User login

Acne Treatment: Analysis of Acne-Related Social Media Posts and the Impact on Patient Care

Social media has become a prominent source of medical information for patients, including those with dermatologic conditions.1,2 Physicians, patients, and pharmaceutical companies can use social media platforms to communicate with each other and share knowledge and advertisements related to conditions. Social media can influence patients’ perceptions of their disease and serve as a modality to acquire medical treatments.3 Furthermore, social media posts from illicit pharmacies can result in patients buying harmful medications without physician oversight.4,5 Examination of the content and sources of social media posts related to acne may be useful in determining those who are primarily utilizing social media and for what purpose. The goal of this systematic review was to identify sources of acne-related social media posts to determine communication trends to gain a better understanding of the potential impact social media may have on patient care.

Methods

Social media posts were identified (May 2008 to May 2016) using the search terms acne and treatment across all social media platforms available through a commercial social media data aggregating software (Crimson Hexagon). Information from relevant posts was extracted and compiled into a spreadsheet that included the content, post date, social media platform, and hyperlink. To further analyze the data, the first 100 posts on acne treatment from May 2008 to May 2016 were selected and manually classified by the following types of communication: (1) patient-to-patient (eg, testimonies of patients’ medical experiences); (2) professional-to-patient (eg, clinical knowledge or experience provided by a medical provider and/or cited article in reference to relevant treatments); (3) pharmaceutical company–to-patient (eg, information from reputable drug manufacturers regarding drug activity and adverse effects); (4) illicit pharmacy–to-patient (eg, pharmacies with advertisements calling patients to buy a drug online or offering discrete shipping without a prescription)4,5; or (5) other-to-patient (eg, posts that did not contain enough detail to be classified).

