User login

Testosterone Replacement May Cause ... Fracture?

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

I am showing you a graph without any labels.

What could this line represent? The stock price of some company that made a big splash but failed to live up to expectations? An outbreak curve charting the introduction of a new infectious agent to a population? The performance of a viral tweet?

I’ll tell you what it is in a moment, but I wanted you to recognize that there is something inherently wistful in this shape, something that speaks of past glory and inevitable declines. It’s a graph that induces a feeling of resistance — no, do not go gently into that good night.

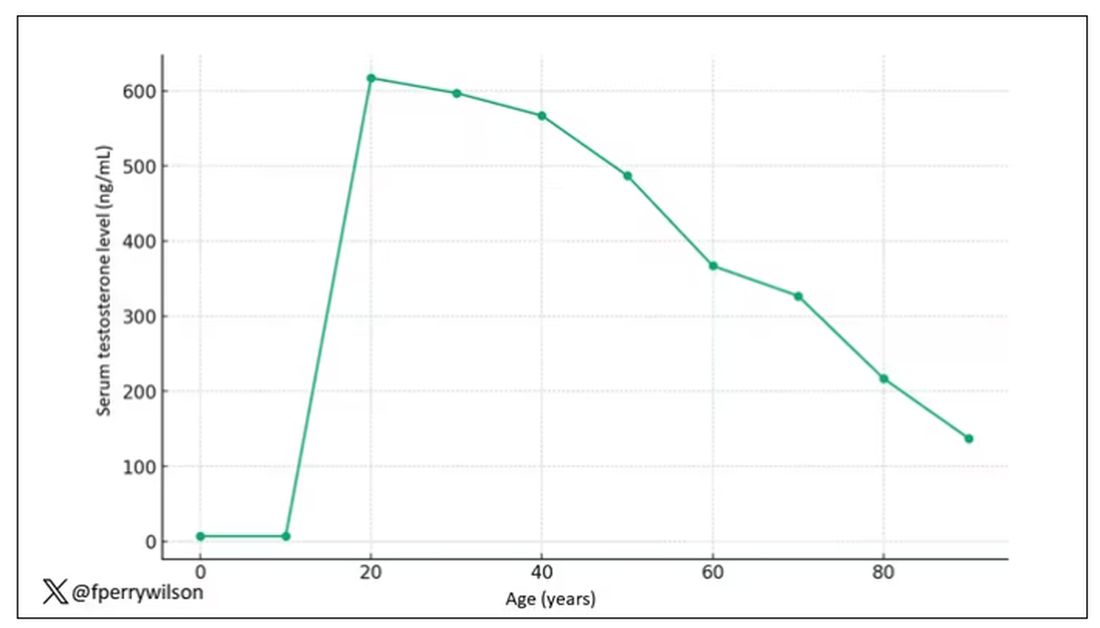

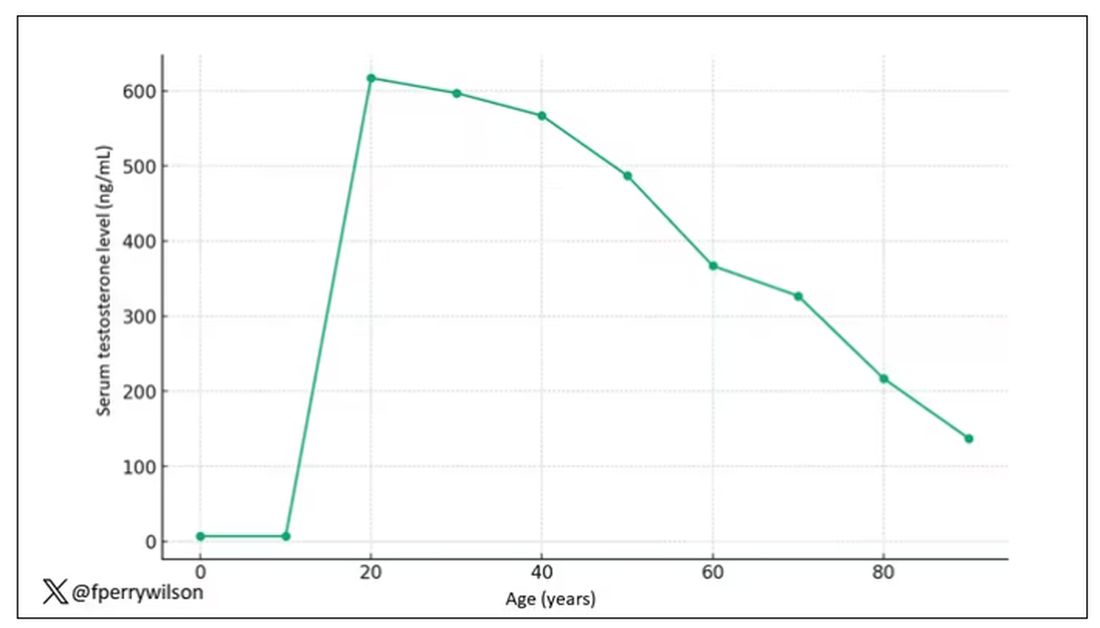

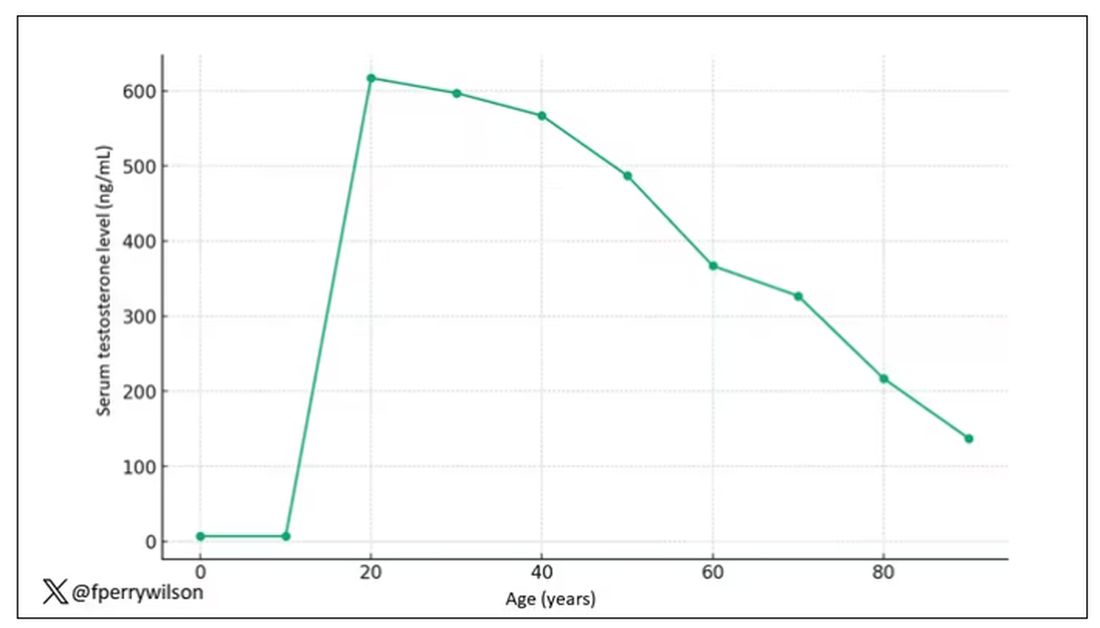

The graph actually represents (roughly) the normal level of serum testosterone in otherwise-healthy men as they age.

A caveat here: These numbers are not as well defined as I made them seem on this graph, particularly for those older than 65 years. But it is clear that testosterone levels decline with time, and the idea to supplement testosterone is hardly new. Like all treatments, testosterone supplementation has risks and benefits. Some risks are predictable, like exacerbating the symptoms of benign prostatic hyperplasia. Some risks seem to come completely out of left field. That’s what we have today, in a study suggesting that testosterone supplementation increases the risk for bone fractures.

Let me set the stage here by saying that nearly all prior research into the effects of testosterone supplementation has suggested that it is pretty good for bone health. It increases bone mineral density, bone strength, and improves bone architecture.

So if you were to do a randomized trial of testosterone supplementation and look at fracture risk in the testosterone group compared with the placebo group, you would expect the fracture risk would be much lower in those getting supplemented. Of course, this is why we actually do studies instead of assuming we know the answer already — because in this case, you’d be wrong.

I’m talking about this study, appearing in The New England Journal of Medicine.

