User login

Paper-based diagnostic device is like ‘portable lab’

Researchers say they have developed self-powered, paper-based electrochemical devices (SPEDs) that can provide sensitive diagnostics in low-resource settings and at the point of care.

The SPEDs can detect biomarkers in the blood and identify conditions such as anemia by performing electrochemical analyses that are powered by the user’s touch.

The devices produce color-coded test results that are easy for non-experts to understand.

“You could consider this a portable laboratory that is just completely made out of paper, is inexpensive, and can be disposed of through incineration,” said Ramses V. Martinez, PhD, of Purdue University in West Lafayette, Indiana.

“We hope these devices will serve untrained people located in remote villages or military bases to test for a variety of diseases without requiring any source of electricity, clean water, or additional equipment.”

Dr Martinez and his colleagues developed the SPEDs and described them in a paper published in Advanced Materials Technologies.

SPED testing is initiated by placing a pinprick of blood in a circular feature on the device, which is less than 2-inches square. The SPEDs also contain “self-pipetting test zones” that can be dipped into a sample instead of using a finger-prick test.

The top layer of each SPED is made of untreated cellulose paper with patterned hydrophobic domains that define channels that wick up blood samples for testing. These microfluidic channels allow for assays that change color to indicate specific test results.

The researchers also created a machine-vision diagnostic application to identify and quantify each of these colorimetric tests from a digital image of the SPED, perhaps taken with a cell phone. This provides rapid results for the user and allows for consultation with a remote expert if necessary.

The bottom layer of the SPED is a triboelectric generator (TEG), which generates the electric current necessary to run the diagnostic test by rubbing or pressing it.

An inexpensive, hand-held device called a potentiostat can be plugged into the SPED to automate the diagnostic tests so they can be performed by untrained users. The battery powering the potentiostat can be recharged using the TEG built into the SPEDs.

“To our knowledge, this work reports the first self-powered, paper-based devices capable of performing rapid, accurate, and sensitive electrochemical assays in combination with a low-cost, portable potentiostat that can be recharged using a paper-based TEG,” Dr Martinez said.

SPEDs can perform multiplexed analyses, enabling the detection of various targets for a range of point-of-care testing applications. In addition, the devices are compatible with mass-printing technologies, such as roll-to-roll printing or spray deposition. And the SPEDs can be used to power other electronic devices to facilitate telemedicine applications in resource-limited settings.

Dr Martinez and his colleagues used the SPEDs to detect biomarkers such as glucose, uric acid and L-lactate, ketones, and white blood cells, which indicate factors related to liver and kidney function, malnutrition, and anemia.

The researchers said future versions of the technology will contain several additional layers for more complex assays to detect diseases such as malaria, dengue fever, yellow fever, hepatitis, and HIV. ![]()

Researchers say they have developed self-powered, paper-based electrochemical devices (SPEDs) that can provide sensitive diagnostics in low-resource settings and at the point of care.

The SPEDs can detect biomarkers in the blood and identify conditions such as anemia by performing electrochemical analyses that are powered by the user’s touch.

The devices produce color-coded test results that are easy for non-experts to understand.

“You could consider this a portable laboratory that is just completely made out of paper, is inexpensive, and can be disposed of through incineration,” said Ramses V. Martinez, PhD, of Purdue University in West Lafayette, Indiana.

“We hope these devices will serve untrained people located in remote villages or military bases to test for a variety of diseases without requiring any source of electricity, clean water, or additional equipment.”

Dr Martinez and his colleagues developed the SPEDs and described them in a paper published in Advanced Materials Technologies.

SPED testing is initiated by placing a pinprick of blood in a circular feature on the device, which is less than 2-inches square. The SPEDs also contain “self-pipetting test zones” that can be dipped into a sample instead of using a finger-prick test.

The top layer of each SPED is made of untreated cellulose paper with patterned hydrophobic domains that define channels that wick up blood samples for testing. These microfluidic channels allow for assays that change color to indicate specific test results.

The researchers also created a machine-vision diagnostic application to identify and quantify each of these colorimetric tests from a digital image of the SPED, perhaps taken with a cell phone. This provides rapid results for the user and allows for consultation with a remote expert if necessary.

The bottom layer of the SPED is a triboelectric generator (TEG), which generates the electric current necessary to run the diagnostic test by rubbing or pressing it.

An inexpensive, hand-held device called a potentiostat can be plugged into the SPED to automate the diagnostic tests so they can be performed by untrained users. The battery powering the potentiostat can be recharged using the TEG built into the SPEDs.

“To our knowledge, this work reports the first self-powered, paper-based devices capable of performing rapid, accurate, and sensitive electrochemical assays in combination with a low-cost, portable potentiostat that can be recharged using a paper-based TEG,” Dr Martinez said.

SPEDs can perform multiplexed analyses, enabling the detection of various targets for a range of point-of-care testing applications. In addition, the devices are compatible with mass-printing technologies, such as roll-to-roll printing or spray deposition. And the SPEDs can be used to power other electronic devices to facilitate telemedicine applications in resource-limited settings.

Dr Martinez and his colleagues used the SPEDs to detect biomarkers such as glucose, uric acid and L-lactate, ketones, and white blood cells, which indicate factors related to liver and kidney function, malnutrition, and anemia.

The researchers said future versions of the technology will contain several additional layers for more complex assays to detect diseases such as malaria, dengue fever, yellow fever, hepatitis, and HIV. ![]()

Researchers say they have developed self-powered, paper-based electrochemical devices (SPEDs) that can provide sensitive diagnostics in low-resource settings and at the point of care.

The SPEDs can detect biomarkers in the blood and identify conditions such as anemia by performing electrochemical analyses that are powered by the user’s touch.

The devices produce color-coded test results that are easy for non-experts to understand.

“You could consider this a portable laboratory that is just completely made out of paper, is inexpensive, and can be disposed of through incineration,” said Ramses V. Martinez, PhD, of Purdue University in West Lafayette, Indiana.

“We hope these devices will serve untrained people located in remote villages or military bases to test for a variety of diseases without requiring any source of electricity, clean water, or additional equipment.”

Dr Martinez and his colleagues developed the SPEDs and described them in a paper published in Advanced Materials Technologies.

SPED testing is initiated by placing a pinprick of blood in a circular feature on the device, which is less than 2-inches square. The SPEDs also contain “self-pipetting test zones” that can be dipped into a sample instead of using a finger-prick test.

The top layer of each SPED is made of untreated cellulose paper with patterned hydrophobic domains that define channels that wick up blood samples for testing. These microfluidic channels allow for assays that change color to indicate specific test results.

The researchers also created a machine-vision diagnostic application to identify and quantify each of these colorimetric tests from a digital image of the SPED, perhaps taken with a cell phone. This provides rapid results for the user and allows for consultation with a remote expert if necessary.

The bottom layer of the SPED is a triboelectric generator (TEG), which generates the electric current necessary to run the diagnostic test by rubbing or pressing it.

An inexpensive, hand-held device called a potentiostat can be plugged into the SPED to automate the diagnostic tests so they can be performed by untrained users. The battery powering the potentiostat can be recharged using the TEG built into the SPEDs.

“To our knowledge, this work reports the first self-powered, paper-based devices capable of performing rapid, accurate, and sensitive electrochemical assays in combination with a low-cost, portable potentiostat that can be recharged using a paper-based TEG,” Dr Martinez said.

SPEDs can perform multiplexed analyses, enabling the detection of various targets for a range of point-of-care testing applications. In addition, the devices are compatible with mass-printing technologies, such as roll-to-roll printing or spray deposition. And the SPEDs can be used to power other electronic devices to facilitate telemedicine applications in resource-limited settings.

Dr Martinez and his colleagues used the SPEDs to detect biomarkers such as glucose, uric acid and L-lactate, ketones, and white blood cells, which indicate factors related to liver and kidney function, malnutrition, and anemia.

The researchers said future versions of the technology will contain several additional layers for more complex assays to detect diseases such as malaria, dengue fever, yellow fever, hepatitis, and HIV. ![]()

Bridging clinical medicine, research, and quality

Editor’s note: The Society of Hospital Medicine’s (SHM’s) Physician in Training Committee launched a scholarship program in 2015 for medical students to help transform health care and revolutionize patient care. The program has been expanded for the 2017-2018 year, offering two options for students to receive funding and engage in scholarly work during their first, second, and third years of medical school. As a part of the longitudinal (18-month) program, recipients are required to write about their experiences on a monthly basis.

I am a third-year medical student at the University of California, San Diego, as well as a recipient of the SHM Longitudinal Scholar Grant. Ultimately, I intend to pursue a career in academic medicine as a clinician-scientist, where I hope to bridge my interests in neuroscience, research, and clinical medicine.

Prior to entering medical school, I participated in a wide array of basic science, translational, and clinical research projects, but none in the area of quality improvement (QI). Given the breadth of my previous research experiences, an attractive feature of the SHM Hospitalist grant was the opportunity to complement this breadth of research exposure with increasing depth by exploring a QI project.

This year, I’ll be getting my first exposure to a QI project under the fine mentorship of Ian Jenkins, MD, SFHM, an attending in the division of hospital medicine at UCSD, who is working on an ongoing effort to combat catheter–associated urinary tract infections (CAUTI). Methods for reducing CAUTI include reducing indwelling urinary catheter (IUC) placement, performing proper maintenance of IUCs, and ensuring prompt removal of unnecessary urinary catheters.

