User login

I want you to do my job

It is never easy to replace a legend. The Vascular Specialist that Russell Samson has left behind does not require saving. There are, however, problems ahead for all vascular surgeons, and my hope is to use this forum to unite us. Vascular surgery is a small specialty in an existential crisis. There are just over 3,000 of us in the United States. Think of Vascular Specialist as your hometown newspaper. Instead of high school sports and bake sales we will cover scientific meetings, clinical trials, and relevant legislation. And maybe the occasional swap meet.

Different points of view are going to be an essential part of this process. Russell Samson represented the posh, privileged world of private practice while I come from the rough and tumble streets of academia (just checking to see if he is still reading). My hope is to bring more. More Tips and Tricks, more Point/Counterpoint, more Letters to the Editor, more input from you.

How can you get involved? If you read something and have a response, send it to me. Volunteer to write up a technical tip or provide a medical debate. Have an idea for a guest editorial? Let me know, preferably before you write it. If it is good I will likely publish it. If not, well we can still be friends. Keep in mind, unlike book publishing, we work on strict deadlines. (To the three people I owe book chapters: Soon, I promise!) We will also be starting a vascular news section for brief committee updates, course registration openings, and relevant policy changes.

Vascular Specialist is now open for submissions. Contact us at [email protected].

It is never easy to replace a legend. The Vascular Specialist that Russell Samson has left behind does not require saving. There are, however, problems ahead for all vascular surgeons, and my hope is to use this forum to unite us. Vascular surgery is a small specialty in an existential crisis. There are just over 3,000 of us in the United States. Think of Vascular Specialist as your hometown newspaper. Instead of high school sports and bake sales we will cover scientific meetings, clinical trials, and relevant legislation. And maybe the occasional swap meet.

Different points of view are going to be an essential part of this process. Russell Samson represented the posh, privileged world of private practice while I come from the rough and tumble streets of academia (just checking to see if he is still reading). My hope is to bring more. More Tips and Tricks, more Point/Counterpoint, more Letters to the Editor, more input from you.

How can you get involved? If you read something and have a response, send it to me. Volunteer to write up a technical tip or provide a medical debate. Have an idea for a guest editorial? Let me know, preferably before you write it. If it is good I will likely publish it. If not, well we can still be friends. Keep in mind, unlike book publishing, we work on strict deadlines. (To the three people I owe book chapters: Soon, I promise!) We will also be starting a vascular news section for brief committee updates, course registration openings, and relevant policy changes.

Vascular Specialist is now open for submissions. Contact us at [email protected].

It is never easy to replace a legend. The Vascular Specialist that Russell Samson has left behind does not require saving. There are, however, problems ahead for all vascular surgeons, and my hope is to use this forum to unite us. Vascular surgery is a small specialty in an existential crisis. There are just over 3,000 of us in the United States. Think of Vascular Specialist as your hometown newspaper. Instead of high school sports and bake sales we will cover scientific meetings, clinical trials, and relevant legislation. And maybe the occasional swap meet.

Different points of view are going to be an essential part of this process. Russell Samson represented the posh, privileged world of private practice while I come from the rough and tumble streets of academia (just checking to see if he is still reading). My hope is to bring more. More Tips and Tricks, more Point/Counterpoint, more Letters to the Editor, more input from you.

How can you get involved? If you read something and have a response, send it to me. Volunteer to write up a technical tip or provide a medical debate. Have an idea for a guest editorial? Let me know, preferably before you write it. If it is good I will likely publish it. If not, well we can still be friends. Keep in mind, unlike book publishing, we work on strict deadlines. (To the three people I owe book chapters: Soon, I promise!) We will also be starting a vascular news section for brief committee updates, course registration openings, and relevant policy changes.

Vascular Specialist is now open for submissions. Contact us at [email protected].

Get up to Speed with VESAP4

With certification exams coming up, some surgeons may want to brush up.

The Vascular Educational Self-Assessment Program (VESAP), fourth edition, is a great study tool. As with previous editions, VESAP4 contains 10 topic sections, each with dozens of study and test questions, with 550 questions overall. VESAP4 offers both learning and testing modes, plus both Continuing Medical Education and Maintenance of Certification self-assessment credits. This edition also includes a mobile app (Apple products only) for off-line study. The program can be purchased as a comprehensive package or by individual modules. Package cost is $549 for members, $449 for candidates and $649 for non-members. Module pricing is $75, $65 and $85 per module, respectively.

With certification exams coming up, some surgeons may want to brush up.

The Vascular Educational Self-Assessment Program (VESAP), fourth edition, is a great study tool. As with previous editions, VESAP4 contains 10 topic sections, each with dozens of study and test questions, with 550 questions overall. VESAP4 offers both learning and testing modes, plus both Continuing Medical Education and Maintenance of Certification self-assessment credits. This edition also includes a mobile app (Apple products only) for off-line study. The program can be purchased as a comprehensive package or by individual modules. Package cost is $549 for members, $449 for candidates and $649 for non-members. Module pricing is $75, $65 and $85 per module, respectively.

With certification exams coming up, some surgeons may want to brush up.

The Vascular Educational Self-Assessment Program (VESAP), fourth edition, is a great study tool. As with previous editions, VESAP4 contains 10 topic sections, each with dozens of study and test questions, with 550 questions overall. VESAP4 offers both learning and testing modes, plus both Continuing Medical Education and Maintenance of Certification self-assessment credits. This edition also includes a mobile app (Apple products only) for off-line study. The program can be purchased as a comprehensive package or by individual modules. Package cost is $549 for members, $449 for candidates and $649 for non-members. Module pricing is $75, $65 and $85 per module, respectively.

Familial risk of myeloid malignancies

A large study has revealed “the strongest evidence yet” supporting genetic susceptibility to myeloid malignancies, according to a researcher.

The study showed that first-degree relatives of patients with myeloid malignancies had double the risk of developing a myeloid malignancy themselves, when compared to the general population.

The researchers observed significant risks for developing acute myeloid leukemia (AML), myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS), essential thrombocythemia (ET), and polycythemia vera (PV).

“Our study provides the strongest evidence yet for inherited risk for these diseases—evidence that has proved evasive before, in part, because these cancers are relatively uncommon, and our ability to characterize these diseases has, until recently, been limited,” said Amit Sud, MBChB, PhD, of The Institute of Cancer Research in London, UK.

Dr Sud and his colleagues described their research in a letter to Blood.

The researchers analyzed data from the Swedish Family-Cancer Database, which included 93,199 first-degree relatives of 35,037 patients with myeloid malignancies. The patients had been diagnosed between 1958 and 2015.

First-degree relatives of the patients had an increased risk of all myeloid malignancies, with a standardized incidence ratio (SIR) of 1.99 (95% CI 1.12-2.04).

For individual diseases, there was a significant association between family history and increased risk for:

- AML—SIR=1.53 (95% CI 1.21-2.17)

- ET—SIR=6.30 (95% CI 3.95-9.54)

- MDS—SIR=6.87 (95% CI 4.07-10.86)

- PV—SIR=7.66 (95% CI 5.74-10.02).

Dr Sud and his colleagues noted that the strongest familial relative risks tended to occur for the same disease, but there were significant associations between different myeloid malignancies as well.

Risk by age group

The researchers also looked at familial relative risk for the same disease by patients’ age at diagnosis and observed a significantly increased risk for younger cases for all myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPNs) combined, PV, and MDS.

The SIRs for MPNs were 6.46 (95% CI 5.12-8.04) for patients age 59 or younger and 4.15 (95% CI 3.38-5.04) for patients older than 59.

The SIRs for PV were 10.90 (95% CI 7.12-15.97) for patients age 59 or younger and 5.96 (95% CI 3.93-8.67) for patients older than 59.

The SIRs for MDS were 11.95 (95% CI 6.36-20.43) for patients age 68 or younger and 3.27 (95% CI 1.06-7.63) for patients older than 68.

Risk by number of relatives

Dr Sud and his colleagues also discovered that familial relative risks of all myeloid malignancies and MPNs were significantly associated with the number of first-degree relatives affected by myeloid malignancies or MPNs.

The SIRs for first-degree relatives with 2 or more affected relatives were 4.55 (95% CI 2.08-8.64) for all myeloid malignancies and 17.82 (95% CI 5.79-24.89) for MPNs.

The SIRs for first-degree relatives with 1 affected relative were 1.96 (95% CI 1.79-2.15) for all myeloid malignancies and 4.83 (95% CI 4.14-5.60) for MPNs.

The researchers said these results suggest inherited genetic changes increase the risk of myeloid malignancies, although environmental factors shared in families could also play a role.

“In the future, our findings could help identify people at higher risk than normal because of their family background who could be prioritized for medical help like screening to catch the disease earlier if it arises,” Dr Sud said.

This study was funded by German Cancer Aid, the Swedish Research Council, ALF funding from Region Skåne, DKFZ, and Bloodwise.

A large study has revealed “the strongest evidence yet” supporting genetic susceptibility to myeloid malignancies, according to a researcher.

The study showed that first-degree relatives of patients with myeloid malignancies had double the risk of developing a myeloid malignancy themselves, when compared to the general population.

The researchers observed significant risks for developing acute myeloid leukemia (AML), myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS), essential thrombocythemia (ET), and polycythemia vera (PV).

“Our study provides the strongest evidence yet for inherited risk for these diseases—evidence that has proved evasive before, in part, because these cancers are relatively uncommon, and our ability to characterize these diseases has, until recently, been limited,” said Amit Sud, MBChB, PhD, of The Institute of Cancer Research in London, UK.

Dr Sud and his colleagues described their research in a letter to Blood.

The researchers analyzed data from the Swedish Family-Cancer Database, which included 93,199 first-degree relatives of 35,037 patients with myeloid malignancies. The patients had been diagnosed between 1958 and 2015.

First-degree relatives of the patients had an increased risk of all myeloid malignancies, with a standardized incidence ratio (SIR) of 1.99 (95% CI 1.12-2.04).

For individual diseases, there was a significant association between family history and increased risk for:

- AML—SIR=1.53 (95% CI 1.21-2.17)

- ET—SIR=6.30 (95% CI 3.95-9.54)

- MDS—SIR=6.87 (95% CI 4.07-10.86)

- PV—SIR=7.66 (95% CI 5.74-10.02).

