User login

Digital Ischemia From Accidental Epinephrine Injection

Patients presenting to the ED with injuries due to accidental self-injection with an epinephrine pen typically receive treatment to alleviate symptoms and reduce the potential of digital ischemia leading to gangrene and loss of tissue and function. Although there is no consensus or set guidelines in the literature regarding the management protocol of such cases, many reports support pharmacological intervention. There are, however, other reports that advocate conservative, nonpharmaceutical management (eg, immersing the affected digit in warm water) or an observation-only approach.

We present the first case report in Saudi Arabia of digital ischemia due to accidental injection of an epinephrine autoinjector, along with a review of the literature and management recommendations.

Case

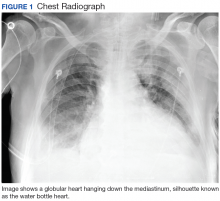

A 28-year-old woman presented to the ED in significant pain and discomfort 20 minutes after she accidentally injected the entire contents of her aunt’s epinephrine autoinjector (0.3 mg of 1:1000) into her right thumb. The patient, who was in significant pain and discomfort, stated that she was unable to remove the injector needle, which was firmly embedded in the bone of the palmer aspect of the distal phalanx in a manner similar to that of an intraosseous injection (Figure 1).

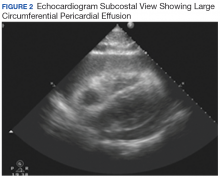

The patient’s vital signs and oxygen saturation on presentation were within normal limits. The emergency physician successfully removed the embedded needle through moderate countertraction. On examination, the patient’s right thumb was pale and cold, and had poor capillary refill (Figure 2). Due to concerns of the potential for digital tissue ischemia leading to tissue loss and gangrene, warm, moist compresses were applied to the affected thumb, followed by 2% topical nitroglycerin paste, after which the thumb was covered with an occlusive dressing. Since there was no improvement in circulation after 20 minutes, an infiltrate of 5 mg (0.5 mL of 10 mg/mL) of phentolamine (α-agonist) mixed with 2.5 mL of 2% lidocaine was injected at the puncture site and base of the right thumb.1 Hyperemia developed immediately at both injection sites, and the patient’s right thumb returned to a normal color and sensation 1 hour later, with a return to normal capillary refill. She remained in stable condition and was discharged home. Prior to discharge, the patient was educated on the proper handling and administration of an epinephrine autoinjector.

Discussion

Epinephrine is an ὰ- and β-adrenergic agonist that binds to the ὰ-adrenergic receptors of blood vessels, causing an increase in vascular resistance and vasoconstriction. Although the plasma half-life of epinephrine is approximately 2 to 3 minutes, subcutaneous or intramuscular injection resulting in local vasoconstriction may delay absorption; therefore, the effects of epinephrine may last much longer than its half-life.

The incidence of accidental injection from an epinephrine autoinjector is estimated to be 1 per 50,000 units dispensed.2 To date, there are no established treatment guidelines on managing cases of digital injection. An online PubMed and Google Scholar search of the literature found one systematic review,3 four observational studies,4-7 seven case series,8-14 and several case reports1,15-33 on the subject. Most of the patients in the published retrospective studies (71%) were treated conservatively with warming of the affected hand and observation, and the majority of patients in the case reports (87%) were treated pharmacologically, most commonly with topical nitroglycerin and phentolamine.1,3-34 All of the patients in both the retrospective studies and case reports had restoration of perfusion without necrosis, irrespective of treatment modality. However, patients who were managed conservatively or who were treated with topical nitroglycerin required a longer duration of stay in the ED, suffered from severe reperfusion pain, and in some cases, had a longer time to complete recovery (≥10 weeks).8

Pharmaceutical and Nonpharmaceutical Management

Phentolamine. Phentolamine is a nonselective ὰ-adrenergic antagonist that binds to ὰ1 and ὰ2 receptors of blood vessels, resulting in a decrease in peripheral vascular resistance and vasodilation. Phentolamine directly antagonizes the effect of epinephrine by blocking the ὰ-adrenergic receptors, which in our patient resulted in immediate return of digital circulation and full resolution of symptoms.

Topical Nitroglycerin. Nitroglycerin is a nitrate vasodilator that when metabolically converted to nitric oxide, results in smooth muscle relaxation, venodilation, and arteriodilation. Patients suffering from digital ischemia and vasoconstriction may be treated with topical nitroglycerin paste to reverse ischemia by causing smooth muscle relaxation of digital blood vessels. Conservative Management. As previously noted, not all cases of digital epinephrine injection are treated pharmacologically. Some patients are not treated, but kept in observation until the ischemic effects of epinephrine have resolved. Likewise, some patients are treated conservatively with warm water compresses or by fully immersing the affected digit in warm water to facilitate reversal of vasoconstriction and ischemia.3,8

Treatment Efficacy

In 2007, Fitzcharles-Bowe et al8 published a review of 59 cases of digital injection with high-dose epinephrine from 1989 to 2005. In this review, 32 of the 59 patients received no treatment, 25 patients received pharmacological treatment and in two patients, the treatment was unknown. Phentolamine was the most commonly used pharmacological agent (15 of 25 cases or 60%). Although none of the patients experienced digital necrosis, those treated with a local infiltration of phentolamine experienced a faster resolution of symptoms and normalization of perfusion. In 2004, Turner1 reported a case of a 10-year-old boy who was treated with phentolamine following an accidental injection of epinephrine into his left hand. While circulation returned to the affected digit within 5 minutes of receiving the phentolamine injection, the patient continued to experience reduced sensation in the digit 6 weeks later.8

Interestingly, one of the coauthors of the Fitzcharles-Bowe et al8 report intentionally injected three of the digits of his left hand (middle, ring, and small fingers) at the same time with high-dose epinephrine to carefully observe and document the outcomes. All three of the digits became very pale and cool, with decreased sensation. The author treated himself conservatively (observation-only). He experienced spontaneous return of circulation in two of the digits within 6 to 10 hours. Although there was some spontaneous return of circulation to the third digit after 13 hours, the author noted prolonged, intense reperfusion pain 4 hours after return of circulation. He also suffered from neuropraxia in the third digit, which did not fully resolve until 10 weeks after the injury.8

A review of the literature shows phentolamine to be a safe and effective treatment for patients presenting with digital ischemia, with no long-term adverse effects or complications. Moreover, phentolamine appears to be safe and effective for use in both adult and pediatric patients.3,8,35-38

Accidental Injection Prevention

Some of the cases of accidental epinephrine injection are due to user error. For example, a novice user may be holding the incorrect end of the injector in his or her hand when attempting to administer/deploy the device, resulting in premature dislodgement of the needle.39

Although, most of the autoinjector devices available today are user-friendly, we believe the addition of a safety feature such as a trigger or safety-lock may further help to reduce accidents. The European Medicines Agency recommends that all patients and caregivers receive training on the proper handling and administration of epinephrine autoinjectors, citing this as the most important factor to ensure successful use of an epinephrine autoinjector and reduce accidental injury.40 The patient in this case had not received any formal education or training regarding autoinjector use prior to this incident.

Safety of Lidocaine-Containing Epinephrine in Digital Anesthesia

Aside from cases of accidental digital epinephrine injection, clinicians have traditionally been taught to avoid using lidocaine with epinephrine for digital anesthesia. However, since the introduction of commercial lidocaine with epinephrine in 1948, there are no case reports of digital gangrene from commercially available lidocaine-epinephrine formulations.41,42 In a multicenter prospective study by Lalonde et al43 of 3,110 consecutive cases of elective injection of low-dose epinephrine in the hand, the authors concluded the likelihood of finger infarction is remote, particularly with possible phentolamine rescue therapy. Moreover, lidocaine-containing epinephrine (1%-2%) has a much lower concentration of epinephrine per mL of solution (5-10 mcg/mL) and appears to be safe for digital use.

Conclusion

This case describes the presentation and treatment of accidental digital injection of epinephrine, highlighting and supporting the benefits of local infiltration with phentolamine and observation until full recovery of perfusion. Local treatment with phentolamine not only facilitates recovery and return of capillary refill, but also shortens the duration of symptoms and alleviates vasoconstriction. In less severe cases, watchful waiting and observation may be appropriate and effective.

This case also underscores the importance of patient and caregiver education on the proper handling and administration of epinephrine autoinjectors to decrease the incidence of accidental injection.

1. Turner MJ. Accidental Epipen injection into a digit - the value of a Google search. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2004;86(3):218-219. doi:10.1308/003588404323043391.

2. McGovern SJ. Treatment of accidental digital injection of adrenaline from an auto-injector device. J Accid Emerg Med. 1997;14(6):379-380.

3. Wright M. Treatment after accidental injection with epinephrine autoinjector: a systematic review. J Allergy & Therapy. 2014;5(3):1000175. doi:10.4172/2155-6121.1000175.

