User login

Hypothermia and severe first-degree heart block

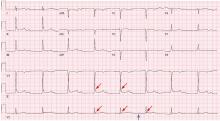

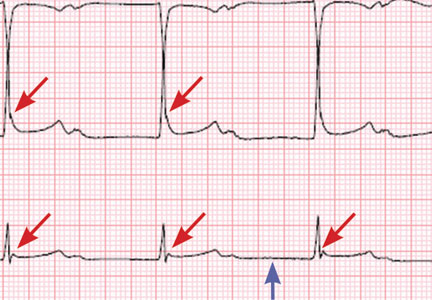

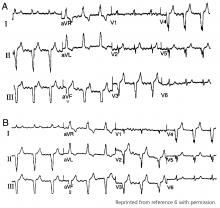

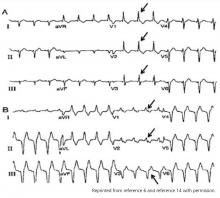

A 96-year-old woman with hypertension, diabetes, and dementia was found unresponsive in her nursing home and was transferred to the hospital.

At presentation to the hospital, her blood pressure was 76/43 mm Hg, heart rate 42 beats per minute, rectal temperature 31.6°C (88.8°F), and blood glucose 36 mg/dL.

Causes of secondary hypothermia were sought. Blood and urine cultures were negative. Computed tomography of the head showed no acute intracranial abnormalities. Tests for adrenal insufficiency and hypothyroidism were negative.

HYPOTHERMIA AND THE ECG

Hypothermia can produce a number of changes on the ECG. At the start of hypothermia, a stress reaction is induced, resulting in sinus tachycardia. But when the temperature goes below 32°C, sinus bradycardia ensues,1 resulting in various degrees of heart block.2 In our patient, a severely prolonged PR interval resulted in first-degree heart block.

Other findings on ECG associated with hypothermia include atrial fibrillation, widening of the P and T waves, prolonging of the QT interval, and widening of the QRS interval. Progressive widening of the QRS interval can predispose to ventricular fibrillation.1,3

An Osborn or J wave is a wave found between the end of the QRS and the beginning of the ST segment and is usually seen on the inferior and lateral precordial leads. It is found in as many as 80% of patients when the body temperature is below 30°C.1,3,4

Although Osborn waves are a common finding in hypothermia, they are also seen in electrolyte imbalances such as hypercalcemia and in central nervous system diseases.5,6 Hypothermia-associated changes on ECG are usually readily reversible with rewarming.1

TAKE-HOME MESSAGES

The ECG should always be interpreted in the proper clinical context and, whenever possible, compared with a previous ECG. It is prudent to always consider potentially reversible triggers of hypothermia other than environmental exposure such as hypothyroidism, infection, adrenal insufficiency, ketoacidosis, medication side effects, and alcohol use.

Hypothermia, especially in elderly patients with multiple comorbidities, can lead to bradycardia and varying degrees of heart block.

- Alhaddad IA, Khalil M, Brown EJ Jr. Osborn waves of hypothermia. Circulation 2000; 101:E233–E244.

- Bashour TT, Gualberto A, Ryan C. Atrioventricular block in accidental hypothermia—a case report. Angiology 1989; 40:63–66.

- Okada M, Nishimura F, Yoshino H, Kimura M, Ogino T. The J wave in accidental hypothermia. J Electrocardiol 1983; 16:23–28.

- Kukla P, Baranchuk A, Jastrzebski M, Zabojszcz M, Bryniarski L. Electrocardiographic landmarks of hypothermia. Kardiol Pol 2013; 71:1188–1189.

- Maruyama M, Kobayashi Y, Kodani E, et al. Osborn waves: history and significance. Indian Pacing Electrophysiol J 2004; 4:33–39.

- Sheikh AM, Hurst JW. Osborn waves in the electrocardiogram, hypothermia not due to exposure, and death due to diabetic ketoacidosis. Clin Cardiol 2003; 26:555–560.

A 96-year-old woman with hypertension, diabetes, and dementia was found unresponsive in her nursing home and was transferred to the hospital.

At presentation to the hospital, her blood pressure was 76/43 mm Hg, heart rate 42 beats per minute, rectal temperature 31.6°C (88.8°F), and blood glucose 36 mg/dL.

Causes of secondary hypothermia were sought. Blood and urine cultures were negative. Computed tomography of the head showed no acute intracranial abnormalities. Tests for adrenal insufficiency and hypothyroidism were negative.

HYPOTHERMIA AND THE ECG

Hypothermia can produce a number of changes on the ECG. At the start of hypothermia, a stress reaction is induced, resulting in sinus tachycardia. But when the temperature goes below 32°C, sinus bradycardia ensues,1 resulting in various degrees of heart block.2 In our patient, a severely prolonged PR interval resulted in first-degree heart block.

Other findings on ECG associated with hypothermia include atrial fibrillation, widening of the P and T waves, prolonging of the QT interval, and widening of the QRS interval. Progressive widening of the QRS interval can predispose to ventricular fibrillation.1,3

An Osborn or J wave is a wave found between the end of the QRS and the beginning of the ST segment and is usually seen on the inferior and lateral precordial leads. It is found in as many as 80% of patients when the body temperature is below 30°C.1,3,4

Although Osborn waves are a common finding in hypothermia, they are also seen in electrolyte imbalances such as hypercalcemia and in central nervous system diseases.5,6 Hypothermia-associated changes on ECG are usually readily reversible with rewarming.1

TAKE-HOME MESSAGES

The ECG should always be interpreted in the proper clinical context and, whenever possible, compared with a previous ECG. It is prudent to always consider potentially reversible triggers of hypothermia other than environmental exposure such as hypothyroidism, infection, adrenal insufficiency, ketoacidosis, medication side effects, and alcohol use.

Hypothermia, especially in elderly patients with multiple comorbidities, can lead to bradycardia and varying degrees of heart block.

A 96-year-old woman with hypertension, diabetes, and dementia was found unresponsive in her nursing home and was transferred to the hospital.

At presentation to the hospital, her blood pressure was 76/43 mm Hg, heart rate 42 beats per minute, rectal temperature 31.6°C (88.8°F), and blood glucose 36 mg/dL.

Causes of secondary hypothermia were sought. Blood and urine cultures were negative. Computed tomography of the head showed no acute intracranial abnormalities. Tests for adrenal insufficiency and hypothyroidism were negative.

HYPOTHERMIA AND THE ECG

Hypothermia can produce a number of changes on the ECG. At the start of hypothermia, a stress reaction is induced, resulting in sinus tachycardia. But when the temperature goes below 32°C, sinus bradycardia ensues,1 resulting in various degrees of heart block.2 In our patient, a severely prolonged PR interval resulted in first-degree heart block.

Other findings on ECG associated with hypothermia include atrial fibrillation, widening of the P and T waves, prolonging of the QT interval, and widening of the QRS interval. Progressive widening of the QRS interval can predispose to ventricular fibrillation.1,3

An Osborn or J wave is a wave found between the end of the QRS and the beginning of the ST segment and is usually seen on the inferior and lateral precordial leads. It is found in as many as 80% of patients when the body temperature is below 30°C.1,3,4

Although Osborn waves are a common finding in hypothermia, they are also seen in electrolyte imbalances such as hypercalcemia and in central nervous system diseases.5,6 Hypothermia-associated changes on ECG are usually readily reversible with rewarming.1

TAKE-HOME MESSAGES

The ECG should always be interpreted in the proper clinical context and, whenever possible, compared with a previous ECG. It is prudent to always consider potentially reversible triggers of hypothermia other than environmental exposure such as hypothyroidism, infection, adrenal insufficiency, ketoacidosis, medication side effects, and alcohol use.

Hypothermia, especially in elderly patients with multiple comorbidities, can lead to bradycardia and varying degrees of heart block.

- Alhaddad IA, Khalil M, Brown EJ Jr. Osborn waves of hypothermia. Circulation 2000; 101:E233–E244.

- Bashour TT, Gualberto A, Ryan C. Atrioventricular block in accidental hypothermia—a case report. Angiology 1989; 40:63–66.

- Okada M, Nishimura F, Yoshino H, Kimura M, Ogino T. The J wave in accidental hypothermia. J Electrocardiol 1983; 16:23–28.

- Kukla P, Baranchuk A, Jastrzebski M, Zabojszcz M, Bryniarski L. Electrocardiographic landmarks of hypothermia. Kardiol Pol 2013; 71:1188–1189.

- Maruyama M, Kobayashi Y, Kodani E, et al. Osborn waves: history and significance. Indian Pacing Electrophysiol J 2004; 4:33–39.

- Sheikh AM, Hurst JW. Osborn waves in the electrocardiogram, hypothermia not due to exposure, and death due to diabetic ketoacidosis. Clin Cardiol 2003; 26:555–560.

- Alhaddad IA, Khalil M, Brown EJ Jr. Osborn waves of hypothermia. Circulation 2000; 101:E233–E244.

- Bashour TT, Gualberto A, Ryan C. Atrioventricular block in accidental hypothermia—a case report. Angiology 1989; 40:63–66.

