User login

New medical ethics series debuts

Dear colleagues,

The first issue of The New Gastroenterologist in 2020 consists of a particularly interesting array of articles and the introduction of a new medical ethics series!

This month’s “In Focus” article, brought to you by Jennifer Maratt (Indiana University) and Elena Stoffel (University of Michigan), provides a high yield overview of hereditary colorectal cancer and polyposis syndromes, with guidance on when a referral to a high risk cancer specialist and geneticist is warranted.

Daniel Mills (Cunningham, Meyer & Vedrine P.C.) gives us a valuable legal perspective of the role of electronic patient portals in the dissemination of information and medical advice to patients – such an important topic for everyone to be aware of as the nature of patient communication now strongly relies on electronic messaging.

R. Thomas Finn III (Palo Alto Medical Foundation) and David Leiman (Duke) nicely broach the issue of patient satisfaction. This is a timely topic as many institutions are not only publishing patient reviews online so that they are readily available to the public, but are also making financial incentives contingent on high patient ratings. The article discusses the evolution of the emphasis placed on patient satisfaction throughout the years with tips on how to navigate some of the distinct challenges within gastroenterology.

As part of our DHPA Private Practice Perspectives series, David Stokesberry (Digestive Disease Specialists Inc, Oklahoma City) discusses the nuts and bolts of ambulatory endoscopy centers and some of the challenges and benefits that accompany ownership of such centers.

An often overlooked aspect of gastroenterology training is nutrition. In our postfellowship pathways section, Dejan Micic (University of Chicago) outlines his decision to pursue a career in nutrition support, small bowel disorders, and the practice of deep enteroscopy.

Finally, this quarter’s newsletter features the start of a new section, which I am very excited to introduce – a case based series which will address issues in clinical medical ethics specific to gastroenterology. Lauren Feld (University of Washington) writes the inaugural piece for the section, providing a systematic approach to the patient with an existing do-not-resuscitate (DNR) order that is about to undergo endoscopy.

If you have interest in contributing or have ideas for future TNG topics, please contact me ([email protected]), or Ryan Farrell ([email protected]), managing editor of TNG.

Sincerely,

Vijaya L. Rao, MD

Editor in Chief

Dear colleagues,

The first issue of The New Gastroenterologist in 2020 consists of a particularly interesting array of articles and the introduction of a new medical ethics series!

This month’s “In Focus” article, brought to you by Jennifer Maratt (Indiana University) and Elena Stoffel (University of Michigan), provides a high yield overview of hereditary colorectal cancer and polyposis syndromes, with guidance on when a referral to a high risk cancer specialist and geneticist is warranted.

Daniel Mills (Cunningham, Meyer & Vedrine P.C.) gives us a valuable legal perspective of the role of electronic patient portals in the dissemination of information and medical advice to patients – such an important topic for everyone to be aware of as the nature of patient communication now strongly relies on electronic messaging.

R. Thomas Finn III (Palo Alto Medical Foundation) and David Leiman (Duke) nicely broach the issue of patient satisfaction. This is a timely topic as many institutions are not only publishing patient reviews online so that they are readily available to the public, but are also making financial incentives contingent on high patient ratings. The article discusses the evolution of the emphasis placed on patient satisfaction throughout the years with tips on how to navigate some of the distinct challenges within gastroenterology.

As part of our DHPA Private Practice Perspectives series, David Stokesberry (Digestive Disease Specialists Inc, Oklahoma City) discusses the nuts and bolts of ambulatory endoscopy centers and some of the challenges and benefits that accompany ownership of such centers.

An often overlooked aspect of gastroenterology training is nutrition. In our postfellowship pathways section, Dejan Micic (University of Chicago) outlines his decision to pursue a career in nutrition support, small bowel disorders, and the practice of deep enteroscopy.

Finally, this quarter’s newsletter features the start of a new section, which I am very excited to introduce – a case based series which will address issues in clinical medical ethics specific to gastroenterology. Lauren Feld (University of Washington) writes the inaugural piece for the section, providing a systematic approach to the patient with an existing do-not-resuscitate (DNR) order that is about to undergo endoscopy.

If you have interest in contributing or have ideas for future TNG topics, please contact me ([email protected]), or Ryan Farrell ([email protected]), managing editor of TNG.

Sincerely,

Vijaya L. Rao, MD

Editor in Chief

Dear colleagues,

The first issue of The New Gastroenterologist in 2020 consists of a particularly interesting array of articles and the introduction of a new medical ethics series!

This month’s “In Focus” article, brought to you by Jennifer Maratt (Indiana University) and Elena Stoffel (University of Michigan), provides a high yield overview of hereditary colorectal cancer and polyposis syndromes, with guidance on when a referral to a high risk cancer specialist and geneticist is warranted.

Daniel Mills (Cunningham, Meyer & Vedrine P.C.) gives us a valuable legal perspective of the role of electronic patient portals in the dissemination of information and medical advice to patients – such an important topic for everyone to be aware of as the nature of patient communication now strongly relies on electronic messaging.

R. Thomas Finn III (Palo Alto Medical Foundation) and David Leiman (Duke) nicely broach the issue of patient satisfaction. This is a timely topic as many institutions are not only publishing patient reviews online so that they are readily available to the public, but are also making financial incentives contingent on high patient ratings. The article discusses the evolution of the emphasis placed on patient satisfaction throughout the years with tips on how to navigate some of the distinct challenges within gastroenterology.

As part of our DHPA Private Practice Perspectives series, David Stokesberry (Digestive Disease Specialists Inc, Oklahoma City) discusses the nuts and bolts of ambulatory endoscopy centers and some of the challenges and benefits that accompany ownership of such centers.

An often overlooked aspect of gastroenterology training is nutrition. In our postfellowship pathways section, Dejan Micic (University of Chicago) outlines his decision to pursue a career in nutrition support, small bowel disorders, and the practice of deep enteroscopy.

Finally, this quarter’s newsletter features the start of a new section, which I am very excited to introduce – a case based series which will address issues in clinical medical ethics specific to gastroenterology. Lauren Feld (University of Washington) writes the inaugural piece for the section, providing a systematic approach to the patient with an existing do-not-resuscitate (DNR) order that is about to undergo endoscopy.

If you have interest in contributing or have ideas for future TNG topics, please contact me ([email protected]), or Ryan Farrell ([email protected]), managing editor of TNG.

Sincerely,

Vijaya L. Rao, MD

Editor in Chief

Colorectal polyps and cancer – when to refer to genetics

Introduction

Genetic predisposition to colorectal polyps and colorectal cancer (CRC) is more common than previously recognized. Approximately 5%-10% of all individuals diagnosed with CRC have a known genetic association. However, among those with early-onset CRC (diagnosed at age less than 50 years), recent studies show that up to 20% have an associated genetic mutation.1,2 In addition, the risk of CRC in patients with certain hereditary syndromes, such as familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP), approaches 80%-90% without timely management.3 This overall high risk of CRC and extracolonic malignancies in patients with a hereditary syndrome, along with the rising rates of early-onset CRC, underscores the importance of early diagnosis and management of a hereditary condition.

Despite increasing awareness of hereditary polyposis and nonpolyposis syndromes, referral rates for genetic counseling and testing remain low.4 As gastroenterologists we have several unique opportunities, in clinic and in endoscopy, to identify patients at risk for hereditary syndromes.

Risk stratification

Personal and family history

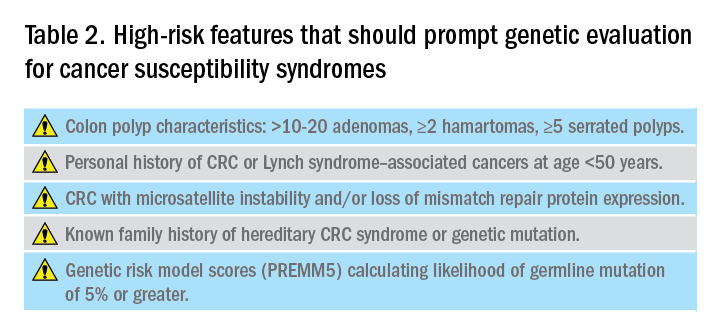

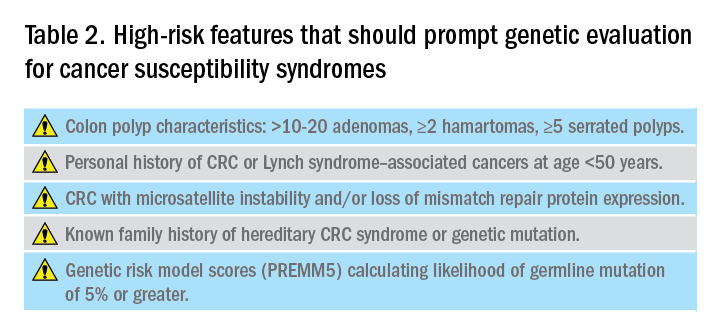

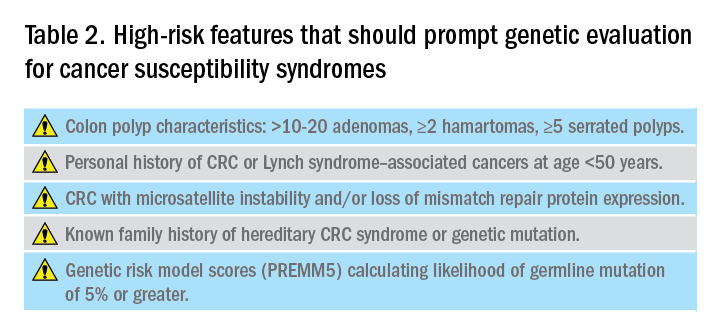

Reviewing personal medical history and family history in detail should be a routine part of our practice. This is often when initial signs of a potential hereditary syndrome can be detected. For example, if a patient reports a personal or family history of colorectal polyps or CRC, additional information that becomes important includes age at time of diagnosis, polyp burden (number and histologic subtype), presence of inflammatory bowel disease, and history of any extracolonic malignancies. Patients with multiple colorectal polyps (e.g. more than 10-20 adenomas or more than 2 hamartomas) and those with CRC diagnosed at a young age (younger than 50 years) should be considered candidates for genetic evaluation.5

