User login

Bacterial signals set the stage for PMP

Preclinical research suggests bacterial signals are crucial to the development of pre-leukemic myeloproliferation (PMP).

Researchers found that bacterial translocation leads to increased production of interleukin-6 (IL-6), which prompts PMP development in mice with Tet2 deficiency.

However, antibiotics and blockade of IL-6 were able to reverse PMP in the mice.

Bana Jabri, MD, PhD, of the University of Chicago in Illinois, and her colleagues reported these findings in Nature.

The researchers noted that, in humans and mice, TET2 deficiency leads to increased self-renewal of hematopoietic stem cells favoring the myeloid lineage, and this can lead to PMP.

However, not all humans or mice with TET2 deficiency actually develop PMP, which suggests other factors are at play.

With this in mind, the researchers studied Tet2-deficient mice. The team found that loss of Tet2 expression leads to defects in the intestinal barrier, although it isn’t clear how this occurs.

The intestinal defects allow bacteria living in the gut to spread into the blood and peripheral organs. The spread of bacteria prompts an increase in IL-6. This promotes proliferation of granulocyte–macrophage progenitors that express high levels of IL-6Rα in the absence of Tet2, and this leads to PMP.

The researchers found they could induce PMP in symptom-free Tet2−/− mice by disrupting intestinal barrier integrity. PMP also developed in response to systemic bacterial stimuli.

However, antibiotics and blockade of IL-6 signals could reverse PMP in mice that developed symptoms. And germ-free Tet2−/− mice did not develop symptoms, which supports the idea that bacteria must be present to drive the development of PMP.

Dr Jabri said the next step is to conduct studies in humans to see if patients with PMP also have signs of bacterial translocation. Then, clinical trials could test whether treatments that target aberrant IL-6 signals in response to bacteria can reverse the course of PMP.

Preclinical research suggests bacterial signals are crucial to the development of pre-leukemic myeloproliferation (PMP).

Researchers found that bacterial translocation leads to increased production of interleukin-6 (IL-6), which prompts PMP development in mice with Tet2 deficiency.

However, antibiotics and blockade of IL-6 were able to reverse PMP in the mice.

Bana Jabri, MD, PhD, of the University of Chicago in Illinois, and her colleagues reported these findings in Nature.

The researchers noted that, in humans and mice, TET2 deficiency leads to increased self-renewal of hematopoietic stem cells favoring the myeloid lineage, and this can lead to PMP.

However, not all humans or mice with TET2 deficiency actually develop PMP, which suggests other factors are at play.

With this in mind, the researchers studied Tet2-deficient mice. The team found that loss of Tet2 expression leads to defects in the intestinal barrier, although it isn’t clear how this occurs.

The intestinal defects allow bacteria living in the gut to spread into the blood and peripheral organs. The spread of bacteria prompts an increase in IL-6. This promotes proliferation of granulocyte–macrophage progenitors that express high levels of IL-6Rα in the absence of Tet2, and this leads to PMP.

The researchers found they could induce PMP in symptom-free Tet2−/− mice by disrupting intestinal barrier integrity. PMP also developed in response to systemic bacterial stimuli.

However, antibiotics and blockade of IL-6 signals could reverse PMP in mice that developed symptoms. And germ-free Tet2−/− mice did not develop symptoms, which supports the idea that bacteria must be present to drive the development of PMP.

Dr Jabri said the next step is to conduct studies in humans to see if patients with PMP also have signs of bacterial translocation. Then, clinical trials could test whether treatments that target aberrant IL-6 signals in response to bacteria can reverse the course of PMP.

Preclinical research suggests bacterial signals are crucial to the development of pre-leukemic myeloproliferation (PMP).

Researchers found that bacterial translocation leads to increased production of interleukin-6 (IL-6), which prompts PMP development in mice with Tet2 deficiency.

However, antibiotics and blockade of IL-6 were able to reverse PMP in the mice.

Bana Jabri, MD, PhD, of the University of Chicago in Illinois, and her colleagues reported these findings in Nature.

The researchers noted that, in humans and mice, TET2 deficiency leads to increased self-renewal of hematopoietic stem cells favoring the myeloid lineage, and this can lead to PMP.

However, not all humans or mice with TET2 deficiency actually develop PMP, which suggests other factors are at play.

With this in mind, the researchers studied Tet2-deficient mice. The team found that loss of Tet2 expression leads to defects in the intestinal barrier, although it isn’t clear how this occurs.

The intestinal defects allow bacteria living in the gut to spread into the blood and peripheral organs. The spread of bacteria prompts an increase in IL-6. This promotes proliferation of granulocyte–macrophage progenitors that express high levels of IL-6Rα in the absence of Tet2, and this leads to PMP.

The researchers found they could induce PMP in symptom-free Tet2−/− mice by disrupting intestinal barrier integrity. PMP also developed in response to systemic bacterial stimuli.

However, antibiotics and blockade of IL-6 signals could reverse PMP in mice that developed symptoms. And germ-free Tet2−/− mice did not develop symptoms, which supports the idea that bacteria must be present to drive the development of PMP.

Dr Jabri said the next step is to conduct studies in humans to see if patients with PMP also have signs of bacterial translocation. Then, clinical trials could test whether treatments that target aberrant IL-6 signals in response to bacteria can reverse the course of PMP.

EHRs enhance clinical trial follow-up

Electronic health records (EHRs) can enhance results from randomized controlled trials (RCTs), according to research published in Scientific Reports.

Researchers found EHRs could be used to track trial participants, enabling long-term monitoring of medical interventions and health outcomes and providing new insights into population health.

“In this study, we reported on the feasibility and efficiency of electronic follow-up and compared it with traditional trial follow-up,” said study author Sue Jordan, PhD, MB BCh, of Swansea University in Swansea, UK.

“We gained new insights from outcomes electronically recorded 3 years after the end of the trial and could then identify the differences between trial data and electronic data.”

Dr Jordan and her colleagues followed up on RCT participants using EHRs in the Secure Anonymised Information Linkage (SAIL) databank at Swansea University Medical School.

In this RCT, investigators had assessed the impact of probiotics on asthma and eczema in children born from 2005 to 2007. The trial had 2 years of traditional fieldwork follow-up.

Dr Jordan and her colleagues compared field results to EHR results at 2 years in 93% of trial participants.

The researchers said EHRs improved retention of children from lower socio-economic groups, which helped reduce volunteer bias.

The team also performed electronic follow-up at 5 years, which provided the “first robust analysis of asthma endpoints.”

The researchers said the asthma endpoints are “generally more reliable” in the 5-year EHR data for 2 reasons. The first is that the children are older, and asthma typically appears after 2 years of age.

The second reason is that, with the fieldwork follow-up, parents or guardians may have mistakenly identified symptoms as asthma without a child actually having an asthma diagnosis.

“Trial data are vulnerable to misunderstandings of questionnaires or definitions of illness,” Dr Jordan noted.

She and her colleagues also pointed out that retention was still high (82%) and free of bias in socio-economic status with the 5-year EHR data.

“These results lead us to conclude that using electronic health records have benefits relating to the cost-effective, long-term monitoring of complex interventions, which could have a positive impact for future clinical trial design,” said study author Michael Gravenor, DPhil, of Swansea University.

Electronic health records (EHRs) can enhance results from randomized controlled trials (RCTs), according to research published in Scientific Reports.

Researchers found EHRs could be used to track trial participants, enabling long-term monitoring of medical interventions and health outcomes and providing new insights into population health.

“In this study, we reported on the feasibility and efficiency of electronic follow-up and compared it with traditional trial follow-up,” said study author Sue Jordan, PhD, MB BCh, of Swansea University in Swansea, UK.

