User login

Tau imaging predicts looming cognitive decline in cognitively normal elderly

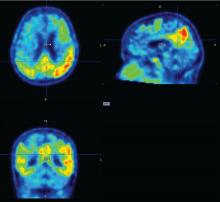

BOSTON – Progressive tau accumulation in the temporal lobe of cognitively normal older adults was associated with cognitive decline over time in a prospective, longitudinal study presented at the Clinical Trials on Alzheimer’s Disease conference.

This track of cognitive impairment following tau pathology in a preclinical Alzheimer’s disease (AD) population suggests two roles for serial positron emission tomography (PET) scans with a tau binding agent, Bernard Hanseeuw, MD, PhD, said at the meeting. In the near future, they could be used to track therapeutic response in clinical trials. Farther out, if future validation studies confirm these preliminary results, they might be a useful clinical tool for predicting how fast an individual Alzheimer’s patient will progress, he said in an interview.

Serial tau scans, however, would, he said.

“Every patient with Alzheimer’s disease is different, with a different disease course. Amyloid scans can tell us if someone is on the wrong path, but tau scans could tell us how fast they are going. If you have Alzheimer’s, it’s important to know if you may not be able to live in your own home in a year. With tau PET, we could track the disease and predict how fast it might evolve. That is very clinically relevant,” said Dr. Hanseeuw.

Tau imaging remains investigational only. Several tau imaging agents are being developed, but none has yet been approved in the United States or in Europe.

To investigate the correlation of tau and cognitive decline in preclinical Alzheimer’s, Dr. Hanseeuw examined serial tau and amyloid PET scans conducted on 60 clinically normal older adults with a mean age of 75 years. About one-third of the cohort was positive for the APOE4 allele. All of them had a baseline Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) score of 0 and a mean Mini-Mental State Exam score of at least 27. They also scored in the normal range on the Preclinical Alzheimer’s Cognitive Composite (PACC) test. This relatively new cognitive scale is an increasingly popular item in clinical trials. The PACC is a composite of the WAIS-R Digit Symbol Substitution Test, Mini-Mental State Exam, Free and Cued Selective Reminding Test, and Logical Memory IIA Delayed Recall, and correlates well with amyloid accumulation in the brain.

The study included up to 4 years of data on cognition and amyloid PET imaging, and up to 3 years of tau PET imaging data. The investigators assessed amyloid as a whole-brain aggregate and tau in the bilateral inferior temporal neocortex. “This is where the change is most happening in patients, and it’s a place where relatively few normal elderly would have tau,” Dr. Hanseeuw said. All of the analyses controlled for age, sex, and years of education.

Baseline amyloid levels were low in 36 participants and high in 24. At least some tau was present in all of the subjects. This is not an unexpected finding, since tau accumulates with age, Dr. Hanseeuw said. Over the study period, six subjects progressed to a CDR of 0.5 – a rating consistent with mild cognitive impairment. At baseline, high tau and high amyloid levels were both associated with a progressive decline in PACC scores in the following years. However, the rate of change in tau predicted change in cognition better than did the baseline measurements. In contrast, the rate of change in amyloid was not associated with cognitive decline.

“What is interesting here is that tau changed four times faster than amyloid,” Dr. Hanseeuw said. “The average subject needed 5 years to change 1 standard deviation in tau, but would have needed 20 years to change 1 standard deviation in amyloid.”

Fast-changing outcomes are important to accelerate drug assessment in clinical trials. Currently, it takes 3-5 years to conduct most anti-AD trials, he added.

Dr. Hanseeuw had no relevant financial disclosures.

BOSTON – Progressive tau accumulation in the temporal lobe of cognitively normal older adults was associated with cognitive decline over time in a prospective, longitudinal study presented at the Clinical Trials on Alzheimer’s Disease conference.

This track of cognitive impairment following tau pathology in a preclinical Alzheimer’s disease (AD) population suggests two roles for serial positron emission tomography (PET) scans with a tau binding agent, Bernard Hanseeuw, MD, PhD, said at the meeting. In the near future, they could be used to track therapeutic response in clinical trials. Farther out, if future validation studies confirm these preliminary results, they might be a useful clinical tool for predicting how fast an individual Alzheimer’s patient will progress, he said in an interview.

Serial tau scans, however, would, he said.

“Every patient with Alzheimer’s disease is different, with a different disease course. Amyloid scans can tell us if someone is on the wrong path, but tau scans could tell us how fast they are going. If you have Alzheimer’s, it’s important to know if you may not be able to live in your own home in a year. With tau PET, we could track the disease and predict how fast it might evolve. That is very clinically relevant,” said Dr. Hanseeuw.

Tau imaging remains investigational only. Several tau imaging agents are being developed, but none has yet been approved in the United States or in Europe.

To investigate the correlation of tau and cognitive decline in preclinical Alzheimer’s, Dr. Hanseeuw examined serial tau and amyloid PET scans conducted on 60 clinically normal older adults with a mean age of 75 years. About one-third of the cohort was positive for the APOE4 allele. All of them had a baseline Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) score of 0 and a mean Mini-Mental State Exam score of at least 27. They also scored in the normal range on the Preclinical Alzheimer’s Cognitive Composite (PACC) test. This relatively new cognitive scale is an increasingly popular item in clinical trials. The PACC is a composite of the WAIS-R Digit Symbol Substitution Test, Mini-Mental State Exam, Free and Cued Selective Reminding Test, and Logical Memory IIA Delayed Recall, and correlates well with amyloid accumulation in the brain.

The study included up to 4 years of data on cognition and amyloid PET imaging, and up to 3 years of tau PET imaging data. The investigators assessed amyloid as a whole-brain aggregate and tau in the bilateral inferior temporal neocortex. “This is where the change is most happening in patients, and it’s a place where relatively few normal elderly would have tau,” Dr. Hanseeuw said. All of the analyses controlled for age, sex, and years of education.

Baseline amyloid levels were low in 36 participants and high in 24. At least some tau was present in all of the subjects. This is not an unexpected finding, since tau accumulates with age, Dr. Hanseeuw said. Over the study period, six subjects progressed to a CDR of 0.5 – a rating consistent with mild cognitive impairment. At baseline, high tau and high amyloid levels were both associated with a progressive decline in PACC scores in the following years. However, the rate of change in tau predicted change in cognition better than did the baseline measurements. In contrast, the rate of change in amyloid was not associated with cognitive decline.

“What is interesting here is that tau changed four times faster than amyloid,” Dr. Hanseeuw said. “The average subject needed 5 years to change 1 standard deviation in tau, but would have needed 20 years to change 1 standard deviation in amyloid.”

Fast-changing outcomes are important to accelerate drug assessment in clinical trials. Currently, it takes 3-5 years to conduct most anti-AD trials, he added.

Dr. Hanseeuw had no relevant financial disclosures.

BOSTON – Progressive tau accumulation in the temporal lobe of cognitively normal older adults was associated with cognitive decline over time in a prospective, longitudinal study presented at the Clinical Trials on Alzheimer’s Disease conference.

This track of cognitive impairment following tau pathology in a preclinical Alzheimer’s disease (AD) population suggests two roles for serial positron emission tomography (PET) scans with a tau binding agent, Bernard Hanseeuw, MD, PhD, said at the meeting. In the near future, they could be used to track therapeutic response in clinical trials. Farther out, if future validation studies confirm these preliminary results, they might be a useful clinical tool for predicting how fast an individual Alzheimer’s patient will progress, he said in an interview.

Serial tau scans, however, would, he said.

“Every patient with Alzheimer’s disease is different, with a different disease course. Amyloid scans can tell us if someone is on the wrong path, but tau scans could tell us how fast they are going. If you have Alzheimer’s, it’s important to know if you may not be able to live in your own home in a year. With tau PET, we could track the disease and predict how fast it might evolve. That is very clinically relevant,” said Dr. Hanseeuw.

Tau imaging remains investigational only. Several tau imaging agents are being developed, but none has yet been approved in the United States or in Europe.

