User login

Planned Parenthood withdraws from Title X

Planned Parenthood will no longer participate in the federal Title X family planning program in response to a Trump administration rule that prohibits physicians from counseling patients about abortion and referring patients for the procedure.

In an Aug. 19 announcement, Alexis McGill Johnson, Planned Parenthood Federation of America president and CEO, said the Title X changes, which amount to “an unethical and dangerous gag rule,” has forced the organization out of Title X after being part of the program for 50 years. Planned Parenthood health centers are the largest Title X provider, serving 40% of patients who receive care through the program.

“We believe that the Trump administration is doing this as an attack on reproductive health care and to keep providers like Planned Parenthood from serving our patients,” Ms. McGill said in a statement. “Health care shouldn’t come down to how much you earn, where you live, or who you are. Congress must act now. It’s time for the U.S. Senate to act to pass a spending bill that will reverse the harmful rule and restore access to birth control, STD testing, and other critical services to people with low incomes.”

In an Aug. 19 statement, Mia Palmieri Heck, director of external affairs for the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services said every current Title X grantee has the choice to accept their grant and comply with the changes, or reject their funding by refusing to comply.

“The new Title X regulations were final at the time the current grant awards were announced,” Ms. Heck said a statement. “Some grantees are now blaming the government for their own actions – having chosen to accept the grant while failing to comply with the regulations that accompany it – and they are abandoning their obligations to serve their patients under the program. HHS is grateful for the many grantees who continue to serve their patients under the Title X program, and we will work to ensure all patients continue to be served.”

The announcement by Planned Parenthood comes about a month after HHS gave family planning clinics more time to comply with the new rule if they are making good faith efforts to comply with the new rules. The changes to the Title X program make health clinics ineligible for funding if they offer, promote, or support abortion as a method of family planning.

So far, more than 20 states and several abortion rights organizations, including Planned Parenthood, have sued over the rules in four separate states. District judges in Oregon, Washington, and California temporarily blocked the rules from taking effect. In a June 20 decision, the 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals ruled that the federal government may go forward with its plan to restrict Title X funding from clinics that provide abortion counseling or referrals. The decision overturned the lower court injunctions.

Clare Coleman, president and CEO for the National Family Planning & Reproductive Health Association, said she expects further withdrawals from the Title X program to follow Planned Parenthood’s departure.

“The administration’s Title X rule is forcing the program’s 90 grantees and nearly 4,000 service sites to make gut-wrenching choices,” Ms. Coleman said in a statement. “They can stay in the program, despite the rule’s harms and compromises to Title X’s quality of care, for the sake of continuing to offer some Title X care for low-income individuals [or] they can leave the program and forego funding in order to avoid the rule’s limits on pregnancy counseling and other essential care, contrary to HHS’s own professional standards.”

HHS has previously said that the Title X changes ensure that grants and contracts awarded under the program fully comply with the statutory program integrity requirements, “thereby fulfilling the purpose of Title X, so that more women and men can receive services that help them consider and achieve both their short-term and long-term family planning needs.” The agency recently posted guidance on its website on myths vs. facts about the changes.

Ms. Johnson meanwhile, said Planned Parenthood clinics will remain open to serve patients, and that the organization will continue to fight the Title X changes in court.

[email protected]

Planned Parenthood will no longer participate in the federal Title X family planning program in response to a Trump administration rule that prohibits physicians from counseling patients about abortion and referring patients for the procedure.

In an Aug. 19 announcement, Alexis McGill Johnson, Planned Parenthood Federation of America president and CEO, said the Title X changes, which amount to “an unethical and dangerous gag rule,” has forced the organization out of Title X after being part of the program for 50 years. Planned Parenthood health centers are the largest Title X provider, serving 40% of patients who receive care through the program.

“We believe that the Trump administration is doing this as an attack on reproductive health care and to keep providers like Planned Parenthood from serving our patients,” Ms. McGill said in a statement. “Health care shouldn’t come down to how much you earn, where you live, or who you are. Congress must act now. It’s time for the U.S. Senate to act to pass a spending bill that will reverse the harmful rule and restore access to birth control, STD testing, and other critical services to people with low incomes.”

In an Aug. 19 statement, Mia Palmieri Heck, director of external affairs for the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services said every current Title X grantee has the choice to accept their grant and comply with the changes, or reject their funding by refusing to comply.

“The new Title X regulations were final at the time the current grant awards were announced,” Ms. Heck said a statement. “Some grantees are now blaming the government for their own actions – having chosen to accept the grant while failing to comply with the regulations that accompany it – and they are abandoning their obligations to serve their patients under the program. HHS is grateful for the many grantees who continue to serve their patients under the Title X program, and we will work to ensure all patients continue to be served.”

The announcement by Planned Parenthood comes about a month after HHS gave family planning clinics more time to comply with the new rule if they are making good faith efforts to comply with the new rules. The changes to the Title X program make health clinics ineligible for funding if they offer, promote, or support abortion as a method of family planning.

So far, more than 20 states and several abortion rights organizations, including Planned Parenthood, have sued over the rules in four separate states. District judges in Oregon, Washington, and California temporarily blocked the rules from taking effect. In a June 20 decision, the 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals ruled that the federal government may go forward with its plan to restrict Title X funding from clinics that provide abortion counseling or referrals. The decision overturned the lower court injunctions.

Clare Coleman, president and CEO for the National Family Planning & Reproductive Health Association, said she expects further withdrawals from the Title X program to follow Planned Parenthood’s departure.

“The administration’s Title X rule is forcing the program’s 90 grantees and nearly 4,000 service sites to make gut-wrenching choices,” Ms. Coleman said in a statement. “They can stay in the program, despite the rule’s harms and compromises to Title X’s quality of care, for the sake of continuing to offer some Title X care for low-income individuals [or] they can leave the program and forego funding in order to avoid the rule’s limits on pregnancy counseling and other essential care, contrary to HHS’s own professional standards.”

HHS has previously said that the Title X changes ensure that grants and contracts awarded under the program fully comply with the statutory program integrity requirements, “thereby fulfilling the purpose of Title X, so that more women and men can receive services that help them consider and achieve both their short-term and long-term family planning needs.” The agency recently posted guidance on its website on myths vs. facts about the changes.

Ms. Johnson meanwhile, said Planned Parenthood clinics will remain open to serve patients, and that the organization will continue to fight the Title X changes in court.

[email protected]

Planned Parenthood will no longer participate in the federal Title X family planning program in response to a Trump administration rule that prohibits physicians from counseling patients about abortion and referring patients for the procedure.

In an Aug. 19 announcement, Alexis McGill Johnson, Planned Parenthood Federation of America president and CEO, said the Title X changes, which amount to “an unethical and dangerous gag rule,” has forced the organization out of Title X after being part of the program for 50 years. Planned Parenthood health centers are the largest Title X provider, serving 40% of patients who receive care through the program.

“We believe that the Trump administration is doing this as an attack on reproductive health care and to keep providers like Planned Parenthood from serving our patients,” Ms. McGill said in a statement. “Health care shouldn’t come down to how much you earn, where you live, or who you are. Congress must act now. It’s time for the U.S. Senate to act to pass a spending bill that will reverse the harmful rule and restore access to birth control, STD testing, and other critical services to people with low incomes.”

In an Aug. 19 statement, Mia Palmieri Heck, director of external affairs for the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services said every current Title X grantee has the choice to accept their grant and comply with the changes, or reject their funding by refusing to comply.

“The new Title X regulations were final at the time the current grant awards were announced,” Ms. Heck said a statement. “Some grantees are now blaming the government for their own actions – having chosen to accept the grant while failing to comply with the regulations that accompany it – and they are abandoning their obligations to serve their patients under the program. HHS is grateful for the many grantees who continue to serve their patients under the Title X program, and we will work to ensure all patients continue to be served.”

The announcement by Planned Parenthood comes about a month after HHS gave family planning clinics more time to comply with the new rule if they are making good faith efforts to comply with the new rules. The changes to the Title X program make health clinics ineligible for funding if they offer, promote, or support abortion as a method of family planning.

So far, more than 20 states and several abortion rights organizations, including Planned Parenthood, have sued over the rules in four separate states. District judges in Oregon, Washington, and California temporarily blocked the rules from taking effect. In a June 20 decision, the 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals ruled that the federal government may go forward with its plan to restrict Title X funding from clinics that provide abortion counseling or referrals. The decision overturned the lower court injunctions.

