User login

To avoid Hep B reactivation, screen before immunosuppression

CASE A 53-year-old woman you are seeing for the first time has been taking 10 mg of prednisone daily for a month, prescribed by another practitioner for polymyalgia rheumatica. Testing is negative for hepatitis B surface antigen but is positive for hepatitis B core antibody total, indicating a resolved hepatitis B infection. The absence of hepatitis B DNA is confirmed.

How would you proceed with this patient?

Patients with resolved hepatitis B virus (HBV) or chronic hepatitis B (CHB) infections are at risk for HBV reactivation (HBVr) if they undergo immunosuppressive therapy for a condition such as cancer. HBVr can in turn lead to delays in treatment and increased morbidity and mortality.

HBVr is a well-documented adverse outcome in patients treated with rituximab and in those undergoing stem cell transplantation. Current oncology guidelines recommend screening for HBV prior to initiating these treatments.1,2 More recent evidence shows that many other immunosuppressive therapies can also lead to HBVr.3 Such treatments are now used across a multitude of specialties and conditions. For many of these conditions, there are no consistent guidelines regarding HBV screening.

In 2013, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) announced the requirement of a Boxed Warning for the immunosuppressive drugs ofatumumab and rituximab. In 2016, the FDA announced the same requirement for certain direct-acting antiviral medicines for hepatitis C virus.

Among patients who are positive for hepatitis-B surface antigen (HBsAg) and who are treated with immunosuppression, the frequency of HBVr has ranged from 0% to 39%.4,5

As the list of immunosuppressive therapies that can cause HBVr grows, specialty guidelines are evolving to address the risk that HBVr poses.

Continue to: An underrecognized problem

An underrecognized problem. CHB affects an estimated 350 million people worldwide6 but remains underrecognized and underdiagnosed. An estimated 1.4 million Americans6 have CHB, but only a minority of them are aware of their positive status and are followed by a hepatologist or receive medical care for their disease.7 Compared with the natural-born US population, a higher prevalence of CHB exists among immigrants to this country from the Asian Pacific and Eastern Mediterranean regions, sub-Saharan Africa, and certain parts of South America.8-10 In 2008, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) updated its recommendations on screening for HBV to include immigrants to the United States from intermediate and high endemic areas.6 Unfortunately, data published on physicians’ adherence to the CDC guidelines for screening show that only 60% correctly screened at-risk patients.11

Individuals with CHB are at risk and rely on a robust immune system to keep their disease from becoming active. During infection, the virus gains entry into the hepatocytes and the double-stranded viral genome is imported into the nucleus of the cell, where it is repaired into covalently closed circular DNA (cccDNA). Research has demonstrated the stability of cccDNA and its persistence as a latent reservoir for HBV reactivation, even decades after recovery from infection.12

Also at risk are individuals who have unrecovered from HBV infection and are HBsAg negative and anti-HBc positive. To avert reverse seroconversion, they also rely on a robust immune system.13 Reverse seroconversion is defined as a reappearance of HBV DNA and HBsAg positivity in individuals who were previously negative.13 In these individuals, HBV DNA may not be quantifiable in circulation, but trace amounts of viral DNA found in the liver are enough to pose a reactivation risk in the setting of immune suppression.14

Moreover, often overlooked is the fact that reactivation or reverse seroconversion can necessitate disruptions and delays in immunosuppressive treatment for other life-threatening disease processes.14,15

Universal screening reduces risk for HBVr. Patients with CHB are at risk for reactivation, as are patients with resolved HBV infection. Many patients, however, do not know their status. By screening all patients before beginning immunosuppressive therapy, physicians can provide effective prophylaxis, which has been shown to significantly reduce the risk for HBVr.8.15

Continue to: Recognizing the onset of HBVr

Recognizing the onset of HBVr

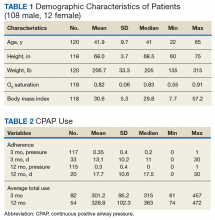

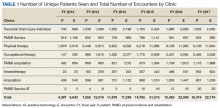

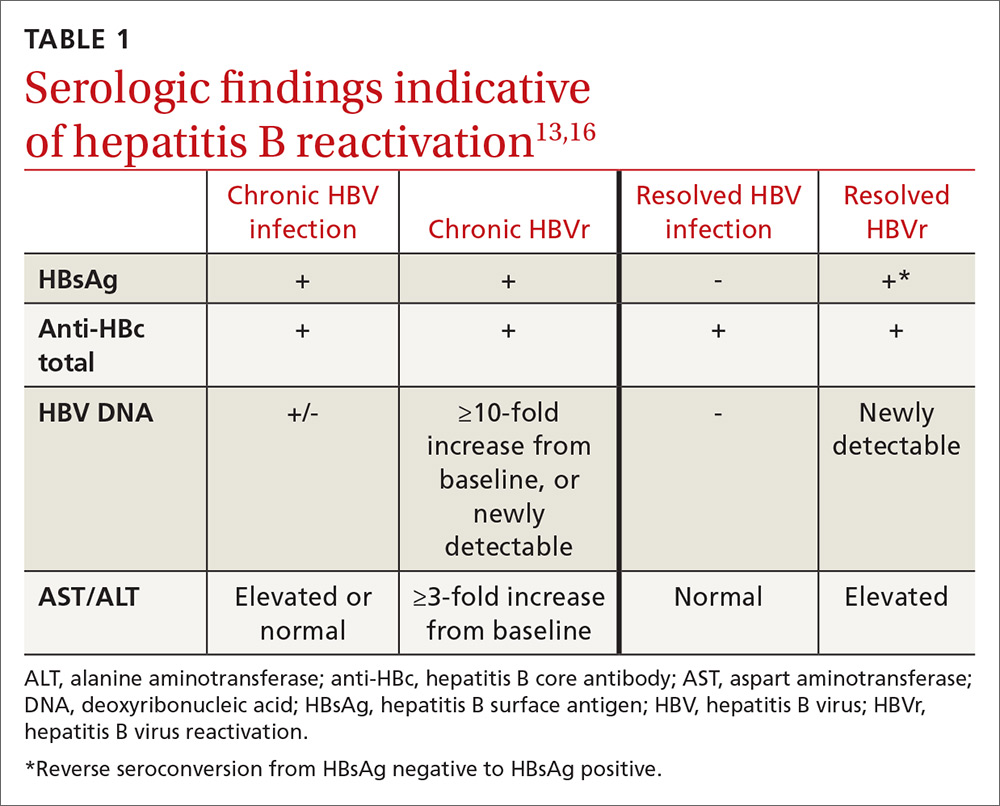

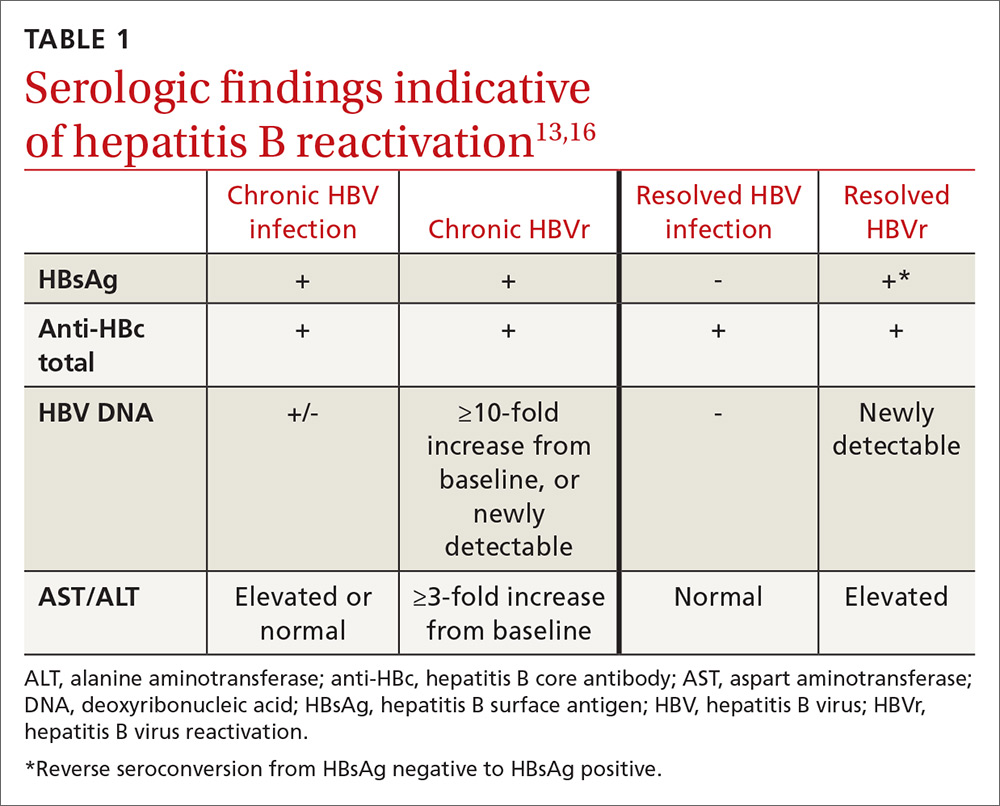

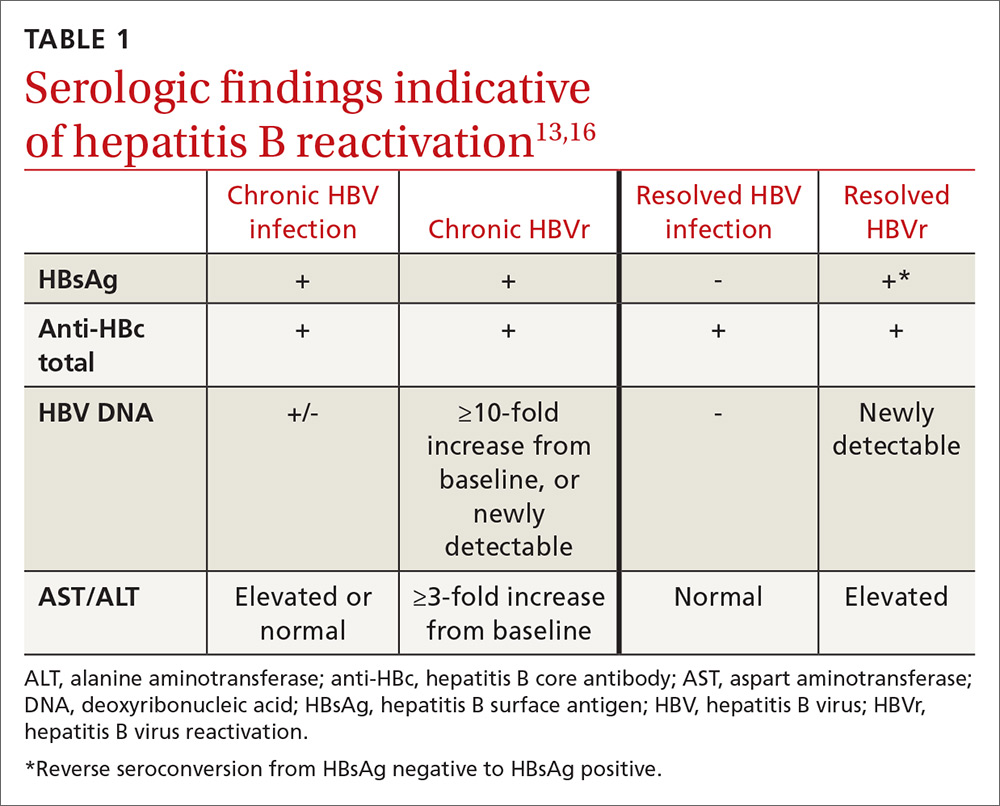

In patients with CHB, HBVr is defined as at least a 3-fold increase in aspart aminotransferase (AST) and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and at least a 10-fold increase from baseline in HBV DNA. In patients with resolved HBV infection, there may be reverse seroconversion from HbsAg-negative to HBsAg-positive status (TABLE 113,16).

Not all elevations in AST/ALT in patients undergoing chemotherapy or immunosuppressive therapy indicate HBVr. Very often, derangements in AST/ALT may be related to the toxic effects of therapy or to the underlying disease process. However, as immunosuppressive therapy is now used for a wide array of medical conditions, consider HBVr as a potential cause of abnormal liver function in all patients receiving such therapy

A patient is at risk for HBVr when starting immunosuppression and up to a year following the completion of therapy. With suppression of the immune system, HBV replication increases and serum AST/ALT concentrations may rise. HBVr may also present with the appearance of HBV DNA in patients with previously undetectable levels.12,17

Most patients remain asymptomatic, and abnormal AST/ALT levels eventually resolve after completion of immunosuppression. However, some patients' liver enzymes may rise, indicating a more severe hepatic flare. These patients may present with right upper-quadrant tenderness, jaundice, or fatigue. In these cases, recognizing HBVr and starting antivirals may reduce hepatitis flare.

Unfortunately, despite early recognition of HBVr and initiation of appropriate therapy, some patients can progress to hepatic decompensation and even fulminant hepatic failure that may have been prevented with prophylaxis.

Continue to: The justification for universal screening

The justification for universal screening

Although nongastroenterology societies differ in their recommendations on screening for HBV, universal screening before implementing prolonged immunosuppressive treatment is recommended by the CDC,6 the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases,18 the Asian Pacific Association for the Study of the Liver,19 the European Association for the Study of the Liver,20 and the American Gastroenterological Association (AGA).21

Older guidelines recommended screening only high-risk populations. But such screening has downfalls. It requires that patients or their physicians recognize that they are at high risk. In one study, nearly 65% of an infected Asian-American population was unaware of their positive HBV status.22 Risk-based screening also requires that physicians ask the appropriate questions and that patients admit to high-risk behavior. Screening patients based only on risk factors may easily overlook patients who need prophylaxis against HBVr.

Common arguments against universal screening include the cost of testing, the possibility of false-positive results, and the implications of a new diagnosis of hepatitis B. However, the potential benefits of screening are significant, and HBV screening in the general population has been shown to be cost effective when the prevalence of HBV is 0.3%.21 In the United States, conservative estimates are a prevalence of HBsAg positivity of 0.4% and past infection of 3%, making screening a cost-effective recommendation.16 It is therefore prudent to screen all patients before starting immunosuppressive therapy.