Dr Sud and his colleagues noted that the strongest familial relative risks tended to occur for the same disease, but there were significant associations between different myeloid malignancies as well.

Risk by age group

The researchers also looked at familial relative risk for the same disease by patients’ age at diagnosis and observed a significantly increased risk for younger cases for all myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPNs) combined, PV, and MDS.

The SIRs for MPNs were 6.46 (95% CI 5.12-8.04) for patients age 59 or younger and 4.15 (95% CI 3.38-5.04) for patients older than 59.

The SIRs for PV were 10.90 (95% CI 7.12-15.97) for patients age 59 or younger and 5.96 (95% CI 3.93-8.67) for patients older than 59.

The SIRs for MDS were 11.95 (95% CI 6.36-20.43) for patients age 68 or younger and 3.27 (95% CI 1.06-7.63) for patients older than 68.

Risk by number of relatives

Dr Sud and his colleagues also discovered that familial relative risks of all myeloid malignancies and MPNs were significantly associated with the number of first-degree relatives affected by myeloid malignancies or MPNs.

The SIRs for first-degree relatives with 2 or more affected relatives were 4.55 (95% CI 2.08-8.64) for all myeloid malignancies and 17.82 (95% CI 5.79-24.89) for MPNs.

The SIRs for first-degree relatives with 1 affected relative were 1.96 (95% CI 1.79-2.15) for all myeloid malignancies and 4.83 (95% CI 4.14-5.60) for MPNs.

The researchers said these results suggest inherited genetic changes increase the risk of myeloid malignancies, although environmental factors shared in families could also play a role.

“In the future, our findings could help identify people at higher risk than normal because of their family background who could be prioritized for medical help like screening to catch the disease earlier if it arises,” Dr Sud said.

This study was funded by German Cancer Aid, the Swedish Research Council, ALF funding from Region Skåne, DKFZ, and Bloodwise.

A large study has revealed “the strongest evidence yet” supporting genetic susceptibility to myeloid malignancies, according to a researcher.

The study showed that first-degree relatives of patients with myeloid malignancies had double the risk of developing a myeloid malignancy themselves, when compared to the general population.

The researchers observed significant risks for developing acute myeloid leukemia (AML), myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS), essential thrombocythemia (ET), and polycythemia vera (PV).

“Our study provides the strongest evidence yet for inherited risk for these diseases—evidence that has proved evasive before, in part, because these cancers are relatively uncommon, and our ability to characterize these diseases has, until recently, been limited,” said Amit Sud, MBChB, PhD, of The Institute of Cancer Research in London, UK.

Dr Sud and his colleagues described their research in a letter to Blood.

The researchers analyzed data from the Swedish Family-Cancer Database, which included 93,199 first-degree relatives of 35,037 patients with myeloid malignancies. The patients had been diagnosed between 1958 and 2015.

First-degree relatives of the patients had an increased risk of all myeloid malignancies, with a standardized incidence ratio (SIR) of 1.99 (95% CI 1.12-2.04).

For individual diseases, there was a significant association between family history and increased risk for:

- AML—SIR=1.53 (95% CI 1.21-2.17)

- ET—SIR=6.30 (95% CI 3.95-9.54)

- MDS—SIR=6.87 (95% CI 4.07-10.86)

- PV—SIR=7.66 (95% CI 5.74-10.02).

Dr Sud and his colleagues noted that the strongest familial relative risks tended to occur for the same disease, but there were significant associations between different myeloid malignancies as well.

Risk by age group

The researchers also looked at familial relative risk for the same disease by patients’ age at diagnosis and observed a significantly increased risk for younger cases for all myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPNs) combined, PV, and MDS.

The SIRs for MPNs were 6.46 (95% CI 5.12-8.04) for patients age 59 or younger and 4.15 (95% CI 3.38-5.04) for patients older than 59.

The SIRs for PV were 10.90 (95% CI 7.12-15.97) for patients age 59 or younger and 5.96 (95% CI 3.93-8.67) for patients older than 59.

The SIRs for MDS were 11.95 (95% CI 6.36-20.43) for patients age 68 or younger and 3.27 (95% CI 1.06-7.63) for patients older than 68.

Risk by number of relatives

Dr Sud and his colleagues also discovered that familial relative risks of all myeloid malignancies and MPNs were significantly associated with the number of first-degree relatives affected by myeloid malignancies or MPNs.

The SIRs for first-degree relatives with 2 or more affected relatives were 4.55 (95% CI 2.08-8.64) for all myeloid malignancies and 17.82 (95% CI 5.79-24.89) for MPNs.

The SIRs for first-degree relatives with 1 affected relative were 1.96 (95% CI 1.79-2.15) for all myeloid malignancies and 4.83 (95% CI 4.14-5.60) for MPNs.

The researchers said these results suggest inherited genetic changes increase the risk of myeloid malignancies, although environmental factors shared in families could also play a role.

“In the future, our findings could help identify people at higher risk than normal because of their family background who could be prioritized for medical help like screening to catch the disease earlier if it arises,” Dr Sud said.

This study was funded by German Cancer Aid, the Swedish Research Council, ALF funding from Region Skåne, DKFZ, and Bloodwise.

Man, 25, With Sinus Pain, Sore Throat, and Rash

A 25-year-old white man presents to urgent care with a nine-day history of increasing sinus pressure, mild sore throat, dry cough, and low-grade fever. Physical exam of the ears, nose, throat, and chest is unremarkable, but the patient does display mild maxillary sinus tenderness. Sinus pain (and symptom duration) is the primary complaint. The patient was recently exposed to influenza B, but a rapid flu test is negative. A five-day course of amoxicillin-clavulanate is prescribed for a presumed diagnosis of bacterial sinusitis.