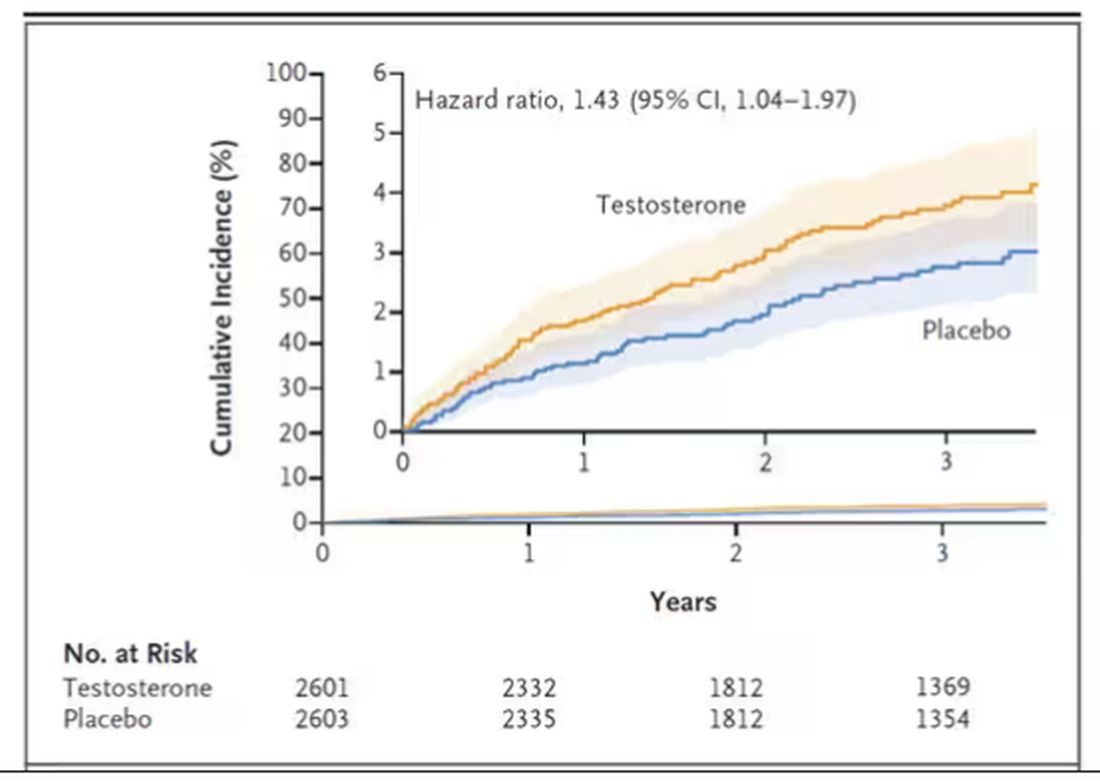

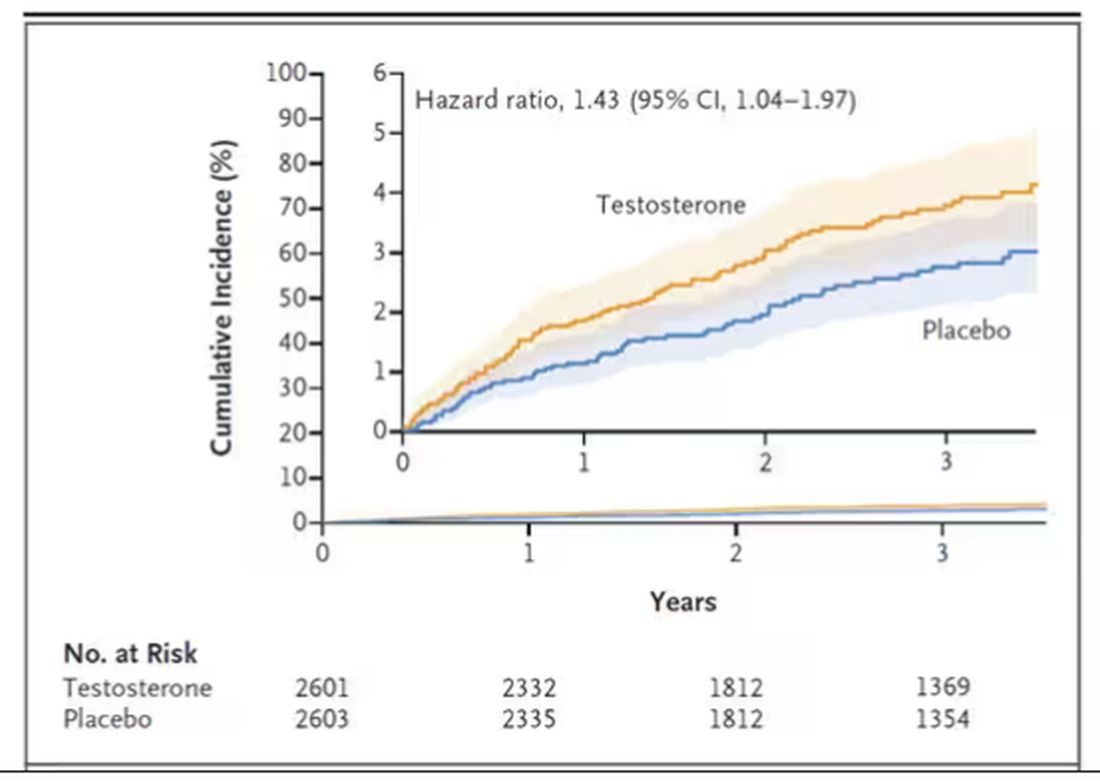

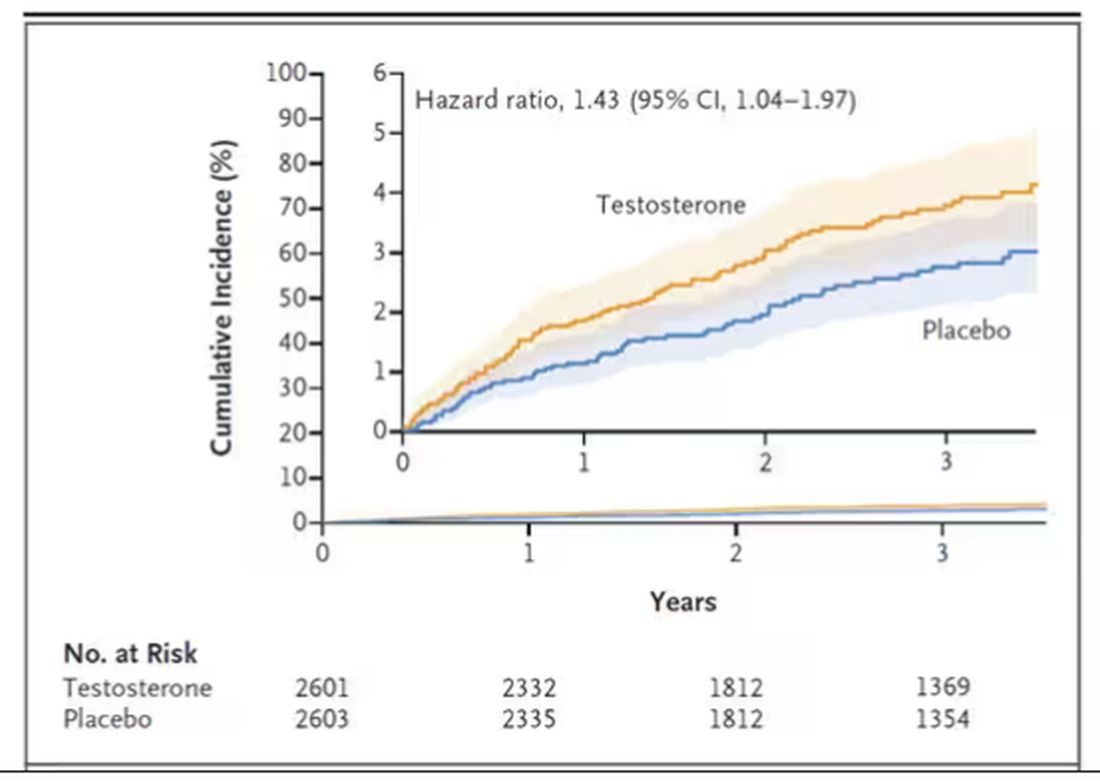

It’s a prespecified secondary analysis of a randomized trial known as the TRAVERSE trial, which randomly assigned 5246 men with low testosterone levels to transdermal testosterone gel vs placebo. The primary goal of that trial was to assess the cardiovascular risk associated with testosterone supplementation, and the major take-home was that there was no difference in cardiovascular event rates between the testosterone and placebo groups.

This secondary analysis looked at fracture incidence. Researchers contacted participants multiple times in the first year of the study and yearly thereafter. Each time, they asked whether the participant had sustained a fracture. If they answered in the affirmative, a request for medical records was made and the researchers, still blinded to randomization status, adjudicated whether there was indeed a fracture or not, along with some details as to location, situation, and so on.

