User login

FDA grants fast track designation to CX-01 for AML

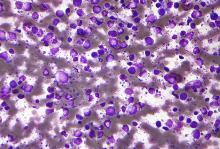

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has granted fast track designation to CX-01 as a treatment for patients older than 60 receiving induction therapy for newly diagnosed acute myeloid leukemia (AML).

CX-01 also has orphan drug designation from the FDA.

CX-01 is a polysaccharide derived from heparin that is thought to enhance chemotherapy by disrupting the adhesion of leukemia cells in the bone marrow.

CX-01 inhibits the activity of HMGB1, disrupts the CXCL12/CXCR4 axis, and neutralizes the activity of platelet factor 4. HMGB1 has been implicated in autophagy, a mechanism by which cells withstand the effects of chemotherapy.

The CXCL12/CXCR4 axis is thought to be involved in protecting leukemia cells from chemotherapy. And platelet factor 4 inhibits bone marrow recovery after chemotherapy.

CX-01 research

Cantex Pharmaceuticals, Inc., is conducting a randomized, phase 2b study to determine whether CX-01 can improve the efficacy of frontline chemotherapy in patients with AML.

This study builds upon results of a pilot study, which were published in Blood Advances in February.

The study enrolled 12 adults with newly diagnosed AML. Patients had good-risk (n=3), intermediate-risk (n=5), and poor-risk (n=4) disease.

They received CX-01 as a 7-day continuous infusion, along with standard induction chemotherapy (cytarabine and idarubicin).

Eleven patients (92%) achieved morphologic complete remission after one cycle of induction. This includes two patients who did not complete induction. All patients received subsequent therapy—consolidation, salvage, or transplant—on- or off-study.

At a median follow-up of 24 months, 8 patients were still alive. Two patients died of transplant-related complications, one died of infectious complications, and one died of cerebral hemorrhage.

The median disease-free survival was 14.8 months, and the median overall survival was not reached.

There were five serious adverse events (AEs) in five patients. Most of these AEs were considered unrelated to CX-01, but a case of grade 4 sepsis was considered possibly related to CX-01.

Transient, asymptomatic, low-grade elevations of liver transaminases observed during induction were considered possibly related to CX-01. There were also transient, asymptomatic, grade 3-4 liver transaminase elevations observed during consolidation that were considered possibly related to CX-01.

The researchers said the most frequent nonserious AEs were hematologic toxicities, infectious complications, and organ toxicity complications resulting from treatment and/or the underlying leukemia.

About fast track, orphan designations

The FDA’s fast track development program is designed to expedite clinical development and submission of applications for products with the potential to treat serious or life-threatening conditions and address unmet medical needs.

Fast track designation facilitates frequent interactions with the FDA review team, including meetings to discuss the product’s development plan and written communications about issues such as trial design and use of biomarkers.

Products that receive fast track designation may be eligible for accelerated approval and priority review if relevant criteria are met. Such products may also be eligible for rolling review, which allows a developer to submit individual sections of a product’s application for review as they are ready, rather than waiting until all sections are complete.

The FDA grants orphan designation to products intended to treat, diagnose, or prevent diseases/disorders that affect fewer than 200,000 people in the US.

The designation provides incentives for sponsors to develop products for rare diseases. This may include tax credits toward the cost of clinical trials, prescription drug user fee waivers, and 7 years of market exclusivity if the product is approved.

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has granted fast track designation to CX-01 as a treatment for patients older than 60 receiving induction therapy for newly diagnosed acute myeloid leukemia (AML).

CX-01 also has orphan drug designation from the FDA.

CX-01 is a polysaccharide derived from heparin that is thought to enhance chemotherapy by disrupting the adhesion of leukemia cells in the bone marrow.

CX-01 inhibits the activity of HMGB1, disrupts the CXCL12/CXCR4 axis, and neutralizes the activity of platelet factor 4. HMGB1 has been implicated in autophagy, a mechanism by which cells withstand the effects of chemotherapy.

The CXCL12/CXCR4 axis is thought to be involved in protecting leukemia cells from chemotherapy. And platelet factor 4 inhibits bone marrow recovery after chemotherapy.

CX-01 research

Cantex Pharmaceuticals, Inc., is conducting a randomized, phase 2b study to determine whether CX-01 can improve the efficacy of frontline chemotherapy in patients with AML.

This study builds upon results of a pilot study, which were published in Blood Advances in February.

The study enrolled 12 adults with newly diagnosed AML. Patients had good-risk (n=3), intermediate-risk (n=5), and poor-risk (n=4) disease.

They received CX-01 as a 7-day continuous infusion, along with standard induction chemotherapy (cytarabine and idarubicin).

Eleven patients (92%) achieved morphologic complete remission after one cycle of induction. This includes two patients who did not complete induction. All patients received subsequent therapy—consolidation, salvage, or transplant—on- or off-study.

At a median follow-up of 24 months, 8 patients were still alive. Two patients died of transplant-related complications, one died of infectious complications, and one died of cerebral hemorrhage.

The median disease-free survival was 14.8 months, and the median overall survival was not reached.

There were five serious adverse events (AEs) in five patients. Most of these AEs were considered unrelated to CX-01, but a case of grade 4 sepsis was considered possibly related to CX-01.

Transient, asymptomatic, low-grade elevations of liver transaminases observed during induction were considered possibly related to CX-01. There were also transient, asymptomatic, grade 3-4 liver transaminase elevations observed during consolidation that were considered possibly related to CX-01.

The researchers said the most frequent nonserious AEs were hematologic toxicities, infectious complications, and organ toxicity complications resulting from treatment and/or the underlying leukemia.

About fast track, orphan designations

The FDA’s fast track development program is designed to expedite clinical development and submission of applications for products with the potential to treat serious or life-threatening conditions and address unmet medical needs.

Fast track designation facilitates frequent interactions with the FDA review team, including meetings to discuss the product’s development plan and written communications about issues such as trial design and use of biomarkers.

Products that receive fast track designation may be eligible for accelerated approval and priority review if relevant criteria are met. Such products may also be eligible for rolling review, which allows a developer to submit individual sections of a product’s application for review as they are ready, rather than waiting until all sections are complete.

The FDA grants orphan designation to products intended to treat, diagnose, or prevent diseases/disorders that affect fewer than 200,000 people in the US.

The designation provides incentives for sponsors to develop products for rare diseases. This may include tax credits toward the cost of clinical trials, prescription drug user fee waivers, and 7 years of market exclusivity if the product is approved.

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has granted fast track designation to CX-01 as a treatment for patients older than 60 receiving induction therapy for newly diagnosed acute myeloid leukemia (AML).

CX-01 also has orphan drug designation from the FDA.

CX-01 is a polysaccharide derived from heparin that is thought to enhance chemotherapy by disrupting the adhesion of leukemia cells in the bone marrow.

CX-01 inhibits the activity of HMGB1, disrupts the CXCL12/CXCR4 axis, and neutralizes the activity of platelet factor 4. HMGB1 has been implicated in autophagy, a mechanism by which cells withstand the effects of chemotherapy.

The CXCL12/CXCR4 axis is thought to be involved in protecting leukemia cells from chemotherapy. And platelet factor 4 inhibits bone marrow recovery after chemotherapy.

CX-01 research

Cantex Pharmaceuticals, Inc., is conducting a randomized, phase 2b study to determine whether CX-01 can improve the efficacy of frontline chemotherapy in patients with AML.

This study builds upon results of a pilot study, which were published in Blood Advances in February.

The study enrolled 12 adults with newly diagnosed AML. Patients had good-risk (n=3), intermediate-risk (n=5), and poor-risk (n=4) disease.

They received CX-01 as a 7-day continuous infusion, along with standard induction chemotherapy (cytarabine and idarubicin).

Eleven patients (92%) achieved morphologic complete remission after one cycle of induction. This includes two patients who did not complete induction. All patients received subsequent therapy—consolidation, salvage, or transplant—on- or off-study.

