User login

‘Mechanoprimed’ MSCs aid hematopoietic recovery

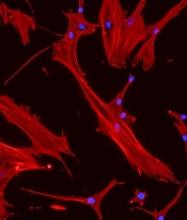

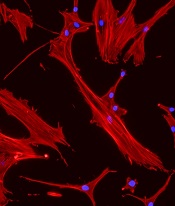

Specially grown mesenchymal stromal cells (MSCs) can improve hematopoietic recovery, according to preclinical research published in Stem Cell Research and Therapy.

Researchers grew MSCs on a surface with mechanical properties similar to those of bone marrow, which prompted the MSCs to secrete growth factors that aid hematopoietic recovery.

When implanted in irradiated mice, these “mechanoprimed” MSCs sped recovery of all hematopoietic lineages and improved the animals’ survival.

“[MSCs] act like drug factories,” explained study author Krystyn Van Vliet, PhD, of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in Cambridge.

“They can become tissue lineage cells, but they also pump out a lot of factors that change the environment that the hematopoietic stem cells are operating in.”

Dr. Van Vliet and her colleagues noted that MSCs play an important role in supporting, maintaining, and expanding hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs). However, in a given population of MSCs, usually only about 20% of the cells produce the factors needed to stimulate hematopoietic recovery.

In an earlier study, Dr. Van Vliet and her colleagues showed they could sort MSCs with a microfluidic device that can identify the 20% of cells that promote hematopoietic recovery.

However, the researchers wanted to improve on that by finding a way to stimulate an entire population of MSCs to produce the necessary factors. To do that, they first had to discover which factors were the most important.

Analyses in mice suggested eight factors were associated with improved survival after irradiation—IL-6, IL-8, BMP2, EGF, FGF1, RANTES, VEGF-A, and ANG-1.

Mechanopriming

Having identified factors associated with hematopoietic recovery, Dr. Van Vliet and her colleagues explored the idea of mechanopriming MSCs so they would produce more of these factors.

Over the past decade, researchers have shown that varying the mechanical properties of surfaces on which stem cells are grown can affect their differentiation into mature cell types. However, in this study, the researchers showed that mechanical properties can also affect the factors stem cells secrete before committing to a specific lineage.

For the growth surface, Dr. Van Vliet and her colleagues tested a polymer called polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS). The team varied the mechanical stiffness of the PDMS surface to see how this would affect the MSCs.

MSCs grown on the least stiff PDMS surface produced the greatest number of factors necessary to induce differentiation in HSPCs. These MSCs were able to promote hematopoiesis in an in vitro co-culture model with HSPCs.

Testing in mice

The researchers then tested the mechanoprimed MSCs by implanting them into irradiated mice.

The mechanoprimed MSCs quickly repopulated the animals’ blood cells and helped them recover more quickly than mice treated with MSCs grown on traditional glass surfaces.

Mice that received mechanoprimed MSCs also recovered faster than mice treated with factor-producing MSCs selected by the microfluidic sorting device.

Dr. Van Vliet’s lab is now performing more animal studies in hopes of developing a combination treatment of MSCs and HSPCs that could be tested in humans.

The current research was funded by the National Institutes of Health and the BioSystems and Micromechanics Interdisciplinary Research Group of the Singapore-MIT Alliance for Research and Technology through the Singapore National Research Foundation.

The researchers said they had no competing interests.

Specially grown mesenchymal stromal cells (MSCs) can improve hematopoietic recovery, according to preclinical research published in Stem Cell Research and Therapy.

Researchers grew MSCs on a surface with mechanical properties similar to those of bone marrow, which prompted the MSCs to secrete growth factors that aid hematopoietic recovery.

When implanted in irradiated mice, these “mechanoprimed” MSCs sped recovery of all hematopoietic lineages and improved the animals’ survival.

“[MSCs] act like drug factories,” explained study author Krystyn Van Vliet, PhD, of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in Cambridge.

“They can become tissue lineage cells, but they also pump out a lot of factors that change the environment that the hematopoietic stem cells are operating in.”

Dr. Van Vliet and her colleagues noted that MSCs play an important role in supporting, maintaining, and expanding hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs). However, in a given population of MSCs, usually only about 20% of the cells produce the factors needed to stimulate hematopoietic recovery.

In an earlier study, Dr. Van Vliet and her colleagues showed they could sort MSCs with a microfluidic device that can identify the 20% of cells that promote hematopoietic recovery.

However, the researchers wanted to improve on that by finding a way to stimulate an entire population of MSCs to produce the necessary factors. To do that, they first had to discover which factors were the most important.

Analyses in mice suggested eight factors were associated with improved survival after irradiation—IL-6, IL-8, BMP2, EGF, FGF1, RANTES, VEGF-A, and ANG-1.

Mechanopriming

Having identified factors associated with hematopoietic recovery, Dr. Van Vliet and her colleagues explored the idea of mechanopriming MSCs so they would produce more of these factors.

Over the past decade, researchers have shown that varying the mechanical properties of surfaces on which stem cells are grown can affect their differentiation into mature cell types. However, in this study, the researchers showed that mechanical properties can also affect the factors stem cells secrete before committing to a specific lineage.

For the growth surface, Dr. Van Vliet and her colleagues tested a polymer called polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS). The team varied the mechanical stiffness of the PDMS surface to see how this would affect the MSCs.

MSCs grown on the least stiff PDMS surface produced the greatest number of factors necessary to induce differentiation in HSPCs. These MSCs were able to promote hematopoiesis in an in vitro co-culture model with HSPCs.

Testing in mice

The researchers then tested the mechanoprimed MSCs by implanting them into irradiated mice.

The mechanoprimed MSCs quickly repopulated the animals’ blood cells and helped them recover more quickly than mice treated with MSCs grown on traditional glass surfaces.

Mice that received mechanoprimed MSCs also recovered faster than mice treated with factor-producing MSCs selected by the microfluidic sorting device.

Dr. Van Vliet’s lab is now performing more animal studies in hopes of developing a combination treatment of MSCs and HSPCs that could be tested in humans.

The current research was funded by the National Institutes of Health and the BioSystems and Micromechanics Interdisciplinary Research Group of the Singapore-MIT Alliance for Research and Technology through the Singapore National Research Foundation.

The researchers said they had no competing interests.

Specially grown mesenchymal stromal cells (MSCs) can improve hematopoietic recovery, according to preclinical research published in Stem Cell Research and Therapy.

Researchers grew MSCs on a surface with mechanical properties similar to those of bone marrow, which prompted the MSCs to secrete growth factors that aid hematopoietic recovery.

When implanted in irradiated mice, these “mechanoprimed” MSCs sped recovery of all hematopoietic lineages and improved the animals’ survival.

“[MSCs] act like drug factories,” explained study author Krystyn Van Vliet, PhD, of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in Cambridge.

“They can become tissue lineage cells, but they also pump out a lot of factors that change the environment that the hematopoietic stem cells are operating in.”

Dr. Van Vliet and her colleagues noted that MSCs play an important role in supporting, maintaining, and expanding hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs). However, in a given population of MSCs, usually only about 20% of the cells produce the factors needed to stimulate hematopoietic recovery.

In an earlier study, Dr. Van Vliet and her colleagues showed they could sort MSCs with a microfluidic device that can identify the 20% of cells that promote hematopoietic recovery.

However, the researchers wanted to improve on that by finding a way to stimulate an entire population of MSCs to produce the necessary factors. To do that, they first had to discover which factors were the most important.

Analyses in mice suggested eight factors were associated with improved survival after irradiation—IL-6, IL-8, BMP2, EGF, FGF1, RANTES, VEGF-A, and ANG-1.

Mechanopriming

Having identified factors associated with hematopoietic recovery, Dr. Van Vliet and her colleagues explored the idea of mechanopriming MSCs so they would produce more of these factors.

Over the past decade, researchers have shown that varying the mechanical properties of surfaces on which stem cells are grown can affect their differentiation into mature cell types. However, in this study, the researchers showed that mechanical properties can also affect the factors stem cells secrete before committing to a specific lineage.

For the growth surface, Dr. Van Vliet and her colleagues tested a polymer called polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS). The team varied the mechanical stiffness of the PDMS surface to see how this would affect the MSCs.

