User login

Reduce unnecessary imaging by refining clinical exam skills

“Good morning, Mr. Harris. What can I do for you today?”

“Dr. Hickner, I need an MRI of my right knee. I hurt it last week, and I need to find out if I tore something.”

We all know that too many patients request—and often get—costly (and unnecessary) magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and computed tomography (CT) scans of their joints and backs. That’s why such imaging is targeted in the Choosing Wisely campaign, which aims to eliminate needless testing.1

But how can we confidently tell Mr. Harris that he doesn’t need an MRI or CT scan? One approach is to explain that imaging is generally reserved for those considering surgery, as it serves to inform the surgeon of the exact procedure needed. Another approach is to be skilled in physical exam techniques that increase our confidence in the clinical diagnosis.

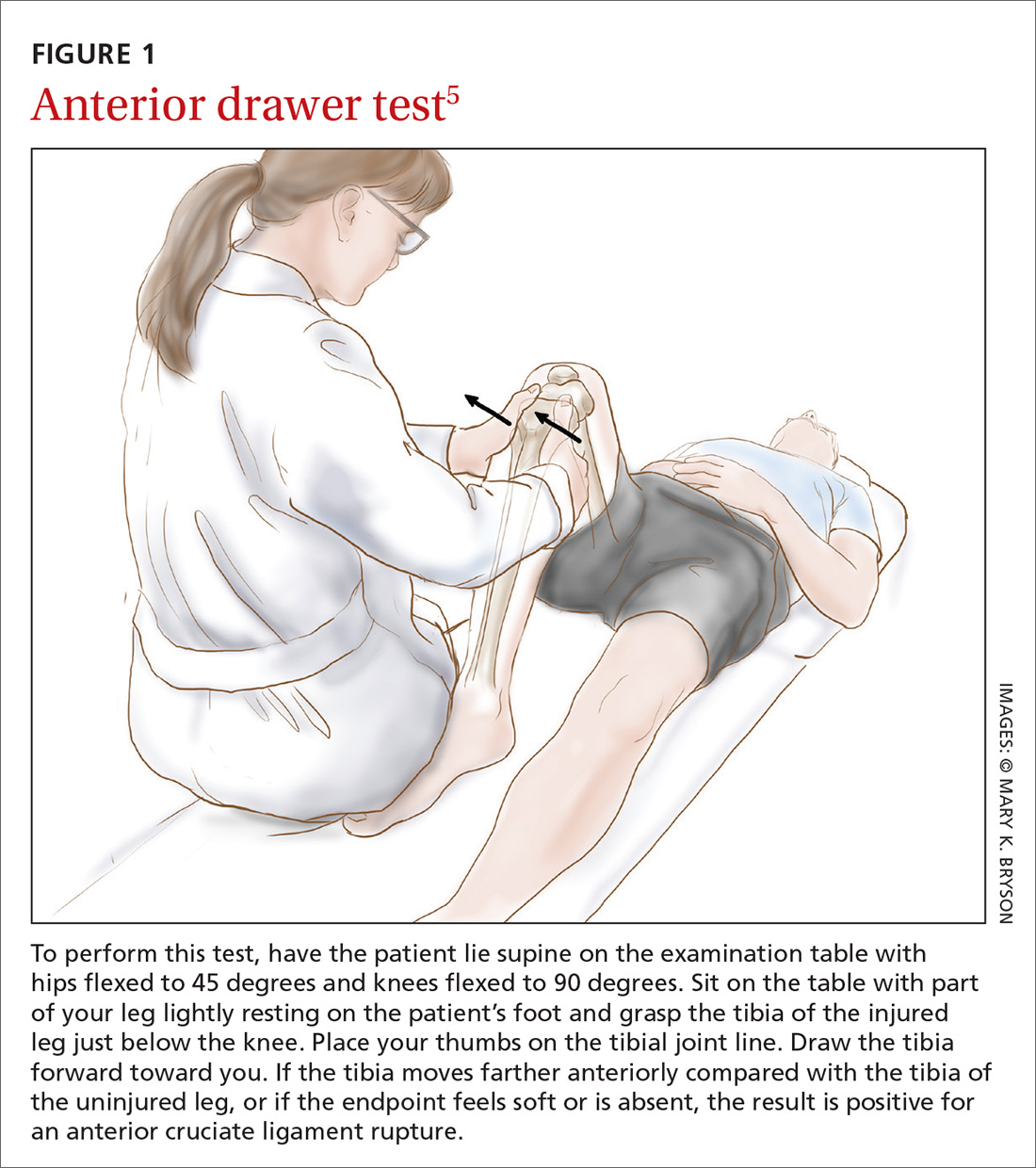

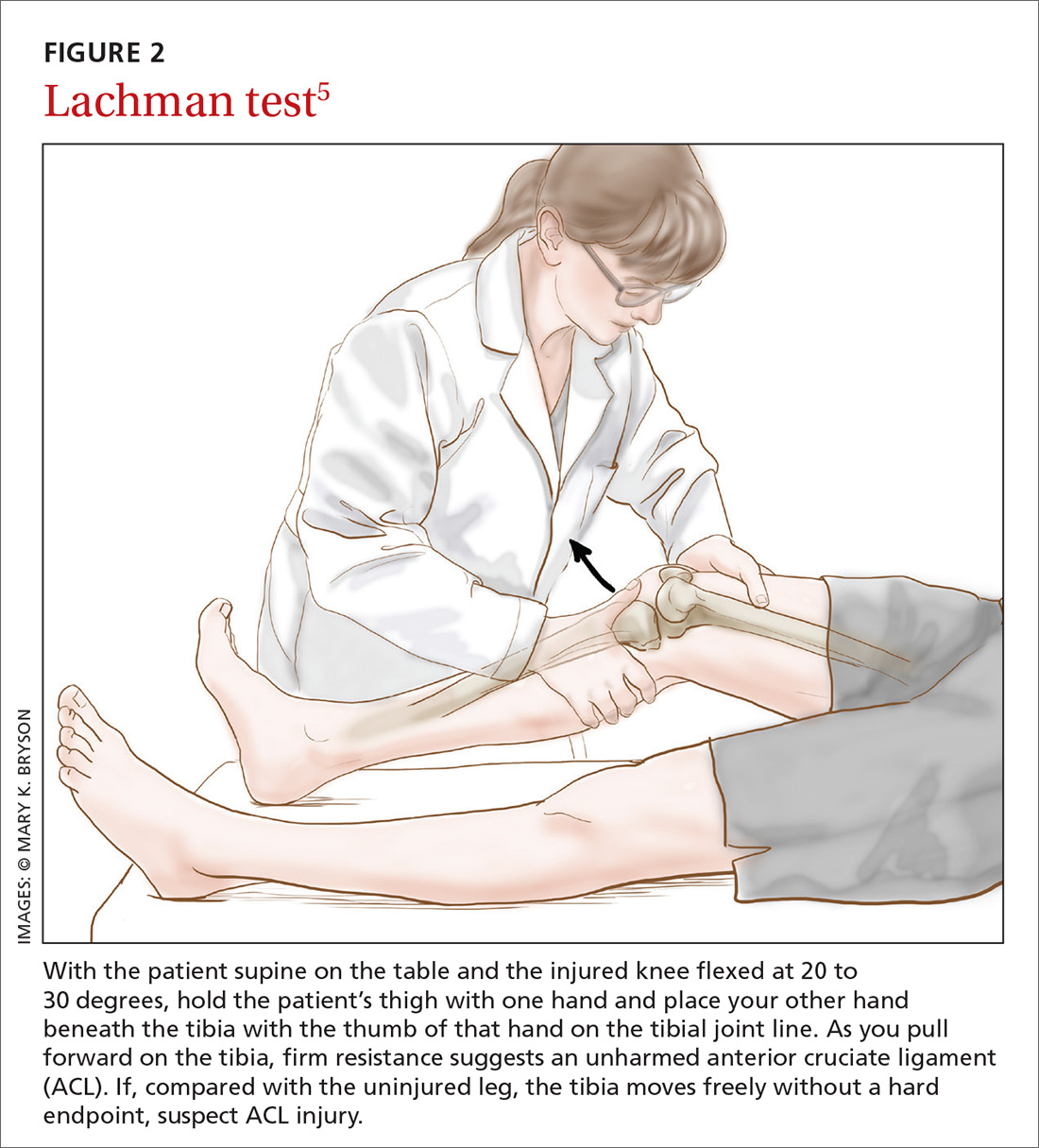

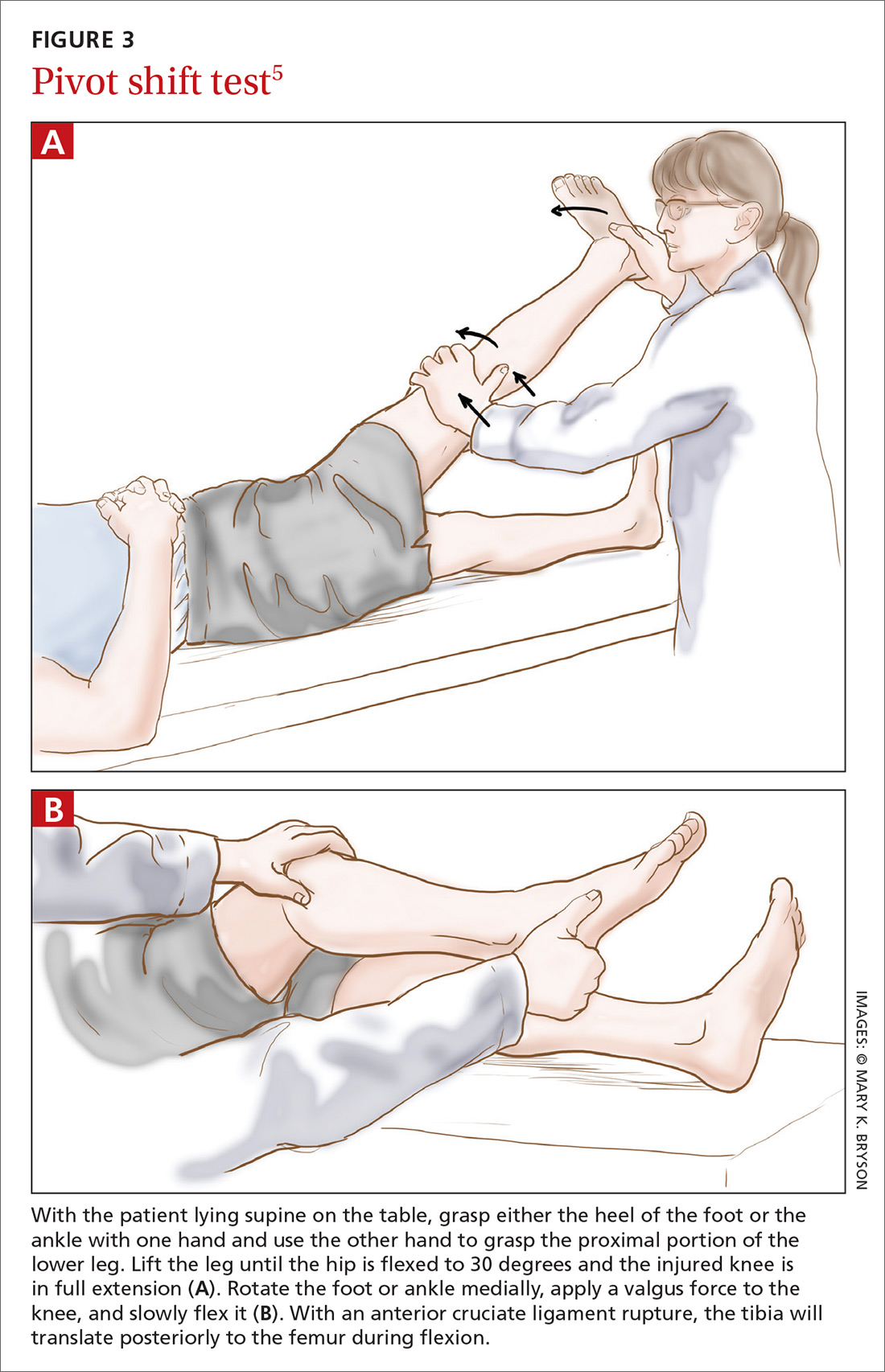

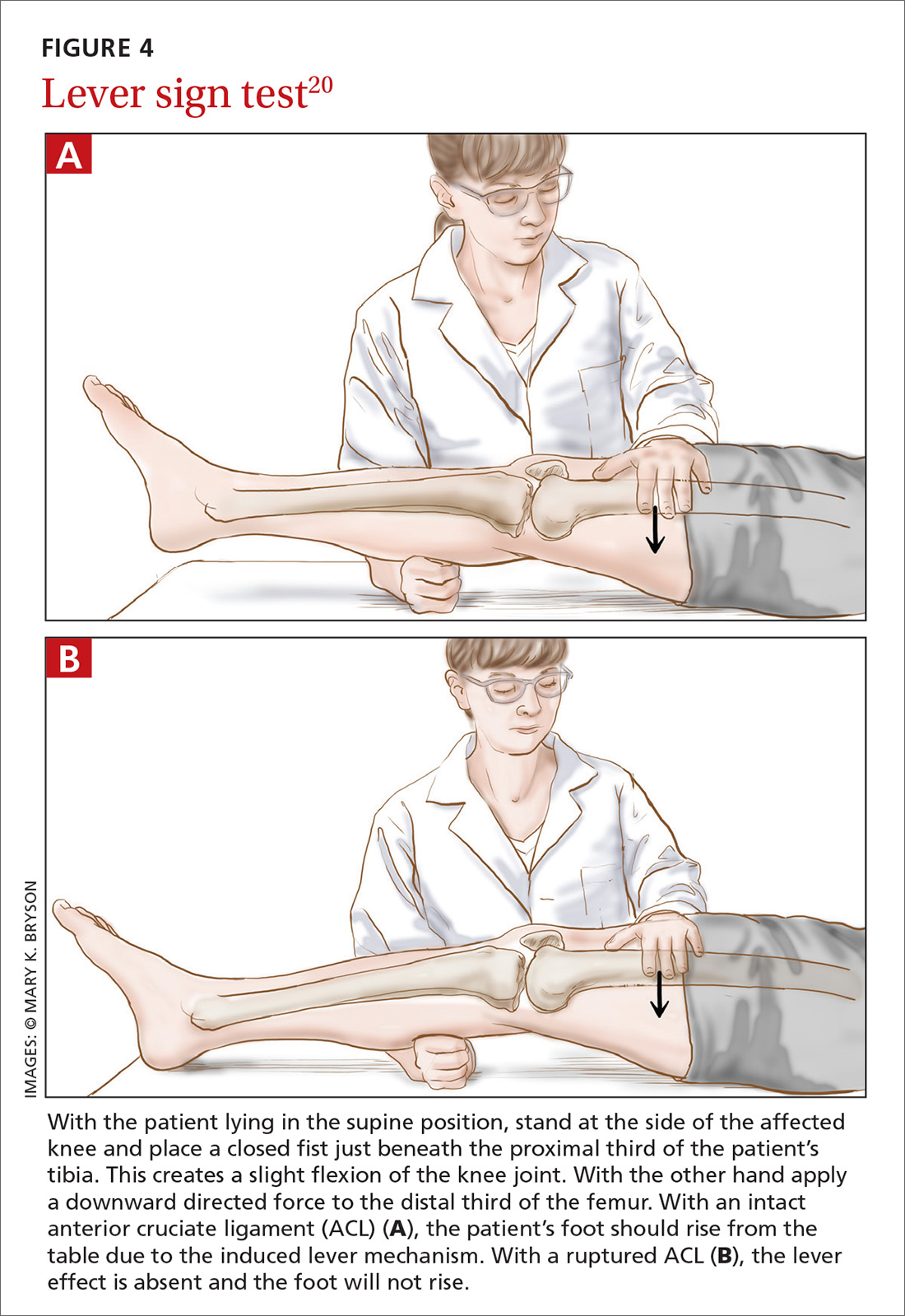

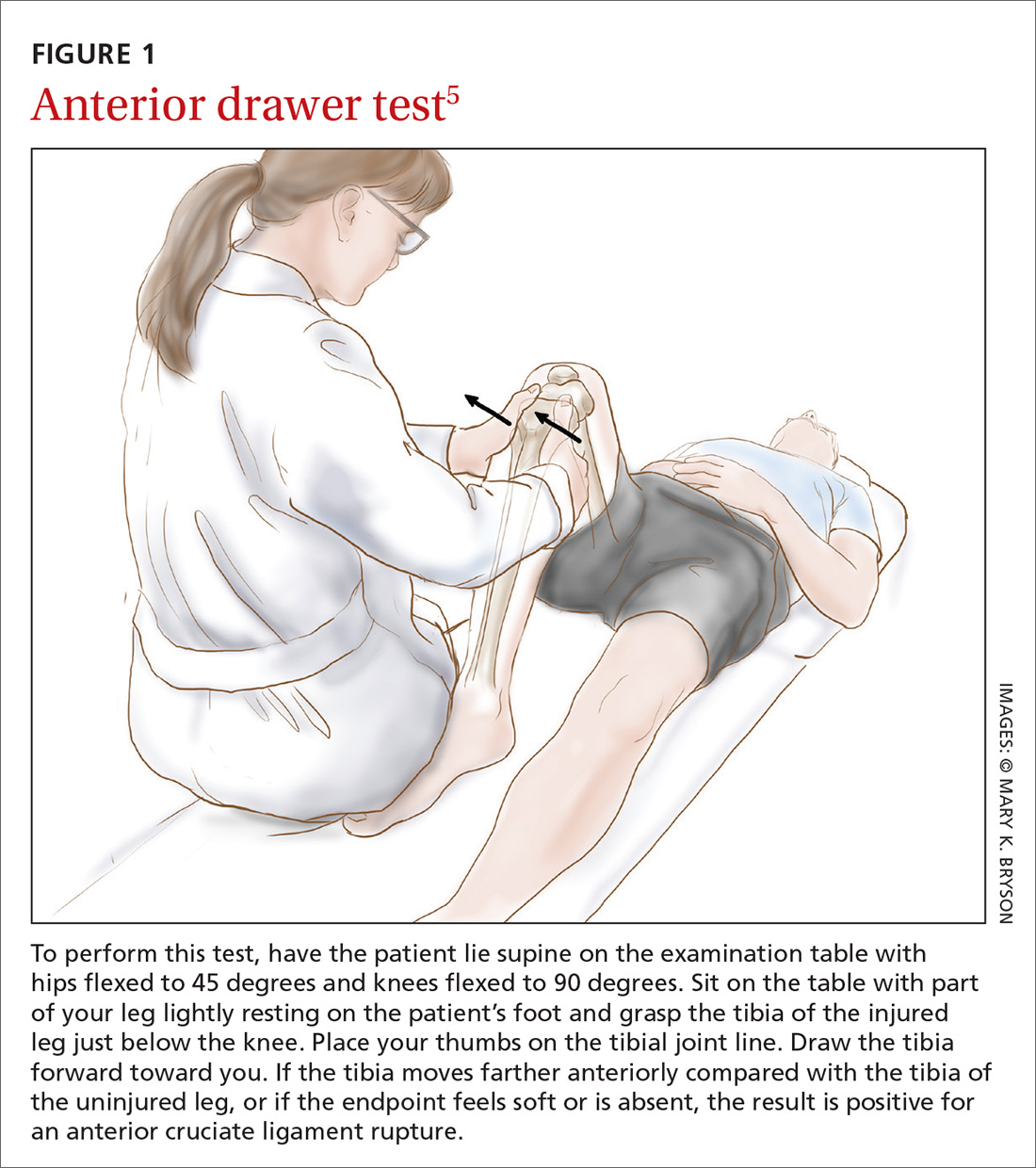

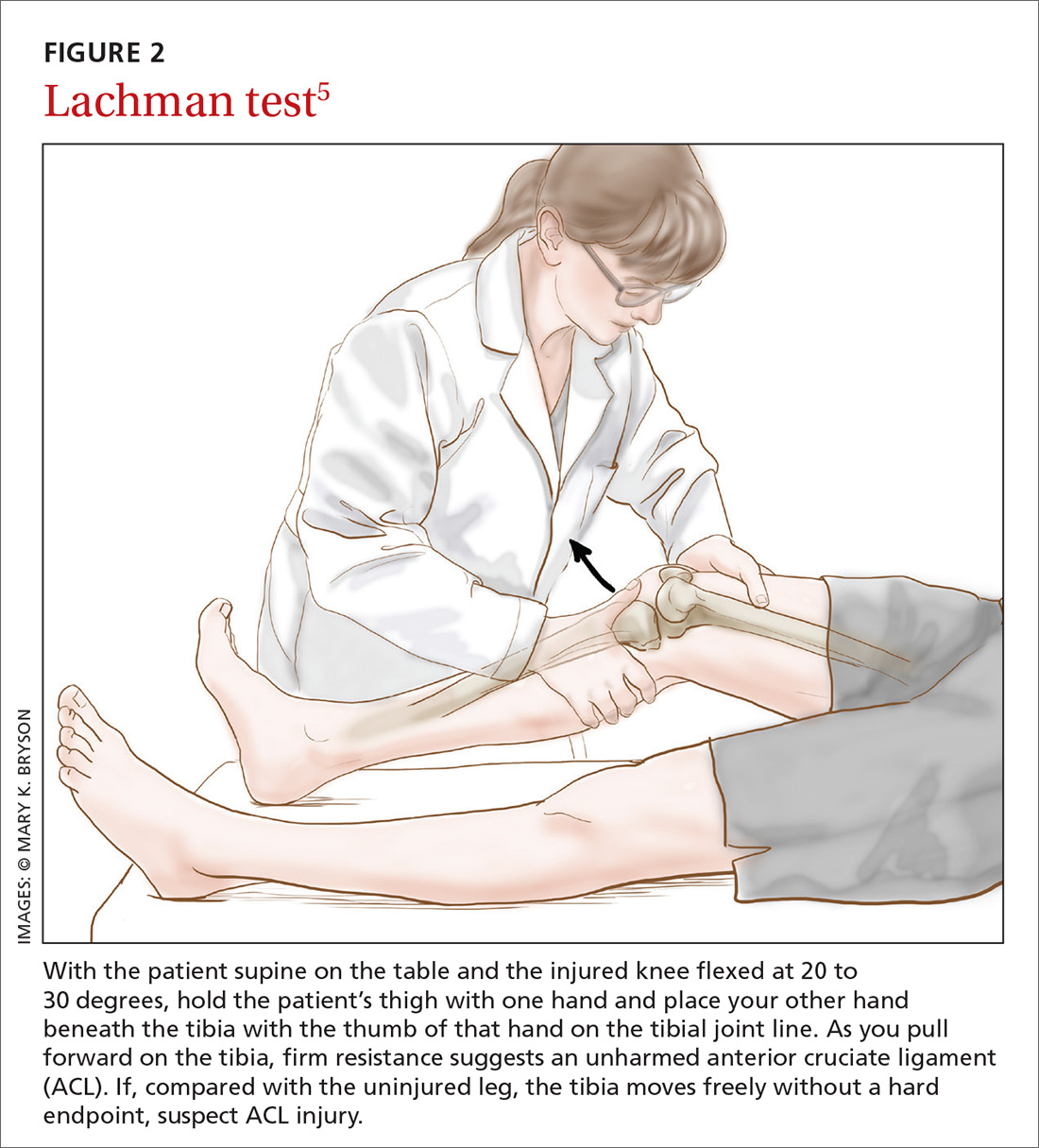

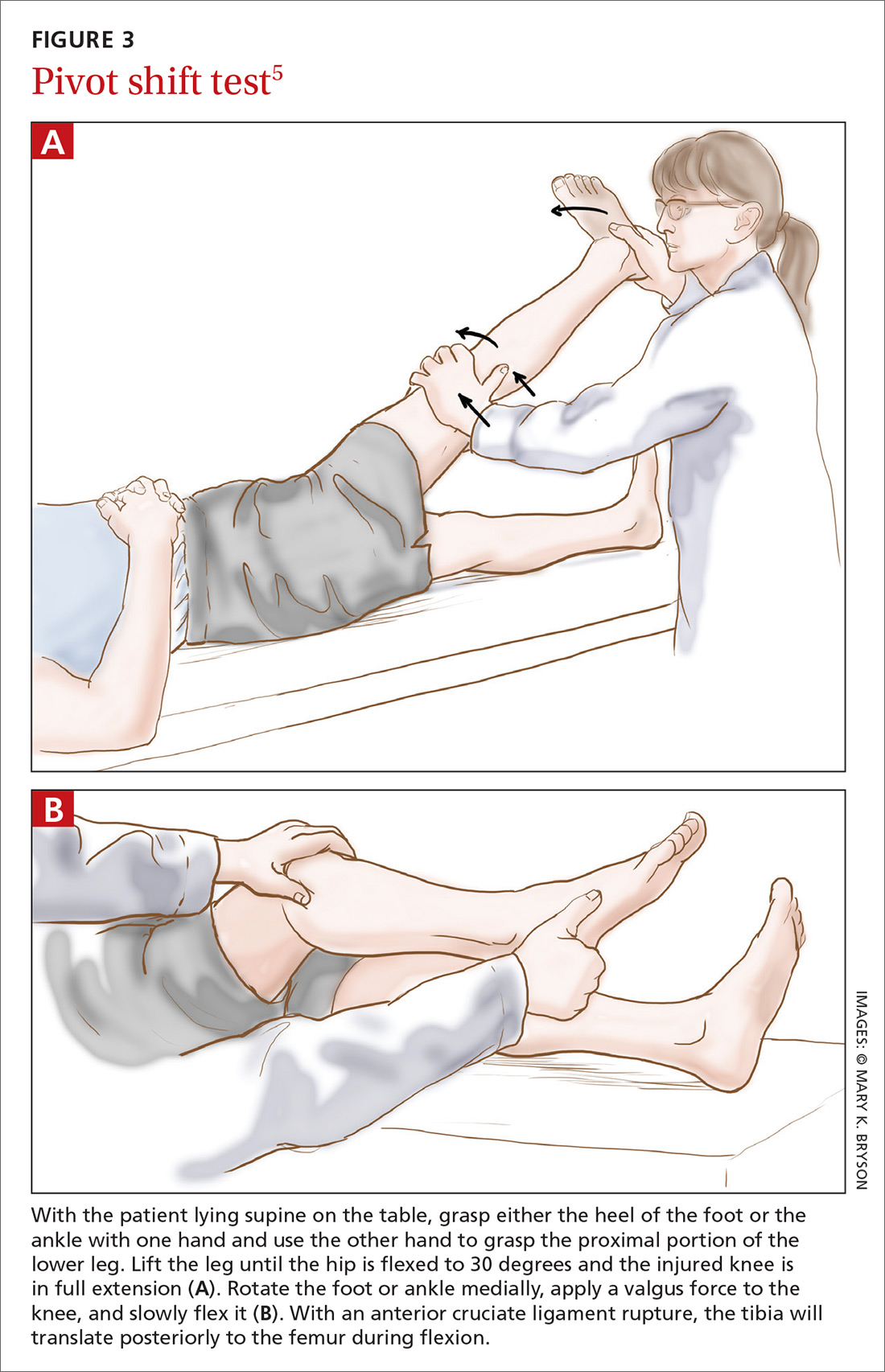

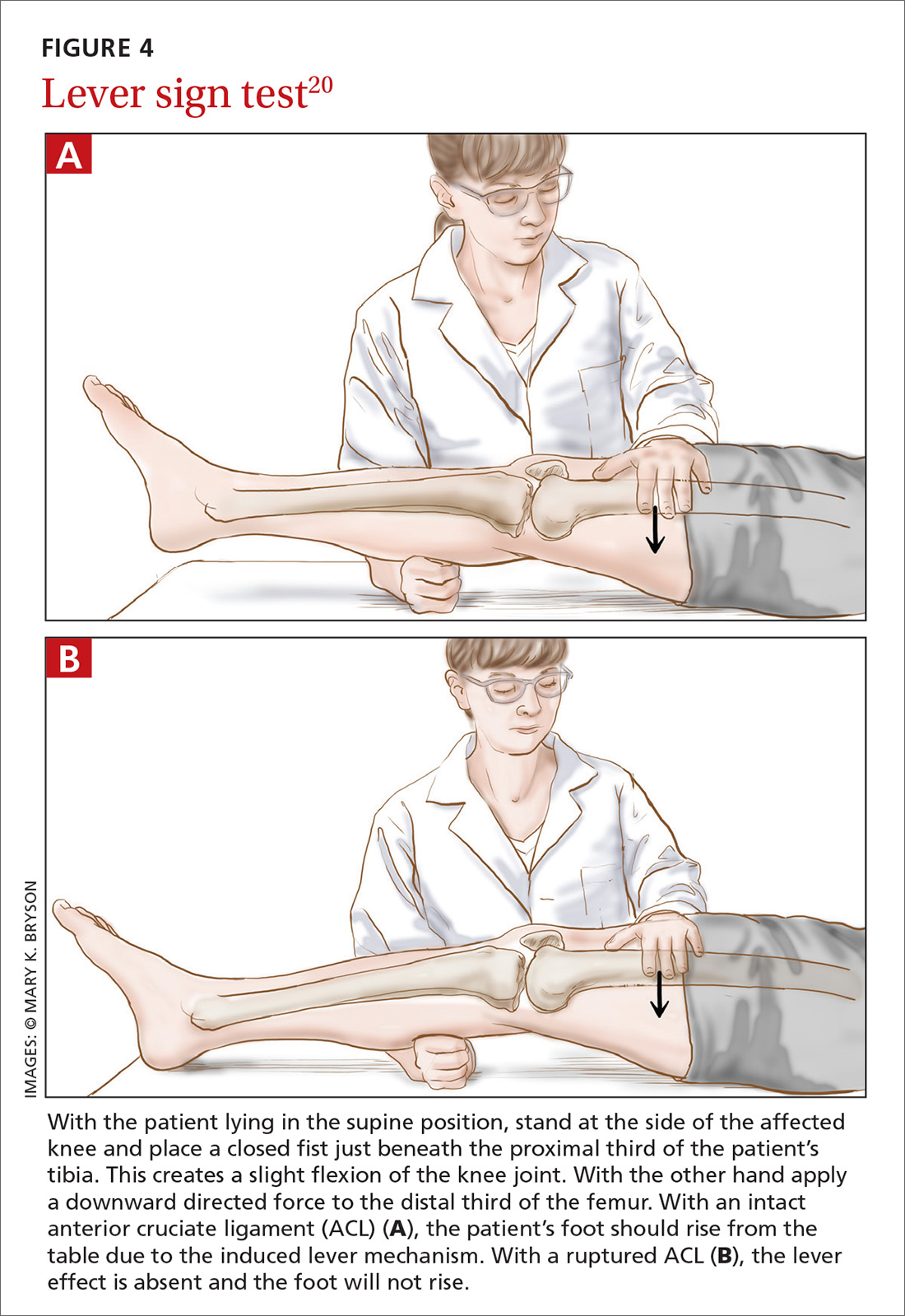

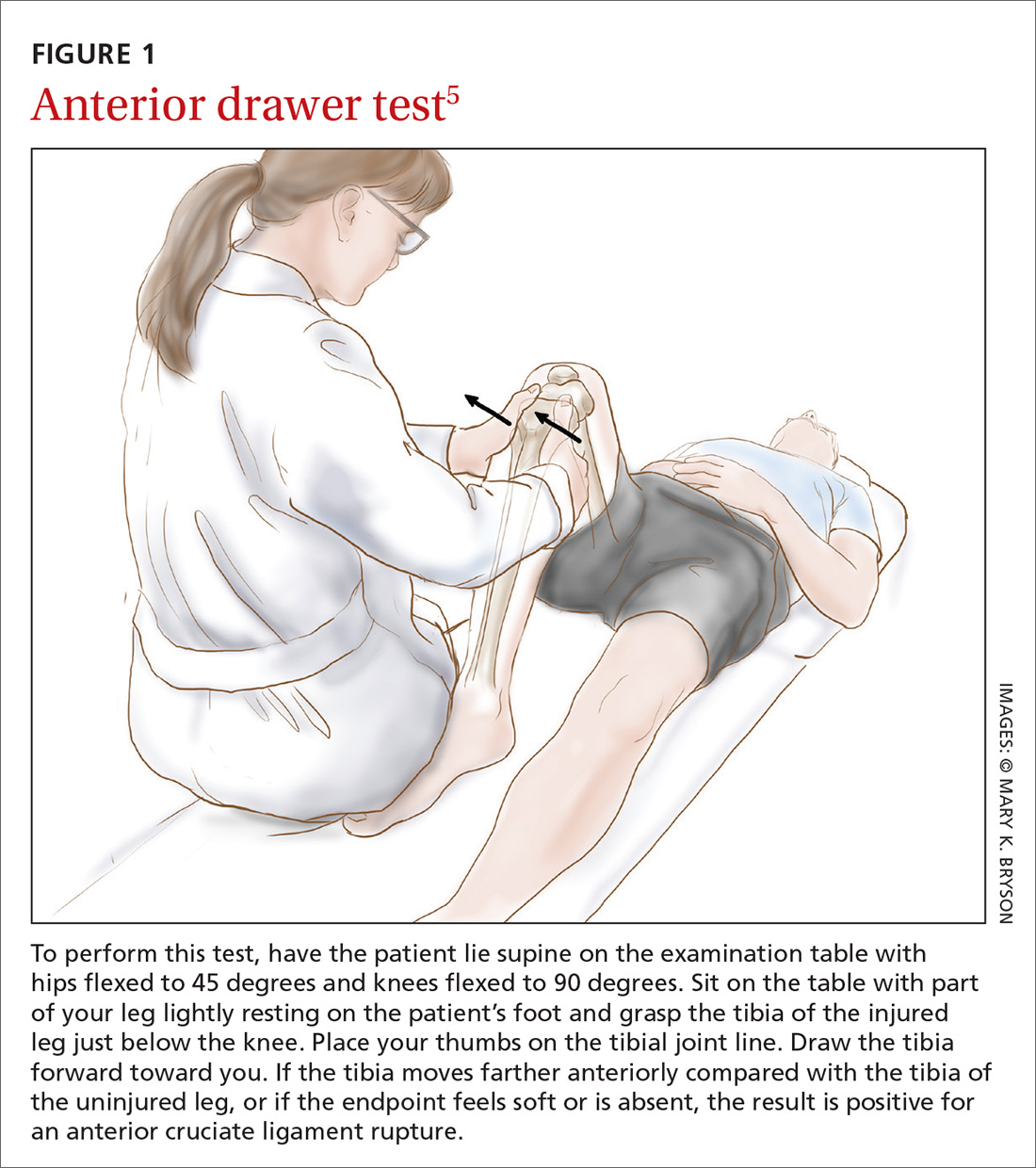

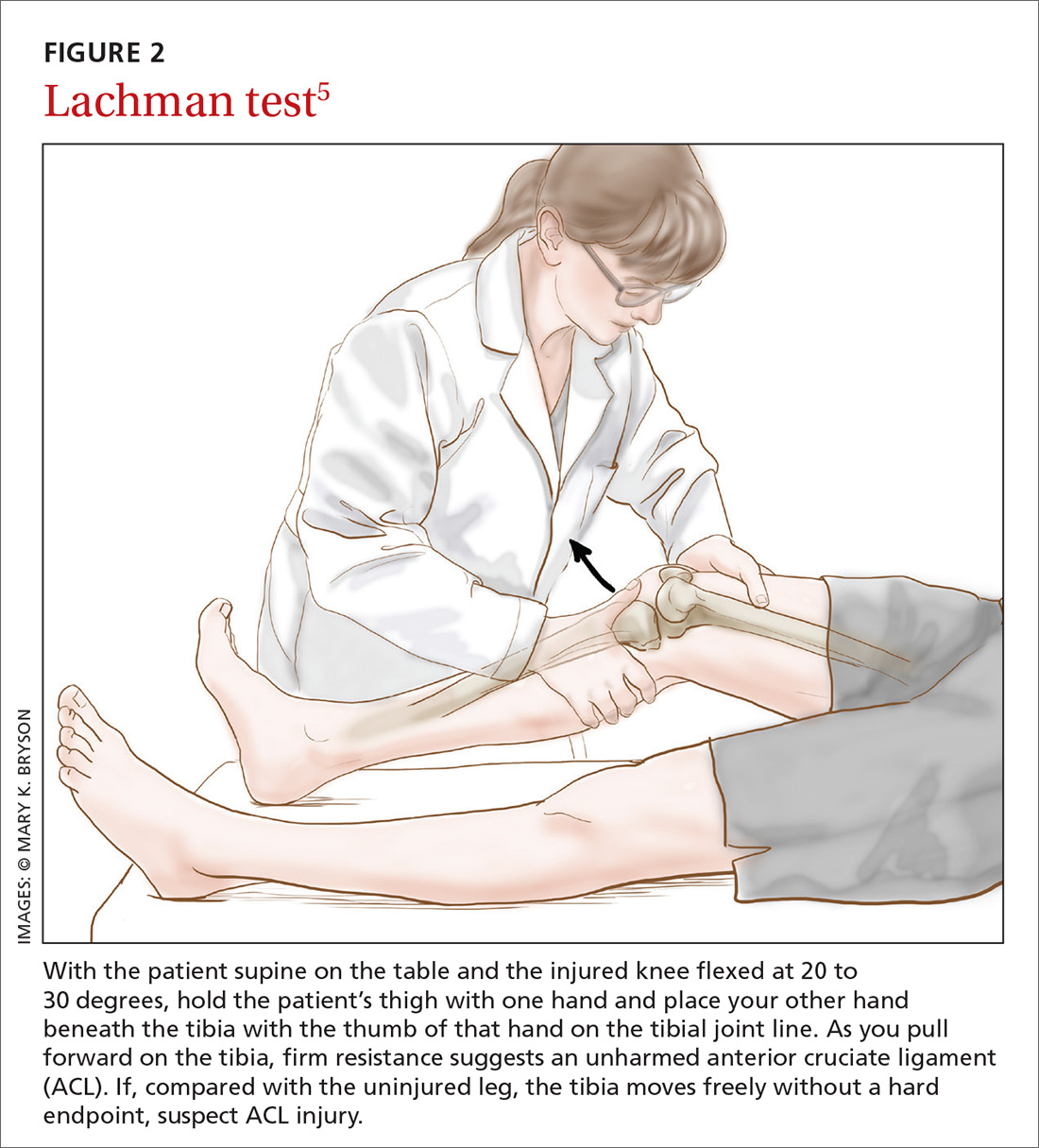

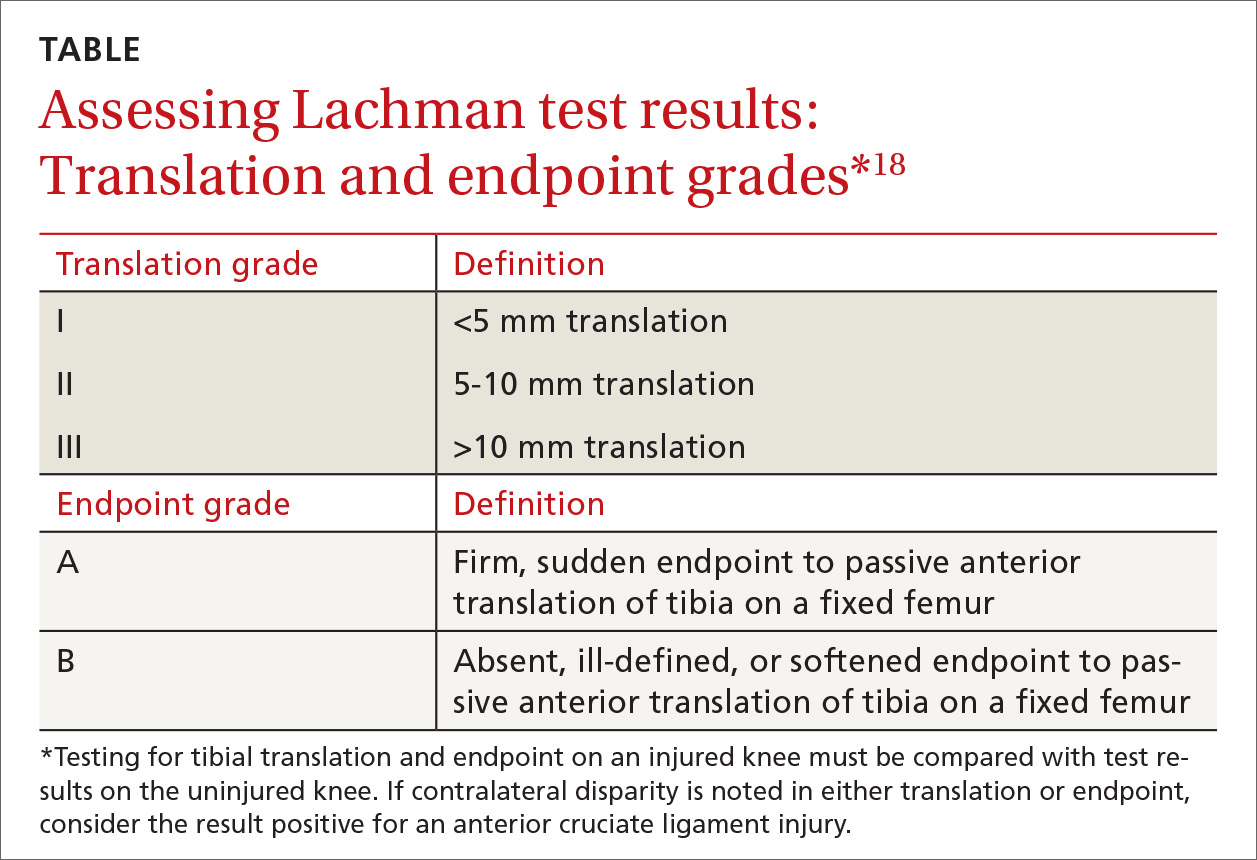

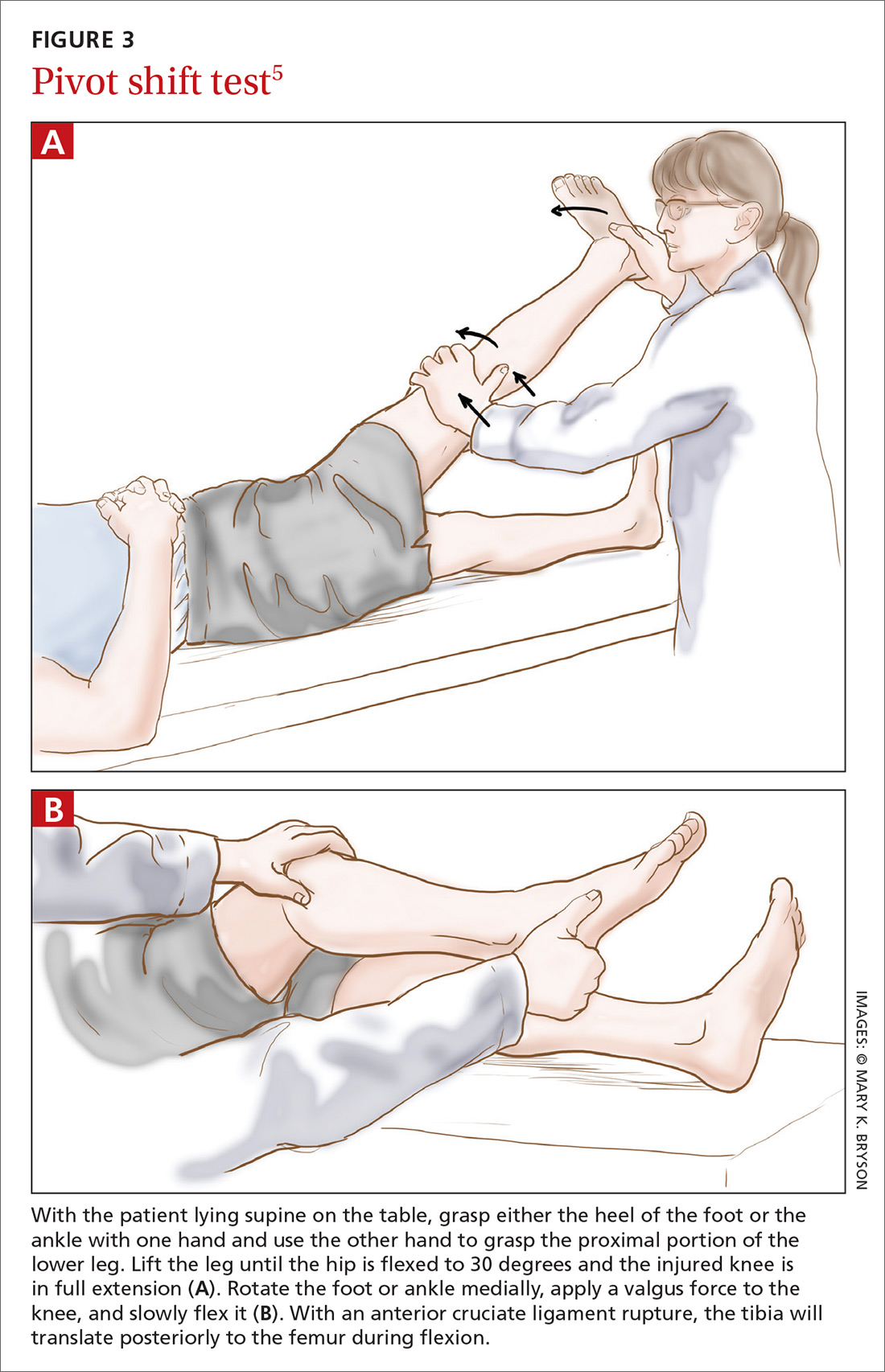

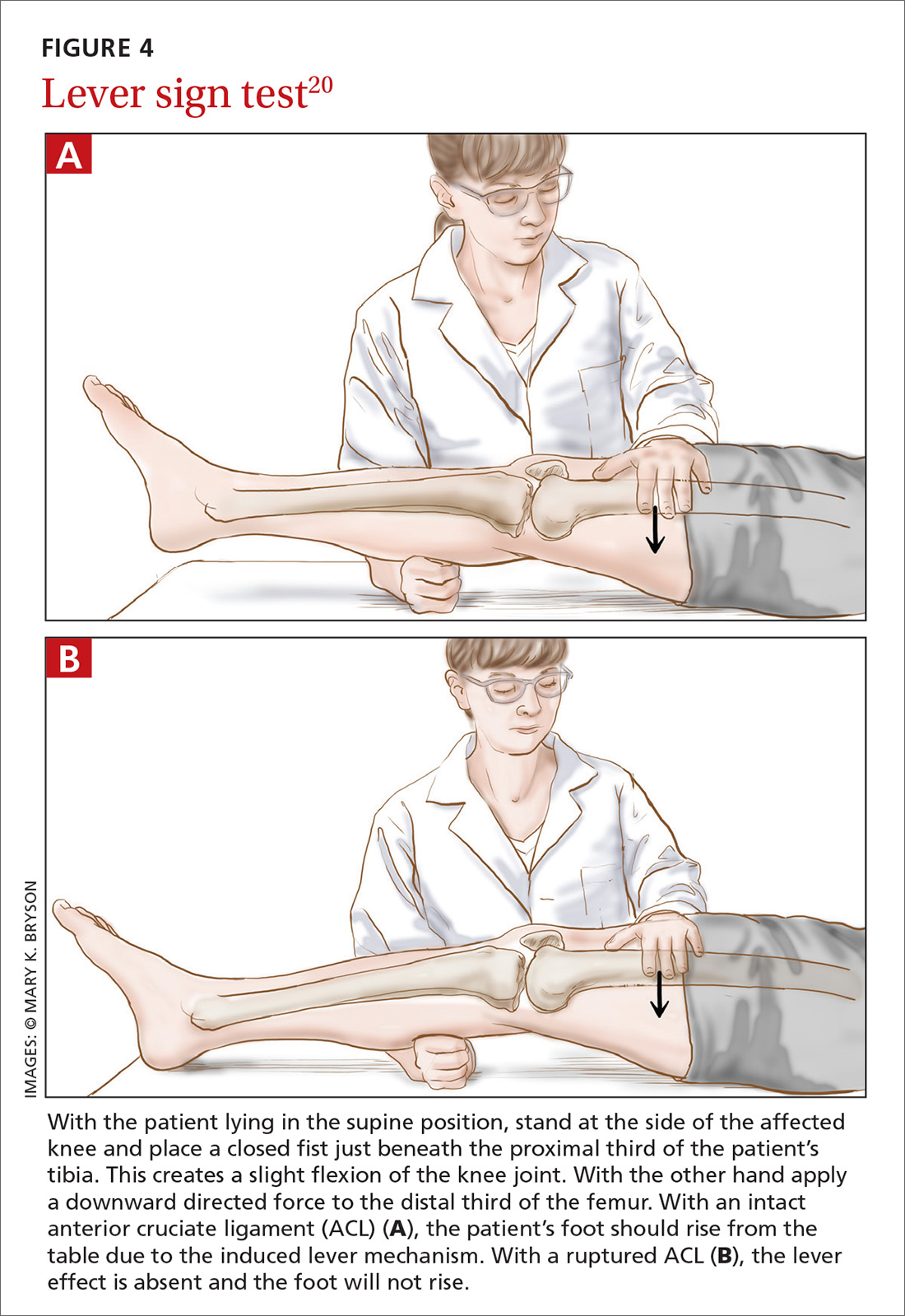

Applying this to acute knee injuries. In this issue of JFP, Koster and colleagues explain that the Lachman test (and possibly the newer lever sign test) are maneuvers that have a high probability of ruling out complete anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) tears when performed properly. The Lachman test, for example, has a 96% sensitivity for complete ACL ruptures.2 (The anterior drawer test has too low a sensitivity to rule out ACL injuries, and the pivot shift test is a bit too challenging to be performed reliably.)

This is important information because early surgery for ACL tears leads to better outcomes for athletes, and a reliable physical exam to rule out an ACL tear reduces the need for imaging. Moreover, other than fractures near the knee, no other knee injuries require early surgery. So a thorough physical exam and selective plain x-rays are all that is needed for the initial evaluation of most knee injuries.

The same is true for back and shoulder injuries, where acute imaging with MRI or CT is rarely called for. A thorough and accurate physical examination is usually sufficient, supplemented with plain X-rays on a selective basis.

Going one step further, consider taking a look at the JAMA series called, “The Rational Clinical Examination,” which has been compiled into a single publication by the same name.3 It is an excellent guide to the sensitivity, specificity, and positive and negative likelihood ratios of a host of clinical findings and tests. It can help to greatly improve clinical skills and reduce unnecessary testing.

1. Choosing Wisely. Available at: http://www.choosingwisely.org. Accessed February 14, 2018.

2. Leblanc MC, Kowalczuk M, Andruszkiewicz N, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of physical examination for anterior knee instability: a systematic review. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2015;10:2805-2813.

3. The Rational Clinical Examination. Available at: https://medicinainternaucv.files.wordpress.com/2013/02/jama-the-rational-clinical-examination.pdf. Accessed February 14, 2018.

