User login

Acknowledging Disparities in Dementia Care for Increasingly Diverse Ethnoracial Patient Populations

Alzheimer disease and related dementias are a global health concern, affecting nearly 47 million people worldwide. Alzheimer disease and related dementias were among the top 10 causes of death worldwide in 2015 and are expected to increase by 10 million cases annually.1 Despite the ethnic diversity of the US, there are considerable gaps in the literature regarding dementia and how it is diagnosed and treated among many ethnic and racial groups.

In 2012, President Barack Obama signed a declaration with the intention of decreasing ethnoracial disparities in Alzheimer disease research and treatment by increasing clinical care, research, and services targeted to racial and ethnic minorities.2 Despite that declaration, in the US there are gaps in access to care for the geriatric population in general. The American Geriatrics Society estimates that the US has fewer than half the needed number of practicing geriatricians. In 2016, there was 1 geriatrician for every 1,924 Americans aged ≥ 65 years.3 Furthermore, health care providers (HCPs) are often not of the same ethnicity or adequately trained to assess and build relationships with ethnically and racially diverse populations.2 Given the projected growth in the numbers of individuals worldwide with dementia, we have a responsibility to continue to develop strategies to provide more inclusive care.

By 2060, minority populations aged ≥ 65 years are expected to represent 45% of the US population, up from 22% in 2014.4 The growth of racial and ethnic minority groups are expected to exceed the growth of the non-Hispanic white population in the next few decades. By 2060, it is estimated that the US population will increase by 75% for non-Hispanic whites, 172% for African Americans, 270% for Asian and Pacific Islanders, 274% for American Indian and Alaska Natives, and 391% for Hispanics.4

A growing body of evidence suggests that Alzheimer disease and related dementias may disproportionately afflict minority groups in the US, which will become quite significant in the years ahead. The Alzheimer’s Association estimates that the prevalence of Alzheimer disease and other dementias among those aged > 65 years, is about twice the rate in African Americans and about 1.5 times the rate in Hispanics when compared with non-Hispanic whites.5 While increases in the incidence of Alzheimer disease and related dementias in non-Hispanic whites is expected to plateau around 2050, its incidence in ethnic and racial minority groups will continue to grow, especially among Hispanics.4 This stark realization provides additional compelling reasons for the US to develop preventative interventions or treatment options that may help delay the onset of the disease and to improve the quality of life of those with the disease or caregiving for those afflicted with it. Culturally competent care of these individuals is paramount.

Diagnosis

Early and accurate diagnosis of individuals with dementia confers many benefits, including early treatment; clinical trial participation; management of comorbid conditions; training, education, and support for patients and families; and legal, financial, and end of life care planning.3 Beyond the logistical concerns (such as HCP shortages), one of the challenges of assessing minority groups is finding staff who are culturally competent or speak the language necessary to accurately communicate and interact with these subgroups. Hispanics and African Americans often receive delayed or inadequate health care services or are diagnosed in an emergency department or other nontraditional setting.5

Even those individuals seeking or receiving care in primary care settings are not always forthcoming about their cognitive status. Only 56% of respondents in a recent survey of patients who had experienced subjective cognitive decline reported that they had discussed it with their HCP.4 This reticence is thought to be influenced by multiple factors, including distrust of the medical establishment, religious or spiritual beliefs, cultural or family beliefs and expectations about geriatric care, and lack of understanding about normal aging vs cognitive disorders. Furthermore, the sensitivity and specificity of current diagnostic tests for dementia have been questioned for nonwhite populations given the clinical presentation of dementia can vary across ethnoracial groups.5

As Luria noted, cognitive assessment tools developed and validated for use with one culture frequently results in experimental failures and are not valid for use with other cultural groups.1 Cognitive testing results are influenced by educational and cultural factors, and this is one of the challenges in correctly diagnosing those of differing ethnoracial backgrounds. Individuals in racial and ethnic minorities may have limited formal education and/or high illiteracy rates and/or cultural nuances to problem solving, thinking, and memory that may not be reflected in current assessment tools.1

There is hope that testing bias could be altered or eliminated using neuroimaging or biomarkers. However, the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative study of patients in the US and Canada included < 5% African American or Hispanic participants in its total sample. Few studies have systematically examined ethnoracial differences in amyloid positron emission tomography, and none have been published to date in ethnoracially diverse groups that assess the more recently developed tau imaging agents.1

Diversity Among Caregivers

The research community must make greater efforts to improve recruitment of more diverse populations into clinical trials. Recent efforts by the National Institute on Aging in conjunction with the Alzheimer’s Association include developing a national strategy for clinical research recruitment and retention with an emphasis on local and diverse populations. This strategy should include various training modules, webinars, and similar educational opportunities for researchers and clinical HCPs, including HCPs from diverse ethnoracial backgrounds, to implement culturally appropriate research methodologies across these diverse groups. It is important that these educational materials be disseminated to caregivers in a way they can comprehend, as the impact on caregivers of those with Alzheimer disease and related dementias is considerable.

The US currently has 7 unpaid caregivers for every adult in the high-risk group of patients aged ≥ 65 years, but this will decline to a ratio of 4:1 by 2030.4 More than two-thirds of caregivers are non-Hispanic white, while 10% are African American, 8% are Hispanic, and 5% are Asian.3 About 34% of caregivers are themselves aged ≥ 65 years and are at risk for declines in their own health given the time and financial requirements of caring for someone else.3 In 2017, the 16.1 million family and other unpaid caregivers of people with dementia provided an estimated 18.4 billion hours of unpaid care, often resulting in considerable financial strain for these individuals. More than half of the caregivers report providing ≥ 21 hours of care per week; and 42% reported providing an average of 9 hours of care per day for people with dementia.

Caregivers report increased stress, sleep deprivation, depression and anxiety, and uncertainty in their ability to provide quality care to the individual with Alzheimer or a related dementia.3 The disproportionate prevalence of Alzheimer disease and other dementias in racially and ethnically diverse populations could further magnify already existing socioeconomic and other disparities and potentially lead to worsening of health outcomes in these groups.4 Given that minority populations tend to cluster geographically, community partnerships with local churches, senior centers, community centers, and other nontraditional settings may offer better opportunities for connecting with caregivers.

Conclusions

The growth and increasing diversity of the US older adult population in the coming decades require us as HCPs, researchers, and educators to dedicate more resources to ethnoracially diverse populations. There are still a great many unknowns about Alzheimer disease and dementia, most especially among nonwhites. Research, clinical care, and education must focus on outreach to marginalized groups so we may better be able to diagnose and treat the fastest growing older adult populations in the US. A complex combination of educational, cultural, social, and environmental factors likely contribute to delayed diagnosis and care of these groups, as well as lack of access to medical care, research venues, and trust issues between minority groups and the medical establishment. We all have an obligation to acknowledge these disparities and elicit the support of our colleagues and workplaces to raise awareness and dedicate necessary resources to this growing concern.

1. Babulal GM, Quiroz YT, Albensi BC, et al; International Society to Advance Alzheimer’s Research and Treatment, Alzheimer’s Association. Perspectives on ethnic and racial disparities in Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias: update and areas of immediate need. Alzheimers Dement. 2019;15(2):292-312.

2. Brewster P, Barnes L, Haan M, et al. Progress and future challenges in aging and diversity research in the United States. Alzheimers Dement. 2019;15(7):995-1003.

3. Alzheimer’s Association. 2019 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimers Dement. 2019;15(3):321-387.

4. Matthews KA, Xu W, Gaglioti AH, et al. Racial and ethnic estimates of Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias in the United States (2015-2060) in adults aged ≥65 years. Alzheimers Dement. 2019;15(1):17-24.

5. Chin AL, Negash S, Hamilton R. Diversity and disparity in dementia: the impact of ethnoracial differences in Alzheimer disease. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2011;25(3):187-195.

Alzheimer disease and related dementias are a global health concern, affecting nearly 47 million people worldwide. Alzheimer disease and related dementias were among the top 10 causes of death worldwide in 2015 and are expected to increase by 10 million cases annually.1 Despite the ethnic diversity of the US, there are considerable gaps in the literature regarding dementia and how it is diagnosed and treated among many ethnic and racial groups.