MSCs grown on the least stiff PDMS surface produced the greatest number of factors necessary to induce differentiation in HSPCs. These MSCs were able to promote hematopoiesis in an in vitro co-culture model with HSPCs.

Testing in mice

The researchers then tested the mechanoprimed MSCs by implanting them into irradiated mice.

The mechanoprimed MSCs quickly repopulated the animals’ blood cells and helped them recover more quickly than mice treated with MSCs grown on traditional glass surfaces.

Mice that received mechanoprimed MSCs also recovered faster than mice treated with factor-producing MSCs selected by the microfluidic sorting device.

Dr. Van Vliet’s lab is now performing more animal studies in hopes of developing a combination treatment of MSCs and HSPCs that could be tested in humans.

The current research was funded by the National Institutes of Health and the BioSystems and Micromechanics Interdisciplinary Research Group of the Singapore-MIT Alliance for Research and Technology through the Singapore National Research Foundation.

The researchers said they had no competing interests.

Three gene types drive MM disparity in African Americans

Researchers say they may have determined why African Americans have a two- to three-fold increased risk of multiple myeloma (MM) compared to European Americans.

The team genotyped 881 MM samples from various racial groups and identified three gene subtypes—t(11;14), t(14;16), and t(14;20)—that explain the racial disparity.

They found that patients with African ancestry of 80% or more had a significantly higher occurrence of these subtypes compared to individuals with African ancestry less than 0.1%.

And these subtypes are driving the disparity in MM diagnoses between the populations.

The researchers state that previous attempts to explain the disparity relied on self-reported race rather than quantitatively measured genetic ancestry, which could result in bias.

“A major new aspect of this study is that we identified the ancestry of each patient through DNA sequencing, which allowed us to determine ancestry more accurately,” said study author Vincent Rajkumar, MD, of the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota.

He and his colleagues reported their findings in Blood Cancer Journal.

All 881 samples had abnormal plasma cell FISH, 851 had a normal chromosome study, and 30 had an abnormal study.

Median age for the entire group was 64 (range, 26–90), with 35.4% in the 60–69 age category. More samples were from men (n=478, 54.3%) than women (n=403, 45.7%).

Researchers observed no significant difference between men and women in the proportion of primary cytogenetic abnormalities.

Of the 881 samples, the median African ancestry was 2.3%, the median European ancestry was 64.7%, and Northern European ancestry was 26.6%.

Thirty percent of the entire cohort had less than 0.1% African ancestry, and 13.6% had 80% or greater African ancestry.

Using a logistic regression model, the researchers determined that a 10% increase in the percentage of African ancestry was associated with a 6% increase in the odds of detecting t(11;14), t(14;16), or t(14;20) (odds ratio=1.06, 95% CI: 1.02–1.11; P=0.05).

The researchers plotted the probability of observing these cytogenetic abnormalities with the percentage of African ancestry and found the differences were most striking in the extreme populations—individuals with ≥80.0% African ancestry and individuals with <0.1% African ancestry.

Upon further analysis, the team found a significantly higher prevalence of t(11;14), t(14;16), and t(14;20) in the group of patients with the greatest proportion of African ancestry (P=0.008) compared to the European cohort.

The researchers said the differences only emerged in the highest (n=120 individuals) and lowest (n=235 individuals) cohorts. Most patients (n=526, 60%) were not included in these extreme populations because they had mixed ancestry.

The team observed no significant differences when the cutoff of African ancestry was greater than 50%.

“Our findings provide important information that will help us determine the mechanism by which myeloma is more common in African Americans, as well as help us in our quest to find out what causes myeloma in the first place,” Dr. Rajkumar said.

The research was supported by the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health and the Mayo Clinic Department of Laboratory Medicine and Pathology and Center for Individualized Medicine. One study author reported relationships with Celgene, Takeda, Prothena, Janssen, Pfizer, Alnylam, and GSK. Two authors reported relationships with the DNA Diagnostics Center.

Researchers say they may have determined why African Americans have a two- to three-fold increased risk of multiple myeloma (MM) compared to European Americans.

The team genotyped 881 MM samples from various racial groups and identified three gene subtypes—t(11;14), t(14;16), and t(14;20)—that explain the racial disparity.

They found that patients with African ancestry of 80% or more had a significantly higher occurrence of these subtypes compared to individuals with African ancestry less than 0.1%.

And these subtypes are driving the disparity in MM diagnoses between the populations.

The researchers state that previous attempts to explain the disparity relied on self-reported race rather than quantitatively measured genetic ancestry, which could result in bias.

“A major new aspect of this study is that we identified the ancestry of each patient through DNA sequencing, which allowed us to determine ancestry more accurately,” said study author Vincent Rajkumar, MD, of the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota.

He and his colleagues reported their findings in Blood Cancer Journal.

All 881 samples had abnormal plasma cell FISH, 851 had a normal chromosome study, and 30 had an abnormal study.

Median age for the entire group was 64 (range, 26–90), with 35.4% in the 60–69 age category. More samples were from men (n=478, 54.3%) than women (n=403, 45.7%).

Researchers observed no significant difference between men and women in the proportion of primary cytogenetic abnormalities.

Of the 881 samples, the median African ancestry was 2.3%, the median European ancestry was 64.7%, and Northern European ancestry was 26.6%.

Thirty percent of the entire cohort had less than 0.1% African ancestry, and 13.6% had 80% or greater African ancestry.

Using a logistic regression model, the researchers determined that a 10% increase in the percentage of African ancestry was associated with a 6% increase in the odds of detecting t(11;14), t(14;16), or t(14;20) (odds ratio=1.06, 95% CI: 1.02–1.11; P=0.05).

The researchers plotted the probability of observing these cytogenetic abnormalities with the percentage of African ancestry and found the differences were most striking in the extreme populations—individuals with ≥80.0% African ancestry and individuals with <0.1% African ancestry.

Upon further analysis, the team found a significantly higher prevalence of t(11;14), t(14;16), and t(14;20) in the group of patients with the greatest proportion of African ancestry (P=0.008) compared to the European cohort.

The researchers said the differences only emerged in the highest (n=120 individuals) and lowest (n=235 individuals) cohorts. Most patients (n=526, 60%) were not included in these extreme populations because they had mixed ancestry.

The team observed no significant differences when the cutoff of African ancestry was greater than 50%.

“Our findings provide important information that will help us determine the mechanism by which myeloma is more common in African Americans, as well as help us in our quest to find out what causes myeloma in the first place,” Dr. Rajkumar said.

The research was supported by the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health and the Mayo Clinic Department of Laboratory Medicine and Pathology and Center for Individualized Medicine. One study author reported relationships with Celgene, Takeda, Prothena, Janssen, Pfizer, Alnylam, and GSK. Two authors reported relationships with the DNA Diagnostics Center.

Researchers say they may have determined why African Americans have a two- to three-fold increased risk of multiple myeloma (MM) compared to European Americans.

The team genotyped 881 MM samples from various racial groups and identified three gene subtypes—t(11;14), t(14;16), and t(14;20)—that explain the racial disparity.

They found that patients with African ancestry of 80% or more had a significantly higher occurrence of these subtypes compared to individuals with African ancestry less than 0.1%.

And these subtypes are driving the disparity in MM diagnoses between the populations.

The researchers state that previous attempts to explain the disparity relied on self-reported race rather than quantitatively measured genetic ancestry, which could result in bias.

“A major new aspect of this study is that we identified the ancestry of each patient through DNA sequencing, which allowed us to determine ancestry more accurately,” said study author Vincent Rajkumar, MD, of the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota.

He and his colleagues reported their findings in Blood Cancer Journal.

All 881 samples had abnormal plasma cell FISH, 851 had a normal chromosome study, and 30 had an abnormal study.

Median age for the entire group was 64 (range, 26–90), with 35.4% in the 60–69 age category. More samples were from men (n=478, 54.3%) than women (n=403, 45.7%).

Researchers observed no significant difference between men and women in the proportion of primary cytogenetic abnormalities.

Of the 881 samples, the median African ancestry was 2.3%, the median European ancestry was 64.7%, and Northern European ancestry was 26.6%.

Thirty percent of the entire cohort had less than 0.1% African ancestry, and 13.6% had 80% or greater African ancestry.

