User login

Nivolumab linked to CNS disorder in case report

Autoimmune encephalitis may be a potentially severe complication of immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy, a case report suggests.

The recently published report describes a 53-year-old man with B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma who presented with double vision, ataxia, impaired speech, and mild cognitive dysfunction following treatment with the immune checkpoint inhibitor nivolumab.

Neuropathologic examination of a biopsied brain lesion found on cranial MRI showed a T cell–dominated inflammatory process thought to be autoimmune in origin, according to Herwig Strik, MD, of the department of neurology at Philipps University of Marburg (Germany), and his colleagues (Eur J Cancer. 2017 Oct 16. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2017.09.026).

After the patient stopped taking nivolumab and the inflammatory process was treated, his “clinical neurological and radiological status remained stable but disabling with fluctuating dysarthria and ataxia,” Dr. Strik and his colleagues wrote.

“Since these novel anticancer agents are increasingly used, this severe complication should be recognized soon and treatment should be terminated to avoid chronification,” they said in the report.

Nivolumab and other checkpoint inhibitors are known to have autoimmune side effects in some cases that can affect the pulmonary, gastrointestinal, and endocrine systems, the authors said.

Several previous case reports have detailed encephalitis occurring in cancer patients receiving nivolumab, the combination of nivolumab plus the immune checkpoint inhibitor ipilimumab, or ipilimumab alone. The authors said they believe that this case report is the first to describe multifocal CNS inflammation following nivolumab treatment for systemic lymphoma.

The patient was diagnosed with B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma in 2005, according to the case report. He was first treated in 2009 with R-CHOP (rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisolone), followed by stem cell apheresis, radioimmunotherapy, and rituximab; he then received R-DHAP (rituximab, dexamethasone, high-dose cytarabine, and cisplatin) in August 2014, followed by autologous stem cell transplantation in October of that year. The patient started nivolumab maintenance therapy in February 2015 but started experiencing neurological symptoms that eventually led to ending nivolumab treatment in September 2015.

The patient’s lymphoma relapsed in June 2016. “The disabling neurological symptoms and his personal situation, however, worsened the patient’s depressive symptoms so severely that he went abroad to commit assisted suicide,” wrote Dr. Strik and his colleagues.

The authors proposed the term “immune checkpoint inhibitor–associated CNS autoimmune disorder (ICICAD)” to describe the inflammatory condition described in the case report.

They declared no conflicts of interest related to the case report and did not receive grant support for conducting the research described in it.

Autoimmune encephalitis may be a potentially severe complication of immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy, a case report suggests.

The recently published report describes a 53-year-old man with B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma who presented with double vision, ataxia, impaired speech, and mild cognitive dysfunction following treatment with the immune checkpoint inhibitor nivolumab.

Neuropathologic examination of a biopsied brain lesion found on cranial MRI showed a T cell–dominated inflammatory process thought to be autoimmune in origin, according to Herwig Strik, MD, of the department of neurology at Philipps University of Marburg (Germany), and his colleagues (Eur J Cancer. 2017 Oct 16. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2017.09.026).

After the patient stopped taking nivolumab and the inflammatory process was treated, his “clinical neurological and radiological status remained stable but disabling with fluctuating dysarthria and ataxia,” Dr. Strik and his colleagues wrote.

“Since these novel anticancer agents are increasingly used, this severe complication should be recognized soon and treatment should be terminated to avoid chronification,” they said in the report.

Nivolumab and other checkpoint inhibitors are known to have autoimmune side effects in some cases that can affect the pulmonary, gastrointestinal, and endocrine systems, the authors said.

Several previous case reports have detailed encephalitis occurring in cancer patients receiving nivolumab, the combination of nivolumab plus the immune checkpoint inhibitor ipilimumab, or ipilimumab alone. The authors said they believe that this case report is the first to describe multifocal CNS inflammation following nivolumab treatment for systemic lymphoma.

The patient was diagnosed with B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma in 2005, according to the case report. He was first treated in 2009 with R-CHOP (rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisolone), followed by stem cell apheresis, radioimmunotherapy, and rituximab; he then received R-DHAP (rituximab, dexamethasone, high-dose cytarabine, and cisplatin) in August 2014, followed by autologous stem cell transplantation in October of that year. The patient started nivolumab maintenance therapy in February 2015 but started experiencing neurological symptoms that eventually led to ending nivolumab treatment in September 2015.

The patient’s lymphoma relapsed in June 2016. “The disabling neurological symptoms and his personal situation, however, worsened the patient’s depressive symptoms so severely that he went abroad to commit assisted suicide,” wrote Dr. Strik and his colleagues.

The authors proposed the term “immune checkpoint inhibitor–associated CNS autoimmune disorder (ICICAD)” to describe the inflammatory condition described in the case report.

They declared no conflicts of interest related to the case report and did not receive grant support for conducting the research described in it.

Autoimmune encephalitis may be a potentially severe complication of immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy, a case report suggests.

The recently published report describes a 53-year-old man with B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma who presented with double vision, ataxia, impaired speech, and mild cognitive dysfunction following treatment with the immune checkpoint inhibitor nivolumab.

Neuropathologic examination of a biopsied brain lesion found on cranial MRI showed a T cell–dominated inflammatory process thought to be autoimmune in origin, according to Herwig Strik, MD, of the department of neurology at Philipps University of Marburg (Germany), and his colleagues (Eur J Cancer. 2017 Oct 16. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2017.09.026).

After the patient stopped taking nivolumab and the inflammatory process was treated, his “clinical neurological and radiological status remained stable but disabling with fluctuating dysarthria and ataxia,” Dr. Strik and his colleagues wrote.

“Since these novel anticancer agents are increasingly used, this severe complication should be recognized soon and treatment should be terminated to avoid chronification,” they said in the report.

Nivolumab and other checkpoint inhibitors are known to have autoimmune side effects in some cases that can affect the pulmonary, gastrointestinal, and endocrine systems, the authors said.

Several previous case reports have detailed encephalitis occurring in cancer patients receiving nivolumab, the combination of nivolumab plus the immune checkpoint inhibitor ipilimumab, or ipilimumab alone. The authors said they believe that this case report is the first to describe multifocal CNS inflammation following nivolumab treatment for systemic lymphoma.

The patient was diagnosed with B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma in 2005, according to the case report. He was first treated in 2009 with R-CHOP (rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisolone), followed by stem cell apheresis, radioimmunotherapy, and rituximab; he then received R-DHAP (rituximab, dexamethasone, high-dose cytarabine, and cisplatin) in August 2014, followed by autologous stem cell transplantation in October of that year. The patient started nivolumab maintenance therapy in February 2015 but started experiencing neurological symptoms that eventually led to ending nivolumab treatment in September 2015.

The patient’s lymphoma relapsed in June 2016. “The disabling neurological symptoms and his personal situation, however, worsened the patient’s depressive symptoms so severely that he went abroad to commit assisted suicide,” wrote Dr. Strik and his colleagues.

The authors proposed the term “immune checkpoint inhibitor–associated CNS autoimmune disorder (ICICAD)” to describe the inflammatory condition described in the case report.

They declared no conflicts of interest related to the case report and did not receive grant support for conducting the research described in it.

FROM THE EUROPEAN JOURNAL OF CANCER

Key clinical point: Autoimmune encephalitis may be a potential complication of checkpoint inhibitor therapy.

Major finding: A patient with B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma presented with double vision, ataxia, impaired speech, and mild cognitive dysfunction following treatment with nivolumab. Examination of a brain lesion showed a T cell–dominated inflammatory process thought to be autoimmune in origin.

Data source: A case report of a 53-year-old man with B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma (B-NHL) who received nivolumab maintenance treatment.

Disclosures: The authors declared no conflicts of interest and did not receive grant support for the research.

Atypical Disseminated Herpes Zoster: Management Guidelines in Immunocompromised Patients

Well-known for its typical presentation, classic herpes zoster (HZ) presents as a dermatomal eruption of painful erythematous papules that evolve into grouped vesicles or bullae.1,2 Thereafter, the lesions can become pustular or hemorrhagic.1 Although the diagnosis most often is made clinically, confirmatory techniques for diagnosis include viral culture, direct fluorescent antibody testing, or polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assay.1,3

The main risk factor for HZ is advanced age, most commonly affecting elderly patients.4 It is hypothesized that a physiological decline in varicella-zoster virus (VZV)–specific cell-mediated immunity among elderly individuals helps trigger reactivation of the virus within the dorsal root ganglion.1,5 Similarly affected are immunocompromised individuals, including those with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, due to suppression of T cells immune to VZV,1,5 as well as immunosuppressed transplant recipients who have diminished VZV-specific cellular responses and VZV IgG antibody avidity.6

Secondary complications of VZV infection (eg, postherpetic neuralgia, bacterial superinfection progressing to cellulitis) lead to increased morbidity.7,8 Disseminated cutaneous HZ is another grave complication of VZV infection and almost exclusively occurs with immunosuppression.1,8 It manifests as an eruption of at least 20 widespread vesiculobullous lesions outside the primary and adjacent dermatomes.6 Immunocompromised patients also are at increased risk for visceral involvement of VZV infection, which may affect vital organs such as the brain, liver, or lungs.7,8 Given the atypical presentation of VZV infection among some immunocompromised individuals, these patients are at increased risk for diagnostic delay and morbidity in the absence of high clinical suspicion for disseminated HZ.

Case Reports

Patient 1

A 52-year-old man developed a painless nonpruritic rash on the left leg of 4 days’ duration. It initially appeared as an erythematous maculopapular rash on the medial aspect of the left knee without any prodromal symptoms. Over the next 4 days, erythematous vesicles developed that progressed to pustules, and the rash spread both proximally and distally along the left leg. Shortly following hospital admission, he developed a fever (temperature, 38.4°C). His medical history included alcoholic liver cirrhosis and AIDS, with a CD4 count of 174 cells/µL (reference range, 500–1500 cells/µL). He had been taking antiretroviral therapy (abacavir-lamivudine and dolutegravir) and prophylaxis against opportunistic infections (dapsone and itraconazole).

Physical examination was remarkable for an extensive rash consisting of multiple 1-cm clusters of approximately 40 pustules each scattered in a nondermatomal distribution along the left leg (Figure 1). Many of the vesicles were confluent with an erythematous base and were in different stages of evolution with some crusted and others emanating a thin liquid exudate. The lesions were nontender and without notable induration. The leg was warm and edematous.

Clinically, the differential diagnosis included disseminated HZ with bacterial superinfection, Vibrio vulnificus infection, and herpes simplex virus (HSV) infection. The patient was treated with intravenous vancomycin, levofloxacin, and acyclovir, and no new lesions developed throughout the course of treatment. On this regimen, his fever resolved after 1 day, the active lesions began to crust, and the edema and erythema diminished. Results of bacterial cultures and plasma PCR and IgM for HSV types 1 and 2 were negative. Viral culture results were negative, but a PCR assay for VZV was positive, reflective of acute reactivation of VZV.

Patient 2

A 63-year-old man developed a pruritic burning rash involving the face, trunk, arms, and legs of 6 days’ duration. His medical history included a heart transplant 6 months prior to presentation, type 2 diabetes mellitus, and chronic kidney disease. He was taking antirejection therapy with mycophenolate mofetil (MMF), prednisone, and tacrolimus.

Physical examination was remarkable for an extensive rash consisting of clusters of 1- to 2-mm vesicles scattered in a nondermatomal pattern. Isolated vesicles involved the forehead, nose, and left ear, and diffuse vesicles with a relatively symmetric distribution were scattered across the back, chest, and proximal and distal arms and legs (Figure 2). Many of the vesicles had an associated overlying crust with hemorrhage. Some of the vesicles coalesced with central necrotic plaques.

