User login

Unsuspected Lymphomatoid Granulomatosis in a Patient With Antisynthetase Syndrome

Lymphomatoid granulomatosis (LYG) is a rare Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)–related extranodal angiocentric lymphoproliferative disorder. Most patients are adults in the fifth decade of life, and men are twice as likely as women to be affected.1 The most common site of involvement is the lungs, which has been observed in more than 90% of patients.2 The skin is the most common extrapulmonary site of involvement with variable manifestations including “rash,” subcutaneous nodules, and ulceration. Although a small subset of patients experience remission without treatment, most patients report a progressive course with median survival of less than 2 years.1,2 Clinical diagnosis often is challenging due to underrecognition of this rare condition by multidisciplinary physicians.

Case Report

A 60-year-old woman presented with fatigue, night sweats, poor appetite, unintentional weight loss, and dyspnea with minor exertion of 2 weeks’ duration. Her medical history was remarkable for antisynthetase syndrome manifested as polymyositis and interstitial lung disease, as well as recurrent breast cancer treated with wide excision, chemotherapy, and radiation therapy completed 2 months prior. Antisynthetase syndrome was controlled with azathioprine for 2 years, which was stopped during chemotherapy but restarted to treat worsened myalgia 4 months prior to presentation. Two weeks prior to hospital admission, she was treated with antibiotics at an outside hospital for presumed pneumonia without improvement. Upon admission to our hospital she was pancytopenic. Chest computed tomography showed interval development of extensive patchy ground-glass opacities in all lung lobes with areas of confluent consolidation. Broad infectious workup was negative. Given the time course of presentation and anterior accentuation of the lung infiltrates, the greatest clinical concern was radiation pneumonitis followed by drug toxicity. A bone marrow biopsy was hypocellular but without evidence of malignancy. Her pancytopenia was thought to be induced by azathioprine and/or antibiotics. Antibiotics were discontinued and prednisone was started for treatment of presumed radiation pneumonitis.

A few days later, the patient developed new skin lesions and worsening bilateral leg edema. There were multiple small erythematous and hemorrhagic papules, macules, and blisters on the medial aspect of the right lower leg and ankle, each measuring less than 1 cm in diameter (Figure 1). The clinical differential diagnosis included vasculitis related to an underlying collagen vascular disease, atypical edema blisters, and drug hypersensitivity reaction. A punch biopsy of one of the lesions showed a moderately dense superficial and deep perivascular lymphoid infiltrate with marked papillary dermal edema and early subepidermal split (Figure 2). The infiltrate was comprised of small- to medium-sized lymphocytes admixed with large cells, histiocytes, and plasma cells (Figure 3). Immunohistochemistry revealed a predominance of CD3+ and CD4+ small- to medium-sized T cells. CD20 highlighted the large angiocentric B cells (Figure 4), which also were positive on EBV-encoded small RNA (EBER) in situ hybridization (Figure 5). A diagnosis of LYG was rendered. Approximately 40 to 50 EBV-positive large B cells were present per high-power field (HPF), consistent with grade 2 disease.

Soon after diagnosis, follow-up computed tomography of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis revealed suspicious lesions in the kidneys, liver, spleen, and inguinal and iliac lymph nodes. The ground-glass opacities in the lungs continued to progress, with 2 additional nodules noted in the right upper and lower lobes. Four days later, core needle biopsies of the right inguinal lymph node showed a large B-cell lymphoma with extensive necrosis (Figure 6). EBER in situ hybridization was suboptimal, probably due to extensive necrosis.

She was started on etoposide, prednisolone, vincristine, cyclophosphamide, and doxorubicin (EPOCH) for 5 days before developing Klebsiella pneumoniae sepsis and acute kidney injury. She was transferred to the critical care unit due to increasing oxygen requirement. Despite medical interventions, she continued to decompensate and elected to transition to palliative care. She died 6 weeks after the initial presentation. Her family did not request an autopsy.

Comment

Lymphomatoid granulomatosis is a rare lymphoproliferative disorder associated with various immunocompromised states including primary immunodeficiency disorders, human immunodeficiency virus infection, and immunosuppression for organ transplantation and autoimmune diseases. Our patient was receiving azathioprine for antisynthetase syndrome, which put her at risk for EBV infection and LYG. Azathioprine rarely has been reported as a possible culprit of LYG,3,4 but there are no known reported cases that were related to antisynthetase syndrome. There are multiple reports of development of LYG in patients receiving methotrexate for rheumatoid arthritis.5-10 Other iatrogenic causes reported in the literature include thiopurines11,12 and imatinib.13,14

The clinical diagnosis of our patient was particularly challenging given her complicated medical history including interstitial lung disease, predisposition to infection secondary to immunosuppression, and recent radiation therapy to the chest. This case illustrates the importance of maintaining a high index of suspicion for LYG in immunosuppressed patients presenting with lung infiltrates.

Presentation

Radiologically, LYG typically manifests as nodular densities accentuated in the lower lung lobes, which may become confluent.15 Because the nodular pattern in LYG is nonspecific and may mimic sarcoidosis, hypersensitivity pneumonitis, vasculitis, and infectious and neoplastic diseases,16 open lung biopsy often is required to establish the diagnosis in the absence of more accessible lesions.

Cutaneous lesions are seen in 40% to 50% of patients2 and may be the presenting sign of LYG. In a retrospective study, 16% (3/19) of LYG patients presented with cutaneous lesions months before diagnostic pulmonary lesions were identified.17 The skin is the most accessible site for biopsy, allowing definitive tissue diagnosis even when the condition is not clinically suspected. Therefore, dermatologists and dermatopathologists should be aware of this rare entity.

The clinical morphologies of the skin lesions are nonspecific, ranging from erythematous papules and subcutaneous nodules to indurated plaques. Ulceration may be present. The lesions may be widely disseminated or limited to the arms and legs. Our patient presented with erythematous and hemorrhagic papules, macules, and blisters on the lower leg. The hemorrhagic and blistering nature of some of these lesions in our patient may be attributable to thrombocytopenia and lymphedema in addition to LYG.

Histopathology and Differential

The skin biopsy from our patient demonstrated typical features of LYG, namely EBV-positive neoplastic large B cells in a background of predominating reactive T cells.18 The neoplastic large cells frequently invade blood vessels, leading to luminal narrowing without necrosis of the vessel walls. Grading is based on the density of EBV-positive large B cells: grade 1 is defined as fewer than 5 cells per HPF; grade 2, 5 to 50 cells per HPF; and grade 3, more than 50 cells per HPF.18 Grade 2 or 3 disease predicts worse outcome,2 as observed in our case. It is important for pathologists and clinicians to be aware that the proportion of EBV-positive large B cells is variable even within a single lesion; therefore, more than 1 biopsy may be necessary for appropriate grading and management.1,17 Additionally, skin biopsy may have a lower sensitivity for detecting EBV-positive B cells compared to lung biopsy, possibly due to sampling error in small biopsies.17

The histopathologic features of LYG frequently overlap with other lymphomas. Due to the abundance of T cells, LYG may be misclassified as T-cell/histiocyte-rich large B-cell lymphoma.19 Because the latter is not associated with EBV, EBER in situ hybridization is helpful in distinguishing the 2 conditions. On the other hand, EBER in situ hybridization has no value in discriminating LYG and extranodal natural killer (NK)/T-cell lymphoma, as both are EBV driven. Unlike LYG, the neoplastic EBV-positive cells in extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma make up the majority of the infiltrate and exhibit an NK-cell immunophenotype (positive CD56 and cytoplasmic CD3 epsilon).20 Pulmonary involvement also is uncommon in NK/T-cell lymphoma.

Aside from lymphomas, LYG also resembles granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA)(formerly known as Wegener granulomatosis). Clinically, both LYG and GPA can present with constitutional symptoms, as well as lung, kidney, and skin lesions. The 2 conditions differ microscopically, with leukocytoclastic vasculitis and necrotizing granulomatous inflammation being characteristic of GPA but absent in LYG.1,21 Neutrophils and eosinophils are much more likely to be present in GPA.22,23

Disease Progression

Although LYG is an extranodal disease, there is a 7% to 45% risk of progression to nodal lymphoma in patients with high-grade disease.2,22,24 Our patient progressed to nodal large B-cell lymphoma shortly after the diagnosis of high-grade LYG. She developed additional lesions in the liver, spleen, and kidneys, and ultimately succumbed to the disease. Prior studies have shown higher mortality in patients with bilateral lung involvement and neurologic abnormalities, whereas cutaneous involvement does not affect outcome.2

Treatment

A prospective study used an initial treatment regimen of cyclophosphamide and prednisone but mortality was high.24 More recently, chemotherapy regimens including CHOP (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone), CVP (cyclophosphamide, vincristine, and prednisone), CVP or CHOP combined with rituximab, C-MOPP (cyclophosphamide, vincristine, prednisone, and procarbazine), EPOCH, and rituximab with high-dose cytarabine have been used with variable success for grades 2 and 3 LYG.17,23,25,26 Antiviral and immunomodulatory (interferon alfa) therapy has been used to induce remission in a majority of patients with grades 1 or 2 LYG.3,17,27,28 There is a report of successful treatment of relapsed LYG with the retinoid agent bexarotene.29 Autologous or allogeneic stem cell transplantation was effective for some patients with refractory or relapsed LYG.30 Further studies are needed to clarify optimal treatment of LYG, especially high-grade disease.

Conclusion

We report a rare case of LYG in a patient with antisynthetase syndrome, which highlights the critical role of skin biopsy in establishing the diagnosis of LYG when the clinical and radiologic presentations are obscured by other comorbidities. Dermatologists should be familiar with this rare disease and maintain a low threshold for biopsy in immunocompromised patients presenting with nodular lung infiltrates and/or nonspecific skin lesions.

- Katzenstein AL, Doxtader E, Narendra S. Lymphomatoid granulomatosis: insights gained over 4 decades. Am J Surg Pathol. 2010;34:E35-E48.

- Katzenstein AL, Carrington CB, Liebow AA. Lymphomatoid granulomatosis: a clinicopathologic study of 152 cases. Cancer. 1979;43:360-373.

- Connors W, Griffiths C, Patel J, et al. Lymphomatoid granulomatosis associated with azathioprine therapy in Crohn disease. BMC Gastroenterol. 2014;14:127.

- Katherine Martin L, Porcu P, Baiocchi RA, et al. Primary central nervous system lymphomatoid granulomatosis in a patient receiving azathioprine therapy. Clin Adv Hematol Oncol. 2009;7:65-68.

- Barakat A, Grover K, Peshin R. Rituximab for pulmonary lymphomatoid granulomatosis which developed as a complication of methotrexate and azathioprine therapy for rheumatoid arthritis. Springerplus. 2014;3:751.

