User login

Pulmonary arterial hypertension: Promising results for investigational agents and catheter-based denervation

PHILADELPHIA — Promise that the unmet need for more effective pulmonary artery hypertension treatments may soon be met was in strong evidence in research into three strategies presented at this year’s recent American Heart Association scientific sessions; one was based on an ancient Chinese herb epimedium (yin yang huo or horny goat weed) commonly used for treating sexual dysfunction and directly related to the phosphodiesterase inhibitors sildenafil, vardenafil, and tadalafil (sold as Viagra, Levitra, and Cialis). A second studied sotatercept, an investigational, potential first-in-class activin signaling inhibitor biologic, and a third evaluated physically ablating the baroreceptor nerves that stimulate vasoconstriction of the pulmonary artery via catheter-based techniques.

Until as recently as the late 1970s, a pulmonary arterial hypertension diagnosis was a uniformly fatal one.1 While associated with pulmonary and right ventricle remodeling, and leads toward heart failure and death. The complex underlying pathogenesis was divided into six groups by the 6th World Symposium on Pulmonary Hypertension (WSPH) in 2018, and includes as its most common features pulmonary artery endothelial cell dysfunction, pulmonary artery smooth muscle cell proliferation and migration, and dysregulated fibroblast activity leading to dysregulated vasoconstriction, micro and in-situ vascular thrombosis, vascular fibrosis and pathogenic remodeling of pulmonary vessels.1 The threshold mean arterial pressure (mPAP) for pulmonary arterial hypertension was defined by the 6th [WSPH] at mPAP ≥ 20 mm Hg, twice the upper limit of a normal mPAP of 14.0 ± 3.3 mm Hg as reported by Kovacs et al. in 2018.2

Pathways for current therapies

Current drugs for pulmonary arterial hypertension focus on three signaling pathways, including the endothelin receptor, prostacyclin and nitric oxide pathways, stated Zhi-Cheng Jing, MD, professor of medicine, head of the cardiology department at Peking Union Medical College Hospital, Peking, China. While the phosphodiesterase 5 inhibitors sildenafil and tadalafil, which target the nitric oxide pathway, came into wide use after Food and Drug Administration approval, the need for higher PDE5-selectivity remains, Dr. Jing said. Structurally modified from the active ingredient in epimedium, TPN171H is an investigational PDE5 inhibitor which has shown several favorable features: a greater PDE5 selectivity than both sildenafil and tadalafil in vitro, an ability to decrease right ventricular systolic pressure and alleviate arterial remodeling in animal studies, and safety and tolerability in healthy human subjects.

The current randomized, double-blind, placebo-and active-controlled phase IIa study assessed the hemodynamic impact of a single oral dose of TPN171H in 60 pulmonary arterial hypertension patients (mean age ~34 years, 83.3% female), all with negative vasodilation test results and in WHO class 2 or 3. Only patients aged 18-75 years with group 1 pulmonary arterial hypertension of idiopathic, connective tissue disorder, or repaired congenital heart defects etiology were included. Patients were divided into six groups: placebo, TPN171H at 2.5, 5, and 10 milligrams, and tadalafil at 20 and 40 milligrams.

For the primary endpoint of maximum decrease in pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR), significant reductions vs. placebo were found only for the TPN171H 5-mg group (–41.2% vs. –24.4%; P = .008) and for the 20-mg (–39.8%) and 40-mg (–37.6%) tadalafil groups (both P < .05). What was not seen in the tadalafil groups, but was evident in the TPN171H 5-mg group, was a significant reduction in the secondary endpoint of PVR/SVR (systolic vascular resistance) at 2, 3, and 5 hours (all P < .05). “As we know,” Dr. Jing said in an interview, “the PDE5 inhibitor functions as a vasodilator, having an impact on both pulmonary circulation and systemic circulation. So, to evaluate the selectivity for pulmonary circulation is crucial when exploring a novel drug for pulmonary arterial hypertension. The change of PVR/SVR ratio from baseline is an indicator for selectivity for pulmonary circulation and implies that TPN171H has good PDE5 selectivity in the pulmonary vasculature,” Dr. Jing said.

TPN171H was well tolerated with no serious adverse effects (vomiting 10% and headache 10% were most common with no discontinuations).

TGF-signaling pathway

A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials of sotatercept, an investigational fusion protein under priority FDA review that modulates the TGF-beta superfamily signaling pathway, looked at PVR, pulmonary arterial pressure (PAP), right arterial pressure (RAP) and N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP). A literature search by corresponding author Vamsikalyan Borra, MD, Knapp Medical Center, Weslaco, Texas, and colleagues identified two trials (STELLAR and PULSAR) comprising 429 patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension. The experimental arms (sotatercept) had 237 patients (mean age ~49 years, ~82% female) and the placebo arm had 192 patients (mean age ~47 years, ~80% female).

A pooled analysis showed significant reductions with sotatercept in PVR (standardization mean difference [SMD] = –1.00, 95% confidence interval [CI] = –1.2, –.79, P < .001), PAP (SMD = –1.34, 95% CI = 1.6, –1.08, P < .001), RAP (SMD = –0.66, 95% CI = –0.93, –0.39, P < .001), and the levels of NT-proBNP (SMD = –0.64, 95% CI = –1.01, –0.27, P < .001) at 24 weeks from baseline. The sotatercept safety profile was favorable, with lower overall incidence of adverse events (84.8% vs. 87.5%) and fewer adverse events leading to death (0.4% vs. 3.1%) compared with placebo. Further investigation is needed, however, according to Dr. Borra, into the higher frequency of reported thrombocytopenia (71.7% vs. 20.8%) with sotatercept. “Our findings,” Dr. Borra said in a poster session, “suggest that sotatercept is an effective treatment option for pulmonary arterial hypertension, with the potential to improve both pulmonary and cardiac function.”

Denervation technique

Catheter-based ablation techniques, most commonly using thermal energy, target the afferent and efferent fibers of the baroreceptor reflex in the main pulmonary artery trunk and bifurcation involved in elevated pulmonary artery pressure. Mounica Vorla, MD, Carle Foundation Hospital, Urbana, Illinois, and colleagues conducted an updated systematic review and meta-analysis of the safety and efficacy of pulmonary artery denervation (PADN) for pulmonary arterial hypertension in seven clinical trials with 506 patients with moderate-severe pulmonary arterial hypertension conducted from 2013 to 2022.

Compared with placebo, PADN treatment was associated with a significant reduction in mean pulmonary artery pressure (weighted mean difference [WMD] = –6.9 mm Hg; 95% CI = –9.7, –4.1; P < .01; I2 = 61) and pulmonary vascular resistance (WMD = –3.2; 95% CI = –5.4, –0.9; P = .005). PADN improvements in cardiac output were also statistically significant (WMD = 0.3; 95% CI = 0.07, 0.6; P = .012), with numerical improvement in 6-minute walking distance (WMD = 67.7; 95% CI = –3.73, 139.2; P = .06) in the PADN group. Side effects were less common in the PADN group as compared with the placebo group, Dr. Vorla reported. She concluded, “This updated meta-analysis supports PADN as a safe and efficacious therapy for severe pulmonary arterial hypertension.” The authors noted limitations imposed by the small sample size, large data heterogeneity, and medium-quality literature. Larger randomized, controlled trials with clinical endpoints comparing PADN with optimal medical therapy are needed, they stated.

References

1. Shah AJ et al. New Drugs and Therapies in Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension. Int J Mol Sci. 2023 Mar 19;24(6):5850. doi: 10.3390/ijms24065850. PMID: 36982922; PMCID: PMC10058689.

2. Kovacs G et al. Pulmonary Vascular Involvement in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Is There a Pulmonary Vascular Phenotype? Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2018 Oct 15;198(8):1000-11. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201801-0095PP. PMID: 29746142.

PHILADELPHIA — Promise that the unmet need for more effective pulmonary artery hypertension treatments may soon be met was in strong evidence in research into three strategies presented at this year’s recent American Heart Association scientific sessions; one was based on an ancient Chinese herb epimedium (yin yang huo or horny goat weed) commonly used for treating sexual dysfunction and directly related to the phosphodiesterase inhibitors sildenafil, vardenafil, and tadalafil (sold as Viagra, Levitra, and Cialis). A second studied sotatercept, an investigational, potential first-in-class activin signaling inhibitor biologic, and a third evaluated physically ablating the baroreceptor nerves that stimulate vasoconstriction of the pulmonary artery via catheter-based techniques.

Until as recently as the late 1970s, a pulmonary arterial hypertension diagnosis was a uniformly fatal one.1 While associated with pulmonary and right ventricle remodeling, and leads toward heart failure and death. The complex underlying pathogenesis was divided into six groups by the 6th World Symposium on Pulmonary Hypertension (WSPH) in 2018, and includes as its most common features pulmonary artery endothelial cell dysfunction, pulmonary artery smooth muscle cell proliferation and migration, and dysregulated fibroblast activity leading to dysregulated vasoconstriction, micro and in-situ vascular thrombosis, vascular fibrosis and pathogenic remodeling of pulmonary vessels.1 The threshold mean arterial pressure (mPAP) for pulmonary arterial hypertension was defined by the 6th [WSPH] at mPAP ≥ 20 mm Hg, twice the upper limit of a normal mPAP of 14.0 ± 3.3 mm Hg as reported by Kovacs et al. in 2018.2

Pathways for current therapies

Current drugs for pulmonary arterial hypertension focus on three signaling pathways, including the endothelin receptor, prostacyclin and nitric oxide pathways, stated Zhi-Cheng Jing, MD, professor of medicine, head of the cardiology department at Peking Union Medical College Hospital, Peking, China. While the phosphodiesterase 5 inhibitors sildenafil and tadalafil, which target the nitric oxide pathway, came into wide use after Food and Drug Administration approval, the need for higher PDE5-selectivity remains, Dr. Jing said. Structurally modified from the active ingredient in epimedium, TPN171H is an investigational PDE5 inhibitor which has shown several favorable features: a greater PDE5 selectivity than both sildenafil and tadalafil in vitro, an ability to decrease right ventricular systolic pressure and alleviate arterial remodeling in animal studies, and safety and tolerability in healthy human subjects.