Our project aims to combine all three approaches, along with staff education on IUC management and IUC alternatives. We plan to perform a “measure-vention,” or real-time monitoring and correction of defects by examining the rate of CAUTI as well as the percentage IUC utilization rate in participating units. Ultimately, we hope to optimize patient comfort and publicize our experience to help other health care facilities reduce IUC use and CAUTI.

I am excited to see how basic interventions, such as education and measure-vention can drive the development of improved health outcomes and quality patient care.

Victor Ekuta is a third-year medical student at the University of California, San Diego.

Editor’s note: The Society of Hospital Medicine’s (SHM’s) Physician in Training Committee launched a scholarship program in 2015 for medical students to help transform health care and revolutionize patient care. The program has been expanded for the 2017-2018 year, offering two options for students to receive funding and engage in scholarly work during their first, second, and third years of medical school. As a part of the longitudinal (18-month) program, recipients are required to write about their experiences on a monthly basis.

I am a third-year medical student at the University of California, San Diego, as well as a recipient of the SHM Longitudinal Scholar Grant. Ultimately, I intend to pursue a career in academic medicine as a clinician-scientist, where I hope to bridge my interests in neuroscience, research, and clinical medicine.

Prior to entering medical school, I participated in a wide array of basic science, translational, and clinical research projects, but none in the area of quality improvement (QI). Given the breadth of my previous research experiences, an attractive feature of the SHM Hospitalist grant was the opportunity to complement this breadth of research exposure with increasing depth by exploring a QI project.

This year, I’ll be getting my first exposure to a QI project under the fine mentorship of Ian Jenkins, MD, SFHM, an attending in the division of hospital medicine at UCSD, who is working on an ongoing effort to combat catheter–associated urinary tract infections (CAUTI). Methods for reducing CAUTI include reducing indwelling urinary catheter (IUC) placement, performing proper maintenance of IUCs, and ensuring prompt removal of unnecessary urinary catheters.

Our project aims to combine all three approaches, along with staff education on IUC management and IUC alternatives. We plan to perform a “measure-vention,” or real-time monitoring and correction of defects by examining the rate of CAUTI as well as the percentage IUC utilization rate in participating units. Ultimately, we hope to optimize patient comfort and publicize our experience to help other health care facilities reduce IUC use and CAUTI.

I am excited to see how basic interventions, such as education and measure-vention can drive the development of improved health outcomes and quality patient care.

Victor Ekuta is a third-year medical student at the University of California, San Diego.

Editor’s note: The Society of Hospital Medicine’s (SHM’s) Physician in Training Committee launched a scholarship program in 2015 for medical students to help transform health care and revolutionize patient care. The program has been expanded for the 2017-2018 year, offering two options for students to receive funding and engage in scholarly work during their first, second, and third years of medical school. As a part of the longitudinal (18-month) program, recipients are required to write about their experiences on a monthly basis.

I am a third-year medical student at the University of California, San Diego, as well as a recipient of the SHM Longitudinal Scholar Grant. Ultimately, I intend to pursue a career in academic medicine as a clinician-scientist, where I hope to bridge my interests in neuroscience, research, and clinical medicine.

Prior to entering medical school, I participated in a wide array of basic science, translational, and clinical research projects, but none in the area of quality improvement (QI). Given the breadth of my previous research experiences, an attractive feature of the SHM Hospitalist grant was the opportunity to complement this breadth of research exposure with increasing depth by exploring a QI project.

This year, I’ll be getting my first exposure to a QI project under the fine mentorship of Ian Jenkins, MD, SFHM, an attending in the division of hospital medicine at UCSD, who is working on an ongoing effort to combat catheter–associated urinary tract infections (CAUTI). Methods for reducing CAUTI include reducing indwelling urinary catheter (IUC) placement, performing proper maintenance of IUCs, and ensuring prompt removal of unnecessary urinary catheters.

Our project aims to combine all three approaches, along with staff education on IUC management and IUC alternatives. We plan to perform a “measure-vention,” or real-time monitoring and correction of defects by examining the rate of CAUTI as well as the percentage IUC utilization rate in participating units. Ultimately, we hope to optimize patient comfort and publicize our experience to help other health care facilities reduce IUC use and CAUTI.

I am excited to see how basic interventions, such as education and measure-vention can drive the development of improved health outcomes and quality patient care.

Victor Ekuta is a third-year medical student at the University of California, San Diego.

HEART score can safely identify low risk chest pain

Clinical Question: Can the HEART score risk stratify emergency department patients with chest pain?

Background: Many patients with chest pain are subjected to unnecessary admission and testing. The HEART (History, Electrocardiogram, Age, Risk factors, and initial Troponin) score can accurately predict outcomes in chest pain patients, though it has undergone limited evaluation in real world settings.

Setting: Nine emergency departments in the Netherlands.

Synopsis: All sites started by providing usual care, then sequentially switched over to use of the HEART score to guide treatment. HEART care recommended early discharge if low risk (HEART score, 0-3), admission and further testing if intermediate risk (4-6), and early invasive testing if high risk (7-10).

The study included 3,648 adults presenting with chest pain. The HEART score was noninferior to usual care for the safety outcome of major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) within 6 weeks. Only 2.0% of low risk patients experienced MACE, though 41% of these patients were still admitted or sent for further testing, and reduction in health care cost was minimal.

Bottom Line: The HEART score accurately predicted risk in patients with chest pain, but a significant portion of low risk patients underwent further testing anyway.

Citation: Poldervaart JM, Reitsma JB, Backus BE, et al. Effect of using the HEART score in patients with chest pain in the emergency department. Ann Intern Med. 2017 May 16;166(10):689-97.

Dr. Troy is assistant professor in the University of Kentucky division of hospital medicine.

Clinical Question: Can the HEART score risk stratify emergency department patients with chest pain?

Background: Many patients with chest pain are subjected to unnecessary admission and testing. The HEART (History, Electrocardiogram, Age, Risk factors, and initial Troponin) score can accurately predict outcomes in chest pain patients, though it has undergone limited evaluation in real world settings.

Setting: Nine emergency departments in the Netherlands.

Synopsis: All sites started by providing usual care, then sequentially switched over to use of the HEART score to guide treatment. HEART care recommended early discharge if low risk (HEART score, 0-3), admission and further testing if intermediate risk (4-6), and early invasive testing if high risk (7-10).

The study included 3,648 adults presenting with chest pain. The HEART score was noninferior to usual care for the safety outcome of major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) within 6 weeks. Only 2.0% of low risk patients experienced MACE, though 41% of these patients were still admitted or sent for further testing, and reduction in health care cost was minimal.

Bottom Line: The HEART score accurately predicted risk in patients with chest pain, but a significant portion of low risk patients underwent further testing anyway.

Citation: Poldervaart JM, Reitsma JB, Backus BE, et al. Effect of using the HEART score in patients with chest pain in the emergency department. Ann Intern Med. 2017 May 16;166(10):689-97.

Dr. Troy is assistant professor in the University of Kentucky division of hospital medicine.

Clinical Question: Can the HEART score risk stratify emergency department patients with chest pain?

Background: Many patients with chest pain are subjected to unnecessary admission and testing. The HEART (History, Electrocardiogram, Age, Risk factors, and initial Troponin) score can accurately predict outcomes in chest pain patients, though it has undergone limited evaluation in real world settings.

Setting: Nine emergency departments in the Netherlands.

Synopsis: All sites started by providing usual care, then sequentially switched over to use of the HEART score to guide treatment. HEART care recommended early discharge if low risk (HEART score, 0-3), admission and further testing if intermediate risk (4-6), and early invasive testing if high risk (7-10).

The study included 3,648 adults presenting with chest pain. The HEART score was noninferior to usual care for the safety outcome of major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) within 6 weeks. Only 2.0% of low risk patients experienced MACE, though 41% of these patients were still admitted or sent for further testing, and reduction in health care cost was minimal.

Bottom Line: The HEART score accurately predicted risk in patients with chest pain, but a significant portion of low risk patients underwent further testing anyway.

Citation: Poldervaart JM, Reitsma JB, Backus BE, et al. Effect of using the HEART score in patients with chest pain in the emergency department. Ann Intern Med. 2017 May 16;166(10):689-97.

Dr. Troy is assistant professor in the University of Kentucky division of hospital medicine.

Withdrawn AML drug back on market in US

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved use of gemtuzumab ozogamicin (GO, Mylotarg), a treatment that was initially approved by the agency in 2000 but later pulled from the US market.

GO is an antibody-drug conjugate that consists of the cytotoxic agent calicheamicin attached to a monoclonal antibody targeting CD33.

GO is now approved to treat adults with newly diagnosed, CD33-positive acute myeloid leukemia (AML) and patients age 2 and older with CD33-positive, relapsed or refractory AML.

GO can be given alone or in combination with daunorubicin and cytarabine.

The prescribing information for GO includes a boxed warning detailing the risk of hepatotoxicity, including veno-occlusive disease or sinusoidal obstruction syndrome, associated with GO.

GO originates from a collaboration between Pfizer and Celltech, now UCB. Pfizer has sole responsibility for all manufacturing, clinical development, and commercialization activities for this molecule.