Lynch syndrome (LS), an autosomal dominant condition caused by loss of DNA mismatch repair (MMR) genes, is the most common hereditary CRC syndrome, accounting for 2%-4% of all CRCs.3,6 Extracolonic LS-associated cancers to keep in mind while reviewing personal and family histories include those involving the gastrointestinal (GI) tract such as gastric, pancreatic, biliary tract, and small intestine cancers, and also non-GI tract cancers including endometrial, ovarian, urinary tract, and renal cancers along with brain tumors, and skin lesions including sebaceous adenomas, sebaceous carcinomas, and keratoacanthomas. Notably, after CRC, endometrial cancer is the second most common cancer among women with LS. Prior diagnosis of endometrial cancer should also prompt additional history-taking and evaluation for LS.

As the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) highlights in its recent guidelines, several key findings in family history that should prompt referral to genetics for evaluation and testing for LS include: one or more first-degree relatives (FDR) with CRC or endometrial cancer diagnosed at less than 50 years of age, one or more FDR with CRC or endometrial cancer and another synchronous or metachronous LS-related cancer, two or more FDR or second-degree relatives (SDR) with LS-related cancer (including at least one diagnosed at age less than 50 years), and three or more FDR or SDR with LS-related cancers (regardless of age).5

Comprehensive assessment of family history should include all cancer diagnoses in first- and second-degree relatives, including age at diagnosis and cancer type, as well as ethnicity, as these inform the likelihood that the patient harbors a germline pathogenic variant associated with cancer predisposition.5 Given the difficulty of eliciting this level of detail, the family histories elicited in clinical settings are often limited or incomplete. Unknown family history should not be mistaken for unremarkable family history. Alternatively, if family history is unimpressive, this is not necessarily reassuring, as there can be variability in disease penetrance, including autosomal recessive syndromes that may skip generations, and de novo mutations do occur. In fact, among individuals with early-onset CRC diagnosed at age less than 50, only half of mutation carriers reported a family history of CRC in an FDR.2 Thus, individuals with concerning personal histories should undergo a genetic evaluation even if family history is not concerning.

Polyp phenotype

In addition to personal and family history, colon polyp history (including number, size, and histology) can provide important clues to identifying individuals with genetic predisposition to CRC. Table 1 highlights hereditary syndromes and polyp phenotypes associated with increased CRC risk. Based on consensus guidelines, individuals with a history of greater than 10-20 adenomas, 2 or more hamartomas, or 5 or more sessile serrated polyps should be referred for genetic testing.5,7 Serrated polyposis syndrome (SPS) is diagnosed based on at least one of the following criteria: 1) 5 or more serrated polyps, all at least 5 mm in size, proximal to the rectum including at least 2 that are 10 mm or larger in size, or 2) more than 20 serrated polyps distributed throughout the colon with at least 5 proximal to the rectum.8 Pathogenic germline variants in RNF43, a tumor suppressor gene, have been associated with SPS in rare families; however, in most cases genetic testing is uninformative and further genetic and environmental discovery studies are needed to determine the underlying cause.8,9

Risk prediction models

Models have been developed that integrate family history and phenotype data to help identify patients who may be at risk for LS. The Amsterdam criteria (more than 3 relatives with LS-associated cancers, more than 2 generations involving LS-associated cancers, and more than 1 cancer diagnosed before the age of 50; “3:2:1” criteria) were initially developed for research purposes to identify individuals who were likely to be carriers of mutations of LS based on CRC and later revised to include extracolonic malignancies (Amsterdam II).11 However, they have limited sensitivity for identifying high-risk patients. Similarly, the Bethesda guidelines have also been modified and revised to identify patients at risk for LS whose tumors should be tested with microsatellite instability (MSI), but also with limited sensitivity.12

Several risk prediction models have been developed that perform better than the Amsterdam criteria or Bethesda guidelines for determining which patients should be referred for genetic testing for LS. These include MMRPredict, MMRpro, and PREMM5.13-16 These models use clinical data (personal and family history of cancer and tumor phenotypes) to calculate the probability of a germline mutation in one of the mismatch repair (MMR) genes associated with LS. The current threshold at which to refer a patient for genetic counseling and testing is a predicted probability of 5% or greater using any one of these models, though some have proposed lowering the threshold to 2.5%.16,17

Universal tumor testing

Because of the limitations of relying on clinical family history, such as with the Amsterdam criteria and the Bethesda guidelines,18,19 as of 2014 the NCCN recommended universal tumor screening for DNA MMR deficiency associated with LS. This approach, also known as “universal testing,” has been shown to be cost effective and more sensitive in identifying at-risk patients than clinical criteria alone.20,21 Specifically, the NCCN recommends that tumor specimens of all patients diagnosed with CRC undergo testing for microsatellite instability (MSI) or loss of MMR proteins (MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, PMS2) expression by immunohistochemistry (IHC).5 Loss of MMR proteins or MSI-high findings should prompt a referral to genetics for counseling and consideration of testing for germline mutations. Universal testing of CRC and endometrial cancers is considered the most reliable way to screen patients for LS.

Universal testing by MSI or IHC may be performed on premalignant or malignant lesions. However, it is important to recognize that DNA MMR deficiency testing may not be as reliable when applied to colorectal polyps. Using data from three cancer registries (Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, University of Michigan, MD Anderson Cancer Center), Yurgelun and colleagues investigated the yield of MSI and IHC in colorectal polyps removed from patients with known LS.22 Overall, high-level MSI was found in only 41% of Lynch-associated adenomas and loss of MMR protein expression was evident in only 50%. While adenomas 8 mm in size or greater were more likely to have MSI-high or loss of MMR protein expression compared with those less than 8 mm in size, MMR-deficiency phenotype was less reliable in smaller adenomas. Consequently, results of MSI and/or IHC should therefore be interpreted with caution and in the context of the specimen upon which they are performed.

Considerations for clinical genetic testing

Genetic testing for cancer susceptibility should include informed consent and counseling for patients regarding potential risks and benefits. Clinicians ordering genetic testing should have the expertise necessary to interpret test results, which may be positive (pathogenic or likely pathogenic germline variant identified), or negative (no variants identified), or may yield one or more variants of uncertain clinical significance. Individuals found to carry a pathogenic or likely pathogenic germline variant associated with cancer susceptibility should be referred for additional genetic counseling and may require additional expert consultation for management of extracolonic cancer risks. It is important that individuals diagnosed with a hereditary cancer syndrome be informed that this diagnosis has implications for family members, who may also be at risk for the condition and may benefit from genetic testing.

Practical considerations

Given the difficulty in obtaining a detailed family history while in clinic or in endoscopy, several studies have investigated strategies that may be integrated into practice to identify high-risk patients without substantial burden on providers or patients. Kastrinos and colleagues identified the following three high-yield questions as part of a CRC Risk Assessment Tool that can be used while performing a precolonoscopy assessment: 1) Do you have a first-degree relative with CRC or LS-related cancer diagnosed before age 50?; 2) Have you had CRC or polyps diagnosed prior to age 50?; and 3) Do you have three or more relatives with CRC? The authors found that these three questions alone identified 77% of high-risk individuals.23 In addition, implementation of family history screening instruments using standardized surveys or self-administered risk prediction models at the time of colonoscopy have been shown to improve ascertainment of high-risk patients.24,25 Such strategies may become increasingly easier to implement with integration into patients’ electronic medical records.

Conclusions

Hereditary CRC syndromes are becoming increasingly important to identify, especially in an era where we are seeing rising rates of early-onset CRC. Early identification of high-risk features (Table 2) can lead to timely diagnosis with the goal to implement preventive strategies for screening and/or surveillance, ideally prior to development of cancers.

As gastroenterologists, we have several unique opportunities to identify these individuals and must maintain a high level of suspicion with careful attention when obtaining personal and family history details in clinic and in endoscopy.

