User login

Can You Predict How Often Patients Will Have Seizures?

A mathematical formula may help determine the variability in the frequency of patients’ seizures, according to researchers from the National Institutes of Health, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, and other institutions.

- Because clinicians and researchers have yet to develop a reliable way to predict the range of each patient’s seizure counts, investigators analyzed 3 independent seizure diary databases to look for patterns.

- The databases included 3106 entries in Seizure Tracker, 93 from the Human Epilepsy Project, and 15 from NeuroVista.

- The analysis looked at the relationship between mean seizure frequency and the standard deviation of seizure frequency.

- The analysis revealed that the logarithm of the mean seizure count had a linear relationship with the log of the standard deviation (R2 >0.83).

- Using this mathematical relationship, researchers were able to predict variability in seizure frequency with a 94% accuracy rate, compared to only 77% using traditional prediction methods.

Goldenholz DM, Goldenholz SR, Moss R, et al. Is seizure frequency variance a predictable quantity? Ann Clin Transl Neurol. 2018;5(2):201-207.

A mathematical formula may help determine the variability in the frequency of patients’ seizures, according to researchers from the National Institutes of Health, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, and other institutions.

- Because clinicians and researchers have yet to develop a reliable way to predict the range of each patient’s seizure counts, investigators analyzed 3 independent seizure diary databases to look for patterns.

- The databases included 3106 entries in Seizure Tracker, 93 from the Human Epilepsy Project, and 15 from NeuroVista.

- The analysis looked at the relationship between mean seizure frequency and the standard deviation of seizure frequency.

- The analysis revealed that the logarithm of the mean seizure count had a linear relationship with the log of the standard deviation (R2 >0.83).

- Using this mathematical relationship, researchers were able to predict variability in seizure frequency with a 94% accuracy rate, compared to only 77% using traditional prediction methods.

Goldenholz DM, Goldenholz SR, Moss R, et al. Is seizure frequency variance a predictable quantity? Ann Clin Transl Neurol. 2018;5(2):201-207.

A mathematical formula may help determine the variability in the frequency of patients’ seizures, according to researchers from the National Institutes of Health, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, and other institutions.

- Because clinicians and researchers have yet to develop a reliable way to predict the range of each patient’s seizure counts, investigators analyzed 3 independent seizure diary databases to look for patterns.

- The databases included 3106 entries in Seizure Tracker, 93 from the Human Epilepsy Project, and 15 from NeuroVista.

- The analysis looked at the relationship between mean seizure frequency and the standard deviation of seizure frequency.

- The analysis revealed that the logarithm of the mean seizure count had a linear relationship with the log of the standard deviation (R2 >0.83).

- Using this mathematical relationship, researchers were able to predict variability in seizure frequency with a 94% accuracy rate, compared to only 77% using traditional prediction methods.

Goldenholz DM, Goldenholz SR, Moss R, et al. Is seizure frequency variance a predictable quantity? Ann Clin Transl Neurol. 2018;5(2):201-207.

Amygdalohippocampectomy For Intractable Mesial TLE

Amygdalohippocampectomy may offer hope for select patients with intractable temporal lobe epilepsy according to a review published in Brain Sciences by Warren Boling, MD, a neurosurgeon at Loma Linda University Health.

- Patients with mesial temporal lobe epilepsy that does not respond to medical therapy may experience freedom from their seizures by means of resection surgery.

- Two surgical approaches worth considering in this patient population are standard anterior temporal removal and selective amygdalohippocampectomy.

- The advantage of selective amygdalohippocampectomy is the potential to remove the seizure focal point, thus avoiding the removal of portions of the temporary lobe that are not actually part of the epileptogenic zone.

- Selective amygdalohippocampectomy (SAH), if performed using a minimally access approach, also has the advantage of allowing patients to recover more quickly.

- Evidence also suggests that SAH may provide cognitive benefits that standard temporal resections do not.

Boling WW. Surgical Considerations of Intractable Mesial Temporal Lobe Epilepsy. Brain Sciences. 2018;8:35. doi:10.3390/brainsci8020035.

Amygdalohippocampectomy may offer hope for select patients with intractable temporal lobe epilepsy according to a review published in Brain Sciences by Warren Boling, MD, a neurosurgeon at Loma Linda University Health.

- Patients with mesial temporal lobe epilepsy that does not respond to medical therapy may experience freedom from their seizures by means of resection surgery.

- Two surgical approaches worth considering in this patient population are standard anterior temporal removal and selective amygdalohippocampectomy.

- The advantage of selective amygdalohippocampectomy is the potential to remove the seizure focal point, thus avoiding the removal of portions of the temporary lobe that are not actually part of the epileptogenic zone.

- Selective amygdalohippocampectomy (SAH), if performed using a minimally access approach, also has the advantage of allowing patients to recover more quickly.

- Evidence also suggests that SAH may provide cognitive benefits that standard temporal resections do not.

Boling WW. Surgical Considerations of Intractable Mesial Temporal Lobe Epilepsy. Brain Sciences. 2018;8:35. doi:10.3390/brainsci8020035.

Amygdalohippocampectomy may offer hope for select patients with intractable temporal lobe epilepsy according to a review published in Brain Sciences by Warren Boling, MD, a neurosurgeon at Loma Linda University Health.

- Patients with mesial temporal lobe epilepsy that does not respond to medical therapy may experience freedom from their seizures by means of resection surgery.

- Two surgical approaches worth considering in this patient population are standard anterior temporal removal and selective amygdalohippocampectomy.

- The advantage of selective amygdalohippocampectomy is the potential to remove the seizure focal point, thus avoiding the removal of portions of the temporary lobe that are not actually part of the epileptogenic zone.

- Selective amygdalohippocampectomy (SAH), if performed using a minimally access approach, also has the advantage of allowing patients to recover more quickly.

- Evidence also suggests that SAH may provide cognitive benefits that standard temporal resections do not.

Boling WW. Surgical Considerations of Intractable Mesial Temporal Lobe Epilepsy. Brain Sciences. 2018;8:35. doi:10.3390/brainsci8020035.

Intermittent dosing cuts time to extubation for surgical patients

SAN ANTONIO – according to a preliminary analysis of a randomized trial.

Additionally, the researchers found that much lower amounts of sedation and analgesia were given to patients who underwent intermittent dosing, compared with patients who received a continuous infusion.

Of the 95 patients in the trial, 39 were randomized to intermittent dosing and 56 to the control group of continuous infusion, with the drugs midazolam and fentanyl having been given to both groups.

Mean mechanical ventilation time was 65 hours in the intermittent dosing arm, versus 111 hours in the continuous infusion arm (P less than 0.03), noted Dr. Sich, a fourth-year general surgery resident at Abington Memorial Hospital, Abington, Pa., during his presentation.

Patients in the continuous infusions arm of the trial received a mean of 73.1 mg of midazolam, compared with 18 mg for the intermittent dosing arm, a difference that approached very closely to statistical significance (P = 0.06) and was thrown off in the latest iteration by an outlier, Dr. Sich explained. The relative difference between the mean fentanyl doses administered was even greater between the two groups, with 5,848 mcg given to patients in the control group, versus the 942 mcg given to participants in the intermittent dosing group (P less than 0.01).

“This is a new way to use an old drug, and it really might be beneficial, and can even be used as first-line therapy and a way to keep patients awake and off the ventilator,” said Dr. Sich, referring to the intermittent dosing. Continuous infusions leave patients oversedated and prolong ventilation time.

“What we propose, rather, is using a sliding-scale intermittent pain and sedation regimen,” he said. “We believe that it won’t compromise patient care and won’t compromise patient comfort, and it will lead to shorter mechanical ventilation times for surgical patients than continuous infusions.”

Dr. Sich also pointed out that there was no difference in time spent at target levels of sedation and analgesia between the two trial groups. Referring to this finding, he noted that “we wanted to make sure that in the intermittent arm we’re giving them less drug, but we don’t want them to be [less comfortable].”

One potential drawback to the intermittent dosing approach is that it is more nursing intensive, according to Dr. Sich, since it is based on a nursing treatment protocol to give medications every hour.

Intermittent dosing is “more hands-on” than a typical continuous infusion approach and so was more challenging for nurses who, per the treatment protocol, had to give medications every hour, he explained. However, “when they saw the data in the months and year as we’ve been going on, they’re actually quite proud of our work and their work.”

Gilman Baker Allen, MD, a pulmonologist and intensivist at the University of Vermont Medical Center, Burlington, said the study was “terrific work” and acknowledged the importance of gauging nurse satisfaction with the protocol.