4. Mrvos R, Anderson BD, Krenzelok EP. Accidental injection of epinephrine from an autoinjector: invasive treatment not always required. South Med J. 2002;95(3):318-320.

5. Muck AE, Bebarta VS, Borys DJ, Morgan DL. Six years of epinephrine digital injections: absence of significant local or systemic effects. Ann Emerg Med. 2010;56(3):270-274. doi:10.1016/j.annemergmed.2010.02.019.

6. Simons FE, Edwards ES, Read EJ Jr, Clark S, Liebelt EL. Voluntarily reported unintentional injections from epinephrine auto-injectors. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;125(2):419-423. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2009.10.056.

7. Blume-Odom CM, Scalzo AJ, Weber JA. EpiPen accidental injection-134 cases over 10 years. Clin Toxicol. 2010;48:651.

8. Fitzcharles-Bowe C, Denkler K, Lalonde D. Finger injection with high-dose (1:1,000) epinephrine: Does it cause finger necrosis and should it be treated? Hand. 2007;2(1):5-11. doi:10.1007/s11552-006-9012-4.

9. Velissariou I, Cottrell S, Berry K, Wilson B. Management of adrenaline (epinephrine) induced digital ischaemia in children after accidental injection from an EpiPen. Emerg Med J. 2004;21(3):387-388.

10. ElMaraghy MW, ElMaraghy AW, Evans HB. Digital adrenaline injection injuries: a case series and review. Can J Plast Surg. 1998;6:196-200.

11. Skorpinski EW, McGeady SJ, Yousef E. Two cases of accidental epinephrine injection into a finger. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006;117(2):463-464.

12. Nagaraj J, Reddy S, Murray R, Murphy N. Use of glyceryl trinitrate patches in the treatment of accidental digital injection of epinephrine from an autoinjector. Eur J Emerg Med. 2009;16(4):227-228. doi:10.1097/MEJ.0b013e328306f0ee.

13. Stier PA, Bogner MP, Webster K, Leikin JB, Burda A. Use of subcutaneous terbutaline to reverse peripheral ischemia. Am J Emerg Med. 1999;17(1):91-94.

14. Lee G, Thomas PC. Accidental digital injection of adrenaline from an autoinjector device. J Accid Emerg Med. 1998;15(4):287.

15. Baris S, Saricoban HE, Ak K, Ozdemir C. Papaverine chloride as a topical vasodilator in accidental injection of adrenaline into a digital finger. Allergy. 2011;66(11):1495-1496. doi:10.1111/j.1398-9995.2011.02664.x.

16. Buse K, Hein W, Drager N. Making Sense of Global Health Governance: A Policy Perspective. Basingstoke, England: Palgrave Macmillan UK; 2009.

17. Sherman SC. Digital Epipen® injection: a case of conservative management. J Emerg Med. 2011;41(6):672-674. doi:10.1016/j.jemermed.2009.07.027.

18. Janssen RL, Roeleveld-Versteegh AB, Wessels-Basten SJ, Hendriks T. [Auto-injection with epinephrine in the finger of a 5-year-old child]. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd. 2008;152(17):1005-1008.

19. Singh T, Randhawa S, Khanna R. The EpiPen and the ischaemic finger. Eur J Emerg Med. 2007;14(4):222-223.

20. Barkhordarian AR, Wakelin SH, Paes TR. Accidental digital injection of adrenaline from an autoinjector device. Br J Dermatol. 2000;143(6):1359.

21. Deshmukh N, Tolland JT. Treatment of accidental epinephrine injection in a finger. J Emerg Med. 1989;7(4):408.

22. Hinterberger JW, Kintzi HE. Phentolamine reversal of epinephrine-induced digital vasospasm. How to save an ischemic finger. Arch Fam Med. 1994;3(2):193-195.

23. Peyko V, Cohen V, Jellinek-Cohen SP, Pearl-Davis M. Evaluation and treatment of accidental autoinjection of epinephrine. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2013;70(9):778-781. doi:10.2146/ajhp120316.

24. Hardy SJ, Agostini DE. Accidental epinephrine auto-injector-induced digital ischemia reversed by phentolamine digital block. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 1995;95(6):377-378.

25. Kaspersen J, Vedsted P. [Accidental injection of adrenaline in a finger with EpiPen]. Ugeskr Laeger. 1998;160(45):6531-6532.

26. Schintler MV, Arbab E, Aberer W, Spendel S, Scharnagl E. Accidental perforating bone injury using the EpiPen autoinjection device. Allergy. 2005;60(2):259-260.

27. Khairalla E. Epinephrine-induced digital ischemia relieved by phentolamine. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2001;108(6):1831-1832.

28. Murali KS, Nayeem N. Accidental digital injection of adrenaline from an autoinjector device. J Accid Emerg Med. 1998;15(4):287.

29. Sellens C, Morrison L. Accidental injection of epinephrine by a child: a unique approach to treatment. CJEM. 1999;1(1):34-36.

30. Klemawesch P. Hyperbaric oxygen relieves severe digital ischaemia from accidental EpiPen injection. 2009 American Academy of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology Annual Meeting.

31. McCauley WA, Gerace RV, Scilley C. Treatment of accidental digital injection of epinephrine. Ann Emerg Med. 1991;20(6):665-668.

32. Mathez C, Favrat B, Staeger P. Management options for accidental injection of epinephrine from an autoinjector: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2009;3:7268. doi:10.4076/1752-1947-3-7268.

33. Molony D. Adrenaline-induced digital ischaemia reversed with phentolamine. ANZ J Surg. 2006;76(12):1125-1126.

34. Carrascosa MF, Gallastegui-Menéndez A, Teja-Santamaría C, Caviedes JR. Accidental finger ischaemia induced by epinephrine autoinjector. BMJ Case Rep. 2013;2013. pii:bcr2013200783. doi:10.1136/bcr-2013-200783.

35. Patel R, Kumar H. Epinephrine induced digital ischemia after accidental injection from an auto-injector device. Indian Pediatr. 2013;50(2):247.

36. Xu J, Holt A. Use of Phentolamine in the treatment of Epipen induced digital ischemia. BMJ Case Rep. 2012;2012. doi:10.1136/bcr.12.2011.5450.

37. McNeil C, Copeland J. Accidental digital epinephrine injection: to treat or not to treat? Can Fam Physician. 2014;60(8):726-728.

38. Bodkin RP, Acquisto NM, Gunyan H, Wiegand TJ. Two cases of accidental injection of epinephrine into a digit treated with subcutaneous phentolamine injections. Case Rep Emerg Med. 2013;2013:586207. doi:10.1155/2013/586207.

39. Simons FE, Lieberman PL, Read EJ Jr, Edwards ES. Hazards of unintentional injection of epinephrine from autoinjectors: a systematic review. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2009;102(4):282-287. doi:10.1016/S1081-1206(10)60332-8.

40. European Medicines Agency. Better training tools recommended to support patients using adrenaline auto-injectors. European Medicines Agency, 2015.

41. Denkler K. A comprehensive review of epinephrine in the finger: to do or not to do.

42. Thomson CJ, Lalonde DH, Denkler KA, Feicht AJ. A critical look at the evidence for and against elective epinephrine use in the finger. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2007;119(1):260-266.

43. Lalonde D, Bell M, Benoit P, Sparkes G, Denkler K, Chang P. A multicenter prospective study of 3,110 consecutive cases of elective epinephrine use in the fingers and hand: the Dalhousie Project clinical phase. J Hand Surg Am. 2005;30(5):1061-1067. doi:10.1016/j.jhsa.2005.05.006.

Patients presenting to the ED with injuries due to accidental self-injection with an epinephrine pen typically receive treatment to alleviate symptoms and reduce the potential of digital ischemia leading to gangrene and loss of tissue and function. Although there is no consensus or set guidelines in the literature regarding the management protocol of such cases, many reports support pharmacological intervention. There are, however, other reports that advocate conservative, nonpharmaceutical management (eg, immersing the affected digit in warm water) or an observation-only approach.

We present the first case report in Saudi Arabia of digital ischemia due to accidental injection of an epinephrine autoinjector, along with a review of the literature and management recommendations.

Case

A 28-year-old woman presented to the ED in significant pain and discomfort 20 minutes after she accidentally injected the entire contents of her aunt’s epinephrine autoinjector (0.3 mg of 1:1000) into her right thumb. The patient, who was in significant pain and discomfort, stated that she was unable to remove the injector needle, which was firmly embedded in the bone of the palmer aspect of the distal phalanx in a manner similar to that of an intraosseous injection (Figure 1).

