User login

Bedside Microscopy for the Beginner

Dermatologists are uniquely equipped amongst clinicians to make bedside diagnoses because of the focus on histopathology and microscopy inherent in our training. This skill is highly valuable in both an inpatient and outpatient setting because it may lead to a rapid diagnosis or be a useful adjunct in the initial clinical decision-making process. Although expert microscopists may be able to garner relevant information from scraping almost any type of lesion, bedside microscopy primarily is used by dermatologists in the United States for consideration of infectious etiologies of a variety of cutaneous manifestations.1,2

Basic Principles

Lesions that should be considered for bedside microscopic analysis in outpatient settings are scaly lesions, vesiculobullous lesions, inflammatory papules, and pustules1; microscopic evaluation also can be useful for myriad trichoscopic considerations.3,4 In some instances, direct visualization of the pathogen is possible (eg, cutaneous fungal infections, demodicidosis, scabetic infections), and in other circumstances reactive changes of keratinocytes or the presence of specific cell types can aid in diagnosis (eg, ballooning degeneration and multinucleation of keratinocytes in herpetic lesions, an abundance of eosinophils in erythema toxicum neonatorum). Different types of media are used to best prepare tissue based on the suspected etiology of the condition.

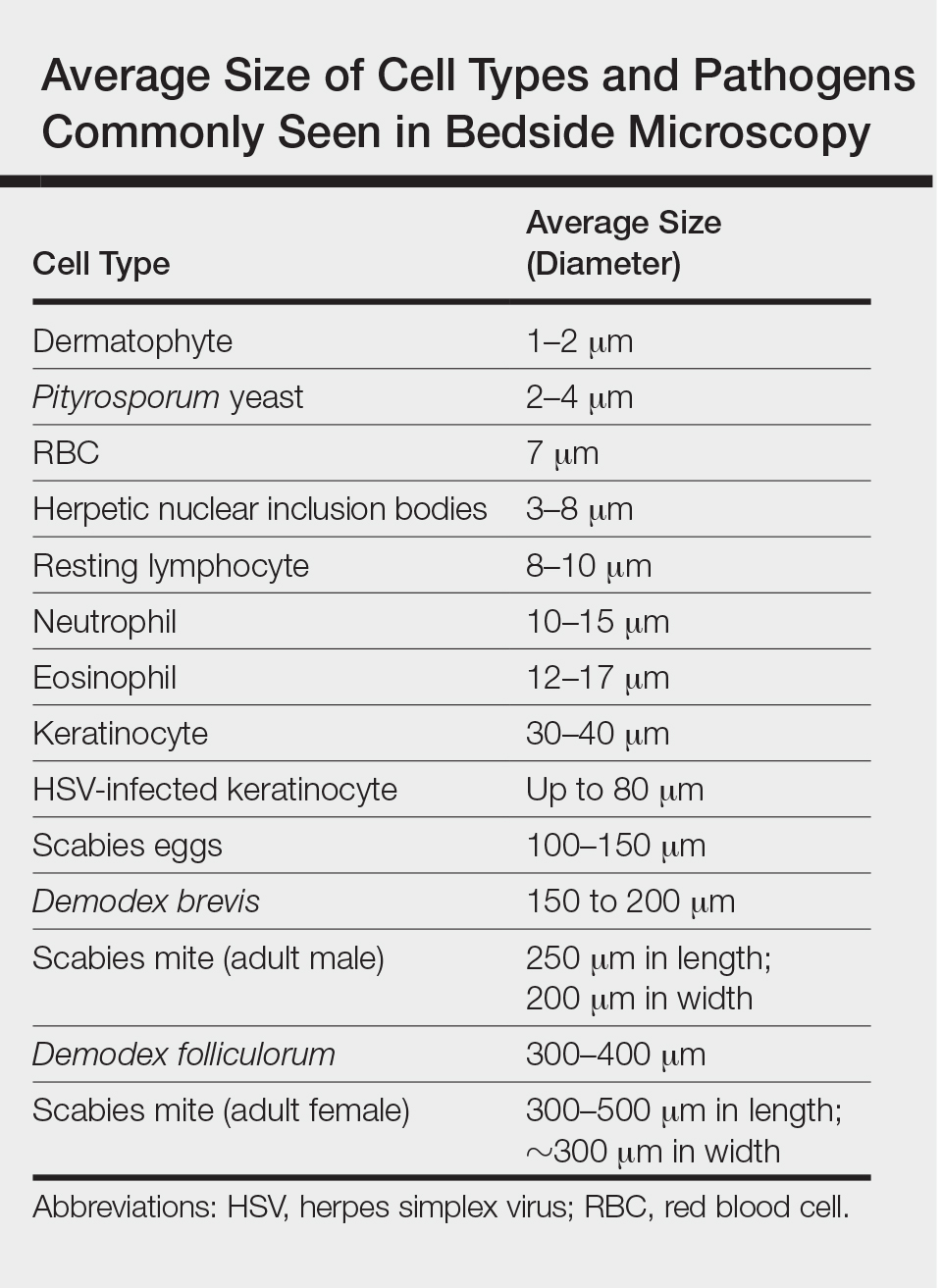

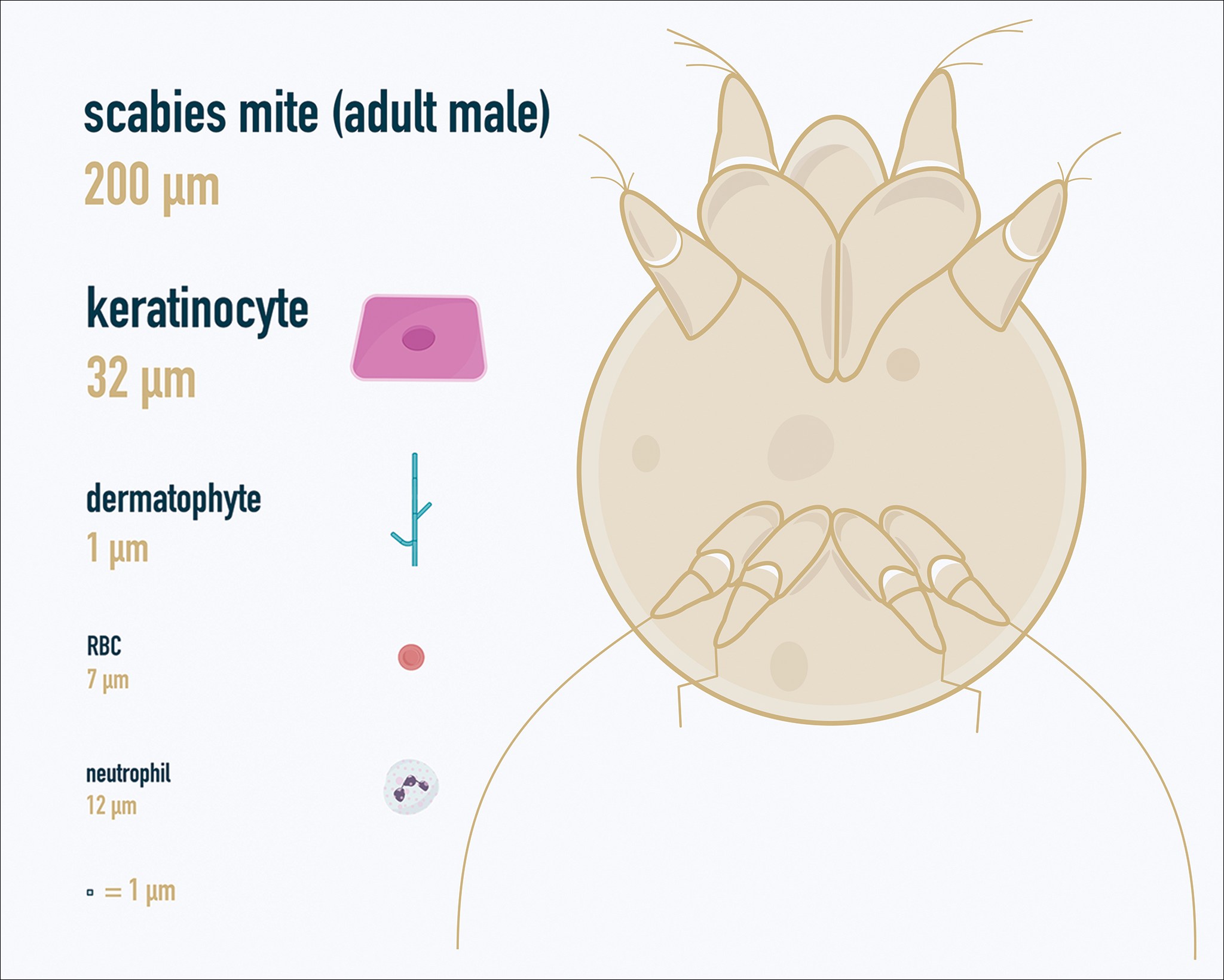

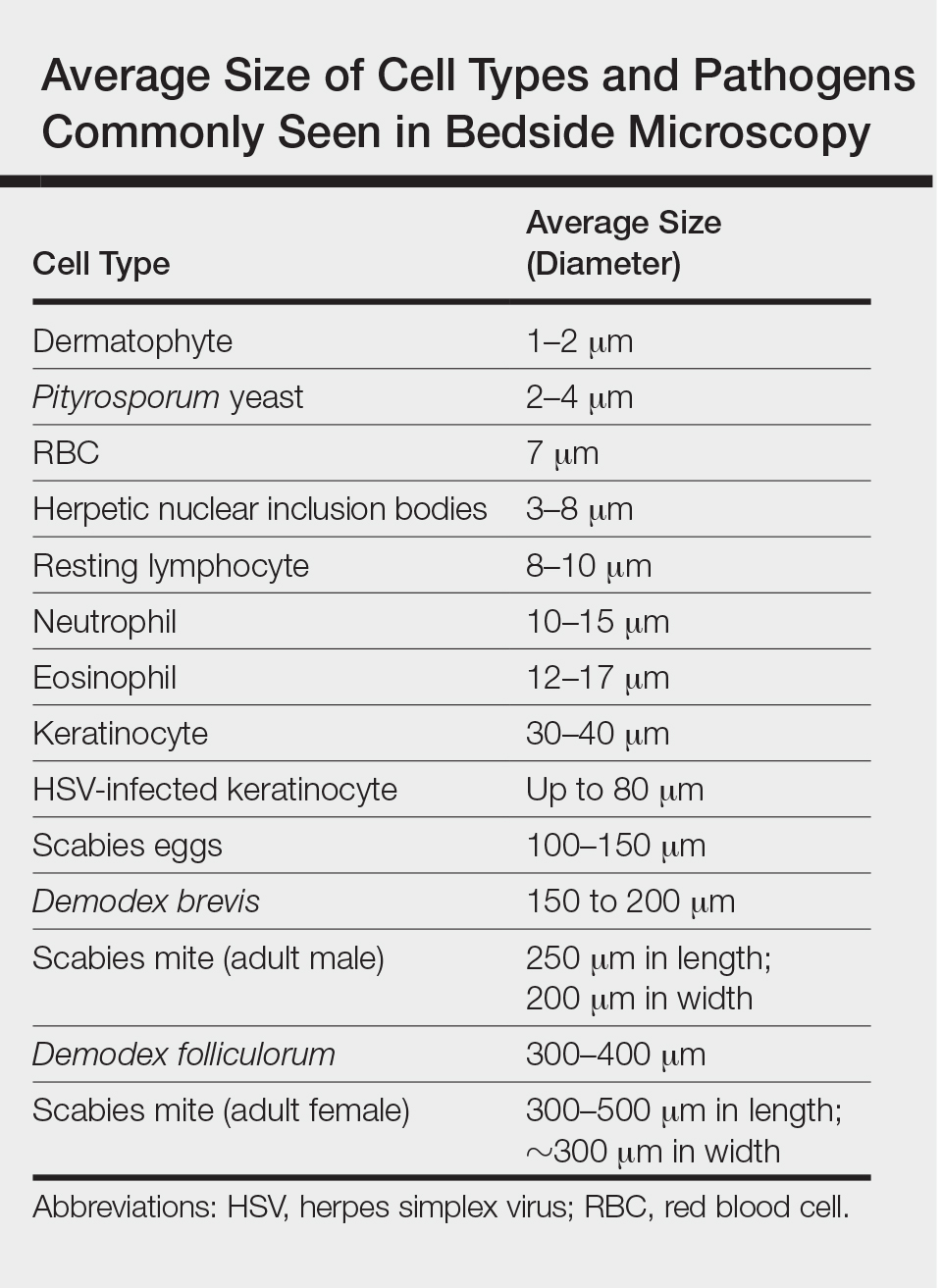

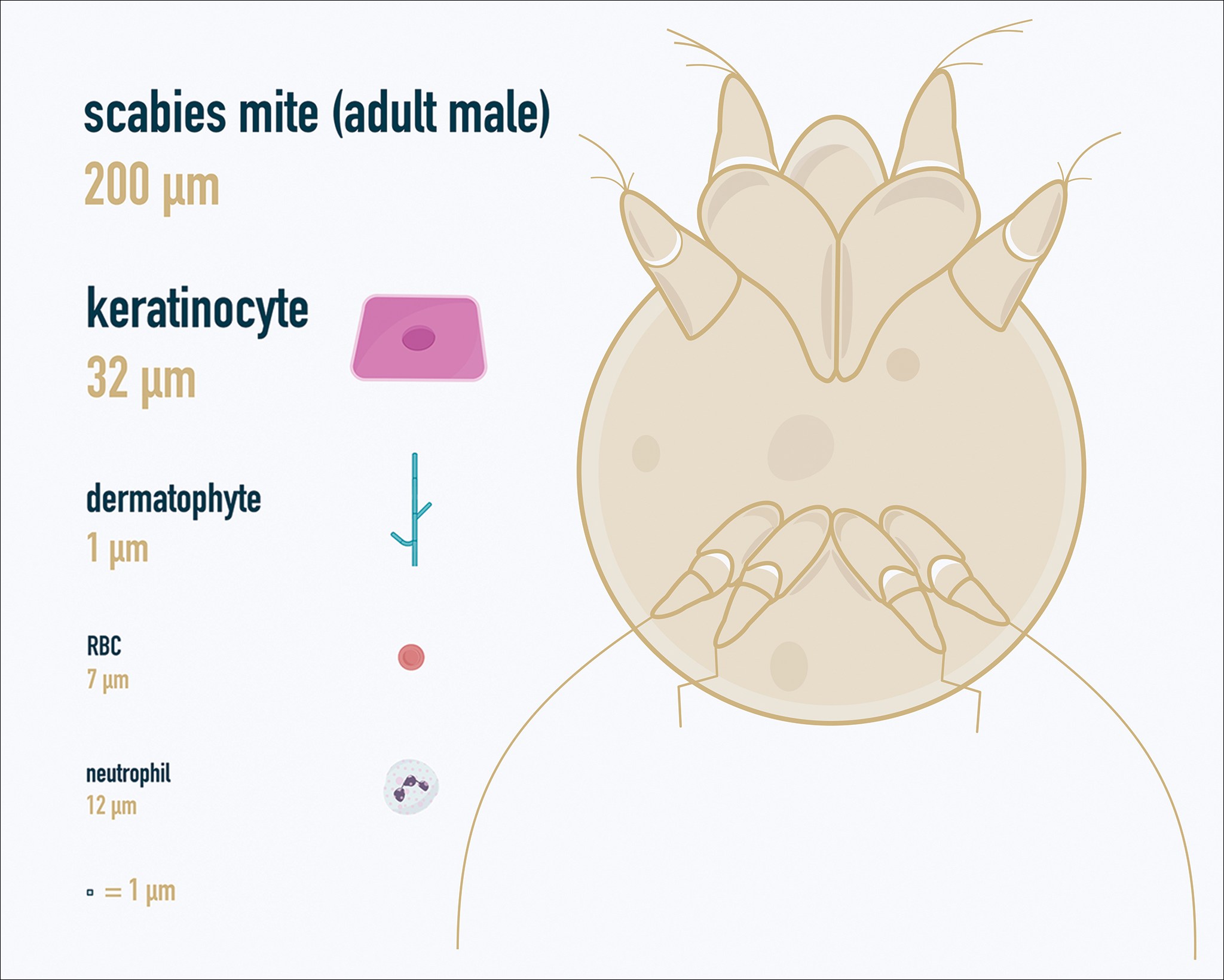

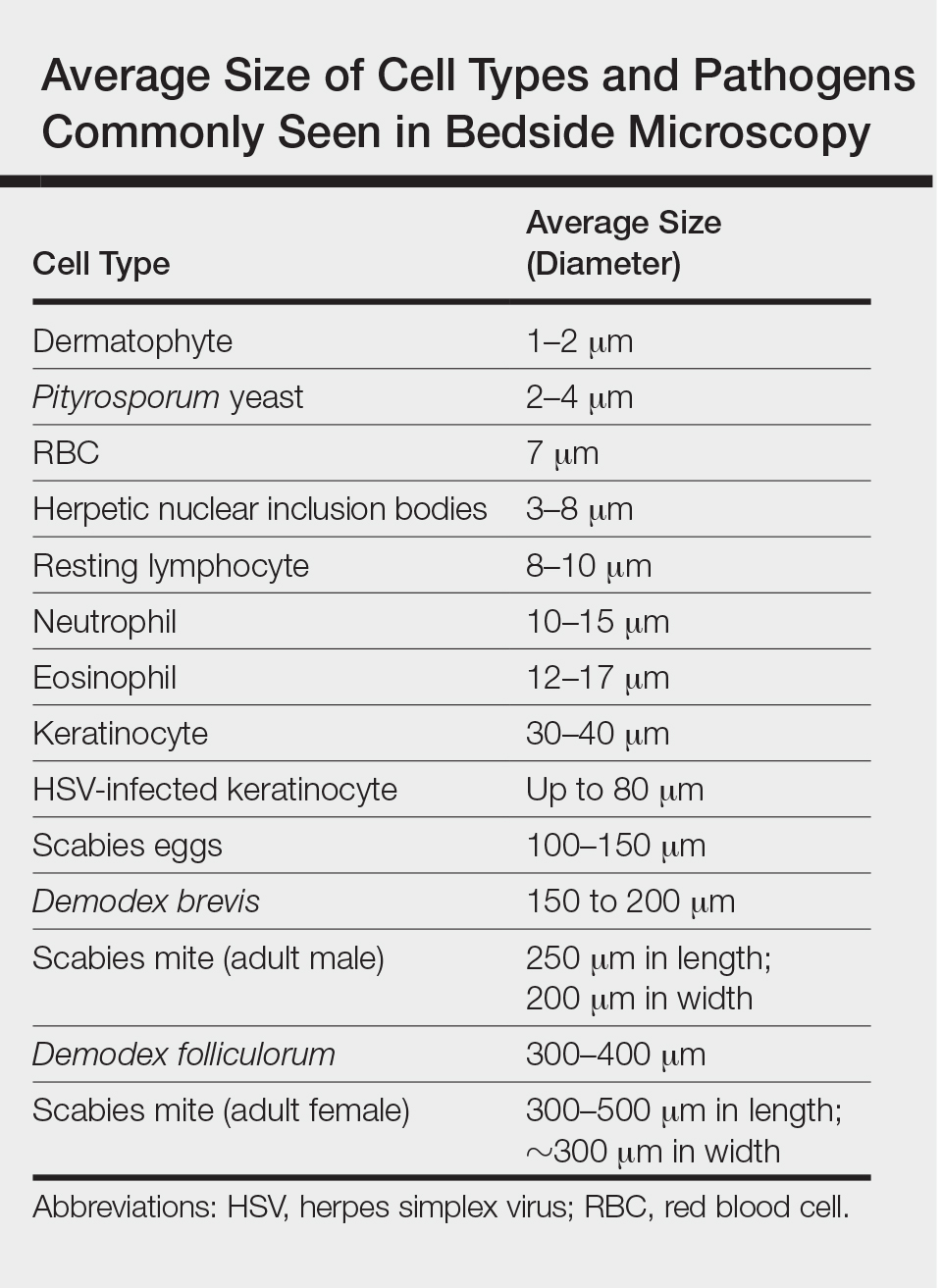

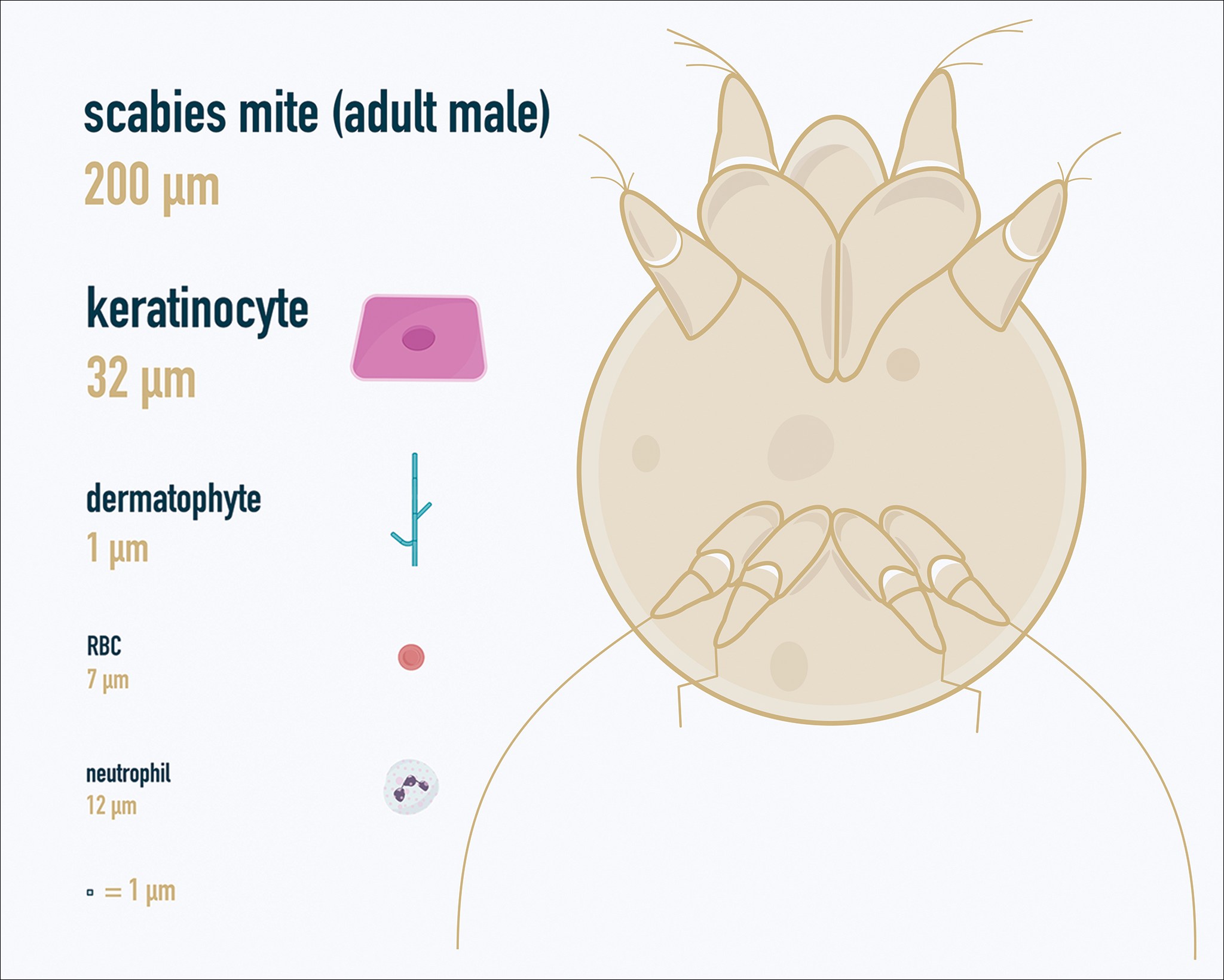

One major stumbling block for residents when beginning to perform bedside testing is the lack of dimensional understanding of the structures they are searching for; for example, medical students and residents often may mistake fibers for dermatophytes, which typically are much larger than fungal hyphae. Familiarizing oneself with the basic dimensions of different cell types or pathogens in relation to each other (Table) will help further refine the beginner’s ability to effectively search for and identify pathogenic features. This concept is further schematized in Figure 1 to help visualize scale differences.

Examination of the Specimen

Slide preparation depends on the primary lesion in consideration and will be discussed in greater detail in the following sections. Once the slide is prepared, place it on the microscope stage and adjust the condenser and light source for optimal visualization. Scan the specimen in a gridlike fashion on low power (usually ×10) and then inspect suspicious findings on higher power (×40 or higher).

Dermatomycoses

Fungal infections of the skin can present as annular papulosquamous lesions, follicular pustules or papules, bullous lesions, hypopigmented patches, and mucosal exudate or erosions, among other manifestations.5 Potassium hydroxide (KOH) is the classic medium used in preparation of lesions being assessed for evidence of fungus because it leads to lysis of keratinocytes for better visualization of fungal hyphae and spores. Other media that contain KOH and additional substrates such as dimethyl sulfoxide or chlorazol black E can be used to better highlight fungal elements.6

Dermatophytosis

