User login

Silent ischemia isn’t what it used to be

SNOWMASS, COLO. – The concept that silent myocardial ischemia is clinically detrimental has fallen by the wayside, and routine screening for this phenomenon can no longer be recommended, Patrick T. O’Gara, MD, said at the annual Cardiovascular Conference at Snowmass sponsored by the American College of Cardiology.

What a difference a decade or 2 can make.

“Think about where we were 25 years ago, when we worried about people who had transient ST-segment depression without angina on Holter monitoring. We would wig out, chase them down the street, try to tackle them and load them up with medications and think about balloon [percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty]. And now we’re at the point where it doesn’t seem to help with respect to quality of life, let alone death or myocardial infarction,” observed Dr. O’Gara, director of clinical cardiology at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, both in Boston.

The end of the line for the now-discredited notion that silent ischemia carries clinical significance approaching that of ischemia plus angina pectoris was the landmark ISCHEMIA trial, reported in November 2019 at the annual scientific sessions of the American Heart Association. This randomized trial asked the question: Is there any high-risk subgroup of patients with stable ischemic heart disease not involving the left main coronary artery for whom a strategy of routine revascularization improves hard outcomes in the current era of highly effective, guideline-directed medical therapy?

The answer turned out to be no. At 5 years of follow-up of 5,179 randomized patients with baseline stable coronary artery disease (CAD) and rigorously determined baseline moderate or severe ischemia affecting more than 10% of the myocardium, there was no difference between patients randomized to routine revascularization plus optimal medical therapy versus those on optimal medical therapy alone in the primary combined outcome of cardiovascular death, MI, heart failure, cardiac arrest, or hospitalization for unstable angina.

Of note, 35% of participants in the ISCHEMIA trial had moderate or severe silent ischemia. Like those who had angina, they achieved no additional benefit from a strategy of routine revascularization in terms of the primary outcome. ISCHEMIA participants with angina did show significant and durable improvements in quality of life and angina control with routine revascularization; however, those with silent ischemia showed little or no such improvement with an invasive strategy.

That being said, Dr. O’Gara added that he supports the ISCHEMIA investigators’ efforts to obtain funding from the National Institutes of Health for another 5 years or so of follow-up in order to determine whether revascularization actually does lead to improvement in the hard outcomes.

“Remember, in the STICH trial it took 10 years to show superiority of CABG [coronary artery bypass surgery] versus medical therapy to treat ischemic cardiomyopathy [N Engl J Med 2016; 374:1511-20]. My own view is that it’s too premature to throw the baby out with the bathwater. I think shared decision making is still very important, and I think, for many of our patients, relief of angina and improved quality of life are legitimate reasons in a low-risk situation with a good interventionalist to proceed,” he said.

Dr. O’Gara traced the history of medical thinking about silent ischemia. The notion that silent ischemia carried a clinical significance comparable with ischemia with angina gained wide credence more than 30 years ago, when investigators from the National Institutes of Health–sponsored Coronary Artery Surgery Study registry reported: “Patients with either silent or symptomatic ischemia during exercise testing have a similar risk of developing an acute myocardial infarction or sudden death – except in the three-vessel CAD subgroup, where the risk is greater in silent ischemia” (Am J Cardiol. 1988 Dec 1;62[17]:1155-8).

“This was a very important observation and led to many, many recommendations about screening and making sure that you took the expression of ST-segment depression on exercise treadmill testing pretty seriously, even if your patient did not have angina,” Dr. O’Gara recalled.

The prevailing wisdom that silent ischemia was detrimental took a hit in the Detection of Ischemia in Asymptomatic Diabetics (DIAC) trial. DIAC was conducted at a time when it had become clear that type 2 diabetes was a condition associated with increased cardiovascular risk, and that various methods of imaging were more accurate than treadmill exercise testing for the detection of underlying CAD. But when 1,123 DIAC participants with type 2 diabetes were randomized to screening with adenosine-stress radionuclide myocardial perfusion imaging or not and prospectively followed for roughly 5 years, it turned out there was no between-group difference in cardiac death or MI (JAMA. 2009 Apr 15;301[15]:1547-55).

“This pretty much put the lid on going out of one’s way to do routine screening of this nature in persons with diabetes who were considered to be at higher than average risk for the development of coronary disease,” the cardiologist commented.

Another fissure in the idea that silent ischemia was worth searching for and treating came from CLARIFY, an observational international registry of more than 20,000 individuals with stable CAD, roughly 12% of whom had silent ischemia, a figure in line with the prevalence reported in other studies. The 2-year rate of cardiovascular death or MI in the group with silent ischemia didn’t differ from the rate in patients with neither angina nor provocable ischemia. In contrast, rates of cardiovascular death or MI were significantly higher in the groups with angina but no ischemia or angina with ischemia (JAMA Intern Med. 2014 Oct;174[10]:1651-9).

“There’s something about the expression of angina that’s a very key clinical marker,” Dr. O’Gara observed.

He noted that just a few months before the ISCHEMIA trial results were released, a report from the far-smaller, randomized second Medicine, Angioplasty, or Surgery Study “threw cold water” on the notion that stress-induced ischemia in patients with multivessel CAD is a bad thing. Over 10 years of follow-up, the risk of major adverse cardiovascular events or deterioration in left ventricular function was identical in patients with or without baseline ischemia on stress testing performed after percutaneous coronary intervention, CABG surgery, or initiation of medical therapy (JAMA Intern Med. 2019 Jul 22. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.2227).

What the guidelines say

The 6-year-old U.S. guidelines on the diagnosis and management of patients with stable ischemic heart disease are clearly out of date on the topic of silent ischemia (Circulation. 2014 Nov 4;130[19]:1749-67). The recommendations are based on expert opinion formed prior to the massive amount of new evidence that has since become available. For example, the current guidelines state as a class IIa, level of evidence C recommendation that exercise or pharmacologic stress can be useful for follow-up assessment at 2-year or greater intervals in patients with stable ischemic heart disease with prior evidence of silent ischemia.

“This is a very weak recommendation. The class of recommendation says it would be reasonable, but in the absence of an evidence base and in light of newer information, I’m not sure that it approaches even a class IIa level of recommendation,” according to Dr. O’Gara.

The 2019 European Society of Cardiology guidelines on chronic coronary syndromes are similarly weak on silent ischemia. The European guidelines state that patients with diabetes or chronic kidney disease may have a higher burden of silent ischemia, might be at higher risk for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease events, and that periodic ECGs and functional testing every 3-5 years might be considered.

“Obviously there’s a lot of leeway there in how you wish to interpret that,” Dr. O’Gara said. “And this did not rise to the level where they’d put it in the table of recommendations, but it’s simply included as part of the explanatory text.”

What’s coming next in stable ischemic heart disease

“Nowadays all the rage has to do with coronary microvascular dysfunction,” according to Dr. O’Gara. “I think all of the research interest currently is focused on the coronary microcirculation as perhaps the next frontier in our understanding of why it is that ischemia can occur in the absence of epicardial coronary disease.”

He highly recommended a review article entitled: “Reappraisal of Ischemic Heart Disease,” in which an international trio of prominent cardiologists asserted that coronary microvascular dysfunction not only plays a pivotal pathogenic role in angina pectoris, but also in a phenomenon known as microvascular angina – that is, angina in the absence of obstructive CAD. Microvascular angina may explain the roughly one-third of patients who experience acute coronary syndrome without epicardial coronary artery stenosis or thrombosis. The authors delved into the structural and functional mechanisms underlying coronary microvascular dysfunction, while noting that effective treatment of this common phenomenon remains a major unmet need (Circulation. 2018 Oct 2;138[14]:1463-80).

Dr. O’Gara reported receiving funding from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; from Medtronic in conjunction with the ongoing pivotal APOLLO transcatheter mitral valve replacement trial; from Edwards Lifesciences for the ongoing EARLY TAVR trial; and from Medtrace Pharma, a Danish company developing an innovative form of PET diagnostic imaging.

SNOWMASS, COLO. – The concept that silent myocardial ischemia is clinically detrimental has fallen by the wayside, and routine screening for this phenomenon can no longer be recommended, Patrick T. O’Gara, MD, said at the annual Cardiovascular Conference at Snowmass sponsored by the American College of Cardiology.

What a difference a decade or 2 can make.

“Think about where we were 25 years ago, when we worried about people who had transient ST-segment depression without angina on Holter monitoring. We would wig out, chase them down the street, try to tackle them and load them up with medications and think about balloon [percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty]. And now we’re at the point where it doesn’t seem to help with respect to quality of life, let alone death or myocardial infarction,” observed Dr. O’Gara, director of clinical cardiology at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, both in Boston.

The end of the line for the now-discredited notion that silent ischemia carries clinical significance approaching that of ischemia plus angina pectoris was the landmark ISCHEMIA trial, reported in November 2019 at the annual scientific sessions of the American Heart Association. This randomized trial asked the question: Is there any high-risk subgroup of patients with stable ischemic heart disease not involving the left main coronary artery for whom a strategy of routine revascularization improves hard outcomes in the current era of highly effective, guideline-directed medical therapy?

