User login

Study highlights need for induction strategy in elderly, frail MM patients

ATLANTA—Initial results of the phase 2 HOVON-126 trial in newly diagnosed multiple myeloma (MM) patients have highlighted the need for an induction strategy in elderly and frail patients.

The trial showed high overall response rates (ORRs) after induction with ixazomib, thalidomide, and low-dose dexamethasone.

However, 62% of patients older than 75 and 60% of frail patients discontinued therapy prior to starting maintenance.

HOVON-126 was designed to determine the ORR of induction therapy with ixazomib, thalidomide, and dexamethasone but also compare progression-free survival in patients who received ixazomib maintenance and those who received placebo.

Sonja Zweegman, MD, of VUmc in Amsterdam, The Netherlands, presented induction results from HOVON-126 at the 2017 ASH Annual Meeting (abstract 433).

The study was supported by Takeda and the Dutch Cancer Society. Dr Zweegman disclosed research funding from, and advisory board participation for, Takeda.

Study design

Investigators enrolled patients with previously untreated, symptomatic MM who were not eligible for stem cell transplant. Patients had to have measurable disease and a WHO performance status of 0 to 3 for patients younger than 75 and 0 to 2 for patients 75 or older.

Patients were not eligible if they had grade 3 neuropathy or grade 2 with pain. They were also ineligible if their creatinine clearance was less than 30 mL/minute.

All patients received ixazomib at 4 mg on days 1, 8, and 15; thalidomide at 100 mg on days 1 to 28; and dexamethasone at 40 mg on days 1, 8, 15, and 22 for nine 28-day cycles.

They could then be randomized to ixazomib maintenance (on the aforementioned schedule) or placebo for 28-day cycles until progression.

Investigators performed subgroup analyses based on cytogenetic risk and frailty.

They defined frailty according to the modified IMWG frailty index, which takes into account age, the Charlson Comorbidity Index, and the WHO performance scale as a proxy for Activities of Daily Living.

They defined high-risk cytogenetics as del17p, t(4;14), or t(14;16).

Investigators planned to enroll 142 patients and expected 94 patients to be randomized.

Patient demographics

The first 120 patients enrolled had a median age of 74 (range, 64–90). Thirty percent (n=38) were older than 75, and 8% (n=10) were older than 80.

More than two-thirds had an ISS score of I or II, and three-quarters had a WHO performance status of 0 or 1. Twenty-four percent had a performance status of 2, and 1% had a performance status of 3.

Eighty percent had lytic bone disease.

One hundred thirteen patients (94%) had FISH analysis performed. Of those, 10% had del17p, 7% had t(4;14), and 1% had t(14;16).

Eighty-one percent of patients fell into the standard-risk category and 19% into the high-risk category.

Almost half of patients (47%) were considered frail, 28% unfit, 21% fit, and 4% unknown.

Response

The ORR for induction was 81%. Ten percent of patients achieved a complete response (CR), 34% had a very good partial response (VGPR), and 37% had a partial response (PR).

The median time to response was 1.1 months, and the median time to maximum response was 4.7 months.

The response rate was independent of cytogenetic risk. Standard-risk patients achieved an ORR of 84%, a VGPR rate of 48%, and a CR rate of 10%. High-risk patients had an ORR of 79%, VGPR of 42%, and CR of 11%.

The response rate was also independent of frailty. Fit patients had an ORR of 88%, unfit patients 85%, and frail patients 75%. The VGPR rate was 36% for fit, 53% for unfit, and 43% for frail patients. The CR rate was 16% for fit, 9% for unfit, and 9% for frail patients.

Safety

“Grade 3 and 4 toxicities were found to be limited, with mainly infections, [gastrointestinal], and skin toxicity,” Dr Zweegman noted. “There was also a very low incidence of neuropathy, with only 3% grade 3 neuropathy and no grade 4 neuropathy.”

Grade 3 adverse events (AEs) occurred in 50% of patients and grade 4 in 11%.

Hematologic AEs of grade 3 and 4, respectively, included anemia (5%, 1%), thrombocytopenia (3%, 1%), and neutropenia (1%, 0).

Nonhematologic AEs of grade 3 and 4, respectively, included infections (12%, 3%), neuropathy (3%, 0), cardiac events (7%, 3%), gastrointestinal events (8%, 0), skin AEs (10%, 0), and venous thromboembolism (0, 2%).

The incidence of severe neuropathy was low. Fifty-eight percent of patients had grade 0 neuropathy, 24% grade 1, 14% grade 2, 3% grade 3, and no grade 4.

Discontinuation

Fifty-four patients (45%) discontinued therapy. The reasons for discontinuation were:

- Progressive disease, 13%

- Toxicity, 15%

- Death, 4%

- Noncompliance, 8%

- Not eligible for randomization, 0.8%

- Other, 4%.

“And when looking in detail into the toxicity, it was shown that it was mainly asthenia and neuropathy being judged by the treating physicians as caused by thalidomide,” Dr Zweegman explained.

Investigators also evaluated discontinuation according to age and found that 35% of patients 75 or younger discontinued therapy, compared with 62% of those older than 75.

However, there was no significant difference in discontinuation rate during the first 6 cycles. Seventy-seven percent of the younger patients and 69% of the older group completed 6 cycles.

Older patients who discontinued early had rates of progressive disease and toxicity comparable to the younger patients, but “there was a difference in early mortality,” Dr Zweegman added.

Nine percent of older patients discontinued before maintenance due to early mortality, compared with 1% of younger patients. And mortality in the older group was mainly due to infections and 1 cardiac arrest.

“So I think that highlights the need for antibiotic prophylaxis, which was not mandatory in this study,” Dr Zweegman said.

And finally, the investigators evaluated discontinuation according to frailty. Twenty-four percent of fit patients discontinued prior to maintenance, 32% of unfit, and 60% of frail.

Again, investigators found no significant difference in discontinuation rate during the first 6 cycles of induction. Eighty percent of fit patients completed 6 cycles, as did 79% of unfit patients and 70% of frail patients.

Despite the feasibility of the treatment and an ORR of 81%, the investigators say novel approaches are needed for frail patients and those older than 75.

“One possibility is to limit the duration of induction therapy . . . ,” Dr Zweegman said. “That would allow the start of long-term administration of maintenance treatment.”

The investigators also suggest evaluating less toxic combinations, such as ixazomib and daratumumab with lower doses of dexamethasone, the combination used in the HOVON-143 study.

Ixazomib is approved by the US Food and Drug Administration, Health Canada, and conditionally approved by the European Commission for use in combination with lenalidomide and dexamethasone to treat MM patients who have received at least 1 prior therapy. ![]()

ATLANTA—Initial results of the phase 2 HOVON-126 trial in newly diagnosed multiple myeloma (MM) patients have highlighted the need for an induction strategy in elderly and frail patients.

The trial showed high overall response rates (ORRs) after induction with ixazomib, thalidomide, and low-dose dexamethasone.

However, 62% of patients older than 75 and 60% of frail patients discontinued therapy prior to starting maintenance.

HOVON-126 was designed to determine the ORR of induction therapy with ixazomib, thalidomide, and dexamethasone but also compare progression-free survival in patients who received ixazomib maintenance and those who received placebo.

Sonja Zweegman, MD, of VUmc in Amsterdam, The Netherlands, presented induction results from HOVON-126 at the 2017 ASH Annual Meeting (abstract 433).

The study was supported by Takeda and the Dutch Cancer Society. Dr Zweegman disclosed research funding from, and advisory board participation for, Takeda.

Study design

Investigators enrolled patients with previously untreated, symptomatic MM who were not eligible for stem cell transplant. Patients had to have measurable disease and a WHO performance status of 0 to 3 for patients younger than 75 and 0 to 2 for patients 75 or older.

Patients were not eligible if they had grade 3 neuropathy or grade 2 with pain. They were also ineligible if their creatinine clearance was less than 30 mL/minute.

All patients received ixazomib at 4 mg on days 1, 8, and 15; thalidomide at 100 mg on days 1 to 28; and dexamethasone at 40 mg on days 1, 8, 15, and 22 for nine 28-day cycles.

They could then be randomized to ixazomib maintenance (on the aforementioned schedule) or placebo for 28-day cycles until progression.

Investigators performed subgroup analyses based on cytogenetic risk and frailty.