Market withdrawal and subsequent trials

GO was originally approved under the FDA’s accelerated approval program in 2000 for use as a single agent in patients with CD33-positive AML who had experienced their first relapse and were 60 years of age or older.

In 2010, Pfizer voluntarily withdrew GO from the US market due to the results of a confirmatory phase 3 trial, SWOG S0106.

This trial showed there was no clinical benefit for patients who received GO plus daunorubicin and cytarabine over patients who received only daunorubicin and cytarabine.

In addition, the rate of fatal, treatment-related toxicity was significantly higher in the GO arm of the study.

Because of the unmet need for effective treatments in AML, investigators expressed an interest in evaluating different doses and schedules of GO.

These independent investigators, with Pfizer’s support, conducted clinical trials that yielded more information on the efficacy and safety of GO.

The trials—ALFA-0701, AML-19, and MyloFrance-1—supported the new approval of GO. Updated data from these trials are included in the prescribing information, which is available for download at www.mylotarg.com. ![]()

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved use of gemtuzumab ozogamicin (GO, Mylotarg), a treatment that was initially approved by the agency in 2000 but later pulled from the US market.

GO is an antibody-drug conjugate that consists of the cytotoxic agent calicheamicin attached to a monoclonal antibody targeting CD33.

GO is now approved to treat adults with newly diagnosed, CD33-positive acute myeloid leukemia (AML) and patients age 2 and older with CD33-positive, relapsed or refractory AML.

GO can be given alone or in combination with daunorubicin and cytarabine.

The prescribing information for GO includes a boxed warning detailing the risk of hepatotoxicity, including veno-occlusive disease or sinusoidal obstruction syndrome, associated with GO.

GO originates from a collaboration between Pfizer and Celltech, now UCB. Pfizer has sole responsibility for all manufacturing, clinical development, and commercialization activities for this molecule.

Market withdrawal and subsequent trials

GO was originally approved under the FDA’s accelerated approval program in 2000 for use as a single agent in patients with CD33-positive AML who had experienced their first relapse and were 60 years of age or older.

In 2010, Pfizer voluntarily withdrew GO from the US market due to the results of a confirmatory phase 3 trial, SWOG S0106.

This trial showed there was no clinical benefit for patients who received GO plus daunorubicin and cytarabine over patients who received only daunorubicin and cytarabine.

In addition, the rate of fatal, treatment-related toxicity was significantly higher in the GO arm of the study.

Because of the unmet need for effective treatments in AML, investigators expressed an interest in evaluating different doses and schedules of GO.

These independent investigators, with Pfizer’s support, conducted clinical trials that yielded more information on the efficacy and safety of GO.

The trials—ALFA-0701, AML-19, and MyloFrance-1—supported the new approval of GO. Updated data from these trials are included in the prescribing information, which is available for download at www.mylotarg.com. ![]()

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved use of gemtuzumab ozogamicin (GO, Mylotarg), a treatment that was initially approved by the agency in 2000 but later pulled from the US market.

GO is an antibody-drug conjugate that consists of the cytotoxic agent calicheamicin attached to a monoclonal antibody targeting CD33.

GO is now approved to treat adults with newly diagnosed, CD33-positive acute myeloid leukemia (AML) and patients age 2 and older with CD33-positive, relapsed or refractory AML.

GO can be given alone or in combination with daunorubicin and cytarabine.

The prescribing information for GO includes a boxed warning detailing the risk of hepatotoxicity, including veno-occlusive disease or sinusoidal obstruction syndrome, associated with GO.

GO originates from a collaboration between Pfizer and Celltech, now UCB. Pfizer has sole responsibility for all manufacturing, clinical development, and commercialization activities for this molecule.

Market withdrawal and subsequent trials

GO was originally approved under the FDA’s accelerated approval program in 2000 for use as a single agent in patients with CD33-positive AML who had experienced their first relapse and were 60 years of age or older.

In 2010, Pfizer voluntarily withdrew GO from the US market due to the results of a confirmatory phase 3 trial, SWOG S0106.

This trial showed there was no clinical benefit for patients who received GO plus daunorubicin and cytarabine over patients who received only daunorubicin and cytarabine.

In addition, the rate of fatal, treatment-related toxicity was significantly higher in the GO arm of the study.

Because of the unmet need for effective treatments in AML, investigators expressed an interest in evaluating different doses and schedules of GO.

These independent investigators, with Pfizer’s support, conducted clinical trials that yielded more information on the efficacy and safety of GO.

The trials—ALFA-0701, AML-19, and MyloFrance-1—supported the new approval of GO. Updated data from these trials are included in the prescribing information, which is available for download at www.mylotarg.com. ![]()

Are Aspartame’s Benefits Sugarcoated?

Since my high school days, I have used some form of artificial sweetener in lieu of sugar. Long believing that sugar avoidance was the key to weight maintenance, I didn’t give much thought to the published ill effects of sugar substitutes—after all, I wasn’t a mouse, and I wasn’t consuming mass doses. Did the artificial sweeteners assist in controlling my weight? Quite honestly, I doubt it—but I was so used to being “sugar free” that I was habituated to using these products.

Several years ago at a luncheon, I was reaching for a packet of artificial sweetener to pour into my iced tea when an NP friend stopped me. She and her husband (a pharmacist) had sworn off these products after noting that he was having issues with his cognition and experiencing increased irritability. With no obvious cause for these symptoms, they investigated his diet. He had, over the previous year, increased his use of aspartame. They found research supporting an association between aspartame and changes in behavior and cognition. When he stopped using the product, they both noticed a return to his former jovial, intellectual self. I acknowledged their research conclusion as an “n = 1” but gave it no further credence.

More recently, friends who had adopted an “all-natural” diet chastised me for drinking sugar-free seltzer. I had switched years ago from diet sodas to this beverage as my primary source of hydration. What could be wrong? It had zero calories, no sodium, and no sugar. Ah, but it contained aspartame! Since switching to a food plan without aspartame, my friends had observed that they were feeling better and more alert. Hmm, sounded familiar … maybe there was something to these claims after all. I did a little research of my own, and was I surprised!

