User login

Sudden-onset rash on the trunk and limbs • morbid obesity • family history of diabetes mellitus • Dx?

THE CASE

A 37-year-old man presented with a sudden-onset, nonpruritic, nonpainful, papular rash of 1 month’s duration on his trunk and both arms and legs. Two weeks prior to the current presentation, he consulted a general practitioner, who treated the rash with a course of unknown oral antibiotics; the patient showed no improvement. He recalled that on a few occasions, he used his fingers to express a creamy discharge from some of the lesions. This temporarily reduced the size of those papules.

His medical history was unremarkable except for morbid obesity. He did not drink alcohol regularly and was not taking any medications prior to the onset of the rash. He had no family history of hyperlipidemia, but his mother had a history of diabetes mellitus.

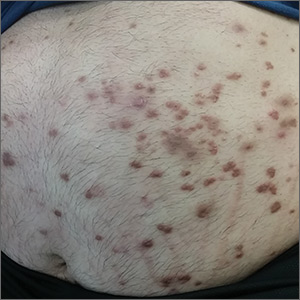

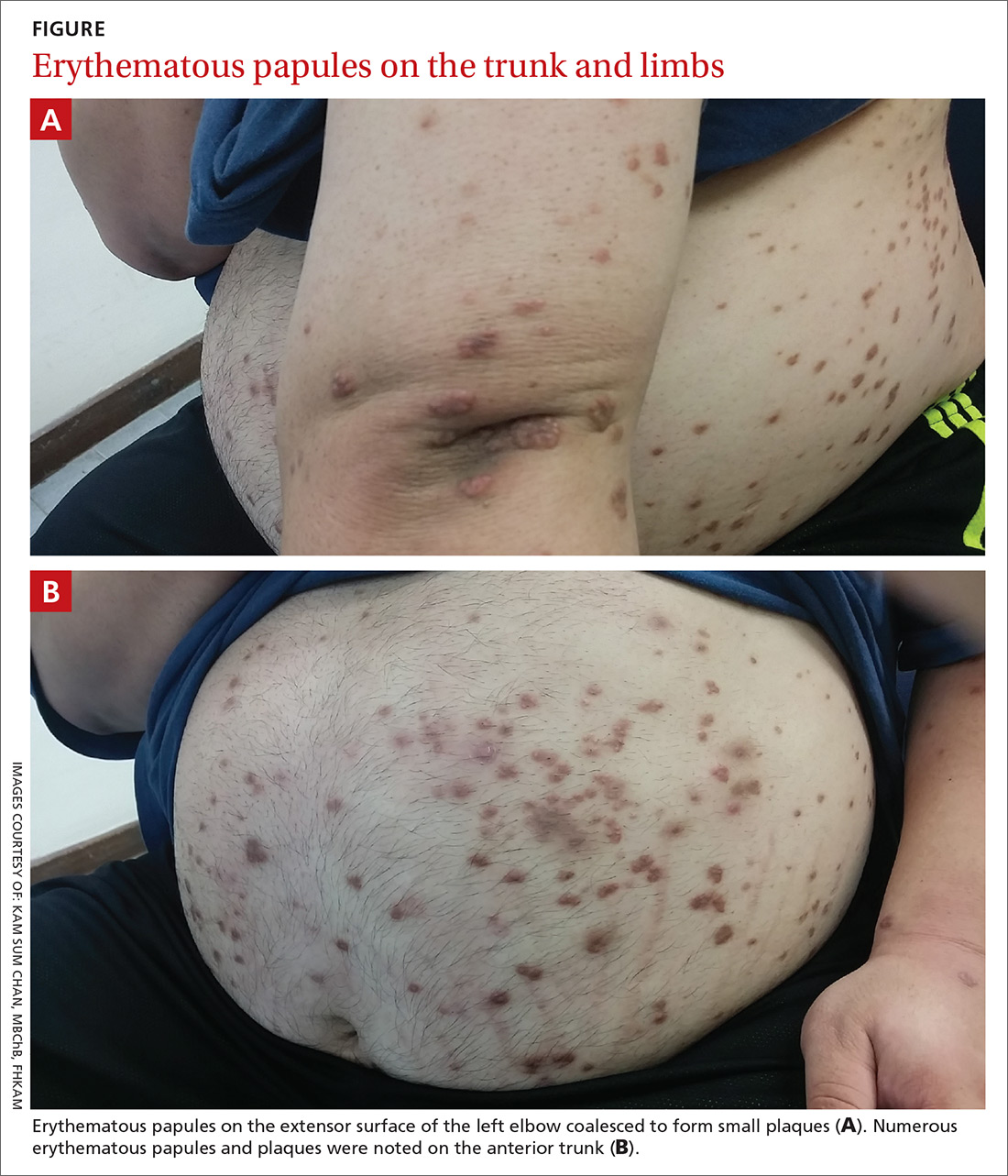

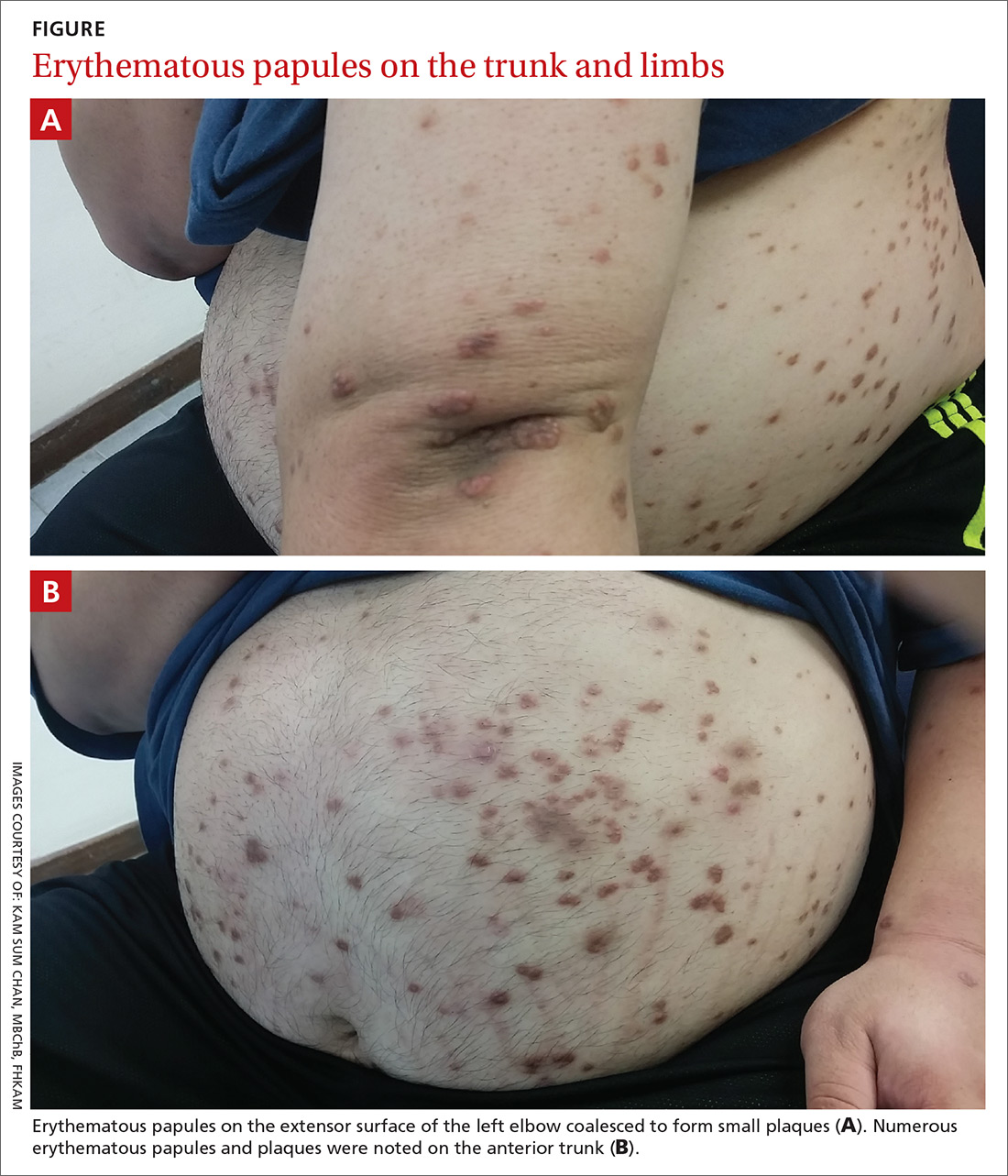

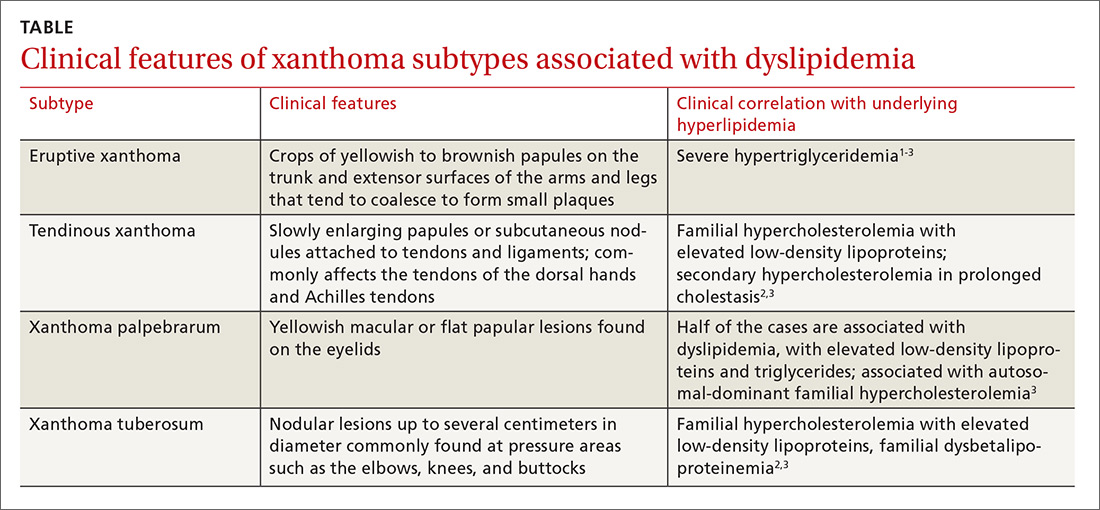

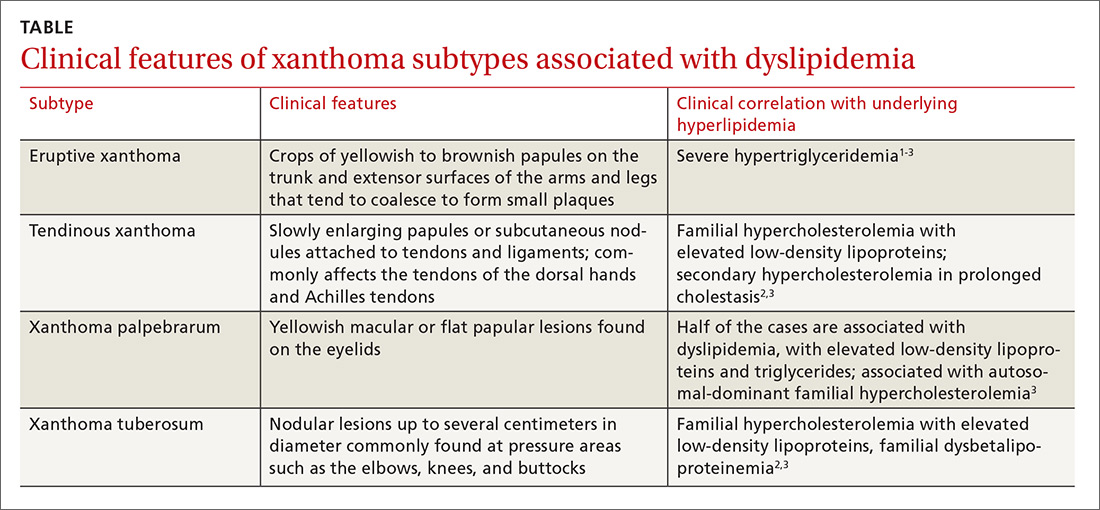

Physical examination showed numerous discrete erythematous papules with a creamy center on his trunk and his arms and legs. The lesions were more numerous on the extensor surfaces of the arms and legs. Some of the papules coalesced to form small plaques (FIGURE). There was no scaling, and the lesions were firm in texture. The patient’s face was spared, and there was no mucosal involvement. The patient was otherwise systemically well.

