User login

Disaster response, practice operations, transplant, women's health

Disaster Response and Global Health

Epigenetics and Disasters

The configuration of the DNA bordering a gene dictates under what conditions a gene is expressed. Random errors or mutations affecting the neighboring DNA or the gene itself can affect how the gene functions. Epigenetics is an emerging field of science looking at environmental and psychosocial factors that do not directly cause mutations but still affect how genes are expressed with implications for the development and inheritance of disease. These external influences are thought to affect why some segments of DNA become accessible for protein production while other segments may not.

Disasters represent stressors with potential for epigenetic impact. Women who were pregnant during the 1998 Quebec ice storm were found to have a correlation between maternal objective stress and a distinctive pattern of DNA methylation in their children 13 years later (Cao-Lei L, et al. PLoS ONE. 2014;9[9] e10765). Methylation is known to affect the activity of a DNA segment and how genes are expressed. Associations have also been found between the severity of hurricanes and the prevalence of autism in the offspring of pregnant women experiencing these disasters (Kinney DK, et al. J Autism Dev Disord. 2008;38:481).

Anthropogenic hazards may also affect the offspring of survivors as suggested by studies of civil war POWs and Dutch Hunger Winter during WW II (Costa, DL, et al. Proc Nat Acad Sci 2018;. 115:44; Heijmans BT et al. Proc Nat Acad Sci. 2008;105[44]: 17046-9).

Epigenetics represents an area for additional research as natural and man-made disasters increase.

Omesh Toolsie, MBBS

Steering Committee Fellow-in-Training

Practice Operations

Medicare Competitive Bidding Process Update

Medicare’s Competitive Bidding Program (CBP), mandated since 2003, asks providers of specific durable medical equipment (including oxygen) to submit competing proposals for services. The best offer is then awarded a 3-year contract. Recently, several reforms to CBP have been proposed. The payment structure has changed to “lead-item pricing,” where a single bid in each category is selected and payment amounts for each product are then calculated based on pricing ratios and fee schedules (CMS DMEPOS Competitive Bidding).

This is in contrast to the prior method of median pricing, which caused financial difficulty and access concerns (Council for Quality Respiratory Care. The Rationale for Reforming Medicare Home Respiratory Therapy Payment Methodology. 2018). Budget neutrality requirements should relax, and oxygen payment structures improve. These proposed changes also include improved coverage of liquid oxygen and addition of home ventilator supplies.

However, effective January 1, 2019, all CBP is suspended through CMS. During the anticipated 2-year gap, any Medicare-enrolled supplier will be able to provide items until new contracts are awarded. Pricing during the gap period is based on a current single price plus consumer price index. These changes will impact CHEST members and their patients moving forward. During the temporary gap period, some areas are seeing decreased accessibility of some DME due to demand. Once reinstated, the changes to the oxygen payment structure should improve access and reduce out-of-pocket costs. The Practice Operations NetWork will continue to provide updates on this topic as they become available.

Timothy Dempsey, MD, MPH

Steering Committee Fellow-in-Training

Megan Sisk, DO

Steering Committee Member

Transplant

Medicare Part D Plans Can Deny Coverage of Select Immunosuppressant Medications in Solid Organ Transplant Recipients

An alarming problem has emerged with some solid organ transplant recipients experiencing immunosuppressant medication claim denials by Medicare Part D plans. Affected patients are those who convert from some other insurance (ie, private insurance or state Medicaid) to Medicare after their transplant and, therefore, rely on Medicare Part D for immunosuppressant drug coverage.

Insurance companies who offer Medicare Part D plans must follow the rules described in the Medicare Prescription Drug Benefit Manual.1 Although the Manual mandates that all immunosuppressant medications are on plan formularies, Part D plans are only required to cover immunosuppressant medications when used for indications approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) or for off-label indications supported by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS)-approved compendia (Drugdex® and AHFS Drug Information®).

A recent study examining the extent of the problem demonstrated non-renal organ transplant recipients are frequently prescribed and maintained on at least one medication vulnerable to Medicare Part D claim denials at 1 year posttransplant (lung: 71.1%; intestine: 39.7%; pancreas: 36.8%; liver: 19.7%; heart: 18.5%).2 Lung transplant recipients are most vulnerable since no immunosuppressant is FDA-approved for use in lung transplantation, and CMS-approved compendia only support off-label use for tacrolimus and cyclosporine in this population. Therefore, mycophenolate mofetil, mycophenolic acid, azathioprine, everolimus, and sirolimus are vulnerable to denial by Medicare Part D plans when used in lung transplant recipients. Over 95% of lung transplant recipients are maintained on an anti-metabolite, with the majority (88%) maintained on mycophenolate, so this is frequently impacted.2,3 While the transplant community is aware of this issue and has begun work to correct it, it has yet to be solved.2,4 In the meantime, if transplant recipients have been denied for this off-label and off-compendia reason, and appeals of those decisions have also been denied, options for obtaining the denied immunosuppressant medication include discount programs, foundation/grant funding, and industry-sponsored assistance programs.

Jennifer K. McDermott, PharmD

NetWork Member

1. Prescription Drug Benefit Manual. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Chapter 6: Part D Drugs and Formulary Requirements. Available at: https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Prescription-Drug-Coverage/PrescriptionDrugCovContra/Downloads/Part-D-Benefits-Manual-Chapter-6.pdf

2. Potter LM et al. Transplant recipients are vulnerable to coverage denial under Medicare Part D. Am J Transplant. 2018;18:1502.

3. Valapour M et al. OPTN/SRTR 2016 Annual Data Report: Lung. Am J Transplant. 2018;18 (Suppl 1): 363.

4. Immunusuppressant Drug Coverage Under Medicare Part D Benefit. American Society of Transplantation. Available at: www.myast.org/public-policy/key-position-statements/immunosuppressant-drug-coverage-under-medicare-part-d-benefit.

Women’s Health

Cannabis Use Affects Women Differently

As we enter an era of legalization, cannabis use is increasingly prevalent. Variances in the risks for women and men have been observed. For most age groups, men have higher rates of use or dependence on illicit drugs than women. However, women are equally likely as men to progress to a substance use disorder. Women may be more susceptible to craving and relapse , which are key phases of the addiction cycle. A study on use among adolescents concluded there was preliminary evidence of a faster transition from initiation of marijuana use to regular use in women, when compared with men (Schepis, et al. J Addict Med. 2011;5[1]:65).

Research studies suggest that marijuana impairs spatial memory in women more so than in men. Studies have suggested that teenage girls who use marijuana may have a higher risk of brain structural abnormalities associated with regular marijuana exposure than teenage boys (Tapert, et al. Addict Biol. 2009;14[4]:457).

A study published in Psychoneuroendocrinology showed that cannabinoid receptor binding site densities exhibit sex differences and can be modulated by estradiol in several limbic brain regions. These findings may account for the sex differences observed with respect to the effects of cannabinoids (Riebe, et al. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2010;35[8]:1265).

Further research is needed to expand our understanding of the interactions between cannabinoids and sex steroids. Detoxification treatments tailored toward women and men with cannabis addiction show a promising future and necessitate further research.

Anita Rajagopal, MD

Steering Committee Member

Disaster Response and Global Health

Epigenetics and Disasters

The configuration of the DNA bordering a gene dictates under what conditions a gene is expressed. Random errors or mutations affecting the neighboring DNA or the gene itself can affect how the gene functions. Epigenetics is an emerging field of science looking at environmental and psychosocial factors that do not directly cause mutations but still affect how genes are expressed with implications for the development and inheritance of disease. These external influences are thought to affect why some segments of DNA become accessible for protein production while other segments may not.

Disasters represent stressors with potential for epigenetic impact. Women who were pregnant during the 1998 Quebec ice storm were found to have a correlation between maternal objective stress and a distinctive pattern of DNA methylation in their children 13 years later (Cao-Lei L, et al. PLoS ONE. 2014;9[9] e10765). Methylation is known to affect the activity of a DNA segment and how genes are expressed. Associations have also been found between the severity of hurricanes and the prevalence of autism in the offspring of pregnant women experiencing these disasters (Kinney DK, et al. J Autism Dev Disord. 2008;38:481).

Anthropogenic hazards may also affect the offspring of survivors as suggested by studies of civil war POWs and Dutch Hunger Winter during WW II (Costa, DL, et al. Proc Nat Acad Sci 2018;. 115:44; Heijmans BT et al. Proc Nat Acad Sci. 2008;105[44]: 17046-9).

