User login

Government uncertainty drives jump in ACA silver plan insurance premiums

Silver plans on the Affordable Care Act insurance exchanges in 2018 will see an average premium increase of 34% nationwide, according to new research from Avalere Health.

“Plans are raising premiums in 2018 to account for market uncertainty and the federal government’s failure to pay for cost-sharing reductions,” Caroline Pearson, senior vice president at Avalere, said in a statement. “These premium increases may allow insurers to remain in the market and enrollees in all regions to have access to coverage.”

The expected premium changes are highly variable by state. Iowa has the highest change in its silver plans, with an average premium increase of 69% for its silver plans, while at the other end of the spectrum, Alaska is actually seeing a 22% decrease.

“These rates may change prior to open enrollment depending on how states respond to the elimination of CSR [cost-sharing reduction] funding for the 2018 plan year,” Avalere notes in its new analysis, adding that states may allow plans to refile for rate hikes now that CSR funding is likely dead. “In states where this occurs, it is expected that the newly updated rates will be substantially higher for the 2018 plan year.”

There was a glimmer of hope that the CSR payments would resume after a compromise was reached in the Senate Health, Education, Labor & Pensions Committee by Chairman Lamar Alexander (R-Tenn.) and Ranking Member Patty Murray (D-Wash.) that would offer 2 years of funding along with flexibility in the waiver program to allow states to tweak Affordable Care Act requirements, which is supported by AGA (http://www.gastro.org/news_items/aga-supports-alexander-murray-agreement-to-stabilize-individual-market). However, Speaker Paul Ryan (R-Wisc.) said the House would not be taking on any more health care action for the remainder of the year.

A spokeswoman from America’s Health Insurance Plans said in an interview that, although the CSR payments are no more, premium tax credits still exist to help lower-income individuals obtain insurance coverage.

Silver plans on the Affordable Care Act insurance exchanges in 2018 will see an average premium increase of 34% nationwide, according to new research from Avalere Health.

“Plans are raising premiums in 2018 to account for market uncertainty and the federal government’s failure to pay for cost-sharing reductions,” Caroline Pearson, senior vice president at Avalere, said in a statement. “These premium increases may allow insurers to remain in the market and enrollees in all regions to have access to coverage.”

The expected premium changes are highly variable by state. Iowa has the highest change in its silver plans, with an average premium increase of 69% for its silver plans, while at the other end of the spectrum, Alaska is actually seeing a 22% decrease.

“These rates may change prior to open enrollment depending on how states respond to the elimination of CSR [cost-sharing reduction] funding for the 2018 plan year,” Avalere notes in its new analysis, adding that states may allow plans to refile for rate hikes now that CSR funding is likely dead. “In states where this occurs, it is expected that the newly updated rates will be substantially higher for the 2018 plan year.”

There was a glimmer of hope that the CSR payments would resume after a compromise was reached in the Senate Health, Education, Labor & Pensions Committee by Chairman Lamar Alexander (R-Tenn.) and Ranking Member Patty Murray (D-Wash.) that would offer 2 years of funding along with flexibility in the waiver program to allow states to tweak Affordable Care Act requirements, which is supported by AGA (http://www.gastro.org/news_items/aga-supports-alexander-murray-agreement-to-stabilize-individual-market). However, Speaker Paul Ryan (R-Wisc.) said the House would not be taking on any more health care action for the remainder of the year.

A spokeswoman from America’s Health Insurance Plans said in an interview that, although the CSR payments are no more, premium tax credits still exist to help lower-income individuals obtain insurance coverage.

Silver plans on the Affordable Care Act insurance exchanges in 2018 will see an average premium increase of 34% nationwide, according to new research from Avalere Health.

“Plans are raising premiums in 2018 to account for market uncertainty and the federal government’s failure to pay for cost-sharing reductions,” Caroline Pearson, senior vice president at Avalere, said in a statement. “These premium increases may allow insurers to remain in the market and enrollees in all regions to have access to coverage.”

The expected premium changes are highly variable by state. Iowa has the highest change in its silver plans, with an average premium increase of 69% for its silver plans, while at the other end of the spectrum, Alaska is actually seeing a 22% decrease.

“These rates may change prior to open enrollment depending on how states respond to the elimination of CSR [cost-sharing reduction] funding for the 2018 plan year,” Avalere notes in its new analysis, adding that states may allow plans to refile for rate hikes now that CSR funding is likely dead. “In states where this occurs, it is expected that the newly updated rates will be substantially higher for the 2018 plan year.”

There was a glimmer of hope that the CSR payments would resume after a compromise was reached in the Senate Health, Education, Labor & Pensions Committee by Chairman Lamar Alexander (R-Tenn.) and Ranking Member Patty Murray (D-Wash.) that would offer 2 years of funding along with flexibility in the waiver program to allow states to tweak Affordable Care Act requirements, which is supported by AGA (http://www.gastro.org/news_items/aga-supports-alexander-murray-agreement-to-stabilize-individual-market). However, Speaker Paul Ryan (R-Wisc.) said the House would not be taking on any more health care action for the remainder of the year.

A spokeswoman from America’s Health Insurance Plans said in an interview that, although the CSR payments are no more, premium tax credits still exist to help lower-income individuals obtain insurance coverage.

DDSEP® 8 Quick quiz - November 2017 Question 1

Answer: C

Rationale: The patient presents with acute gallstone pancreatitis. In patients with gallstone pancreatitis and evidence of cholangitis, ERCP with sphincterotomy and stone extraction should be performed. The patient’s fever, jaundice, and right upper-quadrant pain are sufficient to make the diagnosis of cholangitis. It is too early in the course of the disease to evaluate for pancreatic necrosis. Typically, triglyceride levels above 1,000 mg/dL are required to induce pancreatitis. Finally, while the patient has cholelithiasis, there is no evidence of cholecystitis. Therefore, a HIDA scan is not warranted.

Reference

1. Behrns K.E., Ashley S.W., Hunter J.G., Carr-Locke D. Early ERCP for gallstone pancreatitis: for whom and when? J Gastrointest Surg. 2008;12(4):629-33.

Answer: C

Rationale: The patient presents with acute gallstone pancreatitis. In patients with gallstone pancreatitis and evidence of cholangitis, ERCP with sphincterotomy and stone extraction should be performed. The patient’s fever, jaundice, and right upper-quadrant pain are sufficient to make the diagnosis of cholangitis. It is too early in the course of the disease to evaluate for pancreatic necrosis. Typically, triglyceride levels above 1,000 mg/dL are required to induce pancreatitis. Finally, while the patient has cholelithiasis, there is no evidence of cholecystitis. Therefore, a HIDA scan is not warranted.

Reference

1. Behrns K.E., Ashley S.W., Hunter J.G., Carr-Locke D. Early ERCP for gallstone pancreatitis: for whom and when? J Gastrointest Surg. 2008;12(4):629-33.

Answer: C

Rationale: The patient presents with acute gallstone pancreatitis. In patients with gallstone pancreatitis and evidence of cholangitis, ERCP with sphincterotomy and stone extraction should be performed. The patient’s fever, jaundice, and right upper-quadrant pain are sufficient to make the diagnosis of cholangitis. It is too early in the course of the disease to evaluate for pancreatic necrosis. Typically, triglyceride levels above 1,000 mg/dL are required to induce pancreatitis. Finally, while the patient has cholelithiasis, there is no evidence of cholecystitis. Therefore, a HIDA scan is not warranted.

Reference

1. Behrns K.E., Ashley S.W., Hunter J.G., Carr-Locke D. Early ERCP for gallstone pancreatitis: for whom and when? J Gastrointest Surg. 2008;12(4):629-33.

A 50-year-old woman with no past medical history presents to the emergency department with the acute onset of severe epigastric pain and vomiting. She is afebrile with a blood pressure of 100/50 mm Hg, and pulse of 110 bpm. Physical exam shows right upper-quadrant and epigastric tenderness to palpation without rebound. Labs demonstrate a WBC count of 17,000/mm3, hemoglobin of 16 g/dL, creatinine of 1.4 mg/dL, ALT of 215 U/L, AST of 190 U/L, a total bilirubin of 2.1 mg/dL, and triglycerides of 492 mg/dL. Right upper-quadrant ultrasound reveals gallstones and a 1.2-cm common bile duct. The following day, despite being hydrated aggressively, the patient develops a fever and becomes jaundiced with worsening abdominal pain.