How to screen

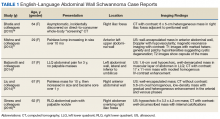

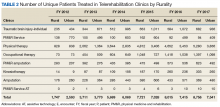

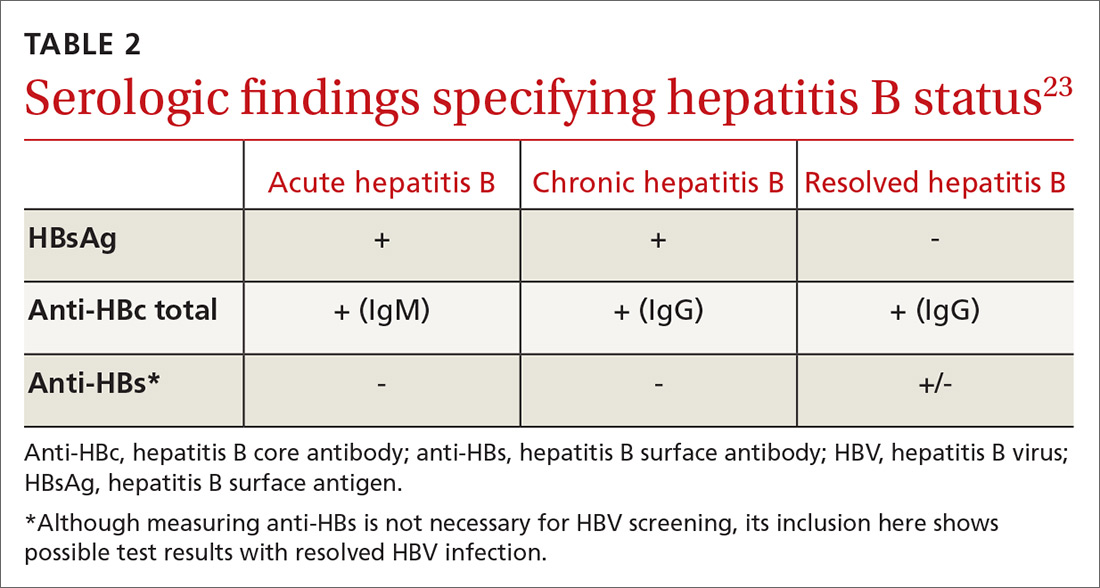

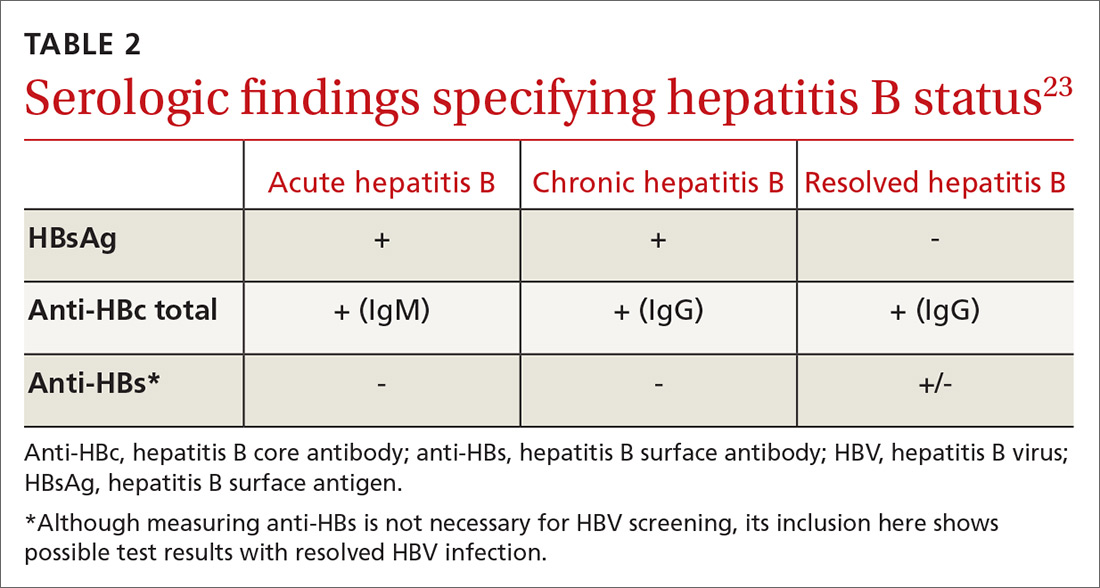

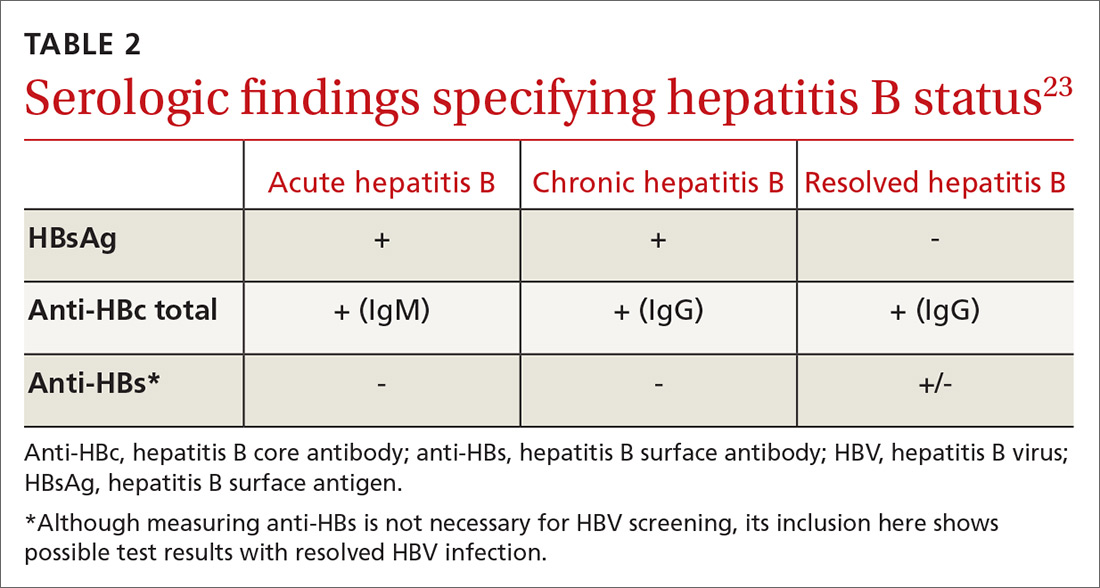

All guidelines agree on how to test for HBV. Measuring levels of HBsAg and hepatitis B core antibody (anti-HBc total) allows the clinician to ascertain whether the patient’s HBV infection status is acute, chronic, or resolved (TABLE 223) and to perform HBVr risk stratification (discussed later).

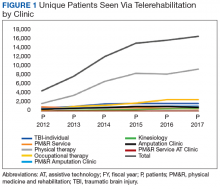

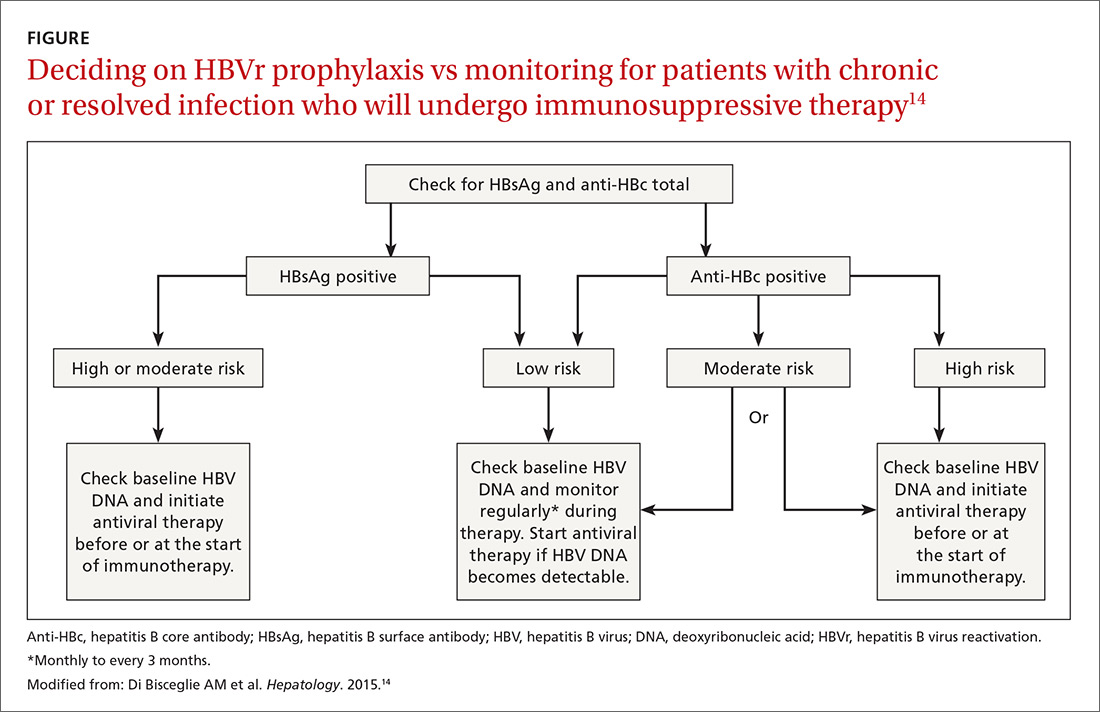

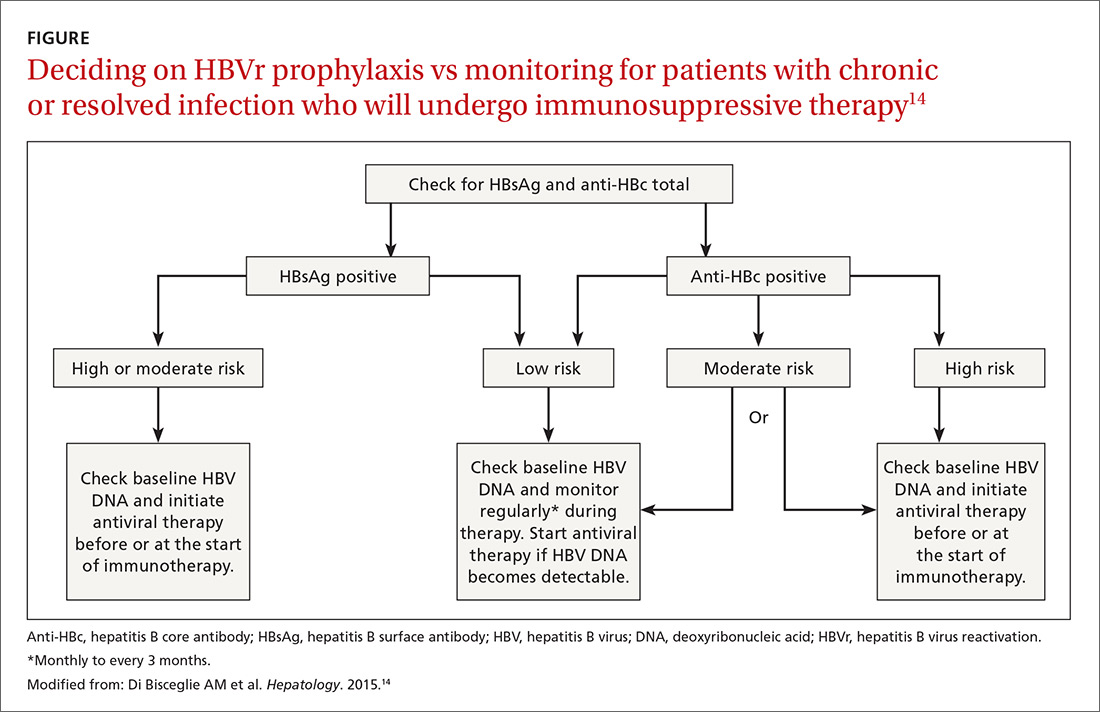

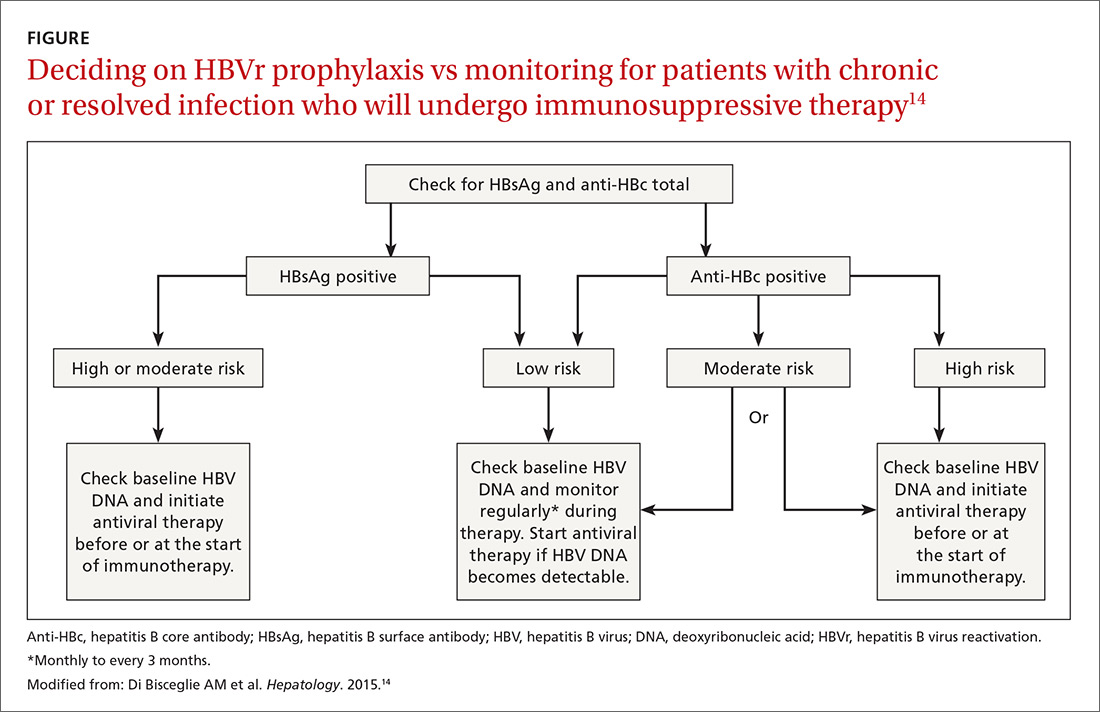

Patients with acute infections should be referred to a hepatologist. With chronic or resolved HBV, stratify patients into a prophylaxis group or monitoring group (FIGURE14). Stratification involves identifying HBV status (chronic or resolved) and selecting a type of immunosuppressive therapy. Whether the patient falls into prophylaxis or monitoring, obtain a baseline level of viral DNA, as this has proven to be the best predictor of HBV reactivation.16

Continue to: In screening, be sure the appropriate...