Using a logistic regression model, the researchers determined that a 10% increase in the percentage of African ancestry was associated with a 6% increase in the odds of detecting t(11;14), t(14;16), or t(14;20) (odds ratio=1.06, 95% CI: 1.02–1.11; P=0.05).

The researchers plotted the probability of observing these cytogenetic abnormalities with the percentage of African ancestry and found the differences were most striking in the extreme populations—individuals with ≥80.0% African ancestry and individuals with <0.1% African ancestry.

Upon further analysis, the team found a significantly higher prevalence of t(11;14), t(14;16), and t(14;20) in the group of patients with the greatest proportion of African ancestry (P=0.008) compared to the European cohort.

The researchers said the differences only emerged in the highest (n=120 individuals) and lowest (n=235 individuals) cohorts. Most patients (n=526, 60%) were not included in these extreme populations because they had mixed ancestry.

The team observed no significant differences when the cutoff of African ancestry was greater than 50%.

“Our findings provide important information that will help us determine the mechanism by which myeloma is more common in African Americans, as well as help us in our quest to find out what causes myeloma in the first place,” Dr. Rajkumar said.

The research was supported by the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health and the Mayo Clinic Department of Laboratory Medicine and Pathology and Center for Individualized Medicine. One study author reported relationships with Celgene, Takeda, Prothena, Janssen, Pfizer, Alnylam, and GSK. Two authors reported relationships with the DNA Diagnostics Center.

Combo can prolong overall survival in MCL

Final results of a phase 3 trial suggest bortezomib plus rituximab and chemotherapy can significantly improve overall survival (OS) in transplant-ineligible patients with newly diagnosed mantle cell lymphoma (MCL).

In the LYM-3002 trial, researchers compared bortezomib plus rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, and prednisone (VR-CAP) to rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone (R-CHOP).

The median OS was significantly longer in patients who received VR-CAP than in those who received R-CHOP—90.7 months and 55.7 months, respectively.

This survival benefit was observed in patients with low- and intermediate-risk disease but not high-risk disease.

Tadeusz Robak, MD, of the Medical University of Lodz in Poland, and his colleagues reported these results in The Lancet Oncology alongside a related commentary.

The LYM-3002 trial began more than a decade ago, and initial results were published in 2015. At that time, the VR-CAP group showed a significant increase in progression-free survival compared with the R-CHOP group.

The final analysis of LYM-3002 included 268 of the original 487 MCL patients. Twenty-three percent of patients in the VR-CAP group (n=32) discontinued due to death, as did 40% of patients in the R-CHOP group (n=51). The main cause of death was progression—29% and 14%, respectively.

Among the 268 patients in the final analysis, 140 belonged to the VR-CAP group and 128 to the R-CHOP group. The patients’ median age was 66 (range, 26-83), 71% (n=190) were male, 74% (n=199) had stage IV disease, and 31% were classified as high risk based on the MCL-specific International Prognostic Index (MIPI).

About half of patients received therapies after the trial interventions (n=255, 52%)—43% (n=104) in the VR-CAP group and 62% (n=151) in the R-CHOP group. Most patients received subsequent antineoplastic therapy—77% (n=80) and 81% (n=123), respectively—and more than half received rituximab as second-line therapy—53% (n=55) and 59% (n=89), respectively.

Results

At a median follow-up of 82.0 months, the median OS was significantly longer in the VR-CAP group than in the R-CHOP group—90.7 months (95% CI, 71.4 to not estimable) and 55.7 months (95% CI, 47.2 to 68.9), respectively (hazard ratio [HR]=0.66 [95% CI, 0.51–0.85]; P=0.001).

The 4-year OS was 67.3% in the VR-CAP group and 54.3% in the R-CHOP group. The 6-year OS was 56.6% and 42.0%, respectively.

The researchers noted that VR-CAP was associated with significantly improved OS among patients in the low-risk and intermediate-risk MIPI categories but not in the high-risk category.

In the low-risk cohort, the median OS was 81.7 months in the R-CHOP group and not estimable in the VR-CAP group (HR=0.54 [95% CI, 0.30–0.95]; P≤0.05).

In the intermediate-risk cohort, the median OS was 62.2 months in the R-CHOP group and not estimable in the VR-CAP group (HR=0.55 [95% CI, 0.36–0.85]; P≤0.01).

In the high-risk cohort, the median OS was 37.1 months in the R-CHOP group and 30.4 months in the VR-CAP group (HR=1.02 [95% CI, 0.69–1.50]).

The researchers reported three new adverse events in the final analysis—grade 4 lung adenocarcinoma and grade 4 gastric cancer in the VR-CAP group as well as grade 2 pneumonia in the R-CHOP group.

The team acknowledged that a key limitation of this study was that rituximab was not given as maintenance since it was not considered standard care at the time of study initiation.

Moving forward, Dr. Robak and his colleagues recommend that bortezomib be investigated in combination with newer targeted therapies in order to establish best practice for treating MCL.

The LYM-3002 study was sponsored by Janssen Research & Development. The study authors reported financial ties to Janssen, Celgene, Ipsen, Johnson & Johnson, Novartis, and other companies.

Final results of a phase 3 trial suggest bortezomib plus rituximab and chemotherapy can significantly improve overall survival (OS) in transplant-ineligible patients with newly diagnosed mantle cell lymphoma (MCL).

In the LYM-3002 trial, researchers compared bortezomib plus rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, and prednisone (VR-CAP) to rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone (R-CHOP).

The median OS was significantly longer in patients who received VR-CAP than in those who received R-CHOP—90.7 months and 55.7 months, respectively.

This survival benefit was observed in patients with low- and intermediate-risk disease but not high-risk disease.

Tadeusz Robak, MD, of the Medical University of Lodz in Poland, and his colleagues reported these results in The Lancet Oncology alongside a related commentary.

The LYM-3002 trial began more than a decade ago, and initial results were published in 2015. At that time, the VR-CAP group showed a significant increase in progression-free survival compared with the R-CHOP group.

The final analysis of LYM-3002 included 268 of the original 487 MCL patients. Twenty-three percent of patients in the VR-CAP group (n=32) discontinued due to death, as did 40% of patients in the R-CHOP group (n=51). The main cause of death was progression—29% and 14%, respectively.

Among the 268 patients in the final analysis, 140 belonged to the VR-CAP group and 128 to the R-CHOP group. The patients’ median age was 66 (range, 26-83), 71% (n=190) were male, 74% (n=199) had stage IV disease, and 31% were classified as high risk based on the MCL-specific International Prognostic Index (MIPI).

About half of patients received therapies after the trial interventions (n=255, 52%)—43% (n=104) in the VR-CAP group and 62% (n=151) in the R-CHOP group. Most patients received subsequent antineoplastic therapy—77% (n=80) and 81% (n=123), respectively—and more than half received rituximab as second-line therapy—53% (n=55) and 59% (n=89), respectively.

Results

At a median follow-up of 82.0 months, the median OS was significantly longer in the VR-CAP group than in the R-CHOP group—90.7 months (95% CI, 71.4 to not estimable) and 55.7 months (95% CI, 47.2 to 68.9), respectively (hazard ratio [HR]=0.66 [95% CI, 0.51–0.85]; P=0.001).

The 4-year OS was 67.3% in the VR-CAP group and 54.3% in the R-CHOP group. The 6-year OS was 56.6% and 42.0%, respectively.

The researchers noted that VR-CAP was associated with significantly improved OS among patients in the low-risk and intermediate-risk MIPI categories but not in the high-risk category.

In the low-risk cohort, the median OS was 81.7 months in the R-CHOP group and not estimable in the VR-CAP group (HR=0.54 [95% CI, 0.30–0.95]; P≤0.05).

In the intermediate-risk cohort, the median OS was 62.2 months in the R-CHOP group and not estimable in the VR-CAP group (HR=0.55 [95% CI, 0.36–0.85]; P≤0.01).

In the high-risk cohort, the median OS was 37.1 months in the R-CHOP group and 30.4 months in the VR-CAP group (HR=1.02 [95% CI, 0.69–1.50]).

The researchers reported three new adverse events in the final analysis—grade 4 lung adenocarcinoma and grade 4 gastric cancer in the VR-CAP group as well as grade 2 pneumonia in the R-CHOP group.

The team acknowledged that a key limitation of this study was that rituximab was not given as maintenance since it was not considered standard care at the time of study initiation.