The current randomized, double-blind, placebo-and active-controlled phase IIa study assessed the hemodynamic impact of a single oral dose of TPN171H in 60 pulmonary arterial hypertension patients (mean age ~34 years, 83.3% female), all with negative vasodilation test results and in WHO class 2 or 3. Only patients aged 18-75 years with group 1 pulmonary arterial hypertension of idiopathic, connective tissue disorder, or repaired congenital heart defects etiology were included. Patients were divided into six groups: placebo, TPN171H at 2.5, 5, and 10 milligrams, and tadalafil at 20 and 40 milligrams.

For the primary endpoint of maximum decrease in pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR), significant reductions vs. placebo were found only for the TPN171H 5-mg group (–41.2% vs. –24.4%; P = .008) and for the 20-mg (–39.8%) and 40-mg (–37.6%) tadalafil groups (both P < .05). What was not seen in the tadalafil groups, but was evident in the TPN171H 5-mg group, was a significant reduction in the secondary endpoint of PVR/SVR (systolic vascular resistance) at 2, 3, and 5 hours (all P < .05). “As we know,” Dr. Jing said in an interview, “the PDE5 inhibitor functions as a vasodilator, having an impact on both pulmonary circulation and systemic circulation. So, to evaluate the selectivity for pulmonary circulation is crucial when exploring a novel drug for pulmonary arterial hypertension. The change of PVR/SVR ratio from baseline is an indicator for selectivity for pulmonary circulation and implies that TPN171H has good PDE5 selectivity in the pulmonary vasculature,” Dr. Jing said.

TPN171H was well tolerated with no serious adverse effects (vomiting 10% and headache 10% were most common with no discontinuations).

TGF-signaling pathway

A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials of sotatercept, an investigational fusion protein under priority FDA review that modulates the TGF-beta superfamily signaling pathway, looked at PVR, pulmonary arterial pressure (PAP), right arterial pressure (RAP) and N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP). A literature search by corresponding author Vamsikalyan Borra, MD, Knapp Medical Center, Weslaco, Texas, and colleagues identified two trials (STELLAR and PULSAR) comprising 429 patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension. The experimental arms (sotatercept) had 237 patients (mean age ~49 years, ~82% female) and the placebo arm had 192 patients (mean age ~47 years, ~80% female).

A pooled analysis showed significant reductions with sotatercept in PVR (standardization mean difference [SMD] = –1.00, 95% confidence interval [CI] = –1.2, –.79, P < .001), PAP (SMD = –1.34, 95% CI = 1.6, –1.08, P < .001), RAP (SMD = –0.66, 95% CI = –0.93, –0.39, P < .001), and the levels of NT-proBNP (SMD = –0.64, 95% CI = –1.01, –0.27, P < .001) at 24 weeks from baseline. The sotatercept safety profile was favorable, with lower overall incidence of adverse events (84.8% vs. 87.5%) and fewer adverse events leading to death (0.4% vs. 3.1%) compared with placebo. Further investigation is needed, however, according to Dr. Borra, into the higher frequency of reported thrombocytopenia (71.7% vs. 20.8%) with sotatercept. “Our findings,” Dr. Borra said in a poster session, “suggest that sotatercept is an effective treatment option for pulmonary arterial hypertension, with the potential to improve both pulmonary and cardiac function.”

Denervation technique

Catheter-based ablation techniques, most commonly using thermal energy, target the afferent and efferent fibers of the baroreceptor reflex in the main pulmonary artery trunk and bifurcation involved in elevated pulmonary artery pressure. Mounica Vorla, MD, Carle Foundation Hospital, Urbana, Illinois, and colleagues conducted an updated systematic review and meta-analysis of the safety and efficacy of pulmonary artery denervation (PADN) for pulmonary arterial hypertension in seven clinical trials with 506 patients with moderate-severe pulmonary arterial hypertension conducted from 2013 to 2022.

Compared with placebo, PADN treatment was associated with a significant reduction in mean pulmonary artery pressure (weighted mean difference [WMD] = –6.9 mm Hg; 95% CI = –9.7, –4.1; P < .01; I2 = 61) and pulmonary vascular resistance (WMD = –3.2; 95% CI = –5.4, –0.9; P = .005). PADN improvements in cardiac output were also statistically significant (WMD = 0.3; 95% CI = 0.07, 0.6; P = .012), with numerical improvement in 6-minute walking distance (WMD = 67.7; 95% CI = –3.73, 139.2; P = .06) in the PADN group. Side effects were less common in the PADN group as compared with the placebo group, Dr. Vorla reported. She concluded, “This updated meta-analysis supports PADN as a safe and efficacious therapy for severe pulmonary arterial hypertension.” The authors noted limitations imposed by the small sample size, large data heterogeneity, and medium-quality literature. Larger randomized, controlled trials with clinical endpoints comparing PADN with optimal medical therapy are needed, they stated.

References

1. Shah AJ et al. New Drugs and Therapies in Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension. Int J Mol Sci. 2023 Mar 19;24(6):5850. doi: 10.3390/ijms24065850. PMID: 36982922; PMCID: PMC10058689.

2. Kovacs G et al. Pulmonary Vascular Involvement in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Is There a Pulmonary Vascular Phenotype? Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2018 Oct 15;198(8):1000-11. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201801-0095PP. PMID: 29746142.

PHILADELPHIA — Promise that the unmet need for more effective pulmonary artery hypertension treatments may soon be met was in strong evidence in research into three strategies presented at this year’s recent American Heart Association scientific sessions; one was based on an ancient Chinese herb epimedium (yin yang huo or horny goat weed) commonly used for treating sexual dysfunction and directly related to the phosphodiesterase inhibitors sildenafil, vardenafil, and tadalafil (sold as Viagra, Levitra, and Cialis). A second studied sotatercept, an investigational, potential first-in-class activin signaling inhibitor biologic, and a third evaluated physically ablating the baroreceptor nerves that stimulate vasoconstriction of the pulmonary artery via catheter-based techniques.

Until as recently as the late 1970s, a pulmonary arterial hypertension diagnosis was a uniformly fatal one.1 While associated with pulmonary and right ventricle remodeling, and leads toward heart failure and death. The complex underlying pathogenesis was divided into six groups by the 6th World Symposium on Pulmonary Hypertension (WSPH) in 2018, and includes as its most common features pulmonary artery endothelial cell dysfunction, pulmonary artery smooth muscle cell proliferation and migration, and dysregulated fibroblast activity leading to dysregulated vasoconstriction, micro and in-situ vascular thrombosis, vascular fibrosis and pathogenic remodeling of pulmonary vessels.1 The threshold mean arterial pressure (mPAP) for pulmonary arterial hypertension was defined by the 6th [WSPH] at mPAP ≥ 20 mm Hg, twice the upper limit of a normal mPAP of 14.0 ± 3.3 mm Hg as reported by Kovacs et al. in 2018.2

Pathways for current therapies

Current drugs for pulmonary arterial hypertension focus on three signaling pathways, including the endothelin receptor, prostacyclin and nitric oxide pathways, stated Zhi-Cheng Jing, MD, professor of medicine, head of the cardiology department at Peking Union Medical College Hospital, Peking, China. While the phosphodiesterase 5 inhibitors sildenafil and tadalafil, which target the nitric oxide pathway, came into wide use after Food and Drug Administration approval, the need for higher PDE5-selectivity remains, Dr. Jing said. Structurally modified from the active ingredient in epimedium, TPN171H is an investigational PDE5 inhibitor which has shown several favorable features: a greater PDE5 selectivity than both sildenafil and tadalafil in vitro, an ability to decrease right ventricular systolic pressure and alleviate arterial remodeling in animal studies, and safety and tolerability in healthy human subjects.

The current randomized, double-blind, placebo-and active-controlled phase IIa study assessed the hemodynamic impact of a single oral dose of TPN171H in 60 pulmonary arterial hypertension patients (mean age ~34 years, 83.3% female), all with negative vasodilation test results and in WHO class 2 or 3. Only patients aged 18-75 years with group 1 pulmonary arterial hypertension of idiopathic, connective tissue disorder, or repaired congenital heart defects etiology were included. Patients were divided into six groups: placebo, TPN171H at 2.5, 5, and 10 milligrams, and tadalafil at 20 and 40 milligrams.

For the primary endpoint of maximum decrease in pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR), significant reductions vs. placebo were found only for the TPN171H 5-mg group (–41.2% vs. –24.4%; P = .008) and for the 20-mg (–39.8%) and 40-mg (–37.6%) tadalafil groups (both P < .05). What was not seen in the tadalafil groups, but was evident in the TPN171H 5-mg group, was a significant reduction in the secondary endpoint of PVR/SVR (systolic vascular resistance) at 2, 3, and 5 hours (all P < .05). “As we know,” Dr. Jing said in an interview, “the PDE5 inhibitor functions as a vasodilator, having an impact on both pulmonary circulation and systemic circulation. So, to evaluate the selectivity for pulmonary circulation is crucial when exploring a novel drug for pulmonary arterial hypertension. The change of PVR/SVR ratio from baseline is an indicator for selectivity for pulmonary circulation and implies that TPN171H has good PDE5 selectivity in the pulmonary vasculature,” Dr. Jing said.

