User login

Patient-Reported Outcomes of Knotted and Knotless Glenohumeral Labral Repairs Are Equivalent

Take-Home Points

- There is no difference in PROMs following knotless or knotted labral repair.

- Operative time is shorter for knotless compared to knotted glenoid labral tears.

- Knotless constructs may be more predictable than knotted constructs biomechanically.

Orthopedic surgeons often encounter labral pathology, and labral tears historically have required open techniques.1-3 Arthroscopy allows for advanced visualization and treatment of shoulder lesions,4,5 including anterior, posterior, and superior labrum anterior to posterior (SLAP) lesions.6

The goal of arthroscopic labral repair is to restore joint stability while maintaining range of motion. Arthroscopically repairing the labrum with suture anchors has become the standard technique, and several studies have reported satisfactory biomechanical and clinical results.1,7-12 Surgeons traditionally have been required to tie knots for these anchors, but knot security varies significantly among experienced arthroscopic surgeons.13 In addition, knots can migrate,14 and bulky knots can cause chondral abrasion.15,16 Several manufacturers have introduced knotless anchors for soft-tissue fixation.15,17 The knotless technique provides a low-profile repair with potentially less operating time.8 These factors may warrant switching from knotted to knotless techniques if outcomes are clinically acceptable. However, few studies have compared knotted and knotless techniques for glenohumeral labral repair.8,15,18-21

We conducted a study to compare the clinical results and operative times of knotless and knotted fixation of anterior and posterior glenohumeral labral repairs and SLAP repairs. We hypothesized there would be no difference in patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) between knotted and knotless techniques.

Methods

We retrospectively evaluated data that had been prospectively collected between 2012 and 2016 in a Surgical Outcomes System (SOS; Arthrex) database. Participation in this registry is elective, and enrollment can occur on a case-by-case basis. The database stores data on basic demographics, PROMs, and operative time. Data for our specific analysis were available for surgeries performed by 115 different surgeons. Inclusion criteria included primary isolated arthroscopic anterior, isolated posterior, and isolated SLAP repair with completely knotted or completely knotless labral repair and minimum 1-year follow-up. Exclusion criteria included hybrid knotted–knotless repair, rotator cuff repair, revision surgery, open surgery, and lack of complete follow-up data.

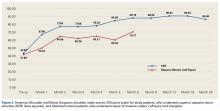

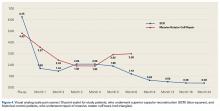

SOS is a proprietary registry that allows for the collection of basic patient demographics, diagnostic and operative data, and PROMs. PROMs in the SOS shoulder arthroscopy module include Veterans RAND 12-Item Health Survey (VR-12) mental health and physical health component summary scores, visual analog scale (VAS) pain scores, and American Shoulder and Elbow Surgeons (ASES) scores. For this study, PROMs were reviewed before surgery and 6 and 12 months after surgery. In addition, operative times of all procedures were collected.

For the analysis, completely knotted and completely knotless techniques were compared for anterior repair, posterior repair, and SLAP repair. A t test was used to compare the techniques on PROMs, and χ2 test was used to evaluate proportion differences. Statistical significance was set at P < .05.

Results

Anterior Labral Repairs

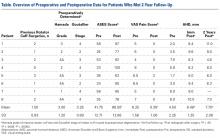

Of the 102 knotted anterior labral repairs that met the study criteria, 26 (25%) had minimum 1-year follow-up. Of the 122 knotless labral repairs, 33 (27%) had minimum 1-year follow-up. Seventy-five percent of knotted repairs and 80% of knotless repairs were performed in men. Mean (SD) age was 25.3 (11.7) years for the knotted group and 26.9 (10.6) years for the knotless group (P = .109). Anterior labral repairs did not differ in PROMs at any point (Table 1).

A mean of 2.8 anchors was used for knotted repairs, and a mean of 3.1 anchors was used for knotless repairs. Mean operative time was 75.8 minutes for knotted repairs and 67.5 minutes for knotless repairs. Mean (SD) time per anchor was 30.9 (13.9) minutes for knotted repairs and 25.6 (19.5) minutes for knotless repairs (P = .021).

Posterior Labral Repairs

Of the 165 knotted posterior labral repairs that met the study criteria, 39 (29%) had minimum 1-year follow-up. Of the 229 knotless labral repairs, 56 (24%) had minimum 1-year follow-up. Eighty-five percent of knotted repairs and 74% of knotless repairs were performed in men. Mean (SD) age was 29.1 (12.0) years for the knotted group and 27.5 (11.9) years for the knotless group (P = .148). Posterior labral repairs did not differ in PROMs before surgery or 1 year after surgery; 6 months after surgery, these repairs differed only in ASES scores (Table 2).

A mean of 3.6 anchors was used for knotted repairs, and a mean of 3.0 anchors was used for knotless repairs. Mean operative time was 67.0 minutes for knotted repairs and 43.1 minutes for knotless repairs. Mean (SD) time per anchor was 21.1 (10.7) minutes for knotted repairs and 17.5 (14.7) minutes for knotless repairs (P = .031).

SLAP Repairs

Of the 54 knotted SLAP repairs that met the study criteria, 24 (44%) had minimum 1-year follow-up. Of the 138 knotless SLAP repairs, 48 (35%) had minimum 1-year follow-up. Seventy-two percent of knotted repairs and 72% of knotless repairs were performed in men. Mean (SD) age was 32.1 (11.6) years for the knotted group and 35.0 (12.8) years for the knotless group (P = .246). SLAP repairs did not differ in PROMs at any point (Table 3).

A mean of 1.9 anchors was used for knotted repairs, and a mean of 2.1 anchors was used for knotless repairs. Mean operative time was 59.0 minutes for knotted repairs and 40.9 minutes for knotless repairs. Mean (SD) time per anchor was 36.6 (22.4) minutes for knotted repairs and 26.3 (14.0) minutes for knotless repairs (P = .080).

Discussion

Our hypothesis that there would be no difference in PROMs between knotted and knotless labral repairs was confirmed. Our findings are important because this study compared the gold standard of knotted suture anchor with the alternative knotless suture anchor in glenohumeral labral repair. These findings have several important implications for labral repair.

Knot tying traditionally has been used to achieve fixation with an anchor. Although simple in concept, knot tying can be challenging and its quality variable. Thal15 wrote that good-quality arthroscopic suture anchor repair is difficult to achieve because satisfactory knot tying requires significant practice with certain devices designed specifically for knot tying. Multiple surgeons have noted a significant learning curve associated with knot tying, and there is no agreement on which knot is superior.22-26 Leedle and Miller17 even suggested that, because knot tying is difficult, tying knots arthroscopically can lead to knot failure. In their study, they concluded that the knot is consistently the weakest link in suture repair of an anterior labrum construct. In a controlled laboratory study, Hanypsiak and colleagues13 found considerable knot-strength variability among expert arthroscopists. Only 65 (18%) of 365 knots tied fell within 20% of the mean for ultimate load failure, and only 128 (36%) of 365 fell within 20% of the mean for clinical failure (3 mm of displacement). These data suggested expert arthroscopists were unable to tie 5 consecutive knots of the same type consistently. Even among experts, it seems, knot strength varies significantly, and knot-strength issues may affect the rates of labral repair failure.

Multiple authors have also reported that bulky knots can cause chondral abrasion or that knots can migrate.25,27 Rhee and Ha27 reported that, when another knot (eg, a half-hitch knot) is tied to prevent knot failure, the resulting overall knot can be too bulky for a limited space, and chondral abrasion can result. In addition, regardless of size, a knot can migrate and, in its new position, start rubbing against the head of the humerus. Kim and colleagues14 found that, even when a knot is placed away from the humeral head, migration and repeated contact with the head are possible. Park and colleagues28 found that a significant number of knotted SLAP repairs required arthroscopic knot removal for relief of knot-induced pain and clicking.

Knotless constructs have several theoretical advantages over knotted constructs. Compared with a knotted technique, a knotless technique appears to provide more predictable strength, as variability in knot tying is eliminated (unpublished data). A knotless repair also has a lower profile,8 which should lead to less contact with the humeral head.19 Last, a knotless repair is more efficient—it takes less time to perform. In our study, operative time was reduced by a mean of 5.3 minutes per anchor for anterior labral repair. Assuming a mean of 3 anchors, this reduction equates to 16 minutes per case. Therefore, a surgeon who performs 25 labral repairs a year can save 6.7 hours a year. Reduced operative time benefits the patient (ie, lower risk of infection and other complications29), the surgeon, and the healthcare system (ie, cost savings). Macario30 found that operating room costs averaged $62 per minute (range, $22-$133 per minute). Therefore, saving 16 minutes per case could lead to saving $992 per case. In summary, a knotless technique appears to be clinically and financially advantageous as long as its results are the same as or better than those of a knotted technique.