- Kobayashi S, Kikuchi Y, Sato K, et al. Reversible iatrogenic, MTX-associated EBV-driven lymphoproliferation with histopathological features of a lymphomatoid granulomatosis in a patient with rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Hematol. 2013;92:1561-1564.

- Kameda H, Okuyama A, Tamaru J, et al. Lymphomatoid granulomatosis and diffuse alveolar damage associated with methotrexate therapy in a patient with rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Rheumatol. 2007;26:1585-1589.

- Oiwa H, Mihara K, Kan T, et al. Grade 3 lymphomatoid granulomatosis in a patient receiving methotrexate therapy for rheumatoid arthritis. Intern Med. 2014;53:1873-1875.

- Blanchart K, Paciencia M, Seguin A, et al. Fatal pulmonary lymphomatoid granulomatosis in a patient taking methotrexate for rheumatoid arthritis. Minerva Anestesiol. 2014;80:119-120.

- Schalk E, Krogel C, Scheinpflug K, et al. Lymphomatoid granulomatosis in a patient with rheumatoid arthritis receiving methotrexate: successful treatment with the anti-CD20 antibody mabthera. Onkologie. 2009;32:440-441.

- Subramaniam K, Cherian M, Jain S, et al. Two rare cases of Epstein-Barr virus-associated lymphoproliferative disorders in inflammatory bowel disease patients on thiopurines and other immunosuppressive medications. Intern Med J. 2013;43:1339-1342.

- Destombe S, Bouron-DalSoglio D, Rougemont AL, et al. Lymphomatoid granulomatosis: a unique complication of Crohn disease and its treatment in pediatrics. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2010;50:559-561.

- Yazdi AS, Metzler G, Weyrauch S, et al. Lymphomatoid granulomatosis induced by imatinib treatment. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143:1222-1223.

- Salmons N, Gregg RJ, Pallalau A, et al. Lymphomatoid granulomatosis in a patient previously diagnosed with a gastrointestinal stromal tumour and treated with imatinib. J Clin Pathol. 2007;60:199-201.

- Dee PM, Arora NS, Innes DJ Jr. The pulmonary manifestations of lymphomatoid granulomatosis. Radiology. 1982;143:613-618.

- Rezai P, Hart EM, Patel SK. Case 169: lymphomatoid granulomatosis. Radiology. 2011;259:604-609.

- Beaty MW, Toro J, Sorbara L, et al. Cutaneous lymphomatoid granulomatosis: correlation of clinical and biologic features. Am J Surg Pathol. 2001;25:1111-1120.

- Pittaluga S, Wilson WH, Jaffe E. Lymphomatoid granulomatosis. In: Swerdlow S, Campo E, Harris NL, et al, eds. World Health Organization Classification of Tumours of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues. Lyon, France: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2008:247-249.

- Abramson JS. T-cell/histiocyte-rich B-cell lymphoma: biology, diagnosis, and management. Oncologist. 2006;11:384-392.

- Jaffe E. Nasal and nasal-type T/NK cell lymphoma: a unique form of lymphoma associated with the Epstein-Barr virus. Histopathology. 1995;27:581-583.

- Barksdale SK, Hallahan CW, Kerr GS, et al. Cutaneous pathology in Wegener’s granulomatosis: a clinicopathologic study of 74 biopsies in 46 patients. Am J Surg Pathol. 1995;19:161-172.

- Koss MN, Hochholzer L, Langloss JM, et al. Lymphomatoid granulomatosis: a clinicopathologic study of 42 patients. Pathology. 1986;18:283-288.

- Aoki T, Harada Y, Matsubara E, et al. Long-term remission after multiple relapses in an elderly patient with lymphomatoid granulomatosis after rituximab and high-dose cytarabine chemotherapy without stem-cell transplantation. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:E390-E393.

- Fauci AS, Haynes BF, Costa J, et al. Lymphomatoid granulomatosis: prospective clinical and therapeutic experience over 10 years. N Engl J Med. 1982;306:68-74.

- Jung KH, Sung HJ, Lee JH, et al. A case of pulmonary lymphomatoid granulomatosis successfully treated by combination chemotherapy with rituximab. Chemotherapy. 2009;55:386-390.

- Hernandez-Marques C, Lassaletta A, Torrelo A, et al. Rituximab in lymphomatoid granulomatosis. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2014;36:E69-E74.

- Wilson WH, Gutierrez M, Raffeld M, et al. Lymphomatoid granulomatosis: phase 2 study of dose-adjusted interferon-alfa or EPOCH chemotherapy. Blood. 1999;94:599A.

- Wilson WH, Kingma DW, Raffeld M, et al. Association of lymphomatoid granulomatosis with Epstein-Barr viral infection of B lymphocytes and response to interferon-alpha 2b. Blood. 1996;87:4531-4537.

- Berg SE, Downs LH, Torigian DA, et al. Successful treatment of relapsed lymphomatoid granulomatosis with bexarotene. Cancer Biol Ther. 2008;7:1544-1546.

- Siegloch K, Schmitz N, Wu HS, et al. Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in patients with lymphomatoid granulomatosis: a European group for blood and marrow transplantation report. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2013;19:1522-1525.

Lymphomatoid granulomatosis (LYG) is a rare Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)–related extranodal angiocentric lymphoproliferative disorder. Most patients are adults in the fifth decade of life, and men are twice as likely as women to be affected.1 The most common site of involvement is the lungs, which has been observed in more than 90% of patients.2 The skin is the most common extrapulmonary site of involvement with variable manifestations including “rash,” subcutaneous nodules, and ulceration. Although a small subset of patients experience remission without treatment, most patients report a progressive course with median survival of less than 2 years.1,2 Clinical diagnosis often is challenging due to underrecognition of this rare condition by multidisciplinary physicians.

Case Report

A 60-year-old woman presented with fatigue, night sweats, poor appetite, unintentional weight loss, and dyspnea with minor exertion of 2 weeks’ duration. Her medical history was remarkable for antisynthetase syndrome manifested as polymyositis and interstitial lung disease, as well as recurrent breast cancer treated with wide excision, chemotherapy, and radiation therapy completed 2 months prior. Antisynthetase syndrome was controlled with azathioprine for 2 years, which was stopped during chemotherapy but restarted to treat worsened myalgia 4 months prior to presentation. Two weeks prior to hospital admission, she was treated with antibiotics at an outside hospital for presumed pneumonia without improvement. Upon admission to our hospital she was pancytopenic. Chest computed tomography showed interval development of extensive patchy ground-glass opacities in all lung lobes with areas of confluent consolidation. Broad infectious workup was negative. Given the time course of presentation and anterior accentuation of the lung infiltrates, the greatest clinical concern was radiation pneumonitis followed by drug toxicity. A bone marrow biopsy was hypocellular but without evidence of malignancy. Her pancytopenia was thought to be induced by azathioprine and/or antibiotics. Antibiotics were discontinued and prednisone was started for treatment of presumed radiation pneumonitis.

A few days later, the patient developed new skin lesions and worsening bilateral leg edema. There were multiple small erythematous and hemorrhagic papules, macules, and blisters on the medial aspect of the right lower leg and ankle, each measuring less than 1 cm in diameter (Figure 1). The clinical differential diagnosis included vasculitis related to an underlying collagen vascular disease, atypical edema blisters, and drug hypersensitivity reaction. A punch biopsy of one of the lesions showed a moderately dense superficial and deep perivascular lymphoid infiltrate with marked papillary dermal edema and early subepidermal split (Figure 2). The infiltrate was comprised of small- to medium-sized lymphocytes admixed with large cells, histiocytes, and plasma cells (Figure 3). Immunohistochemistry revealed a predominance of CD3+ and CD4+ small- to medium-sized T cells. CD20 highlighted the large angiocentric B cells (Figure 4), which also were positive on EBV-encoded small RNA (EBER) in situ hybridization (Figure 5). A diagnosis of LYG was rendered. Approximately 40 to 50 EBV-positive large B cells were present per high-power field (HPF), consistent with grade 2 disease.

Soon after diagnosis, follow-up computed tomography of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis revealed suspicious lesions in the kidneys, liver, spleen, and inguinal and iliac lymph nodes. The ground-glass opacities in the lungs continued to progress, with 2 additional nodules noted in the right upper and lower lobes. Four days later, core needle biopsies of the right inguinal lymph node showed a large B-cell lymphoma with extensive necrosis (Figure 6). EBER in situ hybridization was suboptimal, probably due to extensive necrosis.

She was started on etoposide, prednisolone, vincristine, cyclophosphamide, and doxorubicin (EPOCH) for 5 days before developing Klebsiella pneumoniae sepsis and acute kidney injury. She was transferred to the critical care unit due to increasing oxygen requirement. Despite medical interventions, she continued to decompensate and elected to transition to palliative care. She died 6 weeks after the initial presentation. Her family did not request an autopsy.

Comment

Lymphomatoid granulomatosis is a rare lymphoproliferative disorder associated with various immunocompromised states including primary immunodeficiency disorders, human immunodeficiency virus infection, and immunosuppression for organ transplantation and autoimmune diseases. Our patient was receiving azathioprine for antisynthetase syndrome, which put her at risk for EBV infection and LYG. Azathioprine rarely has been reported as a possible culprit of LYG,3,4 but there are no known reported cases that were related to antisynthetase syndrome. There are multiple reports of development of LYG in patients receiving methotrexate for rheumatoid arthritis.5-10 Other iatrogenic causes reported in the literature include thiopurines11,12 and imatinib.13,14

The clinical diagnosis of our patient was particularly challenging given her complicated medical history including interstitial lung disease, predisposition to infection secondary to immunosuppression, and recent radiation therapy to the chest. This case illustrates the importance of maintaining a high index of suspicion for LYG in immunosuppressed patients presenting with lung infiltrates.

Presentation

Radiologically, LYG typically manifests as nodular densities accentuated in the lower lung lobes, which may become confluent.15 Because the nodular pattern in LYG is nonspecific and may mimic sarcoidosis, hypersensitivity pneumonitis, vasculitis, and infectious and neoplastic diseases,16 open lung biopsy often is required to establish the diagnosis in the absence of more accessible lesions.

Cutaneous lesions are seen in 40% to 50% of patients2 and may be the presenting sign of LYG. In a retrospective study, 16% (3/19) of LYG patients presented with cutaneous lesions months before diagnostic pulmonary lesions were identified.17 The skin is the most accessible site for biopsy, allowing definitive tissue diagnosis even when the condition is not clinically suspected. Therefore, dermatologists and dermatopathologists should be aware of this rare entity.

The clinical morphologies of the skin lesions are nonspecific, ranging from erythematous papules and subcutaneous nodules to indurated plaques. Ulceration may be present. The lesions may be widely disseminated or limited to the arms and legs. Our patient presented with erythematous and hemorrhagic papules, macules, and blisters on the lower leg. The hemorrhagic and blistering nature of some of these lesions in our patient may be attributable to thrombocytopenia and lymphedema in addition to LYG.

