User login

Primary Cutaneous Follicle Center Lymphoma Mimicking Folliculitis

The 2008 World Health Organization and European Organization for Treatment of Cancer joint classification has distinguished 3 categories of primary cutaneous B-cell lymphomas: primary cutaneous follicle center lymphoma (PCFCL), primary cutaneous diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, and primary cutaneous marginal zone lymphoma.1-3 Primary cutaneous follicle center lymphoma is the most common type of cutaneous B-cell lymphoma, accounting for approximately 60% of cases worldwide.4 The median age at diagnosis is 60 years, and most lesions are located on the scalp, forehead, neck, and trunk.5 Histologically, PCFCL is characterized by dermal proliferation of centrocytes and centroblasts derived from germinal center B cells that are arranged in either a follicular, diffuse, or mixed growth pattern.1 The cutaneous manifestations of PCFCL include solitary erythematous or violaceous plaques, nodules, or tumors of varying sizes.4 Grouped lesions also may be observed, but multifocal disease is rare.1 We report a rare presentation of PCFCL mimicking folliculitis with multiple multifocal papules on the back.

Case Report

A 54-year-old woman presented with fever and leukocytosis of 4 days’ duration and was admitted to the hospital for presumed sepsis. She had a history of mastectomy for treatment of ductal carcinoma in situ of the right breast 5 years prior to the current presentation and endocrine therapy with tamoxifen. Her symptoms were thought to be a complication from a surgery for implantation of a tissue expander in the right breast 5 years prior to presentation.

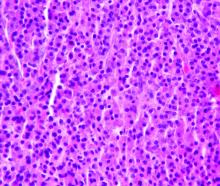

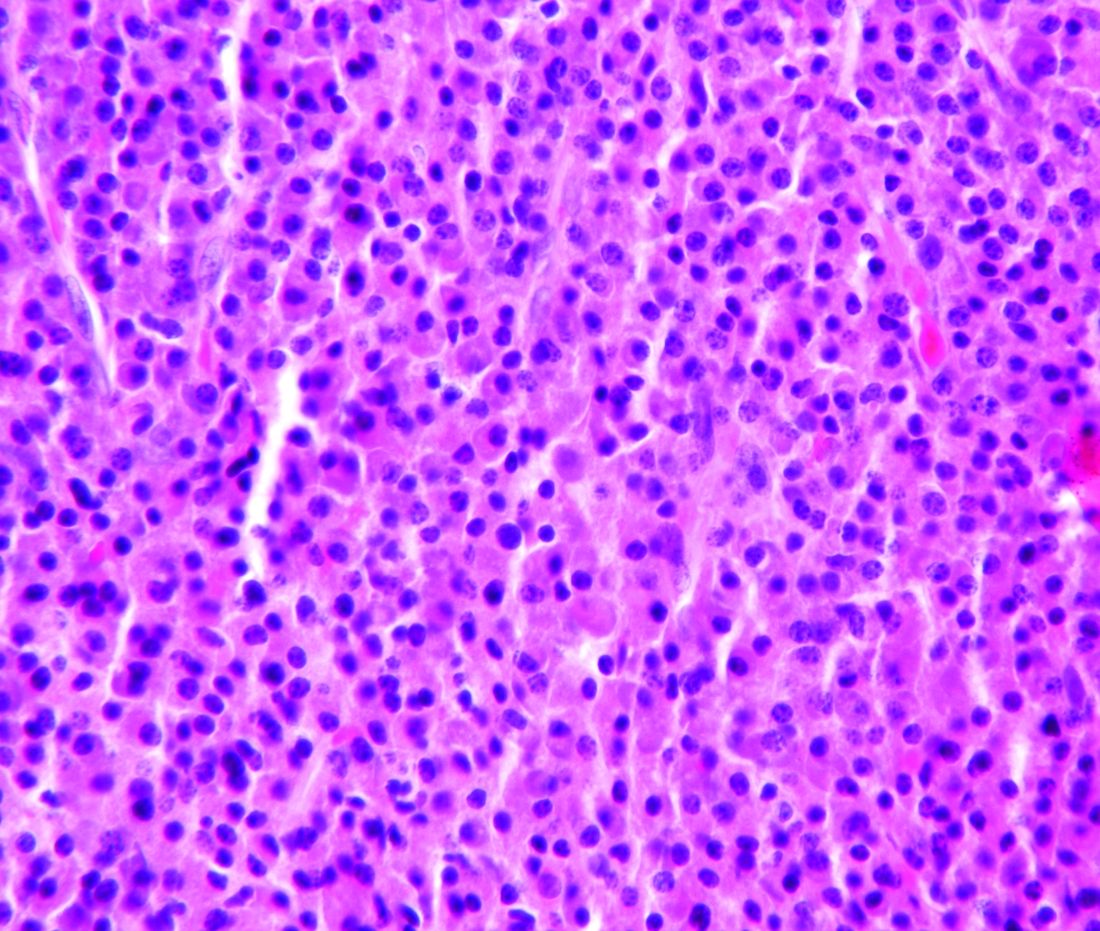

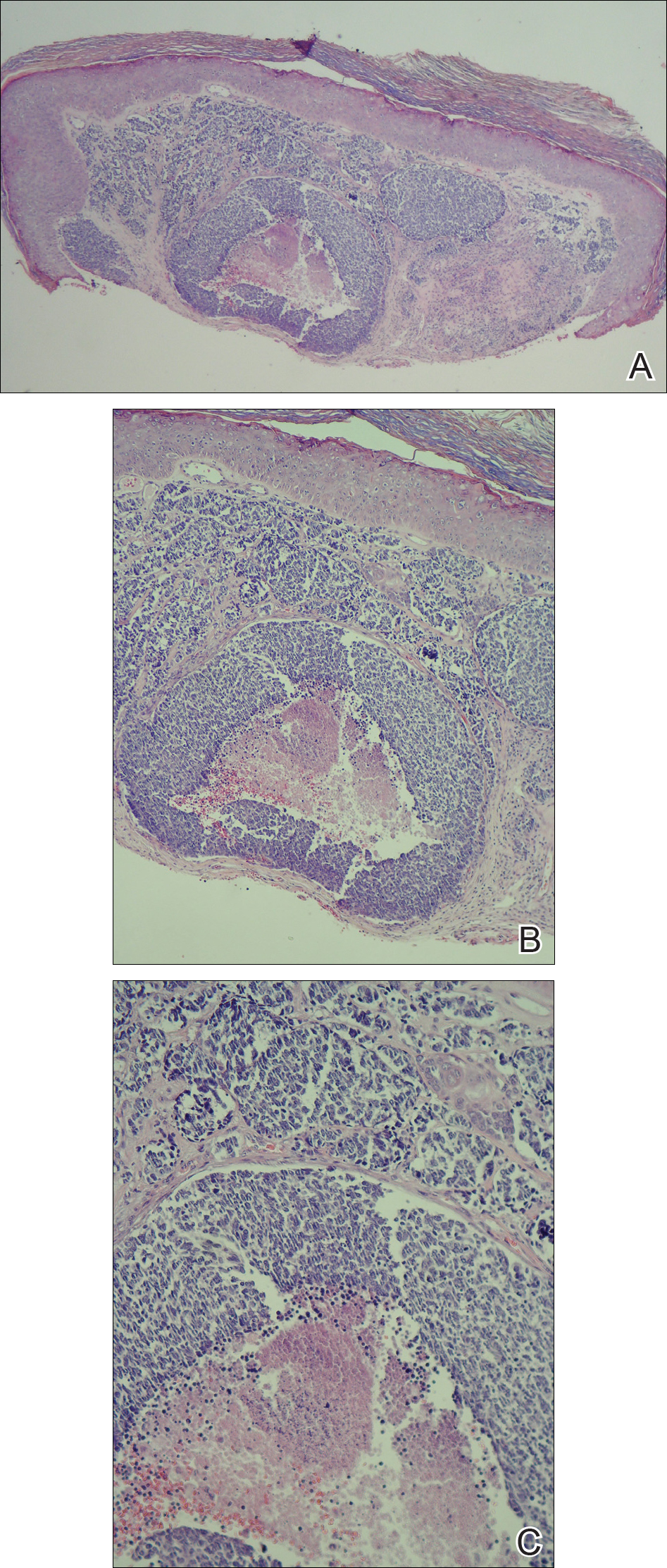

During her hospital admission, she developed a papular and cystic eruption on the back that was clinically suggestive of folliculitis, transient acantholytic dermatosis (Grover disease), or miliaria rubra (Figure 1). This papular and cystic eruption initially was managed conservatively with observation as she recovered from an occult infection. Due to the persistent nature of the eruption on the back, an excisional biopsy of the cystic component was performed 2 months after her discharge from the hospital. Histologic studies showed a dense infiltrate of lymphocytes, which expanded into the deep dermis in a nodular and diffuse growth pattern that was accentuated in the periadnexal areas. The B lymphocytes were small and hyperchromatic with few scattered centroblasts (Figure 2). Further immunohistochemical studies demonstrated that the neoplastic cells were positive for CD20, CD79a, BCL-2, and BCL-6; CD3, CD5, and cyclin D1 were negative. Staining for antigen Ki-67 revealed a proliferation index of 15% to 20% among the neoplastic cells (Figure 3). These findings were consistent with either PCFCL or secondary cutaneous follicle center lymphoma.

Further evaluation for systemic disease was unremarkable. Positron emission tomography–computed tomography revealed no evidence of nodal lymphoma, and a bone marrow biopsy was negative. Other laboratory studies including lactate dehydrogenase were within reference range, which conferred a diagnosis of PCFCL. The patient was treated with localized electron beam radiation therapy to the skin of the mid back for a total dose of 24 Gy in 12 fractions at 2 Gy per fraction once daily over a 12-day period. She tolerated the treatment well and has remained clinically and radiographically without evidence of disease for more than 3 years.