What’s Eating You? Scabies in the Developing World

Scabies is caused by the mite Sarcoptes scabiei var hominis.1 It is in the arthropod class Arachnida, subclass Acari, and family Sarcoptidae.2 Historically, scabies was first described in the Old Testament and by Aristotle,2 but the causative organism was not identified until 1687 using a light microscope.3 Scabies affects all age groups, races, and social classes and is globally widespread. It is most prevalent in developing tropical countries.1 It is estimated that 300 million individuals worldwide are infested with scabies mites annually, with the highest burden in young children.4-7 In industrialized societies, infections often are seen in young adults and in institutional settings such as nursing homes.8 Scabies disproportionately impacts impoverished communities with crowded living conditions, poor hygiene and nutrition, and substandard housing.5,9 Controlling the spread of the disease in these communities presents challenges but is important because of the connection between scabies and chronic kidney disease.10 As such, scabies represents a major health problem in the developing world and has been the focus of major health initiatives.1,11

Identifying Characteristics

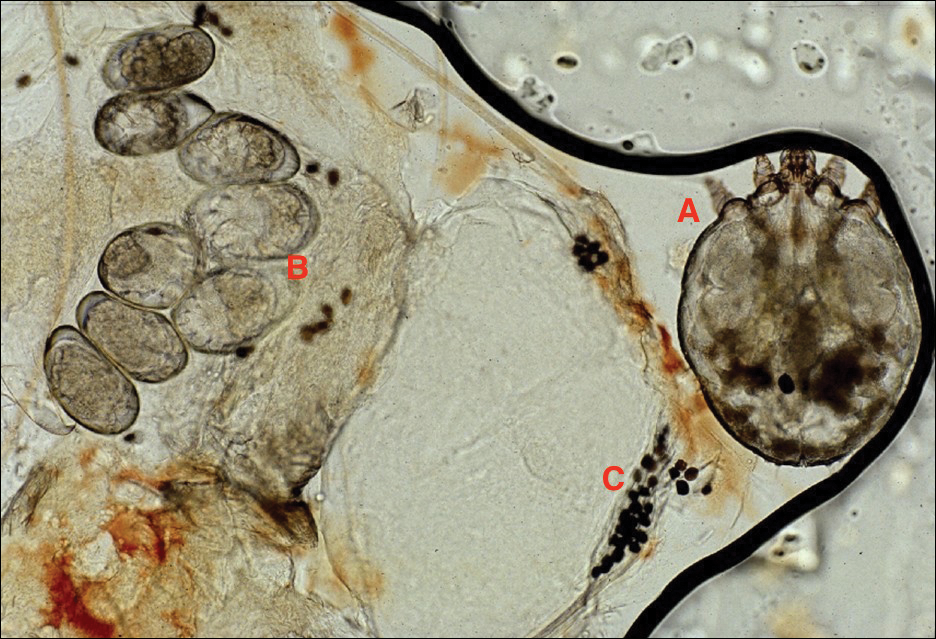

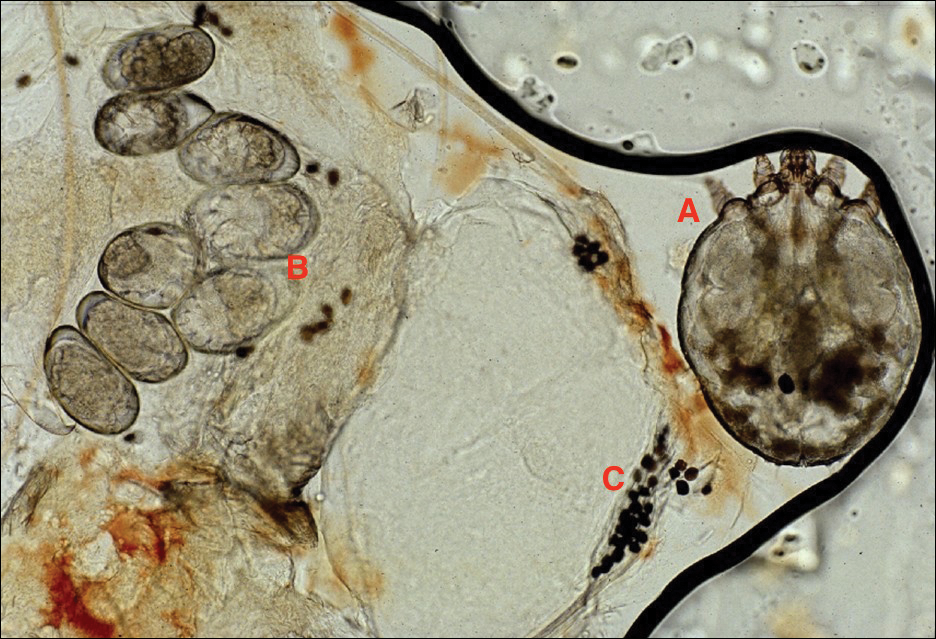

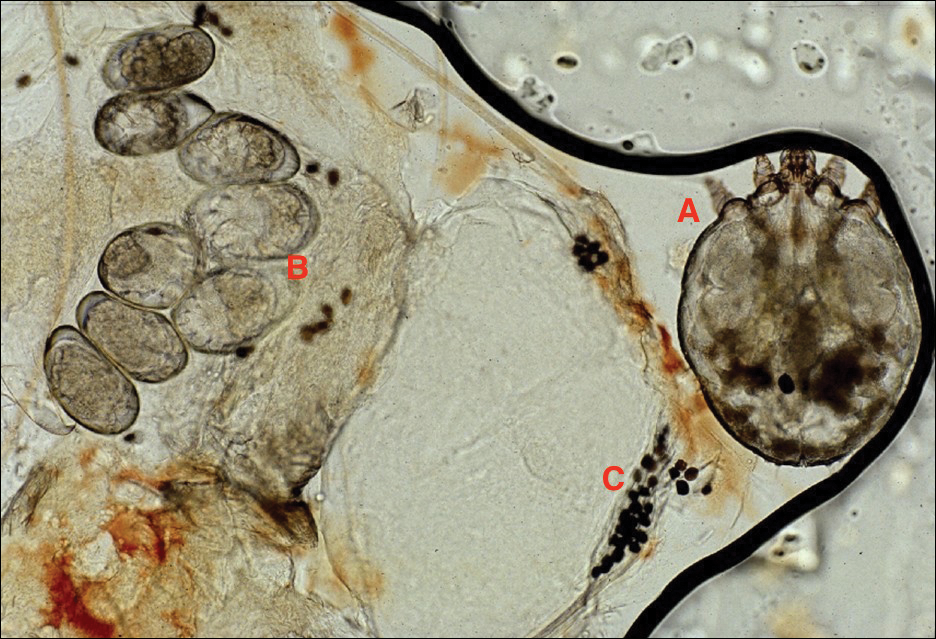

Adult females are 0.4-mm long and 0.3-mm wide, with males being smaller. Adult nymphs have 8 legs and larvae have 6 legs. Scabies mites are distinguishable from other arachnids by the position of a distinct gnathosoma and the lack of a division between the abdomen and cephalothorax.12 They are ovoid with a small anterior cephalic and caudal thoracoabdominal portion with hairlike projections coming off from the rudimentary legs. They can crawl as fast as 2.5 cm per minute on warm skin.2 The life cycle of the mite begins after mating: the male mite dies, and the female lays up to 3 eggs per day, which hatch in 3 to 4 days,2 in skin burrows within the stratum granulosum.12 Maturation from larva to adult takes 10 to 14 days.12 A female mite can live for 4 to 6 weeks and can produce up to 40 ova (Figure 1).

Disease Transmission

Without a host, mites are able to survive and remain capable of infestation for 24 to 36 hours at 21°C and 40% to 80% relative humidity. Lower temperatures and higher humidity prolong survival, but infectivity decreases the longer they are without a host.13

An adult human with ordinary scabies will have an average of 12 adult female mites on the body surface at a given time.14 However, hundreds of mites can be found in neglected children in underprivileged communities and millions in patients with crusted scabies.13 Transmission of typical scabies requires close direct skin-to-skin contact for 15 to 20 minutes.2,8 Transmission from clothing or fomites are an unlikely source of infestation with the exception of patients who are heavily infested such as in crusted scabies.12 In adults, sexual contact is an important method of transmission,12 and patients with scabies should be screened for other sexually transmitted diseases.8

Clinical Manifestations

Signs of scabies on the skin include burrows, erythematous papules, and generalized pruritus (Figure 2).12 The scalp, face, and neck frequently are involved in infants and children,2 and the hands, wrists, elbows, genitalia, axillae, umbilicus, belt line, nipples, and buttocks commonly are involved in adults.12 Itching is characteristically worse at night.8 In tropical climates, patients with scabies are predisposed to secondary bacterial skin infections, particularly Streptococcus pyogenes (group A streptococci). The association between scabies and pyoderma caused by group A streptococci has been well established.15,16 Mika et al10 suggested that local complement inhibition plays an important role in the development of pyoderma in scabies-infested skin.

Prevention and Control in the Developing World

Low-cost diagnostic equipment can play a key role in the definitive diagnosis and management of scabies outbreaks in the developing world. Micali et al28 found that a $30 videomicroscope was as effective in scabies diagnosis as a $20,000 videodermatoscope. Because of the low cost of benzyl benzoate, it is commonly used as a first-line drug in many parts of the world,13 whereas permethrin cream 5% is the standard treatment in the developed world.29 Recognition of the role of scabies in patients with pyoderma is key, and one study indicated clinically apparent scabies went unnoticed by physicians in 52% of patients presenting with skin lesions.30 Drug shortages also can contribute to a high prevalence of scabies infestation in the community.31 Mass treatment with ivermectin has proven to be an effective means of reducing the prevalence of many parasitic diseases,1,32,33 and it shows great promise for crusted scabies, institutional outbreaks, and mass administration in highly endemic communites.8 However, there is evidence of ivermectin tolerance among mites, which could undermine the success of mass drug administration.34 Another important consideration is population mobility and the risk for rapid reintroduction of scabies infection across regions.35

Complicating disease control are the socioeconomic factors associated with scabies in the developing world. Families with scabies infestation typically do not own their homes, are less likely to have constant electricity, have a lower monthly income, and live in substandard housing.20 Families can spend a substantial part of their household income on treatment, impacting what they can spend on food.8,11 In addition to medication, control of scabies requires community education and involvement, along with access to primary care and attention to living conditions and environmental factors.34,36

- Romani L, Whitfeld MJ, Koroivueta J, et al. Mass drug administration for scabies control in a population with endemic disease. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:2305-2313.

- Hicks MI, Elston DM. Scabies. Dermatol Ther. 2009;22:279-292.

