User login

Progressive myeloma after induction? Go straight to transplant

Patients with multiple myeloma who don’t respond to induction therapy may be better off advancing straight to autologous stem cell therapy, rather than undergoing salvage therapy before transplant, according to findings of an analysis that included both real-world and clinical trial patients.

Joanna Blocka, MD, of the University Hospital of Heidelberg (Germany) and colleagues found similar progression-free and overall survival rates for patients who had progressive disease and underwent autologous stem cell therapy (ASCT), compared with patients who underwent salvage therapy and improved to at least stable disease before proceeding to transplant. The findings were published in Leukemia & Lymphoma.

The real-world analysis included 1,599 patients with multiple myeloma who had undergone ASCT between 1991 and 2016. More than half of the patients (58%) were not enrolled in clinical trials. The remainder were split between the German-Speaking Myeloma Multicenter Group (GMMG)-HD3 and GMMG-HD4 trials, which compared various induction regimens.

Just 23 patients in the analysis received salvage therapy because of progressive disease and deepened their response before ASCT. Of these patients, 12 received novel agents in induction therapy and 11 received older medications.

Looking across all 1,599 patients, 5.3% achieved complete remission before first ASCT. Most patients (71.8%) achieved partial remission, 9.7% had a minimal response, and 5.7% had stable disease. A group of 120 patients (7.5%) progressed between the last course of induction and ASCT.

The researchers compared the progression-free and overall survival rates of patients with progressive disease versus those who had stable disease or better before their first transplant. Both univariable and multivariable analysis showed no statistically significant differences in either survival outcome between the two groups.

In the multivariable analysis, there was a hazard ratio of 1.23 (95% confidence interval, 0.98-1.56) for progression-free survival for patients with progressive disease versus those who responded to induction therapy. Similarly, the HR for overall survival between the two groups was 1.24 (95% CI, 0.93-1.65).

The researchers also analyzed the groups based on whether they received novel or older agents during induction.

Patients with progressive disease who received novel agents had significantly worse progression-free survival (22.2 months), compared with patients who responded to treatment with novel agents (22.2 months vs. 29.1 months; P = .03). The same trend was seen with overall survival in these groups (54.4 months vs. 97.5 months; P less than .001).

Rates of survival were similar for patients with progressive disease and responders who had received older medications at induction.

“This might be explained by a prognostically disadvantageous disease biology in patients nonresponsive to novel agents,” the researchers wrote.

The researchers also compared survival outcomes for the 120 patients who underwent ASCT with progressive disease versus the 23 patients who received salvage therapy and improved their response to at least stable disease before transplant. Univariable analysis showed that salvage patients actually did worse than those with progressive disease who proceeded straight to transplant – 12.1 months versus 22.9 months of progression-free survival (P = .04) and 33.1 versus 69.5 months of overall survival (P = .08). But on multivariable analysis, there was no significant difference between the two groups for progression-free survival (HR, 0.71; 95% CI, 0.28-1.80; P = .5) or overall survival (HR, 0.77; 95% CI, 0.30-1.95; P = .6). The use of novel agents did not appear to affect the survival outcomes in these patients.

The worse outcomes seen among salvage patients observed in univariable analysis “might be due to a cumulative toxic effect of salvage therapy,” the researchers suggested. “An alternative explanation could be that the patients who were offered salvage therapy might have had more aggressive disease than those who did not undergo salvage therapy.”

Dr. Blocka reported having no relevant financial disclosures. Other coauthors reported relationships with Janssen, Amgen, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Celgene, and others.

SOURCE: Blocka J et al. Leuk Lymphoma. 2019 Aug 19. doi: 10.1080/10428194.2019.1646905.

Patients with multiple myeloma who don’t respond to induction therapy may be better off advancing straight to autologous stem cell therapy, rather than undergoing salvage therapy before transplant, according to findings of an analysis that included both real-world and clinical trial patients.

Joanna Blocka, MD, of the University Hospital of Heidelberg (Germany) and colleagues found similar progression-free and overall survival rates for patients who had progressive disease and underwent autologous stem cell therapy (ASCT), compared with patients who underwent salvage therapy and improved to at least stable disease before proceeding to transplant. The findings were published in Leukemia & Lymphoma.

The real-world analysis included 1,599 patients with multiple myeloma who had undergone ASCT between 1991 and 2016. More than half of the patients (58%) were not enrolled in clinical trials. The remainder were split between the German-Speaking Myeloma Multicenter Group (GMMG)-HD3 and GMMG-HD4 trials, which compared various induction regimens.

Just 23 patients in the analysis received salvage therapy because of progressive disease and deepened their response before ASCT. Of these patients, 12 received novel agents in induction therapy and 11 received older medications.

Looking across all 1,599 patients, 5.3% achieved complete remission before first ASCT. Most patients (71.8%) achieved partial remission, 9.7% had a minimal response, and 5.7% had stable disease. A group of 120 patients (7.5%) progressed between the last course of induction and ASCT.

The researchers compared the progression-free and overall survival rates of patients with progressive disease versus those who had stable disease or better before their first transplant. Both univariable and multivariable analysis showed no statistically significant differences in either survival outcome between the two groups.

In the multivariable analysis, there was a hazard ratio of 1.23 (95% confidence interval, 0.98-1.56) for progression-free survival for patients with progressive disease versus those who responded to induction therapy. Similarly, the HR for overall survival between the two groups was 1.24 (95% CI, 0.93-1.65).

The researchers also analyzed the groups based on whether they received novel or older agents during induction.

Patients with progressive disease who received novel agents had significantly worse progression-free survival (22.2 months), compared with patients who responded to treatment with novel agents (22.2 months vs. 29.1 months; P = .03). The same trend was seen with overall survival in these groups (54.4 months vs. 97.5 months; P less than .001).

Rates of survival were similar for patients with progressive disease and responders who had received older medications at induction.

“This might be explained by a prognostically disadvantageous disease biology in patients nonresponsive to novel agents,” the researchers wrote.

The researchers also compared survival outcomes for the 120 patients who underwent ASCT with progressive disease versus the 23 patients who received salvage therapy and improved their response to at least stable disease before transplant. Univariable analysis showed that salvage patients actually did worse than those with progressive disease who proceeded straight to transplant – 12.1 months versus 22.9 months of progression-free survival (P = .04) and 33.1 versus 69.5 months of overall survival (P = .08). But on multivariable analysis, there was no significant difference between the two groups for progression-free survival (HR, 0.71; 95% CI, 0.28-1.80; P = .5) or overall survival (HR, 0.77; 95% CI, 0.30-1.95; P = .6). The use of novel agents did not appear to affect the survival outcomes in these patients.

The worse outcomes seen among salvage patients observed in univariable analysis “might be due to a cumulative toxic effect of salvage therapy,” the researchers suggested. “An alternative explanation could be that the patients who were offered salvage therapy might have had more aggressive disease than those who did not undergo salvage therapy.”

Dr. Blocka reported having no relevant financial disclosures. Other coauthors reported relationships with Janssen, Amgen, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Celgene, and others.

SOURCE: Blocka J et al. Leuk Lymphoma. 2019 Aug 19. doi: 10.1080/10428194.2019.1646905.

Patients with multiple myeloma who don’t respond to induction therapy may be better off advancing straight to autologous stem cell therapy, rather than undergoing salvage therapy before transplant, according to findings of an analysis that included both real-world and clinical trial patients.

Joanna Blocka, MD, of the University Hospital of Heidelberg (Germany) and colleagues found similar progression-free and overall survival rates for patients who had progressive disease and underwent autologous stem cell therapy (ASCT), compared with patients who underwent salvage therapy and improved to at least stable disease before proceeding to transplant. The findings were published in Leukemia & Lymphoma.

The real-world analysis included 1,599 patients with multiple myeloma who had undergone ASCT between 1991 and 2016. More than half of the patients (58%) were not enrolled in clinical trials. The remainder were split between the German-Speaking Myeloma Multicenter Group (GMMG)-HD3 and GMMG-HD4 trials, which compared various induction regimens.

Just 23 patients in the analysis received salvage therapy because of progressive disease and deepened their response before ASCT. Of these patients, 12 received novel agents in induction therapy and 11 received older medications.

Looking across all 1,599 patients, 5.3% achieved complete remission before first ASCT. Most patients (71.8%) achieved partial remission, 9.7% had a minimal response, and 5.7% had stable disease. A group of 120 patients (7.5%) progressed between the last course of induction and ASCT.

The researchers compared the progression-free and overall survival rates of patients with progressive disease versus those who had stable disease or better before their first transplant. Both univariable and multivariable analysis showed no statistically significant differences in either survival outcome between the two groups.

In the multivariable analysis, there was a hazard ratio of 1.23 (95% confidence interval, 0.98-1.56) for progression-free survival for patients with progressive disease versus those who responded to induction therapy. Similarly, the HR for overall survival between the two groups was 1.24 (95% CI, 0.93-1.65).

The researchers also analyzed the groups based on whether they received novel or older agents during induction.

Patients with progressive disease who received novel agents had significantly worse progression-free survival (22.2 months), compared with patients who responded to treatment with novel agents (22.2 months vs. 29.1 months; P = .03). The same trend was seen with overall survival in these groups (54.4 months vs. 97.5 months; P less than .001).

Rates of survival were similar for patients with progressive disease and responders who had received older medications at induction.

“This might be explained by a prognostically disadvantageous disease biology in patients nonresponsive to novel agents,” the researchers wrote.

The researchers also compared survival outcomes for the 120 patients who underwent ASCT with progressive disease versus the 23 patients who received salvage therapy and improved their response to at least stable disease before transplant. Univariable analysis showed that salvage patients actually did worse than those with progressive disease who proceeded straight to transplant – 12.1 months versus 22.9 months of progression-free survival (P = .04) and 33.1 versus 69.5 months of overall survival (P = .08). But on multivariable analysis, there was no significant difference between the two groups for progression-free survival (HR, 0.71; 95% CI, 0.28-1.80; P = .5) or overall survival (HR, 0.77; 95% CI, 0.30-1.95; P = .6). The use of novel agents did not appear to affect the survival outcomes in these patients.

The worse outcomes seen among salvage patients observed in univariable analysis “might be due to a cumulative toxic effect of salvage therapy,” the researchers suggested. “An alternative explanation could be that the patients who were offered salvage therapy might have had more aggressive disease than those who did not undergo salvage therapy.”

Dr. Blocka reported having no relevant financial disclosures. Other coauthors reported relationships with Janssen, Amgen, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Celgene, and others.

SOURCE: Blocka J et al. Leuk Lymphoma. 2019 Aug 19. doi: 10.1080/10428194.2019.1646905.

FROM LEUKEMIA & LYMPHOMA

Key clinical point:

Major finding: There was no difference between patients with progressive disease who went straight to ASCT and patients who received salvage therapy, both in terms of progression-free survival (hazard ratio, 0.71; 95% confidence interval, 0.28-1.80; P = .5) and overall survival (HR, 0.77; 95% CI, 0.30-1.95; P = .6).

Study details: An analysis of 1,599 patients with multiple myeloma who underwent ASCT. A subanalysis compared 120 patients with progressive disease before ASCT with 23 patients who received salvage treatment before ASCT.

Disclosures: Dr. Blocka reported having no relevant financial disclosures. Other coauthors reported relationships with Janssen, Amgen, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Celgene, and others.

Source: Blocka J et al. Leuk Lymphoma. 2019 Aug 19. doi: 10.1080/10428194.2019.1646905.