Comment

Because the incidence of cutaneous B-cell lymphomas has been increasing, especially among males, non-Hispanic whites, and adults older than 50 years,1 it is important for clinicians to have a high index of suspicion for this entity. In our patient, the clinical findings of a papular, largely asymptomatic eruption on the back with acute onset were initially thought to be consistent with folliculitis; the differential diagnosis included transient acantholytic dermatosis and miliaria rubra. Lymphoma was not in the initial clinical differential, and we only arrived at this diagnosis based on histopathologic evaluation.

The neoplastic cells typically are positive for CD20, CD79a, and BCL-6, and negative for BCL-2.4 Most cases of PCFCL do not express the t(14;18) translocation involving the BCL-2 locus, in contrast to systemic follicular lymphoma.1 Systemic imaging and evaluation is needed to definitively differentiate PCFCL from systemic lymphoma with cutaneous involvement. Our patient was unusual in that BCL-2 was strongly staining in the setting of a negative systemic workup.

With regard to treatment of PCFCL, electron beam radiation therapy is highly effective and safe in patients with solitary lesions, as the remission rate is close to 100%.1 For patients with multiple lesions confined to one area, electron beam radiation therapy also can be helpful, as in our patient. In patients with more extensive skin involvement, rituximab therapy may be preferable. Relapse following treatment with either radiation or rituximab occurs in approximately one-third of patients, but these relapses generally are limited to the skin.1 The International Extranodal Lymphoma Study Group has noted that elevated lactate dehydrogenase, presence of more than 2 skin lesions, and presence of nodular lesions are negative prognostic factors in patients with PCFCL6; however, PCFCL has an excellent prognosis overall with a 5-year survival rate of 95%.1

Other rare heterogeneous presentations of PCFCL have been reported in the literature. A large multinodular mass on the scalp with multifocal facial lesions has been described in a patient with essential thrombocytopenia.7 Another report identified a variant of PCFCL characterized by multiple erythematous firm papules that were distributed in a miliary pattern, predominantly on the forehead and cheeks.8 Barzilai et al9 described 4 patients with PCFCL who developed lesions that were clinically similar to rosacea or rhinophyma, including papulonodular eruptions on the cheeks; infiltrated erythematous nasal plaques; and small flesh-colored to erythematous papules on the cheeks, nose, helices, and upper back. Hodak et al10 identified 2 cases of PCFCL that manifested as anetoderma, a condition characterized by the focal loss of elastic tissue. In the setting of chronic lymphocytic leukemia, PCFCL has been observed as a red or violaceous nodule with a centrally depressed scar on the legs.11 In one case, PCFCL manifested as recurrent episodes of extraorbital swelling and a multifocal red-blue macular lesion that extended from the inferior orbital rim to the nasojugal fold.12 An interesting presentation of PCFCL was noted as a small, recurring, blood-filled blister on the cheek with perineural spread of the tumor along cranial nerves V2, V3, VII, and VIII.13 In the pediatric literature, PCFCL has been reported to present as an erythematous nodule with a smooth surface and a hard elastic consistency that appeared on the nose and nasolabial fold and spread to the ipsilateral cheek, maxillary sinus, and soft palate.14 In many of these unusual cases, the diagnosis of PCFCL was made after treatment with topical or systemic anti-inflammatory therapies failed.

Increased recognition of anomalous presentations of PCFCL among dermatologists can lead to more timely diagnoses and treatment. Based on our experience with this patient, we recommend considering biopsy for histopathologic evaluation when treating patients with presumed folliculitis or transient acantholytic dermatosis that does not improve with routine treatment or is accompanied by systemic symptoms.

- Wilcox RA. Cutaneous B-cell lymphomas: 2015 update on diagnosis, risk-stratification, and management. Am J Hematol. 2015;90:73-76.

- Kim YH, Willemze R, Pimpinelli N, et al. TNM classification system for primary cutaneous lymphomas other than mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome: a proposal of the International Society for Cutaneous Lymphomas (ISCL) and the Cutaneous Lymphoma Task Force of the European Organization of Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC). Blood. 2007;110:479-484.

- World Health Organization. WHO Classification of Tumors of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues. Lyon, France: World Health Organization; 2008: 227.

- Dilly M, Ben-Rejeb H, Vergier B, et al. Primary cutaneous follicle center lymphoma with Hodgkin and Reed-Sternberg-like cells: a new histopathologic variant. J Cutan Pathol. 2014;41:797-801.

- Suárez AL, Pulitzer M, Horwitz S, et al. Primary cutaneous B-cell lymphomas: part I. clinical features, diagnosis, and classification. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:329.e1-13; quiz 341-342.

- Mian M, Marcheselli L, Luminari S, et al. CLIPI: a new prognostic index for indolent cutaneous B cell lymphoma proposed by the International Extranodal Lymphoma Study Group (IELSG 11) [published online September 25, 2010]. Ann Hematol. 2011;90:401-408.

- Tirefort Y, Pham XC, Ibrahim YL, et al. A rare case of primary cutaneous follicle centre lymphoma presenting as a giant tumour of the scalp and combined with JAK2V617F positive essential thrombocythaemia. Biomark Res. 2014;2:7.

- Massone C, Fink-Puches R, Laimer M, et al. Miliary and agminated-type primary cutaneous follicle center lymphoma: report of 18 cases.J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:749-755.

- Barzilai A, Feuerman H, Quaglino P, et al. Cutaneous B-cell neoplasms mimicking granulomatous rosacea or rhinophyma. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:824-831.

- Hodak E, Feuerman H, Barzilai A, et al. Anetodermic primary cutaneous B-cell lymphoma: a unique clinicopathological presentation of lymphoma possibly associated with antiphospholipid antibodies. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:175-182.

- Konda S, Beckford A, Demierre MF, et al. Primary cutaneous follicle center lymphoma in the setting of chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2011;77:314-317.

- Pandya VB, Conway RM, Taylor SF. Primary cutaneous B cell lymphoma presenting as recurrent eyelid swelling. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2008;36:672-674.

- Buda-Okreglak EM, Walden MJ, Brissette MD. Perineural CNS invasion in primary cutaneous follicular center lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:4684-4686.

- Ghislanzoni M, Gambini D, Perrone T, et al. Primary cutaneous follicular center cell lymphoma of the nose with maxillary sinus involvement in a pediatric patient. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52(5 suppl 1):S73-S75.

The 2008 World Health Organization and European Organization for Treatment of Cancer joint classification has distinguished 3 categories of primary cutaneous B-cell lymphomas: primary cutaneous follicle center lymphoma (PCFCL), primary cutaneous diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, and primary cutaneous marginal zone lymphoma.1-3 Primary cutaneous follicle center lymphoma is the most common type of cutaneous B-cell lymphoma, accounting for approximately 60% of cases worldwide.4 The median age at diagnosis is 60 years, and most lesions are located on the scalp, forehead, neck, and trunk.5 Histologically, PCFCL is characterized by dermal proliferation of centrocytes and centroblasts derived from germinal center B cells that are arranged in either a follicular, diffuse, or mixed growth pattern.1 The cutaneous manifestations of PCFCL include solitary erythematous or violaceous plaques, nodules, or tumors of varying sizes.4 Grouped lesions also may be observed, but multifocal disease is rare.1 We report a rare presentation of PCFCL mimicking folliculitis with multiple multifocal papules on the back.

Case Report

A 54-year-old woman presented with fever and leukocytosis of 4 days’ duration and was admitted to the hospital for presumed sepsis. She had a history of mastectomy for treatment of ductal carcinoma in situ of the right breast 5 years prior to the current presentation and endocrine therapy with tamoxifen. Her symptoms were thought to be a complication from a surgery for implantation of a tissue expander in the right breast 5 years prior to presentation.

During her hospital admission, she developed a papular and cystic eruption on the back that was clinically suggestive of folliculitis, transient acantholytic dermatosis (Grover disease), or miliaria rubra (Figure 1). This papular and cystic eruption initially was managed conservatively with observation as she recovered from an occult infection. Due to the persistent nature of the eruption on the back, an excisional biopsy of the cystic component was performed 2 months after her discharge from the hospital. Histologic studies showed a dense infiltrate of lymphocytes, which expanded into the deep dermis in a nodular and diffuse growth pattern that was accentuated in the periadnexal areas. The B lymphocytes were small and hyperchromatic with few scattered centroblasts (Figure 2). Further immunohistochemical studies demonstrated that the neoplastic cells were positive for CD20, CD79a, BCL-2, and BCL-6; CD3, CD5, and cyclin D1 were negative. Staining for antigen Ki-67 revealed a proliferation index of 15% to 20% among the neoplastic cells (Figure 3). These findings were consistent with either PCFCL or secondary cutaneous follicle center lymphoma.

Further evaluation for systemic disease was unremarkable. Positron emission tomography–computed tomography revealed no evidence of nodal lymphoma, and a bone marrow biopsy was negative. Other laboratory studies including lactate dehydrogenase were within reference range, which conferred a diagnosis of PCFCL. The patient was treated with localized electron beam radiation therapy to the skin of the mid back for a total dose of 24 Gy in 12 fractions at 2 Gy per fraction once daily over a 12-day period. She tolerated the treatment well and has remained clinically and radiographically without evidence of disease for more than 3 years.

Comment

Because the incidence of cutaneous B-cell lymphomas has been increasing, especially among males, non-Hispanic whites, and adults older than 50 years,1 it is important for clinicians to have a high index of suspicion for this entity. In our patient, the clinical findings of a papular, largely asymptomatic eruption on the back with acute onset were initially thought to be consistent with folliculitis; the differential diagnosis included transient acantholytic dermatosis and miliaria rubra. Lymphoma was not in the initial clinical differential, and we only arrived at this diagnosis based on histopathologic evaluation.

The neoplastic cells typically are positive for CD20, CD79a, and BCL-6, and negative for BCL-2.4 Most cases of PCFCL do not express the t(14;18) translocation involving the BCL-2 locus, in contrast to systemic follicular lymphoma.1 Systemic imaging and evaluation is needed to definitively differentiate PCFCL from systemic lymphoma with cutaneous involvement. Our patient was unusual in that BCL-2 was strongly staining in the setting of a negative systemic workup.

