User login

Nabilone May Reduce Agitation in People With Alzheimer’s Disease

The treatment also improves behavioral symptoms such as delusions, hallucinations, anxiety, and apathy.

CHICAGO—Nabilone, a synthetic cannabinoid, may effectively treat agitation in people with Alzheimer’s disease, according to a randomized, double-blind clinical trial presented at AAIC 2018.

“Agitation, including verbal or physical outbursts, general emotional distress, restlessness, and pacing, is one of the most common behavioral changes associated with Alzheimer’s disease as it progresses and can be a significant cause of caregiver stress,” said Krista L. Lanctôt, PhD, Senior Scientist at Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre and Professor of Pharmacology and Psychiatry at the University of Toronto.

Dr. Lanctôt and colleagues investigated the potential benefits of nabilone for adults with moderate-to-severe Alzheimer’s dementia and clinically significant agitation. During the 14-week trial, 39 participants (77% male; average age, 87) received nabilone in capsule form (mean therapeutic dose, 1.6 mg) for six weeks, followed by one week without treatment and six weeks of placebo. In addition to measuring agitation, the researchers assessed overall behavioral symptoms, memory, physical changes, and safety.

Dr. Lanctôt’s group found that agitation improved significantly when participants were taking nabilone, compared with when they were receiving placebo, as measured by the Cohen-Mansfield Agitation Inventory. Nabilone also significantly improved overall behavioral symptoms, compared with placebo, as measured by the Neuropsychiatric Inventory.

In addition, the researchers observed small benefits in cognition and nutrition when participants received nabilone during the study. More people in the study experienced sedation when taking nabilone (45%) than when taking placebo (16%).

“Currently prescribed treatments for agitation in Alzheimer’s disease do not work in everybody. And when they do work, the effect is small, and they increase the risk of harmful side effects, including increased risk of death. As a result, there is an urgent need for safer medication options,” said Dr. Lanctôt. “These findings suggest that nabilone may be an effective treatment for agitation; however, the risk of sedation must be carefully monitored. A larger clinical trial would allow us to confirm our findings regarding how effective and safe nabilone is in the treatment of agitation for Alzheimer’s disease.”The FDA has not approved marijuana for the treatment or management of Alzheimer’s disease or other dementias. The use of marijuana as medical treatment is increasingly common, but much about the drug’s use in people with Alzheimer’s disease or other dementias is unknown. No robust, consistent clinical trial data support marijuana for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease dementia or for related issues.

The treatment also improves behavioral symptoms such as delusions, hallucinations, anxiety, and apathy.

The treatment also improves behavioral symptoms such as delusions, hallucinations, anxiety, and apathy.

CHICAGO—Nabilone, a synthetic cannabinoid, may effectively treat agitation in people with Alzheimer’s disease, according to a randomized, double-blind clinical trial presented at AAIC 2018.

“Agitation, including verbal or physical outbursts, general emotional distress, restlessness, and pacing, is one of the most common behavioral changes associated with Alzheimer’s disease as it progresses and can be a significant cause of caregiver stress,” said Krista L. Lanctôt, PhD, Senior Scientist at Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre and Professor of Pharmacology and Psychiatry at the University of Toronto.

Dr. Lanctôt and colleagues investigated the potential benefits of nabilone for adults with moderate-to-severe Alzheimer’s dementia and clinically significant agitation. During the 14-week trial, 39 participants (77% male; average age, 87) received nabilone in capsule form (mean therapeutic dose, 1.6 mg) for six weeks, followed by one week without treatment and six weeks of placebo. In addition to measuring agitation, the researchers assessed overall behavioral symptoms, memory, physical changes, and safety.

Dr. Lanctôt’s group found that agitation improved significantly when participants were taking nabilone, compared with when they were receiving placebo, as measured by the Cohen-Mansfield Agitation Inventory. Nabilone also significantly improved overall behavioral symptoms, compared with placebo, as measured by the Neuropsychiatric Inventory.

In addition, the researchers observed small benefits in cognition and nutrition when participants received nabilone during the study. More people in the study experienced sedation when taking nabilone (45%) than when taking placebo (16%).

“Currently prescribed treatments for agitation in Alzheimer’s disease do not work in everybody. And when they do work, the effect is small, and they increase the risk of harmful side effects, including increased risk of death. As a result, there is an urgent need for safer medication options,” said Dr. Lanctôt. “These findings suggest that nabilone may be an effective treatment for agitation; however, the risk of sedation must be carefully monitored. A larger clinical trial would allow us to confirm our findings regarding how effective and safe nabilone is in the treatment of agitation for Alzheimer’s disease.”The FDA has not approved marijuana for the treatment or management of Alzheimer’s disease or other dementias. The use of marijuana as medical treatment is increasingly common, but much about the drug’s use in people with Alzheimer’s disease or other dementias is unknown. No robust, consistent clinical trial data support marijuana for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease dementia or for related issues.

CHICAGO—Nabilone, a synthetic cannabinoid, may effectively treat agitation in people with Alzheimer’s disease, according to a randomized, double-blind clinical trial presented at AAIC 2018.

“Agitation, including verbal or physical outbursts, general emotional distress, restlessness, and pacing, is one of the most common behavioral changes associated with Alzheimer’s disease as it progresses and can be a significant cause of caregiver stress,” said Krista L. Lanctôt, PhD, Senior Scientist at Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre and Professor of Pharmacology and Psychiatry at the University of Toronto.

Dr. Lanctôt and colleagues investigated the potential benefits of nabilone for adults with moderate-to-severe Alzheimer’s dementia and clinically significant agitation. During the 14-week trial, 39 participants (77% male; average age, 87) received nabilone in capsule form (mean therapeutic dose, 1.6 mg) for six weeks, followed by one week without treatment and six weeks of placebo. In addition to measuring agitation, the researchers assessed overall behavioral symptoms, memory, physical changes, and safety.

Dr. Lanctôt’s group found that agitation improved significantly when participants were taking nabilone, compared with when they were receiving placebo, as measured by the Cohen-Mansfield Agitation Inventory. Nabilone also significantly improved overall behavioral symptoms, compared with placebo, as measured by the Neuropsychiatric Inventory.

In addition, the researchers observed small benefits in cognition and nutrition when participants received nabilone during the study. More people in the study experienced sedation when taking nabilone (45%) than when taking placebo (16%).

“Currently prescribed treatments for agitation in Alzheimer’s disease do not work in everybody. And when they do work, the effect is small, and they increase the risk of harmful side effects, including increased risk of death. As a result, there is an urgent need for safer medication options,” said Dr. Lanctôt. “These findings suggest that nabilone may be an effective treatment for agitation; however, the risk of sedation must be carefully monitored. A larger clinical trial would allow us to confirm our findings regarding how effective and safe nabilone is in the treatment of agitation for Alzheimer’s disease.”The FDA has not approved marijuana for the treatment or management of Alzheimer’s disease or other dementias. The use of marijuana as medical treatment is increasingly common, but much about the drug’s use in people with Alzheimer’s disease or other dementias is unknown. No robust, consistent clinical trial data support marijuana for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease dementia or for related issues.

Pregnancy and Years of Reproductive Capability Are Associated With Dementia Risk

Miscarriages and age at menarche and menopause may influence the likelihood of dementia.

CHICAGO—More pregnancies and a longer span of reproductive years appear to protect women against dementia, according to a study presented at AAIC 2018. The results suggest that lifetime estrogen exposure may be an important modulator of long-term cognitive health.

The study by Paola Gilsanz, ScD, staff scientist at Kaiser Permanente in Oakland, California, and colleagues included more than 14,500 women and 50 years of follow-up data. Earlier age of menarche, later menopause, and more completed pregnancies all independently reduced the risk of dementia in women.

Reproductive Years

The researchers analyzed data from a cohort of 14,595 women in the Kaiser Permanente health care database. All of them had completed a comprehensive health checkup between 1964 and 1973 when they were ages 40 to 55. They reported their number of miscarriages, number of children, ages at first and last menstrual period, and the total number of years in their reproductive period. Most of the women in the group (68%) were white, but 16% were black, 6% Asian, and 5% Hispanic. Dr. Gilsanz looked at rates of dementia during 1996 to 2017, when the women were ages 62 to 86.

A multivariate regression model controlled for age, race, education, midlife health issues (eg, hypertension, smoking, and BMI), hysterectomy, and late-life health issues (eg, stroke, heart failure, and diabetes).

Half of the cohort had at least three children, and 75% had at least one miscarriage. The average age at menarche was 13, and the average age at last natural menstrual period was 47. This equated to an average reproductive period of 34 years.

At the end of follow-up, 36% of the cohort had developed dementia.

Women with at least three children were 12% less likely to develop dementia, compared with those with one child. The association remained significant even after researchers controlled for age, race, education, and hysterectomy.