Dr. Maratt is assistant professor, Indiana University, Richard L. Roudebush VA Medical Center, Indianapolis. Dr. Stoffel is assistant professor, University of Michigan; director of Cancer Genetic Clinic, Rogel Cancer Center, Ann Arbor. They have no conflicts of interest.

References

1. Pearlman R et al. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3(4):464-71.

2. Stoffel EM et al. Gastroenterology. 2018;154(4):897-905.

3. Kanth P et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017;112:1509-25.

4. Brennan B et al. Ther Adv Gastroenterol. 2017;10:361-71.

5. National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Available at: nccn.org.

6. Lynch HT et al. Nat Rev Cancer. 2015;15:181-94.

7. Syngal S et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015;110:223-62.

8. Mankaney G et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020:(in press)

9. Yan HHN et al. Gut 2017;66:1645-56.

10. Ma H et al. Pathology. 2018;50:49-59.

11. Vasen H et al. Gastroenterology 1999;116:1453-6.

12. Umar A et al. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2004;96:261-8.

13. Kastrinos F et al. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2015;108(2):1-9.

14. Chen S et al. JAMA. 2006;296(12):1479-87.

15. Barnetson RA et al. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(26):2751-63.

16. Kastrinos F et al. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35:2165-72.

17. Kastrinos F et al. Fam Cancer. 2018;17:567-67.

18. Cohen SA et al. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet. 2019;20:293-307.

19. Matloff J et al. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2013;11:1380-5.

20. Ladabaum U et al. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155(2):69-79.

21. Hampel H et al. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(18):1851-60.

22. Yurgelun MB et al. Cancer Prev Res. 2012;5:574-82.

23. Kastrinos F et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:1508-18.

24. Luba DG et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;16:49-58.

25. Guivatchian T et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2017;86:684-91.

Introduction

Genetic predisposition to colorectal polyps and colorectal cancer (CRC) is more common than previously recognized. Approximately 5%-10% of all individuals diagnosed with CRC have a known genetic association. However, among those with early-onset CRC (diagnosed at age less than 50 years), recent studies show that up to 20% have an associated genetic mutation.1,2 In addition, the risk of CRC in patients with certain hereditary syndromes, such as familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP), approaches 80%-90% without timely management.3 This overall high risk of CRC and extracolonic malignancies in patients with a hereditary syndrome, along with the rising rates of early-onset CRC, underscores the importance of early diagnosis and management of a hereditary condition.

Despite increasing awareness of hereditary polyposis and nonpolyposis syndromes, referral rates for genetic counseling and testing remain low.4 As gastroenterologists we have several unique opportunities, in clinic and in endoscopy, to identify patients at risk for hereditary syndromes.

Risk stratification

Personal and family history

Reviewing personal medical history and family history in detail should be a routine part of our practice. This is often when initial signs of a potential hereditary syndrome can be detected. For example, if a patient reports a personal or family history of colorectal polyps or CRC, additional information that becomes important includes age at time of diagnosis, polyp burden (number and histologic subtype), presence of inflammatory bowel disease, and history of any extracolonic malignancies. Patients with multiple colorectal polyps (e.g. more than 10-20 adenomas or more than 2 hamartomas) and those with CRC diagnosed at a young age (younger than 50 years) should be considered candidates for genetic evaluation.5

Lynch syndrome (LS), an autosomal dominant condition caused by loss of DNA mismatch repair (MMR) genes, is the most common hereditary CRC syndrome, accounting for 2%-4% of all CRCs.3,6 Extracolonic LS-associated cancers to keep in mind while reviewing personal and family histories include those involving the gastrointestinal (GI) tract such as gastric, pancreatic, biliary tract, and small intestine cancers, and also non-GI tract cancers including endometrial, ovarian, urinary tract, and renal cancers along with brain tumors, and skin lesions including sebaceous adenomas, sebaceous carcinomas, and keratoacanthomas. Notably, after CRC, endometrial cancer is the second most common cancer among women with LS. Prior diagnosis of endometrial cancer should also prompt additional history-taking and evaluation for LS.

As the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) highlights in its recent guidelines, several key findings in family history that should prompt referral to genetics for evaluation and testing for LS include: one or more first-degree relatives (FDR) with CRC or endometrial cancer diagnosed at less than 50 years of age, one or more FDR with CRC or endometrial cancer and another synchronous or metachronous LS-related cancer, two or more FDR or second-degree relatives (SDR) with LS-related cancer (including at least one diagnosed at age less than 50 years), and three or more FDR or SDR with LS-related cancers (regardless of age).5

Comprehensive assessment of family history should include all cancer diagnoses in first- and second-degree relatives, including age at diagnosis and cancer type, as well as ethnicity, as these inform the likelihood that the patient harbors a germline pathogenic variant associated with cancer predisposition.5 Given the difficulty of eliciting this level of detail, the family histories elicited in clinical settings are often limited or incomplete. Unknown family history should not be mistaken for unremarkable family history. Alternatively, if family history is unimpressive, this is not necessarily reassuring, as there can be variability in disease penetrance, including autosomal recessive syndromes that may skip generations, and de novo mutations do occur. In fact, among individuals with early-onset CRC diagnosed at age less than 50, only half of mutation carriers reported a family history of CRC in an FDR.2 Thus, individuals with concerning personal histories should undergo a genetic evaluation even if family history is not concerning.

Polyp phenotype

In addition to personal and family history, colon polyp history (including number, size, and histology) can provide important clues to identifying individuals with genetic predisposition to CRC. Table 1 highlights hereditary syndromes and polyp phenotypes associated with increased CRC risk. Based on consensus guidelines, individuals with a history of greater than 10-20 adenomas, 2 or more hamartomas, or 5 or more sessile serrated polyps should be referred for genetic testing.5,7 Serrated polyposis syndrome (SPS) is diagnosed based on at least one of the following criteria: 1) 5 or more serrated polyps, all at least 5 mm in size, proximal to the rectum including at least 2 that are 10 mm or larger in size, or 2) more than 20 serrated polyps distributed throughout the colon with at least 5 proximal to the rectum.8 Pathogenic germline variants in RNF43, a tumor suppressor gene, have been associated with SPS in rare families; however, in most cases genetic testing is uninformative and further genetic and environmental discovery studies are needed to determine the underlying cause.8,9

Risk prediction models

Models have been developed that integrate family history and phenotype data to help identify patients who may be at risk for LS. The Amsterdam criteria (more than 3 relatives with LS-associated cancers, more than 2 generations involving LS-associated cancers, and more than 1 cancer diagnosed before the age of 50; “3:2:1” criteria) were initially developed for research purposes to identify individuals who were likely to be carriers of mutations of LS based on CRC and later revised to include extracolonic malignancies (Amsterdam II).11 However, they have limited sensitivity for identifying high-risk patients. Similarly, the Bethesda guidelines have also been modified and revised to identify patients at risk for LS whose tumors should be tested with microsatellite instability (MSI), but also with limited sensitivity.12

Several risk prediction models have been developed that perform better than the Amsterdam criteria or Bethesda guidelines for determining which patients should be referred for genetic testing for LS. These include MMRPredict, MMRpro, and PREMM5.13-16 These models use clinical data (personal and family history of cancer and tumor phenotypes) to calculate the probability of a germline mutation in one of the mismatch repair (MMR) genes associated with LS. The current threshold at which to refer a patient for genetic counseling and testing is a predicted probability of 5% or greater using any one of these models, though some have proposed lowering the threshold to 2.5%.16,17

Universal tumor testing

Because of the limitations of relying on clinical family history, such as with the Amsterdam criteria and the Bethesda guidelines,18,19 as of 2014 the NCCN recommended universal tumor screening for DNA MMR deficiency associated with LS. This approach, also known as “universal testing,” has been shown to be cost effective and more sensitive in identifying at-risk patients than clinical criteria alone.20,21 Specifically, the NCCN recommends that tumor specimens of all patients diagnosed with CRC undergo testing for microsatellite instability (MSI) or loss of MMR proteins (MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, PMS2) expression by immunohistochemistry (IHC).5 Loss of MMR proteins or MSI-high findings should prompt a referral to genetics for counseling and consideration of testing for germline mutations. Universal testing of CRC and endometrial cancers is considered the most reliable way to screen patients for LS.

Universal testing by MSI or IHC may be performed on premalignant or malignant lesions. However, it is important to recognize that DNA MMR deficiency testing may not be as reliable when applied to colorectal polyps. Using data from three cancer registries (Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, University of Michigan, MD Anderson Cancer Center), Yurgelun and colleagues investigated the yield of MSI and IHC in colorectal polyps removed from patients with known LS.22 Overall, high-level MSI was found in only 41% of Lynch-associated adenomas and loss of MMR protein expression was evident in only 50%. While adenomas 8 mm in size or greater were more likely to have MSI-high or loss of MMR protein expression compared with those less than 8 mm in size, MMR-deficiency phenotype was less reliable in smaller adenomas. Consequently, results of MSI and/or IHC should therefore be interpreted with caution and in the context of the specimen upon which they are performed.

