User login

Dear patients: Letters psychiatrists should and should not write

After several months of difficulty living in her current apartment complex, Ms. M asks you as her psychiatrist to write a letter to the management company requesting she be moved to an apartment on the opposite side of the maintenance closet because the noise aggravates her posttraumatic stress disorder. What should you consider when asked to write such a letter?

Psychiatric practice often extends beyond the treatment of mental illness to include addressing patients’ social well-being. Psychiatrists commonly inquire about a patient’s social situation to understand the impact of these environmental factors. Similarly, psychiatric illness may affect a patient’s ability to work or fulfill responsibilities. As a result, patients may ask their psychiatrists for assistance by requesting letters that address various aspects of their social well-being.1 These communications may address an array of topics, from a patient’s readiness to return to work to their ability to pay child support. This article focuses on the role psychiatrists have in writing patient-requested letters across a variety of topics, including the consideration of potential legal liability and ethical implications.

Types of letters

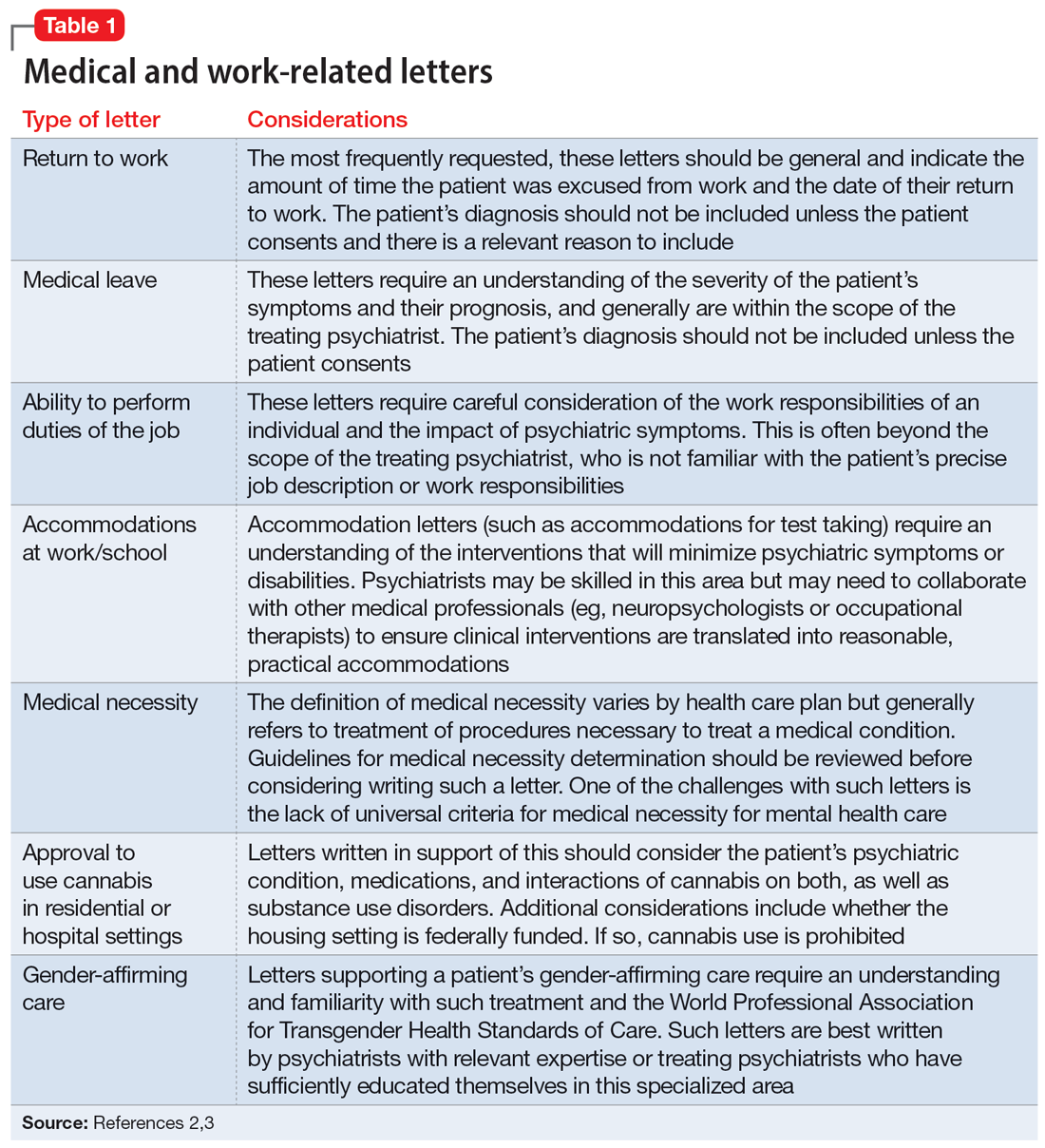

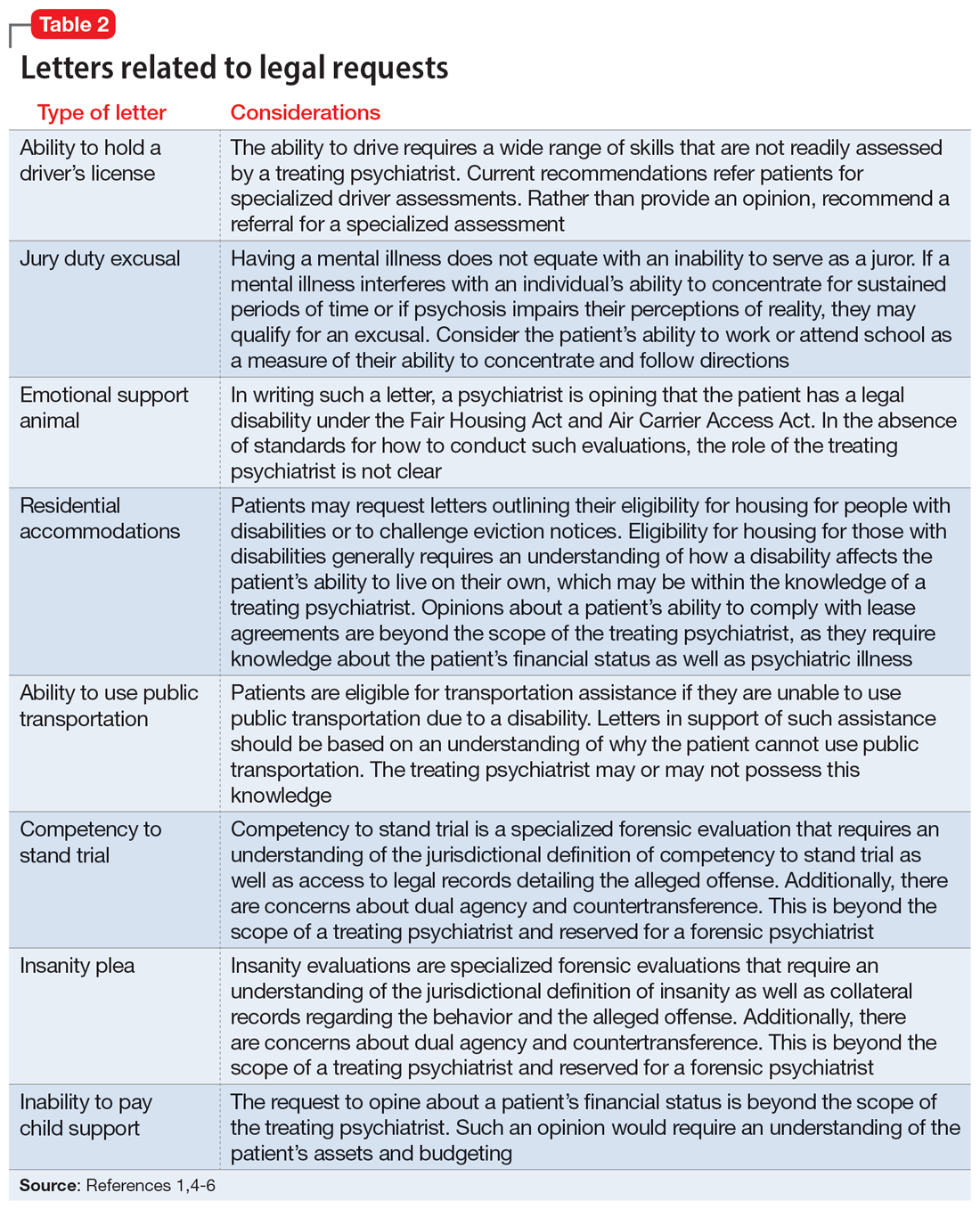

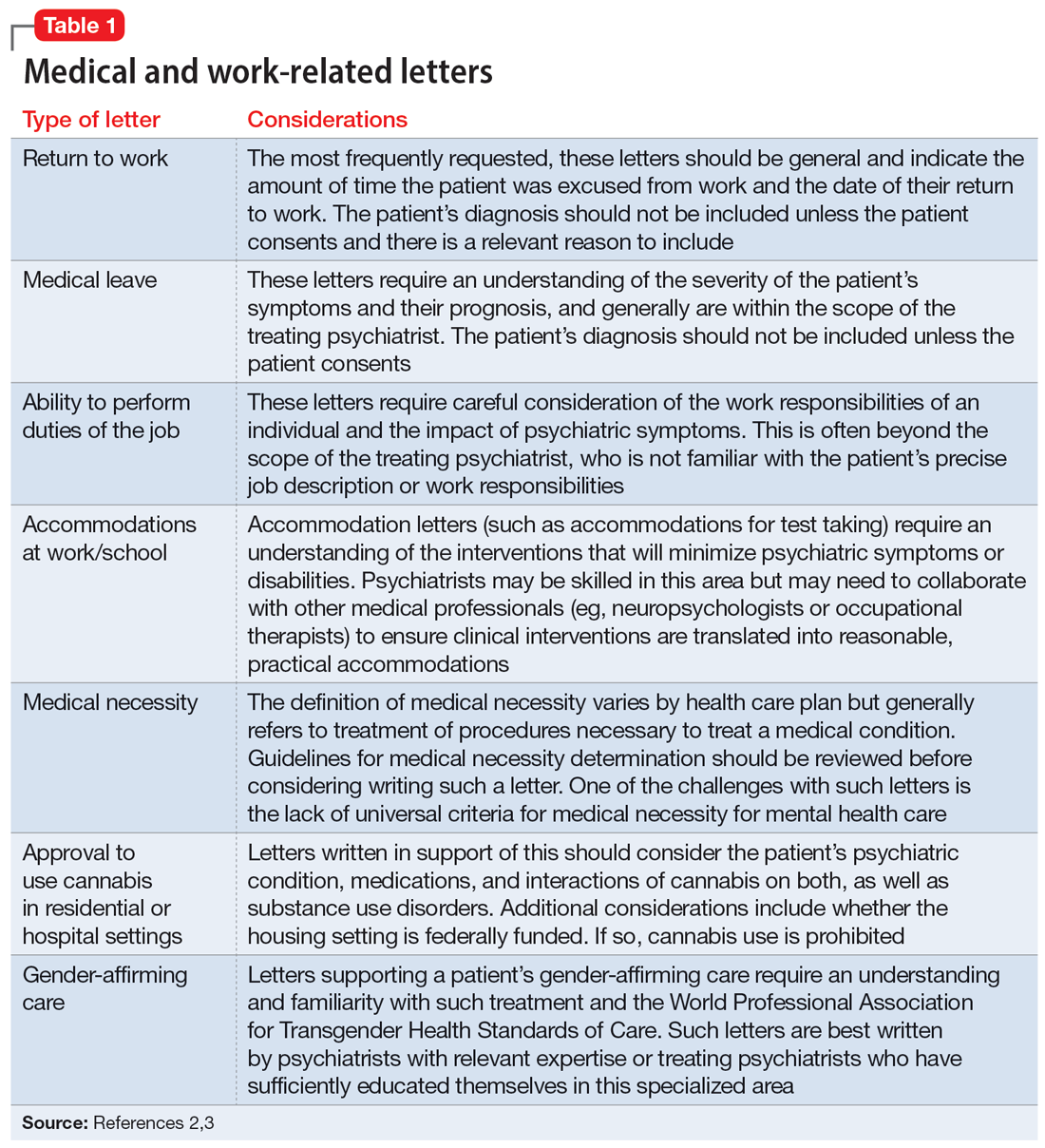

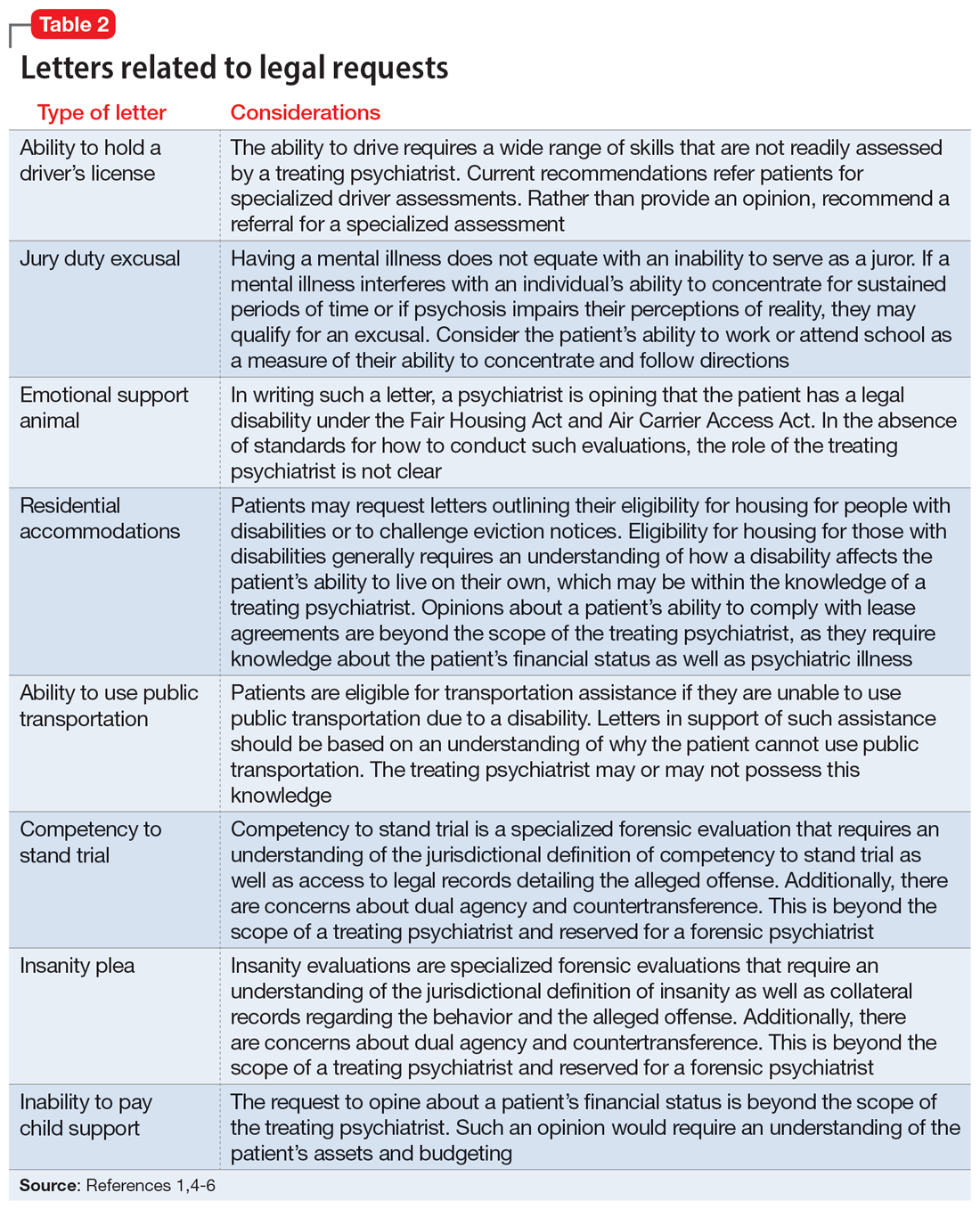