Dermatophytes lead to superficial infection of the epidermis and epidermal appendages and present in a variety of ways, including site-specific infections manifesting typically as erythematous, annular or arcuate scaling (eg, tinea faciei, tinea corporis, tinea cruris, tinea manus, tinea pedis), alopecia with broken hair shafts, black dots, boggy nodules and/or scaling of the scalp (eg, tinea capitis, favus, kerion), and dystrophic nails (eg, onychomycosis).5,7 For examination of lesional skin scrapings, one can either use clear cellophane tape against the skin to remove scale, which is especially useful in the case of pediatric patients, and then press the tape against a slide prepared with several drops of a KOH-based medium to directly visualize without a coverslip, or scrape the lesion with a No. 15 blade and place the scales onto the glass slide, with further preparation as described below.8 For assessment of alopecia or dystrophic nails, scrape lesional skin with a No. 15 blade to obtain affected hair follicles and proximal subungual debris, respectively.6,9

Once the cellular debris has been obtained and placed on the slide, a coverslip can be overlaid and KOH applied laterally to be taken up across the slide by capillary action. Allow the slide to sit for at least 5 minutes before analyzing to better visualize fungal elements. Both tinea and onychomycosis will show branching septate hyphae extending across keratinocytes; a common false-positive is identifying overlapping keratinocyte edges, which are a similar size, but they can be distinguished from fungi because they do not cross multiple keratinocytes.1,8 Tinea capitis may demonstrate similar findings or may reveal hair shafts with spores contained within or surrounding it, corresponding to endothrix or ectothrix infection, respectively.5

Pityriasis Versicolor and Malassezia Folliculitis

Pityriasis versicolor presents with hypopigmented to pink, finely scaling ovoid papules, usually on the upper back, shoulders, and neck, and is caused by Malassezia furfur and other Malassezia species.5 Malassezia folliculitis also is caused by this fungus and presents with monomorphic follicular papules and pustules. Scrapings from the scaly papules will demonstrate keratinocytes with the classic “spaghetti and meatballs” fungal elements, whereas Malassezia folliculitis demonstrates only spores.5,7

Candidiasis

One possible outpatient presentation of candidiasis is oral thrush, which can exhibit white mucosal exudate or erythematous patches. A tongue blade can be used to scrape the tongue or cheek wall, with subsequent preparatory steps with application of KOH as described for dermatophytes. Cutaneous candidiasis most often develops in intertriginous regions and will exhibit erosive painful lesions with satellite pustules. In both cases, analysis of the specimen will show shorter fatter hyphal elements than seen in dermatophytosis, with pseudohyphae, blunted ends, and potentially yeast forms.5

Vesiculobullous Lesions

The Tzanck smear has been used since the 1940s to differentiate between etiologies of blistering disorders and is now most commonly used for the quick identification of herpetic lesions.1 The test is performed by scraping the base of a deroofed vesicle, pustule, or bulla, and smearing the cellular materials onto a glass slide. The most commonly utilized media for staining in the outpatient setting at my institution (University of Texas Dell Medical School, Austin) is Giemsa, which is composed of azure II–eosin, glycerin, and methanol. It stains nuclei a reddish blue to pink and the cytoplasm blue.10 After being applied to the slide, the cells are allowed to air-dry for 5 to 10 minutes, and Giemsa stain is subsequently applied and allowed to incubate for 15 minutes, then rinsed carefully with water and directly examined.