The answer turned out to be no. At 5 years of follow-up of 5,179 randomized patients with baseline stable coronary artery disease (CAD) and rigorously determined baseline moderate or severe ischemia affecting more than 10% of the myocardium, there was no difference between patients randomized to routine revascularization plus optimal medical therapy versus those on optimal medical therapy alone in the primary combined outcome of cardiovascular death, MI, heart failure, cardiac arrest, or hospitalization for unstable angina.

Of note, 35% of participants in the ISCHEMIA trial had moderate or severe silent ischemia. Like those who had angina, they achieved no additional benefit from a strategy of routine revascularization in terms of the primary outcome. ISCHEMIA participants with angina did show significant and durable improvements in quality of life and angina control with routine revascularization; however, those with silent ischemia showed little or no such improvement with an invasive strategy.

That being said, Dr. O’Gara added that he supports the ISCHEMIA investigators’ efforts to obtain funding from the National Institutes of Health for another 5 years or so of follow-up in order to determine whether revascularization actually does lead to improvement in the hard outcomes.

“Remember, in the STICH trial it took 10 years to show superiority of CABG [coronary artery bypass surgery] versus medical therapy to treat ischemic cardiomyopathy [N Engl J Med 2016; 374:1511-20]. My own view is that it’s too premature to throw the baby out with the bathwater. I think shared decision making is still very important, and I think, for many of our patients, relief of angina and improved quality of life are legitimate reasons in a low-risk situation with a good interventionalist to proceed,” he said.

Dr. O’Gara traced the history of medical thinking about silent ischemia. The notion that silent ischemia carried a clinical significance comparable with ischemia with angina gained wide credence more than 30 years ago, when investigators from the National Institutes of Health–sponsored Coronary Artery Surgery Study registry reported: “Patients with either silent or symptomatic ischemia during exercise testing have a similar risk of developing an acute myocardial infarction or sudden death – except in the three-vessel CAD subgroup, where the risk is greater in silent ischemia” (Am J Cardiol. 1988 Dec 1;62[17]:1155-8).

“This was a very important observation and led to many, many recommendations about screening and making sure that you took the expression of ST-segment depression on exercise treadmill testing pretty seriously, even if your patient did not have angina,” Dr. O’Gara recalled.

The prevailing wisdom that silent ischemia was detrimental took a hit in the Detection of Ischemia in Asymptomatic Diabetics (DIAC) trial. DIAC was conducted at a time when it had become clear that type 2 diabetes was a condition associated with increased cardiovascular risk, and that various methods of imaging were more accurate than treadmill exercise testing for the detection of underlying CAD. But when 1,123 DIAC participants with type 2 diabetes were randomized to screening with adenosine-stress radionuclide myocardial perfusion imaging or not and prospectively followed for roughly 5 years, it turned out there was no between-group difference in cardiac death or MI (JAMA. 2009 Apr 15;301[15]:1547-55).

“This pretty much put the lid on going out of one’s way to do routine screening of this nature in persons with diabetes who were considered to be at higher than average risk for the development of coronary disease,” the cardiologist commented.

Another fissure in the idea that silent ischemia was worth searching for and treating came from CLARIFY, an observational international registry of more than 20,000 individuals with stable CAD, roughly 12% of whom had silent ischemia, a figure in line with the prevalence reported in other studies. The 2-year rate of cardiovascular death or MI in the group with silent ischemia didn’t differ from the rate in patients with neither angina nor provocable ischemia. In contrast, rates of cardiovascular death or MI were significantly higher in the groups with angina but no ischemia or angina with ischemia (JAMA Intern Med. 2014 Oct;174[10]:1651-9).

“There’s something about the expression of angina that’s a very key clinical marker,” Dr. O’Gara observed.

He noted that just a few months before the ISCHEMIA trial results were released, a report from the far-smaller, randomized second Medicine, Angioplasty, or Surgery Study “threw cold water” on the notion that stress-induced ischemia in patients with multivessel CAD is a bad thing. Over 10 years of follow-up, the risk of major adverse cardiovascular events or deterioration in left ventricular function was identical in patients with or without baseline ischemia on stress testing performed after percutaneous coronary intervention, CABG surgery, or initiation of medical therapy (JAMA Intern Med. 2019 Jul 22. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.2227).

What the guidelines say

The 6-year-old U.S. guidelines on the diagnosis and management of patients with stable ischemic heart disease are clearly out of date on the topic of silent ischemia (Circulation. 2014 Nov 4;130[19]:1749-67). The recommendations are based on expert opinion formed prior to the massive amount of new evidence that has since become available. For example, the current guidelines state as a class IIa, level of evidence C recommendation that exercise or pharmacologic stress can be useful for follow-up assessment at 2-year or greater intervals in patients with stable ischemic heart disease with prior evidence of silent ischemia.

“This is a very weak recommendation. The class of recommendation says it would be reasonable, but in the absence of an evidence base and in light of newer information, I’m not sure that it approaches even a class IIa level of recommendation,” according to Dr. O’Gara.

The 2019 European Society of Cardiology guidelines on chronic coronary syndromes are similarly weak on silent ischemia. The European guidelines state that patients with diabetes or chronic kidney disease may have a higher burden of silent ischemia, might be at higher risk for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease events, and that periodic ECGs and functional testing every 3-5 years might be considered.

“Obviously there’s a lot of leeway there in how you wish to interpret that,” Dr. O’Gara said. “And this did not rise to the level where they’d put it in the table of recommendations, but it’s simply included as part of the explanatory text.”

What’s coming next in stable ischemic heart disease

“Nowadays all the rage has to do with coronary microvascular dysfunction,” according to Dr. O’Gara. “I think all of the research interest currently is focused on the coronary microcirculation as perhaps the next frontier in our understanding of why it is that ischemia can occur in the absence of epicardial coronary disease.”

He highly recommended a review article entitled: “Reappraisal of Ischemic Heart Disease,” in which an international trio of prominent cardiologists asserted that coronary microvascular dysfunction not only plays a pivotal pathogenic role in angina pectoris, but also in a phenomenon known as microvascular angina – that is, angina in the absence of obstructive CAD. Microvascular angina may explain the roughly one-third of patients who experience acute coronary syndrome without epicardial coronary artery stenosis or thrombosis. The authors delved into the structural and functional mechanisms underlying coronary microvascular dysfunction, while noting that effective treatment of this common phenomenon remains a major unmet need (Circulation. 2018 Oct 2;138[14]:1463-80).

Dr. O’Gara reported receiving funding from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; from Medtronic in conjunction with the ongoing pivotal APOLLO transcatheter mitral valve replacement trial; from Edwards Lifesciences for the ongoing EARLY TAVR trial; and from Medtrace Pharma, a Danish company developing an innovative form of PET diagnostic imaging.

SNOWMASS, COLO. – The concept that silent myocardial ischemia is clinically detrimental has fallen by the wayside, and routine screening for this phenomenon can no longer be recommended, Patrick T. O’Gara, MD, said at the annual Cardiovascular Conference at Snowmass sponsored by the American College of Cardiology.

What a difference a decade or 2 can make.

“Think about where we were 25 years ago, when we worried about people who had transient ST-segment depression without angina on Holter monitoring. We would wig out, chase them down the street, try to tackle them and load them up with medications and think about balloon [percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty]. And now we’re at the point where it doesn’t seem to help with respect to quality of life, let alone death or myocardial infarction,” observed Dr. O’Gara, director of clinical cardiology at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, both in Boston.

The end of the line for the now-discredited notion that silent ischemia carries clinical significance approaching that of ischemia plus angina pectoris was the landmark ISCHEMIA trial, reported in November 2019 at the annual scientific sessions of the American Heart Association. This randomized trial asked the question: Is there any high-risk subgroup of patients with stable ischemic heart disease not involving the left main coronary artery for whom a strategy of routine revascularization improves hard outcomes in the current era of highly effective, guideline-directed medical therapy?

The answer turned out to be no. At 5 years of follow-up of 5,179 randomized patients with baseline stable coronary artery disease (CAD) and rigorously determined baseline moderate or severe ischemia affecting more than 10% of the myocardium, there was no difference between patients randomized to routine revascularization plus optimal medical therapy versus those on optimal medical therapy alone in the primary combined outcome of cardiovascular death, MI, heart failure, cardiac arrest, or hospitalization for unstable angina.

Of note, 35% of participants in the ISCHEMIA trial had moderate or severe silent ischemia. Like those who had angina, they achieved no additional benefit from a strategy of routine revascularization in terms of the primary outcome. ISCHEMIA participants with angina did show significant and durable improvements in quality of life and angina control with routine revascularization; however, those with silent ischemia showed little or no such improvement with an invasive strategy.

That being said, Dr. O’Gara added that he supports the ISCHEMIA investigators’ efforts to obtain funding from the National Institutes of Health for another 5 years or so of follow-up in order to determine whether revascularization actually does lead to improvement in the hard outcomes.

