User login

FDA grants accelerated approval for Opdivo in metastatic SCLC

The Food and Drug Administration has granted accelerated approval to nivolumab (Opdivo) for treating patients with metastatic small-cell lung cancer (SCLC) whose cancer has progressed after platinum-based chemotherapy and at least one other line of therapy.

Approval was based on an overall response rate and duration of response in the monotherapy arm of the multicohort phase 1/2 CheckMate 032 trial. Of 109 patients with SCLC and progression after at least one previous platinum-containing regimen, 12% responded to monotherapy treatment with nivolumab regardless of PD-L1 status, 12 patients had a partial response, and one patient had a complete response.

Among responders, the median duration of response was 17.9 months. Results of the trial were presented at the ASCO annual meeting and published online in The Lancet Oncology in 2016.

Serious adverse reactions occurred in 45% of patients. The most frequent serious adverse reactions were pneumonia, dyspnea, pneumonitis, pleural effusion, and dehydration.

The approved dose is 240 milligrams administered every 2 weeks by intravenous infusion until disease progression or unacceptable toxicity, the company said in a press statement announcing the approval.

The checkpoint inhibitor was approved for treating patients with metastatic non–small-cell lung cancer with progression on or after platinum-based chemotherapy in 2015.

The Food and Drug Administration has granted accelerated approval to nivolumab (Opdivo) for treating patients with metastatic small-cell lung cancer (SCLC) whose cancer has progressed after platinum-based chemotherapy and at least one other line of therapy.

Approval was based on an overall response rate and duration of response in the monotherapy arm of the multicohort phase 1/2 CheckMate 032 trial. Of 109 patients with SCLC and progression after at least one previous platinum-containing regimen, 12% responded to monotherapy treatment with nivolumab regardless of PD-L1 status, 12 patients had a partial response, and one patient had a complete response.

Among responders, the median duration of response was 17.9 months. Results of the trial were presented at the ASCO annual meeting and published online in The Lancet Oncology in 2016.

Serious adverse reactions occurred in 45% of patients. The most frequent serious adverse reactions were pneumonia, dyspnea, pneumonitis, pleural effusion, and dehydration.

The approved dose is 240 milligrams administered every 2 weeks by intravenous infusion until disease progression or unacceptable toxicity, the company said in a press statement announcing the approval.

The checkpoint inhibitor was approved for treating patients with metastatic non–small-cell lung cancer with progression on or after platinum-based chemotherapy in 2015.

The Food and Drug Administration has granted accelerated approval to nivolumab (Opdivo) for treating patients with metastatic small-cell lung cancer (SCLC) whose cancer has progressed after platinum-based chemotherapy and at least one other line of therapy.

Approval was based on an overall response rate and duration of response in the monotherapy arm of the multicohort phase 1/2 CheckMate 032 trial. Of 109 patients with SCLC and progression after at least one previous platinum-containing regimen, 12% responded to monotherapy treatment with nivolumab regardless of PD-L1 status, 12 patients had a partial response, and one patient had a complete response.

Among responders, the median duration of response was 17.9 months. Results of the trial were presented at the ASCO annual meeting and published online in The Lancet Oncology in 2016.

Serious adverse reactions occurred in 45% of patients. The most frequent serious adverse reactions were pneumonia, dyspnea, pneumonitis, pleural effusion, and dehydration.

The approved dose is 240 milligrams administered every 2 weeks by intravenous infusion until disease progression or unacceptable toxicity, the company said in a press statement announcing the approval.

The checkpoint inhibitor was approved for treating patients with metastatic non–small-cell lung cancer with progression on or after platinum-based chemotherapy in 2015.

Nighttime media use threatens teen sleep

Nighttime media use was associated with less sleep, as well as self-reported anxiety and depression, in teens with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, based on data from 81 adolescents.

“This is the first study to document an association between nighttime media use and more sleep problems and internalizing symptoms in adolescents diagnosed with ADHD,” wrote Stephen P. Becker, PhD, of the University of Cincinnati and colleagues.

Although previous research has addressed the impact of screen time on sleep, anxiety, and depression in children and teens, the impact on adolescents with conditions such as ADHD has not been well studied, the researchers noted.

In a study published in Sleep Medicine, the researchers conducted a study of 81 adolescents aged 13-17 years who met diagnostic criteria for ADHD. The School Sleep Habits Survey (SSHS) was used to measure sleep patterns based on self-reports, and parents reported on teens’ sleep using the Sleep Disturbance Scale for Children. In addition, several other tools that measured ADHD symptoms, daytime sleepiness, anxiety, and depression were administered to both the teens and their parents.

The researchers assessed the number of technologies in each participant’s bedroom and the total hours of electronic media use at night, defined as after 9:00 p.m.

Overall, approximately 60% of the teens in the sample reported more than 4 hours of nighttime media use; 63% reported less than 8 hours of sleep on school nights, but this figure reached 76% when parent reports of teens’ sleep was used. When the teens’ self-reports were used, media use was not significantly different between those who had less than 8 hours of sleep vs. those who had 8 hours or more (5.85 vs. 4.39 hours of nighttime media use). But their parents’ reports told another story. In the parent reports, media use was significantly higher in the short sleepers vs. long sleepers (6.12 vs. 2.65 hours of nighttime media use).

After controlling for factors including age, sex, pubertal stage, use of stimulant medication, and severity of ADHD symptoms, nighttime media use was significantly associated with shorter sleep duration, the researchers said.

Nighttime media use also was significantly associated with greater adolescent-reported depressive symptoms, total anxiety symptoms overall, and panic symptoms in particular, as well as with parent-reported generalized anxiety symptoms.

The study findings were limited by several factors including the cross-sectional design, the lack of an objective sleep measure, and the lack of non-ADHD controls, the researchers noted. Also, the researchers were unable to measure parental control over teen media use or to examine different types of media use, including media multitasking (such as texting while video gaming).

However, the findings “suggest that it is important for clinicians to consider nighttime media use when assessing and treating adolescent ADHD, specifically regarding sleep issues and co-occurring depression and anxiety,” they said.

The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose. The study was funded by grants from the National Institutes of Mental Health.

SOURCE: Becker S et al. Sleep Med. 2018. doi: 10.1016/ j.sleep.2018.06.021.

Nighttime media use was associated with less sleep, as well as self-reported anxiety and depression, in teens with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, based on data from 81 adolescents.

“This is the first study to document an association between nighttime media use and more sleep problems and internalizing symptoms in adolescents diagnosed with ADHD,” wrote Stephen P. Becker, PhD, of the University of Cincinnati and colleagues.

Although previous research has addressed the impact of screen time on sleep, anxiety, and depression in children and teens, the impact on adolescents with conditions such as ADHD has not been well studied, the researchers noted.

In a study published in Sleep Medicine, the researchers conducted a study of 81 adolescents aged 13-17 years who met diagnostic criteria for ADHD. The School Sleep Habits Survey (SSHS) was used to measure sleep patterns based on self-reports, and parents reported on teens’ sleep using the Sleep Disturbance Scale for Children. In addition, several other tools that measured ADHD symptoms, daytime sleepiness, anxiety, and depression were administered to both the teens and their parents.

The researchers assessed the number of technologies in each participant’s bedroom and the total hours of electronic media use at night, defined as after 9:00 p.m.

Overall, approximately 60% of the teens in the sample reported more than 4 hours of nighttime media use; 63% reported less than 8 hours of sleep on school nights, but this figure reached 76% when parent reports of teens’ sleep was used. When the teens’ self-reports were used, media use was not significantly different between those who had less than 8 hours of sleep vs. those who had 8 hours or more (5.85 vs. 4.39 hours of nighttime media use). But their parents’ reports told another story. In the parent reports, media use was significantly higher in the short sleepers vs. long sleepers (6.12 vs. 2.65 hours of nighttime media use).

After controlling for factors including age, sex, pubertal stage, use of stimulant medication, and severity of ADHD symptoms, nighttime media use was significantly associated with shorter sleep duration, the researchers said.

Nighttime media use also was significantly associated with greater adolescent-reported depressive symptoms, total anxiety symptoms overall, and panic symptoms in particular, as well as with parent-reported generalized anxiety symptoms.

The study findings were limited by several factors including the cross-sectional design, the lack of an objective sleep measure, and the lack of non-ADHD controls, the researchers noted. Also, the researchers were unable to measure parental control over teen media use or to examine different types of media use, including media multitasking (such as texting while video gaming).