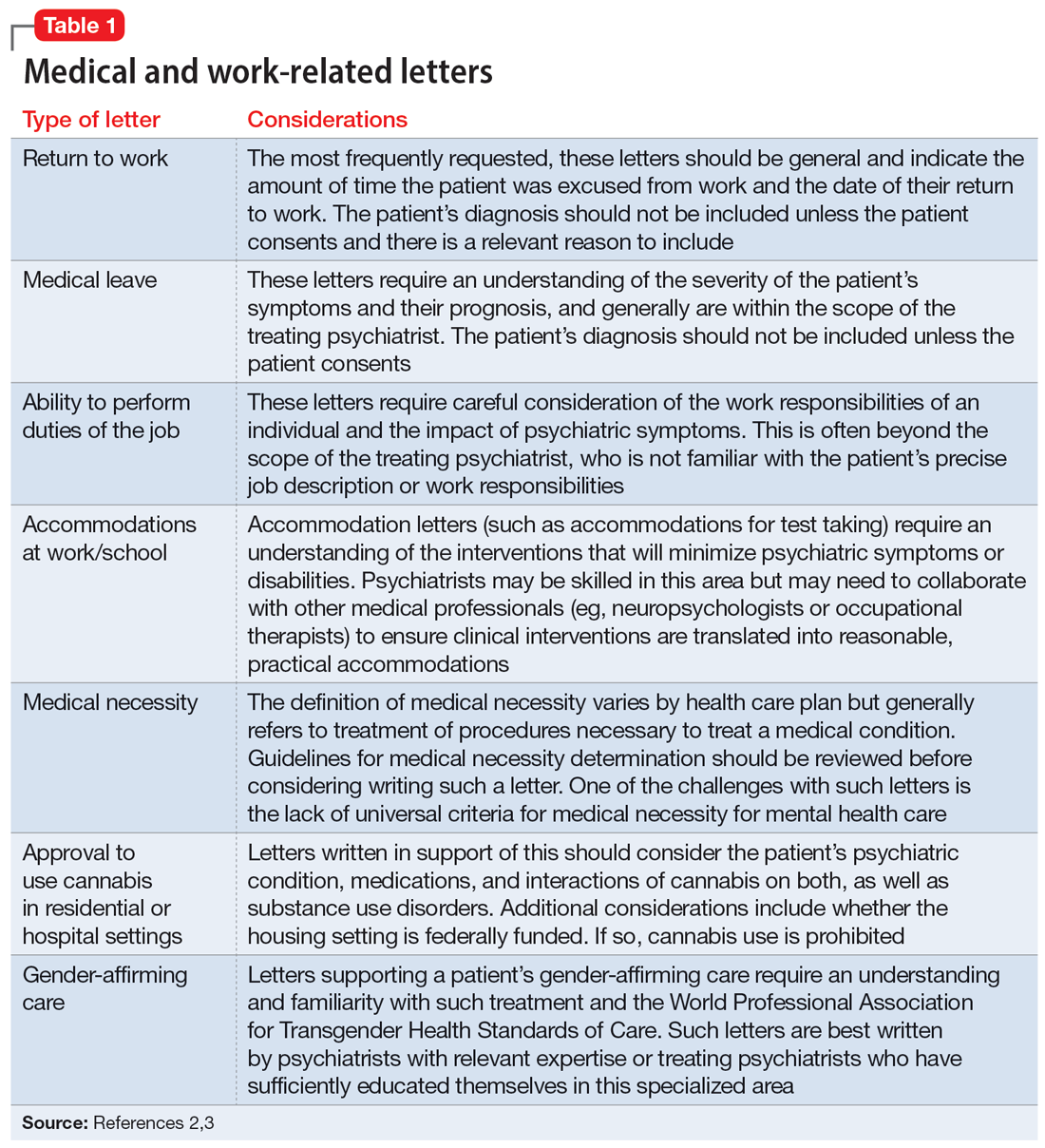

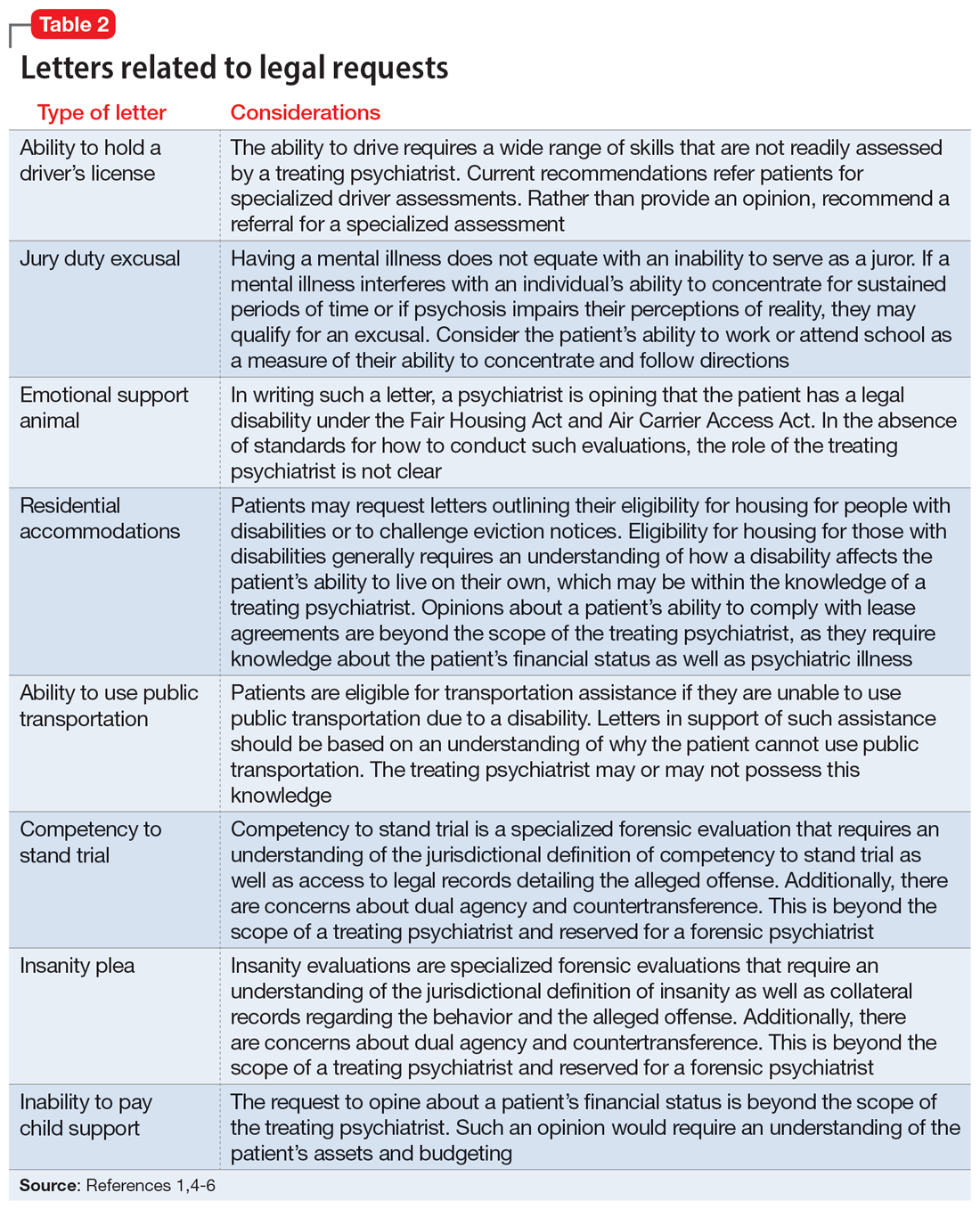

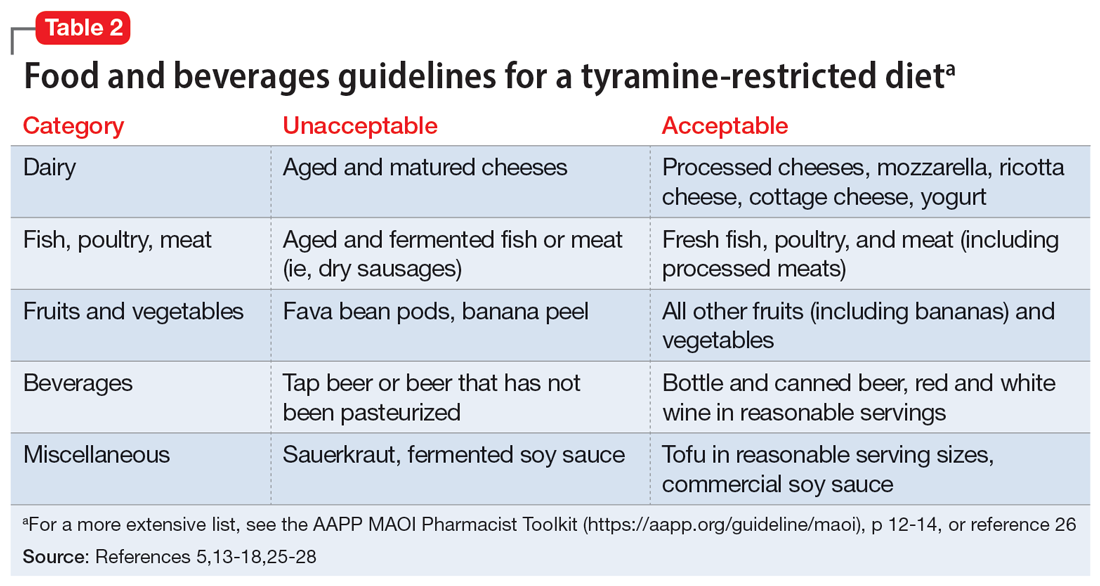

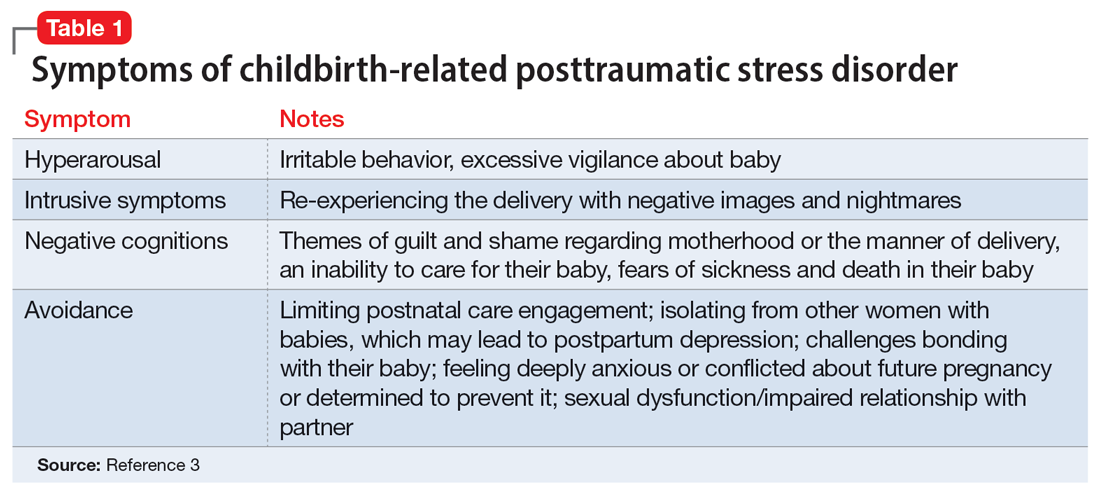

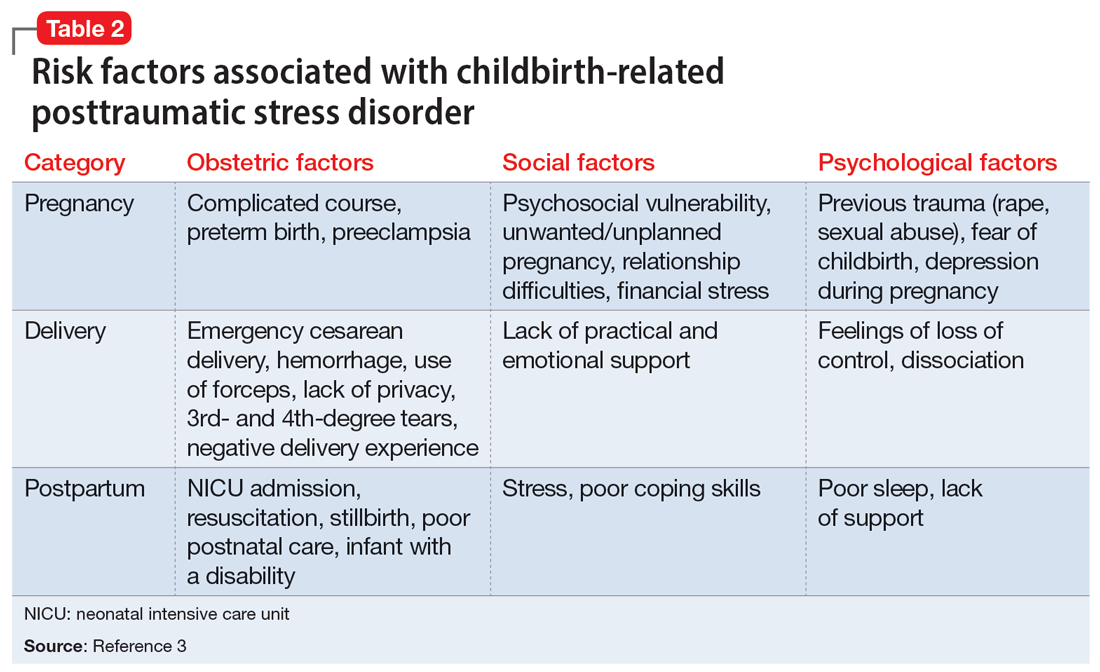

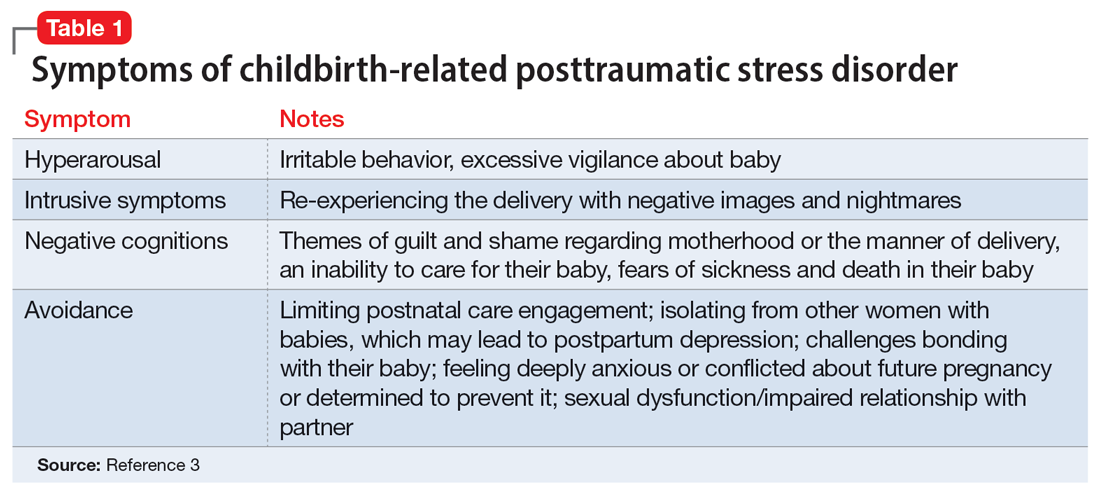

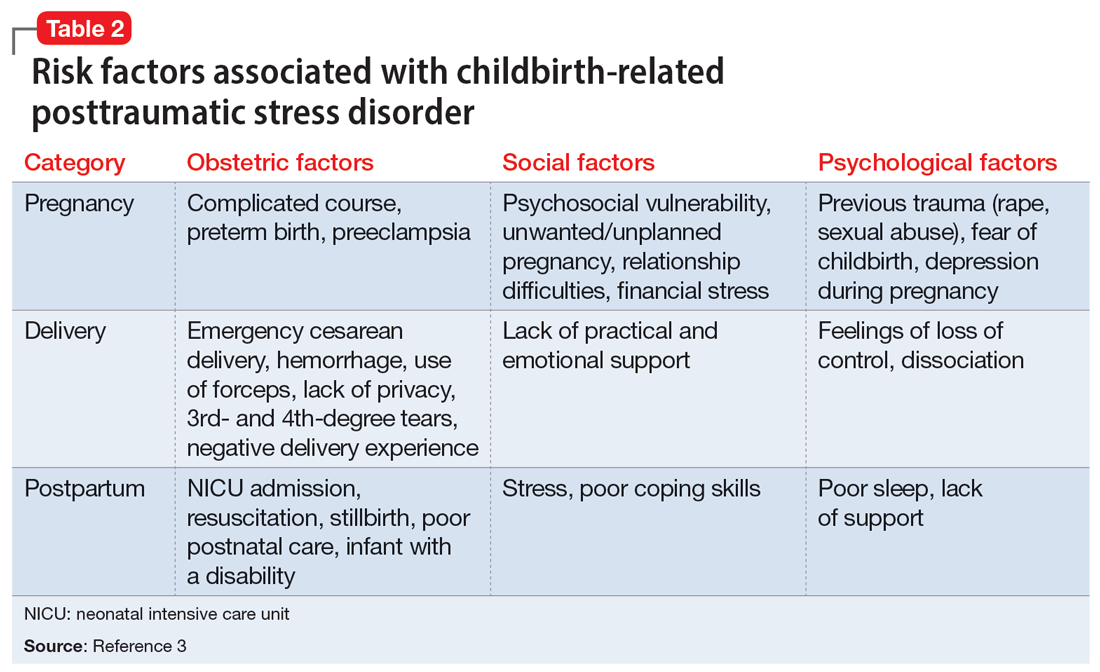

The categories of letters patients request can be divided into 2 groups. The first is comprised of letters relating to the patient’s medical needs (Table 12,3). These address the patient’s ability to work (eg, medical leave, return to work, or accommodations) or travel (eg, ability to drive or use public transportation), or need for specific medical treatment (ie, gender-affirming care or cannabis use in specific settings). The second group relates to legal requests such as excusal from jury duty, emotional support animals, or any other letter used specifically for legal purposes (in civil or criminal cases) (Table 21,4-6).

The decision to write a letter on behalf of a patient should be based on whether you have sufficient knowledge to answer the referral question, and whether the requested evaluation fits within your role as the treating psychiatrist. Many requests fall short of the first condition. For example, a request to opine about an individual’s ability to perform their job duties requires specific knowledge and careful consideration of the patient’s work responsibilities, knowledge of the impact of their psychiatric symptoms, and specialized knowledge about interventions that would ameliorate symptoms in the specialized work setting. Most psychiatrists are not sufficiently familiar with a specific workplace to provide opinions regarding reasonable accommodations.