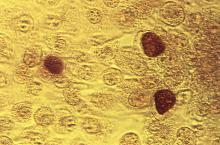

Chlamydia trachomatis is associated with adverse reproductive health outcomes

compared with women who have tested negative for C. trachomatis or who have not been tested for the bacterium, according to a retrospective cohort study.

The risk of PID increases with repeat chlamydial infections, and the use of antibiotics that are effective against C. trachomatis does not decrease the risk of subsequent PID, the researchers reported in Clinical Infectious Diseases.

Prior studies have yielded different estimates of the risk of reproductive complications after chlamydia infection, said Casper den Heijer, MD, PhD, a researcher at Utrecht Institute of Pharmaceutical Sciences in Heerlen, the Netherlands, and colleagues. To assess the risk of PID, ectopic pregnancy, and infertility in women with a previous C. trachomatis diagnosis, Dr. den Heijer and coauthors conducted a retrospective study of women aged 12-25 years at baseline in the Clinical Practice Research Datalink GOLD database. Their analysis included data from women living in England between 2000 and 2013. The investigators used Cox proportional hazard models to evaluate the risk of adverse outcomes.

The researchers analyzed data from 857,324 women with a mean follow-up of 7.5 years. Patients’ mean age at baseline was 15 years. In all, the participants had 8,346 occurrences of PID, 2,484 occurrences of ectopic pregnancy, and 2,066 occurrences of female infertility.

For PID, incidence rates per 1,000 person-years were 1.1 among women untested for C. trachomatis, 1.4 among women who tested negative, and 5.4 among women who tested positive. For ectopic pregnancy, the incidence rates were 0.3 for untested women, 0.4 for negatively tested women, and 1.2 for positively tested women. Infertility incidence rates were 0.3 for untested women, 0.3 for negatively tested women, and 0.9 for positively tested women.

Compared with women who tested negative for C. trachomatis, women who tested positive had an increased risk of PID (adjusted hazard ratio, 2.36), ectopic pregnancy (aHR, 1.87), and female infertility (aHR, 1.85). Untested women had a lower risk for PID, compared with women who tested negative (aHR, 0.57).

C. trachomatis–effective antibiotic use was associated with higher PID risk, and that risk increased as the women used more of the antibiotic prescriptions, Dr. den Heijer and associates said. This occurred in all three groups of women. A possible explanation for this association between the antibiotics and higher PID risk could be that PID can be caused by other infectious diseases that could be treated with C. trachomatis–effective antibiotics.

While the study relied on primary care data, genitourinary medicine clinics diagnose and treat “a sizable proportion” of sexually transmitted infections in the United Kingdom, the authors noted. This limitation means that the study underestimates the number of C. trachomatis diagnoses in the cohort, they said.

Nonetheless, “Our results confirm the reproductive health burden of [C. trachomatis] and show the need for adequate public health interventions,” Dr. den Heijer and associates concluded.

Iris Krishna, MD, said in an interview, “This is a well-designed population-based retrospective cohort study evaluating the incidence of PID, ectopic pregnancy, and female infertility amongst more than 850,000 women in a primary care setting with a previous diagnosis of C. trachomatis, compared with women who have tested negative for C. trachomatis and women who have not been tested for C. trachomatis. This study also evaluated the impact of antibiotic use on PID.”

Dr. Krishna, assistant professor of gynecology and obstetrics in the division of maternal-fetal medicine at Emory University in Atlanta, continued, “This study demonstrates an association between C. trachomatis infection and adverse reproductive health outcomes. It highlights the importance of prompt diagnosis and treatment of C. trachomatis to reduce the risk of both short- and long-term reproductive health complications, as well as highlighting the importance of preventing recurrent C. trachomatis infections. It also emphasizes the importance of targeted screening for high-risk groups and appropriate follow-up to ensure that optimal antibiotic treatment is provided, especially amongst women who have recently used C. trachomatis–effective antibiotics.

“The finding of progression to PID despite C. trachomatis-effective antibiotic use indicates a more complex relationship where perhaps host immunological factors or effects of antibiotics on the vaginal microbiome may play a role and requires further study,” concluded Dr. Krishna. She was not involved in the current study, and was asked to comment on the findings.

The study was supported by the Netherlands Organization for Health Research and Development. Dr. den Heijer had no relevant disclosures. Dr. Krishna said she had no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: den Heijer CDJ et al. Clin Infect Dis. 2019 Aug 24. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciz429.

compared with women who have tested negative for C. trachomatis or who have not been tested for the bacterium, according to a retrospective cohort study.

The risk of PID increases with repeat chlamydial infections, and the use of antibiotics that are effective against C. trachomatis does not decrease the risk of subsequent PID, the researchers reported in Clinical Infectious Diseases.

Prior studies have yielded different estimates of the risk of reproductive complications after chlamydia infection, said Casper den Heijer, MD, PhD, a researcher at Utrecht Institute of Pharmaceutical Sciences in Heerlen, the Netherlands, and colleagues. To assess the risk of PID, ectopic pregnancy, and infertility in women with a previous C. trachomatis diagnosis, Dr. den Heijer and coauthors conducted a retrospective study of women aged 12-25 years at baseline in the Clinical Practice Research Datalink GOLD database. Their analysis included data from women living in England between 2000 and 2013. The investigators used Cox proportional hazard models to evaluate the risk of adverse outcomes.

The researchers analyzed data from 857,324 women with a mean follow-up of 7.5 years. Patients’ mean age at baseline was 15 years. In all, the participants had 8,346 occurrences of PID, 2,484 occurrences of ectopic pregnancy, and 2,066 occurrences of female infertility.

For PID, incidence rates per 1,000 person-years were 1.1 among women untested for C. trachomatis, 1.4 among women who tested negative, and 5.4 among women who tested positive. For ectopic pregnancy, the incidence rates were 0.3 for untested women, 0.4 for negatively tested women, and 1.2 for positively tested women. Infertility incidence rates were 0.3 for untested women, 0.3 for negatively tested women, and 0.9 for positively tested women.

Compared with women who tested negative for C. trachomatis, women who tested positive had an increased risk of PID (adjusted hazard ratio, 2.36), ectopic pregnancy (aHR, 1.87), and female infertility (aHR, 1.85). Untested women had a lower risk for PID, compared with women who tested negative (aHR, 0.57).

C. trachomatis–effective antibiotic use was associated with higher PID risk, and that risk increased as the women used more of the antibiotic prescriptions, Dr. den Heijer and associates said. This occurred in all three groups of women. A possible explanation for this association between the antibiotics and higher PID risk could be that PID can be caused by other infectious diseases that could be treated with C. trachomatis–effective antibiotics.

While the study relied on primary care data, genitourinary medicine clinics diagnose and treat “a sizable proportion” of sexually transmitted infections in the United Kingdom, the authors noted. This limitation means that the study underestimates the number of C. trachomatis diagnoses in the cohort, they said.

Nonetheless, “Our results confirm the reproductive health burden of [C. trachomatis] and show the need for adequate public health interventions,” Dr. den Heijer and associates concluded.

Iris Krishna, MD, said in an interview, “This is a well-designed population-based retrospective cohort study evaluating the incidence of PID, ectopic pregnancy, and female infertility amongst more than 850,000 women in a primary care setting with a previous diagnosis of C. trachomatis, compared with women who have tested negative for C. trachomatis and women who have not been tested for C. trachomatis. This study also evaluated the impact of antibiotic use on PID.”

Dr. Krishna, assistant professor of gynecology and obstetrics in the division of maternal-fetal medicine at Emory University in Atlanta, continued, “This study demonstrates an association between C. trachomatis infection and adverse reproductive health outcomes. It highlights the importance of prompt diagnosis and treatment of C. trachomatis to reduce the risk of both short- and long-term reproductive health complications, as well as highlighting the importance of preventing recurrent C. trachomatis infections. It also emphasizes the importance of targeted screening for high-risk groups and appropriate follow-up to ensure that optimal antibiotic treatment is provided, especially amongst women who have recently used C. trachomatis–effective antibiotics.

“The finding of progression to PID despite C. trachomatis-effective antibiotic use indicates a more complex relationship where perhaps host immunological factors or effects of antibiotics on the vaginal microbiome may play a role and requires further study,” concluded Dr. Krishna. She was not involved in the current study, and was asked to comment on the findings.

The study was supported by the Netherlands Organization for Health Research and Development. Dr. den Heijer had no relevant disclosures. Dr. Krishna said she had no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: den Heijer CDJ et al. Clin Infect Dis. 2019 Aug 24. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciz429.

compared with women who have tested negative for C. trachomatis or who have not been tested for the bacterium, according to a retrospective cohort study.

The risk of PID increases with repeat chlamydial infections, and the use of antibiotics that are effective against C. trachomatis does not decrease the risk of subsequent PID, the researchers reported in Clinical Infectious Diseases.

Prior studies have yielded different estimates of the risk of reproductive complications after chlamydia infection, said Casper den Heijer, MD, PhD, a researcher at Utrecht Institute of Pharmaceutical Sciences in Heerlen, the Netherlands, and colleagues. To assess the risk of PID, ectopic pregnancy, and infertility in women with a previous C. trachomatis diagnosis, Dr. den Heijer and coauthors conducted a retrospective study of women aged 12-25 years at baseline in the Clinical Practice Research Datalink GOLD database. Their analysis included data from women living in England between 2000 and 2013. The investigators used Cox proportional hazard models to evaluate the risk of adverse outcomes.

The researchers analyzed data from 857,324 women with a mean follow-up of 7.5 years. Patients’ mean age at baseline was 15 years. In all, the participants had 8,346 occurrences of PID, 2,484 occurrences of ectopic pregnancy, and 2,066 occurrences of female infertility.

For PID, incidence rates per 1,000 person-years were 1.1 among women untested for C. trachomatis, 1.4 among women who tested negative, and 5.4 among women who tested positive. For ectopic pregnancy, the incidence rates were 0.3 for untested women, 0.4 for negatively tested women, and 1.2 for positively tested women. Infertility incidence rates were 0.3 for untested women, 0.3 for negatively tested women, and 0.9 for positively tested women.

Compared with women who tested negative for C. trachomatis, women who tested positive had an increased risk of PID (adjusted hazard ratio, 2.36), ectopic pregnancy (aHR, 1.87), and female infertility (aHR, 1.85). Untested women had a lower risk for PID, compared with women who tested negative (aHR, 0.57).

C. trachomatis–effective antibiotic use was associated with higher PID risk, and that risk increased as the women used more of the antibiotic prescriptions, Dr. den Heijer and associates said. This occurred in all three groups of women. A possible explanation for this association between the antibiotics and higher PID risk could be that PID can be caused by other infectious diseases that could be treated with C. trachomatis–effective antibiotics.

While the study relied on primary care data, genitourinary medicine clinics diagnose and treat “a sizable proportion” of sexually transmitted infections in the United Kingdom, the authors noted. This limitation means that the study underestimates the number of C. trachomatis diagnoses in the cohort, they said.

Nonetheless, “Our results confirm the reproductive health burden of [C. trachomatis] and show the need for adequate public health interventions,” Dr. den Heijer and associates concluded.

Iris Krishna, MD, said in an interview, “This is a well-designed population-based retrospective cohort study evaluating the incidence of PID, ectopic pregnancy, and female infertility amongst more than 850,000 women in a primary care setting with a previous diagnosis of C. trachomatis, compared with women who have tested negative for C. trachomatis and women who have not been tested for C. trachomatis. This study also evaluated the impact of antibiotic use on PID.”