However, the findings “suggest that it is important for clinicians to consider nighttime media use when assessing and treating adolescent ADHD, specifically regarding sleep issues and co-occurring depression and anxiety,” they said.

The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose. The study was funded by grants from the National Institutes of Mental Health.

SOURCE: Becker S et al. Sleep Med. 2018. doi: 10.1016/ j.sleep.2018.06.021.

Nighttime media use was associated with less sleep, as well as self-reported anxiety and depression, in teens with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, based on data from 81 adolescents.

“This is the first study to document an association between nighttime media use and more sleep problems and internalizing symptoms in adolescents diagnosed with ADHD,” wrote Stephen P. Becker, PhD, of the University of Cincinnati and colleagues.

Although previous research has addressed the impact of screen time on sleep, anxiety, and depression in children and teens, the impact on adolescents with conditions such as ADHD has not been well studied, the researchers noted.

In a study published in Sleep Medicine, the researchers conducted a study of 81 adolescents aged 13-17 years who met diagnostic criteria for ADHD. The School Sleep Habits Survey (SSHS) was used to measure sleep patterns based on self-reports, and parents reported on teens’ sleep using the Sleep Disturbance Scale for Children. In addition, several other tools that measured ADHD symptoms, daytime sleepiness, anxiety, and depression were administered to both the teens and their parents.

The researchers assessed the number of technologies in each participant’s bedroom and the total hours of electronic media use at night, defined as after 9:00 p.m.

Overall, approximately 60% of the teens in the sample reported more than 4 hours of nighttime media use; 63% reported less than 8 hours of sleep on school nights, but this figure reached 76% when parent reports of teens’ sleep was used. When the teens’ self-reports were used, media use was not significantly different between those who had less than 8 hours of sleep vs. those who had 8 hours or more (5.85 vs. 4.39 hours of nighttime media use). But their parents’ reports told another story. In the parent reports, media use was significantly higher in the short sleepers vs. long sleepers (6.12 vs. 2.65 hours of nighttime media use).

After controlling for factors including age, sex, pubertal stage, use of stimulant medication, and severity of ADHD symptoms, nighttime media use was significantly associated with shorter sleep duration, the researchers said.

Nighttime media use also was significantly associated with greater adolescent-reported depressive symptoms, total anxiety symptoms overall, and panic symptoms in particular, as well as with parent-reported generalized anxiety symptoms.

The study findings were limited by several factors including the cross-sectional design, the lack of an objective sleep measure, and the lack of non-ADHD controls, the researchers noted. Also, the researchers were unable to measure parental control over teen media use or to examine different types of media use, including media multitasking (such as texting while video gaming).

However, the findings “suggest that it is important for clinicians to consider nighttime media use when assessing and treating adolescent ADHD, specifically regarding sleep issues and co-occurring depression and anxiety,” they said.

The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose. The study was funded by grants from the National Institutes of Mental Health.

SOURCE: Becker S et al. Sleep Med. 2018. doi: 10.1016/ j.sleep.2018.06.021.

FROM SLEEP MEDICINE

Key clinical point: Among teens with ADHD, those who had significantly more nighttime media use tended to get less than 8 hours of sleep at night.

Major finding: About 60% of the teens reported more than 4 hours of nighttime media use; 63% reported less than 8 hours of sleep on school nights.

Study details: The data come from a range of research tools used to gather sleep and media use data on 81 adolescents with ADHD, aged 13-17 years.

Disclosures: The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose. The study was funded by grants from the National Institutes of Mental Health.

Source: Becker S et al. Sleep Med. 2018. doi: 10.1016/ j.sleep.2018.06.021.

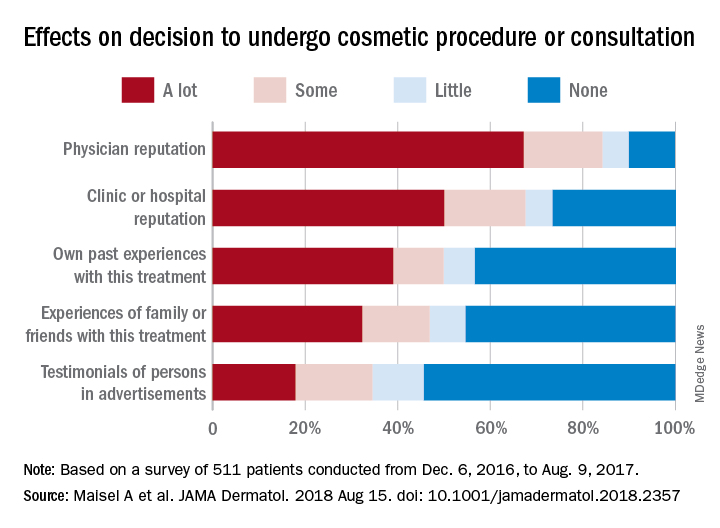

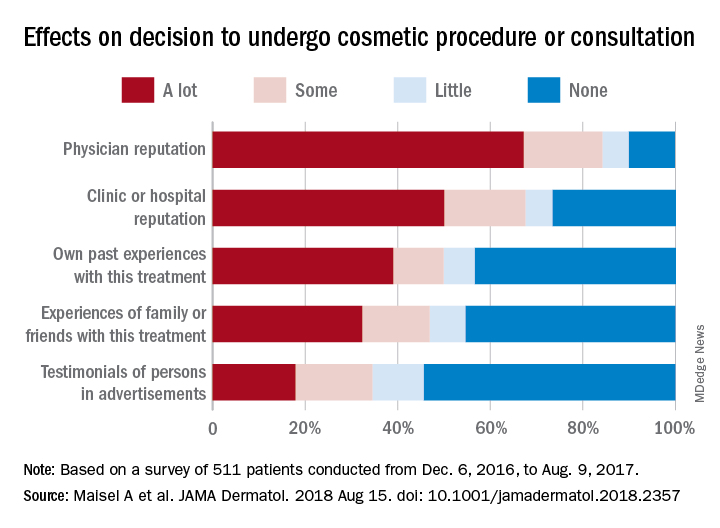

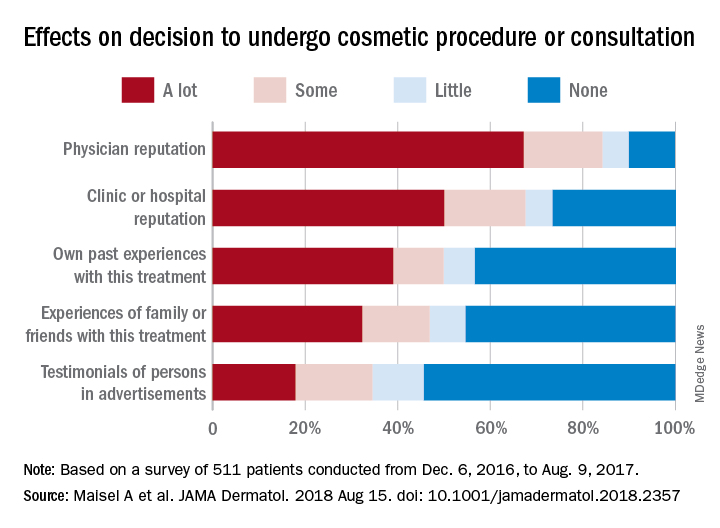

Cosmetic surgery patients want beauty ... and more

but motives involving mental and social well-being and physical health are common as well, according to a prospective national study involving more than 500 patients.

“Cosmetic procedures may also be necessary to correct significant physical disfigurement interfering with work or daily living. Most patients were concerned with how they looked at work and in protecting their physical health, and for some, this motive was the most important. Together, these data add to the growing body of evidence that treatments aimed at improving physical appearance can treat significant physical and psychological illness,” Amanda L. Maisel, of Northwestern University, Chicago, and her associates wrote in JAMA Dermatology.

Among the motives related to appearance, 88.5% of patients said that they “wanted to look better, prettier, or more attractive for themselves,” compared with 64.4% who wanted to look good for others. Patients also were interested in “looking younger or fresher” (83.4%) and having “clear-looking or beautiful skin” (81.4%), the investigators said.

The most common mental or emotional motive was increased self-confidence (69.5%), followed by the desire to “feel happier or better overall or improve quality of life” at 67.2% and to “treat oneself, feel rewarded, or celebrate” at 61.3%. As for social well-being, 56.6% of patients “reported wanting to look good when running into people they knew” and 50.3% reported that they wanted “to feel less self-conscious around others.”

