User login

Acne severity shows negative impact on women’s self esteem

The severity of acne has a substantial negative impact on patients’ self-esteem in different age groups and cultures, with the greatest impact on women and in those with more severe acne, according to the authors of a review of studies that evaluated self-esteem in patients with acne.

Dermatologists Stephanie M. Gallitano, MD, of Columbia University, and Diane S. Berson, MD, of Cornell University, both in New York City, conducted a literature search of studies using the terms “acne vulgaris” and “self-esteem.” They identified 13 studies in 11 countries, including India, Singapore, Brazil, Greece, the United Kingdom, Egypt, South Korea, and Australia.

In the review, published in the International Journal of Women’s Dermatology, they wrote that most of the study authors determined that women with acne were more likely to have a greater degree of feelings that involved self-consciousness, lower self-esteem, and self-worth. In four studies, though, “men and women were equally affected by their disease,” and in one study in Egypt, self-esteem was significantly lower in males with acne than in women with acne, they wrote.

In all the studies, “self-esteem became lower as severity of acne increased,” they observed. There was evidence that subjective perceptions of acne severity affected self-esteem, with a few studies associating subjective evaluations of acne severity, but not objective evaluations, with lower self-esteem. They included a study of 550 students in Turkey, which found “a significant relationship between subjective acne severity and self-esteem but no relationship between objective acne severity and self-esteem.”

Most – between 70% and 80% – of patients used self-prescribed treatments, and 5% to almost 30% had seen a dermatologist. But patients with more severe acne were more likely to have seen a dermatologist, with 61% of those with moderate to severe acne having seen a dermatologist in a Greek study, for example. In addition, in an adult study and in an adolescent study, patients who felt that they had benefited from treatment also had improved self-esteem, improved quality of life, and less anxiety compared with those who did not feel they had benefited from treatment, the authors wrote.

Their review shows that acne “has a substantial negative impact on patients’ self-esteem” and that more severe acne and acne in women “tend to have the greatest impact across cultures,” they concluded.

Read the full study in the International Journal of Women’s Dermatology.

SOURCE: Gallitano S.M, et al. Int J Womens Dermatol 2017 Oct. doi: 10.1016/j.ijwd.2017.10.004

The severity of acne has a substantial negative impact on patients’ self-esteem in different age groups and cultures, with the greatest impact on women and in those with more severe acne, according to the authors of a review of studies that evaluated self-esteem in patients with acne.

Dermatologists Stephanie M. Gallitano, MD, of Columbia University, and Diane S. Berson, MD, of Cornell University, both in New York City, conducted a literature search of studies using the terms “acne vulgaris” and “self-esteem.” They identified 13 studies in 11 countries, including India, Singapore, Brazil, Greece, the United Kingdom, Egypt, South Korea, and Australia.

In the review, published in the International Journal of Women’s Dermatology, they wrote that most of the study authors determined that women with acne were more likely to have a greater degree of feelings that involved self-consciousness, lower self-esteem, and self-worth. In four studies, though, “men and women were equally affected by their disease,” and in one study in Egypt, self-esteem was significantly lower in males with acne than in women with acne, they wrote.

In all the studies, “self-esteem became lower as severity of acne increased,” they observed. There was evidence that subjective perceptions of acne severity affected self-esteem, with a few studies associating subjective evaluations of acne severity, but not objective evaluations, with lower self-esteem. They included a study of 550 students in Turkey, which found “a significant relationship between subjective acne severity and self-esteem but no relationship between objective acne severity and self-esteem.”

Most – between 70% and 80% – of patients used self-prescribed treatments, and 5% to almost 30% had seen a dermatologist. But patients with more severe acne were more likely to have seen a dermatologist, with 61% of those with moderate to severe acne having seen a dermatologist in a Greek study, for example. In addition, in an adult study and in an adolescent study, patients who felt that they had benefited from treatment also had improved self-esteem, improved quality of life, and less anxiety compared with those who did not feel they had benefited from treatment, the authors wrote.

Their review shows that acne “has a substantial negative impact on patients’ self-esteem” and that more severe acne and acne in women “tend to have the greatest impact across cultures,” they concluded.

Read the full study in the International Journal of Women’s Dermatology.

SOURCE: Gallitano S.M, et al. Int J Womens Dermatol 2017 Oct. doi: 10.1016/j.ijwd.2017.10.004

The severity of acne has a substantial negative impact on patients’ self-esteem in different age groups and cultures, with the greatest impact on women and in those with more severe acne, according to the authors of a review of studies that evaluated self-esteem in patients with acne.

Dermatologists Stephanie M. Gallitano, MD, of Columbia University, and Diane S. Berson, MD, of Cornell University, both in New York City, conducted a literature search of studies using the terms “acne vulgaris” and “self-esteem.” They identified 13 studies in 11 countries, including India, Singapore, Brazil, Greece, the United Kingdom, Egypt, South Korea, and Australia.

In the review, published in the International Journal of Women’s Dermatology, they wrote that most of the study authors determined that women with acne were more likely to have a greater degree of feelings that involved self-consciousness, lower self-esteem, and self-worth. In four studies, though, “men and women were equally affected by their disease,” and in one study in Egypt, self-esteem was significantly lower in males with acne than in women with acne, they wrote.

In all the studies, “self-esteem became lower as severity of acne increased,” they observed. There was evidence that subjective perceptions of acne severity affected self-esteem, with a few studies associating subjective evaluations of acne severity, but not objective evaluations, with lower self-esteem. They included a study of 550 students in Turkey, which found “a significant relationship between subjective acne severity and self-esteem but no relationship between objective acne severity and self-esteem.”

Most – between 70% and 80% – of patients used self-prescribed treatments, and 5% to almost 30% had seen a dermatologist. But patients with more severe acne were more likely to have seen a dermatologist, with 61% of those with moderate to severe acne having seen a dermatologist in a Greek study, for example. In addition, in an adult study and in an adolescent study, patients who felt that they had benefited from treatment also had improved self-esteem, improved quality of life, and less anxiety compared with those who did not feel they had benefited from treatment, the authors wrote.

Their review shows that acne “has a substantial negative impact on patients’ self-esteem” and that more severe acne and acne in women “tend to have the greatest impact across cultures,” they concluded.

Read the full study in the International Journal of Women’s Dermatology.

SOURCE: Gallitano S.M, et al. Int J Womens Dermatol 2017 Oct. doi: 10.1016/j.ijwd.2017.10.004

FROM THE INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF WOMEN’S DERMATOLOGY

CRB-410 update: Multiple myeloma response rates remain high with bb2121 CAR T-cell therapy

ATLANTA – A novel chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy that targets B-cell maturation antigen showed promising efficacy with a manageable adverse event profile in heavily pretreated patients with relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma in the CRB-410 multicenter phase 1 dose escalation trial.

The product, known as bb2121, received breakthrough therapy designation from the Food and Drug Administration in November 2017 based on preliminary data from the ongoing trial. Those data showed that as of May 2017, the overall response rate at 1 month in 18 evaluable patients was 89%, whereas the response in those who received active dosing (150 x 106 CAR+ T cells or higher) was 100%.

Multiple myeloma currently is “essentially incurable,” and new treatments are desperately needed; B-cell maturation antigen (BCMA) – which is a member of the tumor necrosis factor superfamily that is expressed primarily by malignant myeloma cells, plasma cells, and some mature B cells – is a promising target, said Dr. Kochenderfer of the National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, Md.

The bb2121 product is a second-generation CAR construct targeting BCMA to redirect T cells to multiple myeloma cells. It was tested at doses of 50, 150, 450, and 800 x 106 CAR+ T cells in patients who first underwent chemotherapy as a conditioning regimen to enhance the activity of the CAR T cells.

A total of 24 patients were enrolled, but three had clinical deterioration and were not dosed. The remaining 21 patients had a median age of 58 years, performance scores of 0 or 1, and a median of 5 years since multiple myeloma diagnosis. A high percentage (43%) had high-risk cytogenetics. The median number of prior lines of therapy was seven, and all patients had undergone prior autologous stem cell transplant.

“Generally, this was a very well tolerated CAR T-cell product, especially in comparison to other protocols that I’ve participated in,” he said, noting that the incidence of adverse events, including dose-limiting toxicities, was the primary outcome measure of this phase of the study.

Cytokine release syndrome occurred in 71% of the 21 patients evaluable for response with a median follow-up of 35 weeks at the Oct. 2, 2017, data cutoff, but was grade 3 or greater in just 10% of those patients. Neurological toxicity occurred in 24% of patients, as well, but no cases were grade 3 or above, he said.

“The neurotoxicity was generally much milder and less prevalent than what I’ve seen in previous anti-CD19 CAR studies,” he said.

