User login

Werewolf babies, blinding fries, and the gut library

Someone needs carrots, stat

Eat your veggies or you’ll … go blind? A U.K. teen took picky eating to a whole new level, literally losing his vision after a steady decade-long diet of strictly fries, Pringles, white bread, and ham.

Looks like Pringles needs to change their tagline a little bit: “Once you pop, the fun don’t stop – until you start losing hearing and vision!” We think it’s really catchy.

The teen first visited a doctor several years ago complaining of tiredness and was given B12 injections and sent on his merry way. Unfortunately, he quickly developed hearing and vision loss, and by age 17 years was diagnosed with nutritional optic neuropathy.

Somehow through all of this, he maintained a normal weight, proving once and for all the metabolism of teenage boys can withstand just about anything.

The chip-loving teen now joins the (very small) Nutritional Optic Neuropathy Hall of Fame of Developed Countries, previously only occupied by a man who pretty much drank vodka every day for breakfast, lunch, and dinner. Cheers!

Teen wolf? Try baby wolf

Every parent just wants their child to be happy, healthy, and covered in a thick layer of hair, right?

No?

Well, that’s too bad for dozens of parents in Spain, whose children developed hypertrichosis, aka “werewolf syndrome,” and suddenly sprouted full-body hair growth that Tom Selleck would be jealous of. After a brief investigation, they discovered the fast-paced hair growth was caused by an unfortunate medicine mix-up at the lab. Instead of receiving omeprazole for their gastric reflux, the children had been given minoxidil, a drug that treats alopecia.

Luckily for the children who don’t want to impersonate Michael J. Fox anymore, the hair will go away when they stop taking the drug.

No official statement yet on the mysterious sightings of wolf children roaming the Spanish countryside terrorizing locals and howling at the full moon.

Mouthwash in my veins

Let’s say you’re a person with hypertension. After years of your doctor badgering you to do more cardio exercise, you’ve finally committed to the morning jog. It’s a pain getting up that early in the morning, but the benefits will be worth it, right? You head back to your physician, eager to show off the new you. The doctor weighs you (down a few pounds, not bad), then takes a blood pressure reading, and ... it’s exactly the same.

What happened? Was all that work wasted?

Well, according to a study published in Free Radical Biology and Medicine, you may have an excuse: mouthwash usage.

It all has to do with nitric acid. Normally during cardio exercise, bacteria in the mouth convert nitrates into nitrites, and when these nitrites are swallowed, they are converted into nitric acid after being absorbed by the circulatory system. That widens the blood vessels and reduces blood pressure. Mouthwash changes all that. It inhibits those oral bacteria, and the whole process is stopped before it can begin.

The investigators found that, after 1 hour of exercise on a treadmill, study participants who received mouthwash beforehand saw their systolic blood pressure reduced by 2 mm Hg. And those who received the placebo (mint-flavored water)? They saw a 5.2-mm Hg reduction.

Bottom line to those with hypertension: You may have to start flossing. We know it’s annoying, but it’ll make your doctor happy, and it’ll make your dentist especially happy.

No books at this library

The human microbiome is a pretty hot scientific topic right now, but we here at LOTME are not scientists, or doctors, or experts of any kind, so we have a simple question: What’s in a gut?

Happily (yes, this is the sort of thing that makes us happy), researchers at MIT and the Broad Institute, both in Cambridge, Mass., have taken a very detailed look at the guts of about 90 people, with a dozen or so providing samples for up to 2 years, and can now tell us what’s in a gut: bacteria. Lots of bacteria … 7,758 different strains of bacteria.

According to a statement from MIT, the samples were obtained “through the OpenBiome organization, which collects stool samples for research and therapeutic purposes.” It also sounds like a fun place to work.

Those samples presented “a unique opportunity, and we thought that would be a great set of individuals to really try to dig down and characterize the microbial populations more thoroughly,” said Eric Alm, PhD, one of the investigators.

All of their data, along with samples of the bacteria strains they isolated, are available online at the Broad Institute–OpenBiome Microbiome Library. Which, if you think about it (and that is what we do here), makes it kind of like an Amazon for bacteria.

Hmmm … Alexa, order Turicibacter sanguinis. Uncle Leo’s birthday is coming up.

Someone needs carrots, stat

Eat your veggies or you’ll … go blind? A U.K. teen took picky eating to a whole new level, literally losing his vision after a steady decade-long diet of strictly fries, Pringles, white bread, and ham.

Looks like Pringles needs to change their tagline a little bit: “Once you pop, the fun don’t stop – until you start losing hearing and vision!” We think it’s really catchy.

The teen first visited a doctor several years ago complaining of tiredness and was given B12 injections and sent on his merry way. Unfortunately, he quickly developed hearing and vision loss, and by age 17 years was diagnosed with nutritional optic neuropathy.

Somehow through all of this, he maintained a normal weight, proving once and for all the metabolism of teenage boys can withstand just about anything.

The chip-loving teen now joins the (very small) Nutritional Optic Neuropathy Hall of Fame of Developed Countries, previously only occupied by a man who pretty much drank vodka every day for breakfast, lunch, and dinner. Cheers!

Teen wolf? Try baby wolf

Every parent just wants their child to be happy, healthy, and covered in a thick layer of hair, right?

No?

Well, that’s too bad for dozens of parents in Spain, whose children developed hypertrichosis, aka “werewolf syndrome,” and suddenly sprouted full-body hair growth that Tom Selleck would be jealous of. After a brief investigation, they discovered the fast-paced hair growth was caused by an unfortunate medicine mix-up at the lab. Instead of receiving omeprazole for their gastric reflux, the children had been given minoxidil, a drug that treats alopecia.

Luckily for the children who don’t want to impersonate Michael J. Fox anymore, the hair will go away when they stop taking the drug.

No official statement yet on the mysterious sightings of wolf children roaming the Spanish countryside terrorizing locals and howling at the full moon.

Mouthwash in my veins

Let’s say you’re a person with hypertension. After years of your doctor badgering you to do more cardio exercise, you’ve finally committed to the morning jog. It’s a pain getting up that early in the morning, but the benefits will be worth it, right? You head back to your physician, eager to show off the new you. The doctor weighs you (down a few pounds, not bad), then takes a blood pressure reading, and ... it’s exactly the same.

What happened? Was all that work wasted?

Well, according to a study published in Free Radical Biology and Medicine, you may have an excuse: mouthwash usage.

It all has to do with nitric acid. Normally during cardio exercise, bacteria in the mouth convert nitrates into nitrites, and when these nitrites are swallowed, they are converted into nitric acid after being absorbed by the circulatory system. That widens the blood vessels and reduces blood pressure. Mouthwash changes all that. It inhibits those oral bacteria, and the whole process is stopped before it can begin.

The investigators found that, after 1 hour of exercise on a treadmill, study participants who received mouthwash beforehand saw their systolic blood pressure reduced by 2 mm Hg. And those who received the placebo (mint-flavored water)? They saw a 5.2-mm Hg reduction.

Bottom line to those with hypertension: You may have to start flossing. We know it’s annoying, but it’ll make your doctor happy, and it’ll make your dentist especially happy.

No books at this library

The human microbiome is a pretty hot scientific topic right now, but we here at LOTME are not scientists, or doctors, or experts of any kind, so we have a simple question: What’s in a gut?

Happily (yes, this is the sort of thing that makes us happy), researchers at MIT and the Broad Institute, both in Cambridge, Mass., have taken a very detailed look at the guts of about 90 people, with a dozen or so providing samples for up to 2 years, and can now tell us what’s in a gut: bacteria. Lots of bacteria … 7,758 different strains of bacteria.

According to a statement from MIT, the samples were obtained “through the OpenBiome organization, which collects stool samples for research and therapeutic purposes.” It also sounds like a fun place to work.

Those samples presented “a unique opportunity, and we thought that would be a great set of individuals to really try to dig down and characterize the microbial populations more thoroughly,” said Eric Alm, PhD, one of the investigators.

All of their data, along with samples of the bacteria strains they isolated, are available online at the Broad Institute–OpenBiome Microbiome Library. Which, if you think about it (and that is what we do here), makes it kind of like an Amazon for bacteria.

Hmmm … Alexa, order Turicibacter sanguinis. Uncle Leo’s birthday is coming up.

Someone needs carrots, stat

Eat your veggies or you’ll … go blind? A U.K. teen took picky eating to a whole new level, literally losing his vision after a steady decade-long diet of strictly fries, Pringles, white bread, and ham.

Looks like Pringles needs to change their tagline a little bit: “Once you pop, the fun don’t stop – until you start losing hearing and vision!” We think it’s really catchy.