Other stains that can be used to perform the Tzanck smear include commercial preparations that may be more accessible in the inpatient settings such as the Wright-Giemsa, Quik-Dip, and Diff-Quick.1,10

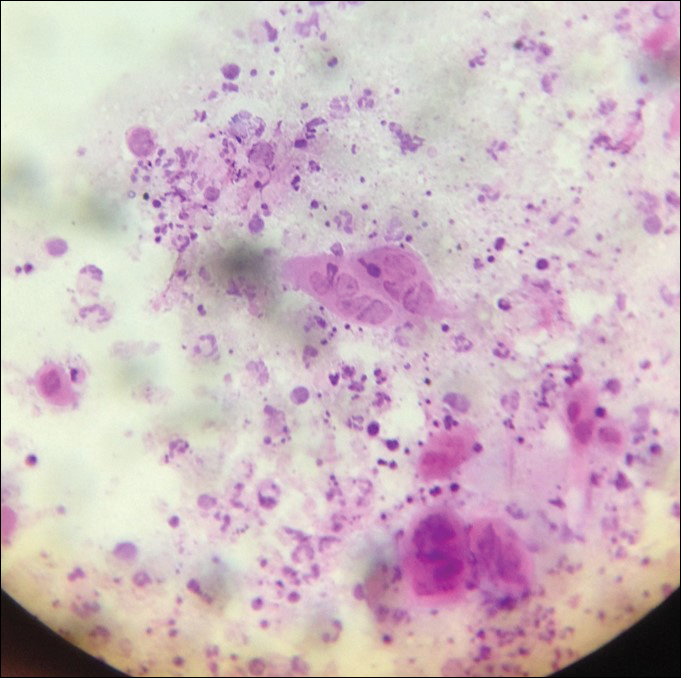

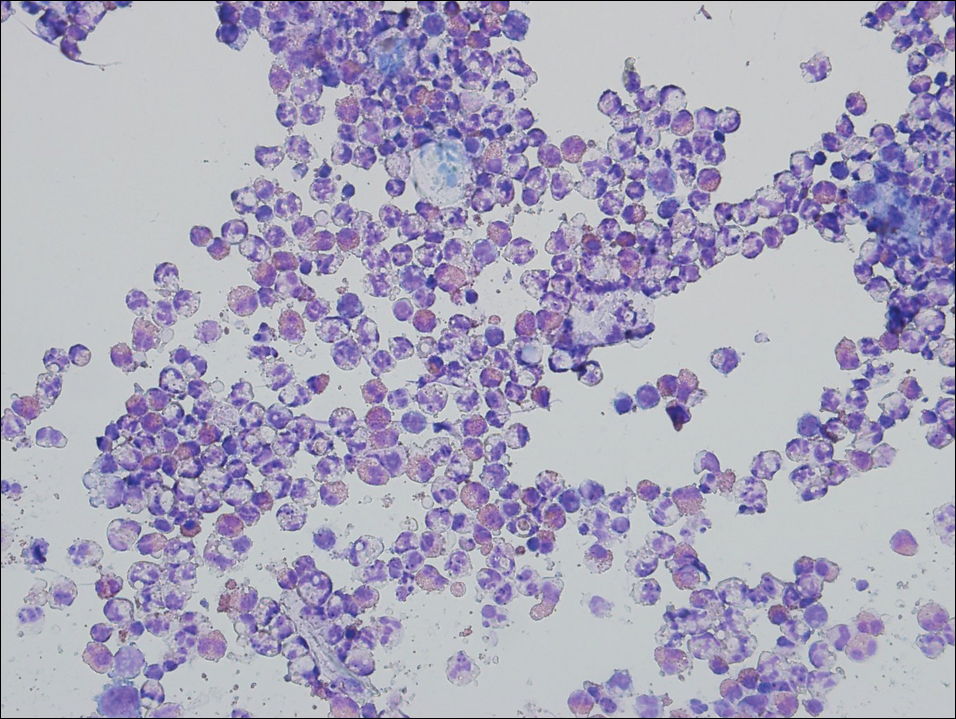

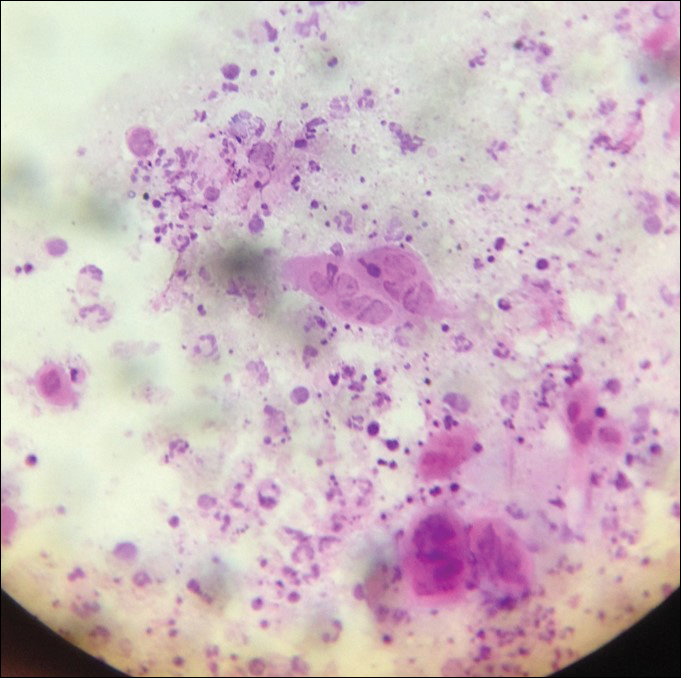

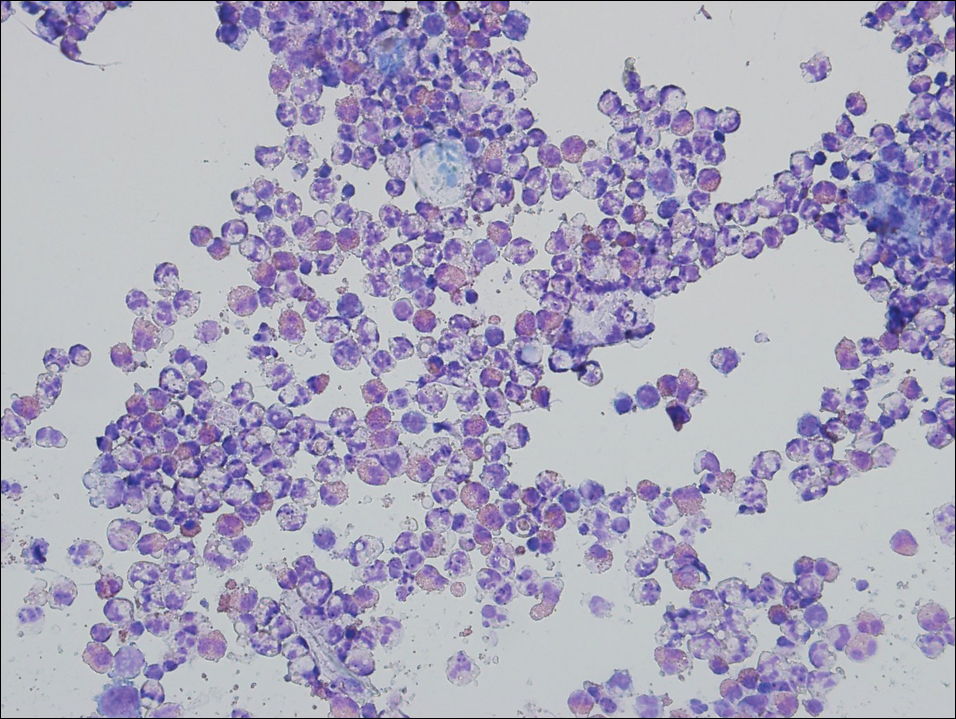

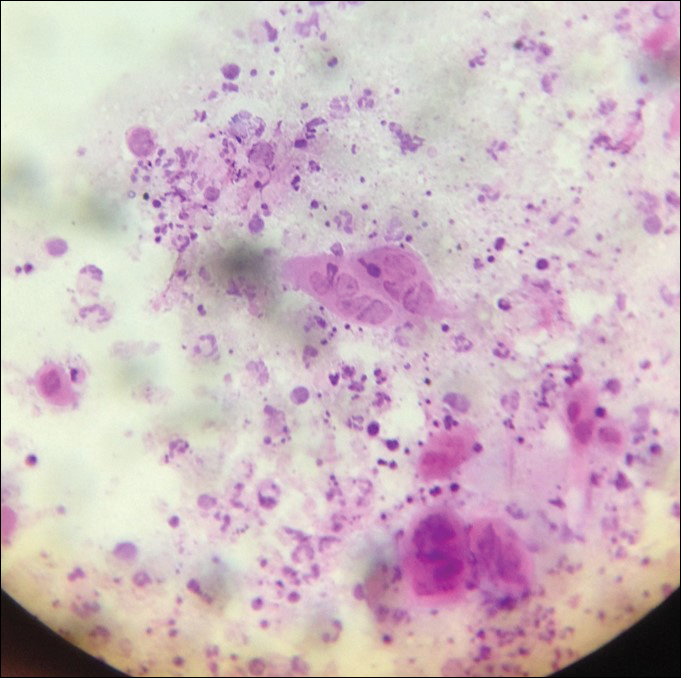

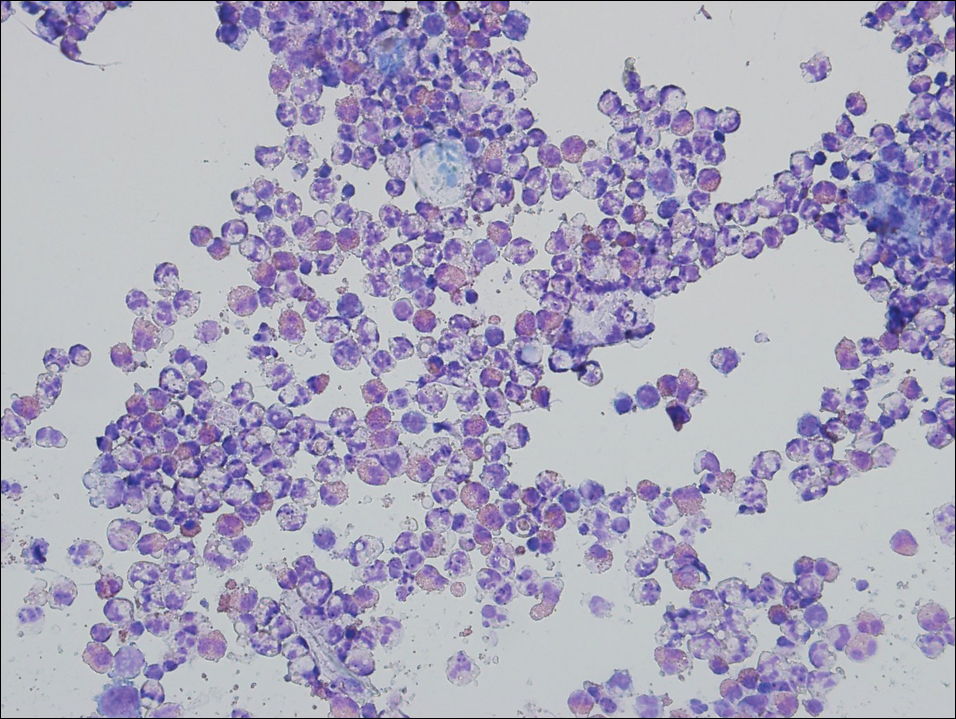

Examination of a Tzanck smear from a herpetic lesion will yield acantholytic, enlarged keratinocytes up to twice their usual size (referred to as ballooning degeneration), and multinucleation. In addition, molding of the nuclei to each other within the multinucleated cells and margination of the nuclear chromatin may be appreciated (Figure 2). Intranuclear inclusion bodies, also known as Cowdry type A bodies, can be seen that are nearly the size of red blood cells but are rare to find, with only 10% of specimens exhibiting this finding in a prospective review of 299 patients with herpetic vesiculobullous lesions.11 Evaluation of the contents of blisters caused by bullous pemphigoid and erythema toxicum neonatorum may yield high densities of eosinophils with normal keratinocyte morphology (Figure 3). Other blistering eruptions such as pemphigus vulgaris and bullous drug eruptions also have characteristic findings.1,2