To investigate the correlation of tau and cognitive decline in preclinical Alzheimer’s, Dr. Hanseeuw examined serial tau and amyloid PET scans conducted on 60 clinically normal older adults with a mean age of 75 years. About one-third of the cohort was positive for the APOE4 allele. All of them had a baseline Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) score of 0 and a mean Mini-Mental State Exam score of at least 27. They also scored in the normal range on the Preclinical Alzheimer’s Cognitive Composite (PACC) test. This relatively new cognitive scale is an increasingly popular item in clinical trials. The PACC is a composite of the WAIS-R Digit Symbol Substitution Test, Mini-Mental State Exam, Free and Cued Selective Reminding Test, and Logical Memory IIA Delayed Recall, and correlates well with amyloid accumulation in the brain.

The study included up to 4 years of data on cognition and amyloid PET imaging, and up to 3 years of tau PET imaging data. The investigators assessed amyloid as a whole-brain aggregate and tau in the bilateral inferior temporal neocortex. “This is where the change is most happening in patients, and it’s a place where relatively few normal elderly would have tau,” Dr. Hanseeuw said. All of the analyses controlled for age, sex, and years of education.

Baseline amyloid levels were low in 36 participants and high in 24. At least some tau was present in all of the subjects. This is not an unexpected finding, since tau accumulates with age, Dr. Hanseeuw said. Over the study period, six subjects progressed to a CDR of 0.5 – a rating consistent with mild cognitive impairment. At baseline, high tau and high amyloid levels were both associated with a progressive decline in PACC scores in the following years. However, the rate of change in tau predicted change in cognition better than did the baseline measurements. In contrast, the rate of change in amyloid was not associated with cognitive decline.

“What is interesting here is that tau changed four times faster than amyloid,” Dr. Hanseeuw said. “The average subject needed 5 years to change 1 standard deviation in tau, but would have needed 20 years to change 1 standard deviation in amyloid.”

Fast-changing outcomes are important to accelerate drug assessment in clinical trials. Currently, it takes 3-5 years to conduct most anti-AD trials, he added.

Dr. Hanseeuw had no relevant financial disclosures.

REPORTING FROM CTAD

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Tau levels changed twice as fast as cognition, suggesting that the protein is a significant marker of future cognitive change.

Data source: A prospective, longitudinal study of 60 cognitively normal subjects.

Disclosures: Dr. Hanseeuw had no relevant financial disclosures.

Source: Hanseeuw B et al. CTAD 2017 Abstract OC2.

Retinal changes may reflect brain changes in preclinical Alzheimer’s

BOSTON – Changes in the retina seem to mirror changes that begin to reshape the brain in preclinical Alzheimer’s disease.

Manifested as a reduction in volume in the retinal nerve fiber layer, these changes appear to track the aggregation of beta amyloid brain plaques well before cognitive problems arise – and can be easily measured with a piece of equipment already in many optometry offices, Peter J. Snyder, PhD, said at the Clinical Trials in Alzheimer’s Disease conference.

“If we are lucky enough to live past age 45, then it’s a given that we’re all going to develop some presbyopia. So we all have to go to the optometrist sometime, and that may become a point of entry for broad screening and to track changes over time, to keep an eye on at-risk patients, and to refer those with retinal changes that fit the preclinical AD profile to specialty care for more comprehensive diagnostic evaluations.”

The retina begins to form in the third week of embryologic life, arising from the neural tube cells that also form the brain and spinal cord. It makes sense then that very early neuronal changes in Alzheimer’s disease could be occurring in the retina as well, said Dr. Snyder, professor of neurology and surgery (ophthalmology) at Rhode Island Hospital and Brown University, Providence.

“The retina is really a protrusion of the brain, and it is part and parcel of the central nervous system. In terms of the neuronal structure, the retina develops in layers with very specific cell types that are neurochemically and physiologically the same as the nervous tissue in the brain. That’s why it is, potentially, literally a window that could let us see what’s happening in the brain in early Alzheimer’s disease.”

Other researchers have explored amyloid in the lens and retina as a possible early Alzheimer’s identification tool. But Dr. Snyder’s study is the first to demonstrate a longitudinal association between neuronal changes in the eye and amyloid burden in the brain among clinically normal subjects.

For 27 months, he followed 56 people who had normal cognition but were beginning to experience subjective memory complaints. All subjects had at least one parent with Alzheimer’s disease. Everyone underwent an amyloid PET scan at baseline. Of the cohort, 15 had PET imaging evidence of abnormal beta-amyloid protein aggregation in the neocortex. This group was deemed to have preclinical Alzheimer’s disease, while the remainder served as a control group.

Dr. Snyder imaged each subject’s retinas twice – once at baseline and once at 27 months, when everyone underwent a second amyloid PET scan as well. He examined the retina with spectral domain optical coherence tomography, a relatively new method of imaging the retina.

These scanners are becoming increasingly more common in optometry practices, Dr. Snyder said. “Graduate optometrists tell me they would not want to be in a practice without one.” The scanners are typically used to detect retinal and ocular changes associated with diabetes, macular degeneration, glaucoma and multiple sclerosis.

Dr. Snyder used the scanner to examine the optic nerve head and macula at both baseline and 27 months in his cohort. He was looking for volumetric changes in several of the retinal layers: the peripapillary retinal nerve fiber layer (pRNFL), macular RNFL (mRNFL), ganglion cell layer (GCL), inner plexiform layer (IPL), outer nuclear layer (ONL), outer plexiform layer (OPL), and inner nuclear layer (INL). He also computed changes in total retinal volume.

Even at baseline, he found a significant difference between the groups. Among the amyloid-positive subjects, the inner plexiform layer was slightly larger in volume. “This seems a bit counterintuitive, but I think it suggests that there may be some inflammatory processes going on in this early stage and that we are catching that inflammation.”

Dr. Snyder noted that this finding has recently been replicated by an independent research group in Perth, Australia – with a much larger sample of participants – and will be reported at international conferences this coming year.

At 27 months, both the total retinal volume and the macular retinal nerve fiber layer volume were significantly lower in the preclinical AD group than in the control group. There was also a volume reduction in the peripapillary retinal nerve fiber layer, although the between-group difference was not statistically significant.

In a multivariate linear regression model that controlled for age and total amyloid burden, the mean volume change in the macular retinal nerve fiber layer accounted for about 10% of the variation in PET binding to brain amyloid by 27 months. Volume reductions in all the other layers appeared to be associated only with age, representing normal age-related changes in the eye.

Dr. Snyder said this volume loss in the retinal nerve fiber layer probably represents early demyelination and/or degeneration of the axons coursing from the cell bodies in the ganglion cell layer, which project to the optic nerve head.

“This finding in the retina appears analogous, and possibly directly related to, a similar loss of white matter that is readily observable in the early stages of Alzheimer’s disease. At the same time, patients are beginning to experience both cholinergic changes in the basal forebrain and the abnormal aggregation of fibrillar beta-amyloid plaques. I don’t know to what extent these changes are mechanistically dependent on each other, but they appear to also be happening, in the earliest stages of the disease course, in the retina.”

There is a lot of work left to be done before retinal scanning could be employed as a risk-assessment tool, however. With every new biomarker – and especially with imaging – the ability to measure change occurs far in advance of an understanding of what those changes mean, and how to judge them accurately.

“Every time we have a major advance in imaging, the technical engineering breakthroughs precede our detailed understanding of what we’re looking at and what to measure. This is where we are right now with retinal imaging. Biologically, it makes sense to be looking at this as a marker of risk in those who are clinically healthy, and maybe later as a marker of disease progression. But there is a lot of work to be done here yet.”

Dr. Snyder’s project was funded in part by a research award from Pfizer, with PET imaging supported in part by a grant from Avid Radiopharmaceuticals. He has no financial ties to the company, or other financial interest related to the study.

[email protected]

On Twitter @Alz_Gal

BOSTON – Changes in the retina seem to mirror changes that begin to reshape the brain in preclinical Alzheimer’s disease.

Manifested as a reduction in volume in the retinal nerve fiber layer, these changes appear to track the aggregation of beta amyloid brain plaques well before cognitive problems arise – and can be easily measured with a piece of equipment already in many optometry offices, Peter J. Snyder, PhD, said at the Clinical Trials in Alzheimer’s Disease conference.