At a median follow-up of 24 months, 8 patients were still alive. Two patients died of transplant-related complications, one died of infectious complications, and one died of cerebral hemorrhage.

The median disease-free survival was 14.8 months, and the median overall survival was not reached.

There were five serious adverse events (AEs) in five patients. Most of these AEs were considered unrelated to CX-01, but a case of grade 4 sepsis was considered possibly related to CX-01.

Transient, asymptomatic, low-grade elevations of liver transaminases observed during induction were considered possibly related to CX-01. There were also transient, asymptomatic, grade 3-4 liver transaminase elevations observed during consolidation that were considered possibly related to CX-01.

The researchers said the most frequent nonserious AEs were hematologic toxicities, infectious complications, and organ toxicity complications resulting from treatment and/or the underlying leukemia.

About fast track, orphan designations

The FDA’s fast track development program is designed to expedite clinical development and submission of applications for products with the potential to treat serious or life-threatening conditions and address unmet medical needs.

Fast track designation facilitates frequent interactions with the FDA review team, including meetings to discuss the product’s development plan and written communications about issues such as trial design and use of biomarkers.

Products that receive fast track designation may be eligible for accelerated approval and priority review if relevant criteria are met. Such products may also be eligible for rolling review, which allows a developer to submit individual sections of a product’s application for review as they are ready, rather than waiting until all sections are complete.

The FDA grants orphan designation to products intended to treat, diagnose, or prevent diseases/disorders that affect fewer than 200,000 people in the US.

The designation provides incentives for sponsors to develop products for rare diseases. This may include tax credits toward the cost of clinical trials, prescription drug user fee waivers, and 7 years of market exclusivity if the product is approved.

Negative chest x-ray to rule out pediatric pneumonia

, researchers say.

In a paper published in the September issue of Pediatrics, researchers report the results of a prospective cohort study in 683 children – with a median age of 3.1 years – presenting to emergency departments with suspected pneumonia.

Dr. Susan C. Lipsett, from the division of emergency medicine at Boston Children’s Hospital, and co-authors, wrote that the use of chest radiograph to diagnose pneumonia is thought to have limitations such as its inability to distinguish between bacteria and viral infection, and the possible absence of radiographic presentations early in the disease in patients with dehydration.

In this study, 457 (72.8%) of the children had negative chest radiographs. Of these, 44 were clinically diagnosed with pneumonia, despite the radiograph results, and prescribed antibiotics. These children were more likely to have rales or respiratory distress and less likely to have wheezing compared with the children with negative radiographs who were not initially diagnosed with pneumonia.

Among the remaining 411 children with negative radiographs – who were not prescribed antibiotics – five (1.2%) were subsequently diagnosed with pneumonia within 2 weeks of the radiograph. These five children were all under 3 years of age, but none had been treated with intravenous fluids for dehydration. Only one had radiographic findings of pneumonia on a follow-up visit.

Counting the 44 children diagnosed with pneumonia despite the negative x-ray, chest radiography showed a negative predictive value of 89.2% (95% confidence interval, 85.9%-91.9%). Without those children, the negative predictive value was 98.8% (95% CI, 97%-99.6%).

There were also 113 children (16.5%) with positive chest radiographs, and 72 (10.7%) with equivocal radiographs.

The authors said their results showed that most children with negative chest radiograph would recover fully without needing antibiotics, and argued there was a place for chest radiography in the diagnostic process, to rule out bacterial pneumonia.

“Most clinicians caring for children in the outpatient setting rely on clinical signs and symptoms to determine whether to prescribe an antibiotic for the treatment of pneumonia,” they wrote. “However, given recent literature in which the poor reliability and validity of physical examination findings are cited, reliance on physical examination alone may lead to the overdiagnosis of pneumonia.”

They acknowledged that the lack of a universally accepted gold standard for the diagnosis of pneumonia in children was a significant limitation of the research. In addition, the lack of systematic radiographs meant some children who initially had a negative result and recovered without antibiotics may have shown a positive result on a second scan.

No conflicts of interest were declared.

SOURCE: Lipsett S et al. Pediatrics 2018 142(3):e20180236.

While the results of this study offer reassurance that chest radiograph for suspected pneumonia in children has a high negative predictive value, perhaps a more important question is the accuracy of chest radiography at ruling in bacterial pneumonia – its positive predictive value.

There are reasons to suspect that the positive predictive value of chest radiography may not be as high as the negative predictive value found in this study. This is particularly important given that questions have been raised about the utility of antibiotic therapy in treating Mycoplasma pneumonia infection in children.

Leaving out chest radiography altogether in children with a low clinical suspicion for pneumonia would decreased radi-ation use, cost, and perhaps also unnecessary antibiotic prescriptions.

Matthew D. Garber, MD, is from the department of pediatrics at the University of Florida College of Medicine in Jacksonville and Ricardo A. Quinonez, MD, is from the department of pediatrics at the Baylor College of Medicine and Texas Children’s Hospital. These comments are taken from an accompanying editorial (Pediatrics 2018, 142(3): e20182025. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2018-2025). No conflicts of interest were declared.

While the results of this study offer reassurance that chest radiograph for suspected pneumonia in children has a high negative predictive value, perhaps a more important question is the accuracy of chest radiography at ruling in bacterial pneumonia – its positive predictive value.

There are reasons to suspect that the positive predictive value of chest radiography may not be as high as the negative predictive value found in this study. This is particularly important given that questions have been raised about the utility of antibiotic therapy in treating Mycoplasma pneumonia infection in children.

Leaving out chest radiography altogether in children with a low clinical suspicion for pneumonia would decreased radi-ation use, cost, and perhaps also unnecessary antibiotic prescriptions.

Matthew D. Garber, MD, is from the department of pediatrics at the University of Florida College of Medicine in Jacksonville and Ricardo A. Quinonez, MD, is from the department of pediatrics at the Baylor College of Medicine and Texas Children’s Hospital. These comments are taken from an accompanying editorial (Pediatrics 2018, 142(3): e20182025. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2018-2025). No conflicts of interest were declared.

While the results of this study offer reassurance that chest radiograph for suspected pneumonia in children has a high negative predictive value, perhaps a more important question is the accuracy of chest radiography at ruling in bacterial pneumonia – its positive predictive value.

There are reasons to suspect that the positive predictive value of chest radiography may not be as high as the negative predictive value found in this study. This is particularly important given that questions have been raised about the utility of antibiotic therapy in treating Mycoplasma pneumonia infection in children.

Leaving out chest radiography altogether in children with a low clinical suspicion for pneumonia would decreased radi-ation use, cost, and perhaps also unnecessary antibiotic prescriptions.

Matthew D. Garber, MD, is from the department of pediatrics at the University of Florida College of Medicine in Jacksonville and Ricardo A. Quinonez, MD, is from the department of pediatrics at the Baylor College of Medicine and Texas Children’s Hospital. These comments are taken from an accompanying editorial (Pediatrics 2018, 142(3): e20182025. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2018-2025). No conflicts of interest were declared.

, researchers say.

In a paper published in the September issue of Pediatrics, researchers report the results of a prospective cohort study in 683 children – with a median age of 3.1 years – presenting to emergency departments with suspected pneumonia.

Dr. Susan C. Lipsett, from the division of emergency medicine at Boston Children’s Hospital, and co-authors, wrote that the use of chest radiograph to diagnose pneumonia is thought to have limitations such as its inability to distinguish between bacteria and viral infection, and the possible absence of radiographic presentations early in the disease in patients with dehydration.

In this study, 457 (72.8%) of the children had negative chest radiographs. Of these, 44 were clinically diagnosed with pneumonia, despite the radiograph results, and prescribed antibiotics. These children were more likely to have rales or respiratory distress and less likely to have wheezing compared with the children with negative radiographs who were not initially diagnosed with pneumonia.

Among the remaining 411 children with negative radiographs – who were not prescribed antibiotics – five (1.2%) were subsequently diagnosed with pneumonia within 2 weeks of the radiograph. These five children were all under 3 years of age, but none had been treated with intravenous fluids for dehydration. Only one had radiographic findings of pneumonia on a follow-up visit.