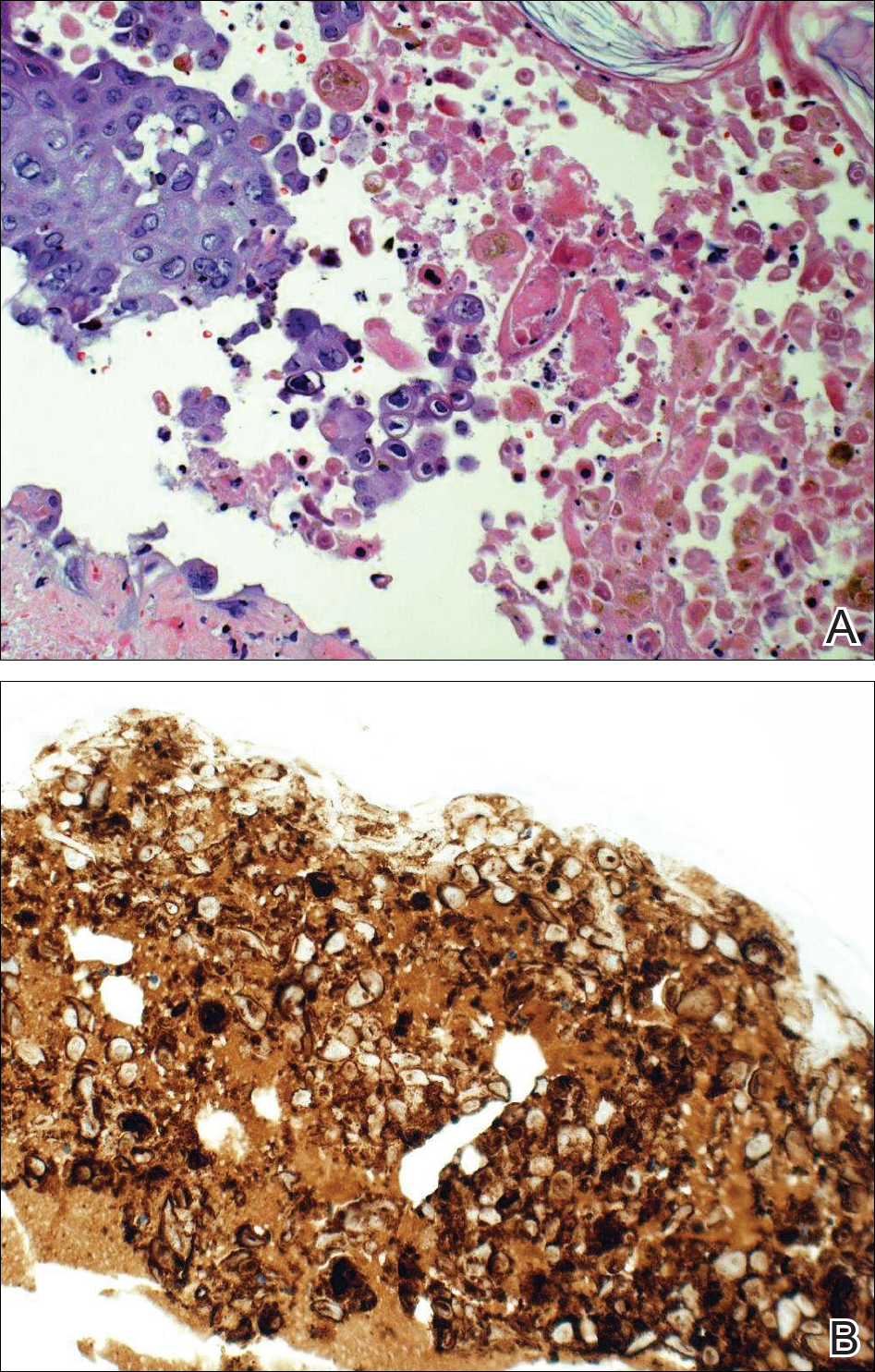

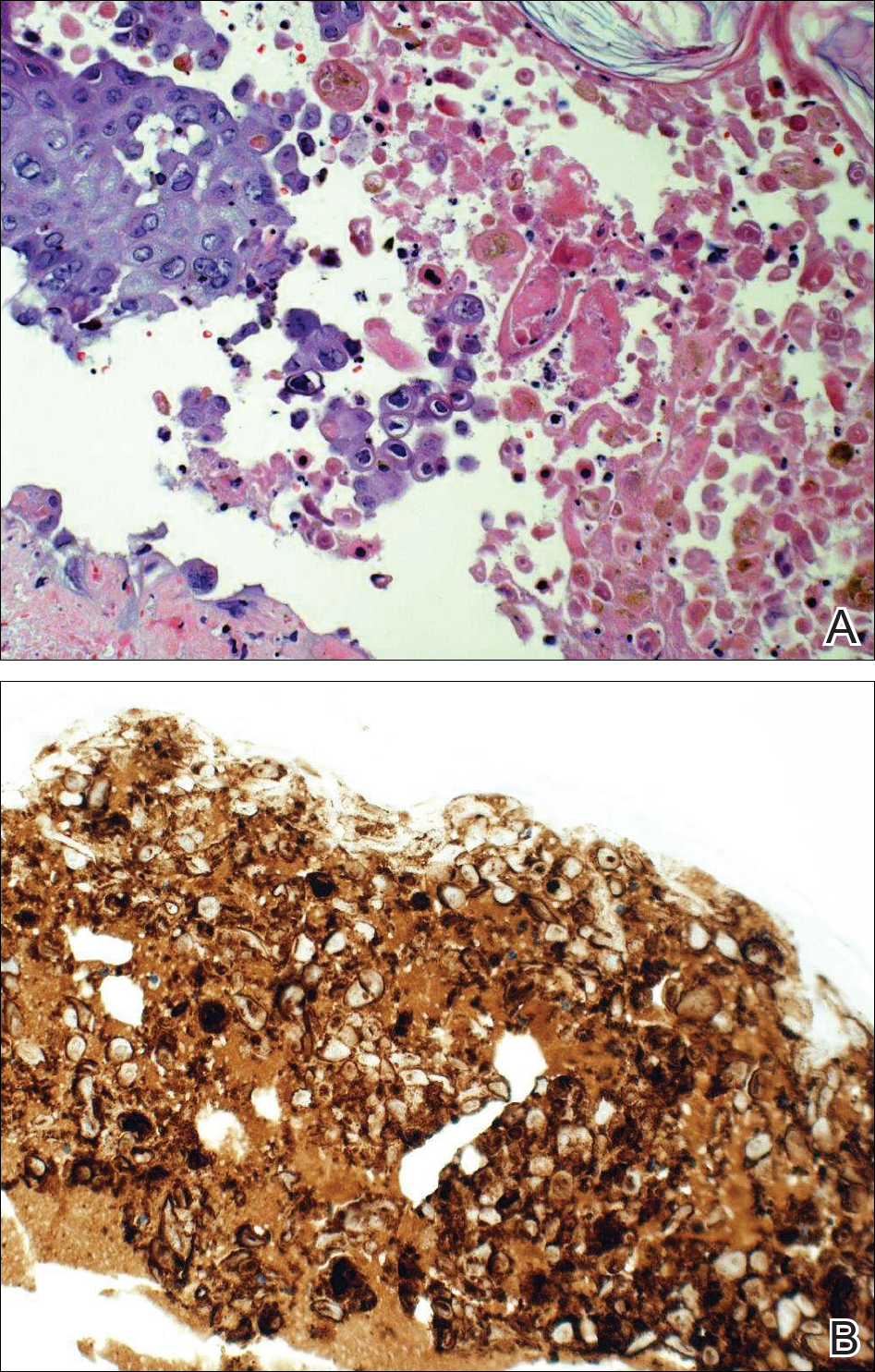

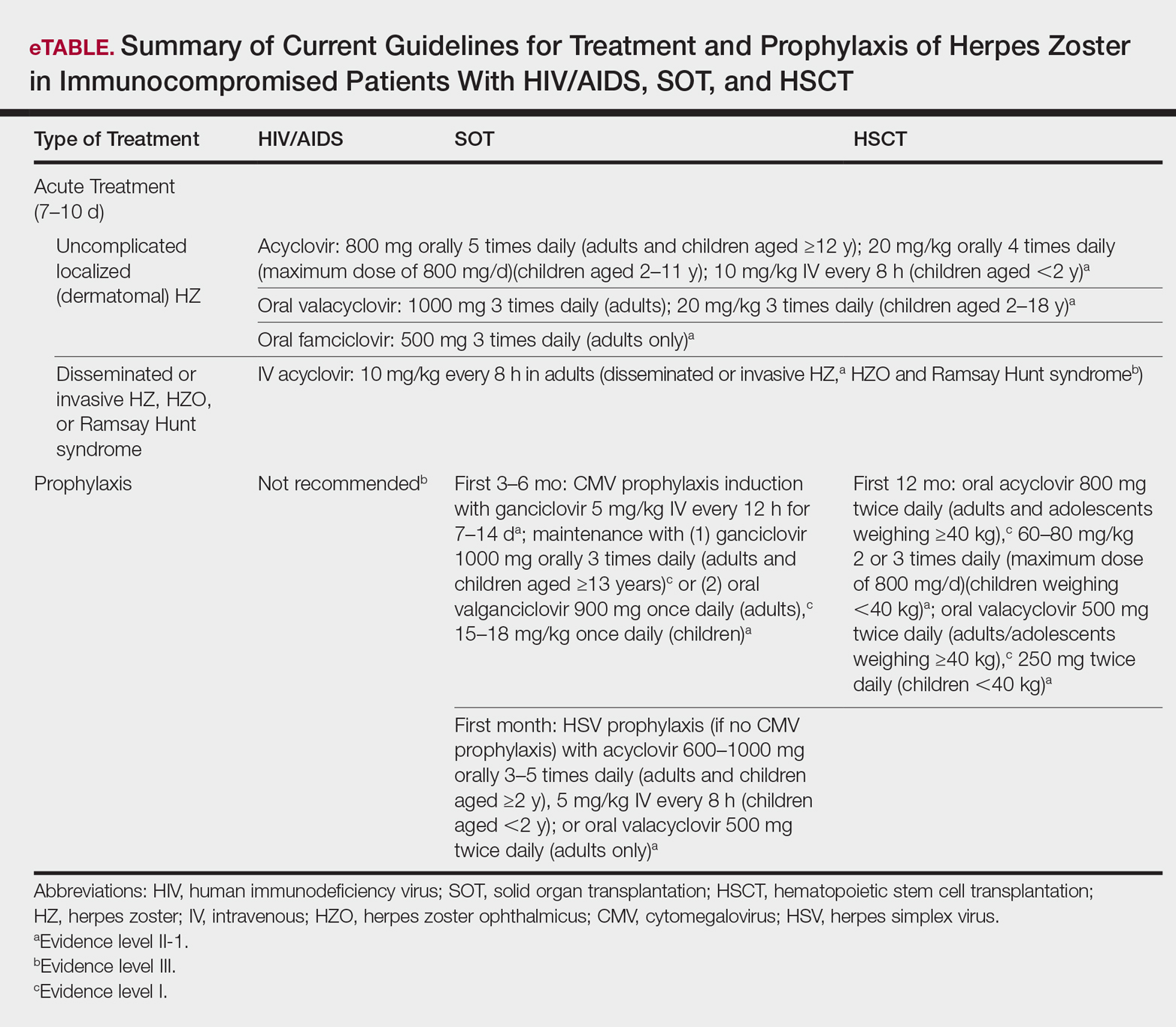

Given a clinical suspicion for disseminated HZ, therapy with oral valacyclovir was initiated. Two punch biopsies were consistent with herpesvirus cytopathic changes. Multiple sections demonstrated ulceration as well as acantholysis and necrosis of keratinocytes with multinucleation and margination of chromatin. There was an intense lichenoid and perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate in the dermis. Immunohistochemistry staining was positive for VZV and negative for HSV, indicating acute reactivation of VZV (Figure 3). Upon completion of an antiviral regimen, the patient returned to clinic with healed crusted lesions.

Comment

Frequently, the clinical features of HZ in immunocompromised patients mirror those in immunocompetent hosts.8 However, each of our 2 patients developed an unusual presentation of atypical generalized HZ.7 In this clinical variant, lesions develop along a single dermatome, then a diffuse vesicular eruption subsequently develops without dermatomal localization. These lesions can be chronic, persisting for months or years.7

The classic clinical presentation of HZ is distinct and often is readily diagnosed by visual inspection.7 However, atypical presentations and their associated complications can pose diagnostic and therapeutic challenges.7 Painless HZ lesions in a nondermatomal pattern were described in a patient who also had AIDS.9 Interestingly, multiple reports have found that patients with a severe but painless rash are less likely to have experienced a viral prodrome consisting of hyperesthesia, paresthesia, or pruritus.2,10 This observation suggests that lack of a prodrome, as in the case of patient 1 in our report, may aid in the recognition of painless HZ. Because of these atypical presentations, laboratory testing is even more important than in immunocompetent hosts, as diagnosis may be more difficult to establish on clinical presentation alone.

