User login

CHMP endorses drug delivery system

The European Medicines Agency’s Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP) has recommended a label variation for Neulasta® (pegfilgrastim) to include the Neulasta® Onpro® Kit.

The Neulasta Onpro Kit is an on-body injector (OBI) delivery system for Neulasta, which is approved in the European Union to reduce the duration of neutropenia and the incidence of febrile neutropenia in adults treated with cytotoxic chemotherapy for malignancy (with the exception of chronic myeloid leukemia and myelodysplastic syndromes).

The Neulasta Onpro Kit includes a specifically designed Neulasta pre-filled syringe along with a single-use OBI. The small, lightweight OBI is applied to a patient’s skin on the same day of chemotherapy.

The OBI is intended to facilitate timed delivery of the correct dose of Neulasta and eliminate the need for patients to return to a healthcare setting the day after they receive chemotherapy.

The CHMP’s opinion on the Neulasta Onpro Kit will be reviewed by the European Commission (EC).

If the EC agrees with the CHMP, the centralized marketing authorization of Neulasta will be updated to include information on the Neulasta Onpro Kit in the drug’s label.

This change will be valid throughout the European Union. Norway, Iceland, and Liechtenstein will make corresponding decisions about Neulasta’s label on the basis of the EC’s decision.

The EC typically makes a decision within 67 days of the CHMP’s recommendation.

The European Medicines Agency’s Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP) has recommended a label variation for Neulasta® (pegfilgrastim) to include the Neulasta® Onpro® Kit.

The Neulasta Onpro Kit is an on-body injector (OBI) delivery system for Neulasta, which is approved in the European Union to reduce the duration of neutropenia and the incidence of febrile neutropenia in adults treated with cytotoxic chemotherapy for malignancy (with the exception of chronic myeloid leukemia and myelodysplastic syndromes).

The Neulasta Onpro Kit includes a specifically designed Neulasta pre-filled syringe along with a single-use OBI. The small, lightweight OBI is applied to a patient’s skin on the same day of chemotherapy.

The OBI is intended to facilitate timed delivery of the correct dose of Neulasta and eliminate the need for patients to return to a healthcare setting the day after they receive chemotherapy.

The CHMP’s opinion on the Neulasta Onpro Kit will be reviewed by the European Commission (EC).

If the EC agrees with the CHMP, the centralized marketing authorization of Neulasta will be updated to include information on the Neulasta Onpro Kit in the drug’s label.

This change will be valid throughout the European Union. Norway, Iceland, and Liechtenstein will make corresponding decisions about Neulasta’s label on the basis of the EC’s decision.

The EC typically makes a decision within 67 days of the CHMP’s recommendation.

The European Medicines Agency’s Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP) has recommended a label variation for Neulasta® (pegfilgrastim) to include the Neulasta® Onpro® Kit.

The Neulasta Onpro Kit is an on-body injector (OBI) delivery system for Neulasta, which is approved in the European Union to reduce the duration of neutropenia and the incidence of febrile neutropenia in adults treated with cytotoxic chemotherapy for malignancy (with the exception of chronic myeloid leukemia and myelodysplastic syndromes).

The Neulasta Onpro Kit includes a specifically designed Neulasta pre-filled syringe along with a single-use OBI. The small, lightweight OBI is applied to a patient’s skin on the same day of chemotherapy.

The OBI is intended to facilitate timed delivery of the correct dose of Neulasta and eliminate the need for patients to return to a healthcare setting the day after they receive chemotherapy.

The CHMP’s opinion on the Neulasta Onpro Kit will be reviewed by the European Commission (EC).

If the EC agrees with the CHMP, the centralized marketing authorization of Neulasta will be updated to include information on the Neulasta Onpro Kit in the drug’s label.

This change will be valid throughout the European Union. Norway, Iceland, and Liechtenstein will make corresponding decisions about Neulasta’s label on the basis of the EC’s decision.

The EC typically makes a decision within 67 days of the CHMP’s recommendation.

Ketamine for mood disorders?

Audacious advances to discover new treatments for psychiatric brain disorders

In recent years, the pace of the development of novel new treatments for brain disorders in both psychiatry and neurology, including psychiatric disorders, has been the subject of much worry and hand-wringing.1

Some major pharmaceutical companies have stopped research programs in neuropsychiatry to focus on other, “easier” therapeutic areas where they think the biology is better understood and therefore drug development is more feasible.

However, I am now more optimistic than I have been in many years that we are on the verge of a promising era of pharmacotherapy that will usher in far better prevention, diagnosis, and management of neuropsychiatric disorders, and a better outcome for our patients. Why the optimism? There is a series of converging trends that justify it.

Funding for basic neuroscience research. Governments all over the world have woken up to the fact that brain disorders will account for the largest economic impact unless new treatments are developed. This has spurred multiple initiatives to better understand the underlying neurobiologic mechanisms of the brain in health and disease.2

Renewed enthusiasm for brain disorders from small pharmaceutical and mid-size biotechnology companies. While some of the larger pharmaceutical companies have withdrawn from pursuing new treatments for psychiatric disorders due to the need to satisfy “shareholders,” small and nimble biotechnology companies have stepped up, seeing an opportunity in a field that is not overcrowded and still has an extensive unmet need. These companies are developing truly novel treatments and approaches that can differentiate from current treatments. These include:

- rapid-acting antidepressants

- targeting specific symptom domains of psychiatric disorders, such as cognition, apathy, or anhedonia, that currently have no adequate or effective treatment

- novel therapeutic targets in a range of indications

- nonpharmacologic approaches.

Leading companies in this space include Allergan and Blackthorn Therapeutics. These companies and others have publicly discussed their commitment to developing new treatments for psychiatric disorders.

But large pharmaceutical companies should not be discounted. Examples of advances by larger companies include the recent FDA “breakthrough designation” for the development of balovaptan by Roche, a medication with the potential to improve “core social interaction and communication” in patients with autism, and the work Johnson & Johnson is conducting with S-ketamine for depression and acutely suicidal patients.

New scientific breakthroughs in areas such as synthetic biology, gene editing, nanotechnology, pluripotent cells, understanding the impact of the microbiome, and many other fields will dramatically accelerate the pace of scientific progress, allowing new treatment approaches not previously imagined.

New technologies. An array of new technologies—such as biosensors, artificial intelligence and machine learning, augmented and virtual reality, and other digital health tools—will impact every step of the “patient journey.” These will enable earlier detection and diagnosis, ongoing real-time assessment of symptoms, and more objective assessments, and they will facilitate the delivery of, and assessment of adherence to, treatments such as pharmacotherapy, neuromodulation, video games, apps, or a combination of these modalities.

Until recently, the idea of a video game or augmented reality glasses being viewed as serious and validated treatment modalities would have been considered science fiction. New ways of assessing patients—including voice, typing, activity on smartphones, diurnal rhythm, etc.—have the potential to dramatically improve the information clinicians will have about patient functioning in the real world. Another area where new technologies may eventually have a huge impact is in facilitating the prediction of suicide attempts.3

New digital therapeutics companies. It is no coincidence that the digital therapeutics companies that have been making the news and obtaining FDA approvals, such as Proteus Digital Health, Pear Therapeutics, Akili, and Click Therapeutics, are all addressing brain disorders.

Patient empowerment. With these new tools, the patient can become a true partner in the therapeutic alliance more than ever before. Patients can have an active role in diagnosis and be active participants in many new treatment modalities. There will be many new ways for patients to share their data to improve their care and to advance the science of these tools. Utilizing blockchain protocols, patients will have more control over how and with whom their data is shared, and even be compensated for it.

This may all seem like a medical “brave new world,” and perhaps a long way away. However, I believe these changes are happening at an exponential rate. It is hard to believe that common technological tools such as Google Maps, Gmail, and the smartphone first became available only a few years ago. The merging of biology and technology will have profound effects, and will be recognized as the momentous scientific achievement of the early 21st century.

Unlike clunky technologies such as electronic medical records, which have in fact made the clinician–patient experience worse, I believe that the technologies I describe above will enhance and augment the clinician–patient relationship. As health care practitioners, we need to be open to new technologies and ways of assessing and treating our patients while making sure our clinical insights and experience inform the development of these new technologies.

Let’s buckle up. Life in psychiatry is going to get more interesting than ever!

1. O’Hara M, Duncan P. The Guardian. Why ‘big pharma’ stopped searching for the next prozac. https://www.theguardian.com/society/2016/jan/27/prozac-next-psychiatric-wonder-drug-research-medicine-mental-illness. Published January 27, 2016. Accessed February 7, 2018.

2. Insel TR, Landis SC, Collins FS. The NIH BRAIN Initiative. Science. 2013;340(6133):687-688.

3. Vahabzadeh A, Sahin N, Kalali A. Digital suicide prevention: can technology become a game-changer? Innov Clin Neurosci. 2016;13(5-6):16-20.

In recent years, the pace of the development of novel new treatments for brain disorders in both psychiatry and neurology, including psychiatric disorders, has been the subject of much worry and hand-wringing.1

Some major pharmaceutical companies have stopped research programs in neuropsychiatry to focus on other, “easier” therapeutic areas where they think the biology is better understood and therefore drug development is more feasible.

However, I am now more optimistic than I have been in many years that we are on the verge of a promising era of pharmacotherapy that will usher in far better prevention, diagnosis, and management of neuropsychiatric disorders, and a better outcome for our patients. Why the optimism? There is a series of converging trends that justify it.

Funding for basic neuroscience research. Governments all over the world have woken up to the fact that brain disorders will account for the largest economic impact unless new treatments are developed. This has spurred multiple initiatives to better understand the underlying neurobiologic mechanisms of the brain in health and disease.2

Renewed enthusiasm for brain disorders from small pharmaceutical and mid-size biotechnology companies. While some of the larger pharmaceutical companies have withdrawn from pursuing new treatments for psychiatric disorders due to the need to satisfy “shareholders,” small and nimble biotechnology companies have stepped up, seeing an opportunity in a field that is not overcrowded and still has an extensive unmet need. These companies are developing truly novel treatments and approaches that can differentiate from current treatments. These include:

- rapid-acting antidepressants

- targeting specific symptom domains of psychiatric disorders, such as cognition, apathy, or anhedonia, that currently have no adequate or effective treatment

- novel therapeutic targets in a range of indications

- nonpharmacologic approaches.

Leading companies in this space include Allergan and Blackthorn Therapeutics. These companies and others have publicly discussed their commitment to developing new treatments for psychiatric disorders.

But large pharmaceutical companies should not be discounted. Examples of advances by larger companies include the recent FDA “breakthrough designation” for the development of balovaptan by Roche, a medication with the potential to improve “core social interaction and communication” in patients with autism, and the work Johnson & Johnson is conducting with S-ketamine for depression and acutely suicidal patients.

New scientific breakthroughs in areas such as synthetic biology, gene editing, nanotechnology, pluripotent cells, understanding the impact of the microbiome, and many other fields will dramatically accelerate the pace of scientific progress, allowing new treatment approaches not previously imagined.

