User login

Differential monocytic HLA-DR expression prognostically useful in PICU

LJUBLJANA, SLOVENIA – During their first 4 days in the pediatric ICU, critically ill children have significantly reduced human leukocyte antigen (HLA)–DR expression within all three major subsets of monocytes. The reductions are seen regardless of whether the children were admitted for sepsis, trauma, or after surgery, Navin Boeddha, MD, PhD, reported in his PIDJ Award Lecture at the annual meeting of the European Society for Paediatric Infectious Diseases.

The PIDJ Award is given annually by the editors of the Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal in recognition of what they deem the most important study published in the journal during the prior year. This one stood out because it identified promising potential laboratory markers that have been sought as a prerequisite to developing immunostimulatory therapies aimed at improving outcomes in severely immunosuppressed children.

Researchers are particularly eager to explore this investigative treatment strategy because the mortality and long-term morbidity of pediatric sepsis, in particular, remain unacceptably high. The hope now is that HLA-DR expression on monocyte subsets will be helpful in directing granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor, interferon-gamma, and other immunostimulatory therapies to the pediatric ICU patients with the most favorable benefit/risk ratio, according to Dr. Boeddha of Sophia Children’s Hospital and Erasmus University, Rotterdam, the Netherlands.

He reported on 37 critically ill children admitted to a pediatric ICU – 12 for sepsis, 11 post surgery, 10 for trauma, and 4 for other reasons – as well as 37 healthy controls. HLA-DR expression on monocyte subsets was measured by flow cytometry upon admission and again on each of the following 3 days.

The impetus for this study is that severe infection, major surgery, and severe trauma are often associated with immunosuppression. And while prior work in septic adults has concluded that decreased monocytic HLA-DR expression is a marker for immunosuppression – and that the lower the level of such expression, the greater the risk of nosocomial infection and death – this phenomenon hasn’t been well studied in critically ill children, he explained.

Dr. Boeddha and coinvestigators found that monocytic HLA-DR expression, which plays a major role in presenting antigens to T cells, decreased over time during the critically ill children’s first 4 days in the pediatric ICU. Moreover, it was lower than in controls at all four time points. This was true both for the percentage of HLA-DR–expressing monocytes of all subsets, as well as for HLA-DR mean fluorescence intensity.

In the critically ill study population as a whole, the percentage of classical monocytes – that is, CD14++ CD16– monocytes – was significantly greater at admission than in healthy controls by margins of 95% and 87%, while the percentage of nonclassical CD14+/-CD16++ monocytes was markedly lower at 2% than the 9% figure in controls.

The biggest discrepancy in monocyte subset distribution was seen in patients admitted for sepsis. Their percentage of classical monocytes was lower than in controls by a margin of 82% versus 87%; however, their proportion of intermediate monocytes (CD14++ CD16+) upon admission was twice that of controls, and it climbed further to 14% on day 2.

Among the key findings in the Rotterdam study: 13 of 37 critically ill patients experienced at least one nosocomial infection while in the pediatric ICU. Their day 2 percentage of HLA-DR–expressing classical monocytes was 42%, strikingly lower than the 78% figure in patients who didn’t develop an infection. Also, the 6 patients who died had only a 33% rate of HLA-DR–expressing classical monocytes on day 3 after pediatric ICU admission versus a 63% rate in survivors of their critical illness.

Thus, low HLA-DR expression on classical monocytes early during the course of a pediatric ICU stay may be the sought-after biomarker that identifies a particularly high-risk subgroup of critically ill children in whom immunostimulatory therapies should be studied. However, future confirmatory studies should monitor monocytic HLA-DR expression in a larger critically ill patient population for a longer period in order to establish the time to recovery of low expression and its impact on long-term complications, the physician said.

Dr. Boeddha reported having no financial conflicts regarding the award-winning study, supported by the European Union and Erasmus University.

SOURCE: Boeddha NP et al. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2018 Oct;37(10):1034-40.

LJUBLJANA, SLOVENIA – During their first 4 days in the pediatric ICU, critically ill children have significantly reduced human leukocyte antigen (HLA)–DR expression within all three major subsets of monocytes. The reductions are seen regardless of whether the children were admitted for sepsis, trauma, or after surgery, Navin Boeddha, MD, PhD, reported in his PIDJ Award Lecture at the annual meeting of the European Society for Paediatric Infectious Diseases.

The PIDJ Award is given annually by the editors of the Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal in recognition of what they deem the most important study published in the journal during the prior year. This one stood out because it identified promising potential laboratory markers that have been sought as a prerequisite to developing immunostimulatory therapies aimed at improving outcomes in severely immunosuppressed children.

Researchers are particularly eager to explore this investigative treatment strategy because the mortality and long-term morbidity of pediatric sepsis, in particular, remain unacceptably high. The hope now is that HLA-DR expression on monocyte subsets will be helpful in directing granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor, interferon-gamma, and other immunostimulatory therapies to the pediatric ICU patients with the most favorable benefit/risk ratio, according to Dr. Boeddha of Sophia Children’s Hospital and Erasmus University, Rotterdam, the Netherlands.

He reported on 37 critically ill children admitted to a pediatric ICU – 12 for sepsis, 11 post surgery, 10 for trauma, and 4 for other reasons – as well as 37 healthy controls. HLA-DR expression on monocyte subsets was measured by flow cytometry upon admission and again on each of the following 3 days.

The impetus for this study is that severe infection, major surgery, and severe trauma are often associated with immunosuppression. And while prior work in septic adults has concluded that decreased monocytic HLA-DR expression is a marker for immunosuppression – and that the lower the level of such expression, the greater the risk of nosocomial infection and death – this phenomenon hasn’t been well studied in critically ill children, he explained.

Dr. Boeddha and coinvestigators found that monocytic HLA-DR expression, which plays a major role in presenting antigens to T cells, decreased over time during the critically ill children’s first 4 days in the pediatric ICU. Moreover, it was lower than in controls at all four time points. This was true both for the percentage of HLA-DR–expressing monocytes of all subsets, as well as for HLA-DR mean fluorescence intensity.

In the critically ill study population as a whole, the percentage of classical monocytes – that is, CD14++ CD16– monocytes – was significantly greater at admission than in healthy controls by margins of 95% and 87%, while the percentage of nonclassical CD14+/-CD16++ monocytes was markedly lower at 2% than the 9% figure in controls.

The biggest discrepancy in monocyte subset distribution was seen in patients admitted for sepsis. Their percentage of classical monocytes was lower than in controls by a margin of 82% versus 87%; however, their proportion of intermediate monocytes (CD14++ CD16+) upon admission was twice that of controls, and it climbed further to 14% on day 2.

Among the key findings in the Rotterdam study: 13 of 37 critically ill patients experienced at least one nosocomial infection while in the pediatric ICU. Their day 2 percentage of HLA-DR–expressing classical monocytes was 42%, strikingly lower than the 78% figure in patients who didn’t develop an infection. Also, the 6 patients who died had only a 33% rate of HLA-DR–expressing classical monocytes on day 3 after pediatric ICU admission versus a 63% rate in survivors of their critical illness.

Thus, low HLA-DR expression on classical monocytes early during the course of a pediatric ICU stay may be the sought-after biomarker that identifies a particularly high-risk subgroup of critically ill children in whom immunostimulatory therapies should be studied. However, future confirmatory studies should monitor monocytic HLA-DR expression in a larger critically ill patient population for a longer period in order to establish the time to recovery of low expression and its impact on long-term complications, the physician said.

Dr. Boeddha reported having no financial conflicts regarding the award-winning study, supported by the European Union and Erasmus University.

SOURCE: Boeddha NP et al. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2018 Oct;37(10):1034-40.

LJUBLJANA, SLOVENIA – During their first 4 days in the pediatric ICU, critically ill children have significantly reduced human leukocyte antigen (HLA)–DR expression within all three major subsets of monocytes. The reductions are seen regardless of whether the children were admitted for sepsis, trauma, or after surgery, Navin Boeddha, MD, PhD, reported in his PIDJ Award Lecture at the annual meeting of the European Society for Paediatric Infectious Diseases.

The PIDJ Award is given annually by the editors of the Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal in recognition of what they deem the most important study published in the journal during the prior year. This one stood out because it identified promising potential laboratory markers that have been sought as a prerequisite to developing immunostimulatory therapies aimed at improving outcomes in severely immunosuppressed children.

Researchers are particularly eager to explore this investigative treatment strategy because the mortality and long-term morbidity of pediatric sepsis, in particular, remain unacceptably high. The hope now is that HLA-DR expression on monocyte subsets will be helpful in directing granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor, interferon-gamma, and other immunostimulatory therapies to the pediatric ICU patients with the most favorable benefit/risk ratio, according to Dr. Boeddha of Sophia Children’s Hospital and Erasmus University, Rotterdam, the Netherlands.

He reported on 37 critically ill children admitted to a pediatric ICU – 12 for sepsis, 11 post surgery, 10 for trauma, and 4 for other reasons – as well as 37 healthy controls. HLA-DR expression on monocyte subsets was measured by flow cytometry upon admission and again on each of the following 3 days.

The impetus for this study is that severe infection, major surgery, and severe trauma are often associated with immunosuppression. And while prior work in septic adults has concluded that decreased monocytic HLA-DR expression is a marker for immunosuppression – and that the lower the level of such expression, the greater the risk of nosocomial infection and death – this phenomenon hasn’t been well studied in critically ill children, he explained.

Dr. Boeddha and coinvestigators found that monocytic HLA-DR expression, which plays a major role in presenting antigens to T cells, decreased over time during the critically ill children’s first 4 days in the pediatric ICU. Moreover, it was lower than in controls at all four time points. This was true both for the percentage of HLA-DR–expressing monocytes of all subsets, as well as for HLA-DR mean fluorescence intensity.

In the critically ill study population as a whole, the percentage of classical monocytes – that is, CD14++ CD16– monocytes – was significantly greater at admission than in healthy controls by margins of 95% and 87%, while the percentage of nonclassical CD14+/-CD16++ monocytes was markedly lower at 2% than the 9% figure in controls.

The biggest discrepancy in monocyte subset distribution was seen in patients admitted for sepsis. Their percentage of classical monocytes was lower than in controls by a margin of 82% versus 87%; however, their proportion of intermediate monocytes (CD14++ CD16+) upon admission was twice that of controls, and it climbed further to 14% on day 2.

