User login

CDC, SAMHSA commit $1.8 billion to combat opioid crisis

More financial reinforcements are arriving in the battle against the opioid crisis, with the Trump administration promising more than $1.8 billion in new funds to help states address the crisis.

Speaking at a Sept. 4 press conference announcing the funding, President Donald Trump said the money will be used “to increase access to medication and medication-assisted treatment and mental health resources, which are critical for ending homelessness and getting people the help they deserve.” The president added that the grants also will help state and local governments obtain high-quality, comprehensive data.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention will provide more than $900 million in new funding over the next 3 years to “advance the understanding of the opioid overdose epidemic and to scale-up prevention and response activities,” the Department of Health & Human Services said in a statement announcing the funding.

“This money will help states and local communities track overdose data and develop strategies that save lives,” HHS Secretary Alex Azar said during the press conference.

He noted that, when the Trump administration began, overdose data were published with a 12-month lag. That lag has since shortened to 6 months. One of the goals with the new funding is to bring data publishing as close to real time as possible.

Separately, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration awarded $932 million to all 50 states as part of its State Opioid Response grants, which “provide flexible funding to state governments to support prevention, treatment, and recovery services in the ways that meet the needs of their state,” according to the HHS statement.

That flexibility “can mean everything from expanding the use of medication-assisted treatment in criminal justice settings or in rural areas via telemedicine, to youth-focused community-based prevention efforts,” Secretary Azar explained. The funds can also support employment coaching and naloxone distribution, he added.

More financial reinforcements are arriving in the battle against the opioid crisis, with the Trump administration promising more than $1.8 billion in new funds to help states address the crisis.

Speaking at a Sept. 4 press conference announcing the funding, President Donald Trump said the money will be used “to increase access to medication and medication-assisted treatment and mental health resources, which are critical for ending homelessness and getting people the help they deserve.” The president added that the grants also will help state and local governments obtain high-quality, comprehensive data.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention will provide more than $900 million in new funding over the next 3 years to “advance the understanding of the opioid overdose epidemic and to scale-up prevention and response activities,” the Department of Health & Human Services said in a statement announcing the funding.

“This money will help states and local communities track overdose data and develop strategies that save lives,” HHS Secretary Alex Azar said during the press conference.

He noted that, when the Trump administration began, overdose data were published with a 12-month lag. That lag has since shortened to 6 months. One of the goals with the new funding is to bring data publishing as close to real time as possible.

Separately, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration awarded $932 million to all 50 states as part of its State Opioid Response grants, which “provide flexible funding to state governments to support prevention, treatment, and recovery services in the ways that meet the needs of their state,” according to the HHS statement.

That flexibility “can mean everything from expanding the use of medication-assisted treatment in criminal justice settings or in rural areas via telemedicine, to youth-focused community-based prevention efforts,” Secretary Azar explained. The funds can also support employment coaching and naloxone distribution, he added.

More financial reinforcements are arriving in the battle against the opioid crisis, with the Trump administration promising more than $1.8 billion in new funds to help states address the crisis.

Speaking at a Sept. 4 press conference announcing the funding, President Donald Trump said the money will be used “to increase access to medication and medication-assisted treatment and mental health resources, which are critical for ending homelessness and getting people the help they deserve.” The president added that the grants also will help state and local governments obtain high-quality, comprehensive data.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention will provide more than $900 million in new funding over the next 3 years to “advance the understanding of the opioid overdose epidemic and to scale-up prevention and response activities,” the Department of Health & Human Services said in a statement announcing the funding.

“This money will help states and local communities track overdose data and develop strategies that save lives,” HHS Secretary Alex Azar said during the press conference.

He noted that, when the Trump administration began, overdose data were published with a 12-month lag. That lag has since shortened to 6 months. One of the goals with the new funding is to bring data publishing as close to real time as possible.

Separately, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration awarded $932 million to all 50 states as part of its State Opioid Response grants, which “provide flexible funding to state governments to support prevention, treatment, and recovery services in the ways that meet the needs of their state,” according to the HHS statement.

That flexibility “can mean everything from expanding the use of medication-assisted treatment in criminal justice settings or in rural areas via telemedicine, to youth-focused community-based prevention efforts,” Secretary Azar explained. The funds can also support employment coaching and naloxone distribution, he added.

SAGE-217 shows reduction in depression with no safety concerns

A new oral antidepressant that targets the gamma-aminobutyric acid type A (GABAA) receptors in the brain has been found to achieve a reduction in symptoms in adult patients with moderate to severe major depressive disorder, with no serious safety signals, results of a double-blind, phase 2 trial show.

The study involved 89 participants with major depression, excluding those with a history of treatment-resistant depression, who were randomized either to a once-daily dose of 30 mg of SAGE-217, a synthetic neurosteroid that acts as a positive allosteric modulator of GABAA receptors, or placebo for 14 days. Thirty-six of the 45 patients in the SAGE-217 group were black, as were 28 of the 44 patients in the placebo group, reported Handan Gunduz-Bruce, MD, of Sage Therapeutics and coauthors. Their study was published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

“One hypothesis for the mechanism of depression implicates deficits in gamma-aminobutyric acid and downstream alterations in monoaminergic neurotransmission,” wrote Dr. Gunduz-Bruce and coauthors. “Preclinical studies have shown that the naturally occurring neurosteroid allopregnanolone is a positive allosteric modulator of synaptic and extrasynaptic GABAA receptors that affects both phasic and tonic inhibition of neurons.”

At day 15 of the study, there was a significantly greater mean change from baseline in Hamilton Depression Rating Scale scores in the treatment group, compared with the placebo group (–17.4 vs. –10.3, P less than .001), and 79% of participants in the treatment arm showed a greater than 50% reduction in depression scores, compared with 41% of the placebo group.

At day 28, 62% of the treatment group and 46% of the placebo group had a reduction of more than 50% from baseline depression scores.

No serious or severe adverse events were seen in either group, and the most common adverse events in the SAGE-217 group included headache (18%), dizziness (11%), and nausea (11%). One patient in the treatment arm also reported euphoria.

The authors commented that somnolence and sedation were expected adverse events, based on the pharmacological properties of SAGE-217.

Six patients in the treatment arm also had dose reductions as a result of adverse events. Two patients in the SAGE-217 arm stopped treatment because they met prespecified criteria for discontinuation; the investigators reported nausea, dizziness, and headache in one patient, and increased levels of alkaline phosphatase, alanine aminotransferase, aspartate aminotransferase, and gamma-glutamyltransferase in the other. However, the second patient had shown mildly elevated values of these at baseline, was asymptomatic throughout the trial, and the patient’s values returned to baseline or near-baseline after stopping treatment.

About one-quarter of both the SAGE-217 and placebo groups were receiving antidepressant treatment at baseline (27% and 23% respectively), with the duration of prior treatment ranging from 2 to 48 months. Investigators also gave three patients in the treatment arm and 11 in the placebo arm concomitant antidepressants during the follow-up period.

The small sample size and limited racial diversity among the participants were cited as limitations.

The study was supported by SAGE-217 manufacturer Sage Therapeutics. Ten authors were employees or directors of Sage Therapeutics, with stock options and patent interests. Three authors declared grants, personal fees, or advisory board positions with the pharmaceutical sector, including from Sage, and one also declared interest in a range of patents outside the study. One author had no disclosures.

SOURCE: Gunduz-Bruce H et al. N Engl J Med. 2019 Sep 5;381:903-11. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1815981.

Glutamate modulators, such as ketamine, recently have been found to achieve a rapid reduction in depressive symptoms – often within 24 hours. This is a significant development given that most existing antidepressants do not work quickly, and time is critical for patients with suicidal ideation.

This trial of SAGE-217 also shows a more rapid clinical response than is typical of existing antidepressants. However, the absence of a significant difference between the treatment and placebo arm in change of depression scores from baseline to day 28 suggests that the drug should be administered for longer than 14 days. It is also important to note that the trial excluded patients with treatment-resistant depression.

Emil F. Coccaro, MD, is affiliated with the department of psychiatry and behavioral neuroscience at the University of Chicago. These comments are adapted from an accompanying editorial (N Engl J Med. 2019 Sep 5;381:980-1. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1907638). Dr. Coccaro declared grants from the National Institutes of Health and personal fees or stock options in the pharmaceutical sector.

Glutamate modulators, such as ketamine, recently have been found to achieve a rapid reduction in depressive symptoms – often within 24 hours. This is a significant development given that most existing antidepressants do not work quickly, and time is critical for patients with suicidal ideation.

This trial of SAGE-217 also shows a more rapid clinical response than is typical of existing antidepressants. However, the absence of a significant difference between the treatment and placebo arm in change of depression scores from baseline to day 28 suggests that the drug should be administered for longer than 14 days. It is also important to note that the trial excluded patients with treatment-resistant depression.

Emil F. Coccaro, MD, is affiliated with the department of psychiatry and behavioral neuroscience at the University of Chicago. These comments are adapted from an accompanying editorial (N Engl J Med. 2019 Sep 5;381:980-1. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1907638). Dr. Coccaro declared grants from the National Institutes of Health and personal fees or stock options in the pharmaceutical sector.

Glutamate modulators, such as ketamine, recently have been found to achieve a rapid reduction in depressive symptoms – often within 24 hours. This is a significant development given that most existing antidepressants do not work quickly, and time is critical for patients with suicidal ideation.