In 2012, President Barack Obama signed a declaration with the intention of decreasing ethnoracial disparities in Alzheimer disease research and treatment by increasing clinical care, research, and services targeted to racial and ethnic minorities.2 Despite that declaration, in the US there are gaps in access to care for the geriatric population in general. The American Geriatrics Society estimates that the US has fewer than half the needed number of practicing geriatricians. In 2016, there was 1 geriatrician for every 1,924 Americans aged ≥ 65 years.3 Furthermore, health care providers (HCPs) are often not of the same ethnicity or adequately trained to assess and build relationships with ethnically and racially diverse populations.2 Given the projected growth in the numbers of individuals worldwide with dementia, we have a responsibility to continue to develop strategies to provide more inclusive care.

By 2060, minority populations aged ≥ 65 years are expected to represent 45% of the US population, up from 22% in 2014.4 The growth of racial and ethnic minority groups are expected to exceed the growth of the non-Hispanic white population in the next few decades. By 2060, it is estimated that the US population will increase by 75% for non-Hispanic whites, 172% for African Americans, 270% for Asian and Pacific Islanders, 274% for American Indian and Alaska Natives, and 391% for Hispanics.4

A growing body of evidence suggests that Alzheimer disease and related dementias may disproportionately afflict minority groups in the US, which will become quite significant in the years ahead. The Alzheimer’s Association estimates that the prevalence of Alzheimer disease and other dementias among those aged > 65 years, is about twice the rate in African Americans and about 1.5 times the rate in Hispanics when compared with non-Hispanic whites.5 While increases in the incidence of Alzheimer disease and related dementias in non-Hispanic whites is expected to plateau around 2050, its incidence in ethnic and racial minority groups will continue to grow, especially among Hispanics.4 This stark realization provides additional compelling reasons for the US to develop preventative interventions or treatment options that may help delay the onset of the disease and to improve the quality of life of those with the disease or caregiving for those afflicted with it. Culturally competent care of these individuals is paramount.

Diagnosis

Early and accurate diagnosis of individuals with dementia confers many benefits, including early treatment; clinical trial participation; management of comorbid conditions; training, education, and support for patients and families; and legal, financial, and end of life care planning.3 Beyond the logistical concerns (such as HCP shortages), one of the challenges of assessing minority groups is finding staff who are culturally competent or speak the language necessary to accurately communicate and interact with these subgroups. Hispanics and African Americans often receive delayed or inadequate health care services or are diagnosed in an emergency department or other nontraditional setting.5

Even those individuals seeking or receiving care in primary care settings are not always forthcoming about their cognitive status. Only 56% of respondents in a recent survey of patients who had experienced subjective cognitive decline reported that they had discussed it with their HCP.4 This reticence is thought to be influenced by multiple factors, including distrust of the medical establishment, religious or spiritual beliefs, cultural or family beliefs and expectations about geriatric care, and lack of understanding about normal aging vs cognitive disorders. Furthermore, the sensitivity and specificity of current diagnostic tests for dementia have been questioned for nonwhite populations given the clinical presentation of dementia can vary across ethnoracial groups.5

As Luria noted, cognitive assessment tools developed and validated for use with one culture frequently results in experimental failures and are not valid for use with other cultural groups.1 Cognitive testing results are influenced by educational and cultural factors, and this is one of the challenges in correctly diagnosing those of differing ethnoracial backgrounds. Individuals in racial and ethnic minorities may have limited formal education and/or high illiteracy rates and/or cultural nuances to problem solving, thinking, and memory that may not be reflected in current assessment tools.1

There is hope that testing bias could be altered or eliminated using neuroimaging or biomarkers. However, the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative study of patients in the US and Canada included < 5% African American or Hispanic participants in its total sample. Few studies have systematically examined ethnoracial differences in amyloid positron emission tomography, and none have been published to date in ethnoracially diverse groups that assess the more recently developed tau imaging agents.1

Diversity Among Caregivers

The research community must make greater efforts to improve recruitment of more diverse populations into clinical trials. Recent efforts by the National Institute on Aging in conjunction with the Alzheimer’s Association include developing a national strategy for clinical research recruitment and retention with an emphasis on local and diverse populations. This strategy should include various training modules, webinars, and similar educational opportunities for researchers and clinical HCPs, including HCPs from diverse ethnoracial backgrounds, to implement culturally appropriate research methodologies across these diverse groups. It is important that these educational materials be disseminated to caregivers in a way they can comprehend, as the impact on caregivers of those with Alzheimer disease and related dementias is considerable.

The US currently has 7 unpaid caregivers for every adult in the high-risk group of patients aged ≥ 65 years, but this will decline to a ratio of 4:1 by 2030.4 More than two-thirds of caregivers are non-Hispanic white, while 10% are African American, 8% are Hispanic, and 5% are Asian.3 About 34% of caregivers are themselves aged ≥ 65 years and are at risk for declines in their own health given the time and financial requirements of caring for someone else.3 In 2017, the 16.1 million family and other unpaid caregivers of people with dementia provided an estimated 18.4 billion hours of unpaid care, often resulting in considerable financial strain for these individuals. More than half of the caregivers report providing ≥ 21 hours of care per week; and 42% reported providing an average of 9 hours of care per day for people with dementia.

Caregivers report increased stress, sleep deprivation, depression and anxiety, and uncertainty in their ability to provide quality care to the individual with Alzheimer or a related dementia.3 The disproportionate prevalence of Alzheimer disease and other dementias in racially and ethnically diverse populations could further magnify already existing socioeconomic and other disparities and potentially lead to worsening of health outcomes in these groups.4 Given that minority populations tend to cluster geographically, community partnerships with local churches, senior centers, community centers, and other nontraditional settings may offer better opportunities for connecting with caregivers.

Conclusions

The growth and increasing diversity of the US older adult population in the coming decades require us as HCPs, researchers, and educators to dedicate more resources to ethnoracially diverse populations. There are still a great many unknowns about Alzheimer disease and dementia, most especially among nonwhites. Research, clinical care, and education must focus on outreach to marginalized groups so we may better be able to diagnose and treat the fastest growing older adult populations in the US. A complex combination of educational, cultural, social, and environmental factors likely contribute to delayed diagnosis and care of these groups, as well as lack of access to medical care, research venues, and trust issues between minority groups and the medical establishment. We all have an obligation to acknowledge these disparities and elicit the support of our colleagues and workplaces to raise awareness and dedicate necessary resources to this growing concern.

Alzheimer disease and related dementias are a global health concern, affecting nearly 47 million people worldwide. Alzheimer disease and related dementias were among the top 10 causes of death worldwide in 2015 and are expected to increase by 10 million cases annually.1 Despite the ethnic diversity of the US, there are considerable gaps in the literature regarding dementia and how it is diagnosed and treated among many ethnic and racial groups.

In 2012, President Barack Obama signed a declaration with the intention of decreasing ethnoracial disparities in Alzheimer disease research and treatment by increasing clinical care, research, and services targeted to racial and ethnic minorities.2 Despite that declaration, in the US there are gaps in access to care for the geriatric population in general. The American Geriatrics Society estimates that the US has fewer than half the needed number of practicing geriatricians. In 2016, there was 1 geriatrician for every 1,924 Americans aged ≥ 65 years.3 Furthermore, health care providers (HCPs) are often not of the same ethnicity or adequately trained to assess and build relationships with ethnically and racially diverse populations.2 Given the projected growth in the numbers of individuals worldwide with dementia, we have a responsibility to continue to develop strategies to provide more inclusive care.