Miscarriages also influenced the risk of dementia. Those who did not report a miscarriage were 20% less likely to develop dementia than were those who had experienced at least one miscarriage. The benefit of no miscarriage was greater among women with at least three children, conferring a 28% reduced risk.

A shorter reproductive period increased the risk of dementia. Those who experienced menarche at age 16 or older had a 31% increased risk of dementia, and those who experienced their last period at age 45 or younger had a 28% greater risk. Each additional year of reproductive capability was associated with a 2% decreased risk.

Women with between 21 and 30 reproductive years were 33% more likely to develop dementia than were those with longer reproductive periods.

Renewed Interest

“Reproductive events that signal different exposures to estrogen, like pregnancy and reproductive period, may play a role in modulating dementia risk,” Dr. Gilsanz said. “Women who are less likely to have a miscarriage may have different hormonal milieus that may be neuroprotective. Underlying health conditions increasing the risk of miscarriages may also elevate risk of dementia.”

Researchers are exploring the link between hormones and cognition with renewed interest, said Suzanne Craft, PhD, of Wake Forest University in Winston-Salem, North Carolina, who moderated a press briefing on the topic. The Women’s Heath Initiative study had a chilling effect on funding for this area of research, Dr. Craft said. “But now I think the pendulum is slowly moving back” toward supporting investigations of hormones and cognition. “It’s clear that something is going on, that there is a link. I am glad we are starting to explore this again.”

—Michele G. Sullivan

Miscarriages and age at menarche and menopause may influence the likelihood of dementia.

Miscarriages and age at menarche and menopause may influence the likelihood of dementia.

CHICAGO—More pregnancies and a longer span of reproductive years appear to protect women against dementia, according to a study presented at AAIC 2018. The results suggest that lifetime estrogen exposure may be an important modulator of long-term cognitive health.

The study by Paola Gilsanz, ScD, staff scientist at Kaiser Permanente in Oakland, California, and colleagues included more than 14,500 women and 50 years of follow-up data. Earlier age of menarche, later menopause, and more completed pregnancies all independently reduced the risk of dementia in women.

Reproductive Years

The researchers analyzed data from a cohort of 14,595 women in the Kaiser Permanente health care database. All of them had completed a comprehensive health checkup between 1964 and 1973 when they were ages 40 to 55. They reported their number of miscarriages, number of children, ages at first and last menstrual period, and the total number of years in their reproductive period. Most of the women in the group (68%) were white, but 16% were black, 6% Asian, and 5% Hispanic. Dr. Gilsanz looked at rates of dementia during 1996 to 2017, when the women were ages 62 to 86.

A multivariate regression model controlled for age, race, education, midlife health issues (eg, hypertension, smoking, and BMI), hysterectomy, and late-life health issues (eg, stroke, heart failure, and diabetes).

Half of the cohort had at least three children, and 75% had at least one miscarriage. The average age at menarche was 13, and the average age at last natural menstrual period was 47. This equated to an average reproductive period of 34 years.

At the end of follow-up, 36% of the cohort had developed dementia.

Women with at least three children were 12% less likely to develop dementia, compared with those with one child. The association remained significant even after researchers controlled for age, race, education, and hysterectomy.

Miscarriages also influenced the risk of dementia. Those who did not report a miscarriage were 20% less likely to develop dementia than were those who had experienced at least one miscarriage. The benefit of no miscarriage was greater among women with at least three children, conferring a 28% reduced risk.

A shorter reproductive period increased the risk of dementia. Those who experienced menarche at age 16 or older had a 31% increased risk of dementia, and those who experienced their last period at age 45 or younger had a 28% greater risk. Each additional year of reproductive capability was associated with a 2% decreased risk.

Women with between 21 and 30 reproductive years were 33% more likely to develop dementia than were those with longer reproductive periods.

Renewed Interest

“Reproductive events that signal different exposures to estrogen, like pregnancy and reproductive period, may play a role in modulating dementia risk,” Dr. Gilsanz said. “Women who are less likely to have a miscarriage may have different hormonal milieus that may be neuroprotective. Underlying health conditions increasing the risk of miscarriages may also elevate risk of dementia.”

Researchers are exploring the link between hormones and cognition with renewed interest, said Suzanne Craft, PhD, of Wake Forest University in Winston-Salem, North Carolina, who moderated a press briefing on the topic. The Women’s Heath Initiative study had a chilling effect on funding for this area of research, Dr. Craft said. “But now I think the pendulum is slowly moving back” toward supporting investigations of hormones and cognition. “It’s clear that something is going on, that there is a link. I am glad we are starting to explore this again.”

—Michele G. Sullivan

CHICAGO—More pregnancies and a longer span of reproductive years appear to protect women against dementia, according to a study presented at AAIC 2018. The results suggest that lifetime estrogen exposure may be an important modulator of long-term cognitive health.

The study by Paola Gilsanz, ScD, staff scientist at Kaiser Permanente in Oakland, California, and colleagues included more than 14,500 women and 50 years of follow-up data. Earlier age of menarche, later menopause, and more completed pregnancies all independently reduced the risk of dementia in women.

Reproductive Years

The researchers analyzed data from a cohort of 14,595 women in the Kaiser Permanente health care database. All of them had completed a comprehensive health checkup between 1964 and 1973 when they were ages 40 to 55. They reported their number of miscarriages, number of children, ages at first and last menstrual period, and the total number of years in their reproductive period. Most of the women in the group (68%) were white, but 16% were black, 6% Asian, and 5% Hispanic. Dr. Gilsanz looked at rates of dementia during 1996 to 2017, when the women were ages 62 to 86.

A multivariate regression model controlled for age, race, education, midlife health issues (eg, hypertension, smoking, and BMI), hysterectomy, and late-life health issues (eg, stroke, heart failure, and diabetes).

Half of the cohort had at least three children, and 75% had at least one miscarriage. The average age at menarche was 13, and the average age at last natural menstrual period was 47. This equated to an average reproductive period of 34 years.

At the end of follow-up, 36% of the cohort had developed dementia.

Women with at least three children were 12% less likely to develop dementia, compared with those with one child. The association remained significant even after researchers controlled for age, race, education, and hysterectomy.

Miscarriages also influenced the risk of dementia. Those who did not report a miscarriage were 20% less likely to develop dementia than were those who had experienced at least one miscarriage. The benefit of no miscarriage was greater among women with at least three children, conferring a 28% reduced risk.

A shorter reproductive period increased the risk of dementia. Those who experienced menarche at age 16 or older had a 31% increased risk of dementia, and those who experienced their last period at age 45 or younger had a 28% greater risk. Each additional year of reproductive capability was associated with a 2% decreased risk.

Women with between 21 and 30 reproductive years were 33% more likely to develop dementia than were those with longer reproductive periods.

Renewed Interest

“Reproductive events that signal different exposures to estrogen, like pregnancy and reproductive period, may play a role in modulating dementia risk,” Dr. Gilsanz said. “Women who are less likely to have a miscarriage may have different hormonal milieus that may be neuroprotective. Underlying health conditions increasing the risk of miscarriages may also elevate risk of dementia.”

Researchers are exploring the link between hormones and cognition with renewed interest, said Suzanne Craft, PhD, of Wake Forest University in Winston-Salem, North Carolina, who moderated a press briefing on the topic. The Women’s Heath Initiative study had a chilling effect on funding for this area of research, Dr. Craft said. “But now I think the pendulum is slowly moving back” toward supporting investigations of hormones and cognition. “It’s clear that something is going on, that there is a link. I am glad we are starting to explore this again.”

—Michele G. Sullivan

Quality and safety of hospital care from the patient perspective

Background: Delivery of high-quality, safe care is key to earning the trust and confidence of patients. Patients can be a valuable asset in determining and evaluating the quality and safety of the care they receive. Collectively analyzing patient perceptions remains a challenge.

Study design: Multicenter, wait-list design, cluster-randomized controlled trial.

Setting: Five National Health Service Trusts Hospital sites in the north of England.

Synopsis: Data were collected via validated survey of inpatients; 1,155 patient incident reports were gathered from 579 patients. Patient volunteers were trained to group these reports into 14 categories. Next, clinical researchers and physicians independently reviewed all reports for presence of a patient safety incident (PSI) using a previously determined consensus definition.

One in 10 patients identified a PSI. There was variability in classifying incidents as PSIs in some categories. Of the concerns expressed by patients, 65% were not classified as PSI. Limitations included a focus on patient’s concerns rather than safety, PSI estimates based on patient’s feedback without clinical information, and lack of inter-rater reliability estimates.

Bottom line: Effective translation of patient experience can provide valuable insights about safety and quality of care in hospital.

Citation: O’Hara JK et al. What can patients tell us about the quality and safety of hospital care? Findings from a UK multicentre survey study. BMJ Qual Saf. 2018 Mar 15. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2017-006974.

Dr. Chikkanna is an assistant professor in the division of hospital medicine at the University of Kentucky, Lexington.