- Okada M, Nishimura F, Yoshino H, Kimura M, Ogino T. The J wave in accidental hypothermia. J Electrocardiol 1983; 16:23–28.

- Kukla P, Baranchuk A, Jastrzebski M, Zabojszcz M, Bryniarski L. Electrocardiographic landmarks of hypothermia. Kardiol Pol 2013; 71:1188–1189.

- Maruyama M, Kobayashi Y, Kodani E, et al. Osborn waves: history and significance. Indian Pacing Electrophysiol J 2004; 4:33–39.

- Sheikh AM, Hurst JW. Osborn waves in the electrocardiogram, hypothermia not due to exposure, and death due to diabetic ketoacidosis. Clin Cardiol 2003; 26:555–560.

BTK inhibitor zanubrutinib active in non-Hodgkin lymphomas

ATLANTA – , according to data presented at the annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology.

Response rates ranged from 31% to 88% depending on the lymphoma subtype. Overall, approximately 10% of patients discontinued the drug because of adverse events, reported Constantine S. Tam, MBBS, MD, of Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre & St. Vincent’s Hospital, Melbourne.

“There was encouraging activity against all the spectrum of indolent and aggressive NHL subtypes … and durable responses were observed across a variety of histologies,” Dr. Tam said.

Zanubrutinib is a second-generation BTK inhibitor that, based on biochemical assays, has higher selectivity against BTK than ibrutinib, Dr. Tam said.

He presented results of an open-label, multicenter, phase 1b study of daily or twice-daily zanubrutinib in patients with B-cell malignancies, most of them relapsed or refractory to prior therapies. The lymphoma subtypes he presented included diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), follicular lymphoma (FL), mantle cell lymphoma (MCL), and marginal zone lymphoma (MZL).

For 34 patients with indolent lymphomas (FL and MZL), the most frequent adverse events were petechiae/purpura/contusion and upper respiratory tract infection. Eleven grade 3-5 adverse events were reported, including neutropenia, infection, nausea, urinary tract infection, and abdominal pain.

Atrial fibrillation was observed in two patients in the aggressive NHL cohort, for an overall AF rate of approximately 2%, Dr. Tam said.

For 65 patients with aggressive lymphomas (DLBCL and MCL), the most frequent adverse events were petechiae/purpura/contusion and diarrhea; 27 grade 3-5 adverse events were reported, including neutropenia, pneumonia, and anemia.

The highest overall response rate reported was for MCL, at 88% (28 of 32 patients) followed by MZL at 78% (7 of 9 patients), FL at 41% (7 of 17 patients), and DLBCL 31% (8 of 26 patients).

The recommended phase 2 dose for zanubrutinib is either 320 mg/day once daily or a split dose of 160 mg twice daily, Dr. Tam said.

Based on this experience, investigators started a registration trial of zanubrutinib in combination with obinutuzumab for FL, and additional trials are planned, according to Dr. Tam.

There are also registration trials in Waldenstrom macroglobulinemia and chronic lymphocytic leukemia based on other data suggesting activity of zanubrutinib in those disease types, he added.

Zanubrutinib is a product of BeiGene. Dr. Tam reported disclosures related to Roche, Janssen Cilag, Abbvie, Celgene, Pharmacyclics, Onyx, and Amgen.

SOURCE: Tam C et al, ASH 2017, Abstract 152

ATLANTA – , according to data presented at the annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology.

Response rates ranged from 31% to 88% depending on the lymphoma subtype. Overall, approximately 10% of patients discontinued the drug because of adverse events, reported Constantine S. Tam, MBBS, MD, of Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre & St. Vincent’s Hospital, Melbourne.

“There was encouraging activity against all the spectrum of indolent and aggressive NHL subtypes … and durable responses were observed across a variety of histologies,” Dr. Tam said.

Zanubrutinib is a second-generation BTK inhibitor that, based on biochemical assays, has higher selectivity against BTK than ibrutinib, Dr. Tam said.

He presented results of an open-label, multicenter, phase 1b study of daily or twice-daily zanubrutinib in patients with B-cell malignancies, most of them relapsed or refractory to prior therapies. The lymphoma subtypes he presented included diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), follicular lymphoma (FL), mantle cell lymphoma (MCL), and marginal zone lymphoma (MZL).

For 34 patients with indolent lymphomas (FL and MZL), the most frequent adverse events were petechiae/purpura/contusion and upper respiratory tract infection. Eleven grade 3-5 adverse events were reported, including neutropenia, infection, nausea, urinary tract infection, and abdominal pain.

Atrial fibrillation was observed in two patients in the aggressive NHL cohort, for an overall AF rate of approximately 2%, Dr. Tam said.

For 65 patients with aggressive lymphomas (DLBCL and MCL), the most frequent adverse events were petechiae/purpura/contusion and diarrhea; 27 grade 3-5 adverse events were reported, including neutropenia, pneumonia, and anemia.

The highest overall response rate reported was for MCL, at 88% (28 of 32 patients) followed by MZL at 78% (7 of 9 patients), FL at 41% (7 of 17 patients), and DLBCL 31% (8 of 26 patients).

The recommended phase 2 dose for zanubrutinib is either 320 mg/day once daily or a split dose of 160 mg twice daily, Dr. Tam said.

Based on this experience, investigators started a registration trial of zanubrutinib in combination with obinutuzumab for FL, and additional trials are planned, according to Dr. Tam.

There are also registration trials in Waldenstrom macroglobulinemia and chronic lymphocytic leukemia based on other data suggesting activity of zanubrutinib in those disease types, he added.

Zanubrutinib is a product of BeiGene. Dr. Tam reported disclosures related to Roche, Janssen Cilag, Abbvie, Celgene, Pharmacyclics, Onyx, and Amgen.

SOURCE: Tam C et al, ASH 2017, Abstract 152

ATLANTA – , according to data presented at the annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology.

Response rates ranged from 31% to 88% depending on the lymphoma subtype. Overall, approximately 10% of patients discontinued the drug because of adverse events, reported Constantine S. Tam, MBBS, MD, of Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre & St. Vincent’s Hospital, Melbourne.

“There was encouraging activity against all the spectrum of indolent and aggressive NHL subtypes … and durable responses were observed across a variety of histologies,” Dr. Tam said.

Zanubrutinib is a second-generation BTK inhibitor that, based on biochemical assays, has higher selectivity against BTK than ibrutinib, Dr. Tam said.

He presented results of an open-label, multicenter, phase 1b study of daily or twice-daily zanubrutinib in patients with B-cell malignancies, most of them relapsed or refractory to prior therapies. The lymphoma subtypes he presented included diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), follicular lymphoma (FL), mantle cell lymphoma (MCL), and marginal zone lymphoma (MZL).

For 34 patients with indolent lymphomas (FL and MZL), the most frequent adverse events were petechiae/purpura/contusion and upper respiratory tract infection. Eleven grade 3-5 adverse events were reported, including neutropenia, infection, nausea, urinary tract infection, and abdominal pain.

Atrial fibrillation was observed in two patients in the aggressive NHL cohort, for an overall AF rate of approximately 2%, Dr. Tam said.

For 65 patients with aggressive lymphomas (DLBCL and MCL), the most frequent adverse events were petechiae/purpura/contusion and diarrhea; 27 grade 3-5 adverse events were reported, including neutropenia, pneumonia, and anemia.

The highest overall response rate reported was for MCL, at 88% (28 of 32 patients) followed by MZL at 78% (7 of 9 patients), FL at 41% (7 of 17 patients), and DLBCL 31% (8 of 26 patients).

The recommended phase 2 dose for zanubrutinib is either 320 mg/day once daily or a split dose of 160 mg twice daily, Dr. Tam said.

Based on this experience, investigators started a registration trial of zanubrutinib in combination with obinutuzumab for FL, and additional trials are planned, according to Dr. Tam.

There are also registration trials in Waldenstrom macroglobulinemia and chronic lymphocytic leukemia based on other data suggesting activity of zanubrutinib in those disease types, he added.

Zanubrutinib is a product of BeiGene. Dr. Tam reported disclosures related to Roche, Janssen Cilag, Abbvie, Celgene, Pharmacyclics, Onyx, and Amgen.

SOURCE: Tam C et al, ASH 2017, Abstract 152

REPORTING FROM ASH 2017

Key clinical point: Monotherapy with the BTK inhibitor zanubrutinib (BGB-3111) was active and well tolerated in patients with a variety of non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) subtypes.

Major finding: Response rates ranged from 31% to 88% depending on the lymphoma subtype.

Data source: Preliminary results of an open-label, multicenter, phase 1b study including 99 patients with relapsed or refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, follicular lymphoma, mantle cell lymphoma, or marginal zone lymphoma.

Disclosures: Zanubrutinib is a product of BeiGene. Constantine S. Tam, MBBS, MD, reported disclosures related to Roche, Janssen Cilag, Abbvie, Celgene, Pharmacyclics, Onyx, and Amgen.

Source: Tam C et al. ASH 2017, Abstract 152.

