(3):570-579.

26. Webster K, Cella D, Yost K. The Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy (FACIT) Measurement System: properties, applications, and interpretation. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2003;1:79. doi:10.1186/1477-7525-1-79.

27. Oken MMMD a, Creech RHMD b, Tormey DCMD, et al. Toxicity and response criteria of the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group. J Clin Oncol. 1982;5(6):649-656.

© 2017 Society of Hospital Medicine

2017 Update on female sexual dysfunction

Sexual function is a complex, multifaceted process mediated by neurologic functions, hormonal regulation, and ps