The second condition refers to the role and responsibilities of the psychiatrist. Many letter requests are clearly within the scope of the clinical psychiatrist, such as a medical leave note due to a psychiatric decompensation or a jury duty excusal due to an unstable mental state. Other letters reach beyond the role of the general or treating psychiatrist, such as opinions about suitable housing or a patient’s competency to stand trial.

Components of letters

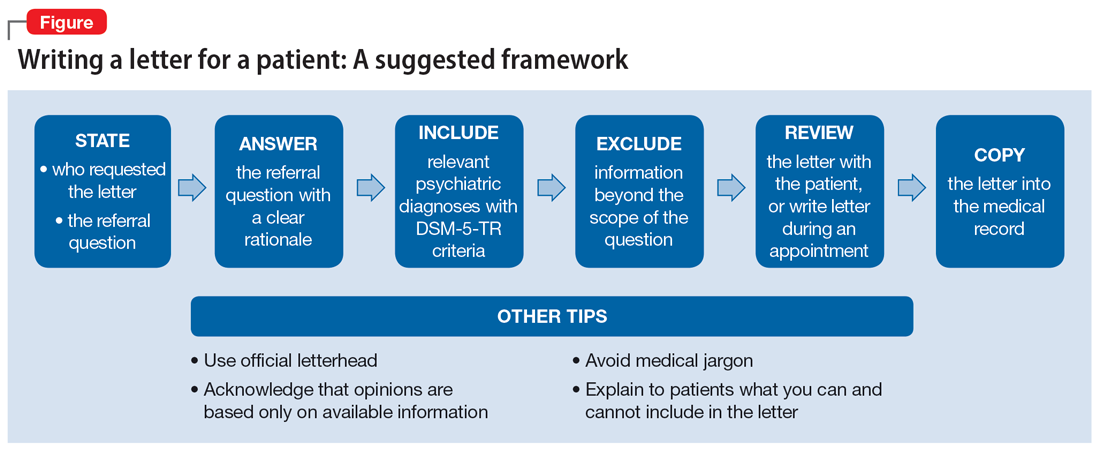

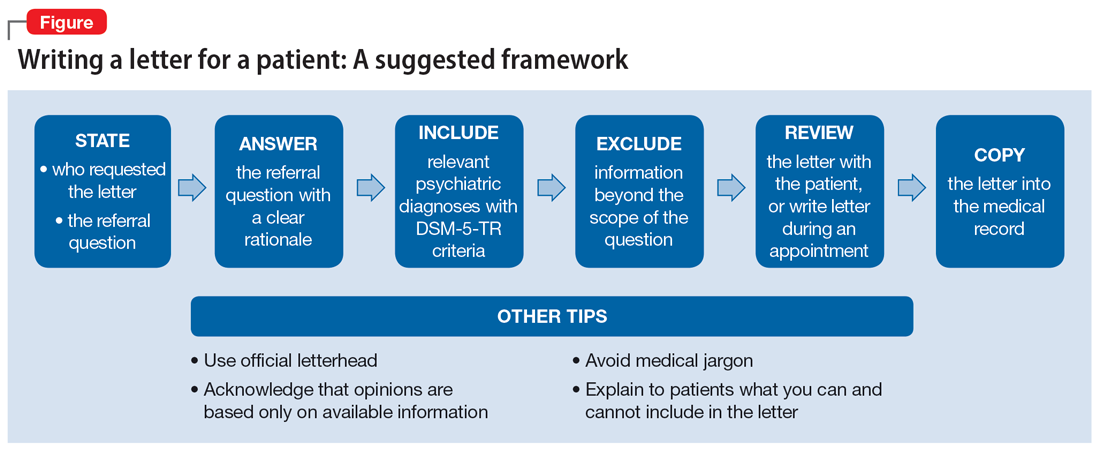

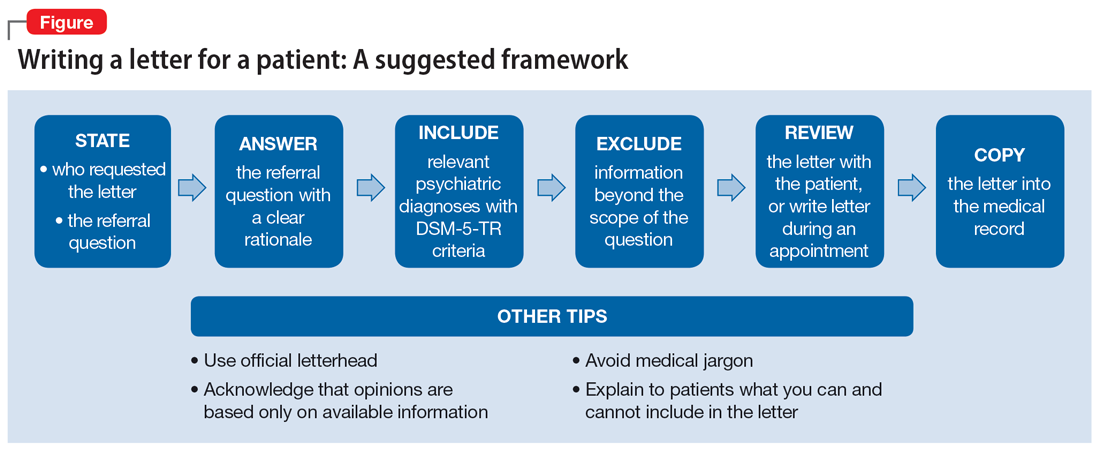

The decision to write or not to write a letter should be discussed with the patient. Identify the reasons for and against letter writing. If you decide to write a letter, the letter should have the following basic framework (Figure): the identity of the person who requested the letter, the referral question, and an answer to the referral question with a clear rationale. Describe the patient’s psychiatric diagnosis using DSM criteria. Any limitations to the answer should be identified. The letter should not go beyond the referral question and should not include information that was not requested. It also should be preserved in the medical record.