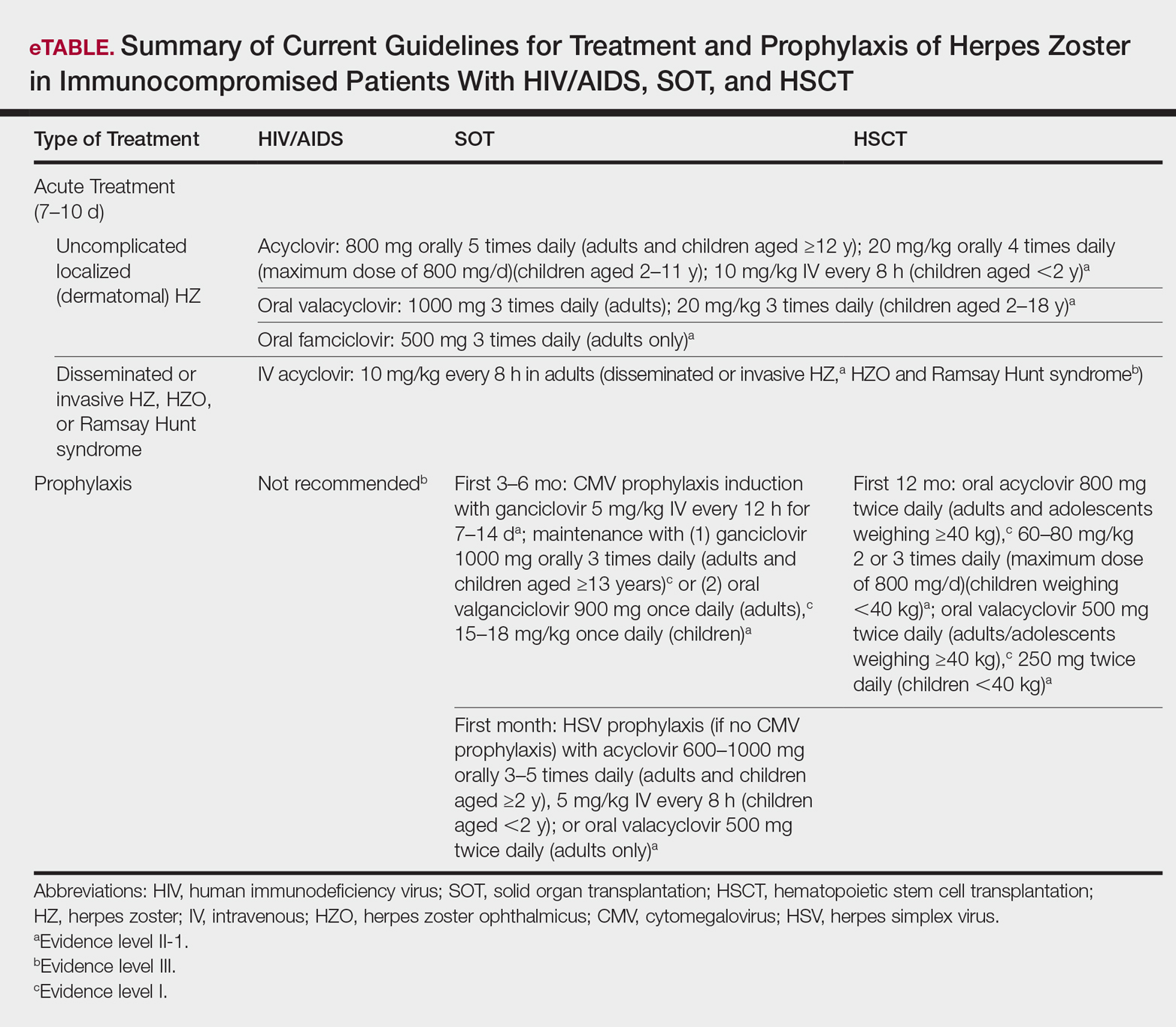

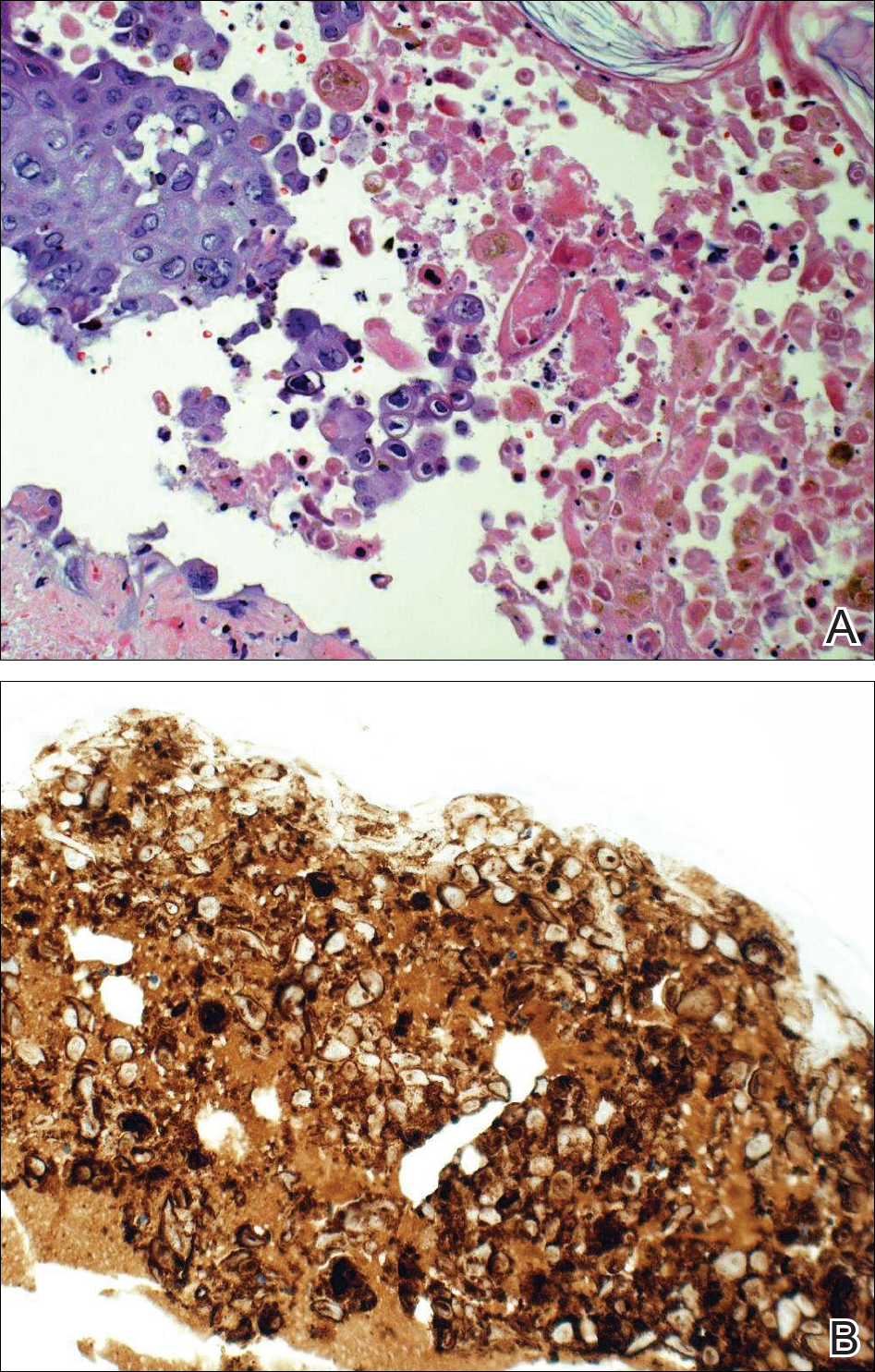

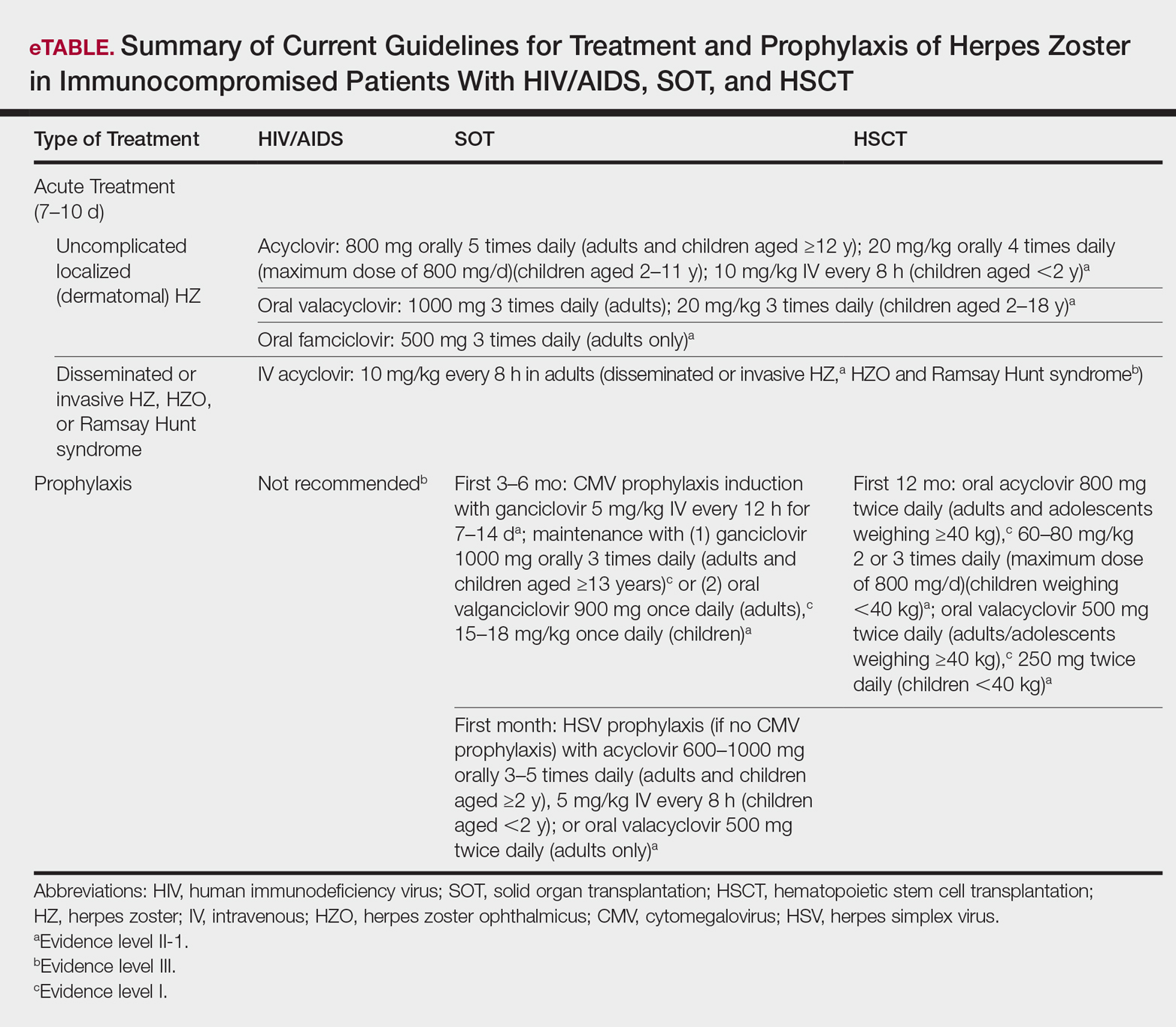

Several studies11-32 have evaluated modalities for treatment and prophylaxis for disseminated HZ in immunocompromised hosts, given its increased risk and potentially fatal complications in this population. The current guidelines in patients with HIV/AIDS, solid organ transplantation (SOT), and hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) are summarized in the eTable.

HIV/AIDS Patients

Given their efficacy and low rate of toxicity, oral acyclovir, valacyclovir, and famciclovir are recommended treatment options for HIV patients with localized, mild, dermatomal HZ.11 Two exceptions include HZ ophthalmicus and Ramsay Hunt syndrome for which some experts recommend intravenous acyclovir given the risk for vision loss and facial palsy, respectively. Intravenous acyclovir often is the drug of choice for treating complicated, disseminated, or severe HZ in HIV-infected patients, though prospective efficacy data remain limited.11

With regard to prevention of infection, a large randomized trial in 2016 found that acyclovir prophylaxis resulted in a 68% reduction in HZ over 2 years among HIV patients.12 Despite data that acyclovir may be effective for this purpose, long-term antiviral prophylaxis is not routinely recommended for HZ,11,13 as it has been linked to rare cases of acyclovir-resistant HZ in HIV patients.14,15 However, antiviral prophylaxis against HSV type 2 reactivation in HIV patients also confers protection against VZV reactivation.11,12

Solid Organ Transplantation

Localized, mild to moderately severe dermatomal HZ can be treated with oral acyclovir, valacyclovir, or famciclovir. As in HIV patients, SOT patients with severe, disseminated, or complicated HZ should receive IV acyclovir.11 In the first 3 to 6 months following the procedure, SOT patients receive cytomegalovirus prophylaxis with ganciclovir or valgan-ciclovir, which also provides protection against HZ.13-18 For patients not receiving cytomegalovirus prophylaxis, HSV prophylaxis with oral acyclovir or valacyclovir is given for at least the first month after transplantation, which also confers protection against HZ.16,19 Antiviral therapy is critical during the early posttransplantation period when patients are most severely immunosuppressed and thus have the highest risk for VZV-associated complications.20 Although immunosuppression is lifelong in most SOT recipients, there is insufficient evidence for extending prophylaxis beyond 6 months.16,21

As a possible risk factor for HZ,22 MMF use is another consideration among SOT patients, similar to patient 2 in our report. A 2003 observational study supported withdrawal of MMF therapy during active VZV infection due to clinical observation of an association with HZ.23 However, a multicenter, randomized, controlled trial reported no cases of HZ in renal transplant recipients on MMF.24 Additionally, MMF has been observed to enhance the antiviral activity of acyclovir, at least in vitro.25 Given the lack of evidence of MMF as a risk factor for HZ, there is insufficient evidence for cessation of use during VZVreactivation in SOT patients.

Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation

The preferred agents for treatment of localized mild dermatomal HZ are oral acyclovir or valacyclovir, as data on the safety and efficacy of famciclovir among HSCT recipients are limited.13,26 Patients should receive antiviral prophylaxis with one of these agents during the first year following allogeneic or autologous HSCT. This 1-year course has proven highly effective in reducing HZ in the first year following transplantation when most severe cases occur,21,26-29 and it has been associated with a persistently decreased risk for HZ even after discontinuation.21 Prophylaxis may be continued beyond 1 year in allogeneic HSCT recipients experiencing graft-versus-host disease who should receive acyclovir until 6 months after the end of immunosuppressive therapy.21,26

Vaccination remains a potential strategy to reduce the incidence of HZ in this patient population. A heat-inactivated vaccine administered within the first 3 months after the procedure has been shown to be safe among autologous and allogeneic HSCT patients.30,31 The vaccine notably reduced the incidence of HZ in patients who underwent autologous HSCT,32 but no known data are available on its clinical efficacy in allogeneic HSCT patients. Accordingly, there are no known official recommendations to date regarding vaccine use in these patient populations.26

Conclusion

It is incumbent upon clinicians to recognize the spectrum of atypical presentations of HZ and maintain a low threshold for performing appropriate diagnostic or confirmatory studies among at-risk patients with impaired immune function. Disseminated HZ can have potentially life-threatening visceral complications such as encephalitis, hepatitis, or pneumonitis.7,8 As such, an understanding of prevention and treatment modalities for VZV infection among immunocompromised patients is critical. Because the morbidity associated with complications of VZV infection is substantial and the risks associated with antiviral agents are minimal, antiviral prophylaxis is recommended for 6 months following SOT or 1 year following HSCT, and prompt treatment is warranted in cases of reasonable clinical suspicion for HZ.

Acknowledgment

The authors gratefully acknowledge the generosity of our patients in permitting photography of their skin findings for the furthering of medical education.

- McCrary ML, Severson J, Tyring SK. Varicella zoster virus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41:1-16.

- Nagasako EM, Johnson RW, Griffin DR, et al. Rash severity in herpes zoster: correlates and relationship to postherpetic neuralgia. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46:834-839.

- Leung J, Harpaz R, Baughman AL, et al. Evaluation of laboratory methods for diagnosis of varicella. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;51:23-32.

- Herpes Zoster and Functional Decline Consortium. Functional decline and herpes zoster in older people: an interplay of multiple factors. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2015;27:757-765.

- Weinberg A, Levin MJ. VZV T cell-mediated immunity. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2010;342:341-357.

- Prelog M, Schonlaub J, Jeller V, et al. Reduced varicella-zoster-virus (VZV)-specific lymphocytes and IgG antibody avidity in solid organ transplant recipients. Vaccine. 2013;31:2420-2426.

- Gnann JW Jr. Varicella-zoster virus: atypical presentations and unusual complications. J Infect Dis. 2002;186(suppl 1):S91-S98.

- Glesby MJ, Moore RD, Chaisson RE. Clinical spectrum of herpes zoster in adults infected with human immunodeficiency virus. Clin Infect Dis. 1995;21:370-375.

- Blankenship W, Herchline T, Hockley A. Asymptomatic vesicles in a patient with the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. disseminated varicella-zoster virus (VZV) infection. Arch Dermatol. 1994;130:1193, 1196.

- Katz J, Cooper EM, Walther RR, et al. Acute pain in herpes zoster and its impact on health-related quality of life. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;39:342-348.

- Gnann JW. Antiviral therapy of varicella-zoster virus infections. In: Arvin A, Campadelli-Fiume G, Mocarski E, et al, eds. Human Herpesviruses: Biology, Therapy, and Immunoprophylaxis. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press; 2007:1175-1191.

- Barnabas RV, Baeten JM, Lingappa JR, et al. Acyclovir prophylaxis reduces the incidence of herpes zoster among HIV-infected individuals: results of a randomized clinical trial. J Infect Dis. 2016;213:551-555.

- Dworkin RH, Johnson RW, Breuer J, et al. Recommendations for the management of herpes zoster. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44(suppl 1):S1-S26.

- Jacobson MA, Berger TG, Fikrig S, et al. Acyclovir-resistant varicella zoster virus infection after chronic oral acyclovir therapy in patients with the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS). Ann Intern Med. 1990;112:187-191.

- Linnemann CC Jr, Biron KK, Hoppenjans WG, et al. Emergence of acyclovir-resistant varicella zoster virus in an AIDS patient on prolonged acyclovir therapy. AIDS. 1990;4:577-579.

- Pergam SA, Limaye AP; AST Infectious Diseases Community of Practice. Varicella zoster virus (VZV) in solid organ transplant recipients. Am J Transplant. 2009;9(suppl 4):S108-S115.

- Preiksaitis JK, Brennan DC, Fishman J, et al. Canadian society of transplantation consensus workshop on cytomegalovirus management in solid organ transplantation final report. Am J Transplant. 2005;5:218-227.

- Fishman JA, Doran MT, Volpicelli SA, et al. Dosing of intravenous ganciclovir for the prophylaxis and treatment of cytomegalovirus infection in solid organ transplant recipients. Transplantation. 2000;69:389-394.

- Zuckerman R, Wald A; AST Infectious Diseases Community of Practice. Herpes simplex virus infections in solid organ transplant recipients. Am J Transplant. 2009;9(suppl 4):S104-S107.

- Arness T, Pedersen R, Dierkhising R, et al. Varicella zoster virus-associated disease in adult kidney transplant recipients: incidence and risk-factor analysis. Transpl Infect Dis. 2008;10:260-268.

- Erard V, Guthrie KA, Varley C, et al. One-year acyclovir prophylaxis for preventing varicella-zoster virus disease after hematopoietic cell transplantation: no evidence of rebound varicella-zoster virus disease after drug discontinuation. Blood. 2007;110:3071-3077.

- Rothwell WS, Gloor JM, Morgenstern BZ, et al. Disseminated varicella infection in pediatric renal transplant recipients treated with mycophenolate mofetil. Transplantation. 1999;68:158-161.

- Lauzurica R, Bayés B, Frías C, et al. Disseminated varicella infection in adult renal allograft recipients: role of mycophenolate mofetil. Transplant Proc. 2003;35:1758-1759.

- A blinded, randomized clinical trial of mycophenolate mofetil for the prevention of acute rejection in cadaveric renal transplantation. TheTricontinental Mycophenolate Mofetil Renal Transplantation Study Group. Transplantation. 1996;61:1029-1037.

- Neyts J, De Clercq E. Mycophenolate mofetil strongly potentiates the anti-herpesvirus activity of acyclovir. Antiviral Res. 1998;40:53-56.

- Tomblyn M, Chiller T, Einsele H, et al. Guidelines for preventing infectious complications among hematopoietic cell transplantation recipients: a global perspective. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2009;15:1143-1238.

