User login

Study eyed natural history of branch-duct intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms

Branch-duct intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms (BD-IPMNs) grew at a median annual rate of 0.8 mm in a retrospective study of 1,369 patients.

While most of these cysts were “indolent and dormant,” some grew rapidly and developed “other worrisome features,” Youngmin Han, MS, of Seoul (South Korea) National University reported with his associates in the February issue of Gastroenterology. Therefore, clinicians should plan follow-up surveillance based on initial cyst size and growth rate, they concluded.

Based on their findings, the researchers recommended surgery for young, fit, asymptomatic patients who have BD-IPMNs with a diameter of least 30 mm or with thickened cyst walls or those who have a main pancreatic duct measuring 5-9 mm. Surgery also should be considered when patients have lymphadenopathy, high tumor marker levels, or an abrupt change in pancreatic duct caliber with distal pancreatic atrophy or a rapidly growing cyst, they said.

For asymptomatic patients whose cysts are under 10 mm and who do not have worrisome features, they recommended follow-up with CT or MRI at 6 months and then every 2 years after that. Cysts of 10-20 mm should be imaged at 6 months, at 12 months, and then every 1.5-2 years after that, they said. Patients with cyst diameters greater than 20 mm “should undergo MRI or CT or EUS [endoscopic ultrasound] every 6 months for 1 year and then annually thereafter, until the cyst size and features become stable,” they added. Patients whose cysts have a diameter of 30 mm or greater “should be closely monitored with MRI or CT or EUS every 6 months. Surgical resection can be considered in younger patients or those with other combined worrisome features.”

To characterize the natural history of BD-IPMN, the investigators evaluated clinical and imaging data collected between 2001 and 2016 from patients with classical features of BD-IPMN. Each patient included in the study provided 3 or more years of CT, MRI, EUS, and endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography data. The researchers used regression models to estimate changes in sizes of cysts and main pancreatic ducts.

Median follow-up time was 61 months (range, 36-189 months). Cyst diameter averaged 12.8 mm (standard deviation, 6.5 mm) at baseline and 17 mm (SD, 9.2 mm) at final measurement. Larger baseline diameter was associated with faster growth (P = .046): Cysts measuring less than 10 mm at baseline grew at a median annual rate of 0.8 mm (SD, 1.1 mm), while those measuring at least 30 mm grew at a median annual rate of 1.2 mm (SD, 2.1 mm).

Worrisome features were present in 59 patients at baseline and emerged in another 150 patients during follow-up. At baseline, only 2.3% of cysts exceeded 30 mm in diameter, but 8.0% did at final measurement. Cyst wall thickening was found in 0.5% of patients at baseline and 3.7% of patients at final measurement. Main pancreatic ducts measured 5-9 mm in 1.9% of patients at baseline and in 5.6% of patients at final measurement. Additionally, the prevalence of mural nodules rose from 0.4% at baseline to 3.1% at final measurement.

Main pancreatic ducts averaged 1.8 mm (SD, 1.0 mm) at baseline and 2.4 mm (SD, 1.8 mm) at final measurement. Compared with the values seen with smaller cysts, larger baseline cyst diameter correlated significantly with larger main pancreatic ducts, more cases of cyst wall thickening, and more cases with mural nodules (P less than .001 for all comparisons).

The study was funded by a grant from Korean Health Technology R&D Project of Ministry of Health and Welfare, Republic of Korea. The investigators reported having no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Han Y et al. Gastroenterology. 2018. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.10.013.

The appropriate management of branch-duct intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms (BD-IPMNs), a precursor cystic lesion to pancreatic cancer, has been a controversial issue since their initial description in 1982. Current national and international guidelines are primarily based on surgical series with potential selection bias and on observational studies with short surveillance periods. Consequently, there is limited information on the natural history and, more importantly, the malignant potential of BD-IPMNs.

The study by Youngmin Han and colleagues represents a comprehensive analysis of over 1,000 patients, each with at least 3 years of follow-up for a suspected BD-IPMN. In addition, the authors identified an optimal screening method for patients based on cyst size. Their data largely validates prior reports and will undoubtedly serve as the basis for future pancreatic cyst guidelines.

However, as the authors note, limitations of their study include its retrospective design and validation of their screening protocol. Moreover, several lingering questions remain for patients with BD-IPMNs: What is the best method of measuring a BD-IPMN (for example, CT, MRI, or endoscopic ultrasound)? How long should surveillance continue? And what is the role for cytopathology and ancillary studies, such as carcinoembryonic antigen testing, molecular testing, and testing for other pancreatic cyst biomarkers? At the risk of enouncing a cliché, “further studies are needed” to identify an optimal treatment algorithm and, considering the increasingly frequent detection of pancreatic cysts, a cost-effective approach to the evaluation of patients with BD-IPMNs.

Aatur D. Singhi, MD, PhD, is in the division of anatomic pathology in the department of pathology at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center. He has no conflicts of interest.

The appropriate management of branch-duct intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms (BD-IPMNs), a precursor cystic lesion to pancreatic cancer, has been a controversial issue since their initial description in 1982. Current national and international guidelines are primarily based on surgical series with potential selection bias and on observational studies with short surveillance periods. Consequently, there is limited information on the natural history and, more importantly, the malignant potential of BD-IPMNs.

The study by Youngmin Han and colleagues represents a comprehensive analysis of over 1,000 patients, each with at least 3 years of follow-up for a suspected BD-IPMN. In addition, the authors identified an optimal screening method for patients based on cyst size. Their data largely validates prior reports and will undoubtedly serve as the basis for future pancreatic cyst guidelines.

However, as the authors note, limitations of their study include its retrospective design and validation of their screening protocol. Moreover, several lingering questions remain for patients with BD-IPMNs: What is the best method of measuring a BD-IPMN (for example, CT, MRI, or endoscopic ultrasound)? How long should surveillance continue? And what is the role for cytopathology and ancillary studies, such as carcinoembryonic antigen testing, molecular testing, and testing for other pancreatic cyst biomarkers? At the risk of enouncing a cliché, “further studies are needed” to identify an optimal treatment algorithm and, considering the increasingly frequent detection of pancreatic cysts, a cost-effective approach to the evaluation of patients with BD-IPMNs.

Aatur D. Singhi, MD, PhD, is in the division of anatomic pathology in the department of pathology at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center. He has no conflicts of interest.

The appropriate management of branch-duct intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms (BD-IPMNs), a precursor cystic lesion to pancreatic cancer, has been a controversial issue since their initial description in 1982. Current national and international guidelines are primarily based on surgical series with potential selection bias and on observational studies with short surveillance periods. Consequently, there is limited information on the natural history and, more importantly, the malignant potential of BD-IPMNs.

The study by Youngmin Han and colleagues represents a comprehensive analysis of over 1,000 patients, each with at least 3 years of follow-up for a suspected BD-IPMN. In addition, the authors identified an optimal screening method for patients based on cyst size. Their data largely validates prior reports and will undoubtedly serve as the basis for future pancreatic cyst guidelines.

However, as the authors note, limitations of their study include its retrospective design and validation of their screening protocol. Moreover, several lingering questions remain for patients with BD-IPMNs: What is the best method of measuring a BD-IPMN (for example, CT, MRI, or endoscopic ultrasound)? How long should surveillance continue? And what is the role for cytopathology and ancillary studies, such as carcinoembryonic antigen testing, molecular testing, and testing for other pancreatic cyst biomarkers? At the risk of enouncing a cliché, “further studies are needed” to identify an optimal treatment algorithm and, considering the increasingly frequent detection of pancreatic cysts, a cost-effective approach to the evaluation of patients with BD-IPMNs.

Aatur D. Singhi, MD, PhD, is in the division of anatomic pathology in the department of pathology at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center. He has no conflicts of interest.

Branch-duct intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms (BD-IPMNs) grew at a median annual rate of 0.8 mm in a retrospective study of 1,369 patients.

While most of these cysts were “indolent and dormant,” some grew rapidly and developed “other worrisome features,” Youngmin Han, MS, of Seoul (South Korea) National University reported with his associates in the February issue of Gastroenterology. Therefore, clinicians should plan follow-up surveillance based on initial cyst size and growth rate, they concluded.

Based on their findings, the researchers recommended surgery for young, fit, asymptomatic patients who have BD-IPMNs with a diameter of least 30 mm or with thickened cyst walls or those who have a main pancreatic duct measuring 5-9 mm. Surgery also should be considered when patients have lymphadenopathy, high tumor marker levels, or an abrupt change in pancreatic duct caliber with distal pancreatic atrophy or a rapidly growing cyst, they said.