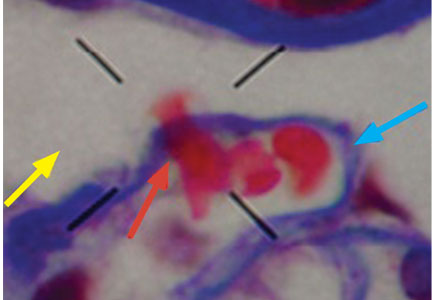

Dysmorphic red blood cell formation

A 23-year-old woman presented with hematuria. Her blood pressure was normal, and she had no rash, joint pain, or other symptoms. Urinalysis was positive for proteinuria and hematuria, and urinary sediment analysis showed dysmorphic red blood cells (RBCs) and red cell casts, leading to a diagnosis of glomerulonephritis. She had proteinuria of 1.2 g/24 hours. Laboratory tests for systemic diseases were negative. Renal biopsy study revealed stage III immunoglobulin A (IgA) nephropathy.

GLOMERULAR HEMATURIA

Glomerular hematuria may represent an immune-mediated injury to the glomerular capillary wall, but it can also be present in noninflammatory glomerulopathies.1

The type of dysmorphic RBCs (crenated or misshapen cells, acanthocytes) may be of diagnostic importance. In particular, dysmorphic red cells alone may be predictive of only renal bleeding, while acanthocytes (ring-shaped RBCs with vesicle-shaped protrusions best seen on phase-contrast microscopy) appear to be most predictive of glomerular disease.2 For example, in 1 study,3 the presence of acanthocytes comprising at least 5% of excreted RBCs had a sensitivity of 52% for glomerular disease and a specificity of 98%.3

- Collar JE, Ladva S, Cairns TD, Cattell V. Red cell traverse through thin glomerular basement membranes. Kidney Int 2001; 59:2069–2072.

- Fogazzi GB, Ponticelli C, Ritz E. The Urinary Sediment: An Integrated View. 2nd ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1999:30.

- Köhler H, Wandel E, Brunck B. Acanthocyturia—a characteristic marker for glomerular bleeding. Kidney Int 1991; 40:115–120.

- Fogazzi GB. The Urinary Sediment: An Integrated View. 3rd ed. France: Elsevier; 2010.

- Briner VA, Reinhart WH. In vitro production of ‘glomerular red cells’: role of pH and osmolality. Nephron 1990; 56:13–18.

- Schramek P, Moritsch A, Haschkowitz H, Binder BR, Maier M. In vitro generation of dysmorphic erythrocytes. Kidney Int 1989; 36:72–77.

- Pollock C, Liu PL, Györy AZ, et al. Dysmorphism of urinary red blood cells—value in diagnosis. Kidney Int 1989; 36:1045–1049.

- Shichiri M, Hosoda K, Nishio Y, et al. Red-cell-volume distribution curves in diagnosis of glomerular and non-glomerular haematuria. Lancet 1988; 1:908–911.

A 23-year-old woman presented with hematuria. Her blood pressure was normal, and she had no rash, joint pain, or other symptoms. Urinalysis was positive for proteinuria and hematuria, and urinary sediment analysis showed dysmorphic red blood cells (RBCs) and red cell casts, leading to a diagnosis of glomerulonephritis. She had proteinuria of 1.2 g/24 hours. Laboratory tests for systemic diseases were negative. Renal biopsy study revealed stage III immunoglobulin A (IgA) nephropathy.

GLOMERULAR HEMATURIA

Glomerular hematuria may represent an immune-mediated injury to the glomerular capillary wall, but it can also be present in noninflammatory glomerulopathies.1

The type of dysmorphic RBCs (crenated or misshapen cells, acanthocytes) may be of diagnostic importance. In particular, dysmorphic red cells alone may be predictive of only renal bleeding, while acanthocytes (ring-shaped RBCs with vesicle-shaped protrusions best seen on phase-contrast microscopy) appear to be most predictive of glomerular disease.2 For example, in 1 study,3 the presence of acanthocytes comprising at least 5% of excreted RBCs had a sensitivity of 52% for glomerular disease and a specificity of 98%.3

A 23-year-old woman presented with hematuria. Her blood pressure was normal, and she had no rash, joint pain, or other symptoms. Urinalysis was positive for proteinuria and hematuria, and urinary sediment analysis showed dysmorphic red blood cells (RBCs) and red cell casts, leading to a diagnosis of glomerulonephritis. She had proteinuria of 1.2 g/24 hours. Laboratory tests for systemic diseases were negative. Renal biopsy study revealed stage III immunoglobulin A (IgA) nephropathy.

GLOMERULAR HEMATURIA

Glomerular hematuria may represent an immune-mediated injury to the glomerular capillary wall, but it can also be present in noninflammatory glomerulopathies.1

The type of dysmorphic RBCs (crenated or misshapen cells, acanthocytes) may be of diagnostic importance. In particular, dysmorphic red cells alone may be predictive of only renal bleeding, while acanthocytes (ring-shaped RBCs with vesicle-shaped protrusions best seen on phase-contrast microscopy) appear to be most predictive of glomerular disease.2 For example, in 1 study,3 the presence of acanthocytes comprising at least 5% of excreted RBCs had a sensitivity of 52% for glomerular disease and a specificity of 98%.3

- Collar JE, Ladva S, Cairns TD, Cattell V. Red cell traverse through thin glomerular basement membranes. Kidney Int 2001; 59:2069–2072.

- Fogazzi GB, Ponticelli C, Ritz E. The Urinary Sediment: An Integrated View. 2nd ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1999:30.

- Köhler H, Wandel E, Brunck B. Acanthocyturia—a characteristic marker for glomerular bleeding. Kidney Int 1991; 40:115–120.

- Fogazzi GB. The Urinary Sediment: An Integrated View. 3rd ed. France: Elsevier; 2010.

- Briner VA, Reinhart WH. In vitro production of ‘glomerular red cells’: role of pH and osmolality. Nephron 1990; 56:13–18.

- Schramek P, Moritsch A, Haschkowitz H, Binder BR, Maier M. In vitro generation of dysmorphic erythrocytes. Kidney Int 1989; 36:72–77.

- Pollock C, Liu PL, Györy AZ, et al. Dysmorphism of urinary red blood cells—value in diagnosis. Kidney Int 1989; 36:1045–1049.

- Shichiri M, Hosoda K, Nishio Y, et al. Red-cell-volume distribution curves in diagnosis of glomerular and non-glomerular haematuria. Lancet 1988; 1:908–911.

- Collar JE, Ladva S, Cairns TD, Cattell V. Red cell traverse through thin glomerular basement membranes. Kidney Int 2001; 59:2069–2072.

- Fogazzi GB, Ponticelli C, Ritz E. The Urinary Sediment: An Integrated View. 2nd ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1999:30.

- Köhler H, Wandel E, Brunck B. Acanthocyturia—a characteristic marker for glomerular bleeding. Kidney Int 1991; 40:115–120.

- Fogazzi GB. The Urinary Sediment: An Integrated View. 3rd ed. France: Elsevier; 2010.

- Briner VA, Reinhart WH. In vitro production of ‘glomerular red cells’: role of pH and osmolality. Nephron 1990; 56:13–18.

- Schramek P, Moritsch A, Haschkowitz H, Binder BR, Maier M. In vitro generation of dysmorphic erythrocytes. Kidney Int 1989; 36:72–77.

- Pollock C, Liu PL, Györy AZ, et al. Dysmorphism of urinary red blood cells—value in diagnosis. Kidney Int 1989; 36:1045–1049.

- Shichiri M, Hosoda K, Nishio Y, et al. Red-cell-volume distribution curves in diagnosis of glomerular and non-glomerular haematuria. Lancet 1988; 1:908–911.

Quality in urine microscopy: The eyes of the beholder

The urine is the window to the kidney.This oft-repeated adage impresses upon medical students and residents the importance of urine microscopy in the evaluation of patients with renal disorders.

While this phrase is likely an adaptation of the idea in ancient times that the urine reflected on humors or the quality of the soul, the understanding of the relevance of urine findings to the state of the kidneys likely rests with the pioneers of urine microscopy. As reviewed by Fogazzi and Cameron,1,2 the origins of direct inspection of urine under a microscope lie in the 17th century, with industrious physicians who used rudimentary microscopes to identify basic structures in the urine and correlated them to clinical presentations.1 At first, only larger structures could be seen, mostly crystals in patients with nephrolithiasis. As microscopes advanced, smaller structures such as “corpuscles” and “cylinders” could be seen that described cells and casts.1

In correlating these findings to patient presentations, a rudimentary understanding of renal pathology evolved long before the advent of the kidney biopsy. Lipid droplets were seen1 in patients swollen from dropsy, and later known to have nephrotic syndromes. In 1872, Harley first described the altered morphology of dysmorphic red blood cells in patients with Bright disease or glomerulonephritis.1,3 In 1979, Birch and Fairley recognized that the presence of acanthocytes differentiated glomerular from nonglomerular hematuria.4

DYSMORPHIC RED BLOOD CELLS: TYPES AND SIGNIFICANCE

URINE MICROSCOPY: THE NEPHROLOGIST’S ROLE

The tools used in urine microscopy have advanced significantly since its advent. But not all advances have led to improved patient care. Laboratories have trained technicians to perform urine microscopy. Analyzers can identify basic urinary structures using algorithms to compare them against stored reference images. More important, urine microscopy has been categorized by accreditation and inspection bodies as a “test” rather than a physician-performed competency. As such, definitions of quality in urine microscopy have shifted from the application of urinary findings to the care of the patient to the reproducibility of identifying individual structures in ways that can be documented with quality checks performed by nonclinicians. And since the governing bodies require laboratories to adhere to burdensome procedures to maintain accreditation (eg, the US Food and Drug Administration’s Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments), many hospitals have closed nephrologist-based urine laboratories.

