User login

FDA approves fidaxomicin for treatment of C. difficile–associated diarrhea

The Food and Drug Administration has approved fidaxomicin (Dificid) for the treatment of Clostridioides difficile–associated diarrhea in children aged 6 months and older.

Approval was based on results from SUNSHINE, a phase 3, multicenter, investigator-blind, randomized, parallel-group study in 142 pediatric patients aged between 6 months and 18 years with confirmed C. difficile infection who received either fidaxomicin or vancomycin for 10 days. Clinical response 2 days after the conclusion of treatment was similar in both groups (77.6% for fidaxomicin vs. 70.5% for vancomycin), and fidaxomicin had a superior sustained response 30 days after the conclusion of treatment (68.4% vs. 50.0%).

The safety of fidaxomicin was assessed in a pair of clinical trials involving 136 patients; the most common adverse events were pyrexia, abdominal pain, vomiting, diarrhea, constipation, increased aminotransferases, and rash. Four patients discontinued fidaxomicin treatment because of adverse events, and four patients died during the trials, though all deaths were in patients aged younger than 2 years and seemed to be related to other comorbidities.

“C. difficile is an important cause of health care– and community-associated diarrheal illness in children, and sustained cure is difficult to achieve in some patients. The fidaxomicin pediatric trial was the first randomized, controlled trial of C. difficile infection treatment in children,” Larry K. Kociolek, MD, associate medical director of infection prevention and control at Ann & Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago, said in the press release from Merck, manufacturer of fidaxomicin.

*This story was updated on 1/27/2020.

The Food and Drug Administration has approved fidaxomicin (Dificid) for the treatment of Clostridioides difficile–associated diarrhea in children aged 6 months and older.

Approval was based on results from SUNSHINE, a phase 3, multicenter, investigator-blind, randomized, parallel-group study in 142 pediatric patients aged between 6 months and 18 years with confirmed C. difficile infection who received either fidaxomicin or vancomycin for 10 days. Clinical response 2 days after the conclusion of treatment was similar in both groups (77.6% for fidaxomicin vs. 70.5% for vancomycin), and fidaxomicin had a superior sustained response 30 days after the conclusion of treatment (68.4% vs. 50.0%).

The safety of fidaxomicin was assessed in a pair of clinical trials involving 136 patients; the most common adverse events were pyrexia, abdominal pain, vomiting, diarrhea, constipation, increased aminotransferases, and rash. Four patients discontinued fidaxomicin treatment because of adverse events, and four patients died during the trials, though all deaths were in patients aged younger than 2 years and seemed to be related to other comorbidities.

“C. difficile is an important cause of health care– and community-associated diarrheal illness in children, and sustained cure is difficult to achieve in some patients. The fidaxomicin pediatric trial was the first randomized, controlled trial of C. difficile infection treatment in children,” Larry K. Kociolek, MD, associate medical director of infection prevention and control at Ann & Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago, said in the press release from Merck, manufacturer of fidaxomicin.

*This story was updated on 1/27/2020.

The Food and Drug Administration has approved fidaxomicin (Dificid) for the treatment of Clostridioides difficile–associated diarrhea in children aged 6 months and older.

Approval was based on results from SUNSHINE, a phase 3, multicenter, investigator-blind, randomized, parallel-group study in 142 pediatric patients aged between 6 months and 18 years with confirmed C. difficile infection who received either fidaxomicin or vancomycin for 10 days. Clinical response 2 days after the conclusion of treatment was similar in both groups (77.6% for fidaxomicin vs. 70.5% for vancomycin), and fidaxomicin had a superior sustained response 30 days after the conclusion of treatment (68.4% vs. 50.0%).

The safety of fidaxomicin was assessed in a pair of clinical trials involving 136 patients; the most common adverse events were pyrexia, abdominal pain, vomiting, diarrhea, constipation, increased aminotransferases, and rash. Four patients discontinued fidaxomicin treatment because of adverse events, and four patients died during the trials, though all deaths were in patients aged younger than 2 years and seemed to be related to other comorbidities.

“C. difficile is an important cause of health care– and community-associated diarrheal illness in children, and sustained cure is difficult to achieve in some patients. The fidaxomicin pediatric trial was the first randomized, controlled trial of C. difficile infection treatment in children,” Larry K. Kociolek, MD, associate medical director of infection prevention and control at Ann & Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago, said in the press release from Merck, manufacturer of fidaxomicin.

*This story was updated on 1/27/2020.

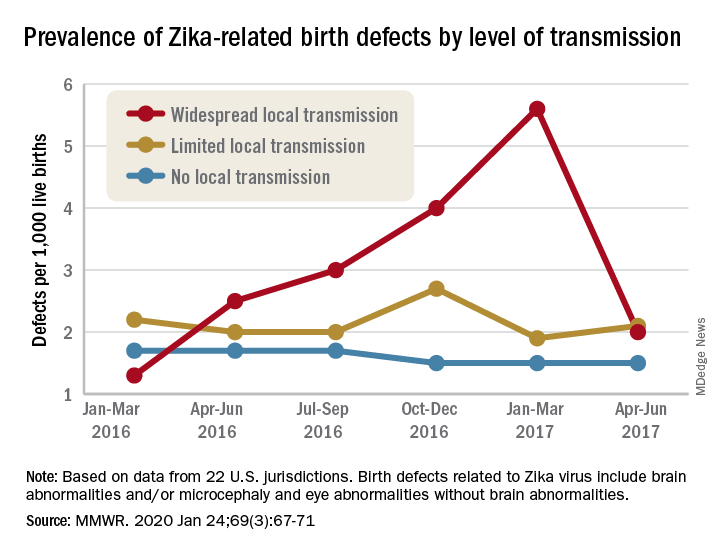

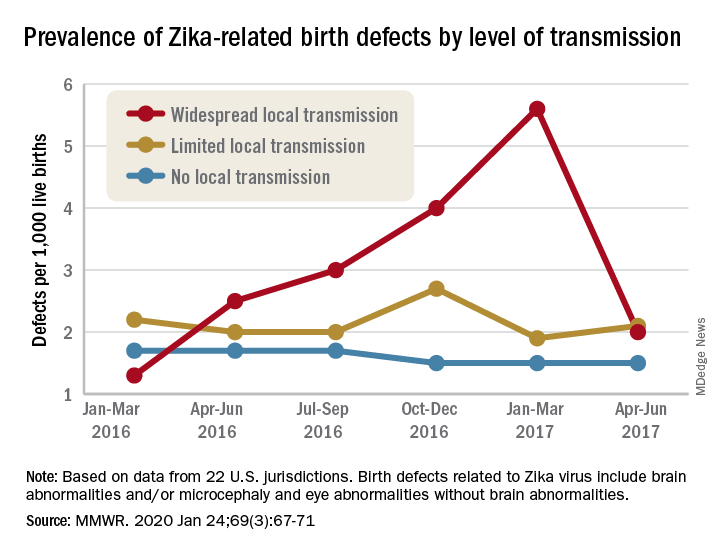

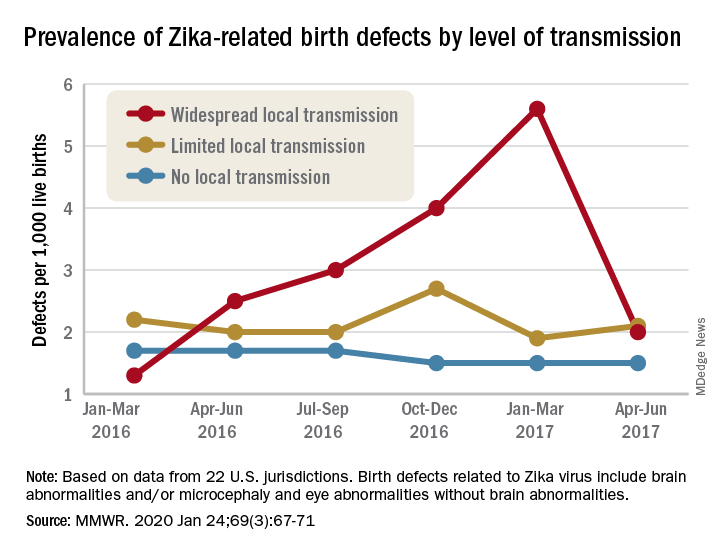

Zika virus: Birth defects rose fourfold in U.S. hardest-hit areas

according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

That spike in the prevalence of brain abnormalities and/or microcephaly or eye abnormalities without brain abnormalities came during January through March 2017, about 6 months after the Zika outbreak’s reported peak in the jurisdictions with widespread local transmission, Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands, wrote Ashley N. Smoots, MPH, of the CDC’s National Center on Birth Defects and Developmental Disabilities and associates in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

In those two territories, the prevalence of birth defects potentially related to Zika virus infection was 5.6 per 1,000 live births during January through March 2017, compared with 1.3 per 1,000 in January through March 2016, they reported.

In the southern areas of Florida and Texas, where there was limited local Zika transmission, the highest prevalence of birth defects, 2.7 per 1,000, occurred during October through December 2016, and was only slightly greater than the baseline rate of 2.2 per 1,000 in January through March 2016, the investigators reported.

Among the other 19 jurisdictions (including Illinois, Louisiana, New Jersey, South Carolina, and Virginia) involved in the analysis, the rate of Zika virus–related birth defects never reached any higher than the 1.7 per 1,000 recorded at the start of the study period in January through March 2016, they said.

“Population-based birth defects surveillance is critical for identifying infants and fetuses with birth defects potentially related to Zika virus regardless of whether Zika virus testing was conducted, especially given the high prevalence of asymptomatic disease. These data can be used to inform follow-up care and services as well as strengthen surveillance,” the investigators wrote.

SOURCE: Smoots AN et al. MMWR. 2020 Jan 24;69(3):67-71.

according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

That spike in the prevalence of brain abnormalities and/or microcephaly or eye abnormalities without brain abnormalities came during January through March 2017, about 6 months after the Zika outbreak’s reported peak in the jurisdictions with widespread local transmission, Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands, wrote Ashley N. Smoots, MPH, of the CDC’s National Center on Birth Defects and Developmental Disabilities and associates in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

In those two territories, the prevalence of birth defects potentially related to Zika virus infection was 5.6 per 1,000 live births during January through March 2017, compared with 1.3 per 1,000 in January through March 2016, they reported.