Clare Coleman, president and CEO for the National Family Planning & Reproductive Health Association, said she expects further withdrawals from the Title X program to follow Planned Parenthood’s departure.

“The administration’s Title X rule is forcing the program’s 90 grantees and nearly 4,000 service sites to make gut-wrenching choices,” Ms. Coleman said in a statement. “They can stay in the program, despite the rule’s harms and compromises to Title X’s quality of care, for the sake of continuing to offer some Title X care for low-income individuals [or] they can leave the program and forego funding in order to avoid the rule’s limits on pregnancy counseling and other essential care, contrary to HHS’s own professional standards.”

HHS has previously said that the Title X changes ensure that grants and contracts awarded under the program fully comply with the statutory program integrity requirements, “thereby fulfilling the purpose of Title X, so that more women and men can receive services that help them consider and achieve both their short-term and long-term family planning needs.” The agency recently posted guidance on its website on myths vs. facts about the changes.

Ms. Johnson meanwhile, said Planned Parenthood clinics will remain open to serve patients, and that the organization will continue to fight the Title X changes in court.

[email protected]

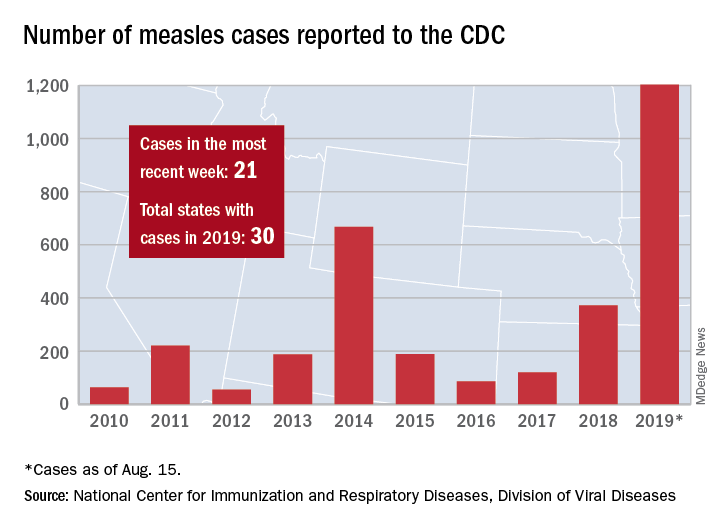

New measles outbreak reported in western N.Y.

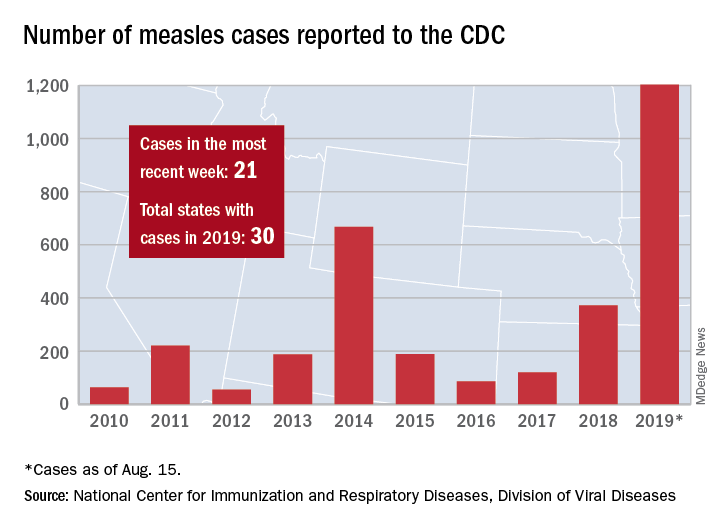

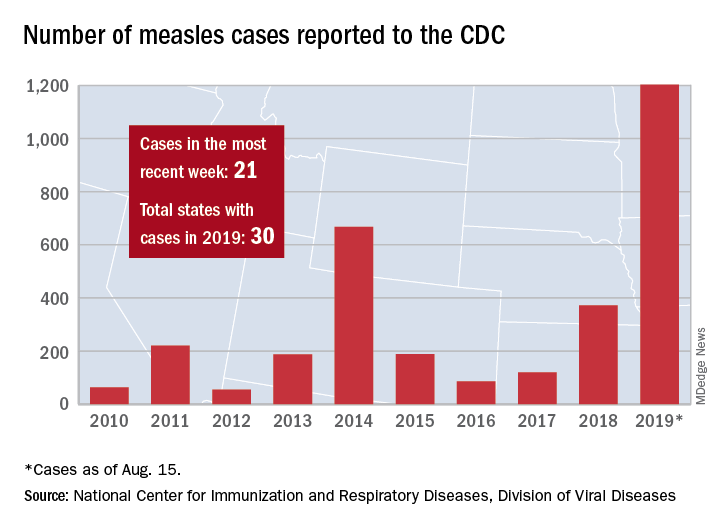

A new measles outbreak in western New York has affected five people within a Mennonite community, according to the New York State Department of Health.

The five cases in Wyoming County, located east of Buffalo, were reported Aug. 8 and no further cases have been confirmed as of Aug. 16, the county health department said on its website.

Those five cases, along with six new cases in Rockland County, N.Y., and 10 more around the country, brought the total for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s latest reporting week to 21 and the total for the year to 1,203, the CDC said Aug. 19.

Along with Wyoming County and Rockland County (296 cases since Sept. 2018), the CDC currently is tracking outbreaks in New York City (653 cases since Sept. 2018), Washington state (85 cases in 2019; 13 in the current outbreak), California (65 cases in 2019; 5 in the current outbreak), and Texas (21 cases in 2019; 6 in the current outbreak).

“More than 75% of the cases this year are linked to outbreaks in New York and New York City,” the CDC said on its website, while also noting that “124 of the people who got measles this year were hospitalized, and 64 reported having complications, including pneumonia and encephalitis.”

A new measles outbreak in western New York has affected five people within a Mennonite community, according to the New York State Department of Health.

The five cases in Wyoming County, located east of Buffalo, were reported Aug. 8 and no further cases have been confirmed as of Aug. 16, the county health department said on its website.

Those five cases, along with six new cases in Rockland County, N.Y., and 10 more around the country, brought the total for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s latest reporting week to 21 and the total for the year to 1,203, the CDC said Aug. 19.

Along with Wyoming County and Rockland County (296 cases since Sept. 2018), the CDC currently is tracking outbreaks in New York City (653 cases since Sept. 2018), Washington state (85 cases in 2019; 13 in the current outbreak), California (65 cases in 2019; 5 in the current outbreak), and Texas (21 cases in 2019; 6 in the current outbreak).

“More than 75% of the cases this year are linked to outbreaks in New York and New York City,” the CDC said on its website, while also noting that “124 of the people who got measles this year were hospitalized, and 64 reported having complications, including pneumonia and encephalitis.”

A new measles outbreak in western New York has affected five people within a Mennonite community, according to the New York State Department of Health.

The five cases in Wyoming County, located east of Buffalo, were reported Aug. 8 and no further cases have been confirmed as of Aug. 16, the county health department said on its website.

Those five cases, along with six new cases in Rockland County, N.Y., and 10 more around the country, brought the total for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s latest reporting week to 21 and the total for the year to 1,203, the CDC said Aug. 19.

Along with Wyoming County and Rockland County (296 cases since Sept. 2018), the CDC currently is tracking outbreaks in New York City (653 cases since Sept. 2018), Washington state (85 cases in 2019; 13 in the current outbreak), California (65 cases in 2019; 5 in the current outbreak), and Texas (21 cases in 2019; 6 in the current outbreak).

“More than 75% of the cases this year are linked to outbreaks in New York and New York City,” the CDC said on its website, while also noting that “124 of the people who got measles this year were hospitalized, and 64 reported having complications, including pneumonia and encephalitis.”

ACP unveils clinical guideline disclosure strategy

The American College of Physicians recently described its methods for developing clinical guidelines and guidance statements, in a paper published in the Annals of Internal Medicine.

Any person involved in the development of an ACP clinical guideline or guidance statement must disclose all financial and intellectual interests related to health care from the previous 3 years,” Amir Qaseem, MD, and Timothy J. Wilt, MD, wrote.

