User login

‘Self-anesthetizing’ to cope with grief

CASE Grieving, delusional

Mr. M, age 51, is brought to the emergency department (ED) because of new-onset delusions and decreased self-care over the last 2 weeks following the sudden death of his wife. He has become expansive and grandiose, with pressured speech, increased energy, and markedly reduced sleep. Mr. M is preoccupied with the idea that he is “the first to survive a human reboot process” and says that his and his wife’s bodies and brains had been “split apart.” Mr. M has limited his food and fluid intake and lost 15 lb within the past 2 to 3 weeks.

Mr. M has no history of any affective, psychotic, or other major mental disorders or treatment. He reports that he has regularly used Cannabis over the last 10 years, and a few years ago, he started occasionally using nitrous oxide (N2O). He says that in the week following his wife’s death, he used N2O almost daily and in copious amounts. In an attempt to “self-anesthetize” himself after his wife’s funeral, he isolated himself in his bedroom and used escalating amounts of Cannabis and N2O, while continually working on a book about their life together.

At first, Mr. M shows little emotion and describes his situation as “interesting and fascinating.” He mentions that he thinks he might have been “psychotic” the week after his wife’s death, but he shows no sustained insight and immediately relapses into psychotic thinking. Over several hours in the ED, he is tearful and sad about his wife’s death. Mr. M recalls a similar experience of grief after his mother died when he was a teenager, but at that time he did not abuse substances or have psychotic symptoms. He is fully alert, fully oriented, and has no significant deficits of attention or memory.

[polldaddy:9859135]

The authors’ observations

Grief was a precipitating event, but by itself grief cannot explain psychosis. Psychotic depression is a possibility, but Mr. M’s psychotic features are incongruent with his mood. Mania would be a diagnosis of exclusion. Mr. M had no prior history of major affective illness. Mr. M was abusing Cannabis, which might independently contribute to psychosis1; however, he had been using it recreationally for 10 years without psychiatric problems. N2O, however, can cause symptoms consistent with Mr. M’s presentation.

[polldaddy:9859140]

EVALUATION Laboratory tests

Mr. M’s physical examination is notable only for an elevated blood pressure of 196/120 mm Hg. Neurologic examination is normal. Toxicology is positive for cannabinoids and negative for amphetamines, cocaine, opiates, and phencyclidine. Chemistries are normal except for a potassium of 3.4 mEq/L (reference range, 3.7 to 5.2 mEq/L) and a blood urine nitrogen of 25 mg/dL (reference range, 6 to 20 mg/dL), which are consistent with reduced food and fluid intake. Mr. M shows no signs of anemia. Hematocrit is 42% and mean corpuscular volume is 90 fL. Syphilis screen is negative; a head CT scan is unremarkable.

The authors’ observations

N2O, also known as “laughing gas,” is routinely used by dentists and pediatric anesthesiologists, and has other medical uses. Some studies have examined an adjunctive use of N2O for pain control in the ED and during colonoscopies.3,4

In the 2013 U.S. National Survey on Drug Use and Health, 16% of respondents reported lifetime illicit use of N2O.5,6 It is readily available in tanks used in medicine and industry and in small dispensers called “whippits” that can be legally purchased. Acute effects of N2O include euphoric mood, numbness, feeling of warmth, dizziness, and auditory hallucinations.7 The anesthetic effects of N2O are linked to endogenous release of opiates, and recent research links its anxiolytic activity to the facilitation of GABAergic inhibitory and N-methyl-

Beginning with a 1960 report of a series of patients with “megaloblastic madness,”17 there have been calls for increased awareness of the potential for vitamin B12 deficiency–induced psychiatric disorders, even in the absence of other hematologic or neurologic sequelae that would alert clinicians of the deficiency. In a case series of 141 patients with a broad array of neurologic and psychiatric symptoms associated with vitamin B12 deficiency, 40 (28%) patients had no anemia or macrocytosis.2