Background: Delivery of high-quality, safe care is key to earning the trust and confidence of patients. Patients can be a valuable asset in determining and evaluating the quality and safety of the care they receive. Collectively analyzing patient perceptions remains a challenge.

Study design: Multicenter, wait-list design, cluster-randomized controlled trial.

Setting: Five National Health Service Trusts Hospital sites in the north of England.

Synopsis: Data were collected via validated survey of inpatients; 1,155 patient incident reports were gathered from 579 patients. Patient volunteers were trained to group these reports into 14 categories. Next, clinical researchers and physicians independently reviewed all reports for presence of a patient safety incident (PSI) using a previously determined consensus definition.

One in 10 patients identified a PSI. There was variability in classifying incidents as PSIs in some categories. Of the concerns expressed by patients, 65% were not classified as PSI. Limitations included a focus on patient’s concerns rather than safety, PSI estimates based on patient’s feedback without clinical information, and lack of inter-rater reliability estimates.

Bottom line: Effective translation of patient experience can provide valuable insights about safety and quality of care in hospital.

Citation: O’Hara JK et al. What can patients tell us about the quality and safety of hospital care? Findings from a UK multicentre survey study. BMJ Qual Saf. 2018 Mar 15. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2017-006974.

Dr. Chikkanna is an assistant professor in the division of hospital medicine at the University of Kentucky, Lexington.

Background: Delivery of high-quality, safe care is key to earning the trust and confidence of patients. Patients can be a valuable asset in determining and evaluating the quality and safety of the care they receive. Collectively analyzing patient perceptions remains a challenge.

Study design: Multicenter, wait-list design, cluster-randomized controlled trial.

Setting: Five National Health Service Trusts Hospital sites in the north of England.

Synopsis: Data were collected via validated survey of inpatients; 1,155 patient incident reports were gathered from 579 patients. Patient volunteers were trained to group these reports into 14 categories. Next, clinical researchers and physicians independently reviewed all reports for presence of a patient safety incident (PSI) using a previously determined consensus definition.

One in 10 patients identified a PSI. There was variability in classifying incidents as PSIs in some categories. Of the concerns expressed by patients, 65% were not classified as PSI. Limitations included a focus on patient’s concerns rather than safety, PSI estimates based on patient’s feedback without clinical information, and lack of inter-rater reliability estimates.

Bottom line: Effective translation of patient experience can provide valuable insights about safety and quality of care in hospital.

Citation: O’Hara JK et al. What can patients tell us about the quality and safety of hospital care? Findings from a UK multicentre survey study. BMJ Qual Saf. 2018 Mar 15. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2017-006974.

Dr. Chikkanna is an assistant professor in the division of hospital medicine at the University of Kentucky, Lexington.

Does BAN2401 Benefit Patients With Alzheimer’s Disease?

The study arms did not contain comparable numbers of patients who carried APOE4.

CHICAGO—BAN2401, a monoclonal antibody that targets soluble amyloid-beta oligomers, slows cognitive decline by as much as 47% and clears brain amyloid in 81% of patients with mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and very mild Alzheimer’s disease, according to the results of a phase II study presented at AAIC 2018.

Imbalanced Treatment Groups

The treatment groups were not well balanced in at least one respect, however, which could influence the interpretation of the data. APOE4-positive patients were unequally distributed through the six treatment groups, which included BAN2401 (2.5 mg/kg biweekly, 5 mg/kg monthly, 5 mg/kg biweekly, 10 mg/kg monthly, and 10 mg/kg biweekly) and placebo. This imbalance could have biased cognitive results in the antibody’s favor. APOE4 carriers represented between 70% and 80% of every unsuccessful treatment arm in the trial and approximately 29% of the arm that enjoyed significant cognitive benefits.

“This is a big confound,” said Keith Fargo, PhD, Director of Scientific Programs and Outreach at the Alzheimer’s Association. “According to the trial sponsors, … a regulatory body requested that people with the APOE4 Alzheimer’s risk gene not be included in the highest dose group for safety reasons. Because of this [request], the people in the highest-dose group are different from people in the other groups on an important dimension: they were much less likely to have the APOE4 gene, which is known to be a major risk factor for cognitive decline. So, it is plausible that the people on the highest dose declined differently due to genetic differences, rather than due to being on the highest dose. A planned subgroup analysis will shed more light on this [question] and [on] whether it reduces confidence in the overall findings.”

Regulators Influenced the Trial

Eisai, which is headquartered in Tokyo, and Biogen, which is based in Cambridge, Massachusetts, are developing the antibody. The decision to restructure the randomization was not Eisai’s, according to David Knopman, MD, a consultant in the department of neurology at Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota.

“European regulators did not allow randomization of [some] APOE4 carriers to the highest dose,” he said in an interview. “I ultimately don’t know what it would do to the results except make them even more difficult to justify as sufficient for registration. In general, in symptomatic Alzheimer’s dementia patients, APOE4 carriage has no substantial impact on rate of decline, but whether [APOE4] status interacted with the treatment is of course completely unknown. Bottom line: just another feature that makes this a phase II study that needs to be followed by a phase III study with a simple design using the high dose.”

“Regardless of who made the decision and why, the data is what it is, and the question remains,” said Michael S. Wolfe, PhD, the Mathias P. Mertes Professor of Medicinal Chemistry at the University of Kansas in Lawrence. “Given the numbers of E4-positive [patients] versus E4-negative [patients] for each treatment group, the interpretation of the results is now seriously thrown into question. The one group that showed a clear slowing of cognitive decline versus placebo—10 mg/kg biweekly—also has far fewer E4-positive [patients] versus E4-negative [patients]. This difference in proportion of E4-positive [patients] could be a major factor in the apparent reduced rate of cognitive decline and confounds the ability to tell if the 10-mg/kg biweekly dose is effective. In contrast, the 10-mg/kg monthly dose group has an E4-positive to E4-negative ratio more comparable to that of placebo, and the effect of the drug on cognitive decline under this dosing regimen is not clearly distinguishable from that seen with placebo.”

Treatment Reduced Amyloid Levels

In addition, BAN2401 failed to meet its 12-month prespecified primary cognitive end points. The investigators reached this conclusion through Bayesian analysis that strove to predict an 80% probability of achieving at least a 25% cognitive benefit. In December 2017, Eisai announced that the treatment had reached 64% probability. Because the company was optimistic about the treatment’s success, it continued with the additional six months of treatment, as the study design allowed, and reanalyzed results with a simpler and more straightforward method. This analysis concluded that the 10-mg/kg biweekly dose slowed decline on the Alzheimer’s Disease Composite Score (ADCOMS), a new tool developed and promoted by Eisai, by 30%. It also found that treatment slowed decline on the Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale-cognitive subscale (ADAS-Cog) by 47%. Treatment cleared brain amyloid in 81% of subjects and had positive effects on CSF biomarkers. CSF amyloid levels increased, and CSF total tau levels decreased, which indicated decreased neuronal injury.

—Michele G. Sullivan

The study arms did not contain comparable numbers of patients who carried APOE4.

The study arms did not contain comparable numbers of patients who carried APOE4.

CHICAGO—BAN2401, a monoclonal antibody that targets soluble amyloid-beta oligomers, slows cognitive decline by as much as 47% and clears brain amyloid in 81% of patients with mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and very mild Alzheimer’s disease, according to the results of a phase II study presented at AAIC 2018.

Imbalanced Treatment Groups

The treatment groups were not well balanced in at least one respect, however, which could influence the interpretation of the data. APOE4-positive patients were unequally distributed through the six treatment groups, which included BAN2401 (2.5 mg/kg biweekly, 5 mg/kg monthly, 5 mg/kg biweekly, 10 mg/kg monthly, and 10 mg/kg biweekly) and placebo. This imbalance could have biased cognitive results in the antibody’s favor. APOE4 carriers represented between 70% and 80% of every unsuccessful treatment arm in the trial and approximately 29% of the arm that enjoyed significant cognitive benefits.

“This is a big confound,” said Keith Fargo, PhD, Director of Scientific Programs and Outreach at the Alzheimer’s Association. “According to the trial sponsors, … a regulatory body requested that people with the APOE4 Alzheimer’s risk gene not be included in the highest dose group for safety reasons. Because of this [request], the people in the highest-dose group are different from people in the other groups on an important dimension: they were much less likely to have the APOE4 gene, which is known to be a major risk factor for cognitive decline. So, it is plausible that the people on the highest dose declined differently due to genetic differences, rather than due to being on the highest dose. A planned subgroup analysis will shed more light on this [question] and [on] whether it reduces confidence in the overall findings.”

Regulators Influenced the Trial

Eisai, which is headquartered in Tokyo, and Biogen, which is based in Cambridge, Massachusetts, are developing the antibody. The decision to restructure the randomization was not Eisai’s, according to David Knopman, MD, a consultant in the department of neurology at Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota.

