User login

Prurigo Nodularis: Moving Forward

Prurigo nodularis (PN), a condition that historically has been a challenge to treat, now has a US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)–approved therapy—dupilumab—with other agents in the pipeline. As clinicians, we recognize PN as typically symmetric, keratotic, papular and nodular lesions presenting in older adults with chronic pruritus; patients with atopic dermatitis make up roughly half of patients with PN, but a workup for pruritus is indicated in other settings.1 In the United States, Black patients are 3.4-times more likely than White patients to have PN.2 The differential diagnosis includes conditions such nodular scabies, pemphigoid nodularis, acquired perforating disorders, and hypertrophic lichen planus, which also should be considered, especially in cases that are refractory to first-line therapies. Recent breakthroughs in therapy have come from substantial progress in our understanding of the pathogenesis of PN as driven by disorders of cytokine expression and/or neurocutaneous aberrations. We review progress in the treatment of PN over the last 3 years.

Treatment Guidelines

In 2020, an expert panel published consensus treatment guidelines for PN.1 The panel, which proposed a 4-tiered approach targeting both neural and immunologic mechanisms in the pathogenesis of PN, emphasized the importance of tailoring treatment to the individual patient. Topical therapies remained the mainstay of treatment, with agents such as topical capsaicin, ketamine, lidocaine, and amitriptyline targeting the neural component and topical corticosteroids, calcineurin inhibitors, and calcipotriol and intralesional corticosteroids targeting the immunologic component. Phototherapy, methotrexate, cyclosporine, antidepressants, and gabapentinoids used with varying degrees of success were noted to have acceptable tolerability.1

FDA-Approved Therapy

In September 2022, the FDA approved dupilumab for the treatment of PN. An antagonist of the IL-4 receptor, dupilumab was found to reduce both pruritus and skin lesions over a 24-week period in 2 phase 3 clinical trials.3 Results also demonstrated progressive improvements in measures assessing quality of life and pruritus over the study period, suggesting that continued treatment could lead to even further improvements in these measures. Adverse events were minimal and similar between the dupilumab- and placebo-treated groups.3

The FDA approval of dupilumab is a promising step in decreasing the disease burden of widespread or refractory PN, both for patients and the health care system. The treatment of patients with PN has been more challenging due to comorbidities, including mental health conditions, endocrine disorders, cardiovascular conditions, renal conditions, malignancy, and HIV.4,5 These comorbidities can complicate the use of traditional systemic and immunosuppressive agents. Dupilumab has virtually no contraindications and has demonstrated safety in almost all patient populations.6

Consistent insurance coverage for patients who respond to dupilumab remains to be determined. A review investigating the use of dupilumab in patients with atopic dermatitis at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center (Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania) found that of 179 patients, 67 (37.4%) did not start dupilumab, mainly due to insurance denial (34/179 [19%]) or copay (20/179 [11%]). Medicare patients were less likely to receive treatment compared to those on private insurance or Medicaid.7 In a recent review of 701 patients with PN, the mean age was 64.8 years,5 highlighting the concern about obtaining insurance coverage for dupilumab in this population given the higher likelihood that these patients will be on Medicare. Prescribers should be aware that coverage denials are likely and should be prepared to advocate for their patients by citing recent studies to hopefully obtain coverage for dupilumab in the treatment of PN. Resources such as the Dupixent MyWay program (https://www.dupixent.com/support-savings/dupixent-my-way) can provide useful recommendations for pursuing insurance approval for this agent.

Investigation of Janus Kinase Inhibitors

Emerging data suggest that Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors may be beneficial in the treatment of PN. Patients with refractory PN have been treated off label with the JAK inhibitor tofacitinib at a dosage of 5 mg twice daily with improvement in symptoms and minimal side effects.8,9 Similarly, a case report showed that off-label use of the JAK inhibitor baricitinib resulted in marked improvement in pruritus and clearance of lesions at a dosage of 4 mg daily, with reduction in pruritus seen as early as 1 week after treatment initiation.10 Although most patients are able to tolerate JAK inhibitors, known side effects include acne, viral infections, gastrointestinal tract upset, and the potential increased risk for malignancy.11 The use of topical JAK inhibitors such as ruxolitinib has not yet been studied in PN, though cost may limit use to localized disease.

Other New Therapies

Recent case reports and case series have found the vitamin A derivative alitretinoin to be an effective treatment for recalcitrant PN, typically at a dosage of 30 mg daily.12,13 Sustained remission was noted even after discontinuation of the medication.12 Alitretinoin, which has been demonstrated to be effective in treating dermatitis,14 was well tolerated. Similar to JAK inhibitors, there are minimal data investigating the use of topical retinoids in the treatment of localized PN.

Topical cannabinoids have shown benefit in the treatment of pruritus15 and may be beneficial for the treatment of PN, though there currently are limited data in the literature. With the use of both medical and legal recreational marijuana on the rise, there is an increased interest in cannabinoids, particularly as many patients consider these agents to be more “natural”—and therefore preferable—treatment options. As the use of cannabis derivatives become more commonplace in both traditional and complementary medicine, providers should be prepared to field questions from patients about their potential for PN.

Finally, the IL-31RA inhibitor nemolizumab also has shown promise in the treatment of PN. A recent study suggested that nemolizumab helps modulate inflammatory and neural signaling in PN.16 Nemolizumab has been granted breakthrough therapy designation for the treatment of pruritus in PN based on a phase 2 study that demonstrated improvement in pruritus and skin lesions in a group of 70 patients with moderate to severe PN.17 Nemolizumab, which is used to treat pruritus in atopic dermatitis, has minimal side effects including upper respiratory tract infections and peripheral edema.18

Final Thoughts

Prurigo nodularis historically has been considered difficult to treat, particularly in those with widespread lesions. Dupilumab—the first FDA-approved treatment of PN—is now an exciting option, not just for patients with underlying atopic dermatitis. Not all patients will respond to the medication, and the ease of obtaining insurance approval has yet to be established; therefore, having other treatment options will be imperative. In patients with recalcitrant disease, several other treatment options have shown promise in the treatment of PN; in particular, JAK inhibitors, alitretinoin, and nemolizumab should be considered in patients with widespread refractory PN who are willing to try alternative agents. Ongoing research should be focused on these medications as well as on the development of other novel treatments aimed at relieving affected patients.

- Elmariah S, Kim B, Berger T, et al. Practical approaches for diagnosis and management of prurigo nodularis: United States expert panel consensus [published online July 15, 2020]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:747-760. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.07.025

- Boozalis E, Tang O, Patel S, et al. Ethnic differences and comorbidities of 909 prurigo nodularis patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79:714.

- Yosipovitch G, Mollanazar N, Ständer S, et al. Dupilumab in patients with prurigo nodularis: two randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 trials. Nat Med. 2023;29:1180-1190. doi:10.1038/s41591-023-02320-9

- Huang AH, Williams KA, Kwatra SG. Prurigo nodularis: epidemiology and clinical features. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:1559-1565. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.04.183

- Joel MZ, Hydol-Smith J, Kambala A, et al. Prevalence and comorbidity burden of prurigo nodularis in United States adults enrolled in the All of Us research program. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2023;89:1056-1058. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2023.06.045

- Dupixent. Package insert. Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc; 2017.

- Khosravi H, Zhang S, Anderson AM, et al. Dupilumab drug survival, treatment failures, and insurance approval at a tertiary care center in the United States. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:1023-1024. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.12.034

- Liu T, Chu Y, Wang Y, et al. Successful treatment of prurigo nodularis with tofacitinib: the experience from a single center. Int J Dermatol. 2023;62:E293-E295. doi:10.1111/ijd.16568

- Molloy OE, Kearney N, Byrne N, et al. Successful treatment of recalcitrant nodular prurigo with tofacitinib. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2020;45:918-920. doi:10.1111/ced.14320

- Yin M, Wu R, Chen J, et al. Successful treatment of refractory prurigo nodularis with baricitinib. Dermatol Ther. 2022;35:E15642. doi:10.1111/dth.15642

- Klein B, Treudler R, Simon JC. JAK-inhibitors in dermatology—small molecules, big impact? overview of the mechanism of action, previous study results and potential adverse effects. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2022;20:19-24. doi:10.1111/ddg.14668

- Chung BY, Um JY, Kang SY, et al. Oral alitretinoin for patients with refractory prurigo. Medicina (Kaunas). 2020;56:599. doi:10.3390/medicina56110599

- Maqbool T, Kraft JN. Alitretinoin for prurigo nodularis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2021;46:362-363. doi:10.1111/ced.14385

- Grahovac M, Molin S, Prinz JC, et al. Treatment of atopic eczema with oral alitretinoin. Br J Dermatol. 2010;162:217-218. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.2009.09522.x

- Avila C, Massick S, Kaffenberger BH, et al. Cannabinoids for the treatment of chronic pruritus: a review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:1205-1212. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.01.036

- Deng J, Liao V, Parthasarathy V, et al. Modulation of neuroimmune and epithelial dysregulation in patients with moderate to severe prurigo nodularis treated with nemolizumab. JAMA Dermatol. 2023;159:977-985. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2023.2609