They defined frailty according to the modified IMWG frailty index, which takes into account age, the Charlson Comorbidity Index, and the WHO performance scale as a proxy for Activities of Daily Living.

They defined high-risk cytogenetics as del17p, t(4;14), or t(14;16).

Investigators planned to enroll 142 patients and expected 94 patients to be randomized.

Patient demographics

The first 120 patients enrolled had a median age of 74 (range, 64–90). Thirty percent (n=38) were older than 75, and 8% (n=10) were older than 80.

More than two-thirds had an ISS score of I or II, and three-quarters had a WHO performance status of 0 or 1. Twenty-four percent had a performance status of 2, and 1% had a performance status of 3.

Eighty percent had lytic bone disease.

One hundred thirteen patients (94%) had FISH analysis performed. Of those, 10% had del17p, 7% had t(4;14), and 1% had t(14;16).

Eighty-one percent of patients fell into the standard-risk category and 19% into the high-risk category.

Almost half of patients (47%) were considered frail, 28% unfit, 21% fit, and 4% unknown.

Response

The ORR for induction was 81%. Ten percent of patients achieved a complete response (CR), 34% had a very good partial response (VGPR), and 37% had a partial response (PR).

The median time to response was 1.1 months, and the median time to maximum response was 4.7 months.

The response rate was independent of cytogenetic risk. Standard-risk patients achieved an ORR of 84%, a VGPR rate of 48%, and a CR rate of 10%. High-risk patients had an ORR of 79%, VGPR of 42%, and CR of 11%.

The response rate was also independent of frailty. Fit patients had an ORR of 88%, unfit patients 85%, and frail patients 75%. The VGPR rate was 36% for fit, 53% for unfit, and 43% for frail patients. The CR rate was 16% for fit, 9% for unfit, and 9% for frail patients.

Safety

“Grade 3 and 4 toxicities were found to be limited, with mainly infections, [gastrointestinal], and skin toxicity,” Dr Zweegman noted. “There was also a very low incidence of neuropathy, with only 3% grade 3 neuropathy and no grade 4 neuropathy.”

Grade 3 adverse events (AEs) occurred in 50% of patients and grade 4 in 11%.

Hematologic AEs of grade 3 and 4, respectively, included anemia (5%, 1%), thrombocytopenia (3%, 1%), and neutropenia (1%, 0).

Nonhematologic AEs of grade 3 and 4, respectively, included infections (12%, 3%), neuropathy (3%, 0), cardiac events (7%, 3%), gastrointestinal events (8%, 0), skin AEs (10%, 0), and venous thromboembolism (0, 2%).

The incidence of severe neuropathy was low. Fifty-eight percent of patients had grade 0 neuropathy, 24% grade 1, 14% grade 2, 3% grade 3, and no grade 4.

Discontinuation

Fifty-four patients (45%) discontinued therapy. The reasons for discontinuation were:

- Progressive disease, 13%

- Toxicity, 15%

- Death, 4%

- Noncompliance, 8%

- Not eligible for randomization, 0.8%

- Other, 4%.

“And when looking in detail into the toxicity, it was shown that it was mainly asthenia and neuropathy being judged by the treating physicians as caused by thalidomide,” Dr Zweegman explained.

Investigators also evaluated discontinuation according to age and found that 35% of patients 75 or younger discontinued therapy, compared with 62% of those older than 75.

However, there was no significant difference in discontinuation rate during the first 6 cycles. Seventy-seven percent of the younger patients and 69% of the older group completed 6 cycles.

Older patients who discontinued early had rates of progressive disease and toxicity comparable to the younger patients, but “there was a difference in early mortality,” Dr Zweegman added.

Nine percent of older patients discontinued before maintenance due to early mortality, compared with 1% of younger patients. And mortality in the older group was mainly due to infections and 1 cardiac arrest.

“So I think that highlights the need for antibiotic prophylaxis, which was not mandatory in this study,” Dr Zweegman said.

And finally, the investigators evaluated discontinuation according to frailty. Twenty-four percent of fit patients discontinued prior to maintenance, 32% of unfit, and 60% of frail.

Again, investigators found no significant difference in discontinuation rate during the first 6 cycles of induction. Eighty percent of fit patients completed 6 cycles, as did 79% of unfit patients and 70% of frail patients.

Despite the feasibility of the treatment and an ORR of 81%, the investigators say novel approaches are needed for frail patients and those older than 75.

“One possibility is to limit the duration of induction therapy . . . ,” Dr Zweegman said. “That would allow the start of long-term administration of maintenance treatment.”

The investigators also suggest evaluating less toxic combinations, such as ixazomib and daratumumab with lower doses of dexamethasone, the combination used in the HOVON-143 study.

Ixazomib is approved by the US Food and Drug Administration, Health Canada, and conditionally approved by the European Commission for use in combination with lenalidomide and dexamethasone to treat MM patients who have received at least 1 prior therapy. ![]()

ATLANTA—Initial results of the phase 2 HOVON-126 trial in newly diagnosed multiple myeloma (MM) patients have highlighted the need for an induction strategy in elderly and frail patients.

The trial showed high overall response rates (ORRs) after induction with ixazomib, thalidomide, and low-dose dexamethasone.

However, 62% of patients older than 75 and 60% of frail patients discontinued therapy prior to starting maintenance.

HOVON-126 was designed to determine the ORR of induction therapy with ixazomib, thalidomide, and dexamethasone but also compare progression-free survival in patients who received ixazomib maintenance and those who received placebo.

Sonja Zweegman, MD, of VUmc in Amsterdam, The Netherlands, presented induction results from HOVON-126 at the 2017 ASH Annual Meeting (abstract 433).

The study was supported by Takeda and the Dutch Cancer Society. Dr Zweegman disclosed research funding from, and advisory board participation for, Takeda.

Study design

Investigators enrolled patients with previously untreated, symptomatic MM who were not eligible for stem cell transplant. Patients had to have measurable disease and a WHO performance status of 0 to 3 for patients younger than 75 and 0 to 2 for patients 75 or older.

Patients were not eligible if they had grade 3 neuropathy or grade 2 with pain. They were also ineligible if their creatinine clearance was less than 30 mL/minute.

All patients received ixazomib at 4 mg on days 1, 8, and 15; thalidomide at 100 mg on days 1 to 28; and dexamethasone at 40 mg on days 1, 8, 15, and 22 for nine 28-day cycles.

They could then be randomized to ixazomib maintenance (on the aforementioned schedule) or placebo for 28-day cycles until progression.

Investigators performed subgroup analyses based on cytogenetic risk and frailty.

They defined frailty according to the modified IMWG frailty index, which takes into account age, the Charlson Comorbidity Index, and the WHO performance scale as a proxy for Activities of Daily Living.

They defined high-risk cytogenetics as del17p, t(4;14), or t(14;16).

Investigators planned to enroll 142 patients and expected 94 patients to be randomized.

Patient demographics

The first 120 patients enrolled had a median age of 74 (range, 64–90). Thirty percent (n=38) were older than 75, and 8% (n=10) were older than 80.

More than two-thirds had an ISS score of I or II, and three-quarters had a WHO performance status of 0 or 1. Twenty-four percent had a performance status of 2, and 1% had a performance status of 3.

Eighty percent had lytic bone disease.

One hundred thirteen patients (94%) had FISH analysis performed. Of those, 10% had del17p, 7% had t(4;14), and 1% had t(14;16).

Eighty-one percent of patients fell into the standard-risk category and 19% into the high-risk category.

Almost half of patients (47%) were considered frail, 28% unfit, 21% fit, and 4% unknown.

Response

The ORR for induction was 81%. Ten percent of patients achieved a complete response (CR), 34% had a very good partial response (VGPR), and 37% had a partial response (PR).

The median time to response was 1.1 months, and the median time to maximum response was 4.7 months.

The response rate was independent of cytogenetic risk. Standard-risk patients achieved an ORR of 84%, a VGPR rate of 48%, and a CR rate of 10%. High-risk patients had an ORR of 79%, VGPR of 42%, and CR of 11%.

The response rate was also independent of frailty. Fit patients had an ORR of 88%, unfit patients 85%, and frail patients 75%. The VGPR rate was 36% for fit, 53% for unfit, and 43% for frail patients. The CR rate was 16% for fit, 9% for unfit, and 9% for frail patients.