The teen first visited a doctor several years ago complaining of tiredness and was given B12 injections and sent on his merry way. Unfortunately, he quickly developed hearing and vision loss, and by age 17 years was diagnosed with nutritional optic neuropathy.

Somehow through all of this, he maintained a normal weight, proving once and for all the metabolism of teenage boys can withstand just about anything.

The chip-loving teen now joins the (very small) Nutritional Optic Neuropathy Hall of Fame of Developed Countries, previously only occupied by a man who pretty much drank vodka every day for breakfast, lunch, and dinner. Cheers!

Teen wolf? Try baby wolf

Every parent just wants their child to be happy, healthy, and covered in a thick layer of hair, right?

No?

Well, that’s too bad for dozens of parents in Spain, whose children developed hypertrichosis, aka “werewolf syndrome,” and suddenly sprouted full-body hair growth that Tom Selleck would be jealous of. After a brief investigation, they discovered the fast-paced hair growth was caused by an unfortunate medicine mix-up at the lab. Instead of receiving omeprazole for their gastric reflux, the children had been given minoxidil, a drug that treats alopecia.

Luckily for the children who don’t want to impersonate Michael J. Fox anymore, the hair will go away when they stop taking the drug.

No official statement yet on the mysterious sightings of wolf children roaming the Spanish countryside terrorizing locals and howling at the full moon.

Mouthwash in my veins

Let’s say you’re a person with hypertension. After years of your doctor badgering you to do more cardio exercise, you’ve finally committed to the morning jog. It’s a pain getting up that early in the morning, but the benefits will be worth it, right? You head back to your physician, eager to show off the new you. The doctor weighs you (down a few pounds, not bad), then takes a blood pressure reading, and ... it’s exactly the same.

What happened? Was all that work wasted?

Well, according to a study published in Free Radical Biology and Medicine, you may have an excuse: mouthwash usage.

It all has to do with nitric acid. Normally during cardio exercise, bacteria in the mouth convert nitrates into nitrites, and when these nitrites are swallowed, they are converted into nitric acid after being absorbed by the circulatory system. That widens the blood vessels and reduces blood pressure. Mouthwash changes all that. It inhibits those oral bacteria, and the whole process is stopped before it can begin.

The investigators found that, after 1 hour of exercise on a treadmill, study participants who received mouthwash beforehand saw their systolic blood pressure reduced by 2 mm Hg. And those who received the placebo (mint-flavored water)? They saw a 5.2-mm Hg reduction.

Bottom line to those with hypertension: You may have to start flossing. We know it’s annoying, but it’ll make your doctor happy, and it’ll make your dentist especially happy.

No books at this library

The human microbiome is a pretty hot scientific topic right now, but we here at LOTME are not scientists, or doctors, or experts of any kind, so we have a simple question: What’s in a gut?

Happily (yes, this is the sort of thing that makes us happy), researchers at MIT and the Broad Institute, both in Cambridge, Mass., have taken a very detailed look at the guts of about 90 people, with a dozen or so providing samples for up to 2 years, and can now tell us what’s in a gut: bacteria. Lots of bacteria … 7,758 different strains of bacteria.

According to a statement from MIT, the samples were obtained “through the OpenBiome organization, which collects stool samples for research and therapeutic purposes.” It also sounds like a fun place to work.

Those samples presented “a unique opportunity, and we thought that would be a great set of individuals to really try to dig down and characterize the microbial populations more thoroughly,” said Eric Alm, PhD, one of the investigators.

All of their data, along with samples of the bacteria strains they isolated, are available online at the Broad Institute–OpenBiome Microbiome Library. Which, if you think about it (and that is what we do here), makes it kind of like an Amazon for bacteria.

Hmmm … Alexa, order Turicibacter sanguinis. Uncle Leo’s birthday is coming up.

Hyperphosphorylated tau visible in TBI survivors decades after brain injury

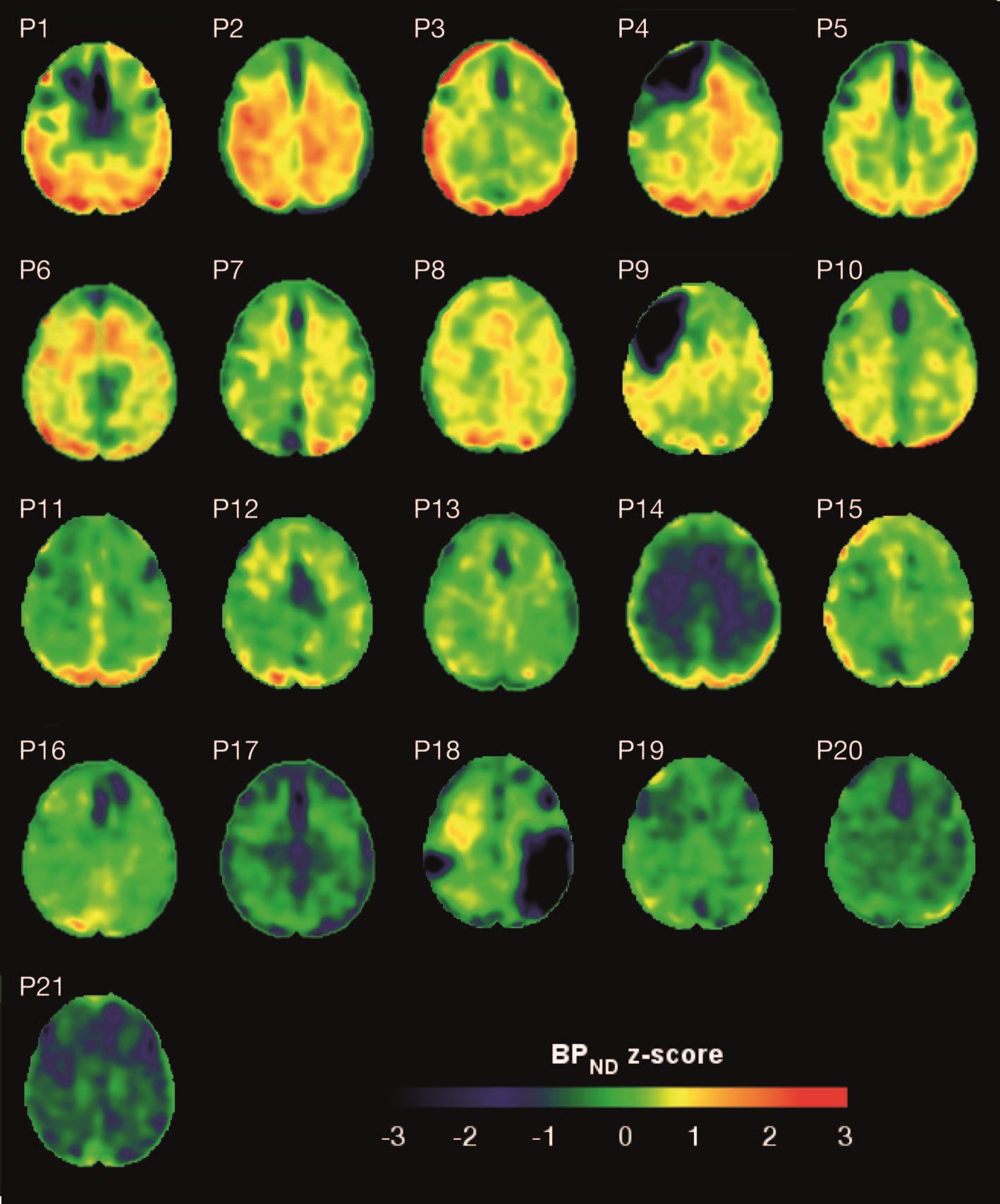

Brain deposits of hyperphosphorylated tau are detectable in traumatic brain injury (TBI) patients 18-51 years after a single moderate to severe incident occurred, researchers reported Sept. 4 in Science Translational Medicine.

Imaging with the tau-specific PET radioligand flortaucipir showed that the protein was most apparent in the right occipital cortex, and was associated with changes in cognitive scores, tau and beta amyloid in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), and white matter density, Nikos Gorgoraptis, PhD, of Imperial College London and his colleagues wrote.

“The ability to detect tau pathology in vivo after TBI has major potential implications for diagnosis and prognostication of clinical outcomes after TBI,” the researchers explained. “It is also likely to assist in patient selection and stratification for future treatment trials targeting tau.”