“Good morning, Mr. Harris. What can I do for you today?”

“Dr. Hickner, I need an MRI of my right knee. I hurt it last week, and I need to find out if I tore something.”

We all know that too many patients request—and often get—costly (and unnecessary) magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and computed tomography (CT) scans of their joints and backs. That’s why such imaging is targeted in the Choosing Wisely campaign, which aims to eliminate needless testing.1

But how can we confidently tell Mr. Harris that he doesn’t need an MRI or CT scan? One approach is to explain that imaging is generally reserved for those considering surgery, as it serves to inform the surgeon of the exact procedure needed. Another approach is to be skilled in physical exam techniques that increase our confidence in the clinical diagnosis.

Applying this to acute knee injuries. In this issue of JFP, Koster and colleagues explain that the Lachman test (and possibly the newer lever sign test) are maneuvers that have a high probability of ruling out complete anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) tears when performed properly. The Lachman test, for example, has a 96% sensitivity for complete ACL ruptures.2 (The anterior drawer test has too low a sensitivity to rule out ACL injuries, and the pivot shift test is a bit too challenging to be performed reliably.)

This is important information because early surgery for ACL tears leads to better outcomes for athletes, and a reliable physical exam to rule out an ACL tear reduces the need for imaging. Moreover, other than fractures near the knee, no other knee injuries require early surgery. So a thorough physical exam and selective plain x-rays are all that is needed for the initial evaluation of most knee injuries.

The same is true for back and shoulder injuries, where acute imaging with MRI or CT is rarely called for. A thorough and accurate physical examination is usually sufficient, supplemented with plain X-rays on a selective basis.

Going one step further, consider taking a look at the JAMA series called, “The Rational Clinical Examination,” which has been compiled into a single publication by the same name.3 It is an excellent guide to the sensitivity, specificity, and positive and negative likelihood ratios of a host of clinical findings and tests. It can help to greatly improve clinical skills and reduce unnecessary testing.

“Good morning, Mr. Harris. What can I do for you today?”

“Dr. Hickner, I need an MRI of my right knee. I hurt it last week, and I need to find out if I tore something.”

We all know that too many patients request—and often get—costly (and unnecessary) magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and computed tomography (CT) scans of their joints and backs. That’s why such imaging is targeted in the Choosing Wisely campaign, which aims to eliminate needless testing.1

But how can we confidently tell Mr. Harris that he doesn’t need an MRI or CT scan? One approach is to explain that imaging is generally reserved for those considering surgery, as it serves to inform the surgeon of the exact procedure needed. Another approach is to be skilled in physical exam techniques that increase our confidence in the clinical diagnosis.

