User login

Suicide prevention gets ‘standard care’ recommendations

WASHINGTON – The National Action Alliance for Suicide Prevention released in April 2018 what the organization said was the first set of “standard care” recommendations for suicide prevention in people with suicide risk.

Care for people with a suicide risk in the United States “is not working very well. Evidence-based tools exist to detect and manage suicidality, but they are new and infrequently used” by many clinicians, including those seeing suicidal patients in primary care, emergency, or hospital settings, said Michael F. Hogan, PhD, during a session on the new standard-care recommendations at the annual conference of the American Association of Suicidology.

The Action Alliance seeks to have the standard care recommendations widely disseminated and hopes the document will receive endorsement from other organizations, said Dr. Hogan, a health policy consultant in Delmar, N.Y., and a member of the eight-person panel that wrote the recommendations.

These recommendations specify interventions for caregivers in four separate settings: primary care, outpatient behavioral health care (mental health and substance use treatment settings), emergency departments, and behavioral health inpatient care (hospital-level psychiatric or addiction treatment). For each setting, the recommendations highlight one or more core approaches, and then specify standards for identification and assessment, safety planning, means reduction, and follow-up contacts.

For example, within the primary care setting, the recommendations say the goals are to identify suicide risk, enhance the safety for those at risk, refer for specialized care, and provide “caring contacts.” The specifications note that this is achieved with standardized screening and assessment instruments (the recommendations cite eight screening tool options and also suggest three different possible assessment tools); referral as appropriate; a brief safety-planning intervention (the recommendations list five options for this) that includes lethality means reduction along with follow-up to be sure that lethal means have been removed; arranging for rapid follow-up with a mental health professional; and follow-up contact by the primary care clinician within the next 48 hours.

According to Dr. Hogan, a motivation for releasing these recommendations has been the growing U.S. incidence of suicide, rising from 10.4 deaths/100,000 in 2000 to 13.3/100,000 in 2015, a 28% relative increase during a period when the rates of the top killers in the United States – cancer, heart disease, and stroke – were falling. Other telling statistics are that most people who die from suicide had seen a primary care provider during the year before death, and nearly half had seen a primary care provider during the month before their death.

But often the indicators of impending suicide are missed or not acted on. a misperception that contributes to a “failure to ask about suicide risk” on the part of health care professionals, the recommendations said. The document also highlighted the idea that, “most health care professionals are not aware of newly developed brief interventions for suicide, leading to the assumption that they should not ask about suicide because there is nothing practical that can be done in ordinary health care settings.”

One limitation of the recommendations is that they might be interpreted as “standard of care” for medicolegal purposes, warned Alan L. Berman, PhD, during the session’s discussion period. In addition, the evidence base for some of the recommended procedures is not very strong, such as risk stratification, said Dr. Berman, a clinical psychologist and former executive director of the American Association of Suicidology.

Dr. Hogan, Dr. Andrews, and Dr. Berman had no disclosures.

WASHINGTON – The National Action Alliance for Suicide Prevention released in April 2018 what the organization said was the first set of “standard care” recommendations for suicide prevention in people with suicide risk.

Care for people with a suicide risk in the United States “is not working very well. Evidence-based tools exist to detect and manage suicidality, but they are new and infrequently used” by many clinicians, including those seeing suicidal patients in primary care, emergency, or hospital settings, said Michael F. Hogan, PhD, during a session on the new standard-care recommendations at the annual conference of the American Association of Suicidology.

The Action Alliance seeks to have the standard care recommendations widely disseminated and hopes the document will receive endorsement from other organizations, said Dr. Hogan, a health policy consultant in Delmar, N.Y., and a member of the eight-person panel that wrote the recommendations.

These recommendations specify interventions for caregivers in four separate settings: primary care, outpatient behavioral health care (mental health and substance use treatment settings), emergency departments, and behavioral health inpatient care (hospital-level psychiatric or addiction treatment). For each setting, the recommendations highlight one or more core approaches, and then specify standards for identification and assessment, safety planning, means reduction, and follow-up contacts.

For example, within the primary care setting, the recommendations say the goals are to identify suicide risk, enhance the safety for those at risk, refer for specialized care, and provide “caring contacts.” The specifications note that this is achieved with standardized screening and assessment instruments (the recommendations cite eight screening tool options and also suggest three different possible assessment tools); referral as appropriate; a brief safety-planning intervention (the recommendations list five options for this) that includes lethality means reduction along with follow-up to be sure that lethal means have been removed; arranging for rapid follow-up with a mental health professional; and follow-up contact by the primary care clinician within the next 48 hours.

According to Dr. Hogan, a motivation for releasing these recommendations has been the growing U.S. incidence of suicide, rising from 10.4 deaths/100,000 in 2000 to 13.3/100,000 in 2015, a 28% relative increase during a period when the rates of the top killers in the United States – cancer, heart disease, and stroke – were falling. Other telling statistics are that most people who die from suicide had seen a primary care provider during the year before death, and nearly half had seen a primary care provider during the month before their death.

But often the indicators of impending suicide are missed or not acted on. a misperception that contributes to a “failure to ask about suicide risk” on the part of health care professionals, the recommendations said. The document also highlighted the idea that, “most health care professionals are not aware of newly developed brief interventions for suicide, leading to the assumption that they should not ask about suicide because there is nothing practical that can be done in ordinary health care settings.”

One limitation of the recommendations is that they might be interpreted as “standard of care” for medicolegal purposes, warned Alan L. Berman, PhD, during the session’s discussion period. In addition, the evidence base for some of the recommended procedures is not very strong, such as risk stratification, said Dr. Berman, a clinical psychologist and former executive director of the American Association of Suicidology.

Dr. Hogan, Dr. Andrews, and Dr. Berman had no disclosures.

WASHINGTON – The National Action Alliance for Suicide Prevention released in April 2018 what the organization said was the first set of “standard care” recommendations for suicide prevention in people with suicide risk.

Care for people with a suicide risk in the United States “is not working very well. Evidence-based tools exist to detect and manage suicidality, but they are new and infrequently used” by many clinicians, including those seeing suicidal patients in primary care, emergency, or hospital settings, said Michael F. Hogan, PhD, during a session on the new standard-care recommendations at the annual conference of the American Association of Suicidology.

The Action Alliance seeks to have the standard care recommendations widely disseminated and hopes the document will receive endorsement from other organizations, said Dr. Hogan, a health policy consultant in Delmar, N.Y., and a member of the eight-person panel that wrote the recommendations.

These recommendations specify interventions for caregivers in four separate settings: primary care, outpatient behavioral health care (mental health and substance use treatment settings), emergency departments, and behavioral health inpatient care (hospital-level psychiatric or addiction treatment). For each setting, the recommendations highlight one or more core approaches, and then specify standards for identification and assessment, safety planning, means reduction, and follow-up contacts.

For example, within the primary care setting, the recommendations say the goals are to identify suicide risk, enhance the safety for those at risk, refer for specialized care, and provide “caring contacts.” The specifications note that this is achieved with standardized screening and assessment instruments (the recommendations cite eight screening tool options and also suggest three different possible assessment tools); referral as appropriate; a brief safety-planning intervention (the recommendations list five options for this) that includes lethality means reduction along with follow-up to be sure that lethal means have been removed; arranging for rapid follow-up with a mental health professional; and follow-up contact by the primary care clinician within the next 48 hours.

According to Dr. Hogan, a motivation for releasing these recommendations has been the growing U.S. incidence of suicide, rising from 10.4 deaths/100,000 in 2000 to 13.3/100,000 in 2015, a 28% relative increase during a period when the rates of the top killers in the United States – cancer, heart disease, and stroke – were falling. Other telling statistics are that most people who die from suicide had seen a primary care provider during the year before death, and nearly half had seen a primary care provider during the month before their death.

But often the indicators of impending suicide are missed or not acted on. a misperception that contributes to a “failure to ask about suicide risk” on the part of health care professionals, the recommendations said. The document also highlighted the idea that, “most health care professionals are not aware of newly developed brief interventions for suicide, leading to the assumption that they should not ask about suicide because there is nothing practical that can be done in ordinary health care settings.”

One limitation of the recommendations is that they might be interpreted as “standard of care” for medicolegal purposes, warned Alan L. Berman, PhD, during the session’s discussion period. In addition, the evidence base for some of the recommended procedures is not very strong, such as risk stratification, said Dr. Berman, a clinical psychologist and former executive director of the American Association of Suicidology.