Safety

“Grade 3 and 4 toxicities were found to be limited, with mainly infections, [gastrointestinal], and skin toxicity,” Dr Zweegman noted. “There was also a very low incidence of neuropathy, with only 3% grade 3 neuropathy and no grade 4 neuropathy.”

Grade 3 adverse events (AEs) occurred in 50% of patients and grade 4 in 11%.

Hematologic AEs of grade 3 and 4, respectively, included anemia (5%, 1%), thrombocytopenia (3%, 1%), and neutropenia (1%, 0).

Nonhematologic AEs of grade 3 and 4, respectively, included infections (12%, 3%), neuropathy (3%, 0), cardiac events (7%, 3%), gastrointestinal events (8%, 0), skin AEs (10%, 0), and venous thromboembolism (0, 2%).

The incidence of severe neuropathy was low. Fifty-eight percent of patients had grade 0 neuropathy, 24% grade 1, 14% grade 2, 3% grade 3, and no grade 4.

Discontinuation

Fifty-four patients (45%) discontinued therapy. The reasons for discontinuation were:

- Progressive disease, 13%

- Toxicity, 15%

- Death, 4%

- Noncompliance, 8%

- Not eligible for randomization, 0.8%

- Other, 4%.

“And when looking in detail into the toxicity, it was shown that it was mainly asthenia and neuropathy being judged by the treating physicians as caused by thalidomide,” Dr Zweegman explained.

Investigators also evaluated discontinuation according to age and found that 35% of patients 75 or younger discontinued therapy, compared with 62% of those older than 75.

However, there was no significant difference in discontinuation rate during the first 6 cycles. Seventy-seven percent of the younger patients and 69% of the older group completed 6 cycles.

Older patients who discontinued early had rates of progressive disease and toxicity comparable to the younger patients, but “there was a difference in early mortality,” Dr Zweegman added.

Nine percent of older patients discontinued before maintenance due to early mortality, compared with 1% of younger patients. And mortality in the older group was mainly due to infections and 1 cardiac arrest.

“So I think that highlights the need for antibiotic prophylaxis, which was not mandatory in this study,” Dr Zweegman said.

And finally, the investigators evaluated discontinuation according to frailty. Twenty-four percent of fit patients discontinued prior to maintenance, 32% of unfit, and 60% of frail.

Again, investigators found no significant difference in discontinuation rate during the first 6 cycles of induction. Eighty percent of fit patients completed 6 cycles, as did 79% of unfit patients and 70% of frail patients.

Despite the feasibility of the treatment and an ORR of 81%, the investigators say novel approaches are needed for frail patients and those older than 75.

“One possibility is to limit the duration of induction therapy . . . ,” Dr Zweegman said. “That would allow the start of long-term administration of maintenance treatment.”

The investigators also suggest evaluating less toxic combinations, such as ixazomib and daratumumab with lower doses of dexamethasone, the combination used in the HOVON-143 study.

Ixazomib is approved by the US Food and Drug Administration, Health Canada, and conditionally approved by the European Commission for use in combination with lenalidomide and dexamethasone to treat MM patients who have received at least 1 prior therapy. ![]()

Iron chelating agent could enhance chemo in AML

Chemotherapy for acute myeloid leukemia (AML) might be improved by the addition of deferoxamine, according to preclinical research published in Cell Stem Cell.

Researchers found that, when certain areas of the bone marrow are overtaken by AML cells, hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) are lost, and the delivery of chemotherapy may be compromised.

However, the team also discovered that deferoxamine, a drug already approved to treat iron overload, can protect these areas of the bone marrow, allowing HSCs to survive and improving the efficacy of chemotherapy.

“Since the drug is already approved for human use for a different condition, we already know that it is safe,” said study author Cristina Lo Celso, PhD, of Imperial College London in the UK.

“We still need to test it in the context of leukemia and chemotherapy, but, because it is already in use, we can progress to clinical trials much quicker than we could with a brand-new drug.”

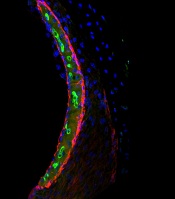

For the current study, Dr Lo Celso and her colleagues used intravital microscopy to study AML cells, healthy hematopoietic cells, and the bone marrow microenvironment in mice.

The researchers found the endosteal microenvironment was hit particularly hard by AML. Specifically, AML progression led to endosteal remodeling, with AML cells degrading endosteal endothelium, stromal cells, and osteoblastic cells.

This remodeling resulted in the loss of nonleukemic HSCs, which hindered hematopoiesis. However, preserving endosteal vessels prevented the loss of HSCs.

Previous research had shown that deferoxamine could induce endosteal vessel expansion through enhancement of hypoxia-inducible factor 1a stability and activity. So the researchers administered deferoxamine to mice with AML.

The drug had a protective effect on endosteal vessels, which were able to support healthy HSCs and improve HSC homing.

The researchers also found that enhanced endosteal vessels improved the efficacy of chemotherapy (cytarabine and doxorubicin) in mice with AML.

The team compared Fbxw7iΔEC-mutant mice, in which the administration of tamoxifen increases the number of endosteal vessels and arterioles, to control mice. Both sets of mice had AML.

After confirming the mutant mice had increased numbers of endosteal vessels, the researchers treated the mutant mice and controls with cytarabine and doxorubicin.

Both sets of mice had significant chemotherapy-induced damage to the bone marrow vasculature, including endosteal vessels.

However, after treatment, the Fbxw7iΔEC-mutant mice had lower numbers of surviving AML cells in the bone marrow, delayed relapse, and longer survival than control mice.

The researchers therefore concluded that rescuing endosteal vessels before starting chemotherapy can improve the efficacy of treatment in AML.

“Our work suggests that therapies targeting these blood vessels may improve existing therapeutic regimens for AML and perhaps other leukemias too,” said study author Delfim Duarte, MD, of Imperial College London.

Based on this work, the researchers are hoping to start trials of deferoxamine in patients with AML. ![]()

Chemotherapy for acute myeloid leukemia (AML) might be improved by the addition of deferoxamine, according to preclinical research published in Cell Stem Cell.

Researchers found that, when certain areas of the bone marrow are overtaken by AML cells, hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) are lost, and the delivery of chemotherapy may be compromised.

However, the team also discovered that deferoxamine, a drug already approved to treat iron overload, can protect these areas of the bone marrow, allowing HSCs to survive and improving the efficacy of chemotherapy.

“Since the drug is already approved for human use for a different condition, we already know that it is safe,” said study author Cristina Lo Celso, PhD, of Imperial College London in the UK.

“We still need to test it in the context of leukemia and chemotherapy, but, because it is already in use, we can progress to clinical trials much quicker than we could with a brand-new drug.”

For the current study, Dr Lo Celso and her colleagues used intravital microscopy to study AML cells, healthy hematopoietic cells, and the bone marrow microenvironment in mice.

The researchers found the endosteal microenvironment was hit particularly hard by AML. Specifically, AML progression led to endosteal remodeling, with AML cells degrading endosteal endothelium, stromal cells, and osteoblastic cells.

This remodeling resulted in the loss of nonleukemic HSCs, which hindered hematopoiesis. However, preserving endosteal vessels prevented the loss of HSCs.

Previous research had shown that deferoxamine could induce endosteal vessel expansion through enhancement of hypoxia-inducible factor 1a stability and activity. So the researchers administered deferoxamine to mice with AML.

The drug had a protective effect on endosteal vessels, which were able to support healthy HSCs and improve HSC homing.

The researchers also found that enhanced endosteal vessels improved the efficacy of chemotherapy (cytarabine and doxorubicin) in mice with AML.

The team compared Fbxw7iΔEC-mutant mice, in which the administration of tamoxifen increases the number of endosteal vessels and arterioles, to control mice. Both sets of mice had AML.

After confirming the mutant mice had increased numbers of endosteal vessels, the researchers treated the mutant mice and controls with cytarabine and doxorubicin.

Both sets of mice had significant chemotherapy-induced damage to the bone marrow vasculature, including endosteal vessels.

However, after treatment, the Fbxw7iΔEC-mutant mice had lower numbers of surviving AML cells in the bone marrow, delayed relapse, and longer survival than control mice.

The researchers therefore concluded that rescuing endosteal vessels before starting chemotherapy can improve the efficacy of treatment in AML.

“Our work suggests that therapies targeting these blood vessels may improve existing therapeutic regimens for AML and perhaps other leukemias too,” said study author Delfim Duarte, MD, of Imperial College London.