A few other studies have compared knotted and knotless techniques. In a cadaveric study, Slabaugh and colleagues20 found no difference in labral height between traditional and knotless suture anchors. Leedle and Miller17 found that knotless constructs are biomechanically stronger than knotted constructs in anterior labral repair. In a level 3 clinical study, Yang and colleagues21 compared a conventional vertical knot with a knotless horizontal mattress suture in 41 patients who underwent SLAP repair. Functional outcome was no different between the 2 groups, but postoperative range of motion was improved in the knotless group. Ng and Kumar31 compared 45 patients who had knotted Bankart repair with 42 patients who had knotless Bankart repair and found no difference in functional outcome or rate of recurrent dislocation. Similarly, Kocaoglu and colleagues22 found no difference in recurrence rate between 18 patients who underwent a knotted technique for arthroscopic Bankart repair and 20 patients who underwent a knotless technique. Our findings corroborate the findings of these studies and further support the idea that there is no difference between knotted and knotless constructs with respect to PROMs.

Study Limitations

The major strength of this study was its large cohort and large population of surgeons. However, there were several study limitations. First, we could not detail specific repair techniques, such as simple or horizontal mattress orientation, and rehabilitation protocols and other variables are likely as well. Second, the repair technique was not randomized, and therefore there may have been a selection bias based on tissue quality. Although we cannot prove no bias, we think it was unlikely given that the groups were similar in age. Third, our data did not include information on range of motion or recurrent instability. Our goal was simply to evaluate PROMs among multiple surgeons using the 2 techniques. Fourth, there was substantial follow-up loss, which introduced potential selection bias. Last, there may have been conditions under which a hybrid technique with inferior knot tying, combined with a hybrid knotless construct, could have proved advantageous.

Conclusion

Our data showed that the advantages of knotless repair are not compromised in clinical situations. Although the data showed no significant difference in clinical outcomes, knotless repairs may provide surgeons with shorter surgeries, simpler constructs, less potential for chondral damage, and more consistent suture tensioning. Additional studies may further confirm these results.

1. Levy DM, Cole BJ, Bach BR Jr. History of surgical intervention of anterior shoulder instability. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2016;25(6):e139-e150.

2. Gill TJ, Zarins B. Open repairs for the treatment of anterior shoulder instability. Am J Sports Med. 2003;31(1):142-153.

3. Millett PJ, Clavert P, Warner JJ. Open operative treatment for anterior shoulder instability: when and why? J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87(2):419-432.

4. Stein DA, Jazrawi L, Bartolozzi AR. Arthroscopic stabilization of anterior shoulder instability: a review of the literature. Arthroscopy. 2002;18(8):912-924.

5. Kim SH, Ha KI, Kim SH. Bankart repair in traumatic anterior shoulder instability: open versus arthroscopic technique. Arthroscopy. 2002;18(7):755-763.

6. Snyder SJ, Karzel RP, Del Pizzo W, Ferkel RD, Friedman MJ. SLAP lesions of the shoulder. Arthroscopy. 1990;6(4):274-279.

7. Hantes M, Raoulis V. Arthroscopic findings in anterior shoulder instability. Open Orthop J. 2017;11:119-132.

8. Sileo MJ, Lee SJ, Kremenic IJ, et al. Biomechanical comparison of a knotless suture anchor with standard suture anchor in the repair of type II SLAP tears. Arthroscopy. 2009;25(4):348-354.

9. Iqbal S, Jacobs U, Akhtar A, Macfarlane RJ, Waseem M. A history of shoulder surgery. Open Orthop J. 2013;7:305-309.

10. Garofalo R, Mocci A, Moretti B, et al. Arthroscopic treatment of anterior shoulder instability using knotless suture anchors. Arthroscopy. 2005;21(11):1283-1289.

11. Kersten AD, Fabing M, Ensminger S, et al. Suture capsulorrhaphy versus capsulolabral advancement for shoulder instability. Arthroscopy. 2012;28(10):1344-1351.

12. Cole BJ, Warner JJ. Arthroscopic versus open Bankart repair for traumatic anterior shoulder instability. Clin Sports Med. 2000;19(1):19-48.

13. Hanypsiak BT, DeLong JM, Simmons L, Lowe W, Burkhart S. Knot strength varies widely among expert arthroscopists. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42(8):1978-1984.

14. Kim SH, Ha KI, Park JH, et al. Arthroscopic posterior labral repair and capsular shift for traumatic unidirectional recurrent posterior subluxation of the shoulder. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003;85(8):1479-1487.

15. Thal R. Knotless suture anchor. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2001;(390):42-51.

16. Loutzenheiser TD, Harryman DT 2nd, Yung SW, France MP, Sidles JA. Optimizing arthroscopic knots. Arthroscopy. 1995;11(2):199-206.

17. Leedle BP, Miller MD. Pullout strength of knotless suture anchors. Arthroscopy. 2005;21(1):81-85.

18. Caldwell PE 3rd, Pearson SE, D’Angelo MS. Arthroscopic knotless repair of the posterior labrum using LabralTape. Arthrosc Tech. 2016;5(2):e315-e320.

19. Tennent D, Concina C, Pearse E. Arthroscopic posterior stabilization of the shoulder using a percutaneous knotless mattress suture technique. Arthrosc Tech. 2014;3(1):e161-e164.

20. Slabaugh MA, Friel NA, Wang VM, Cole BJ. Restoring the labral height for treatment of Bankart lesions: a comparison of suture anchor constructs. Arthroscopy. 2010;26(5):587-591.

21. Yang HJ, Yoon K, Jin H, Song HS. Clinical outcome of arthroscopic SLAP repair: conventional vertical knot versus knotless horizontal mattress sutures. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2016;24(2):464-469.

22. Kocaoglu B, Guven O, Nalbantoglu U, Aydin N, Haklar U. No difference between knotless sutures and suture anchors in arthroscopic repair of Bankart lesions in collision athletes. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2009;17(7):844-849.

23. Aboalata M, Halawa A, Basyoni Y. The double Bankart bridge: a technique for restoration of the labral footprint in arthroscopic shoulder instability repair. Arthrosc Tech. 2017;6(1):e43-e47.

24. Rhee SM, Kang SY, Jang EC, Kim JY, Ha YC. Clinical outcomes after arthroscopic acetabular labral repair using knot-tying or knotless suture technique. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2016;136(10):1411-1416.

25. Oh JH, Lee HK, Kim JY, Kim SH, Gong HS. Clinical and radiologic outcomes of arthroscopic glenoid labrum repair with the BioKnotless suture anchor. Am J Sports Med. 2009;37(12):2340-2348.

26. Yian E, Wang C, Millett PJ, Warner JJ. Arthroscopic repair of SLAP lesions with a BioKnotless suture anchor. Arthroscopy. 2004;20(5):547-551.

27. Rhee YG, Ha JH. Knot-induced glenoid erosion after arthroscopic fixation for unstable superior labrum anterior-posterior lesion: case report. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2006;15(3):391-393.

28. Park JG, Cho NS, Kim JY, Song JH, Hong SJ, Rhee YG. Arthroscopic knot removal for failed superior labrum anterior-posterior repair secondary to knot-induced pain. Am J Sports Med. 2017;45(11):2563-2568.

29. Wang DS. Re: how slow is too slow? Correlation of operative time to complications: an analysis from the Tennessee Surgical Quality Collaborative. J Urol. 2016;195(5):1510-1511.

30. Macario A. What does one minute of operating room time cost? J Clin Anesth. 2010;22(4):233-236.

31. Ng DZ, Kumar VP. Arthroscopic Bankart repair using knot-tying versus knotless suture anchors: is there a difference? Arthroscopy. 2014;30(4):422-427.

Take-Home Points

- There is no difference in PROMs following knotless or knotted labral repair.

- Operative time is shorter for knotless compared to knotted glenoid labral tears.

- Knotless constructs may be more predictable than knotted constructs biomechanically.

Orthopedic surgeons often encounter labral pathology, and labral tears historically have required open techniques.1-3 Arthroscopy allows for advanced visualization and treatment of shoulder lesions,4,5 including anterior, posterior, and superior labrum anterior to posterior (SLAP) lesions.6

The goal of arthroscopic labral repair is to restore joint stability while maintaining range of motion. Arthroscopically repairing the labrum with suture anchors has become the standard technique, and several studies have reported satisfactory biomechanical and clinical results.1,7-12 Surgeons traditionally have been required to tie knots for these anchors, but knot security varies significantly among experienced arthroscopic surgeons.13 In addition, knots can migrate,14 and bulky knots can cause chondral abrasion.15,16 Several manufacturers have introduced knotless anchors for soft-tissue fixation.15,17 The knotless technique provides a low-profile repair with potentially less operating time.8 These factors may warrant switching from knotted to knotless techniques if outcomes are clinically acceptable. However, few studies have compared knotted and knotless techniques for glenohumeral labral repair.8,15,18-21

We conducted a study to compare the clinical results and operative times of knotless and knotted fixation of anterior and posterior glenohumeral labral repairs and SLAP repairs. We hypothesized there would be no difference in patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) between knotted and knotless techniques.