The cohort study comprised 21 subjects (median age, 49 years) who had experienced a single moderate to severe TBI a median of 32 years (range, 18-51 years) before enrollment. A control group comprised 11 noninjured adults who were matched for age and other demographic factors. Everyone underwent a PET scan with flortaucipir, brain MRI, CSF sampling, apolipoprotein E genotyping, and neuropsychological testing.

TBI subjects were grouped according to recovery status: good and disabled. Overall, they showed impairments on multiple cognitive domains (processing speed, executive function, motivation, inhibition, and verbal and visual memory), compared with controls. These findings were largely driven by the disabled group.

Eight TBI subjects had elevated tau binding greater than 2,000 voxels above the threshold of detection (equivalent to 16 cm3 of brain volume), and seven had an increase of 249-1,999 voxels above threshold. Tau binding in the remainder was similar to that in controls. Recovery status didn’t correlate with the tau-binding strength.

Overall, the tau-binding signal appeared most strongly in the right lateral occipital cortex, regardless of functional recovery status.

In TBI subjects, CSF total tau correlated significantly with flortaucipir uptake in cortical gray matter, but not white matter. CSF phosphorylated tau correlated with uptake in white matter, but not gray matter.

The investigators also examined fractional anisotropy, a measure of fiber density, axonal diameter, and myelination in white matter. In TBI subjects, there was more flortaucipir uptake in areas of decreased fractional anisotropy, including association, commissural, and projection tracts.

“Correlations were observed in the genu and body of the corpus callosum, as well as in several association tracts within the ipsilateral (right) hemisphere, including the cingulum bundle, inferior longitudinal fasciculus, uncinate fasciculus, and anterior thalamic radiation, but not in the contralateral hemisphere. Higher cortical flortaucipir [signal] was associated with reduced tissue density in remote white matter regions including the corpus callosum and right prefrontal white matter. The same analysis for gray matter density did not show an association.”

The increased tau signal in TBI subjects “is in keeping with a causative role for traumatic axonal injury in the pathophysiology of posttraumatic tau pathology,” the authors said. “Mechanical forces exerted at the time of head injury are thought to disrupt axonal organization, producing damage to microtubule structure and associated axonal tau. This damage may lead to hyperphosphorylation of tau, misfolding, and neurofibrillary tangle formation, which eventually causes neurodegeneration. Mechanical forces are maximal in points of geometric inflection such as the base of cortical sulci, where tau pathology is seen in chronic traumatic encephalopathy.”

These patterns suggest that tau imaging could provide valuable diagnostic information about the type of posttraumatic neurodegeneration, they said.

The work was supported by the Medical Research Council and UK Dementia Research Institute. None of the authors declared having any competing interests related to the current study. Some authors reported financial ties to pharmaceutical companies.

SOURCE: Gorgoraptis N et al. Sci Transl Med. 2019;11:eaaw1993. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaw1993.

Brain deposits of hyperphosphorylated tau are detectable in traumatic brain injury (TBI) patients 18-51 years after a single moderate to severe incident occurred, researchers reported Sept. 4 in Science Translational Medicine.

Imaging with the tau-specific PET radioligand flortaucipir showed that the protein was most apparent in the right occipital cortex, and was associated with changes in cognitive scores, tau and beta amyloid in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), and white matter density, Nikos Gorgoraptis, PhD, of Imperial College London and his colleagues wrote.

“The ability to detect tau pathology in vivo after TBI has major potential implications for diagnosis and prognostication of clinical outcomes after TBI,” the researchers explained. “It is also likely to assist in patient selection and stratification for future treatment trials targeting tau.”

The cohort study comprised 21 subjects (median age, 49 years) who had experienced a single moderate to severe TBI a median of 32 years (range, 18-51 years) before enrollment. A control group comprised 11 noninjured adults who were matched for age and other demographic factors. Everyone underwent a PET scan with flortaucipir, brain MRI, CSF sampling, apolipoprotein E genotyping, and neuropsychological testing.

TBI subjects were grouped according to recovery status: good and disabled. Overall, they showed impairments on multiple cognitive domains (processing speed, executive function, motivation, inhibition, and verbal and visual memory), compared with controls. These findings were largely driven by the disabled group.

Eight TBI subjects had elevated tau binding greater than 2,000 voxels above the threshold of detection (equivalent to 16 cm3 of brain volume), and seven had an increase of 249-1,999 voxels above threshold. Tau binding in the remainder was similar to that in controls. Recovery status didn’t correlate with the tau-binding strength.

Overall, the tau-binding signal appeared most strongly in the right lateral occipital cortex, regardless of functional recovery status.

In TBI subjects, CSF total tau correlated significantly with flortaucipir uptake in cortical gray matter, but not white matter. CSF phosphorylated tau correlated with uptake in white matter, but not gray matter.

The investigators also examined fractional anisotropy, a measure of fiber density, axonal diameter, and myelination in white matter. In TBI subjects, there was more flortaucipir uptake in areas of decreased fractional anisotropy, including association, commissural, and projection tracts.

“Correlations were observed in the genu and body of the corpus callosum, as well as in several association tracts within the ipsilateral (right) hemisphere, including the cingulum bundle, inferior longitudinal fasciculus, uncinate fasciculus, and anterior thalamic radiation, but not in the contralateral hemisphere. Higher cortical flortaucipir [signal] was associated with reduced tissue density in remote white matter regions including the corpus callosum and right prefrontal white matter. The same analysis for gray matter density did not show an association.”

The increased tau signal in TBI subjects “is in keeping with a causative role for traumatic axonal injury in the pathophysiology of posttraumatic tau pathology,” the authors said. “Mechanical forces exerted at the time of head injury are thought to disrupt axonal organization, producing damage to microtubule structure and associated axonal tau. This damage may lead to hyperphosphorylation of tau, misfolding, and neurofibrillary tangle formation, which eventually causes neurodegeneration. Mechanical forces are maximal in points of geometric inflection such as the base of cortical sulci, where tau pathology is seen in chronic traumatic encephalopathy.”

These patterns suggest that tau imaging could provide valuable diagnostic information about the type of posttraumatic neurodegeneration, they said.

The work was supported by the Medical Research Council and UK Dementia Research Institute. None of the authors declared having any competing interests related to the current study. Some authors reported financial ties to pharmaceutical companies.

SOURCE: Gorgoraptis N et al. Sci Transl Med. 2019;11:eaaw1993. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaw1993.

Brain deposits of hyperphosphorylated tau are detectable in traumatic brain injury (TBI) patients 18-51 years after a single moderate to severe incident occurred, researchers reported Sept. 4 in Science Translational Medicine.

Imaging with the tau-specific PET radioligand flortaucipir showed that the protein was most apparent in the right occipital cortex, and was associated with changes in cognitive scores, tau and beta amyloid in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), and white matter density, Nikos Gorgoraptis, PhD, of Imperial College London and his colleagues wrote.

“The ability to detect tau pathology in vivo after TBI has major potential implications for diagnosis and prognostication of clinical outcomes after TBI,” the researchers explained. “It is also likely to assist in patient selection and stratification for future treatment trials targeting tau.”

The cohort study comprised 21 subjects (median age, 49 years) who had experienced a single moderate to severe TBI a median of 32 years (range, 18-51 years) before enrollment. A control group comprised 11 noninjured adults who were matched for age and other demographic factors. Everyone underwent a PET scan with flortaucipir, brain MRI, CSF sampling, apolipoprotein E genotyping, and neuropsychological testing.

TBI subjects were grouped according to recovery status: good and disabled. Overall, they showed impairments on multiple cognitive domains (processing speed, executive function, motivation, inhibition, and verbal and visual memory), compared with controls. These findings were largely driven by the disabled group.

Eight TBI subjects had elevated tau binding greater than 2,000 voxels above the threshold of detection (equivalent to 16 cm3 of brain volume), and seven had an increase of 249-1,999 voxels above threshold. Tau binding in the remainder was similar to that in controls. Recovery status didn’t correlate with the tau-binding strength.

Overall, the tau-binding signal appeared most strongly in the right lateral occipital cortex, regardless of functional recovery status.

In TBI subjects, CSF total tau correlated significantly with flortaucipir uptake in cortical gray matter, but not white matter. CSF phosphorylated tau correlated with uptake in white matter, but not gray matter.

The investigators also examined fractional anisotropy, a measure of fiber density, axonal diameter, and myelination in white matter. In TBI subjects, there was more flortaucipir uptake in areas of decreased fractional anisotropy, including association, commissural, and projection tracts.