Based on this work, the researchers are hoping to start trials of deferoxamine in patients with AML. ![]()

Chemotherapy for acute myeloid leukemia (AML) might be improved by the addition of deferoxamine, according to preclinical research published in Cell Stem Cell.

Researchers found that, when certain areas of the bone marrow are overtaken by AML cells, hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) are lost, and the delivery of chemotherapy may be compromised.

However, the team also discovered that deferoxamine, a drug already approved to treat iron overload, can protect these areas of the bone marrow, allowing HSCs to survive and improving the efficacy of chemotherapy.

“Since the drug is already approved for human use for a different condition, we already know that it is safe,” said study author Cristina Lo Celso, PhD, of Imperial College London in the UK.

“We still need to test it in the context of leukemia and chemotherapy, but, because it is already in use, we can progress to clinical trials much quicker than we could with a brand-new drug.”

For the current study, Dr Lo Celso and her colleagues used intravital microscopy to study AML cells, healthy hematopoietic cells, and the bone marrow microenvironment in mice.

The researchers found the endosteal microenvironment was hit particularly hard by AML. Specifically, AML progression led to endosteal remodeling, with AML cells degrading endosteal endothelium, stromal cells, and osteoblastic cells.

This remodeling resulted in the loss of nonleukemic HSCs, which hindered hematopoiesis. However, preserving endosteal vessels prevented the loss of HSCs.

Previous research had shown that deferoxamine could induce endosteal vessel expansion through enhancement of hypoxia-inducible factor 1a stability and activity. So the researchers administered deferoxamine to mice with AML.

The drug had a protective effect on endosteal vessels, which were able to support healthy HSCs and improve HSC homing.

The researchers also found that enhanced endosteal vessels improved the efficacy of chemotherapy (cytarabine and doxorubicin) in mice with AML.

The team compared Fbxw7iΔEC-mutant mice, in which the administration of tamoxifen increases the number of endosteal vessels and arterioles, to control mice. Both sets of mice had AML.

After confirming the mutant mice had increased numbers of endosteal vessels, the researchers treated the mutant mice and controls with cytarabine and doxorubicin.

Both sets of mice had significant chemotherapy-induced damage to the bone marrow vasculature, including endosteal vessels.

However, after treatment, the Fbxw7iΔEC-mutant mice had lower numbers of surviving AML cells in the bone marrow, delayed relapse, and longer survival than control mice.

The researchers therefore concluded that rescuing endosteal vessels before starting chemotherapy can improve the efficacy of treatment in AML.

“Our work suggests that therapies targeting these blood vessels may improve existing therapeutic regimens for AML and perhaps other leukemias too,” said study author Delfim Duarte, MD, of Imperial College London.

Based on this work, the researchers are hoping to start trials of deferoxamine in patients with AML. ![]()

Research explains why cisplatin causes hearing loss

Researchers have gained new insight into hearing loss caused by cisplatin.

By measuring and mapping cisplatin retention in mouse and human inner ear tissues, the researchers found that cisplatin builds up in the inner ear and can remain there for years.

The team also found that a region in the inner ear called the stria vascularis could be targeted to prevent hearing loss resulting from cisplatin.

Lisa L. Cunningham, PhD, of the National Institute on Deafness and other Communications Disorders (NIDCD) in Bethesda, Maryland, and her colleagues reported these findings in Nature Communications.

The researchers noted that cisplatin can cause permanent hearing loss in 40% to 80% of treated patients. The team’s new findings help explain why.

The researchers found that, in most areas of the body, cisplatin is eliminated within days or weeks of treatment, but, in the inner ear, the drug remains much longer.

The team developed a mouse model that represents cisplatin-induced hearing loss seen in human patients.

By looking at inner ear tissue of mice after the first, second, and third cisplatin treatment, the researchers saw that cisplatin remained in the mouse inner ear much longer than in most other body tissues, and the drug builds up with each successive treatment.

The team also studied inner ear tissue donated by deceased adults who had been treated with cisplatin and found the drug is retained in the inner ear months or years after treatment.

When the researchers examined inner ear tissue from a child, they found cisplatin buildup that was even higher than that seen in adults.

Taken together, these results suggest the inner ear readily takes up cisplatin but has limited ability to remove the drug.

In mice and human tissues, the researchers saw the highest buildup of cisplatin in a part of the inner ear called the stria vascularis, which helps maintain the positive electrical charge in inner ear fluid that certain cells need to detect sound.

The team found the accumulation of cisplatin in the stria vascularis contributed to cisplatin-related hearing loss.

“Our findings suggest that if we can prevent cisplatin from entering the stria vascularis in the inner ear during treatment, we may be able to protect cancer patients from developing cisplatin-induced hearing loss,” Dr Cunningham said. ![]()

Researchers have gained new insight into hearing loss caused by cisplatin.

By measuring and mapping cisplatin retention in mouse and human inner ear tissues, the researchers found that cisplatin builds up in the inner ear and can remain there for years.

The team also found that a region in the inner ear called the stria vascularis could be targeted to prevent hearing loss resulting from cisplatin.

Lisa L. Cunningham, PhD, of the National Institute on Deafness and other Communications Disorders (NIDCD) in Bethesda, Maryland, and her colleagues reported these findings in Nature Communications.

The researchers noted that cisplatin can cause permanent hearing loss in 40% to 80% of treated patients. The team’s new findings help explain why.

The researchers found that, in most areas of the body, cisplatin is eliminated within days or weeks of treatment, but, in the inner ear, the drug remains much longer.

The team developed a mouse model that represents cisplatin-induced hearing loss seen in human patients.

By looking at inner ear tissue of mice after the first, second, and third cisplatin treatment, the researchers saw that cisplatin remained in the mouse inner ear much longer than in most other body tissues, and the drug builds up with each successive treatment.

The team also studied inner ear tissue donated by deceased adults who had been treated with cisplatin and found the drug is retained in the inner ear months or years after treatment.

When the researchers examined inner ear tissue from a child, they found cisplatin buildup that was even higher than that seen in adults.

Taken together, these results suggest the inner ear readily takes up cisplatin but has limited ability to remove the drug.

In mice and human tissues, the researchers saw the highest buildup of cisplatin in a part of the inner ear called the stria vascularis, which helps maintain the positive electrical charge in inner ear fluid that certain cells need to detect sound.

The team found the accumulation of cisplatin in the stria vascularis contributed to cisplatin-related hearing loss.

“Our findings suggest that if we can prevent cisplatin from entering the stria vascularis in the inner ear during treatment, we may be able to protect cancer patients from developing cisplatin-induced hearing loss,” Dr Cunningham said. ![]()

Researchers have gained new insight into hearing loss caused by cisplatin.

By measuring and mapping cisplatin retention in mouse and human inner ear tissues, the researchers found that cisplatin builds up in the inner ear and can remain there for years.

The team also found that a region in the inner ear called the stria vascularis could be targeted to prevent hearing loss resulting from cisplatin.

Lisa L. Cunningham, PhD, of the National Institute on Deafness and other Communications Disorders (NIDCD) in Bethesda, Maryland, and her colleagues reported these findings in Nature Communications.

The researchers noted that cisplatin can cause permanent hearing loss in 40% to 80% of treated patients. The team’s new findings help explain why.

The researchers found that, in most areas of the body, cisplatin is eliminated within days or weeks of treatment, but, in the inner ear, the drug remains much longer.

The team developed a mouse model that represents cisplatin-induced hearing loss seen in human patients.

By looking at inner ear tissue of mice after the first, second, and third cisplatin treatment, the researchers saw that cisplatin remained in the mouse inner ear much longer than in most other body tissues, and the drug builds up with each successive treatment.

The team also studied inner ear tissue donated by deceased adults who had been treated with cisplatin and found the drug is retained in the inner ear months or years after treatment.

When the researchers examined inner ear tissue from a child, they found cisplatin buildup that was even higher than that seen in adults.

Taken together, these results suggest the inner ear readily takes up cisplatin but has limited ability to remove the drug.

In mice and human tissues, the researchers saw the highest buildup of cisplatin in a part of the inner ear called the stria vascularis, which helps maintain the positive electrical charge in inner ear fluid that certain cells need to detect sound.

The team found the accumulation of cisplatin in the stria vascularis contributed to cisplatin-related hearing loss.

