User login

Identifying the right database

Editor’s note: The Society of Hospital Medicine’s (SHM’s) Physician in Training Committee launched a scholarship program in 2015 for medical students to help transform health care and revolutionize patient care. The program has been expanded for the 2017-2018 year, offering two options for students to receive funding and engage in scholarly work during their first, second, and third years of medical school. As a part of the longitudinal (18-month) program, recipients are required to write about their experience on a monthly basis.

Vanderbilt University Medical Center will be converting to the most common electronic medical record (EMR) systems used today: Epic. Until that time, Vanderbilt used a homegrown system to keep track of patient data. The “system” was actual comprised of a few separate programs that integrated data, depending on the functions being accessed and who was accessing them.

For many research projects across the hospital, including my own, we are going to be limiting ourselves to data from the time period when our homegrown EMR was functioning. This is thinking a few steps ahead, but it would be interesting to see if our model, once validated, performed similarly in a new EMR environment. Unfortunately, this is thinking a few too many steps ahead for me, as I will have graduated (hopefully) by the time the new EMR is up and running reliably enough for EMR-based research like this project.

The first step in our study was identifying the right database to use, and now the next step will be extracting the data we need. Moving forward, I am continuing to work with my mentors, Dr. Eduard Vasilevskis and Dr. Jesse Ehrenfeld closely. We resubmitted our IRB application now that we have identified how we can pull the data we need, and we identified a few specialized patient populations for whom a separate scoring tool might be useful (e.g., stroke patients). I am looking forward to learning the particulars how our dataset will be built. The potential for finding the answers to many patient-care questions probably lies in the EMR data we already have, but you need to know how to get them to study them.

Monisha Bhatia, a native of Nashville, Tenn., is a fourth-year medical student at Vanderbilt University in Nashville. She is hoping to pursue either a residency in internal medicine or a combined internal medicine/emergency medicine program. Prior to medical school, she completed a JD/MPH program at Boston University, and she hopes to use her legal training in working with regulatory authorities to improve access to health care for all Americans.

Editor’s note: The Society of Hospital Medicine’s (SHM’s) Physician in Training Committee launched a scholarship program in 2015 for medical students to help transform health care and revolutionize patient care. The program has been expanded for the 2017-2018 year, offering two options for students to receive funding and engage in scholarly work during their first, second, and third years of medical school. As a part of the longitudinal (18-month) program, recipients are required to write about their experience on a monthly basis.

Vanderbilt University Medical Center will be converting to the most common electronic medical record (EMR) systems used today: Epic. Until that time, Vanderbilt used a homegrown system to keep track of patient data. The “system” was actual comprised of a few separate programs that integrated data, depending on the functions being accessed and who was accessing them.

For many research projects across the hospital, including my own, we are going to be limiting ourselves to data from the time period when our homegrown EMR was functioning. This is thinking a few steps ahead, but it would be interesting to see if our model, once validated, performed similarly in a new EMR environment. Unfortunately, this is thinking a few too many steps ahead for me, as I will have graduated (hopefully) by the time the new EMR is up and running reliably enough for EMR-based research like this project.

The first step in our study was identifying the right database to use, and now the next step will be extracting the data we need. Moving forward, I am continuing to work with my mentors, Dr. Eduard Vasilevskis and Dr. Jesse Ehrenfeld closely. We resubmitted our IRB application now that we have identified how we can pull the data we need, and we identified a few specialized patient populations for whom a separate scoring tool might be useful (e.g., stroke patients). I am looking forward to learning the particulars how our dataset will be built. The potential for finding the answers to many patient-care questions probably lies in the EMR data we already have, but you need to know how to get them to study them.

Monisha Bhatia, a native of Nashville, Tenn., is a fourth-year medical student at Vanderbilt University in Nashville. She is hoping to pursue either a residency in internal medicine or a combined internal medicine/emergency medicine program. Prior to medical school, she completed a JD/MPH program at Boston University, and she hopes to use her legal training in working with regulatory authorities to improve access to health care for all Americans.

Editor’s note: The Society of Hospital Medicine’s (SHM’s) Physician in Training Committee launched a scholarship program in 2015 for medical students to help transform health care and revolutionize patient care. The program has been expanded for the 2017-2018 year, offering two options for students to receive funding and engage in scholarly work during their first, second, and third years of medical school. As a part of the longitudinal (18-month) program, recipients are required to write about their experience on a monthly basis.

Vanderbilt University Medical Center will be converting to the most common electronic medical record (EMR) systems used today: Epic. Until that time, Vanderbilt used a homegrown system to keep track of patient data. The “system” was actual comprised of a few separate programs that integrated data, depending on the functions being accessed and who was accessing them.

For many research projects across the hospital, including my own, we are going to be limiting ourselves to data from the time period when our homegrown EMR was functioning. This is thinking a few steps ahead, but it would be interesting to see if our model, once validated, performed similarly in a new EMR environment. Unfortunately, this is thinking a few too many steps ahead for me, as I will have graduated (hopefully) by the time the new EMR is up and running reliably enough for EMR-based research like this project.

The first step in our study was identifying the right database to use, and now the next step will be extracting the data we need. Moving forward, I am continuing to work with my mentors, Dr. Eduard Vasilevskis and Dr. Jesse Ehrenfeld closely. We resubmitted our IRB application now that we have identified how we can pull the data we need, and we identified a few specialized patient populations for whom a separate scoring tool might be useful (e.g., stroke patients). I am looking forward to learning the particulars how our dataset will be built. The potential for finding the answers to many patient-care questions probably lies in the EMR data we already have, but you need to know how to get them to study them.

Monisha Bhatia, a native of Nashville, Tenn., is a fourth-year medical student at Vanderbilt University in Nashville. She is hoping to pursue either a residency in internal medicine or a combined internal medicine/emergency medicine program. Prior to medical school, she completed a JD/MPH program at Boston University, and she hopes to use her legal training in working with regulatory authorities to improve access to health care for all Americans.

2017 Update in perioperative medicine: 6 questions answered

Perioperative care is increasingly complex, and the rapid evolution of literature in this field makes it a challenge for clinicians to stay up-to-date. To help meet this challenge, we used a systematic approach to identify appropriate articles in the medical literature and then, by consensus, to develop a list of 6 clinical questions based on their novelty and potential to change perioperative medical practice:

- How should we screen for cardiac risk in patients undergoing noncardiac surgery?

- What is the appropriate timing for surgery after coronary intervention?

- Can we use statin therapy to reduce perioperative cardiac risk?

- How should we manage sleep apnea risk perioperatively?

- Which patients with atrial fibrillation should receive perioperative bridging anticoagulation?

- Is frailty screening beneficial for elderly patients before noncardiac surgery?

The summaries in this article are a composite of perioperative medicine updates presented at the Perioperative Medicine Summit and the annual meetings of the Society for General Internal Medicine and the Society of Hospital Medicine. “Perioperative care is complex and changing”1–10 (page 864) offers a brief overview.

HOW TO SCREEN FOR CARDIAC RISK BEFORE NONCARDIAC SURGERY

Perioperative cardiac risk can be estimated by clinical risk indexes (based on history, physical examination, common blood tests, and electrocardiography), cardiac biomarkers (natriuretic peptide or troponin levels), and noninvasive cardiac tests.

American and European guidelines

In 2014, the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association2 and the European Society of Cardiology11 published guidelines on perioperative cardiovascular evaluation and management. They recommended several tools to calculate the risk of postoperative cardiac complications but did not specify a preference. These tools include:

- The Revised Cardiac Risk Index (RCRI)12 (www.mdcalc.com/revised-cardiac-risk-index-pre-operative-risk), which has been externally validated in multiple studies and is the most widely used

- The American College of Surgeons surgical risk calculator13 (www.riskcalculator.facs.org), derived from the National Surgery Quality Improvement Program (NSQIP) database

- The myocardial infarction or cardiac arrest (MICA) calculator14 (www.surgicalriskcalculator.com/miorcardiacarrest), also derived from the NSQIP database.

2017 Canadian guidelines differ

In 2017, the Canadian Cardiovascular Society published its own guidelines on perioperative risk assessment and management.1 These differ from the American and European guidelines on several points.