“We gained new insights from outcomes electronically recorded 3 years after the end of the trial and could then identify the differences between trial data and electronic data.”

Dr Jordan and her colleagues followed up on RCT participants using EHRs in the Secure Anonymised Information Linkage (SAIL) databank at Swansea University Medical School.

In this RCT, investigators had assessed the impact of probiotics on asthma and eczema in children born from 2005 to 2007. The trial had 2 years of traditional fieldwork follow-up.

Dr Jordan and her colleagues compared field results to EHR results at 2 years in 93% of trial participants.

The researchers said EHRs improved retention of children from lower socio-economic groups, which helped reduce volunteer bias.

The team also performed electronic follow-up at 5 years, which provided the “first robust analysis of asthma endpoints.”

The researchers said the asthma endpoints are “generally more reliable” in the 5-year EHR data for 2 reasons. The first is that the children are older, and asthma typically appears after 2 years of age.

The second reason is that, with the fieldwork follow-up, parents or guardians may have mistakenly identified symptoms as asthma without a child actually having an asthma diagnosis.

“Trial data are vulnerable to misunderstandings of questionnaires or definitions of illness,” Dr Jordan noted.

She and her colleagues also pointed out that retention was still high (82%) and free of bias in socio-economic status with the 5-year EHR data.

“These results lead us to conclude that using electronic health records have benefits relating to the cost-effective, long-term monitoring of complex interventions, which could have a positive impact for future clinical trial design,” said study author Michael Gravenor, DPhil, of Swansea University.

Electronic health records (EHRs) can enhance results from randomized controlled trials (RCTs), according to research published in Scientific Reports.

Researchers found EHRs could be used to track trial participants, enabling long-term monitoring of medical interventions and health outcomes and providing new insights into population health.

“In this study, we reported on the feasibility and efficiency of electronic follow-up and compared it with traditional trial follow-up,” said study author Sue Jordan, PhD, MB BCh, of Swansea University in Swansea, UK.

“We gained new insights from outcomes electronically recorded 3 years after the end of the trial and could then identify the differences between trial data and electronic data.”

Dr Jordan and her colleagues followed up on RCT participants using EHRs in the Secure Anonymised Information Linkage (SAIL) databank at Swansea University Medical School.

In this RCT, investigators had assessed the impact of probiotics on asthma and eczema in children born from 2005 to 2007. The trial had 2 years of traditional fieldwork follow-up.

Dr Jordan and her colleagues compared field results to EHR results at 2 years in 93% of trial participants.

The researchers said EHRs improved retention of children from lower socio-economic groups, which helped reduce volunteer bias.

The team also performed electronic follow-up at 5 years, which provided the “first robust analysis of asthma endpoints.”

The researchers said the asthma endpoints are “generally more reliable” in the 5-year EHR data for 2 reasons. The first is that the children are older, and asthma typically appears after 2 years of age.

The second reason is that, with the fieldwork follow-up, parents or guardians may have mistakenly identified symptoms as asthma without a child actually having an asthma diagnosis.

“Trial data are vulnerable to misunderstandings of questionnaires or definitions of illness,” Dr Jordan noted.

She and her colleagues also pointed out that retention was still high (82%) and free of bias in socio-economic status with the 5-year EHR data.

“These results lead us to conclude that using electronic health records have benefits relating to the cost-effective, long-term monitoring of complex interventions, which could have a positive impact for future clinical trial design,” said study author Michael Gravenor, DPhil, of Swansea University.

Abstract: Divergent Responses to Mammography and Prostate-Specific Antigen Recommendations

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Martinez, K.A., et al, Am J Prev Med 53(4):533, October 2017

The authors, from the Cleveland Clinic, explore the reasons for divergent responses to recent guideline recommendations against screening for breast cancer and prostate cancer. Both cancers are common (lifetime incidence of 12% and 16%, respectively), with indolent forms that are more prevalent with age. Screening with mammography and prostate-specific antigen (PSA) testing achieves earlier detection and relative risk reductions in cancer-specific mortality of 15% to 20%, but negligible effects on overall mortality and a risk of overtreatment that is estimated to be 30% to 80%. Benefits of screening and risks of overtreatment are unclear because of study limitations and evolution in diagnostic criteria, screening and management. Beginning in 2008, the US Preventive Services Task Force downgraded its recommendations for routine mammography (e.g., a rating of C for average-risk women aged 40-49) and for routine PSA testing (rating of D regardless of age). [EDITOR’S NOTE: USPSTF PSA screening recommendations have changed. See “USPSTF advises against widespread prostate cancer screening.”] While objections to the PSA rating were minimal, the public and professional backlash about mammography was profound. Reasons may include unique characteristics of breast (versus prostate) cancer, including mortality at a younger age, financial conflicts of interest (with mammography generating $8 billion per year in the US), bureaucratic incentives (e.g., quality measures, insurance reimbursement), and the influence of profit-generating advocacy groups. Many physicians do not understand the risks and harms of overtreatment or the inability of early detection to prevent metastasis, and patients want to be “better safe than sorry.” Rates of screening mammography may not decrease until truly informed decisions are possible, which will necessitate better algorithms to predict those cancers that are likely to spread. 20 references ([email protected] – no reprints)

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Martinez, K.A., et al, Am J Prev Med 53(4):533, October 2017

The authors, from the Cleveland Clinic, explore the reasons for divergent responses to recent guideline recommendations against screening for breast cancer and prostate cancer. Both cancers are common (lifetime incidence of 12% and 16%, respectively), with indolent forms that are more prevalent with age. Screening with mammography and prostate-specific antigen (PSA) testing achieves earlier detection and relative risk reductions in cancer-specific mortality of 15% to 20%, but negligible effects on overall mortality and a risk of overtreatment that is estimated to be 30% to 80%. Benefits of screening and risks of overtreatment are unclear because of study limitations and evolution in diagnostic criteria, screening and management. Beginning in 2008, the US Preventive Services Task Force downgraded its recommendations for routine mammography (e.g., a rating of C for average-risk women aged 40-49) and for routine PSA testing (rating of D regardless of age). [EDITOR’S NOTE: USPSTF PSA screening recommendations have changed. See “USPSTF advises against widespread prostate cancer screening.”] While objections to the PSA rating were minimal, the public and professional backlash about mammography was profound. Reasons may include unique characteristics of breast (versus prostate) cancer, including mortality at a younger age, financial conflicts of interest (with mammography generating $8 billion per year in the US), bureaucratic incentives (e.g., quality measures, insurance reimbursement), and the influence of profit-generating advocacy groups. Many physicians do not understand the risks and harms of overtreatment or the inability of early detection to prevent metastasis, and patients want to be “better safe than sorry.” Rates of screening mammography may not decrease until truly informed decisions are possible, which will necessitate better algorithms to predict those cancers that are likely to spread. 20 references ([email protected] – no reprints)

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Martinez, K.A., et al, Am J Prev Med 53(4):533, October 2017

The authors, from the Cleveland Clinic, explore the reasons for divergent responses to recent guideline recommendations against screening for breast cancer and prostate cancer. Both cancers are common (lifetime incidence of 12% and 16%, respectively), with indolent forms that are more prevalent with age. Screening with mammography and prostate-specific antigen (PSA) testing achieves earlier detection and relative risk reductions in cancer-specific mortality of 15% to 20%, but negligible effects on overall mortality and a risk of overtreatment that is estimated to be 30% to 80%. Benefits of screening and risks of overtreatment are unclear because of study limitations and evolution in diagnostic criteria, screening and management. Beginning in 2008, the US Preventive Services Task Force downgraded its recommendations for routine mammography (e.g., a rating of C for average-risk women aged 40-49) and for routine PSA testing (rating of D regardless of age). [EDITOR’S NOTE: USPSTF PSA screening recommendations have changed. See “USPSTF advises against widespread prostate cancer screening.”] While objections to the PSA rating were minimal, the public and professional backlash about mammography was profound. Reasons may include unique characteristics of breast (versus prostate) cancer, including mortality at a younger age, financial conflicts of interest (with mammography generating $8 billion per year in the US), bureaucratic incentives (e.g., quality measures, insurance reimbursement), and the influence of profit-generating advocacy groups. Many physicians do not understand the risks and harms of overtreatment or the inability of early detection to prevent metastasis, and patients want to be “better safe than sorry.” Rates of screening mammography may not decrease until truly informed decisions are possible, which will necessitate better algorithms to predict those cancers that are likely to spread. 20 references ([email protected] – no reprints)

Learn more about the Primary Care Medical Abstracts and podcasts, for which you can earn up to 9 CME credits per month.