Considerations for clinical genetic testing

Genetic testing for cancer susceptibility should include informed consent and counseling for patients regarding potential risks and benefits. Clinicians ordering genetic testing should have the expertise necessary to interpret test results, which may be positive (pathogenic or likely pathogenic germline variant identified), or negative (no variants identified), or may yield one or more variants of uncertain clinical significance. Individuals found to carry a pathogenic or likely pathogenic germline variant associated with cancer susceptibility should be referred for additional genetic counseling and may require additional expert consultation for management of extracolonic cancer risks. It is important that individuals diagnosed with a hereditary cancer syndrome be informed that this diagnosis has implications for family members, who may also be at risk for the condition and may benefit from genetic testing.

Practical considerations

Given the difficulty in obtaining a detailed family history while in clinic or in endoscopy, several studies have investigated strategies that may be integrated into practice to identify high-risk patients without substantial burden on providers or patients. Kastrinos and colleagues identified the following three high-yield questions as part of a CRC Risk Assessment Tool that can be used while performing a precolonoscopy assessment: 1) Do you have a first-degree relative with CRC or LS-related cancer diagnosed before age 50?; 2) Have you had CRC or polyps diagnosed prior to age 50?; and 3) Do you have three or more relatives with CRC? The authors found that these three questions alone identified 77% of high-risk individuals.23 In addition, implementation of family history screening instruments using standardized surveys or self-administered risk prediction models at the time of colonoscopy have been shown to improve ascertainment of high-risk patients.24,25 Such strategies may become increasingly easier to implement with integration into patients’ electronic medical records.

Conclusions

Hereditary CRC syndromes are becoming increasingly important to identify, especially in an era where we are seeing rising rates of early-onset CRC. Early identification of high-risk features (Table 2) can lead to timely diagnosis with the goal to implement preventive strategies for screening and/or surveillance, ideally prior to development of cancers.

As gastroenterologists, we have several unique opportunities to identify these individuals and must maintain a high level of suspicion with careful attention when obtaining personal and family history details in clinic and in endoscopy.

Dr. Maratt is assistant professor, Indiana University, Richard L. Roudebush VA Medical Center, Indianapolis. Dr. Stoffel is assistant professor, University of Michigan; director of Cancer Genetic Clinic, Rogel Cancer Center, Ann Arbor. They have no conflicts of interest.

References

1. Pearlman R et al. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3(4):464-71.

2. Stoffel EM et al. Gastroenterology. 2018;154(4):897-905.

3. Kanth P et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017;112:1509-25.

4. Brennan B et al. Ther Adv Gastroenterol. 2017;10:361-71.

5. National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Available at: nccn.org.

6. Lynch HT et al. Nat Rev Cancer. 2015;15:181-94.

7. Syngal S et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015;110:223-62.

8. Mankaney G et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020:(in press)

9. Yan HHN et al. Gut 2017;66:1645-56.

10. Ma H et al. Pathology. 2018;50:49-59.

11. Vasen H et al. Gastroenterology 1999;116:1453-6.

12. Umar A et al. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2004;96:261-8.

13. Kastrinos F et al. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2015;108(2):1-9.

14. Chen S et al. JAMA. 2006;296(12):1479-87.

15. Barnetson RA et al. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(26):2751-63.

16. Kastrinos F et al. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35:2165-72.

17. Kastrinos F et al. Fam Cancer. 2018;17:567-67.

18. Cohen SA et al. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet. 2019;20:293-307.

19. Matloff J et al. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2013;11:1380-5.

20. Ladabaum U et al. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155(2):69-79.

21. Hampel H et al. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(18):1851-60.

22. Yurgelun MB et al. Cancer Prev Res. 2012;5:574-82.

23. Kastrinos F et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:1508-18.

24. Luba DG et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;16:49-58.

25. Guivatchian T et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2017;86:684-91.

Introduction

Genetic predisposition to colorectal polyps and colorectal cancer (CRC) is more common than previously recognized. Approximately 5%-10% of all individuals diagnosed with CRC have a known genetic association. However, among those with early-onset CRC (diagnosed at age less than 50 years), recent studies show that up to 20% have an associated genetic mutation.1,2 In addition, the risk of CRC in patients with certain hereditary syndromes, such as familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP), approaches 80%-90% without timely management.3 This overall high risk of CRC and extracolonic malignancies in patients with a hereditary syndrome, along with the rising rates of early-onset CRC, underscores the importance of early diagnosis and management of a hereditary condition.

Despite increasing awareness of hereditary polyposis and nonpolyposis syndromes, referral rates for genetic counseling and testing remain low.4 As gastroenterologists we have several unique opportunities, in clinic and in endoscopy, to identify patients at risk for hereditary syndromes.

Risk stratification

Personal and family history

Reviewing personal medical history and family history in detail should be a routine part of our practice. This is often when initial signs of a potential hereditary syndrome can be detected. For example, if a patient reports a personal or family history of colorectal polyps or CRC, additional information that becomes important includes age at time of diagnosis, polyp burden (number and histologic subtype), presence of inflammatory bowel disease, and history of any extracolonic malignancies. Patients with multiple colorectal polyps (e.g. more than 10-20 adenomas or more than 2 hamartomas) and those with CRC diagnosed at a young age (younger than 50 years) should be considered candidates for genetic evaluation.5

Lynch syndrome (LS), an autosomal dominant condition caused by loss of DNA mismatch repair (MMR) genes, is the most common hereditary CRC syndrome, accounting for 2%-4% of all CRCs.3,6 Extracolonic LS-associated cancers to keep in mind while reviewing personal and family histories include those involving the gastrointestinal (GI) tract such as gastric, pancreatic, biliary tract, and small intestine cancers, and also non-GI tract cancers including endometrial, ovarian, urinary tract, and renal cancers along with brain tumors, and skin lesions including sebaceous adenomas, sebaceous carcinomas, and keratoacanthomas. Notably, after CRC, endometrial cancer is the second most common cancer among women with LS. Prior diagnosis of endometrial cancer should also prompt additional history-taking and evaluation for LS.

As the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) highlights in its recent guidelines, several key findings in family history that should prompt referral to genetics for evaluation and testing for LS include: one or more first-degree relatives (FDR) with CRC or endometrial cancer diagnosed at less than 50 years of age, one or more FDR with CRC or endometrial cancer and another synchronous or metachronous LS-related cancer, two or more FDR or second-degree relatives (SDR) with LS-related cancer (including at least one diagnosed at age less than 50 years), and three or more FDR or SDR with LS-related cancers (regardless of age).5

Comprehensive assessment of family history should include all cancer diagnoses in first- and second-degree relatives, including age at diagnosis and cancer type, as well as ethnicity, as these inform the likelihood that the patient harbors a germline pathogenic variant associated with cancer predisposition.5 Given the difficulty of eliciting this level of detail, the family histories elicited in clinical settings are often limited or incomplete. Unknown family history should not be mistaken for unremarkable family history. Alternatively, if family history is unimpressive, this is not necessarily reassuring, as there can be variability in disease penetrance, including autosomal recessive syndromes that may skip generations, and de novo mutations do occur. In fact, among individuals with early-onset CRC diagnosed at age less than 50, only half of mutation carriers reported a family history of CRC in an FDR.2 Thus, individuals with concerning personal histories should undergo a genetic evaluation even if family history is not concerning.

Polyp phenotype

In addition to personal and family history, colon polyp history (including number, size, and histology) can provide important clues to identifying individuals with genetic predisposition to CRC. Table 1 highlights hereditary syndromes and polyp phenotypes associated with increased CRC risk. Based on consensus guidelines, individuals with a history of greater than 10-20 adenomas, 2 or more hamartomas, or 5 or more sessile serrated polyps should be referred for genetic testing.5,7 Serrated polyposis syndrome (SPS) is diagnosed based on at least one of the following criteria: 1) 5 or more serrated polyps, all at least 5 mm in size, proximal to the rectum including at least 2 that are 10 mm or larger in size, or 2) more than 20 serrated polyps distributed throughout the colon with at least 5 proximal to the rectum.8 Pathogenic germline variants in RNF43, a tumor suppressor gene, have been associated with SPS in rare families; however, in most cases genetic testing is uninformative and further genetic and environmental discovery studies are needed to determine the underlying cause.8,9

Risk prediction models

Models have been developed that integrate family history and phenotype data to help identify patients who may be at risk for LS. The Amsterdam criteria (more than 3 relatives with LS-associated cancers, more than 2 generations involving LS-associated cancers, and more than 1 cancer diagnosed before the age of 50; “3:2:1” criteria) were initially developed for research purposes to identify individuals who were likely to be carriers of mutations of LS based on CRC and later revised to include extracolonic malignancies (Amsterdam II).11 However, they have limited sensitivity for identifying high-risk patients. Similarly, the Bethesda guidelines have also been modified and revised to identify patients at risk for LS whose tumors should be tested with microsatellite instability (MSI), but also with limited sensitivity.12