RCRI recommended. The Canadian guidelines suggested using the RCRI over the other risk predictors, which despite superior discrimination lacked external validation (conditional recommendation; low-quality evidence). Additionally, the Canadians believed that the NSQIP risk indexes underestimated cardiac risk because patients did not undergo routine biomarker screening.

Biomarker measurement. The Canadian guidelines went a step further in their algorithm (Figure 1) and recommended measuring N-terminal-pro B-type natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) or BNP preoperatively to improve risk prediction in 3 groups (strong recommendation; moderate-quality evidence):

- Patients ages 65 and older

- Patients ages 45 to 64 with significant cardiovascular disease

- Patients with an RCRI score of 1 or more.

This differs from the American guidelines, which did not recommend measuring preoperative biomarkers but did acknowledge that they may provide incremental value. The American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association authors felt that there were no data to suggest that targeting these biomarkers for treatment and intervention would reduce postoperative risk. The European guidelines did not recommend routinely using biomarkers, but stated that they may be considered in high-risk patients (who have a functional capacity ≤ 4 metabolic equivalents or an RCRI score > 1 undergoing vascular surgery, or > 2 undergoing nonvascular surgery).

Stress testing deemphasized. The Canadian guidelines recommended biomarker testing rather than noninvasive tests to enhance risk assessment based on cost, potential delays in surgery, and absence of evidence of an overall absolute net improvement in risk reclassification. This contrasts with the American and European guidelines and algorithms, which recommended pharmacologic stress testing in patients at elevated risk with poor functional capacity undergoing intermediate- to high-risk surgery if the results would change how they are managed.

Postoperative monitoring. The Canadian guidelines recommended that if patients have an NT-proBNP level higher than 300 mg/L or a BNP level higher than 92 mg/L, they should receive postoperative monitoring with electrocardiography in the postanesthesia care unit and daily troponin measurements for 48 to 72 hours. The American guidelines recommended postoperative electrocardiography and troponin measurement only for patients suspected of having myocardial ischemia, and the European guidelines said postoperative biomarkers may be considered in patients at high risk.

Physician judgment needed

While guidelines and risk calculators are potentially helpful in risk assessment, the lack of consensus and the conflicting recommendations force the physician to weigh the evidence and make individual decisions based on his or her interpretation of the data.

Until there are studies directly comparing the various risk calculators, physicians will most likely use the RCRI, which is simple and has been externally validated, in conjunction with the American guidelines.

At this time, it is unclear how biomarkers should be used—preoperatively, postoperatively, or both—because there are no studies demonstrating that management strategies based on the results lead to better outcomes. We do not believe that biomarker testing will be accepted in lieu of stress testing by our surgery, anesthesiology, or cardiology colleagues, but going forward, it will probably be used more frequently postoperatively, particularly in patients at moderate to high risk.

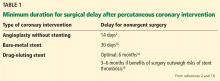

WHAT IS THE APPROPRIATE TIMING FOR SURGERY AFTER PCI?

A 2014 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association guideline recommended delaying noncardiac surgery for 1 month after percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) with bare-metal stents and 1 year after PCI with drug-eluting stents.15 The guideline suggested that surgery may be performed 6 months after drug-eluting stent placement if the risks of delaying surgery outweigh the risk of thrombosis.15

The primary rationale behind these timeframes was to provide dual antiplatelet therapy for a minimally acceptable duration before temporary interruption for a procedure. These recommendations were influenced largely by observational studies of first-generation devices, which are no longer used. Studies of newer-generation stents have suggested that the risk of stent thrombosis reaches a plateau considerably earlier than 6 to 12 months after PCI.

2016 Revised guideline on dual antiplatelet therapy

Although not separately delineated in the recommendations, risk factors for stent thrombosis that should influence the decision include smoking, multivessel coronary artery disease, and suboptimally controlled diabetes mellitus or hyperlipidemia.17 The presence of such stent thrombosis risk factors should be factored into the decision about proceeding with surgery within 3 to 6 months after drug-eluting stent placement.

Holcomb et al: Higher postoperative risk after PCI for myocardial infarction

Another important consideration is the indication for which PCI was performed. In a recent study, Holcomb et al16 found an association between postoperative major adverse cardiac events and PCI for myocardial infarction (MI) that was independent of stent type.

Compared with patients who underwent PCI not associated with acute coronary syndrome, the odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for major adverse cardiac events in those who underwent PCI for MI were:

- 5.25 (4.08–6.75) in the first 3 months

- 2.45 (1.80–3.35) in months 3 to 6

- 2.50 (1.90–3.28) in months 6 to 12.

In absolute terms, patients with stenting performed for an MI had an incidence of major adverse cardiac events of:

- 22.2% in the first 3 months

- 9.4% in months 3 to 6

- 5.8% in months 6 to 12

- 4.4% in months 12 to 24.

The perioperative risks were reduced after 12 months but still remained greater in patients whose PCI was performed for MI rather than another indication.16

The authors of this study suggested delaying noncardiac surgery for up to 6 months after PCI for MI, regardless of stent type.16

A careful, individualized approach

Optimal timing of noncardiac surgery PCI requires a careful, individualized approach and should always be coordinated with the patient’s cardiologist, surgeon, and anesthesiologist.3,15 For most patients, surgery should be delayed for 30 days after bare-metal stent placement and 6 months after drug-eluting stent placement.3 However, for those with greater surgical need and less thrombotic risk, noncardiac surgery can be considered 3 to 6 months after drug-eluting stent placement.3

Additional discussion of the prolonged increased risk of postoperative major adverse cardiac events is warranted in patients whose PCI was performed for MI, in whom delaying noncardiac surgery for up to 6 months (irrespective of stent type) should be considered.16

CAN WE USE STATINS TO REDUCE PERIOPERATIVE RISK?

Current recommendations from the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association support continuing statins in the perioperative period, but the evidence supporting starting statins in this period has yet to be fully determined. In 2013, a Cochrane review18 found insufficient evidence to conclude that statins reduced perioperative adverse cardiac events, though several large studies were excluded due to controversial methods and data.

In contrast, the Vascular Events in Noncardiac Surgery Patients Cohort Evaluation (VISION) study,4 a multicenter, prospective, cohort-matched study of approximately 7,200 patients, found a lower risk of a composite primary outcome of all-cause mortality, myocardial injury after noncardiac surgery, or stroke at 30 days for patients exposed to statin therapy (relative risk [RR] 0.83, 95% CI 0.73–0.95, P = .007).4

London et al retrospective study: 30-day mortality rate is lower with statins

In 2017, London et al5 published the results of a very large retrospective, observational cohort study of approximately 96,000 elective or emergency surgery patients in Department of Veterans Affairs hospitals. The patients were propensity-matched and evaluated for exposure to statins on the day of or the day after surgery, for a total of approximately 48,000 pairs.

The primary outcome was death at 30 days, and statin exposure was associated with a significant reduction (RR 0.82; 95% CI 0.75–0.89; P < .001). Significant risk reductions were demonstrated in nearly all secondary end points as well, except for stroke or coma and thrombosis (pulmonary embolism, deep vein thrombosis, or graft failure). Overall, the number needed to treat to prevent any complication was 67. Statin therapy did not show significant harm, though on subgroup analysis, those who received high-intensity statin therapy had a slightly higher risk of renal injury (odds ratio 1.18, 95% CI 1.02–1.37, P = .03). Also on subgroup analysis, after propensity matching, patients on long-term moderate- or high-intensity statin therapy for 6 to 12 months before surgery had a small risk reduction for many of the outcomes, including death.

The authors also noted that only 62% of the patients who were prescribed statins as outpatients received them in the hospital, which suggests that improvement is necessary in educating perioperative physicians about the benefits and widespread support for continuing statins perioperatively.5

LOAD trial: No benefit from starting statins

Both London et al5 and the VISION investigators4 called for a large randomized controlled trial of perioperative statin initiation. The Lowering the Risk of Operative Complications Using Atorvastatin Loading Dose (LOAD) trial attempted to answer this call.6

This trial randomized 648 statin-naïve Brazilian patients at high risk of perioperative cardiac events to receive either atorvastatin or placebo before surgery and then continuously for another 7 days. The primary outcomes were the rates of death, nonfatal myocardial injury after noncardiac surgery, and cerebrovascular accident at 30 days.6

The investigators found no significant difference in outcomes between the two groups and estimated that the sample size would need to be approximately 7,000 patients to demonstrate a significant benefit. Nonetheless, this trial established that a prospective perioperative statin trial is feasible.