Among the key findings in the Rotterdam study: 13 of 37 critically ill patients experienced at least one nosocomial infection while in the pediatric ICU. Their day 2 percentage of HLA-DR–expressing classical monocytes was 42%, strikingly lower than the 78% figure in patients who didn’t develop an infection. Also, the 6 patients who died had only a 33% rate of HLA-DR–expressing classical monocytes on day 3 after pediatric ICU admission versus a 63% rate in survivors of their critical illness.

Thus, low HLA-DR expression on classical monocytes early during the course of a pediatric ICU stay may be the sought-after biomarker that identifies a particularly high-risk subgroup of critically ill children in whom immunostimulatory therapies should be studied. However, future confirmatory studies should monitor monocytic HLA-DR expression in a larger critically ill patient population for a longer period in order to establish the time to recovery of low expression and its impact on long-term complications, the physician said.

Dr. Boeddha reported having no financial conflicts regarding the award-winning study, supported by the European Union and Erasmus University.

SOURCE: Boeddha NP et al. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2018 Oct;37(10):1034-40.

REPORTING FROM ESPID 2019

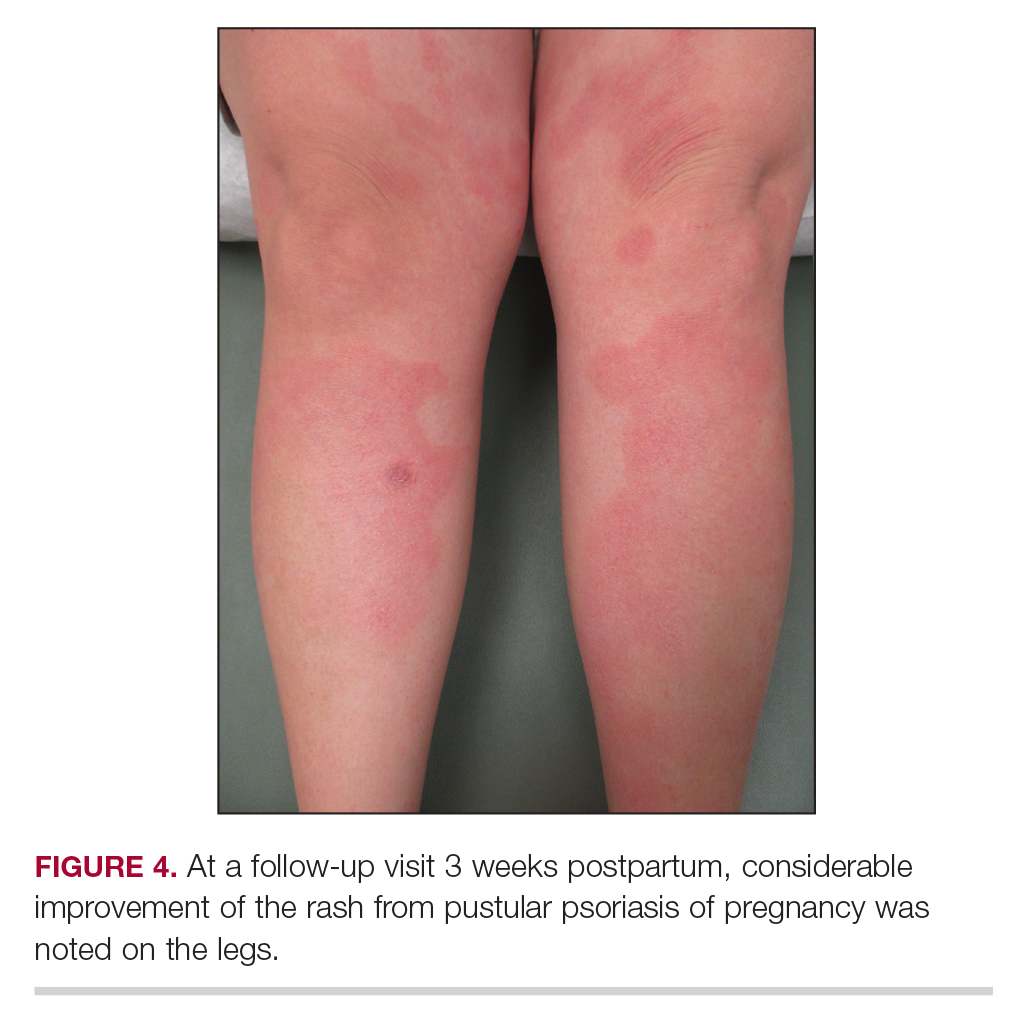

Considerations for Psoriasis in Pregnancy

1. Trivedi MK, Vaughn AR, Murase JE. Pustular psoriasis of pregnancy: current perspectives. Int J Womens Health. 2018;10:109-115.

2. Kondo RN, Araújo FM, Pereira AM, et al. Pustular psoriasis of pregnancy (impetigo herpetiformis)—case report. An Bras Dermatol. 2013;88(6 suppl 1):186-189.

3. Oumeish OY, Farraj SE, Bataineh AS. Some aspects of impetigo herpetiformis. Arch Dermatol. 1982;118:103-105.

4. Flynn A, Burke N, Byrne B, et al. Two case reports of generalized pustular psoriasis of pregnancy: different outcomes. Obstet Med. 2016;9:55-59.

5. Shaw CJ, Wu P, Sriemevan A. First trimester impetigo herpetiformis in multiparous female successfully treated with oral cyclosporine. BMJ Case Rep. 2011;2011:bcr0220113915.

6. Pitch M, Somers K, Scott G, et al. A case of pustular psoriasis of pregnancy with positive maternal-fetal outcomes. Cutis. 2018;101:278-280.

7. Namazi N, Dadkhahfar S. Impetigo herpetiformis: review of pathogenesis, complication, and treatment [published April 4, 2018]. Dermatol Res Pract. 2018;2018:5801280. doi:10.1155/2018/5801280. eCollection 2018.

8. Lehrhoff S, Pomeranz MK. Specific dermatoses of pregnancy and their treatment. Dermatol Ther. 2013;26:274-284.

9. Ulubay M, Keskin U, Fidan U, et al. Case report of a rare dermatosis in pregnancy: impetigo herpetiformis. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2015;41:301-303.

10. Robinson A, Van Voorhees AS, Hsu S, et al. Treatment of pustular psoriasis: from the Medical Board of the National Psoriasis Foundation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:279-288.

11. Hazarika D. Generalized pustular psoriasis of pregnancy successfully treated with cyclosporine. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2009;75:638.

12. Puig L, Barco D, Alomar A. Treatment of psoriasis with anti-TNF drugs during pregnancy: case report and review of the literature. Dermatology. 2010;220:71-76.

13. Bozdag K, Ozturk S, Ermete M. A case of recurrent impetigo herpetiformis treated with systemic corticosteroids and narrow¬band UVB [published online January 20, 2012]. Cutan Ocul Toxicol. 2012;31:67-69.

1. Trivedi MK, Vaughn AR, Murase JE. Pustular psoriasis of pregnancy: current perspectives. Int J Womens Health. 2018;10:109-115.

2. Kondo RN, Araújo FM, Pereira AM, et al. Pustular psoriasis of pregnancy (impetigo herpetiformis)—case report. An Bras Dermatol. 2013;88(6 suppl 1):186-189.

3. Oumeish OY, Farraj SE, Bataineh AS. Some aspects of impetigo herpetiformis. Arch Dermatol. 1982;118:103-105.

4. Flynn A, Burke N, Byrne B, et al. Two case reports of generalized pustular psoriasis of pregnancy: different outcomes. Obstet Med. 2016;9:55-59.

5. Shaw CJ, Wu P, Sriemevan A. First trimester impetigo herpetiformis in multiparous female successfully treated with oral cyclosporine. BMJ Case Rep. 2011;2011:bcr0220113915.

6. Pitch M, Somers K, Scott G, et al. A case of pustular psoriasis of pregnancy with positive maternal-fetal outcomes. Cutis. 2018;101:278-280.

7. Namazi N, Dadkhahfar S. Impetigo herpetiformis: review of pathogenesis, complication, and treatment [published April 4, 2018]. Dermatol Res Pract. 2018;2018:5801280. doi:10.1155/2018/5801280. eCollection 2018.

8. Lehrhoff S, Pomeranz MK. Specific dermatoses of pregnancy and their treatment. Dermatol Ther. 2013;26:274-284.

9. Ulubay M, Keskin U, Fidan U, et al. Case report of a rare dermatosis in pregnancy: impetigo herpetiformis. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2015;41:301-303.

10. Robinson A, Van Voorhees AS, Hsu S, et al. Treatment of pustular psoriasis: from the Medical Board of the National Psoriasis Foundation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:279-288.

11. Hazarika D. Generalized pustular psoriasis of pregnancy successfully treated with cyclosporine. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2009;75:638.

12. Puig L, Barco D, Alomar A. Treatment of psoriasis with anti-TNF drugs during pregnancy: case report and review of the literature. Dermatology. 2010;220:71-76.

13. Bozdag K, Ozturk S, Ermete M. A case of recurrent impetigo herpetiformis treated with systemic corticosteroids and narrow¬band UVB [published online January 20, 2012]. Cutan Ocul Toxicol. 2012;31:67-69.

1. Trivedi MK, Vaughn AR, Murase JE. Pustular psoriasis of pregnancy: current perspectives. Int J Womens Health. 2018;10:109-115.

2. Kondo RN, Araújo FM, Pereira AM, et al. Pustular psoriasis of pregnancy (impetigo herpetiformis)—case report. An Bras Dermatol. 2013;88(6 suppl 1):186-189.

3. Oumeish OY, Farraj SE, Bataineh AS. Some aspects of impetigo herpetiformis. Arch Dermatol. 1982;118:103-105.

4. Flynn A, Burke N, Byrne B, et al. Two case reports of generalized pustular psoriasis of pregnancy: different outcomes. Obstet Med. 2016;9:55-59.

5. Shaw CJ, Wu P, Sriemevan A. First trimester impetigo herpetiformis in multiparous female successfully treated with oral cyclosporine. BMJ Case Rep. 2011;2011:bcr0220113915.