Counting the 44 children diagnosed with pneumonia despite the negative x-ray, chest radiography showed a negative predictive value of 89.2% (95% confidence interval, 85.9%-91.9%). Without those children, the negative predictive value was 98.8% (95% CI, 97%-99.6%).

There were also 113 children (16.5%) with positive chest radiographs, and 72 (10.7%) with equivocal radiographs.

The authors said their results showed that most children with negative chest radiograph would recover fully without needing antibiotics, and argued there was a place for chest radiography in the diagnostic process, to rule out bacterial pneumonia.

“Most clinicians caring for children in the outpatient setting rely on clinical signs and symptoms to determine whether to prescribe an antibiotic for the treatment of pneumonia,” they wrote. “However, given recent literature in which the poor reliability and validity of physical examination findings are cited, reliance on physical examination alone may lead to the overdiagnosis of pneumonia.”

They acknowledged that the lack of a universally accepted gold standard for the diagnosis of pneumonia in children was a significant limitation of the research. In addition, the lack of systematic radiographs meant some children who initially had a negative result and recovered without antibiotics may have shown a positive result on a second scan.

No conflicts of interest were declared.

SOURCE: Lipsett S et al. Pediatrics 2018 142(3):e20180236.

, researchers say.

In a paper published in the September issue of Pediatrics, researchers report the results of a prospective cohort study in 683 children – with a median age of 3.1 years – presenting to emergency departments with suspected pneumonia.

Dr. Susan C. Lipsett, from the division of emergency medicine at Boston Children’s Hospital, and co-authors, wrote that the use of chest radiograph to diagnose pneumonia is thought to have limitations such as its inability to distinguish between bacteria and viral infection, and the possible absence of radiographic presentations early in the disease in patients with dehydration.

In this study, 457 (72.8%) of the children had negative chest radiographs. Of these, 44 were clinically diagnosed with pneumonia, despite the radiograph results, and prescribed antibiotics. These children were more likely to have rales or respiratory distress and less likely to have wheezing compared with the children with negative radiographs who were not initially diagnosed with pneumonia.

Among the remaining 411 children with negative radiographs – who were not prescribed antibiotics – five (1.2%) were subsequently diagnosed with pneumonia within 2 weeks of the radiograph. These five children were all under 3 years of age, but none had been treated with intravenous fluids for dehydration. Only one had radiographic findings of pneumonia on a follow-up visit.

Counting the 44 children diagnosed with pneumonia despite the negative x-ray, chest radiography showed a negative predictive value of 89.2% (95% confidence interval, 85.9%-91.9%). Without those children, the negative predictive value was 98.8% (95% CI, 97%-99.6%).

There were also 113 children (16.5%) with positive chest radiographs, and 72 (10.7%) with equivocal radiographs.

The authors said their results showed that most children with negative chest radiograph would recover fully without needing antibiotics, and argued there was a place for chest radiography in the diagnostic process, to rule out bacterial pneumonia.

“Most clinicians caring for children in the outpatient setting rely on clinical signs and symptoms to determine whether to prescribe an antibiotic for the treatment of pneumonia,” they wrote. “However, given recent literature in which the poor reliability and validity of physical examination findings are cited, reliance on physical examination alone may lead to the overdiagnosis of pneumonia.”

They acknowledged that the lack of a universally accepted gold standard for the diagnosis of pneumonia in children was a significant limitation of the research. In addition, the lack of systematic radiographs meant some children who initially had a negative result and recovered without antibiotics may have shown a positive result on a second scan.

No conflicts of interest were declared.

SOURCE: Lipsett S et al. Pediatrics 2018 142(3):e20180236.

FROM PEDIATRICS

Key clinical point: Negative chest radiograph can rule out pneumonia in children.

Major finding: Chest radiograph has a negative predictive value of 89.2% in children with suspected pneumonia.

Study details: Prospective cohort study in 683 children with suspected pneumonia.

Disclosures: No conflicts of interest were declared.

Source: Lipsett S et al. Pediatrics 2018 142(3):e20180236. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2018-0236.

Principles for freshly minted psychiatrists

I just finished reading Dr. Nasrallah’s editorial “The DNA of psychiatric practice: A covenant with our patients” (From the Editor,

David W. Goodman, MD, FAPA

Assistant Professor

Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences

Johns Hopkins School of Medicine

Baltimore, Maryland

Unfortunately, there is no way a physician who uses an electronic medical record can “Maintain total and unimpeachable confidentiality” as the “The medical record is a clinical, billing, legal, and research document.” Since 2003, patients no longer need to give consent for their medical records to be seen by the many staff members who work in treatment, payment, and health care operations, as long as these individuals follow the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA). Even de-identified data is no longer safe because re-identification is still possible with all the databases available for cross-referencing (ie, Facebook and hospitals as one instance).

So, when a patient finally tells you about a history of sexual abuse, do you make it clear to him or her that although this information is no longer private, it can be expected to be kept confidential by all the business associates, covered entities, government agencies, etc., who see their records?

Maybe there also would be fewer physician suicides if they could be assured of receiving truly private, off-the-grid psychiatric treatment.

Susan Israel, MD

Private psychiatric practice (retired)

Woodbridge, Connecticut

I just read your excellent and exhaustive May editorial, which offered advice for new psychiatrists. I was surprised to see that nowhere on the list was “Please remember to practice what you preach and be vigilant about self-care. We have become increasingly aware of the high rates of burnout among physicians. Know your own limitations so that you can appreciate the work that you do.”

Hal D. Cash, MD

Private psychiatric practice (retired)

Mica Collaborative

Wellesley, Massachusetts

Continue to: Dr. Nasrallah's editorial should have...

Dr. Nasrallah’s editorial should have listed something about the terms of payment for the psychiatrist who “provides” his or her clinical services to patients. This is an ethical issue. As you know, usually a corporation, rather than a patient, pays the psychiatrist. This payment may come from a health insurance company, government program, or (increasingly) a large clinic. When an organization pays the psychiatrist, it calls the tune for both the doctor’s employment and the patient’s access to quality care. Contracts between the hiring organization and psychiatrists are crucial, and therefore, most young doctors must join a hiring organization for financial reasons after completing their psychiatric residency. The young psychiatrists with whom I speak tell me they have no alternative but to be a “corporate dependent” in the world of 2018 psychiatric practice. They are aware of your (and my) noble principles, which should govern their relationships with patients. But the boss often does not agree with such principles.

In my book Passion for Patients1 and as President of the 501(c)3 Minnesota Physician-Patient Alliance think tank (www.physician-patient.org), I argue for empowering patients with the means to direct payments to their physicians. Allowing patients this option is especially important for forming and maintaining strong relationship-based psychiatric and other medical treatments. In 1996, I was fed up with being a psychiatric medical director for 5 years at a large Minnesota Preferred Provider Organization. For me, the saving grace was being able to have an independent, private psychiatric practice. Most of my patients agreed.Therefore, I suggest another principle: “Build and maintain an independent psychiatric practice as an escape option no matter what you do should you decide the ethical practice of psychiatry is not possible if you are employed by a given organization.”

Lee Beecher, MD

Member

Editorial Advisory Board

Clinical Psychiatry News

Adjunct Professor of Psychiatry

University of Minnesota

Minneapolis, Minnesota

Reference

1. Beecher L, Racer D. Passion for patients. St. Paul, MN: Alethos Press; 2017.

I agree with Dr. Nasrallah’s guiding principles of psychiatry, which he proposes to govern the relationships of psychiatrists with their patients. However, there is one glaring omission. The first principle should be “to appropriately diagnose the patient’s condition,” which may or may not be based in psychiatry. Misdiagnoses and inappropriate pharmacologic therapy have ruined the lives of some very good friends of mine, and the need to first do no harm by misdiagnosing the patient, especially in psychiatric emergency rooms and on inpatient units, cannot be overemphasized.

These situations may not rear their head in the everyday practice of psychiatry. However, medical malpractice, especially in the field of psychiatry, is a constant caution that all new physicians need to watch for.