By 2060, minority populations aged ≥ 65 years are expected to represent 45% of the US population, up from 22% in 2014.4 The growth of racial and ethnic minority groups are expected to exceed the growth of the non-Hispanic white population in the next few decades. By 2060, it is estimated that the US population will increase by 75% for non-Hispanic whites, 172% for African Americans, 270% for Asian and Pacific Islanders, 274% for American Indian and Alaska Natives, and 391% for Hispanics.4

A growing body of evidence suggests that Alzheimer disease and related dementias may disproportionately afflict minority groups in the US, which will become quite significant in the years ahead. The Alzheimer’s Association estimates that the prevalence of Alzheimer disease and other dementias among those aged > 65 years, is about twice the rate in African Americans and about 1.5 times the rate in Hispanics when compared with non-Hispanic whites.5 While increases in the incidence of Alzheimer disease and related dementias in non-Hispanic whites is expected to plateau around 2050, its incidence in ethnic and racial minority groups will continue to grow, especially among Hispanics.4 This stark realization provides additional compelling reasons for the US to develop preventative interventions or treatment options that may help delay the onset of the disease and to improve the quality of life of those with the disease or caregiving for those afflicted with it. Culturally competent care of these individuals is paramount.

Diagnosis

Early and accurate diagnosis of individuals with dementia confers many benefits, including early treatment; clinical trial participation; management of comorbid conditions; training, education, and support for patients and families; and legal, financial, and end of life care planning.3 Beyond the logistical concerns (such as HCP shortages), one of the challenges of assessing minority groups is finding staff who are culturally competent or speak the language necessary to accurately communicate and interact with these subgroups. Hispanics and African Americans often receive delayed or inadequate health care services or are diagnosed in an emergency department or other nontraditional setting.5

Even those individuals seeking or receiving care in primary care settings are not always forthcoming about their cognitive status. Only 56% of respondents in a recent survey of patients who had experienced subjective cognitive decline reported that they had discussed it with their HCP.4 This reticence is thought to be influenced by multiple factors, including distrust of the medical establishment, religious or spiritual beliefs, cultural or family beliefs and expectations about geriatric care, and lack of understanding about normal aging vs cognitive disorders. Furthermore, the sensitivity and specificity of current diagnostic tests for dementia have been questioned for nonwhite populations given the clinical presentation of dementia can vary across ethnoracial groups.5

As Luria noted, cognitive assessment tools developed and validated for use with one culture frequently results in experimental failures and are not valid for use with other cultural groups.1 Cognitive testing results are influenced by educational and cultural factors, and this is one of the challenges in correctly diagnosing those of differing ethnoracial backgrounds. Individuals in racial and ethnic minorities may have limited formal education and/or high illiteracy rates and/or cultural nuances to problem solving, thinking, and memory that may not be reflected in current assessment tools.1

There is hope that testing bias could be altered or eliminated using neuroimaging or biomarkers. However, the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative study of patients in the US and Canada included < 5% African American or Hispanic participants in its total sample. Few studies have systematically examined ethnoracial differences in amyloid positron emission tomography, and none have been published to date in ethnoracially diverse groups that assess the more recently developed tau imaging agents.1

Diversity Among Caregivers

The research community must make greater efforts to improve recruitment of more diverse populations into clinical trials. Recent efforts by the National Institute on Aging in conjunction with the Alzheimer’s Association include developing a national strategy for clinical research recruitment and retention with an emphasis on local and diverse populations. This strategy should include various training modules, webinars, and similar educational opportunities for researchers and clinical HCPs, including HCPs from diverse ethnoracial backgrounds, to implement culturally appropriate research methodologies across these diverse groups. It is important that these educational materials be disseminated to caregivers in a way they can comprehend, as the impact on caregivers of those with Alzheimer disease and related dementias is considerable.

The US currently has 7 unpaid caregivers for every adult in the high-risk group of patients aged ≥ 65 years, but this will decline to a ratio of 4:1 by 2030.4 More than two-thirds of caregivers are non-Hispanic white, while 10% are African American, 8% are Hispanic, and 5% are Asian.3 About 34% of caregivers are themselves aged ≥ 65 years and are at risk for declines in their own health given the time and financial requirements of caring for someone else.3 In 2017, the 16.1 million family and other unpaid caregivers of people with dementia provided an estimated 18.4 billion hours of unpaid care, often resulting in considerable financial strain for these individuals. More than half of the caregivers report providing ≥ 21 hours of care per week; and 42% reported providing an average of 9 hours of care per day for people with dementia.

Caregivers report increased stress, sleep deprivation, depression and anxiety, and uncertainty in their ability to provide quality care to the individual with Alzheimer or a related dementia.3 The disproportionate prevalence of Alzheimer disease and other dementias in racially and ethnically diverse populations could further magnify already existing socioeconomic and other disparities and potentially lead to worsening of health outcomes in these groups.4 Given that minority populations tend to cluster geographically, community partnerships with local churches, senior centers, community centers, and other nontraditional settings may offer better opportunities for connecting with caregivers.

Conclusions

The growth and increasing diversity of the US older adult population in the coming decades require us as HCPs, researchers, and educators to dedicate more resources to ethnoracially diverse populations. There are still a great many unknowns about Alzheimer disease and dementia, most especially among nonwhites. Research, clinical care, and education must focus on outreach to marginalized groups so we may better be able to diagnose and treat the fastest growing older adult populations in the US. A complex combination of educational, cultural, social, and environmental factors likely contribute to delayed diagnosis and care of these groups, as well as lack of access to medical care, research venues, and trust issues between minority groups and the medical establishment. We all have an obligation to acknowledge these disparities and elicit the support of our colleagues and workplaces to raise awareness and dedicate necessary resources to this growing concern.

1. Babulal GM, Quiroz YT, Albensi BC, et al; International Society to Advance Alzheimer’s Research and Treatment, Alzheimer’s Association. Perspectives on ethnic and racial disparities in Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias: update and areas of immediate need. Alzheimers Dement. 2019;15(2):292-312.

2. Brewster P, Barnes L, Haan M, et al. Progress and future challenges in aging and diversity research in the United States. Alzheimers Dement. 2019;15(7):995-1003.

3. Alzheimer’s Association. 2019 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimers Dement. 2019;15(3):321-387.

4. Matthews KA, Xu W, Gaglioti AH, et al. Racial and ethnic estimates of Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias in the United States (2015-2060) in adults aged ≥65 years. Alzheimers Dement. 2019;15(1):17-24.

5. Chin AL, Negash S, Hamilton R. Diversity and disparity in dementia: the impact of ethnoracial differences in Alzheimer disease. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2011;25(3):187-195.

1. Babulal GM, Quiroz YT, Albensi BC, et al; International Society to Advance Alzheimer’s Research and Treatment, Alzheimer’s Association. Perspectives on ethnic and racial disparities in Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias: update and areas of immediate need. Alzheimers Dement. 2019;15(2):292-312.

2. Brewster P, Barnes L, Haan M, et al. Progress and future challenges in aging and diversity research in the United States. Alzheimers Dement. 2019;15(7):995-1003.

3. Alzheimer’s Association. 2019 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimers Dement. 2019;15(3):321-387.

4. Matthews KA, Xu W, Gaglioti AH, et al. Racial and ethnic estimates of Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias in the United States (2015-2060) in adults aged ≥65 years. Alzheimers Dement. 2019;15(1):17-24.

5. Chin AL, Negash S, Hamilton R. Diversity and disparity in dementia: the impact of ethnoracial differences in Alzheimer disease. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2011;25(3):187-195.

Defending the Home Planet

Like me, some of you may have been following the agonizing news about the unprecedented brushfires in Australia that have devastated human, animal, and vegetative life in that country so culturally akin to our own.1 For many people who believe the overwhelming majority of scientific reports on climate change, these apocalyptic fires are an empirical demonstration of the truth of the dire prophecies for the future of our planet. Scientists have demonstrated that although climate change may not have caused the worst fires in Australia’s history, they may have contributed to the conditions that enabled them to spread so far and wide and reach such a destructive intensity.2The heartbreaking pictures of singed koalas and displaced people and the helpless feeling that all I can do from here is donate money set me to thinking about the relationship between the military, health, and climate change, which is the subject of this column.

As I write this in mid-January of a new decade and glance at the weather headlines, I read about an earthquake in Puerto Rico and tornadoes in the southern US. This makes it quite plausible that our comfortable lifestyle and technological civilization could in the coming decades go the way of the dinosaurs, also victims of climate change.