New technologies. An array of new technologies—such as biosensors, artificial intelligence and machine learning, augmented and virtual reality, and other digital health tools—will impact every step of the “patient journey.” These will enable earlier detection and diagnosis, ongoing real-time assessment of symptoms, and more objective assessments, and they will facilitate the delivery of, and assessment of adherence to, treatments such as pharmacotherapy, neuromodulation, video games, apps, or a combination of these modalities.

Until recently, the idea of a video game or augmented reality glasses being viewed as serious and validated treatment modalities would have been considered science fiction. New ways of assessing patients—including voice, typing, activity on smartphones, diurnal rhythm, etc.—have the potential to dramatically improve the information clinicians will have about patient functioning in the real world. Another area where new technologies may eventually have a huge impact is in facilitating the prediction of suicide attempts.3

New digital therapeutics companies. It is no coincidence that the digital therapeutics companies that have been making the news and obtaining FDA approvals, such as Proteus Digital Health, Pear Therapeutics, Akili, and Click Therapeutics, are all addressing brain disorders.

Patient empowerment. With these new tools, the patient can become a true partner in the therapeutic alliance more than ever before. Patients can have an active role in diagnosis and be active participants in many new treatment modalities. There will be many new ways for patients to share their data to improve their care and to advance the science of these tools. Utilizing blockchain protocols, patients will have more control over how and with whom their data is shared, and even be compensated for it.

This may all seem like a medical “brave new world,” and perhaps a long way away. However, I believe these changes are happening at an exponential rate. It is hard to believe that common technological tools such as Google Maps, Gmail, and the smartphone first became available only a few years ago. The merging of biology and technology will have profound effects, and will be recognized as the momentous scientific achievement of the early 21st century.

Unlike clunky technologies such as electronic medical records, which have in fact made the clinician–patient experience worse, I believe that the technologies I describe above will enhance and augment the clinician–patient relationship. As health care practitioners, we need to be open to new technologies and ways of assessing and treating our patients while making sure our clinical insights and experience inform the development of these new technologies.

Let’s buckle up. Life in psychiatry is going to get more interesting than ever!

In recent years, the pace of the development of novel new treatments for brain disorders in both psychiatry and neurology, including psychiatric disorders, has been the subject of much worry and hand-wringing.1

Some major pharmaceutical companies have stopped research programs in neuropsychiatry to focus on other, “easier” therapeutic areas where they think the biology is better understood and therefore drug development is more feasible.

However, I am now more optimistic than I have been in many years that we are on the verge of a promising era of pharmacotherapy that will usher in far better prevention, diagnosis, and management of neuropsychiatric disorders, and a better outcome for our patients. Why the optimism? There is a series of converging trends that justify it.

Funding for basic neuroscience research. Governments all over the world have woken up to the fact that brain disorders will account for the largest economic impact unless new treatments are developed. This has spurred multiple initiatives to better understand the underlying neurobiologic mechanisms of the brain in health and disease.2

Renewed enthusiasm for brain disorders from small pharmaceutical and mid-size biotechnology companies. While some of the larger pharmaceutical companies have withdrawn from pursuing new treatments for psychiatric disorders due to the need to satisfy “shareholders,” small and nimble biotechnology companies have stepped up, seeing an opportunity in a field that is not overcrowded and still has an extensive unmet need. These companies are developing truly novel treatments and approaches that can differentiate from current treatments. These include:

- rapid-acting antidepressants

- targeting specific symptom domains of psychiatric disorders, such as cognition, apathy, or anhedonia, that currently have no adequate or effective treatment

- novel therapeutic targets in a range of indications

- nonpharmacologic approaches.

Leading companies in this space include Allergan and Blackthorn Therapeutics. These companies and others have publicly discussed their commitment to developing new treatments for psychiatric disorders.

But large pharmaceutical companies should not be discounted. Examples of advances by larger companies include the recent FDA “breakthrough designation” for the development of balovaptan by Roche, a medication with the potential to improve “core social interaction and communication” in patients with autism, and the work Johnson & Johnson is conducting with S-ketamine for depression and acutely suicidal patients.

New scientific breakthroughs in areas such as synthetic biology, gene editing, nanotechnology, pluripotent cells, understanding the impact of the microbiome, and many other fields will dramatically accelerate the pace of scientific progress, allowing new treatment approaches not previously imagined.

New technologies. An array of new technologies—such as biosensors, artificial intelligence and machine learning, augmented and virtual reality, and other digital health tools—will impact every step of the “patient journey.” These will enable earlier detection and diagnosis, ongoing real-time assessment of symptoms, and more objective assessments, and they will facilitate the delivery of, and assessment of adherence to, treatments such as pharmacotherapy, neuromodulation, video games, apps, or a combination of these modalities.

Until recently, the idea of a video game or augmented reality glasses being viewed as serious and validated treatment modalities would have been considered science fiction. New ways of assessing patients—including voice, typing, activity on smartphones, diurnal rhythm, etc.—have the potential to dramatically improve the information clinicians will have about patient functioning in the real world. Another area where new technologies may eventually have a huge impact is in facilitating the prediction of suicide attempts.3

New digital therapeutics companies. It is no coincidence that the digital therapeutics companies that have been making the news and obtaining FDA approvals, such as Proteus Digital Health, Pear Therapeutics, Akili, and Click Therapeutics, are all addressing brain disorders.

Patient empowerment. With these new tools, the patient can become a true partner in the therapeutic alliance more than ever before. Patients can have an active role in diagnosis and be active participants in many new treatment modalities. There will be many new ways for patients to share their data to improve their care and to advance the science of these tools. Utilizing blockchain protocols, patients will have more control over how and with whom their data is shared, and even be compensated for it.

This may all seem like a medical “brave new world,” and perhaps a long way away. However, I believe these changes are happening at an exponential rate. It is hard to believe that common technological tools such as Google Maps, Gmail, and the smartphone first became available only a few years ago. The merging of biology and technology will have profound effects, and will be recognized as the momentous scientific achievement of the early 21st century.

Unlike clunky technologies such as electronic medical records, which have in fact made the clinician–patient experience worse, I believe that the technologies I describe above will enhance and augment the clinician–patient relationship. As health care practitioners, we need to be open to new technologies and ways of assessing and treating our patients while making sure our clinical insights and experience inform the development of these new technologies.

Let’s buckle up. Life in psychiatry is going to get more interesting than ever!

1. O’Hara M, Duncan P. The Guardian. Why ‘big pharma’ stopped searching for the next prozac. https://www.theguardian.com/society/2016/jan/27/prozac-next-psychiatric-wonder-drug-research-medicine-mental-illness. Published January 27, 2016. Accessed February 7, 2018.

2. Insel TR, Landis SC, Collins FS. The NIH BRAIN Initiative. Science. 2013;340(6133):687-688.

3. Vahabzadeh A, Sahin N, Kalali A. Digital suicide prevention: can technology become a game-changer? Innov Clin Neurosci. 2016;13(5-6):16-20.

1. O’Hara M, Duncan P. The Guardian. Why ‘big pharma’ stopped searching for the next prozac. https://www.theguardian.com/society/2016/jan/27/prozac-next-psychiatric-wonder-drug-research-medicine-mental-illness. Published January 27, 2016. Accessed February 7, 2018.

2. Insel TR, Landis SC, Collins FS. The NIH BRAIN Initiative. Science. 2013;340(6133):687-688.

3. Vahabzadeh A, Sahin N, Kalali A. Digital suicide prevention: can technology become a game-changer? Innov Clin Neurosci. 2016;13(5-6):16-20.

Psychiatry 2.0: Experiencing psychiatry’s new challenges together

“It is beyond a doubt that all our knowledge begins with experience.”

- Immanuel Kant

Medicine, a highly experiential profession, is constantly evolving. The consistency of change and the psychiatrist’s inherent wonder offers a paradoxical sense of comfort and conundrum.

As students, we look to our predecessors, associations, and peers to master concepts both concrete and abstract. And once we achieve competence at understanding mechanisms, applying biopsychosocial formulations, and effectively teaching what we’ve learned—everything changes!

We journey through a new era of medicine together. With burgeoning technology, intense politics, and confounding social media, we are undergoing new applications, hurdles to health care, and personal exposure to extremes that have never been experienced before. The landscape of psychiatric practice is changing. Its transformation inherently challenges our existing practices and standards.

It wasn’t too long ago that classroom fodder included how to deal with seeing your patient at a cocktail party. Contemporary discussions are more likely to address the patient who follows you on Twitter (and whom you follow back). Long ago are the days of educating students through a didactic model. Learning now occurs in collaborative group settings with a focus on the practical and hands-on experience. Budding psychiatrists are interested these days in talking about setting up their own apps, establishing a start-up company for health care, working on policy reform, and innovating new approaches to achieve social justice.

A history of challenge and change

Developing variables and expectations in this Millennial Age makes it an exciting time for psychiatrists to explore, adapt, and lead into the future. Fortunately, the field has had ample practice with challenge and changes. Social constructs of how individuals with mental illness were treated altered with William Battie, an English physician whose 1758 Treatise on Madness called for treatments to be utilized on rich and poor mental patients alike in asylums.1 Remember the days of chaining patients to bedposts on psychiatric wards? Of course not! Such archaic practices thankfully disappeared, due in large part to French physician Philippe Pinel. Patient care has evolved to encompass empathy, rights, and dignity.2

German physician Johann Christian Reil, who coined the term “psychiatry” more than 200 years ago, asserted that mental illness should be treated by the most highly qualified physicians.3 Such thinking seems obvious in 2018, but before Reil, the mental and physical states were seen as unrelated.

Modern psychiatry has certainly come a long way.4 We recognize mental health as being essential to overall health. Medications have evolved beyond lithium, chlorpromazine, and fluoxetine. We now have quarterly injectable antipsychotics and pills that patients can swallow and actually be monitored by their clinicians!4

The American Psychiatric Association (APA) has published multiple iterations of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders since its inception in 1968.5 And with those revisions have come changes that most contemporary colleagues could only describe as self-evident—such as the declassification of homosexuality as a mental disorder in 1973.

Despite these advances and the advent of the Mental Health Parity Act of 2008, experience has shown us that some things have seen little progress. Reil, who saw a nexus between mental and physical health, launched an anti-stigma campaign more than 200 years ago. This begs a question to colleagues: How far have we come? Or better yet, capitalizing on our knowledge, experience, and hopes: What else can we do?

The essential interaction between mental, chemical, and physical domains has given rise to psychiatry and its many subspecialties. Among them is forensic psychiatry, which deals with the overlap of mental health and legal matters.6

While often recognized for its relation to criminology, forensic psychiatry encompasses the entirety of legal mental health matters.7 These are things that the daily practitioner faces on a routine basis.

My mentor, Dr. Douglas Mossman, author of

A new department for a new era

The world is changing very rapidly, and we face new dilemmas in the midst of trying to uphold our duties to patients and the profession. There are emerging domains that psychiatrists will experience for the first time—leaving us with more questions than direction. And that is the impetus for this new department, Psychiatry 2.0.