Neutropenia, thrombocytopenia, and anemia also occurred, but there were no dose-limiting toxicities observed during dose escalation.

Five deaths occurred. Three were due to disease progression and occurred in patients on the lowest dose (50 x 106 CAR+ T cells), which was deemed inactive. The other deaths occurred in patients receiving higher (active) doses; one was a result of myelodysplastic syndrome, and one from cardiac arrest, he said.

One or more serious adverse events occurred in 14 patients, and in some cases were characterized as such due to strict study protocols, Dr. Kochenderfer said.

Of note, one patient out of 12 in an ongoing dose expansion phase of the study, for which data have not yet been fully reported, experienced a delayed onset reversible grade 4 neurological toxicity associated with tumor lysis syndrome and cytokine release syndrome. The patient, who had the highest disease burden in the trial, completely recovered and has obtained a very good partial response despite low BCMA expression on the myeloma cells, Dr. Kochenderfer said.

In terms of response rates, 17 of 18 patients who received doses above 50 x 106 CAR+ T cells had overall responses, and 10 of the 18 achieved complete remission.

The median time to first response was 1 month, and the times to best response and complete response were 3.74 and 3.84 months, respectively. The rates of progression-free survival were 81% at 6 months, and 71% at 9 months, and responses deepened over time: as of May, the complete response rate was 27%, and as of October, it was 56%.

“Five of these patients so far have met the 1-year progression-free survival standard,” Dr. Kochenderfer said, adding that responses have endured for more than a year in several patients. The longest was 68 weeks at the time of the data presentation, and responses continued to improve as late as 15 months, with very good partial remission to complete remission transitions.

The median progression-free survival had not been reached in the active dose cohorts.

“So, in general, very impressive responses compared to my previous experience treating multiple myeloma,” he said.

The findings support the potential of CAR T therapy with bb2121 as a new treatment paradigm in relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma, he concluded, noting that a global pivotal trial of bb2121 (the phase 2 KarMMa trial) is now enrolling and will dose patients at between 150 and 350 x 106 CAR+ T cells. Under the breakthrough therapy designation granted for bb2121, the product will receive expedited review by the FDA.The CRB-410 trial is sponsored by bluebird bio and Celgene. Dr. Kochenderfer reported receiving research funding from bluebird bio and Kite Pharma, and having multiple patents in the CAR field.

ATLANTA – A novel chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy that targets B-cell maturation antigen showed promising efficacy with a manageable adverse event profile in heavily pretreated patients with relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma in the CRB-410 multicenter phase 1 dose escalation trial.

The product, known as bb2121, received breakthrough therapy designation from the Food and Drug Administration in November 2017 based on preliminary data from the ongoing trial. Those data showed that as of May 2017, the overall response rate at 1 month in 18 evaluable patients was 89%, whereas the response in those who received active dosing (150 x 106 CAR+ T cells or higher) was 100%.

Multiple myeloma currently is “essentially incurable,” and new treatments are desperately needed; B-cell maturation antigen (BCMA) – which is a member of the tumor necrosis factor superfamily that is expressed primarily by malignant myeloma cells, plasma cells, and some mature B cells – is a promising target, said Dr. Kochenderfer of the National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, Md.

The bb2121 product is a second-generation CAR construct targeting BCMA to redirect T cells to multiple myeloma cells. It was tested at doses of 50, 150, 450, and 800 x 106 CAR+ T cells in patients who first underwent chemotherapy as a conditioning regimen to enhance the activity of the CAR T cells.

A total of 24 patients were enrolled, but three had clinical deterioration and were not dosed. The remaining 21 patients had a median age of 58 years, performance scores of 0 or 1, and a median of 5 years since multiple myeloma diagnosis. A high percentage (43%) had high-risk cytogenetics. The median number of prior lines of therapy was seven, and all patients had undergone prior autologous stem cell transplant.

“Generally, this was a very well tolerated CAR T-cell product, especially in comparison to other protocols that I’ve participated in,” he said, noting that the incidence of adverse events, including dose-limiting toxicities, was the primary outcome measure of this phase of the study.

Cytokine release syndrome occurred in 71% of the 21 patients evaluable for response with a median follow-up of 35 weeks at the Oct. 2, 2017, data cutoff, but was grade 3 or greater in just 10% of those patients. Neurological toxicity occurred in 24% of patients, as well, but no cases were grade 3 or above, he said.

“The neurotoxicity was generally much milder and less prevalent than what I’ve seen in previous anti-CD19 CAR studies,” he said.

Neutropenia, thrombocytopenia, and anemia also occurred, but there were no dose-limiting toxicities observed during dose escalation.

Five deaths occurred. Three were due to disease progression and occurred in patients on the lowest dose (50 x 106 CAR+ T cells), which was deemed inactive. The other deaths occurred in patients receiving higher (active) doses; one was a result of myelodysplastic syndrome, and one from cardiac arrest, he said.

One or more serious adverse events occurred in 14 patients, and in some cases were characterized as such due to strict study protocols, Dr. Kochenderfer said.

Of note, one patient out of 12 in an ongoing dose expansion phase of the study, for which data have not yet been fully reported, experienced a delayed onset reversible grade 4 neurological toxicity associated with tumor lysis syndrome and cytokine release syndrome. The patient, who had the highest disease burden in the trial, completely recovered and has obtained a very good partial response despite low BCMA expression on the myeloma cells, Dr. Kochenderfer said.

In terms of response rates, 17 of 18 patients who received doses above 50 x 106 CAR+ T cells had overall responses, and 10 of the 18 achieved complete remission.

The median time to first response was 1 month, and the times to best response and complete response were 3.74 and 3.84 months, respectively. The rates of progression-free survival were 81% at 6 months, and 71% at 9 months, and responses deepened over time: as of May, the complete response rate was 27%, and as of October, it was 56%.

“Five of these patients so far have met the 1-year progression-free survival standard,” Dr. Kochenderfer said, adding that responses have endured for more than a year in several patients. The longest was 68 weeks at the time of the data presentation, and responses continued to improve as late as 15 months, with very good partial remission to complete remission transitions.

The median progression-free survival had not been reached in the active dose cohorts.

“So, in general, very impressive responses compared to my previous experience treating multiple myeloma,” he said.

The findings support the potential of CAR T therapy with bb2121 as a new treatment paradigm in relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma, he concluded, noting that a global pivotal trial of bb2121 (the phase 2 KarMMa trial) is now enrolling and will dose patients at between 150 and 350 x 106 CAR+ T cells. Under the breakthrough therapy designation granted for bb2121, the product will receive expedited review by the FDA.The CRB-410 trial is sponsored by bluebird bio and Celgene. Dr. Kochenderfer reported receiving research funding from bluebird bio and Kite Pharma, and having multiple patents in the CAR field.

ATLANTA – A novel chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy that targets B-cell maturation antigen showed promising efficacy with a manageable adverse event profile in heavily pretreated patients with relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma in the CRB-410 multicenter phase 1 dose escalation trial.

The product, known as bb2121, received breakthrough therapy designation from the Food and Drug Administration in November 2017 based on preliminary data from the ongoing trial. Those data showed that as of May 2017, the overall response rate at 1 month in 18 evaluable patients was 89%, whereas the response in those who received active dosing (150 x 106 CAR+ T cells or higher) was 100%.

Multiple myeloma currently is “essentially incurable,” and new treatments are desperately needed; B-cell maturation antigen (BCMA) – which is a member of the tumor necrosis factor superfamily that is expressed primarily by malignant myeloma cells, plasma cells, and some mature B cells – is a promising target, said Dr. Kochenderfer of the National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, Md.

The bb2121 product is a second-generation CAR construct targeting BCMA to redirect T cells to multiple myeloma cells. It was tested at doses of 50, 150, 450, and 800 x 106 CAR+ T cells in patients who first underwent chemotherapy as a conditioning regimen to enhance the activity of the CAR T cells.

A total of 24 patients were enrolled, but three had clinical deterioration and were not dosed. The remaining 21 patients had a median age of 58 years, performance scores of 0 or 1, and a median of 5 years since multiple myeloma diagnosis. A high percentage (43%) had high-risk cytogenetics. The median number of prior lines of therapy was seven, and all patients had undergone prior autologous stem cell transplant.

“Generally, this was a very well tolerated CAR T-cell product, especially in comparison to other protocols that I’ve participated in,” he said, noting that the incidence of adverse events, including dose-limiting toxicities, was the primary outcome measure of this phase of the study.

Cytokine release syndrome occurred in 71% of the 21 patients evaluable for response with a median follow-up of 35 weeks at the Oct. 2, 2017, data cutoff, but was grade 3 or greater in just 10% of those patients. Neurological toxicity occurred in 24% of patients, as well, but no cases were grade 3 or above, he said.