“Correlations were observed in the genu and body of the corpus callosum, as well as in several association tracts within the ipsilateral (right) hemisphere, including the cingulum bundle, inferior longitudinal fasciculus, uncinate fasciculus, and anterior thalamic radiation, but not in the contralateral hemisphere. Higher cortical flortaucipir [signal] was associated with reduced tissue density in remote white matter regions including the corpus callosum and right prefrontal white matter. The same analysis for gray matter density did not show an association.”

The increased tau signal in TBI subjects “is in keeping with a causative role for traumatic axonal injury in the pathophysiology of posttraumatic tau pathology,” the authors said. “Mechanical forces exerted at the time of head injury are thought to disrupt axonal organization, producing damage to microtubule structure and associated axonal tau. This damage may lead to hyperphosphorylation of tau, misfolding, and neurofibrillary tangle formation, which eventually causes neurodegeneration. Mechanical forces are maximal in points of geometric inflection such as the base of cortical sulci, where tau pathology is seen in chronic traumatic encephalopathy.”

These patterns suggest that tau imaging could provide valuable diagnostic information about the type of posttraumatic neurodegeneration, they said.

The work was supported by the Medical Research Council and UK Dementia Research Institute. None of the authors declared having any competing interests related to the current study. Some authors reported financial ties to pharmaceutical companies.

SOURCE: Gorgoraptis N et al. Sci Transl Med. 2019;11:eaaw1993. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaw1993.

FROM SCIENCE TRANSLATIONAL MEDICINE

Type of renal dysfunction affects liver cirrhosis mortality risk

For non–status 1 patients with cirrhosis who are awaiting liver transplantation, type of renal dysfunction may be a key determinant of mortality risk, based on a retrospective analysis of more than 22,000 patients.

Risk of death was greatest for patients with acute on chronic kidney disease (AKI on CKD), followed by AKI alone, then CKD alone, reported lead author Giuseppe Cullaro, MD, of the University of California, San Francisco, and colleagues.

Although it is well known that renal dysfunction worsens outcomes among patients with liver cirrhosis, the impact of different types of kidney pathology on mortality risk has been minimally researched, the investigators wrote in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. “To date, studies evaluating the impact of renal dysfunction on prognosis in patients with cirrhosis have mostly focused on AKI.”

To learn more, the investigators performed a retrospective study involving acute, chronic, and acute on chronic kidney disease among patients with cirrhosis. They included data from 22,680 non–status 1 adults who were awaiting liver transplantation between 2007 and 2014, with at least 90 days on the wait list. Information was gathered from the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network registry.

AKI was defined by fewer than 72 days of hemodialysis, or an increase in creatinine of at least 0.3 mg/dL or at least 50% in the last 7 days. CKD was identified by more than 72 days of hemodialysis, or an estimated glomerular filtration rate less than 60 mL/min/1.73 m2 for 90 days with a final rate of at least 30 mL/min/1.73 m2. Using these criteria, the researchers put patients into four possible categories: AKI on CKD, AKI, CKD, or normal renal function. The primary outcome was wait list mortality, which was defined as death, or removal from the wait list for illness. Follow-up started at the time of addition to the wait list and continued until transplant, removal from the wait list, or death.

Multivariate analysis, which accounted for final MELD-Na score and other confounders, showed that patients with AKI on CKD fared worst, with a 2.86-fold higher mortality risk (subhazard [SHR] ratio, 2.86) than that of patients with normal renal function. The mortality risk for acute on chronic kidney disease was followed closely by patients with AKI alone (SHR, 2.42), and more distantly by patients with CKD alone (SHR, 1.56). Further analysis showed that the disparity between mortality risks of each subgroup became more pronounced with increased MELD-Na score. In addition, evaluation of receiver operating characteristic curves for 6-month wait list mortality showed that the addition of renal function to MELD-Na score increased the accuracy of prognosis from an area under the curve of 0.71 to 0.80 (P less than .001).

“This suggests that incorporating the pattern of renal function could provide an opportunity to better prognosticate risk of mortality in the patients with cirrhosis who are the sickest,” the investigators concluded.

They also speculated about why outcomes may vary by type of kidney dysfunction.

“We suspect that those patients who experience AKI and AKI on CKD in our cohort likely had a triggering event – infection, bleeding, hypovolemia – that put these patients at greater risk for waitlist mortality,” the investigators wrote. “These events inherently carry more risk than stable nonliver-related elevations in serum creatinine that are seen in patients with CKD. Because of this heterogeneity of etiology in renal dysfunction in patients with cirrhosis, it is perhaps not surprising that unique renal function patterns variably impact mortality.”

The investigators noted that the findings from the study have “important implications for clinical practice,” and suggested that including type of renal dysfunction would have the most significant affect on accuracy of prognoses among patients at greatest risk of mortality.

The study was funded by a Paul B. Beeson Career Development Award and the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Dr. Verna disclosed relationships with Salix, Merck, and Gilead.

SOURCE: Cullaro et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019 Feb 1. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2019.01.043.

Cirrhotic patients with renal failure have a sevenfold increase in mortality compared with those without renal failure. Acute kidney injury (AKI) is common in cirrhosis; increasingly, cirrhotic patients awaiting liver transplantation have or are also at risk for CKD. They are sicker, older, and have more comorbidities such as obesity and diabetes. In this study, the cumulative incidence of death on the wait list was much more pronounced for any form of AKI, with those with AKI on CKD having the highest cumulative incidence of wait list mortality compared with those with normal renal function. The study notably raises several important issues. First, AKI exerts a greater influence in risk of mortality on CKD than it does on those with normal renal function. This is relevant given the increasing prevalence of CKD in this population. Second, it emphasizes the need to effectively measure renal function. All serum creatinine-based equations overestimate glomerular filtration rate in the presence of renal dysfunction. Finally, the study highlights the importance of extrahepatic factors in determining mortality on the wait list. While in all comers, a mathematical model such as the MELDNa score may be able to predict mortality, for a specific patient the presence of comorbid conditions, malnutrition and sarcopenia, infections, critical illness, and now pattern of renal dysfunction, may all play a role.

Sumeet K. Asrani, MD, MSc, is a hepatologist affiliated with Baylor University Medical Center, Dallas. He has no conflicts of interest.

Cirrhotic patients with renal failure have a sevenfold increase in mortality compared with those without renal failure. Acute kidney injury (AKI) is common in cirrhosis; increasingly, cirrhotic patients awaiting liver transplantation have or are also at risk for CKD. They are sicker, older, and have more comorbidities such as obesity and diabetes. In this study, the cumulative incidence of death on the wait list was much more pronounced for any form of AKI, with those with AKI on CKD having the highest cumulative incidence of wait list mortality compared with those with normal renal function. The study notably raises several important issues. First, AKI exerts a greater influence in risk of mortality on CKD than it does on those with normal renal function. This is relevant given the increasing prevalence of CKD in this population. Second, it emphasizes the need to effectively measure renal function. All serum creatinine-based equations overestimate glomerular filtration rate in the presence of renal dysfunction. Finally, the study highlights the importance of extrahepatic factors in determining mortality on the wait list. While in all comers, a mathematical model such as the MELDNa score may be able to predict mortality, for a specific patient the presence of comorbid conditions, malnutrition and sarcopenia, infections, critical illness, and now pattern of renal dysfunction, may all play a role.

Sumeet K. Asrani, MD, MSc, is a hepatologist affiliated with Baylor University Medical Center, Dallas. He has no conflicts of interest.

Cirrhotic patients with renal failure have a sevenfold increase in mortality compared with those without renal failure. Acute kidney injury (AKI) is common in cirrhosis; increasingly, cirrhotic patients awaiting liver transplantation have or are also at risk for CKD. They are sicker, older, and have more comorbidities such as obesity and diabetes. In this study, the cumulative incidence of death on the wait list was much more pronounced for any form of AKI, with those with AKI on CKD having the highest cumulative incidence of wait list mortality compared with those with normal renal function. The study notably raises several important issues. First, AKI exerts a greater influence in risk of mortality on CKD than it does on those with normal renal function. This is relevant given the increasing prevalence of CKD in this population. Second, it emphasizes the need to effectively measure renal function. All serum creatinine-based equations overestimate glomerular filtration rate in the presence of renal dysfunction. Finally, the study highlights the importance of extrahepatic factors in determining mortality on the wait list. While in all comers, a mathematical model such as the MELDNa score may be able to predict mortality, for a specific patient the presence of comorbid conditions, malnutrition and sarcopenia, infections, critical illness, and now pattern of renal dysfunction, may all play a role.

Sumeet K. Asrani, MD, MSc, is a hepatologist affiliated with Baylor University Medical Center, Dallas. He has no conflicts of interest.