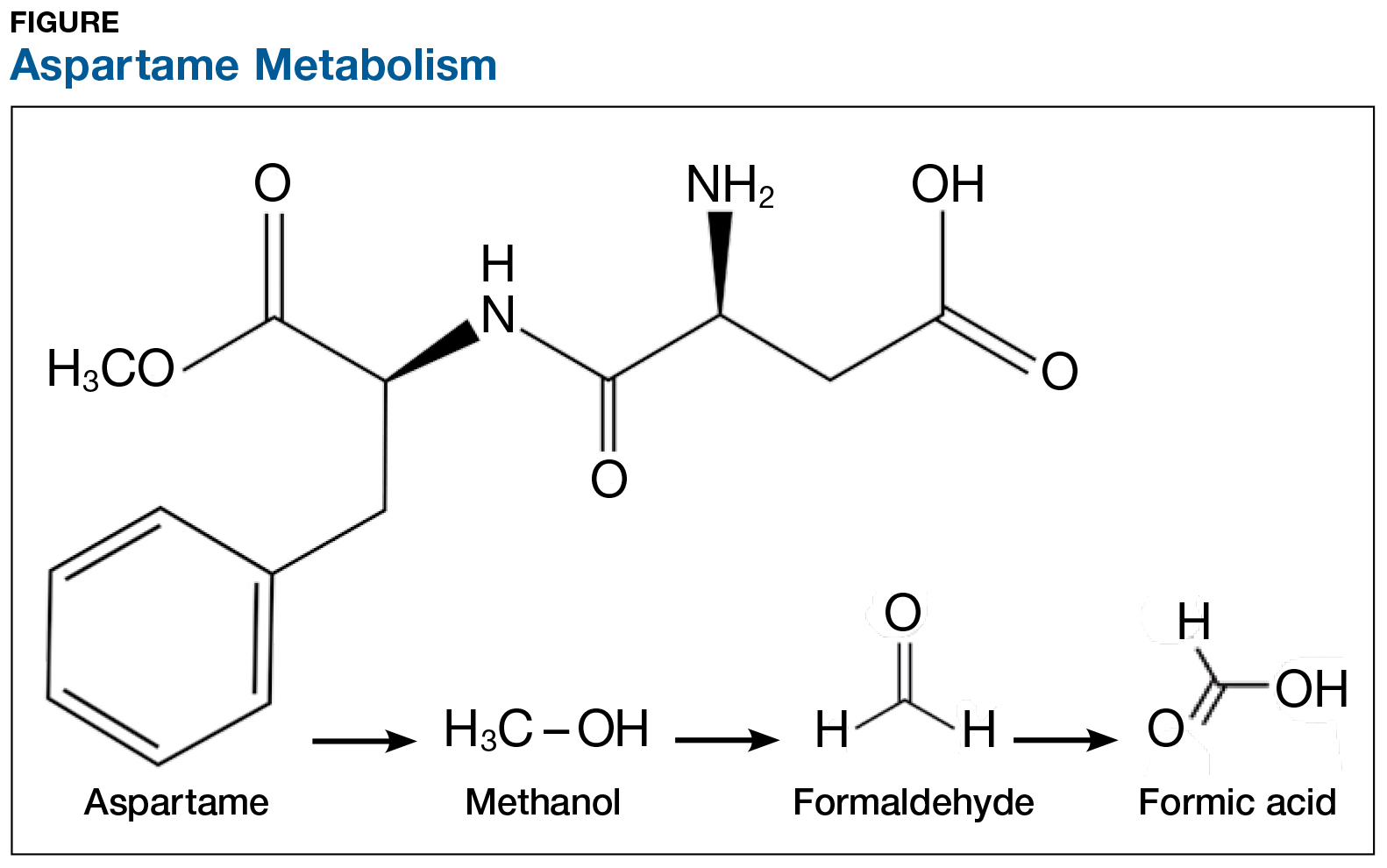

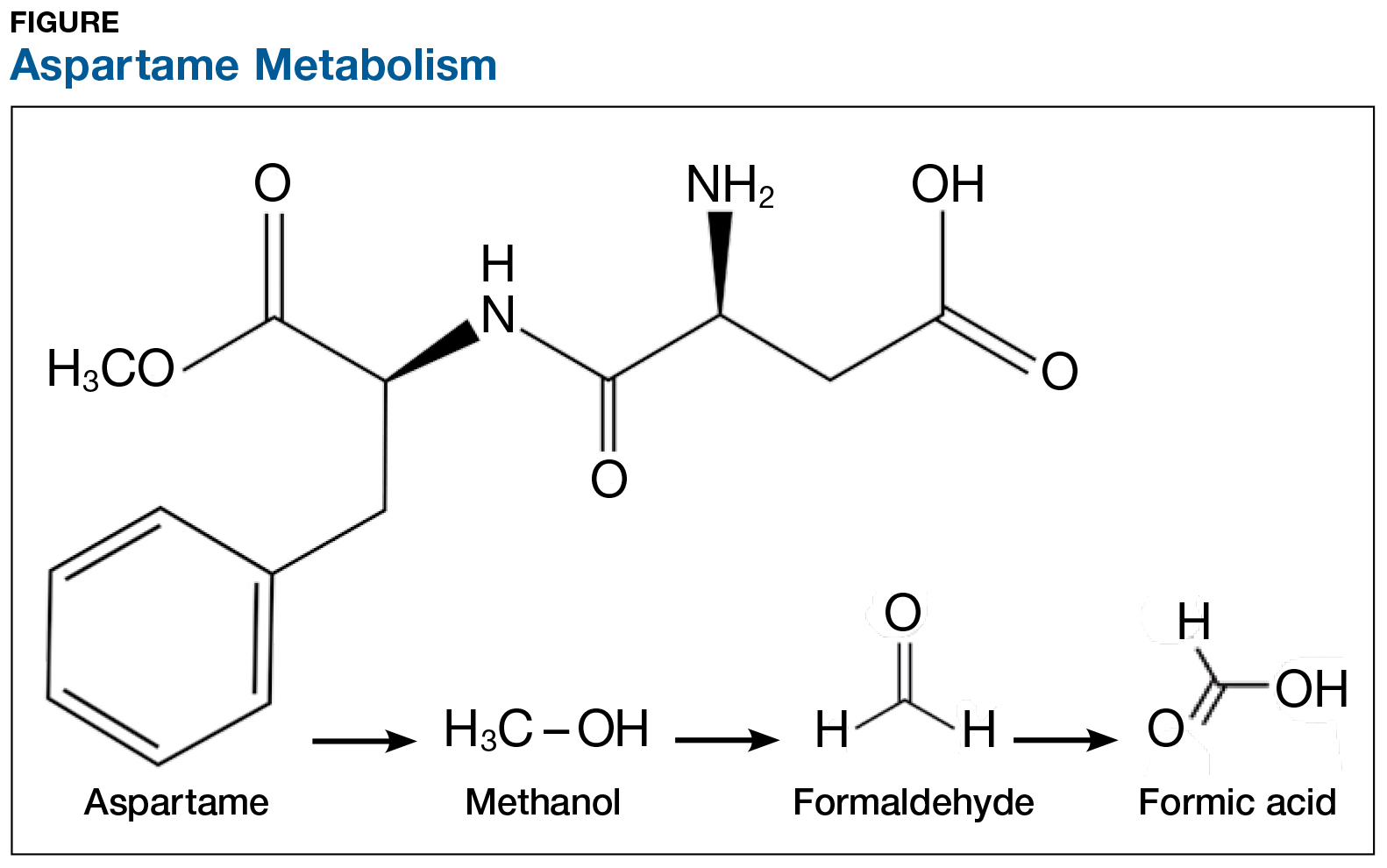

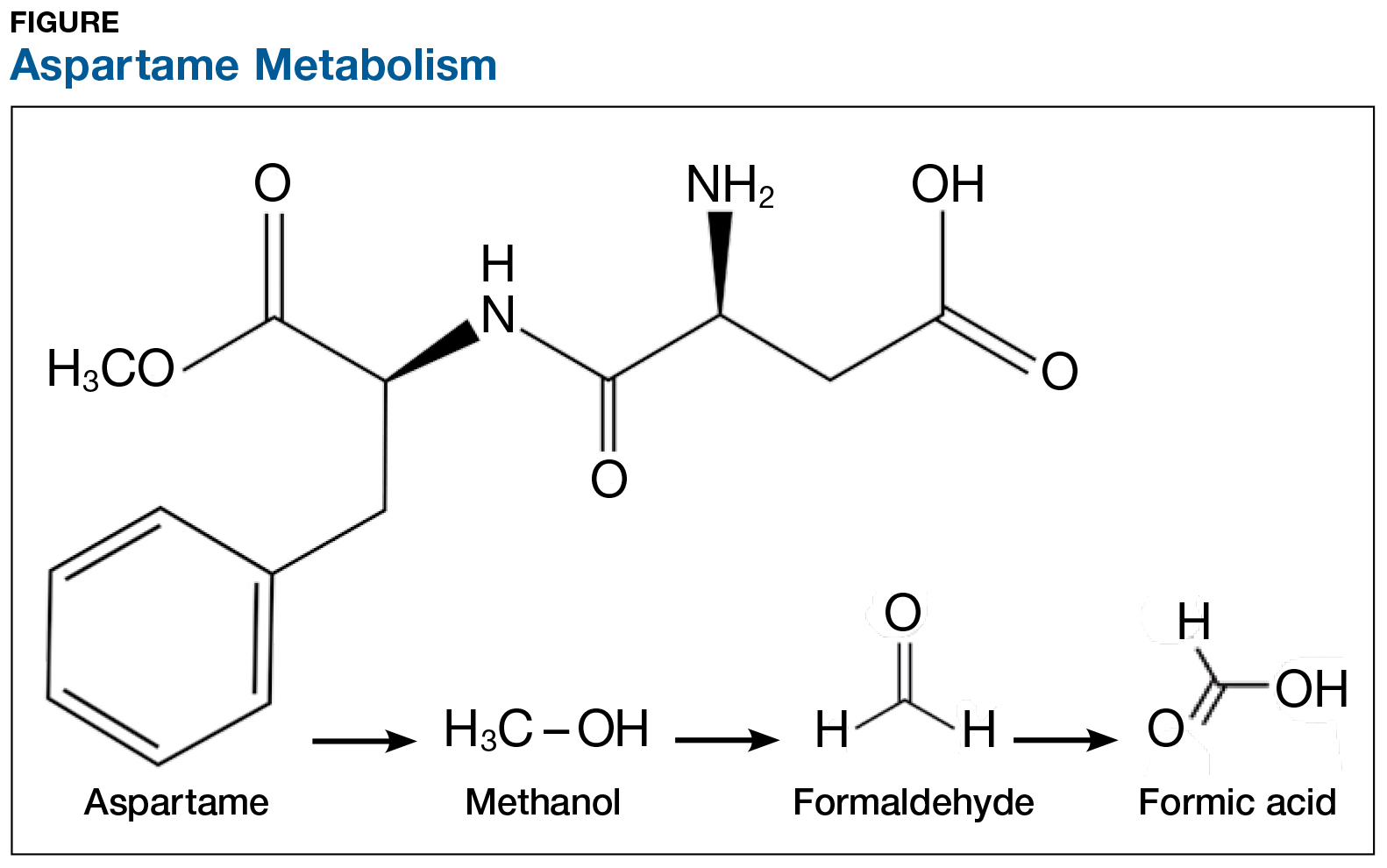

On the exterior, aspartame is a highly studied food additive with decades of research demonstrating its safety for human consumption.1 But what exactly happens when this sweetener is ingested? First, aspartame breaks down into amino acids and methanol (ie, wood alcohol). The methanol continues to break down into formaldehyde and formic acid, a substance commonly found in bee and ant venom (see Figure). And if that weren’t enough, a potential brain tumor agent (aspartylphenylalanine diketopiperazine) is also a residual byproduct.2,3 As you might expect, these components and byproducts come with varying adverse effects and potential health risks.