Applying this to acute knee injuries. In this issue of JFP, Koster and colleagues explain that the Lachman test (and possibly the newer lever sign test) are maneuvers that have a high probability of ruling out complete anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) tears when performed properly. The Lachman test, for example, has a 96% sensitivity for complete ACL ruptures.2 (The anterior drawer test has too low a sensitivity to rule out ACL injuries, and the pivot shift test is a bit too challenging to be performed reliably.)

This is important information because early surgery for ACL tears leads to better outcomes for athletes, and a reliable physical exam to rule out an ACL tear reduces the need for imaging. Moreover, other than fractures near the knee, no other knee injuries require early surgery. So a thorough physical exam and selective plain x-rays are all that is needed for the initial evaluation of most knee injuries.

The same is true for back and shoulder injuries, where acute imaging with MRI or CT is rarely called for. A thorough and accurate physical examination is usually sufficient, supplemented with plain X-rays on a selective basis.

Going one step further, consider taking a look at the JAMA series called, “The Rational Clinical Examination,” which has been compiled into a single publication by the same name.3 It is an excellent guide to the sensitivity, specificity, and positive and negative likelihood ratios of a host of clinical findings and tests. It can help to greatly improve clinical skills and reduce unnecessary testing.

1. Choosing Wisely. Available at: http://www.choosingwisely.org. Accessed February 14, 2018.

2. Leblanc MC, Kowalczuk M, Andruszkiewicz N, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of physical examination for anterior knee instability: a systematic review. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2015;10:2805-2813.

3. The Rational Clinical Examination. Available at: https://medicinainternaucv.files.wordpress.com/2013/02/jama-the-rational-clinical-examination.pdf. Accessed February 14, 2018.

1. Choosing Wisely. Available at: http://www.choosingwisely.org. Accessed February 14, 2018.

2. Leblanc MC, Kowalczuk M, Andruszkiewicz N, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of physical examination for anterior knee instability: a systematic review. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2015;10:2805-2813.

3. The Rational Clinical Examination. Available at: https://medicinainternaucv.files.wordpress.com/2013/02/jama-the-rational-clinical-examination.pdf. Accessed February 14, 2018.

Bilateral wrist pain • limited range of motion • tenderness to palpation • Dx?

THE CASE

A 12-year-old girl presented to my office (JH) with bilateral wrist pain. She had fallen on both wrists palmar-flexed and then, while trying to get up, landed on both wrists dorsi-flexed. The patient did not hear any “pops,” but felt immediate pain when her wrists hyperextended. Hand, wrist, and forearm x-rays were negative bilaterally for fractures. She was placed in bilateral thumb spica splints.

At follow-up one week later, the patient reported 6/10 pain in her left wrist and 7/10 pain in her right wrist. The pain increased to 10/10 bilaterally with movement and was not relieved by icing or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. On physical exam, there was bilateral swelling of the wrists without ecchymosis or erythema. The patient had limited passive and active range of motion, especially during wrist extension. She also had tenderness to palpation over the anatomical snuff box, extending proximally to the distal radius bilaterally. She had no tenderness over the ulna or metacarpals, no loss of sensation in any area nerves, and she was neurovascularly intact bilaterally.