Dr. Hogan, Dr. Andrews, and Dr. Berman had no disclosures.

REPORTING FROM THE AAS ANNUAL CONFERENCE

FDA approves subcutaneous tocilizumab for polyarticular JIA

in patients aged 2 years and older, according to a statement released May 14 by the drug’s manufacturer, Genentech.

While a intravenous formulation of the treatment was approved in 2013, this new delivery method may help make this treatment more accessible to the approximately 30 in every 100,000 children affected by PJIA, according to the release.

Doses were determined based on weight. Patients under 30 kg received 162 mg of tocilizumab every 3 weeks, while those 30 kg and over received 162 mg tocilizumab every 2 weeks.

Overall, safety of the subcutaneous delivery method was consistent with the IV study, as was the efficacy of the drug, the company said. A total of 28.8% of patients reported injection-site reactions – all moderate – and 15.4% reported neutrophil counts below 1 x 109 per liter.Tocilizumab can be taken either by itself or with methotrexate.

in patients aged 2 years and older, according to a statement released May 14 by the drug’s manufacturer, Genentech.

While a intravenous formulation of the treatment was approved in 2013, this new delivery method may help make this treatment more accessible to the approximately 30 in every 100,000 children affected by PJIA, according to the release.

Doses were determined based on weight. Patients under 30 kg received 162 mg of tocilizumab every 3 weeks, while those 30 kg and over received 162 mg tocilizumab every 2 weeks.

Overall, safety of the subcutaneous delivery method was consistent with the IV study, as was the efficacy of the drug, the company said. A total of 28.8% of patients reported injection-site reactions – all moderate – and 15.4% reported neutrophil counts below 1 x 109 per liter.Tocilizumab can be taken either by itself or with methotrexate.

in patients aged 2 years and older, according to a statement released May 14 by the drug’s manufacturer, Genentech.

While a intravenous formulation of the treatment was approved in 2013, this new delivery method may help make this treatment more accessible to the approximately 30 in every 100,000 children affected by PJIA, according to the release.

Doses were determined based on weight. Patients under 30 kg received 162 mg of tocilizumab every 3 weeks, while those 30 kg and over received 162 mg tocilizumab every 2 weeks.

Overall, safety of the subcutaneous delivery method was consistent with the IV study, as was the efficacy of the drug, the company said. A total of 28.8% of patients reported injection-site reactions – all moderate – and 15.4% reported neutrophil counts below 1 x 109 per liter.Tocilizumab can be taken either by itself or with methotrexate.

Emergency Imaging: Femoral Pseudoaneurysm

Case

An 84-year-old man, who was a resident at a local nursing home, presented for evaluation after the nursing staff noticed an increasingly swollen mass on the patient’s left groin. The patient’s medical history was significant for bilateral aortofemoral graft surgery, dementia, hypertension, and severe peripheral artery disease (PAD). He was not on any anticoagulation or antiplatelet agents. Due to the patient’s dementia, he was unable to provide a history regarding the onset of the swelling or any other signs or symptoms.

On examination, the patient did not appear in distress. His son, who was the patient’s durable power of attorney, was likewise unable to provide a clear timeframe regarding onset of the mass. The patient had no recent history of trauma and had not undergone any recent medical procedures. Vital signs at presentation were: blood pressure, 110/70 mm Hg; heart rate, 84 beats/min; respiratory rate, 13 breaths/min; and temperature, 98.6°F. Oxygen saturation was 94% on room air.

Clinical examination revealed a pulsatile, purple left groin mass and bruit. The mass was located around the left inguinal ligament and extended down the proximal, inner thigh (Figure 1). There was no drainage or lesions from the mass. Inspection of the patient’s hip demonstrated decreased adduction, limited by the mass; otherwise, there was normal range of motion. The dorsalis pedis and posterior tibial pulses were equal and intact, and the rest of the physical examination was unremarkable.

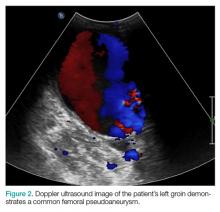

The patient tolerated the examination without focal signs of discomfort. A Doppler ultrasound revealed findings consistent with a common femoral pseudoaneurysm (PSA) (Figure 2). For better visualization and extension, a computed tomography angiogram (CTA) was obtained, which demonstrated a PSA measuring 11.7 x 10.7 x 7.3 cm; there was no active extravasation (Figure 3).

The patient was started on intravenous normal saline while vascular surgery services was consulted for management and repair. After a discussion with the son regarding the patient’s wishes, surgical intervention was refused and the patient was conservatively managed and transitioned to hospice care.

Discussion

A true aneurysm differs from a PSA in that true aneurysms involve all three layers of the vessel wall. A PSA consists partly of the vessel wall and partly of encapsulating fibrous tissue or surrounding tissue.

Etiology

Femoral artery PSAs can be iatrogenic, for example, develop following cardiac catheterization or at the anastomotic site of previous surgery.1 The incidence of diagnostic postcatheterization PSA ranges from 0.05% to 2%, whereas interventional postcatheterization PSA ranges from 2% to 6%.2

With the increasing number of peripheral coronary diagnostics and interventions, emergency physicians should include PSA in the differential diagnosis of patients with a recent or remote history of catheterization or bypass grafts. Less commonly, femoral PSAs are caused by non-surgical trauma or infection (ie, mycotic PSA). Patient risk factors for development of PSA include obesity, hypertension, PAD, and anticoagulation.3 Patients with femoral artery PSAs may present with a painful or painless pulsatile mass. Mass effect of the PSA can compress nearby neurovascular structures, leading to femoral neuropathies or limb edema secondary to venous obstruction.4 Complications of embolization or thrombosis can cause limb ischemia, neuropathy, and claudication, while rupture may present with a rapidly expanding groin hematoma. Additionally, sizeable PSAs can cause overlying skin necrosis.5

Imaging Studies

Diagnosis of a PSA can be made through Doppler ultrasound, which is the preferred imaging modality due to its accuracy, noninvasive nature, and low cost. Doppler ultrasound has been found to have a sensitivity of 94% and specificity of 97% in detecting PSAs. Additional imaging with CTA can provide further definition of vasculopathy.6 Treatment should be considered for patients with a symptomatic femoral PSA, a PSA measuring more than 3 cm, or patients who are on anticoagulation therapy. Studies have shown that observation-only and follow-up may be appropriate for patients with a PSA measuring less than 3 cm. A study by Toursarkissian et al7 found that the majority of PSAs smaller than 3 cm spontaneously resolved in a mean of 23 days without limb-threatening complications.

Treatment

Traditionally, open surgical repair techniques were the only treatment option for PSAs. However, in the early 1990s, the advent of new techniques such as stenting, coil insertion, ultrasound-guided compression, and ultrasound-guided thrombin injection, have developed as alternatives to open surgical repair; there has been variable success to these minimally invasive approaches.5,8

Ultrasound-Guided Compression. A conservative approach to treating PSAs, ultrasound-guided compression requires sustained compression by a skilled physician. This technique is associated with significant discomfort to the patient.5 Ultrasound-Guided Thrombin Injection. This technique is the treatment of choice for postcatheterization PSA. However, this intervention is contraindicated in patients who have concerning features such as an infected PSA, rapid expansion, skin necrosis, or signs of limb ischemia. Additionally, ultrasound-guided thrombin injection is not appropriate for use in patients with a PSA occurring at anastomosis of a synthetic graft and native artery.5

Conclusion

Based on our patient’s clinical presentation and history of aortofemoral bypass surgery, we suspected a femoral PSA. While the PSA noted in our patient was sizeable, imaging studies and clinical examination showed no sign of limb ischemia or rupture.

Femoral PSAs are usually iatrogenic in nature, typically developing shortly after catheterization or a previous bypass surgery. The most serious complication of a PSA is rupture, but a thorough examination of the distal extremity is warranted to assess for limb ischemia as well. Ultrasound imaging is considered the modality of choice based on its high sensitivity and sensitivity for detecting PSAs.

Small PSAs (<3 cm) can be managed medically, but larger PSAs (>3 cm) require treatment. Newer techniques, including stenting, coil insertion, ultrasound-guided compression, and ultrasound-guided thrombin injection are alternatives to open surgical repair of larger, uncomplicated PSAs. However, urgent open surgical repair is the only option when there is evidence of a ruptured PSA, ischemia, or skin necrosis.

1. Faggioli GL, Stella A, Gargiulo M, Tarantini S, D’Addato M, Ricotta JJ. Morphology of small aneurysms: definition and impact on risk of rupture. Am J Surg. 1994;168(2):131-135.