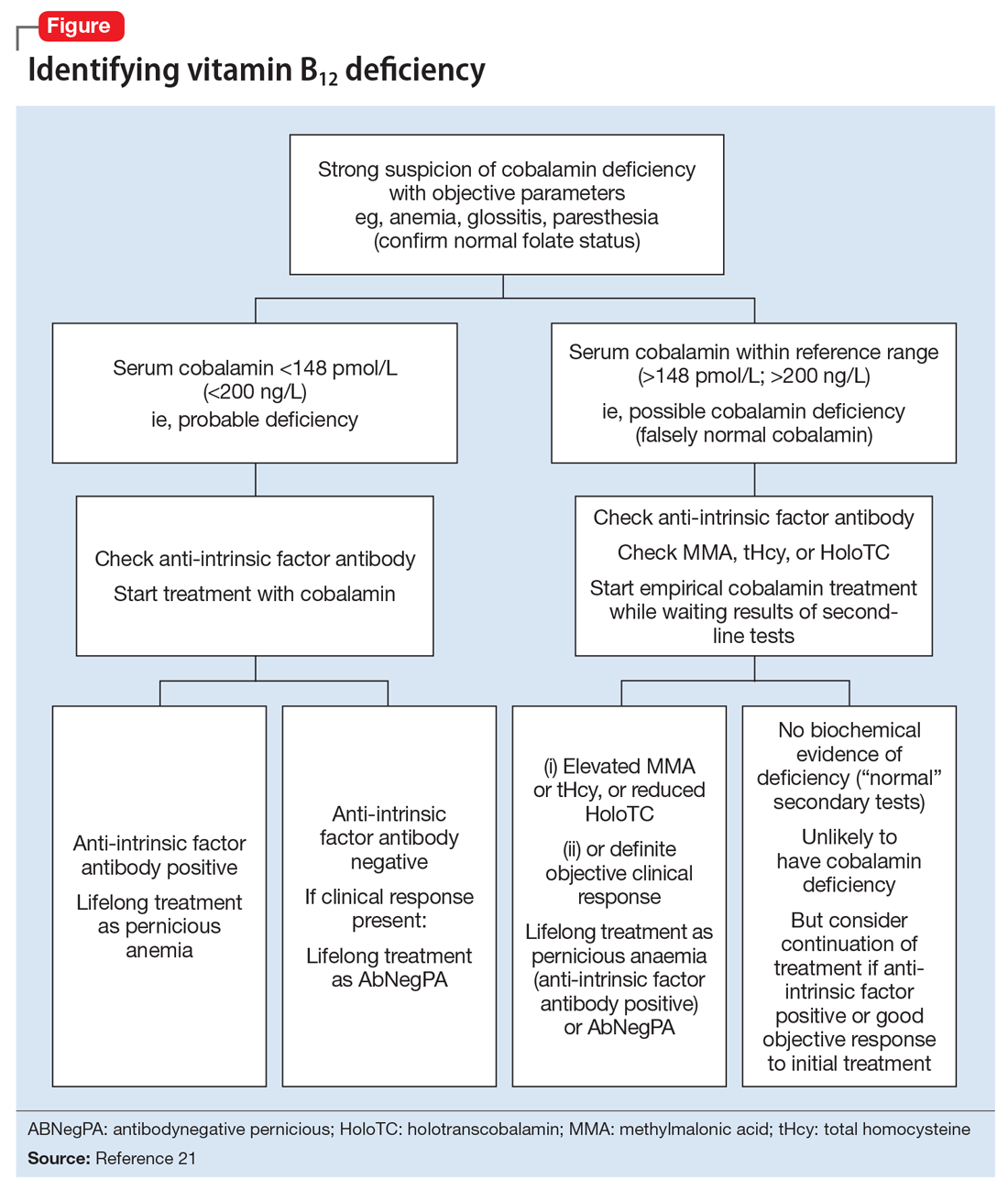

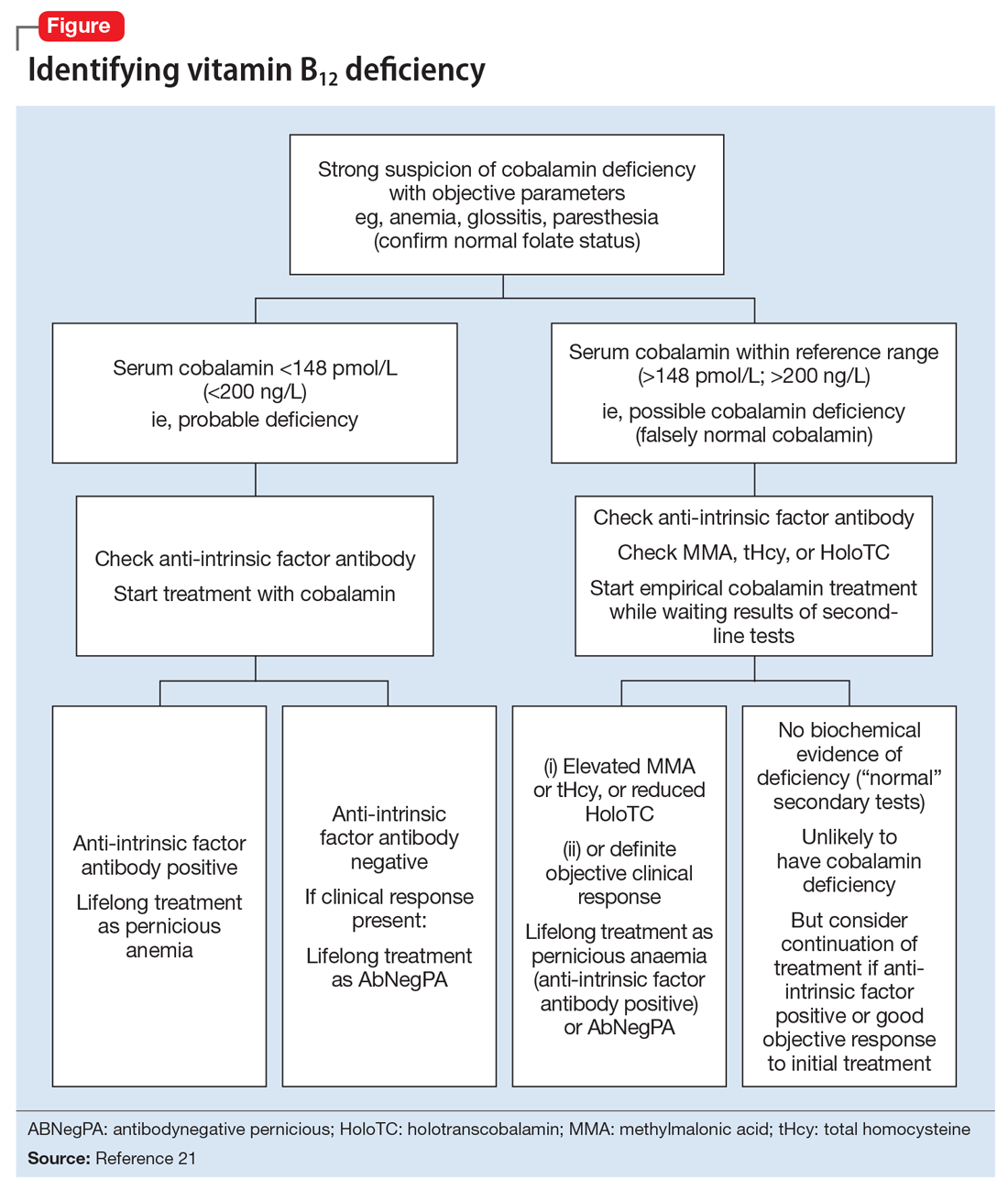

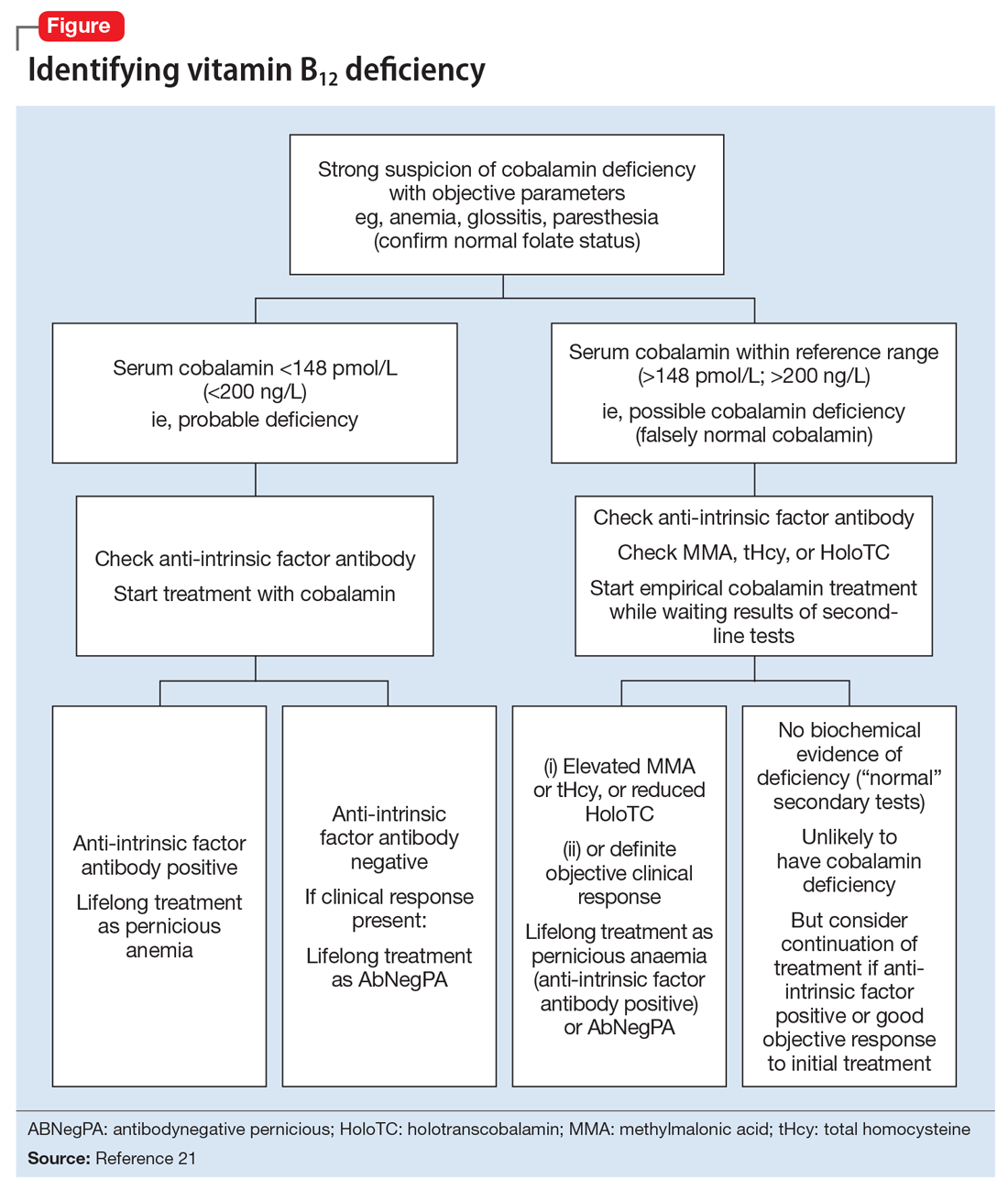

Vitamin B12-responsive psychosis has been reported as the sole manifestation of illness, without associated neurologic or hematologic symptoms, in only a few case reports. Vitamin B12 levels in these cases ranged from 75 to 236 pg/mL (reference range, 160 to 950 pg/mL).18-20 In all of these cases, the vitamin B12 deficiency was traced to dietary causes. The clinical evaluation of suspected vitamin B12 deficiency is outlined in the Figure.21 Mr. M had used Cannabis recreationally for a long time, and his Cannabis use acutely escalated with use of N2O. Long-term use of Cannabis alone is a risk factor for psychotic illness.22 Combined abuse of Cannabis and N2O has been reported to provoke psychotic illness. In a case report of a 22-year-old male who was treated for paranoid delusions, using Cannabis and 100 cartridges of N2O daily was associated with low vitamin B12 and elevated homocysteine and methylmalonic acid levels.23

Cannabis use may have played a role in Mr. M’s escalating N2O use. In a study comparing 9 active Cannabis users with 9 non-using controls, users rated the subjective effects of N2O as more intense than non-users.24 In our patient’s case, Cannabis may have played a role in both sustaining his escalating N2O abuse and potentiating its psychotomimetic effects.

It also is possible that Mr. M may have been “self-medicating” his grief with N2O. In a recent placebo-controlled crossover trial of 20 patients with treatment-resistant depression, Nagele et al25 found a significant rapid and week-long antidepressant effect of subanesthetic N2O use. A model involving NMDA receptor activation has been proposed.25,26 Zorumski et al26 further reviewed possible antidepressant mechanisms of N2O. They compared N2O with ketamine as an NMDA receptor antagonist, but also noted its distinct effects on glutaminergic and GABAergic neurotransmitter systems as well as other receptors and channels.26 However, illicit use of N2O poses toxicity dangers and has no current indication for psychiatric treatment.

TREATMENT Supplementation

Mr. M is diagnosed with substance-induced psychotic disorder. His symptoms were precipitated by an acute increase in N2O use, which has been shown to cause vitamin B12 deficiency, which we consider was likely a primary contributor to his presentation. Other potential contributing factors are premorbid hyperthymic temperament, a possible propensity to psychotic thinking under stress, the sudden death of his wife, acute grief, the potentiating role of Cannabis, dehydration, and general malnutrition. The death of a loved one is associated with an increased risk of developing substance use disorders.27

During a 15-day psychiatric hospitalization, Mr. M is given olanzapine, increased to 15 mg/d and oral vitamin B12, 1,000 mcg/d for 4 days, then IM cyanocobalamin for 7 days. Mr. M’s symptoms steadily improve, with normalization of sleep and near-total resolution of delusions. On hospital Day 14, his vitamin B12 levels are within normal limits (844 pg/mL). At discharge, Mr. M shows residual mild grandiosity, with limited insight into his illness and what caused it, but frank delusional ideation has clearly receded. He still shows some signs of grief. Mr. M is advised to stop using Cannabis and N2O and about the potential consequences of continued use.

The authors’ observations

For patients with vitamin B12 deficiency, guidelines from the National Health Service in the United Kingdom and the British Society for Haematology recommend treatment with IM hydroxocobalamin, 1,000 IU, 3 times weekly, for 2 weeks.21,28 For patients with neurologic symptoms, the British National Foundation recommends treatment with IM hydroxocobalamin, 1,000 IU, on alternative days until there is no further improvement.21

This case is a reminder for clinicians to screen for inhalant use, specifically N2O, which can precipitate vitamin B12 deficiency with psychiatric symptoms as the only presenting concern. Clinicians should consider measuring vitamin B12 levels in psychiatric patients at risk of deficiency of this nutrient, including older adults, vegetarians, and those with alimentary disorders.29,30 Dietary sources of vitamin B12 include meat, milk, egg, fish, and shellfish.31 The body can store a total of 2 to 5 mg of vitamin B12; thus, it takes 2 to 5 years to develop vitamin B12 deficiency from malabsorption and can take as long as 20 years to develop vitamin B12 deficiency from vegetarianism.32 However, by chemically inactivating vitamin B12, N2O causes a rapid functional deficiency, as was seen in our patient.

OUTCOME Improved insight

At a 1-week follow-up appointment with a psychiatrist, Mr. M has no evident psychotic symptoms. He reports that he has not used Cannabis or N2O, and he discontinues olanzapine following this visit. Two weeks later, Mr. M shows no psychotic or affective symptoms other than grief, which is appropriately expressed. His insight has improved. He commits to not using Cannabis, N2O, or any other illicit substances. Mr. M is referred back to his long-standing primary care provider with the understanding that if any psychiatric symptoms recur he will see a psychiatrist again.

1. Semple DM, McIntosh AM, Lawrie SM. Cannabis as a risk factor for psychosis: systematic review. J Psychopharmacol. 2005;19(2):187-194.

2. Lindenbaum J, Healton EB, Savage DG, et al. Neuropsychiatric disorders caused by cobalamin deficiency in the absence of anemia or macrocytosis. N Engl J Med. 1988;318(26)1720-1728.