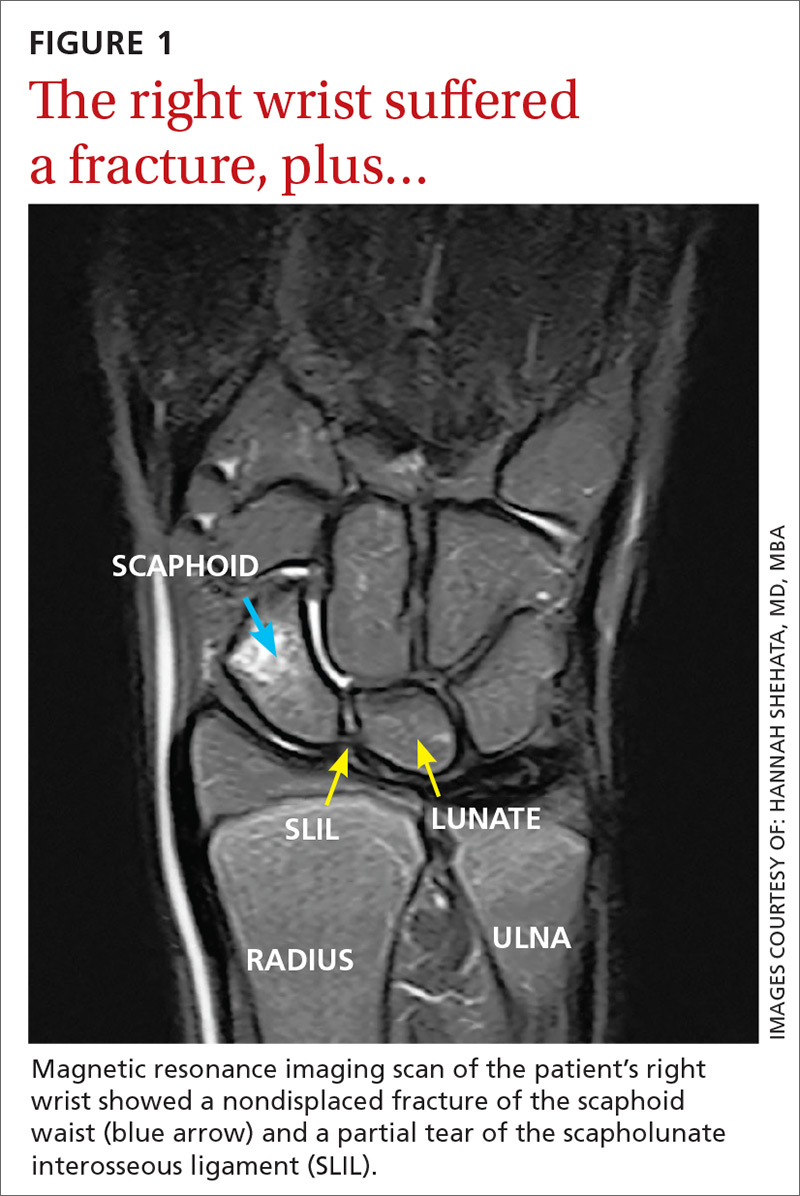

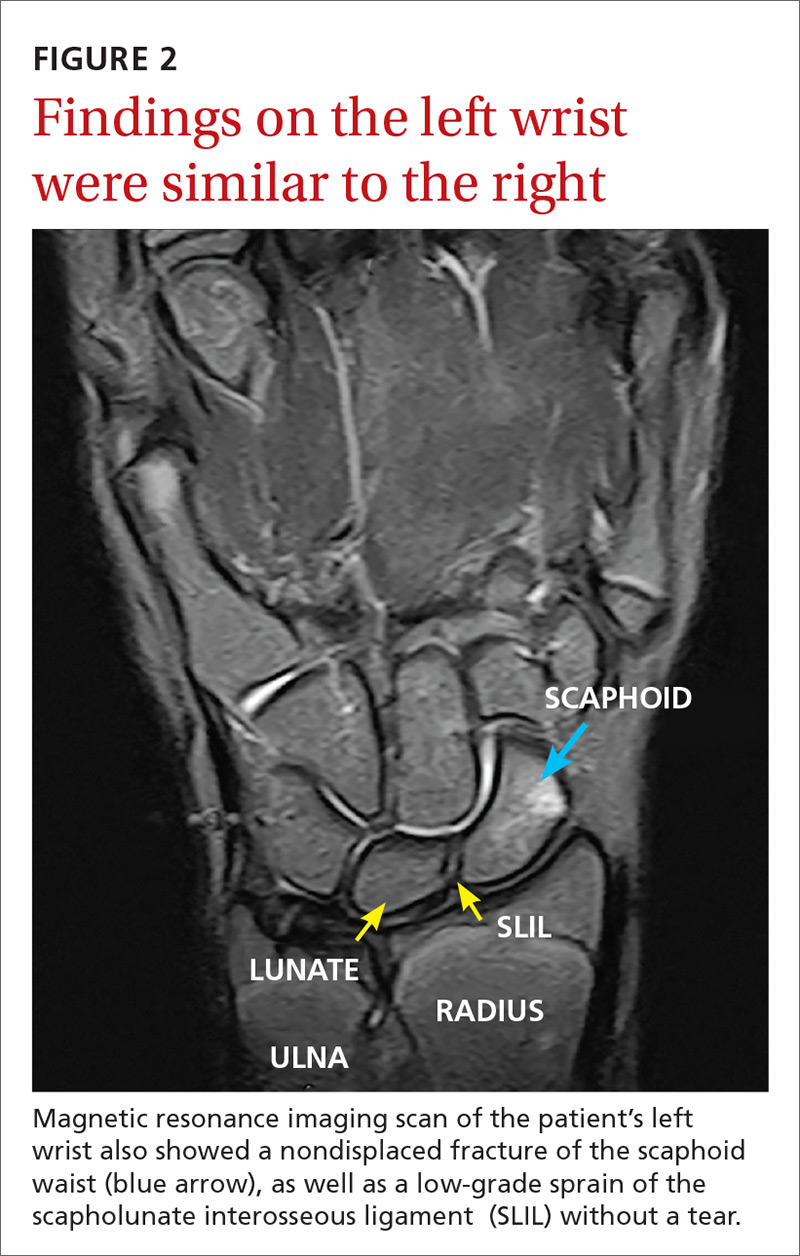

Based on the mechanism of injury, undetected fracture or full thickness ligament tear were both possible. Because of this, and because magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) entails no radiation exposure, MRI was chosen for additional imaging of both wrists.

THE DIAGNOSIS

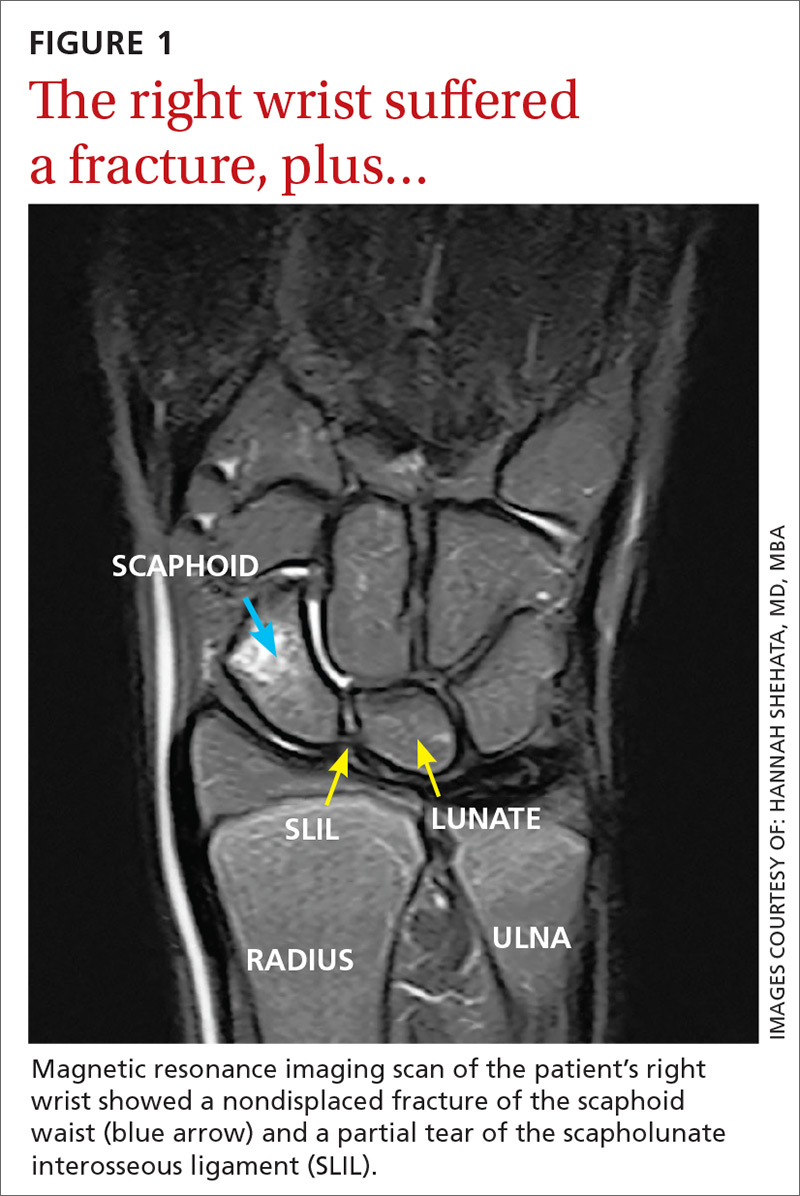

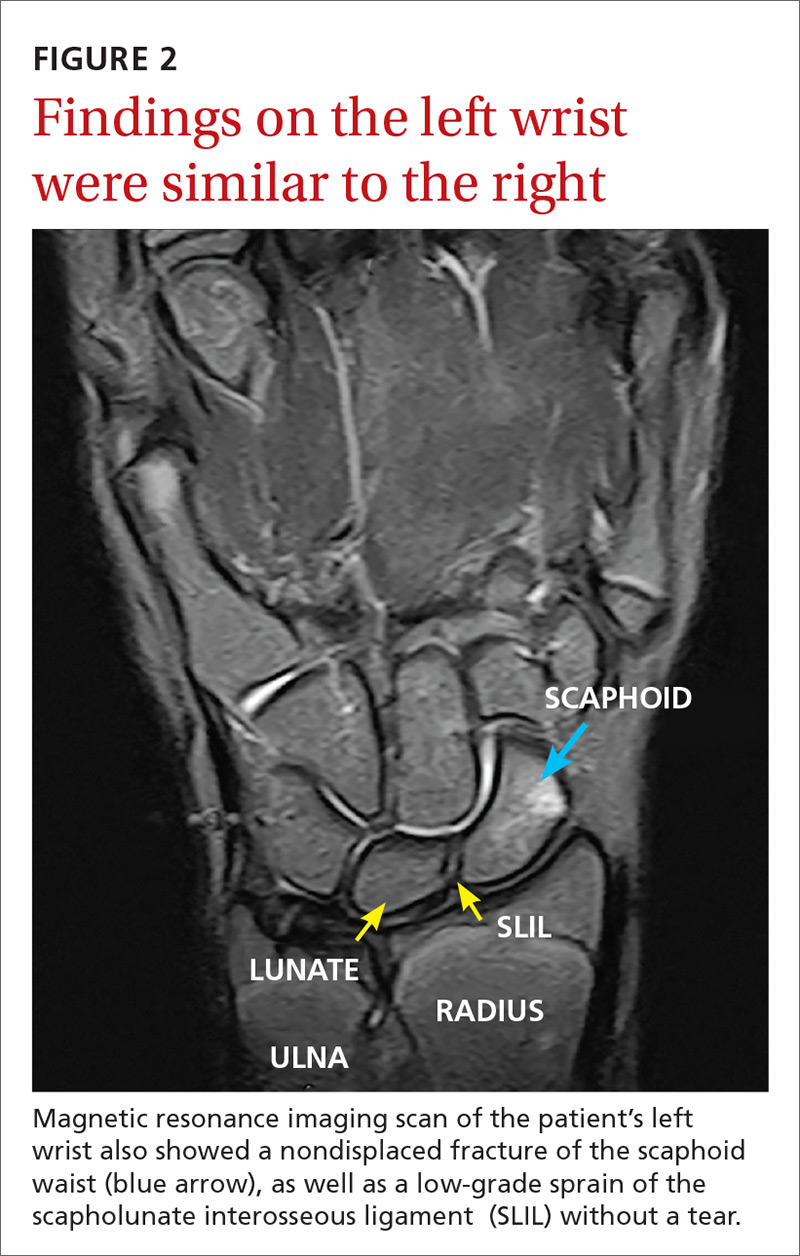

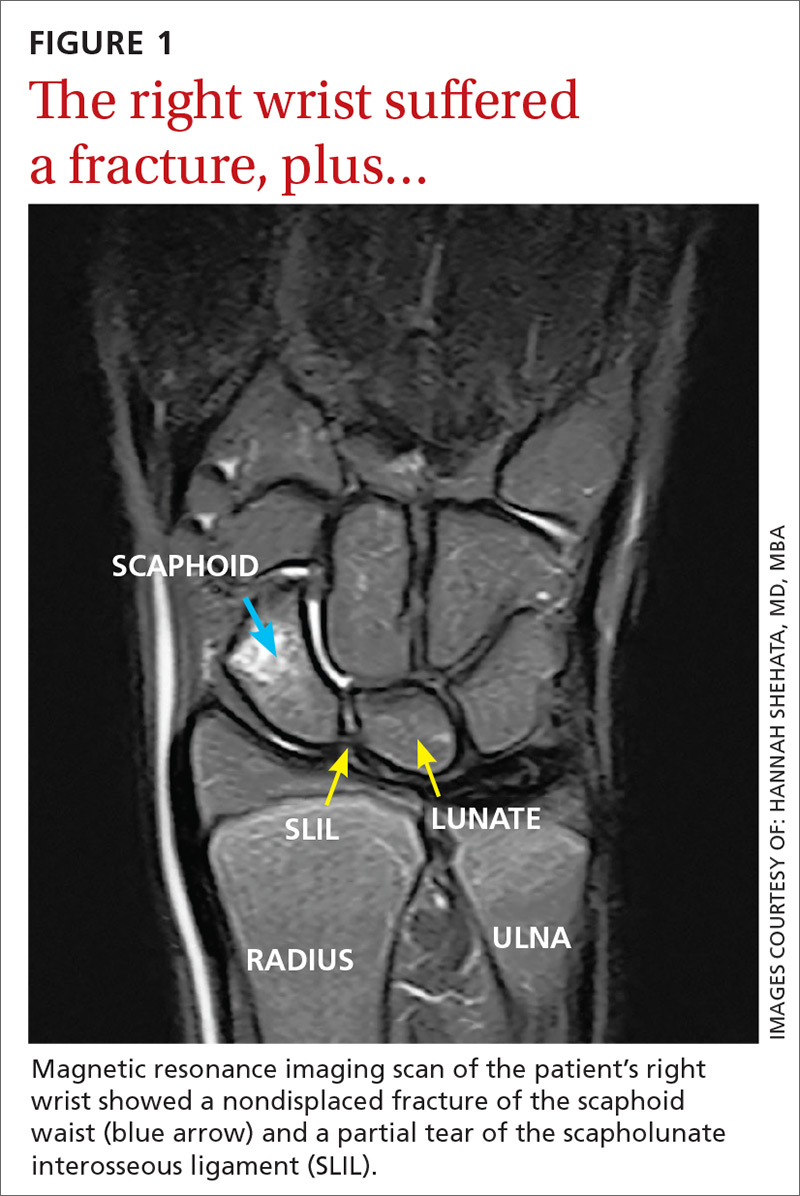

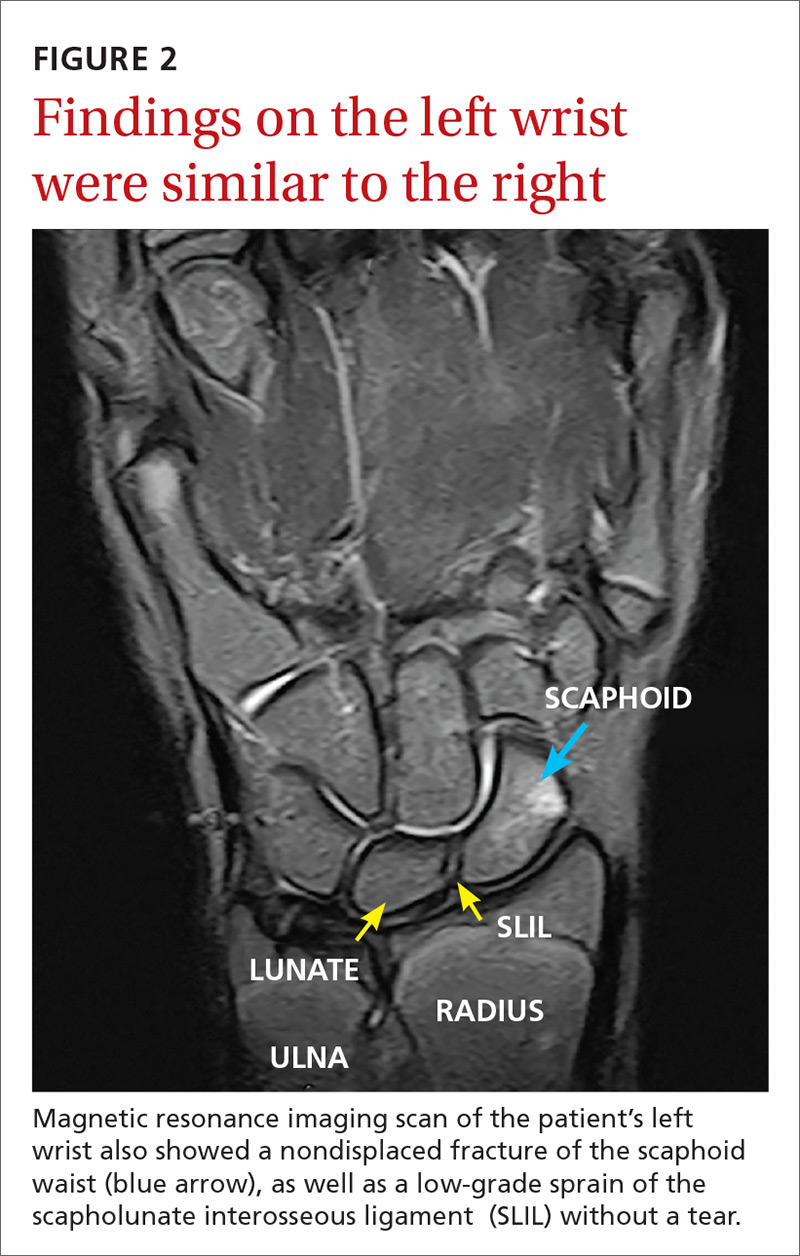

The MRI revealed bilateral, nondisplaced, extra-articular fractures extending through the scaphoid waist, with surrounding bone marrow edema. In the right wrist, the patient also had a low-grade partial tear of the membranous portion of the scapholunate interosseous ligament (SLIL) at the scaphoid attachment (FIGURE 1). In the left wrist, she also had a low-grade sprain of the SLIL without tear (FIGURE 2).