The leading motive involving physical health was “preventing worsening of their condition/symptoms,” which was reported by 53.3% of patients, the investigators reported.

They also examined how reputation and experience influenced patients’ decision to have cosmetic surgery. When asked to what degree a physician’s reputation affected their decision, 67.2% of respondents said a lot, 17% said that it had some effect, 5.7% said it had little effect, and 10% said none. Half of the patients surveyed said the clinic or hospital’s reputation had a lot of influence on their decision, compared with 39% for their own past experiences, 32.2% for experiences of family or friends, and 17.9% for testimonials of persons in advertisements, the researchers said.

The survey was conducted from Dec. 4, 2016, to Aug. 9, 2017, at 2 academic and 11 private dermatology practices. A total of 511 patients were involved, although not all individuals answered every question, so sample sizes varied. The study was supported by a research grant from the American Society for Dermatologic Surgery. The senior investigator reported consulting for Pulse Biosciences that was unrelated to this research and being principal investigator for studies funded in part by Regeneron.

SOURCE: Maisel A et al. JAMA Dermatol. 2018 Aug 15. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.2357.

but motives involving mental and social well-being and physical health are common as well, according to a prospective national study involving more than 500 patients.

“Cosmetic procedures may also be necessary to correct significant physical disfigurement interfering with work or daily living. Most patients were concerned with how they looked at work and in protecting their physical health, and for some, this motive was the most important. Together, these data add to the growing body of evidence that treatments aimed at improving physical appearance can treat significant physical and psychological illness,” Amanda L. Maisel, of Northwestern University, Chicago, and her associates wrote in JAMA Dermatology.

Among the motives related to appearance, 88.5% of patients said that they “wanted to look better, prettier, or more attractive for themselves,” compared with 64.4% who wanted to look good for others. Patients also were interested in “looking younger or fresher” (83.4%) and having “clear-looking or beautiful skin” (81.4%), the investigators said.

The most common mental or emotional motive was increased self-confidence (69.5%), followed by the desire to “feel happier or better overall or improve quality of life” at 67.2% and to “treat oneself, feel rewarded, or celebrate” at 61.3%. As for social well-being, 56.6% of patients “reported wanting to look good when running into people they knew” and 50.3% reported that they wanted “to feel less self-conscious around others.”

The leading motive involving physical health was “preventing worsening of their condition/symptoms,” which was reported by 53.3% of patients, the investigators reported.

They also examined how reputation and experience influenced patients’ decision to have cosmetic surgery. When asked to what degree a physician’s reputation affected their decision, 67.2% of respondents said a lot, 17% said that it had some effect, 5.7% said it had little effect, and 10% said none. Half of the patients surveyed said the clinic or hospital’s reputation had a lot of influence on their decision, compared with 39% for their own past experiences, 32.2% for experiences of family or friends, and 17.9% for testimonials of persons in advertisements, the researchers said.

The survey was conducted from Dec. 4, 2016, to Aug. 9, 2017, at 2 academic and 11 private dermatology practices. A total of 511 patients were involved, although not all individuals answered every question, so sample sizes varied. The study was supported by a research grant from the American Society for Dermatologic Surgery. The senior investigator reported consulting for Pulse Biosciences that was unrelated to this research and being principal investigator for studies funded in part by Regeneron.

SOURCE: Maisel A et al. JAMA Dermatol. 2018 Aug 15. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.2357.

but motives involving mental and social well-being and physical health are common as well, according to a prospective national study involving more than 500 patients.

“Cosmetic procedures may also be necessary to correct significant physical disfigurement interfering with work or daily living. Most patients were concerned with how they looked at work and in protecting their physical health, and for some, this motive was the most important. Together, these data add to the growing body of evidence that treatments aimed at improving physical appearance can treat significant physical and psychological illness,” Amanda L. Maisel, of Northwestern University, Chicago, and her associates wrote in JAMA Dermatology.

Among the motives related to appearance, 88.5% of patients said that they “wanted to look better, prettier, or more attractive for themselves,” compared with 64.4% who wanted to look good for others. Patients also were interested in “looking younger or fresher” (83.4%) and having “clear-looking or beautiful skin” (81.4%), the investigators said.

The most common mental or emotional motive was increased self-confidence (69.5%), followed by the desire to “feel happier or better overall or improve quality of life” at 67.2% and to “treat oneself, feel rewarded, or celebrate” at 61.3%. As for social well-being, 56.6% of patients “reported wanting to look good when running into people they knew” and 50.3% reported that they wanted “to feel less self-conscious around others.”

The leading motive involving physical health was “preventing worsening of their condition/symptoms,” which was reported by 53.3% of patients, the investigators reported.

They also examined how reputation and experience influenced patients’ decision to have cosmetic surgery. When asked to what degree a physician’s reputation affected their decision, 67.2% of respondents said a lot, 17% said that it had some effect, 5.7% said it had little effect, and 10% said none. Half of the patients surveyed said the clinic or hospital’s reputation had a lot of influence on their decision, compared with 39% for their own past experiences, 32.2% for experiences of family or friends, and 17.9% for testimonials of persons in advertisements, the researchers said.

The survey was conducted from Dec. 4, 2016, to Aug. 9, 2017, at 2 academic and 11 private dermatology practices. A total of 511 patients were involved, although not all individuals answered every question, so sample sizes varied. The study was supported by a research grant from the American Society for Dermatologic Surgery. The senior investigator reported consulting for Pulse Biosciences that was unrelated to this research and being principal investigator for studies funded in part by Regeneron.

SOURCE: Maisel A et al. JAMA Dermatol. 2018 Aug 15. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.2357.

FROM JAMA DERMATOLOGY

What is your treatment plan?

The treatment choice is oral terbinafine for tinea capitis with kerion, a scalp dermatophyte infection with a concurrent inflammatory process. Tinea capitis is a very common infection with the peak occurrence at age 3-7 years. Tinea capitis is caused by a variety of dermatophyte species, most commonly by Trichophyton tonsurans or Microsporum canis. T. tonsurans is an endothrix infection, invading the hair shaft and superficial hair while M. canis is an ectothrix infection. T. tonsurans has a person to person transmission; in contrast, M. canis is a zoonotic infection most commonly acquired from infected pets.1 The epidemiology of tinea capitis is affected by multiple factors, including immigration patterns. For example, in Montreal, a study showed a sixfold increase of African dermatophyte species, M. audouinii and T. soudanense.2 Similarly, global variation has increased prevalence of T. violaceum, more commonly found in Europe and Africa, which has been seen in immigrant populations in the United States.1 Kerion is thought to be a hypersensitivity reaction to dermatophytes. Often, misdiagnosis of kerion can result in unnecessary antibiotic prescription and delays in initiation of antifungal therapy.3,4

Tinea capitis can present with focal, “patchy,” well-demarcated hair loss and overlying scale, broken-off hairs at the scalp, and often with pustules. It may be associated with occipital or posterior cervical lymphadenopathy. which presents as a painful boggy scalp mass with or without purulent drainage. Kerions can have associated fever. It is important to differentiate tinea capitis with kerion from processes requiring a different treatment course.3,5 Bacterial folliculitis may have erythema and pustules but only rarely causes hair loss. Similarly, alopecia areata can present with focal alopecia but lacks the scalp inflammation and pustules. Scalp psoriasis is quite scaly, but is more thickened, and usually does not have pustules, nor would purulent drainage be evident. There is a broader differential for other inflammatory focal alopecias including discoid lupus, lichen planopilaris, and dissecting cellulitis of the scalp, which can have similar pus-filled lumps, and cause permanent hair loss, but may be differentiated by associated conditions such as acne conglobata, hidradenitis suppurativa, and pilonidal sinus.

While some clinicians advocate clinical diagnosis of tinea capitis, we advocate confirmation of infection by fungal culture, which can identify the causative organism and influence therapy selection.1 The presence of a fungal infection can be confirmed on potassium hydroxide wet mount prep if hyphae and small spores are seen.6,7 Wood lamp examination will fluoresce if there are ectothrix species, however a negative fluorescence does not differentiate between an endothrix species or lack of infection.

