User login

Hip pain • difficulty walking • tenderness along the anteromedial thigh and groin • Dx?

THE CASE

A 14-year-old Caucasian boy presented to our clinic with a complaint of left anterior hip pain. The patient had been running during a flag football match when he suddenly developed a sharp, stabbing pain in his left hip. He said he felt a “pop” in his left groin while his left foot was planted and he was cutting to the right. The patient said this was followed by worsening pain with ambulation and hip flexion.

The patient had considerable difficulty walking into the exam room. On physical examination, he had significant tenderness to palpation along the anteromedial thigh and groin. The patient’s strength was 1/5 with left hip flexion. There was apparent muscle firing, but no significant leg movement. He had full passive range of motion and there was no soft-tissue swelling, erythema, or other integumentary changes.

THE DIAGNOSIS

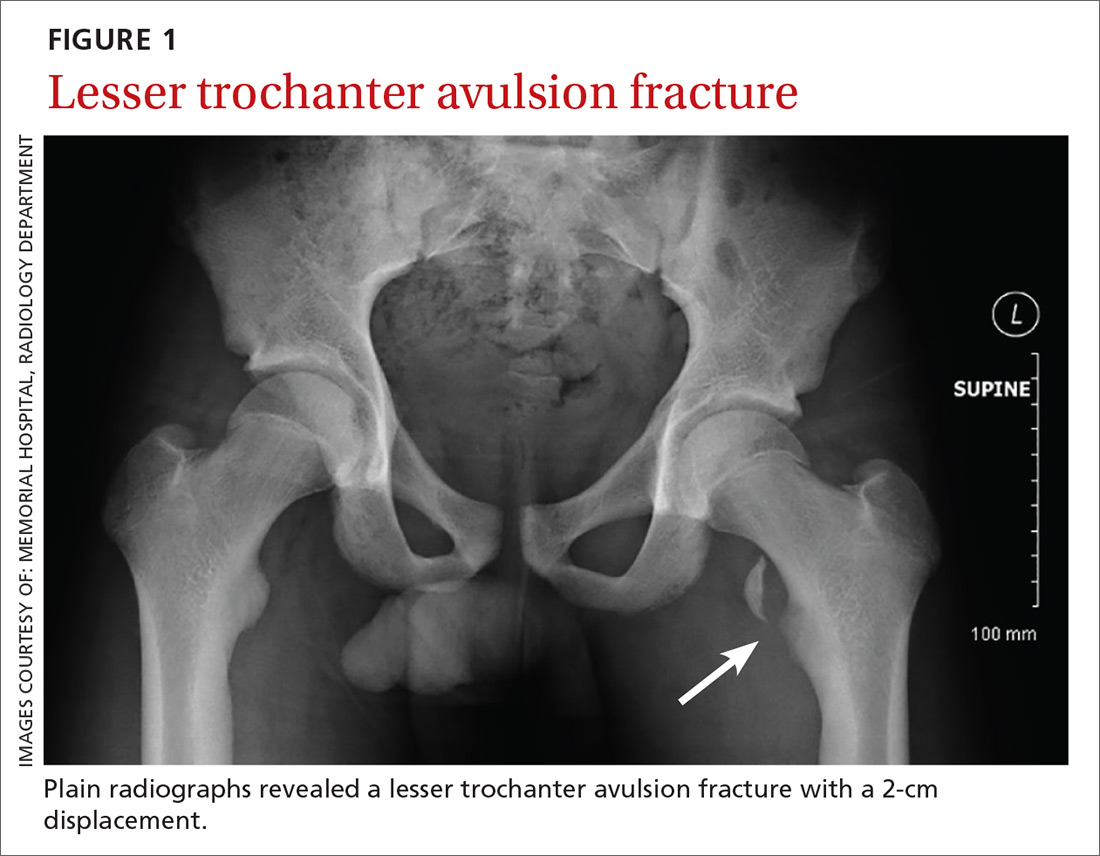

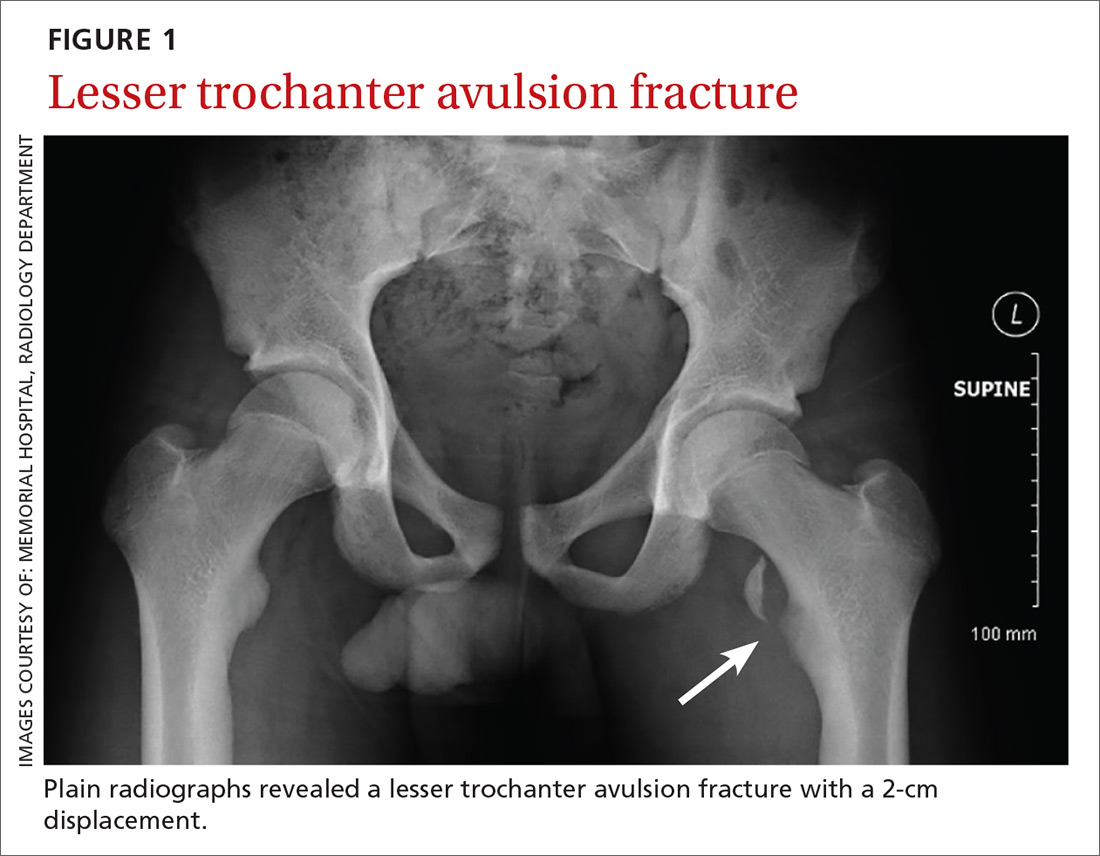

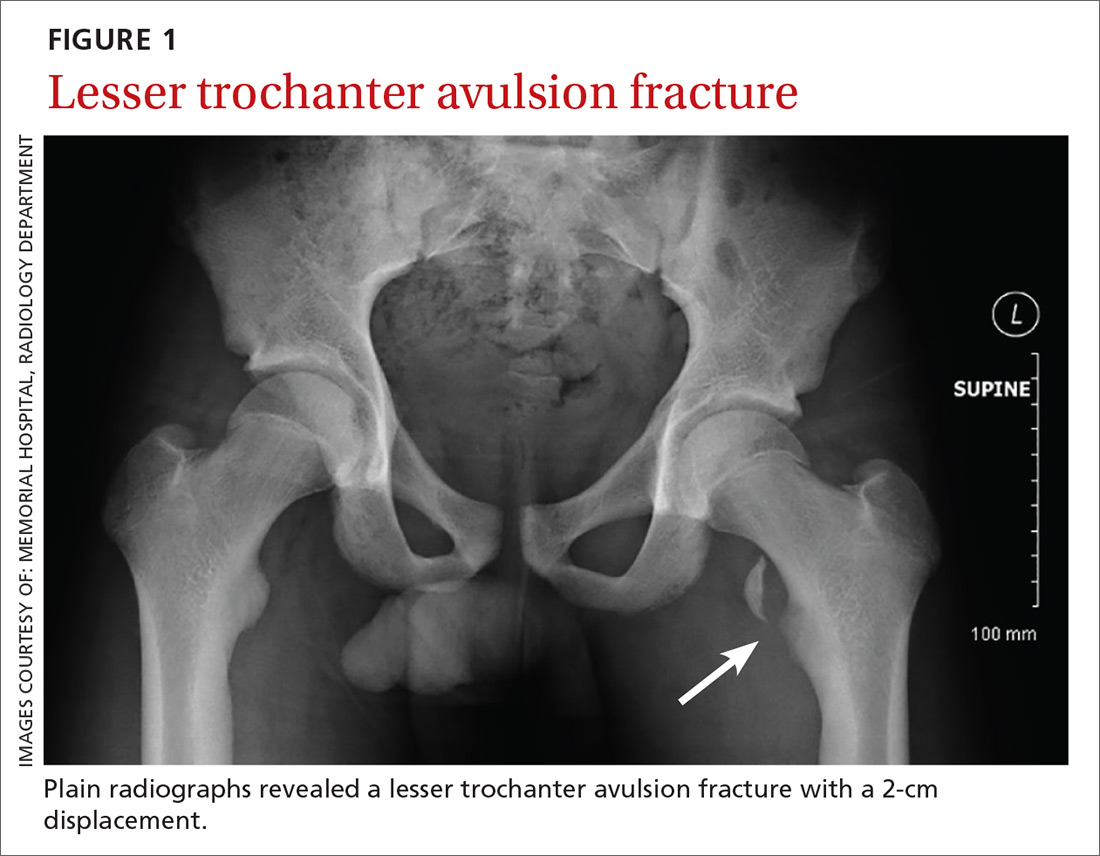

Plain radiographs revealed a lesser trochanter avulsion fracture with a 2-cm displacement (FIGURE 1).