This trial of SAGE-217 also shows a more rapid clinical response than is typical of existing antidepressants. However, the absence of a significant difference between the treatment and placebo arm in change of depression scores from baseline to day 28 suggests that the drug should be administered for longer than 14 days. It is also important to note that the trial excluded patients with treatment-resistant depression.

Emil F. Coccaro, MD, is affiliated with the department of psychiatry and behavioral neuroscience at the University of Chicago. These comments are adapted from an accompanying editorial (N Engl J Med. 2019 Sep 5;381:980-1. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1907638). Dr. Coccaro declared grants from the National Institutes of Health and personal fees or stock options in the pharmaceutical sector.

A new oral antidepressant that targets the gamma-aminobutyric acid type A (GABAA) receptors in the brain has been found to achieve a reduction in symptoms in adult patients with moderate to severe major depressive disorder, with no serious safety signals, results of a double-blind, phase 2 trial show.

The study involved 89 participants with major depression, excluding those with a history of treatment-resistant depression, who were randomized either to a once-daily dose of 30 mg of SAGE-217, a synthetic neurosteroid that acts as a positive allosteric modulator of GABAA receptors, or placebo for 14 days. Thirty-six of the 45 patients in the SAGE-217 group were black, as were 28 of the 44 patients in the placebo group, reported Handan Gunduz-Bruce, MD, of Sage Therapeutics and coauthors. Their study was published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

“One hypothesis for the mechanism of depression implicates deficits in gamma-aminobutyric acid and downstream alterations in monoaminergic neurotransmission,” wrote Dr. Gunduz-Bruce and coauthors. “Preclinical studies have shown that the naturally occurring neurosteroid allopregnanolone is a positive allosteric modulator of synaptic and extrasynaptic GABAA receptors that affects both phasic and tonic inhibition of neurons.”

At day 15 of the study, there was a significantly greater mean change from baseline in Hamilton Depression Rating Scale scores in the treatment group, compared with the placebo group (–17.4 vs. –10.3, P less than .001), and 79% of participants in the treatment arm showed a greater than 50% reduction in depression scores, compared with 41% of the placebo group.

At day 28, 62% of the treatment group and 46% of the placebo group had a reduction of more than 50% from baseline depression scores.

No serious or severe adverse events were seen in either group, and the most common adverse events in the SAGE-217 group included headache (18%), dizziness (11%), and nausea (11%). One patient in the treatment arm also reported euphoria.

The authors commented that somnolence and sedation were expected adverse events, based on the pharmacological properties of SAGE-217.

Six patients in the treatment arm also had dose reductions as a result of adverse events. Two patients in the SAGE-217 arm stopped treatment because they met prespecified criteria for discontinuation; the investigators reported nausea, dizziness, and headache in one patient, and increased levels of alkaline phosphatase, alanine aminotransferase, aspartate aminotransferase, and gamma-glutamyltransferase in the other. However, the second patient had shown mildly elevated values of these at baseline, was asymptomatic throughout the trial, and the patient’s values returned to baseline or near-baseline after stopping treatment.

About one-quarter of both the SAGE-217 and placebo groups were receiving antidepressant treatment at baseline (27% and 23% respectively), with the duration of prior treatment ranging from 2 to 48 months. Investigators also gave three patients in the treatment arm and 11 in the placebo arm concomitant antidepressants during the follow-up period.

The small sample size and limited racial diversity among the participants were cited as limitations.

The study was supported by SAGE-217 manufacturer Sage Therapeutics. Ten authors were employees or directors of Sage Therapeutics, with stock options and patent interests. Three authors declared grants, personal fees, or advisory board positions with the pharmaceutical sector, including from Sage, and one also declared interest in a range of patents outside the study. One author had no disclosures.

SOURCE: Gunduz-Bruce H et al. N Engl J Med. 2019 Sep 5;381:903-11. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1815981.

A new oral antidepressant that targets the gamma-aminobutyric acid type A (GABAA) receptors in the brain has been found to achieve a reduction in symptoms in adult patients with moderate to severe major depressive disorder, with no serious safety signals, results of a double-blind, phase 2 trial show.

The study involved 89 participants with major depression, excluding those with a history of treatment-resistant depression, who were randomized either to a once-daily dose of 30 mg of SAGE-217, a synthetic neurosteroid that acts as a positive allosteric modulator of GABAA receptors, or placebo for 14 days. Thirty-six of the 45 patients in the SAGE-217 group were black, as were 28 of the 44 patients in the placebo group, reported Handan Gunduz-Bruce, MD, of Sage Therapeutics and coauthors. Their study was published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

“One hypothesis for the mechanism of depression implicates deficits in gamma-aminobutyric acid and downstream alterations in monoaminergic neurotransmission,” wrote Dr. Gunduz-Bruce and coauthors. “Preclinical studies have shown that the naturally occurring neurosteroid allopregnanolone is a positive allosteric modulator of synaptic and extrasynaptic GABAA receptors that affects both phasic and tonic inhibition of neurons.”

At day 15 of the study, there was a significantly greater mean change from baseline in Hamilton Depression Rating Scale scores in the treatment group, compared with the placebo group (–17.4 vs. –10.3, P less than .001), and 79% of participants in the treatment arm showed a greater than 50% reduction in depression scores, compared with 41% of the placebo group.

At day 28, 62% of the treatment group and 46% of the placebo group had a reduction of more than 50% from baseline depression scores.

No serious or severe adverse events were seen in either group, and the most common adverse events in the SAGE-217 group included headache (18%), dizziness (11%), and nausea (11%). One patient in the treatment arm also reported euphoria.

The authors commented that somnolence and sedation were expected adverse events, based on the pharmacological properties of SAGE-217.

Six patients in the treatment arm also had dose reductions as a result of adverse events. Two patients in the SAGE-217 arm stopped treatment because they met prespecified criteria for discontinuation; the investigators reported nausea, dizziness, and headache in one patient, and increased levels of alkaline phosphatase, alanine aminotransferase, aspartate aminotransferase, and gamma-glutamyltransferase in the other. However, the second patient had shown mildly elevated values of these at baseline, was asymptomatic throughout the trial, and the patient’s values returned to baseline or near-baseline after stopping treatment.

About one-quarter of both the SAGE-217 and placebo groups were receiving antidepressant treatment at baseline (27% and 23% respectively), with the duration of prior treatment ranging from 2 to 48 months. Investigators also gave three patients in the treatment arm and 11 in the placebo arm concomitant antidepressants during the follow-up period.

The small sample size and limited racial diversity among the participants were cited as limitations.

The study was supported by SAGE-217 manufacturer Sage Therapeutics. Ten authors were employees or directors of Sage Therapeutics, with stock options and patent interests. Three authors declared grants, personal fees, or advisory board positions with the pharmaceutical sector, including from Sage, and one also declared interest in a range of patents outside the study. One author had no disclosures.

SOURCE: Gunduz-Bruce H et al. N Engl J Med. 2019 Sep 5;381:903-11. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1815981.

FROM THE NEW ENGLAND JOURNAL OF MEDICINE

Key clinical point: Taking SAGE-217 – a new oral antidepressant – for 14 days leads to reductions in depressive symptoms at day 15.

Major finding: Treatment with SAGE-217 was associated with significantly greater improvements in depression scores, compared with placebo.

Study details: Phase 2, randomized, placebo-controlled trial in 89 patients with major depression.

Disclosures: The study was supported by SAGE-217 manufacturer Sage Therapeutics. Ten authors were employees or directors of Sage Therapeutics, with stock options and patent interests. Three authors declared grants, personal fees, or advisory board positions with the pharmaceutical sector, including from Sage, and one also declared interest in a range of patents outside the study. One author had no disclosures.

Source: Gunduz-Bruce H et al. N Engl J Med. 2019 Sep 5;381:903-11. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1815981.

Mitapivat elicits positive response in pyruvate kinase deficiency

Mitapivat showed positive safety and efficacy outcomes in patients with pyruvate kinase deficiency, according to results from a phase 2 trial.

After 24 weeks of treatment, the therapy was associated with a rapid rise in hemoglobin levels in 50% of study participants, while the majority of toxicities reported were transient and low grade.

“The primary objective of this study was to assess the safety and side-effect profile of mitapivat administration in patients with pyruvate kinase deficiency,” wrote Rachael F. Grace, MD, of the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute and Harvard Medical School, Boston, and coinvestigators. The findings were published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The uncontrolled study included 52 adults with pyruvate kinase deficiency who were not undergoing regular transfusions.

The median age at baseline was 34 years (range, 18-61 years), 62% of patients were male, and the median baseline hemoglobin level was 8.9 g/dL (range, 6.5-12.3 g/dL). In addition, 73% and 83% of patients had previously undergone cholecystectomy and splenectomy, respectively.

Study patients received oral mitapivat at 50 mg or 300 mg twice weekly for a total of 24 weeks. Eligible participants were subsequently enrolled into an extension phase that continued to monitor safety.

At 24 weeks, the team reported that 26 patients – 50% – experienced a greater than 1.0-g/dL rise in hemoglobin levels, with a maximum mean increase of 3.4 g/dL (range, 1.1-5.8 g/dL). The first rise of greater than 1.0 g/dL was observed after a median duration of 10 days (range, 7-187 days).

Of the 26 patients, 20 had an increase from baseline of more than 1.0 g/dL at more than half of the assessment during the core study period. That met the definition for hemoglobin response, according to the researchers.