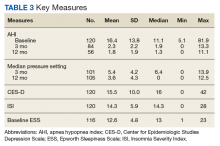

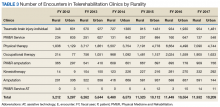

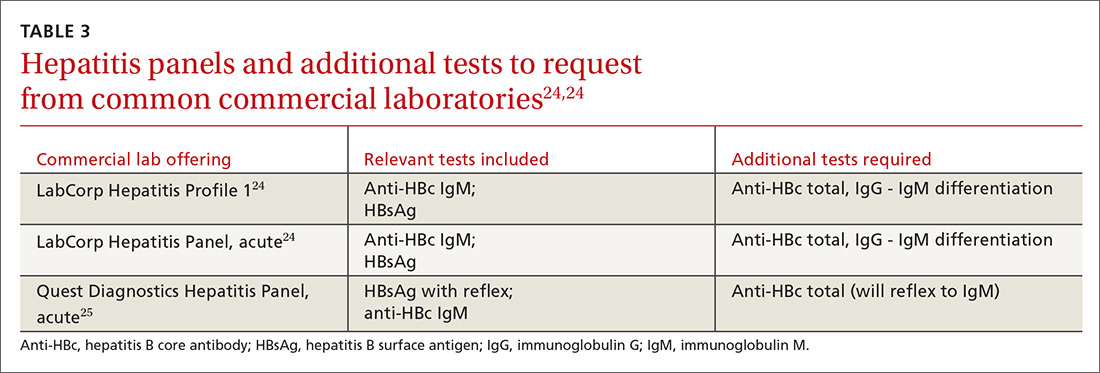

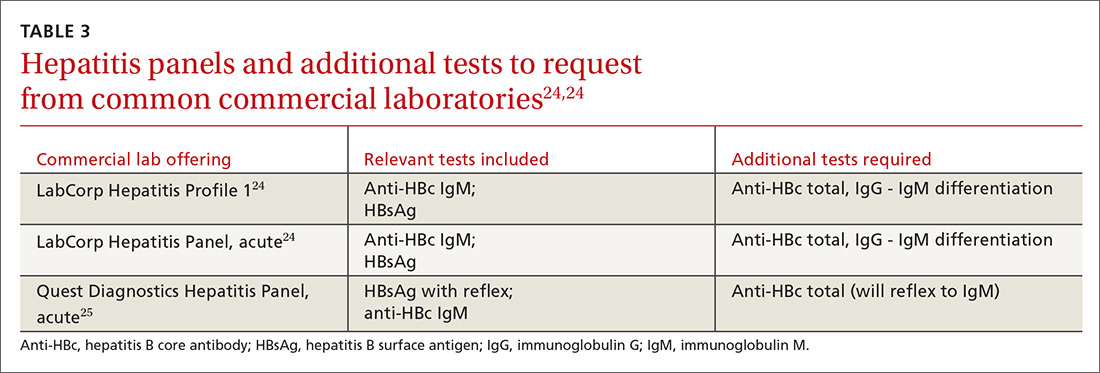

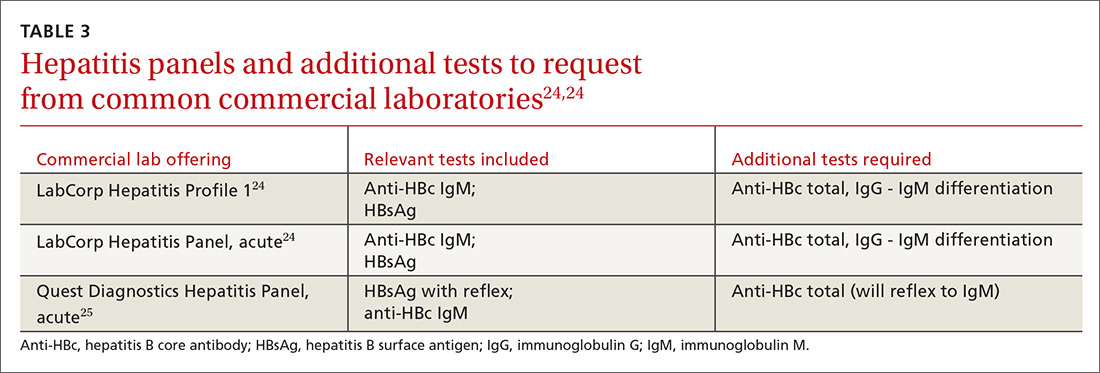

In screening, be sure the appropriate anti-HBc testing is covered. Common usage of the term anti-HBc may refer to immunoglobulin G (IgG) or immunoglobulin M (IgM)or total core antibody, containing both IgG and IgM. But in this context, accurate screening requires either total core antibody or anti-HBc IgG. Anti-IgM alone is inadequate. Many commercial laboratories offer acute hepatitis panels or hepatitis profiles (TABLE 324,25), and it is important to confirm that such order sets contain the tests necessary to allow for risk stratification.

Testing for hepatitis B surface antibody (anti-HBs) is not useful in screening. Although it was hypothesized that the presence of this antibody lowered risk, recent studies have proven no change in risk based on this value.21