This would be acceptable if laboratory-generated reports provided information equivalent to that obtained by the nephrologist. But such reports rarely include anything beyond the most rudimentary findings. In these reports, the red blood cell is not differentiated as dysmorphic or monomorphic. All casts are granular. Crystals are often the highlight of the report, usually an incidental finding of little relevance. Phase contrast and polarization are never performed.

Despite the poor quality of data provided in these reports, because of increasing regulations and time restrictions, a dwindling number of nephrologists perform urine microscopy even at teaching institutions. In an informal 2009 survey of nephrology fellowship program directors, 79% of responding programs relied solely on lab-generated reports for microscopic findings (verbal communication, Perazella, 2017).

There is general concern among medical educators about the surrendering of the physical examination and other techniques to technology.7,8 However, in many cases, such changes may improve the ability to make a correct diagnosis. When performed properly, urine microscopy can help determine the need for kidney biopsy, differentiate causes of acute kidney injury, and help guide decisions about therapy. Perazella showed that urine microscopy could reliably differentiate acute tubular necrosis from prerenal azotemia.9 Further, the severity of findings on urine microscopy has been associated with worse renal outcomes.10 At our institution, nephrologist-performed urine microscopy resulted in a change in cause of acute kidney injury in 25% of cases and a concrete change in management in 12% of patients (unpublished data).

With this in mind, it is concerning that the only evidence in the literature on this topic demonstrated that laboratory-based urine microscopy is actually a hindrance to its underlying purpose in acute kidney injury, which is to help identify the cause of the injury. Tsai et al11 showed that nephrologists identified the cause of acute kidney injury correctly 90% of the time when they performed their own urine microscopy, but this dropped to 23% when they relied on a laboratory-generated report. Interestingly, knowing the patient’s clinical history when performing the microscopy was important, as the accuracy was 69% when a report of another nephrologist’s microscopy findings was used.11

APPLYING RESULTS TO THE PATIENT

The purpose of urine microscopy in clinical care is to identify and understand the findings as they apply to the patient. When viewed from this perspective, the renal patient is clearly best served when the nephrologist familiar with the case performs urine microscopy, rather than a technician or analyzer in remote parts of the hospital with no connection to the patient.

Advances in technology or streamlining of hospital services do not always produce improvements in patient care, and how we define quality is integral to identifying when this is the case. Quality checklists can serve as guides to safe patient care but should not replace clinical decision-making. Direct physician involvement with our patients has concrete benefits, whether taking a history, performing a physical examination, reviewing radiologic images, or looking at specimens such as urine. It allows us to experience the amazing pathophysiology of human illness and to understand the nuances unique to each of our patients.

But most important, it reinforces the need for the direct bond, both emotional and physical, between us as healers and our patients.

- Fogazzi GB, Cameron JS. Urinary microscopy from the seventeenth century to the present day. Kidney Int 1996; 50:1058–1068.

- Cameron JS. A history of urine microscopy. Clin Chem Lab Med 2015; 53(suppl 2):s1453–s1464.

- Harley G. The Urine and Its Derangements. London: J and A Churchill, 1872:178–179.

- Birch DF, Fairley K. Hematuria: glomerular or non-glomerular? Lancet 1979; 314:845–846.

- Köhler H, Wandel E, Brunck B. Acanthocyturia—a characteristic marker for glomerular bleeding. Kidney Int 1991; 40:115–120.

- Daza JL, De Rosa M, De Rosa G. Dysmorphic red blood cells. Cleve Clin J Med 2018; 85:12–13.

- Jauhar S. The demise of the physical exam. N Engl J Med 2006; 354:548–551.

- Mangione S. When the tail wags the dog: clinical skills in the age of technology. Cleve Clin J Med 2017; 84:278–280.

- Perazella MA, Coca SG, Kanbay M, Brewster UC, Parikh CR. Diagnostic value of urine microscopy for differential diagnosis of acute kidney injury in hospitalized patients. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2008; 3:1615–1619.

- Perazella MA, Coca SG, Hall IE, Iyanam U, Koraishy M, Parikh CR. Urine microscopy is associated with severity and worsening of acute kidney injury in hospitalized patients. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2010; 5:402–408.

- Tsai JJ, Yeun JY, Kumar VA, Don BR. Comparison and interpretation of urinalysis performed by a nephrologist versus a hospital-based clinical laboratory. Am J Kidney Dis 2005; 46:820–829.

Additional Reading

Fogazzi GB, Garigali G, Pirovano B, Muratore MT, Raimondi S, Berti S. How to improve the teaching of urine microscopy. Clin Chem Lab Med 2007; 45:407–412.

Fogazzi GB, Secchiero S. The role of nephrologists in teaching urinary sediment examination. Am J Kidney Dis 2006; 47:713.

Fogazzi GB, Verdesca S, Garigali G. Urinalysis: core curriculum 2008. Am J Kidney Dis 2008; 51:1052–1067.

The urine is the window to the kidney.This oft-repeated adage impresses upon medical students and residents the importance of urine microscopy in the evaluation of patients with renal disorders.

While this phrase is likely an adaptation of the idea in ancient times that the urine reflected on humors or the quality of the soul, the understanding of the relevance of urine findings to the state of the kidneys likely rests with the pioneers of urine microscopy. As reviewed by Fogazzi and Cameron,1,2 the origins of direct inspection of urine under a microscope lie in the 17th century, with industrious physicians who used rudimentary microscopes to identify basic structures in the urine and correlated them to clinical presentations.1 At first, only larger structures could be seen, mostly crystals in patients with nephrolithiasis. As microscopes advanced, smaller structures such as “corpuscles” and “cylinders” could be seen that described cells and casts.1

In correlating these findings to patient presentations, a rudimentary understanding of renal pathology evolved long before the advent of the kidney biopsy. Lipid droplets were seen1 in patients swollen from dropsy, and later known to have nephrotic syndromes. In 1872, Harley first described the altered morphology of dysmorphic red blood cells in patients with Bright disease or glomerulonephritis.1,3 In 1979, Birch and Fairley recognized that the presence of acanthocytes differentiated glomerular from nonglomerular hematuria.4

DYSMORPHIC RED BLOOD CELLS: TYPES AND SIGNIFICANCE

URINE MICROSCOPY: THE NEPHROLOGIST’S ROLE

The tools used in urine microscopy have advanced significantly since its advent. But not all advances have led to improved patient care. Laboratories have trained technicians to perform urine microscopy. Analyzers can identify basic urinary structures using algorithms to compare them against stored reference images. More important, urine microscopy has been categorized by accreditation and inspection bodies as a “test” rather than a physician-performed competency. As such, definitions of quality in urine microscopy have shifted from the application of urinary findings to the care of the patient to the reproducibility of identifying individual structures in ways that can be documented with quality checks performed by nonclinicians. And since the governing bodies require laboratories to adhere to burdensome procedures to maintain accreditation (eg, the US Food and Drug Administration’s Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments), many hospitals have closed nephrologist-based urine laboratories.

This would be acceptable if laboratory-generated reports provided information equivalent to that obtained by the nephrologist. But such reports rarely include anything beyond the most rudimentary findings. In these reports, the red blood cell is not differentiated as dysmorphic or monomorphic. All casts are granular. Crystals are often the highlight of the report, usually an incidental finding of little relevance. Phase contrast and polarization are never performed.

Despite the poor quality of data provided in these reports, because of increasing regulations and time restrictions, a dwindling number of nephrologists perform urine microscopy even at teaching institutions. In an informal 2009 survey of nephrology fellowship program directors, 79% of responding programs relied solely on lab-generated reports for microscopic findings (verbal communication, Perazella, 2017).

There is general concern among medical educators about the surrendering of the physical examination and other techniques to technology.7,8 However, in many cases, such changes may improve the ability to make a correct diagnosis. When performed properly, urine microscopy can help determine the need for kidney biopsy, differentiate causes of acute kidney injury, and help guide decisions about therapy. Perazella showed that urine microscopy could reliably differentiate acute tubular necrosis from prerenal azotemia.9 Further, the severity of findings on urine microscopy has been associated with worse renal outcomes.10 At our institution, nephrologist-performed urine microscopy resulted in a change in cause of acute kidney injury in 25% of cases and a concrete change in management in 12% of patients (unpublished data).