Gout Preparation

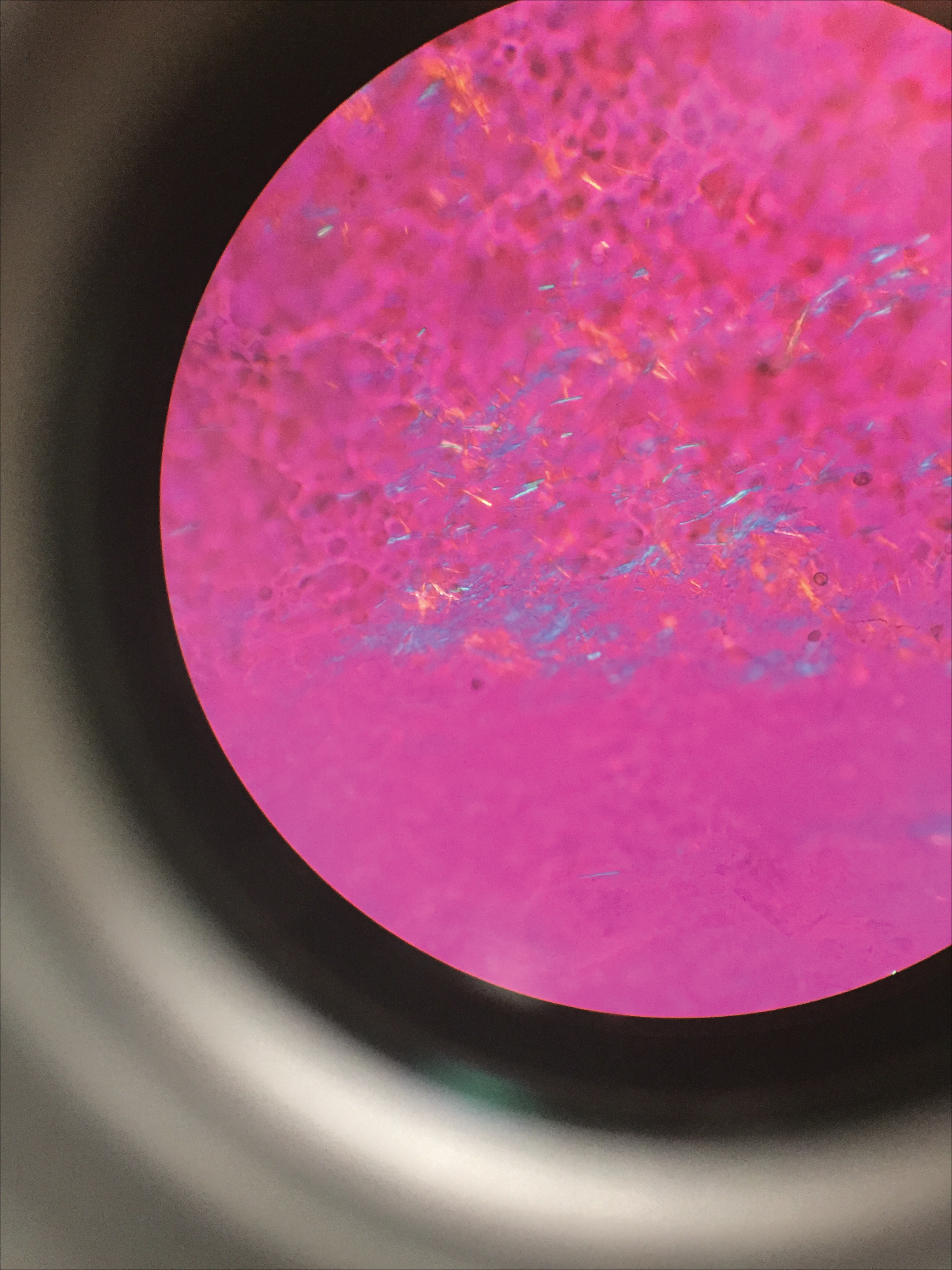

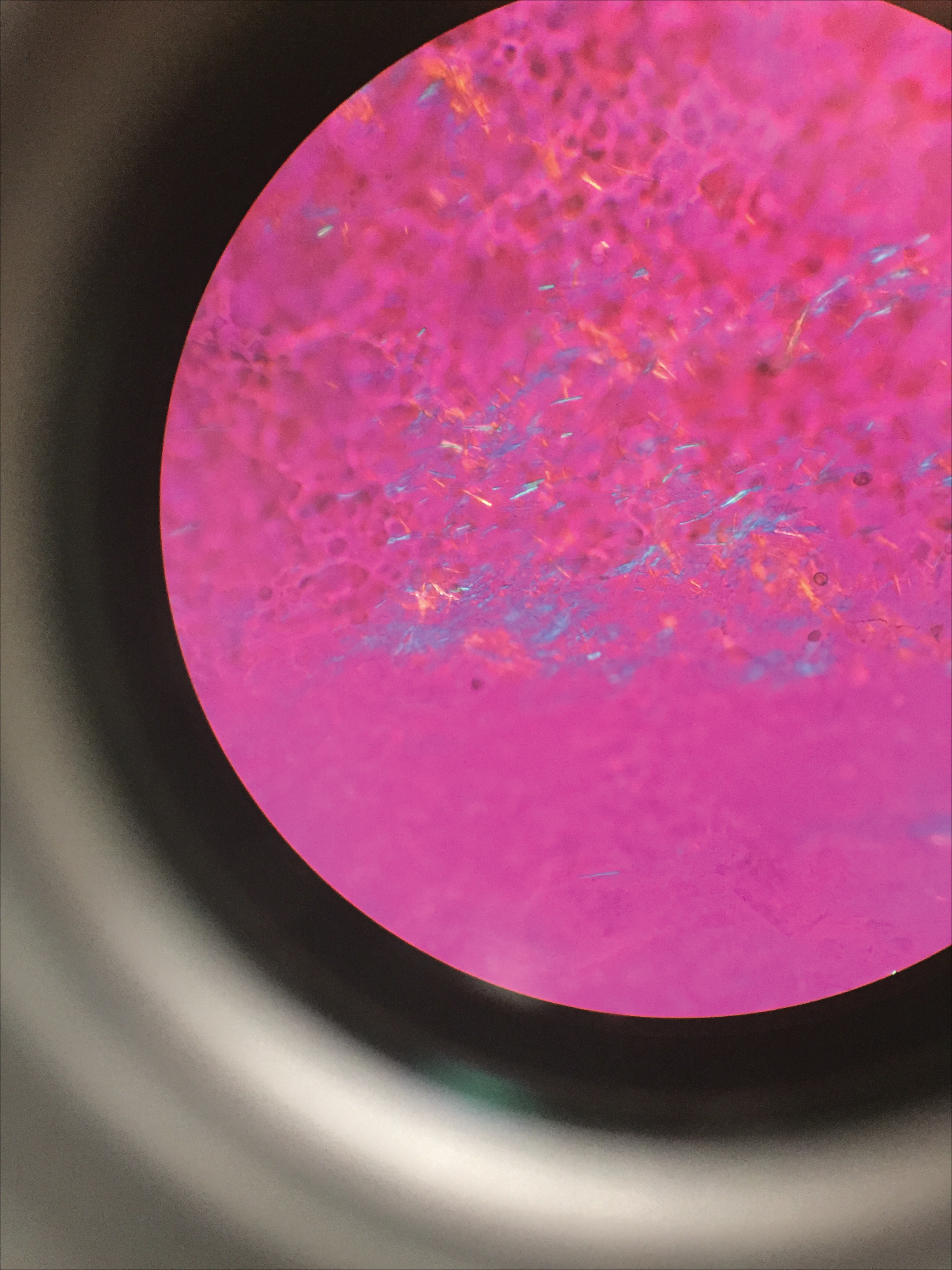

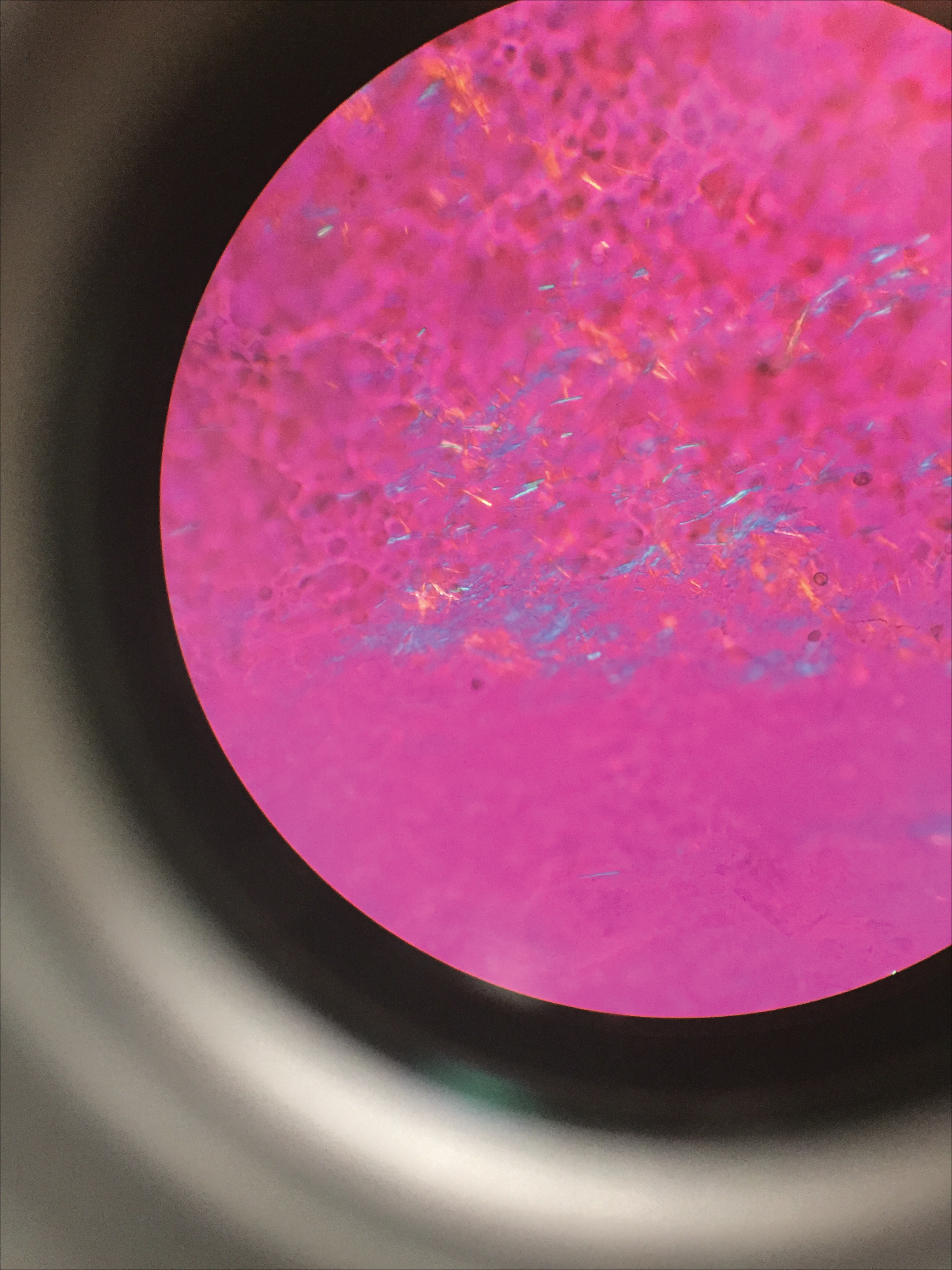

Gout is a systemic disease caused by uric acid accumulation that can present with joint pain and white to red nodules on digits, joints, and ears (known as tophi). Material may be expressed from tophi and examined immediately by polarized light microscopy to confirm the diagnosis.5 Specimens will demonstrate needle-shaped, negatively birefringent monosodium urate crystals on polarized light microscopy (Figure 4). An ordinary light microscope can be converted for such use with the lenses of inexpensive polarized sunglasses, placing one lens between the light source and specimen and the other lens between the examiner’s eye and the specimen.12

Parasitic Infections

Two common parasitic infections identified in outpatient dermatology clinics are scabies mites and Demodex mites. Human scabies is extremely pruritic and caused by infestation with Sarcoptes scabiei var hominis; the typical presentation in an adult is erythematous and crusted papules, linear burrows, and vesiculopustules, especially of the interdigital spaces, wrists, axillae, umbilicus, and genital region.1,13 Demodicidosis presents with papules and pustules on the face, usually in a patient with background rosacea and diffuse erythema.1,5,14

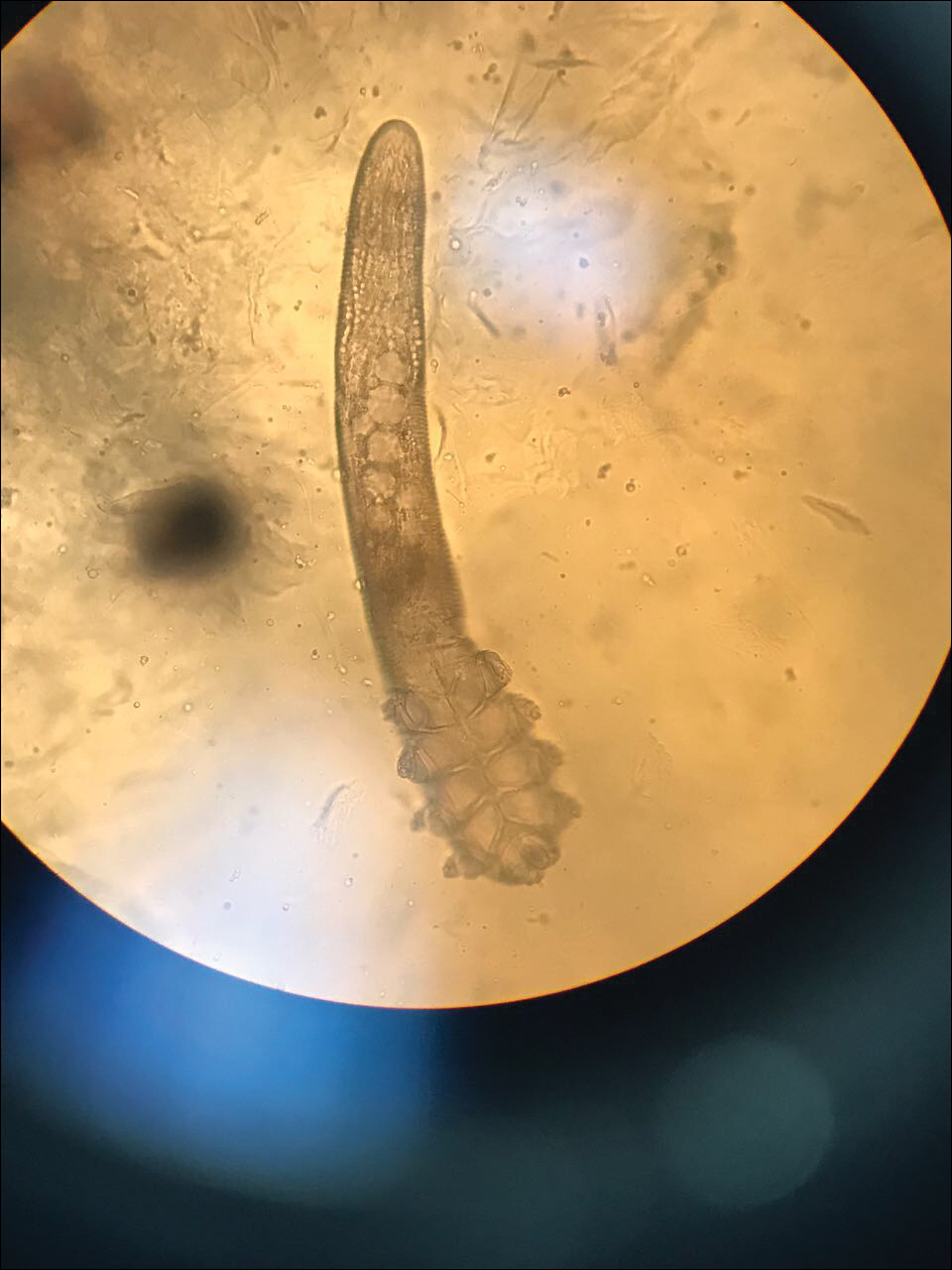

If either of these conditions are suspected, mineral oil should be used to prepare the slide because it will maintain viability of the organisms, which are visualized better in motion. Adult scabies mites are roughly 10 times larger than keratinocytes, measuring approximately 250 to 450 µm in length with 8 legs.13 Eggs also may be visualized within the cellular debris and typically are 100 to 150 µm in size and ovoid in shape. Of note, polariscopic examination may be a useful adjunct for evaluation of scabies because scabetic spines and scybala (or fecal material) are polarizable.15