“The goals of our process are to mitigate any actual bias during the development of ACP’s clinical recommendations and to ensure creditability and public trust in our clinical policies by reducing the potential for perceived bias,” noted Robert M. McLean, MD, president of the ACP, in a statement.

This paper’s publication comes on the heels of authors of a Cancer paper having reported that nearly 25% of the American Society of Clinical Oncology’s guideline authors who were not exempt from reporting conflicts of interest failed to disclose receiving industry payments.

The ACP committee’s guiding principle for collection of disclosures of interest and management of conflicts of interests “is to prioritize the interests of the patient over any competing or professional interests via an evidence-based assessment of the benefits, harms, and costs of an intervention,” wrote the authors on behalf of the CGC.

The CGC created a tiered system to classify potential conflicts as low level, moderate level, or high level based on three tenets: transparency (all disclosures are freely accessible so readers can assess them for themselves), proportionality (not all conflicts of interest have equal risk), and consistency (policies should be impartially applied across all variables).

Examples of low-level conflicts of interest (COIs) include high-level COIs that have become inactive and intellectual interests tangentially related to the topic under discussion. Moderate-level COIs are usually intellectual interests clinically relevant to the guideline topic; these interests might prompt an individual to seek professional or financial advantages through association with guideline development.

High-level COIs are active relationships with high-risk entities, defined by the CGC as “an entity that has a direct financial stake in the clinical conclusions of a guideline or guidance statement.”

While the time frame for reporting health-related interests is 3 years, disclosure is an ongoing process when clinical guidelines are in development because interests change over time, the authors said. Prospective guidelines committee members complete disclosure of interest forms before working on CGC projects, and they update these forms before each in-person CGC meeting.

“The CGC’s policy does not mandate disclosure of interests related primarily to personal matters or relationships outside the household,” such as political, religious, or ideological views, they noted.

The CGC maintains a DOI-COI Review and Management Panel to reviews conflicts, and all ACP guidelines include a list of relevant conflicts for committee members.

The authors of this paper disclosed no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Qaseem A and TJ Wilt. Ann Intern Med. 2019 Aug 20. doi: 10.7326/M18-3279 .

This article was updated 8/22/19.

The American College of Physicians recently described its methods for developing clinical guidelines and guidance statements, in a paper published in the Annals of Internal Medicine.

Any person involved in the development of an ACP clinical guideline or guidance statement must disclose all financial and intellectual interests related to health care from the previous 3 years,” Amir Qaseem, MD, and Timothy J. Wilt, MD, wrote.

“The goals of our process are to mitigate any actual bias during the development of ACP’s clinical recommendations and to ensure creditability and public trust in our clinical policies by reducing the potential for perceived bias,” noted Robert M. McLean, MD, president of the ACP, in a statement.

This paper’s publication comes on the heels of authors of a Cancer paper having reported that nearly 25% of the American Society of Clinical Oncology’s guideline authors who were not exempt from reporting conflicts of interest failed to disclose receiving industry payments.

The ACP committee’s guiding principle for collection of disclosures of interest and management of conflicts of interests “is to prioritize the interests of the patient over any competing or professional interests via an evidence-based assessment of the benefits, harms, and costs of an intervention,” wrote the authors on behalf of the CGC.

The CGC created a tiered system to classify potential conflicts as low level, moderate level, or high level based on three tenets: transparency (all disclosures are freely accessible so readers can assess them for themselves), proportionality (not all conflicts of interest have equal risk), and consistency (policies should be impartially applied across all variables).

Examples of low-level conflicts of interest (COIs) include high-level COIs that have become inactive and intellectual interests tangentially related to the topic under discussion. Moderate-level COIs are usually intellectual interests clinically relevant to the guideline topic; these interests might prompt an individual to seek professional or financial advantages through association with guideline development.

High-level COIs are active relationships with high-risk entities, defined by the CGC as “an entity that has a direct financial stake in the clinical conclusions of a guideline or guidance statement.”

While the time frame for reporting health-related interests is 3 years, disclosure is an ongoing process when clinical guidelines are in development because interests change over time, the authors said. Prospective guidelines committee members complete disclosure of interest forms before working on CGC projects, and they update these forms before each in-person CGC meeting.

“The CGC’s policy does not mandate disclosure of interests related primarily to personal matters or relationships outside the household,” such as political, religious, or ideological views, they noted.

The CGC maintains a DOI-COI Review and Management Panel to reviews conflicts, and all ACP guidelines include a list of relevant conflicts for committee members.

The authors of this paper disclosed no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Qaseem A and TJ Wilt. Ann Intern Med. 2019 Aug 20. doi: 10.7326/M18-3279 .

This article was updated 8/22/19.

The American College of Physicians recently described its methods for developing clinical guidelines and guidance statements, in a paper published in the Annals of Internal Medicine.

Any person involved in the development of an ACP clinical guideline or guidance statement must disclose all financial and intellectual interests related to health care from the previous 3 years,” Amir Qaseem, MD, and Timothy J. Wilt, MD, wrote.

“The goals of our process are to mitigate any actual bias during the development of ACP’s clinical recommendations and to ensure creditability and public trust in our clinical policies by reducing the potential for perceived bias,” noted Robert M. McLean, MD, president of the ACP, in a statement.

This paper’s publication comes on the heels of authors of a Cancer paper having reported that nearly 25% of the American Society of Clinical Oncology’s guideline authors who were not exempt from reporting conflicts of interest failed to disclose receiving industry payments.

The ACP committee’s guiding principle for collection of disclosures of interest and management of conflicts of interests “is to prioritize the interests of the patient over any competing or professional interests via an evidence-based assessment of the benefits, harms, and costs of an intervention,” wrote the authors on behalf of the CGC.

The CGC created a tiered system to classify potential conflicts as low level, moderate level, or high level based on three tenets: transparency (all disclosures are freely accessible so readers can assess them for themselves), proportionality (not all conflicts of interest have equal risk), and consistency (policies should be impartially applied across all variables).

Examples of low-level conflicts of interest (COIs) include high-level COIs that have become inactive and intellectual interests tangentially related to the topic under discussion. Moderate-level COIs are usually intellectual interests clinically relevant to the guideline topic; these interests might prompt an individual to seek professional or financial advantages through association with guideline development.

High-level COIs are active relationships with high-risk entities, defined by the CGC as “an entity that has a direct financial stake in the clinical conclusions of a guideline or guidance statement.”

While the time frame for reporting health-related interests is 3 years, disclosure is an ongoing process when clinical guidelines are in development because interests change over time, the authors said. Prospective guidelines committee members complete disclosure of interest forms before working on CGC projects, and they update these forms before each in-person CGC meeting.

“The CGC’s policy does not mandate disclosure of interests related primarily to personal matters or relationships outside the household,” such as political, religious, or ideological views, they noted.

The CGC maintains a DOI-COI Review and Management Panel to reviews conflicts, and all ACP guidelines include a list of relevant conflicts for committee members.

The authors of this paper disclosed no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Qaseem A and TJ Wilt. Ann Intern Med. 2019 Aug 20. doi: 10.7326/M18-3279 .

This article was updated 8/22/19.

FROM THE ANNALS OF INTERNAL MEDICINE

Statins hamper hepatocellular carcinoma in viral hepatitis patients

Lipophilic statin therapy significantly reduced the incidence and mortality of hepatocellular carcinoma in adults with viral hepatitis, based on data from 16,668 patients.

The mortality rates for hepatocellular carcinoma in the United States and Europe have been on the rise for decades, and the risk may persist in severe cases despite the use of hepatitis B virus suppression or hepatitis C virus eradication, wrote Tracey G. Simon, MD, of Harvard Medical School, Boston, and colleagues. Previous studies suggest that statins might reduce HCC risk in viral hepatitis patients, but evidence supporting one type of statin over another for HCC prevention is limited, they said.

In a study published in the Annals of Internal Medicine, the researchers reviewed data from a national registry of hepatitis patients in Sweden to assess the effect of lipophilic or hydrophilic statin use on HCC incidence and mortality.