I would like to thank Dr. Nasrallah for his efforts to strengthen the patient–psychiatrist contract.

Rama Kasturi, PhD

Associate Professor (retired)

Department of Pharmacology and Cell Biophysics

Director (1999 to 2013)

Medical Pharmacology Tutorial Program University of Cincinnati, College of Medicine

Cincinnati, Ohio

Continue to: Dr. Nasrallah responds

Dr. Nasrallah responds

I thank my 5 colleagues for their perspectives on my editorial. You all made cogent points.

I agree with Dr. Israel that our patients’ records are now accessible by many entities due to the drastic changes in our health care delivery system. However, while I regard the basic psychiatric signs and symptoms as medical data, like heart disease or cancer, there are personal details that emerge during psychotherapy that should remain confidential and not be included in the written record, and thus are not accessible to billers, health insurance companies, or malpractice lawyers. As for physicians who consider suicide because of fear of the consequences of receiving psychiatric treatment that becomes a matter of record, that is a matter of the unfortunate stigma and ignorance about mental illness and how treatable it can be.

Regarding Dr. Cash’s comments, I agree that psychiatrists should be (and are almost always are) introspective about their vulnerabilities and limitations, and should act accordingly, which includes taking care of their needs to stay healthy and avoid burnout.

As Dr. Beecher pointed out, the employment model for psychiatrists does have many implications and constraints for patient care. I concur that having a small direct-care practice, sometimes called a “cash practice,” provides patients who can afford it the complete privacy they desire, with no one having access to their medical records except for their psychiatrist. Your book is a useful resource in that regard.

Dr. Kasturi is right about the importance of arriving at an accurate diagnosis before embarking on treatment; otherwise, patients will suffer from “therapeutic misadventures.” I have observed this being experienced by some of the patients referred to me because of “treatment resistance.”

Thanks again to my colleagues for their comments and suggestions to the newly minted psychiatrists for whom my editorial was intended.

Henry A. Nasrallah, MD

The Sydney W. Souers Endowed ChairProfessor and Chairman

Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Neuroscience

Saint Louis University School of Medicine

St. Louis, Missouri

I just finished reading Dr. Nasrallah’s editorial “The DNA of psychiatric practice: A covenant with our patients” (From the Editor,

David W. Goodman, MD, FAPA

Assistant Professor

Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences

Johns Hopkins School of Medicine

Baltimore, Maryland

Unfortunately, there is no way a physician who uses an electronic medical record can “Maintain total and unimpeachable confidentiality” as the “The medical record is a clinical, billing, legal, and research document.” Since 2003, patients no longer need to give consent for their medical records to be seen by the many staff members who work in treatment, payment, and health care operations, as long as these individuals follow the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA). Even de-identified data is no longer safe because re-identification is still possible with all the databases available for cross-referencing (ie, Facebook and hospitals as one instance).

So, when a patient finally tells you about a history of sexual abuse, do you make it clear to him or her that although this information is no longer private, it can be expected to be kept confidential by all the business associates, covered entities, government agencies, etc., who see their records?

Maybe there also would be fewer physician suicides if they could be assured of receiving truly private, off-the-grid psychiatric treatment.

Susan Israel, MD

Private psychiatric practice (retired)

Woodbridge, Connecticut

I just read your excellent and exhaustive May editorial, which offered advice for new psychiatrists. I was surprised to see that nowhere on the list was “Please remember to practice what you preach and be vigilant about self-care. We have become increasingly aware of the high rates of burnout among physicians. Know your own limitations so that you can appreciate the work that you do.”

Hal D. Cash, MD

Private psychiatric practice (retired)

Mica Collaborative

Wellesley, Massachusetts

Continue to: Dr. Nasrallah's editorial should have...

Dr. Nasrallah’s editorial should have listed something about the terms of payment for the psychiatrist who “provides” his or her clinical services to patients. This is an ethical issue. As you know, usually a corporation, rather than a patient, pays the psychiatrist. This payment may come from a health insurance company, government program, or (increasingly) a large clinic. When an organization pays the psychiatrist, it calls the tune for both the doctor’s employment and the patient’s access to quality care. Contracts between the hiring organization and psychiatrists are crucial, and therefore, most young doctors must join a hiring organization for financial reasons after completing their psychiatric residency. The young psychiatrists with whom I speak tell me they have no alternative but to be a “corporate dependent” in the world of 2018 psychiatric practice. They are aware of your (and my) noble principles, which should govern their relationships with patients. But the boss often does not agree with such principles.

In my book Passion for Patients1 and as President of the 501(c)3 Minnesota Physician-Patient Alliance think tank (www.physician-patient.org), I argue for empowering patients with the means to direct payments to their physicians. Allowing patients this option is especially important for forming and maintaining strong relationship-based psychiatric and other medical treatments. In 1996, I was fed up with being a psychiatric medical director for 5 years at a large Minnesota Preferred Provider Organization. For me, the saving grace was being able to have an independent, private psychiatric practice. Most of my patients agreed.Therefore, I suggest another principle: “Build and maintain an independent psychiatric practice as an escape option no matter what you do should you decide the ethical practice of psychiatry is not possible if you are employed by a given organization.”

Lee Beecher, MD

Member

Editorial Advisory Board

Clinical Psychiatry News

Adjunct Professor of Psychiatry

University of Minnesota

Minneapolis, Minnesota

Reference

1. Beecher L, Racer D. Passion for patients. St. Paul, MN: Alethos Press; 2017.

I agree with Dr. Nasrallah’s guiding principles of psychiatry, which he proposes to govern the relationships of psychiatrists with their patients. However, there is one glaring omission. The first principle should be “to appropriately diagnose the patient’s condition,” which may or may not be based in psychiatry. Misdiagnoses and inappropriate pharmacologic therapy have ruined the lives of some very good friends of mine, and the need to first do no harm by misdiagnosing the patient, especially in psychiatric emergency rooms and on inpatient units, cannot be overemphasized.

These situations may not rear their head in the everyday practice of psychiatry. However, medical malpractice, especially in the field of psychiatry, is a constant caution that all new physicians need to watch for.

I would like to thank Dr. Nasrallah for his efforts to strengthen the patient–psychiatrist contract.

Rama Kasturi, PhD

Associate Professor (retired)

Department of Pharmacology and Cell Biophysics

Director (1999 to 2013)

Medical Pharmacology Tutorial Program University of Cincinnati, College of Medicine

Cincinnati, Ohio

Continue to: Dr. Nasrallah responds

Dr. Nasrallah responds

I thank my 5 colleagues for their perspectives on my editorial. You all made cogent points.

I agree with Dr. Israel that our patients’ records are now accessible by many entities due to the drastic changes in our health care delivery system. However, while I regard the basic psychiatric signs and symptoms as medical data, like heart disease or cancer, there are personal details that emerge during psychotherapy that should remain confidential and not be included in the written record, and thus are not accessible to billers, health insurance companies, or malpractice lawyers. As for physicians who consider suicide because of fear of the consequences of receiving psychiatric treatment that becomes a matter of record, that is a matter of the unfortunate stigma and ignorance about mental illness and how treatable it can be.

Regarding Dr. Cash’s comments, I agree that psychiatrists should be (and are almost always are) introspective about their vulnerabilities and limitations, and should act accordingly, which includes taking care of their needs to stay healthy and avoid burnout.

As Dr. Beecher pointed out, the employment model for psychiatrists does have many implications and constraints for patient care. I concur that having a small direct-care practice, sometimes called a “cash practice,” provides patients who can afford it the complete privacy they desire, with no one having access to their medical records except for their psychiatrist. Your book is a useful resource in that regard.

Dr. Kasturi is right about the importance of arriving at an accurate diagnosis before embarking on treatment; otherwise, patients will suffer from “therapeutic misadventures.” I have observed this being experienced by some of the patients referred to me because of “treatment resistance.”

Thanks again to my colleagues for their comments and suggestions to the newly minted psychiatrists for whom my editorial was intended.