When to continue or start statins

Although we cannot recommend starting statins for all perioperative patients, perioperative statins clearly can carry significant benefit and should be continued in all patients who have been taking them. It is also likely beneficial to initiate statins in those patients who would otherwise warrant therapy based on the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Pooled Cohort Equations Risk calculator.19

HOW SHOULD WE MANAGE SLEEP APNEA RISK PERIOPERATIVELY?

From 20% to 30% of US men and 10% to 15% of US women have obstructive sleep apnea, and many are undiagnosed. Obstructive sleep apnea increases the risk of perioperative respiratory failure, unplanned reintubation, unplanned transfer to the intensive care unit, and death.20 Sentinel events (unexpected respiratory arrest after surgery on general surgical wards) have prompted the development of guidelines that aim to identify patients with previously undiagnosed obstructive sleep apnea before surgery and to develop approaches to reduce perioperative morbidity and mortality.

Kaw et al: Beware obesity hypoventilation syndrome

A 2016 study suggested that patients with obstructive sleep apnea and obesity hypoventilation syndrome may be at particularly high risk of perioperative complications.21

Kaw et al21 queried a database of patients with obstructive sleep apnea undergoing elective noncardiac surgery at Cleveland Clinic. All patients (N = 519) had obstructive sleep apnea confirmed by polysomnography, and a body mass index greater than 30 kg/m2. The authors considered a patient to have obesity hypoventilation syndrome (n = 194) if he or she also had hypercapnia (Paco2 ≥ 45 mm Hg) on at least 2 occasions before or after surgery.

In an adjusted analysis, the odds ratios and 95% CIs for adverse outcomes in patients with obesity hypoventilation syndrome were:

- 10.9 (3.7–32.3) for respiratory failure

- 5.4 (1.9–15.7) for heart failure

- 10.9 (3.7–32.3) for intensive care unit transfer.

The absolute increases in risk in the presence of obesity hypoventilation syndrome were:

- 19% (21% vs 2%) for respiratory failure

- 8% (8% vs 0) for heart failure

- 15% (21% vs 6%) for intensive care unit transfer.

There was no difference in rates of perioperative mortality.21

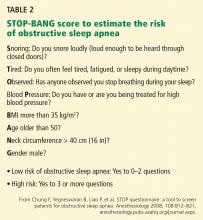

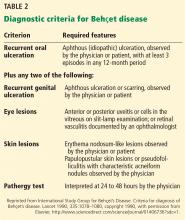

The authors proposed an algorithm to identify patients with possible obesity hypoventilation syndrome before surgery that included prior sleep study results, STOP-BANG score (Table 2),22 and serum bicarbonate level.

Important limitations of the study were that most patients with obesity hypoventilation syndrome were undiagnosed at the time of surgery. Still, the study does offer a tool to potentially identify patients at high risk for perioperative morbidity due to obesity hypoventilation syndrome. Clinicians could then choose to cancel nonessential surgery, propose a lower-risk alternative procedure, or maximize the use of strategies known to reduce perioperative risk for patients with obstructive sleep apnea in general.

Two guidelines on obstructive sleep apnea

Two professional societies have issued guidelines aiming to improve detection of previously undiagnosed obstructive sleep apnea and perioperative outcomes in patients known to have it or suspected of having it:

- The American Society of Anesthesiologists in 201423

- The Society of Anesthesia and Sleep Medicine in 2016.7

Both guidelines recommend that each institution develop a local protocol to screen patients for possible obstructive sleep apnea before elective surgery. The American Society of Anesthesiologists does not recommend any particular tool, but does recommend taking a history and performing a focused examination that includes evaluation of the airway, nasopharyngeal characteristics, neck circumference, and tonsil and tongue size. The Society of Anesthesia and Sleep Medicine recommends using a validated tool such as the STOP-BANG score to estimate the risk of obstructive sleep apnea.

If this screening suggests that a patient has obstructive sleep apnea, should surgery be delayed until a formal sleep study can be done? Or should the patient be treated empirically as if he or she has obstructive sleep apnea? Both professional societies recommend shared decision-making with the patient in this situation, with the Society of Anesthesia and Sleep Medicine recommending additional cardiopulmonary evaluation for patients with hypoventilation, severe pulmonary hypertension, or resting hypoxemia.

Both recommend using continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) after surgery in patients with known obstructive sleep apnea, although there is not enough evidence to determine if empiric CPAP for screening-positive patients (without polysomnography-diagnosed obstructive sleep apnea) is beneficial. The Society of Anesthesia and Sleep Medicine advises that it is safe to proceed to surgery if obstructive sleep apnea is suspected as long as monitoring and risk-reduction strategies are implemented after surgery to reduce complication rates.

During surgery, the American Society of Anesthesiologists advises peripheral nerve blocks when appropriate, general anesthesia with a secure airway rather than deep sedation, capnography when using moderate sedation, awake extubation, and full reversal of neuromuscular blockade before extubation. After surgery, they recommend reducing opioid use, minimizing postoperative sedatives, supplemental oxygen, and continuous pulse oximetry. The Society of Anesthesia and Sleep Medicine guideline addresses preoperative assessment and therefore makes no recommendations regarding postoperative care.

In conclusion, use of pertinent findings from the history and physical examination and a validated obstructive sleep apnea screening tool such as STOP-BANG before surgery are recommended, with joint decision-making as to proceeding with surgery with empiric CPAP vs a formal sleep study for patients who screen as high risk. The Society of Anesthesia and Sleep Medicine recommends further cardiopulmonary evaluation if there is evidence of hypoventilation, hypoxemia, or pulmonary hypertension in addition to likely obstructive sleep apnea.

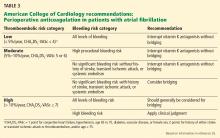

WHICH ATRIAL FIBRILLATION PATIENTS NEED BRIDGING ANTICOAGULATION?

When patients receiving anticoagulation need surgery, we need to carefully assess the risks of thromboembolism without anticoagulation vs bleeding with anticoagulation.

Historically, we tended to worry more about thromboembolism24; however, recent studies have revealed a significant risk of bleeding when long-term anticoagulant therapy is bridged (ie, interrupted and replaced with a shorter-acting agent in the perioperative period), with minimal to no decrease in thromboembolic events.25–27

American College of Cardiology guideline

In 2017, the American College of Cardiology8 published a guideline on periprocedural management of anticoagulation in patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. The guideline includes a series of decision algorithms on whether and when to interrupt anticoagulation, whether and how to provide bridging anticoagulation, and how to restart postprocedural anticoagulation.

When deciding whether to interrupt anticoagulation, we need to consider the risk of bleeding posed both by patient-specific factors and by the type of surgery. Bridging anticoagulation is not indicated when direct oral anticoagulants (eg, dabigatran, apixaban, edoxaban, rivaroxaban) are interrupted for procedures.

Unlike an earlier guideline statement by the American College of Chest Physicians,24 this consensus statement emphasizes using the CHA2DS2-VASc score as a predictor of thromboembolic events rather than the CHADS2 core.

Table 3 summarizes the key points in the guidance statement about which patients should receive periprocedural bridging anticoagulation.

As evidence continues to evolve in this complicated area of perioperative medicine, it will remain important to continue to create patient management plans that take individual patient and procedural risks into account.

IS FRAILTY SCREENING BENEFICIAL BEFORE NONCARDIAC SURGERY?

Frailty, defined as a composite score of a patient’s age and comorbidities, has great potential to become an obligatory factor in perioperative risk assessment. However, it remains difficult to incorporate frailty scoring into clinical practice due to variations among scoring systems,28 uncertain outcome data, and the imprecise role of socioeconomic factors. In particular, the effect of frailty on perioperative mortality over longer periods of time is uncertain.