“Remember, in the STICH trial it took 10 years to show superiority of CABG [coronary artery bypass surgery] versus medical therapy to treat ischemic cardiomyopathy [N Engl J Med 2016; 374:1511-20]. My own view is that it’s too premature to throw the baby out with the bathwater. I think shared decision making is still very important, and I think, for many of our patients, relief of angina and improved quality of life are legitimate reasons in a low-risk situation with a good interventionalist to proceed,” he said.

Dr. O’Gara traced the history of medical thinking about silent ischemia. The notion that silent ischemia carried a clinical significance comparable with ischemia with angina gained wide credence more than 30 years ago, when investigators from the National Institutes of Health–sponsored Coronary Artery Surgery Study registry reported: “Patients with either silent or symptomatic ischemia during exercise testing have a similar risk of developing an acute myocardial infarction or sudden death – except in the three-vessel CAD subgroup, where the risk is greater in silent ischemia” (Am J Cardiol. 1988 Dec 1;62[17]:1155-8).

“This was a very important observation and led to many, many recommendations about screening and making sure that you took the expression of ST-segment depression on exercise treadmill testing pretty seriously, even if your patient did not have angina,” Dr. O’Gara recalled.

The prevailing wisdom that silent ischemia was detrimental took a hit in the Detection of Ischemia in Asymptomatic Diabetics (DIAC) trial. DIAC was conducted at a time when it had become clear that type 2 diabetes was a condition associated with increased cardiovascular risk, and that various methods of imaging were more accurate than treadmill exercise testing for the detection of underlying CAD. But when 1,123 DIAC participants with type 2 diabetes were randomized to screening with adenosine-stress radionuclide myocardial perfusion imaging or not and prospectively followed for roughly 5 years, it turned out there was no between-group difference in cardiac death or MI (JAMA. 2009 Apr 15;301[15]:1547-55).

“This pretty much put the lid on going out of one’s way to do routine screening of this nature in persons with diabetes who were considered to be at higher than average risk for the development of coronary disease,” the cardiologist commented.

Another fissure in the idea that silent ischemia was worth searching for and treating came from CLARIFY, an observational international registry of more than 20,000 individuals with stable CAD, roughly 12% of whom had silent ischemia, a figure in line with the prevalence reported in other studies. The 2-year rate of cardiovascular death or MI in the group with silent ischemia didn’t differ from the rate in patients with neither angina nor provocable ischemia. In contrast, rates of cardiovascular death or MI were significantly higher in the groups with angina but no ischemia or angina with ischemia (JAMA Intern Med. 2014 Oct;174[10]:1651-9).

“There’s something about the expression of angina that’s a very key clinical marker,” Dr. O’Gara observed.

He noted that just a few months before the ISCHEMIA trial results were released, a report from the far-smaller, randomized second Medicine, Angioplasty, or Surgery Study “threw cold water” on the notion that stress-induced ischemia in patients with multivessel CAD is a bad thing. Over 10 years of follow-up, the risk of major adverse cardiovascular events or deterioration in left ventricular function was identical in patients with or without baseline ischemia on stress testing performed after percutaneous coronary intervention, CABG surgery, or initiation of medical therapy (JAMA Intern Med. 2019 Jul 22. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.2227).

What the guidelines say

The 6-year-old U.S. guidelines on the diagnosis and management of patients with stable ischemic heart disease are clearly out of date on the topic of silent ischemia (Circulation. 2014 Nov 4;130[19]:1749-67). The recommendations are based on expert opinion formed prior to the massive amount of new evidence that has since become available. For example, the current guidelines state as a class IIa, level of evidence C recommendation that exercise or pharmacologic stress can be useful for follow-up assessment at 2-year or greater intervals in patients with stable ischemic heart disease with prior evidence of silent ischemia.

“This is a very weak recommendation. The class of recommendation says it would be reasonable, but in the absence of an evidence base and in light of newer information, I’m not sure that it approaches even a class IIa level of recommendation,” according to Dr. O’Gara.

The 2019 European Society of Cardiology guidelines on chronic coronary syndromes are similarly weak on silent ischemia. The European guidelines state that patients with diabetes or chronic kidney disease may have a higher burden of silent ischemia, might be at higher risk for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease events, and that periodic ECGs and functional testing every 3-5 years might be considered.

“Obviously there’s a lot of leeway there in how you wish to interpret that,” Dr. O’Gara said. “And this did not rise to the level where they’d put it in the table of recommendations, but it’s simply included as part of the explanatory text.”

What’s coming next in stable ischemic heart disease

“Nowadays all the rage has to do with coronary microvascular dysfunction,” according to Dr. O’Gara. “I think all of the research interest currently is focused on the coronary microcirculation as perhaps the next frontier in our understanding of why it is that ischemia can occur in the absence of epicardial coronary disease.”

He highly recommended a review article entitled: “Reappraisal of Ischemic Heart Disease,” in which an international trio of prominent cardiologists asserted that coronary microvascular dysfunction not only plays a pivotal pathogenic role in angina pectoris, but also in a phenomenon known as microvascular angina – that is, angina in the absence of obstructive CAD. Microvascular angina may explain the roughly one-third of patients who experience acute coronary syndrome without epicardial coronary artery stenosis or thrombosis. The authors delved into the structural and functional mechanisms underlying coronary microvascular dysfunction, while noting that effective treatment of this common phenomenon remains a major unmet need (Circulation. 2018 Oct 2;138[14]:1463-80).

Dr. O’Gara reported receiving funding from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; from Medtronic in conjunction with the ongoing pivotal APOLLO transcatheter mitral valve replacement trial; from Edwards Lifesciences for the ongoing EARLY TAVR trial; and from Medtrace Pharma, a Danish company developing an innovative form of PET diagnostic imaging.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM ACC SNOWMASS 2020

Docs weigh pulling out of MIPS over paltry payments

If you’ve knocked yourself out to earn a Merit-Based Incentive Payment System (MIPS) bonus payment, it’s pretty safe to say that getting a 1.68% payment boost probably didn’t feel like a “win” that was worth the effort.

And although it saved you from having a negative 5% payment adjustment, many physicians don’t feel that it was worth the effort.

On Jan. 6, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services announced the 2020 payouts for MIPS.

Based on 2018 participation, the bonus for those who scored a perfect 100 is only a 1.68% boost in Medicare reimbursement, slightly lower than last year’s 1.88%. This decline comes as no surprise as the agency leader admits: “As the program matures, we expect that the increases in the performance thresholds in future program years will create a smaller distribution of positive payment adjustments.” Overall, more than 97% of participants avoided having a negative 5% payment adjustment.

Indeed, these bonus monies are based on a short-term appropriation of extra funds from Congress. After these temporary funds are no longer available, there will be little, if any, monies to distribute as the program is based on a “losers-feed-the-winners” construct.

It may be very tempting for many physicians to decide to ignore MIPS, with the rationale that 1.68% is not worth the effort. But don’t let your foot off the gas pedal yet, since the penalty for not participating in 2020 is a substantial 9%.

However, it is certainly time to reconsider efforts to participate at the highest level.

Should you or shouldn’t you bother with MIPS?

Let’s say you have $75,000 in revenue from Medicare Part B per year. Depending on the services you offer in your practice, that equates to 500-750 encounters with Medicare beneficiaries per year. (A reminder that MIPS affects only Part B; Medicare Advantage plans do not partake in the program.)

The recent announcement reveals that perfection would equate to an additional $1,260 per year. That’s only if you received the full 100 points; if you were simply an “exceptional performer,” the government will allot an additional $157. That’s less than you get paid for a single office visit.

The difference between perfection and compliance is approximately $1,000. Failure to participate, however, knocks $6,750 off your bottom line. Clearly, that’s a substantial financial loss that would affect most practices. Obviously, the numbers change if you have higher – or lower – Medicare revenue, but it’s important to do the math.

Why? Physicians are spending a significant amount of money to comply with the program requirements. This includes substantial payments to registries – typically $200 to >$1,000 per year – to report the quality measures for the program; electronic health record (EHR) systems, many of which require additional funding for the “upgrade” to a MIPS-compatible system, are also a sizable investment.

These hard costs pale in comparison with the time spent on understanding the ever-changing requirements of the program and the process by which your practice will implement them. Take, for example, something as innocuous as the required “Support Electronic Referral Loops by Receiving and Incorporating Health Information.”

You first must understand the elements of the measure: What is a “referral loop?” When do we need to generate one? To whom shall it be sent? What needs to be included in “health information?” What is the electronic address to which we should route the information? How do we obtain that address? Then you must determine how your EHR system captures and reports it.

Only then comes the hard part: How are we going to implement this? That’s only one of more than a dozen required elements: six quality measures, two (to four) improvement activities, and four promoting interoperability requirements. Each one of these elements has a host of requirements, all listed on multipage specification sheets.

The government does not seem to be listening. John Cullen, MD, president of the American Academy of Family Physicians, testified at the Senate Finance Committee in May 2019 that MIPS “has created a burdensome and extremely complex program that has increased practice costs ... ” Yet, later that year, CMS issued another hefty ruling that outlines significant changes to the program, despite the fact that it’s in its fourth performance year.