THE DIAGNOSIS

Based on the morphology, distribution, and abrupt onset of the diffuse nonpruritic papules in this morbidly obese (but otherwise systemically well) middle-aged man, a clinical diagnosis of eruptive xanthoma was suspected. Subsequent blood testing revealed an elevated serum triglyceride level of 47.8 mmol/L (reference range, <1.7 mmol/L), elevated serum total cholesterol of 7.1 mmol/L (reference range, <6.2 mmol/L), and low serum high-density lipoprotein cholesterol of 0.7 mmol/L (reference range, >1 mmol/L in men). He also had an elevated fasting serum glucose level of 12.9 mmol/L (reference range, 3.9–5.6 mmol/L) and an elevated hemoglobin A1c (glycated hemoglobin) level of 10.9%.

Subsequent thyroid, liver, and renal function tests were normal, but the patient had heavy proteinuria, with an elevated urine albumin-to-creatinine ratio of 355.6 mg/mmol (reference range, ≤2.5 mg/mmol). The patient was referred to a dermatologist, who confirmed the clinical diagnosis without the need for a skin biopsy.

DISCUSSION

Eruptive xanthoma is characterized by an abrupt onset of crops of multiple yellowish to brownish papules that can coalesce into small plaques. The lesions can be generalized, but tend to be more densely distributed on the extensor surfaces of the arms and legs, buttocks, and thighs.5 Eruptive xanthoma often is associated with hypertriglyceridemia, which can be primary—as a result of a genetic defect caused by familial hypertriglyceridemia—or secondary, associated with poorly controlled diabetes mellitus, morbid obesity, excessive alcohol consumption, nephrotic syndrome, hypothyroidism, primary biliary cholangitis, and drugs like estrogen replacement therapies, corticosteroids, and isotretinoin.6 Pruritus and tenderness may or may not be present, and the Köbner phenomenon may occur.7

Continue to: The differential diagnosis

The differential diagnosis for eruptive xanthoma includes xanthoma disseminatum, non–Langerhans cell histiocytoses (eg, generalized eruptive histiocytosis), and cutaneous mastocytosis.1

Xanthoma disseminatum is an extremely rare, but benign, disorder of non–Langerhans cell origin. The average age of onset is older than 40 years. The rash consists of multiple red-yellow papules and nodules that most commonly present in flexural areas. Forty percent to 60% of patients have mucosal involvement, and rarely the central nervous system is involved.8

Generalized eruptive histiocytosis is another rare non–Langerhans cell histiocytosis that occurs mainly in adults and is characterized by widespread, symmetric, red-brown papules on the trunk, arms, and legs, and rarely the mucous membranes.9

Cutaneous mastocytosis, especially xanthelasmoid mastocytosis, consists of multiple pruritic, yellowish, papular or nodular lesions that may mimic eruptive xanthoma. It occurs mainly in children and rarely in adults.10

Confirming the diagnosis, initiating treatment

The diagnosis of eruptive xanthoma can be confirmed by skin biopsy if other differential diagnoses cannot be ruled out or the lesions do not resolve with treatment. Skin biopsy will reveal lipid-laden macrophages (known as foam cells) deposited in the dermis.7

Continue to: Treatment of eruptive xanthoma

Treatment of eruptive xanthoma involves management of the underlying causes of the condition. In most cases, dietary control, intensive triglyceride-lowering therapies, and treatment of other secondary causes of hypertriglyceridemia result in complete resolution of the lesions within several weeks.5

Our patient’s outcome

Our patient’s sudden-onset rash alerted us to the presence of type 2 diabetes mellitus, hypertriglyceridemia, and heavy proteinuria, which he was not aware of previously. We counselled him about stringent low-sugar, low-lipid diet control and exercise, and we started him on metformin and gemfibrozil. He was referred to an internal medicine specialist for further assessment and management of his severe hypertriglyceridemia and heavy proteinuria.

The rash started to wane 1 month after the patient started the metformin and gemfibrozil, and his drug regimen was changed to combination therapy with metformin/glimepiride and fenofibrate/simvastatin 6 weeks later when he was seen in the medical specialty clinic. Fundus photography performed 1 month after starting oral antidiabetic therapy showed no diabetic retinopathy or lipemia retinalis.

After 3 months of treatment, his serum triglycerides and hemoglobin A1c levels dropped to 3.8 mmol/L and 8.7%, respectively. The rash also resolved considerably, with only residual papules on the abdomen. This rapid clinical response to treatment of the underlying hypertriglyceridemia and diabetes further supported the clinical diagnosis of eruptive xanthoma.

THE TAKEAWAY

Eruptive xanthoma is relatively rare, but it is important for family physicians to recognize this clinical presentation as a potential indicator of severe hypertriglyceridemia. Recognizing hypertriglyceridemia early is important, as it can be associated with an increased risk for acute pancreatitis. Moreover, eruptive xanthoma might be the sole presenting symptom of underlying diabetes mellitus or familial hyperlipidemia, both of which can lead to a significant increase in cardiovascular risk if uncontrolled.

CORRESPONDENCE

Chan Kam Sum, MBChB, FRACGP, Tseung Kwan O Jockey Club General Out-patient Clinic, 99 Po Lam Road North, G/F, Tseung Kwan O, Kowloon, Hong Kong; [email protected]

1. Tang WK. Eruptive xanthoma. [case reports]. Hong Kong Dermatol Venereol Bull. 2001;9:172-175.

2. Frew J, Murrell D, Haber R. Fifty shades of yellow: a review of the xanthodermatoses. Int J Dermatol. 2015;54:1109-1123.

3. Zak A, Zeman M, Slaby A, et al. Xanthomas: clinical and pathophysiological relations. Biomed Pap Med Fac Univ Palacky Olomouc Czech Repub. 2014;158:181-188.

4. Sandhu S, Al-Sarraf A, Taraboanta C, et al. Incidence of pancreatitis, secondary causes, and treatment of patients referred to specialty lipid clinic with severe hypertriglyceridemia: a retrospective cohort study. Lipids Health Dis. 2011;10:157.

5. Holsinger JM, Campbell SM, Witman P. Multiple erythematous-yellow, dome-shaped papules. Am Fam Physician. 2010;82:517.

6. Loeckermann S, Braun-Falco M. Eruptive xanthomas in association with metabolic syndrome. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2010;35:565-566.

7. Merola JF, Mengden SJ, Soldano A, et al. Eruptive xanthomas. Dermatol Online J. 2008;14:10.

8. Park M, Boone B, Devas S. Xanthoma disseminatum: case report and mini-review of the literature. Acta Dermatovenerol Croat. 2014;22:150-154.