Copyright © The Center for Medical Education

Guidelines to optimize treatment of reduced ejection fraction heart failure

Clinical question: What guidance is there for clinical care of complex heart failure patients?

Background: The prevalence of heart failure (HF)is escalating and consumes significant health care resources, inflicts significant morbidity and mortality, and greatly affects quality of life. There is a plethora of research, multiple medical therapies, devices, and care strategies that have been shown to improve outcomes in heart failure patients. Previous publications have reviewed evidence-based literature but left a gap in knowledge for those more-complex areas or lacked practical clinical guidance. This policy document was created to guide physicians in informed decision making in a directed decision pathway form.

Study design: Expert consensus guidelines.

Setting: American College of Cardiology Task Force on Expert Consensus Decision Pathways.

Synopsis: A multidisciplinary group of specialties including physicians, nurses, pharmacists, epidemiologists, and patient advocacy groups addressed 10 pivotal issues in heart failure through literature review, expert consensus, and round table discussion.

Ten principles were identified and addressed:

- Initiating, adding, or switching to new evidenced-based guideline-directed therapy.

- Achieving optimal therapy using multiple HF drugs and therapies.

- Knowing when to refer a patient to an HF specialist.

- Addressing the challenges of care coordination for team-based HF treatment.

- Improving patient adherence.

- Managing specific patient cohorts, such as African Americans, older adults, and the frail.

- Managing your patients’ cost of care for HF.

- Reducing costs and managing the increased complexity of HF.

- Managing the most common cardiac and noncardiac comorbidities.

- Integrating palliative care and transitioning patients to hospice care

Bottom line: Structured guidelines to provide practical and actionable recommendations to improve heart failure outcomes, integrate evidence-based medicine when available, and utilize expert conscious when evidence-based medicine is not available.

Citation: Yancy CW et al. 2017 ACC expert consensus on decision pathway for optimizing of heart failure treatment: Answers to 10 pivotal issues about heart failure with reduced ejection fraction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018 Jan 16;71(2):201-30.

Dr. Muñoa is a hospitalist at Denver Health Medical Center and an assistant professor of medicine at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora.

Clinical question: What guidance is there for clinical care of complex heart failure patients?

Background: The prevalence of heart failure (HF)is escalating and consumes significant health care resources, inflicts significant morbidity and mortality, and greatly affects quality of life. There is a plethora of research, multiple medical therapies, devices, and care strategies that have been shown to improve outcomes in heart failure patients. Previous publications have reviewed evidence-based literature but left a gap in knowledge for those more-complex areas or lacked practical clinical guidance. This policy document was created to guide physicians in informed decision making in a directed decision pathway form.

Study design: Expert consensus guidelines.

Setting: American College of Cardiology Task Force on Expert Consensus Decision Pathways.

Synopsis: A multidisciplinary group of specialties including physicians, nurses, pharmacists, epidemiologists, and patient advocacy groups addressed 10 pivotal issues in heart failure through literature review, expert consensus, and round table discussion.

Ten principles were identified and addressed:

- Initiating, adding, or switching to new evidenced-based guideline-directed therapy.

- Achieving optimal therapy using multiple HF drugs and therapies.

- Knowing when to refer a patient to an HF specialist.

- Addressing the challenges of care coordination for team-based HF treatment.

- Improving patient adherence.

- Managing specific patient cohorts, such as African Americans, older adults, and the frail.

- Managing your patients’ cost of care for HF.

- Reducing costs and managing the increased complexity of HF.

- Managing the most common cardiac and noncardiac comorbidities.

- Integrating palliative care and transitioning patients to hospice care

Bottom line: Structured guidelines to provide practical and actionable recommendations to improve heart failure outcomes, integrate evidence-based medicine when available, and utilize expert conscious when evidence-based medicine is not available.

Citation: Yancy CW et al. 2017 ACC expert consensus on decision pathway for optimizing of heart failure treatment: Answers to 10 pivotal issues about heart failure with reduced ejection fraction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018 Jan 16;71(2):201-30.

Dr. Muñoa is a hospitalist at Denver Health Medical Center and an assistant professor of medicine at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora.

Clinical question: What guidance is there for clinical care of complex heart failure patients?

Background: The prevalence of heart failure (HF)is escalating and consumes significant health care resources, inflicts significant morbidity and mortality, and greatly affects quality of life. There is a plethora of research, multiple medical therapies, devices, and care strategies that have been shown to improve outcomes in heart failure patients. Previous publications have reviewed evidence-based literature but left a gap in knowledge for those more-complex areas or lacked practical clinical guidance. This policy document was created to guide physicians in informed decision making in a directed decision pathway form.

Study design: Expert consensus guidelines.

Setting: American College of Cardiology Task Force on Expert Consensus Decision Pathways.

Synopsis: A multidisciplinary group of specialties including physicians, nurses, pharmacists, epidemiologists, and patient advocacy groups addressed 10 pivotal issues in heart failure through literature review, expert consensus, and round table discussion.

Ten principles were identified and addressed:

- Initiating, adding, or switching to new evidenced-based guideline-directed therapy.

- Achieving optimal therapy using multiple HF drugs and therapies.

- Knowing when to refer a patient to an HF specialist.

- Addressing the challenges of care coordination for team-based HF treatment.

- Improving patient adherence.

- Managing specific patient cohorts, such as African Americans, older adults, and the frail.

- Managing your patients’ cost of care for HF.

- Reducing costs and managing the increased complexity of HF.

- Managing the most common cardiac and noncardiac comorbidities.

- Integrating palliative care and transitioning patients to hospice care

Bottom line: Structured guidelines to provide practical and actionable recommendations to improve heart failure outcomes, integrate evidence-based medicine when available, and utilize expert conscious when evidence-based medicine is not available.

Citation: Yancy CW et al. 2017 ACC expert consensus on decision pathway for optimizing of heart failure treatment: Answers to 10 pivotal issues about heart failure with reduced ejection fraction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018 Jan 16;71(2):201-30.

Dr. Muñoa is a hospitalist at Denver Health Medical Center and an assistant professor of medicine at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora.

The double-edged sword

Veterinarians and farmers have known it for decades. If you give a herd or flock antibiotics, its members grow better and have a better survival rate than an equivalent group of unmedicated animals. The economic benefits of administering antibiotics are so great that until very recently the practice has been the norm. However, the “everything organic” movement has begun to turn the tide as more consumers have become aware of the hazards inherent in the agricultural use of antibiotics.

Following this conservative and prudent party line can be difficult, and few of us can claim to have never sinned and written a less-than-defensible prescription for an antibiotic. However, for physicians who work in places where the mortality rate for children under age 5 years can be as high as 25%, the temptation to treat the entire population with an antibiotic must be very real.