TPN171H was well tolerated with no serious adverse effects (vomiting 10% and headache 10% were most common with no discontinuations).

TGF-signaling pathway

A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials of sotatercept, an investigational fusion protein under priority FDA review that modulates the TGF-beta superfamily signaling pathway, looked at PVR, pulmonary arterial pressure (PAP), right arterial pressure (RAP) and N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP). A literature search by corresponding author Vamsikalyan Borra, MD, Knapp Medical Center, Weslaco, Texas, and colleagues identified two trials (STELLAR and PULSAR) comprising 429 patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension. The experimental arms (sotatercept) had 237 patients (mean age ~49 years, ~82% female) and the placebo arm had 192 patients (mean age ~47 years, ~80% female).

A pooled analysis showed significant reductions with sotatercept in PVR (standardization mean difference [SMD] = –1.00, 95% confidence interval [CI] = –1.2, –.79, P < .001), PAP (SMD = –1.34, 95% CI = 1.6, –1.08, P < .001), RAP (SMD = –0.66, 95% CI = –0.93, –0.39, P < .001), and the levels of NT-proBNP (SMD = –0.64, 95% CI = –1.01, –0.27, P < .001) at 24 weeks from baseline. The sotatercept safety profile was favorable, with lower overall incidence of adverse events (84.8% vs. 87.5%) and fewer adverse events leading to death (0.4% vs. 3.1%) compared with placebo. Further investigation is needed, however, according to Dr. Borra, into the higher frequency of reported thrombocytopenia (71.7% vs. 20.8%) with sotatercept. “Our findings,” Dr. Borra said in a poster session, “suggest that sotatercept is an effective treatment option for pulmonary arterial hypertension, with the potential to improve both pulmonary and cardiac function.”

Denervation technique

Catheter-based ablation techniques, most commonly using thermal energy, target the afferent and efferent fibers of the baroreceptor reflex in the main pulmonary artery trunk and bifurcation involved in elevated pulmonary artery pressure. Mounica Vorla, MD, Carle Foundation Hospital, Urbana, Illinois, and colleagues conducted an updated systematic review and meta-analysis of the safety and efficacy of pulmonary artery denervation (PADN) for pulmonary arterial hypertension in seven clinical trials with 506 patients with moderate-severe pulmonary arterial hypertension conducted from 2013 to 2022.

Compared with placebo, PADN treatment was associated with a significant reduction in mean pulmonary artery pressure (weighted mean difference [WMD] = –6.9 mm Hg; 95% CI = –9.7, –4.1; P < .01; I2 = 61) and pulmonary vascular resistance (WMD = –3.2; 95% CI = –5.4, –0.9; P = .005). PADN improvements in cardiac output were also statistically significant (WMD = 0.3; 95% CI = 0.07, 0.6; P = .012), with numerical improvement in 6-minute walking distance (WMD = 67.7; 95% CI = –3.73, 139.2; P = .06) in the PADN group. Side effects were less common in the PADN group as compared with the placebo group, Dr. Vorla reported. She concluded, “This updated meta-analysis supports PADN as a safe and efficacious therapy for severe pulmonary arterial hypertension.” The authors noted limitations imposed by the small sample size, large data heterogeneity, and medium-quality literature. Larger randomized, controlled trials with clinical endpoints comparing PADN with optimal medical therapy are needed, they stated.

References

1. Shah AJ et al. New Drugs and Therapies in Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension. Int J Mol Sci. 2023 Mar 19;24(6):5850. doi: 10.3390/ijms24065850. PMID: 36982922; PMCID: PMC10058689.

2. Kovacs G et al. Pulmonary Vascular Involvement in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Is There a Pulmonary Vascular Phenotype? Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2018 Oct 15;198(8):1000-11. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201801-0095PP. PMID: 29746142.

FROM AHA 2023

EMRs: gumming up the works

I don’t like EMR systems, with all their requirements, click boxes, endless cut & paste abuse, and 20-page notes that say nothing.

But I am a fan of what computers have brought to medical charts.

When I started out in 2000, I had no patients, hence no charts. I had the advantage of being able to start from scratch — there was nothing to convert to digital. So, from the beginning, that’s how I went. Back then, of course, everything came to the office as paper. It had to be scanned in, then named, then placed in the right computer file.

But it was still easier than amassing paper records. At that time I subleased from a doc who’d been in practice for 15 years. His charts were all paper. Charts were neatly filed on shelves, everything was initialed, hole-punched, and put in the right section (which involved pulling out other stuff and putting it back). A few times a year, his staff would comb through the charts in front, and anyone who hadn’t been seen in 2 years would have their chart moved to a storage room in the back. Once a year they’d pull the charts of anyone not seen in 7 years and a company would come in and shred those records.

After 23 years, I still have it all. The whole thing takes up a little over 50 gigabytes on a hard drive, which realistically is nothing these days. Electrons don’t take up much space.

The majority of the charts — those that are more than 7 years old — I’ll probably never need to access, but it still happens sometimes. People call in and say they’ve moved back to Phoenix, or need to see a neurologist again, or need the records for insurance reasons, or whatever. My staff is also spared from moving charts to a storage room, then to shredding. Since they don’t take up any physical space, it’s no effort to keep everything.

And they aren’t just at my office. They’re at home, on my phone, wherever I am. If I get called from an ER, I can pull them up quickly. If I travel, they’re with me. My memory is good, but not that good, and I’d rather be able to look things up than guess.

This, at least to me, is the advantage of computers. Their data storage and retrieval advantages far exceed that of paper. In my opinion EMRs, while well-intentioned, have taken these benefits and twisted them into something cumbersome, geared more to meet nonmedical requirements and billing purposes.

In the process they’ve lost sight of our age-old job of caring for patients.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

I don’t like EMR systems, with all their requirements, click boxes, endless cut & paste abuse, and 20-page notes that say nothing.

But I am a fan of what computers have brought to medical charts.

When I started out in 2000, I had no patients, hence no charts. I had the advantage of being able to start from scratch — there was nothing to convert to digital. So, from the beginning, that’s how I went. Back then, of course, everything came to the office as paper. It had to be scanned in, then named, then placed in the right computer file.

But it was still easier than amassing paper records. At that time I subleased from a doc who’d been in practice for 15 years. His charts were all paper. Charts were neatly filed on shelves, everything was initialed, hole-punched, and put in the right section (which involved pulling out other stuff and putting it back). A few times a year, his staff would comb through the charts in front, and anyone who hadn’t been seen in 2 years would have their chart moved to a storage room in the back. Once a year they’d pull the charts of anyone not seen in 7 years and a company would come in and shred those records.

After 23 years, I still have it all. The whole thing takes up a little over 50 gigabytes on a hard drive, which realistically is nothing these days. Electrons don’t take up much space.

The majority of the charts — those that are more than 7 years old — I’ll probably never need to access, but it still happens sometimes. People call in and say they’ve moved back to Phoenix, or need to see a neurologist again, or need the records for insurance reasons, or whatever. My staff is also spared from moving charts to a storage room, then to shredding. Since they don’t take up any physical space, it’s no effort to keep everything.

And they aren’t just at my office. They’re at home, on my phone, wherever I am. If I get called from an ER, I can pull them up quickly. If I travel, they’re with me. My memory is good, but not that good, and I’d rather be able to look things up than guess.

This, at least to me, is the advantage of computers. Their data storage and retrieval advantages far exceed that of paper. In my opinion EMRs, while well-intentioned, have taken these benefits and twisted them into something cumbersome, geared more to meet nonmedical requirements and billing purposes.

In the process they’ve lost sight of our age-old job of caring for patients.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

I don’t like EMR systems, with all their requirements, click boxes, endless cut & paste abuse, and 20-page notes that say nothing.

But I am a fan of what computers have brought to medical charts.

When I started out in 2000, I had no patients, hence no charts. I had the advantage of being able to start from scratch — there was nothing to convert to digital. So, from the beginning, that’s how I went. Back then, of course, everything came to the office as paper. It had to be scanned in, then named, then placed in the right computer file.

But it was still easier than amassing paper records. At that time I subleased from a doc who’d been in practice for 15 years. His charts were all paper. Charts were neatly filed on shelves, everything was initialed, hole-punched, and put in the right section (which involved pulling out other stuff and putting it back). A few times a year, his staff would comb through the charts in front, and anyone who hadn’t been seen in 2 years would have their chart moved to a storage room in the back. Once a year they’d pull the charts of anyone not seen in 7 years and a company would come in and shred those records.

After 23 years, I still have it all. The whole thing takes up a little over 50 gigabytes on a hard drive, which realistically is nothing these days. Electrons don’t take up much space.

The majority of the charts — those that are more than 7 years old — I’ll probably never need to access, but it still happens sometimes. People call in and say they’ve moved back to Phoenix, or need to see a neurologist again, or need the records for insurance reasons, or whatever. My staff is also spared from moving charts to a storage room, then to shredding. Since they don’t take up any physical space, it’s no effort to keep everything.

And they aren’t just at my office. They’re at home, on my phone, wherever I am. If I get called from an ER, I can pull them up quickly. If I travel, they’re with me. My memory is good, but not that good, and I’d rather be able to look things up than guess.

This, at least to me, is the advantage of computers. Their data storage and retrieval advantages far exceed that of paper. In my opinion EMRs, while well-intentioned, have taken these benefits and twisted them into something cumbersome, geared more to meet nonmedical requirements and billing purposes.