DISCUSSION

Pelvic and proximal femur avulsion fractures tend to occur during the second decade of life.1,2 They’re more frequently seen in boys and adolescent athletes, especially those involved in soccer and gymnastics.3,4

Anterior superior iliac spine (ASIS), ischial tuberosity (IT), and anterior inferior iliac spine (AIIS) avulsion fractures are more prevalent,4 while lesser trochanter avulsion fractures are more rare. In one review of 1126 children with femoral neck and proximal 1/3 femoral shaft fractures, only 3 of them had lesser trochanter avulsion fractures.5

Clinical presentation. Presenting symptoms of lesser trochanter avulsion fractures can be vague, but are usually localized to the groin and medial hip region. Patients will demonstrate pain and weakness with hip flexion.3,6 There may be signs of inflammation, tenderness, and ecchymosis near the site of injury.

On physical exam, a positive Ludloff sign helps localize the injury to the iliopsoas muscle, which inserts at the lesser trochanter and is involved in hip flexion.3,6,7 The Ludloff test is performed by flexing the patient’s hip while he/she is in a seated position.

BIOMECHANICS OF AVULSION FRACTURES

Perhaps surprisingly, the majority of avulsion injuries in children and adolescents are the result of non-contact athletic movement and indirect trauma.4 In children, muscles and tendons are often stronger than their bones,7 and physes—structurally weak regions—are particularly predisposed to fractures.2,4,6

The mechanism of injury in children and adolescents is commonly a sudden, forceful contraction of the iliopsoas muscle.6,7 While similar movement in adults will produce tendon sprains and muscle strains, children often experience a complete avulsion fracture.7 So uncommon are these fractures among adults that an adult patient presenting with one should receive further work-up for underlying pathology such as malignancy.8,9

While other hip and femur avulsion fractures in children and adolescents involve different muscle groups, the etiologic mechanism—forceful muscle contraction—is usually the same.2,4,7 IT injuries are often seen with sudden, aggressive lengthening of the hamstring muscles, whereas injuries to the ASIS and AIIS are the result of abrupt eccentric contraction of hip extensor muscles while the knee is flexed.4

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

There are several entities that can mimic a lesser trochanter avulsion fracture including Legg-Calve-Perthes disease (LCPD), slipped capital femoral epiphysis (SCFE), snapping hip with the iliofemoral ligament, iliopsoas tendonitis, referred pain from the gastrointestinal region, and a genito-urologic etiology.1,7,10

Diagnostic studies. Physical exam findings of severe pain and reduced strength are clear indications for obtaining baseline imaging. Baseline radiographs are key to the diagnosis of avulsion fractures. They help differentiate between more benign fractures, such as a nondisplaced avulsion fracture, and more substantial conditions, such as LCPD and SCFE, which require significantly different approaches to treatment and follow-up.1,7

Anteroposterior, oblique, and axial views of the pelvis all assist in assessing avulsion fractures radiographically.3,4,7 In the event that an avulsion fracture is not radiographically visible, but is still suspected, additional imaging should be obtained.10 A computerized tomography (CT) scan is an appropriate follow-up, given its meticulous detail of bony anatomy.3,10 Alternatively, if physes have yet to ossify or there are concerns about soft tissue injury, magnetic resonance imaging can be useful.3,7,10

MANAGEMENT

The majority of lesser trochanter avulsion fractures are managed conservatively with rest, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), and physical therapy. Patients are often placed on non-weight bearing activity for up to 6 weeks while the fracture repairs and forms a new union.7 Current management strategies have moved away from immobilization with splints and braces.

In rare instances when the fragment is displaced >2 cm, or there is inadequate healing or pain relief after 3 months of supportive care, surgery may be required.1 With appropriate diagnosis and medical care, the injured athlete should fully recover with no impairment or chronic pain.2