“If we are lucky enough to live past age 45, then it’s a given that we’re all going to develop some presbyopia. So we all have to go to the optometrist sometime, and that may become a point of entry for broad screening and to track changes over time, to keep an eye on at-risk patients, and to refer those with retinal changes that fit the preclinical AD profile to specialty care for more comprehensive diagnostic evaluations.”

The retina begins to form in the third week of embryologic life, arising from the neural tube cells that also form the brain and spinal cord. It makes sense then that very early neuronal changes in Alzheimer’s disease could be occurring in the retina as well, said Dr. Snyder, professor of neurology and surgery (ophthalmology) at Rhode Island Hospital and Brown University, Providence.

“The retina is really a protrusion of the brain, and it is part and parcel of the central nervous system. In terms of the neuronal structure, the retina develops in layers with very specific cell types that are neurochemically and physiologically the same as the nervous tissue in the brain. That’s why it is, potentially, literally a window that could let us see what’s happening in the brain in early Alzheimer’s disease.”

Other researchers have explored amyloid in the lens and retina as a possible early Alzheimer’s identification tool. But Dr. Snyder’s study is the first to demonstrate a longitudinal association between neuronal changes in the eye and amyloid burden in the brain among clinically normal subjects.

For 27 months, he followed 56 people who had normal cognition but were beginning to experience subjective memory complaints. All subjects had at least one parent with Alzheimer’s disease. Everyone underwent an amyloid PET scan at baseline. Of the cohort, 15 had PET imaging evidence of abnormal beta-amyloid protein aggregation in the neocortex. This group was deemed to have preclinical Alzheimer’s disease, while the remainder served as a control group.

Dr. Snyder imaged each subject’s retinas twice – once at baseline and once at 27 months, when everyone underwent a second amyloid PET scan as well. He examined the retina with spectral domain optical coherence tomography, a relatively new method of imaging the retina.

These scanners are becoming increasingly more common in optometry practices, Dr. Snyder said. “Graduate optometrists tell me they would not want to be in a practice without one.” The scanners are typically used to detect retinal and ocular changes associated with diabetes, macular degeneration, glaucoma and multiple sclerosis.

Dr. Snyder used the scanner to examine the optic nerve head and macula at both baseline and 27 months in his cohort. He was looking for volumetric changes in several of the retinal layers: the peripapillary retinal nerve fiber layer (pRNFL), macular RNFL (mRNFL), ganglion cell layer (GCL), inner plexiform layer (IPL), outer nuclear layer (ONL), outer plexiform layer (OPL), and inner nuclear layer (INL). He also computed changes in total retinal volume.

Even at baseline, he found a significant difference between the groups. Among the amyloid-positive subjects, the inner plexiform layer was slightly larger in volume. “This seems a bit counterintuitive, but I think it suggests that there may be some inflammatory processes going on in this early stage and that we are catching that inflammation.”

Dr. Snyder noted that this finding has recently been replicated by an independent research group in Perth, Australia – with a much larger sample of participants – and will be reported at international conferences this coming year.

At 27 months, both the total retinal volume and the macular retinal nerve fiber layer volume were significantly lower in the preclinical AD group than in the control group. There was also a volume reduction in the peripapillary retinal nerve fiber layer, although the between-group difference was not statistically significant.

In a multivariate linear regression model that controlled for age and total amyloid burden, the mean volume change in the macular retinal nerve fiber layer accounted for about 10% of the variation in PET binding to brain amyloid by 27 months. Volume reductions in all the other layers appeared to be associated only with age, representing normal age-related changes in the eye.

Dr. Snyder said this volume loss in the retinal nerve fiber layer probably represents early demyelination and/or degeneration of the axons coursing from the cell bodies in the ganglion cell layer, which project to the optic nerve head.

“This finding in the retina appears analogous, and possibly directly related to, a similar loss of white matter that is readily observable in the early stages of Alzheimer’s disease. At the same time, patients are beginning to experience both cholinergic changes in the basal forebrain and the abnormal aggregation of fibrillar beta-amyloid plaques. I don’t know to what extent these changes are mechanistically dependent on each other, but they appear to also be happening, in the earliest stages of the disease course, in the retina.”

There is a lot of work left to be done before retinal scanning could be employed as a risk-assessment tool, however. With every new biomarker – and especially with imaging – the ability to measure change occurs far in advance of an understanding of what those changes mean, and how to judge them accurately.

“Every time we have a major advance in imaging, the technical engineering breakthroughs precede our detailed understanding of what we’re looking at and what to measure. This is where we are right now with retinal imaging. Biologically, it makes sense to be looking at this as a marker of risk in those who are clinically healthy, and maybe later as a marker of disease progression. But there is a lot of work to be done here yet.”

Dr. Snyder’s project was funded in part by a research award from Pfizer, with PET imaging supported in part by a grant from Avid Radiopharmaceuticals. He has no financial ties to the company, or other financial interest related to the study.

[email protected]

On Twitter @Alz_Gal

BOSTON – Changes in the retina seem to mirror changes that begin to reshape the brain in preclinical Alzheimer’s disease.

Manifested as a reduction in volume in the retinal nerve fiber layer, these changes appear to track the aggregation of beta amyloid brain plaques well before cognitive problems arise – and can be easily measured with a piece of equipment already in many optometry offices, Peter J. Snyder, PhD, said at the Clinical Trials in Alzheimer’s Disease conference.

“If we are lucky enough to live past age 45, then it’s a given that we’re all going to develop some presbyopia. So we all have to go to the optometrist sometime, and that may become a point of entry for broad screening and to track changes over time, to keep an eye on at-risk patients, and to refer those with retinal changes that fit the preclinical AD profile to specialty care for more comprehensive diagnostic evaluations.”

The retina begins to form in the third week of embryologic life, arising from the neural tube cells that also form the brain and spinal cord. It makes sense then that very early neuronal changes in Alzheimer’s disease could be occurring in the retina as well, said Dr. Snyder, professor of neurology and surgery (ophthalmology) at Rhode Island Hospital and Brown University, Providence.

“The retina is really a protrusion of the brain, and it is part and parcel of the central nervous system. In terms of the neuronal structure, the retina develops in layers with very specific cell types that are neurochemically and physiologically the same as the nervous tissue in the brain. That’s why it is, potentially, literally a window that could let us see what’s happening in the brain in early Alzheimer’s disease.”

Other researchers have explored amyloid in the lens and retina as a possible early Alzheimer’s identification tool. But Dr. Snyder’s study is the first to demonstrate a longitudinal association between neuronal changes in the eye and amyloid burden in the brain among clinically normal subjects.

For 27 months, he followed 56 people who had normal cognition but were beginning to experience subjective memory complaints. All subjects had at least one parent with Alzheimer’s disease. Everyone underwent an amyloid PET scan at baseline. Of the cohort, 15 had PET imaging evidence of abnormal beta-amyloid protein aggregation in the neocortex. This group was deemed to have preclinical Alzheimer’s disease, while the remainder served as a control group.

Dr. Snyder imaged each subject’s retinas twice – once at baseline and once at 27 months, when everyone underwent a second amyloid PET scan as well. He examined the retina with spectral domain optical coherence tomography, a relatively new method of imaging the retina.

These scanners are becoming increasingly more common in optometry practices, Dr. Snyder said. “Graduate optometrists tell me they would not want to be in a practice without one.” The scanners are typically used to detect retinal and ocular changes associated with diabetes, macular degeneration, glaucoma and multiple sclerosis.

Dr. Snyder used the scanner to examine the optic nerve head and macula at both baseline and 27 months in his cohort. He was looking for volumetric changes in several of the retinal layers: the peripapillary retinal nerve fiber layer (pRNFL), macular RNFL (mRNFL), ganglion cell layer (GCL), inner plexiform layer (IPL), outer nuclear layer (ONL), outer plexiform layer (OPL), and inner nuclear layer (INL). He also computed changes in total retinal volume.

Even at baseline, he found a significant difference between the groups. Among the amyloid-positive subjects, the inner plexiform layer was slightly larger in volume. “This seems a bit counterintuitive, but I think it suggests that there may be some inflammatory processes going on in this early stage and that we are catching that inflammation.”