How to assess HBVr risk

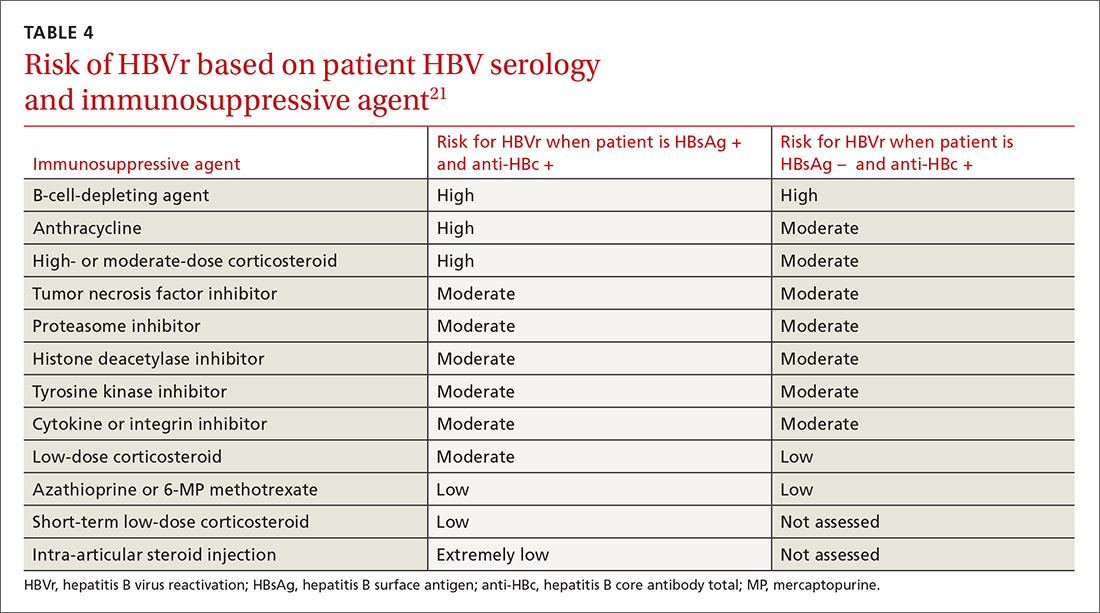

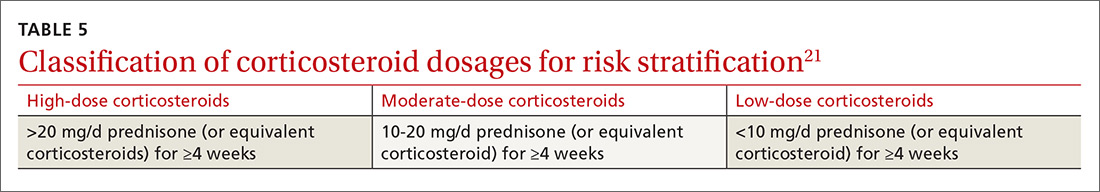

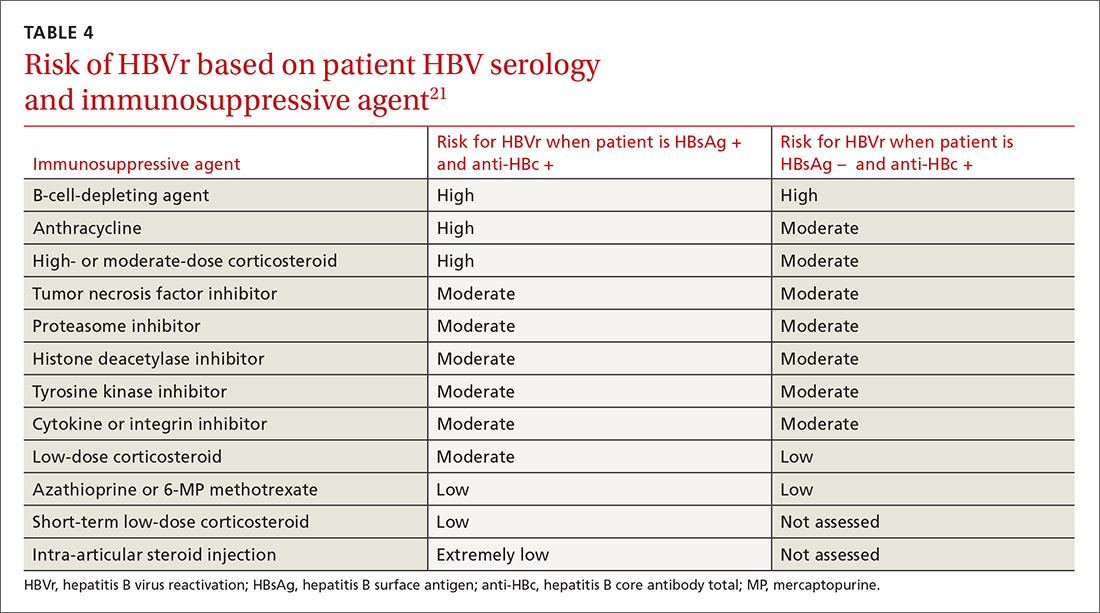

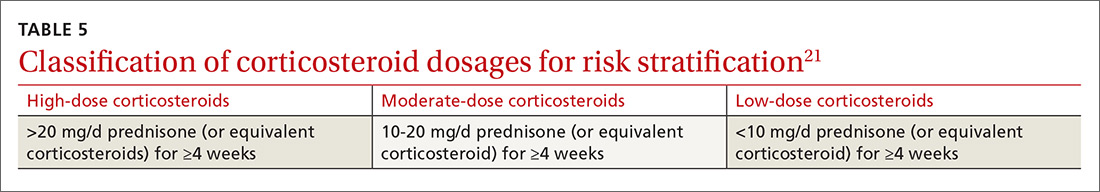

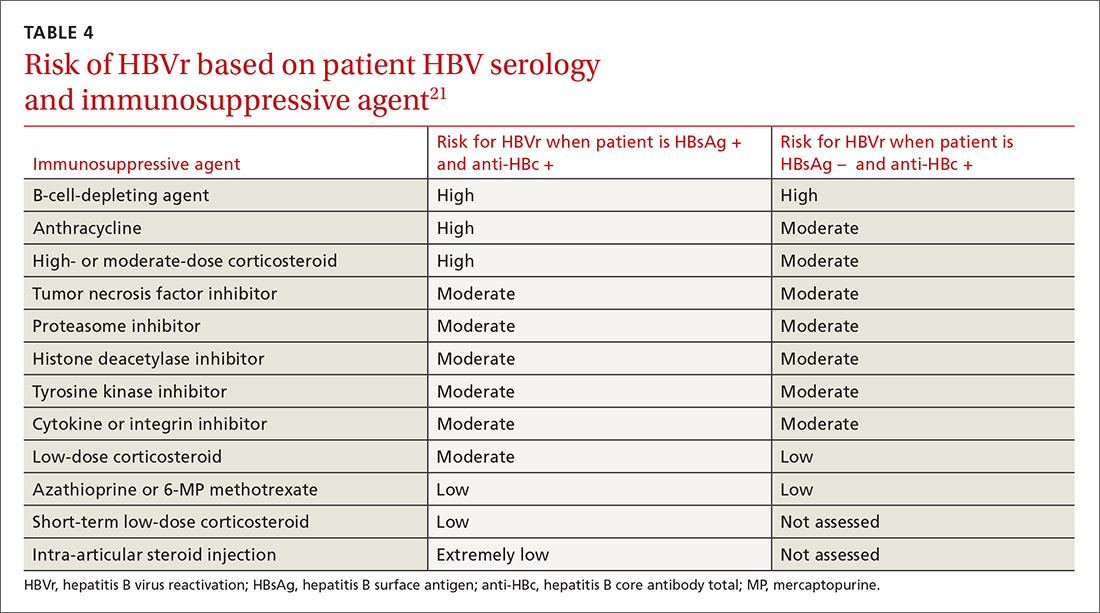

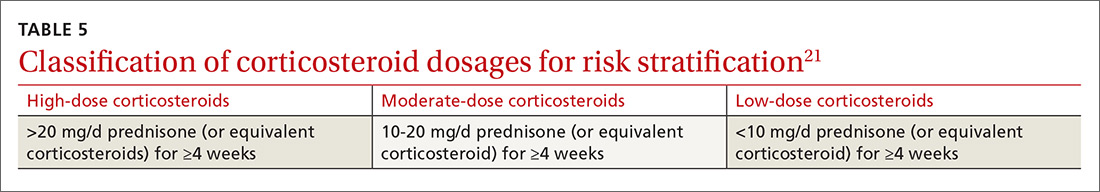

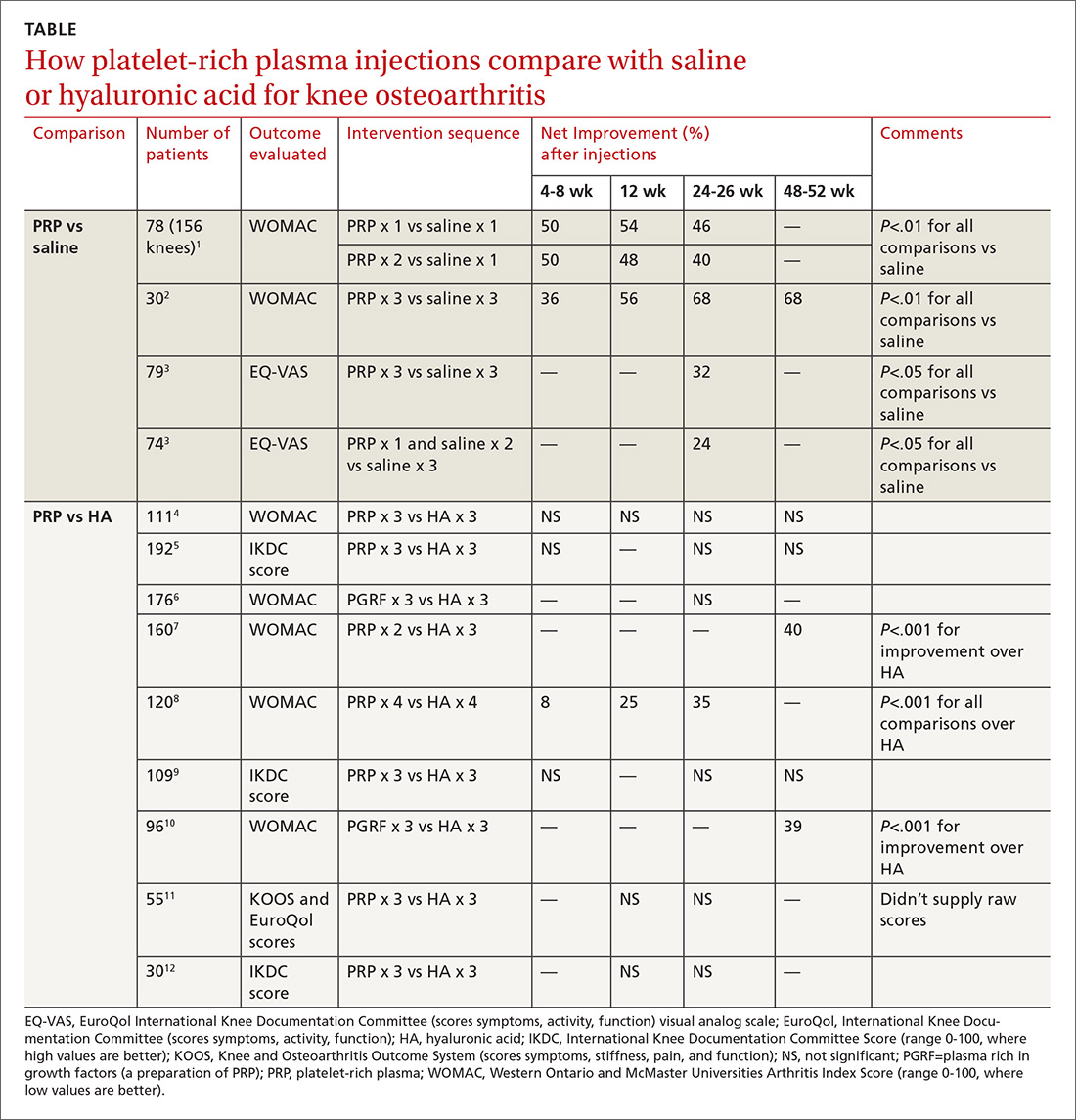

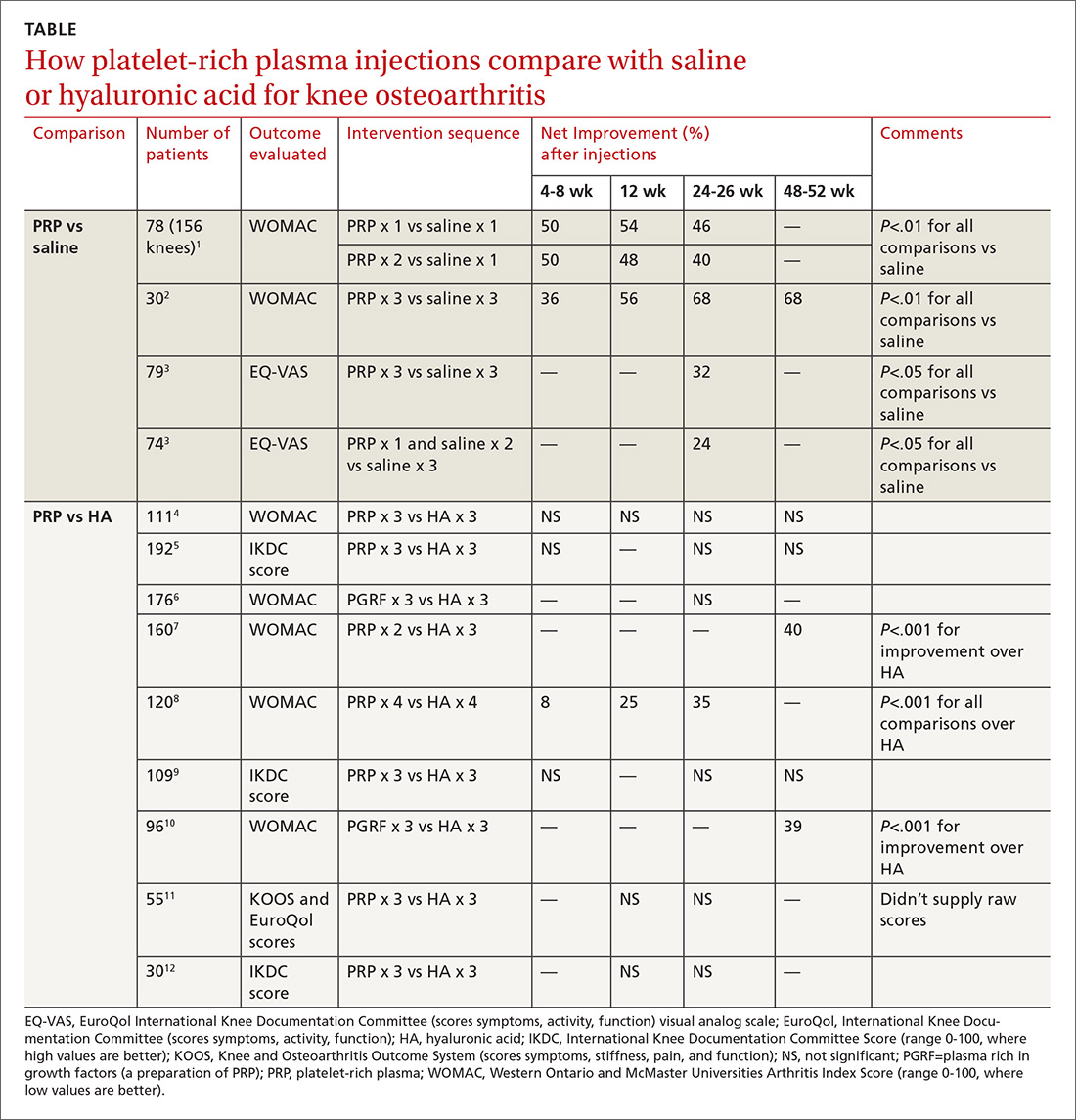

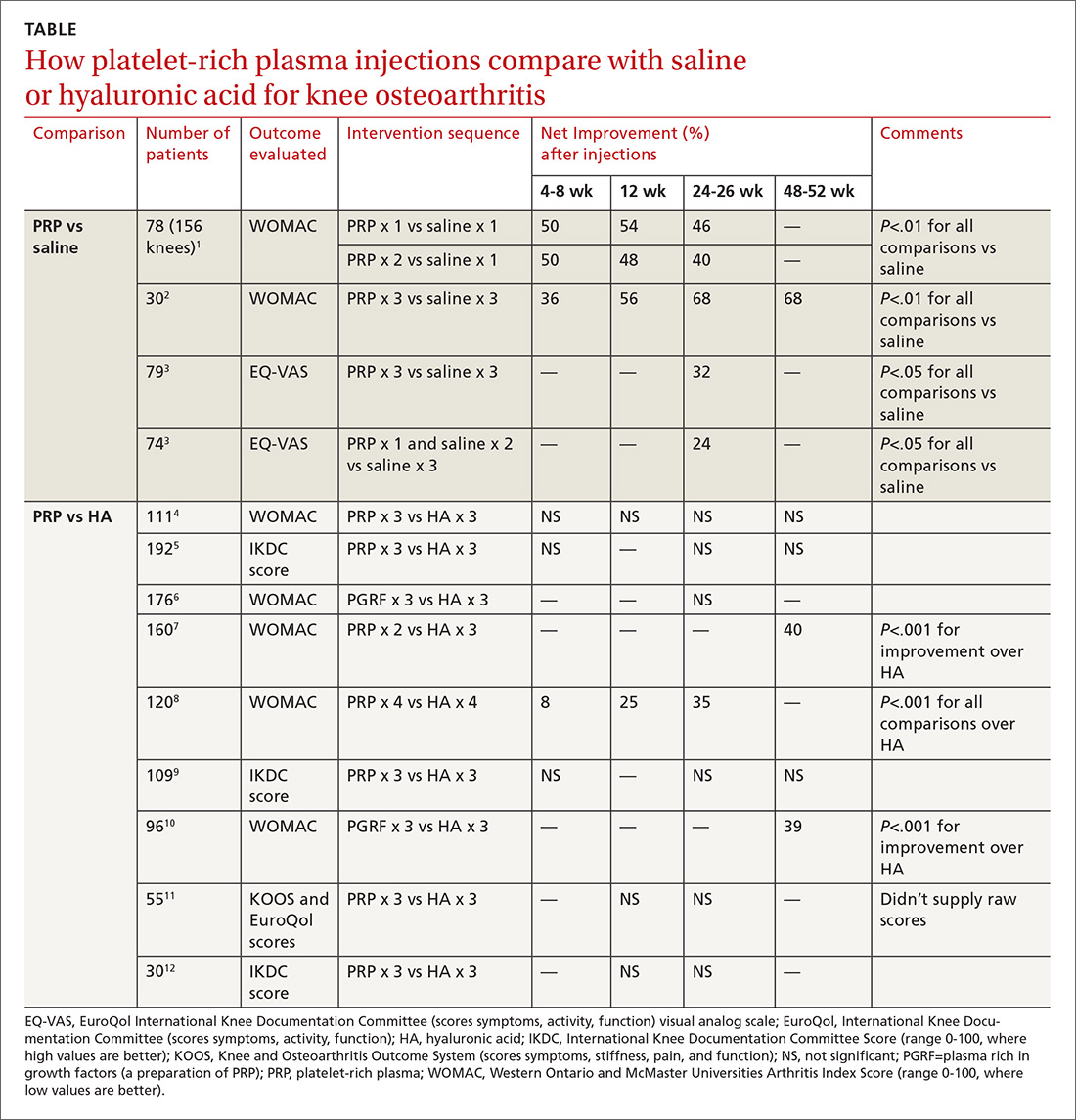

Assessing risk for HBVr takes into account both the patient’s serology and intended treatment. Reddy et al delineated patient groups into high, moderate, and low risk (TABLES 4 and 5).21 The high-risk group was defined by anticipated incidence of HBVr in > 10% of cases; the moderate-risk group had an anticipated incidence of 1% to 10%; and the low-risk group had an anticipated incidence of <1%.21 Evidence was strongest in the high-risk group.

Patients with CHB (HBsAg positive and anti-HBc positive) are considered high risk for reactivation with a wide variety of immunosuppressive therapies. Such patients are 5 to 8 times more likely to develop HBVr than patients with an HBsAg-negative status signifying a resolved infection.16

Immunosuppressive agents and associated risks. The AGA guidelines consider treatment with B-cell-depleting agents, such as rituximab and ofatumumab, to be high risk, regardless of a patient’s surface antigen status. Additionally, for patients who are HBsAg positive, high-risk treatments include anthracycline derivatives, such as doxorubicin and epirubicin, or high- or moderate-dose steroids. These treatments are considered moderate risk when used in patients who have resolved HBV infection (HBsAg negative/anti-HBc positive). Moderate-risk modalities also include tumor necrosis factor inhibitors and tyrosine kinase inhibitors, regardless of surface antigen status; and low-dose steroids or cytokine or integrin inhibitors in HbsAg-positive individuals.21

Continue to: Other immunosuppression modalities...

Other immunosuppression modalities considered to be moderate risk independent of HBV serology include proteasome inhibitors, such as bortezomib, used for multiple myeloma treatment, and histone deacetylase inhibitors, such as romidepsin, used to treat T-cell lymphoma.13 Low-dose steroids or cytokine or integrin inhibitors are considered to be low risk in surface antigen-negative individuals; azathioprine, mercaptopurine, or methotrexate are low risk regardless of HBsAg status.21 Intra-articular steroid injections are considered extremely low risk in HbsAg-positive individuals, and are unclassified for HbsAg-negative individuals.13

More recent evidence has implicated other medication classes in triggering HBVr — (eg, direct-acting antivirals.)26

Prophylaxis options: High to moderate risk vs low risk

The consensus of major guideline issuers is to offer prophylaxis to high-risk patients and to monitor low-risk patients. The AGA additionally recommends prophylaxis for patients at moderate risk.

Controversy surrounding the moderate-risk group. Some authors argue that monitoring HBV DNA in the moderate-risk group is preferable to committing patients to long periods of prophylaxis, and that rescue treatment could be initiated as needed. However, the ideal monitoring period has not been determined, and the effectiveness of prophylaxis over monitoring is so significant that monitoring is losing favor.