In the southern areas of Florida and Texas, where there was limited local Zika transmission, the highest prevalence of birth defects, 2.7 per 1,000, occurred during October through December 2016, and was only slightly greater than the baseline rate of 2.2 per 1,000 in January through March 2016, the investigators reported.

Among the other 19 jurisdictions (including Illinois, Louisiana, New Jersey, South Carolina, and Virginia) involved in the analysis, the rate of Zika virus–related birth defects never reached any higher than the 1.7 per 1,000 recorded at the start of the study period in January through March 2016, they said.

“Population-based birth defects surveillance is critical for identifying infants and fetuses with birth defects potentially related to Zika virus regardless of whether Zika virus testing was conducted, especially given the high prevalence of asymptomatic disease. These data can be used to inform follow-up care and services as well as strengthen surveillance,” the investigators wrote.

SOURCE: Smoots AN et al. MMWR. 2020 Jan 24;69(3):67-71.

according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

That spike in the prevalence of brain abnormalities and/or microcephaly or eye abnormalities without brain abnormalities came during January through March 2017, about 6 months after the Zika outbreak’s reported peak in the jurisdictions with widespread local transmission, Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands, wrote Ashley N. Smoots, MPH, of the CDC’s National Center on Birth Defects and Developmental Disabilities and associates in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

In those two territories, the prevalence of birth defects potentially related to Zika virus infection was 5.6 per 1,000 live births during January through March 2017, compared with 1.3 per 1,000 in January through March 2016, they reported.

In the southern areas of Florida and Texas, where there was limited local Zika transmission, the highest prevalence of birth defects, 2.7 per 1,000, occurred during October through December 2016, and was only slightly greater than the baseline rate of 2.2 per 1,000 in January through March 2016, the investigators reported.

Among the other 19 jurisdictions (including Illinois, Louisiana, New Jersey, South Carolina, and Virginia) involved in the analysis, the rate of Zika virus–related birth defects never reached any higher than the 1.7 per 1,000 recorded at the start of the study period in January through March 2016, they said.

“Population-based birth defects surveillance is critical for identifying infants and fetuses with birth defects potentially related to Zika virus regardless of whether Zika virus testing was conducted, especially given the high prevalence of asymptomatic disease. These data can be used to inform follow-up care and services as well as strengthen surveillance,” the investigators wrote.

SOURCE: Smoots AN et al. MMWR. 2020 Jan 24;69(3):67-71.

FROM MMWR

Doctor wins $4.75 million award in defamation suit against hospital

Jurors awarded Carmel, Ind.–based ob.gyn. Rebecca Denman, MD, $4.75 million in damages against St. Vincent Carmel Hospital and St. Vincent Carmel Medical Group on Jan. 16, 2020, after a 4-day trial in Indiana Commercial Court. Dr. Denman sued after the hospital and medical group took a series of actions in response to a nurse practitioner’s claim that Dr. Denman smelled of alcohol while on duty. The doctor’s lawsuit alleged the NP’s claim was unproven; that administrators failed to conduct a proper peer-review investigation; and that repercussions from the false allegation resulted in lost compensation, out-of-pocket expenses, emotional distress, and damage to her professional reputation.

Indianapolis attorney Kathleen DeLaney, who represented Dr. Denman in the case, said that her client was pleased with the verdict.

“Dr. Denman feels vindicated that a group of jurors spent 4 days listening to all the evidence and gave her a resounding victory,” she said in an interview.

Dr. Denman declined to comment for this story through her attorney.

In a statement, a spokesman for Ascension, the hospital’s parent company, said the hospital was disappointed by the verdict and that it was “exploring all options available to us, including appeal.” The spokesman declined to answer further questions about the case or its peer-review process.

The case stems from an NP’s claim that Dr. Denman’s breath smelled of alcohol during an evening shift on Dec. 11, 2017. Dr. Denman was not informed of the allegation on Dec. 11 and was not tested for alcohol at the time, according to Dr. Denman’s lawsuit. Under hospital policy, if a physician is suspected of being under the influence of alcohol at work, the employer must immediately assess the doctor, relieve the doctor of duty, and request the physician submit to immediate blood testing at an external facility.

The NP reported the allegation to her supervisor through an email on Dec. 12, 2017. The supervisor relayed the information to the hospital’s chief medical officer who met with other administrators and physicians to discuss the claim. During the discussions, a previous concern about Dr. Denman’s drinking was raised, according to deposition information included in court documents. In 2015, two physicians had suggested Dr. Denman consider an assistance program after expressing concerns that she was arriving late to work and missing partner meetings. At the time, Dr. Denman did not enter an assistance program, but she changed her drinking habits, began seeing a therapist, and started arriving on-time to work and to partner meetings, according to court documents. No other criticism or complaints regarding her drinking or workplace behavior had been reported since, according to court documents.

When confronted with the NP’s claim on Dec. 13, 2017, Dr. Denman denied consuming alcohol on Dec. 11, 2017, and questioned why the hospital’s substance abuse protocol was not followed.

St. Vincent Carmel Hospital conducted a preliminary review of the allegation through its peer-review process and turned the matter over to St. Vincent Medical Group for further review, according to court documents. St. Vincent Medical Group later informed Dr. Denman they had reviewed the allegation through its peer-review process and that she was suspended with partial pay until she underwent an evaluation for alcohol abuse through the Indiana State Medical Association, according to the lawsuit.

“They falsely misrepresented to her that peer review had been done,” Ms. DeLaney said in an interview. “In spite of that statement, they never offered her a hearing before a peer-review committee, they never shared with her the substance of any evidence they had against her, they never gave her an opportunity to respond to the allegations. In fact, she wasn’t interviewed at all until the deposition in the lawsuit.”

According to the Indiana Peer Review law, a health care provider under investigation is permitted to see any records accumulated by a peer-review committee pertaining to the provider’s personal practice, and the provider shall be offered the opportunity to appear before the peer-review committee with adequate representation to hear all charges and findings concerning the provider and to offer rebuttal information. The rebuttal shall be part of the record before any disclosure of the charges and before any findings can be made, according to the statute.

Dr. Denman was referred by the medical association to an addiction treatment center that evaluated Dr. Denman and diagnosed her with alcohol use disorder, according to the lawsuit. As a result of the report and as a condition of retaining her medical license, the medical association and St. Vincent Medical Group required Dr. Denman to enter a treatment program at the same addiction treatment center. Dr. Denman was also required to sign a 5-year monitoring contract with the Indiana State Medical Association as a condition of her employment, according to the lawsuit.

“The actions had life-changing consequences,” Ms. DeLaney said. “As a result, she was required to sign a contract that mandates she do a breathalyzer test four times a day for the first year and then three times a day for 4 more years. She has to go for random drug screenings. For the first year, she had to go to four [Alcoholics Anonymous] meetings a week. Now that number has been reduced, but she’s on a 5-year monitoring contract because of all of this.”

Dr. Denman sued the hospital, the medical group, and the NP in July 2018 alleging fraud, defamation, tortuous interference with an employment relationship, and negligent misrepresentation. The NP was dismissed from the case shortly before trial.

In its response to the lawsuit, attorneys for St. Vincent wrote that Dr. Denman’s action was frivolous, vexatious, and executed in bad faith. The defendants requested that a judge dismiss the lawsuit, noting that they were entitled to immunity pursuant to Indiana state and federal laws, including protection by Indiana’s Peer Review statute. In October 2019, a judge denied the hospital’s request to dismiss the lawsuit and allowed the case to proceed.

In their verdict, jurors awarded Dr. Denman $2 million for her defamation claims, $2 million for her claims of fraud and constructive fraud, $500,000 for her claim of tortious interference with an employment relationship, and $250,000 for her claim of negligent misrepresentation.

Dr. Denman remains employed by the medical group and must continue the conditions of her 5-year monitoring contract, Ms. DeLaney said. She hopes Dr. Denman’s case raises awareness about physicians’ due process rights.

“We hope that Dr. Denman’s case emboldens physicians to stand up for themselves in the face of false accusations and rushes to judgment,” she said. “We hope the verdict leads to fair, prompt, and unbiased investigations by hospital and medical practice administrators, which include due process for accused physicians.”

Jurors awarded Carmel, Ind.–based ob.gyn. Rebecca Denman, MD, $4.75 million in damages against St. Vincent Carmel Hospital and St. Vincent Carmel Medical Group on Jan. 16, 2020, after a 4-day trial in Indiana Commercial Court. Dr. Denman sued after the hospital and medical group took a series of actions in response to a nurse practitioner’s claim that Dr. Denman smelled of alcohol while on duty. The doctor’s lawsuit alleged the NP’s claim was unproven; that administrators failed to conduct a proper peer-review investigation; and that repercussions from the false allegation resulted in lost compensation, out-of-pocket expenses, emotional distress, and damage to her professional reputation.

Indianapolis attorney Kathleen DeLaney, who represented Dr. Denman in the case, said that her client was pleased with the verdict.

“Dr. Denman feels vindicated that a group of jurors spent 4 days listening to all the evidence and gave her a resounding victory,” she said in an interview.

Dr. Denman declined to comment for this story through her attorney.

In a statement, a spokesman for Ascension, the hospital’s parent company, said the hospital was disappointed by the verdict and that it was “exploring all options available to us, including appeal.” The spokesman declined to answer further questions about the case or its peer-review process.

The case stems from an NP’s claim that Dr. Denman’s breath smelled of alcohol during an evening shift on Dec. 11, 2017. Dr. Denman was not informed of the allegation on Dec. 11 and was not tested for alcohol at the time, according to Dr. Denman’s lawsuit. Under hospital policy, if a physician is suspected of being under the influence of alcohol at work, the employer must immediately assess the doctor, relieve the doctor of duty, and request the physician submit to immediate blood testing at an external facility.