McIsaac et al: Higher risk in frail patients

McIsaac and colleagues at the University of Ottawa used a frailty scoring system developed at Johns Hopkins University to evaluate the effect of frailty on all-cause postoperative mortality in approximately 202,000 patients over a 10-year period.9 Although this scoring system is proprietary, it is based on factors such as malnutrition, dementia, impaired vision, decubitus ulcers, urinary incontinence, weight loss, poverty, barriers to access of care, difficulty in walking, and falls.

After adjusting for the procedure risk, patient age, sex, and neighborhood income quintile, the 1-year mortality risk was significantly higher in the frail group (absolute risk 13.6% vs 4.8%; adjusted hazard ratio 2.23; 95% CI 2.08–2.40). The risk of death in the first 3 days was much higher in frail than in nonfrail patients (hazard ratio 35.58; 95% CI 29.78–40.1), but the hazard ratio decreased to approximately 2.4 by day 90.

The authors emphasize that the elevated risk for frail patients warrants particular perioperative planning, though it is not yet clear what frailty-specific interventions should be performed. Further study is needed into the benefit of “prehabilitation” (ie, exercise training to “build up” a patient before surgery) for perioperative risk reduction.

Hall et al: Better care for frail patients

Hall et al10 instituted a quality improvement initiative for perioperative care of patients at the Omaha Veterans Affairs Hospital. Frail patients were identified using the Risk Analysis Index, a 14-question screening tool previously developed and validated over several years using Veterans Administration databases.29 Questions in the Risk Analysis Index cover living situation, any diagnosis of cancer, ability to perform activities of daily living, and others.

To maximize compliance, a Risk Analysis Index score was required to schedule a surgery. Patients with high scores underwent further review by a designated team of physicians who initiated informal and formal consultations with anesthesiologists, critical care physicians, surgeons, and palliative care providers, with the goals of minimizing risk, clarifying patient goals or resuscitation wishes, and developing comprehensive perioperative planning.10

Approximately 9,100 patients were included in the cohort. The authors demonstrated a significant improvement in mortality for frail patients at 30, 180, and 365 days, but noted an improvement in postoperative mortality for the nonfrail patients as well, perhaps due to increased focus on geriatric patient care. In particular, the mortality rate at 365 days dropped from 34.5% to 11.7% for frail patients who underwent this intervention.

While this quality improvement initiative was unable to examine how surgical rates changed in frail patients, it is highly likely that very high-risk patients opted out of surgery or had their surgical plan change, though the authors point out that the overall surgical volume at the institution did not change significantly. As well, it remains unclear which particular interventions may have had the most effect in improving survival, as the perioperative plans were individualized and continually adjusted throughout the study period.

Nonetheless, this article highlights how higher vigilance, individualized planning and appreciation of the high risks of frail patients is associated with improved patient survival postoperatively. Although frailty screening is still in its early stages and further work is needed, it is likely that performing frailty screening in elderly patients and utilizing interdisciplinary collaboration for comprehensive management of frail patients can improve their postoperative course.

- Duceppe E, Parlow J, MacDonald P, et al. Canadian Cardiovascular Society guidelines on perioperative cardiac risk assessment and management for patients who undergo noncardiac surgery. Can J Cardiol 2017; 33:17–32.

- Fleisher LA, Fleischmann KE, Auerbach AD, et al. 2014 ACC/AHA guideline on perioperative cardiovascular evaluation and management of patients undergoing noncardiac surgery: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on practice guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol 2014; 64:2373–2405.

- Levine GN, Bates ER, Bittl JA, et al. 2016 ACC/AHA guideline focused update on duration of dual antiplatelet therapy in patients with coronary artery disease. Circulation 2016; 134:e123–e155.

- Berwanger O, Le Manach Y, Suzumura EA, et al. Association between pre-operative statin use and major cardiovascular complications among patients undergoing non-cardiac surgery: the VISION study. Eur Heart J 2016; 37:177–185.

- London MJ, Schwartz GG, Hur K, Henderson WG. Association of perioperative statin use with mortality and morbidity after major noncardiac surgery. JAMA Intern Med 2017; 177:231–242.

- Berwanger O, de Barros E Silva PG, Barbosa RR, et al. Atorvastatin for high-risk statin-naïve patients undergoing noncardiac surgery: the Lowering the Risk of Operative Complications Using Atorvastatin Loading Dose (LOAD) randomized trial. Am Heart J 2017; 184:88–96.

- Chung F, Memtsoudis SG, Ramachandran SK, et al. Society of Anesthesia and Sleep Medicine guidelines on preoperative screening and assessment of adult patients with obstructive sleep apnea. Anesth Analg 2016; 123:452–473.

- Doherty JU, Gluckman TJ, Hucker W, et al. 2017 ACC expert consensus decision pathway for periprocedural management of anticoagulation in patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation: a report of the American College of Cardiology Clinical Expert Consensus Document Task Force. J Am Coll Cardiol 2017; 69:871–898.

- McIsaac DI, Bryson GL, van Walraven C. Association of frailty and 1-year postoperative mortality following major elective noncardiac surgery: a population-based cohort study. JAMA Surg 2016; 151:538–545.

- Hall DE, Arya S, Schmid KK, et al. Association of a frailty screening initiative with postoperative survival at 30, 180, and 365 days. JAMA Surg 2017; 152:233–240.

- Kristensen SD, Knuuti J, Saraste A, et al. 2014 ESC/ESA Guidelines on non-cardiac surgery: cardiovascular assessment and management: The Joint Task Force on non-cardiac surgery: cardiovascular assessment and management of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Society of Anaesthesiology (ESA). Eur Heart J 2014; 35:2383–2431.

- Lee TH, Marcantonio ER, Mangione CM, et al. Derivation and prospective validation of a simple index for prediction of cardiac risk of major noncardiac surgery. Circulation 1999; 100:1043–1049.

- Bilimoria KY, Liu Y, Paruch JL, Zhou L, Kmiecik TE, Ko CY, Cohen ME. Development and evaluation of the universal ACS NSQIP surgical risk calculator: a decision aid and informed consent tool for patients and surgeons. J Am Coll Surg 2013; 217:833–842.

- Gupta PK, Gupta H, Sundaram A, et al. Development and validation of a risk calculator for prediction of cardiac risk after surgery. Circulation 2011; 124:381–387.

- Fleisher LA, Fleischmann KE, Auerbach AD, et al. 2014 ACC/AHA guideline on perioperative cardiovascular evaluation and management of patients undergoing noncardiac surgery: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol 2014; 64:e77–e137.

- Holcomb CN, Hollis RH, Graham LA, et al. Association of coronary stent indication with postoperative outcomes following noncardiac surgery. JAMA Surg 2016; 151:462–469.

- Lemesle G, Tricot O, Meurice T, et al. Incident myocardial infarction and very late stent thrombosis in outpatients with stable coronary artery disease. J Am Coll Cardiol 2017; 69:2149–2156.

- Sanders RD, Nicholson A, Lewis SR, Smith AF, Alderson P. Perioperative statin therapy for improving outcomes during and after noncardiac vascular surgery. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013; 7:CD009971.

- Goff DC, Lloyd-Jones DM, Bennett G, et al. 2013 ACC/AHA guideline on the assessment of cardiovascular risk: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol 2014; 63:2935–2959.

- Kaw R, Pasupuleti V, Walker E, et al. Postoperative complications in patients with obstructive sleep apnea. Chest 2012; 141:436–441.

- Kaw R, Bhateja P, Mar HP, et al. Postoperative complications in patients with unrecognized obesity hypoventilation syndrome undergoing elective noncardiac surgery. Chest 2016; 149:84–91.

- Chung F, Yegneswaran B, Liao P, et al. STOP questionnaire: a tool to screen patients for obstructive sleep apnea. Anesthesiology 2008; 108:812–821.

- Gross JB, Apfelbaum JL, Caplan RA, et al. Practice guidelines for the perioperative management of patients with obstructive sleep apnea: an updated report by the American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Perioperative Management of Patients with Obstructive Sleep Apnea. Anesthesiology 2014; 120:268–286.

- Douketis JD, Spyropoulos AC, Spencer FA, et al. Perioperative management of antithrombotic therapy: Antithrombotic Therapy and Prevention of Thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest 2012; 141(2 suppl):e326S–e350S.