Methods

We retrospectively evaluated data that had been prospectively collected between 2012 and 2016 in a Surgical Outcomes System (SOS; Arthrex) database. Participation in this registry is elective, and enrollment can occur on a case-by-case basis. The database stores data on basic demographics, PROMs, and operative time. Data for our specific analysis were available for surgeries performed by 115 different surgeons. Inclusion criteria included primary isolated arthroscopic anterior, isolated posterior, and isolated SLAP repair with completely knotted or completely knotless labral repair and minimum 1-year follow-up. Exclusion criteria included hybrid knotted–knotless repair, rotator cuff repair, revision surgery, open surgery, and lack of complete follow-up data.

SOS is a proprietary registry that allows for the collection of basic patient demographics, diagnostic and operative data, and PROMs. PROMs in the SOS shoulder arthroscopy module include Veterans RAND 12-Item Health Survey (VR-12) mental health and physical health component summary scores, visual analog scale (VAS) pain scores, and American Shoulder and Elbow Surgeons (ASES) scores. For this study, PROMs were reviewed before surgery and 6 and 12 months after surgery. In addition, operative times of all procedures were collected.

For the analysis, completely knotted and completely knotless techniques were compared for anterior repair, posterior repair, and SLAP repair. A t test was used to compare the techniques on PROMs, and χ2 test was used to evaluate proportion differences. Statistical significance was set at P < .05.

Results

Anterior Labral Repairs

Of the 102 knotted anterior labral repairs that met the study criteria, 26 (25%) had minimum 1-year follow-up. Of the 122 knotless labral repairs, 33 (27%) had minimum 1-year follow-up. Seventy-five percent of knotted repairs and 80% of knotless repairs were performed in men. Mean (SD) age was 25.3 (11.7) years for the knotted group and 26.9 (10.6) years for the knotless group (P = .109). Anterior labral repairs did not differ in PROMs at any point (Table 1).

A mean of 2.8 anchors was used for knotted repairs, and a mean of 3.1 anchors was used for knotless repairs. Mean operative time was 75.8 minutes for knotted repairs and 67.5 minutes for knotless repairs. Mean (SD) time per anchor was 30.9 (13.9) minutes for knotted repairs and 25.6 (19.5) minutes for knotless repairs (P = .021).

Posterior Labral Repairs

Of the 165 knotted posterior labral repairs that met the study criteria, 39 (29%) had minimum 1-year follow-up. Of the 229 knotless labral repairs, 56 (24%) had minimum 1-year follow-up. Eighty-five percent of knotted repairs and 74% of knotless repairs were performed in men. Mean (SD) age was 29.1 (12.0) years for the knotted group and 27.5 (11.9) years for the knotless group (P = .148). Posterior labral repairs did not differ in PROMs before surgery or 1 year after surgery; 6 months after surgery, these repairs differed only in ASES scores (Table 2).

A mean of 3.6 anchors was used for knotted repairs, and a mean of 3.0 anchors was used for knotless repairs. Mean operative time was 67.0 minutes for knotted repairs and 43.1 minutes for knotless repairs. Mean (SD) time per anchor was 21.1 (10.7) minutes for knotted repairs and 17.5 (14.7) minutes for knotless repairs (P = .031).

SLAP Repairs

Of the 54 knotted SLAP repairs that met the study criteria, 24 (44%) had minimum 1-year follow-up. Of the 138 knotless SLAP repairs, 48 (35%) had minimum 1-year follow-up. Seventy-two percent of knotted repairs and 72% of knotless repairs were performed in men. Mean (SD) age was 32.1 (11.6) years for the knotted group and 35.0 (12.8) years for the knotless group (P = .246). SLAP repairs did not differ in PROMs at any point (Table 3).

A mean of 1.9 anchors was used for knotted repairs, and a mean of 2.1 anchors was used for knotless repairs. Mean operative time was 59.0 minutes for knotted repairs and 40.9 minutes for knotless repairs. Mean (SD) time per anchor was 36.6 (22.4) minutes for knotted repairs and 26.3 (14.0) minutes for knotless repairs (P = .080).

Discussion

Our hypothesis that there would be no difference in PROMs between knotted and knotless labral repairs was confirmed. Our findings are important because this study compared the gold standard of knotted suture anchor with the alternative knotless suture anchor in glenohumeral labral repair. These findings have several important implications for labral repair.

Knot tying traditionally has been used to achieve fixation with an anchor. Although simple in concept, knot tying can be challenging and its quality variable. Thal15 wrote that good-quality arthroscopic suture anchor repair is difficult to achieve because satisfactory knot tying requires significant practice with certain devices designed specifically for knot tying. Multiple surgeons have noted a significant learning curve associated with knot tying, and there is no agreement on which knot is superior.22-26 Leedle and Miller17 even suggested that, because knot tying is difficult, tying knots arthroscopically can lead to knot failure. In their study, they concluded that the knot is consistently the weakest link in suture repair of an anterior labrum construct. In a controlled laboratory study, Hanypsiak and colleagues13 found considerable knot-strength variability among expert arthroscopists. Only 65 (18%) of 365 knots tied fell within 20% of the mean for ultimate load failure, and only 128 (36%) of 365 fell within 20% of the mean for clinical failure (3 mm of displacement). These data suggested expert arthroscopists were unable to tie 5 consecutive knots of the same type consistently. Even among experts, it seems, knot strength varies significantly, and knot-strength issues may affect the rates of labral repair failure.

Multiple authors have also reported that bulky knots can cause chondral abrasion or that knots can migrate.25,27 Rhee and Ha27 reported that, when another knot (eg, a half-hitch knot) is tied to prevent knot failure, the resulting overall knot can be too bulky for a limited space, and chondral abrasion can result. In addition, regardless of size, a knot can migrate and, in its new position, start rubbing against the head of the humerus. Kim and colleagues14 found that, even when a knot is placed away from the humeral head, migration and repeated contact with the head are possible. Park and colleagues28 found that a significant number of knotted SLAP repairs required arthroscopic knot removal for relief of knot-induced pain and clicking.

Knotless constructs have several theoretical advantages over knotted constructs. Compared with a knotted technique, a knotless technique appears to provide more predictable strength, as variability in knot tying is eliminated (unpublished data). A knotless repair also has a lower profile,8 which should lead to less contact with the humeral head.19 Last, a knotless repair is more efficient—it takes less time to perform. In our study, operative time was reduced by a mean of 5.3 minutes per anchor for anterior labral repair. Assuming a mean of 3 anchors, this reduction equates to 16 minutes per case. Therefore, a surgeon who performs 25 labral repairs a year can save 6.7 hours a year. Reduced operative time benefits the patient (ie, lower risk of infection and other complications29), the surgeon, and the healthcare system (ie, cost savings). Macario30 found that operating room costs averaged $62 per minute (range, $22-$133 per minute). Therefore, saving 16 minutes per case could lead to saving $992 per case. In summary, a knotless technique appears to be clinically and financially advantageous as long as its results are the same as or better than those of a knotted technique.

A few other studies have compared knotted and knotless techniques. In a cadaveric study, Slabaugh and colleagues20 found no difference in labral height between traditional and knotless suture anchors. Leedle and Miller17 found that knotless constructs are biomechanically stronger than knotted constructs in anterior labral repair. In a level 3 clinical study, Yang and colleagues21 compared a conventional vertical knot with a knotless horizontal mattress suture in 41 patients who underwent SLAP repair. Functional outcome was no different between the 2 groups, but postoperative range of motion was improved in the knotless group. Ng and Kumar31 compared 45 patients who had knotted Bankart repair with 42 patients who had knotless Bankart repair and found no difference in functional outcome or rate of recurrent dislocation. Similarly, Kocaoglu and colleagues22 found no difference in recurrence rate between 18 patients who underwent a knotted technique for arthroscopic Bankart repair and 20 patients who underwent a knotless technique. Our findings corroborate the findings of these studies and further support the idea that there is no difference between knotted and knotless constructs with respect to PROMs.

Study Limitations

The major strength of this study was its large cohort and large population of surgeons. However, there were several study limitations. First, we could not detail specific repair techniques, such as simple or horizontal mattress orientation, and rehabilitation protocols and other variables are likely as well. Second, the repair technique was not randomized, and therefore there may have been a selection bias based on tissue quality. Although we cannot prove no bias, we think it was unlikely given that the groups were similar in age. Third, our data did not include information on range of motion or recurrent instability. Our goal was simply to evaluate PROMs among multiple surgeons using the 2 techniques. Fourth, there was substantial follow-up loss, which introduced potential selection bias. Last, there may have been conditions under which a hybrid technique with inferior knot tying, combined with a hybrid knotless construct, could have proved advantageous.