Initially, my first thought about this relationship is a negative one—images of scorched earth policies that stretch back to ancient wars jump to mind. Reflection and research on the topic though suggest that the relationship may be more complicated and conflicted. Alas, I can only touch on a few of the themes in this brief format.

It may not be as obvious that climate change also threatens the military, which is the guardian of that civilization. In 2018, for example, Hurricane Michael caused nearly $5 billion in damages to Tyndall Air Force Base in Florida.3 A year later, the US Department of Defense (DoD) released a report on the effects of climate change as mandated by Congress.4 Even though some congressional critics expressed concern about the report’s lack of depth and detail,5 the report asserted that, “The effects of a changing climate are a national security issue with potential impacts to Department of Defense (DoD or the Department) missions, operational plans, and installations.”4

The US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) is not immune either. Natural disasters have already disrupted the delivery of health care at its many aging facilities. Climate change was called the “engine”6 driving Hurricane Maria, which in 2017 slammed into Puerto Rico, including its VA medical center, and resulted in shortages of supplies, staff, and basic utilities.7 The facility and the island are still trying to rebuild. In response to weather-exposed vulnerability in VA infrastructure, Senator and presidential candidate Elizabeth Warren (D-MA) and Senator Brian Schatz (D-HI), the ranking member of the Subcommittee on Military Construction, sent a letter to VA leadership arguing that “Strengthening VA’s resilience to climate change is consistent with the agency’s mission to deliver timely, high-quality care and benefits to America’s veterans.”8

It has been reported that the current administration has countered initiatives to prepare for the challenges of providing health care to service members and veterans in a climate changed world.9 Sadly, but predictably, in the politicized federal health care arena, the safety of our service members and, in turn, the domestic and national security and peace that depend on them are caught in the partisan debate over global warming, though it is not likely Congress or federal agency leaders will abandon planning to safeguard service members who will see duty and combat in a radically altered ecology and veterans and who will need to have VA continue to be the reliable safety net despite an increasingly erratic environment.10

Climate change is a divisive political issue; there is a proud tradition of conservatism and self-reliance in military members, active duty and veteran alike. That was why I was surprised and impressed when I saw the results of a recent survey on climate change. In January 2019, 293 active-duty service members and veterans were surveyed.

Participants were selected to reflect the ethnic makeup, educational level, and political allegiance of the military population, which enhanced the validity of the findings.11Participants were asked to indicate whether they believed that the earth was warming secondary to human or natural processes; not growing warmer at all; or whether they were unsure. Similar to the general population, 46% agreed that climate change is anthropogenic.11 More than three-fourths believed it was likely climate change would adversely affect the places they worked, like military installations; 61% thought it likely that global warming could lead to armed conflict over resources. Seven in 10 respondents believed that climate is changing vs 46% who did not. Of respondents who believe climate change is real, 87% see it as a threat to military bases compared with 60% who do not accept the science that the earth is warming.11

This survey, though, is only a small study, and the military and VA are big tents under which a wide range of political persuasions and diverse beliefs co-exist. There are many readers of Federal Practitioner who will no doubt reject nearly every word I have written, in what I know is a controversial column. But it matters that the military and veteran constituency are thinking and speaking about the issue of climate change.11 Why? The answer takes us back to the disaster in Australia. When the fires and the devastation they wrought escalated beyond the powers of the civil authorities to handle, it was the military whose technical skill, coordinated readiness, and personal courage and dedication that was called on to rescue thousands of civilians from the inferno.12 So it will be in our country and around the world when disasters—manmade, natural, or both—threaten to engulf life in all its wondrous variety. Those who battle extreme weather will have unique health needs, and their valiant sacrifices deserve to have health care systems ready and able to treat them.

1. Thompson A. Australia’s bushfires have likely devastated wildlife–and the impact will only get worse. Scientific American. https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/australias-bushfires-have-likely-devastated-wildlife-and-the-impact-will-only-get-worse. Published January 8, 2020. Accessed January 16, 2020.

2. Gibbens S. Intense ‘firestorms’ forming from Australia’s deadly wildfires. https://www.nationalgeographic.com/science/2020/01/australian-wildfires-cause-firestorms. Published January 9, 2020. Accessed January 15, 2020.

3. Shapiro A. Tyndall Air Force Base still faces challenges in recovering from Hurricane Michael. https://www.npr.org/2019/05/31/728754872/tyndall-air-force-base-still-faces-challenges-in-recovering-from-hurricane-micha. Published May 31, 2019. Accessed January 16, 2020.

4. US Department of Defense, Office of the Undersecretary for Acquisition and Sustainment. Report on effects of a changing climate to the Department of Defense. https://www.documentcloud.org/documents/5689153-DoD-Final-Climate-Report.html. Published January 2019. Accessed January 16, 2020.

5. Maucione S. DoD justifies climate change report, says response was mission-centric. https://federalnewsnetwork.com/defense-main/2019/03/dod-justifies-climate-change-report-says-response-was-mission-centric. Published March 28, 2019. Accessed January 16, 2020.

6. Shane L 3rd. Puerto Rico’s VA hospital weathers Maria, but challenges loom. https://www.armytimes.com/veterans/2017/09/22/puerto-ricos-va-hospital-weathers-hurricane-maria-but-challenges-loom. Published September 22, 2017. Accessed January 16, 2020.

7. Hersher R. Climate change was the engine that powered Hurricane Maria’s devastating rains. https://www.npr.org/2019/04/17/714098828/climate-change-was-the-engine-that-powered-hurricane-marias-devastating-rains. Published April 17, 2019. Accessed January 16, 2020.

8. Senators Warren and Schatz request an update from the Department of Veterans Affairs on efforts to build resilience to climate change [press release]. https://www.warren.senate.gov/oversight/letters/senators-warren-and-schatz-request-an-update-from-the-department-of-veterans-affairs-on-efforts-to-build-resilience-to-climate-change. Published October 1, 2019. Accessed January 16, 2020.

9. Simkins JD. Navy quietly ends climate change task force, reversing Obama initiative. https://www.navytimes.com/off-duty/military-culture/2019/08/26/navy-quietly-ends-climate-change-task-force-reversing-obama-initiative. Published August 26, 2019. Accessed January 16, 2020.

10. Eilperin J, Dennis B, Ryan M. As White House questions climate change, U.S. military is planning for it. https://www.washingtonpost.com/national/health-science/as-white-house-questions-climate-change-us-military-is-planning-for-it/2019/04/08/78142546-57c0-11e9-814f-e2f46684196e_story.html. Published April 8, 2019. Accessed January 16, 2020.

11. Motta M, Spindel J, Ralston R. Veterans are concerned about climate change and that matters. http://theconversation.com/veterans-are-concerned-about-climate-change-and-that-matters-110685. Published March 8, 2019. Accessed January 16, 2020.

12. Albeck-Ripka L, Kwai I, Fuller T, Tarabay J. ‘It’s an atomic bomb’: Australia deploys military as fires spread. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/01/04/world/australia/fires-military.html. Updated January 5, 2020. Accessed January 18, 2020.

Like me, some of you may have been following the agonizing news about the unprecedented brushfires in Australia that have devastated human, animal, and vegetative life in that country so culturally akin to our own.1 For many people who believe the overwhelming majority of scientific reports on climate change, these apocalyptic fires are an empirical demonstration of the truth of the dire prophecies for the future of our planet. Scientists have demonstrated that although climate change may not have caused the worst fires in Australia’s history, they may have contributed to the conditions that enabled them to spread so far and wide and reach such a destructive intensity.2The heartbreaking pictures of singed koalas and displaced people and the helpless feeling that all I can do from here is donate money set me to thinking about the relationship between the military, health, and climate change, which is the subject of this column.

As I write this in mid-January of a new decade and glance at the weather headlines, I read about an earthquake in Puerto Rico and tornadoes in the southern US. This makes it quite plausible that our comfortable lifestyle and technological civilization could in the coming decades go the way of the dinosaurs, also victims of climate change.