“The neurotoxicity was generally much milder and less prevalent than what I’ve seen in previous anti-CD19 CAR studies,” he said.

Neutropenia, thrombocytopenia, and anemia also occurred, but there were no dose-limiting toxicities observed during dose escalation.

Five deaths occurred. Three were due to disease progression and occurred in patients on the lowest dose (50 x 106 CAR+ T cells), which was deemed inactive. The other deaths occurred in patients receiving higher (active) doses; one was a result of myelodysplastic syndrome, and one from cardiac arrest, he said.

One or more serious adverse events occurred in 14 patients, and in some cases were characterized as such due to strict study protocols, Dr. Kochenderfer said.

Of note, one patient out of 12 in an ongoing dose expansion phase of the study, for which data have not yet been fully reported, experienced a delayed onset reversible grade 4 neurological toxicity associated with tumor lysis syndrome and cytokine release syndrome. The patient, who had the highest disease burden in the trial, completely recovered and has obtained a very good partial response despite low BCMA expression on the myeloma cells, Dr. Kochenderfer said.

In terms of response rates, 17 of 18 patients who received doses above 50 x 106 CAR+ T cells had overall responses, and 10 of the 18 achieved complete remission.

The median time to first response was 1 month, and the times to best response and complete response were 3.74 and 3.84 months, respectively. The rates of progression-free survival were 81% at 6 months, and 71% at 9 months, and responses deepened over time: as of May, the complete response rate was 27%, and as of October, it was 56%.

“Five of these patients so far have met the 1-year progression-free survival standard,” Dr. Kochenderfer said, adding that responses have endured for more than a year in several patients. The longest was 68 weeks at the time of the data presentation, and responses continued to improve as late as 15 months, with very good partial remission to complete remission transitions.

The median progression-free survival had not been reached in the active dose cohorts.

“So, in general, very impressive responses compared to my previous experience treating multiple myeloma,” he said.

The findings support the potential of CAR T therapy with bb2121 as a new treatment paradigm in relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma, he concluded, noting that a global pivotal trial of bb2121 (the phase 2 KarMMa trial) is now enrolling and will dose patients at between 150 and 350 x 106 CAR+ T cells. Under the breakthrough therapy designation granted for bb2121, the product will receive expedited review by the FDA.The CRB-410 trial is sponsored by bluebird bio and Celgene. Dr. Kochenderfer reported receiving research funding from bluebird bio and Kite Pharma, and having multiple patents in the CAR field.

REPORTING FROM ASH 2017

Key clinical point:

Major finding: The overall response rate was 94%.

Study details: An update from the phase 1 CRB-410 dose trial of 21 patients.

Disclosures: The CRB-410 trial is sponsored by bluebird bio and Celgene. Dr. Kochenderfer reported receiving research funding from bluebird bio and Kite Pharma, and having multiple patents in the CAR field.

Source: Berdeja J et al. ASH 2017 Abstract 740.

Medicaid’s share of state budgets continues to grow

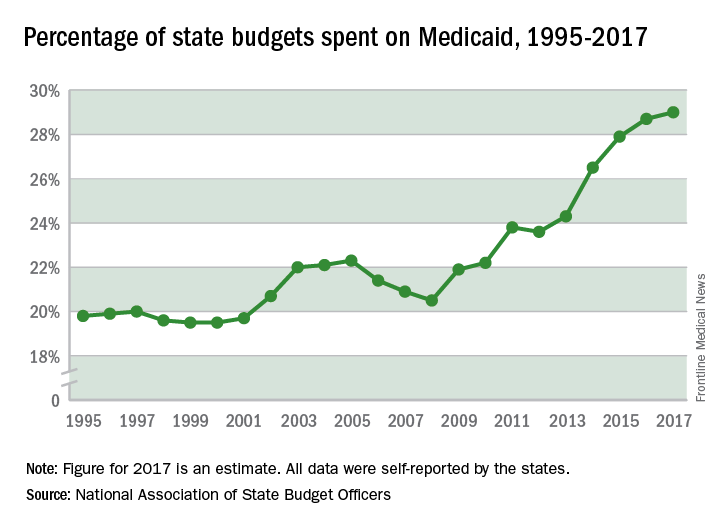

State spending on Medicaid in fiscal 2017 was up 6.1% over 2016, and the program’s share of state budgets increased for the fifth year in a row, according to the National Association of State Budget Officers.

Total spending by the states on Medicaid benefits for more than 74 million individuals was an estimated $574 billion in 2017, which represented 29% of all expenditures. That compares with 28.7% in 2016 and 23.6% in 2012 – the last year that Medicaid’s share of state spending decreased, NASBO said in its annual State Expenditure Report.

Enrollment rose by 2.9% from 2016 to 2017, which was down from the 3.9% increase seen from 2015 to 2016. Since October 2013, Medicaid enrollment is up 38% in expansion states and 12% in nonexpansion states, the report noted.

Enrollment increases are “the major driver” of spending growth, NASBO said, and “Medicaid’s annual spending growth from all fund sources has averaged 8.1% over the past 5 years, while the rest of total spending growth has averaged 2.2% annually.”

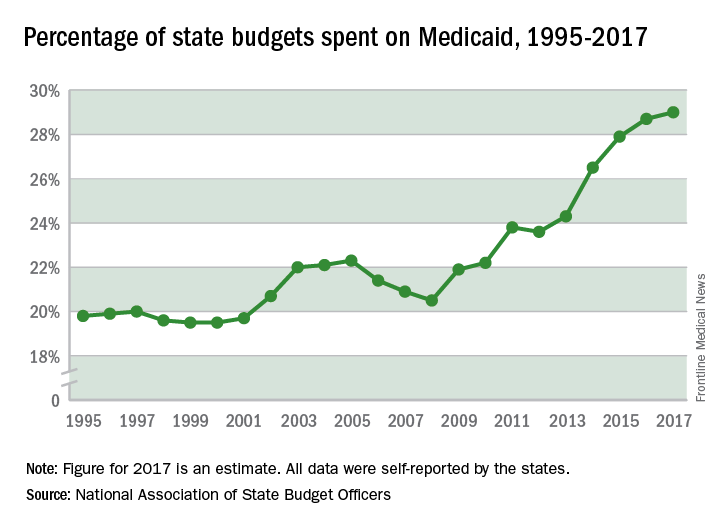

State spending on Medicaid in fiscal 2017 was up 6.1% over 2016, and the program’s share of state budgets increased for the fifth year in a row, according to the National Association of State Budget Officers.

Total spending by the states on Medicaid benefits for more than 74 million individuals was an estimated $574 billion in 2017, which represented 29% of all expenditures. That compares with 28.7% in 2016 and 23.6% in 2012 – the last year that Medicaid’s share of state spending decreased, NASBO said in its annual State Expenditure Report.

Enrollment rose by 2.9% from 2016 to 2017, which was down from the 3.9% increase seen from 2015 to 2016. Since October 2013, Medicaid enrollment is up 38% in expansion states and 12% in nonexpansion states, the report noted.

Enrollment increases are “the major driver” of spending growth, NASBO said, and “Medicaid’s annual spending growth from all fund sources has averaged 8.1% over the past 5 years, while the rest of total spending growth has averaged 2.2% annually.”

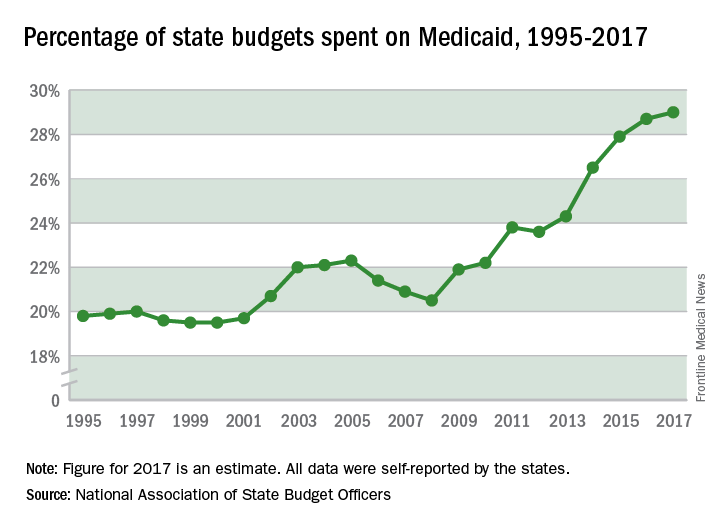

State spending on Medicaid in fiscal 2017 was up 6.1% over 2016, and the program’s share of state budgets increased for the fifth year in a row, according to the National Association of State Budget Officers.