Perrillo et al performed a meta-analysis of 5 randomized controlled trials evaluating antiviral agents vs no prophylaxis.16 The analysis included 139 patients receiving prophylaxis and 137 controls. The pooled results demonstrated an 87% relative risk reduction with prophylaxis, supporting the trend toward treating patients with moderate risk.16

Continue to: Prophylactic treatment options are safe...

Prophylactic treatment options are safe and well tolerated. For this reason, committing a high- or moderate-risk patient to a course of treatment should be less of a concern than the risk for HBVr.

In the early randomized controlled trials for HBVr prophylaxis, lamivudine, although effective, unfortunately led to a high incidence of viral resistance after prolonged use, thus diminishing its desirability.18 Newer agents, such as entecavir and tenofovir, have proven just as effective as lamivudine and are largely unaffected by viral resistance.27

In retrospective and prospective studies on HBVr prophylaxis, patients treated with entecavir had less HBV-related hepatitis, less delay in chemotherapy, and a lower rate of HBVr when compared with lamivudine.28,29 Tenofovir is recommended, however, if patients were previously treated with lamivudine.30

A recent meta-analysis demonstrated that tenofovir and entecavir are preferable to lamivudine in preventing HBVr.31

Looking ahead

Screening for HBsAg and anti-HBc total before starting immunosuppressive therapy can reduce morbidity and mortality in patients undergoing such treatment. The AGA recommends screening all patients about to begin high- or moderate-risk therapy or patients in populations with a prevalence of CHB ≥2%, per the CDC.6,21

Continue to: Classes of medications...

Classes of medications other than immunosuppressants may also trigger HBVr. The FDA has issued a warning regarding direct-acting antivirals, but optimal management of these patients is still evolving.

Once HBV status is established, a patient’s risk for HBVr can be specified as high, moderate, or low using their HBV status and the type of therapy being initiated. The AGA recommends prophylactic treatment with well-tolerated and effective agents for patients classified as high or moderate risk. If a patient’s risk is low, regular monitoring of HBV DNA and AST and ALT levels is sufficient. Recommendations of monitoring intervals span from monthly to every 3 months.13,14

CASE Given the patient’s status of resolved HBV infection and her current moderate-dose regimen of prednisone, her risk for HBV reactivation is moderate. She could either receive antiviral prophylaxis or undergo regular monitoring. Following a discussion of the options, she opts for referral to a hepatologist to discuss possible prophylactic treatment.

Increased awareness of HBVr risk associated with immunosuppressive therapy, coupled with a planned approach to appropriate screening and risk stratification, can help health care providers prevent the reactivation of HBV or initiate early intervention for CHB.

CORRESPONDENCE

Ronan Farrell, MD, Rhode Island Hospital, 593 Eddy Street, Providence, RI 02903; [email protected].

1. Artz AS, Somerfield MR, Feld JJ, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology provisional clinical opinion: chronic hepatitis B virus infection screening in patients receiving cytotoxic chemotherapy for treatment of malignant diseases. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:3199-3202.

2. Day FL, Link E, Thursky K, et al. Current hepatitis B screening practices and clinical experience of reactivation in patients undergoing chemotherapy for solid tumors: a nationwide survey of medical oncologists. J Oncol Pract. 2011;7:141-147.

3. Paul S, Saxena A, Terrin N, et al. Hepatitis B virus reactivation and prophylaxis during solid tumor chemotherapy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Internal Med. 2016;164:30-40.

4. Kim MK, Ahn JH, Kim SB, et al. Hepatitis B reactivation during adjuvant anthracycline-based chemotherapy in patients with breast cancer: a single institution’s experience. Korean J Intern Med. 2007;22:237-243.

5. Esteve M, Saro C, González-Huix F, et al. Chronic hepatitis B reactivation following infliximab therapy in Crohn’s disease patients: need for primary prophylaxis. Gut. 2004;53:1363-1365.

6. Weinbaum CM, Williams I, Mast EE, et al. Recommendations for identification and public health management of persons with chronic hepatitis B virus infection. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2008;57:1-20.

7. Liang TJ, Block TM, McMahon BJ, et al. Present and future therapies of hepatitis B: from discovery to cure. Hepatology. 2015;62:1893-1908.

8, , , A mathematical model to estimate global hepatitis B disease burden and vaccination impact. Int J Epidemiol. 2005;34:1329-1339.

9. WHO. Hepatitis B. www.who.int/en/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/hepatitis-b. Accessed February 28, 2019.

10. Kowdley KV, Wang CC, Welch S, et al. Prevalence of chronic hepatitis B among foreign-born persons living in the United States by country of origin. Hepatology. 2012;56:422-433.

11. Foster T, Hon H, Kanwal F, et al. Screening high risk individuals for hepatitis B: physician knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs. Dig Dis Sci. 2011;56:3471-3487.

12. Rehermann B, Ferrari C, Pasquinelli C, et al. The hepatitis B virus persists for decades after patients’ recovery from acute viral hepatitis despite active maintenance of a cytotoxic T-lymphocyte response. Nat Med. 1996;2:1104-1108.

13. Loomba R, Liang TJ. Hepatitis B reactivation associated with immune suppressive and biological modifier therapies: current concepts, management strategies, and future directions. Gastroenterology. 2017;152:1297-1309.

14. Di Bisceglie AM, Lok AS, Martin P, et al. Recent US Food and Drug Administration warnings on hepatitis B reactivation with immune-suppressing and anticancer drugs: just the tip of the iceberg? Hepatology. 2015;61:703-711.

15. Lok AS, Ward JW, Perrillo RP, et al. Reactivation of hepatitis B during immunosuppressive therapy: potentially fatal yet preventable. Ann Intern Med. 2012;156:743-745.

16. Perrillo RP, Gish R, Falck-Ytter YT. American Gastroenterological Association Institute technical review on prevention and treatment of hepatitis B virus reactivation during immunosuppressive drug therapy. Gastroenterology. 2015;148:221-244.

17. Hwang JP, Lok AS. Management of patients with hepatitis B who require immunosuppressive therapy. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;11:209-219.

18. Lok AS, McMahon BJ. Chronic hepatitis B: update 2009. Hepatology. 2009;50:661-662.

19. Asian-Pacific consensus statement on the management of chronic hepatitis B: a 2012 update. Hepatol Int. 2012;6:531-561.

20. EASL clinical practice guidelines: management of chronic hepatitis B virus infection. J Hepatol. 2012;57:167-185.

21. Reddy KR, Beavers KL, Hammond SP, et al. American Gastroenterological Association Institute guideline on the prevention and treatment of hepatitis B virus reactivation during immunosuppressive drug therapy. Gastroenterology. 2015;148:215-219.

, , . Why we should routinely screen Asian American adults for hepatitis B: a cross-sectional study of Asians in California. Hepatology. 2007;46:1034-1040.

23. Hwang JP, Artz AS, Somerfield MR. Hepatitis B virus screening for patients with cancer before therapy: American Society of Clinical Oncology Provisional Clinical Opinion Update. J Oncol Pract. 2015;11:e487-489.

24. LabCorp. Hepatitis B core antibody, IgG, IgM, differentiation. www.labcorp.com/test-menu/27196/hepatitis-b-core-antibody-igg-igm-differentiation. Accessed February 28, 2019.

25. Quest diagnostics. Hepatitis B Core Antibody, Total. www.questdiagnostics.com/testcenter/TestDetail.action?ntc=501.Accessed November 5, 2018.

26. The Food and Drug Administration Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS). www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/ucm522932.htm. Accessed February 28, 2019.

27. Lim YS. Management of antiviral resistance in chronic hepatitis B. Gut Liver. 2017;11:189-195.

28. Huang H, Li X, Zhu J, et al. Entecavir vs lamivudine for prevention of hepatitis B virus reactivation among patients with untreated diffuse large B-cell lymphoma receiving R-CHOP chemotherapy: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2014;312:2521-2530.

29. Chen WC, Cheng JS, Chiang PH, et al. A comparison of entecavir and lamivudine for the prophylaxis of hepatitis B virus reactivation in solid tumor patients undergoing systemic cytotoxic chemotherapy. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0131545.

30. Tenney DJ, Rose RE, Baldick CJ, et al. Long-term monitoring shows hepatitis B virus resistance to entecavir in nucleoside-naïve patients is rare through 5 years of therapy. Hepatology. 2009;49:1503-1514.

31. Zhang MY, Zhu GQ, Shi KQ, et al. Systematic review with network meta-analysis: comparative efficacy of oral nucleos(t)ide analogues for the prevention of chemotherapy-induced hepatitis B virus reactivation. Oncotarget. 2016;7:30642-30658.

CASE A 53-year-old woman you are seeing for the first time has been taking 10 mg of prednisone daily for a month, prescribed by another practitioner for polymyalgia rheumatica. Testing is negative for hepatitis B surface antigen but is positive for hepatitis B core antibody total, indicating a resolved hepatitis B infection. The absence of hepatitis B DNA is confirmed.

How would you proceed with this patient?

Patients with resolved hepatitis B virus (HBV) or chronic hepatitis B (CHB) infections are at risk for HBV reactivation (HBVr) if they undergo immunosuppressive therapy for a condition such as cancer. HBVr can in turn lead to delays in treatment and increased morbidity and mortality.

HBVr is a well-documented adverse outcome in patients treated with rituximab and in those undergoing stem cell transplantation. Current oncology guidelines recommend screening for HBV prior to initiating these treatments.1,2 More recent evidence shows that many other immunosuppressive therapies can also lead to HBVr.3 Such treatments are now used across a multitude of specialties and conditions. For many of these conditions, there are no consistent guidelines regarding HBV screening.

In 2013, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) announced the requirement of a Boxed Warning for the immunosuppressive drugs ofatumumab and rituximab. In 2016, the FDA announced the same requirement for certain direct-acting antiviral medicines for hepatitis C virus.

Among patients who are positive for hepatitis-B surface antigen (HBsAg) and who are treated with immunosuppression, the frequency of HBVr has ranged from 0% to 39%.4,5

As the list of immunosuppressive therapies that can cause HBVr grows, specialty guidelines are evolving to address the risk that HBVr poses.

Continue to: An underrecognized problem

An underrecognized problem. CHB affects an estimated 350 million people worldwide6 but remains underrecognized and underdiagnosed. An estimated 1.4 million Americans6 have CHB, but only a minority of them are aware of their positive status and are followed by a hepatologist or receive medical care for their disease.7 Compared with the natural-born US population, a higher prevalence of CHB exists among immigrants to this country from the Asian Pacific and Eastern Mediterranean regions, sub-Saharan Africa, and certain parts of South America.8-10 In 2008, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) updated its recommendations on screening for HBV to include immigrants to the United States from intermediate and high endemic areas.6 Unfortunately, data published on physicians’ adherence to the CDC guidelines for screening show that only 60% correctly screened at-risk patients.11

Individuals with CHB are at risk and rely on a robust immune system to keep their disease from becoming active. During infection, the virus gains entry into the hepatocytes and the double-stranded viral genome is imported into the nucleus of the cell, where it is repaired into covalently closed circular DNA (cccDNA). Research has demonstrated the stability of cccDNA and its persistence as a latent reservoir for HBV reactivation, even decades after recovery from infection.12

Also at risk are individuals who have unrecovered from HBV infection and are HBsAg negative and anti-HBc positive. To avert reverse seroconversion, they also rely on a robust immune system.13 Reverse seroconversion is defined as a reappearance of HBV DNA and HBsAg positivity in individuals who were previously negative.13 In these individuals, HBV DNA may not be quantifiable in circulation, but trace amounts of viral DNA found in the liver are enough to pose a reactivation risk in the setting of immune suppression.14

Moreover, often overlooked is the fact that reactivation or reverse seroconversion can necessitate disruptions and delays in immunosuppressive treatment for other life-threatening disease processes.14,15

Universal screening reduces risk for HBVr. Patients with CHB are at risk for reactivation, as are patients with resolved HBV infection. Many patients, however, do not know their status. By screening all patients before beginning immunosuppressive therapy, physicians can provide effective prophylaxis, which has been shown to significantly reduce the risk for HBVr.8.15

Continue to: Recognizing the onset of HBVr

Recognizing the onset of HBVr

In patients with CHB, HBVr is defined as at least a 3-fold increase in aspart aminotransferase (AST) and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and at least a 10-fold increase from baseline in HBV DNA. In patients with resolved HBV infection, there may be reverse seroconversion from HbsAg-negative to HBsAg-positive status (TABLE 113,16).

Not all elevations in AST/ALT in patients undergoing chemotherapy or immunosuppressive therapy indicate HBVr. Very often, derangements in AST/ALT may be related to the toxic effects of therapy or to the underlying disease process. However, as immunosuppressive therapy is now used for a wide array of medical conditions, consider HBVr as a potential cause of abnormal liver function in all patients receiving such therapy

A patient is at risk for HBVr when starting immunosuppression and up to a year following the completion of therapy. With suppression of the immune system, HBV replication increases and serum AST/ALT concentrations may rise. HBVr may also present with the appearance of HBV DNA in patients with previously undetectable levels.12,17

Most patients remain asymptomatic, and abnormal AST/ALT levels eventually resolve after completion of immunosuppression. However, some patients' liver enzymes may rise, indicating a more severe hepatic flare. These patients may present with right upper-quadrant tenderness, jaundice, or fatigue. In these cases, recognizing HBVr and starting antivirals may reduce hepatitis flare.

Unfortunately, despite early recognition of HBVr and initiation of appropriate therapy, some patients can progress to hepatic decompensation and even fulminant hepatic failure that may have been prevented with prophylaxis.

Continue to: The justification for universal screening

The justification for universal screening

Although nongastroenterology societies differ in their recommendations on screening for HBV, universal screening before implementing prolonged immunosuppressive treatment is recommended by the CDC,6 the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases,18 the Asian Pacific Association for the Study of the Liver,19 the European Association for the Study of the Liver,20 and the American Gastroenterological Association (AGA).21

Older guidelines recommended screening only high-risk populations. But such screening has downfalls. It requires that patients or their physicians recognize that they are at high risk. In one study, nearly 65% of an infected Asian-American population was unaware of their positive HBV status.22 Risk-based screening also requires that physicians ask the appropriate questions and that patients admit to high-risk behavior. Screening patients based only on risk factors may easily overlook patients who need prophylaxis against HBVr.