9. Attia A, Seleit I, El Badawy N, et al. Photoletter to the editor: generalized eruptive histiocytoma. J Dermatol Case Rep. 2011;5:53-55.

10. Nabavi NS, Nejad MH, Feli S, et al. Adult onset of xanthelasmoid mastocytosis: report of a rare entity. Indian J Dermatol. 2016;61:468.

THE CASE

A 37-year-old man presented with a sudden-onset, nonpruritic, nonpainful, papular rash of 1 month’s duration on his trunk and both arms and legs. Two weeks prior to the current presentation, he consulted a general practitioner, who treated the rash with a course of unknown oral antibiotics; the patient showed no improvement. He recalled that on a few occasions, he used his fingers to express a creamy discharge from some of the lesions. This temporarily reduced the size of those papules.

His medical history was unremarkable except for morbid obesity. He did not drink alcohol regularly and was not taking any medications prior to the onset of the rash. He had no family history of hyperlipidemia, but his mother had a history of diabetes mellitus.

Physical examination showed numerous discrete erythematous papules with a creamy center on his trunk and his arms and legs. The lesions were more numerous on the extensor surfaces of the arms and legs. Some of the papules coalesced to form small plaques (FIGURE). There was no scaling, and the lesions were firm in texture. The patient’s face was spared, and there was no mucosal involvement. The patient was otherwise systemically well.

THE DIAGNOSIS

Based on the morphology, distribution, and abrupt onset of the diffuse nonpruritic papules in this morbidly obese (but otherwise systemically well) middle-aged man, a clinical diagnosis of eruptive xanthoma was suspected. Subsequent blood testing revealed an elevated serum triglyceride level of 47.8 mmol/L (reference range, <1.7 mmol/L), elevated serum total cholesterol of 7.1 mmol/L (reference range, <6.2 mmol/L), and low serum high-density lipoprotein cholesterol of 0.7 mmol/L (reference range, >1 mmol/L in men). He also had an elevated fasting serum glucose level of 12.9 mmol/L (reference range, 3.9–5.6 mmol/L) and an elevated hemoglobin A1c (glycated hemoglobin) level of 10.9%.

Subsequent thyroid, liver, and renal function tests were normal, but the patient had heavy proteinuria, with an elevated urine albumin-to-creatinine ratio of 355.6 mg/mmol (reference range, ≤2.5 mg/mmol). The patient was referred to a dermatologist, who confirmed the clinical diagnosis without the need for a skin biopsy.

DISCUSSION

Eruptive xanthoma is characterized by an abrupt onset of crops of multiple yellowish to brownish papules that can coalesce into small plaques. The lesions can be generalized, but tend to be more densely distributed on the extensor surfaces of the arms and legs, buttocks, and thighs.5 Eruptive xanthoma often is associated with hypertriglyceridemia, which can be primary—as a result of a genetic defect caused by familial hypertriglyceridemia—or secondary, associated with poorly controlled diabetes mellitus, morbid obesity, excessive alcohol consumption, nephrotic syndrome, hypothyroidism, primary biliary cholangitis, and drugs like estrogen replacement therapies, corticosteroids, and isotretinoin.6 Pruritus and tenderness may or may not be present, and the Köbner phenomenon may occur.7

Continue to: The differential diagnosis

The differential diagnosis for eruptive xanthoma includes xanthoma disseminatum, non–Langerhans cell histiocytoses (eg, generalized eruptive histiocytosis), and cutaneous mastocytosis.1

Xanthoma disseminatum is an extremely rare, but benign, disorder of non–Langerhans cell origin. The average age of onset is older than 40 years. The rash consists of multiple red-yellow papules and nodules that most commonly present in flexural areas. Forty percent to 60% of patients have mucosal involvement, and rarely the central nervous system is involved.8

Generalized eruptive histiocytosis is another rare non–Langerhans cell histiocytosis that occurs mainly in adults and is characterized by widespread, symmetric, red-brown papules on the trunk, arms, and legs, and rarely the mucous membranes.9

Cutaneous mastocytosis, especially xanthelasmoid mastocytosis, consists of multiple pruritic, yellowish, papular or nodular lesions that may mimic eruptive xanthoma. It occurs mainly in children and rarely in adults.10

Confirming the diagnosis, initiating treatment

The diagnosis of eruptive xanthoma can be confirmed by skin biopsy if other differential diagnoses cannot be ruled out or the lesions do not resolve with treatment. Skin biopsy will reveal lipid-laden macrophages (known as foam cells) deposited in the dermis.7

Continue to: Treatment of eruptive xanthoma

Treatment of eruptive xanthoma involves management of the underlying causes of the condition. In most cases, dietary control, intensive triglyceride-lowering therapies, and treatment of other secondary causes of hypertriglyceridemia result in complete resolution of the lesions within several weeks.5

Our patient’s outcome

Our patient’s sudden-onset rash alerted us to the presence of type 2 diabetes mellitus, hypertriglyceridemia, and heavy proteinuria, which he was not aware of previously. We counselled him about stringent low-sugar, low-lipid diet control and exercise, and we started him on metformin and gemfibrozil. He was referred to an internal medicine specialist for further assessment and management of his severe hypertriglyceridemia and heavy proteinuria.

The rash started to wane 1 month after the patient started the metformin and gemfibrozil, and his drug regimen was changed to combination therapy with metformin/glimepiride and fenofibrate/simvastatin 6 weeks later when he was seen in the medical specialty clinic. Fundus photography performed 1 month after starting oral antidiabetic therapy showed no diabetic retinopathy or lipemia retinalis.

After 3 months of treatment, his serum triglycerides and hemoglobin A1c levels dropped to 3.8 mmol/L and 8.7%, respectively. The rash also resolved considerably, with only residual papules on the abdomen. This rapid clinical response to treatment of the underlying hypertriglyceridemia and diabetes further supported the clinical diagnosis of eruptive xanthoma.

THE TAKEAWAY

Eruptive xanthoma is relatively rare, but it is important for family physicians to recognize this clinical presentation as a potential indicator of severe hypertriglyceridemia. Recognizing hypertriglyceridemia early is important, as it can be associated with an increased risk for acute pancreatitis. Moreover, eruptive xanthoma might be the sole presenting symptom of underlying diabetes mellitus or familial hyperlipidemia, both of which can lead to a significant increase in cardiovascular risk if uncontrolled.