3. Herres J, Chudnofsky CR, Manur R, et al. The use of inhaled nitrous oxide for analgesia in adult ED patients: a pilot study. Am J Emerg Med. 2016;34(2):269-273.

4. Aboumarzouk OM, Agarwal T, Syed Nong Chek SA, et al. Nitrous oxide for colonoscopy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;(8):CD008506.

5. National Institute on Drug Abuse. Drug facts: inhalants. http://www.drugabuse.gov/publications/drugfacts/inhalants. Updated February 2017. Accessed September 30, 2017.

6. SAMHSA, Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, National Survey on Drug Use and Health 2012 and 2013: Table 1.88C. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/NSDUH-DetTabs2013.pdf. Published September 4, 2017. Accessed September 30, 2017.

7. Brouette T, Anton R. Clinical review of inhalants. Am J Addict. 2001;10(1):79-94.

8. Emmanouil DE, Quock RM. Advances in understanding the actions of nitrous oxide. Anesth Prog. 2007;54(1):9-18.

9. Garakani A, Jaffe RJ, Savla D, et al. Neurologic, psychiatric, and other medical manifestations of nitrous oxide abuse: a systematic review of the case literature. Am J Addict. 2016;25(5):358-369.

10. Hathout L, El-Saden S. Nitrous oxide-induced B12 deficiency myelopathy: perspectives on the clinical biochemistry of vitamin B12. J Neurol Sci. 2011;301(1-2):1-8.

11. van Tonder SV, Ruck A, van der Westhuyzen J, et al. Dissociation of methionine synthetase (EC 2.1.1.13) activity and impairment of DNA synthesis in fruit bats (Rousettus aegyptiacus) with nitrous oxide-induced vitamin B12 deficiency. Br J Nutr. 1986;55(1):187-192.

12. Schrier SL, Mentzer WC, Tirnauer JS. Diagnosis and treatment of vitamin B12 and folate deficiency. UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/clinical-manifestations-and-diagnosis-of-vitamin-b12-and-folate-deficiency. Updated September 30, 2011. Accessed September 8, 2015.

13. Sethi NK, Mullin P, Torgovnick J, et al. Nitrous oxide “whippit” abuse presenting with cobalamin responsive psychosis. J Med Toxicol. 2006;2(2):71-74.

14. Cousaert C, Heylens G, Audenaert K. Laughing gas abuse is no joke. An overview of the implications for psychiatric practice. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2013;115(7):859-862.

15. Brodsky L, Zuniga J. Nitrous oxide: a psychotogenic agent. Compr Psychiatry. 1975;16(2):185-188.

16. Wong SL, Harrison R, Mattman A, et al. Nitrous oxide (N2O)-induced acute psychosis. Can J Neurol Sci. 2014;41(5):672-674.

17. Smith AD. Megaloblastic madness. Br Med J. 1960;2(5216):1840-1845.

18. Masalha R, Chudakov B, Muhamad M, et al. Cobalamin-responsive psychosis as the sole manifestation of vitamin B12 deficiency. Isr Med Associ J. 2001;3(9):701-703.

19. Kuo SC, Yeh SB, Yeh YW, et al. Schizophrenia-like psychotic episode precipitated by cobalamin deficiency. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2009;31(6):586-588.

20. Raveendranathan D, Shiva L, Venkatasubramanian G, et al. Vitamin B12 deficiency masquerading as clozapine-resistant psychotic symptoms in schizophrenia. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2013;25(2):E34-E35.

21. Devalia V, Hamilton MS, Molloy AM; British Committee for Standards in Haematology. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of cobalamin and folate disorders. Br J Haematol. 2014;166(4):496-513.

22. Moore THM, Zammit S, Lingford-Hughes A, et al. Cannabis use and risk of psychotic or affective mental health outcomes: a systematic review. Lancet. 2007;370:319-328.

23. Garakani A, Welch AK, Jaffe RJ, et al. Psychosis and low cyanocobalamin in a patient abusing nitrous oxide and cannabis. Psychosomatics. 2014;55(6):715-719.

24. Yajnik S, Thapar P, Lichtor JL, et al. Effects of marijuana history on the subjective, psychomotor, and reinforcing effects of nitrous oxide in human. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1994;36(3):227-236.

25. Nagele P, Duma A, Kopec M, et al. Nitrous oxide for treatment-resistant major depression: a proof-of-concept trial. Biol Psychiatry. 2015;78(1):10-18.

26. Zorumski CF, Nagele P, Mennerick S, et al. Treatment-resistant major depression: rationale for NMDA receptors as targets and nitrous oxide as therapy. Front Psychiatry. 2015;6:172.

27. Shear MK. Clinical practice. Complicated grief. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(2):153-160.

28. Knechtli CJC, Crowe JN. Guidelines for the investigation & management of vitamin B12 deficiency. Royal United Hospital Bath, National Health Service. http://www.ruh.nhs.uk/For_Clinicians/departments_ruh/Pathology/documents/haematology/B12_-_advice_on_investigation_management.pdf. Accessed June 14, 2016.

29. Jayaram N, Rao MG, Narashima A, et al. Vitamin B12 levels and psychiatric symptomatology: a case series. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2013;25(2):150-152.

30. Marks PW, Zukerberg LR. Case records of the Massachusetts General Hospital. Weekly clinicopathological exercises. Case 30-2004. A 37-year-old woman with paresthesias of the arms and legs. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(13):1333-1341.

31. Watanabe F. Vitamin B12 sources and bioavailablility. Exp Biol Med (Maywood). 2007;232(10):1266-1274.

32. Green R, Kinsella LJ. Current concepts in the diagnosis of cobalamin deficiency. Neurology. 1995;45(8):1435-1440.

CASE Grieving, delusional

Mr. M, age 51, is brought to the emergency department (ED) because of new-onset delusions and decreased self-care over the last 2 weeks following the sudden death of his wife. He has become expansive and grandiose, with pressured speech, increased energy, and markedly reduced sleep. Mr. M is preoccupied with the idea that he is “the first to survive a human reboot process” and says that his and his wife’s bodies and brains had been “split apart.” Mr. M has limited his food and fluid intake and lost 15 lb within the past 2 to 3 weeks.

Mr. M has no history of any affective, psychotic, or other major mental disorders or treatment. He reports that he has regularly used Cannabis over the last 10 years, and a few years ago, he started occasionally using nitrous oxide (N2O). He says that in the week following his wife’s death, he used N2O almost daily and in copious amounts. In an attempt to “self-anesthetize” himself after his wife’s funeral, he isolated himself in his bedroom and used escalating amounts of Cannabis and N2O, while continually working on a book about their life together.

At first, Mr. M shows little emotion and describes his situation as “interesting and fascinating.” He mentions that he thinks he might have been “psychotic” the week after his wife’s death, but he shows no sustained insight and immediately relapses into psychotic thinking. Over several hours in the ED, he is tearful and sad about his wife’s death. Mr. M recalls a similar experience of grief after his mother died when he was a teenager, but at that time he did not abuse substances or have psychotic symptoms. He is fully alert, fully oriented, and has no significant deficits of attention or memory.

[polldaddy:9859135]

The authors’ observations

Grief was a precipitating event, but by itself grief cannot explain psychosis. Psychotic depression is a possibility, but Mr. M’s psychotic features are incongruent with his mood. Mania would be a diagnosis of exclusion. Mr. M had no prior history of major affective illness. Mr. M was abusing Cannabis, which might independently contribute to psychosis1; however, he had been using it recreationally for 10 years without psychiatric problems. N2O, however, can cause symptoms consistent with Mr. M’s presentation.

[polldaddy:9859140]

EVALUATION Laboratory tests

Mr. M’s physical examination is notable only for an elevated blood pressure of 196/120 mm Hg. Neurologic examination is normal. Toxicology is positive for cannabinoids and negative for amphetamines, cocaine, opiates, and phencyclidine. Chemistries are normal except for a potassium of 3.4 mEq/L (reference range, 3.7 to 5.2 mEq/L) and a blood urine nitrogen of 25 mg/dL (reference range, 6 to 20 mg/dL), which are consistent with reduced food and fluid intake. Mr. M shows no signs of anemia. Hematocrit is 42% and mean corpuscular volume is 90 fL. Syphilis screen is negative; a head CT scan is unremarkable.

The authors’ observations

N2O, also known as “laughing gas,” is routinely used by dentists and pediatric anesthesiologists, and has other medical uses. Some studies have examined an adjunctive use of N2O for pain control in the ED and during colonoscopies.3,4

In the 2013 U.S. National Survey on Drug Use and Health, 16% of respondents reported lifetime illicit use of N2O.5,6 It is readily available in tanks used in medicine and industry and in small dispensers called “whippits” that can be legally purchased. Acute effects of N2O include euphoric mood, numbness, feeling of warmth, dizziness, and auditory hallucinations.7 The anesthetic effects of N2O are linked to endogenous release of opiates, and recent research links its anxiolytic activity to the facilitation of GABAergic inhibitory and N-methyl-

Beginning with a 1960 report of a series of patients with “megaloblastic madness,”17 there have been calls for increased awareness of the potential for vitamin B12 deficiency–induced psychiatric disorders, even in the absence of other hematologic or neurologic sequelae that would alert clinicians of the deficiency. In a case series of 141 patients with a broad array of neurologic and psychiatric symptoms associated with vitamin B12 deficiency, 40 (28%) patients had no anemia or macrocytosis.2

Vitamin B12-responsive psychosis has been reported as the sole manifestation of illness, without associated neurologic or hematologic symptoms, in only a few case reports. Vitamin B12 levels in these cases ranged from 75 to 236 pg/mL (reference range, 160 to 950 pg/mL).18-20 In all of these cases, the vitamin B12 deficiency was traced to dietary causes. The clinical evaluation of suspected vitamin B12 deficiency is outlined in the Figure.21 Mr. M had used Cannabis recreationally for a long time, and his Cannabis use acutely escalated with use of N2O. Long-term use of Cannabis alone is a risk factor for psychotic illness.22 Combined abuse of Cannabis and N2O has been reported to provoke psychotic illness. In a case report of a 22-year-old male who was treated for paranoid delusions, using Cannabis and 100 cartridges of N2O daily was associated with low vitamin B12 and elevated homocysteine and methylmalonic acid levels.23

Cannabis use may have played a role in Mr. M’s escalating N2O use. In a study comparing 9 active Cannabis users with 9 non-using controls, users rated the subjective effects of N2O as more intense than non-users.24 In our patient’s case, Cannabis may have played a role in both sustaining his escalating N2O abuse and potentiating its psychotomimetic effects.