Conclusion

Our data showed that the advantages of knotless repair are not compromised in clinical situations. Although the data showed no significant difference in clinical outcomes, knotless repairs may provide surgeons with shorter surgeries, simpler constructs, less potential for chondral damage, and more consistent suture tensioning. Additional studies may further confirm these results.

Take-Home Points

- There is no difference in PROMs following knotless or knotted labral repair.

- Operative time is shorter for knotless compared to knotted glenoid labral tears.

- Knotless constructs may be more predictable than knotted constructs biomechanically.

Orthopedic surgeons often encounter labral pathology, and labral tears historically have required open techniques.1-3 Arthroscopy allows for advanced visualization and treatment of shoulder lesions,4,5 including anterior, posterior, and superior labrum anterior to posterior (SLAP) lesions.6

The goal of arthroscopic labral repair is to restore joint stability while maintaining range of motion. Arthroscopically repairing the labrum with suture anchors has become the standard technique, and several studies have reported satisfactory biomechanical and clinical results.1,7-12 Surgeons traditionally have been required to tie knots for these anchors, but knot security varies significantly among experienced arthroscopic surgeons.13 In addition, knots can migrate,14 and bulky knots can cause chondral abrasion.15,16 Several manufacturers have introduced knotless anchors for soft-tissue fixation.15,17 The knotless technique provides a low-profile repair with potentially less operating time.8 These factors may warrant switching from knotted to knotless techniques if outcomes are clinically acceptable. However, few studies have compared knotted and knotless techniques for glenohumeral labral repair.8,15,18-21

We conducted a study to compare the clinical results and operative times of knotless and knotted fixation of anterior and posterior glenohumeral labral repairs and SLAP repairs. We hypothesized there would be no difference in patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) between knotted and knotless techniques.

Methods

We retrospectively evaluated data that had been prospectively collected between 2012 and 2016 in a Surgical Outcomes System (SOS; Arthrex) database. Participation in this registry is elective, and enrollment can occur on a case-by-case basis. The database stores data on basic demographics, PROMs, and operative time. Data for our specific analysis were available for surgeries performed by 115 different surgeons. Inclusion criteria included primary isolated arthroscopic anterior, isolated posterior, and isolated SLAP repair with completely knotted or completely knotless labral repair and minimum 1-year follow-up. Exclusion criteria included hybrid knotted–knotless repair, rotator cuff repair, revision surgery, open surgery, and lack of complete follow-up data.

SOS is a proprietary registry that allows for the collection of basic patient demographics, diagnostic and operative data, and PROMs. PROMs in the SOS shoulder arthroscopy module include Veterans RAND 12-Item Health Survey (VR-12) mental health and physical health component summary scores, visual analog scale (VAS) pain scores, and American Shoulder and Elbow Surgeons (ASES) scores. For this study, PROMs were reviewed before surgery and 6 and 12 months after surgery. In addition, operative times of all procedures were collected.

For the analysis, completely knotted and completely knotless techniques were compared for anterior repair, posterior repair, and SLAP repair. A t test was used to compare the techniques on PROMs, and χ2 test was used to evaluate proportion differences. Statistical significance was set at P < .05.

Results

Anterior Labral Repairs

Of the 102 knotted anterior labral repairs that met the study criteria, 26 (25%) had minimum 1-year follow-up. Of the 122 knotless labral repairs, 33 (27%) had minimum 1-year follow-up. Seventy-five percent of knotted repairs and 80% of knotless repairs were performed in men. Mean (SD) age was 25.3 (11.7) years for the knotted group and 26.9 (10.6) years for the knotless group (P = .109). Anterior labral repairs did not differ in PROMs at any point (Table 1).

A mean of 2.8 anchors was used for knotted repairs, and a mean of 3.1 anchors was used for knotless repairs. Mean operative time was 75.8 minutes for knotted repairs and 67.5 minutes for knotless repairs. Mean (SD) time per anchor was 30.9 (13.9) minutes for knotted repairs and 25.6 (19.5) minutes for knotless repairs (P = .021).

Posterior Labral Repairs

Of the 165 knotted posterior labral repairs that met the study criteria, 39 (29%) had minimum 1-year follow-up. Of the 229 knotless labral repairs, 56 (24%) had minimum 1-year follow-up. Eighty-five percent of knotted repairs and 74% of knotless repairs were performed in men. Mean (SD) age was 29.1 (12.0) years for the knotted group and 27.5 (11.9) years for the knotless group (P = .148). Posterior labral repairs did not differ in PROMs before surgery or 1 year after surgery; 6 months after surgery, these repairs differed only in ASES scores (Table 2).

A mean of 3.6 anchors was used for knotted repairs, and a mean of 3.0 anchors was used for knotless repairs. Mean operative time was 67.0 minutes for knotted repairs and 43.1 minutes for knotless repairs. Mean (SD) time per anchor was 21.1 (10.7) minutes for knotted repairs and 17.5 (14.7) minutes for knotless repairs (P = .031).

SLAP Repairs

Of the 54 knotted SLAP repairs that met the study criteria, 24 (44%) had minimum 1-year follow-up. Of the 138 knotless SLAP repairs, 48 (35%) had minimum 1-year follow-up. Seventy-two percent of knotted repairs and 72% of knotless repairs were performed in men. Mean (SD) age was 32.1 (11.6) years for the knotted group and 35.0 (12.8) years for the knotless group (P = .246). SLAP repairs did not differ in PROMs at any point (Table 3).

A mean of 1.9 anchors was used for knotted repairs, and a mean of 2.1 anchors was used for knotless repairs. Mean operative time was 59.0 minutes for knotted repairs and 40.9 minutes for knotless repairs. Mean (SD) time per anchor was 36.6 (22.4) minutes for knotted repairs and 26.3 (14.0) minutes for knotless repairs (P = .080).

Discussion

Our hypothesis that there would be no difference in PROMs between knotted and knotless labral repairs was confirmed. Our findings are important because this study compared the gold standard of knotted suture anchor with the alternative knotless suture anchor in glenohumeral labral repair. These findings have several important implications for labral repair.

Knot tying traditionally has been used to achieve fixation with an anchor. Although simple in concept, knot tying can be challenging and its quality variable. Thal15 wrote that good-quality arthroscopic suture anchor repair is difficult to achieve because satisfactory knot tying requires significant practice with certain devices designed specifically for knot tying. Multiple surgeons have noted a significant learning curve associated with knot tying, and there is no agreement on which knot is superior.22-26 Leedle and Miller17 even suggested that, because knot tying is difficult, tying knots arthroscopically can lead to knot failure. In their study, they concluded that the knot is consistently the weakest link in suture repair of an anterior labrum construct. In a controlled laboratory study, Hanypsiak and colleagues13 found considerable knot-strength variability among expert arthroscopists. Only 65 (18%) of 365 knots tied fell within 20% of the mean for ultimate load failure, and only 128 (36%) of 365 fell within 20% of the mean for clinical failure (3 mm of displacement). These data suggested expert arthroscopists were unable to tie 5 consecutive knots of the same type consistently. Even among experts, it seems, knot strength varies significantly, and knot-strength issues may affect the rates of labral repair failure.

Multiple authors have also reported that bulky knots can cause chondral abrasion or that knots can migrate.25,27 Rhee and Ha27 reported that, when another knot (eg, a half-hitch knot) is tied to prevent knot failure, the resulting overall knot can be too bulky for a limited space, and chondral abrasion can result. In addition, regardless of size, a knot can migrate and, in its new position, start rubbing against the head of the humerus. Kim and colleagues14 found that, even when a knot is placed away from the humeral head, migration and repeated contact with the head are possible. Park and colleagues28 found that a significant number of knotted SLAP repairs required arthroscopic knot removal for relief of knot-induced pain and clicking.

Knotless constructs have several theoretical advantages over knotted constructs. Compared with a knotted technique, a knotless technique appears to provide more predictable strength, as variability in knot tying is eliminated (unpublished data). A knotless repair also has a lower profile,8 which should lead to less contact with the humeral head.19 Last, a knotless repair is more efficient—it takes less time to perform. In our study, operative time was reduced by a mean of 5.3 minutes per anchor for anterior labral repair. Assuming a mean of 3 anchors, this reduction equates to 16 minutes per case. Therefore, a surgeon who performs 25 labral repairs a year can save 6.7 hours a year. Reduced operative time benefits the patient (ie, lower risk of infection and other complications29), the surgeon, and the healthcare system (ie, cost savings). Macario30 found that operating room costs averaged $62 per minute (range, $22-$133 per minute). Therefore, saving 16 minutes per case could lead to saving $992 per case. In summary, a knotless technique appears to be clinically and financially advantageous as long as its results are the same as or better than those of a knotted technique.