In the process they’ve lost sight of our age-old job of caring for patients.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

An alternative to walking out

Organized labor seems to be experiencing a rebirth of sorts. In October 2022 a strike by railroad workers was averted when a tentative agreement about wages, working conditions, health insurance, and medical leave was hammered out. This past fall, strikes by auto workers that threatened to paralyze the big three manufacturers have now been resolved with agreements that meet many of the workers’ demands. The President even made an appearance on a picket line. Baristas at coffee shops, screenwriters, and actors have all been involved in work actions around the country.

While the health care industry has been relatively immune to threatened work stoppages, there are a growing number of hospitals and clinics where nurses and physicians are exploring the possibility of organizing to give themselves a stronger voice in how health care is being delivered. The realities that come when you transition from owner to employee are finally beginning to sink in for physicians, whether they are specialists or primary care providers.

One of the most significant efforts toward unionization recently occurred in Minnesota and Wisconsin. About 400 physicians and 150 physician’s assistants and nurse practitioners employed at Allina Health System voted to unionize and join the Doctors Council.

In an interview with Jacobin, a publication that offers a socialist perspective, three of the providers involved in the process that led to the vote shared their observations. The physicians claim that the first steps toward unionization came after multiple efforts to work with the Allina’s administration were rebuffed. As primary care physicians, their initial demands focused on getting help with hiring staffing and getting support with paperwork and administrative obligations.

The organizers complained that while Medicare hoped to bolster primary care by paying the providers more, the funds went to the companies, who then distributed them in a way that often did little to help the overworked providers. In addition to achieving a more equitable distribution of the monies, one of the organizers sees unionization as a way to provide a layer of protection when providers feel they must speak out about situations which clearly put quality of care at risk.

The organizers say the idea of unionization has been particularly appealing to the younger providers who are feeling threatened by burnout. When these new physicians look to their older coworkers for advice, they often find that the seasoned employees are as stressed as they are. Realizing that things aren’t going to improve with time, acting now to strengthen their voices sounds appealing.

With the vote for unionization behind them, the organizers are now ready to formulate a prioritized list of demands. Those of you who are regular readers of Letters from Maine know that I have been urging primary care physicians to find their voices. Unfortunately, unionization seems to be becoming a more common fall-back strategy when other avenues have failed to reach a sympathetic ear in the corporate boardrooms.

As more unions form, it will be interesting to see how the organizers structure their demands and job actions. While walkouts and strikes can certainly be effective in gaining attention, that attention can carry a risk of counter productivity sometimes by alienating patients, who should become allies.

Since an unsustainable burden of paperwork and administrative demands seems to be at the top of everyone’s priority list, it might make sense to adopt this message as a scaffolding on which to built a work action. Instead of walking off the job or marching on a picket line, why not stay in the hospital and continue to see patients but only for part of the work day. The remainder of the day would be spent doing all the clerical work that has become so onerous.

Providers would agree to see patients in the mornings, saving up the clerical work and administrative obligations for the afternoon. The definition of “morning” could vary depending on local conditions.

The important message to the public and the patients would be that the providers were not abandoning them by walking out. The patients’ access to face-to-face care was being limited not because the doctors didn’t want to see them but because the providers were being forced to accept other responsibilities by the administration. The physicians would always be on site in case of a crisis, but until reasonable demands for support from the company were met, a certain portion of the providers’ day would be spent doing things not directly related to face-to-face patient care. This burden of meaningless work is the reality as it stands already. Why not organize it in a way that makes it startlingly visible to the patients and the public.

There would be no video clips of physicians walking the picket lines carrying signs. Any images released to the media would be of empty waiting rooms while providers sat hunched over their computers or talking on the phone to insurance companies.

The strategy needs a catchy phrase like “a paperwork-in” but I’m still struggling with a name. Let me know if you have a better one or even a better strategy.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Other than a Littman stethoscope he accepted as a first-year medical student in 1966, Dr. Wilkoff reports having nothing to disclose. Email him at [email protected].

Organized labor seems to be experiencing a rebirth of sorts. In October 2022 a strike by railroad workers was averted when a tentative agreement about wages, working conditions, health insurance, and medical leave was hammered out. This past fall, strikes by auto workers that threatened to paralyze the big three manufacturers have now been resolved with agreements that meet many of the workers’ demands. The President even made an appearance on a picket line. Baristas at coffee shops, screenwriters, and actors have all been involved in work actions around the country.

While the health care industry has been relatively immune to threatened work stoppages, there are a growing number of hospitals and clinics where nurses and physicians are exploring the possibility of organizing to give themselves a stronger voice in how health care is being delivered. The realities that come when you transition from owner to employee are finally beginning to sink in for physicians, whether they are specialists or primary care providers.

One of the most significant efforts toward unionization recently occurred in Minnesota and Wisconsin. About 400 physicians and 150 physician’s assistants and nurse practitioners employed at Allina Health System voted to unionize and join the Doctors Council.

In an interview with Jacobin, a publication that offers a socialist perspective, three of the providers involved in the process that led to the vote shared their observations. The physicians claim that the first steps toward unionization came after multiple efforts to work with the Allina’s administration were rebuffed. As primary care physicians, their initial demands focused on getting help with hiring staffing and getting support with paperwork and administrative obligations.

The organizers complained that while Medicare hoped to bolster primary care by paying the providers more, the funds went to the companies, who then distributed them in a way that often did little to help the overworked providers. In addition to achieving a more equitable distribution of the monies, one of the organizers sees unionization as a way to provide a layer of protection when providers feel they must speak out about situations which clearly put quality of care at risk.

The organizers say the idea of unionization has been particularly appealing to the younger providers who are feeling threatened by burnout. When these new physicians look to their older coworkers for advice, they often find that the seasoned employees are as stressed as they are. Realizing that things aren’t going to improve with time, acting now to strengthen their voices sounds appealing.

With the vote for unionization behind them, the organizers are now ready to formulate a prioritized list of demands. Those of you who are regular readers of Letters from Maine know that I have been urging primary care physicians to find their voices. Unfortunately, unionization seems to be becoming a more common fall-back strategy when other avenues have failed to reach a sympathetic ear in the corporate boardrooms.

As more unions form, it will be interesting to see how the organizers structure their demands and job actions. While walkouts and strikes can certainly be effective in gaining attention, that attention can carry a risk of counter productivity sometimes by alienating patients, who should become allies.

Since an unsustainable burden of paperwork and administrative demands seems to be at the top of everyone’s priority list, it might make sense to adopt this message as a scaffolding on which to built a work action. Instead of walking off the job or marching on a picket line, why not stay in the hospital and continue to see patients but only for part of the work day. The remainder of the day would be spent doing all the clerical work that has become so onerous.

Providers would agree to see patients in the mornings, saving up the clerical work and administrative obligations for the afternoon. The definition of “morning” could vary depending on local conditions.

The important message to the public and the patients would be that the providers were not abandoning them by walking out. The patients’ access to face-to-face care was being limited not because the doctors didn’t want to see them but because the providers were being forced to accept other responsibilities by the administration. The physicians would always be on site in case of a crisis, but until reasonable demands for support from the company were met, a certain portion of the providers’ day would be spent doing things not directly related to face-to-face patient care. This burden of meaningless work is the reality as it stands already. Why not organize it in a way that makes it startlingly visible to the patients and the public.

There would be no video clips of physicians walking the picket lines carrying signs. Any images released to the media would be of empty waiting rooms while providers sat hunched over their computers or talking on the phone to insurance companies.

The strategy needs a catchy phrase like “a paperwork-in” but I’m still struggling with a name. Let me know if you have a better one or even a better strategy.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Other than a Littman stethoscope he accepted as a first-year medical student in 1966, Dr. Wilkoff reports having nothing to disclose. Email him at [email protected].

Organized labor seems to be experiencing a rebirth of sorts. In October 2022 a strike by railroad workers was averted when a tentative agreement about wages, working conditions, health insurance, and medical leave was hammered out. This past fall, strikes by auto workers that threatened to paralyze the big three manufacturers have now been resolved with agreements that meet many of the workers’ demands. The President even made an appearance on a picket line. Baristas at coffee shops, screenwriters, and actors have all been involved in work actions around the country.

While the health care industry has been relatively immune to threatened work stoppages, there are a growing number of hospitals and clinics where nurses and physicians are exploring the possibility of organizing to give themselves a stronger voice in how health care is being delivered. The realities that come when you transition from owner to employee are finally beginning to sink in for physicians, whether they are specialists or primary care providers.

One of the most significant efforts toward unionization recently occurred in Minnesota and Wisconsin. About 400 physicians and 150 physician’s assistants and nurse practitioners employed at Allina Health System voted to unionize and join the Doctors Council.

In an interview with Jacobin, a publication that offers a socialist perspective, three of the providers involved in the process that led to the vote shared their observations. The physicians claim that the first steps toward unionization came after multiple efforts to work with the Allina’s administration were rebuffed. As primary care physicians, their initial demands focused on getting help with hiring staffing and getting support with paperwork and administrative obligations.

The organizers complained that while Medicare hoped to bolster primary care by paying the providers more, the funds went to the companies, who then distributed them in a way that often did little to help the overworked providers. In addition to achieving a more equitable distribution of the monies, one of the organizers sees unionization as a way to provide a layer of protection when providers feel they must speak out about situations which clearly put quality of care at risk.

The organizers say the idea of unionization has been particularly appealing to the younger providers who are feeling threatened by burnout. When these new physicians look to their older coworkers for advice, they often find that the seasoned employees are as stressed as they are. Realizing that things aren’t going to improve with time, acting now to strengthen their voices sounds appealing.