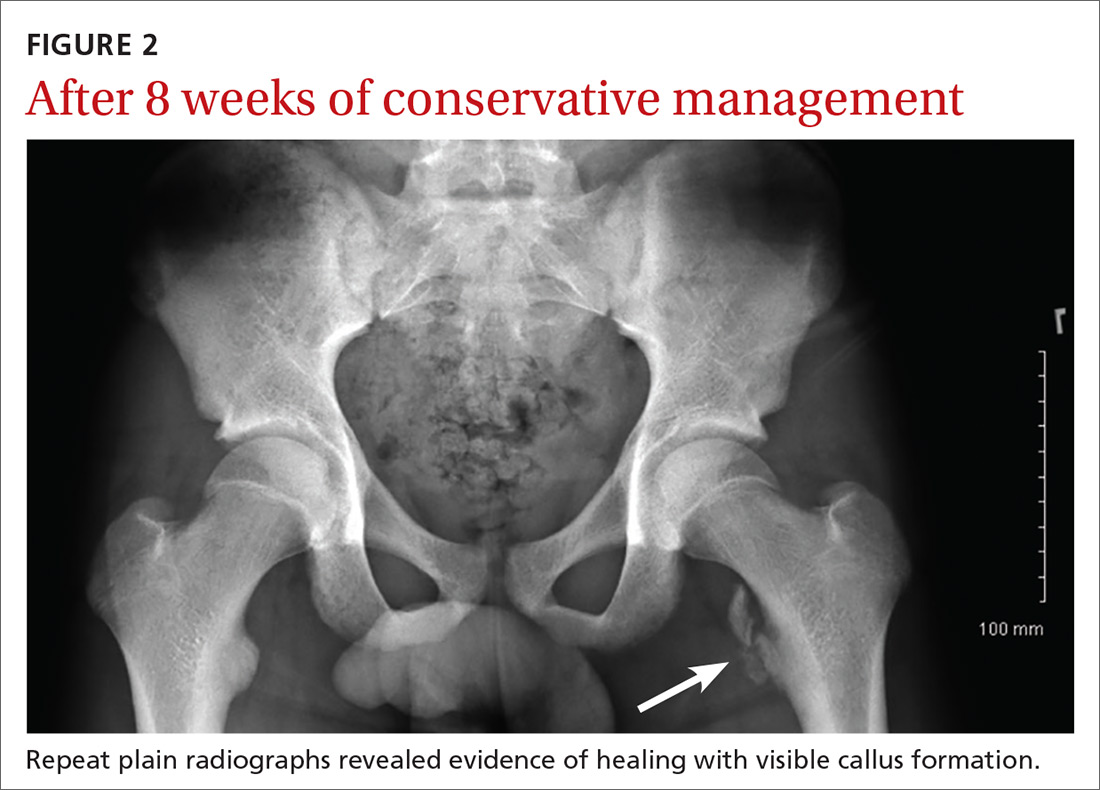

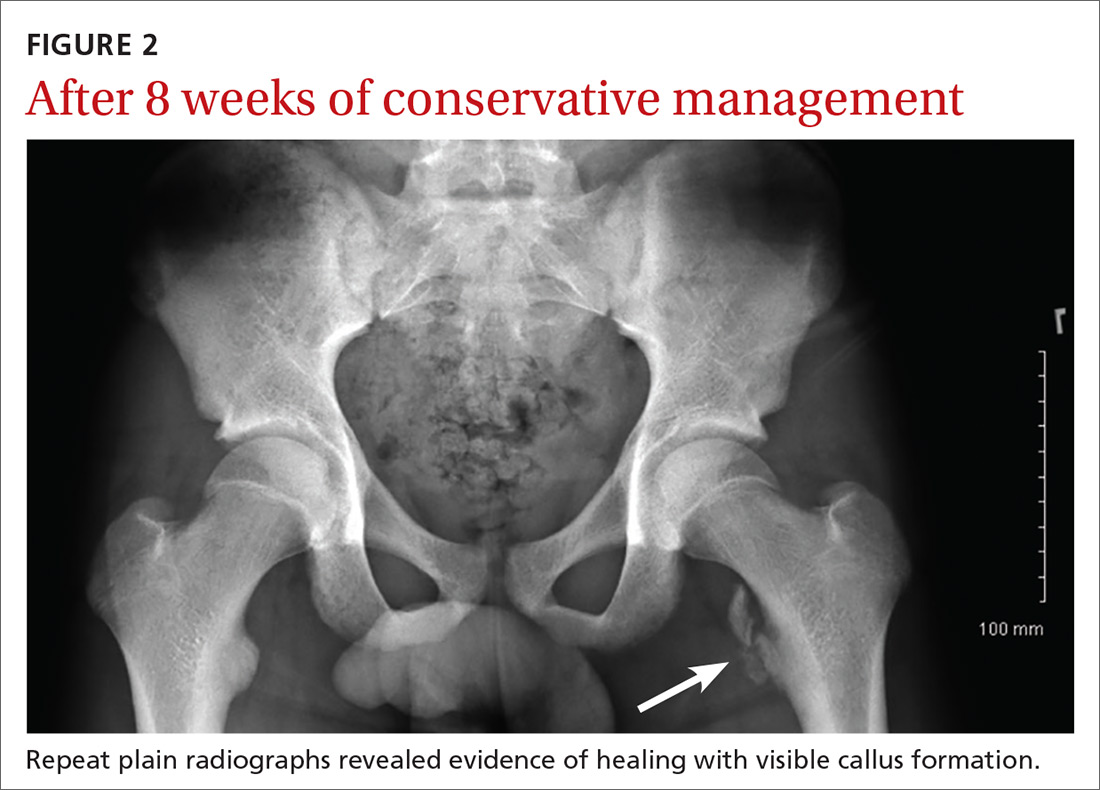

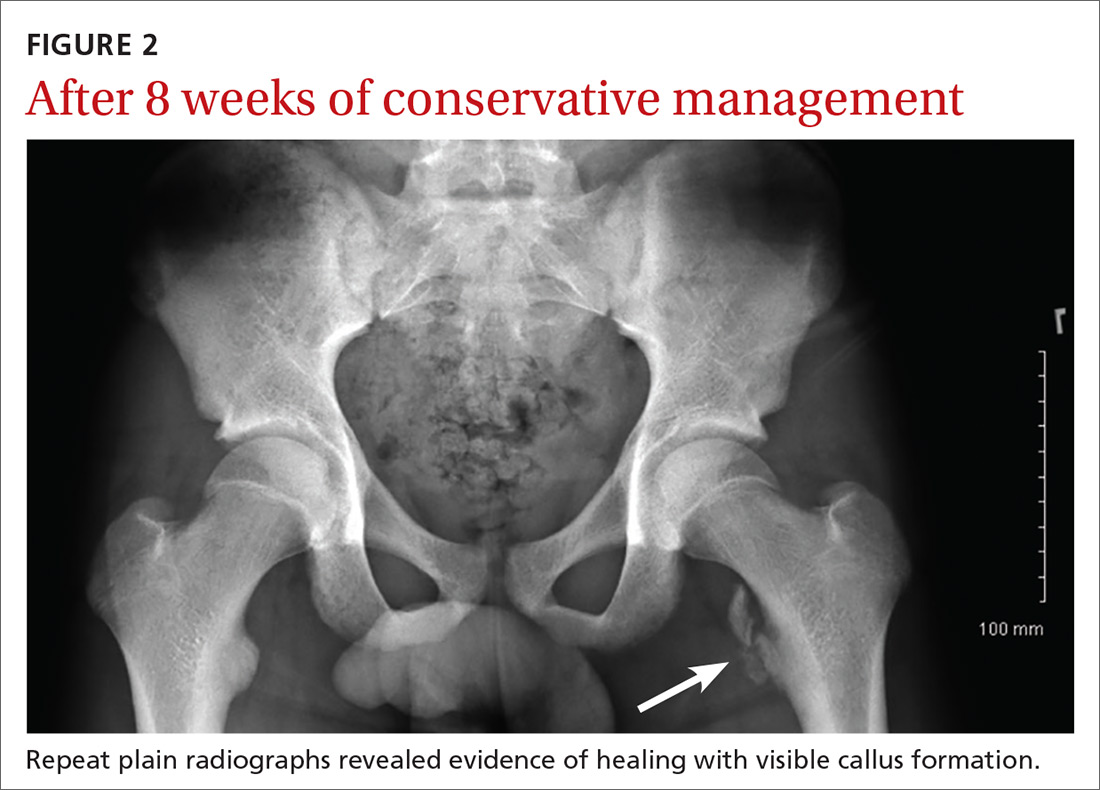

Our patient was placed on non-weight-bearing activity and treated with NSAIDs and acetaminophen. We advanced him to weight-bearing activities 4 weeks after injury. After 8 weeks of conservative management, he returned to competitive play with no further complications (FIGURE 2).

THE TAKEAWAY

Pelvic and proximal femur avulsion fractures occur more often in child and adolescent athletes. As this population becomes increasingly competitive in athletics, the risk of injury increases. Infrequent fractures such as lesser trochanter avulsion fractures may become more common, as well. The majority of avulsion fractures don’t require surgical intervention, but it’s important to obtain baseline radiographs to rule out other injuries or pathologies that may lead to poor prognoses if they are left untreated.

1. Byrne A, Reidy D. Acute groin pain in an adolescent sprinter: a case report. Int J Clin Pediatr. 2012;1:46-48.

2. Fernbach SK, Wilkinson RH. Avulsion injuries of the pelvis and proximal femur. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1981;137:581-584.

3. McKinney BI, Nelson C, Carrion W. Apophyseal avulsion fractures of the hip and pelvis. Orthopedics. 2009;32:42.

4. Rossi F, Dragoni S. Acute avulsion fractures of the pelvis in adolescent competitive athletes: prevalence, location and sports distribution of 203 cases collected. Skeletal Radiol. 2001;30:127-131.

5. Theologis TN, Epps H, Latz K, et al. Isolated fractures of the lesser trochanter in children. Injury. 1997;28:363-364.