Turning frustration into action

Frustration or even anger may be one reaction, but now is an opportune time to determine your investment in the program. At a minimum, it’s vital to understand and meet the threshold to avoid the penalty. It’s been shifting to date, but it’s now set at 9% for perpetuity.

First, it’s crucial to check on your participation status. CMS revealed that the participation database was recently corrected for so-called inconsistencies, so it pays to double-check. It only takes seconds: Insert your NPI in the QPP Participation Status Tool to determine your eligibility for 2020.

In 2020, the threshold to avoid the penalty is 45 points. To get the 45 points, practices must participate in two improvement activities, which is not difficult as there are 118 options. That will garner 15 points. Then there are 45 points available from the quality category; you need at least 30 to reach the 45-point threshold for penalty avoidance.

Smart MIPS hacks that can help you

To obtain the additional 30 points, turn your attention to the quality category. There are 268 quality measures; choose at least six to measure. If you report directly from your EHR system, you’ll get a bonus point for each reported measure, plus one just for trying. (There are a few other opportunities for bonus points, such as improving your scores over last year.) Those bonus points give you a base with which to work, but getting to 45 will require effort to report successfully on at least a couple of the measures.

The quality category has a total of 100 points available, which are converted to 45 toward your composite score. Since you need 30 to reach that magical 45 (if 15 were attained from improvement activities), that means you must come up with 75 points in the quality category. Between the bonus points and measuring a handful of measures successfully through the year, you’ll achieve this threshold.

There are two other categories in the program: promoting interoperability (PI) and cost. The PI category mirrors the old “meaningful use” program; however, it has become increasingly difficult over the years. If you think that you can meet the required elements, you can pick up 25 more points toward your composite score.

Cost is a bit of an unknown, as the scoring is based on a retrospective review of your claims. You’ll likely pick up a few more points on this 15-point category, but there’s no method to determine performance until after the reporting period. Therefore, be cautious about relying on this category.

The best MIPS hack, however, is if you are a small practice. CMS – remarkably – defines a “small practice” as 15 or fewer eligible professionals. If you qualify under this paradigm, you have multiple options to ease compliance:

Apply for a “hardship exemption” simply on the basis of being small; the exemption relates to the promoting operability category, shifting those points to the quality category.

Gain three points per quality measure, regardless of data completeness; this compares to just one point for other physicians.

Capture all of the points available from the Improvement Activities category by confirming participation with just a single activity. (This also applies to all physicians in rural or Health Professional Shortage Areas.)

In the event that you don’t qualify as a “small practice” or you’re still falling short of the requirements, CMS allows for the ultimate “out”: You can apply for exemption on the basis of an “extreme and uncontrollable circumstance.” The applications for these exceptions open this summer.

Unless you qualify for the program exemption, it’s important to keep pace with the program to ensure that you reach the 45-point threshold. It may not, however, be worthwhile to gear up for all 100 points unless your estimate of the potential return – and what it costs you to get there – reveals otherwise. MIPS is not going anywhere; the program is written into the law.

But that doesn’t mean that CMS can’t make tweaks and updates. Hopefully, the revisions won’t create even more administrative burden as the program is quickly turning into a big stick with only a small carrot at the end.

Elizabeth Woodcock is president of Woodcock & Associates in Atlanta. She has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

If you’ve knocked yourself out to earn a Merit-Based Incentive Payment System (MIPS) bonus payment, it’s pretty safe to say that getting a 1.68% payment boost probably didn’t feel like a “win” that was worth the effort.

And although it saved you from having a negative 5% payment adjustment, many physicians don’t feel that it was worth the effort.

On Jan. 6, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services announced the 2020 payouts for MIPS.

Based on 2018 participation, the bonus for those who scored a perfect 100 is only a 1.68% boost in Medicare reimbursement, slightly lower than last year’s 1.88%. This decline comes as no surprise as the agency leader admits: “As the program matures, we expect that the increases in the performance thresholds in future program years will create a smaller distribution of positive payment adjustments.” Overall, more than 97% of participants avoided having a negative 5% payment adjustment.

Indeed, these bonus monies are based on a short-term appropriation of extra funds from Congress. After these temporary funds are no longer available, there will be little, if any, monies to distribute as the program is based on a “losers-feed-the-winners” construct.

It may be very tempting for many physicians to decide to ignore MIPS, with the rationale that 1.68% is not worth the effort. But don’t let your foot off the gas pedal yet, since the penalty for not participating in 2020 is a substantial 9%.

However, it is certainly time to reconsider efforts to participate at the highest level.

Should you or shouldn’t you bother with MIPS?

Let’s say you have $75,000 in revenue from Medicare Part B per year. Depending on the services you offer in your practice, that equates to 500-750 encounters with Medicare beneficiaries per year. (A reminder that MIPS affects only Part B; Medicare Advantage plans do not partake in the program.)

The recent announcement reveals that perfection would equate to an additional $1,260 per year. That’s only if you received the full 100 points; if you were simply an “exceptional performer,” the government will allot an additional $157. That’s less than you get paid for a single office visit.

The difference between perfection and compliance is approximately $1,000. Failure to participate, however, knocks $6,750 off your bottom line. Clearly, that’s a substantial financial loss that would affect most practices. Obviously, the numbers change if you have higher – or lower – Medicare revenue, but it’s important to do the math.

Why? Physicians are spending a significant amount of money to comply with the program requirements. This includes substantial payments to registries – typically $200 to >$1,000 per year – to report the quality measures for the program; electronic health record (EHR) systems, many of which require additional funding for the “upgrade” to a MIPS-compatible system, are also a sizable investment.

These hard costs pale in comparison with the time spent on understanding the ever-changing requirements of the program and the process by which your practice will implement them. Take, for example, something as innocuous as the required “Support Electronic Referral Loops by Receiving and Incorporating Health Information.”

You first must understand the elements of the measure: What is a “referral loop?” When do we need to generate one? To whom shall it be sent? What needs to be included in “health information?” What is the electronic address to which we should route the information? How do we obtain that address? Then you must determine how your EHR system captures and reports it.

Only then comes the hard part: How are we going to implement this? That’s only one of more than a dozen required elements: six quality measures, two (to four) improvement activities, and four promoting interoperability requirements. Each one of these elements has a host of requirements, all listed on multipage specification sheets.

The government does not seem to be listening. John Cullen, MD, president of the American Academy of Family Physicians, testified at the Senate Finance Committee in May 2019 that MIPS “has created a burdensome and extremely complex program that has increased practice costs ... ” Yet, later that year, CMS issued another hefty ruling that outlines significant changes to the program, despite the fact that it’s in its fourth performance year.

Turning frustration into action

Frustration or even anger may be one reaction, but now is an opportune time to determine your investment in the program. At a minimum, it’s vital to understand and meet the threshold to avoid the penalty. It’s been shifting to date, but it’s now set at 9% for perpetuity.

First, it’s crucial to check on your participation status. CMS revealed that the participation database was recently corrected for so-called inconsistencies, so it pays to double-check. It only takes seconds: Insert your NPI in the QPP Participation Status Tool to determine your eligibility for 2020.

In 2020, the threshold to avoid the penalty is 45 points. To get the 45 points, practices must participate in two improvement activities, which is not difficult as there are 118 options. That will garner 15 points. Then there are 45 points available from the quality category; you need at least 30 to reach the 45-point threshold for penalty avoidance.

Smart MIPS hacks that can help you

To obtain the additional 30 points, turn your attention to the quality category. There are 268 quality measures; choose at least six to measure. If you report directly from your EHR system, you’ll get a bonus point for each reported measure, plus one just for trying. (There are a few other opportunities for bonus points, such as improving your scores over last year.) Those bonus points give you a base with which to work, but getting to 45 will require effort to report successfully on at least a couple of the measures.

The quality category has a total of 100 points available, which are converted to 45 toward your composite score. Since you need 30 to reach that magical 45 (if 15 were attained from improvement activities), that means you must come up with 75 points in the quality category. Between the bonus points and measuring a handful of measures successfully through the year, you’ll achieve this threshold.

There are two other categories in the program: promoting interoperability (PI) and cost. The PI category mirrors the old “meaningful use” program; however, it has become increasingly difficult over the years. If you think that you can meet the required elements, you can pick up 25 more points toward your composite score.

Cost is a bit of an unknown, as the scoring is based on a retrospective review of your claims. You’ll likely pick up a few more points on this 15-point category, but there’s no method to determine performance until after the reporting period. Therefore, be cautious about relying on this category.

The best MIPS hack, however, is if you are a small practice. CMS – remarkably – defines a “small practice” as 15 or fewer eligible professionals. If you qualify under this paradigm, you have multiple options to ease compliance:

Apply for a “hardship exemption” simply on the basis of being small; the exemption relates to the promoting operability category, shifting those points to the quality category.

Gain three points per quality measure, regardless of data completeness; this compares to just one point for other physicians.

Capture all of the points available from the Improvement Activities category by confirming participation with just a single activity. (This also applies to all physicians in rural or Health Professional Shortage Areas.)