6. Pitch M, Somers K, Scott G, et al. A case of pustular psoriasis of pregnancy with positive maternal-fetal outcomes. Cutis. 2018;101:278-280.

7. Namazi N, Dadkhahfar S. Impetigo herpetiformis: review of pathogenesis, complication, and treatment [published April 4, 2018]. Dermatol Res Pract. 2018;2018:5801280. doi:10.1155/2018/5801280. eCollection 2018.

8. Lehrhoff S, Pomeranz MK. Specific dermatoses of pregnancy and their treatment. Dermatol Ther. 2013;26:274-284.

9. Ulubay M, Keskin U, Fidan U, et al. Case report of a rare dermatosis in pregnancy: impetigo herpetiformis. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2015;41:301-303.

10. Robinson A, Van Voorhees AS, Hsu S, et al. Treatment of pustular psoriasis: from the Medical Board of the National Psoriasis Foundation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:279-288.

11. Hazarika D. Generalized pustular psoriasis of pregnancy successfully treated with cyclosporine. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2009;75:638.

12. Puig L, Barco D, Alomar A. Treatment of psoriasis with anti-TNF drugs during pregnancy: case report and review of the literature. Dermatology. 2010;220:71-76.

13. Bozdag K, Ozturk S, Ermete M. A case of recurrent impetigo herpetiformis treated with systemic corticosteroids and narrow¬band UVB [published online January 20, 2012]. Cutan Ocul Toxicol. 2012;31:67-69.

To be, or not to be ... on backup?

A staffing backup system is essential

It was late 2011. We were a practice of around 20 physicians, and just starting to integrate advanced practice providers into our practice. Our average daily census was about 100 patients and slightly more than 50% of our services were resident services.

My boss, colleague, friend, and mentor – Charles “Chuck” Sargent, MD, and I were on service together early one Saturday morning; Chuck gets a phone call that one of our colleagues was ill. With just 10 physicians working and 10 off, it was an ordeal for Chuck to call all 10 colleagues. Unlike most times, no one could come to moonlight that day. In the end Chuck and I took care of our colleague’s patients.

Yes, it was an exhausting few days, but illness and family needs do not come announced. Now, close to a decade later, we are a practice of 70 physicians and 16 advanced practice providers, our average daily census is about 270 patients, and we have two backup physicians every day – known as Jeopardy-1 and Jeopardy-2. Paternity leave, maternity leave, minor illness, minor trauma, surgery, and family needs are common for our practice. We considered it a good year when we utilized our Jeopardy-1 and Jeopardy-2 for 10% and 1% respectively; and for the past year with a lot of needs, we employed Jeopardy-1 and Jeopardy-2 for 25% and 10%, respectively.

A staffing backup system is a necessary tool for almost every practice. Not having a formal backup system doesn’t mean you don’t need one or you don’t have one – it is just called “no formal backup system.” The Society of Hospital Medicine’s State of Hospital Medicine Reports (SoHM) have been providing data about staffing backup systems every other year. Backup systems come in three flavors. The first system is no formal backup, which means the leaders of the program scramble for coverage every time there is a need. The second is a voluntary backup system in which clinicians volunteer to be on a backup schedule, and the third is a mandatory system in which all or most clinicians are required to be on the backup schedule.

The cumulative data reported in the 2014, 2016, and 2018 SoHM for hospital medicine groups serving adults only, children only, and both adults and children (weighted for number of groups reporting), suggests that 48.3% of respondent practices had no formal backup system, 31.7% had a voluntary system, and 20% had a mandatory backup system.

When we look at different populations served, the trend of “no formal backup system” responses is in decline. The 2014, 2016, and 2018 SoHM reports for hospital medicine groups serving adults, children, and both adults and children, reinforce such trends. The SoHM 2018 report shows 65.6% of hospital medicine groups serving children, 41.6% of groups serving adults, and only 25% of groups serving both adults and children have “no formal backup system.” Our medicine-pediatrics colleagues seem to be leading the trend and have already deduced that, for a solid practice, a backup system is a necessity.

It is also important to see the trend of “no formal backup system” based on geographic area, employer type, academic status, or total number of full-time employees. As we would have predicted, the larger the group the more likely they are to have a backup system. For academic practices a similar trend was seen; they had a higher percentage of some type of backup system year after year.

When it comes to compensation for backup work, four patterns were explored by the SoHM over the years. The most common type of arrangement was “no additional compensation for being on the backup schedule, but additional compensation was provided when called into work.” This kind of arrangement would be easiest to negotiate when the hospitalist and the employer sit across a table. There is nothing at risk for the employer when there isn’t a need, or when there is a need to fill a shift.

The least common method was “additional compensation for being on the backup schedule, but no additional compensation if called into work.” From employers’ perspectives, this is an extra expense and is not ideal for the hospitalist either. In the middle of the pack were “no additional compensation associated with the backup plan” (the second most common model), while the third most common model was “additional compensation for being on the backup schedule, as well as additional compensation if called into work.”

Once you have seen one hospital medicine practice, you have seen one hospital medicine practice. There are different needs for every group, and the backup system – as well its compensation model – has to be designed for it. Thankfully, the SoHM reports reveal the patterns and trends so that we don’t have to reinvent the wheel. For our practice, we decreased a week of clinical service for 2 weeks a year of backup. Every time we activate our backup system, the person coming in receives extra compensation or a similar shift off. In the long run, our backup system didn’t kill us, but rather made us stronger as a group.

Dr. Chadha is interim division chief in the division of hospital medicine at the University of Kentucky HealthCare in Lexington. He actively leads efforts of recruiting, scheduling, practice analysis, and operation of the group. He is a first-time member of the SHM Practice Analysis Committee. Ms. Babb is administrative support associate in the division of hospital medicine at University of Kentucky HealthCare.

A staffing backup system is essential

A staffing backup system is essential

It was late 2011. We were a practice of around 20 physicians, and just starting to integrate advanced practice providers into our practice. Our average daily census was about 100 patients and slightly more than 50% of our services were resident services.

My boss, colleague, friend, and mentor – Charles “Chuck” Sargent, MD, and I were on service together early one Saturday morning; Chuck gets a phone call that one of our colleagues was ill. With just 10 physicians working and 10 off, it was an ordeal for Chuck to call all 10 colleagues. Unlike most times, no one could come to moonlight that day. In the end Chuck and I took care of our colleague’s patients.

Yes, it was an exhausting few days, but illness and family needs do not come announced. Now, close to a decade later, we are a practice of 70 physicians and 16 advanced practice providers, our average daily census is about 270 patients, and we have two backup physicians every day – known as Jeopardy-1 and Jeopardy-2. Paternity leave, maternity leave, minor illness, minor trauma, surgery, and family needs are common for our practice. We considered it a good year when we utilized our Jeopardy-1 and Jeopardy-2 for 10% and 1% respectively; and for the past year with a lot of needs, we employed Jeopardy-1 and Jeopardy-2 for 25% and 10%, respectively.

A staffing backup system is a necessary tool for almost every practice. Not having a formal backup system doesn’t mean you don’t need one or you don’t have one – it is just called “no formal backup system.” The Society of Hospital Medicine’s State of Hospital Medicine Reports (SoHM) have been providing data about staffing backup systems every other year. Backup systems come in three flavors. The first system is no formal backup, which means the leaders of the program scramble for coverage every time there is a need. The second is a voluntary backup system in which clinicians volunteer to be on a backup schedule, and the third is a mandatory system in which all or most clinicians are required to be on the backup schedule.

The cumulative data reported in the 2014, 2016, and 2018 SoHM for hospital medicine groups serving adults only, children only, and both adults and children (weighted for number of groups reporting), suggests that 48.3% of respondent practices had no formal backup system, 31.7% had a voluntary system, and 20% had a mandatory backup system.

When we look at different populations served, the trend of “no formal backup system” responses is in decline. The 2014, 2016, and 2018 SoHM reports for hospital medicine groups serving adults, children, and both adults and children, reinforce such trends. The SoHM 2018 report shows 65.6% of hospital medicine groups serving children, 41.6% of groups serving adults, and only 25% of groups serving both adults and children have “no formal backup system.” Our medicine-pediatrics colleagues seem to be leading the trend and have already deduced that, for a solid practice, a backup system is a necessity.

It is also important to see the trend of “no formal backup system” based on geographic area, employer type, academic status, or total number of full-time employees. As we would have predicted, the larger the group the more likely they are to have a backup system. For academic practices a similar trend was seen; they had a higher percentage of some type of backup system year after year.

When it comes to compensation for backup work, four patterns were explored by the SoHM over the years. The most common type of arrangement was “no additional compensation for being on the backup schedule, but additional compensation was provided when called into work.” This kind of arrangement would be easiest to negotiate when the hospitalist and the employer sit across a table. There is nothing at risk for the employer when there isn’t a need, or when there is a need to fill a shift.

The least common method was “additional compensation for being on the backup schedule, but no additional compensation if called into work.” From employers’ perspectives, this is an extra expense and is not ideal for the hospitalist either. In the middle of the pack were “no additional compensation associated with the backup plan” (the second most common model), while the third most common model was “additional compensation for being on the backup schedule, as well as additional compensation if called into work.”

Once you have seen one hospital medicine practice, you have seen one hospital medicine practice. There are different needs for every group, and the backup system – as well its compensation model – has to be designed for it. Thankfully, the SoHM reports reveal the patterns and trends so that we don’t have to reinvent the wheel. For our practice, we decreased a week of clinical service for 2 weeks a year of backup. Every time we activate our backup system, the person coming in receives extra compensation or a similar shift off. In the long run, our backup system didn’t kill us, but rather made us stronger as a group.

Dr. Chadha is interim division chief in the division of hospital medicine at the University of Kentucky HealthCare in Lexington. He actively leads efforts of recruiting, scheduling, practice analysis, and operation of the group. He is a first-time member of the SHM Practice Analysis Committee. Ms. Babb is administrative support associate in the division of hospital medicine at University of Kentucky HealthCare.

It was late 2011. We were a practice of around 20 physicians, and just starting to integrate advanced practice providers into our practice. Our average daily census was about 100 patients and slightly more than 50% of our services were resident services.

My boss, colleague, friend, and mentor – Charles “Chuck” Sargent, MD, and I were on service together early one Saturday morning; Chuck gets a phone call that one of our colleagues was ill. With just 10 physicians working and 10 off, it was an ordeal for Chuck to call all 10 colleagues. Unlike most times, no one could come to moonlight that day. In the end Chuck and I took care of our colleague’s patients.