It is recommended to write or review the letter in the presence of the patient to discuss the contents of the letter and what the psychiatrist can or cannot write. As in forensic reports, conclusory statements are not helpful. Provide descriptive information instead of relying on psychiatric jargon, and a rationale for the opinion as opposed to stating an opinion as fact. In the letter, you must acknowledge that your opinion is based upon information provided by the patient (and the patient’s family, when accurate) and as a result, is not fully objective.

Continue to: Liability and dual agency

Liability and dual agency

Psychiatrists are familiar with clinical situations in which a duty to the patient is mitigated or superseded by a duty to a third party. As the Tarasoff court famously stated, “the protective privilege ends where the public peril begins.”7

To be liable to either a patient or a third party means to be “bound or obliged in law or equity; responsible; chargeable; answerable; compellable to make satisfaction, compensation, or restitution.”8 Liabilities related to clinical treatment are well-established; medical students learn the fundamentals before ever treating a patient, and physicians carry malpractice insurance throughout their careers.

Less well-established is the liability a treating psychiatrist owes a third party when forming an opinion that impacts both their patient and the third party (eg, an employer when writing a return-to-work letter, or a disability insurer when qualifying a patient for disability benefits). The American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law discourages treating psychiatrists from performing these types of evaluations of their patients based on the inherent conflict of serving as a dual agent, or acting both as an advocate for the patient and as an independent evaluator striving for objectivity.9 However, such requests commonly arise, and some may be unavoidable.

Dual-agency situations subject the treating psychiatrist to avenues of legal action arising from the patient-doctor relationship as well as the forensic evaluator relationship. If a letter is written during a clinical treatment, all duties owed to the patient continue to apply, and the relevant benchmarks of local statutes and principle of a standard of care are relevant. It is conceivable that a patient could bring a negligence lawsuit based on a standard of care allegation (eg, that writing certain types of letters is so ordinary that failure to write them would fall below the standard of care). Confidentiality is also of the utmost importance,10 and you should obtain a written release of information from the patient before releasing any letter with privileged information about the patient.11 Additional relevant legal causes of action the patient could include are torts such as defamation of character, invasion of privacy, breach of contract, and intentional infliction of emotional distress. There is limited case law supporting patients’ rights to sue psychiatrists for defamation.10

A psychiatrist writing a letter to a third party may also subject themselves to avenues of legal action occurring outside the physician-patient relationship. Importantly, damages resulting from these breaches would not be covered by your malpractice insurance. Extreme cases involve allegations of fraud or perjury, which could be pursued in criminal court. If a psychiatrist intentionally deceives a third party for the purpose of obtaining some benefit for the patient, this is clear grounds for civil or criminal action. Fraud is defined as “a false representation of a matter of fact, whether by words or by conduct, by false or misleading allegations, or by concealment of that which should have been disclosed, which deceives and is intended to deceive another so that he shall act upon it to his legal injury.”8 Negligence can also be grounds for liability if a third party suffers injury or loss. Although the liability is clearer if the third party retains an independent psychiatrist rather than soliciting an opinion from a patient’s treating psychiatrist, both parties are subject to the claim of negligence.10

Continue to: There are some important protections...

There are some important protections that limit psychiatrists’ good-faith opinions from litigation. The primary one is the “professional medical judgment rule,” which shields physicians from the consequences of erroneous opinions so long as the examination was competent, complete, and performed in an ordinary fashion.10 In some cases, psychiatrists writing a letter or report for a government agency may also qualify for quasi-judicial immunity or witness immunity, but case law shows significant variation in when and how these privileges apply and whether such privileges would be applied to a clinical psychiatrist in the context of a traditional physician-patient relationship.12 In general, these privileges are not absolute and may not be sufficiently well-established to discourage a plaintiff from filing suit or prompt early judicial dismissal of a case.

Like all aspects of practicing medicine, letter writing is subject to scrutiny and accountability. Think carefully about your obligations and the potential consequences of writing or not writing a letter to a third party.

Ethical considerations

The decision to write a letter for a patient must be carefully considered from multiple angles.6 In addition to liability concerns, various ethical considerations also arise. Guided by the principles of beneficence, nonmaleficence, autonomy, and justice,13 we recommend the following approaches.

Maintain objectivity

During letter writing, a conflict of interest may arise between your allegiance to the patient and the imperative to provide accurate information.14-16 If the conflict is overwhelming, the most appropriate approach is to recuse yourself from the case and refer the patient to a third party. When electing to write a letter, you accept the responsibility to provide an objective assessment of the relevant situation. This promotes a just outcome and may also serve to promote the patient’s or society’s well-being.

Encourage activity and overall function

Evidence suggests that participation in multiple aspects of life promotes positive health outcomes.17,18 As a physician, it is your duty to promote health and support and facilitate accommodations that allow patients to participate and flourish in society. By the same logic, when approached by patients with a request for letters in support of reduced activity, you should consider not only the benefits but also the potential detriments of such disruptions. This may entail recommending temporary restrictions or modifications, as appropriate.

Continue to: Think beyond the patient

Think beyond the patient

Letter writing, particularly when recommending accommodations, can have implications beyond the patient.16 Such letters may cause unintended societal harm. For example, others may have to assume additional responsibilities; competitive goods (eg, housing) may be rendered to the patient rather than to a person with greater needs; and workplace safety could be compromised due to absence. Consider not only the individual patient but also possible public health and societal effects of letter writing.

Deciding not to write

From an ethical perspective, a physician cannot be compelled to write a letter if such an undertaking violates a stronger moral obligation. An example of this is if writing a letter could cause significant harm to the patient or society, or if writing a letter might compromise a physician’s professionalism.19 When you elect to not write a letter, the ethical principles of autonomy and truth telling dictate that you must inform your patients of this choice.6 You should also provide an explanation to the patient as long as such information would not cause undue psychological or physical harm.20,21

Schedule time to write letters

Some physicians implement policies that all letters are to be completed during scheduled appointments. Others designate administrative time to complete requested letters. Finally, some physicians flexibly complete such requests between appointments or during other undedicated time slots. Any of these approaches are justifiable, though some urgent requests may require more immediate attention outside of appointments. Some physicians may choose to bill for the letter writing if completed outside an appointment and the patient is treated in private practice. Whatever your policy, inform patients of it at the beginning of care and remind them when appropriate, such as before completing a letter that may be billed.

Manage uncertainty

Always strive for objectivity in letter writing. However, some requests inherently hinge on subjective reports and assessments. For example, a patient may request an excuse letter due to feeling unwell. In the absence of objective findings, what should you do? We advise the following.

Acquire collateral information. Adequate information is essential when making any medical recommendation. The same is true for writing letters. With the patient’s permission, you may need to contact relevant parties to better understand the circumstance or activity about which you are being asked to write a letter. For example, a patient may request leave from work due to injury. If the specific parameters of the work impeded by the injury are unclear to you, refrain from writing the letter and explain the rationale to the patient.

Continue to: Integrate prior knowledge of the patient

Integrate prior knowledge of the patient. No letter writing request exists in a vacuum. If you know the patient, the letter should be contextualized within the patient’s prior behaviors.

Stay within your scope

Given the various dilemmas and challenges, you may want to consider whether some letter writing is out of your professional scope.14-16 One solution would be to leave such requests to other entities (eg, requiring employers to retain medical personnel with specialized skills in occupational evaluations) and make such recommendations to patients. Regardless, physicians should think carefully about their professional boundaries and scope regarding letter requests and adopt and implement a consistent standard for all patients.

Regarding the letter requested by Ms. M, you should consider whether the appeal is consistent with the patient’s psychiatric illness. You should also consider whether you have sufficient knowledge about the patient’s living environment to support their claim. Such a letter should be written only if you understand both considerations. Regardless of your decision, you should explain your rationale to the patient.

Bottom Line

Patients may ask their psychiatrists to write letters that address aspects of their social well-being. However, psychiatrists must be alert to requests that are outside their scope of practice or ethically or legally fraught. Carefully consider whether writing a letter is appropriate and if not, discuss with the patient the reasons you cannot write such a letter and any recommended alternative avenues to address their request.

Related Resources

- Riese A. Writing letters for transgender patients undergoing medical transition. Current Psychiatry. 2021;20(8):51-52. doi:10.12788/cp.0159

- Joshi KG. Service animals and emotional support animals: should you write that letter? Current Psychiatry. 2021;20(11):16-19,24. doi:10.12788/cp.0183

1. West S, Friedman SH. To be or not to be: treating psychiatrist and expert witness. Psychiatric Times. 2007;24(6). Accessed March 14, 2023. https://www.psychiatrictimes.com/view/be-or-not-be-treating-psychiatrist-and-expert-witness

2. Knoepflmacher D. ‘Medical necessity’ in psychiatry: whose definition is it anyway? Psychiatric News. 2016;51(18):12-14. https://psychnews.psychiatryonline.org/doi/10.1176/appi.pn.2016.9b14

3. Lampe JR. Recent developments in marijuana law (LSB10859). Congressional Research Service. 2022. Accessed October 25, 2023. https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/LSB/LSB10859/2

4. Brunnauer A, Buschert V, Segmiller F, et al. Mobility behaviour and driving status of patients with mental disorders – an exploratory study. Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract. 2016;20(1):40-46. doi:10.3109/13651501.2015.1089293

5. Chiu CW, Law CK, Cheng AS. Driver assessment service for people with mental illness. Hong Kong J Occup Ther. 2019;32(2):77-83. doi:10.1177/1569186119886773

6. Joshi KG. Service animals and emotional support animals: should you write that letter? Current Psychiatry. 2021;20(11):16-19. doi:10.12788/cp.0183

7. Tarasoff v Regents of University of California, 17 Cal 3d 425, 551 P2d 334, 131 Cal. Rptr. 14 (Cal 1976).

8. Black HC. Liability. Black’s Law Dictionary. Revised 4th ed. West Publishing; 1975:1060.

9. American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law. Ethics guidelines for the practice of forensic psychiatry. 2005. Accessed March 15, 2023. https://www.aapl.org/ethics.htm

10. Gold LH, Davidson JE. Do you understand your risk? Liability and third-party evaluations in civil litigation. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2007;35(2):200-210.

11. Schouten R. Approach to the patient seeking disability benefits. In: Stern TA, Herman JB, Slavin PL, eds. The MGH Guide to Psychiatry in Primary Care. McGraw Hill; 1998:121-126.

12. Appelbaum PS. Law and psychiatry: liability for forensic evaluations: a word of caution. Psychiatr Serv. 2001;52(7):885-886. doi:10.1176/appi.ps.52.7.885

13. Varkey B. Principles of clinical ethics and their application to practice. Med Princ Pract. 2021;30(1):17-28. doi:10.1159/000509119

14. Mayhew HE, Nordlund DJ. Absenteeism certification: the physician’s role. J Fam Pract. 1988;26(6):651-655.

15. Younggren JN, Boisvert JA, Boness CL. Examining emotional support animals and role conflicts in professional psychology. Prof Psychol Res Pr. 2016;47(4):255-260. doi:10.1037/pro0000083

16. Carroll JD, Mohlenhoff BS, Kersten CM, et al. Laws and ethics related to emotional support animals. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2020;48(4):509-518. doi:1-.29158/JAAPL.200047-20

17. Strully KW. Job loss and health in the U.S. labor market. Demography. 2009;46(2):221-246. doi:10.1353/dem.0.0050

18. Jurisic M, Bean M, Harbaugh J, et al. The personal physician’s role in helping patients with medical conditions stay at work or return to work. J Occup Environ Med. 2017;59(6):e125-131. doi:10.1097/JOM.0000000000001055

19. Munyaradzi M. Critical reflections on the principle of beneficence in biomedicine. Pan Afr Med J. 2012;11:29.

20. Beauchamp TL, Childress JF. Principles of Biomedical Ethics. 7th ed. Oxford University Press; 2012.

21. Gold M. Is honesty always the best policy? Ethical aspects of truth telling. Intern Med J. 2004;34(9-10):578-580. doi:10.1111/j.1445-5994.2004.00673.x

After several months of difficulty living in her current apartment complex, Ms. M asks you as her psychiatrist to write a letter to the management company requesting she be moved to an apartment on the opposite side of the maintenance closet because the noise aggravates her posttraumatic stress disorder. What should you consider when asked to write such a letter?