The patient’s vital signs and oxygen saturation on presentation were within normal limits. The emergency physician successfully removed the embedded needle through moderate countertraction. On examination, the patient’s right thumb was pale and cold, and had poor capillary refill (Figure 2). Due to concerns of the potential for digital tissue ischemia leading to tissue loss and gangrene, warm, moist compresses were applied to the affected thumb, followed by 2% topical nitroglycerin paste, after which the thumb was covered with an occlusive dressing. Since there was no improvement in circulation after 20 minutes, an infiltrate of 5 mg (0.5 mL of 10 mg/mL) of phentolamine (α-agonist) mixed with 2.5 mL of 2% lidocaine was injected at the puncture site and base of the right thumb.1 Hyperemia developed immediately at both injection sites, and the patient’s right thumb returned to a normal color and sensation 1 hour later, with a return to normal capillary refill. She remained in stable condition and was discharged home. Prior to discharge, the patient was educated on the proper handling and administration of an epinephrine autoinjector.

Discussion

Epinephrine is an ὰ- and β-adrenergic agonist that binds to the ὰ-adrenergic receptors of blood vessels, causing an increase in vascular resistance and vasoconstriction. Although the plasma half-life of epinephrine is approximately 2 to 3 minutes, subcutaneous or intramuscular injection resulting in local vasoconstriction may delay absorption; therefore, the effects of epinephrine may last much longer than its half-life.

The incidence of accidental injection from an epinephrine autoinjector is estimated to be 1 per 50,000 units dispensed.2 To date, there are no established treatment guidelines on managing cases of digital injection. An online PubMed and Google Scholar search of the literature found one systematic review,3 four observational studies,4-7 seven case series,8-14 and several case reports1,15-33 on the subject. Most of the patients in the published retrospective studies (71%) were treated conservatively with warming of the affected hand and observation, and the majority of patients in the case reports (87%) were treated pharmacologically, most commonly with topical nitroglycerin and phentolamine.1,3-34 All of the patients in both the retrospective studies and case reports had restoration of perfusion without necrosis, irrespective of treatment modality. However, patients who were managed conservatively or who were treated with topical nitroglycerin required a longer duration of stay in the ED, suffered from severe reperfusion pain, and in some cases, had a longer time to complete recovery (≥10 weeks).8

Pharmaceutical and Nonpharmaceutical Management

Phentolamine. Phentolamine is a nonselective ὰ-adrenergic antagonist that binds to ὰ1 and ὰ2 receptors of blood vessels, resulting in a decrease in peripheral vascular resistance and vasodilation. Phentolamine directly antagonizes the effect of epinephrine by blocking the ὰ-adrenergic receptors, which in our patient resulted in immediate return of digital circulation and full resolution of symptoms.

Topical Nitroglycerin. Nitroglycerin is a nitrate vasodilator that when metabolically converted to nitric oxide, results in smooth muscle relaxation, venodilation, and arteriodilation. Patients suffering from digital ischemia and vasoconstriction may be treated with topical nitroglycerin paste to reverse ischemia by causing smooth muscle relaxation of digital blood vessels. Conservative Management. As previously noted, not all cases of digital epinephrine injection are treated pharmacologically. Some patients are not treated, but kept in observation until the ischemic effects of epinephrine have resolved. Likewise, some patients are treated conservatively with warm water compresses or by fully immersing the affected digit in warm water to facilitate reversal of vasoconstriction and ischemia.3,8

Treatment Efficacy

In 2007, Fitzcharles-Bowe et al8 published a review of 59 cases of digital injection with high-dose epinephrine from 1989 to 2005. In this review, 32 of the 59 patients received no treatment, 25 patients received pharmacological treatment and in two patients, the treatment was unknown. Phentolamine was the most commonly used pharmacological agent (15 of 25 cases or 60%). Although none of the patients experienced digital necrosis, those treated with a local infiltration of phentolamine experienced a faster resolution of symptoms and normalization of perfusion. In 2004, Turner1 reported a case of a 10-year-old boy who was treated with phentolamine following an accidental injection of epinephrine into his left hand. While circulation returned to the affected digit within 5 minutes of receiving the phentolamine injection, the patient continued to experience reduced sensation in the digit 6 weeks later.8

Interestingly, one of the coauthors of the Fitzcharles-Bowe et al8 report intentionally injected three of the digits of his left hand (middle, ring, and small fingers) at the same time with high-dose epinephrine to carefully observe and document the outcomes. All three of the digits became very pale and cool, with decreased sensation. The author treated himself conservatively (observation-only). He experienced spontaneous return of circulation in two of the digits within 6 to 10 hours. Although there was some spontaneous return of circulation to the third digit after 13 hours, the author noted prolonged, intense reperfusion pain 4 hours after return of circulation. He also suffered from neuropraxia in the third digit, which did not fully resolve until 10 weeks after the injury.8

A review of the literature shows phentolamine to be a safe and effective treatment for patients presenting with digital ischemia, with no long-term adverse effects or complications. Moreover, phentolamine appears to be safe and effective for use in both adult and pediatric patients.3,8,35-38

Accidental Injection Prevention

Some of the cases of accidental epinephrine injection are due to user error. For example, a novice user may be holding the incorrect end of the injector in his or her hand when attempting to administer/deploy the device, resulting in premature dislodgement of the needle.39

Although, most of the autoinjector devices available today are user-friendly, we believe the addition of a safety feature such as a trigger or safety-lock may further help to reduce accidents. The European Medicines Agency recommends that all patients and caregivers receive training on the proper handling and administration of epinephrine autoinjectors, citing this as the most important factor to ensure successful use of an epinephrine autoinjector and reduce accidental injury.40 The patient in this case had not received any formal education or training regarding autoinjector use prior to this incident.

Safety of Lidocaine-Containing Epinephrine in Digital Anesthesia

Aside from cases of accidental digital epinephrine injection, clinicians have traditionally been taught to avoid using lidocaine with epinephrine for digital anesthesia. However, since the introduction of commercial lidocaine with epinephrine in 1948, there are no case reports of digital gangrene from commercially available lidocaine-epinephrine formulations.41,42 In a multicenter prospective study by Lalonde et al43 of 3,110 consecutive cases of elective injection of low-dose epinephrine in the hand, the authors concluded the likelihood of finger infarction is remote, particularly with possible phentolamine rescue therapy. Moreover, lidocaine-containing epinephrine (1%-2%) has a much lower concentration of epinephrine per mL of solution (5-10 mcg/mL) and appears to be safe for digital use.

Conclusion

This case describes the presentation and treatment of accidental digital injection of epinephrine, highlighting and supporting the benefits of local infiltration with phentolamine and observation until full recovery of perfusion. Local treatment with phentolamine not only facilitates recovery and return of capillary refill, but also shortens the duration of symptoms and alleviates vasoconstriction. In less severe cases, watchful waiting and observation may be appropriate and effective.

This case also underscores the importance of patient and caregiver education on the proper handling and administration of epinephrine autoinjectors to decrease the incidence of accidental injection.

Patients presenting to the ED with injuries due to accidental self-injection with an epinephrine pen typically receive treatment to alleviate symptoms and reduce the potential of digital ischemia leading to gangrene and loss of tissue and function. Although there is no consensus or set guidelines in the literature regarding the management protocol of such cases, many reports support pharmacological intervention. There are, however, other reports that advocate conservative, nonpharmaceutical management (eg, immersing the affected digit in warm water) or an observation-only approach.

We present the first case report in Saudi Arabia of digital ischemia due to accidental injection of an epinephrine autoinjector, along with a review of the literature and management recommendations.

Case

A 28-year-old woman presented to the ED in significant pain and discomfort 20 minutes after she accidentally injected the entire contents of her aunt’s epinephrine autoinjector (0.3 mg of 1:1000) into her right thumb. The patient, who was in significant pain and discomfort, stated that she was unable to remove the injector needle, which was firmly embedded in the bone of the palmer aspect of the distal phalanx in a manner similar to that of an intraosseous injection (Figure 1).

The patient’s vital signs and oxygen saturation on presentation were within normal limits. The emergency physician successfully removed the embedded needle through moderate countertraction. On examination, the patient’s right thumb was pale and cold, and had poor capillary refill (Figure 2). Due to concerns of the potential for digital tissue ischemia leading to tissue loss and gangrene, warm, moist compresses were applied to the affected thumb, followed by 2% topical nitroglycerin paste, after which the thumb was covered with an occlusive dressing. Since there was no improvement in circulation after 20 minutes, an infiltrate of 5 mg (0.5 mL of 10 mg/mL) of phentolamine (α-agonist) mixed with 2.5 mL of 2% lidocaine was injected at the puncture site and base of the right thumb.1 Hyperemia developed immediately at both injection sites, and the patient’s right thumb returned to a normal color and sensation 1 hour later, with a return to normal capillary refill. She remained in stable condition and was discharged home. Prior to discharge, the patient was educated on the proper handling and administration of an epinephrine autoinjector.