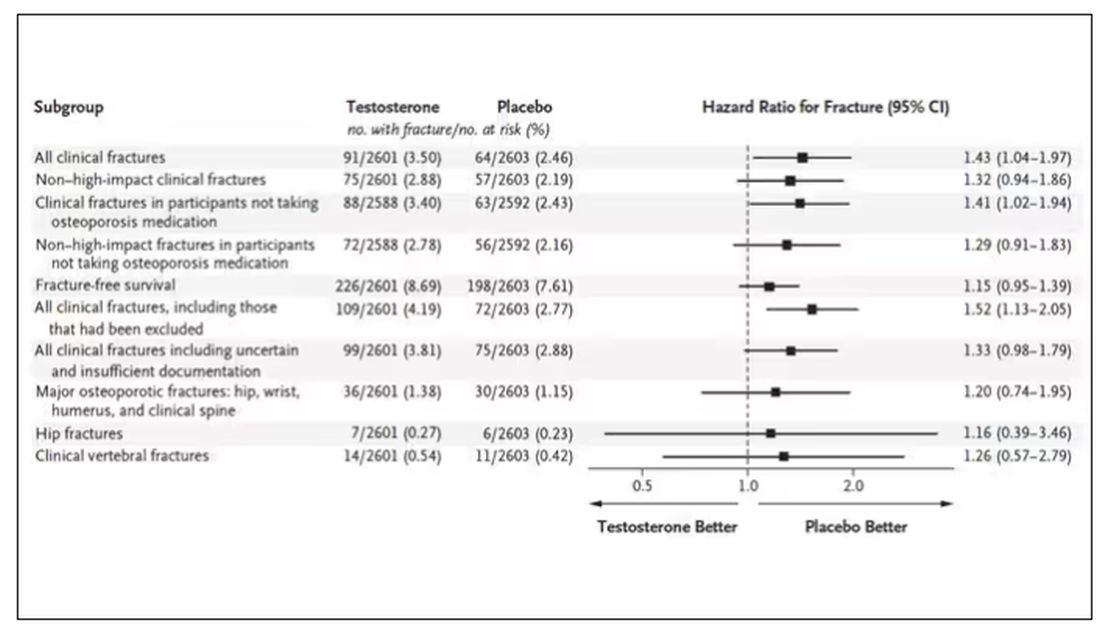

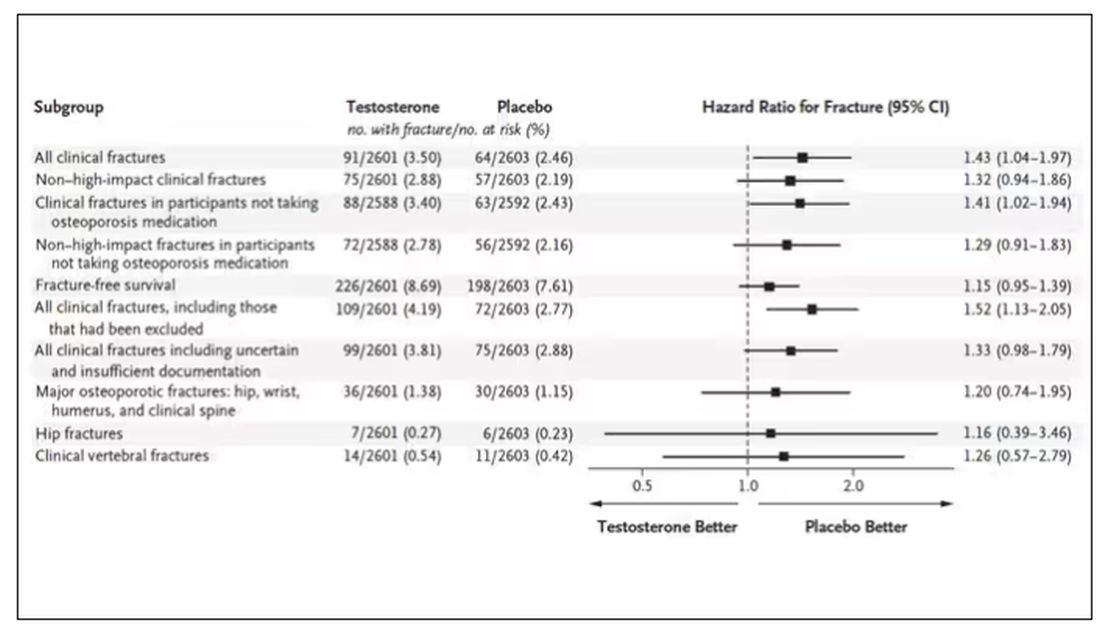

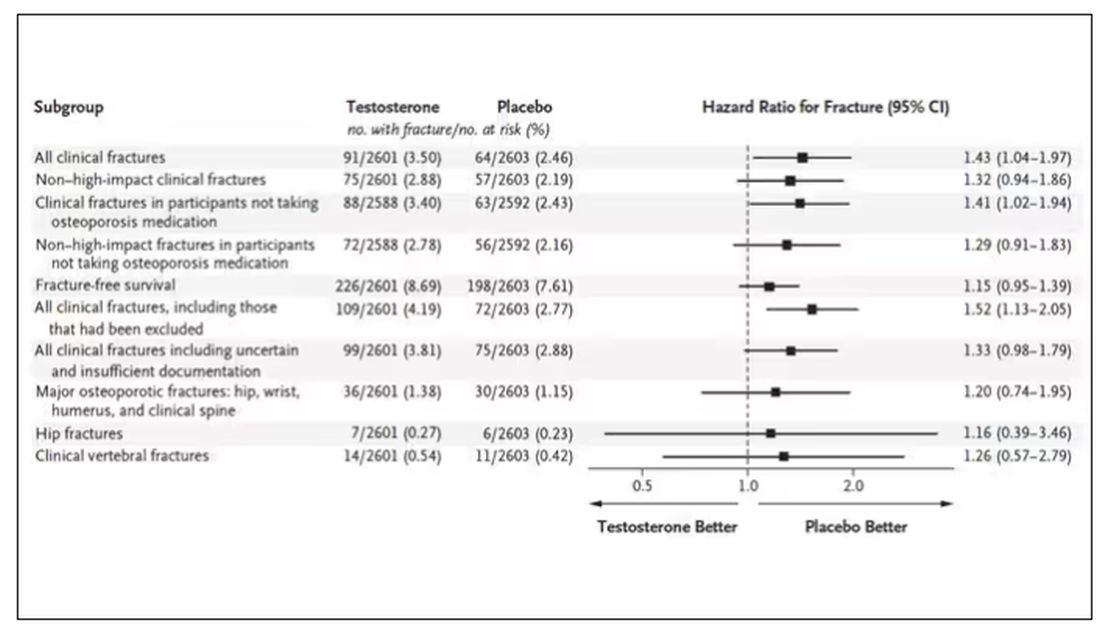

This was a big study, though, and that translates to just a 3.5% fracture rate in testosterone vs 2.5% in control, but the difference was statistically significant.

This difference persisted across various fracture types (non–high-impact fractures, for example) after excluding the small percentage of men taking osteoporosis medication.

How does a drug that increases bone mineral density and bone strength increase the risk for fracture?

Well, one clue — and this was pointed out in a nice editorial by Matthis Grossman and Bradley Anawalt — is that the increased risk for fracture occurs quite soon after starting treatment, which is not consistent with direct bone effects. Rather, this might represent behavioral differences. Testosterone supplementation seems to increase energy levels; might it lead men to engage in activities that put them at higher risk for fracture?

Regardless of the cause, this adds to our knowledge about the rather complex mix of risks and benefits of testosterone supplementation and probably puts a bit more weight on the risks side. The truth is that testosterone levels do decline with age, as do many things, and it may not be appropriate to try to fight against that in all people. It’s worth noting that all of these studies use low levels of total serum testosterone as an entry criterion. But total testosterone is not what your body “sees.” It sees free testosterone, the portion not bound to sex hormone–binding globulin. And that binding protein is affected by lots of stuff — diabetes and obesity lower it, for example — making total testosterone levels seem low when free testosterone might be just fine.

In other words, testosterone supplementation is probably not terrible, but it is definitely not the cure for aging. In situations like this, we need better data to guide exactly who will benefit from the therapy and who will only be exposed to the risks.

Dr. Wilson is associate professor of medicine and public health and director of the Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator at Yale University, New Haven, Conn. He has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

I am showing you a graph without any labels.

What could this line represent? The stock price of some company that made a big splash but failed to live up to expectations? An outbreak curve charting the introduction of a new infectious agent to a population? The performance of a viral tweet?

I’ll tell you what it is in a moment, but I wanted you to recognize that there is something inherently wistful in this shape, something that speaks of past glory and inevitable declines. It’s a graph that induces a feeling of resistance — no, do not go gently into that good night.

The graph actually represents (roughly) the normal level of serum testosterone in otherwise-healthy men as they age.

A caveat here: These numbers are not as well defined as I made them seem on this graph, particularly for those older than 65 years. But it is clear that testosterone levels decline with time, and the idea to supplement testosterone is hardly new. Like all treatments, testosterone supplementation has risks and benefits. Some risks are predictable, like exacerbating the symptoms of benign prostatic hyperplasia. Some risks seem to come completely out of left field. That’s what we have today, in a study suggesting that testosterone supplementation increases the risk for bone fractures.

Let me set the stage here by saying that nearly all prior research into the effects of testosterone supplementation has suggested that it is pretty good for bone health. It increases bone mineral density, bone strength, and improves bone architecture.

So if you were to do a randomized trial of testosterone supplementation and look at fracture risk in the testosterone group compared with the placebo group, you would expect the fracture risk would be much lower in those getting supplemented. Of course, this is why we actually do studies instead of assuming we know the answer already — because in this case, you’d be wrong.

I’m talking about this study, appearing in The New England Journal of Medicine.

It’s a prespecified secondary analysis of a randomized trial known as the TRAVERSE trial, which randomly assigned 5246 men with low testosterone levels to transdermal testosterone gel vs placebo. The primary goal of that trial was to assess the cardiovascular risk associated with testosterone supplementation, and the major take-home was that there was no difference in cardiovascular event rates between the testosterone and placebo groups.

This secondary analysis looked at fracture incidence. Researchers contacted participants multiple times in the first year of the study and yearly thereafter. Each time, they asked whether the participant had sustained a fracture. If they answered in the affirmative, a request for medical records was made and the researchers, still blinded to randomization status, adjudicated whether there was indeed a fracture or not, along with some details as to location, situation, and so on.

This was a big study, though, and that translates to just a 3.5% fracture rate in testosterone vs 2.5% in control, but the difference was statistically significant.

This difference persisted across various fracture types (non–high-impact fractures, for example) after excluding the small percentage of men taking osteoporosis medication.

How does a drug that increases bone mineral density and bone strength increase the risk for fracture?

Well, one clue — and this was pointed out in a nice editorial by Matthis Grossman and Bradley Anawalt — is that the increased risk for fracture occurs quite soon after starting treatment, which is not consistent with direct bone effects. Rather, this might represent behavioral differences. Testosterone supplementation seems to increase energy levels; might it lead men to engage in activities that put them at higher risk for fracture?

Regardless of the cause, this adds to our knowledge about the rather complex mix of risks and benefits of testosterone supplementation and probably puts a bit more weight on the risks side. The truth is that testosterone levels do decline with age, as do many things, and it may not be appropriate to try to fight against that in all people. It’s worth noting that all of these studies use low levels of total serum testosterone as an entry criterion. But total testosterone is not what your body “sees.” It sees free testosterone, the portion not bound to sex hormone–binding globulin. And that binding protein is affected by lots of stuff — diabetes and obesity lower it, for example — making total testosterone levels seem low when free testosterone might be just fine.

In other words, testosterone supplementation is probably not terrible, but it is definitely not the cure for aging. In situations like this, we need better data to guide exactly who will benefit from the therapy and who will only be exposed to the risks.

Dr. Wilson is associate professor of medicine and public health and director of the Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator at Yale University, New Haven, Conn. He has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

I am showing you a graph without any labels.

What could this line represent? The stock price of some company that made a big splash but failed to live up to expectations? An outbreak curve charting the introduction of a new infectious agent to a population? The performance of a viral tweet?

I’ll tell you what it is in a moment, but I wanted you to recognize that there is something inherently wistful in this shape, something that speaks of past glory and inevitable declines. It’s a graph that induces a feeling of resistance — no, do not go gently into that good night.

The graph actually represents (roughly) the normal level of serum testosterone in otherwise-healthy men as they age.

A caveat here: These numbers are not as well defined as I made them seem on this graph, particularly for those older than 65 years. But it is clear that testosterone levels decline with time, and the idea to supplement testosterone is hardly new. Like all treatments, testosterone supplementation has risks and benefits. Some risks are predictable, like exacerbating the symptoms of benign prostatic hyperplasia. Some risks seem to come completely out of left field. That’s what we have today, in a study suggesting that testosterone supplementation increases the risk for bone fractures.

Let me set the stage here by saying that nearly all prior research into the effects of testosterone supplementation has suggested that it is pretty good for bone health. It increases bone mineral density, bone strength, and improves bone architecture.

So if you were to do a randomized trial of testosterone supplementation and look at fracture risk in the testosterone group compared with the placebo group, you would expect the fracture risk would be much lower in those getting supplemented. Of course, this is why we actually do studies instead of assuming we know the answer already — because in this case, you’d be wrong.

I’m talking about this study, appearing in The New England Journal of Medicine.