Dr. Snyder noted that this finding has recently been replicated by an independent research group in Perth, Australia – with a much larger sample of participants – and will be reported at international conferences this coming year.

At 27 months, both the total retinal volume and the macular retinal nerve fiber layer volume were significantly lower in the preclinical AD group than in the control group. There was also a volume reduction in the peripapillary retinal nerve fiber layer, although the between-group difference was not statistically significant.

In a multivariate linear regression model that controlled for age and total amyloid burden, the mean volume change in the macular retinal nerve fiber layer accounted for about 10% of the variation in PET binding to brain amyloid by 27 months. Volume reductions in all the other layers appeared to be associated only with age, representing normal age-related changes in the eye.

Dr. Snyder said this volume loss in the retinal nerve fiber layer probably represents early demyelination and/or degeneration of the axons coursing from the cell bodies in the ganglion cell layer, which project to the optic nerve head.

“This finding in the retina appears analogous, and possibly directly related to, a similar loss of white matter that is readily observable in the early stages of Alzheimer’s disease. At the same time, patients are beginning to experience both cholinergic changes in the basal forebrain and the abnormal aggregation of fibrillar beta-amyloid plaques. I don’t know to what extent these changes are mechanistically dependent on each other, but they appear to also be happening, in the earliest stages of the disease course, in the retina.”

There is a lot of work left to be done before retinal scanning could be employed as a risk-assessment tool, however. With every new biomarker – and especially with imaging – the ability to measure change occurs far in advance of an understanding of what those changes mean, and how to judge them accurately.

“Every time we have a major advance in imaging, the technical engineering breakthroughs precede our detailed understanding of what we’re looking at and what to measure. This is where we are right now with retinal imaging. Biologically, it makes sense to be looking at this as a marker of risk in those who are clinically healthy, and maybe later as a marker of disease progression. But there is a lot of work to be done here yet.”

Dr. Snyder’s project was funded in part by a research award from Pfizer, with PET imaging supported in part by a grant from Avid Radiopharmaceuticals. He has no financial ties to the company, or other financial interest related to the study.

[email protected]

On Twitter @Alz_Gal

AT CTAD

Key clinical point: Retinal scans might eventually be an easy, noninvasive, and inexpensive way to tag people who may be at elevated risk for Alzheimer’s disease.

Major finding: At 27 months, both the total retinal volume and the macular retinal nerve fiber layer volume were significantly lower in 15 patients in the preclinical AD group than in the 41 patients in the control group.

Data source: A follow-up study of 56 people who had at least one parent with Alzheimer’s disease and were beginning to experience subjective memory complaints.

Disclosures: Dr. Snyder’s project was funded in part by a research award from Pfizer, with PET imaging supported in part by a grant from Avid Radiopharmaceuticals. He has no financial ties to the company, or other financial interest related to the study.

Walking has beneficial cognitive effects in amyloid-positive older adults

BOSTON – Walking appears to moderate cognitive decline in people with elevated brain amyloid, a 4-year observational study has determined.

Among a group of cognitively normal older adults with beta-amyloid brain plaques, those who walked the most experienced significantly less decline in memory and thinking than those who didn’t walk much, Dylan Kirn reported at the Clinical Trials on Alzheimer’s Disease conference. Walking didn’t affect any of the hallmark biomarkers of Alzheimer’s disease, such as brain glucose utilization, amyloid accumulation, or hippocampal volume, but it was associated with significantly better cognitive scores on a composite measure of memory over time.

“We should be careful in interpreting these data, because this is an observational cohort and we can’t make claims regarding causality or the mechanism by which physical activity may be influencing cognitive decline,” said Mr. Kirn of the Athinoula A. Martinos Center for Biomedical Imaging at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston. “But I find these results interesting and novel, and I think they support further investigation.”

The walking study comprised 255 subjects with a mean age of 73 years. They were highly educated, with a mean of 16 years’ schooling. About 24% were amyloid-positive by PET imaging. All were cognitively normal, with a Clinical Dementia Rating scale score of 0. Activity was established at baseline with a pedometer, which was worn for 7 consecutive days; only those who walked at least 100 steps per day were included in the analysis.

In addition to amyloid PET imaging, subjects also underwent a 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) PET scan to assess brain glucose utilization, and MRI to measure hippocampal volume changes and assess white matter hyperintensities (WMHs). Changes in all of these biomarkers can herald the onset of Alzheimer’s.

The primary outcome was the relationship between physical activity as measured by number of walking steps per day and changes on the Preclinical Alzheimer’s Cognitive Composite (PACC) test. This relatively new cognitive scale is an increasingly popular item in clinical trials. The PACC is a composite of the Digit Symbol Substitution Test score from the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale–Revised, the Mini Mental State Exam, the Total Recall score from the Free and Cued Selective Reminding Test, and the Delayed Recall score on the Logical Memory IIa sub-test from the Wechsler Memory Scale. It correlates well with amyloid accumulation in the brain, Mr. Kirn said.

The cohort was followed for up to 6 years (median of 4), and PACC scores were calculated annually. The investigators looked at the relationship between walking at baseline and PACC decline over the study period in two multivariate models: One controlling for age, sex, and years of education, and the second for those variables plus the biomarkers of cortical WMHs, bilateral hippocampal volume (HV), and FDG-PET in brain regions typically affected by Alzheimer’s.

Physical activity was divided into tertiles by the average number of steps per day over the 7-day measuring period: Mean (5,616 steps), one standard deviation above mean (high; 8,482 steps), and one standard deviation below mean (low, 2,751 steps). Amyloid-positive patients were further divided into those with high brain amyloid load and those with low amyloid brain load.

There were no significant relationships between any of the biomarkers and any level of physical activity in either of the analyses, Mr. Kirn said. However, when looking at the time-linked changes in the PACC, significant differences did emerge. Subjects who walked at least the mean number of steps per day were much more likely to maintain a stable cognitive score, while those who walked the fewest steps declined about a quarter of a point on the PACC. The difference in decline between the high activity and low activity subjects was statistically significant, even when the investigators controlled for amyloid burden and the other hallmark Alzheimer’s biomarkers.

The level of physical activity at baseline was a particularly strong predictor of cognitive health among amyloid-positive subjects. Those in the high-activity group maintained a steady score on the PACC. Those in the mean activity group declined slightly, and those in the low activity group showed a sharp decline, losing almost a full point on the PACC by the end of follow-up.

In the amyloid-negative group, there was no association between cognition and activity. All the groups improved their PACC scores over the study period, probably reflecting a practice effect, Mr. Kirn said.

Finally, he split the amyloid-positive group into subjects with low and high brain amyloid levels. “We observed that physical activity was significantly predictive of cognitive decline in high-amyloid participants, but not in low-amyloid participants,” he said. “Individuals with high amyloid and low physical activity at baseline had the steepest decline in cognition over time. But in those with high amyloid and high physical activity at baseline, we didn’t see a tremendous amount of decline.”

The study suggests that pedometers may have a place in stratifying patients for clinical trials, or assessing cognitive risk in elderly subjects. “Most studies that have looked at physical activity and dementia use a self-reported activity level, so the results have been varied,” Mr. Kirn said. “These findings support consideration of objectively measured physical activity in clinical research, and perhaps in stratification for risk of cognitive decline.”

He had no financial disclosures.

[email protected]

On Twitter @Alz_Gal

BOSTON – Walking appears to moderate cognitive decline in people with elevated brain amyloid, a 4-year observational study has determined.

Among a group of cognitively normal older adults with beta-amyloid brain plaques, those who walked the most experienced significantly less decline in memory and thinking than those who didn’t walk much, Dylan Kirn reported at the Clinical Trials on Alzheimer’s Disease conference. Walking didn’t affect any of the hallmark biomarkers of Alzheimer’s disease, such as brain glucose utilization, amyloid accumulation, or hippocampal volume, but it was associated with significantly better cognitive scores on a composite measure of memory over time.