“I think that when you feed this kind of data back to nursing staff, they may not be satisfied with the intensity of the work, but when they see the rewards at the end, it oftentimes is a very positive experience,” said Dr. Allen, who moderated the session.

Dr. Sich and his colleagues had no financial disclosures or conflicts of interest related to the study.

SOURCE: Sich N et al. CCC47, Abstract 18.

SAN ANTONIO – according to a preliminary analysis of a randomized trial.

Additionally, the researchers found that much lower amounts of sedation and analgesia were given to patients who underwent intermittent dosing, compared with patients who received a continuous infusion.

Of the 95 patients in the trial, 39 were randomized to intermittent dosing and 56 to the control group of continuous infusion, with the drugs midazolam and fentanyl having been given to both groups.

Mean mechanical ventilation time was 65 hours in the intermittent dosing arm, versus 111 hours in the continuous infusion arm (P less than 0.03), noted Dr. Sich, a fourth-year general surgery resident at Abington Memorial Hospital, Abington, Pa., during his presentation.

Patients in the continuous infusions arm of the trial received a mean of 73.1 mg of midazolam, compared with 18 mg for the intermittent dosing arm, a difference that approached very closely to statistical significance (P = 0.06) and was thrown off in the latest iteration by an outlier, Dr. Sich explained. The relative difference between the mean fentanyl doses administered was even greater between the two groups, with 5,848 mcg given to patients in the control group, versus the 942 mcg given to participants in the intermittent dosing group (P less than 0.01).

“This is a new way to use an old drug, and it really might be beneficial, and can even be used as first-line therapy and a way to keep patients awake and off the ventilator,” said Dr. Sich, referring to the intermittent dosing. Continuous infusions leave patients oversedated and prolong ventilation time.

“What we propose, rather, is using a sliding-scale intermittent pain and sedation regimen,” he said. “We believe that it won’t compromise patient care and won’t compromise patient comfort, and it will lead to shorter mechanical ventilation times for surgical patients than continuous infusions.”

Dr. Sich also pointed out that there was no difference in time spent at target levels of sedation and analgesia between the two trial groups. Referring to this finding, he noted that “we wanted to make sure that in the intermittent arm we’re giving them less drug, but we don’t want them to be [less comfortable].”

One potential drawback to the intermittent dosing approach is that it is more nursing intensive, according to Dr. Sich, since it is based on a nursing treatment protocol to give medications every hour.

Intermittent dosing is “more hands-on” than a typical continuous infusion approach and so was more challenging for nurses who, per the treatment protocol, had to give medications every hour, he explained. However, “when they saw the data in the months and year as we’ve been going on, they’re actually quite proud of our work and their work.”

Gilman Baker Allen, MD, a pulmonologist and intensivist at the University of Vermont Medical Center, Burlington, said the study was “terrific work” and acknowledged the importance of gauging nurse satisfaction with the protocol.

“I think that when you feed this kind of data back to nursing staff, they may not be satisfied with the intensity of the work, but when they see the rewards at the end, it oftentimes is a very positive experience,” said Dr. Allen, who moderated the session.

Dr. Sich and his colleagues had no financial disclosures or conflicts of interest related to the study.

SOURCE: Sich N et al. CCC47, Abstract 18.

SAN ANTONIO – according to a preliminary analysis of a randomized trial.

Additionally, the researchers found that much lower amounts of sedation and analgesia were given to patients who underwent intermittent dosing, compared with patients who received a continuous infusion.

Of the 95 patients in the trial, 39 were randomized to intermittent dosing and 56 to the control group of continuous infusion, with the drugs midazolam and fentanyl having been given to both groups.

Mean mechanical ventilation time was 65 hours in the intermittent dosing arm, versus 111 hours in the continuous infusion arm (P less than 0.03), noted Dr. Sich, a fourth-year general surgery resident at Abington Memorial Hospital, Abington, Pa., during his presentation.

Patients in the continuous infusions arm of the trial received a mean of 73.1 mg of midazolam, compared with 18 mg for the intermittent dosing arm, a difference that approached very closely to statistical significance (P = 0.06) and was thrown off in the latest iteration by an outlier, Dr. Sich explained. The relative difference between the mean fentanyl doses administered was even greater between the two groups, with 5,848 mcg given to patients in the control group, versus the 942 mcg given to participants in the intermittent dosing group (P less than 0.01).

“This is a new way to use an old drug, and it really might be beneficial, and can even be used as first-line therapy and a way to keep patients awake and off the ventilator,” said Dr. Sich, referring to the intermittent dosing. Continuous infusions leave patients oversedated and prolong ventilation time.

“What we propose, rather, is using a sliding-scale intermittent pain and sedation regimen,” he said. “We believe that it won’t compromise patient care and won’t compromise patient comfort, and it will lead to shorter mechanical ventilation times for surgical patients than continuous infusions.”

Dr. Sich also pointed out that there was no difference in time spent at target levels of sedation and analgesia between the two trial groups. Referring to this finding, he noted that “we wanted to make sure that in the intermittent arm we’re giving them less drug, but we don’t want them to be [less comfortable].”

One potential drawback to the intermittent dosing approach is that it is more nursing intensive, according to Dr. Sich, since it is based on a nursing treatment protocol to give medications every hour.

Intermittent dosing is “more hands-on” than a typical continuous infusion approach and so was more challenging for nurses who, per the treatment protocol, had to give medications every hour, he explained. However, “when they saw the data in the months and year as we’ve been going on, they’re actually quite proud of our work and their work.”

Gilman Baker Allen, MD, a pulmonologist and intensivist at the University of Vermont Medical Center, Burlington, said the study was “terrific work” and acknowledged the importance of gauging nurse satisfaction with the protocol.

“I think that when you feed this kind of data back to nursing staff, they may not be satisfied with the intensity of the work, but when they see the rewards at the end, it oftentimes is a very positive experience,” said Dr. Allen, who moderated the session.

Dr. Sich and his colleagues had no financial disclosures or conflicts of interest related to the study.

SOURCE: Sich N et al. CCC47, Abstract 18.

Reporting from CCC47

Key clinical point: Among patients requiring ventilation, intermittent administration of sedation and analgesia significantly reduced mechanical ventilation time and total amount of drugs versus a continuous infusion approach.

Major finding: Mean mechanical ventilation time was 65 hours in the intermittent dosing arm, versus 111 hours in the continuous infusion arm (P less than 0.03).

Data source: A single-blinded, randomized, controlled trial of 95 surgical patients requiring ventilation.

Disclosures: The authors reported no financial disclosures or conflicts of interest related to the study.

Source: Sich N et al. CCC47, Abstract 18.

Do Seizures Have an Impact on Autism Symptom Severity?

Young children with autism spectrum disorder seem to experience less severe symptomology if they have a history of seizures according to a recent study published in Developmental Neurorehabilitation.

- To reach that conclusion, investigators reviewed patient records with the help of a licensed clinical psychologist.

- The study looked at the severity of autism symptoms and developmental functioning in young children, comparing children with and without a history of seizures and comparing those with autism to those who had atypical development.

- Among children with autism spectrum disorders whose parents reported a history of seizures, symptoms of autism were less severe, when compared to children without seizures.

- On the other hand, among children with atypical development, the direction of the correlation was the opposite, with those children with atypical development experiencing more severe symptoms if they had a history of seizures.

Burns CO, Matson JL. An investigation of the association between seizures, autism symptomology, and developmental functioning in young children. [Published online ahead of print February 20, 2018] Dev Neurorehabil. doi: 10.1080/17518423.2018.1437842.

Young children with autism spectrum disorder seem to experience less severe symptomology if they have a history of seizures according to a recent study published in Developmental Neurorehabilitation.

- To reach that conclusion, investigators reviewed patient records with the help of a licensed clinical psychologist.

- The study looked at the severity of autism symptoms and developmental functioning in young children, comparing children with and without a history of seizures and comparing those with autism to those who had atypical development.

- Among children with autism spectrum disorders whose parents reported a history of seizures, symptoms of autism were less severe, when compared to children without seizures.

- On the other hand, among children with atypical development, the direction of the correlation was the opposite, with those children with atypical development experiencing more severe symptoms if they had a history of seizures.

Burns CO, Matson JL. An investigation of the association between seizures, autism symptomology, and developmental functioning in young children. [Published online ahead of print February 20, 2018] Dev Neurorehabil. doi: 10.1080/17518423.2018.1437842.

Young children with autism spectrum disorder seem to experience less severe symptomology if they have a history of seizures according to a recent study published in Developmental Neurorehabilitation.

- To reach that conclusion, investigators reviewed patient records with the help of a licensed clinical psychologist.