- Siegal D, Yudin J, Kaatz S, Douketis JD, Lim W, Spyropoulos AC. Periprocedural heparin bridging in patients receiving vitamin K antagonists: systematic review and meta-analysis of bleeding and thromboembolic rates. Circulation 2012; 126:1630–1639.

- Clark NP, Witt DM, Davies LE, et al. Bleeding, recurrent venous thromboembolism, and mortality risks during warfarin interruption for invasive procedures. JAMA Intern Med 2015; 175:1163–1168.

- Douketis JD, Spyropoulos AC, Kaatz S, et al. Perioperative bridging anticoagulation in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med 2015; 373:823–833.

- Theou O, Brothers TD, Mitnitski A, Rockwood K. Operationalization of frailty using eight commonly used scales and comparison of their ability to predict all-cause mortality. J Am Geriatr Soc 2013; 61:1537–1551.

- Hall DE, Arya S, Schmid KK, et al. Development and initial validation of the risk analysis index for measuring frailty in surgical populations. JAMA Surg 2017; 152:175–182.

Perioperative care is increasingly complex, and the rapid evolution of literature in this field makes it a challenge for clinicians to stay up-to-date. To help meet this challenge, we used a systematic approach to identify appropriate articles in the medical literature and then, by consensus, to develop a list of 6 clinical questions based on their novelty and potential to change perioperative medical practice:

- How should we screen for cardiac risk in patients undergoing noncardiac surgery?

- What is the appropriate timing for surgery after coronary intervention?

- Can we use statin therapy to reduce perioperative cardiac risk?

- How should we manage sleep apnea risk perioperatively?

- Which patients with atrial fibrillation should receive perioperative bridging anticoagulation?

- Is frailty screening beneficial for elderly patients before noncardiac surgery?

The summaries in this article are a composite of perioperative medicine updates presented at the Perioperative Medicine Summit and the annual meetings of the Society for General Internal Medicine and the Society of Hospital Medicine. “Perioperative care is complex and changing”1–10 (page 864) offers a brief overview.

HOW TO SCREEN FOR CARDIAC RISK BEFORE NONCARDIAC SURGERY

Perioperative cardiac risk can be estimated by clinical risk indexes (based on history, physical examination, common blood tests, and electrocardiography), cardiac biomarkers (natriuretic peptide or troponin levels), and noninvasive cardiac tests.

American and European guidelines

In 2014, the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association2 and the European Society of Cardiology11 published guidelines on perioperative cardiovascular evaluation and management. They recommended several tools to calculate the risk of postoperative cardiac complications but did not specify a preference. These tools include:

- The Revised Cardiac Risk Index (RCRI)12 (www.mdcalc.com/revised-cardiac-risk-index-pre-operative-risk), which has been externally validated in multiple studies and is the most widely used

- The American College of Surgeons surgical risk calculator13 (www.riskcalculator.facs.org), derived from the National Surgery Quality Improvement Program (NSQIP) database

- The myocardial infarction or cardiac arrest (MICA) calculator14 (www.surgicalriskcalculator.com/miorcardiacarrest), also derived from the NSQIP database.

2017 Canadian guidelines differ

In 2017, the Canadian Cardiovascular Society published its own guidelines on perioperative risk assessment and management.1 These differ from the American and European guidelines on several points.

RCRI recommended. The Canadian guidelines suggested using the RCRI over the other risk predictors, which despite superior discrimination lacked external validation (conditional recommendation; low-quality evidence). Additionally, the Canadians believed that the NSQIP risk indexes underestimated cardiac risk because patients did not undergo routine biomarker screening.

Biomarker measurement. The Canadian guidelines went a step further in their algorithm (Figure 1) and recommended measuring N-terminal-pro B-type natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) or BNP preoperatively to improve risk prediction in 3 groups (strong recommendation; moderate-quality evidence):

- Patients ages 65 and older

- Patients ages 45 to 64 with significant cardiovascular disease

- Patients with an RCRI score of 1 or more.

This differs from the American guidelines, which did not recommend measuring preoperative biomarkers but did acknowledge that they may provide incremental value. The American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association authors felt that there were no data to suggest that targeting these biomarkers for treatment and intervention would reduce postoperative risk. The European guidelines did not recommend routinely using biomarkers, but stated that they may be considered in high-risk patients (who have a functional capacity ≤ 4 metabolic equivalents or an RCRI score > 1 undergoing vascular surgery, or > 2 undergoing nonvascular surgery).

Stress testing deemphasized. The Canadian guidelines recommended biomarker testing rather than noninvasive tests to enhance risk assessment based on cost, potential delays in surgery, and absence of evidence of an overall absolute net improvement in risk reclassification. This contrasts with the American and European guidelines and algorithms, which recommended pharmacologic stress testing in patients at elevated risk with poor functional capacity undergoing intermediate- to high-risk surgery if the results would change how they are managed.

Postoperative monitoring. The Canadian guidelines recommended that if patients have an NT-proBNP level higher than 300 mg/L or a BNP level higher than 92 mg/L, they should receive postoperative monitoring with electrocardiography in the postanesthesia care unit and daily troponin measurements for 48 to 72 hours. The American guidelines recommended postoperative electrocardiography and troponin measurement only for patients suspected of having myocardial ischemia, and the European guidelines said postoperative biomarkers may be considered in patients at high risk.

Physician judgment needed

While guidelines and risk calculators are potentially helpful in risk assessment, the lack of consensus and the conflicting recommendations force the physician to weigh the evidence and make individual decisions based on his or her interpretation of the data.

Until there are studies directly comparing the various risk calculators, physicians will most likely use the RCRI, which is simple and has been externally validated, in conjunction with the American guidelines.

At this time, it is unclear how biomarkers should be used—preoperatively, postoperatively, or both—because there are no studies demonstrating that management strategies based on the results lead to better outcomes. We do not believe that biomarker testing will be accepted in lieu of stress testing by our surgery, anesthesiology, or cardiology colleagues, but going forward, it will probably be used more frequently postoperatively, particularly in patients at moderate to high risk.

WHAT IS THE APPROPRIATE TIMING FOR SURGERY AFTER PCI?

A 2014 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association guideline recommended delaying noncardiac surgery for 1 month after percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) with bare-metal stents and 1 year after PCI with drug-eluting stents.15 The guideline suggested that surgery may be performed 6 months after drug-eluting stent placement if the risks of delaying surgery outweigh the risk of thrombosis.15

The primary rationale behind these timeframes was to provide dual antiplatelet therapy for a minimally acceptable duration before temporary interruption for a procedure. These recommendations were influenced largely by observational studies of first-generation devices, which are no longer used. Studies of newer-generation stents have suggested that the risk of stent thrombosis reaches a plateau considerably earlier than 6 to 12 months after PCI.

2016 Revised guideline on dual antiplatelet therapy

Although not separately delineated in the recommendations, risk factors for stent thrombosis that should influence the decision include smoking, multivessel coronary artery disease, and suboptimally controlled diabetes mellitus or hyperlipidemia.17 The presence of such stent thrombosis risk factors should be factored into the decision about proceeding with surgery within 3 to 6 months after drug-eluting stent placement.

Holcomb et al: Higher postoperative risk after PCI for myocardial infarction

Another important consideration is the indication for which PCI was performed. In a recent study, Holcomb et al16 found an association between postoperative major adverse cardiac events and PCI for myocardial infarction (MI) that was independent of stent type.

Compared with patients who underwent PCI not associated with acute coronary syndrome, the odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for major adverse cardiac events in those who underwent PCI for MI were:

- 5.25 (4.08–6.75) in the first 3 months

- 2.45 (1.80–3.35) in months 3 to 6

- 2.50 (1.90–3.28) in months 6 to 12.

In absolute terms, patients with stenting performed for an MI had an incidence of major adverse cardiac events of:

- 22.2% in the first 3 months

- 9.4% in months 3 to 6

- 5.8% in months 6 to 12

- 4.4% in months 12 to 24.