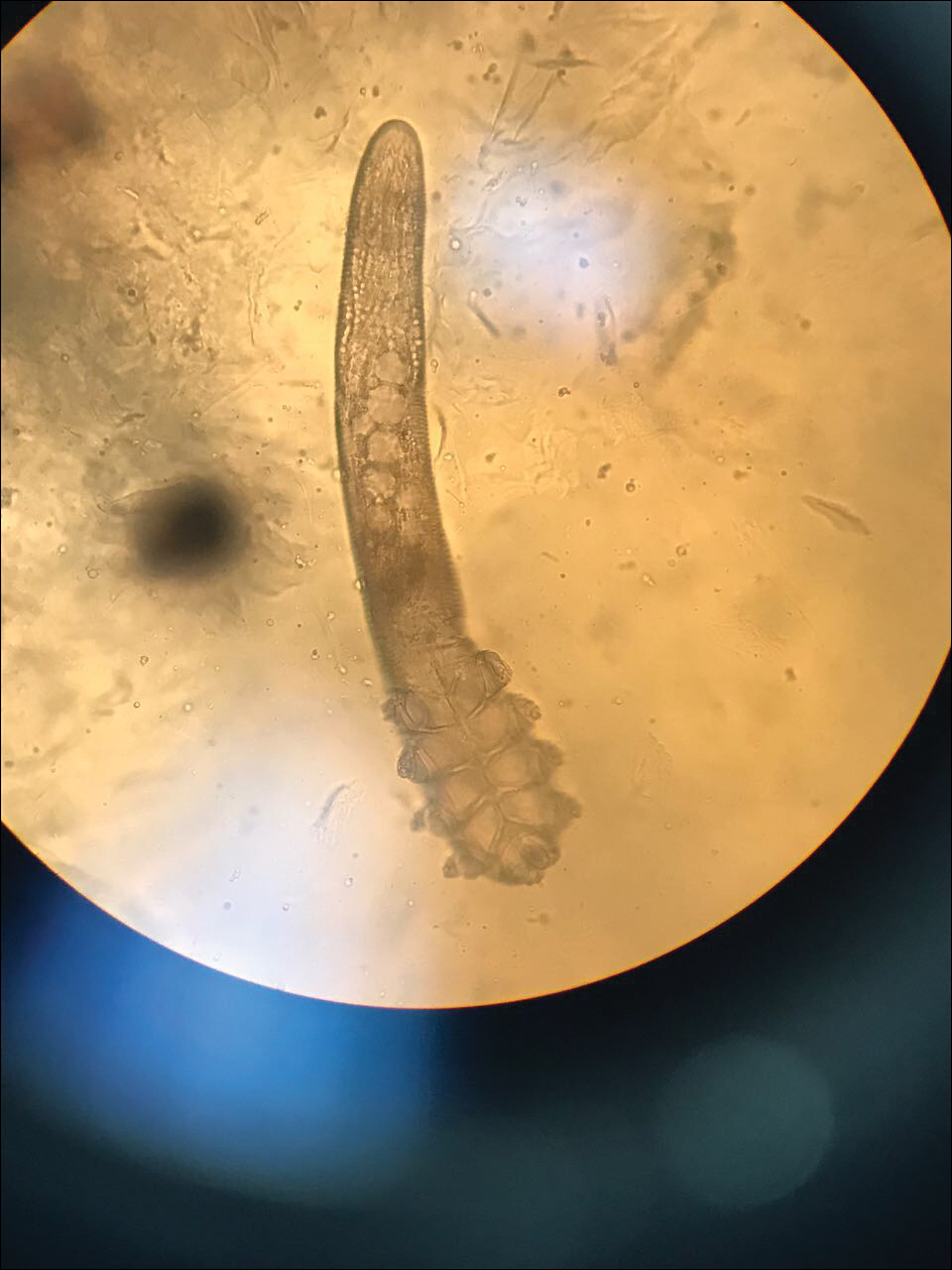

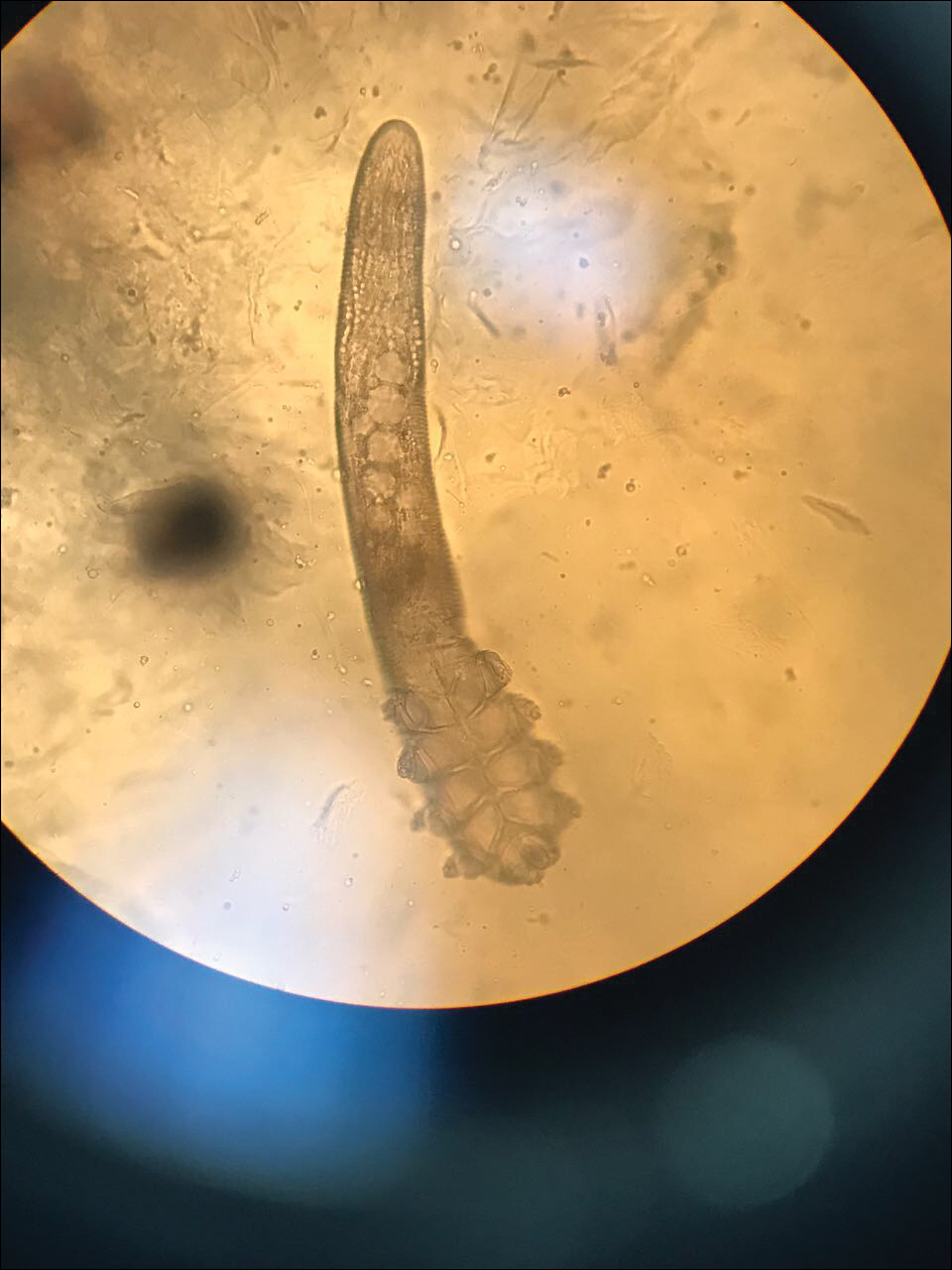

Two types of Demodex mites typically are found in the skin: Demodex folliculorum, which are similarly sized to scabies mites with a more oblong body and occur most commonly in mature hair follicles (eg, eyelashes), and Demodex brevis, which are about half the size (150–200 µm) and live in the sebaceous glands of vellus hairs (Figure 5).14 Both of these mites have 8 legs, similar to the scabies mite.

Hair Preparations

Hair preparations for bulbar examination (eg, trichogram) may prove useful in the evaluation of many types of alopecia, and elaboration on this topic is beyond the scope of this article. Microscopic evaluation of the hair shaft may be an underutilized technique in the outpatient setting and is capable of yielding a variety of diagnoses, including monilethrix, pili torti, and pili trianguli et canaliculi, among others.3 One particularly useful scenario for hair shaft examination (usually of the eyebrow) is in the setting of a patient with severe atopic dermatitis or a baby with ichthyosiform erythroderma, as discovery of trichorrhexis invaginata is pathognomonic for the diagnosis of Netherton syndrome.16 Lastly, evaluation of the hair shaft in patients with patchy and diffuse hair loss whose clinical impression is reminiscent of alopecia areata, or those with concerns of inability to grow hair beyond a short length, may lead to diagnosis of loose anagen syndrome, especially if more than 70% of hair fibers examined exhibit the classic findings of a ruffled proximal cuticle and lack of root sheath.4

Final Thoughts

Bedside microscopy is a rapid and cost-sensitive way to confirm diagnoses that are clinically suspected and remains a valuable tool to acquire during residency training.

- Wanat KA, Dominguez AR, Carter Z, et al. Bedside diagnostics in dermatology: viral, bacterial, and fungal infections. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77:197-218.

- Micheletti RG, Dominguez AR, Wanat KA. Bedside diagnostics in dermatology: parasitic and noninfectious diseases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77:221-230.

- Whiting DA, Dy LC. Office diagnosis of hair shaft defects. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2006;25:24-34.

- Tosti A. Loose anagen hair syndrome and loose anagen hair. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138:521-522.

- Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Philadelphia PA: Elsevier; 2017.

- Lilly KK, Koshnick RL, Grill JP, et al. Cost-effectiveness of diagnostic tests for toenail onychomycosis: a repeated-measure, single-blinded, cross-sectional evaluation of 7 diagnostic tests. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55:620-626.

- Elder DE, ed. Lever’s Histopathology of the Skin. 10th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2009.

- Raghukumar S, Ravikumar BC. Potassium hydroxide mount with cellophane adhesive: a method for direct diagnosis of dermatophyte skin infections [published online May 29, 2018]. Clin Exp Dermatol. doi:10.1111/ced.13573.

- Bhat YJ, Zeerak S, Kanth F, et al. Clinicoepidemiological and mycological study of tinea capitis in the pediatric population of Kashmir Valley: a study from a tertiary care centre. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2017;8:100-103.

- Gupta LK, Singhi MK. Tzanck smear: a useful diagnostic tool. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2005;71:295-299.

- Durdu M, Baba M, Seçkin D. The value of Tzanck smear test in diagnosis of erosive, vesicular, bullous, and pustular skin lesions. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:958-964.

- Fagan TJ, Lidsky MD. Compensated polarized light microscopy using cellophane adhesive tape. Arthritis Rheum. 1974;17:256-262.

- Walton SF, Currie BJ. Problems in diagnosing scabies, a global disease in human and animal populations. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2007;20:268-279.

- Desch C, Nutting WB. Demodex folliculorum (Simon) and D. brevis akbulatova of man: redescription and reevaluation. J Parasitol. 1972;58:169-177.

- Foo CW, Florell SR, Bowen AR. Polarizable elements in scabies infestation: a clue to diagnosis. J Cutan Pathol. 2013;40:6-10.

- Akkurt ZM, Tuncel T, Ayhan E, et al. Rapid and easy diagnosis of Netherton syndrome with dermoscopy. J Cutan Med Surg. 2014;18:280-282.

Dermatologists are uniquely equipped amongst clinicians to make bedside diagnoses because of the focus on histopathology and microscopy inherent in our training. This skill is highly valuable in both an inpatient and outpatient setting because it may lead to a rapid diagnosis or be a useful adjunct in the initial clinical decision-making process. Although expert microscopists may be able to garner relevant information from scraping almost any type of lesion, bedside microscopy primarily is used by dermatologists in the United States for consideration of infectious etiologies of a variety of cutaneous manifestations.1,2

Basic Principles

Lesions that should be considered for bedside microscopic analysis in outpatient settings are scaly lesions, vesiculobullous lesions, inflammatory papules, and pustules1; microscopic evaluation also can be useful for myriad trichoscopic considerations.3,4 In some instances, direct visualization of the pathogen is possible (eg, cutaneous fungal infections, demodicidosis, scabetic infections), and in other circumstances reactive changes of keratinocytes or the presence of specific cell types can aid in diagnosis (eg, ballooning degeneration and multinucleation of keratinocytes in herpetic lesions, an abundance of eosinophils in erythema toxicum neonatorum). Different types of media are used to best prepare tissue based on the suspected etiology of the condition.

One major stumbling block for residents when beginning to perform bedside testing is the lack of dimensional understanding of the structures they are searching for; for example, medical students and residents often may mistake fibers for dermatophytes, which typically are much larger than fungal hyphae. Familiarizing oneself with the basic dimensions of different cell types or pathogens in relation to each other (Table) will help further refine the beginner’s ability to effectively search for and identify pathogenic features. This concept is further schematized in Figure 1 to help visualize scale differences.

Examination of the Specimen

Slide preparation depends on the primary lesion in consideration and will be discussed in greater detail in the following sections. Once the slide is prepared, place it on the microscope stage and adjust the condenser and light source for optimal visualization. Scan the specimen in a gridlike fashion on low power (usually ×10) and then inspect suspicious findings on higher power (×40 or higher).

Dermatomycoses

Fungal infections of the skin can present as annular papulosquamous lesions, follicular pustules or papules, bullous lesions, hypopigmented patches, and mucosal exudate or erosions, among other manifestations.5 Potassium hydroxide (KOH) is the classic medium used in preparation of lesions being assessed for evidence of fungus because it leads to lysis of keratinocytes for better visualization of fungal hyphae and spores. Other media that contain KOH and additional substrates such as dimethyl sulfoxide or chlorazol black E can be used to better highlight fungal elements.6

Dermatophytosis

Dermatophytes lead to superficial infection of the epidermis and epidermal appendages and present in a variety of ways, including site-specific infections manifesting typically as erythematous, annular or arcuate scaling (eg, tinea faciei, tinea corporis, tinea cruris, tinea manus, tinea pedis), alopecia with broken hair shafts, black dots, boggy nodules and/or scaling of the scalp (eg, tinea capitis, favus, kerion), and dystrophic nails (eg, onychomycosis).5,7 For examination of lesional skin scrapings, one can either use clear cellophane tape against the skin to remove scale, which is especially useful in the case of pediatric patients, and then press the tape against a slide prepared with several drops of a KOH-based medium to directly visualize without a coverslip, or scrape the lesion with a No. 15 blade and place the scales onto the glass slide, with further preparation as described below.8 For assessment of alopecia or dystrophic nails, scrape lesional skin with a No. 15 blade to obtain affected hair follicles and proximal subungual debris, respectively.6,9

Once the cellular debris has been obtained and placed on the slide, a coverslip can be overlaid and KOH applied laterally to be taken up across the slide by capillary action. Allow the slide to sit for at least 5 minutes before analyzing to better visualize fungal elements. Both tinea and onychomycosis will show branching septate hyphae extending across keratinocytes; a common false-positive is identifying overlapping keratinocyte edges, which are a similar size, but they can be distinguished from fungi because they do not cross multiple keratinocytes.1,8 Tinea capitis may demonstrate similar findings or may reveal hair shafts with spores contained within or surrounding it, corresponding to endothrix or ectothrix infection, respectively.5

Pityriasis Versicolor and Malassezia Folliculitis

Pityriasis versicolor presents with hypopigmented to pink, finely scaling ovoid papules, usually on the upper back, shoulders, and neck, and is caused by Malassezia furfur and other Malassezia species.5 Malassezia folliculitis also is caused by this fungus and presents with monomorphic follicular papules and pustules. Scrapings from the scaly papules will demonstrate keratinocytes with the classic “spaghetti and meatballs” fungal elements, whereas Malassezia folliculitis demonstrates only spores.5,7

Candidiasis

One possible outpatient presentation of candidiasis is oral thrush, which can exhibit white mucosal exudate or erythematous patches. A tongue blade can be used to scrape the tongue or cheek wall, with subsequent preparatory steps with application of KOH as described for dermatophytes. Cutaneous candidiasis most often develops in intertriginous regions and will exhibit erosive painful lesions with satellite pustules. In both cases, analysis of the specimen will show shorter fatter hyphal elements than seen in dermatophytosis, with pseudohyphae, blunted ends, and potentially yeast forms.5

Vesiculobullous Lesions

The Tzanck smear has been used since the 1940s to differentiate between etiologies of blistering disorders and is now most commonly used for the quick identification of herpetic lesions.1 The test is performed by scraping the base of a deroofed vesicle, pustule, or bulla, and smearing the cellular materials onto a glass slide. The most commonly utilized media for staining in the outpatient setting at my institution (University of Texas Dell Medical School, Austin) is Giemsa, which is composed of azure II–eosin, glycerin, and methanol. It stains nuclei a reddish blue to pink and the cytoplasm blue.10 After being applied to the slide, the cells are allowed to air-dry for 5 to 10 minutes, and Giemsa stain is subsequently applied and allowed to incubate for 15 minutes, then rinsed carefully with water and directly examined.

Other stains that can be used to perform the Tzanck smear include commercial preparations that may be more accessible in the inpatient settings such as the Wright-Giemsa, Quik-Dip, and Diff-Quick.1,10

Examination of a Tzanck smear from a herpetic lesion will yield acantholytic, enlarged keratinocytes up to twice their usual size (referred to as ballooning degeneration), and multinucleation. In addition, molding of the nuclei to each other within the multinucleated cells and margination of the nuclear chromatin may be appreciated (Figure 2). Intranuclear inclusion bodies, also known as Cowdry type A bodies, can be seen that are nearly the size of red blood cells but are rare to find, with only 10% of specimens exhibiting this finding in a prospective review of 299 patients with herpetic vesiculobullous lesions.11 Evaluation of the contents of blisters caused by bullous pemphigoid and erythema toxicum neonatorum may yield high densities of eosinophils with normal keratinocyte morphology (Figure 3). Other blistering eruptions such as pemphigus vulgaris and bullous drug eruptions also have characteristic findings.1,2

Gout Preparation

Gout is a systemic disease caused by uric acid accumulation that can present with joint pain and white to red nodules on digits, joints, and ears (known as tophi). Material may be expressed from tophi and examined immediately by polarized light microscopy to confirm the diagnosis.5 Specimens will demonstrate needle-shaped, negatively birefringent monosodium urate crystals on polarized light microscopy (Figure 4). An ordinary light microscope can be converted for such use with the lenses of inexpensive polarized sunglasses, placing one lens between the light source and specimen and the other lens between the examiner’s eye and the specimen.12

Parasitic Infections

Two common parasitic infections identified in outpatient dermatology clinics are scabies mites and Demodex mites. Human scabies is extremely pruritic and caused by infestation with Sarcoptes scabiei var hominis; the typical presentation in an adult is erythematous and crusted papules, linear burrows, and vesiculopustules, especially of the interdigital spaces, wrists, axillae, umbilicus, and genital region.1,13 Demodicidosis presents with papules and pustules on the face, usually in a patient with background rosacea and diffuse erythema.1,5,14

If either of these conditions are suspected, mineral oil should be used to prepare the slide because it will maintain viability of the organisms, which are visualized better in motion. Adult scabies mites are roughly 10 times larger than keratinocytes, measuring approximately 250 to 450 µm in length with 8 legs.13 Eggs also may be visualized within the cellular debris and typically are 100 to 150 µm in size and ovoid in shape. Of note, polariscopic examination may be a useful adjunct for evaluation of scabies because scabetic spines and scybala (or fecal material) are polarizable.15

Two types of Demodex mites typically are found in the skin: Demodex folliculorum, which are similarly sized to scabies mites with a more oblong body and occur most commonly in mature hair follicles (eg, eyelashes), and Demodex brevis, which are about half the size (150–200 µm) and live in the sebaceous glands of vellus hairs (Figure 5).14 Both of these mites have 8 legs, similar to the scabies mite.