Moving forward, Dr. Robak and his colleagues recommend that bortezomib be investigated in combination with newer targeted therapies in order to establish best practice for treating MCL.

The LYM-3002 study was sponsored by Janssen Research & Development. The study authors reported financial ties to Janssen, Celgene, Ipsen, Johnson & Johnson, Novartis, and other companies.

Final results of a phase 3 trial suggest bortezomib plus rituximab and chemotherapy can significantly improve overall survival (OS) in transplant-ineligible patients with newly diagnosed mantle cell lymphoma (MCL).

In the LYM-3002 trial, researchers compared bortezomib plus rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, and prednisone (VR-CAP) to rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone (R-CHOP).

The median OS was significantly longer in patients who received VR-CAP than in those who received R-CHOP—90.7 months and 55.7 months, respectively.

This survival benefit was observed in patients with low- and intermediate-risk disease but not high-risk disease.

Tadeusz Robak, MD, of the Medical University of Lodz in Poland, and his colleagues reported these results in The Lancet Oncology alongside a related commentary.

The LYM-3002 trial began more than a decade ago, and initial results were published in 2015. At that time, the VR-CAP group showed a significant increase in progression-free survival compared with the R-CHOP group.

The final analysis of LYM-3002 included 268 of the original 487 MCL patients. Twenty-three percent of patients in the VR-CAP group (n=32) discontinued due to death, as did 40% of patients in the R-CHOP group (n=51). The main cause of death was progression—29% and 14%, respectively.

Among the 268 patients in the final analysis, 140 belonged to the VR-CAP group and 128 to the R-CHOP group. The patients’ median age was 66 (range, 26-83), 71% (n=190) were male, 74% (n=199) had stage IV disease, and 31% were classified as high risk based on the MCL-specific International Prognostic Index (MIPI).

About half of patients received therapies after the trial interventions (n=255, 52%)—43% (n=104) in the VR-CAP group and 62% (n=151) in the R-CHOP group. Most patients received subsequent antineoplastic therapy—77% (n=80) and 81% (n=123), respectively—and more than half received rituximab as second-line therapy—53% (n=55) and 59% (n=89), respectively.

Results

At a median follow-up of 82.0 months, the median OS was significantly longer in the VR-CAP group than in the R-CHOP group—90.7 months (95% CI, 71.4 to not estimable) and 55.7 months (95% CI, 47.2 to 68.9), respectively (hazard ratio [HR]=0.66 [95% CI, 0.51–0.85]; P=0.001).

The 4-year OS was 67.3% in the VR-CAP group and 54.3% in the R-CHOP group. The 6-year OS was 56.6% and 42.0%, respectively.

The researchers noted that VR-CAP was associated with significantly improved OS among patients in the low-risk and intermediate-risk MIPI categories but not in the high-risk category.

In the low-risk cohort, the median OS was 81.7 months in the R-CHOP group and not estimable in the VR-CAP group (HR=0.54 [95% CI, 0.30–0.95]; P≤0.05).

In the intermediate-risk cohort, the median OS was 62.2 months in the R-CHOP group and not estimable in the VR-CAP group (HR=0.55 [95% CI, 0.36–0.85]; P≤0.01).

In the high-risk cohort, the median OS was 37.1 months in the R-CHOP group and 30.4 months in the VR-CAP group (HR=1.02 [95% CI, 0.69–1.50]).

The researchers reported three new adverse events in the final analysis—grade 4 lung adenocarcinoma and grade 4 gastric cancer in the VR-CAP group as well as grade 2 pneumonia in the R-CHOP group.

The team acknowledged that a key limitation of this study was that rituximab was not given as maintenance since it was not considered standard care at the time of study initiation.

Moving forward, Dr. Robak and his colleagues recommend that bortezomib be investigated in combination with newer targeted therapies in order to establish best practice for treating MCL.

The LYM-3002 study was sponsored by Janssen Research & Development. The study authors reported financial ties to Janssen, Celgene, Ipsen, Johnson & Johnson, Novartis, and other companies.

Sore on nose

The FP suspected a basal cell carcinoma (BCC) or squamous cell carcinoma.

Informed consent was obtained, and the FP numbed the area with 1% lidocaine and epinephrine using a 30 gauge needle. The area was exquisitely tender, so a small needle was used and the anesthesia was injected slowly. (It is safe and recommended to use epinephrine for biopsy on or around the nose.) The physician performed a shave biopsy. (See the Watch & Learn video on “Shave biopsy.”)

The biopsy results confirmed an infiltrative BCC. The physician recognized this as a more aggressive BCC and its location at the nasolabial fold suggested that the patient was at an increased risk for recurrence. He communicated these risk factors to the patient, and she accepted a referral for Mohs surgery.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Karnes J, Usatine R. Basal cell carcinoma. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:989-998.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/.

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com.

The FP suspected a basal cell carcinoma (BCC) or squamous cell carcinoma.

Informed consent was obtained, and the FP numbed the area with 1% lidocaine and epinephrine using a 30 gauge needle. The area was exquisitely tender, so a small needle was used and the anesthesia was injected slowly. (It is safe and recommended to use epinephrine for biopsy on or around the nose.) The physician performed a shave biopsy. (See the Watch & Learn video on “Shave biopsy.”)

The biopsy results confirmed an infiltrative BCC. The physician recognized this as a more aggressive BCC and its location at the nasolabial fold suggested that the patient was at an increased risk for recurrence. He communicated these risk factors to the patient, and she accepted a referral for Mohs surgery.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Karnes J, Usatine R. Basal cell carcinoma. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:989-998.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/.

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com.

The FP suspected a basal cell carcinoma (BCC) or squamous cell carcinoma.

Informed consent was obtained, and the FP numbed the area with 1% lidocaine and epinephrine using a 30 gauge needle. The area was exquisitely tender, so a small needle was used and the anesthesia was injected slowly. (It is safe and recommended to use epinephrine for biopsy on or around the nose.) The physician performed a shave biopsy. (See the Watch & Learn video on “Shave biopsy.”)

The biopsy results confirmed an infiltrative BCC. The physician recognized this as a more aggressive BCC and its location at the nasolabial fold suggested that the patient was at an increased risk for recurrence. He communicated these risk factors to the patient, and she accepted a referral for Mohs surgery.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Karnes J, Usatine R. Basal cell carcinoma. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:989-998.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/.

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com.

Use of topical agents before RT may be safe

Moderate application of topical therapies directly prior to radiotherapy (RT) treatment sessions may be safe and might exhibit minimal effects on delivered treatment dose, investigators report.

The researchers found that although avoiding topical agents prior to radiation treatments was widespread, preclinical data indicate that there is no difference in the radiation dose on the skin with or without a 1- to 2-mm-thick layer of topical agent.

In an online survey, which queried 133 patients and 108 clinicians in relation to existing practices surrounding topical agent use, 83.4% of patients were informed to discontinue application of topical therapies directly before RT treatment sessions. In addition, 54.1% were told to clean and remove any enduring topical agents before treatment. Among clinicians, 91.4% reported to have received or given advice to stop application of topicals before obtaining RT treatment, Brian C. Baumann, MD, and his associates reported in JAMA Oncology.

However, in a preclinical study using a mouse- and tissue-equivalent phantom model to determine the dosimetric effects of concomitant topical agent use with daily RT treatments, Dr. Baumann, of Washington University in St. Louis, and his colleagues determined that when a topical agent was given prior to RT at a thickness below 2 mm, no changes were seen in radiation treatment dose, irrespective of depth, photon and electron energy level, or beam angle.

However, a proportionally thicker covering (3 mm or more) caused a bolus effect at the surface, which resulted in electron dose increases of 2%-5%, and photon increases of 15%-35%, when compared with controls.

Investigators measured radiation dose and photon beam intensity at various surface depths after applying two commonly used topical therapies, a healing ointment of 41% petrolatum or silver sulfadiazine cream 1%. The agents were administered using a thick (1-2 mm) application and proportionally thicker (3 mm or more) covering.

“Thin or moderately applied topical agents, even if applied just before RT, may have minimal influence on skin dose regardless of beam energy or beam incidence,” the investigators wrote. However, the findings do suggest that “applying very thick amounts of a topical agent before RT may increase the surface dose and should be avoided,” they said.