It is important that tinea capitis with kerion is treated with systemic antifungal treatments to allow resolution of the infection, recovery of hair growth, and to prevent or minimize scarring. Systemic antifungal options include terbinafine, griseofulvin, and azoles. Terbinafine is becoming the treatment of choice given shorter duration of treatment with similar efficacy.1T. tonsurans also is thought to respond better to terbinafine than to griseofulvin.8 Griseofulvin is the historical treatment of choice because of its history of clinical safety and no need for laboratory testing. It is important to note that higher doses of griseofulvin (20-25 mg/kg) are recommended, as older lower dose regimens have high rates of failure. Griseofulvin may be more effective for treatment of Microsporum spp than is terbinafine.8 Fluconazole is the only oral antifungal agent that is approved for patients younger than 2 years of age, however it has lower cure rates, compared with terbinafine and griseofulvin.1 Tinea capitis with kerion does not generally require antibiotics unless there is superimposed bacterial infection. Kerion also do not require incision or drainage, which may increase scarring and complicate the clinical course.

Management of tinea capitis should include evaluation of any other household members for coinfection. Depending on the dermatophyte involved there can be risk of person-to-person transmission.5 Families should be educated about fomite transmission via shared combs or hats. Additionally, if a zoophilic dermatophyte is suspected, pets also should be appropriately examined and treated. Topical antifungals are insufficient to eradicate tinea capitis but can be used as adjunctive therapy. Kerion can be treated with oral prednisone in addition to oral antifungals if the lesions are very painful, however there is limited data on this treatment option.9

Ms. Kaushik is a research fellow and Dr. Eichenfield is professor of dermatology and pediatrics in the division of pediatric and adolescent dermatology at Rady Children’s Hospital and the University of California, both in San Diego. They have no conflicts of interest or relevant financial disclosures.

References

1. “Red Book: Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases,” 31st Edition, (Elk Grove Village, Ill.: American Academy of Pediatrics, 2018, p. 1264).

2. Pediatr Dermatol. 2018 May;35(3):323-8

3. Arch Dis Child. 2016 May;101(5):503.

4. IDCases. 2018 Jun 28;14:e00418.

5. Int J Dermatol. 2018 Jan;57(1):3-9.

6. Pediatr Rev. 2007 May;28(5):164-74.

7. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2010;3:89-98.

8. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016 May 12;(5):CD004685.

9. Med Mycol. 1999 Apr;37(2):97-9.

The treatment choice is oral terbinafine for tinea capitis with kerion, a scalp dermatophyte infection with a concurrent inflammatory process. Tinea capitis is a very common infection with the peak occurrence at age 3-7 years. Tinea capitis is caused by a variety of dermatophyte species, most commonly by Trichophyton tonsurans or Microsporum canis. T. tonsurans is an endothrix infection, invading the hair shaft and superficial hair while M. canis is an ectothrix infection. T. tonsurans has a person to person transmission; in contrast, M. canis is a zoonotic infection most commonly acquired from infected pets.1 The epidemiology of tinea capitis is affected by multiple factors, including immigration patterns. For example, in Montreal, a study showed a sixfold increase of African dermatophyte species, M. audouinii and T. soudanense.2 Similarly, global variation has increased prevalence of T. violaceum, more commonly found in Europe and Africa, which has been seen in immigrant populations in the United States.1 Kerion is thought to be a hypersensitivity reaction to dermatophytes. Often, misdiagnosis of kerion can result in unnecessary antibiotic prescription and delays in initiation of antifungal therapy.3,4

Tinea capitis can present with focal, “patchy,” well-demarcated hair loss and overlying scale, broken-off hairs at the scalp, and often with pustules. It may be associated with occipital or posterior cervical lymphadenopathy. which presents as a painful boggy scalp mass with or without purulent drainage. Kerions can have associated fever. It is important to differentiate tinea capitis with kerion from processes requiring a different treatment course.3,5 Bacterial folliculitis may have erythema and pustules but only rarely causes hair loss. Similarly, alopecia areata can present with focal alopecia but lacks the scalp inflammation and pustules. Scalp psoriasis is quite scaly, but is more thickened, and usually does not have pustules, nor would purulent drainage be evident. There is a broader differential for other inflammatory focal alopecias including discoid lupus, lichen planopilaris, and dissecting cellulitis of the scalp, which can have similar pus-filled lumps, and cause permanent hair loss, but may be differentiated by associated conditions such as acne conglobata, hidradenitis suppurativa, and pilonidal sinus.

While some clinicians advocate clinical diagnosis of tinea capitis, we advocate confirmation of infection by fungal culture, which can identify the causative organism and influence therapy selection.1 The presence of a fungal infection can be confirmed on potassium hydroxide wet mount prep if hyphae and small spores are seen.6,7 Wood lamp examination will fluoresce if there are ectothrix species, however a negative fluorescence does not differentiate between an endothrix species or lack of infection.

It is important that tinea capitis with kerion is treated with systemic antifungal treatments to allow resolution of the infection, recovery of hair growth, and to prevent or minimize scarring. Systemic antifungal options include terbinafine, griseofulvin, and azoles. Terbinafine is becoming the treatment of choice given shorter duration of treatment with similar efficacy.1T. tonsurans also is thought to respond better to terbinafine than to griseofulvin.8 Griseofulvin is the historical treatment of choice because of its history of clinical safety and no need for laboratory testing. It is important to note that higher doses of griseofulvin (20-25 mg/kg) are recommended, as older lower dose regimens have high rates of failure. Griseofulvin may be more effective for treatment of Microsporum spp than is terbinafine.8 Fluconazole is the only oral antifungal agent that is approved for patients younger than 2 years of age, however it has lower cure rates, compared with terbinafine and griseofulvin.1 Tinea capitis with kerion does not generally require antibiotics unless there is superimposed bacterial infection. Kerion also do not require incision or drainage, which may increase scarring and complicate the clinical course.

Management of tinea capitis should include evaluation of any other household members for coinfection. Depending on the dermatophyte involved there can be risk of person-to-person transmission.5 Families should be educated about fomite transmission via shared combs or hats. Additionally, if a zoophilic dermatophyte is suspected, pets also should be appropriately examined and treated. Topical antifungals are insufficient to eradicate tinea capitis but can be used as adjunctive therapy. Kerion can be treated with oral prednisone in addition to oral antifungals if the lesions are very painful, however there is limited data on this treatment option.9

Ms. Kaushik is a research fellow and Dr. Eichenfield is professor of dermatology and pediatrics in the division of pediatric and adolescent dermatology at Rady Children’s Hospital and the University of California, both in San Diego. They have no conflicts of interest or relevant financial disclosures.

References

1. “Red Book: Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases,” 31st Edition, (Elk Grove Village, Ill.: American Academy of Pediatrics, 2018, p. 1264).

2. Pediatr Dermatol. 2018 May;35(3):323-8

3. Arch Dis Child. 2016 May;101(5):503.

4. IDCases. 2018 Jun 28;14:e00418.

5. Int J Dermatol. 2018 Jan;57(1):3-9.

6. Pediatr Rev. 2007 May;28(5):164-74.

7. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2010;3:89-98.

8. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016 May 12;(5):CD004685.

9. Med Mycol. 1999 Apr;37(2):97-9.

The treatment choice is oral terbinafine for tinea capitis with kerion, a scalp dermatophyte infection with a concurrent inflammatory process. Tinea capitis is a very common infection with the peak occurrence at age 3-7 years. Tinea capitis is caused by a variety of dermatophyte species, most commonly by Trichophyton tonsurans or Microsporum canis. T. tonsurans is an endothrix infection, invading the hair shaft and superficial hair while M. canis is an ectothrix infection. T. tonsurans has a person to person transmission; in contrast, M. canis is a zoonotic infection most commonly acquired from infected pets.1 The epidemiology of tinea capitis is affected by multiple factors, including immigration patterns. For example, in Montreal, a study showed a sixfold increase of African dermatophyte species, M. audouinii and T. soudanense.2 Similarly, global variation has increased prevalence of T. violaceum, more commonly found in Europe and Africa, which has been seen in immigrant populations in the United States.1 Kerion is thought to be a hypersensitivity reaction to dermatophytes. Often, misdiagnosis of kerion can result in unnecessary antibiotic prescription and delays in initiation of antifungal therapy.3,4

Tinea capitis can present with focal, “patchy,” well-demarcated hair loss and overlying scale, broken-off hairs at the scalp, and often with pustules. It may be associated with occipital or posterior cervical lymphadenopathy. which presents as a painful boggy scalp mass with or without purulent drainage. Kerions can have associated fever. It is important to differentiate tinea capitis with kerion from processes requiring a different treatment course.3,5 Bacterial folliculitis may have erythema and pustules but only rarely causes hair loss. Similarly, alopecia areata can present with focal alopecia but lacks the scalp inflammation and pustules. Scalp psoriasis is quite scaly, but is more thickened, and usually does not have pustules, nor would purulent drainage be evident. There is a broader differential for other inflammatory focal alopecias including discoid lupus, lichen planopilaris, and dissecting cellulitis of the scalp, which can have similar pus-filled lumps, and cause permanent hair loss, but may be differentiated by associated conditions such as acne conglobata, hidradenitis suppurativa, and pilonidal sinus.