In the event that you don’t qualify as a “small practice” or you’re still falling short of the requirements, CMS allows for the ultimate “out”: You can apply for exemption on the basis of an “extreme and uncontrollable circumstance.” The applications for these exceptions open this summer.

Unless you qualify for the program exemption, it’s important to keep pace with the program to ensure that you reach the 45-point threshold. It may not, however, be worthwhile to gear up for all 100 points unless your estimate of the potential return – and what it costs you to get there – reveals otherwise. MIPS is not going anywhere; the program is written into the law.

But that doesn’t mean that CMS can’t make tweaks and updates. Hopefully, the revisions won’t create even more administrative burden as the program is quickly turning into a big stick with only a small carrot at the end.

Elizabeth Woodcock is president of Woodcock & Associates in Atlanta. She has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

If you’ve knocked yourself out to earn a Merit-Based Incentive Payment System (MIPS) bonus payment, it’s pretty safe to say that getting a 1.68% payment boost probably didn’t feel like a “win” that was worth the effort.

And although it saved you from having a negative 5% payment adjustment, many physicians don’t feel that it was worth the effort.

On Jan. 6, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services announced the 2020 payouts for MIPS.

Based on 2018 participation, the bonus for those who scored a perfect 100 is only a 1.68% boost in Medicare reimbursement, slightly lower than last year’s 1.88%. This decline comes as no surprise as the agency leader admits: “As the program matures, we expect that the increases in the performance thresholds in future program years will create a smaller distribution of positive payment adjustments.” Overall, more than 97% of participants avoided having a negative 5% payment adjustment.

Indeed, these bonus monies are based on a short-term appropriation of extra funds from Congress. After these temporary funds are no longer available, there will be little, if any, monies to distribute as the program is based on a “losers-feed-the-winners” construct.

It may be very tempting for many physicians to decide to ignore MIPS, with the rationale that 1.68% is not worth the effort. But don’t let your foot off the gas pedal yet, since the penalty for not participating in 2020 is a substantial 9%.

However, it is certainly time to reconsider efforts to participate at the highest level.

Should you or shouldn’t you bother with MIPS?

Let’s say you have $75,000 in revenue from Medicare Part B per year. Depending on the services you offer in your practice, that equates to 500-750 encounters with Medicare beneficiaries per year. (A reminder that MIPS affects only Part B; Medicare Advantage plans do not partake in the program.)

The recent announcement reveals that perfection would equate to an additional $1,260 per year. That’s only if you received the full 100 points; if you were simply an “exceptional performer,” the government will allot an additional $157. That’s less than you get paid for a single office visit.

The difference between perfection and compliance is approximately $1,000. Failure to participate, however, knocks $6,750 off your bottom line. Clearly, that’s a substantial financial loss that would affect most practices. Obviously, the numbers change if you have higher – or lower – Medicare revenue, but it’s important to do the math.

Why? Physicians are spending a significant amount of money to comply with the program requirements. This includes substantial payments to registries – typically $200 to >$1,000 per year – to report the quality measures for the program; electronic health record (EHR) systems, many of which require additional funding for the “upgrade” to a MIPS-compatible system, are also a sizable investment.

These hard costs pale in comparison with the time spent on understanding the ever-changing requirements of the program and the process by which your practice will implement them. Take, for example, something as innocuous as the required “Support Electronic Referral Loops by Receiving and Incorporating Health Information.”

You first must understand the elements of the measure: What is a “referral loop?” When do we need to generate one? To whom shall it be sent? What needs to be included in “health information?” What is the electronic address to which we should route the information? How do we obtain that address? Then you must determine how your EHR system captures and reports it.

Only then comes the hard part: How are we going to implement this? That’s only one of more than a dozen required elements: six quality measures, two (to four) improvement activities, and four promoting interoperability requirements. Each one of these elements has a host of requirements, all listed on multipage specification sheets.

The government does not seem to be listening. John Cullen, MD, president of the American Academy of Family Physicians, testified at the Senate Finance Committee in May 2019 that MIPS “has created a burdensome and extremely complex program that has increased practice costs ... ” Yet, later that year, CMS issued another hefty ruling that outlines significant changes to the program, despite the fact that it’s in its fourth performance year.

Turning frustration into action

Frustration or even anger may be one reaction, but now is an opportune time to determine your investment in the program. At a minimum, it’s vital to understand and meet the threshold to avoid the penalty. It’s been shifting to date, but it’s now set at 9% for perpetuity.

First, it’s crucial to check on your participation status. CMS revealed that the participation database was recently corrected for so-called inconsistencies, so it pays to double-check. It only takes seconds: Insert your NPI in the QPP Participation Status Tool to determine your eligibility for 2020.

In 2020, the threshold to avoid the penalty is 45 points. To get the 45 points, practices must participate in two improvement activities, which is not difficult as there are 118 options. That will garner 15 points. Then there are 45 points available from the quality category; you need at least 30 to reach the 45-point threshold for penalty avoidance.

Smart MIPS hacks that can help you

To obtain the additional 30 points, turn your attention to the quality category. There are 268 quality measures; choose at least six to measure. If you report directly from your EHR system, you’ll get a bonus point for each reported measure, plus one just for trying. (There are a few other opportunities for bonus points, such as improving your scores over last year.) Those bonus points give you a base with which to work, but getting to 45 will require effort to report successfully on at least a couple of the measures.

The quality category has a total of 100 points available, which are converted to 45 toward your composite score. Since you need 30 to reach that magical 45 (if 15 were attained from improvement activities), that means you must come up with 75 points in the quality category. Between the bonus points and measuring a handful of measures successfully through the year, you’ll achieve this threshold.

There are two other categories in the program: promoting interoperability (PI) and cost. The PI category mirrors the old “meaningful use” program; however, it has become increasingly difficult over the years. If you think that you can meet the required elements, you can pick up 25 more points toward your composite score.

Cost is a bit of an unknown, as the scoring is based on a retrospective review of your claims. You’ll likely pick up a few more points on this 15-point category, but there’s no method to determine performance until after the reporting period. Therefore, be cautious about relying on this category.

The best MIPS hack, however, is if you are a small practice. CMS – remarkably – defines a “small practice” as 15 or fewer eligible professionals. If you qualify under this paradigm, you have multiple options to ease compliance:

Apply for a “hardship exemption” simply on the basis of being small; the exemption relates to the promoting operability category, shifting those points to the quality category.

Gain three points per quality measure, regardless of data completeness; this compares to just one point for other physicians.

Capture all of the points available from the Improvement Activities category by confirming participation with just a single activity. (This also applies to all physicians in rural or Health Professional Shortage Areas.)

In the event that you don’t qualify as a “small practice” or you’re still falling short of the requirements, CMS allows for the ultimate “out”: You can apply for exemption on the basis of an “extreme and uncontrollable circumstance.” The applications for these exceptions open this summer.

Unless you qualify for the program exemption, it’s important to keep pace with the program to ensure that you reach the 45-point threshold. It may not, however, be worthwhile to gear up for all 100 points unless your estimate of the potential return – and what it costs you to get there – reveals otherwise. MIPS is not going anywhere; the program is written into the law.

But that doesn’t mean that CMS can’t make tweaks and updates. Hopefully, the revisions won’t create even more administrative burden as the program is quickly turning into a big stick with only a small carrot at the end.

Elizabeth Woodcock is president of Woodcock & Associates in Atlanta. She has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Risk of Suicide in the Year After an ED Visit

What happens to patients at risk for suicide after they leave the emergency department (ED)? According to a new study funded by the National Institute of Mental Health and published in JAMA Network Open, people who presented to California EDs with deliberate self-harm or suicidal ideation were not just at risk for a future suicide—they were at extreme risk.

The researchers divided patients into 3 groups: 83,507 who had deliberately self-harmed with or without co-occurring suicidal ideation; 67,379 presenting with suicidal ideation but without deliberate self-harm; and 497,760 without either self-harm or suicidal ideation.

In the first year after the ED visit, the patients who had presented with deliberate self-harm had a suicide rate almost 57 times higher than that of demographically similar Californians. Among those with suicidal ideation, the suicide rate was about 31 times higher. The suicide rate for the reference group, while the lowest of the 3 groups, was still twice the rate among Californians overall.

The researchers found certain clinical and demographic characteristics predicted subsequent suicide. Men and patients aged > 65 years had higher rates of suicide when compared with women or people aged 10 to 24 years. In all groups, suicide rates were higher for non-Hispanic, white patients.

Comorbid diagnoses were associated with suicide risk but with “striking differences” among the groups, the researchers say. Among patients presenting with deliberate self-harm, those with a comorbid diagnosis of bipolar disorder, anxiety disorder, or a psychotic disorder were more likely to die of suicide. Among reference patients, those with bipolar disorder, depression, or alcohol use disorder had a higher risk.

Of note, the researchers say, patients in the deliberate self-harm group who presented with a firearm-related injury had a subsequent suicide rate of 4.4% in the following year, a far higher rate than that in any other patient group. The researchers urge ED physicians to be aware that patients who present with self-harm who use high-lethality methods at a nonfatal event remain at highly increased risk for future suicide.