Henry A. Nasrallah, MD

The Sydney W. Souers Endowed ChairProfessor and Chairman

Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Neuroscience

Saint Louis University School of Medicine

St. Louis, Missouri

I just finished reading Dr. Nasrallah’s editorial “The DNA of psychiatric practice: A covenant with our patients” (From the Editor,

David W. Goodman, MD, FAPA

Assistant Professor

Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences

Johns Hopkins School of Medicine

Baltimore, Maryland

Unfortunately, there is no way a physician who uses an electronic medical record can “Maintain total and unimpeachable confidentiality” as the “The medical record is a clinical, billing, legal, and research document.” Since 2003, patients no longer need to give consent for their medical records to be seen by the many staff members who work in treatment, payment, and health care operations, as long as these individuals follow the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA). Even de-identified data is no longer safe because re-identification is still possible with all the databases available for cross-referencing (ie, Facebook and hospitals as one instance).

So, when a patient finally tells you about a history of sexual abuse, do you make it clear to him or her that although this information is no longer private, it can be expected to be kept confidential by all the business associates, covered entities, government agencies, etc., who see their records?

Maybe there also would be fewer physician suicides if they could be assured of receiving truly private, off-the-grid psychiatric treatment.

Susan Israel, MD

Private psychiatric practice (retired)

Woodbridge, Connecticut

I just read your excellent and exhaustive May editorial, which offered advice for new psychiatrists. I was surprised to see that nowhere on the list was “Please remember to practice what you preach and be vigilant about self-care. We have become increasingly aware of the high rates of burnout among physicians. Know your own limitations so that you can appreciate the work that you do.”

Hal D. Cash, MD

Private psychiatric practice (retired)

Mica Collaborative

Wellesley, Massachusetts

Continue to: Dr. Nasrallah's editorial should have...

Dr. Nasrallah’s editorial should have listed something about the terms of payment for the psychiatrist who “provides” his or her clinical services to patients. This is an ethical issue. As you know, usually a corporation, rather than a patient, pays the psychiatrist. This payment may come from a health insurance company, government program, or (increasingly) a large clinic. When an organization pays the psychiatrist, it calls the tune for both the doctor’s employment and the patient’s access to quality care. Contracts between the hiring organization and psychiatrists are crucial, and therefore, most young doctors must join a hiring organization for financial reasons after completing their psychiatric residency. The young psychiatrists with whom I speak tell me they have no alternative but to be a “corporate dependent” in the world of 2018 psychiatric practice. They are aware of your (and my) noble principles, which should govern their relationships with patients. But the boss often does not agree with such principles.

In my book Passion for Patients1 and as President of the 501(c)3 Minnesota Physician-Patient Alliance think tank (www.physician-patient.org), I argue for empowering patients with the means to direct payments to their physicians. Allowing patients this option is especially important for forming and maintaining strong relationship-based psychiatric and other medical treatments. In 1996, I was fed up with being a psychiatric medical director for 5 years at a large Minnesota Preferred Provider Organization. For me, the saving grace was being able to have an independent, private psychiatric practice. Most of my patients agreed.Therefore, I suggest another principle: “Build and maintain an independent psychiatric practice as an escape option no matter what you do should you decide the ethical practice of psychiatry is not possible if you are employed by a given organization.”

Lee Beecher, MD

Member

Editorial Advisory Board

Clinical Psychiatry News

Adjunct Professor of Psychiatry

University of Minnesota

Minneapolis, Minnesota

Reference

1. Beecher L, Racer D. Passion for patients. St. Paul, MN: Alethos Press; 2017.

I agree with Dr. Nasrallah’s guiding principles of psychiatry, which he proposes to govern the relationships of psychiatrists with their patients. However, there is one glaring omission. The first principle should be “to appropriately diagnose the patient’s condition,” which may or may not be based in psychiatry. Misdiagnoses and inappropriate pharmacologic therapy have ruined the lives of some very good friends of mine, and the need to first do no harm by misdiagnosing the patient, especially in psychiatric emergency rooms and on inpatient units, cannot be overemphasized.

These situations may not rear their head in the everyday practice of psychiatry. However, medical malpractice, especially in the field of psychiatry, is a constant caution that all new physicians need to watch for.

I would like to thank Dr. Nasrallah for his efforts to strengthen the patient–psychiatrist contract.

Rama Kasturi, PhD

Associate Professor (retired)

Department of Pharmacology and Cell Biophysics

Director (1999 to 2013)

Medical Pharmacology Tutorial Program University of Cincinnati, College of Medicine

Cincinnati, Ohio

Continue to: Dr. Nasrallah responds

Dr. Nasrallah responds

I thank my 5 colleagues for their perspectives on my editorial. You all made cogent points.

I agree with Dr. Israel that our patients’ records are now accessible by many entities due to the drastic changes in our health care delivery system. However, while I regard the basic psychiatric signs and symptoms as medical data, like heart disease or cancer, there are personal details that emerge during psychotherapy that should remain confidential and not be included in the written record, and thus are not accessible to billers, health insurance companies, or malpractice lawyers. As for physicians who consider suicide because of fear of the consequences of receiving psychiatric treatment that becomes a matter of record, that is a matter of the unfortunate stigma and ignorance about mental illness and how treatable it can be.

Regarding Dr. Cash’s comments, I agree that psychiatrists should be (and are almost always are) introspective about their vulnerabilities and limitations, and should act accordingly, which includes taking care of their needs to stay healthy and avoid burnout.

As Dr. Beecher pointed out, the employment model for psychiatrists does have many implications and constraints for patient care. I concur that having a small direct-care practice, sometimes called a “cash practice,” provides patients who can afford it the complete privacy they desire, with no one having access to their medical records except for their psychiatrist. Your book is a useful resource in that regard.

Dr. Kasturi is right about the importance of arriving at an accurate diagnosis before embarking on treatment; otherwise, patients will suffer from “therapeutic misadventures.” I have observed this being experienced by some of the patients referred to me because of “treatment resistance.”

Thanks again to my colleagues for their comments and suggestions to the newly minted psychiatrists for whom my editorial was intended.

Henry A. Nasrallah, MD

The Sydney W. Souers Endowed ChairProfessor and Chairman

Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Neuroscience

Saint Louis University School of Medicine

St. Louis, Missouri

ctDNA predicts early outcomes in DLBCL

Measurement of circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) could be a new and useful tool for predicting survival outcomes and response to therapy in patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), according to authors of a recent prospective study.

Pretreatment ctDNA levels predicted 24-month event-free survival – an important disease milestone in DLBCL – as well as overall survival in the study, which included more than 200 patients at six institutions in North America and Europe.

Changes in ctDNA during treatment were prognostic for outcomes as early as 21 days into therapy, according to corresponding author Ash A. Alizadeh, MD, PhD, of Stanford (Calif.) University and his coinvestigators.

“Our data suggest that both pretreatment and dynamic assessments of ctDNA are feasible and can add to established risk factors,” Dr. Alizadeh and his coauthors reported in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

ctDNA was detected in 98% of the 217 patients evaluated, which demonstrated the “potentially universal applicability” of this approach, they wrote in the report.

In an evaluation of pretreatment ctDNA levels, investigators found a 2.5 log haploid genome equivalents per milliliter (hGE/mL) threshold stratified patient outcomes. Event-free survival was significantly inferior at 24 months in patients with ctDNA above that threshold, with hazard ratios of 2.6 (P = .007) for frontline treatment and 2.9 (P = 0.01) for salvage.

On-treatment ctDNA levels were favorably prognostic for outcomes in patients receiving frontline therapy, according to investigators. An early molecular response (EMR), defined as a 2-log decrease in ctDNA levels after one cycle of treatment, was associated with a 24-month event-free survival of 83% versus 50% for no EMR (P = .0015).

Major molecular response (MMR), defined as a 2.5-log drop in ctDNA after two cycles of treatment, was associated with a 24-month event-free survival of 82% versus 46% for no MMR in patients on frontline therapy (P less than .001).