“Our findings suggest that if we can prevent cisplatin from entering the stria vascularis in the inner ear during treatment, we may be able to protect cancer patients from developing cisplatin-induced hearing loss,” Dr Cunningham said. ![]()

Hypercalcemia, Parathyroid Disease, Vitamin D Deficiency

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

This video was filmed at Metabolic & Endocrine Disease Summit (MEDS). Click here to learn more.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

This video was filmed at Metabolic & Endocrine Disease Summit (MEDS). Click here to learn more.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

This video was filmed at Metabolic & Endocrine Disease Summit (MEDS). Click here to learn more.

Cardiology: Step One…

Improvements made in safe opioid prescribing practices but crisis far from over

Clinical question: How have national and county-level opioid prescribing practices changed from the years 2006 to 2015?

Background: The opioid epidemic is currently at the forefront of public health crises, with more than 15,000 deaths caused by prescription opioid overdoses in 2015 alone and an estimated 2 million people with an opioid use disorder associated with prescription opioids. The opioid epidemic also has a significant financial burden with the cost of opioid overdose, abuse, and dependence totaling $78.5 billion/year in the United States. As the utilization of opioids to treat noncancer pain quadrupled during 1999-2010, so did the prevalence of opioid misuse disorder and overdose deaths from prescription opioids. This study reviewed prescribing practices at the national and county level during 2006-2015 in hopes of understanding how this affected the opioid crisis.

Setting: The data were summarized from a sample of pharmacies throughout the United States.

Synopsis: Data were obtained via the QuintilesIMS Data Warehouse, which estimated the number of opioid prescriptions, based upon a sample of 59,000 U.S. pharmacies (88% of total prescriptions). The amount of prescriptions peaked in 2010 then decreased yearly through 2015, yet remained about three times as high as prescription rates from 1999. Opioid prescribing practices had significant variation throughout the country, with higher prescription rates associated with smaller cities, larger white population, higher rates of Medicaid and unemployment, and higher prevalence of arthritis and diabetes. Variation in prescribing practices at the county level represents lack of consensus and evidence-based guidelines.

The authors suggest that providers carefully weigh the risks and benefits of opioids and review the Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. At the state and local levels, mandated pain clinic regulations and Physician Drug Monitoring Programs also are needed for continued improvement in opioid-related deaths. Weaknesses of study included lack of clinical outcomes and use of QuintilesIMS to estimate prescriptions that has not been validated.

Bottom line: Although rates of opioid prescriptions have improved since 2010, substantial changes and regulations for prescribing practices are needed at the state and local levels.

Citation: Guy GP Jr. et al. Vital Signs: Changes in opioid prescribing in the United States, 2006-2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66:697704.

Dr. Farber is a medical instructor, Duke University Health System.

Clinical question: How have national and county-level opioid prescribing practices changed from the years 2006 to 2015?

Background: The opioid epidemic is currently at the forefront of public health crises, with more than 15,000 deaths caused by prescription opioid overdoses in 2015 alone and an estimated 2 million people with an opioid use disorder associated with prescription opioids. The opioid epidemic also has a significant financial burden with the cost of opioid overdose, abuse, and dependence totaling $78.5 billion/year in the United States. As the utilization of opioids to treat noncancer pain quadrupled during 1999-2010, so did the prevalence of opioid misuse disorder and overdose deaths from prescription opioids. This study reviewed prescribing practices at the national and county level during 2006-2015 in hopes of understanding how this affected the opioid crisis.

Setting: The data were summarized from a sample of pharmacies throughout the United States.

Synopsis: Data were obtained via the QuintilesIMS Data Warehouse, which estimated the number of opioid prescriptions, based upon a sample of 59,000 U.S. pharmacies (88% of total prescriptions). The amount of prescriptions peaked in 2010 then decreased yearly through 2015, yet remained about three times as high as prescription rates from 1999. Opioid prescribing practices had significant variation throughout the country, with higher prescription rates associated with smaller cities, larger white population, higher rates of Medicaid and unemployment, and higher prevalence of arthritis and diabetes. Variation in prescribing practices at the county level represents lack of consensus and evidence-based guidelines.

The authors suggest that providers carefully weigh the risks and benefits of opioids and review the Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. At the state and local levels, mandated pain clinic regulations and Physician Drug Monitoring Programs also are needed for continued improvement in opioid-related deaths. Weaknesses of study included lack of clinical outcomes and use of QuintilesIMS to estimate prescriptions that has not been validated.

Bottom line: Although rates of opioid prescriptions have improved since 2010, substantial changes and regulations for prescribing practices are needed at the state and local levels.

Citation: Guy GP Jr. et al. Vital Signs: Changes in opioid prescribing in the United States, 2006-2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66:697704.

Dr. Farber is a medical instructor, Duke University Health System.

Clinical question: How have national and county-level opioid prescribing practices changed from the years 2006 to 2015?

Background: The opioid epidemic is currently at the forefront of public health crises, with more than 15,000 deaths caused by prescription opioid overdoses in 2015 alone and an estimated 2 million people with an opioid use disorder associated with prescription opioids. The opioid epidemic also has a significant financial burden with the cost of opioid overdose, abuse, and dependence totaling $78.5 billion/year in the United States. As the utilization of opioids to treat noncancer pain quadrupled during 1999-2010, so did the prevalence of opioid misuse disorder and overdose deaths from prescription opioids. This study reviewed prescribing practices at the national and county level during 2006-2015 in hopes of understanding how this affected the opioid crisis.

Setting: The data were summarized from a sample of pharmacies throughout the United States.

Synopsis: Data were obtained via the QuintilesIMS Data Warehouse, which estimated the number of opioid prescriptions, based upon a sample of 59,000 U.S. pharmacies (88% of total prescriptions). The amount of prescriptions peaked in 2010 then decreased yearly through 2015, yet remained about three times as high as prescription rates from 1999. Opioid prescribing practices had significant variation throughout the country, with higher prescription rates associated with smaller cities, larger white population, higher rates of Medicaid and unemployment, and higher prevalence of arthritis and diabetes. Variation in prescribing practices at the county level represents lack of consensus and evidence-based guidelines.

The authors suggest that providers carefully weigh the risks and benefits of opioids and review the Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. At the state and local levels, mandated pain clinic regulations and Physician Drug Monitoring Programs also are needed for continued improvement in opioid-related deaths. Weaknesses of study included lack of clinical outcomes and use of QuintilesIMS to estimate prescriptions that has not been validated.

Bottom line: Although rates of opioid prescriptions have improved since 2010, substantial changes and regulations for prescribing practices are needed at the state and local levels.

Citation: Guy GP Jr. et al. Vital Signs: Changes in opioid prescribing in the United States, 2006-2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66:697704.

Dr. Farber is a medical instructor, Duke University Health System.

Hydrochlorothiazide use linked to higher skin cancer risk

The common diuretic hydrochlorothiazide is linked to a dose-dependent increased risk of nonmelanoma skin cancer, in particular, squamous cell carcinoma, a case-controlled registry study showed.

This nationwide, case-matched control study examined patients’ cumulative hydrochlorothiazide use between 1995 and 2012 and found a clear dose-response patterns for both basal cell carcinoma (BCC) and squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), with a more than sevenfold increased risk of SCC for a cumulative use of greater than or equal to 200,000 mg of hydrochlorothiazide (HCTZ).

“Assuming causality, the present results suggest that 1 in 10 SCC cases diagnosed during the study period can be attributed to HCTZ use,” wrote the study authors, who were led by Sidsel Arnspang, MD, of the department of neurology at Odense (Denmark) University Hospital, which is affiliated with the University of Southern Denmark.

The authors noted that they previously had reported a sevenfold increased risk of lip squamous cell carcinoma with hydrochlorothiazide. Furthermore, the International Agency for Research on Cancer recently classified the diuretic and antihypertensive as “possibly carcinogenic to humans.”

“As HCTZ is among the most widely used drugs in the U.S. and Western Europe, a carcinogenic effect of HCTZ would have a considerable impact on public health,” they wrote in their paper, published in the Journal of American Academy of Dermatology.

According to the study authors, the few studies that have investigated a potential link between thiazide use and nonmelanoma skin cancer (NMSC) have reported inconsistent results.

They speculated that this could be because HCTZ often is prescribed in combination with other diuretics, and there may have been difficulties with disentangling its effect from those of the other drugs.