“European regulators did not allow randomization of [some] APOE4 carriers to the highest dose,” he said in an interview. “I ultimately don’t know what it would do to the results except make them even more difficult to justify as sufficient for registration. In general, in symptomatic Alzheimer’s dementia patients, APOE4 carriage has no substantial impact on rate of decline, but whether [APOE4] status interacted with the treatment is of course completely unknown. Bottom line: just another feature that makes this a phase II study that needs to be followed by a phase III study with a simple design using the high dose.”

“Regardless of who made the decision and why, the data is what it is, and the question remains,” said Michael S. Wolfe, PhD, the Mathias P. Mertes Professor of Medicinal Chemistry at the University of Kansas in Lawrence. “Given the numbers of E4-positive [patients] versus E4-negative [patients] for each treatment group, the interpretation of the results is now seriously thrown into question. The one group that showed a clear slowing of cognitive decline versus placebo—10 mg/kg biweekly—also has far fewer E4-positive [patients] versus E4-negative [patients]. This difference in proportion of E4-positive [patients] could be a major factor in the apparent reduced rate of cognitive decline and confounds the ability to tell if the 10-mg/kg biweekly dose is effective. In contrast, the 10-mg/kg monthly dose group has an E4-positive to E4-negative ratio more comparable to that of placebo, and the effect of the drug on cognitive decline under this dosing regimen is not clearly distinguishable from that seen with placebo.”

Treatment Reduced Amyloid Levels

In addition, BAN2401 failed to meet its 12-month prespecified primary cognitive end points. The investigators reached this conclusion through Bayesian analysis that strove to predict an 80% probability of achieving at least a 25% cognitive benefit. In December 2017, Eisai announced that the treatment had reached 64% probability. Because the company was optimistic about the treatment’s success, it continued with the additional six months of treatment, as the study design allowed, and reanalyzed results with a simpler and more straightforward method. This analysis concluded that the 10-mg/kg biweekly dose slowed decline on the Alzheimer’s Disease Composite Score (ADCOMS), a new tool developed and promoted by Eisai, by 30%. It also found that treatment slowed decline on the Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale-cognitive subscale (ADAS-Cog) by 47%. Treatment cleared brain amyloid in 81% of subjects and had positive effects on CSF biomarkers. CSF amyloid levels increased, and CSF total tau levels decreased, which indicated decreased neuronal injury.

—Michele G. Sullivan

CHICAGO—BAN2401, a monoclonal antibody that targets soluble amyloid-beta oligomers, slows cognitive decline by as much as 47% and clears brain amyloid in 81% of patients with mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and very mild Alzheimer’s disease, according to the results of a phase II study presented at AAIC 2018.

Imbalanced Treatment Groups

The treatment groups were not well balanced in at least one respect, however, which could influence the interpretation of the data. APOE4-positive patients were unequally distributed through the six treatment groups, which included BAN2401 (2.5 mg/kg biweekly, 5 mg/kg monthly, 5 mg/kg biweekly, 10 mg/kg monthly, and 10 mg/kg biweekly) and placebo. This imbalance could have biased cognitive results in the antibody’s favor. APOE4 carriers represented between 70% and 80% of every unsuccessful treatment arm in the trial and approximately 29% of the arm that enjoyed significant cognitive benefits.

“This is a big confound,” said Keith Fargo, PhD, Director of Scientific Programs and Outreach at the Alzheimer’s Association. “According to the trial sponsors, … a regulatory body requested that people with the APOE4 Alzheimer’s risk gene not be included in the highest dose group for safety reasons. Because of this [request], the people in the highest-dose group are different from people in the other groups on an important dimension: they were much less likely to have the APOE4 gene, which is known to be a major risk factor for cognitive decline. So, it is plausible that the people on the highest dose declined differently due to genetic differences, rather than due to being on the highest dose. A planned subgroup analysis will shed more light on this [question] and [on] whether it reduces confidence in the overall findings.”

Regulators Influenced the Trial

Eisai, which is headquartered in Tokyo, and Biogen, which is based in Cambridge, Massachusetts, are developing the antibody. The decision to restructure the randomization was not Eisai’s, according to David Knopman, MD, a consultant in the department of neurology at Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota.

“European regulators did not allow randomization of [some] APOE4 carriers to the highest dose,” he said in an interview. “I ultimately don’t know what it would do to the results except make them even more difficult to justify as sufficient for registration. In general, in symptomatic Alzheimer’s dementia patients, APOE4 carriage has no substantial impact on rate of decline, but whether [APOE4] status interacted with the treatment is of course completely unknown. Bottom line: just another feature that makes this a phase II study that needs to be followed by a phase III study with a simple design using the high dose.”

“Regardless of who made the decision and why, the data is what it is, and the question remains,” said Michael S. Wolfe, PhD, the Mathias P. Mertes Professor of Medicinal Chemistry at the University of Kansas in Lawrence. “Given the numbers of E4-positive [patients] versus E4-negative [patients] for each treatment group, the interpretation of the results is now seriously thrown into question. The one group that showed a clear slowing of cognitive decline versus placebo—10 mg/kg biweekly—also has far fewer E4-positive [patients] versus E4-negative [patients]. This difference in proportion of E4-positive [patients] could be a major factor in the apparent reduced rate of cognitive decline and confounds the ability to tell if the 10-mg/kg biweekly dose is effective. In contrast, the 10-mg/kg monthly dose group has an E4-positive to E4-negative ratio more comparable to that of placebo, and the effect of the drug on cognitive decline under this dosing regimen is not clearly distinguishable from that seen with placebo.”

Treatment Reduced Amyloid Levels

In addition, BAN2401 failed to meet its 12-month prespecified primary cognitive end points. The investigators reached this conclusion through Bayesian analysis that strove to predict an 80% probability of achieving at least a 25% cognitive benefit. In December 2017, Eisai announced that the treatment had reached 64% probability. Because the company was optimistic about the treatment’s success, it continued with the additional six months of treatment, as the study design allowed, and reanalyzed results with a simpler and more straightforward method. This analysis concluded that the 10-mg/kg biweekly dose slowed decline on the Alzheimer’s Disease Composite Score (ADCOMS), a new tool developed and promoted by Eisai, by 30%. It also found that treatment slowed decline on the Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale-cognitive subscale (ADAS-Cog) by 47%. Treatment cleared brain amyloid in 81% of subjects and had positive effects on CSF biomarkers. CSF amyloid levels increased, and CSF total tau levels decreased, which indicated decreased neuronal injury.

—Michele G. Sullivan

Are Nonbenzodiazepines Appropriate for Treating Sleep Disturbance in Dementia?

A review of research and hospital data indicates that this drug class increases the risk of fractures.

CHICAGO—Nonbenzodiazepine hypnotic “Z-drugs” (eg, zolpidem, zopiclone, and zaleplon) increase the risk of fractures in a dose-dependent manner in people with dementia, according to research presented at AAIC 2018. Patients with dementia who are receiving these drugs should be monitored, according to the researchers.

Approximately 60% of people with dementia have sleep disturbance. Z-drugs are often prescribed to help treat insomnia in older adults, but observers have raised concerns that these treatments may cause problems such as falls and fractures and increase confusion. Researchers have not fully investigated the safety and efficacy of Z-drugs in this patient population, however.

Chris Fox, MD, Professor of Psychiatry at Norwich Medical School at the University of East Anglia in the United Kingdom, and colleagues analyzed cohort studies using primary care data from the UK Clinical Practice Research Datalink that was linked to hospital admissions data. They also examined data from three clinical studies of people with dementia. To evaluate the benefits and harms of these medicines, the researchers compared data for 2,952 people with dementia who were newly prescribed Z-drugs with data for 1,651 people who were not prescribed sedatives or hypnotics.

Dr. Fox and colleagues defined the index date as the first date of a diagnosis of sleep disturbance or of a Z-drug prescription after dementia diagnosis. They excluded patients who had been prescribed a sedative during the previous year. Patients were followed for as long as two years or until 90 days after their last prescription. Dr. Fox’s group compared the two arms’ outcomes using Cox regression. They adjusted the data for sociodemographic variables, BMI, systolic blood pressure, diagnosed health conditions, and comedications.

The use of Z-drugs was associated with a 47% increased risk of any type of fracture. The risk increased among patients on higher doses. Z-drug use was also associated with greater risks of hip fracture and mortality. The study did not identify a higher risk of other events

“Fractures in people with dementia can have a devastating impact, including loss of mobility, increased dependency, and worsening dementia,” said Dr. Fox. “We desperately need better alternatives to the drugs currently being prescribed for sleep problems and other noncognitive symptoms of dementia. Wherever possible, suitable nonpharmacologic alternatives should be considered, and where Z-drugs are prescribed, patients should receive care that reduces or prevents the occurrence of falls.”

A review of research and hospital data indicates that this drug class increases the risk of fractures.

A review of research and hospital data indicates that this drug class increases the risk of fractures.