Total spending by the states on Medicaid benefits for more than 74 million individuals was an estimated $574 billion in 2017, which represented 29% of all expenditures. That compares with 28.7% in 2016 and 23.6% in 2012 – the last year that Medicaid’s share of state spending decreased, NASBO said in its annual State Expenditure Report.

Enrollment rose by 2.9% from 2016 to 2017, which was down from the 3.9% increase seen from 2015 to 2016. Since October 2013, Medicaid enrollment is up 38% in expansion states and 12% in nonexpansion states, the report noted.

Enrollment increases are “the major driver” of spending growth, NASBO said, and “Medicaid’s annual spending growth from all fund sources has averaged 8.1% over the past 5 years, while the rest of total spending growth has averaged 2.2% annually.”

Guselkumab crushes skin disease in psoriatic arthritis patients

GENEVA – The interleukin-23 inhibitor guselkumab generates the same impressive improvement in skin disease in psoriatic arthritis patients as has been seen in psoriasis without joint disease, Alexa B. Kimball, MD, reported at the annual congress of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology.

However, psoriatic arthritis patients’ improvement in Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) scores is less robust than in patients with psoriasis only, added Dr. Kimball, professor of dermatology at Harvard Medical School, Boston, and CEO of Harvard Medical Faculty Physicians at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center.

The psoriatic arthritis group as a whole had more severe psoriasis, with a baseline mean PASI score of 24.3 and involvement of 32.7% of their body surface area as compared with a PASI score of 21.2 and 27.2% BSA in psoriasis patients without arthritis. A total of 28% of the psoriatic arthritis patients had previously been on other biologics and 77% had been on nonbiologic systemic agents, compared with 19% and 60% of the psoriasis patients, respectively. The psoriatic arthritis group had a mean 19.2-year history of psoriasis, 1.9 years longer than the psoriasis-only group.

Participants were randomized to 100 mg of guselkumab administered subcutaneously at weeks 0, 4, 12, and 20; placebo through week 12, followed by a switch to adalimumab (Humira); or adalimumab at 80 mg at week 0, then 40 mg at week 2 and 40 mg again every 2 weeks until week 23.

The key findings:

The PASI 90 response rate – that is, at least a 90% improvement in Psoriasis Area and Severity Index – in guselkumab-treated patients at week 16 was 72% in patients with psoriatic arthritis and 71% in those without. At week 24, the PASI 90 rate was 74% in guselkumab-treated patients with psoriatic arthritis and similar at 78% in those without. In contrast, the PASI 90 rate at week 24 in patients on adalimumab was significantly lower: 48% in the psoriatic arthritis group and 55% in those with psoriasis only. The PASI 90 rate in placebo-treated controls was single digit.

At week 24, 82% of psoriatic arthritis patients on guselkumab had clear or almost clear skin as reflected in an Investigator’s Global Assessment score of 0 or 1, as did 84% of psoriasis-only patients.

A DLQI score of 0 or 1, meaning the dermatologic disease had no impact on patient quality of life, was documented at week 16 in 46% of psoriatic arthritis patients and 55% of psoriasis-only patients, a trend that didn’t achieve statistical significance. However, by week 24 the difference became significant, with a DLQI of 0 or 1 in 48% of the psoriatic arthritis patients, compared with 62% of psoriasis-only patients.

VOYAGE 1 and 2 were dermatologic studies that didn’t measure changes in joint symptom scores or other psoriatic arthritis outcomes. Guselkumab as a potential treatment for psoriatic arthritis is under investigation in other studies.

The VOYAGE trials and this analysis were sponsored by Janssen. Dr. Kimball reported receiving research funding from and serving as a consultant to Janssen and numerous other pharmaceutical companies.

SOURCE: Kimball A et al. https://eadvgeneva2017.org/

GENEVA – The interleukin-23 inhibitor guselkumab generates the same impressive improvement in skin disease in psoriatic arthritis patients as has been seen in psoriasis without joint disease, Alexa B. Kimball, MD, reported at the annual congress of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology.

However, psoriatic arthritis patients’ improvement in Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) scores is less robust than in patients with psoriasis only, added Dr. Kimball, professor of dermatology at Harvard Medical School, Boston, and CEO of Harvard Medical Faculty Physicians at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center.

The psoriatic arthritis group as a whole had more severe psoriasis, with a baseline mean PASI score of 24.3 and involvement of 32.7% of their body surface area as compared with a PASI score of 21.2 and 27.2% BSA in psoriasis patients without arthritis. A total of 28% of the psoriatic arthritis patients had previously been on other biologics and 77% had been on nonbiologic systemic agents, compared with 19% and 60% of the psoriasis patients, respectively. The psoriatic arthritis group had a mean 19.2-year history of psoriasis, 1.9 years longer than the psoriasis-only group.

Participants were randomized to 100 mg of guselkumab administered subcutaneously at weeks 0, 4, 12, and 20; placebo through week 12, followed by a switch to adalimumab (Humira); or adalimumab at 80 mg at week 0, then 40 mg at week 2 and 40 mg again every 2 weeks until week 23.

The key findings:

The PASI 90 response rate – that is, at least a 90% improvement in Psoriasis Area and Severity Index – in guselkumab-treated patients at week 16 was 72% in patients with psoriatic arthritis and 71% in those without. At week 24, the PASI 90 rate was 74% in guselkumab-treated patients with psoriatic arthritis and similar at 78% in those without. In contrast, the PASI 90 rate at week 24 in patients on adalimumab was significantly lower: 48% in the psoriatic arthritis group and 55% in those with psoriasis only. The PASI 90 rate in placebo-treated controls was single digit.

At week 24, 82% of psoriatic arthritis patients on guselkumab had clear or almost clear skin as reflected in an Investigator’s Global Assessment score of 0 or 1, as did 84% of psoriasis-only patients.

A DLQI score of 0 or 1, meaning the dermatologic disease had no impact on patient quality of life, was documented at week 16 in 46% of psoriatic arthritis patients and 55% of psoriasis-only patients, a trend that didn’t achieve statistical significance. However, by week 24 the difference became significant, with a DLQI of 0 or 1 in 48% of the psoriatic arthritis patients, compared with 62% of psoriasis-only patients.

VOYAGE 1 and 2 were dermatologic studies that didn’t measure changes in joint symptom scores or other psoriatic arthritis outcomes. Guselkumab as a potential treatment for psoriatic arthritis is under investigation in other studies.

The VOYAGE trials and this analysis were sponsored by Janssen. Dr. Kimball reported receiving research funding from and serving as a consultant to Janssen and numerous other pharmaceutical companies.

SOURCE: Kimball A et al. https://eadvgeneva2017.org/

GENEVA – The interleukin-23 inhibitor guselkumab generates the same impressive improvement in skin disease in psoriatic arthritis patients as has been seen in psoriasis without joint disease, Alexa B. Kimball, MD, reported at the annual congress of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology.

However, psoriatic arthritis patients’ improvement in Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) scores is less robust than in patients with psoriasis only, added Dr. Kimball, professor of dermatology at Harvard Medical School, Boston, and CEO of Harvard Medical Faculty Physicians at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center.

The psoriatic arthritis group as a whole had more severe psoriasis, with a baseline mean PASI score of 24.3 and involvement of 32.7% of their body surface area as compared with a PASI score of 21.2 and 27.2% BSA in psoriasis patients without arthritis. A total of 28% of the psoriatic arthritis patients had previously been on other biologics and 77% had been on nonbiologic systemic agents, compared with 19% and 60% of the psoriasis patients, respectively. The psoriatic arthritis group had a mean 19.2-year history of psoriasis, 1.9 years longer than the psoriasis-only group.

Participants were randomized to 100 mg of guselkumab administered subcutaneously at weeks 0, 4, 12, and 20; placebo through week 12, followed by a switch to adalimumab (Humira); or adalimumab at 80 mg at week 0, then 40 mg at week 2 and 40 mg again every 2 weeks until week 23.

The key findings:

The PASI 90 response rate – that is, at least a 90% improvement in Psoriasis Area and Severity Index – in guselkumab-treated patients at week 16 was 72% in patients with psoriatic arthritis and 71% in those without. At week 24, the PASI 90 rate was 74% in guselkumab-treated patients with psoriatic arthritis and similar at 78% in those without. In contrast, the PASI 90 rate at week 24 in patients on adalimumab was significantly lower: 48% in the psoriatic arthritis group and 55% in those with psoriasis only. The PASI 90 rate in placebo-treated controls was single digit.

At week 24, 82% of psoriatic arthritis patients on guselkumab had clear or almost clear skin as reflected in an Investigator’s Global Assessment score of 0 or 1, as did 84% of psoriasis-only patients.

A DLQI score of 0 or 1, meaning the dermatologic disease had no impact on patient quality of life, was documented at week 16 in 46% of psoriatic arthritis patients and 55% of psoriasis-only patients, a trend that didn’t achieve statistical significance. However, by week 24 the difference became significant, with a DLQI of 0 or 1 in 48% of the psoriatic arthritis patients, compared with 62% of psoriasis-only patients.