In one cohort of patients receiving salvage therapy, EMR also predicted superior 24-month event-free survival, according to investigators.

The EMR measure was also favorably prognostic for overall survival in both the frontline and salvage settings.

The prognostic value of measuring ctDNA was independent of International Prognostic Index (IPI) and interim PET/CT studies, results of multivariable analysis showed.

Patients had “excellent outcomes” if they had both molecular response and favorable interim PET results, and conversely, patients were at “extremely high risk” for treatment failure if they had no molecular response and a positive PET scan.

“The identification of patients at exceptionally high risk (i.e., interim PET/CT positive and not achieving EMR/MMR) could provide an opportunity for early intervention with alternative treatments, including autologous bone marrow transplantation or chimeric antigen receptor T cells,” the researchers wrote.

Patients in the study were all treated with combination immunochemotherapy according to local standards.

Dr. Alizadeh reported disclosures related to CiberMed, Forty Seven, Janssen Oncology, Celgene, Roche/Genentech, and Gilead, as well as patent filings on ctDNA detection assigned to Stanford University.

SOURCE: Kurtz DM et al. J Clin Oncol. 2018 Aug 20. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2018.78.5246.

Measurement of circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) could be a new and useful tool for predicting survival outcomes and response to therapy in patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), according to authors of a recent prospective study.

Pretreatment ctDNA levels predicted 24-month event-free survival – an important disease milestone in DLBCL – as well as overall survival in the study, which included more than 200 patients at six institutions in North America and Europe.

Changes in ctDNA during treatment were prognostic for outcomes as early as 21 days into therapy, according to corresponding author Ash A. Alizadeh, MD, PhD, of Stanford (Calif.) University and his coinvestigators.

“Our data suggest that both pretreatment and dynamic assessments of ctDNA are feasible and can add to established risk factors,” Dr. Alizadeh and his coauthors reported in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

ctDNA was detected in 98% of the 217 patients evaluated, which demonstrated the “potentially universal applicability” of this approach, they wrote in the report.

In an evaluation of pretreatment ctDNA levels, investigators found a 2.5 log haploid genome equivalents per milliliter (hGE/mL) threshold stratified patient outcomes. Event-free survival was significantly inferior at 24 months in patients with ctDNA above that threshold, with hazard ratios of 2.6 (P = .007) for frontline treatment and 2.9 (P = 0.01) for salvage.

On-treatment ctDNA levels were favorably prognostic for outcomes in patients receiving frontline therapy, according to investigators. An early molecular response (EMR), defined as a 2-log decrease in ctDNA levels after one cycle of treatment, was associated with a 24-month event-free survival of 83% versus 50% for no EMR (P = .0015).

Major molecular response (MMR), defined as a 2.5-log drop in ctDNA after two cycles of treatment, was associated with a 24-month event-free survival of 82% versus 46% for no MMR in patients on frontline therapy (P less than .001).

In one cohort of patients receiving salvage therapy, EMR also predicted superior 24-month event-free survival, according to investigators.

The EMR measure was also favorably prognostic for overall survival in both the frontline and salvage settings.

The prognostic value of measuring ctDNA was independent of International Prognostic Index (IPI) and interim PET/CT studies, results of multivariable analysis showed.

Patients had “excellent outcomes” if they had both molecular response and favorable interim PET results, and conversely, patients were at “extremely high risk” for treatment failure if they had no molecular response and a positive PET scan.

“The identification of patients at exceptionally high risk (i.e., interim PET/CT positive and not achieving EMR/MMR) could provide an opportunity for early intervention with alternative treatments, including autologous bone marrow transplantation or chimeric antigen receptor T cells,” the researchers wrote.

Patients in the study were all treated with combination immunochemotherapy according to local standards.

Dr. Alizadeh reported disclosures related to CiberMed, Forty Seven, Janssen Oncology, Celgene, Roche/Genentech, and Gilead, as well as patent filings on ctDNA detection assigned to Stanford University.

SOURCE: Kurtz DM et al. J Clin Oncol. 2018 Aug 20. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2018.78.5246.

Measurement of circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) could be a new and useful tool for predicting survival outcomes and response to therapy in patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), according to authors of a recent prospective study.

Pretreatment ctDNA levels predicted 24-month event-free survival – an important disease milestone in DLBCL – as well as overall survival in the study, which included more than 200 patients at six institutions in North America and Europe.

Changes in ctDNA during treatment were prognostic for outcomes as early as 21 days into therapy, according to corresponding author Ash A. Alizadeh, MD, PhD, of Stanford (Calif.) University and his coinvestigators.

“Our data suggest that both pretreatment and dynamic assessments of ctDNA are feasible and can add to established risk factors,” Dr. Alizadeh and his coauthors reported in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

ctDNA was detected in 98% of the 217 patients evaluated, which demonstrated the “potentially universal applicability” of this approach, they wrote in the report.

In an evaluation of pretreatment ctDNA levels, investigators found a 2.5 log haploid genome equivalents per milliliter (hGE/mL) threshold stratified patient outcomes. Event-free survival was significantly inferior at 24 months in patients with ctDNA above that threshold, with hazard ratios of 2.6 (P = .007) for frontline treatment and 2.9 (P = 0.01) for salvage.

On-treatment ctDNA levels were favorably prognostic for outcomes in patients receiving frontline therapy, according to investigators. An early molecular response (EMR), defined as a 2-log decrease in ctDNA levels after one cycle of treatment, was associated with a 24-month event-free survival of 83% versus 50% for no EMR (P = .0015).

Major molecular response (MMR), defined as a 2.5-log drop in ctDNA after two cycles of treatment, was associated with a 24-month event-free survival of 82% versus 46% for no MMR in patients on frontline therapy (P less than .001).

In one cohort of patients receiving salvage therapy, EMR also predicted superior 24-month event-free survival, according to investigators.

The EMR measure was also favorably prognostic for overall survival in both the frontline and salvage settings.

The prognostic value of measuring ctDNA was independent of International Prognostic Index (IPI) and interim PET/CT studies, results of multivariable analysis showed.

Patients had “excellent outcomes” if they had both molecular response and favorable interim PET results, and conversely, patients were at “extremely high risk” for treatment failure if they had no molecular response and a positive PET scan.

“The identification of patients at exceptionally high risk (i.e., interim PET/CT positive and not achieving EMR/MMR) could provide an opportunity for early intervention with alternative treatments, including autologous bone marrow transplantation or chimeric antigen receptor T cells,” the researchers wrote.

Patients in the study were all treated with combination immunochemotherapy according to local standards.

Dr. Alizadeh reported disclosures related to CiberMed, Forty Seven, Janssen Oncology, Celgene, Roche/Genentech, and Gilead, as well as patent filings on ctDNA detection assigned to Stanford University.

SOURCE: Kurtz DM et al. J Clin Oncol. 2018 Aug 20. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2018.78.5246.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF CLINICAL ONCOLOGY

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Early molecular response (a 2-log decrease in ctDNA levels after one treatment cycle) was associated with a 24-month event-free survival of 83% versus 50% for no early molecular response (P = .0015).

Study details: Prospective analysis of pretreatment and dynamic on-treatment ctDNA levels in patients with DLBCL who received standard immunochemotherapy.

Disclosures: Study authors reported disclosures related to CiberMed, Forty Seven, Janssen Oncology, Celgene, Roche/Genentech, and Gilead, among others.

Source: Kurtz DM et al. J Clin Oncol. 2018 Aug 20. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2018.78.5246.

FDA approves ibrutinib with rituximab in Waldenström’s macroglobulinemia

The Food and Drug Administration has approved ibrutinib (Imbruvica) for use in combination with rituximab to treat adults with Waldenström’s macroglobulinemia (WM).

Ibrutinib was approved for use as a single agent in adults with WM in January 2015.

The latest approval was supported by the phase 3 iNNOVATE trial, in which researchers compared ibrutinib plus rituximab to rituximab alone in patients with previously untreated or relapsed/refractory WM.

Results from iNNOVATE were presented at the 2018 annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology and simultaneously published in the New England Journal of Medicine (2018;378:2399-2410).