It’s a prespecified secondary analysis of a randomized trial known as the TRAVERSE trial, which randomly assigned 5246 men with low testosterone levels to transdermal testosterone gel vs placebo. The primary goal of that trial was to assess the cardiovascular risk associated with testosterone supplementation, and the major take-home was that there was no difference in cardiovascular event rates between the testosterone and placebo groups.

This secondary analysis looked at fracture incidence. Researchers contacted participants multiple times in the first year of the study and yearly thereafter. Each time, they asked whether the participant had sustained a fracture. If they answered in the affirmative, a request for medical records was made and the researchers, still blinded to randomization status, adjudicated whether there was indeed a fracture or not, along with some details as to location, situation, and so on.

This was a big study, though, and that translates to just a 3.5% fracture rate in testosterone vs 2.5% in control, but the difference was statistically significant.

This difference persisted across various fracture types (non–high-impact fractures, for example) after excluding the small percentage of men taking osteoporosis medication.

How does a drug that increases bone mineral density and bone strength increase the risk for fracture?

Well, one clue — and this was pointed out in a nice editorial by Matthis Grossman and Bradley Anawalt — is that the increased risk for fracture occurs quite soon after starting treatment, which is not consistent with direct bone effects. Rather, this might represent behavioral differences. Testosterone supplementation seems to increase energy levels; might it lead men to engage in activities that put them at higher risk for fracture?

Regardless of the cause, this adds to our knowledge about the rather complex mix of risks and benefits of testosterone supplementation and probably puts a bit more weight on the risks side. The truth is that testosterone levels do decline with age, as do many things, and it may not be appropriate to try to fight against that in all people. It’s worth noting that all of these studies use low levels of total serum testosterone as an entry criterion. But total testosterone is not what your body “sees.” It sees free testosterone, the portion not bound to sex hormone–binding globulin. And that binding protein is affected by lots of stuff — diabetes and obesity lower it, for example — making total testosterone levels seem low when free testosterone might be just fine.

In other words, testosterone supplementation is probably not terrible, but it is definitely not the cure for aging. In situations like this, we need better data to guide exactly who will benefit from the therapy and who will only be exposed to the risks.

Dr. Wilson is associate professor of medicine and public health and director of the Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator at Yale University, New Haven, Conn. He has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Smoking Associated With Increased Risk for Hair Loss Among Men

, according to a new study.

In addition, the odds of developing AGA are higher among those who smoke at least 10 cigarettes per day than among those who smoke less, the study authors found.

“Men who smoke are more likely to develop and experience progression of male pattern hair loss,” lead author Aditya Gupta, MD, PhD, professor of medicine at the University of Toronto, Toronto, and director of clinical research at Mediprobe Research Inc., London, Ontario, Canada, told this news organization.

“Our patients with male pattern baldness need to be educated about the negative effects of smoking, given that this condition can have a profound negative psychological impact on those who suffer from it,” he said.

The study was published online in the Journal of Cosmetic Dermatology.

Analyzing Smoking’s Effects

Smoking generally has been accepted as a risk factor for the development and progression of AGA or the most common form of hair loss. The research evidence on this association has been inconsistent, however, the authors wrote.

The investigators conducted a review and meta-analysis of eight observational studies to understand the links between smoking and AGA. Ever-smokers were defined as current and former smokers.

Overall, based on six studies, men who have ever smoked are 1.8 times more likely (P < .05) to develop AGA.

Based on two studies, men who smoke 10 or more cigarettes daily are about twice as likely (P < .05) to develop AGA than those who smoke up to 10 cigarettes per day.

Based on four studies, ever smoking is associated with 1.3 times higher odds of AGA progressing from mild (ie, Norwood-Hamilton stages I-III) to more severe (stages IV-VII) than among those who have never smoked.

Based on two studies, there’s no association between AGA progression and smoking intensity (as defined as smoking up to 20 cigarettes daily vs smoking 20 or more cigarettes per day).

“Though our pooled analysis found no significant association between smoking intensity and severity of male AGA, a positive correlation may exist and be detected through an analysis that is statistically better powered,” said Dr. Gupta.

The investigators noted the limitations of their analysis, such as its reliance on observational studies and its lack of data about nicotine levels, smoking intensity, and smoking cessation among study participants.

Additional studies are needed to better understand the links between smoking and hair loss, said Dr. Gupta, as well as the effects of smoking cessation.

Improving Practice and Research

Commenting on the findings for this news organization, Arash Babadjouni, MD, a dermatologist at Midwestern University, Glendale, Arizona, said, “Smoking is not only a preventable cause of significant systemic disease but also affects the follicular growth cycle and fiber pigmentation. The prevalence of hair loss and premature hair graying is higher in smokers than nonsmokers.”

Dr. Babadjouni, who wasn’t involved with this study, has researched the associations between smoking and hair loss and premature hair graying.

“Evidence of this association can be used to clinically promote smoking cessation and emphasize the consequences of smoking on hair,” he said. “Smoking status should be assessed in patients who are presenting to their dermatologist and physicians alike for evaluation of alopecia and premature hair graying.”

The study was conducted without outside funding, and the authors declared no conflicts of interest. Dr. Babadjouni reported no relevant disclosures.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

, according to a new study.

In addition, the odds of developing AGA are higher among those who smoke at least 10 cigarettes per day than among those who smoke less, the study authors found.

“Men who smoke are more likely to develop and experience progression of male pattern hair loss,” lead author Aditya Gupta, MD, PhD, professor of medicine at the University of Toronto, Toronto, and director of clinical research at Mediprobe Research Inc., London, Ontario, Canada, told this news organization.

“Our patients with male pattern baldness need to be educated about the negative effects of smoking, given that this condition can have a profound negative psychological impact on those who suffer from it,” he said.

The study was published online in the Journal of Cosmetic Dermatology.

Analyzing Smoking’s Effects

Smoking generally has been accepted as a risk factor for the development and progression of AGA or the most common form of hair loss. The research evidence on this association has been inconsistent, however, the authors wrote.

The investigators conducted a review and meta-analysis of eight observational studies to understand the links between smoking and AGA. Ever-smokers were defined as current and former smokers.

Overall, based on six studies, men who have ever smoked are 1.8 times more likely (P < .05) to develop AGA.

Based on two studies, men who smoke 10 or more cigarettes daily are about twice as likely (P < .05) to develop AGA than those who smoke up to 10 cigarettes per day.

Based on four studies, ever smoking is associated with 1.3 times higher odds of AGA progressing from mild (ie, Norwood-Hamilton stages I-III) to more severe (stages IV-VII) than among those who have never smoked.

Based on two studies, there’s no association between AGA progression and smoking intensity (as defined as smoking up to 20 cigarettes daily vs smoking 20 or more cigarettes per day).

“Though our pooled analysis found no significant association between smoking intensity and severity of male AGA, a positive correlation may exist and be detected through an analysis that is statistically better powered,” said Dr. Gupta.

The investigators noted the limitations of their analysis, such as its reliance on observational studies and its lack of data about nicotine levels, smoking intensity, and smoking cessation among study participants.

Additional studies are needed to better understand the links between smoking and hair loss, said Dr. Gupta, as well as the effects of smoking cessation.

Improving Practice and Research

Commenting on the findings for this news organization, Arash Babadjouni, MD, a dermatologist at Midwestern University, Glendale, Arizona, said, “Smoking is not only a preventable cause of significant systemic disease but also affects the follicular growth cycle and fiber pigmentation. The prevalence of hair loss and premature hair graying is higher in smokers than nonsmokers.”

Dr. Babadjouni, who wasn’t involved with this study, has researched the associations between smoking and hair loss and premature hair graying.

“Evidence of this association can be used to clinically promote smoking cessation and emphasize the consequences of smoking on hair,” he said. “Smoking status should be assessed in patients who are presenting to their dermatologist and physicians alike for evaluation of alopecia and premature hair graying.”

The study was conducted without outside funding, and the authors declared no conflicts of interest. Dr. Babadjouni reported no relevant disclosures.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

, according to a new study.

In addition, the odds of developing AGA are higher among those who smoke at least 10 cigarettes per day than among those who smoke less, the study authors found.

“Men who smoke are more likely to develop and experience progression of male pattern hair loss,” lead author Aditya Gupta, MD, PhD, professor of medicine at the University of Toronto, Toronto, and director of clinical research at Mediprobe Research Inc., London, Ontario, Canada, told this news organization.

“Our patients with male pattern baldness need to be educated about the negative effects of smoking, given that this condition can have a profound negative psychological impact on those who suffer from it,” he said.

The study was published online in the Journal of Cosmetic Dermatology.

Analyzing Smoking’s Effects

Smoking generally has been accepted as a risk factor for the development and progression of AGA or the most common form of hair loss. The research evidence on this association has been inconsistent, however, the authors wrote.

The investigators conducted a review and meta-analysis of eight observational studies to understand the links between smoking and AGA. Ever-smokers were defined as current and former smokers.

Overall, based on six studies, men who have ever smoked are 1.8 times more likely (P < .05) to develop AGA.

Based on two studies, men who smoke 10 or more cigarettes daily are about twice as likely (P < .05) to develop AGA than those who smoke up to 10 cigarettes per day.

Based on four studies, ever smoking is associated with 1.3 times higher odds of AGA progressing from mild (ie, Norwood-Hamilton stages I-III) to more severe (stages IV-VII) than among those who have never smoked.

Based on two studies, there’s no association between AGA progression and smoking intensity (as defined as smoking up to 20 cigarettes daily vs smoking 20 or more cigarettes per day).

“Though our pooled analysis found no significant association between smoking intensity and severity of male AGA, a positive correlation may exist and be detected through an analysis that is statistically better powered,” said Dr. Gupta.

The investigators noted the limitations of their analysis, such as its reliance on observational studies and its lack of data about nicotine levels, smoking intensity, and smoking cessation among study participants.

Additional studies are needed to better understand the links between smoking and hair loss, said Dr. Gupta, as well as the effects of smoking cessation.

Improving Practice and Research

Commenting on the findings for this news organization, Arash Babadjouni, MD, a dermatologist at Midwestern University, Glendale, Arizona, said, “Smoking is not only a preventable cause of significant systemic disease but also affects the follicular growth cycle and fiber pigmentation. The prevalence of hair loss and premature hair graying is higher in smokers than nonsmokers.”

Dr. Babadjouni, who wasn’t involved with this study, has researched the associations between smoking and hair loss and premature hair graying.