Yes, it was an exhausting few days, but illness and family needs do not come announced. Now, close to a decade later, we are a practice of 70 physicians and 16 advanced practice providers, our average daily census is about 270 patients, and we have two backup physicians every day – known as Jeopardy-1 and Jeopardy-2. Paternity leave, maternity leave, minor illness, minor trauma, surgery, and family needs are common for our practice. We considered it a good year when we utilized our Jeopardy-1 and Jeopardy-2 for 10% and 1% respectively; and for the past year with a lot of needs, we employed Jeopardy-1 and Jeopardy-2 for 25% and 10%, respectively.

A staffing backup system is a necessary tool for almost every practice. Not having a formal backup system doesn’t mean you don’t need one or you don’t have one – it is just called “no formal backup system.” The Society of Hospital Medicine’s State of Hospital Medicine Reports (SoHM) have been providing data about staffing backup systems every other year. Backup systems come in three flavors. The first system is no formal backup, which means the leaders of the program scramble for coverage every time there is a need. The second is a voluntary backup system in which clinicians volunteer to be on a backup schedule, and the third is a mandatory system in which all or most clinicians are required to be on the backup schedule.

The cumulative data reported in the 2014, 2016, and 2018 SoHM for hospital medicine groups serving adults only, children only, and both adults and children (weighted for number of groups reporting), suggests that 48.3% of respondent practices had no formal backup system, 31.7% had a voluntary system, and 20% had a mandatory backup system.

When we look at different populations served, the trend of “no formal backup system” responses is in decline. The 2014, 2016, and 2018 SoHM reports for hospital medicine groups serving adults, children, and both adults and children, reinforce such trends. The SoHM 2018 report shows 65.6% of hospital medicine groups serving children, 41.6% of groups serving adults, and only 25% of groups serving both adults and children have “no formal backup system.” Our medicine-pediatrics colleagues seem to be leading the trend and have already deduced that, for a solid practice, a backup system is a necessity.

It is also important to see the trend of “no formal backup system” based on geographic area, employer type, academic status, or total number of full-time employees. As we would have predicted, the larger the group the more likely they are to have a backup system. For academic practices a similar trend was seen; they had a higher percentage of some type of backup system year after year.

When it comes to compensation for backup work, four patterns were explored by the SoHM over the years. The most common type of arrangement was “no additional compensation for being on the backup schedule, but additional compensation was provided when called into work.” This kind of arrangement would be easiest to negotiate when the hospitalist and the employer sit across a table. There is nothing at risk for the employer when there isn’t a need, or when there is a need to fill a shift.

The least common method was “additional compensation for being on the backup schedule, but no additional compensation if called into work.” From employers’ perspectives, this is an extra expense and is not ideal for the hospitalist either. In the middle of the pack were “no additional compensation associated with the backup plan” (the second most common model), while the third most common model was “additional compensation for being on the backup schedule, as well as additional compensation if called into work.”

Once you have seen one hospital medicine practice, you have seen one hospital medicine practice. There are different needs for every group, and the backup system – as well its compensation model – has to be designed for it. Thankfully, the SoHM reports reveal the patterns and trends so that we don’t have to reinvent the wheel. For our practice, we decreased a week of clinical service for 2 weeks a year of backup. Every time we activate our backup system, the person coming in receives extra compensation or a similar shift off. In the long run, our backup system didn’t kill us, but rather made us stronger as a group.

Dr. Chadha is interim division chief in the division of hospital medicine at the University of Kentucky HealthCare in Lexington. He actively leads efforts of recruiting, scheduling, practice analysis, and operation of the group. He is a first-time member of the SHM Practice Analysis Committee. Ms. Babb is administrative support associate in the division of hospital medicine at University of Kentucky HealthCare.

Timely Diagnosis of Lung Cancer in a Dedicated VA Referral Unit with Endobronchial Ultrasound Capability (FULL)

Lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer death in the US, with 154 050 deaths in 2018.1 There have been many attempts to reduce mortality of the disease through early diagnosis with use of computed tomography (CT). The National Lung Cancer Screening trial showed that screening high-risk populations with low-dose CT (LDCT) can reduce mortality.2 However, implementing LDCT screening in the clinical setting has proven challenging, as illustrated by the VA Lung Cancer Screening Demonstration Project (LCSDP).3 A lung cancer diagnosis typically comprises several steps that require different medical specialties; this can lead to delays. In the LCSDP, the mean time to diagnosis was 137 days.3 There are no federal standards for timeliness of lung cancer diagnosis.

The nonprofit RAND Corporation is the only American research organization that has published guidelines specifying acceptable intervals for the diagnosis and treatment of lung cancer. In Quality of Care for Oncologic Conditions and HIV, RAND Corporation researchers propose management quality indicators: lung cancer diagnosis within 2 months of an abnormal radiologic study and treatment within 6 weeks of diagnosis.4 The Swedish Lung Cancer Study5 and the Canadian Strategy for Cancer Control6 both recommended a standard of about 30 days—half the time recommended by the RAND Corporation.

Bukhari and colleagues at the Dayton US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Medical Center (VAMC) conducted a quality improvement study that examined lung cancer diagnosis and management.7 They found the time (SD) from abnormal chest imaging to diagnosis was 35.5 (31.6) days. Of those veterans who received a lung cancer diagnosis, 89.2% had the diagnosis made within the 60 days recommended by the RAND Corporation. Although these results surpass those of the LCSDP, they can be exceeded.

Beyond the potential emotional distress of awaiting the final diagnosis of a lung lesion, a delay in diagnosis and treatment may adversely affect outcomes. LDCT screening has been shown to reduce mortality, which implies a link between survival and time to intervention. There is no published evidence that time to diagnosis in advanced stage lung cancer affects outcome. The National Cancer Database (NCDB) contains informtion on about 70% of the cancers diagnosed each year in the US.8 An analysis of 4984 patients with stage IA squamous cell lung cancer undergoing lobectomy from NCDB showed that earlier surgery was associated with an absolute decrease in 5-year mortality of 5% to 8%. 9 Hence, at least in early-stage disease, reduced time from initial suspect imaging to definitive treatment may improve survival.

A system that coordinates the requisite diagnostic steps and avoids delays should provide a significant improvement in patient care. The results of such an approach that utilized nurse navigators has been previously published. 10 Here, we present the results of a dedicated VA referral clinic with priority access to pulmonary consultation and procedures in place that are designed to expedite the diagnosis of potential lung cancer.

Methods

The John L. McClellan Memorial Veterans Hospital (JLMMVH) in Little Rock, Arkansas institutional review board approved this study, which was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Requirement for informed consent was waived, and patient confidentiality was maintained throughout.

We have developed a plan of care specifically to facilitate diagnosis and treatment of the large number of veterans referred to the JLMMVH Diagnostic Clinic for abnormal results of chest imaging. The clinic has priority access to same-day imaging and subspecialty consultation services. In the clinic, medical students and residents perform evaluations and a registered nurse (RN) manager coordinates care.