With regard to treatment of PCFCL, electron beam radiation therapy is highly effective and safe in patients with solitary lesions, as the remission rate is close to 100%.1 For patients with multiple lesions confined to one area, electron beam radiation therapy also can be helpful, as in our patient. In patients with more extensive skin involvement, rituximab therapy may be preferable. Relapse following treatment with either radiation or rituximab occurs in approximately one-third of patients, but these relapses generally are limited to the skin.1 The International Extranodal Lymphoma Study Group has noted that elevated lactate dehydrogenase, presence of more than 2 skin lesions, and presence of nodular lesions are negative prognostic factors in patients with PCFCL6; however, PCFCL has an excellent prognosis overall with a 5-year survival rate of 95%.1

Other rare heterogeneous presentations of PCFCL have been reported in the literature. A large multinodular mass on the scalp with multifocal facial lesions has been described in a patient with essential thrombocytopenia.7 Another report identified a variant of PCFCL characterized by multiple erythematous firm papules that were distributed in a miliary pattern, predominantly on the forehead and cheeks.8 Barzilai et al9 described 4 patients with PCFCL who developed lesions that were clinically similar to rosacea or rhinophyma, including papulonodular eruptions on the cheeks; infiltrated erythematous nasal plaques; and small flesh-colored to erythematous papules on the cheeks, nose, helices, and upper back. Hodak et al10 identified 2 cases of PCFCL that manifested as anetoderma, a condition characterized by the focal loss of elastic tissue. In the setting of chronic lymphocytic leukemia, PCFCL has been observed as a red or violaceous nodule with a centrally depressed scar on the legs.11 In one case, PCFCL manifested as recurrent episodes of extraorbital swelling and a multifocal red-blue macular lesion that extended from the inferior orbital rim to the nasojugal fold.12 An interesting presentation of PCFCL was noted as a small, recurring, blood-filled blister on the cheek with perineural spread of the tumor along cranial nerves V2, V3, VII, and VIII.13 In the pediatric literature, PCFCL has been reported to present as an erythematous nodule with a smooth surface and a hard elastic consistency that appeared on the nose and nasolabial fold and spread to the ipsilateral cheek, maxillary sinus, and soft palate.14 In many of these unusual cases, the diagnosis of PCFCL was made after treatment with topical or systemic anti-inflammatory therapies failed.

Increased recognition of anomalous presentations of PCFCL among dermatologists can lead to more timely diagnoses and treatment. Based on our experience with this patient, we recommend considering biopsy for histopathologic evaluation when treating patients with presumed folliculitis or transient acantholytic dermatosis that does not improve with routine treatment or is accompanied by systemic symptoms.

The 2008 World Health Organization and European Organization for Treatment of Cancer joint classification has distinguished 3 categories of primary cutaneous B-cell lymphomas: primary cutaneous follicle center lymphoma (PCFCL), primary cutaneous diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, and primary cutaneous marginal zone lymphoma.1-3 Primary cutaneous follicle center lymphoma is the most common type of cutaneous B-cell lymphoma, accounting for approximately 60% of cases worldwide.4 The median age at diagnosis is 60 years, and most lesions are located on the scalp, forehead, neck, and trunk.5 Histologically, PCFCL is characterized by dermal proliferation of centrocytes and centroblasts derived from germinal center B cells that are arranged in either a follicular, diffuse, or mixed growth pattern.1 The cutaneous manifestations of PCFCL include solitary erythematous or violaceous plaques, nodules, or tumors of varying sizes.4 Grouped lesions also may be observed, but multifocal disease is rare.1 We report a rare presentation of PCFCL mimicking folliculitis with multiple multifocal papules on the back.

Case Report

A 54-year-old woman presented with fever and leukocytosis of 4 days’ duration and was admitted to the hospital for presumed sepsis. She had a history of mastectomy for treatment of ductal carcinoma in situ of the right breast 5 years prior to the current presentation and endocrine therapy with tamoxifen. Her symptoms were thought to be a complication from a surgery for implantation of a tissue expander in the right breast 5 years prior to presentation.

During her hospital admission, she developed a papular and cystic eruption on the back that was clinically suggestive of folliculitis, transient acantholytic dermatosis (Grover disease), or miliaria rubra (Figure 1). This papular and cystic eruption initially was managed conservatively with observation as she recovered from an occult infection. Due to the persistent nature of the eruption on the back, an excisional biopsy of the cystic component was performed 2 months after her discharge from the hospital. Histologic studies showed a dense infiltrate of lymphocytes, which expanded into the deep dermis in a nodular and diffuse growth pattern that was accentuated in the periadnexal areas. The B lymphocytes were small and hyperchromatic with few scattered centroblasts (Figure 2). Further immunohistochemical studies demonstrated that the neoplastic cells were positive for CD20, CD79a, BCL-2, and BCL-6; CD3, CD5, and cyclin D1 were negative. Staining for antigen Ki-67 revealed a proliferation index of 15% to 20% among the neoplastic cells (Figure 3). These findings were consistent with either PCFCL or secondary cutaneous follicle center lymphoma.

Further evaluation for systemic disease was unremarkable. Positron emission tomography–computed tomography revealed no evidence of nodal lymphoma, and a bone marrow biopsy was negative. Other laboratory studies including lactate dehydrogenase were within reference range, which conferred a diagnosis of PCFCL. The patient was treated with localized electron beam radiation therapy to the skin of the mid back for a total dose of 24 Gy in 12 fractions at 2 Gy per fraction once daily over a 12-day period. She tolerated the treatment well and has remained clinically and radiographically without evidence of disease for more than 3 years.

Comment

Because the incidence of cutaneous B-cell lymphomas has been increasing, especially among males, non-Hispanic whites, and adults older than 50 years,1 it is important for clinicians to have a high index of suspicion for this entity. In our patient, the clinical findings of a papular, largely asymptomatic eruption on the back with acute onset were initially thought to be consistent with folliculitis; the differential diagnosis included transient acantholytic dermatosis and miliaria rubra. Lymphoma was not in the initial clinical differential, and we only arrived at this diagnosis based on histopathologic evaluation.

The neoplastic cells typically are positive for CD20, CD79a, and BCL-6, and negative for BCL-2.4 Most cases of PCFCL do not express the t(14;18) translocation involving the BCL-2 locus, in contrast to systemic follicular lymphoma.1 Systemic imaging and evaluation is needed to definitively differentiate PCFCL from systemic lymphoma with cutaneous involvement. Our patient was unusual in that BCL-2 was strongly staining in the setting of a negative systemic workup.

With regard to treatment of PCFCL, electron beam radiation therapy is highly effective and safe in patients with solitary lesions, as the remission rate is close to 100%.1 For patients with multiple lesions confined to one area, electron beam radiation therapy also can be helpful, as in our patient. In patients with more extensive skin involvement, rituximab therapy may be preferable. Relapse following treatment with either radiation or rituximab occurs in approximately one-third of patients, but these relapses generally are limited to the skin.1 The International Extranodal Lymphoma Study Group has noted that elevated lactate dehydrogenase, presence of more than 2 skin lesions, and presence of nodular lesions are negative prognostic factors in patients with PCFCL6; however, PCFCL has an excellent prognosis overall with a 5-year survival rate of 95%.1

Other rare heterogeneous presentations of PCFCL have been reported in the literature. A large multinodular mass on the scalp with multifocal facial lesions has been described in a patient with essential thrombocytopenia.7 Another report identified a variant of PCFCL characterized by multiple erythematous firm papules that were distributed in a miliary pattern, predominantly on the forehead and cheeks.8 Barzilai et al9 described 4 patients with PCFCL who developed lesions that were clinically similar to rosacea or rhinophyma, including papulonodular eruptions on the cheeks; infiltrated erythematous nasal plaques; and small flesh-colored to erythematous papules on the cheeks, nose, helices, and upper back. Hodak et al10 identified 2 cases of PCFCL that manifested as anetoderma, a condition characterized by the focal loss of elastic tissue. In the setting of chronic lymphocytic leukemia, PCFCL has been observed as a red or violaceous nodule with a centrally depressed scar on the legs.11 In one case, PCFCL manifested as recurrent episodes of extraorbital swelling and a multifocal red-blue macular lesion that extended from the inferior orbital rim to the nasojugal fold.12 An interesting presentation of PCFCL was noted as a small, recurring, blood-filled blister on the cheek with perineural spread of the tumor along cranial nerves V2, V3, VII, and VIII.13 In the pediatric literature, PCFCL has been reported to present as an erythematous nodule with a smooth surface and a hard elastic consistency that appeared on the nose and nasolabial fold and spread to the ipsilateral cheek, maxillary sinus, and soft palate.14 In many of these unusual cases, the diagnosis of PCFCL was made after treatment with topical or systemic anti-inflammatory therapies failed.

Increased recognition of anomalous presentations of PCFCL among dermatologists can lead to more timely diagnoses and treatment. Based on our experience with this patient, we recommend considering biopsy for histopathologic evaluation when treating patients with presumed folliculitis or transient acantholytic dermatosis that does not improve with routine treatment or is accompanied by systemic symptoms.

- Wilcox RA. Cutaneous B-cell lymphomas: 2015 update on diagnosis, risk-stratification, and management. Am J Hematol. 2015;90:73-76.

- Kim YH, Willemze R, Pimpinelli N, et al. TNM classification system for primary cutaneous lymphomas other than mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome: a proposal of the International Society for Cutaneous Lymphomas (ISCL) and the Cutaneous Lymphoma Task Force of the European Organization of Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC). Blood. 2007;110:479-484.

- World Health Organization. WHO Classification of Tumors of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues. Lyon, France: World Health Organization; 2008: 227.