6. Paluska SA. An overview of hip injuries in running. Sports Med. 2005;35:991-1014.

7. Vazquez E, Kim TY, Young TP. Avulsion fracture of the lesser trochanter: an unusual cause of hip pain in an adolescent. CJEM. 2013;15:123-125.

8. Afra R, Boardman DL, Kabo JM, et al. Avulsion fracture of the lesser trochanter as a result of a preliminary malignant tumor of bone. A report of four cases. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1999;81:1299-1304.

9. DePasse JM, Varner K, Cosculluela P, et al. Atraumatic avulsion of the distal iliopsoas tendon: an unusual cause of hip pain. Orthopedics. 2010;33.

10. Suarez JC, Ely EE, Mutnal AB, et al. Comprehensive approach to the evaluation of groin pain. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2013;21:558-570.

THE CASE

A 14-year-old Caucasian boy presented to our clinic with a complaint of left anterior hip pain. The patient had been running during a flag football match when he suddenly developed a sharp, stabbing pain in his left hip. He said he felt a “pop” in his left groin while his left foot was planted and he was cutting to the right. The patient said this was followed by worsening pain with ambulation and hip flexion.

The patient had considerable difficulty walking into the exam room. On physical examination, he had significant tenderness to palpation along the anteromedial thigh and groin. The patient’s strength was 1/5 with left hip flexion. There was apparent muscle firing, but no significant leg movement. He had full passive range of motion and there was no soft-tissue swelling, erythema, or other integumentary changes.

THE DIAGNOSIS

Plain radiographs revealed a lesser trochanter avulsion fracture with a 2-cm displacement (FIGURE 1).

DISCUSSION

Pelvic and proximal femur avulsion fractures tend to occur during the second decade of life.1,2 They’re more frequently seen in boys and adolescent athletes, especially those involved in soccer and gymnastics.3,4

Anterior superior iliac spine (ASIS), ischial tuberosity (IT), and anterior inferior iliac spine (AIIS) avulsion fractures are more prevalent,4 while lesser trochanter avulsion fractures are more rare. In one review of 1126 children with femoral neck and proximal 1/3 femoral shaft fractures, only 3 of them had lesser trochanter avulsion fractures.5

Clinical presentation. Presenting symptoms of lesser trochanter avulsion fractures can be vague, but are usually localized to the groin and medial hip region. Patients will demonstrate pain and weakness with hip flexion.3,6 There may be signs of inflammation, tenderness, and ecchymosis near the site of injury.

On physical exam, a positive Ludloff sign helps localize the injury to the iliopsoas muscle, which inserts at the lesser trochanter and is involved in hip flexion.3,6,7 The Ludloff test is performed by flexing the patient’s hip while he/she is in a seated position.

BIOMECHANICS OF AVULSION FRACTURES

Perhaps surprisingly, the majority of avulsion injuries in children and adolescents are the result of non-contact athletic movement and indirect trauma.4 In children, muscles and tendons are often stronger than their bones,7 and physes—structurally weak regions—are particularly predisposed to fractures.2,4,6

The mechanism of injury in children and adolescents is commonly a sudden, forceful contraction of the iliopsoas muscle.6,7 While similar movement in adults will produce tendon sprains and muscle strains, children often experience a complete avulsion fracture.7 So uncommon are these fractures among adults that an adult patient presenting with one should receive further work-up for underlying pathology such as malignancy.8,9

While other hip and femur avulsion fractures in children and adolescents involve different muscle groups, the etiologic mechanism—forceful muscle contraction—is usually the same.2,4,7 IT injuries are often seen with sudden, aggressive lengthening of the hamstring muscles, whereas injuries to the ASIS and AIIS are the result of abrupt eccentric contraction of hip extensor muscles while the knee is flexed.4

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

There are several entities that can mimic a lesser trochanter avulsion fracture including Legg-Calve-Perthes disease (LCPD), slipped capital femoral epiphysis (SCFE), snapping hip with the iliofemoral ligament, iliopsoas tendonitis, referred pain from the gastrointestinal region, and a genito-urologic etiology.1,7,10

Diagnostic studies. Physical exam findings of severe pain and reduced strength are clear indications for obtaining baseline imaging. Baseline radiographs are key to the diagnosis of avulsion fractures. They help differentiate between more benign fractures, such as a nondisplaced avulsion fracture, and more substantial conditions, such as LCPD and SCFE, which require significantly different approaches to treatment and follow-up.1,7

Anteroposterior, oblique, and axial views of the pelvis all assist in assessing avulsion fractures radiographically.3,4,7 In the event that an avulsion fracture is not radiographically visible, but is still suspected, additional imaging should be obtained.10 A computerized tomography (CT) scan is an appropriate follow-up, given its meticulous detail of bony anatomy.3,10 Alternatively, if physes have yet to ossify or there are concerns about soft tissue injury, magnetic resonance imaging can be useful.3,7,10

MANAGEMENT

The majority of lesser trochanter avulsion fractures are managed conservatively with rest, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), and physical therapy. Patients are often placed on non-weight bearing activity for up to 6 weeks while the fracture repairs and forms a new union.7 Current management strategies have moved away from immobilization with splints and braces.