To the researchers’ knowledge, this is the first US population-based study to examine 12-month suicide rates after an index ED visit. These findings reinforce the importance of universal screening for suicide risk in EDs and the need for follow-up care, the researchers add, “an approach that has been found to increase the number of ED patients identified as warranting treatment for suicide risk by approximately 2-fold, but which is also not yet widespread.”

What happens to patients at risk for suicide after they leave the emergency department (ED)? According to a new study funded by the National Institute of Mental Health and published in JAMA Network Open, people who presented to California EDs with deliberate self-harm or suicidal ideation were not just at risk for a future suicide—they were at extreme risk.

The researchers divided patients into 3 groups: 83,507 who had deliberately self-harmed with or without co-occurring suicidal ideation; 67,379 presenting with suicidal ideation but without deliberate self-harm; and 497,760 without either self-harm or suicidal ideation.

In the first year after the ED visit, the patients who had presented with deliberate self-harm had a suicide rate almost 57 times higher than that of demographically similar Californians. Among those with suicidal ideation, the suicide rate was about 31 times higher. The suicide rate for the reference group, while the lowest of the 3 groups, was still twice the rate among Californians overall.

The researchers found certain clinical and demographic characteristics predicted subsequent suicide. Men and patients aged > 65 years had higher rates of suicide when compared with women or people aged 10 to 24 years. In all groups, suicide rates were higher for non-Hispanic, white patients.

Comorbid diagnoses were associated with suicide risk but with “striking differences” among the groups, the researchers say. Among patients presenting with deliberate self-harm, those with a comorbid diagnosis of bipolar disorder, anxiety disorder, or a psychotic disorder were more likely to die of suicide. Among reference patients, those with bipolar disorder, depression, or alcohol use disorder had a higher risk.

Of note, the researchers say, patients in the deliberate self-harm group who presented with a firearm-related injury had a subsequent suicide rate of 4.4% in the following year, a far higher rate than that in any other patient group. The researchers urge ED physicians to be aware that patients who present with self-harm who use high-lethality methods at a nonfatal event remain at highly increased risk for future suicide.

To the researchers’ knowledge, this is the first US population-based study to examine 12-month suicide rates after an index ED visit. These findings reinforce the importance of universal screening for suicide risk in EDs and the need for follow-up care, the researchers add, “an approach that has been found to increase the number of ED patients identified as warranting treatment for suicide risk by approximately 2-fold, but which is also not yet widespread.”

What happens to patients at risk for suicide after they leave the emergency department (ED)? According to a new study funded by the National Institute of Mental Health and published in JAMA Network Open, people who presented to California EDs with deliberate self-harm or suicidal ideation were not just at risk for a future suicide—they were at extreme risk.

The researchers divided patients into 3 groups: 83,507 who had deliberately self-harmed with or without co-occurring suicidal ideation; 67,379 presenting with suicidal ideation but without deliberate self-harm; and 497,760 without either self-harm or suicidal ideation.

In the first year after the ED visit, the patients who had presented with deliberate self-harm had a suicide rate almost 57 times higher than that of demographically similar Californians. Among those with suicidal ideation, the suicide rate was about 31 times higher. The suicide rate for the reference group, while the lowest of the 3 groups, was still twice the rate among Californians overall.

The researchers found certain clinical and demographic characteristics predicted subsequent suicide. Men and patients aged > 65 years had higher rates of suicide when compared with women or people aged 10 to 24 years. In all groups, suicide rates were higher for non-Hispanic, white patients.

Comorbid diagnoses were associated with suicide risk but with “striking differences” among the groups, the researchers say. Among patients presenting with deliberate self-harm, those with a comorbid diagnosis of bipolar disorder, anxiety disorder, or a psychotic disorder were more likely to die of suicide. Among reference patients, those with bipolar disorder, depression, or alcohol use disorder had a higher risk.

Of note, the researchers say, patients in the deliberate self-harm group who presented with a firearm-related injury had a subsequent suicide rate of 4.4% in the following year, a far higher rate than that in any other patient group. The researchers urge ED physicians to be aware that patients who present with self-harm who use high-lethality methods at a nonfatal event remain at highly increased risk for future suicide.

To the researchers’ knowledge, this is the first US population-based study to examine 12-month suicide rates after an index ED visit. These findings reinforce the importance of universal screening for suicide risk in EDs and the need for follow-up care, the researchers add, “an approach that has been found to increase the number of ED patients identified as warranting treatment for suicide risk by approximately 2-fold, but which is also not yet widespread.”