The NP reported the allegation to her supervisor through an email on Dec. 12, 2017. The supervisor relayed the information to the hospital’s chief medical officer who met with other administrators and physicians to discuss the claim. During the discussions, a previous concern about Dr. Denman’s drinking was raised, according to deposition information included in court documents. In 2015, two physicians had suggested Dr. Denman consider an assistance program after expressing concerns that she was arriving late to work and missing partner meetings. At the time, Dr. Denman did not enter an assistance program, but she changed her drinking habits, began seeing a therapist, and started arriving on-time to work and to partner meetings, according to court documents. No other criticism or complaints regarding her drinking or workplace behavior had been reported since, according to court documents.

When confronted with the NP’s claim on Dec. 13, 2017, Dr. Denman denied consuming alcohol on Dec. 11, 2017, and questioned why the hospital’s substance abuse protocol was not followed.

St. Vincent Carmel Hospital conducted a preliminary review of the allegation through its peer-review process and turned the matter over to St. Vincent Medical Group for further review, according to court documents. St. Vincent Medical Group later informed Dr. Denman they had reviewed the allegation through its peer-review process and that she was suspended with partial pay until she underwent an evaluation for alcohol abuse through the Indiana State Medical Association, according to the lawsuit.

“They falsely misrepresented to her that peer review had been done,” Ms. DeLaney said in an interview. “In spite of that statement, they never offered her a hearing before a peer-review committee, they never shared with her the substance of any evidence they had against her, they never gave her an opportunity to respond to the allegations. In fact, she wasn’t interviewed at all until the deposition in the lawsuit.”

According to the Indiana Peer Review law, a health care provider under investigation is permitted to see any records accumulated by a peer-review committee pertaining to the provider’s personal practice, and the provider shall be offered the opportunity to appear before the peer-review committee with adequate representation to hear all charges and findings concerning the provider and to offer rebuttal information. The rebuttal shall be part of the record before any disclosure of the charges and before any findings can be made, according to the statute.

Dr. Denman was referred by the medical association to an addiction treatment center that evaluated Dr. Denman and diagnosed her with alcohol use disorder, according to the lawsuit. As a result of the report and as a condition of retaining her medical license, the medical association and St. Vincent Medical Group required Dr. Denman to enter a treatment program at the same addiction treatment center. Dr. Denman was also required to sign a 5-year monitoring contract with the Indiana State Medical Association as a condition of her employment, according to the lawsuit.

“The actions had life-changing consequences,” Ms. DeLaney said. “As a result, she was required to sign a contract that mandates she do a breathalyzer test four times a day for the first year and then three times a day for 4 more years. She has to go for random drug screenings. For the first year, she had to go to four [Alcoholics Anonymous] meetings a week. Now that number has been reduced, but she’s on a 5-year monitoring contract because of all of this.”

Dr. Denman sued the hospital, the medical group, and the NP in July 2018 alleging fraud, defamation, tortuous interference with an employment relationship, and negligent misrepresentation. The NP was dismissed from the case shortly before trial.

In its response to the lawsuit, attorneys for St. Vincent wrote that Dr. Denman’s action was frivolous, vexatious, and executed in bad faith. The defendants requested that a judge dismiss the lawsuit, noting that they were entitled to immunity pursuant to Indiana state and federal laws, including protection by Indiana’s Peer Review statute. In October 2019, a judge denied the hospital’s request to dismiss the lawsuit and allowed the case to proceed.

In their verdict, jurors awarded Dr. Denman $2 million for her defamation claims, $2 million for her claims of fraud and constructive fraud, $500,000 for her claim of tortious interference with an employment relationship, and $250,000 for her claim of negligent misrepresentation.

Dr. Denman remains employed by the medical group and must continue the conditions of her 5-year monitoring contract, Ms. DeLaney said. She hopes Dr. Denman’s case raises awareness about physicians’ due process rights.

“We hope that Dr. Denman’s case emboldens physicians to stand up for themselves in the face of false accusations and rushes to judgment,” she said. “We hope the verdict leads to fair, prompt, and unbiased investigations by hospital and medical practice administrators, which include due process for accused physicians.”

Jurors awarded Carmel, Ind.–based ob.gyn. Rebecca Denman, MD, $4.75 million in damages against St. Vincent Carmel Hospital and St. Vincent Carmel Medical Group on Jan. 16, 2020, after a 4-day trial in Indiana Commercial Court. Dr. Denman sued after the hospital and medical group took a series of actions in response to a nurse practitioner’s claim that Dr. Denman smelled of alcohol while on duty. The doctor’s lawsuit alleged the NP’s claim was unproven; that administrators failed to conduct a proper peer-review investigation; and that repercussions from the false allegation resulted in lost compensation, out-of-pocket expenses, emotional distress, and damage to her professional reputation.

Indianapolis attorney Kathleen DeLaney, who represented Dr. Denman in the case, said that her client was pleased with the verdict.

“Dr. Denman feels vindicated that a group of jurors spent 4 days listening to all the evidence and gave her a resounding victory,” she said in an interview.

Dr. Denman declined to comment for this story through her attorney.

In a statement, a spokesman for Ascension, the hospital’s parent company, said the hospital was disappointed by the verdict and that it was “exploring all options available to us, including appeal.” The spokesman declined to answer further questions about the case or its peer-review process.

The case stems from an NP’s claim that Dr. Denman’s breath smelled of alcohol during an evening shift on Dec. 11, 2017. Dr. Denman was not informed of the allegation on Dec. 11 and was not tested for alcohol at the time, according to Dr. Denman’s lawsuit. Under hospital policy, if a physician is suspected of being under the influence of alcohol at work, the employer must immediately assess the doctor, relieve the doctor of duty, and request the physician submit to immediate blood testing at an external facility.

The NP reported the allegation to her supervisor through an email on Dec. 12, 2017. The supervisor relayed the information to the hospital’s chief medical officer who met with other administrators and physicians to discuss the claim. During the discussions, a previous concern about Dr. Denman’s drinking was raised, according to deposition information included in court documents. In 2015, two physicians had suggested Dr. Denman consider an assistance program after expressing concerns that she was arriving late to work and missing partner meetings. At the time, Dr. Denman did not enter an assistance program, but she changed her drinking habits, began seeing a therapist, and started arriving on-time to work and to partner meetings, according to court documents. No other criticism or complaints regarding her drinking or workplace behavior had been reported since, according to court documents.

When confronted with the NP’s claim on Dec. 13, 2017, Dr. Denman denied consuming alcohol on Dec. 11, 2017, and questioned why the hospital’s substance abuse protocol was not followed.

St. Vincent Carmel Hospital conducted a preliminary review of the allegation through its peer-review process and turned the matter over to St. Vincent Medical Group for further review, according to court documents. St. Vincent Medical Group later informed Dr. Denman they had reviewed the allegation through its peer-review process and that she was suspended with partial pay until she underwent an evaluation for alcohol abuse through the Indiana State Medical Association, according to the lawsuit.

“They falsely misrepresented to her that peer review had been done,” Ms. DeLaney said in an interview. “In spite of that statement, they never offered her a hearing before a peer-review committee, they never shared with her the substance of any evidence they had against her, they never gave her an opportunity to respond to the allegations. In fact, she wasn’t interviewed at all until the deposition in the lawsuit.”

According to the Indiana Peer Review law, a health care provider under investigation is permitted to see any records accumulated by a peer-review committee pertaining to the provider’s personal practice, and the provider shall be offered the opportunity to appear before the peer-review committee with adequate representation to hear all charges and findings concerning the provider and to offer rebuttal information. The rebuttal shall be part of the record before any disclosure of the charges and before any findings can be made, according to the statute.

Dr. Denman was referred by the medical association to an addiction treatment center that evaluated Dr. Denman and diagnosed her with alcohol use disorder, according to the lawsuit. As a result of the report and as a condition of retaining her medical license, the medical association and St. Vincent Medical Group required Dr. Denman to enter a treatment program at the same addiction treatment center. Dr. Denman was also required to sign a 5-year monitoring contract with the Indiana State Medical Association as a condition of her employment, according to the lawsuit.

“The actions had life-changing consequences,” Ms. DeLaney said. “As a result, she was required to sign a contract that mandates she do a breathalyzer test four times a day for the first year and then three times a day for 4 more years. She has to go for random drug screenings. For the first year, she had to go to four [Alcoholics Anonymous] meetings a week. Now that number has been reduced, but she’s on a 5-year monitoring contract because of all of this.”

Dr. Denman sued the hospital, the medical group, and the NP in July 2018 alleging fraud, defamation, tortuous interference with an employment relationship, and negligent misrepresentation. The NP was dismissed from the case shortly before trial.

In its response to the lawsuit, attorneys for St. Vincent wrote that Dr. Denman’s action was frivolous, vexatious, and executed in bad faith. The defendants requested that a judge dismiss the lawsuit, noting that they were entitled to immunity pursuant to Indiana state and federal laws, including protection by Indiana’s Peer Review statute. In October 2019, a judge denied the hospital’s request to dismiss the lawsuit and allowed the case to proceed.

In their verdict, jurors awarded Dr. Denman $2 million for her defamation claims, $2 million for her claims of fraud and constructive fraud, $500,000 for her claim of tortious interference with an employment relationship, and $250,000 for her claim of negligent misrepresentation.

Dr. Denman remains employed by the medical group and must continue the conditions of her 5-year monitoring contract, Ms. DeLaney said. She hopes Dr. Denman’s case raises awareness about physicians’ due process rights.

“We hope that Dr. Denman’s case emboldens physicians to stand up for themselves in the face of false accusations and rushes to judgment,” she said. “We hope the verdict leads to fair, prompt, and unbiased investigations by hospital and medical practice administrators, which include due process for accused physicians.”

Cisplatin-gemcitabine is highly active in BRCA/PALB2+ pancreatic cancer

SAN FRANCISCO – The combination of cisplatin and gemcitabine is highly efficacious as first-line therapy for advanced pancreatic cancer in patients with a germline BRCA1/2 or PALB2 mutation, with no additional benefit seen from concurrent veliparib, a phase 2 randomized controlled trial finds.