With the vote for unionization behind them, the organizers are now ready to formulate a prioritized list of demands. Those of you who are regular readers of Letters from Maine know that I have been urging primary care physicians to find their voices. Unfortunately, unionization seems to be becoming a more common fall-back strategy when other avenues have failed to reach a sympathetic ear in the corporate boardrooms.

As more unions form, it will be interesting to see how the organizers structure their demands and job actions. While walkouts and strikes can certainly be effective in gaining attention, that attention can carry a risk of counter productivity sometimes by alienating patients, who should become allies.

Since an unsustainable burden of paperwork and administrative demands seems to be at the top of everyone’s priority list, it might make sense to adopt this message as a scaffolding on which to built a work action. Instead of walking off the job or marching on a picket line, why not stay in the hospital and continue to see patients but only for part of the work day. The remainder of the day would be spent doing all the clerical work that has become so onerous.

Providers would agree to see patients in the mornings, saving up the clerical work and administrative obligations for the afternoon. The definition of “morning” could vary depending on local conditions.

The important message to the public and the patients would be that the providers were not abandoning them by walking out. The patients’ access to face-to-face care was being limited not because the doctors didn’t want to see them but because the providers were being forced to accept other responsibilities by the administration. The physicians would always be on site in case of a crisis, but until reasonable demands for support from the company were met, a certain portion of the providers’ day would be spent doing things not directly related to face-to-face patient care. This burden of meaningless work is the reality as it stands already. Why not organize it in a way that makes it startlingly visible to the patients and the public.

There would be no video clips of physicians walking the picket lines carrying signs. Any images released to the media would be of empty waiting rooms while providers sat hunched over their computers or talking on the phone to insurance companies.

The strategy needs a catchy phrase like “a paperwork-in” but I’m still struggling with a name. Let me know if you have a better one or even a better strategy.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Other than a Littman stethoscope he accepted as a first-year medical student in 1966, Dr. Wilkoff reports having nothing to disclose. Email him at [email protected].

FDA mandates five changes to iPLEDGE program for isotretinoin

In a letter dated Nov. 30, 2023, the .

The development follows a March 2023 joint meeting of the FDA’s Drug Safety and Risk Management Advisory Committee and the Dermatologic and Ophthalmic Drugs Advisory Committee about iPLEDGE REMS requirements, which included feedback from patients and dermatologists and recommendations for changes to the REMS program, aimed at minimizing the burden of the program on patients, pharmacies, and prescribers while continuing to maintain safe use of the highly teratogenic drug for patients.

The five changes include the following:

- Remove the requirement that pregnancy tests must be performed in a specially certified (i.e., Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments [CLIA]) laboratory. In the opinion of John S. Barbieri, MD, MBA, director of the Advanced Acne Therapeutics Clinic at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, this change “may make it easier to perform pregnancy tests in a clinic setting without needing to send the patient to a separate lab,” he said in an interview.

- Allow prescribers the option of using home pregnancy testing for their patients during and after isotretinoin treatment. Prescribers who rely on the patient to perform a home pregnancy test need to take steps to minimize patients falsifying the results of these tests. According to Dr. Barbieri, this means that two pregnancy tests prior to starting isotretinoin must be done in a lab or office setting. “However, all the pregnancy tests on therapy can be either in a medical setting or using a home pregnancy test,” he told this news organization. “This option facilitates the use of telemedicine so that patients would not need to come in; they can just share a pregnancy test with their name and date with their dermatologist.”

- Remove the waiting period requirement — also known as the “19-day lockout” — for patients if they do not obtain isotretinoin within the first 7-day prescription window. According to Dr. Barbieri, this change helps to ensure that patients can begin isotretinoin in a timely manner. “Insurance and pharmacy delays that are no fault of the patient can commonly cause missed initial window periods,” he said. “Allowing for immediate repeat of a pregnancy test to start a new window period, rather than requiring the patient to wait 19 more days, can ensure patient safety and pregnancy prevention without negatively impacting access.”

- Revise the pregnancy registry requirement to remove the objective to document the pregnancy and fetal outcomes for each pregnancy.

- Revise the requirement for prescribers to document patient counseling in patients who cannot become pregnant from monthly to only at enrollment. Dr. Barbieri characterized this change as “major” and said that it could eliminate the need for monthly visits for persons of non–childbearing potential. “This could substantially reduce logistical burdens for patients and reduce wait times to see a dermatologist,” he said.

Future changes to iPLEDGE that Dr. Barbieri would like to see include allowing for home pregnancy tests prior to starting therapy — particularly the test after the 30-day window period. “In addition, it would be good to be able to reduce the 30-day waiting period prior to therapy to something shorter,” such as 14 days, which would still “reliably exclude pregnancy, particularly for those on stable long-acting reversible contraception,” he said. There are also opportunities to improve the iPLEDGE website functionality and to ensure that the website is accessible to patients with limited English proficiency, he added.

He also recommended greater transparency by the Isotretinoin Products Manufacturers Group and inclusion of input from diverse stakeholders such as dermatologists, patients, and pharmacists.

Dr. Barbieri reported personal fees from Dexcel Pharma.

In a letter dated Nov. 30, 2023, the .

The development follows a March 2023 joint meeting of the FDA’s Drug Safety and Risk Management Advisory Committee and the Dermatologic and Ophthalmic Drugs Advisory Committee about iPLEDGE REMS requirements, which included feedback from patients and dermatologists and recommendations for changes to the REMS program, aimed at minimizing the burden of the program on patients, pharmacies, and prescribers while continuing to maintain safe use of the highly teratogenic drug for patients.

The five changes include the following:

- Remove the requirement that pregnancy tests must be performed in a specially certified (i.e., Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments [CLIA]) laboratory. In the opinion of John S. Barbieri, MD, MBA, director of the Advanced Acne Therapeutics Clinic at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, this change “may make it easier to perform pregnancy tests in a clinic setting without needing to send the patient to a separate lab,” he said in an interview.

- Allow prescribers the option of using home pregnancy testing for their patients during and after isotretinoin treatment. Prescribers who rely on the patient to perform a home pregnancy test need to take steps to minimize patients falsifying the results of these tests. According to Dr. Barbieri, this means that two pregnancy tests prior to starting isotretinoin must be done in a lab or office setting. “However, all the pregnancy tests on therapy can be either in a medical setting or using a home pregnancy test,” he told this news organization. “This option facilitates the use of telemedicine so that patients would not need to come in; they can just share a pregnancy test with their name and date with their dermatologist.”

- Remove the waiting period requirement — also known as the “19-day lockout” — for patients if they do not obtain isotretinoin within the first 7-day prescription window. According to Dr. Barbieri, this change helps to ensure that patients can begin isotretinoin in a timely manner. “Insurance and pharmacy delays that are no fault of the patient can commonly cause missed initial window periods,” he said. “Allowing for immediate repeat of a pregnancy test to start a new window period, rather than requiring the patient to wait 19 more days, can ensure patient safety and pregnancy prevention without negatively impacting access.”

- Revise the pregnancy registry requirement to remove the objective to document the pregnancy and fetal outcomes for each pregnancy.

- Revise the requirement for prescribers to document patient counseling in patients who cannot become pregnant from monthly to only at enrollment. Dr. Barbieri characterized this change as “major” and said that it could eliminate the need for monthly visits for persons of non–childbearing potential. “This could substantially reduce logistical burdens for patients and reduce wait times to see a dermatologist,” he said.

Future changes to iPLEDGE that Dr. Barbieri would like to see include allowing for home pregnancy tests prior to starting therapy — particularly the test after the 30-day window period. “In addition, it would be good to be able to reduce the 30-day waiting period prior to therapy to something shorter,” such as 14 days, which would still “reliably exclude pregnancy, particularly for those on stable long-acting reversible contraception,” he said. There are also opportunities to improve the iPLEDGE website functionality and to ensure that the website is accessible to patients with limited English proficiency, he added.

He also recommended greater transparency by the Isotretinoin Products Manufacturers Group and inclusion of input from diverse stakeholders such as dermatologists, patients, and pharmacists.

Dr. Barbieri reported personal fees from Dexcel Pharma.

In a letter dated Nov. 30, 2023, the .

The development follows a March 2023 joint meeting of the FDA’s Drug Safety and Risk Management Advisory Committee and the Dermatologic and Ophthalmic Drugs Advisory Committee about iPLEDGE REMS requirements, which included feedback from patients and dermatologists and recommendations for changes to the REMS program, aimed at minimizing the burden of the program on patients, pharmacies, and prescribers while continuing to maintain safe use of the highly teratogenic drug for patients.

The five changes include the following:

- Remove the requirement that pregnancy tests must be performed in a specially certified (i.e., Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments [CLIA]) laboratory. In the opinion of John S. Barbieri, MD, MBA, director of the Advanced Acne Therapeutics Clinic at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, this change “may make it easier to perform pregnancy tests in a clinic setting without needing to send the patient to a separate lab,” he said in an interview.

- Allow prescribers the option of using home pregnancy testing for their patients during and after isotretinoin treatment. Prescribers who rely on the patient to perform a home pregnancy test need to take steps to minimize patients falsifying the results of these tests. According to Dr. Barbieri, this means that two pregnancy tests prior to starting isotretinoin must be done in a lab or office setting. “However, all the pregnancy tests on therapy can be either in a medical setting or using a home pregnancy test,” he told this news organization. “This option facilitates the use of telemedicine so that patients would not need to come in; they can just share a pregnancy test with their name and date with their dermatologist.”