CHICAGO—Nonbenzodiazepine hypnotic “Z-drugs” (eg, zolpidem, zopiclone, and zaleplon) increase the risk of fractures in a dose-dependent manner in people with dementia, according to research presented at AAIC 2018. Patients with dementia who are receiving these drugs should be monitored, according to the researchers.

Approximately 60% of people with dementia have sleep disturbance. Z-drugs are often prescribed to help treat insomnia in older adults, but observers have raised concerns that these treatments may cause problems such as falls and fractures and increase confusion. Researchers have not fully investigated the safety and efficacy of Z-drugs in this patient population, however.

Chris Fox, MD, Professor of Psychiatry at Norwich Medical School at the University of East Anglia in the United Kingdom, and colleagues analyzed cohort studies using primary care data from the UK Clinical Practice Research Datalink that was linked to hospital admissions data. They also examined data from three clinical studies of people with dementia. To evaluate the benefits and harms of these medicines, the researchers compared data for 2,952 people with dementia who were newly prescribed Z-drugs with data for 1,651 people who were not prescribed sedatives or hypnotics.

Dr. Fox and colleagues defined the index date as the first date of a diagnosis of sleep disturbance or of a Z-drug prescription after dementia diagnosis. They excluded patients who had been prescribed a sedative during the previous year. Patients were followed for as long as two years or until 90 days after their last prescription. Dr. Fox’s group compared the two arms’ outcomes using Cox regression. They adjusted the data for sociodemographic variables, BMI, systolic blood pressure, diagnosed health conditions, and comedications.

The use of Z-drugs was associated with a 47% increased risk of any type of fracture. The risk increased among patients on higher doses. Z-drug use was also associated with greater risks of hip fracture and mortality. The study did not identify a higher risk of other events

“Fractures in people with dementia can have a devastating impact, including loss of mobility, increased dependency, and worsening dementia,” said Dr. Fox. “We desperately need better alternatives to the drugs currently being prescribed for sleep problems and other noncognitive symptoms of dementia. Wherever possible, suitable nonpharmacologic alternatives should be considered, and where Z-drugs are prescribed, patients should receive care that reduces or prevents the occurrence of falls.”

CHICAGO—Nonbenzodiazepine hypnotic “Z-drugs” (eg, zolpidem, zopiclone, and zaleplon) increase the risk of fractures in a dose-dependent manner in people with dementia, according to research presented at AAIC 2018. Patients with dementia who are receiving these drugs should be monitored, according to the researchers.

Approximately 60% of people with dementia have sleep disturbance. Z-drugs are often prescribed to help treat insomnia in older adults, but observers have raised concerns that these treatments may cause problems such as falls and fractures and increase confusion. Researchers have not fully investigated the safety and efficacy of Z-drugs in this patient population, however.

Chris Fox, MD, Professor of Psychiatry at Norwich Medical School at the University of East Anglia in the United Kingdom, and colleagues analyzed cohort studies using primary care data from the UK Clinical Practice Research Datalink that was linked to hospital admissions data. They also examined data from three clinical studies of people with dementia. To evaluate the benefits and harms of these medicines, the researchers compared data for 2,952 people with dementia who were newly prescribed Z-drugs with data for 1,651 people who were not prescribed sedatives or hypnotics.

Dr. Fox and colleagues defined the index date as the first date of a diagnosis of sleep disturbance or of a Z-drug prescription after dementia diagnosis. They excluded patients who had been prescribed a sedative during the previous year. Patients were followed for as long as two years or until 90 days after their last prescription. Dr. Fox’s group compared the two arms’ outcomes using Cox regression. They adjusted the data for sociodemographic variables, BMI, systolic blood pressure, diagnosed health conditions, and comedications.

The use of Z-drugs was associated with a 47% increased risk of any type of fracture. The risk increased among patients on higher doses. Z-drug use was also associated with greater risks of hip fracture and mortality. The study did not identify a higher risk of other events

“Fractures in people with dementia can have a devastating impact, including loss of mobility, increased dependency, and worsening dementia,” said Dr. Fox. “We desperately need better alternatives to the drugs currently being prescribed for sleep problems and other noncognitive symptoms of dementia. Wherever possible, suitable nonpharmacologic alternatives should be considered, and where Z-drugs are prescribed, patients should receive care that reduces or prevents the occurrence of falls.”

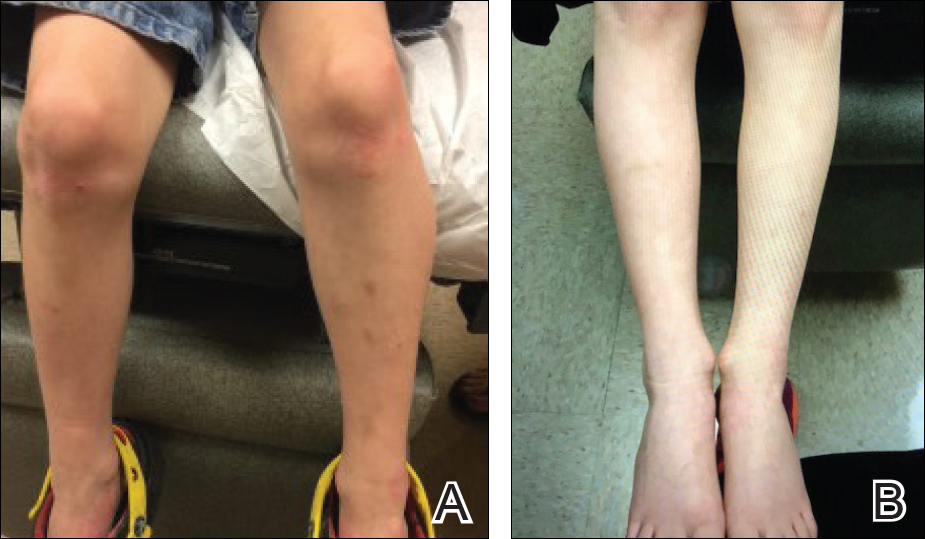

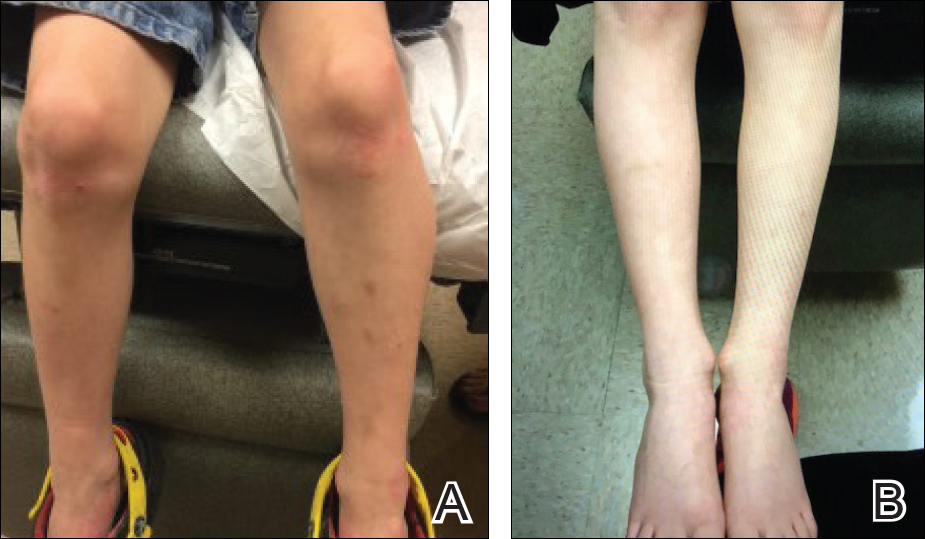

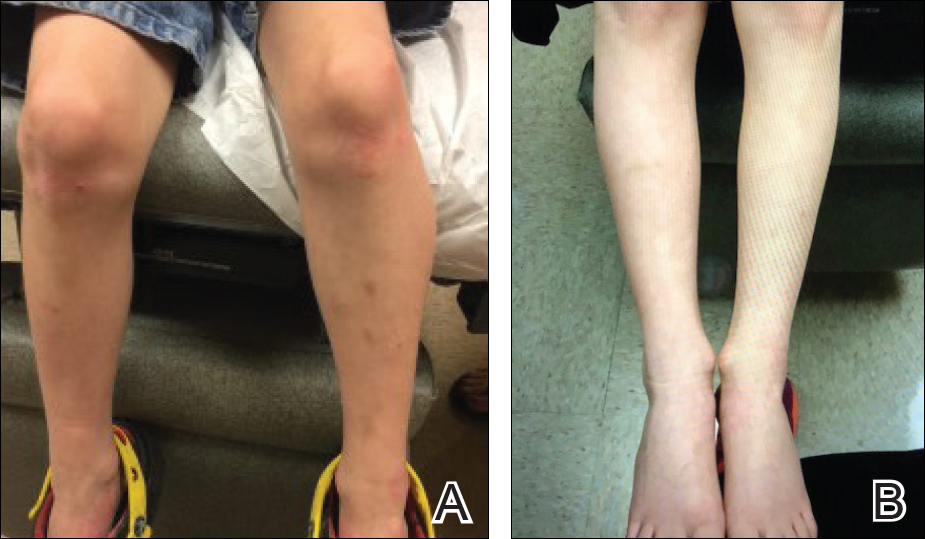

Laser tattoo removal techniques continue to be refined

SAN DIEGO –

“A picosecond is to a second as 1 second is to 37,000 years,” Mathew M. Avram, MD, JD, said at the annual Masters of Aesthetics Symposium. “That’s equivalent to the total energy of the city of San Diego for 300-750 trillionths of a second.”