For asymptomatic patients whose cysts are under 10 mm and who do not have worrisome features, they recommended follow-up with CT or MRI at 6 months and then every 2 years after that. Cysts of 10-20 mm should be imaged at 6 months, at 12 months, and then every 1.5-2 years after that, they said. Patients with cyst diameters greater than 20 mm “should undergo MRI or CT or EUS [endoscopic ultrasound] every 6 months for 1 year and then annually thereafter, until the cyst size and features become stable,” they added. Patients whose cysts have a diameter of 30 mm or greater “should be closely monitored with MRI or CT or EUS every 6 months. Surgical resection can be considered in younger patients or those with other combined worrisome features.”

To characterize the natural history of BD-IPMN, the investigators evaluated clinical and imaging data collected between 2001 and 2016 from patients with classical features of BD-IPMN. Each patient included in the study provided 3 or more years of CT, MRI, EUS, and endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography data. The researchers used regression models to estimate changes in sizes of cysts and main pancreatic ducts.

Median follow-up time was 61 months (range, 36-189 months). Cyst diameter averaged 12.8 mm (standard deviation, 6.5 mm) at baseline and 17 mm (SD, 9.2 mm) at final measurement. Larger baseline diameter was associated with faster growth (P = .046): Cysts measuring less than 10 mm at baseline grew at a median annual rate of 0.8 mm (SD, 1.1 mm), while those measuring at least 30 mm grew at a median annual rate of 1.2 mm (SD, 2.1 mm).

Worrisome features were present in 59 patients at baseline and emerged in another 150 patients during follow-up. At baseline, only 2.3% of cysts exceeded 30 mm in diameter, but 8.0% did at final measurement. Cyst wall thickening was found in 0.5% of patients at baseline and 3.7% of patients at final measurement. Main pancreatic ducts measured 5-9 mm in 1.9% of patients at baseline and in 5.6% of patients at final measurement. Additionally, the prevalence of mural nodules rose from 0.4% at baseline to 3.1% at final measurement.

Main pancreatic ducts averaged 1.8 mm (SD, 1.0 mm) at baseline and 2.4 mm (SD, 1.8 mm) at final measurement. Compared with the values seen with smaller cysts, larger baseline cyst diameter correlated significantly with larger main pancreatic ducts, more cases of cyst wall thickening, and more cases with mural nodules (P less than .001 for all comparisons).

The study was funded by a grant from Korean Health Technology R&D Project of Ministry of Health and Welfare, Republic of Korea. The investigators reported having no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Han Y et al. Gastroenterology. 2018. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.10.013.

Branch-duct intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms (BD-IPMNs) grew at a median annual rate of 0.8 mm in a retrospective study of 1,369 patients.

While most of these cysts were “indolent and dormant,” some grew rapidly and developed “other worrisome features,” Youngmin Han, MS, of Seoul (South Korea) National University reported with his associates in the February issue of Gastroenterology. Therefore, clinicians should plan follow-up surveillance based on initial cyst size and growth rate, they concluded.

Based on their findings, the researchers recommended surgery for young, fit, asymptomatic patients who have BD-IPMNs with a diameter of least 30 mm or with thickened cyst walls or those who have a main pancreatic duct measuring 5-9 mm. Surgery also should be considered when patients have lymphadenopathy, high tumor marker levels, or an abrupt change in pancreatic duct caliber with distal pancreatic atrophy or a rapidly growing cyst, they said.

For asymptomatic patients whose cysts are under 10 mm and who do not have worrisome features, they recommended follow-up with CT or MRI at 6 months and then every 2 years after that. Cysts of 10-20 mm should be imaged at 6 months, at 12 months, and then every 1.5-2 years after that, they said. Patients with cyst diameters greater than 20 mm “should undergo MRI or CT or EUS [endoscopic ultrasound] every 6 months for 1 year and then annually thereafter, until the cyst size and features become stable,” they added. Patients whose cysts have a diameter of 30 mm or greater “should be closely monitored with MRI or CT or EUS every 6 months. Surgical resection can be considered in younger patients or those with other combined worrisome features.”

To characterize the natural history of BD-IPMN, the investigators evaluated clinical and imaging data collected between 2001 and 2016 from patients with classical features of BD-IPMN. Each patient included in the study provided 3 or more years of CT, MRI, EUS, and endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography data. The researchers used regression models to estimate changes in sizes of cysts and main pancreatic ducts.

Median follow-up time was 61 months (range, 36-189 months). Cyst diameter averaged 12.8 mm (standard deviation, 6.5 mm) at baseline and 17 mm (SD, 9.2 mm) at final measurement. Larger baseline diameter was associated with faster growth (P = .046): Cysts measuring less than 10 mm at baseline grew at a median annual rate of 0.8 mm (SD, 1.1 mm), while those measuring at least 30 mm grew at a median annual rate of 1.2 mm (SD, 2.1 mm).

Worrisome features were present in 59 patients at baseline and emerged in another 150 patients during follow-up. At baseline, only 2.3% of cysts exceeded 30 mm in diameter, but 8.0% did at final measurement. Cyst wall thickening was found in 0.5% of patients at baseline and 3.7% of patients at final measurement. Main pancreatic ducts measured 5-9 mm in 1.9% of patients at baseline and in 5.6% of patients at final measurement. Additionally, the prevalence of mural nodules rose from 0.4% at baseline to 3.1% at final measurement.

Main pancreatic ducts averaged 1.8 mm (SD, 1.0 mm) at baseline and 2.4 mm (SD, 1.8 mm) at final measurement. Compared with the values seen with smaller cysts, larger baseline cyst diameter correlated significantly with larger main pancreatic ducts, more cases of cyst wall thickening, and more cases with mural nodules (P less than .001 for all comparisons).

The study was funded by a grant from Korean Health Technology R&D Project of Ministry of Health and Welfare, Republic of Korea. The investigators reported having no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Han Y et al. Gastroenterology. 2018. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.10.013.

FROM GASTROENTEROLOGY

Key clinical point: Tailor the surveillance of BD-IPMNs based on initial diameter and the presence or absence of high-risk features.

Major finding: Median annual growth rate was 0.8 mm.

Data source: A retrospective study of 1,369 patients with BD-IPMNs.

Disclosures: The study was funded by a grant from the Korean Health Technology R&D Project of the Ministry of Health and Welfare, Republic of Korea. The investigators reported having no conflicts of interest.

Source: Han Y et al. Gastroenterology. 2018. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.10.013.

One in five Crohn’s disease patients have major complications after infliximab withdrawal

About , according to research published in the February issue of Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology (doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2017.09.061).

About 70% of patients remained free of both infliximab restart failure and major complications, said Catherine Reenaers, MD, PhD, of Centre Hospitalier Universitaire de Liège (Belgium), and her associates. Significant predictors of major complications included upper gastrointestinal disease at the time of infliximab withdrawal, white blood cell count of at least 5.0 x 109 per L, and hemoglobin level under 12.5 g per dL. “Patients with at least two of these factors had a more than 40% risk of major complication in the 7 years following infliximab withdrawal,” the researchers reported.

Little is known about long-term outcomes after patients with Crohn’s disease withdraw from infliximab. Therefore, Dr. Reenaers and her associates retrospectively studied 102 patients with Crohn’s disease who had received infliximab and an antimetabolite (azathioprine, mercaptopurine, or methotrexate) for at least 12 months, had been in steroid-free clinical remission for at least 6 months, and then withdrew from infliximab. Patients were recruited from 19 centers in Belgium and France and were originally part of a prospective cohort study of infliximab withdrawal in Crohn’s disease (Gastroenterology. 2012;142[1]:63-70.e5).

About half of patients relapsed and restarted infliximab within 12 months, which is in line with other studies, the researchers noted. Over a median follow-up of 83 months (interquartile range, 71-93 months), 21% (95% confidence interval, 13.1%-30.3%) of patients had no complications, did not restart infliximab, and started no other biologics. In all, 70.2% of patients (95% CI, 60.2%-80.1%) had no major complications and did not fail to respond after restarting infliximab.

Eighteen patients (19%; 95% CI, 10%-27%) developed major complications: 14 who required surgery and 4 who developed new complex perianal lesions. In a multivariable model, the strongest independent predictor of major complications was leukocytosis (hazard ratio, 10.5; 95% CI, 1.3-83; P less than .002), followed by upper gastrointestinal disease (HR, 5.8; 95% CI, 1.5-22) and low hemoglobin level (HR, 4.1; 95% CI, 1.5-21.8; P less than .01). The 13 patients who lacked these risk factors had no major complications of infliximab withdrawal. Among 72 patients who had at least one risk factor, 16.3% (95% CI, 7%-25%) developed major complications over 7 years. Strikingly, among 17 with at least two risk factors, 43% (95% CI, 17%-69%) developed major complications over 7 years, the researchers noted.