It also is possible that Mr. M may have been “self-medicating” his grief with N2O. In a recent placebo-controlled crossover trial of 20 patients with treatment-resistant depression, Nagele et al25 found a significant rapid and week-long antidepressant effect of subanesthetic N2O use. A model involving NMDA receptor activation has been proposed.25,26 Zorumski et al26 further reviewed possible antidepressant mechanisms of N2O. They compared N2O with ketamine as an NMDA receptor antagonist, but also noted its distinct effects on glutaminergic and GABAergic neurotransmitter systems as well as other receptors and channels.26 However, illicit use of N2O poses toxicity dangers and has no current indication for psychiatric treatment.

TREATMENT Supplementation

Mr. M is diagnosed with substance-induced psychotic disorder. His symptoms were precipitated by an acute increase in N2O use, which has been shown to cause vitamin B12 deficiency, which we consider was likely a primary contributor to his presentation. Other potential contributing factors are premorbid hyperthymic temperament, a possible propensity to psychotic thinking under stress, the sudden death of his wife, acute grief, the potentiating role of Cannabis, dehydration, and general malnutrition. The death of a loved one is associated with an increased risk of developing substance use disorders.27

During a 15-day psychiatric hospitalization, Mr. M is given olanzapine, increased to 15 mg/d and oral vitamin B12, 1,000 mcg/d for 4 days, then IM cyanocobalamin for 7 days. Mr. M’s symptoms steadily improve, with normalization of sleep and near-total resolution of delusions. On hospital Day 14, his vitamin B12 levels are within normal limits (844 pg/mL). At discharge, Mr. M shows residual mild grandiosity, with limited insight into his illness and what caused it, but frank delusional ideation has clearly receded. He still shows some signs of grief. Mr. M is advised to stop using Cannabis and N2O and about the potential consequences of continued use.

The authors’ observations

For patients with vitamin B12 deficiency, guidelines from the National Health Service in the United Kingdom and the British Society for Haematology recommend treatment with IM hydroxocobalamin, 1,000 IU, 3 times weekly, for 2 weeks.21,28 For patients with neurologic symptoms, the British National Foundation recommends treatment with IM hydroxocobalamin, 1,000 IU, on alternative days until there is no further improvement.21

This case is a reminder for clinicians to screen for inhalant use, specifically N2O, which can precipitate vitamin B12 deficiency with psychiatric symptoms as the only presenting concern. Clinicians should consider measuring vitamin B12 levels in psychiatric patients at risk of deficiency of this nutrient, including older adults, vegetarians, and those with alimentary disorders.29,30 Dietary sources of vitamin B12 include meat, milk, egg, fish, and shellfish.31 The body can store a total of 2 to 5 mg of vitamin B12; thus, it takes 2 to 5 years to develop vitamin B12 deficiency from malabsorption and can take as long as 20 years to develop vitamin B12 deficiency from vegetarianism.32 However, by chemically inactivating vitamin B12, N2O causes a rapid functional deficiency, as was seen in our patient.

OUTCOME Improved insight

At a 1-week follow-up appointment with a psychiatrist, Mr. M has no evident psychotic symptoms. He reports that he has not used Cannabis or N2O, and he discontinues olanzapine following this visit. Two weeks later, Mr. M shows no psychotic or affective symptoms other than grief, which is appropriately expressed. His insight has improved. He commits to not using Cannabis, N2O, or any other illicit substances. Mr. M is referred back to his long-standing primary care provider with the understanding that if any psychiatric symptoms recur he will see a psychiatrist again.

CASE Grieving, delusional

Mr. M, age 51, is brought to the emergency department (ED) because of new-onset delusions and decreased self-care over the last 2 weeks following the sudden death of his wife. He has become expansive and grandiose, with pressured speech, increased energy, and markedly reduced sleep. Mr. M is preoccupied with the idea that he is “the first to survive a human reboot process” and says that his and his wife’s bodies and brains had been “split apart.” Mr. M has limited his food and fluid intake and lost 15 lb within the past 2 to 3 weeks.

Mr. M has no history of any affective, psychotic, or other major mental disorders or treatment. He reports that he has regularly used Cannabis over the last 10 years, and a few years ago, he started occasionally using nitrous oxide (N2O). He says that in the week following his wife’s death, he used N2O almost daily and in copious amounts. In an attempt to “self-anesthetize” himself after his wife’s funeral, he isolated himself in his bedroom and used escalating amounts of Cannabis and N2O, while continually working on a book about their life together.

At first, Mr. M shows little emotion and describes his situation as “interesting and fascinating.” He mentions that he thinks he might have been “psychotic” the week after his wife’s death, but he shows no sustained insight and immediately relapses into psychotic thinking. Over several hours in the ED, he is tearful and sad about his wife’s death. Mr. M recalls a similar experience of grief after his mother died when he was a teenager, but at that time he did not abuse substances or have psychotic symptoms. He is fully alert, fully oriented, and has no significant deficits of attention or memory.

[polldaddy:9859135]

The authors’ observations

Grief was a precipitating event, but by itself grief cannot explain psychosis. Psychotic depression is a possibility, but Mr. M’s psychotic features are incongruent with his mood. Mania would be a diagnosis of exclusion. Mr. M had no prior history of major affective illness. Mr. M was abusing Cannabis, which might independently contribute to psychosis1; however, he had been using it recreationally for 10 years without psychiatric problems. N2O, however, can cause symptoms consistent with Mr. M’s presentation.

[polldaddy:9859140]

EVALUATION Laboratory tests

Mr. M’s physical examination is notable only for an elevated blood pressure of 196/120 mm Hg. Neurologic examination is normal. Toxicology is positive for cannabinoids and negative for amphetamines, cocaine, opiates, and phencyclidine. Chemistries are normal except for a potassium of 3.4 mEq/L (reference range, 3.7 to 5.2 mEq/L) and a blood urine nitrogen of 25 mg/dL (reference range, 6 to 20 mg/dL), which are consistent with reduced food and fluid intake. Mr. M shows no signs of anemia. Hematocrit is 42% and mean corpuscular volume is 90 fL. Syphilis screen is negative; a head CT scan is unremarkable.

The authors’ observations

N2O, also known as “laughing gas,” is routinely used by dentists and pediatric anesthesiologists, and has other medical uses. Some studies have examined an adjunctive use of N2O for pain control in the ED and during colonoscopies.3,4

In the 2013 U.S. National Survey on Drug Use and Health, 16% of respondents reported lifetime illicit use of N2O.5,6 It is readily available in tanks used in medicine and industry and in small dispensers called “whippits” that can be legally purchased. Acute effects of N2O include euphoric mood, numbness, feeling of warmth, dizziness, and auditory hallucinations.7 The anesthetic effects of N2O are linked to endogenous release of opiates, and recent research links its anxiolytic activity to the facilitation of GABAergic inhibitory and N-methyl-

Beginning with a 1960 report of a series of patients with “megaloblastic madness,”17 there have been calls for increased awareness of the potential for vitamin B12 deficiency–induced psychiatric disorders, even in the absence of other hematologic or neurologic sequelae that would alert clinicians of the deficiency. In a case series of 141 patients with a broad array of neurologic and psychiatric symptoms associated with vitamin B12 deficiency, 40 (28%) patients had no anemia or macrocytosis.2

Vitamin B12-responsive psychosis has been reported as the sole manifestation of illness, without associated neurologic or hematologic symptoms, in only a few case reports. Vitamin B12 levels in these cases ranged from 75 to 236 pg/mL (reference range, 160 to 950 pg/mL).18-20 In all of these cases, the vitamin B12 deficiency was traced to dietary causes. The clinical evaluation of suspected vitamin B12 deficiency is outlined in the Figure.21 Mr. M had used Cannabis recreationally for a long time, and his Cannabis use acutely escalated with use of N2O. Long-term use of Cannabis alone is a risk factor for psychotic illness.22 Combined abuse of Cannabis and N2O has been reported to provoke psychotic illness. In a case report of a 22-year-old male who was treated for paranoid delusions, using Cannabis and 100 cartridges of N2O daily was associated with low vitamin B12 and elevated homocysteine and methylmalonic acid levels.23

Cannabis use may have played a role in Mr. M’s escalating N2O use. In a study comparing 9 active Cannabis users with 9 non-using controls, users rated the subjective effects of N2O as more intense than non-users.24 In our patient’s case, Cannabis may have played a role in both sustaining his escalating N2O abuse and potentiating its psychotomimetic effects.

It also is possible that Mr. M may have been “self-medicating” his grief with N2O. In a recent placebo-controlled crossover trial of 20 patients with treatment-resistant depression, Nagele et al25 found a significant rapid and week-long antidepressant effect of subanesthetic N2O use. A model involving NMDA receptor activation has been proposed.25,26 Zorumski et al26 further reviewed possible antidepressant mechanisms of N2O. They compared N2O with ketamine as an NMDA receptor antagonist, but also noted its distinct effects on glutaminergic and GABAergic neurotransmitter systems as well as other receptors and channels.26 However, illicit use of N2O poses toxicity dangers and has no current indication for psychiatric treatment.

TREATMENT Supplementation

Mr. M is diagnosed with substance-induced psychotic disorder. His symptoms were precipitated by an acute increase in N2O use, which has been shown to cause vitamin B12 deficiency, which we consider was likely a primary contributor to his presentation. Other potential contributing factors are premorbid hyperthymic temperament, a possible propensity to psychotic thinking under stress, the sudden death of his wife, acute grief, the potentiating role of Cannabis, dehydration, and general malnutrition. The death of a loved one is associated with an increased risk of developing substance use disorders.27

During a 15-day psychiatric hospitalization, Mr. M is given olanzapine, increased to 15 mg/d and oral vitamin B12, 1,000 mcg/d for 4 days, then IM cyanocobalamin for 7 days. Mr. M’s symptoms steadily improve, with normalization of sleep and near-total resolution of delusions. On hospital Day 14, his vitamin B12 levels are within normal limits (844 pg/mL). At discharge, Mr. M shows residual mild grandiosity, with limited insight into his illness and what caused it, but frank delusional ideation has clearly receded. He still shows some signs of grief. Mr. M is advised to stop using Cannabis and N2O and about the potential consequences of continued use.