VOYAGE 1 and 2 were dermatologic studies that didn’t measure changes in joint symptom scores or other psoriatic arthritis outcomes. Guselkumab as a potential treatment for psoriatic arthritis is under investigation in other studies.

The VOYAGE trials and this analysis were sponsored by Janssen. Dr. Kimball reported receiving research funding from and serving as a consultant to Janssen and numerous other pharmaceutical companies.

SOURCE: Kimball A et al. https://eadvgeneva2017.org/

REPORTING FROM THE EADV CONGRESS

Key clinical point:

Major finding: After 16 weeks on guselkumab, 72% of psoriatic arthritis patients and 71% with psoriasis-only had a PASI 90 response.

Study details: This was a comparison of skin and DLQI outcomes in 335 patients with psoriatic arthritis and 1,494 with psoriasis only who participated in two randomized, double-blind, phase 3 clinical trials.

Disclosures: Janssen sponsored the study. The presenter reported receiving research grants from and serving as a consultant to Janssen and numerous other pharmaceutical companies.

Source: Kimball A et al. https://eadvgeneva2017.org/.

Transition in care from the MICU to the ward

Editor’s Note: The Society of Hospital Medicine’s (SHM’s) Physician in Training Committee launched a scholarship program in 2015 for medical students to help transform healthcare and revolutionize patient care. The program has been expanded for the 2017-18 year, offering two options for students to receive funding and engage in scholarly work during their first, second and third years of medical school. As a part of the program, recipients are required to write about their experience on a biweekly basis.

This summer, my research project focused on the highly vulnerable patients who are transferred from the medical intensive care unit to the general floor. Patients who are readmitted tend to have worse health outcomes, longer stays, higher mortality rates, and higher health care costs. Previous research shows that higher quality handoffs, where receiving and transferring providers share the same shared mental model, result in better outcomes. We were interested in learning whether these shared mental models are being formed as a result of handoffs between the ward and the MICU.

The current results reveal that 18% of MICU teams shared a complete mental model, 25% shared a strong shared mental model, 9% shared a weak mental model, 30% shared no mental model, and 18% of patient encounters did not have a sufficient number of MICU respondents. Regarding inter-team communication, 7% shared a full shared mental model, 49% shared a partial mental model, 30% shared no shared mental model, and 14% of unique patient encounters did not have enough respondents.

With complex patient cases, it can be difficult to identify the most important factor of care for a particular patient. However, I think this information would be very useful in identifying whether these exchanges result in individuals prioritizing the same factor of care for their respective patient. I think this information would be very useful in future quality improvement, and seeing whether this communication results in the formation of shared mental models.

Anton Garazha is a medical student at Chicago Medical School at Rosalind Franklin University in North Chicago. He received his bachelor of science degree in biology from Loyola University in Chicago in 2015 and his master of biomedical science degree from Rosalind Franklin University in 2016. Anton is very interested in community outreach and quality improvement, and in his spare time tutors students in science-based subjects.

Editor’s Note: The Society of Hospital Medicine’s (SHM’s) Physician in Training Committee launched a scholarship program in 2015 for medical students to help transform healthcare and revolutionize patient care. The program has been expanded for the 2017-18 year, offering two options for students to receive funding and engage in scholarly work during their first, second and third years of medical school. As a part of the program, recipients are required to write about their experience on a biweekly basis.

This summer, my research project focused on the highly vulnerable patients who are transferred from the medical intensive care unit to the general floor. Patients who are readmitted tend to have worse health outcomes, longer stays, higher mortality rates, and higher health care costs. Previous research shows that higher quality handoffs, where receiving and transferring providers share the same shared mental model, result in better outcomes. We were interested in learning whether these shared mental models are being formed as a result of handoffs between the ward and the MICU.

The current results reveal that 18% of MICU teams shared a complete mental model, 25% shared a strong shared mental model, 9% shared a weak mental model, 30% shared no mental model, and 18% of patient encounters did not have a sufficient number of MICU respondents. Regarding inter-team communication, 7% shared a full shared mental model, 49% shared a partial mental model, 30% shared no shared mental model, and 14% of unique patient encounters did not have enough respondents.

With complex patient cases, it can be difficult to identify the most important factor of care for a particular patient. However, I think this information would be very useful in identifying whether these exchanges result in individuals prioritizing the same factor of care for their respective patient. I think this information would be very useful in future quality improvement, and seeing whether this communication results in the formation of shared mental models.

Anton Garazha is a medical student at Chicago Medical School at Rosalind Franklin University in North Chicago. He received his bachelor of science degree in biology from Loyola University in Chicago in 2015 and his master of biomedical science degree from Rosalind Franklin University in 2016. Anton is very interested in community outreach and quality improvement, and in his spare time tutors students in science-based subjects.

Editor’s Note: The Society of Hospital Medicine’s (SHM’s) Physician in Training Committee launched a scholarship program in 2015 for medical students to help transform healthcare and revolutionize patient care. The program has been expanded for the 2017-18 year, offering two options for students to receive funding and engage in scholarly work during their first, second and third years of medical school. As a part of the program, recipients are required to write about their experience on a biweekly basis.

This summer, my research project focused on the highly vulnerable patients who are transferred from the medical intensive care unit to the general floor. Patients who are readmitted tend to have worse health outcomes, longer stays, higher mortality rates, and higher health care costs. Previous research shows that higher quality handoffs, where receiving and transferring providers share the same shared mental model, result in better outcomes. We were interested in learning whether these shared mental models are being formed as a result of handoffs between the ward and the MICU.

The current results reveal that 18% of MICU teams shared a complete mental model, 25% shared a strong shared mental model, 9% shared a weak mental model, 30% shared no mental model, and 18% of patient encounters did not have a sufficient number of MICU respondents. Regarding inter-team communication, 7% shared a full shared mental model, 49% shared a partial mental model, 30% shared no shared mental model, and 14% of unique patient encounters did not have enough respondents.

With complex patient cases, it can be difficult to identify the most important factor of care for a particular patient. However, I think this information would be very useful in identifying whether these exchanges result in individuals prioritizing the same factor of care for their respective patient. I think this information would be very useful in future quality improvement, and seeing whether this communication results in the formation of shared mental models.

Anton Garazha is a medical student at Chicago Medical School at Rosalind Franklin University in North Chicago. He received his bachelor of science degree in biology from Loyola University in Chicago in 2015 and his master of biomedical science degree from Rosalind Franklin University in 2016. Anton is very interested in community outreach and quality improvement, and in his spare time tutors students in science-based subjects.

Cancer care in 2017: the promise of more cures with the challenges of an unstable health care system

This past year will likely be remembered as one of breakthrough advances in reducing the burden of cancer, with some landmark “firsts” coming out of the US Food and Drug Admini

Our excitement has also been tempered by the rapid rise in the cost of effective biologic, immunologic, and targeted therapies. With the approval of trastuzumab-dkst (Ogivri), the first targeted biosimilar for HER2-positive breast and gastrointestinal cancers, we can look forward to price decreases possibly in the 20%-30% range over time from a targeted therapy with remarkable clinical efficacy. We know that approved biosimilars have demonstrated clinical efficacy along with similar minor biologic diversity that is also seen in the reference biologic.1 We can also hope that increasing competition among biosimilar and reference compounds will lead to improvements in production methodologies that can allow further price reductions so that even more patients can gain access to these highly effective therapies.

In addition, the first FDA approval for the next-generation sequencing (NGS) FoundationOne profiling test and the rapid announcement by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) that it will cover the cost of that testing brings us a step closer to knowing which patients most likely will or won’t benefit from costly and toxic targeted therapies. Along with the many clinical trials studying which mutations predict which efficacies of individual or combinations of targeted agents, the approval and CMS coverage policy will help us improve value to our patients; when we can recommend the most beneficial therapies and avoid futile ones.

Finally, the approval for the DigniCap Scalp Cooling System for patients on chemotherapy for all solid tumors is of great importance. Pending coverage availability, it may influence some patients to get chemotherapy they might otherwise have forgone to avoid hair loss (see related article).

More consolidation: the best of all worlds?

In my 27 years in private practice, during which practice revenues grew with the favorable profit margins on novel therapies, forward-thinking physician leaders piloted innovations in oncology electronic medical records (EMRs), the delivery of team-based care, clinical research partnerships, and more comprehensive care services to better serve diverse communities, including those in rural areas. At my previous practice, that included adding clinicians to our group to serve patients at hospital clinics in 2 counties in southern California, each county with populations larger than 15 states. Our private practice worked with these public entities to bring state-of-the art care and private practice efficiencies to the uninsured and underserved in our region.