CORRESPONDENCE

Chan Kam Sum, MBChB, FRACGP, Tseung Kwan O Jockey Club General Out-patient Clinic, 99 Po Lam Road North, G/F, Tseung Kwan O, Kowloon, Hong Kong; [email protected]

THE CASE

A 37-year-old man presented with a sudden-onset, nonpruritic, nonpainful, papular rash of 1 month’s duration on his trunk and both arms and legs. Two weeks prior to the current presentation, he consulted a general practitioner, who treated the rash with a course of unknown oral antibiotics; the patient showed no improvement. He recalled that on a few occasions, he used his fingers to express a creamy discharge from some of the lesions. This temporarily reduced the size of those papules.

His medical history was unremarkable except for morbid obesity. He did not drink alcohol regularly and was not taking any medications prior to the onset of the rash. He had no family history of hyperlipidemia, but his mother had a history of diabetes mellitus.

Physical examination showed numerous discrete erythematous papules with a creamy center on his trunk and his arms and legs. The lesions were more numerous on the extensor surfaces of the arms and legs. Some of the papules coalesced to form small plaques (FIGURE). There was no scaling, and the lesions were firm in texture. The patient’s face was spared, and there was no mucosal involvement. The patient was otherwise systemically well.

THE DIAGNOSIS

Based on the morphology, distribution, and abrupt onset of the diffuse nonpruritic papules in this morbidly obese (but otherwise systemically well) middle-aged man, a clinical diagnosis of eruptive xanthoma was suspected. Subsequent blood testing revealed an elevated serum triglyceride level of 47.8 mmol/L (reference range, <1.7 mmol/L), elevated serum total cholesterol of 7.1 mmol/L (reference range, <6.2 mmol/L), and low serum high-density lipoprotein cholesterol of 0.7 mmol/L (reference range, >1 mmol/L in men). He also had an elevated fasting serum glucose level of 12.9 mmol/L (reference range, 3.9–5.6 mmol/L) and an elevated hemoglobin A1c (glycated hemoglobin) level of 10.9%.

Subsequent thyroid, liver, and renal function tests were normal, but the patient had heavy proteinuria, with an elevated urine albumin-to-creatinine ratio of 355.6 mg/mmol (reference range, ≤2.5 mg/mmol). The patient was referred to a dermatologist, who confirmed the clinical diagnosis without the need for a skin biopsy.

DISCUSSION

Eruptive xanthoma is characterized by an abrupt onset of crops of multiple yellowish to brownish papules that can coalesce into small plaques. The lesions can be generalized, but tend to be more densely distributed on the extensor surfaces of the arms and legs, buttocks, and thighs.5 Eruptive xanthoma often is associated with hypertriglyceridemia, which can be primary—as a result of a genetic defect caused by familial hypertriglyceridemia—or secondary, associated with poorly controlled diabetes mellitus, morbid obesity, excessive alcohol consumption, nephrotic syndrome, hypothyroidism, primary biliary cholangitis, and drugs like estrogen replacement therapies, corticosteroids, and isotretinoin.6 Pruritus and tenderness may or may not be present, and the Köbner phenomenon may occur.7

Continue to: The differential diagnosis

The differential diagnosis for eruptive xanthoma includes xanthoma disseminatum, non–Langerhans cell histiocytoses (eg, generalized eruptive histiocytosis), and cutaneous mastocytosis.1

Xanthoma disseminatum is an extremely rare, but benign, disorder of non–Langerhans cell origin. The average age of onset is older than 40 years. The rash consists of multiple red-yellow papules and nodules that most commonly present in flexural areas. Forty percent to 60% of patients have mucosal involvement, and rarely the central nervous system is involved.8

Generalized eruptive histiocytosis is another rare non–Langerhans cell histiocytosis that occurs mainly in adults and is characterized by widespread, symmetric, red-brown papules on the trunk, arms, and legs, and rarely the mucous membranes.9

Cutaneous mastocytosis, especially xanthelasmoid mastocytosis, consists of multiple pruritic, yellowish, papular or nodular lesions that may mimic eruptive xanthoma. It occurs mainly in children and rarely in adults.10

Confirming the diagnosis, initiating treatment

The diagnosis of eruptive xanthoma can be confirmed by skin biopsy if other differential diagnoses cannot be ruled out or the lesions do not resolve with treatment. Skin biopsy will reveal lipid-laden macrophages (known as foam cells) deposited in the dermis.7

Continue to: Treatment of eruptive xanthoma

Treatment of eruptive xanthoma involves management of the underlying causes of the condition. In most cases, dietary control, intensive triglyceride-lowering therapies, and treatment of other secondary causes of hypertriglyceridemia result in complete resolution of the lesions within several weeks.5

Our patient’s outcome

Our patient’s sudden-onset rash alerted us to the presence of type 2 diabetes mellitus, hypertriglyceridemia, and heavy proteinuria, which he was not aware of previously. We counselled him about stringent low-sugar, low-lipid diet control and exercise, and we started him on metformin and gemfibrozil. He was referred to an internal medicine specialist for further assessment and management of his severe hypertriglyceridemia and heavy proteinuria.

The rash started to wane 1 month after the patient started the metformin and gemfibrozil, and his drug regimen was changed to combination therapy with metformin/glimepiride and fenofibrate/simvastatin 6 weeks later when he was seen in the medical specialty clinic. Fundus photography performed 1 month after starting oral antidiabetic therapy showed no diabetic retinopathy or lipemia retinalis.

After 3 months of treatment, his serum triglycerides and hemoglobin A1c levels dropped to 3.8 mmol/L and 8.7%, respectively. The rash also resolved considerably, with only residual papules on the abdomen. This rapid clinical response to treatment of the underlying hypertriglyceridemia and diabetes further supported the clinical diagnosis of eruptive xanthoma.

THE TAKEAWAY

Eruptive xanthoma is relatively rare, but it is important for family physicians to recognize this clinical presentation as a potential indicator of severe hypertriglyceridemia. Recognizing hypertriglyceridemia early is important, as it can be associated with an increased risk for acute pancreatitis. Moreover, eruptive xanthoma might be the sole presenting symptom of underlying diabetes mellitus or familial hyperlipidemia, both of which can lead to a significant increase in cardiovascular risk if uncontrolled.