Dr. Krishna, assistant professor of gynecology and obstetrics in the division of maternal-fetal medicine at Emory University in Atlanta, continued, “This study demonstrates an association between C. trachomatis infection and adverse reproductive health outcomes. It highlights the importance of prompt diagnosis and treatment of C. trachomatis to reduce the risk of both short- and long-term reproductive health complications, as well as highlighting the importance of preventing recurrent C. trachomatis infections. It also emphasizes the importance of targeted screening for high-risk groups and appropriate follow-up to ensure that optimal antibiotic treatment is provided, especially amongst women who have recently used C. trachomatis–effective antibiotics.

“The finding of progression to PID despite C. trachomatis-effective antibiotic use indicates a more complex relationship where perhaps host immunological factors or effects of antibiotics on the vaginal microbiome may play a role and requires further study,” concluded Dr. Krishna. She was not involved in the current study, and was asked to comment on the findings.

The study was supported by the Netherlands Organization for Health Research and Development. Dr. den Heijer had no relevant disclosures. Dr. Krishna said she had no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: den Heijer CDJ et al. Clin Infect Dis. 2019 Aug 24. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciz429.

FROM CLINICAL INFECTIOUS DISEASES

How safe and effective is ondansetron for nausea and vomiting in pregnancy?

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

Efficacy. A 2014 double-blind RCT compared ondansetron with pyridoxine plus doxylamine (standard care) for outpatient treatment of nausea and vomiting in pregnancy.1 The 36 patients had an average gestational age of 8 weeks and received either 4 mg oral ondansetron plus placebo or 25 mg pyridoxine plus 12.5 mg doxylamine 3 times daily for 5 days. Nausea and vomiting severity was measured using 2 separate 10-cm visual analog scales (VAS) with scores ranging from 0 to 10 (worst nausea or vomiting imaginable). Researchers determined that a VAS score reduction of 2.5 cm was clinically significant.

Patients treated with ondansetron described greater improvements in nausea (mean VAS change −5.1 cm vs −2 cm; P = .019) and vomiting (mean VAS change −4.1 cm vs −1.7 cm; P = .049). No patient required hospitalization. The researchers didn’t report on adverse effects or birth outcomes. The study was limited by the small sample size and a high rate (17%) of patients with missing data or who were lost to follow-up.

IV ondansetron vs metoclopramide: Similar efficacy, fewer adverse effects

A 2014 double-blind RCT compared IV ondansetron with IV metoclopramide (standard care) for treating hyperemesis gravidarum.2 The 160 patients had an average gestational age of 9.5 weeks and intractable nausea and vomiting severe enough to cause dehydration, metabolic disturbance, and hospitalization. Patients received either 4 mg ondansetron or 10 mg metoclopramide IV every 8 hours for 24 hours. The primary outcomes were number of episodes of vomiting over 24 hours and self-reported sense of well-being rated on a 10-point scale.

No differences were found between the ondansetron- and metoclopramide-treated groups in terms of vomiting over 24 hours (median episodes 1 and 1; P = .38) or sense of well-being (mean scores 8.7 vs 8.3; P = .13). Patients treated with ondansetron were less likely to have persistent ketonuria at 24 hours (relative risk [RR] = 0.3; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.1-0.8; number needed to treat [NNT] = 6). They also were less likely to feel drowsy (RR = 0.3; 95% CI, 0.1–0.8; NNT = 6) or complain of dry mouth (RR = 0.4; 95% CI, 0.1-0.9; NNT = 8). The study didn’t report birth outcomes or adverse fetal effects.

Oral ondansetron outperforms oral metoclopramide in small study

A 2013 double-blind RCT compared ondansetron with metoclopramide (standard care) for controlling severe nausea and vomiting.3 The 83 patients, with an average gestational age of 8.7 weeks, had more than 3 vomiting episodes daily, weight loss, and ketonuria. They received either 4 mg oral ondansetron or 10 mg oral metoclopramide for 2 weeks as follows: 3 times daily for 1 week, then twice daily for 3 days, then once daily for 4 days. Patients rated nausea severity using a 10-cm VAS from 0 to 10 (severe nausea) and recorded the number of vomiting episodes.

Women treated with ondansetron had significantly lower VAS scores on Days 3 and 4 of treatment (5.4 vs 6, P = .024 on Day 3; 4.1 vs 5.7, P = .023 on Day 4). They also had fewer episodes of vomiting on Days 2, 3, and 4 (3.7 vs 6, P = .006 on Day 2; 3.2 vs 5.3, P = .006 on Day 3; and 3.3 vs 5, P = .013 on Day 4). The study was limited by the small sample size.

Safety. A 2016 systematic review examining the risk of birth defects associated with ondansetron exposure in pregnancy found 8 reports: 5 birth registries, 2 case-control studies, and 1 prospective cohort study.4 Investigators compared rates of major malformations—cleft lips, cleft palates, neural tube defects, cardiac defects, and hypospadias—in 5101 women exposed to ondansetron in the first trimester with birth defect rates in more than 3.1 million nonexposed women.

Continue to: No study demonstrated...

No study demonstrated an increased rate of major malformations associated with ondansetron exposure except for 2 disease registry studies with nearly 2.4 million patients that reported a slight increase in the risk of cardiac defects (odds ratio [OR] = 2; 95% CI, 1.3-3.1; OR = 1.6, 95% CI, 1-2.1). Comparisons of other birth defect rates associated with ondansetron exposure were inconsistent, with studies showing small increases, decreases, or no difference in rates between exposed and nonexposed women.

Exposure vs nonexposure: No difference in adverse outcomes

A 2013 retrospective cohort study looked at 608,385 pregnancies among women in Denmark, of whom 1970 (0.3%) had been exposed to ondansetron.5 The study found that exposure to ondansetron compared with nonexposure was associated with a lower risk for spontaneous abortion between 7 and 12 weeks’ gestation (1.1% vs 3.7%; hazard ratio [HR] = 0.5; 95% CI, 0.3-0.9).

No significant differences between ondansetron exposure and nonexposure were found for the following adverse outcomes: spontaneous abortion between 13 and 22 weeks’ gestation (1% vs 2.1%; HR = 0.6; 95% CI, 0.3-1.2); stillbirth (0.3% vs 0.4%; HR = 0.4; 95% CI, 0.1-1.7); any major birth defect (2.9% in both exposed and nonexposed women; OR = 1.12; 95% CI, 0.69-1.82); preterm delivery (6.2% vs 5.2%; OR = 0.9; 95% CI, 0.7-1.3), low birth weight infant (4.1% vs 3.7%; OR = 0.8; 95% CI, 0.5-1.1); and small-for-gestational-age infant (10.4% vs 9.2%; OR = 1.1; 95% CI, 0.9-1.4).

RECOMMENDATIONS

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) states that insufficient data exist regarding the safety of ondansetron for the fetus.6 ACOG recommends individualizing the use of ondansetron before 10 weeks of pregnancy after weighing the risks and benefits. ACOG also recommends adding ondansetron as third-line treatment for nausea and vomiting unresponsive to first- and second-line treatments.

EDITOR'S TAKEAWAY

Higher-quality studies showed ondansetron to be an effective treatment for hyperemesis gravidarum. Lower-quality studies raised some concerns about adverse fetal effects. Although the adverse effects were rare and the quality of the evidence was lower, the cautionary principle suggests that ondansetron should be a second-line option.

1. Oliveira LG, Capp SM, You WB, et al. Ondansetron compared with doxylamine and pyridoxine for treatment of nausea in pregnancy: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;124:735-742.

2. Abas MN, Tan PC, Azmi N, et al. Ondansetron compared with metoclopramide for hyperemesis gravidarum: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123:1272-1279.

3. Kashifard M, Basirat Z, Kashifard M, et al. Ondansetrone or metoclopromide? Which is more effective in severe nausea and vomiting of pregnancy? A randomized trial double-blind study. Clin Exp Obstet Gynecol. 2013;40:127-130.

4. Carstairs SD. Ondansetron use in pregnancy and birth defects: a systematic review. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;127:878-883.

5. Pasternak B, Svanström H, Hviid A. Ondansetron in pregnancy and risk of adverse fetal outcomes. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:814-823.

6. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, Committee on Practice Bulletins-Obstetrics. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 189: Nausea and vomiting of pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;131:e15-e30.

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

Efficacy. A 2014 double-blind RCT compared ondansetron with pyridoxine plus doxylamine (standard care) for outpatient treatment of nausea and vomiting in pregnancy.1 The 36 patients had an average gestational age of 8 weeks and received either 4 mg oral ondansetron plus placebo or 25 mg pyridoxine plus 12.5 mg doxylamine 3 times daily for 5 days. Nausea and vomiting severity was measured using 2 separate 10-cm visual analog scales (VAS) with scores ranging from 0 to 10 (worst nausea or vomiting imaginable). Researchers determined that a VAS score reduction of 2.5 cm was clinically significant.

Patients treated with ondansetron described greater improvements in nausea (mean VAS change −5.1 cm vs −2 cm; P = .019) and vomiting (mean VAS change −4.1 cm vs −1.7 cm; P = .049). No patient required hospitalization. The researchers didn’t report on adverse effects or birth outcomes. The study was limited by the small sample size and a high rate (17%) of patients with missing data or who were lost to follow-up.

IV ondansetron vs metoclopramide: Similar efficacy, fewer adverse effects

A 2014 double-blind RCT compared IV ondansetron with IV metoclopramide (standard care) for treating hyperemesis gravidarum.2 The 160 patients had an average gestational age of 9.5 weeks and intractable nausea and vomiting severe enough to cause dehydration, metabolic disturbance, and hospitalization. Patients received either 4 mg ondansetron or 10 mg metoclopramide IV every 8 hours for 24 hours. The primary outcomes were number of episodes of vomiting over 24 hours and self-reported sense of well-being rated on a 10-point scale.

No differences were found between the ondansetron- and metoclopramide-treated groups in terms of vomiting over 24 hours (median episodes 1 and 1; P = .38) or sense of well-being (mean scores 8.7 vs 8.3; P = .13). Patients treated with ondansetron were less likely to have persistent ketonuria at 24 hours (relative risk [RR] = 0.3; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.1-0.8; number needed to treat [NNT] = 6). They also were less likely to feel drowsy (RR = 0.3; 95% CI, 0.1–0.8; NNT = 6) or complain of dry mouth (RR = 0.4; 95% CI, 0.1-0.9; NNT = 8). The study didn’t report birth outcomes or adverse fetal effects.

Oral ondansetron outperforms oral metoclopramide in small study

A 2013 double-blind RCT compared ondansetron with metoclopramide (standard care) for controlling severe nausea and vomiting.3 The 83 patients, with an average gestational age of 8.7 weeks, had more than 3 vomiting episodes daily, weight loss, and ketonuria. They received either 4 mg oral ondansetron or 10 mg oral metoclopramide for 2 weeks as follows: 3 times daily for 1 week, then twice daily for 3 days, then once daily for 4 days. Patients rated nausea severity using a 10-cm VAS from 0 to 10 (severe nausea) and recorded the number of vomiting episodes.

Women treated with ondansetron had significantly lower VAS scores on Days 3 and 4 of treatment (5.4 vs 6, P = .024 on Day 3; 4.1 vs 5.7, P = .023 on Day 4). They also had fewer episodes of vomiting on Days 2, 3, and 4 (3.7 vs 6, P = .006 on Day 2; 3.2 vs 5.3, P = .006 on Day 3; and 3.3 vs 5, P = .013 on Day 4). The study was limited by the small sample size.