Common arguments against universal screening include the cost of testing, the possibility of false-positive results, and the implications of a new diagnosis of hepatitis B. However, the potential benefits of screening are significant, and HBV screening in the general population has been shown to be cost effective when the prevalence of HBV is 0.3%.21 In the United States, conservative estimates are a prevalence of HBsAg positivity of 0.4% and past infection of 3%, making screening a cost-effective recommendation.16 It is therefore prudent to screen all patients before starting immunosuppressive therapy.

How to screen

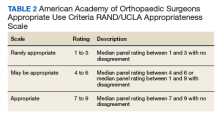

All guidelines agree on how to test for HBV. Measuring levels of HBsAg and hepatitis B core antibody (anti-HBc total) allows the clinician to ascertain whether the patient’s HBV infection status is acute, chronic, or resolved (TABLE 223) and to perform HBVr risk stratification (discussed later).

Patients with acute infections should be referred to a hepatologist. With chronic or resolved HBV, stratify patients into a prophylaxis group or monitoring group (FIGURE14). Stratification involves identifying HBV status (chronic or resolved) and selecting a type of immunosuppressive therapy. Whether the patient falls into prophylaxis or monitoring, obtain a baseline level of viral DNA, as this has proven to be the best predictor of HBV reactivation.16

Continue to: In screening, be sure the appropriate...

In screening, be sure the appropriate anti-HBc testing is covered. Common usage of the term anti-HBc may refer to immunoglobulin G (IgG) or immunoglobulin M (IgM)or total core antibody, containing both IgG and IgM. But in this context, accurate screening requires either total core antibody or anti-HBc IgG. Anti-IgM alone is inadequate. Many commercial laboratories offer acute hepatitis panels or hepatitis profiles (TABLE 324,25), and it is important to confirm that such order sets contain the tests necessary to allow for risk stratification.

Testing for hepatitis B surface antibody (anti-HBs) is not useful in screening. Although it was hypothesized that the presence of this antibody lowered risk, recent studies have proven no change in risk based on this value.21

How to assess HBVr risk

Assessing risk for HBVr takes into account both the patient’s serology and intended treatment. Reddy et al delineated patient groups into high, moderate, and low risk (TABLES 4 and 5).21 The high-risk group was defined by anticipated incidence of HBVr in > 10% of cases; the moderate-risk group had an anticipated incidence of 1% to 10%; and the low-risk group had an anticipated incidence of <1%.21 Evidence was strongest in the high-risk group.

Patients with CHB (HBsAg positive and anti-HBc positive) are considered high risk for reactivation with a wide variety of immunosuppressive therapies. Such patients are 5 to 8 times more likely to develop HBVr than patients with an HBsAg-negative status signifying a resolved infection.16

Immunosuppressive agents and associated risks. The AGA guidelines consider treatment with B-cell-depleting agents, such as rituximab and ofatumumab, to be high risk, regardless of a patient’s surface antigen status. Additionally, for patients who are HBsAg positive, high-risk treatments include anthracycline derivatives, such as doxorubicin and epirubicin, or high- or moderate-dose steroids. These treatments are considered moderate risk when used in patients who have resolved HBV infection (HBsAg negative/anti-HBc positive). Moderate-risk modalities also include tumor necrosis factor inhibitors and tyrosine kinase inhibitors, regardless of surface antigen status; and low-dose steroids or cytokine or integrin inhibitors in HbsAg-positive individuals.21

Continue to: Other immunosuppression modalities...

Other immunosuppression modalities considered to be moderate risk independent of HBV serology include proteasome inhibitors, such as bortezomib, used for multiple myeloma treatment, and histone deacetylase inhibitors, such as romidepsin, used to treat T-cell lymphoma.13 Low-dose steroids or cytokine or integrin inhibitors are considered to be low risk in surface antigen-negative individuals; azathioprine, mercaptopurine, or methotrexate are low risk regardless of HBsAg status.21 Intra-articular steroid injections are considered extremely low risk in HbsAg-positive individuals, and are unclassified for HbsAg-negative individuals.13

More recent evidence has implicated other medication classes in triggering HBVr — (eg, direct-acting antivirals.)26

Prophylaxis options: High to moderate risk vs low risk

The consensus of major guideline issuers is to offer prophylaxis to high-risk patients and to monitor low-risk patients. The AGA additionally recommends prophylaxis for patients at moderate risk.

Controversy surrounding the moderate-risk group. Some authors argue that monitoring HBV DNA in the moderate-risk group is preferable to committing patients to long periods of prophylaxis, and that rescue treatment could be initiated as needed. However, the ideal monitoring period has not been determined, and the effectiveness of prophylaxis over monitoring is so significant that monitoring is losing favor.

Perrillo et al performed a meta-analysis of 5 randomized controlled trials evaluating antiviral agents vs no prophylaxis.16 The analysis included 139 patients receiving prophylaxis and 137 controls. The pooled results demonstrated an 87% relative risk reduction with prophylaxis, supporting the trend toward treating patients with moderate risk.16

Continue to: Prophylactic treatment options are safe...

Prophylactic treatment options are safe and well tolerated. For this reason, committing a high- or moderate-risk patient to a course of treatment should be less of a concern than the risk for HBVr.

In the early randomized controlled trials for HBVr prophylaxis, lamivudine, although effective, unfortunately led to a high incidence of viral resistance after prolonged use, thus diminishing its desirability.18 Newer agents, such as entecavir and tenofovir, have proven just as effective as lamivudine and are largely unaffected by viral resistance.27

In retrospective and prospective studies on HBVr prophylaxis, patients treated with entecavir had less HBV-related hepatitis, less delay in chemotherapy, and a lower rate of HBVr when compared with lamivudine.28,29 Tenofovir is recommended, however, if patients were previously treated with lamivudine.30

A recent meta-analysis demonstrated that tenofovir and entecavir are preferable to lamivudine in preventing HBVr.31

Looking ahead

Screening for HBsAg and anti-HBc total before starting immunosuppressive therapy can reduce morbidity and mortality in patients undergoing such treatment. The AGA recommends screening all patients about to begin high- or moderate-risk therapy or patients in populations with a prevalence of CHB ≥2%, per the CDC.6,21

Continue to: Classes of medications...

Classes of medications other than immunosuppressants may also trigger HBVr. The FDA has issued a warning regarding direct-acting antivirals, but optimal management of these patients is still evolving.

Once HBV status is established, a patient’s risk for HBVr can be specified as high, moderate, or low using their HBV status and the type of therapy being initiated. The AGA recommends prophylactic treatment with well-tolerated and effective agents for patients classified as high or moderate risk. If a patient’s risk is low, regular monitoring of HBV DNA and AST and ALT levels is sufficient. Recommendations of monitoring intervals span from monthly to every 3 months.13,14

CASE Given the patient’s status of resolved HBV infection and her current moderate-dose regimen of prednisone, her risk for HBV reactivation is moderate. She could either receive antiviral prophylaxis or undergo regular monitoring. Following a discussion of the options, she opts for referral to a hepatologist to discuss possible prophylactic treatment.

Increased awareness of HBVr risk associated with immunosuppressive therapy, coupled with a planned approach to appropriate screening and risk stratification, can help health care providers prevent the reactivation of HBV or initiate early intervention for CHB.

CORRESPONDENCE

Ronan Farrell, MD, Rhode Island Hospital, 593 Eddy Street, Providence, RI 02903; [email protected].

CASE A 53-year-old woman you are seeing for the first time has been taking 10 mg of prednisone daily for a month, prescribed by another practitioner for polymyalgia rheumatica. Testing is negative for hepatitis B surface antigen but is positive for hepatitis B core antibody total, indicating a resolved hepatitis B infection. The absence of hepatitis B DNA is confirmed.

How would you proceed with this patient?

Patients with resolved hepatitis B virus (HBV) or chronic hepatitis B (CHB) infections are at risk for HBV reactivation (HBVr) if they undergo immunosuppressive therapy for a condition such as cancer. HBVr can in turn lead to delays in treatment and increased morbidity and mortality.

HBVr is a well-documented adverse outcome in patients treated with rituximab and in those undergoing stem cell transplantation. Current oncology guidelines recommend screening for HBV prior to initiating these treatments.1,2 More recent evidence shows that many other immunosuppressive therapies can also lead to HBVr.3 Such treatments are now used across a multitude of specialties and conditions. For many of these conditions, there are no consistent guidelines regarding HBV screening.

In 2013, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) announced the requirement of a Boxed Warning for the immunosuppressive drugs ofatumumab and rituximab. In 2016, the FDA announced the same requirement for certain direct-acting antiviral medicines for hepatitis C virus.

Among patients who are positive for hepatitis-B surface antigen (HBsAg) and who are treated with immunosuppression, the frequency of HBVr has ranged from 0% to 39%.4,5

As the list of immunosuppressive therapies that can cause HBVr grows, specialty guidelines are evolving to address the risk that HBVr poses.

Continue to: An underrecognized problem

An underrecognized problem. CHB affects an estimated 350 million people worldwide6 but remains underrecognized and underdiagnosed. An estimated 1.4 million Americans6 have CHB, but only a minority of them are aware of their positive status and are followed by a hepatologist or receive medical care for their disease.7 Compared with the natural-born US population, a higher prevalence of CHB exists among immigrants to this country from the Asian Pacific and Eastern Mediterranean regions, sub-Saharan Africa, and certain parts of South America.8-10 In 2008, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) updated its recommendations on screening for HBV to include immigrants to the United States from intermediate and high endemic areas.6 Unfortunately, data published on physicians’ adherence to the CDC guidelines for screening show that only 60% correctly screened at-risk patients.11

Individuals with CHB are at risk and rely on a robust immune system to keep their disease from becoming active. During infection, the virus gains entry into the hepatocytes and the double-stranded viral genome is imported into the nucleus of the cell, where it is repaired into covalently closed circular DNA (cccDNA). Research has demonstrated the stability of cccDNA and its persistence as a latent reservoir for HBV reactivation, even decades after recovery from infection.12

Also at risk are individuals who have unrecovered from HBV infection and are HBsAg negative and anti-HBc positive. To avert reverse seroconversion, they also rely on a robust immune system.13 Reverse seroconversion is defined as a reappearance of HBV DNA and HBsAg positivity in individuals who were previously negative.13 In these individuals, HBV DNA may not be quantifiable in circulation, but trace amounts of viral DNA found in the liver are enough to pose a reactivation risk in the setting of immune suppression.14

Moreover, often overlooked is the fact that reactivation or reverse seroconversion can necessitate disruptions and delays in immunosuppressive treatment for other life-threatening disease processes.14,15

Universal screening reduces risk for HBVr. Patients with CHB are at risk for reactivation, as are patients with resolved HBV infection. Many patients, however, do not know their status. By screening all patients before beginning immunosuppressive therapy, physicians can provide effective prophylaxis, which has been shown to significantly reduce the risk for HBVr.8.15

Continue to: Recognizing the onset of HBVr

Recognizing the onset of HBVr

In patients with CHB, HBVr is defined as at least a 3-fold increase in aspart aminotransferase (AST) and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and at least a 10-fold increase from baseline in HBV DNA. In patients with resolved HBV infection, there may be reverse seroconversion from HbsAg-negative to HBsAg-positive status (TABLE 113,16).

Not all elevations in AST/ALT in patients undergoing chemotherapy or immunosuppressive therapy indicate HBVr. Very often, derangements in AST/ALT may be related to the toxic effects of therapy or to the underlying disease process. However, as immunosuppressive therapy is now used for a wide array of medical conditions, consider HBVr as a potential cause of abnormal liver function in all patients receiving such therapy

A patient is at risk for HBVr when starting immunosuppression and up to a year following the completion of therapy. With suppression of the immune system, HBV replication increases and serum AST/ALT concentrations may rise. HBVr may also present with the appearance of HBV DNA in patients with previously undetectable levels.12,17

Most patients remain asymptomatic, and abnormal AST/ALT levels eventually resolve after completion of immunosuppression. However, some patients' liver enzymes may rise, indicating a more severe hepatic flare. These patients may present with right upper-quadrant tenderness, jaundice, or fatigue. In these cases, recognizing HBVr and starting antivirals may reduce hepatitis flare.

Unfortunately, despite early recognition of HBVr and initiation of appropriate therapy, some patients can progress to hepatic decompensation and even fulminant hepatic failure that may have been prevented with prophylaxis.

Continue to: The justification for universal screening

The justification for universal screening

Although nongastroenterology societies differ in their recommendations on screening for HBV, universal screening before implementing prolonged immunosuppressive treatment is recommended by the CDC,6 the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases,18 the Asian Pacific Association for the Study of the Liver,19 the European Association for the Study of the Liver,20 and the American Gastroenterological Association (AGA).21

Older guidelines recommended screening only high-risk populations. But such screening has downfalls. It requires that patients or their physicians recognize that they are at high risk. In one study, nearly 65% of an infected Asian-American population was unaware of their positive HBV status.22 Risk-based screening also requires that physicians ask the appropriate questions and that patients admit to high-risk behavior. Screening patients based only on risk factors may easily overlook patients who need prophylaxis against HBVr.

Common arguments against universal screening include the cost of testing, the possibility of false-positive results, and the implications of a new diagnosis of hepatitis B. However, the potential benefits of screening are significant, and HBV screening in the general population has been shown to be cost effective when the prevalence of HBV is 0.3%.21 In the United States, conservative estimates are a prevalence of HBsAg positivity of 0.4% and past infection of 3%, making screening a cost-effective recommendation.16 It is therefore prudent to screen all patients before starting immunosuppressive therapy.

How to screen

All guidelines agree on how to test for HBV. Measuring levels of HBsAg and hepatitis B core antibody (anti-HBc total) allows the clinician to ascertain whether the patient’s HBV infection status is acute, chronic, or resolved (TABLE 223) and to perform HBVr risk stratification (discussed later).

Patients with acute infections should be referred to a hepatologist. With chronic or resolved HBV, stratify patients into a prophylaxis group or monitoring group (FIGURE14). Stratification involves identifying HBV status (chronic or resolved) and selecting a type of immunosuppressive therapy. Whether the patient falls into prophylaxis or monitoring, obtain a baseline level of viral DNA, as this has proven to be the best predictor of HBV reactivation.16

Continue to: In screening, be sure the appropriate...