With this in mind, it is concerning that the only evidence in the literature on this topic demonstrated that laboratory-based urine microscopy is actually a hindrance to its underlying purpose in acute kidney injury, which is to help identify the cause of the injury. Tsai et al11 showed that nephrologists identified the cause of acute kidney injury correctly 90% of the time when they performed their own urine microscopy, but this dropped to 23% when they relied on a laboratory-generated report. Interestingly, knowing the patient’s clinical history when performing the microscopy was important, as the accuracy was 69% when a report of another nephrologist’s microscopy findings was used.11

APPLYING RESULTS TO THE PATIENT

The purpose of urine microscopy in clinical care is to identify and understand the findings as they apply to the patient. When viewed from this perspective, the renal patient is clearly best served when the nephrologist familiar with the case performs urine microscopy, rather than a technician or analyzer in remote parts of the hospital with no connection to the patient.

Advances in technology or streamlining of hospital services do not always produce improvements in patient care, and how we define quality is integral to identifying when this is the case. Quality checklists can serve as guides to safe patient care but should not replace clinical decision-making. Direct physician involvement with our patients has concrete benefits, whether taking a history, performing a physical examination, reviewing radiologic images, or looking at specimens such as urine. It allows us to experience the amazing pathophysiology of human illness and to understand the nuances unique to each of our patients.

But most important, it reinforces the need for the direct bond, both emotional and physical, between us as healers and our patients.

The urine is the window to the kidney.This oft-repeated adage impresses upon medical students and residents the importance of urine microscopy in the evaluation of patients with renal disorders.

While this phrase is likely an adaptation of the idea in ancient times that the urine reflected on humors or the quality of the soul, the understanding of the relevance of urine findings to the state of the kidneys likely rests with the pioneers of urine microscopy. As reviewed by Fogazzi and Cameron,1,2 the origins of direct inspection of urine under a microscope lie in the 17th century, with industrious physicians who used rudimentary microscopes to identify basic structures in the urine and correlated them to clinical presentations.1 At first, only larger structures could be seen, mostly crystals in patients with nephrolithiasis. As microscopes advanced, smaller structures such as “corpuscles” and “cylinders” could be seen that described cells and casts.1

In correlating these findings to patient presentations, a rudimentary understanding of renal pathology evolved long before the advent of the kidney biopsy. Lipid droplets were seen1 in patients swollen from dropsy, and later known to have nephrotic syndromes. In 1872, Harley first described the altered morphology of dysmorphic red blood cells in patients with Bright disease or glomerulonephritis.1,3 In 1979, Birch and Fairley recognized that the presence of acanthocytes differentiated glomerular from nonglomerular hematuria.4

DYSMORPHIC RED BLOOD CELLS: TYPES AND SIGNIFICANCE

URINE MICROSCOPY: THE NEPHROLOGIST’S ROLE

The tools used in urine microscopy have advanced significantly since its advent. But not all advances have led to improved patient care. Laboratories have trained technicians to perform urine microscopy. Analyzers can identify basic urinary structures using algorithms to compare them against stored reference images. More important, urine microscopy has been categorized by accreditation and inspection bodies as a “test” rather than a physician-performed competency. As such, definitions of quality in urine microscopy have shifted from the application of urinary findings to the care of the patient to the reproducibility of identifying individual structures in ways that can be documented with quality checks performed by nonclinicians. And since the governing bodies require laboratories to adhere to burdensome procedures to maintain accreditation (eg, the US Food and Drug Administration’s Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments), many hospitals have closed nephrologist-based urine laboratories.

This would be acceptable if laboratory-generated reports provided information equivalent to that obtained by the nephrologist. But such reports rarely include anything beyond the most rudimentary findings. In these reports, the red blood cell is not differentiated as dysmorphic or monomorphic. All casts are granular. Crystals are often the highlight of the report, usually an incidental finding of little relevance. Phase contrast and polarization are never performed.

Despite the poor quality of data provided in these reports, because of increasing regulations and time restrictions, a dwindling number of nephrologists perform urine microscopy even at teaching institutions. In an informal 2009 survey of nephrology fellowship program directors, 79% of responding programs relied solely on lab-generated reports for microscopic findings (verbal communication, Perazella, 2017).

There is general concern among medical educators about the surrendering of the physical examination and other techniques to technology.7,8 However, in many cases, such changes may improve the ability to make a correct diagnosis. When performed properly, urine microscopy can help determine the need for kidney biopsy, differentiate causes of acute kidney injury, and help guide decisions about therapy. Perazella showed that urine microscopy could reliably differentiate acute tubular necrosis from prerenal azotemia.9 Further, the severity of findings on urine microscopy has been associated with worse renal outcomes.10 At our institution, nephrologist-performed urine microscopy resulted in a change in cause of acute kidney injury in 25% of cases and a concrete change in management in 12% of patients (unpublished data).

With this in mind, it is concerning that the only evidence in the literature on this topic demonstrated that laboratory-based urine microscopy is actually a hindrance to its underlying purpose in acute kidney injury, which is to help identify the cause of the injury. Tsai et al11 showed that nephrologists identified the cause of acute kidney injury correctly 90% of the time when they performed their own urine microscopy, but this dropped to 23% when they relied on a laboratory-generated report. Interestingly, knowing the patient’s clinical history when performing the microscopy was important, as the accuracy was 69% when a report of another nephrologist’s microscopy findings was used.11

APPLYING RESULTS TO THE PATIENT

The purpose of urine microscopy in clinical care is to identify and understand the findings as they apply to the patient. When viewed from this perspective, the renal patient is clearly best served when the nephrologist familiar with the case performs urine microscopy, rather than a technician or analyzer in remote parts of the hospital with no connection to the patient.

Advances in technology or streamlining of hospital services do not always produce improvements in patient care, and how we define quality is integral to identifying when this is the case. Quality checklists can serve as guides to safe patient care but should not replace clinical decision-making. Direct physician involvement with our patients has concrete benefits, whether taking a history, performing a physical examination, reviewing radiologic images, or looking at specimens such as urine. It allows us to experience the amazing pathophysiology of human illness and to understand the nuances unique to each of our patients.

But most important, it reinforces the need for the direct bond, both emotional and physical, between us as healers and our patients.

- Fogazzi GB, Cameron JS. Urinary microscopy from the seventeenth century to the present day. Kidney Int 1996; 50:1058–1068.

- Cameron JS. A history of urine microscopy. Clin Chem Lab Med 2015; 53(suppl 2):s1453–s1464.

- Harley G. The Urine and Its Derangements. London: J and A Churchill, 1872:178–179.

- Birch DF, Fairley K. Hematuria: glomerular or non-glomerular? Lancet 1979; 314:845–846.

- Köhler H, Wandel E, Brunck B. Acanthocyturia—a characteristic marker for glomerular bleeding. Kidney Int 1991; 40:115–120.

- Daza JL, De Rosa M, De Rosa G. Dysmorphic red blood cells. Cleve Clin J Med 2018; 85:12–13.

- Jauhar S. The demise of the physical exam. N Engl J Med 2006; 354:548–551.

- Mangione S. When the tail wags the dog: clinical skills in the age of technology. Cleve Clin J Med 2017; 84:278–280.

- Perazella MA, Coca SG, Kanbay M, Brewster UC, Parikh CR. Diagnostic value of urine microscopy for differential diagnosis of acute kidney injury in hospitalized patients. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2008; 3:1615–1619.

- Perazella MA, Coca SG, Hall IE, Iyanam U, Koraishy M, Parikh CR. Urine microscopy is associated with severity and worsening of acute kidney injury in hospitalized patients. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2010; 5:402–408.

- Tsai JJ, Yeun JY, Kumar VA, Don BR. Comparison and interpretation of urinalysis performed by a nephrologist versus a hospital-based clinical laboratory. Am J Kidney Dis 2005; 46:820–829.

Additional Reading

Fogazzi GB, Garigali G, Pirovano B, Muratore MT, Raimondi S, Berti S. How to improve the teaching of urine microscopy. Clin Chem Lab Med 2007; 45:407–412.

Fogazzi GB, Secchiero S. The role of nephrologists in teaching urinary sediment examination. Am J Kidney Dis 2006; 47:713.

Fogazzi GB, Verdesca S, Garigali G. Urinalysis: core curriculum 2008. Am J Kidney Dis 2008; 51:1052–1067.

- Fogazzi GB, Cameron JS. Urinary microscopy from the seventeenth century to the present day. Kidney Int 1996; 50:1058–1068.

- Cameron JS. A history of urine microscopy. Clin Chem Lab Med 2015; 53(suppl 2):s1453–s1464.

- Harley G. The Urine and Its Derangements. London: J and A Churchill, 1872:178–179.

- Birch DF, Fairley K. Hematuria: glomerular or non-glomerular? Lancet 1979; 314:845–846.

- Köhler H, Wandel E, Brunck B. Acanthocyturia—a characteristic marker for glomerular bleeding. Kidney Int 1991; 40:115–120.