Up to 9% of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinomas occur in individuals with one of these germline mutations, which render cells more sensitive to platinum agents and PARP inhibitors because of ineffective DNA repair.

In the trial, nearly two-thirds of patients had a response to cisplatin-gemcitabine alone, according to results reported at the 2020 GI Cancers Symposium and simultaneously published (J Clin Oncol. 2020 Jan 24. doi: 10.1200/JCO.19.02931). Although almost three-quarters had a response when the investigational PARP 1/2 inhibitor veliparib was added, the difference was not statistically significant and toxicity was greater.

“Both arms were very active and substantially exceeded the prespecified thresholds,” said lead investigator Eileen Mary O’Reilly, MD, section head of Hepatopancreaticobilary & Neuroendocrine Cancers at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York.

“The doublet is our recommendation for moving forward, and we believe these data define a reference regimen for germline BRCA-mutated or PALB2-mutated pancreas cancer,” she stated, noting that the PARP inhibitor olaparib (Lynparza) conferred benefit when used as maintenance therapy in the POLO trial. “I think the strategy that at the current time is best supported by the totality of the data is platinum-based therapy upfront and then sequential use of the PARP inhibitor as a maintenance approach.”

The trial was designed in 2012, before efficacy of the FOLFIRINOX regimen was well established, so an obvious question is which chemotherapy to use, Dr. O’Reilly acknowledged.

“I would say these are the only prospective randomized data we have with platinum-based therapy in germline-mutated pancreas cancer. So it comes with a high level of evidence,” she maintained. “Nonetheless, I think FOLFIRINOX is also an option. The options are good, and it probably will depend on the patient in front of you because there certainly are some lack of toxicity advantages, for the most part, to cisplatin and gemcitabine. This was a well-tolerated regimen.”

Implications for practice

“I wouldn’t say this is a negative study. It’s negative with respect to the veliparib question, but otherwise, it’s a very exciting study,” Richard L. Schilsky, MD, chief medical officer and executive vice president of ASCO, said in an interview. “Seeing response rates of 60% and 70% in patients with metastatic pancreatic cancer is kind of unprecedented, and that’s quite remarkable.”

The reason for the lack of additional benefit from veliparib is unclear, he said. But it may be related to the specific PARP inhibitor or to the smaller sample size or very high response rate seen with chemotherapy alone, which possibly precluded detection of a significant difference.

When choosing between chemotherapy regimens, evidence favors the doublet, according to Dr. Schilsky. “FOLFIRINOX doesn’t have a 70% response rate; it may be 35%. If it was my family member, I would say, get gemcitabine-platinum if you have a BRCA mutation.”

“I think the real take-home message, quite honestly, for most oncologists is that patients with pancreatic cancer should be tested for germline BRCA mutations,” he recommended. “It can not only help inform the therapy choice, but of course, some of these cancers are going to run in families because these are germline mutations and they are going to reveal families that have a high risk of not only pancreatic cancer, but breast, ovarian, and all the other BRCA-associated cancers.”

Study details

The trial was conducted among 52 patients with untreated locally advanced or metastatic pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Fully 94% had a BRCA mutation, while the rest had a PALB2 mutation, according to data reported at the symposium, sponsored by the American Gastroenterological Association, the American Society of Clinical Oncology, the American Society for Radiation Oncology, and the Society of Surgical Oncology.

The response rate – the trial’s primary endpoint – was 65.2% with cisplatin-gemcitabine alone and 74.1% with cisplatin-gemcitabine plus veliparib (P = .55), with both arms far exceeding not only the 10% prespecified as “acceptable,” but also the 30% prespecified as “promising.” The respective disease control rates were 78.3% and 100% (P = .02).

Median progression-free survival was 9.7 months with chemotherapy alone and 10.1 months with chemotherapy plus the PARP inhibitor (P = .73). “If you reference an unselected population, that would be about 5 to 7 months,” Dr. O’Reilly noted. Median overall survival was 16.4 months and 15.5 months, respectively (P = .6). For the entire trial cohort, the 2-year overall survival rate was 30.6% and the 3-year overall survival rate was 17.8%.

“The combination came at the expense of hematologic toxicity,” Dr. O’Reilly said, with patients given veliparib having higher rates of grade 3 or 4 neutropenia (48% vs. 30%), thrombocytopenia (55% vs. 9%), and anemia (52% vs. 35%).

In an exploratory analysis among all patients receiving 4 or more months of chemotherapy and then continuing on or starting a PARP inhibitor as their next therapy, without disease progression, median overall survival was 23.4 months, very similar to what was seen in the POLO trial, she noted.

Dr. O’Reilly disclosed that she has ties with Vesselon, Polaris, and CytomX, and that her institution receives grant/research support from Celgene, Sanofi, Genentech-Roche, AstraZeneca, BMS, Silenseed, MabVax, Halozyme, and Acta Biologica. The trial was funded by the Lustgarten Foundation, the David M. Rubenstein Center for Pancreatic Cancer Research, the Reiss Family Foundation, the National Cancer Institute’s Cancer Therapy Evaluation Program, and NCI grants. Dr. Schilsky disclosed that he has no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: O’Reilly EM et al. 2020 GI Cancers Symposium. Abstract 639.

SAN FRANCISCO – The combination of cisplatin and gemcitabine is highly efficacious as first-line therapy for advanced pancreatic cancer in patients with a germline BRCA1/2 or PALB2 mutation, with no additional benefit seen from concurrent veliparib, a phase 2 randomized controlled trial finds.

Up to 9% of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinomas occur in individuals with one of these germline mutations, which render cells more sensitive to platinum agents and PARP inhibitors because of ineffective DNA repair.

In the trial, nearly two-thirds of patients had a response to cisplatin-gemcitabine alone, according to results reported at the 2020 GI Cancers Symposium and simultaneously published (J Clin Oncol. 2020 Jan 24. doi: 10.1200/JCO.19.02931). Although almost three-quarters had a response when the investigational PARP 1/2 inhibitor veliparib was added, the difference was not statistically significant and toxicity was greater.

“Both arms were very active and substantially exceeded the prespecified thresholds,” said lead investigator Eileen Mary O’Reilly, MD, section head of Hepatopancreaticobilary & Neuroendocrine Cancers at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York.

“The doublet is our recommendation for moving forward, and we believe these data define a reference regimen for germline BRCA-mutated or PALB2-mutated pancreas cancer,” she stated, noting that the PARP inhibitor olaparib (Lynparza) conferred benefit when used as maintenance therapy in the POLO trial. “I think the strategy that at the current time is best supported by the totality of the data is platinum-based therapy upfront and then sequential use of the PARP inhibitor as a maintenance approach.”

The trial was designed in 2012, before efficacy of the FOLFIRINOX regimen was well established, so an obvious question is which chemotherapy to use, Dr. O’Reilly acknowledged.

“I would say these are the only prospective randomized data we have with platinum-based therapy in germline-mutated pancreas cancer. So it comes with a high level of evidence,” she maintained. “Nonetheless, I think FOLFIRINOX is also an option. The options are good, and it probably will depend on the patient in front of you because there certainly are some lack of toxicity advantages, for the most part, to cisplatin and gemcitabine. This was a well-tolerated regimen.”

Implications for practice

“I wouldn’t say this is a negative study. It’s negative with respect to the veliparib question, but otherwise, it’s a very exciting study,” Richard L. Schilsky, MD, chief medical officer and executive vice president of ASCO, said in an interview. “Seeing response rates of 60% and 70% in patients with metastatic pancreatic cancer is kind of unprecedented, and that’s quite remarkable.”

The reason for the lack of additional benefit from veliparib is unclear, he said. But it may be related to the specific PARP inhibitor or to the smaller sample size or very high response rate seen with chemotherapy alone, which possibly precluded detection of a significant difference.

When choosing between chemotherapy regimens, evidence favors the doublet, according to Dr. Schilsky. “FOLFIRINOX doesn’t have a 70% response rate; it may be 35%. If it was my family member, I would say, get gemcitabine-platinum if you have a BRCA mutation.”

“I think the real take-home message, quite honestly, for most oncologists is that patients with pancreatic cancer should be tested for germline BRCA mutations,” he recommended. “It can not only help inform the therapy choice, but of course, some of these cancers are going to run in families because these are germline mutations and they are going to reveal families that have a high risk of not only pancreatic cancer, but breast, ovarian, and all the other BRCA-associated cancers.”

Study details

The trial was conducted among 52 patients with untreated locally advanced or metastatic pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Fully 94% had a BRCA mutation, while the rest had a PALB2 mutation, according to data reported at the symposium, sponsored by the American Gastroenterological Association, the American Society of Clinical Oncology, the American Society for Radiation Oncology, and the Society of Surgical Oncology.

The response rate – the trial’s primary endpoint – was 65.2% with cisplatin-gemcitabine alone and 74.1% with cisplatin-gemcitabine plus veliparib (P = .55), with both arms far exceeding not only the 10% prespecified as “acceptable,” but also the 30% prespecified as “promising.” The respective disease control rates were 78.3% and 100% (P = .02).

Median progression-free survival was 9.7 months with chemotherapy alone and 10.1 months with chemotherapy plus the PARP inhibitor (P = .73). “If you reference an unselected population, that would be about 5 to 7 months,” Dr. O’Reilly noted. Median overall survival was 16.4 months and 15.5 months, respectively (P = .6). For the entire trial cohort, the 2-year overall survival rate was 30.6% and the 3-year overall survival rate was 17.8%.

“The combination came at the expense of hematologic toxicity,” Dr. O’Reilly said, with patients given veliparib having higher rates of grade 3 or 4 neutropenia (48% vs. 30%), thrombocytopenia (55% vs. 9%), and anemia (52% vs. 35%).

In an exploratory analysis among all patients receiving 4 or more months of chemotherapy and then continuing on or starting a PARP inhibitor as their next therapy, without disease progression, median overall survival was 23.4 months, very similar to what was seen in the POLO trial, she noted.