- The study looked at the severity of autism symptoms and developmental functioning in young children, comparing children with and without a history of seizures and comparing those with autism to those who had atypical development.

- Among children with autism spectrum disorders whose parents reported a history of seizures, symptoms of autism were less severe, when compared to children without seizures.

- On the other hand, among children with atypical development, the direction of the correlation was the opposite, with those children with atypical development experiencing more severe symptoms if they had a history of seizures.

Burns CO, Matson JL. An investigation of the association between seizures, autism symptomology, and developmental functioning in young children. [Published online ahead of print February 20, 2018] Dev Neurorehabil. doi: 10.1080/17518423.2018.1437842.

High dose of novel compound for relapsing-remitting MS shows promise

SAN DIEGO – Early results of the novel human endogenous retrovirus-W antagonist GNbAC1 in a phase 2 trial of patients with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis demonstrated evidence of remyelination at week 24 among high-dose users, but it did not meet its primary endpoint of active lesions seen on MRI.

In an interview at ACTRIMS Forum 2018, held by the Americas Committee for Treatment and Research in Multiple Sclerosis, study author Robert Glanzman, MD, said that GNbAC1 is a monoclonal antibody that targets and blocks the envelope protein pHER-W ENV, a potent agonist of Toll-like receptor 4. It thereby inhibits TLR4-mediated pathogenicity, which includes activation of macrophages and microglia into proinflammatory phenotypes and direct inhibition of remyelination via TLR4.

In a study known as CHANGE-MS, 270 patients with relapsing-remitting MS were randomized to one of three doses of the GNbAC1 (6, 12, or 18 mg/kg), or placebo via monthly IV infusion over 6 months. The study was conducted at 70 centers in 13 European countries over the past 3 years. It had a 24-week, double-blind, placebo-controlled period, followed by a 24-week, dose-blind, active-only treatment period, with placebo patients randomized to the three different doses of GNbA1C. Brain MRI scans were performed at weeks 12, 16, 20, 24, and 48, to look for evidence of remyelination.

The mean age of patients was 38 years and 65% were female. The researchers observed no safety concerns and no significant effect on inflammatory measures over weeks 12-24, even though the absolute number of lesions was reduced by about 50%. Although the primary endpoint of the cumulative number of gadolinium-enhancing lesions seen on brain MRI scans every 4 weeks during weeks 12-24 was not met, post hoc analyses suggest a decrease in neuroinflammation in the 18 mg/kg GNbA1C group at week 24, compared with placebo (P = .008). “A consistent increase in MT [magnetization transfer] ratio signal was observed in normal-appearing white matter and cerebral cortex at the highest dose, suggesting remyelination,” Dr. Glanzman added. “We gained about a quarter or half of percent in normal-appearing white matter at the cerebral cortex at the high dose. Normally, MS patients lose white matter over time, both in the cortex and in gray matter. We’re actually showing evidence of remyelination, which is really exciting. If these data are replicated and confirmed at week 48, we think we really have an exciting compound.”

GeNeuro sponsored the study.

Full 48-week analyses from CHANGE-MS are expected to be unveiled at the 2018 annual meeting American Academy of Neurology.

SOURCE: Glanzman R et al. Abstract P034.

SAN DIEGO – Early results of the novel human endogenous retrovirus-W antagonist GNbAC1 in a phase 2 trial of patients with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis demonstrated evidence of remyelination at week 24 among high-dose users, but it did not meet its primary endpoint of active lesions seen on MRI.

In an interview at ACTRIMS Forum 2018, held by the Americas Committee for Treatment and Research in Multiple Sclerosis, study author Robert Glanzman, MD, said that GNbAC1 is a monoclonal antibody that targets and blocks the envelope protein pHER-W ENV, a potent agonist of Toll-like receptor 4. It thereby inhibits TLR4-mediated pathogenicity, which includes activation of macrophages and microglia into proinflammatory phenotypes and direct inhibition of remyelination via TLR4.

In a study known as CHANGE-MS, 270 patients with relapsing-remitting MS were randomized to one of three doses of the GNbAC1 (6, 12, or 18 mg/kg), or placebo via monthly IV infusion over 6 months. The study was conducted at 70 centers in 13 European countries over the past 3 years. It had a 24-week, double-blind, placebo-controlled period, followed by a 24-week, dose-blind, active-only treatment period, with placebo patients randomized to the three different doses of GNbA1C. Brain MRI scans were performed at weeks 12, 16, 20, 24, and 48, to look for evidence of remyelination.

The mean age of patients was 38 years and 65% were female. The researchers observed no safety concerns and no significant effect on inflammatory measures over weeks 12-24, even though the absolute number of lesions was reduced by about 50%. Although the primary endpoint of the cumulative number of gadolinium-enhancing lesions seen on brain MRI scans every 4 weeks during weeks 12-24 was not met, post hoc analyses suggest a decrease in neuroinflammation in the 18 mg/kg GNbA1C group at week 24, compared with placebo (P = .008). “A consistent increase in MT [magnetization transfer] ratio signal was observed in normal-appearing white matter and cerebral cortex at the highest dose, suggesting remyelination,” Dr. Glanzman added. “We gained about a quarter or half of percent in normal-appearing white matter at the cerebral cortex at the high dose. Normally, MS patients lose white matter over time, both in the cortex and in gray matter. We’re actually showing evidence of remyelination, which is really exciting. If these data are replicated and confirmed at week 48, we think we really have an exciting compound.”

GeNeuro sponsored the study.

Full 48-week analyses from CHANGE-MS are expected to be unveiled at the 2018 annual meeting American Academy of Neurology.

SOURCE: Glanzman R et al. Abstract P034.

SAN DIEGO – Early results of the novel human endogenous retrovirus-W antagonist GNbAC1 in a phase 2 trial of patients with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis demonstrated evidence of remyelination at week 24 among high-dose users, but it did not meet its primary endpoint of active lesions seen on MRI.

In an interview at ACTRIMS Forum 2018, held by the Americas Committee for Treatment and Research in Multiple Sclerosis, study author Robert Glanzman, MD, said that GNbAC1 is a monoclonal antibody that targets and blocks the envelope protein pHER-W ENV, a potent agonist of Toll-like receptor 4. It thereby inhibits TLR4-mediated pathogenicity, which includes activation of macrophages and microglia into proinflammatory phenotypes and direct inhibition of remyelination via TLR4.

In a study known as CHANGE-MS, 270 patients with relapsing-remitting MS were randomized to one of three doses of the GNbAC1 (6, 12, or 18 mg/kg), or placebo via monthly IV infusion over 6 months. The study was conducted at 70 centers in 13 European countries over the past 3 years. It had a 24-week, double-blind, placebo-controlled period, followed by a 24-week, dose-blind, active-only treatment period, with placebo patients randomized to the three different doses of GNbA1C. Brain MRI scans were performed at weeks 12, 16, 20, 24, and 48, to look for evidence of remyelination.

The mean age of patients was 38 years and 65% were female. The researchers observed no safety concerns and no significant effect on inflammatory measures over weeks 12-24, even though the absolute number of lesions was reduced by about 50%. Although the primary endpoint of the cumulative number of gadolinium-enhancing lesions seen on brain MRI scans every 4 weeks during weeks 12-24 was not met, post hoc analyses suggest a decrease in neuroinflammation in the 18 mg/kg GNbA1C group at week 24, compared with placebo (P = .008). “A consistent increase in MT [magnetization transfer] ratio signal was observed in normal-appearing white matter and cerebral cortex at the highest dose, suggesting remyelination,” Dr. Glanzman added. “We gained about a quarter or half of percent in normal-appearing white matter at the cerebral cortex at the high dose. Normally, MS patients lose white matter over time, both in the cortex and in gray matter. We’re actually showing evidence of remyelination, which is really exciting. If these data are replicated and confirmed at week 48, we think we really have an exciting compound.”

GeNeuro sponsored the study.

Full 48-week analyses from CHANGE-MS are expected to be unveiled at the 2018 annual meeting American Academy of Neurology.

SOURCE: Glanzman R et al. Abstract P034.

REPORTING FROM ACTRIMS FORUM 2018

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Although the primary endpoint was not met, post hoc analyses suggest a decrease in neuroinflammation in the 18 mg/kg GNbA1C group at week 24, compared with placebo (P = .008).

Study details: A phase 2 study of 270 patients with relapsing-remitting MS who were randomized to one of three doses of GNbAC1.

Disclosures: Dr. Glanzman is chief medical officer for GeNeuro, which sponsored the study.

Source: Glanzman R et al. Abstract P034.