The majority of artificially sweetened beverages (ASBs) contain aspartame. As early as 1984—a mere six months after aspartame was approved for use in soft drinks—the FDA, with the assistance of the CDC, undertook an investigation of consumer complaints related to its use. The research team interviewed 517 complainants; 346 (67%) reported neurologic/behavioral symptoms, including headache, dizziness, and mood alteration.4 Despite that statistic, however, the researchers reported no evidence for the existence of serious, widespread, adverse health consequences resulting from aspartame consumption.4

Reading these reports reminded me of my friends’ comments and strongly suggested to me that soft drinks containing aspartame may be hard on the brain. Further to this point, a recent study found that ASB consumption is associated with an increased risk for stroke and dementia.5

Additional studies—including evaluations of possible associations between aspartame and headaches, seizures, behavior, cognition, and mood, as well as allergic-type reactions and use by potentially sensitive subpopulations—have been conducted. The verdict? Scientists maintain that aspartame is safe and that there are no unresolved questions regarding its safety when used as intended.6 Some researchers question the validity of the link between ASB consumption and negative health consequences, suggesting that individuals in worse health consume diet beverages in an effort to slow health deterioration or to lose weight.7 Yet, the debate about the effects of aspartame on our organs continues.

The number of epidemiologic studies that document strong associations between frequent ASB consumption and illness suggests that substituting or promoting artificial sweeteners as “healthy alternatives” to sugar may not be advisable.8 In fact, the most recent studies indicate that artificial sweeteners—the very compounds marketed to assist with weight control—can lead to weight gain, as they trick our brains into craving high-calorie foods. Moreover, ASB consumption is associated with a 21% increased risk for type 2 diabetes.9 Azad and colleagues found that evidence does not clearly support the use of nonnutritive sweeteners for weight management; they recommend using caution with these products until the long-term risks and benefits are fully understood.7

Is satisfying your sweet tooth with sugar alternatives worth the potential risk? Most of the studies conducted to support or refute aspartame-related health concerns prove correlation, not causality. A purist might point out that many of the studies have limitations that can lead to faulty conclusions. Be that as it may, it still gives one pause.

Small doses of aspartame each day might not be a tipping point toward the documented health complaints, but the consistent concerns about its effects were enough for me to make the switch to plain water, and sugar for my coffee. I do believe that Mary Poppins was correct—a spoonful of sugar does help—and I, for one, am following her lead.

What do you think? Are these concerns unfounded, or are we sweetening our road to poor health? Share your thoughts with me at [email protected].

1. Novella S. Aspartame: truth vs. fiction. https://sciencebasedmedicine.org/aspartame-truth-vs-fiction/. Accessed August 1, 2017.

2. Barua J, Bal A. Emerging facts about aspartame. www.manningsscience.com/uploads/8/6/8/1/8681125/article-on-aspartame.pdf. Accessed August 1, 2017.

3. Supersweet blog. Learning about sweeteners. https://supersweetblog.wordpress.com/aspartame/. Accessed August 1, 2017.

4. CDC. Evaluation of consumer complaints related to aspartame use. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1984;33(43):605-607.

5. Pase MP, Himali JJ, Beiser AS, et al. Sugar- and artificially sweetened beverages and the risks of incident stroke and dementia: a prospective cohort study. Stroke. 2017;48(5): 1139-1146.

6. Butchko HH, Stargel WW, Comer CP, et al. Aspartame: review of safety. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol. 2002;35(2):S1- S93.

7. Azad MB, Abou-Setta AM, Chauhan BF, et al. Nonnutritive sweeteners and cardiometabolic health: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials and prospective cohort studies. CMAJ. 2017;189(28): E929-E939.

8. Wersching H, Gardener H, Sacco L. Sugar-sweetened and artificially sweetened beverages in relation to stroke and dementia. Stroke. 2017;48(5):1129-1131.

9. Huang M, Quddus A, Stinson L, et al. Artificially sweetened beverages, sugar-sweetened beverages, plain water, and incident diabetes mellitus in postmenopausal women: the prospective Women’s Health Initiative observational study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2017;106:614-622.

Since my high school days, I have used some form of artificial sweetener in lieu of sugar. Long believing that sugar avoidance was the key to weight maintenance, I didn’t give much thought to the published ill effects of sugar substitutes—after all, I wasn’t a mouse, and I wasn’t consuming mass doses. Did the artificial sweeteners assist in controlling my weight? Quite honestly, I doubt it—but I was so used to being “sugar free” that I was habituated to using these products.

Several years ago at a luncheon, I was reaching for a packet of artificial sweetener to pour into my iced tea when an NP friend stopped me. She and her husband (a pharmacist) had sworn off these products after noting that he was having issues with his cognition and experiencing increased irritability. With no obvious cause for these symptoms, they investigated his diet. He had, over the previous year, increased his use of aspartame. They found research supporting an association between aspartame and changes in behavior and cognition. When he stopped using the product, they both noticed a return to his former jovial, intellectual self. I acknowledged their research conclusion as an “n = 1” but gave it no further credence.

More recently, friends who had adopted an “all-natural” diet chastised me for drinking sugar-free seltzer. I had switched years ago from diet sodas to this beverage as my primary source of hydration. What could be wrong? It had zero calories, no sodium, and no sugar. Ah, but it contained aspartame! Since switching to a food plan without aspartame, my friends had observed that they were feeling better and more alert. Hmm, sounded familiar … maybe there was something to these claims after all. I did a little research of my own, and was I surprised!

On the exterior, aspartame is a highly studied food additive with decades of research demonstrating its safety for human consumption.1 But what exactly happens when this sweetener is ingested? First, aspartame breaks down into amino acids and methanol (ie, wood alcohol). The methanol continues to break down into formaldehyde and formic acid, a substance commonly found in bee and ant venom (see Figure). And if that weren’t enough, a potential brain tumor agent (aspartylphenylalanine diketopiperazine) is also a residual byproduct.2,3 As you might expect, these components and byproducts come with varying adverse effects and potential health risks.

The majority of artificially sweetened beverages (ASBs) contain aspartame. As early as 1984—a mere six months after aspartame was approved for use in soft drinks—the FDA, with the assistance of the CDC, undertook an investigation of consumer complaints related to its use. The research team interviewed 517 complainants; 346 (67%) reported neurologic/behavioral symptoms, including headache, dizziness, and mood alteration.4 Despite that statistic, however, the researchers reported no evidence for the existence of serious, widespread, adverse health consequences resulting from aspartame consumption.4

Reading these reports reminded me of my friends’ comments and strongly suggested to me that soft drinks containing aspartame may be hard on the brain. Further to this point, a recent study found that ASB consumption is associated with an increased risk for stroke and dementia.5

Additional studies—including evaluations of possible associations between aspartame and headaches, seizures, behavior, cognition, and mood, as well as allergic-type reactions and use by potentially sensitive subpopulations—have been conducted. The verdict? Scientists maintain that aspartame is safe and that there are no unresolved questions regarding its safety when used as intended.6 Some researchers question the validity of the link between ASB consumption and negative health consequences, suggesting that individuals in worse health consume diet beverages in an effort to slow health deterioration or to lose weight.7 Yet, the debate about the effects of aspartame on our organs continues.

The number of epidemiologic studies that document strong associations between frequent ASB consumption and illness suggests that substituting or promoting artificial sweeteners as “healthy alternatives” to sugar may not be advisable.8 In fact, the most recent studies indicate that artificial sweeteners—the very compounds marketed to assist with weight control—can lead to weight gain, as they trick our brains into craving high-calorie foods. Moreover, ASB consumption is associated with a 21% increased risk for type 2 diabetes.9 Azad and colleagues found that evidence does not clearly support the use of nonnutritive sweeteners for weight management; they recommend using caution with these products until the long-term risks and benefits are fully understood.7

Is satisfying your sweet tooth with sugar alternatives worth the potential risk? Most of the studies conducted to support or refute aspartame-related health concerns prove correlation, not causality. A purist might point out that many of the studies have limitations that can lead to faulty conclusions. Be that as it may, it still gives one pause.

Small doses of aspartame each day might not be a tipping point toward the documented health complaints, but the consistent concerns about its effects were enough for me to make the switch to plain water, and sugar for my coffee. I do believe that Mary Poppins was correct—a spoonful of sugar does help—and I, for one, am following her lead.

What do you think? Are these concerns unfounded, or are we sweetening our road to poor health? Share your thoughts with me at [email protected].

Since my high school days, I have used some form of artificial sweetener in lieu of sugar. Long believing that sugar avoidance was the key to weight maintenance, I didn’t give much thought to the published ill effects of sugar substitutes—after all, I wasn’t a mouse, and I wasn’t consuming mass doses. Did the artificial sweeteners assist in controlling my weight? Quite honestly, I doubt it—but I was so used to being “sugar free” that I was habituated to using these products.

Several years ago at a luncheon, I was reaching for a packet of artificial sweetener to pour into my iced tea when an NP friend stopped me. She and her husband (a pharmacist) had sworn off these products after noting that he was having issues with his cognition and experiencing increased irritability. With no obvious cause for these symptoms, they investigated his diet. He had, over the previous year, increased his use of aspartame. They found research supporting an association between aspartame and changes in behavior and cognition. When he stopped using the product, they both noticed a return to his former jovial, intellectual self. I acknowledged their research conclusion as an “n = 1” but gave it no further credence.

More recently, friends who had adopted an “all-natural” diet chastised me for drinking sugar-free seltzer. I had switched years ago from diet sodas to this beverage as my primary source of hydration. What could be wrong? It had zero calories, no sodium, and no sugar. Ah, but it contained aspartame! Since switching to a food plan without aspartame, my friends had observed that they were feeling better and more alert. Hmm, sounded familiar … maybe there was something to these claims after all. I did a little research of my own, and was I surprised!