According to Dr. Avram, director of laser, cosmetics, and dermatologic surgery at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, picosecond lasers produce extreme cavitation and cell rupture, with a desired clinical endpoint of immediate dermal whitening of tattooed skin. The process causes transdermal elimination of the tattoo ink. Some of the ink flows into the lymphatic system, while the rest undergoes rephagocytosis by dermal scavenger cells.

Commercially available picosecond lasers include devices with wavelengths of 532 nm, 755 nm, and 1,064 nm that deliver energy in a range of 300-750 picoseconds. Nd:YAG lasers work best for red and black ink, while alexandrite lasers work best for green and blue ink. In Dr. Avram’s experience, picosecond lasers are generally more effective for tattoo removal, compared with nanosecond lasers. “There is some nonselective targeting of other pigments, and they’re particularly effective for faded tattoos, but the devices are more expensive,” he said.

Dr. Avram, who is also the faculty director for laser and cosmetic dermatology training at Harvard Medical School, also in Boston, advises against promising a certain number of laser treatments during initial patient consultations. “You will regret it,” he said. “Tattoos are notoriously unpredictable in how they respond. I often hear people say they get rid of these in three to five treatments. That isn’t my experience with these lasers. Often, all you’re going to be able to do is get significant clearing rather than tattoo removal. Professional tattoos are the most difficult to treat because they are the deepest and they have the most amount of ink.”

On the other hand, amateur tattoos, traumatic tattoos, and radiation tattoos require far fewer treatments. “The color is important,” he said. “Multicolored tattoos, regardless of the colors, are always going to be more difficult to clear than a single-color tattoo.” Black and dark-blue tattoos respond best to laser light; light-blue and green also respond well. Red responds well, while purple can be challenging. Yellow and orange do not respond very well, but they do respond partially.

According to a trial that analyzed variables influencing the outcome of tattoos treated by Q-switched lasers, 47% were cleared after 10 sessions, while 75% were cleared after 15 sessions (Arch Dermatol 2012;148[12]:1364-9). “It’s very important to message to your patients how many treatments this might take, because there is going to be an annuity of patients who are unhappy because they have to keep coming back,” said Dr. Avram, who is the immediate past president of the American Society for Laser Medicine and Surgery. Skin type and pigmentation also affect treatment outcomes. “For darker skin types or tanned individuals, hyper- or hypopigmentation is a greater concern than in patients with lighter skin types,” he said. “A test spot may be beneficial. The 1,064-nm Q-switched Nd:YAG laser is least likely to affect skin pigment; it’s safest for skin types IV-VI . This is great if it’s a black tattoo. But if it’s a green, blue, or red tattoo, you have a problem because you’re not going to target it very effectively.”

Some degree of posttreatment hypopigmentation is likely to occur, regardless of skin type. “Let patients know this is going to happen, but over time, this usually resolves, because you’re not destroying the melanocytes, unless you’re going too strong,” Dr. Avram said. “It may take a few months. It may take a year or 2, but the pigment should recur.”

He emphasized that the key variable during laser treatment of tattoos is the clinical endpoint, not the energy setting of the device. “What you want to see is immediate whitening of the treated area,” he said. “With the 1,064-nm Nd:YAG, you may get a little pinpoint bleeding in addition to whitening. Do not memorize treatment settings. Many Q-switched lasers are not externally calibrated. Thus, energy levels may change day to day or before and after servicing [of the device]. Trust your eyes; trust your clinical skills.” If you see epidermal disruption and bleeding during treatment, you’re probably being too aggressive. If that happens, “decrease your fluence,” he recommended. “You also want to decrease fluences when treating tattoos that are placed over other tattoos.”

Another rule of thumb is to use larger spot sizes during treatment sessions. “The larger the spot size, the more efficient the energy is going to get more deeply, and less is going to be at the dermal-epidermal junction,” Dr. Avram said. “So you’re going to get less hypopigmentation and less hyperpigmentation. Follow your endpoints and you are less likely to get pigmentation changes.”

Posttreatment care typically includes the application of topical petroleum jelly and a Telfa dressing. “Wait about a week to heal, counsel patients to keep out of the sun, and avoid friction to the treated area during healing,” he said. Patients can be rescheduled for retreatment 6-8 weeks later.

Common adverse events during laser treatment of tattoos include erythema, blistering, hyperpigmentation, hypopigmentation, and scarring, which occurs in about 5% of cases. Less common adverse events include allergic reaction, darkening of cosmetic tattoos, immune reaction, and chrysiasis, which is a dark-blue pigmentation caused by Q-switched laser treatment in patients with a history of gold salt ingestion. “Any history of gold salt ingestion will produce this characteristic finding, even if they took it when they were 5 years old and they come to you when they’re 85,” Dr. Avram said. “All of our intake forms include a question about this, and before I treat patients I always ask if they have a history of gold ingestion, because it’s very difficult to treat.”

Surgical excision may be an alternative for smaller tattoos. “Another option is ablative fractional resurfacing as a solo treatment or in combination with the Q-switched or picosecond laser, which has better efficacy,” he said. “The ablative fractional laser also may help with fibrosis after multiple treatments in a recalcitrant tattoo.” He noted that cosmetic tattoos such as lip liner and blush tattoos might darken because of oxidation of ferric oxide or titanium oxide pigment. The best approach to such cases is to perform an inconspicuous test spot prior to treatment.

Clinicians continue to explore the optimal interval between treatments. For example, the “R20” method consists of four consecutive treatment passes separated by 20 minutes. The initial study found that this approach led to better outcomes, compared with conventional, single-pass laser treatment (J Am Acad Dermatol 2012;66[2]:271-7). A follow-up study by Dr. Avram and his colleagues contradicted these findings, while another follow-up study was supportive.

Another technology playing a role in such repeat treatments is a perfluorodecalin-infused silicone patch, which is placed over the treatment area. According to Dr. Avram, the FDA-cleared patch helps reduce scatter during treatment and likely improves efficacy. It also allows for performing consecutive repeat laser treatments at the same visit. In one study, 11 of 17 patients had more rapid clearance on the side treated with the perfluorodecalin patch, compared with the side treated without the patch (Laser Surg Med 2015;47[8]:613-8).

Dr. Avram disclosed that he has received consulting fees from Allergan, Merz, Sciton, Soliton, and Zalea. He also reported having ownership and/or shareholder interest in Cytrellis, Invasix, and Zalea.

[email protected]

SAN DIEGO –

“A picosecond is to a second as 1 second is to 37,000 years,” Mathew M. Avram, MD, JD, said at the annual Masters of Aesthetics Symposium. “That’s equivalent to the total energy of the city of San Diego for 300-750 trillionths of a second.”

According to Dr. Avram, director of laser, cosmetics, and dermatologic surgery at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, picosecond lasers produce extreme cavitation and cell rupture, with a desired clinical endpoint of immediate dermal whitening of tattooed skin. The process causes transdermal elimination of the tattoo ink. Some of the ink flows into the lymphatic system, while the rest undergoes rephagocytosis by dermal scavenger cells.

Commercially available picosecond lasers include devices with wavelengths of 532 nm, 755 nm, and 1,064 nm that deliver energy in a range of 300-750 picoseconds. Nd:YAG lasers work best for red and black ink, while alexandrite lasers work best for green and blue ink. In Dr. Avram’s experience, picosecond lasers are generally more effective for tattoo removal, compared with nanosecond lasers. “There is some nonselective targeting of other pigments, and they’re particularly effective for faded tattoos, but the devices are more expensive,” he said.

Dr. Avram, who is also the faculty director for laser and cosmetic dermatology training at Harvard Medical School, also in Boston, advises against promising a certain number of laser treatments during initial patient consultations. “You will regret it,” he said. “Tattoos are notoriously unpredictable in how they respond. I often hear people say they get rid of these in three to five treatments. That isn’t my experience with these lasers. Often, all you’re going to be able to do is get significant clearing rather than tattoo removal. Professional tattoos are the most difficult to treat because they are the deepest and they have the most amount of ink.”