DISCUSSION

Carpal fractures account for 6% of all fractures.1 Scaphoid fractures are the most common carpal bone fracture among all age groups, but account for only 0.4% of all pediatric fractures.1-3 They’re commonly missed on x-rays because they are usually nondisplaced and hidden by other structures superimposed on the image.1,2,4 Undetected, scaphoid fractures can cause prolonged interruption to the bone’s architecture, leading to avascular necrosis of the proximal portion of the scaphoid bone.5,6

Bilateral scaphoid fractures are extremely rare and account for less than 1% of all scaphoid fractures.7 Very few of these cases have been published in the literature, and those that have been published have talked about the fractures being secondary to chronic stress fractures and as being treated with internal fixation (regardless of whether the fractures were nondisplaced or if the ligaments were intact).6-9

Our patient was placed in bilateral fiberglass short-arm thumb spica casts. We tried conservative treatment measures first because she had help with her activities of daily living (ADLs). At a follow-up visit 2 weeks later, we switched the casts to long-arm thumb spica casts because of the patient’s ability to pronate and supinate her wrists in the short-arm versions. After one month of wearing the long-arm casts, we placed her back in bilateral short-arm casts for 2 weeks. Eight weeks after the fall, we removed the short-arm casts for reevaluation.

We obtained x-rays to assess for any new changes to the wrist and specifically the scaphoid bones. The x-rays showed almost completely healed scaphoid bones with good alignment, but the patient still had 5/10 pain in the left wrist and 8/10 pain in the right wrist with movement. We placed her in adjustable thermoformable polymer braces, which were removed when she bathed.

Due to the uniqueness of her injuries, our patient had weekly visits with her primary care provider (PCP) for the first 2 months of treatment, followed by bimonthly visits for the remainder. At 10 weeks after the fall, her pain with movement was almost gone and she began physical therapy. She also began removing the braces during sedentary activity in order to practice range-of-motion exercises to prevent excessive stiffness in her wrists. Our patient regained full strength and range of motion one month later.

One other published case report describes the successful union of bilateral scaphoid fractures using bilateral long-arm casts followed by short-arm casts.7 Similar to our patient’s case, full union of the scaphoid bones was achieved within 12 weeks.7 Together, these cases suggest that conservative treatment methods are a viable alternative to surgery.

TAKEAWAY

For patients presenting with wrist pain after trauma to the wrists, assess anatomical snuffbox tenderness and obtain x-rays. Do not be falsely reassured by negative x-rays in the presence of a positive physical exam, however, as scaphoid fractures are often hidden on x-rays. If tenderness at the anatomical snuffbox is present and doesn’t subside within a few days, apply a short-arm thumb splint and obtain subsequent imaging.

If bilateral, nondisplaced, stable scaphoid fractures are diagnosed, conservative treatment with long-arm and short-arm casts is a viable alternative to surgery. This treatment decision should be made on an individual basis, however, as it requires the patient to have frequent PCP visits, assistance with ADLs, and complete adherence to the treatment plan.

1. Pillai A, Jain M. Management of clinical fractures of the scaphoid: results of an audit and literature review. Eur J Emerg Med. 2005;12:47-51.

2. Evenski AJ, Adamczyk MJ, Steiner RP, et al. Clinically suspected scaphoid fractures in children. J Pediatr Orthop. 2009;29:352-355.

3. Wulff R, Schmidt T. Carpal fractures in children. J Pediatr Orthop. 1998;18:462-465.

4. Nellans KW, Chung KC. Pediatric hand fractures. Hand Clin. 2013;29:569-578.

5. Jernigan EW, Smetana BS, Patterson JM. Pediatric scaphoid proximal pole nonunion with avascular necrosis. J Hand Surgery. 2017;42:299.e1-299.e4.

6. Pidemunt G, Torres-Claramunt R, Ginés A, et al. Bilateral stress fracture of the carpal scaphoid: report in a child and review of the literature. Clin J Sport Med. 2012;22:511-513.

7. Saglam F, Gulabi D, Baysal Ö, et al. Chronic wrist pain in a goalkeeper; bilateral scaphoid stress fracture: a case report. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2015;7:20-22.

8. Muzaffar N, Wani I, Ehsan M, et al. Simultaneous bilateral scaphoid fractures in a soldier managed conservatively by scaphoid casts. Arch Clin Exp Surg. 2016;5:63-64.

9. Mohamed Haflah NH, Mat Nor NF, Abdullah S, et al. Bilateral scaphoid stress fracture in a platform diver presenting with unilateral symptoms. Singapore Med J. 2014;55:e159-e161.

THE CASE

A 12-year-old girl presented to my office (JH) with bilateral wrist pain. She had fallen on both wrists palmar-flexed and then, while trying to get up, landed on both wrists dorsi-flexed. The patient did not hear any “pops,” but felt immediate pain when her wrists hyperextended. Hand, wrist, and forearm x-rays were negative bilaterally for fractures. She was placed in bilateral thumb spica splints.

At follow-up one week later, the patient reported 6/10 pain in her left wrist and 7/10 pain in her right wrist. The pain increased to 10/10 bilaterally with movement and was not relieved by icing or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. On physical exam, there was bilateral swelling of the wrists without ecchymosis or erythema. The patient had limited passive and active range of motion, especially during wrist extension. She also had tenderness to palpation over the anatomical snuff box, extending proximally to the distal radius bilaterally. She had no tenderness over the ulna or metacarpals, no loss of sensation in any area nerves, and she was neurovascularly intact bilaterally.

Based on the mechanism of injury, undetected fracture or full thickness ligament tear were both possible. Because of this, and because magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) entails no radiation exposure, MRI was chosen for additional imaging of both wrists.

THE DIAGNOSIS

The MRI revealed bilateral, nondisplaced, extra-articular fractures extending through the scaphoid waist, with surrounding bone marrow edema. In the right wrist, the patient also had a low-grade partial tear of the membranous portion of the scapholunate interosseous ligament (SLIL) at the scaphoid attachment (FIGURE 1). In the left wrist, she also had a low-grade sprain of the SLIL without tear (FIGURE 2).

DISCUSSION

Carpal fractures account for 6% of all fractures.1 Scaphoid fractures are the most common carpal bone fracture among all age groups, but account for only 0.4% of all pediatric fractures.1-3 They’re commonly missed on x-rays because they are usually nondisplaced and hidden by other structures superimposed on the image.1,2,4 Undetected, scaphoid fractures can cause prolonged interruption to the bone’s architecture, leading to avascular necrosis of the proximal portion of the scaphoid bone.5,6

Bilateral scaphoid fractures are extremely rare and account for less than 1% of all scaphoid fractures.7 Very few of these cases have been published in the literature, and those that have been published have talked about the fractures being secondary to chronic stress fractures and as being treated with internal fixation (regardless of whether the fractures were nondisplaced or if the ligaments were intact).6-9

Our patient was placed in bilateral fiberglass short-arm thumb spica casts. We tried conservative treatment measures first because she had help with her activities of daily living (ADLs). At a follow-up visit 2 weeks later, we switched the casts to long-arm thumb spica casts because of the patient’s ability to pronate and supinate her wrists in the short-arm versions. After one month of wearing the long-arm casts, we placed her back in bilateral short-arm casts for 2 weeks. Eight weeks after the fall, we removed the short-arm casts for reevaluation.

We obtained x-rays to assess for any new changes to the wrist and specifically the scaphoid bones. The x-rays showed almost completely healed scaphoid bones with good alignment, but the patient still had 5/10 pain in the left wrist and 8/10 pain in the right wrist with movement. We placed her in adjustable thermoformable polymer braces, which were removed when she bathed.

Due to the uniqueness of her injuries, our patient had weekly visits with her primary care provider (PCP) for the first 2 months of treatment, followed by bimonthly visits for the remainder. At 10 weeks after the fall, her pain with movement was almost gone and she began physical therapy. She also began removing the braces during sedentary activity in order to practice range-of-motion exercises to prevent excessive stiffness in her wrists. Our patient regained full strength and range of motion one month later.

One other published case report describes the successful union of bilateral scaphoid fractures using bilateral long-arm casts followed by short-arm casts.7 Similar to our patient’s case, full union of the scaphoid bones was achieved within 12 weeks.7 Together, these cases suggest that conservative treatment methods are a viable alternative to surgery.

TAKEAWAY

For patients presenting with wrist pain after trauma to the wrists, assess anatomical snuffbox tenderness and obtain x-rays. Do not be falsely reassured by negative x-rays in the presence of a positive physical exam, however, as scaphoid fractures are often hidden on x-rays. If tenderness at the anatomical snuffbox is present and doesn’t subside within a few days, apply a short-arm thumb splint and obtain subsequent imaging.

If bilateral, nondisplaced, stable scaphoid fractures are diagnosed, conservative treatment with long-arm and short-arm casts is a viable alternative to surgery. This treatment decision should be made on an individual basis, however, as it requires the patient to have frequent PCP visits, assistance with ADLs, and complete adherence to the treatment plan.

THE CASE

A 12-year-old girl presented to my office (JH) with bilateral wrist pain. She had fallen on both wrists palmar-flexed and then, while trying to get up, landed on both wrists dorsi-flexed. The patient did not hear any “pops,” but felt immediate pain when her wrists hyperextended. Hand, wrist, and forearm x-rays were negative bilaterally for fractures. She was placed in bilateral thumb spica splints.

At follow-up one week later, the patient reported 6/10 pain in her left wrist and 7/10 pain in her right wrist. The pain increased to 10/10 bilaterally with movement and was not relieved by icing or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. On physical exam, there was bilateral swelling of the wrists without ecchymosis or erythema. The patient had limited passive and active range of motion, especially during wrist extension. She also had tenderness to palpation over the anatomical snuff box, extending proximally to the distal radius bilaterally. She had no tenderness over the ulna or metacarpals, no loss of sensation in any area nerves, and she was neurovascularly intact bilaterally.

Based on the mechanism of injury, undetected fracture or full thickness ligament tear were both possible. Because of this, and because magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) entails no radiation exposure, MRI was chosen for additional imaging of both wrists.

THE DIAGNOSIS

The MRI revealed bilateral, nondisplaced, extra-articular fractures extending through the scaphoid waist, with surrounding bone marrow edema. In the right wrist, the patient also had a low-grade partial tear of the membranous portion of the scapholunate interosseous ligament (SLIL) at the scaphoid attachment (FIGURE 1). In the left wrist, she also had a low-grade sprain of the SLIL without tear (FIGURE 2).

DISCUSSION

Carpal fractures account for 6% of all fractures.1 Scaphoid fractures are the most common carpal bone fracture among all age groups, but account for only 0.4% of all pediatric fractures.1-3 They’re commonly missed on x-rays because they are usually nondisplaced and hidden by other structures superimposed on the image.1,2,4 Undetected, scaphoid fractures can cause prolonged interruption to the bone’s architecture, leading to avascular necrosis of the proximal portion of the scaphoid bone.5,6

Bilateral scaphoid fractures are extremely rare and account for less than 1% of all scaphoid fractures.7 Very few of these cases have been published in the literature, and those that have been published have talked about the fractures being secondary to chronic stress fractures and as being treated with internal fixation (regardless of whether the fractures were nondisplaced or if the ligaments were intact).6-9

Our patient was placed in bilateral fiberglass short-arm thumb spica casts. We tried conservative treatment measures first because she had help with her activities of daily living (ADLs). At a follow-up visit 2 weeks later, we switched the casts to long-arm thumb spica casts because of the patient’s ability to pronate and supinate her wrists in the short-arm versions. After one month of wearing the long-arm casts, we placed her back in bilateral short-arm casts for 2 weeks. Eight weeks after the fall, we removed the short-arm casts for reevaluation.

We obtained x-rays to assess for any new changes to the wrist and specifically the scaphoid bones. The x-rays showed almost completely healed scaphoid bones with good alignment, but the patient still had 5/10 pain in the left wrist and 8/10 pain in the right wrist with movement. We placed her in adjustable thermoformable polymer braces, which were removed when she bathed.

Due to the uniqueness of her injuries, our patient had weekly visits with her primary care provider (PCP) for the first 2 months of treatment, followed by bimonthly visits for the remainder. At 10 weeks after the fall, her pain with movement was almost gone and she began physical therapy. She also began removing the braces during sedentary activity in order to practice range-of-motion exercises to prevent excessive stiffness in her wrists. Our patient regained full strength and range of motion one month later.

One other published case report describes the successful union of bilateral scaphoid fractures using bilateral long-arm casts followed by short-arm casts.7 Similar to our patient’s case, full union of the scaphoid bones was achieved within 12 weeks.7 Together, these cases suggest that conservative treatment methods are a viable alternative to surgery.

TAKEAWAY

For patients presenting with wrist pain after trauma to the wrists, assess anatomical snuffbox tenderness and obtain x-rays. Do not be falsely reassured by negative x-rays in the presence of a positive physical exam, however, as scaphoid fractures are often hidden on x-rays. If tenderness at the anatomical snuffbox is present and doesn’t subside within a few days, apply a short-arm thumb splint and obtain subsequent imaging.

If bilateral, nondisplaced, stable scaphoid fractures are diagnosed, conservative treatment with long-arm and short-arm casts is a viable alternative to surgery. This treatment decision should be made on an individual basis, however, as it requires the patient to have frequent PCP visits, assistance with ADLs, and complete adherence to the treatment plan.

1. Pillai A, Jain M. Management of clinical fractures of the scaphoid: results of an audit and literature review. Eur J Emerg Med. 2005;12:47-51.

2. Evenski AJ, Adamczyk MJ, Steiner RP, et al. Clinically suspected scaphoid fractures in children. J Pediatr Orthop. 2009;29:352-355.

3. Wulff R, Schmidt T. Carpal fractures in children. J Pediatr Orthop. 1998;18:462-465.

4. Nellans KW, Chung KC. Pediatric hand fractures. Hand Clin. 2013;29:569-578.

5. Jernigan EW, Smetana BS, Patterson JM. Pediatric scaphoid proximal pole nonunion with avascular necrosis. J Hand Surgery. 2017;42:299.e1-299.e4.

6. Pidemunt G, Torres-Claramunt R, Ginés A, et al. Bilateral stress fracture of the carpal scaphoid: report in a child and review of the literature. Clin J Sport Med. 2012;22:511-513.

7. Saglam F, Gulabi D, Baysal Ö, et al. Chronic wrist pain in a goalkeeper; bilateral scaphoid stress fracture: a case report. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2015;7:20-22.

8. Muzaffar N, Wani I, Ehsan M, et al. Simultaneous bilateral scaphoid fractures in a soldier managed conservatively by scaphoid casts. Arch Clin Exp Surg. 2016;5:63-64.

9. Mohamed Haflah NH, Mat Nor NF, Abdullah S, et al. Bilateral scaphoid stress fracture in a platform diver presenting with unilateral symptoms. Singapore Med J. 2014;55:e159-e161.

1. Pillai A, Jain M. Management of clinical fractures of the scaphoid: results of an audit and literature review. Eur J Emerg Med. 2005;12:47-51.

2. Evenski AJ, Adamczyk MJ, Steiner RP, et al. Clinically suspected scaphoid fractures in children. J Pediatr Orthop. 2009;29:352-355.

3. Wulff R, Schmidt T. Carpal fractures in children. J Pediatr Orthop. 1998;18:462-465.

4. Nellans KW, Chung KC. Pediatric hand fractures. Hand Clin. 2013;29:569-578.

5. Jernigan EW, Smetana BS, Patterson JM. Pediatric scaphoid proximal pole nonunion with avascular necrosis. J Hand Surgery. 2017;42:299.e1-299.e4.

6. Pidemunt G, Torres-Claramunt R, Ginés A, et al. Bilateral stress fracture of the carpal scaphoid: report in a child and review of the literature. Clin J Sport Med. 2012;22:511-513.

7. Saglam F, Gulabi D, Baysal Ö, et al. Chronic wrist pain in a goalkeeper; bilateral scaphoid stress fracture: a case report. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2015;7:20-22.

8. Muzaffar N, Wani I, Ehsan M, et al. Simultaneous bilateral scaphoid fractures in a soldier managed conservatively by scaphoid casts. Arch Clin Exp Surg. 2016;5:63-64.

9. Mohamed Haflah NH, Mat Nor NF, Abdullah S, et al. Bilateral scaphoid stress fracture in a platform diver presenting with unilateral symptoms. Singapore Med J. 2014;55:e159-e161.

An easy approach to obtaining clean-catch urine from infants

ILLUSTRATIVE CASE

A fussy 6-month-old infant is brought into the emergency department (ED) with a rectal temperature of 101.5° F. She is consolable, breathing normally, and appears well hydrated. You find no clear etiology for her fever and suspect that a urinary tract infection (UTI) may be the source of her illness. How do you proceed with obtaining a urine sample?

A febrile infant in the family physician’s office or ED is a familiar clinical situation that may require an invasive diagnostic work-up. Up to 7% of infants ages 2 to 24 months with fever of unknown origin may have a UTI.2 Collecting a urine sample from pre-toilet-trained children can be time consuming. In fact, obtaining a clean-catch urine sample in this age group took an average of more than one hour in one randomized controlled trial (RCT).3 More convenient methods of urine collection, such as placing a cotton ball in the diaper or using a perineal collection bag, have contamination rates of up to 63%.4

The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) guidelines for evaluating possible UTI in a febrile child <2 years of age recommend obtaining a sample for urinalysis “through the most convenient means.”5 If urinalysis is positive, only urine obtained by catheterization or suprapubic aspiration should be cultured. Guidelines from the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence in the United Kingdom are similar, but allow for culture of clean-catch urine samples.6

A recent prospective cohort study examined a noninvasive alternating lumbar-bladder tapping method to stimulate voiding in infants ages 0 to 6 months.7 Within 5 minutes, 49% of the infants provided a clean-catch sample, with contamination rates similar to those of samples obtained using invasive methods.7 Younger infants were more likely to void within the time allotted. Another trial of bladder tapping conducted in hospitalized infants <30 days old showed similar results.8

There are, however, no previously reported randomized trials demonstrating the efficacy of a noninvasive urine collection technique in the outpatient setting.

Use of invasive collection methods requires skilled personnel and may cause significant discomfort for patients (and parents). Noninvasive methods, such as bag urine collection, have unacceptable contamination rates. In addition, waiting to catch a potentially cleaner urine sample is time-consuming, so better strategies to collect urine from infants are needed. This RCT is the first to examine the efficacy of a unique stimulation technique to obtain a clean-catch urine sample from infants ages 1 to 12 months.

STUDY SUMMARY

Noninvasive stimulation method triggers faster clean urine samples

A nonblinded, single-center RCT conducted in Australia compared 2 methods for obtaining a clean-catch urine sample within 5 minutes: the Quick-Wee method (suprapubic stimulation with gauze soaked in cold fluid) or usual care (waiting for spontaneous voiding with no stimulation).1 Three hundred fifty-four infants (ages 1-12 months) who required urine sample collection were randomized in a 1:1 ratio; allocation was concealed. Infants with anatomic or neurologic abnormalities and those needing immediate antibiotic therapy were excluded.

The most common reasons for obtaining the urine sample were fever of unknown origin and “unsettled baby,” followed by poor feeding and suspected UTI. The primary outcome was voiding within 5 minutes; secondary outcomes included time to void, whether urine was successfully caught, contamination rate, and parent/clinician satisfaction.