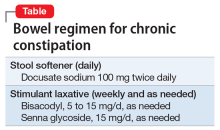

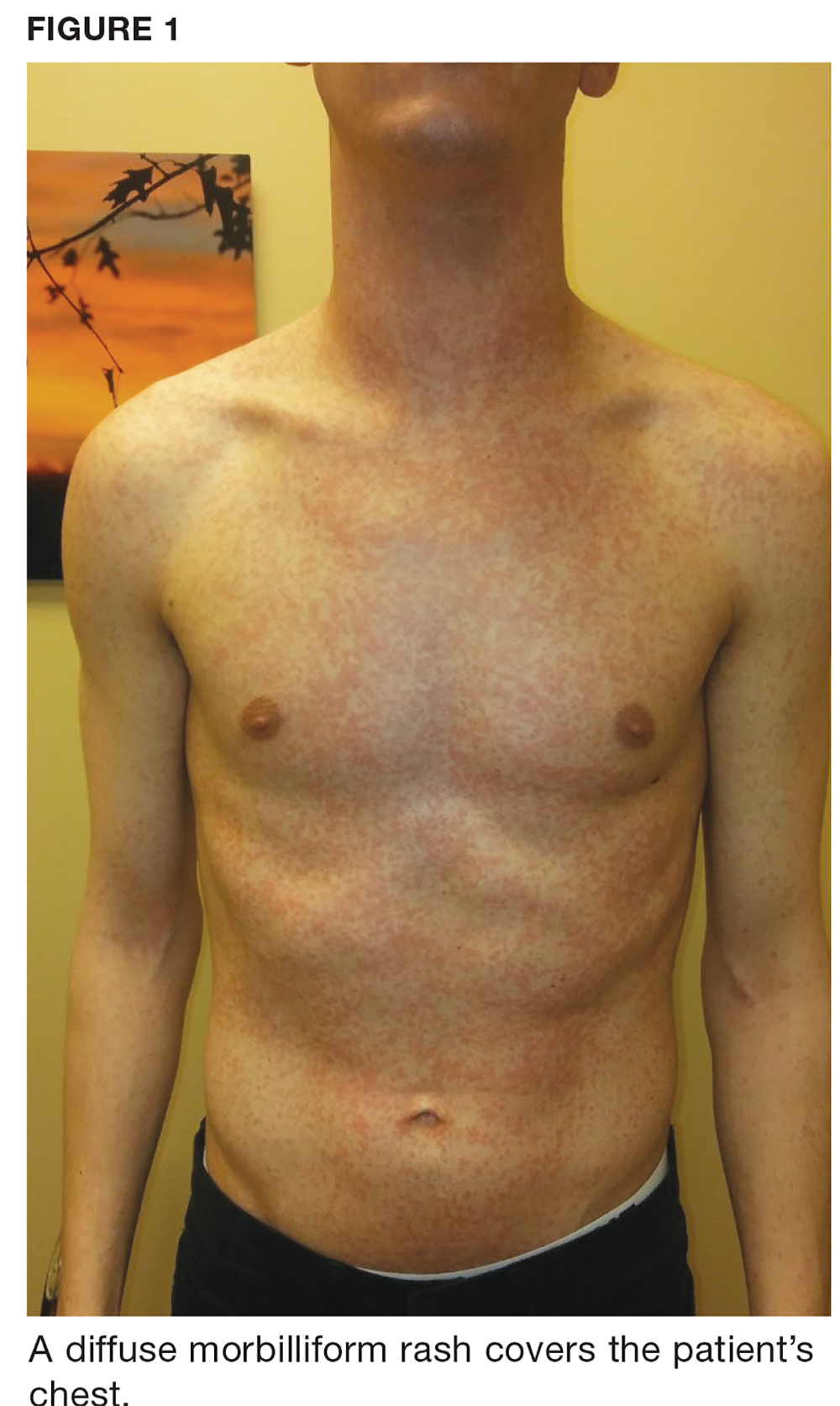

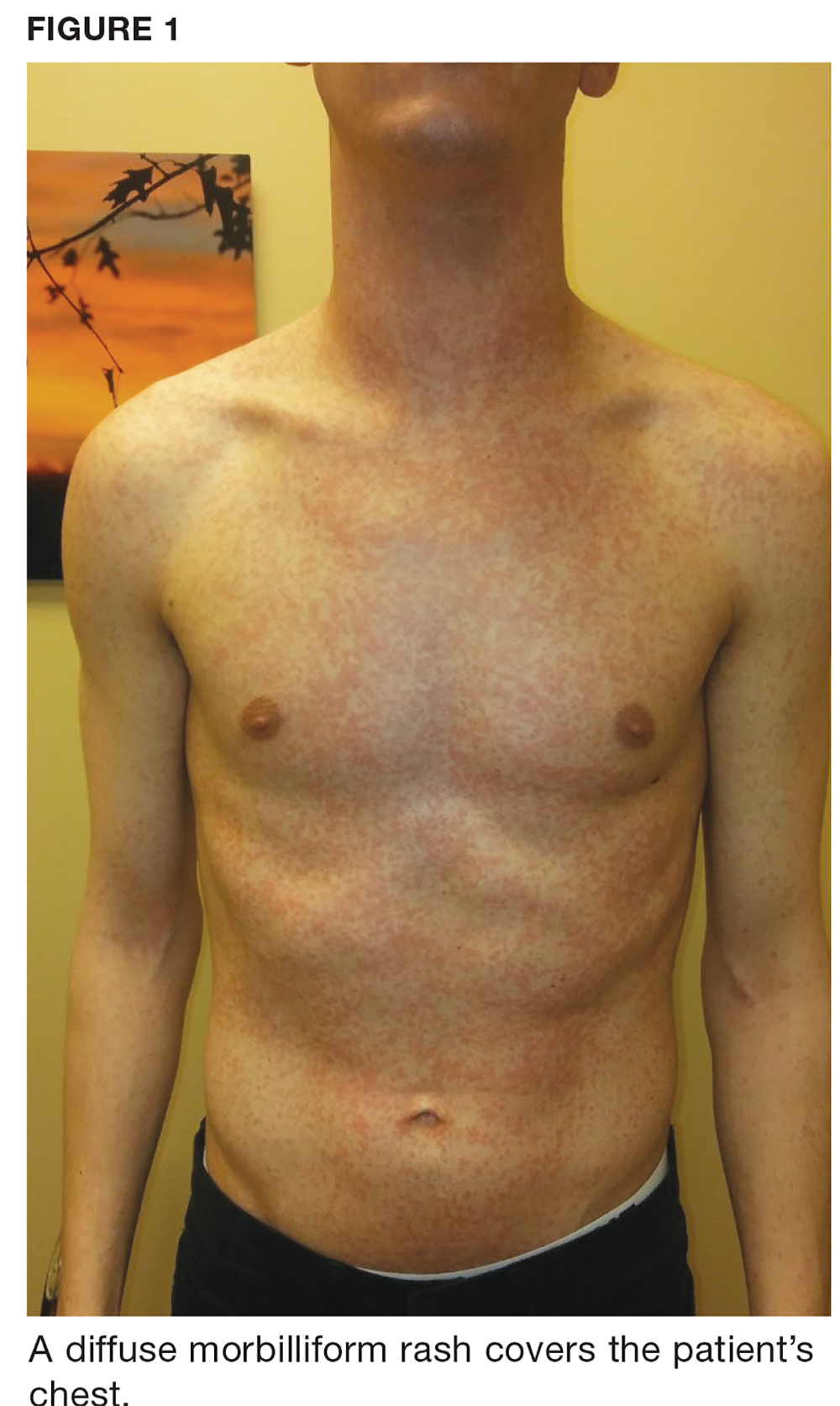

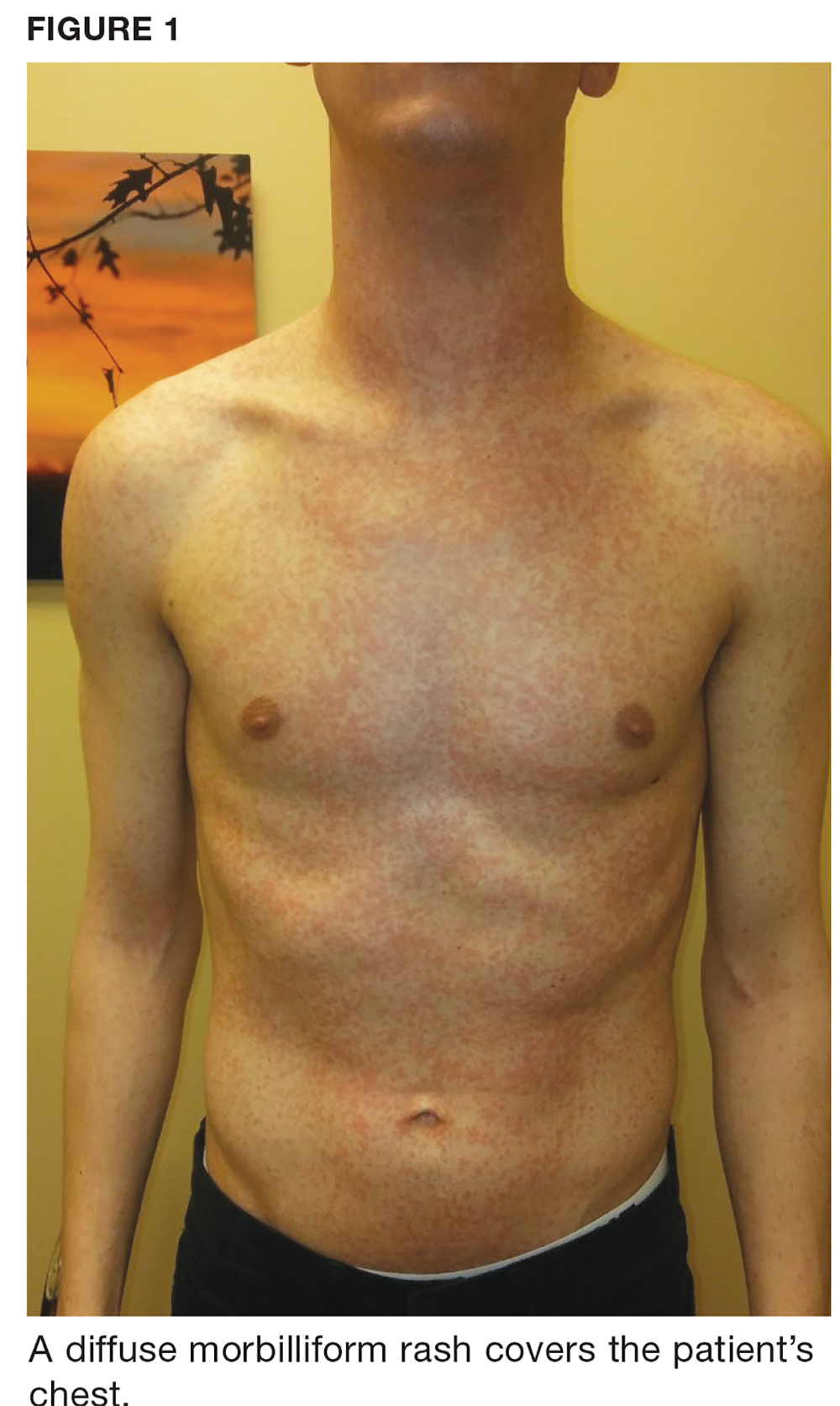

One week later, the patient returns with worsening sore throat and a morbilliform rash (see Figures 1 and 2), which covers the trunk, upper arms, and thighs. He has no known allergies to drugs, foods, or other environmental triggers. Examination reveals slightly tender, mobile anterior and posterior cervical lymphadenopathy, as well as bilateral tonsillar erythema and exudates, which were not present at the initial visit.

The rest of the exam is normal, and the patient’s sinus symptoms have resolved. Heterophile antibody testing yields positive results, suggesting infection with Epstein-Barr virus (EBV).

DISCUSSION

EBV is a pervasive herpesvirus that infects approximately 95% of adults worldwide.1 More than 90% of adults are seropositive for EBV antibodies by the age of 30.2 Although affected individuals are often asymptomatic, some patients develop symptoms of infectious mononucleosis (IM).2 An aminopenicillin rash can occur in patients with IM who are treated with amoxicillin or ampicillin, as was the case with this patient.

Incidence and pathophysiology

Infection with EBV most commonly occurs between the ages of 15 and 24.1,2 Infection before the age of 1 is rarely seen due to circulating maternal antibodies; incidence of IM in those younger than 1 or older than 30 is < 1 per 1,000 cases annually.2 The average annual incidence of infection is 0.5% in young adults (ages 15 and 24) but has been reported as high as 4.8%.2 About 10% to 20% of people who never knowingly come into contact with the virus will become infected annually; of those, up to 50% will develop IM.2 There are no known correlations in incidence based on sex or seasonal changes.2

Like all herpesviridae, EBV causes a latent infection that persists for a lifetime, specifically in replicating B lymphocytes.1 Saliva is the most common mode of EBV transmission, as viral shedding occurs in the throat and mouth.1,3 While the viral load in saliva is the highest during the first six months of infection, there are no clear data determining the risk for transmission throughout the course of asymptomatic shedding.4 There is a 30-to-50–day incubation period of EBV infection before a patient experiences symptoms of IM.1 During this period, B lymphocytes and epithelial cells (specifically in the tonsillar crypts) are believed to be the source of viral replication.1,3

Clinical presentation of IM

Common symptoms of IM include sore throat, fever, and fatigue. Approximately one in 13 patients ages 16 to 20 who present with a fever and sore throat will be diagnosed with IM.6 However, symptomatology alone is more sensitive than specific and is not sufficient to diagnose IM.6 Combined fatigue and pharyngitis is sensitive (81%-83%) but not specific, and posterior cervical lymphadenopathy increases the likelihood of IM (specificity, 87%).6

Continue to: The classic triad associated with IM includes...