A few other studies have compared knotted and knotless techniques. In a cadaveric study, Slabaugh and colleagues20 found no difference in labral height between traditional and knotless suture anchors. Leedle and Miller17 found that knotless constructs are biomechanically stronger than knotted constructs in anterior labral repair. In a level 3 clinical study, Yang and colleagues21 compared a conventional vertical knot with a knotless horizontal mattress suture in 41 patients who underwent SLAP repair. Functional outcome was no different between the 2 groups, but postoperative range of motion was improved in the knotless group. Ng and Kumar31 compared 45 patients who had knotted Bankart repair with 42 patients who had knotless Bankart repair and found no difference in functional outcome or rate of recurrent dislocation. Similarly, Kocaoglu and colleagues22 found no difference in recurrence rate between 18 patients who underwent a knotted technique for arthroscopic Bankart repair and 20 patients who underwent a knotless technique. Our findings corroborate the findings of these studies and further support the idea that there is no difference between knotted and knotless constructs with respect to PROMs.

Study Limitations

The major strength of this study was its large cohort and large population of surgeons. However, there were several study limitations. First, we could not detail specific repair techniques, such as simple or horizontal mattress orientation, and rehabilitation protocols and other variables are likely as well. Second, the repair technique was not randomized, and therefore there may have been a selection bias based on tissue quality. Although we cannot prove no bias, we think it was unlikely given that the groups were similar in age. Third, our data did not include information on range of motion or recurrent instability. Our goal was simply to evaluate PROMs among multiple surgeons using the 2 techniques. Fourth, there was substantial follow-up loss, which introduced potential selection bias. Last, there may have been conditions under which a hybrid technique with inferior knot tying, combined with a hybrid knotless construct, could have proved advantageous.

Conclusion

Our data showed that the advantages of knotless repair are not compromised in clinical situations. Although the data showed no significant difference in clinical outcomes, knotless repairs may provide surgeons with shorter surgeries, simpler constructs, less potential for chondral damage, and more consistent suture tensioning. Additional studies may further confirm these results.

1. Levy DM, Cole BJ, Bach BR Jr. History of surgical intervention of anterior shoulder instability. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2016;25(6):e139-e150.

2. Gill TJ, Zarins B. Open repairs for the treatment of anterior shoulder instability. Am J Sports Med. 2003;31(1):142-153.

3. Millett PJ, Clavert P, Warner JJ. Open operative treatment for anterior shoulder instability: when and why? J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87(2):419-432.

4. Stein DA, Jazrawi L, Bartolozzi AR. Arthroscopic stabilization of anterior shoulder instability: a review of the literature. Arthroscopy. 2002;18(8):912-924.

5. Kim SH, Ha KI, Kim SH. Bankart repair in traumatic anterior shoulder instability: open versus arthroscopic technique. Arthroscopy. 2002;18(7):755-763.

6. Snyder SJ, Karzel RP, Del Pizzo W, Ferkel RD, Friedman MJ. SLAP lesions of the shoulder. Arthroscopy. 1990;6(4):274-279.

7. Hantes M, Raoulis V. Arthroscopic findings in anterior shoulder instability. Open Orthop J. 2017;11:119-132.

8. Sileo MJ, Lee SJ, Kremenic IJ, et al. Biomechanical comparison of a knotless suture anchor with standard suture anchor in the repair of type II SLAP tears. Arthroscopy. 2009;25(4):348-354.

9. Iqbal S, Jacobs U, Akhtar A, Macfarlane RJ, Waseem M. A history of shoulder surgery. Open Orthop J. 2013;7:305-309.

10. Garofalo R, Mocci A, Moretti B, et al. Arthroscopic treatment of anterior shoulder instability using knotless suture anchors. Arthroscopy. 2005;21(11):1283-1289.

11. Kersten AD, Fabing M, Ensminger S, et al. Suture capsulorrhaphy versus capsulolabral advancement for shoulder instability. Arthroscopy. 2012;28(10):1344-1351.

12. Cole BJ, Warner JJ. Arthroscopic versus open Bankart repair for traumatic anterior shoulder instability. Clin Sports Med. 2000;19(1):19-48.

13. Hanypsiak BT, DeLong JM, Simmons L, Lowe W, Burkhart S. Knot strength varies widely among expert arthroscopists. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42(8):1978-1984.

14. Kim SH, Ha KI, Park JH, et al. Arthroscopic posterior labral repair and capsular shift for traumatic unidirectional recurrent posterior subluxation of the shoulder. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003;85(8):1479-1487.

15. Thal R. Knotless suture anchor. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2001;(390):42-51.

16. Loutzenheiser TD, Harryman DT 2nd, Yung SW, France MP, Sidles JA. Optimizing arthroscopic knots. Arthroscopy. 1995;11(2):199-206.

17. Leedle BP, Miller MD. Pullout strength of knotless suture anchors. Arthroscopy. 2005;21(1):81-85.

18. Caldwell PE 3rd, Pearson SE, D’Angelo MS. Arthroscopic knotless repair of the posterior labrum using LabralTape. Arthrosc Tech. 2016;5(2):e315-e320.

19. Tennent D, Concina C, Pearse E. Arthroscopic posterior stabilization of the shoulder using a percutaneous knotless mattress suture technique. Arthrosc Tech. 2014;3(1):e161-e164.

20. Slabaugh MA, Friel NA, Wang VM, Cole BJ. Restoring the labral height for treatment of Bankart lesions: a comparison of suture anchor constructs. Arthroscopy. 2010;26(5):587-591.

21. Yang HJ, Yoon K, Jin H, Song HS. Clinical outcome of arthroscopic SLAP repair: conventional vertical knot versus knotless horizontal mattress sutures. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2016;24(2):464-469.

22. Kocaoglu B, Guven O, Nalbantoglu U, Aydin N, Haklar U. No difference between knotless sutures and suture anchors in arthroscopic repair of Bankart lesions in collision athletes. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2009;17(7):844-849.

23. Aboalata M, Halawa A, Basyoni Y. The double Bankart bridge: a technique for restoration of the labral footprint in arthroscopic shoulder instability repair. Arthrosc Tech. 2017;6(1):e43-e47.

24. Rhee SM, Kang SY, Jang EC, Kim JY, Ha YC. Clinical outcomes after arthroscopic acetabular labral repair using knot-tying or knotless suture technique. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2016;136(10):1411-1416.

25. Oh JH, Lee HK, Kim JY, Kim SH, Gong HS. Clinical and radiologic outcomes of arthroscopic glenoid labrum repair with the BioKnotless suture anchor. Am J Sports Med. 2009;37(12):2340-2348.

26. Yian E, Wang C, Millett PJ, Warner JJ. Arthroscopic repair of SLAP lesions with a BioKnotless suture anchor. Arthroscopy. 2004;20(5):547-551.

27. Rhee YG, Ha JH. Knot-induced glenoid erosion after arthroscopic fixation for unstable superior labrum anterior-posterior lesion: case report. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2006;15(3):391-393.

28. Park JG, Cho NS, Kim JY, Song JH, Hong SJ, Rhee YG. Arthroscopic knot removal for failed superior labrum anterior-posterior repair secondary to knot-induced pain. Am J Sports Med. 2017;45(11):2563-2568.

29. Wang DS. Re: how slow is too slow? Correlation of operative time to complications: an analysis from the Tennessee Surgical Quality Collaborative. J Urol. 2016;195(5):1510-1511.

30. Macario A. What does one minute of operating room time cost? J Clin Anesth. 2010;22(4):233-236.

31. Ng DZ, Kumar VP. Arthroscopic Bankart repair using knot-tying versus knotless suture anchors: is there a difference? Arthroscopy. 2014;30(4):422-427.

1. Levy DM, Cole BJ, Bach BR Jr. History of surgical intervention of anterior shoulder instability. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2016;25(6):e139-e150.

2. Gill TJ, Zarins B. Open repairs for the treatment of anterior shoulder instability. Am J Sports Med. 2003;31(1):142-153.

3. Millett PJ, Clavert P, Warner JJ. Open operative treatment for anterior shoulder instability: when and why? J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87(2):419-432.

4. Stein DA, Jazrawi L, Bartolozzi AR. Arthroscopic stabilization of anterior shoulder instability: a review of the literature. Arthroscopy. 2002;18(8):912-924.

5. Kim SH, Ha KI, Kim SH. Bankart repair in traumatic anterior shoulder instability: open versus arthroscopic technique. Arthroscopy. 2002;18(7):755-763.

6. Snyder SJ, Karzel RP, Del Pizzo W, Ferkel RD, Friedman MJ. SLAP lesions of the shoulder. Arthroscopy. 1990;6(4):274-279.