- Boeckh M, Kim HW, Flowers ME, et al. Long-term acyclovir for prevention of varicella zoster virus disease after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation—a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled study. Blood. 2006;107:1800-1805.

- Kawamura K, Hayakawa J, Akahoshi Y, et al. Low-dose acyclovir prophylaxis for the prevention of herpes simplex virus and varicella zoster virus diseases after autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Int J Hematol. 2015;102:230-237.

- Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center/Seattle Cancer Care Alliance. Long-term follow-up after hematopoietic stem cell transplant general guidelines for referring physicians. Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center website. https://www.fredhutch.org/content/dam/public/Treatment-Suport/Long-Term-Follow-Up/physician.pdf. Published July 17, 2014. Accessed October 19, 2017.

- Kussmaul SC, Horn BN, Dvorak CC, et al. Safety of the live, attenuated varicella vaccine in pediatric recipients of hematopoietic SCTs. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2010;45:1602-1606.

- Hata A, Asanuma H, Rinki M, et al. Use of an inactivated varicella vaccine in recipients of hematopoietic-cell transplants. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:26-34.

- Issa NC, Marty FM, Leblebjian H, et al. Live attenuated varicella-zoster vaccine in hematopoietic stem cell transplantation recipients. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2014;20:285-287.

Well-known for its typical presentation, classic herpes zoster (HZ) presents as a dermatomal eruption of painful erythematous papules that evolve into grouped vesicles or bullae.1,2 Thereafter, the lesions can become pustular or hemorrhagic.1 Although the diagnosis most often is made clinically, confirmatory techniques for diagnosis include viral culture, direct fluorescent antibody testing, or polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assay.1,3

The main risk factor for HZ is advanced age, most commonly affecting elderly patients.4 It is hypothesized that a physiological decline in varicella-zoster virus (VZV)–specific cell-mediated immunity among elderly individuals helps trigger reactivation of the virus within the dorsal root ganglion.1,5 Similarly affected are immunocompromised individuals, including those with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, due to suppression of T cells immune to VZV,1,5 as well as immunosuppressed transplant recipients who have diminished VZV-specific cellular responses and VZV IgG antibody avidity.6

Secondary complications of VZV infection (eg, postherpetic neuralgia, bacterial superinfection progressing to cellulitis) lead to increased morbidity.7,8 Disseminated cutaneous HZ is another grave complication of VZV infection and almost exclusively occurs with immunosuppression.1,8 It manifests as an eruption of at least 20 widespread vesiculobullous lesions outside the primary and adjacent dermatomes.6 Immunocompromised patients also are at increased risk for visceral involvement of VZV infection, which may affect vital organs such as the brain, liver, or lungs.7,8 Given the atypical presentation of VZV infection among some immunocompromised individuals, these patients are at increased risk for diagnostic delay and morbidity in the absence of high clinical suspicion for disseminated HZ.

Case Reports

Patient 1

A 52-year-old man developed a painless nonpruritic rash on the left leg of 4 days’ duration. It initially appeared as an erythematous maculopapular rash on the medial aspect of the left knee without any prodromal symptoms. Over the next 4 days, erythematous vesicles developed that progressed to pustules, and the rash spread both proximally and distally along the left leg. Shortly following hospital admission, he developed a fever (temperature, 38.4°C). His medical history included alcoholic liver cirrhosis and AIDS, with a CD4 count of 174 cells/µL (reference range, 500–1500 cells/µL). He had been taking antiretroviral therapy (abacavir-lamivudine and dolutegravir) and prophylaxis against opportunistic infections (dapsone and itraconazole).

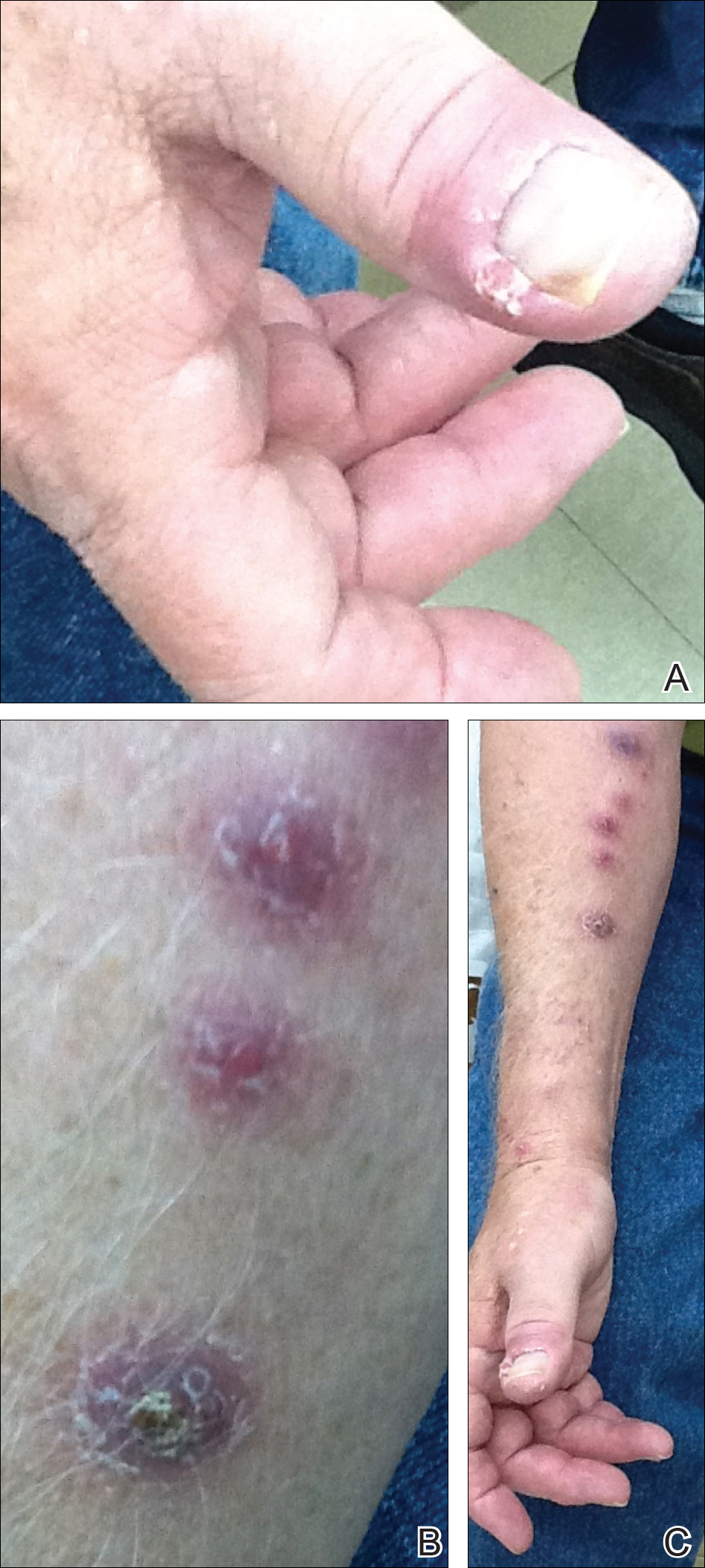

Physical examination was remarkable for an extensive rash consisting of multiple 1-cm clusters of approximately 40 pustules each scattered in a nondermatomal distribution along the left leg (Figure 1). Many of the vesicles were confluent with an erythematous base and were in different stages of evolution with some crusted and others emanating a thin liquid exudate. The lesions were nontender and without notable induration. The leg was warm and edematous.

Clinically, the differential diagnosis included disseminated HZ with bacterial superinfection, Vibrio vulnificus infection, and herpes simplex virus (HSV) infection. The patient was treated with intravenous vancomycin, levofloxacin, and acyclovir, and no new lesions developed throughout the course of treatment. On this regimen, his fever resolved after 1 day, the active lesions began to crust, and the edema and erythema diminished. Results of bacterial cultures and plasma PCR and IgM for HSV types 1 and 2 were negative. Viral culture results were negative, but a PCR assay for VZV was positive, reflective of acute reactivation of VZV.

Patient 2

A 63-year-old man developed a pruritic burning rash involving the face, trunk, arms, and legs of 6 days’ duration. His medical history included a heart transplant 6 months prior to presentation, type 2 diabetes mellitus, and chronic kidney disease. He was taking antirejection therapy with mycophenolate mofetil (MMF), prednisone, and tacrolimus.

Physical examination was remarkable for an extensive rash consisting of clusters of 1- to 2-mm vesicles scattered in a nondermatomal pattern. Isolated vesicles involved the forehead, nose, and left ear, and diffuse vesicles with a relatively symmetric distribution were scattered across the back, chest, and proximal and distal arms and legs (Figure 2). Many of the vesicles had an associated overlying crust with hemorrhage. Some of the vesicles coalesced with central necrotic plaques.

Given a clinical suspicion for disseminated HZ, therapy with oral valacyclovir was initiated. Two punch biopsies were consistent with herpesvirus cytopathic changes. Multiple sections demonstrated ulceration as well as acantholysis and necrosis of keratinocytes with multinucleation and margination of chromatin. There was an intense lichenoid and perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate in the dermis. Immunohistochemistry staining was positive for VZV and negative for HSV, indicating acute reactivation of VZV (Figure 3). Upon completion of an antiviral regimen, the patient returned to clinic with healed crusted lesions.

Comment

Frequently, the clinical features of HZ in immunocompromised patients mirror those in immunocompetent hosts.8 However, each of our 2 patients developed an unusual presentation of atypical generalized HZ.7 In this clinical variant, lesions develop along a single dermatome, then a diffuse vesicular eruption subsequently develops without dermatomal localization. These lesions can be chronic, persisting for months or years.7

The classic clinical presentation of HZ is distinct and often is readily diagnosed by visual inspection.7 However, atypical presentations and their associated complications can pose diagnostic and therapeutic challenges.7 Painless HZ lesions in a nondermatomal pattern were described in a patient who also had AIDS.9 Interestingly, multiple reports have found that patients with a severe but painless rash are less likely to have experienced a viral prodrome consisting of hyperesthesia, paresthesia, or pruritus.2,10 This observation suggests that lack of a prodrome, as in the case of patient 1 in our report, may aid in the recognition of painless HZ. Because of these atypical presentations, laboratory testing is even more important than in immunocompetent hosts, as diagnosis may be more difficult to establish on clinical presentation alone.

Several studies11-32 have evaluated modalities for treatment and prophylaxis for disseminated HZ in immunocompromised hosts, given its increased risk and potentially fatal complications in this population. The current guidelines in patients with HIV/AIDS, solid organ transplantation (SOT), and hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) are summarized in the eTable.

HIV/AIDS Patients

Given their efficacy and low rate of toxicity, oral acyclovir, valacyclovir, and famciclovir are recommended treatment options for HIV patients with localized, mild, dermatomal HZ.11 Two exceptions include HZ ophthalmicus and Ramsay Hunt syndrome for which some experts recommend intravenous acyclovir given the risk for vision loss and facial palsy, respectively. Intravenous acyclovir often is the drug of choice for treating complicated, disseminated, or severe HZ in HIV-infected patients, though prospective efficacy data remain limited.11

With regard to prevention of infection, a large randomized trial in 2016 found that acyclovir prophylaxis resulted in a 68% reduction in HZ over 2 years among HIV patients.12 Despite data that acyclovir may be effective for this purpose, long-term antiviral prophylaxis is not routinely recommended for HZ,11,13 as it has been linked to rare cases of acyclovir-resistant HZ in HIV patients.14,15 However, antiviral prophylaxis against HSV type 2 reactivation in HIV patients also confers protection against VZV reactivation.11,12

Solid Organ Transplantation

Localized, mild to moderately severe dermatomal HZ can be treated with oral acyclovir, valacyclovir, or famciclovir. As in HIV patients, SOT patients with severe, disseminated, or complicated HZ should receive IV acyclovir.11 In the first 3 to 6 months following the procedure, SOT patients receive cytomegalovirus prophylaxis with ganciclovir or valgan-ciclovir, which also provides protection against HZ.13-18 For patients not receiving cytomegalovirus prophylaxis, HSV prophylaxis with oral acyclovir or valacyclovir is given for at least the first month after transplantation, which also confers protection against HZ.16,19 Antiviral therapy is critical during the early posttransplantation period when patients are most severely immunosuppressed and thus have the highest risk for VZV-associated complications.20 Although immunosuppression is lifelong in most SOT recipients, there is insufficient evidence for extending prophylaxis beyond 6 months.16,21

As a possible risk factor for HZ,22 MMF use is another consideration among SOT patients, similar to patient 2 in our report. A 2003 observational study supported withdrawal of MMF therapy during active VZV infection due to clinical observation of an association with HZ.23 However, a multicenter, randomized, controlled trial reported no cases of HZ in renal transplant recipients on MMF.24 Additionally, MMF has been observed to enhance the antiviral activity of acyclovir, at least in vitro.25 Given the lack of evidence of MMF as a risk factor for HZ, there is insufficient evidence for cessation of use during VZVreactivation in SOT patients.

Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation

The preferred agents for treatment of localized mild dermatomal HZ are oral acyclovir or valacyclovir, as data on the safety and efficacy of famciclovir among HSCT recipients are limited.13,26 Patients should receive antiviral prophylaxis with one of these agents during the first year following allogeneic or autologous HSCT. This 1-year course has proven highly effective in reducing HZ in the first year following transplantation when most severe cases occur,21,26-29 and it has been associated with a persistently decreased risk for HZ even after discontinuation.21 Prophylaxis may be continued beyond 1 year in allogeneic HSCT recipients experiencing graft-versus-host disease who should receive acyclovir until 6 months after the end of immunosuppressive therapy.21,26

Vaccination remains a potential strategy to reduce the incidence of HZ in this patient population. A heat-inactivated vaccine administered within the first 3 months after the procedure has been shown to be safe among autologous and allogeneic HSCT patients.30,31 The vaccine notably reduced the incidence of HZ in patients who underwent autologous HSCT,32 but no known data are available on its clinical efficacy in allogeneic HSCT patients. Accordingly, there are no known official recommendations to date regarding vaccine use in these patient populations.26

Conclusion

It is incumbent upon clinicians to recognize the spectrum of atypical presentations of HZ and maintain a low threshold for performing appropriate diagnostic or confirmatory studies among at-risk patients with impaired immune function. Disseminated HZ can have potentially life-threatening visceral complications such as encephalitis, hepatitis, or pneumonitis.7,8 As such, an understanding of prevention and treatment modalities for VZV infection among immunocompromised patients is critical. Because the morbidity associated with complications of VZV infection is substantial and the risks associated with antiviral agents are minimal, antiviral prophylaxis is recommended for 6 months following SOT or 1 year following HSCT, and prompt treatment is warranted in cases of reasonable clinical suspicion for HZ.

Acknowledgment

The authors gratefully acknowledge the generosity of our patients in permitting photography of their skin findings for the furthering of medical education.