Results

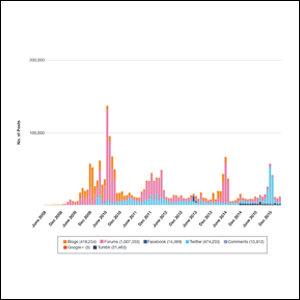

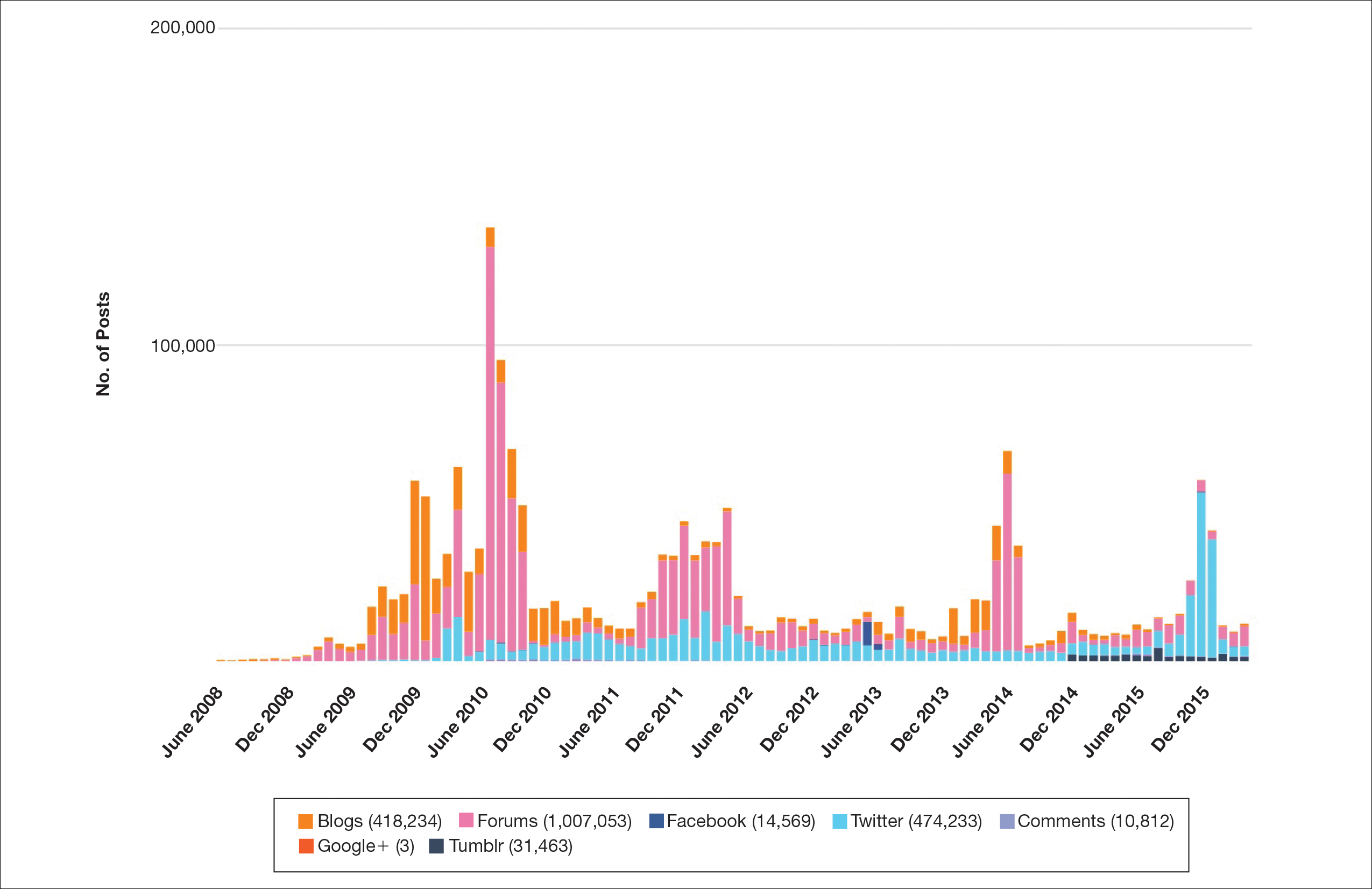

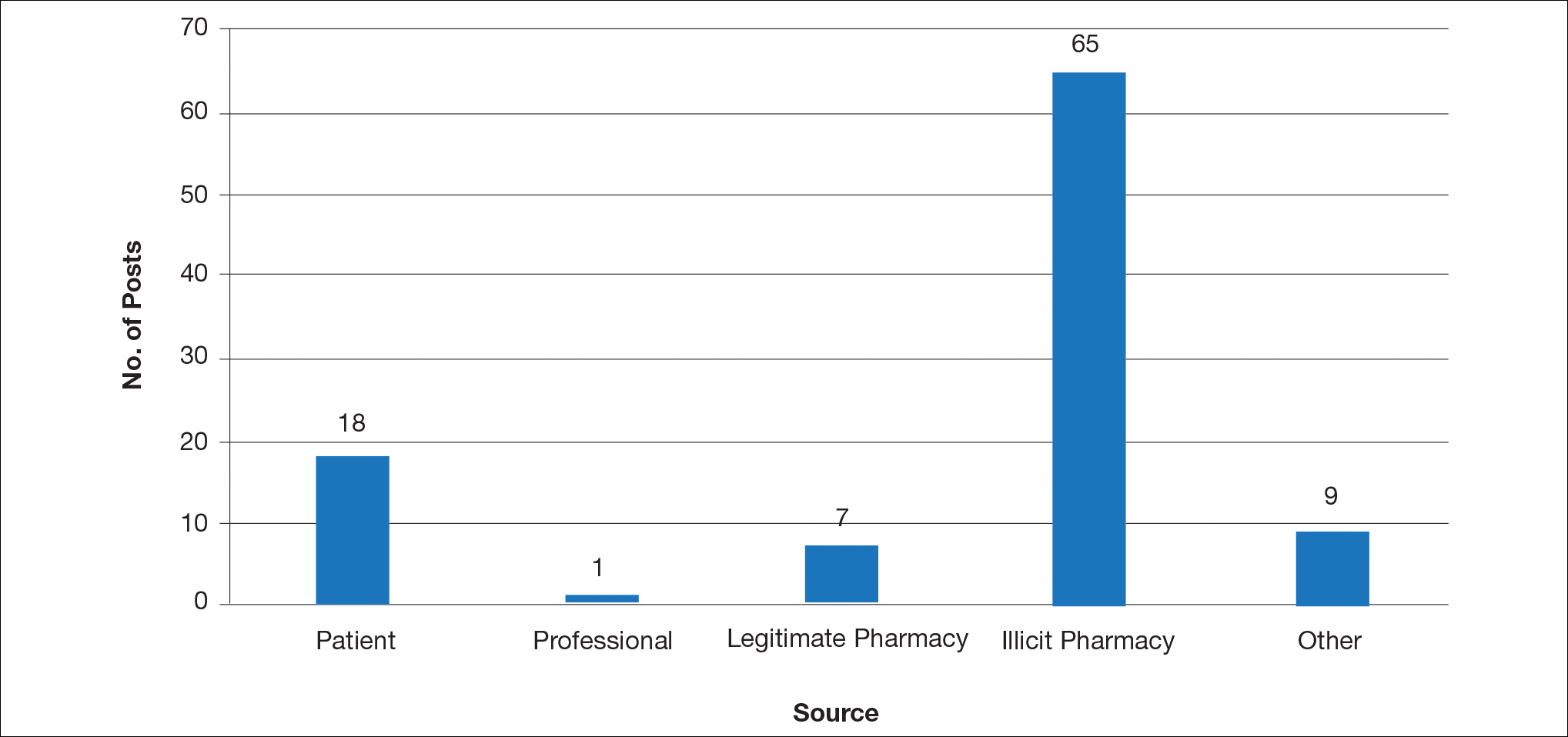

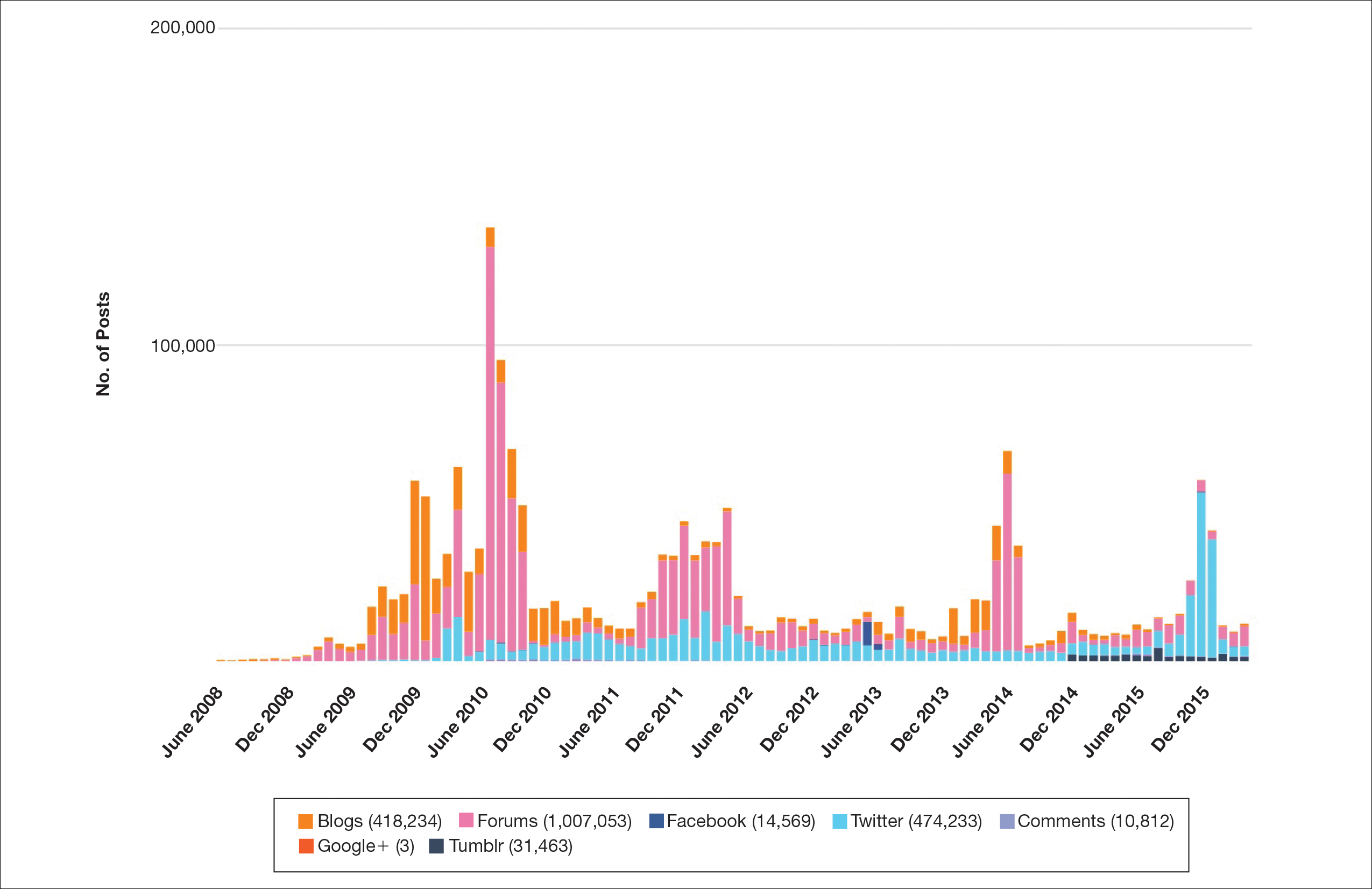

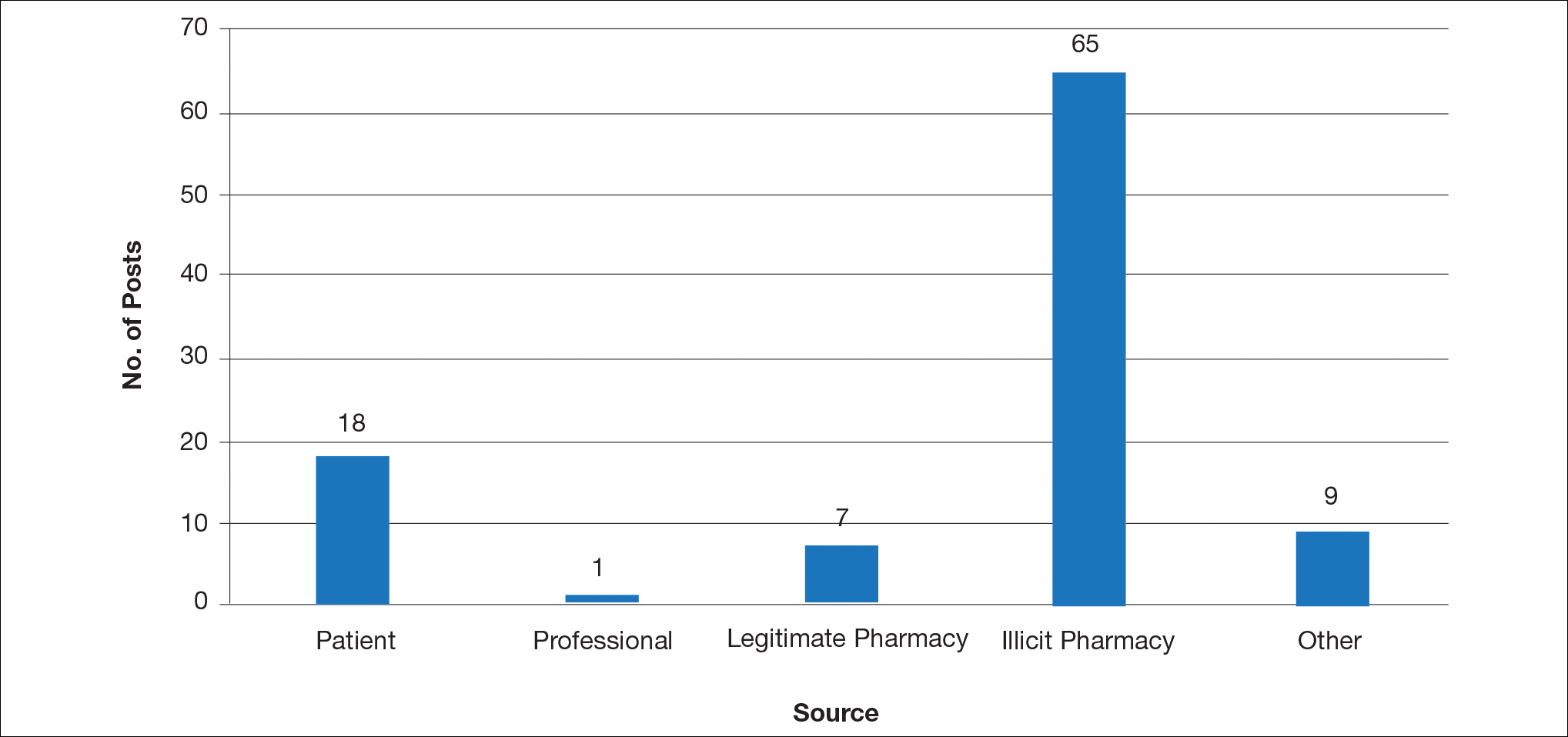

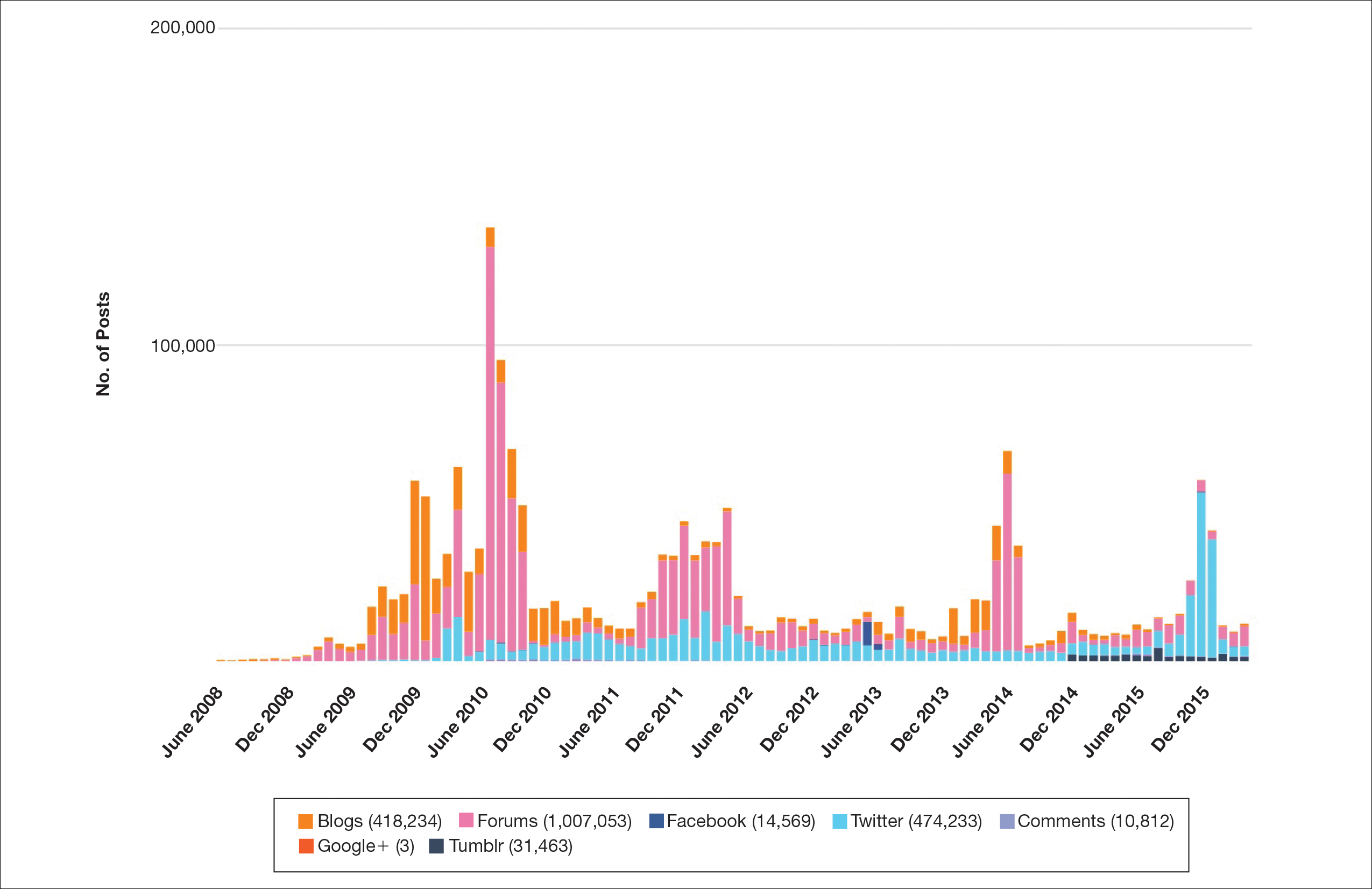

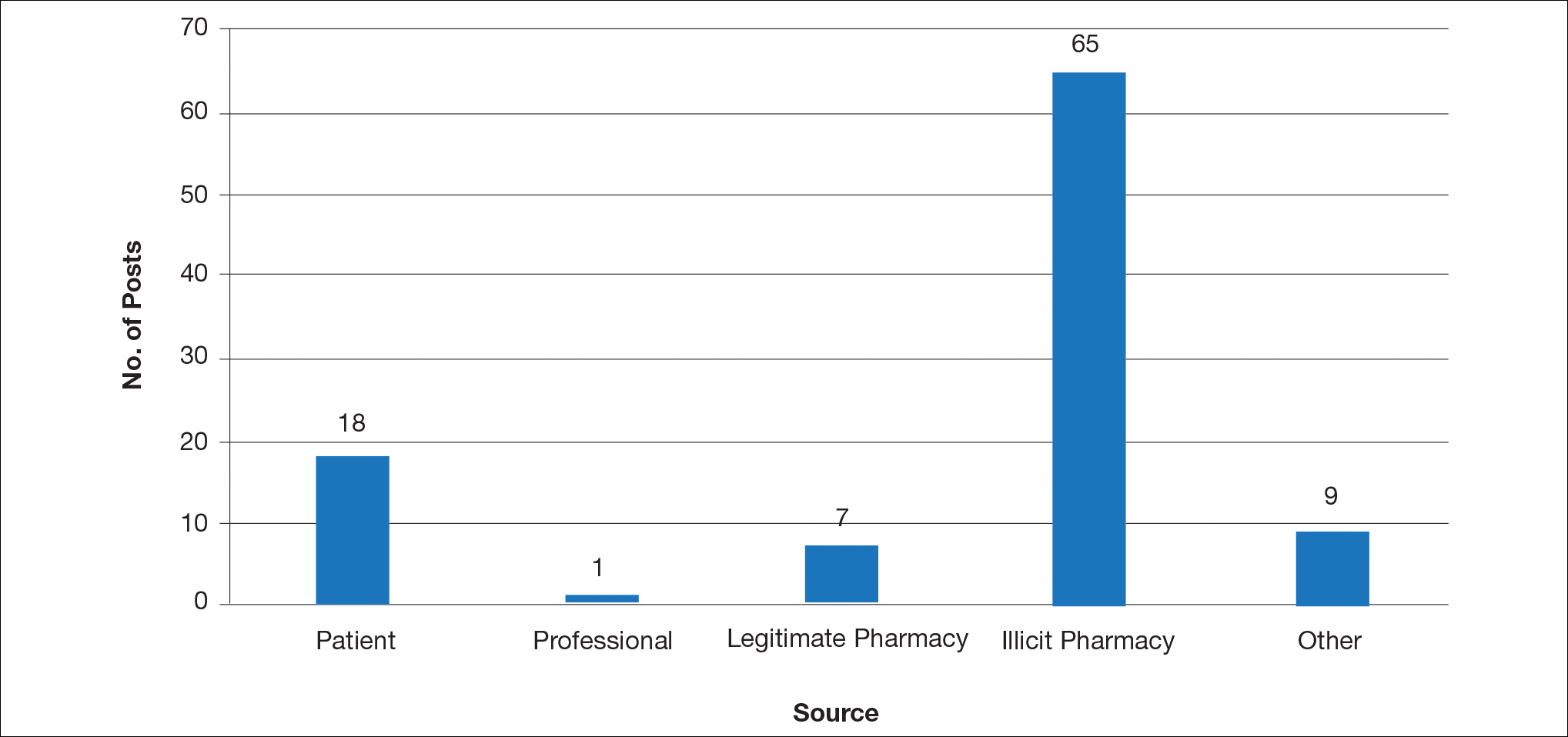

Hundreds of thousands of social media posts discussing acne treatment were identified over the 8-year study period (Figure 1). The social media data aggregator extracted posts from various blogs, website comment sections, and online forums, as well as major social media platforms (ie, Facebook, Twitter, Google+, Tumblr). The first 100 posts selected for further analysis included 0 from 2008, 6 from 2009, 36 from 2010, 15 from 2011, 7 from 2012, 8 from 2013, 12 from 2014, 11 from 2015, and 5 from 2016. From this sample, 65 posts were considered to have an illicit source; conversely, 18 posts were from patients and 7 posts were from pharmaceutical companies (Figure 2).

Comment

This study demonstrated that discussion of acne treatment is prevalent in social media. Although our research underrepresents the social media interest in specific acne treatments, as only posts mentioning the terms acne and treatment were evaluated to gain insights into how social media platforms are being used by individuals with cutaneous disease. As such, even with this potential underrepresentation, our study demonstrated a high incidence of illicit marketing of prescription acne medications across multiple social media platforms (Figure 2). The sale of dermatologic pharmaceuticals (eg, isotretinoin) without a prescription is recognized by the US Government as a problem that is rapidly growing.4,5 Illicit pharmacies pose as legitimate pharmacies that can provide prescription medications to consumers without a prescription.5,6 The fact that these illicit pharmacy–to-patient posts were the most abundant in our study may speak to their relative success on social media platforms in encouraging patients to purchase prescription medications without physician oversight. These findings should concern health care providers, as the procurement of prescription medications without a prescription may put patients at risk.

- Alinia H, Moradi Tuchayi S, Farhangian ME, et al. Rosacea patients seeking advice: qualitative analysis of patients’ posts on a rosacea support forum. J Dermatolog Treat. 2016;27:99-102.

- Karimkhani C, Connett J, Boyers L, et al. Dermatology on Instagram. Dermatology Online J. 2014:20. pii:13030/qt71g178w9.

- Smailhodzic E, Hooijsma W, Boonstra A, et al. Social media use in healthcare: a systematic review of effects on patients and on their relationship with healthcare professionals. BMC Health Serv Res. 2016;16:442.

- Lagan BM, Dolk H, White B, et al. Assessing the availability of the teratogenic drug isotretinoin outside the pregnancy prevention programme: a survey of e-pharmacies. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2014;23:411-418.

- Lott JP, Kovarik CL. Availability of oral isotretinoin and terbinafine on the Internet. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62:153-154.

- Mahé E, Beauchet A. Dermatologists and the Internet. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:908.

Social media has become a prominent source of medical information for patients, including those with dermatologic conditions.1,2 Physicians, patients, and pharmaceutical companies can use social media platforms to communicate with each other and share knowledge and advertisements related to conditions. Social media can influence patients’ perceptions of their disease and serve as a modality to acquire medical treatments.3 Furthermore, social media posts from illicit pharmacies can result in patients buying harmful medications without physician oversight.4,5 Examination of the content and sources of social media posts related to acne may be useful in determining those who are primarily utilizing social media and for what purpose. The goal of this systematic review was to identify sources of acne-related social media posts to determine communication trends to gain a better understanding of the potential impact social media may have on patient care.

Methods

Social media posts were identified (May 2008 to May 2016) using the search terms acne and treatment across all social media platforms available through a commercial social media data aggregating software (Crimson Hexagon). Information from relevant posts was extracted and compiled into a spreadsheet that included the content, post date, social media platform, and hyperlink. To further analyze the data, the first 100 posts on acne treatment from May 2008 to May 2016 were selected and manually classified by the following types of communication: (1) patient-to-patient (eg, testimonies of patients’ medical experiences); (2) professional-to-patient (eg, clinical knowledge or experience provided by a medical provider and/or cited article in reference to relevant treatments); (3) pharmaceutical company–to-patient (eg, information from reputable drug manufacturers regarding drug activity and adverse effects); (4) illicit pharmacy–to-patient (eg, pharmacies with advertisements calling patients to buy a drug online or offering discrete shipping without a prescription)4,5; or (5) other-to-patient (eg, posts that did not contain enough detail to be classified).

Results

Hundreds of thousands of social media posts discussing acne treatment were identified over the 8-year study period (Figure 1). The social media data aggregator extracted posts from various blogs, website comment sections, and online forums, as well as major social media platforms (ie, Facebook, Twitter, Google+, Tumblr). The first 100 posts selected for further analysis included 0 from 2008, 6 from 2009, 36 from 2010, 15 from 2011, 7 from 2012, 8 from 2013, 12 from 2014, 11 from 2015, and 5 from 2016. From this sample, 65 posts were considered to have an illicit source; conversely, 18 posts were from patients and 7 posts were from pharmaceutical companies (Figure 2).