The classic triad associated with IM includes fever, pharyngitis, and cervical lymphadenopathy, with morbilliform rash and palatal petechiae appearing less commonly (3%-15% and 25%, respectively).1,2,9 In affected patients, a transient truncal rash manifests within the first few days of disease onset.7 Tonsillar enlargement is also a common, but not specific, sign of acute IM.2 Splenomegaly is found in 15% to 65% of patients, typically developing within three weeks of disease onset.1,5,9

Hematologic complications occur in 25% to 50% of cases.5 Mild thrombocytopenia is common; however, more severe complications—such as hemolytic anemia, hemolytic-uremic syndrome, aplastic anemia, and disseminated intravascular coagulation—have also been associated with IM.5 Fulminant and potentially fatal complications are more common in immunocompromised patients.1,2

Pediatric and geriatric patients (those older than 65) may present with atypical signs and symptoms. For example, children are commonly asymptomatic or may present with a nonspecific viral illness.1 In addition, pediatric and elderly populations can develop elevated aminotransferase levels, and 26% of elderly patients present with jaundice (compared with 8% of young adults).2,3,7

Workup/differential diagnosis

Heterophile antibody testing is the most efficient and least expensive diagnostic test to confirm IM (sensitivity, 63%-84%; specificity, 84%-100%).2 Within the first week of IM, however, 25% of patients will produce a false-negative antibody test; a complete blood count (CBC) with differential and peripheral smear are appropriate follow-up tests.1,2,5 Detecting 10% or more atypical lymphocytes on a peripheral smear has a specificity of 95% and sensitivity of 61.3% for detecting IM, and a CBC with a lymphocyte count of less than 4,000 mm has a 99% negative predictive value.2 Viral capsid IgM testing can confirm the diagnosis of IM in an unclear clinical situation, such as a negative heterophile antibody test with an absolute lymphocyte count > 4,000 mm or in which 10% or more atypical lymphocytes were detected.2

Pharyngitis is caused by group A streptococci in 15% to 30% of children and 10% of adults worldwide, and 30% of patients with IM have a concomitant infection with group A streptococci.1,5 Because pharyngitis is a common presenting symptom of IM, rapid antigen strep test is appropriate when working up these patients.2 In addition, HIV, cytomegalovirus, human herpesvirus-6, and Toxoplasma gondii should be considered in the differential for patients with pharyngitis, fatigue, malaise, and lymphadenopathy—especially if the group A streptococci/EBV workup is negative.1,2,5

Continue to: EBV is also a known trigger of...

EBV is also a known trigger of hemophagocytic lymphohistocytosis (HLH). In a Japanese study, half of all HLH cases correlated with a primary infection of EBV.2,3,8 EBV is also the first confirmed oncogenic virus.3 EBV DNA in the plasma is now a tumor marker for nasopharyngeal carcinoma (sensitivity, 96%; specificity, 93%).8 Hodgkin lymphoma tumors are associated with EBV infection in 50% of cases.4 However, EBV seropositivity is ubiquitous (approximately 95%), while these correlated conditions are relatively uncommon; patient education on these issues is therefore not needed.

Treatment/complications

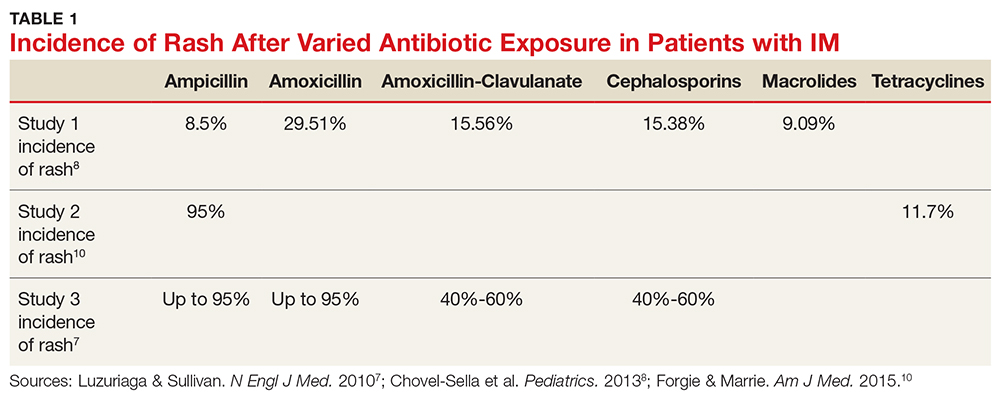

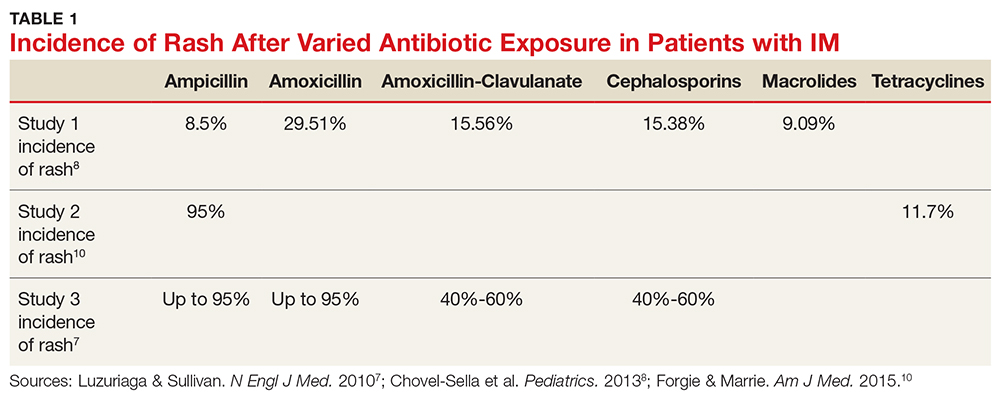

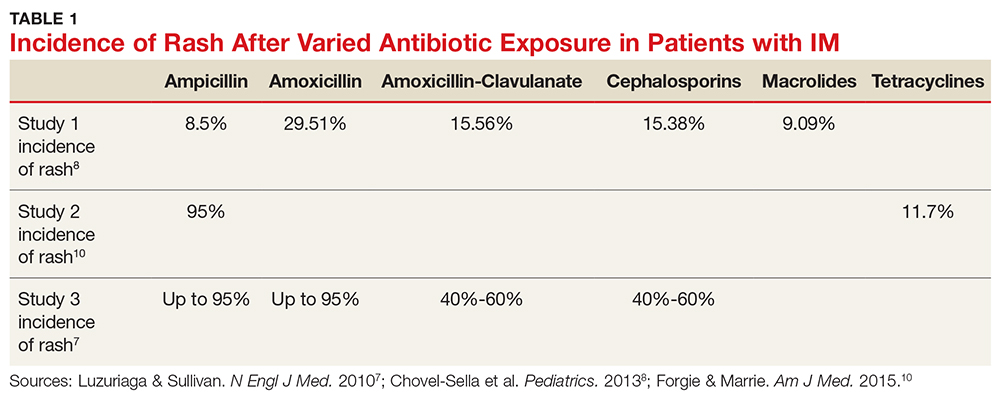

Aminopenicillin rash classically occurs in patients with IM who are treated with amoxicillin or ampicillin. These antibiotics are most commonly prescribed for suspected group A streptococci infection.7 Up to 95% of patients with IM who are exposed to these drugs develop this rash within two to 10 days of receiving the first dose of the antibiotic.9,10 Similar eruptions are often reported following administration of other penicillins, but not with the same frequency seen with ampicillin or amoxicillin (see Table 1).11

The mechanism of the aminopenicillin rash is not completely understood, but one theory is that the activated CD8+ cells react with the drug antigens and deposit in the skin.10 Another proposed mechanism is that antigens formed against activated polyclonal B cells create immune complexes with the drug, which then deposit in the skin.10

No known factors increase the incidence of this rash in patients after antibiotic exposure (eg, previous penicillin exposure, antibiotic dose or duration, patient age or ethnicity, atopic history).7 The rash generally resolves within a week after antibiotic discontinuation.7 Importantly, the development of a rash in a patient with EBV after administration of an aminopenicillin is not associated with an allergy nor is it a sign of an unfavorable reaction to such drugs in the future.12

The rash can be described as morbilliform or scarlatiniform and should be distinguished from the rash that acute IM can cause. Five percent of patients with an aminopenicillin rash will have an urticarial presentation, whereas 95% of patients have an exanthematous presentation.1,9,10 Although it can be quite difficult to distinguish one rash from the other, the aminopenicillin rash is more widespread than that associated with acute IM, covering extensor surfaces and spreading to the face, trunk, neck, mucous membranes, and sometimes the palms and soles.1,7,9,10 The rash caused by IM begins within the first few days of disease, whereas the aminopenicillin rash will manifest seven to 10 days after antibiotic exposure and is commonly pruritic.1 Each rash will last about one week.1

Continue to: CONCLUSION

CONCLUSION

The diagnosis of EBV can be challenging due to its similarity to group A streptococcal pharyngitis and other viral syndromes. In this case, the development of classic symptoms, along with the morbilliform eruption following administration of an aminopenicillin, was strongly suggestive of this diagnosis. This pairing of EBV infection and aminopenicillin rash does not indicate a penicillin allergy.

1. Hall LD, Eminger LA, Hesterman KS, Heymann WR. Epstein-Barr virus: dermatologic associations and implications. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72(1):1-19.

2. Womack J, Jimenez M. Common questions about infectious mononucleosis. Am Fam Physician. 2015;91(6): 372-376.

3. Tangye SG, Palendira U, Edwards ES. Human immunity against EBV—lessons from the clinic. J Exp Med. 2017; 214(2):269-283.

4. Guidry JT, Birdwell CE, Scott RS. Epstein-Barr virus in the pathogenesis of oral cancers. Oral Dis. 2018;24:497-508.

5. Ebell MH, Call M, Shinholser J, Gardner J. Does this patient have infectious mononucleosis? The rational clinical examination systematic review. JAMA. 2016; 315(14):1502-1509.

6. Lernia VD, Mansouri Y. Epstein-Barr virus and skin manifestations in childhood. Int J Dermatol. 2013;52(10):1177-1184.

7. Luzuriaga K, Sullivan JL. Infectious mononucleosis. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1993-2000.

8. Chovel-Sella A, Ben Tov A, Lahav A, et al. Incidence of rash after amoxicillin treatment in children with infectious mononucleosis. Pediatrics. 2013;131(5):e1424-e1427.

9. Chan KCA, Woo JKS, King A, et al. Analysis of plasma Epstein-Barr virus DNA to screen for nasopharyngeal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:513-522.

10. Forgie SED, Marrie TJ. Cutaneous eruptions associated with antimicrobials in patients with infectious mononucleosis. Am J Med. 2015;128(1):e1-e2.

11. Haverkos HW, Amsel Z, Drotman DP. Adverse virus-drug interactions. Rev Infect Dis. 1991;13(4):697-704.

12. Nazareth I, Mortimer P, McKendrick GD. Ampicillin sensitivity in infectious mononucleosis: temporary or permanent? Scand J Infect Dis. 1972;4(3):229-230.

A 25-year-old white man presents to urgent care with a nine-day history of increasing sinus pressure, mild sore throat, dry cough, and low-grade fever. Physical exam of the ears, nose, throat, and chest is unremarkable, but the patient does display mild maxillary sinus tenderness. Sinus pain (and symptom duration) is the primary complaint. The patient was recently exposed to influenza B, but a rapid flu test is negative. A five-day course of amoxicillin-clavulanate is prescribed for a presumed diagnosis of bacterial sinusitis.