The authors’ observations

For patients with vitamin B12 deficiency, guidelines from the National Health Service in the United Kingdom and the British Society for Haematology recommend treatment with IM hydroxocobalamin, 1,000 IU, 3 times weekly, for 2 weeks.21,28 For patients with neurologic symptoms, the British National Foundation recommends treatment with IM hydroxocobalamin, 1,000 IU, on alternative days until there is no further improvement.21

This case is a reminder for clinicians to screen for inhalant use, specifically N2O, which can precipitate vitamin B12 deficiency with psychiatric symptoms as the only presenting concern. Clinicians should consider measuring vitamin B12 levels in psychiatric patients at risk of deficiency of this nutrient, including older adults, vegetarians, and those with alimentary disorders.29,30 Dietary sources of vitamin B12 include meat, milk, egg, fish, and shellfish.31 The body can store a total of 2 to 5 mg of vitamin B12; thus, it takes 2 to 5 years to develop vitamin B12 deficiency from malabsorption and can take as long as 20 years to develop vitamin B12 deficiency from vegetarianism.32 However, by chemically inactivating vitamin B12, N2O causes a rapid functional deficiency, as was seen in our patient.

OUTCOME Improved insight

At a 1-week follow-up appointment with a psychiatrist, Mr. M has no evident psychotic symptoms. He reports that he has not used Cannabis or N2O, and he discontinues olanzapine following this visit. Two weeks later, Mr. M shows no psychotic or affective symptoms other than grief, which is appropriately expressed. His insight has improved. He commits to not using Cannabis, N2O, or any other illicit substances. Mr. M is referred back to his long-standing primary care provider with the understanding that if any psychiatric symptoms recur he will see a psychiatrist again.

1. Semple DM, McIntosh AM, Lawrie SM. Cannabis as a risk factor for psychosis: systematic review. J Psychopharmacol. 2005;19(2):187-194.

2. Lindenbaum J, Healton EB, Savage DG, et al. Neuropsychiatric disorders caused by cobalamin deficiency in the absence of anemia or macrocytosis. N Engl J Med. 1988;318(26)1720-1728.

3. Herres J, Chudnofsky CR, Manur R, et al. The use of inhaled nitrous oxide for analgesia in adult ED patients: a pilot study. Am J Emerg Med. 2016;34(2):269-273.

4. Aboumarzouk OM, Agarwal T, Syed Nong Chek SA, et al. Nitrous oxide for colonoscopy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;(8):CD008506.

5. National Institute on Drug Abuse. Drug facts: inhalants. http://www.drugabuse.gov/publications/drugfacts/inhalants. Updated February 2017. Accessed September 30, 2017.

6. SAMHSA, Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, National Survey on Drug Use and Health 2012 and 2013: Table 1.88C. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/NSDUH-DetTabs2013.pdf. Published September 4, 2017. Accessed September 30, 2017.

7. Brouette T, Anton R. Clinical review of inhalants. Am J Addict. 2001;10(1):79-94.

8. Emmanouil DE, Quock RM. Advances in understanding the actions of nitrous oxide. Anesth Prog. 2007;54(1):9-18.

9. Garakani A, Jaffe RJ, Savla D, et al. Neurologic, psychiatric, and other medical manifestations of nitrous oxide abuse: a systematic review of the case literature. Am J Addict. 2016;25(5):358-369.

10. Hathout L, El-Saden S. Nitrous oxide-induced B12 deficiency myelopathy: perspectives on the clinical biochemistry of vitamin B12. J Neurol Sci. 2011;301(1-2):1-8.

11. van Tonder SV, Ruck A, van der Westhuyzen J, et al. Dissociation of methionine synthetase (EC 2.1.1.13) activity and impairment of DNA synthesis in fruit bats (Rousettus aegyptiacus) with nitrous oxide-induced vitamin B12 deficiency. Br J Nutr. 1986;55(1):187-192.

12. Schrier SL, Mentzer WC, Tirnauer JS. Diagnosis and treatment of vitamin B12 and folate deficiency. UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/clinical-manifestations-and-diagnosis-of-vitamin-b12-and-folate-deficiency. Updated September 30, 2011. Accessed September 8, 2015.

13. Sethi NK, Mullin P, Torgovnick J, et al. Nitrous oxide “whippit” abuse presenting with cobalamin responsive psychosis. J Med Toxicol. 2006;2(2):71-74.

14. Cousaert C, Heylens G, Audenaert K. Laughing gas abuse is no joke. An overview of the implications for psychiatric practice. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2013;115(7):859-862.

15. Brodsky L, Zuniga J. Nitrous oxide: a psychotogenic agent. Compr Psychiatry. 1975;16(2):185-188.

16. Wong SL, Harrison R, Mattman A, et al. Nitrous oxide (N2O)-induced acute psychosis. Can J Neurol Sci. 2014;41(5):672-674.

17. Smith AD. Megaloblastic madness. Br Med J. 1960;2(5216):1840-1845.

18. Masalha R, Chudakov B, Muhamad M, et al. Cobalamin-responsive psychosis as the sole manifestation of vitamin B12 deficiency. Isr Med Associ J. 2001;3(9):701-703.

19. Kuo SC, Yeh SB, Yeh YW, et al. Schizophrenia-like psychotic episode precipitated by cobalamin deficiency. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2009;31(6):586-588.

20. Raveendranathan D, Shiva L, Venkatasubramanian G, et al. Vitamin B12 deficiency masquerading as clozapine-resistant psychotic symptoms in schizophrenia. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2013;25(2):E34-E35.

21. Devalia V, Hamilton MS, Molloy AM; British Committee for Standards in Haematology. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of cobalamin and folate disorders. Br J Haematol. 2014;166(4):496-513.

22. Moore THM, Zammit S, Lingford-Hughes A, et al. Cannabis use and risk of psychotic or affective mental health outcomes: a systematic review. Lancet. 2007;370:319-328.

23. Garakani A, Welch AK, Jaffe RJ, et al. Psychosis and low cyanocobalamin in a patient abusing nitrous oxide and cannabis. Psychosomatics. 2014;55(6):715-719.

24. Yajnik S, Thapar P, Lichtor JL, et al. Effects of marijuana history on the subjective, psychomotor, and reinforcing effects of nitrous oxide in human. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1994;36(3):227-236.

25. Nagele P, Duma A, Kopec M, et al. Nitrous oxide for treatment-resistant major depression: a proof-of-concept trial. Biol Psychiatry. 2015;78(1):10-18.

26. Zorumski CF, Nagele P, Mennerick S, et al. Treatment-resistant major depression: rationale for NMDA receptors as targets and nitrous oxide as therapy. Front Psychiatry. 2015;6:172.

27. Shear MK. Clinical practice. Complicated grief. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(2):153-160.

28. Knechtli CJC, Crowe JN. Guidelines for the investigation & management of vitamin B12 deficiency. Royal United Hospital Bath, National Health Service. http://www.ruh.nhs.uk/For_Clinicians/departments_ruh/Pathology/documents/haematology/B12_-_advice_on_investigation_management.pdf. Accessed June 14, 2016.

29. Jayaram N, Rao MG, Narashima A, et al. Vitamin B12 levels and psychiatric symptomatology: a case series. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2013;25(2):150-152.

30. Marks PW, Zukerberg LR. Case records of the Massachusetts General Hospital. Weekly clinicopathological exercises. Case 30-2004. A 37-year-old woman with paresthesias of the arms and legs. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(13):1333-1341.

31. Watanabe F. Vitamin B12 sources and bioavailablility. Exp Biol Med (Maywood). 2007;232(10):1266-1274.

32. Green R, Kinsella LJ. Current concepts in the diagnosis of cobalamin deficiency. Neurology. 1995;45(8):1435-1440.

1. Semple DM, McIntosh AM, Lawrie SM. Cannabis as a risk factor for psychosis: systematic review. J Psychopharmacol. 2005;19(2):187-194.

2. Lindenbaum J, Healton EB, Savage DG, et al. Neuropsychiatric disorders caused by cobalamin deficiency in the absence of anemia or macrocytosis. N Engl J Med. 1988;318(26)1720-1728.

3. Herres J, Chudnofsky CR, Manur R, et al. The use of inhaled nitrous oxide for analgesia in adult ED patients: a pilot study. Am J Emerg Med. 2016;34(2):269-273.

4. Aboumarzouk OM, Agarwal T, Syed Nong Chek SA, et al. Nitrous oxide for colonoscopy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;(8):CD008506.

5. National Institute on Drug Abuse. Drug facts: inhalants. http://www.drugabuse.gov/publications/drugfacts/inhalants. Updated February 2017. Accessed September 30, 2017.

6. SAMHSA, Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, National Survey on Drug Use and Health 2012 and 2013: Table 1.88C. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/NSDUH-DetTabs2013.pdf. Published September 4, 2017. Accessed September 30, 2017.

7. Brouette T, Anton R. Clinical review of inhalants. Am J Addict. 2001;10(1):79-94.

8. Emmanouil DE, Quock RM. Advances in understanding the actions of nitrous oxide. Anesth Prog. 2007;54(1):9-18.

9. Garakani A, Jaffe RJ, Savla D, et al. Neurologic, psychiatric, and other medical manifestations of nitrous oxide abuse: a systematic review of the case literature. Am J Addict. 2016;25(5):358-369.

10. Hathout L, El-Saden S. Nitrous oxide-induced B12 deficiency myelopathy: perspectives on the clinical biochemistry of vitamin B12. J Neurol Sci. 2011;301(1-2):1-8.

11. van Tonder SV, Ruck A, van der Westhuyzen J, et al. Dissociation of methionine synthetase (EC 2.1.1.13) activity and impairment of DNA synthesis in fruit bats (Rousettus aegyptiacus) with nitrous oxide-induced vitamin B12 deficiency. Br J Nutr. 1986;55(1):187-192.