- Daza JL, De Rosa M, De Rosa G. Dysmorphic red blood cells. Cleve Clin J Med 2018; 85:12–13.

- Jauhar S. The demise of the physical exam. N Engl J Med 2006; 354:548–551.

- Mangione S. When the tail wags the dog: clinical skills in the age of technology. Cleve Clin J Med 2017; 84:278–280.

- Perazella MA, Coca SG, Kanbay M, Brewster UC, Parikh CR. Diagnostic value of urine microscopy for differential diagnosis of acute kidney injury in hospitalized patients. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2008; 3:1615–1619.

- Perazella MA, Coca SG, Hall IE, Iyanam U, Koraishy M, Parikh CR. Urine microscopy is associated with severity and worsening of acute kidney injury in hospitalized patients. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2010; 5:402–408.

- Tsai JJ, Yeun JY, Kumar VA, Don BR. Comparison and interpretation of urinalysis performed by a nephrologist versus a hospital-based clinical laboratory. Am J Kidney Dis 2005; 46:820–829.

Additional Reading

Fogazzi GB, Garigali G, Pirovano B, Muratore MT, Raimondi S, Berti S. How to improve the teaching of urine microscopy. Clin Chem Lab Med 2007; 45:407–412.

Fogazzi GB, Secchiero S. The role of nephrologists in teaching urinary sediment examination. Am J Kidney Dis 2006; 47:713.

Fogazzi GB, Verdesca S, Garigali G. Urinalysis: core curriculum 2008. Am J Kidney Dis 2008; 51:1052–1067.

A 50-year-old woman with new-onset seizure

A 50-year-old woman presented to the emergency department after a witnessed loss of consciousness and seizurelike activity. She reported that she had been sitting outside her home, drinking coffee in the morning, but became very lightheaded when she went back into her house. At that time she felt could not focus and had a sense of impending doom. She sat down in a chair and her symptoms worsened.

According to her family, her eyes rolled back and she became rigid. The family helped her to the floor. Her body then made jerking movements that lasted for about 1 minute. She regained consciousness but was very confused for about 10 minutes until emergency medical services personnel arrived. She had no recollection of passing out. She said nothing like this had ever happened to her before.

On arrival in the emergency department, she complained of generalized headache and muscle soreness. She said the headache had been present for 1 week and was constant and dull. There were no aggravating or alleviating factors associated with the headache, and she denied fever, chills, nausea, numbness, tingling, incontinence, tongue biting, tremor, poor balance, ringing in ears, speech difficulty, or weakness.

Medical history: Multiple problems, medications

The patient’s medical history included depression, hypertension, anxiety, osteoarthritis, and asthma. She was allergic to penicillin. She had undergone carpal tunnel surgery on her right hand 5 years previously. She was perimenopausal with no children.

She denied using illicit drugs. She said she had smoked a half pack of cigarettes per day for more than 10 years and was a current smoker but was actively trying to quit. She said she occasionally used alcohol but had not consumed any alcohol in the last 2 weeks.

She had no history of central nervous system infection. She did report an episode of head trauma in grade school when a portable basketball hoop fell, striking her on the top of the head and causing her to briefly lose consciousness, but she did not seek medical attention.

She had no family history of seizure or neurologic disease.

Her current medications included atenolol, naproxen, gabapentin, venlafaxine, zolpidem, lorazepam, bupropion, and meloxicam. The bupropion and lorazepam had been prescribed recently for her anxiety. She reported that she had been given only 10 tablets of lorazepam and had taken the last tablet 48 hours previously. She had been taking the bupropion for 7 days. She reported an increase in stress lately and had been taking zolpidem due to an altered sleep pattern.

PHYSICAL EXAMINATION, INITIAL TESTS

On examination, the patient did not appear to be in acute distress. Her blood pressure was 107/22 mm Hg, pulse 100 beats per minute, respiratory rate 16 breaths per minute, temperature 37.1°C (98.8°F), and oxygen saturation 98% on room air.

Examination of her head, eyes, mouth, and neck were unremarkable. Cardiovascular, pulmonary, and abdominal examinations were normal. She had no neurologic deficits and was fully alert and oriented. She had no visible injuries.

Blood and urine samples were obtained about 15 minutes after her arrival to the emergency department. Results showed:

- Glucose 73 mg/dL (reference range 74–99)

- Sodium 142 mmol/L (136–144)

- Blood urea nitrogen 12 mg/dL (7–21)

- Creatinine 0.95 mg/dL (0.58–0.96)

- Chloride 97 mmol/L (97–105)

- Carbon dioxide (bicarbonate) 16 mmol/L (22–30)

- Prolactin 50.9 ng/mL (4.5–26.8)

- Anion gap 29 mmol/L (9–18)

- Ethanol undetectable

- White blood cell count 11.03 × 109/L (3.70–11.00)

- Creatine kinase 89 U/L (30–220)

- Urinalysis normal, specific gravity 1.010 (1.005–1.030), no detectable ketones, and no crystals seen on microscopic evaluation.

Electrocardiography showed normal sinus rhythm with no ectopy and no ST-segment changes. Chest radiography was negative for any acute process.

The patient was transferred to the 23-hour observation unit in stable condition for further evaluation, monitoring, and management.

SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS OF SEIZURE

1. What findings are consistent with seizure?

- Jerking movements

- Confusion following the event

- Tongue-biting

- Focal motor weakness

- Urinary incontinence

- Aura before the event

All of the above findings are consistent with seizure.

The first consideration in evaluating a patient who presents with a possible seizure is whether the patient’s recollections of the event—and those of the witnesses—are consistent with the symptoms of seizure.1

In generalized tonic-clonic or grand mal seizure, the patient may experience an aura or subjective sensations before the onset. These vary greatly among patients.2 There may be an initial vocalization at the onset of the seizure, such as crying out or unintelligible speech. The patient’s eyes may roll back in the head. This is followed by loss of muscle tone, and if the patient is standing, he or she may fall to the ground. The patient becomes unresponsive and may go into respiratory arrest. There is tonic stiffening of the limbs and body, followed by clonic movements typically lasting 1 to 2 minutes, or sometimes longer.1,3,4 The patient will then relax and experience a period of unconsciousness or confusion (postictal state).

Urinary incontinence and tongue-biting strongly suggest seizure activity, and turning the head to one side and posturing may also be seen.3,5 After the event, the patient may report headache, generalized muscle soreness, exhaustion, or periods of transient focal weakness, also known as Todd paralysis.2,5

Our patient had aura-like symptoms at the outset. She felt very lightheaded, had difficulty focusing, and felt a sense of impending doom. She did not make any vocalizations at the onset, but her eyes did roll backward and she became rigid (tonic). She then lost muscle tone and became unresponsive. Her family had to help her to the floor. Jerking (clonic) movements were witnessed.

She regained consciousness but was described as being confused (postictal) for 10 minutes. Additionally, she denied ever having had symptoms like this previously. On arrival in the emergency department, she reported generalized headache and muscle soreness, but no tongue-biting or urinary incontinence. Her event did not last for more than 1 to 2 minutes according to her family.

Her symptoms strongly suggest new-onset tonic-clonic or grand mal seizure, though this is not completely certain.

LABORATORY FINDINGS IN SEIZURES

2. What laboratory results are consistent with seizure?

- Prolactin elevation

- Anion gap acidosis

- Leukocytosis

As noted above, the patient had an elevated prolactin level and elevated anion gap. Both of these findings can be used, with caution, in evaluating seizure activity.

Prolactin testing is controversial

Prolactin testing in diagnosing seizure activity is controversial. The exact mechanism of prolactin release in seizures is not fully understood. Generalized tonic-clonic seizures and complex partial seizures have both been shown to elevate prolactin. Prolactin levels after these types of seizures should rise within 30 minutes of the event and normalize 1 hour later.6

However, other events and conditions that mimic seizure have been shown to cause a rise in prolactin; these include syncope, transient ischemic attack, cardiac dysrhythmia, migraine, and other epilepsy-like variants. This effect has not been adequately studied. Therefore, an elevated prolactin level alone cannot diagnose or exclude seizure.7

For the prolactin level to be helpful, the blood sample must be drawn within 10 to 20 minutes after a possible seizure. Even if the prolactin level remains normal, it does not rule out seizure. Prolactin levels should therefore be used in combination with other testing to make a definitive diagnosis or exclusion of seizure.8

Anion gap and Denver Seizure Score

The anion gap has also been shown to rise after generalized seizure due to the metabolic acidosis that occurs. With a bicarbonate level of 16 mmol/L, an elevated anion gap, and normal breathing, our patient very likely had metabolic acidosis.

It is sometimes difficult to differentiate syncope from seizure, as they share several features.

The Denver Seizure Score can help differentiate these two conditions. It is based on the patient’s anion gap and bicarbonate level and is calculated as follows:

(24 – bicarbonate) + [2 × (anion gap – 12)]

A score above 20 strongly indicates seizure activity. However, this is not a definitive tool for diagnosis. Like an elevated prolactin level, the Denver Seizure Score should be used in combination with other testing to move toward a definitive diagnosis.9

Our patient’s anion gap was 29 mmol/L and her bicarbonate level was 16 mmol/L. Her Denver Seizure Score was therefore 42, which supports this being an episode of generalized seizure activity.