One week later, the patient returns with worsening sore throat and a morbilliform rash (see Figures 1 and 2), which covers the trunk, upper arms, and thighs. He has no known allergies to drugs, foods, or other environmental triggers. Examination reveals slightly tender, mobile anterior and posterior cervical lymphadenopathy, as well as bilateral tonsillar erythema and exudates, which were not present at the initial visit.

The rest of the exam is normal, and the patient’s sinus symptoms have resolved. Heterophile antibody testing yields positive results, suggesting infection with Epstein-Barr virus (EBV).

DISCUSSION

EBV is a pervasive herpesvirus that infects approximately 95% of adults worldwide.1 More than 90% of adults are seropositive for EBV antibodies by the age of 30.2 Although affected individuals are often asymptomatic, some patients develop symptoms of infectious mononucleosis (IM).2 An aminopenicillin rash can occur in patients with IM who are treated with amoxicillin or ampicillin, as was the case with this patient.

Incidence and pathophysiology

Infection with EBV most commonly occurs between the ages of 15 and 24.1,2 Infection before the age of 1 is rarely seen due to circulating maternal antibodies; incidence of IM in those younger than 1 or older than 30 is < 1 per 1,000 cases annually.2 The average annual incidence of infection is 0.5% in young adults (ages 15 and 24) but has been reported as high as 4.8%.2 About 10% to 20% of people who never knowingly come into contact with the virus will become infected annually; of those, up to 50% will develop IM.2 There are no known correlations in incidence based on sex or seasonal changes.2

Like all herpesviridae, EBV causes a latent infection that persists for a lifetime, specifically in replicating B lymphocytes.1 Saliva is the most common mode of EBV transmission, as viral shedding occurs in the throat and mouth.1,3 While the viral load in saliva is the highest during the first six months of infection, there are no clear data determining the risk for transmission throughout the course of asymptomatic shedding.4 There is a 30-to-50–day incubation period of EBV infection before a patient experiences symptoms of IM.1 During this period, B lymphocytes and epithelial cells (specifically in the tonsillar crypts) are believed to be the source of viral replication.1,3

Clinical presentation of IM

Common symptoms of IM include sore throat, fever, and fatigue. Approximately one in 13 patients ages 16 to 20 who present with a fever and sore throat will be diagnosed with IM.6 However, symptomatology alone is more sensitive than specific and is not sufficient to diagnose IM.6 Combined fatigue and pharyngitis is sensitive (81%-83%) but not specific, and posterior cervical lymphadenopathy increases the likelihood of IM (specificity, 87%).6

Continue to: The classic triad associated with IM includes...

The classic triad associated with IM includes fever, pharyngitis, and cervical lymphadenopathy, with morbilliform rash and palatal petechiae appearing less commonly (3%-15% and 25%, respectively).1,2,9 In affected patients, a transient truncal rash manifests within the first few days of disease onset.7 Tonsillar enlargement is also a common, but not specific, sign of acute IM.2 Splenomegaly is found in 15% to 65% of patients, typically developing within three weeks of disease onset.1,5,9

Hematologic complications occur in 25% to 50% of cases.5 Mild thrombocytopenia is common; however, more severe complications—such as hemolytic anemia, hemolytic-uremic syndrome, aplastic anemia, and disseminated intravascular coagulation—have also been associated with IM.5 Fulminant and potentially fatal complications are more common in immunocompromised patients.1,2

Pediatric and geriatric patients (those older than 65) may present with atypical signs and symptoms. For example, children are commonly asymptomatic or may present with a nonspecific viral illness.1 In addition, pediatric and elderly populations can develop elevated aminotransferase levels, and 26% of elderly patients present with jaundice (compared with 8% of young adults).2,3,7

Workup/differential diagnosis

Heterophile antibody testing is the most efficient and least expensive diagnostic test to confirm IM (sensitivity, 63%-84%; specificity, 84%-100%).2 Within the first week of IM, however, 25% of patients will produce a false-negative antibody test; a complete blood count (CBC) with differential and peripheral smear are appropriate follow-up tests.1,2,5 Detecting 10% or more atypical lymphocytes on a peripheral smear has a specificity of 95% and sensitivity of 61.3% for detecting IM, and a CBC with a lymphocyte count of less than 4,000 mm has a 99% negative predictive value.2 Viral capsid IgM testing can confirm the diagnosis of IM in an unclear clinical situation, such as a negative heterophile antibody test with an absolute lymphocyte count > 4,000 mm or in which 10% or more atypical lymphocytes were detected.2

Pharyngitis is caused by group A streptococci in 15% to 30% of children and 10% of adults worldwide, and 30% of patients with IM have a concomitant infection with group A streptococci.1,5 Because pharyngitis is a common presenting symptom of IM, rapid antigen strep test is appropriate when working up these patients.2 In addition, HIV, cytomegalovirus, human herpesvirus-6, and Toxoplasma gondii should be considered in the differential for patients with pharyngitis, fatigue, malaise, and lymphadenopathy—especially if the group A streptococci/EBV workup is negative.1,2,5

Continue to: EBV is also a known trigger of...

EBV is also a known trigger of hemophagocytic lymphohistocytosis (HLH). In a Japanese study, half of all HLH cases correlated with a primary infection of EBV.2,3,8 EBV is also the first confirmed oncogenic virus.3 EBV DNA in the plasma is now a tumor marker for nasopharyngeal carcinoma (sensitivity, 96%; specificity, 93%).8 Hodgkin lymphoma tumors are associated with EBV infection in 50% of cases.4 However, EBV seropositivity is ubiquitous (approximately 95%), while these correlated conditions are relatively uncommon; patient education on these issues is therefore not needed.

Treatment/complications

Aminopenicillin rash classically occurs in patients with IM who are treated with amoxicillin or ampicillin. These antibiotics are most commonly prescribed for suspected group A streptococci infection.7 Up to 95% of patients with IM who are exposed to these drugs develop this rash within two to 10 days of receiving the first dose of the antibiotic.9,10 Similar eruptions are often reported following administration of other penicillins, but not with the same frequency seen with ampicillin or amoxicillin (see Table 1).11

The mechanism of the aminopenicillin rash is not completely understood, but one theory is that the activated CD8+ cells react with the drug antigens and deposit in the skin.10 Another proposed mechanism is that antigens formed against activated polyclonal B cells create immune complexes with the drug, which then deposit in the skin.10

No known factors increase the incidence of this rash in patients after antibiotic exposure (eg, previous penicillin exposure, antibiotic dose or duration, patient age or ethnicity, atopic history).7 The rash generally resolves within a week after antibiotic discontinuation.7 Importantly, the development of a rash in a patient with EBV after administration of an aminopenicillin is not associated with an allergy nor is it a sign of an unfavorable reaction to such drugs in the future.12

The rash can be described as morbilliform or scarlatiniform and should be distinguished from the rash that acute IM can cause. Five percent of patients with an aminopenicillin rash will have an urticarial presentation, whereas 95% of patients have an exanthematous presentation.1,9,10 Although it can be quite difficult to distinguish one rash from the other, the aminopenicillin rash is more widespread than that associated with acute IM, covering extensor surfaces and spreading to the face, trunk, neck, mucous membranes, and sometimes the palms and soles.1,7,9,10 The rash caused by IM begins within the first few days of disease, whereas the aminopenicillin rash will manifest seven to 10 days after antibiotic exposure and is commonly pruritic.1 Each rash will last about one week.1

Continue to: CONCLUSION

CONCLUSION

The diagnosis of EBV can be challenging due to its similarity to group A streptococcal pharyngitis and other viral syndromes. In this case, the development of classic symptoms, along with the morbilliform eruption following administration of an aminopenicillin, was strongly suggestive of this diagnosis. This pairing of EBV infection and aminopenicillin rash does not indicate a penicillin allergy.

A 25-year-old white man presents to urgent care with a nine-day history of increasing sinus pressure, mild sore throat, dry cough, and low-grade fever. Physical exam of the ears, nose, throat, and chest is unremarkable, but the patient does display mild maxillary sinus tenderness. Sinus pain (and symptom duration) is the primary complaint. The patient was recently exposed to influenza B, but a rapid flu test is negative. A five-day course of amoxicillin-clavulanate is prescribed for a presumed diagnosis of bacterial sinusitis.

One week later, the patient returns with worsening sore throat and a morbilliform rash (see Figures 1 and 2), which covers the trunk, upper arms, and thighs. He has no known allergies to drugs, foods, or other environmental triggers. Examination reveals slightly tender, mobile anterior and posterior cervical lymphadenopathy, as well as bilateral tonsillar erythema and exudates, which were not present at the initial visit.

The rest of the exam is normal, and the patient’s sinus symptoms have resolved. Heterophile antibody testing yields positive results, suggesting infection with Epstein-Barr virus (EBV).

DISCUSSION

EBV is a pervasive herpesvirus that infects approximately 95% of adults worldwide.1 More than 90% of adults are seropositive for EBV antibodies by the age of 30.2 Although affected individuals are often asymptomatic, some patients develop symptoms of infectious mononucleosis (IM).2 An aminopenicillin rash can occur in patients with IM who are treated with amoxicillin or ampicillin, as was the case with this patient.

Incidence and pathophysiology

Infection with EBV most commonly occurs between the ages of 15 and 24.1,2 Infection before the age of 1 is rarely seen due to circulating maternal antibodies; incidence of IM in those younger than 1 or older than 30 is < 1 per 1,000 cases annually.2 The average annual incidence of infection is 0.5% in young adults (ages 15 and 24) but has been reported as high as 4.8%.2 About 10% to 20% of people who never knowingly come into contact with the virus will become infected annually; of those, up to 50% will develop IM.2 There are no known correlations in incidence based on sex or seasonal changes.2

Like all herpesviridae, EBV causes a latent infection that persists for a lifetime, specifically in replicating B lymphocytes.1 Saliva is the most common mode of EBV transmission, as viral shedding occurs in the throat and mouth.1,3 While the viral load in saliva is the highest during the first six months of infection, there are no clear data determining the risk for transmission throughout the course of asymptomatic shedding.4 There is a 30-to-50–day incubation period of EBV infection before a patient experiences symptoms of IM.1 During this period, B lymphocytes and epithelial cells (specifically in the tonsillar crypts) are believed to be the source of viral replication.1,3

Clinical presentation of IM

Common symptoms of IM include sore throat, fever, and fatigue. Approximately one in 13 patients ages 16 to 20 who present with a fever and sore throat will be diagnosed with IM.6 However, symptomatology alone is more sensitive than specific and is not sufficient to diagnose IM.6 Combined fatigue and pharyngitis is sensitive (81%-83%) but not specific, and posterior cervical lymphadenopathy increases the likelihood of IM (specificity, 87%).6

Continue to: The classic triad associated with IM includes...