While some clinicians advocate clinical diagnosis of tinea capitis, we advocate confirmation of infection by fungal culture, which can identify the causative organism and influence therapy selection.1 The presence of a fungal infection can be confirmed on potassium hydroxide wet mount prep if hyphae and small spores are seen.6,7 Wood lamp examination will fluoresce if there are ectothrix species, however a negative fluorescence does not differentiate between an endothrix species or lack of infection.

It is important that tinea capitis with kerion is treated with systemic antifungal treatments to allow resolution of the infection, recovery of hair growth, and to prevent or minimize scarring. Systemic antifungal options include terbinafine, griseofulvin, and azoles. Terbinafine is becoming the treatment of choice given shorter duration of treatment with similar efficacy.1T. tonsurans also is thought to respond better to terbinafine than to griseofulvin.8 Griseofulvin is the historical treatment of choice because of its history of clinical safety and no need for laboratory testing. It is important to note that higher doses of griseofulvin (20-25 mg/kg) are recommended, as older lower dose regimens have high rates of failure. Griseofulvin may be more effective for treatment of Microsporum spp than is terbinafine.8 Fluconazole is the only oral antifungal agent that is approved for patients younger than 2 years of age, however it has lower cure rates, compared with terbinafine and griseofulvin.1 Tinea capitis with kerion does not generally require antibiotics unless there is superimposed bacterial infection. Kerion also do not require incision or drainage, which may increase scarring and complicate the clinical course.

Management of tinea capitis should include evaluation of any other household members for coinfection. Depending on the dermatophyte involved there can be risk of person-to-person transmission.5 Families should be educated about fomite transmission via shared combs or hats. Additionally, if a zoophilic dermatophyte is suspected, pets also should be appropriately examined and treated. Topical antifungals are insufficient to eradicate tinea capitis but can be used as adjunctive therapy. Kerion can be treated with oral prednisone in addition to oral antifungals if the lesions are very painful, however there is limited data on this treatment option.9

Ms. Kaushik is a research fellow and Dr. Eichenfield is professor of dermatology and pediatrics in the division of pediatric and adolescent dermatology at Rady Children’s Hospital and the University of California, both in San Diego. They have no conflicts of interest or relevant financial disclosures.

References

1. “Red Book: Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases,” 31st Edition, (Elk Grove Village, Ill.: American Academy of Pediatrics, 2018, p. 1264).

2. Pediatr Dermatol. 2018 May;35(3):323-8

3. Arch Dis Child. 2016 May;101(5):503.

4. IDCases. 2018 Jun 28;14:e00418.

5. Int J Dermatol. 2018 Jan;57(1):3-9.

6. Pediatr Rev. 2007 May;28(5):164-74.

7. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2010;3:89-98.

8. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016 May 12;(5):CD004685.

9. Med Mycol. 1999 Apr;37(2):97-9.

A 10-year-old otherwise-healthy male presents for a progressing lesion on his scalp. One month prior to coming in, he developed some peeling and itch followed by loss of hair. This had worsened, becoming a painful and boggy mass on the back of his head with focal alopecia. He went to the local ED, where he had plain films of his skull, which were normal and was prescribed cephalexin. He has not shown any improvement after starting the antibiotics. He has had no fevers in this time, but the pain persists.

On physical exam, he is noted to have a hairless patch on a boggy left occipital mass, which is tender to palpation. There is a small amount of overlying honey-colored crusting. He has associated posterior occipital nontender lymphadenopathy.

The patient's older sister has a small area of scalp hair loss.

SMART Self-Management Program Enhances Epilepsy Care

A self-management program called SMART can help patients with epilepsy reduce the risk of negative health events according to researchers at Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine.

- A 6-month randomized controlled trial of the community-based program included 60 adult patients and was compared to 60 control patients on a waitlist.

- The experiment monitored a variety of events, including seizures, accidents, attempts at self-harm, emergency department visits, and hospitalizations.

- The average patient in this trial was about 41 years old, about 70% were African American, 74% were unemployed.

- Patients who were randomized to the SMART program had fewer negative health events by 6 months compared to controls.

- SMART was also linked to improved scores on the Patient Health Questionnaire (P=.002), the 10 item Quality of Life in Epilepsy Inventory, and the Short Form Health Survey.

Sajatovic M, Colon-Zimmermann K, Kahriman M, et al. A 6-month prospective randomized controlled trial of remotely delivered group format epilepsy self-management versus waitlist control for high-risk people with epilepsy. [Published online ahead of print August 10, 2018]. Epilepsia. https://doi.org/10.1111/epi.14527.

A self-management program called SMART can help patients with epilepsy reduce the risk of negative health events according to researchers at Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine.

- A 6-month randomized controlled trial of the community-based program included 60 adult patients and was compared to 60 control patients on a waitlist.

- The experiment monitored a variety of events, including seizures, accidents, attempts at self-harm, emergency department visits, and hospitalizations.

- The average patient in this trial was about 41 years old, about 70% were African American, 74% were unemployed.

- Patients who were randomized to the SMART program had fewer negative health events by 6 months compared to controls.

- SMART was also linked to improved scores on the Patient Health Questionnaire (P=.002), the 10 item Quality of Life in Epilepsy Inventory, and the Short Form Health Survey.

Sajatovic M, Colon-Zimmermann K, Kahriman M, et al. A 6-month prospective randomized controlled trial of remotely delivered group format epilepsy self-management versus waitlist control for high-risk people with epilepsy. [Published online ahead of print August 10, 2018]. Epilepsia. https://doi.org/10.1111/epi.14527.

A self-management program called SMART can help patients with epilepsy reduce the risk of negative health events according to researchers at Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine.

- A 6-month randomized controlled trial of the community-based program included 60 adult patients and was compared to 60 control patients on a waitlist.

- The experiment monitored a variety of events, including seizures, accidents, attempts at self-harm, emergency department visits, and hospitalizations.

- The average patient in this trial was about 41 years old, about 70% were African American, 74% were unemployed.

- Patients who were randomized to the SMART program had fewer negative health events by 6 months compared to controls.

- SMART was also linked to improved scores on the Patient Health Questionnaire (P=.002), the 10 item Quality of Life in Epilepsy Inventory, and the Short Form Health Survey.

Sajatovic M, Colon-Zimmermann K, Kahriman M, et al. A 6-month prospective randomized controlled trial of remotely delivered group format epilepsy self-management versus waitlist control for high-risk people with epilepsy. [Published online ahead of print August 10, 2018]. Epilepsia. https://doi.org/10.1111/epi.14527.

FDA puts partial hold on trial of vascular agent for AML, MDS

The Food and Drug Administration has placed a partial clinical hold on a phase 1b/2 study of OXi4503, a vascular disrupting agent.

In this trial (NCT02576301), researchers are evaluating OXi4503 alone and in combination with cytarabine in patients with relapsed/refractory acute myeloid leukemia (AML) and myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS).

The partial clinical hold applies to the 12.2 mg/m2 dose of OXi4503. The FDA is allowing the continued treatment and enrollment of patients using a dose of 9.76 mg/m2. Additional data on patients receiving OXi4503 at 9.76 mg/m2 must be evaluated before dosing at 12.2 mg/m2 can be resumed.

The partial clinical hold is a result of two potential dose-limiting toxicities (DLTs) observed at the 12.2-mg/m2 dose level: hypotension, which occurred shortly after initial treatment with OXi4503, and acute hypoxic respiratory failure, which occurred approximately 2 weeks after receiving OXi4503 and cytarabine.

Both events were deemed “possibly related” to OXi4503, and both patients recovered following treatment.

“Although it is disappointing that we are not currently continuing with the higher dose of OXi4503, we look forward to gathering more safety and efficacy data at the previous dose level, where we observed 2 complete remissions in the 4 patients that we treated,” William D. Schwieterman, MD, chief executive officer of Mateon Therapeutics Inc., the company developing OXi4503, said in a statement.