- Ramos-e-Silva M. Giovan Cosimo Bonomo (1663-1696): discoverer of the etiology of scabies. Int J Dermatol. 1998;37:625-630.

- Chung SD, Wang KH, Huang CC, et al. Scabies increased the risk of chronic kidney disease: a 5-year follow-up study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2014;28:286-292.

- Wong SS, Poon RW, Chau S, et al. Development of conventional and real-time quantitative PCR assays for diagnosis and monitoring of scabies. J Clin Microbiol. 2015;53:2095-2102.

- Kearns TM, Speare R, Cheng AC, et al. Impact of an ivermectin mass drug administration on scabies prevalence in a remote Australian aboriginal community. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2015;9:e0004151.

- Gilmore SJ. Control strategies for endemic childhood scabies. PLoS One. 2011;6:e15990.

- Hay RJ, Steer AC, Engelman D, Walton S. Scabies in the developing world—its prevalence, complications, and management. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2012;18:313-323.

- Hoy WE, White AV, Dowling A, et al. Post-streptococcal glomerulonephritis is a strong risk factor for chronic kidney disease in later life. Kidney Int. 2012;81:1026-1032.

- Mika A, Reynolds SL, Pickering D, et al. Complement inhibitors from scabies mites promote streptococcal growth—a novel mechanism in infected epidermis? PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2012;6:e1563.

- McLean FE. The elimination of scabies: a task for our generation. Int J Dermatol. 2013;52:1215-1223.

- Hengge UR, Currie BJ, Jäger G, et al. Scabies: a ubiquitous neglected skin disease. Lancet Infect Dis. 2006;6:769-779.

- Heukelbach J, Feldmeier H. Scabies. Lancet. 2006;367:1767-1774.

- Johnston G, Sladden M. Scabies: diagnosis and treatment. BMJ. 2005;331:619-622.

- Yeoh DK, Bowen AC, Carapetis JR. Impetigo and scabies—disease burden and modern treatment strategies [published online May 11, 2016]. J Infect. 2016;(72 suppl):S61-S67.

- Bowen AC, Mahé A, Hay RJ, et al. The global epidemiology of impetigo: a systematic review of the population prevalence of impetigo and pyoderma. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0136789.

- Bowen AC, Tong SY, Chatfield MD, et al. The microbiology of impetigo in indigenous children: associations between Streptococcus pyogenes, Staphylococcus aureus, scabies, and nasal carriage. BMC Infect Dis. 2014;14:727.

- Sesso R, Pinto SW. Five-year follow-up of patients with epidemic glomerulonephritis due to Streptococcus zooepidemicus. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2005;20:1808-1812.

- Singh GR. Glomerulonephritis and managing the risks of chronic renal disease. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2009;56:1363-1382.

- La Vincente S, Kearns T, Connors C, et al. Community management of endemic scabies in remote aboriginal communities of northern Australia: low treatment uptake and high ongoing acquisition. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2009;3:e444.

- Clucas DB, Carville KS, Connors C, et al. Disease burden and health-care clinic attendances for young children in remote aboriginal communities of northern Australia. Bull World Health Organ. 2008;86:275-281.

- Stanton B, Khanam S, Nazrul H, et al. Scabies in urban Bangladesh. J Trop Med Hyg. 1987;90:219-226.

- Heukelbach J, de Oliveira FA, Feldmeier H. Ecoparasitoses and public health in Brazil: challenges for control [in Portuguese]. Cad Saude Publica. 2003;19:1535-1540.

- Edison L, Beaudoin A, Goh L, et al. Scabies and bacterial superinfection among American Samoan children, 2011-2012. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0139336.

- Steer AC, Jenney AW, Kado J, et al. High burden of impetigo and scabies in a tropical country. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2009;3:e467.

- Romani L, Steer AC, Whitfeld MJ, et al. Prevalence of scabies and impetigo worldwide: a systematic review. Lancet Infect Dis. 2015;15:960-967.

- Romani L, Koroivueta J, Steer AC, et al. Scabies and impetigo prevalence and risk factors in Fiji: a national survey. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2015;9:e0003452.

- Micali G, Lacarrubba F, Verzì AE, et al. Low-cost equipment for diagnosis and management of endemic scabies outbreaks in underserved populations. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;60:327-329.

- Pasay C, Walton S, Fischer K, et al. PCR-based assay to survey for knockdown resistance to pyrethroid acaricides in human scabies mites (Sarcoptes scabiei var hominis). Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2006;74:649-657.

- Heukelbach J, van Haeff E, Rump B, et al. Parasitic skin diseases: health care-seeking in a slum in north-east Brazil. Trop Med Int Health. 2003;8:368-373.

- Potter EV, Mayon-White R, Poon-King T, et al. Acute glomerulonephritis as a complication of scabies. In: Orkin M, Maibach HI, eds. Cutaneous Infestations and Insect Bites. New York, NY: Marcel Dekker; 1985.

- Mahé A. Mass drug administration for scabies control. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:1689.

- Steer AC, Romani L, Kaldor JM. Mass drug administration for scabies control. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:1690.

- Mounsey KE, Holt DC, McCarthy JS, et al. Longitudinal evidence of increasing in vitro tolerance of scabies mites to ivermectin in scabies-endemic communities. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:840-841.

- Currie BJ. Scabies and global control of neglected tropical diseases. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:2371-2372.

- O’Donnell V, Morris S, Ward J. Mass drug administration for scabies control. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:1689-1690.

Scabies is caused by the mite Sarcoptes scabiei var hominis.1 It is in the arthropod class Arachnida, subclass Acari, and family Sarcoptidae.2 Historically, scabies was first described in the Old Testament and by Aristotle,2 but the causative organism was not identified until 1687 using a light microscope.3 Scabies affects all age groups, races, and social classes and is globally widespread. It is most prevalent in developing tropical countries.1 It is estimated that 300 million individuals worldwide are infested with scabies mites annually, with the highest burden in young children.4-7 In industrialized societies, infections often are seen in young adults and in institutional settings such as nursing homes.8 Scabies disproportionately impacts impoverished communities with crowded living conditions, poor hygiene and nutrition, and substandard housing.5,9 Controlling the spread of the disease in these communities presents challenges but is important because of the connection between scabies and chronic kidney disease.10 As such, scabies represents a major health problem in the developing world and has been the focus of major health initiatives.1,11

Identifying Characteristics

Adult females are 0.4-mm long and 0.3-mm wide, with males being smaller. Adult nymphs have 8 legs and larvae have 6 legs. Scabies mites are distinguishable from other arachnids by the position of a distinct gnathosoma and the lack of a division between the abdomen and cephalothorax.12 They are ovoid with a small anterior cephalic and caudal thoracoabdominal portion with hairlike projections coming off from the rudimentary legs. They can crawl as fast as 2.5 cm per minute on warm skin.2 The life cycle of the mite begins after mating: the male mite dies, and the female lays up to 3 eggs per day, which hatch in 3 to 4 days,2 in skin burrows within the stratum granulosum.12 Maturation from larva to adult takes 10 to 14 days.12 A female mite can live for 4 to 6 weeks and can produce up to 40 ova (Figure 1).

Disease Transmission

Without a host, mites are able to survive and remain capable of infestation for 24 to 36 hours at 21°C and 40% to 80% relative humidity. Lower temperatures and higher humidity prolong survival, but infectivity decreases the longer they are without a host.13

An adult human with ordinary scabies will have an average of 12 adult female mites on the body surface at a given time.14 However, hundreds of mites can be found in neglected children in underprivileged communities and millions in patients with crusted scabies.13 Transmission of typical scabies requires close direct skin-to-skin contact for 15 to 20 minutes.2,8 Transmission from clothing or fomites are an unlikely source of infestation with the exception of patients who are heavily infested such as in crusted scabies.12 In adults, sexual contact is an important method of transmission,12 and patients with scabies should be screened for other sexually transmitted diseases.8

Clinical Manifestations

Signs of scabies on the skin include burrows, erythematous papules, and generalized pruritus (Figure 2).12 The scalp, face, and neck frequently are involved in infants and children,2 and the hands, wrists, elbows, genitalia, axillae, umbilicus, belt line, nipples, and buttocks commonly are involved in adults.12 Itching is characteristically worse at night.8 In tropical climates, patients with scabies are predisposed to secondary bacterial skin infections, particularly Streptococcus pyogenes (group A streptococci). The association between scabies and pyoderma caused by group A streptococci has been well established.15,16 Mika et al10 suggested that local complement inhibition plays an important role in the development of pyoderma in scabies-infested skin.