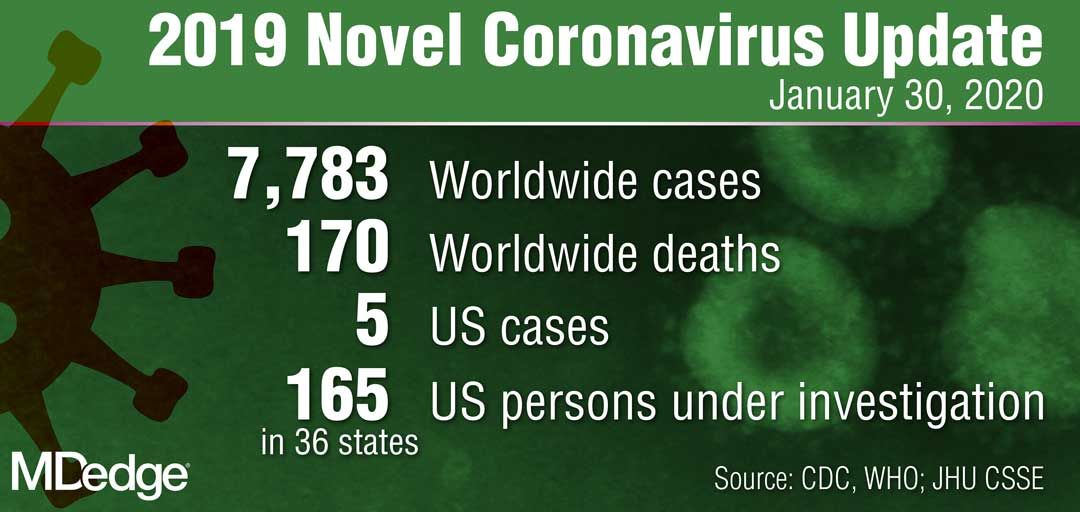

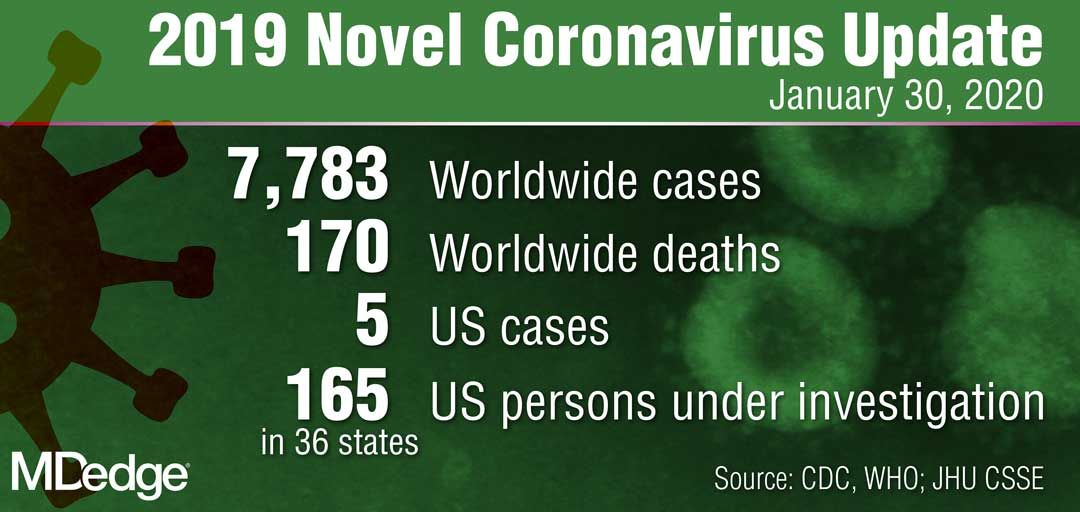

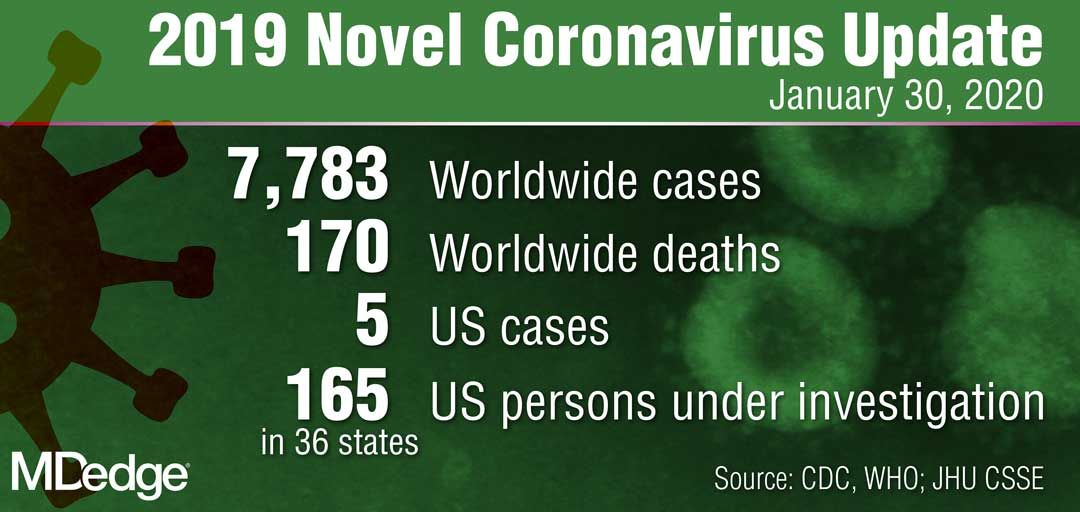

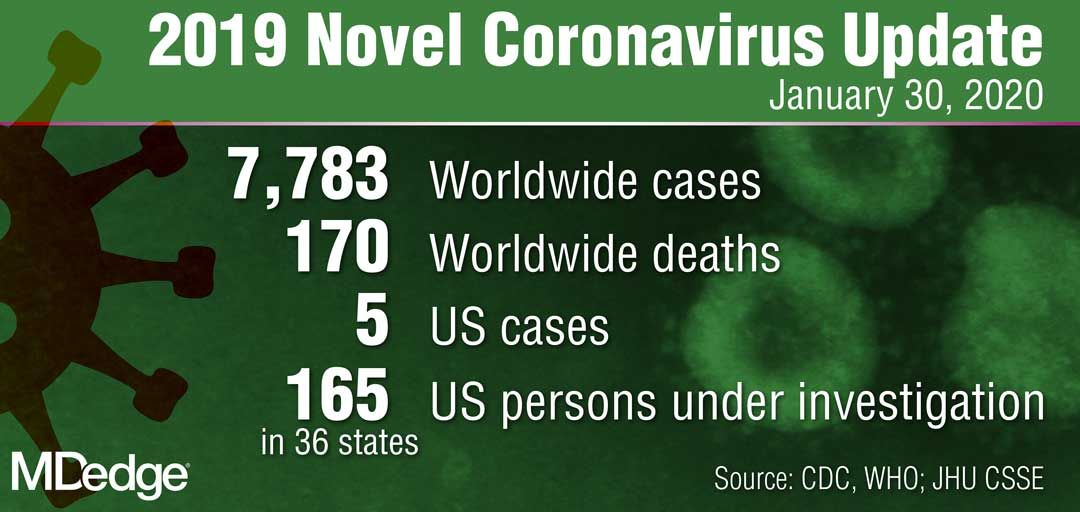

CDC: Risk in U.S. from 2019-nCoV remains low

A total of 165 persons in the United States are under investigation for infection with the 2019 Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV), with 68 testing negative and only 5 confirming positive, according to data presented Jan. 29 during a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) briefing.

The remaining samples are in transit or are being processed at the CDC for testing, Nancy Messonnier, MD, director of the National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, said during the briefing.

“The genetic sequence for all five viruses detected in the United States to date has been uploaded to the CDC website,” she said. “We are working quickly through the process to get the CDC-developed test into the hands of public health partners in the U.S. and internationally.”

Dr. Messonnier reported that the CDC is expanding screening efforts to U.S. ports of entry that house CDC quarantine stations. Also, in collaboration with U.S. Customs and Border Protection, the agency is expanding distribution of travel health education materials to all travelers from China.

“The good news here is that, despite an aggressive public health investigation to find new cases [of 2019-nCoV], we have not,” she said. “The situation in China is concerning, however, we are looking hard here in the U.S. We will continue to be proactive. I still expect that we will find additional cases.”

In another development, the federal government facilitated the return of a plane full of U.S. citizens living in Wuhan, China, to March Air Reserve Force Base in Riverside County, Calif. “We have taken every precaution to ensure their safety while also continuing to protect the health of our nation and the people around them,” Dr. Messonnier said.

All 195 passengers have been screened, monitored, and evaluated by medical personnel “every step of the way,” including before takeoff, during the flight, during a refueling stop in Alaska, and again upon landing at March Air Reserve Force Base on Jan. 28. “All 195 patients are without the symptoms of the novel coronavirus, and all have been assigned living quarters at the Air Force base,” Dr. Messonnier said.

The CDC has launched a second stage of further screening and information gathering from the passengers, who will be offered testing as part of a thorough risk assessment.

“I understand that many people in the U.S. are worried about this virus and whether it will affect them,” Dr. Messonnier said. “Outbreaks like this are always concerning, particularly when a new virus is emerging. But we are well prepared and working closely with federal, state, and local partners to protect our communities and others nationwide from this public health threat. At this time, we continue to believe that the immediate health risk from this new virus to the general American public is low.”

A total of 165 persons in the United States are under investigation for infection with the 2019 Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV), with 68 testing negative and only 5 confirming positive, according to data presented Jan. 29 during a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) briefing.

The remaining samples are in transit or are being processed at the CDC for testing, Nancy Messonnier, MD, director of the National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, said during the briefing.

“The genetic sequence for all five viruses detected in the United States to date has been uploaded to the CDC website,” she said. “We are working quickly through the process to get the CDC-developed test into the hands of public health partners in the U.S. and internationally.”

Dr. Messonnier reported that the CDC is expanding screening efforts to U.S. ports of entry that house CDC quarantine stations. Also, in collaboration with U.S. Customs and Border Protection, the agency is expanding distribution of travel health education materials to all travelers from China.

“The good news here is that, despite an aggressive public health investigation to find new cases [of 2019-nCoV], we have not,” she said. “The situation in China is concerning, however, we are looking hard here in the U.S. We will continue to be proactive. I still expect that we will find additional cases.”

In another development, the federal government facilitated the return of a plane full of U.S. citizens living in Wuhan, China, to March Air Reserve Force Base in Riverside County, Calif. “We have taken every precaution to ensure their safety while also continuing to protect the health of our nation and the people around them,” Dr. Messonnier said.

All 195 passengers have been screened, monitored, and evaluated by medical personnel “every step of the way,” including before takeoff, during the flight, during a refueling stop in Alaska, and again upon landing at March Air Reserve Force Base on Jan. 28. “All 195 patients are without the symptoms of the novel coronavirus, and all have been assigned living quarters at the Air Force base,” Dr. Messonnier said.

The CDC has launched a second stage of further screening and information gathering from the passengers, who will be offered testing as part of a thorough risk assessment.

“I understand that many people in the U.S. are worried about this virus and whether it will affect them,” Dr. Messonnier said. “Outbreaks like this are always concerning, particularly when a new virus is emerging. But we are well prepared and working closely with federal, state, and local partners to protect our communities and others nationwide from this public health threat. At this time, we continue to believe that the immediate health risk from this new virus to the general American public is low.”

A total of 165 persons in the United States are under investigation for infection with the 2019 Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV), with 68 testing negative and only 5 confirming positive, according to data presented Jan. 29 during a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) briefing.

The remaining samples are in transit or are being processed at the CDC for testing, Nancy Messonnier, MD, director of the National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, said during the briefing.

“The genetic sequence for all five viruses detected in the United States to date has been uploaded to the CDC website,” she said. “We are working quickly through the process to get the CDC-developed test into the hands of public health partners in the U.S. and internationally.”

Dr. Messonnier reported that the CDC is expanding screening efforts to U.S. ports of entry that house CDC quarantine stations. Also, in collaboration with U.S. Customs and Border Protection, the agency is expanding distribution of travel health education materials to all travelers from China.

“The good news here is that, despite an aggressive public health investigation to find new cases [of 2019-nCoV], we have not,” she said. “The situation in China is concerning, however, we are looking hard here in the U.S. We will continue to be proactive. I still expect that we will find additional cases.”

In another development, the federal government facilitated the return of a plane full of U.S. citizens living in Wuhan, China, to March Air Reserve Force Base in Riverside County, Calif. “We have taken every precaution to ensure their safety while also continuing to protect the health of our nation and the people around them,” Dr. Messonnier said.

All 195 passengers have been screened, monitored, and evaluated by medical personnel “every step of the way,” including before takeoff, during the flight, during a refueling stop in Alaska, and again upon landing at March Air Reserve Force Base on Jan. 28. “All 195 patients are without the symptoms of the novel coronavirus, and all have been assigned living quarters at the Air Force base,” Dr. Messonnier said.

The CDC has launched a second stage of further screening and information gathering from the passengers, who will be offered testing as part of a thorough risk assessment.

“I understand that many people in the U.S. are worried about this virus and whether it will affect them,” Dr. Messonnier said. “Outbreaks like this are always concerning, particularly when a new virus is emerging. But we are well prepared and working closely with federal, state, and local partners to protect our communities and others nationwide from this public health threat. At this time, we continue to believe that the immediate health risk from this new virus to the general American public is low.”