- Park B. Nemolizumab gets breakthrough therapy status for prurigo nodularis. Medical Professionals Reference website. Published December 9, 2019. Accessed November 13, 2023. https://www.empr.com/home/news/nemolizumab-gets-breakthrough-therapy-status-for-prurigo-nodularis/

- Labib A, Vander Does A, Yosipovitch G. Nemolizumab for atopic dermatitis. Drugs Today (Barc). 2022;58:159-173. doi:10.1358/dot.2022.58.4.3378056

Prurigo nodularis (PN), a condition that historically has been a challenge to treat, now has a US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)–approved therapy—dupilumab—with other agents in the pipeline. As clinicians, we recognize PN as typically symmetric, keratotic, papular and nodular lesions presenting in older adults with chronic pruritus; patients with atopic dermatitis make up roughly half of patients with PN, but a workup for pruritus is indicated in other settings.1 In the United States, Black patients are 3.4-times more likely than White patients to have PN.2 The differential diagnosis includes conditions such nodular scabies, pemphigoid nodularis, acquired perforating disorders, and hypertrophic lichen planus, which also should be considered, especially in cases that are refractory to first-line therapies. Recent breakthroughs in therapy have come from substantial progress in our understanding of the pathogenesis of PN as driven by disorders of cytokine expression and/or neurocutaneous aberrations. We review progress in the treatment of PN over the last 3 years.

Treatment Guidelines

In 2020, an expert panel published consensus treatment guidelines for PN.1 The panel, which proposed a 4-tiered approach targeting both neural and immunologic mechanisms in the pathogenesis of PN, emphasized the importance of tailoring treatment to the individual patient. Topical therapies remained the mainstay of treatment, with agents such as topical capsaicin, ketamine, lidocaine, and amitriptyline targeting the neural component and topical corticosteroids, calcineurin inhibitors, and calcipotriol and intralesional corticosteroids targeting the immunologic component. Phototherapy, methotrexate, cyclosporine, antidepressants, and gabapentinoids used with varying degrees of success were noted to have acceptable tolerability.1

FDA-Approved Therapy

In September 2022, the FDA approved dupilumab for the treatment of PN. An antagonist of the IL-4 receptor, dupilumab was found to reduce both pruritus and skin lesions over a 24-week period in 2 phase 3 clinical trials.3 Results also demonstrated progressive improvements in measures assessing quality of life and pruritus over the study period, suggesting that continued treatment could lead to even further improvements in these measures. Adverse events were minimal and similar between the dupilumab- and placebo-treated groups.3

The FDA approval of dupilumab is a promising step in decreasing the disease burden of widespread or refractory PN, both for patients and the health care system. The treatment of patients with PN has been more challenging due to comorbidities, including mental health conditions, endocrine disorders, cardiovascular conditions, renal conditions, malignancy, and HIV.4,5 These comorbidities can complicate the use of traditional systemic and immunosuppressive agents. Dupilumab has virtually no contraindications and has demonstrated safety in almost all patient populations.6

Consistent insurance coverage for patients who respond to dupilumab remains to be determined. A review investigating the use of dupilumab in patients with atopic dermatitis at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center (Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania) found that of 179 patients, 67 (37.4%) did not start dupilumab, mainly due to insurance denial (34/179 [19%]) or copay (20/179 [11%]). Medicare patients were less likely to receive treatment compared to those on private insurance or Medicaid.7 In a recent review of 701 patients with PN, the mean age was 64.8 years,5 highlighting the concern about obtaining insurance coverage for dupilumab in this population given the higher likelihood that these patients will be on Medicare. Prescribers should be aware that coverage denials are likely and should be prepared to advocate for their patients by citing recent studies to hopefully obtain coverage for dupilumab in the treatment of PN. Resources such as the Dupixent MyWay program (https://www.dupixent.com/support-savings/dupixent-my-way) can provide useful recommendations for pursuing insurance approval for this agent.

Investigation of Janus Kinase Inhibitors

Emerging data suggest that Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors may be beneficial in the treatment of PN. Patients with refractory PN have been treated off label with the JAK inhibitor tofacitinib at a dosage of 5 mg twice daily with improvement in symptoms and minimal side effects.8,9 Similarly, a case report showed that off-label use of the JAK inhibitor baricitinib resulted in marked improvement in pruritus and clearance of lesions at a dosage of 4 mg daily, with reduction in pruritus seen as early as 1 week after treatment initiation.10 Although most patients are able to tolerate JAK inhibitors, known side effects include acne, viral infections, gastrointestinal tract upset, and the potential increased risk for malignancy.11 The use of topical JAK inhibitors such as ruxolitinib has not yet been studied in PN, though cost may limit use to localized disease.

Other New Therapies

Recent case reports and case series have found the vitamin A derivative alitretinoin to be an effective treatment for recalcitrant PN, typically at a dosage of 30 mg daily.12,13 Sustained remission was noted even after discontinuation of the medication.12 Alitretinoin, which has been demonstrated to be effective in treating dermatitis,14 was well tolerated. Similar to JAK inhibitors, there are minimal data investigating the use of topical retinoids in the treatment of localized PN.

Topical cannabinoids have shown benefit in the treatment of pruritus15 and may be beneficial for the treatment of PN, though there currently are limited data in the literature. With the use of both medical and legal recreational marijuana on the rise, there is an increased interest in cannabinoids, particularly as many patients consider these agents to be more “natural”—and therefore preferable—treatment options. As the use of cannabis derivatives become more commonplace in both traditional and complementary medicine, providers should be prepared to field questions from patients about their potential for PN.

Finally, the IL-31RA inhibitor nemolizumab also has shown promise in the treatment of PN. A recent study suggested that nemolizumab helps modulate inflammatory and neural signaling in PN.16 Nemolizumab has been granted breakthrough therapy designation for the treatment of pruritus in PN based on a phase 2 study that demonstrated improvement in pruritus and skin lesions in a group of 70 patients with moderate to severe PN.17 Nemolizumab, which is used to treat pruritus in atopic dermatitis, has minimal side effects including upper respiratory tract infections and peripheral edema.18

Final Thoughts

Prurigo nodularis historically has been considered difficult to treat, particularly in those with widespread lesions. Dupilumab—the first FDA-approved treatment of PN—is now an exciting option, not just for patients with underlying atopic dermatitis. Not all patients will respond to the medication, and the ease of obtaining insurance approval has yet to be established; therefore, having other treatment options will be imperative. In patients with recalcitrant disease, several other treatment options have shown promise in the treatment of PN; in particular, JAK inhibitors, alitretinoin, and nemolizumab should be considered in patients with widespread refractory PN who are willing to try alternative agents. Ongoing research should be focused on these medications as well as on the development of other novel treatments aimed at relieving affected patients.

Prurigo nodularis (PN), a condition that historically has been a challenge to treat, now has a US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)–approved therapy—dupilumab—with other agents in the pipeline. As clinicians, we recognize PN as typically symmetric, keratotic, papular and nodular lesions presenting in older adults with chronic pruritus; patients with atopic dermatitis make up roughly half of patients with PN, but a workup for pruritus is indicated in other settings.1 In the United States, Black patients are 3.4-times more likely than White patients to have PN.2 The differential diagnosis includes conditions such nodular scabies, pemphigoid nodularis, acquired perforating disorders, and hypertrophic lichen planus, which also should be considered, especially in cases that are refractory to first-line therapies. Recent breakthroughs in therapy have come from substantial progress in our understanding of the pathogenesis of PN as driven by disorders of cytokine expression and/or neurocutaneous aberrations. We review progress in the treatment of PN over the last 3 years.

Treatment Guidelines

In 2020, an expert panel published consensus treatment guidelines for PN.1 The panel, which proposed a 4-tiered approach targeting both neural and immunologic mechanisms in the pathogenesis of PN, emphasized the importance of tailoring treatment to the individual patient. Topical therapies remained the mainstay of treatment, with agents such as topical capsaicin, ketamine, lidocaine, and amitriptyline targeting the neural component and topical corticosteroids, calcineurin inhibitors, and calcipotriol and intralesional corticosteroids targeting the immunologic component. Phototherapy, methotrexate, cyclosporine, antidepressants, and gabapentinoids used with varying degrees of success were noted to have acceptable tolerability.1

FDA-Approved Therapy

In September 2022, the FDA approved dupilumab for the treatment of PN. An antagonist of the IL-4 receptor, dupilumab was found to reduce both pruritus and skin lesions over a 24-week period in 2 phase 3 clinical trials.3 Results also demonstrated progressive improvements in measures assessing quality of life and pruritus over the study period, suggesting that continued treatment could lead to even further improvements in these measures. Adverse events were minimal and similar between the dupilumab- and placebo-treated groups.3

The FDA approval of dupilumab is a promising step in decreasing the disease burden of widespread or refractory PN, both for patients and the health care system. The treatment of patients with PN has been more challenging due to comorbidities, including mental health conditions, endocrine disorders, cardiovascular conditions, renal conditions, malignancy, and HIV.4,5 These comorbidities can complicate the use of traditional systemic and immunosuppressive agents. Dupilumab has virtually no contraindications and has demonstrated safety in almost all patient populations.6

Consistent insurance coverage for patients who respond to dupilumab remains to be determined. A review investigating the use of dupilumab in patients with atopic dermatitis at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center (Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania) found that of 179 patients, 67 (37.4%) did not start dupilumab, mainly due to insurance denial (34/179 [19%]) or copay (20/179 [11%]). Medicare patients were less likely to receive treatment compared to those on private insurance or Medicaid.7 In a recent review of 701 patients with PN, the mean age was 64.8 years,5 highlighting the concern about obtaining insurance coverage for dupilumab in this population given the higher likelihood that these patients will be on Medicare. Prescribers should be aware that coverage denials are likely and should be prepared to advocate for their patients by citing recent studies to hopefully obtain coverage for dupilumab in the treatment of PN. Resources such as the Dupixent MyWay program (https://www.dupixent.com/support-savings/dupixent-my-way) can provide useful recommendations for pursuing insurance approval for this agent.