On the exterior, aspartame is a highly studied food additive with decades of research demonstrating its safety for human consumption.1 But what exactly happens when this sweetener is ingested? First, aspartame breaks down into amino acids and methanol (ie, wood alcohol). The methanol continues to break down into formaldehyde and formic acid, a substance commonly found in bee and ant venom (see Figure). And if that weren’t enough, a potential brain tumor agent (aspartylphenylalanine diketopiperazine) is also a residual byproduct.2,3 As you might expect, these components and byproducts come with varying adverse effects and potential health risks.

The majority of artificially sweetened beverages (ASBs) contain aspartame. As early as 1984—a mere six months after aspartame was approved for use in soft drinks—the FDA, with the assistance of the CDC, undertook an investigation of consumer complaints related to its use. The research team interviewed 517 complainants; 346 (67%) reported neurologic/behavioral symptoms, including headache, dizziness, and mood alteration.4 Despite that statistic, however, the researchers reported no evidence for the existence of serious, widespread, adverse health consequences resulting from aspartame consumption.4

Reading these reports reminded me of my friends’ comments and strongly suggested to me that soft drinks containing aspartame may be hard on the brain. Further to this point, a recent study found that ASB consumption is associated with an increased risk for stroke and dementia.5

Additional studies—including evaluations of possible associations between aspartame and headaches, seizures, behavior, cognition, and mood, as well as allergic-type reactions and use by potentially sensitive subpopulations—have been conducted. The verdict? Scientists maintain that aspartame is safe and that there are no unresolved questions regarding its safety when used as intended.6 Some researchers question the validity of the link between ASB consumption and negative health consequences, suggesting that individuals in worse health consume diet beverages in an effort to slow health deterioration or to lose weight.7 Yet, the debate about the effects of aspartame on our organs continues.

The number of epidemiologic studies that document strong associations between frequent ASB consumption and illness suggests that substituting or promoting artificial sweeteners as “healthy alternatives” to sugar may not be advisable.8 In fact, the most recent studies indicate that artificial sweeteners—the very compounds marketed to assist with weight control—can lead to weight gain, as they trick our brains into craving high-calorie foods. Moreover, ASB consumption is associated with a 21% increased risk for type 2 diabetes.9 Azad and colleagues found that evidence does not clearly support the use of nonnutritive sweeteners for weight management; they recommend using caution with these products until the long-term risks and benefits are fully understood.7

Is satisfying your sweet tooth with sugar alternatives worth the potential risk? Most of the studies conducted to support or refute aspartame-related health concerns prove correlation, not causality. A purist might point out that many of the studies have limitations that can lead to faulty conclusions. Be that as it may, it still gives one pause.

Small doses of aspartame each day might not be a tipping point toward the documented health complaints, but the consistent concerns about its effects were enough for me to make the switch to plain water, and sugar for my coffee. I do believe that Mary Poppins was correct—a spoonful of sugar does help—and I, for one, am following her lead.

What do you think? Are these concerns unfounded, or are we sweetening our road to poor health? Share your thoughts with me at [email protected].

1. Novella S. Aspartame: truth vs. fiction. https://sciencebasedmedicine.org/aspartame-truth-vs-fiction/. Accessed August 1, 2017.

2. Barua J, Bal A. Emerging facts about aspartame. www.manningsscience.com/uploads/8/6/8/1/8681125/article-on-aspartame.pdf. Accessed August 1, 2017.

3. Supersweet blog. Learning about sweeteners. https://supersweetblog.wordpress.com/aspartame/. Accessed August 1, 2017.

4. CDC. Evaluation of consumer complaints related to aspartame use. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1984;33(43):605-607.

5. Pase MP, Himali JJ, Beiser AS, et al. Sugar- and artificially sweetened beverages and the risks of incident stroke and dementia: a prospective cohort study. Stroke. 2017;48(5): 1139-1146.

6. Butchko HH, Stargel WW, Comer CP, et al. Aspartame: review of safety. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol. 2002;35(2):S1- S93.

7. Azad MB, Abou-Setta AM, Chauhan BF, et al. Nonnutritive sweeteners and cardiometabolic health: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials and prospective cohort studies. CMAJ. 2017;189(28): E929-E939.

8. Wersching H, Gardener H, Sacco L. Sugar-sweetened and artificially sweetened beverages in relation to stroke and dementia. Stroke. 2017;48(5):1129-1131.

9. Huang M, Quddus A, Stinson L, et al. Artificially sweetened beverages, sugar-sweetened beverages, plain water, and incident diabetes mellitus in postmenopausal women: the prospective Women’s Health Initiative observational study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2017;106:614-622.

1. Novella S. Aspartame: truth vs. fiction. https://sciencebasedmedicine.org/aspartame-truth-vs-fiction/. Accessed August 1, 2017.

2. Barua J, Bal A. Emerging facts about aspartame. www.manningsscience.com/uploads/8/6/8/1/8681125/article-on-aspartame.pdf. Accessed August 1, 2017.

3. Supersweet blog. Learning about sweeteners. https://supersweetblog.wordpress.com/aspartame/. Accessed August 1, 2017.

4. CDC. Evaluation of consumer complaints related to aspartame use. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1984;33(43):605-607.

5. Pase MP, Himali JJ, Beiser AS, et al. Sugar- and artificially sweetened beverages and the risks of incident stroke and dementia: a prospective cohort study. Stroke. 2017;48(5): 1139-1146.

6. Butchko HH, Stargel WW, Comer CP, et al. Aspartame: review of safety. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol. 2002;35(2):S1- S93.

7. Azad MB, Abou-Setta AM, Chauhan BF, et al. Nonnutritive sweeteners and cardiometabolic health: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials and prospective cohort studies. CMAJ. 2017;189(28): E929-E939.

8. Wersching H, Gardener H, Sacco L. Sugar-sweetened and artificially sweetened beverages in relation to stroke and dementia. Stroke. 2017;48(5):1129-1131.

9. Huang M, Quddus A, Stinson L, et al. Artificially sweetened beverages, sugar-sweetened beverages, plain water, and incident diabetes mellitus in postmenopausal women: the prospective Women’s Health Initiative observational study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2017;106:614-622.

Using EHR data to predict post-acute care placement

Editor’s Note: The Society of Hospital Medicine’s (SHM’s) Physician in Training Committee launched a scholarship program in 2015 for medical students to help transform health care and revolutionize patient care. The program has been expanded for the 2017-2018 year, offering two options for students to receive funding and engage in scholarly work during their first, second, and third years of medical school. As a part of the longitudinal (18-month) program, recipients are required to write about their experience on a monthly basis.

When patients are admitted to the hospital, the focus for the first 24 hours is on the work-up: What do the data point values tell you about how sick this patient is, and what will they need to get better? While the goal for this information is to develop the appropriate treatment and management for the patient’s acute problem, it could be leveraged to help with other parts of the patient’s hospital stay as well. In particular, it could help avoid unnecessarily long stays in the hospital caused by patients’ waiting for a bed at a lower level of care.

My research mentor, Eduard Vasilevskis, MD, created a rough scoring system for predicting post-acute care placement using admission data, just based on his clinical gestalt. Even at this preliminary stage, the model has already functioned well without much refinement; however a validated, statistically robust model could potentially transform the way that we initiate the discharge planning process. Jesse Ehrenfeld, MD has helped us develop it further by giving us access to a curated database of deidentified EHR data, which contains all of the variables we would like to assess.

The strengths of this potential model are manifold. First, it relies on data collected early in the patient’s hospital course. Second, it relies on routinely collected information (both at our home institution and elsewhere, making it potentially generalizable). And third, it relies on objective patient data rather than requiring providers use their impressions of the patients’ functional status to guess whether they will require discharge planning services. Although such prediction models have been generated before, this model would be among the first to incorporate information routinely collected by nursing staff, such as the Braden Scale, instead of relying on additional instruments or surveys. In addition to predicting placement destination, the model may also be predictive of in-hospital mortality.

With this information, we hope to give hospital teams an additional tool to help mobilize resources toward patients who need the most attention – not just while they’re in the hospital, but also on their way out.

Monisha Bhatia, a native of Nashville, Tenn., is a fourth-year medical student at Vanderbilt University in Nashville. She is hoping to pursue either a residency in internal medicine or a combined internal medicine/emergency medicine program. Prior to medical school, she completed a JD/MPH program at Boston University, and she hopes to use her legal training in working with regulatory authorities to improve access to health care for all Americans.

Editor’s Note: The Society of Hospital Medicine’s (SHM’s) Physician in Training Committee launched a scholarship program in 2015 for medical students to help transform health care and revolutionize patient care. The program has been expanded for the 2017-2018 year, offering two options for students to receive funding and engage in scholarly work during their first, second, and third years of medical school. As a part of the longitudinal (18-month) program, recipients are required to write about their experience on a monthly basis.

When patients are admitted to the hospital, the focus for the first 24 hours is on the work-up: What do the data point values tell you about how sick this patient is, and what will they need to get better? While the goal for this information is to develop the appropriate treatment and management for the patient’s acute problem, it could be leveraged to help with other parts of the patient’s hospital stay as well. In particular, it could help avoid unnecessarily long stays in the hospital caused by patients’ waiting for a bed at a lower level of care.