The classic triad associated with IM includes fever, pharyngitis, and cervical lymphadenopathy, with morbilliform rash and palatal petechiae appearing less commonly (3%-15% and 25%, respectively).1,2,9 In affected patients, a transient truncal rash manifests within the first few days of disease onset.7 Tonsillar enlargement is also a common, but not specific, sign of acute IM.2 Splenomegaly is found in 15% to 65% of patients, typically developing within three weeks of disease onset.1,5,9

Hematologic complications occur in 25% to 50% of cases.5 Mild thrombocytopenia is common; however, more severe complications—such as hemolytic anemia, hemolytic-uremic syndrome, aplastic anemia, and disseminated intravascular coagulation—have also been associated with IM.5 Fulminant and potentially fatal complications are more common in immunocompromised patients.1,2

Pediatric and geriatric patients (those older than 65) may present with atypical signs and symptoms. For example, children are commonly asymptomatic or may present with a nonspecific viral illness.1 In addition, pediatric and elderly populations can develop elevated aminotransferase levels, and 26% of elderly patients present with jaundice (compared with 8% of young adults).2,3,7

Workup/differential diagnosis

Heterophile antibody testing is the most efficient and least expensive diagnostic test to confirm IM (sensitivity, 63%-84%; specificity, 84%-100%).2 Within the first week of IM, however, 25% of patients will produce a false-negative antibody test; a complete blood count (CBC) with differential and peripheral smear are appropriate follow-up tests.1,2,5 Detecting 10% or more atypical lymphocytes on a peripheral smear has a specificity of 95% and sensitivity of 61.3% for detecting IM, and a CBC with a lymphocyte count of less than 4,000 mm has a 99% negative predictive value.2 Viral capsid IgM testing can confirm the diagnosis of IM in an unclear clinical situation, such as a negative heterophile antibody test with an absolute lymphocyte count > 4,000 mm or in which 10% or more atypical lymphocytes were detected.2

Pharyngitis is caused by group A streptococci in 15% to 30% of children and 10% of adults worldwide, and 30% of patients with IM have a concomitant infection with group A streptococci.1,5 Because pharyngitis is a common presenting symptom of IM, rapid antigen strep test is appropriate when working up these patients.2 In addition, HIV, cytomegalovirus, human herpesvirus-6, and Toxoplasma gondii should be considered in the differential for patients with pharyngitis, fatigue, malaise, and lymphadenopathy—especially if the group A streptococci/EBV workup is negative.1,2,5

Continue to: EBV is also a known trigger of...

EBV is also a known trigger of hemophagocytic lymphohistocytosis (HLH). In a Japanese study, half of all HLH cases correlated with a primary infection of EBV.2,3,8 EBV is also the first confirmed oncogenic virus.3 EBV DNA in the plasma is now a tumor marker for nasopharyngeal carcinoma (sensitivity, 96%; specificity, 93%).8 Hodgkin lymphoma tumors are associated with EBV infection in 50% of cases.4 However, EBV seropositivity is ubiquitous (approximately 95%), while these correlated conditions are relatively uncommon; patient education on these issues is therefore not needed.

Treatment/complications

Aminopenicillin rash classically occurs in patients with IM who are treated with amoxicillin or ampicillin. These antibiotics are most commonly prescribed for suspected group A streptococci infection.7 Up to 95% of patients with IM who are exposed to these drugs develop this rash within two to 10 days of receiving the first dose of the antibiotic.9,10 Similar eruptions are often reported following administration of other penicillins, but not with the same frequency seen with ampicillin or amoxicillin (see Table 1).11

The mechanism of the aminopenicillin rash is not completely understood, but one theory is that the activated CD8+ cells react with the drug antigens and deposit in the skin.10 Another proposed mechanism is that antigens formed against activated polyclonal B cells create immune complexes with the drug, which then deposit in the skin.10

No known factors increase the incidence of this rash in patients after antibiotic exposure (eg, previous penicillin exposure, antibiotic dose or duration, patient age or ethnicity, atopic history).7 The rash generally resolves within a week after antibiotic discontinuation.7 Importantly, the development of a rash in a patient with EBV after administration of an aminopenicillin is not associated with an allergy nor is it a sign of an unfavorable reaction to such drugs in the future.12

The rash can be described as morbilliform or scarlatiniform and should be distinguished from the rash that acute IM can cause. Five percent of patients with an aminopenicillin rash will have an urticarial presentation, whereas 95% of patients have an exanthematous presentation.1,9,10 Although it can be quite difficult to distinguish one rash from the other, the aminopenicillin rash is more widespread than that associated with acute IM, covering extensor surfaces and spreading to the face, trunk, neck, mucous membranes, and sometimes the palms and soles.1,7,9,10 The rash caused by IM begins within the first few days of disease, whereas the aminopenicillin rash will manifest seven to 10 days after antibiotic exposure and is commonly pruritic.1 Each rash will last about one week.1

Continue to: CONCLUSION

CONCLUSION

The diagnosis of EBV can be challenging due to its similarity to group A streptococcal pharyngitis and other viral syndromes. In this case, the development of classic symptoms, along with the morbilliform eruption following administration of an aminopenicillin, was strongly suggestive of this diagnosis. This pairing of EBV infection and aminopenicillin rash does not indicate a penicillin allergy.

1. Hall LD, Eminger LA, Hesterman KS, Heymann WR. Epstein-Barr virus: dermatologic associations and implications. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72(1):1-19.

2. Womack J, Jimenez M. Common questions about infectious mononucleosis. Am Fam Physician. 2015;91(6): 372-376.

3. Tangye SG, Palendira U, Edwards ES. Human immunity against EBV—lessons from the clinic. J Exp Med. 2017; 214(2):269-283.

4. Guidry JT, Birdwell CE, Scott RS. Epstein-Barr virus in the pathogenesis of oral cancers. Oral Dis. 2018;24:497-508.

5. Ebell MH, Call M, Shinholser J, Gardner J. Does this patient have infectious mononucleosis? The rational clinical examination systematic review. JAMA. 2016; 315(14):1502-1509.

6. Lernia VD, Mansouri Y. Epstein-Barr virus and skin manifestations in childhood. Int J Dermatol. 2013;52(10):1177-1184.

7. Luzuriaga K, Sullivan JL. Infectious mononucleosis. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1993-2000.

8. Chovel-Sella A, Ben Tov A, Lahav A, et al. Incidence of rash after amoxicillin treatment in children with infectious mononucleosis. Pediatrics. 2013;131(5):e1424-e1427.

9. Chan KCA, Woo JKS, King A, et al. Analysis of plasma Epstein-Barr virus DNA to screen for nasopharyngeal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:513-522.

10. Forgie SED, Marrie TJ. Cutaneous eruptions associated with antimicrobials in patients with infectious mononucleosis. Am J Med. 2015;128(1):e1-e2.

11. Haverkos HW, Amsel Z, Drotman DP. Adverse virus-drug interactions. Rev Infect Dis. 1991;13(4):697-704.

12. Nazareth I, Mortimer P, McKendrick GD. Ampicillin sensitivity in infectious mononucleosis: temporary or permanent? Scand J Infect Dis. 1972;4(3):229-230.

1. Hall LD, Eminger LA, Hesterman KS, Heymann WR. Epstein-Barr virus: dermatologic associations and implications. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72(1):1-19.

2. Womack J, Jimenez M. Common questions about infectious mononucleosis. Am Fam Physician. 2015;91(6): 372-376.

3. Tangye SG, Palendira U, Edwards ES. Human immunity against EBV—lessons from the clinic. J Exp Med. 2017; 214(2):269-283.

4. Guidry JT, Birdwell CE, Scott RS. Epstein-Barr virus in the pathogenesis of oral cancers. Oral Dis. 2018;24:497-508.

5. Ebell MH, Call M, Shinholser J, Gardner J. Does this patient have infectious mononucleosis? The rational clinical examination systematic review. JAMA. 2016; 315(14):1502-1509.

6. Lernia VD, Mansouri Y. Epstein-Barr virus and skin manifestations in childhood. Int J Dermatol. 2013;52(10):1177-1184.

7. Luzuriaga K, Sullivan JL. Infectious mononucleosis. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1993-2000.

8. Chovel-Sella A, Ben Tov A, Lahav A, et al. Incidence of rash after amoxicillin treatment in children with infectious mononucleosis. Pediatrics. 2013;131(5):e1424-e1427.

9. Chan KCA, Woo JKS, King A, et al. Analysis of plasma Epstein-Barr virus DNA to screen for nasopharyngeal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:513-522.

10. Forgie SED, Marrie TJ. Cutaneous eruptions associated with antimicrobials in patients with infectious mononucleosis. Am J Med. 2015;128(1):e1-e2.

11. Haverkos HW, Amsel Z, Drotman DP. Adverse virus-drug interactions. Rev Infect Dis. 1991;13(4):697-704.

12. Nazareth I, Mortimer P, McKendrick GD. Ampicillin sensitivity in infectious mononucleosis: temporary or permanent? Scand J Infect Dis. 1972;4(3):229-230.

How to avoid denied claims

Unless your practice is cash-only, reimbursements from your patients’ health insurance companies are necessary to ensure its survival. Although the reimbursement process appears straightforward (provide a service, submit a claim, and receive a payment), it is actually quite complex, and, if not properly managed, a claim can be denied at any stage of the process.1 In its 2013 National Health Insurer Report Card, the American Medical Association reported that major payers returned 11% to 29% of claim lines with $0 for payment.1,2 This often is the case because patients are responsible for the balance, but it also occurs as the result of claim edits (up to 7%) and other denials (up to 5%).1,2

Claims can be denied for various reasons, including1:

- missed filing deadlines

- billing for non-covered services

- discrepancies between diagnostic codes, procedures codes, modifiers, and clinician documentation

- missing pre-authorization documentation or a signed Advanced Beneficiary Notice of Non-Coverage.