- Dilly M, Ben-Rejeb H, Vergier B, et al. Primary cutaneous follicle center lymphoma with Hodgkin and Reed-Sternberg-like cells: a new histopathologic variant. J Cutan Pathol. 2014;41:797-801.

- Suárez AL, Pulitzer M, Horwitz S, et al. Primary cutaneous B-cell lymphomas: part I. clinical features, diagnosis, and classification. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:329.e1-13; quiz 341-342.

- Mian M, Marcheselli L, Luminari S, et al. CLIPI: a new prognostic index for indolent cutaneous B cell lymphoma proposed by the International Extranodal Lymphoma Study Group (IELSG 11) [published online September 25, 2010]. Ann Hematol. 2011;90:401-408.

- Tirefort Y, Pham XC, Ibrahim YL, et al. A rare case of primary cutaneous follicle centre lymphoma presenting as a giant tumour of the scalp and combined with JAK2V617F positive essential thrombocythaemia. Biomark Res. 2014;2:7.

- Massone C, Fink-Puches R, Laimer M, et al. Miliary and agminated-type primary cutaneous follicle center lymphoma: report of 18 cases.J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:749-755.

- Barzilai A, Feuerman H, Quaglino P, et al. Cutaneous B-cell neoplasms mimicking granulomatous rosacea or rhinophyma. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:824-831.

- Hodak E, Feuerman H, Barzilai A, et al. Anetodermic primary cutaneous B-cell lymphoma: a unique clinicopathological presentation of lymphoma possibly associated with antiphospholipid antibodies. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:175-182.

- Konda S, Beckford A, Demierre MF, et al. Primary cutaneous follicle center lymphoma in the setting of chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2011;77:314-317.

- Pandya VB, Conway RM, Taylor SF. Primary cutaneous B cell lymphoma presenting as recurrent eyelid swelling. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2008;36:672-674.

- Buda-Okreglak EM, Walden MJ, Brissette MD. Perineural CNS invasion in primary cutaneous follicular center lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:4684-4686.

- Ghislanzoni M, Gambini D, Perrone T, et al. Primary cutaneous follicular center cell lymphoma of the nose with maxillary sinus involvement in a pediatric patient. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52(5 suppl 1):S73-S75.

- Wilcox RA. Cutaneous B-cell lymphomas: 2015 update on diagnosis, risk-stratification, and management. Am J Hematol. 2015;90:73-76.

- Kim YH, Willemze R, Pimpinelli N, et al. TNM classification system for primary cutaneous lymphomas other than mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome: a proposal of the International Society for Cutaneous Lymphomas (ISCL) and the Cutaneous Lymphoma Task Force of the European Organization of Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC). Blood. 2007;110:479-484.

- World Health Organization. WHO Classification of Tumors of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues. Lyon, France: World Health Organization; 2008: 227.

- Dilly M, Ben-Rejeb H, Vergier B, et al. Primary cutaneous follicle center lymphoma with Hodgkin and Reed-Sternberg-like cells: a new histopathologic variant. J Cutan Pathol. 2014;41:797-801.

- Suárez AL, Pulitzer M, Horwitz S, et al. Primary cutaneous B-cell lymphomas: part I. clinical features, diagnosis, and classification. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:329.e1-13; quiz 341-342.

- Mian M, Marcheselli L, Luminari S, et al. CLIPI: a new prognostic index for indolent cutaneous B cell lymphoma proposed by the International Extranodal Lymphoma Study Group (IELSG 11) [published online September 25, 2010]. Ann Hematol. 2011;90:401-408.

- Tirefort Y, Pham XC, Ibrahim YL, et al. A rare case of primary cutaneous follicle centre lymphoma presenting as a giant tumour of the scalp and combined with JAK2V617F positive essential thrombocythaemia. Biomark Res. 2014;2:7.

- Massone C, Fink-Puches R, Laimer M, et al. Miliary and agminated-type primary cutaneous follicle center lymphoma: report of 18 cases.J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:749-755.

- Barzilai A, Feuerman H, Quaglino P, et al. Cutaneous B-cell neoplasms mimicking granulomatous rosacea or rhinophyma. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:824-831.

- Hodak E, Feuerman H, Barzilai A, et al. Anetodermic primary cutaneous B-cell lymphoma: a unique clinicopathological presentation of lymphoma possibly associated with antiphospholipid antibodies. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:175-182.

- Konda S, Beckford A, Demierre MF, et al. Primary cutaneous follicle center lymphoma in the setting of chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2011;77:314-317.

- Pandya VB, Conway RM, Taylor SF. Primary cutaneous B cell lymphoma presenting as recurrent eyelid swelling. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2008;36:672-674.

- Buda-Okreglak EM, Walden MJ, Brissette MD. Perineural CNS invasion in primary cutaneous follicular center lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:4684-4686.

- Ghislanzoni M, Gambini D, Perrone T, et al. Primary cutaneous follicular center cell lymphoma of the nose with maxillary sinus involvement in a pediatric patient. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52(5 suppl 1):S73-S75.

Practice Points

- Atypical or unresponsive folliculitis should be biopsied.

- Primary cutaneous follicle center lymphoma can mimic folliculitis or Grover disease.

Surgery team scorecard improved patient satisfaction

JACKSONVILLE, FLA. – A scorecard enables spectators at a baseball game to keep track of who the players are, and a scorecard of the surgery team can do the same for inpatients, researchers at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore found.

They gave patients a “facesheet” that included photographs and biographies of all members of their surgery team, which helped patients to better understand the team members’ roles in their care and led to improvements in overall satisfaction scores, according to a study reported at the Association for Academic Surgery/Society of University Surgeons Academic Surgical Congress.

The study involved two intervals: a prefacesheet phase of 153 patients and a postfacesheet phase of 100 patients. The two groups, all gastrointestinal surgery inpatients, were administered preintervention discharge surveys to evaluate their level of patient satisfaction according to a 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree and 5 = strongly agree).

“We found that using these facesheets helped patients know the roles of their team members, and the patients felt that it was important to [have this information],” Dr. DiBrito said.

The share of patients answering 4 (agreed) or 5 (strongly agreed) for overall satisfaction rose from 83% before the facesheet intervention to 88% afterward (P = .5). The number of patients agreeing that they understood their providers’ roles increased from 72% to 83% (P = .05), and the number who agreed that it was important to know who their surgical team members were increased from 85% to 94% (P = .04). The latter finding somewhat surprised the researchers. Dr. DiBrito said, “That’s not exactly what we were anticipating.”

The study also revealed a trend in patients’ feeling more confident in their team overall after the facesheet intervention, rising from 89% to 95%, Dr. DiBrito said.

She said the Johns Hopkins team is not continuing the initiative currently but would like to roll it out more broadly to other hospital services. Other groups within the hospital, including nursing and clinical customer services, must get on board, she said. “We really need buy-in from higher levels in the hospital, and this was part of the proof that we needed,” Dr. DiBrito said.

The premise of the study was that patients need to identify a member of their care team as a point person, she added. “We’re trying to give the patients, and their family members as well, some people to look out for,” Dr. DiBrito said.

Dr. DiBrito and her coauthors had no financial relationships to disclose.

SOURCE: Dibrito SR et al. Academic Surgical Congress 2018, Abstract 09.04.

JACKSONVILLE, FLA. – A scorecard enables spectators at a baseball game to keep track of who the players are, and a scorecard of the surgery team can do the same for inpatients, researchers at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore found.

They gave patients a “facesheet” that included photographs and biographies of all members of their surgery team, which helped patients to better understand the team members’ roles in their care and led to improvements in overall satisfaction scores, according to a study reported at the Association for Academic Surgery/Society of University Surgeons Academic Surgical Congress.

The study involved two intervals: a prefacesheet phase of 153 patients and a postfacesheet phase of 100 patients. The two groups, all gastrointestinal surgery inpatients, were administered preintervention discharge surveys to evaluate their level of patient satisfaction according to a 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree and 5 = strongly agree).

“We found that using these facesheets helped patients know the roles of their team members, and the patients felt that it was important to [have this information],” Dr. DiBrito said.

The share of patients answering 4 (agreed) or 5 (strongly agreed) for overall satisfaction rose from 83% before the facesheet intervention to 88% afterward (P = .5). The number of patients agreeing that they understood their providers’ roles increased from 72% to 83% (P = .05), and the number who agreed that it was important to know who their surgical team members were increased from 85% to 94% (P = .04). The latter finding somewhat surprised the researchers. Dr. DiBrito said, “That’s not exactly what we were anticipating.”

The study also revealed a trend in patients’ feeling more confident in their team overall after the facesheet intervention, rising from 89% to 95%, Dr. DiBrito said.

She said the Johns Hopkins team is not continuing the initiative currently but would like to roll it out more broadly to other hospital services. Other groups within the hospital, including nursing and clinical customer services, must get on board, she said. “We really need buy-in from higher levels in the hospital, and this was part of the proof that we needed,” Dr. DiBrito said.

The premise of the study was that patients need to identify a member of their care team as a point person, she added. “We’re trying to give the patients, and their family members as well, some people to look out for,” Dr. DiBrito said.

Dr. DiBrito and her coauthors had no financial relationships to disclose.

SOURCE: Dibrito SR et al. Academic Surgical Congress 2018, Abstract 09.04.

JACKSONVILLE, FLA. – A scorecard enables spectators at a baseball game to keep track of who the players are, and a scorecard of the surgery team can do the same for inpatients, researchers at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore found.

They gave patients a “facesheet” that included photographs and biographies of all members of their surgery team, which helped patients to better understand the team members’ roles in their care and led to improvements in overall satisfaction scores, according to a study reported at the Association for Academic Surgery/Society of University Surgeons Academic Surgical Congress.

The study involved two intervals: a prefacesheet phase of 153 patients and a postfacesheet phase of 100 patients. The two groups, all gastrointestinal surgery inpatients, were administered preintervention discharge surveys to evaluate their level of patient satisfaction according to a 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree and 5 = strongly agree).