2. Hessel SJ, Adams DF, Abrams HL. Complications of angiography. Radiology. 1981;138(2):273-281. doi:10.1148/radiology.138.2.7455105.

3. Petrou E, Malakos I, Kampanarou S, Doulas N, Voudris V. Life-threatening rupture of a femoral pseudoaneurysm after cardiac catheterization. Open Cardiovasc Med J. 2016;10:201-204. doi:10.2174/1874192401610010201.

4. Mees B, Robinson D, Verhagen H, Chuen J. Non-aortic aneurysms—natural history and recommendations for referral and treatment. Aust Fam Physician. 2013;42(6):370-374.

5. Webber GW, Jang J, Gustavson S, Olin JW. Contemporary management of postcatheterization pseudoaneurysms. Circulation. 2007;115(20):2666-2674. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.681973.

6. Coughlin BF, Paushter DM. Peripheral pseudoaneurysms: evaluation with duplex US. Radiology. 1988;168(2):339-342. doi:10.1148/radiology.168.2.3293107.

7. Toursarkissian B, Allen BT, Petrinec D, et al. Spontaneous closure of selected iatrogenic pseudoaneurysms and arteriovenous fistulae. J Vasc Surg. 1997;25(5):803-809; discussion 808-809.

8. Corriere MA, Guzman RJ. True and false aneurysms of the femoral artery. Semin Vasc Surg. 2005;18(4):216-223. doi:10.1053/j.semvascsurg.2005.09.008.

Case

An 84-year-old man, who was a resident at a local nursing home, presented for evaluation after the nursing staff noticed an increasingly swollen mass on the patient’s left groin. The patient’s medical history was significant for bilateral aortofemoral graft surgery, dementia, hypertension, and severe peripheral artery disease (PAD). He was not on any anticoagulation or antiplatelet agents. Due to the patient’s dementia, he was unable to provide a history regarding the onset of the swelling or any other signs or symptoms.

On examination, the patient did not appear in distress. His son, who was the patient’s durable power of attorney, was likewise unable to provide a clear timeframe regarding onset of the mass. The patient had no recent history of trauma and had not undergone any recent medical procedures. Vital signs at presentation were: blood pressure, 110/70 mm Hg; heart rate, 84 beats/min; respiratory rate, 13 breaths/min; and temperature, 98.6°F. Oxygen saturation was 94% on room air.

Clinical examination revealed a pulsatile, purple left groin mass and bruit. The mass was located around the left inguinal ligament and extended down the proximal, inner thigh (Figure 1). There was no drainage or lesions from the mass. Inspection of the patient’s hip demonstrated decreased adduction, limited by the mass; otherwise, there was normal range of motion. The dorsalis pedis and posterior tibial pulses were equal and intact, and the rest of the physical examination was unremarkable.

The patient tolerated the examination without focal signs of discomfort. A Doppler ultrasound revealed findings consistent with a common femoral pseudoaneurysm (PSA) (Figure 2). For better visualization and extension, a computed tomography angiogram (CTA) was obtained, which demonstrated a PSA measuring 11.7 x 10.7 x 7.3 cm; there was no active extravasation (Figure 3).

The patient was started on intravenous normal saline while vascular surgery services was consulted for management and repair. After a discussion with the son regarding the patient’s wishes, surgical intervention was refused and the patient was conservatively managed and transitioned to hospice care.

Discussion

A true aneurysm differs from a PSA in that true aneurysms involve all three layers of the vessel wall. A PSA consists partly of the vessel wall and partly of encapsulating fibrous tissue or surrounding tissue.

Etiology

Femoral artery PSAs can be iatrogenic, for example, develop following cardiac catheterization or at the anastomotic site of previous surgery.1 The incidence of diagnostic postcatheterization PSA ranges from 0.05% to 2%, whereas interventional postcatheterization PSA ranges from 2% to 6%.2

With the increasing number of peripheral coronary diagnostics and interventions, emergency physicians should include PSA in the differential diagnosis of patients with a recent or remote history of catheterization or bypass grafts. Less commonly, femoral PSAs are caused by non-surgical trauma or infection (ie, mycotic PSA). Patient risk factors for development of PSA include obesity, hypertension, PAD, and anticoagulation.3 Patients with femoral artery PSAs may present with a painful or painless pulsatile mass. Mass effect of the PSA can compress nearby neurovascular structures, leading to femoral neuropathies or limb edema secondary to venous obstruction.4 Complications of embolization or thrombosis can cause limb ischemia, neuropathy, and claudication, while rupture may present with a rapidly expanding groin hematoma. Additionally, sizeable PSAs can cause overlying skin necrosis.5

Imaging Studies

Diagnosis of a PSA can be made through Doppler ultrasound, which is the preferred imaging modality due to its accuracy, noninvasive nature, and low cost. Doppler ultrasound has been found to have a sensitivity of 94% and specificity of 97% in detecting PSAs. Additional imaging with CTA can provide further definition of vasculopathy.6 Treatment should be considered for patients with a symptomatic femoral PSA, a PSA measuring more than 3 cm, or patients who are on anticoagulation therapy. Studies have shown that observation-only and follow-up may be appropriate for patients with a PSA measuring less than 3 cm. A study by Toursarkissian et al7 found that the majority of PSAs smaller than 3 cm spontaneously resolved in a mean of 23 days without limb-threatening complications.

Treatment

Traditionally, open surgical repair techniques were the only treatment option for PSAs. However, in the early 1990s, the advent of new techniques such as stenting, coil insertion, ultrasound-guided compression, and ultrasound-guided thrombin injection, have developed as alternatives to open surgical repair; there has been variable success to these minimally invasive approaches.5,8

Ultrasound-Guided Compression. A conservative approach to treating PSAs, ultrasound-guided compression requires sustained compression by a skilled physician. This technique is associated with significant discomfort to the patient.5 Ultrasound-Guided Thrombin Injection. This technique is the treatment of choice for postcatheterization PSA. However, this intervention is contraindicated in patients who have concerning features such as an infected PSA, rapid expansion, skin necrosis, or signs of limb ischemia. Additionally, ultrasound-guided thrombin injection is not appropriate for use in patients with a PSA occurring at anastomosis of a synthetic graft and native artery.5

Conclusion

Based on our patient’s clinical presentation and history of aortofemoral bypass surgery, we suspected a femoral PSA. While the PSA noted in our patient was sizeable, imaging studies and clinical examination showed no sign of limb ischemia or rupture.

Femoral PSAs are usually iatrogenic in nature, typically developing shortly after catheterization or a previous bypass surgery. The most serious complication of a PSA is rupture, but a thorough examination of the distal extremity is warranted to assess for limb ischemia as well. Ultrasound imaging is considered the modality of choice based on its high sensitivity and sensitivity for detecting PSAs.

Small PSAs (<3 cm) can be managed medically, but larger PSAs (>3 cm) require treatment. Newer techniques, including stenting, coil insertion, ultrasound-guided compression, and ultrasound-guided thrombin injection are alternatives to open surgical repair of larger, uncomplicated PSAs. However, urgent open surgical repair is the only option when there is evidence of a ruptured PSA, ischemia, or skin necrosis.

Case

An 84-year-old man, who was a resident at a local nursing home, presented for evaluation after the nursing staff noticed an increasingly swollen mass on the patient’s left groin. The patient’s medical history was significant for bilateral aortofemoral graft surgery, dementia, hypertension, and severe peripheral artery disease (PAD). He was not on any anticoagulation or antiplatelet agents. Due to the patient’s dementia, he was unable to provide a history regarding the onset of the swelling or any other signs or symptoms.

On examination, the patient did not appear in distress. His son, who was the patient’s durable power of attorney, was likewise unable to provide a clear timeframe regarding onset of the mass. The patient had no recent history of trauma and had not undergone any recent medical procedures. Vital signs at presentation were: blood pressure, 110/70 mm Hg; heart rate, 84 beats/min; respiratory rate, 13 breaths/min; and temperature, 98.6°F. Oxygen saturation was 94% on room air.

Clinical examination revealed a pulsatile, purple left groin mass and bruit. The mass was located around the left inguinal ligament and extended down the proximal, inner thigh (Figure 1). There was no drainage or lesions from the mass. Inspection of the patient’s hip demonstrated decreased adduction, limited by the mass; otherwise, there was normal range of motion. The dorsalis pedis and posterior tibial pulses were equal and intact, and the rest of the physical examination was unremarkable.