In preclinical research, OXi4503 demonstrated activity against AML, both when given alone and in combination with bevacizumab. These results were published in Blood in 2010.

In a phase 1 trial (NCT01085656), researchers evaluated OXi4503 in patients with relapsed or refractory AML or MDS. OXi4503 demonstrated preliminary evidence of disease response in heavily pretreated, refractory AML and advanced MDS.

The maximum tolerated dose of OXi4503 was not identified, but adverse events attributable to the drug included hypertension, bone pain, fever, anemia, thrombocytopenia, and coagulopathies.

Results from this study were presented at the 2013 annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology.

In 2015, Mateon Therapeutics initiated the phase 1b/2 study of OXi4503 (NCT02576301) that is now on partial clinical hold.

The phase 1 portion of this study was designed to assess the safety, pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, and preliminary efficacy of single-agent OXi4503 in patients with relapsed/refractory AML and MDS. It is also aimed at determining the safety, pharmacokinetics, and pharmacodynamics of OXi4503 plus intermediate-dose cytarabine.

The goal of the phase 2 portion is to assess the preliminary efficacy of OXi4503 and cytarabine in patients with AML and MDS.

The Food and Drug Administration has placed a partial clinical hold on a phase 1b/2 study of OXi4503, a vascular disrupting agent.

In this trial (NCT02576301), researchers are evaluating OXi4503 alone and in combination with cytarabine in patients with relapsed/refractory acute myeloid leukemia (AML) and myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS).

The partial clinical hold applies to the 12.2 mg/m2 dose of OXi4503. The FDA is allowing the continued treatment and enrollment of patients using a dose of 9.76 mg/m2. Additional data on patients receiving OXi4503 at 9.76 mg/m2 must be evaluated before dosing at 12.2 mg/m2 can be resumed.

The partial clinical hold is a result of two potential dose-limiting toxicities (DLTs) observed at the 12.2-mg/m2 dose level: hypotension, which occurred shortly after initial treatment with OXi4503, and acute hypoxic respiratory failure, which occurred approximately 2 weeks after receiving OXi4503 and cytarabine.

Both events were deemed “possibly related” to OXi4503, and both patients recovered following treatment.

“Although it is disappointing that we are not currently continuing with the higher dose of OXi4503, we look forward to gathering more safety and efficacy data at the previous dose level, where we observed 2 complete remissions in the 4 patients that we treated,” William D. Schwieterman, MD, chief executive officer of Mateon Therapeutics Inc., the company developing OXi4503, said in a statement.

In preclinical research, OXi4503 demonstrated activity against AML, both when given alone and in combination with bevacizumab. These results were published in Blood in 2010.

In a phase 1 trial (NCT01085656), researchers evaluated OXi4503 in patients with relapsed or refractory AML or MDS. OXi4503 demonstrated preliminary evidence of disease response in heavily pretreated, refractory AML and advanced MDS.

The maximum tolerated dose of OXi4503 was not identified, but adverse events attributable to the drug included hypertension, bone pain, fever, anemia, thrombocytopenia, and coagulopathies.

Results from this study were presented at the 2013 annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology.

In 2015, Mateon Therapeutics initiated the phase 1b/2 study of OXi4503 (NCT02576301) that is now on partial clinical hold.

The phase 1 portion of this study was designed to assess the safety, pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, and preliminary efficacy of single-agent OXi4503 in patients with relapsed/refractory AML and MDS. It is also aimed at determining the safety, pharmacokinetics, and pharmacodynamics of OXi4503 plus intermediate-dose cytarabine.

The goal of the phase 2 portion is to assess the preliminary efficacy of OXi4503 and cytarabine in patients with AML and MDS.

The Food and Drug Administration has placed a partial clinical hold on a phase 1b/2 study of OXi4503, a vascular disrupting agent.

In this trial (NCT02576301), researchers are evaluating OXi4503 alone and in combination with cytarabine in patients with relapsed/refractory acute myeloid leukemia (AML) and myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS).

The partial clinical hold applies to the 12.2 mg/m2 dose of OXi4503. The FDA is allowing the continued treatment and enrollment of patients using a dose of 9.76 mg/m2. Additional data on patients receiving OXi4503 at 9.76 mg/m2 must be evaluated before dosing at 12.2 mg/m2 can be resumed.

The partial clinical hold is a result of two potential dose-limiting toxicities (DLTs) observed at the 12.2-mg/m2 dose level: hypotension, which occurred shortly after initial treatment with OXi4503, and acute hypoxic respiratory failure, which occurred approximately 2 weeks after receiving OXi4503 and cytarabine.

Both events were deemed “possibly related” to OXi4503, and both patients recovered following treatment.

“Although it is disappointing that we are not currently continuing with the higher dose of OXi4503, we look forward to gathering more safety and efficacy data at the previous dose level, where we observed 2 complete remissions in the 4 patients that we treated,” William D. Schwieterman, MD, chief executive officer of Mateon Therapeutics Inc., the company developing OXi4503, said in a statement.

In preclinical research, OXi4503 demonstrated activity against AML, both when given alone and in combination with bevacizumab. These results were published in Blood in 2010.

In a phase 1 trial (NCT01085656), researchers evaluated OXi4503 in patients with relapsed or refractory AML or MDS. OXi4503 demonstrated preliminary evidence of disease response in heavily pretreated, refractory AML and advanced MDS.

The maximum tolerated dose of OXi4503 was not identified, but adverse events attributable to the drug included hypertension, bone pain, fever, anemia, thrombocytopenia, and coagulopathies.

Results from this study were presented at the 2013 annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology.

In 2015, Mateon Therapeutics initiated the phase 1b/2 study of OXi4503 (NCT02576301) that is now on partial clinical hold.

The phase 1 portion of this study was designed to assess the safety, pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, and preliminary efficacy of single-agent OXi4503 in patients with relapsed/refractory AML and MDS. It is also aimed at determining the safety, pharmacokinetics, and pharmacodynamics of OXi4503 plus intermediate-dose cytarabine.

The goal of the phase 2 portion is to assess the preliminary efficacy of OXi4503 and cytarabine in patients with AML and MDS.

Don’t Ignore Sleep Complaints in PNES Patients

Patients with psychogenic nonepileptic seizures (PNES) are more likely to suffer from sleep complaints than are patients with epilepsy according to an analysis conducted by clinicians at the Brigham and Women’s Hospital.

- 149 patients with PNES and 82 patients with epilepsy completed the Beck Depression Inventory and the Quality of Life in Epilepsy Inventory-10.

- By analyzing item 16 on the Beck Depression Inventory, which looks at changes in sleep patterns, the investigators found that PNES patients were more likely to report moderate to severe changes in sleep patterns, including waking up too early, sleeping less than usual, and having trouble falling back to sleep.

- The sleep complaints were associated with poorer quality of life, suggesting that they need to be addressed more closely in PNES patients.

Latreille V, Baslet G, Sarkis R, et al. Sleep in psychogenic nonepileptic seizures: time to raise a red flag. Epilepsy Behav. 2018;86:6-8.

Patients with psychogenic nonepileptic seizures (PNES) are more likely to suffer from sleep complaints than are patients with epilepsy according to an analysis conducted by clinicians at the Brigham and Women’s Hospital.

- 149 patients with PNES and 82 patients with epilepsy completed the Beck Depression Inventory and the Quality of Life in Epilepsy Inventory-10.

- By analyzing item 16 on the Beck Depression Inventory, which looks at changes in sleep patterns, the investigators found that PNES patients were more likely to report moderate to severe changes in sleep patterns, including waking up too early, sleeping less than usual, and having trouble falling back to sleep.

- The sleep complaints were associated with poorer quality of life, suggesting that they need to be addressed more closely in PNES patients.

Latreille V, Baslet G, Sarkis R, et al. Sleep in psychogenic nonepileptic seizures: time to raise a red flag. Epilepsy Behav. 2018;86:6-8.

Patients with psychogenic nonepileptic seizures (PNES) are more likely to suffer from sleep complaints than are patients with epilepsy according to an analysis conducted by clinicians at the Brigham and Women’s Hospital.

- 149 patients with PNES and 82 patients with epilepsy completed the Beck Depression Inventory and the Quality of Life in Epilepsy Inventory-10.