Strategies for avoiding denials

A psychiatric practice requires a practical system to prevent the occurrence of denials, starting from the point of referral. Working through denials is more costly and timeconsuming than preventing them from occurring in the first place. For every 15 denials prevented each month, your practice can save approximately $4,500 per year in costs associated with correcting those claims; by preventing denials, the practice also receives reimbursement sooner.1 You can be guaranteed to leave significant amounts of money on the table if you are not able to prevent or reduce denials.

The following methods can be used to help reduce the likelihood of having a claim denied.1,3

Obtain the patient’s health insurance information at first contact and confirm his or her coverage benefits, deductibles, copay requirements, and exclusions before scheduling the first appointment. Verify this information at each of the patient’s subsequent visits to reduce the chances of having a claim denied due to invalid subscriber information. Also, keep in mind that Medicaid eligibility can change daily.

Employ a digital record system, such as electronic medical records, to track authorizations.

Know the filing deadlines for each of your payers. If you miss a deadline, there is no recourse.

Continue to: Check each claim

Check each claim for accurate coding, diagnosis, and payment (eg, copay, co-insurance, and/or deductible, depending on the health insurance plan) taken before the claim is submitted. If your practice size permits, assign a staff member to confirm this information and keep track of deadlines for submissions, resubmissions, and appeals of denied claims. Using a single gatekeeper can help decrease the chances that a denial will “slip through the cracks.”

Confirm that diagnostic codes, procedures codes, and modifiers are justified by the clinician’s documentation. Have a medical coder compare notes with the clinician to determine if any critical information needed to justify the codes used has been omitted.

Implement an electronic system that can automatically identify any changes and updates to the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) regulations and guidance, International Classification of Diseases (ICD) versions and codes, and Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes and guidelines. To help reduce denied claims, educate all staff (schedulers, coders, billers, nursing staff, and other clinicians) frequently about these changes, and provide regular feedback to those involved in correcting denials.

1. Marting R. The cure for claims denials. Fam Pract Manag. 2015;22(2):7-10.

2. American Medical Association. 2013 National Health Insurer Report Card. Chicago, IL: American Medical Association; 2013.

3. Tohill M. 8 tips for avoiding denials, improving claims reimbursement . RevCycle Intelligence. https://revcycleintelligence.com/news/8-tips-for-avoiding-denials-improving-claims-reimbursement. Published June 6, 2016. Accessed February 19, 2018.

Unless your practice is cash-only, reimbursements from your patients’ health insurance companies are necessary to ensure its survival. Although the reimbursement process appears straightforward (provide a service, submit a claim, and receive a payment), it is actually quite complex, and, if not properly managed, a claim can be denied at any stage of the process.1 In its 2013 National Health Insurer Report Card, the American Medical Association reported that major payers returned 11% to 29% of claim lines with $0 for payment.1,2 This often is the case because patients are responsible for the balance, but it also occurs as the result of claim edits (up to 7%) and other denials (up to 5%).1,2

Claims can be denied for various reasons, including1:

- missed filing deadlines

- billing for non-covered services

- discrepancies between diagnostic codes, procedures codes, modifiers, and clinician documentation

- missing pre-authorization documentation or a signed Advanced Beneficiary Notice of Non-Coverage.

Strategies for avoiding denials

A psychiatric practice requires a practical system to prevent the occurrence of denials, starting from the point of referral. Working through denials is more costly and timeconsuming than preventing them from occurring in the first place. For every 15 denials prevented each month, your practice can save approximately $4,500 per year in costs associated with correcting those claims; by preventing denials, the practice also receives reimbursement sooner.1 You can be guaranteed to leave significant amounts of money on the table if you are not able to prevent or reduce denials.

The following methods can be used to help reduce the likelihood of having a claim denied.1,3

Obtain the patient’s health insurance information at first contact and confirm his or her coverage benefits, deductibles, copay requirements, and exclusions before scheduling the first appointment. Verify this information at each of the patient’s subsequent visits to reduce the chances of having a claim denied due to invalid subscriber information. Also, keep in mind that Medicaid eligibility can change daily.

Employ a digital record system, such as electronic medical records, to track authorizations.

Know the filing deadlines for each of your payers. If you miss a deadline, there is no recourse.

Continue to: Check each claim

Check each claim for accurate coding, diagnosis, and payment (eg, copay, co-insurance, and/or deductible, depending on the health insurance plan) taken before the claim is submitted. If your practice size permits, assign a staff member to confirm this information and keep track of deadlines for submissions, resubmissions, and appeals of denied claims. Using a single gatekeeper can help decrease the chances that a denial will “slip through the cracks.”

Confirm that diagnostic codes, procedures codes, and modifiers are justified by the clinician’s documentation. Have a medical coder compare notes with the clinician to determine if any critical information needed to justify the codes used has been omitted.

Implement an electronic system that can automatically identify any changes and updates to the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) regulations and guidance, International Classification of Diseases (ICD) versions and codes, and Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes and guidelines. To help reduce denied claims, educate all staff (schedulers, coders, billers, nursing staff, and other clinicians) frequently about these changes, and provide regular feedback to those involved in correcting denials.

Unless your practice is cash-only, reimbursements from your patients’ health insurance companies are necessary to ensure its survival. Although the reimbursement process appears straightforward (provide a service, submit a claim, and receive a payment), it is actually quite complex, and, if not properly managed, a claim can be denied at any stage of the process.1 In its 2013 National Health Insurer Report Card, the American Medical Association reported that major payers returned 11% to 29% of claim lines with $0 for payment.1,2 This often is the case because patients are responsible for the balance, but it also occurs as the result of claim edits (up to 7%) and other denials (up to 5%).1,2

Claims can be denied for various reasons, including1:

- missed filing deadlines

- billing for non-covered services

- discrepancies between diagnostic codes, procedures codes, modifiers, and clinician documentation

- missing pre-authorization documentation or a signed Advanced Beneficiary Notice of Non-Coverage.

Strategies for avoiding denials

A psychiatric practice requires a practical system to prevent the occurrence of denials, starting from the point of referral. Working through denials is more costly and timeconsuming than preventing them from occurring in the first place. For every 15 denials prevented each month, your practice can save approximately $4,500 per year in costs associated with correcting those claims; by preventing denials, the practice also receives reimbursement sooner.1 You can be guaranteed to leave significant amounts of money on the table if you are not able to prevent or reduce denials.

The following methods can be used to help reduce the likelihood of having a claim denied.1,3

Obtain the patient’s health insurance information at first contact and confirm his or her coverage benefits, deductibles, copay requirements, and exclusions before scheduling the first appointment. Verify this information at each of the patient’s subsequent visits to reduce the chances of having a claim denied due to invalid subscriber information. Also, keep in mind that Medicaid eligibility can change daily.

Employ a digital record system, such as electronic medical records, to track authorizations.

Know the filing deadlines for each of your payers. If you miss a deadline, there is no recourse.

Continue to: Check each claim

Check each claim for accurate coding, diagnosis, and payment (eg, copay, co-insurance, and/or deductible, depending on the health insurance plan) taken before the claim is submitted. If your practice size permits, assign a staff member to confirm this information and keep track of deadlines for submissions, resubmissions, and appeals of denied claims. Using a single gatekeeper can help decrease the chances that a denial will “slip through the cracks.”

Confirm that diagnostic codes, procedures codes, and modifiers are justified by the clinician’s documentation. Have a medical coder compare notes with the clinician to determine if any critical information needed to justify the codes used has been omitted.

Implement an electronic system that can automatically identify any changes and updates to the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) regulations and guidance, International Classification of Diseases (ICD) versions and codes, and Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes and guidelines. To help reduce denied claims, educate all staff (schedulers, coders, billers, nursing staff, and other clinicians) frequently about these changes, and provide regular feedback to those involved in correcting denials.

1. Marting R. The cure for claims denials. Fam Pract Manag. 2015;22(2):7-10.

2. American Medical Association. 2013 National Health Insurer Report Card. Chicago, IL: American Medical Association; 2013.

3. Tohill M. 8 tips for avoiding denials, improving claims reimbursement . RevCycle Intelligence. https://revcycleintelligence.com/news/8-tips-for-avoiding-denials-improving-claims-reimbursement. Published June 6, 2016. Accessed February 19, 2018.

1. Marting R. The cure for claims denials. Fam Pract Manag. 2015;22(2):7-10.

2. American Medical Association. 2013 National Health Insurer Report Card. Chicago, IL: American Medical Association; 2013.

3. Tohill M. 8 tips for avoiding denials, improving claims reimbursement . RevCycle Intelligence. https://revcycleintelligence.com/news/8-tips-for-avoiding-denials-improving-claims-reimbursement. Published June 6, 2016. Accessed February 19, 2018.

Group releases new CLL guidelines

Fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, and rituximab are recommended as initial therapy for fit patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) who do not have TP53 disruption, according to new guidelines from the British Society for Haematology.

The guidelines update the 2012 recommendations on CLL to include “significant” developments in treatment.

The new guidelines were published in the British Journal of Haematology.

Anna H. Schuh, MD, of the University of Oxford in the UK, and her coauthors noted that, while these guidelines apply to treatments available outside clinical trials, wherever possible, patients with CLL should be treated within the clinical trial setting.

While recommending fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, and rituximab as first-line therapy, the guideline authors acknowledged that the combination of bendamustine and rituximab is an acceptable alternative for patients who cannot take the triple therapy because of comorbidities such as advanced age, renal impairment, or issues with marrow capacity.

Similarly, less-fit patients can also be considered for chlorambucil-obinutuzumab or chlorambucil-ofatumumab combinations.

All patients diagnosed with CLL should be tested for TP53 deletions and mutations before each line of therapy, the guideline committee recommended.

TP53 disruption makes chemoimmunotherapy ineffective because of either a deletion of chromosome 17p or a mutation in the TP53 gene. However, there is compelling evidence for the efficacy of ibrutinib in these patients, or idelalisib and rituximab for those with cardiac disease or receiving vitamin K antagonists.

With respect to maintenance therapy, the guidelines noted that this was not routinely recommended in CLL as “it is unclear to what extent the progression-free survival benefit is offset by long-term toxicity.”