Epigenetics represents an area for additional research as natural and man-made disasters increase.

Omesh Toolsie, MBBS

Steering Committee Fellow-in-Training

Practice Operations

Medicare Competitive Bidding Process Update

Medicare’s Competitive Bidding Program (CBP), mandated since 2003, asks providers of specific durable medical equipment (including oxygen) to submit competing proposals for services. The best offer is then awarded a 3-year contract. Recently, several reforms to CBP have been proposed. The payment structure has changed to “lead-item pricing,” where a single bid in each category is selected and payment amounts for each product are then calculated based on pricing ratios and fee schedules (CMS DMEPOS Competitive Bidding).

This is in contrast to the prior method of median pricing, which caused financial difficulty and access concerns (Council for Quality Respiratory Care. The Rationale for Reforming Medicare Home Respiratory Therapy Payment Methodology. 2018). Budget neutrality requirements should relax, and oxygen payment structures improve. These proposed changes also include improved coverage of liquid oxygen and addition of home ventilator supplies.

However, effective January 1, 2019, all CBP is suspended through CMS. During the anticipated 2-year gap, any Medicare-enrolled supplier will be able to provide items until new contracts are awarded. Pricing during the gap period is based on a current single price plus consumer price index. These changes will impact CHEST members and their patients moving forward. During the temporary gap period, some areas are seeing decreased accessibility of some DME due to demand. Once reinstated, the changes to the oxygen payment structure should improve access and reduce out-of-pocket costs. The Practice Operations NetWork will continue to provide updates on this topic as they become available.

Timothy Dempsey, MD, MPH

Steering Committee Fellow-in-Training

Megan Sisk, DO

Steering Committee Member

Transplant

Medicare Part D Plans Can Deny Coverage of Select Immunosuppressant Medications in Solid Organ Transplant Recipients

An alarming problem has emerged with some solid organ transplant recipients experiencing immunosuppressant medication claim denials by Medicare Part D plans. Affected patients are those who convert from some other insurance (ie, private insurance or state Medicaid) to Medicare after their transplant and, therefore, rely on Medicare Part D for immunosuppressant drug coverage.

Insurance companies who offer Medicare Part D plans must follow the rules described in the Medicare Prescription Drug Benefit Manual.1 Although the Manual mandates that all immunosuppressant medications are on plan formularies, Part D plans are only required to cover immunosuppressant medications when used for indications approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) or for off-label indications supported by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS)-approved compendia (Drugdex® and AHFS Drug Information®).

A recent study examining the extent of the problem demonstrated non-renal organ transplant recipients are frequently prescribed and maintained on at least one medication vulnerable to Medicare Part D claim denials at 1 year posttransplant (lung: 71.1%; intestine: 39.7%; pancreas: 36.8%; liver: 19.7%; heart: 18.5%).2 Lung transplant recipients are most vulnerable since no immunosuppressant is FDA-approved for use in lung transplantation, and CMS-approved compendia only support off-label use for tacrolimus and cyclosporine in this population. Therefore, mycophenolate mofetil, mycophenolic acid, azathioprine, everolimus, and sirolimus are vulnerable to denial by Medicare Part D plans when used in lung transplant recipients. Over 95% of lung transplant recipients are maintained on an anti-metabolite, with the majority (88%) maintained on mycophenolate, so this is frequently impacted.2,3 While the transplant community is aware of this issue and has begun work to correct it, it has yet to be solved.2,4 In the meantime, if transplant recipients have been denied for this off-label and off-compendia reason, and appeals of those decisions have also been denied, options for obtaining the denied immunosuppressant medication include discount programs, foundation/grant funding, and industry-sponsored assistance programs.

Jennifer K. McDermott, PharmD

NetWork Member

1. Prescription Drug Benefit Manual. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Chapter 6: Part D Drugs and Formulary Requirements. Available at: https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Prescription-Drug-Coverage/PrescriptionDrugCovContra/Downloads/Part-D-Benefits-Manual-Chapter-6.pdf

2. Potter LM et al. Transplant recipients are vulnerable to coverage denial under Medicare Part D. Am J Transplant. 2018;18:1502.

3. Valapour M et al. OPTN/SRTR 2016 Annual Data Report: Lung. Am J Transplant. 2018;18 (Suppl 1): 363.

4. Immunusuppressant Drug Coverage Under Medicare Part D Benefit. American Society of Transplantation. Available at: www.myast.org/public-policy/key-position-statements/immunosuppressant-drug-coverage-under-medicare-part-d-benefit.

Women’s Health

Cannabis Use Affects Women Differently

As we enter an era of legalization, cannabis use is increasingly prevalent. Variances in the risks for women and men have been observed. For most age groups, men have higher rates of use or dependence on illicit drugs than women. However, women are equally likely as men to progress to a substance use disorder. Women may be more susceptible to craving and relapse , which are key phases of the addiction cycle. A study on use among adolescents concluded there was preliminary evidence of a faster transition from initiation of marijuana use to regular use in women, when compared with men (Schepis, et al. J Addict Med. 2011;5[1]:65).

Research studies suggest that marijuana impairs spatial memory in women more so than in men. Studies have suggested that teenage girls who use marijuana may have a higher risk of brain structural abnormalities associated with regular marijuana exposure than teenage boys (Tapert, et al. Addict Biol. 2009;14[4]:457).

A study published in Psychoneuroendocrinology showed that cannabinoid receptor binding site densities exhibit sex differences and can be modulated by estradiol in several limbic brain regions. These findings may account for the sex differences observed with respect to the effects of cannabinoids (Riebe, et al. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2010;35[8]:1265).

Further research is needed to expand our understanding of the interactions between cannabinoids and sex steroids. Detoxification treatments tailored toward women and men with cannabis addiction show a promising future and necessitate further research.

Anita Rajagopal, MD

Steering Committee Member

Disaster Response and Global Health

Epigenetics and Disasters

The configuration of the DNA bordering a gene dictates under what conditions a gene is expressed. Random errors or mutations affecting the neighboring DNA or the gene itself can affect how the gene functions. Epigenetics is an emerging field of science looking at environmental and psychosocial factors that do not directly cause mutations but still affect how genes are expressed with implications for the development and inheritance of disease. These external influences are thought to affect why some segments of DNA become accessible for protein production while other segments may not.

Disasters represent stressors with potential for epigenetic impact. Women who were pregnant during the 1998 Quebec ice storm were found to have a correlation between maternal objective stress and a distinctive pattern of DNA methylation in their children 13 years later (Cao-Lei L, et al. PLoS ONE. 2014;9[9] e10765). Methylation is known to affect the activity of a DNA segment and how genes are expressed. Associations have also been found between the severity of hurricanes and the prevalence of autism in the offspring of pregnant women experiencing these disasters (Kinney DK, et al. J Autism Dev Disord. 2008;38:481).

Anthropogenic hazards may also affect the offspring of survivors as suggested by studies of civil war POWs and Dutch Hunger Winter during WW II (Costa, DL, et al. Proc Nat Acad Sci 2018;. 115:44; Heijmans BT et al. Proc Nat Acad Sci. 2008;105[44]: 17046-9).

Epigenetics represents an area for additional research as natural and man-made disasters increase.

Omesh Toolsie, MBBS

Steering Committee Fellow-in-Training

Practice Operations

Medicare Competitive Bidding Process Update

Medicare’s Competitive Bidding Program (CBP), mandated since 2003, asks providers of specific durable medical equipment (including oxygen) to submit competing proposals for services. The best offer is then awarded a 3-year contract. Recently, several reforms to CBP have been proposed. The payment structure has changed to “lead-item pricing,” where a single bid in each category is selected and payment amounts for each product are then calculated based on pricing ratios and fee schedules (CMS DMEPOS Competitive Bidding).

This is in contrast to the prior method of median pricing, which caused financial difficulty and access concerns (Council for Quality Respiratory Care. The Rationale for Reforming Medicare Home Respiratory Therapy Payment Methodology. 2018). Budget neutrality requirements should relax, and oxygen payment structures improve. These proposed changes also include improved coverage of liquid oxygen and addition of home ventilator supplies.