Initially, my first thought about this relationship is a negative one—images of scorched earth policies that stretch back to ancient wars jump to mind. Reflection and research on the topic though suggest that the relationship may be more complicated and conflicted. Alas, I can only touch on a few of the themes in this brief format.

It may not be as obvious that climate change also threatens the military, which is the guardian of that civilization. In 2018, for example, Hurricane Michael caused nearly $5 billion in damages to Tyndall Air Force Base in Florida.3 A year later, the US Department of Defense (DoD) released a report on the effects of climate change as mandated by Congress.4 Even though some congressional critics expressed concern about the report’s lack of depth and detail,5 the report asserted that, “The effects of a changing climate are a national security issue with potential impacts to Department of Defense (DoD or the Department) missions, operational plans, and installations.”4

The US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) is not immune either. Natural disasters have already disrupted the delivery of health care at its many aging facilities. Climate change was called the “engine”6 driving Hurricane Maria, which in 2017 slammed into Puerto Rico, including its VA medical center, and resulted in shortages of supplies, staff, and basic utilities.7 The facility and the island are still trying to rebuild. In response to weather-exposed vulnerability in VA infrastructure, Senator and presidential candidate Elizabeth Warren (D-MA) and Senator Brian Schatz (D-HI), the ranking member of the Subcommittee on Military Construction, sent a letter to VA leadership arguing that “Strengthening VA’s resilience to climate change is consistent with the agency’s mission to deliver timely, high-quality care and benefits to America’s veterans.”8

It has been reported that the current administration has countered initiatives to prepare for the challenges of providing health care to service members and veterans in a climate changed world.9 Sadly, but predictably, in the politicized federal health care arena, the safety of our service members and, in turn, the domestic and national security and peace that depend on them are caught in the partisan debate over global warming, though it is not likely Congress or federal agency leaders will abandon planning to safeguard service members who will see duty and combat in a radically altered ecology and veterans and who will need to have VA continue to be the reliable safety net despite an increasingly erratic environment.10

Climate change is a divisive political issue; there is a proud tradition of conservatism and self-reliance in military members, active duty and veteran alike. That was why I was surprised and impressed when I saw the results of a recent survey on climate change. In January 2019, 293 active-duty service members and veterans were surveyed.

Participants were selected to reflect the ethnic makeup, educational level, and political allegiance of the military population, which enhanced the validity of the findings.11Participants were asked to indicate whether they believed that the earth was warming secondary to human or natural processes; not growing warmer at all; or whether they were unsure. Similar to the general population, 46% agreed that climate change is anthropogenic.11 More than three-fourths believed it was likely climate change would adversely affect the places they worked, like military installations; 61% thought it likely that global warming could lead to armed conflict over resources. Seven in 10 respondents believed that climate is changing vs 46% who did not. Of respondents who believe climate change is real, 87% see it as a threat to military bases compared with 60% who do not accept the science that the earth is warming.11

This survey, though, is only a small study, and the military and VA are big tents under which a wide range of political persuasions and diverse beliefs co-exist. There are many readers of Federal Practitioner who will no doubt reject nearly every word I have written, in what I know is a controversial column. But it matters that the military and veteran constituency are thinking and speaking about the issue of climate change.11 Why? The answer takes us back to the disaster in Australia. When the fires and the devastation they wrought escalated beyond the powers of the civil authorities to handle, it was the military whose technical skill, coordinated readiness, and personal courage and dedication that was called on to rescue thousands of civilians from the inferno.12 So it will be in our country and around the world when disasters—manmade, natural, or both—threaten to engulf life in all its wondrous variety. Those who battle extreme weather will have unique health needs, and their valiant sacrifices deserve to have health care systems ready and able to treat them.

Like me, some of you may have been following the agonizing news about the unprecedented brushfires in Australia that have devastated human, animal, and vegetative life in that country so culturally akin to our own.1 For many people who believe the overwhelming majority of scientific reports on climate change, these apocalyptic fires are an empirical demonstration of the truth of the dire prophecies for the future of our planet. Scientists have demonstrated that although climate change may not have caused the worst fires in Australia’s history, they may have contributed to the conditions that enabled them to spread so far and wide and reach such a destructive intensity.2The heartbreaking pictures of singed koalas and displaced people and the helpless feeling that all I can do from here is donate money set me to thinking about the relationship between the military, health, and climate change, which is the subject of this column.

As I write this in mid-January of a new decade and glance at the weather headlines, I read about an earthquake in Puerto Rico and tornadoes in the southern US. This makes it quite plausible that our comfortable lifestyle and technological civilization could in the coming decades go the way of the dinosaurs, also victims of climate change.

Initially, my first thought about this relationship is a negative one—images of scorched earth policies that stretch back to ancient wars jump to mind. Reflection and research on the topic though suggest that the relationship may be more complicated and conflicted. Alas, I can only touch on a few of the themes in this brief format.

It may not be as obvious that climate change also threatens the military, which is the guardian of that civilization. In 2018, for example, Hurricane Michael caused nearly $5 billion in damages to Tyndall Air Force Base in Florida.3 A year later, the US Department of Defense (DoD) released a report on the effects of climate change as mandated by Congress.4 Even though some congressional critics expressed concern about the report’s lack of depth and detail,5 the report asserted that, “The effects of a changing climate are a national security issue with potential impacts to Department of Defense (DoD or the Department) missions, operational plans, and installations.”4

The US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) is not immune either. Natural disasters have already disrupted the delivery of health care at its many aging facilities. Climate change was called the “engine”6 driving Hurricane Maria, which in 2017 slammed into Puerto Rico, including its VA medical center, and resulted in shortages of supplies, staff, and basic utilities.7 The facility and the island are still trying to rebuild. In response to weather-exposed vulnerability in VA infrastructure, Senator and presidential candidate Elizabeth Warren (D-MA) and Senator Brian Schatz (D-HI), the ranking member of the Subcommittee on Military Construction, sent a letter to VA leadership arguing that “Strengthening VA’s resilience to climate change is consistent with the agency’s mission to deliver timely, high-quality care and benefits to America’s veterans.”8

It has been reported that the current administration has countered initiatives to prepare for the challenges of providing health care to service members and veterans in a climate changed world.9 Sadly, but predictably, in the politicized federal health care arena, the safety of our service members and, in turn, the domestic and national security and peace that depend on them are caught in the partisan debate over global warming, though it is not likely Congress or federal agency leaders will abandon planning to safeguard service members who will see duty and combat in a radically altered ecology and veterans and who will need to have VA continue to be the reliable safety net despite an increasingly erratic environment.10

Climate change is a divisive political issue; there is a proud tradition of conservatism and self-reliance in military members, active duty and veteran alike. That was why I was surprised and impressed when I saw the results of a recent survey on climate change. In January 2019, 293 active-duty service members and veterans were surveyed.

Participants were selected to reflect the ethnic makeup, educational level, and political allegiance of the military population, which enhanced the validity of the findings.11Participants were asked to indicate whether they believed that the earth was warming secondary to human or natural processes; not growing warmer at all; or whether they were unsure. Similar to the general population, 46% agreed that climate change is anthropogenic.11 More than three-fourths believed it was likely climate change would adversely affect the places they worked, like military installations; 61% thought it likely that global warming could lead to armed conflict over resources. Seven in 10 respondents believed that climate is changing vs 46% who did not. Of respondents who believe climate change is real, 87% see it as a threat to military bases compared with 60% who do not accept the science that the earth is warming.11

This survey, though, is only a small study, and the military and VA are big tents under which a wide range of political persuasions and diverse beliefs co-exist. There are many readers of Federal Practitioner who will no doubt reject nearly every word I have written, in what I know is a controversial column. But it matters that the military and veteran constituency are thinking and speaking about the issue of climate change.11 Why? The answer takes us back to the disaster in Australia. When the fires and the devastation they wrought escalated beyond the powers of the civil authorities to handle, it was the military whose technical skill, coordinated readiness, and personal courage and dedication that was called on to rescue thousands of civilians from the inferno.12 So it will be in our country and around the world when disasters—manmade, natural, or both—threaten to engulf life in all its wondrous variety. Those who battle extreme weather will have unique health needs, and their valiant sacrifices deserve to have health care systems ready and able to treat them.