My research mentor, Eduard Vasilevskis, MD, created a rough scoring system for predicting post-acute care placement using admission data, just based on his clinical gestalt. Even at this preliminary stage, the model has already functioned well without much refinement; however a validated, statistically robust model could potentially transform the way that we initiate the discharge planning process. Jesse Ehrenfeld, MD has helped us develop it further by giving us access to a curated database of deidentified EHR data, which contains all of the variables we would like to assess.

The strengths of this potential model are manifold. First, it relies on data collected early in the patient’s hospital course. Second, it relies on routinely collected information (both at our home institution and elsewhere, making it potentially generalizable). And third, it relies on objective patient data rather than requiring providers use their impressions of the patients’ functional status to guess whether they will require discharge planning services. Although such prediction models have been generated before, this model would be among the first to incorporate information routinely collected by nursing staff, such as the Braden Scale, instead of relying on additional instruments or surveys. In addition to predicting placement destination, the model may also be predictive of in-hospital mortality.

With this information, we hope to give hospital teams an additional tool to help mobilize resources toward patients who need the most attention – not just while they’re in the hospital, but also on their way out.

Monisha Bhatia, a native of Nashville, Tenn., is a fourth-year medical student at Vanderbilt University in Nashville. She is hoping to pursue either a residency in internal medicine or a combined internal medicine/emergency medicine program. Prior to medical school, she completed a JD/MPH program at Boston University, and she hopes to use her legal training in working with regulatory authorities to improve access to health care for all Americans.

Editor’s Note: The Society of Hospital Medicine’s (SHM’s) Physician in Training Committee launched a scholarship program in 2015 for medical students to help transform health care and revolutionize patient care. The program has been expanded for the 2017-2018 year, offering two options for students to receive funding and engage in scholarly work during their first, second, and third years of medical school. As a part of the longitudinal (18-month) program, recipients are required to write about their experience on a monthly basis.

When patients are admitted to the hospital, the focus for the first 24 hours is on the work-up: What do the data point values tell you about how sick this patient is, and what will they need to get better? While the goal for this information is to develop the appropriate treatment and management for the patient’s acute problem, it could be leveraged to help with other parts of the patient’s hospital stay as well. In particular, it could help avoid unnecessarily long stays in the hospital caused by patients’ waiting for a bed at a lower level of care.

My research mentor, Eduard Vasilevskis, MD, created a rough scoring system for predicting post-acute care placement using admission data, just based on his clinical gestalt. Even at this preliminary stage, the model has already functioned well without much refinement; however a validated, statistically robust model could potentially transform the way that we initiate the discharge planning process. Jesse Ehrenfeld, MD has helped us develop it further by giving us access to a curated database of deidentified EHR data, which contains all of the variables we would like to assess.

The strengths of this potential model are manifold. First, it relies on data collected early in the patient’s hospital course. Second, it relies on routinely collected information (both at our home institution and elsewhere, making it potentially generalizable). And third, it relies on objective patient data rather than requiring providers use their impressions of the patients’ functional status to guess whether they will require discharge planning services. Although such prediction models have been generated before, this model would be among the first to incorporate information routinely collected by nursing staff, such as the Braden Scale, instead of relying on additional instruments or surveys. In addition to predicting placement destination, the model may also be predictive of in-hospital mortality.

With this information, we hope to give hospital teams an additional tool to help mobilize resources toward patients who need the most attention – not just while they’re in the hospital, but also on their way out.

Monisha Bhatia, a native of Nashville, Tenn., is a fourth-year medical student at Vanderbilt University in Nashville. She is hoping to pursue either a residency in internal medicine or a combined internal medicine/emergency medicine program. Prior to medical school, she completed a JD/MPH program at Boston University, and she hopes to use her legal training in working with regulatory authorities to improve access to health care for all Americans.

FDA reapproves gemtuzumab ozogamicin for CD33-positive AML treatment

The Food and Drug Administration has approved gemtuzumab ozogamicin (Mylotarg) for the treatment of newly diagnosed CD33-positive acute myeloid leukemia in adults, according to a press release.

Approval was based on results from three clinical trials. In the first, newly diagnosed AML patients who received gemtuzumab ozogamicin plus chemotherapy had significantly longer event-free survival than did patients who received chemotherapy alone. In a second trial, patients who received gemtuzumab ozogamicin alone had better overall survival compared to those who received only best supportive care. In the third clinical trial, 26% of patients who had experienced a relapse and received gemtuzumab ozogamicin experienced a remission.

Common side effects of gemtuzumab ozogamicin include fever, nausea, infection, vomiting, bleeding, thrombocytopenia, stomatitis, constipation, rash, headache, elevated liver function tests, and neutropenia; it is not recommended for women who are pregnant or breastfeeding.

Gemtuzumab ozogamicin was also approved to treat patients older than 2 years old who have experienced a relapse or have not responded to initial treatment.

“Mylotarg’s history underscores the importance of examining alternative dosing, scheduling, and administration of therapies for patients with cancer, especially in those who may be most vulnerable to the side effects of treatment,” Richard Pazdur, MD, director of the FDA’s Oncology Center of Excellence, said in the press release.

The Food and Drug Administration has approved gemtuzumab ozogamicin (Mylotarg) for the treatment of newly diagnosed CD33-positive acute myeloid leukemia in adults, according to a press release.

Approval was based on results from three clinical trials. In the first, newly diagnosed AML patients who received gemtuzumab ozogamicin plus chemotherapy had significantly longer event-free survival than did patients who received chemotherapy alone. In a second trial, patients who received gemtuzumab ozogamicin alone had better overall survival compared to those who received only best supportive care. In the third clinical trial, 26% of patients who had experienced a relapse and received gemtuzumab ozogamicin experienced a remission.

Common side effects of gemtuzumab ozogamicin include fever, nausea, infection, vomiting, bleeding, thrombocytopenia, stomatitis, constipation, rash, headache, elevated liver function tests, and neutropenia; it is not recommended for women who are pregnant or breastfeeding.

Gemtuzumab ozogamicin was also approved to treat patients older than 2 years old who have experienced a relapse or have not responded to initial treatment.

“Mylotarg’s history underscores the importance of examining alternative dosing, scheduling, and administration of therapies for patients with cancer, especially in those who may be most vulnerable to the side effects of treatment,” Richard Pazdur, MD, director of the FDA’s Oncology Center of Excellence, said in the press release.

The Food and Drug Administration has approved gemtuzumab ozogamicin (Mylotarg) for the treatment of newly diagnosed CD33-positive acute myeloid leukemia in adults, according to a press release.

Approval was based on results from three clinical trials. In the first, newly diagnosed AML patients who received gemtuzumab ozogamicin plus chemotherapy had significantly longer event-free survival than did patients who received chemotherapy alone. In a second trial, patients who received gemtuzumab ozogamicin alone had better overall survival compared to those who received only best supportive care. In the third clinical trial, 26% of patients who had experienced a relapse and received gemtuzumab ozogamicin experienced a remission.

Common side effects of gemtuzumab ozogamicin include fever, nausea, infection, vomiting, bleeding, thrombocytopenia, stomatitis, constipation, rash, headache, elevated liver function tests, and neutropenia; it is not recommended for women who are pregnant or breastfeeding.

Gemtuzumab ozogamicin was also approved to treat patients older than 2 years old who have experienced a relapse or have not responded to initial treatment.

“Mylotarg’s history underscores the importance of examining alternative dosing, scheduling, and administration of therapies for patients with cancer, especially in those who may be most vulnerable to the side effects of treatment,” Richard Pazdur, MD, director of the FDA’s Oncology Center of Excellence, said in the press release.

Medicare fee schedule: Proposed pay bump falls short of promise

Physicians will likely see a 0.31% uptick in their Medicare payments in 2018 and not the 0.5% promised in the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act.

Officials at the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services were not able to find adequate funding in so-called misvalued codes to back the larger increase, as required by law, according to the proposed Medicare physician fee schedule for 2018.

Other provisions in the proposed Medicare physician fee schedule may be more palatable than the petite pay raise.

The proposal would roll back data reporting requirements of the Physician Quality Reporting System (PQRS), to better align them with the new Quality Payment Program (QPP), and will waive half of penalties assessed for not meeting PQRS requirements in 2016.

“We are proposing these changes based on stakeholder feedback and to better align with the MIPS [Merit-based Incentive Payment System track of the QPP] data submission requirements for the quality performance category,” according to a CMS fact sheet on the proposed fee schedule.

“This will allow some physicians who attempted to report for the 2016 performance period to avoid penalties and better align PQRS with MIPS as physicians transition to QPP,” officials from the American College of Physicians said in a statement.

Other physician organizations said they believed the proposal did not go far enough.

“While the reductions in penalties represent a move in the right direction, the [American College of Rheumatology] believes CMS should establish a value modifier adjustment of zero for 2018,” ACR officials said in a statement. “This would align with the agency’s policy to ‘zero out’ the impact of the resource use component of the Merit-based Incentive Payment System in 2019, the successor to the value modifier program. This provides additional time to continue refining the cost measures and gives physicians more time to understand the program.”