Investigation of Janus Kinase Inhibitors

Emerging data suggest that Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors may be beneficial in the treatment of PN. Patients with refractory PN have been treated off label with the JAK inhibitor tofacitinib at a dosage of 5 mg twice daily with improvement in symptoms and minimal side effects.8,9 Similarly, a case report showed that off-label use of the JAK inhibitor baricitinib resulted in marked improvement in pruritus and clearance of lesions at a dosage of 4 mg daily, with reduction in pruritus seen as early as 1 week after treatment initiation.10 Although most patients are able to tolerate JAK inhibitors, known side effects include acne, viral infections, gastrointestinal tract upset, and the potential increased risk for malignancy.11 The use of topical JAK inhibitors such as ruxolitinib has not yet been studied in PN, though cost may limit use to localized disease.

Other New Therapies

Recent case reports and case series have found the vitamin A derivative alitretinoin to be an effective treatment for recalcitrant PN, typically at a dosage of 30 mg daily.12,13 Sustained remission was noted even after discontinuation of the medication.12 Alitretinoin, which has been demonstrated to be effective in treating dermatitis,14 was well tolerated. Similar to JAK inhibitors, there are minimal data investigating the use of topical retinoids in the treatment of localized PN.

Topical cannabinoids have shown benefit in the treatment of pruritus15 and may be beneficial for the treatment of PN, though there currently are limited data in the literature. With the use of both medical and legal recreational marijuana on the rise, there is an increased interest in cannabinoids, particularly as many patients consider these agents to be more “natural”—and therefore preferable—treatment options. As the use of cannabis derivatives become more commonplace in both traditional and complementary medicine, providers should be prepared to field questions from patients about their potential for PN.

Finally, the IL-31RA inhibitor nemolizumab also has shown promise in the treatment of PN. A recent study suggested that nemolizumab helps modulate inflammatory and neural signaling in PN.16 Nemolizumab has been granted breakthrough therapy designation for the treatment of pruritus in PN based on a phase 2 study that demonstrated improvement in pruritus and skin lesions in a group of 70 patients with moderate to severe PN.17 Nemolizumab, which is used to treat pruritus in atopic dermatitis, has minimal side effects including upper respiratory tract infections and peripheral edema.18

Final Thoughts

Prurigo nodularis historically has been considered difficult to treat, particularly in those with widespread lesions. Dupilumab—the first FDA-approved treatment of PN—is now an exciting option, not just for patients with underlying atopic dermatitis. Not all patients will respond to the medication, and the ease of obtaining insurance approval has yet to be established; therefore, having other treatment options will be imperative. In patients with recalcitrant disease, several other treatment options have shown promise in the treatment of PN; in particular, JAK inhibitors, alitretinoin, and nemolizumab should be considered in patients with widespread refractory PN who are willing to try alternative agents. Ongoing research should be focused on these medications as well as on the development of other novel treatments aimed at relieving affected patients.

- Elmariah S, Kim B, Berger T, et al. Practical approaches for diagnosis and management of prurigo nodularis: United States expert panel consensus [published online July 15, 2020]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:747-760. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.07.025

- Boozalis E, Tang O, Patel S, et al. Ethnic differences and comorbidities of 909 prurigo nodularis patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79:714.

- Yosipovitch G, Mollanazar N, Ständer S, et al. Dupilumab in patients with prurigo nodularis: two randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 trials. Nat Med. 2023;29:1180-1190. doi:10.1038/s41591-023-02320-9

- Huang AH, Williams KA, Kwatra SG. Prurigo nodularis: epidemiology and clinical features. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:1559-1565. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.04.183

- Joel MZ, Hydol-Smith J, Kambala A, et al. Prevalence and comorbidity burden of prurigo nodularis in United States adults enrolled in the All of Us research program. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2023;89:1056-1058. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2023.06.045

- Dupixent. Package insert. Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc; 2017.

- Khosravi H, Zhang S, Anderson AM, et al. Dupilumab drug survival, treatment failures, and insurance approval at a tertiary care center in the United States. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:1023-1024. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.12.034

- Liu T, Chu Y, Wang Y, et al. Successful treatment of prurigo nodularis with tofacitinib: the experience from a single center. Int J Dermatol. 2023;62:E293-E295. doi:10.1111/ijd.16568

- Molloy OE, Kearney N, Byrne N, et al. Successful treatment of recalcitrant nodular prurigo with tofacitinib. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2020;45:918-920. doi:10.1111/ced.14320

- Yin M, Wu R, Chen J, et al. Successful treatment of refractory prurigo nodularis with baricitinib. Dermatol Ther. 2022;35:E15642. doi:10.1111/dth.15642

- Klein B, Treudler R, Simon JC. JAK-inhibitors in dermatology—small molecules, big impact? overview of the mechanism of action, previous study results and potential adverse effects. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2022;20:19-24. doi:10.1111/ddg.14668

- Chung BY, Um JY, Kang SY, et al. Oral alitretinoin for patients with refractory prurigo. Medicina (Kaunas). 2020;56:599. doi:10.3390/medicina56110599

- Maqbool T, Kraft JN. Alitretinoin for prurigo nodularis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2021;46:362-363. doi:10.1111/ced.14385

- Grahovac M, Molin S, Prinz JC, et al. Treatment of atopic eczema with oral alitretinoin. Br J Dermatol. 2010;162:217-218. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.2009.09522.x

- Avila C, Massick S, Kaffenberger BH, et al. Cannabinoids for the treatment of chronic pruritus: a review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:1205-1212. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.01.036

- Deng J, Liao V, Parthasarathy V, et al. Modulation of neuroimmune and epithelial dysregulation in patients with moderate to severe prurigo nodularis treated with nemolizumab. JAMA Dermatol. 2023;159:977-985. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2023.2609

- Park B. Nemolizumab gets breakthrough therapy status for prurigo nodularis. Medical Professionals Reference website. Published December 9, 2019. Accessed November 13, 2023. https://www.empr.com/home/news/nemolizumab-gets-breakthrough-therapy-status-for-prurigo-nodularis/

- Labib A, Vander Does A, Yosipovitch G. Nemolizumab for atopic dermatitis. Drugs Today (Barc). 2022;58:159-173. doi:10.1358/dot.2022.58.4.3378056

- Elmariah S, Kim B, Berger T, et al. Practical approaches for diagnosis and management of prurigo nodularis: United States expert panel consensus [published online July 15, 2020]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:747-760. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.07.025

- Boozalis E, Tang O, Patel S, et al. Ethnic differences and comorbidities of 909 prurigo nodularis patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79:714.

- Yosipovitch G, Mollanazar N, Ständer S, et al. Dupilumab in patients with prurigo nodularis: two randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 trials. Nat Med. 2023;29:1180-1190. doi:10.1038/s41591-023-02320-9

- Huang AH, Williams KA, Kwatra SG. Prurigo nodularis: epidemiology and clinical features. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:1559-1565. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.04.183

- Joel MZ, Hydol-Smith J, Kambala A, et al. Prevalence and comorbidity burden of prurigo nodularis in United States adults enrolled in the All of Us research program. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2023;89:1056-1058. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2023.06.045

- Dupixent. Package insert. Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc; 2017.