However, effective January 1, 2019, all CBP is suspended through CMS. During the anticipated 2-year gap, any Medicare-enrolled supplier will be able to provide items until new contracts are awarded. Pricing during the gap period is based on a current single price plus consumer price index. These changes will impact CHEST members and their patients moving forward. During the temporary gap period, some areas are seeing decreased accessibility of some DME due to demand. Once reinstated, the changes to the oxygen payment structure should improve access and reduce out-of-pocket costs. The Practice Operations NetWork will continue to provide updates on this topic as they become available.

Timothy Dempsey, MD, MPH

Steering Committee Fellow-in-Training

Megan Sisk, DO

Steering Committee Member

Transplant

Medicare Part D Plans Can Deny Coverage of Select Immunosuppressant Medications in Solid Organ Transplant Recipients

An alarming problem has emerged with some solid organ transplant recipients experiencing immunosuppressant medication claim denials by Medicare Part D plans. Affected patients are those who convert from some other insurance (ie, private insurance or state Medicaid) to Medicare after their transplant and, therefore, rely on Medicare Part D for immunosuppressant drug coverage.

Insurance companies who offer Medicare Part D plans must follow the rules described in the Medicare Prescription Drug Benefit Manual.1 Although the Manual mandates that all immunosuppressant medications are on plan formularies, Part D plans are only required to cover immunosuppressant medications when used for indications approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) or for off-label indications supported by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS)-approved compendia (Drugdex® and AHFS Drug Information®).

A recent study examining the extent of the problem demonstrated non-renal organ transplant recipients are frequently prescribed and maintained on at least one medication vulnerable to Medicare Part D claim denials at 1 year posttransplant (lung: 71.1%; intestine: 39.7%; pancreas: 36.8%; liver: 19.7%; heart: 18.5%).2 Lung transplant recipients are most vulnerable since no immunosuppressant is FDA-approved for use in lung transplantation, and CMS-approved compendia only support off-label use for tacrolimus and cyclosporine in this population. Therefore, mycophenolate mofetil, mycophenolic acid, azathioprine, everolimus, and sirolimus are vulnerable to denial by Medicare Part D plans when used in lung transplant recipients. Over 95% of lung transplant recipients are maintained on an anti-metabolite, with the majority (88%) maintained on mycophenolate, so this is frequently impacted.2,3 While the transplant community is aware of this issue and has begun work to correct it, it has yet to be solved.2,4 In the meantime, if transplant recipients have been denied for this off-label and off-compendia reason, and appeals of those decisions have also been denied, options for obtaining the denied immunosuppressant medication include discount programs, foundation/grant funding, and industry-sponsored assistance programs.

Jennifer K. McDermott, PharmD

NetWork Member

1. Prescription Drug Benefit Manual. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Chapter 6: Part D Drugs and Formulary Requirements. Available at: https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Prescription-Drug-Coverage/PrescriptionDrugCovContra/Downloads/Part-D-Benefits-Manual-Chapter-6.pdf

2. Potter LM et al. Transplant recipients are vulnerable to coverage denial under Medicare Part D. Am J Transplant. 2018;18:1502.

3. Valapour M et al. OPTN/SRTR 2016 Annual Data Report: Lung. Am J Transplant. 2018;18 (Suppl 1): 363.

4. Immunusuppressant Drug Coverage Under Medicare Part D Benefit. American Society of Transplantation. Available at: www.myast.org/public-policy/key-position-statements/immunosuppressant-drug-coverage-under-medicare-part-d-benefit.

Women’s Health

Cannabis Use Affects Women Differently

As we enter an era of legalization, cannabis use is increasingly prevalent. Variances in the risks for women and men have been observed. For most age groups, men have higher rates of use or dependence on illicit drugs than women. However, women are equally likely as men to progress to a substance use disorder. Women may be more susceptible to craving and relapse , which are key phases of the addiction cycle. A study on use among adolescents concluded there was preliminary evidence of a faster transition from initiation of marijuana use to regular use in women, when compared with men (Schepis, et al. J Addict Med. 2011;5[1]:65).

Research studies suggest that marijuana impairs spatial memory in women more so than in men. Studies have suggested that teenage girls who use marijuana may have a higher risk of brain structural abnormalities associated with regular marijuana exposure than teenage boys (Tapert, et al. Addict Biol. 2009;14[4]:457).

A study published in Psychoneuroendocrinology showed that cannabinoid receptor binding site densities exhibit sex differences and can be modulated by estradiol in several limbic brain regions. These findings may account for the sex differences observed with respect to the effects of cannabinoids (Riebe, et al. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2010;35[8]:1265).

Further research is needed to expand our understanding of the interactions between cannabinoids and sex steroids. Detoxification treatments tailored toward women and men with cannabis addiction show a promising future and necessitate further research.

Anita Rajagopal, MD

Steering Committee Member

CHEST Foundation’s NetWorks Challenge is just around the corner

The NetWorks Challenge is an annual fundraising competition that encourages NetWork members to contribute to the CHEST Foundation - supporting clinical research grants and community service programs and creating patient education materials - while earning travel grants for their NetWork members to the CHEST Annual Meeting 2019 in New Orleans. Because of your generosity throughout the 2018 NetWorks Challenge, the CHEST Foundation was able to send 59 early career clinicians to CHEST 2018 in San Antonio - marked growth from the 25 clinicians who received the travel grants in 2017.

As we further improve this program based on feedback from NetWorks members, a few elements of the fundraiser are changing in 2019.

Length: This year, the NetWorks Challenge will span 3 months. Contributions made between April 1 and June 30 count toward your NetWork’s fundraising total! Just be sure to list your NetWork when making your contribution on chestfoundation.org/donate. Each month has a unique theme related to CHEST, so be sure to watch our social media profiles to engage with us and each other during the drive.

Additionally, ANY contributions made to the CHEST Foundation during your membership renewal will count toward your NetWorks total amount raised - no matter when your membership is up for renewal. Contributions made in this manner after June 30 will count toward your Network’s 2020 amount raised.

Prizes: This year, every NetWork is eligible to receive travel grants to CHEST 2019 in New Orleans based on the amount raised by the NetWork. Our final winners – the NetWork with the highest amount raised, and the NetWork with the highest percentage of participation from their NetWork, will each receive two additional travel grants to CHEST 2019. Plus, the NetWork with the highest amount raised over the course of the challenge receives an additional prize – a seat in a CHEST Live Learning course of the winner’s choosing, offered at CHEST’s Innovation, Simulation, and Training Center in Glenview, Illinois.

Visit chestfoundation.org/nc for more detailed information.

The NetWorks Challenge is an annual fundraising competition that encourages NetWork members to contribute to the CHEST Foundation - supporting clinical research grants and community service programs and creating patient education materials - while earning travel grants for their NetWork members to the CHEST Annual Meeting 2019 in New Orleans. Because of your generosity throughout the 2018 NetWorks Challenge, the CHEST Foundation was able to send 59 early career clinicians to CHEST 2018 in San Antonio - marked growth from the 25 clinicians who received the travel grants in 2017.

As we further improve this program based on feedback from NetWorks members, a few elements of the fundraiser are changing in 2019.

Length: This year, the NetWorks Challenge will span 3 months. Contributions made between April 1 and June 30 count toward your NetWork’s fundraising total! Just be sure to list your NetWork when making your contribution on chestfoundation.org/donate. Each month has a unique theme related to CHEST, so be sure to watch our social media profiles to engage with us and each other during the drive.

Additionally, ANY contributions made to the CHEST Foundation during your membership renewal will count toward your NetWorks total amount raised - no matter when your membership is up for renewal. Contributions made in this manner after June 30 will count toward your Network’s 2020 amount raised.

Prizes: This year, every NetWork is eligible to receive travel grants to CHEST 2019 in New Orleans based on the amount raised by the NetWork. Our final winners – the NetWork with the highest amount raised, and the NetWork with the highest percentage of participation from their NetWork, will each receive two additional travel grants to CHEST 2019. Plus, the NetWork with the highest amount raised over the course of the challenge receives an additional prize – a seat in a CHEST Live Learning course of the winner’s choosing, offered at CHEST’s Innovation, Simulation, and Training Center in Glenview, Illinois.

Visit chestfoundation.org/nc for more detailed information.