They found a significant reduction in 10-year HCC risk for lipophilic statin users, compared with nonusers (8.1% vs. 3.3%. However, the difference was not significant for hydrophilic statin users vs. nonusers (8.0% vs. 6.8%). The effect of lipophilic statin use was dose dependent; the largest effect on reduction in HCC risk occurred with 600 or more lipophilic statin cumulative daily doses in users, compared with nonusers (8.4% vs. 2.5%).

The study population included 6,554 lipophilic statin users and 1,780 hydrophilic statin users, matched with 8,334 nonusers. Patient demographics were similar between both types of statin user and nonuser groups.

In addition, 10-year mortality was significantly lower for lipophilic statin users compared with nonusers (15.2% vs. 7.3%) and also for hydrophilic statin users, compared with nonusers (16.0% vs. 11.5%).

In a small number of patients with liver disease (462), liver-specific mortality was significantly reduced in lipophilic statin users, compared with nonusers (adjusted hazard ratio, 0.76 vs. 0.98).

“Of note, our findings were robust across several sensitivity analyses and were similar in all predefined subgroups, including among men and women and persons with and without cirrhosis or antiviral therapy use,” the researchers noted.

The study findings were limited by several factors including the potential confounding from variables such as smoking, hepatitis B viral DNA, hepatitis C virus eradication, stage of fibrosis, and HCC screening, as well as a lack of laboratory data to assess cholesterol levels’ impact on statin use, the researchers said. In addition, the study did not compare lipophilic and hydrophilic statins.

However, the results suggest potential distinct benefits of lipophilic statins to reduce HCC risk and support the need for further research, the researchers concluded.

Dr. Simon had no financial conflicts to disclose, but disclosed support from a North American Training Grant from the American College of Gastroenterology. Several coauthors disclosed relationships with multiple companies including AbbVie, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Gilead, Janssen, and Merck Sharp & Dohme. The study was supported in part by the American College of Gastroenterology, the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases, the Boston Nutrition Obesity Research Center, the National Institutes of Health, Nyckelfonden, Region Orebro (Sweden) County, and the Karolinska Institutet.

SOURCE: Simon TG et al. Ann Intern Med. 2019 Aug 19. doi: 10.7326/M18-2753.

Lipophilic statin therapy significantly reduced the incidence and mortality of hepatocellular carcinoma in adults with viral hepatitis, based on data from 16,668 patients.

The mortality rates for hepatocellular carcinoma in the United States and Europe have been on the rise for decades, and the risk may persist in severe cases despite the use of hepatitis B virus suppression or hepatitis C virus eradication, wrote Tracey G. Simon, MD, of Harvard Medical School, Boston, and colleagues. Previous studies suggest that statins might reduce HCC risk in viral hepatitis patients, but evidence supporting one type of statin over another for HCC prevention is limited, they said.

In a study published in the Annals of Internal Medicine, the researchers reviewed data from a national registry of hepatitis patients in Sweden to assess the effect of lipophilic or hydrophilic statin use on HCC incidence and mortality.

They found a significant reduction in 10-year HCC risk for lipophilic statin users, compared with nonusers (8.1% vs. 3.3%. However, the difference was not significant for hydrophilic statin users vs. nonusers (8.0% vs. 6.8%). The effect of lipophilic statin use was dose dependent; the largest effect on reduction in HCC risk occurred with 600 or more lipophilic statin cumulative daily doses in users, compared with nonusers (8.4% vs. 2.5%).

The study population included 6,554 lipophilic statin users and 1,780 hydrophilic statin users, matched with 8,334 nonusers. Patient demographics were similar between both types of statin user and nonuser groups.

In addition, 10-year mortality was significantly lower for lipophilic statin users compared with nonusers (15.2% vs. 7.3%) and also for hydrophilic statin users, compared with nonusers (16.0% vs. 11.5%).

In a small number of patients with liver disease (462), liver-specific mortality was significantly reduced in lipophilic statin users, compared with nonusers (adjusted hazard ratio, 0.76 vs. 0.98).

“Of note, our findings were robust across several sensitivity analyses and were similar in all predefined subgroups, including among men and women and persons with and without cirrhosis or antiviral therapy use,” the researchers noted.

The study findings were limited by several factors including the potential confounding from variables such as smoking, hepatitis B viral DNA, hepatitis C virus eradication, stage of fibrosis, and HCC screening, as well as a lack of laboratory data to assess cholesterol levels’ impact on statin use, the researchers said. In addition, the study did not compare lipophilic and hydrophilic statins.

However, the results suggest potential distinct benefits of lipophilic statins to reduce HCC risk and support the need for further research, the researchers concluded.

Dr. Simon had no financial conflicts to disclose, but disclosed support from a North American Training Grant from the American College of Gastroenterology. Several coauthors disclosed relationships with multiple companies including AbbVie, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Gilead, Janssen, and Merck Sharp & Dohme. The study was supported in part by the American College of Gastroenterology, the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases, the Boston Nutrition Obesity Research Center, the National Institutes of Health, Nyckelfonden, Region Orebro (Sweden) County, and the Karolinska Institutet.

SOURCE: Simon TG et al. Ann Intern Med. 2019 Aug 19. doi: 10.7326/M18-2753.

Lipophilic statin therapy significantly reduced the incidence and mortality of hepatocellular carcinoma in adults with viral hepatitis, based on data from 16,668 patients.

The mortality rates for hepatocellular carcinoma in the United States and Europe have been on the rise for decades, and the risk may persist in severe cases despite the use of hepatitis B virus suppression or hepatitis C virus eradication, wrote Tracey G. Simon, MD, of Harvard Medical School, Boston, and colleagues. Previous studies suggest that statins might reduce HCC risk in viral hepatitis patients, but evidence supporting one type of statin over another for HCC prevention is limited, they said.

In a study published in the Annals of Internal Medicine, the researchers reviewed data from a national registry of hepatitis patients in Sweden to assess the effect of lipophilic or hydrophilic statin use on HCC incidence and mortality.

They found a significant reduction in 10-year HCC risk for lipophilic statin users, compared with nonusers (8.1% vs. 3.3%. However, the difference was not significant for hydrophilic statin users vs. nonusers (8.0% vs. 6.8%). The effect of lipophilic statin use was dose dependent; the largest effect on reduction in HCC risk occurred with 600 or more lipophilic statin cumulative daily doses in users, compared with nonusers (8.4% vs. 2.5%).

The study population included 6,554 lipophilic statin users and 1,780 hydrophilic statin users, matched with 8,334 nonusers. Patient demographics were similar between both types of statin user and nonuser groups.

In addition, 10-year mortality was significantly lower for lipophilic statin users compared with nonusers (15.2% vs. 7.3%) and also for hydrophilic statin users, compared with nonusers (16.0% vs. 11.5%).

In a small number of patients with liver disease (462), liver-specific mortality was significantly reduced in lipophilic statin users, compared with nonusers (adjusted hazard ratio, 0.76 vs. 0.98).

“Of note, our findings were robust across several sensitivity analyses and were similar in all predefined subgroups, including among men and women and persons with and without cirrhosis or antiviral therapy use,” the researchers noted.

The study findings were limited by several factors including the potential confounding from variables such as smoking, hepatitis B viral DNA, hepatitis C virus eradication, stage of fibrosis, and HCC screening, as well as a lack of laboratory data to assess cholesterol levels’ impact on statin use, the researchers said. In addition, the study did not compare lipophilic and hydrophilic statins.

However, the results suggest potential distinct benefits of lipophilic statins to reduce HCC risk and support the need for further research, the researchers concluded.

Dr. Simon had no financial conflicts to disclose, but disclosed support from a North American Training Grant from the American College of Gastroenterology. Several coauthors disclosed relationships with multiple companies including AbbVie, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Gilead, Janssen, and Merck Sharp & Dohme. The study was supported in part by the American College of Gastroenterology, the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases, the Boston Nutrition Obesity Research Center, the National Institutes of Health, Nyckelfonden, Region Orebro (Sweden) County, and the Karolinska Institutet.

SOURCE: Simon TG et al. Ann Intern Med. 2019 Aug 19. doi: 10.7326/M18-2753.

FROM THE ANNALS OF INTERNAL MEDICINE

Key clinical point: Use of lipophilic statins significantly reduced incidence and mortality of hepatocellular cancer in adults with viral hepatitis.