The ever-evolving Internet opens doors for psychiatrists to access and educate a larger audience. It also provides a tool for psychiatrists to keep a web-based presence, something essential for competitive business practices to stay relevant. We are languishing in a political climate that challenges our sense of duty to the public, which often is in contrast with the ethical principles of our association. Technology also poses problems, whether it’s tracking our patients through the pills they ingest, following them on an app, or relying on data from wearable devices in lieu of a patient’s report. All of this suggests a potential for progress as well as problems.

The goal of Psychiatry 2.0 is to experience new challenges together. As Department Editor, I will cover an array of cutting-edge and controversial topics. Continuing with Dr. Mossman’s teachings—that forensic understanding enhances the clinical practice—this department will routinely combine evidence-based information with legal concepts.

Each article in Psychiatry 2.0 will be divided into 3 parts, focusing on a clinician’s dilemma, a duty, and a discussion. The dilemma will be relatable to the clinician in everyday practice. A practical and evidence-based approach will be taken to expound upon our duty as physicians. And finally, there will be discussion about where the field is going, and how it will likely change. In its quarterly publication, Psychiatry 2.0 will explore a diverse range of topics, including technology, social media, stigma, social justice, and politics.

In memoriam: Douglas Mossman, MD

In my role as Department Editor, I find myself already reflecting on the experience, wisdom, compassion, encouragement, and legacy of Dr. Mossman. A distinguished psychiatrist, gifted musician, and inspiring mentor and academician, Dr. Mossman embodied knowledge, creativity, and devotion.

Among Dr. Mossman’s many accolades, including more than 180 authored publications, he was recipient of the Guttmacher Award (2008, the APA) and Golden Apple (2017, the American Academy of Psychiatry and Law). Dr. Mossman was further known to many as a mentor and friend. He was generous with his experiences as a highly accomplished physician and thoughtful in his teachings and publications, leaving an enduring legacy.

Remembering Dr. Mossman’s sage voice and articulate writings will be essential to moving forward in this modern age of psychiatry, as we experience new dilemmas and opportunities.

1. Morris A. William Battie’s Treatise on Madness (1758) and John Monro’s remarks on Dr Battie’s Treatise (1758). Br J Psychiatry. 2008;192(4):257.

2. Scull A. Moral treatment reconsidered. Social order/mental disorder: Anglo-American psychiatry in historical perspective. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press; 1986;81-95.

3. Marneros A. Psychiatry’s 200th birthday. Br J Psychiatry. 2008;193(1):1-3.

4. Cade JF. Lithium salts in the treatment of psychotic excitement. Med J Aust. 1949;2(10):349-352.

5. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013.

6. Gold LH. Rediscovering forensic psychiatry. The American Psychiatric Publishing Textbook of Forensic Psychiatry. Simon RI, Gold LH, eds. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2004;3-36.

7. Gutheil TG. The history of forensic psychiatry. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2005;33(2):259-262.

“It is beyond a doubt that all our knowledge begins with experience.”

- Immanuel Kant

Medicine, a highly experiential profession, is constantly evolving. The consistency of change and the psychiatrist’s inherent wonder offers a paradoxical sense of comfort and conundrum.

As students, we look to our predecessors, associations, and peers to master concepts both concrete and abstract. And once we achieve competence at understanding mechanisms, applying biopsychosocial formulations, and effectively teaching what we’ve learned—everything changes!

We journey through a new era of medicine together. With burgeoning technology, intense politics, and confounding social media, we are undergoing new applications, hurdles to health care, and personal exposure to extremes that have never been experienced before. The landscape of psychiatric practice is changing. Its transformation inherently challenges our existing practices and standards.

It wasn’t too long ago that classroom fodder included how to deal with seeing your patient at a cocktail party. Contemporary discussions are more likely to address the patient who follows you on Twitter (and whom you follow back). Long ago are the days of educating students through a didactic model. Learning now occurs in collaborative group settings with a focus on the practical and hands-on experience. Budding psychiatrists are interested these days in talking about setting up their own apps, establishing a start-up company for health care, working on policy reform, and innovating new approaches to achieve social justice.

A history of challenge and change

Developing variables and expectations in this Millennial Age makes it an exciting time for psychiatrists to explore, adapt, and lead into the future. Fortunately, the field has had ample practice with challenge and changes. Social constructs of how individuals with mental illness were treated altered with William Battie, an English physician whose 1758 Treatise on Madness called for treatments to be utilized on rich and poor mental patients alike in asylums.1 Remember the days of chaining patients to bedposts on psychiatric wards? Of course not! Such archaic practices thankfully disappeared, due in large part to French physician Philippe Pinel. Patient care has evolved to encompass empathy, rights, and dignity.2

German physician Johann Christian Reil, who coined the term “psychiatry” more than 200 years ago, asserted that mental illness should be treated by the most highly qualified physicians.3 Such thinking seems obvious in 2018, but before Reil, the mental and physical states were seen as unrelated.

Modern psychiatry has certainly come a long way.4 We recognize mental health as being essential to overall health. Medications have evolved beyond lithium, chlorpromazine, and fluoxetine. We now have quarterly injectable antipsychotics and pills that patients can swallow and actually be monitored by their clinicians!4

The American Psychiatric Association (APA) has published multiple iterations of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders since its inception in 1968.5 And with those revisions have come changes that most contemporary colleagues could only describe as self-evident—such as the declassification of homosexuality as a mental disorder in 1973.

Despite these advances and the advent of the Mental Health Parity Act of 2008, experience has shown us that some things have seen little progress. Reil, who saw a nexus between mental and physical health, launched an anti-stigma campaign more than 200 years ago. This begs a question to colleagues: How far have we come? Or better yet, capitalizing on our knowledge, experience, and hopes: What else can we do?

The essential interaction between mental, chemical, and physical domains has given rise to psychiatry and its many subspecialties. Among them is forensic psychiatry, which deals with the overlap of mental health and legal matters.6

While often recognized for its relation to criminology, forensic psychiatry encompasses the entirety of legal mental health matters.7 These are things that the daily practitioner faces on a routine basis.

My mentor, Dr. Douglas Mossman, author of

A new department for a new era

The world is changing very rapidly, and we face new dilemmas in the midst of trying to uphold our duties to patients and the profession. There are emerging domains that psychiatrists will experience for the first time—leaving us with more questions than direction. And that is the impetus for this new department, Psychiatry 2.0.

The ever-evolving Internet opens doors for psychiatrists to access and educate a larger audience. It also provides a tool for psychiatrists to keep a web-based presence, something essential for competitive business practices to stay relevant. We are languishing in a political climate that challenges our sense of duty to the public, which often is in contrast with the ethical principles of our association. Technology also poses problems, whether it’s tracking our patients through the pills they ingest, following them on an app, or relying on data from wearable devices in lieu of a patient’s report. All of this suggests a potential for progress as well as problems.

The goal of Psychiatry 2.0 is to experience new challenges together. As Department Editor, I will cover an array of cutting-edge and controversial topics. Continuing with Dr. Mossman’s teachings—that forensic understanding enhances the clinical practice—this department will routinely combine evidence-based information with legal concepts.

Each article in Psychiatry 2.0 will be divided into 3 parts, focusing on a clinician’s dilemma, a duty, and a discussion. The dilemma will be relatable to the clinician in everyday practice. A practical and evidence-based approach will be taken to expound upon our duty as physicians. And finally, there will be discussion about where the field is going, and how it will likely change. In its quarterly publication, Psychiatry 2.0 will explore a diverse range of topics, including technology, social media, stigma, social justice, and politics.

In memoriam: Douglas Mossman, MD

In my role as Department Editor, I find myself already reflecting on the experience, wisdom, compassion, encouragement, and legacy of Dr. Mossman. A distinguished psychiatrist, gifted musician, and inspiring mentor and academician, Dr. Mossman embodied knowledge, creativity, and devotion.

Among Dr. Mossman’s many accolades, including more than 180 authored publications, he was recipient of the Guttmacher Award (2008, the APA) and Golden Apple (2017, the American Academy of Psychiatry and Law). Dr. Mossman was further known to many as a mentor and friend. He was generous with his experiences as a highly accomplished physician and thoughtful in his teachings and publications, leaving an enduring legacy.

Remembering Dr. Mossman’s sage voice and articulate writings will be essential to moving forward in this modern age of psychiatry, as we experience new dilemmas and opportunities.

“It is beyond a doubt that all our knowledge begins with experience.”

- Immanuel Kant

Medicine, a highly experiential profession, is constantly evolving. The consistency of change and the psychiatrist’s inherent wonder offers a paradoxical sense of comfort and conundrum.

As students, we look to our predecessors, associations, and peers to master concepts both concrete and abstract. And once we achieve competence at understanding mechanisms, applying biopsychosocial formulations, and effectively teaching what we’ve learned—everything changes!

We journey through a new era of medicine together. With burgeoning technology, intense politics, and confounding social media, we are undergoing new applications, hurdles to health care, and personal exposure to extremes that have never been experienced before. The landscape of psychiatric practice is changing. Its transformation inherently challenges our existing practices and standards.

It wasn’t too long ago that classroom fodder included how to deal with seeing your patient at a cocktail party. Contemporary discussions are more likely to address the patient who follows you on Twitter (and whom you follow back). Long ago are the days of educating students through a didactic model. Learning now occurs in collaborative group settings with a focus on the practical and hands-on experience. Budding psychiatrists are interested these days in talking about setting up their own apps, establishing a start-up company for health care, working on policy reform, and innovating new approaches to achieve social justice.

A history of challenge and change

Developing variables and expectations in this Millennial Age makes it an exciting time for psychiatrists to explore, adapt, and lead into the future. Fortunately, the field has had ample practice with challenge and changes. Social constructs of how individuals with mental illness were treated altered with William Battie, an English physician whose 1758 Treatise on Madness called for treatments to be utilized on rich and poor mental patients alike in asylums.1 Remember the days of chaining patients to bedposts on psychiatric wards? Of course not! Such archaic practices thankfully disappeared, due in large part to French physician Philippe Pinel. Patient care has evolved to encompass empathy, rights, and dignity.2

German physician Johann Christian Reil, who coined the term “psychiatry” more than 200 years ago, asserted that mental illness should be treated by the most highly qualified physicians.3 Such thinking seems obvious in 2018, but before Reil, the mental and physical states were seen as unrelated.

Modern psychiatry has certainly come a long way.4 We recognize mental health as being essential to overall health. Medications have evolved beyond lithium, chlorpromazine, and fluoxetine. We now have quarterly injectable antipsychotics and pills that patients can swallow and actually be monitored by their clinicians!4

The American Psychiatric Association (APA) has published multiple iterations of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders since its inception in 1968.5 And with those revisions have come changes that most contemporary colleagues could only describe as self-evident—such as the declassification of homosexuality as a mental disorder in 1973.

Despite these advances and the advent of the Mental Health Parity Act of 2008, experience has shown us that some things have seen little progress. Reil, who saw a nexus between mental and physical health, launched an anti-stigma campaign more than 200 years ago. This begs a question to colleagues: How far have we come? Or better yet, capitalizing on our knowledge, experience, and hopes: What else can we do?