In screening, be sure the appropriate anti-HBc testing is covered. Common usage of the term anti-HBc may refer to immunoglobulin G (IgG) or immunoglobulin M (IgM)or total core antibody, containing both IgG and IgM. But in this context, accurate screening requires either total core antibody or anti-HBc IgG. Anti-IgM alone is inadequate. Many commercial laboratories offer acute hepatitis panels or hepatitis profiles (TABLE 324,25), and it is important to confirm that such order sets contain the tests necessary to allow for risk stratification.

Testing for hepatitis B surface antibody (anti-HBs) is not useful in screening. Although it was hypothesized that the presence of this antibody lowered risk, recent studies have proven no change in risk based on this value.21

How to assess HBVr risk

Assessing risk for HBVr takes into account both the patient’s serology and intended treatment. Reddy et al delineated patient groups into high, moderate, and low risk (TABLES 4 and 5).21 The high-risk group was defined by anticipated incidence of HBVr in > 10% of cases; the moderate-risk group had an anticipated incidence of 1% to 10%; and the low-risk group had an anticipated incidence of <1%.21 Evidence was strongest in the high-risk group.

Patients with CHB (HBsAg positive and anti-HBc positive) are considered high risk for reactivation with a wide variety of immunosuppressive therapies. Such patients are 5 to 8 times more likely to develop HBVr than patients with an HBsAg-negative status signifying a resolved infection.16

Immunosuppressive agents and associated risks. The AGA guidelines consider treatment with B-cell-depleting agents, such as rituximab and ofatumumab, to be high risk, regardless of a patient’s surface antigen status. Additionally, for patients who are HBsAg positive, high-risk treatments include anthracycline derivatives, such as doxorubicin and epirubicin, or high- or moderate-dose steroids. These treatments are considered moderate risk when used in patients who have resolved HBV infection (HBsAg negative/anti-HBc positive). Moderate-risk modalities also include tumor necrosis factor inhibitors and tyrosine kinase inhibitors, regardless of surface antigen status; and low-dose steroids or cytokine or integrin inhibitors in HbsAg-positive individuals.21

Continue to: Other immunosuppression modalities...

Other immunosuppression modalities considered to be moderate risk independent of HBV serology include proteasome inhibitors, such as bortezomib, used for multiple myeloma treatment, and histone deacetylase inhibitors, such as romidepsin, used to treat T-cell lymphoma.13 Low-dose steroids or cytokine or integrin inhibitors are considered to be low risk in surface antigen-negative individuals; azathioprine, mercaptopurine, or methotrexate are low risk regardless of HBsAg status.21 Intra-articular steroid injections are considered extremely low risk in HbsAg-positive individuals, and are unclassified for HbsAg-negative individuals.13

More recent evidence has implicated other medication classes in triggering HBVr — (eg, direct-acting antivirals.)26

Prophylaxis options: High to moderate risk vs low risk

The consensus of major guideline issuers is to offer prophylaxis to high-risk patients and to monitor low-risk patients. The AGA additionally recommends prophylaxis for patients at moderate risk.

Controversy surrounding the moderate-risk group. Some authors argue that monitoring HBV DNA in the moderate-risk group is preferable to committing patients to long periods of prophylaxis, and that rescue treatment could be initiated as needed. However, the ideal monitoring period has not been determined, and the effectiveness of prophylaxis over monitoring is so significant that monitoring is losing favor.

Perrillo et al performed a meta-analysis of 5 randomized controlled trials evaluating antiviral agents vs no prophylaxis.16 The analysis included 139 patients receiving prophylaxis and 137 controls. The pooled results demonstrated an 87% relative risk reduction with prophylaxis, supporting the trend toward treating patients with moderate risk.16

Continue to: Prophylactic treatment options are safe...

Prophylactic treatment options are safe and well tolerated. For this reason, committing a high- or moderate-risk patient to a course of treatment should be less of a concern than the risk for HBVr.

In the early randomized controlled trials for HBVr prophylaxis, lamivudine, although effective, unfortunately led to a high incidence of viral resistance after prolonged use, thus diminishing its desirability.18 Newer agents, such as entecavir and tenofovir, have proven just as effective as lamivudine and are largely unaffected by viral resistance.27

In retrospective and prospective studies on HBVr prophylaxis, patients treated with entecavir had less HBV-related hepatitis, less delay in chemotherapy, and a lower rate of HBVr when compared with lamivudine.28,29 Tenofovir is recommended, however, if patients were previously treated with lamivudine.30

A recent meta-analysis demonstrated that tenofovir and entecavir are preferable to lamivudine in preventing HBVr.31

Looking ahead

Screening for HBsAg and anti-HBc total before starting immunosuppressive therapy can reduce morbidity and mortality in patients undergoing such treatment. The AGA recommends screening all patients about to begin high- or moderate-risk therapy or patients in populations with a prevalence of CHB ≥2%, per the CDC.6,21

Continue to: Classes of medications...

Classes of medications other than immunosuppressants may also trigger HBVr. The FDA has issued a warning regarding direct-acting antivirals, but optimal management of these patients is still evolving.

Once HBV status is established, a patient’s risk for HBVr can be specified as high, moderate, or low using their HBV status and the type of therapy being initiated. The AGA recommends prophylactic treatment with well-tolerated and effective agents for patients classified as high or moderate risk. If a patient’s risk is low, regular monitoring of HBV DNA and AST and ALT levels is sufficient. Recommendations of monitoring intervals span from monthly to every 3 months.13,14

CASE Given the patient’s status of resolved HBV infection and her current moderate-dose regimen of prednisone, her risk for HBV reactivation is moderate. She could either receive antiviral prophylaxis or undergo regular monitoring. Following a discussion of the options, she opts for referral to a hepatologist to discuss possible prophylactic treatment.

Increased awareness of HBVr risk associated with immunosuppressive therapy, coupled with a planned approach to appropriate screening and risk stratification, can help health care providers prevent the reactivation of HBV or initiate early intervention for CHB.

CORRESPONDENCE

Ronan Farrell, MD, Rhode Island Hospital, 593 Eddy Street, Providence, RI 02903; [email protected].

1. Artz AS, Somerfield MR, Feld JJ, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology provisional clinical opinion: chronic hepatitis B virus infection screening in patients receiving cytotoxic chemotherapy for treatment of malignant diseases. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:3199-3202.

2. Day FL, Link E, Thursky K, et al. Current hepatitis B screening practices and clinical experience of reactivation in patients undergoing chemotherapy for solid tumors: a nationwide survey of medical oncologists. J Oncol Pract. 2011;7:141-147.

3. Paul S, Saxena A, Terrin N, et al. Hepatitis B virus reactivation and prophylaxis during solid tumor chemotherapy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Internal Med. 2016;164:30-40.

4. Kim MK, Ahn JH, Kim SB, et al. Hepatitis B reactivation during adjuvant anthracycline-based chemotherapy in patients with breast cancer: a single institution’s experience. Korean J Intern Med. 2007;22:237-243.

5. Esteve M, Saro C, González-Huix F, et al. Chronic hepatitis B reactivation following infliximab therapy in Crohn’s disease patients: need for primary prophylaxis. Gut. 2004;53:1363-1365.

6. Weinbaum CM, Williams I, Mast EE, et al. Recommendations for identification and public health management of persons with chronic hepatitis B virus infection. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2008;57:1-20.

7. Liang TJ, Block TM, McMahon BJ, et al. Present and future therapies of hepatitis B: from discovery to cure. Hepatology. 2015;62:1893-1908.

8, , , A mathematical model to estimate global hepatitis B disease burden and vaccination impact. Int J Epidemiol. 2005;34:1329-1339.

9. WHO. Hepatitis B. www.who.int/en/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/hepatitis-b. Accessed February 28, 2019.

10. Kowdley KV, Wang CC, Welch S, et al. Prevalence of chronic hepatitis B among foreign-born persons living in the United States by country of origin. Hepatology. 2012;56:422-433.

11. Foster T, Hon H, Kanwal F, et al. Screening high risk individuals for hepatitis B: physician knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs. Dig Dis Sci. 2011;56:3471-3487.

12. Rehermann B, Ferrari C, Pasquinelli C, et al. The hepatitis B virus persists for decades after patients’ recovery from acute viral hepatitis despite active maintenance of a cytotoxic T-lymphocyte response. Nat Med. 1996;2:1104-1108.

13. Loomba R, Liang TJ. Hepatitis B reactivation associated with immune suppressive and biological modifier therapies: current concepts, management strategies, and future directions. Gastroenterology. 2017;152:1297-1309.

14. Di Bisceglie AM, Lok AS, Martin P, et al. Recent US Food and Drug Administration warnings on hepatitis B reactivation with immune-suppressing and anticancer drugs: just the tip of the iceberg? Hepatology. 2015;61:703-711.

15. Lok AS, Ward JW, Perrillo RP, et al. Reactivation of hepatitis B during immunosuppressive therapy: potentially fatal yet preventable. Ann Intern Med. 2012;156:743-745.

16. Perrillo RP, Gish R, Falck-Ytter YT. American Gastroenterological Association Institute technical review on prevention and treatment of hepatitis B virus reactivation during immunosuppressive drug therapy. Gastroenterology. 2015;148:221-244.

17. Hwang JP, Lok AS. Management of patients with hepatitis B who require immunosuppressive therapy. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;11:209-219.

18. Lok AS, McMahon BJ. Chronic hepatitis B: update 2009. Hepatology. 2009;50:661-662.

19. Asian-Pacific consensus statement on the management of chronic hepatitis B: a 2012 update. Hepatol Int. 2012;6:531-561.

20. EASL clinical practice guidelines: management of chronic hepatitis B virus infection. J Hepatol. 2012;57:167-185.

21. Reddy KR, Beavers KL, Hammond SP, et al. American Gastroenterological Association Institute guideline on the prevention and treatment of hepatitis B virus reactivation during immunosuppressive drug therapy. Gastroenterology. 2015;148:215-219.

, , . Why we should routinely screen Asian American adults for hepatitis B: a cross-sectional study of Asians in California. Hepatology. 2007;46:1034-1040.

23. Hwang JP, Artz AS, Somerfield MR. Hepatitis B virus screening for patients with cancer before therapy: American Society of Clinical Oncology Provisional Clinical Opinion Update. J Oncol Pract. 2015;11:e487-489.

24. LabCorp. Hepatitis B core antibody, IgG, IgM, differentiation. www.labcorp.com/test-menu/27196/hepatitis-b-core-antibody-igg-igm-differentiation. Accessed February 28, 2019.

25. Quest diagnostics. Hepatitis B Core Antibody, Total. www.questdiagnostics.com/testcenter/TestDetail.action?ntc=501.Accessed November 5, 2018.

26. The Food and Drug Administration Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS). www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/ucm522932.htm. Accessed February 28, 2019.

27. Lim YS. Management of antiviral resistance in chronic hepatitis B. Gut Liver. 2017;11:189-195.

28. Huang H, Li X, Zhu J, et al. Entecavir vs lamivudine for prevention of hepatitis B virus reactivation among patients with untreated diffuse large B-cell lymphoma receiving R-CHOP chemotherapy: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2014;312:2521-2530.

29. Chen WC, Cheng JS, Chiang PH, et al. A comparison of entecavir and lamivudine for the prophylaxis of hepatitis B virus reactivation in solid tumor patients undergoing systemic cytotoxic chemotherapy. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0131545.

30. Tenney DJ, Rose RE, Baldick CJ, et al. Long-term monitoring shows hepatitis B virus resistance to entecavir in nucleoside-naïve patients is rare through 5 years of therapy. Hepatology. 2009;49:1503-1514.

31. Zhang MY, Zhu GQ, Shi KQ, et al. Systematic review with network meta-analysis: comparative efficacy of oral nucleos(t)ide analogues for the prevention of chemotherapy-induced hepatitis B virus reactivation. Oncotarget. 2016;7:30642-30658.

1. Artz AS, Somerfield MR, Feld JJ, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology provisional clinical opinion: chronic hepatitis B virus infection screening in patients receiving cytotoxic chemotherapy for treatment of malignant diseases. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:3199-3202.

2. Day FL, Link E, Thursky K, et al. Current hepatitis B screening practices and clinical experience of reactivation in patients undergoing chemotherapy for solid tumors: a nationwide survey of medical oncologists. J Oncol Pract. 2011;7:141-147.

3. Paul S, Saxena A, Terrin N, et al. Hepatitis B virus reactivation and prophylaxis during solid tumor chemotherapy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Internal Med. 2016;164:30-40.

4. Kim MK, Ahn JH, Kim SB, et al. Hepatitis B reactivation during adjuvant anthracycline-based chemotherapy in patients with breast cancer: a single institution’s experience. Korean J Intern Med. 2007;22:237-243.

5. Esteve M, Saro C, González-Huix F, et al. Chronic hepatitis B reactivation following infliximab therapy in Crohn’s disease patients: need for primary prophylaxis. Gut. 2004;53:1363-1365.

6. Weinbaum CM, Williams I, Mast EE, et al. Recommendations for identification and public health management of persons with chronic hepatitis B virus infection. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2008;57:1-20.

7. Liang TJ, Block TM, McMahon BJ, et al. Present and future therapies of hepatitis B: from discovery to cure. Hepatology. 2015;62:1893-1908.

8, , , A mathematical model to estimate global hepatitis B disease burden and vaccination impact. Int J Epidemiol. 2005;34:1329-1339.

9. WHO. Hepatitis B. www.who.int/en/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/hepatitis-b. Accessed February 28, 2019.

10. Kowdley KV, Wang CC, Welch S, et al. Prevalence of chronic hepatitis B among foreign-born persons living in the United States by country of origin. Hepatology. 2012;56:422-433.

11. Foster T, Hon H, Kanwal F, et al. Screening high risk individuals for hepatitis B: physician knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs. Dig Dis Sci. 2011;56:3471-3487.

12. Rehermann B, Ferrari C, Pasquinelli C, et al. The hepatitis B virus persists for decades after patients’ recovery from acute viral hepatitis despite active maintenance of a cytotoxic T-lymphocyte response. Nat Med. 1996;2:1104-1108.

13. Loomba R, Liang TJ. Hepatitis B reactivation associated with immune suppressive and biological modifier therapies: current concepts, management strategies, and future directions. Gastroenterology. 2017;152:1297-1309.