Comment

This study demonstrated that discussion of acne treatment is prevalent in social media. Although our research underrepresents the social media interest in specific acne treatments, as only posts mentioning the terms acne and treatment were evaluated to gain insights into how social media platforms are being used by individuals with cutaneous disease. As such, even with this potential underrepresentation, our study demonstrated a high incidence of illicit marketing of prescription acne medications across multiple social media platforms (Figure 2). The sale of dermatologic pharmaceuticals (eg, isotretinoin) without a prescription is recognized by the US Government as a problem that is rapidly growing.4,5 Illicit pharmacies pose as legitimate pharmacies that can provide prescription medications to consumers without a prescription.5,6 The fact that these illicit pharmacy–to-patient posts were the most abundant in our study may speak to their relative success on social media platforms in encouraging patients to purchase prescription medications without physician oversight. These findings should concern health care providers, as the procurement of prescription medications without a prescription may put patients at risk.

Social media has become a prominent source of medical information for patients, including those with dermatologic conditions.1,2 Physicians, patients, and pharmaceutical companies can use social media platforms to communicate with each other and share knowledge and advertisements related to conditions. Social media can influence patients’ perceptions of their disease and serve as a modality to acquire medical treatments.3 Furthermore, social media posts from illicit pharmacies can result in patients buying harmful medications without physician oversight.4,5 Examination of the content and sources of social media posts related to acne may be useful in determining those who are primarily utilizing social media and for what purpose. The goal of this systematic review was to identify sources of acne-related social media posts to determine communication trends to gain a better understanding of the potential impact social media may have on patient care.

Methods

Social media posts were identified (May 2008 to May 2016) using the search terms acne and treatment across all social media platforms available through a commercial social media data aggregating software (Crimson Hexagon). Information from relevant posts was extracted and compiled into a spreadsheet that included the content, post date, social media platform, and hyperlink. To further analyze the data, the first 100 posts on acne treatment from May 2008 to May 2016 were selected and manually classified by the following types of communication: (1) patient-to-patient (eg, testimonies of patients’ medical experiences); (2) professional-to-patient (eg, clinical knowledge or experience provided by a medical provider and/or cited article in reference to relevant treatments); (3) pharmaceutical company–to-patient (eg, information from reputable drug manufacturers regarding drug activity and adverse effects); (4) illicit pharmacy–to-patient (eg, pharmacies with advertisements calling patients to buy a drug online or offering discrete shipping without a prescription)4,5; or (5) other-to-patient (eg, posts that did not contain enough detail to be classified).

Results

Hundreds of thousands of social media posts discussing acne treatment were identified over the 8-year study period (Figure 1). The social media data aggregator extracted posts from various blogs, website comment sections, and online forums, as well as major social media platforms (ie, Facebook, Twitter, Google+, Tumblr). The first 100 posts selected for further analysis included 0 from 2008, 6 from 2009, 36 from 2010, 15 from 2011, 7 from 2012, 8 from 2013, 12 from 2014, 11 from 2015, and 5 from 2016. From this sample, 65 posts were considered to have an illicit source; conversely, 18 posts were from patients and 7 posts were from pharmaceutical companies (Figure 2).

Comment

This study demonstrated that discussion of acne treatment is prevalent in social media. Although our research underrepresents the social media interest in specific acne treatments, as only posts mentioning the terms acne and treatment were evaluated to gain insights into how social media platforms are being used by individuals with cutaneous disease. As such, even with this potential underrepresentation, our study demonstrated a high incidence of illicit marketing of prescription acne medications across multiple social media platforms (Figure 2). The sale of dermatologic pharmaceuticals (eg, isotretinoin) without a prescription is recognized by the US Government as a problem that is rapidly growing.4,5 Illicit pharmacies pose as legitimate pharmacies that can provide prescription medications to consumers without a prescription.5,6 The fact that these illicit pharmacy–to-patient posts were the most abundant in our study may speak to their relative success on social media platforms in encouraging patients to purchase prescription medications without physician oversight. These findings should concern health care providers, as the procurement of prescription medications without a prescription may put patients at risk.

- Alinia H, Moradi Tuchayi S, Farhangian ME, et al. Rosacea patients seeking advice: qualitative analysis of patients’ posts on a rosacea support forum. J Dermatolog Treat. 2016;27:99-102.