Major finding: The 10-year risk of HCC was 8.1% among patients taking lipophilic statins, compared with 3.3% among those not on statins.

Study details: The data come from a population-based cohort study of 16,668 adult with viral hepatitis from a national registry in Sweden.

Disclosures: Dr. Simon had no financial conflicts to disclose, but disclosed support from a North American Training Grant from the American College of Gastroenterology. Several coauthors disclosed relationships with multiple companies including AbbVie, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Gilead, Janssen, and MSD.

Source: Simon TG et al. Ann Intern Med. 2019 Aug 19. doi: 10.7326/M18-2753.

Digital health and big data: New tools for making the most of real-world evidence

LAKE BUENA VISTA, FLA. – Digital health technology is vastly expanding the real-world data pool for clinical and comparative effectiveness research, according to Jeffrey Curtis, MD.

The trick is to harness the power of that data to improve patient care and outcomes, and that can be achieved in part through linkage of data sources and through point-of-care access, Dr. Curtis, professor of medicine in the division of clinical immunology and rheumatology at the University of Alabama at Birmingham (UAB), said at the annual meeting of the Florida Society of Rheumatology.

“We want to take care of patients, but probably what you and I also want is to have real-world evidence ... evidence relevant for people [we] take care of on a day-to-day basis – not people in highly selected phase 3 or even phase 4 trials,” he said.

Real-world data, which gained particular cachet through the 21st Century Cures Act permitting the Food and Drug Administration to consider real-world evidence as part of the regulatory process and in post-marketing surveillance, includes information from electronic health records (EHRs), health plan claims, traditional registries, and mobile health and technology, explained Dr. Curtis, who also is codirector of the UAB Pharmacoepidemiology and Pharmacoeconomics Unit.

“And you and I want it because patients are different, and in medicine we only have about 20% of patients where there is direct evidence about what we should do,” he added. “Give me the trial that describes the 75-year-old African American smoker with diabetes and how well he does on biologic du jour; there’s no trial like that, and yet you and I need to make those kinds of decisions in light of patients’ comorbidities and other features.”

Generating real-world evidence, however, requires new approaches and new tools, he said, explaining that efficiency is key for applying the data in busy practices, as is compatibility with delivering an intervention and with randomization.

Imagine using the EHR at the point of care to look up what happened to “the last 10 patients like this” based on how they were treated by you or your colleagues, he said.

“That would be useful information to have. In fact, the day is not so far in the future where you could, perhaps, randomize within your EHR if you had a clinically important question that really needed an answer and a protocol attached,” he added.

Real-world data collection

Pragmatic trials offer one approach to garnering real-world data by addressing a simple question – usually with a hard outcome – using very few inclusion and exclusion criteria, Dr. Curtis said, describing the recently completed VERVE Zoster Vaccine trial.

He and his colleagues randomized 617 patients from 33 sites to look at the safety of the live-virus Zostavax herpes zoster vaccine in rheumatoid arthritis patients over age 50 years on any anti–tumor necrosis factor (anti-TNF) therapy. Half of the patients received saline, the other half received the vaccine, and no cases of varicella zoster occurred in either group.

“So, to the extent that half of 617 people with zero cases was reassuring, we now have some evidence where heretofore there was none,” he said, noting that those results will be presented at the 2019 American College of Rheumatology annual meeting. “But the focus of this talk is not on vaccination, it’s really on how we do real-world effectiveness or safety studies in a way that doesn’t slow us way down and doesn’t require some big research operation.”

One way is through efficient recruitment, and depending on how complicated the study is, qualified patients may be easily identifiable through the EHR. In fact, numerous tools are available to codify and search both structured and unstructured data, Dr. Curtis said, noting that he and his colleagues used the web-based i2b2 Query Tool for the VERVE study.

The study sites that did the best with recruiting had the ability to search their own EHRs for patients who met the inclusion criteria, and those patients were then invited to participate. A short video was created to educate those who were interested, and a “knowledge review” quiz was administered afterward to ensure informed consent, which was provided via digital signature.

Health plan and other “big data” can also be very useful for answering certain questions. One example is how soon biologics should be stopped before elective orthopedic surgery? Dr. Curtis and colleagues looked at this using claims data for nearly 4,300 patients undergoing elective hip or knee arthroplasty and found no evidence that administering infliximab within 4 weeks of surgery increased serious infection risk within 30 days or prosthetic joint infection within 1 year.

“Where else are you going to go run a prospective study of 4,300 elective hips and knees,” he said, stressing that it wouldn’t be easy.

Other sources that can help generate real-world effectiveness data include traditional or single-center registries and EHR-based registries.

“The EHR registries are, I think, the newest that many are part of in our field,” he said, noting that “a number of groups are aggregating that,” including the ACR RISE registry and some physician groups, for example.

“What we’re really after is to have a clinically integrated network and a learning health care environment,” he explained, adding that the goal is to develop care pathways.

The approach represents a shift from evidence-based practice to practice-based evidence, he noted.

“When you and I practice, we’re generating that evidence and now we just need to harness that data to get smarter to take care of patients,” he said, adding that the lack of randomization for much of these data isn’t necessarily a problem.

“Do you have to randomize? I would argue that you don’t necessarily have to randomize if the source of variability in how we treat patients is very related to patients’ characteristics,” he said.

If the evidence for a specific approach is weak, or a decision is based on physician preference, physician practice, or insurance company considerations instead of patient characteristics, randomization may not be necessary, he explained.

In fact, insurance company requirements often create “natural experiments” that can be used to help identify better practices. For example, if one only covers adalimumab for first-line TNF inhibition, and another has a “different fail-first policy and that’s not first line and everybody gets some other TNF inhibitor, then I can probably compare those quite reasonably,” he said.

“That’s a great setting where you might not need randomization.”

Of note, “having more data sometimes trumps smarter algorithms,” but that means finding and linking more data that “exist in the wild,” Dr. Curtis said.

Linking data sources

When he and his colleagues wanted to assess the cost of not achieving RA remission, no single data source provided all of the information they needed. They used both CORRONA registry data and health claims data to look at various outcome measures across disease activity categories and with adjustment for comorbidity clusters. They previously reported on the feasibility and validity of the approach.

“We’re currently doing another project where one of the local Blue Cross plans said ‘I’m interested to support you to see how efficient you are; we will donate or loan you our claims data [and] let you link it to your practice so you can actually tell us ... cost conditional on [a patient’s] disease activity,’ ” he said.

Another example involves a recent study looking at biomarker-based cardiovascular disease risk prediction in RA using data from nearly 31,000 Medicare patients linked with multibiomarker disease activity (MBDA) test results, with which they “basically built and validated a risk prediction model,” he said.

The point is that such data linkage provided tools for use at the point of care that can predict CVD risk using “some simple things that you and I have in our EHR,” he said. “But you couldn’t do this if you had to assemble a prospective cohort of tens of thousands of arthritis patients and then wait years for follow-up.”

Patient-reported outcomes collected at the point of care and by patients at home between visits, such as digital data collected via wearable technology, can provide additional information to help improve patient care and management.

“My interest is not to think about [these data sources] in isolation, but really to think about how we bring these together,” he said. “I’m interested in maximizing value for both patients and clinicians, and not having to pick only one of these data sources, but really to harness several of them if that’s what we need to take better care of patients and to answer important questions.”

Doing so is increasingly important given the workforce shortage in rheumatology, he noted.

“The point is that we’re going to need to be a whole lot more efficient as a field because there are going to be fewer of us even at a time when more of us are needed,” he said.

It’s a topic in which the ACR has shown a lot of interest, he said, noting that he cochaired a preconference course on mobile health technologies at the 2018 ACR annual meeting and is involved with a similar course on “big data” ahead of the 2019 meeting.

The thought of making use of the various digital health and “big data” sources can be overwhelming, but the key is to start with the question that needs an answer or the problem that needs to be solved.

“Don’t start with the data,” he explained. “Start with [asking] ... ‘What am I trying to do?’ ”

Dr. Curtis reported funding from the National Institute on Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases and the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute. He has also consulted for or received research grants from Amgen, AbbVie, Bristol-Myers Squibb, CORRONA, Lilly, Janssen, Myriad, Novartis, Roche, Pfizer, and Sanofi/Regeneron.