Psychiatric practice often extends beyond the treatment of mental illness to include addressing patients’ social well-being. Psychiatrists commonly inquire about a patient’s social situation to understand the impact of these environmental factors. Similarly, psychiatric illness may affect a patient’s ability to work or fulfill responsibilities. As a result, patients may ask their psychiatrists for assistance by requesting letters that address various aspects of their social well-being.1 These communications may address an array of topics, from a patient’s readiness to return to work to their ability to pay child support. This article focuses on the role psychiatrists have in writing patient-requested letters across a variety of topics, including the consideration of potential legal liability and ethical implications.

Types of letters

The categories of letters patients request can be divided into 2 groups. The first is comprised of letters relating to the patient’s medical needs (Table 12,3). These address the patient’s ability to work (eg, medical leave, return to work, or accommodations) or travel (eg, ability to drive or use public transportation), or need for specific medical treatment (ie, gender-affirming care or cannabis use in specific settings). The second group relates to legal requests such as excusal from jury duty, emotional support animals, or any other letter used specifically for legal purposes (in civil or criminal cases) (Table 21,4-6).

The decision to write a letter on behalf of a patient should be based on whether you have sufficient knowledge to answer the referral question, and whether the requested evaluation fits within your role as the treating psychiatrist. Many requests fall short of the first condition. For example, a request to opine about an individual’s ability to perform their job duties requires specific knowledge and careful consideration of the patient’s work responsibilities, knowledge of the impact of their psychiatric symptoms, and specialized knowledge about interventions that would ameliorate symptoms in the specialized work setting. Most psychiatrists are not sufficiently familiar with a specific workplace to provide opinions regarding reasonable accommodations.

The second condition refers to the role and responsibilities of the psychiatrist. Many letter requests are clearly within the scope of the clinical psychiatrist, such as a medical leave note due to a psychiatric decompensation or a jury duty excusal due to an unstable mental state. Other letters reach beyond the role of the general or treating psychiatrist, such as opinions about suitable housing or a patient’s competency to stand trial.

Components of letters

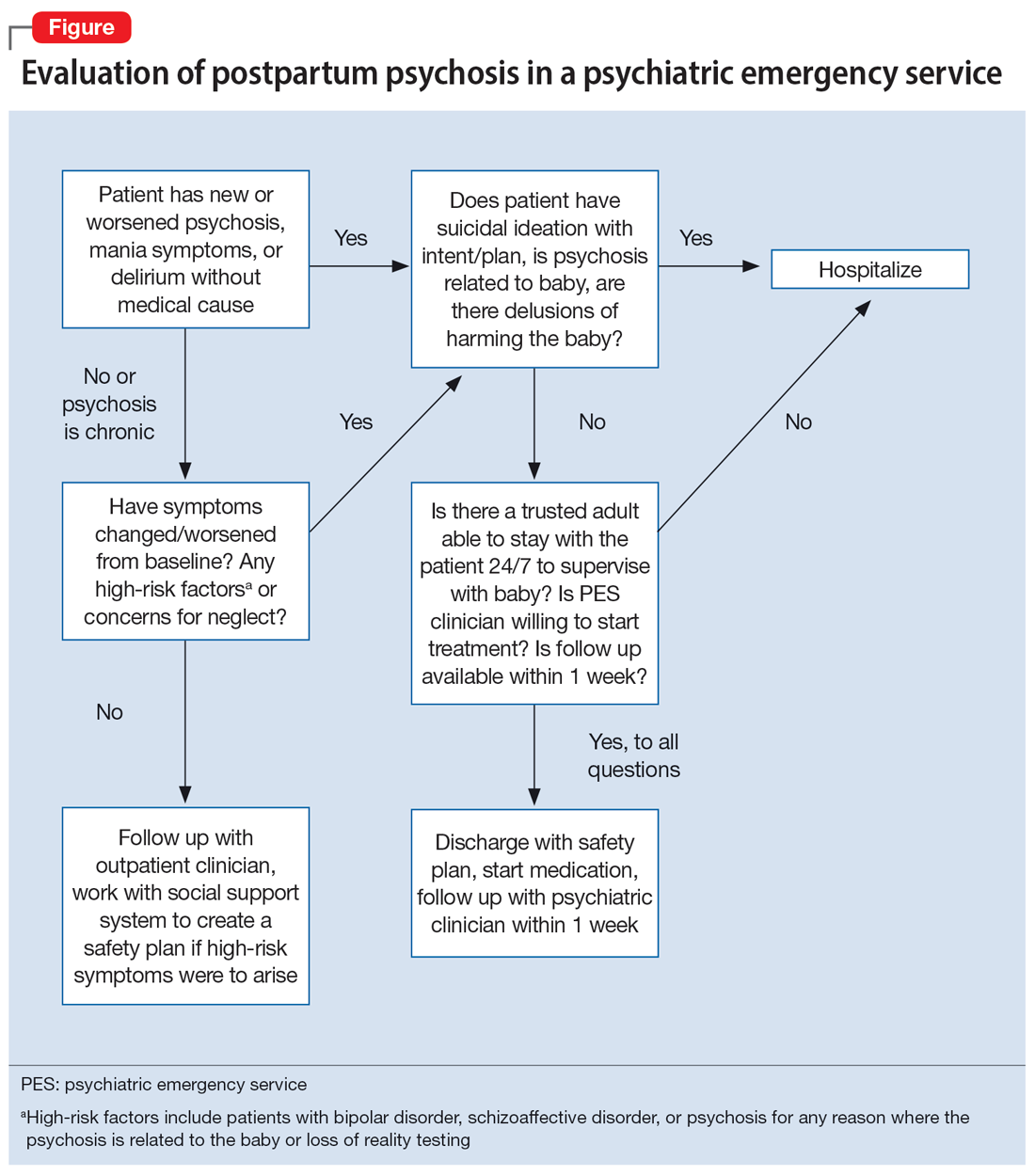

The decision to write or not to write a letter should be discussed with the patient. Identify the reasons for and against letter writing. If you decide to write a letter, the letter should have the following basic framework (Figure): the identity of the person who requested the letter, the referral question, and an answer to the referral question with a clear rationale. Describe the patient’s psychiatric diagnosis using DSM criteria. Any limitations to the answer should be identified. The letter should not go beyond the referral question and should not include information that was not requested. It also should be preserved in the medical record.

It is recommended to write or review the letter in the presence of the patient to discuss the contents of the letter and what the psychiatrist can or cannot write. As in forensic reports, conclusory statements are not helpful. Provide descriptive information instead of relying on psychiatric jargon, and a rationale for the opinion as opposed to stating an opinion as fact. In the letter, you must acknowledge that your opinion is based upon information provided by the patient (and the patient’s family, when accurate) and as a result, is not fully objective.

Continue to: Liability and dual agency

Liability and dual agency

Psychiatrists are familiar with clinical situations in which a duty to the patient is mitigated or superseded by a duty to a third party. As the Tarasoff court famously stated, “the protective privilege ends where the public peril begins.”7

To be liable to either a patient or a third party means to be “bound or obliged in law or equity; responsible; chargeable; answerable; compellable to make satisfaction, compensation, or restitution.”8 Liabilities related to clinical treatment are well-established; medical students learn the fundamentals before ever treating a patient, and physicians carry malpractice insurance throughout their careers.

Less well-established is the liability a treating psychiatrist owes a third party when forming an opinion that impacts both their patient and the third party (eg, an employer when writing a return-to-work letter, or a disability insurer when qualifying a patient for disability benefits). The American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law discourages treating psychiatrists from performing these types of evaluations of their patients based on the inherent conflict of serving as a dual agent, or acting both as an advocate for the patient and as an independent evaluator striving for objectivity.9 However, such requests commonly arise, and some may be unavoidable.

Dual-agency situations subject the treating psychiatrist to avenues of legal action arising from the patient-doctor relationship as well as the forensic evaluator relationship. If a letter is written during a clinical treatment, all duties owed to the patient continue to apply, and the relevant benchmarks of local statutes and principle of a standard of care are relevant. It is conceivable that a patient could bring a negligence lawsuit based on a standard of care allegation (eg, that writing certain types of letters is so ordinary that failure to write them would fall below the standard of care). Confidentiality is also of the utmost importance,10 and you should obtain a written release of information from the patient before releasing any letter with privileged information about the patient.11 Additional relevant legal causes of action the patient could include are torts such as defamation of character, invasion of privacy, breach of contract, and intentional infliction of emotional distress. There is limited case law supporting patients’ rights to sue psychiatrists for defamation.10

A psychiatrist writing a letter to a third party may also subject themselves to avenues of legal action occurring outside the physician-patient relationship. Importantly, damages resulting from these breaches would not be covered by your malpractice insurance. Extreme cases involve allegations of fraud or perjury, which could be pursued in criminal court. If a psychiatrist intentionally deceives a third party for the purpose of obtaining some benefit for the patient, this is clear grounds for civil or criminal action. Fraud is defined as “a false representation of a matter of fact, whether by words or by conduct, by false or misleading allegations, or by concealment of that which should have been disclosed, which deceives and is intended to deceive another so that he shall act upon it to his legal injury.”8 Negligence can also be grounds for liability if a third party suffers injury or loss. Although the liability is clearer if the third party retains an independent psychiatrist rather than soliciting an opinion from a patient’s treating psychiatrist, both parties are subject to the claim of negligence.10

Continue to: There are some important protections...

There are some important protections that limit psychiatrists’ good-faith opinions from litigation. The primary one is the “professional medical judgment rule,” which shields physicians from the consequences of erroneous opinions so long as the examination was competent, complete, and performed in an ordinary fashion.10 In some cases, psychiatrists writing a letter or report for a government agency may also qualify for quasi-judicial immunity or witness immunity, but case law shows significant variation in when and how these privileges apply and whether such privileges would be applied to a clinical psychiatrist in the context of a traditional physician-patient relationship.12 In general, these privileges are not absolute and may not be sufficiently well-established to discourage a plaintiff from filing suit or prompt early judicial dismissal of a case.

Like all aspects of practicing medicine, letter writing is subject to scrutiny and accountability. Think carefully about your obligations and the potential consequences of writing or not writing a letter to a third party.

Ethical considerations

The decision to write a letter for a patient must be carefully considered from multiple angles.6 In addition to liability concerns, various ethical considerations also arise. Guided by the principles of beneficence, nonmaleficence, autonomy, and justice,13 we recommend the following approaches.

Maintain objectivity

During letter writing, a conflict of interest may arise between your allegiance to the patient and the imperative to provide accurate information.14-16 If the conflict is overwhelming, the most appropriate approach is to recuse yourself from the case and refer the patient to a third party. When electing to write a letter, you accept the responsibility to provide an objective assessment of the relevant situation. This promotes a just outcome and may also serve to promote the patient’s or society’s well-being.

Encourage activity and overall function

Evidence suggests that participation in multiple aspects of life promotes positive health outcomes.17,18 As a physician, it is your duty to promote health and support and facilitate accommodations that allow patients to participate and flourish in society. By the same logic, when approached by patients with a request for letters in support of reduced activity, you should consider not only the benefits but also the potential detriments of such disruptions. This may entail recommending temporary restrictions or modifications, as appropriate.

Continue to: Think beyond the patient

Think beyond the patient

Letter writing, particularly when recommending accommodations, can have implications beyond the patient.16 Such letters may cause unintended societal harm. For example, others may have to assume additional responsibilities; competitive goods (eg, housing) may be rendered to the patient rather than to a person with greater needs; and workplace safety could be compromised due to absence. Consider not only the individual patient but also possible public health and societal effects of letter writing.

Deciding not to write

From an ethical perspective, a physician cannot be compelled to write a letter if such an undertaking violates a stronger moral obligation. An example of this is if writing a letter could cause significant harm to the patient or society, or if writing a letter might compromise a physician’s professionalism.19 When you elect to not write a letter, the ethical principles of autonomy and truth telling dictate that you must inform your patients of this choice.6 You should also provide an explanation to the patient as long as such information would not cause undue psychological or physical harm.20,21

Schedule time to write letters

Some physicians implement policies that all letters are to be completed during scheduled appointments. Others designate administrative time to complete requested letters. Finally, some physicians flexibly complete such requests between appointments or during other undedicated time slots. Any of these approaches are justifiable, though some urgent requests may require more immediate attention outside of appointments. Some physicians may choose to bill for the letter writing if completed outside an appointment and the patient is treated in private practice. Whatever your policy, inform patients of it at the beginning of care and remind them when appropriate, such as before completing a letter that may be billed.

Manage uncertainty

Always strive for objectivity in letter writing. However, some requests inherently hinge on subjective reports and assessments. For example, a patient may request an excuse letter due to feeling unwell. In the absence of objective findings, what should you do? We advise the following.

Acquire collateral information. Adequate information is essential when making any medical recommendation. The same is true for writing letters. With the patient’s permission, you may need to contact relevant parties to better understand the circumstance or activity about which you are being asked to write a letter. For example, a patient may request leave from work due to injury. If the specific parameters of the work impeded by the injury are unclear to you, refrain from writing the letter and explain the rationale to the patient.