- Karimkhani C, Connett J, Boyers L, et al. Dermatology on Instagram. Dermatology Online J. 2014:20. pii:13030/qt71g178w9.

- Smailhodzic E, Hooijsma W, Boonstra A, et al. Social media use in healthcare: a systematic review of effects on patients and on their relationship with healthcare professionals. BMC Health Serv Res. 2016;16:442.

- Lagan BM, Dolk H, White B, et al. Assessing the availability of the teratogenic drug isotretinoin outside the pregnancy prevention programme: a survey of e-pharmacies. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2014;23:411-418.

- Lott JP, Kovarik CL. Availability of oral isotretinoin and terbinafine on the Internet. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62:153-154.

- Mahé E, Beauchet A. Dermatologists and the Internet. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:908.

- Alinia H, Moradi Tuchayi S, Farhangian ME, et al. Rosacea patients seeking advice: qualitative analysis of patients’ posts on a rosacea support forum. J Dermatolog Treat. 2016;27:99-102.

- Karimkhani C, Connett J, Boyers L, et al. Dermatology on Instagram. Dermatology Online J. 2014:20. pii:13030/qt71g178w9.

- Smailhodzic E, Hooijsma W, Boonstra A, et al. Social media use in healthcare: a systematic review of effects on patients and on their relationship with healthcare professionals. BMC Health Serv Res. 2016;16:442.

- Lagan BM, Dolk H, White B, et al. Assessing the availability of the teratogenic drug isotretinoin outside the pregnancy prevention programme: a survey of e-pharmacies. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2014;23:411-418.

- Lott JP, Kovarik CL. Availability of oral isotretinoin and terbinafine on the Internet. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62:153-154.

- Mahé E, Beauchet A. Dermatologists and the Internet. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:908.

Practice Points

- Social media content can influence patients’ perceptions of their disease and serve as a modality to acquire medical treatments, though the source often is unknown.

- This study aimed to identify sources of acne-related social media posts to determine communication trends to gain a better understanding of the potential impact social media may have on patient care.

- Due to the potential for illicit marketing of prescription acne medications across multiple social media platforms, it is important to ask your patients what resources they use to learn about acne and offer to answer any questions regarding acne and its treatment.

CMS holds ACA risk adjustment payments following legal ruling

The risk adjustment payment uses statewide average premiums to draw money from health insurance plans within a state that have low levels of high-need patients and funnels that money to plans in that state with high amounts of high-need patients, as a way to minimize adverse selection and to spread risk.

The government was set to make a budget neutral payment of $10.4 billion for the 2017 plan year. But in a rare Saturday announcement, the agency said July 7 that the reason for putting the risk adjustment payments on hold was differing legal opinions on the validity of the payments.

The CMS filed a motion to reconsider following the New Mexico verdict, a hearing of which was held June 21.

“We are disappointed by the court’s recent ruling,” CMS Administrator Seema Verma said in a statement. “As a result of this litigation, billions of dollars in risk adjustment payments are now on hold. CMS has asked the court to reconsider its ruling, and hopes for a prompt resolution that allows CMS to prevent more adverse impacts on Americans who receive their insurance in the individual and small group markets.”

“We are very discouraged by the new market disruption brought about by the decision to freeze risk adjustment payments,” insurance trade group America’s Health Insurance Plans said in a statement. “The decision comes at a critical time when insurance providers are developing premiums for 2019 and states are reviewing rates. ... It will create more market uncertainty and increase premiums for many health plans.”

Likewise, the Blue Cross Blue Shield Association predicted higher premiums if the agency does not make payments.

““Without a quick resolution to this matter, this action will significantly increase 2019 premiums for millions of individuals and small business owners and could result in far fewer health plan choices,” BCBSA said in a statement. “It will undermine Americans’ access to affordable coverage, particularly for those who need medical care the most.”

The action comes as the Department of Justice is choosing not to defend the ACA in court against a lawsuit looking to declare the individual mandate unconstitutional in a case that would also eliminate the guaranteed issue provisions of the Affordable Care Act.

The risk adjustment payment uses statewide average premiums to draw money from health insurance plans within a state that have low levels of high-need patients and funnels that money to plans in that state with high amounts of high-need patients, as a way to minimize adverse selection and to spread risk.

The government was set to make a budget neutral payment of $10.4 billion for the 2017 plan year. But in a rare Saturday announcement, the agency said July 7 that the reason for putting the risk adjustment payments on hold was differing legal opinions on the validity of the payments.

The CMS filed a motion to reconsider following the New Mexico verdict, a hearing of which was held June 21.

“We are disappointed by the court’s recent ruling,” CMS Administrator Seema Verma said in a statement. “As a result of this litigation, billions of dollars in risk adjustment payments are now on hold. CMS has asked the court to reconsider its ruling, and hopes for a prompt resolution that allows CMS to prevent more adverse impacts on Americans who receive their insurance in the individual and small group markets.”

“We are very discouraged by the new market disruption brought about by the decision to freeze risk adjustment payments,” insurance trade group America’s Health Insurance Plans said in a statement. “The decision comes at a critical time when insurance providers are developing premiums for 2019 and states are reviewing rates. ... It will create more market uncertainty and increase premiums for many health plans.”

Likewise, the Blue Cross Blue Shield Association predicted higher premiums if the agency does not make payments.

““Without a quick resolution to this matter, this action will significantly increase 2019 premiums for millions of individuals and small business owners and could result in far fewer health plan choices,” BCBSA said in a statement. “It will undermine Americans’ access to affordable coverage, particularly for those who need medical care the most.”

The action comes as the Department of Justice is choosing not to defend the ACA in court against a lawsuit looking to declare the individual mandate unconstitutional in a case that would also eliminate the guaranteed issue provisions of the Affordable Care Act.

The risk adjustment payment uses statewide average premiums to draw money from health insurance plans within a state that have low levels of high-need patients and funnels that money to plans in that state with high amounts of high-need patients, as a way to minimize adverse selection and to spread risk.

The government was set to make a budget neutral payment of $10.4 billion for the 2017 plan year. But in a rare Saturday announcement, the agency said July 7 that the reason for putting the risk adjustment payments on hold was differing legal opinions on the validity of the payments.

The CMS filed a motion to reconsider following the New Mexico verdict, a hearing of which was held June 21.

“We are disappointed by the court’s recent ruling,” CMS Administrator Seema Verma said in a statement. “As a result of this litigation, billions of dollars in risk adjustment payments are now on hold. CMS has asked the court to reconsider its ruling, and hopes for a prompt resolution that allows CMS to prevent more adverse impacts on Americans who receive their insurance in the individual and small group markets.”

“We are very discouraged by the new market disruption brought about by the decision to freeze risk adjustment payments,” insurance trade group America’s Health Insurance Plans said in a statement. “The decision comes at a critical time when insurance providers are developing premiums for 2019 and states are reviewing rates. ... It will create more market uncertainty and increase premiums for many health plans.”

Likewise, the Blue Cross Blue Shield Association predicted higher premiums if the agency does not make payments.

““Without a quick resolution to this matter, this action will significantly increase 2019 premiums for millions of individuals and small business owners and could result in far fewer health plan choices,” BCBSA said in a statement. “It will undermine Americans’ access to affordable coverage, particularly for those who need medical care the most.”

The action comes as the Department of Justice is choosing not to defend the ACA in court against a lawsuit looking to declare the individual mandate unconstitutional in a case that would also eliminate the guaranteed issue provisions of the Affordable Care Act.

Oral arsenic/ATRA is noninferior to IV form in APML

For patients with non–high-risk acute promyelocytic leukemia (APML), the combination of an oral arsenic formulation and all-trans retinoic acid (ATRA) was noninferior to standard therapy with intravenous arsenic trioxide and ATRA, results of a randomized phase 3 trial show.

Among 109 patients with APML from one of 14 centers in China, the 2-year event-free survival rate after a median follow-up of 32 months was 97% for patients randomized to receive oral arsenic realgar-Indigo naturalis formula (RIF) plus ATRA, and 94% for patients randomized to IV arsenic trioxide plus ATRA, reported Hong-Hu Zhu, MD, of Peking University People’s Hospital in Beijing, China, and his colleagues.

“Our results suggest that non–high-risk acute promyelocytic leukemia can be cured using complete oral arsenic plus ATRA without conventional chemotherapy,” the investigators wrote. The report was published in The Lancet Oncology. “Although longer-term follow-up is needed to draw firm conclusions, our results support previously reported clinical and experimental evidence indicating that ATRA and arsenic act synergistically to eradicate acute promyelocytic leukemia.”

The combination of IV arsenic trioxide and ATRA has revolutionized the care of patients with APML, producing complete and durable remissions in more than 95% of patients with non–high-risk disease, defined as white blood cell counts of 10 x 109/L or less. The trial was designed to see whether an easier-to-administer all-oral regimen could be similarly efficacious and safe, the investigators said.

A total of 109 patients with newly diagnosed APML were randomly assigned on 2:1 basis to receive either RIF-ATRA (72 patients) or arsenic trioxide ATRA (37). Three patients in the oral arm and one in the arsenic trioxide arm did not receive the assigned therapy, but instead received ATRA and chemotherapy.

For induction, RIF was delivered 60 mg/kg daily in an oral divided dose; arsenic trioxide was delivered 0.15 mg/kg daily in an IV. ATRA was delivered 25 mg/m2 daily in an oral divided dose. Treatments were used until complete remissions were achieved.

Consolidation was home based and consisted of the same daily doses of RIF or arsenic trioxide in a 4-week-on/4-week-off regimen for four cycles, plus ATRA in the same daily dose in a 2-week-on/2-week-off regimen for seven cycles.

In a modified intention-to-treat analysis with 105 patients, 2-year EFS rates (the primary endpoint) were 97% with oral arsenic and 94% with arsenic trioxide. The percentage difference in EFS was 2.7% and RIF met the prespecified requirement for noninferiority because the lower limit of the 95% confidence interval (-5.8%) was greater than the noninferiority margin of –10%. The noninferiority of the oral formulation was confirmed in a per-protocol analysis, the investigators noted.

Grade 3 or 4 hepatotoxicities during induction were seen in 9% of patients treated with RIF-ATRA versus 14% of patients in the arsenic trioxide–ATRA group. Grade 3 or 4 infections occurred in 23% and 42% of patients, respectively.

Two patients in the arsenic trioxide–ATRA group died during induction therapy, one from hemorrhage and one from thrombocytopenia. There were no deaths during induction in the RIF-ATRA arm and no additional deaths in either arm during the consolidation phase.

All of the 103 surviving patients achieved complete remissions after consolidation.

The investigators acknowledged that the study was limited by a median follow-up time that was too short to allow definitive conclusions about overall survival. They plan to compare the costs of the two regimens in a future study.

SOURCE: Zhu HH et al. Lancet Oncol 2018;19:871-9.

The study by Dr. Zhu and colleagues advances the field of acute promyelocytic leukaemia treatment, but it also exposes important challenges in safely monitoring patients. Experienced hematologic oncologists are aware of the significant potential toxicity from arsenic treatment, including differentiation syndrome and thrombohemorrhagic events. Due to these potential complications, patients should always be managed in hospital during the first 2-3 weeks of induction, at least, so that they have the benefit of clinical and laboratory monitoring, transfusion support, and rapid supportive and therapeutic measures.