Dr. O’Reilly disclosed that she has ties with Vesselon, Polaris, and CytomX, and that her institution receives grant/research support from Celgene, Sanofi, Genentech-Roche, AstraZeneca, BMS, Silenseed, MabVax, Halozyme, and Acta Biologica. The trial was funded by the Lustgarten Foundation, the David M. Rubenstein Center for Pancreatic Cancer Research, the Reiss Family Foundation, the National Cancer Institute’s Cancer Therapy Evaluation Program, and NCI grants. Dr. Schilsky disclosed that he has no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: O’Reilly EM et al. 2020 GI Cancers Symposium. Abstract 639.

SAN FRANCISCO – The combination of cisplatin and gemcitabine is highly efficacious as first-line therapy for advanced pancreatic cancer in patients with a germline BRCA1/2 or PALB2 mutation, with no additional benefit seen from concurrent veliparib, a phase 2 randomized controlled trial finds.

Up to 9% of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinomas occur in individuals with one of these germline mutations, which render cells more sensitive to platinum agents and PARP inhibitors because of ineffective DNA repair.

In the trial, nearly two-thirds of patients had a response to cisplatin-gemcitabine alone, according to results reported at the 2020 GI Cancers Symposium and simultaneously published (J Clin Oncol. 2020 Jan 24. doi: 10.1200/JCO.19.02931). Although almost three-quarters had a response when the investigational PARP 1/2 inhibitor veliparib was added, the difference was not statistically significant and toxicity was greater.

“Both arms were very active and substantially exceeded the prespecified thresholds,” said lead investigator Eileen Mary O’Reilly, MD, section head of Hepatopancreaticobilary & Neuroendocrine Cancers at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York.

“The doublet is our recommendation for moving forward, and we believe these data define a reference regimen for germline BRCA-mutated or PALB2-mutated pancreas cancer,” she stated, noting that the PARP inhibitor olaparib (Lynparza) conferred benefit when used as maintenance therapy in the POLO trial. “I think the strategy that at the current time is best supported by the totality of the data is platinum-based therapy upfront and then sequential use of the PARP inhibitor as a maintenance approach.”

The trial was designed in 2012, before efficacy of the FOLFIRINOX regimen was well established, so an obvious question is which chemotherapy to use, Dr. O’Reilly acknowledged.

“I would say these are the only prospective randomized data we have with platinum-based therapy in germline-mutated pancreas cancer. So it comes with a high level of evidence,” she maintained. “Nonetheless, I think FOLFIRINOX is also an option. The options are good, and it probably will depend on the patient in front of you because there certainly are some lack of toxicity advantages, for the most part, to cisplatin and gemcitabine. This was a well-tolerated regimen.”

Implications for practice

“I wouldn’t say this is a negative study. It’s negative with respect to the veliparib question, but otherwise, it’s a very exciting study,” Richard L. Schilsky, MD, chief medical officer and executive vice president of ASCO, said in an interview. “Seeing response rates of 60% and 70% in patients with metastatic pancreatic cancer is kind of unprecedented, and that’s quite remarkable.”

The reason for the lack of additional benefit from veliparib is unclear, he said. But it may be related to the specific PARP inhibitor or to the smaller sample size or very high response rate seen with chemotherapy alone, which possibly precluded detection of a significant difference.

When choosing between chemotherapy regimens, evidence favors the doublet, according to Dr. Schilsky. “FOLFIRINOX doesn’t have a 70% response rate; it may be 35%. If it was my family member, I would say, get gemcitabine-platinum if you have a BRCA mutation.”

“I think the real take-home message, quite honestly, for most oncologists is that patients with pancreatic cancer should be tested for germline BRCA mutations,” he recommended. “It can not only help inform the therapy choice, but of course, some of these cancers are going to run in families because these are germline mutations and they are going to reveal families that have a high risk of not only pancreatic cancer, but breast, ovarian, and all the other BRCA-associated cancers.”

Study details

The trial was conducted among 52 patients with untreated locally advanced or metastatic pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Fully 94% had a BRCA mutation, while the rest had a PALB2 mutation, according to data reported at the symposium, sponsored by the American Gastroenterological Association, the American Society of Clinical Oncology, the American Society for Radiation Oncology, and the Society of Surgical Oncology.

The response rate – the trial’s primary endpoint – was 65.2% with cisplatin-gemcitabine alone and 74.1% with cisplatin-gemcitabine plus veliparib (P = .55), with both arms far exceeding not only the 10% prespecified as “acceptable,” but also the 30% prespecified as “promising.” The respective disease control rates were 78.3% and 100% (P = .02).

Median progression-free survival was 9.7 months with chemotherapy alone and 10.1 months with chemotherapy plus the PARP inhibitor (P = .73). “If you reference an unselected population, that would be about 5 to 7 months,” Dr. O’Reilly noted. Median overall survival was 16.4 months and 15.5 months, respectively (P = .6). For the entire trial cohort, the 2-year overall survival rate was 30.6% and the 3-year overall survival rate was 17.8%.

“The combination came at the expense of hematologic toxicity,” Dr. O’Reilly said, with patients given veliparib having higher rates of grade 3 or 4 neutropenia (48% vs. 30%), thrombocytopenia (55% vs. 9%), and anemia (52% vs. 35%).

In an exploratory analysis among all patients receiving 4 or more months of chemotherapy and then continuing on or starting a PARP inhibitor as their next therapy, without disease progression, median overall survival was 23.4 months, very similar to what was seen in the POLO trial, she noted.

Dr. O’Reilly disclosed that she has ties with Vesselon, Polaris, and CytomX, and that her institution receives grant/research support from Celgene, Sanofi, Genentech-Roche, AstraZeneca, BMS, Silenseed, MabVax, Halozyme, and Acta Biologica. The trial was funded by the Lustgarten Foundation, the David M. Rubenstein Center for Pancreatic Cancer Research, the Reiss Family Foundation, the National Cancer Institute’s Cancer Therapy Evaluation Program, and NCI grants. Dr. Schilsky disclosed that he has no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: O’Reilly EM et al. 2020 GI Cancers Symposium. Abstract 639.

REPORTING FROM THE 2020 GI CANCERS SYMPOSIUM

Barbers have role in encouraging diabetes screening in black men

Shave and a haircut … and a blood glucose test? A study shows that barbershops owned by black proprietors can play a role in encouraging black men to get screened for diabetes.

In research letter published in the Jan. 27 edition of JAMA Internal Medicine, Marcela Osorio, BA, from New York University and coauthors wrote that black men with diabetes have disproportionately high rates of diabetes complications and lower survival rates. Their diagnosis is often delayed, particularly among men without regular primary health care.

“In barbershops, which are places of trust among black men, community-based interventions have been successful in identifying and treating men with hypertension,” they wrote.

In this study, the researchers approached customers in eight barbershops in Brooklyn, in areas associated with a high prevalence of individuals with poor glycemic control, to encourage them to get tested for diabetes. All barbershops were owned by black individuals.

Around one-third of the 895 black men who were asked to participate in the study agreed to be screened, and 290 (32.4%) were successfully tested using point-of-care hemoglobin A1c testing.

The screening revealed that 9% of those tested had an HbA1c level of 6.5% or higher, and 16 of these individuals were obese. Three men had an HbA1c level of 7.5% or higher. The investigators noted that this prevalence of undiagnosed diabetes was much higher than the 3.6% estimated prevalence among New York City residents.

The highest HbA1c level recorded during testing was 7.8%, and 28.3% of those tested had a level between 5.7% and 6.4%, which meets the criteria for a diagnosis of prediabetes.

“We also found that barbers were important health advocates; although we do not have exact numbers, some customers (who initially declined testing) agreed after encouragement from their barber,” the authors wrote.

Of the 583 men who declined to participate, around one-quarter did so on the grounds that they already knew their health status or had been checked by their doctor, one-third (35.3%) said they were healthy or didn’t have the time or interest, or didn’t want to know the results. There were also 26 individuals who reported being scared of needles.

“Black men who live in urban areas of the United States may face socioeconomic barriers to good health, including poor food environments and difficulty in obtaining primary care,” the authors wrote. “Our findings suggest that community-based diabetes screening in barbershops owned by black individuals may play a role in the timely diagnosis of diabetes and may help to identify black men who need appropriate care for their newly diagnosed diabetes.”

The study was supported by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Two authors declared grants from the institute during the study, and one also reported grants from other research foundations outside the study.

SOURCE: Osorio M et al. JAMA Intern Med. 2020 Jan 27. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.6867.

Shave and a haircut … and a blood glucose test? A study shows that barbershops owned by black proprietors can play a role in encouraging black men to get screened for diabetes.

In research letter published in the Jan. 27 edition of JAMA Internal Medicine, Marcela Osorio, BA, from New York University and coauthors wrote that black men with diabetes have disproportionately high rates of diabetes complications and lower survival rates. Their diagnosis is often delayed, particularly among men without regular primary health care.

“In barbershops, which are places of trust among black men, community-based interventions have been successful in identifying and treating men with hypertension,” they wrote.

In this study, the researchers approached customers in eight barbershops in Brooklyn, in areas associated with a high prevalence of individuals with poor glycemic control, to encourage them to get tested for diabetes. All barbershops were owned by black individuals.

Around one-third of the 895 black men who were asked to participate in the study agreed to be screened, and 290 (32.4%) were successfully tested using point-of-care hemoglobin A1c testing.

The screening revealed that 9% of those tested had an HbA1c level of 6.5% or higher, and 16 of these individuals were obese. Three men had an HbA1c level of 7.5% or higher. The investigators noted that this prevalence of undiagnosed diabetes was much higher than the 3.6% estimated prevalence among New York City residents.

The highest HbA1c level recorded during testing was 7.8%, and 28.3% of those tested had a level between 5.7% and 6.4%, which meets the criteria for a diagnosis of prediabetes.

“We also found that barbers were important health advocates; although we do not have exact numbers, some customers (who initially declined testing) agreed after encouragement from their barber,” the authors wrote.

Of the 583 men who declined to participate, around one-quarter did so on the grounds that they already knew their health status or had been checked by their doctor, one-third (35.3%) said they were healthy or didn’t have the time or interest, or didn’t want to know the results. There were also 26 individuals who reported being scared of needles.