- Khosravi H, Zhang S, Anderson AM, et al. Dupilumab drug survival, treatment failures, and insurance approval at a tertiary care center in the United States. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:1023-1024. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.12.034

- Liu T, Chu Y, Wang Y, et al. Successful treatment of prurigo nodularis with tofacitinib: the experience from a single center. Int J Dermatol. 2023;62:E293-E295. doi:10.1111/ijd.16568

- Molloy OE, Kearney N, Byrne N, et al. Successful treatment of recalcitrant nodular prurigo with tofacitinib. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2020;45:918-920. doi:10.1111/ced.14320

- Yin M, Wu R, Chen J, et al. Successful treatment of refractory prurigo nodularis with baricitinib. Dermatol Ther. 2022;35:E15642. doi:10.1111/dth.15642

- Klein B, Treudler R, Simon JC. JAK-inhibitors in dermatology—small molecules, big impact? overview of the mechanism of action, previous study results and potential adverse effects. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2022;20:19-24. doi:10.1111/ddg.14668

- Chung BY, Um JY, Kang SY, et al. Oral alitretinoin for patients with refractory prurigo. Medicina (Kaunas). 2020;56:599. doi:10.3390/medicina56110599

- Maqbool T, Kraft JN. Alitretinoin for prurigo nodularis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2021;46:362-363. doi:10.1111/ced.14385

- Grahovac M, Molin S, Prinz JC, et al. Treatment of atopic eczema with oral alitretinoin. Br J Dermatol. 2010;162:217-218. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.2009.09522.x

- Avila C, Massick S, Kaffenberger BH, et al. Cannabinoids for the treatment of chronic pruritus: a review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:1205-1212. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.01.036

- Deng J, Liao V, Parthasarathy V, et al. Modulation of neuroimmune and epithelial dysregulation in patients with moderate to severe prurigo nodularis treated with nemolizumab. JAMA Dermatol. 2023;159:977-985. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2023.2609

- Park B. Nemolizumab gets breakthrough therapy status for prurigo nodularis. Medical Professionals Reference website. Published December 9, 2019. Accessed November 13, 2023. https://www.empr.com/home/news/nemolizumab-gets-breakthrough-therapy-status-for-prurigo-nodularis/

- Labib A, Vander Does A, Yosipovitch G. Nemolizumab for atopic dermatitis. Drugs Today (Barc). 2022;58:159-173. doi:10.1358/dot.2022.58.4.3378056

Blood Glucose Testing Lancet and Paper Clip as a Milia Extractor

Practice Gap

In low-resource settings, dermatologists may not have the preferred tools to evaluate a patient or perform a procedure. Commonplace affordable supplies can be substituted when needed.

Traditionally, tools readily available for comedone extraction in dermatology clinics include sterile disposable hypodermic needles to open the skin and either a comedone extractor or 2 cotton-tip applicators to apply pressure for extraction. However, when these tools are not available, resourceful techniques have been utilized. Ashique and Srinivas1 described a less-painful method for extracting conchae comedones that they called “pen punching,” which involved using the rim of the tip of a ballpoint pen to apply pressure to extract lesions. Mukhtar and Gupta2 used a 3-mL disposable syringe as a comedone extractor; the syringe was cut at the needle hub using a surgical blade, with one half at 30° to 45°. Kaya et al3 used sharp-tipped cautery to puncture closed macrocomedones. Cvancara and Meffert4 described how an autoclaved paper clip could be fashioned into a disposable comedone extractor, highlighting its potential use in humanitarian work or military deployments. A sterilized safety pin has been demonstrated to be an inexpensive tool to extract open and closed comedones without a surgical blade.5 We describe the use of a blood glucose testing lancet and a paper clip for comedone extraction.

Tools and Technique

A patient presented to a satellite clinic requesting extraction of multiple bothersome milia. A comedone extractor was unavailable at that location, and the patient’s access to care elsewhere was limited.