LAKE BUENA VISTA, FLA. – Digital health technology is vastly expanding the real-world data pool for clinical and comparative effectiveness research, according to Jeffrey Curtis, MD.

The trick is to harness the power of that data to improve patient care and outcomes, and that can be achieved in part through linkage of data sources and through point-of-care access, Dr. Curtis, professor of medicine in the division of clinical immunology and rheumatology at the University of Alabama at Birmingham (UAB), said at the annual meeting of the Florida Society of Rheumatology.

“We want to take care of patients, but probably what you and I also want is to have real-world evidence ... evidence relevant for people [we] take care of on a day-to-day basis – not people in highly selected phase 3 or even phase 4 trials,” he said.

Real-world data, which gained particular cachet through the 21st Century Cures Act permitting the Food and Drug Administration to consider real-world evidence as part of the regulatory process and in post-marketing surveillance, includes information from electronic health records (EHRs), health plan claims, traditional registries, and mobile health and technology, explained Dr. Curtis, who also is codirector of the UAB Pharmacoepidemiology and Pharmacoeconomics Unit.

“And you and I want it because patients are different, and in medicine we only have about 20% of patients where there is direct evidence about what we should do,” he added. “Give me the trial that describes the 75-year-old African American smoker with diabetes and how well he does on biologic du jour; there’s no trial like that, and yet you and I need to make those kinds of decisions in light of patients’ comorbidities and other features.”

Generating real-world evidence, however, requires new approaches and new tools, he said, explaining that efficiency is key for applying the data in busy practices, as is compatibility with delivering an intervention and with randomization.

Imagine using the EHR at the point of care to look up what happened to “the last 10 patients like this” based on how they were treated by you or your colleagues, he said.

“That would be useful information to have. In fact, the day is not so far in the future where you could, perhaps, randomize within your EHR if you had a clinically important question that really needed an answer and a protocol attached,” he added.

Real-world data collection

Pragmatic trials offer one approach to garnering real-world data by addressing a simple question – usually with a hard outcome – using very few inclusion and exclusion criteria, Dr. Curtis said, describing the recently completed VERVE Zoster Vaccine trial.

He and his colleagues randomized 617 patients from 33 sites to look at the safety of the live-virus Zostavax herpes zoster vaccine in rheumatoid arthritis patients over age 50 years on any anti–tumor necrosis factor (anti-TNF) therapy. Half of the patients received saline, the other half received the vaccine, and no cases of varicella zoster occurred in either group.

“So, to the extent that half of 617 people with zero cases was reassuring, we now have some evidence where heretofore there was none,” he said, noting that those results will be presented at the 2019 American College of Rheumatology annual meeting. “But the focus of this talk is not on vaccination, it’s really on how we do real-world effectiveness or safety studies in a way that doesn’t slow us way down and doesn’t require some big research operation.”

One way is through efficient recruitment, and depending on how complicated the study is, qualified patients may be easily identifiable through the EHR. In fact, numerous tools are available to codify and search both structured and unstructured data, Dr. Curtis said, noting that he and his colleagues used the web-based i2b2 Query Tool for the VERVE study.

The study sites that did the best with recruiting had the ability to search their own EHRs for patients who met the inclusion criteria, and those patients were then invited to participate. A short video was created to educate those who were interested, and a “knowledge review” quiz was administered afterward to ensure informed consent, which was provided via digital signature.

Health plan and other “big data” can also be very useful for answering certain questions. One example is how soon biologics should be stopped before elective orthopedic surgery? Dr. Curtis and colleagues looked at this using claims data for nearly 4,300 patients undergoing elective hip or knee arthroplasty and found no evidence that administering infliximab within 4 weeks of surgery increased serious infection risk within 30 days or prosthetic joint infection within 1 year.

“Where else are you going to go run a prospective study of 4,300 elective hips and knees,” he said, stressing that it wouldn’t be easy.

Other sources that can help generate real-world effectiveness data include traditional or single-center registries and EHR-based registries.

“The EHR registries are, I think, the newest that many are part of in our field,” he said, noting that “a number of groups are aggregating that,” including the ACR RISE registry and some physician groups, for example.

“What we’re really after is to have a clinically integrated network and a learning health care environment,” he explained, adding that the goal is to develop care pathways.

The approach represents a shift from evidence-based practice to practice-based evidence, he noted.

“When you and I practice, we’re generating that evidence and now we just need to harness that data to get smarter to take care of patients,” he said, adding that the lack of randomization for much of these data isn’t necessarily a problem.

“Do you have to randomize? I would argue that you don’t necessarily have to randomize if the source of variability in how we treat patients is very related to patients’ characteristics,” he said.

If the evidence for a specific approach is weak, or a decision is based on physician preference, physician practice, or insurance company considerations instead of patient characteristics, randomization may not be necessary, he explained.

In fact, insurance company requirements often create “natural experiments” that can be used to help identify better practices. For example, if one only covers adalimumab for first-line TNF inhibition, and another has a “different fail-first policy and that’s not first line and everybody gets some other TNF inhibitor, then I can probably compare those quite reasonably,” he said.

“That’s a great setting where you might not need randomization.”

Of note, “having more data sometimes trumps smarter algorithms,” but that means finding and linking more data that “exist in the wild,” Dr. Curtis said.

Linking data sources

When he and his colleagues wanted to assess the cost of not achieving RA remission, no single data source provided all of the information they needed. They used both CORRONA registry data and health claims data to look at various outcome measures across disease activity categories and with adjustment for comorbidity clusters. They previously reported on the feasibility and validity of the approach.

“We’re currently doing another project where one of the local Blue Cross plans said ‘I’m interested to support you to see how efficient you are; we will donate or loan you our claims data [and] let you link it to your practice so you can actually tell us ... cost conditional on [a patient’s] disease activity,’ ” he said.

Another example involves a recent study looking at biomarker-based cardiovascular disease risk prediction in RA using data from nearly 31,000 Medicare patients linked with multibiomarker disease activity (MBDA) test results, with which they “basically built and validated a risk prediction model,” he said.

The point is that such data linkage provided tools for use at the point of care that can predict CVD risk using “some simple things that you and I have in our EHR,” he said. “But you couldn’t do this if you had to assemble a prospective cohort of tens of thousands of arthritis patients and then wait years for follow-up.”

Patient-reported outcomes collected at the point of care and by patients at home between visits, such as digital data collected via wearable technology, can provide additional information to help improve patient care and management.

“My interest is not to think about [these data sources] in isolation, but really to think about how we bring these together,” he said. “I’m interested in maximizing value for both patients and clinicians, and not having to pick only one of these data sources, but really to harness several of them if that’s what we need to take better care of patients and to answer important questions.”

Doing so is increasingly important given the workforce shortage in rheumatology, he noted.

“The point is that we’re going to need to be a whole lot more efficient as a field because there are going to be fewer of us even at a time when more of us are needed,” he said.

It’s a topic in which the ACR has shown a lot of interest, he said, noting that he cochaired a preconference course on mobile health technologies at the 2018 ACR annual meeting and is involved with a similar course on “big data” ahead of the 2019 meeting.

The thought of making use of the various digital health and “big data” sources can be overwhelming, but the key is to start with the question that needs an answer or the problem that needs to be solved.

“Don’t start with the data,” he explained. “Start with [asking] ... ‘What am I trying to do?’ ”

Dr. Curtis reported funding from the National Institute on Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases and the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute. He has also consulted for or received research grants from Amgen, AbbVie, Bristol-Myers Squibb, CORRONA, Lilly, Janssen, Myriad, Novartis, Roche, Pfizer, and Sanofi/Regeneron.

LAKE BUENA VISTA, FLA. – Digital health technology is vastly expanding the real-world data pool for clinical and comparative effectiveness research, according to Jeffrey Curtis, MD.

The trick is to harness the power of that data to improve patient care and outcomes, and that can be achieved in part through linkage of data sources and through point-of-care access, Dr. Curtis, professor of medicine in the division of clinical immunology and rheumatology at the University of Alabama at Birmingham (UAB), said at the annual meeting of the Florida Society of Rheumatology.

“We want to take care of patients, but probably what you and I also want is to have real-world evidence ... evidence relevant for people [we] take care of on a day-to-day basis – not people in highly selected phase 3 or even phase 4 trials,” he said.