The patient tolerated the examination without focal signs of discomfort. A Doppler ultrasound revealed findings consistent with a common femoral pseudoaneurysm (PSA) (Figure 2). For better visualization and extension, a computed tomography angiogram (CTA) was obtained, which demonstrated a PSA measuring 11.7 x 10.7 x 7.3 cm; there was no active extravasation (Figure 3).

The patient was started on intravenous normal saline while vascular surgery services was consulted for management and repair. After a discussion with the son regarding the patient’s wishes, surgical intervention was refused and the patient was conservatively managed and transitioned to hospice care.

Discussion

A true aneurysm differs from a PSA in that true aneurysms involve all three layers of the vessel wall. A PSA consists partly of the vessel wall and partly of encapsulating fibrous tissue or surrounding tissue.

Etiology

Femoral artery PSAs can be iatrogenic, for example, develop following cardiac catheterization or at the anastomotic site of previous surgery.1 The incidence of diagnostic postcatheterization PSA ranges from 0.05% to 2%, whereas interventional postcatheterization PSA ranges from 2% to 6%.2

With the increasing number of peripheral coronary diagnostics and interventions, emergency physicians should include PSA in the differential diagnosis of patients with a recent or remote history of catheterization or bypass grafts. Less commonly, femoral PSAs are caused by non-surgical trauma or infection (ie, mycotic PSA). Patient risk factors for development of PSA include obesity, hypertension, PAD, and anticoagulation.3 Patients with femoral artery PSAs may present with a painful or painless pulsatile mass. Mass effect of the PSA can compress nearby neurovascular structures, leading to femoral neuropathies or limb edema secondary to venous obstruction.4 Complications of embolization or thrombosis can cause limb ischemia, neuropathy, and claudication, while rupture may present with a rapidly expanding groin hematoma. Additionally, sizeable PSAs can cause overlying skin necrosis.5

Imaging Studies

Diagnosis of a PSA can be made through Doppler ultrasound, which is the preferred imaging modality due to its accuracy, noninvasive nature, and low cost. Doppler ultrasound has been found to have a sensitivity of 94% and specificity of 97% in detecting PSAs. Additional imaging with CTA can provide further definition of vasculopathy.6 Treatment should be considered for patients with a symptomatic femoral PSA, a PSA measuring more than 3 cm, or patients who are on anticoagulation therapy. Studies have shown that observation-only and follow-up may be appropriate for patients with a PSA measuring less than 3 cm. A study by Toursarkissian et al7 found that the majority of PSAs smaller than 3 cm spontaneously resolved in a mean of 23 days without limb-threatening complications.

Treatment

Traditionally, open surgical repair techniques were the only treatment option for PSAs. However, in the early 1990s, the advent of new techniques such as stenting, coil insertion, ultrasound-guided compression, and ultrasound-guided thrombin injection, have developed as alternatives to open surgical repair; there has been variable success to these minimally invasive approaches.5,8

Ultrasound-Guided Compression. A conservative approach to treating PSAs, ultrasound-guided compression requires sustained compression by a skilled physician. This technique is associated with significant discomfort to the patient.5 Ultrasound-Guided Thrombin Injection. This technique is the treatment of choice for postcatheterization PSA. However, this intervention is contraindicated in patients who have concerning features such as an infected PSA, rapid expansion, skin necrosis, or signs of limb ischemia. Additionally, ultrasound-guided thrombin injection is not appropriate for use in patients with a PSA occurring at anastomosis of a synthetic graft and native artery.5

Conclusion

Based on our patient’s clinical presentation and history of aortofemoral bypass surgery, we suspected a femoral PSA. While the PSA noted in our patient was sizeable, imaging studies and clinical examination showed no sign of limb ischemia or rupture.

Femoral PSAs are usually iatrogenic in nature, typically developing shortly after catheterization or a previous bypass surgery. The most serious complication of a PSA is rupture, but a thorough examination of the distal extremity is warranted to assess for limb ischemia as well. Ultrasound imaging is considered the modality of choice based on its high sensitivity and sensitivity for detecting PSAs.

Small PSAs (<3 cm) can be managed medically, but larger PSAs (>3 cm) require treatment. Newer techniques, including stenting, coil insertion, ultrasound-guided compression, and ultrasound-guided thrombin injection are alternatives to open surgical repair of larger, uncomplicated PSAs. However, urgent open surgical repair is the only option when there is evidence of a ruptured PSA, ischemia, or skin necrosis.

1. Faggioli GL, Stella A, Gargiulo M, Tarantini S, D’Addato M, Ricotta JJ. Morphology of small aneurysms: definition and impact on risk of rupture. Am J Surg. 1994;168(2):131-135.

2. Hessel SJ, Adams DF, Abrams HL. Complications of angiography. Radiology. 1981;138(2):273-281. doi:10.1148/radiology.138.2.7455105.

3. Petrou E, Malakos I, Kampanarou S, Doulas N, Voudris V. Life-threatening rupture of a femoral pseudoaneurysm after cardiac catheterization. Open Cardiovasc Med J. 2016;10:201-204. doi:10.2174/1874192401610010201.

4. Mees B, Robinson D, Verhagen H, Chuen J. Non-aortic aneurysms—natural history and recommendations for referral and treatment. Aust Fam Physician. 2013;42(6):370-374.

5. Webber GW, Jang J, Gustavson S, Olin JW. Contemporary management of postcatheterization pseudoaneurysms. Circulation. 2007;115(20):2666-2674. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.681973.

6. Coughlin BF, Paushter DM. Peripheral pseudoaneurysms: evaluation with duplex US. Radiology. 1988;168(2):339-342. doi:10.1148/radiology.168.2.3293107.

7. Toursarkissian B, Allen BT, Petrinec D, et al. Spontaneous closure of selected iatrogenic pseudoaneurysms and arteriovenous fistulae. J Vasc Surg. 1997;25(5):803-809; discussion 808-809.

8. Corriere MA, Guzman RJ. True and false aneurysms of the femoral artery. Semin Vasc Surg. 2005;18(4):216-223. doi:10.1053/j.semvascsurg.2005.09.008.

1. Faggioli GL, Stella A, Gargiulo M, Tarantini S, D’Addato M, Ricotta JJ. Morphology of small aneurysms: definition and impact on risk of rupture. Am J Surg. 1994;168(2):131-135.

2. Hessel SJ, Adams DF, Abrams HL. Complications of angiography. Radiology. 1981;138(2):273-281. doi:10.1148/radiology.138.2.7455105.

3. Petrou E, Malakos I, Kampanarou S, Doulas N, Voudris V. Life-threatening rupture of a femoral pseudoaneurysm after cardiac catheterization. Open Cardiovasc Med J. 2016;10:201-204. doi:10.2174/1874192401610010201.

4. Mees B, Robinson D, Verhagen H, Chuen J. Non-aortic aneurysms—natural history and recommendations for referral and treatment. Aust Fam Physician. 2013;42(6):370-374.

5. Webber GW, Jang J, Gustavson S, Olin JW. Contemporary management of postcatheterization pseudoaneurysms. Circulation. 2007;115(20):2666-2674. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.681973.

6. Coughlin BF, Paushter DM. Peripheral pseudoaneurysms: evaluation with duplex US. Radiology. 1988;168(2):339-342. doi:10.1148/radiology.168.2.3293107.

7. Toursarkissian B, Allen BT, Petrinec D, et al. Spontaneous closure of selected iatrogenic pseudoaneurysms and arteriovenous fistulae. J Vasc Surg. 1997;25(5):803-809; discussion 808-809.

8. Corriere MA, Guzman RJ. True and false aneurysms of the femoral artery. Semin Vasc Surg. 2005;18(4):216-223. doi:10.1053/j.semvascsurg.2005.09.008.

Design limitations may have compromised DVT intervention trial

WASHINGTON – On the basis of a large randomized trial called ATTRACT, many clinicians have concluded that pharmacomechanical intervention is ineffective for preventing postthrombotic syndrome (PTS) in patients with deep venous thrombosis (DVT). But weaknesses in the study design challenge this conclusion, according to several experts in a DVT symposium at the 2018 Cardiovascular Research Technologies (CRT) meeting.

“The diagnosis and evaluation of DVT must be performed with IVUS [intravascular ultrasound], not with venography,” said Peter A. Soukas, MD, director of vascular medicine at Miriam Hospital in Providence, R.I. “You cannot know whether you successfully treated the clot if you cannot see it.”