“Black men who live in urban areas of the United States may face socioeconomic barriers to good health, including poor food environments and difficulty in obtaining primary care,” the authors wrote. “Our findings suggest that community-based diabetes screening in barbershops owned by black individuals may play a role in the timely diagnosis of diabetes and may help to identify black men who need appropriate care for their newly diagnosed diabetes.”

The study was supported by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Two authors declared grants from the institute during the study, and one also reported grants from other research foundations outside the study.

SOURCE: Osorio M et al. JAMA Intern Med. 2020 Jan 27. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.6867.

Shave and a haircut … and a blood glucose test? A study shows that barbershops owned by black proprietors can play a role in encouraging black men to get screened for diabetes.

In research letter published in the Jan. 27 edition of JAMA Internal Medicine, Marcela Osorio, BA, from New York University and coauthors wrote that black men with diabetes have disproportionately high rates of diabetes complications and lower survival rates. Their diagnosis is often delayed, particularly among men without regular primary health care.

“In barbershops, which are places of trust among black men, community-based interventions have been successful in identifying and treating men with hypertension,” they wrote.

In this study, the researchers approached customers in eight barbershops in Brooklyn, in areas associated with a high prevalence of individuals with poor glycemic control, to encourage them to get tested for diabetes. All barbershops were owned by black individuals.

Around one-third of the 895 black men who were asked to participate in the study agreed to be screened, and 290 (32.4%) were successfully tested using point-of-care hemoglobin A1c testing.

The screening revealed that 9% of those tested had an HbA1c level of 6.5% or higher, and 16 of these individuals were obese. Three men had an HbA1c level of 7.5% or higher. The investigators noted that this prevalence of undiagnosed diabetes was much higher than the 3.6% estimated prevalence among New York City residents.

The highest HbA1c level recorded during testing was 7.8%, and 28.3% of those tested had a level between 5.7% and 6.4%, which meets the criteria for a diagnosis of prediabetes.

“We also found that barbers were important health advocates; although we do not have exact numbers, some customers (who initially declined testing) agreed after encouragement from their barber,” the authors wrote.

Of the 583 men who declined to participate, around one-quarter did so on the grounds that they already knew their health status or had been checked by their doctor, one-third (35.3%) said they were healthy or didn’t have the time or interest, or didn’t want to know the results. There were also 26 individuals who reported being scared of needles.

“Black men who live in urban areas of the United States may face socioeconomic barriers to good health, including poor food environments and difficulty in obtaining primary care,” the authors wrote. “Our findings suggest that community-based diabetes screening in barbershops owned by black individuals may play a role in the timely diagnosis of diabetes and may help to identify black men who need appropriate care for their newly diagnosed diabetes.”

The study was supported by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Two authors declared grants from the institute during the study, and one also reported grants from other research foundations outside the study.

SOURCE: Osorio M et al. JAMA Intern Med. 2020 Jan 27. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.6867.

FROM JAMA INTERNAL MEDICINE

Key clinical point: Barbershops could offer a way to encourage diabetes screening among black men.

Major finding: HbA1c testing in barbershops identified a significant number of individuals with undiagnosed diabetes.

Study details: Study involving 895 black men attending eight barbershops in Brooklyn.

Disclosures: The study was supported by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Two authors declared grants from the institute during the study, and one also reported grants from other research foundations outside the study.

Source: Osorio M et al. JAMA Intern Med. 2020 Jan 27. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.6867.

Sociodemographic disadvantage confers poorer survival in young adults with CRC

SAN FRANCISCO – Young adults with colorectal cancer who live in neighborhoods with higher levels of disadvantage differ on health measures, present with more advanced disease, and have poorer survival. These were among key findings of a retrospective cohort study reported at the 2020 GI Cancers Symposium.

The incidence of colorectal cancer has risen sharply – 51% – since 1994 among individuals aged younger than age 50 years, with the greatest uptick seen among those aged 20-29 years (J Natl Cancer Inst. 2017;109[8]. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djw322).

“Sociodemographic disparities have been linked to inferior survival. However, their impact and association with outcome in young adults is not well described,” said lead investigator Ashley Matusz-Fisher, MD, of the Levine Cancer Institute in Charlotte, N.C.

The investigators analyzed data from the National Cancer Database for the years 2004-2016, identifying 26,768 patients who received a colorectal cancer diagnosis when aged 18-40 years.

Results showed that those living in areas with low income (less than $38,000 annually) and low educational attainment (high school graduation rate less than 79%), and those living in urban or rural areas (versus metropolitan areas) had 24% and 10% higher risks of death, respectively.

Patients in the low-income, low-education group were more than six times as likely to be black and to lack private health insurance, had greater comorbidity, had larger tumors and more nodal involvement at diagnosis, and were less likely to undergo surgery.

Several factors may be at play for the low-income, low-education group, Dr. Matusz-Fisher speculated: limited access to care, lack of awareness of important symptoms, and inability to afford treatment when it is needed. “That could very well be contributing to them presenting at later stages and then maybe not getting the treatment that other people who have insurance would be getting.

“To try to eliminate these disparities, the first step is recognition, which is what we are doing – recognizing there are disparities – and then making people aware of these disparities,” she commented. “More efforts are needed to increase access and remove barriers to care, with the hope of eliminating disparities and achieving health equity.”

Mitigating disparities

Several studies have looked at mitigating sociodemographic-related disparities in colorectal cancer outcomes, according to session cochair John M. Carethers, MD, AGAF, professor and chair of the department of internal medicine at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.

A large Delaware initiative tackled the problem via screening (J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:1928-30). “Now this was over 50 – we don’t typically screen under 50 – but over 50, you can essentially eliminate this disparity with navigation services and screening. How do you do that under 50? I’m not quite sure,” he said in an interview, adding that some organizations are recommending lowering the screening age to 45 or even 40 years in light of rising incidence among young adults.

However, accumulating evidence suggests that there may be inherent biological differences that are harder to overcome. “There is a lot of data … showing that polyps happen earlier and they are bigger in certain racial groups, particularly African Americans and American Indians,” Dr. Carethers elaborated. What is driving the biology is unknown, but the microbiome has come under scrutiny.

“So you are a victim of your circumstances,” he summarized. “You are living in a low-income area, you are eating more proinflammatory-type foods, you are getting your polyps earlier, and then you are getting your cancers earlier.”

Study details

Rural, urban, or metropolitan status was ascertained for 25,861 patients in the study, and area income and education were ascertained for 7,743 patients, according to data reported at the symposium, sponsored by the American Gastroenterological Association, the American Society of Clinical Oncology, the American Society for Radiation Oncology, and the Society of Surgical Oncology.

Compared with counterparts living in areas with both high annual income (greater than $68,000) and education (greater than 93% high school graduation rate), patients living in areas with both low annual income (less than $38,000) and education ( less than 79% high school graduation rate) were significantly more likely to be black (odds ratio, 6.4), not have private insurance (odds ratio, 6.3), have pathologic T3/T4 stage (OR, 1.4), have positive nodes (OR, 1.2), and have a Charlson-Deyo comorbidity score of 1 or greater (OR, 1.6). They also were less likely to undergo surgery (OR, 0.63) and more likely to be rehospitalized within 30 days (OR, 1.3).

After adjusting for race, insurance status, T/N stage, and comorbidity score, relative to counterparts in the high-income, high-education group, patients in the low-income, low-education group had an increased risk of death (hazard ratio, 1.24; P = .004). And relative to counterparts living in metropolitan areas, patients living in urban or rural areas had an increased risk of death (HR, 1.10; P = .02).

Among patients with stage IV disease, median overall survival was 26.1 months for those from high-income, high-education areas, but 20.7 months for those from low-income, low-education areas (P less than .001).

Dr. Matusz-Fisher did not report any conflicts of interest. The study did not receive any funding.

SOURCE: Matusz-Fisher A et al. 2020 GI Cancers Symposium, Abstract 13.

SAN FRANCISCO – Young adults with colorectal cancer who live in neighborhoods with higher levels of disadvantage differ on health measures, present with more advanced disease, and have poorer survival. These were among key findings of a retrospective cohort study reported at the 2020 GI Cancers Symposium.

The incidence of colorectal cancer has risen sharply – 51% – since 1994 among individuals aged younger than age 50 years, with the greatest uptick seen among those aged 20-29 years (J Natl Cancer Inst. 2017;109[8]. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djw322).

“Sociodemographic disparities have been linked to inferior survival. However, their impact and association with outcome in young adults is not well described,” said lead investigator Ashley Matusz-Fisher, MD, of the Levine Cancer Institute in Charlotte, N.C.

The investigators analyzed data from the National Cancer Database for the years 2004-2016, identifying 26,768 patients who received a colorectal cancer diagnosis when aged 18-40 years.

Results showed that those living in areas with low income (less than $38,000 annually) and low educational attainment (high school graduation rate less than 79%), and those living in urban or rural areas (versus metropolitan areas) had 24% and 10% higher risks of death, respectively.

Patients in the low-income, low-education group were more than six times as likely to be black and to lack private health insurance, had greater comorbidity, had larger tumors and more nodal involvement at diagnosis, and were less likely to undergo surgery.

Several factors may be at play for the low-income, low-education group, Dr. Matusz-Fisher speculated: limited access to care, lack of awareness of important symptoms, and inability to afford treatment when it is needed. “That could very well be contributing to them presenting at later stages and then maybe not getting the treatment that other people who have insurance would be getting.

“To try to eliminate these disparities, the first step is recognition, which is what we are doing – recognizing there are disparities – and then making people aware of these disparities,” she commented. “More efforts are needed to increase access and remove barriers to care, with the hope of eliminating disparities and achieving health equity.”

Mitigating disparities

Several studies have looked at mitigating sociodemographic-related disparities in colorectal cancer outcomes, according to session cochair John M. Carethers, MD, AGAF, professor and chair of the department of internal medicine at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.