- By analyzing item 16 on the Beck Depression Inventory, which looks at changes in sleep patterns, the investigators found that PNES patients were more likely to report moderate to severe changes in sleep patterns, including waking up too early, sleeping less than usual, and having trouble falling back to sleep.

- The sleep complaints were associated with poorer quality of life, suggesting that they need to be addressed more closely in PNES patients.

Latreille V, Baslet G, Sarkis R, et al. Sleep in psychogenic nonepileptic seizures: time to raise a red flag. Epilepsy Behav. 2018;86:6-8.

Analysis of Epilepsy Self-Management Skills

Although patients with epilepsy can benefit from self-management programs, a recent analysis from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has found that competency in self-management skills varies considerably across behavioral domains.

- Data from the Prevention Managing Epilepsy Well Network found that competencies in information and lifestyle management were considerably weaker than competencies in medication, safety, and seizure management.

- The Managing Epilepsy Well database analysis included 436 patients with epilepsy from 5 studies in the United States.

- Self-management behavioral skills were stronger in females and among patients with less education.

- The same skills were weaker in patients with depression and in those who reported a lower quality of life.

Begley C, Shegog R, Liu H, et al. Correlates of epilepsy self-management in MEW Network participants: From the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Managing Epilepsy Well Network. Epilepsy Behav. 2018;85:243-247.

Although patients with epilepsy can benefit from self-management programs, a recent analysis from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has found that competency in self-management skills varies considerably across behavioral domains.

- Data from the Prevention Managing Epilepsy Well Network found that competencies in information and lifestyle management were considerably weaker than competencies in medication, safety, and seizure management.

- The Managing Epilepsy Well database analysis included 436 patients with epilepsy from 5 studies in the United States.

- Self-management behavioral skills were stronger in females and among patients with less education.

- The same skills were weaker in patients with depression and in those who reported a lower quality of life.

Begley C, Shegog R, Liu H, et al. Correlates of epilepsy self-management in MEW Network participants: From the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Managing Epilepsy Well Network. Epilepsy Behav. 2018;85:243-247.

Although patients with epilepsy can benefit from self-management programs, a recent analysis from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has found that competency in self-management skills varies considerably across behavioral domains.

- Data from the Prevention Managing Epilepsy Well Network found that competencies in information and lifestyle management were considerably weaker than competencies in medication, safety, and seizure management.

- The Managing Epilepsy Well database analysis included 436 patients with epilepsy from 5 studies in the United States.

- Self-management behavioral skills were stronger in females and among patients with less education.

- The same skills were weaker in patients with depression and in those who reported a lower quality of life.

Begley C, Shegog R, Liu H, et al. Correlates of epilepsy self-management in MEW Network participants: From the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Managing Epilepsy Well Network. Epilepsy Behav. 2018;85:243-247.

Comparison of analgesia methods for neonatal circumcision

Multiple pain management interventions exist

Clinical question

What is the optimal way to manage analgesia during neonatal circumcision?

Background

Neonatal circumcision is one of the most commonly performed surgical procedures. The American Academy of Pediatrics in 2012 noted that the health benefits outweigh the minor risks of the procedure, but that parents should make the decision to circumcise based on their own cultural, ethical, and religious beliefs.

One of the primary risks of neonatal circumcision is pain during and after the procedure. Multiple methods for managing analgesia exist, but it is unknown what combination of methods is optimal. Usual analgesia techniques include: local anesthetic cream composed of lidocaine and prilocaine (EMLA) applied to the skin prior to the procedure; oral sucrose solution given throughout the procedure; dorsal penile nerve block (DPNB); and penile ring block (RB).

Study design

Single-center, double-blinded, randomized, controlled trial.

Setting

Multispecialty freestanding hospital.

Synopsis

Parents of infant boys born at 36-41 weeks’ gestation who chose to have their children circumcised were offered participation in the study. Of 83 eligible participants, 70 were randomized, with 10 in the control group (EMLA only) and 20 in each intervention (EMLA + sucrose, EMLA + sucrose + RB, EMLA + sucrose + DPNB). A single pediatric urologist performed all circumcisions using the Gomco clamp technique.

A video camera recorded the infant’s face and upper torso during the procedure. Two researchers, who were blinded to the analgesia plan, scored these videos using a modified Neonatal Infant Pain Scale (NIPS). The NIPS used ranged from 0 to 6, with 6 considered severe pain. For rating purposes, the procedure was divided into 6 stages with a NIPS score assigned at each stage. There were no significant differences in baseline characteristics among the groups; no significant differences in the duration of the procedure by intervention; and there were no complications. Interrater reliability for the NIPS was good (kappa, 0.84). All interventions were superior to EMLA alone, with significantly decreased NIPS for all stages of the procedure. No significant differences in NIPS were found among the following:

EMLA + sucrose.

EMLA + sucrose + RB.

EMLA + sucrose + DPNB (for any stage of the procedure).

The one exception was that following lysis of foreskin adhesions, EMLA + sucrose + RB was superior (NIPS 2.25 for EMLA + sucrose + RB vs. NIPS 4.4 for EMLA + sucrose + DPNB vs. NIPS 4.3 for EMLA + sucrose vs. NIPS 5.8 for EMLA alone). In terms of crying time during the procedure, all interventions were significantly superior to EMLA alone. Of the interventions, crying time was statistically and clinically significantly shorter with EMLA + sucrose + RB (5.78 seconds vs. 11.5 for EMLA + sucrose + DPNB vs. 16.5 for EMLA + sucrose vs. 45.4 for EMLA alone). This was a single-center study and the procedures were performed by a pediatric urologist rather than by a general pediatrician, which potentially limits applicability.

Bottom line

All tested analgesia modalities for neonatal circumcision were superior to EMLA alone. The most effective analgesia of those tested was EMLA + sucrose + penile ring block.

Citation

Sharara-Chami R et al. Combination analgesia for neonatal circumcision: a randomized controlled trial. Pediatrics. 2017. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-1935.

Dr. Stubblefield is a pediatric hospitalist at Nemours/Alfred I. duPont Hospital for Children in Wilmington, Del., and a clinical assistant professor of pediatrics at Sidney Kimmel Medical College at Thomas Jefferson University in Philadelphia.

Multiple pain management interventions exist

Multiple pain management interventions exist

Clinical question

What is the optimal way to manage analgesia during neonatal circumcision?

Background

Neonatal circumcision is one of the most commonly performed surgical procedures. The American Academy of Pediatrics in 2012 noted that the health benefits outweigh the minor risks of the procedure, but that parents should make the decision to circumcise based on their own cultural, ethical, and religious beliefs.

One of the primary risks of neonatal circumcision is pain during and after the procedure. Multiple methods for managing analgesia exist, but it is unknown what combination of methods is optimal. Usual analgesia techniques include: local anesthetic cream composed of lidocaine and prilocaine (EMLA) applied to the skin prior to the procedure; oral sucrose solution given throughout the procedure; dorsal penile nerve block (DPNB); and penile ring block (RB).

Study design

Single-center, double-blinded, randomized, controlled trial.

Setting

Multispecialty freestanding hospital.

Synopsis

Parents of infant boys born at 36-41 weeks’ gestation who chose to have their children circumcised were offered participation in the study. Of 83 eligible participants, 70 were randomized, with 10 in the control group (EMLA only) and 20 in each intervention (EMLA + sucrose, EMLA + sucrose + RB, EMLA + sucrose + DPNB). A single pediatric urologist performed all circumcisions using the Gomco clamp technique.

A video camera recorded the infant’s face and upper torso during the procedure. Two researchers, who were blinded to the analgesia plan, scored these videos using a modified Neonatal Infant Pain Scale (NIPS). The NIPS used ranged from 0 to 6, with 6 considered severe pain. For rating purposes, the procedure was divided into 6 stages with a NIPS score assigned at each stage. There were no significant differences in baseline characteristics among the groups; no significant differences in the duration of the procedure by intervention; and there were no complications. Interrater reliability for the NIPS was good (kappa, 0.84). All interventions were superior to EMLA alone, with significantly decreased NIPS for all stages of the procedure. No significant differences in NIPS were found among the following:

EMLA + sucrose.

EMLA + sucrose + RB.

EMLA + sucrose + DPNB (for any stage of the procedure).