“There were lots of limitations to that study. Here are some,” said Dr. Soukas, who then listed on a list of several considerations, including the fact that venograms – rather than IVUS, which Dr. Soukas labeled the “current gold standard” – were taken to evaluate procedure success. Another was that only half of patients had a moderate to severe DVT based on a Villalta score.

“If you look at the subgroup with a Villalta score of 10 or greater, the benefit [of pharmacomechanical intervention] was statistically significant,” he said.

In addition, the study enrolled a substantial number of patients with femoral-popliteal DVTs even though iliofemoral DVTs pose the greatest risk of postthrombotic syndrome. Dr. Soukas suggested these would have been a more appropriate focus of a study exploring the benefits of an intervention.

The limitations of the ATTRACT trial, which was conceived more than 5 years ago, have arisen primarily from advances in the field rather than problems with the design, Dr. Soukas explained. IVUS was not the preferred method for deep vein thrombosis evaluation then as it is now, and there have been several advances in current models of pharmacomechanical devices, which involve catheter-directed delivery of fibrinolytic therapy into the thrombus along with mechanical destruction of the clot.

Although further steps beyond clot lysis, such as stenting, were encouraged in ATTRACT to maintain venous patency, Dr. Soukas questioned whether these were employed sufficiently. For example, the rate of stenting in the experimental arm was 28%, a rate that “is not what we currently do” for patients at high risk of PTS, Dr. Soukas said.

In ATTRACT, major bleeding events were significantly higher in the experimental group (1.7% vs. 0.3%; P = .049). The authors cited this finding when they concluded that the experimental intervention was ineffective. Dr. Soukas acknowledged that bleeding risk is an important factor to consider, but he also emphasized the serious risks for failing to treat patients at high risk for PTS.

“PTS is devastating for patients, both functionally and economically,” Dr. Soukas said. He called the morbidity of deep vein thrombosis “staggering,” with in-hospital mortality in some series exceeding 10% and a risk of late development of postthrombotic syndrome persisting for up to 5 years. For those with proximal iliofemoral DVT, the PTS rate can reach 90%, about 15% of which can develop claudication with ulcerations, according to Dr. Soukas.

A large trial that was published in a prominent journal, ATTRACT has the potential to dissuade clinicians from considering pharmacomechanical intervention in high-risk patients who could benefit, Dr. Soukas said. Others speaking during the same symposium about advances in this field, such as John Fritz Angle, MD, director of the division of vascular and interventional radiology at the University of Virginia, Charlottesville, agreed with this assessment. Although other studies underway will reexamine this issue, there was consensus from several speakers at the CRT symposium that the results of ATTRACT should not preclude intervention in patients at high risk of PTS.

“I believe there is a role for DVT intervention for symptomatic patients with an extensive [proximal iliofemoral] clot provided they have a low bleeding risk,” Dr. Soukas said.

Dr. Soukas reported no potential conflicts of interest.

WASHINGTON – On the basis of a large randomized trial called ATTRACT, many clinicians have concluded that pharmacomechanical intervention is ineffective for preventing postthrombotic syndrome (PTS) in patients with deep venous thrombosis (DVT). But weaknesses in the study design challenge this conclusion, according to several experts in a DVT symposium at the 2018 Cardiovascular Research Technologies (CRT) meeting.

“The diagnosis and evaluation of DVT must be performed with IVUS [intravascular ultrasound], not with venography,” said Peter A. Soukas, MD, director of vascular medicine at Miriam Hospital in Providence, R.I. “You cannot know whether you successfully treated the clot if you cannot see it.”

“There were lots of limitations to that study. Here are some,” said Dr. Soukas, who then listed on a list of several considerations, including the fact that venograms – rather than IVUS, which Dr. Soukas labeled the “current gold standard” – were taken to evaluate procedure success. Another was that only half of patients had a moderate to severe DVT based on a Villalta score.

“If you look at the subgroup with a Villalta score of 10 or greater, the benefit [of pharmacomechanical intervention] was statistically significant,” he said.

In addition, the study enrolled a substantial number of patients with femoral-popliteal DVTs even though iliofemoral DVTs pose the greatest risk of postthrombotic syndrome. Dr. Soukas suggested these would have been a more appropriate focus of a study exploring the benefits of an intervention.

The limitations of the ATTRACT trial, which was conceived more than 5 years ago, have arisen primarily from advances in the field rather than problems with the design, Dr. Soukas explained. IVUS was not the preferred method for deep vein thrombosis evaluation then as it is now, and there have been several advances in current models of pharmacomechanical devices, which involve catheter-directed delivery of fibrinolytic therapy into the thrombus along with mechanical destruction of the clot.

Although further steps beyond clot lysis, such as stenting, were encouraged in ATTRACT to maintain venous patency, Dr. Soukas questioned whether these were employed sufficiently. For example, the rate of stenting in the experimental arm was 28%, a rate that “is not what we currently do” for patients at high risk of PTS, Dr. Soukas said.

In ATTRACT, major bleeding events were significantly higher in the experimental group (1.7% vs. 0.3%; P = .049). The authors cited this finding when they concluded that the experimental intervention was ineffective. Dr. Soukas acknowledged that bleeding risk is an important factor to consider, but he also emphasized the serious risks for failing to treat patients at high risk for PTS.

“PTS is devastating for patients, both functionally and economically,” Dr. Soukas said. He called the morbidity of deep vein thrombosis “staggering,” with in-hospital mortality in some series exceeding 10% and a risk of late development of postthrombotic syndrome persisting for up to 5 years. For those with proximal iliofemoral DVT, the PTS rate can reach 90%, about 15% of which can develop claudication with ulcerations, according to Dr. Soukas.

A large trial that was published in a prominent journal, ATTRACT has the potential to dissuade clinicians from considering pharmacomechanical intervention in high-risk patients who could benefit, Dr. Soukas said. Others speaking during the same symposium about advances in this field, such as John Fritz Angle, MD, director of the division of vascular and interventional radiology at the University of Virginia, Charlottesville, agreed with this assessment. Although other studies underway will reexamine this issue, there was consensus from several speakers at the CRT symposium that the results of ATTRACT should not preclude intervention in patients at high risk of PTS.

“I believe there is a role for DVT intervention for symptomatic patients with an extensive [proximal iliofemoral] clot provided they have a low bleeding risk,” Dr. Soukas said.

Dr. Soukas reported no potential conflicts of interest.

WASHINGTON – On the basis of a large randomized trial called ATTRACT, many clinicians have concluded that pharmacomechanical intervention is ineffective for preventing postthrombotic syndrome (PTS) in patients with deep venous thrombosis (DVT). But weaknesses in the study design challenge this conclusion, according to several experts in a DVT symposium at the 2018 Cardiovascular Research Technologies (CRT) meeting.

“The diagnosis and evaluation of DVT must be performed with IVUS [intravascular ultrasound], not with venography,” said Peter A. Soukas, MD, director of vascular medicine at Miriam Hospital in Providence, R.I. “You cannot know whether you successfully treated the clot if you cannot see it.”

“There were lots of limitations to that study. Here are some,” said Dr. Soukas, who then listed on a list of several considerations, including the fact that venograms – rather than IVUS, which Dr. Soukas labeled the “current gold standard” – were taken to evaluate procedure success. Another was that only half of patients had a moderate to severe DVT based on a Villalta score.

“If you look at the subgroup with a Villalta score of 10 or greater, the benefit [of pharmacomechanical intervention] was statistically significant,” he said.

In addition, the study enrolled a substantial number of patients with femoral-popliteal DVTs even though iliofemoral DVTs pose the greatest risk of postthrombotic syndrome. Dr. Soukas suggested these would have been a more appropriate focus of a study exploring the benefits of an intervention.

The limitations of the ATTRACT trial, which was conceived more than 5 years ago, have arisen primarily from advances in the field rather than problems with the design, Dr. Soukas explained. IVUS was not the preferred method for deep vein thrombosis evaluation then as it is now, and there have been several advances in current models of pharmacomechanical devices, which involve catheter-directed delivery of fibrinolytic therapy into the thrombus along with mechanical destruction of the clot.

Although further steps beyond clot lysis, such as stenting, were encouraged in ATTRACT to maintain venous patency, Dr. Soukas questioned whether these were employed sufficiently. For example, the rate of stenting in the experimental arm was 28%, a rate that “is not what we currently do” for patients at high risk of PTS, Dr. Soukas said.