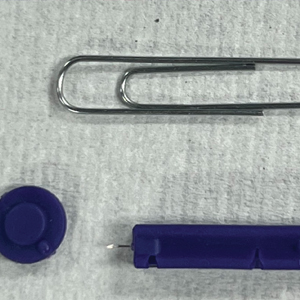

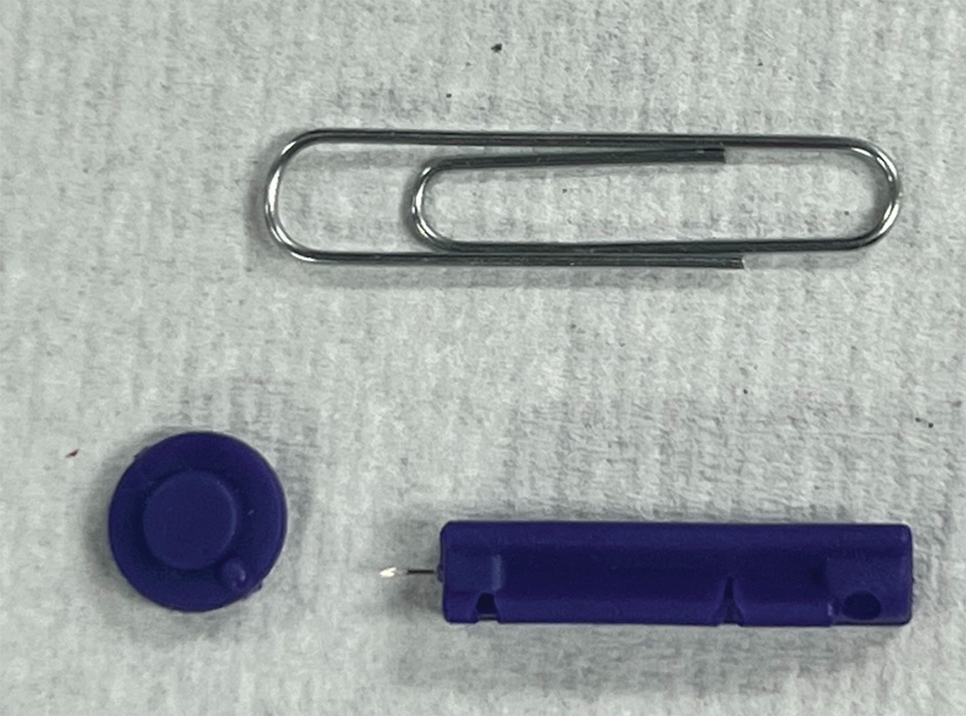

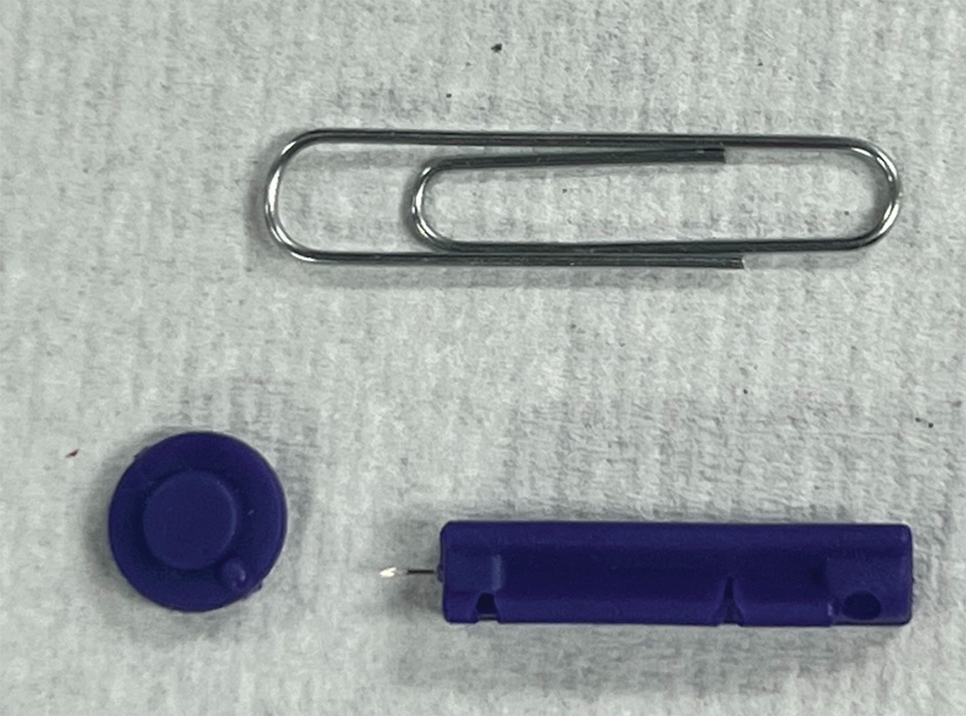

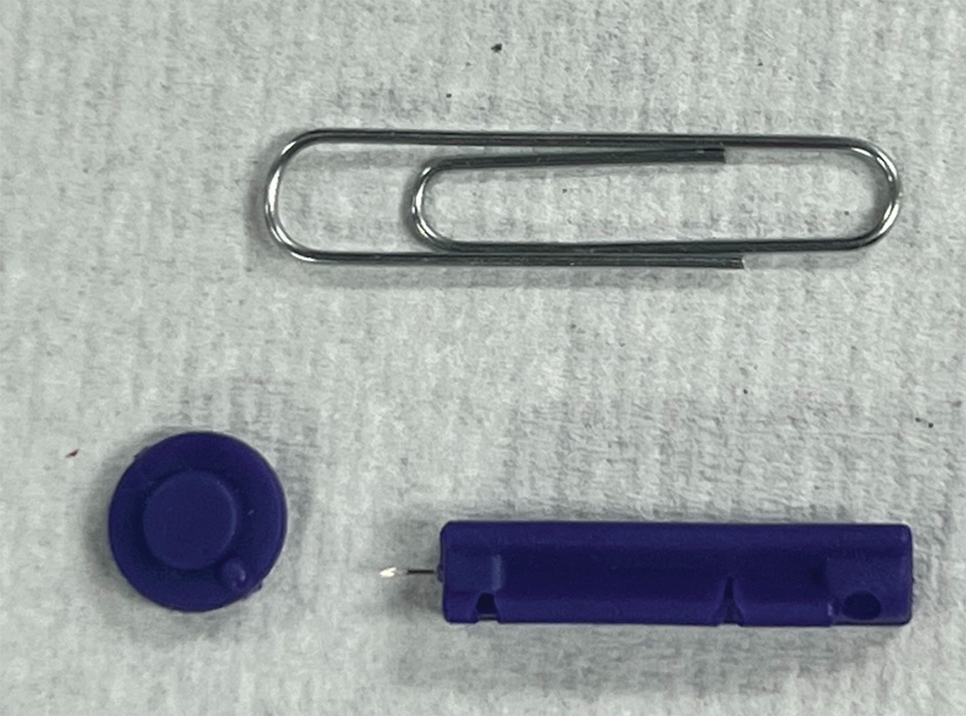

To perform extraction of milia in this case, we used a sterile, twist-top, stainless steel, 30-gauge blood glucose testing lancet and a paper clip sterilized with an isopropyl alcohol wipe (Figure). The beveled edge of the lancet was used to make a superficial opening to the skin, and the end loop of the paper clip was used as a comedone extractor. Applying moderate vertical pressure, 15 milia were expressed from the forearms. The patient tolerated the procedure well and reported minimal pain.

Practical Implications

The cost of the paper clip and lancet for our technique was $0.07. These materials are affordable, easy to use, and readily found in a variety of settings, making them a feasible option for performing this procedure.

- Ashique KT, Srinivas CR. Pen punching: an innovative technique for comedone extraction from the well of the concha. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73:E177. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2015.07.033

- Mukhtar M, Gupta S. Surgical pearl: disposable syringe as modified customized comedone extractor. J Cutan Aesthet Surg. 2022;15:185-186. doi:10.4103/JCAS.JCAS_112_21

- Kaya TI, Tursen U, Kokturk A, et al. An effective extraction technique for the treatment of closed macrocomedones. Dermatol Surg. 2003;29:741-744. doi:10.1046/j.1524-4725.2003.29190.x

- Cvancara JL, Meffert JJ. Surgical pearl: versatile paper clip comedo extractor for acne surgery. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;40:477-478. doi:10.1016/s0190-9622(99)70501-3

- Mukhtar M, Sharma R. Surgical pearl: the safety pin as a better alternative to the versatile paper clip comedo extractor. Int J Dermatol. 2004;43:967-968. doi:10.1111/j.1365-4632.2004.02293.x

Practice Gap

In low-resource settings, dermatologists may not have the preferred tools to evaluate a patient or perform a procedure. Commonplace affordable supplies can be substituted when needed.

Traditionally, tools readily available for comedone extraction in dermatology clinics include sterile disposable hypodermic needles to open the skin and either a comedone extractor or 2 cotton-tip applicators to apply pressure for extraction. However, when these tools are not available, resourceful techniques have been utilized. Ashique and Srinivas1 described a less-painful method for extracting conchae comedones that they called “pen punching,” which involved using the rim of the tip of a ballpoint pen to apply pressure to extract lesions. Mukhtar and Gupta2 used a 3-mL disposable syringe as a comedone extractor; the syringe was cut at the needle hub using a surgical blade, with one half at 30° to 45°. Kaya et al3 used sharp-tipped cautery to puncture closed macrocomedones. Cvancara and Meffert4 described how an autoclaved paper clip could be fashioned into a disposable comedone extractor, highlighting its potential use in humanitarian work or military deployments. A sterilized safety pin has been demonstrated to be an inexpensive tool to extract open and closed comedones without a surgical blade.5 We describe the use of a blood glucose testing lancet and a paper clip for comedone extraction.

Tools and Technique

A patient presented to a satellite clinic requesting extraction of multiple bothersome milia. A comedone extractor was unavailable at that location, and the patient’s access to care elsewhere was limited.

To perform extraction of milia in this case, we used a sterile, twist-top, stainless steel, 30-gauge blood glucose testing lancet and a paper clip sterilized with an isopropyl alcohol wipe (Figure). The beveled edge of the lancet was used to make a superficial opening to the skin, and the end loop of the paper clip was used as a comedone extractor. Applying moderate vertical pressure, 15 milia were expressed from the forearms. The patient tolerated the procedure well and reported minimal pain.

Practical Implications

The cost of the paper clip and lancet for our technique was $0.07. These materials are affordable, easy to use, and readily found in a variety of settings, making them a feasible option for performing this procedure.

Practice Gap

In low-resource settings, dermatologists may not have the preferred tools to evaluate a patient or perform a procedure. Commonplace affordable supplies can be substituted when needed.

Traditionally, tools readily available for comedone extraction in dermatology clinics include sterile disposable hypodermic needles to open the skin and either a comedone extractor or 2 cotton-tip applicators to apply pressure for extraction. However, when these tools are not available, resourceful techniques have been utilized. Ashique and Srinivas1 described a less-painful method for extracting conchae comedones that they called “pen punching,” which involved using the rim of the tip of a ballpoint pen to apply pressure to extract lesions. Mukhtar and Gupta2 used a 3-mL disposable syringe as a comedone extractor; the syringe was cut at the needle hub using a surgical blade, with one half at 30° to 45°. Kaya et al3 used sharp-tipped cautery to puncture closed macrocomedones. Cvancara and Meffert4 described how an autoclaved paper clip could be fashioned into a disposable comedone extractor, highlighting its potential use in humanitarian work or military deployments. A sterilized safety pin has been demonstrated to be an inexpensive tool to extract open and closed comedones without a surgical blade.5 We describe the use of a blood glucose testing lancet and a paper clip for comedone extraction.

Tools and Technique

A patient presented to a satellite clinic requesting extraction of multiple bothersome milia. A comedone extractor was unavailable at that location, and the patient’s access to care elsewhere was limited.

To perform extraction of milia in this case, we used a sterile, twist-top, stainless steel, 30-gauge blood glucose testing lancet and a paper clip sterilized with an isopropyl alcohol wipe (Figure). The beveled edge of the lancet was used to make a superficial opening to the skin, and the end loop of the paper clip was used as a comedone extractor. Applying moderate vertical pressure, 15 milia were expressed from the forearms. The patient tolerated the procedure well and reported minimal pain.

Practical Implications

The cost of the paper clip and lancet for our technique was $0.07. These materials are affordable, easy to use, and readily found in a variety of settings, making them a feasible option for performing this procedure.

- Ashique KT, Srinivas CR. Pen punching: an innovative technique for comedone extraction from the well of the concha. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73:E177. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2015.07.033

- Mukhtar M, Gupta S. Surgical pearl: disposable syringe as modified customized comedone extractor. J Cutan Aesthet Surg. 2022;15:185-186. doi:10.4103/JCAS.JCAS_112_21

- Kaya TI, Tursen U, Kokturk A, et al. An effective extraction technique for the treatment of closed macrocomedones. Dermatol Surg. 2003;29:741-744. doi:10.1046/j.1524-4725.2003.29190.x

- Cvancara JL, Meffert JJ. Surgical pearl: versatile paper clip comedo extractor for acne surgery. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;40:477-478. doi:10.1016/s0190-9622(99)70501-3

- Mukhtar M, Sharma R. Surgical pearl: the safety pin as a better alternative to the versatile paper clip comedo extractor. Int J Dermatol. 2004;43:967-968. doi:10.1111/j.1365-4632.2004.02293.x

- Ashique KT, Srinivas CR. Pen punching: an innovative technique for comedone extraction from the well of the concha. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73:E177. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2015.07.033

- Mukhtar M, Gupta S. Surgical pearl: disposable syringe as modified customized comedone extractor. J Cutan Aesthet Surg. 2022;15:185-186. doi:10.4103/JCAS.JCAS_112_21

- Kaya TI, Tursen U, Kokturk A, et al. An effective extraction technique for the treatment of closed macrocomedones. Dermatol Surg. 2003;29:741-744. doi:10.1046/j.1524-4725.2003.29190.x

- Cvancara JL, Meffert JJ. Surgical pearl: versatile paper clip comedo extractor for acne surgery. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;40:477-478. doi:10.1016/s0190-9622(99)70501-3

- Mukhtar M, Sharma R. Surgical pearl: the safety pin as a better alternative to the versatile paper clip comedo extractor. Int J Dermatol. 2004;43:967-968. doi:10.1111/j.1365-4632.2004.02293.x

ASH 2023: Equity, Sickle Cell, and Real-Life Outcomes

Cynthia E. Dunbar, MD, chief of the Translational Stem Cell Biology Branch at the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and secretary of ASH, added that insight into actual patient experiences also will be a major theme at ASH 2023.

“There is a huge growth in research on outcomes and focusing on using real-world data and how important that is,” Dr. Dunbar said. “Academic research and hematology is really focusing on patient-reported outcomes and how care is delivered in a real-world setting – actually looking at what matters to patients. Are they alive in a certain number of years? And how are they feeling?”