Safety. A 2016 systematic review examining the risk of birth defects associated with ondansetron exposure in pregnancy found 8 reports: 5 birth registries, 2 case-control studies, and 1 prospective cohort study.4 Investigators compared rates of major malformations—cleft lips, cleft palates, neural tube defects, cardiac defects, and hypospadias—in 5101 women exposed to ondansetron in the first trimester with birth defect rates in more than 3.1 million nonexposed women.

Continue to: No study demonstrated...

No study demonstrated an increased rate of major malformations associated with ondansetron exposure except for 2 disease registry studies with nearly 2.4 million patients that reported a slight increase in the risk of cardiac defects (odds ratio [OR] = 2; 95% CI, 1.3-3.1; OR = 1.6, 95% CI, 1-2.1). Comparisons of other birth defect rates associated with ondansetron exposure were inconsistent, with studies showing small increases, decreases, or no difference in rates between exposed and nonexposed women.

Exposure vs nonexposure: No difference in adverse outcomes

A 2013 retrospective cohort study looked at 608,385 pregnancies among women in Denmark, of whom 1970 (0.3%) had been exposed to ondansetron.5 The study found that exposure to ondansetron compared with nonexposure was associated with a lower risk for spontaneous abortion between 7 and 12 weeks’ gestation (1.1% vs 3.7%; hazard ratio [HR] = 0.5; 95% CI, 0.3-0.9).

No significant differences between ondansetron exposure and nonexposure were found for the following adverse outcomes: spontaneous abortion between 13 and 22 weeks’ gestation (1% vs 2.1%; HR = 0.6; 95% CI, 0.3-1.2); stillbirth (0.3% vs 0.4%; HR = 0.4; 95% CI, 0.1-1.7); any major birth defect (2.9% in both exposed and nonexposed women; OR = 1.12; 95% CI, 0.69-1.82); preterm delivery (6.2% vs 5.2%; OR = 0.9; 95% CI, 0.7-1.3), low birth weight infant (4.1% vs 3.7%; OR = 0.8; 95% CI, 0.5-1.1); and small-for-gestational-age infant (10.4% vs 9.2%; OR = 1.1; 95% CI, 0.9-1.4).

RECOMMENDATIONS

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) states that insufficient data exist regarding the safety of ondansetron for the fetus.6 ACOG recommends individualizing the use of ondansetron before 10 weeks of pregnancy after weighing the risks and benefits. ACOG also recommends adding ondansetron as third-line treatment for nausea and vomiting unresponsive to first- and second-line treatments.

EDITOR'S TAKEAWAY

Higher-quality studies showed ondansetron to be an effective treatment for hyperemesis gravidarum. Lower-quality studies raised some concerns about adverse fetal effects. Although the adverse effects were rare and the quality of the evidence was lower, the cautionary principle suggests that ondansetron should be a second-line option.

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

Efficacy. A 2014 double-blind RCT compared ondansetron with pyridoxine plus doxylamine (standard care) for outpatient treatment of nausea and vomiting in pregnancy.1 The 36 patients had an average gestational age of 8 weeks and received either 4 mg oral ondansetron plus placebo or 25 mg pyridoxine plus 12.5 mg doxylamine 3 times daily for 5 days. Nausea and vomiting severity was measured using 2 separate 10-cm visual analog scales (VAS) with scores ranging from 0 to 10 (worst nausea or vomiting imaginable). Researchers determined that a VAS score reduction of 2.5 cm was clinically significant.

Patients treated with ondansetron described greater improvements in nausea (mean VAS change −5.1 cm vs −2 cm; P = .019) and vomiting (mean VAS change −4.1 cm vs −1.7 cm; P = .049). No patient required hospitalization. The researchers didn’t report on adverse effects or birth outcomes. The study was limited by the small sample size and a high rate (17%) of patients with missing data or who were lost to follow-up.

IV ondansetron vs metoclopramide: Similar efficacy, fewer adverse effects

A 2014 double-blind RCT compared IV ondansetron with IV metoclopramide (standard care) for treating hyperemesis gravidarum.2 The 160 patients had an average gestational age of 9.5 weeks and intractable nausea and vomiting severe enough to cause dehydration, metabolic disturbance, and hospitalization. Patients received either 4 mg ondansetron or 10 mg metoclopramide IV every 8 hours for 24 hours. The primary outcomes were number of episodes of vomiting over 24 hours and self-reported sense of well-being rated on a 10-point scale.

No differences were found between the ondansetron- and metoclopramide-treated groups in terms of vomiting over 24 hours (median episodes 1 and 1; P = .38) or sense of well-being (mean scores 8.7 vs 8.3; P = .13). Patients treated with ondansetron were less likely to have persistent ketonuria at 24 hours (relative risk [RR] = 0.3; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.1-0.8; number needed to treat [NNT] = 6). They also were less likely to feel drowsy (RR = 0.3; 95% CI, 0.1–0.8; NNT = 6) or complain of dry mouth (RR = 0.4; 95% CI, 0.1-0.9; NNT = 8). The study didn’t report birth outcomes or adverse fetal effects.

Oral ondansetron outperforms oral metoclopramide in small study

A 2013 double-blind RCT compared ondansetron with metoclopramide (standard care) for controlling severe nausea and vomiting.3 The 83 patients, with an average gestational age of 8.7 weeks, had more than 3 vomiting episodes daily, weight loss, and ketonuria. They received either 4 mg oral ondansetron or 10 mg oral metoclopramide for 2 weeks as follows: 3 times daily for 1 week, then twice daily for 3 days, then once daily for 4 days. Patients rated nausea severity using a 10-cm VAS from 0 to 10 (severe nausea) and recorded the number of vomiting episodes.

Women treated with ondansetron had significantly lower VAS scores on Days 3 and 4 of treatment (5.4 vs 6, P = .024 on Day 3; 4.1 vs 5.7, P = .023 on Day 4). They also had fewer episodes of vomiting on Days 2, 3, and 4 (3.7 vs 6, P = .006 on Day 2; 3.2 vs 5.3, P = .006 on Day 3; and 3.3 vs 5, P = .013 on Day 4). The study was limited by the small sample size.

Safety. A 2016 systematic review examining the risk of birth defects associated with ondansetron exposure in pregnancy found 8 reports: 5 birth registries, 2 case-control studies, and 1 prospective cohort study.4 Investigators compared rates of major malformations—cleft lips, cleft palates, neural tube defects, cardiac defects, and hypospadias—in 5101 women exposed to ondansetron in the first trimester with birth defect rates in more than 3.1 million nonexposed women.

Continue to: No study demonstrated...

No study demonstrated an increased rate of major malformations associated with ondansetron exposure except for 2 disease registry studies with nearly 2.4 million patients that reported a slight increase in the risk of cardiac defects (odds ratio [OR] = 2; 95% CI, 1.3-3.1; OR = 1.6, 95% CI, 1-2.1). Comparisons of other birth defect rates associated with ondansetron exposure were inconsistent, with studies showing small increases, decreases, or no difference in rates between exposed and nonexposed women.

Exposure vs nonexposure: No difference in adverse outcomes

A 2013 retrospective cohort study looked at 608,385 pregnancies among women in Denmark, of whom 1970 (0.3%) had been exposed to ondansetron.5 The study found that exposure to ondansetron compared with nonexposure was associated with a lower risk for spontaneous abortion between 7 and 12 weeks’ gestation (1.1% vs 3.7%; hazard ratio [HR] = 0.5; 95% CI, 0.3-0.9).

No significant differences between ondansetron exposure and nonexposure were found for the following adverse outcomes: spontaneous abortion between 13 and 22 weeks’ gestation (1% vs 2.1%; HR = 0.6; 95% CI, 0.3-1.2); stillbirth (0.3% vs 0.4%; HR = 0.4; 95% CI, 0.1-1.7); any major birth defect (2.9% in both exposed and nonexposed women; OR = 1.12; 95% CI, 0.69-1.82); preterm delivery (6.2% vs 5.2%; OR = 0.9; 95% CI, 0.7-1.3), low birth weight infant (4.1% vs 3.7%; OR = 0.8; 95% CI, 0.5-1.1); and small-for-gestational-age infant (10.4% vs 9.2%; OR = 1.1; 95% CI, 0.9-1.4).

RECOMMENDATIONS

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) states that insufficient data exist regarding the safety of ondansetron for the fetus.6 ACOG recommends individualizing the use of ondansetron before 10 weeks of pregnancy after weighing the risks and benefits. ACOG also recommends adding ondansetron as third-line treatment for nausea and vomiting unresponsive to first- and second-line treatments.

EDITOR'S TAKEAWAY

Higher-quality studies showed ondansetron to be an effective treatment for hyperemesis gravidarum. Lower-quality studies raised some concerns about adverse fetal effects. Although the adverse effects were rare and the quality of the evidence was lower, the cautionary principle suggests that ondansetron should be a second-line option.

1. Oliveira LG, Capp SM, You WB, et al. Ondansetron compared with doxylamine and pyridoxine for treatment of nausea in pregnancy: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;124:735-742.

2. Abas MN, Tan PC, Azmi N, et al. Ondansetron compared with metoclopramide for hyperemesis gravidarum: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123:1272-1279.

3. Kashifard M, Basirat Z, Kashifard M, et al. Ondansetrone or metoclopromide? Which is more effective in severe nausea and vomiting of pregnancy? A randomized trial double-blind study. Clin Exp Obstet Gynecol. 2013;40:127-130.

4. Carstairs SD. Ondansetron use in pregnancy and birth defects: a systematic review. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;127:878-883.

5. Pasternak B, Svanström H, Hviid A. Ondansetron in pregnancy and risk of adverse fetal outcomes. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:814-823.

6. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, Committee on Practice Bulletins-Obstetrics. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 189: Nausea and vomiting of pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;131:e15-e30.

1. Oliveira LG, Capp SM, You WB, et al. Ondansetron compared with doxylamine and pyridoxine for treatment of nausea in pregnancy: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;124:735-742.

2. Abas MN, Tan PC, Azmi N, et al. Ondansetron compared with metoclopramide for hyperemesis gravidarum: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123:1272-1279.

3. Kashifard M, Basirat Z, Kashifard M, et al. Ondansetrone or metoclopromide? Which is more effective in severe nausea and vomiting of pregnancy? A randomized trial double-blind study. Clin Exp Obstet Gynecol. 2013;40:127-130.

4. Carstairs SD. Ondansetron use in pregnancy and birth defects: a systematic review. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;127:878-883.

5. Pasternak B, Svanström H, Hviid A. Ondansetron in pregnancy and risk of adverse fetal outcomes. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:814-823.

6. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, Committee on Practice Bulletins-Obstetrics. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 189: Nausea and vomiting of pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;131:e15-e30.

EVIDENCE-BASED ANSWER:

Oral ondansetron is more effective than a combination of pyridoxine and doxylamine for outpatient treatment of nausea and vomiting in pregnancy (strength of recommendation [SOR]: B, randomized controlled trial [RCT]).

For moderate to severe nausea and vomiting, intravenous (IV) ondansetron is at least as effective as IV metoclopramide and may cause fewer adverse reactions (SOR: B, RCTs).

Disease registry, case-control, and cohort studies report a slight increase in the risk of cardiac defects with ondansetron use in first-trimester pregnancies, but no major or other birth defects are associated with ondansetron exposure (SOR: B, a systematic review of observational trials and a single retrospective cohort study).

A specialty society guideline recommends weighing the risks and benefits of ondansetron use before 10 weeks’ gestational age and suggests reserving ondansetron for patients who have persistent nausea and vomiting unresponsive to first- and second-line treatments (SOR: C, expert opinion).