7. Hantes M, Raoulis V. Arthroscopic findings in anterior shoulder instability. Open Orthop J. 2017;11:119-132.

8. Sileo MJ, Lee SJ, Kremenic IJ, et al. Biomechanical comparison of a knotless suture anchor with standard suture anchor in the repair of type II SLAP tears. Arthroscopy. 2009;25(4):348-354.

9. Iqbal S, Jacobs U, Akhtar A, Macfarlane RJ, Waseem M. A history of shoulder surgery. Open Orthop J. 2013;7:305-309.

10. Garofalo R, Mocci A, Moretti B, et al. Arthroscopic treatment of anterior shoulder instability using knotless suture anchors. Arthroscopy. 2005;21(11):1283-1289.

11. Kersten AD, Fabing M, Ensminger S, et al. Suture capsulorrhaphy versus capsulolabral advancement for shoulder instability. Arthroscopy. 2012;28(10):1344-1351.

12. Cole BJ, Warner JJ. Arthroscopic versus open Bankart repair for traumatic anterior shoulder instability. Clin Sports Med. 2000;19(1):19-48.

13. Hanypsiak BT, DeLong JM, Simmons L, Lowe W, Burkhart S. Knot strength varies widely among expert arthroscopists. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42(8):1978-1984.

14. Kim SH, Ha KI, Park JH, et al. Arthroscopic posterior labral repair and capsular shift for traumatic unidirectional recurrent posterior subluxation of the shoulder. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003;85(8):1479-1487.

15. Thal R. Knotless suture anchor. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2001;(390):42-51.

16. Loutzenheiser TD, Harryman DT 2nd, Yung SW, France MP, Sidles JA. Optimizing arthroscopic knots. Arthroscopy. 1995;11(2):199-206.

17. Leedle BP, Miller MD. Pullout strength of knotless suture anchors. Arthroscopy. 2005;21(1):81-85.

18. Caldwell PE 3rd, Pearson SE, D’Angelo MS. Arthroscopic knotless repair of the posterior labrum using LabralTape. Arthrosc Tech. 2016;5(2):e315-e320.

19. Tennent D, Concina C, Pearse E. Arthroscopic posterior stabilization of the shoulder using a percutaneous knotless mattress suture technique. Arthrosc Tech. 2014;3(1):e161-e164.

20. Slabaugh MA, Friel NA, Wang VM, Cole BJ. Restoring the labral height for treatment of Bankart lesions: a comparison of suture anchor constructs. Arthroscopy. 2010;26(5):587-591.

21. Yang HJ, Yoon K, Jin H, Song HS. Clinical outcome of arthroscopic SLAP repair: conventional vertical knot versus knotless horizontal mattress sutures. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2016;24(2):464-469.

22. Kocaoglu B, Guven O, Nalbantoglu U, Aydin N, Haklar U. No difference between knotless sutures and suture anchors in arthroscopic repair of Bankart lesions in collision athletes. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2009;17(7):844-849.

23. Aboalata M, Halawa A, Basyoni Y. The double Bankart bridge: a technique for restoration of the labral footprint in arthroscopic shoulder instability repair. Arthrosc Tech. 2017;6(1):e43-e47.

24. Rhee SM, Kang SY, Jang EC, Kim JY, Ha YC. Clinical outcomes after arthroscopic acetabular labral repair using knot-tying or knotless suture technique. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2016;136(10):1411-1416.

25. Oh JH, Lee HK, Kim JY, Kim SH, Gong HS. Clinical and radiologic outcomes of arthroscopic glenoid labrum repair with the BioKnotless suture anchor. Am J Sports Med. 2009;37(12):2340-2348.

26. Yian E, Wang C, Millett PJ, Warner JJ. Arthroscopic repair of SLAP lesions with a BioKnotless suture anchor. Arthroscopy. 2004;20(5):547-551.

27. Rhee YG, Ha JH. Knot-induced glenoid erosion after arthroscopic fixation for unstable superior labrum anterior-posterior lesion: case report. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2006;15(3):391-393.

28. Park JG, Cho NS, Kim JY, Song JH, Hong SJ, Rhee YG. Arthroscopic knot removal for failed superior labrum anterior-posterior repair secondary to knot-induced pain. Am J Sports Med. 2017;45(11):2563-2568.

29. Wang DS. Re: how slow is too slow? Correlation of operative time to complications: an analysis from the Tennessee Surgical Quality Collaborative. J Urol. 2016;195(5):1510-1511.

30. Macario A. What does one minute of operating room time cost? J Clin Anesth. 2010;22(4):233-236.

31. Ng DZ, Kumar VP. Arthroscopic Bankart repair using knot-tying versus knotless suture anchors: is there a difference? Arthroscopy. 2014;30(4):422-427.

Update on Internet-Based Orthopedic Registries

Take-Home Points

- PRO data collection can provide feedback for improvements in patient care and physician performance.

- Many options exist for orthopedic physicians to establish clinical data registries.

- Registry systems can help improve patient follow-up with system monitoring and patient reminders.

- Clinical registries can offer many advantages to observational research.

- With registry use becoming more prevalent, work needs to be done to establish standards for validity and reliability.

In a 2012 review of database tools, Lubowitz and Smith1 examined Internet-based applications that arthroscopic surgeons could use to record and monitor patient-reported outcome (PRO) data and potential adverse effects. In this article, we update orthopedic surgeons on the registries and monitoring software mentioned in that earlier publication and in other publications that have since become available.

Most orthopedic surgery candidates are seeking pain relief and improved function. Many patients expect their pain to be completely relieved by surgical intervention and their function to return to what it was before they became stricken.2,3 Therefore, PRO measures (PROMs) are now standard in post-orthopedic surgery outcome reporting.4 PROMs, which include any measurement that assesses a patient’s health, illness, or benefits from the perspective of the patient, are often administered as a questionnaire or survey.5 The collection of PROMs continues to increase and evolve, creating a need for data storage and analysis. Registries, large collections of patient information and outcomes, allow for evaluation of patient outcomes, monitoring of adverse effects, identification of procedure incidence, understanding of predictors of prognosis, generation of feedback for quality of care, monitoring of the safety of implantable devices, and the conducting of hypothesis-driven scientific research.6-9

Orthopedic surgery has registries at regional, national, and international levels. Although the United States has fallen well behind other countries in establishing a national registry,9 it has made some recent progress. The United States now has several national registries, including the American Joint Replacement Registry (AJRR), Function and Outcomes Research for Comparative Effectiveness in Total Joint Replacement (FORCE-TJR), the Kaiser Permanente National Total Joint Replacement Registry (TJRR), the Veterans Affairs (VA) and American College of Surgeons (ACS) National Surgical Quality Improvement Programs (NSQIPs), and the National Trauma Data Bank (NTDB).9 AJRR currently has 960 hospitals participating and is tracking 1,084,664 hip and knee replacements.10

These orthopedic registries, however, are limited in 2 ways. First, the majority are joint replacement registries. Second, though registries are established to determine patterns of care and predict patient outcomes, many are not set up to report care data back to healthcare providers.7 For procedures other than joint arthroplasty and for providers interested in tracking their patients’ PROs, systems are available for establishing clinical quality registries in orthopedics.

Registry Systems

CareSense

CareSense (Medtrak) is an Internet-based care management and data collection system designed for patient engagement, which results in fewer missed appointments, increased patient adherence, enhanced patient education, and improved patient satisfaction.11 CareSense features email/text reminders for data entry, custom and standard reports, import and export of electronic medical record (EMR) information, and tools for running research studies.12 CareSense emphasizes care navigation by helping hospitals educate and guide patients through their care by sending exercise videos to patients for home rehabilitation, transferring messages from post-acute care facilities to surgeons and caregivers, and alerting the care team to any potential readmission symptoms.11,13 CareSense is also a Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) approved qualified clinical data registry (QCDR). QCDRs collect data for Merit-Based Incentive Payment System (MIPS) clinicians and submit the data to CMS.12

KareOutcomes

KareOutcomes, a healthcare technology and support firm founded in 2009, advocates transparency and trust among providers and patients, and aims to optimize PROs.14 The KareOutcomes team incorporates patient follow-up personnel, administrators, engineers, physicians, software developers, and technicians. The KareOutcomes software, which is backed by a 6-month guarantee, includes system design and implementation, data collection and entry, methods of submitting data to statewide or nationwide registries and sending standardized and customized surveys, and accessible and meaningful data presentation. KareOutcomes allows patient follow-up through automated reminders by telephone, SMS text message, and email. Patients can respond to surveys or questionnaires whichever way is most convenient—by telephone, Internet, SMS text message, or on paper, either in the office or by mail.