The one exception was that following lysis of foreskin adhesions, EMLA + sucrose + RB was superior (NIPS 2.25 for EMLA + sucrose + RB vs. NIPS 4.4 for EMLA + sucrose + DPNB vs. NIPS 4.3 for EMLA + sucrose vs. NIPS 5.8 for EMLA alone). In terms of crying time during the procedure, all interventions were significantly superior to EMLA alone. Of the interventions, crying time was statistically and clinically significantly shorter with EMLA + sucrose + RB (5.78 seconds vs. 11.5 for EMLA + sucrose + DPNB vs. 16.5 for EMLA + sucrose vs. 45.4 for EMLA alone). This was a single-center study and the procedures were performed by a pediatric urologist rather than by a general pediatrician, which potentially limits applicability.

Bottom line

All tested analgesia modalities for neonatal circumcision were superior to EMLA alone. The most effective analgesia of those tested was EMLA + sucrose + penile ring block.

Citation

Sharara-Chami R et al. Combination analgesia for neonatal circumcision: a randomized controlled trial. Pediatrics. 2017. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-1935.

Dr. Stubblefield is a pediatric hospitalist at Nemours/Alfred I. duPont Hospital for Children in Wilmington, Del., and a clinical assistant professor of pediatrics at Sidney Kimmel Medical College at Thomas Jefferson University in Philadelphia.

Clinical question

What is the optimal way to manage analgesia during neonatal circumcision?

Background

Neonatal circumcision is one of the most commonly performed surgical procedures. The American Academy of Pediatrics in 2012 noted that the health benefits outweigh the minor risks of the procedure, but that parents should make the decision to circumcise based on their own cultural, ethical, and religious beliefs.

One of the primary risks of neonatal circumcision is pain during and after the procedure. Multiple methods for managing analgesia exist, but it is unknown what combination of methods is optimal. Usual analgesia techniques include: local anesthetic cream composed of lidocaine and prilocaine (EMLA) applied to the skin prior to the procedure; oral sucrose solution given throughout the procedure; dorsal penile nerve block (DPNB); and penile ring block (RB).

Study design

Single-center, double-blinded, randomized, controlled trial.

Setting

Multispecialty freestanding hospital.

Synopsis

Parents of infant boys born at 36-41 weeks’ gestation who chose to have their children circumcised were offered participation in the study. Of 83 eligible participants, 70 were randomized, with 10 in the control group (EMLA only) and 20 in each intervention (EMLA + sucrose, EMLA + sucrose + RB, EMLA + sucrose + DPNB). A single pediatric urologist performed all circumcisions using the Gomco clamp technique.

A video camera recorded the infant’s face and upper torso during the procedure. Two researchers, who were blinded to the analgesia plan, scored these videos using a modified Neonatal Infant Pain Scale (NIPS). The NIPS used ranged from 0 to 6, with 6 considered severe pain. For rating purposes, the procedure was divided into 6 stages with a NIPS score assigned at each stage. There were no significant differences in baseline characteristics among the groups; no significant differences in the duration of the procedure by intervention; and there were no complications. Interrater reliability for the NIPS was good (kappa, 0.84). All interventions were superior to EMLA alone, with significantly decreased NIPS for all stages of the procedure. No significant differences in NIPS were found among the following:

EMLA + sucrose.

EMLA + sucrose + RB.

EMLA + sucrose + DPNB (for any stage of the procedure).

The one exception was that following lysis of foreskin adhesions, EMLA + sucrose + RB was superior (NIPS 2.25 for EMLA + sucrose + RB vs. NIPS 4.4 for EMLA + sucrose + DPNB vs. NIPS 4.3 for EMLA + sucrose vs. NIPS 5.8 for EMLA alone). In terms of crying time during the procedure, all interventions were significantly superior to EMLA alone. Of the interventions, crying time was statistically and clinically significantly shorter with EMLA + sucrose + RB (5.78 seconds vs. 11.5 for EMLA + sucrose + DPNB vs. 16.5 for EMLA + sucrose vs. 45.4 for EMLA alone). This was a single-center study and the procedures were performed by a pediatric urologist rather than by a general pediatrician, which potentially limits applicability.

Bottom line

All tested analgesia modalities for neonatal circumcision were superior to EMLA alone. The most effective analgesia of those tested was EMLA + sucrose + penile ring block.

Citation

Sharara-Chami R et al. Combination analgesia for neonatal circumcision: a randomized controlled trial. Pediatrics. 2017. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-1935.

Dr. Stubblefield is a pediatric hospitalist at Nemours/Alfred I. duPont Hospital for Children in Wilmington, Del., and a clinical assistant professor of pediatrics at Sidney Kimmel Medical College at Thomas Jefferson University in Philadelphia.

FDA allows marketing of TMS to treat OCD

The Food and Drug Administration has cleared the way for marketing of the BrainsWay deep transcranial magnetic stimulation system for treating patients with treatment-resistant obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD).

“With today’s marketing authorization, patients with OCD who have not responded to traditional treatments now have another option,” said Carlos Peña, PhD, director of the division of neurological and physical medicine devices in the FDA’s Center for Devices and Radiological Health, in an Aug. 17 news release.

49 of whom were treated with the BrainsWay device and 51 of whom with a sham device. Of the patients treated with the BrainsWay device, 38% had a 30% or greater reduction in their Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale scores, which measures severity of OCD symptoms, whereas only 11% treated with the sham device experienced such a reduction.

The most common adverse reaction was headache, experienced by 37.5% of patients treated with the BrainsWay device and 35.0% of those treated with the sham device. No serious adverse events were reported. Other common reactions included application site pain or discomfort, spasm or twitching, and jaw, facial, muscle, or neck pain; all of those were reported as mild or moderate and resolved quickly after each treatment was completed.

The device is contraindicated in patients with any sort of metal in or near their heads, such as cochlear implants or vagus nerve stimulators. Patients with a history of seizure should discuss it with their health care clinician.

Transcranial magnetic stimulation also has been approved to treat major depressive disorder and migraine with aura.

The full press release can be found on the FDA website.

The Food and Drug Administration has cleared the way for marketing of the BrainsWay deep transcranial magnetic stimulation system for treating patients with treatment-resistant obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD).

“With today’s marketing authorization, patients with OCD who have not responded to traditional treatments now have another option,” said Carlos Peña, PhD, director of the division of neurological and physical medicine devices in the FDA’s Center for Devices and Radiological Health, in an Aug. 17 news release.

49 of whom were treated with the BrainsWay device and 51 of whom with a sham device. Of the patients treated with the BrainsWay device, 38% had a 30% or greater reduction in their Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale scores, which measures severity of OCD symptoms, whereas only 11% treated with the sham device experienced such a reduction.

The most common adverse reaction was headache, experienced by 37.5% of patients treated with the BrainsWay device and 35.0% of those treated with the sham device. No serious adverse events were reported. Other common reactions included application site pain or discomfort, spasm or twitching, and jaw, facial, muscle, or neck pain; all of those were reported as mild or moderate and resolved quickly after each treatment was completed.

The device is contraindicated in patients with any sort of metal in or near their heads, such as cochlear implants or vagus nerve stimulators. Patients with a history of seizure should discuss it with their health care clinician.

Transcranial magnetic stimulation also has been approved to treat major depressive disorder and migraine with aura.

The full press release can be found on the FDA website.

The Food and Drug Administration has cleared the way for marketing of the BrainsWay deep transcranial magnetic stimulation system for treating patients with treatment-resistant obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD).

“With today’s marketing authorization, patients with OCD who have not responded to traditional treatments now have another option,” said Carlos Peña, PhD, director of the division of neurological and physical medicine devices in the FDA’s Center for Devices and Radiological Health, in an Aug. 17 news release.

49 of whom were treated with the BrainsWay device and 51 of whom with a sham device. Of the patients treated with the BrainsWay device, 38% had a 30% or greater reduction in their Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale scores, which measures severity of OCD symptoms, whereas only 11% treated with the sham device experienced such a reduction.

The most common adverse reaction was headache, experienced by 37.5% of patients treated with the BrainsWay device and 35.0% of those treated with the sham device. No serious adverse events were reported. Other common reactions included application site pain or discomfort, spasm or twitching, and jaw, facial, muscle, or neck pain; all of those were reported as mild or moderate and resolved quickly after each treatment was completed.

The device is contraindicated in patients with any sort of metal in or near their heads, such as cochlear implants or vagus nerve stimulators. Patients with a history of seizure should discuss it with their health care clinician.

Transcranial magnetic stimulation also has been approved to treat major depressive disorder and migraine with aura.

The full press release can be found on the FDA website.