Several risk prediction models have been developed that perform better than the Amsterdam criteria or Bethesda guidelines for determining which patients should be referred for genetic testing for LS. These include MMRPredict, MMRpro, and PREMM5.13-16 These models use clinical data (personal and family history of cancer and tumor phenotypes) to calculate the probability of a germline mutation in one of the mismatch repair (MMR) genes associated with LS. The current threshold at which to refer a patient for genetic counseling and testing is a predicted probability of 5% or greater using any one of these models, though some have proposed lowering the threshold to 2.5%.16,17

Universal tumor testing

Because of the limitations of relying on clinical family history, such as with the Amsterdam criteria and the Bethesda guidelines,18,19 as of 2014 the NCCN recommended universal tumor screening for DNA MMR deficiency associated with LS. This approach, also known as “universal testing,” has been shown to be cost effective and more sensitive in identifying at-risk patients than clinical criteria alone.20,21 Specifically, the NCCN recommends that tumor specimens of all patients diagnosed with CRC undergo testing for microsatellite instability (MSI) or loss of MMR proteins (MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, PMS2) expression by immunohistochemistry (IHC).5 Loss of MMR proteins or MSI-high findings should prompt a referral to genetics for counseling and consideration of testing for germline mutations. Universal testing of CRC and endometrial cancers is considered the most reliable way to screen patients for LS.

Universal testing by MSI or IHC may be performed on premalignant or malignant lesions. However, it is important to recognize that DNA MMR deficiency testing may not be as reliable when applied to colorectal polyps. Using data from three cancer registries (Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, University of Michigan, MD Anderson Cancer Center), Yurgelun and colleagues investigated the yield of MSI and IHC in colorectal polyps removed from patients with known LS.22 Overall, high-level MSI was found in only 41% of Lynch-associated adenomas and loss of MMR protein expression was evident in only 50%. While adenomas 8 mm in size or greater were more likely to have MSI-high or loss of MMR protein expression compared with those less than 8 mm in size, MMR-deficiency phenotype was less reliable in smaller adenomas. Consequently, results of MSI and/or IHC should therefore be interpreted with caution and in the context of the specimen upon which they are performed.

Considerations for clinical genetic testing

Genetic testing for cancer susceptibility should include informed consent and counseling for patients regarding potential risks and benefits. Clinicians ordering genetic testing should have the expertise necessary to interpret test results, which may be positive (pathogenic or likely pathogenic germline variant identified), or negative (no variants identified), or may yield one or more variants of uncertain clinical significance. Individuals found to carry a pathogenic or likely pathogenic germline variant associated with cancer susceptibility should be referred for additional genetic counseling and may require additional expert consultation for management of extracolonic cancer risks. It is important that individuals diagnosed with a hereditary cancer syndrome be informed that this diagnosis has implications for family members, who may also be at risk for the condition and may benefit from genetic testing.

Practical considerations

Given the difficulty in obtaining a detailed family history while in clinic or in endoscopy, several studies have investigated strategies that may be integrated into practice to identify high-risk patients without substantial burden on providers or patients. Kastrinos and colleagues identified the following three high-yield questions as part of a CRC Risk Assessment Tool that can be used while performing a precolonoscopy assessment: 1) Do you have a first-degree relative with CRC or LS-related cancer diagnosed before age 50?; 2) Have you had CRC or polyps diagnosed prior to age 50?; and 3) Do you have three or more relatives with CRC? The authors found that these three questions alone identified 77% of high-risk individuals.23 In addition, implementation of family history screening instruments using standardized surveys or self-administered risk prediction models at the time of colonoscopy have been shown to improve ascertainment of high-risk patients.24,25 Such strategies may become increasingly easier to implement with integration into patients’ electronic medical records.

Conclusions

Hereditary CRC syndromes are becoming increasingly important to identify, especially in an era where we are seeing rising rates of early-onset CRC. Early identification of high-risk features (Table 2) can lead to timely diagnosis with the goal to implement preventive strategies for screening and/or surveillance, ideally prior to development of cancers.

As gastroenterologists, we have several unique opportunities to identify these individuals and must maintain a high level of suspicion with careful attention when obtaining personal and family history details in clinic and in endoscopy.

Dr. Maratt is assistant professor, Indiana University, Richard L. Roudebush VA Medical Center, Indianapolis. Dr. Stoffel is assistant professor, University of Michigan; director of Cancer Genetic Clinic, Rogel Cancer Center, Ann Arbor. They have no conflicts of interest.

References

1. Pearlman R et al. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3(4):464-71.

2. Stoffel EM et al. Gastroenterology. 2018;154(4):897-905.

3. Kanth P et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017;112:1509-25.

4. Brennan B et al. Ther Adv Gastroenterol. 2017;10:361-71.

5. National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Available at: nccn.org.

6. Lynch HT et al. Nat Rev Cancer. 2015;15:181-94.

7. Syngal S et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015;110:223-62.

8. Mankaney G et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020:(in press)

9. Yan HHN et al. Gut 2017;66:1645-56.

10. Ma H et al. Pathology. 2018;50:49-59.

11. Vasen H et al. Gastroenterology 1999;116:1453-6.

12. Umar A et al. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2004;96:261-8.

13. Kastrinos F et al. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2015;108(2):1-9.

14. Chen S et al. JAMA. 2006;296(12):1479-87.

15. Barnetson RA et al. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(26):2751-63.

16. Kastrinos F et al. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35:2165-72.

17. Kastrinos F et al. Fam Cancer. 2018;17:567-67.

18. Cohen SA et al. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet. 2019;20:293-307.

19. Matloff J et al. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2013;11:1380-5.

20. Ladabaum U et al. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155(2):69-79.

21. Hampel H et al. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(18):1851-60.

22. Yurgelun MB et al. Cancer Prev Res. 2012;5:574-82.

23. Kastrinos F et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:1508-18.

24. Luba DG et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;16:49-58.

25. Guivatchian T et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2017;86:684-91.

Hope springs eternal

As practicing clinicians, we all want to do what is best for patients. We hope our treatments will improve actual health outcomes (and not intermediate process metrics), so we make decisions based on “evidence” that lies on a continuum from “I hope” on one end to “I’m sure” on the other. This month, our three lead articles represent differing points along that continuum.

First, we consider H. pylori and gastric cancer. We know H. pylori eradication reduces ulcer risk and that H. pylori is a risk for gastric cancer. We did not know whether eradication reduces cancer risk. In a large retrospective study from the VA, Kumar et al demonstrated that eradication (not just treatment) substantially reduced subsequent gastric cancers. These data are not definitive, but they nudge us towards the “I’m sure” end of the continuum.

A second group of studies (both retrospective and prospective) suggests that successful weight loss after bariatric surgery was associated with a substantial reduction of risk for 13 cancer types related to obesity. Moderate evidence but again nudging us away from “I hope.”

A third article highlights the recent Clinical Practice Update on Barrett’s esophagus published by the AGA Clinical Practice Update Committee in Gastroenterology’s February 2020 issue. This practice update helps us understand the impact we will make on cancer reduction with surveillance and treatment of Barrett’s. Despite this publication, Barrett’s management remains closer to “hope” than “sure.”

The difficulty we face, as clinician or patient, is what to do when outcomes are really serious but evidence remains close to the “I hope” end. Take a reasonably healthy 68-year-old man with asymptomatic coronary disease, but a very high (and increasing) coronary artery calcium score, despite maximum statins and appropriate lifestyle practices. Should he initiate a PCSK9 inhibitor ($14,000 per year) absent evidence that it would alter cardiac risk? Recently, a retrospective study nudged us along the continuum (Peng et al. JACC Cardiovascular Imaging. 2020 Jan;13[1 Pt 1]:83-93). A serious outcome, suggestive but not definitive evidence, and no time for an RCT. Will such aggressive therapy help? I sure hope so.

John I. Allen, MD, MBA, AGAF

Editor in Chief

As practicing clinicians, we all want to do what is best for patients. We hope our treatments will improve actual health outcomes (and not intermediate process metrics), so we make decisions based on “evidence” that lies on a continuum from “I hope” on one end to “I’m sure” on the other. This month, our three lead articles represent differing points along that continuum.

First, we consider H. pylori and gastric cancer. We know H. pylori eradication reduces ulcer risk and that H. pylori is a risk for gastric cancer. We did not know whether eradication reduces cancer risk. In a large retrospective study from the VA, Kumar et al demonstrated that eradication (not just treatment) substantially reduced subsequent gastric cancers. These data are not definitive, but they nudge us towards the “I’m sure” end of the continuum.

A second group of studies (both retrospective and prospective) suggests that successful weight loss after bariatric surgery was associated with a substantial reduction of risk for 13 cancer types related to obesity. Moderate evidence but again nudging us away from “I hope.”

A third article highlights the recent Clinical Practice Update on Barrett’s esophagus published by the AGA Clinical Practice Update Committee in Gastroenterology’s February 2020 issue. This practice update helps us understand the impact we will make on cancer reduction with surveillance and treatment of Barrett’s. Despite this publication, Barrett’s management remains closer to “hope” than “sure.”