Racial disparities by region persist despite multiple liver transplant allocation schemes

Racial and regional disparities in liver transplant allocation persist despite multiple allocation schemes as identified in a large dataset spanning at least 30 years, according to a study.

The Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) score was put forth in 1998 by the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network under the guidance of the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services and the Department of Health & Human Services, to indicate that organs should be allocated to the sickest patients as interpreted by the MELD score. Since then, four separate liver allocation systems are being followed across the country owing to disagreements over a universal allocation scheme. These include MELD score, the initial three-tier UNOS (United Network for Organ Sharing) Status, Share 35, and now MELD Na.

Unfavorable supply and demand ratios for liver allograft allocation persist across the country with differential and limited access to care, which leads to decreased wellness, lower life expectancies, and higher baseline morbidity and mortality rates in some areas. Furthermore, a short cold storage capacity of liver allografts limits greater allocation and distribution schema.

Dominique J. Monlezun, MD, PhD, MPH, and his colleagues at the Tulane Transplant Institute at Tulane University, New Orleans, evaluated the effect of MELD and other allocation schemes on the incidence of racial and regional disparities in a study published in Surgery. They performed fixed-effects multivariate logistic regression augmented by modified forward and backward stepwise-regression of transplanted patients from the United Network for Organ Sharing Standard Transplant Analysis and Research database (1985-2016) to assess causal inference of such disparities.

“Significant disparities in the odds of receiving a liver were found: African Americans, odds ratio, 1.12 (95% confidence interval, 1.08-1.17); Asians, 1.12 (95% CI, 1.07-1.18); females, 0.80 (95% CI, 0.78-0.83); and malignancy 1.18 (95% CI, 1.13-1.22). Significant racial disparities by region were identified using Caucasian Region 7 (Ill., Minn., N.D., S.D., and Wisc.) as the reference: Hispanic Region 9 (N.Y., West Vt.) 1.22 (1.02-1.45), Hispanic Region 1 (New England) 1.26 (1.01-1.57), Hispanic Region 4 (Ok., Tex.) 1.23 (1.05-1.43), and Asian Region 4 (Ok., Tex.) 1.35 (1.05-1.73).” Since the transplantation rate in Region 7 closely approximated the sex and race-matched rate of the national post–Share 35 average, it was used as a reference in the study.

“Although traditional disparities as with African Americans and [whites] have been improved during the past 30 years, new disparities as with Hispanics and Asians have developed in certain regions,” stated the authors.

They acknowledged the limitations in the observational nature of the study and those of the statistical analyses, which could only approximate, rather than perfectly replicate, a randomized trial. Big Data tools such as artificial intelligence–based machine learning can provide real-time analysis of large heterogeneous datasets for patients across different regions.

The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Monlezun DJ et al. Surgery. 2018 doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2017.10.009.

Racial and regional disparities in liver transplant allocation persist despite multiple allocation schemes as identified in a large dataset spanning at least 30 years, according to a study.

The Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) score was put forth in 1998 by the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network under the guidance of the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services and the Department of Health & Human Services, to indicate that organs should be allocated to the sickest patients as interpreted by the MELD score. Since then, four separate liver allocation systems are being followed across the country owing to disagreements over a universal allocation scheme. These include MELD score, the initial three-tier UNOS (United Network for Organ Sharing) Status, Share 35, and now MELD Na.

Unfavorable supply and demand ratios for liver allograft allocation persist across the country with differential and limited access to care, which leads to decreased wellness, lower life expectancies, and higher baseline morbidity and mortality rates in some areas. Furthermore, a short cold storage capacity of liver allografts limits greater allocation and distribution schema.

Dominique J. Monlezun, MD, PhD, MPH, and his colleagues at the Tulane Transplant Institute at Tulane University, New Orleans, evaluated the effect of MELD and other allocation schemes on the incidence of racial and regional disparities in a study published in Surgery. They performed fixed-effects multivariate logistic regression augmented by modified forward and backward stepwise-regression of transplanted patients from the United Network for Organ Sharing Standard Transplant Analysis and Research database (1985-2016) to assess causal inference of such disparities.

“Significant disparities in the odds of receiving a liver were found: African Americans, odds ratio, 1.12 (95% confidence interval, 1.08-1.17); Asians, 1.12 (95% CI, 1.07-1.18); females, 0.80 (95% CI, 0.78-0.83); and malignancy 1.18 (95% CI, 1.13-1.22). Significant racial disparities by region were identified using Caucasian Region 7 (Ill., Minn., N.D., S.D., and Wisc.) as the reference: Hispanic Region 9 (N.Y., West Vt.) 1.22 (1.02-1.45), Hispanic Region 1 (New England) 1.26 (1.01-1.57), Hispanic Region 4 (Ok., Tex.) 1.23 (1.05-1.43), and Asian Region 4 (Ok., Tex.) 1.35 (1.05-1.73).” Since the transplantation rate in Region 7 closely approximated the sex and race-matched rate of the national post–Share 35 average, it was used as a reference in the study.

“Although traditional disparities as with African Americans and [whites] have been improved during the past 30 years, new disparities as with Hispanics and Asians have developed in certain regions,” stated the authors.

They acknowledged the limitations in the observational nature of the study and those of the statistical analyses, which could only approximate, rather than perfectly replicate, a randomized trial. Big Data tools such as artificial intelligence–based machine learning can provide real-time analysis of large heterogeneous datasets for patients across different regions.

The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Monlezun DJ et al. Surgery. 2018 doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2017.10.009.

Racial and regional disparities in liver transplant allocation persist despite multiple allocation schemes as identified in a large dataset spanning at least 30 years, according to a study.

The Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) score was put forth in 1998 by the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network under the guidance of the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services and the Department of Health & Human Services, to indicate that organs should be allocated to the sickest patients as interpreted by the MELD score. Since then, four separate liver allocation systems are being followed across the country owing to disagreements over a universal allocation scheme. These include MELD score, the initial three-tier UNOS (United Network for Organ Sharing) Status, Share 35, and now MELD Na.

Unfavorable supply and demand ratios for liver allograft allocation persist across the country with differential and limited access to care, which leads to decreased wellness, lower life expectancies, and higher baseline morbidity and mortality rates in some areas. Furthermore, a short cold storage capacity of liver allografts limits greater allocation and distribution schema.

Dominique J. Monlezun, MD, PhD, MPH, and his colleagues at the Tulane Transplant Institute at Tulane University, New Orleans, evaluated the effect of MELD and other allocation schemes on the incidence of racial and regional disparities in a study published in Surgery. They performed fixed-effects multivariate logistic regression augmented by modified forward and backward stepwise-regression of transplanted patients from the United Network for Organ Sharing Standard Transplant Analysis and Research database (1985-2016) to assess causal inference of such disparities.

“Significant disparities in the odds of receiving a liver were found: African Americans, odds ratio, 1.12 (95% confidence interval, 1.08-1.17); Asians, 1.12 (95% CI, 1.07-1.18); females, 0.80 (95% CI, 0.78-0.83); and malignancy 1.18 (95% CI, 1.13-1.22). Significant racial disparities by region were identified using Caucasian Region 7 (Ill., Minn., N.D., S.D., and Wisc.) as the reference: Hispanic Region 9 (N.Y., West Vt.) 1.22 (1.02-1.45), Hispanic Region 1 (New England) 1.26 (1.01-1.57), Hispanic Region 4 (Ok., Tex.) 1.23 (1.05-1.43), and Asian Region 4 (Ok., Tex.) 1.35 (1.05-1.73).” Since the transplantation rate in Region 7 closely approximated the sex and race-matched rate of the national post–Share 35 average, it was used as a reference in the study.

“Although traditional disparities as with African Americans and [whites] have been improved during the past 30 years, new disparities as with Hispanics and Asians have developed in certain regions,” stated the authors.

They acknowledged the limitations in the observational nature of the study and those of the statistical analyses, which could only approximate, rather than perfectly replicate, a randomized trial. Big Data tools such as artificial intelligence–based machine learning can provide real-time analysis of large heterogeneous datasets for patients across different regions.

The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Monlezun DJ et al. Surgery. 2018 doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2017.10.009.

FROM SURGERY

Key clinical point: The existence of racial disparity in liver allograft distribution is undisputed. Disagreements persist over optimal allocation schemes, with centers using different schemes.

Major finding: A rigorous causal inference statistic on a large national dataset spanning at least 30 years showed that racial disparities by region persist despite multiple allocation schemes.

Study details: Patients from the United Network for Organ Sharing Standard Transplant Analysis and Research database (1985-2016) were used to assess causal inference of racial and regional disparities.

Disclosures: None reported.