“We found that using these facesheets helped patients know the roles of their team members, and the patients felt that it was important to [have this information],” Dr. DiBrito said.

The share of patients answering 4 (agreed) or 5 (strongly agreed) for overall satisfaction rose from 83% before the facesheet intervention to 88% afterward (P = .5). The number of patients agreeing that they understood their providers’ roles increased from 72% to 83% (P = .05), and the number who agreed that it was important to know who their surgical team members were increased from 85% to 94% (P = .04). The latter finding somewhat surprised the researchers. Dr. DiBrito said, “That’s not exactly what we were anticipating.”

The study also revealed a trend in patients’ feeling more confident in their team overall after the facesheet intervention, rising from 89% to 95%, Dr. DiBrito said.

She said the Johns Hopkins team is not continuing the initiative currently but would like to roll it out more broadly to other hospital services. Other groups within the hospital, including nursing and clinical customer services, must get on board, she said. “We really need buy-in from higher levels in the hospital, and this was part of the proof that we needed,” Dr. DiBrito said.

The premise of the study was that patients need to identify a member of their care team as a point person, she added. “We’re trying to give the patients, and their family members as well, some people to look out for,” Dr. DiBrito said.

Dr. DiBrito and her coauthors had no financial relationships to disclose.

SOURCE: Dibrito SR et al. Academic Surgical Congress 2018, Abstract 09.04.

REPORTING FROM THE ACADEMIC SURGICAL CONGRESS

Key clinical point: A “facesheet” that includes photographs and biographies of the surgical care team improves patient satisfaction.

Major finding: Overall satisfaction scores increased from 83% preintervention to 88% postintervention.

Data source: Analysis of the survey responses from 253 gastrointestinal surgery patients pre- and postintervention from February 2017 to May 2017.

Disclosures: Dr. DiBrito and her coauthors had no financial relationships to disclose.

Source: Dibrito SR et al. Academic Surgical Congress 2018, Abstract 09.04.

FDA issues safety alert for loperamide

The Food and Drug Administration announced Jan. 30 that is has issued a MedWatch safety alert on the use of the over-the-counter (OTC) antidiarrhea drug, loperamide.

Currently, the FDA is working with manufacturers to use blister packs or other single-dose packaging and to limit the number of doses in a package.

The alert comes after receiving continuous reports of serious heart problems and deaths with the use of much higher than recommended doses of loperamide, mainly among people who are intentionally misusing or abusing the product, regardless of the addition of a warning to the medicine label and a previous communication. The FDA states that loperamide is a safe drug when used as directed.

Loperamide is approved to help control symptoms of diarrhea. The maximum recommended daily dose for adults is 8 mg per day for OTC use and 16 mg per day for prescription use. It acts on opioid receptors in the gut to slow the movement in the intestines and decrease the number of bowel movements.

It is noted that much higher than recommended doses of loperamide, either intentionally or unintentionally, can result in serious cardiac adverse events, including QT interval prolongation, torsade de pointes or other ventricular arrhythmias, syncope, and cardiac arrest. Health care professionals and patients can report adverse events or side effects related to the use of these products to the FDA’s MedWatch Safety Information and Adverse Event Reporting Program.

In 2016, the FDA issued a Drug Safety Communication and added warnings about serious heart problems to the drug label of prescription loperamide and to the Drug Facts label of OTC loperamide products. The FDA is working to evaluate this safety issue and will update the public when more information is available.

Read the full safety alert here.

The Food and Drug Administration announced Jan. 30 that is has issued a MedWatch safety alert on the use of the over-the-counter (OTC) antidiarrhea drug, loperamide.

Currently, the FDA is working with manufacturers to use blister packs or other single-dose packaging and to limit the number of doses in a package.

The alert comes after receiving continuous reports of serious heart problems and deaths with the use of much higher than recommended doses of loperamide, mainly among people who are intentionally misusing or abusing the product, regardless of the addition of a warning to the medicine label and a previous communication. The FDA states that loperamide is a safe drug when used as directed.

Loperamide is approved to help control symptoms of diarrhea. The maximum recommended daily dose for adults is 8 mg per day for OTC use and 16 mg per day for prescription use. It acts on opioid receptors in the gut to slow the movement in the intestines and decrease the number of bowel movements.

It is noted that much higher than recommended doses of loperamide, either intentionally or unintentionally, can result in serious cardiac adverse events, including QT interval prolongation, torsade de pointes or other ventricular arrhythmias, syncope, and cardiac arrest. Health care professionals and patients can report adverse events or side effects related to the use of these products to the FDA’s MedWatch Safety Information and Adverse Event Reporting Program.

In 2016, the FDA issued a Drug Safety Communication and added warnings about serious heart problems to the drug label of prescription loperamide and to the Drug Facts label of OTC loperamide products. The FDA is working to evaluate this safety issue and will update the public when more information is available.

Read the full safety alert here.

The Food and Drug Administration announced Jan. 30 that is has issued a MedWatch safety alert on the use of the over-the-counter (OTC) antidiarrhea drug, loperamide.

Currently, the FDA is working with manufacturers to use blister packs or other single-dose packaging and to limit the number of doses in a package.

The alert comes after receiving continuous reports of serious heart problems and deaths with the use of much higher than recommended doses of loperamide, mainly among people who are intentionally misusing or abusing the product, regardless of the addition of a warning to the medicine label and a previous communication. The FDA states that loperamide is a safe drug when used as directed.

Loperamide is approved to help control symptoms of diarrhea. The maximum recommended daily dose for adults is 8 mg per day for OTC use and 16 mg per day for prescription use. It acts on opioid receptors in the gut to slow the movement in the intestines and decrease the number of bowel movements.

It is noted that much higher than recommended doses of loperamide, either intentionally or unintentionally, can result in serious cardiac adverse events, including QT interval prolongation, torsade de pointes or other ventricular arrhythmias, syncope, and cardiac arrest. Health care professionals and patients can report adverse events or side effects related to the use of these products to the FDA’s MedWatch Safety Information and Adverse Event Reporting Program.

In 2016, the FDA issued a Drug Safety Communication and added warnings about serious heart problems to the drug label of prescription loperamide and to the Drug Facts label of OTC loperamide products. The FDA is working to evaluate this safety issue and will update the public when more information is available.

Read the full safety alert here.

Periorbital Lupuslike Presentation of Graft-versus-host Disease

To the Editor:

A 79-year-old man presented with a scaling eruption in the periorbital area, on the bilateral forearms, and on the chest of 4 weeks’ duration. The patient denied systemic symptoms including lethargy, muscle weakness, and fevers. His medical history was notable for blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm, a form of acute myeloid leukemia, diagnosed 3 years prior to presentation. The patient received an allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant 8 months later. His posttransplant course was complicated by gastrointestinal graft-versus-host disease (GVHD); progressive graft loss requiring a donor lymphocyte infusion after 1 month; and leukemia cutis, which spontaneously resolved after 1 month. The patient was taken off all immunosuppressive therapy 5 months after the transplant and had been doing well for 2 years with only mild mucosal GVHD affecting the oral mucosa and the head of the penis.