For non–status 1 patients with cirrhosis who are awaiting liver transplantation, type of renal dysfunction may be a key determinant of mortality risk, based on a retrospective analysis of more than 22,000 patients.

Risk of death was greatest for patients with acute on chronic kidney disease (AKI on CKD), followed by AKI alone, then CKD alone, reported lead author Giuseppe Cullaro, MD, of the University of California, San Francisco, and colleagues.

Although it is well known that renal dysfunction worsens outcomes among patients with liver cirrhosis, the impact of different types of kidney pathology on mortality risk has been minimally researched, the investigators wrote in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. “To date, studies evaluating the impact of renal dysfunction on prognosis in patients with cirrhosis have mostly focused on AKI.”

To learn more, the investigators performed a retrospective study involving acute, chronic, and acute on chronic kidney disease among patients with cirrhosis. They included data from 22,680 non–status 1 adults who were awaiting liver transplantation between 2007 and 2014, with at least 90 days on the wait list. Information was gathered from the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network registry.

AKI was defined by fewer than 72 days of hemodialysis, or an increase in creatinine of at least 0.3 mg/dL or at least 50% in the last 7 days. CKD was identified by more than 72 days of hemodialysis, or an estimated glomerular filtration rate less than 60 mL/min/1.73 m2 for 90 days with a final rate of at least 30 mL/min/1.73 m2. Using these criteria, the researchers put patients into four possible categories: AKI on CKD, AKI, CKD, or normal renal function. The primary outcome was wait list mortality, which was defined as death, or removal from the wait list for illness. Follow-up started at the time of addition to the wait list and continued until transplant, removal from the wait list, or death.

Multivariate analysis, which accounted for final MELD-Na score and other confounders, showed that patients with AKI on CKD fared worst, with a 2.86-fold higher mortality risk (subhazard [SHR] ratio, 2.86) than that of patients with normal renal function. The mortality risk for acute on chronic kidney disease was followed closely by patients with AKI alone (SHR, 2.42), and more distantly by patients with CKD alone (SHR, 1.56). Further analysis showed that the disparity between mortality risks of each subgroup became more pronounced with increased MELD-Na score. In addition, evaluation of receiver operating characteristic curves for 6-month wait list mortality showed that the addition of renal function to MELD-Na score increased the accuracy of prognosis from an area under the curve of 0.71 to 0.80 (P less than .001).

“This suggests that incorporating the pattern of renal function could provide an opportunity to better prognosticate risk of mortality in the patients with cirrhosis who are the sickest,” the investigators concluded.

They also speculated about why outcomes may vary by type of kidney dysfunction.

“We suspect that those patients who experience AKI and AKI on CKD in our cohort likely had a triggering event – infection, bleeding, hypovolemia – that put these patients at greater risk for waitlist mortality,” the investigators wrote. “These events inherently carry more risk than stable nonliver-related elevations in serum creatinine that are seen in patients with CKD. Because of this heterogeneity of etiology in renal dysfunction in patients with cirrhosis, it is perhaps not surprising that unique renal function patterns variably impact mortality.”

The investigators noted that the findings from the study have “important implications for clinical practice,” and suggested that including type of renal dysfunction would have the most significant affect on accuracy of prognoses among patients at greatest risk of mortality.

The study was funded by a Paul B. Beeson Career Development Award and the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Dr. Verna disclosed relationships with Salix, Merck, and Gilead.

SOURCE: Cullaro et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019 Feb 1. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2019.01.043.

For non–status 1 patients with cirrhosis who are awaiting liver transplantation, type of renal dysfunction may be a key determinant of mortality risk, based on a retrospective analysis of more than 22,000 patients.

Risk of death was greatest for patients with acute on chronic kidney disease (AKI on CKD), followed by AKI alone, then CKD alone, reported lead author Giuseppe Cullaro, MD, of the University of California, San Francisco, and colleagues.

Although it is well known that renal dysfunction worsens outcomes among patients with liver cirrhosis, the impact of different types of kidney pathology on mortality risk has been minimally researched, the investigators wrote in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. “To date, studies evaluating the impact of renal dysfunction on prognosis in patients with cirrhosis have mostly focused on AKI.”

To learn more, the investigators performed a retrospective study involving acute, chronic, and acute on chronic kidney disease among patients with cirrhosis. They included data from 22,680 non–status 1 adults who were awaiting liver transplantation between 2007 and 2014, with at least 90 days on the wait list. Information was gathered from the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network registry.

AKI was defined by fewer than 72 days of hemodialysis, or an increase in creatinine of at least 0.3 mg/dL or at least 50% in the last 7 days. CKD was identified by more than 72 days of hemodialysis, or an estimated glomerular filtration rate less than 60 mL/min/1.73 m2 for 90 days with a final rate of at least 30 mL/min/1.73 m2. Using these criteria, the researchers put patients into four possible categories: AKI on CKD, AKI, CKD, or normal renal function. The primary outcome was wait list mortality, which was defined as death, or removal from the wait list for illness. Follow-up started at the time of addition to the wait list and continued until transplant, removal from the wait list, or death.

Multivariate analysis, which accounted for final MELD-Na score and other confounders, showed that patients with AKI on CKD fared worst, with a 2.86-fold higher mortality risk (subhazard [SHR] ratio, 2.86) than that of patients with normal renal function. The mortality risk for acute on chronic kidney disease was followed closely by patients with AKI alone (SHR, 2.42), and more distantly by patients with CKD alone (SHR, 1.56). Further analysis showed that the disparity between mortality risks of each subgroup became more pronounced with increased MELD-Na score. In addition, evaluation of receiver operating characteristic curves for 6-month wait list mortality showed that the addition of renal function to MELD-Na score increased the accuracy of prognosis from an area under the curve of 0.71 to 0.80 (P less than .001).

“This suggests that incorporating the pattern of renal function could provide an opportunity to better prognosticate risk of mortality in the patients with cirrhosis who are the sickest,” the investigators concluded.

They also speculated about why outcomes may vary by type of kidney dysfunction.

“We suspect that those patients who experience AKI and AKI on CKD in our cohort likely had a triggering event – infection, bleeding, hypovolemia – that put these patients at greater risk for waitlist mortality,” the investigators wrote. “These events inherently carry more risk than stable nonliver-related elevations in serum creatinine that are seen in patients with CKD. Because of this heterogeneity of etiology in renal dysfunction in patients with cirrhosis, it is perhaps not surprising that unique renal function patterns variably impact mortality.”

The investigators noted that the findings from the study have “important implications for clinical practice,” and suggested that including type of renal dysfunction would have the most significant affect on accuracy of prognoses among patients at greatest risk of mortality.

The study was funded by a Paul B. Beeson Career Development Award and the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Dr. Verna disclosed relationships with Salix, Merck, and Gilead.

SOURCE: Cullaro et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019 Feb 1. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2019.01.043.

FROM CLINICAL GASTROENTEROLOGY AND HEPATOLOGY

Part 1: Finding Your Inner Leader

Is it my imagination, or has there been a lot of discussion on leadership lately? In the past 3 years, all the meetings I have attended had at least 1 presentation on leadership or the traits of leaders. Sometimes—even in the oddest places—I have come across an article with “leadership” in the title. In fact, a serendipitous discovery of 2 publications is what inspired me to write this.

I spotted the first one in a reading basket when I was on vacation: It was an interview with Benjamin Zander, the conductor of the Boston Philharmonic Orchestra and the Boston Philharmonic Youth Orchestra.1 I was especially interested to read this because when I was in graduate school, Benjamin (the father of one of my classmates) visited our campus to give a presentation on talent and self-confidence. I can still hear him conducting us to emphatically believe in ourselves and others. This was echoed in his interview: “Never doubt the capacity of the people you lead to accomplish whatever you dream for them.” What a powerful concept: Believe in the possibilities of someone!

The second was an American Legion Auxiliary column, which emphasized that “leadership is not a title, but a responsibility.”2 This struck a chord with me because some prominent leaders don’t appear to ascribe to that assessment (although they should!).

After digesting these articles, I started thinking: What, exactly, is leadership? What do we even mean by leadership? How do we measure it? Is it measurable? How do we know when we see or experience good leadership? Can one learn to become a leader by simply reading a “how-to” article?

I think I can answer these questions with 2 principles that have guided me through my career as an NP: (1) Make use of another leader’s expertise to guide you, and (2) Continue to grow amid any setbacks.