Leukocytosis

The patient had a white blood cell count of 11.03 × 109/L, which was mildly elevated. She had no history of fever and no source of infection by history.

Leukocytosis is common following generalized tonic-clonic seizure. A fever may lower the seizure threshold; however, our patient was not febrile and clinically had no factors that raised concern for an underlying infection.

ANION GAP ACIDOSIS AND SEIZURE

3. Which of the following can cause both anion gap acidosis and seizure?

- Ethylene glycol

- Salicylate overdose

- Ethanol withdrawal without ketosis

- Alcoholic ketoacidosis

- Methanol

All of the above except for ethanol withdrawal without ketosis can cause both anion gap acidosis and seizure.

Ethylene glycol can cause seizure and an elevated anion gap acidosis. However, this patient had no history of ingesting antifreeze (the most common source of ethylene glycol in the home) and no evidence of calcium oxalate crystals in the urine, which would be a sign of ethylene glycol toxicity. Additional testing for ethylene glycol may include serum ethylene glycol levels and ultraviolet light testing of the urine to detect fluorescein, which is commonly added to automotive antifreeze to help mechanics find fluid leaks in engines.

Salicylate overdose can cause seizure and an elevated anion gap acidosis. However, this patient has no history of aspirin ingestion, and a serum aspirin level was later ordered and found to be negative. In addition, the acid-base disorder in salicylate overdose may be respiratory alkalosis from direct stimulation of respiratory centers in conjunction with metabolic acidosis.

Ethanol withdrawal can cause seizure and may result in ketoacidosis, which would appear as anion gap acidosis. The undetectable ethanol level in this patient would be consistent with withdrawal from ethanol, which may also lead to ketoacidosis.

Alcoholic ketoacidosis is a late finding in patients who have been drinking ethanol and is thus a possible cause of an elevated anion gap in this patient. However, the absence of ketones in her urine speaks against this diagnosis.

Methanol can cause seizure and acidosis, but laboratory testing would reveal a normal anion gap and an elevated osmolar gap. This was not likely in this patient.

The presence of anion gap acidosis is important in forming a differential diagnosis. Several causes of anion gap acidosis may also cause seizure. These include salicylates, ethanol withdrawal with ketosis, methanol, and isoniazid. None of these appears to be a factor in this patient’s case.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS IN OUR PATIENT

4. What is the most likely cause of this patient’s seizure?

- Bupropion side effect

- Benzodiazepine withdrawal

- Ethanol withdrawal

- Brain lesion

- Central nervous system infection

- Unprovoked seizure (new-onset epilepsy)

Bupropion, an inhibitor of neuronal reuptake of norepinephrine and dopamine, has been used in the United States since 1989 to treat major depression.10 At therapeutic doses, it lowers the seizure threshold; in cases of acute overdose, seizures typically occur within hours of the dose, or up to 24 hours in patients taking extended-release formulations.11

Bupropion should be used with caution or avoided in patients taking other medications that also lower the seizure threshold, or during withdrawal from alcohol, benzodiazepines, or barbiturates.10

Benzodiazepine withdrawal. Abrupt cessation of benzodiazepines also lowers the seizure threshold, and seizures are commonly seen in benzodiazepine withdrawal syndrome. The use of benzodiazepines is controversial in many situations, and discontinuing them may prove problematic for both the patient and physician, as the potential for abuse and addiction is significant.

Seizures have occurred during withdrawal from even short-term benzodiazepine use. Other factors, such as concomitant use of other medications that lower the seizure threshold, may play a more significant role in causing withdrawal seizures than the duration of benzodiazepine therapy.12

Medications shown to be useful in managing withdrawal from benzodiazepines include carbamazepine, imipramine, valproate, and trazodone. Paroxetine has also been shown to be helpful in patients with major depression who are being taken off a benzodiazepine.13

Ethanol withdrawal is common in patients presenting to emergency departments, and seizures are frequently seen in these patients. This patient reported social drinking but not drinking ethanol daily, although many patients are not forthcoming about alcohol or drug use when talking with a physician or other healthcare provider.

Alcohol withdrawal seizures may accompany delirium tremens or major withdrawal syndrome, but they are seen more often in the absence of major withdrawal or delirium tremens. Seizures are typically single or occur in a short grouping over a brief period of time and mostly occur in chronic alcoholism. The role of anticonvulsants in patients with alcohol withdrawal seizure has not been established.14

Brain lesion. A previously undiagnosed brain tumor is not a common cause of new-onset seizure, although it is not unusual for a brain tumor to cause new-onset seizure. In 1 study, 6% of patients with new-onset seizure had a clinically significant lesion on brain imaging.15 In addition, 15% to 30% of patients with a previously undiagnosed brain tumor present with seizure as the first symptom.16 Patients with abnormal findings on neurologic examination after the seizure activity are more likely to have a structural lesion that may be identified by computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging. (MRI)15

Unprovoked seizure occurs without an identifiable precipitating factor, or from a central nervous system insult that occurred more than 7 days earlier. Patients who may have recurrent unprovoked seizure will likely be diagnosed with epilepsy.15 Patients with a first-time unprovoked seizure have a 30% or higher likelihood of having another unprovoked seizure within 5 years.17

It is most likely that bupropion is the key factor in lowering the seizure threshold in this patient. However, patients sometimes underreport the amount of alcohol they consume, and though less likely, our patient’s report of not drinking for 2 weeks may also be unreliable. Ethanol withdrawal, though unlikely, may also be a consideration with this case.

FURTHER TESTING FOR OUR PATIENT

5. Which tests may be helpful in this patient’s workup?

- CT of the brain

- Lumbar puncture for spinal fluid analysis

- MRI of the brain

- Electroencephalography (EEG)

This patient had had a headache for 1 week before presenting to the emergency department. Indications for neuroimaging in a patient with headache include sudden onset of severe headache, neurologic deficits, human immunodeficiency virus infection, loss of consciousness, immunosuppression, pregnancy, malignancy, and age over 50 with a new type of headache.18,19 Therefore, she should undergo some form of neuroimaging, either CT or MRI.

CT is the most readily available and fastest imaging study for the central nervous system available to emergency physicians. CT is limited, however, due to its decreased sensitivity in detecting some brain lesions. Therefore, many patients with first-time seizure may eventually require MRI.15 Furthermore, patients with focal onset of the seizure activity are more likely to have a structural lesion precipitating the seizure. MRI may have a higher yield than CT in these cases.15,20

Lumbar puncture for spinal fluid analysis is helpful in evaluating a patient with a suspected central nervous system infection such as meningitis or encephalitis, or subarachnoid hemorrhage.

This patient had a normal neurologic examination, no fever, and no meningeal signs, and central nervous system infection was very unlikely. Also, because she had had a headache for 1 week before the presentation with seizurelike activity, subarachnoid hemorrhage was very unlikely, and emergency lumbar puncture was not indicated.

MRI is less readily available than CT in a timely fashion in most emergency departments in the United States. It offers a higher yield than CT in diagnosing pathology such as acute stroke, brain tumor, and plaques seen in multiple sclerosis. CT is superior to MRI in diagnosing bony abnormalities and is very sensitive for detecting acute bleeding.

If MRI is performed, it should follow a specific protocol that includes high-resolution images for epilepsy evaluation rather than the more commonly ordered stroke protocol. The stroke protocol is more likely to be ordered in the emergency department.

EEG is well established in evaluating new-onset seizure in pediatric patients. Studies also demonstrate its utility in evaluating first-time seizure in adults, providing evidence that both epileptiform and nonepileptiform abnormalities seen on EEG are associated with a higher risk of recurrent seizure activity than in patients with normal findings on EEG.1

EEG may be difficult to interpret in adults. According to Benbadis,5 as many as one-third of adult patients diagnosed with epilepsy on EEG did not have epilepsy. This is because of normal variants, simple fluctuations of background rhythms, or fragmented alpha activity that can have a similar appearance to epileptiform patterns. EEG must always be interpreted in the context of the patient’s history and symptoms.5

Though EEG has limitations, it remains a crucial tool for identifying epilepsy. Following a single seizure, the decision to prescribe antiepileptic drugs is highly influenced by patterns on EEG associated with a risk of recurrence. In fact, a patient experiencing a single, idiopathic seizure and exhibiting an EEG pattern of spike wave discharges is likely to have recurrent seizure activity.21 Also, the appropriate use of EEG after even a single unprovoked seizure can identify patients with epilepsy and a risk of recurrent seizure greater than 60%.21,22

NO FURTHER SEIZURES

The patient was admitted to the observation unit from the emergency department after undergoing CT without intravenous contrast. While in observation, she had no additional episodes, and her vital signs remained within normal limits.