In rare instances when the fragment is displaced >2 cm, or there is inadequate healing or pain relief after 3 months of supportive care, surgery may be required.1 With appropriate diagnosis and medical care, the injured athlete should fully recover with no impairment or chronic pain.2

Our patient was placed on non-weight-bearing activity and treated with NSAIDs and acetaminophen. We advanced him to weight-bearing activities 4 weeks after injury. After 8 weeks of conservative management, he returned to competitive play with no further complications (FIGURE 2).

THE TAKEAWAY

Pelvic and proximal femur avulsion fractures occur more often in child and adolescent athletes. As this population becomes increasingly competitive in athletics, the risk of injury increases. Infrequent fractures such as lesser trochanter avulsion fractures may become more common, as well. The majority of avulsion fractures don’t require surgical intervention, but it’s important to obtain baseline radiographs to rule out other injuries or pathologies that may lead to poor prognoses if they are left untreated.

THE CASE

A 14-year-old Caucasian boy presented to our clinic with a complaint of left anterior hip pain. The patient had been running during a flag football match when he suddenly developed a sharp, stabbing pain in his left hip. He said he felt a “pop” in his left groin while his left foot was planted and he was cutting to the right. The patient said this was followed by worsening pain with ambulation and hip flexion.

The patient had considerable difficulty walking into the exam room. On physical examination, he had significant tenderness to palpation along the anteromedial thigh and groin. The patient’s strength was 1/5 with left hip flexion. There was apparent muscle firing, but no significant leg movement. He had full passive range of motion and there was no soft-tissue swelling, erythema, or other integumentary changes.

THE DIAGNOSIS

Plain radiographs revealed a lesser trochanter avulsion fracture with a 2-cm displacement (FIGURE 1).

DISCUSSION

Pelvic and proximal femur avulsion fractures tend to occur during the second decade of life.1,2 They’re more frequently seen in boys and adolescent athletes, especially those involved in soccer and gymnastics.3,4

Anterior superior iliac spine (ASIS), ischial tuberosity (IT), and anterior inferior iliac spine (AIIS) avulsion fractures are more prevalent,4 while lesser trochanter avulsion fractures are more rare. In one review of 1126 children with femoral neck and proximal 1/3 femoral shaft fractures, only 3 of them had lesser trochanter avulsion fractures.5

Clinical presentation. Presenting symptoms of lesser trochanter avulsion fractures can be vague, but are usually localized to the groin and medial hip region. Patients will demonstrate pain and weakness with hip flexion.3,6 There may be signs of inflammation, tenderness, and ecchymosis near the site of injury.

On physical exam, a positive Ludloff sign helps localize the injury to the iliopsoas muscle, which inserts at the lesser trochanter and is involved in hip flexion.3,6,7 The Ludloff test is performed by flexing the patient’s hip while he/she is in a seated position.

BIOMECHANICS OF AVULSION FRACTURES

Perhaps surprisingly, the majority of avulsion injuries in children and adolescents are the result of non-contact athletic movement and indirect trauma.4 In children, muscles and tendons are often stronger than their bones,7 and physes—structurally weak regions—are particularly predisposed to fractures.2,4,6

The mechanism of injury in children and adolescents is commonly a sudden, forceful contraction of the iliopsoas muscle.6,7 While similar movement in adults will produce tendon sprains and muscle strains, children often experience a complete avulsion fracture.7 So uncommon are these fractures among adults that an adult patient presenting with one should receive further work-up for underlying pathology such as malignancy.8,9

While other hip and femur avulsion fractures in children and adolescents involve different muscle groups, the etiologic mechanism—forceful muscle contraction—is usually the same.2,4,7 IT injuries are often seen with sudden, aggressive lengthening of the hamstring muscles, whereas injuries to the ASIS and AIIS are the result of abrupt eccentric contraction of hip extensor muscles while the knee is flexed.4

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

There are several entities that can mimic a lesser trochanter avulsion fracture including Legg-Calve-Perthes disease (LCPD), slipped capital femoral epiphysis (SCFE), snapping hip with the iliofemoral ligament, iliopsoas tendonitis, referred pain from the gastrointestinal region, and a genito-urologic etiology.1,7,10

Diagnostic studies. Physical exam findings of severe pain and reduced strength are clear indications for obtaining baseline imaging. Baseline radiographs are key to the diagnosis of avulsion fractures. They help differentiate between more benign fractures, such as a nondisplaced avulsion fracture, and more substantial conditions, such as LCPD and SCFE, which require significantly different approaches to treatment and follow-up.1,7