“Evidence of this association can be used to clinically promote smoking cessation and emphasize the consequences of smoking on hair,” he said. “Smoking status should be assessed in patients who are presenting to their dermatologist and physicians alike for evaluation of alopecia and premature hair graying.”

The study was conducted without outside funding, and the authors declared no conflicts of interest. Dr. Babadjouni reported no relevant disclosures.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF COSMETIC DERMATOLOGY

Spotting Varicocele: A Common Cause of Male Infertility

The report from the 2023 annual conference of French Urology Association (AFU), which was dedicated to male fertility, focused heavily on the diagnosis and treatment of varicocele, the most common reversible cause of infertility in men. Long a controversial subject, it has now been determined that treating this condition improves sperm analysis results, spontaneous fertility, and outcomes from medically assisted reproduction techniques. The AFU’s conference was a chance to present an overall snapshot of the issue.

Between 1973 and 2018, male sperm concentration dropped by 51.6% around the world, whereas total sperm counts dropped by 62.3%, according to Charlotte Methorst, MD, urological surgeon in Saint Cloud, France, president of the French Language Andrology Society, and coordinator of the AFU 2023 Report on Male Fertility. What’s more,

Declining Fertility

Nowadays, around 15% of couples experience infertility (60,000 new cases/year in France). About 20% of these are strictly attributed to male infertility and 40% are mixed, implying a male factor. Consequently, Dr. Methorst explained that “we must routinely assess male fertility within the context of a medically assisted reproduction (MAR) pathway, without limiting testing to semen analysis. Varicocele, one of the causes of infertility that men should be screened for and defined as an abnormal and/or tortuous enlargement of the pampiniform plexus veins, is present in 15%-20% of the overall male population, 35% of men with primary infertility, and more than 70% of those experiencing secondary infertility.”

In infertile men, varicocele is mostly unilateral, occurring on the left side (85%-90% of cases). A link has been established between varicocele and insufficiency at the saphenofemoral junction, as well as venous insufficiency of the lower limbs (odds ratio, 2.34; P < .0001), suggesting a predisposition towards a vascular network favoring the presence of varicoceles.

Varicocele Underdiagnosed

Analysis of a large multicenter database recently suggested the underdiagnosis of varicocele in men being assessed for infertility. Diagnosis is primarily based on physical examination, with physicians finding a soft, serpiginous swelling in the upper and posterior part of the affected side of the scrotum. Testicular Doppler ultrasonography provides confirmation of a varicocele, taking into account aspects such as size and reflux duration during the Valsalva maneuver. Generally, this is enough to make a differential diagnosis, but MRI may be considered, especially in cases where a millimeter-sized nodule is also found.

Reversal Improves Fertility

A Cochrane meta-analysis, despite containing significant bias, raised doubts about the efficacy of varicocele treatment. Nevertheless, over the past 10 years, a randomized trial and several meta-analyses have put an end to the controversy, confirming that treatment for varicocele significantly improves natural pregnancy rates.

Microscopic subinguinal varicocelectomy is the gold-standard option for cases of clinical varicocele and for those in which sperm analysis findings are abnormal. This approach is associated with superior efficacy outcomes, such as improvement in sperm analysis results and pregnancy rates while leading to lower rates of recurrence (< 4%) and a favorable outcome in terms of complications. It should be noted that treating subclinical varicocele is not recommended.

Specifically, microscopic subinguinal varicocelectomy improves live birth and pregnancy rates, both naturally and via in vitro fertilization. What’s more, it has a positive impact on sperm count, total and progressive motility, morphology, and DNA fragmentation levels. Overall, this surgery changes the MAR approach used in around one in two cases. The grade and unilateral or bilateral nature of varicocele are important predictive factors of improvement in sperm analysis findings and pregnancy rates associated with this interventional procedure. Treating clinical varicocele (grades 1-3) leads to improved sperm analysis results, observed in 60%-70% of cases. According to a meta-analysis, the mean increase is said to be a concentration of 12 million spermatozoids per milliliter, as well as a mean improvement of 11% in sperm motility.

Notably, embolization can be considered as an alternative to surgery. This minimally invasive X-ray-guided procedure performed by an interventional radiologist attempts to block the dilated testicular vein.

Guidelines for clinical practice in treating varicocele were recently published by the AFU’s Andrology committee.

This article was translated from the Medscape French edition. A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

The report from the 2023 annual conference of French Urology Association (AFU), which was dedicated to male fertility, focused heavily on the diagnosis and treatment of varicocele, the most common reversible cause of infertility in men. Long a controversial subject, it has now been determined that treating this condition improves sperm analysis results, spontaneous fertility, and outcomes from medically assisted reproduction techniques. The AFU’s conference was a chance to present an overall snapshot of the issue.

Between 1973 and 2018, male sperm concentration dropped by 51.6% around the world, whereas total sperm counts dropped by 62.3%, according to Charlotte Methorst, MD, urological surgeon in Saint Cloud, France, president of the French Language Andrology Society, and coordinator of the AFU 2023 Report on Male Fertility. What’s more,

Declining Fertility

Nowadays, around 15% of couples experience infertility (60,000 new cases/year in France). About 20% of these are strictly attributed to male infertility and 40% are mixed, implying a male factor. Consequently, Dr. Methorst explained that “we must routinely assess male fertility within the context of a medically assisted reproduction (MAR) pathway, without limiting testing to semen analysis. Varicocele, one of the causes of infertility that men should be screened for and defined as an abnormal and/or tortuous enlargement of the pampiniform plexus veins, is present in 15%-20% of the overall male population, 35% of men with primary infertility, and more than 70% of those experiencing secondary infertility.”

In infertile men, varicocele is mostly unilateral, occurring on the left side (85%-90% of cases). A link has been established between varicocele and insufficiency at the saphenofemoral junction, as well as venous insufficiency of the lower limbs (odds ratio, 2.34; P < .0001), suggesting a predisposition towards a vascular network favoring the presence of varicoceles.

Varicocele Underdiagnosed

Analysis of a large multicenter database recently suggested the underdiagnosis of varicocele in men being assessed for infertility. Diagnosis is primarily based on physical examination, with physicians finding a soft, serpiginous swelling in the upper and posterior part of the affected side of the scrotum. Testicular Doppler ultrasonography provides confirmation of a varicocele, taking into account aspects such as size and reflux duration during the Valsalva maneuver. Generally, this is enough to make a differential diagnosis, but MRI may be considered, especially in cases where a millimeter-sized nodule is also found.

Reversal Improves Fertility

A Cochrane meta-analysis, despite containing significant bias, raised doubts about the efficacy of varicocele treatment. Nevertheless, over the past 10 years, a randomized trial and several meta-analyses have put an end to the controversy, confirming that treatment for varicocele significantly improves natural pregnancy rates.

Microscopic subinguinal varicocelectomy is the gold-standard option for cases of clinical varicocele and for those in which sperm analysis findings are abnormal. This approach is associated with superior efficacy outcomes, such as improvement in sperm analysis results and pregnancy rates while leading to lower rates of recurrence (< 4%) and a favorable outcome in terms of complications. It should be noted that treating subclinical varicocele is not recommended.

Specifically, microscopic subinguinal varicocelectomy improves live birth and pregnancy rates, both naturally and via in vitro fertilization. What’s more, it has a positive impact on sperm count, total and progressive motility, morphology, and DNA fragmentation levels. Overall, this surgery changes the MAR approach used in around one in two cases. The grade and unilateral or bilateral nature of varicocele are important predictive factors of improvement in sperm analysis findings and pregnancy rates associated with this interventional procedure. Treating clinical varicocele (grades 1-3) leads to improved sperm analysis results, observed in 60%-70% of cases. According to a meta-analysis, the mean increase is said to be a concentration of 12 million spermatozoids per milliliter, as well as a mean improvement of 11% in sperm motility.

Notably, embolization can be considered as an alternative to surgery. This minimally invasive X-ray-guided procedure performed by an interventional radiologist attempts to block the dilated testicular vein.

Guidelines for clinical practice in treating varicocele were recently published by the AFU’s Andrology committee.

This article was translated from the Medscape French edition. A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

The report from the 2023 annual conference of French Urology Association (AFU), which was dedicated to male fertility, focused heavily on the diagnosis and treatment of varicocele, the most common reversible cause of infertility in men. Long a controversial subject, it has now been determined that treating this condition improves sperm analysis results, spontaneous fertility, and outcomes from medically assisted reproduction techniques. The AFU’s conference was a chance to present an overall snapshot of the issue.

Between 1973 and 2018, male sperm concentration dropped by 51.6% around the world, whereas total sperm counts dropped by 62.3%, according to Charlotte Methorst, MD, urological surgeon in Saint Cloud, France, president of the French Language Andrology Society, and coordinator of the AFU 2023 Report on Male Fertility. What’s more,

Declining Fertility

Nowadays, around 15% of couples experience infertility (60,000 new cases/year in France). About 20% of these are strictly attributed to male infertility and 40% are mixed, implying a male factor. Consequently, Dr. Methorst explained that “we must routinely assess male fertility within the context of a medically assisted reproduction (MAR) pathway, without limiting testing to semen analysis. Varicocele, one of the causes of infertility that men should be screened for and defined as an abnormal and/or tortuous enlargement of the pampiniform plexus veins, is present in 15%-20% of the overall male population, 35% of men with primary infertility, and more than 70% of those experiencing secondary infertility.”

In infertile men, varicocele is mostly unilateral, occurring on the left side (85%-90% of cases). A link has been established between varicocele and insufficiency at the saphenofemoral junction, as well as venous insufficiency of the lower limbs (odds ratio, 2.34; P < .0001), suggesting a predisposition towards a vascular network favoring the presence of varicoceles.

Varicocele Underdiagnosed

Analysis of a large multicenter database recently suggested the underdiagnosis of varicocele in men being assessed for infertility. Diagnosis is primarily based on physical examination, with physicians finding a soft, serpiginous swelling in the upper and posterior part of the affected side of the scrotum. Testicular Doppler ultrasonography provides confirmation of a varicocele, taking into account aspects such as size and reflux duration during the Valsalva maneuver. Generally, this is enough to make a differential diagnosis, but MRI may be considered, especially in cases where a millimeter-sized nodule is also found.