The essential interaction between mental, chemical, and physical domains has given rise to psychiatry and its many subspecialties. Among them is forensic psychiatry, which deals with the overlap of mental health and legal matters.6

While often recognized for its relation to criminology, forensic psychiatry encompasses the entirety of legal mental health matters.7 These are things that the daily practitioner faces on a routine basis.

My mentor, Dr. Douglas Mossman, author of

A new department for a new era

The world is changing very rapidly, and we face new dilemmas in the midst of trying to uphold our duties to patients and the profession. There are emerging domains that psychiatrists will experience for the first time—leaving us with more questions than direction. And that is the impetus for this new department, Psychiatry 2.0.

The ever-evolving Internet opens doors for psychiatrists to access and educate a larger audience. It also provides a tool for psychiatrists to keep a web-based presence, something essential for competitive business practices to stay relevant. We are languishing in a political climate that challenges our sense of duty to the public, which often is in contrast with the ethical principles of our association. Technology also poses problems, whether it’s tracking our patients through the pills they ingest, following them on an app, or relying on data from wearable devices in lieu of a patient’s report. All of this suggests a potential for progress as well as problems.

The goal of Psychiatry 2.0 is to experience new challenges together. As Department Editor, I will cover an array of cutting-edge and controversial topics. Continuing with Dr. Mossman’s teachings—that forensic understanding enhances the clinical practice—this department will routinely combine evidence-based information with legal concepts.

Each article in Psychiatry 2.0 will be divided into 3 parts, focusing on a clinician’s dilemma, a duty, and a discussion. The dilemma will be relatable to the clinician in everyday practice. A practical and evidence-based approach will be taken to expound upon our duty as physicians. And finally, there will be discussion about where the field is going, and how it will likely change. In its quarterly publication, Psychiatry 2.0 will explore a diverse range of topics, including technology, social media, stigma, social justice, and politics.

In memoriam: Douglas Mossman, MD

In my role as Department Editor, I find myself already reflecting on the experience, wisdom, compassion, encouragement, and legacy of Dr. Mossman. A distinguished psychiatrist, gifted musician, and inspiring mentor and academician, Dr. Mossman embodied knowledge, creativity, and devotion.

Among Dr. Mossman’s many accolades, including more than 180 authored publications, he was recipient of the Guttmacher Award (2008, the APA) and Golden Apple (2017, the American Academy of Psychiatry and Law). Dr. Mossman was further known to many as a mentor and friend. He was generous with his experiences as a highly accomplished physician and thoughtful in his teachings and publications, leaving an enduring legacy.

Remembering Dr. Mossman’s sage voice and articulate writings will be essential to moving forward in this modern age of psychiatry, as we experience new dilemmas and opportunities.

1. Morris A. William Battie’s Treatise on Madness (1758) and John Monro’s remarks on Dr Battie’s Treatise (1758). Br J Psychiatry. 2008;192(4):257.

2. Scull A. Moral treatment reconsidered. Social order/mental disorder: Anglo-American psychiatry in historical perspective. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press; 1986;81-95.

3. Marneros A. Psychiatry’s 200th birthday. Br J Psychiatry. 2008;193(1):1-3.

4. Cade JF. Lithium salts in the treatment of psychotic excitement. Med J Aust. 1949;2(10):349-352.

5. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013.

6. Gold LH. Rediscovering forensic psychiatry. The American Psychiatric Publishing Textbook of Forensic Psychiatry. Simon RI, Gold LH, eds. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2004;3-36.

7. Gutheil TG. The history of forensic psychiatry. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2005;33(2):259-262.

1. Morris A. William Battie’s Treatise on Madness (1758) and John Monro’s remarks on Dr Battie’s Treatise (1758). Br J Psychiatry. 2008;192(4):257.

2. Scull A. Moral treatment reconsidered. Social order/mental disorder: Anglo-American psychiatry in historical perspective. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press; 1986;81-95.

3. Marneros A. Psychiatry’s 200th birthday. Br J Psychiatry. 2008;193(1):1-3.

4. Cade JF. Lithium salts in the treatment of psychotic excitement. Med J Aust. 1949;2(10):349-352.

5. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013.

6. Gold LH. Rediscovering forensic psychiatry. The American Psychiatric Publishing Textbook of Forensic Psychiatry. Simon RI, Gold LH, eds. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2004;3-36.

7. Gutheil TG. The history of forensic psychiatry. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2005;33(2):259-262.

Strategies for managing medication-induced hyperprolactinemia

Ms. E, age 23, presents to your office for a routine visit for management of bipolar I disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder with comorbid type 2 diabetes mellitus. She currently is taking

Ms. E has a history of self-discontinuing medication when adverse events occur. She has been hospitalized twice for psychosis and suicide attempts. Past psychotropic medications that have been discontinued due to adverse effects include ziprasidone (mild abnormal lip movement), olanzapine (ineffective and drowsy), valproic acid (tremor and abdominal discomfort), lithium (rash), and aripiprazole (increased fasting blood sugar and labile mood).

At her appointment today, Ms. E says she is concerned because she has been experiencing galactorrhea for the past 4 weeks. Her prolactin level is 14.4 ng/mL; a normal level for a woman who is not pregnant is <25 ng/mL. However, a repeat prolactin level is obtained, and is found to be elevated at 38 ng/mL.

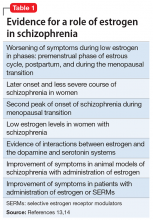

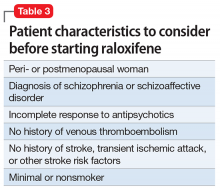

Prolactin, a polypeptide hormone that is secreted from the pituitary gland, has many functions, including involvement in the synthesis and maintenance of breast milk production, in reproductive behavior, and in luteal function.1,2 Hyperprolactinemia—an elevated prolactin level—is a common endocrinologic disorder of the hypothalamic–pituitary–axis.3 Children, adolescents, premenopausal women, and women in the perinatal period are more vulnerable to medication-induced hyperprolactinemia.4 If not asymptomatic, patients with hyperprolactinemia may experience amenorrhea, galactorrhea, hypogonadism, sexual dysfunction, or infertility.1,4 Chronic hyperprolactinemia may increase the risk for long-term complications, such as decreased bone mineral density and osteoporosis, although available evidence has conflicting findings.1

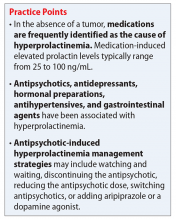

Hyperprolactinemia is diagnosed by a prolactin concentration above the upper reference range.3 Various hormones and neurotransmitters can impact inhibition or stimulation of prolactin release.5 For example, dopamine tonically inhibits prolactin release and synthesis, whereas estrogen stimulates prolactin secretion.1,5 Prolactin also can be elevated under several physiologic and pathologic conditions, such as during stressful situations, meals, or sexual activity.1,5 A prolactin level >250 ng/mL is usually indicative of a prolactinoma; however, some medications, such as strong D2 receptor antagonists (eg, risperidone, haloperidol), can cause significant elevation without evidence of prolactinoma.3 In the absence of a tumor, medications are often identified as the cause of hyperprolactinemia.3 According to the Endocrinology Society clinical practice guideline, medication-induced elevated prolactin levels are typically between 25 to 100 ng/mL.3