Histopathology and Differential

The skin biopsy from our patient demonstrated typical features of LYG, namely EBV-positive neoplastic large B cells in a background of predominating reactive T cells.18 The neoplastic large cells frequently invade blood vessels, leading to luminal narrowing without necrosis of the vessel walls. Grading is based on the density of EBV-positive large B cells: grade 1 is defined as fewer than 5 cells per HPF; grade 2, 5 to 50 cells per HPF; and grade 3, more than 50 cells per HPF.18 Grade 2 or 3 disease predicts worse outcome,2 as observed in our case. It is important for pathologists and clinicians to be aware that the proportion of EBV-positive large B cells is variable even within a single lesion; therefore, more than 1 biopsy may be necessary for appropriate grading and management.1,17 Additionally, skin biopsy may have a lower sensitivity for detecting EBV-positive B cells compared to lung biopsy, possibly due to sampling error in small biopsies.17

The histopathologic features of LYG frequently overlap with other lymphomas. Due to the abundance of T cells, LYG may be misclassified as T-cell/histiocyte-rich large B-cell lymphoma.19 Because the latter is not associated with EBV, EBER in situ hybridization is helpful in distinguishing the 2 conditions. On the other hand, EBER in situ hybridization has no value in discriminating LYG and extranodal natural killer (NK)/T-cell lymphoma, as both are EBV driven. Unlike LYG, the neoplastic EBV-positive cells in extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma make up the majority of the infiltrate and exhibit an NK-cell immunophenotype (positive CD56 and cytoplasmic CD3 epsilon).20 Pulmonary involvement also is uncommon in NK/T-cell lymphoma.

Aside from lymphomas, LYG also resembles granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA)(formerly known as Wegener granulomatosis). Clinically, both LYG and GPA can present with constitutional symptoms, as well as lung, kidney, and skin lesions. The 2 conditions differ microscopically, with leukocytoclastic vasculitis and necrotizing granulomatous inflammation being characteristic of GPA but absent in LYG.1,21 Neutrophils and eosinophils are much more likely to be present in GPA.22,23

Disease Progression

Although LYG is an extranodal disease, there is a 7% to 45% risk of progression to nodal lymphoma in patients with high-grade disease.2,22,24 Our patient progressed to nodal large B-cell lymphoma shortly after the diagnosis of high-grade LYG. She developed additional lesions in the liver, spleen, and kidneys, and ultimately succumbed to the disease. Prior studies have shown higher mortality in patients with bilateral lung involvement and neurologic abnormalities, whereas cutaneous involvement does not affect outcome.2

Treatment

A prospective study used an initial treatment regimen of cyclophosphamide and prednisone but mortality was high.24 More recently, chemotherapy regimens including CHOP (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone), CVP (cyclophosphamide, vincristine, and prednisone), CVP or CHOP combined with rituximab, C-MOPP (cyclophosphamide, vincristine, prednisone, and procarbazine), EPOCH, and rituximab with high-dose cytarabine have been used with variable success for grades 2 and 3 LYG.17,23,25,26 Antiviral and immunomodulatory (interferon alfa) therapy has been used to induce remission in a majority of patients with grades 1 or 2 LYG.3,17,27,28 There is a report of successful treatment of relapsed LYG with the retinoid agent bexarotene.29 Autologous or allogeneic stem cell transplantation was effective for some patients with refractory or relapsed LYG.30 Further studies are needed to clarify optimal treatment of LYG, especially high-grade disease.

Conclusion

We report a rare case of LYG in a patient with antisynthetase syndrome, which highlights the critical role of skin biopsy in establishing the diagnosis of LYG when the clinical and radiologic presentations are obscured by other comorbidities. Dermatologists should be familiar with this rare disease and maintain a low threshold for biopsy in immunocompromised patients presenting with nodular lung infiltrates and/or nonspecific skin lesions.

Lymphomatoid granulomatosis (LYG) is a rare Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)–related extranodal angiocentric lymphoproliferative disorder. Most patients are adults in the fifth decade of life, and men are twice as likely as women to be affected.1 The most common site of involvement is the lungs, which has been observed in more than 90% of patients.2 The skin is the most common extrapulmonary site of involvement with variable manifestations including “rash,” subcutaneous nodules, and ulceration. Although a small subset of patients experience remission without treatment, most patients report a progressive course with median survival of less than 2 years.1,2 Clinical diagnosis often is challenging due to underrecognition of this rare condition by multidisciplinary physicians.

Case Report

A 60-year-old woman presented with fatigue, night sweats, poor appetite, unintentional weight loss, and dyspnea with minor exertion of 2 weeks’ duration. Her medical history was remarkable for antisynthetase syndrome manifested as polymyositis and interstitial lung disease, as well as recurrent breast cancer treated with wide excision, chemotherapy, and radiation therapy completed 2 months prior. Antisynthetase syndrome was controlled with azathioprine for 2 years, which was stopped during chemotherapy but restarted to treat worsened myalgia 4 months prior to presentation. Two weeks prior to hospital admission, she was treated with antibiotics at an outside hospital for presumed pneumonia without improvement. Upon admission to our hospital she was pancytopenic. Chest computed tomography showed interval development of extensive patchy ground-glass opacities in all lung lobes with areas of confluent consolidation. Broad infectious workup was negative. Given the time course of presentation and anterior accentuation of the lung infiltrates, the greatest clinical concern was radiation pneumonitis followed by drug toxicity. A bone marrow biopsy was hypocellular but without evidence of malignancy. Her pancytopenia was thought to be induced by azathioprine and/or antibiotics. Antibiotics were discontinued and prednisone was started for treatment of presumed radiation pneumonitis.

A few days later, the patient developed new skin lesions and worsening bilateral leg edema. There were multiple small erythematous and hemorrhagic papules, macules, and blisters on the medial aspect of the right lower leg and ankle, each measuring less than 1 cm in diameter (Figure 1). The clinical differential diagnosis included vasculitis related to an underlying collagen vascular disease, atypical edema blisters, and drug hypersensitivity reaction. A punch biopsy of one of the lesions showed a moderately dense superficial and deep perivascular lymphoid infiltrate with marked papillary dermal edema and early subepidermal split (Figure 2). The infiltrate was comprised of small- to medium-sized lymphocytes admixed with large cells, histiocytes, and plasma cells (Figure 3). Immunohistochemistry revealed a predominance of CD3+ and CD4+ small- to medium-sized T cells. CD20 highlighted the large angiocentric B cells (Figure 4), which also were positive on EBV-encoded small RNA (EBER) in situ hybridization (Figure 5). A diagnosis of LYG was rendered. Approximately 40 to 50 EBV-positive large B cells were present per high-power field (HPF), consistent with grade 2 disease.

Soon after diagnosis, follow-up computed tomography of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis revealed suspicious lesions in the kidneys, liver, spleen, and inguinal and iliac lymph nodes. The ground-glass opacities in the lungs continued to progress, with 2 additional nodules noted in the right upper and lower lobes. Four days later, core needle biopsies of the right inguinal lymph node showed a large B-cell lymphoma with extensive necrosis (Figure 6). EBER in situ hybridization was suboptimal, probably due to extensive necrosis.

She was started on etoposide, prednisolone, vincristine, cyclophosphamide, and doxorubicin (EPOCH) for 5 days before developing Klebsiella pneumoniae sepsis and acute kidney injury. She was transferred to the critical care unit due to increasing oxygen requirement. Despite medical interventions, she continued to decompensate and elected to transition to palliative care. She died 6 weeks after the initial presentation. Her family did not request an autopsy.

Comment

Lymphomatoid granulomatosis is a rare lymphoproliferative disorder associated with various immunocompromised states including primary immunodeficiency disorders, human immunodeficiency virus infection, and immunosuppression for organ transplantation and autoimmune diseases. Our patient was receiving azathioprine for antisynthetase syndrome, which put her at risk for EBV infection and LYG. Azathioprine rarely has been reported as a possible culprit of LYG,3,4 but there are no known reported cases that were related to antisynthetase syndrome. There are multiple reports of development of LYG in patients receiving methotrexate for rheumatoid arthritis.5-10 Other iatrogenic causes reported in the literature include thiopurines11,12 and imatinib.13,14

The clinical diagnosis of our patient was particularly challenging given her complicated medical history including interstitial lung disease, predisposition to infection secondary to immunosuppression, and recent radiation therapy to the chest. This case illustrates the importance of maintaining a high index of suspicion for LYG in immunosuppressed patients presenting with lung infiltrates.

Presentation

Radiologically, LYG typically manifests as nodular densities accentuated in the lower lung lobes, which may become confluent.15 Because the nodular pattern in LYG is nonspecific and may mimic sarcoidosis, hypersensitivity pneumonitis, vasculitis, and infectious and neoplastic diseases,16 open lung biopsy often is required to establish the diagnosis in the absence of more accessible lesions.

Cutaneous lesions are seen in 40% to 50% of patients2 and may be the presenting sign of LYG. In a retrospective study, 16% (3/19) of LYG patients presented with cutaneous lesions months before diagnostic pulmonary lesions were identified.17 The skin is the most accessible site for biopsy, allowing definitive tissue diagnosis even when the condition is not clinically suspected. Therefore, dermatologists and dermatopathologists should be aware of this rare entity.

The clinical morphologies of the skin lesions are nonspecific, ranging from erythematous papules and subcutaneous nodules to indurated plaques. Ulceration may be present. The lesions may be widely disseminated or limited to the arms and legs. Our patient presented with erythematous and hemorrhagic papules, macules, and blisters on the lower leg. The hemorrhagic and blistering nature of some of these lesions in our patient may be attributable to thrombocytopenia and lymphedema in addition to LYG.

Histopathology and Differential

The skin biopsy from our patient demonstrated typical features of LYG, namely EBV-positive neoplastic large B cells in a background of predominating reactive T cells.18 The neoplastic large cells frequently invade blood vessels, leading to luminal narrowing without necrosis of the vessel walls. Grading is based on the density of EBV-positive large B cells: grade 1 is defined as fewer than 5 cells per HPF; grade 2, 5 to 50 cells per HPF; and grade 3, more than 50 cells per HPF.18 Grade 2 or 3 disease predicts worse outcome,2 as observed in our case. It is important for pathologists and clinicians to be aware that the proportion of EBV-positive large B cells is variable even within a single lesion; therefore, more than 1 biopsy may be necessary for appropriate grading and management.1,17 Additionally, skin biopsy may have a lower sensitivity for detecting EBV-positive B cells compared to lung biopsy, possibly due to sampling error in small biopsies.17

The histopathologic features of LYG frequently overlap with other lymphomas. Due to the abundance of T cells, LYG may be misclassified as T-cell/histiocyte-rich large B-cell lymphoma.19 Because the latter is not associated with EBV, EBER in situ hybridization is helpful in distinguishing the 2 conditions. On the other hand, EBER in situ hybridization has no value in discriminating LYG and extranodal natural killer (NK)/T-cell lymphoma, as both are EBV driven. Unlike LYG, the neoplastic EBV-positive cells in extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma make up the majority of the infiltrate and exhibit an NK-cell immunophenotype (positive CD56 and cytoplasmic CD3 epsilon).20 Pulmonary involvement also is uncommon in NK/T-cell lymphoma.