Francesco Lo-Coco, MD, and Laura Cicconi, MD, are with University Tor Vergata in Rome. Dr. Lo-Coco reported consultancy and speaker honoraria from Teva and Orsenix. Dr. Cicconi reported speaker honoraria from Teva. Their remarks are adapted and condensed from an accompanying editorial (Lancet Oncol. 2018;19:846-7).

The study by Dr. Zhu and colleagues advances the field of acute promyelocytic leukaemia treatment, but it also exposes important challenges in safely monitoring patients. Experienced hematologic oncologists are aware of the significant potential toxicity from arsenic treatment, including differentiation syndrome and thrombohemorrhagic events. Due to these potential complications, patients should always be managed in hospital during the first 2-3 weeks of induction, at least, so that they have the benefit of clinical and laboratory monitoring, transfusion support, and rapid supportive and therapeutic measures.

Francesco Lo-Coco, MD, and Laura Cicconi, MD, are with University Tor Vergata in Rome. Dr. Lo-Coco reported consultancy and speaker honoraria from Teva and Orsenix. Dr. Cicconi reported speaker honoraria from Teva. Their remarks are adapted and condensed from an accompanying editorial (Lancet Oncol. 2018;19:846-7).

The study by Dr. Zhu and colleagues advances the field of acute promyelocytic leukaemia treatment, but it also exposes important challenges in safely monitoring patients. Experienced hematologic oncologists are aware of the significant potential toxicity from arsenic treatment, including differentiation syndrome and thrombohemorrhagic events. Due to these potential complications, patients should always be managed in hospital during the first 2-3 weeks of induction, at least, so that they have the benefit of clinical and laboratory monitoring, transfusion support, and rapid supportive and therapeutic measures.

Francesco Lo-Coco, MD, and Laura Cicconi, MD, are with University Tor Vergata in Rome. Dr. Lo-Coco reported consultancy and speaker honoraria from Teva and Orsenix. Dr. Cicconi reported speaker honoraria from Teva. Their remarks are adapted and condensed from an accompanying editorial (Lancet Oncol. 2018;19:846-7).

For patients with non–high-risk acute promyelocytic leukemia (APML), the combination of an oral arsenic formulation and all-trans retinoic acid (ATRA) was noninferior to standard therapy with intravenous arsenic trioxide and ATRA, results of a randomized phase 3 trial show.

Among 109 patients with APML from one of 14 centers in China, the 2-year event-free survival rate after a median follow-up of 32 months was 97% for patients randomized to receive oral arsenic realgar-Indigo naturalis formula (RIF) plus ATRA, and 94% for patients randomized to IV arsenic trioxide plus ATRA, reported Hong-Hu Zhu, MD, of Peking University People’s Hospital in Beijing, China, and his colleagues.

“Our results suggest that non–high-risk acute promyelocytic leukemia can be cured using complete oral arsenic plus ATRA without conventional chemotherapy,” the investigators wrote. The report was published in The Lancet Oncology. “Although longer-term follow-up is needed to draw firm conclusions, our results support previously reported clinical and experimental evidence indicating that ATRA and arsenic act synergistically to eradicate acute promyelocytic leukemia.”

The combination of IV arsenic trioxide and ATRA has revolutionized the care of patients with APML, producing complete and durable remissions in more than 95% of patients with non–high-risk disease, defined as white blood cell counts of 10 x 109/L or less. The trial was designed to see whether an easier-to-administer all-oral regimen could be similarly efficacious and safe, the investigators said.

A total of 109 patients with newly diagnosed APML were randomly assigned on 2:1 basis to receive either RIF-ATRA (72 patients) or arsenic trioxide ATRA (37). Three patients in the oral arm and one in the arsenic trioxide arm did not receive the assigned therapy, but instead received ATRA and chemotherapy.

For induction, RIF was delivered 60 mg/kg daily in an oral divided dose; arsenic trioxide was delivered 0.15 mg/kg daily in an IV. ATRA was delivered 25 mg/m2 daily in an oral divided dose. Treatments were used until complete remissions were achieved.

Consolidation was home based and consisted of the same daily doses of RIF or arsenic trioxide in a 4-week-on/4-week-off regimen for four cycles, plus ATRA in the same daily dose in a 2-week-on/2-week-off regimen for seven cycles.

In a modified intention-to-treat analysis with 105 patients, 2-year EFS rates (the primary endpoint) were 97% with oral arsenic and 94% with arsenic trioxide. The percentage difference in EFS was 2.7% and RIF met the prespecified requirement for noninferiority because the lower limit of the 95% confidence interval (-5.8%) was greater than the noninferiority margin of –10%. The noninferiority of the oral formulation was confirmed in a per-protocol analysis, the investigators noted.

Grade 3 or 4 hepatotoxicities during induction were seen in 9% of patients treated with RIF-ATRA versus 14% of patients in the arsenic trioxide–ATRA group. Grade 3 or 4 infections occurred in 23% and 42% of patients, respectively.

Two patients in the arsenic trioxide–ATRA group died during induction therapy, one from hemorrhage and one from thrombocytopenia. There were no deaths during induction in the RIF-ATRA arm and no additional deaths in either arm during the consolidation phase.

All of the 103 surviving patients achieved complete remissions after consolidation.

The investigators acknowledged that the study was limited by a median follow-up time that was too short to allow definitive conclusions about overall survival. They plan to compare the costs of the two regimens in a future study.

SOURCE: Zhu HH et al. Lancet Oncol 2018;19:871-9.

For patients with non–high-risk acute promyelocytic leukemia (APML), the combination of an oral arsenic formulation and all-trans retinoic acid (ATRA) was noninferior to standard therapy with intravenous arsenic trioxide and ATRA, results of a randomized phase 3 trial show.

Among 109 patients with APML from one of 14 centers in China, the 2-year event-free survival rate after a median follow-up of 32 months was 97% for patients randomized to receive oral arsenic realgar-Indigo naturalis formula (RIF) plus ATRA, and 94% for patients randomized to IV arsenic trioxide plus ATRA, reported Hong-Hu Zhu, MD, of Peking University People’s Hospital in Beijing, China, and his colleagues.

“Our results suggest that non–high-risk acute promyelocytic leukemia can be cured using complete oral arsenic plus ATRA without conventional chemotherapy,” the investigators wrote. The report was published in The Lancet Oncology. “Although longer-term follow-up is needed to draw firm conclusions, our results support previously reported clinical and experimental evidence indicating that ATRA and arsenic act synergistically to eradicate acute promyelocytic leukemia.”

The combination of IV arsenic trioxide and ATRA has revolutionized the care of patients with APML, producing complete and durable remissions in more than 95% of patients with non–high-risk disease, defined as white blood cell counts of 10 x 109/L or less. The trial was designed to see whether an easier-to-administer all-oral regimen could be similarly efficacious and safe, the investigators said.

A total of 109 patients with newly diagnosed APML were randomly assigned on 2:1 basis to receive either RIF-ATRA (72 patients) or arsenic trioxide ATRA (37). Three patients in the oral arm and one in the arsenic trioxide arm did not receive the assigned therapy, but instead received ATRA and chemotherapy.

For induction, RIF was delivered 60 mg/kg daily in an oral divided dose; arsenic trioxide was delivered 0.15 mg/kg daily in an IV. ATRA was delivered 25 mg/m2 daily in an oral divided dose. Treatments were used until complete remissions were achieved.

Consolidation was home based and consisted of the same daily doses of RIF or arsenic trioxide in a 4-week-on/4-week-off regimen for four cycles, plus ATRA in the same daily dose in a 2-week-on/2-week-off regimen for seven cycles.

In a modified intention-to-treat analysis with 105 patients, 2-year EFS rates (the primary endpoint) were 97% with oral arsenic and 94% with arsenic trioxide. The percentage difference in EFS was 2.7% and RIF met the prespecified requirement for noninferiority because the lower limit of the 95% confidence interval (-5.8%) was greater than the noninferiority margin of –10%. The noninferiority of the oral formulation was confirmed in a per-protocol analysis, the investigators noted.

Grade 3 or 4 hepatotoxicities during induction were seen in 9% of patients treated with RIF-ATRA versus 14% of patients in the arsenic trioxide–ATRA group. Grade 3 or 4 infections occurred in 23% and 42% of patients, respectively.

Two patients in the arsenic trioxide–ATRA group died during induction therapy, one from hemorrhage and one from thrombocytopenia. There were no deaths during induction in the RIF-ATRA arm and no additional deaths in either arm during the consolidation phase.

All of the 103 surviving patients achieved complete remissions after consolidation.

The investigators acknowledged that the study was limited by a median follow-up time that was too short to allow definitive conclusions about overall survival. They plan to compare the costs of the two regimens in a future study.

SOURCE: Zhu HH et al. Lancet Oncol 2018;19:871-9.

FROM THE LANCET ONCOLOGY

Key clinical point:

Major finding: The 2-year event-free survival was 97% with oral arsenic/ATRA versus 94% with IV arsenic trioxide/ATRA.

Study details: Randomized open-label phase 3 trial of 109 patients with APML.

Disclosures: The National Natural Science Foundation of China, the Beijing Municipal Science and Technology Commission, and the National Key R&D Program of China supported the study. The investigators reported having no financial disclosures.

Source: Zhu HH et al. Lancet Oncol. 2018;19:871-9.

Intensive nonaspirin NSAID use linked to reduced ovarian cancer mortality

Intensive use of nonaspirin nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) was associated with improved survival of patients with serous ovarian cancer in a recent population-based study.

By contrast, any use of nonaspirin NSAIDs was not associated with survival benefit, according to the authors of the study, which was based on records for more than 4,000 patients in the Danish Cancer Registry.

“More intensive use of nonaspirin NSAIDs appears necessary to obtain a prognostic benefit,” wrote Freija Verdoodt, PhD, postdoctoral researcher with the Danish Cancer Society Research Center, Copenhagen and her coauthors. The report was published in Gynecologic Oncology.

In addition, there was a suggestion that use of these drugs was associated with increased mortality in patients that with nonserous ovarian cancer, Dr. Verdoodt and her colleagues noted.

The study population comprised 4,117 women who were alive 1 year after a diagnosis of epithelial ovarian cancer. Ovarian cancer–specific mortality, the primary outcome of the analysis, was evaluated in relation to postdiagnosis use of nonaspirin NSAIDs.

The investigators found that any postdiagnosis use of nonaspirin NSAIDs was not associated with a difference in mortality, with a hazard ratio of 0.97 (95% confidence interval, 0.87-1.08) after adjusting for factors such as age, clinical stage, and year of diagnosis.

“Nonaspirin NSAIDs are typically used sporadically, and thus limited use among a substantial proportion of the postdiagnosis users may have attenuated the mortality risk estimates of our main analysis,” Dr. Verdoodt and her coauthors wrote.

However, increasing cumulative dose was associated with decreases in mortality, with hazard ratios of 1.03, 0.96, and 0.75 for low, medium, and high cumulative doses, respectively.

Likewise, the intensity of use, defined as cumulative dose divided by the number of days between the first and most recent postdiagnosis NSAID prescription, was associated with decreased mortality, with hazard ratios of 1.04, 0.98, and 0.86 for low, medium, and high use intensity, the reported data show.