Complications emerged a median of 50 months (interquartile range, 41-73 months) after patients received their last infliximab infusion, highlighting the need for close long-term monitoring even if patients show no signs of early clinical relapse after infliximab withdrawal, the investigators said. “One strength of this cohort was the homogeneity of the population,” they stressed. “Most studies of anti–tumor necrosis factor withdrawal after clinical remission were limited by heterogeneous populations, variable lengths of infliximab treatment before discontinuation, and variable use of immunomodulators and corticosteroids. In [our] cohort, the population was homogenous, infliximab withdrawal was standardized, and the disease characteristics at the time of stopping were collected prospectively.” Although follow-up times varied, less than 5% of patients were followed for less than 3 years, they noted.

The researchers did not acknowledge external funding sources. Dr. Reenaers disclosed ties to AbbVie, Takeda, MSD, Mundipharma, Hospira, and Ferring.

SOURCE: Reenaers C et al. Clin Gastro Hepatol 2018 February (in press).

The option of stopping a biologic agent is an attractive prospect for most Crohn's disease (CD) patients in stable clinical remission. The STORI trial, published in 2012, was among the earliest and select few studies addressing withdrawal of biologic therapy in CD among patients in sustained clinical remission with combination therapy (infliximab and thiopurine/methotrexate) for at least 6 months. Almost 50% of patients experienced disease relapse within a year of stopping infliximab in the trial.

Reenaers et al. recently published long-term follow-up of the original STORI cohort. After a median follow-up time of 7 years; four out five patients previously in clinical remission with combination therapy experienced worsening disease activity following withdrawal of infliximab. While the majority (70%) were able to resume infliximab and recapture disease response without any untoward adverse effects; one in five patients experienced major disease-related complications such as complex perianal disease or need for abdominal surgery. Upper GI tract involvement, high white blood cell count, and low hemoglobin concentration were associated with increased likelihood of a major complication. Notably, median time to a major complication was almost 4 years.

These results are similar to long-term relapse rates reported in other studies of withdrawal of therapy in CD. While biomarkers such as C-reactive protein, fecal calprotectin, along with endoscopic disease activity are reliable predictors of short-term relapse; clinical factors such as family history of CD, disease extent, stricturing or penetrating disease, and cigarette smoking are more relevant predictors of long-term disease activity. It is important to consider both types of predictors when considering withdrawal of therapy in CD.

Lastly, while the majority of patients who relapse following withdrawal of a biologic agent will do so within a year or two, a subset may not experience disease-related complications for several years - underscoring the need for long-term follow-up.

Manreet Kaur, MD, is assistant professor in the division of gastroenterology and hepatology; medical director, Inflammatory Bowel Disease Center, and medical director, faculty group practice, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston.

The option of stopping a biologic agent is an attractive prospect for most Crohn's disease (CD) patients in stable clinical remission. The STORI trial, published in 2012, was among the earliest and select few studies addressing withdrawal of biologic therapy in CD among patients in sustained clinical remission with combination therapy (infliximab and thiopurine/methotrexate) for at least 6 months. Almost 50% of patients experienced disease relapse within a year of stopping infliximab in the trial.

Reenaers et al. recently published long-term follow-up of the original STORI cohort. After a median follow-up time of 7 years; four out five patients previously in clinical remission with combination therapy experienced worsening disease activity following withdrawal of infliximab. While the majority (70%) were able to resume infliximab and recapture disease response without any untoward adverse effects; one in five patients experienced major disease-related complications such as complex perianal disease or need for abdominal surgery. Upper GI tract involvement, high white blood cell count, and low hemoglobin concentration were associated with increased likelihood of a major complication. Notably, median time to a major complication was almost 4 years.

These results are similar to long-term relapse rates reported in other studies of withdrawal of therapy in CD. While biomarkers such as C-reactive protein, fecal calprotectin, along with endoscopic disease activity are reliable predictors of short-term relapse; clinical factors such as family history of CD, disease extent, stricturing or penetrating disease, and cigarette smoking are more relevant predictors of long-term disease activity. It is important to consider both types of predictors when considering withdrawal of therapy in CD.

Lastly, while the majority of patients who relapse following withdrawal of a biologic agent will do so within a year or two, a subset may not experience disease-related complications for several years - underscoring the need for long-term follow-up.

Manreet Kaur, MD, is assistant professor in the division of gastroenterology and hepatology; medical director, Inflammatory Bowel Disease Center, and medical director, faculty group practice, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston.

The option of stopping a biologic agent is an attractive prospect for most Crohn's disease (CD) patients in stable clinical remission. The STORI trial, published in 2012, was among the earliest and select few studies addressing withdrawal of biologic therapy in CD among patients in sustained clinical remission with combination therapy (infliximab and thiopurine/methotrexate) for at least 6 months. Almost 50% of patients experienced disease relapse within a year of stopping infliximab in the trial.

Reenaers et al. recently published long-term follow-up of the original STORI cohort. After a median follow-up time of 7 years; four out five patients previously in clinical remission with combination therapy experienced worsening disease activity following withdrawal of infliximab. While the majority (70%) were able to resume infliximab and recapture disease response without any untoward adverse effects; one in five patients experienced major disease-related complications such as complex perianal disease or need for abdominal surgery. Upper GI tract involvement, high white blood cell count, and low hemoglobin concentration were associated with increased likelihood of a major complication. Notably, median time to a major complication was almost 4 years.

These results are similar to long-term relapse rates reported in other studies of withdrawal of therapy in CD. While biomarkers such as C-reactive protein, fecal calprotectin, along with endoscopic disease activity are reliable predictors of short-term relapse; clinical factors such as family history of CD, disease extent, stricturing or penetrating disease, and cigarette smoking are more relevant predictors of long-term disease activity. It is important to consider both types of predictors when considering withdrawal of therapy in CD.

Lastly, while the majority of patients who relapse following withdrawal of a biologic agent will do so within a year or two, a subset may not experience disease-related complications for several years - underscoring the need for long-term follow-up.

Manreet Kaur, MD, is assistant professor in the division of gastroenterology and hepatology; medical director, Inflammatory Bowel Disease Center, and medical director, faculty group practice, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston.

About , according to research published in the February issue of Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology (doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2017.09.061).

About 70% of patients remained free of both infliximab restart failure and major complications, said Catherine Reenaers, MD, PhD, of Centre Hospitalier Universitaire de Liège (Belgium), and her associates. Significant predictors of major complications included upper gastrointestinal disease at the time of infliximab withdrawal, white blood cell count of at least 5.0 x 109 per L, and hemoglobin level under 12.5 g per dL. “Patients with at least two of these factors had a more than 40% risk of major complication in the 7 years following infliximab withdrawal,” the researchers reported.

Little is known about long-term outcomes after patients with Crohn’s disease withdraw from infliximab. Therefore, Dr. Reenaers and her associates retrospectively studied 102 patients with Crohn’s disease who had received infliximab and an antimetabolite (azathioprine, mercaptopurine, or methotrexate) for at least 12 months, had been in steroid-free clinical remission for at least 6 months, and then withdrew from infliximab. Patients were recruited from 19 centers in Belgium and France and were originally part of a prospective cohort study of infliximab withdrawal in Crohn’s disease (Gastroenterology. 2012;142[1]:63-70.e5).

About half of patients relapsed and restarted infliximab within 12 months, which is in line with other studies, the researchers noted. Over a median follow-up of 83 months (interquartile range, 71-93 months), 21% (95% confidence interval, 13.1%-30.3%) of patients had no complications, did not restart infliximab, and started no other biologics. In all, 70.2% of patients (95% CI, 60.2%-80.1%) had no major complications and did not fail to respond after restarting infliximab.

Eighteen patients (19%; 95% CI, 10%-27%) developed major complications: 14 who required surgery and 4 who developed new complex perianal lesions. In a multivariable model, the strongest independent predictor of major complications was leukocytosis (hazard ratio, 10.5; 95% CI, 1.3-83; P less than .002), followed by upper gastrointestinal disease (HR, 5.8; 95% CI, 1.5-22) and low hemoglobin level (HR, 4.1; 95% CI, 1.5-21.8; P less than .01). The 13 patients who lacked these risk factors had no major complications of infliximab withdrawal. Among 72 patients who had at least one risk factor, 16.3% (95% CI, 7%-25%) developed major complications over 7 years. Strikingly, among 17 with at least two risk factors, 43% (95% CI, 17%-69%) developed major complications over 7 years, the researchers noted.