Study personnel removed the diaper, then cleaned the genitals of all patients with room temperature sterile water. A caregiver or clinician was ready and waiting to catch urine when the patient voided. In the Quick-Wee group, a clinician rubbed the patient’s suprapubic area in a circular fashion with gauze soaked in refrigerated saline (2.8° C). At 5 minutes, clinicians recorded the voiding status and decided how to proceed.

Using intention-to-treat analysis, 31% of the patients in the Quick-Wee group voided within 5 minutes, compared with 12% of the usual-care patients. Similarly, 30% of patients in the Quick-Wee group provided a successful clean-catch sample within 5 minutes compared with 9% in the usual-care group (P<.001; number needed to treat=4.7; 95% CI, 3.4-7.7). Contamination rates were no different between the Quick-Wee and usual-care samples. Both parents and clinicians were more satisfied with the Quick-Wee method than with usual care (median score of 2 vs 3 on a 5-point Likert scale, in which 1 is most satisfied; P<.001). There was no difference when results were adjusted for age or sex. No adverse events occurred.

WHAT’S NEW

New method could reduce the need for invasive sampling

A simple suprapubic stimulation technique increased the number of infants who provided a clean-catch voided urine sample within 5 minutes—a clinically relevant and satisfying outcome. In appropriate patients, use of the Quick-Wee method to obtain a clean-catch voided sample for initial urinalysis, rather than attempting methods with known high contamination rates, may potentially reduce the need for invasive sampling using catheterization or suprapubic aspiration.

CAVEATS

Complete age range and ideal storage temperature are unknown

Neonates and pre-continent children older than 12 months were not included in this trial, so these conclusions do not apply to those groups of patients. The intervention period lasted only 5 minutes, but other published studies suggest that this amount of time is adequate for voiding to occur.6,7 Although this study used soaking fluid stored at 2.8° C, the ideal storage temperature is unknown.

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION

AAP doesn’t endorse clean-catch urine samples for culture

The Quick-Wee method is simple and easy to implement, and requires no specialized training or equipment. AAP guidelines do not endorse the use of clean-catch voided urine for culture, which may be a barrier to changing urine collection practices in some settings.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The PURLs Surveillance System was supported in part by Grant Number UL1RR024999 from the National Center For Research Resources, a Clinical Translational Science Award to the University of Chicago. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center For Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

1. Kaufman J, Fitzpatrick P, Tosif S, et al. Faster clean catch urine collection (Quick-Wee method) from infants: randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2017;357:j1341.

2. Shaikh N, Morone NE, Bost JE, et al. Prevalence of urinary tract infection in childhood: a meta-analysis. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2008;27:302-308.

3. Davies P, Greenwood R, Benger J. Randomised trial of a vibrating bladder stimulator—the time to pee study. Arch Dis Child. 2008;93:423-424.

4. Al-Orifi F, McGillivray D, Tange S, et al. Urine culture from bag specimens in young children: are the risks too high? J Pediatr. 2000;137:221-226.

5. Reaffirmation of AAP clinical practice guideline: the diagnosis and management of the initial urinary tract infection in febrile infants and young children 2-24 months of age. Pediatrics. 2016;138:e20163026.

6. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Urinary tract infection in under 16s: diagnosis and management. Clinical guideline CG54. Published August 2007. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg54/chapter/1-guidance. Accessed May 30, 2017.

7. Labrosse M, Levy A, Autmizguine J, et al. Evaluation of a new strategy for clean-catch urine in infants. Pediatrics. 2016;138:e20160573.

8. Herreros Fernández ML, González Merino N, Tagarro García A, et al. A new technique for fast and safe collection of urine in newborns. Arch Dis Child. 2013;98:27-29.

ILLUSTRATIVE CASE

A fussy 6-month-old infant is brought into the emergency department (ED) with a rectal temperature of 101.5° F. She is consolable, breathing normally, and appears well hydrated. You find no clear etiology for her fever and suspect that a urinary tract infection (UTI) may be the source of her illness. How do you proceed with obtaining a urine sample?

A febrile infant in the family physician’s office or ED is a familiar clinical situation that may require an invasive diagnostic work-up. Up to 7% of infants ages 2 to 24 months with fever of unknown origin may have a UTI.2 Collecting a urine sample from pre-toilet-trained children can be time consuming. In fact, obtaining a clean-catch urine sample in this age group took an average of more than one hour in one randomized controlled trial (RCT).3 More convenient methods of urine collection, such as placing a cotton ball in the diaper or using a perineal collection bag, have contamination rates of up to 63%.4

The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) guidelines for evaluating possible UTI in a febrile child <2 years of age recommend obtaining a sample for urinalysis “through the most convenient means.”5 If urinalysis is positive, only urine obtained by catheterization or suprapubic aspiration should be cultured. Guidelines from the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence in the United Kingdom are similar, but allow for culture of clean-catch urine samples.6

A recent prospective cohort study examined a noninvasive alternating lumbar-bladder tapping method to stimulate voiding in infants ages 0 to 6 months.7 Within 5 minutes, 49% of the infants provided a clean-catch sample, with contamination rates similar to those of samples obtained using invasive methods.7 Younger infants were more likely to void within the time allotted. Another trial of bladder tapping conducted in hospitalized infants <30 days old showed similar results.8

There are, however, no previously reported randomized trials demonstrating the efficacy of a noninvasive urine collection technique in the outpatient setting.

Use of invasive collection methods requires skilled personnel and may cause significant discomfort for patients (and parents). Noninvasive methods, such as bag urine collection, have unacceptable contamination rates. In addition, waiting to catch a potentially cleaner urine sample is time-consuming, so better strategies to collect urine from infants are needed. This RCT is the first to examine the efficacy of a unique stimulation technique to obtain a clean-catch urine sample from infants ages 1 to 12 months.

STUDY SUMMARY

Noninvasive stimulation method triggers faster clean urine samples

A nonblinded, single-center RCT conducted in Australia compared 2 methods for obtaining a clean-catch urine sample within 5 minutes: the Quick-Wee method (suprapubic stimulation with gauze soaked in cold fluid) or usual care (waiting for spontaneous voiding with no stimulation).1 Three hundred fifty-four infants (ages 1-12 months) who required urine sample collection were randomized in a 1:1 ratio; allocation was concealed. Infants with anatomic or neurologic abnormalities and those needing immediate antibiotic therapy were excluded.

The most common reasons for obtaining the urine sample were fever of unknown origin and “unsettled baby,” followed by poor feeding and suspected UTI. The primary outcome was voiding within 5 minutes; secondary outcomes included time to void, whether urine was successfully caught, contamination rate, and parent/clinician satisfaction.

Study personnel removed the diaper, then cleaned the genitals of all patients with room temperature sterile water. A caregiver or clinician was ready and waiting to catch urine when the patient voided. In the Quick-Wee group, a clinician rubbed the patient’s suprapubic area in a circular fashion with gauze soaked in refrigerated saline (2.8° C). At 5 minutes, clinicians recorded the voiding status and decided how to proceed.

Using intention-to-treat analysis, 31% of the patients in the Quick-Wee group voided within 5 minutes, compared with 12% of the usual-care patients. Similarly, 30% of patients in the Quick-Wee group provided a successful clean-catch sample within 5 minutes compared with 9% in the usual-care group (P<.001; number needed to treat=4.7; 95% CI, 3.4-7.7). Contamination rates were no different between the Quick-Wee and usual-care samples. Both parents and clinicians were more satisfied with the Quick-Wee method than with usual care (median score of 2 vs 3 on a 5-point Likert scale, in which 1 is most satisfied; P<.001). There was no difference when results were adjusted for age or sex. No adverse events occurred.

WHAT’S NEW

New method could reduce the need for invasive sampling

A simple suprapubic stimulation technique increased the number of infants who provided a clean-catch voided urine sample within 5 minutes—a clinically relevant and satisfying outcome. In appropriate patients, use of the Quick-Wee method to obtain a clean-catch voided sample for initial urinalysis, rather than attempting methods with known high contamination rates, may potentially reduce the need for invasive sampling using catheterization or suprapubic aspiration.

CAVEATS

Complete age range and ideal storage temperature are unknown

Neonates and pre-continent children older than 12 months were not included in this trial, so these conclusions do not apply to those groups of patients. The intervention period lasted only 5 minutes, but other published studies suggest that this amount of time is adequate for voiding to occur.6,7 Although this study used soaking fluid stored at 2.8° C, the ideal storage temperature is unknown.

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION

AAP doesn’t endorse clean-catch urine samples for culture

The Quick-Wee method is simple and easy to implement, and requires no specialized training or equipment. AAP guidelines do not endorse the use of clean-catch voided urine for culture, which may be a barrier to changing urine collection practices in some settings.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The PURLs Surveillance System was supported in part by Grant Number UL1RR024999 from the National Center For Research Resources, a Clinical Translational Science Award to the University of Chicago. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center For Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

ILLUSTRATIVE CASE

A fussy 6-month-old infant is brought into the emergency department (ED) with a rectal temperature of 101.5° F. She is consolable, breathing normally, and appears well hydrated. You find no clear etiology for her fever and suspect that a urinary tract infection (UTI) may be the source of her illness. How do you proceed with obtaining a urine sample?

A febrile infant in the family physician’s office or ED is a familiar clinical situation that may require an invasive diagnostic work-up. Up to 7% of infants ages 2 to 24 months with fever of unknown origin may have a UTI.2 Collecting a urine sample from pre-toilet-trained children can be time consuming. In fact, obtaining a clean-catch urine sample in this age group took an average of more than one hour in one randomized controlled trial (RCT).3 More convenient methods of urine collection, such as placing a cotton ball in the diaper or using a perineal collection bag, have contamination rates of up to 63%.4

The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) guidelines for evaluating possible UTI in a febrile child <2 years of age recommend obtaining a sample for urinalysis “through the most convenient means.”5 If urinalysis is positive, only urine obtained by catheterization or suprapubic aspiration should be cultured. Guidelines from the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence in the United Kingdom are similar, but allow for culture of clean-catch urine samples.6

A recent prospective cohort study examined a noninvasive alternating lumbar-bladder tapping method to stimulate voiding in infants ages 0 to 6 months.7 Within 5 minutes, 49% of the infants provided a clean-catch sample, with contamination rates similar to those of samples obtained using invasive methods.7 Younger infants were more likely to void within the time allotted. Another trial of bladder tapping conducted in hospitalized infants <30 days old showed similar results.8

There are, however, no previously reported randomized trials demonstrating the efficacy of a noninvasive urine collection technique in the outpatient setting.

Use of invasive collection methods requires skilled personnel and may cause significant discomfort for patients (and parents). Noninvasive methods, such as bag urine collection, have unacceptable contamination rates. In addition, waiting to catch a potentially cleaner urine sample is time-consuming, so better strategies to collect urine from infants are needed. This RCT is the first to examine the efficacy of a unique stimulation technique to obtain a clean-catch urine sample from infants ages 1 to 12 months.

STUDY SUMMARY

Noninvasive stimulation method triggers faster clean urine samples

A nonblinded, single-center RCT conducted in Australia compared 2 methods for obtaining a clean-catch urine sample within 5 minutes: the Quick-Wee method (suprapubic stimulation with gauze soaked in cold fluid) or usual care (waiting for spontaneous voiding with no stimulation).1 Three hundred fifty-four infants (ages 1-12 months) who required urine sample collection were randomized in a 1:1 ratio; allocation was concealed. Infants with anatomic or neurologic abnormalities and those needing immediate antibiotic therapy were excluded.

The most common reasons for obtaining the urine sample were fever of unknown origin and “unsettled baby,” followed by poor feeding and suspected UTI. The primary outcome was voiding within 5 minutes; secondary outcomes included time to void, whether urine was successfully caught, contamination rate, and parent/clinician satisfaction.

Study personnel removed the diaper, then cleaned the genitals of all patients with room temperature sterile water. A caregiver or clinician was ready and waiting to catch urine when the patient voided. In the Quick-Wee group, a clinician rubbed the patient’s suprapubic area in a circular fashion with gauze soaked in refrigerated saline (2.8° C). At 5 minutes, clinicians recorded the voiding status and decided how to proceed.

Using intention-to-treat analysis, 31% of the patients in the Quick-Wee group voided within 5 minutes, compared with 12% of the usual-care patients. Similarly, 30% of patients in the Quick-Wee group provided a successful clean-catch sample within 5 minutes compared with 9% in the usual-care group (P<.001; number needed to treat=4.7; 95% CI, 3.4-7.7). Contamination rates were no different between the Quick-Wee and usual-care samples. Both parents and clinicians were more satisfied with the Quick-Wee method than with usual care (median score of 2 vs 3 on a 5-point Likert scale, in which 1 is most satisfied; P<.001). There was no difference when results were adjusted for age or sex. No adverse events occurred.

WHAT’S NEW

New method could reduce the need for invasive sampling

A simple suprapubic stimulation technique increased the number of infants who provided a clean-catch voided urine sample within 5 minutes—a clinically relevant and satisfying outcome. In appropriate patients, use of the Quick-Wee method to obtain a clean-catch voided sample for initial urinalysis, rather than attempting methods with known high contamination rates, may potentially reduce the need for invasive sampling using catheterization or suprapubic aspiration.

CAVEATS

Complete age range and ideal storage temperature are unknown

Neonates and pre-continent children older than 12 months were not included in this trial, so these conclusions do not apply to those groups of patients. The intervention period lasted only 5 minutes, but other published studies suggest that this amount of time is adequate for voiding to occur.6,7 Although this study used soaking fluid stored at 2.8° C, the ideal storage temperature is unknown.

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION

AAP doesn’t endorse clean-catch urine samples for culture

The Quick-Wee method is simple and easy to implement, and requires no specialized training or equipment. AAP guidelines do not endorse the use of clean-catch voided urine for culture, which may be a barrier to changing urine collection practices in some settings.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The PURLs Surveillance System was supported in part by Grant Number UL1RR024999 from the National Center For Research Resources, a Clinical Translational Science Award to the University of Chicago. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center For Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

1. Kaufman J, Fitzpatrick P, Tosif S, et al. Faster clean catch urine collection (Quick-Wee method) from infants: randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2017;357:j1341.

2. Shaikh N, Morone NE, Bost JE, et al. Prevalence of urinary tract infection in childhood: a meta-analysis. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2008;27:302-308.

3. Davies P, Greenwood R, Benger J. Randomised trial of a vibrating bladder stimulator—the time to pee study. Arch Dis Child. 2008;93:423-424.

4. Al-Orifi F, McGillivray D, Tange S, et al. Urine culture from bag specimens in young children: are the risks too high? J Pediatr. 2000;137:221-226.

5. Reaffirmation of AAP clinical practice guideline: the diagnosis and management of the initial urinary tract infection in febrile infants and young children 2-24 months of age. Pediatrics. 2016;138:e20163026.

6. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Urinary tract infection in under 16s: diagnosis and management. Clinical guideline CG54. Published August 2007. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg54/chapter/1-guidance. Accessed May 30, 2017.

7. Labrosse M, Levy A, Autmizguine J, et al. Evaluation of a new strategy for clean-catch urine in infants. Pediatrics. 2016;138:e20160573.

8. Herreros Fernández ML, González Merino N, Tagarro García A, et al. A new technique for fast and safe collection of urine in newborns. Arch Dis Child. 2013;98:27-29.

1. Kaufman J, Fitzpatrick P, Tosif S, et al. Faster clean catch urine collection (Quick-Wee method) from infants: randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2017;357:j1341.

2. Shaikh N, Morone NE, Bost JE, et al. Prevalence of urinary tract infection in childhood: a meta-analysis. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2008;27:302-308.

3. Davies P, Greenwood R, Benger J. Randomised trial of a vibrating bladder stimulator—the time to pee study. Arch Dis Child. 2008;93:423-424.

4. Al-Orifi F, McGillivray D, Tange S, et al. Urine culture from bag specimens in young children: are the risks too high? J Pediatr. 2000;137:221-226.

5. Reaffirmation of AAP clinical practice guideline: the diagnosis and management of the initial urinary tract infection in febrile infants and young children 2-24 months of age. Pediatrics. 2016;138:e20163026.

6. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Urinary tract infection in under 16s: diagnosis and management. Clinical guideline CG54. Published August 2007. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg54/chapter/1-guidance. Accessed May 30, 2017.

7. Labrosse M, Levy A, Autmizguine J, et al. Evaluation of a new strategy for clean-catch urine in infants. Pediatrics. 2016;138:e20160573.

8. Herreros Fernández ML, González Merino N, Tagarro García A, et al. A new technique for fast and safe collection of urine in newborns. Arch Dis Child. 2013;98:27-29.

Copyright © 2018. The Family Physicians Inquiries Network. All rights reserved.

PRACTICE CHANGER

Apply gauze soaked in cold sterile saline to the suprapubic area to stimulate infants ages 1 to 12 months to provide a clean-catch urine sample. Doing so produces significantly more clean-catch urine samples within 5 minutes than simply waiting for the patient to void, with no difference in contamination and with increased parental and provider satisfaction.1

STRENGTH OF RECOMMENDATION

B: Based on a single good-quality, randomized controlled trial.

Kaufman J, Fitzpatrick P, Tosif S, et al. Faster clean catch urine collection (Quick-Wee method) from infants: randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2017;357:j1341.