- Remove the waiting period requirement — also known as the “19-day lockout” — for patients if they do not obtain isotretinoin within the first 7-day prescription window. According to Dr. Barbieri, this change helps to ensure that patients can begin isotretinoin in a timely manner. “Insurance and pharmacy delays that are no fault of the patient can commonly cause missed initial window periods,” he said. “Allowing for immediate repeat of a pregnancy test to start a new window period, rather than requiring the patient to wait 19 more days, can ensure patient safety and pregnancy prevention without negatively impacting access.”

- Revise the pregnancy registry requirement to remove the objective to document the pregnancy and fetal outcomes for each pregnancy.

- Revise the requirement for prescribers to document patient counseling in patients who cannot become pregnant from monthly to only at enrollment. Dr. Barbieri characterized this change as “major” and said that it could eliminate the need for monthly visits for persons of non–childbearing potential. “This could substantially reduce logistical burdens for patients and reduce wait times to see a dermatologist,” he said.

Future changes to iPLEDGE that Dr. Barbieri would like to see include allowing for home pregnancy tests prior to starting therapy — particularly the test after the 30-day window period. “In addition, it would be good to be able to reduce the 30-day waiting period prior to therapy to something shorter,” such as 14 days, which would still “reliably exclude pregnancy, particularly for those on stable long-acting reversible contraception,” he said. There are also opportunities to improve the iPLEDGE website functionality and to ensure that the website is accessible to patients with limited English proficiency, he added.

He also recommended greater transparency by the Isotretinoin Products Manufacturers Group and inclusion of input from diverse stakeholders such as dermatologists, patients, and pharmacists.

Dr. Barbieri reported personal fees from Dexcel Pharma.

Are you sure your patient is alive?

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Much of my research focuses on what is known as clinical decision support — prompts and messages to providers to help them make good decisions for their patients. I know that these things can be annoying, which is exactly why I study them — to figure out which ones actually help.

When I got started on this about 10 years ago, we were learning a lot about how best to message providers about their patients. My team had developed a simple alert for acute kidney injury (AKI). We knew that providers often missed the diagnosis, so maybe letting them know would improve patient outcomes.

As we tested the alert, we got feedback, and I have kept an email from an ICU doctor from those early days. It read:

Dear Dr. Wilson: Thank you for the automated alert informing me that my patient had AKI. Regrettably, the alert fired about an hour after the patient had died. I feel that the information is less than actionable at this time.

Our early system had neglected to add a conditional flag ensuring that the patient was still alive at the time it sent the alert message. A small oversight, but one that had very large implications. Future studies would show that “false positive” alerts like this seriously degrade physician confidence in the system. And why wouldn’t they?

Not knowing the vital status of a patient can have major consequences.

Health systems send messages to their patients all the time: reminders of appointments, reminders for preventive care, reminders for vaccinations, and so on.

But what if the patient being reminded has died? It’s a waste of resources, of course, but more than that, it can be painful for their families and reflects poorly on the health care system. Of all the people who should know whether someone is alive or dead, shouldn’t their doctor be at the top of the list?

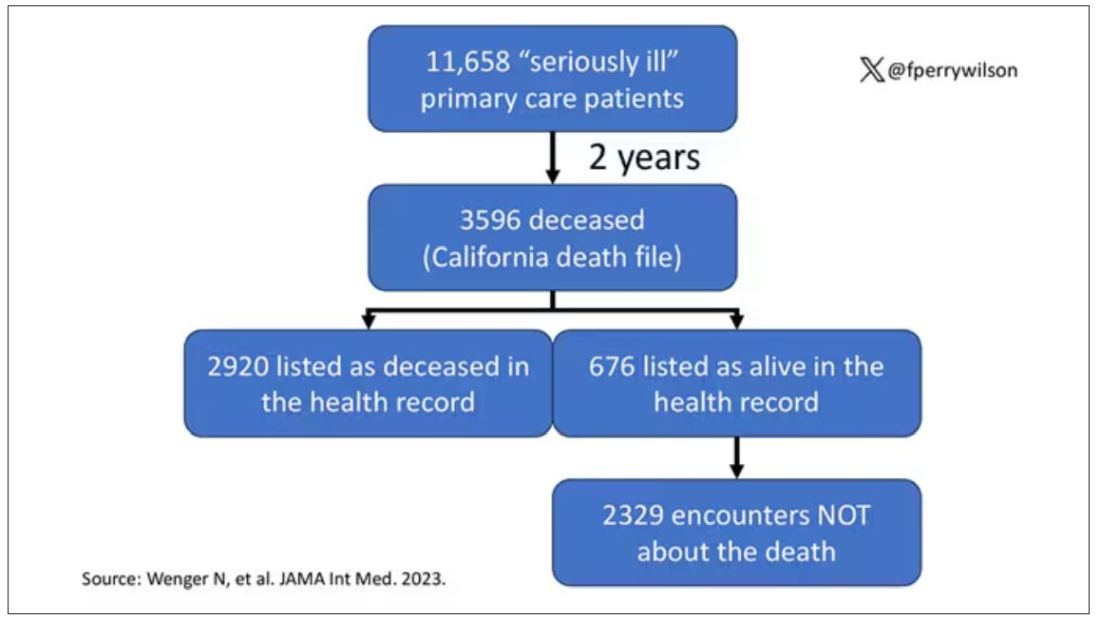

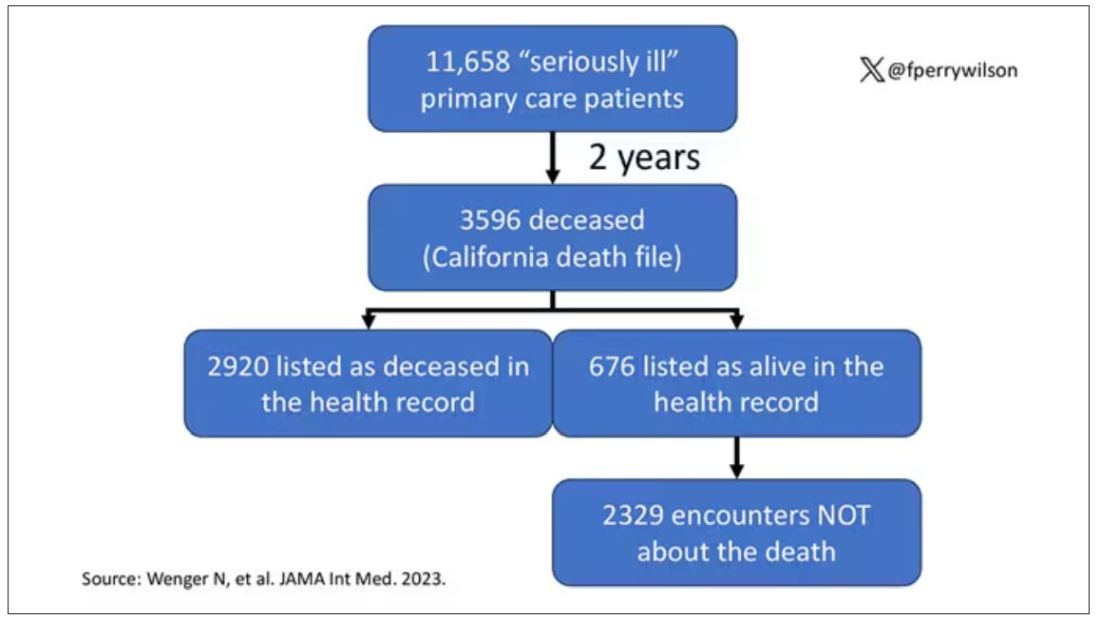

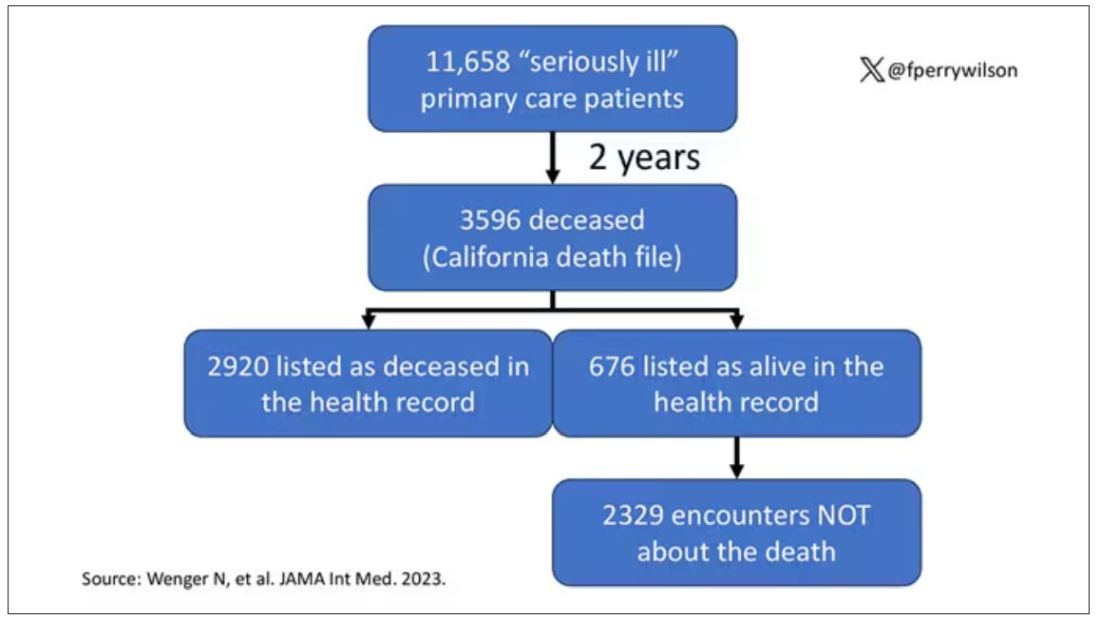

A new study in JAMA Internal Medicine quantifies this very phenomenon.