Complications emerged a median of 50 months (interquartile range, 41-73 months) after patients received their last infliximab infusion, highlighting the need for close long-term monitoring even if patients show no signs of early clinical relapse after infliximab withdrawal, the investigators said. “One strength of this cohort was the homogeneity of the population,” they stressed. “Most studies of anti–tumor necrosis factor withdrawal after clinical remission were limited by heterogeneous populations, variable lengths of infliximab treatment before discontinuation, and variable use of immunomodulators and corticosteroids. In [our] cohort, the population was homogenous, infliximab withdrawal was standardized, and the disease characteristics at the time of stopping were collected prospectively.” Although follow-up times varied, less than 5% of patients were followed for less than 3 years, they noted.

The researchers did not acknowledge external funding sources. Dr. Reenaers disclosed ties to AbbVie, Takeda, MSD, Mundipharma, Hospira, and Ferring.

SOURCE: Reenaers C et al. Clin Gastro Hepatol 2018 February (in press).

About , according to research published in the February issue of Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology (doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2017.09.061).

About 70% of patients remained free of both infliximab restart failure and major complications, said Catherine Reenaers, MD, PhD, of Centre Hospitalier Universitaire de Liège (Belgium), and her associates. Significant predictors of major complications included upper gastrointestinal disease at the time of infliximab withdrawal, white blood cell count of at least 5.0 x 109 per L, and hemoglobin level under 12.5 g per dL. “Patients with at least two of these factors had a more than 40% risk of major complication in the 7 years following infliximab withdrawal,” the researchers reported.

Little is known about long-term outcomes after patients with Crohn’s disease withdraw from infliximab. Therefore, Dr. Reenaers and her associates retrospectively studied 102 patients with Crohn’s disease who had received infliximab and an antimetabolite (azathioprine, mercaptopurine, or methotrexate) for at least 12 months, had been in steroid-free clinical remission for at least 6 months, and then withdrew from infliximab. Patients were recruited from 19 centers in Belgium and France and were originally part of a prospective cohort study of infliximab withdrawal in Crohn’s disease (Gastroenterology. 2012;142[1]:63-70.e5).

About half of patients relapsed and restarted infliximab within 12 months, which is in line with other studies, the researchers noted. Over a median follow-up of 83 months (interquartile range, 71-93 months), 21% (95% confidence interval, 13.1%-30.3%) of patients had no complications, did not restart infliximab, and started no other biologics. In all, 70.2% of patients (95% CI, 60.2%-80.1%) had no major complications and did not fail to respond after restarting infliximab.

Eighteen patients (19%; 95% CI, 10%-27%) developed major complications: 14 who required surgery and 4 who developed new complex perianal lesions. In a multivariable model, the strongest independent predictor of major complications was leukocytosis (hazard ratio, 10.5; 95% CI, 1.3-83; P less than .002), followed by upper gastrointestinal disease (HR, 5.8; 95% CI, 1.5-22) and low hemoglobin level (HR, 4.1; 95% CI, 1.5-21.8; P less than .01). The 13 patients who lacked these risk factors had no major complications of infliximab withdrawal. Among 72 patients who had at least one risk factor, 16.3% (95% CI, 7%-25%) developed major complications over 7 years. Strikingly, among 17 with at least two risk factors, 43% (95% CI, 17%-69%) developed major complications over 7 years, the researchers noted.

Complications emerged a median of 50 months (interquartile range, 41-73 months) after patients received their last infliximab infusion, highlighting the need for close long-term monitoring even if patients show no signs of early clinical relapse after infliximab withdrawal, the investigators said. “One strength of this cohort was the homogeneity of the population,” they stressed. “Most studies of anti–tumor necrosis factor withdrawal after clinical remission were limited by heterogeneous populations, variable lengths of infliximab treatment before discontinuation, and variable use of immunomodulators and corticosteroids. In [our] cohort, the population was homogenous, infliximab withdrawal was standardized, and the disease characteristics at the time of stopping were collected prospectively.” Although follow-up times varied, less than 5% of patients were followed for less than 3 years, they noted.

The researchers did not acknowledge external funding sources. Dr. Reenaers disclosed ties to AbbVie, Takeda, MSD, Mundipharma, Hospira, and Ferring.

SOURCE: Reenaers C et al. Clin Gastro Hepatol 2018 February (in press).

FROM CLINICAL GASTROENTEROLOGY AND HEPATOLOGY

Key clinical point: Over 7 years, about one in five patients with remitted Crohn’s disease developed a major complication after withdrawing from infliximab, despite remaining on an antimetabolite.

Major finding: Eighteen patients (19%; 95% CI, 10%-27%) developed major complications: Fourteen needed surgery and four developed new complex perianal lesions.

Data source: A cohort study of 102 patients with Crohn’s disease who had received infliximab and an antimetabolite for at least 12 months, had been in steroid-free clinical remission for at least 6 months, and who then withdrew from infliximab.

Disclosures: The researchers did not acknowledge external funding sources. Dr. Reenaers disclosed ties to AbbVie, Takeda, MSD, Mundipharma, Hospira, and Ferring.

Source: Reenaers C et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018 February (in press).

APOE4: Elders with allele benefit from lifestyle changes

allele, Alina Solomon, MD, PhD, reported in JAMA Neurology.

“Whether such benefits are more pronounced in APOE4 carriers, compared with noncarriers, should be further investigated,” wrote Dr. Solomon of the Institute of Clinical Medicine/Neurology at the University of Eastern Finland, Kuopio, and her associates.

The investigators analyzed data of 1,109 participants in the multicenter Finnish Geriatric Intervention Study to Prevent Cognitive Impairment and Disability (FINGER), a randomized, controlled trial of at-risk individuals from the general population. Participants were aged 60-77 years, and 362 of them were carriers of the APOE4 allele.

Those randomized to the intervention group received targeted information about nutrition, instructions about physical exercise, and cognitive training – including group sessions led by a psychologist. The control group received “regular health advice” (JAMA Neurol. 2018 Jan 22. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2017.4365).

After the interventions, participants underwent a battery of neuropsychological testing. Dr. Solomon and her associates found that the per-year difference between the intervention and control groups in the total score change was 0.037 (95% confidence interval, 0.001-0.073) among APOE4 carriers and 0.014 (95% CI, −0.011-0.039) among noncarriers.

Among other things, the findings stress the importance of early prevention strategies targeting simultaneously many risk factors that are modifiable, the investigators said.

To read the full story, click here.

allele, Alina Solomon, MD, PhD, reported in JAMA Neurology.

“Whether such benefits are more pronounced in APOE4 carriers, compared with noncarriers, should be further investigated,” wrote Dr. Solomon of the Institute of Clinical Medicine/Neurology at the University of Eastern Finland, Kuopio, and her associates.

The investigators analyzed data of 1,109 participants in the multicenter Finnish Geriatric Intervention Study to Prevent Cognitive Impairment and Disability (FINGER), a randomized, controlled trial of at-risk individuals from the general population. Participants were aged 60-77 years, and 362 of them were carriers of the APOE4 allele.

Those randomized to the intervention group received targeted information about nutrition, instructions about physical exercise, and cognitive training – including group sessions led by a psychologist. The control group received “regular health advice” (JAMA Neurol. 2018 Jan 22. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2017.4365).

After the interventions, participants underwent a battery of neuropsychological testing. Dr. Solomon and her associates found that the per-year difference between the intervention and control groups in the total score change was 0.037 (95% confidence interval, 0.001-0.073) among APOE4 carriers and 0.014 (95% CI, −0.011-0.039) among noncarriers.

Among other things, the findings stress the importance of early prevention strategies targeting simultaneously many risk factors that are modifiable, the investigators said.

To read the full story, click here.

allele, Alina Solomon, MD, PhD, reported in JAMA Neurology.

“Whether such benefits are more pronounced in APOE4 carriers, compared with noncarriers, should be further investigated,” wrote Dr. Solomon of the Institute of Clinical Medicine/Neurology at the University of Eastern Finland, Kuopio, and her associates.

The investigators analyzed data of 1,109 participants in the multicenter Finnish Geriatric Intervention Study to Prevent Cognitive Impairment and Disability (FINGER), a randomized, controlled trial of at-risk individuals from the general population. Participants were aged 60-77 years, and 362 of them were carriers of the APOE4 allele.