The NetWorks Challenge is an annual fundraising competition that encourages NetWork members to contribute to the CHEST Foundation - supporting clinical research grants and community service programs and creating patient education materials - while earning travel grants for their NetWork members to the CHEST Annual Meeting 2019 in New Orleans. Because of your generosity throughout the 2018 NetWorks Challenge, the CHEST Foundation was able to send 59 early career clinicians to CHEST 2018 in San Antonio - marked growth from the 25 clinicians who received the travel grants in 2017.

As we further improve this program based on feedback from NetWorks members, a few elements of the fundraiser are changing in 2019.

Length: This year, the NetWorks Challenge will span 3 months. Contributions made between April 1 and June 30 count toward your NetWork’s fundraising total! Just be sure to list your NetWork when making your contribution on chestfoundation.org/donate. Each month has a unique theme related to CHEST, so be sure to watch our social media profiles to engage with us and each other during the drive.

Additionally, ANY contributions made to the CHEST Foundation during your membership renewal will count toward your NetWorks total amount raised - no matter when your membership is up for renewal. Contributions made in this manner after June 30 will count toward your Network’s 2020 amount raised.

Prizes: This year, every NetWork is eligible to receive travel grants to CHEST 2019 in New Orleans based on the amount raised by the NetWork. Our final winners – the NetWork with the highest amount raised, and the NetWork with the highest percentage of participation from their NetWork, will each receive two additional travel grants to CHEST 2019. Plus, the NetWork with the highest amount raised over the course of the challenge receives an additional prize – a seat in a CHEST Live Learning course of the winner’s choosing, offered at CHEST’s Innovation, Simulation, and Training Center in Glenview, Illinois.

Visit chestfoundation.org/nc for more detailed information.

Sleep Strategies

Compared with obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), the prevalence of central sleep apnea (CSA) is low in the general population. However, in adults, CSA may be highly prevalent in certain conditions, most commonly among those with left ventricular systolic dysfunction, left ventricular diastolic dysfunction, atrial fibrillation, stroke, and opioid users (Javaheri S, et al. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017; 69:841). CSA may also be found in patients with carotid artery stenosis, cervical neck injury, and renal dysfunction. CSA can occur when OSA is treated (treatment-emergent central sleep apnea, or TECA), notably, and most frequently, with continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) devices. Though in many individuals, this frequently resolves with continued use of the device.

In addition, unlike OSA, adequate treatment of CSA has proven difficult. Specifically, the response to CPAP, oxygen, theophylline, acetazolamide, and adaptive-servo ventilation (ASV) is highly variable, with individuals who respond well, and individuals in whom therapy fails to fully suppress the disorder.

Our interest in phrenic nerve stimulation increased after it was shown that CPAP therapy failed to improve morbidity and mortality of CSA in patients with heart failure and reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) (CANPAP trial, Bradley et al. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(19):2025). In fact, in this trial, treatment with CPAP was associated with significantly increased mortality during the first few months of therapy. We reason that a potential mechanism was positive airway pressure that had adverse cardiovascular effects (Javaheri S. J Clin Sleep Med. 2006;2:399). This is because positive airway pressure therapy decreases venous return to the right side of the heart and increases lung volume. This could increase pulmonary vascular resistance (right ventricular afterload), which is lung volume-dependent. Therefore, the subgroup of individuals with heart failure whose right ventricular function is preload-dependent and has pulmonary hypertension is at risk for premature mortality with any PAP device.

Interestingly, investigators of the SERVE-HF trial (Cowie MR, et al. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:1095) also hypothesized that one reason for excess mortality associated with ASV use might have been due to an ASV-associated excessive rise in intrathoracic pressure, similar to the hypothesis we proposed earlier for CPAP. We expanded on this hypothesis and reasoned that based on the algorithm of the device, in some patients, it could have generated excessive minute ventilation and pressure contributing to excess mortality, either at night or daytime (Javaheri S, et al. Chest. 2016;149:900). Other deficiencies of the algorithm of the ASV device could have contributed to excess mortality as well (Javaheri S, et al. Chest. 2014;146:514). These deficiencies of the ASV device used in the SERVE-HF trial have been significantly improved in the new generation of ASV devices.

Undoubtedly, therefore, mask therapy with positive airway pressures increases intrathoracic pressure and will adversely affect cardiovascular function in some patients with heart failure. Another issue for mask therapy is adherence to the device remains poor, as demonstrated both in the CANPAP and SERVE-HF trials, confirming the need for new approaches utilizing non-mask therapies both for CSA and OSA.

Given the limitations of mask-based therapies, over the last several years, we have performed studies exploring the use of oxygen, acetazolamide, theophylline, and, most recently, phrenic nerve stimulation (PNS). In general, these therapies are devoid of increasing intrathoracic pressure and are expected to be less reliant on patients’ adherence than PAP therapy. Long-term randomized clinical trials are needed, and, most recently, the NIH approved a phase 3 trial for a randomized placebo-controlled low flow oxygen therapy for treatment of CSA in HFrEF. This is a modified trial proposed by one of us more than 20 years ago!

Regarding PNS, CSA is characterized by intermittent phrenic nerve (and intercostal nerves) deactivation. It, therefore, makes sense to have an implanted stimulator for the phrenic nerve to prevent development of central apneas during sleep. This is not a new idea. In 1948, Sarnoff and colleagues demonstrated for the first time that artificial respiration could be effectively administered to the cat, dog, monkey, and rabbit in the absence of spontaneous respiration by electrical stimulation of one (or both) phrenic nerves (Sarnoff SJ, et al. Science. 1948;108:482). In later experiments, these investigators showed that unilateral phrenic nerve stimulation is also equally effective in man as that shown in animal models.

The phrenic nerves comes in contact with veins on both the right (brachiocephalic) and the left (pericardiophrenic vein) side of the mediastinum. Like a cardiac pacemaker, an electrophysiologist places the stimulator within the vein at the point of encounter with the phrenic nerve. Only unilateral stimulation is needed for the therapy. The device is typically placed on the right side of the chest as many patients may already have a cardiac implanted electronic device such as a pacemaker. Like the hypoglossal nerve stimulation, the FDA approved this device for the treatment of OSA. The system can be programmed using an external programmer in the office.

Phrenic nerve stimulation system is initially activated 1 month after the device is placed. It is programmed to be automatically activated at night when the patient is at rest. First, a time is set on the device for when the patient typically goes to bed and awakens. This allows the therapy to activate. The device contains a position sensor and accelerometer, which determine position and activity level. Once appropriate time, position, and activity are confirmed, the device activates automatically. Therapy comes on and can increase in level over several minutes. The device senses transthoracic impedance and can use this measurement to make changes in the therapy output and activity. If the patient gets up at night, the device automatically stops and restarts when the patient is back in a sleeping position. How quickly the therapy restarts and at what energy is programmable. The device may allow from 1 to 15 minutes for the patient to get back to sleep before beginning therapy. These programming changes allow for patient acceptance and comfort with the therapy even in very sensitive patients. Importantly, no patient activation is needed, so that therapy delivery is independent of patient’s adherence over time.

In the prospective, randomized pivotal trial (Costanzo et al. Lancet. 2016;388:974), 151 eligible patients with moderate-severe central sleep apnea were implanted and randomly assigned to the treatment (n=73) or control (n=78) groups. Participants in the active arm received PNS for 6 months. All polysomnograms were centrally and blindly scored. There were significant decreases in AHI (50 to 26/per hour of sleep), CAI (32 to 6), arousal index (46 to 25), and ODI (44 to 25). Two points should be emphasized: first, changes in AHI with PNS are similar to those in CANPAP trial, and there remained a significant number of hypopneas (some of these hypopneas are at least in part related to the speed of the titration when the subject sits up and the device automatically is deactivated, only to resume therapy in supine position); second, in contrast to the CANPAP trial, there was a significant reduction in arousals. Probably for this reason, subjective daytime sleepiness, as measured by the ESS, improved. In addition, PNS improved quality of life, in contrast to lack of effect of CPAP or ASV in this domain. Regarding side effects, 138 (91%) of 151 patients had no serious-related adverse events at 12 months. Seven (9%) cases of related-serious adverse events occurred in the control group and six (8%) cases were reported in the treatment group.—3.4% needed lead repositioning, a rate which is like that of cardiac implantable devices. Seven patients died (unrelated to implant, system, or therapy), four deaths (two in treatment group and two in control group) during the 6-month randomization period when neurostimulation was delivered to only the treatment and was off in the control group, and three deaths between 6 months and 12 months of follow-up when all patients received neurostimulation. Of 73 patients in the treatment group, 27 (37%) reported nonserious therapy-related discomfort that was resolved with simple system reprogramming in 26 (36%) patients but was unresolved in one (1%) patient.