CORRESPONDENCE

Chan Kam Sum, MBChB, FRACGP, Tseung Kwan O Jockey Club General Out-patient Clinic, 99 Po Lam Road North, G/F, Tseung Kwan O, Kowloon, Hong Kong; [email protected]

1. Tang WK. Eruptive xanthoma. [case reports]. Hong Kong Dermatol Venereol Bull. 2001;9:172-175.

2. Frew J, Murrell D, Haber R. Fifty shades of yellow: a review of the xanthodermatoses. Int J Dermatol. 2015;54:1109-1123.

3. Zak A, Zeman M, Slaby A, et al. Xanthomas: clinical and pathophysiological relations. Biomed Pap Med Fac Univ Palacky Olomouc Czech Repub. 2014;158:181-188.

4. Sandhu S, Al-Sarraf A, Taraboanta C, et al. Incidence of pancreatitis, secondary causes, and treatment of patients referred to specialty lipid clinic with severe hypertriglyceridemia: a retrospective cohort study. Lipids Health Dis. 2011;10:157.

5. Holsinger JM, Campbell SM, Witman P. Multiple erythematous-yellow, dome-shaped papules. Am Fam Physician. 2010;82:517.

6. Loeckermann S, Braun-Falco M. Eruptive xanthomas in association with metabolic syndrome. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2010;35:565-566.

7. Merola JF, Mengden SJ, Soldano A, et al. Eruptive xanthomas. Dermatol Online J. 2008;14:10.

8. Park M, Boone B, Devas S. Xanthoma disseminatum: case report and mini-review of the literature. Acta Dermatovenerol Croat. 2014;22:150-154.

9. Attia A, Seleit I, El Badawy N, et al. Photoletter to the editor: generalized eruptive histiocytoma. J Dermatol Case Rep. 2011;5:53-55.

10. Nabavi NS, Nejad MH, Feli S, et al. Adult onset of xanthelasmoid mastocytosis: report of a rare entity. Indian J Dermatol. 2016;61:468.

1. Tang WK. Eruptive xanthoma. [case reports]. Hong Kong Dermatol Venereol Bull. 2001;9:172-175.

2. Frew J, Murrell D, Haber R. Fifty shades of yellow: a review of the xanthodermatoses. Int J Dermatol. 2015;54:1109-1123.

3. Zak A, Zeman M, Slaby A, et al. Xanthomas: clinical and pathophysiological relations. Biomed Pap Med Fac Univ Palacky Olomouc Czech Repub. 2014;158:181-188.

4. Sandhu S, Al-Sarraf A, Taraboanta C, et al. Incidence of pancreatitis, secondary causes, and treatment of patients referred to specialty lipid clinic with severe hypertriglyceridemia: a retrospective cohort study. Lipids Health Dis. 2011;10:157.

5. Holsinger JM, Campbell SM, Witman P. Multiple erythematous-yellow, dome-shaped papules. Am Fam Physician. 2010;82:517.

6. Loeckermann S, Braun-Falco M. Eruptive xanthomas in association with metabolic syndrome. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2010;35:565-566.

7. Merola JF, Mengden SJ, Soldano A, et al. Eruptive xanthomas. Dermatol Online J. 2008;14:10.

8. Park M, Boone B, Devas S. Xanthoma disseminatum: case report and mini-review of the literature. Acta Dermatovenerol Croat. 2014;22:150-154.

9. Attia A, Seleit I, El Badawy N, et al. Photoletter to the editor: generalized eruptive histiocytoma. J Dermatol Case Rep. 2011;5:53-55.

10. Nabavi NS, Nejad MH, Feli S, et al. Adult onset of xanthelasmoid mastocytosis: report of a rare entity. Indian J Dermatol. 2016;61:468.

Linear rash from shoulder to wrist

A 19-year-old woman came to our outpatient clinic with a rash on her upper left arm that she’d had for a month. Small pink and flesh-colored spots that first appeared over her left shoulder had spread down her arm and forearm to her wrist. The rash was initially scattered, but within a few weeks it had joined together to form a linear band. It was not itchy or painful.

Our patient had no changes to her fingernails, no contact with potential allergens, and no history of skin disease, atopy, or drug allergies. She was not taking any medication, but had received the second of 3 doses of the human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine 2 months before she’d developed the rash. She had tried to treat the rash with an over-the-counter steroid cream, but it had not been effective.

On physical examination, we noted flat-topped, slightly scaly, pinkish papules that were about 3 mm in diameter and formed an interrupted linear pattern that extended down the patient’s left shoulder and arm, cubital fossa, and forearm to her wrist (FIGURE). There were no vesicles, pustules, erosions, ulcers, or excoriation. The rash was non-tender and Koebner’s phenomenon was absent.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Lichen striatus

Based on the appearance and distribution of our patient’s lesions, we made a clinical diagnosis of lichen striatus, an uncommon condition that typically affects children younger than age 15.1

Lichen striatus usually presents as papulovesicular lesions in bands that follow Blaschko’s lines. (Blaschko’s lines are patterns of lines on the skin that represent the developmental growth pattern of the skin during epidermal cell migration; these lines usually aren’t visible but can be seen in patients with certain skin diseases.2) Lichen striatus most frequently affects the neck, trunk, and limbs; nail involvement is rare.1 Patients with lichen striatus are usually asymptomatic, but they occasionally have various degrees of pruritus.

The etiology of lichen striatus is unknown, but it has been reported to occur after flu-like illnesses, tonsillitis, the application of retinoic acid lotions, sunburn, hepatitis B virus infection, and bacille Calmette-Guerin vaccination.3 There is no documented relationship between lichen striatus and the HPV vaccine. Atopy may be a predisposing factor for lichen striatus, but does not trigger the disease.1

The diagnosis is typically made based on the appearance and distribution of the rash. Skin biopsy is rarely needed to establish the diagnosis.3

Distinguishing lichen striatus from other linear skin disorders

Other lesions that could follow Blaschko’s lines include linear psoriasis, linear lichen planus, inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus, and linear Darier’s disease (keratosis follicularis).3

Linear psoriasis usually presents as late-onset, mildly pruritic linear scaly plaques with a positive Auspitz sign. This form of psoriasis responds well to topical or systemic psoriatic treatment, such as topical steroids, coal tar preparation, or vitamin D derivatives.4

Linear lichen planus involves pruritic, hyperpigmented, well-demarcated, flat-topped papules and small, thin plaques without scale. Linear lichen planus can be the result of scratching or injuring the skin.5

Inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus usually presents as erythematous and verrucous papules with a psoriasiform appearance. It is accompanied by intense pruritus. Girls are more commonly affected than boys and the condition is refractory to psoriatic therapy.6

Darier’s disease (keratosis follicularis) is an autosomal dominant inherited disease that usually presents as an eruption of keratotic papules. Nails may be affected, with longitudinal nail striations and subungual hyperkeratosis.7

Lichen striatus typically resolves without treatment

The role of topical steroids, nonsteroidal antiinflammatory agents, or tacrolimus for treating ichen striatus is unclear.8 Observation is thought to be the best approach.8 Lichen striatus usually resolves spontaneously in 6 to 9 months, although relapses have been reported.3

We advised our patient that no treatment was required and asked that she return for a follow-up appointment in 2 weeks. When she came in for her follow-up appointment, her rash had stopped spreading. Approximately 6 months after onset, the rash was less pink.