Aside from lymphomas, LYG also resembles granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA)(formerly known as Wegener granulomatosis). Clinically, both LYG and GPA can present with constitutional symptoms, as well as lung, kidney, and skin lesions. The 2 conditions differ microscopically, with leukocytoclastic vasculitis and necrotizing granulomatous inflammation being characteristic of GPA but absent in LYG.1,21 Neutrophils and eosinophils are much more likely to be present in GPA.22,23

Disease Progression

Although LYG is an extranodal disease, there is a 7% to 45% risk of progression to nodal lymphoma in patients with high-grade disease.2,22,24 Our patient progressed to nodal large B-cell lymphoma shortly after the diagnosis of high-grade LYG. She developed additional lesions in the liver, spleen, and kidneys, and ultimately succumbed to the disease. Prior studies have shown higher mortality in patients with bilateral lung involvement and neurologic abnormalities, whereas cutaneous involvement does not affect outcome.2

Treatment

A prospective study used an initial treatment regimen of cyclophosphamide and prednisone but mortality was high.24 More recently, chemotherapy regimens including CHOP (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone), CVP (cyclophosphamide, vincristine, and prednisone), CVP or CHOP combined with rituximab, C-MOPP (cyclophosphamide, vincristine, prednisone, and procarbazine), EPOCH, and rituximab with high-dose cytarabine have been used with variable success for grades 2 and 3 LYG.17,23,25,26 Antiviral and immunomodulatory (interferon alfa) therapy has been used to induce remission in a majority of patients with grades 1 or 2 LYG.3,17,27,28 There is a report of successful treatment of relapsed LYG with the retinoid agent bexarotene.29 Autologous or allogeneic stem cell transplantation was effective for some patients with refractory or relapsed LYG.30 Further studies are needed to clarify optimal treatment of LYG, especially high-grade disease.

Conclusion

We report a rare case of LYG in a patient with antisynthetase syndrome, which highlights the critical role of skin biopsy in establishing the diagnosis of LYG when the clinical and radiologic presentations are obscured by other comorbidities. Dermatologists should be familiar with this rare disease and maintain a low threshold for biopsy in immunocompromised patients presenting with nodular lung infiltrates and/or nonspecific skin lesions.

- Katzenstein AL, Doxtader E, Narendra S. Lymphomatoid granulomatosis: insights gained over 4 decades. Am J Surg Pathol. 2010;34:E35-E48.

- Katzenstein AL, Carrington CB, Liebow AA. Lymphomatoid granulomatosis: a clinicopathologic study of 152 cases. Cancer. 1979;43:360-373.

- Connors W, Griffiths C, Patel J, et al. Lymphomatoid granulomatosis associated with azathioprine therapy in Crohn disease. BMC Gastroenterol. 2014;14:127.

- Katherine Martin L, Porcu P, Baiocchi RA, et al. Primary central nervous system lymphomatoid granulomatosis in a patient receiving azathioprine therapy. Clin Adv Hematol Oncol. 2009;7:65-68.

- Barakat A, Grover K, Peshin R. Rituximab for pulmonary lymphomatoid granulomatosis which developed as a complication of methotrexate and azathioprine therapy for rheumatoid arthritis. Springerplus. 2014;3:751.

- Kobayashi S, Kikuchi Y, Sato K, et al. Reversible iatrogenic, MTX-associated EBV-driven lymphoproliferation with histopathological features of a lymphomatoid granulomatosis in a patient with rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Hematol. 2013;92:1561-1564.

- Kameda H, Okuyama A, Tamaru J, et al. Lymphomatoid granulomatosis and diffuse alveolar damage associated with methotrexate therapy in a patient with rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Rheumatol. 2007;26:1585-1589.

- Oiwa H, Mihara K, Kan T, et al. Grade 3 lymphomatoid granulomatosis in a patient receiving methotrexate therapy for rheumatoid arthritis. Intern Med. 2014;53:1873-1875.

- Blanchart K, Paciencia M, Seguin A, et al. Fatal pulmonary lymphomatoid granulomatosis in a patient taking methotrexate for rheumatoid arthritis. Minerva Anestesiol. 2014;80:119-120.

- Schalk E, Krogel C, Scheinpflug K, et al. Lymphomatoid granulomatosis in a patient with rheumatoid arthritis receiving methotrexate: successful treatment with the anti-CD20 antibody mabthera. Onkologie. 2009;32:440-441.

- Subramaniam K, Cherian M, Jain S, et al. Two rare cases of Epstein-Barr virus-associated lymphoproliferative disorders in inflammatory bowel disease patients on thiopurines and other immunosuppressive medications. Intern Med J. 2013;43:1339-1342.

- Destombe S, Bouron-DalSoglio D, Rougemont AL, et al. Lymphomatoid granulomatosis: a unique complication of Crohn disease and its treatment in pediatrics. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2010;50:559-561.

- Yazdi AS, Metzler G, Weyrauch S, et al. Lymphomatoid granulomatosis induced by imatinib treatment. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143:1222-1223.

- Salmons N, Gregg RJ, Pallalau A, et al. Lymphomatoid granulomatosis in a patient previously diagnosed with a gastrointestinal stromal tumour and treated with imatinib. J Clin Pathol. 2007;60:199-201.

- Dee PM, Arora NS, Innes DJ Jr. The pulmonary manifestations of lymphomatoid granulomatosis. Radiology. 1982;143:613-618.

- Rezai P, Hart EM, Patel SK. Case 169: lymphomatoid granulomatosis. Radiology. 2011;259:604-609.

- Beaty MW, Toro J, Sorbara L, et al. Cutaneous lymphomatoid granulomatosis: correlation of clinical and biologic features. Am J Surg Pathol. 2001;25:1111-1120.

- Pittaluga S, Wilson WH, Jaffe E. Lymphomatoid granulomatosis. In: Swerdlow S, Campo E, Harris NL, et al, eds. World Health Organization Classification of Tumours of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues. Lyon, France: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2008:247-249.

- Abramson JS. T-cell/histiocyte-rich B-cell lymphoma: biology, diagnosis, and management. Oncologist. 2006;11:384-392.

- Jaffe E. Nasal and nasal-type T/NK cell lymphoma: a unique form of lymphoma associated with the Epstein-Barr virus. Histopathology. 1995;27:581-583.

- Barksdale SK, Hallahan CW, Kerr GS, et al. Cutaneous pathology in Wegener’s granulomatosis: a clinicopathologic study of 74 biopsies in 46 patients. Am J Surg Pathol. 1995;19:161-172.

- Koss MN, Hochholzer L, Langloss JM, et al. Lymphomatoid granulomatosis: a clinicopathologic study of 42 patients. Pathology. 1986;18:283-288.

- Aoki T, Harada Y, Matsubara E, et al. Long-term remission after multiple relapses in an elderly patient with lymphomatoid granulomatosis after rituximab and high-dose cytarabine chemotherapy without stem-cell transplantation. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:E390-E393.

- Fauci AS, Haynes BF, Costa J, et al. Lymphomatoid granulomatosis: prospective clinical and therapeutic experience over 10 years. N Engl J Med. 1982;306:68-74.

- Jung KH, Sung HJ, Lee JH, et al. A case of pulmonary lymphomatoid granulomatosis successfully treated by combination chemotherapy with rituximab. Chemotherapy. 2009;55:386-390.

- Hernandez-Marques C, Lassaletta A, Torrelo A, et al. Rituximab in lymphomatoid granulomatosis. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2014;36:E69-E74.

- Wilson WH, Gutierrez M, Raffeld M, et al. Lymphomatoid granulomatosis: phase 2 study of dose-adjusted interferon-alfa or EPOCH chemotherapy. Blood. 1999;94:599A.

- Wilson WH, Kingma DW, Raffeld M, et al. Association of lymphomatoid granulomatosis with Epstein-Barr viral infection of B lymphocytes and response to interferon-alpha 2b. Blood. 1996;87:4531-4537.

- Berg SE, Downs LH, Torigian DA, et al. Successful treatment of relapsed lymphomatoid granulomatosis with bexarotene. Cancer Biol Ther. 2008;7:1544-1546.

- Siegloch K, Schmitz N, Wu HS, et al. Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in patients with lymphomatoid granulomatosis: a European group for blood and marrow transplantation report. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2013;19:1522-1525.

- Katzenstein AL, Doxtader E, Narendra S. Lymphomatoid granulomatosis: insights gained over 4 decades. Am J Surg Pathol. 2010;34:E35-E48.

- Katzenstein AL, Carrington CB, Liebow AA. Lymphomatoid granulomatosis: a clinicopathologic study of 152 cases. Cancer. 1979;43:360-373.

- Connors W, Griffiths C, Patel J, et al. Lymphomatoid granulomatosis associated with azathioprine therapy in Crohn disease. BMC Gastroenterol. 2014;14:127.

- Katherine Martin L, Porcu P, Baiocchi RA, et al. Primary central nervous system lymphomatoid granulomatosis in a patient receiving azathioprine therapy. Clin Adv Hematol Oncol. 2009;7:65-68.

- Barakat A, Grover K, Peshin R. Rituximab for pulmonary lymphomatoid granulomatosis which developed as a complication of methotrexate and azathioprine therapy for rheumatoid arthritis. Springerplus. 2014;3:751.

- Kobayashi S, Kikuchi Y, Sato K, et al. Reversible iatrogenic, MTX-associated EBV-driven lymphoproliferation with histopathological features of a lymphomatoid granulomatosis in a patient with rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Hematol. 2013;92:1561-1564.

- Kameda H, Okuyama A, Tamaru J, et al. Lymphomatoid granulomatosis and diffuse alveolar damage associated with methotrexate therapy in a patient with rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Rheumatol. 2007;26:1585-1589.

- Oiwa H, Mihara K, Kan T, et al. Grade 3 lymphomatoid granulomatosis in a patient receiving methotrexate therapy for rheumatoid arthritis. Intern Med. 2014;53:1873-1875.

- Blanchart K, Paciencia M, Seguin A, et al. Fatal pulmonary lymphomatoid granulomatosis in a patient taking methotrexate for rheumatoid arthritis. Minerva Anestesiol. 2014;80:119-120.

- Schalk E, Krogel C, Scheinpflug K, et al. Lymphomatoid granulomatosis in a patient with rheumatoid arthritis receiving methotrexate: successful treatment with the anti-CD20 antibody mabthera. Onkologie. 2009;32:440-441.