The authors reported that the study was funded by development funds from the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia. One of the coauthors, James M. Metz, MD, disclosed service on advisory boards for Ion Beam Applications and Varian Medical Systems for proton therapy; however, these roles were not relevant to this study.

SOURCE: Baumann BC et al. JAMA Oncol. 2018 Oct 18. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.4292.

The common practice of discontinuing topical therapies immediately prior to radiotherapy (RT) is likely an accepted myth, and through allowance of these agents, quality of life for patients may improve, according to Simon A. Brown, MD, and Chelsea C. Pinnix, MD, PhD.

The dogma stems from a period known as the “orthovoltage era,” which started in the 1920s, lasting into the 1950s. During this time, radiation oncologists recommended against the use of topical therapies or related agents directly preceding RT sessions, Dr. Brown and Dr. Pinnix wrote in invited commentary. The assumption was that using these agents could lead to increased dermatologic toxicities, because of the alleged bolus effects, or interactions with metal salts present in the topical. Bolus effects are sometimes beneficial, by reducing the delivered treatment dose in deeper tissues; but they also may be harmful, if unanticipated.

A similar study that took place in 1997, in which a group of researchers from the Medical College of Georgia, Augusta, investigated links between various topical agents and irradiation surface dose using a 6-MV photon beam. The results, similar to those reported by Dr. Baumann and his colleagues, showed that surface doses were affected only if agents were applied in a very thick manner, beyond what is considered normal. In addition, metal salts contained within the topical agents did not alter administered surface dose.

Taken together, the commentators stated that the common proposition that topical therapies must be avoided prior to RT is likely not relevant in many clinical situations.

Dr. Brown is affiliated with the department of radiation medicine at Oregon Health & Science University in Portland and Dr. Pinnix is with the department of radiation oncology at the University of Texas at the MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston. These comments are adapted from their invited commentary.

The common practice of discontinuing topical therapies immediately prior to radiotherapy (RT) is likely an accepted myth, and through allowance of these agents, quality of life for patients may improve, according to Simon A. Brown, MD, and Chelsea C. Pinnix, MD, PhD.

The dogma stems from a period known as the “orthovoltage era,” which started in the 1920s, lasting into the 1950s. During this time, radiation oncologists recommended against the use of topical therapies or related agents directly preceding RT sessions, Dr. Brown and Dr. Pinnix wrote in invited commentary. The assumption was that using these agents could lead to increased dermatologic toxicities, because of the alleged bolus effects, or interactions with metal salts present in the topical. Bolus effects are sometimes beneficial, by reducing the delivered treatment dose in deeper tissues; but they also may be harmful, if unanticipated.

A similar study that took place in 1997, in which a group of researchers from the Medical College of Georgia, Augusta, investigated links between various topical agents and irradiation surface dose using a 6-MV photon beam. The results, similar to those reported by Dr. Baumann and his colleagues, showed that surface doses were affected only if agents were applied in a very thick manner, beyond what is considered normal. In addition, metal salts contained within the topical agents did not alter administered surface dose.

Taken together, the commentators stated that the common proposition that topical therapies must be avoided prior to RT is likely not relevant in many clinical situations.

Dr. Brown is affiliated with the department of radiation medicine at Oregon Health & Science University in Portland and Dr. Pinnix is with the department of radiation oncology at the University of Texas at the MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston. These comments are adapted from their invited commentary.

The common practice of discontinuing topical therapies immediately prior to radiotherapy (RT) is likely an accepted myth, and through allowance of these agents, quality of life for patients may improve, according to Simon A. Brown, MD, and Chelsea C. Pinnix, MD, PhD.

The dogma stems from a period known as the “orthovoltage era,” which started in the 1920s, lasting into the 1950s. During this time, radiation oncologists recommended against the use of topical therapies or related agents directly preceding RT sessions, Dr. Brown and Dr. Pinnix wrote in invited commentary. The assumption was that using these agents could lead to increased dermatologic toxicities, because of the alleged bolus effects, or interactions with metal salts present in the topical. Bolus effects are sometimes beneficial, by reducing the delivered treatment dose in deeper tissues; but they also may be harmful, if unanticipated.

A similar study that took place in 1997, in which a group of researchers from the Medical College of Georgia, Augusta, investigated links between various topical agents and irradiation surface dose using a 6-MV photon beam. The results, similar to those reported by Dr. Baumann and his colleagues, showed that surface doses were affected only if agents were applied in a very thick manner, beyond what is considered normal. In addition, metal salts contained within the topical agents did not alter administered surface dose.

Taken together, the commentators stated that the common proposition that topical therapies must be avoided prior to RT is likely not relevant in many clinical situations.

Dr. Brown is affiliated with the department of radiation medicine at Oregon Health & Science University in Portland and Dr. Pinnix is with the department of radiation oncology at the University of Texas at the MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston. These comments are adapted from their invited commentary.

Moderate application of topical therapies directly prior to radiotherapy (RT) treatment sessions may be safe and might exhibit minimal effects on delivered treatment dose, investigators report.

The researchers found that although avoiding topical agents prior to radiation treatments was widespread, preclinical data indicate that there is no difference in the radiation dose on the skin with or without a 1- to 2-mm-thick layer of topical agent.

In an online survey, which queried 133 patients and 108 clinicians in relation to existing practices surrounding topical agent use, 83.4% of patients were informed to discontinue application of topical therapies directly before RT treatment sessions. In addition, 54.1% were told to clean and remove any enduring topical agents before treatment. Among clinicians, 91.4% reported to have received or given advice to stop application of topicals before obtaining RT treatment, Brian C. Baumann, MD, and his associates reported in JAMA Oncology.

However, in a preclinical study using a mouse- and tissue-equivalent phantom model to determine the dosimetric effects of concomitant topical agent use with daily RT treatments, Dr. Baumann, of Washington University in St. Louis, and his colleagues determined that when a topical agent was given prior to RT at a thickness below 2 mm, no changes were seen in radiation treatment dose, irrespective of depth, photon and electron energy level, or beam angle.

However, a proportionally thicker covering (3 mm or more) caused a bolus effect at the surface, which resulted in electron dose increases of 2%-5%, and photon increases of 15%-35%, when compared with controls.

Investigators measured radiation dose and photon beam intensity at various surface depths after applying two commonly used topical therapies, a healing ointment of 41% petrolatum or silver sulfadiazine cream 1%. The agents were administered using a thick (1-2 mm) application and proportionally thicker (3 mm or more) covering.

“Thin or moderately applied topical agents, even if applied just before RT, may have minimal influence on skin dose regardless of beam energy or beam incidence,” the investigators wrote. However, the findings do suggest that “applying very thick amounts of a topical agent before RT may increase the surface dose and should be avoided,” they said.

The authors reported that the study was funded by development funds from the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia. One of the coauthors, James M. Metz, MD, disclosed service on advisory boards for Ion Beam Applications and Varian Medical Systems for proton therapy; however, these roles were not relevant to this study.

SOURCE: Baumann BC et al. JAMA Oncol. 2018 Oct 18. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.4292.

Moderate application of topical therapies directly prior to radiotherapy (RT) treatment sessions may be safe and might exhibit minimal effects on delivered treatment dose, investigators report.

The researchers found that although avoiding topical agents prior to radiation treatments was widespread, preclinical data indicate that there is no difference in the radiation dose on the skin with or without a 1- to 2-mm-thick layer of topical agent.

In an online survey, which queried 133 patients and 108 clinicians in relation to existing practices surrounding topical agent use, 83.4% of patients were informed to discontinue application of topical therapies directly before RT treatment sessions. In addition, 54.1% were told to clean and remove any enduring topical agents before treatment. Among clinicians, 91.4% reported to have received or given advice to stop application of topicals before obtaining RT treatment, Brian C. Baumann, MD, and his associates reported in JAMA Oncology.

However, in a preclinical study using a mouse- and tissue-equivalent phantom model to determine the dosimetric effects of concomitant topical agent use with daily RT treatments, Dr. Baumann, of Washington University in St. Louis, and his colleagues determined that when a topical agent was given prior to RT at a thickness below 2 mm, no changes were seen in radiation treatment dose, irrespective of depth, photon and electron energy level, or beam angle.