Anteroposterior, oblique, and axial views of the pelvis all assist in assessing avulsion fractures radiographically.3,4,7 In the event that an avulsion fracture is not radiographically visible, but is still suspected, additional imaging should be obtained.10 A computerized tomography (CT) scan is an appropriate follow-up, given its meticulous detail of bony anatomy.3,10 Alternatively, if physes have yet to ossify or there are concerns about soft tissue injury, magnetic resonance imaging can be useful.3,7,10

MANAGEMENT

The majority of lesser trochanter avulsion fractures are managed conservatively with rest, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), and physical therapy. Patients are often placed on non-weight bearing activity for up to 6 weeks while the fracture repairs and forms a new union.7 Current management strategies have moved away from immobilization with splints and braces.

In rare instances when the fragment is displaced >2 cm, or there is inadequate healing or pain relief after 3 months of supportive care, surgery may be required.1 With appropriate diagnosis and medical care, the injured athlete should fully recover with no impairment or chronic pain.2

Our patient was placed on non-weight-bearing activity and treated with NSAIDs and acetaminophen. We advanced him to weight-bearing activities 4 weeks after injury. After 8 weeks of conservative management, he returned to competitive play with no further complications (FIGURE 2).

THE TAKEAWAY

Pelvic and proximal femur avulsion fractures occur more often in child and adolescent athletes. As this population becomes increasingly competitive in athletics, the risk of injury increases. Infrequent fractures such as lesser trochanter avulsion fractures may become more common, as well. The majority of avulsion fractures don’t require surgical intervention, but it’s important to obtain baseline radiographs to rule out other injuries or pathologies that may lead to poor prognoses if they are left untreated.

1. Byrne A, Reidy D. Acute groin pain in an adolescent sprinter: a case report. Int J Clin Pediatr. 2012;1:46-48.

2. Fernbach SK, Wilkinson RH. Avulsion injuries of the pelvis and proximal femur. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1981;137:581-584.

3. McKinney BI, Nelson C, Carrion W. Apophyseal avulsion fractures of the hip and pelvis. Orthopedics. 2009;32:42.

4. Rossi F, Dragoni S. Acute avulsion fractures of the pelvis in adolescent competitive athletes: prevalence, location and sports distribution of 203 cases collected. Skeletal Radiol. 2001;30:127-131.

5. Theologis TN, Epps H, Latz K, et al. Isolated fractures of the lesser trochanter in children. Injury. 1997;28:363-364.

6. Paluska SA. An overview of hip injuries in running. Sports Med. 2005;35:991-1014.

7. Vazquez E, Kim TY, Young TP. Avulsion fracture of the lesser trochanter: an unusual cause of hip pain in an adolescent. CJEM. 2013;15:123-125.

8. Afra R, Boardman DL, Kabo JM, et al. Avulsion fracture of the lesser trochanter as a result of a preliminary malignant tumor of bone. A report of four cases. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1999;81:1299-1304.

9. DePasse JM, Varner K, Cosculluela P, et al. Atraumatic avulsion of the distal iliopsoas tendon: an unusual cause of hip pain. Orthopedics. 2010;33.

10. Suarez JC, Ely EE, Mutnal AB, et al. Comprehensive approach to the evaluation of groin pain. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2013;21:558-570.

1. Byrne A, Reidy D. Acute groin pain in an adolescent sprinter: a case report. Int J Clin Pediatr. 2012;1:46-48.

2. Fernbach SK, Wilkinson RH. Avulsion injuries of the pelvis and proximal femur. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1981;137:581-584.

3. McKinney BI, Nelson C, Carrion W. Apophyseal avulsion fractures of the hip and pelvis. Orthopedics. 2009;32:42.

4. Rossi F, Dragoni S. Acute avulsion fractures of the pelvis in adolescent competitive athletes: prevalence, location and sports distribution of 203 cases collected. Skeletal Radiol. 2001;30:127-131.

5. Theologis TN, Epps H, Latz K, et al. Isolated fractures of the lesser trochanter in children. Injury. 1997;28:363-364.

6. Paluska SA. An overview of hip injuries in running. Sports Med. 2005;35:991-1014.

7. Vazquez E, Kim TY, Young TP. Avulsion fracture of the lesser trochanter: an unusual cause of hip pain in an adolescent. CJEM. 2013;15:123-125.

8. Afra R, Boardman DL, Kabo JM, et al. Avulsion fracture of the lesser trochanter as a result of a preliminary malignant tumor of bone. A report of four cases. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1999;81:1299-1304.

9. DePasse JM, Varner K, Cosculluela P, et al. Atraumatic avulsion of the distal iliopsoas tendon: an unusual cause of hip pain. Orthopedics. 2010;33.

10. Suarez JC, Ely EE, Mutnal AB, et al. Comprehensive approach to the evaluation of groin pain. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2013;21:558-570.