Source: Monlezun DJ et al. Surgery. 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2017.10.009.

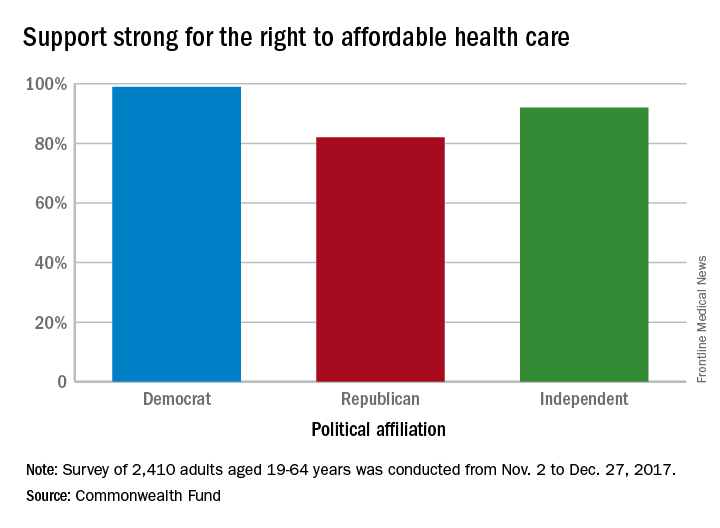

Americans support the right to affordable health care

Despite the rhetorical winds blowing out of Washington, 92% of Americans believe that they have the right to affordable health care, according to a recent survey by the Commonwealth Fund.

Political affiliation, it turns out, does not appear to determine support for such a right. Democrats aged 19-64 years voiced their support to the tune of 99% in favor of a right to affordable care, compared with 82% of Republicans and 92% of independents, the Commonwealth Fund said in a survey brief released March 1.

“This survey’s finding that strong majorities of U.S. adults, regardless of party affiliation, believe that all Americans should have a right to affordable health care suggests there may be popular support for a discussion over our preferred path,” the report’s authors wrote.

The survey showed that 36% of those who have health care insurance through the Affordable Care Act marketplaces are pessimistic about their chances of keeping that coverage, compared with 27% of those with Medicaid and 9% of adults with employer-sponsored health benefits.

Among those who lacked confidence about maintaining their coverage, the largest proportion (32%) of respondents believe that they will lose it because the “Trump administration will not carry out the law” and 19% think that they won’t be able to afford it in the future, they said.

“ Such a shift also would provide a more stable regulatory environment for insurers participating in both the marketplaces and Medicaid,” according to the report.

The Commonwealth Fund’s sixth Affordable Care Act Tracking Survey was conducted by the research firm SSRS between Nov. 2 and Dec. 27, 2017, with responses from 2,410 adults aged 19-64 years. The overall margin of error was ±2.7 percentage points at the 95% confidence level.

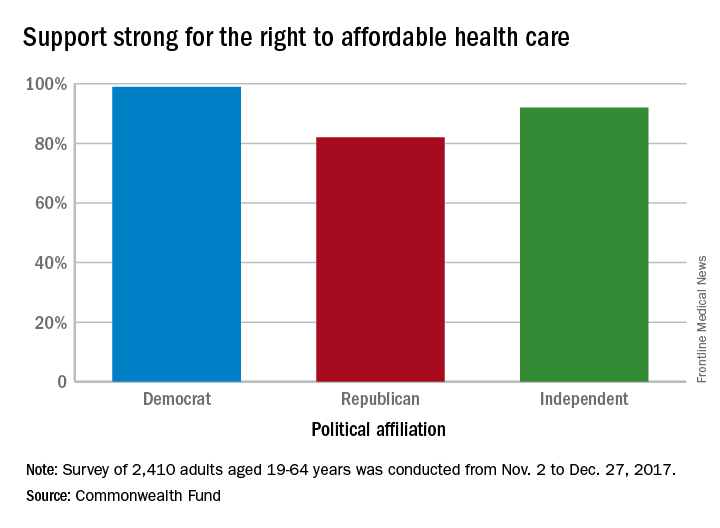

Despite the rhetorical winds blowing out of Washington, 92% of Americans believe that they have the right to affordable health care, according to a recent survey by the Commonwealth Fund.

Political affiliation, it turns out, does not appear to determine support for such a right. Democrats aged 19-64 years voiced their support to the tune of 99% in favor of a right to affordable care, compared with 82% of Republicans and 92% of independents, the Commonwealth Fund said in a survey brief released March 1.

“This survey’s finding that strong majorities of U.S. adults, regardless of party affiliation, believe that all Americans should have a right to affordable health care suggests there may be popular support for a discussion over our preferred path,” the report’s authors wrote.

The survey showed that 36% of those who have health care insurance through the Affordable Care Act marketplaces are pessimistic about their chances of keeping that coverage, compared with 27% of those with Medicaid and 9% of adults with employer-sponsored health benefits.

Among those who lacked confidence about maintaining their coverage, the largest proportion (32%) of respondents believe that they will lose it because the “Trump administration will not carry out the law” and 19% think that they won’t be able to afford it in the future, they said.

“ Such a shift also would provide a more stable regulatory environment for insurers participating in both the marketplaces and Medicaid,” according to the report.

The Commonwealth Fund’s sixth Affordable Care Act Tracking Survey was conducted by the research firm SSRS between Nov. 2 and Dec. 27, 2017, with responses from 2,410 adults aged 19-64 years. The overall margin of error was ±2.7 percentage points at the 95% confidence level.

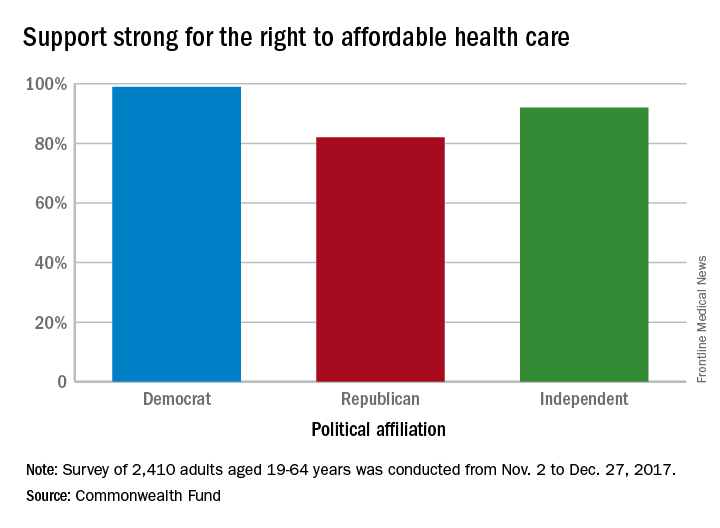

Despite the rhetorical winds blowing out of Washington, 92% of Americans believe that they have the right to affordable health care, according to a recent survey by the Commonwealth Fund.

Political affiliation, it turns out, does not appear to determine support for such a right. Democrats aged 19-64 years voiced their support to the tune of 99% in favor of a right to affordable care, compared with 82% of Republicans and 92% of independents, the Commonwealth Fund said in a survey brief released March 1.

“This survey’s finding that strong majorities of U.S. adults, regardless of party affiliation, believe that all Americans should have a right to affordable health care suggests there may be popular support for a discussion over our preferred path,” the report’s authors wrote.

The survey showed that 36% of those who have health care insurance through the Affordable Care Act marketplaces are pessimistic about their chances of keeping that coverage, compared with 27% of those with Medicaid and 9% of adults with employer-sponsored health benefits.

Among those who lacked confidence about maintaining their coverage, the largest proportion (32%) of respondents believe that they will lose it because the “Trump administration will not carry out the law” and 19% think that they won’t be able to afford it in the future, they said.

“ Such a shift also would provide a more stable regulatory environment for insurers participating in both the marketplaces and Medicaid,” according to the report.

The Commonwealth Fund’s sixth Affordable Care Act Tracking Survey was conducted by the research firm SSRS between Nov. 2 and Dec. 27, 2017, with responses from 2,410 adults aged 19-64 years. The overall margin of error was ±2.7 percentage points at the 95% confidence level.

Aesthetic procedures becoming more popular in skin of color patients

in a presentation at the Caribbean Dermatology Symposium.

In 2015, ethnic minority patients accounted for 25% of aesthetic procedures in the United States, up from 20% in 2010, according to data from the American Society for Aesthetic Plastic Surgery, said Dr. Alexis, chair of dermatology and director of the Skin of Color Center at Mount Sinai St. Luke’s and Mount Sinai West hospitals in New York.