A large Delaware initiative tackled the problem via screening (J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:1928-30). “Now this was over 50 – we don’t typically screen under 50 – but over 50, you can essentially eliminate this disparity with navigation services and screening. How do you do that under 50? I’m not quite sure,” he said in an interview, adding that some organizations are recommending lowering the screening age to 45 or even 40 years in light of rising incidence among young adults.

However, accumulating evidence suggests that there may be inherent biological differences that are harder to overcome. “There is a lot of data … showing that polyps happen earlier and they are bigger in certain racial groups, particularly African Americans and American Indians,” Dr. Carethers elaborated. What is driving the biology is unknown, but the microbiome has come under scrutiny.

“So you are a victim of your circumstances,” he summarized. “You are living in a low-income area, you are eating more proinflammatory-type foods, you are getting your polyps earlier, and then you are getting your cancers earlier.”

Study details

Rural, urban, or metropolitan status was ascertained for 25,861 patients in the study, and area income and education were ascertained for 7,743 patients, according to data reported at the symposium, sponsored by the American Gastroenterological Association, the American Society of Clinical Oncology, the American Society for Radiation Oncology, and the Society of Surgical Oncology.

Compared with counterparts living in areas with both high annual income (greater than $68,000) and education (greater than 93% high school graduation rate), patients living in areas with both low annual income (less than $38,000) and education ( less than 79% high school graduation rate) were significantly more likely to be black (odds ratio, 6.4), not have private insurance (odds ratio, 6.3), have pathologic T3/T4 stage (OR, 1.4), have positive nodes (OR, 1.2), and have a Charlson-Deyo comorbidity score of 1 or greater (OR, 1.6). They also were less likely to undergo surgery (OR, 0.63) and more likely to be rehospitalized within 30 days (OR, 1.3).

After adjusting for race, insurance status, T/N stage, and comorbidity score, relative to counterparts in the high-income, high-education group, patients in the low-income, low-education group had an increased risk of death (hazard ratio, 1.24; P = .004). And relative to counterparts living in metropolitan areas, patients living in urban or rural areas had an increased risk of death (HR, 1.10; P = .02).

Among patients with stage IV disease, median overall survival was 26.1 months for those from high-income, high-education areas, but 20.7 months for those from low-income, low-education areas (P less than .001).

Dr. Matusz-Fisher did not report any conflicts of interest. The study did not receive any funding.

SOURCE: Matusz-Fisher A et al. 2020 GI Cancers Symposium, Abstract 13.

SAN FRANCISCO – Young adults with colorectal cancer who live in neighborhoods with higher levels of disadvantage differ on health measures, present with more advanced disease, and have poorer survival. These were among key findings of a retrospective cohort study reported at the 2020 GI Cancers Symposium.

The incidence of colorectal cancer has risen sharply – 51% – since 1994 among individuals aged younger than age 50 years, with the greatest uptick seen among those aged 20-29 years (J Natl Cancer Inst. 2017;109[8]. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djw322).

“Sociodemographic disparities have been linked to inferior survival. However, their impact and association with outcome in young adults is not well described,” said lead investigator Ashley Matusz-Fisher, MD, of the Levine Cancer Institute in Charlotte, N.C.

The investigators analyzed data from the National Cancer Database for the years 2004-2016, identifying 26,768 patients who received a colorectal cancer diagnosis when aged 18-40 years.

Results showed that those living in areas with low income (less than $38,000 annually) and low educational attainment (high school graduation rate less than 79%), and those living in urban or rural areas (versus metropolitan areas) had 24% and 10% higher risks of death, respectively.

Patients in the low-income, low-education group were more than six times as likely to be black and to lack private health insurance, had greater comorbidity, had larger tumors and more nodal involvement at diagnosis, and were less likely to undergo surgery.

Several factors may be at play for the low-income, low-education group, Dr. Matusz-Fisher speculated: limited access to care, lack of awareness of important symptoms, and inability to afford treatment when it is needed. “That could very well be contributing to them presenting at later stages and then maybe not getting the treatment that other people who have insurance would be getting.

“To try to eliminate these disparities, the first step is recognition, which is what we are doing – recognizing there are disparities – and then making people aware of these disparities,” she commented. “More efforts are needed to increase access and remove barriers to care, with the hope of eliminating disparities and achieving health equity.”

Mitigating disparities

Several studies have looked at mitigating sociodemographic-related disparities in colorectal cancer outcomes, according to session cochair John M. Carethers, MD, AGAF, professor and chair of the department of internal medicine at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.

A large Delaware initiative tackled the problem via screening (J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:1928-30). “Now this was over 50 – we don’t typically screen under 50 – but over 50, you can essentially eliminate this disparity with navigation services and screening. How do you do that under 50? I’m not quite sure,” he said in an interview, adding that some organizations are recommending lowering the screening age to 45 or even 40 years in light of rising incidence among young adults.

However, accumulating evidence suggests that there may be inherent biological differences that are harder to overcome. “There is a lot of data … showing that polyps happen earlier and they are bigger in certain racial groups, particularly African Americans and American Indians,” Dr. Carethers elaborated. What is driving the biology is unknown, but the microbiome has come under scrutiny.

“So you are a victim of your circumstances,” he summarized. “You are living in a low-income area, you are eating more proinflammatory-type foods, you are getting your polyps earlier, and then you are getting your cancers earlier.”

Study details

Rural, urban, or metropolitan status was ascertained for 25,861 patients in the study, and area income and education were ascertained for 7,743 patients, according to data reported at the symposium, sponsored by the American Gastroenterological Association, the American Society of Clinical Oncology, the American Society for Radiation Oncology, and the Society of Surgical Oncology.

Compared with counterparts living in areas with both high annual income (greater than $68,000) and education (greater than 93% high school graduation rate), patients living in areas with both low annual income (less than $38,000) and education ( less than 79% high school graduation rate) were significantly more likely to be black (odds ratio, 6.4), not have private insurance (odds ratio, 6.3), have pathologic T3/T4 stage (OR, 1.4), have positive nodes (OR, 1.2), and have a Charlson-Deyo comorbidity score of 1 or greater (OR, 1.6). They also were less likely to undergo surgery (OR, 0.63) and more likely to be rehospitalized within 30 days (OR, 1.3).

After adjusting for race, insurance status, T/N stage, and comorbidity score, relative to counterparts in the high-income, high-education group, patients in the low-income, low-education group had an increased risk of death (hazard ratio, 1.24; P = .004). And relative to counterparts living in metropolitan areas, patients living in urban or rural areas had an increased risk of death (HR, 1.10; P = .02).

Among patients with stage IV disease, median overall survival was 26.1 months for those from high-income, high-education areas, but 20.7 months for those from low-income, low-education areas (P less than .001).

Dr. Matusz-Fisher did not report any conflicts of interest. The study did not receive any funding.

SOURCE: Matusz-Fisher A et al. 2020 GI Cancers Symposium, Abstract 13.