Unfortunately, revenues plummeted with changes in reimbursement after passage of the Medicare Modernization Act in 2003 and they continue to destabilize and reduce the number of community practices across the country. Many oncologists and oncology practices, including mine, chose to join larger academic or hospital systems or larger oncology networks at a time they are also facing growing pressures to contain costs, focus on out-patient care, complex clinical trials, and expanded access to care.

Although we may lament the shrinking landscape of private oncology practices, we can also be inspired by the physicians who have joined ranks with the better-funded, better-resourced, more traditional hospital and academic systems. These larger systems have more resources, more clincial trial offerings, staffing, technology, and analytics to expand value-based care initiatives to larger numbers of patients.

The hub-and-spoke models of oncology care with integrated networks linked by technology, and networked into larger analytic and decision support systems such as CancerLinQ, the health information technology program of the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO),2 could facilitate documentable delivery of comprehensive, evidence-based care, moving us closer to meeting the Quadruple Aim of optimal health care: improving the patient experience of care (including quality and satisfaction); improving the health of populations; reducing the per capita cost of health care; and improving the work life of those who deliver care.3,4

Payment reform: working to align incentives

Everyone seems to agree that the fee-for-service payment models do not align incentives for improving total health outcomes at the lowest costs, but at the moment, there seems to be no best way of aligning them. Robinson has reported on the oncology payment initiatives at four major health insurance plans – Medicare (public) and Anthem, Aetna, and UnitedHealthcare (all private), noting that:5

- Medicare is testing its Oncology Care Model at more than 200 sites in the United States, and early data are expected to be released in 2018.

- Anthem continues with its Cancer Care Quality Program that includes adherence to 2 key requirements: that participants are compliant with Anthem-approved drug pathways, and that they register their patients at the insurer’s oncology website and enter their clinical data. Anthem is also considering expanding the management fee for certain high priority clinical trials.

- Aetna’s Oncology Solutions takes a different approach by providing increased payments for generic chemotherapies.

- United has eliminated the mark-up for new drugs and continues to mark up the prices of the older and generic therapies. Its episode-based pricing gives practices upfront payments based on expected drug margins so that practices can fund more comprehensive evidence-based care. In a presentation at a Washington State Medical Oncology Society meeting recently, United’s Lee Newcomer, reported that the insurer continues to see improved clinical and financial outcomes as well as encouraging early data showing that patients might do better in the real-world setting on some therapies that have not been fully compared in head-to-head randomized clinical trials.6,7

ASCO is pulling these ideas together at the national level with its Patient-Centered Oncology Payment (PCOP) model, which is similar to Medicare’s alternative payment model. The PCOP model focuses on high-value, quality care. Higher upfront payments would cover the additional diagnostic services, care planning, and management to improve compliance and adherence as well as clinical trial evaluations. The model was developed and vetted by the ASCO Clinical Practice Committee and practicing oncologists, and is supported by staff and consultants. It is currently in its second year of operation with a commercial payer and will be submitted for review to the Physician-Focused Payment Model Technical Advisory Committee of the Health and Human Services. The results of the review are expected in 2018. If the model is approved, it could provide a uniform approach for payers that would align incentives for high-quality cancer care and allow for better predictive modeling for practices, irrespective of size, to invest in infrastructure and staffing to meet the growing demand for high-quality, value-based cancer care.

Better science: the promise of more cures

The FDA approved a record number drugs and biologics in 2017 for various cancers,8 including the landmark approval of the first CART therapy for cancer, tisagenlecleucel, which targets CD19 on B cells in the treatment of acute leukemia. That approval was rapidly followed by a second anti-CD19 CART therapy, axicabtagene ciloluecel, for refractory, aggressive B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma.9,10 Although these therapies can achieve remarkable response and even complete response rates in otherwise refractory patients, only some achieve a long-term remission, and the costs are an order of magnitude above most other cancer therapies. That raises the question of what duration of benefit we should expect for treatments that cost in the range of $500,000 for the therapy alone, along with the additional costs for care, hospitalization, monitoring, expensive biologics (eg, tocilizumab, for the severe and potentially life-threatening cytokine-release syndrome associated with CART therapies), and significant neurologic and other therapy-related toxicities.

Novel arrangements between pharmaceutical companies and payers are currently being discussed so that only patients who meet specific response criteria would be charged for the therapy. In addition, we await findings from ongoing research to see if new approaches can find specific targetable sites on solid tumors that could spare the healthy organ tissues while eliminating highly resistant or heterogeneous populations of mutations in patients with advanced solid tumors. Such development of highly specific targets for CART therapies would improve their efficacy and safety, and with defined protocols in place to address toxicities and efforts to reduce the costs of the therapies, we can hopefully ensure broader access for patients to this potentially transformative therapeutic tool.

In addition to the excitement around the CART therapies, many of the years other new approvals will bring incremental but meaningful improvement in outcomes for patients with common cancers. The approval of neratinib, the first agent approved as extended adjuvant therapy for women with early-stage HER2/neu-positive breast cancer, is welcome, given the current 30% recurrence risk that extends past 10 years for women in that disease population who have completed standard adjuvant HER2-directed therapies. The 34% reduction in recurrence risk with a year of extended oral adjuvant therapy, as reported by Martin and colleagues,11 with benefits sustained out to 5 years and with controllable diarrhea as the major toxicity, are encouraging. This oral therapy may be especially beneficial for hormone-receptor–positive women in whom blocking the HER2/neu pathway may enhance cell signaling through the hormone pathways, which can be blocked with oral agents at the same time to provide significant reduction of recurrence risk.

Diagnostics

The concept of personalized medicine is based on identifying biomarkers that are predictive of a patient’s response to treatment. There has been much progress toward applying NGS of tumors for use in the clinic, but we are still awaiting evidence from randomized clinical trials that such approaches prolong overall or progression-free survival.12 Dr Julie Lange, an associate professor of clinical surgery and director of the Breast Cancer Program at the Keck School of Medicine at the University of Southern California, Los Angeles, provided me with the references to key studies in this field in which she is a leading researcher.13 However, she pointed out that in the absence of effective therapies, advanced biomarker testing may be less helpful, as is the case in heavily pretreated patients,14 unless a molecular test can pinpoint a potentially clinically actionable mutation. With the plethora of available assays and the high costs of molecular testing, clinicians are challenged in knowing what testing is best for which patients. Findings from a number of key ongoing national trials may eventually help us understand which tumor mutations in which tumor types can be most effectively targeted when multiple targetable mutations are found (TAPUR,15 MATCH,16 and QUILT17 and other basket trials18). The complexity of molecular testing has led to the development of institutional, trial-based, or co-operative group molecular tumor boards to provide guidance on specific targeted therapies for specific tumor mutations.

ASCO has launched a monthly series called Molecular Oncology Tumor Boards19 to expand the knowledge base in this field. It is presented as user-driven discussions designed to help providers integrate the use of the new genetic and genomic tests and their results into the day-to-day clinical care of patients with cancer.20

Liquid biopsies

As busy clinicians, we need to understand the differences in liquid biopsy tests and their correlation with actionable targets, especially given the rapid progress in this field. Again, Dr Lange offered clarity on those differences. Liquid biopsy, refers to using a blood draw to isolate circulating tumor cells (CTCs) or circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) to assess tumor biomarkers.21 Both CTCs and ctDNA tests have been shown to be prognostic of worse survival.22-24 Liquid biopsies are currently supplemental to direct tumor biopsies, not replacements for them. The theoretical advantage of liquid biopsies is that they may reflect tumor heterogeneity by examining the repertoire of mutations contributed by diverse metastatic sites that shed CTCs or ctDNA into the circulation. The question is which type of testing can best inform therapy decisions.

Assays for ctDNA using droplet digital PCR [polymerase chain reaction], a digital PCR method based on water-oil emulsion droplet technology, require a priori knowledge of the specific mutation associated with response or lack of response to a specific therapy.25,26 Technical issues related to the detection of rare alleles present within a mixed population of leukocytes, and ctDNA remains a challenge for many ctDNA assays. However, there is evidence to suggest that whole-exome sequencing of ctDNA is concordant with mutations in metastases,27 however benchmarking ctDNA against tissue biopsies of metastases was not possible in all studies because tumor blocks were not available or because of the failure of tumor NGS assays. 28,29

Newer generations of CTC assays take advantage of the circulating tumor cell as a functional assay for mutational status, gene expression, proteomics, epigenetics, and/or chemosensitivity of cultured cells. The relationship between CTCs and ctDNA remains uncertain as to whether CTCs are the cell of origin for ctDNA or if ctDNA may reflect responding or resistant tumor populations. The use of NGS on tumor specimens, ctDNA, and CTCs as a discovery tool is advancing the field by improving the understanding of disease heterogeneity and potential treatment targets. These results require correlation with patterns of response to therapy, and ultimately require validation in randomized clinical trials to provide strong evidence justifying their use outside of clinical trials. We can look forward to a time in the not distant future when specific liquid biopsy assays will reflect the array of mutations in different metastatic sites with validation that they correlate with efficacy of targeting those mutations that have targetable therapies.