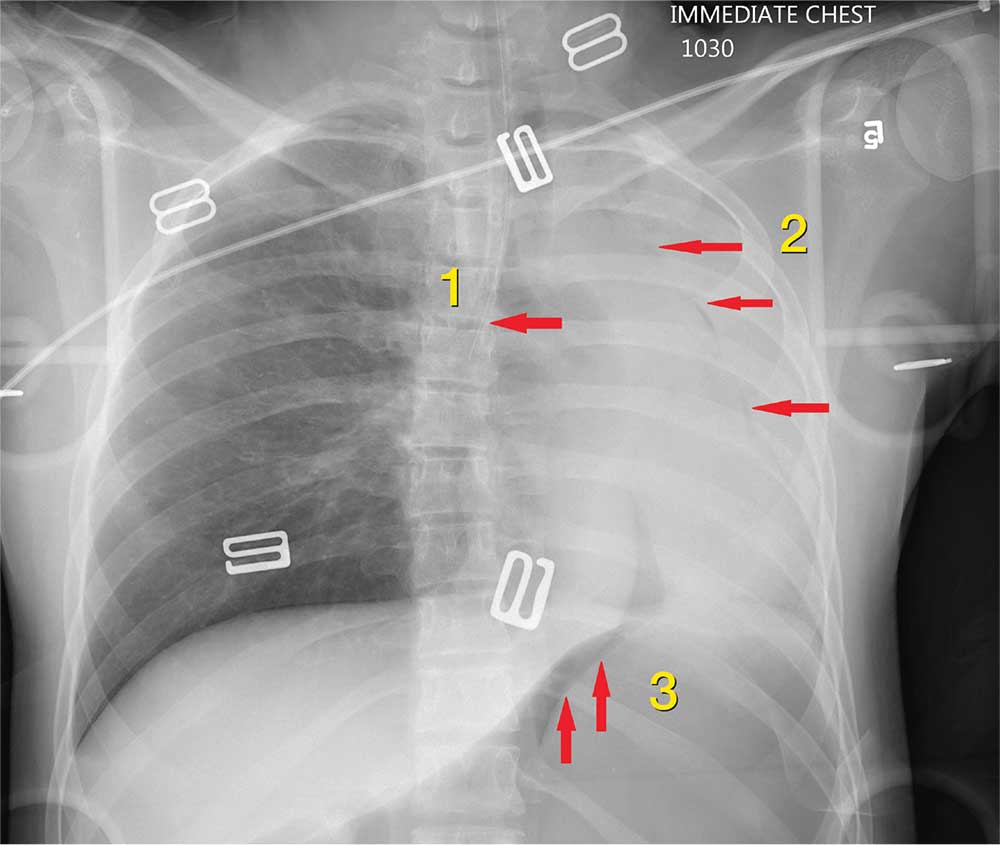

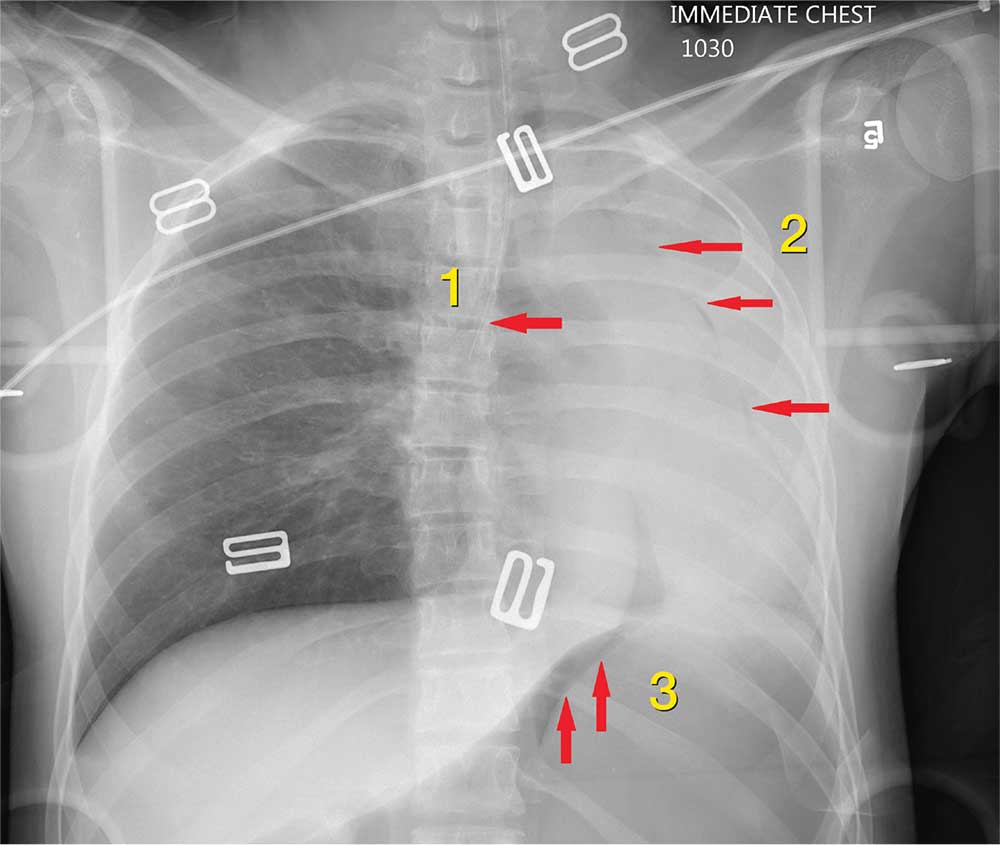

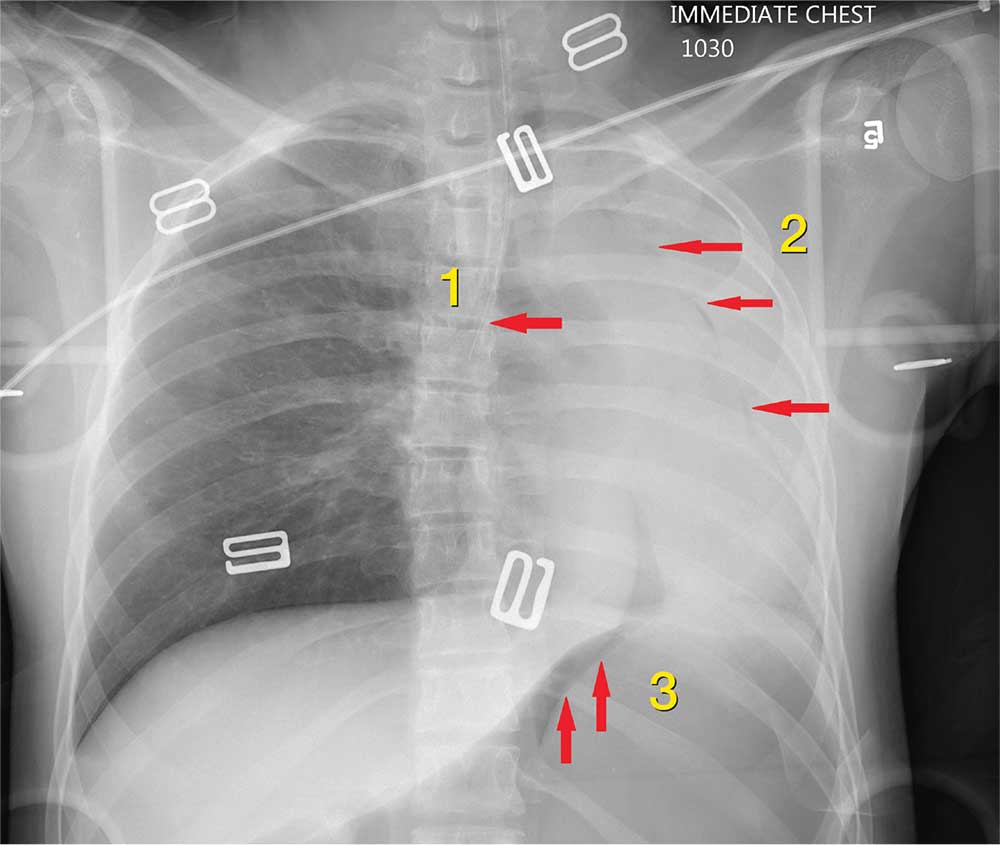

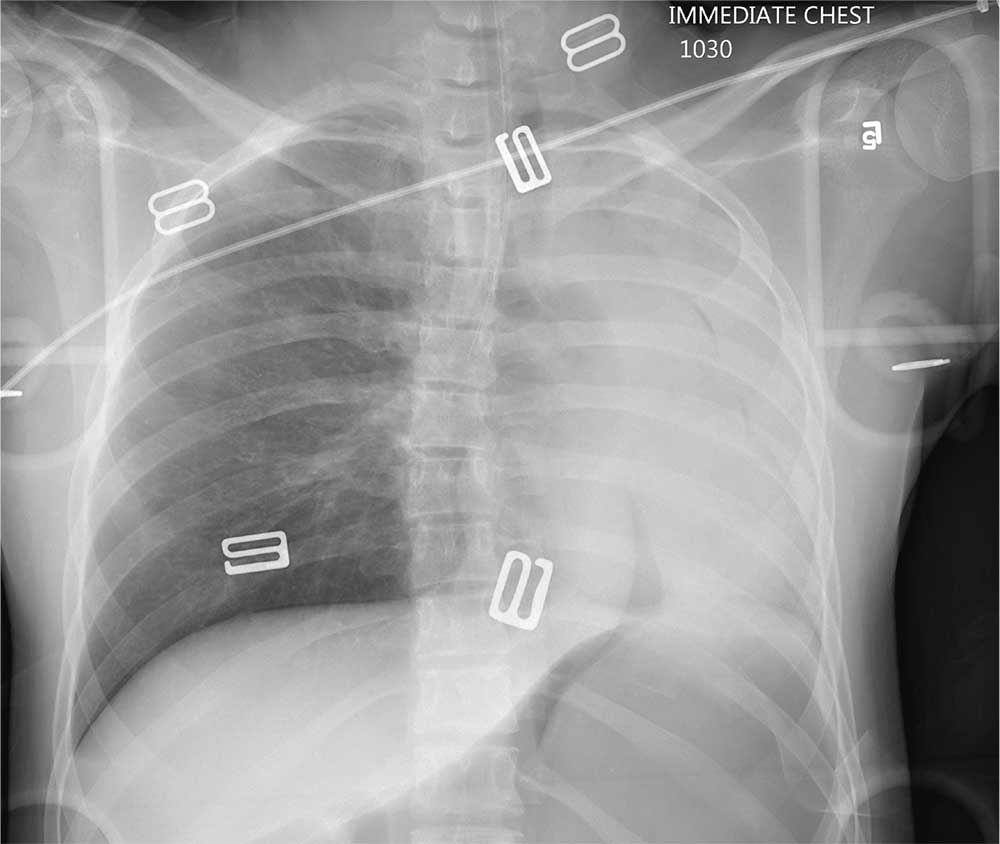

A Diagnostic Clinic consult for abnormal thoracic imaging immediately triggers an e-consult to an interventional pulmonologist (Figure). The RN manager and pulmonologist perform a joint review of records/imaging prior to scheduling, and the pulmonologist triages the patient. Triage options include follow-up imaging, bronchoscopy with endobronchial ultrasound (EBUS), endoscopic ultrasound (EUS), and CT-guided biopsy.

The RN manager then schedules a clinic visit that includes a medical evaluation by clinic staff and any indicated procedures on the same day. The interventional pulmonologist performs EBUS, EUS with the convex curvilinear bronchoscope, or both combined as indicated for diagnosis and staging. All procedures are performed in the JLMMVH bronchoscopy suite with standard conscious sedation using midazolam and fentanyl. Any other relevant procedures, such as pleural tap, also are performed at time of procedure. The pulmonologist and an attending pathologist interpret biopsies obtained in the bronchoscopy suite.

We performed a retrospective chart review of patients diagnosed with primary lung cancer through referral to the JLMMVH Diagnostic Clinic. The primary outcome was time from initial suspect chest imaging to cancer diagnosis. The study population consisted of patients referred for abnormal thoracic imaging between January 1, 2013 and December 31, 2016 and subsequently diagnosed with a primary lung cancer.

Subjects were excluded if (1) the patient was referred from outside our care network and a delay of > 10 days occurred between initial lesion imaging and referral; (2) the patient did not show up for appointments or chose to delay evaluation following referral; (3) biopsy demonstrated a nonlung primary cancer; and (4) serious intercurrent illness interrupted the diagnostic plan. In some cases, the radiologist or consulting pulmonologist had judged the lung lesion too small for immediate biopsy and recommended repeat imaging at a later date.

Patients were included in the study if the follow- up imaging led to a lung cancer diagnosis. However, because the interval between the initial imaging and the follow-up imaging in these patients did not represent a systems delay problem, the date of the scheduled follow-up abnormal imaging, which resulted in initiation of a potential cancer evaluation, served as the index suspect imaging date for this study.

Patient electronic medical records were reviewed and the following data were abstracted: date of the abnormal imaging that led to referral and time from abnormal chest X-ray to chest CT scan if applicable; date of referral and date of clinic visit; date of biopsy; date of lung cancer diagnosis; method of obtaining diagnostic specimen; lung cancer type and stage; type and date of treatment initiation or decision for supportive care only; and decision to seek further evaluation or care outside of our system.