“The hemoglobin response was maintained in the 19 patients who were continuing to be treated in the extension phase, all of whom had at least 21.6 months of treatment,” they wrote.

With respect to safety, the majority of adverse events were of low severity (grade 1-2) and transient in nature, with most resolving within 7 days. The most frequently reported toxicities in the core period and extension phase were headache (46%), insomnia (42%), and nausea (40%). The most serious reported toxicities were pharyngitis (4%) and hemolytic anemia (4%).

“Patient-reported quality of life was not assessed in this phase 2 safety study, although such outcome measures are being evaluated in the ongoing phase 3 trials,” Dr. Grace and colleagues wrote. “This study establishes proof of concept for a molecular therapy targeting the underlying enzymatic defect of a hereditary enzymopathy,” they concluded.

Agios Pharmaceuticals funded the study. Dr. Grace reported research funding from and consulting for Agios, and several authors reported employment, consulting, or research funding with the company.

SOURCE: Grace RF et al. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:933-44.

Mitapivat showed positive safety and efficacy outcomes in patients with pyruvate kinase deficiency, according to results from a phase 2 trial.

After 24 weeks of treatment, the therapy was associated with a rapid rise in hemoglobin levels in 50% of study participants, while the majority of toxicities reported were transient and low grade.

“The primary objective of this study was to assess the safety and side-effect profile of mitapivat administration in patients with pyruvate kinase deficiency,” wrote Rachael F. Grace, MD, of the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute and Harvard Medical School, Boston, and coinvestigators. The findings were published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The uncontrolled study included 52 adults with pyruvate kinase deficiency who were not undergoing regular transfusions.

The median age at baseline was 34 years (range, 18-61 years), 62% of patients were male, and the median baseline hemoglobin level was 8.9 g/dL (range, 6.5-12.3 g/dL). In addition, 73% and 83% of patients had previously undergone cholecystectomy and splenectomy, respectively.

Study patients received oral mitapivat at 50 mg or 300 mg twice weekly for a total of 24 weeks. Eligible participants were subsequently enrolled into an extension phase that continued to monitor safety.

At 24 weeks, the team reported that 26 patients – 50% – experienced a greater than 1.0-g/dL rise in hemoglobin levels, with a maximum mean increase of 3.4 g/dL (range, 1.1-5.8 g/dL). The first rise of greater than 1.0 g/dL was observed after a median duration of 10 days (range, 7-187 days).

Of the 26 patients, 20 had an increase from baseline of more than 1.0 g/dL at more than half of the assessment during the core study period. That met the definition for hemoglobin response, according to the researchers.

“The hemoglobin response was maintained in the 19 patients who were continuing to be treated in the extension phase, all of whom had at least 21.6 months of treatment,” they wrote.

With respect to safety, the majority of adverse events were of low severity (grade 1-2) and transient in nature, with most resolving within 7 days. The most frequently reported toxicities in the core period and extension phase were headache (46%), insomnia (42%), and nausea (40%). The most serious reported toxicities were pharyngitis (4%) and hemolytic anemia (4%).

“Patient-reported quality of life was not assessed in this phase 2 safety study, although such outcome measures are being evaluated in the ongoing phase 3 trials,” Dr. Grace and colleagues wrote. “This study establishes proof of concept for a molecular therapy targeting the underlying enzymatic defect of a hereditary enzymopathy,” they concluded.

Agios Pharmaceuticals funded the study. Dr. Grace reported research funding from and consulting for Agios, and several authors reported employment, consulting, or research funding with the company.

SOURCE: Grace RF et al. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:933-44.

Mitapivat showed positive safety and efficacy outcomes in patients with pyruvate kinase deficiency, according to results from a phase 2 trial.

After 24 weeks of treatment, the therapy was associated with a rapid rise in hemoglobin levels in 50% of study participants, while the majority of toxicities reported were transient and low grade.

“The primary objective of this study was to assess the safety and side-effect profile of mitapivat administration in patients with pyruvate kinase deficiency,” wrote Rachael F. Grace, MD, of the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute and Harvard Medical School, Boston, and coinvestigators. The findings were published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The uncontrolled study included 52 adults with pyruvate kinase deficiency who were not undergoing regular transfusions.

The median age at baseline was 34 years (range, 18-61 years), 62% of patients were male, and the median baseline hemoglobin level was 8.9 g/dL (range, 6.5-12.3 g/dL). In addition, 73% and 83% of patients had previously undergone cholecystectomy and splenectomy, respectively.

Study patients received oral mitapivat at 50 mg or 300 mg twice weekly for a total of 24 weeks. Eligible participants were subsequently enrolled into an extension phase that continued to monitor safety.

At 24 weeks, the team reported that 26 patients – 50% – experienced a greater than 1.0-g/dL rise in hemoglobin levels, with a maximum mean increase of 3.4 g/dL (range, 1.1-5.8 g/dL). The first rise of greater than 1.0 g/dL was observed after a median duration of 10 days (range, 7-187 days).

Of the 26 patients, 20 had an increase from baseline of more than 1.0 g/dL at more than half of the assessment during the core study period. That met the definition for hemoglobin response, according to the researchers.

“The hemoglobin response was maintained in the 19 patients who were continuing to be treated in the extension phase, all of whom had at least 21.6 months of treatment,” they wrote.

With respect to safety, the majority of adverse events were of low severity (grade 1-2) and transient in nature, with most resolving within 7 days. The most frequently reported toxicities in the core period and extension phase were headache (46%), insomnia (42%), and nausea (40%). The most serious reported toxicities were pharyngitis (4%) and hemolytic anemia (4%).

“Patient-reported quality of life was not assessed in this phase 2 safety study, although such outcome measures are being evaluated in the ongoing phase 3 trials,” Dr. Grace and colleagues wrote. “This study establishes proof of concept for a molecular therapy targeting the underlying enzymatic defect of a hereditary enzymopathy,” they concluded.

Agios Pharmaceuticals funded the study. Dr. Grace reported research funding from and consulting for Agios, and several authors reported employment, consulting, or research funding with the company.

SOURCE: Grace RF et al. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:933-44.

FROM THE NEW ENGLAND JOURNAL OF MEDICINE

Key clinical point: Major finding: At 24 weeks, 50% of patients experienced a greater than 1.0-g/dL rise in hemoglobin levels, with a maximum mean increase of 3.4 g/dL (range, 1.1-5.8 g/dL).

Study details: A phase 2 study of 52 patients with pyruvate kinase deficiency.

Disclosures: Agios Pharmaceuticals funded the study. Dr. Grace reported research funding from and consulting for Agios, and several authors reported employment, consulting, or research funding with the company.

Source: Grace RF et al. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:933-44.

Embryologic development of the external genitalia as it relates to vaginoplasty for the transgender woman

Women with epilepsy: 5 clinical pearls for contraception and preconception counseling

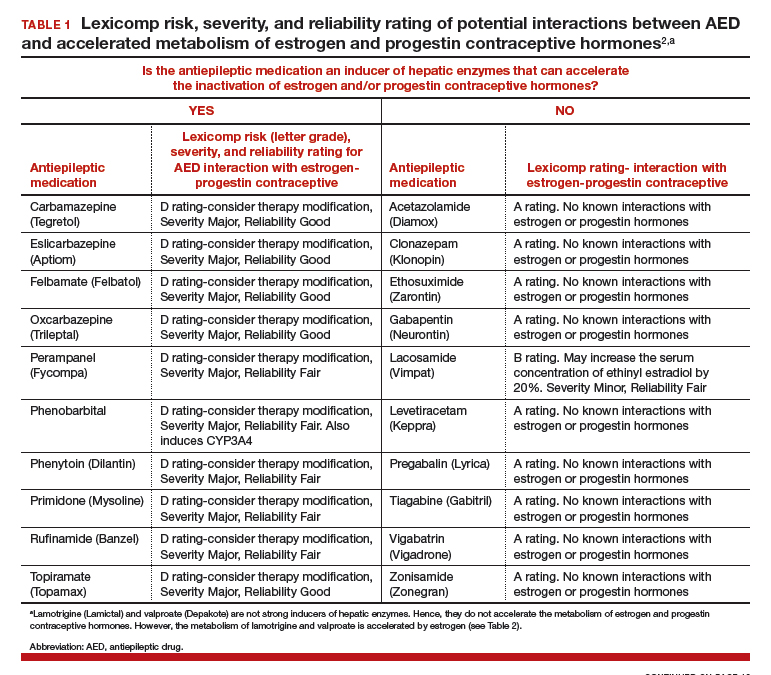

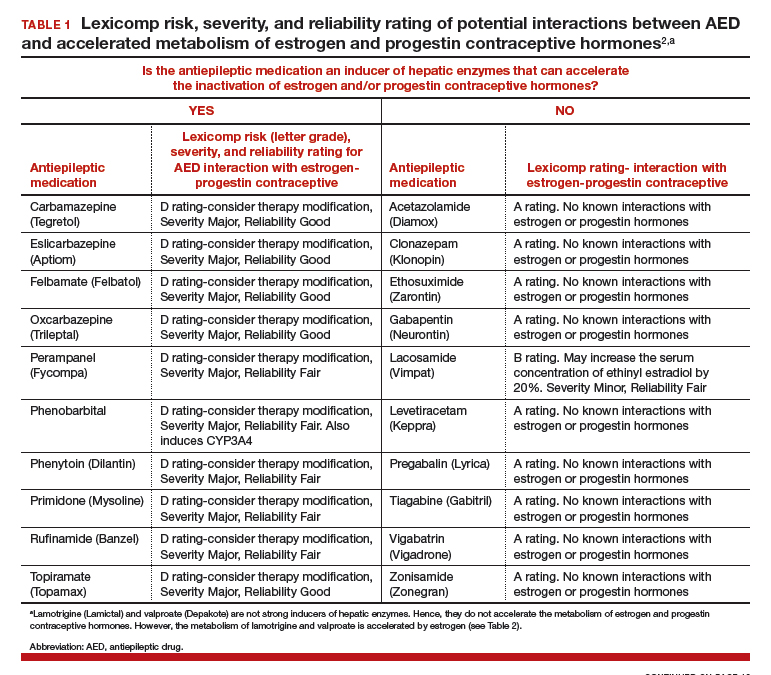

In 2015, 1.2% of the US population was estimated to have active epilepsy.1 For neurologists, key goals in the treatment of epilepsy include: controlling seizures, minimizing adverse effects of antiepileptic drugs (AEDs) and optimizing quality of life. For obstetrician-gynecologists, women with epilepsy (WWE) have unique contraceptive, preconception, and obstetric needs that require highly specialized approaches to care. Here, I highlight 5 care points that are important to keep in mind when counseling WWE.