The difficulty we face, as clinician or patient, is what to do when outcomes are really serious but evidence remains close to the “I hope” end. Take a reasonably healthy 68-year-old man with asymptomatic coronary disease, but a very high (and increasing) coronary artery calcium score, despite maximum statins and appropriate lifestyle practices. Should he initiate a PCSK9 inhibitor ($14,000 per year) absent evidence that it would alter cardiac risk? Recently, a retrospective study nudged us along the continuum (Peng et al. JACC Cardiovascular Imaging. 2020 Jan;13[1 Pt 1]:83-93). A serious outcome, suggestive but not definitive evidence, and no time for an RCT. Will such aggressive therapy help? I sure hope so.

John I. Allen, MD, MBA, AGAF

Editor in Chief

As practicing clinicians, we all want to do what is best for patients. We hope our treatments will improve actual health outcomes (and not intermediate process metrics), so we make decisions based on “evidence” that lies on a continuum from “I hope” on one end to “I’m sure” on the other. This month, our three lead articles represent differing points along that continuum.

First, we consider H. pylori and gastric cancer. We know H. pylori eradication reduces ulcer risk and that H. pylori is a risk for gastric cancer. We did not know whether eradication reduces cancer risk. In a large retrospective study from the VA, Kumar et al demonstrated that eradication (not just treatment) substantially reduced subsequent gastric cancers. These data are not definitive, but they nudge us towards the “I’m sure” end of the continuum.

A second group of studies (both retrospective and prospective) suggests that successful weight loss after bariatric surgery was associated with a substantial reduction of risk for 13 cancer types related to obesity. Moderate evidence but again nudging us away from “I hope.”

A third article highlights the recent Clinical Practice Update on Barrett’s esophagus published by the AGA Clinical Practice Update Committee in Gastroenterology’s February 2020 issue. This practice update helps us understand the impact we will make on cancer reduction with surveillance and treatment of Barrett’s. Despite this publication, Barrett’s management remains closer to “hope” than “sure.”

The difficulty we face, as clinician or patient, is what to do when outcomes are really serious but evidence remains close to the “I hope” end. Take a reasonably healthy 68-year-old man with asymptomatic coronary disease, but a very high (and increasing) coronary artery calcium score, despite maximum statins and appropriate lifestyle practices. Should he initiate a PCSK9 inhibitor ($14,000 per year) absent evidence that it would alter cardiac risk? Recently, a retrospective study nudged us along the continuum (Peng et al. JACC Cardiovascular Imaging. 2020 Jan;13[1 Pt 1]:83-93). A serious outcome, suggestive but not definitive evidence, and no time for an RCT. Will such aggressive therapy help? I sure hope so.

John I. Allen, MD, MBA, AGAF

Editor in Chief

Dependent trait in chronic migraine may predict nonresponse to onabotulinumtoxin A

according to research published in the January issue of Headache. The research may be the first to show that personality traits predict response to onabotulinumtoxin A in this population.

“These findings point out that conducting an evaluation of personality traits in patients with chronic migraine might be helpful in the prediction of the course and election of the treatment, as well as identifying patients who might benefit from a multidisciplinary approach,” wrote Alicia Gonzalez-Martinez, MD, of the Hospital Universitario de La Princesa and Instituto de Investigación Sanitaria de La Princesa in Madrid and colleagues. “Categorical questionnaires such as the Salamanca screening test seem to be useful for this purpose.”

Researchers used ICD-10 personality criteria

Personality patterns in patients with migraine and other primary headaches have been the subject of decades of research. Munoz et al. found that certain personality traits are associated with migraine and chronic migraine, and this association may influence clinical management and treatment. The effect of personality traits on response to treatment, however, had not been studied previously.

Dr. Gonzalez-Martinez and colleagues hypothesized that cluster C traits (e.g., obsessive-compulsive, dependent, and anxious), as defined by ICD-10, are associated with nonresponse to onabotulinumtoxin A. To test this hypothesis, they conducted a case-control observational study in a cohort of patients with chronic migraine. Eligible patients presented to one of two headache units of a tertiary hospital between January and May 2018. The investigators obtained a complete headache history and demographic information from each patient. Patients had at least two treatment cycles of onabotulinumtoxin A. Dr. Gonzalez-Martinez and colleagues defined treatment response as a reduction in the number of monthly migraine days of at least 50% after at least two treatment cycles.

The investigators assessed participants’ personality traits by administering the Salamanca test, a brief categorical inventory that examines 11 personality traits using 22 questions. Patients completed the test at the beginning of the study period and before they were classified as responders or nonresponders.

Medication overuse was a potential confounder

The study population included 112 patients with chronic migraine. One hundred patients (89%) were women. Participants’ mean age at initiation of onabotulinumtoxin A treatment was 43 years. The population’s mean duration of chronic migraine was 29 months. Eighty-three patients (74.1%) had medication overuse, and 96 (85.7%) responded to onabotulinumtoxin A.

Cluster A traits in the population included paranoid (prevalence, 10.7%), schizoid (38.4%), and schizotypal (7.1%). Cluster B traits included histrionic (50%), antisocial (1.8%), narcissistic (9.8%), emotional instability subtype impulsive (27.7%), and emotional instability subtype limit (EISL, 24.1%). Cluster C traits were anxious (58.9%) anancastic (i.e., obsessive-compulsive, 54.5%), and dependent (32.1%).

The investigators found no differences in demographics between responders and nonresponders. In a univariate analysis, dependent traits (e.g., passivity and emotional overdependence on others) and EISL traits (e.g., impulsivity and disturbed self-image) were significantly more common among nonresponders. In a multivariate analysis, dependent traits remained significantly associated with nonresponse to onabotulinumtoxin A.

Medication overuse was a potential confounder in the study, according to Dr. Gonzalez-Martinez and colleagues. One of the study’s limitations was its absence of a healthy control group. Another was the fact that the psychometrics of the Salamanca screening test have not been published in a peer-reviewed journal and may need further examination.

Dependent personality “may also be part of the proposed chronic pain sufferer personality,” wrote the investigators. “Early detection of personality traits could improve management and outcome of chronic migraine patients. Additionally, the possibility to predict the effectiveness of onabotulinumtoxin A therapy may reduce costs and latency time of effect in patients with improbable effectiveness.”

The study had no outside funding, and the authors reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Gonzalez-Martinez A et al. Headache. 2020;60(1):153-61.

according to research published in the January issue of Headache. The research may be the first to show that personality traits predict response to onabotulinumtoxin A in this population.

“These findings point out that conducting an evaluation of personality traits in patients with chronic migraine might be helpful in the prediction of the course and election of the treatment, as well as identifying patients who might benefit from a multidisciplinary approach,” wrote Alicia Gonzalez-Martinez, MD, of the Hospital Universitario de La Princesa and Instituto de Investigación Sanitaria de La Princesa in Madrid and colleagues. “Categorical questionnaires such as the Salamanca screening test seem to be useful for this purpose.”

Researchers used ICD-10 personality criteria

Personality patterns in patients with migraine and other primary headaches have been the subject of decades of research. Munoz et al. found that certain personality traits are associated with migraine and chronic migraine, and this association may influence clinical management and treatment. The effect of personality traits on response to treatment, however, had not been studied previously.

Dr. Gonzalez-Martinez and colleagues hypothesized that cluster C traits (e.g., obsessive-compulsive, dependent, and anxious), as defined by ICD-10, are associated with nonresponse to onabotulinumtoxin A. To test this hypothesis, they conducted a case-control observational study in a cohort of patients with chronic migraine. Eligible patients presented to one of two headache units of a tertiary hospital between January and May 2018. The investigators obtained a complete headache history and demographic information from each patient. Patients had at least two treatment cycles of onabotulinumtoxin A. Dr. Gonzalez-Martinez and colleagues defined treatment response as a reduction in the number of monthly migraine days of at least 50% after at least two treatment cycles.

The investigators assessed participants’ personality traits by administering the Salamanca test, a brief categorical inventory that examines 11 personality traits using 22 questions. Patients completed the test at the beginning of the study period and before they were classified as responders or nonresponders.

Medication overuse was a potential confounder

The study population included 112 patients with chronic migraine. One hundred patients (89%) were women. Participants’ mean age at initiation of onabotulinumtoxin A treatment was 43 years. The population’s mean duration of chronic migraine was 29 months. Eighty-three patients (74.1%) had medication overuse, and 96 (85.7%) responded to onabotulinumtoxin A.

Cluster A traits in the population included paranoid (prevalence, 10.7%), schizoid (38.4%), and schizotypal (7.1%). Cluster B traits included histrionic (50%), antisocial (1.8%), narcissistic (9.8%), emotional instability subtype impulsive (27.7%), and emotional instability subtype limit (EISL, 24.1%). Cluster C traits were anxious (58.9%) anancastic (i.e., obsessive-compulsive, 54.5%), and dependent (32.1%).