“We should be careful in interpreting these data, because this is an observational cohort and we can’t make claims regarding causality or the mechanism by which physical activity may be influencing cognitive decline,” said Mr. Kirn of the Athinoula A. Martinos Center for Biomedical Imaging at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston. “But I find these results interesting and novel, and I think they support further investigation.”

The walking study comprised 255 subjects with a mean age of 73 years. They were highly educated, with a mean of 16 years’ schooling. About 24% were amyloid-positive by PET imaging. All were cognitively normal, with a Clinical Dementia Rating scale score of 0. Activity was established at baseline with a pedometer, which was worn for 7 consecutive days; only those who walked at least 100 steps per day were included in the analysis.

In addition to amyloid PET imaging, subjects also underwent a 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) PET scan to assess brain glucose utilization, and MRI to measure hippocampal volume changes and assess white matter hyperintensities (WMHs). Changes in all of these biomarkers can herald the onset of Alzheimer’s.

The primary outcome was the relationship between physical activity as measured by number of walking steps per day and changes on the Preclinical Alzheimer’s Cognitive Composite (PACC) test. This relatively new cognitive scale is an increasingly popular item in clinical trials. The PACC is a composite of the Digit Symbol Substitution Test score from the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale–Revised, the Mini Mental State Exam, the Total Recall score from the Free and Cued Selective Reminding Test, and the Delayed Recall score on the Logical Memory IIa sub-test from the Wechsler Memory Scale. It correlates well with amyloid accumulation in the brain, Mr. Kirn said.

The cohort was followed for up to 6 years (median of 4), and PACC scores were calculated annually. The investigators looked at the relationship between walking at baseline and PACC decline over the study period in two multivariate models: One controlling for age, sex, and years of education, and the second for those variables plus the biomarkers of cortical WMHs, bilateral hippocampal volume (HV), and FDG-PET in brain regions typically affected by Alzheimer’s.

Physical activity was divided into tertiles by the average number of steps per day over the 7-day measuring period: Mean (5,616 steps), one standard deviation above mean (high; 8,482 steps), and one standard deviation below mean (low, 2,751 steps). Amyloid-positive patients were further divided into those with high brain amyloid load and those with low amyloid brain load.

There were no significant relationships between any of the biomarkers and any level of physical activity in either of the analyses, Mr. Kirn said. However, when looking at the time-linked changes in the PACC, significant differences did emerge. Subjects who walked at least the mean number of steps per day were much more likely to maintain a stable cognitive score, while those who walked the fewest steps declined about a quarter of a point on the PACC. The difference in decline between the high activity and low activity subjects was statistically significant, even when the investigators controlled for amyloid burden and the other hallmark Alzheimer’s biomarkers.

The level of physical activity at baseline was a particularly strong predictor of cognitive health among amyloid-positive subjects. Those in the high-activity group maintained a steady score on the PACC. Those in the mean activity group declined slightly, and those in the low activity group showed a sharp decline, losing almost a full point on the PACC by the end of follow-up.

In the amyloid-negative group, there was no association between cognition and activity. All the groups improved their PACC scores over the study period, probably reflecting a practice effect, Mr. Kirn said.

Finally, he split the amyloid-positive group into subjects with low and high brain amyloid levels. “We observed that physical activity was significantly predictive of cognitive decline in high-amyloid participants, but not in low-amyloid participants,” he said. “Individuals with high amyloid and low physical activity at baseline had the steepest decline in cognition over time. But in those with high amyloid and high physical activity at baseline, we didn’t see a tremendous amount of decline.”

The study suggests that pedometers may have a place in stratifying patients for clinical trials, or assessing cognitive risk in elderly subjects. “Most studies that have looked at physical activity and dementia use a self-reported activity level, so the results have been varied,” Mr. Kirn said. “These findings support consideration of objectively measured physical activity in clinical research, and perhaps in stratification for risk of cognitive decline.”

He had no financial disclosures.

[email protected]

On Twitter @Alz_Gal

BOSTON – Walking appears to moderate cognitive decline in people with elevated brain amyloid, a 4-year observational study has determined.

Among a group of cognitively normal older adults with beta-amyloid brain plaques, those who walked the most experienced significantly less decline in memory and thinking than those who didn’t walk much, Dylan Kirn reported at the Clinical Trials on Alzheimer’s Disease conference. Walking didn’t affect any of the hallmark biomarkers of Alzheimer’s disease, such as brain glucose utilization, amyloid accumulation, or hippocampal volume, but it was associated with significantly better cognitive scores on a composite measure of memory over time.

“We should be careful in interpreting these data, because this is an observational cohort and we can’t make claims regarding causality or the mechanism by which physical activity may be influencing cognitive decline,” said Mr. Kirn of the Athinoula A. Martinos Center for Biomedical Imaging at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston. “But I find these results interesting and novel, and I think they support further investigation.”

The walking study comprised 255 subjects with a mean age of 73 years. They were highly educated, with a mean of 16 years’ schooling. About 24% were amyloid-positive by PET imaging. All were cognitively normal, with a Clinical Dementia Rating scale score of 0. Activity was established at baseline with a pedometer, which was worn for 7 consecutive days; only those who walked at least 100 steps per day were included in the analysis.

In addition to amyloid PET imaging, subjects also underwent a 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) PET scan to assess brain glucose utilization, and MRI to measure hippocampal volume changes and assess white matter hyperintensities (WMHs). Changes in all of these biomarkers can herald the onset of Alzheimer’s.

The primary outcome was the relationship between physical activity as measured by number of walking steps per day and changes on the Preclinical Alzheimer’s Cognitive Composite (PACC) test. This relatively new cognitive scale is an increasingly popular item in clinical trials. The PACC is a composite of the Digit Symbol Substitution Test score from the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale–Revised, the Mini Mental State Exam, the Total Recall score from the Free and Cued Selective Reminding Test, and the Delayed Recall score on the Logical Memory IIa sub-test from the Wechsler Memory Scale. It correlates well with amyloid accumulation in the brain, Mr. Kirn said.

The cohort was followed for up to 6 years (median of 4), and PACC scores were calculated annually. The investigators looked at the relationship between walking at baseline and PACC decline over the study period in two multivariate models: One controlling for age, sex, and years of education, and the second for those variables plus the biomarkers of cortical WMHs, bilateral hippocampal volume (HV), and FDG-PET in brain regions typically affected by Alzheimer’s.

Physical activity was divided into tertiles by the average number of steps per day over the 7-day measuring period: Mean (5,616 steps), one standard deviation above mean (high; 8,482 steps), and one standard deviation below mean (low, 2,751 steps). Amyloid-positive patients were further divided into those with high brain amyloid load and those with low amyloid brain load.

There were no significant relationships between any of the biomarkers and any level of physical activity in either of the analyses, Mr. Kirn said. However, when looking at the time-linked changes in the PACC, significant differences did emerge. Subjects who walked at least the mean number of steps per day were much more likely to maintain a stable cognitive score, while those who walked the fewest steps declined about a quarter of a point on the PACC. The difference in decline between the high activity and low activity subjects was statistically significant, even when the investigators controlled for amyloid burden and the other hallmark Alzheimer’s biomarkers.

The level of physical activity at baseline was a particularly strong predictor of cognitive health among amyloid-positive subjects. Those in the high-activity group maintained a steady score on the PACC. Those in the mean activity group declined slightly, and those in the low activity group showed a sharp decline, losing almost a full point on the PACC by the end of follow-up.

In the amyloid-negative group, there was no association between cognition and activity. All the groups improved their PACC scores over the study period, probably reflecting a practice effect, Mr. Kirn said.

Finally, he split the amyloid-positive group into subjects with low and high brain amyloid levels. “We observed that physical activity was significantly predictive of cognitive decline in high-amyloid participants, but not in low-amyloid participants,” he said. “Individuals with high amyloid and low physical activity at baseline had the steepest decline in cognition over time. But in those with high amyloid and high physical activity at baseline, we didn’t see a tremendous amount of decline.”

The study suggests that pedometers may have a place in stratifying patients for clinical trials, or assessing cognitive risk in elderly subjects. “Most studies that have looked at physical activity and dementia use a self-reported activity level, so the results have been varied,” Mr. Kirn said. “These findings support consideration of objectively measured physical activity in clinical research, and perhaps in stratification for risk of cognitive decline.”