The perioperative risks were reduced after 12 months but still remained greater in patients whose PCI was performed for MI rather than another indication.16

The authors of this study suggested delaying noncardiac surgery for up to 6 months after PCI for MI, regardless of stent type.16

A careful, individualized approach

Optimal timing of noncardiac surgery PCI requires a careful, individualized approach and should always be coordinated with the patient’s cardiologist, surgeon, and anesthesiologist.3,15 For most patients, surgery should be delayed for 30 days after bare-metal stent placement and 6 months after drug-eluting stent placement.3 However, for those with greater surgical need and less thrombotic risk, noncardiac surgery can be considered 3 to 6 months after drug-eluting stent placement.3

Additional discussion of the prolonged increased risk of postoperative major adverse cardiac events is warranted in patients whose PCI was performed for MI, in whom delaying noncardiac surgery for up to 6 months (irrespective of stent type) should be considered.16

CAN WE USE STATINS TO REDUCE PERIOPERATIVE RISK?

Current recommendations from the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association support continuing statins in the perioperative period, but the evidence supporting starting statins in this period has yet to be fully determined. In 2013, a Cochrane review18 found insufficient evidence to conclude that statins reduced perioperative adverse cardiac events, though several large studies were excluded due to controversial methods and data.

In contrast, the Vascular Events in Noncardiac Surgery Patients Cohort Evaluation (VISION) study,4 a multicenter, prospective, cohort-matched study of approximately 7,200 patients, found a lower risk of a composite primary outcome of all-cause mortality, myocardial injury after noncardiac surgery, or stroke at 30 days for patients exposed to statin therapy (relative risk [RR] 0.83, 95% CI 0.73–0.95, P = .007).4

London et al retrospective study: 30-day mortality rate is lower with statins

In 2017, London et al5 published the results of a very large retrospective, observational cohort study of approximately 96,000 elective or emergency surgery patients in Department of Veterans Affairs hospitals. The patients were propensity-matched and evaluated for exposure to statins on the day of or the day after surgery, for a total of approximately 48,000 pairs.

The primary outcome was death at 30 days, and statin exposure was associated with a significant reduction (RR 0.82; 95% CI 0.75–0.89; P < .001). Significant risk reductions were demonstrated in nearly all secondary end points as well, except for stroke or coma and thrombosis (pulmonary embolism, deep vein thrombosis, or graft failure). Overall, the number needed to treat to prevent any complication was 67. Statin therapy did not show significant harm, though on subgroup analysis, those who received high-intensity statin therapy had a slightly higher risk of renal injury (odds ratio 1.18, 95% CI 1.02–1.37, P = .03). Also on subgroup analysis, after propensity matching, patients on long-term moderate- or high-intensity statin therapy for 6 to 12 months before surgery had a small risk reduction for many of the outcomes, including death.

The authors also noted that only 62% of the patients who were prescribed statins as outpatients received them in the hospital, which suggests that improvement is necessary in educating perioperative physicians about the benefits and widespread support for continuing statins perioperatively.5

LOAD trial: No benefit from starting statins

Both London et al5 and the VISION investigators4 called for a large randomized controlled trial of perioperative statin initiation. The Lowering the Risk of Operative Complications Using Atorvastatin Loading Dose (LOAD) trial attempted to answer this call.6

This trial randomized 648 statin-naïve Brazilian patients at high risk of perioperative cardiac events to receive either atorvastatin or placebo before surgery and then continuously for another 7 days. The primary outcomes were the rates of death, nonfatal myocardial injury after noncardiac surgery, and cerebrovascular accident at 30 days.6

The investigators found no significant difference in outcomes between the two groups and estimated that the sample size would need to be approximately 7,000 patients to demonstrate a significant benefit. Nonetheless, this trial established that a prospective perioperative statin trial is feasible.

When to continue or start statins

Although we cannot recommend starting statins for all perioperative patients, perioperative statins clearly can carry significant benefit and should be continued in all patients who have been taking them. It is also likely beneficial to initiate statins in those patients who would otherwise warrant therapy based on the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Pooled Cohort Equations Risk calculator.19

HOW SHOULD WE MANAGE SLEEP APNEA RISK PERIOPERATIVELY?

From 20% to 30% of US men and 10% to 15% of US women have obstructive sleep apnea, and many are undiagnosed. Obstructive sleep apnea increases the risk of perioperative respiratory failure, unplanned reintubation, unplanned transfer to the intensive care unit, and death.20 Sentinel events (unexpected respiratory arrest after surgery on general surgical wards) have prompted the development of guidelines that aim to identify patients with previously undiagnosed obstructive sleep apnea before surgery and to develop approaches to reduce perioperative morbidity and mortality.

Kaw et al: Beware obesity hypoventilation syndrome

A 2016 study suggested that patients with obstructive sleep apnea and obesity hypoventilation syndrome may be at particularly high risk of perioperative complications.21

Kaw et al21 queried a database of patients with obstructive sleep apnea undergoing elective noncardiac surgery at Cleveland Clinic. All patients (N = 519) had obstructive sleep apnea confirmed by polysomnography, and a body mass index greater than 30 kg/m2. The authors considered a patient to have obesity hypoventilation syndrome (n = 194) if he or she also had hypercapnia (Paco2 ≥ 45 mm Hg) on at least 2 occasions before or after surgery.

In an adjusted analysis, the odds ratios and 95% CIs for adverse outcomes in patients with obesity hypoventilation syndrome were:

- 10.9 (3.7–32.3) for respiratory failure

- 5.4 (1.9–15.7) for heart failure

- 10.9 (3.7–32.3) for intensive care unit transfer.

The absolute increases in risk in the presence of obesity hypoventilation syndrome were:

- 19% (21% vs 2%) for respiratory failure

- 8% (8% vs 0) for heart failure

- 15% (21% vs 6%) for intensive care unit transfer.

There was no difference in rates of perioperative mortality.21

The authors proposed an algorithm to identify patients with possible obesity hypoventilation syndrome before surgery that included prior sleep study results, STOP-BANG score (Table 2),22 and serum bicarbonate level.

Important limitations of the study were that most patients with obesity hypoventilation syndrome were undiagnosed at the time of surgery. Still, the study does offer a tool to potentially identify patients at high risk for perioperative morbidity due to obesity hypoventilation syndrome. Clinicians could then choose to cancel nonessential surgery, propose a lower-risk alternative procedure, or maximize the use of strategies known to reduce perioperative risk for patients with obstructive sleep apnea in general.

Two guidelines on obstructive sleep apnea

Two professional societies have issued guidelines aiming to improve detection of previously undiagnosed obstructive sleep apnea and perioperative outcomes in patients known to have it or suspected of having it:

- The American Society of Anesthesiologists in 201423

- The Society of Anesthesia and Sleep Medicine in 2016.7

Both guidelines recommend that each institution develop a local protocol to screen patients for possible obstructive sleep apnea before elective surgery. The American Society of Anesthesiologists does not recommend any particular tool, but does recommend taking a history and performing a focused examination that includes evaluation of the airway, nasopharyngeal characteristics, neck circumference, and tonsil and tongue size. The Society of Anesthesia and Sleep Medicine recommends using a validated tool such as the STOP-BANG score to estimate the risk of obstructive sleep apnea.

If this screening suggests that a patient has obstructive sleep apnea, should surgery be delayed until a formal sleep study can be done? Or should the patient be treated empirically as if he or she has obstructive sleep apnea? Both professional societies recommend shared decision-making with the patient in this situation, with the Society of Anesthesia and Sleep Medicine recommending additional cardiopulmonary evaluation for patients with hypoventilation, severe pulmonary hypertension, or resting hypoxemia.

Both recommend using continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) after surgery in patients with known obstructive sleep apnea, although there is not enough evidence to determine if empiric CPAP for screening-positive patients (without polysomnography-diagnosed obstructive sleep apnea) is beneficial. The Society of Anesthesia and Sleep Medicine advises that it is safe to proceed to surgery if obstructive sleep apnea is suspected as long as monitoring and risk-reduction strategies are implemented after surgery to reduce complication rates.

During surgery, the American Society of Anesthesiologists advises peripheral nerve blocks when appropriate, general anesthesia with a secure airway rather than deep sedation, capnography when using moderate sedation, awake extubation, and full reversal of neuromuscular blockade before extubation. After surgery, they recommend reducing opioid use, minimizing postoperative sedatives, supplemental oxygen, and continuous pulse oximetry. The Society of Anesthesia and Sleep Medicine guideline addresses preoperative assessment and therefore makes no recommendations regarding postoperative care.