The investigators found no differences in demographics between responders and nonresponders. In a univariate analysis, dependent traits (e.g., passivity and emotional overdependence on others) and EISL traits (e.g., impulsivity and disturbed self-image) were significantly more common among nonresponders. In a multivariate analysis, dependent traits remained significantly associated with nonresponse to onabotulinumtoxin A.

Medication overuse was a potential confounder in the study, according to Dr. Gonzalez-Martinez and colleagues. One of the study’s limitations was its absence of a healthy control group. Another was the fact that the psychometrics of the Salamanca screening test have not been published in a peer-reviewed journal and may need further examination.

Dependent personality “may also be part of the proposed chronic pain sufferer personality,” wrote the investigators. “Early detection of personality traits could improve management and outcome of chronic migraine patients. Additionally, the possibility to predict the effectiveness of onabotulinumtoxin A therapy may reduce costs and latency time of effect in patients with improbable effectiveness.”

The study had no outside funding, and the authors reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Gonzalez-Martinez A et al. Headache. 2020;60(1):153-61.

according to research published in the January issue of Headache. The research may be the first to show that personality traits predict response to onabotulinumtoxin A in this population.

“These findings point out that conducting an evaluation of personality traits in patients with chronic migraine might be helpful in the prediction of the course and election of the treatment, as well as identifying patients who might benefit from a multidisciplinary approach,” wrote Alicia Gonzalez-Martinez, MD, of the Hospital Universitario de La Princesa and Instituto de Investigación Sanitaria de La Princesa in Madrid and colleagues. “Categorical questionnaires such as the Salamanca screening test seem to be useful for this purpose.”

Researchers used ICD-10 personality criteria

Personality patterns in patients with migraine and other primary headaches have been the subject of decades of research. Munoz et al. found that certain personality traits are associated with migraine and chronic migraine, and this association may influence clinical management and treatment. The effect of personality traits on response to treatment, however, had not been studied previously.

Dr. Gonzalez-Martinez and colleagues hypothesized that cluster C traits (e.g., obsessive-compulsive, dependent, and anxious), as defined by ICD-10, are associated with nonresponse to onabotulinumtoxin A. To test this hypothesis, they conducted a case-control observational study in a cohort of patients with chronic migraine. Eligible patients presented to one of two headache units of a tertiary hospital between January and May 2018. The investigators obtained a complete headache history and demographic information from each patient. Patients had at least two treatment cycles of onabotulinumtoxin A. Dr. Gonzalez-Martinez and colleagues defined treatment response as a reduction in the number of monthly migraine days of at least 50% after at least two treatment cycles.

The investigators assessed participants’ personality traits by administering the Salamanca test, a brief categorical inventory that examines 11 personality traits using 22 questions. Patients completed the test at the beginning of the study period and before they were classified as responders or nonresponders.

Medication overuse was a potential confounder

The study population included 112 patients with chronic migraine. One hundred patients (89%) were women. Participants’ mean age at initiation of onabotulinumtoxin A treatment was 43 years. The population’s mean duration of chronic migraine was 29 months. Eighty-three patients (74.1%) had medication overuse, and 96 (85.7%) responded to onabotulinumtoxin A.

Cluster A traits in the population included paranoid (prevalence, 10.7%), schizoid (38.4%), and schizotypal (7.1%). Cluster B traits included histrionic (50%), antisocial (1.8%), narcissistic (9.8%), emotional instability subtype impulsive (27.7%), and emotional instability subtype limit (EISL, 24.1%). Cluster C traits were anxious (58.9%) anancastic (i.e., obsessive-compulsive, 54.5%), and dependent (32.1%).

The investigators found no differences in demographics between responders and nonresponders. In a univariate analysis, dependent traits (e.g., passivity and emotional overdependence on others) and EISL traits (e.g., impulsivity and disturbed self-image) were significantly more common among nonresponders. In a multivariate analysis, dependent traits remained significantly associated with nonresponse to onabotulinumtoxin A.

Medication overuse was a potential confounder in the study, according to Dr. Gonzalez-Martinez and colleagues. One of the study’s limitations was its absence of a healthy control group. Another was the fact that the psychometrics of the Salamanca screening test have not been published in a peer-reviewed journal and may need further examination.

Dependent personality “may also be part of the proposed chronic pain sufferer personality,” wrote the investigators. “Early detection of personality traits could improve management and outcome of chronic migraine patients. Additionally, the possibility to predict the effectiveness of onabotulinumtoxin A therapy may reduce costs and latency time of effect in patients with improbable effectiveness.”

The study had no outside funding, and the authors reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Gonzalez-Martinez A et al. Headache. 2020;60(1):153-61.

FROM HEADACHE

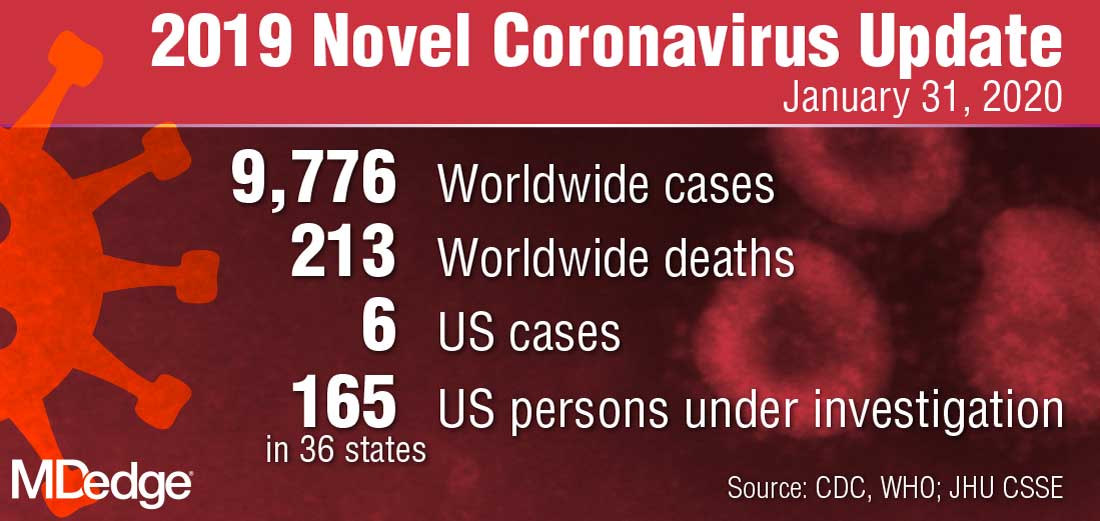

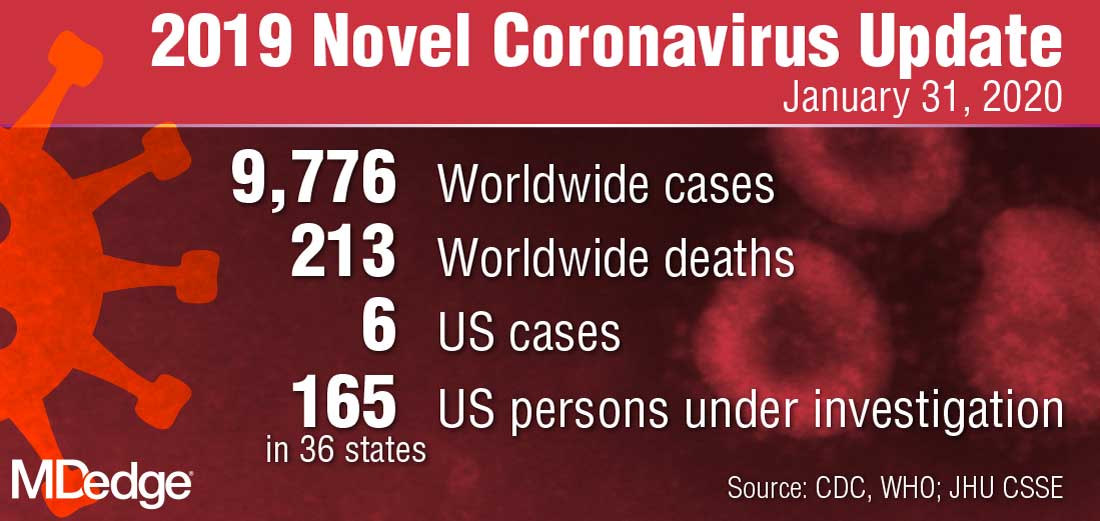

HHS declares coronavirus emergency, orders quarantine

The federal government declared a formal public health emergency on Jan. 31 to aid in the response to the 2019 Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV). The declaration, issued by Health and Human Services Secretary Alex. M. Azar II gives state, tribal, and local health departments additional flexibility to request assistance from the federal government in responding to the coronavirus.

"While this virus poses a serious public health threat, the risk to the American public remains low at this time, and we are working to keep this risk low."*

2019-nCoV—the first such action taken by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in more than 50 years.