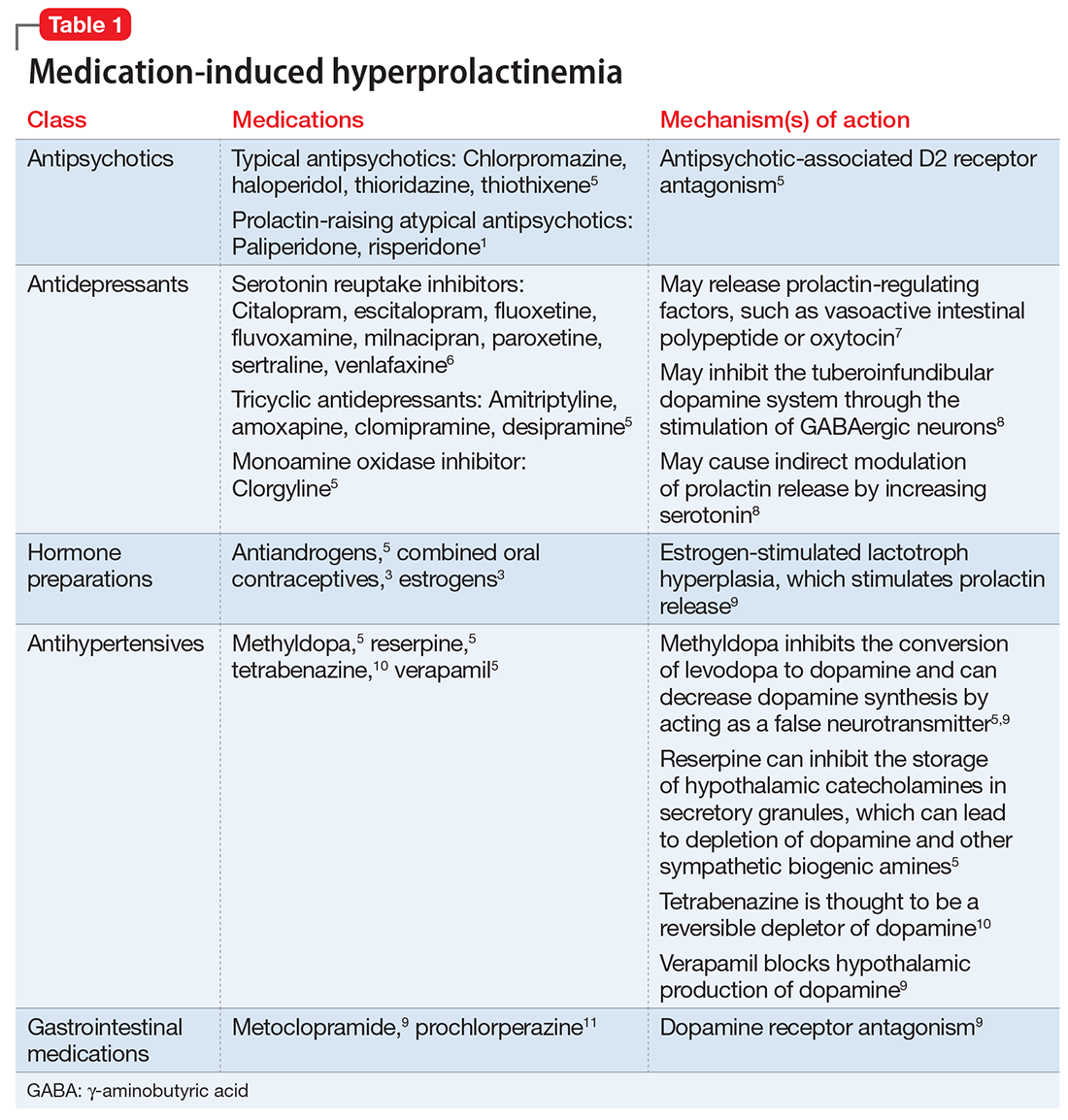

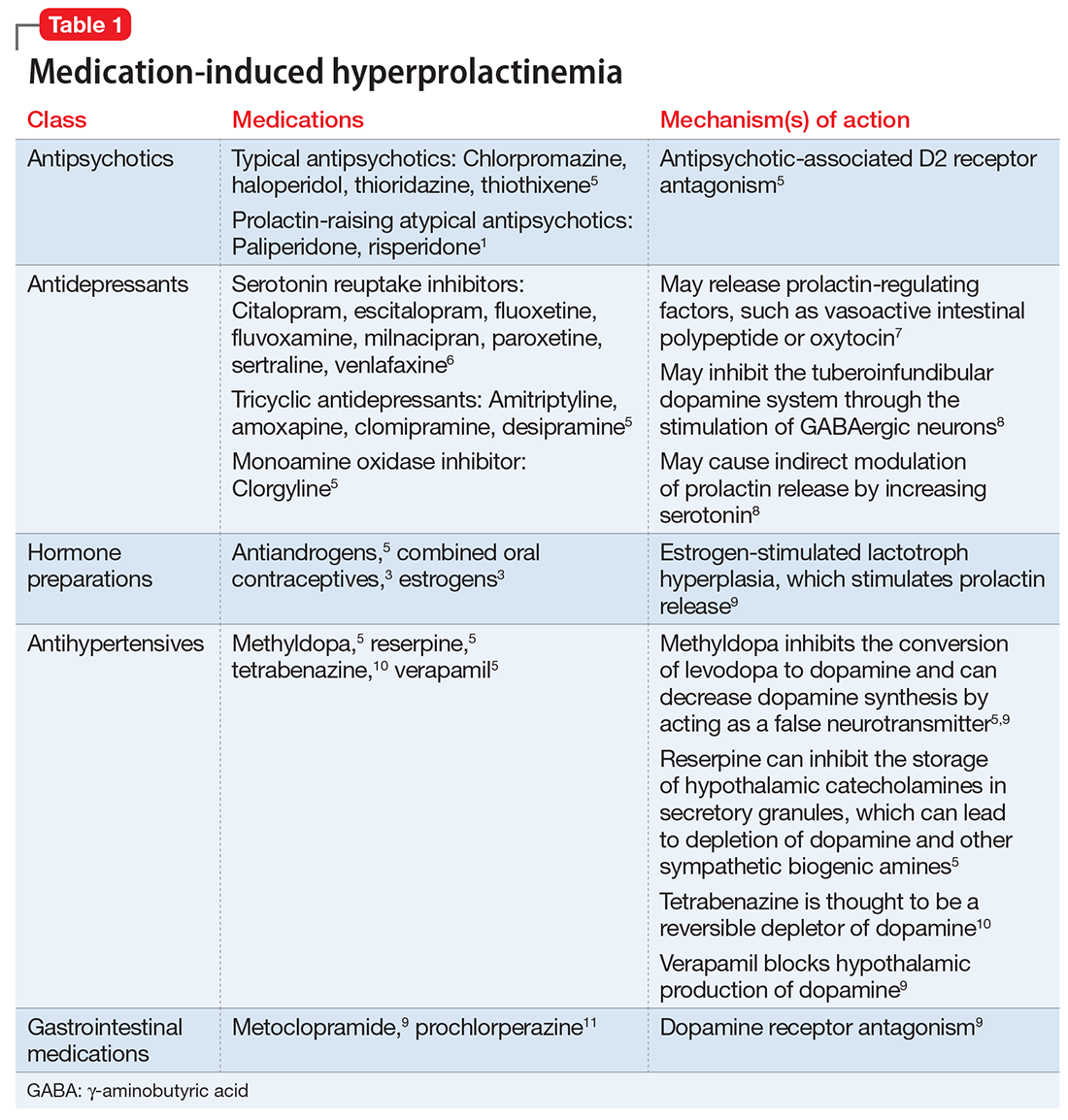

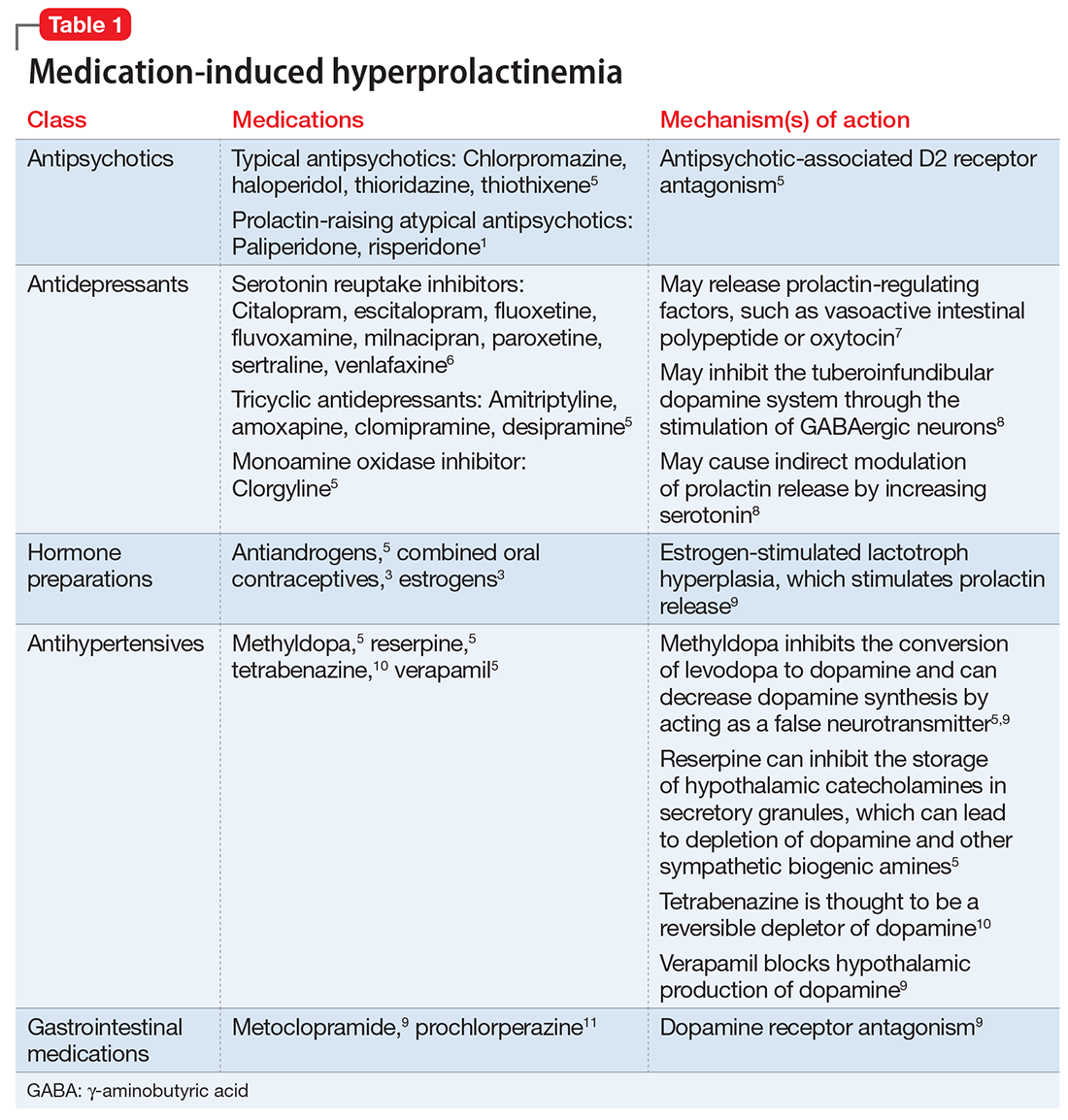

Medication-induced hyperprolactinemia

Antipsychotics, antidepressants, hormonal preparations, antihypertensives, and gastrointestinal agents have been associated with hyperprolactinemia (Table 11,3,5-11). These medication classes increase prolactin by decreasing dopamine, which facilitates disinhibition of prolactin synthesis and release, or increasing prolactin stimulating hormones, such as serotonin or estrogen.5

Antipsychotics are the most common medication-related cause of hyperprolactinemia.3 Typical antipsychotics are more likely to cause hyperprolactinemia than atypical antipsychotics; the incidence among patients taking typical antipsychotics is 40% to 90%.3 Atypical antipsychotics, except risperidone and paliperidone, are considered to cause less endocrinologic effects than typical antipsychotics through various mechanisms: serotonergic receptor antagonism, fast dissociation from D2 receptors, D2 receptor partial agonism, and preferential binding of D3 vs D2 receptors.1,5 By having transient D2 receptor association, clozapine and quetiapine are considered to have less risk of hyperprolactinemia compared with other atypical antipsychotics.1,5 Aripiprazole, brexpiprazole, and cariprazine are partial D2 receptor agonists, and cariprazine is the only agent that exhibits preferential binding to D3 receptors.12,13 Based on limited data, brexpiprazole and cariprazine may have prolactin-sparing properties given their partial D2 receptor agonism.12,13 However, one study found increased prolactin levels in some patients after treatment with brexpiprazole, 4 mg/d.14 Similarly, another study found that cariprazine could increase prolactin levels as much as 4.1 ng/mL, depending on the dose.15 Except for aripiprazole, brexpiprazole, cariprazine, and clozapine, all other atypical antipsychotics marketed in the United States have a standard warning in the package insert regarding prolactin elevations.1,16,17

Because antidepressants are less well-studied as a cause of medication-induced hyperprolactinemia, drawing definitive conclusions regarding incidence rates is limited, but the incidence seems to be fairly low.6,18 A French pharmacovigilance study found that of 182,836 spontaneous adverse drug events reported between 1985 and 2009, there were 159 reports of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) inducing hyperprolactinemia.6 F

Mirtazapine and bupropion have been found to be prolactin-neutral.5 Bupropion also has been reported to decrease prolactin levels, potentially via its ability to block dopamine reuptake.19