All patients diagnosed with lung cancer during the study period were reviewed for inclusion, hence no required sample-size estimate was calculated. All outcomes were assessed as calendar days. The primary outcome was the time from the index suspect chest imaging study to the date of diagnosis of lung cancer. Prior to the initiation of our study, we chose this more stringent 30-day recommendation of the Canadian6 and Swedish5 studies as the comparator for our primary outcome, although data with respect to the 60-day Rand Corporation guidelines also are reported.4

Statistical Methods

The mean time to lung cancer diagnosis in our cohort was compared with this 30-day standard using a 2-sided Mann–Whitney U test. Normality of data distribution was determined using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. For statistical significance testing a P value of .05 was used. Statistical calculations were performed using R statistical software version 3.2.4. Secondary outcomes consisted of time from diagnosis to treatment; proportion of subjects diagnosed within 60 days; time from initial clinic visit to biopsy; and time from biopsy to diagnosis.

Results

Overall, 222 patients were diagnosed with a malignant lung lesion, of which 63 were excluded from analysis: 22 cancelled or did not appear for appointments, declined further evaluation, or completed evaluation outside of our network; 13 had the diagnosis made prior to Diagnostic Clinic visit; 13 proved to have a nonlung primary tumor presenting in the lung or mediastinal nodes; 12 were delayed > 10 days in referral from an outside network; and 3 had an intervening serious acute medical problem forcing delay in the diagnostic process.

Of the 159 included subjects, 154 (96.9%) were male, and the mean (SD) age was 67.6 (8.1) years. For 76 subjects, the abnormal chest X-ray and subsequent chest CT scan were performed the same day or the lung lesion had initially been noted on a CT scan. For 54 subjects, there was a delay of ≥ 1 week in obtaining a chest CT scan. The mean (SD) time from placement of the Diagnostic Clinic consultation by the primary care provider (PCP) or other provider and the initial Diagnostic Clinic visit was 6.3 (4.4) days. The mean (SD) time from suspect imaging to diagnosis (primary outcome) was 22.6(16.6) days.

The distribution of this outcome was nonnormal (Kolmogorov-Smirnov test P < .01). When compared with the standard of 30 days, the primary outcome of 22.6 days was significantly shorter (2-sided Mann–Whitney U test P < .01). Three-quarters (76.1%) of subjects were diagnosed within 30 days and 95.0% of subjects were diagnosed within 60 days of the initial imaging. For the 8 subjects diagnosed after 60 days, contributing factors included PCP delay in Diagnostic Clinic consultation, initial negative biopsy, delay in performance of chest CT scan prior to consultation, and outsourcing of positron emission tomography (PET) scans.

Overall, 57 (35.8%) of the subjects underwent biopsy on the day of their Diagnostic Clinic visit: 14 underwent CT-guided biopsy and 43 underwent EBUS/EUS. Within 2 days of the initial visit 106 subjects (66.7%) had undergone biopsy. The mean (SD) time from initial Diagnostic Clinic visit to biopsy was 6.3 (9.5) days. The mean (SD) interval was 1.8 (3.0) days for EBUS/ EUS and 11.3 (11.7) days for CT-guided biopsy. The mean (SD) interval from biopsy to diagnosis was 3.2 (6.2) days with 64 cases (40.3%) diagnosed the day of biopsy.

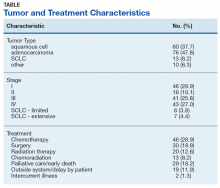

Excluding subjects whose treatment was delayed by patient choice or intercurrent illness, and those who left the VA system to seek treatment elsewhere (n = 21), 24 opted for palliative care, 5 died before treatment could be initiated, and 109 underwent treatment for their tumors (Table). The mean times (SD) from diagnosis to treatment were: chemotherapy alone 34.7 (25.3) days; chemoradiation 37.0 (22.8) days; surgery 44.3 (24.4) days; radiation therapy alone 47.9 (26.0) days. With respect to the RAND Corporation recommended diagnosis to treatment time, 60.9% of chemotherapy alone, 61.5% of chemoradiation, 66.7% of surgery, and 45.0% of radiation therapy alone treatments were initiated within the 6-week window.

Discussion

This retrospective case study demonstrates the effectiveness of a dedicated diagnostic clinic with priority EBUS/EUS access in diagnosing lung cancer within the VA system. Although there is no universally accepted quality standard for comparison, the RAND Corporation recommendation of 60 days from abnormal imaging to diagnosis and the Dayton VAMC published mean of 35.5 days are guideposts; however, the results from the Dayton VAMC may have been affected negatively by some subjects undergoing serial imaging for asymptomatic nodules. We chose a more stringent standard of 30 days as recommended by Swedish and Canadian task forces.

When diagnosing lung cancer, the overriding purpose of the Diagnostic Clinic is to minimize system delays. The method is to have as simple a task as possible for the PCP or other provider who identifies a lung nodule or mass and submits a single consultation request to the Diagnostic Clinic. Once this consultation is placed, the clinic RN manager oversees all further steps required for diagnosis and referral for treatment. The key factor in achieving a mean diagnosis time of 22.6 days is the cooperation between the RN manager and the interventional pulmonologist. When a consultation is received, the RN manager and pulmonologist review the data together and schedule the initial clinic visit; the goal is same-day biopsy, which is achieved in more than one-third of cases. Not all patients with a chest image suspected for lung cancer had it ordered by their PCP. For this reason, a Diagnostic Clinic consultation is available to all health care providers in our system. Many patients reach the clinic after the discovery of a suspect chest X-ray during an emergency department visit, a regularly scheduled subspecialty appointment, or during a preoperative evaluation.

The mean time from initial visit to biopsy was 1.8 days for EBUS/EUS compared with an interval of 11.3 days for CT-guided biopsy. This difference reflects the pulmonologist’s involvement in initial scheduling of Diagnostic Clinic patients. The ability of the pulmonologist to provide an accurate assessment of sample adequacy and a preliminary diagnosis at bedside, with concurrent confirmation by a staff pathologist, permitted the Diagnostic Clinic to inform 40.3% of patients of the finding of malignancy on the day of biopsy. A published comparison of the onsite review of biopsy material showed our pulmonologist and staff pathologists to be equally accurate in their interpretations.11

Sources of Delays

While this study documents the shortest intervals from suspect imaging to diagnosis reported to date, it also identifies sources of system delay in diagnosing lung cancer that JLMMVH could further optimize. The first is the time from initial abnormal chest X-ray imaging to performance of the chest CT scan. On occasion, the index lung lesion is identified unexpectedly on an outpatient or emergency department chest CT scan. With greater use of LDCT lung cancer screening, the initial detection of suspect lesions by CT scanning will increase in the future. However, the PCP most often investigates a patient complaint with a standard chest X-ray that reveals a suspect nodule or mass. When ordered by the PCP as an outpatient test, scheduling of the follow-up chest CT scan is not given priority. More than a third of subjects experienced a delay ≥ 1 week in obtaining a chest CT scan ordered by the PCP; for 29 subjects the delay was ≥ 3weeks. At JLMMVH, the Diagnostic Clinic is given priority in scheduling CT scans. Hence, for suspect lung lesions, the chest CT scan, if not already obtained, is generally performed on the morning of the clinic visit. Educating the PCP to refer the patient immediately to the Diagnostic Clinic rather than waiting to obtain an outpatient chest CT scan may remove this source of unnecessary delay.

Scheduling a CT-guided fine needle aspiration of a lung lesion is another source of system delay. When the chest CT scan is available at the time of the Diagnostic Clinic referral, the clinic visit is scheduled for the earliest day a required CT-guided biopsy can be performed. However, the mean time of 11.3 days from initial Diagnostic Clinic visit to CT-guided biopsy is indicative of the backlog faced by the interventional radiologists.

Although infrequent, PET scans that are required before biopsy can lead to substantial delays. PET scans are performed at our university affiliate, and the joint VA-university lung tumor board sometimes generates requests for such scans prior to tissue diagnosis, yet another source of delay.

The time from referral receipt to the Diagnostic Clinic visit averaged 6.3 days. This delay usually was determined by the availability of the CT-guided biopsy or the dedicated interventional pulmonologist. Although other interventional pulmonologists at JLMMVH may perform the requisite diagnostic procedures, they are not always available for immediate review of imaging studies of referred patients nor can their schedules flexibly accommodate the number of patients seen in our clinic for evaluation.

Lung Cancer Diagnosis

Prompt diagnosis in the setting of a worrisome chest X-ray may help decrease patient anxiety, but does the clinic improve lung cancer treatment outcomes? Such improvement has been demonstrated only in stage IA squamous cell lung cancer.9 Of our study population, 37.7% had squamous cell carcinoma, and 85.5% had non-small cell lung cancer. Of those with non-small cell lung cancer, 28.9% had a clinical stage I tumor. Stage I squamous cell carcinoma, the type of tumor most likely to benefit from early diagnosis and treatment, was diagnosed in 11.3% of patients. With the increased application of LDCT screening, the proportion of veterans identified with early stage lung cancer may rise. The Providence VAMC in Rhode Island reported its results from instituting LDCT screening.12 Prior to screening, 28% of patients diagnosed with lung cancer had a stage I tumor. Following the introduction of LDCT screening, 49% diagnosed by LDCT screening had a stage I tumor. Nearly a third of their patients diagnosed with lung cancer through LDCT screening had squamous cell tumor histology. Thus, we can anticipate an increasing number of veterans with early stage lung cancer who would benefit from timely diagnosis.

The JLMMVH is a referral center for the entire state of Arkansas. Quite a few of its referred patients come from a long distance, which may require overnight housing and other related travel expenses. Apart from any potential outcome benefit, the efficiencies of the system described herein include the minimization of extra trips, an inconvenience and cost to both patient and JLMMVH.

Although the primary task of the clinic is diagnosis, we also seek to facilitate timely treatment. Our lack of an on-site PET scanner and radiation therapy, resources present on-site at the Dayton VAMC, contribute to longer therapy wait times. The shortest mean wait time at JLMMVH is for chemotherapy alone (34.7 days), in part because the JLMMVH oncologists, performing initial consultations 2 to 3 times weekly in the Diagnostic Clinic, are more readily available than are our thoracic surgeons or radiation therapists. Yet overall, JLMMVH patients often face delay from the time of lung cancer diagnosis to initiation of treatment.