Chemical peels can be used successfully to treat a range of conditions in skin of color patients, including postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, acne, melasma, textural irregularities, and pseudofolliculitis barbae. They also can be used for skin brightening, said Dr. Alexis, who recommended a chemical peel protocol of salicylic acid, glycolic acid, or Jessner’s every 2-4 weeks. “Consider hydroquinone 4% concurrently to enhance efficacy for treating hyperpigmentation and to prevent postinflammatory hyperpigmentation,” he said. Patients on retinoids should discontinue them for 1 week prior to a chemical peel, he added.

Dr. Alexis shared several treatment pearls to promote successful peels in skin of color patients:

- Salicylic acid: Resist the urge to overapply and “titrate according to patient tolerability.” The endpoint of a salicylic acid peel is white precipitate, not frost; cool compresses can be used for patient comfort and for later removal of the white precipitate.

- Glycolic acid: Stick to a contact time of 2-4 minutes to avoid epidermolysis. “Completely neutralize all areas of application to avoid overpeeling.”

- Trichloroacetic acid (TCA): TCA carries a greater risk of dyspigmentation, and should be reserved for patients who have not been successfully treated with salicylic or glycolic acid; a 10%-15% concentration of TCA, applied conservatively, is recommended.

Regardless of the type of chemical, potential pitfalls of peels in patients of color include using too much product, allowing too long of an application time, and applying the chemical to an inflamed or excoriated area, Dr. Alexis said. Patients who don’t discontinue retinoids before a peel are at increased risk of developing erosions or crusting, he added.

Dr. Alexis disclosed relationships with Allergan, BioPharmX, Dermira, Galderma, Novan, Novartis, RXi, Unilever, and Valeant.

Global Academy and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

in a presentation at the Caribbean Dermatology Symposium.

In 2015, ethnic minority patients accounted for 25% of aesthetic procedures in the United States, up from 20% in 2010, according to data from the American Society for Aesthetic Plastic Surgery, said Dr. Alexis, chair of dermatology and director of the Skin of Color Center at Mount Sinai St. Luke’s and Mount Sinai West hospitals in New York.

Chemical peels can be used successfully to treat a range of conditions in skin of color patients, including postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, acne, melasma, textural irregularities, and pseudofolliculitis barbae. They also can be used for skin brightening, said Dr. Alexis, who recommended a chemical peel protocol of salicylic acid, glycolic acid, or Jessner’s every 2-4 weeks. “Consider hydroquinone 4% concurrently to enhance efficacy for treating hyperpigmentation and to prevent postinflammatory hyperpigmentation,” he said. Patients on retinoids should discontinue them for 1 week prior to a chemical peel, he added.

Dr. Alexis shared several treatment pearls to promote successful peels in skin of color patients:

- Salicylic acid: Resist the urge to overapply and “titrate according to patient tolerability.” The endpoint of a salicylic acid peel is white precipitate, not frost; cool compresses can be used for patient comfort and for later removal of the white precipitate.

- Glycolic acid: Stick to a contact time of 2-4 minutes to avoid epidermolysis. “Completely neutralize all areas of application to avoid overpeeling.”

- Trichloroacetic acid (TCA): TCA carries a greater risk of dyspigmentation, and should be reserved for patients who have not been successfully treated with salicylic or glycolic acid; a 10%-15% concentration of TCA, applied conservatively, is recommended.

Regardless of the type of chemical, potential pitfalls of peels in patients of color include using too much product, allowing too long of an application time, and applying the chemical to an inflamed or excoriated area, Dr. Alexis said. Patients who don’t discontinue retinoids before a peel are at increased risk of developing erosions or crusting, he added.

Dr. Alexis disclosed relationships with Allergan, BioPharmX, Dermira, Galderma, Novan, Novartis, RXi, Unilever, and Valeant.

Global Academy and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

in a presentation at the Caribbean Dermatology Symposium.

In 2015, ethnic minority patients accounted for 25% of aesthetic procedures in the United States, up from 20% in 2010, according to data from the American Society for Aesthetic Plastic Surgery, said Dr. Alexis, chair of dermatology and director of the Skin of Color Center at Mount Sinai St. Luke’s and Mount Sinai West hospitals in New York.

Chemical peels can be used successfully to treat a range of conditions in skin of color patients, including postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, acne, melasma, textural irregularities, and pseudofolliculitis barbae. They also can be used for skin brightening, said Dr. Alexis, who recommended a chemical peel protocol of salicylic acid, glycolic acid, or Jessner’s every 2-4 weeks. “Consider hydroquinone 4% concurrently to enhance efficacy for treating hyperpigmentation and to prevent postinflammatory hyperpigmentation,” he said. Patients on retinoids should discontinue them for 1 week prior to a chemical peel, he added.

Dr. Alexis shared several treatment pearls to promote successful peels in skin of color patients:

- Salicylic acid: Resist the urge to overapply and “titrate according to patient tolerability.” The endpoint of a salicylic acid peel is white precipitate, not frost; cool compresses can be used for patient comfort and for later removal of the white precipitate.

- Glycolic acid: Stick to a contact time of 2-4 minutes to avoid epidermolysis. “Completely neutralize all areas of application to avoid overpeeling.”

- Trichloroacetic acid (TCA): TCA carries a greater risk of dyspigmentation, and should be reserved for patients who have not been successfully treated with salicylic or glycolic acid; a 10%-15% concentration of TCA, applied conservatively, is recommended.

Regardless of the type of chemical, potential pitfalls of peels in patients of color include using too much product, allowing too long of an application time, and applying the chemical to an inflamed or excoriated area, Dr. Alexis said. Patients who don’t discontinue retinoids before a peel are at increased risk of developing erosions or crusting, he added.

Dr. Alexis disclosed relationships with Allergan, BioPharmX, Dermira, Galderma, Novan, Novartis, RXi, Unilever, and Valeant.

Global Academy and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM THE CARIBBEAN DERMATOLOGY SYMPOSIUM

Demand, not need, may drive further expansion of telepsychiatry

TAMPA – The growth of telepsychiatry has been driven largely by needs of access, particularly in rural areas without specialists. But telemedicine is convenient, and those growing up with computers, smartphones, and other technology are going to demand this type of access to their clinicians, according to a leader of a course on telepsychiatry at the annual meeting of the American College of Psychiatrists.

“Digital natives – the consumers – are going to drive the use of technology more and more. They are used to videoconferencing. They want to see their doctors over video. They want to communicate via text and email. They want that convenience, and they are much more comfortable with it,” said James (Jay) H. Shore, MD, director of telemedicine at the Johnson Depression Center at the University of Colorado Denver.

Meanwhile, telepsychiatry is evolving, allowing for more sophisticated approaches and expanded applications.

“When we started doing video conferencing technologies, we basically were taking what we do in person and just doing that over video,” Dr. Shore said. “Where we are now, .”

A prolific author on the topic of telepsychiatry and long involved in this practice, Dr. Shore has said that the widespread introduction of fiber optic networks and other technological advances over the last 15 years has advanced all forms of digital technology. These are enabling and will likely accelerate synergies possible with integration of different platforms, such as electronic health records, patient portals, videoconferencing, and various methods of communication.

In his own experience, which includes providing remote services from his office in Denver to native populations in Alaska, he has discovered some unexpected advantages to telepsychiatry. For example, some victims recounting histories of domestic abuse feel more secure during videoconferencing than during a face-to-face interview, facilitating capture of a complete history. In general, he now prefers telepsychiatry in those situations.

As telepsychiatry advances, it will be increasingly integrated into hybrid models of care that involve communicating with both the patient and other clinicians over multiple platforms (for example, in-person, video, patient portals). This is not just relevant to patients in a geographically distant facility. With greater acceptance and integration, videoconferencing will be part of this mix of communication tools that might also include in-person consultations. The goal will be to use the most convenient communication strategies to coordinate the diagnosis, a treatment plan, and follow-up.

“The neat thing about telepsychiatry is really the virtual teaming models that we can create,” Dr. Shore said. However, he acknowledged that this type of team participation requires an adjustment in reimbursement models for psychiatrists that traditionally have centered on psychopharmacology. The problem with the models limited to prescription writing is that they “do not tap into the psychiatrist’s leadership of the mental health team, knowledge of human behavior, and they are not, at least for me, as personally rewarding.”

He believes that the growing array of technologies contained in telepsychiatry will increase opportunities for psychiatrists in a host of such settings such as crisis management in emergency care settings or coordination of psychiatric care in residential treatment settings.

The expansion of telemedicine already is reflected in the growing number of companies marketing services directly to consumers. Dr. Shore listed several offering virtual health care that may contribute to both acceptance and demand for medical care delivered digitally. Although telepsychiatry already is associated with many effective applications, Dr. Shore reiterated that consumer demand will be a driver for further expansion of telemedicine in general.