From the FDA

New approvals

- Trastuzumab-dkst (Ogivri, Mylan; Dec 1) was approved as a biosimilar to trastuzumab (Herceptin, Genentech) for the treatment of patients with HER2-overexpressing breast or metastatic stomach cancer (gastric or gastroesophageal junction adenocarcinoma).

- Sunitinib malate (Sutent, Pfizer; Nov 16) was approved for the adjuvant treatment of adult patients at high risk of recurrent renal cell carcinoma after nephrectomy.

- Obinutuzumab (Gazyva, Genentech; Nov 16) received regular approval in combination with chemotherapy, followed by obinutuzumab monotherapy in patients achieving partial remission, for adult patients with previously untreated stage II bulky, III, or IV follicular lymphoma.

- Emicizumab-kxwh (Hemlibra, Genentech; Nov 16) was approved for routine prophylaxis to prevent or reduce the frequency of bleeding episodes in adult and pediatric patients with hemophilia A with factor VIII inhibitors.

- Dasatinib (Sprycel, Bristol-Myers Squibb; Nov 9) was approved for the treatment of pediatric patients with Philadelphia chromosome-positive chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) in the chronic phase.

- Brentuximab vedotin (Adcetris, Seattle Genetics; Nov 9) for the treatment of previously treated adult patients with primary cutaneous anaplastic large cell lymphoma (pcALCL) or CD30-expressing mycosis fungoides.

- Alectinib (Alecensa, Hoffmann-La Roche/Genentech; Nov 6) was approved for treatment of patients with anaplastic lymphoma kinase–positive metastatic non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), as detected by an FDA-approved test.

- Vemurafenib (Zelboraf, Hoffmann-La Roche; Nov 6) received approval for the treatment of Acalabrutinib (Calquence, AstraZeneca/Acerta; Oct 31) was granted accelerated approval for treatment of adult patients with mantle cell lymphoma (MCL) who have received at least one previous therapy.

- Axicabtagene ciloleucel (Yescarta, Kite; Oct 18), a CART therapy, was approved for treatment of adult patients with relapsed or refractory large B-cell lymphoma after two or more lines of systemic therapy, including diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) not otherwise specified, primary mediastinal large B-cell lymphoma, high-grade B-cell lymphoma, and DLBCL arising from follicular lymphoma. The complete remission rate reviewed by the FDA for trial patients was 51%.30 It was the second CART therapy this year to receive approval (see tisagenlecleucel; Aug 30). The agency granted orphan drug designation and priority review to therapy for this indication.

- Abemaciclib (Verzenio, Eli Lilly; Sep 28) was approved in combination with fulvestrant for women with hormone receptor-positive, HER2-negative advanced or metastatic breast cancer with disease progression following endocrine therapy.

- Copanlisib (Aliqopa, Bayer; Sep 14) got accelerated approval for the treatment of adult patients with relapsed follicular lymphoma who have received at least two prior systemic therapies.

- Bevacizumab-awwb (Mvasi, Amgen; Sep 14) was approved as a biosimilar to bevacizumab (Avastin, Genentech) for treating multiple types of cancer. It was the first biosimilar approved in the US for the treatment of cancer.

- Gemtuzumab ozogamicin (Mylotarg, Pfizer; Sep 1) was approved for the treatment of newly diagnosed CD33-positive acute myeloid leukemia (AML) in adults and of relapsed/refractory CD33-positive AML in adults and pediatric patients aged 2 or older. It can be used in combination with daunorubicin and cytarabine for adults with newly diagnosed AML, or as a standalone treatment for certain adult and pediatric patients. The drug was originally approved in 2000 as a standalone treatment for CD33-positive AML in patients older than 60 years, but was withdrawn in 2010 because of safety concerns and postmarketing trials could not confirm benefit. The current approval is for a lower recommended dose and schedule.31

- Tisagenlecleucel (Kymriah, Novartis; Aug 30) was approved for the treatment of patients up to age 25 years with B-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) that is refractory or in second or later relapse. It is the first CART immunotherapy approved by the agency.

- Inotuzumab ozogamicin (Besponsa, Wyeth; Aug 17) was approved for the treatment of adults with relapsed or refractory B-cell precursor ALL.

- A liposome-encapsulated combination of daunorubicin and cytarabine (Vyxeos, Jazz; Aug 3) was approved for the treatment of adults with newly diagnosed therapy-related AML (t-AML) or AML with myelodysplasia-related changes (AML-MRC), two types of AML having a poor prognosis.

- Enasidenib (Idhifa, Celgene; Aug 1) was approved for the treatment of adult patients with relapsed or refractory AML with an isocitrate dehydrogenase-2 mutation as detected by an FDA-approved test.

- Neratinib (Nerlynx, Puma; Jul 17) was approved as the first extended adjuvant therapy for adult patients with early stage HER2-overexpressed/amplified breast cancer, to follow adjuvant trastuzumab-based therapy.

- Blinatumomab (Blincyto, Amgen; Jul 11) was approved for the treatment of relapsed or refractory B-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia in adults and children.

- L-glutamine oral powder (Endari, Emmaus; Jul 7) was approved for oral administration to reduce the acute complications of sickle cell disease in adult and pediatric patients 5 years and older.

- Betrixaban (Bevyxxa, Portola; Jun 23) was approved for the prophylaxis of venous thromboembolism (VTE) in adult patients hospitalized for an acute medical illness who are at risk for thromboembolic complications because of moderate or severe restricted mobility and other risk factors for VTE.

- The combination of rituximab and hyaluronidase human (Rituxan Hycela, Genentech; Jun 22) was approved for adult patients with follicular lymphoma, DLBCL, and chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Hyaluronidase human is an enzyme that helps deliver the rituximab. This formulation allows subcutaneous administration of the combination, which will shorten patient visit times and potentially even allow at-home therapy delivery.

- Ceritinib (Zykadia, Novartis; May 26) was approved for patients with metastatic NSCLC whose tumors are anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK)-positive as detected by an FDA-approved test.

- Avelumab (Bavencio, EMD Serono; May 9) got accelerated approval for patients with locally advanced or metastatic urothelial carcinoma whose disease progressed during or following platinum-containing chemotherapy or within 12 months of neoadjuvant or adjuvant platinum-containing chemotherapy.

- Durvalumab (ImfinzI, AstraZeneca; May 1) got accelerated approval for the treatment of patients with locally advanced or metastatic urothelial carcinoma who have disease progression during or following platinum-containing chemotherapy or who have disease progression within 12 months of neoadjuvant or adjuvant treatment with platinum-containing chemotherapy.

- Brigatinib (Alunbrig tablets, Takeda through Ariad; Apr 28) got accelerated approval for the treatment of patients with metastatic anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK)-positive NSCLC who have progressed on or are intolerant to crizotinib.

- Midostaurin (Rydapt, Novartis; Apr 28) was approved for the treatment of adult patients with newly diagnosed AML who are FLT3 mutation-positive, as detected by an FDA-approved test, in combination with standard cytarabine and daunorubicin induction and cytarabine consolidation.

- Osimertinib (Tagrisso, AstraZeneca; Mar 30) got regular approval for the treatment of patients with metastatic epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) T790M mutation-positive NSCLC, as detected by an FDA-approved test, whose disease has progressed on or after EGFR tyrosine-kinase inhibitor therapy.

- Niraparib (Zejula, Tesaro; Mar 27), a poly ADP-ribose polymerase (PARP) inhibitor, was approved for the maintenance treatment of adult patients with recurrent epithelial ovarian, fallopian tube, or primary peritoneal cancer who are in complete or partial response to platinum-based chemotherapy.

- Avelumab (Mar 23), a PD-L1–blocking human IgG1 lambda monoclonal antibody, got accelerated approval for the treatment of patients 12 years and older with metastatic Merkel cell carcinoma. It is the first FDA-approved product to treat this type of cancer.

- Ribociclib (Kisqali, Novartis; Mar 13), a CDK4/6 inhibitor, was approved as a breakthrough therapy after priority review for use in combination with an aromatase inhibitor as initial endocrine-based therapy for the treatment of postmenopausal women with HR-positive, HER2-negative advanced or metastatic breast cancer.

Expanded/additional indications

- Nivolumab (Opdivo, Bristol-Myers Squibb; Sep 22) got accelerated expanded indication approval for treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) in patients previously treated with sorafenib.