Continue to: Integrate prior knowledge of the patient

Integrate prior knowledge of the patient. No letter writing request exists in a vacuum. If you know the patient, the letter should be contextualized within the patient’s prior behaviors.

Stay within your scope

Given the various dilemmas and challenges, you may want to consider whether some letter writing is out of your professional scope.14-16 One solution would be to leave such requests to other entities (eg, requiring employers to retain medical personnel with specialized skills in occupational evaluations) and make such recommendations to patients. Regardless, physicians should think carefully about their professional boundaries and scope regarding letter requests and adopt and implement a consistent standard for all patients.

Regarding the letter requested by Ms. M, you should consider whether the appeal is consistent with the patient’s psychiatric illness. You should also consider whether you have sufficient knowledge about the patient’s living environment to support their claim. Such a letter should be written only if you understand both considerations. Regardless of your decision, you should explain your rationale to the patient.

Bottom Line

Patients may ask their psychiatrists to write letters that address aspects of their social well-being. However, psychiatrists must be alert to requests that are outside their scope of practice or ethically or legally fraught. Carefully consider whether writing a letter is appropriate and if not, discuss with the patient the reasons you cannot write such a letter and any recommended alternative avenues to address their request.

Related Resources

- Riese A. Writing letters for transgender patients undergoing medical transition. Current Psychiatry. 2021;20(8):51-52. doi:10.12788/cp.0159

- Joshi KG. Service animals and emotional support animals: should you write that letter? Current Psychiatry. 2021;20(11):16-19,24. doi:10.12788/cp.0183

After several months of difficulty living in her current apartment complex, Ms. M asks you as her psychiatrist to write a letter to the management company requesting she be moved to an apartment on the opposite side of the maintenance closet because the noise aggravates her posttraumatic stress disorder. What should you consider when asked to write such a letter?

Psychiatric practice often extends beyond the treatment of mental illness to include addressing patients’ social well-being. Psychiatrists commonly inquire about a patient’s social situation to understand the impact of these environmental factors. Similarly, psychiatric illness may affect a patient’s ability to work or fulfill responsibilities. As a result, patients may ask their psychiatrists for assistance by requesting letters that address various aspects of their social well-being.1 These communications may address an array of topics, from a patient’s readiness to return to work to their ability to pay child support. This article focuses on the role psychiatrists have in writing patient-requested letters across a variety of topics, including the consideration of potential legal liability and ethical implications.

Types of letters

The categories of letters patients request can be divided into 2 groups. The first is comprised of letters relating to the patient’s medical needs (Table 12,3). These address the patient’s ability to work (eg, medical leave, return to work, or accommodations) or travel (eg, ability to drive or use public transportation), or need for specific medical treatment (ie, gender-affirming care or cannabis use in specific settings). The second group relates to legal requests such as excusal from jury duty, emotional support animals, or any other letter used specifically for legal purposes (in civil or criminal cases) (Table 21,4-6).

The decision to write a letter on behalf of a patient should be based on whether you have sufficient knowledge to answer the referral question, and whether the requested evaluation fits within your role as the treating psychiatrist. Many requests fall short of the first condition. For example, a request to opine about an individual’s ability to perform their job duties requires specific knowledge and careful consideration of the patient’s work responsibilities, knowledge of the impact of their psychiatric symptoms, and specialized knowledge about interventions that would ameliorate symptoms in the specialized work setting. Most psychiatrists are not sufficiently familiar with a specific workplace to provide opinions regarding reasonable accommodations.

The second condition refers to the role and responsibilities of the psychiatrist. Many letter requests are clearly within the scope of the clinical psychiatrist, such as a medical leave note due to a psychiatric decompensation or a jury duty excusal due to an unstable mental state. Other letters reach beyond the role of the general or treating psychiatrist, such as opinions about suitable housing or a patient’s competency to stand trial.

Components of letters

The decision to write or not to write a letter should be discussed with the patient. Identify the reasons for and against letter writing. If you decide to write a letter, the letter should have the following basic framework (Figure): the identity of the person who requested the letter, the referral question, and an answer to the referral question with a clear rationale. Describe the patient’s psychiatric diagnosis using DSM criteria. Any limitations to the answer should be identified. The letter should not go beyond the referral question and should not include information that was not requested. It also should be preserved in the medical record.

It is recommended to write or review the letter in the presence of the patient to discuss the contents of the letter and what the psychiatrist can or cannot write. As in forensic reports, conclusory statements are not helpful. Provide descriptive information instead of relying on psychiatric jargon, and a rationale for the opinion as opposed to stating an opinion as fact. In the letter, you must acknowledge that your opinion is based upon information provided by the patient (and the patient’s family, when accurate) and as a result, is not fully objective.

Continue to: Liability and dual agency

Liability and dual agency

Psychiatrists are familiar with clinical situations in which a duty to the patient is mitigated or superseded by a duty to a third party. As the Tarasoff court famously stated, “the protective privilege ends where the public peril begins.”7

To be liable to either a patient or a third party means to be “bound or obliged in law or equity; responsible; chargeable; answerable; compellable to make satisfaction, compensation, or restitution.”8 Liabilities related to clinical treatment are well-established; medical students learn the fundamentals before ever treating a patient, and physicians carry malpractice insurance throughout their careers.

Less well-established is the liability a treating psychiatrist owes a third party when forming an opinion that impacts both their patient and the third party (eg, an employer when writing a return-to-work letter, or a disability insurer when qualifying a patient for disability benefits). The American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law discourages treating psychiatrists from performing these types of evaluations of their patients based on the inherent conflict of serving as a dual agent, or acting both as an advocate for the patient and as an independent evaluator striving for objectivity.9 However, such requests commonly arise, and some may be unavoidable.

Dual-agency situations subject the treating psychiatrist to avenues of legal action arising from the patient-doctor relationship as well as the forensic evaluator relationship. If a letter is written during a clinical treatment, all duties owed to the patient continue to apply, and the relevant benchmarks of local statutes and principle of a standard of care are relevant. It is conceivable that a patient could bring a negligence lawsuit based on a standard of care allegation (eg, that writing certain types of letters is so ordinary that failure to write them would fall below the standard of care). Confidentiality is also of the utmost importance,10 and you should obtain a written release of information from the patient before releasing any letter with privileged information about the patient.11 Additional relevant legal causes of action the patient could include are torts such as defamation of character, invasion of privacy, breach of contract, and intentional infliction of emotional distress. There is limited case law supporting patients’ rights to sue psychiatrists for defamation.10

A psychiatrist writing a letter to a third party may also subject themselves to avenues of legal action occurring outside the physician-patient relationship. Importantly, damages resulting from these breaches would not be covered by your malpractice insurance. Extreme cases involve allegations of fraud or perjury, which could be pursued in criminal court. If a psychiatrist intentionally deceives a third party for the purpose of obtaining some benefit for the patient, this is clear grounds for civil or criminal action. Fraud is defined as “a false representation of a matter of fact, whether by words or by conduct, by false or misleading allegations, or by concealment of that which should have been disclosed, which deceives and is intended to deceive another so that he shall act upon it to his legal injury.”8 Negligence can also be grounds for liability if a third party suffers injury or loss. Although the liability is clearer if the third party retains an independent psychiatrist rather than soliciting an opinion from a patient’s treating psychiatrist, both parties are subject to the claim of negligence.10

Continue to: There are some important protections...

There are some important protections that limit psychiatrists’ good-faith opinions from litigation. The primary one is the “professional medical judgment rule,” which shields physicians from the consequences of erroneous opinions so long as the examination was competent, complete, and performed in an ordinary fashion.10 In some cases, psychiatrists writing a letter or report for a government agency may also qualify for quasi-judicial immunity or witness immunity, but case law shows significant variation in when and how these privileges apply and whether such privileges would be applied to a clinical psychiatrist in the context of a traditional physician-patient relationship.12 In general, these privileges are not absolute and may not be sufficiently well-established to discourage a plaintiff from filing suit or prompt early judicial dismissal of a case.

Like all aspects of practicing medicine, letter writing is subject to scrutiny and accountability. Think carefully about your obligations and the potential consequences of writing or not writing a letter to a third party.

Ethical considerations

The decision to write a letter for a patient must be carefully considered from multiple angles.6 In addition to liability concerns, various ethical considerations also arise. Guided by the principles of beneficence, nonmaleficence, autonomy, and justice,13 we recommend the following approaches.

Maintain objectivity

During letter writing, a conflict of interest may arise between your allegiance to the patient and the imperative to provide accurate information.14-16 If the conflict is overwhelming, the most appropriate approach is to recuse yourself from the case and refer the patient to a third party. When electing to write a letter, you accept the responsibility to provide an objective assessment of the relevant situation. This promotes a just outcome and may also serve to promote the patient’s or society’s well-being.

Encourage activity and overall function

Evidence suggests that participation in multiple aspects of life promotes positive health outcomes.17,18 As a physician, it is your duty to promote health and support and facilitate accommodations that allow patients to participate and flourish in society. By the same logic, when approached by patients with a request for letters in support of reduced activity, you should consider not only the benefits but also the potential detriments of such disruptions. This may entail recommending temporary restrictions or modifications, as appropriate.

Continue to: Think beyond the patient

Think beyond the patient

Letter writing, particularly when recommending accommodations, can have implications beyond the patient.16 Such letters may cause unintended societal harm. For example, others may have to assume additional responsibilities; competitive goods (eg, housing) may be rendered to the patient rather than to a person with greater needs; and workplace safety could be compromised due to absence. Consider not only the individual patient but also possible public health and societal effects of letter writing.

Deciding not to write

From an ethical perspective, a physician cannot be compelled to write a letter if such an undertaking violates a stronger moral obligation. An example of this is if writing a letter could cause significant harm to the patient or society, or if writing a letter might compromise a physician’s professionalism.19 When you elect to not write a letter, the ethical principles of autonomy and truth telling dictate that you must inform your patients of this choice.6 You should also provide an explanation to the patient as long as such information would not cause undue psychological or physical harm.20,21

Schedule time to write letters

Some physicians implement policies that all letters are to be completed during scheduled appointments. Others designate administrative time to complete requested letters. Finally, some physicians flexibly complete such requests between appointments or during other undedicated time slots. Any of these approaches are justifiable, though some urgent requests may require more immediate attention outside of appointments. Some physicians may choose to bill for the letter writing if completed outside an appointment and the patient is treated in private practice. Whatever your policy, inform patients of it at the beginning of care and remind them when appropriate, such as before completing a letter that may be billed.

Manage uncertainty

Always strive for objectivity in letter writing. However, some requests inherently hinge on subjective reports and assessments. For example, a patient may request an excuse letter due to feeling unwell. In the absence of objective findings, what should you do? We advise the following.

Acquire collateral information. Adequate information is essential when making any medical recommendation. The same is true for writing letters. With the patient’s permission, you may need to contact relevant parties to better understand the circumstance or activity about which you are being asked to write a letter. For example, a patient may request leave from work due to injury. If the specific parameters of the work impeded by the injury are unclear to you, refrain from writing the letter and explain the rationale to the patient.

Continue to: Integrate prior knowledge of the patient

Integrate prior knowledge of the patient. No letter writing request exists in a vacuum. If you know the patient, the letter should be contextualized within the patient’s prior behaviors.

Stay within your scope

Given the various dilemmas and challenges, you may want to consider whether some letter writing is out of your professional scope.14-16 One solution would be to leave such requests to other entities (eg, requiring employers to retain medical personnel with specialized skills in occupational evaluations) and make such recommendations to patients. Regardless, physicians should think carefully about their professional boundaries and scope regarding letter requests and adopt and implement a consistent standard for all patients.

Regarding the letter requested by Ms. M, you should consider whether the appeal is consistent with the patient’s psychiatric illness. You should also consider whether you have sufficient knowledge about the patient’s living environment to support their claim. Such a letter should be written only if you understand both considerations. Regardless of your decision, you should explain your rationale to the patient.

Bottom Line

Patients may ask their psychiatrists to write letters that address aspects of their social well-being. However, psychiatrists must be alert to requests that are outside their scope of practice or ethically or legally fraught. Carefully consider whether writing a letter is appropriate and if not, discuss with the patient the reasons you cannot write such a letter and any recommended alternative avenues to address their request.