Real-world data, which gained particular cachet through the 21st Century Cures Act permitting the Food and Drug Administration to consider real-world evidence as part of the regulatory process and in post-marketing surveillance, includes information from electronic health records (EHRs), health plan claims, traditional registries, and mobile health and technology, explained Dr. Curtis, who also is codirector of the UAB Pharmacoepidemiology and Pharmacoeconomics Unit.

“And you and I want it because patients are different, and in medicine we only have about 20% of patients where there is direct evidence about what we should do,” he added. “Give me the trial that describes the 75-year-old African American smoker with diabetes and how well he does on biologic du jour; there’s no trial like that, and yet you and I need to make those kinds of decisions in light of patients’ comorbidities and other features.”

Generating real-world evidence, however, requires new approaches and new tools, he said, explaining that efficiency is key for applying the data in busy practices, as is compatibility with delivering an intervention and with randomization.

Imagine using the EHR at the point of care to look up what happened to “the last 10 patients like this” based on how they were treated by you or your colleagues, he said.

“That would be useful information to have. In fact, the day is not so far in the future where you could, perhaps, randomize within your EHR if you had a clinically important question that really needed an answer and a protocol attached,” he added.

Real-world data collection

Pragmatic trials offer one approach to garnering real-world data by addressing a simple question – usually with a hard outcome – using very few inclusion and exclusion criteria, Dr. Curtis said, describing the recently completed VERVE Zoster Vaccine trial.

He and his colleagues randomized 617 patients from 33 sites to look at the safety of the live-virus Zostavax herpes zoster vaccine in rheumatoid arthritis patients over age 50 years on any anti–tumor necrosis factor (anti-TNF) therapy. Half of the patients received saline, the other half received the vaccine, and no cases of varicella zoster occurred in either group.

“So, to the extent that half of 617 people with zero cases was reassuring, we now have some evidence where heretofore there was none,” he said, noting that those results will be presented at the 2019 American College of Rheumatology annual meeting. “But the focus of this talk is not on vaccination, it’s really on how we do real-world effectiveness or safety studies in a way that doesn’t slow us way down and doesn’t require some big research operation.”

One way is through efficient recruitment, and depending on how complicated the study is, qualified patients may be easily identifiable through the EHR. In fact, numerous tools are available to codify and search both structured and unstructured data, Dr. Curtis said, noting that he and his colleagues used the web-based i2b2 Query Tool for the VERVE study.

The study sites that did the best with recruiting had the ability to search their own EHRs for patients who met the inclusion criteria, and those patients were then invited to participate. A short video was created to educate those who were interested, and a “knowledge review” quiz was administered afterward to ensure informed consent, which was provided via digital signature.

Health plan and other “big data” can also be very useful for answering certain questions. One example is how soon biologics should be stopped before elective orthopedic surgery? Dr. Curtis and colleagues looked at this using claims data for nearly 4,300 patients undergoing elective hip or knee arthroplasty and found no evidence that administering infliximab within 4 weeks of surgery increased serious infection risk within 30 days or prosthetic joint infection within 1 year.

“Where else are you going to go run a prospective study of 4,300 elective hips and knees,” he said, stressing that it wouldn’t be easy.

Other sources that can help generate real-world effectiveness data include traditional or single-center registries and EHR-based registries.

“The EHR registries are, I think, the newest that many are part of in our field,” he said, noting that “a number of groups are aggregating that,” including the ACR RISE registry and some physician groups, for example.

“What we’re really after is to have a clinically integrated network and a learning health care environment,” he explained, adding that the goal is to develop care pathways.

The approach represents a shift from evidence-based practice to practice-based evidence, he noted.

“When you and I practice, we’re generating that evidence and now we just need to harness that data to get smarter to take care of patients,” he said, adding that the lack of randomization for much of these data isn’t necessarily a problem.

“Do you have to randomize? I would argue that you don’t necessarily have to randomize if the source of variability in how we treat patients is very related to patients’ characteristics,” he said.

If the evidence for a specific approach is weak, or a decision is based on physician preference, physician practice, or insurance company considerations instead of patient characteristics, randomization may not be necessary, he explained.

In fact, insurance company requirements often create “natural experiments” that can be used to help identify better practices. For example, if one only covers adalimumab for first-line TNF inhibition, and another has a “different fail-first policy and that’s not first line and everybody gets some other TNF inhibitor, then I can probably compare those quite reasonably,” he said.

“That’s a great setting where you might not need randomization.”

Of note, “having more data sometimes trumps smarter algorithms,” but that means finding and linking more data that “exist in the wild,” Dr. Curtis said.

Linking data sources

When he and his colleagues wanted to assess the cost of not achieving RA remission, no single data source provided all of the information they needed. They used both CORRONA registry data and health claims data to look at various outcome measures across disease activity categories and with adjustment for comorbidity clusters. They previously reported on the feasibility and validity of the approach.

“We’re currently doing another project where one of the local Blue Cross plans said ‘I’m interested to support you to see how efficient you are; we will donate or loan you our claims data [and] let you link it to your practice so you can actually tell us ... cost conditional on [a patient’s] disease activity,’ ” he said.

Another example involves a recent study looking at biomarker-based cardiovascular disease risk prediction in RA using data from nearly 31,000 Medicare patients linked with multibiomarker disease activity (MBDA) test results, with which they “basically built and validated a risk prediction model,” he said.

The point is that such data linkage provided tools for use at the point of care that can predict CVD risk using “some simple things that you and I have in our EHR,” he said. “But you couldn’t do this if you had to assemble a prospective cohort of tens of thousands of arthritis patients and then wait years for follow-up.”

Patient-reported outcomes collected at the point of care and by patients at home between visits, such as digital data collected via wearable technology, can provide additional information to help improve patient care and management.

“My interest is not to think about [these data sources] in isolation, but really to think about how we bring these together,” he said. “I’m interested in maximizing value for both patients and clinicians, and not having to pick only one of these data sources, but really to harness several of them if that’s what we need to take better care of patients and to answer important questions.”

Doing so is increasingly important given the workforce shortage in rheumatology, he noted.

“The point is that we’re going to need to be a whole lot more efficient as a field because there are going to be fewer of us even at a time when more of us are needed,” he said.

It’s a topic in which the ACR has shown a lot of interest, he said, noting that he cochaired a preconference course on mobile health technologies at the 2018 ACR annual meeting and is involved with a similar course on “big data” ahead of the 2019 meeting.

The thought of making use of the various digital health and “big data” sources can be overwhelming, but the key is to start with the question that needs an answer or the problem that needs to be solved.

“Don’t start with the data,” he explained. “Start with [asking] ... ‘What am I trying to do?’ ”

Dr. Curtis reported funding from the National Institute on Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases and the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute. He has also consulted for or received research grants from Amgen, AbbVie, Bristol-Myers Squibb, CORRONA, Lilly, Janssen, Myriad, Novartis, Roche, Pfizer, and Sanofi/Regeneron.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM FSR 2019

Post-TAVR anticoagulation alone fails to cut stroke risk in AFib

In patients with atrial fibrillation (AFib) who have undergone transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) and had a CHA2DS2-VASc score of at least 2, oral anticoagulant (OAC) therapy alone was not linked to reduced stroke risk.

By contrast, antiplatelet therapy was linked to a reduced risk of stroke in those AFib-TAVR patients, regardless of whether an oral anticoagulant was on board, according to results of a substudy of the randomized PARTNER II (Placement of Aortic Transcatheter Valve II) trial and its associated registries.

“Anticoagulant therapy was associated with a reduced risk of stroke and the composite of death or stroke when used concomitantly with uninterrupted antiplatelet therapy following TAVR,” concluded authors of the analysis, led by Ioanna Kosmidou, MD, PhD, of Columbia University in New York.

Taken together, these findings suggest OAC alone is “not sufficient” to prevent cerebrovascular events after TAVR in patients with AFib, Dr. Kosmidou and colleagues reported in JACC: Cardiovascular Interventions.

The analysis of the PARTNER II substudy included a total of 1,621 patients with aortic stenosis treated with TAVR who had a history of AFib and an absolute indication for anticoagulation as evidenced by a CHA2DS2-VASc score of at least 2.