Long-term studies have shown sustained effects of PNS on CSA with improvement in both sleep metrics and QOL, as measured by the Minnesota Living with Heart Failure Questionnaire (MLWHF) and patient global assessment (PGA). Furthermore, in the subgroup of patients with concomitant heart failure with LVEF ≤ 45%, PNS was associated with both improvements in LVEF and a trend toward lower hospitalization rates (Costanzo et al. Eur J Heart Fail. 2018; doi:10.1002/ejhf.1312).

Several issues must be emphasized. One advantage of PNS is complete adherence resulting in a major reduction in apnea burden across the whole night. Second, the mechanism of action prevents any potential adverse consequences related to increased intrathoracic pressure. However, the cost of this therapy is high, similar to that of hypoglossal nerve stimulation. Large scale, long-term studies related to mortality are not yet available, and continued research should help identify those patients most likely to benefit from this therapeutic approach.

Compared with obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), the prevalence of central sleep apnea (CSA) is low in the general population. However, in adults, CSA may be highly prevalent in certain conditions, most commonly among those with left ventricular systolic dysfunction, left ventricular diastolic dysfunction, atrial fibrillation, stroke, and opioid users (Javaheri S, et al. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017; 69:841). CSA may also be found in patients with carotid artery stenosis, cervical neck injury, and renal dysfunction. CSA can occur when OSA is treated (treatment-emergent central sleep apnea, or TECA), notably, and most frequently, with continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) devices. Though in many individuals, this frequently resolves with continued use of the device.

In addition, unlike OSA, adequate treatment of CSA has proven difficult. Specifically, the response to CPAP, oxygen, theophylline, acetazolamide, and adaptive-servo ventilation (ASV) is highly variable, with individuals who respond well, and individuals in whom therapy fails to fully suppress the disorder.

Our interest in phrenic nerve stimulation increased after it was shown that CPAP therapy failed to improve morbidity and mortality of CSA in patients with heart failure and reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) (CANPAP trial, Bradley et al. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(19):2025). In fact, in this trial, treatment with CPAP was associated with significantly increased mortality during the first few months of therapy. We reason that a potential mechanism was positive airway pressure that had adverse cardiovascular effects (Javaheri S. J Clin Sleep Med. 2006;2:399). This is because positive airway pressure therapy decreases venous return to the right side of the heart and increases lung volume. This could increase pulmonary vascular resistance (right ventricular afterload), which is lung volume-dependent. Therefore, the subgroup of individuals with heart failure whose right ventricular function is preload-dependent and has pulmonary hypertension is at risk for premature mortality with any PAP device.

Interestingly, investigators of the SERVE-HF trial (Cowie MR, et al. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:1095) also hypothesized that one reason for excess mortality associated with ASV use might have been due to an ASV-associated excessive rise in intrathoracic pressure, similar to the hypothesis we proposed earlier for CPAP. We expanded on this hypothesis and reasoned that based on the algorithm of the device, in some patients, it could have generated excessive minute ventilation and pressure contributing to excess mortality, either at night or daytime (Javaheri S, et al. Chest. 2016;149:900). Other deficiencies of the algorithm of the ASV device could have contributed to excess mortality as well (Javaheri S, et al. Chest. 2014;146:514). These deficiencies of the ASV device used in the SERVE-HF trial have been significantly improved in the new generation of ASV devices.

Undoubtedly, therefore, mask therapy with positive airway pressures increases intrathoracic pressure and will adversely affect cardiovascular function in some patients with heart failure. Another issue for mask therapy is adherence to the device remains poor, as demonstrated both in the CANPAP and SERVE-HF trials, confirming the need for new approaches utilizing non-mask therapies both for CSA and OSA.

Given the limitations of mask-based therapies, over the last several years, we have performed studies exploring the use of oxygen, acetazolamide, theophylline, and, most recently, phrenic nerve stimulation (PNS). In general, these therapies are devoid of increasing intrathoracic pressure and are expected to be less reliant on patients’ adherence than PAP therapy. Long-term randomized clinical trials are needed, and, most recently, the NIH approved a phase 3 trial for a randomized placebo-controlled low flow oxygen therapy for treatment of CSA in HFrEF. This is a modified trial proposed by one of us more than 20 years ago!

Regarding PNS, CSA is characterized by intermittent phrenic nerve (and intercostal nerves) deactivation. It, therefore, makes sense to have an implanted stimulator for the phrenic nerve to prevent development of central apneas during sleep. This is not a new idea. In 1948, Sarnoff and colleagues demonstrated for the first time that artificial respiration could be effectively administered to the cat, dog, monkey, and rabbit in the absence of spontaneous respiration by electrical stimulation of one (or both) phrenic nerves (Sarnoff SJ, et al. Science. 1948;108:482). In later experiments, these investigators showed that unilateral phrenic nerve stimulation is also equally effective in man as that shown in animal models.

The phrenic nerves comes in contact with veins on both the right (brachiocephalic) and the left (pericardiophrenic vein) side of the mediastinum. Like a cardiac pacemaker, an electrophysiologist places the stimulator within the vein at the point of encounter with the phrenic nerve. Only unilateral stimulation is needed for the therapy. The device is typically placed on the right side of the chest as many patients may already have a cardiac implanted electronic device such as a pacemaker. Like the hypoglossal nerve stimulation, the FDA approved this device for the treatment of OSA. The system can be programmed using an external programmer in the office.

Phrenic nerve stimulation system is initially activated 1 month after the device is placed. It is programmed to be automatically activated at night when the patient is at rest. First, a time is set on the device for when the patient typically goes to bed and awakens. This allows the therapy to activate. The device contains a position sensor and accelerometer, which determine position and activity level. Once appropriate time, position, and activity are confirmed, the device activates automatically. Therapy comes on and can increase in level over several minutes. The device senses transthoracic impedance and can use this measurement to make changes in the therapy output and activity. If the patient gets up at night, the device automatically stops and restarts when the patient is back in a sleeping position. How quickly the therapy restarts and at what energy is programmable. The device may allow from 1 to 15 minutes for the patient to get back to sleep before beginning therapy. These programming changes allow for patient acceptance and comfort with the therapy even in very sensitive patients. Importantly, no patient activation is needed, so that therapy delivery is independent of patient’s adherence over time.

In the prospective, randomized pivotal trial (Costanzo et al. Lancet. 2016;388:974), 151 eligible patients with moderate-severe central sleep apnea were implanted and randomly assigned to the treatment (n=73) or control (n=78) groups. Participants in the active arm received PNS for 6 months. All polysomnograms were centrally and blindly scored. There were significant decreases in AHI (50 to 26/per hour of sleep), CAI (32 to 6), arousal index (46 to 25), and ODI (44 to 25). Two points should be emphasized: first, changes in AHI with PNS are similar to those in CANPAP trial, and there remained a significant number of hypopneas (some of these hypopneas are at least in part related to the speed of the titration when the subject sits up and the device automatically is deactivated, only to resume therapy in supine position); second, in contrast to the CANPAP trial, there was a significant reduction in arousals. Probably for this reason, subjective daytime sleepiness, as measured by the ESS, improved. In addition, PNS improved quality of life, in contrast to lack of effect of CPAP or ASV in this domain. Regarding side effects, 138 (91%) of 151 patients had no serious-related adverse events at 12 months. Seven (9%) cases of related-serious adverse events occurred in the control group and six (8%) cases were reported in the treatment group.—3.4% needed lead repositioning, a rate which is like that of cardiac implantable devices. Seven patients died (unrelated to implant, system, or therapy), four deaths (two in treatment group and two in control group) during the 6-month randomization period when neurostimulation was delivered to only the treatment and was off in the control group, and three deaths between 6 months and 12 months of follow-up when all patients received neurostimulation. Of 73 patients in the treatment group, 27 (37%) reported nonserious therapy-related discomfort that was resolved with simple system reprogramming in 26 (36%) patients but was unresolved in one (1%) patient.

Long-term studies have shown sustained effects of PNS on CSA with improvement in both sleep metrics and QOL, as measured by the Minnesota Living with Heart Failure Questionnaire (MLWHF) and patient global assessment (PGA). Furthermore, in the subgroup of patients with concomitant heart failure with LVEF ≤ 45%, PNS was associated with both improvements in LVEF and a trend toward lower hospitalization rates (Costanzo et al. Eur J Heart Fail. 2018; doi:10.1002/ejhf.1312).