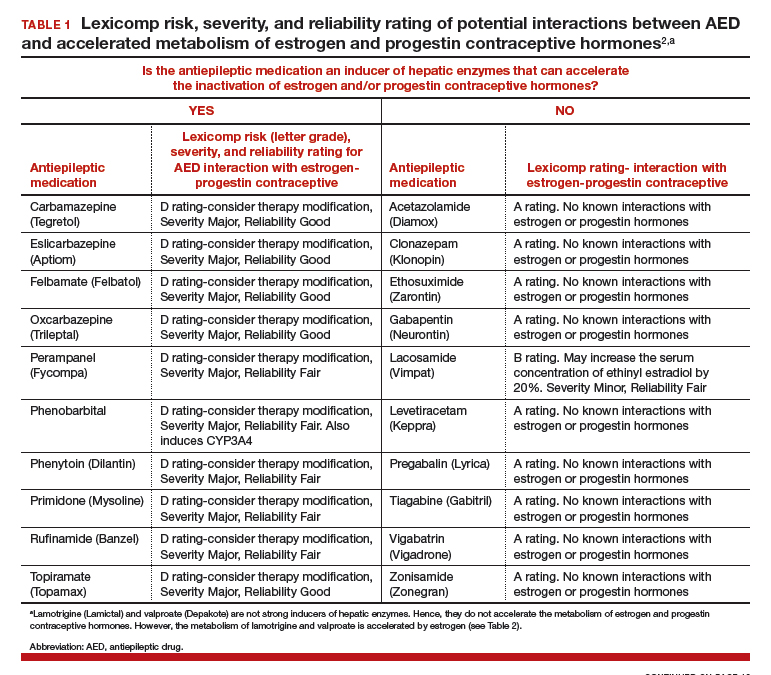

1. Enzyme-inducing AEDs reduce the effectiveness of estrogen-progestin and some progestin contraceptives.

AEDs can induce hepatic enzymes that accelerate steroid hormone metabolism, producing clinically important reductions in bioavailable steroid hormone concentration (TABLE 1). According to Lexicomp, AEDs that are inducers of hepatic enzymes that metabolize steroid hormones include: carbamazepine (Tegretol), eslicarbazepine (Aptiom), felbamate (Felbatol), oxcarbazepine (Trileptal), perampanel (Fycompa), phenobarbital, phenytoin (Dilantin), primidone (Mysoline), rufinamide (Banzel), and topiramate (Topamax) (at dosages >200 mg daily). According to Lexicomp, the following AEDs do not cause clinically significant changes in hepatic enzymes that metabolize steroid hormones: acetazolamide (Diamox), clonazepam (Klonopin), ethosuximide (Zarontin), gabapentin (Neurontin), lacosamide (Vimpat), levetiracetam (Keppra), pregabalin (Lyrica), tiagabine (Gabitril), vigabatrin (Vigadrone), and zonisamide (Zonegran).2,3 In addition, lamotrigine (Lamictal) and valproate (Depakote) do not significantly influence the metabolism of contraceptive steroids,4,5 but contraceptive steroids significantly influence their metabolism (TABLE 2).

For WWE taking an AED that accelerates steroid hormone metabolism, estrogen-progestin contraceptive failure is common. In a survey of 111 WWE taking both an oral contraceptive and an AED, 27 reported becoming pregnant while taking the oral contraceptive.6 Carbamazepine, a strong inducer of hepatic enzymes, was the most frequently used AED in this sample.

Many studies report that carbamazepine accelerates the metabolisms of estrogen and progestins and reduces contraceptive efficacy. For example, in one study 20 healthy women were administered an ethinyl estradiol (20 µg)-levonorgestrel (100 µg) contraceptive, and randomly assigned to either receive carbamazepine 600 mg daily or a placebo pill.7 In this study, based on serum progesterone measurements, 5 of 10 women in the carbamazepine group ovulated, compared with 1 of 10 women in the placebo group. Women taking carbamazepine had integrated serum ethinyl estradiol and levonorgestrel concentrations approximately 45% lower than women taking placebo.7 Other studies also report that carbamazepine accelerates steroid hormone metabolism and reduces the circulating concentration of ethinyl estradiol, norethindrone, and levonorgestrel by about 50%.5,8

WWE taking an AED that induces hepatic enzymes should be counseled to use a copper or levonorgestrel (LNG) intrauterine device (IUD) or depot medroxyprogesterone acetate (DMPA) for contraception.9 WWE taking AEDs that do not induce hepatic enzymes can be offered the full array of contraceptive options, as outlined in Table 1. Occasionally, a WWE taking an AED that is an inducer of hepatic enzymes may strongly prefer to use an estrogen-progestin contraceptive and decline the preferred option of using an IUD or DMPA. If an estrogen-progestin contraceptive is to be prescribed, safeguards to reduce the risk of pregnancy include:

- prescribe a contraceptive with ≥35 µg of ethinyl estradiol

- prescribe a contraceptive with the highest dose of progestin with a long half-life (drospirenone, desogestrel, levonorgestrel)

- consider continuous hormonal contraception rather than 4 or 7 days off hormones and

- recommend use of a barrier contraceptive in addition to the hormonal contraceptive.

The effectiveness of levonorgestrel emergency contraception may also be reduced in WWE taking an enzyme-inducing AED. In these cases, some experts recommend a regimen of two doses of levonorgestrel 1.5 mg, separated by 12 hours.10 The effectiveness of progestin subdermal contraceptives may be reduced in women taking phenytoin. In one study of 9 WWE using a progestin subdermal implant, phenytoin reduced the circulating levonorgestrel level by approximately 40%.11

Continue to: 2. Do not use lamotrigine with cyclic estrogen-progestin contraceptives...

2. Do not use lamotrigine with cyclic estrogen-progestin contraceptives.

Estrogens, but not progestins, are known to reduce the serum concentration of lamotrigine by about 50%.12,13 This is a clinically significant pharmacologic interaction. Consequently, when a cyclic estrogen-progestin contraceptive is prescribed to a woman taking lamotrigine, oscillation in lamotrigine serum concentration can occur. When the woman is taking estrogen-containing pills, lamotrigine levels decrease, which increases the risk of seizure. When the woman is not taking the estrogen-containing pills, lamotrigine levels increase, possibly causing such adverse effects as nausea and vomiting. If a woman taking lamotrigine insists on using an estrogen-progestin contraceptive, the medication should be prescribed in a continuous regimen and the neurologist alerted so that they can increase the dose of lamotrigine and intensify their monitoring of lamotrigine levels. Lamotrigine does not change the metabolism of ethinyl estradiol and has minimal impact on the metabolism of levonorgestrel.4

3. Estrogen-progestin contraceptives require valproate dosage adjustment.

A few studies report that estrogen-progestin contraceptives accelerate the metabolism of valproate and reduce circulating valproate concentration,14,15 as noted in Table 2.In one study, estrogen-progestin contraceptive was associated with 18% and 29% decreases in total and unbound valproate concentrations, respectively.14 Valproate may induce polycystic ovary syndrome in women.16 Therefore, it is common that valproate and an estrogen-progestin contraceptive are co-prescribed. In these situations, the neurologist should be alerted prior to prescribing an estrogen-progestin contraceptive to WWE taking valproate so that dosage adjustment may occur, if indicated. Valproate does not appear to change the metabolism of ethinyl estradiol or levonorgestrel.5

4. Preconception counseling: Before conception consider using an AED with low teratogenicity.

Valproate is a potent teratogen, and consideration should be given to discontinuing valproate prior to conception. In a study of 1,788 pregnancies exposed to valproate, the risk of a major congenital malformation was 10% for valproate monotherapy, 11.3% for valproate combined with lamotrigine, and 11.7% for valproate combined with another AED, but not lamotrigine.17 At a valproate dose of ≥1,500 mg daily, the risk of major malformation was 24% for valproate monotherapy, 31% for valproate plus lamotrigine, and 19% for valproate plus another AED, but not lamotrigine.17 Valproate is reported to be associated with the following major congenital malformations: spina bifida, ventricular and atrial septal defects, pulmonary valve atresia, hypoplastic left heart syndrome, cleft palate, anorectal atresia, and hypospadias.18

In a study of 7,555 pregnancies in women using a single AED, the risk of major congenital anomalies varied greatly among the AEDs, including: valproate (10.3%), phenobarbital (6.5%), phenytoin (6.4%), carbamazepine (5.5%), topiramate (3.9%), oxcarbazepine (3.0%), lamotrigine (2.9%), and levetiracetam (2.8%).19 For WWE considering pregnancy, many experts recommend use of lamotrigine, levetiracetam, or oxcarbazepine to minimize the risk of fetal anomalies.