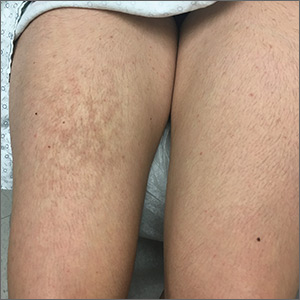

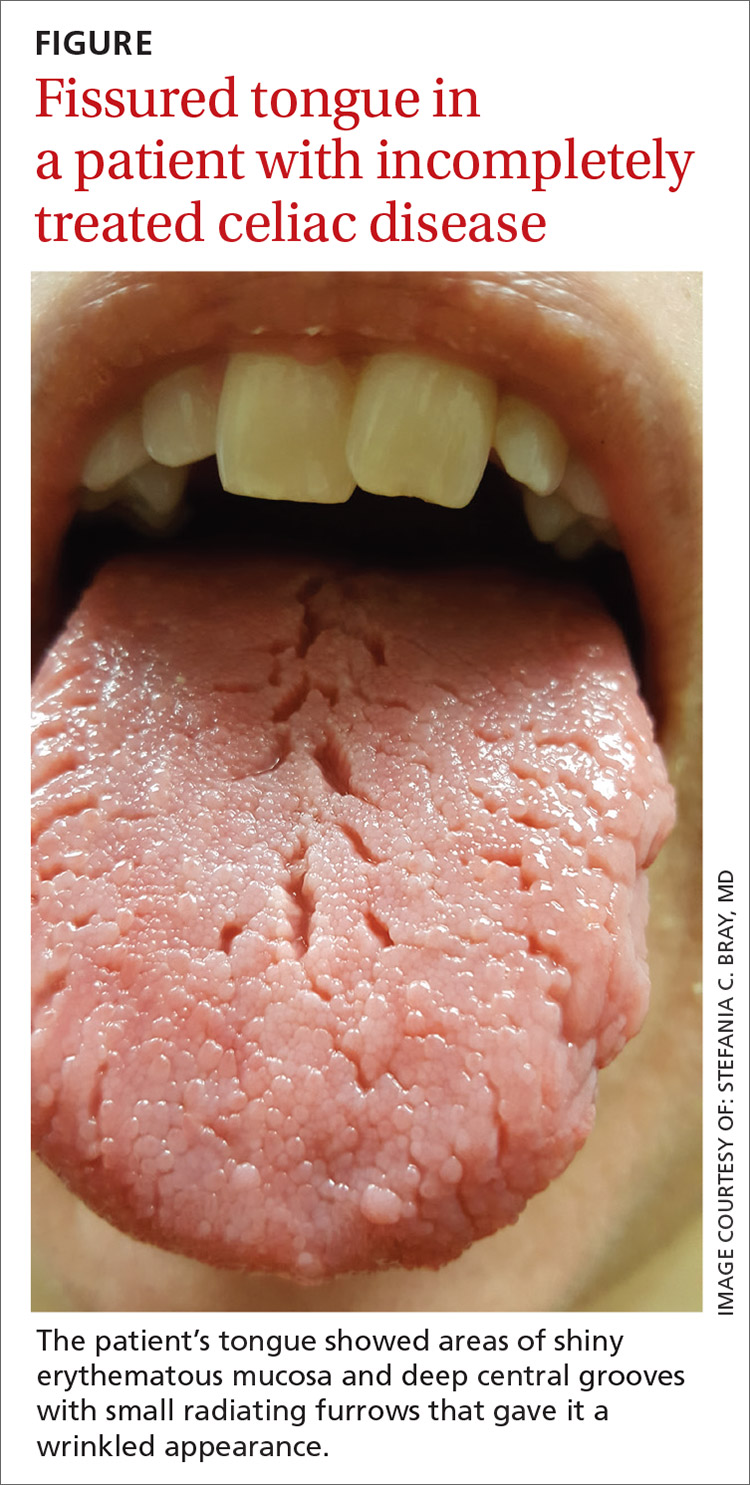

Red patches on the tongue with white borders • history of geographic tongue • incompletely treated celiac disease • Dx?

THE CASE

A 49-year-old woman presented to our clinic with concerns about the changing appearance of her tongue over the past 2 to 3 weeks. She had been given a diagnosis of celiac disease by her gastroenterologist approximately 5 years earlier. At the time of that diagnosis, she had smooth patches on the surface of her tongue with missing papillae and slightly raised borders. (This gave her tongue a map-like appearance, consistent with geographic tongue [GT].) The patient’s symptoms improved after she started a gluten-free diet, but she reported occasional noncompliance over the past year.

At the current presentation, the patient noted that new lesions on the tongue had started as diffuse shiny red patches surrounded by clearly delineated white borders, ultimately progressing to structural changes. She denied any burning of the tongue or other oral symptoms but reported feelings of anxiety, a “foggy mind,” and diffuse arthralgia for the past several weeks. The patient’s list of medications included vitamin D and magnesium supplements, a multivitamin, and probiotics.

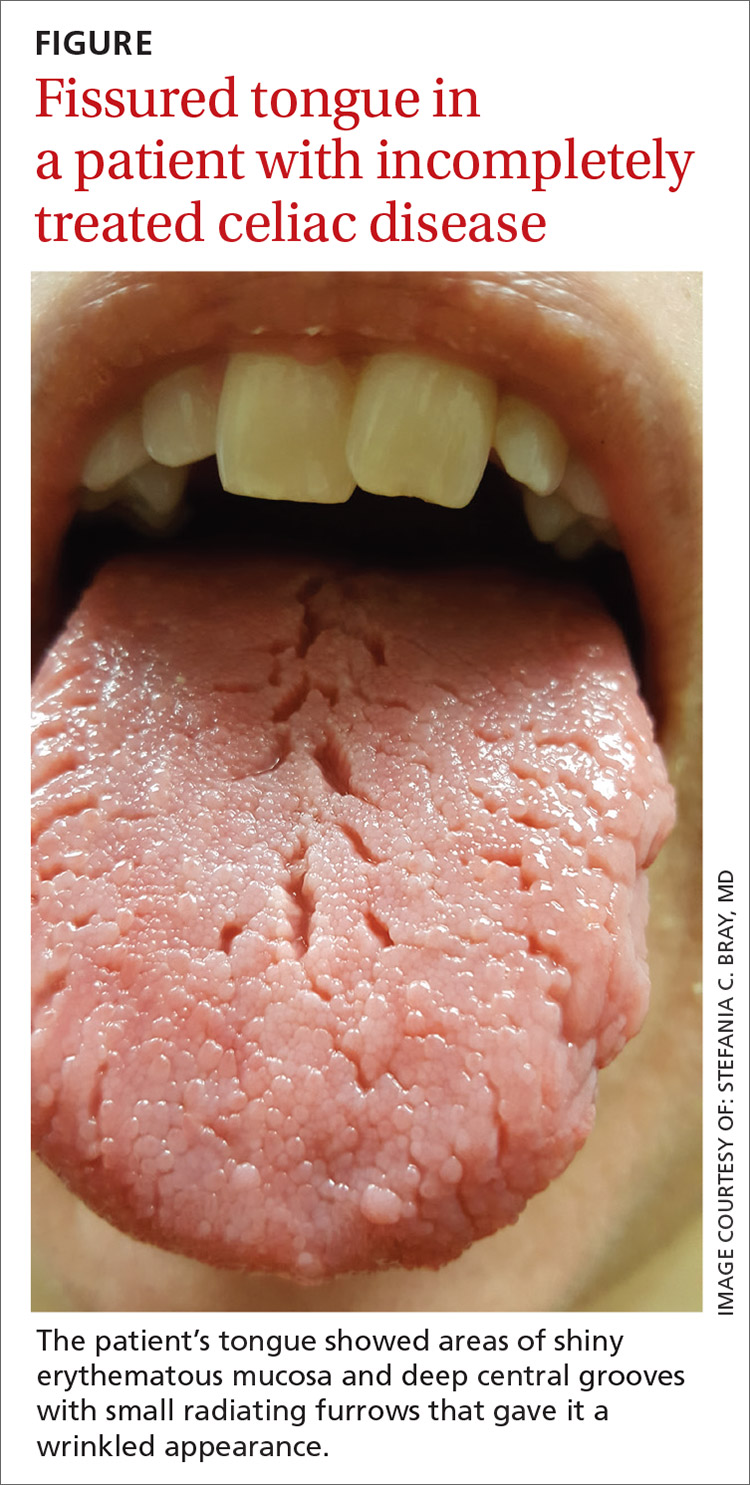

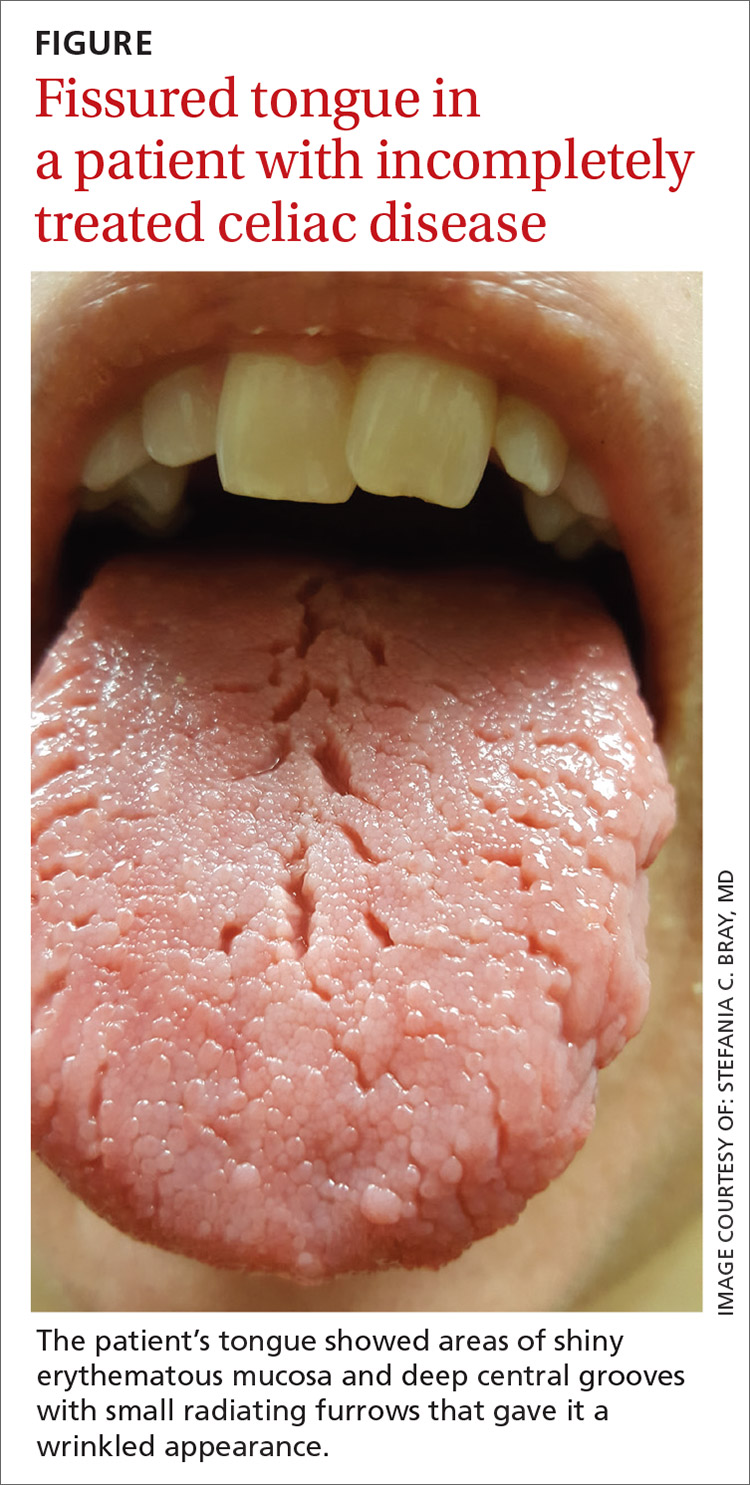

On physical examination, her tongue showed areas of shiny erythematous mucosa and deep central grooves with small radiating furrows giving a wrinkled appearance (FIGURE). A review of systems revealed nonspecific abdominal pain including bloating, cramping, and gas for the previous few months. An examination of her throat and oral cavity was unremarkable, and the remainder of the physical examination was normal.