Hair Preparations

Hair preparations for bulbar examination (eg, trichogram) may prove useful in the evaluation of many types of alopecia, and elaboration on this topic is beyond the scope of this article. Microscopic evaluation of the hair shaft may be an underutilized technique in the outpatient setting and is capable of yielding a variety of diagnoses, including monilethrix, pili torti, and pili trianguli et canaliculi, among others.3 One particularly useful scenario for hair shaft examination (usually of the eyebrow) is in the setting of a patient with severe atopic dermatitis or a baby with ichthyosiform erythroderma, as discovery of trichorrhexis invaginata is pathognomonic for the diagnosis of Netherton syndrome.16 Lastly, evaluation of the hair shaft in patients with patchy and diffuse hair loss whose clinical impression is reminiscent of alopecia areata, or those with concerns of inability to grow hair beyond a short length, may lead to diagnosis of loose anagen syndrome, especially if more than 70% of hair fibers examined exhibit the classic findings of a ruffled proximal cuticle and lack of root sheath.4

Final Thoughts

Bedside microscopy is a rapid and cost-sensitive way to confirm diagnoses that are clinically suspected and remains a valuable tool to acquire during residency training.

Dermatologists are uniquely equipped amongst clinicians to make bedside diagnoses because of the focus on histopathology and microscopy inherent in our training. This skill is highly valuable in both an inpatient and outpatient setting because it may lead to a rapid diagnosis or be a useful adjunct in the initial clinical decision-making process. Although expert microscopists may be able to garner relevant information from scraping almost any type of lesion, bedside microscopy primarily is used by dermatologists in the United States for consideration of infectious etiologies of a variety of cutaneous manifestations.1,2

Basic Principles

Lesions that should be considered for bedside microscopic analysis in outpatient settings are scaly lesions, vesiculobullous lesions, inflammatory papules, and pustules1; microscopic evaluation also can be useful for myriad trichoscopic considerations.3,4 In some instances, direct visualization of the pathogen is possible (eg, cutaneous fungal infections, demodicidosis, scabetic infections), and in other circumstances reactive changes of keratinocytes or the presence of specific cell types can aid in diagnosis (eg, ballooning degeneration and multinucleation of keratinocytes in herpetic lesions, an abundance of eosinophils in erythema toxicum neonatorum). Different types of media are used to best prepare tissue based on the suspected etiology of the condition.

One major stumbling block for residents when beginning to perform bedside testing is the lack of dimensional understanding of the structures they are searching for; for example, medical students and residents often may mistake fibers for dermatophytes, which typically are much larger than fungal hyphae. Familiarizing oneself with the basic dimensions of different cell types or pathogens in relation to each other (Table) will help further refine the beginner’s ability to effectively search for and identify pathogenic features. This concept is further schematized in Figure 1 to help visualize scale differences.

Examination of the Specimen

Slide preparation depends on the primary lesion in consideration and will be discussed in greater detail in the following sections. Once the slide is prepared, place it on the microscope stage and adjust the condenser and light source for optimal visualization. Scan the specimen in a gridlike fashion on low power (usually ×10) and then inspect suspicious findings on higher power (×40 or higher).

Dermatomycoses

Fungal infections of the skin can present as annular papulosquamous lesions, follicular pustules or papules, bullous lesions, hypopigmented patches, and mucosal exudate or erosions, among other manifestations.5 Potassium hydroxide (KOH) is the classic medium used in preparation of lesions being assessed for evidence of fungus because it leads to lysis of keratinocytes for better visualization of fungal hyphae and spores. Other media that contain KOH and additional substrates such as dimethyl sulfoxide or chlorazol black E can be used to better highlight fungal elements.6

Dermatophytosis

Dermatophytes lead to superficial infection of the epidermis and epidermal appendages and present in a variety of ways, including site-specific infections manifesting typically as erythematous, annular or arcuate scaling (eg, tinea faciei, tinea corporis, tinea cruris, tinea manus, tinea pedis), alopecia with broken hair shafts, black dots, boggy nodules and/or scaling of the scalp (eg, tinea capitis, favus, kerion), and dystrophic nails (eg, onychomycosis).5,7 For examination of lesional skin scrapings, one can either use clear cellophane tape against the skin to remove scale, which is especially useful in the case of pediatric patients, and then press the tape against a slide prepared with several drops of a KOH-based medium to directly visualize without a coverslip, or scrape the lesion with a No. 15 blade and place the scales onto the glass slide, with further preparation as described below.8 For assessment of alopecia or dystrophic nails, scrape lesional skin with a No. 15 blade to obtain affected hair follicles and proximal subungual debris, respectively.6,9

Once the cellular debris has been obtained and placed on the slide, a coverslip can be overlaid and KOH applied laterally to be taken up across the slide by capillary action. Allow the slide to sit for at least 5 minutes before analyzing to better visualize fungal elements. Both tinea and onychomycosis will show branching septate hyphae extending across keratinocytes; a common false-positive is identifying overlapping keratinocyte edges, which are a similar size, but they can be distinguished from fungi because they do not cross multiple keratinocytes.1,8 Tinea capitis may demonstrate similar findings or may reveal hair shafts with spores contained within or surrounding it, corresponding to endothrix or ectothrix infection, respectively.5

Pityriasis Versicolor and Malassezia Folliculitis

Pityriasis versicolor presents with hypopigmented to pink, finely scaling ovoid papules, usually on the upper back, shoulders, and neck, and is caused by Malassezia furfur and other Malassezia species.5 Malassezia folliculitis also is caused by this fungus and presents with monomorphic follicular papules and pustules. Scrapings from the scaly papules will demonstrate keratinocytes with the classic “spaghetti and meatballs” fungal elements, whereas Malassezia folliculitis demonstrates only spores.5,7

Candidiasis

One possible outpatient presentation of candidiasis is oral thrush, which can exhibit white mucosal exudate or erythematous patches. A tongue blade can be used to scrape the tongue or cheek wall, with subsequent preparatory steps with application of KOH as described for dermatophytes. Cutaneous candidiasis most often develops in intertriginous regions and will exhibit erosive painful lesions with satellite pustules. In both cases, analysis of the specimen will show shorter fatter hyphal elements than seen in dermatophytosis, with pseudohyphae, blunted ends, and potentially yeast forms.5

Vesiculobullous Lesions

The Tzanck smear has been used since the 1940s to differentiate between etiologies of blistering disorders and is now most commonly used for the quick identification of herpetic lesions.1 The test is performed by scraping the base of a deroofed vesicle, pustule, or bulla, and smearing the cellular materials onto a glass slide. The most commonly utilized media for staining in the outpatient setting at my institution (University of Texas Dell Medical School, Austin) is Giemsa, which is composed of azure II–eosin, glycerin, and methanol. It stains nuclei a reddish blue to pink and the cytoplasm blue.10 After being applied to the slide, the cells are allowed to air-dry for 5 to 10 minutes, and Giemsa stain is subsequently applied and allowed to incubate for 15 minutes, then rinsed carefully with water and directly examined.

Other stains that can be used to perform the Tzanck smear include commercial preparations that may be more accessible in the inpatient settings such as the Wright-Giemsa, Quik-Dip, and Diff-Quick.1,10

Examination of a Tzanck smear from a herpetic lesion will yield acantholytic, enlarged keratinocytes up to twice their usual size (referred to as ballooning degeneration), and multinucleation. In addition, molding of the nuclei to each other within the multinucleated cells and margination of the nuclear chromatin may be appreciated (Figure 2). Intranuclear inclusion bodies, also known as Cowdry type A bodies, can be seen that are nearly the size of red blood cells but are rare to find, with only 10% of specimens exhibiting this finding in a prospective review of 299 patients with herpetic vesiculobullous lesions.11 Evaluation of the contents of blisters caused by bullous pemphigoid and erythema toxicum neonatorum may yield high densities of eosinophils with normal keratinocyte morphology (Figure 3). Other blistering eruptions such as pemphigus vulgaris and bullous drug eruptions also have characteristic findings.1,2

Gout Preparation

Gout is a systemic disease caused by uric acid accumulation that can present with joint pain and white to red nodules on digits, joints, and ears (known as tophi). Material may be expressed from tophi and examined immediately by polarized light microscopy to confirm the diagnosis.5 Specimens will demonstrate needle-shaped, negatively birefringent monosodium urate crystals on polarized light microscopy (Figure 4). An ordinary light microscope can be converted for such use with the lenses of inexpensive polarized sunglasses, placing one lens between the light source and specimen and the other lens between the examiner’s eye and the specimen.12

Parasitic Infections

Two common parasitic infections identified in outpatient dermatology clinics are scabies mites and Demodex mites. Human scabies is extremely pruritic and caused by infestation with Sarcoptes scabiei var hominis; the typical presentation in an adult is erythematous and crusted papules, linear burrows, and vesiculopustules, especially of the interdigital spaces, wrists, axillae, umbilicus, and genital region.1,13 Demodicidosis presents with papules and pustules on the face, usually in a patient with background rosacea and diffuse erythema.1,5,14

If either of these conditions are suspected, mineral oil should be used to prepare the slide because it will maintain viability of the organisms, which are visualized better in motion. Adult scabies mites are roughly 10 times larger than keratinocytes, measuring approximately 250 to 450 µm in length with 8 legs.13 Eggs also may be visualized within the cellular debris and typically are 100 to 150 µm in size and ovoid in shape. Of note, polariscopic examination may be a useful adjunct for evaluation of scabies because scabetic spines and scybala (or fecal material) are polarizable.15

Two types of Demodex mites typically are found in the skin: Demodex folliculorum, which are similarly sized to scabies mites with a more oblong body and occur most commonly in mature hair follicles (eg, eyelashes), and Demodex brevis, which are about half the size (150–200 µm) and live in the sebaceous glands of vellus hairs (Figure 5).14 Both of these mites have 8 legs, similar to the scabies mite.

Hair Preparations

Hair preparations for bulbar examination (eg, trichogram) may prove useful in the evaluation of many types of alopecia, and elaboration on this topic is beyond the scope of this article. Microscopic evaluation of the hair shaft may be an underutilized technique in the outpatient setting and is capable of yielding a variety of diagnoses, including monilethrix, pili torti, and pili trianguli et canaliculi, among others.3 One particularly useful scenario for hair shaft examination (usually of the eyebrow) is in the setting of a patient with severe atopic dermatitis or a baby with ichthyosiform erythroderma, as discovery of trichorrhexis invaginata is pathognomonic for the diagnosis of Netherton syndrome.16 Lastly, evaluation of the hair shaft in patients with patchy and diffuse hair loss whose clinical impression is reminiscent of alopecia areata, or those with concerns of inability to grow hair beyond a short length, may lead to diagnosis of loose anagen syndrome, especially if more than 70% of hair fibers examined exhibit the classic findings of a ruffled proximal cuticle and lack of root sheath.4

Final Thoughts

Bedside microscopy is a rapid and cost-sensitive way to confirm diagnoses that are clinically suspected and remains a valuable tool to acquire during residency training.

- Wanat KA, Dominguez AR, Carter Z, et al. Bedside diagnostics in dermatology: viral, bacterial, and fungal infections. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77:197-218.

- Micheletti RG, Dominguez AR, Wanat KA. Bedside diagnostics in dermatology: parasitic and noninfectious diseases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77:221-230.

- Whiting DA, Dy LC. Office diagnosis of hair shaft defects. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2006;25:24-34.

- Tosti A. Loose anagen hair syndrome and loose anagen hair. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138:521-522.

- Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Philadelphia PA: Elsevier; 2017.

- Lilly KK, Koshnick RL, Grill JP, et al. Cost-effectiveness of diagnostic tests for toenail onychomycosis: a repeated-measure, single-blinded, cross-sectional evaluation of 7 diagnostic tests. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55:620-626.

- Elder DE, ed. Lever’s Histopathology of the Skin. 10th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2009.

- Raghukumar S, Ravikumar BC. Potassium hydroxide mount with cellophane adhesive: a method for direct diagnosis of dermatophyte skin infections [published online May 29, 2018]. Clin Exp Dermatol. doi:10.1111/ced.13573.

- Bhat YJ, Zeerak S, Kanth F, et al. Clinicoepidemiological and mycological study of tinea capitis in the pediatric population of Kashmir Valley: a study from a tertiary care centre. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2017;8:100-103.

- Gupta LK, Singhi MK. Tzanck smear: a useful diagnostic tool. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2005;71:295-299.

- Durdu M, Baba M, Seçkin D. The value of Tzanck smear test in diagnosis of erosive, vesicular, bullous, and pustular skin lesions. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:958-964.

- Fagan TJ, Lidsky MD. Compensated polarized light microscopy using cellophane adhesive tape. Arthritis Rheum. 1974;17:256-262.

- Walton SF, Currie BJ. Problems in diagnosing scabies, a global disease in human and animal populations. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2007;20:268-279.

- Desch C, Nutting WB. Demodex folliculorum (Simon) and D. brevis akbulatova of man: redescription and reevaluation. J Parasitol. 1972;58:169-177.

- Foo CW, Florell SR, Bowen AR. Polarizable elements in scabies infestation: a clue to diagnosis. J Cutan Pathol. 2013;40:6-10.

- Akkurt ZM, Tuncel T, Ayhan E, et al. Rapid and easy diagnosis of Netherton syndrome with dermoscopy. J Cutan Med Surg. 2014;18:280-282.

- Wanat KA, Dominguez AR, Carter Z, et al. Bedside diagnostics in dermatology: viral, bacterial, and fungal infections. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77:197-218.

- Micheletti RG, Dominguez AR, Wanat KA. Bedside diagnostics in dermatology: parasitic and noninfectious diseases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77:221-230.

- Whiting DA, Dy LC. Office diagnosis of hair shaft defects. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2006;25:24-34.

- Tosti A. Loose anagen hair syndrome and loose anagen hair. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138:521-522.

- Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Philadelphia PA: Elsevier; 2017.