CORRESPONDENCE

Kai Lim Chow, MBChB, FHKAM, Tseung Kwan O Jockey Club General Outpatient Clinic, 99 Po Lam Road North, G/F, Tseung Kwan O, Hong Kong, China; [email protected].

1. Patrizi A, Neri I, Fiorentini C, et al. Lichen striatus: clinical and laboratory features of 115 children. Pediatr Dermatol. 2004;21:197-204.

2. Keegan BR, Kamino H, Fangman W, et al. “Pediatric blaschkitis”: expanding the spectrum of childhood acquired Blaschkolinear dermatoses. Pediatr Dermatol. 2007;24:621-627.

3. Skvarka CB, Ko CJ. Lichenoid dermatoses. In: Schwarzenberger K, Werchniak AE, Ko CJ, eds. General Dermatology: Requisites in Dermatology. London: Elsevier; 2008;13:204-205.

4. Happle R. Linear psoriasis and ILVEN: is lumping or splitting appropriate? Dermatology. 2006;212:101-102.

5. Batra P, Wang N, Kamino H, et al. Linear lichen planus. Dermatol Online J. 2008;14:16.

6. Kumar CA, Yeluri G, Raghav N. Inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus syndrome with its polymorphic presentation—A rare case report. Contemp Clin Dent. 2012;3:119-122.

7. Meziane M, Chraibi R, Kihel N, et al. Linear Darier disease. Dermatol Online J. 2008;14:11.

8. Mu EW, Abuav R, Cohen BA. Facial lichen striatus in children: retracing the lines of Blaschko. Pediatr Dermatol. 2013;30:364-366.

A 19-year-old woman came to our outpatient clinic with a rash on her upper left arm that she’d had for a month. Small pink and flesh-colored spots that first appeared over her left shoulder had spread down her arm and forearm to her wrist. The rash was initially scattered, but within a few weeks it had joined together to form a linear band. It was not itchy or painful.

Our patient had no changes to her fingernails, no contact with potential allergens, and no history of skin disease, atopy, or drug allergies. She was not taking any medication, but had received the second of 3 doses of the human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine 2 months before she’d developed the rash. She had tried to treat the rash with an over-the-counter steroid cream, but it had not been effective.

On physical examination, we noted flat-topped, slightly scaly, pinkish papules that were about 3 mm in diameter and formed an interrupted linear pattern that extended down the patient’s left shoulder and arm, cubital fossa, and forearm to her wrist (FIGURE). There were no vesicles, pustules, erosions, ulcers, or excoriation. The rash was non-tender and Koebner’s phenomenon was absent.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Lichen striatus

Based on the appearance and distribution of our patient’s lesions, we made a clinical diagnosis of lichen striatus, an uncommon condition that typically affects children younger than age 15.1

Lichen striatus usually presents as papulovesicular lesions in bands that follow Blaschko’s lines. (Blaschko’s lines are patterns of lines on the skin that represent the developmental growth pattern of the skin during epidermal cell migration; these lines usually aren’t visible but can be seen in patients with certain skin diseases.2) Lichen striatus most frequently affects the neck, trunk, and limbs; nail involvement is rare.1 Patients with lichen striatus are usually asymptomatic, but they occasionally have various degrees of pruritus.

The etiology of lichen striatus is unknown, but it has been reported to occur after flu-like illnesses, tonsillitis, the application of retinoic acid lotions, sunburn, hepatitis B virus infection, and bacille Calmette-Guerin vaccination.3 There is no documented relationship between lichen striatus and the HPV vaccine. Atopy may be a predisposing factor for lichen striatus, but does not trigger the disease.1

The diagnosis is typically made based on the appearance and distribution of the rash. Skin biopsy is rarely needed to establish the diagnosis.3

Distinguishing lichen striatus from other linear skin disorders

Other lesions that could follow Blaschko’s lines include linear psoriasis, linear lichen planus, inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus, and linear Darier’s disease (keratosis follicularis).3

Linear psoriasis usually presents as late-onset, mildly pruritic linear scaly plaques with a positive Auspitz sign. This form of psoriasis responds well to topical or systemic psoriatic treatment, such as topical steroids, coal tar preparation, or vitamin D derivatives.4

Linear lichen planus involves pruritic, hyperpigmented, well-demarcated, flat-topped papules and small, thin plaques without scale. Linear lichen planus can be the result of scratching or injuring the skin.5

Inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus usually presents as erythematous and verrucous papules with a psoriasiform appearance. It is accompanied by intense pruritus. Girls are more commonly affected than boys and the condition is refractory to psoriatic therapy.6

Darier’s disease (keratosis follicularis) is an autosomal dominant inherited disease that usually presents as an eruption of keratotic papules. Nails may be affected, with longitudinal nail striations and subungual hyperkeratosis.7

Lichen striatus typically resolves without treatment

The role of topical steroids, nonsteroidal antiinflammatory agents, or tacrolimus for treating ichen striatus is unclear.8 Observation is thought to be the best approach.8 Lichen striatus usually resolves spontaneously in 6 to 9 months, although relapses have been reported.3

We advised our patient that no treatment was required and asked that she return for a follow-up appointment in 2 weeks. When she came in for her follow-up appointment, her rash had stopped spreading. Approximately 6 months after onset, the rash was less pink.

CORRESPONDENCE

Kai Lim Chow, MBChB, FHKAM, Tseung Kwan O Jockey Club General Outpatient Clinic, 99 Po Lam Road North, G/F, Tseung Kwan O, Hong Kong, China; [email protected].

A 19-year-old woman came to our outpatient clinic with a rash on her upper left arm that she’d had for a month. Small pink and flesh-colored spots that first appeared over her left shoulder had spread down her arm and forearm to her wrist. The rash was initially scattered, but within a few weeks it had joined together to form a linear band. It was not itchy or painful.