He had no financial disclosures.

[email protected]

On Twitter @Alz_Gal

AT CTAD

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Subjects with high amyloid burden who walked the least declined by almost 1 point on the PACC score; high-amyloid subjects who walked the most stayed at their baseline score.

Data source: A prospective, observational study comprising 255 elderly subjects with normal cognition.

Disclosures: The presenter had no financial disclosures.

Intepirdine flops in phase 3 study of mild to moderate Alzheimer’s patients

BOSTON – An investigational Alzheimer’s drug intended to potentiate acetylcholine release didn’t pass muster in a global phase 3 study, despite a successful phase 2 trial.

Intepirdine on a background of stable-dose donepezil failed to confer any cognitive or functional benefit in patients with mild to moderate Alzheimer’s disease, Ilise Lombardo, PhD, said at the Clinical Trials on Alzheimer’s Disease conference.

Intepirdine blocks the 5-hydroxytryptamine receptor 6 and increases the release of acetylcholine, according to Dr. Lombardo. By giving it on a stable background of an acetylcholinesterase inhibitor, researchers hoped to improve cognition by increasing acetylcholine signaling between neurons. In a modestly successful phase 2b study reported out last summer, intepirdine did confer some cognitive and functional benefits.

The study was scheduled to be presented at the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference, but was pulled at the last minute when Axovant announced its initial public offering of stock shortly before the July meeting. However, Dr. Lombardo did review study 866 at CTAD. It randomized 269 patients with mild to moderate AD to placebo or intepirdine at 15 mg or 35 mg/day for 24 weeks. By 12 weeks, patients taking the 35-mg dose had declined 1.6 points less than those on placebo on the Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale–cognitive subscale (ADAS-cog) and 1.94 points on the Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study–Activities of Daily Living (ADCS-ADL). Both differences were statistically significant. The drug moved into a phase 3 study, dubbed MINDSET, at 35 mg.

MINDSET enrolled 1, 315 patients with mild to moderate Alzheimer’s disease and randomized them to placebo or 35 mg intepirdine for 24 weeks. All patients were on stable background donepezil. Again, the coprimary endpoints were the ADAS-cog and the ADCS-ADL at the end of the study. There were three secondary endpoints: the Clinician Interview-Based Impression of Change plus caregiver interview (CIBIC+), the Dependence Scale, and the Neuropsychiatric Inventory.

Patients were a mean of 70 years old with a mean Mini-Mental State Exam (MMSE) score of 18.5. The mean ADAS-cog score was 24 and the mean ADCS-ADL score, 58.

On the ADAS-cog, both groups exhibited a positive placebo response in the first 6 weeks, followed by a mean decline of 0.36 points. There was no statistically significant between-group difference. The story was much the same on the ADCS-ADL measure. Both groups had a brief placebo response, followed by a mean decline of 1.06 points. Again, the intepirdine and placebo groups declined similarly. There were no significant differences on either measure when the groups were broken down into patients with mild and moderate disease.

The CIBIC+ score was the only positive response among the secondary endpoints. Compared with those taking placebo, those taking intepirdine were more likely to be rated as minimally improved or unchanged.

The drug was safe however, with virtually no between-group difference in the occurrence of or the type of serious adverse events (about 6% in each group). Five patents died during the study; none of the deaths were related to the study drug.

Although Axovant no longer lists intepirdine as a potential Alzheimer’s treatment, investigation continues in a phase 3 placebo-controlled study in patients with Lewy body dementia. HEADWAY is testing a 70-mg dose, Dr. Lombardo said.

“Enrollment is finished and we are looking forward to results,” in early 2018. Answering a question about why the company went with 35 mg instead of 70 mg in MINDSET, she said that Axovant wanted to recreate the success of study 866.

“Since we had statistical significance even at 12 weeks with 35 mg, that’s what we went with,” she said. However, reviewing the adverse events told investigators that “we were not even near the maximum tolerated dose” at 35 mg. “Certainly we are now faced with the question of whether there will be a better response with 70 mg, and we are looking forward to answering that question with HEADWAY.”

Dr. Lombardo is senior vice president for clinical research at Axovant Sciences.

[email protected]

On Twitter @alz_gal

BOSTON – An investigational Alzheimer’s drug intended to potentiate acetylcholine release didn’t pass muster in a global phase 3 study, despite a successful phase 2 trial.

Intepirdine on a background of stable-dose donepezil failed to confer any cognitive or functional benefit in patients with mild to moderate Alzheimer’s disease, Ilise Lombardo, PhD, said at the Clinical Trials on Alzheimer’s Disease conference.

Intepirdine blocks the 5-hydroxytryptamine receptor 6 and increases the release of acetylcholine, according to Dr. Lombardo. By giving it on a stable background of an acetylcholinesterase inhibitor, researchers hoped to improve cognition by increasing acetylcholine signaling between neurons. In a modestly successful phase 2b study reported out last summer, intepirdine did confer some cognitive and functional benefits.

The study was scheduled to be presented at the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference, but was pulled at the last minute when Axovant announced its initial public offering of stock shortly before the July meeting. However, Dr. Lombardo did review study 866 at CTAD. It randomized 269 patients with mild to moderate AD to placebo or intepirdine at 15 mg or 35 mg/day for 24 weeks. By 12 weeks, patients taking the 35-mg dose had declined 1.6 points less than those on placebo on the Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale–cognitive subscale (ADAS-cog) and 1.94 points on the Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study–Activities of Daily Living (ADCS-ADL). Both differences were statistically significant. The drug moved into a phase 3 study, dubbed MINDSET, at 35 mg.

MINDSET enrolled 1, 315 patients with mild to moderate Alzheimer’s disease and randomized them to placebo or 35 mg intepirdine for 24 weeks. All patients were on stable background donepezil. Again, the coprimary endpoints were the ADAS-cog and the ADCS-ADL at the end of the study. There were three secondary endpoints: the Clinician Interview-Based Impression of Change plus caregiver interview (CIBIC+), the Dependence Scale, and the Neuropsychiatric Inventory.

Patients were a mean of 70 years old with a mean Mini-Mental State Exam (MMSE) score of 18.5. The mean ADAS-cog score was 24 and the mean ADCS-ADL score, 58.

On the ADAS-cog, both groups exhibited a positive placebo response in the first 6 weeks, followed by a mean decline of 0.36 points. There was no statistically significant between-group difference. The story was much the same on the ADCS-ADL measure. Both groups had a brief placebo response, followed by a mean decline of 1.06 points. Again, the intepirdine and placebo groups declined similarly. There were no significant differences on either measure when the groups were broken down into patients with mild and moderate disease.

The CIBIC+ score was the only positive response among the secondary endpoints. Compared with those taking placebo, those taking intepirdine were more likely to be rated as minimally improved or unchanged.

The drug was safe however, with virtually no between-group difference in the occurrence of or the type of serious adverse events (about 6% in each group). Five patents died during the study; none of the deaths were related to the study drug.

Although Axovant no longer lists intepirdine as a potential Alzheimer’s treatment, investigation continues in a phase 3 placebo-controlled study in patients with Lewy body dementia. HEADWAY is testing a 70-mg dose, Dr. Lombardo said.

“Enrollment is finished and we are looking forward to results,” in early 2018. Answering a question about why the company went with 35 mg instead of 70 mg in MINDSET, she said that Axovant wanted to recreate the success of study 866.

“Since we had statistical significance even at 12 weeks with 35 mg, that’s what we went with,” she said. However, reviewing the adverse events told investigators that “we were not even near the maximum tolerated dose” at 35 mg. “Certainly we are now faced with the question of whether there will be a better response with 70 mg, and we are looking forward to answering that question with HEADWAY.”

Dr. Lombardo is senior vice president for clinical research at Axovant Sciences.

[email protected]

On Twitter @alz_gal

BOSTON – An investigational Alzheimer’s drug intended to potentiate acetylcholine release didn’t pass muster in a global phase 3 study, despite a successful phase 2 trial.