- Pembrolizumab (Keytruda, Merck; Sep 22) got accelerated expanded indication approval for recurrent locally advanced or metastatic gastric or gastroesophageal junction adenocarcinoma in patients whose tumors express PD-L1 as determined by an FDA-approved test.

- DigniCap Scalp Cooling System (Dignitana Inc; Jul 3) was cleared for expanded use for reducing hair loss during chemotherapy for all solid tumors. Marketing authorization for the cooling cap had been granted in 2015 for patients with breast cancer.

- Olaparib tablets (Lynparza, AstraZeneca; Aug 17) got approval for an expanded indication as maintenance treatment of adult patients with recurrent epithelial ovarian, fallopian tube, or primary peritoneal cancer, who are in a complete or partial response to platinum-based chemotherapy.

- Ibrutinib (Imbruvica, Pharmacyclics; Aug 2) got expanded indication approval for the treatment of adult patients with chronic graft-versus-host disease (cGVHD) after failure of one or more lines of systemic therapy. It was the first FDA-approved therapy for the treatment of cGVHD. (Ibrutinib was previously approved for chronic lymphocytic leukemia/small lymphocytic lymphoma, chronic lymphocytic leukemia/small lymphocytic lymphoma with 17p deletion, Waldenström’s macroglobulinemia, marginal zone lymphoma, and mantle cell lymphoma).

- Nivolumab (Aug 2) got an accelerated expanded indication for the treatment of patients 12 years and older with mismatch repair deficient (dMMR) and microsatellite instability-high (MSI-H) metastatic colorectal cancer that has progressed after treatment with a fluoropyrimidine, oxaliplatin, and irinotecan.

- Dabrafenib and trametinib (Tafinlar and Mekinist, Novartis; Jun 22) were approved for the expanded indication in combination for patients with metastatic NSCLC with BRAF V600E mutation as detected by an FDA-approved test. The combination demonstrated superior efficacy compared with dabrafenib alone (overall response rate: 61% and 27%, respectively).32

- Pembrolizumab (May 23) got approved for expanded indication for adult and pediatric patients with unresectable or metastatic, MSI-H or dMMR solid tumors that have progressed after treatment and who have no satisfactory alternative treatment options or with MSI-H or dMMR colorectal cancer that has progressed after treatment with a fluoropyrimidine, oxaliplatin, and irinotecan.

- Pembrolizumab (May 18) got approval for expanded indication for patients with locally advanced or metastatic urothelial carcinoma who have disease progression during or following platinum-containing chemotherapy or within 12 months of neoadjuvant or adjuvant treatment with platinum-containing chemotherapy.

- Pembrolizumab (May 10) got accelerated expanded indication for use combination with pemetrexed and carboplatin for the treatment of patients with previously untreated metastatic NSCLC.

- Regorafenib (Stivarga, Bayer; Apr 27) got an additional indication for the treatment of patients with HCC who have been previously treated with sorafenib.

- Palbociclib (Ibrance, Pfizer; Mar 31) got an expanded indication that includes first-line therapy for the treatment of hormone receptor–positive, HER2-negative advanced or metastatic breast cancer in combination with an aromatase inhibitor as initial endocrine based therapy in postmenopausal women.

- Pembrolizumab (Mar 15) got an accelerated additional indication approval for treatment of adult and pediatric patients with refractory classical Hodgkin lymphoma, or those who have relapsed after three or more previous lines of therapy.

- Lenalidomide (Revlimid, Celgene; Feb 22) got an additional indication as maintenance therapy for patients with multiple myeloma following autologous stem cell transplant.

- Nivolumab (Feb 2) got an accelerated expanded indication for treatment of patients with locally advanced or metastatic urothelial carcinoma who have disease progression during or following platinum-containing chemotherapy or have disease progression within 12 months of neoadjuvant or adjuvant treatment with a platinum-containing chemotherapy.

Modified use

- Cabazitaxel (Jevtana, Sanofi-Aventis; Sep 14) in combination with prednisone was approved at a lower dose of 20 mg/m2 every 3 weeks for the treatment of patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer previously treated with a docetaxel-containing treatment regimen. It had been approved at 25 mg/m2 every 3 weeks for this indication in 2010.

Tests/diagnostics

- Marketing approval was given to the FoundationOne CDx (Foundation Medicine; Nov 30), an NGS-based in vitro diagnostic to detect genetic mutations in 324 genes and 2 genomic signatures in any solid tumor type.

- Marketing approval was given to the Praxis Extended RAS Panel (Illumina; Jun 29), a next generation sequencing test to detect certain genetic mutations in RAS genes in tumor samples of patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. The test is used to aid in the identification of patients who may be eligible for treatment with panitumumab (Vectibix, Amgen).

- Marketing was approved for ipsogen JAK2 RGQ PCR Kit (Qiagen ; Mar 27) to detect mutations affecting the Janus tyrosine kinase 2 gene. This is the first FDA-authorized test intended to help physicians in evaluating patients for suspected polycythemia vera.

Imaging and pathology aids

- Aminolevulinic acid hydrochloride, known as ALA HCl (Gleolan, NX; Jun 6) was approved as an optical imaging agent indicated in patients with gliomas (suspected World Health Organization grades III or IV on preoperative imaging) as an adjunct for the visualization of malignant tissue during surgery.

- Marketing was approved for the Philips IntelliSite Pathology Solution (PIPS, Philips Medical Systems Nederland; Apr 17), as an aid to the pathologist to review and interpret digital images of surgical pathology slides prepared from formalin-fixed paraffin embedded tissue.

Challenges and uncertainties

The current administration’s initiatives to reduce administrative burdens is underway with the Patients Over Paperwork initiative. Eliminating and streamlining regulations to increase efficiency and improve beneficiary experience could be helpful to both oncologists and patients. For now, the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act (MACRA) program, allows you to “pick your pace” in the 2017 performance year and report on at least one measure to avoid a payment reduction penalty on your Medicare payments in 2019. In the final rule for 2018, the CMS finalized a proposal to apply the MIPS [Merit-based Incentive Payment System] adjustment to all Part B items and services, which will include Part B drugs. This would be unfair to oncologists who treat on the basis of evidence-based guidelines and pathways and have no control over the costs of the drugs they prescribe.

In addition, more requirements will be imposed in 2018 in a move toward full MACRA implementation. All four composite categories (Quality – 60% for 2017; Advancing Care Information (ACI, renamed from Meaningful Use) – 25% for 2017; Improvement Activities (IA) – 15% for 2017; and Cost – 0% for 2017, but weighted in the future) will be scored, including resource use (cost) at 10%. CMS will collect data to assess the total cost of care and the Medicare Spend per Beneficiary to assess use. Full program implementation, with cost being assessed at 30% of your score is expected in the 2019 performance year. ASCO’s clinical affairs and policy experts have studied the implications of Part B chemotherapy drugs being included in the cost component of the MIPS scoring and will continue advocating for policies that hold clinicians responsible only for the aspects of care they can control, such as providing high-quality care based on the patient’s disease, biomarkers, comorbidities, and preferences, and not the costs of the evidence-based therapies needed by patients.

Toward a better 2018 for ourselves and our patients

As an eternal optimist, I remain enthusiastic that despite the many challenges, we will find effective ways to bring standard as well as newer, cell-based and targeted therapies to our patients and cover the costs of highly effective therapies. I also remain hopeful that improving technological capabilities and payment reforms will be used by innovative clinical and administrative care teams to give clinicians more time to improve the care and health of patients while validating the methodologies so that real world data can help us further craft therapies to improve the health of each individual who needs our care. As we close this 15th year of our journal, we hope our presentations of practical science and implementation content has helped support your work while freeing some time for you to enjoy the journey. Our best wishes for a joyful holiday season celebrated with friends and family and the patients who entrust us to help them face and live beyond their cancer diagnoses.

1. US Food & Drug Administration. Biosimilar and interchangeable

products. https://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DevelopmentApprovalProcess/

HowDrugsareDevelopedandApproved/ApprovalApplications/

¬erapeuticBiologicApplications/Biosimilars/ucm580419.htm. Last

updated October 23, 2017. Accessed December 11, 2017.

2. ASCO CancerLinQ website. https://cancerlinq.org/. Publishing/

update information not available. Accessed November 3, 2017.

3. Bodenheimer T, Sinsky C. From triple to quadruple aim: care of the

patient requires care of the provider. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/

pmc/articles/PMC4226781/. Published November 2014. Accessed

November 7.

4. Institute for Healthcare Improvement. http://www.ihi.org/Engage/

Initiatives/TripleAim/Pages/default.aspx. No update information

given. Accessed November 3, 2017.

5. Robinson JC. Value-based physician payment in oncology: public and

private insurer initiatives. Milbank Q. 2017;95(1);184-203.