Discussion

Epinephrine is an ὰ- and β-adrenergic agonist that binds to the ὰ-adrenergic receptors of blood vessels, causing an increase in vascular resistance and vasoconstriction. Although the plasma half-life of epinephrine is approximately 2 to 3 minutes, subcutaneous or intramuscular injection resulting in local vasoconstriction may delay absorption; therefore, the effects of epinephrine may last much longer than its half-life.

The incidence of accidental injection from an epinephrine autoinjector is estimated to be 1 per 50,000 units dispensed.2 To date, there are no established treatment guidelines on managing cases of digital injection. An online PubMed and Google Scholar search of the literature found one systematic review,3 four observational studies,4-7 seven case series,8-14 and several case reports1,15-33 on the subject. Most of the patients in the published retrospective studies (71%) were treated conservatively with warming of the affected hand and observation, and the majority of patients in the case reports (87%) were treated pharmacologically, most commonly with topical nitroglycerin and phentolamine.1,3-34 All of the patients in both the retrospective studies and case reports had restoration of perfusion without necrosis, irrespective of treatment modality. However, patients who were managed conservatively or who were treated with topical nitroglycerin required a longer duration of stay in the ED, suffered from severe reperfusion pain, and in some cases, had a longer time to complete recovery (≥10 weeks).8

Pharmaceutical and Nonpharmaceutical Management

Phentolamine. Phentolamine is a nonselective ὰ-adrenergic antagonist that binds to ὰ1 and ὰ2 receptors of blood vessels, resulting in a decrease in peripheral vascular resistance and vasodilation. Phentolamine directly antagonizes the effect of epinephrine by blocking the ὰ-adrenergic receptors, which in our patient resulted in immediate return of digital circulation and full resolution of symptoms.

Topical Nitroglycerin. Nitroglycerin is a nitrate vasodilator that when metabolically converted to nitric oxide, results in smooth muscle relaxation, venodilation, and arteriodilation. Patients suffering from digital ischemia and vasoconstriction may be treated with topical nitroglycerin paste to reverse ischemia by causing smooth muscle relaxation of digital blood vessels. Conservative Management. As previously noted, not all cases of digital epinephrine injection are treated pharmacologically. Some patients are not treated, but kept in observation until the ischemic effects of epinephrine have resolved. Likewise, some patients are treated conservatively with warm water compresses or by fully immersing the affected digit in warm water to facilitate reversal of vasoconstriction and ischemia.3,8

Treatment Efficacy

In 2007, Fitzcharles-Bowe et al8 published a review of 59 cases of digital injection with high-dose epinephrine from 1989 to 2005. In this review, 32 of the 59 patients received no treatment, 25 patients received pharmacological treatment and in two patients, the treatment was unknown. Phentolamine was the most commonly used pharmacological agent (15 of 25 cases or 60%). Although none of the patients experienced digital necrosis, those treated with a local infiltration of phentolamine experienced a faster resolution of symptoms and normalization of perfusion. In 2004, Turner1 reported a case of a 10-year-old boy who was treated with phentolamine following an accidental injection of epinephrine into his left hand. While circulation returned to the affected digit within 5 minutes of receiving the phentolamine injection, the patient continued to experience reduced sensation in the digit 6 weeks later.8

Interestingly, one of the coauthors of the Fitzcharles-Bowe et al8 report intentionally injected three of the digits of his left hand (middle, ring, and small fingers) at the same time with high-dose epinephrine to carefully observe and document the outcomes. All three of the digits became very pale and cool, with decreased sensation. The author treated himself conservatively (observation-only). He experienced spontaneous return of circulation in two of the digits within 6 to 10 hours. Although there was some spontaneous return of circulation to the third digit after 13 hours, the author noted prolonged, intense reperfusion pain 4 hours after return of circulation. He also suffered from neuropraxia in the third digit, which did not fully resolve until 10 weeks after the injury.8

A review of the literature shows phentolamine to be a safe and effective treatment for patients presenting with digital ischemia, with no long-term adverse effects or complications. Moreover, phentolamine appears to be safe and effective for use in both adult and pediatric patients.3,8,35-38

Accidental Injection Prevention

Some of the cases of accidental epinephrine injection are due to user error. For example, a novice user may be holding the incorrect end of the injector in his or her hand when attempting to administer/deploy the device, resulting in premature dislodgement of the needle.39

Although, most of the autoinjector devices available today are user-friendly, we believe the addition of a safety feature such as a trigger or safety-lock may further help to reduce accidents. The European Medicines Agency recommends that all patients and caregivers receive training on the proper handling and administration of epinephrine autoinjectors, citing this as the most important factor to ensure successful use of an epinephrine autoinjector and reduce accidental injury.40 The patient in this case had not received any formal education or training regarding autoinjector use prior to this incident.

Safety of Lidocaine-Containing Epinephrine in Digital Anesthesia

Aside from cases of accidental digital epinephrine injection, clinicians have traditionally been taught to avoid using lidocaine with epinephrine for digital anesthesia. However, since the introduction of commercial lidocaine with epinephrine in 1948, there are no case reports of digital gangrene from commercially available lidocaine-epinephrine formulations.41,42 In a multicenter prospective study by Lalonde et al43 of 3,110 consecutive cases of elective injection of low-dose epinephrine in the hand, the authors concluded the likelihood of finger infarction is remote, particularly with possible phentolamine rescue therapy. Moreover, lidocaine-containing epinephrine (1%-2%) has a much lower concentration of epinephrine per mL of solution (5-10 mcg/mL) and appears to be safe for digital use.

Conclusion

This case describes the presentation and treatment of accidental digital injection of epinephrine, highlighting and supporting the benefits of local infiltration with phentolamine and observation until full recovery of perfusion. Local treatment with phentolamine not only facilitates recovery and return of capillary refill, but also shortens the duration of symptoms and alleviates vasoconstriction. In less severe cases, watchful waiting and observation may be appropriate and effective.

This case also underscores the importance of patient and caregiver education on the proper handling and administration of epinephrine autoinjectors to decrease the incidence of accidental injection.

1. Turner MJ. Accidental Epipen injection into a digit - the value of a Google search. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2004;86(3):218-219. doi:10.1308/003588404323043391.

2. McGovern SJ. Treatment of accidental digital injection of adrenaline from an auto-injector device. J Accid Emerg Med. 1997;14(6):379-380.

3. Wright M. Treatment after accidental injection with epinephrine autoinjector: a systematic review. J Allergy & Therapy. 2014;5(3):1000175. doi:10.4172/2155-6121.1000175.

4. Mrvos R, Anderson BD, Krenzelok EP. Accidental injection of epinephrine from an autoinjector: invasive treatment not always required. South Med J. 2002;95(3):318-320.

5. Muck AE, Bebarta VS, Borys DJ, Morgan DL. Six years of epinephrine digital injections: absence of significant local or systemic effects. Ann Emerg Med. 2010;56(3):270-274. doi:10.1016/j.annemergmed.2010.02.019.

6. Simons FE, Edwards ES, Read EJ Jr, Clark S, Liebelt EL. Voluntarily reported unintentional injections from epinephrine auto-injectors. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;125(2):419-423. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2009.10.056.

7. Blume-Odom CM, Scalzo AJ, Weber JA. EpiPen accidental injection-134 cases over 10 years. Clin Toxicol. 2010;48:651.

8. Fitzcharles-Bowe C, Denkler K, Lalonde D. Finger injection with high-dose (1:1,000) epinephrine: Does it cause finger necrosis and should it be treated? Hand. 2007;2(1):5-11. doi:10.1007/s11552-006-9012-4.

9. Velissariou I, Cottrell S, Berry K, Wilson B. Management of adrenaline (epinephrine) induced digital ischaemia in children after accidental injection from an EpiPen. Emerg Med J. 2004;21(3):387-388.

10. ElMaraghy MW, ElMaraghy AW, Evans HB. Digital adrenaline injection injuries: a case series and review. Can J Plast Surg. 1998;6:196-200.

11. Skorpinski EW, McGeady SJ, Yousef E. Two cases of accidental epinephrine injection into a finger. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006;117(2):463-464.

12. Nagaraj J, Reddy S, Murray R, Murphy N. Use of glyceryl trinitrate patches in the treatment of accidental digital injection of epinephrine from an autoinjector. Eur J Emerg Med. 2009;16(4):227-228. doi:10.1097/MEJ.0b013e328306f0ee.

13. Stier PA, Bogner MP, Webster K, Leikin JB, Burda A. Use of subcutaneous terbutaline to reverse peripheral ischemia. Am J Emerg Med. 1999;17(1):91-94.

14. Lee G, Thomas PC. Accidental digital injection of adrenaline from an autoinjector device. J Accid Emerg Med. 1998;15(4):287.

15. Baris S, Saricoban HE, Ak K, Ozdemir C. Papaverine chloride as a topical vasodilator in accidental injection of adrenaline into a digital finger. Allergy. 2011;66(11):1495-1496. doi:10.1111/j.1398-9995.2011.02664.x.