12. Schrier SL, Mentzer WC, Tirnauer JS. Diagnosis and treatment of vitamin B12 and folate deficiency. UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/clinical-manifestations-and-diagnosis-of-vitamin-b12-and-folate-deficiency. Updated September 30, 2011. Accessed September 8, 2015.

13. Sethi NK, Mullin P, Torgovnick J, et al. Nitrous oxide “whippit” abuse presenting with cobalamin responsive psychosis. J Med Toxicol. 2006;2(2):71-74.

14. Cousaert C, Heylens G, Audenaert K. Laughing gas abuse is no joke. An overview of the implications for psychiatric practice. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2013;115(7):859-862.

15. Brodsky L, Zuniga J. Nitrous oxide: a psychotogenic agent. Compr Psychiatry. 1975;16(2):185-188.

16. Wong SL, Harrison R, Mattman A, et al. Nitrous oxide (N2O)-induced acute psychosis. Can J Neurol Sci. 2014;41(5):672-674.

17. Smith AD. Megaloblastic madness. Br Med J. 1960;2(5216):1840-1845.

18. Masalha R, Chudakov B, Muhamad M, et al. Cobalamin-responsive psychosis as the sole manifestation of vitamin B12 deficiency. Isr Med Associ J. 2001;3(9):701-703.

19. Kuo SC, Yeh SB, Yeh YW, et al. Schizophrenia-like psychotic episode precipitated by cobalamin deficiency. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2009;31(6):586-588.

20. Raveendranathan D, Shiva L, Venkatasubramanian G, et al. Vitamin B12 deficiency masquerading as clozapine-resistant psychotic symptoms in schizophrenia. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2013;25(2):E34-E35.

21. Devalia V, Hamilton MS, Molloy AM; British Committee for Standards in Haematology. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of cobalamin and folate disorders. Br J Haematol. 2014;166(4):496-513.

22. Moore THM, Zammit S, Lingford-Hughes A, et al. Cannabis use and risk of psychotic or affective mental health outcomes: a systematic review. Lancet. 2007;370:319-328.

23. Garakani A, Welch AK, Jaffe RJ, et al. Psychosis and low cyanocobalamin in a patient abusing nitrous oxide and cannabis. Psychosomatics. 2014;55(6):715-719.

24. Yajnik S, Thapar P, Lichtor JL, et al. Effects of marijuana history on the subjective, psychomotor, and reinforcing effects of nitrous oxide in human. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1994;36(3):227-236.

25. Nagele P, Duma A, Kopec M, et al. Nitrous oxide for treatment-resistant major depression: a proof-of-concept trial. Biol Psychiatry. 2015;78(1):10-18.

26. Zorumski CF, Nagele P, Mennerick S, et al. Treatment-resistant major depression: rationale for NMDA receptors as targets and nitrous oxide as therapy. Front Psychiatry. 2015;6:172.

27. Shear MK. Clinical practice. Complicated grief. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(2):153-160.

28. Knechtli CJC, Crowe JN. Guidelines for the investigation & management of vitamin B12 deficiency. Royal United Hospital Bath, National Health Service. http://www.ruh.nhs.uk/For_Clinicians/departments_ruh/Pathology/documents/haematology/B12_-_advice_on_investigation_management.pdf. Accessed June 14, 2016.

29. Jayaram N, Rao MG, Narashima A, et al. Vitamin B12 levels and psychiatric symptomatology: a case series. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2013;25(2):150-152.

30. Marks PW, Zukerberg LR. Case records of the Massachusetts General Hospital. Weekly clinicopathological exercises. Case 30-2004. A 37-year-old woman with paresthesias of the arms and legs. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(13):1333-1341.

31. Watanabe F. Vitamin B12 sources and bioavailablility. Exp Biol Med (Maywood). 2007;232(10):1266-1274.

32. Green R, Kinsella LJ. Current concepts in the diagnosis of cobalamin deficiency. Neurology. 1995;45(8):1435-1440.

The art of psychopharmacology: Avoiding medication changes and slowing down

As physicians, we are cognizant of the importance of patient-centered care, active listening, empathy, and patience—the so-called “hidden curriculum of medicine.”1 However, our attempts to centralize these concepts may be overshadowed by the deeply rooted drive to treat and fix. At times, we are simply treating uncertainty, whether it be diagnostic uncertainty or the uncertainty arising from clinical responses and outcomes that are far from binary. Definitive actions, such as adding medications or altering dosages, may appear to both patients and physicians to be a step closer to a “cure.” However, watchful waiting, re-evaluation, and accepting uncertainty are the true skills of effective care.

Be savvy about psychopharmacology

Psychotropics can take weeks to months to reach their full potential, and have varying responses and adverse effects. Beware of changing regimens prematurely, and keep in mind basic, yet crucial, pharmacokinetic concepts (eg, 4 to 5 half-lives to reach steady state, variations in metabolism). Receptor binding and dosing heuristics are notably common in psychiatry. Although such concepts are important to grasp, there is no one-size-fits-all rule. The brain simply does not possess the heart’s machine-like, linear functioning. Therefore, targeting individual parts (ie, receptors) will not equate to fixing the whole organ systematically or predictably.

Is the patient truly treatment-resistant?

Even the best treatment regimen has no clinical benefit if the patient cannot afford the prescription or does not take the medication. If cost is an impediment, switch from brand name drugs to generic formulations or to older medications in the same class. Before declaring the patient “treatment-resistant” and making medication changes, assess for compliance. This may require assistance from collateral informants. Ask family members to count the number of pills remaining in the bottle, and call the pharmacy to find out the last refill dates. If the patient exhibits a partial response to what should be a therapeutic dose, consider obtaining drug plasma levels to rule out rapid metabolism before deeming the medication trial a failure.2

Medications as liabilities

Overreliance on medications can result in the medications becoming liabilities. The polypharmacy problem is not unique to psychiatry.3 However, psychiatric patients may be more likely to inadvertently use medications in a maladaptive manner and disrupt the fundamental goals of long-term care. Avoid making medication adjustments in response to a patient’s life stressors and normative situational reactions. Doing so is a disservice to patients, because we are robbing them of chances to develop necessary coping skills and defenses. This can be overtly damaging in certain patient populations, such as those with borderline personality disorder, who may use medication adjustments as a crutch during crises.4

Treat the patient, not yourself

We physicians mean well in prescribing evidence-based treatments; however, if the symptoms or adverse effects are not bothersome or cause functional impairment, we risk losing sight of the patient’s goals in treatment and imposing our own instead. Displacing the treatment focus can alienate the patient, harm the therapeutic alliance, and result in “pill fatigue.” For example, we may be tempted to treat antipsychotic-induced tardive dyskinesia, even if the patient is not concerned about abnormal movements. Although we see this adverse effect

Change does not happen overnight

Picking a treatment option out of a lineup of choices, à la UWorld questions, does not always translate into patients agreeing with the suggested treatment, let alone the idea of receiving treatment at all. Motivational interviewing is our chance to shine in such situations and the reason why we are physicians, rather than answer-picking bots. Patients cannot change if they are not ready. However, we should be ready to roll with resistance while looking for signs of readiness to change. We must accept that it may take a week, a month, a year, or even longer for patients to align with our plan of action. The only futile decision is deeming our efforts as futile while discounting the benefits of incremental care.

1. Hafferty FW, Gaufberg EH, O’Donnell JF. The role of the hidden curriculum in “on doctoring” courses. AMA J Ethics. 2015;17(2):130-139.

2. Horvitz-Lennon M, Mattke S, Predmore Z, et al. The role of antipsychotic plasma levels in the treatment of schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2017;174(5):421-426.

3. Kantor ED, Rehm CD, Haas JS, et al. Trends in prescription drug use among adults in the United States from 1999-2012. JAMA. 2015;314(17):1818-1831.

4. Gunderson JG. The emergence of a generalist model to meet public health needs for patients with borderline personality disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2016;173(5):452-458.

5. Kikkert MJ, Schene AH, Koeter MW, et al. Medication adherence in schizophrenia: exploring patients’, carers’ and professionals’ views. Schizophr Bull. 2005;32(4):786-794.

As physicians, we are cognizant of the importance of patient-centered care, active listening, empathy, and patience—the so-called “hidden curriculum of medicine.”1 However, our attempts to centralize these concepts may be overshadowed by the deeply rooted drive to treat and fix. At times, we are simply treating uncertainty, whether it be diagnostic uncertainty or the uncertainty arising from clinical responses and outcomes that are far from binary. Definitive actions, such as adding medications or altering dosages, may appear to both patients and physicians to be a step closer to a “cure.” However, watchful waiting, re-evaluation, and accepting uncertainty are the true skills of effective care.

Be savvy about psychopharmacology

Psychotropics can take weeks to months to reach their full potential, and have varying responses and adverse effects. Beware of changing regimens prematurely, and keep in mind basic, yet crucial, pharmacokinetic concepts (eg, 4 to 5 half-lives to reach steady state, variations in metabolism). Receptor binding and dosing heuristics are notably common in psychiatry. Although such concepts are important to grasp, there is no one-size-fits-all rule. The brain simply does not possess the heart’s machine-like, linear functioning. Therefore, targeting individual parts (ie, receptors) will not equate to fixing the whole organ systematically or predictably.

Is the patient truly treatment-resistant?