When decreased early-childhood mortality was observed in several populations that had been given prophylactic azithromycin for trachoma, a group of scientists from the University of California, San Francisco, were prompted to take a longer look at the phenomenon (“Azithromycin to Reduce Childhood Mortality in Sub-Saharan Africa,” N Engl J Med. 2018 Apr 26;378[17]:1583-92). Almost 200,000 children aged 1 month to 5 years in Niger, Malawi, and Tanzania were enrolled in the study. Half received a single dose of azithromycin every 6 months for 2 years. Overall, the mortality rate was 14% lower in the experimental group (P less than .001) and 25% lower in the children aged 1-5 months. Most of the effect was observed in Niger where only one in four children live until their fifth birthday.

Like any good experiment, this study raises more questions than it answers. Will the emergence of antibiotic resistance make broader application of the strategy impractical? Keenan et al. refer to previous trachoma treatment programs in which resistance occurred but seemed to recede when the programs were halted. What conditions were being treated successfully but blindly? Respiratory disease, diarrhea illness, and malaria are most prevalent and are the likely suspects. The authors acknowledge that more studies need to be done.

And of course, we must remember that, when it comes to antibiotic resistance, ultimately we are all neighbors.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Email him at [email protected].

Veterinarians and farmers have known it for decades. If you give a herd or flock antibiotics, its members grow better and have a better survival rate than an equivalent group of unmedicated animals. The economic benefits of administering antibiotics are so great that until very recently the practice has been the norm. However, the “everything organic” movement has begun to turn the tide as more consumers have become aware of the hazards inherent in the agricultural use of antibiotics.

Following this conservative and prudent party line can be difficult, and few of us can claim to have never sinned and written a less-than-defensible prescription for an antibiotic. However, for physicians who work in places where the mortality rate for children under age 5 years can be as high as 25%, the temptation to treat the entire population with an antibiotic must be very real.

When decreased early-childhood mortality was observed in several populations that had been given prophylactic azithromycin for trachoma, a group of scientists from the University of California, San Francisco, were prompted to take a longer look at the phenomenon (“Azithromycin to Reduce Childhood Mortality in Sub-Saharan Africa,” N Engl J Med. 2018 Apr 26;378[17]:1583-92). Almost 200,000 children aged 1 month to 5 years in Niger, Malawi, and Tanzania were enrolled in the study. Half received a single dose of azithromycin every 6 months for 2 years. Overall, the mortality rate was 14% lower in the experimental group (P less than .001) and 25% lower in the children aged 1-5 months. Most of the effect was observed in Niger where only one in four children live until their fifth birthday.

Like any good experiment, this study raises more questions than it answers. Will the emergence of antibiotic resistance make broader application of the strategy impractical? Keenan et al. refer to previous trachoma treatment programs in which resistance occurred but seemed to recede when the programs were halted. What conditions were being treated successfully but blindly? Respiratory disease, diarrhea illness, and malaria are most prevalent and are the likely suspects. The authors acknowledge that more studies need to be done.

And of course, we must remember that, when it comes to antibiotic resistance, ultimately we are all neighbors.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Email him at [email protected].

Veterinarians and farmers have known it for decades. If you give a herd or flock antibiotics, its members grow better and have a better survival rate than an equivalent group of unmedicated animals. The economic benefits of administering antibiotics are so great that until very recently the practice has been the norm. However, the “everything organic” movement has begun to turn the tide as more consumers have become aware of the hazards inherent in the agricultural use of antibiotics.

Following this conservative and prudent party line can be difficult, and few of us can claim to have never sinned and written a less-than-defensible prescription for an antibiotic. However, for physicians who work in places where the mortality rate for children under age 5 years can be as high as 25%, the temptation to treat the entire population with an antibiotic must be very real.

When decreased early-childhood mortality was observed in several populations that had been given prophylactic azithromycin for trachoma, a group of scientists from the University of California, San Francisco, were prompted to take a longer look at the phenomenon (“Azithromycin to Reduce Childhood Mortality in Sub-Saharan Africa,” N Engl J Med. 2018 Apr 26;378[17]:1583-92). Almost 200,000 children aged 1 month to 5 years in Niger, Malawi, and Tanzania were enrolled in the study. Half received a single dose of azithromycin every 6 months for 2 years. Overall, the mortality rate was 14% lower in the experimental group (P less than .001) and 25% lower in the children aged 1-5 months. Most of the effect was observed in Niger where only one in four children live until their fifth birthday.

Like any good experiment, this study raises more questions than it answers. Will the emergence of antibiotic resistance make broader application of the strategy impractical? Keenan et al. refer to previous trachoma treatment programs in which resistance occurred but seemed to recede when the programs were halted. What conditions were being treated successfully but blindly? Respiratory disease, diarrhea illness, and malaria are most prevalent and are the likely suspects. The authors acknowledge that more studies need to be done.

And of course, we must remember that, when it comes to antibiotic resistance, ultimately we are all neighbors.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Email him at [email protected].

FDA queries more companies about youth e-cig use

Four more e-cigarette manufacturers are facing Food and Drug Administration scrutiny in an effort for the agency to better understand youth appeal and usage of e-cigarettes.

“These products should never be marketed to, sold to, or used by kids, and it’s critical that we take aggressive steps to address the youth use of these products.”

The agency is seeking information including, but not limited to, “documents related to product marketing, documents related to research on product design (as it may relate to the appeal or addictive potential for youth, youth-related adverse experiences), and consumer complaints associated with products,” the agency said in a statement.

The May 17 letters note that the four companies manufacture products similar to JUUL’s product offering, sharing similar characteristics, “including e-liquids that contain nicotine salts with corresponding high nicotine concentration, small size which makes them easily concealable, and product design features that are intuitive, even for novice [electronic nicotine delivery system] users. These attributes may relate to the appeal and addictiveness of the product, particularly for youth who may be experimenting with tobacco products.”

The action is the latest in the agency’s effort to combat nicotine addiction. In March, the agency issues an advanced notice of proposed rule making seeking information on the role flavoring plays in youth tobacco consumption.

Four more e-cigarette manufacturers are facing Food and Drug Administration scrutiny in an effort for the agency to better understand youth appeal and usage of e-cigarettes.

“These products should never be marketed to, sold to, or used by kids, and it’s critical that we take aggressive steps to address the youth use of these products.”

The agency is seeking information including, but not limited to, “documents related to product marketing, documents related to research on product design (as it may relate to the appeal or addictive potential for youth, youth-related adverse experiences), and consumer complaints associated with products,” the agency said in a statement.

The May 17 letters note that the four companies manufacture products similar to JUUL’s product offering, sharing similar characteristics, “including e-liquids that contain nicotine salts with corresponding high nicotine concentration, small size which makes them easily concealable, and product design features that are intuitive, even for novice [electronic nicotine delivery system] users. These attributes may relate to the appeal and addictiveness of the product, particularly for youth who may be experimenting with tobacco products.”

The action is the latest in the agency’s effort to combat nicotine addiction. In March, the agency issues an advanced notice of proposed rule making seeking information on the role flavoring plays in youth tobacco consumption.

Four more e-cigarette manufacturers are facing Food and Drug Administration scrutiny in an effort for the agency to better understand youth appeal and usage of e-cigarettes.

“These products should never be marketed to, sold to, or used by kids, and it’s critical that we take aggressive steps to address the youth use of these products.”

The agency is seeking information including, but not limited to, “documents related to product marketing, documents related to research on product design (as it may relate to the appeal or addictive potential for youth, youth-related adverse experiences), and consumer complaints associated with products,” the agency said in a statement.

The May 17 letters note that the four companies manufacture products similar to JUUL’s product offering, sharing similar characteristics, “including e-liquids that contain nicotine salts with corresponding high nicotine concentration, small size which makes them easily concealable, and product design features that are intuitive, even for novice [electronic nicotine delivery system] users. These attributes may relate to the appeal and addictiveness of the product, particularly for youth who may be experimenting with tobacco products.”