Prevention and Control in the Developing World

Low-cost diagnostic equipment can play a key role in the definitive diagnosis and management of scabies outbreaks in the developing world. Micali et al28 found that a $30 videomicroscope was as effective in scabies diagnosis as a $20,000 videodermatoscope. Because of the low cost of benzyl benzoate, it is commonly used as a first-line drug in many parts of the world,13 whereas permethrin cream 5% is the standard treatment in the developed world.29 Recognition of the role of scabies in patients with pyoderma is key, and one study indicated clinically apparent scabies went unnoticed by physicians in 52% of patients presenting with skin lesions.30 Drug shortages also can contribute to a high prevalence of scabies infestation in the community.31 Mass treatment with ivermectin has proven to be an effective means of reducing the prevalence of many parasitic diseases,1,32,33 and it shows great promise for crusted scabies, institutional outbreaks, and mass administration in highly endemic communites.8 However, there is evidence of ivermectin tolerance among mites, which could undermine the success of mass drug administration.34 Another important consideration is population mobility and the risk for rapid reintroduction of scabies infection across regions.35

Complicating disease control are the socioeconomic factors associated with scabies in the developing world. Families with scabies infestation typically do not own their homes, are less likely to have constant electricity, have a lower monthly income, and live in substandard housing.20 Families can spend a substantial part of their household income on treatment, impacting what they can spend on food.8,11 In addition to medication, control of scabies requires community education and involvement, along with access to primary care and attention to living conditions and environmental factors.34,36

Scabies is caused by the mite Sarcoptes scabiei var hominis.1 It is in the arthropod class Arachnida, subclass Acari, and family Sarcoptidae.2 Historically, scabies was first described in the Old Testament and by Aristotle,2 but the causative organism was not identified until 1687 using a light microscope.3 Scabies affects all age groups, races, and social classes and is globally widespread. It is most prevalent in developing tropical countries.1 It is estimated that 300 million individuals worldwide are infested with scabies mites annually, with the highest burden in young children.4-7 In industrialized societies, infections often are seen in young adults and in institutional settings such as nursing homes.8 Scabies disproportionately impacts impoverished communities with crowded living conditions, poor hygiene and nutrition, and substandard housing.5,9 Controlling the spread of the disease in these communities presents challenges but is important because of the connection between scabies and chronic kidney disease.10 As such, scabies represents a major health problem in the developing world and has been the focus of major health initiatives.1,11

Identifying Characteristics

Adult females are 0.4-mm long and 0.3-mm wide, with males being smaller. Adult nymphs have 8 legs and larvae have 6 legs. Scabies mites are distinguishable from other arachnids by the position of a distinct gnathosoma and the lack of a division between the abdomen and cephalothorax.12 They are ovoid with a small anterior cephalic and caudal thoracoabdominal portion with hairlike projections coming off from the rudimentary legs. They can crawl as fast as 2.5 cm per minute on warm skin.2 The life cycle of the mite begins after mating: the male mite dies, and the female lays up to 3 eggs per day, which hatch in 3 to 4 days,2 in skin burrows within the stratum granulosum.12 Maturation from larva to adult takes 10 to 14 days.12 A female mite can live for 4 to 6 weeks and can produce up to 40 ova (Figure 1).

Disease Transmission

Without a host, mites are able to survive and remain capable of infestation for 24 to 36 hours at 21°C and 40% to 80% relative humidity. Lower temperatures and higher humidity prolong survival, but infectivity decreases the longer they are without a host.13

An adult human with ordinary scabies will have an average of 12 adult female mites on the body surface at a given time.14 However, hundreds of mites can be found in neglected children in underprivileged communities and millions in patients with crusted scabies.13 Transmission of typical scabies requires close direct skin-to-skin contact for 15 to 20 minutes.2,8 Transmission from clothing or fomites are an unlikely source of infestation with the exception of patients who are heavily infested such as in crusted scabies.12 In adults, sexual contact is an important method of transmission,12 and patients with scabies should be screened for other sexually transmitted diseases.8

Clinical Manifestations

Signs of scabies on the skin include burrows, erythematous papules, and generalized pruritus (Figure 2).12 The scalp, face, and neck frequently are involved in infants and children,2 and the hands, wrists, elbows, genitalia, axillae, umbilicus, belt line, nipples, and buttocks commonly are involved in adults.12 Itching is characteristically worse at night.8 In tropical climates, patients with scabies are predisposed to secondary bacterial skin infections, particularly Streptococcus pyogenes (group A streptococci). The association between scabies and pyoderma caused by group A streptococci has been well established.15,16 Mika et al10 suggested that local complement inhibition plays an important role in the development of pyoderma in scabies-infested skin.

Prevention and Control in the Developing World

Low-cost diagnostic equipment can play a key role in the definitive diagnosis and management of scabies outbreaks in the developing world. Micali et al28 found that a $30 videomicroscope was as effective in scabies diagnosis as a $20,000 videodermatoscope. Because of the low cost of benzyl benzoate, it is commonly used as a first-line drug in many parts of the world,13 whereas permethrin cream 5% is the standard treatment in the developed world.29 Recognition of the role of scabies in patients with pyoderma is key, and one study indicated clinically apparent scabies went unnoticed by physicians in 52% of patients presenting with skin lesions.30 Drug shortages also can contribute to a high prevalence of scabies infestation in the community.31 Mass treatment with ivermectin has proven to be an effective means of reducing the prevalence of many parasitic diseases,1,32,33 and it shows great promise for crusted scabies, institutional outbreaks, and mass administration in highly endemic communites.8 However, there is evidence of ivermectin tolerance among mites, which could undermine the success of mass drug administration.34 Another important consideration is population mobility and the risk for rapid reintroduction of scabies infection across regions.35

Complicating disease control are the socioeconomic factors associated with scabies in the developing world. Families with scabies infestation typically do not own their homes, are less likely to have constant electricity, have a lower monthly income, and live in substandard housing.20 Families can spend a substantial part of their household income on treatment, impacting what they can spend on food.8,11 In addition to medication, control of scabies requires community education and involvement, along with access to primary care and attention to living conditions and environmental factors.34,36

- Romani L, Whitfeld MJ, Koroivueta J, et al. Mass drug administration for scabies control in a population with endemic disease. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:2305-2313.

- Hicks MI, Elston DM. Scabies. Dermatol Ther. 2009;22:279-292.

- Ramos-e-Silva M. Giovan Cosimo Bonomo (1663-1696): discoverer of the etiology of scabies. Int J Dermatol. 1998;37:625-630.

- Chung SD, Wang KH, Huang CC, et al. Scabies increased the risk of chronic kidney disease: a 5-year follow-up study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2014;28:286-292.

- Wong SS, Poon RW, Chau S, et al. Development of conventional and real-time quantitative PCR assays for diagnosis and monitoring of scabies. J Clin Microbiol. 2015;53:2095-2102.

- Kearns TM, Speare R, Cheng AC, et al. Impact of an ivermectin mass drug administration on scabies prevalence in a remote Australian aboriginal community. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2015;9:e0004151.

- Gilmore SJ. Control strategies for endemic childhood scabies. PLoS One. 2011;6:e15990.

- Hay RJ, Steer AC, Engelman D, Walton S. Scabies in the developing world—its prevalence, complications, and management. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2012;18:313-323.

- Hoy WE, White AV, Dowling A, et al. Post-streptococcal glomerulonephritis is a strong risk factor for chronic kidney disease in later life. Kidney Int. 2012;81:1026-1032.

- Mika A, Reynolds SL, Pickering D, et al. Complement inhibitors from scabies mites promote streptococcal growth—a novel mechanism in infected epidermis? PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2012;6:e1563.

- McLean FE. The elimination of scabies: a task for our generation. Int J Dermatol. 2013;52:1215-1223.

- Hengge UR, Currie BJ, Jäger G, et al. Scabies: a ubiquitous neglected skin disease. Lancet Infect Dis. 2006;6:769-779.

- Heukelbach J, Feldmeier H. Scabies. Lancet. 2006;367:1767-1774.

- Johnston G, Sladden M. Scabies: diagnosis and treatment. BMJ. 2005;331:619-622.

- Yeoh DK, Bowen AC, Carapetis JR. Impetigo and scabies—disease burden and modern treatment strategies [published online May 11, 2016]. J Infect. 2016;(72 suppl):S61-S67.

- Bowen AC, Mahé A, Hay RJ, et al. The global epidemiology of impetigo: a systematic review of the population prevalence of impetigo and pyoderma. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0136789.

- Bowen AC, Tong SY, Chatfield MD, et al. The microbiology of impetigo in indigenous children: associations between Streptococcus pyogenes, Staphylococcus aureus, scabies, and nasal carriage. BMC Infect Dis. 2014;14:727.

- Sesso R, Pinto SW. Five-year follow-up of patients with epidemic glomerulonephritis due to Streptococcus zooepidemicus. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2005;20:1808-1812.

- Singh GR. Glomerulonephritis and managing the risks of chronic renal disease. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2009;56:1363-1382.

- La Vincente S, Kearns T, Connors C, et al. Community management of endemic scabies in remote aboriginal communities of northern Australia: low treatment uptake and high ongoing acquisition. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2009;3:e444.

- Clucas DB, Carville KS, Connors C, et al. Disease burden and health-care clinic attendances for young children in remote aboriginal communities of northern Australia. Bull World Health Organ. 2008;86:275-281.

- Stanton B, Khanam S, Nazrul H, et al. Scabies in urban Bangladesh. J Trop Med Hyg. 1987;90:219-226.

- Heukelbach J, de Oliveira FA, Feldmeier H. Ecoparasitoses and public health in Brazil: challenges for control [in Portuguese]. Cad Saude Publica. 2003;19:1535-1540.

- Edison L, Beaudoin A, Goh L, et al. Scabies and bacterial superinfection among American Samoan children, 2011-2012. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0139336.

- Steer AC, Jenney AW, Kado J, et al. High burden of impetigo and scabies in a tropical country. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2009;3:e467.

- Romani L, Steer AC, Whitfeld MJ, et al. Prevalence of scabies and impetigo worldwide: a systematic review. Lancet Infect Dis. 2015;15:960-967.

- Romani L, Koroivueta J, Steer AC, et al. Scabies and impetigo prevalence and risk factors in Fiji: a national survey. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2015;9:e0003452.

- Micali G, Lacarrubba F, Verzì AE, et al. Low-cost equipment for diagnosis and management of endemic scabies outbreaks in underserved populations. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;60:327-329.