1. Thompson A. Australia’s bushfires have likely devastated wildlife–and the impact will only get worse. Scientific American. https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/australias-bushfires-have-likely-devastated-wildlife-and-the-impact-will-only-get-worse. Published January 8, 2020. Accessed January 16, 2020.

2. Gibbens S. Intense ‘firestorms’ forming from Australia’s deadly wildfires. https://www.nationalgeographic.com/science/2020/01/australian-wildfires-cause-firestorms. Published January 9, 2020. Accessed January 15, 2020.

3. Shapiro A. Tyndall Air Force Base still faces challenges in recovering from Hurricane Michael. https://www.npr.org/2019/05/31/728754872/tyndall-air-force-base-still-faces-challenges-in-recovering-from-hurricane-micha. Published May 31, 2019. Accessed January 16, 2020.

4. US Department of Defense, Office of the Undersecretary for Acquisition and Sustainment. Report on effects of a changing climate to the Department of Defense. https://www.documentcloud.org/documents/5689153-DoD-Final-Climate-Report.html. Published January 2019. Accessed January 16, 2020.

5. Maucione S. DoD justifies climate change report, says response was mission-centric. https://federalnewsnetwork.com/defense-main/2019/03/dod-justifies-climate-change-report-says-response-was-mission-centric. Published March 28, 2019. Accessed January 16, 2020.

6. Shane L 3rd. Puerto Rico’s VA hospital weathers Maria, but challenges loom. https://www.armytimes.com/veterans/2017/09/22/puerto-ricos-va-hospital-weathers-hurricane-maria-but-challenges-loom. Published September 22, 2017. Accessed January 16, 2020.

7. Hersher R. Climate change was the engine that powered Hurricane Maria’s devastating rains. https://www.npr.org/2019/04/17/714098828/climate-change-was-the-engine-that-powered-hurricane-marias-devastating-rains. Published April 17, 2019. Accessed January 16, 2020.

8. Senators Warren and Schatz request an update from the Department of Veterans Affairs on efforts to build resilience to climate change [press release]. https://www.warren.senate.gov/oversight/letters/senators-warren-and-schatz-request-an-update-from-the-department-of-veterans-affairs-on-efforts-to-build-resilience-to-climate-change. Published October 1, 2019. Accessed January 16, 2020.

9. Simkins JD. Navy quietly ends climate change task force, reversing Obama initiative. https://www.navytimes.com/off-duty/military-culture/2019/08/26/navy-quietly-ends-climate-change-task-force-reversing-obama-initiative. Published August 26, 2019. Accessed January 16, 2020.

10. Eilperin J, Dennis B, Ryan M. As White House questions climate change, U.S. military is planning for it. https://www.washingtonpost.com/national/health-science/as-white-house-questions-climate-change-us-military-is-planning-for-it/2019/04/08/78142546-57c0-11e9-814f-e2f46684196e_story.html. Published April 8, 2019. Accessed January 16, 2020.

11. Motta M, Spindel J, Ralston R. Veterans are concerned about climate change and that matters. http://theconversation.com/veterans-are-concerned-about-climate-change-and-that-matters-110685. Published March 8, 2019. Accessed January 16, 2020.

12. Albeck-Ripka L, Kwai I, Fuller T, Tarabay J. ‘It’s an atomic bomb’: Australia deploys military as fires spread. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/01/04/world/australia/fires-military.html. Updated January 5, 2020. Accessed January 18, 2020.

1. Thompson A. Australia’s bushfires have likely devastated wildlife–and the impact will only get worse. Scientific American. https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/australias-bushfires-have-likely-devastated-wildlife-and-the-impact-will-only-get-worse. Published January 8, 2020. Accessed January 16, 2020.

2. Gibbens S. Intense ‘firestorms’ forming from Australia’s deadly wildfires. https://www.nationalgeographic.com/science/2020/01/australian-wildfires-cause-firestorms. Published January 9, 2020. Accessed January 15, 2020.

3. Shapiro A. Tyndall Air Force Base still faces challenges in recovering from Hurricane Michael. https://www.npr.org/2019/05/31/728754872/tyndall-air-force-base-still-faces-challenges-in-recovering-from-hurricane-micha. Published May 31, 2019. Accessed January 16, 2020.

4. US Department of Defense, Office of the Undersecretary for Acquisition and Sustainment. Report on effects of a changing climate to the Department of Defense. https://www.documentcloud.org/documents/5689153-DoD-Final-Climate-Report.html. Published January 2019. Accessed January 16, 2020.

5. Maucione S. DoD justifies climate change report, says response was mission-centric. https://federalnewsnetwork.com/defense-main/2019/03/dod-justifies-climate-change-report-says-response-was-mission-centric. Published March 28, 2019. Accessed January 16, 2020.

6. Shane L 3rd. Puerto Rico’s VA hospital weathers Maria, but challenges loom. https://www.armytimes.com/veterans/2017/09/22/puerto-ricos-va-hospital-weathers-hurricane-maria-but-challenges-loom. Published September 22, 2017. Accessed January 16, 2020.

7. Hersher R. Climate change was the engine that powered Hurricane Maria’s devastating rains. https://www.npr.org/2019/04/17/714098828/climate-change-was-the-engine-that-powered-hurricane-marias-devastating-rains. Published April 17, 2019. Accessed January 16, 2020.

8. Senators Warren and Schatz request an update from the Department of Veterans Affairs on efforts to build resilience to climate change [press release]. https://www.warren.senate.gov/oversight/letters/senators-warren-and-schatz-request-an-update-from-the-department-of-veterans-affairs-on-efforts-to-build-resilience-to-climate-change. Published October 1, 2019. Accessed January 16, 2020.

9. Simkins JD. Navy quietly ends climate change task force, reversing Obama initiative. https://www.navytimes.com/off-duty/military-culture/2019/08/26/navy-quietly-ends-climate-change-task-force-reversing-obama-initiative. Published August 26, 2019. Accessed January 16, 2020.

10. Eilperin J, Dennis B, Ryan M. As White House questions climate change, U.S. military is planning for it. https://www.washingtonpost.com/national/health-science/as-white-house-questions-climate-change-us-military-is-planning-for-it/2019/04/08/78142546-57c0-11e9-814f-e2f46684196e_story.html. Published April 8, 2019. Accessed January 16, 2020.

11. Motta M, Spindel J, Ralston R. Veterans are concerned about climate change and that matters. http://theconversation.com/veterans-are-concerned-about-climate-change-and-that-matters-110685. Published March 8, 2019. Accessed January 16, 2020.

12. Albeck-Ripka L, Kwai I, Fuller T, Tarabay J. ‘It’s an atomic bomb’: Australia deploys military as fires spread. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/01/04/world/australia/fires-military.html. Updated January 5, 2020. Accessed January 18, 2020.