- Lilly KK, Koshnick RL, Grill JP, et al. Cost-effectiveness of diagnostic tests for toenail onychomycosis: a repeated-measure, single-blinded, cross-sectional evaluation of 7 diagnostic tests. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55:620-626.

- Elder DE, ed. Lever’s Histopathology of the Skin. 10th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2009.

- Raghukumar S, Ravikumar BC. Potassium hydroxide mount with cellophane adhesive: a method for direct diagnosis of dermatophyte skin infections [published online May 29, 2018]. Clin Exp Dermatol. doi:10.1111/ced.13573.

- Bhat YJ, Zeerak S, Kanth F, et al. Clinicoepidemiological and mycological study of tinea capitis in the pediatric population of Kashmir Valley: a study from a tertiary care centre. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2017;8:100-103.

- Gupta LK, Singhi MK. Tzanck smear: a useful diagnostic tool. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2005;71:295-299.

- Durdu M, Baba M, Seçkin D. The value of Tzanck smear test in diagnosis of erosive, vesicular, bullous, and pustular skin lesions. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:958-964.

- Fagan TJ, Lidsky MD. Compensated polarized light microscopy using cellophane adhesive tape. Arthritis Rheum. 1974;17:256-262.

- Walton SF, Currie BJ. Problems in diagnosing scabies, a global disease in human and animal populations. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2007;20:268-279.

- Desch C, Nutting WB. Demodex folliculorum (Simon) and D. brevis akbulatova of man: redescription and reevaluation. J Parasitol. 1972;58:169-177.

- Foo CW, Florell SR, Bowen AR. Polarizable elements in scabies infestation: a clue to diagnosis. J Cutan Pathol. 2013;40:6-10.

- Akkurt ZM, Tuncel T, Ayhan E, et al. Rapid and easy diagnosis of Netherton syndrome with dermoscopy. J Cutan Med Surg. 2014;18:280-282.

Docs push back on step therapy in Medicare Advantage

A new policy that allows Medicare Advantage plans to use step therapy to control spending on prescription drug administered in the office is not going over well with doctors.

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services announced the policy change Aug. 7, which will give Medicare Advantage plan sponsors the “choice of implementing step therapy to manage Part B drugs, beginning Jan. 1, 2019,” the agency said in a statement.

The action is part of the broader Trump administration initiative to lower the prices and out-of-pocket costs of prescription drugs as outlined in the American Patients First blueprint.

By “implementing step therapy along with care coordination and drug adherence programs in [Medicare Advantage], it will lower costs and improve the quality of care for Medicare beneficiaries,” CMS officials said in a statement. The move to allow step therapy will give Medicare Advantage plan sponsors the ability to negotiate the designation of a preferred drug, something the agency believes could result in lower prices for these drugs, which in turn will lower the copays for Medicare beneficiaries.

Plan sponsors will be required to pass savings onto beneficiaries through some sort of rewards program, according to a memo detailing the policy change, which also notes that plan rewards “cannot be offered in the form of cash or monetary rebate, but may be offered as gift cards or other items value to all eligible enrollees.”

The value of the rewards must be more than half of the savings generated from implementing the step therapy program, according to the memo.

CMS officials noted that there will be a process that beneficiaries can follow if they believe they need direct access to a drug that would otherwise be available only after failing on another drug.

The American Gastroenterological Association “is concerned that the proposal could limit access for current and future beneficiaries and could add to the growing regulatory burden that physicians already face,” according to a statement. AGA stated that “any change in policy must ensure that patients have access to the appropriate therapies to manage their diseases and not contribute to additional administrative burdens for physician practices.” In addition to responding to CMS, AGA continues to advocate to Congress for patient protections for those subject to step therapy protocols in employer-sponsored health plans; learn more at http:/ow.ly/kp8l30lnDmp.

The new policy applies to only new prescriptions or administrations of Part B drugs. Patients will not have current treatments disrupted if that drug is not the first drug on the step therapy ladder. Additionally, patients will have the opportunity to make a one-time change in plans during the first quarter annually if they are finding the plan is not working for them. Plan sponsors must disclose that Part B drugs may be subject to step therapy.

A new policy that allows Medicare Advantage plans to use step therapy to control spending on prescription drug administered in the office is not going over well with doctors.

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services announced the policy change Aug. 7, which will give Medicare Advantage plan sponsors the “choice of implementing step therapy to manage Part B drugs, beginning Jan. 1, 2019,” the agency said in a statement.

The action is part of the broader Trump administration initiative to lower the prices and out-of-pocket costs of prescription drugs as outlined in the American Patients First blueprint.

By “implementing step therapy along with care coordination and drug adherence programs in [Medicare Advantage], it will lower costs and improve the quality of care for Medicare beneficiaries,” CMS officials said in a statement. The move to allow step therapy will give Medicare Advantage plan sponsors the ability to negotiate the designation of a preferred drug, something the agency believes could result in lower prices for these drugs, which in turn will lower the copays for Medicare beneficiaries.

Plan sponsors will be required to pass savings onto beneficiaries through some sort of rewards program, according to a memo detailing the policy change, which also notes that plan rewards “cannot be offered in the form of cash or monetary rebate, but may be offered as gift cards or other items value to all eligible enrollees.”

The value of the rewards must be more than half of the savings generated from implementing the step therapy program, according to the memo.

CMS officials noted that there will be a process that beneficiaries can follow if they believe they need direct access to a drug that would otherwise be available only after failing on another drug.

The American Gastroenterological Association “is concerned that the proposal could limit access for current and future beneficiaries and could add to the growing regulatory burden that physicians already face,” according to a statement. AGA stated that “any change in policy must ensure that patients have access to the appropriate therapies to manage their diseases and not contribute to additional administrative burdens for physician practices.” In addition to responding to CMS, AGA continues to advocate to Congress for patient protections for those subject to step therapy protocols in employer-sponsored health plans; learn more at http:/ow.ly/kp8l30lnDmp.

The new policy applies to only new prescriptions or administrations of Part B drugs. Patients will not have current treatments disrupted if that drug is not the first drug on the step therapy ladder. Additionally, patients will have the opportunity to make a one-time change in plans during the first quarter annually if they are finding the plan is not working for them. Plan sponsors must disclose that Part B drugs may be subject to step therapy.

A new policy that allows Medicare Advantage plans to use step therapy to control spending on prescription drug administered in the office is not going over well with doctors.

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services announced the policy change Aug. 7, which will give Medicare Advantage plan sponsors the “choice of implementing step therapy to manage Part B drugs, beginning Jan. 1, 2019,” the agency said in a statement.

The action is part of the broader Trump administration initiative to lower the prices and out-of-pocket costs of prescription drugs as outlined in the American Patients First blueprint.

By “implementing step therapy along with care coordination and drug adherence programs in [Medicare Advantage], it will lower costs and improve the quality of care for Medicare beneficiaries,” CMS officials said in a statement. The move to allow step therapy will give Medicare Advantage plan sponsors the ability to negotiate the designation of a preferred drug, something the agency believes could result in lower prices for these drugs, which in turn will lower the copays for Medicare beneficiaries.

Plan sponsors will be required to pass savings onto beneficiaries through some sort of rewards program, according to a memo detailing the policy change, which also notes that plan rewards “cannot be offered in the form of cash or monetary rebate, but may be offered as gift cards or other items value to all eligible enrollees.”

The value of the rewards must be more than half of the savings generated from implementing the step therapy program, according to the memo.

CMS officials noted that there will be a process that beneficiaries can follow if they believe they need direct access to a drug that would otherwise be available only after failing on another drug.

The American Gastroenterological Association “is concerned that the proposal could limit access for current and future beneficiaries and could add to the growing regulatory burden that physicians already face,” according to a statement. AGA stated that “any change in policy must ensure that patients have access to the appropriate therapies to manage their diseases and not contribute to additional administrative burdens for physician practices.” In addition to responding to CMS, AGA continues to advocate to Congress for patient protections for those subject to step therapy protocols in employer-sponsored health plans; learn more at http:/ow.ly/kp8l30lnDmp.

The new policy applies to only new prescriptions or administrations of Part B drugs. Patients will not have current treatments disrupted if that drug is not the first drug on the step therapy ladder. Additionally, patients will have the opportunity to make a one-time change in plans during the first quarter annually if they are finding the plan is not working for them. Plan sponsors must disclose that Part B drugs may be subject to step therapy.

CMS proposes site-neutral payments for hospital outpatient settings

In the proposed update to the Outpatient Prospective Payment System (OPPS) and Ambulatory Surgical Center (ASC) Payment System for 2019, CMS is proposing to apply a physician fee schedule–equivalent for the clinic visit service when provided at an off-campus, provider-based department that is paid under OPPS.

According to CMS, the average current clinical visit paid by CMS is $116 with $23 being the average copay by the patient. If the proposal is finalized, the payment would drop to about $46 with an average patient copay of $9.

“This is intended to address concerns about recent consolidations in the market that reduce competition,” CMS Administrator Seema Verma said during a July 25 press conference.

The American Hospital Association already is pushing back on this proposal.

“With today’s proposed rule, CMS has once again showed a lack of understanding about the reality in which hospitals and health systems operate daily to serve the needs of their communities,” AHA Executive Vice President Tom Nickels said in a statement. “In 2015, Congress clearly intended to provide current off-campus hospital clinics with the existing outpatient payment rate in recognition of the critical role they play in their communities. But CMS’s proposal runs counter to this and will instead impede access to care for the most vulnerable patients.”

The OPPS/ASC update also includes proposals to expand the list of covered surgical procedures that can be performed in an ASC, a move that Ms. Verma said would “provide patients with more choices and options for lower-priced care.”

“For CY 2019, CMS is proposing to allow certain CPT codes outside of the surgical code range that directly crosswalk or are clinically similar to procedures within the CPT surgical code range to be included on the [covered procedure list] and is proposing to add certain cardiovascular codes to the ASC [covered procedure list] as a result,” the CMS fact sheet notes.

Another change proposed by CMS relates to how ASC reimbursement rates are updated. They have been based on the consumer price index-urban, which has resulted in a decline in ASC payments relative to hospitals for the same service. For 2019-2023, CMS proposes to use the hospital market basket instead, which will help promote site neutrality between hospitals and ASCs. The AGA applauds this proposal, and has been working for it with the ACG and ASGE for nearly a decade.

In addition, the OPPS is seeking feedback on a number of topics.

One is related to price transparency. The agency is asking “whether providers and suppliers can and should be required to inform patients about charges and payment information for healthcare services and out-of-pocket costs, what data elements the public would find most useful, and what other charges are needed to empower patients,” according to the fact sheet.

Finally, the agency is seeking more information on solutions to better promote interoperability.

In the proposed update to the Outpatient Prospective Payment System (OPPS) and Ambulatory Surgical Center (ASC) Payment System for 2019, CMS is proposing to apply a physician fee schedule–equivalent for the clinic visit service when provided at an off-campus, provider-based department that is paid under OPPS.

According to CMS, the average current clinical visit paid by CMS is $116 with $23 being the average copay by the patient. If the proposal is finalized, the payment would drop to about $46 with an average patient copay of $9.

“This is intended to address concerns about recent consolidations in the market that reduce competition,” CMS Administrator Seema Verma said during a July 25 press conference.

The American Hospital Association already is pushing back on this proposal.

“With today’s proposed rule, CMS has once again showed a lack of understanding about the reality in which hospitals and health systems operate daily to serve the needs of their communities,” AHA Executive Vice President Tom Nickels said in a statement. “In 2015, Congress clearly intended to provide current off-campus hospital clinics with the existing outpatient payment rate in recognition of the critical role they play in their communities. But CMS’s proposal runs counter to this and will instead impede access to care for the most vulnerable patients.”

The OPPS/ASC update also includes proposals to expand the list of covered surgical procedures that can be performed in an ASC, a move that Ms. Verma said would “provide patients with more choices and options for lower-priced care.”

“For CY 2019, CMS is proposing to allow certain CPT codes outside of the surgical code range that directly crosswalk or are clinically similar to procedures within the CPT surgical code range to be included on the [covered procedure list] and is proposing to add certain cardiovascular codes to the ASC [covered procedure list] as a result,” the CMS fact sheet notes.

Another change proposed by CMS relates to how ASC reimbursement rates are updated. They have been based on the consumer price index-urban, which has resulted in a decline in ASC payments relative to hospitals for the same service. For 2019-2023, CMS proposes to use the hospital market basket instead, which will help promote site neutrality between hospitals and ASCs. The AGA applauds this proposal, and has been working for it with the ACG and ASGE for nearly a decade.

In addition, the OPPS is seeking feedback on a number of topics.

One is related to price transparency. The agency is asking “whether providers and suppliers can and should be required to inform patients about charges and payment information for healthcare services and out-of-pocket costs, what data elements the public would find most useful, and what other charges are needed to empower patients,” according to the fact sheet.

Finally, the agency is seeking more information on solutions to better promote interoperability.

In the proposed update to the Outpatient Prospective Payment System (OPPS) and Ambulatory Surgical Center (ASC) Payment System for 2019, CMS is proposing to apply a physician fee schedule–equivalent for the clinic visit service when provided at an off-campus, provider-based department that is paid under OPPS.

According to CMS, the average current clinical visit paid by CMS is $116 with $23 being the average copay by the patient. If the proposal is finalized, the payment would drop to about $46 with an average patient copay of $9.

“This is intended to address concerns about recent consolidations in the market that reduce competition,” CMS Administrator Seema Verma said during a July 25 press conference.

The American Hospital Association already is pushing back on this proposal.

“With today’s proposed rule, CMS has once again showed a lack of understanding about the reality in which hospitals and health systems operate daily to serve the needs of their communities,” AHA Executive Vice President Tom Nickels said in a statement. “In 2015, Congress clearly intended to provide current off-campus hospital clinics with the existing outpatient payment rate in recognition of the critical role they play in their communities. But CMS’s proposal runs counter to this and will instead impede access to care for the most vulnerable patients.”

The OPPS/ASC update also includes proposals to expand the list of covered surgical procedures that can be performed in an ASC, a move that Ms. Verma said would “provide patients with more choices and options for lower-priced care.”

“For CY 2019, CMS is proposing to allow certain CPT codes outside of the surgical code range that directly crosswalk or are clinically similar to procedures within the CPT surgical code range to be included on the [covered procedure list] and is proposing to add certain cardiovascular codes to the ASC [covered procedure list] as a result,” the CMS fact sheet notes.

Another change proposed by CMS relates to how ASC reimbursement rates are updated. They have been based on the consumer price index-urban, which has resulted in a decline in ASC payments relative to hospitals for the same service. For 2019-2023, CMS proposes to use the hospital market basket instead, which will help promote site neutrality between hospitals and ASCs. The AGA applauds this proposal, and has been working for it with the ACG and ASGE for nearly a decade.

In addition, the OPPS is seeking feedback on a number of topics.

One is related to price transparency. The agency is asking “whether providers and suppliers can and should be required to inform patients about charges and payment information for healthcare services and out-of-pocket costs, what data elements the public would find most useful, and what other charges are needed to empower patients,” according to the fact sheet.

Finally, the agency is seeking more information on solutions to better promote interoperability.

CMS proposal to level E/M payments raises concerns

Citing the need to reduce paperwork hassles, officials at the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services are proposing to flatten the payment for evaluation and management (E/M) visits coded at levels 2-5.