“This decision is based on the current scientific facts,” Nancy Messonnier, MD, director of the National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, said during a press briefing Jan. 31. “While we understand the action seems drastic, our goal today, tomorrow, and always continues to be the safety of the American public. We would rather be remembered for over-reacting than under-reacting.”

These actions come on the heels of the World Health Organization’s Jan. 30 declaration of 2019-nCoV as a public health emergency of international concern, and from a recent spike in cases reported by Chinese health officials. “Every day this week China has reported additional cases,” Dr. Messonnier said. “Today’s numbers are a 26% increase since yesterday. Over the course of the last week, there have been nearly 7,000 new cases reported. This tells us the virus is continuing to spread rapidly in China. The reported deaths have continued to rise as well. In addition, locations outside China have continued to report cases. There have been an increasing number of reports of person-to-person spread, and now, most recently, a report in the New England Journal of Medicine of asymptomatic spread.”

The quarantine of passengers will last 14 days from when the plane left Wuhan, China. Martin Cetron, MD, who directs the CDC’s Division of Global Migration and Quarantine, said that the quarantine order “offers the greatest level of protection for the American public in preventing introduction and spread. That is our primary concern. Prior epidemics suggest that when people are properly informed, they’re usually very compliant with this request to restrict their movement. This allows someone who would become symptomatic to be rapidly identified. Offering early, rapid diagnosis of their illness could alleviate a lot of anxiety and uncertainty. In addition, this is a protective effect on family members. No individual wants to be the source of introducing or exposing a family member or a loved one to their virus. Additionally, this is part of their civic responsibility to protect their communities.”

* This story was updated on 01/31/2020.

The federal government declared a formal public health emergency on Jan. 31 to aid in the response to the 2019 Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV). The declaration, issued by Health and Human Services Secretary Alex. M. Azar II gives state, tribal, and local health departments additional flexibility to request assistance from the federal government in responding to the coronavirus.

"While this virus poses a serious public health threat, the risk to the American public remains low at this time, and we are working to keep this risk low."*

2019-nCoV—the first such action taken by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in more than 50 years.

“This decision is based on the current scientific facts,” Nancy Messonnier, MD, director of the National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, said during a press briefing Jan. 31. “While we understand the action seems drastic, our goal today, tomorrow, and always continues to be the safety of the American public. We would rather be remembered for over-reacting than under-reacting.”

These actions come on the heels of the World Health Organization’s Jan. 30 declaration of 2019-nCoV as a public health emergency of international concern, and from a recent spike in cases reported by Chinese health officials. “Every day this week China has reported additional cases,” Dr. Messonnier said. “Today’s numbers are a 26% increase since yesterday. Over the course of the last week, there have been nearly 7,000 new cases reported. This tells us the virus is continuing to spread rapidly in China. The reported deaths have continued to rise as well. In addition, locations outside China have continued to report cases. There have been an increasing number of reports of person-to-person spread, and now, most recently, a report in the New England Journal of Medicine of asymptomatic spread.”

The quarantine of passengers will last 14 days from when the plane left Wuhan, China. Martin Cetron, MD, who directs the CDC’s Division of Global Migration and Quarantine, said that the quarantine order “offers the greatest level of protection for the American public in preventing introduction and spread. That is our primary concern. Prior epidemics suggest that when people are properly informed, they’re usually very compliant with this request to restrict their movement. This allows someone who would become symptomatic to be rapidly identified. Offering early, rapid diagnosis of their illness could alleviate a lot of anxiety and uncertainty. In addition, this is a protective effect on family members. No individual wants to be the source of introducing or exposing a family member or a loved one to their virus. Additionally, this is part of their civic responsibility to protect their communities.”

* This story was updated on 01/31/2020.

The federal government declared a formal public health emergency on Jan. 31 to aid in the response to the 2019 Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV). The declaration, issued by Health and Human Services Secretary Alex. M. Azar II gives state, tribal, and local health departments additional flexibility to request assistance from the federal government in responding to the coronavirus.

"While this virus poses a serious public health threat, the risk to the American public remains low at this time, and we are working to keep this risk low."*

2019-nCoV—the first such action taken by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in more than 50 years.

“This decision is based on the current scientific facts,” Nancy Messonnier, MD, director of the National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, said during a press briefing Jan. 31. “While we understand the action seems drastic, our goal today, tomorrow, and always continues to be the safety of the American public. We would rather be remembered for over-reacting than under-reacting.”

These actions come on the heels of the World Health Organization’s Jan. 30 declaration of 2019-nCoV as a public health emergency of international concern, and from a recent spike in cases reported by Chinese health officials. “Every day this week China has reported additional cases,” Dr. Messonnier said. “Today’s numbers are a 26% increase since yesterday. Over the course of the last week, there have been nearly 7,000 new cases reported. This tells us the virus is continuing to spread rapidly in China. The reported deaths have continued to rise as well. In addition, locations outside China have continued to report cases. There have been an increasing number of reports of person-to-person spread, and now, most recently, a report in the New England Journal of Medicine of asymptomatic spread.”

The quarantine of passengers will last 14 days from when the plane left Wuhan, China. Martin Cetron, MD, who directs the CDC’s Division of Global Migration and Quarantine, said that the quarantine order “offers the greatest level of protection for the American public in preventing introduction and spread. That is our primary concern. Prior epidemics suggest that when people are properly informed, they’re usually very compliant with this request to restrict their movement. This allows someone who would become symptomatic to be rapidly identified. Offering early, rapid diagnosis of their illness could alleviate a lot of anxiety and uncertainty. In addition, this is a protective effect on family members. No individual wants to be the source of introducing or exposing a family member or a loved one to their virus. Additionally, this is part of their civic responsibility to protect their communities.”

* This story was updated on 01/31/2020.

Is anxiety about the coronavirus out of proportion?

A number of years ago, a patient I was treating mentioned that she was not eating tomatoes. There had been stories in the news about people contracting bacterial infections from tomatoes, but I paused for a moment, then asked her: “Have there been any contaminated tomatoes here in Maryland?” There had not been and I was still happily eating salsa, but my patient thought about this differently: If disease-causing tomatoes were to come to our state, someone would be the first person to become ill. She did not want to take any risks. My patient, however, was a heavy smoker and already grappling with health issues that were caused by smoking, so I found her choice of what she should worry about and how it influenced her behavior to be perplexing. I realize it’s not the same; nicotine is an addiction, while tomatoes remain a choice for most of us, and it’s common for people to worry about very unlikely events even when we are surrounded by very real and statistically more probable threats to our well-being.

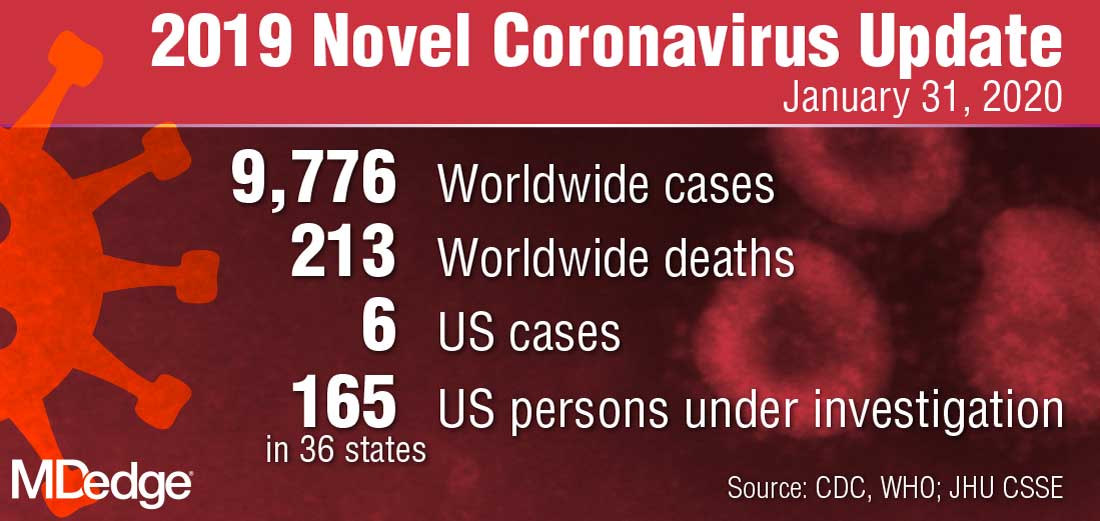

Today’s news reports are filled with stories about 2019 Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV), an illness that started in Wuhan, China; as of Jan. 31, 2020, there were 9,776 confirmed cases and 213 deaths. There have been an additional 118 cases reported outside of mainland China, including 6 in the United States, and no one outside of China has died.

The response to the virus has been remarkable: Wuhan, a city of more than 11 million inhabitants, is on lockdown, as are 15 other cities in China; 46 million people have been affected, the largest quarantine in human history. Travel is restricted in parts of China, airports all over the world are screening those who fly in from Wuhan, foreign governments are bringing their citizens home from Wuhan, and even Starbucks has temporarily closed half its stores in China. The economics of containing this virus are astounding.