When stratified by tumor histology, the data showed an association between reduced ovarian cancer–specific mortality and serous ovarian tumors (hazard ratio, 0.87; 95% CI, 0.77-0.99), and post hoc analyses confirmed further reductions in mortality based on high cumulative doses, with a hazard ratio of 0.62, and high intensity of use, with a hazard ratio of 0.79.

Conversely, other histologies were associated with increases in ovarian cancer mortality, though the numbers of patients in these subgroups were small, limiting interpretation of the results, investigators said.

Prior to this study, there were few epidemiologic investigations of the impact of nonaspirin NSAIDs on ovarian cancer prognosis, and of those, most did not include separate estimates based on histological subtypes, according to the investigators.

Although this study suggests intensive nonaspirin NSAID use comes with a potential prognostic benefit, these drugs also have potential adverse effects, including serious cardiovascular adverse events, the investigators said.

“A consideration of such risks in the light of a survival benefit among poor-prognosis serous ovarian cancer patients should guide further research,” they wrote.

The study was supported by the Sapere Aude program of the Independent Research Fund Denmark and the Mermaid project. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Verdoodt F et al. Gynecol Oncol. 2018 Jun 27. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2018.06.018.

Intensive use of nonaspirin nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) was associated with improved survival of patients with serous ovarian cancer in a recent population-based study.

By contrast, any use of nonaspirin NSAIDs was not associated with survival benefit, according to the authors of the study, which was based on records for more than 4,000 patients in the Danish Cancer Registry.

“More intensive use of nonaspirin NSAIDs appears necessary to obtain a prognostic benefit,” wrote Freija Verdoodt, PhD, postdoctoral researcher with the Danish Cancer Society Research Center, Copenhagen and her coauthors. The report was published in Gynecologic Oncology.

In addition, there was a suggestion that use of these drugs was associated with increased mortality in patients that with nonserous ovarian cancer, Dr. Verdoodt and her colleagues noted.

The study population comprised 4,117 women who were alive 1 year after a diagnosis of epithelial ovarian cancer. Ovarian cancer–specific mortality, the primary outcome of the analysis, was evaluated in relation to postdiagnosis use of nonaspirin NSAIDs.

The investigators found that any postdiagnosis use of nonaspirin NSAIDs was not associated with a difference in mortality, with a hazard ratio of 0.97 (95% confidence interval, 0.87-1.08) after adjusting for factors such as age, clinical stage, and year of diagnosis.

“Nonaspirin NSAIDs are typically used sporadically, and thus limited use among a substantial proportion of the postdiagnosis users may have attenuated the mortality risk estimates of our main analysis,” Dr. Verdoodt and her coauthors wrote.

However, increasing cumulative dose was associated with decreases in mortality, with hazard ratios of 1.03, 0.96, and 0.75 for low, medium, and high cumulative doses, respectively.

Likewise, the intensity of use, defined as cumulative dose divided by the number of days between the first and most recent postdiagnosis NSAID prescription, was associated with decreased mortality, with hazard ratios of 1.04, 0.98, and 0.86 for low, medium, and high use intensity, the reported data show.

When stratified by tumor histology, the data showed an association between reduced ovarian cancer–specific mortality and serous ovarian tumors (hazard ratio, 0.87; 95% CI, 0.77-0.99), and post hoc analyses confirmed further reductions in mortality based on high cumulative doses, with a hazard ratio of 0.62, and high intensity of use, with a hazard ratio of 0.79.

Conversely, other histologies were associated with increases in ovarian cancer mortality, though the numbers of patients in these subgroups were small, limiting interpretation of the results, investigators said.

Prior to this study, there were few epidemiologic investigations of the impact of nonaspirin NSAIDs on ovarian cancer prognosis, and of those, most did not include separate estimates based on histological subtypes, according to the investigators.

Although this study suggests intensive nonaspirin NSAID use comes with a potential prognostic benefit, these drugs also have potential adverse effects, including serious cardiovascular adverse events, the investigators said.

“A consideration of such risks in the light of a survival benefit among poor-prognosis serous ovarian cancer patients should guide further research,” they wrote.

The study was supported by the Sapere Aude program of the Independent Research Fund Denmark and the Mermaid project. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Verdoodt F et al. Gynecol Oncol. 2018 Jun 27. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2018.06.018.

Intensive use of nonaspirin nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) was associated with improved survival of patients with serous ovarian cancer in a recent population-based study.

By contrast, any use of nonaspirin NSAIDs was not associated with survival benefit, according to the authors of the study, which was based on records for more than 4,000 patients in the Danish Cancer Registry.

“More intensive use of nonaspirin NSAIDs appears necessary to obtain a prognostic benefit,” wrote Freija Verdoodt, PhD, postdoctoral researcher with the Danish Cancer Society Research Center, Copenhagen and her coauthors. The report was published in Gynecologic Oncology.

In addition, there was a suggestion that use of these drugs was associated with increased mortality in patients that with nonserous ovarian cancer, Dr. Verdoodt and her colleagues noted.

The study population comprised 4,117 women who were alive 1 year after a diagnosis of epithelial ovarian cancer. Ovarian cancer–specific mortality, the primary outcome of the analysis, was evaluated in relation to postdiagnosis use of nonaspirin NSAIDs.

The investigators found that any postdiagnosis use of nonaspirin NSAIDs was not associated with a difference in mortality, with a hazard ratio of 0.97 (95% confidence interval, 0.87-1.08) after adjusting for factors such as age, clinical stage, and year of diagnosis.

“Nonaspirin NSAIDs are typically used sporadically, and thus limited use among a substantial proportion of the postdiagnosis users may have attenuated the mortality risk estimates of our main analysis,” Dr. Verdoodt and her coauthors wrote.

However, increasing cumulative dose was associated with decreases in mortality, with hazard ratios of 1.03, 0.96, and 0.75 for low, medium, and high cumulative doses, respectively.

Likewise, the intensity of use, defined as cumulative dose divided by the number of days between the first and most recent postdiagnosis NSAID prescription, was associated with decreased mortality, with hazard ratios of 1.04, 0.98, and 0.86 for low, medium, and high use intensity, the reported data show.

When stratified by tumor histology, the data showed an association between reduced ovarian cancer–specific mortality and serous ovarian tumors (hazard ratio, 0.87; 95% CI, 0.77-0.99), and post hoc analyses confirmed further reductions in mortality based on high cumulative doses, with a hazard ratio of 0.62, and high intensity of use, with a hazard ratio of 0.79.

Conversely, other histologies were associated with increases in ovarian cancer mortality, though the numbers of patients in these subgroups were small, limiting interpretation of the results, investigators said.

Prior to this study, there were few epidemiologic investigations of the impact of nonaspirin NSAIDs on ovarian cancer prognosis, and of those, most did not include separate estimates based on histological subtypes, according to the investigators.

Although this study suggests intensive nonaspirin NSAID use comes with a potential prognostic benefit, these drugs also have potential adverse effects, including serious cardiovascular adverse events, the investigators said.

“A consideration of such risks in the light of a survival benefit among poor-prognosis serous ovarian cancer patients should guide further research,” they wrote.

The study was supported by the Sapere Aude program of the Independent Research Fund Denmark and the Mermaid project. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Verdoodt F et al. Gynecol Oncol. 2018 Jun 27. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2018.06.018.

FROM GYNECOLOGIC ONCOLOGY

Key clinical point: Intensive use of nonaspirin nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) was associated with improved survival of patients with serous ovarian cancer

Major finding: Serous ovarian tumors were associated with reduced ovarian cancer-specific mortality (HR, 0.87; 95% CI, 0.77-0.99), while post hoc analyses confirmed further reductions in mortality based on high cumulative doses (HR, 0.62), and high use intensity (HR, 0.79).

Study details: A population-based study of the Danish Cancer Registry including 4,117 women alive at least 1 year after an ovarian cancer diagnosis.

Disclosures: The study was supported by the Sapere Aude program of the Independent Research Fund Denmark and the Mermaid project. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Verdoodt F et al. Gynecol Oncol. 2018 Jun 27. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2018.06.018.

Mutations may be detectable years before AML diagnosis

Individuals who develop acute myeloid leukemia (AML) may have somatic mutations detectable years before diagnosis, a newly published analysis shows.

Mutations in IDH1, IDH2, TP53, DNMT3A, TET2, and spliceosome genes at baseline assessment increased the odds of developing AML with a median follow-up of 9.6 years in the study, which was based on blood samples from participants in the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI).

The findings suggest a “premalignant landscape of mutations” that may precede overt AML by many years, according to Pinkal Desai, MD, assistant professor of medicine at Cornell University and oncologist at New York–Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center, New York, and her coauthors.

“The ability to detect and identify high-risk mutations suggests that monitoring strategies for patients, as well as clinical trials of potentially preventative or disease-intercepting interventions should be considered,” wrote Dr. Desai and her colleagues. The report was published in Nature Medicine.

Their analysis comprised 212 women who participated in the WHI who were healthy at the baseline evaluation but went on to develop AML during follow-up. They performed deep sequencing on peripheral blood DNA for these cases and for 212 age-matched controls.

Women who developed AML were more likely than were controls to have mutations in baseline assessment (odds ratio, 4.86; 95% confidence interval, 3.07-7.77), and had demonstrated greater clonal complexity versus controls (comutations in 46.8% and 5.5%, respectively; odds ratio, 9.01; 95% CI, 4.1-21.4), investigators found.

All 21 patients with TP53 mutations went on to develop AML, as did all 15 with IDH1 or IDH2 mutations and all 3 with RUNX1 mutations. Multivariate analysis showed that TP53, IDH1 and IDH2, TET2, DNMT3A and several spliceosome genes were associated with significantly increased odds of AML versus controls.

Based on these results, Dr. Desai and colleagues proposed that patients at increased AML risk should be followed in long-term monitoring studies that incorporate next-generation sequencing.

“Data from these studies will provide a robust rationale for clinical trials of preventative intervention strategies in populations at high risk of developing AML,” they wrote.

In clinical practice, monitoring individuals for AML-associated mutations will become more feasible as costs decrease and new therapies with favorable toxicity profiles are introduced, they added.

“Molecularly targeted therapy is already available for IDH2 mutations and is under development for mutations in other candidate genes found in this study including IDH1, TP53 and spliceosome genes,” they wrote.

The authors reported having no relevant financial disclosures. The WHI program is funded by the National Institutes of Health.

SOURCE: Desai P et al. Nat Med. 2018;24:1015-23.

Individuals who develop acute myeloid leukemia (AML) may have somatic mutations detectable years before diagnosis, a newly published analysis shows.

Mutations in IDH1, IDH2, TP53, DNMT3A, TET2, and spliceosome genes at baseline assessment increased the odds of developing AML with a median follow-up of 9.6 years in the study, which was based on blood samples from participants in the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI).

The findings suggest a “premalignant landscape of mutations” that may precede overt AML by many years, according to Pinkal Desai, MD, assistant professor of medicine at Cornell University and oncologist at New York–Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center, New York, and her coauthors.

“The ability to detect and identify high-risk mutations suggests that monitoring strategies for patients, as well as clinical trials of potentially preventative or disease-intercepting interventions should be considered,” wrote Dr. Desai and her colleagues. The report was published in Nature Medicine.