The 30-month progression-free survival rates were 82% in the ibrutinib arm and 28% in the placebo arm. The median progression-free survival was not reached in the ibrutinib arm and was 20.3 months in the placebo arm (hazard ratio, 0.20; P less than .0001).

The 30-month overall survival rates were 94% in the ibrutinib arm and 92% in the placebo arm.

Grade 3 or higher treatment-emergent adverse events (AEs) occurred in 60% of patients in the ibrutinib arm and 61% in the placebo arm. Serious AEs occurred in 43% and 33%, respectively. There were no fatal AEs in the ibrutinib arm and three in the rituximab arm.

Ibrutinib is jointly developed and commercialized by Pharmacyclics, an AbbVie company, and Janssen Biotech.

The Food and Drug Administration has approved ibrutinib (Imbruvica) for use in combination with rituximab to treat adults with Waldenström’s macroglobulinemia (WM).

Ibrutinib was approved for use as a single agent in adults with WM in January 2015.

The latest approval was supported by the phase 3 iNNOVATE trial, in which researchers compared ibrutinib plus rituximab to rituximab alone in patients with previously untreated or relapsed/refractory WM.

Results from iNNOVATE were presented at the 2018 annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology and simultaneously published in the New England Journal of Medicine (2018;378:2399-2410).

The 30-month progression-free survival rates were 82% in the ibrutinib arm and 28% in the placebo arm. The median progression-free survival was not reached in the ibrutinib arm and was 20.3 months in the placebo arm (hazard ratio, 0.20; P less than .0001).

The 30-month overall survival rates were 94% in the ibrutinib arm and 92% in the placebo arm.

Grade 3 or higher treatment-emergent adverse events (AEs) occurred in 60% of patients in the ibrutinib arm and 61% in the placebo arm. Serious AEs occurred in 43% and 33%, respectively. There were no fatal AEs in the ibrutinib arm and three in the rituximab arm.

Ibrutinib is jointly developed and commercialized by Pharmacyclics, an AbbVie company, and Janssen Biotech.

The Food and Drug Administration has approved ibrutinib (Imbruvica) for use in combination with rituximab to treat adults with Waldenström’s macroglobulinemia (WM).

Ibrutinib was approved for use as a single agent in adults with WM in January 2015.

The latest approval was supported by the phase 3 iNNOVATE trial, in which researchers compared ibrutinib plus rituximab to rituximab alone in patients with previously untreated or relapsed/refractory WM.

Results from iNNOVATE were presented at the 2018 annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology and simultaneously published in the New England Journal of Medicine (2018;378:2399-2410).

The 30-month progression-free survival rates were 82% in the ibrutinib arm and 28% in the placebo arm. The median progression-free survival was not reached in the ibrutinib arm and was 20.3 months in the placebo arm (hazard ratio, 0.20; P less than .0001).

The 30-month overall survival rates were 94% in the ibrutinib arm and 92% in the placebo arm.

Grade 3 or higher treatment-emergent adverse events (AEs) occurred in 60% of patients in the ibrutinib arm and 61% in the placebo arm. Serious AEs occurred in 43% and 33%, respectively. There were no fatal AEs in the ibrutinib arm and three in the rituximab arm.

Ibrutinib is jointly developed and commercialized by Pharmacyclics, an AbbVie company, and Janssen Biotech.

Nivolumab plus ipilimumab effective in melanoma brain metastases

Treatment with nivolumab plus ipilimumab resulted in clinically meaningful efficacy for melanoma patients with asymptomatic, previously untreated brain metastases, results of an open-label, multicenter, phase 2 study have shown.

The combination of these two immune checkpoint inhibitors produced intracranial responses in more than half of the patients treated, and perhaps more importantly, according to the study investigators, the combination treatment prevented intracranial progression for more than 6 months in 64% of the study population.

“These results are relevant in a population in whom progression can quickly result in substantial neurologic symptoms, functional impairment, and the need for glucocorticoid therapy,” the study investigators wrote in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The investigators, led by Hussein A. Tawbi, MD, PhD, of the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer, Houston, initially enrolled 101 patients with histologically confirmed melanoma and metastases to the brain that were asymptomatic. All patients had an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status of 0-1 and had not received systemic glucocorticoid therapy within 10 days of study treatment.

The primary endpoint of the study was the rate of intracranial benefit, defined as the percentage of patients with complete response, partial response, or stable disease for at least 6 months after starting treatment.

For 94 patients with at least 6 months of follow-up at the time of analysis (median follow-up, 14 months), the rate of intracranial benefit was 57%, including complete responses in 26%, partial responses in 30%, and stable disease in 2%, the investigators reported. The rate of extracranial benefit was similar, at 56%.

The 6-month rate of progression-free survival was 64.2% for intracranial assessments, while the 6-month overall survival rate was 92.3%, according to results of an initial assessment.

Grade 3 or 4 adverse events thought to be related to treatment occurred in 55% of patients and led to treatment discontinuation in 20%; the most common were increased levels of ALT and AST.

Dr. Tawbi and his colleagues said that, while cross-trial comparisons have inherent limitations, the rate of intracranial response seen in this trial is similar to what was seen in the COMBI-MB study of dabrafenib plus trametinib in patients with BRAF-mutant melanoma and brain metastases. However, in that study, published in 2017 in the Lancet, the combination of a BRAF inhibitor and MEK inhibitor had rates of intracranial response and progression-free survival that were “substantially shorter” than the rates of extracranial response and progression-free survival.

“In our study, the use of immunotherapy seemed capable of inducing intracranial responses that were very similar to extracranial responses in character, depth, and duration,” they wrote.

Dr. Tawbi and his coinvestigators enrolled an additional 20 symptomatic patients with brain metastases following a study protocol amendment; however, results from that cohort are not being reported yet because of inadequate follow-up length, they said.

The study was supported by Bristol-Myers Squibb and a grant from the National Cancer Institute. Dr. Tawbi reported disclosures related to Bristol-Myers Squibb, Merck, Genentech, and Novartis. His coauthors reported additional disclosures related to MedImmune, AstraZeneca, Dynavax Technologies, Genoptix, Exelixis, Acceleron Pharma, and Eisai, among others.

SOURCE: Tawbi HA et al. N Engl J Med. 2018 Aug 23. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1805453.

These data show that checkpoint inhibitors can be similarly effective in CNS metastases as they can be in extracranial metastases related to melanoma, according to Samra Turajlic, MD, PhD, and James Larkin, FRCP, PhD, of the Renal and Skin Units at the Royal Marsden National Health Service Foundation Trust in London.

Based on the study results, larger trials are warranted, including patients with CNS metastases from melanoma, kidney, lung, and other cancers where checkpoint inhibitors have demonstrated efficacy, Dr. Turajlic, who is also with the Translational Cancer Therapeutics Laboratory at the Francis Crick Institute in London, and Dr. Larkin wrote in an editorial.

“Such patients should no longer generally be excluded from clinical trials,” they wrote.

While the study by Dr. Tawbi and his colleagues was small, they added, its results are relevant to clinical practice because of the high rate of response, rapid response time, and side effect profile, which was manageable.

In fact, the nivolumab plus ipilimumab regimen described in this study should be considered first-line therapy for all patients who meet the study’s inclusion criteria, they asserted.

However, the results should “absolutely not” be extrapolated to higher-risk patients, such as those with leptomeningeal disease or with low performance status, which investigators excluded from the present study.

“There are good data showing that patients with cerebral metastases can be stratified into groups that have very different survival and morbidity,” Dr. Turajlic and Dr. Larkin wrote. “Caution is necessary until we have data across all the groups.”

These comment are based on an editorial in the New England Journal of Medicine (doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1807752) . Dr. Turajlic reported patents pending for an indel biomarker (PCT/GB2018/051893) and an indel therapeutic (PCT/GB2018/051892). Dr. Larkin reported disclosures related to Bristol-Myers Squibb, Novartis, Genentech, Pierre-Fabre, Incyte, and AstraZeneca.