The action is the latest in the agency’s effort to combat nicotine addiction. In March, the agency issues an advanced notice of proposed rule making seeking information on the role flavoring plays in youth tobacco consumption.

VIDEO: BMI helps predict bone fragility in obese patients

BOSTON – An index that takes into account the ratio between body mass index (BMI) and bone mineral density (BMD) correlated well with trabecular bone scores, a newer assessment of bone fragility. The index may help predict risk for fragility fractures in individuals with obesity when trabecular bone scores are not available.

“Obesity is traditionally thought to be protective against bone fractures,” said Mikiko Watanabe, MD, an endocrinologist at Sapienza University of Rome. “But recent evidence suggests that this is not entirely true, especially in morbidly obese patients.”

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Lumbar spine BMD alone may not accurately capture bone fragility in patients with obesity, said Dr. Watanabe in an interview at the annual meeting of the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists.

Adding the trabecular bone score (TBS) to BMD gives additional information about bone microarchitecture, refining risk assessment for fragility fractures. This newer technology, however, may not be readily available and may be associated with extra cost.

Accordingly, said Dr. Watanabe, the study’s senior investigator, Sapienza University’s Carla Lubrano, MD, had the idea to index bone density to BMI, and then see how well the ratio correlated to TBS; obesity is known to be associated with lower TBS scores, indicating increased bone fragility.

Living in Italy, with relatively fewer medical resources available, “We were trying to find some readily available index that could predict the risk of fracture as well as the indexes that are around right now,” said Dr. Watanabe.

“We did find some very interesting data in our population of over 2,000 obese patients living in Rome,” she said. “We do confirm something from the literature, where BMD tends to go high with increasing BMI.” Further, the relatively weak correlation between TBS and BMI was confirmed in the investigators’ work (r = 0.3).

“If you correct the BMD by BMI – so if you use our index – then the correlation becomes more stringent, and definitely so much better,” she said (r = 0.54).

Dr. Watanabe and her colleagues also conducted an analysis to see if there were differences between participants with and without metabolic syndrome. The 45.7% of participants who had metabolic syndrome had similar lumbar spine BMD scores to the rest of the cohort (1.067 versus 1.063 g/cm2, P = .50754).

However, both the TBS and BMD/BMI ratio were significantly lower for those with metabolic syndrome than for the metabolically healthy participants. The TBS, as expected, was 1.21 in patients with metabolic syndrome, and 1.31 in patients without metabolic syndrome; the BMD/BMI ratio followed the same pattern, with ratios of 0.28 for those with, and 0.30 for those without, metabolic syndrome (P less than .00001 for both).

Dr. Watanabe said that she and her associates are continuing research “to see whether our ratio is actually able to predict the risk of fractures." The hope, she said, is to use the BMD/BMI index together with or instead of TBS to better assess bone strength in patients with obesity.

Dr. Watanabe reported that she had no relevant conflicts of interest.

BOSTON – An index that takes into account the ratio between body mass index (BMI) and bone mineral density (BMD) correlated well with trabecular bone scores, a newer assessment of bone fragility. The index may help predict risk for fragility fractures in individuals with obesity when trabecular bone scores are not available.

“Obesity is traditionally thought to be protective against bone fractures,” said Mikiko Watanabe, MD, an endocrinologist at Sapienza University of Rome. “But recent evidence suggests that this is not entirely true, especially in morbidly obese patients.”

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Lumbar spine BMD alone may not accurately capture bone fragility in patients with obesity, said Dr. Watanabe in an interview at the annual meeting of the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists.

Adding the trabecular bone score (TBS) to BMD gives additional information about bone microarchitecture, refining risk assessment for fragility fractures. This newer technology, however, may not be readily available and may be associated with extra cost.

Accordingly, said Dr. Watanabe, the study’s senior investigator, Sapienza University’s Carla Lubrano, MD, had the idea to index bone density to BMI, and then see how well the ratio correlated to TBS; obesity is known to be associated with lower TBS scores, indicating increased bone fragility.

Living in Italy, with relatively fewer medical resources available, “We were trying to find some readily available index that could predict the risk of fracture as well as the indexes that are around right now,” said Dr. Watanabe.

“We did find some very interesting data in our population of over 2,000 obese patients living in Rome,” she said. “We do confirm something from the literature, where BMD tends to go high with increasing BMI.” Further, the relatively weak correlation between TBS and BMI was confirmed in the investigators’ work (r = 0.3).

“If you correct the BMD by BMI – so if you use our index – then the correlation becomes more stringent, and definitely so much better,” she said (r = 0.54).

Dr. Watanabe and her colleagues also conducted an analysis to see if there were differences between participants with and without metabolic syndrome. The 45.7% of participants who had metabolic syndrome had similar lumbar spine BMD scores to the rest of the cohort (1.067 versus 1.063 g/cm2, P = .50754).

However, both the TBS and BMD/BMI ratio were significantly lower for those with metabolic syndrome than for the metabolically healthy participants. The TBS, as expected, was 1.21 in patients with metabolic syndrome, and 1.31 in patients without metabolic syndrome; the BMD/BMI ratio followed the same pattern, with ratios of 0.28 for those with, and 0.30 for those without, metabolic syndrome (P less than .00001 for both).

Dr. Watanabe said that she and her associates are continuing research “to see whether our ratio is actually able to predict the risk of fractures." The hope, she said, is to use the BMD/BMI index together with or instead of TBS to better assess bone strength in patients with obesity.

Dr. Watanabe reported that she had no relevant conflicts of interest.

BOSTON – An index that takes into account the ratio between body mass index (BMI) and bone mineral density (BMD) correlated well with trabecular bone scores, a newer assessment of bone fragility. The index may help predict risk for fragility fractures in individuals with obesity when trabecular bone scores are not available.

“Obesity is traditionally thought to be protective against bone fractures,” said Mikiko Watanabe, MD, an endocrinologist at Sapienza University of Rome. “But recent evidence suggests that this is not entirely true, especially in morbidly obese patients.”

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Lumbar spine BMD alone may not accurately capture bone fragility in patients with obesity, said Dr. Watanabe in an interview at the annual meeting of the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists.

Adding the trabecular bone score (TBS) to BMD gives additional information about bone microarchitecture, refining risk assessment for fragility fractures. This newer technology, however, may not be readily available and may be associated with extra cost.

Accordingly, said Dr. Watanabe, the study’s senior investigator, Sapienza University’s Carla Lubrano, MD, had the idea to index bone density to BMI, and then see how well the ratio correlated to TBS; obesity is known to be associated with lower TBS scores, indicating increased bone fragility.

Living in Italy, with relatively fewer medical resources available, “We were trying to find some readily available index that could predict the risk of fracture as well as the indexes that are around right now,” said Dr. Watanabe.

“We did find some very interesting data in our population of over 2,000 obese patients living in Rome,” she said. “We do confirm something from the literature, where BMD tends to go high with increasing BMI.” Further, the relatively weak correlation between TBS and BMI was confirmed in the investigators’ work (r = 0.3).

“If you correct the BMD by BMI – so if you use our index – then the correlation becomes more stringent, and definitely so much better,” she said (r = 0.54).

Dr. Watanabe and her colleagues also conducted an analysis to see if there were differences between participants with and without metabolic syndrome. The 45.7% of participants who had metabolic syndrome had similar lumbar spine BMD scores to the rest of the cohort (1.067 versus 1.063 g/cm2, P = .50754).