Using data from five nationwide data sources, the research team compared HCTZ use among people diagnosed with SCC or BCC of the skin to use among a matched control group without such cancers. People were excluded from the analysis if they had SCC of the lip because they had been evaluated in the research team’s previous study.

High use of HCTZ was defined as filled prescriptions totaling greater than or equal to 50,000 mg of HCTZ, which corresponds to greater than or equal to 2,000 defined daily doses (for example, approximately 6 years of cumulative use).

Overall, the study population involved 71,533 BCC and 8,629 SCC cases that were matched to 1,430,883 and 172,462 population controls, respectively.

Baseline characteristics of the cases and controls were similar, except BCC cases were slightly more educated than controls. Results showed that high use of hydrochlorothiazide was associated with odds ratios of 1.29 (95% confidence interval, 1.23-1.35) for BCC and 3.98 (95% CI, 3.68-4.31) for SCC.

A clear dose-response relationship was observed with HCTZ use for both BCC and SCC, with the highest ORs observed in the upper exposure category (greater than or equal to 200,000 mg): The OR for BCC in this category was 1.54 (95% CI, 1.38-1.71) and 7.38 for SCC (95% CI, 6.32-8.60).

The researchers observed no associations for BCC or SCC risk with use of other diuretics and other hypertensives, a finding that they said supported a potential causal association between HCTZ and NMSC risk.

Little variation was seen in the association between HCTZ use and BCC or SCC risk in the subgroup analyses, except for notably stronger associations among younger individuals and females.

In analyses stratified according to tumor localization, the authors saw stronger associations for cancers at sun-exposed skin sites, especially the skin of the lower limbs.

“Given the considerable use of HCTZ worldwide and the morbidity associated with NMSC, a causal association between HCTZ use and NMSC risk would have significant public health implications,” Dr. Arnspang and associates concluded. “The use of HCTZ should be carefully considered as several other antihypertensive agents with similar indications and efficiency are available but without known associations with skin cancer.”

The investigators cited several limitations. For example, information on ethnicity and skin type was not available. This information would have been useful in evaluating participants’ photosensitivity as a possible mechanism for a higher skin cancer risk with the use of HCTZ.

The study was funded by a grant from the Danish Cancer Society and the Danish Council of Independent Research. Several of the authors reported receiving grants and or honoraria from pharmaceutical companies.

SOURCE: Arnspang S et al. JAAD. 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2017.11.042.

The common diuretic hydrochlorothiazide is linked to a dose-dependent increased risk of nonmelanoma skin cancer, in particular, squamous cell carcinoma, a case-controlled registry study showed.

This nationwide, case-matched control study examined patients’ cumulative hydrochlorothiazide use between 1995 and 2012 and found a clear dose-response patterns for both basal cell carcinoma (BCC) and squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), with a more than sevenfold increased risk of SCC for a cumulative use of greater than or equal to 200,000 mg of hydrochlorothiazide (HCTZ).

“Assuming causality, the present results suggest that 1 in 10 SCC cases diagnosed during the study period can be attributed to HCTZ use,” wrote the study authors, who were led by Sidsel Arnspang, MD, of the department of neurology at Odense (Denmark) University Hospital, which is affiliated with the University of Southern Denmark.

The authors noted that they previously had reported a sevenfold increased risk of lip squamous cell carcinoma with hydrochlorothiazide. Furthermore, the International Agency for Research on Cancer recently classified the diuretic and antihypertensive as “possibly carcinogenic to humans.”

“As HCTZ is among the most widely used drugs in the U.S. and Western Europe, a carcinogenic effect of HCTZ would have a considerable impact on public health,” they wrote in their paper, published in the Journal of American Academy of Dermatology.

According to the study authors, the few studies that have investigated a potential link between thiazide use and nonmelanoma skin cancer (NMSC) have reported inconsistent results.

They speculated that this could be because HCTZ often is prescribed in combination with other diuretics, and there may have been difficulties with disentangling its effect from those of the other drugs.

Using data from five nationwide data sources, the research team compared HCTZ use among people diagnosed with SCC or BCC of the skin to use among a matched control group without such cancers. People were excluded from the analysis if they had SCC of the lip because they had been evaluated in the research team’s previous study.

High use of HCTZ was defined as filled prescriptions totaling greater than or equal to 50,000 mg of HCTZ, which corresponds to greater than or equal to 2,000 defined daily doses (for example, approximately 6 years of cumulative use).

Overall, the study population involved 71,533 BCC and 8,629 SCC cases that were matched to 1,430,883 and 172,462 population controls, respectively.

Baseline characteristics of the cases and controls were similar, except BCC cases were slightly more educated than controls. Results showed that high use of hydrochlorothiazide was associated with odds ratios of 1.29 (95% confidence interval, 1.23-1.35) for BCC and 3.98 (95% CI, 3.68-4.31) for SCC.

A clear dose-response relationship was observed with HCTZ use for both BCC and SCC, with the highest ORs observed in the upper exposure category (greater than or equal to 200,000 mg): The OR for BCC in this category was 1.54 (95% CI, 1.38-1.71) and 7.38 for SCC (95% CI, 6.32-8.60).

The researchers observed no associations for BCC or SCC risk with use of other diuretics and other hypertensives, a finding that they said supported a potential causal association between HCTZ and NMSC risk.

Little variation was seen in the association between HCTZ use and BCC or SCC risk in the subgroup analyses, except for notably stronger associations among younger individuals and females.

In analyses stratified according to tumor localization, the authors saw stronger associations for cancers at sun-exposed skin sites, especially the skin of the lower limbs.

“Given the considerable use of HCTZ worldwide and the morbidity associated with NMSC, a causal association between HCTZ use and NMSC risk would have significant public health implications,” Dr. Arnspang and associates concluded. “The use of HCTZ should be carefully considered as several other antihypertensive agents with similar indications and efficiency are available but without known associations with skin cancer.”

The investigators cited several limitations. For example, information on ethnicity and skin type was not available. This information would have been useful in evaluating participants’ photosensitivity as a possible mechanism for a higher skin cancer risk with the use of HCTZ.

The study was funded by a grant from the Danish Cancer Society and the Danish Council of Independent Research. Several of the authors reported receiving grants and or honoraria from pharmaceutical companies.

SOURCE: Arnspang S et al. JAAD. 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2017.11.042.

The common diuretic hydrochlorothiazide is linked to a dose-dependent increased risk of nonmelanoma skin cancer, in particular, squamous cell carcinoma, a case-controlled registry study showed.

This nationwide, case-matched control study examined patients’ cumulative hydrochlorothiazide use between 1995 and 2012 and found a clear dose-response patterns for both basal cell carcinoma (BCC) and squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), with a more than sevenfold increased risk of SCC for a cumulative use of greater than or equal to 200,000 mg of hydrochlorothiazide (HCTZ).

“Assuming causality, the present results suggest that 1 in 10 SCC cases diagnosed during the study period can be attributed to HCTZ use,” wrote the study authors, who were led by Sidsel Arnspang, MD, of the department of neurology at Odense (Denmark) University Hospital, which is affiliated with the University of Southern Denmark.

The authors noted that they previously had reported a sevenfold increased risk of lip squamous cell carcinoma with hydrochlorothiazide. Furthermore, the International Agency for Research on Cancer recently classified the diuretic and antihypertensive as “possibly carcinogenic to humans.”

“As HCTZ is among the most widely used drugs in the U.S. and Western Europe, a carcinogenic effect of HCTZ would have a considerable impact on public health,” they wrote in their paper, published in the Journal of American Academy of Dermatology.

According to the study authors, the few studies that have investigated a potential link between thiazide use and nonmelanoma skin cancer (NMSC) have reported inconsistent results.

They speculated that this could be because HCTZ often is prescribed in combination with other diuretics, and there may have been difficulties with disentangling its effect from those of the other drugs.

Using data from five nationwide data sources, the research team compared HCTZ use among people diagnosed with SCC or BCC of the skin to use among a matched control group without such cancers. People were excluded from the analysis if they had SCC of the lip because they had been evaluated in the research team’s previous study.

High use of HCTZ was defined as filled prescriptions totaling greater than or equal to 50,000 mg of HCTZ, which corresponds to greater than or equal to 2,000 defined daily doses (for example, approximately 6 years of cumulative use).