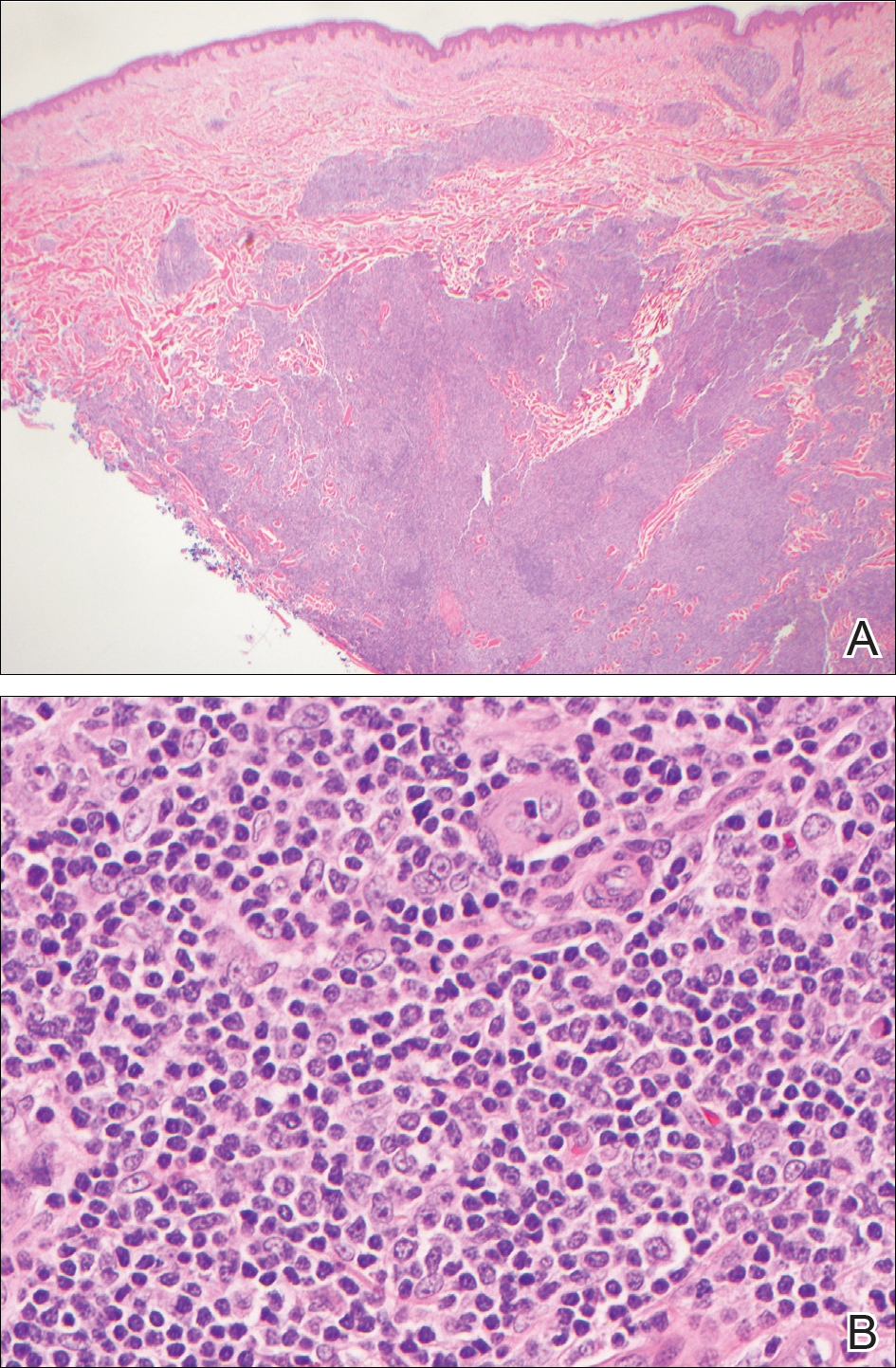

Physical examination at the current presentation revealed linear, atrophic, scaling, purplish plaques with adherent white scale on the upper and lower eyelids (Figure 1). The patient also had scattered purple scaling patches on the bilateral forearms and chest. Laboratory tests including complete blood cell count, comprehensive metabolic panel, and lactate dehydrogenase demonstrated no gross abnormalities. Two shave biopsies of the right lower eyelid (Figure 2) and left arm (Figure 3) were performed for histologic examination and revealed basket weave hyperkeratosis, irregular acanthosis, sawtooth rete ridges, and scattered dyskeratotic cells. Vacuolar changes and smudging of the basement membrane zone along with a bandlike lymphocytic infiltrate in the upper dermis also were noted in both biopsies. A diagnosis of lupuslike grade 1 GVHD was made.

Graft-versus-host disease remains a notable cause of morbidity and mortality in allogenic hematopoietic stem cell transplant patients.1 Skin manifestations represent the most common manifestation of GVHD and have been reclassified as acute or chronic disease based on clinical and histologic findings rather than time of onset. Although acute GVHD classically presents as diffuse morbilliform papules and macules, chronic GVHD has a large range of clinical presentations most commonly mimicking the skin findings of lichen planus, morphea, scleroderma, or lichen sclerosus.1

Lupuslike GVHD is a rarely reported manifestation of chronic GVHD that predominantly affects the lower eyelids and malar regions.2,3 Our case documents extensive involvement of both the upper and lower eyelids. A lupuslike manifestation of GVHD may portend a poor prognosis. In a case series of 5 patients with chronic GVHD presenting as facial lupuslike plaques, 1 patient died from a relapse of leukemia and 3 patients developed sclerodermatous GVHD. The fifth patient was lost to follow-up.2 In another case series, a retrospective analysis discovered that 3 of 7 patients with sclerodermatous GVHD initially presented with hyperpigmented periorbital plaques.4 Resolution of skin findings with topical steroids and oral tacrolimus was reported in a case of GVHD presenting with periorbital lupuslike plaques.3 Although further reports are needed to validate the relationship, a lupuslike presentation of chronic GVHD may be an important harbinger for the development of extensive sclerodermatous GVHD.

A diagnosis of lupuslike GVHD is made based on the correlation of a comprehensive medical history, clinical examination, and histopathologic findings. Although other cases of chronic GVHD resembling dermatomyositis presented with purple periorbital plaques, these patients demonstrated dermatomyositislike systemic symptoms including muscle weakness and fatigue, which were not present in our patient.5,6 Antinuclear antibody (ANA) testing is unlikely to be helpful in the diagnosis of this uncommon presentation, as 65% (41/63) of chronic GVHD patients developed ANA antibodies in one study.7 Also, other patients with lupuslike GVHD who progressed to sclerodermatous GVHD have had both positive and negative ANA serology.2 The histopathology of GVHD and lupus erythematosus can exhibit overlapping features, such as lymphocytic infiltrate with interface changes; however, in lupus erythematosus, mucin usually is present, the infiltrate usually is denser and deeper, and a thickened basement membrane zone may be present. Necrotic keratinocytes also usually are not seen in lupus erythematosus unless the patient’s photosensitivity has led to a sunburn reaction.

After his initial presentation, our patient’s mucosal GVHD flared in the mouth and on the penis, and he was started on prednisone 50 mg once daily and mycophenolate mofetil 1 g twice daily. With this treatment, our patient’s periorbital scaling plaques resolved to residual hyperpigmentation along with remarkable improvement of the mucosal GVHD. He has not manifested any signs of leukemia relapse or sclerodermatous GVHD; however, he remains under close clinical evaluation.

This case highlights an unusual presentation of GVHD with periorbital plaques mimicking hypertrophic lupus erythematous. A greater recognition of this rare entity is essential to further elucidate its prognosis and its relationship with sclerodermatous GVHD.

- Hymes SR, Alousi AM, Cowen EW. Graft-versus-host disease: part I. pathogenesis and clinical manifestations of graft-versus-host disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66:515.e1-5.15e18; quiz 533-534.

- Goiriz R, Peñas PF, Delgado-Jiménez Y, et al. Cutaneous lichenoid graft-versus-host disease mimicking lupus erythematosus. Lupus. 2008;17:591-595.

- Hu SW, Myskowski PL, Papadopoulos EB, et al. Chronic cutaneous graft-versus host disease simulating hypertrophic lupus erythematosus—a case report of a new morphologic variant of graft-versus-host disease. Am J Dermatopathol. 2012;34:E81-E83.

- Chosidow O, Bagot M, Vernant JP, et al. Sclerodermatous chronic graft-versus-host disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;26:49-55.

- Ollivier I, Wolkenstein P, Gherardi R, et al. Dermatomyositis-like graft-versus-host disease. Br J Dermatol. 1998;138:558-559.

- Arin MJ, Scheid C, Hübel K, et al. Chronic graft-versus-host disease with skin signs suggestive of dermatomyositis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2006;31:141-143.

- Patriarca F, Skert C, Sperotto A, et al. The development of autoantibodies after allogeneic stem cell transplantation is related with chronic graft-vs-host disease and immune recovery. Exp Hematol. 2006;34:389-396.

To the Editor:

A 79-year-old man presented with a scaling eruption in the periorbital area, on the bilateral forearms, and on the chest of 4 weeks’ duration. The patient denied systemic symptoms including lethargy, muscle weakness, and fevers. His medical history was notable for blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm, a form of acute myeloid leukemia, diagnosed 3 years prior to presentation. The patient received an allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant 8 months later. His posttransplant course was complicated by gastrointestinal graft-versus-host disease (GVHD); progressive graft loss requiring a donor lymphocyte infusion after 1 month; and leukemia cutis, which spontaneously resolved after 1 month. The patient was taken off all immunosuppressive therapy 5 months after the transplant and had been doing well for 2 years with only mild mucosal GVHD affecting the oral mucosa and the head of the penis.

Physical examination at the current presentation revealed linear, atrophic, scaling, purplish plaques with adherent white scale on the upper and lower eyelids (Figure 1). The patient also had scattered purple scaling patches on the bilateral forearms and chest. Laboratory tests including complete blood cell count, comprehensive metabolic panel, and lactate dehydrogenase demonstrated no gross abnormalities. Two shave biopsies of the right lower eyelid (Figure 2) and left arm (Figure 3) were performed for histologic examination and revealed basket weave hyperkeratosis, irregular acanthosis, sawtooth rete ridges, and scattered dyskeratotic cells. Vacuolar changes and smudging of the basement membrane zone along with a bandlike lymphocytic infiltrate in the upper dermis also were noted in both biopsies. A diagnosis of lupuslike grade 1 GVHD was made.

Graft-versus-host disease remains a notable cause of morbidity and mortality in allogenic hematopoietic stem cell transplant patients.1 Skin manifestations represent the most common manifestation of GVHD and have been reclassified as acute or chronic disease based on clinical and histologic findings rather than time of onset. Although acute GVHD classically presents as diffuse morbilliform papules and macules, chronic GVHD has a large range of clinical presentations most commonly mimicking the skin findings of lichen planus, morphea, scleroderma, or lichen sclerosus.1

Lupuslike GVHD is a rarely reported manifestation of chronic GVHD that predominantly affects the lower eyelids and malar regions.2,3 Our case documents extensive involvement of both the upper and lower eyelids. A lupuslike manifestation of GVHD may portend a poor prognosis. In a case series of 5 patients with chronic GVHD presenting as facial lupuslike plaques, 1 patient died from a relapse of leukemia and 3 patients developed sclerodermatous GVHD. The fifth patient was lost to follow-up.2 In another case series, a retrospective analysis discovered that 3 of 7 patients with sclerodermatous GVHD initially presented with hyperpigmented periorbital plaques.4 Resolution of skin findings with topical steroids and oral tacrolimus was reported in a case of GVHD presenting with periorbital lupuslike plaques.3 Although further reports are needed to validate the relationship, a lupuslike presentation of chronic GVHD may be an important harbinger for the development of extensive sclerodermatous GVHD.

A diagnosis of lupuslike GVHD is made based on the correlation of a comprehensive medical history, clinical examination, and histopathologic findings. Although other cases of chronic GVHD resembling dermatomyositis presented with purple periorbital plaques, these patients demonstrated dermatomyositislike systemic symptoms including muscle weakness and fatigue, which were not present in our patient.5,6 Antinuclear antibody (ANA) testing is unlikely to be helpful in the diagnosis of this uncommon presentation, as 65% (41/63) of chronic GVHD patients developed ANA antibodies in one study.7 Also, other patients with lupuslike GVHD who progressed to sclerodermatous GVHD have had both positive and negative ANA serology.2 The histopathology of GVHD and lupus erythematosus can exhibit overlapping features, such as lymphocytic infiltrate with interface changes; however, in lupus erythematosus, mucin usually is present, the infiltrate usually is denser and deeper, and a thickened basement membrane zone may be present. Necrotic keratinocytes also usually are not seen in lupus erythematosus unless the patient’s photosensitivity has led to a sunburn reaction.