14. Di Bisceglie AM, Lok AS, Martin P, et al. Recent US Food and Drug Administration warnings on hepatitis B reactivation with immune-suppressing and anticancer drugs: just the tip of the iceberg? Hepatology. 2015;61:703-711.

15. Lok AS, Ward JW, Perrillo RP, et al. Reactivation of hepatitis B during immunosuppressive therapy: potentially fatal yet preventable. Ann Intern Med. 2012;156:743-745.

16. Perrillo RP, Gish R, Falck-Ytter YT. American Gastroenterological Association Institute technical review on prevention and treatment of hepatitis B virus reactivation during immunosuppressive drug therapy. Gastroenterology. 2015;148:221-244.

17. Hwang JP, Lok AS. Management of patients with hepatitis B who require immunosuppressive therapy. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;11:209-219.

18. Lok AS, McMahon BJ. Chronic hepatitis B: update 2009. Hepatology. 2009;50:661-662.

19. Asian-Pacific consensus statement on the management of chronic hepatitis B: a 2012 update. Hepatol Int. 2012;6:531-561.

20. EASL clinical practice guidelines: management of chronic hepatitis B virus infection. J Hepatol. 2012;57:167-185.

21. Reddy KR, Beavers KL, Hammond SP, et al. American Gastroenterological Association Institute guideline on the prevention and treatment of hepatitis B virus reactivation during immunosuppressive drug therapy. Gastroenterology. 2015;148:215-219.

, , . Why we should routinely screen Asian American adults for hepatitis B: a cross-sectional study of Asians in California. Hepatology. 2007;46:1034-1040.

23. Hwang JP, Artz AS, Somerfield MR. Hepatitis B virus screening for patients with cancer before therapy: American Society of Clinical Oncology Provisional Clinical Opinion Update. J Oncol Pract. 2015;11:e487-489.

24. LabCorp. Hepatitis B core antibody, IgG, IgM, differentiation. www.labcorp.com/test-menu/27196/hepatitis-b-core-antibody-igg-igm-differentiation. Accessed February 28, 2019.

25. Quest diagnostics. Hepatitis B Core Antibody, Total. www.questdiagnostics.com/testcenter/TestDetail.action?ntc=501.Accessed November 5, 2018.

26. The Food and Drug Administration Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS). www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/ucm522932.htm. Accessed February 28, 2019.

27. Lim YS. Management of antiviral resistance in chronic hepatitis B. Gut Liver. 2017;11:189-195.

28. Huang H, Li X, Zhu J, et al. Entecavir vs lamivudine for prevention of hepatitis B virus reactivation among patients with untreated diffuse large B-cell lymphoma receiving R-CHOP chemotherapy: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2014;312:2521-2530.

29. Chen WC, Cheng JS, Chiang PH, et al. A comparison of entecavir and lamivudine for the prophylaxis of hepatitis B virus reactivation in solid tumor patients undergoing systemic cytotoxic chemotherapy. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0131545.

30. Tenney DJ, Rose RE, Baldick CJ, et al. Long-term monitoring shows hepatitis B virus resistance to entecavir in nucleoside-naïve patients is rare through 5 years of therapy. Hepatology. 2009;49:1503-1514.

31. Zhang MY, Zhu GQ, Shi KQ, et al. Systematic review with network meta-analysis: comparative efficacy of oral nucleos(t)ide analogues for the prevention of chemotherapy-induced hepatitis B virus reactivation. Oncotarget. 2016;7:30642-30658.

PRACTICE RECOMMENDATIONS

› Measure levels of hepatitis B surface antigen and core antibody total. Although testing for IgG alone can be acceptable, testing for IgM alone is unacceptable. C

› Use both a patient’s serologic findings and the recognized risk associated with intended therapy to determine the threat of hepatitis B virus (HBV) reactivation. C

› Offer antiviral prophylaxis when risk for HBV reactivation is high. Consider prophylaxis or monitoring for those at moderate risk. C

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

Letters: National Suicide Strategy

To the Editor: Even one death by suicide is too many. Suicide is complex and a serious national public health issue that affects people from all walks of life—not just veterans—for a variety of reasons. While there is still a lot we can learn about suicide, we know that suicide is preventable, treatment works, and there is hope.

At the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), our suicide prevention efforts are guided by the National Strategy for Preventing Veteran Suicide.1 Published in 2018, this long-term strategy expands beyond crisis intervention and provides a framework for identifying priorities, organizing efforts, and focusing national attention and community resources to prevent suicide among veterans through a broad public health approach with an emphasis on comprehensive, community-based engagement.

This approach is grounded in 4 key areas: Primary prevention focuses on preventing suicidal behavior before it occurs; whole health considers factors beyond mental health, such as physical health, alcohol or substance misuse, and life events; application of data and research emphasizes evidence-based approaches that can be tailored to the needs of veterans in local communities; and collaboration educates and empowers diverse communities to participate in suicide prevention efforts through coordination.

A recent article by Russell Lemle, PhD, noted that the National Strategy does not emphasize the work of the VA, and he is correct.2 Rather than perpetuate the myth that VA can address suicide alone, the strategy was intended to guide veteran suicide prevention efforts across the entire nation, not just within VA’s walls. It is a plan for how we can ALL work together to prevent veteran suicide. The National Strategy does not minimize VA’s role in suicide prevention. It enhances VA’s ability and expectation to engage in collaborative efforts across the nation.

Every year, about 6,000 veterans die by suicide, the majority of whom have not received recent VA care. We are mindful that some veterans may not receive any or all of their health care services from the VA, for various reasons, and want to be respectful and cognizant of those choices. To save lives, VA needs the support of partners across sectors. We need to ensure that multiple systems are working in a coordinated way to reach veterans where they live, work, and thrive.

Our philosophy is that there is no wrong door to care. That is why we focused on universal, non-VA community interventions. Preventing suicide among all of the nation’s 20 million veterans cannot be the sole responsibility of VA—it requires a nationwide effort. As there is no single cause of suicide, no single organization can tackle suicide prevention alone. Put simply, VA must ensure suicide prevention is a part of every aspect of veterans’ lives, not just their VA interactions. At VA, we know that the care and support that veterans need often comes before a mental health crisis occurs, and communities and families may be better equipped to provide these types of supports.

Activities or special interest groups can boost protective factors against suicide and combat risk factors. Communities can foster an environment where veterans can find connection and camaraderie, achieve a sense of purpose, bolster their coping skills, and live healthily. And partners like the National Shooting Sports Foundation help VA to address sensitive issues, such as lethal means safety, while correcting misconceptions about how VA handles gun ownership.

Data also are an integral piece of our public health approach, driving how VA defines the problem, targets its programs, and delivers and implements interventions. VA was one of the first institutions to implement comprehensive suicide analysis and predictive analytics, and VA has continuously improved data surveillance related to veteran suicide.

We began comprehensive suicide monitoring for the entire VA patient population in 2006, and in 2012, VA released its first report of suicide surveillance among all veterans in select partnering states. Though we are able to share data, we acknowledge the limitations Dr. Lemle highlighted in implementing predictive analytics program outside the VA. However, VA continues to improve reporting and surveillance efforts, especially to better understand the 20 veterans and service members who die by suicide each day.

As Lemle noted, little was previously known about the 14 of 20 veterans who die by suicide every day who weren’t recent users of VA health services. Since the September 2018 release of the National Strategy, VA has obtained additional data. In addition to sharing data, VA will focus on helping non-VA entities understand the problem so that they can help reach veterans who may never go to VA for care. Efforts are underway to better understand specific groups that are at elevated risk, such as veterans aged 18 to 34 years, women veterans, never federally activated guardsmen and reservists, recently separated veterans, and former service members with Other Than Honorable discharges.

To end veteran suicide, VA is relentlessly working to make improvements to existing suicide prevention programs, develop VA-specific plans to advance the National Strategy, find innovative ways to get people into care, and educate veterans and family members about VA care. Through Executive Order 13822, for example, VA has partnered with the Departments of Defense and Homeland Security, which allows us to educate service members about VA offerings before they become veterans. We also are making it easier for them to quickly find information online about VA mental health services.

We acknowledge VA is not a perfect organization, and a negative image can turn away veterans. VA is actively working with the media to get more good news stories published. We have many exciting things to talk about, such as a newly implemented Comprehensive Suicide Risk Assessment, and it is important for people to know that VA is providing the gold standard of care. Sometimes, those stories are better messaged and amplified by partners and non-VA entities, and this is a key part of our approach.

Lemle also raised a concern around funding this new public health initiative. While we recognize the challenges in advancing this new public health approach without additional funding, we are hopeful we can energize communities to work with us to find a solution.

The National Strategy is not the end of the conversation. It is a starting point. We are thankful for Lemle’s thoughtful questions and are actively pursuing and investigating solutions regarding veteran suicide studies, peer support, and community care guidelines for partners as we seek to improve our services. We also are putting pen to paper on a plan to strengthen family involvement and integrate suicide prevention within VA’s whole health and social services strategies.

The National Strategy is a call to action to every organization, system, and institution interested in preventing veteran suicide to help do this work where we cannot. For our part, VA will continue to energize communities to increase local involvement to reach all veterans, and we will continue to empower and equip ALL veterans with the resources and care they need to thrive.

To learn about the resources available for veterans and how you can #BeThere as a VA employee, family member, friend, community partner, or clinician, visit www.mentalhealth.va.gov/suicide_prevention/resources.asp. If you or someone you know is having thoughts of suicide, contact the Veterans Crisis Line to receive free, confidential support and crisis intervention available 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, 365 days a year. Call 800-273-8255 and press 1, text to 838255, or chat online at VeteransCrisisLine.net/Chat.

- Keita Franklin, LCSD, PhD

Author affiliations: Executive Director, Suicide Prevention VA Office of Mental Health and Suicide Prevention.

Author disclosures: Keita Franklin participated in the development of the National Strategy for Preventing Veteran Suicide .

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed herein are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of Federal Practitioner , Frontline Medical Communications Inc., the US Government, or any of its agencies.

Author Response: Keita Franklin, PhD, offers a valuable response to my December critique of the VA National Strategy to Prevent Veteran Suicide. Dr. Franklin thoughtfully articulates why public health approaches to prevent suicide must be a core component of a multifaceted strategy. She is right about that.

While I see considerable overlap between our statements, there are 2 important points where we diverge: (1) Unless Congress appropriates sufficient funds for extensive public health outreach, there is a danger that funds to implement it would be diverted from VA’s extant effective VA suicide prevention programs. (2) A prospective suicide prevention plan requires 3 prongs of universal, group, and individually focused strategies, because suicide cannot be prevented by any single strategy. The VA National Strategy as well as the March 2019 Executive Order on a National Roadmap to Empower Veterans and End Suicide, focus predominantly on universal strategies, and I believe its overall approach would be improved by also explicitly supporting VA’s targeted programs for at-risk veterans.

- Russell B. Lemle, PhD

Author affiliations: Policy Analyst at the Veterans Healthcare Policy Institute in Oakland, California.

1. US Department of Veterans Affairs. National strategy for preventing veteran suicide 2018–2028. https://www.mentalhealth.va.gov/suicide_prevention/docs/Office-of-Mental-Health-and-Suicide-Prevention-National-Strategy-for-Preventing-Veterans-Suicide.pdf. Published September 2018. Accessed February 19, 2019.

2. Lemle R. Communities emphasis could undercut VA successes in National Strategy for Preventing Veteran Suicide. Fed Pract. 2018;35(12):16-17.

To the Editor: Even one death by suicide is too many. Suicide is complex and a serious national public health issue that affects people from all walks of life—not just veterans—for a variety of reasons. While there is still a lot we can learn about suicide, we know that suicide is preventable, treatment works, and there is hope.

At the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), our suicide prevention efforts are guided by the National Strategy for Preventing Veteran Suicide.1 Published in 2018, this long-term strategy expands beyond crisis intervention and provides a framework for identifying priorities, organizing efforts, and focusing national attention and community resources to prevent suicide among veterans through a broad public health approach with an emphasis on comprehensive, community-based engagement.

This approach is grounded in 4 key areas: Primary prevention focuses on preventing suicidal behavior before it occurs; whole health considers factors beyond mental health, such as physical health, alcohol or substance misuse, and life events; application of data and research emphasizes evidence-based approaches that can be tailored to the needs of veterans in local communities; and collaboration educates and empowers diverse communities to participate in suicide prevention efforts through coordination.

A recent article by Russell Lemle, PhD, noted that the National Strategy does not emphasize the work of the VA, and he is correct.2 Rather than perpetuate the myth that VA can address suicide alone, the strategy was intended to guide veteran suicide prevention efforts across the entire nation, not just within VA’s walls. It is a plan for how we can ALL work together to prevent veteran suicide. The National Strategy does not minimize VA’s role in suicide prevention. It enhances VA’s ability and expectation to engage in collaborative efforts across the nation.

Every year, about 6,000 veterans die by suicide, the majority of whom have not received recent VA care. We are mindful that some veterans may not receive any or all of their health care services from the VA, for various reasons, and want to be respectful and cognizant of those choices. To save lives, VA needs the support of partners across sectors. We need to ensure that multiple systems are working in a coordinated way to reach veterans where they live, work, and thrive.

Our philosophy is that there is no wrong door to care. That is why we focused on universal, non-VA community interventions. Preventing suicide among all of the nation’s 20 million veterans cannot be the sole responsibility of VA—it requires a nationwide effort. As there is no single cause of suicide, no single organization can tackle suicide prevention alone. Put simply, VA must ensure suicide prevention is a part of every aspect of veterans’ lives, not just their VA interactions. At VA, we know that the care and support that veterans need often comes before a mental health crisis occurs, and communities and families may be better equipped to provide these types of supports.

Activities or special interest groups can boost protective factors against suicide and combat risk factors. Communities can foster an environment where veterans can find connection and camaraderie, achieve a sense of purpose, bolster their coping skills, and live healthily. And partners like the National Shooting Sports Foundation help VA to address sensitive issues, such as lethal means safety, while correcting misconceptions about how VA handles gun ownership.

Data also are an integral piece of our public health approach, driving how VA defines the problem, targets its programs, and delivers and implements interventions. VA was one of the first institutions to implement comprehensive suicide analysis and predictive analytics, and VA has continuously improved data surveillance related to veteran suicide.