Even the best treatment regimen has no clinical benefit if the patient cannot afford the prescription or does not take the medication. If cost is an impediment, switch from brand name drugs to generic formulations or to older medications in the same class. Before declaring the patient “treatment-resistant” and making medication changes, assess for compliance. This may require assistance from collateral informants. Ask family members to count the number of pills remaining in the bottle, and call the pharmacy to find out the last refill dates. If the patient exhibits a partial response to what should be a therapeutic dose, consider obtaining drug plasma levels to rule out rapid metabolism before deeming the medication trial a failure.2

Medications as liabilities

Overreliance on medications can result in the medications becoming liabilities. The polypharmacy problem is not unique to psychiatry.3 However, psychiatric patients may be more likely to inadvertently use medications in a maladaptive manner and disrupt the fundamental goals of long-term care. Avoid making medication adjustments in response to a patient’s life stressors and normative situational reactions. Doing so is a disservice to patients, because we are robbing them of chances to develop necessary coping skills and defenses. This can be overtly damaging in certain patient populations, such as those with borderline personality disorder, who may use medication adjustments as a crutch during crises.4

Treat the patient, not yourself

We physicians mean well in prescribing evidence-based treatments; however, if the symptoms or adverse effects are not bothersome or cause functional impairment, we risk losing sight of the patient’s goals in treatment and imposing our own instead. Displacing the treatment focus can alienate the patient, harm the therapeutic alliance, and result in “pill fatigue.” For example, we may be tempted to treat antipsychotic-induced tardive dyskinesia, even if the patient is not concerned about abnormal movements. Although we see this adverse effect

Change does not happen overnight

Picking a treatment option out of a lineup of choices, à la UWorld questions, does not always translate into patients agreeing with the suggested treatment, let alone the idea of receiving treatment at all. Motivational interviewing is our chance to shine in such situations and the reason why we are physicians, rather than answer-picking bots. Patients cannot change if they are not ready. However, we should be ready to roll with resistance while looking for signs of readiness to change. We must accept that it may take a week, a month, a year, or even longer for patients to align with our plan of action. The only futile decision is deeming our efforts as futile while discounting the benefits of incremental care.

As physicians, we are cognizant of the importance of patient-centered care, active listening, empathy, and patience—the so-called “hidden curriculum of medicine.”1 However, our attempts to centralize these concepts may be overshadowed by the deeply rooted drive to treat and fix. At times, we are simply treating uncertainty, whether it be diagnostic uncertainty or the uncertainty arising from clinical responses and outcomes that are far from binary. Definitive actions, such as adding medications or altering dosages, may appear to both patients and physicians to be a step closer to a “cure.” However, watchful waiting, re-evaluation, and accepting uncertainty are the true skills of effective care.

Be savvy about psychopharmacology

Psychotropics can take weeks to months to reach their full potential, and have varying responses and adverse effects. Beware of changing regimens prematurely, and keep in mind basic, yet crucial, pharmacokinetic concepts (eg, 4 to 5 half-lives to reach steady state, variations in metabolism). Receptor binding and dosing heuristics are notably common in psychiatry. Although such concepts are important to grasp, there is no one-size-fits-all rule. The brain simply does not possess the heart’s machine-like, linear functioning. Therefore, targeting individual parts (ie, receptors) will not equate to fixing the whole organ systematically or predictably.

Is the patient truly treatment-resistant?

Even the best treatment regimen has no clinical benefit if the patient cannot afford the prescription or does not take the medication. If cost is an impediment, switch from brand name drugs to generic formulations or to older medications in the same class. Before declaring the patient “treatment-resistant” and making medication changes, assess for compliance. This may require assistance from collateral informants. Ask family members to count the number of pills remaining in the bottle, and call the pharmacy to find out the last refill dates. If the patient exhibits a partial response to what should be a therapeutic dose, consider obtaining drug plasma levels to rule out rapid metabolism before deeming the medication trial a failure.2

Medications as liabilities

Overreliance on medications can result in the medications becoming liabilities. The polypharmacy problem is not unique to psychiatry.3 However, psychiatric patients may be more likely to inadvertently use medications in a maladaptive manner and disrupt the fundamental goals of long-term care. Avoid making medication adjustments in response to a patient’s life stressors and normative situational reactions. Doing so is a disservice to patients, because we are robbing them of chances to develop necessary coping skills and defenses. This can be overtly damaging in certain patient populations, such as those with borderline personality disorder, who may use medication adjustments as a crutch during crises.4

Treat the patient, not yourself

We physicians mean well in prescribing evidence-based treatments; however, if the symptoms or adverse effects are not bothersome or cause functional impairment, we risk losing sight of the patient’s goals in treatment and imposing our own instead. Displacing the treatment focus can alienate the patient, harm the therapeutic alliance, and result in “pill fatigue.” For example, we may be tempted to treat antipsychotic-induced tardive dyskinesia, even if the patient is not concerned about abnormal movements. Although we see this adverse effect

Change does not happen overnight

Picking a treatment option out of a lineup of choices, à la UWorld questions, does not always translate into patients agreeing with the suggested treatment, let alone the idea of receiving treatment at all. Motivational interviewing is our chance to shine in such situations and the reason why we are physicians, rather than answer-picking bots. Patients cannot change if they are not ready. However, we should be ready to roll with resistance while looking for signs of readiness to change. We must accept that it may take a week, a month, a year, or even longer for patients to align with our plan of action. The only futile decision is deeming our efforts as futile while discounting the benefits of incremental care.

1. Hafferty FW, Gaufberg EH, O’Donnell JF. The role of the hidden curriculum in “on doctoring” courses. AMA J Ethics. 2015;17(2):130-139.

2. Horvitz-Lennon M, Mattke S, Predmore Z, et al. The role of antipsychotic plasma levels in the treatment of schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2017;174(5):421-426.

3. Kantor ED, Rehm CD, Haas JS, et al. Trends in prescription drug use among adults in the United States from 1999-2012. JAMA. 2015;314(17):1818-1831.

4. Gunderson JG. The emergence of a generalist model to meet public health needs for patients with borderline personality disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2016;173(5):452-458.

5. Kikkert MJ, Schene AH, Koeter MW, et al. Medication adherence in schizophrenia: exploring patients’, carers’ and professionals’ views. Schizophr Bull. 2005;32(4):786-794.

1. Hafferty FW, Gaufberg EH, O’Donnell JF. The role of the hidden curriculum in “on doctoring” courses. AMA J Ethics. 2015;17(2):130-139.

2. Horvitz-Lennon M, Mattke S, Predmore Z, et al. The role of antipsychotic plasma levels in the treatment of schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2017;174(5):421-426.

3. Kantor ED, Rehm CD, Haas JS, et al. Trends in prescription drug use among adults in the United States from 1999-2012. JAMA. 2015;314(17):1818-1831.

4. Gunderson JG. The emergence of a generalist model to meet public health needs for patients with borderline personality disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2016;173(5):452-458.

5. Kikkert MJ, Schene AH, Koeter MW, et al. Medication adherence in schizophrenia: exploring patients’, carers’ and professionals’ views. Schizophr Bull. 2005;32(4):786-794.

Providing psychotherapy? Keep these principles in mind

Although the biological aspects of psychiatry are crucial, psychotherapy is an integral part of psychiatry. Unfortunately, the emphasis on psychotherapy training in psychiatry residency programs has declined compared with a decade or more ago. In an era of dwindling psychotherapy training and resources, the quality and type of psychotherapy training has become more variable. In addition to helping maintain the therapeutic alliance, nuanced psychotherapy by a trained professional can be transformational by helping patients to:

- process complex life events and emotions

- feel understood

- overcome psychological barriers to recovery

- enhance self-esteem.

When providing psychotherapy for adult patients, consider these basic, but salient points that are often overlooked.

Refrain from making life decisions for patients, except in exceptional circumstances, such as in situations of abuse and other crises.1 Telling an adult patient what to do about life decisions that he finds challenging fits more under life coaching than psychotherapy. Through therapy, patients should be helped in processing the pros and cons of certain decisions and in navigating the decision-making process to arrive at a decision that makes the most sense to them. Also, it’s not uncommon for therapeutic relationships to rupture when therapists give advice such as suggesting that a patient divorce his spouse, date a certain individual, or have children.

There are many reasons why giving advice in psychotherapy is not recommended. Giving advice can be an impediment to the therapeutic process.2 What is good advice for one patient may not be good for another. Therapists who give advice often do so from their own lens and perspective. This perspective may not only be different from the patient’s priorities and life circumstances, but the therapist also may have inadequate information about the patient’s situation,1,2 which could lead to providing advice that could even harm the patient. In addition, providing advice might prevent a patient from gaining adequate agency or self-directedness while promoting an unhealthy dependence on the therapist and reinforcing the patient’s self-doubt or lack of confidence. In these cases, the patient may later resent the therapist for the advice.

Address the ‘here and now.’1 Pay attention to immediate issues or themes that emerge, and address them with the patient gently and thoughtfully, as appropriate. Ignoring these may create risks of missing vital, underlying material that could reveal more of the patient’s inner world, as these themes can sometimes reflect other themes of the patient’s life outside of treatment.

Acknowledging and empathizing, when appropriate, are key initial steps that help decrease resistance and facilitate the therapeutic process.

Explore the affect. Paying attention to the patient’s emotional state is critical.3 This holds true for all types of psychotherapy. For example, if a patient suddenly becomes tearful when telling his story or describing recent events, this is usually a sign that the subject matter affects or holds value to the patient in a significant or meaningful way and should be further explored.

‘Meet the patient where they are.’ This doesn’t mean you should yield to the patient or give in to his demands. It implies that you should assess the patient’s readiness for a particular intervention and devise interventions from that standpoint, exploring the patient’s ambivalence, noticing resistance, and continuing to acknowledge and empathize with where the patient is in life or treatment. When utilized judiciously, this technique can help the therapist align with the patient, and help the patient move forward through resistance and ambivalence.

Be nonjudgmental and empathetic. Patients place trust in their therapists when they disclose thoughts or emotions that are sensitive, meaningful, or close to the heart. A nonjudgmental response helps the patient accept his experiences and emotions. Being empathetic requires putting oneself in another’s shoes; it does not mean agreeing with the patient. Of course, if you learn that your patient abused a child or an older adult, you are required to report it to the appropriate state agency. In addition, follow the duty to warn and protect in case of any other safety issues, as appropriate.

Do not assume. Open-ended questions and exploration are key. For example, a patient told her resident therapist that her father recently passed away. The therapist expressed to the patient how hard this must be for her. However, the patient said she was relieved by her father’s death, because he had been abusive to her for years. Because of the therapist’s comment, the patient doubted her own reaction and felt guilty for not being more upset about her father’s death.