He also emphasized that change involving digital advances in psychiatry is inevitable. According to Dr. Shore, artificial intelligence, virtual reality treatments, and social networking are among potential tools for altering care. Inside and outside of medicine, the pace of change driven by advances in digital exchange of information has been and is expected to continue to be brisk.

“Then there is the technology that is going to disrupt us all that we can’t see coming,” Dr. Shore said. “It is being invented right now in somebody’s garage in Palo Alto.”

Dr. Shore reported that he is chief medical officer of AccessCare Services, which provides telehealth services and technologies.

TAMPA – The growth of telepsychiatry has been driven largely by needs of access, particularly in rural areas without specialists. But telemedicine is convenient, and those growing up with computers, smartphones, and other technology are going to demand this type of access to their clinicians, according to a leader of a course on telepsychiatry at the annual meeting of the American College of Psychiatrists.

“Digital natives – the consumers – are going to drive the use of technology more and more. They are used to videoconferencing. They want to see their doctors over video. They want to communicate via text and email. They want that convenience, and they are much more comfortable with it,” said James (Jay) H. Shore, MD, director of telemedicine at the Johnson Depression Center at the University of Colorado Denver.

Meanwhile, telepsychiatry is evolving, allowing for more sophisticated approaches and expanded applications.

“When we started doing video conferencing technologies, we basically were taking what we do in person and just doing that over video,” Dr. Shore said. “Where we are now, .”

A prolific author on the topic of telepsychiatry and long involved in this practice, Dr. Shore has said that the widespread introduction of fiber optic networks and other technological advances over the last 15 years has advanced all forms of digital technology. These are enabling and will likely accelerate synergies possible with integration of different platforms, such as electronic health records, patient portals, videoconferencing, and various methods of communication.

In his own experience, which includes providing remote services from his office in Denver to native populations in Alaska, he has discovered some unexpected advantages to telepsychiatry. For example, some victims recounting histories of domestic abuse feel more secure during videoconferencing than during a face-to-face interview, facilitating capture of a complete history. In general, he now prefers telepsychiatry in those situations.

As telepsychiatry advances, it will be increasingly integrated into hybrid models of care that involve communicating with both the patient and other clinicians over multiple platforms (for example, in-person, video, patient portals). This is not just relevant to patients in a geographically distant facility. With greater acceptance and integration, videoconferencing will be part of this mix of communication tools that might also include in-person consultations. The goal will be to use the most convenient communication strategies to coordinate the diagnosis, a treatment plan, and follow-up.

“The neat thing about telepsychiatry is really the virtual teaming models that we can create,” Dr. Shore said. However, he acknowledged that this type of team participation requires an adjustment in reimbursement models for psychiatrists that traditionally have centered on psychopharmacology. The problem with the models limited to prescription writing is that they “do not tap into the psychiatrist’s leadership of the mental health team, knowledge of human behavior, and they are not, at least for me, as personally rewarding.”

He believes that the growing array of technologies contained in telepsychiatry will increase opportunities for psychiatrists in a host of such settings such as crisis management in emergency care settings or coordination of psychiatric care in residential treatment settings.

The expansion of telemedicine already is reflected in the growing number of companies marketing services directly to consumers. Dr. Shore listed several offering virtual health care that may contribute to both acceptance and demand for medical care delivered digitally. Although telepsychiatry already is associated with many effective applications, Dr. Shore reiterated that consumer demand will be a driver for further expansion of telemedicine in general.

He also emphasized that change involving digital advances in psychiatry is inevitable. According to Dr. Shore, artificial intelligence, virtual reality treatments, and social networking are among potential tools for altering care. Inside and outside of medicine, the pace of change driven by advances in digital exchange of information has been and is expected to continue to be brisk.

“Then there is the technology that is going to disrupt us all that we can’t see coming,” Dr. Shore said. “It is being invented right now in somebody’s garage in Palo Alto.”

Dr. Shore reported that he is chief medical officer of AccessCare Services, which provides telehealth services and technologies.

TAMPA – The growth of telepsychiatry has been driven largely by needs of access, particularly in rural areas without specialists. But telemedicine is convenient, and those growing up with computers, smartphones, and other technology are going to demand this type of access to their clinicians, according to a leader of a course on telepsychiatry at the annual meeting of the American College of Psychiatrists.

“Digital natives – the consumers – are going to drive the use of technology more and more. They are used to videoconferencing. They want to see their doctors over video. They want to communicate via text and email. They want that convenience, and they are much more comfortable with it,” said James (Jay) H. Shore, MD, director of telemedicine at the Johnson Depression Center at the University of Colorado Denver.

Meanwhile, telepsychiatry is evolving, allowing for more sophisticated approaches and expanded applications.

“When we started doing video conferencing technologies, we basically were taking what we do in person and just doing that over video,” Dr. Shore said. “Where we are now, .”

A prolific author on the topic of telepsychiatry and long involved in this practice, Dr. Shore has said that the widespread introduction of fiber optic networks and other technological advances over the last 15 years has advanced all forms of digital technology. These are enabling and will likely accelerate synergies possible with integration of different platforms, such as electronic health records, patient portals, videoconferencing, and various methods of communication.

In his own experience, which includes providing remote services from his office in Denver to native populations in Alaska, he has discovered some unexpected advantages to telepsychiatry. For example, some victims recounting histories of domestic abuse feel more secure during videoconferencing than during a face-to-face interview, facilitating capture of a complete history. In general, he now prefers telepsychiatry in those situations.

As telepsychiatry advances, it will be increasingly integrated into hybrid models of care that involve communicating with both the patient and other clinicians over multiple platforms (for example, in-person, video, patient portals). This is not just relevant to patients in a geographically distant facility. With greater acceptance and integration, videoconferencing will be part of this mix of communication tools that might also include in-person consultations. The goal will be to use the most convenient communication strategies to coordinate the diagnosis, a treatment plan, and follow-up.

“The neat thing about telepsychiatry is really the virtual teaming models that we can create,” Dr. Shore said. However, he acknowledged that this type of team participation requires an adjustment in reimbursement models for psychiatrists that traditionally have centered on psychopharmacology. The problem with the models limited to prescription writing is that they “do not tap into the psychiatrist’s leadership of the mental health team, knowledge of human behavior, and they are not, at least for me, as personally rewarding.”

He believes that the growing array of technologies contained in telepsychiatry will increase opportunities for psychiatrists in a host of such settings such as crisis management in emergency care settings or coordination of psychiatric care in residential treatment settings.

The expansion of telemedicine already is reflected in the growing number of companies marketing services directly to consumers. Dr. Shore listed several offering virtual health care that may contribute to both acceptance and demand for medical care delivered digitally. Although telepsychiatry already is associated with many effective applications, Dr. Shore reiterated that consumer demand will be a driver for further expansion of telemedicine in general.

He also emphasized that change involving digital advances in psychiatry is inevitable. According to Dr. Shore, artificial intelligence, virtual reality treatments, and social networking are among potential tools for altering care. Inside and outside of medicine, the pace of change driven by advances in digital exchange of information has been and is expected to continue to be brisk.

“Then there is the technology that is going to disrupt us all that we can’t see coming,” Dr. Shore said. “It is being invented right now in somebody’s garage in Palo Alto.”

Dr. Shore reported that he is chief medical officer of AccessCare Services, which provides telehealth services and technologies.

REPORTING FROM THE COLLEGE 2018

Acute cardiorenal syndrome: Mechanisms and clinical implications

As the heart goes, so go the kidneys—and vice versa. Cardiac and renal function are intricately interdependent, and failure of either organ causes injury to the other in a vicious circle of worsening function.1

Here, we discuss acute cardiorenal syndrome, ie, acute exacerbation of heart failure leading to acute kidney injury, a common cause of hospitalization and admission to the intensive care unit. We examine its clinical definition, pathophysiology, hemodynamic derangements, clues that help in diagnosing it, and its treatment.

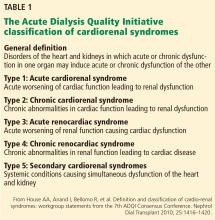

A GROUP OF LINKED DISORDERS

Two types of acute cardiac dysfunction

Although these definitions offer a good general description, further clarification of the nature of organ dysfunction is needed. Acute renal dysfunction can be unambiguously defined using the AKIN (Acute Kidney Injury Network) and RIFLE (risk, injury, failure, loss of kidney function, and end-stage kidney disease) classifications.3 Acute cardiac dysfunction, on the other hand, is an ambiguous term that encompasses 2 clinically and pathophysiologically distinct conditions: cardiogenic shock and acute heart failure.