For example, my transition from a full-time clinician to a Health Policy Coordinator or “policy wonk” did not have a distinct trajectory. Although my core set of clinical skills were essential, I knew early on that I had to expand by adapting specific organizational skills that would enable me to grow in my new role. But how was I to prioritize which skills to improve? More than a simple trial-and-error approach was required; I needed guidance. Fortunately, my new boss was willing to share her experience and the lessons she learned on the job. Key among them was to recognize the skills I already had—communicating and coordinating—and to develop those skills to be more effective in my new position.

Later in my career, I worked with colleagues to pursue legislation for NP prescriptive authority in Massachusetts. The political arena of Commonwealth’s health care laws was especially pivotal in changing how I saw setbacks. These weren’t to be accepted as a failure but as a challenge to figure out how to better succeed the next time. For several years, I was told “No” before we finally got a bill passed. But each round of my testimony was an opportunity to educate lawmakers and the public on the valuable role of NPs and the quality of care we provide. I try to share this story with new NPs as a good example of why they should persist through adversity.

Continue to: Over the next 3 weeks...

Over the next 3 weeks, join us on Thursdays as we continue to discuss what it means to be a leader—from the pitfalls to the victories. For those who are leaders or who work for one, please share your thoughts, experiences, and lessons learned. Maybe you can give a shoutout to someone who was a positive influence!

1. Labarre P. Leadership—Ben Zander. Fast Company website. www.fastcompany.com/35825/leadership-ben-zander. Published November 30, 1998. Accessed August 27, 2019.

2. Volunteer beyond the ALA: serve on boards, committees. American Legion Auxiliary. November 2018:29.

Is it my imagination, or has there been a lot of discussion on leadership lately? In the past 3 years, all the meetings I have attended had at least 1 presentation on leadership or the traits of leaders. Sometimes—even in the oddest places—I have come across an article with “leadership” in the title. In fact, a serendipitous discovery of 2 publications is what inspired me to write this.

I spotted the first one in a reading basket when I was on vacation: It was an interview with Benjamin Zander, the conductor of the Boston Philharmonic Orchestra and the Boston Philharmonic Youth Orchestra.1 I was especially interested to read this because when I was in graduate school, Benjamin (the father of one of my classmates) visited our campus to give a presentation on talent and self-confidence. I can still hear him conducting us to emphatically believe in ourselves and others. This was echoed in his interview: “Never doubt the capacity of the people you lead to accomplish whatever you dream for them.” What a powerful concept: Believe in the possibilities of someone!

The second was an American Legion Auxiliary column, which emphasized that “leadership is not a title, but a responsibility.”2 This struck a chord with me because some prominent leaders don’t appear to ascribe to that assessment (although they should!).

After digesting these articles, I started thinking: What, exactly, is leadership? What do we even mean by leadership? How do we measure it? Is it measurable? How do we know when we see or experience good leadership? Can one learn to become a leader by simply reading a “how-to” article?

I think I can answer these questions with 2 principles that have guided me through my career as an NP: (1) Make use of another leader’s expertise to guide you, and (2) Continue to grow amid any setbacks.

For example, my transition from a full-time clinician to a Health Policy Coordinator or “policy wonk” did not have a distinct trajectory. Although my core set of clinical skills were essential, I knew early on that I had to expand by adapting specific organizational skills that would enable me to grow in my new role. But how was I to prioritize which skills to improve? More than a simple trial-and-error approach was required; I needed guidance. Fortunately, my new boss was willing to share her experience and the lessons she learned on the job. Key among them was to recognize the skills I already had—communicating and coordinating—and to develop those skills to be more effective in my new position.

Later in my career, I worked with colleagues to pursue legislation for NP prescriptive authority in Massachusetts. The political arena of Commonwealth’s health care laws was especially pivotal in changing how I saw setbacks. These weren’t to be accepted as a failure but as a challenge to figure out how to better succeed the next time. For several years, I was told “No” before we finally got a bill passed. But each round of my testimony was an opportunity to educate lawmakers and the public on the valuable role of NPs and the quality of care we provide. I try to share this story with new NPs as a good example of why they should persist through adversity.

Continue to: Over the next 3 weeks...

Over the next 3 weeks, join us on Thursdays as we continue to discuss what it means to be a leader—from the pitfalls to the victories. For those who are leaders or who work for one, please share your thoughts, experiences, and lessons learned. Maybe you can give a shoutout to someone who was a positive influence!

Is it my imagination, or has there been a lot of discussion on leadership lately? In the past 3 years, all the meetings I have attended had at least 1 presentation on leadership or the traits of leaders. Sometimes—even in the oddest places—I have come across an article with “leadership” in the title. In fact, a serendipitous discovery of 2 publications is what inspired me to write this.

I spotted the first one in a reading basket when I was on vacation: It was an interview with Benjamin Zander, the conductor of the Boston Philharmonic Orchestra and the Boston Philharmonic Youth Orchestra.1 I was especially interested to read this because when I was in graduate school, Benjamin (the father of one of my classmates) visited our campus to give a presentation on talent and self-confidence. I can still hear him conducting us to emphatically believe in ourselves and others. This was echoed in his interview: “Never doubt the capacity of the people you lead to accomplish whatever you dream for them.” What a powerful concept: Believe in the possibilities of someone!

The second was an American Legion Auxiliary column, which emphasized that “leadership is not a title, but a responsibility.”2 This struck a chord with me because some prominent leaders don’t appear to ascribe to that assessment (although they should!).

After digesting these articles, I started thinking: What, exactly, is leadership? What do we even mean by leadership? How do we measure it? Is it measurable? How do we know when we see or experience good leadership? Can one learn to become a leader by simply reading a “how-to” article?

I think I can answer these questions with 2 principles that have guided me through my career as an NP: (1) Make use of another leader’s expertise to guide you, and (2) Continue to grow amid any setbacks.

For example, my transition from a full-time clinician to a Health Policy Coordinator or “policy wonk” did not have a distinct trajectory. Although my core set of clinical skills were essential, I knew early on that I had to expand by adapting specific organizational skills that would enable me to grow in my new role. But how was I to prioritize which skills to improve? More than a simple trial-and-error approach was required; I needed guidance. Fortunately, my new boss was willing to share her experience and the lessons she learned on the job. Key among them was to recognize the skills I already had—communicating and coordinating—and to develop those skills to be more effective in my new position.

Later in my career, I worked with colleagues to pursue legislation for NP prescriptive authority in Massachusetts. The political arena of Commonwealth’s health care laws was especially pivotal in changing how I saw setbacks. These weren’t to be accepted as a failure but as a challenge to figure out how to better succeed the next time. For several years, I was told “No” before we finally got a bill passed. But each round of my testimony was an opportunity to educate lawmakers and the public on the valuable role of NPs and the quality of care we provide. I try to share this story with new NPs as a good example of why they should persist through adversity.

Continue to: Over the next 3 weeks...

Over the next 3 weeks, join us on Thursdays as we continue to discuss what it means to be a leader—from the pitfalls to the victories. For those who are leaders or who work for one, please share your thoughts, experiences, and lessons learned. Maybe you can give a shoutout to someone who was a positive influence!

1. Labarre P. Leadership—Ben Zander. Fast Company website. www.fastcompany.com/35825/leadership-ben-zander. Published November 30, 1998. Accessed August 27, 2019.

2. Volunteer beyond the ALA: serve on boards, committees. American Legion Auxiliary. November 2018:29.

1. Labarre P. Leadership—Ben Zander. Fast Company website. www.fastcompany.com/35825/leadership-ben-zander. Published November 30, 1998. Accessed August 27, 2019.

2. Volunteer beyond the ALA: serve on boards, committees. American Legion Auxiliary. November 2018:29.

VA Pathologist Indicted for Patient Deaths Due to Misdiagnoses

Levy was chief pathologist at Veterans Health Care System of the Ozarks in Fayetteville, Arkansas. During his 12-year tenure at the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), he read almost 34,000 pathology slides. However, at the same time, he was working under the influence of alcohol and 2-methyl-2-butanol (2M2B)—a substance that intoxicates but cannot be detected in routine tests.

The VA fired Levy last year, and the VA Office of the Inspector General (OIG) began an investigation of his actions and of agency lapses in overseeing him. The 18-month review found that 8.9% of Levy’s diagnoses involved clinical errors—the normal misdiagnosis rate for pathologists is 0.7%. Hundreds of Levy’s misdiagnoses were not serious, but ≥ 15 may have led to deaths and harmful illness in 15 other patients. Some patients were not diagnosed when they should have been. Some were told they were sick when they were not and suffered unnecessary invasive treatment.