Avoid over-identifying with your patient. If you find yourself over-identifying with a patient because you have a common background or life events, seek supervision. Over-identification not only can pose barriers to objectively identifying patterns and trends in the patient’s behavior or presentation but also can increase the risk of crossing boundaries or even minimizing the patient’s experience. Exercise caution if you find yourself wanting to be liked by your patient; this is a common mistake among beginning therapists.4

Seek supervision. If you are feeling angry, frustrated, indifferent, or overly attached toward a patient, recognize this countertransference and seek consultation or supervision from an experienced colleague or supervisor. These emotions can be valuable tools that shed light not only on the patient’s life and the session itself, but also help you identify any other factors, such as your own feelings or experiences, that might be contributing to these reactions.

1. Yalom ID. The gift of therapy: an open letter to a new generation of therapists and their patients. New York, NY: HarperCollins Publishers; 2002:46-73,142-145.

2. Bender S, Messner E. Management of impasses. In: Bender S, Messner E. Becoming a therapist: what do I say, and why? New York, NY: The Guilford Press; 2003:235-258.

3.

4. Buckley P, Karasu TB, Charles E. Common mistakes in psychotherapy. Am J Psychiatry. 1979;136(12):1578-1580.

Although the biological aspects of psychiatry are crucial, psychotherapy is an integral part of psychiatry. Unfortunately, the emphasis on psychotherapy training in psychiatry residency programs has declined compared with a decade or more ago. In an era of dwindling psychotherapy training and resources, the quality and type of psychotherapy training has become more variable. In addition to helping maintain the therapeutic alliance, nuanced psychotherapy by a trained professional can be transformational by helping patients to:

- process complex life events and emotions

- feel understood

- overcome psychological barriers to recovery

- enhance self-esteem.

When providing psychotherapy for adult patients, consider these basic, but salient points that are often overlooked.

Refrain from making life decisions for patients, except in exceptional circumstances, such as in situations of abuse and other crises.1 Telling an adult patient what to do about life decisions that he finds challenging fits more under life coaching than psychotherapy. Through therapy, patients should be helped in processing the pros and cons of certain decisions and in navigating the decision-making process to arrive at a decision that makes the most sense to them. Also, it’s not uncommon for therapeutic relationships to rupture when therapists give advice such as suggesting that a patient divorce his spouse, date a certain individual, or have children.

There are many reasons why giving advice in psychotherapy is not recommended. Giving advice can be an impediment to the therapeutic process.2 What is good advice for one patient may not be good for another. Therapists who give advice often do so from their own lens and perspective. This perspective may not only be different from the patient’s priorities and life circumstances, but the therapist also may have inadequate information about the patient’s situation,1,2 which could lead to providing advice that could even harm the patient. In addition, providing advice might prevent a patient from gaining adequate agency or self-directedness while promoting an unhealthy dependence on the therapist and reinforcing the patient’s self-doubt or lack of confidence. In these cases, the patient may later resent the therapist for the advice.

Address the ‘here and now.’1 Pay attention to immediate issues or themes that emerge, and address them with the patient gently and thoughtfully, as appropriate. Ignoring these may create risks of missing vital, underlying material that could reveal more of the patient’s inner world, as these themes can sometimes reflect other themes of the patient’s life outside of treatment.

Acknowledging and empathizing, when appropriate, are key initial steps that help decrease resistance and facilitate the therapeutic process.

Explore the affect. Paying attention to the patient’s emotional state is critical.3 This holds true for all types of psychotherapy. For example, if a patient suddenly becomes tearful when telling his story or describing recent events, this is usually a sign that the subject matter affects or holds value to the patient in a significant or meaningful way and should be further explored.

‘Meet the patient where they are.’ This doesn’t mean you should yield to the patient or give in to his demands. It implies that you should assess the patient’s readiness for a particular intervention and devise interventions from that standpoint, exploring the patient’s ambivalence, noticing resistance, and continuing to acknowledge and empathize with where the patient is in life or treatment. When utilized judiciously, this technique can help the therapist align with the patient, and help the patient move forward through resistance and ambivalence.

Be nonjudgmental and empathetic. Patients place trust in their therapists when they disclose thoughts or emotions that are sensitive, meaningful, or close to the heart. A nonjudgmental response helps the patient accept his experiences and emotions. Being empathetic requires putting oneself in another’s shoes; it does not mean agreeing with the patient. Of course, if you learn that your patient abused a child or an older adult, you are required to report it to the appropriate state agency. In addition, follow the duty to warn and protect in case of any other safety issues, as appropriate.

Do not assume. Open-ended questions and exploration are key. For example, a patient told her resident therapist that her father recently passed away. The therapist expressed to the patient how hard this must be for her. However, the patient said she was relieved by her father’s death, because he had been abusive to her for years. Because of the therapist’s comment, the patient doubted her own reaction and felt guilty for not being more upset about her father’s death.

Avoid over-identifying with your patient. If you find yourself over-identifying with a patient because you have a common background or life events, seek supervision. Over-identification not only can pose barriers to objectively identifying patterns and trends in the patient’s behavior or presentation but also can increase the risk of crossing boundaries or even minimizing the patient’s experience. Exercise caution if you find yourself wanting to be liked by your patient; this is a common mistake among beginning therapists.4

Seek supervision. If you are feeling angry, frustrated, indifferent, or overly attached toward a patient, recognize this countertransference and seek consultation or supervision from an experienced colleague or supervisor. These emotions can be valuable tools that shed light not only on the patient’s life and the session itself, but also help you identify any other factors, such as your own feelings or experiences, that might be contributing to these reactions.

Although the biological aspects of psychiatry are crucial, psychotherapy is an integral part of psychiatry. Unfortunately, the emphasis on psychotherapy training in psychiatry residency programs has declined compared with a decade or more ago. In an era of dwindling psychotherapy training and resources, the quality and type of psychotherapy training has become more variable. In addition to helping maintain the therapeutic alliance, nuanced psychotherapy by a trained professional can be transformational by helping patients to:

- process complex life events and emotions

- feel understood

- overcome psychological barriers to recovery

- enhance self-esteem.

When providing psychotherapy for adult patients, consider these basic, but salient points that are often overlooked.

Refrain from making life decisions for patients, except in exceptional circumstances, such as in situations of abuse and other crises.1 Telling an adult patient what to do about life decisions that he finds challenging fits more under life coaching than psychotherapy. Through therapy, patients should be helped in processing the pros and cons of certain decisions and in navigating the decision-making process to arrive at a decision that makes the most sense to them. Also, it’s not uncommon for therapeutic relationships to rupture when therapists give advice such as suggesting that a patient divorce his spouse, date a certain individual, or have children.

There are many reasons why giving advice in psychotherapy is not recommended. Giving advice can be an impediment to the therapeutic process.2 What is good advice for one patient may not be good for another. Therapists who give advice often do so from their own lens and perspective. This perspective may not only be different from the patient’s priorities and life circumstances, but the therapist also may have inadequate information about the patient’s situation,1,2 which could lead to providing advice that could even harm the patient. In addition, providing advice might prevent a patient from gaining adequate agency or self-directedness while promoting an unhealthy dependence on the therapist and reinforcing the patient’s self-doubt or lack of confidence. In these cases, the patient may later resent the therapist for the advice.

Address the ‘here and now.’1 Pay attention to immediate issues or themes that emerge, and address them with the patient gently and thoughtfully, as appropriate. Ignoring these may create risks of missing vital, underlying material that could reveal more of the patient’s inner world, as these themes can sometimes reflect other themes of the patient’s life outside of treatment.

Acknowledging and empathizing, when appropriate, are key initial steps that help decrease resistance and facilitate the therapeutic process.

Explore the affect. Paying attention to the patient’s emotional state is critical.3 This holds true for all types of psychotherapy. For example, if a patient suddenly becomes tearful when telling his story or describing recent events, this is usually a sign that the subject matter affects or holds value to the patient in a significant or meaningful way and should be further explored.

‘Meet the patient where they are.’ This doesn’t mean you should yield to the patient or give in to his demands. It implies that you should assess the patient’s readiness for a particular intervention and devise interventions from that standpoint, exploring the patient’s ambivalence, noticing resistance, and continuing to acknowledge and empathize with where the patient is in life or treatment. When utilized judiciously, this technique can help the therapist align with the patient, and help the patient move forward through resistance and ambivalence.

Be nonjudgmental and empathetic. Patients place trust in their therapists when they disclose thoughts or emotions that are sensitive, meaningful, or close to the heart. A nonjudgmental response helps the patient accept his experiences and emotions. Being empathetic requires putting oneself in another’s shoes; it does not mean agreeing with the patient. Of course, if you learn that your patient abused a child or an older adult, you are required to report it to the appropriate state agency. In addition, follow the duty to warn and protect in case of any other safety issues, as appropriate.

Do not assume. Open-ended questions and exploration are key. For example, a patient told her resident therapist that her father recently passed away. The therapist expressed to the patient how hard this must be for her. However, the patient said she was relieved by her father’s death, because he had been abusive to her for years. Because of the therapist’s comment, the patient doubted her own reaction and felt guilty for not being more upset about her father’s death.

Avoid over-identifying with your patient. If you find yourself over-identifying with a patient because you have a common background or life events, seek supervision. Over-identification not only can pose barriers to objectively identifying patterns and trends in the patient’s behavior or presentation but also can increase the risk of crossing boundaries or even minimizing the patient’s experience. Exercise caution if you find yourself wanting to be liked by your patient; this is a common mistake among beginning therapists.4

Seek supervision. If you are feeling angry, frustrated, indifferent, or overly attached toward a patient, recognize this countertransference and seek consultation or supervision from an experienced colleague or supervisor. These emotions can be valuable tools that shed light not only on the patient’s life and the session itself, but also help you identify any other factors, such as your own feelings or experiences, that might be contributing to these reactions.

1. Yalom ID. The gift of therapy: an open letter to a new generation of therapists and their patients. New York, NY: HarperCollins Publishers; 2002:46-73,142-145.

2. Bender S, Messner E. Management of impasses. In: Bender S, Messner E. Becoming a therapist: what do I say, and why? New York, NY: The Guilford Press; 2003:235-258.

3.

4. Buckley P, Karasu TB, Charles E. Common mistakes in psychotherapy. Am J Psychiatry. 1979;136(12):1578-1580.

1. Yalom ID. The gift of therapy: an open letter to a new generation of therapists and their patients. New York, NY: HarperCollins Publishers; 2002:46-73,142-145.