Reversal Improves Fertility

A Cochrane meta-analysis, despite containing significant bias, raised doubts about the efficacy of varicocele treatment. Nevertheless, over the past 10 years, a randomized trial and several meta-analyses have put an end to the controversy, confirming that treatment for varicocele significantly improves natural pregnancy rates.

Microscopic subinguinal varicocelectomy is the gold-standard option for cases of clinical varicocele and for those in which sperm analysis findings are abnormal. This approach is associated with superior efficacy outcomes, such as improvement in sperm analysis results and pregnancy rates while leading to lower rates of recurrence (< 4%) and a favorable outcome in terms of complications. It should be noted that treating subclinical varicocele is not recommended.

Specifically, microscopic subinguinal varicocelectomy improves live birth and pregnancy rates, both naturally and via in vitro fertilization. What’s more, it has a positive impact on sperm count, total and progressive motility, morphology, and DNA fragmentation levels. Overall, this surgery changes the MAR approach used in around one in two cases. The grade and unilateral or bilateral nature of varicocele are important predictive factors of improvement in sperm analysis findings and pregnancy rates associated with this interventional procedure. Treating clinical varicocele (grades 1-3) leads to improved sperm analysis results, observed in 60%-70% of cases. According to a meta-analysis, the mean increase is said to be a concentration of 12 million spermatozoids per milliliter, as well as a mean improvement of 11% in sperm motility.

Notably, embolization can be considered as an alternative to surgery. This minimally invasive X-ray-guided procedure performed by an interventional radiologist attempts to block the dilated testicular vein.

Guidelines for clinical practice in treating varicocele were recently published by the AFU’s Andrology committee.

This article was translated from the Medscape French edition. A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Traumatic Brain Injury and CVD: What’s the Link?

The long-term impact of traumatic brain injury (TBI) on neurologic and psychiatric function is well-established, but a growing body of research is pointing to unexpected medical sequalae, including cardiovascular disease (CVD).

A recent review looked at the investigation to date into this surprising connection, not only summarizing study findings but also suggesting potential mechanisms that might account for the association.

“; consequently, they should undergo regular monitoring,” senior author Ross Zafonte, DO, president of Spaulding Rehabilitation Network, Boston, and lead author Saef Izzy, MD, MBChB, a neurologist at the Stroke and Cerebrovascular Center of Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts, told this news organization.

“This holds significant importance for healthcare practitioners, as there exist several strategies to mitigate cardiovascular disease risk — including weight management, adopting a healthy diet, engaging in regular physical activity, and quitting smoking,” they stated.

Leslie Croll, MD, American Heart Association volunteer and assistant professor of clinical neurology at the Temple University Lewis Katz School of Medicine, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, told this news organization that it’s “extremely important to learn more about the interplay between TBI, neurologic disease, psychiatric complications, and the cardiovascular system.”

Hopefully, she added, “future research will help us understand what kind of cardiovascular disease monitoring and prevention measures stand to give TBI patients the most benefit.”

Chronic Condition

TBI is “a major cause of long-term disability and premature death,” and is “highly prevalent among contact sports players, military personnel (eg, due to injuries sustained during conflict), and the general population (eg, due to falls and road traffic incidents),” the authors wrote.

Most studies pertaining to TBI have “primarily focused on establishing connections between single TBI, repetitive TBI, and their acute and chronic neurological and psychiatric consequences, such as Parkinson’s disease, Alzheimer’s disease, and chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE),” Drs. Zafonte and Izzy noted. By contrast, there has been a “notable lack of research attention given to non-neurological conditions associated with TBI.”

They pointed out that recent insights into TBI — particularly the acknowledgment of TBI as an “emerging chronic condition rather than merely an acute aftermath of brain injury” — have come to light through epidemiologic and pathologic investigations involving military veterans, professional American-style football players, and the civilian population. “This recognition opens up an opportunity to broaden our perspective and delve into the medical aspects of health that may be influenced by TBI.”

To broaden the investigation, the researchers reviewed literature published between January 1, 2001, and June 18, 2023. Of 26,335 articles, they narrowed their review down to 15 studies that investigated CVD, CVD risk factors, and cerebrovascular disease in the chronic phase of TBI, including community, military, or sport-related brain trauma, regardless of the timing of disease occurrence with respect to brain injury via TBI or repetitive head impact.

New Cardiovascular Risk

Studies that used national or local registries tended to be retrospective and predominantly conducted in people with preexisting cardiovascular conditions. In these studies, TBI was found to be an independent risk factor for myocardial dysfunction. However, although these studies do provide evidence of elevated cardiovascular risk subsequent to a single TBI, including individuals with preexisting medical comorbidities “makes it difficult to determine the timing of incident cardiovascular disease and cardiovascular risk factors subsequent to brain injury,” they wrote.

However, some studies showed that even individuals with TBI but without preexisting myocardial dysfunction at baseline had a significantly higher risk for CVD than those without a history of TBI.

In fact, several studies included populations without preexisting medical and cardiovascular comorbidities to “better refine the order and timing of CVD and other risk factors in individuals with TBI.”

For example, one study of concussion survivors without preexisting diagnoses showed that cardiovascular, endocrinological, and neuropsychiatric comorbidities occurred at a “significantly higher incidence within 5 years after concussive TBI compared with healthy individuals who were matched in terms of age, race, and sex and didn’t have a TBI exposure.” Other studies yielded similar findings.

Because cardiovascular risk factors and events become more common with age, it’s important to account for age in evaluating the effects of TBI. Although many studies of TBI and subsequent CVD didn’t stratify individuals by age, one 10-year study of people without any known cardiovascular or neuropsychiatric conditions who sustained TBI found that people as young as 18-40 years were more likely to develop hypertension, hyperlipidemia, obesity, and diabetes within 3-5 years following brain injury than matched individuals in the control group.

“Individuals who have encountered TBI, surprisingly even those who are young and in good health with no prior comorbid conditions, face an increased risk of adverse cardiovascular outcomes for an extended duration after the initial event,” Drs. Zafonte and Izzy summarized. “Therefore, it’s imperative that they receive regular and long-term screenings for CVD and associated risk factors.”

Bidirectional Relationship

Brain injury has been associated with acute cardiovascular dysfunction, including autonomic heart-brain axis dysregulation, imbalances between the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems, and excessive catecholamine release, the authors noted.

Drs. Zafonte and Izzy suggested several plausible links between TBI and cardiovascular dysfunction, noting that they are “likely multifaceted, potentially encompassing risk factors that span the pre-injury, injury, and post-injury phases of the condition.”

TBI may induce alterations in neurobiological processes, which have been reported to be associated with an increased risk for CVD (eg, chronic dysfunction of the autonomic system, systemic inflammation, and modifications in the brain-gut connection).

Patients with TBI might develop additional risk factors following the injury, including conditions like posttraumatic stress disorder, depression, and other psychiatric illnesses, which are “known to augment the risk of CVD.”

TBI can lead to subsequent behavioral and lifestyle changes that place patients at an elevated risk for both cardiovascular and cognitive dysfunction when compared to the general population of TBI survivors.

There may be additional as yet undefined risks.

They believe there’s a bidirectional relationship between TBI and CVD. “On one hand, TBI has been associated with an elevated risk of CVD,” they said. “Conversely, cardiovascular risk factors such as diabetes, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and sleep disturbances that have been demonstrated to negatively influence cognitive function and heighten the risk of dementia. Consequently, this interplay can further compound the long-term consequences of the injury.”

Their work aims to try and disentangle this “complex series of relationships.”

They recommend screening to identify diseases in their earliest and “most manageable phases” because TBI has been “unveiled as an underappreciated risk factor for CVD within contact sports, military, and community setting.”

An effective screening program “should rely on quantifiable and dependable biomarkers such as blood pressure, BMI, waist circumference, blood lipid levels, and glucose. Additionally, it should take into account other factors like smoking habits, physical activity, and dietary choices,” they recommended.

Heart-Brain Connection

Dr. Croll noted that TBI is “associated with many poorly understood physiologic changes and complications, so it’s exciting to see research aimed at clarifying this chronic disease process.”

In recent years, “we have seen a greater appreciation and understanding of the heart-brain connection,” she said. “Moving forward, more research, including TBI research, will target that connection.”

She added that there are probably “multiple mechanisms” at play underlying the connection between TBI and CVD.

Most importantly, “we are increasingly learning that TBI is not only a discrete event that requires immediate treatment but also a chronic disease process,” and when we “think about the substantial long-term morbidity associated with TBI, we should keep increased risk for CVD on top of mind,” said Dr. Croll.

The review received no funding. Izzy reported receiving grants from the US National Institutes of Health (NIH) and 2023 Stepping Strong Innovator Award. Dr. Zafonte reported receiving grants from the NIH and royalties from Springer and Demos publishing for serving as a coeditor of Brain Injury Medicine. Dr. Zafonte has also served as an adviser to Myomo, Oncare.ai, Nanodiagnostics, and Kisbee. He reported evaluating patients in the Massachusetts General Hospital Brain and Body–TRUST Program, which is funded by the NFL Players Association. The other authors’ disclosures are listed on the original paper. Dr. Croll declared no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

The long-term impact of traumatic brain injury (TBI) on neurologic and psychiatric function is well-established, but a growing body of research is pointing to unexpected medical sequalae, including cardiovascular disease (CVD).

A recent review looked at the investigation to date into this surprising connection, not only summarizing study findings but also suggesting potential mechanisms that might account for the association.

“; consequently, they should undergo regular monitoring,” senior author Ross Zafonte, DO, president of Spaulding Rehabilitation Network, Boston, and lead author Saef Izzy, MD, MBChB, a neurologist at the Stroke and Cerebrovascular Center of Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts, told this news organization.

“This holds significant importance for healthcare practitioners, as there exist several strategies to mitigate cardiovascular disease risk — including weight management, adopting a healthy diet, engaging in regular physical activity, and quitting smoking,” they stated.

Leslie Croll, MD, American Heart Association volunteer and assistant professor of clinical neurology at the Temple University Lewis Katz School of Medicine, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, told this news organization that it’s “extremely important to learn more about the interplay between TBI, neurologic disease, psychiatric complications, and the cardiovascular system.”

Hopefully, she added, “future research will help us understand what kind of cardiovascular disease monitoring and prevention measures stand to give TBI patients the most benefit.”