Levy knowingly falsified diagnoses for 3 veterans. One patient was diagnosed with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma—a type of cancer he did not have. He received the wrong treatment and died. Levy diagnosed another patient, also wrongly, with small cell carcinoma; that patient died of squamous cell carcinoma that spread. The third patient was given a benign test result for prostate cancer. Untreated, he died after the cancer spread.

One patient was given antibiotics instead of treatment for what was later diagnosed as late-stage neck and throat cancer. In an interview with the Washington Post he said, “I went from ‘Your earache isn’t anything’ to stage 4.”

How was Levy able to wreak such havoc? One reason was that despite concerns and complaints from colleagues, he looked good on paper. He falsified records to indicate that his deputy concurred with his diagnoses in mandated peer reviews. He also appeared “clean” in inspections through using 2M2B.

Levy was fired not for his work performance but for being arrested for driving while intoxicated. He had been a “star hire” with an medical degree from the University of Chicago, who had completed a pathology residency at the University of California at San Francisco and a fellowship at Duke University focusing on disease of the blood. But he also had a 1996 arrest for a driving under the influence (DUI) on his record when he joined the VA in 2005.

In 2015, a fact-finding panel interviewed Levy about reports that he was under the influence while on duty. He denied the allegations. In 2016, Levy arrived at the radiology department to assist with a biopsy with a blood alcohol level of nearly 0.4. He was suspended, his alcohol impairment was reported to the state medical boards, and his medical privileges were revoked. He entered a VA treatment program in 2016, then returned to work. Levy, who also sat on oversight boards and medical committees, seemed drowsy and was speaking “nonsense” at an October 2017 meeting of the hospital’s tumor board, according to meeting minutes provided to The Post.

He was suspended again in 2017 for being under the influence but allowed to continue with nonclinical work until he was again arrested for DUI in 2018, when the police toxicology test detected 2M2B. He was finally dismissed in April 2018. Nonetheless, even after he had arrived impaired at the laboratory twice, the VA had awarded him 2 performance bonuses, based on the supposedly low clinical error rate and 42 urine and blood samples that turned up negative for alcohol and drugs.

In addition to 3 counts of involuntary manslaughter, the indictment charges that Levy devised a scheme to defraud the VA and to obtain money and property from the VA in the form of salary, benefits, and performance awards. He is charged with 12 counts of wire fraud, 12 counts of mail fraud, and 4 counts of making false statements related to 12 occasions between 2017 and 2018, when Levy was reportedly buying 2M2B over the Internet while he was contractually obligated to submit to random drug and alcohol screens.

After being fired, Levy moved to a small island in the Dutch Caribbean and found a position teaching pathology at a local medical school. At the time of his VA hiring, Levy held a medical license issued by Mississippi. His active medical licenses in California and Florida were revoked only this spring. The VA did not notify the3 states where Levy was licensed that he could no longer practice until June 2018.

The Office of Inspector General (OIG) has identified other VA physicians who continued to practice even after they were found to have compromised patient care, and the Government Accountability Office found “weak systems” for ensuring that problems are addressed in a timely fashion. A VA spokesperson, however, quoted in The Washington Post, said the Levy case was “an isolated incident,” and that the agency has “strengthened internal controls” to ensure that errors are more quickly identified and addressed. The Fayetteville Medical Center also has increased monitoring of its clinical laboratory, according to a Washington Post report. VA officials also said they have added oversight of small specialty staffs across the system to ensure “independent and objective oversight.”

The VA has contacted the families in the 30 most serious cases to advise them of their legal and treatment options, according to the Washington Post.

“The arrest of Dr. Levy was accomplished as a result of the strong leadership of the US Attorney’s Office and the extensive work of special agents of the VA OIG, supported by the medical expertise of the OIG’s health care inspection professionals,” said Michael Missal, the VA’s inspector general, in a press release issued by the US Attorney’s Office in the Western District of Arkansas. “These charges send a clear signal that anyone entrusted with the care of veterans will be held accountable for placing them at risk by working while impaired or through other misconduct.”

Levy is in jail in Fayetteville. The trial date for his case is set for October 7.

Levy was chief pathologist at Veterans Health Care System of the Ozarks in Fayetteville, Arkansas. During his 12-year tenure at the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), he read almost 34,000 pathology slides. However, at the same time, he was working under the influence of alcohol and 2-methyl-2-butanol (2M2B)—a substance that intoxicates but cannot be detected in routine tests.

The VA fired Levy last year, and the VA Office of the Inspector General (OIG) began an investigation of his actions and of agency lapses in overseeing him. The 18-month review found that 8.9% of Levy’s diagnoses involved clinical errors—the normal misdiagnosis rate for pathologists is 0.7%. Hundreds of Levy’s misdiagnoses were not serious, but ≥ 15 may have led to deaths and harmful illness in 15 other patients. Some patients were not diagnosed when they should have been. Some were told they were sick when they were not and suffered unnecessary invasive treatment.

Levy knowingly falsified diagnoses for 3 veterans. One patient was diagnosed with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma—a type of cancer he did not have. He received the wrong treatment and died. Levy diagnosed another patient, also wrongly, with small cell carcinoma; that patient died of squamous cell carcinoma that spread. The third patient was given a benign test result for prostate cancer. Untreated, he died after the cancer spread.

One patient was given antibiotics instead of treatment for what was later diagnosed as late-stage neck and throat cancer. In an interview with the Washington Post he said, “I went from ‘Your earache isn’t anything’ to stage 4.”

How was Levy able to wreak such havoc? One reason was that despite concerns and complaints from colleagues, he looked good on paper. He falsified records to indicate that his deputy concurred with his diagnoses in mandated peer reviews. He also appeared “clean” in inspections through using 2M2B.

Levy was fired not for his work performance but for being arrested for driving while intoxicated. He had been a “star hire” with an medical degree from the University of Chicago, who had completed a pathology residency at the University of California at San Francisco and a fellowship at Duke University focusing on disease of the blood. But he also had a 1996 arrest for a driving under the influence (DUI) on his record when he joined the VA in 2005.

In 2015, a fact-finding panel interviewed Levy about reports that he was under the influence while on duty. He denied the allegations. In 2016, Levy arrived at the radiology department to assist with a biopsy with a blood alcohol level of nearly 0.4. He was suspended, his alcohol impairment was reported to the state medical boards, and his medical privileges were revoked. He entered a VA treatment program in 2016, then returned to work. Levy, who also sat on oversight boards and medical committees, seemed drowsy and was speaking “nonsense” at an October 2017 meeting of the hospital’s tumor board, according to meeting minutes provided to The Post.

He was suspended again in 2017 for being under the influence but allowed to continue with nonclinical work until he was again arrested for DUI in 2018, when the police toxicology test detected 2M2B. He was finally dismissed in April 2018. Nonetheless, even after he had arrived impaired at the laboratory twice, the VA had awarded him 2 performance bonuses, based on the supposedly low clinical error rate and 42 urine and blood samples that turned up negative for alcohol and drugs.

In addition to 3 counts of involuntary manslaughter, the indictment charges that Levy devised a scheme to defraud the VA and to obtain money and property from the VA in the form of salary, benefits, and performance awards. He is charged with 12 counts of wire fraud, 12 counts of mail fraud, and 4 counts of making false statements related to 12 occasions between 2017 and 2018, when Levy was reportedly buying 2M2B over the Internet while he was contractually obligated to submit to random drug and alcohol screens.

After being fired, Levy moved to a small island in the Dutch Caribbean and found a position teaching pathology at a local medical school. At the time of his VA hiring, Levy held a medical license issued by Mississippi. His active medical licenses in California and Florida were revoked only this spring. The VA did not notify the3 states where Levy was licensed that he could no longer practice until June 2018.

The Office of Inspector General (OIG) has identified other VA physicians who continued to practice even after they were found to have compromised patient care, and the Government Accountability Office found “weak systems” for ensuring that problems are addressed in a timely fashion. A VA spokesperson, however, quoted in The Washington Post, said the Levy case was “an isolated incident,” and that the agency has “strengthened internal controls” to ensure that errors are more quickly identified and addressed. The Fayetteville Medical Center also has increased monitoring of its clinical laboratory, according to a Washington Post report. VA officials also said they have added oversight of small specialty staffs across the system to ensure “independent and objective oversight.”

The VA has contacted the families in the 30 most serious cases to advise them of their legal and treatment options, according to the Washington Post.

“The arrest of Dr. Levy was accomplished as a result of the strong leadership of the US Attorney’s Office and the extensive work of special agents of the VA OIG, supported by the medical expertise of the OIG’s health care inspection professionals,” said Michael Missal, the VA’s inspector general, in a press release issued by the US Attorney’s Office in the Western District of Arkansas. “These charges send a clear signal that anyone entrusted with the care of veterans will be held accountable for placing them at risk by working while impaired or through other misconduct.”