Oberd

Oberd (Universal Research Solutions) offers a comprehensive package of solutions for collecting optimal PRO data. The package has several modules: outcomes, education, registry, operative notes, data import and export, and data reporting.15 Oberd Outcomes allows convenient and engaging data collection. For example, users can send both standardized and customized forms. Oberd Education allows patients to receive information in an interactive, narrated format that is specific to their physician’s techniques and practices. Oberd Registry allows users to input multiple datasets into a registry, compare data, and generate reports with visuals. Like CareSense, Oberd is a CMS-approved QCDR. Oberd’s MIPS Dashboard helps providers collect and report patients’ reported outcomes, and use that information to modify and improve their practice.

Ortech

Ortech is a web-based data registry system that allows physicians and administrators to mine the data they own, track key metrics in their data, and improve reporting.16 Users can collect PROMs, use them to measure and analyze patient progress, and add to their collection of information that helps support their evidence-based decision making. They can capture intraoperative and implant data through barcode scanning, which then registers the data in an implant product code library that allows quick identification of patients with a specific implant in the event of a product recall. Ortech also allows automatic generation of customized operative reports on data entered from the operating room and populated into the EMR. Ortech offers 2 versions of its data collection platform, phiDB and phiDB Lite. The phiDB Lite version is for smaller practices and focuses mainly on PROMs but lacks many of the other features that phiDB offers, such as operating room modules, automated operative reports, barcode scanning, and unlimited data reporting.

Socrates

Socrates (Standardised Orthopaedic Clinical Research and Treatment Evaluation Software; Ortholink) is dedicated orthopedic software that facilitates following patient outcomes and conducting high-quality research.17 Socrates is fully customizable to fit each user’s needs. It allows for tracking of outcome scores, intraoperative details, nonoperative procedures, clinical examinations, therapies, and adverse effects. Users can also create reports from this information, which is inputted to Socrates and can be exported into EMR. Socrates data are stored on the user’s server, on site; the software generates patient summaries, collective summaries, and follow-up reports through its built-in descriptive statistics module. Raw data can be extracted for statistical analysis. Socrates can catalogue images, radiographs, documents, and videos.

Surgical Outcomes System

Surgical Outcomes System (SOS; Arthrex) is a cloud-based orthopedic and sports medicine global registry that focuses on monitoring and evaluating the outcomes of various orthopedic and sports medicine surgical procedures, as well as nonoperative interventions, to contribute to evidence-based protocols for patient treatment.18 SOS can be fully customized with desired PROMs for arthroplasty and for surgical procedures for extremity joints and even the spine. SOS includes real-time reporting on PROs for individual patients, summary PROMs for all of the physician’s patients who are receiving the same treatment, and comparisons with all registry patients (from global de-identified registry data) who had the same treatment or surgery. This real-time analysis provides immediate patient and physician feedback on treatments and products used. A patient portal for education on surgical procedures is also available. SOS is approved for use in 21 countries and is a benefit included with Arthroscopy Association of North America (AANA) membership. SOS is listed on the National Quality Registry Network (NQRN) website and, as a specialized registry as defined by CMS, can accept data generated by EMR technology.

Discussion

Delaunay19 indicated that successful registry management depends on several factors, including “use of a single identifier for each patient to ensure full traceability of all procedures related to a given implant; a long-term funding source; a contemporary, rapid, Internet-based data collection method; and the collection of exhaustive data, at least for innovative implants.” The registry systems reviewed in this article are Internet based and allow healthcare providers to monitor the clinical outcomes of their patients in the hope of improving clinical decision-making and overall patient care. From the provider perspective, many registry systems allow for integration of outcome data reporting into EMRs, including generation of operative reports. In turn, registries can improve documentation efficiency, as it was estimated that a US physician without a registry spends more than 15 hours a week reporting quality measures,20 or almost 800 hours and $15 billion each year.20,21 It remains to be seen whether registry systems will optimize the documentation process, but there is potential improvement in time and cost-efficiency with registry use.

Although the factors involved in management are important, clinical data registries must have systems in place to help ensure patient adherence and minimize selection bias, as adherence is crucial in data accuracy.3 What helps with adherence is the ability to send automated email or SMS text message reminders to patients. According to a review, email reminders increased the completion of PROM datasets by 26%.22 When the new national quality register (NQR) HAKIR (Handkirurgiskt kvalitetsregister) was established in Sweden, it was found that when only 1 type of reminder was used (SMS text message, in this case), only about 30% of participants completed their questionnaires.23 However, after the system was changed to send both SMS text message and email reminders, the response rate increased from 50% to 60%. Using 2 types of automated reminders might minimize lost data more effectively than 1 type alone.

Another benefit of outcome monitoring through a registry is potential reduction of interviewer- related errors. Interviewer bias can occur in many different ways. Interviewers might not follow the same instructions or administer questionnaires or surveys the same way for different patients,24 the interviewer’s presence might cause the patient to alter responses based on social norms,25 and the patient might report better outcomes in the presence of a physician or interviewer.26,27 Given that clinical registries allow electronic capture of self-administered surveys, interviewer bias is reduced because all patients receive a standardized set of questions and instructions. In addition, electronic questionnaires and surveys prompt users to add or fix missed or incorrectly completed items, further reducing potential data inaccuracies.

Healthcare costs continue to rise in the United States. In 2015, the total cost of healthcare expenditure in the United States was $3.2 trillion, or almost 18% of the US gross domestic product.28 In addition, in the first half of 2016, an estimated 16.2% of people under age 65 years were in families that were struggling to pay medical bills.29,30 Healthcare reform provides a financial incentive to healthcare providers to collaborate to reduce unnecessary costs and procedures and improve the quality of healthcare.31 Porter and Teisberg32 defined value as health outcomes achieved per dollar spent. Registry monitoring of PROMs, which are the numerator in this critical value formula, allows providers to track patient outcomes over time to determine which interventions produce the best outcomes.22 Therefore, clinical registries play an important role in improving health outcomes and reducing the cost of healthcare.7

Since the Swedish Knee Arthroplasty Register (SKAR) was established 40 years ago, NQRs have been commonplace in Scandinavian countries, Australia, and the United Kingdom.23 Between 2001 and 2014, the Australian Orthopaedic Association National Joint Replacement Registry (AOANJRR) documented a decline in the financial burden of hip and knee arthroplasty revision in Australia—in comparison with the United States, which did not have a full national registry at the time and showed a revision rate increase.24 The economic benefit of reducing hip and knee arthroplasty revisions in Australia during that period was an estimated $65 million to $143 million.24 Besides having financial benefits, national registries allow early identification of flawed implantation products and methods, leading to a further reduction in the burden associated with recall and future use of such defective implants—including patient harm.

In addition to monitoring existing techniques and devices, registries can also follow new techniques and, compared with publication in clinical journals, more expeditiously provide clinical data for outcome expectations and treatment methods. This timeliness is particularly valuable given that publication of clinical trials with the usual mandatory 2-year follow-up can take 4 years or longer.33,34 For instance, in the expanding field of hip arthroscopy, data from registries in both Sweden and Denmark are being analyzed.35,36 These data are important in new fields such as hip arthroscopy, in which clinical indications and treatment techniques may vary considerably between locations.35 In 2012, the Danish Hip Arthroscopy Registry (DHAR) was started as a web-based prospective registry.36 Between 2012 and December 2014, DHAR added 2000 procedures, which included all hip arthroscopy procedures performed at 11 centers in Denmark.36 DHAR tracks PROM, surgical procedure, operative, and radiologic data.

Increased use of clinical registries has led to use of their data in clinical research. Registry-based randomized controlled trials (RCTs) are lower in cost than other types of research, allow for rapid enrollment of patients, offer larger population sizes and multi-institutional sampling, and can provide a more diverse patient population.19,37 Although nonregistry RCTs remain the gold standard of clinical research, registry RCTs have several advantages given the abilities and structure of registries. Because of resources and cost, nonregistry RCTs are usually limited in the number of examined exposures and typically focus on only 2.6 Registry RCTs, on the other hand, can monitor multiple exposures, typically at minimal cost difference.6 Another disadvantage of nonregistry RCTs is that they are often performed at institutions providing care that might not be indicative of the quality most patients expect, as these institutions might be selected for a specific clinician or specialty service.

Registry RCTs also have their limitations with respect to clinical research. A major one is their lack of validity standards or accepted benchmarks for accuracy, adherence rates, registry completeness, and data collection.37,38 In addition, lack of standardization across national and international registries could produce conflicting data. Another limitation is that data in most registries are not subjected to any third-party checks or independent auditing.9,39 Furthermore, evaluating the impact of registries is difficult because it is difficult to find comparable outcome data on nonregistry patients.40 A final limitation involves the ethics of including registry data in RCTs. Although data are often added to a registry without patient consent, should the same data be used for research without patient consent? Should patients be able to disallow use of their data for research, or require a notification each time their data are used? These issues must be addressed.