Our patient had no changes to her fingernails, no contact with potential allergens, and no history of skin disease, atopy, or drug allergies. She was not taking any medication, but had received the second of 3 doses of the human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine 2 months before she’d developed the rash. She had tried to treat the rash with an over-the-counter steroid cream, but it had not been effective.

On physical examination, we noted flat-topped, slightly scaly, pinkish papules that were about 3 mm in diameter and formed an interrupted linear pattern that extended down the patient’s left shoulder and arm, cubital fossa, and forearm to her wrist (FIGURE). There were no vesicles, pustules, erosions, ulcers, or excoriation. The rash was non-tender and Koebner’s phenomenon was absent.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Lichen striatus

Based on the appearance and distribution of our patient’s lesions, we made a clinical diagnosis of lichen striatus, an uncommon condition that typically affects children younger than age 15.1

Lichen striatus usually presents as papulovesicular lesions in bands that follow Blaschko’s lines. (Blaschko’s lines are patterns of lines on the skin that represent the developmental growth pattern of the skin during epidermal cell migration; these lines usually aren’t visible but can be seen in patients with certain skin diseases.2) Lichen striatus most frequently affects the neck, trunk, and limbs; nail involvement is rare.1 Patients with lichen striatus are usually asymptomatic, but they occasionally have various degrees of pruritus.

The etiology of lichen striatus is unknown, but it has been reported to occur after flu-like illnesses, tonsillitis, the application of retinoic acid lotions, sunburn, hepatitis B virus infection, and bacille Calmette-Guerin vaccination.3 There is no documented relationship between lichen striatus and the HPV vaccine. Atopy may be a predisposing factor for lichen striatus, but does not trigger the disease.1

The diagnosis is typically made based on the appearance and distribution of the rash. Skin biopsy is rarely needed to establish the diagnosis.3

Distinguishing lichen striatus from other linear skin disorders

Other lesions that could follow Blaschko’s lines include linear psoriasis, linear lichen planus, inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus, and linear Darier’s disease (keratosis follicularis).3

Linear psoriasis usually presents as late-onset, mildly pruritic linear scaly plaques with a positive Auspitz sign. This form of psoriasis responds well to topical or systemic psoriatic treatment, such as topical steroids, coal tar preparation, or vitamin D derivatives.4

Linear lichen planus involves pruritic, hyperpigmented, well-demarcated, flat-topped papules and small, thin plaques without scale. Linear lichen planus can be the result of scratching or injuring the skin.5

Inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus usually presents as erythematous and verrucous papules with a psoriasiform appearance. It is accompanied by intense pruritus. Girls are more commonly affected than boys and the condition is refractory to psoriatic therapy.6

Darier’s disease (keratosis follicularis) is an autosomal dominant inherited disease that usually presents as an eruption of keratotic papules. Nails may be affected, with longitudinal nail striations and subungual hyperkeratosis.7

Lichen striatus typically resolves without treatment

The role of topical steroids, nonsteroidal antiinflammatory agents, or tacrolimus for treating ichen striatus is unclear.8 Observation is thought to be the best approach.8 Lichen striatus usually resolves spontaneously in 6 to 9 months, although relapses have been reported.3

We advised our patient that no treatment was required and asked that she return for a follow-up appointment in 2 weeks. When she came in for her follow-up appointment, her rash had stopped spreading. Approximately 6 months after onset, the rash was less pink.

CORRESPONDENCE

Kai Lim Chow, MBChB, FHKAM, Tseung Kwan O Jockey Club General Outpatient Clinic, 99 Po Lam Road North, G/F, Tseung Kwan O, Hong Kong, China; [email protected].

1. Patrizi A, Neri I, Fiorentini C, et al. Lichen striatus: clinical and laboratory features of 115 children. Pediatr Dermatol. 2004;21:197-204.

2. Keegan BR, Kamino H, Fangman W, et al. “Pediatric blaschkitis”: expanding the spectrum of childhood acquired Blaschkolinear dermatoses. Pediatr Dermatol. 2007;24:621-627.

3. Skvarka CB, Ko CJ. Lichenoid dermatoses. In: Schwarzenberger K, Werchniak AE, Ko CJ, eds. General Dermatology: Requisites in Dermatology. London: Elsevier; 2008;13:204-205.

4. Happle R. Linear psoriasis and ILVEN: is lumping or splitting appropriate? Dermatology. 2006;212:101-102.

5. Batra P, Wang N, Kamino H, et al. Linear lichen planus. Dermatol Online J. 2008;14:16.

6. Kumar CA, Yeluri G, Raghav N. Inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus syndrome with its polymorphic presentation—A rare case report. Contemp Clin Dent. 2012;3:119-122.

7. Meziane M, Chraibi R, Kihel N, et al. Linear Darier disease. Dermatol Online J. 2008;14:11.

8. Mu EW, Abuav R, Cohen BA. Facial lichen striatus in children: retracing the lines of Blaschko. Pediatr Dermatol. 2013;30:364-366.

1. Patrizi A, Neri I, Fiorentini C, et al. Lichen striatus: clinical and laboratory features of 115 children. Pediatr Dermatol. 2004;21:197-204.

2. Keegan BR, Kamino H, Fangman W, et al. “Pediatric blaschkitis”: expanding the spectrum of childhood acquired Blaschkolinear dermatoses. Pediatr Dermatol. 2007;24:621-627.

3. Skvarka CB, Ko CJ. Lichenoid dermatoses. In: Schwarzenberger K, Werchniak AE, Ko CJ, eds. General Dermatology: Requisites in Dermatology. London: Elsevier; 2008;13:204-205.

4. Happle R. Linear psoriasis and ILVEN: is lumping or splitting appropriate? Dermatology. 2006;212:101-102.

5. Batra P, Wang N, Kamino H, et al. Linear lichen planus. Dermatol Online J. 2008;14:16.

6. Kumar CA, Yeluri G, Raghav N. Inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus syndrome with its polymorphic presentation—A rare case report. Contemp Clin Dent. 2012;3:119-122.

7. Meziane M, Chraibi R, Kihel N, et al. Linear Darier disease. Dermatol Online J. 2008;14:11.

8. Mu EW, Abuav R, Cohen BA. Facial lichen striatus in children: retracing the lines of Blaschko. Pediatr Dermatol. 2013;30:364-366.