Researchers examined 11,658 primary care patients in their health system who met the criteria of being “seriously ill” and followed them for 2 years. During that period of time, 25% were recorded as deceased in the electronic health record. But 30.8% had died. That left 676 patients who had died, but were not known to have died, left in the system.

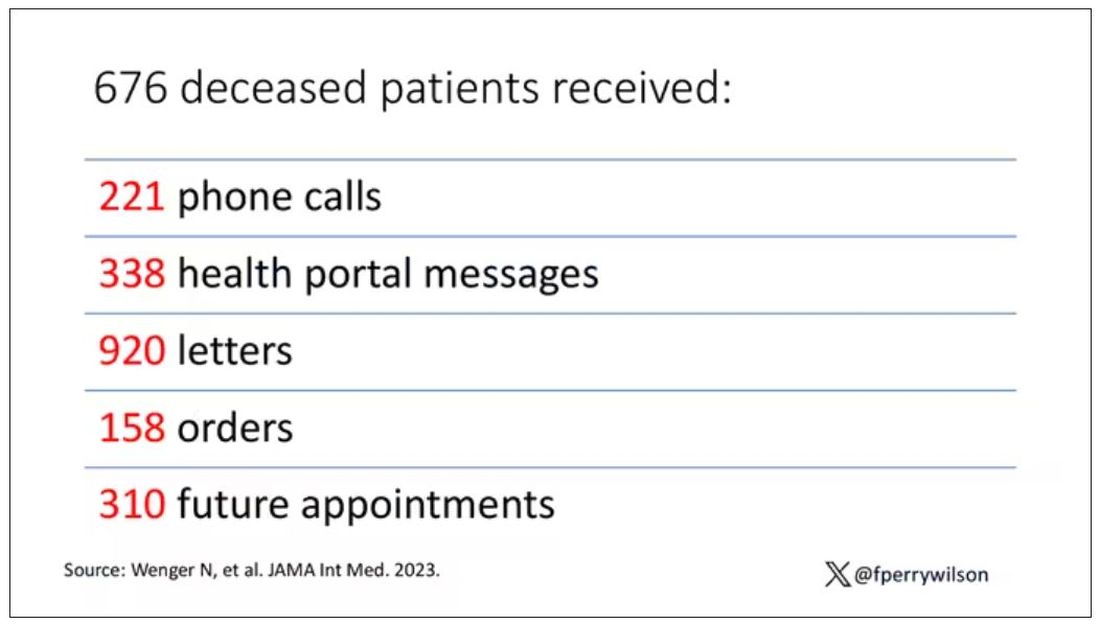

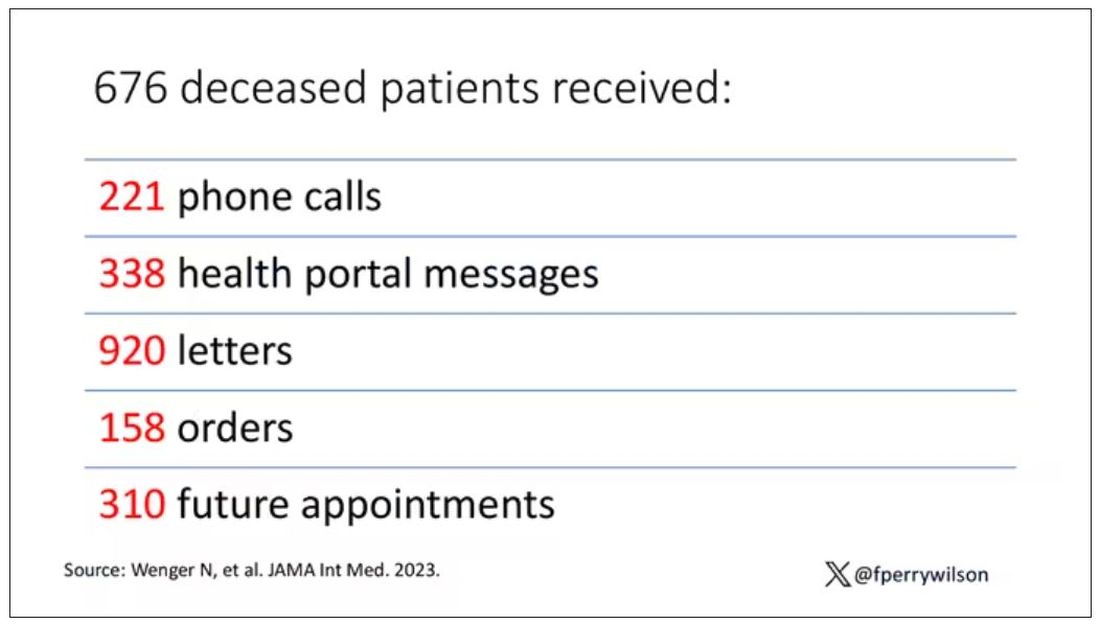

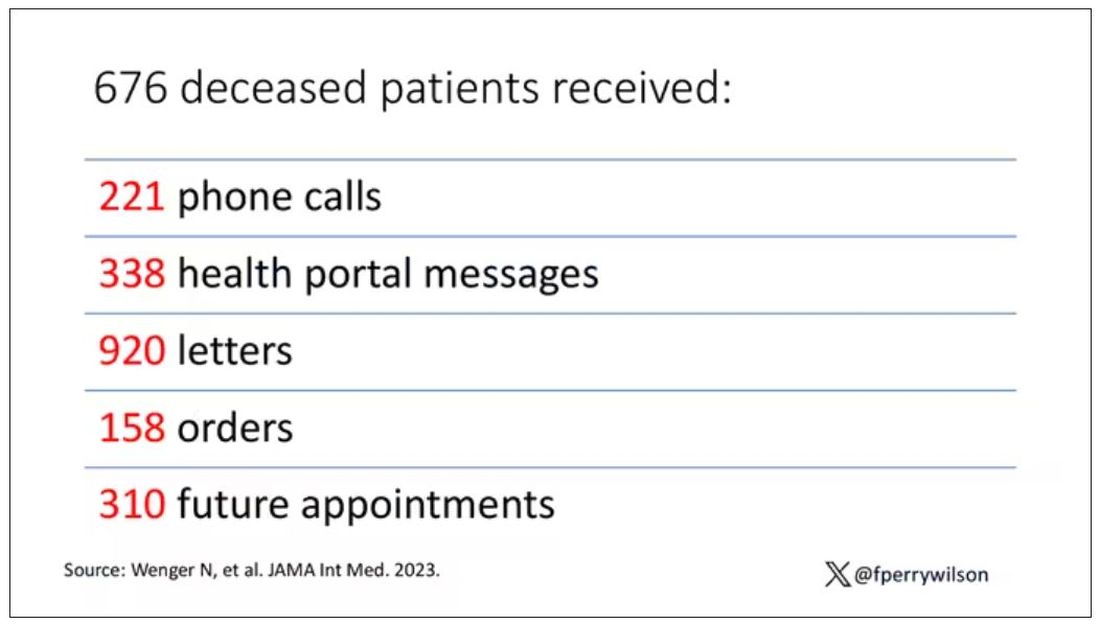

And those 676 were not left to rest in peace. They received 221 telephone and 338 health portal messages not related to death, and 920 letters reminding them about unmet primary care metrics like flu shots and cancer screening. Orders were entered into the health record for things like vaccines and routine screenings for 158 patients, and 310 future appointments — destined to be no-shows — were still on the books. One can only imagine the frustration of families checking their mail and finding yet another letter reminding their deceased loved one to get a mammogram.

How did the researchers figure out who had died? It turns out it’s not that hard. California keeps a record of all deaths in the state; they simply had to search it. Like all state death records, they tend to lag a bit so it’s not clinically terribly useful, but it works. California and most other states also have a very accurate and up-to-date death file which can only be used by law enforcement to investigate criminal activity and fraud; health care is left in the lurch.

Nationwide, there is the real-time fact of death service, supported by the National Association for Public Health Statistics and Information Systems. This allows employers to verify, in real time, whether the person applying for a job is alive. Healthcare systems are not allowed to use it.

Let’s also remember that very few people die in this country without some health care agency knowing about it and recording it. But sharing of medical information is so poor in the United States that your patient could die in a hospital one city away from you and you might not find out until you’re calling them to see why they missed a scheduled follow-up appointment.

These events — the embarrassing lack of knowledge about the very vital status of our patients — highlight a huge problem with health care in our country. The fragmented health care system is terrible at data sharing, in part because of poor protocols, in part because of unfounded concerns about patient privacy, and in part because of a tendency to hoard data that might be valuable in the future. It has to stop. We need to know how our patients are doing even when they are not sitting in front of us. When it comes to life and death, the knowledge is out there; we just can’t access it. Seems like a pretty easy fix.

Dr. Wilson is associate professor of medicine and public health and director of the Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator at Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut. He has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com .

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Much of my research focuses on what is known as clinical decision support — prompts and messages to providers to help them make good decisions for their patients. I know that these things can be annoying, which is exactly why I study them — to figure out which ones actually help.

When I got started on this about 10 years ago, we were learning a lot about how best to message providers about their patients. My team had developed a simple alert for acute kidney injury (AKI). We knew that providers often missed the diagnosis, so maybe letting them know would improve patient outcomes.