Chronic Condition

TBI is “a major cause of long-term disability and premature death,” and is “highly prevalent among contact sports players, military personnel (eg, due to injuries sustained during conflict), and the general population (eg, due to falls and road traffic incidents),” the authors wrote.

Most studies pertaining to TBI have “primarily focused on establishing connections between single TBI, repetitive TBI, and their acute and chronic neurological and psychiatric consequences, such as Parkinson’s disease, Alzheimer’s disease, and chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE),” Drs. Zafonte and Izzy noted. By contrast, there has been a “notable lack of research attention given to non-neurological conditions associated with TBI.”

They pointed out that recent insights into TBI — particularly the acknowledgment of TBI as an “emerging chronic condition rather than merely an acute aftermath of brain injury” — have come to light through epidemiologic and pathologic investigations involving military veterans, professional American-style football players, and the civilian population. “This recognition opens up an opportunity to broaden our perspective and delve into the medical aspects of health that may be influenced by TBI.”

To broaden the investigation, the researchers reviewed literature published between January 1, 2001, and June 18, 2023. Of 26,335 articles, they narrowed their review down to 15 studies that investigated CVD, CVD risk factors, and cerebrovascular disease in the chronic phase of TBI, including community, military, or sport-related brain trauma, regardless of the timing of disease occurrence with respect to brain injury via TBI or repetitive head impact.

New Cardiovascular Risk

Studies that used national or local registries tended to be retrospective and predominantly conducted in people with preexisting cardiovascular conditions. In these studies, TBI was found to be an independent risk factor for myocardial dysfunction. However, although these studies do provide evidence of elevated cardiovascular risk subsequent to a single TBI, including individuals with preexisting medical comorbidities “makes it difficult to determine the timing of incident cardiovascular disease and cardiovascular risk factors subsequent to brain injury,” they wrote.

However, some studies showed that even individuals with TBI but without preexisting myocardial dysfunction at baseline had a significantly higher risk for CVD than those without a history of TBI.

In fact, several studies included populations without preexisting medical and cardiovascular comorbidities to “better refine the order and timing of CVD and other risk factors in individuals with TBI.”

For example, one study of concussion survivors without preexisting diagnoses showed that cardiovascular, endocrinological, and neuropsychiatric comorbidities occurred at a “significantly higher incidence within 5 years after concussive TBI compared with healthy individuals who were matched in terms of age, race, and sex and didn’t have a TBI exposure.” Other studies yielded similar findings.

Because cardiovascular risk factors and events become more common with age, it’s important to account for age in evaluating the effects of TBI. Although many studies of TBI and subsequent CVD didn’t stratify individuals by age, one 10-year study of people without any known cardiovascular or neuropsychiatric conditions who sustained TBI found that people as young as 18-40 years were more likely to develop hypertension, hyperlipidemia, obesity, and diabetes within 3-5 years following brain injury than matched individuals in the control group.

“Individuals who have encountered TBI, surprisingly even those who are young and in good health with no prior comorbid conditions, face an increased risk of adverse cardiovascular outcomes for an extended duration after the initial event,” Drs. Zafonte and Izzy summarized. “Therefore, it’s imperative that they receive regular and long-term screenings for CVD and associated risk factors.”

Bidirectional Relationship

Brain injury has been associated with acute cardiovascular dysfunction, including autonomic heart-brain axis dysregulation, imbalances between the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems, and excessive catecholamine release, the authors noted.

Drs. Zafonte and Izzy suggested several plausible links between TBI and cardiovascular dysfunction, noting that they are “likely multifaceted, potentially encompassing risk factors that span the pre-injury, injury, and post-injury phases of the condition.”

TBI may induce alterations in neurobiological processes, which have been reported to be associated with an increased risk for CVD (eg, chronic dysfunction of the autonomic system, systemic inflammation, and modifications in the brain-gut connection).

Patients with TBI might develop additional risk factors following the injury, including conditions like posttraumatic stress disorder, depression, and other psychiatric illnesses, which are “known to augment the risk of CVD.”

TBI can lead to subsequent behavioral and lifestyle changes that place patients at an elevated risk for both cardiovascular and cognitive dysfunction when compared to the general population of TBI survivors.

There may be additional as yet undefined risks.

They believe there’s a bidirectional relationship between TBI and CVD. “On one hand, TBI has been associated with an elevated risk of CVD,” they said. “Conversely, cardiovascular risk factors such as diabetes, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and sleep disturbances that have been demonstrated to negatively influence cognitive function and heighten the risk of dementia. Consequently, this interplay can further compound the long-term consequences of the injury.”

Their work aims to try and disentangle this “complex series of relationships.”

They recommend screening to identify diseases in their earliest and “most manageable phases” because TBI has been “unveiled as an underappreciated risk factor for CVD within contact sports, military, and community setting.”

An effective screening program “should rely on quantifiable and dependable biomarkers such as blood pressure, BMI, waist circumference, blood lipid levels, and glucose. Additionally, it should take into account other factors like smoking habits, physical activity, and dietary choices,” they recommended.

Heart-Brain Connection

Dr. Croll noted that TBI is “associated with many poorly understood physiologic changes and complications, so it’s exciting to see research aimed at clarifying this chronic disease process.”

In recent years, “we have seen a greater appreciation and understanding of the heart-brain connection,” she said. “Moving forward, more research, including TBI research, will target that connection.”

She added that there are probably “multiple mechanisms” at play underlying the connection between TBI and CVD.

Most importantly, “we are increasingly learning that TBI is not only a discrete event that requires immediate treatment but also a chronic disease process,” and when we “think about the substantial long-term morbidity associated with TBI, we should keep increased risk for CVD on top of mind,” said Dr. Croll.

The review received no funding. Izzy reported receiving grants from the US National Institutes of Health (NIH) and 2023 Stepping Strong Innovator Award. Dr. Zafonte reported receiving grants from the NIH and royalties from Springer and Demos publishing for serving as a coeditor of Brain Injury Medicine. Dr. Zafonte has also served as an adviser to Myomo, Oncare.ai, Nanodiagnostics, and Kisbee. He reported evaluating patients in the Massachusetts General Hospital Brain and Body–TRUST Program, which is funded by the NFL Players Association. The other authors’ disclosures are listed on the original paper. Dr. Croll declared no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

The long-term impact of traumatic brain injury (TBI) on neurologic and psychiatric function is well-established, but a growing body of research is pointing to unexpected medical sequalae, including cardiovascular disease (CVD).

A recent review looked at the investigation to date into this surprising connection, not only summarizing study findings but also suggesting potential mechanisms that might account for the association.

“; consequently, they should undergo regular monitoring,” senior author Ross Zafonte, DO, president of Spaulding Rehabilitation Network, Boston, and lead author Saef Izzy, MD, MBChB, a neurologist at the Stroke and Cerebrovascular Center of Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts, told this news organization.

“This holds significant importance for healthcare practitioners, as there exist several strategies to mitigate cardiovascular disease risk — including weight management, adopting a healthy diet, engaging in regular physical activity, and quitting smoking,” they stated.

Leslie Croll, MD, American Heart Association volunteer and assistant professor of clinical neurology at the Temple University Lewis Katz School of Medicine, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, told this news organization that it’s “extremely important to learn more about the interplay between TBI, neurologic disease, psychiatric complications, and the cardiovascular system.”

Hopefully, she added, “future research will help us understand what kind of cardiovascular disease monitoring and prevention measures stand to give TBI patients the most benefit.”

Chronic Condition

TBI is “a major cause of long-term disability and premature death,” and is “highly prevalent among contact sports players, military personnel (eg, due to injuries sustained during conflict), and the general population (eg, due to falls and road traffic incidents),” the authors wrote.

Most studies pertaining to TBI have “primarily focused on establishing connections between single TBI, repetitive TBI, and their acute and chronic neurological and psychiatric consequences, such as Parkinson’s disease, Alzheimer’s disease, and chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE),” Drs. Zafonte and Izzy noted. By contrast, there has been a “notable lack of research attention given to non-neurological conditions associated with TBI.”

They pointed out that recent insights into TBI — particularly the acknowledgment of TBI as an “emerging chronic condition rather than merely an acute aftermath of brain injury” — have come to light through epidemiologic and pathologic investigations involving military veterans, professional American-style football players, and the civilian population. “This recognition opens up an opportunity to broaden our perspective and delve into the medical aspects of health that may be influenced by TBI.”

To broaden the investigation, the researchers reviewed literature published between January 1, 2001, and June 18, 2023. Of 26,335 articles, they narrowed their review down to 15 studies that investigated CVD, CVD risk factors, and cerebrovascular disease in the chronic phase of TBI, including community, military, or sport-related brain trauma, regardless of the timing of disease occurrence with respect to brain injury via TBI or repetitive head impact.

New Cardiovascular Risk

Studies that used national or local registries tended to be retrospective and predominantly conducted in people with preexisting cardiovascular conditions. In these studies, TBI was found to be an independent risk factor for myocardial dysfunction. However, although these studies do provide evidence of elevated cardiovascular risk subsequent to a single TBI, including individuals with preexisting medical comorbidities “makes it difficult to determine the timing of incident cardiovascular disease and cardiovascular risk factors subsequent to brain injury,” they wrote.

However, some studies showed that even individuals with TBI but without preexisting myocardial dysfunction at baseline had a significantly higher risk for CVD than those without a history of TBI.

In fact, several studies included populations without preexisting medical and cardiovascular comorbidities to “better refine the order and timing of CVD and other risk factors in individuals with TBI.”

For example, one study of concussion survivors without preexisting diagnoses showed that cardiovascular, endocrinological, and neuropsychiatric comorbidities occurred at a “significantly higher incidence within 5 years after concussive TBI compared with healthy individuals who were matched in terms of age, race, and sex and didn’t have a TBI exposure.” Other studies yielded similar findings.

Because cardiovascular risk factors and events become more common with age, it’s important to account for age in evaluating the effects of TBI. Although many studies of TBI and subsequent CVD didn’t stratify individuals by age, one 10-year study of people without any known cardiovascular or neuropsychiatric conditions who sustained TBI found that people as young as 18-40 years were more likely to develop hypertension, hyperlipidemia, obesity, and diabetes within 3-5 years following brain injury than matched individuals in the control group.

“Individuals who have encountered TBI, surprisingly even those who are young and in good health with no prior comorbid conditions, face an increased risk of adverse cardiovascular outcomes for an extended duration after the initial event,” Drs. Zafonte and Izzy summarized. “Therefore, it’s imperative that they receive regular and long-term screenings for CVD and associated risk factors.”