Cardiogenic shock is characterized by a catastrophic compromise of cardiac pump function leading to global hypoperfusion severe enough to cause systemic organ damage.4 The cardiac index at which organs start to fail varies in different cases, but a value of less than 1.8 L/min/m2 is typically used to define cardiogenic shock.4

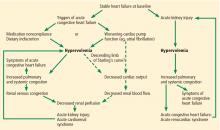

Acute heart failure, on the other hand, is defined as gradually or rapidly worsening signs and symptoms of congestive heart failure due to worsening pulmonary or systemic congestion.5 Hypervolemia is the hallmark of acute heart failure, whereas patients with cardiogenic shock may be hypervolemic, normovolemic, or hypovolemic. Although cardiac output may be mildly reduced in some cases of acute heart failure, systemic perfusion is enough to maintain organ function.

These two conditions cause renal injury by distinct mechanisms and have entirely different therapeutic implications. As we discuss later, reduced renal perfusion due to renal venous congestion is now believed to be the major hemodynamic mechanism of renal injury in acute heart failure. On the other hand, in cardiogenic shock, renal perfusion is reduced due to a critical decline of cardiac pump function.

The ideal definition of acute cardiorenal syndrome should describe a distinct pathophysiology of the syndrome and offer distinct therapeutic options that counteract it. Hence, we propose that renal injury from cardiogenic shock should not be included in its definition, an approach that has been adopted in some of the recent reviews as well.6 Our discussion of acute cardiorenal syndrome is restricted to renal injury caused by acute heart failure.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY OF ACUTE CARDIORENAL SYNDROME

Multiple mechanisms have been implicated in the pathophysiology of cardiorenal syndrome.7,8

Sympathetic hyperactivity is a compensatory mechanism in heart failure and may be aggravated if cardiac output is further reduced. Its effects include constriction of afferent and efferent arterioles, causing reduced renal perfusion and increased tubular sodium and water reabsorption.7

The renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system is activated in patients with stable congestive heart failure and may be further stimulated in a state of reduced renal perfusion, which is a hallmark of acute cardiorenal syndrome. Its activation can cause further salt and water retention.

However, direct hemodynamic mechanisms likely play the most important role and have obvious diagnostic and therapeutic implications.

Elevated venous pressure, not reduced cardiac output, drives kidney injury

The classic view was that renal dysfunction in acute heart failure is caused by reduced renal blood flow due to failing cardiac pump function. Cardiac output may be reduced in acute heart failure for various reasons, such as atrial fibrillation, myocardial infarction, or other processes, but reduced cardiac output has a minimal role, if any, in the pathogenesis of renal injury in acute heart failure.

As evidence of this, acute heart failure is not always associated with reduced cardiac output.5 Even if the cardiac index (cardiac output divided by body surface area) is mildly reduced, renal blood flow is largely unaffected, thanks to effective renal autoregulatory mechanisms. Not until the mean arterial pressure falls below 70 mm Hg do these mechanisms fail and renal blood flow starts to drop.9 Hence, unless cardiac performance is compromised enough to cause cardiogenic shock, renal blood flow usually does not change significantly with mild reduction in cardiac output.

Hanberg et al10 performed a post hoc analysis of the Evaluation Study of Congestive Heart Failure and Pulmonary Artery Catheter Effectiveness (ESCAPE) trial, in which 525 patients with advanced heart failure underwent pulmonary artery catheterization to measure their cardiac index. The authors found no association between the cardiac index and renal function in these patients.

How venous congestion impairs the kidney

In view of the current clinical evidence, the focus has shifted to renal venous congestion. According to Poiseuille’s law, blood flow through the kidneys depends on the pressure gradient—high pressure on the arterial side, low pressure on the venous side.8 Increased renal venous pressure causes reduced renal perfusion pressure, thereby affecting renal perfusion. This is now recognized as an important hemodynamic mechanism of acute cardiorenal syndrome.

Renal congestion can also affect renal function through indirect mechanisms. For example, it can cause renal interstitial edema that may then increase the intratubular pressure, thereby reducing the transglomerular pressure gradient.11

Firth et al,14 in experiments in animals, found that increasing the renal venous pressure above 18.75 mm Hg significantly reduced the glomerular filtration rate, which completely resolved when renal venous pressure was restored to basal levels.

Mullens et al,15 in a study of 145 patients admitted with acute heart failure, reported that 58 (40%) developed acute kidney injury. Pulmonary artery catheterization revealed that elevated central venous pressure, rather than reduced cardiac index, was the primary hemodynamic factor driving renal dysfunction.

DIAGNOSIS AND CLINICAL ASSESSMENT

Patients with acute cardiorenal syndrome present with clinical features of pulmonary or systemic congestion (or both) and acute kidney injury.

Elevated left-sided pressures are usually but not always associated with elevated right-sided pressures. In a study of 1,000 patients with advanced heart failure, a pulmonary capillary wedge pressure of 22 mm Hg or higher had a positive predictive value of 88% for a right atrial pressure of 10 mm Hg or higher.16 Hence, the clinical presentation may vary depending on the location (pulmonary, systemic, or both) and degree of congestion.

Symptoms of pulmonary congestion include worsening exertional dyspnea and orthopnea; bilateral crackles may be heard on physical examination if pulmonary edema is present.

Systemic congestion can cause significant peripheral edema and weight gain. Jugular venous distention may be noted. Oliguria may be present due to renal dysfunction; patients on maintenance diuretic therapy often note its lack of efficacy.

Signs of acute heart failure

Wang et al,17 in a meta-analysis of 22 studies, concluded that the features that most strongly suggested acute heart failure were:

- History of paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea

- A third heart sound

- Evidence of pulmonary venous congestion on chest radiography.

Features that most strongly suggested the patient did not have acute heart failure were:

- Absence of exertional dyspnea

- Absence of rales

- Absence of radiographic evidence of cardiomegaly.

Patients may present without some of these classic clinical features, and the diagnosis of acute heart failure may be challenging. For example, even if left-sided pressures are very high, pulmonary edema may be absent because of pulmonary vascular remodeling in chronic heart failure.18 Pulmonary artery catheterization reveals elevated cardiac filling pressures and can be used to guide therapy, but clinical evidence argues against its routine use.19

Urine electrolytes (fractional excretion of sodium < 1% and fractional excretion of urea < 35%) often suggest a prerenal form of acute kidney injury, since the hemodynamic derangements in acute cardiorenal syndrome reduce renal perfusion.

Biomarkers of cell-cycle arrest such as urine insulinlike growth factor-binding protein 7 and tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase 2 have recently been shown to identify patients with acute heart failure at risk of developing acute cardiorenal syndrome.20

Acute cardiorenal syndrome vs renal injury due to hypovolemia

The major alternative in the differential diagnosis of acute cardiorenal syndrome is renal injury due to hypovolemia. Patients with stable heart failure usually have mild hypervolemia at baseline, but they can become hypovolemic due to overaggressive diuretic therapy, severe diarrhea, or other causes.

Although the fluid status of patients in these 2 conditions is opposite, they can be difficult to distinguish. In both conditions, urine electrolytes suggest a prerenal acute kidney injury. A history of recent fluid losses or diuretic overuse may help identify hypovolemia. If available, analysis of the recent trend in weight can be vital in making the right diagnosis.

Misdiagnosis of acute cardiorenal syndrome as hypovolemia-induced acute kidney injury can be catastrophic. If volume depletion is erroneously judged to be the cause of acute kidney injury, fluid administration can further worsen both cardiac and renal function. This can perpetuate the vicious circle that is already in play. Lack of renal recovery may invite further fluid administration.

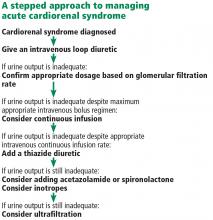

TREATMENT

Fluid removal with diuresis or ultrafiltration is the cornerstone of treatment. Other treatments such as inotropes are reserved for patients with resistant disease.

Diuretics

The goal of therapy in acute cardiorenal syndrome is to achieve aggressive diuresis, typically using intravenous diuretics. Loop diuretics are the most potent class of diuretics and are the first-line drugs for this purpose. Other classes of diuretics can be used in conjunction with loop diuretics; however, using them by themselves is neither effective nor recommended.

Resistance to diuretics at usual doses is common in patients with acute cardiorenal syndrome. Several mechanisms contribute to diuretic resistance in these patients.21

Oral bioavailability of diuretics may be reduced due to intestinal edema.