Several issues must be emphasized. One advantage of PNS is complete adherence resulting in a major reduction in apnea burden across the whole night. Second, the mechanism of action prevents any potential adverse consequences related to increased intrathoracic pressure. However, the cost of this therapy is high, similar to that of hypoglossal nerve stimulation. Large scale, long-term studies related to mortality are not yet available, and continued research should help identify those patients most likely to benefit from this therapeutic approach.

Compared with obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), the prevalence of central sleep apnea (CSA) is low in the general population. However, in adults, CSA may be highly prevalent in certain conditions, most commonly among those with left ventricular systolic dysfunction, left ventricular diastolic dysfunction, atrial fibrillation, stroke, and opioid users (Javaheri S, et al. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017; 69:841). CSA may also be found in patients with carotid artery stenosis, cervical neck injury, and renal dysfunction. CSA can occur when OSA is treated (treatment-emergent central sleep apnea, or TECA), notably, and most frequently, with continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) devices. Though in many individuals, this frequently resolves with continued use of the device.

In addition, unlike OSA, adequate treatment of CSA has proven difficult. Specifically, the response to CPAP, oxygen, theophylline, acetazolamide, and adaptive-servo ventilation (ASV) is highly variable, with individuals who respond well, and individuals in whom therapy fails to fully suppress the disorder.

Our interest in phrenic nerve stimulation increased after it was shown that CPAP therapy failed to improve morbidity and mortality of CSA in patients with heart failure and reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) (CANPAP trial, Bradley et al. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(19):2025). In fact, in this trial, treatment with CPAP was associated with significantly increased mortality during the first few months of therapy. We reason that a potential mechanism was positive airway pressure that had adverse cardiovascular effects (Javaheri S. J Clin Sleep Med. 2006;2:399). This is because positive airway pressure therapy decreases venous return to the right side of the heart and increases lung volume. This could increase pulmonary vascular resistance (right ventricular afterload), which is lung volume-dependent. Therefore, the subgroup of individuals with heart failure whose right ventricular function is preload-dependent and has pulmonary hypertension is at risk for premature mortality with any PAP device.

Interestingly, investigators of the SERVE-HF trial (Cowie MR, et al. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:1095) also hypothesized that one reason for excess mortality associated with ASV use might have been due to an ASV-associated excessive rise in intrathoracic pressure, similar to the hypothesis we proposed earlier for CPAP. We expanded on this hypothesis and reasoned that based on the algorithm of the device, in some patients, it could have generated excessive minute ventilation and pressure contributing to excess mortality, either at night or daytime (Javaheri S, et al. Chest. 2016;149:900). Other deficiencies of the algorithm of the ASV device could have contributed to excess mortality as well (Javaheri S, et al. Chest. 2014;146:514). These deficiencies of the ASV device used in the SERVE-HF trial have been significantly improved in the new generation of ASV devices.

Undoubtedly, therefore, mask therapy with positive airway pressures increases intrathoracic pressure and will adversely affect cardiovascular function in some patients with heart failure. Another issue for mask therapy is adherence to the device remains poor, as demonstrated both in the CANPAP and SERVE-HF trials, confirming the need for new approaches utilizing non-mask therapies both for CSA and OSA.

Given the limitations of mask-based therapies, over the last several years, we have performed studies exploring the use of oxygen, acetazolamide, theophylline, and, most recently, phrenic nerve stimulation (PNS). In general, these therapies are devoid of increasing intrathoracic pressure and are expected to be less reliant on patients’ adherence than PAP therapy. Long-term randomized clinical trials are needed, and, most recently, the NIH approved a phase 3 trial for a randomized placebo-controlled low flow oxygen therapy for treatment of CSA in HFrEF. This is a modified trial proposed by one of us more than 20 years ago!

Regarding PNS, CSA is characterized by intermittent phrenic nerve (and intercostal nerves) deactivation. It, therefore, makes sense to have an implanted stimulator for the phrenic nerve to prevent development of central apneas during sleep. This is not a new idea. In 1948, Sarnoff and colleagues demonstrated for the first time that artificial respiration could be effectively administered to the cat, dog, monkey, and rabbit in the absence of spontaneous respiration by electrical stimulation of one (or both) phrenic nerves (Sarnoff SJ, et al. Science. 1948;108:482). In later experiments, these investigators showed that unilateral phrenic nerve stimulation is also equally effective in man as that shown in animal models.

The phrenic nerves comes in contact with veins on both the right (brachiocephalic) and the left (pericardiophrenic vein) side of the mediastinum. Like a cardiac pacemaker, an electrophysiologist places the stimulator within the vein at the point of encounter with the phrenic nerve. Only unilateral stimulation is needed for the therapy. The device is typically placed on the right side of the chest as many patients may already have a cardiac implanted electronic device such as a pacemaker. Like the hypoglossal nerve stimulation, the FDA approved this device for the treatment of OSA. The system can be programmed using an external programmer in the office.

Phrenic nerve stimulation system is initially activated 1 month after the device is placed. It is programmed to be automatically activated at night when the patient is at rest. First, a time is set on the device for when the patient typically goes to bed and awakens. This allows the therapy to activate. The device contains a position sensor and accelerometer, which determine position and activity level. Once appropriate time, position, and activity are confirmed, the device activates automatically. Therapy comes on and can increase in level over several minutes. The device senses transthoracic impedance and can use this measurement to make changes in the therapy output and activity. If the patient gets up at night, the device automatically stops and restarts when the patient is back in a sleeping position. How quickly the therapy restarts and at what energy is programmable. The device may allow from 1 to 15 minutes for the patient to get back to sleep before beginning therapy. These programming changes allow for patient acceptance and comfort with the therapy even in very sensitive patients. Importantly, no patient activation is needed, so that therapy delivery is independent of patient’s adherence over time.

In the prospective, randomized pivotal trial (Costanzo et al. Lancet. 2016;388:974), 151 eligible patients with moderate-severe central sleep apnea were implanted and randomly assigned to the treatment (n=73) or control (n=78) groups. Participants in the active arm received PNS for 6 months. All polysomnograms were centrally and blindly scored. There were significant decreases in AHI (50 to 26/per hour of sleep), CAI (32 to 6), arousal index (46 to 25), and ODI (44 to 25). Two points should be emphasized: first, changes in AHI with PNS are similar to those in CANPAP trial, and there remained a significant number of hypopneas (some of these hypopneas are at least in part related to the speed of the titration when the subject sits up and the device automatically is deactivated, only to resume therapy in supine position); second, in contrast to the CANPAP trial, there was a significant reduction in arousals. Probably for this reason, subjective daytime sleepiness, as measured by the ESS, improved. In addition, PNS improved quality of life, in contrast to lack of effect of CPAP or ASV in this domain. Regarding side effects, 138 (91%) of 151 patients had no serious-related adverse events at 12 months. Seven (9%) cases of related-serious adverse events occurred in the control group and six (8%) cases were reported in the treatment group.—3.4% needed lead repositioning, a rate which is like that of cardiac implantable devices. Seven patients died (unrelated to implant, system, or therapy), four deaths (two in treatment group and two in control group) during the 6-month randomization period when neurostimulation was delivered to only the treatment and was off in the control group, and three deaths between 6 months and 12 months of follow-up when all patients received neurostimulation. Of 73 patients in the treatment group, 27 (37%) reported nonserious therapy-related discomfort that was resolved with simple system reprogramming in 26 (36%) patients but was unresolved in one (1%) patient.

Long-term studies have shown sustained effects of PNS on CSA with improvement in both sleep metrics and QOL, as measured by the Minnesota Living with Heart Failure Questionnaire (MLWHF) and patient global assessment (PGA). Furthermore, in the subgroup of patients with concomitant heart failure with LVEF ≤ 45%, PNS was associated with both improvements in LVEF and a trend toward lower hospitalization rates (Costanzo et al. Eur J Heart Fail. 2018; doi:10.1002/ejhf.1312).