As an example, Dr. Dunbar pointed to an abstract that examined clinical databases in Canada and found that real-world outcomes in multiple myeloma treatments were much worse than those in the original clinical trials for the therapies. Patients reached relapse 44% faster and their overall survival was 75% worse.

In the media briefing, ASH chair of communications Mikkael A. Sekeres, MD, MS, of the Sylvester Comprehensive Cancer Center at the University of Miami, noted that patients in these types of clinical trials “are just these pristine specimens of human beings except for the cancer that’s being treated.”

Dr. Dunbar agreed, noting that “patients who are able to enroll in clinical trials are more likely to be able to show up at the treatment center at the right time and for every dose, have transportation, and afford drugs to prevent side effects. They might stay on the drug for longer, or they have nurses who are always encouraging them of how to make it through a toxicity.”

Hematologists and patients should consider randomized controlled trials to be “the best possible outcome, and perhaps adjust their thinking if an individual patient is older, sicker, or less able to follow a regimen exactly,” she said.

Another highlighted study linked worse outcomes in African-Americans with pediatric acute myeloid leukemia to genetic traits that are more common in that population. The traits “likely explain at least in part the worst outcomes in Black patients in prior studies and on some regimens,” Dr. Dunbar said.

She added that the findings emphasize how testing for genetic variants and biomarkers that impact outcomes should be performed “instead of assuming that a certain dose should be given simply based on perceived or reported race or ethnicity.”

ASH President Robert A. Brodsky, MD, of Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, highlighted an abstract that reported on the use of AI as a clinical decision support tool to differentiate two easily confused conditions — prefibrotic primary myelofibrosis and essential thrombocythemia.

AI “is a tool that’s going to help pathologists make more accurate and faster diagnoses,” he said. He also spotlighted an abstract about the use of “social media listening” to understand the experiences of patients with SCD and their caregivers. “There can be a lot of misuse and waste of time with social media, but they used this in a way to try and gain insight as to what’s really important to the patients and the caregiver.”

Also, in regard to SCD, Dr. Dunbar pointed to a study that reports on outcomes in patients who received lovotibeglogene autotemcel (lovo-cel) gene therapy for up to 60 months. Both this treatment and a CRISPR-based therapy called exa-cel “appear to result in comparable very impressive efficacy in terms of pain crises and organ dysfunction,” she said. “The hurdle is going to be figuring out how to deliver what will be very expensive and complicated therapies — but likely curative — therapies to patients.”

Another study to be presented at ASH — coauthored by Dr. Brodsky — shows promising results from reduced-intensity haploidentical bone marrow transplantation in adults with severe SCD. Results were similar to those seen with bone marrow from matched siblings, Dr. Sekeres said.

He added that more clarity is needed about new treatment options for SCD, perhaps through a “randomized trial where patients upfront get a haploidentical bone marrow transplant or fully matched bone marrow transplant. Then other patients are randomized to some of these other, newer technology therapies, and we follow them over time. We’re looking not only for overall survival but complications of the therapy itself and how many patients relapse from the treatment.”

Cynthia E. Dunbar, MD, chief of the Translational Stem Cell Biology Branch at the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and secretary of ASH, added that insight into actual patient experiences also will be a major theme at ASH 2023.

“There is a huge growth in research on outcomes and focusing on using real-world data and how important that is,” Dr. Dunbar said. “Academic research and hematology is really focusing on patient-reported outcomes and how care is delivered in a real-world setting – actually looking at what matters to patients. Are they alive in a certain number of years? And how are they feeling?”

As an example, Dr. Dunbar pointed to an abstract that examined clinical databases in Canada and found that real-world outcomes in multiple myeloma treatments were much worse than those in the original clinical trials for the therapies. Patients reached relapse 44% faster and their overall survival was 75% worse.

In the media briefing, ASH chair of communications Mikkael A. Sekeres, MD, MS, of the Sylvester Comprehensive Cancer Center at the University of Miami, noted that patients in these types of clinical trials “are just these pristine specimens of human beings except for the cancer that’s being treated.”

Dr. Dunbar agreed, noting that “patients who are able to enroll in clinical trials are more likely to be able to show up at the treatment center at the right time and for every dose, have transportation, and afford drugs to prevent side effects. They might stay on the drug for longer, or they have nurses who are always encouraging them of how to make it through a toxicity.”

Hematologists and patients should consider randomized controlled trials to be “the best possible outcome, and perhaps adjust their thinking if an individual patient is older, sicker, or less able to follow a regimen exactly,” she said.

Another highlighted study linked worse outcomes in African-Americans with pediatric acute myeloid leukemia to genetic traits that are more common in that population. The traits “likely explain at least in part the worst outcomes in Black patients in prior studies and on some regimens,” Dr. Dunbar said.

She added that the findings emphasize how testing for genetic variants and biomarkers that impact outcomes should be performed “instead of assuming that a certain dose should be given simply based on perceived or reported race or ethnicity.”

ASH President Robert A. Brodsky, MD, of Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, highlighted an abstract that reported on the use of AI as a clinical decision support tool to differentiate two easily confused conditions — prefibrotic primary myelofibrosis and essential thrombocythemia.

AI “is a tool that’s going to help pathologists make more accurate and faster diagnoses,” he said. He also spotlighted an abstract about the use of “social media listening” to understand the experiences of patients with SCD and their caregivers. “There can be a lot of misuse and waste of time with social media, but they used this in a way to try and gain insight as to what’s really important to the patients and the caregiver.”

Also, in regard to SCD, Dr. Dunbar pointed to a study that reports on outcomes in patients who received lovotibeglogene autotemcel (lovo-cel) gene therapy for up to 60 months. Both this treatment and a CRISPR-based therapy called exa-cel “appear to result in comparable very impressive efficacy in terms of pain crises and organ dysfunction,” she said. “The hurdle is going to be figuring out how to deliver what will be very expensive and complicated therapies — but likely curative — therapies to patients.”

Another study to be presented at ASH — coauthored by Dr. Brodsky — shows promising results from reduced-intensity haploidentical bone marrow transplantation in adults with severe SCD. Results were similar to those seen with bone marrow from matched siblings, Dr. Sekeres said.

He added that more clarity is needed about new treatment options for SCD, perhaps through a “randomized trial where patients upfront get a haploidentical bone marrow transplant or fully matched bone marrow transplant. Then other patients are randomized to some of these other, newer technology therapies, and we follow them over time. We’re looking not only for overall survival but complications of the therapy itself and how many patients relapse from the treatment.”

Cynthia E. Dunbar, MD, chief of the Translational Stem Cell Biology Branch at the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and secretary of ASH, added that insight into actual patient experiences also will be a major theme at ASH 2023.

“There is a huge growth in research on outcomes and focusing on using real-world data and how important that is,” Dr. Dunbar said. “Academic research and hematology is really focusing on patient-reported outcomes and how care is delivered in a real-world setting – actually looking at what matters to patients. Are they alive in a certain number of years? And how are they feeling?”

As an example, Dr. Dunbar pointed to an abstract that examined clinical databases in Canada and found that real-world outcomes in multiple myeloma treatments were much worse than those in the original clinical trials for the therapies. Patients reached relapse 44% faster and their overall survival was 75% worse.

In the media briefing, ASH chair of communications Mikkael A. Sekeres, MD, MS, of the Sylvester Comprehensive Cancer Center at the University of Miami, noted that patients in these types of clinical trials “are just these pristine specimens of human beings except for the cancer that’s being treated.”

Dr. Dunbar agreed, noting that “patients who are able to enroll in clinical trials are more likely to be able to show up at the treatment center at the right time and for every dose, have transportation, and afford drugs to prevent side effects. They might stay on the drug for longer, or they have nurses who are always encouraging them of how to make it through a toxicity.”

Hematologists and patients should consider randomized controlled trials to be “the best possible outcome, and perhaps adjust their thinking if an individual patient is older, sicker, or less able to follow a regimen exactly,” she said.

Another highlighted study linked worse outcomes in African-Americans with pediatric acute myeloid leukemia to genetic traits that are more common in that population. The traits “likely explain at least in part the worst outcomes in Black patients in prior studies and on some regimens,” Dr. Dunbar said.

She added that the findings emphasize how testing for genetic variants and biomarkers that impact outcomes should be performed “instead of assuming that a certain dose should be given simply based on perceived or reported race or ethnicity.”

ASH President Robert A. Brodsky, MD, of Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, highlighted an abstract that reported on the use of AI as a clinical decision support tool to differentiate two easily confused conditions — prefibrotic primary myelofibrosis and essential thrombocythemia.

AI “is a tool that’s going to help pathologists make more accurate and faster diagnoses,” he said. He also spotlighted an abstract about the use of “social media listening” to understand the experiences of patients with SCD and their caregivers. “There can be a lot of misuse and waste of time with social media, but they used this in a way to try and gain insight as to what’s really important to the patients and the caregiver.”

Also, in regard to SCD, Dr. Dunbar pointed to a study that reports on outcomes in patients who received lovotibeglogene autotemcel (lovo-cel) gene therapy for up to 60 months. Both this treatment and a CRISPR-based therapy called exa-cel “appear to result in comparable very impressive efficacy in terms of pain crises and organ dysfunction,” she said. “The hurdle is going to be figuring out how to deliver what will be very expensive and complicated therapies — but likely curative — therapies to patients.”