Those randomized to the intervention group received targeted information about nutrition, instructions about physical exercise, and cognitive training – including group sessions led by a psychologist. The control group received “regular health advice” (JAMA Neurol. 2018 Jan 22. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2017.4365).

After the interventions, participants underwent a battery of neuropsychological testing. Dr. Solomon and her associates found that the per-year difference between the intervention and control groups in the total score change was 0.037 (95% confidence interval, 0.001-0.073) among APOE4 carriers and 0.014 (95% CI, −0.011-0.039) among noncarriers.

Among other things, the findings stress the importance of early prevention strategies targeting simultaneously many risk factors that are modifiable, the investigators said.

To read the full story, click here.

FROM JAMA NEUROLOGY

Preparing from the Outside Looking In for Safely Transitioning Pediatric Inpatients to Home

The transition of children from hospital to home introduces a unique set of challenges to patients and families who may not be well-versed in the healthcare system. In addition to juggling the stress and worry of a sick child, which can inhibit the ability to understand complicated discharge instructions prior to leaving the hospital,1 caregivers need to navigate the medical system to ensure continued recovery. The responsibility to fill and administer medications, arrange follow up appointments, and determine when to seek care if the child’s condition changes are burdens we as healthcare providers expect caregivers to manage but may underestimate how frequently they are reliably completed.2-4

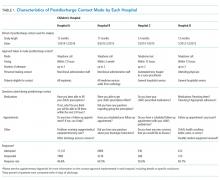

In this issue of the Journal of Hospital Medicine, the article by Rehm et al.5 adds to the growing body of evidence highlighting challenges that caregivers of children face upon discharge from the hospital. The multicenter, retrospective study of postdischarge encounters for over 12,000 patients discharged from 4 children’s hospitals aimed to evaluate the following: (1) various methods for hospital-initiated postdischarge contact of families, (2) the type and frequency of postdischarge issues, and (3) specific characteristics of pediatric patients most commonly affected by postdischarge issues.

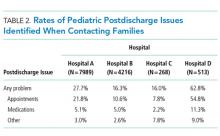

Using standardized questions administered through telephone, text, or e-mail contact, postdischarge issues were identified in 25% of discharges across all hospitals. Notably, there was considerable variation of rates of postdischarge issues among hospitals (from 16% to 62.8%). The hospital with the highest rate of postdischarge issues identified had attending hospitalists calling families after discharge. Thus, postdischarge issues may be most easily identified by providers who are familiar with both the patient and the expected postdischarge care.

Often, postdischarge issues represented events that could be mitigated with intentional planning to better anticipate and address patient and family needs prior to discharge. The vast majority of postdischarge issues identified across all hospitals were related to appointments, accounting for 76.3% of postdischarge issues, which may be attributed to a variety of causes, from inadequate or unclear provider recommendations to difficulty scheduling the appointments. The most common medication postdischarge issue was difficulty filling prescriptions, accounting for 84.8% of the medication issues. “Other” postdischarge issues (12.7%) as reported by caregivers included challenges with understanding discharge instructions and concerns about changes in their child’s clinical status. Forty percent of included patients had a chronic care condition. Older children, patients with more medication classes, shorter length of stay, and neuromuscular chronic care conditions had higher odds of postdischarge issues. Although a high proportion of postdischarge issues suggests a systemic problem addressing the needs of patients and families after hospital discharge, these data likely underestimate the magnitude of the problem; as such, the need for improvement may be higher.

Postdischarge challenges faced by families are not unique to pediatrics. Pediatric and adult medical patients face similar rates of challenges after

Given the prevalence of postdischarge issues after both pediatric and adult hospitalizations, how should hospitalists proceed? Physicians and health systems should explore approaches to better prepare caregivers, perhaps using models akin to the Seamless Transitions and (Re)admissions Network model of enhanced communication, care coordination, and family engagement.10 Pediatric hospitalists can prepare children for discharge long before departure by delivering medications to patients prior to discharge,11,12 providing discharge instructions that are clear and readable,13,14 as well as utilizing admission-discharge teaching nurses,15 inpatient care managers,16,17 and pediatric nurse practitioners18 to aid transition.

While a variety of interventions show promise in securing a successful transition to home from the hospitalist vantage point, a partnership with primary care physicians (PCPs) in our communities is paramount. Though the evidence linking gaps in primary care after discharge and readmission rates remain elusive, effective partnerships with PCPs are important for ensuring discharge plans are carried out, which may ultimately lead to decreased rates of unanticipated adverse outcomes. Several adult studies note that no single intervention is likely to prevent issues after discharge, but interventions should include high-quality communication with and involvement of community partners.9,19,20 In practice, providing a high-quality, reliable handoff can be difficult given competing priorities of busy outpatient clinic schedules and inpatient bed capacity concerns, necessitating efficient discharge practices. Some of these challenges are amenable to quality improvement efforts to improve discharge communication.21 Innovative ideas include collaborating with PCPs earlier in the admission to design the care plan up front, including PCPs in weekly team meetings for patients with chronic care conditions,16,17 and using telehealth to communicate with PCPs.

Ensuring a safe transition to home is our responsibility as hospitalists, but the solutions to doing so reliably require multi-fold interventions that build teams within hospitals, innovative outreach to those patients recently discharged to ensure their well-being and mitigate postdischarge issues and broad community programs—including greater access to primary care—to meet our urgent imperative.

Disclosure

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. Dr. Auger’s research is funded by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (1K08HS024735).

1. Solan LG, Beck AF, Brunswick SA, et al. The Family Perspective on Hospital to Home Transitions: A Qualitative Study. Pediatrics. 2015;136(6):e1539-1549. PubMed

2. Misky GJ, Wald HL, Coleman EA. Post-hospitalization transitions: Examining the effects of timing of primary care provider follow-up. J Hosp Med. 2010;5(7):392-397. PubMed

3. Yin HS, Johnson M, Mendelsohn AL, Abrams MA, Sanders LM, Dreyer BP. The health literacy of parents in the United States: a nationally representative study. Pediatrics. 2009;124 Suppl 3:S289-298. PubMed

4. Glick AF, Farkas JS, Nicholson J, et al. Parental Management of Discharge Instructions: A Systematic Review. Pediatrics. 2017. [Epub ahead of print]. PubMed

5. Rehm KP, Brittan MS, Stephens JR, et al. Issues Identified by Post-Discharge Contact after Pediatric Hospitalization: A Multi-site Study (published online ahead of print February 2, 2018) J Hosp Med. doi: 10.12788/jhm.2934

6. Forster AJ, Murff HJ, Peterson JF, Gandhi TK, Bates DW. The incidence and severity of adverse events affecting patients after discharge from the hospital. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138(3):161-167. PubMed

7. Hansen LO, Greenwald JL, Budnitz T, et al. Project BOOST: effectiveness of a multihospital effort to reduce rehospitalization. J Hosp Med. 2013;8(8):421-427. PubMed

8. Auerbach AD, Kripalani S, Vasilevskis EE, et al. Preventability and Causes of Readmissions in a National Cohort of General Medicine Patients. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(4):484-493. PubMed

9. Kripalani S, LeFevre F, Phillips CO, Williams MV, Basaviah P, Baker DW. Deficits in communication and information transfer between hospital-based and primary care physicians: implications for patient safety and continuity of care. JAMA. 2007;297(8):831-841. PubMed

10. Auger KA, Simon TD, Cooperberg D, et al. Summary of STARNet: Seamless Transitions and (Re)admissions Network. Pediatrics. 2015;135(1):164-175. PubMed

11. Hatoun J, Bair-Merritt M, Cabral H, Moses J. Increasing Medication Possession at Discharge for Patients With Asthma: The Meds-in-Hand Project. Pediatrics. 2016;137(3):e20150461. PubMed

12. White CM, Statile AM, White DL, et al. Using quality improvement to optimise paediatric discharge efficiency. BMJ Qual Saf. 2014;23(5):428-436. PubMed

13. Unaka N, Statile A, Jerardi K, et al. Improving the Readability of Pediatric Hospital Medicine Discharge Instructions. J Hosp Med. 2017;12(7):551-557. PubMed

14. Wu S, Tyler A, Logsdon T, et al. A Quality Improvement Collaborative to Improve the Discharge Process for Hospitalized Children. Pediatrics. 2016;138(2). PubMed

15. Blankenship JS, Winslow SA. Admission-discharge-teaching nurses: bridging the gap in today’s workforce. J Nurs Adm. 2003;33(1):11-13. PubMed