Continue to: 5. Folic acid...

5. Folic acid: Although the optimal dose for WWE taking an AED and planning to become pregnant is unknown, a high dose is reasonable.

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) recommends that women planning pregnancy take 0.4 mg of folic acid daily, starting at least 1 month before pregnancy and continuing through at least the 12th week of gestation.20 ACOG also recommends that women at high risk of a neural tube defect should take 4 mg of folic acid daily. WWE taking a teratogenic AED are known to be at increased risk for fetal malformations, including neural tube defects. Should these women take 4 mg of folic acid daily? ACOG notes that, for women taking valproate, the benefit of high-dose folic acid (4 mg daily) has not been definitively proven,21 and guidelines from the American Academy of Neurology do not recommend high-dose folic acid for women receiving AEDs.22 Hence, ACOG does not recommend that WWE taking an AED take high-dose folic acid.

By contrast, the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (RCOG) recommends that all WWE planning a pregnancy take folic acid 5 mg daily, initiated 3 months before conception and continued through the first trimester of pregnancy.23 The RCOG notes that among WWE taking an AED, intelligence quotient is greater in children whose mothers took folic acid during pregnancy.24 Given the potential benefit of folic acid on long-term outcomes and the known safety of folic acid, it is reasonable to recommend high-dose folic acid for WWE.

Final takeaways

Surveys consistently report that WWE have a low-level of awareness about the interaction between AEDs and hormonal contraceptives and the teratogenicity of AEDs. For example, in a survey of 2,000 WWE, 45% who were taking an enzyme-inducing AED and an estrogen-progestin oral contraceptive reported that they had not been warned about the potential interaction between the medications.25 Surprisingly, surveys of neurologists and obstetrician-gynecologists also report that there is a low level of awareness about the interaction between AEDs and hormonal contraceptives.26 When providing contraceptive counseling for WWE, prioritize the use of a copper or levonorgestrel IUD. When providing preconception counseling for WWE, educate the patient about the high teratogenicity of valproate and the lower risk of malformations associated with the use of lamotrigine, levetiracetam, and oxcarbazepine.

For most women with epilepsy, maintaining a valid driver's license is important for completion of daily life tasks. Most states require that a patient with seizures be seizure-free for 6 to 12 months to operate a motor vehicle. Estrogen-containing hormonal contraceptives can reduce the concentration of some AEDs, such as lamotrigine. Hence, it is important that the patient be aware of this interaction and that the primary neurologist be alerted if an estrogen-containing contraceptive is prescribed to a woman taking lamotrigine or valproate. Specific state laws related to epilepsy and driving are available at the Epilepsy Foundation website (https://www.epilepsy.com/driving-laws).

- Zack MM, Kobau R. National and state estimates of the numbers of adults and children with active epilepsy - United States 2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66:821-825.

- Lexicomp. https://www.wolterskluwercdi.com/lexicomp-online/. Accessed August 16, 2019.

- Reimers A, Brodtkorb E, Sabers A. Interactions between hormonal contraception and antiepileptic drugs: clinical and mechanistic considerations. Seizure. 2015;28:66-70.

- Sidhu J, Job S, Singh S, et al. The pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic consequences of the co-administration of lamotrigine and a combined oral contraceptive in healthy female subjects. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2006;61:191-199.

- Crawford P, Chadwick D, Cleland P, et al. The lack of effect of sodium valproate on the pharmacokinetics of oral contraceptive steroids. Contraception. 1986;33:23-29.

- Fairgrieve SD, Jackson M, Jonas P, et al. Population-based, prospective study of the care of women with epilepsy in pregnancy. BMJ. 2000;321:674-675.

- Davis AR, Westhoff CL, Stanczyk FZ. Carbamazepine coadministration with an oral contraceptive: effects on steroid pharmacokinetics, ovulation, and bleeding. Epilepsia. 2011;52:243-247.

- Doose DR, Wang SS, Padmanabhan M, et al. Effect of topiramate or carbamazepine on the pharmacokinetics of an oral contraceptive containing norethindrone and ethinyl estradiol in healthy obese and nonobese female subjects. Epilepsia. 2003;44:540-549.

- Vieira CS, Pack A, Roberts K, et al. A pilot study of levonorgestrel concentrations and bleeding patterns in women with epilepsy using a levonorgestrel IUD and treated with antiepileptic drugs. Contraception. 2019;99:251-255.

- O'Brien MD, Guillebaud J. Contraception for women with epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2006;47:1419-1422.

- Haukkamaa M. Contraception by Norplant subdermal capsules is not reliable in epileptic patients on anticonvulsant treatment. Contraception. 1986;33:559-565.

- Sabers A, Buchholt JM, Uldall P, et al. Lamotrigine plasma levels reduced by oral contraceptives. Epilepsy Res. 2001;47:151-154.

- Reimers A, Helde G, Brodtkorb E. Ethinyl estradiol, not progestogens, reduces lamotrigine serum concentrations. Epilepsia. 2005;46:1414-1417.

- Galimberti CA, Mazzucchelli I, Arbasino C, et al. Increased apparent oral clearance of valproic acid during intake of combined contraceptive steroids in women with epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2006;47:1569-1572.

- Herzog AG, Farina EL, Blum AS. Serum valproate levels with oral contraceptive use. Epilepsia. 2005;46:970-971.

- Morrell MJ, Hayes FJ, Sluss PM, et al. Hyperandrogenism, ovulatory dysfunction, and polycystic ovary syndrome with valproate versus lamotrigine. Ann Neurol. 2008;64:200-211.

- Tomson T, Battino D, Bonizzoni E, et al; EURAP Study Group. Dose-dependent teratogenicity of valproate in mono- and polytherapy: an observational study. Neurology. 2015;85:866-872.

- Blotière PO, Raguideau F, Weill A, et al. Risks of 23 specific malformations associated with prenatal exposure to 10 antiepileptic drugs. Neurology. 2019;93:e167-e180.

- Tomson T, Battino D, Bonizzoni E, et al; EURAP Study Group. Comparative risk of major congenital malformations with eight different antiepileptic drugs: a prospective cohort study of the EURAP registry. Lancet Neurol. 2018;17:530-538.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Practice Bulletins-Obstetrics. Practice Bulletin No. 187: neural tube defects. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130:e279-e290.

- Ban L, Fleming KM, Doyle P, et al. Congenital anomalies in children of mothers taking antiepileptic drugs with and without periconceptional high dose folic acid use: a population-based cohort study. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0131130.

- Harden CL, Pennell PB, Koppel BS, et al; American Academy of Neurology and American Epilepsy Society. Practice parameter update: management issues for women with epilepsy--focus on pregnancy (an evidence-based review): vitamin K, folic acid, blood levels, and breastfeeding: report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee and Therapeutics and technology Assessment Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology and American Epilepsy Society. Neurology. 2009;73:142-149.

- Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Epilepsy in pregnancy. Green-top Guideline No. 68; June 2016. https://www.rcog.org.uk/globalassets/documents/guidelines/green-top-guidelines/gtg68_epilepsy.pdf. Accessed August 16, 2019.

- Meador KJ, Baker GA, Browning N, et al; NEAD Study Group. Fetal antiepileptic drug exposure and cognitive outcomes at age 6 years (NEAD study): a prospective observational study. Lancet Neurol. 2013;12:244-252.

- Crawford P, Hudson S. Understanding the information needs of women with epilepsy at different life stages: results of the 'Ideal World' survey. Seizure. 2003;12:502-507.

- Krauss GL, Brandt J, Campbell M, et al. Antiepileptic medication and oral contraceptive interactions: a national survey of neurologists and obstetricians. Neurology. 1996;46:1534-1539.

In 2015, 1.2% of the US population was estimated to have active epilepsy.1 For neurologists, key goals in the treatment of epilepsy include: controlling seizures, minimizing adverse effects of antiepileptic drugs (AEDs) and optimizing quality of life. For obstetrician-gynecologists, women with epilepsy (WWE) have unique contraceptive, preconception, and obstetric needs that require highly specialized approaches to care. Here, I highlight 5 care points that are important to keep in mind when counseling WWE.