She underwent MRI and EEG as well as repeat laboratory studies and consultation by a neurologist. CT showed no structural abnormality, MRI results were read as normal, and EEG showed no epileptiform spikes or abnormal slow waves or other abnormality consistent with seizure. The repeat laboratory studies revealed normalization of the prolactin level at 11.3 ng/mL (reference range 2.0–17.4).

The final impression of the neurology consultant was that the patient had had a seizure that was most likely due to recently starting bupropion in combination with the withdrawal of the benzodiazepine, which lowered the seizure threshold. The neurologist also believed that our patient had no findings or symptoms other than the seizure that would suggest benzodiazepine withdrawal syndrome. According to the patient’s social history, it was unlikely that she had the pattern of alcohol consumption that would result in ethanol withdrawal seizure.

Seizures are common. In fact, every year, 180,000 US adults have their first seizure, and 10% of Americans will experience at least 1 seizure during their lifetime. However, only 20% to 25% of seizures are generalized tonic-clonic seizures as in our patient.23

As this patient had an identifiable cause for the seizure, there was no need to initiate anticonvulsant therapy at the time of discharge. She was discharged to home without any anticonvulsant, the bupropion was discontinued, and the lorazepam was not restarted. When contacted by telephone at 1 month and 18 months after discharge, she reported she had not experienced any additional seizures and has not needed antiepileptic medications.

- Seneviratne U. Management of the first seizure: an evidence based approach. Postgrad Med J 2009; 85:667–673.

- Krumholz A, Wiebe S, Gronseth G, et al; Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology; American Epilepsy Society. Practice parameter: evaluating an apparent unprovoked first seizure in adults (an evidence-based review): report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology and the American Epilepsy Society. Neurology 2007; 67:1996–2007.

- Gram L. Epileptic seizures and syndromes. Lancet 1990; 336:161–163.

- Smith PE, Cossburn MD. Seizures: assessment and management in the emergency unit. Clin Med (Lond) 2004; 4:118–122.

- Benbadis S. The differential diagnosis of epilepsy: a critical review. Epilepsy Behav 2009; 15:15–21.

- Lusic I, Pintaric I, Hozo I, Boic L, Capkun V. Serum prolactin levels after seizure and syncopal attacks. Seizure 1999; 8:218–222.

- Chen DK, So YT, Fisher RS; Therapeutics and Technology Assessment Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Use of serum prolactin in diagnosing epileptic seizures: report of the Therapeutics and Technology Assessment Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology 2005; 65:668–675.

- Ben-Menachem E. Is prolactin a clinically useful measure of epilepsy? Epilepsy Curr 2006; 6:78–79.

- Bakes KM, Faragher J, Markovchick VJ, Donahoe K, Haukoos JS. The Denver Seizure Score: anion gap metabolic acidosis predicts generalized seizure. Am J Emerg Med 2011; 29:1097–1102.

- Jefferson JW, Pradok JF, Muir KT. Bupropion for major depressive disorder: pharmacokinetic and formulation considerations. Clin Ther 2005; 27:1685–1695.

- Stall N, Godwin J, Juurlink D. Bupropion abuse and overdose. CMAJ 2014; 186:1015.

- Fialip J, Aumaitre O, Eschalier A, Maradeix B, Dordain G, Lavarenne J. Benzodiazepine withdrawal seizures: analysis of 48 case reports. Clin Neuropharmacol 1987; 10:538–544.

- Lader M, Tylee A, Donoghue J. Withdrawing benzodiazepines in primary care. CNS Drugs 2009; 23:19–34.

- Chance JF. Emergency department treatment of alcohol withdrawal seizures with phenytoin. Ann Emerg Med 1991; 20:520–522.

- ACEP Clinical Policies Committee; Clinical Policies Subcommittee on Seizures. Clinical policy: critical issues in the evaluation and management of adult patients presenting to the emergency department with seizures. Ann Emerg Med 2004; 43:605–625.

- Sperling MR, Ko J. Seizures and brain tumors. Semin Oncol 2006; 33:333–341.

- Musicco M, Beghi E, Solari A, Viani F. Treatment of first tonic-clonic seizure does not improve the prognosis of epilepsy. First Seizure Trial Group (FIRST Group). Neurology 1997; 49:991–998.

- Edlow JA, Panagos PD, Godwin SA, Thomas TL, Decker WW; American College of Emergency Physicians. Clinical policy: critical issues in the evaluation and management of adult patients presenting to the emergency department with acute headache. Ann Emerg Med 2008; 52:407–436.

- Kaniecki R. Headache assessment and management. JAMA 2003; 289:1430–1433.

- Harden CL, Huff JS, Schwartz TH, et al; Therapeutics and Technology Assessment Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Reassessment: neuroimaging in the emergency patient presenting with seizure (an evidence-based review): report of the Therapeutics and Technology Assessment Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology 2007; 69:1772–1780.

- Bergey GK. Management of a first seizure. Continuum (Minneap Minn) 2016; 22:38–50.

- Fisher RS, Acevedo C, Arzimanoglou A, et al. ILAE official report: a practical clinical definition of epilepsy. Epilepsia 2014; 55:475–482.

- Ko DY. Generalized tonic-clonic seizures. Medscape. http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1184608-overview. Accessed December 5, 2017.

A 50-year-old woman presented to the emergency department after a witnessed loss of consciousness and seizurelike activity. She reported that she had been sitting outside her home, drinking coffee in the morning, but became very lightheaded when she went back into her house. At that time she felt could not focus and had a sense of impending doom. She sat down in a chair and her symptoms worsened.

According to her family, her eyes rolled back and she became rigid. The family helped her to the floor. Her body then made jerking movements that lasted for about 1 minute. She regained consciousness but was very confused for about 10 minutes until emergency medical services personnel arrived. She had no recollection of passing out. She said nothing like this had ever happened to her before.

On arrival in the emergency department, she complained of generalized headache and muscle soreness. She said the headache had been present for 1 week and was constant and dull. There were no aggravating or alleviating factors associated with the headache, and she denied fever, chills, nausea, numbness, tingling, incontinence, tongue biting, tremor, poor balance, ringing in ears, speech difficulty, or weakness.

Medical history: Multiple problems, medications

The patient’s medical history included depression, hypertension, anxiety, osteoarthritis, and asthma. She was allergic to penicillin. She had undergone carpal tunnel surgery on her right hand 5 years previously. She was perimenopausal with no children.

She denied using illicit drugs. She said she had smoked a half pack of cigarettes per day for more than 10 years and was a current smoker but was actively trying to quit. She said she occasionally used alcohol but had not consumed any alcohol in the last 2 weeks.

She had no history of central nervous system infection. She did report an episode of head trauma in grade school when a portable basketball hoop fell, striking her on the top of the head and causing her to briefly lose consciousness, but she did not seek medical attention.

She had no family history of seizure or neurologic disease.

Her current medications included atenolol, naproxen, gabapentin, venlafaxine, zolpidem, lorazepam, bupropion, and meloxicam. The bupropion and lorazepam had been prescribed recently for her anxiety. She reported that she had been given only 10 tablets of lorazepam and had taken the last tablet 48 hours previously. She had been taking the bupropion for 7 days. She reported an increase in stress lately and had been taking zolpidem due to an altered sleep pattern.

PHYSICAL EXAMINATION, INITIAL TESTS

On examination, the patient did not appear to be in acute distress. Her blood pressure was 107/22 mm Hg, pulse 100 beats per minute, respiratory rate 16 breaths per minute, temperature 37.1°C (98.8°F), and oxygen saturation 98% on room air.

Examination of her head, eyes, mouth, and neck were unremarkable. Cardiovascular, pulmonary, and abdominal examinations were normal. She had no neurologic deficits and was fully alert and oriented. She had no visible injuries.

Blood and urine samples were obtained about 15 minutes after her arrival to the emergency department. Results showed:

- Glucose 73 mg/dL (reference range 74–99)

- Sodium 142 mmol/L (136–144)

- Blood urea nitrogen 12 mg/dL (7–21)

- Creatinine 0.95 mg/dL (0.58–0.96)

- Chloride 97 mmol/L (97–105)

- Carbon dioxide (bicarbonate) 16 mmol/L (22–30)

- Prolactin 50.9 ng/mL (4.5–26.8)

- Anion gap 29 mmol/L (9–18)

- Ethanol undetectable

- White blood cell count 11.03 × 109/L (3.70–11.00)

- Creatine kinase 89 U/L (30–220)

- Urinalysis normal, specific gravity 1.010 (1.005–1.030), no detectable ketones, and no crystals seen on microscopic evaluation.

Electrocardiography showed normal sinus rhythm with no ectopy and no ST-segment changes. Chest radiography was negative for any acute process.

The patient was transferred to the 23-hour observation unit in stable condition for further evaluation, monitoring, and management.

SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS OF SEIZURE

1. What findings are consistent with seizure?

- Jerking movements

- Confusion following the event

- Tongue-biting

- Focal motor weakness

- Urinary incontinence

- Aura before the event

All of the above findings are consistent with seizure.

The first consideration in evaluating a patient who presents with a possible seizure is whether the patient’s recollections of the event—and those of the witnesses—are consistent with the symptoms of seizure.1