ACIP vaccine update

The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) made relatively few new vaccine recommendations in 2017. One pertained to prevention of hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection in infants born to HBV-infected mothers. Another recommended a new vaccine to prevent shingles. A third advised considering an additional dose of mumps vaccine during an outbreak. This year’s recommendations pertaining to influenza vaccines were covered in a previous Practice Alert.1

Perinatal HBV prevention: New strategy if revaccination is required

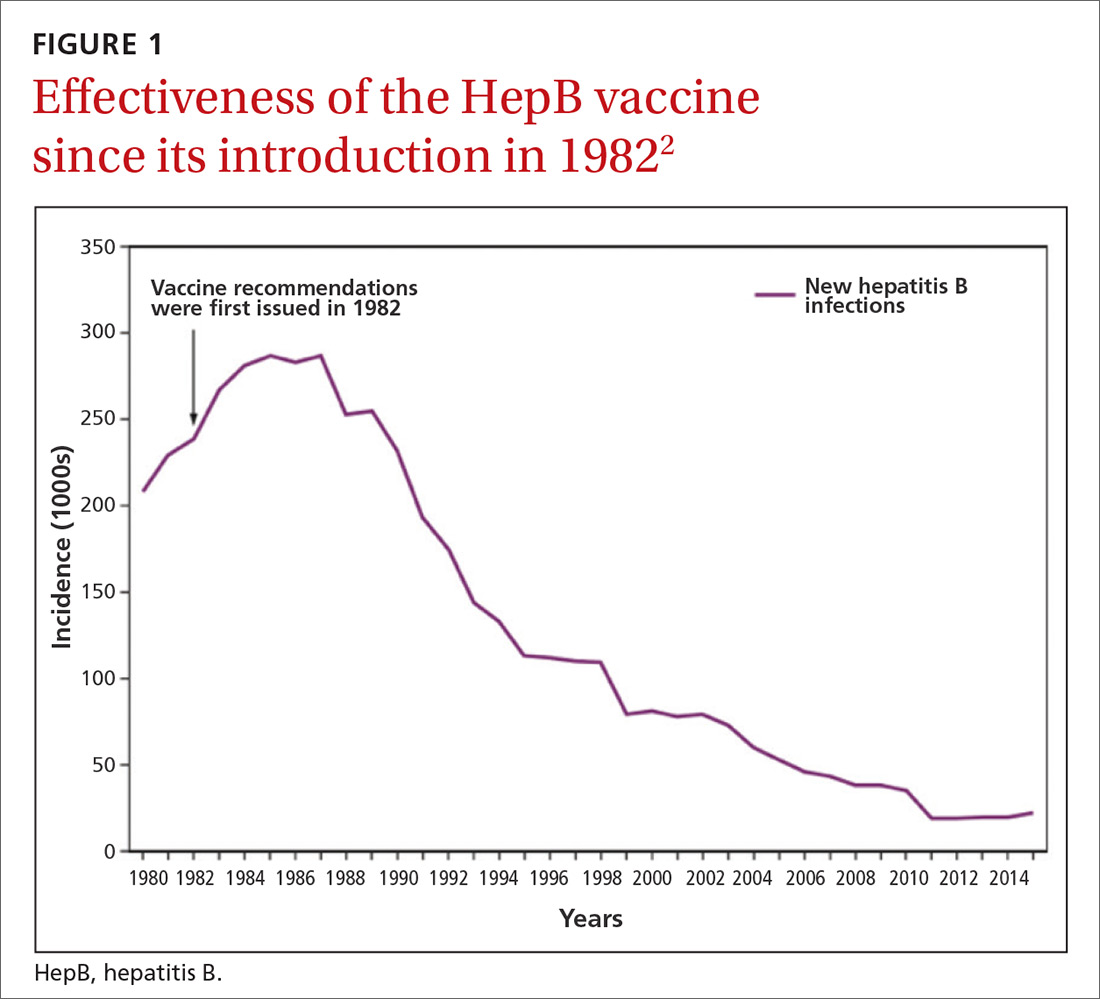

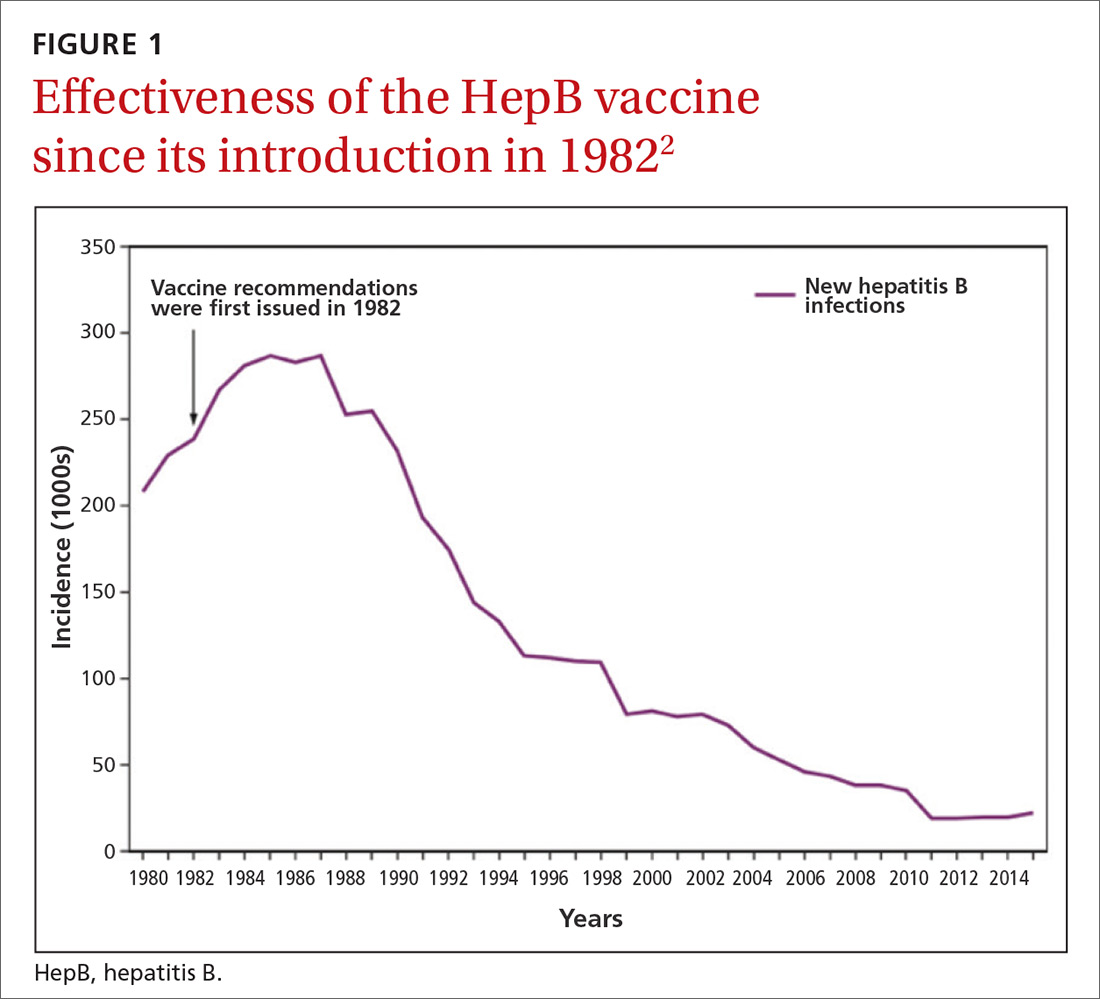

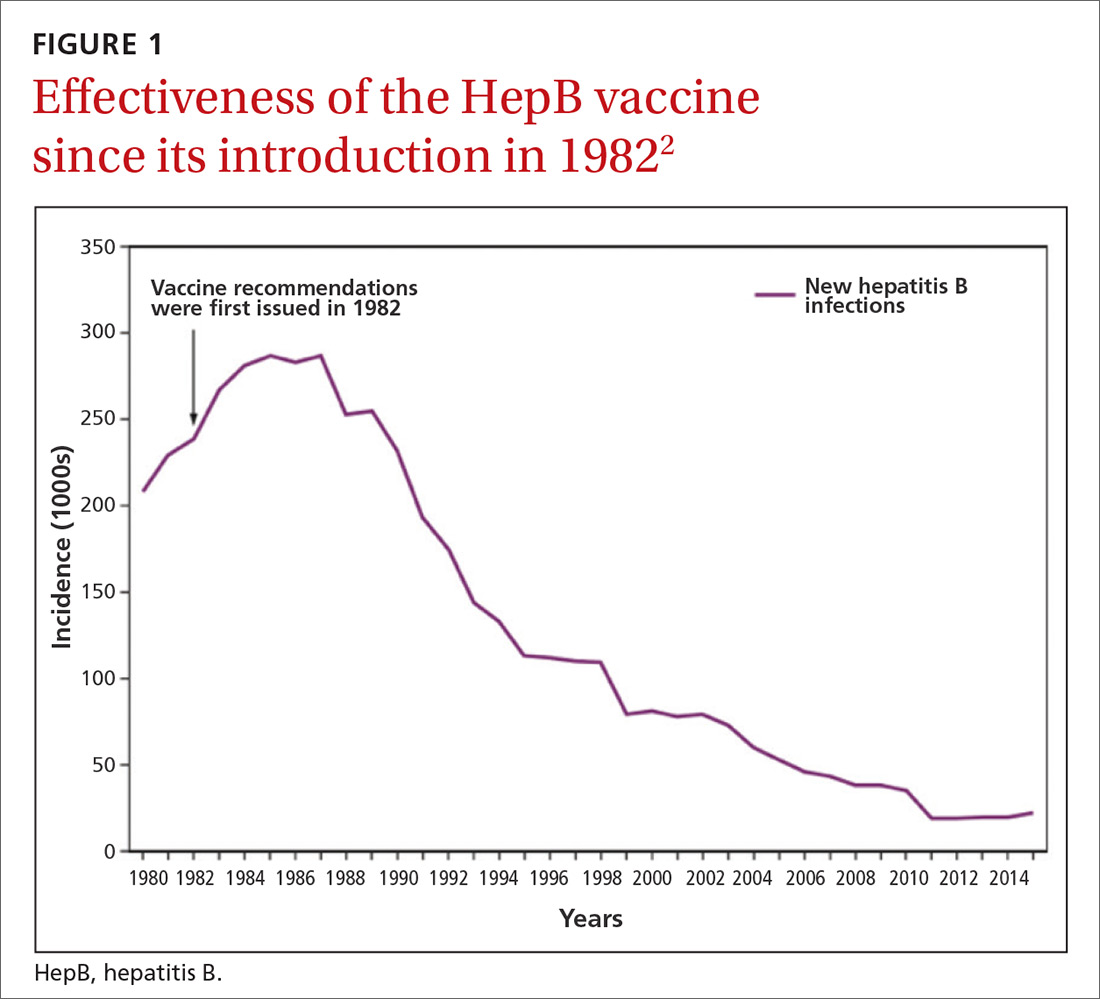

Hepatitis B prevention programs in the United States have decreased the incidence of HBV infections from 9.6 cases per 100,000 population in 1982 (the year the hepatitis B [HepB] vaccine was first available) to 1.1 cases per 100,000 population in 2015 (FIGURE 1).2 One major route of HBV dissemination worldwide is perinatal transmission to infants by HBV-infected mothers. However, this route of infection has been greatly diminished in the United States because of widespread screening of pregnant women and because newborns of mothers with known active HBV infection receive prophylaxis with hepatitis B immune globulin and HBV vaccine.

Each year in the United States an estimated 25,000 infants are born to mothers who are positive for hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg).3 Without post-exposure prophylaxis, 85% of these infants would develop HBV infection if the mother is also hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg) positive; 30% would develop HBV infection if the mother is HBeAg negative.2 Eighty percent to 90% of infected infants develop chronic HBV infection and are at increased risk of chronic liver disease.2 Of all infants receiving the recommended post-exposure prophylaxis, only about 1% develop infection.2

Available HepB vaccines. HepB vaccine consists of HBsAg derived from yeast using recombinant DNA technology, which is then purified by biochemical separation techniques. Three vaccine products are available for newborns and infants in the United States. Two are single-antigen vaccines—Engerix-B (GlaxoSmithKline Biologicals) and Recombivax HB (Merck & Co.)—and both can be used starting at birth. One combination vaccine, Pediarix (GlaxoSmithKline Biologicals) is used for children ages 6 weeks to 6 years. It contains HBsAg as do the other 2 vaccines, as well as diphtheria and tetanus toxoids, acellular pertussis adsorbed, and inactivated poliovirus (DTaP-HepB-IPV).

Until December 31, 2014, a vaccine combining HBsAg and haemophilus-B antigen, Comvax (Merck and Co.), was available for infants 6 weeks or older. Comvax is no longer produced.

Factors affecting the dosing schedule. For infants born to HBsAg-positive mothers, the final dose of the HepB series should be completed at age 6 months with either one of the monovalent HepB vaccines or the DTaP-HepB-IPV vaccine. When the now-discontinued Comvax was used to complete the series, the final dose was administered at 12 to 15 months. The timing of HepB vaccine at birth and at subsequent intervals, and a decision on whether to give hepatitis B immune globulin, depend on the baby’s birth weight, the mother’s HBsAg status, and type of vaccine used.2

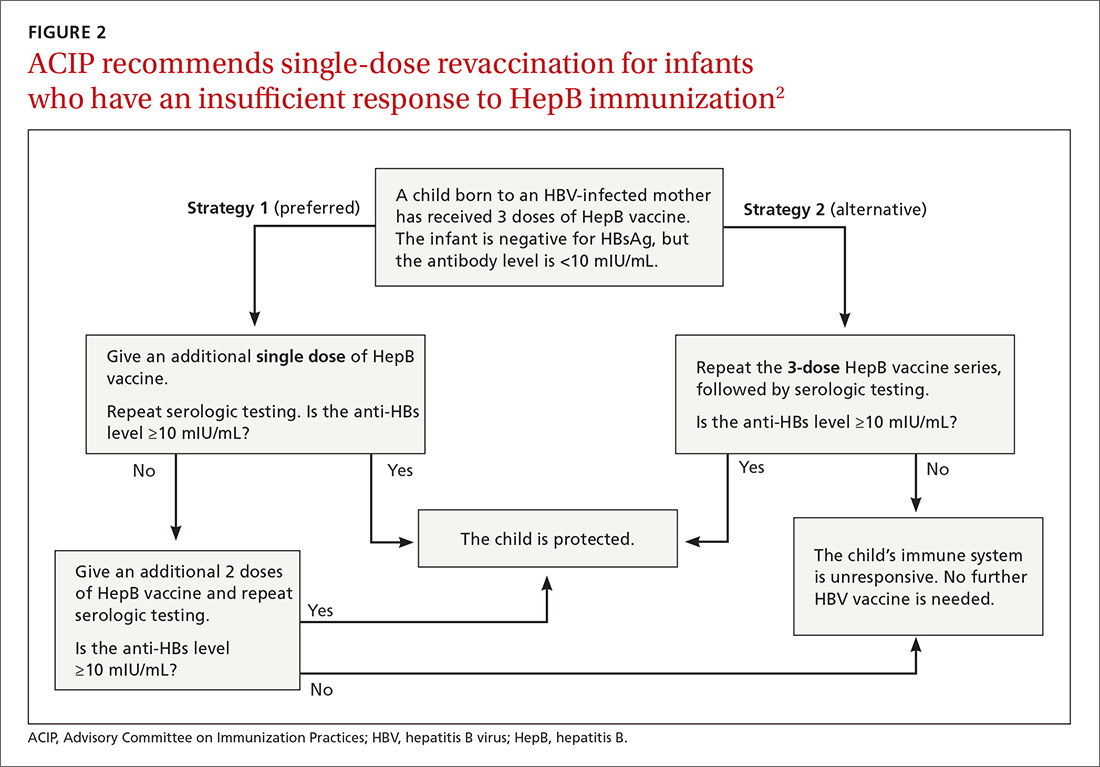

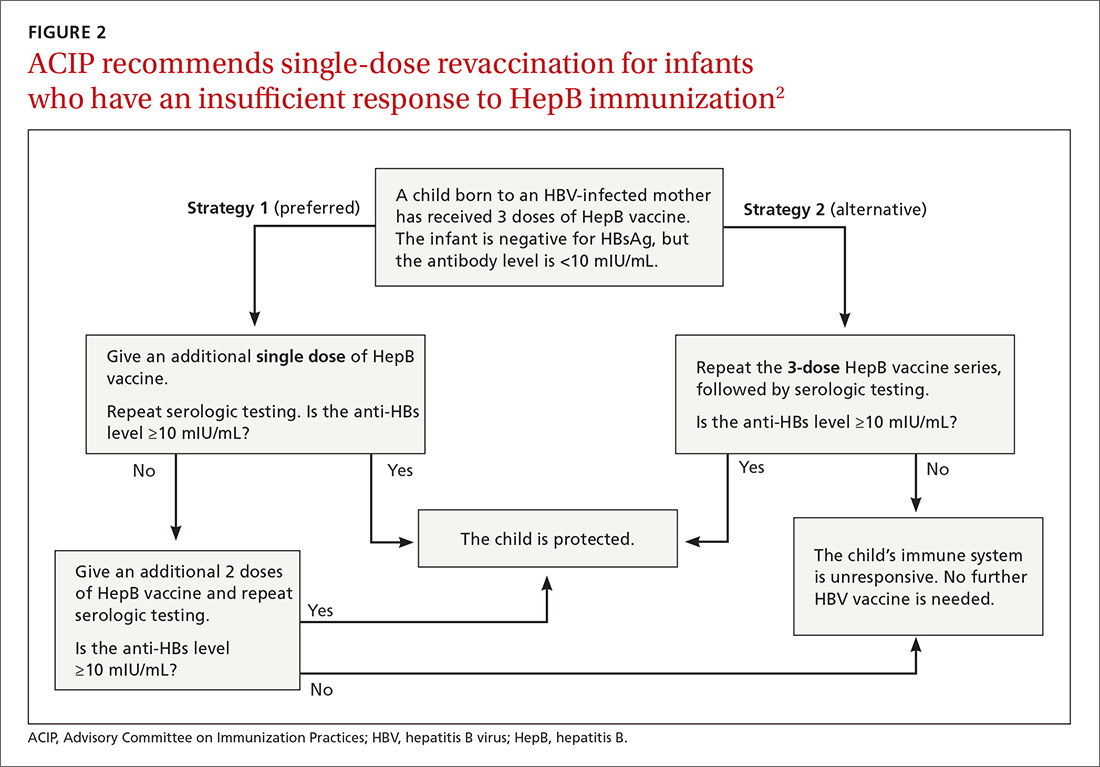

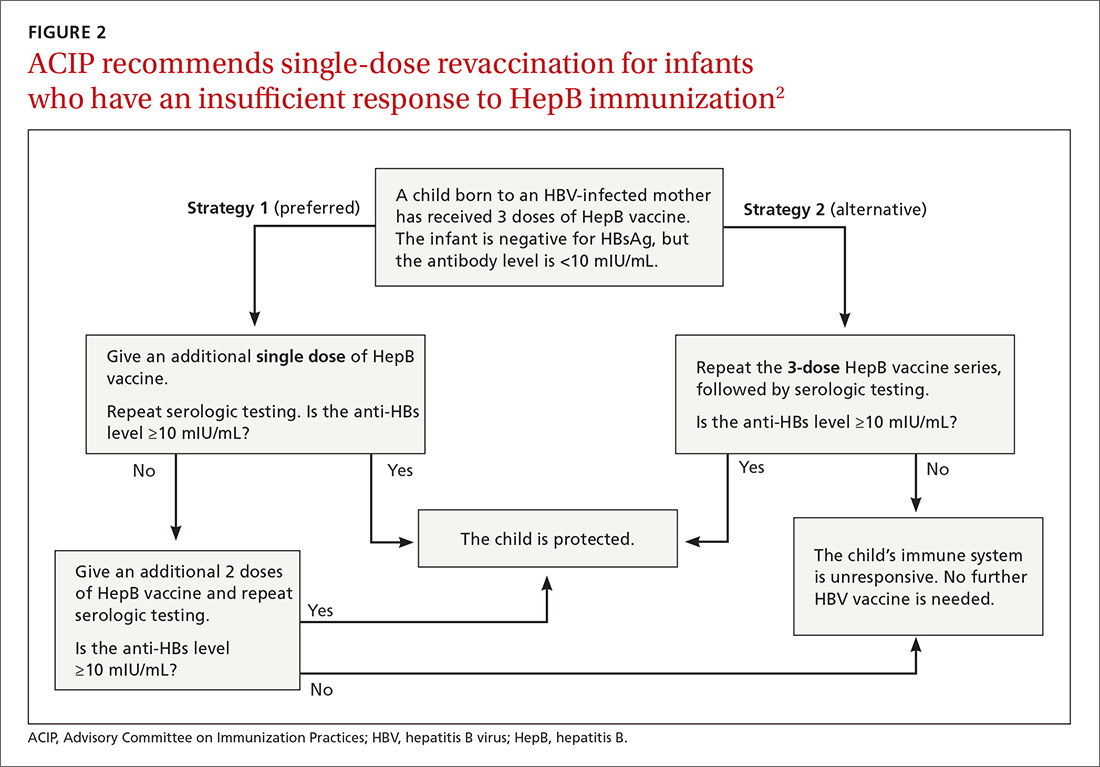

Post-vaccination assessment. ACIP recommends that babies born to HBsAg-positive mothers and having received the final dose of the vaccine series be serologically tested for immunity to HBV at age 9 to 12 months; or if the series is delayed, at one to 2 months after the final dose.4 Infants without evidence of active infection (ie, HBsAg negative) and with levels of antibody to HBsAg ≥10 mIU/mL are considered protected and need no further vaccinations.4 Revaccination is advised for those with antibody levels <10 mIU/mL—who account for only about 2% of infants having received the recommended schedule.4

New revaccination strategy. The previous recommendation on revaccination advised a second 3-dose series with repeat serologic testing one to 2 months after the final dose of vaccine. Although this strategy is still acceptable, the new recommendation for infants with antibody levels <10 mIU/mL favors (for cost savings and convenience) administration of a single dose of HepB vaccine with retesting one to 2 months later.2

Several studies presented at the ACIP meeting in February 2017 showed that more than 90% of infants revaccinated with the single dose will develop a protective antibody level.4 Infants whose anti-HBs remain <10 mIU/mL following the single-dose re-vaccination should receive 2 additional doses of HepB vaccine, followed by testing one to 2 months after the last dose4 (FIGURE 22).