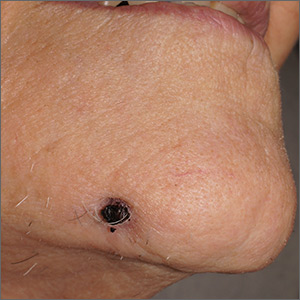

Draining papule on chin

A biopsy of the skin was consistent with folliculitis, but a dental panoramic x-ray revealed an abscess of tooth number 30, which is on the right side. This combination of findings was consistent with a dental sinus.

This unusual diagnosis is most common in adults and arises from dental disease in the mid mandibular pre-molars. It will appear as an abscess or crusted papule and can occur in the lower jaw, neck, or occasionally, the mid cheek. Children are rarely affected. Because the sinus opening relieves pressure from the dental abscess, there is often little to no pain.

It can be challenging to convince a patient that his or her skin lesion derives from dental disease. Often, though, patients are glad it is not cancer. Patients should be referred to an endodontist for a work-up and a root canal, which is the preferred treatment. If a root canal is not feasible, dental extraction will lead to cure.

In this case, the patient promptly underwent a root canal and was cured in 2 weeks. The scar from the papule can have a depressed appearance (FIGURE 2), which can be addressed with excisional scar revision once the underlying abscess is cured.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained). Dr. Karnes is the medical director of MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME.

Janev E, Redzep E. Managing the cutaneous sinus tract of dental origine. Open Access Maced J Med Sci. 2016;4:489-492.

A biopsy of the skin was consistent with folliculitis, but a dental panoramic x-ray revealed an abscess of tooth number 30, which is on the right side. This combination of findings was consistent with a dental sinus.

This unusual diagnosis is most common in adults and arises from dental disease in the mid mandibular pre-molars. It will appear as an abscess or crusted papule and can occur in the lower jaw, neck, or occasionally, the mid cheek. Children are rarely affected. Because the sinus opening relieves pressure from the dental abscess, there is often little to no pain.

It can be challenging to convince a patient that his or her skin lesion derives from dental disease. Often, though, patients are glad it is not cancer. Patients should be referred to an endodontist for a work-up and a root canal, which is the preferred treatment. If a root canal is not feasible, dental extraction will lead to cure.

In this case, the patient promptly underwent a root canal and was cured in 2 weeks. The scar from the papule can have a depressed appearance (FIGURE 2), which can be addressed with excisional scar revision once the underlying abscess is cured.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained). Dr. Karnes is the medical director of MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME.

A biopsy of the skin was consistent with folliculitis, but a dental panoramic x-ray revealed an abscess of tooth number 30, which is on the right side. This combination of findings was consistent with a dental sinus.

This unusual diagnosis is most common in adults and arises from dental disease in the mid mandibular pre-molars. It will appear as an abscess or crusted papule and can occur in the lower jaw, neck, or occasionally, the mid cheek. Children are rarely affected. Because the sinus opening relieves pressure from the dental abscess, there is often little to no pain.

It can be challenging to convince a patient that his or her skin lesion derives from dental disease. Often, though, patients are glad it is not cancer. Patients should be referred to an endodontist for a work-up and a root canal, which is the preferred treatment. If a root canal is not feasible, dental extraction will lead to cure.

In this case, the patient promptly underwent a root canal and was cured in 2 weeks. The scar from the papule can have a depressed appearance (FIGURE 2), which can be addressed with excisional scar revision once the underlying abscess is cured.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained). Dr. Karnes is the medical director of MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME.

Janev E, Redzep E. Managing the cutaneous sinus tract of dental origine. Open Access Maced J Med Sci. 2016;4:489-492.

Janev E, Redzep E. Managing the cutaneous sinus tract of dental origine. Open Access Maced J Med Sci. 2016;4:489-492.

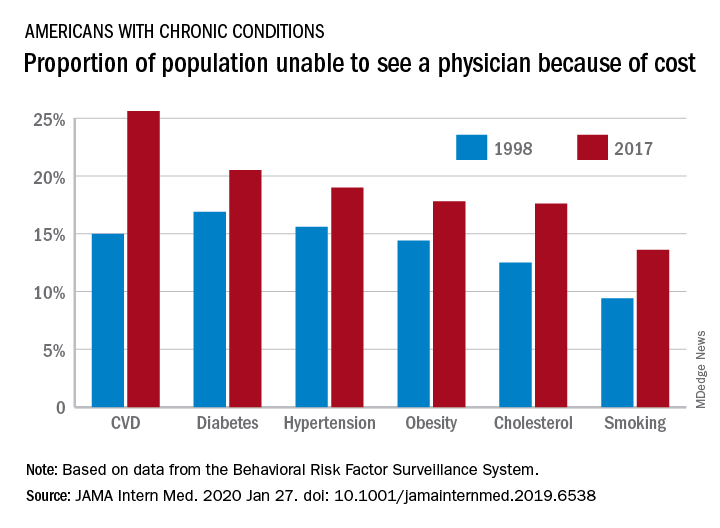

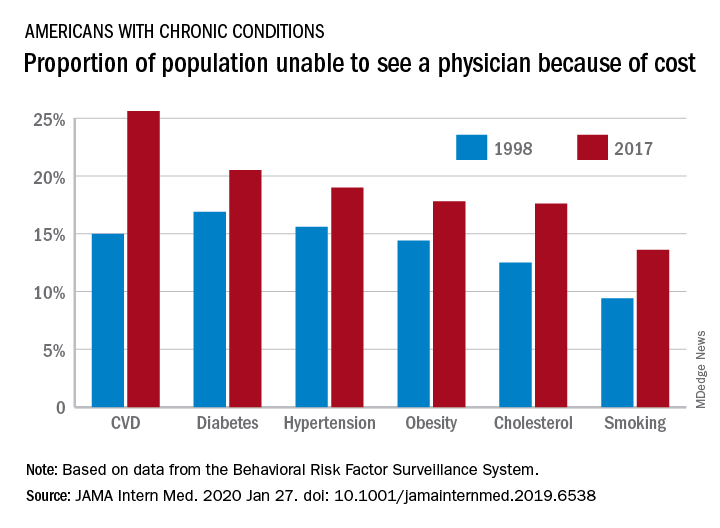

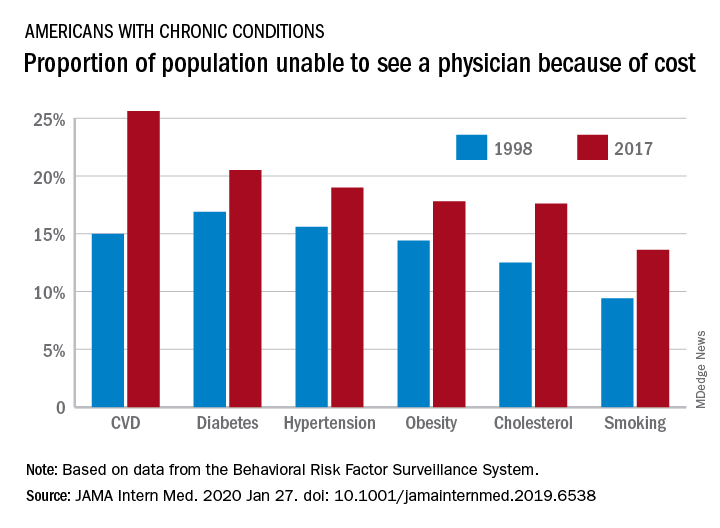

Costs are keeping Americans out of the doctor’s office

The cost of health care is keeping more Americans from seeing a doctor, even as the number of individuals with insurance coverage increases, according to a new study.

“Despite short-term gains owing to the [Affordable Care Act], over the past 20 years the portion of adults aged 18-64 years unable to see a physician owing to the cost increased, mostly because of an increase among persons with insurance,” Laura Hawks, MD, of Cambridge (Mass.) Health Alliance and Harvard Medical School in Boston and colleagues wrote in a new research report published in JAMA Internal Medicine.

“In 2017, nearly one-fifth of individuals with any chronic condition (diabetes, obesity, or cardiovascular disease) said they were unable to see a physician owing to cost,” they continued.

Researchers examined 20 years of data (January 1998 through December 2017) from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System to identify trends in unmet need for physician and preventive services.

Among adults aged 18-64 years who responded to the survey in 1998 and 2017, uninsurance decreased by 2.1 percentage points, falling from 16.9% to 14.8%. But at the same time, the portion of adults who were unable to see a physician because of cost rose by 2.7 percentage points, from 11.4% to 15.7%. Looking specifically at adults who had insurance coverage, the researchers found that cost was a barrier for 11.5% of them in 2017, up from 7.1% in 1998.

These results come against a backdrop of growing medical costs, increasing deductibles and copayments, an increasing use of cost containment measures like prior authorization, and narrow provider networks in the wake of the transition to value-based payment structures, the authors noted.

“Our finding that financial access to physician care worsened is concerning,” Dr. Hawks and her colleagues wrote. “Persons with conditions such as diabetes, hypertension, cardiovascular disease, and poor health status risk substantial harms if they forgo physician care. Financial barriers to care have been associated with increased hospitalizations and worse health outcomes in patients with cardiovascular disease and hypertension and increased morbidity among patients with diabetes.”