Review Limitations

One limitation of this review of clinical Internet-based outcome systems is that it might not have identified comparable systems. In addition, specific costs associated with each system were not addressed, as they depend on PROM licensing fees, total institutional access, other proprietary costs, and other variables. Another limitation, in terms of creating a national or international registry, continues to be Internet access. The Pew Research Center estimated that 84% of US adults used the Internet in 2015.41 Although 84% represents most of the adult population, the other 16% typically is over age 65 years, where only 58% of adults reported using the Internet, or come from lower income households, where access was <75%. For registries in European countries and North America, where Internet usage typically is >70%, this is not a significant problem. However, worldwide, only 47% of the population used the Internet in 2016.42 Internet usage by Asian and Arab states citizens was 41.6% and 41.9%, respectively, and usage by African citizens was only 25.1%. As a significant benefit of registry use is that researchers can obtain larger sample sizes, it is a problem that some populations—elderly people, people of lower socioeconomic standing, people living where the Internet is unavailable—might be underrepresented in registry data.

As mentioned, patient adherence is an ongoing issue for clinical registries. As adherence tends to decrease as more time passes after a patient’s treatment date, it is important to account for and encourage continued patient participation with outcome monitoring. Missing data lessen the validity and accuracy of a registry, increasing the likelihood that certain groups will be underrepresented. Although registry systems can reduce the cost of following PROMs, doing so requires monitoring and following up on issues of patient adherence. In other words, many clinicians will need the help of a research assistant. Makhni and colleagues21 found that adding a research assistant for this task increased survey adherence from 65% to 94% before surgery, from 65% to 72% 6 months after surgery, and from 38% to 56% 12 months after surgery.

Even though studies continue to use clinical data from registries, there is not much research on the impact of these registries on improvement in healthcare. Again, many factors are involved: lack of standardized benchmarks for accuracy and adherence, lack of an accepted method of data auditing and validation, and difficulty evaluating the impact of registries owing to the difficulty obtaining comparable data on nonregistry patients. Registries must adopt accepted forms of standardization in order to allow better comparisons of registries, because comparing data across registries can be useful in determining the strengths and weaknesses of different registries.27,43 As registries support decision making at clinical, institutional, and governmental levels, it is vital that their clinical data be accurate and reliable.38

Conclusion

Rising healthcare costs, and government and third-party pressures are making patient outcomes collection a standard of care. Going forward, orthopedic surgeons must be proactive, and Internet -based registries provide technological advances that facilitate the process.

1. Lubowitz JH, Smith PA. Current concepts in clinical research: web-based, automated, arthroscopic surgery prospective database registry. Arthroscopy. 2012;28(3):425-428.

2. Ayers DC, Bozic KJ. The importance of outcome measurement in orthopaedics. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2013;471(11):3409-3411.

3. Nwachukwu BU, Fields K, Chang B, Nawabi DH, Kelly BT, Ranawat AS. Preoperative outcome scores are predictive of achieving the minimal clinically important difference after arthroscopic treatment of femoroacetabular impingement. Am J Sports Med. 2017;45(3):612-619.

4. Breckenridge K, Bekker HL, Gibbons E, et al. How to routinely collect data on patient-reported outcome and experience measures in renal registries in Europe: an expert consensus meeting. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2015;30(10):1605-1614.

5. Inacio MC, Paxton EW, Dillon MT. Understanding orthopaedic registry studies: a comparison with clinical studies. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2016;98(1):e3.

6. Hoque DME, Kumari V, Hoque M, Ruseckaite R, Romero L, Evans SM. Impact of clinical registries on quality of patient care and clinical outcomes: a systematic review. PLoS One. 2017;12(9):e0183667.

7. Physician Consortium for Performance Improvement. National Quality Registry Network. http://www.thepcpi.org/programs-initiatives/national-quality-registry-network/. Accessed October 5, 2017.

8. Hickey GL, Grant SW, Cosgriff R, et al. Clinical registries: governance, management, analysis and applications. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2013;44(4):605-614.

9. Pugely AJ, Martin CT, Harwood J, Ong KL, Bozic KJ, Callaghan JJ. Database and registry research in orthopaedic surgery: part 2: clinical registry data. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2015;97(21):1799-1808.

10. American Joint Replacement Registry. http://www.ajrr.net/. Accessed October 5, 2017.

11. CareSense. https://www.caresense.com/. Accessed October 4, 2017.

12. US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, Quality Payment Program. Merit-Based Incentive Payment System (MIPS): 2017 CMS-Approved Qualified Clinical Data Registries (QCDRs). https://qpp.cms.gov/docs/QPP_2017_CMS_Approved_QCDRs.pdf. Accessed October 9, 2017.

13. Johnson & Johnson. Johnson & Johnson Medical Devices Companies introduce Orthopaedic Episode of Care Approach, leveraging CareAdvantage capabilities to support better clinical outcomes and reduce the cost of care. https://www.jnj.com/media-center/press-releases/johnson-johnson-medical-devices-companies-introduce-orthopaedic-episode-of-care-approach-leveraging-careadvantage-capabilities-to-support-better-clinical-outcomes-and-reduce-the-cost-of-care. Published January 9, 2017. Accessed October 4, 2017.

14. KareOutcomes. http://www.kareoutcomes.com/. Accessed October 4, 2017.

15. Oberd. http://www.oberd.com/. Accessed October 4, 2017.

16. Ortech Systems. http://www.ortechsystems.com/. Accessed October 4, 2017.

17. Socrates. http://www.socratesortho.com/. Accessed October 4, 2017.

18. Surgical Outcomes System. https://www.surgicaloutcomesystem.com/. Accessed October 4, 2017.

19. Delaunay C. Registries in orthopaedics. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2015;101(1 suppl):S69-S75.

20. Bryan S, Davis J, Broesch J, Doyle-Waters MM, Lewis S, McGrail K. Choosing your partner for the PROM: a review of evidence on patient-reported outcome measures for use in primary and community care. Healthc Policy. 2014;10(2):38-51.

21. Makhni EC, Higgins JD, Hamamoto JT, Cole BJ, Romeo AA, Verma NN. Patient compliance with electronic patient reported outcomes following shoulder arthroscopy [published online ahead of print September 25, 2017]. Arthroscopy. doi:10.1016/j.arthro.2017.06.016.

22. Triplet JJ, Momoh E, Kurowicki J, Villarroel LD, Law T, Levy JC. E-mail reminders improve completion rates of patient-reported outcome measures. JSES Open Access. 2017;1:25-28.

23. Arner M. Developing a national quality registry for hand surgery: challenges and opportunities. EFORT Open Rev. 2016;1(4):100-106.

24. Ngongo CJ, Frick KD, Hightower AW, Mathingau FA, Burke H, Breiman RF. The perils of straying from protocol: sampling bias and interviewer effects. PLoS One. 2015;10(2):e0118025.

25. Hammarstedt JE, Redmond JM, Gupta A, Dunne KF, Vemula SP, Domb BG. Survey mode influence on patient-reported outcome scores in orthopaedic surgery: telephone results may be positively biased. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2017;25(1):50-54.

26. Hoher J, Bach T, Munster A, et al. Does the mode of data collection change results in a subjective knee score? Self-administration versus interview. Am J Sports Med. 1997;25(5):642-647.

27. Lacny S, Bohm E, Hawker G, Powell J, Marshall DA. Assessing the comparability of hip arthroplasty registries in order to improve the recording and monitoring of outcome. Bone Joint J. 2016;98-B(4):442-451.

28. US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, National Center for Health Statistics. Health, United States, 2016: With Chartbook on Long-Term Trends in Health. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, US Dept of Health and Human Services; 2017. DHHS Publication 2017-1232. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/hus/hus16.pdf. Published May 2017. Accessed October 9, 2017.

29. Cohen RA, Zammitti EP. Problems paying medical bills among persons under age 65: early release of estimates from the National Health Interview Survey, 2011-June 2016. National Health Interview Survey Early Release Program, Division of Health Interview Statistics, National Center for Health Statistics, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, US Dept of Health and Human Services. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhis/earlyrelease/probs_paying_medical_bills_jan_2011_jun_2016.pdf. Published November 2016. Accessed October 9, 2017.

30. National Center for Health Statistics. National Health Interview Survey. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhis/releases.htm. Accessed October 5, 2017.

31. Karhade AV, Larsen AMG, Cote DJ, Dubois HM, Smith TR. National databases for neurosurgical outcomes research: options, strengths, and limitations [published online ahead of print August 5, 2017]. Neurosurgery. https://doi.org/10.1093/neuros/nyx408.

32. Porter ME, Teisberg EO. Redefining Health Care: Creating Value-Based Competition on Results. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press; 2006.

33. Chen R, Desai NR, Ross JS, et al. Publication and reporting of clinical trial results: cross sectional analysis across academic medical centers. BMJ. 2016;352:i637.

34. Counsell N, Biri D, Fraczek J, Hackshaw A. Publishing interim results of randomised clinical trials in peer-reviewed journals. Clin Trials. 2017;14(1):67-77.