However, both the TBS and BMD/BMI ratio were significantly lower for those with metabolic syndrome than for the metabolically healthy participants. The TBS, as expected, was 1.21 in patients with metabolic syndrome, and 1.31 in patients without metabolic syndrome; the BMD/BMI ratio followed the same pattern, with ratios of 0.28 for those with, and 0.30 for those without, metabolic syndrome (P less than .00001 for both).

Dr. Watanabe said that she and her associates are continuing research “to see whether our ratio is actually able to predict the risk of fractures." The hope, she said, is to use the BMD/BMI index together with or instead of TBS to better assess bone strength in patients with obesity.

Dr. Watanabe reported that she had no relevant conflicts of interest.

REPORTING FROM AACE 2018

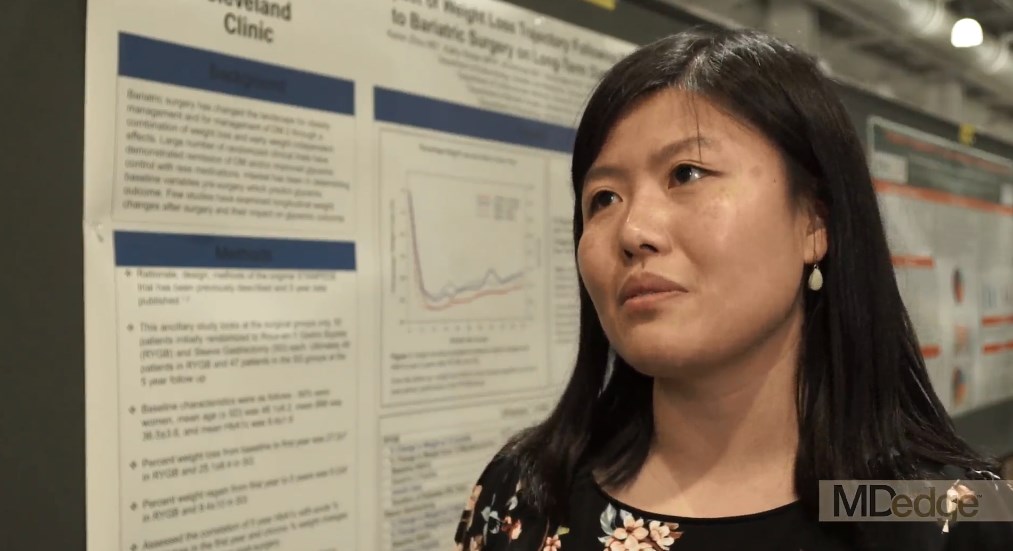

VIDEO: First year after bariatric surgery critical for HbA1c improvement

BOSTON – Acute weight loss during the first year after bariatric surgery has a significant effect on hemoglobin A1c level improvement at 5 years’ follow-up, according to a study presented at the annual meeting of the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists.

The data presented could help clinicians understand when and where to focus their efforts to help patients optimize weight loss in order to see the best long-term benefits of the procedure, according to presenter Keren Zhou, MD, an endocrinology fellow at the Cleveland Clinic.

“Clinicians need to really focus on that first year weight loss after bariatric surgery to try and optimize 5-year A1c outcomes,” said Dr. Zhou. “It also answers another question people have been having, which is how much does weight regain after bariatric surgery really matter? What we’ve been able to show here is that weight regain didn’t look very correlated at all.”

Dr. Zhou and her colleagues developed the ancillary study using data from the STAMPEDE (Surgical Treatment and Medications Potentially Eradicate Diabetes Efficiently) trial, specifically looking at 96 patients: 49 who underwent bariatric surgery and 47 who had a sleeve gastrectomy.

Patients were majority female, on average 48 years old, with a mean body mass index of 36.5 and HbA1c level of 9.4.

Overall, bariatric surgery patients lost an average of 27.2% in the first year, and regained around 8.2% from the first to fifth year, while sleeve gastrectomy lost and regained 25.1% and 9.4% respectively.

When comparing weight loss in the first year and HbA1c levels, Dr. Zhou and her colleagues found a significant correlation for both bariatric surgery and sleeve gastrectomy patients (r +.34; P = .0006).

“It was interesting because when we graphically represented the weight changes in addition to the A1c over time, we found that they actually correlated quite closely, but it was only when we did the statistical analysis on the numbers that we found that [in both groups] people who lost less weight had a higher A1c at the 5-year mark,” said Dr. Zhou.

In the non–multivariable analysis, however, investigators found a more significant correlation between weight regain and HbA1c levels in gastrectomy patients, however these findings changed when Dr. Zhou and her fellow investigators controlled for insulin use and baseline C-peptide.

In continuing studies, Dr. Zhou and her team will dive deeper into why these correlations exist, as right now they can only speculate.

Dr. Zhou reported no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Zhou K et al. AACE 18. Abstract 240-F.

BOSTON – Acute weight loss during the first year after bariatric surgery has a significant effect on hemoglobin A1c level improvement at 5 years’ follow-up, according to a study presented at the annual meeting of the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists.

The data presented could help clinicians understand when and where to focus their efforts to help patients optimize weight loss in order to see the best long-term benefits of the procedure, according to presenter Keren Zhou, MD, an endocrinology fellow at the Cleveland Clinic.

“Clinicians need to really focus on that first year weight loss after bariatric surgery to try and optimize 5-year A1c outcomes,” said Dr. Zhou. “It also answers another question people have been having, which is how much does weight regain after bariatric surgery really matter? What we’ve been able to show here is that weight regain didn’t look very correlated at all.”

Dr. Zhou and her colleagues developed the ancillary study using data from the STAMPEDE (Surgical Treatment and Medications Potentially Eradicate Diabetes Efficiently) trial, specifically looking at 96 patients: 49 who underwent bariatric surgery and 47 who had a sleeve gastrectomy.

Patients were majority female, on average 48 years old, with a mean body mass index of 36.5 and HbA1c level of 9.4.

Overall, bariatric surgery patients lost an average of 27.2% in the first year, and regained around 8.2% from the first to fifth year, while sleeve gastrectomy lost and regained 25.1% and 9.4% respectively.

When comparing weight loss in the first year and HbA1c levels, Dr. Zhou and her colleagues found a significant correlation for both bariatric surgery and sleeve gastrectomy patients (r +.34; P = .0006).

“It was interesting because when we graphically represented the weight changes in addition to the A1c over time, we found that they actually correlated quite closely, but it was only when we did the statistical analysis on the numbers that we found that [in both groups] people who lost less weight had a higher A1c at the 5-year mark,” said Dr. Zhou.

In the non–multivariable analysis, however, investigators found a more significant correlation between weight regain and HbA1c levels in gastrectomy patients, however these findings changed when Dr. Zhou and her fellow investigators controlled for insulin use and baseline C-peptide.

In continuing studies, Dr. Zhou and her team will dive deeper into why these correlations exist, as right now they can only speculate.

Dr. Zhou reported no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Zhou K et al. AACE 18. Abstract 240-F.

BOSTON – Acute weight loss during the first year after bariatric surgery has a significant effect on hemoglobin A1c level improvement at 5 years’ follow-up, according to a study presented at the annual meeting of the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists.

The data presented could help clinicians understand when and where to focus their efforts to help patients optimize weight loss in order to see the best long-term benefits of the procedure, according to presenter Keren Zhou, MD, an endocrinology fellow at the Cleveland Clinic.

“Clinicians need to really focus on that first year weight loss after bariatric surgery to try and optimize 5-year A1c outcomes,” said Dr. Zhou. “It also answers another question people have been having, which is how much does weight regain after bariatric surgery really matter? What we’ve been able to show here is that weight regain didn’t look very correlated at all.”