1. Enzyme-inducing AEDs reduce the effectiveness of estrogen-progestin and some progestin contraceptives.

AEDs can induce hepatic enzymes that accelerate steroid hormone metabolism, producing clinically important reductions in bioavailable steroid hormone concentration (TABLE 1). According to Lexicomp, AEDs that are inducers of hepatic enzymes that metabolize steroid hormones include: carbamazepine (Tegretol), eslicarbazepine (Aptiom), felbamate (Felbatol), oxcarbazepine (Trileptal), perampanel (Fycompa), phenobarbital, phenytoin (Dilantin), primidone (Mysoline), rufinamide (Banzel), and topiramate (Topamax) (at dosages >200 mg daily). According to Lexicomp, the following AEDs do not cause clinically significant changes in hepatic enzymes that metabolize steroid hormones: acetazolamide (Diamox), clonazepam (Klonopin), ethosuximide (Zarontin), gabapentin (Neurontin), lacosamide (Vimpat), levetiracetam (Keppra), pregabalin (Lyrica), tiagabine (Gabitril), vigabatrin (Vigadrone), and zonisamide (Zonegran).2,3 In addition, lamotrigine (Lamictal) and valproate (Depakote) do not significantly influence the metabolism of contraceptive steroids,4,5 but contraceptive steroids significantly influence their metabolism (TABLE 2).

For WWE taking an AED that accelerates steroid hormone metabolism, estrogen-progestin contraceptive failure is common. In a survey of 111 WWE taking both an oral contraceptive and an AED, 27 reported becoming pregnant while taking the oral contraceptive.6 Carbamazepine, a strong inducer of hepatic enzymes, was the most frequently used AED in this sample.

Many studies report that carbamazepine accelerates the metabolisms of estrogen and progestins and reduces contraceptive efficacy. For example, in one study 20 healthy women were administered an ethinyl estradiol (20 µg)-levonorgestrel (100 µg) contraceptive, and randomly assigned to either receive carbamazepine 600 mg daily or a placebo pill.7 In this study, based on serum progesterone measurements, 5 of 10 women in the carbamazepine group ovulated, compared with 1 of 10 women in the placebo group. Women taking carbamazepine had integrated serum ethinyl estradiol and levonorgestrel concentrations approximately 45% lower than women taking placebo.7 Other studies also report that carbamazepine accelerates steroid hormone metabolism and reduces the circulating concentration of ethinyl estradiol, norethindrone, and levonorgestrel by about 50%.5,8

WWE taking an AED that induces hepatic enzymes should be counseled to use a copper or levonorgestrel (LNG) intrauterine device (IUD) or depot medroxyprogesterone acetate (DMPA) for contraception.9 WWE taking AEDs that do not induce hepatic enzymes can be offered the full array of contraceptive options, as outlined in Table 1. Occasionally, a WWE taking an AED that is an inducer of hepatic enzymes may strongly prefer to use an estrogen-progestin contraceptive and decline the preferred option of using an IUD or DMPA. If an estrogen-progestin contraceptive is to be prescribed, safeguards to reduce the risk of pregnancy include:

- prescribe a contraceptive with ≥35 µg of ethinyl estradiol

- prescribe a contraceptive with the highest dose of progestin with a long half-life (drospirenone, desogestrel, levonorgestrel)

- consider continuous hormonal contraception rather than 4 or 7 days off hormones and

- recommend use of a barrier contraceptive in addition to the hormonal contraceptive.

The effectiveness of levonorgestrel emergency contraception may also be reduced in WWE taking an enzyme-inducing AED. In these cases, some experts recommend a regimen of two doses of levonorgestrel 1.5 mg, separated by 12 hours.10 The effectiveness of progestin subdermal contraceptives may be reduced in women taking phenytoin. In one study of 9 WWE using a progestin subdermal implant, phenytoin reduced the circulating levonorgestrel level by approximately 40%.11

Continue to: 2. Do not use lamotrigine with cyclic estrogen-progestin contraceptives...

2. Do not use lamotrigine with cyclic estrogen-progestin contraceptives.

Estrogens, but not progestins, are known to reduce the serum concentration of lamotrigine by about 50%.12,13 This is a clinically significant pharmacologic interaction. Consequently, when a cyclic estrogen-progestin contraceptive is prescribed to a woman taking lamotrigine, oscillation in lamotrigine serum concentration can occur. When the woman is taking estrogen-containing pills, lamotrigine levels decrease, which increases the risk of seizure. When the woman is not taking the estrogen-containing pills, lamotrigine levels increase, possibly causing such adverse effects as nausea and vomiting. If a woman taking lamotrigine insists on using an estrogen-progestin contraceptive, the medication should be prescribed in a continuous regimen and the neurologist alerted so that they can increase the dose of lamotrigine and intensify their monitoring of lamotrigine levels. Lamotrigine does not change the metabolism of ethinyl estradiol and has minimal impact on the metabolism of levonorgestrel.4

3. Estrogen-progestin contraceptives require valproate dosage adjustment.

A few studies report that estrogen-progestin contraceptives accelerate the metabolism of valproate and reduce circulating valproate concentration,14,15 as noted in Table 2.In one study, estrogen-progestin contraceptive was associated with 18% and 29% decreases in total and unbound valproate concentrations, respectively.14 Valproate may induce polycystic ovary syndrome in women.16 Therefore, it is common that valproate and an estrogen-progestin contraceptive are co-prescribed. In these situations, the neurologist should be alerted prior to prescribing an estrogen-progestin contraceptive to WWE taking valproate so that dosage adjustment may occur, if indicated. Valproate does not appear to change the metabolism of ethinyl estradiol or levonorgestrel.5

4. Preconception counseling: Before conception consider using an AED with low teratogenicity.

Valproate is a potent teratogen, and consideration should be given to discontinuing valproate prior to conception. In a study of 1,788 pregnancies exposed to valproate, the risk of a major congenital malformation was 10% for valproate monotherapy, 11.3% for valproate combined with lamotrigine, and 11.7% for valproate combined with another AED, but not lamotrigine.17 At a valproate dose of ≥1,500 mg daily, the risk of major malformation was 24% for valproate monotherapy, 31% for valproate plus lamotrigine, and 19% for valproate plus another AED, but not lamotrigine.17 Valproate is reported to be associated with the following major congenital malformations: spina bifida, ventricular and atrial septal defects, pulmonary valve atresia, hypoplastic left heart syndrome, cleft palate, anorectal atresia, and hypospadias.18

In a study of 7,555 pregnancies in women using a single AED, the risk of major congenital anomalies varied greatly among the AEDs, including: valproate (10.3%), phenobarbital (6.5%), phenytoin (6.4%), carbamazepine (5.5%), topiramate (3.9%), oxcarbazepine (3.0%), lamotrigine (2.9%), and levetiracetam (2.8%).19 For WWE considering pregnancy, many experts recommend use of lamotrigine, levetiracetam, or oxcarbazepine to minimize the risk of fetal anomalies.

Continue to: 5. Folic acid...

5. Folic acid: Although the optimal dose for WWE taking an AED and planning to become pregnant is unknown, a high dose is reasonable.

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) recommends that women planning pregnancy take 0.4 mg of folic acid daily, starting at least 1 month before pregnancy and continuing through at least the 12th week of gestation.20 ACOG also recommends that women at high risk of a neural tube defect should take 4 mg of folic acid daily. WWE taking a teratogenic AED are known to be at increased risk for fetal malformations, including neural tube defects. Should these women take 4 mg of folic acid daily? ACOG notes that, for women taking valproate, the benefit of high-dose folic acid (4 mg daily) has not been definitively proven,21 and guidelines from the American Academy of Neurology do not recommend high-dose folic acid for women receiving AEDs.22 Hence, ACOG does not recommend that WWE taking an AED take high-dose folic acid.

By contrast, the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (RCOG) recommends that all WWE planning a pregnancy take folic acid 5 mg daily, initiated 3 months before conception and continued through the first trimester of pregnancy.23 The RCOG notes that among WWE taking an AED, intelligence quotient is greater in children whose mothers took folic acid during pregnancy.24 Given the potential benefit of folic acid on long-term outcomes and the known safety of folic acid, it is reasonable to recommend high-dose folic acid for WWE.

Final takeaways

Surveys consistently report that WWE have a low-level of awareness about the interaction between AEDs and hormonal contraceptives and the teratogenicity of AEDs. For example, in a survey of 2,000 WWE, 45% who were taking an enzyme-inducing AED and an estrogen-progestin oral contraceptive reported that they had not been warned about the potential interaction between the medications.25 Surprisingly, surveys of neurologists and obstetrician-gynecologists also report that there is a low level of awareness about the interaction between AEDs and hormonal contraceptives.26 When providing contraceptive counseling for WWE, prioritize the use of a copper or levonorgestrel IUD. When providing preconception counseling for WWE, educate the patient about the high teratogenicity of valproate and the lower risk of malformations associated with the use of lamotrigine, levetiracetam, and oxcarbazepine.

For most women with epilepsy, maintaining a valid driver's license is important for completion of daily life tasks. Most states require that a patient with seizures be seizure-free for 6 to 12 months to operate a motor vehicle. Estrogen-containing hormonal contraceptives can reduce the concentration of some AEDs, such as lamotrigine. Hence, it is important that the patient be aware of this interaction and that the primary neurologist be alerted if an estrogen-containing contraceptive is prescribed to a woman taking lamotrigine or valproate. Specific state laws related to epilepsy and driving are available at the Epilepsy Foundation website (https://www.epilepsy.com/driving-laws).

In 2015, 1.2% of the US population was estimated to have active epilepsy.1 For neurologists, key goals in the treatment of epilepsy include: controlling seizures, minimizing adverse effects of antiepileptic drugs (AEDs) and optimizing quality of life. For obstetrician-gynecologists, women with epilepsy (WWE) have unique contraceptive, preconception, and obstetric needs that require highly specialized approaches to care. Here, I highlight 5 care points that are important to keep in mind when counseling WWE.