Overall, the study population involved 71,533 BCC and 8,629 SCC cases that were matched to 1,430,883 and 172,462 population controls, respectively.

Baseline characteristics of the cases and controls were similar, except BCC cases were slightly more educated than controls. Results showed that high use of hydrochlorothiazide was associated with odds ratios of 1.29 (95% confidence interval, 1.23-1.35) for BCC and 3.98 (95% CI, 3.68-4.31) for SCC.

A clear dose-response relationship was observed with HCTZ use for both BCC and SCC, with the highest ORs observed in the upper exposure category (greater than or equal to 200,000 mg): The OR for BCC in this category was 1.54 (95% CI, 1.38-1.71) and 7.38 for SCC (95% CI, 6.32-8.60).

The researchers observed no associations for BCC or SCC risk with use of other diuretics and other hypertensives, a finding that they said supported a potential causal association between HCTZ and NMSC risk.

Little variation was seen in the association between HCTZ use and BCC or SCC risk in the subgroup analyses, except for notably stronger associations among younger individuals and females.

In analyses stratified according to tumor localization, the authors saw stronger associations for cancers at sun-exposed skin sites, especially the skin of the lower limbs.

“Given the considerable use of HCTZ worldwide and the morbidity associated with NMSC, a causal association between HCTZ use and NMSC risk would have significant public health implications,” Dr. Arnspang and associates concluded. “The use of HCTZ should be carefully considered as several other antihypertensive agents with similar indications and efficiency are available but without known associations with skin cancer.”

The investigators cited several limitations. For example, information on ethnicity and skin type was not available. This information would have been useful in evaluating participants’ photosensitivity as a possible mechanism for a higher skin cancer risk with the use of HCTZ.

The study was funded by a grant from the Danish Cancer Society and the Danish Council of Independent Research. Several of the authors reported receiving grants and or honoraria from pharmaceutical companies.

SOURCE: Arnspang S et al. JAAD. 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2017.11.042.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN ACADEMY OF DERMATOLOGY

Key clinical point: The use of hydrochlorothiazide should be carefully considered because it is linked to a substantially increased risk of nonmelanoma skin cancer.

Major finding: A clear, dose-response pattern was found for both basal cell carcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma, with a more than sevenfold increased risk of SCC for a cumulative use of greater than or equal to 200,000 mg of the diuretic and antihypertensive.

Study details: The study population involved 71,533 BCC and 8,629 SCC cases that were matched to 1,430,883 and 172,462 population controls, respectively.

Disclosures: The study was funded by a grant from the Danish Cancer Society and the Danish Council of Independent Research. Several of the authors reported receiving grants and or honoraria from pharmaceutical companies.

Source: Arnspang S et al. JAAD. 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2017.11.042

More evidence backs adjunctive intranasal esketamine for refractory depression

Esketamine – the S-enantiomer of the anesthetic ketamine – continues to look promising as an adjunctive treatment for refractory depression, phase 2 results of a four-phase multicenter trial suggested.

“We observed a significant and clinically meaningful treatment effect (vs. placebo) with 28-mg, 56-mg, and 84-mg doses of esketamine,” reported Ella J. Daly, MD, of Janssen, and her associates. The results were apparent 1 week after treatment, and they persisted over the follow-up phase, which lasted 8 weeks.

“,” Dr. Daly and her associates wrote in JAMA Psychiatry (2017 Dec 27. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.3739).

In the study, patients aged 20-64 years with a diagnosis of major depressive disorder were recruited from several outpatient referral centers. All of the participants had treatment-resistant depression, defined by the study as an inadequate response despite the use of two or more antidepressants. Overall, 67 patients were randomized to receive one of the three doses of intranasal esketamine or a placebo nasal spray. In addition, participants continued to take oral antidepressants during the study period. People with a history of psychotic symptoms, use of substances such as alcohol and cannabis, or significant medical comorbidities were excluded.

Among participants in the treatment groups, the mean total score changes on the Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) surpassed the MADRS score changes among those on placebo. Specifically, the mean MADRS score change for those on the 28-mg dose was –4.2 (P = 0.2), on the 56-mg dose was –6.3 (P = .001), and on the 84-mg dose was –9 (P less than .001).

The most common side effects among participants treated with esketamine were dizziness, headache, and dissociative symptoms. However, most adverse events were transient and “either mild or moderate in severity,” the investigators reported.

Dr. Daly and her associates cited several limitations, including the small sample size and the study’s exclusion criteria. Despite those limitations, Dr. Daly and her associates said, the results support further investigation of intranasal esketamine for treatment-resistant depression. They said a phase 3 study aimed at evaluating the frequency needed for dosing and duration of effect is underway.

Janssen funded the study. Dr. Daly and several of the other investigators are Janssen employees.

SOURCE: Daly et al. JAMA Psychiatry. 2017 Dec 27. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.3739

The study by Daly et al. is of interest for two key reasons, wrote Daniel S. Quintana, PhD, and his associates in an accompanying editorial (JAMA Psychiatry. 2017 Dec 27. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.3738). First, of interest is the drug’s impact on depressive symptoms as measured on the Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale. Second, the delivery mechanism is of interest, particularly in light of the increased bioavailability made possible by intranasal delivery. However, esketamine should be used with caution for psychiatric patients, he said.

“One of the three most common adverse effects was perceptual changes or dissociative symptoms, which fits with the known effect of ketamine and should be further clarified before starting routine in clinical practice,” he wrote. “Moreover, several issues related to long-term use, including the potential for addiction and adverse effects (somatic and cognitive) need to be carefully assessed in forthcoming studies.”

Dr. Quintana is affiliated with Oslo University Hospital & Institute of Clinical Medicine at the University of Oslo.

The study by Daly et al. is of interest for two key reasons, wrote Daniel S. Quintana, PhD, and his associates in an accompanying editorial (JAMA Psychiatry. 2017 Dec 27. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.3738). First, of interest is the drug’s impact on depressive symptoms as measured on the Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale. Second, the delivery mechanism is of interest, particularly in light of the increased bioavailability made possible by intranasal delivery. However, esketamine should be used with caution for psychiatric patients, he said.

“One of the three most common adverse effects was perceptual changes or dissociative symptoms, which fits with the known effect of ketamine and should be further clarified before starting routine in clinical practice,” he wrote. “Moreover, several issues related to long-term use, including the potential for addiction and adverse effects (somatic and cognitive) need to be carefully assessed in forthcoming studies.”

Dr. Quintana is affiliated with Oslo University Hospital & Institute of Clinical Medicine at the University of Oslo.

The study by Daly et al. is of interest for two key reasons, wrote Daniel S. Quintana, PhD, and his associates in an accompanying editorial (JAMA Psychiatry. 2017 Dec 27. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.3738). First, of interest is the drug’s impact on depressive symptoms as measured on the Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale. Second, the delivery mechanism is of interest, particularly in light of the increased bioavailability made possible by intranasal delivery. However, esketamine should be used with caution for psychiatric patients, he said.

“One of the three most common adverse effects was perceptual changes or dissociative symptoms, which fits with the known effect of ketamine and should be further clarified before starting routine in clinical practice,” he wrote. “Moreover, several issues related to long-term use, including the potential for addiction and adverse effects (somatic and cognitive) need to be carefully assessed in forthcoming studies.”

Dr. Quintana is affiliated with Oslo University Hospital & Institute of Clinical Medicine at the University of Oslo.

Esketamine – the S-enantiomer of the anesthetic ketamine – continues to look promising as an adjunctive treatment for refractory depression, phase 2 results of a four-phase multicenter trial suggested.

“We observed a significant and clinically meaningful treatment effect (vs. placebo) with 28-mg, 56-mg, and 84-mg doses of esketamine,” reported Ella J. Daly, MD, of Janssen, and her associates. The results were apparent 1 week after treatment, and they persisted over the follow-up phase, which lasted 8 weeks.

“,” Dr. Daly and her associates wrote in JAMA Psychiatry (2017 Dec 27. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.3739).

In the study, patients aged 20-64 years with a diagnosis of major depressive disorder were recruited from several outpatient referral centers. All of the participants had treatment-resistant depression, defined by the study as an inadequate response despite the use of two or more antidepressants. Overall, 67 patients were randomized to receive one of the three doses of intranasal esketamine or a placebo nasal spray. In addition, participants continued to take oral antidepressants during the study period. People with a history of psychotic symptoms, use of substances such as alcohol and cannabis, or significant medical comorbidities were excluded.