Stimulant Medication Prescribing Practices Within a VA Health Care System

Dispensing of prescription stimulant medications, such as methylphenidate or amphetamine salts, has been expanding at a rapid rate over the past 2 decades. An astounding 58 million stimulant medications were prescribed in 2014.1,2 Adults now exceed youths in the proportion of prescribed stimulant medications.1,3

Off-label use of prescription stimulant medications, such as for performance enhancement, fatigue management, weight loss, medication-assisted therapy for stimulant use disorders, and adjunctive treatment for certain depressive disorders, is reported to be ≥ 40% of total stimulant use and is much more common in adults.1 A 2017 study assessing risk of amphetamine use disorder and mortality among veterans prescribed stimulant medications within the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) reported off-label use in nearly 3 of every 5 incident users in 2012.4 Off-label use also is significantly more common when prescribed by nonpsychiatric physicians compared with that of psychiatrists.1

One study assessing stimulant prescribing from 2006 to 2009 found that nearly 60% of adults were prescribed stimulant medications by nonpsychiatrist physicians, and only 34% of those adults prescribed a stimulant by a nonpsychiatrist physician had a diagnosis of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).5 Findings from managed care plans covering years from 2000 to 2004 were similar, concluding that 30% of the adult patients who were prescribed methylphenidate had at least 1 medical claim with a diagnosis of ADHD.6 Of the approximately 16 million adults prescribed stimulant medications in 2017, > 5 million of them reported stimulant misuse.3 Much attention has been focused on misuse of stimulant medications by youths and young adults, but new information suggests that increased monitoring is needed among the US adult population. Per the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Academic Detailing Stimulant Dashboard, as of October 2018 the national average of veterans with a documented substance use disorder (SUD) who are also prescribed stimulant medications through the VHA exceeds 20%, < 50% have an annual urine drug screen (UDS), and > 10% are coprescribed opioids and benzodiazepines.The percentage of veterans prescribed stimulant medications in the presence of a SUD has increased over the past decade, with a reported 8.7% incidence in 2002 increasing to 14.3% in 2012.4

There are currently no protocols, prescribing restrictions, or required monitoring parameters in place for prescription stimulant use within the Lexington VA Health Care System (LVAHCS). The purpose of this study was to evaluate the prescribing practices at LVAHCS of stimulant medications and identify opportunities for improvement in the prescribing and monitoring of this drug class.

Methods

This study was a single-center quality improvement project evaluating the prescribing practices of stimulant medications within LVAHCS and exempt from institutional review board approval. Veterans were included in the study if they were prescribed amphetamine salts, dextroamphetamine, lisdexamphetamine, or methylphenidate between January 1, 2018 and June 30, 2018; however, the veterans’ entire stimulant use history was assessed. Exclusion criteria included duration of use of < 2 months or < 2 prescriptions filled during the study period. Data for veterans who met the prespecified inclusion and exclusion criteria were collected via chart review and Microsoft SQL Server Management Studio.

Collected data included age, gender, stimulant regimen (drug name, dose, frequency), indication and duration of use, prescriber name and specialty, prescribing origin of initial stimulant medication, and whether stimulant use predated military service. Monitoring of stimulant medications was assessed via UDS at least annually, query of the prescription drug monitoring program (PDMP) at least quarterly, and average time between follow-up appointments with stimulant prescriber.

Monitoring parameters were assessed from January 1, 2017 through June 30, 2018, as it was felt that the 6-month study period would be too narrow to accurately assess monitoring trends. Mental health diagnoses, ADHD diagnostic testing if applicable, documented SUD or stimulant misuse past or present, and concomitant central nervous system (CNS) depressant use also were collected. CNS depressants evaluated were those that have abuse potential or significant psychotropic effects and included benzodiazepines, antipsychotics, opioids, gabapentin/pregabalin, Z-hypnotics, and muscle relaxants.

Results

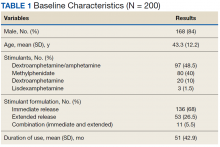

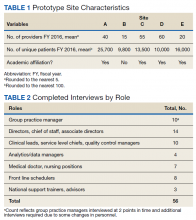

The majority of participants were male (168/200) with an average age of 43.3 years. Dextroamphetamine/amphetamine was the most used stimulant (48.5%), followed by methylphenidate (40%), and dextroamphetamine (10%). Lisdexamphetamine was the least used stimulant, likely due to its formulary-restricted status within this facility. An extended release (ER) formulation was utilized in 1 of 4 participants, with 1 of 20 participants prescribed a combination of immediate release (IR) and ER formulations. Duration of use ranged from 3 months to 14 years, with an average duration of 4 years (Table 1).

Nearly 40% of participants reported an origin of stimulant initiation outside of LVAHCS. Fourteen percent of participants were started on prescription stimulant medications while active-duty service members. Stimulant medications were initiated at another VA facility in 10.5% of instances, and 15% of participants reported being prescribed stimulant medications by a civilian prescriber prior to receiving them at LVAHCS. Seventy-four of 79 (93.6%) participants with an origin of stimulant prescription outside of LVAHCS reported a US Federal Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved indication for use.

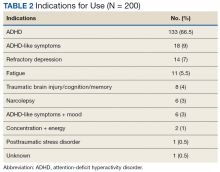

Stimulant medications were used for FDA-approved indications (ADHD and narcolepsy) in 69.5% of participants. Note, this included patients who maintained an ADHD diagnosis in their medical record even if it was not substantiated with diagnostic testing. Of the participants reporting ADHD as an indication for stimulant use, diagnostic testing was conducted at LVAHCS to confirm an ADHD diagnosis in 58.6% (78/133) participants; 20.5% (16/78) of these diagnostic tests did not support the diagnosis of ADHD. All documented indications for use can be found in Table 2.

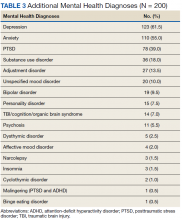

As expected, the most common indication was ADHD (66.5%), followed by ADHD-like symptoms (9%), refractory depression (7%), and fatigue (5.5%). Fourteen percent of participants had ≥ 1 change in indication for use, with some participants having up to 4 different documented indications while being prescribed stimulant medications. Twelve percent of participants were either denied stimulant initiation, or current stimulant medications were discontinued by one health provider and were restarted by another following a prescriber change. Aside from indication for stimulant use, 90% of participants had at least one additional mental health diagnosis. The rate of all mental health diagnoses documented in the medical record problem list can be found in Table 3.

A UDS was collected at least annually in 37% of participants. A methylphenidate confirmatory screen was ordered to assess adherence in just 2 (2.5%) participants prescribed methylphenidate. While actively prescribed stimulant medications, PDMP was queried quarterly in 26% of participants. Time to follow-up with the prescriber ranged from 1 to 15 months, and 40% of participants had follow-up at least quarterly. Instance of SUD, either active or in remission, differed when searched via problem list (36/200) and prescriber documentation (63/200). The most common SUD was alcohol use disorder (13%), followed by cannabis use disorder (5%), polysubstance use disorder (5%), opioid use disorder (4.5%), stimulant use disorder (2.5%), and sedative use disorder (1%). Twenty-five participants currently prescribed stimulant medications had stimulant abuse/misuse documented in their medical record. Fifty-four percent of participants were prescribed at least 1 CNS depressant considered to have abuse potential or significant psychotropic effects. Opioids were most common (23%), followed by muscle relaxants (15.5%), benzodiazepines (15%), antipsychotics (13%), gabapentin/pregabalin (12%), and Z-hypnotics (12%).

Discussion

The source of the initial stimulant prescription was assessed. The majority of veterans had received medical care prior to receiving care at LVAHCS, whether on active duty, from another VA facility throughout the country, or by a private civilian prescriber. The origin of initial stimulant medication and indication for stimulant medication use were patient reported. Requiring medical records from civilian providers prior to continuing stimulant medication is prescriber-dependent and was not available for all participants.

As expected, the majority of participants

The reasons for discontinuation included a positive UDS result for cocaine, psychosis, broken narcotic contract, ADHD diagnosis not supported by psychological testing, chronic bipolar disorder secondary to stimulant use, diversion, stimulant misuse, and lack of indication for use. There also were a handful of veterans whose VA prescribers declined to initiate prescription stimulant medications for various reasons, so the veteran sought care from a civilian prescriber who prescribed stimulant medications, then returned to the VA for medication management, and stimulant medications were continued. Fourteen percent (28/200) of participants had multiple indications for use at some point during stimulant medication therapy. Eight of those were a reasonable change from ADHD to ADHD-like symptoms when diagnosis was not substantiated by testing. The cause of other changes in indication for use was not well documented and often unclear. One veteran had 4 different indications for use documented in the medical record, often changing with each change in prescriber. It appeared that the most recent prescriber was uncertain of the actual indication for use but did not want to discontinue the medication. This prescriber documented that the stimulant medication should continue for presumed ADHD/mood/fatigue/cognitive dysfunction, which were all of the indications documented by the veteran’s previous prescribers.