16. White CM, Thomson JE, Statile AM, et al. Development of a New Care Model for Hospitalized Children With Medical Complexity. Hosp Pediatr. 2017;7(7):410-414. PubMed

17. Statile AM, Schondelmeyer AC, Thomson JE, et al. Improving Discharge Efficiency in Medically Complex Pediatric Patients. Pediatrics. 2016;138(2). PubMed

18. Dunn K, Rogers J. Discharge Facilitation: An Innovative PNP Role. J Pediatr Health Care. 2016;30(5):499-505. PubMed

19. Kripalani S, Jackson AT, Schnipper JL, Coleman EA. Promoting effective transitions of care at hospital discharge: a review of key issues for hospitalists. J Hosp Med. 2007;2(5):314-323. PubMed

20. Scott AM, Li J, Oyewole-Eletu S, et al. Understanding Facilitators and Barriers to Care Transitions: Insights from Project ACHIEVE Site Visits. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2017;43(9):433-447. PubMed

21. Shen MW, Hershey D, Bergert L, Mallory L, Fisher ES, Cooperberg D. Pediatric hospitalists collaborate to improve timeliness of discharge communication. Hosp Pediatr. 2013;3(3):258-265. PubMed

The transition of children from hospital to home introduces a unique set of challenges to patients and families who may not be well-versed in the healthcare system. In addition to juggling the stress and worry of a sick child, which can inhibit the ability to understand complicated discharge instructions prior to leaving the hospital,1 caregivers need to navigate the medical system to ensure continued recovery. The responsibility to fill and administer medications, arrange follow up appointments, and determine when to seek care if the child’s condition changes are burdens we as healthcare providers expect caregivers to manage but may underestimate how frequently they are reliably completed.2-4

In this issue of the Journal of Hospital Medicine, the article by Rehm et al.5 adds to the growing body of evidence highlighting challenges that caregivers of children face upon discharge from the hospital. The multicenter, retrospective study of postdischarge encounters for over 12,000 patients discharged from 4 children’s hospitals aimed to evaluate the following: (1) various methods for hospital-initiated postdischarge contact of families, (2) the type and frequency of postdischarge issues, and (3) specific characteristics of pediatric patients most commonly affected by postdischarge issues.

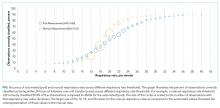

Using standardized questions administered through telephone, text, or e-mail contact, postdischarge issues were identified in 25% of discharges across all hospitals. Notably, there was considerable variation of rates of postdischarge issues among hospitals (from 16% to 62.8%). The hospital with the highest rate of postdischarge issues identified had attending hospitalists calling families after discharge. Thus, postdischarge issues may be most easily identified by providers who are familiar with both the patient and the expected postdischarge care.

Often, postdischarge issues represented events that could be mitigated with intentional planning to better anticipate and address patient and family needs prior to discharge. The vast majority of postdischarge issues identified across all hospitals were related to appointments, accounting for 76.3% of postdischarge issues, which may be attributed to a variety of causes, from inadequate or unclear provider recommendations to difficulty scheduling the appointments. The most common medication postdischarge issue was difficulty filling prescriptions, accounting for 84.8% of the medication issues. “Other” postdischarge issues (12.7%) as reported by caregivers included challenges with understanding discharge instructions and concerns about changes in their child’s clinical status. Forty percent of included patients had a chronic care condition. Older children, patients with more medication classes, shorter length of stay, and neuromuscular chronic care conditions had higher odds of postdischarge issues. Although a high proportion of postdischarge issues suggests a systemic problem addressing the needs of patients and families after hospital discharge, these data likely underestimate the magnitude of the problem; as such, the need for improvement may be higher.

Postdischarge challenges faced by families are not unique to pediatrics. Pediatric and adult medical patients face similar rates of challenges after

Given the prevalence of postdischarge issues after both pediatric and adult hospitalizations, how should hospitalists proceed? Physicians and health systems should explore approaches to better prepare caregivers, perhaps using models akin to the Seamless Transitions and (Re)admissions Network model of enhanced communication, care coordination, and family engagement.10 Pediatric hospitalists can prepare children for discharge long before departure by delivering medications to patients prior to discharge,11,12 providing discharge instructions that are clear and readable,13,14 as well as utilizing admission-discharge teaching nurses,15 inpatient care managers,16,17 and pediatric nurse practitioners18 to aid transition.

While a variety of interventions show promise in securing a successful transition to home from the hospitalist vantage point, a partnership with primary care physicians (PCPs) in our communities is paramount. Though the evidence linking gaps in primary care after discharge and readmission rates remain elusive, effective partnerships with PCPs are important for ensuring discharge plans are carried out, which may ultimately lead to decreased rates of unanticipated adverse outcomes. Several adult studies note that no single intervention is likely to prevent issues after discharge, but interventions should include high-quality communication with and involvement of community partners.9,19,20 In practice, providing a high-quality, reliable handoff can be difficult given competing priorities of busy outpatient clinic schedules and inpatient bed capacity concerns, necessitating efficient discharge practices. Some of these challenges are amenable to quality improvement efforts to improve discharge communication.21 Innovative ideas include collaborating with PCPs earlier in the admission to design the care plan up front, including PCPs in weekly team meetings for patients with chronic care conditions,16,17 and using telehealth to communicate with PCPs.

Ensuring a safe transition to home is our responsibility as hospitalists, but the solutions to doing so reliably require multi-fold interventions that build teams within hospitals, innovative outreach to those patients recently discharged to ensure their well-being and mitigate postdischarge issues and broad community programs—including greater access to primary care—to meet our urgent imperative.

Disclosure

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. Dr. Auger’s research is funded by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (1K08HS024735).

The transition of children from hospital to home introduces a unique set of challenges to patients and families who may not be well-versed in the healthcare system. In addition to juggling the stress and worry of a sick child, which can inhibit the ability to understand complicated discharge instructions prior to leaving the hospital,1 caregivers need to navigate the medical system to ensure continued recovery. The responsibility to fill and administer medications, arrange follow up appointments, and determine when to seek care if the child’s condition changes are burdens we as healthcare providers expect caregivers to manage but may underestimate how frequently they are reliably completed.2-4

In this issue of the Journal of Hospital Medicine, the article by Rehm et al.5 adds to the growing body of evidence highlighting challenges that caregivers of children face upon discharge from the hospital. The multicenter, retrospective study of postdischarge encounters for over 12,000 patients discharged from 4 children’s hospitals aimed to evaluate the following: (1) various methods for hospital-initiated postdischarge contact of families, (2) the type and frequency of postdischarge issues, and (3) specific characteristics of pediatric patients most commonly affected by postdischarge issues.

Using standardized questions administered through telephone, text, or e-mail contact, postdischarge issues were identified in 25% of discharges across all hospitals. Notably, there was considerable variation of rates of postdischarge issues among hospitals (from 16% to 62.8%). The hospital with the highest rate of postdischarge issues identified had attending hospitalists calling families after discharge. Thus, postdischarge issues may be most easily identified by providers who are familiar with both the patient and the expected postdischarge care.

Often, postdischarge issues represented events that could be mitigated with intentional planning to better anticipate and address patient and family needs prior to discharge. The vast majority of postdischarge issues identified across all hospitals were related to appointments, accounting for 76.3% of postdischarge issues, which may be attributed to a variety of causes, from inadequate or unclear provider recommendations to difficulty scheduling the appointments. The most common medication postdischarge issue was difficulty filling prescriptions, accounting for 84.8% of the medication issues. “Other” postdischarge issues (12.7%) as reported by caregivers included challenges with understanding discharge instructions and concerns about changes in their child’s clinical status. Forty percent of included patients had a chronic care condition. Older children, patients with more medication classes, shorter length of stay, and neuromuscular chronic care conditions had higher odds of postdischarge issues. Although a high proportion of postdischarge issues suggests a systemic problem addressing the needs of patients and families after hospital discharge, these data likely underestimate the magnitude of the problem; as such, the need for improvement may be higher.

Postdischarge challenges faced by families are not unique to pediatrics. Pediatric and adult medical patients face similar rates of challenges after

Given the prevalence of postdischarge issues after both pediatric and adult hospitalizations, how should hospitalists proceed? Physicians and health systems should explore approaches to better prepare caregivers, perhaps using models akin to the Seamless Transitions and (Re)admissions Network model of enhanced communication, care coordination, and family engagement.10 Pediatric hospitalists can prepare children for discharge long before departure by delivering medications to patients prior to discharge,11,12 providing discharge instructions that are clear and readable,13,14 as well as utilizing admission-discharge teaching nurses,15 inpatient care managers,16,17 and pediatric nurse practitioners18 to aid transition.