In conclusion, use of pertinent findings from the history and physical examination and a validated obstructive sleep apnea screening tool such as STOP-BANG before surgery are recommended, with joint decision-making as to proceeding with surgery with empiric CPAP vs a formal sleep study for patients who screen as high risk. The Society of Anesthesia and Sleep Medicine recommends further cardiopulmonary evaluation if there is evidence of hypoventilation, hypoxemia, or pulmonary hypertension in addition to likely obstructive sleep apnea.

WHICH ATRIAL FIBRILLATION PATIENTS NEED BRIDGING ANTICOAGULATION?

When patients receiving anticoagulation need surgery, we need to carefully assess the risks of thromboembolism without anticoagulation vs bleeding with anticoagulation.

Historically, we tended to worry more about thromboembolism24; however, recent studies have revealed a significant risk of bleeding when long-term anticoagulant therapy is bridged (ie, interrupted and replaced with a shorter-acting agent in the perioperative period), with minimal to no decrease in thromboembolic events.25–27

American College of Cardiology guideline

In 2017, the American College of Cardiology8 published a guideline on periprocedural management of anticoagulation in patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. The guideline includes a series of decision algorithms on whether and when to interrupt anticoagulation, whether and how to provide bridging anticoagulation, and how to restart postprocedural anticoagulation.

When deciding whether to interrupt anticoagulation, we need to consider the risk of bleeding posed both by patient-specific factors and by the type of surgery. Bridging anticoagulation is not indicated when direct oral anticoagulants (eg, dabigatran, apixaban, edoxaban, rivaroxaban) are interrupted for procedures.

Unlike an earlier guideline statement by the American College of Chest Physicians,24 this consensus statement emphasizes using the CHA2DS2-VASc score as a predictor of thromboembolic events rather than the CHADS2 core.

Table 3 summarizes the key points in the guidance statement about which patients should receive periprocedural bridging anticoagulation.

As evidence continues to evolve in this complicated area of perioperative medicine, it will remain important to continue to create patient management plans that take individual patient and procedural risks into account.

IS FRAILTY SCREENING BENEFICIAL BEFORE NONCARDIAC SURGERY?

Frailty, defined as a composite score of a patient’s age and comorbidities, has great potential to become an obligatory factor in perioperative risk assessment. However, it remains difficult to incorporate frailty scoring into clinical practice due to variations among scoring systems,28 uncertain outcome data, and the imprecise role of socioeconomic factors. In particular, the effect of frailty on perioperative mortality over longer periods of time is uncertain.

McIsaac et al: Higher risk in frail patients

McIsaac and colleagues at the University of Ottawa used a frailty scoring system developed at Johns Hopkins University to evaluate the effect of frailty on all-cause postoperative mortality in approximately 202,000 patients over a 10-year period.9 Although this scoring system is proprietary, it is based on factors such as malnutrition, dementia, impaired vision, decubitus ulcers, urinary incontinence, weight loss, poverty, barriers to access of care, difficulty in walking, and falls.

After adjusting for the procedure risk, patient age, sex, and neighborhood income quintile, the 1-year mortality risk was significantly higher in the frail group (absolute risk 13.6% vs 4.8%; adjusted hazard ratio 2.23; 95% CI 2.08–2.40). The risk of death in the first 3 days was much higher in frail than in nonfrail patients (hazard ratio 35.58; 95% CI 29.78–40.1), but the hazard ratio decreased to approximately 2.4 by day 90.

The authors emphasize that the elevated risk for frail patients warrants particular perioperative planning, though it is not yet clear what frailty-specific interventions should be performed. Further study is needed into the benefit of “prehabilitation” (ie, exercise training to “build up” a patient before surgery) for perioperative risk reduction.

Hall et al: Better care for frail patients

Hall et al10 instituted a quality improvement initiative for perioperative care of patients at the Omaha Veterans Affairs Hospital. Frail patients were identified using the Risk Analysis Index, a 14-question screening tool previously developed and validated over several years using Veterans Administration databases.29 Questions in the Risk Analysis Index cover living situation, any diagnosis of cancer, ability to perform activities of daily living, and others.

To maximize compliance, a Risk Analysis Index score was required to schedule a surgery. Patients with high scores underwent further review by a designated team of physicians who initiated informal and formal consultations with anesthesiologists, critical care physicians, surgeons, and palliative care providers, with the goals of minimizing risk, clarifying patient goals or resuscitation wishes, and developing comprehensive perioperative planning.10

Approximately 9,100 patients were included in the cohort. The authors demonstrated a significant improvement in mortality for frail patients at 30, 180, and 365 days, but noted an improvement in postoperative mortality for the nonfrail patients as well, perhaps due to increased focus on geriatric patient care. In particular, the mortality rate at 365 days dropped from 34.5% to 11.7% for frail patients who underwent this intervention.

While this quality improvement initiative was unable to examine how surgical rates changed in frail patients, it is highly likely that very high-risk patients opted out of surgery or had their surgical plan change, though the authors point out that the overall surgical volume at the institution did not change significantly. As well, it remains unclear which particular interventions may have had the most effect in improving survival, as the perioperative plans were individualized and continually adjusted throughout the study period.

Nonetheless, this article highlights how higher vigilance, individualized planning and appreciation of the high risks of frail patients is associated with improved patient survival postoperatively. Although frailty screening is still in its early stages and further work is needed, it is likely that performing frailty screening in elderly patients and utilizing interdisciplinary collaboration for comprehensive management of frail patients can improve their postoperative course.

Perioperative care is increasingly complex, and the rapid evolution of literature in this field makes it a challenge for clinicians to stay up-to-date. To help meet this challenge, we used a systematic approach to identify appropriate articles in the medical literature and then, by consensus, to develop a list of 6 clinical questions based on their novelty and potential to change perioperative medical practice:

- How should we screen for cardiac risk in patients undergoing noncardiac surgery?

- What is the appropriate timing for surgery after coronary intervention?

- Can we use statin therapy to reduce perioperative cardiac risk?

- How should we manage sleep apnea risk perioperatively?

- Which patients with atrial fibrillation should receive perioperative bridging anticoagulation?

- Is frailty screening beneficial for elderly patients before noncardiac surgery?

The summaries in this article are a composite of perioperative medicine updates presented at the Perioperative Medicine Summit and the annual meetings of the Society for General Internal Medicine and the Society of Hospital Medicine. “Perioperative care is complex and changing”1–10 (page 864) offers a brief overview.

HOW TO SCREEN FOR CARDIAC RISK BEFORE NONCARDIAC SURGERY

Perioperative cardiac risk can be estimated by clinical risk indexes (based on history, physical examination, common blood tests, and electrocardiography), cardiac biomarkers (natriuretic peptide or troponin levels), and noninvasive cardiac tests.

American and European guidelines

In 2014, the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association2 and the European Society of Cardiology11 published guidelines on perioperative cardiovascular evaluation and management. They recommended several tools to calculate the risk of postoperative cardiac complications but did not specify a preference. These tools include:

- The Revised Cardiac Risk Index (RCRI)12 (www.mdcalc.com/revised-cardiac-risk-index-pre-operative-risk), which has been externally validated in multiple studies and is the most widely used

- The American College of Surgeons surgical risk calculator13 (www.riskcalculator.facs.org), derived from the National Surgery Quality Improvement Program (NSQIP) database

- The myocardial infarction or cardiac arrest (MICA) calculator14 (www.surgicalriskcalculator.com/miorcardiacarrest), also derived from the NSQIP database.

2017 Canadian guidelines differ

In 2017, the Canadian Cardiovascular Society published its own guidelines on perioperative risk assessment and management.1 These differ from the American and European guidelines on several points.

RCRI recommended. The Canadian guidelines suggested using the RCRI over the other risk predictors, which despite superior discrimination lacked external validation (conditional recommendation; low-quality evidence). Additionally, the Canadians believed that the NSQIP risk indexes underestimated cardiac risk because patients did not undergo routine biomarker screening.