However, a proportionally thicker covering (3 mm or more) caused a bolus effect at the surface, which resulted in electron dose increases of 2%-5%, and photon increases of 15%-35%, when compared with controls.

Investigators measured radiation dose and photon beam intensity at various surface depths after applying two commonly used topical therapies, a healing ointment of 41% petrolatum or silver sulfadiazine cream 1%. The agents were administered using a thick (1-2 mm) application and proportionally thicker (3 mm or more) covering.

“Thin or moderately applied topical agents, even if applied just before RT, may have minimal influence on skin dose regardless of beam energy or beam incidence,” the investigators wrote. However, the findings do suggest that “applying very thick amounts of a topical agent before RT may increase the surface dose and should be avoided,” they said.

The authors reported that the study was funded by development funds from the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia. One of the coauthors, James M. Metz, MD, disclosed service on advisory boards for Ion Beam Applications and Varian Medical Systems for proton therapy; however, these roles were not relevant to this study.

SOURCE: Baumann BC et al. JAMA Oncol. 2018 Oct 18. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.4292.

REPORTING FROM JAMA ONCOLOGY

Key clinical point: Modest application of topical agents preceding radiotherapy (RT) treatment may be safe for patients.

Major finding: When common topicals were applied at a thickness of less than 2 mm, negligible effects on radiation dose were seen.

Study details: An online survey consisting of 133 patients and 108 clinicians, in addition to a tissue-equivalent phantom and mouse model preclinical study.

Disclosures: The study was funded by development funds from the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia. The authors had no disclosures relevant to this study.

Source: Baumann BC et al. JAMA Oncol. 2018 Oct 18. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.4292.

Pediatric OSA linked to abnormal metabolic values

SAN ANTONIO – Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) in children is associated with an abnormal metabolic profile, but not with body mass index (BMI), according to new research.

“Screening for metabolic dysfunction in obese children with obstructive sleep apnea can help identify those at risk for cardiovascular complications,” Kanika Mathur, MD, of the Albert Einstein College of Medicine and the Children’s Hospital at Montefiore, both in New York, told attendees at the annual meeting of the American College of Chest Physicians. Dr. Mathur explained that no consensus currently exists regarding routine cardiac evaluation of children with OSA.

“The American Academy of Pediatrics does not mention any sort of cardiac evaluation in children with OSA while the most recent guidelines from the American Heart Association and the American Thoracic Society recommend echocardiographic evaluation in children with severe obstructive sleep apnea, specifically to evaluate for pulmonary hypertension and right ventricular dysfunction,” Dr. Mathur told attendees.

OSA’s association with obesity, diabetes, and hypertension is well established in adults. It is an independent risk factor for coronary artery disease, heart failure, stroke and atrial fibrillation, and research has suggested OSA treatment can reduce cardiovascular risk in adults, Dr. Mathur explained, but little data on children exist. She and her colleagues set out to understand the relationship of OSA in children with various measures of cardiovascular and metabolic health.

“Despite similar degrees of obesity and systemic blood pressure, pediatric patients with OSA had significantly higher diastolic blood pressure, heart rate, and abnormal metabolic profile, including elevated alanine transaminase, aspartate transaminase, triglycerides and hemoglobin A1c,” they found.

Their study included patients aged 3-21 years with a BMI of at least the 95th percentile who had undergone sleep study and an echocardiogram at the Children’s Hospital at Montefiore between November 2016 and November 2017.

They excluded those with comorbidities related to cardiovascular morbidity: heart disease, neuromuscular disease, sickle cell disease, rheumatologic diseases, significant cranial facial abnormalities, tracheostomy, and any lung disease. However, 7% of the patients had trisomy 21.

Among the 81 children who met their criteria, 37 were male and 44 were female, with an average age of 14 years old and a mean BMI of 39.4 kg/m2 (mean BMI z score of 2.22). Most of the patients (53.1%) had severe OSA (apnea-hypopnea index of at least 10), 21% had moderate OSA (AHI 5-9.9), 12.3% had mild OSA (AHI 2-4.9), and 13.6% did not have OSA. The median AHI of the children was 10.3.

Among all the children, “about half had elevated systolic blood pressure, which is already a risk factor for cardiovascular morbidity,” Mathur reported.

BMI, BMI z score, systolic blood pressure z score, oxygen saturation and cholesterol (overall and both HDL and LDL cholesterol levels) did not significantly differ between children who had OSA and those who did not, but diastolic blood pressure and heart rate did. Those with OSA had a diastolic blood pressure of 65 mm Hg, compared with 58 mm Hg without OSA (P = .008). Heart rate was 89 bpm in the children with OSA, compared with 78 bpm in those without (P = .004).

The children with OSA also showed higher mean levels of several other metabolic biomarkers:

- Alanine transaminase: 26 U/L with OSA vs. 18 U/L without (P = .01).

- Aspartate transaminase: 23 U/L with OSA vs. 18 U/L without (P = .03).

- Triglycerides: 138 mg/dL with OSA vs 84 mg/dL without (P = .004).

- Hemoglobin A1c: 6.2% with OSA vs. 5.4% without (P = .002).

Children with and without OSA did not have any significant differences in left atrial indexed volume, left ventricular volume, left ventricular ejection fraction, or left ventricular mass (measured by M-mode or 5/6 area length formula). Though research has shown these measures to differ in adults with and without OSA, evidence on echocardiographic changes in children has been conflicting, Dr. Mathur noted.

The researchers also conducted subanalyses according to OSA severity, but BMI, BMI Z-score, systolic or diastolic blood pressure Z-score, heart rate and oxygen saturation did not differ between those with mild OSA vs those with moderate or severe OSA. No differences in echocardiographic measurements existed between these subgroups, either.

However, children with moderate to severe OSA did have higher alanine transaminase (27 U/L with moderate to severe vs. 17 U/L with mild OSA; P = .005) and higher triglycerides (148 vs 74; P = .001).

“Certainly we need further evaluation to see the efficacy of obstructive sleep apnea therapies on metabolic dysfunction and whether weight loss needs to be an adjunct therapy for these patients,” Dr. Mathur told attendees. She also noted the need to define the role of echocardiography in managing children with OSA.

The study had several limitations, including its retrospective cross-sectional nature at a single center and its small sample size.

“Additionally, we have a wide variety of ages, which could represent different pathophysiology of the associated metabolic dysfunction in these patients,” Mathur said. “There is an inherent difficulty to performing echocardiograms in a very obese population as well.”

Both the moderators of the pediatrics section, Christopher Carroll, MD, FCCP, of Connecticut Children’s Medical Center in Hartford, and Shahid Sheikh, MD, FCCP, of Nationwide Children’s Hospital in Columbus, Ohio, were impressed with the research. Dr. Carroll called it a “very elegant” study, and Dr. Sheikh noted the need for these studies in pediatrics “so that we don’t have to rely on grown-up data,” which may or may not generalize to children.

SOURCE: CHEST 2018. https://journal.chestnet.org/article/S0012-3692(18)31935-4/fulltext

SAN ANTONIO – Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) in children is associated with an abnormal metabolic profile, but not with body mass index (BMI), according to new research.

“Screening for metabolic dysfunction in obese children with obstructive sleep apnea can help identify those at risk for cardiovascular complications,” Kanika Mathur, MD, of the Albert Einstein College of Medicine and the Children’s Hospital at Montefiore, both in New York, told attendees at the annual meeting of the American College of Chest Physicians. Dr. Mathur explained that no consensus currently exists regarding routine cardiac evaluation of children with OSA.

“The American Academy of Pediatrics does not mention any sort of cardiac evaluation in children with OSA while the most recent guidelines from the American Heart Association and the American Thoracic Society recommend echocardiographic evaluation in children with severe obstructive sleep apnea, specifically to evaluate for pulmonary hypertension and right ventricular dysfunction,” Dr. Mathur told attendees.

OSA’s association with obesity, diabetes, and hypertension is well established in adults. It is an independent risk factor for coronary artery disease, heart failure, stroke and atrial fibrillation, and research has suggested OSA treatment can reduce cardiovascular risk in adults, Dr. Mathur explained, but little data on children exist. She and her colleagues set out to understand the relationship of OSA in children with various measures of cardiovascular and metabolic health.