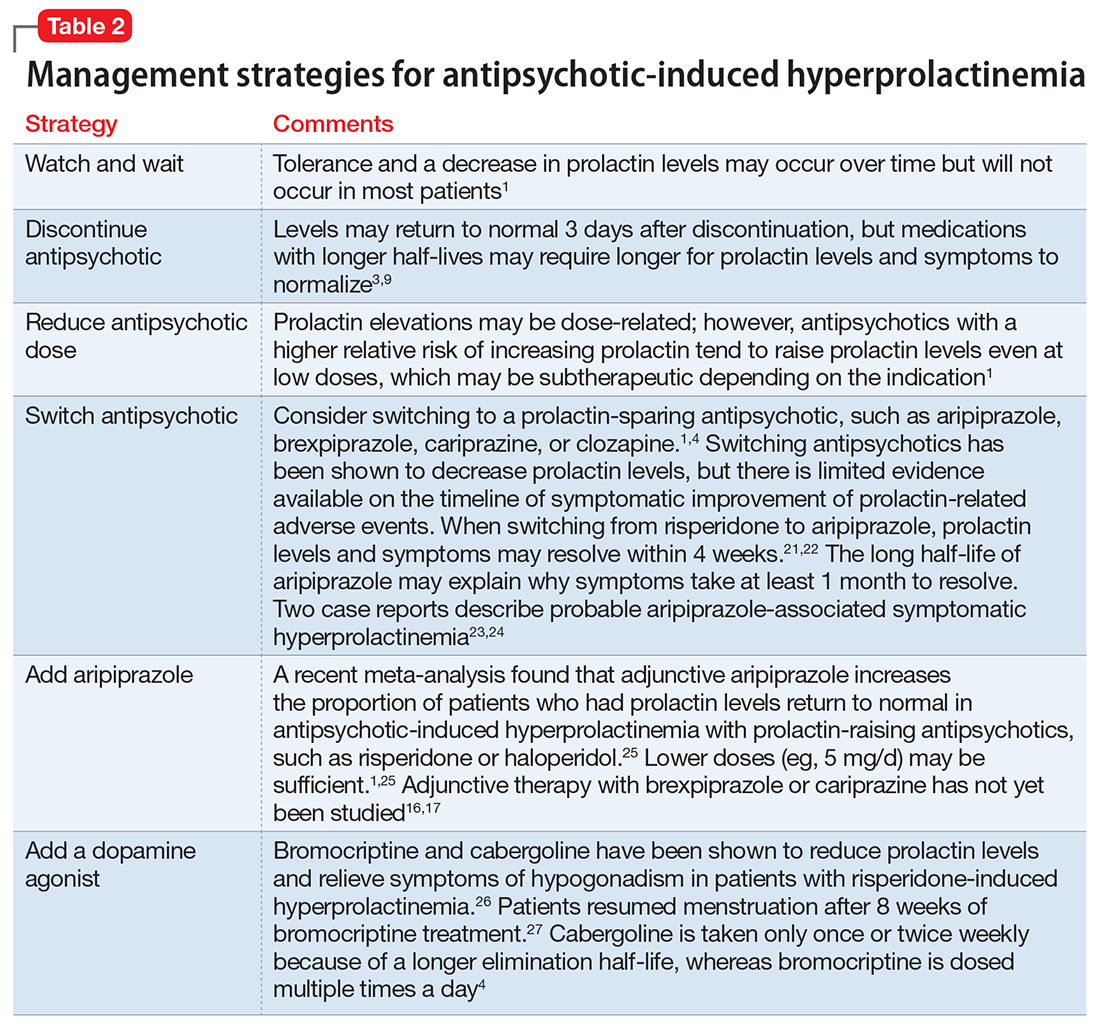

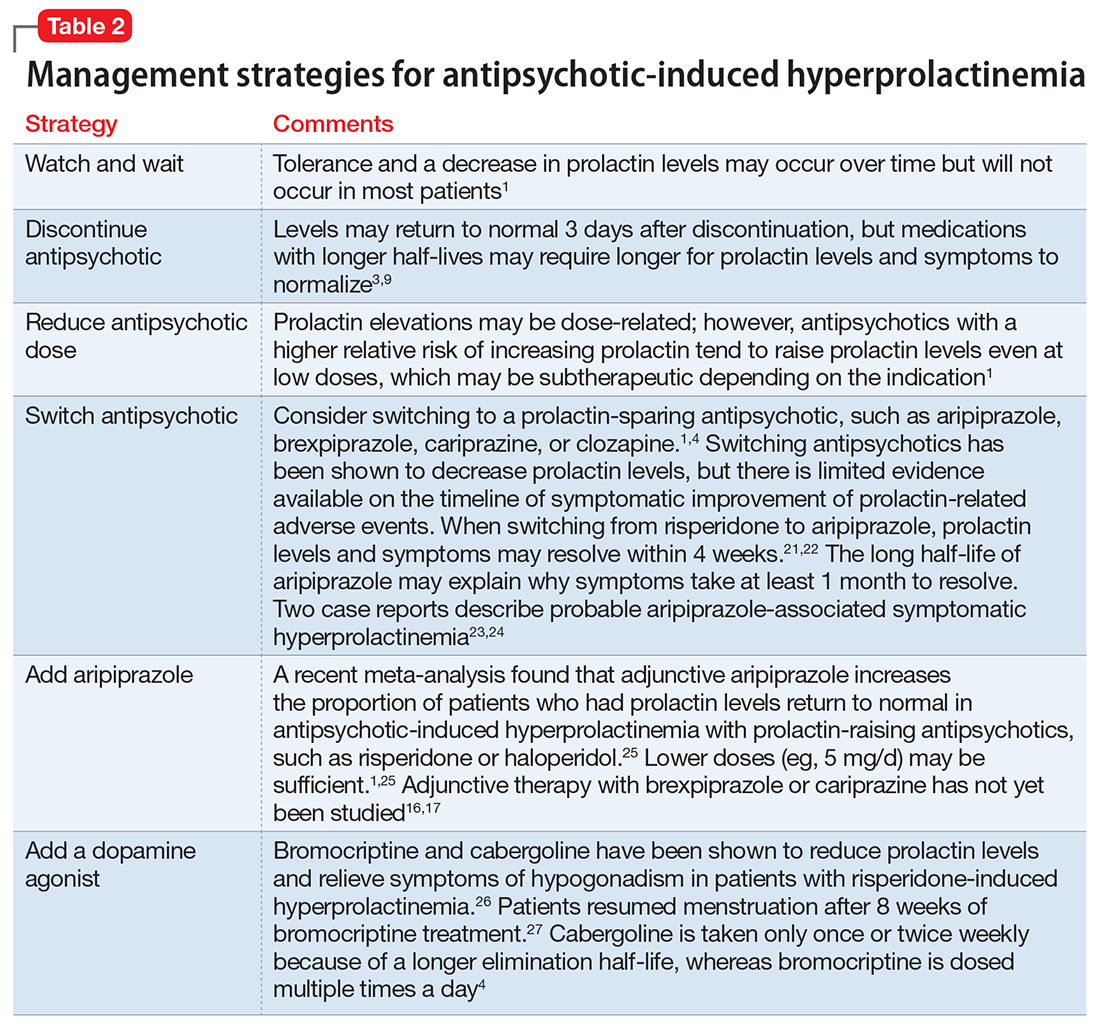

Managing medication-induced hyperprolactinemia

Screening for and identifying clinically significant hyperprolactinemia is critical, because adverse effects of medications can lead to nonadherence and clinical decompensation.20 Patients must be informed of potential symptoms of hyperprolactinemia, and clinicians should inquire about such symptoms at each visit. Routine monitoring of prolactin levels in asymptomatic patients is not necessary, because the Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline does not recommend treating patients with asymptomatic medication-induced hyperprolactinemia.3

In patients who report hyperprolactinemia symptoms, clinicians should review the patient’s prescribed medications and past medical history (eg, chronic renal failure, hypothyroidism) for potential causes or exacerbations, and address these factors accordingly.3 Order a measurement of prolactin level. A patient with a prolactin level >100 ng/mL should be referred to Endocrinology to rule out prolactinoma.1

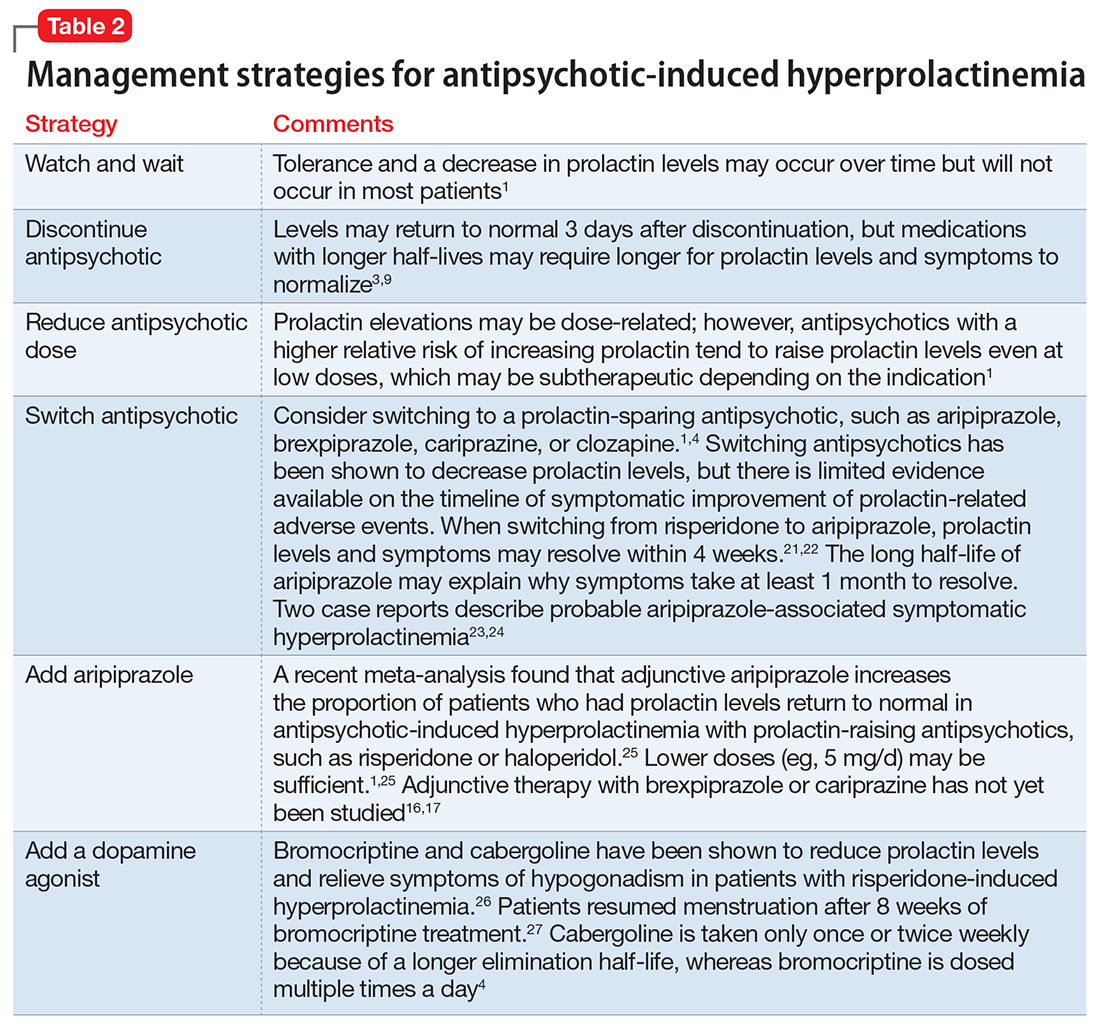

If a patient’s prolactin level is between 25 and 100 ng/mL, review the patient’s medications (Table 11,3,5-11), because prolactin levels within this range usually signal a medication-induced cause.3 For patients with antipsychotic-induced hyperprolactinemia, there are several management strategies (Table 21,3,4,9,16,17,21-27):

- Watch and wait may be warranted when the patient is experiencing mild hyperprolactinemia symptoms.