In ATTRACT, major bleeding events were significantly higher in the experimental group (1.7% vs. 0.3%; P = .049). The authors cited this finding when they concluded that the experimental intervention was ineffective. Dr. Soukas acknowledged that bleeding risk is an important factor to consider, but he also emphasized the serious risks for failing to treat patients at high risk for PTS.

“PTS is devastating for patients, both functionally and economically,” Dr. Soukas said. He called the morbidity of deep vein thrombosis “staggering,” with in-hospital mortality in some series exceeding 10% and a risk of late development of postthrombotic syndrome persisting for up to 5 years. For those with proximal iliofemoral DVT, the PTS rate can reach 90%, about 15% of which can develop claudication with ulcerations, according to Dr. Soukas.

A large trial that was published in a prominent journal, ATTRACT has the potential to dissuade clinicians from considering pharmacomechanical intervention in high-risk patients who could benefit, Dr. Soukas said. Others speaking during the same symposium about advances in this field, such as John Fritz Angle, MD, director of the division of vascular and interventional radiology at the University of Virginia, Charlottesville, agreed with this assessment. Although other studies underway will reexamine this issue, there was consensus from several speakers at the CRT symposium that the results of ATTRACT should not preclude intervention in patients at high risk of PTS.

“I believe there is a role for DVT intervention for symptomatic patients with an extensive [proximal iliofemoral] clot provided they have a low bleeding risk,” Dr. Soukas said.

Dr. Soukas reported no potential conflicts of interest.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM THE 2018 CRT MEETING

Patients Who Die of SUDEP Largely Live Alone and Die Unwitnessed at Home

Patients whose fatality is attributed to sudden unexpected death in epilepsy (SUDEP) largely live alone; die unwitnessed at home at night, usually in the prone position; and have an indication of a preceding seizure, according to research published in the May issue of Epilepsia.

“Our results … highlight the difficulties in implementing preventive efforts that require immediate availability of another person to identify a seizure, to interact and correct body position, or to give pharmacologic emergency treatment,” said Olafur Sveinsson, a graduate student at the Karolinska Institute in Stockholm, and colleagues. “These obstacles need to be considered when strategies for SUDEP prevention are being developed.”

Previous case–control studies have identified a high frequency of tonic-clonic seizures, nocturnal seizures, and lack of nighttime supervision as risk factors for SUDEP, but mechanisms of SUDEP remain unclear. To analyze the circumstances of SUDEP and its incidence in relation to time of year, week, and day, Mr. Sveinsson and colleagues conducted a nationwide, population-based case series.

For their study, the investigators used the Swedish National Patient Registry to identify all persons that, at some point between 1998 and 2005, had an ICD-10 code for epilepsy and were alive on June 30, 2006. Eligible SUDEP cases were all deaths with epilepsy mentioned on the death certificate together with all individuals who died during 2008, irrespective of whether epilepsy was mentioned on the death certificate. Obvious non-SUDEP deaths such as those resulting from cancer, terminal illness, postmortem confirmed pneumonia, stroke, or myocardial infarction were excluded from further analysis.

SUDEP cases were divided into three subgroups based on the certainty of the diagnosis: definite SUDEP (when all clinical criteria were met and an autopsy revealed no alternate cause of death), probable SUDEP (when all clinical criteria were met, but no autopsy was performed), and possible SUDEP (when SUDEP could not be ruled out, but insufficient evidence was available regarding the circumstances of death, and no autopsy was performed). To identify SUDEP cases and related circumstances, investigators reviewed death certificates, medical charts, autopsy, and police records. Autopsied non-SUDEP deaths from the study population served as a reference. Researchers reviewed 3,166 deaths and identified 329 cases of SUDEP (37% were female). Of these cases, 167 were definite, 89 were probable, and 73 were possible. SUDEP cases were younger at death (50.8 years) than non-SUDEP deaths (73.3 years). Most SUDEP cases occurred at night (58%) and at home (91%), and 65% were found dead in bed. When documented, 70% were found in prone position, which may “facilitate SUDEP by compromising postictal ventilation,” said the authors.

Death was witnessed in 17% of SUDEP cases, and in 88% of these, a seizure was observed. In all, 71% of patients were living alone, and 14% shared a bedroom. Among the witnessed definite SUDEP patients, a tonic-clonic seizure was present in 95% of cases, compared with 21% in the autopsied non-SUDEP reference group, strengthening the notion that SUDEP in most cases is a seizure-related event, the researchers said.

Although sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS) and cardiac death have a higher incidence in the winter, the researchers did not find the same to be true in their SUDEP cohort. Furthermore, they did not find a preponderance for Mondays or morning hours, as reported for sudden cardiac death. The researchers did, however, find a clear diurnal variation, with the majority of cases dying during the night hours. Taken together, these findings prompted the researchers to conclude that the underlying mechanisms of SUDEP are different from those of SIDS and sudden cardiac death.

—Erica Tricarico

Suggested Reading

Sveinnson O, Andersson T, Carlsson S, Tomson T. Circumstances of SUDEP: a nationwide population-based case series. Epilepsia. 2018;59(5):1074-1082.

Patients whose fatality is attributed to sudden unexpected death in epilepsy (SUDEP) largely live alone; die unwitnessed at home at night, usually in the prone position; and have an indication of a preceding seizure, according to research published in the May issue of Epilepsia.

“Our results … highlight the difficulties in implementing preventive efforts that require immediate availability of another person to identify a seizure, to interact and correct body position, or to give pharmacologic emergency treatment,” said Olafur Sveinsson, a graduate student at the Karolinska Institute in Stockholm, and colleagues. “These obstacles need to be considered when strategies for SUDEP prevention are being developed.”

Previous case–control studies have identified a high frequency of tonic-clonic seizures, nocturnal seizures, and lack of nighttime supervision as risk factors for SUDEP, but mechanisms of SUDEP remain unclear. To analyze the circumstances of SUDEP and its incidence in relation to time of year, week, and day, Mr. Sveinsson and colleagues conducted a nationwide, population-based case series.

For their study, the investigators used the Swedish National Patient Registry to identify all persons that, at some point between 1998 and 2005, had an ICD-10 code for epilepsy and were alive on June 30, 2006. Eligible SUDEP cases were all deaths with epilepsy mentioned on the death certificate together with all individuals who died during 2008, irrespective of whether epilepsy was mentioned on the death certificate. Obvious non-SUDEP deaths such as those resulting from cancer, terminal illness, postmortem confirmed pneumonia, stroke, or myocardial infarction were excluded from further analysis.

SUDEP cases were divided into three subgroups based on the certainty of the diagnosis: definite SUDEP (when all clinical criteria were met and an autopsy revealed no alternate cause of death), probable SUDEP (when all clinical criteria were met, but no autopsy was performed), and possible SUDEP (when SUDEP could not be ruled out, but insufficient evidence was available regarding the circumstances of death, and no autopsy was performed). To identify SUDEP cases and related circumstances, investigators reviewed death certificates, medical charts, autopsy, and police records. Autopsied non-SUDEP deaths from the study population served as a reference. Researchers reviewed 3,166 deaths and identified 329 cases of SUDEP (37% were female). Of these cases, 167 were definite, 89 were probable, and 73 were possible. SUDEP cases were younger at death (50.8 years) than non-SUDEP deaths (73.3 years). Most SUDEP cases occurred at night (58%) and at home (91%), and 65% were found dead in bed. When documented, 70% were found in prone position, which may “facilitate SUDEP by compromising postictal ventilation,” said the authors.

Death was witnessed in 17% of SUDEP cases, and in 88% of these, a seizure was observed. In all, 71% of patients were living alone, and 14% shared a bedroom. Among the witnessed definite SUDEP patients, a tonic-clonic seizure was present in 95% of cases, compared with 21% in the autopsied non-SUDEP reference group, strengthening the notion that SUDEP in most cases is a seizure-related event, the researchers said.

Although sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS) and cardiac death have a higher incidence in the winter, the researchers did not find the same to be true in their SUDEP cohort. Furthermore, they did not find a preponderance for Mondays or morning hours, as reported for sudden cardiac death. The researchers did, however, find a clear diurnal variation, with the majority of cases dying during the night hours. Taken together, these findings prompted the researchers to conclude that the underlying mechanisms of SUDEP are different from those of SIDS and sudden cardiac death.

—Erica Tricarico

Suggested Reading

Sveinnson O, Andersson T, Carlsson S, Tomson T. Circumstances of SUDEP: a nationwide population-based case series. Epilepsia. 2018;59(5):1074-1082.