Several issues must be emphasized. One advantage of PNS is complete adherence resulting in a major reduction in apnea burden across the whole night. Second, the mechanism of action prevents any potential adverse consequences related to increased intrathoracic pressure. However, the cost of this therapy is high, similar to that of hypoglossal nerve stimulation. Large scale, long-term studies related to mortality are not yet available, and continued research should help identify those patients most likely to benefit from this therapeutic approach.

Blood-based signature helps predict status of early AD indicator

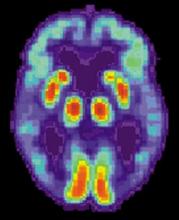

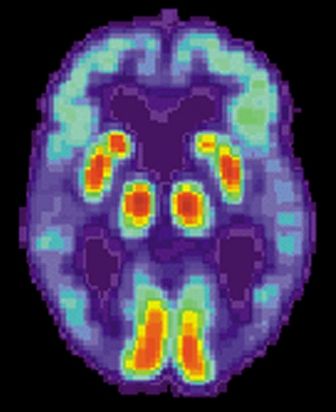

A recently developed blood-based signature can help predict the status of an early Alzheimer’s disease risk indicator with high accuracy, investigators are reporting.

By analyzing as few as four proteins, the machine learning-derived test can predict the status of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) amyloid beta1-42 (Abeta1-42), according to Noel G. Faux, PHD, of IBM Australia and the University of Melbourne, and co-investigators.

While shifts in Abeta1-42 may signal the presence of disease long before significant cognitive decline is clinically apparent, collection of CSF is highly invasive and expensive, Faux and investigators said in their report.

By contrast, blood biomarkers could prove to be a useful alternative not only to invasive lumbar punctures, they said, but also to the positron emission tomography (PET) evaluation of Abeta1-42, which is expensive and limited in some regions.

“In conjunction with biomarkers for neocortical amyloid burden, the CSF Abeta1-42biomarkers presented in this work may help yield a cheap, non-invasive tool for both improving clinical trials targeting amyloid and population screening,” Dr. Faux and co-authors said in Scientific Reports.

Dr. Faux and colleagues used a Random Forest approach to build models for CSF Abeta1-42 using blood biomarkers and other variables.

They found that a model incorporating age, APOEe4 carrier status, and a number of plasma protein levels predicted Abeta1-42 normal/abnormalstatus with an AUC, sensitivity and specificity of 0.84, 0.78 and 0.73 respectively.

In a model they said was more suitable for clinical application, they narrowed down the variables to 4 plasma analytes and APOEe4 carrier status, which had an AUC, sensitivity, and specificity of 0.81, 0.81 and 0.64 respectively.

They validated the models on a cohort of individuals in the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI), a large, longitudinal, multicenter study.

Patients with mild cognitive impairment with predicted abnormal CSF Abeta1-42 levels indeed did transition to a diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease more quickly than those with predicted normal levels, according to investigators.

That helps provide “strong evidence” that the blood-based model is generalizable, robust, and could help stratify patients based on risk of progressing to Alzheimer’s disease, they said in their report.

Dr. Faux and colleagues declared no conflicts of interest related to the research.

SOURCE: Goudey B, et al. Sci Rep. 2019 Mar 10. doi: 10.1101/190207v3.

A recently developed blood-based signature can help predict the status of an early Alzheimer’s disease risk indicator with high accuracy, investigators are reporting.

By analyzing as few as four proteins, the machine learning-derived test can predict the status of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) amyloid beta1-42 (Abeta1-42), according to Noel G. Faux, PHD, of IBM Australia and the University of Melbourne, and co-investigators.

While shifts in Abeta1-42 may signal the presence of disease long before significant cognitive decline is clinically apparent, collection of CSF is highly invasive and expensive, Faux and investigators said in their report.

By contrast, blood biomarkers could prove to be a useful alternative not only to invasive lumbar punctures, they said, but also to the positron emission tomography (PET) evaluation of Abeta1-42, which is expensive and limited in some regions.

“In conjunction with biomarkers for neocortical amyloid burden, the CSF Abeta1-42biomarkers presented in this work may help yield a cheap, non-invasive tool for both improving clinical trials targeting amyloid and population screening,” Dr. Faux and co-authors said in Scientific Reports.

Dr. Faux and colleagues used a Random Forest approach to build models for CSF Abeta1-42 using blood biomarkers and other variables.

They found that a model incorporating age, APOEe4 carrier status, and a number of plasma protein levels predicted Abeta1-42 normal/abnormalstatus with an AUC, sensitivity and specificity of 0.84, 0.78 and 0.73 respectively.

In a model they said was more suitable for clinical application, they narrowed down the variables to 4 plasma analytes and APOEe4 carrier status, which had an AUC, sensitivity, and specificity of 0.81, 0.81 and 0.64 respectively.

They validated the models on a cohort of individuals in the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI), a large, longitudinal, multicenter study.

Patients with mild cognitive impairment with predicted abnormal CSF Abeta1-42 levels indeed did transition to a diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease more quickly than those with predicted normal levels, according to investigators.

That helps provide “strong evidence” that the blood-based model is generalizable, robust, and could help stratify patients based on risk of progressing to Alzheimer’s disease, they said in their report.

Dr. Faux and colleagues declared no conflicts of interest related to the research.

SOURCE: Goudey B, et al. Sci Rep. 2019 Mar 10. doi: 10.1101/190207v3.

A recently developed blood-based signature can help predict the status of an early Alzheimer’s disease risk indicator with high accuracy, investigators are reporting.

By analyzing as few as four proteins, the machine learning-derived test can predict the status of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) amyloid beta1-42 (Abeta1-42), according to Noel G. Faux, PHD, of IBM Australia and the University of Melbourne, and co-investigators.

While shifts in Abeta1-42 may signal the presence of disease long before significant cognitive decline is clinically apparent, collection of CSF is highly invasive and expensive, Faux and investigators said in their report.

By contrast, blood biomarkers could prove to be a useful alternative not only to invasive lumbar punctures, they said, but also to the positron emission tomography (PET) evaluation of Abeta1-42, which is expensive and limited in some regions.

“In conjunction with biomarkers for neocortical amyloid burden, the CSF Abeta1-42biomarkers presented in this work may help yield a cheap, non-invasive tool for both improving clinical trials targeting amyloid and population screening,” Dr. Faux and co-authors said in Scientific Reports.

Dr. Faux and colleagues used a Random Forest approach to build models for CSF Abeta1-42 using blood biomarkers and other variables.

They found that a model incorporating age, APOEe4 carrier status, and a number of plasma protein levels predicted Abeta1-42 normal/abnormalstatus with an AUC, sensitivity and specificity of 0.84, 0.78 and 0.73 respectively.

In a model they said was more suitable for clinical application, they narrowed down the variables to 4 plasma analytes and APOEe4 carrier status, which had an AUC, sensitivity, and specificity of 0.81, 0.81 and 0.64 respectively.

They validated the models on a cohort of individuals in the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI), a large, longitudinal, multicenter study.

Patients with mild cognitive impairment with predicted abnormal CSF Abeta1-42 levels indeed did transition to a diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease more quickly than those with predicted normal levels, according to investigators.

That helps provide “strong evidence” that the blood-based model is generalizable, robust, and could help stratify patients based on risk of progressing to Alzheimer’s disease, they said in their report.

Dr. Faux and colleagues declared no conflicts of interest related to the research.

SOURCE: Goudey B, et al. Sci Rep. 2019 Mar 10. doi: 10.1101/190207v3.

FROM SCIENTIFIC REPORTS

Key clinical point: A blood-based signature can help predict the status of an early Alzheimer’s disease risk indicator.

Major finding:

Study details: Machine learning analysis of blood biomarkers and other variables in a validation cohort of 198 individuals.

Disclosures: The study authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Goudey B, et al. Sci Rep. 2019 Mar 10. doi: 10.1101/190207v3.

Evaluations for possible MS often turn up one of its many mimics

DALLAS – Of 95 patients referred to two multiple sclerosis (MS) centers for a possible diagnosis of MS, 74% did not have MS, according to a study presented at ACTRIMS Forum 2019. A majority had clinical syndromes or imaging findings that are atypical for MS, which “underscores the importance of familiarity with typical MS clinical and imaging findings in avoiding misdiagnosis,” said Marwa Kaisey, MD, and her research colleagues. Dr. Kaisey is a neurologist at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles.