Biomarker measurement. The Canadian guidelines went a step further in their algorithm (Figure 1) and recommended measuring N-terminal-pro B-type natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) or BNP preoperatively to improve risk prediction in 3 groups (strong recommendation; moderate-quality evidence):

- Patients ages 65 and older

- Patients ages 45 to 64 with significant cardiovascular disease

- Patients with an RCRI score of 1 or more.

This differs from the American guidelines, which did not recommend measuring preoperative biomarkers but did acknowledge that they may provide incremental value. The American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association authors felt that there were no data to suggest that targeting these biomarkers for treatment and intervention would reduce postoperative risk. The European guidelines did not recommend routinely using biomarkers, but stated that they may be considered in high-risk patients (who have a functional capacity ≤ 4 metabolic equivalents or an RCRI score > 1 undergoing vascular surgery, or > 2 undergoing nonvascular surgery).

Stress testing deemphasized. The Canadian guidelines recommended biomarker testing rather than noninvasive tests to enhance risk assessment based on cost, potential delays in surgery, and absence of evidence of an overall absolute net improvement in risk reclassification. This contrasts with the American and European guidelines and algorithms, which recommended pharmacologic stress testing in patients at elevated risk with poor functional capacity undergoing intermediate- to high-risk surgery if the results would change how they are managed.

Postoperative monitoring. The Canadian guidelines recommended that if patients have an NT-proBNP level higher than 300 mg/L or a BNP level higher than 92 mg/L, they should receive postoperative monitoring with electrocardiography in the postanesthesia care unit and daily troponin measurements for 48 to 72 hours. The American guidelines recommended postoperative electrocardiography and troponin measurement only for patients suspected of having myocardial ischemia, and the European guidelines said postoperative biomarkers may be considered in patients at high risk.

Physician judgment needed

While guidelines and risk calculators are potentially helpful in risk assessment, the lack of consensus and the conflicting recommendations force the physician to weigh the evidence and make individual decisions based on his or her interpretation of the data.

Until there are studies directly comparing the various risk calculators, physicians will most likely use the RCRI, which is simple and has been externally validated, in conjunction with the American guidelines.

At this time, it is unclear how biomarkers should be used—preoperatively, postoperatively, or both—because there are no studies demonstrating that management strategies based on the results lead to better outcomes. We do not believe that biomarker testing will be accepted in lieu of stress testing by our surgery, anesthesiology, or cardiology colleagues, but going forward, it will probably be used more frequently postoperatively, particularly in patients at moderate to high risk.

WHAT IS THE APPROPRIATE TIMING FOR SURGERY AFTER PCI?

A 2014 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association guideline recommended delaying noncardiac surgery for 1 month after percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) with bare-metal stents and 1 year after PCI with drug-eluting stents.15 The guideline suggested that surgery may be performed 6 months after drug-eluting stent placement if the risks of delaying surgery outweigh the risk of thrombosis.15

The primary rationale behind these timeframes was to provide dual antiplatelet therapy for a minimally acceptable duration before temporary interruption for a procedure. These recommendations were influenced largely by observational studies of first-generation devices, which are no longer used. Studies of newer-generation stents have suggested that the risk of stent thrombosis reaches a plateau considerably earlier than 6 to 12 months after PCI.

2016 Revised guideline on dual antiplatelet therapy

Although not separately delineated in the recommendations, risk factors for stent thrombosis that should influence the decision include smoking, multivessel coronary artery disease, and suboptimally controlled diabetes mellitus or hyperlipidemia.17 The presence of such stent thrombosis risk factors should be factored into the decision about proceeding with surgery within 3 to 6 months after drug-eluting stent placement.

Holcomb et al: Higher postoperative risk after PCI for myocardial infarction

Another important consideration is the indication for which PCI was performed. In a recent study, Holcomb et al16 found an association between postoperative major adverse cardiac events and PCI for myocardial infarction (MI) that was independent of stent type.

Compared with patients who underwent PCI not associated with acute coronary syndrome, the odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for major adverse cardiac events in those who underwent PCI for MI were:

- 5.25 (4.08–6.75) in the first 3 months

- 2.45 (1.80–3.35) in months 3 to 6

- 2.50 (1.90–3.28) in months 6 to 12.

In absolute terms, patients with stenting performed for an MI had an incidence of major adverse cardiac events of:

- 22.2% in the first 3 months

- 9.4% in months 3 to 6

- 5.8% in months 6 to 12

- 4.4% in months 12 to 24.

The perioperative risks were reduced after 12 months but still remained greater in patients whose PCI was performed for MI rather than another indication.16

The authors of this study suggested delaying noncardiac surgery for up to 6 months after PCI for MI, regardless of stent type.16

A careful, individualized approach

Optimal timing of noncardiac surgery PCI requires a careful, individualized approach and should always be coordinated with the patient’s cardiologist, surgeon, and anesthesiologist.3,15 For most patients, surgery should be delayed for 30 days after bare-metal stent placement and 6 months after drug-eluting stent placement.3 However, for those with greater surgical need and less thrombotic risk, noncardiac surgery can be considered 3 to 6 months after drug-eluting stent placement.3

Additional discussion of the prolonged increased risk of postoperative major adverse cardiac events is warranted in patients whose PCI was performed for MI, in whom delaying noncardiac surgery for up to 6 months (irrespective of stent type) should be considered.16

CAN WE USE STATINS TO REDUCE PERIOPERATIVE RISK?

Current recommendations from the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association support continuing statins in the perioperative period, but the evidence supporting starting statins in this period has yet to be fully determined. In 2013, a Cochrane review18 found insufficient evidence to conclude that statins reduced perioperative adverse cardiac events, though several large studies were excluded due to controversial methods and data.

In contrast, the Vascular Events in Noncardiac Surgery Patients Cohort Evaluation (VISION) study,4 a multicenter, prospective, cohort-matched study of approximately 7,200 patients, found a lower risk of a composite primary outcome of all-cause mortality, myocardial injury after noncardiac surgery, or stroke at 30 days for patients exposed to statin therapy (relative risk [RR] 0.83, 95% CI 0.73–0.95, P = .007).4

London et al retrospective study: 30-day mortality rate is lower with statins

In 2017, London et al5 published the results of a very large retrospective, observational cohort study of approximately 96,000 elective or emergency surgery patients in Department of Veterans Affairs hospitals. The patients were propensity-matched and evaluated for exposure to statins on the day of or the day after surgery, for a total of approximately 48,000 pairs.

The primary outcome was death at 30 days, and statin exposure was associated with a significant reduction (RR 0.82; 95% CI 0.75–0.89; P < .001). Significant risk reductions were demonstrated in nearly all secondary end points as well, except for stroke or coma and thrombosis (pulmonary embolism, deep vein thrombosis, or graft failure). Overall, the number needed to treat to prevent any complication was 67. Statin therapy did not show significant harm, though on subgroup analysis, those who received high-intensity statin therapy had a slightly higher risk of renal injury (odds ratio 1.18, 95% CI 1.02–1.37, P = .03). Also on subgroup analysis, after propensity matching, patients on long-term moderate- or high-intensity statin therapy for 6 to 12 months before surgery had a small risk reduction for many of the outcomes, including death.

The authors also noted that only 62% of the patients who were prescribed statins as outpatients received them in the hospital, which suggests that improvement is necessary in educating perioperative physicians about the benefits and widespread support for continuing statins perioperatively.5

LOAD trial: No benefit from starting statins

Both London et al5 and the VISION investigators4 called for a large randomized controlled trial of perioperative statin initiation. The Lowering the Risk of Operative Complications Using Atorvastatin Loading Dose (LOAD) trial attempted to answer this call.6

This trial randomized 648 statin-naïve Brazilian patients at high risk of perioperative cardiac events to receive either atorvastatin or placebo before surgery and then continuously for another 7 days. The primary outcomes were the rates of death, nonfatal myocardial injury after noncardiac surgery, and cerebrovascular accident at 30 days.6

The investigators found no significant difference in outcomes between the two groups and estimated that the sample size would need to be approximately 7,000 patients to demonstrate a significant benefit. Nonetheless, this trial established that a prospective perioperative statin trial is feasible.

When to continue or start statins