These data show that checkpoint inhibitors can be similarly effective in CNS metastases as they can be in extracranial metastases related to melanoma, according to Samra Turajlic, MD, PhD, and James Larkin, FRCP, PhD, of the Renal and Skin Units at the Royal Marsden National Health Service Foundation Trust in London.

Based on the study results, larger trials are warranted, including patients with CNS metastases from melanoma, kidney, lung, and other cancers where checkpoint inhibitors have demonstrated efficacy, Dr. Turajlic, who is also with the Translational Cancer Therapeutics Laboratory at the Francis Crick Institute in London, and Dr. Larkin wrote in an editorial.

“Such patients should no longer generally be excluded from clinical trials,” they wrote.

While the study by Dr. Tawbi and his colleagues was small, they added, its results are relevant to clinical practice because of the high rate of response, rapid response time, and side effect profile, which was manageable.

In fact, the nivolumab plus ipilimumab regimen described in this study should be considered first-line therapy for all patients who meet the study’s inclusion criteria, they asserted.

However, the results should “absolutely not” be extrapolated to higher-risk patients, such as those with leptomeningeal disease or with low performance status, which investigators excluded from the present study.

“There are good data showing that patients with cerebral metastases can be stratified into groups that have very different survival and morbidity,” Dr. Turajlic and Dr. Larkin wrote. “Caution is necessary until we have data across all the groups.”

These comment are based on an editorial in the New England Journal of Medicine (doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1807752) . Dr. Turajlic reported patents pending for an indel biomarker (PCT/GB2018/051893) and an indel therapeutic (PCT/GB2018/051892). Dr. Larkin reported disclosures related to Bristol-Myers Squibb, Novartis, Genentech, Pierre-Fabre, Incyte, and AstraZeneca.

These data show that checkpoint inhibitors can be similarly effective in CNS metastases as they can be in extracranial metastases related to melanoma, according to Samra Turajlic, MD, PhD, and James Larkin, FRCP, PhD, of the Renal and Skin Units at the Royal Marsden National Health Service Foundation Trust in London.

Based on the study results, larger trials are warranted, including patients with CNS metastases from melanoma, kidney, lung, and other cancers where checkpoint inhibitors have demonstrated efficacy, Dr. Turajlic, who is also with the Translational Cancer Therapeutics Laboratory at the Francis Crick Institute in London, and Dr. Larkin wrote in an editorial.

“Such patients should no longer generally be excluded from clinical trials,” they wrote.

While the study by Dr. Tawbi and his colleagues was small, they added, its results are relevant to clinical practice because of the high rate of response, rapid response time, and side effect profile, which was manageable.

In fact, the nivolumab plus ipilimumab regimen described in this study should be considered first-line therapy for all patients who meet the study’s inclusion criteria, they asserted.

However, the results should “absolutely not” be extrapolated to higher-risk patients, such as those with leptomeningeal disease or with low performance status, which investigators excluded from the present study.

“There are good data showing that patients with cerebral metastases can be stratified into groups that have very different survival and morbidity,” Dr. Turajlic and Dr. Larkin wrote. “Caution is necessary until we have data across all the groups.”

These comment are based on an editorial in the New England Journal of Medicine (doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1807752) . Dr. Turajlic reported patents pending for an indel biomarker (PCT/GB2018/051893) and an indel therapeutic (PCT/GB2018/051892). Dr. Larkin reported disclosures related to Bristol-Myers Squibb, Novartis, Genentech, Pierre-Fabre, Incyte, and AstraZeneca.

Treatment with nivolumab plus ipilimumab resulted in clinically meaningful efficacy for melanoma patients with asymptomatic, previously untreated brain metastases, results of an open-label, multicenter, phase 2 study have shown.

The combination of these two immune checkpoint inhibitors produced intracranial responses in more than half of the patients treated, and perhaps more importantly, according to the study investigators, the combination treatment prevented intracranial progression for more than 6 months in 64% of the study population.

“These results are relevant in a population in whom progression can quickly result in substantial neurologic symptoms, functional impairment, and the need for glucocorticoid therapy,” the study investigators wrote in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The investigators, led by Hussein A. Tawbi, MD, PhD, of the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer, Houston, initially enrolled 101 patients with histologically confirmed melanoma and metastases to the brain that were asymptomatic. All patients had an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status of 0-1 and had not received systemic glucocorticoid therapy within 10 days of study treatment.

The primary endpoint of the study was the rate of intracranial benefit, defined as the percentage of patients with complete response, partial response, or stable disease for at least 6 months after starting treatment.

For 94 patients with at least 6 months of follow-up at the time of analysis (median follow-up, 14 months), the rate of intracranial benefit was 57%, including complete responses in 26%, partial responses in 30%, and stable disease in 2%, the investigators reported. The rate of extracranial benefit was similar, at 56%.

The 6-month rate of progression-free survival was 64.2% for intracranial assessments, while the 6-month overall survival rate was 92.3%, according to results of an initial assessment.

Grade 3 or 4 adverse events thought to be related to treatment occurred in 55% of patients and led to treatment discontinuation in 20%; the most common were increased levels of ALT and AST.

Dr. Tawbi and his colleagues said that, while cross-trial comparisons have inherent limitations, the rate of intracranial response seen in this trial is similar to what was seen in the COMBI-MB study of dabrafenib plus trametinib in patients with BRAF-mutant melanoma and brain metastases. However, in that study, published in 2017 in the Lancet, the combination of a BRAF inhibitor and MEK inhibitor had rates of intracranial response and progression-free survival that were “substantially shorter” than the rates of extracranial response and progression-free survival.

“In our study, the use of immunotherapy seemed capable of inducing intracranial responses that were very similar to extracranial responses in character, depth, and duration,” they wrote.

Dr. Tawbi and his coinvestigators enrolled an additional 20 symptomatic patients with brain metastases following a study protocol amendment; however, results from that cohort are not being reported yet because of inadequate follow-up length, they said.

The study was supported by Bristol-Myers Squibb and a grant from the National Cancer Institute. Dr. Tawbi reported disclosures related to Bristol-Myers Squibb, Merck, Genentech, and Novartis. His coauthors reported additional disclosures related to MedImmune, AstraZeneca, Dynavax Technologies, Genoptix, Exelixis, Acceleron Pharma, and Eisai, among others.

SOURCE: Tawbi HA et al. N Engl J Med. 2018 Aug 23. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1805453.

Treatment with nivolumab plus ipilimumab resulted in clinically meaningful efficacy for melanoma patients with asymptomatic, previously untreated brain metastases, results of an open-label, multicenter, phase 2 study have shown.

The combination of these two immune checkpoint inhibitors produced intracranial responses in more than half of the patients treated, and perhaps more importantly, according to the study investigators, the combination treatment prevented intracranial progression for more than 6 months in 64% of the study population.

“These results are relevant in a population in whom progression can quickly result in substantial neurologic symptoms, functional impairment, and the need for glucocorticoid therapy,” the study investigators wrote in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The investigators, led by Hussein A. Tawbi, MD, PhD, of the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer, Houston, initially enrolled 101 patients with histologically confirmed melanoma and metastases to the brain that were asymptomatic. All patients had an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status of 0-1 and had not received systemic glucocorticoid therapy within 10 days of study treatment.

The primary endpoint of the study was the rate of intracranial benefit, defined as the percentage of patients with complete response, partial response, or stable disease for at least 6 months after starting treatment.

For 94 patients with at least 6 months of follow-up at the time of analysis (median follow-up, 14 months), the rate of intracranial benefit was 57%, including complete responses in 26%, partial responses in 30%, and stable disease in 2%, the investigators reported. The rate of extracranial benefit was similar, at 56%.

The 6-month rate of progression-free survival was 64.2% for intracranial assessments, while the 6-month overall survival rate was 92.3%, according to results of an initial assessment.

Grade 3 or 4 adverse events thought to be related to treatment occurred in 55% of patients and led to treatment discontinuation in 20%; the most common were increased levels of ALT and AST.