THE DIAGNOSIS

A diagnosis of fissured tongue (FT) was suspected based on the clinical appearance of the patient’s tongue. Laboratory studies including a complete blood count; antinuclear antibody test; rheumatoid factor test; anticyclic citrullinated peptide test; a comprehensive metabolic panel; and thyroid-stimulating hormone, 25-hydroxyvitamin D, and vitamin B₁₂ level tests were performed based on her symptoms and current medications to rule out any other potential diagnoses. All laboratory results were normal, and a tissue transglutaminase IgA test was not repeated because it was positive when previously tested by the gastroenterologist at the time of her celiac disease diagnosis. A diagnosis of FT due to incompletely treated celiac disease was confirmed.

DISCUSSION

Clinical presentation. FT commonly presents in association with GT,1,2 with some cases of GT naturally progressing to FT.3,4 In most cases, FT is asymptomatic unless debris becomes entrapped in the fissures. Rarely, patients may complain of a burning sensation on the tongue. The clinical appearance of the tongue includes deep grooves with possible malodor or halitosis along with discoloration if trapping of debris and subsequent inflammation occurs.1

Etiology. FT has been linked to celiac disease; systemic conditions such as arthritis, iron deficiency, depression, anxiety, and neuropathy; and poor oral hygiene. Genetics also may play a role, as some cases of FT may be inherited. Getting to the source requires a careful history to uncover signs and symptoms (that may not have been reported until now) and to determine if other family members also have FT. A careful examination of the oral cavity, with an eye toward the patient’s oral hygiene, is also instructive (TABLE).5-8 In general, FT is believed to be a normal tongue variant in less than 10% of the general population.5,6 Additionally, local factors such as ill-fitting prosthesis, infection, parafunctional habits, allergic reaction, xerostomia, and galvanism have been implicated in the etiology of FT.5

In our patient, progression of GT to FT was caused by incompletely treated celiac disease. Both FT and GT may represent different reaction patterns caused by the same hematologic and immunologic diseases.3 In fact, the appearance of the tongue may aid in the diagnosis of celiac disease, which has been observed in 15% of patients with GT.7 Fissured tongue also may indicate an inability of the gastrointestinal mucosa to absorb nutrients; therefore, close nutrition monitoring is recommended.9

Continue to: Other oral and dental manifestations...

Other oral and dental manifestations of celiac disease include enamel defects, delayed tooth eruption, recurrent aphthous ulcers, cheilosis, oral lichen planus, and atrophic glossitis.10 Our patient also reported anxiety, “foggy mind,” diffuse arthralgia, and abdominal pain, which are symptoms of uncontrolled celiac disease. There is no known etiology of tongue manifestations in patients with incompletely treated celiac disease.

Treatment. FT generally does not require specific therapy other than the treatment of the underlying inflammatory condition. It is important to maintain proper oral and dental care, such as brushing the top surface of the tongue to clean and remove food debris. Bacteria and plaque can collect in the fissures, leading to bad breath and an increased potential for tooth decay.

Our patient was referred to a dietitian to assist with adherence to the gluten-free diet. At follow-up 3 months later, the appearance of her tongue had improved and fewer fissures were visible. The majority of her other symptoms also had resolved.

THE TAKEAWAY

FT may be a normal variant of the tongue in some patients or may be associated with poor oral hygiene. Additionally, FT often is associated with an underlying medical or inherited condition and may serve as a marker for an untreated or partially treated condition such as celiac disease, as was the case with our patient. When other signs or symptoms of systemic disease are present, further laboratory and endoscopic workup is necessary to rule out other causes and to diagnose celiac disease, if present.

As FT has been reported to be a natural progression from GT, the appearance of FT may indicate partial treatment of the underlying disease process and therefore more intensive therapy and follow-up would be needed. In this case, more intensive dietary guidance was provided with subsequent improvement of symptoms.

CORRESPONDENCE

Peter J. Carek, MD, MS, Department of Community Health and Family Medicine, College of Medicine, University of Florida, P.O. Box 100237, Gainesville, FL 32610-0237; [email protected]

1. Reamy BV, Cerby R, Bunt CW. Common tongue conditions in primary care. Am Fam Physician. 2010;81:627-634.

2. Yarom N, Cantony U, Gorsky M. Prevalence of fissured tongue, geographic tongue and median rhomboid glossitis among Israeli adults of different ethnic origins. Dermatology. 2004;209:88-94.

3. Dafar A, Cevik-Aras H, Robledo-Sierra J, et al. Factors associated with geographic tongue and fissured tongue. Acta Odontol Scad. 2016;74:210-216.

4. Hume WJ. Geographic stomatitis: a critical review. J Dent. 1975;3:25-43.

5. Sudarshan R, Sree Vijayabala G, Samata Y, et al. Newer classification system for fissured tongue: an epidemiological approach. J Tropical Med. doi:10.1155/2015/262079.

6. Mangold AR, Torgerson RR, Rogers RS. Diseases of the tongue. Clin Dermatol. 2016;34:458-469.

7. Cigic L, Galic T, Kero D, et al. The prevalence of celiac disease in patients with geographic tongue. J Oral Pathol Med. 2016;45:791-796.

8. Zargari O. The prevalence and significance of fissured tongue and geographical tongue in psoriatic patients. Clin Exp Dermatology. 2006;31:192-195.

9. Kullaa-Mikkonen A, Penttila I, Kotilainen R, et al. Haematological and immunological features of patients with fissured tongue syndrome. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1987;25:481-487.

10. Rashid M, Zarkadas M, Anca A, et al. Oral manifestations of celiac disease: a clinical guide for dentists. J Can Dent Assoc. 2011;77:b39.

THE CASE

A 49-year-old woman presented to our clinic with concerns about the changing appearance of her tongue over the past 2 to 3 weeks. She had been given a diagnosis of celiac disease by her gastroenterologist approximately 5 years earlier. At the time of that diagnosis, she had smooth patches on the surface of her tongue with missing papillae and slightly raised borders. (This gave her tongue a map-like appearance, consistent with geographic tongue [GT].) The patient’s symptoms improved after she started a gluten-free diet, but she reported occasional noncompliance over the past year.

At the current presentation, the patient noted that new lesions on the tongue had started as diffuse shiny red patches surrounded by clearly delineated white borders, ultimately progressing to structural changes. She denied any burning of the tongue or other oral symptoms but reported feelings of anxiety, a “foggy mind,” and diffuse arthralgia for the past several weeks. The patient’s list of medications included vitamin D and magnesium supplements, a multivitamin, and probiotics.

On physical examination, her tongue showed areas of shiny erythematous mucosa and deep central grooves with small radiating furrows giving a wrinkled appearance (FIGURE). A review of systems revealed nonspecific abdominal pain including bloating, cramping, and gas for the previous few months. An examination of her throat and oral cavity was unremarkable, and the remainder of the physical examination was normal.

THE DIAGNOSIS

A diagnosis of fissured tongue (FT) was suspected based on the clinical appearance of the patient’s tongue. Laboratory studies including a complete blood count; antinuclear antibody test; rheumatoid factor test; anticyclic citrullinated peptide test; a comprehensive metabolic panel; and thyroid-stimulating hormone, 25-hydroxyvitamin D, and vitamin B₁₂ level tests were performed based on her symptoms and current medications to rule out any other potential diagnoses. All laboratory results were normal, and a tissue transglutaminase IgA test was not repeated because it was positive when previously tested by the gastroenterologist at the time of her celiac disease diagnosis. A diagnosis of FT due to incompletely treated celiac disease was confirmed.

DISCUSSION

Clinical presentation. FT commonly presents in association with GT,1,2 with some cases of GT naturally progressing to FT.3,4 In most cases, FT is asymptomatic unless debris becomes entrapped in the fissures. Rarely, patients may complain of a burning sensation on the tongue. The clinical appearance of the tongue includes deep grooves with possible malodor or halitosis along with discoloration if trapping of debris and subsequent inflammation occurs.1

Etiology. FT has been linked to celiac disease; systemic conditions such as arthritis, iron deficiency, depression, anxiety, and neuropathy; and poor oral hygiene. Genetics also may play a role, as some cases of FT may be inherited. Getting to the source requires a careful history to uncover signs and symptoms (that may not have been reported until now) and to determine if other family members also have FT. A careful examination of the oral cavity, with an eye toward the patient’s oral hygiene, is also instructive (TABLE).5-8 In general, FT is believed to be a normal tongue variant in less than 10% of the general population.5,6 Additionally, local factors such as ill-fitting prosthesis, infection, parafunctional habits, allergic reaction, xerostomia, and galvanism have been implicated in the etiology of FT.5

In our patient, progression of GT to FT was caused by incompletely treated celiac disease. Both FT and GT may represent different reaction patterns caused by the same hematologic and immunologic diseases.3 In fact, the appearance of the tongue may aid in the diagnosis of celiac disease, which has been observed in 15% of patients with GT.7 Fissured tongue also may indicate an inability of the gastrointestinal mucosa to absorb nutrients; therefore, close nutrition monitoring is recommended.9

Continue to: Other oral and dental manifestations...

Other oral and dental manifestations of celiac disease include enamel defects, delayed tooth eruption, recurrent aphthous ulcers, cheilosis, oral lichen planus, and atrophic glossitis.10 Our patient also reported anxiety, “foggy mind,” diffuse arthralgia, and abdominal pain, which are symptoms of uncontrolled celiac disease. There is no known etiology of tongue manifestations in patients with incompletely treated celiac disease.

Treatment. FT generally does not require specific therapy other than the treatment of the underlying inflammatory condition. It is important to maintain proper oral and dental care, such as brushing the top surface of the tongue to clean and remove food debris. Bacteria and plaque can collect in the fissures, leading to bad breath and an increased potential for tooth decay.

Our patient was referred to a dietitian to assist with adherence to the gluten-free diet. At follow-up 3 months later, the appearance of her tongue had improved and fewer fissures were visible. The majority of her other symptoms also had resolved.

THE TAKEAWAY

FT may be a normal variant of the tongue in some patients or may be associated with poor oral hygiene. Additionally, FT often is associated with an underlying medical or inherited condition and may serve as a marker for an untreated or partially treated condition such as celiac disease, as was the case with our patient. When other signs or symptoms of systemic disease are present, further laboratory and endoscopic workup is necessary to rule out other causes and to diagnose celiac disease, if present.

As FT has been reported to be a natural progression from GT, the appearance of FT may indicate partial treatment of the underlying disease process and therefore more intensive therapy and follow-up would be needed. In this case, more intensive dietary guidance was provided with subsequent improvement of symptoms.