Bidirectional Relationship

Brain injury has been associated with acute cardiovascular dysfunction, including autonomic heart-brain axis dysregulation, imbalances between the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems, and excessive catecholamine release, the authors noted.

Drs. Zafonte and Izzy suggested several plausible links between TBI and cardiovascular dysfunction, noting that they are “likely multifaceted, potentially encompassing risk factors that span the pre-injury, injury, and post-injury phases of the condition.”

TBI may induce alterations in neurobiological processes, which have been reported to be associated with an increased risk for CVD (eg, chronic dysfunction of the autonomic system, systemic inflammation, and modifications in the brain-gut connection).

Patients with TBI might develop additional risk factors following the injury, including conditions like posttraumatic stress disorder, depression, and other psychiatric illnesses, which are “known to augment the risk of CVD.”

TBI can lead to subsequent behavioral and lifestyle changes that place patients at an elevated risk for both cardiovascular and cognitive dysfunction when compared to the general population of TBI survivors.

There may be additional as yet undefined risks.

They believe there’s a bidirectional relationship between TBI and CVD. “On one hand, TBI has been associated with an elevated risk of CVD,” they said. “Conversely, cardiovascular risk factors such as diabetes, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and sleep disturbances that have been demonstrated to negatively influence cognitive function and heighten the risk of dementia. Consequently, this interplay can further compound the long-term consequences of the injury.”

Their work aims to try and disentangle this “complex series of relationships.”

They recommend screening to identify diseases in their earliest and “most manageable phases” because TBI has been “unveiled as an underappreciated risk factor for CVD within contact sports, military, and community setting.”

An effective screening program “should rely on quantifiable and dependable biomarkers such as blood pressure, BMI, waist circumference, blood lipid levels, and glucose. Additionally, it should take into account other factors like smoking habits, physical activity, and dietary choices,” they recommended.

Heart-Brain Connection

Dr. Croll noted that TBI is “associated with many poorly understood physiologic changes and complications, so it’s exciting to see research aimed at clarifying this chronic disease process.”

In recent years, “we have seen a greater appreciation and understanding of the heart-brain connection,” she said. “Moving forward, more research, including TBI research, will target that connection.”

She added that there are probably “multiple mechanisms” at play underlying the connection between TBI and CVD.

Most importantly, “we are increasingly learning that TBI is not only a discrete event that requires immediate treatment but also a chronic disease process,” and when we “think about the substantial long-term morbidity associated with TBI, we should keep increased risk for CVD on top of mind,” said Dr. Croll.

The review received no funding. Izzy reported receiving grants from the US National Institutes of Health (NIH) and 2023 Stepping Strong Innovator Award. Dr. Zafonte reported receiving grants from the NIH and royalties from Springer and Demos publishing for serving as a coeditor of Brain Injury Medicine. Dr. Zafonte has also served as an adviser to Myomo, Oncare.ai, Nanodiagnostics, and Kisbee. He reported evaluating patients in the Massachusetts General Hospital Brain and Body–TRUST Program, which is funded by the NFL Players Association. The other authors’ disclosures are listed on the original paper. Dr. Croll declared no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Testosterone Supplements: Overcoming Current Misconceptions

Underdiagnosis, reluctant doctors, patient preconceptions: Treating low testosterone levels is a tricky business in France despite the proven benefits of replacement therapy. About 20% of patients with symptomatic low testosterone levels are treated for the deficiency, said Eric Huygue, MD, PhD, urologic surgeon at Toulouse University Hospital in France, at the 117th annual conference of the French Urology Association (AFU).

, said Dr. Huygue, who was involved in drawing up the first French recommendations on treating low testosterone in 2021.

“We must keep up communication efforts to make patients and doctors aware” of the benefits of supplementation, he said.

Testosterone Levels

Testosterone deficiency mostly affects men older than 40 years. A drop in androgen levels, which varies by individual, can lead to sexual problems (such as erectile dysfunction and low libido), physical symptoms (fatigue, hot flashes, loss of muscle mass, and osteoporosis), and mental disorders (anxiety, irritability, and depression).

There are an estimated 340,000 men with symptomatic testosterone deficiency in France. Just 70,000 of these are receiving replacement therapy (see box), which accounts for only 20% of those affected. For Dr. Huygue, this low treatment rate is due to underdiagnosis, as well as reluctance on the part of doctors and patients.

Although routine screening of low testosterone in the general population is not recommended, some individuals are particularly at risk, noted the urologist.

This is especially true for patients with metabolic disorders associated with insulin resistance (such as obesity and type 2 diabetes), cardiovascular diseases (hypertension, heart failure, and atrial fibrillation), or other chronic conditions (chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, cancer, and depression). Some medications (corticosteroids, antipsychotics, chemotherapy drugs, and antiretroviral therapies) can also lead to low testosterone.

Per the French recommendations for managing low testosterone, diagnosis must be based on free or bioavailable testosterone and not total testosterone levels, which can give a skewed result. Levels must be tested twice, 1 month apart, in the morning and while fasting. The reference range is determined by taking the lower threshold level of young men as measured in the laboratory.

Threshold Values

The current practice of using the reference range associated with the patient’s age group undoubtedly contributes to the underdiagnosis of low testosterone, said Dr. Huygue. According to a survey of AFU members in 2021, the year in which the recommendations were published, 77% of urologists interviewed reported referring to reference ranges for patients of the same age.

In their defense, “this method has long been in use, but it has eventually become apparent that symptomatic patients with an undiagnosed deficiency could be in the reference patients’ group,” Dr. Huygue explained.

Once a deficiency has been diagnosed, doctors may be reluctant to prescribe replacement therapy due to the perceived risk of developing prostate cancer. Several international studies have shown that “the risk of prostate cancer is the single biggest reason for doctors refusing to prescribe testosterone,” said Dr. Huygue.

Despite this reluctance, numerous studies have clearly shown that there is no link between a high testosterone level and the risk of developing prostate cancer. It even seems that a low testosterone level might expose a person to an increased risk for an aggressive form of cancer.

“This is a time of many surprising discoveries concerning the link between the prostate and testosterone, which go against what we have thought up to now. It has been observed that men with low testosterone develop more serious types of cancer,” said Dr. Huygue at a previous meeting of the AFU, during which he announced the publication of the French recommendations.

Prostate Cancer Recurrence

Urologists are also wary of testosterone supplementation in patients with a previous history of prostate cancer. According to the AFU’s survey, 40% of urologists questioned think that testosterone is contraindicated in this population. One in two urologists prescribe testosterone after radical prostatectomy for low or intermediate risk and most commonly after 3 years of undetectable prostate-specific antigen (PSA) levels.

Nevertheless, “several retrospective studies show the safety of testosterone replacement therapy in men who have undergone radical prostatectomy or radiotherapy or who are under active monitoring,” said Dr. Huygue. Testosterone “does not appear to increase the risk of relapse” after treatment of prostate cancer.

Dr. Huygue invited prescribing physicians to refer to the French recommendations, which specify that 1 year of undetectable PSA after prostatectomy is sufficient before prescribing replacement therapy. “This is clearly indicated in the recommendations for patients with a previous history of prostate cancer.”

Neither prostate cancer nor benign prostatic hyperplasia is a contraindication. According to the recommendations, the only contraindications to testosterone prescription are the following:

- Hematocrit > 54%

- Current breast or prostate cancer

- Cardiovascular event less than 3-6 months prior

- Trying to conceive

Cardiovascular Benefits

Another more commonly used argument by general practitioners and endocrinologists to justify their reluctance to prescribe testosterone is the risk to cardiovascular health. In early 2010, a series of American studies alerted clinicians to this risk when taking testosterone. Since then, other studies have had reassuring findings.

In response to the alert issued by the United States, the European Medicines Agency specified that “the data are not sufficient for a warning,” before the American Heart Association colleagues concluded that testosterone should only be avoided in the first 6 months following a severe cardiovascular event.

Conversely, in 2021, the European Society of Cardiology put forward the benefits of testosterone in an article in favor of replacement therapy to prevent cardiovascular risk. In particular, the hormone is thought to have a beneficial effect on arterial stiffness, the appearance of calcified plaques, and coronary artery dilatation.

The final hurdle to overcome before a testosterone prescription is filled relates to patients themselves, who often regard such treatment unfavorably. Many wrongly believe that androgens are hormones that “increase the risk of cancer, make you aggressive, cause weight gain, lead to hair loss, and cause body hair growth,” said Dr. Huygue.

Finally, breaks in the supply chain for Androtardyl, the only injectable form available for reimbursement by French social security schemes, were reported in the country in 2023, said Dr. Huygue. This situation only complicates further the prescription and use of testosterone replacement therapy.

Which Supplement?

Testosterone replacement therapies are available on the market in the following formulations:

Via transcutaneous administration: Testosterone-based gels, not covered by the French social security system (Androgel and Fortigel), to be applied daily. Users must be careful to avoid any potential transfer of the product to women or children in case of contact with the site after application.

Via an injection: Androtardyl (testosterone enanthate), covered by French social security, to be administered intramuscularly once a month. Nebido (testosterone undecanoate), not covered by French social security, with a more beneficial bioavailability profile, to be administered once every 3 months.

Pantestone (testosterone undecanoate), administered orally, is not marketed since 2021. It had the major disadvantage of requiring a high-fat diet to ensure optimal absorption.

This article was translated from the Medscape French edition. A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Underdiagnosis, reluctant doctors, patient preconceptions: Treating low testosterone levels is a tricky business in France despite the proven benefits of replacement therapy. About 20% of patients with symptomatic low testosterone levels are treated for the deficiency, said Eric Huygue, MD, PhD, urologic surgeon at Toulouse University Hospital in France, at the 117th annual conference of the French Urology Association (AFU).

, said Dr. Huygue, who was involved in drawing up the first French recommendations on treating low testosterone in 2021.

“We must keep up communication efforts to make patients and doctors aware” of the benefits of supplementation, he said.

Testosterone Levels

Testosterone deficiency mostly affects men older than 40 years. A drop in androgen levels, which varies by individual, can lead to sexual problems (such as erectile dysfunction and low libido), physical symptoms (fatigue, hot flashes, loss of muscle mass, and osteoporosis), and mental disorders (anxiety, irritability, and depression).