Levy is in jail in Fayetteville. The trial date for his case is set for October 7.

Levy was chief pathologist at Veterans Health Care System of the Ozarks in Fayetteville, Arkansas. During his 12-year tenure at the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), he read almost 34,000 pathology slides. However, at the same time, he was working under the influence of alcohol and 2-methyl-2-butanol (2M2B)—a substance that intoxicates but cannot be detected in routine tests.

The VA fired Levy last year, and the VA Office of the Inspector General (OIG) began an investigation of his actions and of agency lapses in overseeing him. The 18-month review found that 8.9% of Levy’s diagnoses involved clinical errors—the normal misdiagnosis rate for pathologists is 0.7%. Hundreds of Levy’s misdiagnoses were not serious, but ≥ 15 may have led to deaths and harmful illness in 15 other patients. Some patients were not diagnosed when they should have been. Some were told they were sick when they were not and suffered unnecessary invasive treatment.

Levy knowingly falsified diagnoses for 3 veterans. One patient was diagnosed with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma—a type of cancer he did not have. He received the wrong treatment and died. Levy diagnosed another patient, also wrongly, with small cell carcinoma; that patient died of squamous cell carcinoma that spread. The third patient was given a benign test result for prostate cancer. Untreated, he died after the cancer spread.

One patient was given antibiotics instead of treatment for what was later diagnosed as late-stage neck and throat cancer. In an interview with the Washington Post he said, “I went from ‘Your earache isn’t anything’ to stage 4.”

How was Levy able to wreak such havoc? One reason was that despite concerns and complaints from colleagues, he looked good on paper. He falsified records to indicate that his deputy concurred with his diagnoses in mandated peer reviews. He also appeared “clean” in inspections through using 2M2B.

Levy was fired not for his work performance but for being arrested for driving while intoxicated. He had been a “star hire” with an medical degree from the University of Chicago, who had completed a pathology residency at the University of California at San Francisco and a fellowship at Duke University focusing on disease of the blood. But he also had a 1996 arrest for a driving under the influence (DUI) on his record when he joined the VA in 2005.

In 2015, a fact-finding panel interviewed Levy about reports that he was under the influence while on duty. He denied the allegations. In 2016, Levy arrived at the radiology department to assist with a biopsy with a blood alcohol level of nearly 0.4. He was suspended, his alcohol impairment was reported to the state medical boards, and his medical privileges were revoked. He entered a VA treatment program in 2016, then returned to work. Levy, who also sat on oversight boards and medical committees, seemed drowsy and was speaking “nonsense” at an October 2017 meeting of the hospital’s tumor board, according to meeting minutes provided to The Post.

He was suspended again in 2017 for being under the influence but allowed to continue with nonclinical work until he was again arrested for DUI in 2018, when the police toxicology test detected 2M2B. He was finally dismissed in April 2018. Nonetheless, even after he had arrived impaired at the laboratory twice, the VA had awarded him 2 performance bonuses, based on the supposedly low clinical error rate and 42 urine and blood samples that turned up negative for alcohol and drugs.

In addition to 3 counts of involuntary manslaughter, the indictment charges that Levy devised a scheme to defraud the VA and to obtain money and property from the VA in the form of salary, benefits, and performance awards. He is charged with 12 counts of wire fraud, 12 counts of mail fraud, and 4 counts of making false statements related to 12 occasions between 2017 and 2018, when Levy was reportedly buying 2M2B over the Internet while he was contractually obligated to submit to random drug and alcohol screens.

After being fired, Levy moved to a small island in the Dutch Caribbean and found a position teaching pathology at a local medical school. At the time of his VA hiring, Levy held a medical license issued by Mississippi. His active medical licenses in California and Florida were revoked only this spring. The VA did not notify the3 states where Levy was licensed that he could no longer practice until June 2018.

The Office of Inspector General (OIG) has identified other VA physicians who continued to practice even after they were found to have compromised patient care, and the Government Accountability Office found “weak systems” for ensuring that problems are addressed in a timely fashion. A VA spokesperson, however, quoted in The Washington Post, said the Levy case was “an isolated incident,” and that the agency has “strengthened internal controls” to ensure that errors are more quickly identified and addressed. The Fayetteville Medical Center also has increased monitoring of its clinical laboratory, according to a Washington Post report. VA officials also said they have added oversight of small specialty staffs across the system to ensure “independent and objective oversight.”

The VA has contacted the families in the 30 most serious cases to advise them of their legal and treatment options, according to the Washington Post.

“The arrest of Dr. Levy was accomplished as a result of the strong leadership of the US Attorney’s Office and the extensive work of special agents of the VA OIG, supported by the medical expertise of the OIG’s health care inspection professionals,” said Michael Missal, the VA’s inspector general, in a press release issued by the US Attorney’s Office in the Western District of Arkansas. “These charges send a clear signal that anyone entrusted with the care of veterans will be held accountable for placing them at risk by working while impaired or through other misconduct.”

Levy is in jail in Fayetteville. The trial date for his case is set for October 7.

Clinical trial enrollment linked to lower death rate in lung cancer patients

ALEXANDRIA, VA. – Patients with metastatic non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) who enrolled in clinical trials had a near 50% lower risk of death versus patients who received treatment outside a clinical trial, according to results of a single-center, retrospective medical record review.

Median survival was almost doubled for those patients with NSCLC enrolled in therapeutic drug trials, according to lead author Christina Merkhofer, MD, a hematology-oncology fellow at the University of Washington and Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center, both in Seattle.

The findings suggest that clinical trials, beyond supporting drug development, provide a direct benefit to NSCLC patients through provision of promising agents, enhanced supportive care, or both, according to Dr. Merkhofer and coauthors, who will present their findings in a poster at the Quality Care Symposium, sponsored by the American Society of Clinical Oncology.

The retrospective study included a total of 371 patients diagnosed with metastatic NSCLC between 2001 and 2015, of whom 118 (32%) enrolled in at least one clinical trial, Dr. Merkhofer reported at a press briefing ahead of the symposium.

Median survival was 838 days for the clinical trial enrollees versus 454 days for nonenrollees, according to the investigators. The risk of death was 47% lower (hazard ratio, 0.53; 95% confidence interval, 0.13-0.92; P = .002) for enrollees relative to nonenrollees after adjustment for variables including sex, performance status, smoking history, histology, presence of brain metastases, and EGFR/ALK status.

Based on this study by Dr. Merkhofer and colleagues, participating in therapeutic drug trials appears to improve survival in patients with advanced lung cancer, ASCO expert Merry-Jennifer Markham, MD, said in a statement.

Oncologists have a “duty” to enroll patients in clinical trials as appropriate, said Dr. Markham, chair of the Quality Care Symposium’s news planning team.

“We must work to better understand factors associated with enrollment so that the prospective benefits can be made accessible to all who are eligible,” she said.

The research is part of a larger investigation looking at “areas of uncertainty” in clinical trial participation, such as whether specific trial design characteristics are linked to survival benefit, according to Dr. Merkhofer.

“The study can support research evaluating health care policies or research that looks at incentives for patient participation in trials, such as financing transportation or lodging, [and] can help with research that addresses some of these important barriers to trial participation,” Dr. Merkhofer said in an ASCO press release.

Dr. Merkhofer had no disclosures related to the study. Her coauthors reported disclosures related to numerous pharmaceutical companies.

SOURCE: Merkhofer C et al. QCS2019, Abstract 137.

ALEXANDRIA, VA. – Patients with metastatic non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) who enrolled in clinical trials had a near 50% lower risk of death versus patients who received treatment outside a clinical trial, according to results of a single-center, retrospective medical record review.

Median survival was almost doubled for those patients with NSCLC enrolled in therapeutic drug trials, according to lead author Christina Merkhofer, MD, a hematology-oncology fellow at the University of Washington and Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center, both in Seattle.

The findings suggest that clinical trials, beyond supporting drug development, provide a direct benefit to NSCLC patients through provision of promising agents, enhanced supportive care, or both, according to Dr. Merkhofer and coauthors, who will present their findings in a poster at the Quality Care Symposium, sponsored by the American Society of Clinical Oncology.

The retrospective study included a total of 371 patients diagnosed with metastatic NSCLC between 2001 and 2015, of whom 118 (32%) enrolled in at least one clinical trial, Dr. Merkhofer reported at a press briefing ahead of the symposium.