CORRESPONDENCE

Peter J. Carek, MD, MS, Department of Community Health and Family Medicine, College of Medicine, University of Florida, P.O. Box 100237, Gainesville, FL 32610-0237; [email protected]

THE CASE

A 49-year-old woman presented to our clinic with concerns about the changing appearance of her tongue over the past 2 to 3 weeks. She had been given a diagnosis of celiac disease by her gastroenterologist approximately 5 years earlier. At the time of that diagnosis, she had smooth patches on the surface of her tongue with missing papillae and slightly raised borders. (This gave her tongue a map-like appearance, consistent with geographic tongue [GT].) The patient’s symptoms improved after she started a gluten-free diet, but she reported occasional noncompliance over the past year.

At the current presentation, the patient noted that new lesions on the tongue had started as diffuse shiny red patches surrounded by clearly delineated white borders, ultimately progressing to structural changes. She denied any burning of the tongue or other oral symptoms but reported feelings of anxiety, a “foggy mind,” and diffuse arthralgia for the past several weeks. The patient’s list of medications included vitamin D and magnesium supplements, a multivitamin, and probiotics.

On physical examination, her tongue showed areas of shiny erythematous mucosa and deep central grooves with small radiating furrows giving a wrinkled appearance (FIGURE). A review of systems revealed nonspecific abdominal pain including bloating, cramping, and gas for the previous few months. An examination of her throat and oral cavity was unremarkable, and the remainder of the physical examination was normal.

THE DIAGNOSIS

A diagnosis of fissured tongue (FT) was suspected based on the clinical appearance of the patient’s tongue. Laboratory studies including a complete blood count; antinuclear antibody test; rheumatoid factor test; anticyclic citrullinated peptide test; a comprehensive metabolic panel; and thyroid-stimulating hormone, 25-hydroxyvitamin D, and vitamin B₁₂ level tests were performed based on her symptoms and current medications to rule out any other potential diagnoses. All laboratory results were normal, and a tissue transglutaminase IgA test was not repeated because it was positive when previously tested by the gastroenterologist at the time of her celiac disease diagnosis. A diagnosis of FT due to incompletely treated celiac disease was confirmed.

DISCUSSION

Clinical presentation. FT commonly presents in association with GT,1,2 with some cases of GT naturally progressing to FT.3,4 In most cases, FT is asymptomatic unless debris becomes entrapped in the fissures. Rarely, patients may complain of a burning sensation on the tongue. The clinical appearance of the tongue includes deep grooves with possible malodor or halitosis along with discoloration if trapping of debris and subsequent inflammation occurs.1

Etiology. FT has been linked to celiac disease; systemic conditions such as arthritis, iron deficiency, depression, anxiety, and neuropathy; and poor oral hygiene. Genetics also may play a role, as some cases of FT may be inherited. Getting to the source requires a careful history to uncover signs and symptoms (that may not have been reported until now) and to determine if other family members also have FT. A careful examination of the oral cavity, with an eye toward the patient’s oral hygiene, is also instructive (TABLE).5-8 In general, FT is believed to be a normal tongue variant in less than 10% of the general population.5,6 Additionally, local factors such as ill-fitting prosthesis, infection, parafunctional habits, allergic reaction, xerostomia, and galvanism have been implicated in the etiology of FT.5

In our patient, progression of GT to FT was caused by incompletely treated celiac disease. Both FT and GT may represent different reaction patterns caused by the same hematologic and immunologic diseases.3 In fact, the appearance of the tongue may aid in the diagnosis of celiac disease, which has been observed in 15% of patients with GT.7 Fissured tongue also may indicate an inability of the gastrointestinal mucosa to absorb nutrients; therefore, close nutrition monitoring is recommended.9

Continue to: Other oral and dental manifestations...

Other oral and dental manifestations of celiac disease include enamel defects, delayed tooth eruption, recurrent aphthous ulcers, cheilosis, oral lichen planus, and atrophic glossitis.10 Our patient also reported anxiety, “foggy mind,” diffuse arthralgia, and abdominal pain, which are symptoms of uncontrolled celiac disease. There is no known etiology of tongue manifestations in patients with incompletely treated celiac disease.

Treatment. FT generally does not require specific therapy other than the treatment of the underlying inflammatory condition. It is important to maintain proper oral and dental care, such as brushing the top surface of the tongue to clean and remove food debris. Bacteria and plaque can collect in the fissures, leading to bad breath and an increased potential for tooth decay.

Our patient was referred to a dietitian to assist with adherence to the gluten-free diet. At follow-up 3 months later, the appearance of her tongue had improved and fewer fissures were visible. The majority of her other symptoms also had resolved.

THE TAKEAWAY

FT may be a normal variant of the tongue in some patients or may be associated with poor oral hygiene. Additionally, FT often is associated with an underlying medical or inherited condition and may serve as a marker for an untreated or partially treated condition such as celiac disease, as was the case with our patient. When other signs or symptoms of systemic disease are present, further laboratory and endoscopic workup is necessary to rule out other causes and to diagnose celiac disease, if present.

As FT has been reported to be a natural progression from GT, the appearance of FT may indicate partial treatment of the underlying disease process and therefore more intensive therapy and follow-up would be needed. In this case, more intensive dietary guidance was provided with subsequent improvement of symptoms.

CORRESPONDENCE

Peter J. Carek, MD, MS, Department of Community Health and Family Medicine, College of Medicine, University of Florida, P.O. Box 100237, Gainesville, FL 32610-0237; [email protected]

1. Reamy BV, Cerby R, Bunt CW. Common tongue conditions in primary care. Am Fam Physician. 2010;81:627-634.

2. Yarom N, Cantony U, Gorsky M. Prevalence of fissured tongue, geographic tongue and median rhomboid glossitis among Israeli adults of different ethnic origins. Dermatology. 2004;209:88-94.

3. Dafar A, Cevik-Aras H, Robledo-Sierra J, et al. Factors associated with geographic tongue and fissured tongue. Acta Odontol Scad. 2016;74:210-216.

4. Hume WJ. Geographic stomatitis: a critical review. J Dent. 1975;3:25-43.

5. Sudarshan R, Sree Vijayabala G, Samata Y, et al. Newer classification system for fissured tongue: an epidemiological approach. J Tropical Med. doi:10.1155/2015/262079.

6. Mangold AR, Torgerson RR, Rogers RS. Diseases of the tongue. Clin Dermatol. 2016;34:458-469.

7. Cigic L, Galic T, Kero D, et al. The prevalence of celiac disease in patients with geographic tongue. J Oral Pathol Med. 2016;45:791-796.

8. Zargari O. The prevalence and significance of fissured tongue and geographical tongue in psoriatic patients. Clin Exp Dermatology. 2006;31:192-195.

9. Kullaa-Mikkonen A, Penttila I, Kotilainen R, et al. Haematological and immunological features of patients with fissured tongue syndrome. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1987;25:481-487.

10. Rashid M, Zarkadas M, Anca A, et al. Oral manifestations of celiac disease: a clinical guide for dentists. J Can Dent Assoc. 2011;77:b39.

1. Reamy BV, Cerby R, Bunt CW. Common tongue conditions in primary care. Am Fam Physician. 2010;81:627-634.

2. Yarom N, Cantony U, Gorsky M. Prevalence of fissured tongue, geographic tongue and median rhomboid glossitis among Israeli adults of different ethnic origins. Dermatology. 2004;209:88-94.

3. Dafar A, Cevik-Aras H, Robledo-Sierra J, et al. Factors associated with geographic tongue and fissured tongue. Acta Odontol Scad. 2016;74:210-216.

4. Hume WJ. Geographic stomatitis: a critical review. J Dent. 1975;3:25-43.

5. Sudarshan R, Sree Vijayabala G, Samata Y, et al. Newer classification system for fissured tongue: an epidemiological approach. J Tropical Med. doi:10.1155/2015/262079.

6. Mangold AR, Torgerson RR, Rogers RS. Diseases of the tongue. Clin Dermatol. 2016;34:458-469.

7. Cigic L, Galic T, Kero D, et al. The prevalence of celiac disease in patients with geographic tongue. J Oral Pathol Med. 2016;45:791-796.

8. Zargari O. The prevalence and significance of fissured tongue and geographical tongue in psoriatic patients. Clin Exp Dermatology. 2006;31:192-195.

9. Kullaa-Mikkonen A, Penttila I, Kotilainen R, et al. Haematological and immunological features of patients with fissured tongue syndrome. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1987;25:481-487.

10. Rashid M, Zarkadas M, Anca A, et al. Oral manifestations of celiac disease: a clinical guide for dentists. J Can Dent Assoc. 2011;77:b39.