Intepirdine on a background of stable-dose donepezil failed to confer any cognitive or functional benefit in patients with mild to moderate Alzheimer’s disease, Ilise Lombardo, PhD, said at the Clinical Trials on Alzheimer’s Disease conference.

Intepirdine blocks the 5-hydroxytryptamine receptor 6 and increases the release of acetylcholine, according to Dr. Lombardo. By giving it on a stable background of an acetylcholinesterase inhibitor, researchers hoped to improve cognition by increasing acetylcholine signaling between neurons. In a modestly successful phase 2b study reported out last summer, intepirdine did confer some cognitive and functional benefits.

The study was scheduled to be presented at the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference, but was pulled at the last minute when Axovant announced its initial public offering of stock shortly before the July meeting. However, Dr. Lombardo did review study 866 at CTAD. It randomized 269 patients with mild to moderate AD to placebo or intepirdine at 15 mg or 35 mg/day for 24 weeks. By 12 weeks, patients taking the 35-mg dose had declined 1.6 points less than those on placebo on the Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale–cognitive subscale (ADAS-cog) and 1.94 points on the Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study–Activities of Daily Living (ADCS-ADL). Both differences were statistically significant. The drug moved into a phase 3 study, dubbed MINDSET, at 35 mg.

MINDSET enrolled 1, 315 patients with mild to moderate Alzheimer’s disease and randomized them to placebo or 35 mg intepirdine for 24 weeks. All patients were on stable background donepezil. Again, the coprimary endpoints were the ADAS-cog and the ADCS-ADL at the end of the study. There were three secondary endpoints: the Clinician Interview-Based Impression of Change plus caregiver interview (CIBIC+), the Dependence Scale, and the Neuropsychiatric Inventory.

Patients were a mean of 70 years old with a mean Mini-Mental State Exam (MMSE) score of 18.5. The mean ADAS-cog score was 24 and the mean ADCS-ADL score, 58.

On the ADAS-cog, both groups exhibited a positive placebo response in the first 6 weeks, followed by a mean decline of 0.36 points. There was no statistically significant between-group difference. The story was much the same on the ADCS-ADL measure. Both groups had a brief placebo response, followed by a mean decline of 1.06 points. Again, the intepirdine and placebo groups declined similarly. There were no significant differences on either measure when the groups were broken down into patients with mild and moderate disease.

The CIBIC+ score was the only positive response among the secondary endpoints. Compared with those taking placebo, those taking intepirdine were more likely to be rated as minimally improved or unchanged.

The drug was safe however, with virtually no between-group difference in the occurrence of or the type of serious adverse events (about 6% in each group). Five patents died during the study; none of the deaths were related to the study drug.

Although Axovant no longer lists intepirdine as a potential Alzheimer’s treatment, investigation continues in a phase 3 placebo-controlled study in patients with Lewy body dementia. HEADWAY is testing a 70-mg dose, Dr. Lombardo said.

“Enrollment is finished and we are looking forward to results,” in early 2018. Answering a question about why the company went with 35 mg instead of 70 mg in MINDSET, she said that Axovant wanted to recreate the success of study 866.

“Since we had statistical significance even at 12 weeks with 35 mg, that’s what we went with,” she said. However, reviewing the adverse events told investigators that “we were not even near the maximum tolerated dose” at 35 mg. “Certainly we are now faced with the question of whether there will be a better response with 70 mg, and we are looking forward to answering that question with HEADWAY.”

Dr. Lombardo is senior vice president for clinical research at Axovant Sciences.

[email protected]

On Twitter @alz_gal

AT CTAD

Key clinical point:

Major finding: On the ADAS-cog at 24 weeks, there was a mean decline of 0.36 points; on the ADCS-ADL, the mean decline was 1.06 points. There were no between-group differences, either overall or in the mild to moderate groups separately.

Data source: The placebo-controlled study randomized 1,315 patients to placebo or 35 mg daily intepirdine.

Disclosures: Dr. Lombardo is senior vice president for clinical research at Axovant Sciences, which is developing the drug.

Development of a sigma 1 receptor agonist for Alzheimer’s proceeds based on 2-year phase 2 data

BOSTON – A reputedly neuroprotective compound will advance along its developmental pathway after developers said it exerted a blood level–dependent relationship with both cognitive and functional measures in patients with mild to moderate Alzheimer’s.

Most of the 26 patients left in the ongoing phase 2a extension study of ANAVEX 2-73 declined cognitively and functionally by varying degrees over 1 year. But a few, most of whom had high drug plasma levels, did experience cognitive and functional changes for the better. Some maintained stability, and some improved on both measures over 109 weeks, according to Christopher U. Missling, PhD, president and chief executive officer of Anavex.

“Improvement of cognition or function was a rare occurrence, but our analysis showed that patients who had a plasma concentration of 4-12 ng/mL had the best chance of experiencing this,” Dr. Missling said in an interview.

Mohammad Afshar, MD, PhD, presented these data at the Clinical Trials in Alzheimer’s Disease conference. He is the head of Ariana Pharmaceuticals, a firm hired to perform an independent analysis of the Anavex data. Concentrating on the pharmacodynamics data, he said ANAVEX 2-73 exhibits a clear drug concentration–clinical response relationship, which supports taking the drug into a phase 2/3 study.

“When focusing on the best responders at week 57, they continued to perform well. Patients with a score of greater than 20 on the Mini-Mental State Exam at baseline tended to respond better, as well as those with the highest plasma concentration,” he said.

The concentration-response picture is not completely clear, however. While five patients with high levels did improve on the MMSE at 57 weeks, one patient with a low plasma level also improved, and four patients with high levels declined. Functional results appeared more clearly related to drug levels: All of the high-level patients except one improved, as did about half of those with moderate plasma levels. Everyone with a low level declined.

During a later interview, Dr. Missling reviewed the data with an eye toward understatement. The study’s primary endpoints are safety and tolerability, as well as dosing and pharmacokinetics, he noted – cognitive and functional endpoints are exploratory measures. The study never had a control arm, other than several historical cohorts that served as reference points for decline in typically managed Alzheimer’s patients. And of course, he said, the numbers are very, very small.

And yet, the results are a source of “cautious optimism,” Dr. Missling said.

“While we think this is remarkable – because no drug has yet shown this long a response in non-decline among Alzheimer’s patients – we want to be very cautious. We are only looking at six patients here. We can’t overinterpret this.”

Dr. Missling and his colleagues are trying to find commonalities in these patients’ characteristics and clinical responses, hoping to enroll a phase 2/3 cohort of similar profile – whatever that may be. “We’re looking at the patients who improved to try and identify characteristics and be sure to enroll people who match them, to try and maximize our chance of success in phase 2/3,” which he said should be announced by the end of this year.

Just as important, he said, is to scrutinize the outliers – patients whose high and low plasma levels didn’t line up with the group’s overall response curve. “We’re looking at them in depth,” Dr. Missling said, adding that every patient in the study will undergo a full genomic profile, along with both an RNA and gut microbiota profile.

ANAVEX 2-73 is a sigma 1 receptor agonist. A chaperone protein, sigma 1 is activated in response to acute and chronic cellular stressors, several of which are important in neurodegeneration. The sigma 1 receptor is found on neurons and glia in many areas of the central nervous system. It modulates numerous processes implicated in neurodegenerative diseases, including glutamate and calcium activity, reaction to oxidative stress, and mitochondrial function. There is some evidence that sigma 1 receptor activation can induce neuronal regrowth and functional recovery after stroke. Sigma 1 also appears to play a role in helping cells clear misfolded proteins – a pathway that makes it an attractive drug target in Alzheimer’s disease, as well as other neurodegenerative diseases with aberrant proteins, such as Parkinson’s and Huntington’s diseases.

“Sigma 1 is never used except in times of trouble,” Dr. Missling said. “It’s only needed if we have a serious dysfunction in cells. By giving an agonist, we are increasing the expression of this protein, so it’s a bit like immune stimulation in oncology. We’re using the body’s own mechanism,” to fight neurodegeneration.