Patients whose fatality is attributed to sudden unexpected death in epilepsy (SUDEP) largely live alone; die unwitnessed at home at night, usually in the prone position; and have an indication of a preceding seizure, according to research published in the May issue of Epilepsia.

“Our results … highlight the difficulties in implementing preventive efforts that require immediate availability of another person to identify a seizure, to interact and correct body position, or to give pharmacologic emergency treatment,” said Olafur Sveinsson, a graduate student at the Karolinska Institute in Stockholm, and colleagues. “These obstacles need to be considered when strategies for SUDEP prevention are being developed.”

Previous case–control studies have identified a high frequency of tonic-clonic seizures, nocturnal seizures, and lack of nighttime supervision as risk factors for SUDEP, but mechanisms of SUDEP remain unclear. To analyze the circumstances of SUDEP and its incidence in relation to time of year, week, and day, Mr. Sveinsson and colleagues conducted a nationwide, population-based case series.

For their study, the investigators used the Swedish National Patient Registry to identify all persons that, at some point between 1998 and 2005, had an ICD-10 code for epilepsy and were alive on June 30, 2006. Eligible SUDEP cases were all deaths with epilepsy mentioned on the death certificate together with all individuals who died during 2008, irrespective of whether epilepsy was mentioned on the death certificate. Obvious non-SUDEP deaths such as those resulting from cancer, terminal illness, postmortem confirmed pneumonia, stroke, or myocardial infarction were excluded from further analysis.

SUDEP cases were divided into three subgroups based on the certainty of the diagnosis: definite SUDEP (when all clinical criteria were met and an autopsy revealed no alternate cause of death), probable SUDEP (when all clinical criteria were met, but no autopsy was performed), and possible SUDEP (when SUDEP could not be ruled out, but insufficient evidence was available regarding the circumstances of death, and no autopsy was performed). To identify SUDEP cases and related circumstances, investigators reviewed death certificates, medical charts, autopsy, and police records. Autopsied non-SUDEP deaths from the study population served as a reference. Researchers reviewed 3,166 deaths and identified 329 cases of SUDEP (37% were female). Of these cases, 167 were definite, 89 were probable, and 73 were possible. SUDEP cases were younger at death (50.8 years) than non-SUDEP deaths (73.3 years). Most SUDEP cases occurred at night (58%) and at home (91%), and 65% were found dead in bed. When documented, 70% were found in prone position, which may “facilitate SUDEP by compromising postictal ventilation,” said the authors.

Death was witnessed in 17% of SUDEP cases, and in 88% of these, a seizure was observed. In all, 71% of patients were living alone, and 14% shared a bedroom. Among the witnessed definite SUDEP patients, a tonic-clonic seizure was present in 95% of cases, compared with 21% in the autopsied non-SUDEP reference group, strengthening the notion that SUDEP in most cases is a seizure-related event, the researchers said.

Although sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS) and cardiac death have a higher incidence in the winter, the researchers did not find the same to be true in their SUDEP cohort. Furthermore, they did not find a preponderance for Mondays or morning hours, as reported for sudden cardiac death. The researchers did, however, find a clear diurnal variation, with the majority of cases dying during the night hours. Taken together, these findings prompted the researchers to conclude that the underlying mechanisms of SUDEP are different from those of SIDS and sudden cardiac death.

—Erica Tricarico

Suggested Reading

Sveinnson O, Andersson T, Carlsson S, Tomson T. Circumstances of SUDEP: a nationwide population-based case series. Epilepsia. 2018;59(5):1074-1082.

Novel initiative aims to combat resident burnout

TORONTO – Studies have demonstrated that up to 50% of medical residents meet criteria for burnout, but a new initiative aims to change that worrisome trend.

At the Pediatric Academic Societies meeting, Michael Dolinger, MD, shared initial results from ResiLIEnCE (Resident-led Initiative to Empower a Change in Culture and Promote Resilience), a curriculum that is being carried out at Cohen Children’s Medical Center, New York. “We know that medical residents are a prime target for work burnout,” said Dr. Dolinger, one of the center’s pediatric chief residents, in an interview. “We wanted to study what we can do to combat that burnout on a daily basis, a monthly basis, and a longitudinal basis. How specific can we get so it’s portable, and that other programs can adapt what we are doing to help reduce this burnout?”

Interventions were enacted during traditional pediatric resident work hours to improve attendance. These included a resident-led wellness committee with faculty leadership and wellness champions, a longitudinal noon conference lecture series on nutrition (with topics such as how to eat on a budget and quick meal options), financial health (with topics such as student loan repayment, budgeting on a resident’s salary, and retirement planning), mindfulness, and resiliency. Optional activities after work included personal fitness boot camps, a book club, a minority support group, and other peer interest groups. Maslach Burnout Inventories were distributed to residents before implementation of the curriculum and at 3-month intervals. Surveys at the completion of activities assessed the effectiveness of sessions.

A total of 100 pediatric residents were surveyed. Dr. Dolinger reported that before implementation of the curriculum, 41.0% of third-year residents admitted to “feeling burned out from my work” and to “feeling more callous since I took this job,” while 8.8% of rising first-year residents admitted to feeling burned out prior to starting residency. In addition, 3 months after the curriculum began, 48.0% of first-year, 23.5% of second-year, and 83.3% of third-year residents reported believing that residency interfered with their personal wellness.

Analysis of the curriculum’s impact is ongoing, but Dr. Dolinger reported that among those who attended a nutrition series, 80% of residents planned to eat healthier, while only 15% reported eating healthy prior to the session. Among those who attended a financial series, 50% of those who did not previously contribute to their retirement planned to do so. In addition, 80% of residents who attended a resident fitness workshop joined a local fitness center, compared with only 20% of residents prior. Among those who attended a lecture series on resiliency, 90% of residents indicated that they were able to reflect on a negative patient experience and learn something valuable.

“Hopefully this curriculum helps reduce the overall burnout in our residents over time, by increasing their aspects of well-being and promoting resilience for them individually,” Dr. Dolinger said.

The initiative was funded by the Association of Pediatric Program Directors via the Harvey Aiges Memorial Trainee Investigator Award. Dr. Dolinger reported having no financial disclosures.

TORONTO – Studies have demonstrated that up to 50% of medical residents meet criteria for burnout, but a new initiative aims to change that worrisome trend.

At the Pediatric Academic Societies meeting, Michael Dolinger, MD, shared initial results from ResiLIEnCE (Resident-led Initiative to Empower a Change in Culture and Promote Resilience), a curriculum that is being carried out at Cohen Children’s Medical Center, New York. “We know that medical residents are a prime target for work burnout,” said Dr. Dolinger, one of the center’s pediatric chief residents, in an interview. “We wanted to study what we can do to combat that burnout on a daily basis, a monthly basis, and a longitudinal basis. How specific can we get so it’s portable, and that other programs can adapt what we are doing to help reduce this burnout?”

Interventions were enacted during traditional pediatric resident work hours to improve attendance. These included a resident-led wellness committee with faculty leadership and wellness champions, a longitudinal noon conference lecture series on nutrition (with topics such as how to eat on a budget and quick meal options), financial health (with topics such as student loan repayment, budgeting on a resident’s salary, and retirement planning), mindfulness, and resiliency. Optional activities after work included personal fitness boot camps, a book club, a minority support group, and other peer interest groups. Maslach Burnout Inventories were distributed to residents before implementation of the curriculum and at 3-month intervals. Surveys at the completion of activities assessed the effectiveness of sessions.

A total of 100 pediatric residents were surveyed. Dr. Dolinger reported that before implementation of the curriculum, 41.0% of third-year residents admitted to “feeling burned out from my work” and to “feeling more callous since I took this job,” while 8.8% of rising first-year residents admitted to feeling burned out prior to starting residency. In addition, 3 months after the curriculum began, 48.0% of first-year, 23.5% of second-year, and 83.3% of third-year residents reported believing that residency interfered with their personal wellness.

Analysis of the curriculum’s impact is ongoing, but Dr. Dolinger reported that among those who attended a nutrition series, 80% of residents planned to eat healthier, while only 15% reported eating healthy prior to the session. Among those who attended a financial series, 50% of those who did not previously contribute to their retirement planned to do so. In addition, 80% of residents who attended a resident fitness workshop joined a local fitness center, compared with only 20% of residents prior. Among those who attended a lecture series on resiliency, 90% of residents indicated that they were able to reflect on a negative patient experience and learn something valuable.