Related Resources

- Riese A. Writing letters for transgender patients undergoing medical transition. Current Psychiatry. 2021;20(8):51-52. doi:10.12788/cp.0159

- Joshi KG. Service animals and emotional support animals: should you write that letter? Current Psychiatry. 2021;20(11):16-19,24. doi:10.12788/cp.0183

1. West S, Friedman SH. To be or not to be: treating psychiatrist and expert witness. Psychiatric Times. 2007;24(6). Accessed March 14, 2023. https://www.psychiatrictimes.com/view/be-or-not-be-treating-psychiatrist-and-expert-witness

2. Knoepflmacher D. ‘Medical necessity’ in psychiatry: whose definition is it anyway? Psychiatric News. 2016;51(18):12-14. https://psychnews.psychiatryonline.org/doi/10.1176/appi.pn.2016.9b14

3. Lampe JR. Recent developments in marijuana law (LSB10859). Congressional Research Service. 2022. Accessed October 25, 2023. https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/LSB/LSB10859/2

4. Brunnauer A, Buschert V, Segmiller F, et al. Mobility behaviour and driving status of patients with mental disorders – an exploratory study. Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract. 2016;20(1):40-46. doi:10.3109/13651501.2015.1089293

5. Chiu CW, Law CK, Cheng AS. Driver assessment service for people with mental illness. Hong Kong J Occup Ther. 2019;32(2):77-83. doi:10.1177/1569186119886773

6. Joshi KG. Service animals and emotional support animals: should you write that letter? Current Psychiatry. 2021;20(11):16-19. doi:10.12788/cp.0183

7. Tarasoff v Regents of University of California, 17 Cal 3d 425, 551 P2d 334, 131 Cal. Rptr. 14 (Cal 1976).

8. Black HC. Liability. Black’s Law Dictionary. Revised 4th ed. West Publishing; 1975:1060.

9. American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law. Ethics guidelines for the practice of forensic psychiatry. 2005. Accessed March 15, 2023. https://www.aapl.org/ethics.htm

10. Gold LH, Davidson JE. Do you understand your risk? Liability and third-party evaluations in civil litigation. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2007;35(2):200-210.

11. Schouten R. Approach to the patient seeking disability benefits. In: Stern TA, Herman JB, Slavin PL, eds. The MGH Guide to Psychiatry in Primary Care. McGraw Hill; 1998:121-126.

12. Appelbaum PS. Law and psychiatry: liability for forensic evaluations: a word of caution. Psychiatr Serv. 2001;52(7):885-886. doi:10.1176/appi.ps.52.7.885

13. Varkey B. Principles of clinical ethics and their application to practice. Med Princ Pract. 2021;30(1):17-28. doi:10.1159/000509119

14. Mayhew HE, Nordlund DJ. Absenteeism certification: the physician’s role. J Fam Pract. 1988;26(6):651-655.

15. Younggren JN, Boisvert JA, Boness CL. Examining emotional support animals and role conflicts in professional psychology. Prof Psychol Res Pr. 2016;47(4):255-260. doi:10.1037/pro0000083

16. Carroll JD, Mohlenhoff BS, Kersten CM, et al. Laws and ethics related to emotional support animals. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2020;48(4):509-518. doi:1-.29158/JAAPL.200047-20

17. Strully KW. Job loss and health in the U.S. labor market. Demography. 2009;46(2):221-246. doi:10.1353/dem.0.0050

18. Jurisic M, Bean M, Harbaugh J, et al. The personal physician’s role in helping patients with medical conditions stay at work or return to work. J Occup Environ Med. 2017;59(6):e125-131. doi:10.1097/JOM.0000000000001055

19. Munyaradzi M. Critical reflections on the principle of beneficence in biomedicine. Pan Afr Med J. 2012;11:29.

20. Beauchamp TL, Childress JF. Principles of Biomedical Ethics. 7th ed. Oxford University Press; 2012.

21. Gold M. Is honesty always the best policy? Ethical aspects of truth telling. Intern Med J. 2004;34(9-10):578-580. doi:10.1111/j.1445-5994.2004.00673.x

1. West S, Friedman SH. To be or not to be: treating psychiatrist and expert witness. Psychiatric Times. 2007;24(6). Accessed March 14, 2023. https://www.psychiatrictimes.com/view/be-or-not-be-treating-psychiatrist-and-expert-witness

2. Knoepflmacher D. ‘Medical necessity’ in psychiatry: whose definition is it anyway? Psychiatric News. 2016;51(18):12-14. https://psychnews.psychiatryonline.org/doi/10.1176/appi.pn.2016.9b14

3. Lampe JR. Recent developments in marijuana law (LSB10859). Congressional Research Service. 2022. Accessed October 25, 2023. https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/LSB/LSB10859/2

4. Brunnauer A, Buschert V, Segmiller F, et al. Mobility behaviour and driving status of patients with mental disorders – an exploratory study. Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract. 2016;20(1):40-46. doi:10.3109/13651501.2015.1089293

5. Chiu CW, Law CK, Cheng AS. Driver assessment service for people with mental illness. Hong Kong J Occup Ther. 2019;32(2):77-83. doi:10.1177/1569186119886773

6. Joshi KG. Service animals and emotional support animals: should you write that letter? Current Psychiatry. 2021;20(11):16-19. doi:10.12788/cp.0183

7. Tarasoff v Regents of University of California, 17 Cal 3d 425, 551 P2d 334, 131 Cal. Rptr. 14 (Cal 1976).

8. Black HC. Liability. Black’s Law Dictionary. Revised 4th ed. West Publishing; 1975:1060.

9. American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law. Ethics guidelines for the practice of forensic psychiatry. 2005. Accessed March 15, 2023. https://www.aapl.org/ethics.htm

10. Gold LH, Davidson JE. Do you understand your risk? Liability and third-party evaluations in civil litigation. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2007;35(2):200-210.

11. Schouten R. Approach to the patient seeking disability benefits. In: Stern TA, Herman JB, Slavin PL, eds. The MGH Guide to Psychiatry in Primary Care. McGraw Hill; 1998:121-126.

12. Appelbaum PS. Law and psychiatry: liability for forensic evaluations: a word of caution. Psychiatr Serv. 2001;52(7):885-886. doi:10.1176/appi.ps.52.7.885

13. Varkey B. Principles of clinical ethics and their application to practice. Med Princ Pract. 2021;30(1):17-28. doi:10.1159/000509119

14. Mayhew HE, Nordlund DJ. Absenteeism certification: the physician’s role. J Fam Pract. 1988;26(6):651-655.

15. Younggren JN, Boisvert JA, Boness CL. Examining emotional support animals and role conflicts in professional psychology. Prof Psychol Res Pr. 2016;47(4):255-260. doi:10.1037/pro0000083

16. Carroll JD, Mohlenhoff BS, Kersten CM, et al. Laws and ethics related to emotional support animals. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2020;48(4):509-518. doi:1-.29158/JAAPL.200047-20

17. Strully KW. Job loss and health in the U.S. labor market. Demography. 2009;46(2):221-246. doi:10.1353/dem.0.0050

18. Jurisic M, Bean M, Harbaugh J, et al. The personal physician’s role in helping patients with medical conditions stay at work or return to work. J Occup Environ Med. 2017;59(6):e125-131. doi:10.1097/JOM.0000000000001055

19. Munyaradzi M. Critical reflections on the principle of beneficence in biomedicine. Pan Afr Med J. 2012;11:29.

20. Beauchamp TL, Childress JF. Principles of Biomedical Ethics. 7th ed. Oxford University Press; 2012.

21. Gold M. Is honesty always the best policy? Ethical aspects of truth telling. Intern Med J. 2004;34(9-10):578-580. doi:10.1111/j.1445-5994.2004.00673.x

Cannabis and schizophrenia: A complex relationship

Approximately 1 in 200 individuals will be diagnosed with schizophrenia in their lifetime.1 DSM-5 criteria for the diagnosis of schizophrenia require the presence of ≥2 of 5 symptoms: delusions, hallucinations, disordered speech, grossly disorganized (or catatonic) behavior, and negative symptoms such as flat affect or avolition.2 Multiple studies have found increased rates of cannabis use among patients with schizophrenia. Because cognitive deficits are the chief predictor of clinical outcomes and quality of life in individuals with schizophrenia, the cognitive effects of cannabis use among these patients are of clinical significance.3 As legislation increasingly allows for the sale, possession, and consumption of cannabis, it is crucial to provide clinicians with evidence-based recommendations for treating patients who regularly use cannabis (approximately 8% of the adult population3). In this article, we analyze several peer-reviewed studies to investigate the impact of cannabis use on the onset and development of schizophrenia.

A look at substance-induced psychosis

Schizophrenia is associated with several structural brain changes, and some of these changes may be influenced by cannabis use (Box4). The biochemical etiology of schizophrenia is poorly understood but thought to involve dopamine, glutamate, serotonin, and gamma-aminobutyric acid. Certain positive symptoms, such as hallucinations, are uniquely human and difficult to study in animal models.5 Psychoactive substance use, especially cannabis, is frequently comorbid with schizophrenia. Additionally, certain individuals may be more predisposed to substance-induced psychosis than others based on genetic variation and underlying brain structure changes.4 Substance-induced psychosis is a psychotic state following the ingestion of a psychoactive substance or drug withdrawal lasting ≥48 hours.6 The psychoactive effects of cannabis have been associated with an exacerbation of existing schizophrenia symptoms.7 In 1998, Hall7 proposed 2 hypotheses to explain the relationship between cannabis and psychosis. The first was that heavy consumption of cannabis triggers a specific type of cannabis psychosis.7 The second was that cannabis use exacerbates existing schizophrenia, making the symptoms worse.7 Hall7 concluded that there was a complicated interaction among an individual’s vulnerability to their stressors, environment, and genetics.

Box

Schizophrenia is associated with several structural changes in the brain, including lateral ventriculomegaly, reduced prefrontal cortex volume, and generalized atrophy. These changes may precede illness and act as a risk marker.4 A multivariate regression analysis that compared patients with schizophrenia who were cannabis users vs patients with schizophrenia who were nonusers found that those with high-level cannabis use had relatively higher left and right lateral ventricle volume (r = 0.208, P = .13, and r = 0.226, P = .007, respectively) as well as increased third ventricle volume (r = 0.271, P = .001).4 These changes were dose-dependent and may lead to worse disease outcomes.4

Cannabis, COMT, and homocysteine

Great advances have been made in our ability to examine the association between genetics and metabolism. One example of this is the interaction between the catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT) gene and the active component of cannabis, delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC). COMT codes for an enzyme that degrades cortical dopamine. The Val158Met polymorphism of this gene increases COMT activity, leading to increased dopamine catabolism, and thus decreased levels of extracellular dopamine, which induces an increase in mesolimbic dopaminergic activity, thereby increasing susceptibility to psychosis.3

In a study that genotyped 135 patients with schizophrenia, the Val158Met polymorphism was present in 29.63% of participants.3 Because THC can induce episodes of psychosis, individuals with this polymorphism may be at a higher risk of developing schizophrenia. Compared to Met carrier control participants with similar histories of cannabis consumption, those with the Val158Met polymorphism demonstrated markedly worse performance on tests of verbal fluency and processing speed.3 This is clinically significant because cognitive impairments are a major prognostic factor in schizophrenia, and identifying patients with this polymorphism could help personalize interventions for those who consume cannabis and are at risk of developing schizophrenia.

A study that evaluated 56 patients with first-episode schizophrenia found that having a history of cannabis abuse was associated with significantly higher levels of homocysteine as well as lower levels of high-density lipoprotein and vitamin B12.8 Homocysteine is an agonist at the glutamate binding site and a partial antagonist at the glycine co-agonist site in the N-methyl-

The C677T polymorphism in MTHFR may predict the risk of developing metabolic syndrome in patients taking second-generation antipsychotics.8 Elevations in homocysteine by as little as 5 μmol/L may increase schizophrenia risk by 70% compared to controls, possibly due to homocysteine initiating neuronal apoptosis, catalyzing dysfunction of the mitochondria, or increasing oxidative stress.8 There is a positive correlation between homocysteine levels and severity of negative symptoms (P = .006) and general psychopathology (P = .008) of schizophrenia when analyzed using the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale.8 Negative symptoms such as blunted affect, apathy, anhedonia, and loss of motivation significantly impact the social and economic outcomes of patients diagnosed with schizophrenia.

Research paints a mixed picture

A Danish study analyzed the rates of conversion to schizophrenia or bipolar disorder (BD) among 6,788 individuals who received a diagnosis of substance-induced psychosis from 1994 to 2014.6 Ten comparison participants were selected for each case participant, matched on sex and year/month of birth. Participants were followed until the first occurrence of schizophrenia or BD, death, or emigration from Denmark. Substances implicated in the initial psychotic episode included cannabis, alcohol, opioids, sedatives, cocaine, amphetamines, hallucinogens, and combinations of substances.

Continue to: The overall conversion rate...