After his initial presentation, our patient’s mucosal GVHD flared in the mouth and on the penis, and he was started on prednisone 50 mg once daily and mycophenolate mofetil 1 g twice daily. With this treatment, our patient’s periorbital scaling plaques resolved to residual hyperpigmentation along with remarkable improvement of the mucosal GVHD. He has not manifested any signs of leukemia relapse or sclerodermatous GVHD; however, he remains under close clinical evaluation.

This case highlights an unusual presentation of GVHD with periorbital plaques mimicking hypertrophic lupus erythematous. A greater recognition of this rare entity is essential to further elucidate its prognosis and its relationship with sclerodermatous GVHD.

To the Editor:

A 79-year-old man presented with a scaling eruption in the periorbital area, on the bilateral forearms, and on the chest of 4 weeks’ duration. The patient denied systemic symptoms including lethargy, muscle weakness, and fevers. His medical history was notable for blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm, a form of acute myeloid leukemia, diagnosed 3 years prior to presentation. The patient received an allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant 8 months later. His posttransplant course was complicated by gastrointestinal graft-versus-host disease (GVHD); progressive graft loss requiring a donor lymphocyte infusion after 1 month; and leukemia cutis, which spontaneously resolved after 1 month. The patient was taken off all immunosuppressive therapy 5 months after the transplant and had been doing well for 2 years with only mild mucosal GVHD affecting the oral mucosa and the head of the penis.

Physical examination at the current presentation revealed linear, atrophic, scaling, purplish plaques with adherent white scale on the upper and lower eyelids (Figure 1). The patient also had scattered purple scaling patches on the bilateral forearms and chest. Laboratory tests including complete blood cell count, comprehensive metabolic panel, and lactate dehydrogenase demonstrated no gross abnormalities. Two shave biopsies of the right lower eyelid (Figure 2) and left arm (Figure 3) were performed for histologic examination and revealed basket weave hyperkeratosis, irregular acanthosis, sawtooth rete ridges, and scattered dyskeratotic cells. Vacuolar changes and smudging of the basement membrane zone along with a bandlike lymphocytic infiltrate in the upper dermis also were noted in both biopsies. A diagnosis of lupuslike grade 1 GVHD was made.

Graft-versus-host disease remains a notable cause of morbidity and mortality in allogenic hematopoietic stem cell transplant patients.1 Skin manifestations represent the most common manifestation of GVHD and have been reclassified as acute or chronic disease based on clinical and histologic findings rather than time of onset. Although acute GVHD classically presents as diffuse morbilliform papules and macules, chronic GVHD has a large range of clinical presentations most commonly mimicking the skin findings of lichen planus, morphea, scleroderma, or lichen sclerosus.1

Lupuslike GVHD is a rarely reported manifestation of chronic GVHD that predominantly affects the lower eyelids and malar regions.2,3 Our case documents extensive involvement of both the upper and lower eyelids. A lupuslike manifestation of GVHD may portend a poor prognosis. In a case series of 5 patients with chronic GVHD presenting as facial lupuslike plaques, 1 patient died from a relapse of leukemia and 3 patients developed sclerodermatous GVHD. The fifth patient was lost to follow-up.2 In another case series, a retrospective analysis discovered that 3 of 7 patients with sclerodermatous GVHD initially presented with hyperpigmented periorbital plaques.4 Resolution of skin findings with topical steroids and oral tacrolimus was reported in a case of GVHD presenting with periorbital lupuslike plaques.3 Although further reports are needed to validate the relationship, a lupuslike presentation of chronic GVHD may be an important harbinger for the development of extensive sclerodermatous GVHD.

A diagnosis of lupuslike GVHD is made based on the correlation of a comprehensive medical history, clinical examination, and histopathologic findings. Although other cases of chronic GVHD resembling dermatomyositis presented with purple periorbital plaques, these patients demonstrated dermatomyositislike systemic symptoms including muscle weakness and fatigue, which were not present in our patient.5,6 Antinuclear antibody (ANA) testing is unlikely to be helpful in the diagnosis of this uncommon presentation, as 65% (41/63) of chronic GVHD patients developed ANA antibodies in one study.7 Also, other patients with lupuslike GVHD who progressed to sclerodermatous GVHD have had both positive and negative ANA serology.2 The histopathology of GVHD and lupus erythematosus can exhibit overlapping features, such as lymphocytic infiltrate with interface changes; however, in lupus erythematosus, mucin usually is present, the infiltrate usually is denser and deeper, and a thickened basement membrane zone may be present. Necrotic keratinocytes also usually are not seen in lupus erythematosus unless the patient’s photosensitivity has led to a sunburn reaction.

After his initial presentation, our patient’s mucosal GVHD flared in the mouth and on the penis, and he was started on prednisone 50 mg once daily and mycophenolate mofetil 1 g twice daily. With this treatment, our patient’s periorbital scaling plaques resolved to residual hyperpigmentation along with remarkable improvement of the mucosal GVHD. He has not manifested any signs of leukemia relapse or sclerodermatous GVHD; however, he remains under close clinical evaluation.

This case highlights an unusual presentation of GVHD with periorbital plaques mimicking hypertrophic lupus erythematous. A greater recognition of this rare entity is essential to further elucidate its prognosis and its relationship with sclerodermatous GVHD.

- Hymes SR, Alousi AM, Cowen EW. Graft-versus-host disease: part I. pathogenesis and clinical manifestations of graft-versus-host disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66:515.e1-5.15e18; quiz 533-534.

- Goiriz R, Peñas PF, Delgado-Jiménez Y, et al. Cutaneous lichenoid graft-versus-host disease mimicking lupus erythematosus. Lupus. 2008;17:591-595.

- Hu SW, Myskowski PL, Papadopoulos EB, et al. Chronic cutaneous graft-versus host disease simulating hypertrophic lupus erythematosus—a case report of a new morphologic variant of graft-versus-host disease. Am J Dermatopathol. 2012;34:E81-E83.

- Chosidow O, Bagot M, Vernant JP, et al. Sclerodermatous chronic graft-versus-host disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;26:49-55.

- Ollivier I, Wolkenstein P, Gherardi R, et al. Dermatomyositis-like graft-versus-host disease. Br J Dermatol. 1998;138:558-559.

- Arin MJ, Scheid C, Hübel K, et al. Chronic graft-versus-host disease with skin signs suggestive of dermatomyositis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2006;31:141-143.

- Patriarca F, Skert C, Sperotto A, et al. The development of autoantibodies after allogeneic stem cell transplantation is related with chronic graft-vs-host disease and immune recovery. Exp Hematol. 2006;34:389-396.

- Hymes SR, Alousi AM, Cowen EW. Graft-versus-host disease: part I. pathogenesis and clinical manifestations of graft-versus-host disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66:515.e1-5.15e18; quiz 533-534.

- Goiriz R, Peñas PF, Delgado-Jiménez Y, et al. Cutaneous lichenoid graft-versus-host disease mimicking lupus erythematosus. Lupus. 2008;17:591-595.

- Hu SW, Myskowski PL, Papadopoulos EB, et al. Chronic cutaneous graft-versus host disease simulating hypertrophic lupus erythematosus—a case report of a new morphologic variant of graft-versus-host disease. Am J Dermatopathol. 2012;34:E81-E83.

- Chosidow O, Bagot M, Vernant JP, et al. Sclerodermatous chronic graft-versus-host disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;26:49-55.

- Ollivier I, Wolkenstein P, Gherardi R, et al. Dermatomyositis-like graft-versus-host disease. Br J Dermatol. 1998;138:558-559.

- Arin MJ, Scheid C, Hübel K, et al. Chronic graft-versus-host disease with skin signs suggestive of dermatomyositis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2006;31:141-143.

- Patriarca F, Skert C, Sperotto A, et al. The development of autoantibodies after allogeneic stem cell transplantation is related with chronic graft-vs-host disease and immune recovery. Exp Hematol. 2006;34:389-396.

Cold snare polypectomy works for large SSPs

Piecemeal cold snare polypectomy was effective and safe for sessile, serrated colon polyps larger than 10 mm in a series from the University of Sydney.

Endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) is the usual choice for lesions that size, but it comes with the risks of electrocautery, including delayed bleeding in perhaps 10% of patients. The Sydney investigators took a gamble to see if cold snare polypectomy, a technique usually reserved for smaller sessile, serrated polyps (SSPs), worked as well as EMR for larger ones, but without the risks. That seemed to be the case in their pilot study; . The median lesion size was 15 mm, and ranged from 10 to 35 mm. The procedure took a median of 4.5 minutes, much quicker than EMR, and didn’t require submucosal lifting injections. There were no perforations, deep injuries to the colon wall, or intraprocedural bleeding. There were no significant adverse events at 2 weeks, including no delayed bleeding or postpolypectomy syndrome.

Most importantly, there was no evidence of recurrence in the 15 lesions that had surveillance colonoscopy by press time at a median of 6 months. “We suggest, cautiously, that this is related to the wide margin of [normal] tissue [2-3 mm] removed during the initial procedures and the meticulous examination of the defect and margin for residual tissue,” said investigators led by David Tate, MD, of the University of Sydney.

“We have demonstrated the safety and feasibility of pCSP in a tertiary referral cohort of patients referred for the removal of large SSPs. There is potential for pCSP to become the standard of care for nondysplastic SSPs. This could reduce the burden of removing SSPs on patients and health care systems, particularly by avoidance of clinically significant postendoscopic bleeding,” the investigators wrote.

“Because SSPs commonly lack high-grade histology, have a long dwell time prior to developing dysplasia, and recur less frequently than conventional adenomas, they represent comparatively indolent disease and are excellent targets for piecemeal mucosal resection,” the researchers said.