Dr. Zhou and her colleagues developed the ancillary study using data from the STAMPEDE (Surgical Treatment and Medications Potentially Eradicate Diabetes Efficiently) trial, specifically looking at 96 patients: 49 who underwent bariatric surgery and 47 who had a sleeve gastrectomy.

Patients were majority female, on average 48 years old, with a mean body mass index of 36.5 and HbA1c level of 9.4.

Overall, bariatric surgery patients lost an average of 27.2% in the first year, and regained around 8.2% from the first to fifth year, while sleeve gastrectomy lost and regained 25.1% and 9.4% respectively.

When comparing weight loss in the first year and HbA1c levels, Dr. Zhou and her colleagues found a significant correlation for both bariatric surgery and sleeve gastrectomy patients (r +.34; P = .0006).

“It was interesting because when we graphically represented the weight changes in addition to the A1c over time, we found that they actually correlated quite closely, but it was only when we did the statistical analysis on the numbers that we found that [in both groups] people who lost less weight had a higher A1c at the 5-year mark,” said Dr. Zhou.

In the non–multivariable analysis, however, investigators found a more significant correlation between weight regain and HbA1c levels in gastrectomy patients, however these findings changed when Dr. Zhou and her fellow investigators controlled for insulin use and baseline C-peptide.

In continuing studies, Dr. Zhou and her team will dive deeper into why these correlations exist, as right now they can only speculate.

Dr. Zhou reported no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Zhou K et al. AACE 18. Abstract 240-F.

REPORTING FROM AACE 18

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Change in weight within the first year was significantly correlated with lower HbA1c levels at 5 years (P = .0003).

Study details: Ancillary study of 96 patients who underwent either bariatric surgery or sleeve gastrectomy and participated in the STAMPEDE study.

Disclosures: Presenter reported no relevant financial disclosures.

Source: Zhou K et al. AACE 18. Abstract 240-F.

VIDEO: Half of after-hours calls to endocrinology fellows are nonurgent

Many calls to endocrinology fellows are often not urgent and could be directed to the clinic, potentially reducing work burden on the on-call fellows, a review of one center’s call logs suggests.

Nearly half of all calls were not urgent, many were after hours, and refill requests constituted the most common reason the patient initiated contact, according to Uzma Mohammad Siddiqui, MD, who presented results of the call log review in a poster presentation at the annual meeting of the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists.

The log review was part of a quality initiative intended to streamline care of patients to their primary endocrinologists whenever appropriate, according to Dr. Siddiqui, a second-year fellow at the University of Massachusetts Medical School in Worcester.

“A lot of these calls were happening after 6:00 p.m. until midnight, sometimes waking fellows up from their sleep,” Dr. Siddiqui said in an interview. “Fellows thought that these were disruptive to their personal life, and also it was causing frustration among patients when they were not able to reach their primary endocrinologists.”

On-call endocrinology fellows logged a total of 100 calls between July and August 2017. Of those calls, the fellows categorized 47% as nonurgent, Dr. Siddiqui reported.

About one-quarter of the calls came in between 8 p.m. and 3 a.m., with an average of 1.6 calls logged per 24-hour period. The actual average is probably higher, since fellows missed logging some calls during busy inpatient service days, the investigators said.

The most common reason for the calls, at 39%, was for refills of insulin, test strips, or noninsulin medication, which could have been directed to the clinic, according to Dr. Siddiqui and coauthors of the poster.

The rest of the calls were for insulin pump failure (9%), hyperglycemia (14%) or hypoglycemia (9%), concerns related to insulin regimen (9%) or thyroid-related medication (5%), requests for test results (4%), fever or rash reports (6%), and inpatient consults (5%).

To tackle the issue of nonurgent calls, Dr. Siddiqui and colleagues have been educating patients to call during work hours for test results, and to request refills 3 business days ahead of time. In addition, they are reminding providers to ask about refills during the clinic visit and to discuss with patients when an after-hours call because of blood glucose thresholds would be warranted.

Dr. Siddiqui and colleagues are now analyzing results of these initiatives to show to what extent they are reducing work burden on fellows and improving patient satisfaction.

“Even in the past 2-3 months, we have seen a significant improvement,” Dr. Siddiqui said.

“The patients get to speak to their primary endocrinologist and are happier with their care, because they have one provider, one person who’s answering their questions,” she added. “With this, we also reduced the burden of nonurgent calls, so the fellows have more personal time, are not getting disturbed in their sleep, and have less chances of being over worked or fatigued.”

Dr. Siddiqui reported no disclosures related to the presentation.

Many calls to endocrinology fellows are often not urgent and could be directed to the clinic, potentially reducing work burden on the on-call fellows, a review of one center’s call logs suggests.

Nearly half of all calls were not urgent, many were after hours, and refill requests constituted the most common reason the patient initiated contact, according to Uzma Mohammad Siddiqui, MD, who presented results of the call log review in a poster presentation at the annual meeting of the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists.

The log review was part of a quality initiative intended to streamline care of patients to their primary endocrinologists whenever appropriate, according to Dr. Siddiqui, a second-year fellow at the University of Massachusetts Medical School in Worcester.

“A lot of these calls were happening after 6:00 p.m. until midnight, sometimes waking fellows up from their sleep,” Dr. Siddiqui said in an interview. “Fellows thought that these were disruptive to their personal life, and also it was causing frustration among patients when they were not able to reach their primary endocrinologists.”

On-call endocrinology fellows logged a total of 100 calls between July and August 2017. Of those calls, the fellows categorized 47% as nonurgent, Dr. Siddiqui reported.

About one-quarter of the calls came in between 8 p.m. and 3 a.m., with an average of 1.6 calls logged per 24-hour period. The actual average is probably higher, since fellows missed logging some calls during busy inpatient service days, the investigators said.

The most common reason for the calls, at 39%, was for refills of insulin, test strips, or noninsulin medication, which could have been directed to the clinic, according to Dr. Siddiqui and coauthors of the poster.

The rest of the calls were for insulin pump failure (9%), hyperglycemia (14%) or hypoglycemia (9%), concerns related to insulin regimen (9%) or thyroid-related medication (5%), requests for test results (4%), fever or rash reports (6%), and inpatient consults (5%).

To tackle the issue of nonurgent calls, Dr. Siddiqui and colleagues have been educating patients to call during work hours for test results, and to request refills 3 business days ahead of time. In addition, they are reminding providers to ask about refills during the clinic visit and to discuss with patients when an after-hours call because of blood glucose thresholds would be warranted.

Dr. Siddiqui and colleagues are now analyzing results of these initiatives to show to what extent they are reducing work burden on fellows and improving patient satisfaction.

“Even in the past 2-3 months, we have seen a significant improvement,” Dr. Siddiqui said.

“The patients get to speak to their primary endocrinologist and are happier with their care, because they have one provider, one person who’s answering their questions,” she added. “With this, we also reduced the burden of nonurgent calls, so the fellows have more personal time, are not getting disturbed in their sleep, and have less chances of being over worked or fatigued.”

Dr. Siddiqui reported no disclosures related to the presentation.

Many calls to endocrinology fellows are often not urgent and could be directed to the clinic, potentially reducing work burden on the on-call fellows, a review of one center’s call logs suggests.

Nearly half of all calls were not urgent, many were after hours, and refill requests constituted the most common reason the patient initiated contact, according to Uzma Mohammad Siddiqui, MD, who presented results of the call log review in a poster presentation at the annual meeting of the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists.

The log review was part of a quality initiative intended to streamline care of patients to their primary endocrinologists whenever appropriate, according to Dr. Siddiqui, a second-year fellow at the University of Massachusetts Medical School in Worcester.