While a variety of interventions show promise in securing a successful transition to home from the hospitalist vantage point, a partnership with primary care physicians (PCPs) in our communities is paramount. Though the evidence linking gaps in primary care after discharge and readmission rates remain elusive, effective partnerships with PCPs are important for ensuring discharge plans are carried out, which may ultimately lead to decreased rates of unanticipated adverse outcomes. Several adult studies note that no single intervention is likely to prevent issues after discharge, but interventions should include high-quality communication with and involvement of community partners.9,19,20 In practice, providing a high-quality, reliable handoff can be difficult given competing priorities of busy outpatient clinic schedules and inpatient bed capacity concerns, necessitating efficient discharge practices. Some of these challenges are amenable to quality improvement efforts to improve discharge communication.21 Innovative ideas include collaborating with PCPs earlier in the admission to design the care plan up front, including PCPs in weekly team meetings for patients with chronic care conditions,16,17 and using telehealth to communicate with PCPs.

Ensuring a safe transition to home is our responsibility as hospitalists, but the solutions to doing so reliably require multi-fold interventions that build teams within hospitals, innovative outreach to those patients recently discharged to ensure their well-being and mitigate postdischarge issues and broad community programs—including greater access to primary care—to meet our urgent imperative.

Disclosure

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. Dr. Auger’s research is funded by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (1K08HS024735).

1. Solan LG, Beck AF, Brunswick SA, et al. The Family Perspective on Hospital to Home Transitions: A Qualitative Study. Pediatrics. 2015;136(6):e1539-1549. PubMed

2. Misky GJ, Wald HL, Coleman EA. Post-hospitalization transitions: Examining the effects of timing of primary care provider follow-up. J Hosp Med. 2010;5(7):392-397. PubMed

3. Yin HS, Johnson M, Mendelsohn AL, Abrams MA, Sanders LM, Dreyer BP. The health literacy of parents in the United States: a nationally representative study. Pediatrics. 2009;124 Suppl 3:S289-298. PubMed

4. Glick AF, Farkas JS, Nicholson J, et al. Parental Management of Discharge Instructions: A Systematic Review. Pediatrics. 2017. [Epub ahead of print]. PubMed

5. Rehm KP, Brittan MS, Stephens JR, et al. Issues Identified by Post-Discharge Contact after Pediatric Hospitalization: A Multi-site Study (published online ahead of print February 2, 2018) J Hosp Med. doi: 10.12788/jhm.2934

6. Forster AJ, Murff HJ, Peterson JF, Gandhi TK, Bates DW. The incidence and severity of adverse events affecting patients after discharge from the hospital. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138(3):161-167. PubMed

7. Hansen LO, Greenwald JL, Budnitz T, et al. Project BOOST: effectiveness of a multihospital effort to reduce rehospitalization. J Hosp Med. 2013;8(8):421-427. PubMed

8. Auerbach AD, Kripalani S, Vasilevskis EE, et al. Preventability and Causes of Readmissions in a National Cohort of General Medicine Patients. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(4):484-493. PubMed

9. Kripalani S, LeFevre F, Phillips CO, Williams MV, Basaviah P, Baker DW. Deficits in communication and information transfer between hospital-based and primary care physicians: implications for patient safety and continuity of care. JAMA. 2007;297(8):831-841. PubMed

10. Auger KA, Simon TD, Cooperberg D, et al. Summary of STARNet: Seamless Transitions and (Re)admissions Network. Pediatrics. 2015;135(1):164-175. PubMed

11. Hatoun J, Bair-Merritt M, Cabral H, Moses J. Increasing Medication Possession at Discharge for Patients With Asthma: The Meds-in-Hand Project. Pediatrics. 2016;137(3):e20150461. PubMed

12. White CM, Statile AM, White DL, et al. Using quality improvement to optimise paediatric discharge efficiency. BMJ Qual Saf. 2014;23(5):428-436. PubMed

13. Unaka N, Statile A, Jerardi K, et al. Improving the Readability of Pediatric Hospital Medicine Discharge Instructions. J Hosp Med. 2017;12(7):551-557. PubMed

14. Wu S, Tyler A, Logsdon T, et al. A Quality Improvement Collaborative to Improve the Discharge Process for Hospitalized Children. Pediatrics. 2016;138(2). PubMed

15. Blankenship JS, Winslow SA. Admission-discharge-teaching nurses: bridging the gap in today’s workforce. J Nurs Adm. 2003;33(1):11-13. PubMed

16. White CM, Thomson JE, Statile AM, et al. Development of a New Care Model for Hospitalized Children With Medical Complexity. Hosp Pediatr. 2017;7(7):410-414. PubMed

17. Statile AM, Schondelmeyer AC, Thomson JE, et al. Improving Discharge Efficiency in Medically Complex Pediatric Patients. Pediatrics. 2016;138(2). PubMed

18. Dunn K, Rogers J. Discharge Facilitation: An Innovative PNP Role. J Pediatr Health Care. 2016;30(5):499-505. PubMed

19. Kripalani S, Jackson AT, Schnipper JL, Coleman EA. Promoting effective transitions of care at hospital discharge: a review of key issues for hospitalists. J Hosp Med. 2007;2(5):314-323. PubMed

20. Scott AM, Li J, Oyewole-Eletu S, et al. Understanding Facilitators and Barriers to Care Transitions: Insights from Project ACHIEVE Site Visits. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2017;43(9):433-447. PubMed

21. Shen MW, Hershey D, Bergert L, Mallory L, Fisher ES, Cooperberg D. Pediatric hospitalists collaborate to improve timeliness of discharge communication. Hosp Pediatr. 2013;3(3):258-265. PubMed

1. Solan LG, Beck AF, Brunswick SA, et al. The Family Perspective on Hospital to Home Transitions: A Qualitative Study. Pediatrics. 2015;136(6):e1539-1549. PubMed

2. Misky GJ, Wald HL, Coleman EA. Post-hospitalization transitions: Examining the effects of timing of primary care provider follow-up. J Hosp Med. 2010;5(7):392-397. PubMed

3. Yin HS, Johnson M, Mendelsohn AL, Abrams MA, Sanders LM, Dreyer BP. The health literacy of parents in the United States: a nationally representative study. Pediatrics. 2009;124 Suppl 3:S289-298. PubMed

4. Glick AF, Farkas JS, Nicholson J, et al. Parental Management of Discharge Instructions: A Systematic Review. Pediatrics. 2017. [Epub ahead of print]. PubMed

5. Rehm KP, Brittan MS, Stephens JR, et al. Issues Identified by Post-Discharge Contact after Pediatric Hospitalization: A Multi-site Study (published online ahead of print February 2, 2018) J Hosp Med. doi: 10.12788/jhm.2934

6. Forster AJ, Murff HJ, Peterson JF, Gandhi TK, Bates DW. The incidence and severity of adverse events affecting patients after discharge from the hospital. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138(3):161-167. PubMed

7. Hansen LO, Greenwald JL, Budnitz T, et al. Project BOOST: effectiveness of a multihospital effort to reduce rehospitalization. J Hosp Med. 2013;8(8):421-427. PubMed

8. Auerbach AD, Kripalani S, Vasilevskis EE, et al. Preventability and Causes of Readmissions in a National Cohort of General Medicine Patients. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(4):484-493. PubMed

9. Kripalani S, LeFevre F, Phillips CO, Williams MV, Basaviah P, Baker DW. Deficits in communication and information transfer between hospital-based and primary care physicians: implications for patient safety and continuity of care. JAMA. 2007;297(8):831-841. PubMed

10. Auger KA, Simon TD, Cooperberg D, et al. Summary of STARNet: Seamless Transitions and (Re)admissions Network. Pediatrics. 2015;135(1):164-175. PubMed

11. Hatoun J, Bair-Merritt M, Cabral H, Moses J. Increasing Medication Possession at Discharge for Patients With Asthma: The Meds-in-Hand Project. Pediatrics. 2016;137(3):e20150461. PubMed

12. White CM, Statile AM, White DL, et al. Using quality improvement to optimise paediatric discharge efficiency. BMJ Qual Saf. 2014;23(5):428-436. PubMed

13. Unaka N, Statile A, Jerardi K, et al. Improving the Readability of Pediatric Hospital Medicine Discharge Instructions. J Hosp Med. 2017;12(7):551-557. PubMed