Physicians often refer patients to academic MS centers to determine whether patients have MS or one of its many mimics. To study the characteristics and final diagnoses of patients referred to MS centers for evaluation of possible MS, the investigators reviewed electronic medical records and MRI from all new patient evaluations at the Cedars-Sinai Medical Center and University of California, Los Angeles MS clinics between July 2016 and June 2017. The researchers excluded patients referred with a previously established diagnosis of MS.

There were 366 new patients evaluated, including 236 patients with previously established MS diagnoses and 35 patients whose evaluations were not related to MS. Of the 95 patients referred for a question of MS diagnosis, 60% had clinical syndromes that were atypical for MS, 22% had normal neurologic exams, and a third had pain or sensory changes that were not localizable to the CNS.

Sixty-seven percent had MRI that was atypical for MS, and nearly half of the patients without MS had nonspecific MRI changes. “Often, these MRI changes alone prompted referral for an MS evaluation,” Dr. Kaisey and colleagues reported. “This suggests that novel, specific imaging tools may increase diagnostic confidence in the clinical setting.”

In all, the referred patients received 28 diagnoses other than MS, most commonly migraine (10 patients), anxiety or conversion disorder (9), postinfectious or idiopathic transverse myelitis (8), compression myelopathy or spondylopathy (8), and peripheral neuropathy or radiculopathy (7).

The researchers did not have any relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: Kaisey M et al. ACTRIMS Forum 2019, Abstract 90.

DALLAS – Of 95 patients referred to two multiple sclerosis (MS) centers for a possible diagnosis of MS, 74% did not have MS, according to a study presented at ACTRIMS Forum 2019. A majority had clinical syndromes or imaging findings that are atypical for MS, which “underscores the importance of familiarity with typical MS clinical and imaging findings in avoiding misdiagnosis,” said Marwa Kaisey, MD, and her research colleagues. Dr. Kaisey is a neurologist at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles.

Physicians often refer patients to academic MS centers to determine whether patients have MS or one of its many mimics. To study the characteristics and final diagnoses of patients referred to MS centers for evaluation of possible MS, the investigators reviewed electronic medical records and MRI from all new patient evaluations at the Cedars-Sinai Medical Center and University of California, Los Angeles MS clinics between July 2016 and June 2017. The researchers excluded patients referred with a previously established diagnosis of MS.

There were 366 new patients evaluated, including 236 patients with previously established MS diagnoses and 35 patients whose evaluations were not related to MS. Of the 95 patients referred for a question of MS diagnosis, 60% had clinical syndromes that were atypical for MS, 22% had normal neurologic exams, and a third had pain or sensory changes that were not localizable to the CNS.

Sixty-seven percent had MRI that was atypical for MS, and nearly half of the patients without MS had nonspecific MRI changes. “Often, these MRI changes alone prompted referral for an MS evaluation,” Dr. Kaisey and colleagues reported. “This suggests that novel, specific imaging tools may increase diagnostic confidence in the clinical setting.”

In all, the referred patients received 28 diagnoses other than MS, most commonly migraine (10 patients), anxiety or conversion disorder (9), postinfectious or idiopathic transverse myelitis (8), compression myelopathy or spondylopathy (8), and peripheral neuropathy or radiculopathy (7).

The researchers did not have any relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: Kaisey M et al. ACTRIMS Forum 2019, Abstract 90.

DALLAS – Of 95 patients referred to two multiple sclerosis (MS) centers for a possible diagnosis of MS, 74% did not have MS, according to a study presented at ACTRIMS Forum 2019. A majority had clinical syndromes or imaging findings that are atypical for MS, which “underscores the importance of familiarity with typical MS clinical and imaging findings in avoiding misdiagnosis,” said Marwa Kaisey, MD, and her research colleagues. Dr. Kaisey is a neurologist at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles.

Physicians often refer patients to academic MS centers to determine whether patients have MS or one of its many mimics. To study the characteristics and final diagnoses of patients referred to MS centers for evaluation of possible MS, the investigators reviewed electronic medical records and MRI from all new patient evaluations at the Cedars-Sinai Medical Center and University of California, Los Angeles MS clinics between July 2016 and June 2017. The researchers excluded patients referred with a previously established diagnosis of MS.

There were 366 new patients evaluated, including 236 patients with previously established MS diagnoses and 35 patients whose evaluations were not related to MS. Of the 95 patients referred for a question of MS diagnosis, 60% had clinical syndromes that were atypical for MS, 22% had normal neurologic exams, and a third had pain or sensory changes that were not localizable to the CNS.

Sixty-seven percent had MRI that was atypical for MS, and nearly half of the patients without MS had nonspecific MRI changes. “Often, these MRI changes alone prompted referral for an MS evaluation,” Dr. Kaisey and colleagues reported. “This suggests that novel, specific imaging tools may increase diagnostic confidence in the clinical setting.”

In all, the referred patients received 28 diagnoses other than MS, most commonly migraine (10 patients), anxiety or conversion disorder (9), postinfectious or idiopathic transverse myelitis (8), compression myelopathy or spondylopathy (8), and peripheral neuropathy or radiculopathy (7).

The researchers did not have any relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: Kaisey M et al. ACTRIMS Forum 2019, Abstract 90.

REPORTING FROM ACTRIMS FORUM 2019

Low Risk TAVR trial shows 3% mortality at 1 year

WASHINGTON –Anticipating two pivotal trials scheduled for presentation at the 2019 annual meeting of the American College of Cardiology (ACC), an investigator-led study of transaortic valve replacement (TAVR) for aortic stenosis presented as a latebreaker at 2019 CRT meeting produced excellent results.

Not least impressive, “our mortality rates are the lowest ever reported in any TAVR study at one year,” said Ronald Waksman, MD, Associate Director, Division of Cardiology, Medstar Heart Institute, Washington, DC.

In a population of patients with a median age of 71.1 years, all-cause mortality was just 3% at one year while the rate of deaths due to cardiovascular causes was only 1%, according to results of the 200-patient Low Risk TAVR study (LRT 1.0, NCT02628899) that Dr. Waksman presented.

In addition, there were low rates at one year for stroke (2.1%, none of which was deemed disability), myocardial infarction (1%), new onset atrial fibrillation (6.2%), and pacemaker placement (7.3%). The rate of rehospitalization for any cause was 20.4% but only 3.1% were considered related to TAVR. Rehospitalization for any cardiovascular cause at one year occurred in 6.8%.

Although leaflet thickening was observed at one year with imaging in 14%, this has not had any identifiable clinical consequences so far, and hemodynamics have remained stable, according to Dr. Waksman, who presented the interim 30-day outcomes at the 2018 CRT meeting.

These findings are raising expectations for two phase 3 TAVR trials in low-risk patients that are being presented as latebreakers at the 2019 ACC annual meeting. Both are large randomized trials comparing TAVR to surgical aortic valve replacement (SAVR) in low risk patients. Each trial is testing a single type of value and is funded by the valve manufacturers.

In the PARTNER-3 trial, patients randomized to TAVR received the Sapien 3 valve (Edwards Lifesciences). In the other latebreaking trial, patients randomized to TAVR received an Evolut valve (Medtronic Cardiovascular). Both are comparing TAVR to SAVR with a composite primary outcome that includes mortality and stroke measured at 30 days and one year.

In contrast to these trials, LRT 1.0 was conducted with no funding from a third party, according to Dr. Waksman. The eleven centers participated in the study at their own cost. Also, the choice of TAVR device was left to the discretion of the interventional cardiologist. Finally, most of the participating centers, although experienced in TAVR, did not have a high-volume case load. In general, with the exception of Dr. Waksman’s center, most performed 100 to 150 TAVRs per year.

“We were struck by the excellence of the performance of these sites,” said Dr. Waksman, noting that a comparison of outcomes at his center relative to the lower volume centers showed no significant differences in outcome.

This real-world experience raises the bar for the pivotal phase 3 trials, which, if positive, are expected to lead the FDA to grant an indication for TAVR in low-risk patients, according to Dr. Waksman. He announced that an LRT 2.0 trial, which will again include centers performing TAVRs at moderate volumes, is now enrolling.

SOURCE: 2019 Cardiovascular Research Technologies (CRT) Meeting.

WASHINGTON –Anticipating two pivotal trials scheduled for presentation at the 2019 annual meeting of the American College of Cardiology (ACC), an investigator-led study of transaortic valve replacement (TAVR) for aortic stenosis presented as a latebreaker at 2019 CRT meeting produced excellent results.