Well-known for its typical presentation, classic herpes zoster (HZ) presents as a dermatomal eruption of painful erythematous papules that evolve into grouped vesicles or bullae.1,2 Thereafter, the lesions can become pustular or hemorrhagic.1 Although the diagnosis most often is made clinically, confirmatory techniques for diagnosis include viral culture, direct fluorescent antibody testing, or polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assay.1,3

The main risk factor for HZ is advanced age, most commonly affecting elderly patients.4 It is hypothesized that a physiological decline in varicella-zoster virus (VZV)–specific cell-mediated immunity among elderly individuals helps trigger reactivation of the virus within the dorsal root ganglion.1,5 Similarly affected are immunocompromised individuals, including those with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, due to suppression of T cells immune to VZV,1,5 as well as immunosuppressed transplant recipients who have diminished VZV-specific cellular responses and VZV IgG antibody avidity.6

Secondary complications of VZV infection (eg, postherpetic neuralgia, bacterial superinfection progressing to cellulitis) lead to increased morbidity.7,8 Disseminated cutaneous HZ is another grave complication of VZV infection and almost exclusively occurs with immunosuppression.1,8 It manifests as an eruption of at least 20 widespread vesiculobullous lesions outside the primary and adjacent dermatomes.6 Immunocompromised patients also are at increased risk for visceral involvement of VZV infection, which may affect vital organs such as the brain, liver, or lungs.7,8 Given the atypical presentation of VZV infection among some immunocompromised individuals, these patients are at increased risk for diagnostic delay and morbidity in the absence of high clinical suspicion for disseminated HZ.

Case Reports

Patient 1

A 52-year-old man developed a painless nonpruritic rash on the left leg of 4 days’ duration. It initially appeared as an erythematous maculopapular rash on the medial aspect of the left knee without any prodromal symptoms. Over the next 4 days, erythematous vesicles developed that progressed to pustules, and the rash spread both proximally and distally along the left leg. Shortly following hospital admission, he developed a fever (temperature, 38.4°C). His medical history included alcoholic liver cirrhosis and AIDS, with a CD4 count of 174 cells/µL (reference range, 500–1500 cells/µL). He had been taking antiretroviral therapy (abacavir-lamivudine and dolutegravir) and prophylaxis against opportunistic infections (dapsone and itraconazole).

Physical examination was remarkable for an extensive rash consisting of multiple 1-cm clusters of approximately 40 pustules each scattered in a nondermatomal distribution along the left leg (Figure 1). Many of the vesicles were confluent with an erythematous base and were in different stages of evolution with some crusted and others emanating a thin liquid exudate. The lesions were nontender and without notable induration. The leg was warm and edematous.

Clinically, the differential diagnosis included disseminated HZ with bacterial superinfection, Vibrio vulnificus infection, and herpes simplex virus (HSV) infection. The patient was treated with intravenous vancomycin, levofloxacin, and acyclovir, and no new lesions developed throughout the course of treatment. On this regimen, his fever resolved after 1 day, the active lesions began to crust, and the edema and erythema diminished. Results of bacterial cultures and plasma PCR and IgM for HSV types 1 and 2 were negative. Viral culture results were negative, but a PCR assay for VZV was positive, reflective of acute reactivation of VZV.

Patient 2

A 63-year-old man developed a pruritic burning rash involving the face, trunk, arms, and legs of 6 days’ duration. His medical history included a heart transplant 6 months prior to presentation, type 2 diabetes mellitus, and chronic kidney disease. He was taking antirejection therapy with mycophenolate mofetil (MMF), prednisone, and tacrolimus.

Physical examination was remarkable for an extensive rash consisting of clusters of 1- to 2-mm vesicles scattered in a nondermatomal pattern. Isolated vesicles involved the forehead, nose, and left ear, and diffuse vesicles with a relatively symmetric distribution were scattered across the back, chest, and proximal and distal arms and legs (Figure 2). Many of the vesicles had an associated overlying crust with hemorrhage. Some of the vesicles coalesced with central necrotic plaques.

Given a clinical suspicion for disseminated HZ, therapy with oral valacyclovir was initiated. Two punch biopsies were consistent with herpesvirus cytopathic changes. Multiple sections demonstrated ulceration as well as acantholysis and necrosis of keratinocytes with multinucleation and margination of chromatin. There was an intense lichenoid and perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate in the dermis. Immunohistochemistry staining was positive for VZV and negative for HSV, indicating acute reactivation of VZV (Figure 3). Upon completion of an antiviral regimen, the patient returned to clinic with healed crusted lesions.

Comment

Frequently, the clinical features of HZ in immunocompromised patients mirror those in immunocompetent hosts.8 However, each of our 2 patients developed an unusual presentation of atypical generalized HZ.7 In this clinical variant, lesions develop along a single dermatome, then a diffuse vesicular eruption subsequently develops without dermatomal localization. These lesions can be chronic, persisting for months or years.7

The classic clinical presentation of HZ is distinct and often is readily diagnosed by visual inspection.7 However, atypical presentations and their associated complications can pose diagnostic and therapeutic challenges.7 Painless HZ lesions in a nondermatomal pattern were described in a patient who also had AIDS.9 Interestingly, multiple reports have found that patients with a severe but painless rash are less likely to have experienced a viral prodrome consisting of hyperesthesia, paresthesia, or pruritus.2,10 This observation suggests that lack of a prodrome, as in the case of patient 1 in our report, may aid in the recognition of painless HZ. Because of these atypical presentations, laboratory testing is even more important than in immunocompetent hosts, as diagnosis may be more difficult to establish on clinical presentation alone.

Several studies11-32 have evaluated modalities for treatment and prophylaxis for disseminated HZ in immunocompromised hosts, given its increased risk and potentially fatal complications in this population. The current guidelines in patients with HIV/AIDS, solid organ transplantation (SOT), and hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) are summarized in the eTable.

HIV/AIDS Patients

Given their efficacy and low rate of toxicity, oral acyclovir, valacyclovir, and famciclovir are recommended treatment options for HIV patients with localized, mild, dermatomal HZ.11 Two exceptions include HZ ophthalmicus and Ramsay Hunt syndrome for which some experts recommend intravenous acyclovir given the risk for vision loss and facial palsy, respectively. Intravenous acyclovir often is the drug of choice for treating complicated, disseminated, or severe HZ in HIV-infected patients, though prospective efficacy data remain limited.11

With regard to prevention of infection, a large randomized trial in 2016 found that acyclovir prophylaxis resulted in a 68% reduction in HZ over 2 years among HIV patients.12 Despite data that acyclovir may be effective for this purpose, long-term antiviral prophylaxis is not routinely recommended for HZ,11,13 as it has been linked to rare cases of acyclovir-resistant HZ in HIV patients.14,15 However, antiviral prophylaxis against HSV type 2 reactivation in HIV patients also confers protection against VZV reactivation.11,12

Solid Organ Transplantation

Localized, mild to moderately severe dermatomal HZ can be treated with oral acyclovir, valacyclovir, or famciclovir. As in HIV patients, SOT patients with severe, disseminated, or complicated HZ should receive IV acyclovir.11 In the first 3 to 6 months following the procedure, SOT patients receive cytomegalovirus prophylaxis with ganciclovir or valgan-ciclovir, which also provides protection against HZ.13-18 For patients not receiving cytomegalovirus prophylaxis, HSV prophylaxis with oral acyclovir or valacyclovir is given for at least the first month after transplantation, which also confers protection against HZ.16,19 Antiviral therapy is critical during the early posttransplantation period when patients are most severely immunosuppressed and thus have the highest risk for VZV-associated complications.20 Although immunosuppression is lifelong in most SOT recipients, there is insufficient evidence for extending prophylaxis beyond 6 months.16,21

As a possible risk factor for HZ,22 MMF use is another consideration among SOT patients, similar to patient 2 in our report. A 2003 observational study supported withdrawal of MMF therapy during active VZV infection due to clinical observation of an association with HZ.23 However, a multicenter, randomized, controlled trial reported no cases of HZ in renal transplant recipients on MMF.24 Additionally, MMF has been observed to enhance the antiviral activity of acyclovir, at least in vitro.25 Given the lack of evidence of MMF as a risk factor for HZ, there is insufficient evidence for cessation of use during VZVreactivation in SOT patients.

Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation

The preferred agents for treatment of localized mild dermatomal HZ are oral acyclovir or valacyclovir, as data on the safety and efficacy of famciclovir among HSCT recipients are limited.13,26 Patients should receive antiviral prophylaxis with one of these agents during the first year following allogeneic or autologous HSCT. This 1-year course has proven highly effective in reducing HZ in the first year following transplantation when most severe cases occur,21,26-29 and it has been associated with a persistently decreased risk for HZ even after discontinuation.21 Prophylaxis may be continued beyond 1 year in allogeneic HSCT recipients experiencing graft-versus-host disease who should receive acyclovir until 6 months after the end of immunosuppressive therapy.21,26

Vaccination remains a potential strategy to reduce the incidence of HZ in this patient population. A heat-inactivated vaccine administered within the first 3 months after the procedure has been shown to be safe among autologous and allogeneic HSCT patients.30,31 The vaccine notably reduced the incidence of HZ in patients who underwent autologous HSCT,32 but no known data are available on its clinical efficacy in allogeneic HSCT patients. Accordingly, there are no known official recommendations to date regarding vaccine use in these patient populations.26

Conclusion

It is incumbent upon clinicians to recognize the spectrum of atypical presentations of HZ and maintain a low threshold for performing appropriate diagnostic or confirmatory studies among at-risk patients with impaired immune function. Disseminated HZ can have potentially life-threatening visceral complications such as encephalitis, hepatitis, or pneumonitis.7,8 As such, an understanding of prevention and treatment modalities for VZV infection among immunocompromised patients is critical. Because the morbidity associated with complications of VZV infection is substantial and the risks associated with antiviral agents are minimal, antiviral prophylaxis is recommended for 6 months following SOT or 1 year following HSCT, and prompt treatment is warranted in cases of reasonable clinical suspicion for HZ.

Acknowledgment

The authors gratefully acknowledge the generosity of our patients in permitting photography of their skin findings for the furthering of medical education.

- McCrary ML, Severson J, Tyring SK. Varicella zoster virus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41:1-16.

- Nagasako EM, Johnson RW, Griffin DR, et al. Rash severity in herpes zoster: correlates and relationship to postherpetic neuralgia. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46:834-839.

- Leung J, Harpaz R, Baughman AL, et al. Evaluation of laboratory methods for diagnosis of varicella. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;51:23-32.

- Herpes Zoster and Functional Decline Consortium. Functional decline and herpes zoster in older people: an interplay of multiple factors. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2015;27:757-765.

- Weinberg A, Levin MJ. VZV T cell-mediated immunity. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2010;342:341-357.

- Prelog M, Schonlaub J, Jeller V, et al. Reduced varicella-zoster-virus (VZV)-specific lymphocytes and IgG antibody avidity in solid organ transplant recipients. Vaccine. 2013;31:2420-2426.

- Gnann JW Jr. Varicella-zoster virus: atypical presentations and unusual complications. J Infect Dis. 2002;186(suppl 1):S91-S98.

- Glesby MJ, Moore RD, Chaisson RE. Clinical spectrum of herpes zoster in adults infected with human immunodeficiency virus. Clin Infect Dis. 1995;21:370-375.

- Blankenship W, Herchline T, Hockley A. Asymptomatic vesicles in a patient with the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. disseminated varicella-zoster virus (VZV) infection. Arch Dermatol. 1994;130:1193, 1196.

- Katz J, Cooper EM, Walther RR, et al. Acute pain in herpes zoster and its impact on health-related quality of life. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;39:342-348.

- Gnann JW. Antiviral therapy of varicella-zoster virus infections. In: Arvin A, Campadelli-Fiume G, Mocarski E, et al, eds. Human Herpesviruses: Biology, Therapy, and Immunoprophylaxis. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press; 2007:1175-1191.

- Barnabas RV, Baeten JM, Lingappa JR, et al. Acyclovir prophylaxis reduces the incidence of herpes zoster among HIV-infected individuals: results of a randomized clinical trial. J Infect Dis. 2016;213:551-555.

- Dworkin RH, Johnson RW, Breuer J, et al. Recommendations for the management of herpes zoster. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44(suppl 1):S1-S26.

- Jacobson MA, Berger TG, Fikrig S, et al. Acyclovir-resistant varicella zoster virus infection after chronic oral acyclovir therapy in patients with the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS). Ann Intern Med. 1990;112:187-191.

- Linnemann CC Jr, Biron KK, Hoppenjans WG, et al. Emergence of acyclovir-resistant varicella zoster virus in an AIDS patient on prolonged acyclovir therapy. AIDS. 1990;4:577-579.

- Pergam SA, Limaye AP; AST Infectious Diseases Community of Practice. Varicella zoster virus (VZV) in solid organ transplant recipients. Am J Transplant. 2009;9(suppl 4):S108-S115.

- Preiksaitis JK, Brennan DC, Fishman J, et al. Canadian society of transplantation consensus workshop on cytomegalovirus management in solid organ transplantation final report. Am J Transplant. 2005;5:218-227.

- Fishman JA, Doran MT, Volpicelli SA, et al. Dosing of intravenous ganciclovir for the prophylaxis and treatment of cytomegalovirus infection in solid organ transplant recipients. Transplantation. 2000;69:389-394.

- Zuckerman R, Wald A; AST Infectious Diseases Community of Practice. Herpes simplex virus infections in solid organ transplant recipients. Am J Transplant. 2009;9(suppl 4):S104-S107.

- Arness T, Pedersen R, Dierkhising R, et al. Varicella zoster virus-associated disease in adult kidney transplant recipients: incidence and risk-factor analysis. Transpl Infect Dis. 2008;10:260-268.

- Erard V, Guthrie KA, Varley C, et al. One-year acyclovir prophylaxis for preventing varicella-zoster virus disease after hematopoietic cell transplantation: no evidence of rebound varicella-zoster virus disease after drug discontinuation. Blood. 2007;110:3071-3077.

- Rothwell WS, Gloor JM, Morgenstern BZ, et al. Disseminated varicella infection in pediatric renal transplant recipients treated with mycophenolate mofetil. Transplantation. 1999;68:158-161.

- Lauzurica R, Bayés B, Frías C, et al. Disseminated varicella infection in adult renal allograft recipients: role of mycophenolate mofetil. Transplant Proc. 2003;35:1758-1759.

- A blinded, randomized clinical trial of mycophenolate mofetil for the prevention of acute rejection in cadaveric renal transplantation. TheTricontinental Mycophenolate Mofetil Renal Transplantation Study Group. Transplantation. 1996;61:1029-1037.

- Neyts J, De Clercq E. Mycophenolate mofetil strongly potentiates the anti-herpesvirus activity of acyclovir. Antiviral Res. 1998;40:53-56.

- Tomblyn M, Chiller T, Einsele H, et al. Guidelines for preventing infectious complications among hematopoietic cell transplantation recipients: a global perspective. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2009;15:1143-1238.

- Boeckh M, Kim HW, Flowers ME, et al. Long-term acyclovir for prevention of varicella zoster virus disease after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation—a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled study. Blood. 2006;107:1800-1805.

- Kawamura K, Hayakawa J, Akahoshi Y, et al. Low-dose acyclovir prophylaxis for the prevention of herpes simplex virus and varicella zoster virus diseases after autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Int J Hematol. 2015;102:230-237.

- Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center/Seattle Cancer Care Alliance. Long-term follow-up after hematopoietic stem cell transplant general guidelines for referring physicians. Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center website. https://www.fredhutch.org/content/dam/public/Treatment-Suport/Long-Term-Follow-Up/physician.pdf. Published July 17, 2014. Accessed October 19, 2017.