As we tested the alert, we got feedback, and I have kept an email from an ICU doctor from those early days. It read:

Dear Dr. Wilson: Thank you for the automated alert informing me that my patient had AKI. Regrettably, the alert fired about an hour after the patient had died. I feel that the information is less than actionable at this time.

Our early system had neglected to add a conditional flag ensuring that the patient was still alive at the time it sent the alert message. A small oversight, but one that had very large implications. Future studies would show that “false positive” alerts like this seriously degrade physician confidence in the system. And why wouldn’t they?

Not knowing the vital status of a patient can have major consequences.

Health systems send messages to their patients all the time: reminders of appointments, reminders for preventive care, reminders for vaccinations, and so on.

But what if the patient being reminded has died? It’s a waste of resources, of course, but more than that, it can be painful for their families and reflects poorly on the health care system. Of all the people who should know whether someone is alive or dead, shouldn’t their doctor be at the top of the list?

A new study in JAMA Internal Medicine quantifies this very phenomenon.

Researchers examined 11,658 primary care patients in their health system who met the criteria of being “seriously ill” and followed them for 2 years. During that period of time, 25% were recorded as deceased in the electronic health record. But 30.8% had died. That left 676 patients who had died, but were not known to have died, left in the system.

And those 676 were not left to rest in peace. They received 221 telephone and 338 health portal messages not related to death, and 920 letters reminding them about unmet primary care metrics like flu shots and cancer screening. Orders were entered into the health record for things like vaccines and routine screenings for 158 patients, and 310 future appointments — destined to be no-shows — were still on the books. One can only imagine the frustration of families checking their mail and finding yet another letter reminding their deceased loved one to get a mammogram.

How did the researchers figure out who had died? It turns out it’s not that hard. California keeps a record of all deaths in the state; they simply had to search it. Like all state death records, they tend to lag a bit so it’s not clinically terribly useful, but it works. California and most other states also have a very accurate and up-to-date death file which can only be used by law enforcement to investigate criminal activity and fraud; health care is left in the lurch.

Nationwide, there is the real-time fact of death service, supported by the National Association for Public Health Statistics and Information Systems. This allows employers to verify, in real time, whether the person applying for a job is alive. Healthcare systems are not allowed to use it.

Let’s also remember that very few people die in this country without some health care agency knowing about it and recording it. But sharing of medical information is so poor in the United States that your patient could die in a hospital one city away from you and you might not find out until you’re calling them to see why they missed a scheduled follow-up appointment.

These events — the embarrassing lack of knowledge about the very vital status of our patients — highlight a huge problem with health care in our country. The fragmented health care system is terrible at data sharing, in part because of poor protocols, in part because of unfounded concerns about patient privacy, and in part because of a tendency to hoard data that might be valuable in the future. It has to stop. We need to know how our patients are doing even when they are not sitting in front of us. When it comes to life and death, the knowledge is out there; we just can’t access it. Seems like a pretty easy fix.

Dr. Wilson is associate professor of medicine and public health and director of the Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator at Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut. He has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com .

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Much of my research focuses on what is known as clinical decision support — prompts and messages to providers to help them make good decisions for their patients. I know that these things can be annoying, which is exactly why I study them — to figure out which ones actually help.

When I got started on this about 10 years ago, we were learning a lot about how best to message providers about their patients. My team had developed a simple alert for acute kidney injury (AKI). We knew that providers often missed the diagnosis, so maybe letting them know would improve patient outcomes.

As we tested the alert, we got feedback, and I have kept an email from an ICU doctor from those early days. It read:

Dear Dr. Wilson: Thank you for the automated alert informing me that my patient had AKI. Regrettably, the alert fired about an hour after the patient had died. I feel that the information is less than actionable at this time.

Our early system had neglected to add a conditional flag ensuring that the patient was still alive at the time it sent the alert message. A small oversight, but one that had very large implications. Future studies would show that “false positive” alerts like this seriously degrade physician confidence in the system. And why wouldn’t they?

Not knowing the vital status of a patient can have major consequences.

Health systems send messages to their patients all the time: reminders of appointments, reminders for preventive care, reminders for vaccinations, and so on.

But what if the patient being reminded has died? It’s a waste of resources, of course, but more than that, it can be painful for their families and reflects poorly on the health care system. Of all the people who should know whether someone is alive or dead, shouldn’t their doctor be at the top of the list?

A new study in JAMA Internal Medicine quantifies this very phenomenon.

Researchers examined 11,658 primary care patients in their health system who met the criteria of being “seriously ill” and followed them for 2 years. During that period of time, 25% were recorded as deceased in the electronic health record. But 30.8% had died. That left 676 patients who had died, but were not known to have died, left in the system.

And those 676 were not left to rest in peace. They received 221 telephone and 338 health portal messages not related to death, and 920 letters reminding them about unmet primary care metrics like flu shots and cancer screening. Orders were entered into the health record for things like vaccines and routine screenings for 158 patients, and 310 future appointments — destined to be no-shows — were still on the books. One can only imagine the frustration of families checking their mail and finding yet another letter reminding their deceased loved one to get a mammogram.

How did the researchers figure out who had died? It turns out it’s not that hard. California keeps a record of all deaths in the state; they simply had to search it. Like all state death records, they tend to lag a bit so it’s not clinically terribly useful, but it works. California and most other states also have a very accurate and up-to-date death file which can only be used by law enforcement to investigate criminal activity and fraud; health care is left in the lurch.

Nationwide, there is the real-time fact of death service, supported by the National Association for Public Health Statistics and Information Systems. This allows employers to verify, in real time, whether the person applying for a job is alive. Healthcare systems are not allowed to use it.

Let’s also remember that very few people die in this country without some health care agency knowing about it and recording it. But sharing of medical information is so poor in the United States that your patient could die in a hospital one city away from you and you might not find out until you’re calling them to see why they missed a scheduled follow-up appointment.

These events — the embarrassing lack of knowledge about the very vital status of our patients — highlight a huge problem with health care in our country. The fragmented health care system is terrible at data sharing, in part because of poor protocols, in part because of unfounded concerns about patient privacy, and in part because of a tendency to hoard data that might be valuable in the future. It has to stop. We need to know how our patients are doing even when they are not sitting in front of us. When it comes to life and death, the knowledge is out there; we just can’t access it. Seems like a pretty easy fix.

Dr. Wilson is associate professor of medicine and public health and director of the Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator at Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut. He has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com .

Meet the newest acronym in primary care: CKM

The advisory, published recently in Circulation introduces the concept of CKM health and reevaluates the relationships between obesity, diabetes, kidney disease, and cardiovascular disease (CVD).

“This approach not only raises awareness, it also empowers PCPs to diagnose and treat these conditions more holistically,” Salim Hayek, MD, associate professor of cardiovascular disease and internal medicine, and medical director of the Frankel Cardiovascular Center Clinics at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, said in an interview.

New CKM Staging, Testing, and Care Strategies

The advisory introduces a new scoring system that ranges from stage 0 (patients with no risk factors for CKM) through stage 4 (patients with clinical CVD in CKM syndrome). Each stage requires specific management strategies and may include screening starting at age 30 years for diabetes, hypertension, and heart failure.

“Stage 0 CKM is usually found in young people, and CKM risk factors and scores typically increase as people age,” said Sean M. Drake, MD, a primary care physician at Henry Ford Health in Sterling Heights, Michigan.

Dr. Drake advised PCPs to encourage patients who are at stage 0 to maintain ideal cardiovascular health and to monitor those at risk of progressing through the stages.

While PCPs already perform many of the tests the advisory recommends, the conditions overlap and an abnormality in one system should prompt more testing for other conditions. Additional tests, such as urine albumin-creatinine ratio, and more frequent glomerular filtration rate and lipid profile are advised, according to Dr. Drake.

“There also appears to be a role for additional cardiac testing, including echocardiograms and coronary CT scans, and for liver fibrosis screening,” Dr. Drake said. “Medications such as SGLT2 inhibitors, GLP-1 receptor agonists, and ACE inhibitors, beyond current routine use, are emphasized.”

To better characterize body composition and help diagnose metabolic syndrome, the advisory also recommends measuring waist circumference, which is not routine practice, noted Joshua J. Joseph, MD, MPH, an associate professor of endocrinology, diabetes, and metabolism at The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center in Columbus, and a co-author of the advisory.

Recognizing the interconnected nature of cardiac, kidney, and metabolic diseases encourages a shift in mindset for clinicians, according to Neha Pagidipati, MD, MPH, a cardiologist at Duke Health in Durham, North Carolina.

“We have often been trained to focus on the specific problem in front of us,” Dr. Pagidipati said. “We need to be hyper-aware that many patients we see are at risk for multiple CKM entities. We need to be proactive about screening for and treating these when appropriate.”

The advisory emphasizes the need for CKM coordinators to support teams of clinicians from primary care, cardiology, endocrinology, nephrology, nursing, and pharmacy, as well as social workers, care navigators, or community health workers, Dr. Joseph said.

“The advisory repositions the PCP at the forefront of CKM care coordination, marking a departure from the traditional model where subspecialists primarily manage complications,” Dr. Hayek added.

Changes to Payment

The new recommendations are consistent with current management guidelines for obesity, hypertriglyceridemia, hypertension, type 2 diabetes, and chronic kidney disease.

“The advisory provides integrated algorithms for cardiovascular prevention and management, with specific therapeutic guidance tied to CKM stages, bringing together the current evidence for best practices from the various guidelines and filling gaps in a unified approach,” Dr. Joseph said.