16. Buse K, Hein W, Drager N. Making Sense of Global Health Governance: A Policy Perspective. Basingstoke, England: Palgrave Macmillan UK; 2009.

17. Sherman SC. Digital Epipen® injection: a case of conservative management. J Emerg Med. 2011;41(6):672-674. doi:10.1016/j.jemermed.2009.07.027.

18. Janssen RL, Roeleveld-Versteegh AB, Wessels-Basten SJ, Hendriks T. [Auto-injection with epinephrine in the finger of a 5-year-old child]. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd. 2008;152(17):1005-1008.

19. Singh T, Randhawa S, Khanna R. The EpiPen and the ischaemic finger. Eur J Emerg Med. 2007;14(4):222-223.

20. Barkhordarian AR, Wakelin SH, Paes TR. Accidental digital injection of adrenaline from an autoinjector device. Br J Dermatol. 2000;143(6):1359.

21. Deshmukh N, Tolland JT. Treatment of accidental epinephrine injection in a finger. J Emerg Med. 1989;7(4):408.

22. Hinterberger JW, Kintzi HE. Phentolamine reversal of epinephrine-induced digital vasospasm. How to save an ischemic finger. Arch Fam Med. 1994;3(2):193-195.

23. Peyko V, Cohen V, Jellinek-Cohen SP, Pearl-Davis M. Evaluation and treatment of accidental autoinjection of epinephrine. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2013;70(9):778-781. doi:10.2146/ajhp120316.

24. Hardy SJ, Agostini DE. Accidental epinephrine auto-injector-induced digital ischemia reversed by phentolamine digital block. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 1995;95(6):377-378.

25. Kaspersen J, Vedsted P. [Accidental injection of adrenaline in a finger with EpiPen]. Ugeskr Laeger. 1998;160(45):6531-6532.

26. Schintler MV, Arbab E, Aberer W, Spendel S, Scharnagl E. Accidental perforating bone injury using the EpiPen autoinjection device. Allergy. 2005;60(2):259-260.

27. Khairalla E. Epinephrine-induced digital ischemia relieved by phentolamine. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2001;108(6):1831-1832.

28. Murali KS, Nayeem N. Accidental digital injection of adrenaline from an autoinjector device. J Accid Emerg Med. 1998;15(4):287.

29. Sellens C, Morrison L. Accidental injection of epinephrine by a child: a unique approach to treatment. CJEM. 1999;1(1):34-36.

30. Klemawesch P. Hyperbaric oxygen relieves severe digital ischaemia from accidental EpiPen injection. 2009 American Academy of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology Annual Meeting.

31. McCauley WA, Gerace RV, Scilley C. Treatment of accidental digital injection of epinephrine. Ann Emerg Med. 1991;20(6):665-668.

32. Mathez C, Favrat B, Staeger P. Management options for accidental injection of epinephrine from an autoinjector: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2009;3:7268. doi:10.4076/1752-1947-3-7268.

33. Molony D. Adrenaline-induced digital ischaemia reversed with phentolamine. ANZ J Surg. 2006;76(12):1125-1126.

34. Carrascosa MF, Gallastegui-Menéndez A, Teja-Santamaría C, Caviedes JR. Accidental finger ischaemia induced by epinephrine autoinjector. BMJ Case Rep. 2013;2013. pii:bcr2013200783. doi:10.1136/bcr-2013-200783.

35. Patel R, Kumar H. Epinephrine induced digital ischemia after accidental injection from an auto-injector device. Indian Pediatr. 2013;50(2):247.

36. Xu J, Holt A. Use of Phentolamine in the treatment of Epipen induced digital ischemia. BMJ Case Rep. 2012;2012. doi:10.1136/bcr.12.2011.5450.

37. McNeil C, Copeland J. Accidental digital epinephrine injection: to treat or not to treat? Can Fam Physician. 2014;60(8):726-728.

38. Bodkin RP, Acquisto NM, Gunyan H, Wiegand TJ. Two cases of accidental injection of epinephrine into a digit treated with subcutaneous phentolamine injections. Case Rep Emerg Med. 2013;2013:586207. doi:10.1155/2013/586207.

39. Simons FE, Lieberman PL, Read EJ Jr, Edwards ES. Hazards of unintentional injection of epinephrine from autoinjectors: a systematic review. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2009;102(4):282-287. doi:10.1016/S1081-1206(10)60332-8.

40. European Medicines Agency. Better training tools recommended to support patients using adrenaline auto-injectors. European Medicines Agency, 2015.

41. Denkler K. A comprehensive review of epinephrine in the finger: to do or not to do.

42. Thomson CJ, Lalonde DH, Denkler KA, Feicht AJ. A critical look at the evidence for and against elective epinephrine use in the finger. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2007;119(1):260-266.

43. Lalonde D, Bell M, Benoit P, Sparkes G, Denkler K, Chang P. A multicenter prospective study of 3,110 consecutive cases of elective epinephrine use in the fingers and hand: the Dalhousie Project clinical phase. J Hand Surg Am. 2005;30(5):1061-1067. doi:10.1016/j.jhsa.2005.05.006.

1. Turner MJ. Accidental Epipen injection into a digit - the value of a Google search. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2004;86(3):218-219. doi:10.1308/003588404323043391.

2. McGovern SJ. Treatment of accidental digital injection of adrenaline from an auto-injector device. J Accid Emerg Med. 1997;14(6):379-380.

3. Wright M. Treatment after accidental injection with epinephrine autoinjector: a systematic review. J Allergy & Therapy. 2014;5(3):1000175. doi:10.4172/2155-6121.1000175.

4. Mrvos R, Anderson BD, Krenzelok EP. Accidental injection of epinephrine from an autoinjector: invasive treatment not always required. South Med J. 2002;95(3):318-320.

5. Muck AE, Bebarta VS, Borys DJ, Morgan DL. Six years of epinephrine digital injections: absence of significant local or systemic effects. Ann Emerg Med. 2010;56(3):270-274. doi:10.1016/j.annemergmed.2010.02.019.

6. Simons FE, Edwards ES, Read EJ Jr, Clark S, Liebelt EL. Voluntarily reported unintentional injections from epinephrine auto-injectors. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;125(2):419-423. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2009.10.056.

7. Blume-Odom CM, Scalzo AJ, Weber JA. EpiPen accidental injection-134 cases over 10 years. Clin Toxicol. 2010;48:651.

8. Fitzcharles-Bowe C, Denkler K, Lalonde D. Finger injection with high-dose (1:1,000) epinephrine: Does it cause finger necrosis and should it be treated? Hand. 2007;2(1):5-11. doi:10.1007/s11552-006-9012-4.

9. Velissariou I, Cottrell S, Berry K, Wilson B. Management of adrenaline (epinephrine) induced digital ischaemia in children after accidental injection from an EpiPen. Emerg Med J. 2004;21(3):387-388.

10. ElMaraghy MW, ElMaraghy AW, Evans HB. Digital adrenaline injection injuries: a case series and review. Can J Plast Surg. 1998;6:196-200.

11. Skorpinski EW, McGeady SJ, Yousef E. Two cases of accidental epinephrine injection into a finger. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006;117(2):463-464.

12. Nagaraj J, Reddy S, Murray R, Murphy N. Use of glyceryl trinitrate patches in the treatment of accidental digital injection of epinephrine from an autoinjector. Eur J Emerg Med. 2009;16(4):227-228. doi:10.1097/MEJ.0b013e328306f0ee.

13. Stier PA, Bogner MP, Webster K, Leikin JB, Burda A. Use of subcutaneous terbutaline to reverse peripheral ischemia. Am J Emerg Med. 1999;17(1):91-94.

14. Lee G, Thomas PC. Accidental digital injection of adrenaline from an autoinjector device. J Accid Emerg Med. 1998;15(4):287.

15. Baris S, Saricoban HE, Ak K, Ozdemir C. Papaverine chloride as a topical vasodilator in accidental injection of adrenaline into a digital finger. Allergy. 2011;66(11):1495-1496. doi:10.1111/j.1398-9995.2011.02664.x.

16. Buse K, Hein W, Drager N. Making Sense of Global Health Governance: A Policy Perspective. Basingstoke, England: Palgrave Macmillan UK; 2009.

17. Sherman SC. Digital Epipen® injection: a case of conservative management. J Emerg Med. 2011;41(6):672-674. doi:10.1016/j.jemermed.2009.07.027.

18. Janssen RL, Roeleveld-Versteegh AB, Wessels-Basten SJ, Hendriks T. [Auto-injection with epinephrine in the finger of a 5-year-old child]. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd. 2008;152(17):1005-1008.