1. Enzyme-inducing AEDs reduce the effectiveness of estrogen-progestin and some progestin contraceptives.

AEDs can induce hepatic enzymes that accelerate steroid hormone metabolism, producing clinically important reductions in bioavailable steroid hormone concentration (TABLE 1). According to Lexicomp, AEDs that are inducers of hepatic enzymes that metabolize steroid hormones include: carbamazepine (Tegretol), eslicarbazepine (Aptiom), felbamate (Felbatol), oxcarbazepine (Trileptal), perampanel (Fycompa), phenobarbital, phenytoin (Dilantin), primidone (Mysoline), rufinamide (Banzel), and topiramate (Topamax) (at dosages >200 mg daily). According to Lexicomp, the following AEDs do not cause clinically significant changes in hepatic enzymes that metabolize steroid hormones: acetazolamide (Diamox), clonazepam (Klonopin), ethosuximide (Zarontin), gabapentin (Neurontin), lacosamide (Vimpat), levetiracetam (Keppra), pregabalin (Lyrica), tiagabine (Gabitril), vigabatrin (Vigadrone), and zonisamide (Zonegran).2,3 In addition, lamotrigine (Lamictal) and valproate (Depakote) do not significantly influence the metabolism of contraceptive steroids,4,5 but contraceptive steroids significantly influence their metabolism (TABLE 2).

For WWE taking an AED that accelerates steroid hormone metabolism, estrogen-progestin contraceptive failure is common. In a survey of 111 WWE taking both an oral contraceptive and an AED, 27 reported becoming pregnant while taking the oral contraceptive.6 Carbamazepine, a strong inducer of hepatic enzymes, was the most frequently used AED in this sample.

Many studies report that carbamazepine accelerates the metabolisms of estrogen and progestins and reduces contraceptive efficacy. For example, in one study 20 healthy women were administered an ethinyl estradiol (20 µg)-levonorgestrel (100 µg) contraceptive, and randomly assigned to either receive carbamazepine 600 mg daily or a placebo pill.7 In this study, based on serum progesterone measurements, 5 of 10 women in the carbamazepine group ovulated, compared with 1 of 10 women in the placebo group. Women taking carbamazepine had integrated serum ethinyl estradiol and levonorgestrel concentrations approximately 45% lower than women taking placebo.7 Other studies also report that carbamazepine accelerates steroid hormone metabolism and reduces the circulating concentration of ethinyl estradiol, norethindrone, and levonorgestrel by about 50%.5,8

WWE taking an AED that induces hepatic enzymes should be counseled to use a copper or levonorgestrel (LNG) intrauterine device (IUD) or depot medroxyprogesterone acetate (DMPA) for contraception.9 WWE taking AEDs that do not induce hepatic enzymes can be offered the full array of contraceptive options, as outlined in Table 1. Occasionally, a WWE taking an AED that is an inducer of hepatic enzymes may strongly prefer to use an estrogen-progestin contraceptive and decline the preferred option of using an IUD or DMPA. If an estrogen-progestin contraceptive is to be prescribed, safeguards to reduce the risk of pregnancy include:

- prescribe a contraceptive with ≥35 µg of ethinyl estradiol

- prescribe a contraceptive with the highest dose of progestin with a long half-life (drospirenone, desogestrel, levonorgestrel)

- consider continuous hormonal contraception rather than 4 or 7 days off hormones and

- recommend use of a barrier contraceptive in addition to the hormonal contraceptive.

The effectiveness of levonorgestrel emergency contraception may also be reduced in WWE taking an enzyme-inducing AED. In these cases, some experts recommend a regimen of two doses of levonorgestrel 1.5 mg, separated by 12 hours.10 The effectiveness of progestin subdermal contraceptives may be reduced in women taking phenytoin. In one study of 9 WWE using a progestin subdermal implant, phenytoin reduced the circulating levonorgestrel level by approximately 40%.11

Continue to: 2. Do not use lamotrigine with cyclic estrogen-progestin contraceptives...

2. Do not use lamotrigine with cyclic estrogen-progestin contraceptives.

Estrogens, but not progestins, are known to reduce the serum concentration of lamotrigine by about 50%.12,13 This is a clinically significant pharmacologic interaction. Consequently, when a cyclic estrogen-progestin contraceptive is prescribed to a woman taking lamotrigine, oscillation in lamotrigine serum concentration can occur. When the woman is taking estrogen-containing pills, lamotrigine levels decrease, which increases the risk of seizure. When the woman is not taking the estrogen-containing pills, lamotrigine levels increase, possibly causing such adverse effects as nausea and vomiting. If a woman taking lamotrigine insists on using an estrogen-progestin contraceptive, the medication should be prescribed in a continuous regimen and the neurologist alerted so that they can increase the dose of lamotrigine and intensify their monitoring of lamotrigine levels. Lamotrigine does not change the metabolism of ethinyl estradiol and has minimal impact on the metabolism of levonorgestrel.4

3. Estrogen-progestin contraceptives require valproate dosage adjustment.

A few studies report that estrogen-progestin contraceptives accelerate the metabolism of valproate and reduce circulating valproate concentration,14,15 as noted in Table 2.In one study, estrogen-progestin contraceptive was associated with 18% and 29% decreases in total and unbound valproate concentrations, respectively.14 Valproate may induce polycystic ovary syndrome in women.16 Therefore, it is common that valproate and an estrogen-progestin contraceptive are co-prescribed. In these situations, the neurologist should be alerted prior to prescribing an estrogen-progestin contraceptive to WWE taking valproate so that dosage adjustment may occur, if indicated. Valproate does not appear to change the metabolism of ethinyl estradiol or levonorgestrel.5

4. Preconception counseling: Before conception consider using an AED with low teratogenicity.

Valproate is a potent teratogen, and consideration should be given to discontinuing valproate prior to conception. In a study of 1,788 pregnancies exposed to valproate, the risk of a major congenital malformation was 10% for valproate monotherapy, 11.3% for valproate combined with lamotrigine, and 11.7% for valproate combined with another AED, but not lamotrigine.17 At a valproate dose of ≥1,500 mg daily, the risk of major malformation was 24% for valproate monotherapy, 31% for valproate plus lamotrigine, and 19% for valproate plus another AED, but not lamotrigine.17 Valproate is reported to be associated with the following major congenital malformations: spina bifida, ventricular and atrial septal defects, pulmonary valve atresia, hypoplastic left heart syndrome, cleft palate, anorectal atresia, and hypospadias.18

In a study of 7,555 pregnancies in women using a single AED, the risk of major congenital anomalies varied greatly among the AEDs, including: valproate (10.3%), phenobarbital (6.5%), phenytoin (6.4%), carbamazepine (5.5%), topiramate (3.9%), oxcarbazepine (3.0%), lamotrigine (2.9%), and levetiracetam (2.8%).19 For WWE considering pregnancy, many experts recommend use of lamotrigine, levetiracetam, or oxcarbazepine to minimize the risk of fetal anomalies.

Continue to: 5. Folic acid...

5. Folic acid: Although the optimal dose for WWE taking an AED and planning to become pregnant is unknown, a high dose is reasonable.

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) recommends that women planning pregnancy take 0.4 mg of folic acid daily, starting at least 1 month before pregnancy and continuing through at least the 12th week of gestation.20 ACOG also recommends that women at high risk of a neural tube defect should take 4 mg of folic acid daily. WWE taking a teratogenic AED are known to be at increased risk for fetal malformations, including neural tube defects. Should these women take 4 mg of folic acid daily? ACOG notes that, for women taking valproate, the benefit of high-dose folic acid (4 mg daily) has not been definitively proven,21 and guidelines from the American Academy of Neurology do not recommend high-dose folic acid for women receiving AEDs.22 Hence, ACOG does not recommend that WWE taking an AED take high-dose folic acid.

By contrast, the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (RCOG) recommends that all WWE planning a pregnancy take folic acid 5 mg daily, initiated 3 months before conception and continued through the first trimester of pregnancy.23 The RCOG notes that among WWE taking an AED, intelligence quotient is greater in children whose mothers took folic acid during pregnancy.24 Given the potential benefit of folic acid on long-term outcomes and the known safety of folic acid, it is reasonable to recommend high-dose folic acid for WWE.

Final takeaways

Surveys consistently report that WWE have a low-level of awareness about the interaction between AEDs and hormonal contraceptives and the teratogenicity of AEDs. For example, in a survey of 2,000 WWE, 45% who were taking an enzyme-inducing AED and an estrogen-progestin oral contraceptive reported that they had not been warned about the potential interaction between the medications.25 Surprisingly, surveys of neurologists and obstetrician-gynecologists also report that there is a low level of awareness about the interaction between AEDs and hormonal contraceptives.26 When providing contraceptive counseling for WWE, prioritize the use of a copper or levonorgestrel IUD. When providing preconception counseling for WWE, educate the patient about the high teratogenicity of valproate and the lower risk of malformations associated with the use of lamotrigine, levetiracetam, and oxcarbazepine.

For most women with epilepsy, maintaining a valid driver's license is important for completion of daily life tasks. Most states require that a patient with seizures be seizure-free for 6 to 12 months to operate a motor vehicle. Estrogen-containing hormonal contraceptives can reduce the concentration of some AEDs, such as lamotrigine. Hence, it is important that the patient be aware of this interaction and that the primary neurologist be alerted if an estrogen-containing contraceptive is prescribed to a woman taking lamotrigine or valproate. Specific state laws related to epilepsy and driving are available at the Epilepsy Foundation website (https://www.epilepsy.com/driving-laws).