(A new HepB vaccine, HEPLISAV-B [Dynavax Technologies Corp]), has been approved for use in adults. More on this in a bit.)

Herpes zoster vaccine: Data guidance on product selection

In 2017, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved a new vaccine against shingles, an adjuvanted herpes zoster subunit (HZ/su) vaccine, Shingrix (GlaxoSmithKline Biologicals). It is now an alternative to the live attenuated virus (ZVL) vaccine, Zostavax (Merck & Co.), licensed in 2006. ZVL is approved for use in adults ages 50 to 59 years, but ACIP recommends it only for adults 60 and older.5 It is given as a single dose, while HZ/su is given as a 2-dose series at 0 and at 2 to 6 months. By ACIP’s analysis, HZ/su is more effective than ZVL. In a comparison model looking at health outcomes over a lifetime among one million patients 60 to 69 years of age, HZ/su would prevent 53,000 more cases of shingles and 4000 more cases of postherpetic neuralgia than would ZVL.6

Additional mumps vaccine is warranted in an outbreak

While use of mumps-containing vaccine in the United States has led to markedly lower disease incidence rates than existed in the pre-vaccine era, in recent years there have been large mumps outbreaks among young adults at universities and other close-knit communities. These groups have had relatively high rates of completion of 2 doses of measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR) vaccine, and the cause of the outbreaks is not fully understood. Potential contributors include waning immunity following vaccination and antigenic differences between the virus strains circulating and those in the vaccine.

ACIP considered whether a third dose of MMR should be recommended to those fully vaccinated if they are at high risk due to an outbreak. Although the evidence to support the effectiveness of a third dose was scant and of very low quality, the evidence for vaccine safety was reassuring and ACIP voted to recommend the use of a third dose in outbreaks.9

One new vaccine and others on the horizon

ACIP is evaluating a new HepB vaccine, HEPLISAV-B, which was approved by the FDA in November 2017 for use in adults.10,11 The vaccine contains the same antigen as other available HepB vaccines but a different adjuvant. It is administered in 2 doses one month apart, which is preferable to the current 3-dose, 6-month schedule. There is, however, some indication that it causes increased rates of cardiovascular complications.10 ACIP is evaluating the relative effectiveness and safety of HEPLISAV-B and other HepB vaccines, and recommendations are expected this spring.

Other vaccines in various stages of development, but not ready for ACIP evaluation, include those against Zika virus, norovirus, respiratory syncytial virus, and dengue virus.

ACIP is also retrospectively assessing whether adding the 13 valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine to the schedule for those over the age of 65 has led to improved pneumonia outcomes. It will reconsider the previous recommendation based on the results of its assessment.

1. Campos-Outcalt D. Latest recommendations for the 2017-2018 flu season. J Fam Pract. 2017;66:570-572.

2. Schillie S, Vellozzi C, Reingold A, et al. Prevention of hepatitis B virus infection in the United States: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67:1-31. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/67/rr/rr6701a1.htm. Accessed January 19, 2018.

3. CDC. Postvaccination serologic testing results for infants aged ≤24 months exposed to hepatitis B virus at birth: United States, 2008-2011. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2012;61:768-771. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm6138a4.htm. Accessed February 14, 2018.

4. Nelson N. Revaccination for infants born to hepatitis B virus (HBV)-infected mothers. Presented at: Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. February 22, 2017; Atlanta, GA. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/slides-2017-02/hepatitis-02-background-nelson.pdf. Accessed January 19, 2017.

5. Hales CM, Harpaz R, Ortega-Sanchez I, et al. Update on recommendations for use of herpes zoster vaccine. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2014;63:729-731. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm6333a3.htm?s_cid=mm6333a3_w. Accessed January 23, 2018.

6. Dooling KL. Considerations for the use of herpes zoster vaccines. Presented at: Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. October 25, 2017; Atlanta, GA. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/slides-2017-10/zoster-04-dooling.pdf. Accessed January 19, 2018.

7. Dooling KL, Guo A, Patel M, et al. Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices for use of herpes zoster vaccines. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67:103-108.

8. Campos-Outcalt D. The new shingles vaccine: what PCPs need to know. J Fam Pract. 2017;66:audio. Available at: https://www.mdedge.com/jfponline/article/153168/vaccines/new-shingles-vaccine-what-pcps-need-know. Accessed January 19, 2018.

9. Marlow M. Grading of recommendations assessment, development and evaluation (GRADE): third dose of MMR vaccine. Presented at: Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. October 25, 2017; Atlanta, GA. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/slides-2017-10/mumps-03-marlow-508.pdf. Accessed January 19, 2018.

10. HEPLISAV-B [package insert]. Berkeley, CA: Dynavax Technology Corporation; 2017. Available at: https://www.fda.gov/downloads/BiologicsBloodVaccines/Vaccines/ApprovedProducts/UCM584762.pdf. Accessed January 23, 2018.

11. Janssen R. HEPLISAV-B. Presented at: Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. October 25, 2017; Atlanta, GA. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/slides-2017-10/hepatitis-02-janssen.pdf. Accessed January 19, 2018.

The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) made relatively few new vaccine recommendations in 2017. One pertained to prevention of hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection in infants born to HBV-infected mothers. Another recommended a new vaccine to prevent shingles. A third advised considering an additional dose of mumps vaccine during an outbreak. This year’s recommendations pertaining to influenza vaccines were covered in a previous Practice Alert.1

Perinatal HBV prevention: New strategy if revaccination is required

Hepatitis B prevention programs in the United States have decreased the incidence of HBV infections from 9.6 cases per 100,000 population in 1982 (the year the hepatitis B [HepB] vaccine was first available) to 1.1 cases per 100,000 population in 2015 (FIGURE 1).2 One major route of HBV dissemination worldwide is perinatal transmission to infants by HBV-infected mothers. However, this route of infection has been greatly diminished in the United States because of widespread screening of pregnant women and because newborns of mothers with known active HBV infection receive prophylaxis with hepatitis B immune globulin and HBV vaccine.

Each year in the United States an estimated 25,000 infants are born to mothers who are positive for hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg).3 Without post-exposure prophylaxis, 85% of these infants would develop HBV infection if the mother is also hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg) positive; 30% would develop HBV infection if the mother is HBeAg negative.2 Eighty percent to 90% of infected infants develop chronic HBV infection and are at increased risk of chronic liver disease.2 Of all infants receiving the recommended post-exposure prophylaxis, only about 1% develop infection.2

Available HepB vaccines. HepB vaccine consists of HBsAg derived from yeast using recombinant DNA technology, which is then purified by biochemical separation techniques. Three vaccine products are available for newborns and infants in the United States. Two are single-antigen vaccines—Engerix-B (GlaxoSmithKline Biologicals) and Recombivax HB (Merck & Co.)—and both can be used starting at birth. One combination vaccine, Pediarix (GlaxoSmithKline Biologicals) is used for children ages 6 weeks to 6 years. It contains HBsAg as do the other 2 vaccines, as well as diphtheria and tetanus toxoids, acellular pertussis adsorbed, and inactivated poliovirus (DTaP-HepB-IPV).

Until December 31, 2014, a vaccine combining HBsAg and haemophilus-B antigen, Comvax (Merck and Co.), was available for infants 6 weeks or older. Comvax is no longer produced.

Factors affecting the dosing schedule. For infants born to HBsAg-positive mothers, the final dose of the HepB series should be completed at age 6 months with either one of the monovalent HepB vaccines or the DTaP-HepB-IPV vaccine. When the now-discontinued Comvax was used to complete the series, the final dose was administered at 12 to 15 months. The timing of HepB vaccine at birth and at subsequent intervals, and a decision on whether to give hepatitis B immune globulin, depend on the baby’s birth weight, the mother’s HBsAg status, and type of vaccine used.2

Post-vaccination assessment. ACIP recommends that babies born to HBsAg-positive mothers and having received the final dose of the vaccine series be serologically tested for immunity to HBV at age 9 to 12 months; or if the series is delayed, at one to 2 months after the final dose.4 Infants without evidence of active infection (ie, HBsAg negative) and with levels of antibody to HBsAg ≥10 mIU/mL are considered protected and need no further vaccinations.4 Revaccination is advised for those with antibody levels <10 mIU/mL—who account for only about 2% of infants having received the recommended schedule.4

New revaccination strategy. The previous recommendation on revaccination advised a second 3-dose series with repeat serologic testing one to 2 months after the final dose of vaccine. Although this strategy is still acceptable, the new recommendation for infants with antibody levels <10 mIU/mL favors (for cost savings and convenience) administration of a single dose of HepB vaccine with retesting one to 2 months later.2

Several studies presented at the ACIP meeting in February 2017 showed that more than 90% of infants revaccinated with the single dose will develop a protective antibody level.4 Infants whose anti-HBs remain <10 mIU/mL following the single-dose re-vaccination should receive 2 additional doses of HepB vaccine, followed by testing one to 2 months after the last dose4 (FIGURE 22).

(A new HepB vaccine, HEPLISAV-B [Dynavax Technologies Corp]), has been approved for use in adults. More on this in a bit.)

Herpes zoster vaccine: Data guidance on product selection

In 2017, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved a new vaccine against shingles, an adjuvanted herpes zoster subunit (HZ/su) vaccine, Shingrix (GlaxoSmithKline Biologicals). It is now an alternative to the live attenuated virus (ZVL) vaccine, Zostavax (Merck & Co.), licensed in 2006. ZVL is approved for use in adults ages 50 to 59 years, but ACIP recommends it only for adults 60 and older.5 It is given as a single dose, while HZ/su is given as a 2-dose series at 0 and at 2 to 6 months. By ACIP’s analysis, HZ/su is more effective than ZVL. In a comparison model looking at health outcomes over a lifetime among one million patients 60 to 69 years of age, HZ/su would prevent 53,000 more cases of shingles and 4000 more cases of postherpetic neuralgia than would ZVL.6

Additional mumps vaccine is warranted in an outbreak

While use of mumps-containing vaccine in the United States has led to markedly lower disease incidence rates than existed in the pre-vaccine era, in recent years there have been large mumps outbreaks among young adults at universities and other close-knit communities. These groups have had relatively high rates of completion of 2 doses of measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR) vaccine, and the cause of the outbreaks is not fully understood. Potential contributors include waning immunity following vaccination and antigenic differences between the virus strains circulating and those in the vaccine.

ACIP considered whether a third dose of MMR should be recommended to those fully vaccinated if they are at high risk due to an outbreak. Although the evidence to support the effectiveness of a third dose was scant and of very low quality, the evidence for vaccine safety was reassuring and ACIP voted to recommend the use of a third dose in outbreaks.9

One new vaccine and others on the horizon

ACIP is evaluating a new HepB vaccine, HEPLISAV-B, which was approved by the FDA in November 2017 for use in adults.10,11 The vaccine contains the same antigen as other available HepB vaccines but a different adjuvant. It is administered in 2 doses one month apart, which is preferable to the current 3-dose, 6-month schedule. There is, however, some indication that it causes increased rates of cardiovascular complications.10 ACIP is evaluating the relative effectiveness and safety of HEPLISAV-B and other HepB vaccines, and recommendations are expected this spring.

Other vaccines in various stages of development, but not ready for ACIP evaluation, include those against Zika virus, norovirus, respiratory syncytial virus, and dengue virus.

ACIP is also retrospectively assessing whether adding the 13 valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine to the schedule for those over the age of 65 has led to improved pneumonia outcomes. It will reconsider the previous recommendation based on the results of its assessment.

The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) made relatively few new vaccine recommendations in 2017. One pertained to prevention of hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection in infants born to HBV-infected mothers. Another recommended a new vaccine to prevent shingles. A third advised considering an additional dose of mumps vaccine during an outbreak. This year’s recommendations pertaining to influenza vaccines were covered in a previous Practice Alert.1

Perinatal HBV prevention: New strategy if revaccination is required

Hepatitis B prevention programs in the United States have decreased the incidence of HBV infections from 9.6 cases per 100,000 population in 1982 (the year the hepatitis B [HepB] vaccine was first available) to 1.1 cases per 100,000 population in 2015 (FIGURE 1).2 One major route of HBV dissemination worldwide is perinatal transmission to infants by HBV-infected mothers. However, this route of infection has been greatly diminished in the United States because of widespread screening of pregnant women and because newborns of mothers with known active HBV infection receive prophylaxis with hepatitis B immune globulin and HBV vaccine.

Each year in the United States an estimated 25,000 infants are born to mothers who are positive for hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg).3 Without post-exposure prophylaxis, 85% of these infants would develop HBV infection if the mother is also hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg) positive; 30% would develop HBV infection if the mother is HBeAg negative.2 Eighty percent to 90% of infected infants develop chronic HBV infection and are at increased risk of chronic liver disease.2 Of all infants receiving the recommended post-exposure prophylaxis, only about 1% develop infection.2

Available HepB vaccines. HepB vaccine consists of HBsAg derived from yeast using recombinant DNA technology, which is then purified by biochemical separation techniques. Three vaccine products are available for newborns and infants in the United States. Two are single-antigen vaccines—Engerix-B (GlaxoSmithKline Biologicals) and Recombivax HB (Merck & Co.)—and both can be used starting at birth. One combination vaccine, Pediarix (GlaxoSmithKline Biologicals) is used for children ages 6 weeks to 6 years. It contains HBsAg as do the other 2 vaccines, as well as diphtheria and tetanus toxoids, acellular pertussis adsorbed, and inactivated poliovirus (DTaP-HepB-IPV).

Until December 31, 2014, a vaccine combining HBsAg and haemophilus-B antigen, Comvax (Merck and Co.), was available for infants 6 weeks or older. Comvax is no longer produced.

Factors affecting the dosing schedule. For infants born to HBsAg-positive mothers, the final dose of the HepB series should be completed at age 6 months with either one of the monovalent HepB vaccines or the DTaP-HepB-IPV vaccine. When the now-discontinued Comvax was used to complete the series, the final dose was administered at 12 to 15 months. The timing of HepB vaccine at birth and at subsequent intervals, and a decision on whether to give hepatitis B immune globulin, depend on the baby’s birth weight, the mother’s HBsAg status, and type of vaccine used.2

Post-vaccination assessment. ACIP recommends that babies born to HBsAg-positive mothers and having received the final dose of the vaccine series be serologically tested for immunity to HBV at age 9 to 12 months; or if the series is delayed, at one to 2 months after the final dose.4 Infants without evidence of active infection (ie, HBsAg negative) and with levels of antibody to HBsAg ≥10 mIU/mL are considered protected and need no further vaccinations.4 Revaccination is advised for those with antibody levels <10 mIU/mL—who account for only about 2% of infants having received the recommended schedule.4

New revaccination strategy. The previous recommendation on revaccination advised a second 3-dose series with repeat serologic testing one to 2 months after the final dose of vaccine. Although this strategy is still acceptable, the new recommendation for infants with antibody levels <10 mIU/mL favors (for cost savings and convenience) administration of a single dose of HepB vaccine with retesting one to 2 months later.2

Several studies presented at the ACIP meeting in February 2017 showed that more than 90% of infants revaccinated with the single dose will develop a protective antibody level.4 Infants whose anti-HBs remain <10 mIU/mL following the single-dose re-vaccination should receive 2 additional doses of HepB vaccine, followed by testing one to 2 months after the last dose4 (FIGURE 22).

(A new HepB vaccine, HEPLISAV-B [Dynavax Technologies Corp]), has been approved for use in adults. More on this in a bit.)

Herpes zoster vaccine: Data guidance on product selection

In 2017, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved a new vaccine against shingles, an adjuvanted herpes zoster subunit (HZ/su) vaccine, Shingrix (GlaxoSmithKline Biologicals). It is now an alternative to the live attenuated virus (ZVL) vaccine, Zostavax (Merck & Co.), licensed in 2006. ZVL is approved for use in adults ages 50 to 59 years, but ACIP recommends it only for adults 60 and older.5 It is given as a single dose, while HZ/su is given as a 2-dose series at 0 and at 2 to 6 months. By ACIP’s analysis, HZ/su is more effective than ZVL. In a comparison model looking at health outcomes over a lifetime among one million patients 60 to 69 years of age, HZ/su would prevent 53,000 more cases of shingles and 4000 more cases of postherpetic neuralgia than would ZVL.6

Additional mumps vaccine is warranted in an outbreak

While use of mumps-containing vaccine in the United States has led to markedly lower disease incidence rates than existed in the pre-vaccine era, in recent years there have been large mumps outbreaks among young adults at universities and other close-knit communities. These groups have had relatively high rates of completion of 2 doses of measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR) vaccine, and the cause of the outbreaks is not fully understood. Potential contributors include waning immunity following vaccination and antigenic differences between the virus strains circulating and those in the vaccine.

ACIP considered whether a third dose of MMR should be recommended to those fully vaccinated if they are at high risk due to an outbreak. Although the evidence to support the effectiveness of a third dose was scant and of very low quality, the evidence for vaccine safety was reassuring and ACIP voted to recommend the use of a third dose in outbreaks.9

One new vaccine and others on the horizon

ACIP is evaluating a new HepB vaccine, HEPLISAV-B, which was approved by the FDA in November 2017 for use in adults.10,11 The vaccine contains the same antigen as other available HepB vaccines but a different adjuvant. It is administered in 2 doses one month apart, which is preferable to the current 3-dose, 6-month schedule. There is, however, some indication that it causes increased rates of cardiovascular complications.10 ACIP is evaluating the relative effectiveness and safety of HEPLISAV-B and other HepB vaccines, and recommendations are expected this spring.

Other vaccines in various stages of development, but not ready for ACIP evaluation, include those against Zika virus, norovirus, respiratory syncytial virus, and dengue virus.