The proposed fee schedule also would delay implementation of the appropriate use criteria (AUC) for imaging services, a program that would deny payments for imaging services unless the ordering physician consulted the appropriate use criteria.

The American Medical Association “appreciates CMS’ decision to postpone the implementation of this requirement until 2019 and to make the first year an opportunity for testing and education where consultation would not be required as a condition of payment for imaging services,” according to a statement.

“We also applaud the proposed delay in implementing AUC for diagnostic imaging studies,” ACR said in its statement. “We will be gauging the readiness of our members to use clinical support systems. ... We support simplifying and phasing-in the program requirements. The ACR also strongly supports larger exemptions to the program,” such as physicians in small groups and rural and underserved areas.

The proposed fee schedule also seeks feedback from physicians and organizations on how Medicare Part B pays for biosimilars. Under the 2016 fee schedule, the average sales prices (ASPs) for all biosimilar products assigned to the same reference product are included in the same CPT code, meaning the ASPs for all biosimilars of a common reference product are used to determine a single reimbursement rate.

That CMS is looking deeper at this is being seen as a plus.

Biosimilars “tied to the same reference product may not share all indications with one another or the reference product [and] a blended payment model may cause significant confusion in a multitiered biosimilars market that may include both interchangeable and noninterchangeable products,” the Biosimilars Forum said in a statement. The current situation “may lead to decreased physician confidence in how they are reimbursed and also dramatically reduce the investment in the development of biosimilars and thereby limit treatment options available to patients.”

Both the Biosimilars Forum and the ACR support unique codes for each biosimilar.

“Physicians can better track and monitor their effectiveness and ensure adequate pharmacovigilance in the area of biosimilars” by employing unique codes, according to ACR officials.

The fee schedule proposal also would expand the Medicare Diabetes Prevention Program (DPP), currently a demonstration project, taking it nationwide in 2018. The proposal outlines the payment structure and supplier enrollment requirements and compliance standards, as well as beneficiary engagement incentives.

Physicians would be paid based on performance goals being met by patients, including meeting certain numbers of service and maintenance sessions with the program as well as achieving specific weight loss goals. For beneficiaries who are able to lose at least 5% of body weight, physicians could receive up to $810. If that weight loss goal is not achieved, the most a physician could receive is $125, according to a CMS fact sheet. Currently, DPP can only be employed via office visit; however, the proposal would allow virtual make-up sessions.

“The new proposal provides more flexibility to DPP providers in supporting patient engagement and attendance and by making performance-based payments available if patients meet weight-loss targets over longer periods of time,” according to the AMA.

The fee schedule also proposes more telemedicine coverage, specifically for counseling to discuss the need for lung cancer screening, including eligibility determination and shared decision making, as well psychotherapy for crisis, with codes for the first 60 minutes of intervention and a separate code for each additional 30 minutes. Four add-on codes have been proposed to supplement existing codes that cover interactive complexity, chronic care management services, and health risk assessment.

For clinicians providing behavioral health services, CMS is proposing an increased payment for providing face-to-face office-based services that better reflects overhead expenses.

Comments on the fee schedule update are due Sept. 11 and can be made here. The final rule is expected in early November.

Physicians will likely see a 0.31% uptick in their Medicare payments in 2018 and not the 0.5% promised in the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act.

Officials at the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services were not able to find adequate funding in so-called misvalued codes to back the larger increase, as required by law, according to the proposed Medicare physician fee schedule for 2018.

Other provisions in the proposed Medicare physician fee schedule may be more palatable than the petite pay raise.

The proposal would roll back data reporting requirements of the Physician Quality Reporting System (PQRS), to better align them with the new Quality Payment Program (QPP), and will waive half of penalties assessed for not meeting PQRS requirements in 2016.

“We are proposing these changes based on stakeholder feedback and to better align with the MIPS [Merit-based Incentive Payment System track of the QPP] data submission requirements for the quality performance category,” according to a CMS fact sheet on the proposed fee schedule.

“This will allow some physicians who attempted to report for the 2016 performance period to avoid penalties and better align PQRS with MIPS as physicians transition to QPP,” officials from the American College of Physicians said in a statement.

Other physician organizations said they believed the proposal did not go far enough.

“While the reductions in penalties represent a move in the right direction, the [American College of Rheumatology] believes CMS should establish a value modifier adjustment of zero for 2018,” ACR officials said in a statement. “This would align with the agency’s policy to ‘zero out’ the impact of the resource use component of the Merit-based Incentive Payment System in 2019, the successor to the value modifier program. This provides additional time to continue refining the cost measures and gives physicians more time to understand the program.”

The proposed fee schedule also would delay implementation of the appropriate use criteria (AUC) for imaging services, a program that would deny payments for imaging services unless the ordering physician consulted the appropriate use criteria.

The American Medical Association “appreciates CMS’ decision to postpone the implementation of this requirement until 2019 and to make the first year an opportunity for testing and education where consultation would not be required as a condition of payment for imaging services,” according to a statement.

“We also applaud the proposed delay in implementing AUC for diagnostic imaging studies,” ACR said in its statement. “We will be gauging the readiness of our members to use clinical support systems. ... We support simplifying and phasing-in the program requirements. The ACR also strongly supports larger exemptions to the program,” such as physicians in small groups and rural and underserved areas.

The proposed fee schedule also seeks feedback from physicians and organizations on how Medicare Part B pays for biosimilars. Under the 2016 fee schedule, the average sales prices (ASPs) for all biosimilar products assigned to the same reference product are included in the same CPT code, meaning the ASPs for all biosimilars of a common reference product are used to determine a single reimbursement rate.

That CMS is looking deeper at this is being seen as a plus.

Biosimilars “tied to the same reference product may not share all indications with one another or the reference product [and] a blended payment model may cause significant confusion in a multitiered biosimilars market that may include both interchangeable and noninterchangeable products,” the Biosimilars Forum said in a statement. The current situation “may lead to decreased physician confidence in how they are reimbursed and also dramatically reduce the investment in the development of biosimilars and thereby limit treatment options available to patients.”

Both the Biosimilars Forum and the ACR support unique codes for each biosimilar.

“Physicians can better track and monitor their effectiveness and ensure adequate pharmacovigilance in the area of biosimilars” by employing unique codes, according to ACR officials.

The fee schedule proposal also would expand the Medicare Diabetes Prevention Program (DPP), currently a demonstration project, taking it nationwide in 2018. The proposal outlines the payment structure and supplier enrollment requirements and compliance standards, as well as beneficiary engagement incentives.

Physicians would be paid based on performance goals being met by patients, including meeting certain numbers of service and maintenance sessions with the program as well as achieving specific weight loss goals. For beneficiaries who are able to lose at least 5% of body weight, physicians could receive up to $810. If that weight loss goal is not achieved, the most a physician could receive is $125, according to a CMS fact sheet. Currently, DPP can only be employed via office visit; however, the proposal would allow virtual make-up sessions.

“The new proposal provides more flexibility to DPP providers in supporting patient engagement and attendance and by making performance-based payments available if patients meet weight-loss targets over longer periods of time,” according to the AMA.

The fee schedule also proposes more telemedicine coverage, specifically for counseling to discuss the need for lung cancer screening, including eligibility determination and shared decision making, as well psychotherapy for crisis, with codes for the first 60 minutes of intervention and a separate code for each additional 30 minutes. Four add-on codes have been proposed to supplement existing codes that cover interactive complexity, chronic care management services, and health risk assessment.

For clinicians providing behavioral health services, CMS is proposing an increased payment for providing face-to-face office-based services that better reflects overhead expenses.

Comments on the fee schedule update are due Sept. 11 and can be made here. The final rule is expected in early November.

Physicians will likely see a 0.31% uptick in their Medicare payments in 2018 and not the 0.5% promised in the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act.

Officials at the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services were not able to find adequate funding in so-called misvalued codes to back the larger increase, as required by law, according to the proposed Medicare physician fee schedule for 2018.

Other provisions in the proposed Medicare physician fee schedule may be more palatable than the petite pay raise.

The proposal would roll back data reporting requirements of the Physician Quality Reporting System (PQRS), to better align them with the new Quality Payment Program (QPP), and will waive half of penalties assessed for not meeting PQRS requirements in 2016.

“We are proposing these changes based on stakeholder feedback and to better align with the MIPS [Merit-based Incentive Payment System track of the QPP] data submission requirements for the quality performance category,” according to a CMS fact sheet on the proposed fee schedule.

“This will allow some physicians who attempted to report for the 2016 performance period to avoid penalties and better align PQRS with MIPS as physicians transition to QPP,” officials from the American College of Physicians said in a statement.

Other physician organizations said they believed the proposal did not go far enough.

“While the reductions in penalties represent a move in the right direction, the [American College of Rheumatology] believes CMS should establish a value modifier adjustment of zero for 2018,” ACR officials said in a statement. “This would align with the agency’s policy to ‘zero out’ the impact of the resource use component of the Merit-based Incentive Payment System in 2019, the successor to the value modifier program. This provides additional time to continue refining the cost measures and gives physicians more time to understand the program.”

The proposed fee schedule also would delay implementation of the appropriate use criteria (AUC) for imaging services, a program that would deny payments for imaging services unless the ordering physician consulted the appropriate use criteria.