- Subramaniam K, Cherian M, Jain S, et al. Two rare cases of Epstein-Barr virus-associated lymphoproliferative disorders in inflammatory bowel disease patients on thiopurines and other immunosuppressive medications. Intern Med J. 2013;43:1339-1342.

- Destombe S, Bouron-DalSoglio D, Rougemont AL, et al. Lymphomatoid granulomatosis: a unique complication of Crohn disease and its treatment in pediatrics. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2010;50:559-561.

- Yazdi AS, Metzler G, Weyrauch S, et al. Lymphomatoid granulomatosis induced by imatinib treatment. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143:1222-1223.

- Salmons N, Gregg RJ, Pallalau A, et al. Lymphomatoid granulomatosis in a patient previously diagnosed with a gastrointestinal stromal tumour and treated with imatinib. J Clin Pathol. 2007;60:199-201.

- Dee PM, Arora NS, Innes DJ Jr. The pulmonary manifestations of lymphomatoid granulomatosis. Radiology. 1982;143:613-618.

- Rezai P, Hart EM, Patel SK. Case 169: lymphomatoid granulomatosis. Radiology. 2011;259:604-609.

- Beaty MW, Toro J, Sorbara L, et al. Cutaneous lymphomatoid granulomatosis: correlation of clinical and biologic features. Am J Surg Pathol. 2001;25:1111-1120.

- Pittaluga S, Wilson WH, Jaffe E. Lymphomatoid granulomatosis. In: Swerdlow S, Campo E, Harris NL, et al, eds. World Health Organization Classification of Tumours of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues. Lyon, France: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2008:247-249.

- Abramson JS. T-cell/histiocyte-rich B-cell lymphoma: biology, diagnosis, and management. Oncologist. 2006;11:384-392.

- Jaffe E. Nasal and nasal-type T/NK cell lymphoma: a unique form of lymphoma associated with the Epstein-Barr virus. Histopathology. 1995;27:581-583.

- Barksdale SK, Hallahan CW, Kerr GS, et al. Cutaneous pathology in Wegener’s granulomatosis: a clinicopathologic study of 74 biopsies in 46 patients. Am J Surg Pathol. 1995;19:161-172.

- Koss MN, Hochholzer L, Langloss JM, et al. Lymphomatoid granulomatosis: a clinicopathologic study of 42 patients. Pathology. 1986;18:283-288.

- Aoki T, Harada Y, Matsubara E, et al. Long-term remission after multiple relapses in an elderly patient with lymphomatoid granulomatosis after rituximab and high-dose cytarabine chemotherapy without stem-cell transplantation. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:E390-E393.

- Fauci AS, Haynes BF, Costa J, et al. Lymphomatoid granulomatosis: prospective clinical and therapeutic experience over 10 years. N Engl J Med. 1982;306:68-74.

- Jung KH, Sung HJ, Lee JH, et al. A case of pulmonary lymphomatoid granulomatosis successfully treated by combination chemotherapy with rituximab. Chemotherapy. 2009;55:386-390.

- Hernandez-Marques C, Lassaletta A, Torrelo A, et al. Rituximab in lymphomatoid granulomatosis. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2014;36:E69-E74.

- Wilson WH, Gutierrez M, Raffeld M, et al. Lymphomatoid granulomatosis: phase 2 study of dose-adjusted interferon-alfa or EPOCH chemotherapy. Blood. 1999;94:599A.

- Wilson WH, Kingma DW, Raffeld M, et al. Association of lymphomatoid granulomatosis with Epstein-Barr viral infection of B lymphocytes and response to interferon-alpha 2b. Blood. 1996;87:4531-4537.

- Berg SE, Downs LH, Torigian DA, et al. Successful treatment of relapsed lymphomatoid granulomatosis with bexarotene. Cancer Biol Ther. 2008;7:1544-1546.

- Siegloch K, Schmitz N, Wu HS, et al. Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in patients with lymphomatoid granulomatosis: a European group for blood and marrow transplantation report. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2013;19:1522-1525.

Practice Points

- Lymphomatoid granulomatosis (LYG) is a rare extranodal angiocentric large B-cell lymphoma driven by the Epstein-Barr virus.

- Lymphomatoid granulomatosis should be suspected when immunocompromised patients present with nodular lung infiltrates and/or nonspecific skin lesions.

- Skin biopsy serves a critical role in establishing the diagnosis of LYG, especially when clinical and radiologic findings are obscured by other comorbidities.

Expert Panel: Little support for delaying cosmetic procedures after isotretinoin

In most cases, there is little evidence to support delaying cosmetic procedures, such as laser therapy or chemical peels, in patients who have recently been treated with isotretinoin for acne, according to a consensus statement from the American Society of Dermatologic Surgery (ASDS).

An expert panel convened by the ASDS issued specific recommendations that supported safe, early initiation of cosmetic procedures in most cases. It noted that the likelihood of any potential harms from initiating cosmetic procedures after recent isotretinoin treatment is “low to very low” and that such harms have been reported only in case reports and case series.

Notable exceptions included dermabrasion and full-face ablative resurfacing; the experts recommended against having such procedures within 6 months of isotretinoin use because of potentially increased risks of adverse events in some patients.

“Potential benefits of this guideline include early access to scar treatments for many patients who are at the highest risk for scarring and, thereby, potentially improved patient quality of life,” Abigail Waldman, MD, of the department of dermatology at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, and her coauthors wrote in the consensus statement (Dermatol Surg. 2017 Oct;43[10]:1249-62). This is the first consensus statement document published by the ASDS to address this topic.

Isotretinoin was approved by the Food and Drug Administration in 1982 for treating severe and nodulocystic acne. Because of a perceived higher risk of scarring or irritation associated with isotretinoin use, standard clinical practice has been to avoid performing laser procedures, chemical peels, waxing, dermabrasion, and incisional or excisional cutaneous surgeries on patients within 6 months of their using isotretinoin, according to the authors. A warning regarding the potential for scarring with cosmetic procedures meant to smooth the skin is even included in the patient information leaflet for isotretinoin.

“This is in contradistinction to the observation that nodulocystic or severe inflammatory acne patients who have recently completed treatment with isotretinoin are among those most likely to benefit from treatment of their acne scars with modalities such as laser, dermabrasion, or chemical peels,” the experts wrote in the consensus recommendations.

Following a review of the 36 source documents, the task force concluded that, for patients currently or recently receiving isotretinoin, evidence was “insufficient” to justify delaying treatment with superficial chemical peels, vascular lasers, and nonablative modalities, such as hair removal lasers and lights. They also stated that superficial and focal dermabrasion “may also be safe when performed by a well-trained clinician” in a clinical setting.

The panel recommendations covered the following four key areas:

- Dermabrasion. Treating specific facial areas while the patient is on isotretinoin or within 6 months of discontinuation “is not associated with increased risk of scar or delay in wound healing, and there is no evidence in the literature that supports a need to delay treatment,” they wrote. In contrast, they did not recommend full-face or mechanical dermabrasion with rotary devices within the 6-month window because it may be “associated with increased risk of adverse events in selected patients.”

- Lasers and energy devices. Similarly, the panel found no evidence that would justify delaying use of vascular lasers, hair removal lasers and lights, and nonablative or ablative fractional devices among patients recently treated with isotretinoin. However, they said fully ablative treatment of the entire face or regions other than the face should “generally be avoided until 6 months after completion of isotretinoin treatment because of the likely elevated risk of avoidable adverse events.”

- Chemical peels. Patients currently on isotretinoin or who have recently discontinued it can safely undergo superficial chemical peels, according to the panel. For medium or deep chemical peels, there was “insufficient data … to preclude a recommendation in this case,” the panel wrote.

- Other surgeries. Because of the risk of dry eyes, isotretinoin should be discontinued prior to laser eye surgery. For incisional and excisional cutaneous surgery, the data on isotretinoin were insufficient to make any recommendations, the experts concluded, though they acknowledged that in some cases, the surgeries may be “medically necessary.”

Most of these recommendations were based on case series and cohort studies, the panel said, rather than higher-quality, randomized clinical trials, which are “generally impractical and not likely forthcoming in this setting.” Moreover, they cautioned that insufficient evidence to make a recommendation should not be misconstrued as a confirmation of safety or a warning about risk.

Overall, the results of the analysis suggested that “procedural interventions during or soon after isotretinoin treatment can safely and effectively address acne scarring and similar disorders, thus providing relief to patients without the need for protracted waiting,” the authors wrote.

In August, another expert panel’s recommendations were published, which concluded that skin procedures, including superficial chemical peels, laser hair removal, minor cutaneous surgery, manual dermabrasion, and fractional ablative and fractional nonablative laser procedures, can be performed safely on patients who have recently been or are currently being treated with isotretinoin (JAMA Dermatol. 2017 Aug 1;153[8]:802-9).

The authors of the ASDS statement reported no relevant financial conflicts.

In most cases, there is little evidence to support delaying cosmetic procedures, such as laser therapy or chemical peels, in patients who have recently been treated with isotretinoin for acne, according to a consensus statement from the American Society of Dermatologic Surgery (ASDS).

An expert panel convened by the ASDS issued specific recommendations that supported safe, early initiation of cosmetic procedures in most cases. It noted that the likelihood of any potential harms from initiating cosmetic procedures after recent isotretinoin treatment is “low to very low” and that such harms have been reported only in case reports and case series.

Notable exceptions included dermabrasion and full-face ablative resurfacing; the experts recommended against having such procedures within 6 months of isotretinoin use because of potentially increased risks of adverse events in some patients.

“Potential benefits of this guideline include early access to scar treatments for many patients who are at the highest risk for scarring and, thereby, potentially improved patient quality of life,” Abigail Waldman, MD, of the department of dermatology at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, and her coauthors wrote in the consensus statement (Dermatol Surg. 2017 Oct;43[10]:1249-62). This is the first consensus statement document published by the ASDS to address this topic.

Isotretinoin was approved by the Food and Drug Administration in 1982 for treating severe and nodulocystic acne. Because of a perceived higher risk of scarring or irritation associated with isotretinoin use, standard clinical practice has been to avoid performing laser procedures, chemical peels, waxing, dermabrasion, and incisional or excisional cutaneous surgeries on patients within 6 months of their using isotretinoin, according to the authors. A warning regarding the potential for scarring with cosmetic procedures meant to smooth the skin is even included in the patient information leaflet for isotretinoin.

“This is in contradistinction to the observation that nodulocystic or severe inflammatory acne patients who have recently completed treatment with isotretinoin are among those most likely to benefit from treatment of their acne scars with modalities such as laser, dermabrasion, or chemical peels,” the experts wrote in the consensus recommendations.

Following a review of the 36 source documents, the task force concluded that, for patients currently or recently receiving isotretinoin, evidence was “insufficient” to justify delaying treatment with superficial chemical peels, vascular lasers, and nonablative modalities, such as hair removal lasers and lights. They also stated that superficial and focal dermabrasion “may also be safe when performed by a well-trained clinician” in a clinical setting.