- Discontinue. If the patient can be maintained without an antipsychotic, discontinuing the antipsychotic would be a first-line option.3

- Reduce the dose. Reducing the antipsychotic dose may be the preferred strategy for patients with moderate to severe hyperprolactinemia symptoms who responded to the antipsychotic and do not wish to start adjunctive therapy.4

- Switching to a prolactin-sparing antipsychotic may help normalize prolactin levels and may be preferred when the risk of relapse is low.3 Dopamine agonists can treat medication-induced hyperprolactinemia, but may worsen psychiatric symptoms.28,29 Therefore, this may be the preferred strategy if the offending medication cannot be discontinued or switched, or if the patient has a comorbid prolactinoma.

Less data exist on managing hyperprolactinemia that is induced by a medication other than an antipsychotic; however, it seems reasonable that the same strategies could be implemented. Specifically, for SSRI–induced hyperprolactinemia, if clinically appropriate, switching to or adding an alternative antidepressant that may be prolactin-sparing, such as mirtazapine or bupropion, could be attempted.8 One study found that fluoxetine-induced galactorrhea ceased within 10 days of discontinuing the medication.30

CASE CONTINUED

Because Ms. E has been on the same medication regimen for 3 years and recently developed galactorrhea, it seems unlikely that her hyperprolactinemia is medication-induced. However, a tumor-related cause is less likely because the prolactin level is <100 ng/mL. Based on the literature, the only possible medication-induced cause of her galactorrhea is risperidone. Ms. E agrees to a trial of adjunctive oral aripiprazole, 5 mg/d, with close monitoring of her type 2 diabetes mellitus. Because of the long elimination half-life of aripiprazole, 1 month is required to monitor for improvement in galactorrhea. Ms. E is advised to use breast pads as a nonpharmacologic strategy in the interim. After 1 month of treatment, Ms. E denies galactorrhea symptoms and no longer requires the use of breast pads.

1. Peuskens J, Pani L, Detraux J, et al. The effects of novel and newly approved antipsychotics on serum prolactin levels: a comprehensive review. CNS Drugs.2014;28(5):421-453.

2. Freeman ME, Kanyicska B, Lerant A, et al. Prolactin: structure, function, and regulation of secretion. Physiol Rev. 2000;80(4):1523-1631.

3. Melmed S, Casanueva FF, Hoffman AR, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of hyperprolactinemia: an Endocrine Society Clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96(2):273-288.

4. Bostwick JR, Guthrie SK, Ellingrod VL. Antipsychotic-induced hyperprolactinemia. Pharmacotherapy. 2009;29(1):64-73.

5. La Torre D, Falorni A. Pharmacological causes of hyperprolactinemia. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2007;3(5):929-951.

6. Petit A, Piednoir D, Germain ML, et al. Drug-induced hyperprolactinemia: a case-non-case study from the national pharmacovigilance database [in French]. Therapie. 2003;58(2):159-163.

7. Emiliano AB, Fudge JL. From galactorrhea to osteopenia: rethinking serotonin-prolactin interactions. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2004;29(5):833-846.

8. Coker F, Taylor D. Antidepressant-induced hyperprolactinaemia: incidence, mechanisms and management. CNS Drugs. 2010;24(7):563-574.

9. Molitch ME. Medication induced hyperprolactinemia. Mayo Clin Proc. 2005;80(8):1050-1057.

10. Xenazine (tetrabenazine) [package insert]. Washington, DC: Prestwick Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; 2008.

11. Peña KS, Rosenfeld JA. Evaluation and treatment of galactorrhea. Am Fam Physician 2001;63(9):1763-1770.

12. Durgam S, Starace A, Li D, et al. The efficacy and tolerability of cariprazine in acute mania associated with bipolar I disorder: a phase II trial. Bipolar Disord. 2015;17(1):63-75.

13. Das S, Barnwal P, Winston AB, et al. Brexpiprazole: so far so good. Ther Adv Psychopharmacol. 2016;6(1):39-54.

14. Correll CU, Skuban A, Ouyang J, et al. Efficacy and safety of brexpiprazole for the treatment of acute schizophrenia: a 6-week randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Am J Psychiatry. 2015;172(9):870-880.

15. Durgam S, Earley W, Guo H, et al. Efficacy and safety of adjunctive cariprazine in inadequate responders to antidepressants: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study in adult patients with major depressive disorder. J Clin Pscyhiatry. 2016;77(3):371-378.

16. Rexulti (brexpiprazole) [package insert]. Tokyo, Japan: Otsuka Pharmaceuticals Inc.; 2015.

17. Cariprazine (Vraylar) [package insert]. Parsippany, New Jersey: Actavis Pharmacueitcals Inc.; 2015.

18. Marken PA, Haykal RF, Fisher JN. Management of psychotropic-induced hyperprolactinemia. Clin Pharm. 1992;11(10):851-856.

19. Meltzer HY, Fang VS, Tricou BJ, et al. Effect of antidepressants on neuroendocrine axis in humans. Adv Biochem Psychopharmacol. 1982;32:303-316.

20. Tsuboi T, Bies RR, Suzuki T, et al. Hyperprolactinemia and estimated dopamine D2 receptor occupancy in patients with schizophrenia: analysis of the CATIE data. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2013;45:178-182.

21. Lee BH, Kim YK, Park SH. Using aripiprazole to resolve antipsychotic-induced symptomatic hyperprolactinemia: a pilot study. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2006;30(4):714-717.

22. Lu ML, Shen WW, Chen CH. Time course of the changes in antipsychotic-induced hyperprolactinemia following the switch to aripiprazole. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2008;32(8):1978-1981.

23. Mendhekar DN, Andrade C. Galactorrhea with aripiprazole. Can J Psychiatry. 2005;50(4):243.

24. Joseph SP. Aripiprazole induced hyperprolactinemia in a young female with delusional disorder. Indian J Psychol Med. 2016;38(3):260-262.

25. Meng M, Li W, Zhang S, et al. Using aripiprazole to reduce antipsychotic-induced hyperprolactinemia: meta-analysis of currently available randomized controlled trials. Shaghai Arch Psychiatry. 2015;27(1):4-17.

26. Tollin SR. Use of the dopamine agonists bromocriptine and cabergoline in the management of risperidone induced hyperprolactinemia in patients with psychotic disorders. J Endocrinol Invest. 2000;23(11):765-70.

27. Yuan HN, Wang CY, Sze CW, et al. A randomized, crossover comparison of herbal medicine and bromocriptine against risperidone-induced hyperprolactinemia in patients with schizophrenia. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2008;28(3):264-370.

28. Chang SC, Chen CH, Lu ML. Cabergoline-induced psychotic exacerbation in schizophrenic patients. General Hospital Psychiatry. 2008;30(4):378-380.

29. Ishitobi M, Kosaka H, Shukunami K, et al. Adjunctive treatment with low-dosage pramipexole for risperidone-associated hyperprolactinemia and sexual dysfunction in a male patient with schizophrenia. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2011;31(2):243-245.

30. Peterson MC. Reversible galactorrhea and prolactin elevation related to fluoxetine use. Mayo Clin Proc. 2001;76(2):215-216.

Ms. E, age 23, presents to your office for a routine visit for management of bipolar I disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder with comorbid type 2 diabetes mellitus. She currently is taking

Ms. E has a history of self-discontinuing medication when adverse events occur. She has been hospitalized twice for psychosis and suicide attempts. Past psychotropic medications that have been discontinued due to adverse effects include ziprasidone (mild abnormal lip movement), olanzapine (ineffective and drowsy), valproic acid (tremor and abdominal discomfort), lithium (rash), and aripiprazole (increased fasting blood sugar and labile mood).

At her appointment today, Ms. E says she is concerned because she has been experiencing galactorrhea for the past 4 weeks. Her prolactin level is 14.4 ng/mL; a normal level for a woman who is not pregnant is <25 ng/mL. However, a repeat prolactin level is obtained, and is found to be elevated at 38 ng/mL.

Prolactin, a polypeptide hormone that is secreted from the pituitary gland, has many functions, including involvement in the synthesis and maintenance of breast milk production, in reproductive behavior, and in luteal function.1,2 Hyperprolactinemia—an elevated prolactin level—is a common endocrinologic disorder of the hypothalamic–pituitary–axis.3 Children, adolescents, premenopausal women, and women in the perinatal period are more vulnerable to medication-induced hyperprolactinemia.4 If not asymptomatic, patients with hyperprolactinemia may experience amenorrhea, galactorrhea, hypogonadism, sexual dysfunction, or infertility.1,4 Chronic hyperprolactinemia may increase the risk for long-term complications, such as decreased bone mineral density and osteoporosis, although available evidence has conflicting findings.1

Hyperprolactinemia is diagnosed by a prolactin concentration above the upper reference range.3 Various hormones and neurotransmitters can impact inhibition or stimulation of prolactin release.5 For example, dopamine tonically inhibits prolactin release and synthesis, whereas estrogen stimulates prolactin secretion.1,5 Prolactin also can be elevated under several physiologic and pathologic conditions, such as during stressful situations, meals, or sexual activity.1,5 A prolactin level >250 ng/mL is usually indicative of a prolactinoma; however, some medications, such as strong D2 receptor antagonists (eg, risperidone, haloperidol), can cause significant elevation without evidence of prolactinoma.3 In the absence of a tumor, medications are often identified as the cause of hyperprolactinemia.3 According to the Endocrinology Society clinical practice guideline, medication-induced elevated prolactin levels are typically between 25 to 100 ng/mL.3

Medication-induced hyperprolactinemia

Antipsychotics, antidepressants, hormonal preparations, antihypertensives, and gastrointestinal agents have been associated with hyperprolactinemia (Table 11,3,5-11). These medication classes increase prolactin by decreasing dopamine, which facilitates disinhibition of prolactin synthesis and release, or increasing prolactin stimulating hormones, such as serotonin or estrogen.5

Antipsychotics are the most common medication-related cause of hyperprolactinemia.3 Typical antipsychotics are more likely to cause hyperprolactinemia than atypical antipsychotics; the incidence among patients taking typical antipsychotics is 40% to 90%.3 Atypical antipsychotics, except risperidone and paliperidone, are considered to cause less endocrinologic effects than typical antipsychotics through various mechanisms: serotonergic receptor antagonism, fast dissociation from D2 receptors, D2 receptor partial agonism, and preferential binding of D3 vs D2 receptors.1,5 By having transient D2 receptor association, clozapine and quetiapine are considered to have less risk of hyperprolactinemia compared with other atypical antipsychotics.1,5 Aripiprazole, brexpiprazole, and cariprazine are partial D2 receptor agonists, and cariprazine is the only agent that exhibits preferential binding to D3 receptors.12,13 Based on limited data, brexpiprazole and cariprazine may have prolactin-sparing properties given their partial D2 receptor agonism.12,13 However, one study found increased prolactin levels in some patients after treatment with brexpiprazole, 4 mg/d.14 Similarly, another study found that cariprazine could increase prolactin levels as much as 4.1 ng/mL, depending on the dose.15 Except for aripiprazole, brexpiprazole, cariprazine, and clozapine, all other atypical antipsychotics marketed in the United States have a standard warning in the package insert regarding prolactin elevations.1,16,17