- Kussmaul SC, Horn BN, Dvorak CC, et al. Safety of the live, attenuated varicella vaccine in pediatric recipients of hematopoietic SCTs. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2010;45:1602-1606.

- Hata A, Asanuma H, Rinki M, et al. Use of an inactivated varicella vaccine in recipients of hematopoietic-cell transplants. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:26-34.

- Issa NC, Marty FM, Leblebjian H, et al. Live attenuated varicella-zoster vaccine in hematopoietic stem cell transplantation recipients. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2014;20:285-287.

- McCrary ML, Severson J, Tyring SK. Varicella zoster virus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41:1-16.

- Nagasako EM, Johnson RW, Griffin DR, et al. Rash severity in herpes zoster: correlates and relationship to postherpetic neuralgia. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46:834-839.

- Leung J, Harpaz R, Baughman AL, et al. Evaluation of laboratory methods for diagnosis of varicella. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;51:23-32.

- Herpes Zoster and Functional Decline Consortium. Functional decline and herpes zoster in older people: an interplay of multiple factors. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2015;27:757-765.

- Weinberg A, Levin MJ. VZV T cell-mediated immunity. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2010;342:341-357.

- Prelog M, Schonlaub J, Jeller V, et al. Reduced varicella-zoster-virus (VZV)-specific lymphocytes and IgG antibody avidity in solid organ transplant recipients. Vaccine. 2013;31:2420-2426.

- Gnann JW Jr. Varicella-zoster virus: atypical presentations and unusual complications. J Infect Dis. 2002;186(suppl 1):S91-S98.

- Glesby MJ, Moore RD, Chaisson RE. Clinical spectrum of herpes zoster in adults infected with human immunodeficiency virus. Clin Infect Dis. 1995;21:370-375.

- Blankenship W, Herchline T, Hockley A. Asymptomatic vesicles in a patient with the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. disseminated varicella-zoster virus (VZV) infection. Arch Dermatol. 1994;130:1193, 1196.

- Katz J, Cooper EM, Walther RR, et al. Acute pain in herpes zoster and its impact on health-related quality of life. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;39:342-348.

- Gnann JW. Antiviral therapy of varicella-zoster virus infections. In: Arvin A, Campadelli-Fiume G, Mocarski E, et al, eds. Human Herpesviruses: Biology, Therapy, and Immunoprophylaxis. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press; 2007:1175-1191.

- Barnabas RV, Baeten JM, Lingappa JR, et al. Acyclovir prophylaxis reduces the incidence of herpes zoster among HIV-infected individuals: results of a randomized clinical trial. J Infect Dis. 2016;213:551-555.

- Dworkin RH, Johnson RW, Breuer J, et al. Recommendations for the management of herpes zoster. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44(suppl 1):S1-S26.

- Jacobson MA, Berger TG, Fikrig S, et al. Acyclovir-resistant varicella zoster virus infection after chronic oral acyclovir therapy in patients with the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS). Ann Intern Med. 1990;112:187-191.

- Linnemann CC Jr, Biron KK, Hoppenjans WG, et al. Emergence of acyclovir-resistant varicella zoster virus in an AIDS patient on prolonged acyclovir therapy. AIDS. 1990;4:577-579.

- Pergam SA, Limaye AP; AST Infectious Diseases Community of Practice. Varicella zoster virus (VZV) in solid organ transplant recipients. Am J Transplant. 2009;9(suppl 4):S108-S115.

- Preiksaitis JK, Brennan DC, Fishman J, et al. Canadian society of transplantation consensus workshop on cytomegalovirus management in solid organ transplantation final report. Am J Transplant. 2005;5:218-227.

- Fishman JA, Doran MT, Volpicelli SA, et al. Dosing of intravenous ganciclovir for the prophylaxis and treatment of cytomegalovirus infection in solid organ transplant recipients. Transplantation. 2000;69:389-394.

- Zuckerman R, Wald A; AST Infectious Diseases Community of Practice. Herpes simplex virus infections in solid organ transplant recipients. Am J Transplant. 2009;9(suppl 4):S104-S107.

- Arness T, Pedersen R, Dierkhising R, et al. Varicella zoster virus-associated disease in adult kidney transplant recipients: incidence and risk-factor analysis. Transpl Infect Dis. 2008;10:260-268.

- Erard V, Guthrie KA, Varley C, et al. One-year acyclovir prophylaxis for preventing varicella-zoster virus disease after hematopoietic cell transplantation: no evidence of rebound varicella-zoster virus disease after drug discontinuation. Blood. 2007;110:3071-3077.

- Rothwell WS, Gloor JM, Morgenstern BZ, et al. Disseminated varicella infection in pediatric renal transplant recipients treated with mycophenolate mofetil. Transplantation. 1999;68:158-161.

- Lauzurica R, Bayés B, Frías C, et al. Disseminated varicella infection in adult renal allograft recipients: role of mycophenolate mofetil. Transplant Proc. 2003;35:1758-1759.

- A blinded, randomized clinical trial of mycophenolate mofetil for the prevention of acute rejection in cadaveric renal transplantation. TheTricontinental Mycophenolate Mofetil Renal Transplantation Study Group. Transplantation. 1996;61:1029-1037.

- Neyts J, De Clercq E. Mycophenolate mofetil strongly potentiates the anti-herpesvirus activity of acyclovir. Antiviral Res. 1998;40:53-56.

- Tomblyn M, Chiller T, Einsele H, et al. Guidelines for preventing infectious complications among hematopoietic cell transplantation recipients: a global perspective. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2009;15:1143-1238.

- Boeckh M, Kim HW, Flowers ME, et al. Long-term acyclovir for prevention of varicella zoster virus disease after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation—a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled study. Blood. 2006;107:1800-1805.

- Kawamura K, Hayakawa J, Akahoshi Y, et al. Low-dose acyclovir prophylaxis for the prevention of herpes simplex virus and varicella zoster virus diseases after autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Int J Hematol. 2015;102:230-237.

- Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center/Seattle Cancer Care Alliance. Long-term follow-up after hematopoietic stem cell transplant general guidelines for referring physicians. Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center website. https://www.fredhutch.org/content/dam/public/Treatment-Suport/Long-Term-Follow-Up/physician.pdf. Published July 17, 2014. Accessed October 19, 2017.

- Kussmaul SC, Horn BN, Dvorak CC, et al. Safety of the live, attenuated varicella vaccine in pediatric recipients of hematopoietic SCTs. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2010;45:1602-1606.

- Hata A, Asanuma H, Rinki M, et al. Use of an inactivated varicella vaccine in recipients of hematopoietic-cell transplants. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:26-34.

- Issa NC, Marty FM, Leblebjian H, et al. Live attenuated varicella-zoster vaccine in hematopoietic stem cell transplantation recipients. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2014;20:285-287.

Practice Points

- Clinician awareness of management guidelines for the prevention and treatment of varicella-zoster virus infection in immunocompromised individuals is critical to minimize the risk for disease and associated morbidity.

- Antiviral prophylaxis is recommended for 6 months following solid organ transplantation or 1 year following hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, and prompt treatment is warranted in cases of reasonable clinical suspicion for herpes zoster.

Mycobacterium marinum Remains an Unrecognized Cause of Indolent Skin Infections

An environmental pathogen, Mycobacterium marinum can cause cutaneous infection when traumatized skin is exposed to fresh, brackish, or salt water. Fishing, aquarium cleaning, and aquatic recreational activities are risk factors for infection.1,2 Diagnosis often is delayed and is made several weeks or even months after initial symptoms appear.3 Due to the protracted clinical course, patients may not recall the initial exposure, contributing to the delay in diagnosis and initiation of appropriate treatment. It is not uncommon for patients with M marinum infection to be initially treated with antibiotics or antifungal drugs.

We present a review of 5 patients who were diagnosed with M marinum infection at our institution between January 2003 and March 2013.

Methods

This study was conducted at Henry Ford Hospital, a 900-bed tertiary care center in Detroit, Michigan. Patients who had cultures positive for M marinum between January 2003 and March 2013 were identified using the institution’s laboratory database. Medical records were reviewed, and relevant demographic, epidemiologic, and clinical data, including initial clinical presentation, alternative diagnoses, time between initial presentation and definitive diagnosis, and specific treatment, were recorded.