Their analysis comprised 212 women who participated in the WHI who were healthy at the baseline evaluation but went on to develop AML during follow-up. They performed deep sequencing on peripheral blood DNA for these cases and for 212 age-matched controls.

Women who developed AML were more likely than were controls to have mutations in baseline assessment (odds ratio, 4.86; 95% confidence interval, 3.07-7.77), and had demonstrated greater clonal complexity versus controls (comutations in 46.8% and 5.5%, respectively; odds ratio, 9.01; 95% CI, 4.1-21.4), investigators found.

All 21 patients with TP53 mutations went on to develop AML, as did all 15 with IDH1 or IDH2 mutations and all 3 with RUNX1 mutations. Multivariate analysis showed that TP53, IDH1 and IDH2, TET2, DNMT3A and several spliceosome genes were associated with significantly increased odds of AML versus controls.

Based on these results, Dr. Desai and colleagues proposed that patients at increased AML risk should be followed in long-term monitoring studies that incorporate next-generation sequencing.

“Data from these studies will provide a robust rationale for clinical trials of preventative intervention strategies in populations at high risk of developing AML,” they wrote.

In clinical practice, monitoring individuals for AML-associated mutations will become more feasible as costs decrease and new therapies with favorable toxicity profiles are introduced, they added.

“Molecularly targeted therapy is already available for IDH2 mutations and is under development for mutations in other candidate genes found in this study including IDH1, TP53 and spliceosome genes,” they wrote.

The authors reported having no relevant financial disclosures. The WHI program is funded by the National Institutes of Health.

SOURCE: Desai P et al. Nat Med. 2018;24:1015-23.

Individuals who develop acute myeloid leukemia (AML) may have somatic mutations detectable years before diagnosis, a newly published analysis shows.

Mutations in IDH1, IDH2, TP53, DNMT3A, TET2, and spliceosome genes at baseline assessment increased the odds of developing AML with a median follow-up of 9.6 years in the study, which was based on blood samples from participants in the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI).

The findings suggest a “premalignant landscape of mutations” that may precede overt AML by many years, according to Pinkal Desai, MD, assistant professor of medicine at Cornell University and oncologist at New York–Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center, New York, and her coauthors.

“The ability to detect and identify high-risk mutations suggests that monitoring strategies for patients, as well as clinical trials of potentially preventative or disease-intercepting interventions should be considered,” wrote Dr. Desai and her colleagues. The report was published in Nature Medicine.

Their analysis comprised 212 women who participated in the WHI who were healthy at the baseline evaluation but went on to develop AML during follow-up. They performed deep sequencing on peripheral blood DNA for these cases and for 212 age-matched controls.

Women who developed AML were more likely than were controls to have mutations in baseline assessment (odds ratio, 4.86; 95% confidence interval, 3.07-7.77), and had demonstrated greater clonal complexity versus controls (comutations in 46.8% and 5.5%, respectively; odds ratio, 9.01; 95% CI, 4.1-21.4), investigators found.

All 21 patients with TP53 mutations went on to develop AML, as did all 15 with IDH1 or IDH2 mutations and all 3 with RUNX1 mutations. Multivariate analysis showed that TP53, IDH1 and IDH2, TET2, DNMT3A and several spliceosome genes were associated with significantly increased odds of AML versus controls.

Based on these results, Dr. Desai and colleagues proposed that patients at increased AML risk should be followed in long-term monitoring studies that incorporate next-generation sequencing.

“Data from these studies will provide a robust rationale for clinical trials of preventative intervention strategies in populations at high risk of developing AML,” they wrote.

In clinical practice, monitoring individuals for AML-associated mutations will become more feasible as costs decrease and new therapies with favorable toxicity profiles are introduced, they added.

“Molecularly targeted therapy is already available for IDH2 mutations and is under development for mutations in other candidate genes found in this study including IDH1, TP53 and spliceosome genes,” they wrote.

The authors reported having no relevant financial disclosures. The WHI program is funded by the National Institutes of Health.

SOURCE: Desai P et al. Nat Med. 2018;24:1015-23.

FROM NATURE MEDICINE

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Compared with controls, those who eventually developed AML were more likely to have mutations (odds ratio, 4.86; 95% CI, 3.07-7.77) in baseline assessment at a median of 9.6 years before diagnosis.

Study details: Analysis of blood samples from 212 women who developed AML and 212 age-matched controls in the Women’s Health Initiative.

Disclosures: The researchers reported having no relevant financial disclosures. The WHI program is funded by the National Institutes of Health.

Source: Desai P et al. Nat Med. 2018;24:1015-23.

Diagnosis and Management of Aggressive B-Cell Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma

Abstract

- Objective: To review the diagnosis and management of aggressive B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL).

- Methods: Review of the literature.

- Results: NHL comprises a wide variety of malignant hematologic disorders with varying clinical and biological features. Aggressive NHLs are characterized by rapid clinical progression without therapy. However, a significant proportion of patients are cured with appropriate combination chemotherapy or combined modality regimens. In contrast, the indolent lymphomas have a relatively good prognosis (median survival of 10 years or longer) but usually are not curable in advanced clinical stages. Overall 5-year survival for aggressive NHLs with current treatment is approximately 50% to 60%, with relapses typically occurring within the first 5 years.

- Conclusion: Treatment strategies for relapsed patients offer some potential for cure; however, clinical trial participation should be encouraged whenever possible to investigate new approaches for improving outcomes in this patient population.

Non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) comprises a wide variety of malignant hematologic disorders with varying clinical and biological features. The more than 60 separate NHL subtypes can be classified according to cell of origin (B cell versus T cell), anatomical location (eg, orbital, testicular, bone, central nervous system), clinical behavior (indolent versus aggressive), histological features, or cytogenetic abnormalities. Although various NHL classification schemes have been used over the years, the World Health Organization (WHO) classification is now widely accepted as the definitive pathologic classification system for lymphoproliferative disorders, incorporating morphologic, immunohistochemical, flow cytometric, cytogenetic, and molecular features [1]. While the pathologic and molecular subclassification of NHL has become increasingly refined in recent years, from a management standpoint, classification based on clinical behavior remains very useful. This approach separates NHL subtypes into indolent versus aggressive categories. Whereas indolent NHLs may remain clinically insignificant for months to years, aggressive B-cell NHLs generally become life-threatening within weeks to months without treatment.

Epidemiology

Data from cancer registries show a steady, unexplainable increase in the incidence of NHL during the second half of the 20th century; the incidence has subsequently plateaued. There was a significant increase in NHL incidence between 1970 and 1995, which has been attributed in part to the HIV epidemic. More than 72,000 new cases of NHL were diagnosed in the United States in 2017, compared to just over 8000 cases of Hodgkin lymphoma, making NHL the sixth most common cancer in adult men and the fifth most common in adult women [2]. NHL appears to occur more frequently in Western countries than in Asian populations.

Various factors associated with increased risk for B-cell NHL have been identified over the years, including occupational and environmental exposure to certain pesticides and herbicides [3], immunosuppression associated with HIV infection [4], autoimmune disorders [5], iatrogenically induced immune suppression in the post-transplant and other settings [6], family history of NHL [7], and a personal history of a prior cancer, including Hodgkin lymphoma and prior NHL [8]. In terms of infectious agents associated with aggressive B-cell NHLs, Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) has a clear pathogenic role in Burkitt lymphoma, in many cases of post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorders, and in some cases of HIV-related aggressive B-cell lymphoma [9]. Human herpesvirus-8 viral genomes have been found in virtually all cases of primary effusion lymphomas [10]. Epidemiological studies also have linked hepatitis B and C to increased incidences of certain NHL subtypes [11–13], including primary hepatic diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL). Similarly, Helicobacter pylori has been associated with gastric DLBCL.

Staging and Workup

A tissue biopsy is essential in the diagnosis and management of NHL. The most significant disadvantage of fine-needle aspiration cytology is the lack of histologic architecture. The optimal specimen is an excisional biopsy; when this cannot be performed, a core needle biopsy, ideally using a 16-gauge or larger caliber needle, is the next best choice.

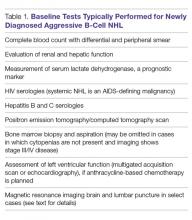

The baseline tests appropriate for most cases of newly diagnosed aggressive B-cell NHL are listed in Table 1.

Prior to the initiation of treatment, patients should always undergo a thorough cardiac and pulmonary evaluation, especially if the patient will be treated with an anthracycline or mediastinal irradiation. Central nervous system (CNS) evaluation with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and lumbar puncture is essential if there are neurological signs or symptoms. In addition, certain anatomical sites including the testicles, paranasal sinuses, kidney, adrenal glands, and epidural space have been associated with increased involvement of the CNS and may warrant MRI evaluation and lumbar puncture. Certain NHL subtypes like Burkitt lymphoma, high-grade NHL with translocations of MYC and BCL-2 or BCL-6 (double-hit lymphoma), blastoid mantle cell lymphoma, and lymphoblastic lymphoma have a high risk of CNS involvement, and patients with these subtypes need CNS evaluation.

The Lugano classification is used to stage patients with NHL [14]. This classification is based on the Ann Arbor staging system and uses the distribution and number of tumor sites to stage disease. In general, this staging system in isolation is of limited value in predicting survival after treatment. However, the Ann Arbor stage does have prognostic impact when incorporated into risk scoring systems such as the International Prognostic Index (IPI). In clinical practice, the Ann Arbor stage is useful primarily to determine eligibility for localized therapy approaches. The absence or presence of systemic symptoms such as fevers, drenching night sweats, or weight loss (> 10% of baseline over 6 months or less) is designated by A or B, respectively.

Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma

DLBCL is the most common lymphoid neoplasm in adults, accounting for about 25% of all NHL cases [2]. It is increasingly clear that the diagnostic category of DLBCL is quite heterogeneous in terms of morphology, genetics, and biologic behavior. A number of clinicopathologic subtypes of DLBCL exist, such as T cell/histiocyte–rich large B-cell lymphoma, primary mediastinal large B-cell lymphoma, intravascular large B-cell lymphoma, DLBCL associated with chronic inflammation, lymphomatoid granulomatosis, and EBV-positive large B-cell lymphoma, among others. Gene expression profiling (GEP) can distinguish 2 cell of origin DLBCL subtypes: the germinal center B-cell (GCB) and activated B-cell (ABC) subtypes [15].

DLBCL may be primary (de novo) or may arise through the transformation of many different types of low-grade B-cell lymphomas. This latter scenario is referred to as histologic transformation or transformed lymphoma. In some cases, patients may have a previously diagnosed low-grade B-cell NHL; in other cases, both low-grade and aggressive B-cell NHL may be diagnosed concurrently. The presence of elements of both low-grade and aggressive B-cell NHL in the same biopsy specimen is sometimes referred to as a composite lymphoma.

In the United States, incidence varies by ethnicity, with DLBCL being more common in Caucasians than other races [16]. There is a slight male predominance (55%), median age at diagnosis is 65 years [16,17] and the incidence increases with age.