Patients who are refractory to chemoimmunotherapy, who have relapsed, or who cannot be retreated with chemoimmunotherapy should be treated with idelalisib plus rituximab or ibrutinib monotherapy, the guidelines suggested.

“Deciding whether ibrutinib or idelalisib with rituximab is most appropriate for an individual patient depends on a range of factors, including toxicity profile and convenience of delivery,” the authors wrote.

However, they noted that the value of adding bendamustine to either option was unclear as research had not shown significant, associated gains in median progression-free survival.

Allogeneic stem cell transplant should be considered as an option for patients who have failed chemotherapy, have a TP53 disruption and have not responded to B-cell receptor signaling pathway inhibitors such as ibrutinib, or have Richter’s transformation.

The guidelines also addressed the issue of autoimmune cytopenias, which occur in 5% to 10% of patients with CLL and can actually precede the diagnosis of CLL in about 9% of cases.

In patients where autoimmune cytopenia is the dominant clinical feature, they should be treated with corticosteroids, intravenous immunoglobulin, or rituximab. However, for patients where the cytopenia is triggered by CLL therapy, the guidelines recommended halting treatment and beginning immunosuppression.

The guideline development was supported by the British Society for Haematology. The UK CLL Forum, which was involved in development as well, is a registered charity that receives funding from a number of pharmaceutical companies.

Fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, and rituximab are recommended as initial therapy for fit patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) who do not have TP53 disruption, according to new guidelines from the British Society for Haematology.

The guidelines update the 2012 recommendations on CLL to include “significant” developments in treatment.

The new guidelines were published in the British Journal of Haematology.

Anna H. Schuh, MD, of the University of Oxford in the UK, and her coauthors noted that, while these guidelines apply to treatments available outside clinical trials, wherever possible, patients with CLL should be treated within the clinical trial setting.

While recommending fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, and rituximab as first-line therapy, the guideline authors acknowledged that the combination of bendamustine and rituximab is an acceptable alternative for patients who cannot take the triple therapy because of comorbidities such as advanced age, renal impairment, or issues with marrow capacity.

Similarly, less-fit patients can also be considered for chlorambucil-obinutuzumab or chlorambucil-ofatumumab combinations.

All patients diagnosed with CLL should be tested for TP53 deletions and mutations before each line of therapy, the guideline committee recommended.

TP53 disruption makes chemoimmunotherapy ineffective because of either a deletion of chromosome 17p or a mutation in the TP53 gene. However, there is compelling evidence for the efficacy of ibrutinib in these patients, or idelalisib and rituximab for those with cardiac disease or receiving vitamin K antagonists.

With respect to maintenance therapy, the guidelines noted that this was not routinely recommended in CLL as “it is unclear to what extent the progression-free survival benefit is offset by long-term toxicity.”

Patients who are refractory to chemoimmunotherapy, who have relapsed, or who cannot be retreated with chemoimmunotherapy should be treated with idelalisib plus rituximab or ibrutinib monotherapy, the guidelines suggested.

“Deciding whether ibrutinib or idelalisib with rituximab is most appropriate for an individual patient depends on a range of factors, including toxicity profile and convenience of delivery,” the authors wrote.

However, they noted that the value of adding bendamustine to either option was unclear as research had not shown significant, associated gains in median progression-free survival.

Allogeneic stem cell transplant should be considered as an option for patients who have failed chemotherapy, have a TP53 disruption and have not responded to B-cell receptor signaling pathway inhibitors such as ibrutinib, or have Richter’s transformation.

The guidelines also addressed the issue of autoimmune cytopenias, which occur in 5% to 10% of patients with CLL and can actually precede the diagnosis of CLL in about 9% of cases.

In patients where autoimmune cytopenia is the dominant clinical feature, they should be treated with corticosteroids, intravenous immunoglobulin, or rituximab. However, for patients where the cytopenia is triggered by CLL therapy, the guidelines recommended halting treatment and beginning immunosuppression.

The guideline development was supported by the British Society for Haematology. The UK CLL Forum, which was involved in development as well, is a registered charity that receives funding from a number of pharmaceutical companies.

Fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, and rituximab are recommended as initial therapy for fit patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) who do not have TP53 disruption, according to new guidelines from the British Society for Haematology.

The guidelines update the 2012 recommendations on CLL to include “significant” developments in treatment.

The new guidelines were published in the British Journal of Haematology.

Anna H. Schuh, MD, of the University of Oxford in the UK, and her coauthors noted that, while these guidelines apply to treatments available outside clinical trials, wherever possible, patients with CLL should be treated within the clinical trial setting.

While recommending fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, and rituximab as first-line therapy, the guideline authors acknowledged that the combination of bendamustine and rituximab is an acceptable alternative for patients who cannot take the triple therapy because of comorbidities such as advanced age, renal impairment, or issues with marrow capacity.

Similarly, less-fit patients can also be considered for chlorambucil-obinutuzumab or chlorambucil-ofatumumab combinations.

All patients diagnosed with CLL should be tested for TP53 deletions and mutations before each line of therapy, the guideline committee recommended.

TP53 disruption makes chemoimmunotherapy ineffective because of either a deletion of chromosome 17p or a mutation in the TP53 gene. However, there is compelling evidence for the efficacy of ibrutinib in these patients, or idelalisib and rituximab for those with cardiac disease or receiving vitamin K antagonists.

With respect to maintenance therapy, the guidelines noted that this was not routinely recommended in CLL as “it is unclear to what extent the progression-free survival benefit is offset by long-term toxicity.”

Patients who are refractory to chemoimmunotherapy, who have relapsed, or who cannot be retreated with chemoimmunotherapy should be treated with idelalisib plus rituximab or ibrutinib monotherapy, the guidelines suggested.

“Deciding whether ibrutinib or idelalisib with rituximab is most appropriate for an individual patient depends on a range of factors, including toxicity profile and convenience of delivery,” the authors wrote.

However, they noted that the value of adding bendamustine to either option was unclear as research had not shown significant, associated gains in median progression-free survival.

Allogeneic stem cell transplant should be considered as an option for patients who have failed chemotherapy, have a TP53 disruption and have not responded to B-cell receptor signaling pathway inhibitors such as ibrutinib, or have Richter’s transformation.

The guidelines also addressed the issue of autoimmune cytopenias, which occur in 5% to 10% of patients with CLL and can actually precede the diagnosis of CLL in about 9% of cases.

In patients where autoimmune cytopenia is the dominant clinical feature, they should be treated with corticosteroids, intravenous immunoglobulin, or rituximab. However, for patients where the cytopenia is triggered by CLL therapy, the guidelines recommended halting treatment and beginning immunosuppression.

The guideline development was supported by the British Society for Haematology. The UK CLL Forum, which was involved in development as well, is a registered charity that receives funding from a number of pharmaceutical companies.

Insurance status linked to survival in FL patients

Having health insurance can mean the difference between life and death for US patients with follicular lymphoma (FL), according to research published in Blood.

The study showed that patients with private health insurance had nearly 2-fold better survival outcomes than patients without insurance or those who were covered by Medicare or Medicaid.

A review of records on more than 43,000 FL patients showed that, compared with patients under age 65 with private insurance, the hazard ratios (HR) for death among patients in the same age bracket were 1.96 for those with no insurance, 1.83 for those with Medicaid, and 1.96 for those with Medicare (P<0.0001 for each comparison).

“Our study finds that insurance status contributes to survival disparities in FL,” Christopher R. Flowers, MD, of Emory University in Atlanta, Georgia, and his colleagues wrote in Blood.

“Future studies on outcomes in FL should include insurance status as an important predictor. Further research on prognosis for FL should examine the impact of public policy, such as the passage of the [Affordable Care Act], on FL outcomes, as well as examine other factors that influence access to care, such as individual-level socioeconomic status, regular primary care visits, access to prescription medications, and care affordability.”

Earlier research showed that patients with Medicaid or no insurance were more likely than privately insured patients to be diagnosed with cancers at advanced stages, and some patients with aggressive non-Hodgkin lymphomas have been shown to have insurance-related disparities in treatments and outcomes.

To see whether the same could be true for patients with indolent-histology lymphomas such as FL, Dr Flowers and his colleagues extracted data from the National Cancer Database, a nationwide hospital-based cancer registry sponsored jointly by the American College of Surgeons and the American Cancer Society.

The investigators identified 43,648 patients, age 18 and older, who were diagnosed with FL from 2004 through 2014. The team looked at patients ages 18 to 64 as well as patients age 65 and older to account for changes in insurance with Medicare eligibility.

Overall survival among patients younger than 65 was significantly worse for patients with public insurance (Medicaid or Medicare) or no insurance in Cox proportional hazard models controlling for available data on sociodemographic factors and prognostic indicators.

However, compared with patients age 65 and older with private insurance, only patients with Medicare as their sole source of insurance had significantly worse overall survival (HR, 1.28; P<0.0001).

Patients who were uninsured or had Medicaid were more likely than others to have lower socioeconomic status, present with advanced-stage disease, have systemic symptoms, and have multiple comorbidities that persisted after controlling for known sociodemographic and prognostic factors.

The investigators found that, among patients under age 65, those with a comorbidity score of 1 had an HR for death of 1.71, compared with patients with no comorbidities, and patients with a score of 2 or greater had an HR of 3.1 (P<0.0001 for each comparison).

“The findings of the study indicate that improving access to affordable, quality healthcare may reduce disparities in survival for those currently lacking coverage,” the investigators wrote.

The study was supported by Emory University, the National Institutes of Health, and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences. Dr Flowers reported financial relationships with AbbVie, Spectrum, Celgene, and several other companies. The other authors reported having nothing to disclose.

Having health insurance can mean the difference between life and death for US patients with follicular lymphoma (FL), according to research published in Blood.

The study showed that patients with private health insurance had nearly 2-fold better survival outcomes than patients without insurance or those who were covered by Medicare or Medicaid.

A review of records on more than 43,000 FL patients showed that, compared with patients under age 65 with private insurance, the hazard ratios (HR) for death among patients in the same age bracket were 1.96 for those with no insurance, 1.83 for those with Medicaid, and 1.96 for those with Medicare (P<0.0001 for each comparison).

“Our study finds that insurance status contributes to survival disparities in FL,” Christopher R. Flowers, MD, of Emory University in Atlanta, Georgia, and his colleagues wrote in Blood.