Results

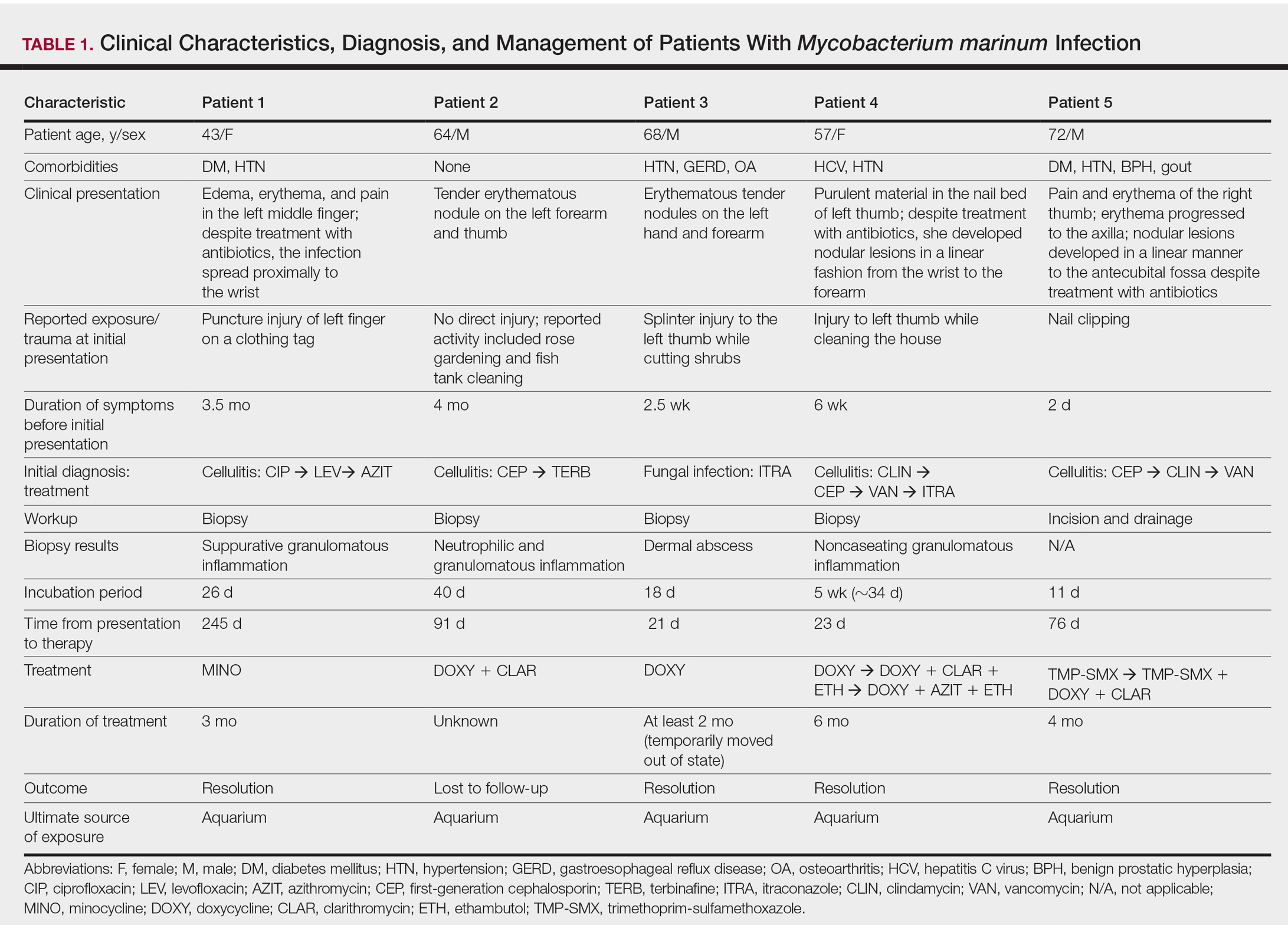

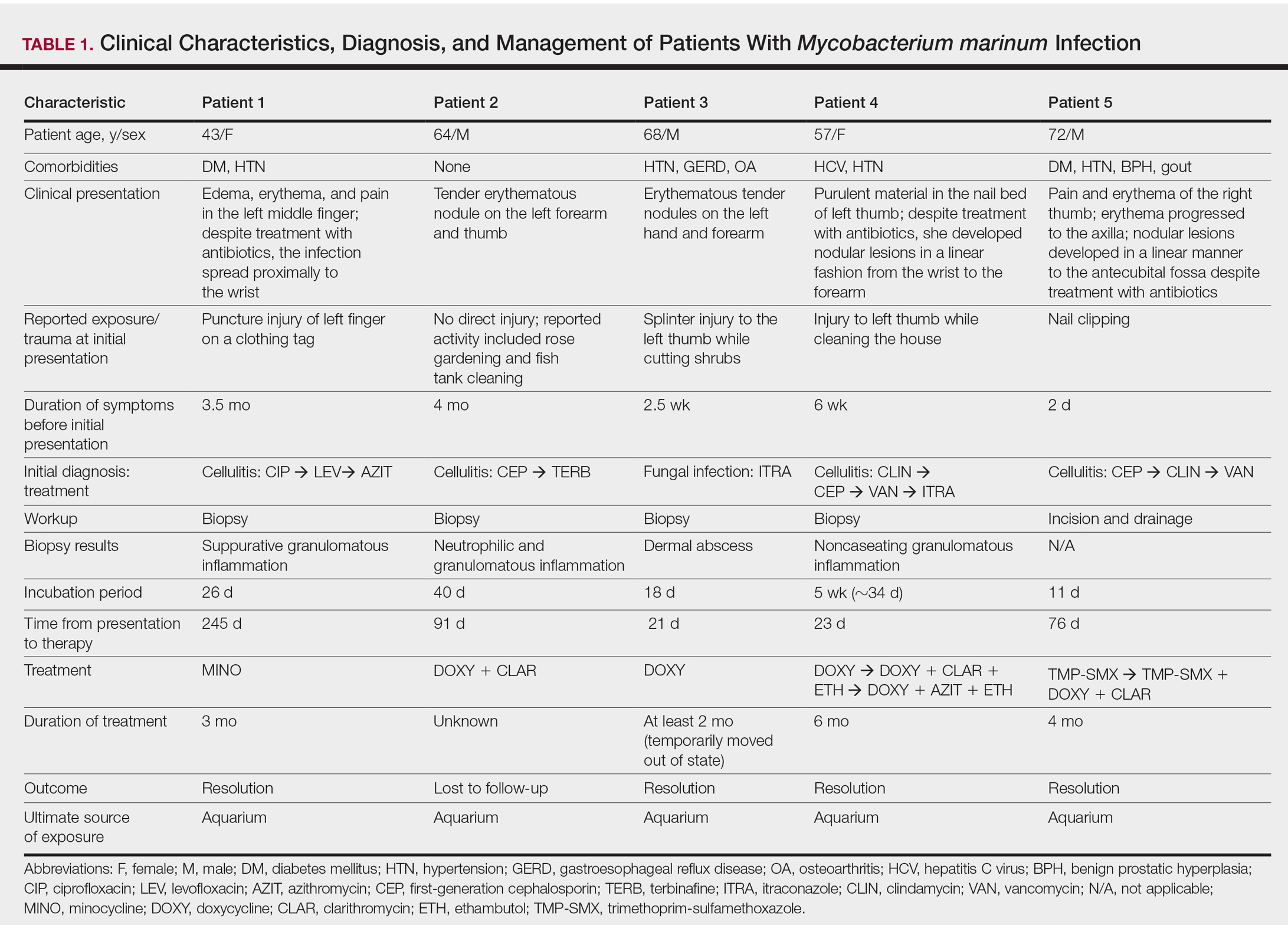

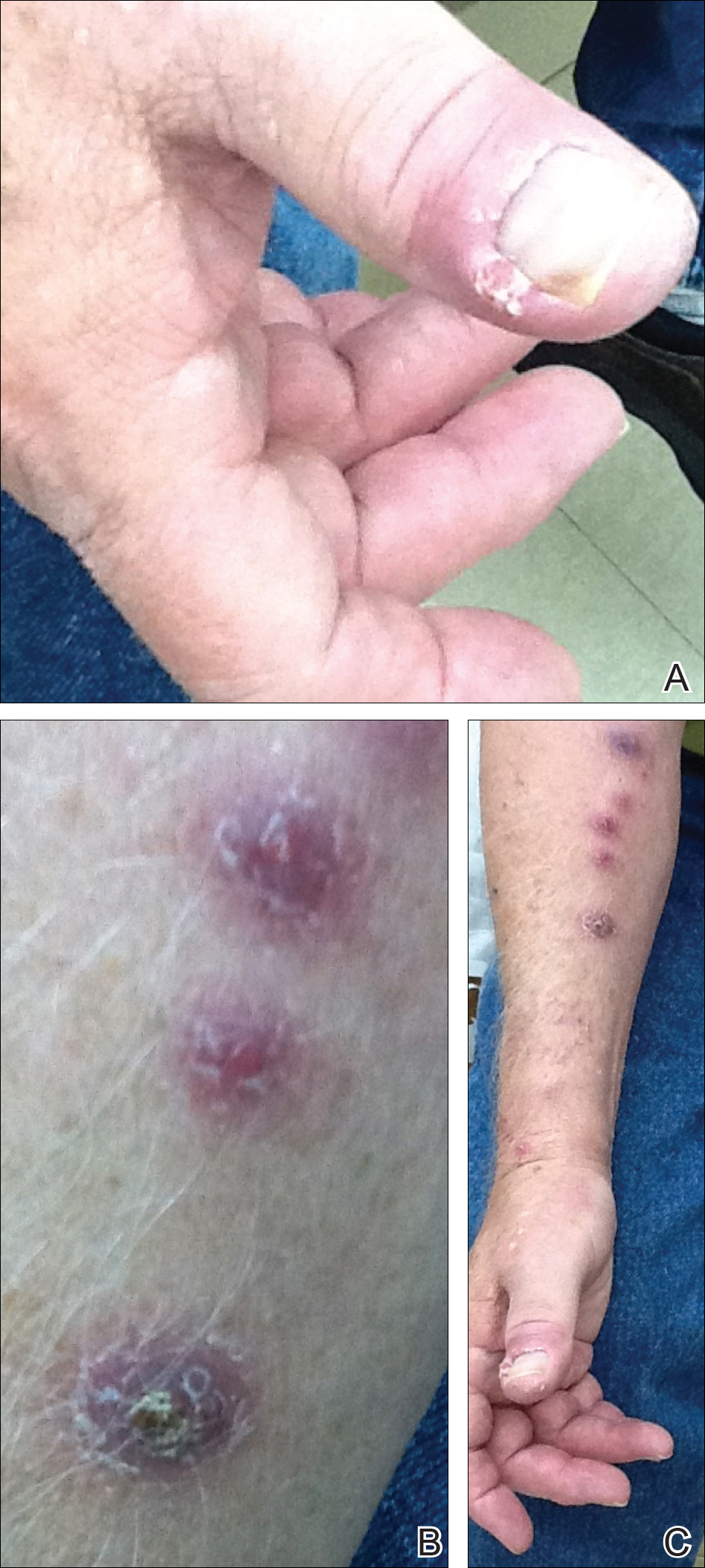

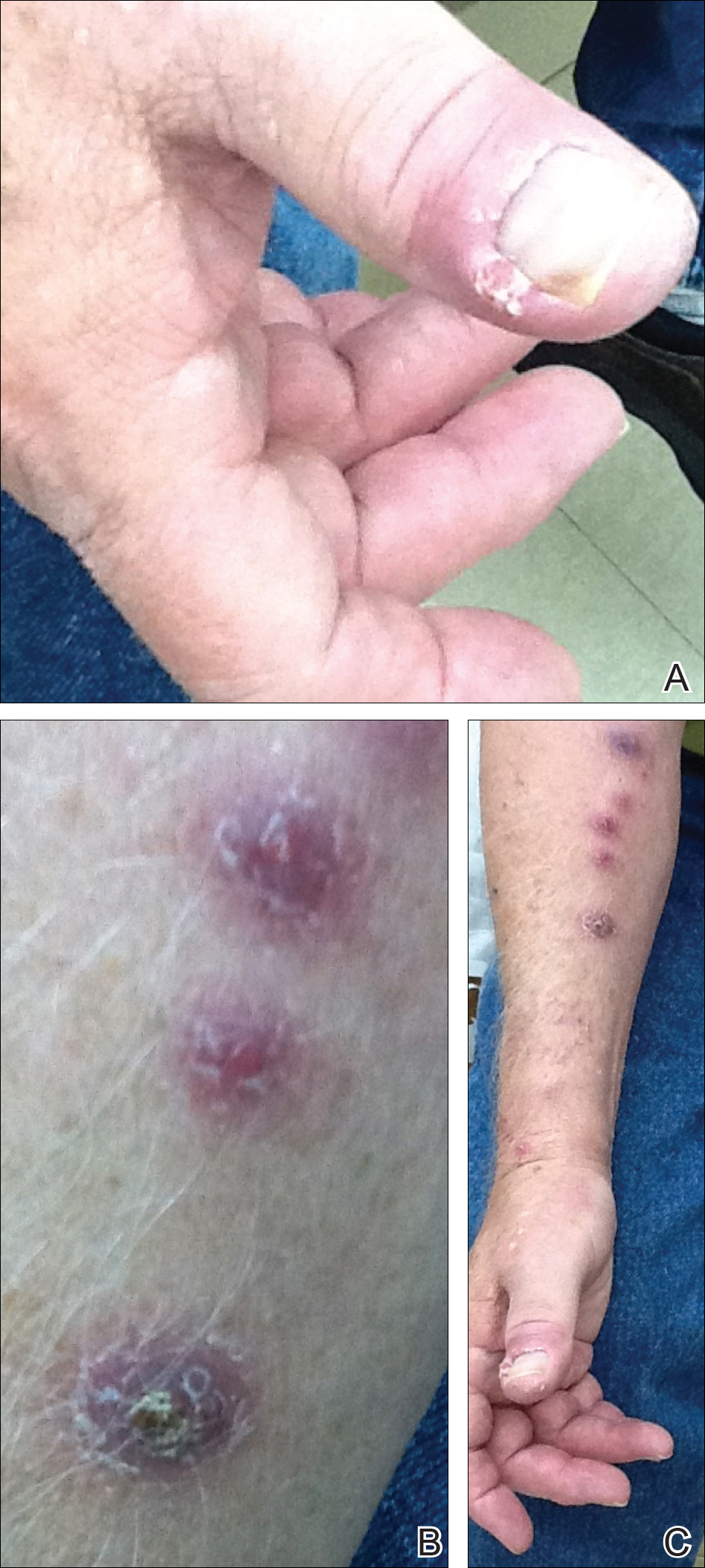

We identified 5 patients who were diagnosed with culture-confirmed M marinum skin infections during the study period: 3 men and 2 women aged 43 to 72 years (Table 1). Two patients had diabetes mellitus and 1 had hepatitis C virus. None had classic immunosuppression. On repeated questioning after the diagnosis was established, all 5 patients reported that they kept a home aquarium, and all recalled mild trauma to the hand prior to the onset of symptoms; however, none of the patients initially linked the minor skin injury to the subsequent infection.

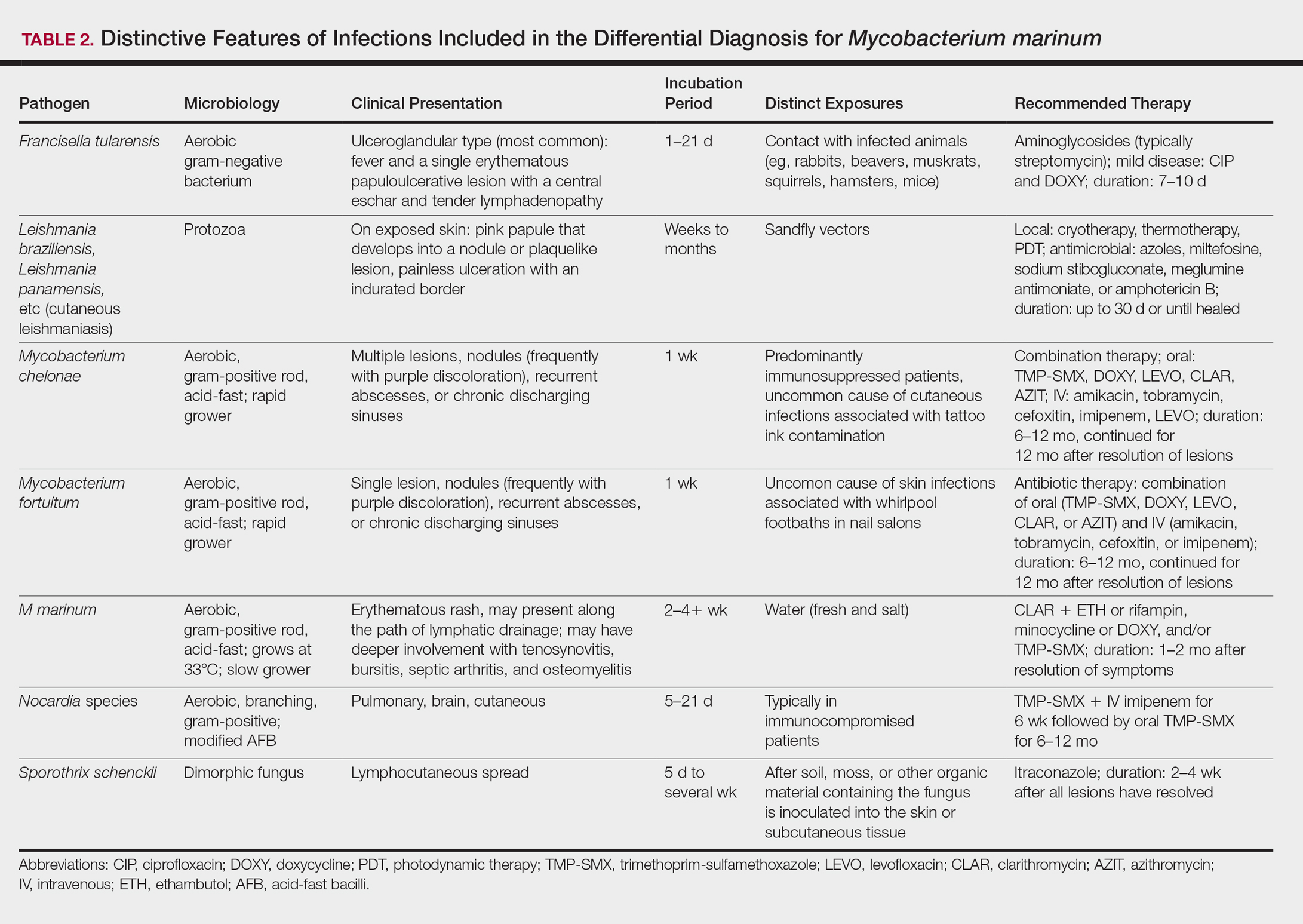

All 5 patients initially presented with erythema and swelling at the site of the injury, which evolved into inflammatory nodules that progressed proximally up to the arm despite empiric treatment with antibiotics active against streptococci and staphylococci (Figures 1 and 2). Three patients also received empiric antifungal therapy due to suspicion of sporotrichosis.

Skin biopsies were performed on 4 patients, and incision and drainage of purulent material was performed on the fifth patient. Histopathologic examination revealed granulomatous inflammation in 3 patients. Stains for acid-fast bacilli were positive in all 5 patients. Definitive diagnosis of the organism was confirmed by growth of M marinum within 11 to 40 days from the tissue in 4 patients and purulent material in the fifth patient. Susceptibility testing was performed on only 1 of the 5 isolates and showed that the organism was susceptible to amikacin, clarithromycin, doxycycline, ethambutol, rifampin, and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (TMP-SMX).

The mean time from initial presentation to initiation of appropriate therapy for M marinum infection was 91 days (range, 21–245 days). Several different treatment regimens were used. All patients received either doxycycline or minocycline with or without a macrolide. Two also received other agents (TMP-SMX or ethambutol). Treatment duration varied from 2 to 6 months in 4 patients, and all 4 had complete resolution of the lesions; 1 patient was lost to follow-up.