The Connecticut Veterans Affairs Healthcare System has published the results of changes in lung cancer management associated with a nurse navigator system.10 Prior to creating the position of cancer care coordinator, filled by an advanced practice RNs, the mean time from clinical suspicion of lung cancer to treatment was 117 days. After 4 years of such care navigation, this waiting time had decreased to 52.4 days. Associated with this dramatic improvement in overall waiting time were decreases in the turnaround time required for performance of CT and PET scans. With respect to this big picture view of lung cancer care, our Diagnostic Clinic serves as a model for the initial step of diagnosis. Coordination and streamlining of the various steps from diagnosis to definitive therapy shall require a more system-wide effort involving all the key players in cancer care.

Conclusion

We have developed a care pathway based in a dedicated diagnostic clinic and have been able to document the shortest interval from abnormality to diagnosis of lung cancer reported in the literature to date. Efficient functioning of this clinic is dependent upon the close cooperation between a full-time RN clinic manager and an interventional pulmonologist experienced in lung cancer management and able to interpret cytologic samples at the time of biopsy. Shortening the delay between diagnosis and definitive therapy remains a challenge and may benefit from the oncology nurse navigator model previously described within the VA system. 10

1. American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts & Figures. https://www.cancer.org/content/dam/cancer-org/research/cancer-facts-and-statistics/annual-cancer-facts-and-figures/2018/cancer-facts-and-figures-2018.pdf. Accessed July 13, 2019.

2. National Lung Screening Trial Research Team, Aberle DR, Adams AM, et al. Reduced lung-cancer mortality with low-dose computed tomographic screening. N Eng J Med. 2011;365(5):395-409.

3. Kinsinger LS, Anderson C, Kim J, et al. Implementation of lung cancer screening in the Veterans Health Administration. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(3):399-406.

4. Asch SM, Kerr EA, Hamilton EG, Reifel JL, McGlynn EA, eds. Quality of Care for Oncologic Conditions and HIV: A Review of the Literature and Quality Indicators. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation; 2000.

5. Hillerdal G. [Recommendations from the Swedish Lung Cancer Study Group: Shorter waiting times are demanded for quality in diagnostic work-ups for lung care.] Swedish Med J 1999; 96: 4691.

6. Simunovic M, Gagliardi A, McCready D, Coates A, Levine M, DePetrillo D. A snapshot of waiting times for cancer surgery provided by surgeons affiliated with regional cancer centres in Ontario. CMAJ. 2001;165(4):421-425. [Canadian Strategy for Cancer Control]

7. Bukhari A, Kumar G, Rajsheker R, Markert R. Timeliness of lung cancer diagnosis and treatment. Fed Pract. 2017;34(suppl 1):24S-29S.

8. Bilimoria KY, Ko CY, Tomlinson JS, et al. Wait times for cancer surgery in the United States: trends and predictors of delays. Ann Surg. 2011;253(4):779-785.

9. Yang CJ, Wang H, Kumar A, et al. Impact of timing of lobectomy on survival for clinical stage IA lung squamous cell carcinoma. Chest. 2017;152(6):1239-1250.

10. Hunnibell LS, Rose MG, Connery DM, et al. Using nurse navigation to improve timeliness of lung cancer care at a veterans hospital. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2012;16(1):29-36.

11. Meena N, Jeffus S, Massoll N, et al. Rapid onsite evaluation: a comparison of cytopathologist and pulmonologist performance. Cancer Cytopatho. 2016;124(4):279-84.

12. Okereke IC, Bates MF, Jankowich MD, et al. Effects of implementation of lung cancer screening at one Veterans Affairs Medical Center. Chest 2016;150(5):1023-1029.

Lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer death in the US, with 154 050 deaths in 2018.1 There have been many attempts to reduce mortality of the disease through early diagnosis with use of computed tomography (CT). The National Lung Cancer Screening trial showed that screening high-risk populations with low-dose CT (LDCT) can reduce mortality.2 However, implementing LDCT screening in the clinical setting has proven challenging, as illustrated by the VA Lung Cancer Screening Demonstration Project (LCSDP).3 A lung cancer diagnosis typically comprises several steps that require different medical specialties; this can lead to delays. In the LCSDP, the mean time to diagnosis was 137 days.3 There are no federal standards for timeliness of lung cancer diagnosis.

The nonprofit RAND Corporation is the only American research organization that has published guidelines specifying acceptable intervals for the diagnosis and treatment of lung cancer. In Quality of Care for Oncologic Conditions and HIV, RAND Corporation researchers propose management quality indicators: lung cancer diagnosis within 2 months of an abnormal radiologic study and treatment within 6 weeks of diagnosis.4 The Swedish Lung Cancer Study5 and the Canadian Strategy for Cancer Control6 both recommended a standard of about 30 days—half the time recommended by the RAND Corporation.

Bukhari and colleagues at the Dayton US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Medical Center (VAMC) conducted a quality improvement study that examined lung cancer diagnosis and management.7 They found the time (SD) from abnormal chest imaging to diagnosis was 35.5 (31.6) days. Of those veterans who received a lung cancer diagnosis, 89.2% had the diagnosis made within the 60 days recommended by the RAND Corporation. Although these results surpass those of the LCSDP, they can be exceeded.

Beyond the potential emotional distress of awaiting the final diagnosis of a lung lesion, a delay in diagnosis and treatment may adversely affect outcomes. LDCT screening has been shown to reduce mortality, which implies a link between survival and time to intervention. There is no published evidence that time to diagnosis in advanced stage lung cancer affects outcome. The National Cancer Database (NCDB) contains informtion on about 70% of the cancers diagnosed each year in the US.8 An analysis of 4984 patients with stage IA squamous cell lung cancer undergoing lobectomy from NCDB showed that earlier surgery was associated with an absolute decrease in 5-year mortality of 5% to 8%. 9 Hence, at least in early-stage disease, reduced time from initial suspect imaging to definitive treatment may improve survival.

A system that coordinates the requisite diagnostic steps and avoids delays should provide a significant improvement in patient care. The results of such an approach that utilized nurse navigators has been previously published. 10 Here, we present the results of a dedicated VA referral clinic with priority access to pulmonary consultation and procedures in place that are designed to expedite the diagnosis of potential lung cancer.

Methods

The John L. McClellan Memorial Veterans Hospital (JLMMVH) in Little Rock, Arkansas institutional review board approved this study, which was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Requirement for informed consent was waived, and patient confidentiality was maintained throughout.

We have developed a plan of care specifically to facilitate diagnosis and treatment of the large number of veterans referred to the JLMMVH Diagnostic Clinic for abnormal results of chest imaging. The clinic has priority access to same-day imaging and subspecialty consultation services. In the clinic, medical students and residents perform evaluations and a registered nurse (RN) manager coordinates care.

A Diagnostic Clinic consult for abnormal thoracic imaging immediately triggers an e-consult to an interventional pulmonologist (Figure). The RN manager and pulmonologist perform a joint review of records/imaging prior to scheduling, and the pulmonologist triages the patient. Triage options include follow-up imaging, bronchoscopy with endobronchial ultrasound (EBUS), endoscopic ultrasound (EUS), and CT-guided biopsy.

The RN manager then schedules a clinic visit that includes a medical evaluation by clinic staff and any indicated procedures on the same day. The interventional pulmonologist performs EBUS, EUS with the convex curvilinear bronchoscope, or both combined as indicated for diagnosis and staging. All procedures are performed in the JLMMVH bronchoscopy suite with standard conscious sedation using midazolam and fentanyl. Any other relevant procedures, such as pleural tap, also are performed at time of procedure. The pulmonologist and an attending pathologist interpret biopsies obtained in the bronchoscopy suite.

We performed a retrospective chart review of patients diagnosed with primary lung cancer through referral to the JLMMVH Diagnostic Clinic. The primary outcome was time from initial suspect chest imaging to cancer diagnosis. The study population consisted of patients referred for abnormal thoracic imaging between January 1, 2013 and December 31, 2016 and subsequently diagnosed with a primary lung cancer.

Subjects were excluded if (1) the patient was referred from outside our care network and a delay of > 10 days occurred between initial lesion imaging and referral; (2) the patient did not show up for appointments or chose to delay evaluation following referral; (3) biopsy demonstrated a nonlung primary cancer; and (4) serious intercurrent illness interrupted the diagnostic plan. In some cases, the radiologist or consulting pulmonologist had judged the lung lesion too small for immediate biopsy and recommended repeat imaging at a later date.

Patients were included in the study if the follow- up imaging led to a lung cancer diagnosis. However, because the interval between the initial imaging and the follow-up imaging in these patients did not represent a systems delay problem, the date of the scheduled follow-up abnormal imaging, which resulted in initiation of a potential cancer evaluation, served as the index suspect imaging date for this study.

Patient electronic medical records were reviewed and the following data were abstracted: date of the abnormal imaging that led to referral and time from abnormal chest X-ray to chest CT scan if applicable; date of referral and date of clinic visit; date of biopsy; date of lung cancer diagnosis; method of obtaining diagnostic specimen; lung cancer type and stage; type and date of treatment initiation or decision for supportive care only; and decision to seek further evaluation or care outside of our system.

All patients diagnosed with lung cancer during the study period were reviewed for inclusion, hence no required sample-size estimate was calculated. All outcomes were assessed as calendar days. The primary outcome was the time from the index suspect chest imaging study to the date of diagnosis of lung cancer. Prior to the initiation of our study, we chose this more stringent 30-day recommendation of the Canadian6 and Swedish5 studies as the comparator for our primary outcome, although data with respect to the 60-day Rand Corporation guidelines also are reported.4

Statistical Methods

The mean time to lung cancer diagnosis in our cohort was compared with this 30-day standard using a 2-sided Mann–Whitney U test. Normality of data distribution was determined using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. For statistical significance testing a P value of .05 was used. Statistical calculations were performed using R statistical software version 3.2.4. Secondary outcomes consisted of time from diagnosis to treatment; proportion of subjects diagnosed within 60 days; time from initial clinic visit to biopsy; and time from biopsy to diagnosis.