Among participants in the treatment groups, the mean total score changes on the Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) surpassed the MADRS score changes among those on placebo. Specifically, the mean MADRS score change for those on the 28-mg dose was –4.2 (P = 0.2), on the 56-mg dose was –6.3 (P = .001), and on the 84-mg dose was –9 (P less than .001).

The most common side effects among participants treated with esketamine were dizziness, headache, and dissociative symptoms. However, most adverse events were transient and “either mild or moderate in severity,” the investigators reported.

Dr. Daly and her associates cited several limitations, including the small sample size and the study’s exclusion criteria. Despite those limitations, Dr. Daly and her associates said, the results support further investigation of intranasal esketamine for treatment-resistant depression. They said a phase 3 study aimed at evaluating the frequency needed for dosing and duration of effect is underway.

Janssen funded the study. Dr. Daly and several of the other investigators are Janssen employees.

SOURCE: Daly et al. JAMA Psychiatry. 2017 Dec 27. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.3739

Esketamine – the S-enantiomer of the anesthetic ketamine – continues to look promising as an adjunctive treatment for refractory depression, phase 2 results of a four-phase multicenter trial suggested.

“We observed a significant and clinically meaningful treatment effect (vs. placebo) with 28-mg, 56-mg, and 84-mg doses of esketamine,” reported Ella J. Daly, MD, of Janssen, and her associates. The results were apparent 1 week after treatment, and they persisted over the follow-up phase, which lasted 8 weeks.

“,” Dr. Daly and her associates wrote in JAMA Psychiatry (2017 Dec 27. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.3739).

In the study, patients aged 20-64 years with a diagnosis of major depressive disorder were recruited from several outpatient referral centers. All of the participants had treatment-resistant depression, defined by the study as an inadequate response despite the use of two or more antidepressants. Overall, 67 patients were randomized to receive one of the three doses of intranasal esketamine or a placebo nasal spray. In addition, participants continued to take oral antidepressants during the study period. People with a history of psychotic symptoms, use of substances such as alcohol and cannabis, or significant medical comorbidities were excluded.

Among participants in the treatment groups, the mean total score changes on the Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) surpassed the MADRS score changes among those on placebo. Specifically, the mean MADRS score change for those on the 28-mg dose was –4.2 (P = 0.2), on the 56-mg dose was –6.3 (P = .001), and on the 84-mg dose was –9 (P less than .001).

The most common side effects among participants treated with esketamine were dizziness, headache, and dissociative symptoms. However, most adverse events were transient and “either mild or moderate in severity,” the investigators reported.

Dr. Daly and her associates cited several limitations, including the small sample size and the study’s exclusion criteria. Despite those limitations, Dr. Daly and her associates said, the results support further investigation of intranasal esketamine for treatment-resistant depression. They said a phase 3 study aimed at evaluating the frequency needed for dosing and duration of effect is underway.

Janssen funded the study. Dr. Daly and several of the other investigators are Janssen employees.

SOURCE: Daly et al. JAMA Psychiatry. 2017 Dec 27. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.3739

FROM JAMA PSYCHIATRY

Key clinical point: Adjunctive intranasal esketamine appears to lift treatment-resistant depression symptoms quickly, and the results last for more than 2 months “with a lower dosing frequency.”

Major finding: The MADRS mean score change for participants on the 28-mg dose was –4.2 (P = .2), –6.3 (P = .001) for those on the 56-mg dose, and –.9.0 (P greater than .001) for those on the 84-mg dose.

Study details: A phase 2 placebo-controlled study of 67 participants with treatment-resistant depression conducted in four phases at several outpatient treatment centers.

Disclosures: Janssen funded the study, and Dr. Daly and several of the other investigators are Janssen employees.

Source: Daly et al. JAMA Psychiatry. 2017 Dec. 27. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.3739.

Survival improvements lag for young Hispanic patients with myeloma

ATLANTA –

Among U.S. adults diagnosed with multiple myeloma by age 40 years, 5-year and 10-year survival improved significantly (P less than .0001) for non-Hispanic blacks and whites, but not for Hispanics (5-year survival, P = .08; 10-year survival, P = .13), Abdel-Ghani Azzouqa, MD, and colleagues reported in a poster at the annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology.

Other population-based studies have uncovered racial and ethnic disparities in myeloma outcomes but had not honed in on the experience of young adult patients, who make up a growing proportion of diagnosed patients, said Dr. Azzouqa.

He and his associates analyzed Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) data on patients diagnosed between ages 18 and 40 years with histologically confirmed multiple myeloma. The dataset spanned 1973-2014 and included 1,460 patients, of whom about 60% were male. Median age at diagnosis was 37 years; 47% of patients were non-Hispanic white, 28% were non-Hispanic black, 18% were Hispanic, 5.5% were Asian, and about 1% were of other ethnicities.

For young Hispanic patients with myeloma, 5-year survival improved from 39% before 1996, when stem cell transplants and novel therapies became available, to 56% from 2002 onward. This change was not statistically significant (P = .08), and 10-year survival rates also did not change significantly (from 21% to 33%; P = .13).

Five-year and 10-year survival did improve significantly for both genders (P = .0001) and among non-Hispanic blacks (P = .0001) and non-Hispanic whites (P = .0001).

Racial/ethnic subgroups did not differ significantly by median age at diagnosis, gender distribution, or listed cause of death, Dr. Azzouqa noted. Thus, reasons for the difference in survival for Hispanic patients remain unclear. Perhaps they reflect differences in disease biology, treatment response, or access or use of effective novel therapies, he said.

The researchers had no external funding sources. Dr. Azzouqa had no conflicts of interest. Lead author Dr. Sikander Ailawadhi disclosed ties to funding Pharmacyclics, Amgen, Novartis, and Takeda.

SOURCE: Ailawadhi S et al. ASH Abstract 2149

ATLANTA –

Among U.S. adults diagnosed with multiple myeloma by age 40 years, 5-year and 10-year survival improved significantly (P less than .0001) for non-Hispanic blacks and whites, but not for Hispanics (5-year survival, P = .08; 10-year survival, P = .13), Abdel-Ghani Azzouqa, MD, and colleagues reported in a poster at the annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology.

Other population-based studies have uncovered racial and ethnic disparities in myeloma outcomes but had not honed in on the experience of young adult patients, who make up a growing proportion of diagnosed patients, said Dr. Azzouqa.

He and his associates analyzed Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) data on patients diagnosed between ages 18 and 40 years with histologically confirmed multiple myeloma. The dataset spanned 1973-2014 and included 1,460 patients, of whom about 60% were male. Median age at diagnosis was 37 years; 47% of patients were non-Hispanic white, 28% were non-Hispanic black, 18% were Hispanic, 5.5% were Asian, and about 1% were of other ethnicities.

For young Hispanic patients with myeloma, 5-year survival improved from 39% before 1996, when stem cell transplants and novel therapies became available, to 56% from 2002 onward. This change was not statistically significant (P = .08), and 10-year survival rates also did not change significantly (from 21% to 33%; P = .13).

Five-year and 10-year survival did improve significantly for both genders (P = .0001) and among non-Hispanic blacks (P = .0001) and non-Hispanic whites (P = .0001).

Racial/ethnic subgroups did not differ significantly by median age at diagnosis, gender distribution, or listed cause of death, Dr. Azzouqa noted. Thus, reasons for the difference in survival for Hispanic patients remain unclear. Perhaps they reflect differences in disease biology, treatment response, or access or use of effective novel therapies, he said.

The researchers had no external funding sources. Dr. Azzouqa had no conflicts of interest. Lead author Dr. Sikander Ailawadhi disclosed ties to funding Pharmacyclics, Amgen, Novartis, and Takeda.

SOURCE: Ailawadhi S et al. ASH Abstract 2149

ATLANTA –

Among U.S. adults diagnosed with multiple myeloma by age 40 years, 5-year and 10-year survival improved significantly (P less than .0001) for non-Hispanic blacks and whites, but not for Hispanics (5-year survival, P = .08; 10-year survival, P = .13), Abdel-Ghani Azzouqa, MD, and colleagues reported in a poster at the annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology.

Other population-based studies have uncovered racial and ethnic disparities in myeloma outcomes but had not honed in on the experience of young adult patients, who make up a growing proportion of diagnosed patients, said Dr. Azzouqa.