The panel recommendations covered the following four key areas:

- Dermabrasion. Treating specific facial areas while the patient is on isotretinoin or within 6 months of discontinuation “is not associated with increased risk of scar or delay in wound healing, and there is no evidence in the literature that supports a need to delay treatment,” they wrote. In contrast, they did not recommend full-face or mechanical dermabrasion with rotary devices within the 6-month window because it may be “associated with increased risk of adverse events in selected patients.”

- Lasers and energy devices. Similarly, the panel found no evidence that would justify delaying use of vascular lasers, hair removal lasers and lights, and nonablative or ablative fractional devices among patients recently treated with isotretinoin. However, they said fully ablative treatment of the entire face or regions other than the face should “generally be avoided until 6 months after completion of isotretinoin treatment because of the likely elevated risk of avoidable adverse events.”

- Chemical peels. Patients currently on isotretinoin or who have recently discontinued it can safely undergo superficial chemical peels, according to the panel. For medium or deep chemical peels, there was “insufficient data … to preclude a recommendation in this case,” the panel wrote.

- Other surgeries. Because of the risk of dry eyes, isotretinoin should be discontinued prior to laser eye surgery. For incisional and excisional cutaneous surgery, the data on isotretinoin were insufficient to make any recommendations, the experts concluded, though they acknowledged that in some cases, the surgeries may be “medically necessary.”

Most of these recommendations were based on case series and cohort studies, the panel said, rather than higher-quality, randomized clinical trials, which are “generally impractical and not likely forthcoming in this setting.” Moreover, they cautioned that insufficient evidence to make a recommendation should not be misconstrued as a confirmation of safety or a warning about risk.

Overall, the results of the analysis suggested that “procedural interventions during or soon after isotretinoin treatment can safely and effectively address acne scarring and similar disorders, thus providing relief to patients without the need for protracted waiting,” the authors wrote.

In August, another expert panel’s recommendations were published, which concluded that skin procedures, including superficial chemical peels, laser hair removal, minor cutaneous surgery, manual dermabrasion, and fractional ablative and fractional nonablative laser procedures, can be performed safely on patients who have recently been or are currently being treated with isotretinoin (JAMA Dermatol. 2017 Aug 1;153[8]:802-9).

The authors of the ASDS statement reported no relevant financial conflicts.

In most cases, there is little evidence to support delaying cosmetic procedures, such as laser therapy or chemical peels, in patients who have recently been treated with isotretinoin for acne, according to a consensus statement from the American Society of Dermatologic Surgery (ASDS).

An expert panel convened by the ASDS issued specific recommendations that supported safe, early initiation of cosmetic procedures in most cases. It noted that the likelihood of any potential harms from initiating cosmetic procedures after recent isotretinoin treatment is “low to very low” and that such harms have been reported only in case reports and case series.

Notable exceptions included dermabrasion and full-face ablative resurfacing; the experts recommended against having such procedures within 6 months of isotretinoin use because of potentially increased risks of adverse events in some patients.

“Potential benefits of this guideline include early access to scar treatments for many patients who are at the highest risk for scarring and, thereby, potentially improved patient quality of life,” Abigail Waldman, MD, of the department of dermatology at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, and her coauthors wrote in the consensus statement (Dermatol Surg. 2017 Oct;43[10]:1249-62). This is the first consensus statement document published by the ASDS to address this topic.

Isotretinoin was approved by the Food and Drug Administration in 1982 for treating severe and nodulocystic acne. Because of a perceived higher risk of scarring or irritation associated with isotretinoin use, standard clinical practice has been to avoid performing laser procedures, chemical peels, waxing, dermabrasion, and incisional or excisional cutaneous surgeries on patients within 6 months of their using isotretinoin, according to the authors. A warning regarding the potential for scarring with cosmetic procedures meant to smooth the skin is even included in the patient information leaflet for isotretinoin.

“This is in contradistinction to the observation that nodulocystic or severe inflammatory acne patients who have recently completed treatment with isotretinoin are among those most likely to benefit from treatment of their acne scars with modalities such as laser, dermabrasion, or chemical peels,” the experts wrote in the consensus recommendations.

Following a review of the 36 source documents, the task force concluded that, for patients currently or recently receiving isotretinoin, evidence was “insufficient” to justify delaying treatment with superficial chemical peels, vascular lasers, and nonablative modalities, such as hair removal lasers and lights. They also stated that superficial and focal dermabrasion “may also be safe when performed by a well-trained clinician” in a clinical setting.

The panel recommendations covered the following four key areas:

- Dermabrasion. Treating specific facial areas while the patient is on isotretinoin or within 6 months of discontinuation “is not associated with increased risk of scar or delay in wound healing, and there is no evidence in the literature that supports a need to delay treatment,” they wrote. In contrast, they did not recommend full-face or mechanical dermabrasion with rotary devices within the 6-month window because it may be “associated with increased risk of adverse events in selected patients.”

- Lasers and energy devices. Similarly, the panel found no evidence that would justify delaying use of vascular lasers, hair removal lasers and lights, and nonablative or ablative fractional devices among patients recently treated with isotretinoin. However, they said fully ablative treatment of the entire face or regions other than the face should “generally be avoided until 6 months after completion of isotretinoin treatment because of the likely elevated risk of avoidable adverse events.”

- Chemical peels. Patients currently on isotretinoin or who have recently discontinued it can safely undergo superficial chemical peels, according to the panel. For medium or deep chemical peels, there was “insufficient data … to preclude a recommendation in this case,” the panel wrote.

- Other surgeries. Because of the risk of dry eyes, isotretinoin should be discontinued prior to laser eye surgery. For incisional and excisional cutaneous surgery, the data on isotretinoin were insufficient to make any recommendations, the experts concluded, though they acknowledged that in some cases, the surgeries may be “medically necessary.”

Most of these recommendations were based on case series and cohort studies, the panel said, rather than higher-quality, randomized clinical trials, which are “generally impractical and not likely forthcoming in this setting.” Moreover, they cautioned that insufficient evidence to make a recommendation should not be misconstrued as a confirmation of safety or a warning about risk.

Overall, the results of the analysis suggested that “procedural interventions during or soon after isotretinoin treatment can safely and effectively address acne scarring and similar disorders, thus providing relief to patients without the need for protracted waiting,” the authors wrote.

In August, another expert panel’s recommendations were published, which concluded that skin procedures, including superficial chemical peels, laser hair removal, minor cutaneous surgery, manual dermabrasion, and fractional ablative and fractional nonablative laser procedures, can be performed safely on patients who have recently been or are currently being treated with isotretinoin (JAMA Dermatol. 2017 Aug 1;153[8]:802-9).

The authors of the ASDS statement reported no relevant financial conflicts.

FROM DERMATOLOGIC SURGERY

Key clinical point: Contrary to current recommendations,

Major finding: Experts convened by the American Society of Dermatologic Surgery found that, in most cases, the likelihood of potential harms of initiating cosmetic procedures after recent isotretinoin use is “low to very low,” and those that did occur were reported only in case reports and case series rather than in higher-quality clinical trials.

Data source: A consensus review of 36 source documents obtained by a literature review, the results of which were then validated by peer review.

Disclosures: The authors reported no relevant financial conflicts.

Vesiculobullous and Pustular Diseases in Newborns

Vesiculobullous eruptions in neonates can readily generate anxiety from parents/guardians and pediatricians over both infectious and noninfectious causes. The role of the dermatology resident is critical to help diminish fear over common vesicular presentations or to escalate care in rarer situations if a more obscure or ominous diagnosis is clouding the patient’s clinical presentation and well-being. This article summarizes both common and uncommon vesiculobullous neonatal diseases to augment precise and efficient diagnoses in this vulnerable patient population.