- Pasay C, Walton S, Fischer K, et al. PCR-based assay to survey for knockdown resistance to pyrethroid acaricides in human scabies mites (Sarcoptes scabiei var hominis). Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2006;74:649-657.

- Heukelbach J, van Haeff E, Rump B, et al. Parasitic skin diseases: health care-seeking in a slum in north-east Brazil. Trop Med Int Health. 2003;8:368-373.

- Potter EV, Mayon-White R, Poon-King T, et al. Acute glomerulonephritis as a complication of scabies. In: Orkin M, Maibach HI, eds. Cutaneous Infestations and Insect Bites. New York, NY: Marcel Dekker; 1985.

- Mahé A. Mass drug administration for scabies control. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:1689.

- Steer AC, Romani L, Kaldor JM. Mass drug administration for scabies control. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:1690.

- Mounsey KE, Holt DC, McCarthy JS, et al. Longitudinal evidence of increasing in vitro tolerance of scabies mites to ivermectin in scabies-endemic communities. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:840-841.

- Currie BJ. Scabies and global control of neglected tropical diseases. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:2371-2372.

- O’Donnell V, Morris S, Ward J. Mass drug administration for scabies control. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:1689-1690.

- Romani L, Whitfeld MJ, Koroivueta J, et al. Mass drug administration for scabies control in a population with endemic disease. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:2305-2313.

- Hicks MI, Elston DM. Scabies. Dermatol Ther. 2009;22:279-292.

- Ramos-e-Silva M. Giovan Cosimo Bonomo (1663-1696): discoverer of the etiology of scabies. Int J Dermatol. 1998;37:625-630.

- Chung SD, Wang KH, Huang CC, et al. Scabies increased the risk of chronic kidney disease: a 5-year follow-up study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2014;28:286-292.

- Wong SS, Poon RW, Chau S, et al. Development of conventional and real-time quantitative PCR assays for diagnosis and monitoring of scabies. J Clin Microbiol. 2015;53:2095-2102.

- Kearns TM, Speare R, Cheng AC, et al. Impact of an ivermectin mass drug administration on scabies prevalence in a remote Australian aboriginal community. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2015;9:e0004151.

- Gilmore SJ. Control strategies for endemic childhood scabies. PLoS One. 2011;6:e15990.

- Hay RJ, Steer AC, Engelman D, Walton S. Scabies in the developing world—its prevalence, complications, and management. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2012;18:313-323.

- Hoy WE, White AV, Dowling A, et al. Post-streptococcal glomerulonephritis is a strong risk factor for chronic kidney disease in later life. Kidney Int. 2012;81:1026-1032.

- Mika A, Reynolds SL, Pickering D, et al. Complement inhibitors from scabies mites promote streptococcal growth—a novel mechanism in infected epidermis? PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2012;6:e1563.

- McLean FE. The elimination of scabies: a task for our generation. Int J Dermatol. 2013;52:1215-1223.

- Hengge UR, Currie BJ, Jäger G, et al. Scabies: a ubiquitous neglected skin disease. Lancet Infect Dis. 2006;6:769-779.

- Heukelbach J, Feldmeier H. Scabies. Lancet. 2006;367:1767-1774.

- Johnston G, Sladden M. Scabies: diagnosis and treatment. BMJ. 2005;331:619-622.

- Yeoh DK, Bowen AC, Carapetis JR. Impetigo and scabies—disease burden and modern treatment strategies [published online May 11, 2016]. J Infect. 2016;(72 suppl):S61-S67.

- Bowen AC, Mahé A, Hay RJ, et al. The global epidemiology of impetigo: a systematic review of the population prevalence of impetigo and pyoderma. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0136789.

- Bowen AC, Tong SY, Chatfield MD, et al. The microbiology of impetigo in indigenous children: associations between Streptococcus pyogenes, Staphylococcus aureus, scabies, and nasal carriage. BMC Infect Dis. 2014;14:727.

- Sesso R, Pinto SW. Five-year follow-up of patients with epidemic glomerulonephritis due to Streptococcus zooepidemicus. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2005;20:1808-1812.

- Singh GR. Glomerulonephritis and managing the risks of chronic renal disease. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2009;56:1363-1382.

- La Vincente S, Kearns T, Connors C, et al. Community management of endemic scabies in remote aboriginal communities of northern Australia: low treatment uptake and high ongoing acquisition. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2009;3:e444.

- Clucas DB, Carville KS, Connors C, et al. Disease burden and health-care clinic attendances for young children in remote aboriginal communities of northern Australia. Bull World Health Organ. 2008;86:275-281.

- Stanton B, Khanam S, Nazrul H, et al. Scabies in urban Bangladesh. J Trop Med Hyg. 1987;90:219-226.

- Heukelbach J, de Oliveira FA, Feldmeier H. Ecoparasitoses and public health in Brazil: challenges for control [in Portuguese]. Cad Saude Publica. 2003;19:1535-1540.

- Edison L, Beaudoin A, Goh L, et al. Scabies and bacterial superinfection among American Samoan children, 2011-2012. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0139336.

- Steer AC, Jenney AW, Kado J, et al. High burden of impetigo and scabies in a tropical country. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2009;3:e467.

- Romani L, Steer AC, Whitfeld MJ, et al. Prevalence of scabies and impetigo worldwide: a systematic review. Lancet Infect Dis. 2015;15:960-967.

- Romani L, Koroivueta J, Steer AC, et al. Scabies and impetigo prevalence and risk factors in Fiji: a national survey. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2015;9:e0003452.

- Micali G, Lacarrubba F, Verzì AE, et al. Low-cost equipment for diagnosis and management of endemic scabies outbreaks in underserved populations. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;60:327-329.

- Pasay C, Walton S, Fischer K, et al. PCR-based assay to survey for knockdown resistance to pyrethroid acaricides in human scabies mites (Sarcoptes scabiei var hominis). Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2006;74:649-657.

- Heukelbach J, van Haeff E, Rump B, et al. Parasitic skin diseases: health care-seeking in a slum in north-east Brazil. Trop Med Int Health. 2003;8:368-373.

- Potter EV, Mayon-White R, Poon-King T, et al. Acute glomerulonephritis as a complication of scabies. In: Orkin M, Maibach HI, eds. Cutaneous Infestations and Insect Bites. New York, NY: Marcel Dekker; 1985.

- Mahé A. Mass drug administration for scabies control. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:1689.

- Steer AC, Romani L, Kaldor JM. Mass drug administration for scabies control. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:1690.

- Mounsey KE, Holt DC, McCarthy JS, et al. Longitudinal evidence of increasing in vitro tolerance of scabies mites to ivermectin in scabies-endemic communities. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:840-841.

- Currie BJ. Scabies and global control of neglected tropical diseases. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:2371-2372.

- O’Donnell V, Morris S, Ward J. Mass drug administration for scabies control. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:1689-1690.

Practice Points

- Scabies infestation is one of the world’s leading causes of chronic kidney disease.

- Ivermectin can be used to treat mass infestations, and older topical therapies also are commonly used.

FDA approves acalabrutinib for second-line treatment of MCL

The Food and Drug Administration has granted accelerated approval to acalabrutinib, a Bruton tyrosine kinase inhibitor, for the treatment of adults with mantle cell lymphoma (MCL) who have received at least one prior therapy.

Approval was based on an 81% overall response rate in a phase 2, single-arm trial (ACE-LY-004) of 124 patients with MCL who had received at least one prior treatment (40% complete response, 41% partial response), the FDA said in a statement.

Serious adverse effects include hemorrhage and atrial fibrillation. Second primary malignancies have occurred in some patients, according to the FDA.

Acalabrutinib will be marketed as Calquence by AstraZeneca. The company is currently enrolling patients in a phase 3 trial evaluating acalabrutinib as a first-line treatment for patients with MCL in combination with bendamustine and rituximab.

[email protected]

On Twitter @NikolaidesLaura

The Food and Drug Administration has granted accelerated approval to acalabrutinib, a Bruton tyrosine kinase inhibitor, for the treatment of adults with mantle cell lymphoma (MCL) who have received at least one prior therapy.

Approval was based on an 81% overall response rate in a phase 2, single-arm trial (ACE-LY-004) of 124 patients with MCL who had received at least one prior treatment (40% complete response, 41% partial response), the FDA said in a statement.

Serious adverse effects include hemorrhage and atrial fibrillation. Second primary malignancies have occurred in some patients, according to the FDA.

Acalabrutinib will be marketed as Calquence by AstraZeneca. The company is currently enrolling patients in a phase 3 trial evaluating acalabrutinib as a first-line treatment for patients with MCL in combination with bendamustine and rituximab.

[email protected]

On Twitter @NikolaidesLaura

The Food and Drug Administration has granted accelerated approval to acalabrutinib, a Bruton tyrosine kinase inhibitor, for the treatment of adults with mantle cell lymphoma (MCL) who have received at least one prior therapy.

Approval was based on an 81% overall response rate in a phase 2, single-arm trial (ACE-LY-004) of 124 patients with MCL who had received at least one prior treatment (40% complete response, 41% partial response), the FDA said in a statement.

Serious adverse effects include hemorrhage and atrial fibrillation. Second primary malignancies have occurred in some patients, according to the FDA.

Acalabrutinib will be marketed as Calquence by AstraZeneca. The company is currently enrolling patients in a phase 3 trial evaluating acalabrutinib as a first-line treatment for patients with MCL in combination with bendamustine and rituximab.