On the other hand, amateur tattoos, traumatic tattoos, and radiation tattoos require far fewer treatments. “The color is important,” he said. “Multicolored tattoos, regardless of the colors, are always going to be more difficult to clear than a single-color tattoo.” Black and dark-blue tattoos respond best to laser light; light-blue and green also respond well. Red responds well, while purple can be challenging. Yellow and orange do not respond very well, but they do respond partially.

According to a trial that analyzed variables influencing the outcome of tattoos treated by Q-switched lasers, 47% were cleared after 10 sessions, while 75% were cleared after 15 sessions (Arch Dermatol 2012;148[12]:1364-9). “It’s very important to message to your patients how many treatments this might take, because there is going to be an annuity of patients who are unhappy because they have to keep coming back,” said Dr. Avram, who is the immediate past president of the American Society for Laser Medicine and Surgery. Skin type and pigmentation also affect treatment outcomes. “For darker skin types or tanned individuals, hyper- or hypopigmentation is a greater concern than in patients with lighter skin types,” he said. “A test spot may be beneficial. The 1,064-nm Q-switched Nd:YAG laser is least likely to affect skin pigment; it’s safest for skin types IV-VI . This is great if it’s a black tattoo. But if it’s a green, blue, or red tattoo, you have a problem because you’re not going to target it very effectively.”

Some degree of posttreatment hypopigmentation is likely to occur, regardless of skin type. “Let patients know this is going to happen, but over time, this usually resolves, because you’re not destroying the melanocytes, unless you’re going too strong,” Dr. Avram said. “It may take a few months. It may take a year or 2, but the pigment should recur.”

He emphasized that the key variable during laser treatment of tattoos is the clinical endpoint, not the energy setting of the device. “What you want to see is immediate whitening of the treated area,” he said. “With the 1,064-nm Nd:YAG, you may get a little pinpoint bleeding in addition to whitening. Do not memorize treatment settings. Many Q-switched lasers are not externally calibrated. Thus, energy levels may change day to day or before and after servicing [of the device]. Trust your eyes; trust your clinical skills.” If you see epidermal disruption and bleeding during treatment, you’re probably being too aggressive. If that happens, “decrease your fluence,” he recommended. “You also want to decrease fluences when treating tattoos that are placed over other tattoos.”

Another rule of thumb is to use larger spot sizes during treatment sessions. “The larger the spot size, the more efficient the energy is going to get more deeply, and less is going to be at the dermal-epidermal junction,” Dr. Avram said. “So you’re going to get less hypopigmentation and less hyperpigmentation. Follow your endpoints and you are less likely to get pigmentation changes.”

Posttreatment care typically includes the application of topical petroleum jelly and a Telfa dressing. “Wait about a week to heal, counsel patients to keep out of the sun, and avoid friction to the treated area during healing,” he said. Patients can be rescheduled for retreatment 6-8 weeks later.

Common adverse events during laser treatment of tattoos include erythema, blistering, hyperpigmentation, hypopigmentation, and scarring, which occurs in about 5% of cases. Less common adverse events include allergic reaction, darkening of cosmetic tattoos, immune reaction, and chrysiasis, which is a dark-blue pigmentation caused by Q-switched laser treatment in patients with a history of gold salt ingestion. “Any history of gold salt ingestion will produce this characteristic finding, even if they took it when they were 5 years old and they come to you when they’re 85,” Dr. Avram said. “All of our intake forms include a question about this, and before I treat patients I always ask if they have a history of gold ingestion, because it’s very difficult to treat.”

Surgical excision may be an alternative for smaller tattoos. “Another option is ablative fractional resurfacing as a solo treatment or in combination with the Q-switched or picosecond laser, which has better efficacy,” he said. “The ablative fractional laser also may help with fibrosis after multiple treatments in a recalcitrant tattoo.” He noted that cosmetic tattoos such as lip liner and blush tattoos might darken because of oxidation of ferric oxide or titanium oxide pigment. The best approach to such cases is to perform an inconspicuous test spot prior to treatment.

Clinicians continue to explore the optimal interval between treatments. For example, the “R20” method consists of four consecutive treatment passes separated by 20 minutes. The initial study found that this approach led to better outcomes, compared with conventional, single-pass laser treatment (J Am Acad Dermatol 2012;66[2]:271-7). A follow-up study by Dr. Avram and his colleagues contradicted these findings, while another follow-up study was supportive.

Another technology playing a role in such repeat treatments is a perfluorodecalin-infused silicone patch, which is placed over the treatment area. According to Dr. Avram, the FDA-cleared patch helps reduce scatter during treatment and likely improves efficacy. It also allows for performing consecutive repeat laser treatments at the same visit. In one study, 11 of 17 patients had more rapid clearance on the side treated with the perfluorodecalin patch, compared with the side treated without the patch (Laser Surg Med 2015;47[8]:613-8).

Dr. Avram disclosed that he has received consulting fees from Allergan, Merz, Sciton, Soliton, and Zalea. He also reported having ownership and/or shareholder interest in Cytrellis, Invasix, and Zalea.

[email protected]

SAN DIEGO –

“A picosecond is to a second as 1 second is to 37,000 years,” Mathew M. Avram, MD, JD, said at the annual Masters of Aesthetics Symposium. “That’s equivalent to the total energy of the city of San Diego for 300-750 trillionths of a second.”

According to Dr. Avram, director of laser, cosmetics, and dermatologic surgery at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, picosecond lasers produce extreme cavitation and cell rupture, with a desired clinical endpoint of immediate dermal whitening of tattooed skin. The process causes transdermal elimination of the tattoo ink. Some of the ink flows into the lymphatic system, while the rest undergoes rephagocytosis by dermal scavenger cells.

Commercially available picosecond lasers include devices with wavelengths of 532 nm, 755 nm, and 1,064 nm that deliver energy in a range of 300-750 picoseconds. Nd:YAG lasers work best for red and black ink, while alexandrite lasers work best for green and blue ink. In Dr. Avram’s experience, picosecond lasers are generally more effective for tattoo removal, compared with nanosecond lasers. “There is some nonselective targeting of other pigments, and they’re particularly effective for faded tattoos, but the devices are more expensive,” he said.

Dr. Avram, who is also the faculty director for laser and cosmetic dermatology training at Harvard Medical School, also in Boston, advises against promising a certain number of laser treatments during initial patient consultations. “You will regret it,” he said. “Tattoos are notoriously unpredictable in how they respond. I often hear people say they get rid of these in three to five treatments. That isn’t my experience with these lasers. Often, all you’re going to be able to do is get significant clearing rather than tattoo removal. Professional tattoos are the most difficult to treat because they are the deepest and they have the most amount of ink.”

On the other hand, amateur tattoos, traumatic tattoos, and radiation tattoos require far fewer treatments. “The color is important,” he said. “Multicolored tattoos, regardless of the colors, are always going to be more difficult to clear than a single-color tattoo.” Black and dark-blue tattoos respond best to laser light; light-blue and green also respond well. Red responds well, while purple can be challenging. Yellow and orange do not respond very well, but they do respond partially.

According to a trial that analyzed variables influencing the outcome of tattoos treated by Q-switched lasers, 47% were cleared after 10 sessions, while 75% were cleared after 15 sessions (Arch Dermatol 2012;148[12]:1364-9). “It’s very important to message to your patients how many treatments this might take, because there is going to be an annuity of patients who are unhappy because they have to keep coming back,” said Dr. Avram, who is the immediate past president of the American Society for Laser Medicine and Surgery. Skin type and pigmentation also affect treatment outcomes. “For darker skin types or tanned individuals, hyper- or hypopigmentation is a greater concern than in patients with lighter skin types,” he said. “A test spot may be beneficial. The 1,064-nm Q-switched Nd:YAG laser is least likely to affect skin pigment; it’s safest for skin types IV-VI . This is great if it’s a black tattoo. But if it’s a green, blue, or red tattoo, you have a problem because you’re not going to target it very effectively.”

Some degree of posttreatment hypopigmentation is likely to occur, regardless of skin type. “Let patients know this is going to happen, but over time, this usually resolves, because you’re not destroying the melanocytes, unless you’re going too strong,” Dr. Avram said. “It may take a few months. It may take a year or 2, but the pigment should recur.”

He emphasized that the key variable during laser treatment of tattoos is the clinical endpoint, not the energy setting of the device. “What you want to see is immediate whitening of the treated area,” he said. “With the 1,064-nm Nd:YAG, you may get a little pinpoint bleeding in addition to whitening. Do not memorize treatment settings. Many Q-switched lasers are not externally calibrated. Thus, energy levels may change day to day or before and after servicing [of the device]. Trust your eyes; trust your clinical skills.” If you see epidermal disruption and bleeding during treatment, you’re probably being too aggressive. If that happens, “decrease your fluence,” he recommended. “You also want to decrease fluences when treating tattoos that are placed over other tattoos.”

Another rule of thumb is to use larger spot sizes during treatment sessions. “The larger the spot size, the more efficient the energy is going to get more deeply, and less is going to be at the dermal-epidermal junction,” Dr. Avram said. “So you’re going to get less hypopigmentation and less hyperpigmentation. Follow your endpoints and you are less likely to get pigmentation changes.”