“A lot of these calls were happening after 6:00 p.m. until midnight, sometimes waking fellows up from their sleep,” Dr. Siddiqui said in an interview. “Fellows thought that these were disruptive to their personal life, and also it was causing frustration among patients when they were not able to reach their primary endocrinologists.”

On-call endocrinology fellows logged a total of 100 calls between July and August 2017. Of those calls, the fellows categorized 47% as nonurgent, Dr. Siddiqui reported.

About one-quarter of the calls came in between 8 p.m. and 3 a.m., with an average of 1.6 calls logged per 24-hour period. The actual average is probably higher, since fellows missed logging some calls during busy inpatient service days, the investigators said.

The most common reason for the calls, at 39%, was for refills of insulin, test strips, or noninsulin medication, which could have been directed to the clinic, according to Dr. Siddiqui and coauthors of the poster.

The rest of the calls were for insulin pump failure (9%), hyperglycemia (14%) or hypoglycemia (9%), concerns related to insulin regimen (9%) or thyroid-related medication (5%), requests for test results (4%), fever or rash reports (6%), and inpatient consults (5%).

To tackle the issue of nonurgent calls, Dr. Siddiqui and colleagues have been educating patients to call during work hours for test results, and to request refills 3 business days ahead of time. In addition, they are reminding providers to ask about refills during the clinic visit and to discuss with patients when an after-hours call because of blood glucose thresholds would be warranted.

Dr. Siddiqui and colleagues are now analyzing results of these initiatives to show to what extent they are reducing work burden on fellows and improving patient satisfaction.

“Even in the past 2-3 months, we have seen a significant improvement,” Dr. Siddiqui said.

“The patients get to speak to their primary endocrinologist and are happier with their care, because they have one provider, one person who’s answering their questions,” she added. “With this, we also reduced the burden of nonurgent calls, so the fellows have more personal time, are not getting disturbed in their sleep, and have less chances of being over worked or fatigued.”

Dr. Siddiqui reported no disclosures related to the presentation.

REPORTING FROM AACE 2018

Key clinical point: Calls to endocrinology fellows often are not urgent and could be directed to the clinic, potentially reducing work burden and improving patient satisfaction.

Major finding: On-call fellows documented 47% of calls as nonurgent, and medication or test strip refills were the most common reason for calls.

Study details: A quality initiative based on 100 calls logged by on-call endocrinology fellows at a single institution in July-August 2017.

Disclosures: The primary study author had no disclosures.

Guidelines-based intervention improves pediatrician management of acne

A guidelines-based educational program on treating acne in teenagers has led to significant improvements in pediatricians’ management of the condition and decreased referrals to dermatologists, new research suggests.

A research letter published online May in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology described the results of a study involving 116 pediatricians, who participated in an educational program, including brief live sessions, on how to manage acne in teenagers.

After 4 months, researchers saw that acne-coded visits to pediatricians increased by 18% (P less than .001), but this did not translate to more work for the physicians involved; instead, three-quarters of those involved said the treatment process involved “minimal to no work.”

At the same time, the intervention was associated with a 26% decrease in the percentage of acne referrals to dermatologists, reported Jenna Borok of the Rady Children’s Hospital in San Diego, and her coauthors.

The researchers saw a fivefold increase in the likelihood of pediatricians prescribing retinoids (P = .003), after controlling for confounding factors such as sex and insurance status, and significantly less topical clindamycin being prescribed.

The study was initiated to address what the authors described as a “practice gap” between pediatricians treating acne, compared with dermatologists treating acne, which included significantly lower prescribing rates of topical retinoids among pediatricians.

Ms. Borok and her coauthors wrote that their educational program and prescribing tool aimed to address this practice gap without increasing the workload for pediatricians or dermatologists. “Adherence to guidelines by pediatricians has the potential to improve treatment provided in the primary care setting, better patient satisfaction, and allow greater access to dermatologists and pediatric dermatologists for patients with more severe acne and other conditions.”

Acknowledging that the study took place over a relatively short period of time, the authors said future research would examine the impact of the educational program and ordering tool on patient acne outcomes.

No funding or conflicts of interest were declared.

SOURCE: Borok J et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018 May 9. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2018.04.055.

A guidelines-based educational program on treating acne in teenagers has led to significant improvements in pediatricians’ management of the condition and decreased referrals to dermatologists, new research suggests.

A research letter published online May in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology described the results of a study involving 116 pediatricians, who participated in an educational program, including brief live sessions, on how to manage acne in teenagers.

After 4 months, researchers saw that acne-coded visits to pediatricians increased by 18% (P less than .001), but this did not translate to more work for the physicians involved; instead, three-quarters of those involved said the treatment process involved “minimal to no work.”

At the same time, the intervention was associated with a 26% decrease in the percentage of acne referrals to dermatologists, reported Jenna Borok of the Rady Children’s Hospital in San Diego, and her coauthors.

The researchers saw a fivefold increase in the likelihood of pediatricians prescribing retinoids (P = .003), after controlling for confounding factors such as sex and insurance status, and significantly less topical clindamycin being prescribed.

The study was initiated to address what the authors described as a “practice gap” between pediatricians treating acne, compared with dermatologists treating acne, which included significantly lower prescribing rates of topical retinoids among pediatricians.

Ms. Borok and her coauthors wrote that their educational program and prescribing tool aimed to address this practice gap without increasing the workload for pediatricians or dermatologists. “Adherence to guidelines by pediatricians has the potential to improve treatment provided in the primary care setting, better patient satisfaction, and allow greater access to dermatologists and pediatric dermatologists for patients with more severe acne and other conditions.”

Acknowledging that the study took place over a relatively short period of time, the authors said future research would examine the impact of the educational program and ordering tool on patient acne outcomes.

No funding or conflicts of interest were declared.

SOURCE: Borok J et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018 May 9. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2018.04.055.

A guidelines-based educational program on treating acne in teenagers has led to significant improvements in pediatricians’ management of the condition and decreased referrals to dermatologists, new research suggests.

A research letter published online May in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology described the results of a study involving 116 pediatricians, who participated in an educational program, including brief live sessions, on how to manage acne in teenagers.

After 4 months, researchers saw that acne-coded visits to pediatricians increased by 18% (P less than .001), but this did not translate to more work for the physicians involved; instead, three-quarters of those involved said the treatment process involved “minimal to no work.”

At the same time, the intervention was associated with a 26% decrease in the percentage of acne referrals to dermatologists, reported Jenna Borok of the Rady Children’s Hospital in San Diego, and her coauthors.

The researchers saw a fivefold increase in the likelihood of pediatricians prescribing retinoids (P = .003), after controlling for confounding factors such as sex and insurance status, and significantly less topical clindamycin being prescribed.

The study was initiated to address what the authors described as a “practice gap” between pediatricians treating acne, compared with dermatologists treating acne, which included significantly lower prescribing rates of topical retinoids among pediatricians.

Ms. Borok and her coauthors wrote that their educational program and prescribing tool aimed to address this practice gap without increasing the workload for pediatricians or dermatologists. “Adherence to guidelines by pediatricians has the potential to improve treatment provided in the primary care setting, better patient satisfaction, and allow greater access to dermatologists and pediatric dermatologists for patients with more severe acne and other conditions.”

Acknowledging that the study took place over a relatively short period of time, the authors said future research would examine the impact of the educational program and ordering tool on patient acne outcomes.

No funding or conflicts of interest were declared.

SOURCE: Borok J et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018 May 9. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2018.04.055.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN ACADEMY OF DERMATOLOGY

Key clinical point:

Major finding: An education program for pediatricians on acne treatment increased retinoid prescribing but decreased referrals to dermatologists.

Study details: Interventional study in 116 pediatricians.

Disclosures: No funding or conflicts of interest were declared.

Source: Borok J et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018 May 9. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2018.04.055.