The CMS outlined how the proposal would affect payment using 2018 rates to model the change. The proposal would set the payment rate for level 1 E/M office visits for new patients at $44, down from the $45 using the current methodology. Levels 2-5 would receive $135. Currently, payments for level 2 visits are set at $76, level 3 at $110, level 4 at $167, and level 5 at $211.

For office visits with established patients, the proposed rate would be $24, up from the current payment of $22 for a level 1 visit. Levels 2-5 would receive $93. Under the current methodology, payments for level 2 visits are set at $45, level 3 at $74, level 4 at $109, and level 5 at $148.

The change also comes with a reduced documentation burden, so the same documentation is needed regardless of which level between 2 and 5 the office visit is, a move that is expected to save time.

The CMS outlined its vision for changes to the E/M payment in the proposed update to the 2019 Medicare physician fee schedule. Comments on the proposal are due Sept. 10, 2018.

The agency estimated that for most specialties, there would be minimal effect on this proposed change. However, for 10 specialties, payment reductions could result from this change. The proposal is raising concerns, particularly from those who stand to see their pay reduced.

CMS officials estimate the proposal would save time. CMS Administrator Seema Verma said that the documentation change would result in an additional 51 hours for patient care per clinician per year.

“The agency has clearly heard from physicians about the need to reduce administrative burdens for physicians,” stated Lisa Gangarosa, MD, AGAF, chair, AGA Government Affairs Committee. “In that regard, CMS should be commended. Unfortunately, in their efforts to reduce burden, CMS has proposed changes that drastically undervalue the care gastroenterologists and hepatologists provide to patients with inflammatory bowel disease, motility disorders, chronic liver disease and other complex gastrointestinal diseases.”

Angus B. Worthing, MD, chair of the American College of Rheumatology’s Committee on Government Affairs, said he was doubtful that any increase in volume would offset the losses from the proposed flat payment across levels 2-5 E/M visits, especially if the pay decrease results in access issues.

SOURCE: CMS proposed rule, CMS-1693-P.

On July 12, 2018, CMS published a set of “proposed rules” that will have substantial impact on your practice. CMS released a 665-page document with 26 proposed changes in Medicare. A public comment period is open until Sept. 10, 2018. Final rules will be published in the fall with implementation expected in January 2019.

Medicare proposes to reduce the number of E/M coding levels to two (from five: these relate to current CPT codes 99201-99205 and 99211-99215), with documentation requirements reduced to those required for current level 2. If you tend to bill levels 4-5, your bottom line will be affected.

CMS wants to eliminate site-of-service differences in both clinic and ASC payments. This will modify the financial advantages gained by practices who sold their centers to hospital systems and for health systems that have HOPD endoscopy centers and clinics.

Endoscopy with biopsy and colonoscopy with polypectomy were again identified as being potentially overvalued and thus may trigger a re-analysis.

A policy change announced recently by CMS would allow Medicare Advantage plans to establish sequence requirements (step therapy) for medical therapies, including biologics.

While community practices clearly will be affected by these changes, the financial pressures on academic medical centers will be immense. AMC’s have high fixed costs and deteriorating clinical margins. Clinical revenue supports not only clinical enterprises (including faculty salaries) but also a large portion of research and education costs. Loss of 340b pharmacy income, the more government payers, CMS regulations and potential penalties, and narrowing clinical networks all have reduced revenue for many AMCs. Adding these proposed rule changes will send many AMCs further into negative margins: This will affect the training of our next-generation leaders and discoveries of new science.

John I. Allen, MD, MBA, AGAF, professor of medicine, division of gastroenterology, University of Michigan School of Medicine, Ann Arbor. He reported no conflicts.

On July 12, 2018, CMS published a set of “proposed rules” that will have substantial impact on your practice. CMS released a 665-page document with 26 proposed changes in Medicare. A public comment period is open until Sept. 10, 2018. Final rules will be published in the fall with implementation expected in January 2019.

Medicare proposes to reduce the number of E/M coding levels to two (from five: these relate to current CPT codes 99201-99205 and 99211-99215), with documentation requirements reduced to those required for current level 2. If you tend to bill levels 4-5, your bottom line will be affected.

CMS wants to eliminate site-of-service differences in both clinic and ASC payments. This will modify the financial advantages gained by practices who sold their centers to hospital systems and for health systems that have HOPD endoscopy centers and clinics.

Endoscopy with biopsy and colonoscopy with polypectomy were again identified as being potentially overvalued and thus may trigger a re-analysis.

A policy change announced recently by CMS would allow Medicare Advantage plans to establish sequence requirements (step therapy) for medical therapies, including biologics.

While community practices clearly will be affected by these changes, the financial pressures on academic medical centers will be immense. AMC’s have high fixed costs and deteriorating clinical margins. Clinical revenue supports not only clinical enterprises (including faculty salaries) but also a large portion of research and education costs. Loss of 340b pharmacy income, the more government payers, CMS regulations and potential penalties, and narrowing clinical networks all have reduced revenue for many AMCs. Adding these proposed rule changes will send many AMCs further into negative margins: This will affect the training of our next-generation leaders and discoveries of new science.

John I. Allen, MD, MBA, AGAF, professor of medicine, division of gastroenterology, University of Michigan School of Medicine, Ann Arbor. He reported no conflicts.

On July 12, 2018, CMS published a set of “proposed rules” that will have substantial impact on your practice. CMS released a 665-page document with 26 proposed changes in Medicare. A public comment period is open until Sept. 10, 2018. Final rules will be published in the fall with implementation expected in January 2019.

Medicare proposes to reduce the number of E/M coding levels to two (from five: these relate to current CPT codes 99201-99205 and 99211-99215), with documentation requirements reduced to those required for current level 2. If you tend to bill levels 4-5, your bottom line will be affected.

CMS wants to eliminate site-of-service differences in both clinic and ASC payments. This will modify the financial advantages gained by practices who sold their centers to hospital systems and for health systems that have HOPD endoscopy centers and clinics.

Endoscopy with biopsy and colonoscopy with polypectomy were again identified as being potentially overvalued and thus may trigger a re-analysis.

A policy change announced recently by CMS would allow Medicare Advantage plans to establish sequence requirements (step therapy) for medical therapies, including biologics.

While community practices clearly will be affected by these changes, the financial pressures on academic medical centers will be immense. AMC’s have high fixed costs and deteriorating clinical margins. Clinical revenue supports not only clinical enterprises (including faculty salaries) but also a large portion of research and education costs. Loss of 340b pharmacy income, the more government payers, CMS regulations and potential penalties, and narrowing clinical networks all have reduced revenue for many AMCs. Adding these proposed rule changes will send many AMCs further into negative margins: This will affect the training of our next-generation leaders and discoveries of new science.

John I. Allen, MD, MBA, AGAF, professor of medicine, division of gastroenterology, University of Michigan School of Medicine, Ann Arbor. He reported no conflicts.

Citing the need to reduce paperwork hassles, officials at the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services are proposing to flatten the payment for evaluation and management (E/M) visits coded at levels 2-5.

The CMS outlined how the proposal would affect payment using 2018 rates to model the change. The proposal would set the payment rate for level 1 E/M office visits for new patients at $44, down from the $45 using the current methodology. Levels 2-5 would receive $135. Currently, payments for level 2 visits are set at $76, level 3 at $110, level 4 at $167, and level 5 at $211.

For office visits with established patients, the proposed rate would be $24, up from the current payment of $22 for a level 1 visit. Levels 2-5 would receive $93. Under the current methodology, payments for level 2 visits are set at $45, level 3 at $74, level 4 at $109, and level 5 at $148.

The change also comes with a reduced documentation burden, so the same documentation is needed regardless of which level between 2 and 5 the office visit is, a move that is expected to save time.

The CMS outlined its vision for changes to the E/M payment in the proposed update to the 2019 Medicare physician fee schedule. Comments on the proposal are due Sept. 10, 2018.

The agency estimated that for most specialties, there would be minimal effect on this proposed change. However, for 10 specialties, payment reductions could result from this change. The proposal is raising concerns, particularly from those who stand to see their pay reduced.

CMS officials estimate the proposal would save time. CMS Administrator Seema Verma said that the documentation change would result in an additional 51 hours for patient care per clinician per year.

“The agency has clearly heard from physicians about the need to reduce administrative burdens for physicians,” stated Lisa Gangarosa, MD, AGAF, chair, AGA Government Affairs Committee. “In that regard, CMS should be commended. Unfortunately, in their efforts to reduce burden, CMS has proposed changes that drastically undervalue the care gastroenterologists and hepatologists provide to patients with inflammatory bowel disease, motility disorders, chronic liver disease and other complex gastrointestinal diseases.”

Angus B. Worthing, MD, chair of the American College of Rheumatology’s Committee on Government Affairs, said he was doubtful that any increase in volume would offset the losses from the proposed flat payment across levels 2-5 E/M visits, especially if the pay decrease results in access issues.

SOURCE: CMS proposed rule, CMS-1693-P.

Citing the need to reduce paperwork hassles, officials at the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services are proposing to flatten the payment for evaluation and management (E/M) visits coded at levels 2-5.

The CMS outlined how the proposal would affect payment using 2018 rates to model the change. The proposal would set the payment rate for level 1 E/M office visits for new patients at $44, down from the $45 using the current methodology. Levels 2-5 would receive $135. Currently, payments for level 2 visits are set at $76, level 3 at $110, level 4 at $167, and level 5 at $211.

For office visits with established patients, the proposed rate would be $24, up from the current payment of $22 for a level 1 visit. Levels 2-5 would receive $93. Under the current methodology, payments for level 2 visits are set at $45, level 3 at $74, level 4 at $109, and level 5 at $148.

The change also comes with a reduced documentation burden, so the same documentation is needed regardless of which level between 2 and 5 the office visit is, a move that is expected to save time.

The CMS outlined its vision for changes to the E/M payment in the proposed update to the 2019 Medicare physician fee schedule. Comments on the proposal are due Sept. 10, 2018.

The agency estimated that for most specialties, there would be minimal effect on this proposed change. However, for 10 specialties, payment reductions could result from this change. The proposal is raising concerns, particularly from those who stand to see their pay reduced.

CMS officials estimate the proposal would save time. CMS Administrator Seema Verma said that the documentation change would result in an additional 51 hours for patient care per clinician per year.

“The agency has clearly heard from physicians about the need to reduce administrative burdens for physicians,” stated Lisa Gangarosa, MD, AGAF, chair, AGA Government Affairs Committee. “In that regard, CMS should be commended. Unfortunately, in their efforts to reduce burden, CMS has proposed changes that drastically undervalue the care gastroenterologists and hepatologists provide to patients with inflammatory bowel disease, motility disorders, chronic liver disease and other complex gastrointestinal diseases.”

Angus B. Worthing, MD, chair of the American College of Rheumatology’s Committee on Government Affairs, said he was doubtful that any increase in volume would offset the losses from the proposed flat payment across levels 2-5 E/M visits, especially if the pay decrease results in access issues.

SOURCE: CMS proposed rule, CMS-1693-P.

Rapid-onset rash in child

A 7-year-old boy was brought to his family physician for evaluation of a mildly pruritic spreading rash. Ten days earlier, the skin eruption had appeared, and he was given a diagnosis of streptococcal pharyngitis, which was confirmed by a throat swab and a positive antistreptolysin O titer. The child had no personal or family history of skin disorders, including eczema or psoriasis. He hadn’t used any topical agents or new medications recently, nor had he been exposed to triggering plants, animals, or chemicals. There was no history of trauma, friction, or rubbing in the area.

Physical examination revealed multiple erythematous, scaly papules and plaques of varying size on the patient’s trunk, arms, and legs (FIGURE). His palms and soles were spared.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Guttate psoriasis

A diagnosis of guttate psoriasis was made based on the physical exam findings and the preceding group A beta-hemolytic streptococcal infection.

This condition affects approximately 2% of all patients with psoriasis; it is characterized by the acute onset of multiple erythematosquamous papules and small plaques that look like droplets (“gutta”).1 It tends to affect children and young adults and typically occurs following an acute infection (eg, streptococcal pharyngitis).2,3 In this case, a rapid strep test and throat culture positive for group A Streptococcus supported the diagnosis.

Although this particular phenotype of psoriasis is usually associated with streptococcal infection and mainly occurs in patients with the HLA-Cw6+ allele, the specific immunologic response that causes these skin lesions is poorly understood.4 Antigenic similarities between streptococcal proteins and keratinocyte antigens might explain why the condition is triggered by streptococcal infections.5

Pityriasis rosea and tinea corporis are part of the differential

The differential includes skin conditions such as pityriasis rosea, tinea corporis, varicella, and insect bites.

Pityriasis rosea can manifest as a papulosquamous eruption, but it has an inward-facing scale, called a collarette. The “Christmas tree” pattern on the back that is preceded by a solitary 2- to 10-cm oval, pink, scaly herald patch (in 17%-50% of cases) is key to the diagnosis.6 (For more information, see “Rash on trunk and upper arms.”)

Continue to: Tinea corporis...

Tinea corporis is a dermatophyte infection that causes flat, red, scaly lesions that progress into annular lesions with central clearing or brown discoloration. The plaques can range from a few centimeters to several inches in size, but are always characterized by the slowly advancing border.6

Varicella also affects the trunk and extremities, but a key clinical finding is crops of characteristic lesions, including papules, vesicles, pustules, and crusted lesions in different stages that manifest simultaneously.6

Insect bites usually appear as urticarial papules and plaques associated with outdoor exposure. The lesions are distributed where insects are likely to bite.6

Treat the infection, control the psoriasis

The first-line treatment for streptococcal infection is amoxicillin (50 mg/kg/d [maximum: 1000 mg/d] orally for 10 d) or penicillin G benzathine (for children < 60 lb, 6 × 105 units intramuscularly; children ≥ 60 lb, 1.2 × 106 units intramuscularly).7 For the psoriasis lesions, treatment options include topical glucocorticosteroids, vitamin D derivatives, or combinations of both.5 In most cases, guttate psoriasis completely resolves. However, one-third of children with guttate psoriasis go on to develop plaque psoriasis later in life.8

Our patient was treated with penicillin G benzathine (1.2 × 106 units intramuscularly) and a calcipotriol/betamethasone combination gel. The streptococcal infection and skin lesions completely resolved. No adverse events were reported, and no relapse was observed after 3 months.

CORRESPONDENCE

Rita Matos, MD, Rua Actor Mário Viegas SN Rio Tinto, Portugal; [email protected]

1. Maciejewska-Radomska A, Szczerkowska-Dobosz A, Rebała K, et al. Frequency of streptococcal upper respiratory tract infections and HLA-Cw*06 allele in 70 patients with guttate psoriasis from northern Poland. Postepy Dermatol Alergol. 2015;32:455-458.

2. Garritsen FM, Kraag DE, de Graaf M. Guttate psoriasis triggered by perianal streptococcal infection. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2017;42:536-538.

3. Pfingstler LF, Maroon M, Mowad C. Guttate psoriasis outcomes. Cutis. 2016;97:140-144.

4. Ruiz-Romeu E, Ferran M, Sagristà M, et al. Streptococcus pyogenes-induced cutaneous lymphocyte antigen-positive T cell-dependent epidermal cell activation triggers TH17 responses in patients with guttate psoriasis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016;138:491-499.

5. Boehncke WH, Schön MP. Psoriasis. Lancet. 2015;386:983-994.