Presentation, Pathology, and Prognostic Factors

The most common presentation of patients with DLBCL is rapidly enlarging lymphadenopathy, usually in the neck or abdomen. Extranodal/extramedullary presentation is seen in approximately 40% of cases, with the gastrointestinal (GI) tract being the most common site. However, extranodal DLBCL can arise in virtually any tissue [18]. Nodal DLBCL presents with symptoms related to the sites of involvement (eg, shortness of breath or chest pain with mediastinal lymphadenopathy), while extranodal DLBCL typically presents with symptoms secondary to dysfunction at the site of origin. Up to one third of patients present with constitutional symptoms (B symptoms) and more than 50% have elevated serum lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) at diagnosis [19].

Approximately 40% of patients present with stage I/II disease. Of these, only a subset present with stage I, or truly localized disease (defined as that which can be contained within 1 irradiation field). About 60% of patients present with advanced (stage III–IV) disease [20]. The bone marrow is involved in about 15% to 30% of cases. DLBCL involvement of the bone marrow is associated with a less favorable prognosis. Patients with DLBCL elsewhere may have low-grade NHL involvement of the bone marrow. Referred to as discordant bone marrow involvement [21], this feature does not carry the same poor prognosis associated with transformed disease [22] or DLBCL involvement of the bone marrow [23].

DLBCL is defined as a neoplasm of large B-lymphoid cells with a diffuse growth pattern. The proliferative fraction of cells, as determined by Ki-67 staining, is usually greater than 40%, and may even exceed 90%. Lymph nodes usually demonstrate complete effacement of the normal architecture by sheets of atypical lymphoid cells. Tumor cells in DLBCL generally express pan B-cell antigens (CD19, CD20, CD22, CD79a, Pax-5) as well as CD45 and surface immunoglobulin. Between 20% and 37% of DLBCL cases express the BCL-2 protein [24], and about 70% express the BCL-6 protein [25]. C-MYC protein expression is seen in a higher percentage (~ 30%–50%) of cases of DLBCL [26].

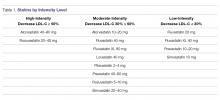

Many factors are associated with outcome in DLBCL. The IPI score was developed in the pre-rituximab era and is a robust prognostic tool. This simple tool uses 5 easily obtained clinical factors (age > 60 years, impaired performance status, elevated LDH, > 1 extranodal site of disease, and stage III/IV disease). By summing these factors, 4 groups with distinct 5-year overall survival (OS) rates ranging from 26% to 73% were identified (Table 2).

Cytogenetic and molecular factors also predict outcome in DLBCL. The ABC subtype distinguished by GEP has consistently been shown to have inferior outcomes with first-line therapy. As GEP is not routinely available in clinical practice, immunohistochemical (IHC) approaches (eg, the Hans algorithm) have been developed that can approximate the GEP subtypes. These IHC approaches have approximately 80% concordance with GEP [28]. The 3 most common chromosomal translocations in DLBCL involve BCL-2, BCL-6 and MYC. MYC-rearranged DLBCLs have a less favorable prognosis [29,30]. Cases in which a MYC translocation occurs in combination with a BCL-2 or BCL-6 translocation are commonly referred to as double-hit lymphoma (DHL); cases with all 3 translocations are referred to as triple-hit lymphoma (THL). Both DHL and THL have a worse prognosis with standard DLBCL therapy compared to non-DHL/THL cases. In the 2016 revised WHO classification, DHL and THL are an entity technically distinct from DLBCL, referred to as high-grade B-cell lymphoma [1]. In some cases, MYC and BCL-2 protein overexpression occurs in the absence of chromosomal translocations. Cases in which MYC and BCL-2 are overexpressed (by IHC) are referred to as double expressor lymphoma (DEL), and also have inferior outcome compared with non-DEL DLBCL [31,32]. Interestingly, MYC protein expression alone does not confer inferior outcomes, unlike isolated MYC translocation, which is associated with inferior outcomes.

Treatment

First-Line Therapy. DLBCL is an aggressive disease and, in most cases, survival without treatment can be measured in weeks to months. The advent of combination chemotherapy (CHOP [cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone] or CHOP-like regimens) led to disease-free survival (DFS) rates of 35% to 40% at 3 to 5 years [33]. The addition of rituximab to CHOP (R-CHOP) has improved both progression-free surivial (PFS) and OS [34,35].

Treatment options vary for patients with localized (stage I/II) and advanced (stage III/IV) disease. Options for limited-stage DLBCL include an abbreviated course of R-CHOP (3 or 4 cycles) with involved-field radiation therapy (IFRT) versus a full course (6–8 cycles) of R-CHOP without radiation therapy (RT). Most studies comparing combined modality therapy (chemotherapy plus RT) versus chemotherapy alone were conducted in the pre-rituximab era. With the introduction of rituximab, Persky and colleagues [36] studied the use of 3 cycles of R-CHOP followed by RT, demonstrating a slightly improved OS of 92% at 4 years as compared to 88% in a historical cohort. The French LYSA/GOELAMS group performed the only direct comparison in the rituximab era (4 cycles of R-CHOP followed by RT versus 4 cycles of R-CHOP followed by 2 additional cycles of R-CHOP) and reported similar outcomes between both arms [37], with OS of 92% in the R-CHOP alone arm and 96% in the R-CHOP + RT arm (nonsignificant difference statistically). IFRT alone is not recommended other than for palliation in patients who cannot tolerate chemotherapy or combined modality therapy. Stage I and II patients with bulky disease (> 10 cm) have a prognosis similar to patients with advanced DLBCL and should be treated aggressively with 6 to 8 cycles of R-CHOP with or without RT [36].

For patients with advanced stage disease, a full course of R-CHOP-21 (6–8 cycles given on a 21-day cycle) is the standard of care. This approach results in OS rates of 70% and 60% at 2 and 5 years, respectively. For older adults unable to tolerate full-dose R-CHOP, attenuated versions of R-CHOP with decreased dose density or decreased dose intensity have been developed [38]. Numerous randomized trials have attempted to improve upon the results of R-CHOP-21 using strategies such as infusional chemotherapy (DA-EPOCH-R [etoposide, prednisone, vincristine, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, rituximab]) [39]; dose-dense therapy (R-CHOP-14); replacement of rituximab with obinutuzuimab [40]; addition of novel agents such as bortezomib [41], lenalidomide[42], or ibrutinib [43,44] to R-CHOP; and various maintenance strategies such as rituximab, lenalidomide [45], enzastaurin [46], and everolimus [47]. Unfortunately, none of these strategies has been shown to improve OS in DLBCL. In part this appears to be due to the fact that inclusion/exclusion criteria for DLBCL trials have been too strict, such that the most severely ill DLBCL patients are typically not included. As a result, the results in the control arms have ended up better than what was expected based on historical data. Efforts are underway to include all patients in future first-line DLBCL studies.

Currently, autologous hematopoietic cell transplantation (auto-HCT) is not routinely used in the initial treatment of DLBCL. In the pre-rituximab era, numerous trials were conducted in DLBCL patients with high and/or high-intermediate risk disease based on the IPI score to determine if outcomes could be improved with high-dose therapy and auto-HCT as consolidation after patients achieved complete remission with first-line therapy. The results of these trials were conflicting. A 2003 meta-analysis of 11 such trials concluded that the results were very heterogeneous and showed no OS benefit [48]. More recently, the Southwestern Oncology Group published the results of a prospective trial testing the impact of auto-HCT for consolidation of aggressive NHL patients with an IPI score of 3 to 5 who achieved complete remission with first-line therapy with CHOP or R-CHOP. In this study, 75% of the patients had DLBCL and, of the B-cell NHL patients, 47% received R-CHOP. A survival benefit was seen only in the subgroup that had an IPI score of 4 or 5; a subgroup analysis restricted to those receiving R-CHOP as induction was not performed, however [49]. As a result, this area remains controversial, with most institutions not routinely performing auto-HCT for any DLBCL patients in first complete remission and some institutions considering auto-HCT in first complete remission for patients with an IPI score of 4 or 5. These studies all used the IPI score to identify high-risk patients. It is possible that the use of newer biomarkers or minimal-residual disease analysis will lead to a more robust algorithm for identifying high-risk patients and selecting patients who might benefit from consolidation of first complete remission with auto-HCT.

For patients with DHL or THL, long-term PFS with standard R-CHOP therapy is poor (20% to 40%) [50,51]. Treatment with more intensive first-line regimens such as DA-EPOCH-R, R-hyperCVAD (rituximab plus hyperfractionated cyclophosphamide, vincristine, doxorubicin, dexamethasone), or CODOX-M/IVAC±R (cyclophosphamide, vincristine, doxorubicin, high‐dose methotrexate/ifosfamide, etoposide, high‐dose cytarabine ± rituximab), along with CNS prophylaxis, however, has been shown to produce superior outcomes [52], with 3-year relapse-free survival rates of 88% compared to 56% for R-CHOP. For patients who achieve a complete response by PET/CT scan after intensive induction, consolidation with auto-HCT has not been shown to improve outcomes based on retrospective analysis. However for DHL/THL patients who achieve complete response after R-CHOP, PFS was improved if auto-HCT was given as consolidation of first remission [53].

Patients with DLBCL have an approximately 5% risk of subsequently developing CNS involvement. Historically (in the pre-rituximab era), patients who presented with multiple sites of extranodal disease and/or extensive bone marrow involvement and/or an elevated LDH had an increased risk (up to 20%–30%) of developing CNS involvement. In addition, patients with involvement of certain anatomical sites (testicular, paranasal sinuses, epidural space) had an increased risk of CNS disease. Several algorithms have been proposed to identify patients who should receive prophylactic CNS therapy. One of the most robust tools for this purpose is the CNS-IPI, which is a 6-point score consisting of the 5 IPI elements, plus 1 additional point if the adrenal glands or kidneys are involved. Importantly, the CNS-IPI was developed and validated in patients treated with R-CHOP-like therapy. Subsequent risk of CNS relapse was 0.6%, 3.4%, and 10.2% for those with low-, intermediate- and high-risk CNS-IPI scores, respectively [54]. A reasonable strategy, therefore, is to perform CNS prophylaxis in those with a CNS-IPI score of 4 to 6. When CNS prophylaxis is used, intrathecal methotrexate or high-dose systemic methotrexate is most frequently given, with high-dose systemic methotrexate favored over intrathecal chemotherapy given that high-dose methotrexate penetrates the brain and spinal cord parenchyma, in addition to treating the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) [55]. In contrast, intrathecal therapy only treats the CSF and requires repeated lumbar punctures or placement of an Ommaya reservoir. For DLBCL patients who present with active CSF involvement (known as lymphomatous meningitis), intrathecal chemotherapy treatments are typically given 2 or 3 times weekly until the CSF clears, followed by weekly intrathecal treatment for 4 weeks, and then monthly intrathecal treatment for 4 months [56]. For those with concurrent systemic and brain parenchymal DLBCL, a strategy of alternating R-CHOP with mid-cycle high-dose methotrexate can be successful. In addition, consolidation with high-dose therapy and auto-HCT improved survival in such patients in 1 retrospective series [57].

Relapsed/Refractory Disease. Between 30% and 40% of patients with advanced stage DLBCL will either fail to attain a remission with primary therapy (referred to as primary induction failure) or will relapse. In general, for those with progressive or relapsed disease, an updated tissue biopsy is recommended. This is especially true for patients who have had prior complete remission and have new lymph node enlargement, or those who have emergence of new sites of disease at the completion of first-line therapy.