- Zack MM, Kobau R. National and state estimates of the numbers of adults and children with active epilepsy - United States 2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66:821-825.

- Lexicomp. https://www.wolterskluwercdi.com/lexicomp-online/. Accessed August 16, 2019.

- Reimers A, Brodtkorb E, Sabers A. Interactions between hormonal contraception and antiepileptic drugs: clinical and mechanistic considerations. Seizure. 2015;28:66-70.

- Sidhu J, Job S, Singh S, et al. The pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic consequences of the co-administration of lamotrigine and a combined oral contraceptive in healthy female subjects. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2006;61:191-199.

- Crawford P, Chadwick D, Cleland P, et al. The lack of effect of sodium valproate on the pharmacokinetics of oral contraceptive steroids. Contraception. 1986;33:23-29.

- Fairgrieve SD, Jackson M, Jonas P, et al. Population-based, prospective study of the care of women with epilepsy in pregnancy. BMJ. 2000;321:674-675.

- Davis AR, Westhoff CL, Stanczyk FZ. Carbamazepine coadministration with an oral contraceptive: effects on steroid pharmacokinetics, ovulation, and bleeding. Epilepsia. 2011;52:243-247.

- Doose DR, Wang SS, Padmanabhan M, et al. Effect of topiramate or carbamazepine on the pharmacokinetics of an oral contraceptive containing norethindrone and ethinyl estradiol in healthy obese and nonobese female subjects. Epilepsia. 2003;44:540-549.

- Vieira CS, Pack A, Roberts K, et al. A pilot study of levonorgestrel concentrations and bleeding patterns in women with epilepsy using a levonorgestrel IUD and treated with antiepileptic drugs. Contraception. 2019;99:251-255.

- O'Brien MD, Guillebaud J. Contraception for women with epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2006;47:1419-1422.

- Haukkamaa M. Contraception by Norplant subdermal capsules is not reliable in epileptic patients on anticonvulsant treatment. Contraception. 1986;33:559-565.

- Sabers A, Buchholt JM, Uldall P, et al. Lamotrigine plasma levels reduced by oral contraceptives. Epilepsy Res. 2001;47:151-154.

- Reimers A, Helde G, Brodtkorb E. Ethinyl estradiol, not progestogens, reduces lamotrigine serum concentrations. Epilepsia. 2005;46:1414-1417.

- Galimberti CA, Mazzucchelli I, Arbasino C, et al. Increased apparent oral clearance of valproic acid during intake of combined contraceptive steroids in women with epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2006;47:1569-1572.

- Herzog AG, Farina EL, Blum AS. Serum valproate levels with oral contraceptive use. Epilepsia. 2005;46:970-971.

- Morrell MJ, Hayes FJ, Sluss PM, et al. Hyperandrogenism, ovulatory dysfunction, and polycystic ovary syndrome with valproate versus lamotrigine. Ann Neurol. 2008;64:200-211.

- Tomson T, Battino D, Bonizzoni E, et al; EURAP Study Group. Dose-dependent teratogenicity of valproate in mono- and polytherapy: an observational study. Neurology. 2015;85:866-872.

- Blotière PO, Raguideau F, Weill A, et al. Risks of 23 specific malformations associated with prenatal exposure to 10 antiepileptic drugs. Neurology. 2019;93:e167-e180.

- Tomson T, Battino D, Bonizzoni E, et al; EURAP Study Group. Comparative risk of major congenital malformations with eight different antiepileptic drugs: a prospective cohort study of the EURAP registry. Lancet Neurol. 2018;17:530-538.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Practice Bulletins-Obstetrics. Practice Bulletin No. 187: neural tube defects. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130:e279-e290.

- Ban L, Fleming KM, Doyle P, et al. Congenital anomalies in children of mothers taking antiepileptic drugs with and without periconceptional high dose folic acid use: a population-based cohort study. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0131130.

- Harden CL, Pennell PB, Koppel BS, et al; American Academy of Neurology and American Epilepsy Society. Practice parameter update: management issues for women with epilepsy--focus on pregnancy (an evidence-based review): vitamin K, folic acid, blood levels, and breastfeeding: report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee and Therapeutics and technology Assessment Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology and American Epilepsy Society. Neurology. 2009;73:142-149.

- Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Epilepsy in pregnancy. Green-top Guideline No. 68; June 2016. https://www.rcog.org.uk/globalassets/documents/guidelines/green-top-guidelines/gtg68_epilepsy.pdf. Accessed August 16, 2019.

- Meador KJ, Baker GA, Browning N, et al; NEAD Study Group. Fetal antiepileptic drug exposure and cognitive outcomes at age 6 years (NEAD study): a prospective observational study. Lancet Neurol. 2013;12:244-252.

- Crawford P, Hudson S. Understanding the information needs of women with epilepsy at different life stages: results of the 'Ideal World' survey. Seizure. 2003;12:502-507.

- Krauss GL, Brandt J, Campbell M, et al. Antiepileptic medication and oral contraceptive interactions: a national survey of neurologists and obstetricians. Neurology. 1996;46:1534-1539.

- Zack MM, Kobau R. National and state estimates of the numbers of adults and children with active epilepsy - United States 2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66:821-825.

- Lexicomp. https://www.wolterskluwercdi.com/lexicomp-online/. Accessed August 16, 2019.

- Reimers A, Brodtkorb E, Sabers A. Interactions between hormonal contraception and antiepileptic drugs: clinical and mechanistic considerations. Seizure. 2015;28:66-70.

- Sidhu J, Job S, Singh S, et al. The pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic consequences of the co-administration of lamotrigine and a combined oral contraceptive in healthy female subjects. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2006;61:191-199.

- Crawford P, Chadwick D, Cleland P, et al. The lack of effect of sodium valproate on the pharmacokinetics of oral contraceptive steroids. Contraception. 1986;33:23-29.

- Fairgrieve SD, Jackson M, Jonas P, et al. Population-based, prospective study of the care of women with epilepsy in pregnancy. BMJ. 2000;321:674-675.

- Davis AR, Westhoff CL, Stanczyk FZ. Carbamazepine coadministration with an oral contraceptive: effects on steroid pharmacokinetics, ovulation, and bleeding. Epilepsia. 2011;52:243-247.

- Doose DR, Wang SS, Padmanabhan M, et al. Effect of topiramate or carbamazepine on the pharmacokinetics of an oral contraceptive containing norethindrone and ethinyl estradiol in healthy obese and nonobese female subjects. Epilepsia. 2003;44:540-549.

- Vieira CS, Pack A, Roberts K, et al. A pilot study of levonorgestrel concentrations and bleeding patterns in women with epilepsy using a levonorgestrel IUD and treated with antiepileptic drugs. Contraception. 2019;99:251-255.

- O'Brien MD, Guillebaud J. Contraception for women with epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2006;47:1419-1422.

- Haukkamaa M. Contraception by Norplant subdermal capsules is not reliable in epileptic patients on anticonvulsant treatment. Contraception. 1986;33:559-565.

- Sabers A, Buchholt JM, Uldall P, et al. Lamotrigine plasma levels reduced by oral contraceptives. Epilepsy Res. 2001;47:151-154.

- Reimers A, Helde G, Brodtkorb E. Ethinyl estradiol, not progestogens, reduces lamotrigine serum concentrations. Epilepsia. 2005;46:1414-1417.

- Galimberti CA, Mazzucchelli I, Arbasino C, et al. Increased apparent oral clearance of valproic acid during intake of combined contraceptive steroids in women with epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2006;47:1569-1572.

- Herzog AG, Farina EL, Blum AS. Serum valproate levels with oral contraceptive use. Epilepsia. 2005;46:970-971.

- Morrell MJ, Hayes FJ, Sluss PM, et al. Hyperandrogenism, ovulatory dysfunction, and polycystic ovary syndrome with valproate versus lamotrigine. Ann Neurol. 2008;64:200-211.

- Tomson T, Battino D, Bonizzoni E, et al; EURAP Study Group. Dose-dependent teratogenicity of valproate in mono- and polytherapy: an observational study. Neurology. 2015;85:866-872.

- Blotière PO, Raguideau F, Weill A, et al. Risks of 23 specific malformations associated with prenatal exposure to 10 antiepileptic drugs. Neurology. 2019;93:e167-e180.

- Tomson T, Battino D, Bonizzoni E, et al; EURAP Study Group. Comparative risk of major congenital malformations with eight different antiepileptic drugs: a prospective cohort study of the EURAP registry. Lancet Neurol. 2018;17:530-538.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Practice Bulletins-Obstetrics. Practice Bulletin No. 187: neural tube defects. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130:e279-e290.

- Ban L, Fleming KM, Doyle P, et al. Congenital anomalies in children of mothers taking antiepileptic drugs with and without periconceptional high dose folic acid use: a population-based cohort study. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0131130.

- Harden CL, Pennell PB, Koppel BS, et al; American Academy of Neurology and American Epilepsy Society. Practice parameter update: management issues for women with epilepsy--focus on pregnancy (an evidence-based review): vitamin K, folic acid, blood levels, and breastfeeding: report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee and Therapeutics and technology Assessment Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology and American Epilepsy Society. Neurology. 2009;73:142-149.