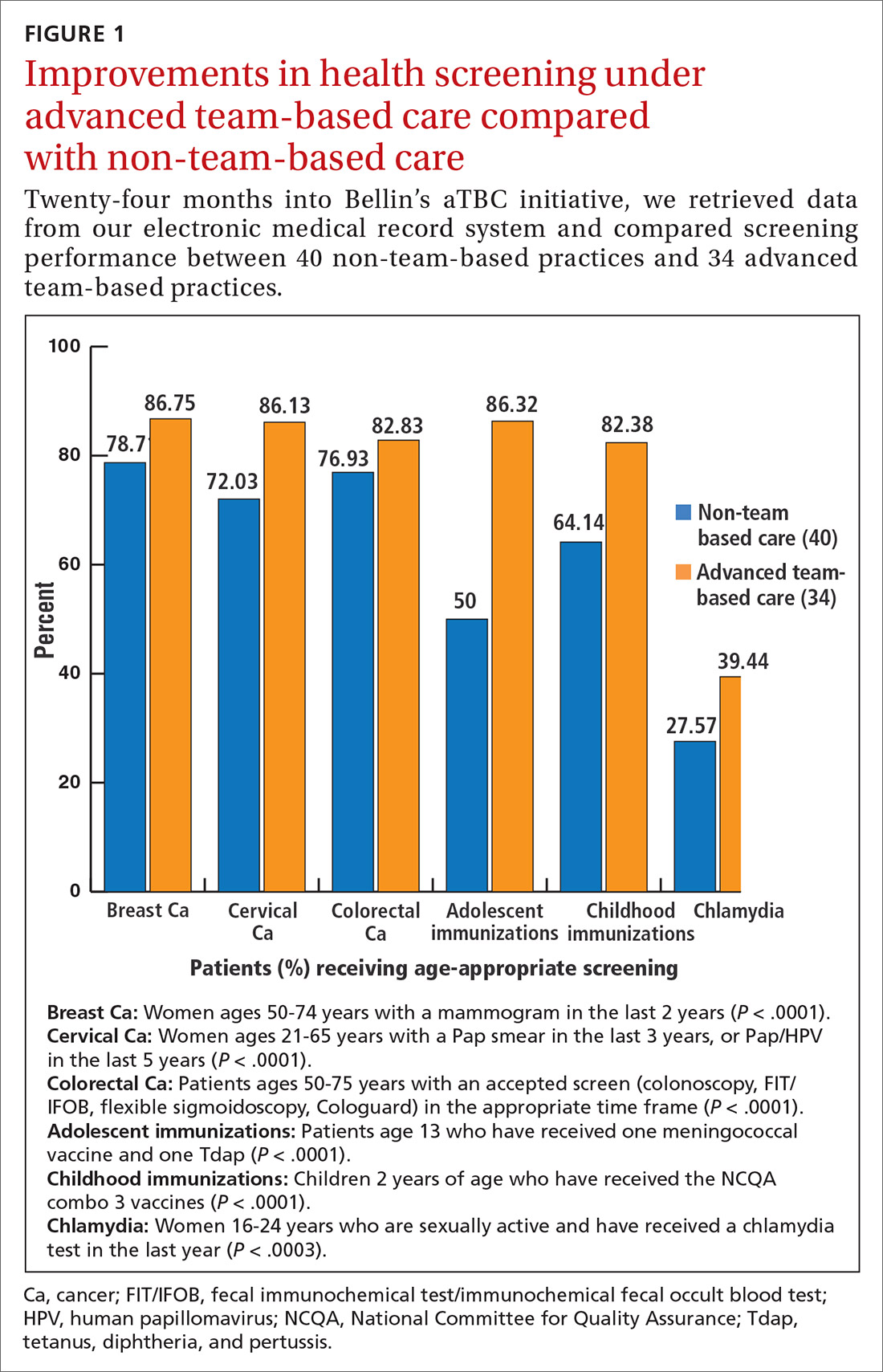

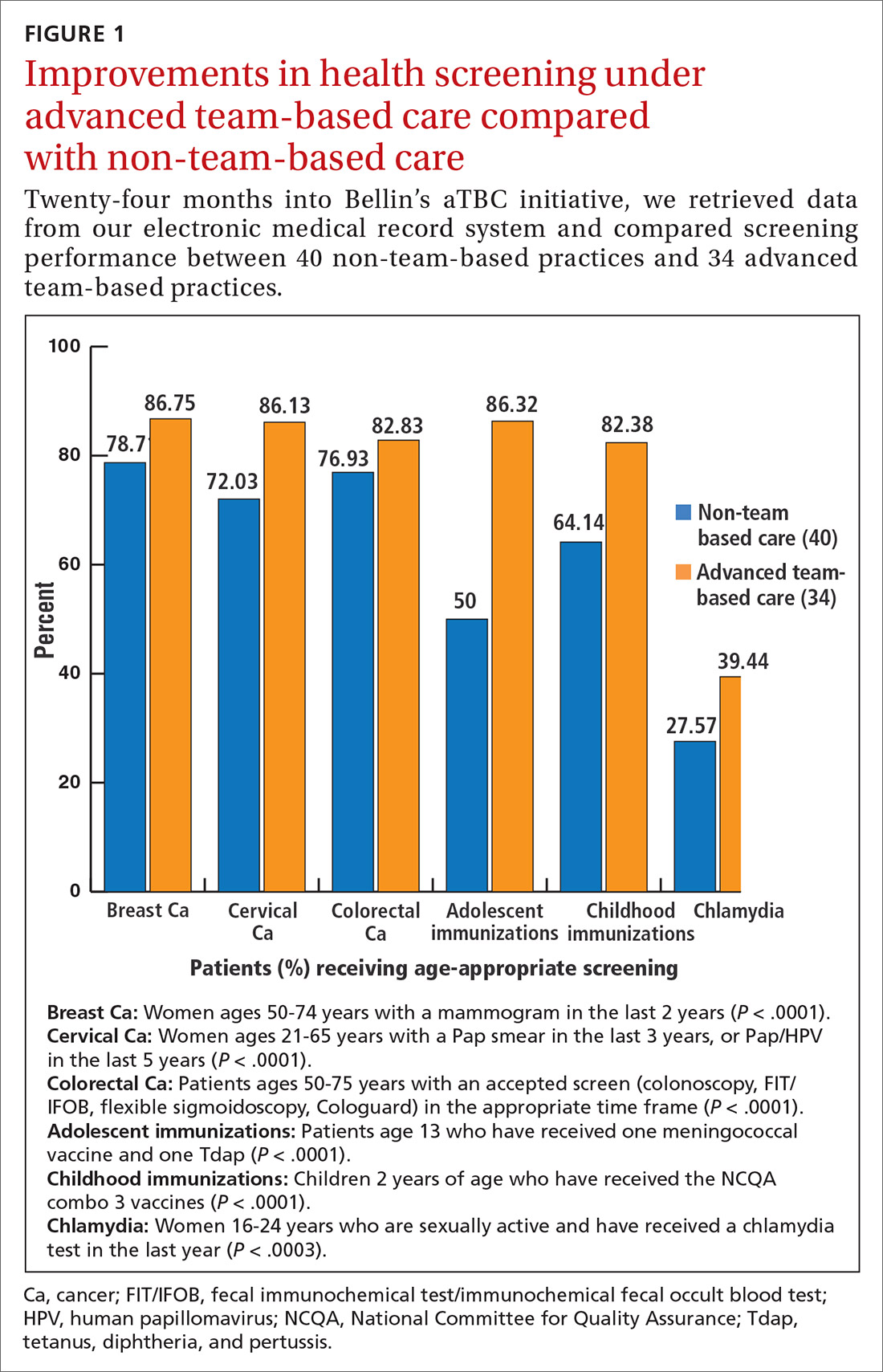

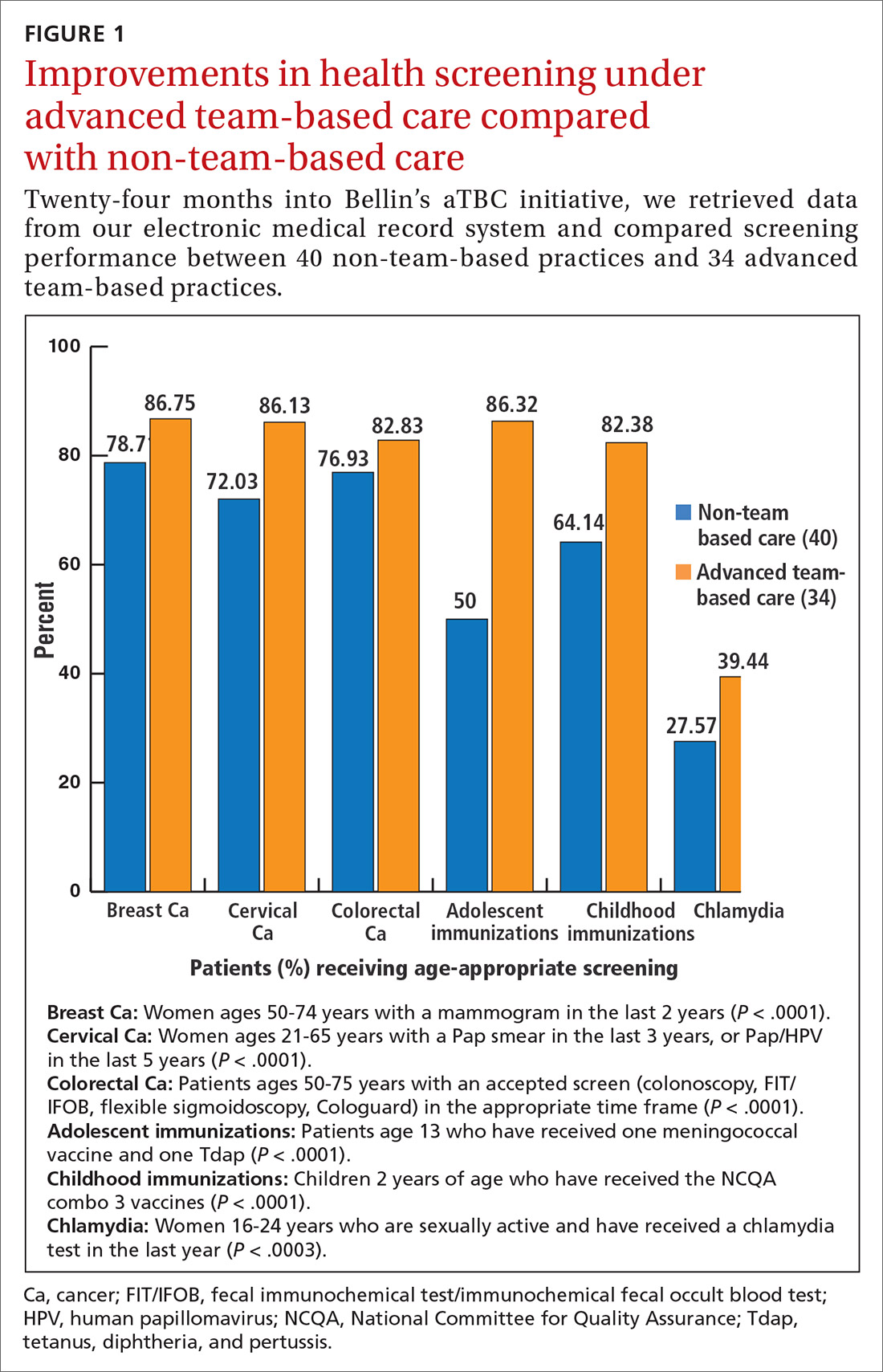

Advanced team-based care: How we made it work

Leaders in health care and practicing physicians recognize the need for changes in how health care is delivered.1-3 Despite this awareness, though, barriers to meaningful change persist and the current practice environment wherein physicians must routinely spend 2 hours on electronic health records (EHRs) and desk work for every hour of direct face time with patients4 is driving trainees away from ambulatory specialties and is contributing to physicians’ decisions to reduce their practices to part-time, retire early, or leave medicine altogether.5,6 Those who persevere in this environment with heavy administrative burdens run the increasing risk of burnout.7

Some physicians and practices are responding by taking creative measures to reform the way patient care is delivered. Bellin Health—a 160-provider, multispecialty health system in northeast Wisconsin where one of the authors (JJ) works—introduced an advanced team-based care (aTBC) model between November 2014 and November 2018, starting with our primary care providers. The development and introduction of this new model arose from an iterative, multidisciplinary process driven by the desire to transform the Triple Aim—enhancing patient experience, improving population health, and reducing costs—into a Quadruple Aim8 by additionally focusing on improving the work life of health care providers, which, in turn, will help achieve the first 3 goals. In introducing an aTBC model, Bellin Health focused on 3 elements: office visit redesign, in-basket management redesign, and the use of extended care team members and system and community resources to assist in the care of complex and high-risk patients.

Herein we describe the 3 components of our aTBC model,1,9 identify the barriers that existed in the minds of multiple stakeholders (from patients to clinicians and Bellin executives), and describe the strategies that enabled us to overcome these barriers.

The impetus behind our move to aTBC

Bellin Health considered a move to an aTBC model to be critical in light of factors in the health care environment, in general, and at Bellin, in particular. The factors included

- an industry-wide shift to value-based payments, which requires new models for long-term financial viability.

- recognition that physician and medical staff burnout leads to lower productivity and, in some cases, workforce losses.5,6 Replacing a physician in a practice can be difficult and expensive, with cost estimates of $500,000 to more than $1 million per physician.10,11

- a belief that aTBC could help the Bellin Health leadership team meet its organizational goals of improved patient satisfaction, achieve gains in quality measures, enhance engagement and loyalty among patients and employees, and lower recruitment costs.

A 3-part aTBC initiative

■ Part 1: Redesign the office visit

We redesigned staffing and workflow for office visits to maximize the core skills of physicians, which required distributing ancillary tasks among support staff. We up-trained certified medical assistants (CMAs) and licensed practical nurses (LPNs) to take on the new role of care team coordinator (CTC) and optimized the direct clinical support ratio for busier physicians. For physicians who were seeing 15 to 19 patients a day, a ratio of 3 CTCs to 2 physicians was implemented; for those seeing 20 or more patients a day, we used a support ratio of 2:1.

The role of CTC was designed so that he or she would accompany a patient throughout the entire appointment. Responsibilities were broken out as follows:

Pre-visit. Before the physician enters the room, the CTC would now perform expanded rooming functions including pending orders, refill management, care gap closure using standing orders, agenda setting, and preliminary documentation.12

Visit. The CTC would now hand off the patient to the physician and stay in the room to document details of the visit and record new orders for consults, x-ray films, referrals, or prescriptions.13 This intensive EHR support was established to ensure that the physician could focus directly on the patient without the distraction of the computer.