“Hopefully this curriculum helps reduce the overall burnout in our residents over time, by increasing their aspects of well-being and promoting resilience for them individually,” Dr. Dolinger said.

The initiative was funded by the Association of Pediatric Program Directors via the Harvey Aiges Memorial Trainee Investigator Award. Dr. Dolinger reported having no financial disclosures.

TORONTO – Studies have demonstrated that up to 50% of medical residents meet criteria for burnout, but a new initiative aims to change that worrisome trend.

At the Pediatric Academic Societies meeting, Michael Dolinger, MD, shared initial results from ResiLIEnCE (Resident-led Initiative to Empower a Change in Culture and Promote Resilience), a curriculum that is being carried out at Cohen Children’s Medical Center, New York. “We know that medical residents are a prime target for work burnout,” said Dr. Dolinger, one of the center’s pediatric chief residents, in an interview. “We wanted to study what we can do to combat that burnout on a daily basis, a monthly basis, and a longitudinal basis. How specific can we get so it’s portable, and that other programs can adapt what we are doing to help reduce this burnout?”

Interventions were enacted during traditional pediatric resident work hours to improve attendance. These included a resident-led wellness committee with faculty leadership and wellness champions, a longitudinal noon conference lecture series on nutrition (with topics such as how to eat on a budget and quick meal options), financial health (with topics such as student loan repayment, budgeting on a resident’s salary, and retirement planning), mindfulness, and resiliency. Optional activities after work included personal fitness boot camps, a book club, a minority support group, and other peer interest groups. Maslach Burnout Inventories were distributed to residents before implementation of the curriculum and at 3-month intervals. Surveys at the completion of activities assessed the effectiveness of sessions.

A total of 100 pediatric residents were surveyed. Dr. Dolinger reported that before implementation of the curriculum, 41.0% of third-year residents admitted to “feeling burned out from my work” and to “feeling more callous since I took this job,” while 8.8% of rising first-year residents admitted to feeling burned out prior to starting residency. In addition, 3 months after the curriculum began, 48.0% of first-year, 23.5% of second-year, and 83.3% of third-year residents reported believing that residency interfered with their personal wellness.

Analysis of the curriculum’s impact is ongoing, but Dr. Dolinger reported that among those who attended a nutrition series, 80% of residents planned to eat healthier, while only 15% reported eating healthy prior to the session. Among those who attended a financial series, 50% of those who did not previously contribute to their retirement planned to do so. In addition, 80% of residents who attended a resident fitness workshop joined a local fitness center, compared with only 20% of residents prior. Among those who attended a lecture series on resiliency, 90% of residents indicated that they were able to reflect on a negative patient experience and learn something valuable.

“Hopefully this curriculum helps reduce the overall burnout in our residents over time, by increasing their aspects of well-being and promoting resilience for them individually,” Dr. Dolinger said.

The initiative was funded by the Association of Pediatric Program Directors via the Harvey Aiges Memorial Trainee Investigator Award. Dr. Dolinger reported having no financial disclosures.

REPORTING FROM PAS 2018

Key clinical point: Interventions targeted at specific aspects of resident well-being yielded tangible improvement in resident wellness behaviors.

Major finding: Among those who attended a nutrition series as part of the curriculum, 80% of residents planned to eat healthier, while only 15% reported eating healthy prior to the session.

Study details: A survey of 100 pediatric residents who took part in a Resident-led Initiative to Empower a Change in Culture and Promote Resilience.

Disclosures: The initiative was funded by the Association of Pediatric Program Directors via the Harvey Aiges Memorial Trainee Investigator Award. Dr. Dolinger reported having no financial disclosures.

Subcutaneous buprenorpine rivals sublingual for opioid use disorder

Long-acting subcutaneous doses of buprenorphine depot are an effective treatment option for opioid use disorder, results of a phase 3 study of 428 adults show.

Sublingual buprenorphine hydrochloride is a standard treatment for opioid use disorder (OUD), but challenges include poor medication adherence, potential for abuse, and accidental exposure to children, Michelle R. Lofwall, MD, of the University of Kentucky, Lexington, and her colleagues reported.

In a study published in JAMA Internal Medicine, Dr. Lofwall and her associates randomized treatment-seeking adults with moderate to severe opioid use disorder to subcutaneous buprenorphine depot weekly for 12 weeks followed by monthly for 12 weeks, or daily sublingual buprenorphine with naloxone for 24 weeks.

The proportion of opioid-negative urine samples was 35% in the subcutaneous buprenorphine depot group (1,347 of 3,834 samples) vs. 29% in the sublingual buprenorphine with naloxone group (1,099 of 3,870 samples) for a statistically significant difference of 6.7%. Urine samples were collected weekly for the first 12 weeks, and then at weeks 16, 20, and 24, reported Dr. Lofall, a psychiatrist and addiction medicine specialist, and her associates.

Patients in the sublingual buprenorphine with naloxone group received 4 mg of sublingual buprenorphine hydrochloride and naloxone hydrochloride at the start of the study, titrated to 16 mg/day. The average treatment dosage was 18-20 mg/day for sublingual buprenorphine with naloxone patients.

Patients in the subcutaneous buprenorphine depot group received 16 mg of subcutaneous buprenorphine in a weekly injection at the start of the study; monthly subcutaneous buprenorphine depot injections were 64, 96, 128, or 160 mg between weeks 12 and 24.

After initial titration, doses were flexible based on clinical judgment, the researchers noted, similar to the way in which patients would be managed in a clinical setting.

Adverse events were similar between the groups. The most common were injection-site pain, headache, constipation, nausea, and injection-site pruritus and erythema. Injection-site reactions were mild to moderate.

As a secondary outcome, the cumulative distribution function (CDF) in the subcutaneous buprenorphine depot group was statistically superior to the CDF found in the sublingual buprenorphine with naloxone in the percentage of opioid-negative results. “Cumulative distribution function values are an established endpoint used in early placebo-controlled, phase 3 clinical trials for OUD treatment,” Dr. Lofall and her associates wrote.

The study findings were limited by several factors, including an absence of assessment of patient adherence to sublingual medication and an inability to assess effectiveness vs. efficacy. However, the large size and diverse study population strengthen the results, which support the use of subcutaneous depot buprenorphine formulations for patients with OUD, the researchers noted.

“These formulations may also address potential limitations and concerns about daily dosing, including diversion, misuse, and accidental exposure of medication to children,” they said.

The study was supported in part by Braeburn Pharmaceuticals and the University of Kentucky, Lexington. Dr. Lofwall disclosed research funding and consulting fees from Braeburn Pharmaceuticals and Indivior.

SOURCE: Lofwall M et al. JAMA Intern Med. 2018 May 14. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.1052.

Long-acting subcutaneous doses of buprenorphine depot are an effective treatment option for opioid use disorder, results of a phase 3 study of 428 adults show.

Sublingual buprenorphine hydrochloride is a standard treatment for opioid use disorder (OUD), but challenges include poor medication adherence, potential for abuse, and accidental exposure to children, Michelle R. Lofwall, MD, of the University of Kentucky, Lexington, and her colleagues reported.

In a study published in JAMA Internal Medicine, Dr. Lofwall and her associates randomized treatment-seeking adults with moderate to severe opioid use disorder to subcutaneous buprenorphine depot weekly for 12 weeks followed by monthly for 12 weeks, or daily sublingual buprenorphine with naloxone for 24 weeks.

The proportion of opioid-negative urine samples was 35% in the subcutaneous buprenorphine depot group (1,347 of 3,834 samples) vs. 29% in the sublingual buprenorphine with naloxone group (1,099 of 3,870 samples) for a statistically significant difference of 6.7%. Urine samples were collected weekly for the first 12 weeks, and then at weeks 16, 20, and 24, reported Dr. Lofall, a psychiatrist and addiction medicine specialist, and her associates.

Patients in the sublingual buprenorphine with naloxone group received 4 mg of sublingual buprenorphine hydrochloride and naloxone hydrochloride at the start of the study, titrated to 16 mg/day. The average treatment dosage was 18-20 mg/day for sublingual buprenorphine with naloxone patients.

Patients in the subcutaneous buprenorphine depot group received 16 mg of subcutaneous buprenorphine in a weekly injection at the start of the study; monthly subcutaneous buprenorphine depot injections were 64, 96, 128, or 160 mg between weeks 12 and 24.

After initial titration, doses were flexible based on clinical judgment, the researchers noted, similar to the way in which patients would be managed in a clinical setting.