Resection was performed with a stiff thin-wire snare (TeleMed 10-mm hexagonal, TeleMed Systems). “A thin-wire snare is paramount, both to aid tissue capture and to create a crisp resection margin that can be examined for residual serrated tissue. Each progressive resection utilizes this margin to ensure snare purchase and avoid tissue islands,” the researchers said.

It took a median of three cuts to remove an SSP; complete resection was achieved in all cases.

The team used high-definition endoscopic imaging to assess the lesion and margins before the procedure, and again to assess the defect margin to ensure the absence of residual serrated tissue. “We did not use submucosal injection or a chromic dye. While we acknowledge their utility for delineation of serrated tissue, we found that high-definition imaging was sufficient for this purpose and for detecting residual serrated tissue at the resection margin,” they said.

Patients were a mean age of 69 years old; almost 80% were women. About two-thirds of the lesions were proximal to the transverse colon.

The work was supported by the Cancer Institute New South Wales. The investigators had no conflicts of interest.

[email protected]

SOURCE: Tate DJ, et al. Endoscopy. 2017 Nov 23. doi: 10.1055/s-0043-121219.

Piecemeal cold snare polypectomy was effective and safe for sessile, serrated colon polyps larger than 10 mm in a series from the University of Sydney.

Endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) is the usual choice for lesions that size, but it comes with the risks of electrocautery, including delayed bleeding in perhaps 10% of patients. The Sydney investigators took a gamble to see if cold snare polypectomy, a technique usually reserved for smaller sessile, serrated polyps (SSPs), worked as well as EMR for larger ones, but without the risks. That seemed to be the case in their pilot study; . The median lesion size was 15 mm, and ranged from 10 to 35 mm. The procedure took a median of 4.5 minutes, much quicker than EMR, and didn’t require submucosal lifting injections. There were no perforations, deep injuries to the colon wall, or intraprocedural bleeding. There were no significant adverse events at 2 weeks, including no delayed bleeding or postpolypectomy syndrome.

Most importantly, there was no evidence of recurrence in the 15 lesions that had surveillance colonoscopy by press time at a median of 6 months. “We suggest, cautiously, that this is related to the wide margin of [normal] tissue [2-3 mm] removed during the initial procedures and the meticulous examination of the defect and margin for residual tissue,” said investigators led by David Tate, MD, of the University of Sydney.

“We have demonstrated the safety and feasibility of pCSP in a tertiary referral cohort of patients referred for the removal of large SSPs. There is potential for pCSP to become the standard of care for nondysplastic SSPs. This could reduce the burden of removing SSPs on patients and health care systems, particularly by avoidance of clinically significant postendoscopic bleeding,” the investigators wrote.

“Because SSPs commonly lack high-grade histology, have a long dwell time prior to developing dysplasia, and recur less frequently than conventional adenomas, they represent comparatively indolent disease and are excellent targets for piecemeal mucosal resection,” the researchers said.

Resection was performed with a stiff thin-wire snare (TeleMed 10-mm hexagonal, TeleMed Systems). “A thin-wire snare is paramount, both to aid tissue capture and to create a crisp resection margin that can be examined for residual serrated tissue. Each progressive resection utilizes this margin to ensure snare purchase and avoid tissue islands,” the researchers said.

It took a median of three cuts to remove an SSP; complete resection was achieved in all cases.

The team used high-definition endoscopic imaging to assess the lesion and margins before the procedure, and again to assess the defect margin to ensure the absence of residual serrated tissue. “We did not use submucosal injection or a chromic dye. While we acknowledge their utility for delineation of serrated tissue, we found that high-definition imaging was sufficient for this purpose and for detecting residual serrated tissue at the resection margin,” they said.

Patients were a mean age of 69 years old; almost 80% were women. About two-thirds of the lesions were proximal to the transverse colon.

The work was supported by the Cancer Institute New South Wales. The investigators had no conflicts of interest.

[email protected]

SOURCE: Tate DJ, et al. Endoscopy. 2017 Nov 23. doi: 10.1055/s-0043-121219.

Piecemeal cold snare polypectomy was effective and safe for sessile, serrated colon polyps larger than 10 mm in a series from the University of Sydney.

Endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) is the usual choice for lesions that size, but it comes with the risks of electrocautery, including delayed bleeding in perhaps 10% of patients. The Sydney investigators took a gamble to see if cold snare polypectomy, a technique usually reserved for smaller sessile, serrated polyps (SSPs), worked as well as EMR for larger ones, but without the risks. That seemed to be the case in their pilot study; . The median lesion size was 15 mm, and ranged from 10 to 35 mm. The procedure took a median of 4.5 minutes, much quicker than EMR, and didn’t require submucosal lifting injections. There were no perforations, deep injuries to the colon wall, or intraprocedural bleeding. There were no significant adverse events at 2 weeks, including no delayed bleeding or postpolypectomy syndrome.

Most importantly, there was no evidence of recurrence in the 15 lesions that had surveillance colonoscopy by press time at a median of 6 months. “We suggest, cautiously, that this is related to the wide margin of [normal] tissue [2-3 mm] removed during the initial procedures and the meticulous examination of the defect and margin for residual tissue,” said investigators led by David Tate, MD, of the University of Sydney.

“We have demonstrated the safety and feasibility of pCSP in a tertiary referral cohort of patients referred for the removal of large SSPs. There is potential for pCSP to become the standard of care for nondysplastic SSPs. This could reduce the burden of removing SSPs on patients and health care systems, particularly by avoidance of clinically significant postendoscopic bleeding,” the investigators wrote.

“Because SSPs commonly lack high-grade histology, have a long dwell time prior to developing dysplasia, and recur less frequently than conventional adenomas, they represent comparatively indolent disease and are excellent targets for piecemeal mucosal resection,” the researchers said.

Resection was performed with a stiff thin-wire snare (TeleMed 10-mm hexagonal, TeleMed Systems). “A thin-wire snare is paramount, both to aid tissue capture and to create a crisp resection margin that can be examined for residual serrated tissue. Each progressive resection utilizes this margin to ensure snare purchase and avoid tissue islands,” the researchers said.

It took a median of three cuts to remove an SSP; complete resection was achieved in all cases.

The team used high-definition endoscopic imaging to assess the lesion and margins before the procedure, and again to assess the defect margin to ensure the absence of residual serrated tissue. “We did not use submucosal injection or a chromic dye. While we acknowledge their utility for delineation of serrated tissue, we found that high-definition imaging was sufficient for this purpose and for detecting residual serrated tissue at the resection margin,” they said.

Patients were a mean age of 69 years old; almost 80% were women. About two-thirds of the lesions were proximal to the transverse colon.

The work was supported by the Cancer Institute New South Wales. The investigators had no conflicts of interest.

[email protected]

SOURCE: Tate DJ, et al. Endoscopy. 2017 Nov 23. doi: 10.1055/s-0043-121219.

FROM ENDOSCOPY

Key clinical point: Piecemeal cold snare polypectomy is effective and safe for sessile, serrated colon polyps larger than 10 mm.

Major finding: There was no delayed bleeding, and no evidence of recurrence, in 15 patients who had surveillance colonoscopies at 6 months.

Study details: A case series of 34 patients.

Disclosures: The work was supported by the Cancer Institute New South Wales, Australia. The investigators had no conflicts of interest.

Source: Tate DJ et al. Endoscopy. 2017 Nov 23. doi: 10.1055/s-0043-121219

Complete Remission of Metastatic Merkel Cell Carcinoma in a Patient With Severe Psoriasis

To the Editor:

A 69-year-old white man presented with a skin lesion on the back of 1 to 2 weeks’ duration. The patient stated he was unaware of it, but his wife had recently noticed the new spot. He denied any bleeding, pain, pruritus, or other associated symptoms with the lesion. He also denied any prior treatment to the area. The patient’s medical history was remarkable for severe psoriasis involving more than 80% body surface area, psoriatic arthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, coronary artery disease, squamous cell carcinoma, and actinic keratoses. He had been on multiple treatment regimens over the last 20 years for control of psoriasis including topical corticosteroids, psoralen plus UVA and UVB phototherapy, gold injections, acitretin, prednisone, efalizumab, ustekinumab, and alefacept upon evaluation of this new skin lesion. Utilization of immunosuppressive agents also provided an additional benefit of controlling the patient’s inflammatory arthritic disease.

On physical examination a 0.6×0.7-cm, pink to erythematous, pearly papule with superficial telangiectases was noted on the right side of the dorsal thorax (Figure 1). Multiple well-demarcated erythematous plaques with silvery scale and areas of secondary excoriation were noted on the trunk and both legs consistent with the patient’s history of psoriasis.

A shave biopsy was performed on the skin lesion on the right side of the dorsal thorax with a suspected clinical diagnosis of basal cell carcinoma. Two weeks later the patient returned for a discussion of the pathology report, which revealed nodules of basaloid cells with tightly packed vesicular nuclei and scant cytoplasm in sheets within the superficial dermis, as well as areas of nuclear molding, numerous mitotic figures, and areas of focal necrosis (Figure 2). In addition, immunostaining was positive for cytokeratin (CK) 20 antibodies with a characteristic paranuclear dot uptake of the antibody. These findings were consistent with a diagnosis of Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC). At that time, alefacept was discontinued and he was referred to a tertiary referral center for further evaluation and treatment.

The patient subsequently underwent wide excision with 1-cm margins of the MCC, with intraoperative lymphatic mapping/sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB) of the right axillary nodal basin 1 month later, which he tolerated well without any associated complications. Further histopathologic examination revealed the deep, medial, and lateral surgical margins to be negative of residual neoplasm. However, one sentinel lymph node indicated positivity for micrometastatic MCC, consistent with stage IIIA disease progression.

He underwent a second procedure the following month for complete right axillary lymph node dissection. Histopathologic examination of the right axillary contents included 28 lymph nodes, which were negative for carcinoma. He continued to do well without any signs of clinical recurrence or distant metastasis at subsequent follow-up visits.