19. Singh T, Randhawa S, Khanna R. The EpiPen and the ischaemic finger. Eur J Emerg Med. 2007;14(4):222-223.

20. Barkhordarian AR, Wakelin SH, Paes TR. Accidental digital injection of adrenaline from an autoinjector device. Br J Dermatol. 2000;143(6):1359.

21. Deshmukh N, Tolland JT. Treatment of accidental epinephrine injection in a finger. J Emerg Med. 1989;7(4):408.

22. Hinterberger JW, Kintzi HE. Phentolamine reversal of epinephrine-induced digital vasospasm. How to save an ischemic finger. Arch Fam Med. 1994;3(2):193-195.

23. Peyko V, Cohen V, Jellinek-Cohen SP, Pearl-Davis M. Evaluation and treatment of accidental autoinjection of epinephrine. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2013;70(9):778-781. doi:10.2146/ajhp120316.

24. Hardy SJ, Agostini DE. Accidental epinephrine auto-injector-induced digital ischemia reversed by phentolamine digital block. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 1995;95(6):377-378.

25. Kaspersen J, Vedsted P. [Accidental injection of adrenaline in a finger with EpiPen]. Ugeskr Laeger. 1998;160(45):6531-6532.

26. Schintler MV, Arbab E, Aberer W, Spendel S, Scharnagl E. Accidental perforating bone injury using the EpiPen autoinjection device. Allergy. 2005;60(2):259-260.

27. Khairalla E. Epinephrine-induced digital ischemia relieved by phentolamine. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2001;108(6):1831-1832.

28. Murali KS, Nayeem N. Accidental digital injection of adrenaline from an autoinjector device. J Accid Emerg Med. 1998;15(4):287.

29. Sellens C, Morrison L. Accidental injection of epinephrine by a child: a unique approach to treatment. CJEM. 1999;1(1):34-36.

30. Klemawesch P. Hyperbaric oxygen relieves severe digital ischaemia from accidental EpiPen injection. 2009 American Academy of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology Annual Meeting.

31. McCauley WA, Gerace RV, Scilley C. Treatment of accidental digital injection of epinephrine. Ann Emerg Med. 1991;20(6):665-668.

32. Mathez C, Favrat B, Staeger P. Management options for accidental injection of epinephrine from an autoinjector: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2009;3:7268. doi:10.4076/1752-1947-3-7268.

33. Molony D. Adrenaline-induced digital ischaemia reversed with phentolamine. ANZ J Surg. 2006;76(12):1125-1126.

34. Carrascosa MF, Gallastegui-Menéndez A, Teja-Santamaría C, Caviedes JR. Accidental finger ischaemia induced by epinephrine autoinjector. BMJ Case Rep. 2013;2013. pii:bcr2013200783. doi:10.1136/bcr-2013-200783.

35. Patel R, Kumar H. Epinephrine induced digital ischemia after accidental injection from an auto-injector device. Indian Pediatr. 2013;50(2):247.

36. Xu J, Holt A. Use of Phentolamine in the treatment of Epipen induced digital ischemia. BMJ Case Rep. 2012;2012. doi:10.1136/bcr.12.2011.5450.

37. McNeil C, Copeland J. Accidental digital epinephrine injection: to treat or not to treat? Can Fam Physician. 2014;60(8):726-728.

38. Bodkin RP, Acquisto NM, Gunyan H, Wiegand TJ. Two cases of accidental injection of epinephrine into a digit treated with subcutaneous phentolamine injections. Case Rep Emerg Med. 2013;2013:586207. doi:10.1155/2013/586207.

39. Simons FE, Lieberman PL, Read EJ Jr, Edwards ES. Hazards of unintentional injection of epinephrine from autoinjectors: a systematic review. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2009;102(4):282-287. doi:10.1016/S1081-1206(10)60332-8.

40. European Medicines Agency. Better training tools recommended to support patients using adrenaline auto-injectors. European Medicines Agency, 2015.

41. Denkler K. A comprehensive review of epinephrine in the finger: to do or not to do.

42. Thomson CJ, Lalonde DH, Denkler KA, Feicht AJ. A critical look at the evidence for and against elective epinephrine use in the finger. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2007;119(1):260-266.

43. Lalonde D, Bell M, Benoit P, Sparkes G, Denkler K, Chang P. A multicenter prospective study of 3,110 consecutive cases of elective epinephrine use in the fingers and hand: the Dalhousie Project clinical phase. J Hand Surg Am. 2005;30(5):1061-1067. doi:10.1016/j.jhsa.2005.05.006.

Cognitive-behavioral therapy modified for maximum efficacy in the elderly

NEW YORK – For elderly individuals with depression exacerbated by physical limitations and personal losses, cognitive-behavioral therapy is a powerful tool for improving quality of life, according to the faculty of a workshop on this topic at the annual meeting of the American Psychiatric Association.

“The focus is on coping skills. It is about how to persevere in the face of adversity,” explained David A. Casey, MD, professor and chair of the department of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at University of Louisville (Ky.).

“It is not always a fair characterization, but CBT is often perceived as a strategy to address negative thoughts that are not real – but many of my elderly patients have losses and difficulties that are very real,” Dr. Casey said.

In the elderly who become increasingly isolated because of the loss of spouses, friends, and siblings while contending with medical problems that cause pain and limit activities, depression can engender withdrawal, a common coping mechanism, he said.

“Withdrawal may be an unexamined response to a sense of helplessness created by the problems of aging, but it can create a vicious cycle when depression contributes to lack of physical activity and further withdrawal,” explained Dr. Casey, who believes that mild cognitive impairment does not preclude the use of CBT.

CBT provides a “here-and-now” approach in which patients are reconnected to daily life by first identifying the activities that once provided pleasure or satisfaction and then developing a plan to reintroduce them into daily life. Except for its value in identifying activities meaningful to the patient, the history that preceded depression or psychological distress is less important than developing an immediate strategy to rebuilding an active life.

“Some patients are essentially immobilized by their withdrawal and convinced that their problems are unsolvable, but most will improve their quality of life through CBT,” he maintained.

There are data to support this contention, according to Jesse H. Wright III, MD, PhD, director of the Depression Center at the University of Louisville. He cited controlled studies demonstrating the efficacy of CBT relative to no CBT in relieving depression in the elderly.

“The evidence suggests that combining CBT with pharmacotherapy is better than either alone for managing depression in this age group,” Dr. Wright said.

In developing a therapeutic plan through CBT, patients are given assignments designed to develop participation in meaningful activities. These must be realistic within physical limitations and within the patient’s readiness to engage. Small steps toward a goal might be needed. At each therapeutic encounter, goals are set, and progress should be evaluated at the subsequent therapeutic encounter.

Dr. Casey cautioned. He said a rehearsal of the actions needed to achieve the assigned goals might be helpful before the patient leaves the treatment session. This allows the clinician to recognize and address potential obstacles, including practical issues, such as mobility, or psychological issues, such as fear of physical activities.

Developing persistence in the face of high levels of negativity can be a challenge not only for the patient but also for the physician. According to Dr. Casey, maintaining a positive attitude can be challenging after treating a series of highly withdrawn and discouraged patients. But he emphasized the need for a professional orientation, recognizing that incremental gains in patient well-being, not cure, should be considered a reasonable goal.

“If I can improve the patient’s quality of life, this is a significant success,” he said. He believes it is sometimes necessary to distract patients from potential problems to focus on expected benefits.

“Patients can have a view of their limitations that is accurate but unhelpful,” Dr. Casey said. The goal of CBT is to move the focus to strategies that can restore lost interest and pleasure in daily life.

Dr. Casey and Dr. Wright reported no potential conflicts of interest related to this topic.

NEW YORK – For elderly individuals with depression exacerbated by physical limitations and personal losses, cognitive-behavioral therapy is a powerful tool for improving quality of life, according to the faculty of a workshop on this topic at the annual meeting of the American Psychiatric Association.

“The focus is on coping skills. It is about how to persevere in the face of adversity,” explained David A. Casey, MD, professor and chair of the department of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at University of Louisville (Ky.).

“It is not always a fair characterization, but CBT is often perceived as a strategy to address negative thoughts that are not real – but many of my elderly patients have losses and difficulties that are very real,” Dr. Casey said.

In the elderly who become increasingly isolated because of the loss of spouses, friends, and siblings while contending with medical problems that cause pain and limit activities, depression can engender withdrawal, a common coping mechanism, he said.

“Withdrawal may be an unexamined response to a sense of helplessness created by the problems of aging, but it can create a vicious cycle when depression contributes to lack of physical activity and further withdrawal,” explained Dr. Casey, who believes that mild cognitive impairment does not preclude the use of CBT.

CBT provides a “here-and-now” approach in which patients are reconnected to daily life by first identifying the activities that once provided pleasure or satisfaction and then developing a plan to reintroduce them into daily life. Except for its value in identifying activities meaningful to the patient, the history that preceded depression or psychological distress is less important than developing an immediate strategy to rebuilding an active life.