Results

Overall, 222 patients were diagnosed with a malignant lung lesion, of which 63 were excluded from analysis: 22 cancelled or did not appear for appointments, declined further evaluation, or completed evaluation outside of our network; 13 had the diagnosis made prior to Diagnostic Clinic visit; 13 proved to have a nonlung primary tumor presenting in the lung or mediastinal nodes; 12 were delayed > 10 days in referral from an outside network; and 3 had an intervening serious acute medical problem forcing delay in the diagnostic process.

Of the 159 included subjects, 154 (96.9%) were male, and the mean (SD) age was 67.6 (8.1) years. For 76 subjects, the abnormal chest X-ray and subsequent chest CT scan were performed the same day or the lung lesion had initially been noted on a CT scan. For 54 subjects, there was a delay of ≥ 1 week in obtaining a chest CT scan. The mean (SD) time from placement of the Diagnostic Clinic consultation by the primary care provider (PCP) or other provider and the initial Diagnostic Clinic visit was 6.3 (4.4) days. The mean (SD) time from suspect imaging to diagnosis (primary outcome) was 22.6(16.6) days.

The distribution of this outcome was nonnormal (Kolmogorov-Smirnov test P < .01). When compared with the standard of 30 days, the primary outcome of 22.6 days was significantly shorter (2-sided Mann–Whitney U test P < .01). Three-quarters (76.1%) of subjects were diagnosed within 30 days and 95.0% of subjects were diagnosed within 60 days of the initial imaging. For the 8 subjects diagnosed after 60 days, contributing factors included PCP delay in Diagnostic Clinic consultation, initial negative biopsy, delay in performance of chest CT scan prior to consultation, and outsourcing of positron emission tomography (PET) scans.

Overall, 57 (35.8%) of the subjects underwent biopsy on the day of their Diagnostic Clinic visit: 14 underwent CT-guided biopsy and 43 underwent EBUS/EUS. Within 2 days of the initial visit 106 subjects (66.7%) had undergone biopsy. The mean (SD) time from initial Diagnostic Clinic visit to biopsy was 6.3 (9.5) days. The mean (SD) interval was 1.8 (3.0) days for EBUS/ EUS and 11.3 (11.7) days for CT-guided biopsy. The mean (SD) interval from biopsy to diagnosis was 3.2 (6.2) days with 64 cases (40.3%) diagnosed the day of biopsy.

Excluding subjects whose treatment was delayed by patient choice or intercurrent illness, and those who left the VA system to seek treatment elsewhere (n = 21), 24 opted for palliative care, 5 died before treatment could be initiated, and 109 underwent treatment for their tumors (Table). The mean times (SD) from diagnosis to treatment were: chemotherapy alone 34.7 (25.3) days; chemoradiation 37.0 (22.8) days; surgery 44.3 (24.4) days; radiation therapy alone 47.9 (26.0) days. With respect to the RAND Corporation recommended diagnosis to treatment time, 60.9% of chemotherapy alone, 61.5% of chemoradiation, 66.7% of surgery, and 45.0% of radiation therapy alone treatments were initiated within the 6-week window.

Discussion

This retrospective case study demonstrates the effectiveness of a dedicated diagnostic clinic with priority EBUS/EUS access in diagnosing lung cancer within the VA system. Although there is no universally accepted quality standard for comparison, the RAND Corporation recommendation of 60 days from abnormal imaging to diagnosis and the Dayton VAMC published mean of 35.5 days are guideposts; however, the results from the Dayton VAMC may have been affected negatively by some subjects undergoing serial imaging for asymptomatic nodules. We chose a more stringent standard of 30 days as recommended by Swedish and Canadian task forces.

When diagnosing lung cancer, the overriding purpose of the Diagnostic Clinic is to minimize system delays. The method is to have as simple a task as possible for the PCP or other provider who identifies a lung nodule or mass and submits a single consultation request to the Diagnostic Clinic. Once this consultation is placed, the clinic RN manager oversees all further steps required for diagnosis and referral for treatment. The key factor in achieving a mean diagnosis time of 22.6 days is the cooperation between the RN manager and the interventional pulmonologist. When a consultation is received, the RN manager and pulmonologist review the data together and schedule the initial clinic visit; the goal is same-day biopsy, which is achieved in more than one-third of cases. Not all patients with a chest image suspected for lung cancer had it ordered by their PCP. For this reason, a Diagnostic Clinic consultation is available to all health care providers in our system. Many patients reach the clinic after the discovery of a suspect chest X-ray during an emergency department visit, a regularly scheduled subspecialty appointment, or during a preoperative evaluation.

The mean time from initial visit to biopsy was 1.8 days for EBUS/EUS compared with an interval of 11.3 days for CT-guided biopsy. This difference reflects the pulmonologist’s involvement in initial scheduling of Diagnostic Clinic patients. The ability of the pulmonologist to provide an accurate assessment of sample adequacy and a preliminary diagnosis at bedside, with concurrent confirmation by a staff pathologist, permitted the Diagnostic Clinic to inform 40.3% of patients of the finding of malignancy on the day of biopsy. A published comparison of the onsite review of biopsy material showed our pulmonologist and staff pathologists to be equally accurate in their interpretations.11

Sources of Delays

While this study documents the shortest intervals from suspect imaging to diagnosis reported to date, it also identifies sources of system delay in diagnosing lung cancer that JLMMVH could further optimize. The first is the time from initial abnormal chest X-ray imaging to performance of the chest CT scan. On occasion, the index lung lesion is identified unexpectedly on an outpatient or emergency department chest CT scan. With greater use of LDCT lung cancer screening, the initial detection of suspect lesions by CT scanning will increase in the future. However, the PCP most often investigates a patient complaint with a standard chest X-ray that reveals a suspect nodule or mass. When ordered by the PCP as an outpatient test, scheduling of the follow-up chest CT scan is not given priority. More than a third of subjects experienced a delay ≥ 1 week in obtaining a chest CT scan ordered by the PCP; for 29 subjects the delay was ≥ 3weeks. At JLMMVH, the Diagnostic Clinic is given priority in scheduling CT scans. Hence, for suspect lung lesions, the chest CT scan, if not already obtained, is generally performed on the morning of the clinic visit. Educating the PCP to refer the patient immediately to the Diagnostic Clinic rather than waiting to obtain an outpatient chest CT scan may remove this source of unnecessary delay.

Scheduling a CT-guided fine needle aspiration of a lung lesion is another source of system delay. When the chest CT scan is available at the time of the Diagnostic Clinic referral, the clinic visit is scheduled for the earliest day a required CT-guided biopsy can be performed. However, the mean time of 11.3 days from initial Diagnostic Clinic visit to CT-guided biopsy is indicative of the backlog faced by the interventional radiologists.

Although infrequent, PET scans that are required before biopsy can lead to substantial delays. PET scans are performed at our university affiliate, and the joint VA-university lung tumor board sometimes generates requests for such scans prior to tissue diagnosis, yet another source of delay.

The time from referral receipt to the Diagnostic Clinic visit averaged 6.3 days. This delay usually was determined by the availability of the CT-guided biopsy or the dedicated interventional pulmonologist. Although other interventional pulmonologists at JLMMVH may perform the requisite diagnostic procedures, they are not always available for immediate review of imaging studies of referred patients nor can their schedules flexibly accommodate the number of patients seen in our clinic for evaluation.

Lung Cancer Diagnosis

Prompt diagnosis in the setting of a worrisome chest X-ray may help decrease patient anxiety, but does the clinic improve lung cancer treatment outcomes? Such improvement has been demonstrated only in stage IA squamous cell lung cancer.9 Of our study population, 37.7% had squamous cell carcinoma, and 85.5% had non-small cell lung cancer. Of those with non-small cell lung cancer, 28.9% had a clinical stage I tumor. Stage I squamous cell carcinoma, the type of tumor most likely to benefit from early diagnosis and treatment, was diagnosed in 11.3% of patients. With the increased application of LDCT screening, the proportion of veterans identified with early stage lung cancer may rise. The Providence VAMC in Rhode Island reported its results from instituting LDCT screening.12 Prior to screening, 28% of patients diagnosed with lung cancer had a stage I tumor. Following the introduction of LDCT screening, 49% diagnosed by LDCT screening had a stage I tumor. Nearly a third of their patients diagnosed with lung cancer through LDCT screening had squamous cell tumor histology. Thus, we can anticipate an increasing number of veterans with early stage lung cancer who would benefit from timely diagnosis.

The JLMMVH is a referral center for the entire state of Arkansas. Quite a few of its referred patients come from a long distance, which may require overnight housing and other related travel expenses. Apart from any potential outcome benefit, the efficiencies of the system described herein include the minimization of extra trips, an inconvenience and cost to both patient and JLMMVH.

Although the primary task of the clinic is diagnosis, we also seek to facilitate timely treatment. Our lack of an on-site PET scanner and radiation therapy, resources present on-site at the Dayton VAMC, contribute to longer therapy wait times. The shortest mean wait time at JLMMVH is for chemotherapy alone (34.7 days), in part because the JLMMVH oncologists, performing initial consultations 2 to 3 times weekly in the Diagnostic Clinic, are more readily available than are our thoracic surgeons or radiation therapists. Yet overall, JLMMVH patients often face delay from the time of lung cancer diagnosis to initiation of treatment.

The Connecticut Veterans Affairs Healthcare System has published the results of changes in lung cancer management associated with a nurse navigator system.10 Prior to creating the position of cancer care coordinator, filled by an advanced practice RNs, the mean time from clinical suspicion of lung cancer to treatment was 117 days. After 4 years of such care navigation, this waiting time had decreased to 52.4 days. Associated with this dramatic improvement in overall waiting time were decreases in the turnaround time required for performance of CT and PET scans. With respect to this big picture view of lung cancer care, our Diagnostic Clinic serves as a model for the initial step of diagnosis. Coordination and streamlining of the various steps from diagnosis to definitive therapy shall require a more system-wide effort involving all the key players in cancer care.

Conclusion

We have developed a care pathway based in a dedicated diagnostic clinic and have been able to document the shortest interval from abnormality to diagnosis of lung cancer reported in the literature to date. Efficient functioning of this clinic is dependent upon the close cooperation between a full-time RN clinic manager and an interventional pulmonologist experienced in lung cancer management and able to interpret cytologic samples at the time of biopsy. Shortening the delay between diagnosis and definitive therapy remains a challenge and may benefit from the oncology nurse navigator model previously described within the VA system. 10