Another study to be presented at ASH — coauthored by Dr. Brodsky — shows promising results from reduced-intensity haploidentical bone marrow transplantation in adults with severe SCD. Results were similar to those seen with bone marrow from matched siblings, Dr. Sekeres said.

He added that more clarity is needed about new treatment options for SCD, perhaps through a “randomized trial where patients upfront get a haploidentical bone marrow transplant or fully matched bone marrow transplant. Then other patients are randomized to some of these other, newer technology therapies, and we follow them over time. We’re looking not only for overall survival but complications of the therapy itself and how many patients relapse from the treatment.”

AT ASH 2023

ASTRO Updates Partial Breast Irradiation Guidance in Early Breast Cancer

The American Society for Radiation Oncology (ASTRO) has issued an updated clinical practice guideline on partial breast irradiation for women with early-stage invasive breast cancer or ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS). The 2023 guideline, which replaces the 2017 recommendations, factors in new clinical trial data that consistently show no significant differences in overall survival, cancer-free survival, and recurrence in the same breast among patients who receive partial breast irradiation compared with whole breast irradiation. The data also indicate similar or improved side effects with partial vs whole breast irradiation.

To develop the 2023 recommendations, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) conducted a systematic review assessing the latest clinical trial evidence, and ASTRO assembled an expert task force to determine best practices for using partial breast irradiation.

“There have been more than 10,000 women included in these randomized controlled trials, with 10 years of follow-up showing equivalency in tumor control between partial breast and whole breast radiation for appropriately selected patients,” Simona Shaitelman, MD, vice chair of the guideline task force, said in a news release.

“These data should be driving a change in practice, and partial breast radiation should be a larger part of the dialogue when we consult with patients on decisions about how best to treat their early-stage breast cancer,” added Dr. Shaitelman, professor of breast radiation oncology at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston.

What’s in the New Guidelines?

For patients with early-stage, node-negative invasive breast cancer, , including grade 1 or 2 disease, estrogen receptor (ER)-positive status, small tumor size, and age 40 or older.

In contrast, the 2017 guideline considered patients aged 50 and older suitable for partial breast irradiation and considered those in their 40s who met certain pathologic criteria “cautionary.”The updated guideline also conditionally recommends partial over whole breast irradiation if the patient has risk factors that indicate a higher likelihood of recurrence, such as grade 3 disease, ER-negative histology, or larger tumor size.

The task force does not recommend partial breast irradiation for patients with positive lymph nodes, positive surgical margins, or germline BRCA1/2 mutations or patients under 40.

Given the lack of robust data in patients with less favorable risk features, such as lymphovascular invasion or lobular histology, partial breast irradiation is conditionally not recommended for these patients.

For DCIS, the updated recommendations mirror those for early-stage breast cancer, with partial breast irradiation strongly recommended as an alternative to whole breast irradiation among patients with favorable clinical and tumor features, such as grade 1 or 2 disease and ER-positive status. Partial breast irradiation is conditionally recommended for higher grade disease or larger tumors, and not recommended for patients with positive surgical margins, BRCA mutations or those younger than 40.

In addition to relevant patient populations, the updated guidelines also address techniques and best practices for delivering partial breast irradiation.

Recommended partial breast irradiation techniques include 3-D conformal radiation therapy, intensity modulated radiation therapy, and multicatheter interstitial brachytherapy, given the evidence showing similar long-term rates of ipsilateral breast recurrence compared with whole breast irradiation.

Single-entry catheter brachytherapy is conditionally recommended, and intraoperative radiation therapy techniques are not recommended unless integrated into a prospective clinical trial or multi-institutional registry.

The guideline also outlines optimal dose, fractionation, target volume, and treatment modality with different partial breast irradiation techniques, taking toxicities and cosmesis into consideration.

“We hope that by laying out the evidence from these major trials and providing guidance on how to administer partial breast radiation, the guideline can help more oncologists feel comfortable offering this option to their patients as an alternative to whole breast radiation,” Janice Lyons, MD, of University Hospitals Seidman Cancer Center, Cleveland, Ohio, and chair of the guideline task force, said in the news release.

The guideline, developed in collaboration with the American Society of Clinical Oncology and the Society of Surgical Oncology, has been endorsed by the Canadian Association of Radiation Oncology, the European Society for Radiotherapy and Oncology, and the Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Radiologists. Guideline development was funded by ASTRO and the systematic evidence review was funded by the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute. Disclosures for the task force are available with the original article.

A version of this article was first published on Medscape.com.

The American Society for Radiation Oncology (ASTRO) has issued an updated clinical practice guideline on partial breast irradiation for women with early-stage invasive breast cancer or ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS). The 2023 guideline, which replaces the 2017 recommendations, factors in new clinical trial data that consistently show no significant differences in overall survival, cancer-free survival, and recurrence in the same breast among patients who receive partial breast irradiation compared with whole breast irradiation. The data also indicate similar or improved side effects with partial vs whole breast irradiation.

To develop the 2023 recommendations, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) conducted a systematic review assessing the latest clinical trial evidence, and ASTRO assembled an expert task force to determine best practices for using partial breast irradiation.

“There have been more than 10,000 women included in these randomized controlled trials, with 10 years of follow-up showing equivalency in tumor control between partial breast and whole breast radiation for appropriately selected patients,” Simona Shaitelman, MD, vice chair of the guideline task force, said in a news release.

“These data should be driving a change in practice, and partial breast radiation should be a larger part of the dialogue when we consult with patients on decisions about how best to treat their early-stage breast cancer,” added Dr. Shaitelman, professor of breast radiation oncology at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston.

What’s in the New Guidelines?

For patients with early-stage, node-negative invasive breast cancer, , including grade 1 or 2 disease, estrogen receptor (ER)-positive status, small tumor size, and age 40 or older.

In contrast, the 2017 guideline considered patients aged 50 and older suitable for partial breast irradiation and considered those in their 40s who met certain pathologic criteria “cautionary.”The updated guideline also conditionally recommends partial over whole breast irradiation if the patient has risk factors that indicate a higher likelihood of recurrence, such as grade 3 disease, ER-negative histology, or larger tumor size.

The task force does not recommend partial breast irradiation for patients with positive lymph nodes, positive surgical margins, or germline BRCA1/2 mutations or patients under 40.

Given the lack of robust data in patients with less favorable risk features, such as lymphovascular invasion or lobular histology, partial breast irradiation is conditionally not recommended for these patients.

For DCIS, the updated recommendations mirror those for early-stage breast cancer, with partial breast irradiation strongly recommended as an alternative to whole breast irradiation among patients with favorable clinical and tumor features, such as grade 1 or 2 disease and ER-positive status. Partial breast irradiation is conditionally recommended for higher grade disease or larger tumors, and not recommended for patients with positive surgical margins, BRCA mutations or those younger than 40.

In addition to relevant patient populations, the updated guidelines also address techniques and best practices for delivering partial breast irradiation.

Recommended partial breast irradiation techniques include 3-D conformal radiation therapy, intensity modulated radiation therapy, and multicatheter interstitial brachytherapy, given the evidence showing similar long-term rates of ipsilateral breast recurrence compared with whole breast irradiation.

Single-entry catheter brachytherapy is conditionally recommended, and intraoperative radiation therapy techniques are not recommended unless integrated into a prospective clinical trial or multi-institutional registry.

The guideline also outlines optimal dose, fractionation, target volume, and treatment modality with different partial breast irradiation techniques, taking toxicities and cosmesis into consideration.

“We hope that by laying out the evidence from these major trials and providing guidance on how to administer partial breast radiation, the guideline can help more oncologists feel comfortable offering this option to their patients as an alternative to whole breast radiation,” Janice Lyons, MD, of University Hospitals Seidman Cancer Center, Cleveland, Ohio, and chair of the guideline task force, said in the news release.

The guideline, developed in collaboration with the American Society of Clinical Oncology and the Society of Surgical Oncology, has been endorsed by the Canadian Association of Radiation Oncology, the European Society for Radiotherapy and Oncology, and the Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Radiologists. Guideline development was funded by ASTRO and the systematic evidence review was funded by the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute. Disclosures for the task force are available with the original article.

A version of this article was first published on Medscape.com.

The American Society for Radiation Oncology (ASTRO) has issued an updated clinical practice guideline on partial breast irradiation for women with early-stage invasive breast cancer or ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS). The 2023 guideline, which replaces the 2017 recommendations, factors in new clinical trial data that consistently show no significant differences in overall survival, cancer-free survival, and recurrence in the same breast among patients who receive partial breast irradiation compared with whole breast irradiation. The data also indicate similar or improved side effects with partial vs whole breast irradiation.

To develop the 2023 recommendations, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) conducted a systematic review assessing the latest clinical trial evidence, and ASTRO assembled an expert task force to determine best practices for using partial breast irradiation.