Despite the absolute indication for anticoagulation, more than 40% of these patients were not prescribed an OAC upon discharge, investigators wrote, though the rate of nonprescribing decreased over the 5-year enrollment period of 2011-2015.

OAC therapy alone was not linked to reduced stroke risk in this cohort, investigators said. After 2 years, the rate of stroke was 6.6% for AFib-TAVR patients on anticoagulant therapy, and 5.6% for those who were not on anticoagulant therapy, a nonsignificant difference at P = 0.53, according to the reported data.

By contrast, uninterrupted antiplatelet therapy reduced both risk of stroke and risk of the composite endpoint of stroke and death at 2 years “irrespective of concomitant anticoagulation,” Dr. Kosmidou and coinvestigators wrote in the report.

The stroke rates were 5.4% for antiplatelet therapy plus OAC, versus 11.1% for those receiving neither antithrombotic treatment (P = 0.03), while the rates of stroke or death were 29.7% and 40.1%, respectively (P = 0.01), according to investigators.

After adjustment, stroke risk was not significantly reduced for OAC when compared with no OAC or antiplatelet therapy (HR, 0.61; P = .16), whereas stroke risk was indeed reduced for antiplatelet therapy alone (HR, 0.32; P = .002) and antiplatelet therapy with oral anticoagulation (HR, 0.44; P = .018).

The PARTNER II study was funded by Edwards Lifesciences. Senior author Martin B. Leon, MD, and several other study coauthors reported disclosures related to Edwards Lifesciences, in addition to Abbott Vascular, Cordis, Medtronic, Boston Scientific, and other companies. Dr. Kosmidou reported no disclosures.

SOURCE: Kosmidou I et al. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2019;12:1580-9.

Results of this PARTNER II substudy investigation by Kosmidou and colleagues are timely and thought provoking because they imply that some current recommendations may be insufficient for preventing stroke in patients with atrial fibrillation (AFib) undergoing transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR).

Specifically, the results showed no difference in risk of stroke or the composite of death and stroke at 2 years in oral anticoagulant (OAC) and non-OAC patient groups, whereas by contrast, antiplatelet therapy was linked with reduced stroke risk versus no antithrombotic therapy, whether or not the patients received OAC.

The substudy reinforces the understanding that TAVR itself is a determinant of stroke because of mechanisms that go beyond thrombus formation in the left atrial appendage and are essentially platelet mediated.

How to manage antithrombotic therapy in patients with AFib who undergo TAVR remains a residual field of ambiguity.

However, observational studies cannot be conclusive, they said, so results of relevant prospective, randomized trials are eagerly awaited.

For example, the effects of novel oral anticoagulants versus vitamin K antagonists will be evaluated in the ENVISAGE-TAVI study, as well as the ATLANTIS trial, which will additionally include non-OAC patients.

The relative benefits of OAC alone versus OAC plus antiplatelet therapy will be evaluated in the AVATAR study, which will include AFib-TAVR patients randomized to OAC versus OAC plus aspirin, while the POPular-TAVI and CLOE trials will also include cohorts that help provide a more eloquent answer regarding the benefit-risk ratio of combining antiplatelet therapy and OAC in these patients.

Davide Capodanno, MD, PhD, and Antonio Greco, MD, of the University of Catania (Italy) made these comments in an accompanying editorial (JACC: Cardiovasc Interv. 2019 Aug 19. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2019.07.004). Dr. Capodanno reported disclosures related to Abbott Vascular, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Daiichi-Sankyo, and Sanofi. Dr. Greco reported having no relevant disclosures.

Results of this PARTNER II substudy investigation by Kosmidou and colleagues are timely and thought provoking because they imply that some current recommendations may be insufficient for preventing stroke in patients with atrial fibrillation (AFib) undergoing transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR).

Specifically, the results showed no difference in risk of stroke or the composite of death and stroke at 2 years in oral anticoagulant (OAC) and non-OAC patient groups, whereas by contrast, antiplatelet therapy was linked with reduced stroke risk versus no antithrombotic therapy, whether or not the patients received OAC.

The substudy reinforces the understanding that TAVR itself is a determinant of stroke because of mechanisms that go beyond thrombus formation in the left atrial appendage and are essentially platelet mediated.

How to manage antithrombotic therapy in patients with AFib who undergo TAVR remains a residual field of ambiguity.

However, observational studies cannot be conclusive, they said, so results of relevant prospective, randomized trials are eagerly awaited.

For example, the effects of novel oral anticoagulants versus vitamin K antagonists will be evaluated in the ENVISAGE-TAVI study, as well as the ATLANTIS trial, which will additionally include non-OAC patients.

The relative benefits of OAC alone versus OAC plus antiplatelet therapy will be evaluated in the AVATAR study, which will include AFib-TAVR patients randomized to OAC versus OAC plus aspirin, while the POPular-TAVI and CLOE trials will also include cohorts that help provide a more eloquent answer regarding the benefit-risk ratio of combining antiplatelet therapy and OAC in these patients.

Davide Capodanno, MD, PhD, and Antonio Greco, MD, of the University of Catania (Italy) made these comments in an accompanying editorial (JACC: Cardiovasc Interv. 2019 Aug 19. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2019.07.004). Dr. Capodanno reported disclosures related to Abbott Vascular, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Daiichi-Sankyo, and Sanofi. Dr. Greco reported having no relevant disclosures.

Results of this PARTNER II substudy investigation by Kosmidou and colleagues are timely and thought provoking because they imply that some current recommendations may be insufficient for preventing stroke in patients with atrial fibrillation (AFib) undergoing transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR).

Specifically, the results showed no difference in risk of stroke or the composite of death and stroke at 2 years in oral anticoagulant (OAC) and non-OAC patient groups, whereas by contrast, antiplatelet therapy was linked with reduced stroke risk versus no antithrombotic therapy, whether or not the patients received OAC.

The substudy reinforces the understanding that TAVR itself is a determinant of stroke because of mechanisms that go beyond thrombus formation in the left atrial appendage and are essentially platelet mediated.

How to manage antithrombotic therapy in patients with AFib who undergo TAVR remains a residual field of ambiguity.

However, observational studies cannot be conclusive, they said, so results of relevant prospective, randomized trials are eagerly awaited.

For example, the effects of novel oral anticoagulants versus vitamin K antagonists will be evaluated in the ENVISAGE-TAVI study, as well as the ATLANTIS trial, which will additionally include non-OAC patients.

The relative benefits of OAC alone versus OAC plus antiplatelet therapy will be evaluated in the AVATAR study, which will include AFib-TAVR patients randomized to OAC versus OAC plus aspirin, while the POPular-TAVI and CLOE trials will also include cohorts that help provide a more eloquent answer regarding the benefit-risk ratio of combining antiplatelet therapy and OAC in these patients.

Davide Capodanno, MD, PhD, and Antonio Greco, MD, of the University of Catania (Italy) made these comments in an accompanying editorial (JACC: Cardiovasc Interv. 2019 Aug 19. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2019.07.004). Dr. Capodanno reported disclosures related to Abbott Vascular, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Daiichi-Sankyo, and Sanofi. Dr. Greco reported having no relevant disclosures.

In patients with atrial fibrillation (AFib) who have undergone transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) and had a CHA2DS2-VASc score of at least 2, oral anticoagulant (OAC) therapy alone was not linked to reduced stroke risk.

By contrast, antiplatelet therapy was linked to a reduced risk of stroke in those AFib-TAVR patients, regardless of whether an oral anticoagulant was on board, according to results of a substudy of the randomized PARTNER II (Placement of Aortic Transcatheter Valve II) trial and its associated registries.

“Anticoagulant therapy was associated with a reduced risk of stroke and the composite of death or stroke when used concomitantly with uninterrupted antiplatelet therapy following TAVR,” concluded authors of the analysis, led by Ioanna Kosmidou, MD, PhD, of Columbia University in New York.

Taken together, these findings suggest OAC alone is “not sufficient” to prevent cerebrovascular events after TAVR in patients with AFib, Dr. Kosmidou and colleagues reported in JACC: Cardiovascular Interventions.

The analysis of the PARTNER II substudy included a total of 1,621 patients with aortic stenosis treated with TAVR who had a history of AFib and an absolute indication for anticoagulation as evidenced by a CHA2DS2-VASc score of at least 2.