Steps for Evaluating a Vesiculopustular Eruption

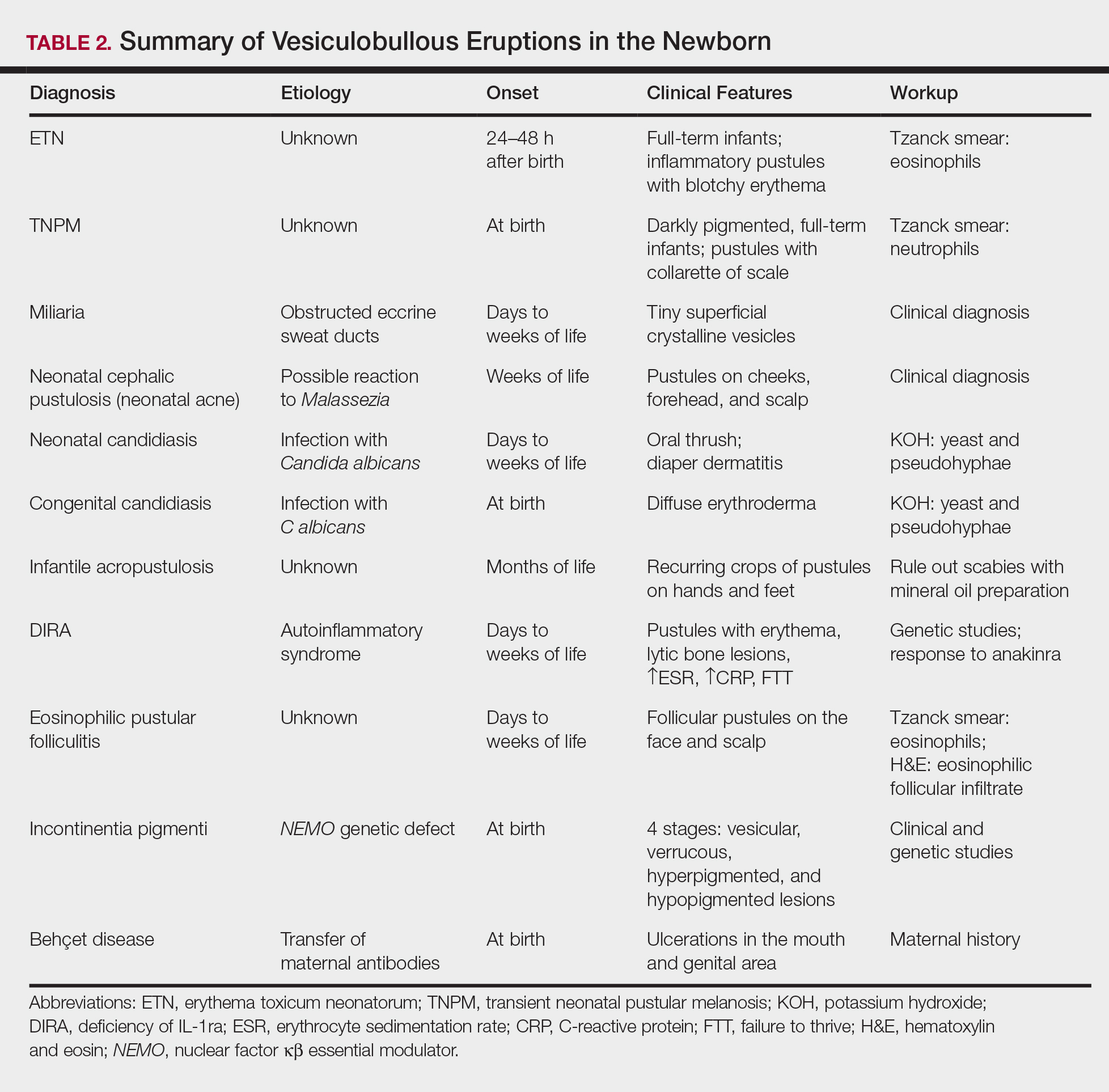

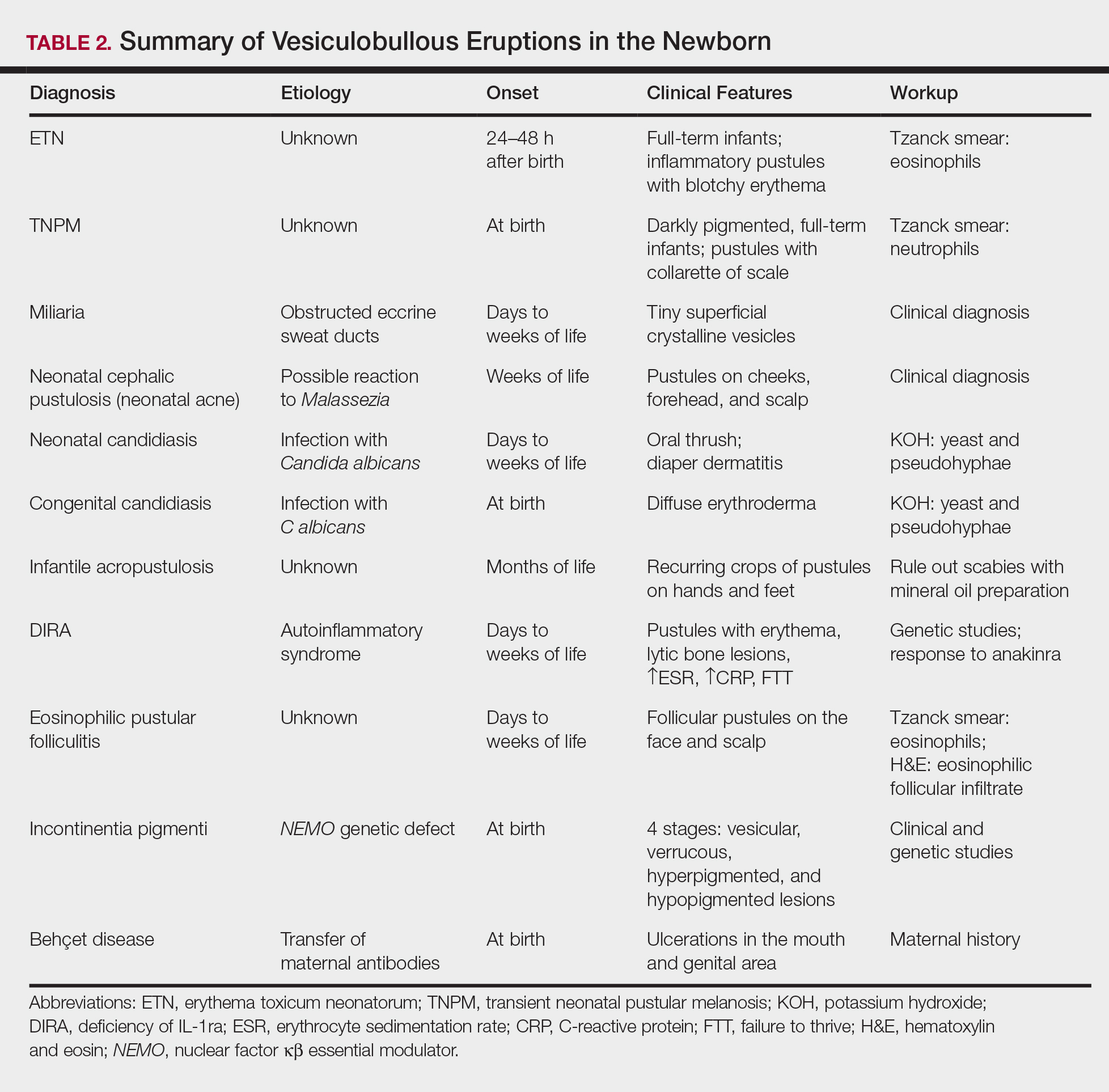

Receiving a consultation for a newborn with widespread vesicles can be a daunting scenario for a dermatology resident. Fear of missing an ominous diagnosis or aggressively treating a newborn for an erroneous infection when the diagnosis is actually a benign presentation can lead to an anxiety-provoking situation. Additionally, performing a procedure on a newborn can cause personal uneasiness. Dr. Lawrence A. Schachner, an eminent pediatric dermatologist at the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine (Miami, Florida), recently lectured on 5 key steps (Table 1) for the evaluation of a vesiculobullous eruption in the newborn to maximize the accuracy of diagnosis and patient care.1

First, draw out the fluid from the vesicle to send for bacterial and viral culture as well as Gram stain. Second, snip the roof of the vesicle to perform potassium hydroxide examination for yeast or fungi and frozen pathology when indicated. Third, use the base of the vesicle to obtain cells for a Tzanck smear to identify the predominant cell infiltrate, such as multinucleated giant cells in herpes simplex virus or eosinophils in erythema toxicum neonatorum (ETN). Fourth, a mineral oil preparation can be performed on several lesions, especially if a burrow is observed, to rule out bullous scabies in the appropriate clinical presentation. Lastly, a perilesional or lesional punch biopsy can be performed if the above steps have not yet clinched the diagnosis.2 By utilizing these steps, the resident efficiently utilizes 1 lesion to narrow down a formidable differential list of bullous disorders in the newborn.