Posttreatment care typically includes the application of topical petroleum jelly and a Telfa dressing. “Wait about a week to heal, counsel patients to keep out of the sun, and avoid friction to the treated area during healing,” he said. Patients can be rescheduled for retreatment 6-8 weeks later.

Common adverse events during laser treatment of tattoos include erythema, blistering, hyperpigmentation, hypopigmentation, and scarring, which occurs in about 5% of cases. Less common adverse events include allergic reaction, darkening of cosmetic tattoos, immune reaction, and chrysiasis, which is a dark-blue pigmentation caused by Q-switched laser treatment in patients with a history of gold salt ingestion. “Any history of gold salt ingestion will produce this characteristic finding, even if they took it when they were 5 years old and they come to you when they’re 85,” Dr. Avram said. “All of our intake forms include a question about this, and before I treat patients I always ask if they have a history of gold ingestion, because it’s very difficult to treat.”

Surgical excision may be an alternative for smaller tattoos. “Another option is ablative fractional resurfacing as a solo treatment or in combination with the Q-switched or picosecond laser, which has better efficacy,” he said. “The ablative fractional laser also may help with fibrosis after multiple treatments in a recalcitrant tattoo.” He noted that cosmetic tattoos such as lip liner and blush tattoos might darken because of oxidation of ferric oxide or titanium oxide pigment. The best approach to such cases is to perform an inconspicuous test spot prior to treatment.

Clinicians continue to explore the optimal interval between treatments. For example, the “R20” method consists of four consecutive treatment passes separated by 20 minutes. The initial study found that this approach led to better outcomes, compared with conventional, single-pass laser treatment (J Am Acad Dermatol 2012;66[2]:271-7). A follow-up study by Dr. Avram and his colleagues contradicted these findings, while another follow-up study was supportive.

Another technology playing a role in such repeat treatments is a perfluorodecalin-infused silicone patch, which is placed over the treatment area. According to Dr. Avram, the FDA-cleared patch helps reduce scatter during treatment and likely improves efficacy. It also allows for performing consecutive repeat laser treatments at the same visit. In one study, 11 of 17 patients had more rapid clearance on the side treated with the perfluorodecalin patch, compared with the side treated without the patch (Laser Surg Med 2015;47[8]:613-8).

Dr. Avram disclosed that he has received consulting fees from Allergan, Merz, Sciton, Soliton, and Zalea. He also reported having ownership and/or shareholder interest in Cytrellis, Invasix, and Zalea.

[email protected]

AT MOAS 2018

Recent Thrombectomy Trials Do Not Reduce Pressure to Treat Acute Stroke Urgently

While findings from the DAWN and DEFUSE3 trials support late thrombectomy, rapid intervention remains the preferred goal.

HILTON HEAD, SC—Although two recent studies demonstrated that endovascular thrombectomy is effective up to 24 hours after acute stroke onset in patients with large vessel occlusions, the findings do not diminish the urgency of rapid intervention. According to one expert who spoke at the 41st Annual Contemporary Clinical Neurology Symposium, findings from studies of late thrombectomy are important to the management of only a small group of acute stroke patients and do nothing to alter the premise that time is brain. For better outcomes, “we need to get more patients into therapy more quickly. If we optimize our systems of care, we can achieve that,” said Michael Froehler, MD, PhD, Director of the Cerebrovascular Program at Vanderbilt University Medical Center in Nashville.

Two Trials of Late Thrombectomy

In an analysis of the significance of these two studies as well as of other advances in stroke management, Dr. Froehler explained that rapid intervention is always the goal. The data from these multicenter trials, DAWN and DEFUSE3, were published earlier this year. Both randomized studies compared

The primary end points of the two trials differed, but the advantage of endovascular thrombectomy was comparable at 90 days when examining a modified Rankin score (mRS). A good outcome, defined as an mRS of 2 or less, was achieved with late endovascular thrombectomy in 49% and 45% of patients in DAWN and DEFUSE3, respectively, versus 13% and 17% of those treated with standard care. According to Dr. Froehler, these results were a surprise, because the effect size was greater in these two late treatment trials when compared with that of early endovascular thrombectomy (46% vs 27%) in a five-trial meta-analysis by Goyal et al published in 2016.

Entry criteria of these late endovascular thrombectomy trials are critical for understanding the results and their clinical significance, according to Dr. Froehler. He explained that both DAWN and DEFUSE3 were designed to enroll patients with salvageable tissue. Selection criteria such as a small infarct volume on imaging assessed with RAPID software ensured a “good collateral” patient population, Dr. Froehler said. Unlike the majority of patients with rapidly advancing infarcts, “good collateral patients hang on to salvageable brain for much longer,” Dr. Froehler explained.

The results of DAWN and DEFUSE3 thus are relevant to a small subpopulation of stroke patients. According to Dr. Froehler, only about 3% of acute stroke patients would meet entry criteria for DAWN or DEFUSE3, and only about 1.1% would meet the criteria for both.

“Unfortunately, the vast majority of patients we are seeing in real life are not going to be eligible for thrombectomy in the six- to 24-hour window,” Dr. Froehler emphasized. As a result, the data from DAWN and DEFUSE3, “do not change the importance of time” as the key factor in achieving good outcomes in patients with acute stroke.

Time Is Still Brain

The standard of care for management of acute stroke is IV t-PA within 4.5 hours, whether or not endovascular thrombectomy is offered, according to Dr. Froehler, but he cited data from the SWIFT PRIME trial, which employed endovascular thrombectomy after t-PA, to emphasize that the earlier the treatment, the better the outcome. In SWIFT PRIME, which was stopped early because of efficacy, the greater overall rate of good outcome (mRS ≤ 2) in the endovascular thrombectomy/t-PA versus t-PA alone groups were impressive (60% vs 35%), but time mattered. “Of those treated within 2.5 hours, 91% went home essentially normal,” according to Dr. Froehler.

Returning to his message that early reperfusion is the critical predictor of a good outcome, Dr. Froehler noted that an estimated 1.9 million neurons die for every minute of ischemia. In one analysis he cited, good outcomes dropped by 10% between 2.5 and 3.5 hours and then 20% for every hour thereafter.

One approach to accelerating time to appropriate therapy is optimizing triage strategies, particularly when patients who will benefit from endovascular thrombectomy will require transfer to a center that offers this intervention. Of triage strategies, Dr. Froehler singled out the 10-point ASPECTS scoring system, which is based on a CT scan. If the score is low, endovascular thrombectomy is not an option. Higher scores, particularly 6 or greater, can be a reason to consider and accelerate the time to transfer, which may mean the difference for a full recovery.

Reevaluating t-PA

“When you look at what t-PA has done for patients with large vessel occlusion, it is noteworthy, but it is not that great,” cautioned Dr. Froehler in making a case for endovascular thrombectomy in eligible patients. He called recanalization rates with IV t-PA in those with the largest clots “pretty low,” showing that the majority of patients achieve either partial or no recanalization with this treatment alone.

In fact, the therapeutic margin is “rather narrow” for t-PA overall, according to Dr. Froehler, citing data from 12 trials with alteplase. He noted that a review of the original publications reveals that only two of the investigating teams characterized their results as positive. Although almost all the others discussed risk-to-benefit ratios without labeling the findings positive or negative, he believes clinician should be aware of the limitations of these data.

For the newer thrombolytic tenecteplase, which was included as an alternative to alteplase in the most recent American Heart Association/American Stroke Association guidelines, Dr. Froehler said the evidence is even more limited, particularly regarding the optimal dose. In the recently published guidelines, the recommended dose was 0.4 mg/kg , even though this dose has been associated with intracranial hemorrhage in at least one clinical study. Lower doses such as 0.25 mg/kg may be a safer alternative, but Dr. Froehler recommended caution. “I do not think there is evidence that we should be transitioning to tenecteplase now,” he said, concluding that more data regarding the most appropriate dose are needed.

Patients with acute stroke can anticipate a favorable outcome with current therapies, but the urgency of reperfusion remains unchanged despite advances. Dr. Froehler concluded, “We must now work toward optimizing stroke systems of care for endovascular thrombectomy” to increase the proportion of patients who benefit.

Dr. Froehler disclosed financial relationships with Balt USA, Control Medical, EndoPhys, Genentech, Medtronic, Microvention, NeurVana, Penumbra, Stryker, and Viz.ai.

Suggested Reading

Albers GW, Marks MP, Kemp S, et al. Thrombectomy for stroke at 6 to 16 hours with selection by perfusion imaging. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(8):708-718.

Goyal M, Menon BK, van Zwam WH, et al. Endovascular thrombectomy after large-vessel ischaemic stroke: a meta-analysis of individual patient data from five randomised trials. Lancet. 2016;387(10029):1723-1731.