“Some patients are essentially immobilized by their withdrawal and convinced that their problems are unsolvable, but most will improve their quality of life through CBT,” he maintained.

There are data to support this contention, according to Jesse H. Wright III, MD, PhD, director of the Depression Center at the University of Louisville. He cited controlled studies demonstrating the efficacy of CBT relative to no CBT in relieving depression in the elderly.

“The evidence suggests that combining CBT with pharmacotherapy is better than either alone for managing depression in this age group,” Dr. Wright said.

In developing a therapeutic plan through CBT, patients are given assignments designed to develop participation in meaningful activities. These must be realistic within physical limitations and within the patient’s readiness to engage. Small steps toward a goal might be needed. At each therapeutic encounter, goals are set, and progress should be evaluated at the subsequent therapeutic encounter.

Dr. Casey cautioned. He said a rehearsal of the actions needed to achieve the assigned goals might be helpful before the patient leaves the treatment session. This allows the clinician to recognize and address potential obstacles, including practical issues, such as mobility, or psychological issues, such as fear of physical activities.

Developing persistence in the face of high levels of negativity can be a challenge not only for the patient but also for the physician. According to Dr. Casey, maintaining a positive attitude can be challenging after treating a series of highly withdrawn and discouraged patients. But he emphasized the need for a professional orientation, recognizing that incremental gains in patient well-being, not cure, should be considered a reasonable goal.

“If I can improve the patient’s quality of life, this is a significant success,” he said. He believes it is sometimes necessary to distract patients from potential problems to focus on expected benefits.

“Patients can have a view of their limitations that is accurate but unhelpful,” Dr. Casey said. The goal of CBT is to move the focus to strategies that can restore lost interest and pleasure in daily life.

Dr. Casey and Dr. Wright reported no potential conflicts of interest related to this topic.

NEW YORK – For elderly individuals with depression exacerbated by physical limitations and personal losses, cognitive-behavioral therapy is a powerful tool for improving quality of life, according to the faculty of a workshop on this topic at the annual meeting of the American Psychiatric Association.

“The focus is on coping skills. It is about how to persevere in the face of adversity,” explained David A. Casey, MD, professor and chair of the department of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at University of Louisville (Ky.).

“It is not always a fair characterization, but CBT is often perceived as a strategy to address negative thoughts that are not real – but many of my elderly patients have losses and difficulties that are very real,” Dr. Casey said.

In the elderly who become increasingly isolated because of the loss of spouses, friends, and siblings while contending with medical problems that cause pain and limit activities, depression can engender withdrawal, a common coping mechanism, he said.

“Withdrawal may be an unexamined response to a sense of helplessness created by the problems of aging, but it can create a vicious cycle when depression contributes to lack of physical activity and further withdrawal,” explained Dr. Casey, who believes that mild cognitive impairment does not preclude the use of CBT.

CBT provides a “here-and-now” approach in which patients are reconnected to daily life by first identifying the activities that once provided pleasure or satisfaction and then developing a plan to reintroduce them into daily life. Except for its value in identifying activities meaningful to the patient, the history that preceded depression or psychological distress is less important than developing an immediate strategy to rebuilding an active life.

“Some patients are essentially immobilized by their withdrawal and convinced that their problems are unsolvable, but most will improve their quality of life through CBT,” he maintained.

There are data to support this contention, according to Jesse H. Wright III, MD, PhD, director of the Depression Center at the University of Louisville. He cited controlled studies demonstrating the efficacy of CBT relative to no CBT in relieving depression in the elderly.

“The evidence suggests that combining CBT with pharmacotherapy is better than either alone for managing depression in this age group,” Dr. Wright said.

In developing a therapeutic plan through CBT, patients are given assignments designed to develop participation in meaningful activities. These must be realistic within physical limitations and within the patient’s readiness to engage. Small steps toward a goal might be needed. At each therapeutic encounter, goals are set, and progress should be evaluated at the subsequent therapeutic encounter.

Dr. Casey cautioned. He said a rehearsal of the actions needed to achieve the assigned goals might be helpful before the patient leaves the treatment session. This allows the clinician to recognize and address potential obstacles, including practical issues, such as mobility, or psychological issues, such as fear of physical activities.

Developing persistence in the face of high levels of negativity can be a challenge not only for the patient but also for the physician. According to Dr. Casey, maintaining a positive attitude can be challenging after treating a series of highly withdrawn and discouraged patients. But he emphasized the need for a professional orientation, recognizing that incremental gains in patient well-being, not cure, should be considered a reasonable goal.

“If I can improve the patient’s quality of life, this is a significant success,” he said. He believes it is sometimes necessary to distract patients from potential problems to focus on expected benefits.

“Patients can have a view of their limitations that is accurate but unhelpful,” Dr. Casey said. The goal of CBT is to move the focus to strategies that can restore lost interest and pleasure in daily life.

Dr. Casey and Dr. Wright reported no potential conflicts of interest related to this topic.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM APA

Poor sleep tied to suicidal behaviors in college students

Poor sleep is associated with increased suicidal behaviors in college students – even when controlling for depression, a study of 1,700 students shows.

“Furthermore, findings suggest that some specific sleep components – shorter sleep duration, more frequent bad dreams, feeling too cold while sleeping, and greater sleep medication use – are particularly associated with increased suicidal behaviors in college students,” reported Stephen P. Becker, PhD, of the Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Center, and his associates.

The researchers recruited students from two universities. Most of the students (65%) were female, white (82%), and in their first year of college (63%). The participants’ sleep was assessed using the nine-item Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI), their depressive symptoms were assessed using the Depressive Anxiety Stress Scales-21, and their suicidal behavior was assessed using the Suicidal Behaviors Questionnaire-Revised (SBQ-R), which is a four-item, self-report measure.

About two-thirds of the students (64%) were found to have sleep problems (total PSQI score greater than 5), and 24% were found to have suicide risk (total SBQ-R score of at least 7). Of the students who were found to have suicide risk, 83% also had sleep problems.

Using regression analysis, Dr. Becker and his associates found that the odds of being classified with suicide risk were 6.5 times greater for students with depression and 2.7 times greater for those with sleep problems.

The results add to the literature suggesting that the researchers wrote.

SOURCE: Becker SP et al. J Psychiatr Res. 2018 Apr;99:123-8.

Poor sleep is associated with increased suicidal behaviors in college students – even when controlling for depression, a study of 1,700 students shows.

“Furthermore, findings suggest that some specific sleep components – shorter sleep duration, more frequent bad dreams, feeling too cold while sleeping, and greater sleep medication use – are particularly associated with increased suicidal behaviors in college students,” reported Stephen P. Becker, PhD, of the Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Center, and his associates.

The researchers recruited students from two universities. Most of the students (65%) were female, white (82%), and in their first year of college (63%). The participants’ sleep was assessed using the nine-item Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI), their depressive symptoms were assessed using the Depressive Anxiety Stress Scales-21, and their suicidal behavior was assessed using the Suicidal Behaviors Questionnaire-Revised (SBQ-R), which is a four-item, self-report measure.

About two-thirds of the students (64%) were found to have sleep problems (total PSQI score greater than 5), and 24% were found to have suicide risk (total SBQ-R score of at least 7). Of the students who were found to have suicide risk, 83% also had sleep problems.

Using regression analysis, Dr. Becker and his associates found that the odds of being classified with suicide risk were 6.5 times greater for students with depression and 2.7 times greater for those with sleep problems.

The results add to the literature suggesting that the researchers wrote.

SOURCE: Becker SP et al. J Psychiatr Res. 2018 Apr;99:123-8.

Poor sleep is associated with increased suicidal behaviors in college students – even when controlling for depression, a study of 1,700 students shows.

“Furthermore, findings suggest that some specific sleep components – shorter sleep duration, more frequent bad dreams, feeling too cold while sleeping, and greater sleep medication use – are particularly associated with increased suicidal behaviors in college students,” reported Stephen P. Becker, PhD, of the Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Center, and his associates.

The researchers recruited students from two universities. Most of the students (65%) were female, white (82%), and in their first year of college (63%). The participants’ sleep was assessed using the nine-item Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI), their depressive symptoms were assessed using the Depressive Anxiety Stress Scales-21, and their suicidal behavior was assessed using the Suicidal Behaviors Questionnaire-Revised (SBQ-R), which is a four-item, self-report measure.

About two-thirds of the students (64%) were found to have sleep problems (total PSQI score greater than 5), and 24% were found to have suicide risk (total SBQ-R score of at least 7). Of the students who were found to have suicide risk, 83% also had sleep problems.

Using regression analysis, Dr. Becker and his associates found that the odds of being classified with suicide risk were 6.5 times greater for students with depression and 2.7 times greater for those with sleep problems.

The results add to the literature suggesting that the researchers wrote.