Comment

Diagnosing the Infection

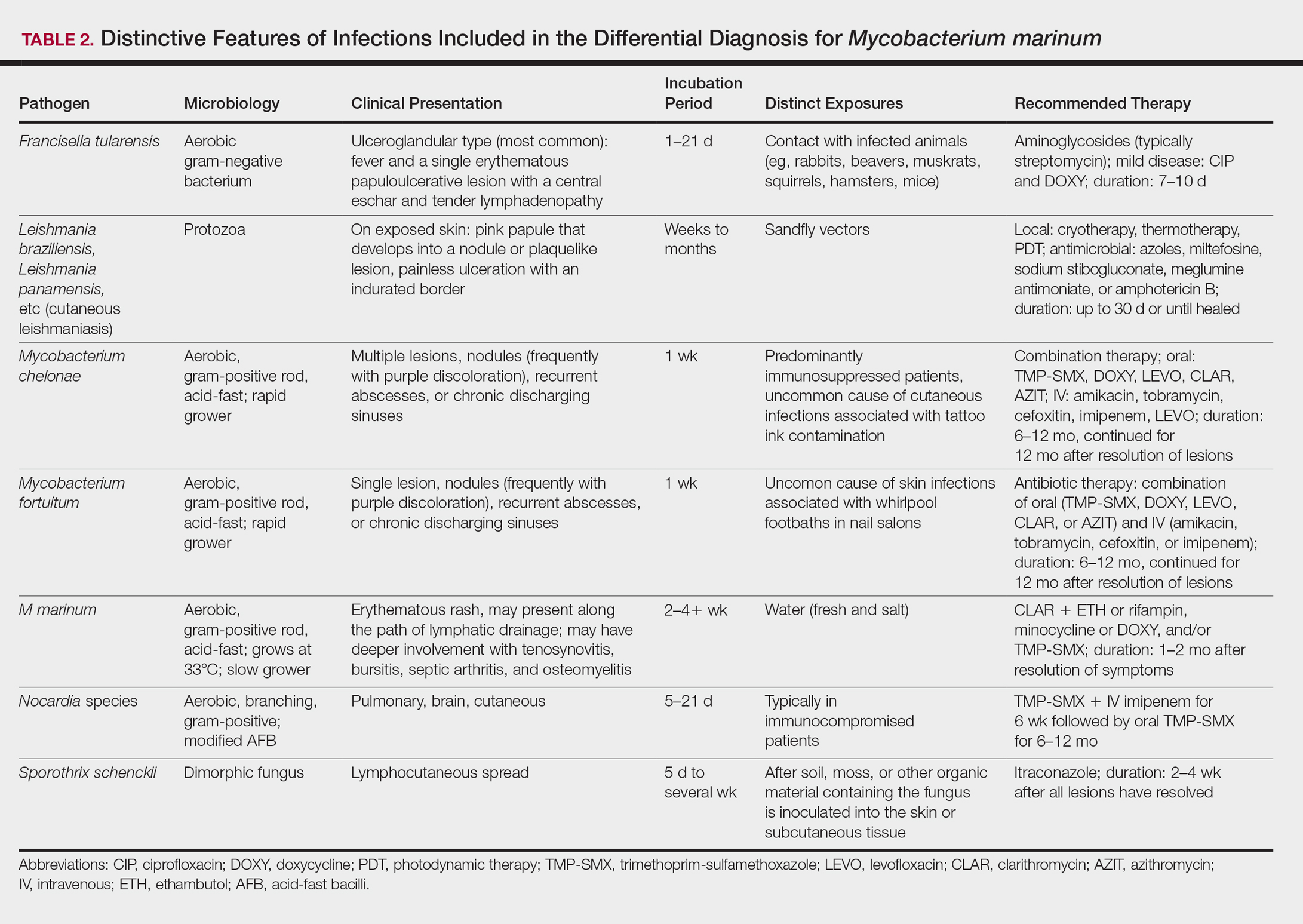

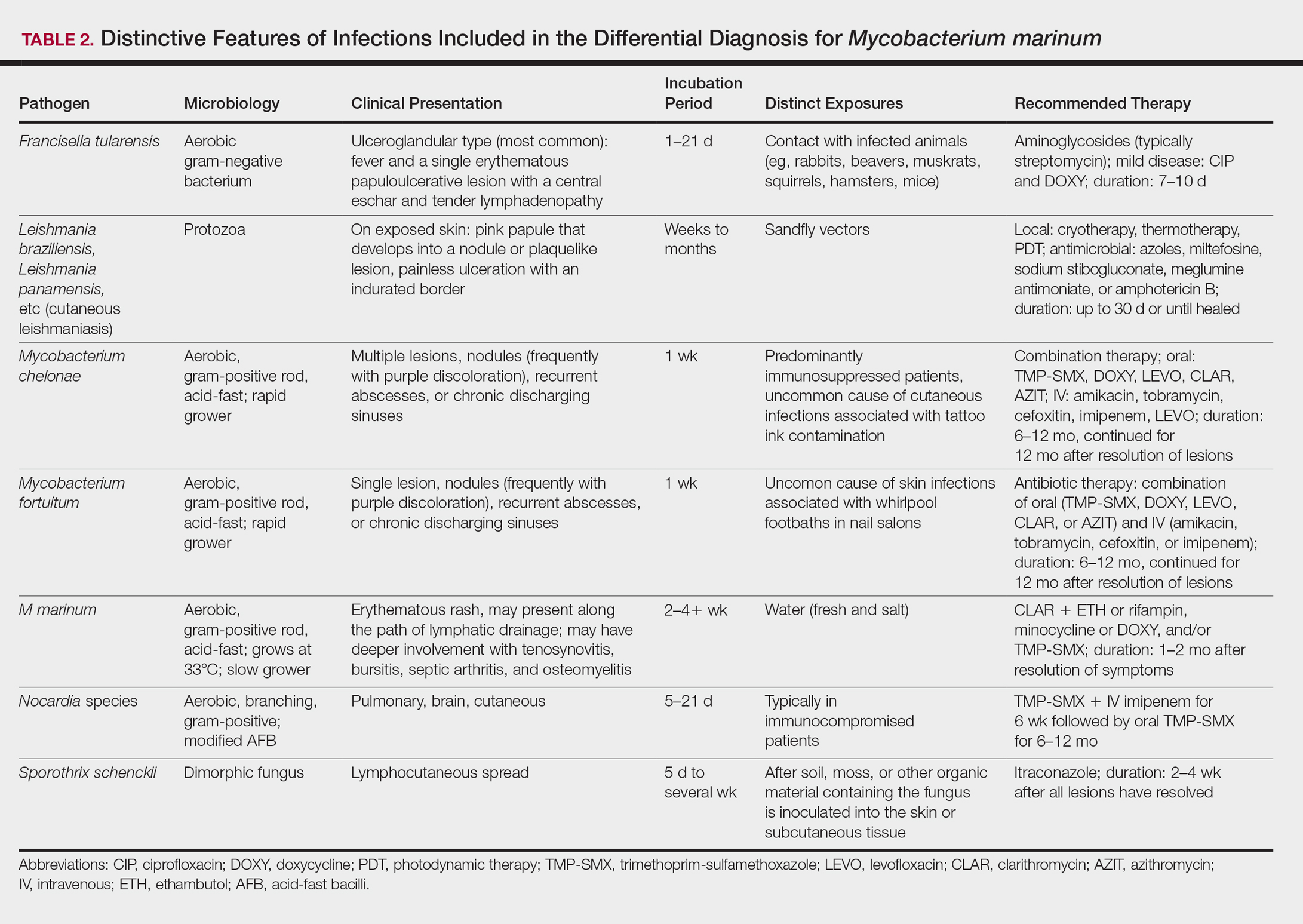

Diagnosis of M marinum infection remains problematic. In the 5 patients included in this study, the time between initial onset of symptoms and diagnosis of M marinum infection was delayed, as has been noted in other reports.4-7 Delays as long as 2 years before the diagnosis is made have been described.7 The clinical presentation of cutaneous infection with M marinum varies, which may delay diagnosis. Nodular lymphangitis is classic, but papules, pustules, ulcers, inflammatory plaques, and single nodules also can occur.1,2 Lymphadenopathy may or may not be present.4,8,9 The differential diagnosis is broad and includes infection by other nontuberculous mycobacteria such as Mycobacterium chelonae; Mycobacterium fortuitum; Nocardia species, especially Nocardia brasiliensis; Francisella tularensis; Sporothrix schenckii; and Leishmania species. It is not surprising that 4 patients in our study were initially treated for a gram-positive bacterial infection and 3 were treated for a fungal infection before the diagnosis of M marinum was made. Distinctive features that may help to differentiate these infections are summarized in Table 2.

We found that the main cause of delayed diagnosis was the failure of physicians to obtain a thorough history regarding patients’ recreational activities and animal exposure. Patients often do not associate a remote aquatic exposure with their symptoms and will not volunteer this information unless directly asked.2,10 It was only after repeated questioning in all of these patients that they recounted prior trauma to the involved hand related to the aquarium.

Biopsy and Culture

Histopathologic examination of material from a biopsied lesion can give an early clue that a mycobacterial infection might be involved. Biopsy can reveal either noncaseating or necrotizing granulomas that have larger numbers of neutrophils in addition to lymphocytes and macrophages. Giant cells often are noted.5,9,11 Organisms can be seen with the use of a tissue acid-fast stain, but species cannot be differentiated by acid-fast staining.12 However, the sensitivity of acid-fast stains on biopsy material is low.3,13,14

Culture of the involved tissue is crucial for establishing the diagnosis of this infection. However, the rate of growth of M marinum is slow. Temperature requirements for incubation and delay in transporting specimens to the laboratory can lead to bacterial overgrowth, resulting in the inability to recover M marinum from the culture.13Mycobacterium marinum grows preferentially between 28°C and 32°C, and growth is limited at temperatures above 33°C.13,15,16 As illustrated in the cases presented, recovery of the organism may not be accomplished from the first culture performed, and additional biopsy material for culture may be needed. Liquid media generally is more sensitive and produces more rapid results than solid media (eg, Löwenstein-Jensen, Middlebrook 7H10/7H11 agar). However, solid media carry the advantage of allowing observation of morphology and estimation of the number of organisms.12,17

Rapid Detection

Advancements in molecular methods have allowed for more definitive and rapid identification of M marinum, substantially reducing the delay in diagnosis. Commercial molecular assays utilize in-solution hybridization or solid-format reverse-hybridization assays to allow mycobacterial detection as soon as growth appears.18 Use of matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry can substantially shorten the time to species identification.19,20 Nonculture-based tests that have been developed for the rapid detection of M marinum infection include polymerase chain reaction-restriction fragment length polymorphism and polymerase chain reaction amplification of the 16S RNA gene.21 It should be noted, however, that M marinum and Mycobacterium ulcerans have a very homologous 16S ribosomal RNA gene sequence, differing by only 1 nucleotide; thus, distinguishing between M marinum and M ulcerans using this method may be challenging.22,23

Management

Treatment depends on the extent of the disease. Generally, localized cutaneous disease can be treated with monotherapy with agents such as doxycycline, clarithromycin, or TMP-SMX. Extensive disease typically requires a combination of 2 antimycobacterial agents, typically clarithromycin-rifampin, clarithromycin-ethambutol, or rifampin-ethambutol.12 Amikacin has been used in combination with other agents such as rifampin and clarithromycin in refractory cases.22,24 The use of ciprofloxacin is not encouraged because some isolates are resistant; however, other fluoroquinolones, such as moxifloxacin, may be options for combination therapy. Isoniazid, pyrazinamide, and streptomycin are not effective to treat M marinum.

Susceptibility testing of M marinum usually is performed to guide antimicrobial therapy in cases of poor clinical response or intolerance to first-line antimicrobials such as macrolides.25 The likelihood of M marinum developing resistance to the agents used for treatment appears to be low. Unfortunately, in vitro antimicrobial susceptibility tests do not correlate well with treatment efficiency.10

The duration of therapy is not standardized but usually is 5 to 6 months,7,10,26 with therapy often continuing 1 to 2 months after lesions appear to have resolved.12 However, in some cases (usually those who have more extensive disease), therapy has been extended to as long as 1 to 2 years.10 The ideal length of therapy in immunocompromised individuals has not been established27; however, a treatment duration of 6 to 9 months was reported in one study.28 Surgical debridement may be necessary in some patients who have involvement of deep structures of the hand or knee, those with persistent pain, or those who fail to respond to a prolonged period of medical therapy.29 Successful use of less conventional therapeutic approaches, including cryotherapy, radiation therapy, electrodesiccation, photodynamic therapy, curettage, and local hyperthermic therapy has been reported.30-32

Conclusion

Diagnosis and management of M marinum infection is difficult. Patients presenting with indolent nodular skin infections affecting the upper extremities should be asked about aquatic exposure. Tissue biopsy for histopathologic examination and culture is essential to establish an early diagnosis and promptly initiate appropriate therapy.

Acknowledgment

We would like to thank Carol A. Kauffman, MD (Ann Arbor, Michigan), for her thoughtful comments that greatly improved this manuscript.

- Lewis FM, Marsh BJ, von Reyn CF. Fish tank exposure and cutaneous infections due to Mycobacterium marinum: tuberculin skin testing, treatment, and prevention. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;37:390-397.

- Jernigan JA, Farr BM. Incubation period and sources of exposure for cutaneous Mycobacterium marinum infection: case report and review of the literature. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;31:439-443.

- Edelstein H. Mycobacterium marinum skin infections. report of 31 cases and review of the literature. Arch Intern Med. 1994;154:1359-1364.

- Janik JP, Bang RH, Palmer CH. Case reports: successful treatment of Mycobacterium marinum infection with minocycline after complication of disease by delayed diagnosis and systemic steroids. J Drugs Dermatol. 2005;4:621-624.

- Jolly HW Jr, Seabury JH. Infections with Myocbacterium marinum. Arch Dermatol. 1972;106:32-36.

- Sette CS, Wachholz PA, Masuda PY, et al. Mycobacterium marinum infection: a case report. J Venom Anim Toxins Incl Trop Dis. 2015;21:7.

- Johnson MG, Stout JE. Twenty-eight cases of Mycobacterium marinum infection: retrospective case series and literature review. Infection. 2015;43:655-662.

- Eberst E, Dereure O, Guillot B, et al. Epidemiological, clinical, and therapeutic pattern of Mycobacterium marinum infection: a retrospective series of 35 cases from southern France. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66:E15-E16.

- Philpott JA Jr, Woodburne AR, Philpott OS, et al. Swimming pool granuloma. a study of 290 cases. Arch Dermatol. 1963;88:158-162.

- Aubry A, Chosidow O, Caumes E, et al. Sixty-three cases of Mycobacterium marinum infection: clinical features, treatment, and antibiotic susceptibility of causative isolates. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162:1746-1752.

- Feng Y, Xu H, Wang H, et al. Outbreak of a cutaneous Mycobacterium marinum infection in Jiangsu Haian, China. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2011;71:267-272.

- Griffith DE, Aksamit T, Brown-Elliott BA, et al; ATS Mycobacterial Diseases Subcommittee; American Thoracic Society; Infectious Disease Society of America. An official ATS/IDSA statement: diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of non-tuberculous mycobacterial diseases. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;175:367-416.

- Ang P, Rattana-Apiromyakij N, Goh CL. Retrospective study of Mycobacterium marinum skin infections. Int J Dermatol. 2000;39:343-347.

- Wu TS, Chiu CH, Yang CH, et al. Fish tank granuloma caused by Mycobacterium marinum. PLoS One. 2012;7:e41296.

- Ho WL, Chuang WY, Kuo AJ, et al. Nasal fish tank granuloma: an uncommon cause for epistaxis. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2011;85:195-196.

- Dobos KM, Quinn FD, Ashford DA, et al. Emergence of a unique group of necrotizing mycobacterial diseases. Emerg Infect Dis. 1999;5:367-378.

- van Ingen J. Diagnosis of non-tuberculous mycobacterial infections. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;34:103-109.

- Piersimoni C, Scarparo C. Extrapulmonary infections associated with non-tuberculous mycobacteria in immunocompetent persons. Emerg Infect Dis. 2009;15:1351-1358; quiz 1544.

- Saleeb PG, Drake SK, Murray PR, et al. Identification of mycobacteria in solid-culture media by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry. J Clin Microbiol. 2011;49:1790-1794.

- Adams LL, Salee P, Dionne K, et al. A novel protein extraction method for identification of mycobacteria using MALDI-ToF MS. J Microbiol Methods. 2015;119:1-3.

- Posteraro B, Sanguinetti M, Garcovich A, et al. Polymerase chain reaction-reverse cross-blot hybridization assay in the diagnosis of sporotrichoid Mycobacterium marinum infection. Br J Dermatol. 1998;139:872-876.

- Lau SK, Curreem SO, Ngan AH, et al. First report of disseminated Mycobacterium skin infections in two liver transplant recipients and rapid diagnosis by hsp65 gene sequencing. J Clin Microbiol. 2011;49:3733-3738.

- Hofer M, Hirschel B, Kirschner P, et al. Brief report: disseminated osteomyelitis from Mycobacterium ulcerans after a snakebite. N Engl J Med. 1993;328:1007-1009.