Reasons for Discontinuation

ADHD was the most prominent indication for use, although the indication was changed to ADHD-like symptoms in several veterans for whom diagnostic testing did not support the ADHD diagnosis. Seventy-eight of 133 veterans prescribed stimulant medications for ADHD received diagnostic testing via a psychologist at LVAHCS. For the 11 veterans who had testing after stimulant initiation, a stimulant-free period was required prior to testing to ensure an accurate diagnosis. For 21% of veterans, the ADHD diagnosis was unsubstantiated by formal testing; however, all of these veterans continued stimulant medication use. For 1 veteran, the psychologist performing the testing documented new diagnoses, including moderate to severe stimulant use disorder and malingering both for PTSD and ADHD. The rate of stimulant prescribing inconsistency, “prescriber-hopping,” and unsupported ADHD diagnosis results warrant a conversation about expectations for transitions of care regarding stimulant medications, not only from outside to inside LVAHCS, but from prescriber to prescriber within the facility.

In some cases, stimulant medications were discontinued by a prescriber secondary to a worsening of another mental health condition. More than half of the participants in this study had an anxiety disorder diagnosis. Whether or not anxiety predated stimulant use or whether the use of stimulant medications contributed to the diagnosis and thus the addition of an additional CNS depressant to treat anxiety may be an area of research for future consideration. Although bipolar disorder, anxiety disorders, psychosis, and SUD are not contraindications for use of stimulant medications, caution must be used in patients with these diagnoses. Prescribers must weigh risks vs benefits as well as perform close monitoring during use. Similarly, one might look further into stimulant medications prescribed for fatigue and assess the role of any simultaneously prescribed CNS depressants. Is the stimulant being used to treat the adverse effect (AE) of another medication? In 2 documented instances in this study, a psychologist conducted diagnostic testing who reported that the veteran did not meet the criteria for ADHD but that a stimulant may help counteract the iatrogenic effect of anticonvulsants. In both instances stimulant use continued.

Prescription Monitoring

Polysubstance use disorder (5%) was the third most common SUD recorded among study participants. The majority of those with polysubstance use disorder reported abuse/misuse of illicit or prescribed stimulants. Stimulant abuse/misuse was documented in 25 of 200 (12.5%) study participants. In several instances, abuse/misuse was detected by the LVAHCS delivery coordination pharmacist who tracks patterns of early fill requests and prescriptions reported lost/stolen. This pharmacist may request that the prescriber obtain PDMP query, UDS, or pill count if concerning patterns are noted. Lisdexamphetamine is a formulary-restricted medication at LVAHCS, but it was noted to be approved for use when prescribers requested an abuse-deterrent formulation. Investigators noticed a trend in veterans whose prescriptions exceeded the recommended maximum dosage also having stimulant abuse/misuse documented in their medical record. The highest documented total daily dose in this study was 120-mg amphetamine salts IR for ADHD, compared with the normal recommended dosing range of 5 to 40 mg/d for the same indication.

Various modalities were used to monitor participants but less than half of veterans had an annual UDS, quarterly PDMP query, and quarterly prescriber follow-up. PDMP queries and prescriber follow-up was assessed quarterly as would be reasonable given that private sector practitioners may issue multiple prescriptions authorizing the patient to receive up to a 90-day supply.7 Prescriber follow-up ranged from 1 to 15 months. A longer time to follow-up was seen more frequently in stimulant medications prescribed by primary care as compared with that of mental health.

Clinical Practice Protocol

Data from this study were collected with the intent to identify opportunities for improvement in the prescribing and monitoring of stimulant medications. From the above results investigators concluded that this facility may benefit from implementation of a facility-specific clinical practice protocol (CPP) for stimulant prescribing. It may also be beneficial to formulate a chronic stimulant management agreement between patient and prescriber to provide informed consent and clear expectations prior to stimulant medication initiation.

A CPP could be used to establish stimulant prescribing rules within a facility, which may limit who can prescribe stimulant medications or include a review process and/or required documentation in the medical record when being prescribed outside of specified dosing range and indications for use designated in the CPP or other evidence-based guidelines. Transition of care was found to be an area of opportunity in this study, which could be mitigated with the requirement of a baseline assessment prior to stimulant initiation with the expectation that it be completed regardless of prior prescription stimulant medication use. There was a lack of consistent monitoring for participants in this study, which may be improved if required monitoring parameters and frequency were provided for prescribers. For example, monitoring of heart rate and blood pressure was not assessed in this study, but a CPP may include monitoring vital signs before and after each dose change and every 6 months, per recommendation from the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence ADHD Diagnosis and Management guideline published in 2018.8The CPP may list the responsibilities of all those involved in the prescribing of stimulant medications, such as mental health service leadership, prescribers, nursing staff, pharmacists, social workers, psychologists, and other mental health staff. For prescribers this may include a thorough baseline assessment and criteria for use that must be met prior to stimulant initiation, documentation that must be included in the medical record and required monitoring during stimulant treatment, and expectations for increased monitoring and/or termination of treatment with nonadherence, diversion, or abuse/misuse.

The responsibilities of pharmacists may include establishing criteria for use of nonformulary and restricted agents as well as completion of nonformulary/restricted requests, reviewing dosages that exceed the recommended FDA daily maximum, reviewing uncommon off-label uses of stimulant medications, review and document early fill requests, potential nonadherence, potential drug-seeking behavior, and communication of the following information to the primary prescriber. For other mental health staff this may include documenting any reported AEs of the medication, referring the patient to their prescriber or pharmacist for any medication questions or concerns, and assessment of effectiveness and/or worsening behavior during patient contact.

Limitations

One limitation of this study was the way that data were pulled from patient charts. For example, only 3/200 participants in this study had insomnia per diagnosis codes, whereas that number was substantially higher when chart review was used to assess active prescriptions for sleep aids or documented complaints of insomnia in prescriber progress notes. For this same reason, rates of SUDs must be interpreted with caution as well. SUD diagnosis, both current and in remission were taken into account during data collection. Per diagnosis codes, 36 (18%) veterans in this study had a history of SUD, but this number was higher (31.5%) during chart review. The majority of discrepancies were found when participants reported a history of SUD to the prescriber, but this information was not captured via the problem list or encounter codes. What some may consider a minor omission in documentation can have a large impact on patient care as it is unlikely that prescribers have adequate administrative time to complete a chart review in order to find a complete past medical history as was required of investigators in this study. For this reason, incomplete provider documentation and human error that can occur as a result of a retrospective chart review were also identified as study limitations.

Conclusion

Our data show that there is still substantial room for improvement in the prescribing and monitoring of stimulant medications. The rate of stimulant prescribing inconsistency, prescriber-hopping, and unsupported ADHD diagnosis resulting from formal diagnostic testing warrant a review in the processes for transition of care regarding stimulant medications, both within and outside of this facility. A lack of consistent monitoring was also identified in this study. One of the most appreciable areas of opportunity resulting from this study is the need for consistency in both the prescribing and monitoring of stimulant medications. From the above results investigators concluded that this facility may benefit from implementation of a CPP for stimulant prescribing as well as a chronic stimulant management agreement to provide clear expectations for patients and prescribers prior to and during prescription stimulant use.

Acknowledgments

We thank Tori Wilhoit, PharmD candidate, and Dana Fischer, PharmD candidate, for their participation in data collection and Courtney Eatmon, PharmD, BCPP, for her general administrative support throughout this study.

1. Safer DJ. Recent trends in stimulant usage. J Atten Disord. 2016;20(6):471-477.

2. Christopher Jones; US Food and Drug Administration. The opioid epidemic overview and a look to the future. http://www.agencymeddirectors.wa.gov/Files/OpioidConference/2Jones_OPIOIDEPIDEMICOVERVIEW.pdf. Published June 12, 2015. Accessed January 16, 2020.

3. Compton WM, Han B, Blanco C, Johnson K, Jones CM. Prevalence and correlates of prescription stimulant use, misuse, use disorders, motivations for misuse among adults in the United States. Am J Psychiatry. 2018;175(8):741-755.