[email protected]

On Twitter @NikolaidesLaura

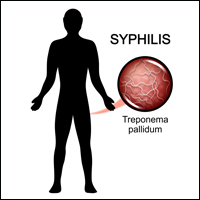

Syphilis and the Dermatologist

Once upon a time, and long ago, dermatology journals included “syphilology” in their names. The first dermatologic journal published in the United States was the American Journal of Syphilology and Dermatology.1 In October 1882 the Journal of Cutaneous and Venereal Diseases appeared and subsequently renamed several times from 1882 to 1919: Journal of Cutaneous Diseases and Genitourinary Diseases and the Journal of Cutaneous Diseases, Including Syphilis. When the American Medical Association (AMA) assumed control, this publication obtained a new name: Archives of Dermatology and Syphilology; in January 1955 syphilology was deleted from the title. According to an editorial in that issue, the rationale for dropping the word syphilology was as follows: “The diagnosis and treatment of patients with syphilis is no longer an important part of dermatologic practice. . . . Few dermatologists now have patients with syphilis; in fact, there are decidedly fewer patients with syphilis, and so continuance of the old label, ‘Syphilology,’ on this publication seems no longer warranted.”1 Needless to say, this decision ignored the obvious fact that the majority of dermatologists traditionally were well trained in and clinically practiced venereology, particularly the management of syphilis,2,3 which makes sense, considering that many of the clinical manifestations of syphilis involve the skin, hair, and oral mucosa. My own mentor and former Baylor College of Medicine dermatology department chair, Dr. John Knox, authored 3 dozen major publications regarding the diagnosis, treatment, and immunology of syphilis. During his chairmanship, all residents were required to rotate in the Harris County sexually transmitted disease (STD) clinic on a weekly basis.

I am confident that the decision to drop “syphilology” from the journal title also was based on the unduly optimistic assumption that syphilis would soon become a rare disease due to the availability of penicillin. Indeed, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in the United States has periodically announced strategic programs designed to eradicate syphilis!4 This rosy outlook reached a fever pitch in 2000 when the number of cases (5979) and the incidence (2.1 cases per 100,000 population) of primary and secondary syphilis reached an all-time low in the United States.5

Unfortunately, no one could accurately predict the future. Although the number of cases and incidence of early infectious syphilis have fluctuated widely since the 1940s, we currently are in a dire period of syphilis resurgence; the largest number of cases (27,814) and the highest incidence rate of primary and secondary syphilis (8.7 cases per 100,000 population) since 1994 were reported in 2016,6 which illustrates the inability of public health initiatives to eliminate syphilis, largely due to the inability of health authorities, health care providers, teachers, parents, clergy, and peer groups to alter sexual behaviors or modify other socioeconomic factors.7 Thus, syphilis lives on! Nobody could have predicted the easy availability of oral contraceptives and the ensuing sexual revolution of the 1960s or the advent of erectile dysfunction drugs decades later that led to increasing STDs among older patients.8 Nobody could have predicted the wholesale acceptance of casual sexual intercourse as popularized on television and in the movies or the pervasive use of sexual images in advertising. Nobody could have predicted the modern phenomena of “booty-call relationships,” “friends with benefits,” and “sexting,” or the nearly ubiquitous and increasingly legal use of noninjectable mind-altering drugs, all of which facilitate the perpetuation of STDs.9-11 Finally, those who removed “syphilology” from that journal title certainly did not foresee the worldwide epidemic now known as human immunodeficiency virus/AIDS, which has most assuredly helped keep syphilis a modern day menace.12-14

How have dermatologists been impacted? Our journals and our teachers have deemphasized STDs, including syphilis, in modern times, yet we are faced with a disease carrying serious, if not often fatal, consequences that is simply refusing to disappear (contrary to wishful thinking). Dermatologists are, however, in a perfect epidemiological position to help in the war against Treponema pallidum, the bacterium that causes syphilis. We frequently see adolescent patients for warts and acne, and we often diagnose and help care for patients with human immunodeficiency virus. We obliterate actinic keratoses and perform cosmetic procedures on those who rely on erectile dysfunction drugs (or their partners do). Who better than a dermatologist to recognize in these high-risk constituencies, and others, that patchy hair loss may represent syphilitic alopecia and that extragenital chancres can mimic nonmelanoma skin cancer? Who better than the dermatologist to distinguish between oral mucous patches and orolabial herpes? Who better than the dermatologist to diagnose the annular syphilid of the face, or ostraceous, florid nodular, or ulceronecrotic lesions of lues maligna? Who better than the dermatologist to differentiate condylomata lata from external genital warts?

I would suggest that the responsible dermatologist become reacquainted with syphilis, in all its various manifestations. I would further suggest that our dermatology training centers spend more time diligently teaching residents about syphilis and other STDs. In conclusion, I fervently hope that organized dermatology will once again dutifully consider venereal disease to be a critical part of our specialty’s skill set.

- Editorial. AMA Arch Dermatol. 1955;71:1.

- Shelley WB. Major contributors to American dermatology—1876 to 1926. Arch Dermatol. 1976;112:1642-1646.

- Lobitz WC Jr. Major contributions of American dermatologists—1926 to 1976. Arch Dermatol. 1976;112:1646-1650.

- Hook EW 3rd. Elimination of syphilis transmission in the United States: historic perspectives and practical considerations. Trans Am ClinClimatol Assoc. 1999;110:195-203.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually Transmitted Disease Surveillance 2000. Atlanta, GA: Department of Health and Human Services; 2001.

- 2016 Sexually transmitted diseases surveillance: syphilis. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. https://www.cdc.gov/std/stats16/syphilis.htm. Updated September 26, 2017. Accessed October 20, 2017.

- Shockman S, Buescher LS, Stone SP. Syphilis in the United States. Clin Dermatol. 2014;32:213-218.

- Jena AB, Goldman DP, Kamdar A, et al. Sexually transmitted diseases among users of erectile dysfunction drugs: analysis of claims data. Ann Intern Med. 2010;153:1-7.

- Jonason PK, Li NP, Richardson J. Positioning the booty-call relationship on the spectrum of relationships: sexual but more emotional than one-night stands. J Sex Res. 2011;48:486-495.

- Temple JR, Choi H. Longitudinal association between teen sexting and sexual behavior. Pediatrics. 2014;134:E1287-E1292.

- Regan R, Dyer TP, Gooding T, et al. Associations between drug use and sexual risks among heterosexual men in the Philippines [published online July 22, 2013]. Int J STD AIDS. 2013;24:969-976.

- Flagg EW, Weinstock HS, Frazier EL, et al. Bacterial sexually transmitted infections among HIV-infected patients in the United States: estimates from the Medical Monitoring Project. Sex Transm Dis. 2015;42:171-179.

- Shilaih M, Marzel A, Braun DL, et al; Swiss HIV Cohort Study. Factors associated with syphilis incidence in the HIV-infected in the era of highly active antiretrovirals. Medicine (Baltimore). 2017;96:E5849.

- Salado-Rasmussen K. Syphilis and HIV co-infection. epidemiology, treatment and molecular typing of Treponema pallidum. Dan Med J. 2015;62:B5176.

Once upon a time, and long ago, dermatology journals included “syphilology” in their names. The first dermatologic journal published in the United States was the American Journal of Syphilology and Dermatology.1 In October 1882 the Journal of Cutaneous and Venereal Diseases appeared and subsequently renamed several times from 1882 to 1919: Journal of Cutaneous Diseases and Genitourinary Diseases and the Journal of Cutaneous Diseases, Including Syphilis. When the American Medical Association (AMA) assumed control, this publication obtained a new name: Archives of Dermatology and Syphilology; in January 1955 syphilology was deleted from the title. According to an editorial in that issue, the rationale for dropping the word syphilology was as follows: “The diagnosis and treatment of patients with syphilis is no longer an important part of dermatologic practice. . . . Few dermatologists now have patients with syphilis; in fact, there are decidedly fewer patients with syphilis, and so continuance of the old label, ‘Syphilology,’ on this publication seems no longer warranted.”1 Needless to say, this decision ignored the obvious fact that the majority of dermatologists traditionally were well trained in and clinically practiced venereology, particularly the management of syphilis,2,3 which makes sense, considering that many of the clinical manifestations of syphilis involve the skin, hair, and oral mucosa. My own mentor and former Baylor College of Medicine dermatology department chair, Dr. John Knox, authored 3 dozen major publications regarding the diagnosis, treatment, and immunology of syphilis. During his chairmanship, all residents were required to rotate in the Harris County sexually transmitted disease (STD) clinic on a weekly basis.