SOURCE: Becker SP et al. J Psychiatr Res. 2018 Apr;99:123-8.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF PSYCHIATRIC RESEARCH

Elagolix shows long-term efficacy

AUSTIN, TEX. – A new treatment for endometriosis-related pain, Elagolix, showed evidence of being effective long term, according to a study presented at the annual clinical and scientific meeting of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

Elagolix, an oral nonpeptide gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) antagonist, manufactured by AbbVie, would be the first treatment of its kind if approved by the Food and Drug Administration, and would fulfill a needed relief for a more tolerable approach to severe endometriosis patients, according to presenter Eric S. Surrey, MD, medical director at the Colorado Center of Reproductive Medicine, Lone Tree.

“There have been no new medications approved for a long time for systematic endometriosis and there is a huge gap because the current options are expensive, and they are often injectable drugs,” said Dr. Surrey in an interview. “This would be an oral agent, which would be fabulous because it allows for a lot of flexibility and for many patients this could be much less concerning than using something long acting.”

To test the long-term effects of Elagolix, investigators studied 570 women with moderate to severe endometriosis-related pain who had gathered to participate in a previous phase 3, randomized, placebo-controlled trial concerning the drug’s effectiveness.

In the two extension studies, all participants were given either a 150- or 200-mg dose of Elagolix.

Average age of each patient group was between 31 and 34 years, and all groups were majority white, with a mean length of time from surgical diagnosis ranging from 45.5 to 56.6 months.

Patient improvements in dysmenorrhea and nonmenstrual pelvic pain continued between the first 6 months and 12 months of treatment, with a decrease of 46%-77% in the overall number of analgesics taken per day.

After 12 months of consecutive treatment, patients given 150 mg of Elagolix saw mean dysmenorrhea scores improve by 49%-53% from baseline, and by 82% for those at 200 mg, with certain expected adverse events, according to Dr. Surrey.

One of the most common adverse events associated with Elagolix was hot flashes, an unsurprising finding for Dr. Surrey and his colleagues considering Elagolix is a drug that lowers estrogen levels. However, any hot flashes patients experienced during the trial were still better than those associated with current medications, according to Dr. Surrey.

“In this extension study nobody dropped out because of hot flashes in the additional 6-month extension time,” Dr. Surrey explained. “If you look at the gold standard drug for endometriosis now, which is a GnRH agonist, which are highly available and are either injectable or implants, [patients taking these drugs] can have very severe hot flashes that require additional medication to alleviate the hot flashes at the same time.”

Patients did also experience some loss in bone density; however, Dr. Surrey argues the frequency and level of these adverse events is still better than current treatment options. One patient was required to discontinue the trial for bone density loss.

Currently, Elagolix is under FDA priority review, and if approved will be the first oral endometriosis treatment approved in over a decade, according to Dr. Surrey.

Dr. Surrey and several coauthors receive financial support from AbbVie as consultants, board members, and/or employees. Dr. Surrey and Dr. Taylor receive additional support from companies including Pfizer, Bayer, and Obseva.

SOURCE: Surrey ES et al. ACOG 2018, Abstract 11OP.

Having had the opportunity to review Dr. Eric Surrey's abstract for this year's annual clinical and scientific meeting of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, entitled "Long-term Safety and Efficacy of Elagolix Treatment in Women With Endometriosis-associated Pain," I believe use of Elagolix, an oral nonpeptide gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) antagonist, is a much-needed advancement in the long-term treatment of endometriosis-related pain. The fact that it is an oral medication, thus, not requiring a monthly or 3-month injection as does Lupron Depot (leuprolide acetate), the most popular GnRH agonist in the United States, is advantageous both for the patient and the busy office staff.

While I certainly understand that it is easy to compare data regarding bone loss in the use of an oral antagonist, Elagolix, with historical data with the GnRH agonist and note a lessening of bone loss in the Elagolix patients, it would be interesting to compare bone loss in patients utilizing Elagolix with bone loss in those treated with GnRH-agonist plus add-back therapy. Many practitioners will utilize progesterone supplementation or estrogen/progesterone supplementation when using GnRH-agonist therapy to decrease this risk. Furthermore, it would be interesting, in the future, to evaluate the impact on efficacy and bone loss if progesterone and estrogen/progesterone add-back were utilized in Elagolix therapy.

While I certainly realize and deeply respect Dr. Surrey's vast experience as both a clinical researcher and clinician utilizing a GnRH-agonist regimen, I am curious as to the basis of Dr. Surrey's comments regarding less severe hot flashes in comparison to GnRH-agonist treatment. I am not aware of any head-to-head studies comparing hot flashes between GnRH agonists (in particular, leuprolide acetate) and Elagolix.

Without a side-by-side comparison utilizing a validated scoring system, I find it hard to accept this conclusion.

Nevertheless, after reviewing this study and Dr. Surrey's comments, I look forward to utilizing Elagolix in my practice for long-term treatment of endometriosis-related pain.

Charles Miller, MD, is a minimally invasive gynecologic surgeon in Naperville, Ill., and a past president of the AAGL. He is a consultant and involved in research for AbbVie.

Having had the opportunity to review Dr. Eric Surrey's abstract for this year's annual clinical and scientific meeting of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, entitled "Long-term Safety and Efficacy of Elagolix Treatment in Women With Endometriosis-associated Pain," I believe use of Elagolix, an oral nonpeptide gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) antagonist, is a much-needed advancement in the long-term treatment of endometriosis-related pain. The fact that it is an oral medication, thus, not requiring a monthly or 3-month injection as does Lupron Depot (leuprolide acetate), the most popular GnRH agonist in the United States, is advantageous both for the patient and the busy office staff.

While I certainly understand that it is easy to compare data regarding bone loss in the use of an oral antagonist, Elagolix, with historical data with the GnRH agonist and note a lessening of bone loss in the Elagolix patients, it would be interesting to compare bone loss in patients utilizing Elagolix with bone loss in those treated with GnRH-agonist plus add-back therapy. Many practitioners will utilize progesterone supplementation or estrogen/progesterone supplementation when using GnRH-agonist therapy to decrease this risk. Furthermore, it would be interesting, in the future, to evaluate the impact on efficacy and bone loss if progesterone and estrogen/progesterone add-back were utilized in Elagolix therapy.

While I certainly realize and deeply respect Dr. Surrey's vast experience as both a clinical researcher and clinician utilizing a GnRH-agonist regimen, I am curious as to the basis of Dr. Surrey's comments regarding less severe hot flashes in comparison to GnRH-agonist treatment. I am not aware of any head-to-head studies comparing hot flashes between GnRH agonists (in particular, leuprolide acetate) and Elagolix.

Without a side-by-side comparison utilizing a validated scoring system, I find it hard to accept this conclusion.

Nevertheless, after reviewing this study and Dr. Surrey's comments, I look forward to utilizing Elagolix in my practice for long-term treatment of endometriosis-related pain.

Charles Miller, MD, is a minimally invasive gynecologic surgeon in Naperville, Ill., and a past president of the AAGL. He is a consultant and involved in research for AbbVie.

Having had the opportunity to review Dr. Eric Surrey's abstract for this year's annual clinical and scientific meeting of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, entitled "Long-term Safety and Efficacy of Elagolix Treatment in Women With Endometriosis-associated Pain," I believe use of Elagolix, an oral nonpeptide gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) antagonist, is a much-needed advancement in the long-term treatment of endometriosis-related pain. The fact that it is an oral medication, thus, not requiring a monthly or 3-month injection as does Lupron Depot (leuprolide acetate), the most popular GnRH agonist in the United States, is advantageous both for the patient and the busy office staff.

While I certainly understand that it is easy to compare data regarding bone loss in the use of an oral antagonist, Elagolix, with historical data with the GnRH agonist and note a lessening of bone loss in the Elagolix patients, it would be interesting to compare bone loss in patients utilizing Elagolix with bone loss in those treated with GnRH-agonist plus add-back therapy. Many practitioners will utilize progesterone supplementation or estrogen/progesterone supplementation when using GnRH-agonist therapy to decrease this risk. Furthermore, it would be interesting, in the future, to evaluate the impact on efficacy and bone loss if progesterone and estrogen/progesterone add-back were utilized in Elagolix therapy.

While I certainly realize and deeply respect Dr. Surrey's vast experience as both a clinical researcher and clinician utilizing a GnRH-agonist regimen, I am curious as to the basis of Dr. Surrey's comments regarding less severe hot flashes in comparison to GnRH-agonist treatment. I am not aware of any head-to-head studies comparing hot flashes between GnRH agonists (in particular, leuprolide acetate) and Elagolix.

Without a side-by-side comparison utilizing a validated scoring system, I find it hard to accept this conclusion.

Nevertheless, after reviewing this study and Dr. Surrey's comments, I look forward to utilizing Elagolix in my practice for long-term treatment of endometriosis-related pain.