REPORTING FROM THE 2020 GI CANCERS SYMPOSIUM

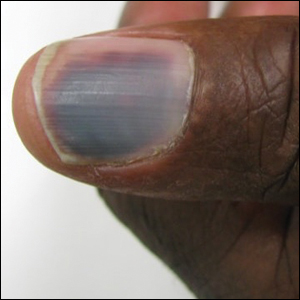

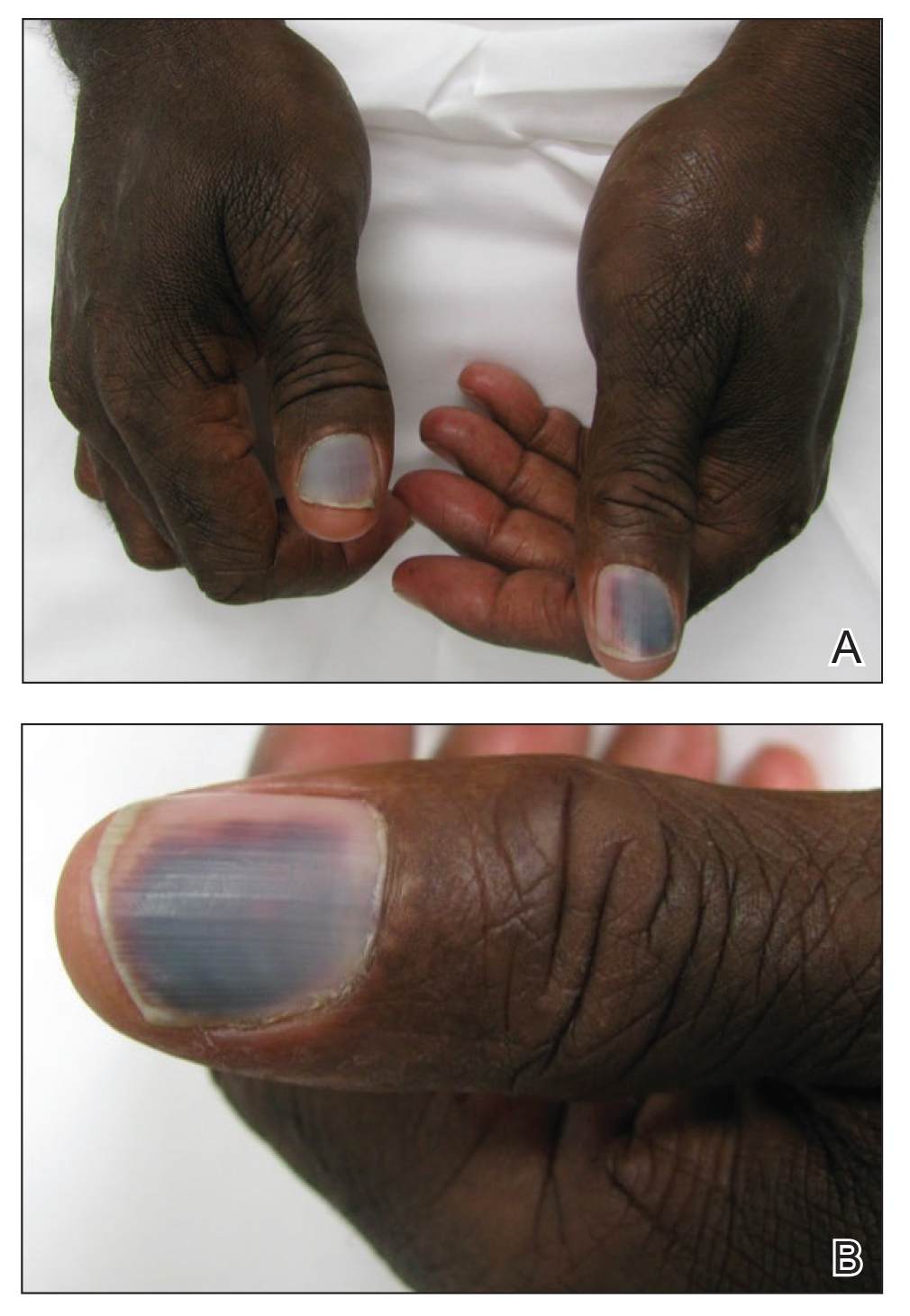

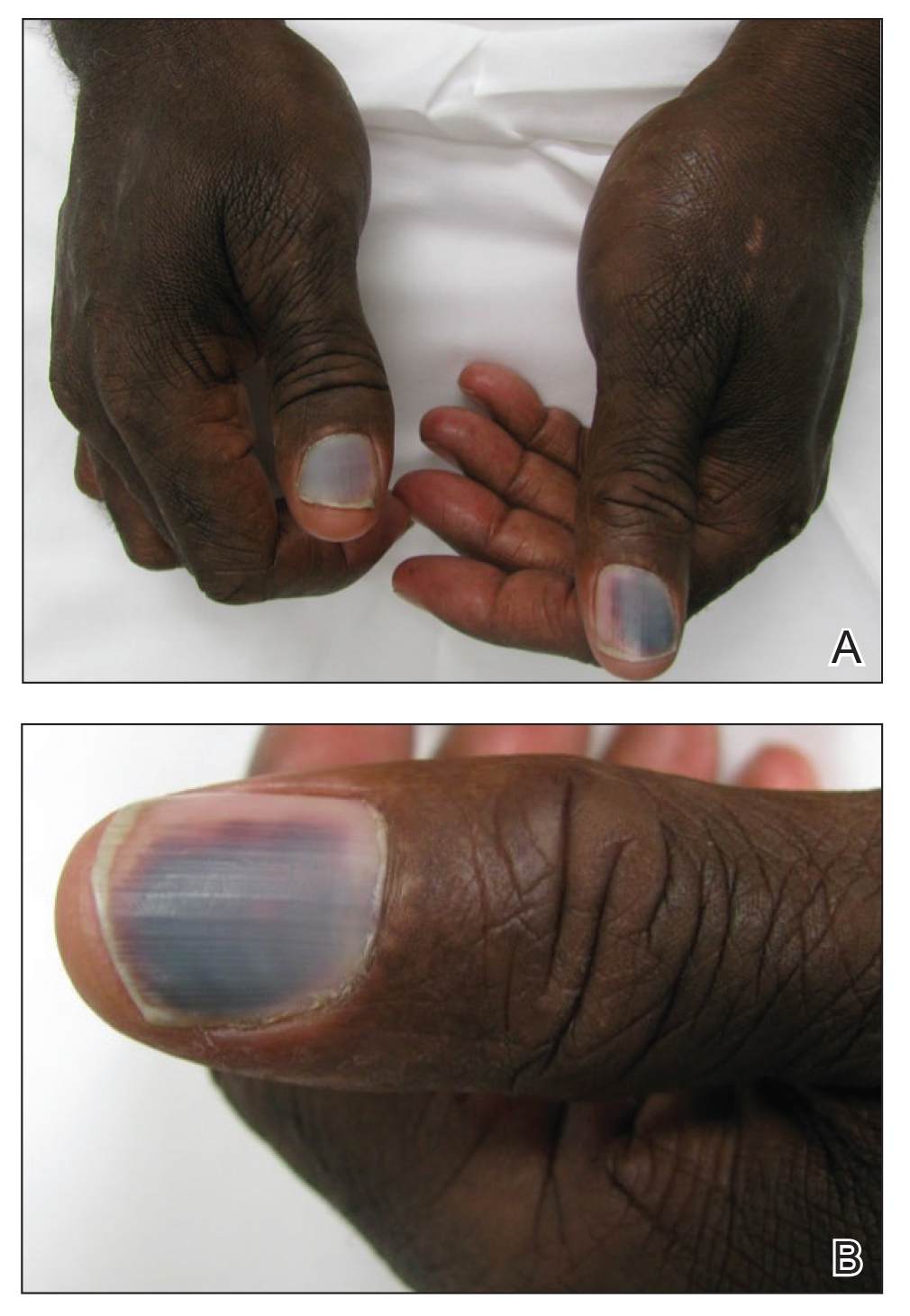

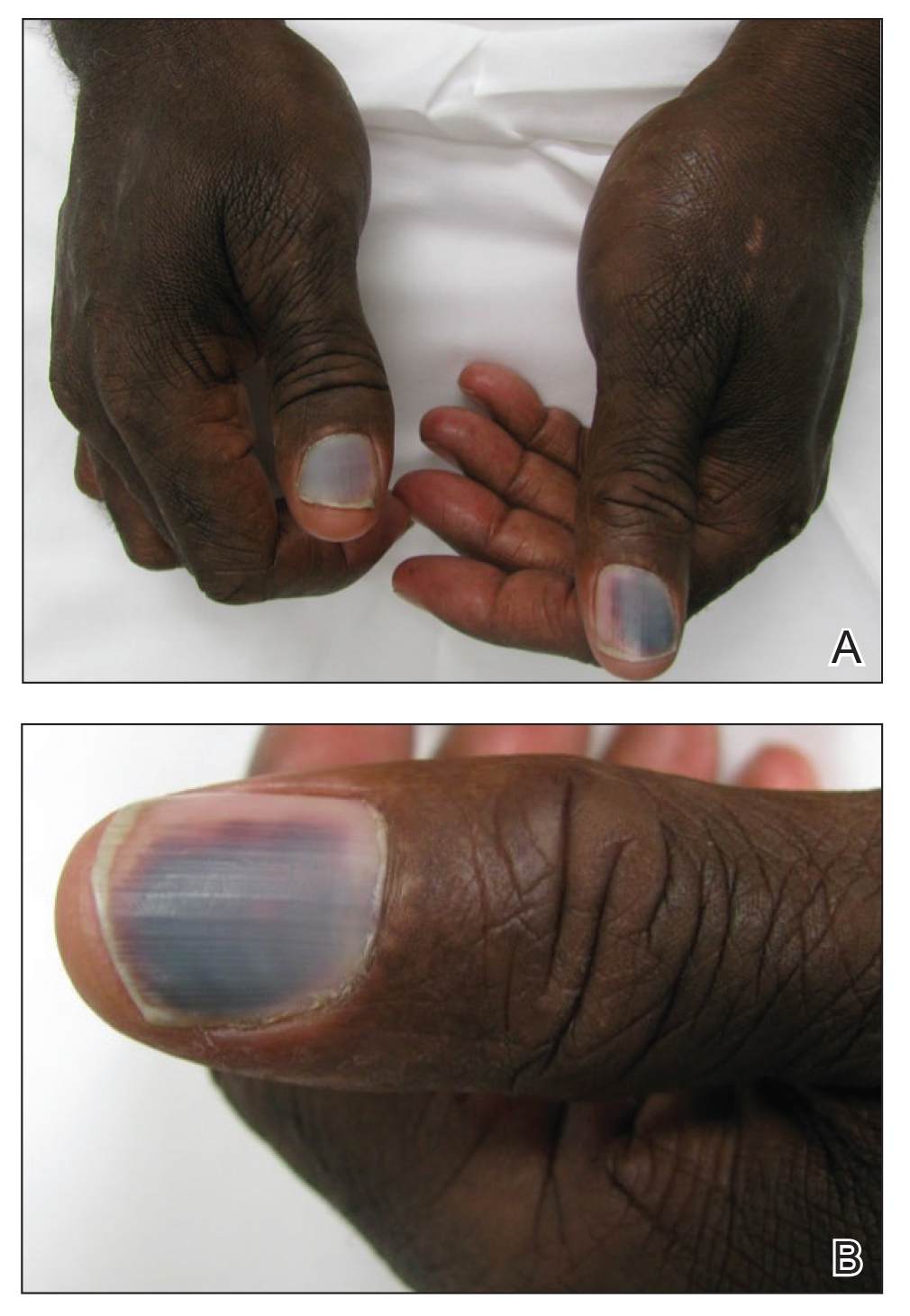

Subungual Hemorrhage From an Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor Inhibitor

To the Editor:

The epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) signaling pathway plays a role in the differentiation, proliferation, and survival of several cell types.1 Erlotinib is an EGFR inhibitor that targets aberrant cells that overexpress this receptor and has been used in the treatment of various solid malignant tumors.2,3 Common dermatologic side effects associated with EGFR inhibitors include papulopustular rash, xeroderma, and paronychia.2,3 We present a unique finding of subungual hemorrhage of the thumbnails in a patient taking erlotinib.

A 50-year-old man presented with acute-onset tenderness and discoloration of the thumbnails of 1 week’s duration. There was no preceding trauma or history of similar symptoms. His medical history was notable for recurrent lung adenocarcinoma with EGFR L858R mutation. Erlotinib therapy was initiated 5 weeks prior to symptom onset. He developed notable xeroderma of the palms and soles that preceded nail changes by a few days. He completed treatment with carboplatin and pemetrexed 16 months prior to relapse after paclitaxel failed due to a severe allergic reaction. There were no nail symptoms during that time. The patient did not have a documented coagulation disorder and was not on any known medications that would predispose him to bleeding. Physical examination demonstrated subungual hemorrhage of the thumbnails with tenderness on palpation (Figure). There was no evidence of periungual changes or nail plate abnormality. All other nails appeared normal. Laboratory test results showed normal platelets. Supportive therapeutic measures were recommended, and the patient was advised to avoid trauma to the nails.