I am confident that the decision to drop “syphilology” from the journal title also was based on the unduly optimistic assumption that syphilis would soon become a rare disease due to the availability of penicillin. Indeed, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in the United States has periodically announced strategic programs designed to eradicate syphilis!4 This rosy outlook reached a fever pitch in 2000 when the number of cases (5979) and the incidence (2.1 cases per 100,000 population) of primary and secondary syphilis reached an all-time low in the United States.5

Unfortunately, no one could accurately predict the future. Although the number of cases and incidence of early infectious syphilis have fluctuated widely since the 1940s, we currently are in a dire period of syphilis resurgence; the largest number of cases (27,814) and the highest incidence rate of primary and secondary syphilis (8.7 cases per 100,000 population) since 1994 were reported in 2016,6 which illustrates the inability of public health initiatives to eliminate syphilis, largely due to the inability of health authorities, health care providers, teachers, parents, clergy, and peer groups to alter sexual behaviors or modify other socioeconomic factors.7 Thus, syphilis lives on! Nobody could have predicted the easy availability of oral contraceptives and the ensuing sexual revolution of the 1960s or the advent of erectile dysfunction drugs decades later that led to increasing STDs among older patients.8 Nobody could have predicted the wholesale acceptance of casual sexual intercourse as popularized on television and in the movies or the pervasive use of sexual images in advertising. Nobody could have predicted the modern phenomena of “booty-call relationships,” “friends with benefits,” and “sexting,” or the nearly ubiquitous and increasingly legal use of noninjectable mind-altering drugs, all of which facilitate the perpetuation of STDs.9-11 Finally, those who removed “syphilology” from that journal title certainly did not foresee the worldwide epidemic now known as human immunodeficiency virus/AIDS, which has most assuredly helped keep syphilis a modern day menace.12-14

How have dermatologists been impacted? Our journals and our teachers have deemphasized STDs, including syphilis, in modern times, yet we are faced with a disease carrying serious, if not often fatal, consequences that is simply refusing to disappear (contrary to wishful thinking). Dermatologists are, however, in a perfect epidemiological position to help in the war against Treponema pallidum, the bacterium that causes syphilis. We frequently see adolescent patients for warts and acne, and we often diagnose and help care for patients with human immunodeficiency virus. We obliterate actinic keratoses and perform cosmetic procedures on those who rely on erectile dysfunction drugs (or their partners do). Who better than a dermatologist to recognize in these high-risk constituencies, and others, that patchy hair loss may represent syphilitic alopecia and that extragenital chancres can mimic nonmelanoma skin cancer? Who better than the dermatologist to distinguish between oral mucous patches and orolabial herpes? Who better than the dermatologist to diagnose the annular syphilid of the face, or ostraceous, florid nodular, or ulceronecrotic lesions of lues maligna? Who better than the dermatologist to differentiate condylomata lata from external genital warts?

I would suggest that the responsible dermatologist become reacquainted with syphilis, in all its various manifestations. I would further suggest that our dermatology training centers spend more time diligently teaching residents about syphilis and other STDs. In conclusion, I fervently hope that organized dermatology will once again dutifully consider venereal disease to be a critical part of our specialty’s skill set.

Once upon a time, and long ago, dermatology journals included “syphilology” in their names. The first dermatologic journal published in the United States was the American Journal of Syphilology and Dermatology.1 In October 1882 the Journal of Cutaneous and Venereal Diseases appeared and subsequently renamed several times from 1882 to 1919: Journal of Cutaneous Diseases and Genitourinary Diseases and the Journal of Cutaneous Diseases, Including Syphilis. When the American Medical Association (AMA) assumed control, this publication obtained a new name: Archives of Dermatology and Syphilology; in January 1955 syphilology was deleted from the title. According to an editorial in that issue, the rationale for dropping the word syphilology was as follows: “The diagnosis and treatment of patients with syphilis is no longer an important part of dermatologic practice. . . . Few dermatologists now have patients with syphilis; in fact, there are decidedly fewer patients with syphilis, and so continuance of the old label, ‘Syphilology,’ on this publication seems no longer warranted.”1 Needless to say, this decision ignored the obvious fact that the majority of dermatologists traditionally were well trained in and clinically practiced venereology, particularly the management of syphilis,2,3 which makes sense, considering that many of the clinical manifestations of syphilis involve the skin, hair, and oral mucosa. My own mentor and former Baylor College of Medicine dermatology department chair, Dr. John Knox, authored 3 dozen major publications regarding the diagnosis, treatment, and immunology of syphilis. During his chairmanship, all residents were required to rotate in the Harris County sexually transmitted disease (STD) clinic on a weekly basis.

I am confident that the decision to drop “syphilology” from the journal title also was based on the unduly optimistic assumption that syphilis would soon become a rare disease due to the availability of penicillin. Indeed, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in the United States has periodically announced strategic programs designed to eradicate syphilis!4 This rosy outlook reached a fever pitch in 2000 when the number of cases (5979) and the incidence (2.1 cases per 100,000 population) of primary and secondary syphilis reached an all-time low in the United States.5

Unfortunately, no one could accurately predict the future. Although the number of cases and incidence of early infectious syphilis have fluctuated widely since the 1940s, we currently are in a dire period of syphilis resurgence; the largest number of cases (27,814) and the highest incidence rate of primary and secondary syphilis (8.7 cases per 100,000 population) since 1994 were reported in 2016,6 which illustrates the inability of public health initiatives to eliminate syphilis, largely due to the inability of health authorities, health care providers, teachers, parents, clergy, and peer groups to alter sexual behaviors or modify other socioeconomic factors.7 Thus, syphilis lives on! Nobody could have predicted the easy availability of oral contraceptives and the ensuing sexual revolution of the 1960s or the advent of erectile dysfunction drugs decades later that led to increasing STDs among older patients.8 Nobody could have predicted the wholesale acceptance of casual sexual intercourse as popularized on television and in the movies or the pervasive use of sexual images in advertising. Nobody could have predicted the modern phenomena of “booty-call relationships,” “friends with benefits,” and “sexting,” or the nearly ubiquitous and increasingly legal use of noninjectable mind-altering drugs, all of which facilitate the perpetuation of STDs.9-11 Finally, those who removed “syphilology” from that journal title certainly did not foresee the worldwide epidemic now known as human immunodeficiency virus/AIDS, which has most assuredly helped keep syphilis a modern day menace.12-14

How have dermatologists been impacted? Our journals and our teachers have deemphasized STDs, including syphilis, in modern times, yet we are faced with a disease carrying serious, if not often fatal, consequences that is simply refusing to disappear (contrary to wishful thinking). Dermatologists are, however, in a perfect epidemiological position to help in the war against Treponema pallidum, the bacterium that causes syphilis. We frequently see adolescent patients for warts and acne, and we often diagnose and help care for patients with human immunodeficiency virus. We obliterate actinic keratoses and perform cosmetic procedures on those who rely on erectile dysfunction drugs (or their partners do). Who better than a dermatologist to recognize in these high-risk constituencies, and others, that patchy hair loss may represent syphilitic alopecia and that extragenital chancres can mimic nonmelanoma skin cancer? Who better than the dermatologist to distinguish between oral mucous patches and orolabial herpes? Who better than the dermatologist to diagnose the annular syphilid of the face, or ostraceous, florid nodular, or ulceronecrotic lesions of lues maligna? Who better than the dermatologist to differentiate condylomata lata from external genital warts?

I would suggest that the responsible dermatologist become reacquainted with syphilis, in all its various manifestations. I would further suggest that our dermatology training centers spend more time diligently teaching residents about syphilis and other STDs. In conclusion, I fervently hope that organized dermatology will once again dutifully consider venereal disease to be a critical part of our specialty’s skill set.

- Editorial. AMA Arch Dermatol. 1955;71:1.

- Shelley WB. Major contributors to American dermatology—1876 to 1926. Arch Dermatol. 1976;112:1642-1646.

- Lobitz WC Jr. Major contributions of American dermatologists—1926 to 1976. Arch Dermatol. 1976;112:1646-1650.

- Hook EW 3rd. Elimination of syphilis transmission in the United States: historic perspectives and practical considerations. Trans Am ClinClimatol Assoc. 1999;110:195-203.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually Transmitted Disease Surveillance 2000. Atlanta, GA: Department of Health and Human Services; 2001.

- 2016 Sexually transmitted diseases surveillance: syphilis. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. https://www.cdc.gov/std/stats16/syphilis.htm. Updated September 26, 2017. Accessed October 20, 2017.

- Shockman S, Buescher LS, Stone SP. Syphilis in the United States. Clin Dermatol. 2014;32:213-218.

- Jena AB, Goldman DP, Kamdar A, et al. Sexually transmitted diseases among users of erectile dysfunction drugs: analysis of claims data. Ann Intern Med. 2010;153:1-7.

- Jonason PK, Li NP, Richardson J. Positioning the booty-call relationship on the spectrum of relationships: sexual but more emotional than one-night stands. J Sex Res. 2011;48:486-495.

- Temple JR, Choi H. Longitudinal association between teen sexting and sexual behavior. Pediatrics. 2014;134:E1287-E1292.

- Regan R, Dyer TP, Gooding T, et al. Associations between drug use and sexual risks among heterosexual men in the Philippines [published online July 22, 2013]. Int J STD AIDS. 2013;24:969-976.

- Flagg EW, Weinstock HS, Frazier EL, et al. Bacterial sexually transmitted infections among HIV-infected patients in the United States: estimates from the Medical Monitoring Project. Sex Transm Dis. 2015;42:171-179.

- Shilaih M, Marzel A, Braun DL, et al; Swiss HIV Cohort Study. Factors associated with syphilis incidence in the HIV-infected in the era of highly active antiretrovirals. Medicine (Baltimore). 2017;96:E5849.

- Salado-Rasmussen K. Syphilis and HIV co-infection. epidemiology, treatment and molecular typing of Treponema pallidum. Dan Med J. 2015;62:B5176.

- Editorial. AMA Arch Dermatol. 1955;71:1.

- Shelley WB. Major contributors to American dermatology—1876 to 1926. Arch Dermatol. 1976;112:1642-1646.

- Lobitz WC Jr. Major contributions of American dermatologists—1926 to 1976. Arch Dermatol. 1976;112:1646-1650.

- Hook EW 3rd. Elimination of syphilis transmission in the United States: historic perspectives and practical considerations. Trans Am ClinClimatol Assoc. 1999;110:195-203.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually Transmitted Disease Surveillance 2000. Atlanta, GA: Department of Health and Human Services; 2001.