“There have been more than 10,000 women included in these randomized controlled trials, with 10 years of follow-up showing equivalency in tumor control between partial breast and whole breast radiation for appropriately selected patients,” Simona Shaitelman, MD, vice chair of the guideline task force, said in a news release.

“These data should be driving a change in practice, and partial breast radiation should be a larger part of the dialogue when we consult with patients on decisions about how best to treat their early-stage breast cancer,” added Dr. Shaitelman, professor of breast radiation oncology at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston.

What’s in the New Guidelines?

For patients with early-stage, node-negative invasive breast cancer, , including grade 1 or 2 disease, estrogen receptor (ER)-positive status, small tumor size, and age 40 or older.

In contrast, the 2017 guideline considered patients aged 50 and older suitable for partial breast irradiation and considered those in their 40s who met certain pathologic criteria “cautionary.”The updated guideline also conditionally recommends partial over whole breast irradiation if the patient has risk factors that indicate a higher likelihood of recurrence, such as grade 3 disease, ER-negative histology, or larger tumor size.

The task force does not recommend partial breast irradiation for patients with positive lymph nodes, positive surgical margins, or germline BRCA1/2 mutations or patients under 40.

Given the lack of robust data in patients with less favorable risk features, such as lymphovascular invasion or lobular histology, partial breast irradiation is conditionally not recommended for these patients.

For DCIS, the updated recommendations mirror those for early-stage breast cancer, with partial breast irradiation strongly recommended as an alternative to whole breast irradiation among patients with favorable clinical and tumor features, such as grade 1 or 2 disease and ER-positive status. Partial breast irradiation is conditionally recommended for higher grade disease or larger tumors, and not recommended for patients with positive surgical margins, BRCA mutations or those younger than 40.

In addition to relevant patient populations, the updated guidelines also address techniques and best practices for delivering partial breast irradiation.

Recommended partial breast irradiation techniques include 3-D conformal radiation therapy, intensity modulated radiation therapy, and multicatheter interstitial brachytherapy, given the evidence showing similar long-term rates of ipsilateral breast recurrence compared with whole breast irradiation.

Single-entry catheter brachytherapy is conditionally recommended, and intraoperative radiation therapy techniques are not recommended unless integrated into a prospective clinical trial or multi-institutional registry.

The guideline also outlines optimal dose, fractionation, target volume, and treatment modality with different partial breast irradiation techniques, taking toxicities and cosmesis into consideration.

“We hope that by laying out the evidence from these major trials and providing guidance on how to administer partial breast radiation, the guideline can help more oncologists feel comfortable offering this option to their patients as an alternative to whole breast radiation,” Janice Lyons, MD, of University Hospitals Seidman Cancer Center, Cleveland, Ohio, and chair of the guideline task force, said in the news release.

The guideline, developed in collaboration with the American Society of Clinical Oncology and the Society of Surgical Oncology, has been endorsed by the Canadian Association of Radiation Oncology, the European Society for Radiotherapy and Oncology, and the Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Radiologists. Guideline development was funded by ASTRO and the systematic evidence review was funded by the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute. Disclosures for the task force are available with the original article.

A version of this article was first published on Medscape.com.

Fewer than 1 out of 4 patients with HCV-related liver cancer receive antivirals

, and rates aren’t much better for patients seen by specialists, based on a retrospective analysis of private insurance claims.

The study also showed that patients receiving DAAs lived significantly longer, emphasizing the importance of prescribing these medications to all eligible patients, reported principal investigator Mindie H. Nguyen, MD, AGAF,, of Stanford University Medical Center, Palo Alto, California, and colleagues.

“Prior studies have shown evidence of improved survival among HCV-related HCC patients who received DAA treatment, but not much is known about the current DAA utilization among these patients in the general US population,” said lead author Leslie Y. Kam, MD, a postdoctoral scholar in gastroenterology at Stanford Medicine, who presented the findings in November at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases.

To generate real-world data, the investigators analyzed medical records from 3922 patients in Optum’s Clinformatics Data Mart Database. All patients had private medical insurance and received care for HCV-related HCC between 2015 and 2021.

“Instead of using institutional databases which tend to bias toward highly specialized tertiary care center patients, our study uses a large, national sample of HCV-HCC patients that represents real-world DAA treatment rates and survival outcomes,” Dr. Kam said in a written comment.

Within this cohort, fewer than one out of four patients (23.5%) received DAA, a rate that Dr. Kam called “dismally low.”

Patients with either compensated or decompensated cirrhosis had higher treatment rates than those without cirrhosis (24.2% or 24.5%, respectively, vs. 16.2%; P = .001). The investigators noted that more than half of the patients had decompensated cirrhosis, suggesting that HCV-related HCC was diagnosed late in the disease course.

Receiving care from a gastroenterologist or infectious disease physician also was associated with a higher treatment rate. Patients managed by a gastroenterologist alone had a treatment rate of 27.0%, while those who received care from a gastroenterologist or infectious disease doctor alongside an oncologist had a treatment rate of 25.6%, versus just 9.4% for those who received care from an oncologist alone, and 12.4% among those who did not see a specialist of any kind (P = .005).

These findings highlight “the need for a multidisciplinary approach to care in this population,” Dr. Kam suggested.

Echoing previous research, DAAs were associated with extended survival. A significantly greater percentage of patients who received DAA were alive after 5 years, compared with patients who did not receive DAA (47.2% vs. 35.2%; P less than .001). After adjustment for comorbidities, HCC treatment, race/ethnicity, sex, and age, DAAs were associated with a 39% reduction in risk of death (adjusted hazard ratio, 0.61; 0.53-0.69; P less than .001).

“There were also racial ethnic disparities in patient survival whether patients received DAA or not, with Black patients having worse survival,” Dr. Kam said. “As such, our study highlights that awareness of HCV remains low as does the use of DAA treatment. Therefore, culturally appropriate efforts to improve awareness of HCV must continue among the general public and health care workers as well as efforts to provide point of care accurate and rapid screening tests for HCV so that DAA treatment can be initiated in a timely manner for eligible patients. Continual education on the use of DAA treatment is also needed.”

Robert John Fontana, MD, AGAF, professor of medicine and transplant hepatologist at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, described the findings as “frustrating,” and “not the kind of stuff I like to hear about.

“Treatment rates are so low,” Dr. Fontana said, noting that even among gastroenterologists and infectious disease doctors, who should be well-versed in DAAs, antivirals were prescribed less than 30% of the time.

In an interview, Dr. Fontana highlighted the benefits of DAAs, including their ease-of-use and effectiveness.

“Hepatitis C was the leading reason that we had to do liver transplants in the United States for years,” he said. “Then once these really amazing drugs called direct-acting antivirals came out, they changed the landscape very quickly. It really was a game changer for my whole practice, and, nationally, the practice of transplant.”

Yet, this study and others suggest that these practice-altering agents are being underutilized, Dr. Fontana said. A variety of reasons could explain suboptimal usage, he suggested, including lack of awareness among medical professionals and the public, the recency of DAA approvals, low HCV testing rates, lack of symptoms in HCV-positive patients, and medication costs.

This latter barrier, at least, is dissolving, Dr. Fontana said. Some payers initially restricted which providers could prescribe DAAs, but now the economic consensus has swung in their favor, since curing patients of HCV brings significant health care savings down the line. This financial advantage—theoretically multiplied across 4-5 million Americans living with HCV—has bolstered a multi-institutional effort toward universal HCV screening, with testing recommended at least once in every person’s lifetime.

“It’s highly cost effective,” Dr. Fontana said. “Even though the drugs are super expensive, you will reduce cost by preventing the people streaming towards liver cancer or streaming towards liver transplant. That’s why all the professional societies—the USPSTF, the CDC—they all say, ‘OK, screen everyone.’ ”

Screening may be getting easier soon, Dr. Fontana predicted, as at-home HCV-testing kits are on the horizon, with development and adoption likely accelerated by the success of at-home viral testing during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Beyond broader screening, Dr. Fontana suggested that greater awareness of DAAs is needed both within and beyond the medical community.

He advised health care providers who don’t yet feel comfortable diagnosing or treating HCV to refer to their local specialist.

“That’s the main message,” Dr. Fontana said. “I’m always eternally hopeful that every little message helps.”

The investigators and Dr. Fontana disclosed no conflicts of interest.

, and rates aren’t much better for patients seen by specialists, based on a retrospective analysis of private insurance claims.

The study also showed that patients receiving DAAs lived significantly longer, emphasizing the importance of prescribing these medications to all eligible patients, reported principal investigator Mindie H. Nguyen, MD, AGAF,, of Stanford University Medical Center, Palo Alto, California, and colleagues.

“Prior studies have shown evidence of improved survival among HCV-related HCC patients who received DAA treatment, but not much is known about the current DAA utilization among these patients in the general US population,” said lead author Leslie Y. Kam, MD, a postdoctoral scholar in gastroenterology at Stanford Medicine, who presented the findings in November at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases.

To generate real-world data, the investigators analyzed medical records from 3922 patients in Optum’s Clinformatics Data Mart Database. All patients had private medical insurance and received care for HCV-related HCC between 2015 and 2021.