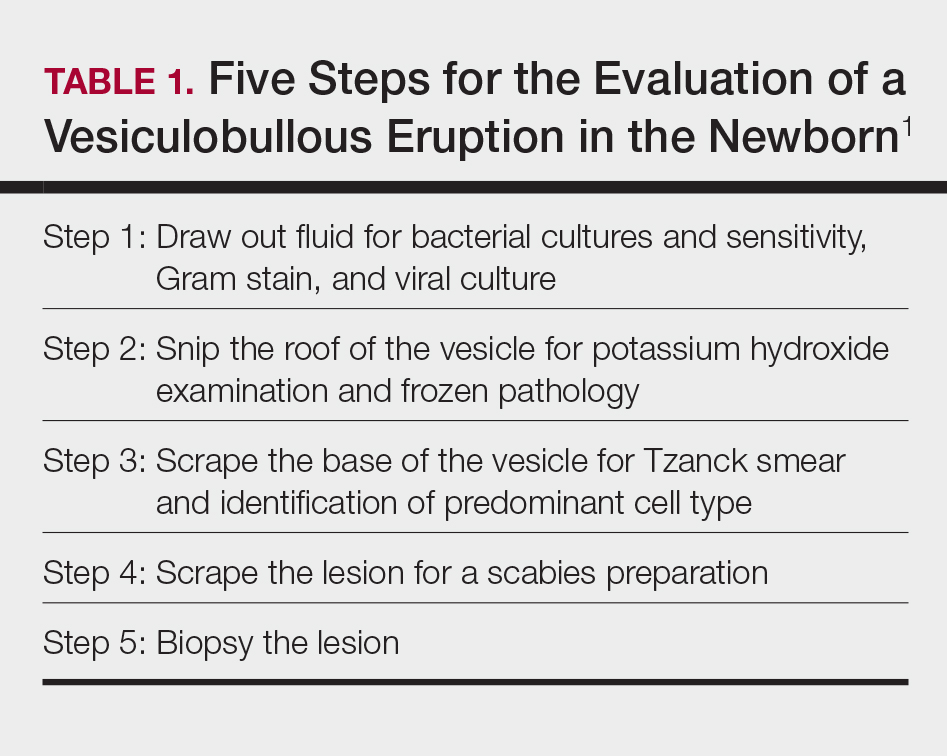

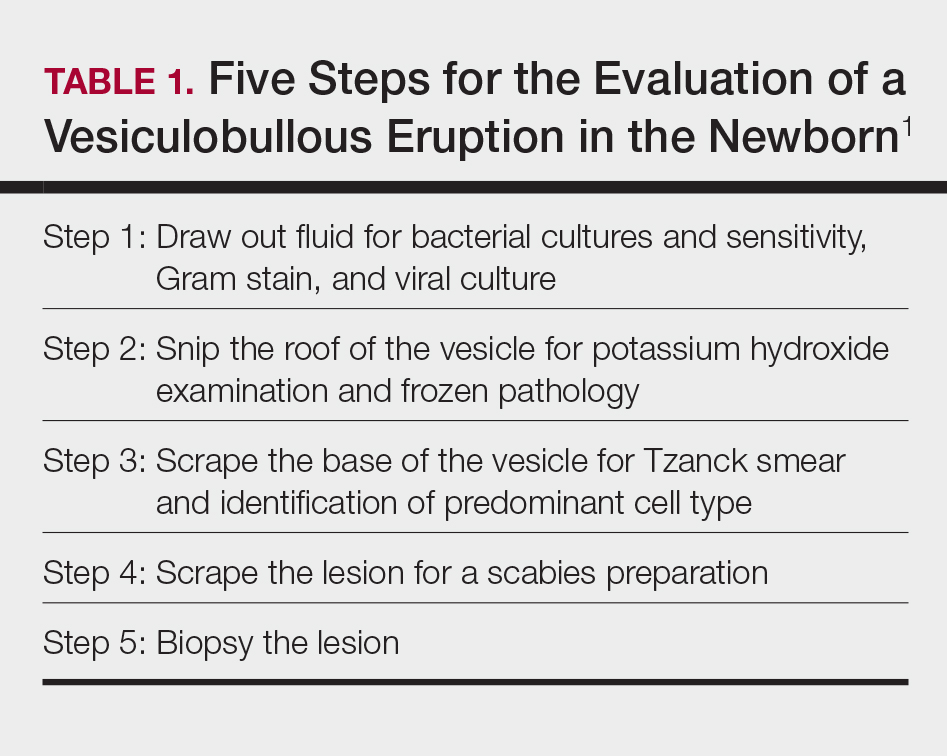

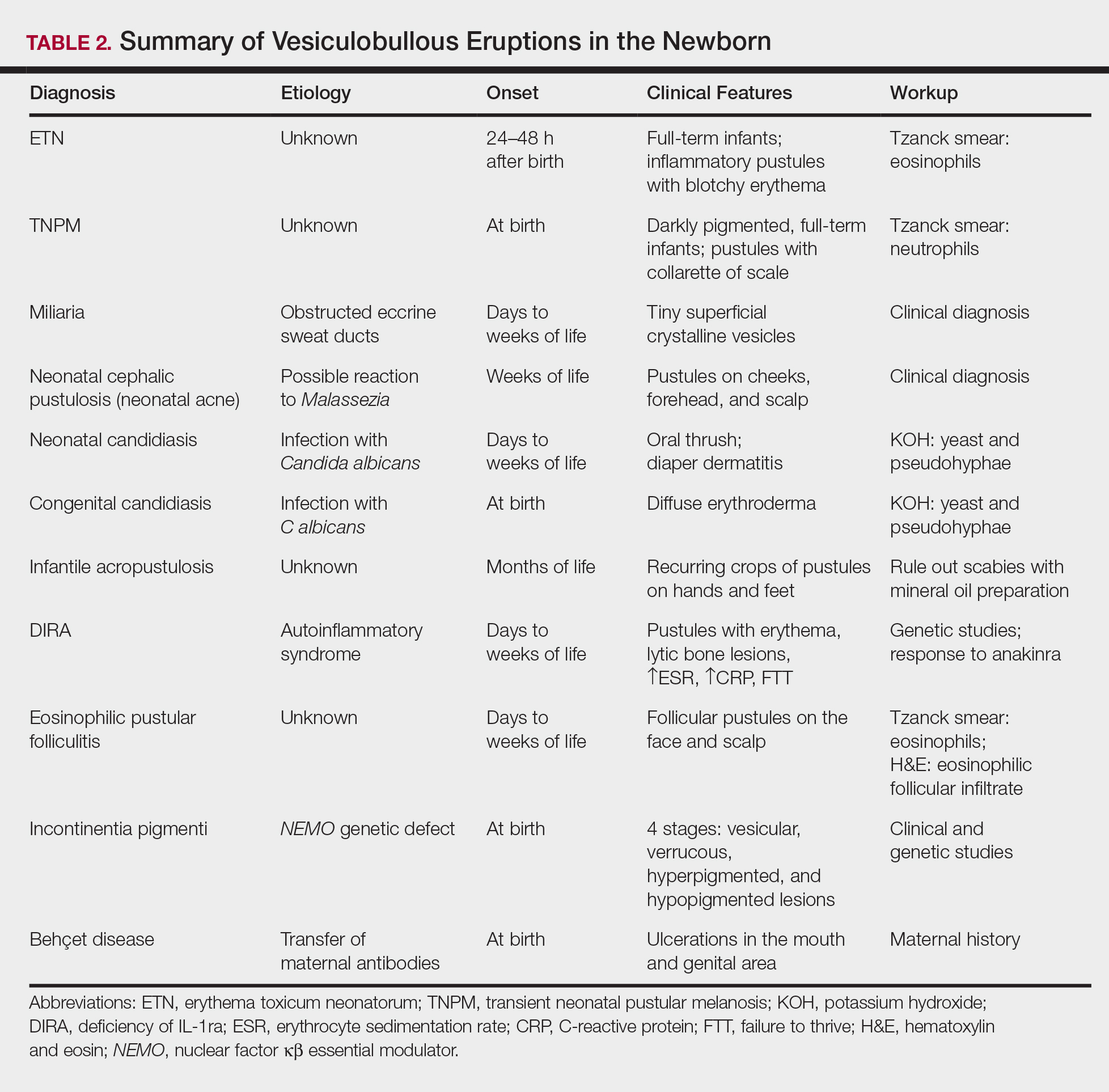

Specific Diagnoses

A number of common diagnoses can present during the newborn period and can usually be readily diagnosed by clinical manifestations alone; a summary of these eruptions is provided in Table 2. Erythema toxicum neonatorum is the most common pustular eruption in neonates and presents in up to 50% of full-term infants at days 1 to 2 of life. Inflammatory pustules surrounded by characteristic blotchy erythema are displayed on the face, trunk, arms, and legs, usually sparing the palms and soles.3 Erythema toxicum neonatorum typically is a clinical diagnosis; however, it can be confirmed by demonstrating the predominance of eosinophils on Tzanck smear.

Transient neonatal pustular melanosis (TNPM) also presents in full-term infants; usually favors darkly pigmented neonates; and exhibits either pustules with a collarette of scale that lack surrounding erythema or with residual brown macules on the face, genitals, and acral surfaces. Postinflammatory pigmentary alteration on lesion clearance is another clue to diagnosis. Similarly, it is a clinical diagnosis but can be confirmed with a Tzanck smear demonstrating neutrophils as the major cell infiltrate.

In a prospective 1-year multicenter study performed by Reginatto et al,4 2831 neonates born in southern Brazil underwent a skin examination by a dermatologist within 72 hours of birth to characterize the prevalence and demographics of ETN and TNPM. They found a 21.3% (602 cases) prevalence of ETN compared to a 3.4% (97 cases) prevalence of TNPM, but they noted that most patients were white, and thus the diagnosis of TNPM likely is less prevalent in this group, as it favors darkly pigmented individuals. Additional predisposing factors associated with ETN were male gender, an Apgar score of 8 to 10 at 1 minute, non–neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) patients, and lack of gestational risk factors. The TNPM population was much smaller, though the authors were able to conclude that the disease also was correlated with healthy, non-NICU patients. The authors hypothesized that there may be a role of immune system maturity in the pathogenesis of ETN and thus dermatology residents should be aware of the setting of their consultation.4 A NICU consultation for ETN should raise suspicion, as ETN and TNPM favor healthy infants who likely are not residing in the NICU; we are reminded of the target populations for these disease processes.

Additional common causes of vesicular eruptions in neonates can likewise be diagnosed chiefly with clinical inspection. Miliaria presents with tiny superficial crystalline vesicles on the neck and back of newborns due to elevated temperature and resultant obstruction of the eccrine sweat ducts. Reassurance can be provided, as spontaneous resolution occurs with cooling and limitation of occlusive clothing and swaddling.2

Infants at a few weeks of life may present with a noncomedonal pustular eruption on the cheeks, forehead, and scalp commonly known as neonatal acne or neonatal cephalic pustulosis. The driving factor is thought to be an abnormal response to Malassezia and can be treated with ketoconazole cream or expectant management.2

Cutaneous candidiasis is the most common infectious cause of vesicles in the neonate and can present in 2 fashions. Neonatal candidiasis is common, presenting a week after birth and manifesting as oral thrush and red plaques with satellite pustules in the diaper area. Congenital candidiasis is due to infection in utero, presents prior to 1 week of life, exhibits diffuse erythroderma, and requires timely parenteral antifungals.5 Newborns and preterm infants are at higher risk for systemic disease, while full-term infants may experience a mild course of skin-limited lesions.

It is imperative to rule out other infectious etiologies in ill-appearing neonates with vesicles such as herpes simplex virus, bacterial infections, syphilis, and vertically transmitted TORCH (toxoplasmosis, other infections rubella, cytomegalovirus infection, and herpes simplex) diagnoses.6 Herpes simplex virus classically presents with grouped vesicles on an erythematous base; however, such characteristic lesions may be subtle in the newborn. The site of skin involvement usually is the area that first comes into contact with maternal lesions, such as the face for a newborn delivered in a cephalic presentation.2 It is critical to be cognizant of this diagnosis, as a delay in antiviral therapy can result in neurologic consequences due to disseminated disease.

If the clinical picture of vesiculobullous disease in the newborn is not as clear, less common causes must be considered. Infantile acropustulosis presents with recurring crops of pustules on the hands and feet at several months of age. The most common differential diagnosis is scabies; therefore, a mineral oil preparation should be performed to rule out this common mimicker. Potent topical corticosteroids are first-line therapy, and episodes generally resolve with time.

Another mimicker of pustules in neonates includes deficiency of IL-1ra, a rare entity described in 2009.7 Deficiency of IL-1ra is an autoinflammatory syndrome of skin and bone due to unopposed action of IL-1 with life-threatening inflammation; infants present with pustules, lytic bone lesions, elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein, and failure to thrive.8 The characteristic mutation was discovered when the infants dramatically responded to therapy with anakinra, an IL-1ra.

Eosinophilic pustular folliculitis is an additional pustular dermatosis that manifests with lesions predominately in the head and neck area, and unlike the adult population, it usually is self-resolving and not associated with other comorbidities in newborns.2

Incontinentia pigmenti is an X-linked dominant syndrome due to a genetic mutation in NEMO, nuclear factor κβ essential modulator, which protects against apoptosis.3 Incontinentia pigmenti presents in newborn girls shortly after birth with vesicles in a blaschkoid distribution before evolving through 4 unique stages of vesicular lesions, verrucous lesions, hyperpigmentation, and ultimately resolves with residual hypopigmentation in the affected area.

Lastly, neonatal Behçet disease can present with vesicles in the mouth and genital region due to transfer of maternal antibodies. It is self-limiting in nature and would be readily diagnosed with a known maternal history, though judicious screening for infections may be needed in specific settings.2

Conclusion

In summary, a vast array of benign and worrisome dermatoses present in the neonatal period. A thorough history and physical examination, including the temporality of the lesions, the health status of the newborn, and the maternal history, can help delineate the diagnosis. The 5-step method presented can further elucidate the underlying mechanism and reduce an overwhelming differential diagnosis list by reviewing each finding yielded from each step. Dermatology residents should feel comfortable addressing this unique patient population to ameliorate unclear cutaneous diagnoses for pediatricians.

Acknowledgment

A special thank you to Lawrence A. Schachner, MD (Miami, Florida), for his help providing resources and guidance for this topic.

- Schachner L. Vesiculopustular dermatosis in neonates and infants. Lecture presented at: University of Miami Department of Dermatology & Cutaneous Surgery Grand Rounds; August 23, 2017; Miami, Florida.

- Eichenfield LF, Lee PW, Larraide M, et al. Neonatal skin and skin disorders. In: Schachner LA, Hansen RC, eds. Pediatric Dermatology. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Mosby; 2011:299-373.

- Goddard DS, Gilliam AE, Frieden IJ. Vesiculobullous and erosive diseases in the newborn. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2012:523-537.

- Reginatto FP, Muller FM, Peruzzo J, et al. Epidemiology and predisposing factors for erythema toxicum neonatorum and transient neonatal pustular melanosis: a multicenter study [published online May 25, 2017]. Pediatr Dermatol. 2017;34:422-426.

- Aruna C, Seetharam K. Congenital candidiasis. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2014;5(suppl 1):S44-S47.

- O’Connor NR, McLaughlin MR, Ham P. Newborn skin: part I. common rashes. Am Fam Physician. 2008;77:47-52.

- Reddy S, Jia S, Geoffrey R, et al. An autoinflammatory disease due to homozygous deletion of the IL1RN locus. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:2438-2444.