Because antidepressants are less well-studied as a cause of medication-induced hyperprolactinemia, drawing definitive conclusions regarding incidence rates is limited, but the incidence seems to be fairly low.6,18 A French pharmacovigilance study found that of 182,836 spontaneous adverse drug events reported between 1985 and 2009, there were 159 reports of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) inducing hyperprolactinemia.6 F

Mirtazapine and bupropion have been found to be prolactin-neutral.5 Bupropion also has been reported to decrease prolactin levels, potentially via its ability to block dopamine reuptake.19

Managing medication-induced hyperprolactinemia

Screening for and identifying clinically significant hyperprolactinemia is critical, because adverse effects of medications can lead to nonadherence and clinical decompensation.20 Patients must be informed of potential symptoms of hyperprolactinemia, and clinicians should inquire about such symptoms at each visit. Routine monitoring of prolactin levels in asymptomatic patients is not necessary, because the Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline does not recommend treating patients with asymptomatic medication-induced hyperprolactinemia.3

In patients who report hyperprolactinemia symptoms, clinicians should review the patient’s prescribed medications and past medical history (eg, chronic renal failure, hypothyroidism) for potential causes or exacerbations, and address these factors accordingly.3 Order a measurement of prolactin level. A patient with a prolactin level >100 ng/mL should be referred to Endocrinology to rule out prolactinoma.1

If a patient’s prolactin level is between 25 and 100 ng/mL, review the patient’s medications (Table 11,3,5-11), because prolactin levels within this range usually signal a medication-induced cause.3 For patients with antipsychotic-induced hyperprolactinemia, there are several management strategies (Table 21,3,4,9,16,17,21-27):

- Watch and wait may be warranted when the patient is experiencing mild hyperprolactinemia symptoms.

- Discontinue. If the patient can be maintained without an antipsychotic, discontinuing the antipsychotic would be a first-line option.3

- Reduce the dose. Reducing the antipsychotic dose may be the preferred strategy for patients with moderate to severe hyperprolactinemia symptoms who responded to the antipsychotic and do not wish to start adjunctive therapy.4

- Switching to a prolactin-sparing antipsychotic may help normalize prolactin levels and may be preferred when the risk of relapse is low.3 Dopamine agonists can treat medication-induced hyperprolactinemia, but may worsen psychiatric symptoms.28,29 Therefore, this may be the preferred strategy if the offending medication cannot be discontinued or switched, or if the patient has a comorbid prolactinoma.

Less data exist on managing hyperprolactinemia that is induced by a medication other than an antipsychotic; however, it seems reasonable that the same strategies could be implemented. Specifically, for SSRI–induced hyperprolactinemia, if clinically appropriate, switching to or adding an alternative antidepressant that may be prolactin-sparing, such as mirtazapine or bupropion, could be attempted.8 One study found that fluoxetine-induced galactorrhea ceased within 10 days of discontinuing the medication.30

CASE CONTINUED

Because Ms. E has been on the same medication regimen for 3 years and recently developed galactorrhea, it seems unlikely that her hyperprolactinemia is medication-induced. However, a tumor-related cause is less likely because the prolactin level is <100 ng/mL. Based on the literature, the only possible medication-induced cause of her galactorrhea is risperidone. Ms. E agrees to a trial of adjunctive oral aripiprazole, 5 mg/d, with close monitoring of her type 2 diabetes mellitus. Because of the long elimination half-life of aripiprazole, 1 month is required to monitor for improvement in galactorrhea. Ms. E is advised to use breast pads as a nonpharmacologic strategy in the interim. After 1 month of treatment, Ms. E denies galactorrhea symptoms and no longer requires the use of breast pads.

Ms. E, age 23, presents to your office for a routine visit for management of bipolar I disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder with comorbid type 2 diabetes mellitus. She currently is taking

Ms. E has a history of self-discontinuing medication when adverse events occur. She has been hospitalized twice for psychosis and suicide attempts. Past psychotropic medications that have been discontinued due to adverse effects include ziprasidone (mild abnormal lip movement), olanzapine (ineffective and drowsy), valproic acid (tremor and abdominal discomfort), lithium (rash), and aripiprazole (increased fasting blood sugar and labile mood).

At her appointment today, Ms. E says she is concerned because she has been experiencing galactorrhea for the past 4 weeks. Her prolactin level is 14.4 ng/mL; a normal level for a woman who is not pregnant is <25 ng/mL. However, a repeat prolactin level is obtained, and is found to be elevated at 38 ng/mL.

Prolactin, a polypeptide hormone that is secreted from the pituitary gland, has many functions, including involvement in the synthesis and maintenance of breast milk production, in reproductive behavior, and in luteal function.1,2 Hyperprolactinemia—an elevated prolactin level—is a common endocrinologic disorder of the hypothalamic–pituitary–axis.3 Children, adolescents, premenopausal women, and women in the perinatal period are more vulnerable to medication-induced hyperprolactinemia.4 If not asymptomatic, patients with hyperprolactinemia may experience amenorrhea, galactorrhea, hypogonadism, sexual dysfunction, or infertility.1,4 Chronic hyperprolactinemia may increase the risk for long-term complications, such as decreased bone mineral density and osteoporosis, although available evidence has conflicting findings.1

Hyperprolactinemia is diagnosed by a prolactin concentration above the upper reference range.3 Various hormones and neurotransmitters can impact inhibition or stimulation of prolactin release.5 For example, dopamine tonically inhibits prolactin release and synthesis, whereas estrogen stimulates prolactin secretion.1,5 Prolactin also can be elevated under several physiologic and pathologic conditions, such as during stressful situations, meals, or sexual activity.1,5 A prolactin level >250 ng/mL is usually indicative of a prolactinoma; however, some medications, such as strong D2 receptor antagonists (eg, risperidone, haloperidol), can cause significant elevation without evidence of prolactinoma.3 In the absence of a tumor, medications are often identified as the cause of hyperprolactinemia.3 According to the Endocrinology Society clinical practice guideline, medication-induced elevated prolactin levels are typically between 25 to 100 ng/mL.3

Medication-induced hyperprolactinemia

Antipsychotics, antidepressants, hormonal preparations, antihypertensives, and gastrointestinal agents have been associated with hyperprolactinemia (Table 11,3,5-11). These medication classes increase prolactin by decreasing dopamine, which facilitates disinhibition of prolactin synthesis and release, or increasing prolactin stimulating hormones, such as serotonin or estrogen.5

Antipsychotics are the most common medication-related cause of hyperprolactinemia.3 Typical antipsychotics are more likely to cause hyperprolactinemia than atypical antipsychotics; the incidence among patients taking typical antipsychotics is 40% to 90%.3 Atypical antipsychotics, except risperidone and paliperidone, are considered to cause less endocrinologic effects than typical antipsychotics through various mechanisms: serotonergic receptor antagonism, fast dissociation from D2 receptors, D2 receptor partial agonism, and preferential binding of D3 vs D2 receptors.1,5 By having transient D2 receptor association, clozapine and quetiapine are considered to have less risk of hyperprolactinemia compared with other atypical antipsychotics.1,5 Aripiprazole, brexpiprazole, and cariprazine are partial D2 receptor agonists, and cariprazine is the only agent that exhibits preferential binding to D3 receptors.12,13 Based on limited data, brexpiprazole and cariprazine may have prolactin-sparing properties given their partial D2 receptor agonism.12,13 However, one study found increased prolactin levels in some patients after treatment with brexpiprazole, 4 mg/d.14 Similarly, another study found that cariprazine could increase prolactin levels as much as 4.1 ng/mL, depending on the dose.15 Except for aripiprazole, brexpiprazole, cariprazine, and clozapine, all other atypical antipsychotics marketed in the United States have a standard warning in the package insert regarding prolactin elevations.1,16,17

Because antidepressants are less well-studied as a cause of medication-induced hyperprolactinemia, drawing definitive conclusions regarding incidence rates is limited, but the incidence seems to be fairly low.6,18 A French pharmacovigilance study found that of 182,836 spontaneous adverse drug events reported between 1985 and 2009, there were 159 reports of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) inducing hyperprolactinemia.6 F

Mirtazapine and bupropion have been found to be prolactin-neutral.5 Bupropion also has been reported to decrease prolactin levels, potentially via its ability to block dopamine reuptake.19

Managing medication-induced hyperprolactinemia

Screening for and identifying clinically significant hyperprolactinemia is critical, because adverse effects of medications can lead to nonadherence and clinical decompensation.20 Patients must be informed of potential symptoms of hyperprolactinemia, and clinicians should inquire about such symptoms at each visit. Routine monitoring of prolactin levels in asymptomatic patients is not necessary, because the Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline does not recommend treating patients with asymptomatic medication-induced hyperprolactinemia.3

In patients who report hyperprolactinemia symptoms, clinicians should review the patient’s prescribed medications and past medical history (eg, chronic renal failure, hypothyroidism) for potential causes or exacerbations, and address these factors accordingly.3 Order a measurement of prolactin level. A patient with a prolactin level >100 ng/mL should be referred to Endocrinology to rule out prolactinoma.1

If a patient’s prolactin level is between 25 and 100 ng/mL, review the patient’s medications (Table 11,3,5-11), because prolactin levels within this range usually signal a medication-induced cause.3 For patients with antipsychotic-induced hyperprolactinemia, there are several management strategies (Table 21,3,4,9,16,17,21-27):

- Watch and wait may be warranted when the patient is experiencing mild hyperprolactinemia symptoms.

- Discontinue. If the patient can be maintained without an antipsychotic, discontinuing the antipsychotic would be a first-line option.3

- Reduce the dose. Reducing the antipsychotic dose may be the preferred strategy for patients with moderate to severe hyperprolactinemia symptoms who responded to the antipsychotic and do not wish to start adjunctive therapy.4

- Switching to a prolactin-sparing antipsychotic may help normalize prolactin levels and may be preferred when the risk of relapse is low.3 Dopamine agonists can treat medication-induced hyperprolactinemia, but may worsen psychiatric symptoms.28,29 Therefore, this may be the preferred strategy if the offending medication cannot be discontinued or switched, or if the patient has a comorbid prolactinoma.

Less data exist on managing hyperprolactinemia that is induced by a medication other than an antipsychotic; however, it seems reasonable that the same strategies could be implemented. Specifically, for SSRI–induced hyperprolactinemia, if clinically appropriate, switching to or adding an alternative antidepressant that may be prolactin-sparing, such as mirtazapine or bupropion, could be attempted.8 One study found that fluoxetine-induced galactorrhea ceased within 10 days of discontinuing the medication.30

CASE CONTINUED