ANAVEX 2-73’s phase 2 development started with a 5-week crossover trial of 32 patients; they were a mean of 71 years old, with a mean MMSE of 21. The initial phase was followed by a 52-week, open-label trial of 10, 20, 30, and 50 mg/day orally, titrating each patient to the maximum tolerated dose.

Dr. Afshar presented 57-week data for the 26 patients who were still in the trial at that point and 109-week data for the six patients who had the best response at 57 weeks. Patients in both analyses were grouped by plasma level, not by their dosage level, although Dr. Missling said higher dosage generally correlated with higher plasma levels.

At 57 weeks, six patients had improved on the MMSE: four with high plasma levels and two with low plasma levels – patients identified as “outliers.” One patient with a high level remained stable. The rest of the cohort declined: seven with low levels, eight with moderate levels, and four with high levels, who were also identified as outliers. Also at 57 weeks, 24 patients had full data on the functional measure, the Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study-Activities of Daily Living (ADCS-ADL). Nine patients had improved: five with high plasma levels, three with moderate levels, and one with a low level, identified as an outlier. One patient, with a moderate level, remained stable. The remaining 14 patients declined: nine with moderate levels, four with low levels, and one with a high level, dubbed an outlier.

Dr. Afshar reported more detailed data on the six best-performing patients. These included the two patients with low plasma levels who were characterized in the 57-week MMSE data as outliers. Their mean baseline MMSE went from 23.2 to 25.7 at 57 weeks; their mean functional score on the ADCS-ADL scale rose from 72 to 73.7.

He then showed each of these patients’ 109-week changes. Each was identified with a unique number in both the 57- and 109-week datasets. Numbers here are estimates drawn from the company’s data slides, which are publicly available on the Anavex website.

The ADCS-ADL is a caregiver-rated questionnaire of 23 items, with possible scores over a range of 0-78, where 78 implies full functioning with no impairment. On the 30-point MMSE scale, a score greater of 24 or higher indicates a normal cognition.

• 101009 (low plasma level)

MMSE: 20-29 ADCS-ADL: 73-71

• 101011 (low plasma level)

MMSE: 20-21 ADCS-ADL: 72-70

•101013 (high plasma level)

MMSE: 22-18 ADCS-ADL: 73-57

• 101014 (high plasma level)

MMSE: 20-25 ADCS-ADL: 75-74

• 102006 (high plasma level)

MMSE: 25-28 ADCS-ADL: 74-78

• 102010 (high plasma level)

MMSE: 25-28 ADCS-ADL: 64-68

Dr. Missling said ANAVEX 2-73 still appears safe and well tolerated. In the initial study phase, 98% of the subjects did have an adverse event; only one was considered serious. This was a case of delirium that developed in a patient who had several risk factors for the disorder, including a prior episode, and was not considered related to the study drug. Three patients withdrew because of an adverse event in the first 57 weeks; no one has withdrawn because of a side effect since then.

Dizziness was the most common adverse event (20 incidents in 15 patients), followed by headache (16 in 10 patients). Most (94%) occurred in the first week of treatment. All were mild or moderate. Headache and dizziness are considered signs that patients are approaching their maximum tolerated dose, Dr. Missling said.

The company’s task now is to find a standard minimum dose that is strong enough to get patients to at least 4 ng/mL plasma level, without inducing these side effects. The extension study will close out in November 2018. Anavex hopes to begin the drug’s next phase of development before then, with a phase 2/3 study of about 200 patients.

“We’re trying to gather as much data as possible so we can do this properly,” Dr. Missling said. “You can make the case that some developers have rushed into these studies after interpreting early results the wrong way. They said the glass was half-full when it was really half-empty. For us, it’s very important not to do that. We won’t go ahead with this until we are completely comfortable with what we see.”

[email protected]

On Twitter @alz_gal

BOSTON – A reputedly neuroprotective compound will advance along its developmental pathway after developers said it exerted a blood level–dependent relationship with both cognitive and functional measures in patients with mild to moderate Alzheimer’s.

Most of the 26 patients left in the ongoing phase 2a extension study of ANAVEX 2-73 declined cognitively and functionally by varying degrees over 1 year. But a few, most of whom had high drug plasma levels, did experience cognitive and functional changes for the better. Some maintained stability, and some improved on both measures over 109 weeks, according to Christopher U. Missling, PhD, president and chief executive officer of Anavex.

“Improvement of cognition or function was a rare occurrence, but our analysis showed that patients who had a plasma concentration of 4-12 ng/mL had the best chance of experiencing this,” Dr. Missling said in an interview.

Mohammad Afshar, MD, PhD, presented these data at the Clinical Trials in Alzheimer’s Disease conference. He is the head of Ariana Pharmaceuticals, a firm hired to perform an independent analysis of the Anavex data. Concentrating on the pharmacodynamics data, he said ANAVEX 2-73 exhibits a clear drug concentration–clinical response relationship, which supports taking the drug into a phase 2/3 study.

“When focusing on the best responders at week 57, they continued to perform well. Patients with a score of greater than 20 on the Mini-Mental State Exam at baseline tended to respond better, as well as those with the highest plasma concentration,” he said.

The concentration-response picture is not completely clear, however. While five patients with high levels did improve on the MMSE at 57 weeks, one patient with a low plasma level also improved, and four patients with high levels declined. Functional results appeared more clearly related to drug levels: All of the high-level patients except one improved, as did about half of those with moderate plasma levels. Everyone with a low level declined.

During a later interview, Dr. Missling reviewed the data with an eye toward understatement. The study’s primary endpoints are safety and tolerability, as well as dosing and pharmacokinetics, he noted – cognitive and functional endpoints are exploratory measures. The study never had a control arm, other than several historical cohorts that served as reference points for decline in typically managed Alzheimer’s patients. And of course, he said, the numbers are very, very small.

And yet, the results are a source of “cautious optimism,” Dr. Missling said.

“While we think this is remarkable – because no drug has yet shown this long a response in non-decline among Alzheimer’s patients – we want to be very cautious. We are only looking at six patients here. We can’t overinterpret this.”

Dr. Missling and his colleagues are trying to find commonalities in these patients’ characteristics and clinical responses, hoping to enroll a phase 2/3 cohort of similar profile – whatever that may be. “We’re looking at the patients who improved to try and identify characteristics and be sure to enroll people who match them, to try and maximize our chance of success in phase 2/3,” which he said should be announced by the end of this year.

Just as important, he said, is to scrutinize the outliers – patients whose high and low plasma levels didn’t line up with the group’s overall response curve. “We’re looking at them in depth,” Dr. Missling said, adding that every patient in the study will undergo a full genomic profile, along with both an RNA and gut microbiota profile.

ANAVEX 2-73 is a sigma 1 receptor agonist. A chaperone protein, sigma 1 is activated in response to acute and chronic cellular stressors, several of which are important in neurodegeneration. The sigma 1 receptor is found on neurons and glia in many areas of the central nervous system. It modulates numerous processes implicated in neurodegenerative diseases, including glutamate and calcium activity, reaction to oxidative stress, and mitochondrial function. There is some evidence that sigma 1 receptor activation can induce neuronal regrowth and functional recovery after stroke. Sigma 1 also appears to play a role in helping cells clear misfolded proteins – a pathway that makes it an attractive drug target in Alzheimer’s disease, as well as other neurodegenerative diseases with aberrant proteins, such as Parkinson’s and Huntington’s diseases.

“Sigma 1 is never used except in times of trouble,” Dr. Missling said. “It’s only needed if we have a serious dysfunction in cells. By giving an agonist, we are increasing the expression of this protein, so it’s a bit like immune stimulation in oncology. We’re using the body’s own mechanism,” to fight neurodegeneration.

ANAVEX 2-73’s phase 2 development started with a 5-week crossover trial of 32 patients; they were a mean of 71 years old, with a mean MMSE of 21. The initial phase was followed by a 52-week, open-label trial of 10, 20, 30, and 50 mg/day orally, titrating each patient to the maximum tolerated dose.

Dr. Afshar presented 57-week data for the 26 patients who were still in the trial at that point and 109-week data for the six patients who had the best response at 57 weeks. Patients in both analyses were grouped by plasma level, not by their dosage level, although Dr. Missling said higher dosage generally correlated with higher plasma levels.