- 2016 Sexually transmitted diseases surveillance: syphilis. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. https://www.cdc.gov/std/stats16/syphilis.htm. Updated September 26, 2017. Accessed October 20, 2017.

- Shockman S, Buescher LS, Stone SP. Syphilis in the United States. Clin Dermatol. 2014;32:213-218.

- Jena AB, Goldman DP, Kamdar A, et al. Sexually transmitted diseases among users of erectile dysfunction drugs: analysis of claims data. Ann Intern Med. 2010;153:1-7.

- Jonason PK, Li NP, Richardson J. Positioning the booty-call relationship on the spectrum of relationships: sexual but more emotional than one-night stands. J Sex Res. 2011;48:486-495.

- Temple JR, Choi H. Longitudinal association between teen sexting and sexual behavior. Pediatrics. 2014;134:E1287-E1292.

- Regan R, Dyer TP, Gooding T, et al. Associations between drug use and sexual risks among heterosexual men in the Philippines [published online July 22, 2013]. Int J STD AIDS. 2013;24:969-976.

- Flagg EW, Weinstock HS, Frazier EL, et al. Bacterial sexually transmitted infections among HIV-infected patients in the United States: estimates from the Medical Monitoring Project. Sex Transm Dis. 2015;42:171-179.

- Shilaih M, Marzel A, Braun DL, et al; Swiss HIV Cohort Study. Factors associated with syphilis incidence in the HIV-infected in the era of highly active antiretrovirals. Medicine (Baltimore). 2017;96:E5849.

- Salado-Rasmussen K. Syphilis and HIV co-infection. epidemiology, treatment and molecular typing of Treponema pallidum. Dan Med J. 2015;62:B5176.

Left main distal bifurcation? Double kiss and crush it

DENVER – A planned two-stent, double-kissing crush PCI technique proved superior to the widely utilized provisional stenting strategy for treatment of unprotected distal left main bifurcation lesions in the randomized DKCRUSH-V trial, Shao-Liang Chen, MD, reported at the Transcatheter Cardiovascular Therapeutics annual educational meeting.

The study randomized 482 patients with unprotected true distal left main bifurcation lesions to one of the two PCI strategies at 26 centers in five countries, including the United States. Roughly 80% of the left main lesions were categorized as Medina 1,1,1.

The primary outcome was the 1-year composite rate of target lesion failure (TLF), defined as cardiac death, target vessel MI, or clinically driven target lesion revascularization. The rate was 10.7% in patients assigned to provisional stenting and 5.0% with double kissing (DK) crush. This clinically and statistically significant difference was driven by a sharp reduction in target vessel MI in the DK crush group: 0.4%, compared with 2.9% in the provisional stenting group.

Moreover, the DK crush group’s 3.8% rate of clinically driven target lesion revascularization and 7.1% rate of angiographic restenosis within the left main complex were both less than half the rates in the provisional stenting group, he added at the meeting, which was sponsored by the Cardiovascular Research Foundation.

The absolute benefit for the DK crush strategy was greatest in the roughly 30% of patients with complex bifurcations, defined as those with an ostial side branch lesion length of at least 10 mm and 70% diameter stenosis while meeting at least two of six minor criteria. The 1-year TLF rate in such patients was 18.2% with provisional stenting versus 7% with DK crush. For simple bifurcations, the TLF rates were 8% versus 1.9%.

The results favored DK crush in all examined subgroups, including those based upon age, gender, SYNTAX score, distal angle, and diabetes status.

Forty-seven percent of patients in the provisional stenting arm received a second stent, typically needed as a bailout for the side branch. Most of the excess target vessel MIs and other TLF events in the provisional stenting group occurred in patients who got a second stent.

The DK crush is an advanced technique with numerous steps involving multiple vessel wirings, rewirings, and stent crushing. It can be challenging to perform. It took an average of 82 minutes, 16 minutes longer than provisional stenting – a difference in procedural time that interventional cardiologists don’t take lightly. It also entailed an average of 36 mL more contrast media than the 191 mL for provisional stenting.

In an earlier multicenter, randomized, prospective trial – DKCRUSH-III – Dr. Chen and his coinvestigators showed that the DK crush technique provides superior outcomes compared with culotte stenting, another widely used treatment strategy for distal left main bifurcation lesions (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013 Apr 9;61[14]:1482-8).

“The take home message on the surface of the data would be that we should consider this particular two-stent bifurcation technique as perhaps the treatment of choice for true distal bifurcation lesions,” said Gregg W. Stone, MD, who was a coinvestigator in DKCRUSH-V and chaired the late-breaking clinical trial session where Dr. Chen presented the results.

“This technique theoretically gives you the largest amount of laminar flow both in the main vessel and the side branch,” added Dr. Stone, professor of medicine and director of cardiovascular research and education at Columbia University Medical Center in New York.

Simultaneously with Dr. Chen’s presentation at TCT 2017, the DKCRUSH-V results were published online (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017 Oct 30. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.09.1066). In an accompanying editorial, Emmanouil S. Brilakis, MD, declared that DK crush should become the preferred strategy for treating unprotected left main bifurcation lesions.

It’s not a technique for the average interventionalist, though. It should be performed in high-volume centers of excellence accustomed to performing complex PCIs. Indeed, the DKCRUSH-V trial required the primary operators to have performed at least 300 PCIs per year for 5 years, including 20 left main PCIs per year or more. To put that in perspective, the median annual PCI volume in the United States is 59 cases, noted Dr. Brilakis of the Minneapolis Heart Institute (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017 Oct. 30. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.09.1083).

At TCT 2017 in Denver, not everyone found the DKCRUSH-V findings persuasive.

“I’m quite surprised by the results,” said panel discussant David Hildick-Smith, MD.

“There’s something we have yet to understand about the divergence between the results that are coming out of China and the results coming out of Europe. Almost everything coming out of Europe tends to suggest that provisional stenting is better, while in Chinese hands the DK crush technique has proved to be an extremely successful strategy,” said Dr. Hildick-Smith, professor of interventional cardiology and director of the cardiac research unit at the Brighton and Sussex (England) Medical School.

He added that he intends to reserve judgment as to the preferred strategy until the results of the ongoing European Bifurcation Club Left Main Study (EBC MAIN) become available late in 2018. EBC MAIN is comparing the DK crush, culotte, and other strategies, with the choice of technique left to the operator’s discretion.

The DKCRUSH-V trial was supported by the National Science Foundation of China, the Nanjing Municipal Medical Development Project, Microport, Abbott Vascular, and Medtronic. Dr. Chen and Dr. Stone reported having no financial conflicts of interest regarding the study.

DENVER – A planned two-stent, double-kissing crush PCI technique proved superior to the widely utilized provisional stenting strategy for treatment of unprotected distal left main bifurcation lesions in the randomized DKCRUSH-V trial, Shao-Liang Chen, MD, reported at the Transcatheter Cardiovascular Therapeutics annual educational meeting.

The study randomized 482 patients with unprotected true distal left main bifurcation lesions to one of the two PCI strategies at 26 centers in five countries, including the United States. Roughly 80% of the left main lesions were categorized as Medina 1,1,1.

The primary outcome was the 1-year composite rate of target lesion failure (TLF), defined as cardiac death, target vessel MI, or clinically driven target lesion revascularization. The rate was 10.7% in patients assigned to provisional stenting and 5.0% with double kissing (DK) crush. This clinically and statistically significant difference was driven by a sharp reduction in target vessel MI in the DK crush group: 0.4%, compared with 2.9% in the provisional stenting group.

Moreover, the DK crush group’s 3.8% rate of clinically driven target lesion revascularization and 7.1% rate of angiographic restenosis within the left main complex were both less than half the rates in the provisional stenting group, he added at the meeting, which was sponsored by the Cardiovascular Research Foundation.

The absolute benefit for the DK crush strategy was greatest in the roughly 30% of patients with complex bifurcations, defined as those with an ostial side branch lesion length of at least 10 mm and 70% diameter stenosis while meeting at least two of six minor criteria. The 1-year TLF rate in such patients was 18.2% with provisional stenting versus 7% with DK crush. For simple bifurcations, the TLF rates were 8% versus 1.9%.

The results favored DK crush in all examined subgroups, including those based upon age, gender, SYNTAX score, distal angle, and diabetes status.

Forty-seven percent of patients in the provisional stenting arm received a second stent, typically needed as a bailout for the side branch. Most of the excess target vessel MIs and other TLF events in the provisional stenting group occurred in patients who got a second stent.

The DK crush is an advanced technique with numerous steps involving multiple vessel wirings, rewirings, and stent crushing. It can be challenging to perform. It took an average of 82 minutes, 16 minutes longer than provisional stenting – a difference in procedural time that interventional cardiologists don’t take lightly. It also entailed an average of 36 mL more contrast media than the 191 mL for provisional stenting.

In an earlier multicenter, randomized, prospective trial – DKCRUSH-III – Dr. Chen and his coinvestigators showed that the DK crush technique provides superior outcomes compared with culotte stenting, another widely used treatment strategy for distal left main bifurcation lesions (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013 Apr 9;61[14]:1482-8).

“The take home message on the surface of the data would be that we should consider this particular two-stent bifurcation technique as perhaps the treatment of choice for true distal bifurcation lesions,” said Gregg W. Stone, MD, who was a coinvestigator in DKCRUSH-V and chaired the late-breaking clinical trial session where Dr. Chen presented the results.

“This technique theoretically gives you the largest amount of laminar flow both in the main vessel and the side branch,” added Dr. Stone, professor of medicine and director of cardiovascular research and education at Columbia University Medical Center in New York.