“Despite similar degrees of obesity and systemic blood pressure, pediatric patients with OSA had significantly higher diastolic blood pressure, heart rate, and abnormal metabolic profile, including elevated alanine transaminase, aspartate transaminase, triglycerides and hemoglobin A1c,” they found.

Their study included patients aged 3-21 years with a BMI of at least the 95th percentile who had undergone sleep study and an echocardiogram at the Children’s Hospital at Montefiore between November 2016 and November 2017.

They excluded those with comorbidities related to cardiovascular morbidity: heart disease, neuromuscular disease, sickle cell disease, rheumatologic diseases, significant cranial facial abnormalities, tracheostomy, and any lung disease. However, 7% of the patients had trisomy 21.

Among the 81 children who met their criteria, 37 were male and 44 were female, with an average age of 14 years old and a mean BMI of 39.4 kg/m2 (mean BMI z score of 2.22). Most of the patients (53.1%) had severe OSA (apnea-hypopnea index of at least 10), 21% had moderate OSA (AHI 5-9.9), 12.3% had mild OSA (AHI 2-4.9), and 13.6% did not have OSA. The median AHI of the children was 10.3.

Among all the children, “about half had elevated systolic blood pressure, which is already a risk factor for cardiovascular morbidity,” Mathur reported.

BMI, BMI z score, systolic blood pressure z score, oxygen saturation and cholesterol (overall and both HDL and LDL cholesterol levels) did not significantly differ between children who had OSA and those who did not, but diastolic blood pressure and heart rate did. Those with OSA had a diastolic blood pressure of 65 mm Hg, compared with 58 mm Hg without OSA (P = .008). Heart rate was 89 bpm in the children with OSA, compared with 78 bpm in those without (P = .004).

The children with OSA also showed higher mean levels of several other metabolic biomarkers:

- Alanine transaminase: 26 U/L with OSA vs. 18 U/L without (P = .01).

- Aspartate transaminase: 23 U/L with OSA vs. 18 U/L without (P = .03).

- Triglycerides: 138 mg/dL with OSA vs 84 mg/dL without (P = .004).

- Hemoglobin A1c: 6.2% with OSA vs. 5.4% without (P = .002).

Children with and without OSA did not have any significant differences in left atrial indexed volume, left ventricular volume, left ventricular ejection fraction, or left ventricular mass (measured by M-mode or 5/6 area length formula). Though research has shown these measures to differ in adults with and without OSA, evidence on echocardiographic changes in children has been conflicting, Dr. Mathur noted.

The researchers also conducted subanalyses according to OSA severity, but BMI, BMI Z-score, systolic or diastolic blood pressure Z-score, heart rate and oxygen saturation did not differ between those with mild OSA vs those with moderate or severe OSA. No differences in echocardiographic measurements existed between these subgroups, either.

However, children with moderate to severe OSA did have higher alanine transaminase (27 U/L with moderate to severe vs. 17 U/L with mild OSA; P = .005) and higher triglycerides (148 vs 74; P = .001).

“Certainly we need further evaluation to see the efficacy of obstructive sleep apnea therapies on metabolic dysfunction and whether weight loss needs to be an adjunct therapy for these patients,” Dr. Mathur told attendees. She also noted the need to define the role of echocardiography in managing children with OSA.

The study had several limitations, including its retrospective cross-sectional nature at a single center and its small sample size.

“Additionally, we have a wide variety of ages, which could represent different pathophysiology of the associated metabolic dysfunction in these patients,” Mathur said. “There is an inherent difficulty to performing echocardiograms in a very obese population as well.”

Both the moderators of the pediatrics section, Christopher Carroll, MD, FCCP, of Connecticut Children’s Medical Center in Hartford, and Shahid Sheikh, MD, FCCP, of Nationwide Children’s Hospital in Columbus, Ohio, were impressed with the research. Dr. Carroll called it a “very elegant” study, and Dr. Sheikh noted the need for these studies in pediatrics “so that we don’t have to rely on grown-up data,” which may or may not generalize to children.

SOURCE: CHEST 2018. https://journal.chestnet.org/article/S0012-3692(18)31935-4/fulltext

SAN ANTONIO – Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) in children is associated with an abnormal metabolic profile, but not with body mass index (BMI), according to new research.

“Screening for metabolic dysfunction in obese children with obstructive sleep apnea can help identify those at risk for cardiovascular complications,” Kanika Mathur, MD, of the Albert Einstein College of Medicine and the Children’s Hospital at Montefiore, both in New York, told attendees at the annual meeting of the American College of Chest Physicians. Dr. Mathur explained that no consensus currently exists regarding routine cardiac evaluation of children with OSA.

“The American Academy of Pediatrics does not mention any sort of cardiac evaluation in children with OSA while the most recent guidelines from the American Heart Association and the American Thoracic Society recommend echocardiographic evaluation in children with severe obstructive sleep apnea, specifically to evaluate for pulmonary hypertension and right ventricular dysfunction,” Dr. Mathur told attendees.

OSA’s association with obesity, diabetes, and hypertension is well established in adults. It is an independent risk factor for coronary artery disease, heart failure, stroke and atrial fibrillation, and research has suggested OSA treatment can reduce cardiovascular risk in adults, Dr. Mathur explained, but little data on children exist. She and her colleagues set out to understand the relationship of OSA in children with various measures of cardiovascular and metabolic health.

“Despite similar degrees of obesity and systemic blood pressure, pediatric patients with OSA had significantly higher diastolic blood pressure, heart rate, and abnormal metabolic profile, including elevated alanine transaminase, aspartate transaminase, triglycerides and hemoglobin A1c,” they found.

Their study included patients aged 3-21 years with a BMI of at least the 95th percentile who had undergone sleep study and an echocardiogram at the Children’s Hospital at Montefiore between November 2016 and November 2017.

They excluded those with comorbidities related to cardiovascular morbidity: heart disease, neuromuscular disease, sickle cell disease, rheumatologic diseases, significant cranial facial abnormalities, tracheostomy, and any lung disease. However, 7% of the patients had trisomy 21.

Among the 81 children who met their criteria, 37 were male and 44 were female, with an average age of 14 years old and a mean BMI of 39.4 kg/m2 (mean BMI z score of 2.22). Most of the patients (53.1%) had severe OSA (apnea-hypopnea index of at least 10), 21% had moderate OSA (AHI 5-9.9), 12.3% had mild OSA (AHI 2-4.9), and 13.6% did not have OSA. The median AHI of the children was 10.3.

Among all the children, “about half had elevated systolic blood pressure, which is already a risk factor for cardiovascular morbidity,” Mathur reported.

BMI, BMI z score, systolic blood pressure z score, oxygen saturation and cholesterol (overall and both HDL and LDL cholesterol levels) did not significantly differ between children who had OSA and those who did not, but diastolic blood pressure and heart rate did. Those with OSA had a diastolic blood pressure of 65 mm Hg, compared with 58 mm Hg without OSA (P = .008). Heart rate was 89 bpm in the children with OSA, compared with 78 bpm in those without (P = .004).

The children with OSA also showed higher mean levels of several other metabolic biomarkers:

- Alanine transaminase: 26 U/L with OSA vs. 18 U/L without (P = .01).

- Aspartate transaminase: 23 U/L with OSA vs. 18 U/L without (P = .03).

- Triglycerides: 138 mg/dL with OSA vs 84 mg/dL without (P = .004).

- Hemoglobin A1c: 6.2% with OSA vs. 5.4% without (P = .002).

Children with and without OSA did not have any significant differences in left atrial indexed volume, left ventricular volume, left ventricular ejection fraction, or left ventricular mass (measured by M-mode or 5/6 area length formula). Though research has shown these measures to differ in adults with and without OSA, evidence on echocardiographic changes in children has been conflicting, Dr. Mathur noted.

The researchers also conducted subanalyses according to OSA severity, but BMI, BMI Z-score, systolic or diastolic blood pressure Z-score, heart rate and oxygen saturation did not differ between those with mild OSA vs those with moderate or severe OSA. No differences in echocardiographic measurements existed between these subgroups, either.

However, children with moderate to severe OSA did have higher alanine transaminase (27 U/L with moderate to severe vs. 17 U/L with mild OSA; P = .005) and higher triglycerides (148 vs 74; P = .001).

“Certainly we need further evaluation to see the efficacy of obstructive sleep apnea therapies on metabolic dysfunction and whether weight loss needs to be an adjunct therapy for these patients,” Dr. Mathur told attendees. She also noted the need to define the role of echocardiography in managing children with OSA.