14. Wu S, Tyler A, Logsdon T, et al. A Quality Improvement Collaborative to Improve the Discharge Process for Hospitalized Children. Pediatrics. 2016;138(2). PubMed

15. Blankenship JS, Winslow SA. Admission-discharge-teaching nurses: bridging the gap in today’s workforce. J Nurs Adm. 2003;33(1):11-13. PubMed

16. White CM, Thomson JE, Statile AM, et al. Development of a New Care Model for Hospitalized Children With Medical Complexity. Hosp Pediatr. 2017;7(7):410-414. PubMed

17. Statile AM, Schondelmeyer AC, Thomson JE, et al. Improving Discharge Efficiency in Medically Complex Pediatric Patients. Pediatrics. 2016;138(2). PubMed

18. Dunn K, Rogers J. Discharge Facilitation: An Innovative PNP Role. J Pediatr Health Care. 2016;30(5):499-505. PubMed

19. Kripalani S, Jackson AT, Schnipper JL, Coleman EA. Promoting effective transitions of care at hospital discharge: a review of key issues for hospitalists. J Hosp Med. 2007;2(5):314-323. PubMed

20. Scott AM, Li J, Oyewole-Eletu S, et al. Understanding Facilitators and Barriers to Care Transitions: Insights from Project ACHIEVE Site Visits. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2017;43(9):433-447. PubMed

21. Shen MW, Hershey D, Bergert L, Mallory L, Fisher ES, Cooperberg D. Pediatric hospitalists collaborate to improve timeliness of discharge communication. Hosp Pediatr. 2013;3(3):258-265. PubMed

© 2018 Society of Hospital Medicine

Accuracy Comparisons between Manual and Automated Respiratory Rate for Detecting Clinical Deterioration in Ward Patients

Respiratory rate is the most accurate vital sign for predicting adverse outcomes in ward patients.1,2 Though other vital signs are typically collected by using machines, respiratory rate is collected manually by caregivers counting the breathing rate. However, studies have shown significant discrepancies between a patient’s respiratory rate documented in the medical record, which is often 18 or 20, and the value measured by counting the rate over a full minute.3 Thus, despite the high accuracy of respiratory rate, it is possible that these values do not represent true patient physiology. It is unknown whether a valid automated measurement of respiratory rate would be more predictive than a manually collected respiratory rate for identifying patients who develop deterioration. The aim of this study was to compare the distribution and predictive accuracy of manually and automatically recorded respiratory rates.

METHODS

In this prospective cohort study, adult patients admitted to one oncology ward at the University of Chicago from April 2015 to May 2016 were approached for consent (Institutional Review Board #14-0682). Enrolled patients were fit with a cableless, FDA-approved respiratory pod device (Philips IntelliVue clResp Pod; Philips Healthcare, Andover, MA) that automatically recorded respiratory rate and heart rate every 15 minutes while they remained on the ward. Pod data were paired with vital sign data documented in the electronic health record (EHR) by taking the automated value closest, but prior to, the manual value up to a maximum of 4 hours. Automated and manual respiratory rate were compared by using the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC) for whether an intensive care unit (ICU) transfer occurred within 24 hours of each paired observation without accounting for patient-level clustering.

RESULTS

DISCUSSION

In this prospective cohort study, we found that manual respiratory rates were different than those collected from an automated system and, yet, were significantly more accurate for predicting ICU transfer. These results suggest that the predictive accuracy of respiratory rates documented in the EHR is due to more than just physiology. Our findings have important implications for the risk stratification of ward patients.

Though previous literature has suggested that respiratory rate is the most accurate predictor of deterioration, this may not be true.1 Respiratory rates manually recorded by clinical staff may contain information beyond pure physiology, such as a proxy of clinician concern, which may inflate the predictive value. Nursing staff may record standard respiratory rate values for patients that appear to be well (eg, 18) but count actual rates for those patients they suspect have a more severe disease, which is one possible explanation for our findings. In addition, automated assessments are likely to be more sensitive to intermittent fluctuations in respiratory rate associated with patient movement or emotion. This might explain the improved accuracy at higher rates for manually recorded vital signs.

Although limited by its small sample size, our results have important implications for patient monitoring and early warning scores designed to identify high-risk ward patients given that both simple scores and statistically derived models include respiratory rates as a predictor.4 As hospitals move to use newer technologies to automate vital sign monitoring and decrease nursing workload, our findings suggest that accuracy for identifying high-risk patients may be lost. Additional methods for capturing subjective assessments from clinical providers may be necessary and could be incorporated into risk scores.5 For example, the 7-point subjective Patient Acuity Rating has been shown to augment the Modified Early Warning Score for predicting ICU transfer, rapid response activation, or cardiac arrest within 24 hours.6

Manually recorded respiratory rate may include information beyond pure physiology, which inflates its predictive value. This has important implications for the use of automated monitoring technology in hospitals and the integration of these measurements into early warning scores.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Pamela McCall, BSN, OCN for her assistance with study implementation, Kevin Ig-Izevbekhai and Shivraj Grewal for assistance with data collection, UCM Clinical Engineering for technical support, and Timothy Holper, MS, Julie Johnson, MPH, RN, and Thomas Sutton for assistance with data abstraction.

Disclosure

Dr. Churpek is supported by a career development award from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (K08 HL121080) and has received honoraria from Chest for invited speaking engagements. Dr. Churpek and Dr. Edelson have a patent pending (ARCD. P0535US.P2) for risk stratification algorithms for hospitalized patients. In addition, Dr. Edelson has received research support from Philips Healthcare (Andover, MA), research support from the American Heart Association (Dallas, TX) and Laerdal Medical (Stavanger, Norway), and research support from EarlySense (Tel Aviv, Israel). She has ownership interest in Quant HC (Chicago, IL), which is developing products for risk stratification of hospitalized patients. This study was supported by a grant from Philips Healthcare in Andover, MA. The sponsor had no role in data collection, interpretation of results, or drafting of the manuscript.

1. Churpek MM, Yuen TC, Huber MT, Park SY, Hall JB, Edelson DP. Predicting cardiac arrest on the wards: a nested case-control study. Chest. 2012;141(5):1170-1176. PubMed

2. Fieselmann JF, Hendryx MS, Helms CM, Wakefield DS. Respiratory rate predicts cardiopulmonary arrest for internal medicine inpatients. J Gen Intern Med. 1993;8(7):354-360. PubMed

3. Semler MW, Stover DG, Copland AP, et al. Flash mob research: a single-day, multicenter, resident-directed study of respiratory rate. Chest. 2013;143(6):1740-1744. PubMed

4. Churpek MM, Yuen TC, Edelson DP. Risk stratification of hospitalized patients on the wards. Chest. 2013;143(6):1758-1765. PubMed

5. Edelson DP, Retzer E, Weidman EK, et al. Patient acuity rating: quantifying clinical judgment regarding inpatient stability. J Hosp Med. 2011;6(8):475-479. PubMed

6. Patel AR, Zadravecz FJ, Young RS, Williams MV, Churpek MM, Edelson DP. The value of clinical judgment in the detection of clinical deterioration. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(3):456-458. PubMed

Respiratory rate is the most accurate vital sign for predicting adverse outcomes in ward patients.1,2 Though other vital signs are typically collected by using machines, respiratory rate is collected manually by caregivers counting the breathing rate. However, studies have shown significant discrepancies between a patient’s respiratory rate documented in the medical record, which is often 18 or 20, and the value measured by counting the rate over a full minute.3 Thus, despite the high accuracy of respiratory rate, it is possible that these values do not represent true patient physiology. It is unknown whether a valid automated measurement of respiratory rate would be more predictive than a manually collected respiratory rate for identifying patients who develop deterioration. The aim of this study was to compare the distribution and predictive accuracy of manually and automatically recorded respiratory rates.

METHODS

In this prospective cohort study, adult patients admitted to one oncology ward at the University of Chicago from April 2015 to May 2016 were approached for consent (Institutional Review Board #14-0682). Enrolled patients were fit with a cableless, FDA-approved respiratory pod device (Philips IntelliVue clResp Pod; Philips Healthcare, Andover, MA) that automatically recorded respiratory rate and heart rate every 15 minutes while they remained on the ward. Pod data were paired with vital sign data documented in the electronic health record (EHR) by taking the automated value closest, but prior to, the manual value up to a maximum of 4 hours. Automated and manual respiratory rate were compared by using the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC) for whether an intensive care unit (ICU) transfer occurred within 24 hours of each paired observation without accounting for patient-level clustering.

RESULTS

DISCUSSION