The overall conversion rate over 20 years was 32.2% (95% CI, 29.7 to 34.9), with 26.0% developing schizophrenia vs 8.4% developing BD.6 Of the substances involved, cannabis was the most common, implicated in 41.2% (95% CI, 36.6 to 46.2) of cases.6 One-half of male patients converted within 2.0 years and one-half of female patients converted within 4.4 years after a cannabis-induced psychosis.6

This study had several limitations. It could not account for any short-term psychotic symptoms experienced by the general population, especially after cannabis use. Such patients might not seek treatment. Thus, the results might not be generalizable to the general population. The study did not evaluate if conversion rates differed based on continued substance use following the psychosis episode, or the amount of each substance taken prior to the episode. Dose-dependence was not well elucidated, and this study only looked at patients from Denmark and did not account for socioeconomic status.6

Another Danish study looked at the influences of gender and cannabis use in the early course of the disease in 133 patients with schizophrenia.9 These researchers found that male gender was a significant predictor of earlier onset of dysfunction socially and in the workplace, as well as a higher risk of developing negative symptoms. However, compared to gender, cannabis use was a stronger predictor of age at first psychotic episode. For cannabis users, the median age of onset of negative symptoms was 23.7, compared to 38.4 for nonusers (P < .001).9

Cannabis use is significantly elevated among individuals with psychosis, with a 12-month prevalence of 29.2% compared to 4.0% among the general population of the United States.10 In a study that assessed 229 patients with a schizophrenia spectrum disorder during their first hospitalization and 6 months, 2 years, 4 years, and 10 years later, Foti et al10 found that the lifetime rate of cannabis use was 66.2%. Survival analysis found cannabis use doubled the risk of the onset of psychosis compared to nonusers of the same age (hazard ratio [HR] = 1.97; 95% CI, 1.48 to 2.62, P < .001), even after adjusting for socioeconomic status, age, and gender (HR = 1.34; 95% CI, 1.01 to 1.77, P < .05).10 Additionally, Foti et al10 found significant positive correlations between psychotic symptoms and cannabis use in patients with schizophrenia over the course of 10 years. An increase in symptoms was associated with a higher likelihood of cannabis use, and a decrease in symptoms was correlated with a lower likelihood of use (adjusted odds ratio = 1.64; 95% CI, 1.12 to 2.43, P < .0125).10

Ortiz-Medina et al11 conducted a meta-analysis of 22 studies of 15 cohorts from healthy populations and 12 other cohort follow-up studies that evaluated the onset of psychotic symptoms in individuals who used cannabis. Most studies found associations between cannabis use and the onset of symptoms of schizophrenia, and most determined cannabis was also a major risk factor for other psychotic disorders. Analyses of dose-dependence indicated that repeated cannabis use increased the risk of developing psychotic symptoms. This risk is increased when an individual starts using cannabis before age 15.11 Age seemed to be a stronger predictor of onset and outcome than sex, with no significant differences between men and women. One study in this review found that approximately 8% to 13% cases of schizophrenia may have been solely due to cannabis.11 The most significant limitation to the studies analyzed in this review is that retrospective studies utilize self-reported questionnaires.

Continue to: Other researchers have found...

Other researchers have found it would take a relatively high number of individuals to stop using cannabis to prevent 1 case of schizophrenia. In a study of data from England and Wales, Hickman et al12 evaluated the best available estimates of the incidence of schizophrenia, rates of heavy and light cannabis use, and risk that cannabis causes schizophrenia to determine the number needed to prevent (NNP) 1 case of schizophrenia. They estimated that it would require approximately 2,800 men age 20 to 24 (90% CI, 2,018 to 4,530) and 4,700 men age 35 to 39 (90% CI, 3,114 to 8,416) who heavily used cannabis to stop their consumption to prevent 1 case of schizophrenia.12 For women with heavy cannabis use, the mean NNP was 5,470 for women age 25 to 29 (90% CI, 3,640 to 9,839) and 10,870 for women age 35 to 39 (90% CI, 6,786 to 22,732).12 For light cannabis users, the NNP was 4 to 5 times higher than the NNP for heavy cannabis users. This suggests that clinical interventions aimed at preventing dependence on cannabis would be more effective than interventions aimed at eliminating cannabis use.

Medical cannabis and increased potency

In recent years, the use of medical cannabis, which is used to address adverse effects of chemotherapy as well as neuropathic pain, Parkinson’s disease, and epilepsy, has been increasing.13 However, there is a lack of well-conducted randomized clinical trials evaluating medical cannabis’ efficacy and safety. As medical cannabis continues to gain public acceptance and more states permit its legal use, patients and physicians should be fully informed of the known adverse effects, including impaired attention, learning, and motivation.13

Several studies have drawn attention to the dose-dependence of many of cannabis’ effects. Since at least the 1960s, the concentration of THC in cannabis has increased substantially, thus increasing its potency. Based on 66,747 samples across 8 studies, 1 meta-analysis estimated that THC concentrations in herbal cannabis increased by 0.29% (P < .001) each year between 1970 and 2017.14 Similarly, THC concentrations in cannabis resins were found to have increased by 0.57% (P = .017) each year between 1975 and 2017.14 Cannabis products with high concentrations of THC carry an increased risk of addiction and mental health disorders.14

Identifying those at highest risk

Despite ongoing research, scientific consensus on the relationship of cannabis to schizophrenia and psychosis has yet to be reached. The disparity between the relatively high prevalence of regular adult use of cannabis (8%7) and the low incidence of cannabis-induced psychosis suggests that cannabis use alone is unlikely to lead to episodes of psychosis in individuals who are not predisposed to such episodes. Sarrazin et al15 evaluated 170 patients with schizophrenia, 31 of whom had cannabis use disorder. They found no significant difference in lifetime symptom dimensions between groups, and proposed that cannabis-associated schizophrenia should not be categorized as a distinct clinical entity of schizophrenia with specific features.15

Policies that encourage follow-up of patients after episodes of drug-induced psychosis may mitigate the adverse social and economic effects of schizophrenia. Currently, these policies are not widely implemented in health care institutions, possibly because psychotic symptoms may fade after the drug’s effects have dissipated. Despite this, these patients are at high risk of developing schizophrenia and self-harm. New-onset schizophrenia should be promptly identified because delayed diagnosis is associated with worse prognosis.6 Additionally, identifying genetic susceptibilities to schizophrenia—such as the Val158Met polymorphisms—in individuals who use cannabis could help clinicians manage or slow the onset or progression of schizophrenia.3 Motivational interviewing strategies should be used to minimize or eliminate cannabis use in individuals with active schizophrenia or psychosis, thus preventing worse outcomes.

Bottom Line

Identifying susceptibilities to schizophrenia may guide interventions in patients who use cannabis. Several large studies have suggested that cannabis use may exacerbate symptoms and worsen the prognosis of schizophrenia. Motivational interviewing strategies aimed at minimizing cannabis use may improve outcomes in patients with schizophrenia.

Related Resources

- Khokhar JY, Dwiel LL, Henricks AM, et al. The link between schizophrenia and substance use disorder: a unifying hypothesis. Schizophr Res. 2018;194:78-85. doi:10.1016/j. schres.2017.04.016

- Otite ES, Solanky A, Doumas S. Adolescents, THC, and the risk of psychosis. Current Psychiatry. 2021;20(12):e1-e2. doi:10.12788/cp.0197

1. Simeone JC, Ward AJ, Rotella P, et al. An evaluation of variation in published estimates of schizophrenia prevalence from 1990-2013: a systematic literature review. BMC Psychiatry. 2015;15(1):193. doi:10.1186/s12888-015-0578-7

2. Tandon R, Gaebel W, Barch DM, et al. Definition and description of schizophrenia in the DSM-5. Schizophr Res. 2013;150(1):3-10. doi:10.1016/j.schres.2013.05.028

3. Bosia M, Buonocore M, Bechi M, et al. Schizophrenia, cannabis use and catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT): modeling the interplay on cognition. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2019;92:363-368. doi:10.1016/j.pnpbp.2019.02.009

4. Welch KA, McIntosh AM, Job DE, et al. The impact of substance use on brain structure in people at high risk of developing schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2011;37(5):1066-1076. doi:10.1093/schbul/sbq013

5. Winship IR, Dursun SM, Baker GB, et al. An overview of animal models related to schizophrenia. Can J Psychiatry. 2019;64(1):5-17. doi:10.1177/0706743718773728

6. Starzer MSK, Nordentoft M, Hjorthøj C. Rates and predictors of conversion to schizophrenia or bipolar disorder following substance-induced psychosis. Am J Psychiatry. 2018;175(4):343-350. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2017.17020223

7. Hall W. Cannabis use and psychosis. Drug Alcohol Rev. 1998;17(4):433-444. doi:10.1080/09595239800187271

8. Misiak B, Frydecka D, Slezak R, et al. Elevated homocysteine level in first-episode schizophrenia patients—the relevance of family history of schizophrenia and lifetime diagnosis of cannabis abuse. Metab Brain Dis. 2014;29(3):661-670. doi:10.1007/s11011-014-9534-3

9. Veen ND, Selten J, van der Tweel I, et al. Cannabis use and age at onset of schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161(3):501-506. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.161.3.501

10. Foti DJ, Kotov R, Guey LT, et al. Cannabis use and the course of schizophrenia: 10-year follow-up after first hospitalization. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167(8):987-993. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.09020189

11. Ortiz-Medina MB, Perea M, Torales J, et al. Cannabis consumption and psychosis or schizophrenia development. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2018;64(7):690-704. doi:10.1177/0020764018801690

12. Hickman M, Vickerman P, Macleod J, et al. If cannabis caused schizophrenia—how many cannabis users may need to be prevented in order to prevent one case of schizophrenia? England and Wales calculations. Addiction. 2009;104(11):1856-1861. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02736.x

13. Gupta S, Phalen T, Gupta S. Medical marijuana: do the benefits outweigh the risks? Current Psychiatry. 2018;17(1):34-41.

14. Freeman TP, Craft S, Wilson J, et al. Changes in delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) and cannabidiol (CBD) concentrations in cannabis over time: systematic review and meta-analysis. Addiction. 2021;116(5):1000-1010. doi:10.1111/add.15253

15. Sarrazin S, Louppe F, Doukhan R, et al. A clinical comparison of schizophrenia with and without pre-onset cannabis use disorder: a retrospective cohort study using categorical and dimensional approaches. Ann Gen Psychiatry. 2015;14:44. doi:10.1186/s12991-015-0083-x

Approximately 1 in 200 individuals will be diagnosed with schizophrenia in their lifetime.1 DSM-5 criteria for the diagnosis of schizophrenia require the presence of ≥2 of 5 symptoms: delusions, hallucinations, disordered speech, grossly disorganized (or catatonic) behavior, and negative symptoms such as flat affect or avolition.2 Multiple studies have found increased rates of cannabis use among patients with schizophrenia. Because cognitive deficits are the chief predictor of clinical outcomes and quality of life in individuals with schizophrenia, the cognitive effects of cannabis use among these patients are of clinical significance.3 As legislation increasingly allows for the sale, possession, and consumption of cannabis, it is crucial to provide clinicians with evidence-based recommendations for treating patients who regularly use cannabis (approximately 8% of the adult population3). In this article, we analyze several peer-reviewed studies to investigate the impact of cannabis use on the onset and development of schizophrenia.

A look at substance-induced psychosis

Schizophrenia is associated with several structural brain changes, and some of these changes may be influenced by cannabis use (Box4). The biochemical etiology of schizophrenia is poorly understood but thought to involve dopamine, glutamate, serotonin, and gamma-aminobutyric acid. Certain positive symptoms, such as hallucinations, are uniquely human and difficult to study in animal models.5 Psychoactive substance use, especially cannabis, is frequently comorbid with schizophrenia. Additionally, certain individuals may be more predisposed to substance-induced psychosis than others based on genetic variation and underlying brain structure changes.4 Substance-induced psychosis is a psychotic state following the ingestion of a psychoactive substance or drug withdrawal lasting ≥48 hours.6 The psychoactive effects of cannabis have been associated with an exacerbation of existing schizophrenia symptoms.7 In 1998, Hall7 proposed 2 hypotheses to explain the relationship between cannabis and psychosis. The first was that heavy consumption of cannabis triggers a specific type of cannabis psychosis.7 The second was that cannabis use exacerbates existing schizophrenia, making the symptoms worse.7 Hall7 concluded that there was a complicated interaction among an individual’s vulnerability to their stressors, environment, and genetics.

Box

Schizophrenia is associated with several structural changes in the brain, including lateral ventriculomegaly, reduced prefrontal cortex volume, and generalized atrophy. These changes may precede illness and act as a risk marker.4 A multivariate regression analysis that compared patients with schizophrenia who were cannabis users vs patients with schizophrenia who were nonusers found that those with high-level cannabis use had relatively higher left and right lateral ventricle volume (r = 0.208, P = .13, and r = 0.226, P = .007, respectively) as well as increased third ventricle volume (r = 0.271, P = .001).4 These changes were dose-dependent and may lead to worse disease outcomes.4

Cannabis, COMT, and homocysteine

Great advances have been made in our ability to examine the association between genetics and metabolism. One example of this is the interaction between the catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT) gene and the active component of cannabis, delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC). COMT codes for an enzyme that degrades cortical dopamine. The Val158Met polymorphism of this gene increases COMT activity, leading to increased dopamine catabolism, and thus decreased levels of extracellular dopamine, which induces an increase in mesolimbic dopaminergic activity, thereby increasing susceptibility to psychosis.3

In a study that genotyped 135 patients with schizophrenia, the Val158Met polymorphism was present in 29.63% of participants.3 Because THC can induce episodes of psychosis, individuals with this polymorphism may be at a higher risk of developing schizophrenia. Compared to Met carrier control participants with similar histories of cannabis consumption, those with the Val158Met polymorphism demonstrated markedly worse performance on tests of verbal fluency and processing speed.3 This is clinically significant because cognitive impairments are a major prognostic factor in schizophrenia, and identifying patients with this polymorphism could help personalize interventions for those who consume cannabis and are at risk of developing schizophrenia.

A study that evaluated 56 patients with first-episode schizophrenia found that having a history of cannabis abuse was associated with significantly higher levels of homocysteine as well as lower levels of high-density lipoprotein and vitamin B12.8 Homocysteine is an agonist at the glutamate binding site and a partial antagonist at the glycine co-agonist site in the N-methyl-