The study had several limitations, including its retrospective cross-sectional nature at a single center and its small sample size.

“Additionally, we have a wide variety of ages, which could represent different pathophysiology of the associated metabolic dysfunction in these patients,” Mathur said. “There is an inherent difficulty to performing echocardiograms in a very obese population as well.”

Both the moderators of the pediatrics section, Christopher Carroll, MD, FCCP, of Connecticut Children’s Medical Center in Hartford, and Shahid Sheikh, MD, FCCP, of Nationwide Children’s Hospital in Columbus, Ohio, were impressed with the research. Dr. Carroll called it a “very elegant” study, and Dr. Sheikh noted the need for these studies in pediatrics “so that we don’t have to rely on grown-up data,” which may or may not generalize to children.

SOURCE: CHEST 2018. https://journal.chestnet.org/article/S0012-3692(18)31935-4/fulltext

REPORTING FROM CHEST 2018

Key clinical point: Children with obesity and obstructive sleep apnea have an abnormal metabolic profile.

Major finding: Diastolic blood pressure (65 vs. 58 mm Hg), heart rate (89 vs. 78 bpm), triglycerides (138 vs. 84 mg/dL), alanine transaminase (26 vs. 18 U/L), aspartate transaminase (23 vs. 18 U/L) and hemoglobin A1c (6.2% vs. 5.4%) were all elevated in obese children with OSA, compared with obese children without OSA.

Study details: The findings are based on a retrospective analysis of 81 patients aged 3-21 years, from the Children’s Hospital at Montefiore between November 2016-November 2017.

Disclosures: No external funding was noted. The authors reported having no disclosures.

Rising microbiome investigator: Ting-Chin David Shen, MD, PhD

We spoke with Dr. Shen, instructor of medicine at the University of Pennsylvania and the recipient of the AGA Research Foundation’s 2016 Microbiome Junior Investigator Award, to learn about his passion for gut microbiome research.

How would you sum up your research in one sentence?

My research examines the metabolic interactions between the gut microbiota and the mammalian host, with a particular emphasis on amino acid metabolism and nitrogen flux via the bacterial enzyme urease.

What impact do you hope your research will have on patients?

My hope is that by better understanding the biological mechanisms by which the gut microbiota impacts host metabolism, we can modulate its effects to treat a variety of conditions and diseases including hepatic encephalopathy, inborn errors of metabolism, obesity, malnutrition, etc.

What inspired you to focus your research career on the gut microbiome?

My clinical experience as a gastroenterologist inspired my interest in metabolic and nutritional research. When I learned of the impact that the gut microbiota has on host metabolism, it created an entirely different perspective for me in terms of thinking about how to treat metabolic and nutritional disorders. There are tremendous opportunities in modifying our gut microbiota in concert with dietary interventions in order to modulate our metabolism.

What recent publication from your lab best represents your work, if anyone wants to learn more?

The following work examined how the use of a defined bacterial consortium without urease activity can reduce colonic ammonia level upon inoculation into the gut and ameliorate morbidity and mortality in a murine model of liver disease.

Shen, T.D., Albenberg, L.A., Bittinger, K., et al, Engineering the Gut Microbiota to Treat Hyperammonemia. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2015 Jul 1;125(7):2841-50.

We spoke with Dr. Shen, instructor of medicine at the University of Pennsylvania and the recipient of the AGA Research Foundation’s 2016 Microbiome Junior Investigator Award, to learn about his passion for gut microbiome research.

How would you sum up your research in one sentence?

My research examines the metabolic interactions between the gut microbiota and the mammalian host, with a particular emphasis on amino acid metabolism and nitrogen flux via the bacterial enzyme urease.

What impact do you hope your research will have on patients?

My hope is that by better understanding the biological mechanisms by which the gut microbiota impacts host metabolism, we can modulate its effects to treat a variety of conditions and diseases including hepatic encephalopathy, inborn errors of metabolism, obesity, malnutrition, etc.

What inspired you to focus your research career on the gut microbiome?

My clinical experience as a gastroenterologist inspired my interest in metabolic and nutritional research. When I learned of the impact that the gut microbiota has on host metabolism, it created an entirely different perspective for me in terms of thinking about how to treat metabolic and nutritional disorders. There are tremendous opportunities in modifying our gut microbiota in concert with dietary interventions in order to modulate our metabolism.

What recent publication from your lab best represents your work, if anyone wants to learn more?

The following work examined how the use of a defined bacterial consortium without urease activity can reduce colonic ammonia level upon inoculation into the gut and ameliorate morbidity and mortality in a murine model of liver disease.

Shen, T.D., Albenberg, L.A., Bittinger, K., et al, Engineering the Gut Microbiota to Treat Hyperammonemia. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2015 Jul 1;125(7):2841-50.

We spoke with Dr. Shen, instructor of medicine at the University of Pennsylvania and the recipient of the AGA Research Foundation’s 2016 Microbiome Junior Investigator Award, to learn about his passion for gut microbiome research.

How would you sum up your research in one sentence?

My research examines the metabolic interactions between the gut microbiota and the mammalian host, with a particular emphasis on amino acid metabolism and nitrogen flux via the bacterial enzyme urease.

What impact do you hope your research will have on patients?

My hope is that by better understanding the biological mechanisms by which the gut microbiota impacts host metabolism, we can modulate its effects to treat a variety of conditions and diseases including hepatic encephalopathy, inborn errors of metabolism, obesity, malnutrition, etc.

What inspired you to focus your research career on the gut microbiome?

My clinical experience as a gastroenterologist inspired my interest in metabolic and nutritional research. When I learned of the impact that the gut microbiota has on host metabolism, it created an entirely different perspective for me in terms of thinking about how to treat metabolic and nutritional disorders. There are tremendous opportunities in modifying our gut microbiota in concert with dietary interventions in order to modulate our metabolism.

What recent publication from your lab best represents your work, if anyone wants to learn more?

The following work examined how the use of a defined bacterial consortium without urease activity can reduce colonic ammonia level upon inoculation into the gut and ameliorate morbidity and mortality in a murine model of liver disease.

Shen, T.D., Albenberg, L.A., Bittinger, K., et al, Engineering the Gut Microbiota to Treat Hyperammonemia. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2015 Jul 1;125(7):2841-50.

AGA’s flagship research grant now accepting applications

The call for applications for 2019 Research Scholar Awards (RSA) is now open. An RSA enables young investigators to develop independent and productive research careers by ensuring protected time for research. And our commitment includes supporting the career development of all GI researchers, whether they focus on clinical or basic research. The deadline to apply is Dec. 14, 2018.

The call for applications for 2019 Research Scholar Awards (RSA) is now open. An RSA enables young investigators to develop independent and productive research careers by ensuring protected time for research. And our commitment includes supporting the career development of all GI researchers, whether they focus on clinical or basic research. The deadline to apply is Dec. 14, 2018.

The call for applications for 2019 Research Scholar Awards (RSA) is now open. An RSA enables young investigators to develop independent and productive research careers by ensuring protected time for research. And our commitment includes supporting the career development of all GI researchers, whether they focus on clinical or basic research. The deadline to apply is Dec. 14, 2018.

Smart insoles reduce ‘high-risk’ diabetic foot ulcer recurrence

BERLIN – Smart insoles that warn diabetic individuals of high plantar pressures could be a simple solution to help them avoid recurrent foot ulcers, according to the results of a randomized trial.

Study participants with a history of diabetic foot ulcers wore the plantar pressure–sensing insoles (SurroSense Rx) and received feedback via sensor linked to a smart watch worn and were 71% less likely to experience a recurrent foot ulceration than were those who wore the insoles but did not get the pressure feedback (incidence rate ratio, 0.29; 95% confidence interval, 0.09-0.93; P = .037). The device has been cleared by the Food and Drug Administration.

Overall, there were few ulcers that occurred in the study, with 10 ulcers from 8,638 person-days from six patients reported in the control group and four ulcers from 11,835 person-days from four patients in the intervention group.

“Diabetic foot ulcers are a major global health and economic burden, but, in theory at least, they are ultimately preventable,” said study investigator Neil Reeves, PhD,, who presented the findings at the annual meeting of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes.