User login

Gardasil-9 approved for prevention of head and neck cancers

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has expanded the indication for the Gardasil-9 (Merck) vaccine to include prevention of oropharyngeal and other head and neck cancers caused by HPV types 16, 18, 31, 33, 45, 52, and 58.

This new indication is approved under the FDA’s accelerated approval program and is based on the vaccine’s effectiveness in preventing HPV-related anogenital disease. Continued approval for this indication may be contingent upon verification and description of clinical benefit in a confirmatory clinical trial, which is currently underway.

“At Merck, working to help prevent certain HPV-related cancers has been a priority for more than two decades,” Alain Luxembourg, MD, director, clinical research, Merck Research Laboratories, said in a statement. “Today’s approval for the prevention of HPV-related oropharyngeal and other head and neck cancers represents an important step in Merck’s mission to help reduce the number of men and women affected by certain HPV-related cancers.”

This new indication doesn’t affect the current recommendations that are already in place. In 2018, a supplemental application for Gardasil 9 was approved to include women and men aged 27 through 45 years for preventing a variety of cancers including cervical, vulvar, vaginal, and anal cancer as well as genital warts. But cancers of the head and neck were not included.

The original Gardasil vaccine came on the market in 2006, with an indication to prevent certain cancers and diseases caused by HPV types 6, 11, 16, and 18. It is no longer distributed in the United States.

In 2014, the FDA approved Gardasil 9, which extends the vaccine coverage for the initial four HPV types as five additional types (31, 33, 45, 52, and 58), and its initial indication was for use in both men and women between the ages of 9 through 26 years.

Head and neck cancers surpass cervical cancer

More than 2 decades ago, researchers first found a connection between HPV and a subset of head and neck cancers (Curr Opin Oncol. 1999;11(3):191-199). The cancers associated with HPV also appeared to have a different biology and disease pattern, as well as a better prognosis, compared with those that were unrelated. HPV is now responsible for the majority of oropharyngeal squamous cell cancers diagnosed in the United States.

A study published last year found that oral HPV infections were occurring with significantly less frequency among sexually active female adolescents who had received the quadrivalent vaccine, as compared with those who were unvaccinated.

These findings provided evidence that HPV vaccination was associated with a reduced frequency of HPV infection in the oral cavity, suggesting that vaccination could decrease the future risk of HPV-associated head and neck cancers.

The omission of head and neck cancers from the initial list of indications for the vaccine is notable because, according to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), oropharyngeal cancers are now the most common malignancy caused by HPV, surpassing cervical cancer.

Who will benefit?

An estimated 14 million new HPV infections occur every year in the United States, according to the CDC, and about 80% of individuals who are sexually active have been exposed at some point during their lifetime. In most people, however, the virus will clear on its own without causing any illness or symptoms.

In a Medscape videoblog, Sandra Adamson Fryhofer, MD, MACP, FRCP, helped clarify the adult population most likely to benefit from the vaccine. She pointed out that the HPV vaccine doesn’t treat HPV-related disease or help clear infections, and there are currently no clinical antibody tests or titers that can predict immunity.

“Many adults aged 27-45 have already been exposed to HPV early in life,” she said. Those in a long-term mutually monogamous relationship are not likely to get a new HPV infection. Those with multiple prior sex partners are more likely to have already been exposed to vaccine serotypes. For them, the vaccine will be less effective.”

Fryhofer added that individuals who are now at risk for exposure to a new HPV infection from a new sex partner are the ones most likely to benefit from HPV vaccination.

Confirmation needed

The FDA’s accelerated approval is contingent on confirmatory data, and Merck opened a clinical trial this past February to evaluate the efficacy, immunogenicity, and safety of the 9-valent HPV vaccine in men 20 to 45 years of age. The phase 3 multicenter randomized trial will have an estimated enrollment of 6000 men.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has expanded the indication for the Gardasil-9 (Merck) vaccine to include prevention of oropharyngeal and other head and neck cancers caused by HPV types 16, 18, 31, 33, 45, 52, and 58.

This new indication is approved under the FDA’s accelerated approval program and is based on the vaccine’s effectiveness in preventing HPV-related anogenital disease. Continued approval for this indication may be contingent upon verification and description of clinical benefit in a confirmatory clinical trial, which is currently underway.

“At Merck, working to help prevent certain HPV-related cancers has been a priority for more than two decades,” Alain Luxembourg, MD, director, clinical research, Merck Research Laboratories, said in a statement. “Today’s approval for the prevention of HPV-related oropharyngeal and other head and neck cancers represents an important step in Merck’s mission to help reduce the number of men and women affected by certain HPV-related cancers.”

This new indication doesn’t affect the current recommendations that are already in place. In 2018, a supplemental application for Gardasil 9 was approved to include women and men aged 27 through 45 years for preventing a variety of cancers including cervical, vulvar, vaginal, and anal cancer as well as genital warts. But cancers of the head and neck were not included.

The original Gardasil vaccine came on the market in 2006, with an indication to prevent certain cancers and diseases caused by HPV types 6, 11, 16, and 18. It is no longer distributed in the United States.

In 2014, the FDA approved Gardasil 9, which extends the vaccine coverage for the initial four HPV types as five additional types (31, 33, 45, 52, and 58), and its initial indication was for use in both men and women between the ages of 9 through 26 years.

Head and neck cancers surpass cervical cancer

More than 2 decades ago, researchers first found a connection between HPV and a subset of head and neck cancers (Curr Opin Oncol. 1999;11(3):191-199). The cancers associated with HPV also appeared to have a different biology and disease pattern, as well as a better prognosis, compared with those that were unrelated. HPV is now responsible for the majority of oropharyngeal squamous cell cancers diagnosed in the United States.

A study published last year found that oral HPV infections were occurring with significantly less frequency among sexually active female adolescents who had received the quadrivalent vaccine, as compared with those who were unvaccinated.

These findings provided evidence that HPV vaccination was associated with a reduced frequency of HPV infection in the oral cavity, suggesting that vaccination could decrease the future risk of HPV-associated head and neck cancers.

The omission of head and neck cancers from the initial list of indications for the vaccine is notable because, according to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), oropharyngeal cancers are now the most common malignancy caused by HPV, surpassing cervical cancer.

Who will benefit?

An estimated 14 million new HPV infections occur every year in the United States, according to the CDC, and about 80% of individuals who are sexually active have been exposed at some point during their lifetime. In most people, however, the virus will clear on its own without causing any illness or symptoms.

In a Medscape videoblog, Sandra Adamson Fryhofer, MD, MACP, FRCP, helped clarify the adult population most likely to benefit from the vaccine. She pointed out that the HPV vaccine doesn’t treat HPV-related disease or help clear infections, and there are currently no clinical antibody tests or titers that can predict immunity.

“Many adults aged 27-45 have already been exposed to HPV early in life,” she said. Those in a long-term mutually monogamous relationship are not likely to get a new HPV infection. Those with multiple prior sex partners are more likely to have already been exposed to vaccine serotypes. For them, the vaccine will be less effective.”

Fryhofer added that individuals who are now at risk for exposure to a new HPV infection from a new sex partner are the ones most likely to benefit from HPV vaccination.

Confirmation needed

The FDA’s accelerated approval is contingent on confirmatory data, and Merck opened a clinical trial this past February to evaluate the efficacy, immunogenicity, and safety of the 9-valent HPV vaccine in men 20 to 45 years of age. The phase 3 multicenter randomized trial will have an estimated enrollment of 6000 men.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has expanded the indication for the Gardasil-9 (Merck) vaccine to include prevention of oropharyngeal and other head and neck cancers caused by HPV types 16, 18, 31, 33, 45, 52, and 58.

This new indication is approved under the FDA’s accelerated approval program and is based on the vaccine’s effectiveness in preventing HPV-related anogenital disease. Continued approval for this indication may be contingent upon verification and description of clinical benefit in a confirmatory clinical trial, which is currently underway.

“At Merck, working to help prevent certain HPV-related cancers has been a priority for more than two decades,” Alain Luxembourg, MD, director, clinical research, Merck Research Laboratories, said in a statement. “Today’s approval for the prevention of HPV-related oropharyngeal and other head and neck cancers represents an important step in Merck’s mission to help reduce the number of men and women affected by certain HPV-related cancers.”

This new indication doesn’t affect the current recommendations that are already in place. In 2018, a supplemental application for Gardasil 9 was approved to include women and men aged 27 through 45 years for preventing a variety of cancers including cervical, vulvar, vaginal, and anal cancer as well as genital warts. But cancers of the head and neck were not included.

The original Gardasil vaccine came on the market in 2006, with an indication to prevent certain cancers and diseases caused by HPV types 6, 11, 16, and 18. It is no longer distributed in the United States.

In 2014, the FDA approved Gardasil 9, which extends the vaccine coverage for the initial four HPV types as five additional types (31, 33, 45, 52, and 58), and its initial indication was for use in both men and women between the ages of 9 through 26 years.

Head and neck cancers surpass cervical cancer

More than 2 decades ago, researchers first found a connection between HPV and a subset of head and neck cancers (Curr Opin Oncol. 1999;11(3):191-199). The cancers associated with HPV also appeared to have a different biology and disease pattern, as well as a better prognosis, compared with those that were unrelated. HPV is now responsible for the majority of oropharyngeal squamous cell cancers diagnosed in the United States.

A study published last year found that oral HPV infections were occurring with significantly less frequency among sexually active female adolescents who had received the quadrivalent vaccine, as compared with those who were unvaccinated.

These findings provided evidence that HPV vaccination was associated with a reduced frequency of HPV infection in the oral cavity, suggesting that vaccination could decrease the future risk of HPV-associated head and neck cancers.

The omission of head and neck cancers from the initial list of indications for the vaccine is notable because, according to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), oropharyngeal cancers are now the most common malignancy caused by HPV, surpassing cervical cancer.

Who will benefit?

An estimated 14 million new HPV infections occur every year in the United States, according to the CDC, and about 80% of individuals who are sexually active have been exposed at some point during their lifetime. In most people, however, the virus will clear on its own without causing any illness or symptoms.

In a Medscape videoblog, Sandra Adamson Fryhofer, MD, MACP, FRCP, helped clarify the adult population most likely to benefit from the vaccine. She pointed out that the HPV vaccine doesn’t treat HPV-related disease or help clear infections, and there are currently no clinical antibody tests or titers that can predict immunity.

“Many adults aged 27-45 have already been exposed to HPV early in life,” she said. Those in a long-term mutually monogamous relationship are not likely to get a new HPV infection. Those with multiple prior sex partners are more likely to have already been exposed to vaccine serotypes. For them, the vaccine will be less effective.”

Fryhofer added that individuals who are now at risk for exposure to a new HPV infection from a new sex partner are the ones most likely to benefit from HPV vaccination.

Confirmation needed

The FDA’s accelerated approval is contingent on confirmatory data, and Merck opened a clinical trial this past February to evaluate the efficacy, immunogenicity, and safety of the 9-valent HPV vaccine in men 20 to 45 years of age. The phase 3 multicenter randomized trial will have an estimated enrollment of 6000 men.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

DAPA-HF: Dapagliflozin slows T2D onset in heart failure patients

Dapagliflozin treatment of patients with heart failure but without diabetes in the DAPA-HF trial led to a one-third cut in the relative incidence of new-onset diabetes over a median follow-up of 18 months in a prespecified analysis from the multicenter trial that included 2,605 heart failure patients without diabetes at baseline.

The findings represented the first evidence that a drug from dapagliflozin’s class, the sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors, could prevent or slow the onset of type 2 diabetes. It represents “an additional benefit” that dapagliflozin (Farxiga) offers to patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) like those enrolled in the DAPA-HF trial, Silvio E. Inzucchi, MD, said at the virtual annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association. DAPA-HF had previously proved that treatment with this drug significantly reduced the study’s primary endpoint of cardiovascular death or heart failure worsening.

During 18 months of follow-up, 7.1% of patients in the placebo arm developed type 2 diabetes, compared with 4.9% in those who received dapagliflozin, a 2.2% absolute difference and a 32% relative risk reduction that was statistically significant for this prespecified but “exploratory” endpoint, reported Dr. Inzucchi, an endocrinologist and professor of medicine at Yale University, New Haven, Conn.

For this analysis, a hemoglobin A1c level of at least 6.5% measured in two consecutive assessments was the criterion for diagnosing incident diabetes. The 2,605 enrolled patients without diabetes in the DAPA-HF trial represented 55% of the entire trial cohort of 4,744 patients with HFrEF.

The 32% relative risk reduction for incident diabetes was primarily relevant to enrolled patients with prediabetes at entry, who constituted 67% of the enrolled cohort based on the usual definition of prediabetes, an A1c of 5.7%-6.4%.

Among all 157 (6%) of the DAPA-HF patients who developed diabetes during the trial, 150 (96%) occurred in patients with prediabetes by the usual definition; 136 of the incident cases (87%) had prediabetes by a more stringent criterion of an A1c of 6.0%-6.4%.

To put the preventive efficacy of dapagliflozin into more context, Dr. Inzucchi cited the 31% relative protection rate exerted by metformin in the Diabetes Prevention Program study (N Engl J Med. 2002 Feb 7;346[6]:393-403).

The findings showed that “dapagliflozin is the first medication demonstrated to reduce both incident type 2 diabetes and mortality in a single trial,” as well as the first agent from the SGLT2 inhibitor class to show a diabetes prevention effect, Dr. Inzucchi noted. Patients with both heart failure and diabetes are known to have a substantially increased mortality risk, compared with patients with just one of these diseases, and the potent risk posed by the confluence of both was confirmed in the results Dr. Inzucchi reported.

The 157 HFrEF patients in the trial who developed diabetes had a statistically significant 70% increased incidence of all-cause mortality during the trial’s follow-up, compared with similar HFrEF patients who remained free from a diabetes diagnosis, and they also had a significant 77% relative increase in their incidence of cardiovascular death. This analysis failed to show that incident diabetes had a significant impact on hospitalizations for heart failure coupled with cardiovascular death, another endpoint of the trial.

“This is a tremendously important analysis. We recognize that diabetes is an important factor that can forecast heart failure risk, even over relatively short follow-up. A drug that targets both diseases can be quite beneficial,” commented Muthiah Vaduganathan, MD, a cardiologist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston.

The impact of dapagliflozin on average A1c levels during the DAPA-HF trial was minimal, reducing levels by an average of 0.04% among those who entered with prediabetes and by 0.05% among the other patients. This suggests that the mechanisms by which dapagliflozin reduced incident diabetes was by routes that did not involve simply reducing hyperglycemia, and the observed decrease in incident diabetes was not apparently caused by “masking” of hyperglycemia by dapagliflozin, said Dr. Inzucchi.

One possibility is that dapagliflozin, which also improved quality of life and reduced hospitalizations in the DAPA-HF trial, led to improved function and mobility among patients that had beneficial effects on their insulin sensitivity, Dr. Vaduganathan speculated in an interview.

The new finding of dapagliflozin’s benefit “is great news,” commented Yehuda Handelsman, MD, an endocrinologist and diabetes specialist who is medical director of the Metabolic Institute of America in Tarzana, Calif. “It’s an impressive and important result, and another reason to use dapagliflozin in patients with HFrEF, a group of patients whom you want to prevent from having worse outcomes” by developing diabetes.

The DAPA-HF (Dapagliflozin and Prevention of Adverse Outcomes in Heart Failure) trial enrolled HFrEF patients at 410 centers in 20 countries during February 2017–August 2018. The study’s primary endpoint was the composite incidence of cardiovascular death or worsening heart failure, which occurred in 16.3% of patients randomized to receive dapagliflozin and in 21.2% of control patients on standard care but on placebo instead of the study drug, a statistically significant relative risk reduction of 26% (N Engl J Med. 2019 Nov 21;381[21]:1995-2008). In the 2,605-patient subgroup without type 2 diabetes at baseline the primary endpoint fell by a statistically significant 27% with dapagliflozin treatment, the first time an SGLT2 inhibitor drug was shown effective for reducing this endpoint in patients with HFrEF but without diabetes. DAPA-HF did not enroll any patients with type 1 diabetes.

DAPA-HF was sponsored by AstraZeneca, the company that markets dapagliflozin (Farxiga). Dr. Inzucchi has been a consultant to AstraZeneca and to Abbott, Boehringer Ingelheim, Merck, Novo Nordisk, Sanofi/Lexicon, and vTv Therapeutics. Dr. Vaduganathan has been an adviser to AstraZeneca and to Amgen, Baxter, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Cytokinetics, and Relypsa. Dr. Handelsman has been a consultant to several drug companies including AstraZeneca.

SOURCE: Inzucchi SE et al. ADA 2020, abstract 271-OR.

Dapagliflozin treatment of patients with heart failure but without diabetes in the DAPA-HF trial led to a one-third cut in the relative incidence of new-onset diabetes over a median follow-up of 18 months in a prespecified analysis from the multicenter trial that included 2,605 heart failure patients without diabetes at baseline.

The findings represented the first evidence that a drug from dapagliflozin’s class, the sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors, could prevent or slow the onset of type 2 diabetes. It represents “an additional benefit” that dapagliflozin (Farxiga) offers to patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) like those enrolled in the DAPA-HF trial, Silvio E. Inzucchi, MD, said at the virtual annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association. DAPA-HF had previously proved that treatment with this drug significantly reduced the study’s primary endpoint of cardiovascular death or heart failure worsening.

During 18 months of follow-up, 7.1% of patients in the placebo arm developed type 2 diabetes, compared with 4.9% in those who received dapagliflozin, a 2.2% absolute difference and a 32% relative risk reduction that was statistically significant for this prespecified but “exploratory” endpoint, reported Dr. Inzucchi, an endocrinologist and professor of medicine at Yale University, New Haven, Conn.

For this analysis, a hemoglobin A1c level of at least 6.5% measured in two consecutive assessments was the criterion for diagnosing incident diabetes. The 2,605 enrolled patients without diabetes in the DAPA-HF trial represented 55% of the entire trial cohort of 4,744 patients with HFrEF.

The 32% relative risk reduction for incident diabetes was primarily relevant to enrolled patients with prediabetes at entry, who constituted 67% of the enrolled cohort based on the usual definition of prediabetes, an A1c of 5.7%-6.4%.

Among all 157 (6%) of the DAPA-HF patients who developed diabetes during the trial, 150 (96%) occurred in patients with prediabetes by the usual definition; 136 of the incident cases (87%) had prediabetes by a more stringent criterion of an A1c of 6.0%-6.4%.

To put the preventive efficacy of dapagliflozin into more context, Dr. Inzucchi cited the 31% relative protection rate exerted by metformin in the Diabetes Prevention Program study (N Engl J Med. 2002 Feb 7;346[6]:393-403).

The findings showed that “dapagliflozin is the first medication demonstrated to reduce both incident type 2 diabetes and mortality in a single trial,” as well as the first agent from the SGLT2 inhibitor class to show a diabetes prevention effect, Dr. Inzucchi noted. Patients with both heart failure and diabetes are known to have a substantially increased mortality risk, compared with patients with just one of these diseases, and the potent risk posed by the confluence of both was confirmed in the results Dr. Inzucchi reported.

The 157 HFrEF patients in the trial who developed diabetes had a statistically significant 70% increased incidence of all-cause mortality during the trial’s follow-up, compared with similar HFrEF patients who remained free from a diabetes diagnosis, and they also had a significant 77% relative increase in their incidence of cardiovascular death. This analysis failed to show that incident diabetes had a significant impact on hospitalizations for heart failure coupled with cardiovascular death, another endpoint of the trial.

“This is a tremendously important analysis. We recognize that diabetes is an important factor that can forecast heart failure risk, even over relatively short follow-up. A drug that targets both diseases can be quite beneficial,” commented Muthiah Vaduganathan, MD, a cardiologist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston.

The impact of dapagliflozin on average A1c levels during the DAPA-HF trial was minimal, reducing levels by an average of 0.04% among those who entered with prediabetes and by 0.05% among the other patients. This suggests that the mechanisms by which dapagliflozin reduced incident diabetes was by routes that did not involve simply reducing hyperglycemia, and the observed decrease in incident diabetes was not apparently caused by “masking” of hyperglycemia by dapagliflozin, said Dr. Inzucchi.

One possibility is that dapagliflozin, which also improved quality of life and reduced hospitalizations in the DAPA-HF trial, led to improved function and mobility among patients that had beneficial effects on their insulin sensitivity, Dr. Vaduganathan speculated in an interview.

The new finding of dapagliflozin’s benefit “is great news,” commented Yehuda Handelsman, MD, an endocrinologist and diabetes specialist who is medical director of the Metabolic Institute of America in Tarzana, Calif. “It’s an impressive and important result, and another reason to use dapagliflozin in patients with HFrEF, a group of patients whom you want to prevent from having worse outcomes” by developing diabetes.

The DAPA-HF (Dapagliflozin and Prevention of Adverse Outcomes in Heart Failure) trial enrolled HFrEF patients at 410 centers in 20 countries during February 2017–August 2018. The study’s primary endpoint was the composite incidence of cardiovascular death or worsening heart failure, which occurred in 16.3% of patients randomized to receive dapagliflozin and in 21.2% of control patients on standard care but on placebo instead of the study drug, a statistically significant relative risk reduction of 26% (N Engl J Med. 2019 Nov 21;381[21]:1995-2008). In the 2,605-patient subgroup without type 2 diabetes at baseline the primary endpoint fell by a statistically significant 27% with dapagliflozin treatment, the first time an SGLT2 inhibitor drug was shown effective for reducing this endpoint in patients with HFrEF but without diabetes. DAPA-HF did not enroll any patients with type 1 diabetes.

DAPA-HF was sponsored by AstraZeneca, the company that markets dapagliflozin (Farxiga). Dr. Inzucchi has been a consultant to AstraZeneca and to Abbott, Boehringer Ingelheim, Merck, Novo Nordisk, Sanofi/Lexicon, and vTv Therapeutics. Dr. Vaduganathan has been an adviser to AstraZeneca and to Amgen, Baxter, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Cytokinetics, and Relypsa. Dr. Handelsman has been a consultant to several drug companies including AstraZeneca.

SOURCE: Inzucchi SE et al. ADA 2020, abstract 271-OR.

Dapagliflozin treatment of patients with heart failure but without diabetes in the DAPA-HF trial led to a one-third cut in the relative incidence of new-onset diabetes over a median follow-up of 18 months in a prespecified analysis from the multicenter trial that included 2,605 heart failure patients without diabetes at baseline.

The findings represented the first evidence that a drug from dapagliflozin’s class, the sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors, could prevent or slow the onset of type 2 diabetes. It represents “an additional benefit” that dapagliflozin (Farxiga) offers to patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) like those enrolled in the DAPA-HF trial, Silvio E. Inzucchi, MD, said at the virtual annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association. DAPA-HF had previously proved that treatment with this drug significantly reduced the study’s primary endpoint of cardiovascular death or heart failure worsening.

During 18 months of follow-up, 7.1% of patients in the placebo arm developed type 2 diabetes, compared with 4.9% in those who received dapagliflozin, a 2.2% absolute difference and a 32% relative risk reduction that was statistically significant for this prespecified but “exploratory” endpoint, reported Dr. Inzucchi, an endocrinologist and professor of medicine at Yale University, New Haven, Conn.

For this analysis, a hemoglobin A1c level of at least 6.5% measured in two consecutive assessments was the criterion for diagnosing incident diabetes. The 2,605 enrolled patients without diabetes in the DAPA-HF trial represented 55% of the entire trial cohort of 4,744 patients with HFrEF.

The 32% relative risk reduction for incident diabetes was primarily relevant to enrolled patients with prediabetes at entry, who constituted 67% of the enrolled cohort based on the usual definition of prediabetes, an A1c of 5.7%-6.4%.

Among all 157 (6%) of the DAPA-HF patients who developed diabetes during the trial, 150 (96%) occurred in patients with prediabetes by the usual definition; 136 of the incident cases (87%) had prediabetes by a more stringent criterion of an A1c of 6.0%-6.4%.

To put the preventive efficacy of dapagliflozin into more context, Dr. Inzucchi cited the 31% relative protection rate exerted by metformin in the Diabetes Prevention Program study (N Engl J Med. 2002 Feb 7;346[6]:393-403).

The findings showed that “dapagliflozin is the first medication demonstrated to reduce both incident type 2 diabetes and mortality in a single trial,” as well as the first agent from the SGLT2 inhibitor class to show a diabetes prevention effect, Dr. Inzucchi noted. Patients with both heart failure and diabetes are known to have a substantially increased mortality risk, compared with patients with just one of these diseases, and the potent risk posed by the confluence of both was confirmed in the results Dr. Inzucchi reported.

The 157 HFrEF patients in the trial who developed diabetes had a statistically significant 70% increased incidence of all-cause mortality during the trial’s follow-up, compared with similar HFrEF patients who remained free from a diabetes diagnosis, and they also had a significant 77% relative increase in their incidence of cardiovascular death. This analysis failed to show that incident diabetes had a significant impact on hospitalizations for heart failure coupled with cardiovascular death, another endpoint of the trial.

“This is a tremendously important analysis. We recognize that diabetes is an important factor that can forecast heart failure risk, even over relatively short follow-up. A drug that targets both diseases can be quite beneficial,” commented Muthiah Vaduganathan, MD, a cardiologist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston.

The impact of dapagliflozin on average A1c levels during the DAPA-HF trial was minimal, reducing levels by an average of 0.04% among those who entered with prediabetes and by 0.05% among the other patients. This suggests that the mechanisms by which dapagliflozin reduced incident diabetes was by routes that did not involve simply reducing hyperglycemia, and the observed decrease in incident diabetes was not apparently caused by “masking” of hyperglycemia by dapagliflozin, said Dr. Inzucchi.

One possibility is that dapagliflozin, which also improved quality of life and reduced hospitalizations in the DAPA-HF trial, led to improved function and mobility among patients that had beneficial effects on their insulin sensitivity, Dr. Vaduganathan speculated in an interview.

The new finding of dapagliflozin’s benefit “is great news,” commented Yehuda Handelsman, MD, an endocrinologist and diabetes specialist who is medical director of the Metabolic Institute of America in Tarzana, Calif. “It’s an impressive and important result, and another reason to use dapagliflozin in patients with HFrEF, a group of patients whom you want to prevent from having worse outcomes” by developing diabetes.

The DAPA-HF (Dapagliflozin and Prevention of Adverse Outcomes in Heart Failure) trial enrolled HFrEF patients at 410 centers in 20 countries during February 2017–August 2018. The study’s primary endpoint was the composite incidence of cardiovascular death or worsening heart failure, which occurred in 16.3% of patients randomized to receive dapagliflozin and in 21.2% of control patients on standard care but on placebo instead of the study drug, a statistically significant relative risk reduction of 26% (N Engl J Med. 2019 Nov 21;381[21]:1995-2008). In the 2,605-patient subgroup without type 2 diabetes at baseline the primary endpoint fell by a statistically significant 27% with dapagliflozin treatment, the first time an SGLT2 inhibitor drug was shown effective for reducing this endpoint in patients with HFrEF but without diabetes. DAPA-HF did not enroll any patients with type 1 diabetes.

DAPA-HF was sponsored by AstraZeneca, the company that markets dapagliflozin (Farxiga). Dr. Inzucchi has been a consultant to AstraZeneca and to Abbott, Boehringer Ingelheim, Merck, Novo Nordisk, Sanofi/Lexicon, and vTv Therapeutics. Dr. Vaduganathan has been an adviser to AstraZeneca and to Amgen, Baxter, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Cytokinetics, and Relypsa. Dr. Handelsman has been a consultant to several drug companies including AstraZeneca.

SOURCE: Inzucchi SE et al. ADA 2020, abstract 271-OR.

FROM ADA 2020

Consider the stresses experienced by LGBTQ people of color

Given that Pride month is coinciding with so much upheaval in our community around racism and oppression, it is important to discuss the overlap in the experiences of both LGBTQ and people of color (POC).

The year 2020 will go down in history books. We will always remember the issues faced during this critical year. At least I hope so, because as we have seen, history repeats itself. How do these issues that we are currently facing relate to LGBTQ youth? The histories are linked. One cannot look at the history of LGBTQ rights without looking at other civil rights movements, particularly those for black people. The timing of these social movements often intertwined, both being inspired by and inspiring each other. For example, Bayard Rustin worked with Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. as an organizer for the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom in addition to being a public advocate for gay rights later on in his life. Similarly, the Stonewall Uprising that is known by many to be one of the first acts of the gay liberation movement, prominently featured Marsha P. Johnson (a black, transgender, self-identified drag queen) and Sylvia Rivera (a Latina American transgender rights activist). As we reflect on these histories, it is important to think about the effect of minority stress and intersectionality and how this impacts LGBTQ-POC and their health disparities.

Minority stress shows that . One example of such stressors is microaggressions – brief interactions that one might not realize are discriminatory or hurtful, but to the person on the receiving end of such comments, they are harmful and they add up. A suspicious look from a store owner as one browses the aisles of a local convenience store, a comment about how one “doesn’t’ seem gay” or “doesn’t sound black” all are examples of microaggressions.

Overt discrimination, expectation of rejection, and hate crimes also contribute to minority stress. LGBTQ individuals often also have to hide their identity whereas POC might not be able to hide their identity. Experiencing constant bombardment of discrimination from the outside world can lead one to internalize these thoughts of homophobia, transphobia, or racism.

Minority stress becomes even more complicated when you apply the theoretical framework of intersectionality – overlapping identities that compound one’s minority stress. Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer people of color (LGBTQ-POC) are a classic example of intersecting identities. They may experience racism from the LGBT community or homophobia/transphobia from their own racial or ethnic community in addition to the discrimination they already face from the majority population for both identities. Some LGBTQ people of color may feel the need to choose between these two identities, forcing them to compartmentalize one aspect of their identity from the other. Imagine how stressful that must be! In addition, LGBTQ-POC are less likely to come out to family members.

Most of us are aware that health disparities exist, both for the LGBTQ community as well as for racial and ethnic minorities; couple these together and the effect can be additive, placing LGBTQ-POC at higher risk for adverse health outcomes. In the late 1990s, racial and ethnic minority men having sex with men made up 48% of all HIV infection cases, a number that is clearly disproportionate to their representation in our overall society. Given both LGBTQ and POC have issues accessing care, one can only imagine that this would make it hard to get diagnosed or treated regularly for these issues.

Transgender POC also are particularly vulnerable to health disparities. The 2015 U.S. Transgender Survey looked at the experiences of over 28,000 transgender people in the United States, but the survey also broke down the experiences for transgender people of color. Black transgender individuals were more likely than their black cisgender counterparts to experience unemployment (20% vs. 10%) and poverty (38% vs. 24%). They were more likely to experience homelessness compared with the overall transgender sample (42% vs. 30%) and more likely to have been sexually assaulted in their lives (53% vs. 47%). Understandably, 67% of black transgender respondents said they would feel somewhat or very uncomfortable asking the police for help.

The findings were similar for Latinx transgender respondents: 21% were unemployed compared with the overall rate of unemployment for Latinx in the United States at 7%, and 43% were living in poverty compared with 18% of their cisgender peers.

Perhaps the most striking result among American Indian and Alaska Native respondents was that 57% had experienced homelessness – nearly twice the rate of the survey sample overall (30%). For the transgender Asian and Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander respondents, 32% were living in poverty and 39% had experienced serious psychological distress in the month before completing the survey.

So please, check in on your patients, friends, and family that identify as both LGBTQ and POC. Imagine how scary this must be for LGBTQ youth of color. They can be targeted for both their race and their sexuality and/or gender identity.

Dr. Lawlis is assistant professor of pediatrics at the University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center, Oklahoma City, and an adolescent medicine specialist at OU Children’s. She has no relevant financial disclosures. Email her at [email protected].

Given that Pride month is coinciding with so much upheaval in our community around racism and oppression, it is important to discuss the overlap in the experiences of both LGBTQ and people of color (POC).

The year 2020 will go down in history books. We will always remember the issues faced during this critical year. At least I hope so, because as we have seen, history repeats itself. How do these issues that we are currently facing relate to LGBTQ youth? The histories are linked. One cannot look at the history of LGBTQ rights without looking at other civil rights movements, particularly those for black people. The timing of these social movements often intertwined, both being inspired by and inspiring each other. For example, Bayard Rustin worked with Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. as an organizer for the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom in addition to being a public advocate for gay rights later on in his life. Similarly, the Stonewall Uprising that is known by many to be one of the first acts of the gay liberation movement, prominently featured Marsha P. Johnson (a black, transgender, self-identified drag queen) and Sylvia Rivera (a Latina American transgender rights activist). As we reflect on these histories, it is important to think about the effect of minority stress and intersectionality and how this impacts LGBTQ-POC and their health disparities.

Minority stress shows that . One example of such stressors is microaggressions – brief interactions that one might not realize are discriminatory or hurtful, but to the person on the receiving end of such comments, they are harmful and they add up. A suspicious look from a store owner as one browses the aisles of a local convenience store, a comment about how one “doesn’t’ seem gay” or “doesn’t sound black” all are examples of microaggressions.

Overt discrimination, expectation of rejection, and hate crimes also contribute to minority stress. LGBTQ individuals often also have to hide their identity whereas POC might not be able to hide their identity. Experiencing constant bombardment of discrimination from the outside world can lead one to internalize these thoughts of homophobia, transphobia, or racism.

Minority stress becomes even more complicated when you apply the theoretical framework of intersectionality – overlapping identities that compound one’s minority stress. Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer people of color (LGBTQ-POC) are a classic example of intersecting identities. They may experience racism from the LGBT community or homophobia/transphobia from their own racial or ethnic community in addition to the discrimination they already face from the majority population for both identities. Some LGBTQ people of color may feel the need to choose between these two identities, forcing them to compartmentalize one aspect of their identity from the other. Imagine how stressful that must be! In addition, LGBTQ-POC are less likely to come out to family members.

Most of us are aware that health disparities exist, both for the LGBTQ community as well as for racial and ethnic minorities; couple these together and the effect can be additive, placing LGBTQ-POC at higher risk for adverse health outcomes. In the late 1990s, racial and ethnic minority men having sex with men made up 48% of all HIV infection cases, a number that is clearly disproportionate to their representation in our overall society. Given both LGBTQ and POC have issues accessing care, one can only imagine that this would make it hard to get diagnosed or treated regularly for these issues.

Transgender POC also are particularly vulnerable to health disparities. The 2015 U.S. Transgender Survey looked at the experiences of over 28,000 transgender people in the United States, but the survey also broke down the experiences for transgender people of color. Black transgender individuals were more likely than their black cisgender counterparts to experience unemployment (20% vs. 10%) and poverty (38% vs. 24%). They were more likely to experience homelessness compared with the overall transgender sample (42% vs. 30%) and more likely to have been sexually assaulted in their lives (53% vs. 47%). Understandably, 67% of black transgender respondents said they would feel somewhat or very uncomfortable asking the police for help.

The findings were similar for Latinx transgender respondents: 21% were unemployed compared with the overall rate of unemployment for Latinx in the United States at 7%, and 43% were living in poverty compared with 18% of their cisgender peers.

Perhaps the most striking result among American Indian and Alaska Native respondents was that 57% had experienced homelessness – nearly twice the rate of the survey sample overall (30%). For the transgender Asian and Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander respondents, 32% were living in poverty and 39% had experienced serious psychological distress in the month before completing the survey.

So please, check in on your patients, friends, and family that identify as both LGBTQ and POC. Imagine how scary this must be for LGBTQ youth of color. They can be targeted for both their race and their sexuality and/or gender identity.

Dr. Lawlis is assistant professor of pediatrics at the University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center, Oklahoma City, and an adolescent medicine specialist at OU Children’s. She has no relevant financial disclosures. Email her at [email protected].

Given that Pride month is coinciding with so much upheaval in our community around racism and oppression, it is important to discuss the overlap in the experiences of both LGBTQ and people of color (POC).

The year 2020 will go down in history books. We will always remember the issues faced during this critical year. At least I hope so, because as we have seen, history repeats itself. How do these issues that we are currently facing relate to LGBTQ youth? The histories are linked. One cannot look at the history of LGBTQ rights without looking at other civil rights movements, particularly those for black people. The timing of these social movements often intertwined, both being inspired by and inspiring each other. For example, Bayard Rustin worked with Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. as an organizer for the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom in addition to being a public advocate for gay rights later on in his life. Similarly, the Stonewall Uprising that is known by many to be one of the first acts of the gay liberation movement, prominently featured Marsha P. Johnson (a black, transgender, self-identified drag queen) and Sylvia Rivera (a Latina American transgender rights activist). As we reflect on these histories, it is important to think about the effect of minority stress and intersectionality and how this impacts LGBTQ-POC and their health disparities.

Minority stress shows that . One example of such stressors is microaggressions – brief interactions that one might not realize are discriminatory or hurtful, but to the person on the receiving end of such comments, they are harmful and they add up. A suspicious look from a store owner as one browses the aisles of a local convenience store, a comment about how one “doesn’t’ seem gay” or “doesn’t sound black” all are examples of microaggressions.

Overt discrimination, expectation of rejection, and hate crimes also contribute to minority stress. LGBTQ individuals often also have to hide their identity whereas POC might not be able to hide their identity. Experiencing constant bombardment of discrimination from the outside world can lead one to internalize these thoughts of homophobia, transphobia, or racism.

Minority stress becomes even more complicated when you apply the theoretical framework of intersectionality – overlapping identities that compound one’s minority stress. Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer people of color (LGBTQ-POC) are a classic example of intersecting identities. They may experience racism from the LGBT community or homophobia/transphobia from their own racial or ethnic community in addition to the discrimination they already face from the majority population for both identities. Some LGBTQ people of color may feel the need to choose between these two identities, forcing them to compartmentalize one aspect of their identity from the other. Imagine how stressful that must be! In addition, LGBTQ-POC are less likely to come out to family members.

Most of us are aware that health disparities exist, both for the LGBTQ community as well as for racial and ethnic minorities; couple these together and the effect can be additive, placing LGBTQ-POC at higher risk for adverse health outcomes. In the late 1990s, racial and ethnic minority men having sex with men made up 48% of all HIV infection cases, a number that is clearly disproportionate to their representation in our overall society. Given both LGBTQ and POC have issues accessing care, one can only imagine that this would make it hard to get diagnosed or treated regularly for these issues.

Transgender POC also are particularly vulnerable to health disparities. The 2015 U.S. Transgender Survey looked at the experiences of over 28,000 transgender people in the United States, but the survey also broke down the experiences for transgender people of color. Black transgender individuals were more likely than their black cisgender counterparts to experience unemployment (20% vs. 10%) and poverty (38% vs. 24%). They were more likely to experience homelessness compared with the overall transgender sample (42% vs. 30%) and more likely to have been sexually assaulted in their lives (53% vs. 47%). Understandably, 67% of black transgender respondents said they would feel somewhat or very uncomfortable asking the police for help.

The findings were similar for Latinx transgender respondents: 21% were unemployed compared with the overall rate of unemployment for Latinx in the United States at 7%, and 43% were living in poverty compared with 18% of their cisgender peers.

Perhaps the most striking result among American Indian and Alaska Native respondents was that 57% had experienced homelessness – nearly twice the rate of the survey sample overall (30%). For the transgender Asian and Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander respondents, 32% were living in poverty and 39% had experienced serious psychological distress in the month before completing the survey.

So please, check in on your patients, friends, and family that identify as both LGBTQ and POC. Imagine how scary this must be for LGBTQ youth of color. They can be targeted for both their race and their sexuality and/or gender identity.

Dr. Lawlis is assistant professor of pediatrics at the University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center, Oklahoma City, and an adolescent medicine specialist at OU Children’s. She has no relevant financial disclosures. Email her at [email protected].

Survey: 26% of parents hesitant about influenza vaccine

according to a nationally representative survey.

Influenza vaccination hesitancy may be driven by concerns about vaccine effectiveness, researchers wrote in Pediatrics. These findings “underscore the importance of better communicating to providers and parents the effectiveness of influenza vaccines in reducing severity and morbidity from influenza, even in years when the vaccine has relatively low effectiveness,” noted Allison Kempe, MD, MPH, professor of pediatrics and director of the Adult and Child Consortium for Health Outcomes Research and Delivery Science at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora, and colleagues.

The World Health Organization considers vaccine hesitancy a leading threat to global health, but national data about vaccine hesitancy in the United States are limited. To assess hesitancy about routine childhood and influenza vaccinations and related factors, Dr. Kempe and colleagues surveyed more than 2,000 parents in February 2019.

The investigators used an online panel to survey a nationally representative sample of families with children aged between 6 months and 18 years. Parents completed a modified version of the Vaccine Hesitancy Scale, which measures confidence in and concerns about vaccines. Parents with an average score greater than 3 on the scale were considered hesitant.

Factors associated with vaccine hesitancy

Of 4,445 parents sampled, 2,176 completed the survey and 2,052 were eligible respondents. For routine childhood vaccines, the average score on the modified Vaccine Hesitancy Scale was 2 and the percentage of hesitant parents was 6%. For influenza vaccine, the average score was 2 and the percentage of hesitant parents was 26%.

Among hesitant parents, 68% had deferred or refused routine childhood vaccination, compared with 9% of nonhesitant parents (risk ratio, 8.0). For the influenza vaccine, 70% of hesitant parents had deferred or refused influenza vaccination for their child versus 10% of nonhesitant parents (RR, 7.0). Parents were more likely to strongly agree that routine childhood vaccines are effective, compared with the influenza vaccine (70% vs. 26%). “Hesitancy about influenza vaccination is largely driven by concerns about low vaccine effectiveness,” Dr. Kempe and associates wrote.

Although concern about serious side effects was the factor most associated with hesitancy, the percentage of parents who were strongly (12%) or somewhat (27%) concerned about serious side effects was the same for routine childhood vaccines and influenza vaccines. Other factors associated with hesitancy for both routine childhood vaccines and influenza vaccines included lower educational level and household income less than 400% of the federal poverty level.

The survey data may be subject to reporting bias based on social desirability, the authors noted. In addition, the exclusion of infants younger than 6 months may have resulted in an underestimate of hesitancy.

“Although influenza vaccine could be included as a ‘routine’ vaccine, in that it is recommended yearly, we hypothesized that parents view it differently from other childhood vaccines because each year it needs to be given again, its content and effectiveness vary, and it addresses a disease that is often perceived as minor, compared with other childhood diseases,” Dr. Kempe and colleagues wrote. Interventions to counter hesitancy have “a surprising lack of evidence,” and “more work needs to be done to develop methods that are practical and effective for convincing vaccine-hesitant parents to vaccinate.”

Logical next step

“From the pragmatic standpoint of improving immunization rates and disease control, determining the correct evidence-based messaging to counter these perceptions is the next logical step,” Annabelle de St. Maurice, MD, MPH, an assistant professor of pediatrics in the division of infectious diseases at University of California, Los Angeles, and Kathryn Edwards, MD, a professor of pediatrics and director of the vaccine research program at Vanderbilt University, Nashville, wrote in an accompanying editorial.

“Communications should be focused on the burden of influenza in children, rebranding influenza vaccine as a ‘routine’ childhood immunization, reassurance on influenza vaccine safety, and discussion of the efficacy of influenza vaccine in preventing severe disease,” they wrote. “Even in the years when there is a poor match, the vaccine is impactful.”

The research was supported by the National Institutes of Health. Two study authors disclosed financial ties to Sanofi Pasteur, with one also disclosing financial ties to Merck, for work related to vaccinations. The remaining investigators had no relevant financial disclosures. Dr. de St. Maurice indicated that she had no relevant financial disclosures. Dr. Edwards disclosed grants from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the NIH; consulting for Merck, Bionet, and IBM; and serving on data safety and monitoring boards for Sanofi, X4 Pharmaceuticals, Seqirus, Moderna, and Pfizer.

SOURCE: Kempe A et al. Pediatrics. 2020 Jun 15. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-3852.

according to a nationally representative survey.

Influenza vaccination hesitancy may be driven by concerns about vaccine effectiveness, researchers wrote in Pediatrics. These findings “underscore the importance of better communicating to providers and parents the effectiveness of influenza vaccines in reducing severity and morbidity from influenza, even in years when the vaccine has relatively low effectiveness,” noted Allison Kempe, MD, MPH, professor of pediatrics and director of the Adult and Child Consortium for Health Outcomes Research and Delivery Science at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora, and colleagues.

The World Health Organization considers vaccine hesitancy a leading threat to global health, but national data about vaccine hesitancy in the United States are limited. To assess hesitancy about routine childhood and influenza vaccinations and related factors, Dr. Kempe and colleagues surveyed more than 2,000 parents in February 2019.

The investigators used an online panel to survey a nationally representative sample of families with children aged between 6 months and 18 years. Parents completed a modified version of the Vaccine Hesitancy Scale, which measures confidence in and concerns about vaccines. Parents with an average score greater than 3 on the scale were considered hesitant.

Factors associated with vaccine hesitancy

Of 4,445 parents sampled, 2,176 completed the survey and 2,052 were eligible respondents. For routine childhood vaccines, the average score on the modified Vaccine Hesitancy Scale was 2 and the percentage of hesitant parents was 6%. For influenza vaccine, the average score was 2 and the percentage of hesitant parents was 26%.

Among hesitant parents, 68% had deferred or refused routine childhood vaccination, compared with 9% of nonhesitant parents (risk ratio, 8.0). For the influenza vaccine, 70% of hesitant parents had deferred or refused influenza vaccination for their child versus 10% of nonhesitant parents (RR, 7.0). Parents were more likely to strongly agree that routine childhood vaccines are effective, compared with the influenza vaccine (70% vs. 26%). “Hesitancy about influenza vaccination is largely driven by concerns about low vaccine effectiveness,” Dr. Kempe and associates wrote.

Although concern about serious side effects was the factor most associated with hesitancy, the percentage of parents who were strongly (12%) or somewhat (27%) concerned about serious side effects was the same for routine childhood vaccines and influenza vaccines. Other factors associated with hesitancy for both routine childhood vaccines and influenza vaccines included lower educational level and household income less than 400% of the federal poverty level.

The survey data may be subject to reporting bias based on social desirability, the authors noted. In addition, the exclusion of infants younger than 6 months may have resulted in an underestimate of hesitancy.

“Although influenza vaccine could be included as a ‘routine’ vaccine, in that it is recommended yearly, we hypothesized that parents view it differently from other childhood vaccines because each year it needs to be given again, its content and effectiveness vary, and it addresses a disease that is often perceived as minor, compared with other childhood diseases,” Dr. Kempe and colleagues wrote. Interventions to counter hesitancy have “a surprising lack of evidence,” and “more work needs to be done to develop methods that are practical and effective for convincing vaccine-hesitant parents to vaccinate.”

Logical next step

“From the pragmatic standpoint of improving immunization rates and disease control, determining the correct evidence-based messaging to counter these perceptions is the next logical step,” Annabelle de St. Maurice, MD, MPH, an assistant professor of pediatrics in the division of infectious diseases at University of California, Los Angeles, and Kathryn Edwards, MD, a professor of pediatrics and director of the vaccine research program at Vanderbilt University, Nashville, wrote in an accompanying editorial.

“Communications should be focused on the burden of influenza in children, rebranding influenza vaccine as a ‘routine’ childhood immunization, reassurance on influenza vaccine safety, and discussion of the efficacy of influenza vaccine in preventing severe disease,” they wrote. “Even in the years when there is a poor match, the vaccine is impactful.”

The research was supported by the National Institutes of Health. Two study authors disclosed financial ties to Sanofi Pasteur, with one also disclosing financial ties to Merck, for work related to vaccinations. The remaining investigators had no relevant financial disclosures. Dr. de St. Maurice indicated that she had no relevant financial disclosures. Dr. Edwards disclosed grants from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the NIH; consulting for Merck, Bionet, and IBM; and serving on data safety and monitoring boards for Sanofi, X4 Pharmaceuticals, Seqirus, Moderna, and Pfizer.

SOURCE: Kempe A et al. Pediatrics. 2020 Jun 15. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-3852.

according to a nationally representative survey.

Influenza vaccination hesitancy may be driven by concerns about vaccine effectiveness, researchers wrote in Pediatrics. These findings “underscore the importance of better communicating to providers and parents the effectiveness of influenza vaccines in reducing severity and morbidity from influenza, even in years when the vaccine has relatively low effectiveness,” noted Allison Kempe, MD, MPH, professor of pediatrics and director of the Adult and Child Consortium for Health Outcomes Research and Delivery Science at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora, and colleagues.

The World Health Organization considers vaccine hesitancy a leading threat to global health, but national data about vaccine hesitancy in the United States are limited. To assess hesitancy about routine childhood and influenza vaccinations and related factors, Dr. Kempe and colleagues surveyed more than 2,000 parents in February 2019.

The investigators used an online panel to survey a nationally representative sample of families with children aged between 6 months and 18 years. Parents completed a modified version of the Vaccine Hesitancy Scale, which measures confidence in and concerns about vaccines. Parents with an average score greater than 3 on the scale were considered hesitant.

Factors associated with vaccine hesitancy

Of 4,445 parents sampled, 2,176 completed the survey and 2,052 were eligible respondents. For routine childhood vaccines, the average score on the modified Vaccine Hesitancy Scale was 2 and the percentage of hesitant parents was 6%. For influenza vaccine, the average score was 2 and the percentage of hesitant parents was 26%.

Among hesitant parents, 68% had deferred or refused routine childhood vaccination, compared with 9% of nonhesitant parents (risk ratio, 8.0). For the influenza vaccine, 70% of hesitant parents had deferred or refused influenza vaccination for their child versus 10% of nonhesitant parents (RR, 7.0). Parents were more likely to strongly agree that routine childhood vaccines are effective, compared with the influenza vaccine (70% vs. 26%). “Hesitancy about influenza vaccination is largely driven by concerns about low vaccine effectiveness,” Dr. Kempe and associates wrote.

Although concern about serious side effects was the factor most associated with hesitancy, the percentage of parents who were strongly (12%) or somewhat (27%) concerned about serious side effects was the same for routine childhood vaccines and influenza vaccines. Other factors associated with hesitancy for both routine childhood vaccines and influenza vaccines included lower educational level and household income less than 400% of the federal poverty level.

The survey data may be subject to reporting bias based on social desirability, the authors noted. In addition, the exclusion of infants younger than 6 months may have resulted in an underestimate of hesitancy.

“Although influenza vaccine could be included as a ‘routine’ vaccine, in that it is recommended yearly, we hypothesized that parents view it differently from other childhood vaccines because each year it needs to be given again, its content and effectiveness vary, and it addresses a disease that is often perceived as minor, compared with other childhood diseases,” Dr. Kempe and colleagues wrote. Interventions to counter hesitancy have “a surprising lack of evidence,” and “more work needs to be done to develop methods that are practical and effective for convincing vaccine-hesitant parents to vaccinate.”

Logical next step

“From the pragmatic standpoint of improving immunization rates and disease control, determining the correct evidence-based messaging to counter these perceptions is the next logical step,” Annabelle de St. Maurice, MD, MPH, an assistant professor of pediatrics in the division of infectious diseases at University of California, Los Angeles, and Kathryn Edwards, MD, a professor of pediatrics and director of the vaccine research program at Vanderbilt University, Nashville, wrote in an accompanying editorial.

“Communications should be focused on the burden of influenza in children, rebranding influenza vaccine as a ‘routine’ childhood immunization, reassurance on influenza vaccine safety, and discussion of the efficacy of influenza vaccine in preventing severe disease,” they wrote. “Even in the years when there is a poor match, the vaccine is impactful.”

The research was supported by the National Institutes of Health. Two study authors disclosed financial ties to Sanofi Pasteur, with one also disclosing financial ties to Merck, for work related to vaccinations. The remaining investigators had no relevant financial disclosures. Dr. de St. Maurice indicated that she had no relevant financial disclosures. Dr. Edwards disclosed grants from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the NIH; consulting for Merck, Bionet, and IBM; and serving on data safety and monitoring boards for Sanofi, X4 Pharmaceuticals, Seqirus, Moderna, and Pfizer.

SOURCE: Kempe A et al. Pediatrics. 2020 Jun 15. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-3852.

FROM PEDIATRICS

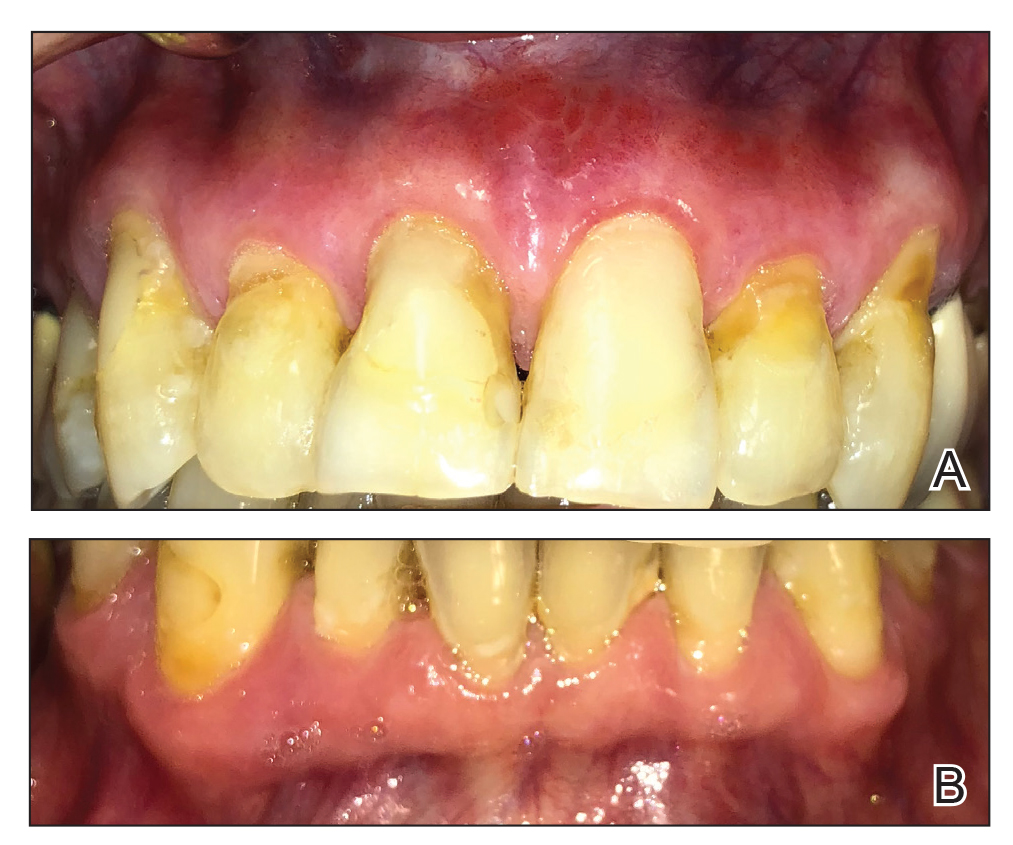

Severe Gingival Swelling and Erythema

The Diagnosis: Plasma Cell Gingivitis

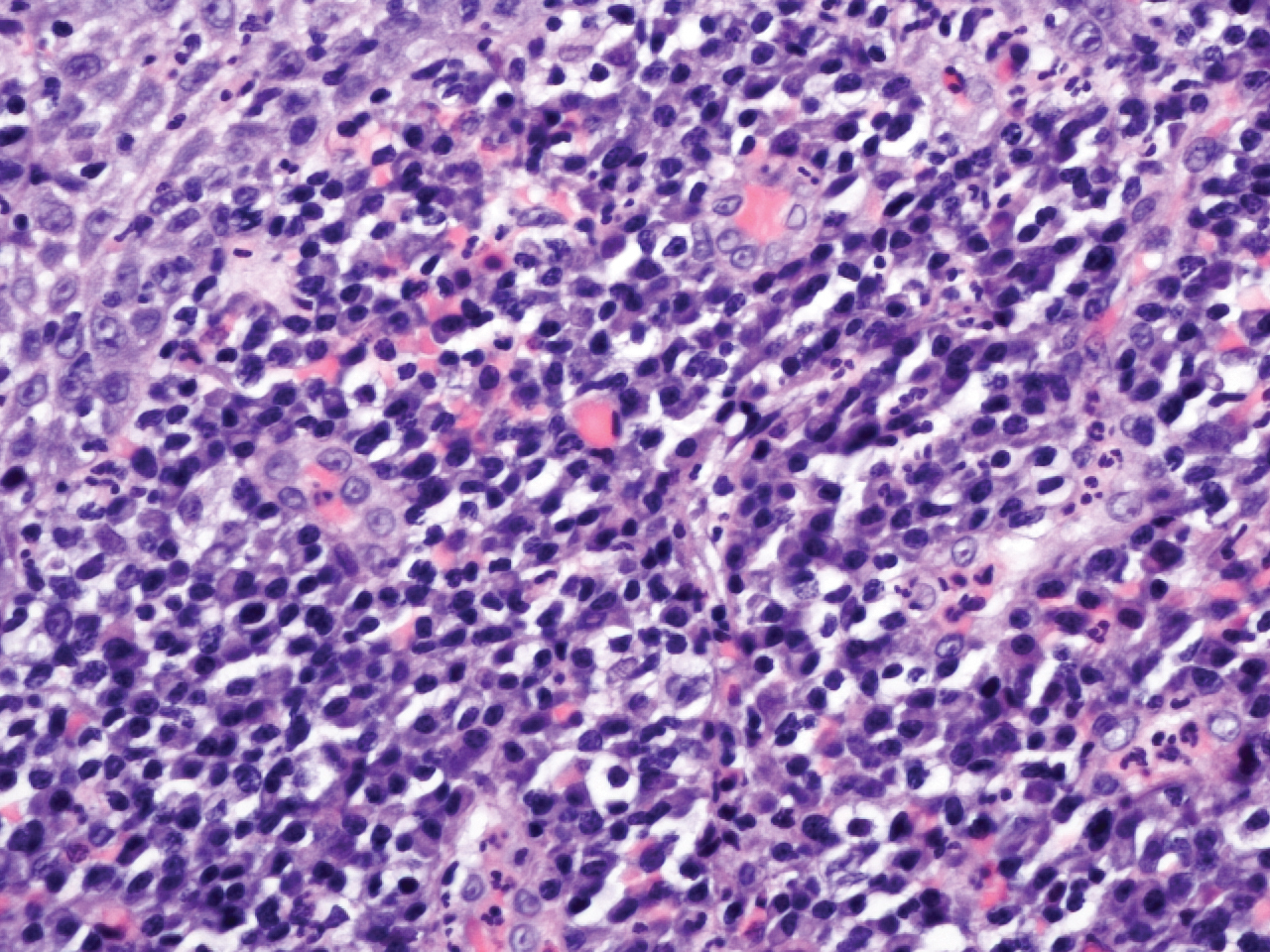

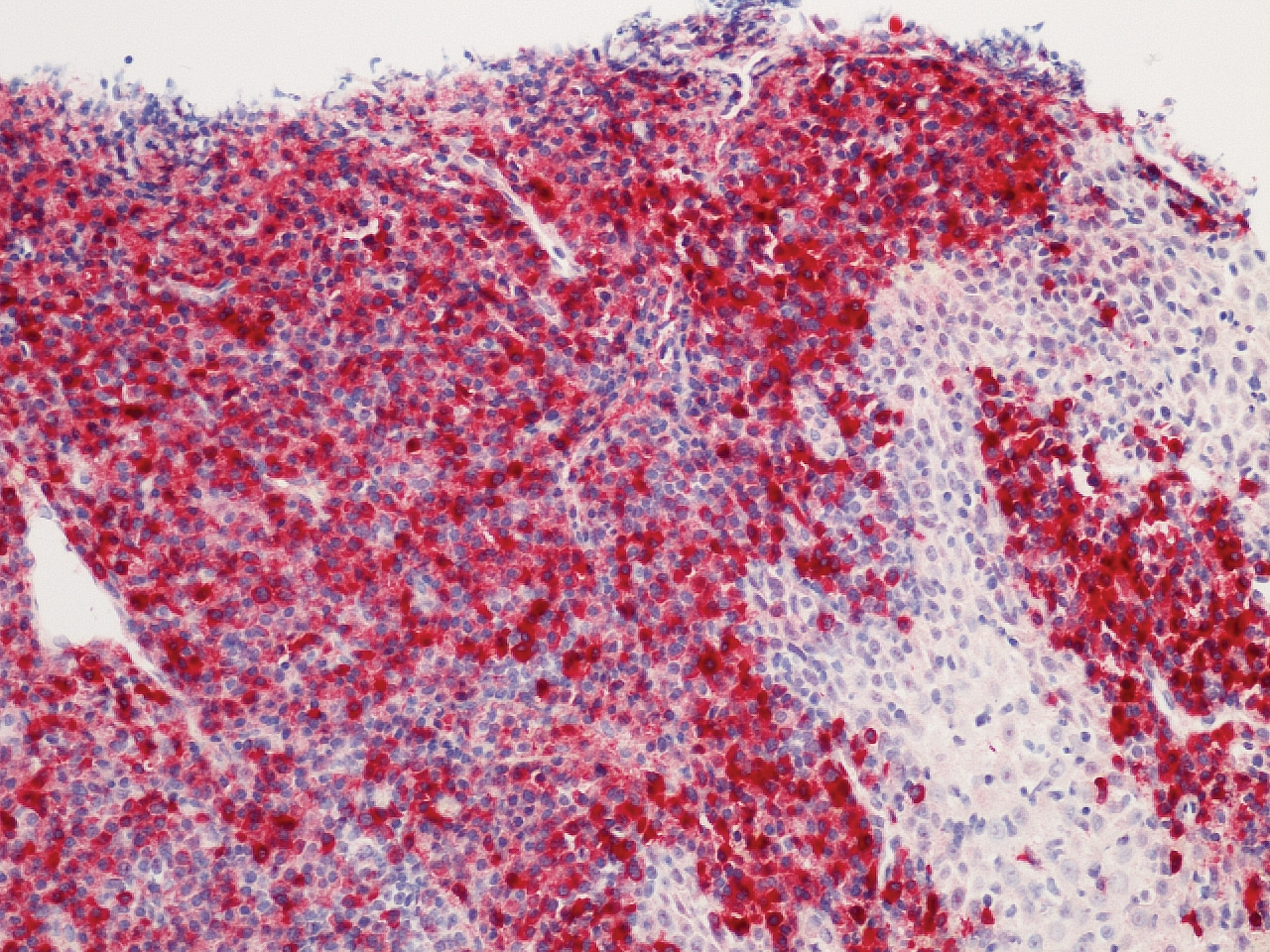

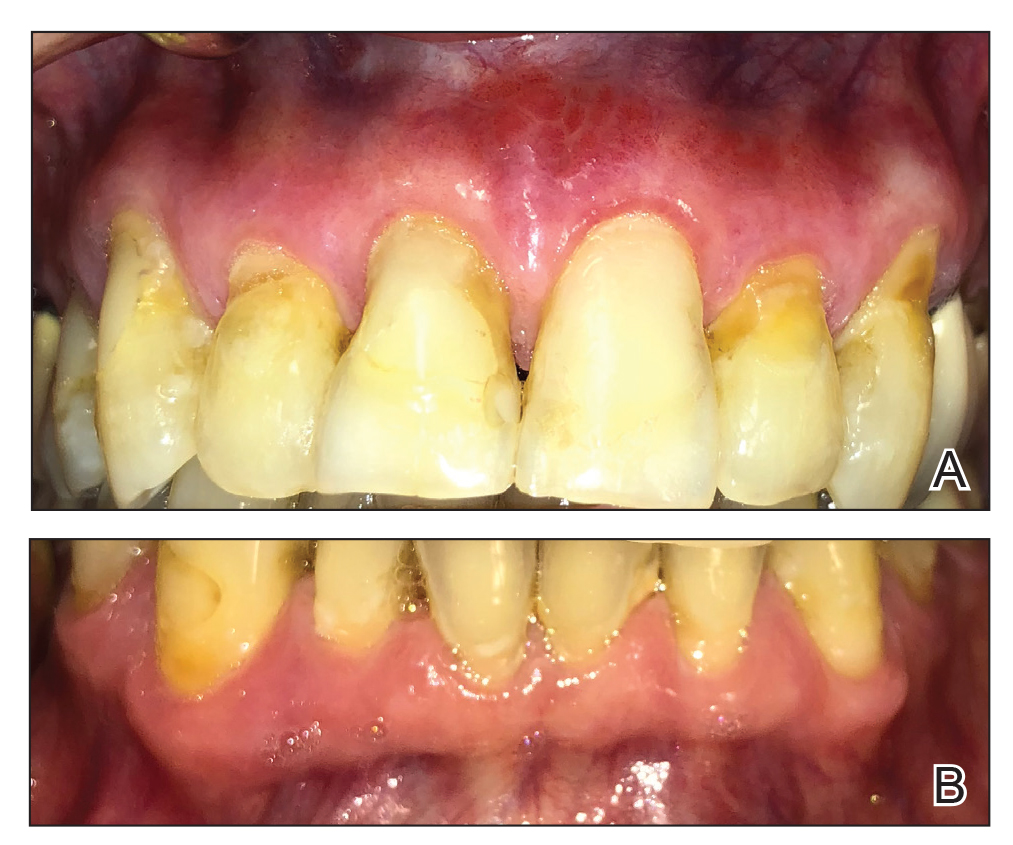

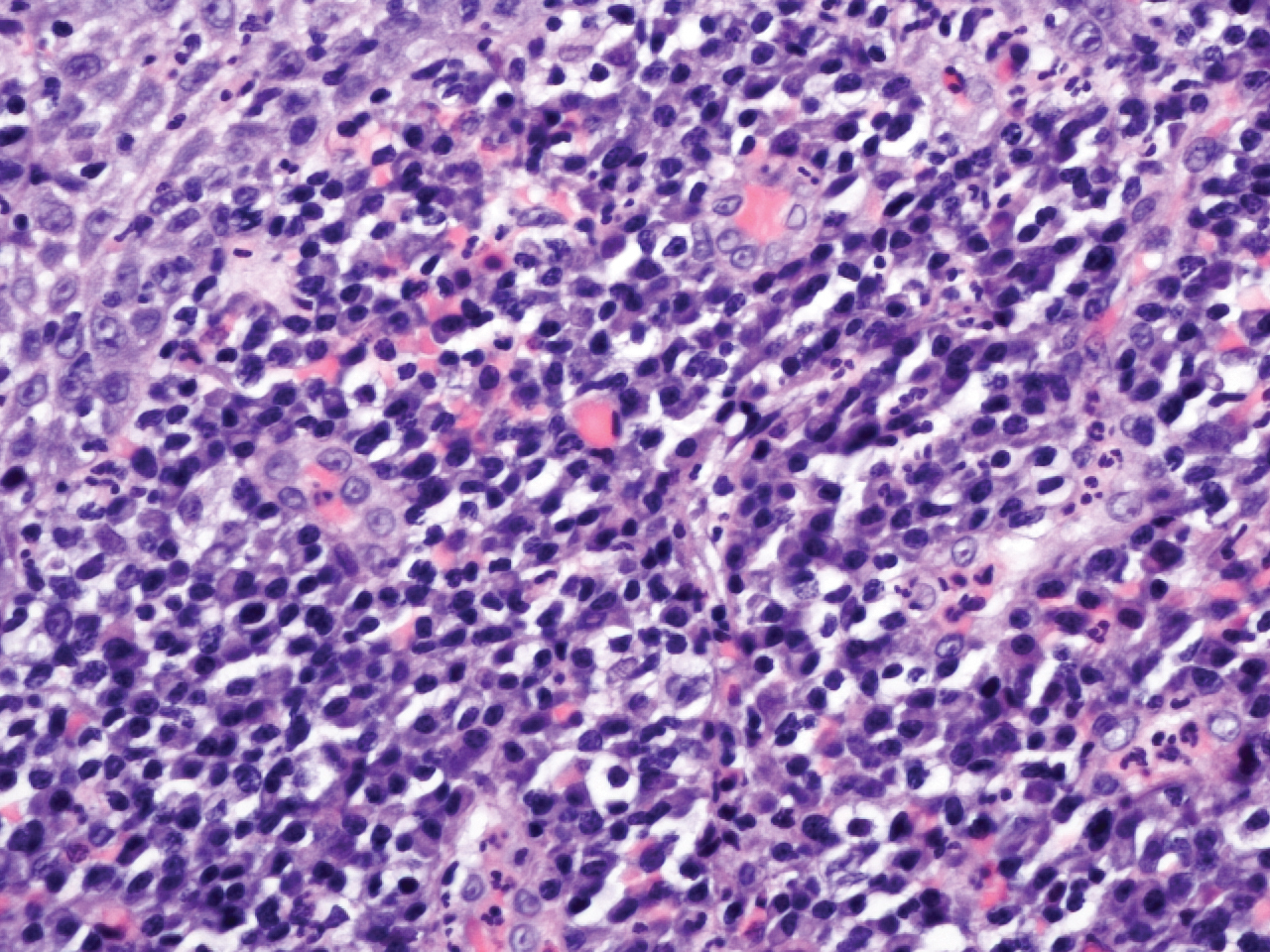

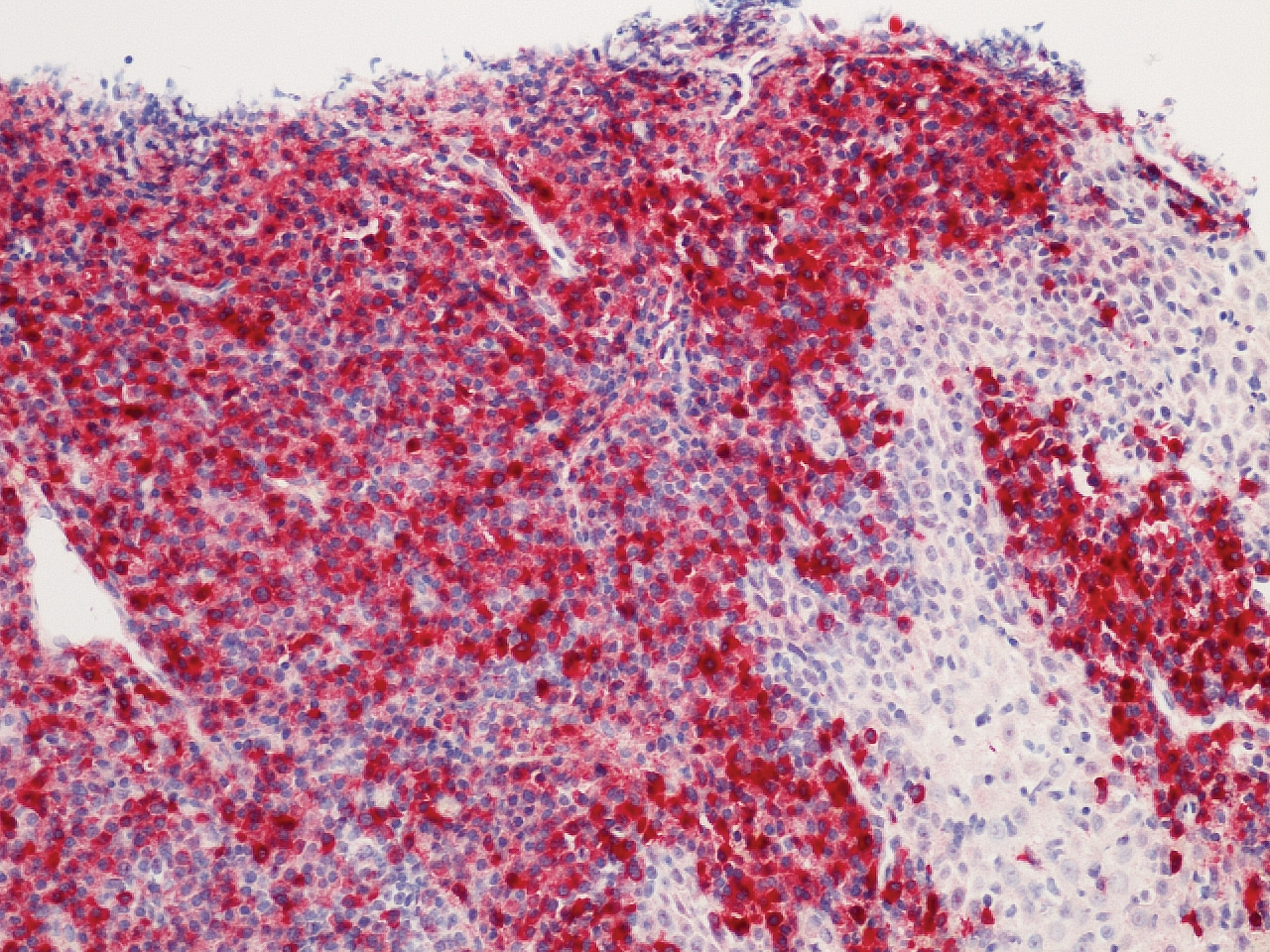

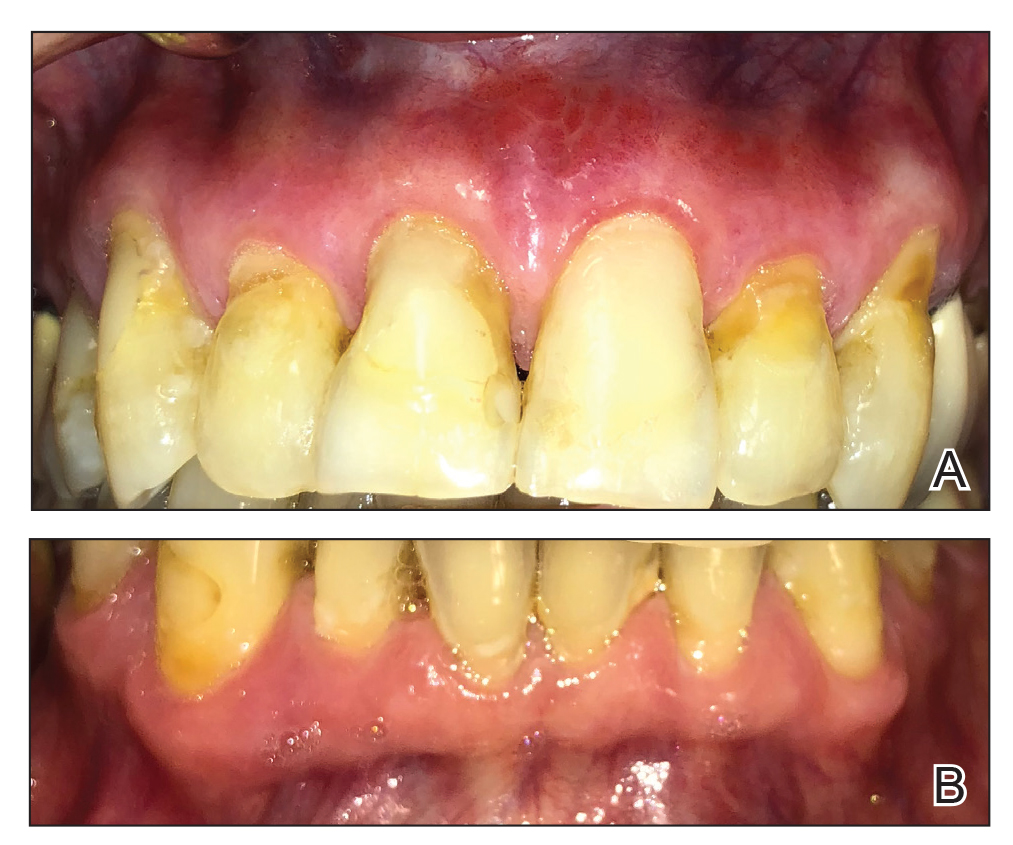

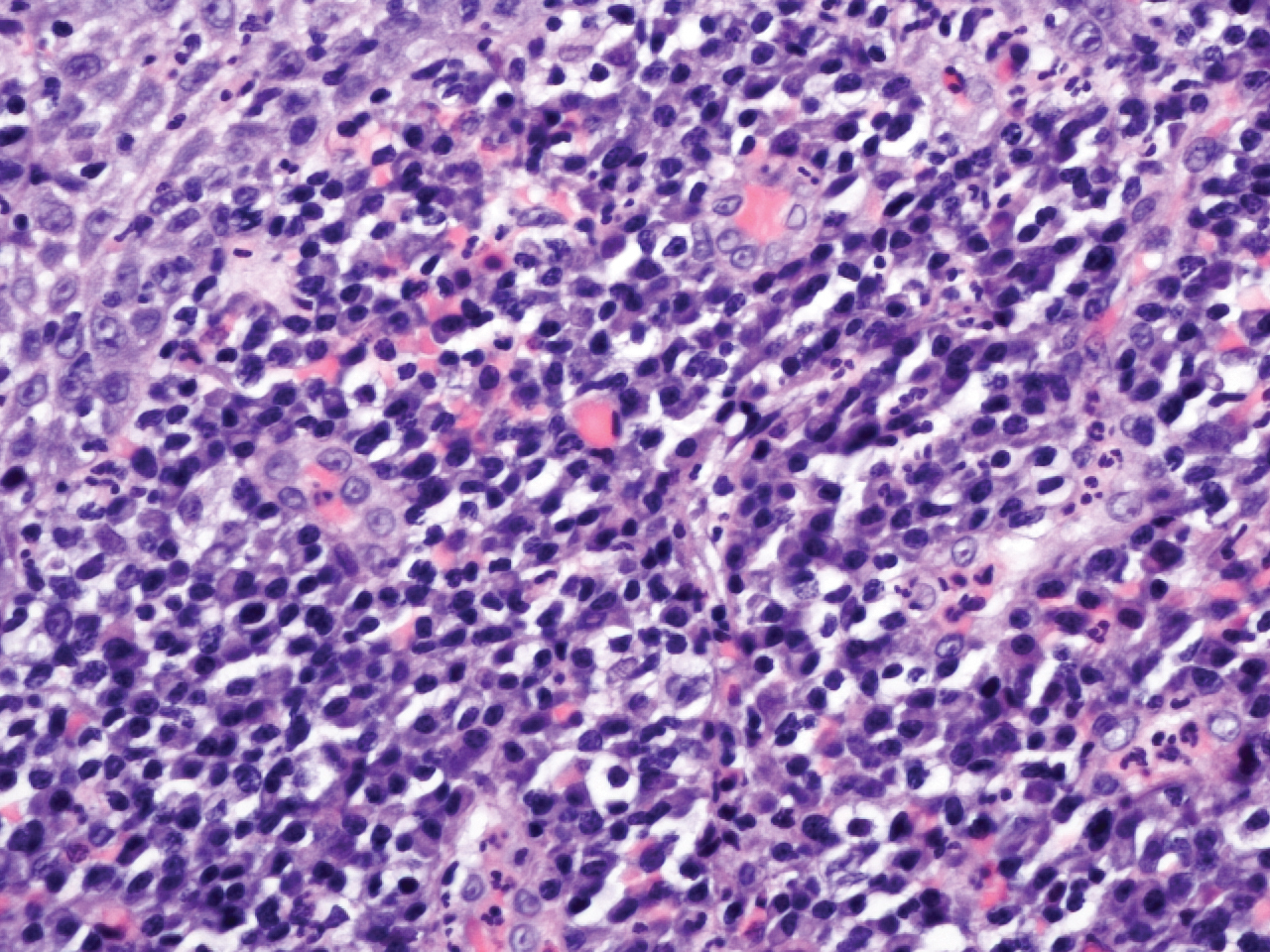

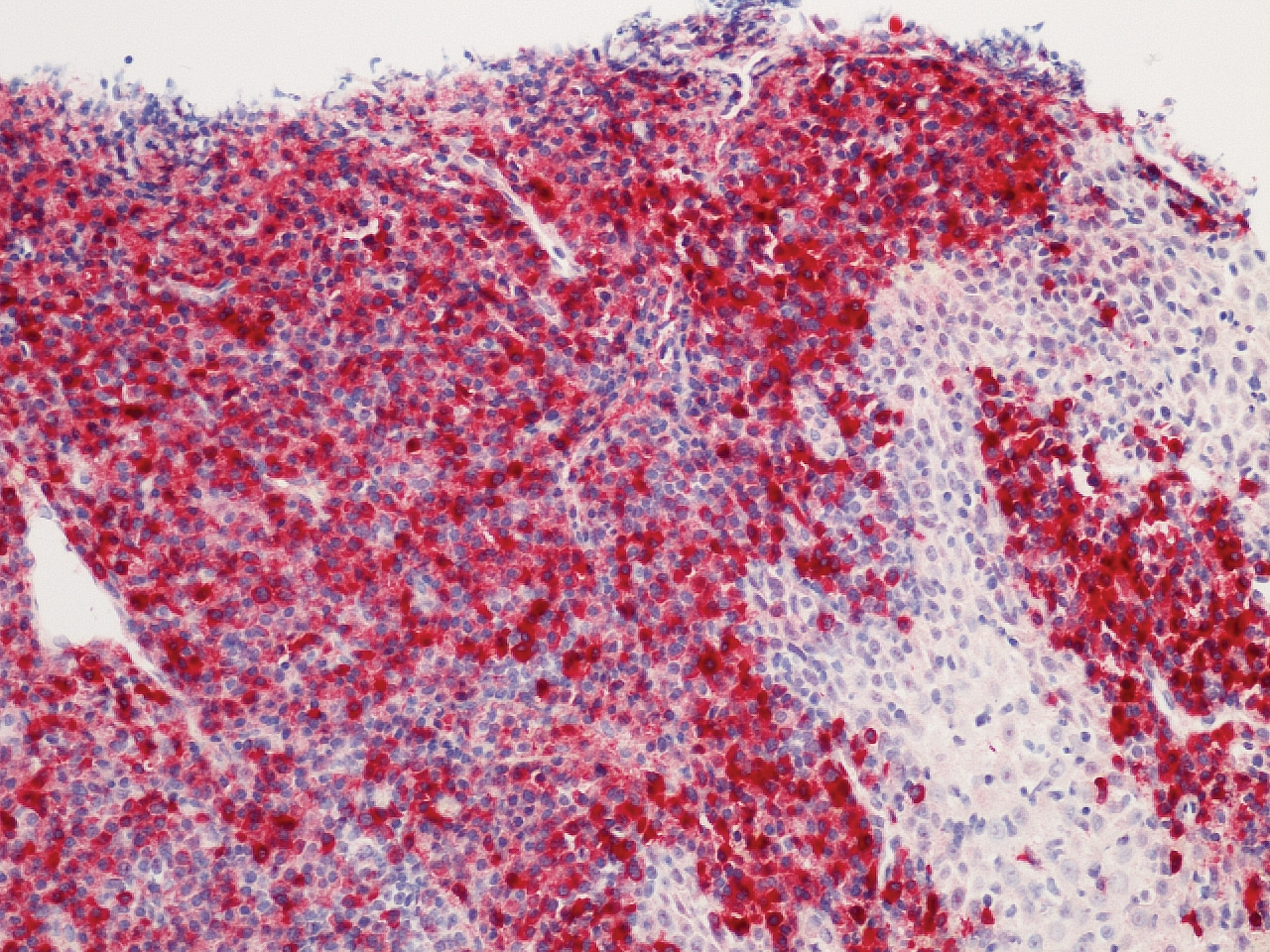

Microscopic analysis demonstrated an acanthotic stratified squamous epithelium with an edematous fibrous stroma containing dense perivascular infiltrates of plasma cells and lymphocytes (Figure 1). Immunohistochemical analysis with kappa, lambda, and CD79a immunostains indicated a polyclonal proliferation of plasma cells that excluded monoclonal plasma cell neoplasia (Figure 2). Direct immunofluorescence (DIF) was negative. Serum enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for bullous pemphigoid 180 and 230 antibodies as well as desmoglein 1 and 3 antibodies was normal. The cumulative findings were consistent with plasma cell gingivitis (PCG). It was recommended that the patient avoid possible foods (eg, citrus) and oral hygiene products (eg, mint-flavored toothpaste) that could trigger PCG. With patient compliance to an elimination diet for 3 months, the condition resolved (Figure 3).

Plasma cell gingivitis is a rare condition characterized by generalized edema and erythema of the attached gingiva. It was described in the 1960s and classified into 3 types based on etiology: (1) hypersensitivity (most common), (2) neoplastic, and (3) PCG of unknown origin.1,2 Spices, herbs, and flavoring agents are implicated as potential triggers of hypersensitivity PCG, while neoplastic PCG is associated with monoclonal plasma cell neoplasms, such as multiple myeloma and extramedullary plasmacytoma.2,3 Histologically, a diffuse subepithelial infiltrate of a polyclonal mixture of plasma cells typically is observed in hypersensitivity PCG.3 The plasma cell infiltration in hypersensitivity PCG is a benign reactive process without known risk for development of plasma cell malignancy, but the presence of a notable number of plasma cells may require special tissue staining to rule out the possibility of associated neoplasia.2,3 There are no standardized protocols for management of PCG.4 Elimination of potential allergens, including flavored oral hygiene products, may result in resolution of hypersensitivity PCG lesions, as exemplified in our patient.1 Neoplastic PCG responds to treatment of the underlying malignancy.5 Topical, intralesional, and/or systemic steroids may be considered in symptomatic cases of PCG.4

Clinical presentation of PCG can mimic immune-mediated mucocutaneous diseases such as mucous membrane pemphigoid (MMP), pemphigus vulgaris (PV), and oral lichen planus; microscopic analysis is needed to establish the diagnosis.6 Mucous membrane pemphigoid is a chronic autoimmune blistering disease involving the mucous membranes with possible cutaneous involvement. It is characterized by a complement-mediated autoantibody process against one or several antigens in the epithelial basement membrane. The oral mucosa is involved in 85% of MMP patients, and 65% of patients experience complications involving the ocular conjunctiva. Intraorally, MMP typically manifests as painful erosions, ulcerations, desquamative gingivitis, and/or occasionally intact blisters. Ocular complications include conjunctivitis and corneal erosions that often scar, resulting in blindness in approximately 15% of patients with ocular involvement. Microscopic features of MMP classically exhibit subepithelial separation with a mixed inflammatory cell infiltrate on routine analysis and linear deposition of IgG, IgA, or C3 within the basement membrane zone on DIF. Treatment of MMP involves topical or systemic immunosuppressants to control symptoms, minimize complications, and alter disease progression.6

Pemphigus vulgaris is an autoimmune vesiculobullous disease that affects the oral mucosa with or without cutaneous involvement.7 Desmogleins 1 and 3, transmembrane glycoproteins of desmosomes that convene cell-to-cell adhesion, are identified as antigens in PV. Antibodies against these desmoglein proteins result in intraepithelial separation, which leads to blister formation.7 Oral manifestations of PV include mucosal erosions and ulcerations as well as desquamative gingivitis. Bullae rarely are seen in the oral cavity, as they tend to rupture, leaving nonhealing ulcerations.8 Histologically, PV is characterized by acantholysis of the suprabasal cell layers with an intact basement membrane zone on routine examination. The distinctive microscopic feature of PV is the detection of cell surface-bound IgG within the epidermis on DIF.7 Treatment of PV may include topical and/or systemic corticosteroids and other immunosuppressants. Rituximab, a monoclonal antibody, has been successful in the management of PV.8

Oral lichen planus is a T-cell mediated autoimmune condition that leads to subepithelial lymphocytic infiltration and excessive keratinocyte apoptosis.9 Women typically are affected more often than men, and 75% of patients also have cutaneous manifestations of the condition. Desquamation and/or erythema of the gingiva may be the initial manifestation of oral lichen planus.9 Other commonly involved sites include the buccal mucosa, tongue, and palate. Biopsy of affected tissues typically demonstrates degeneration of the basal cell layer with subjacent bandlike lymphocytic infiltration on routine staining. Linear fibrinogen at the basement membrane zone usually is observed on DIF. Topical corticosteroids are considered first-line therapy, but systemic therapy including corticosteroids, steroid-sparing agents, or immunomodulators may be used in severe cases.9

There are 3 variants of plasma cell neoplasms including multiple myeloma, medullary plasmacytoma (also known as solitary bone plasmacytoma), and extramedullary plasmacytoma (EMP).10 Extramedullary plasmacytoma, sometimes referred to as extraosseous plasmacytoma, is described as a solitary or multiple plasma cell neoplasm contained in the soft tissue. Its occurrence is rare, accounting for only 3% of plasma cell neoplasms. Approximately 90% of EMPs affect the head and neck region, and males are affected 4 times more often than females. The oral cavity is one of the sites of clinical presentation; the gingival tissue infrequently is affected. When EMP affects the gingiva, it can mimic any form of gingivitis as well as other benign inflammatory conditions, such as pyogenic granuloma. Biopsy is the gold standard diagnostic method for differentiating EMP from other conditions, and specific immunohistochemical stains are essential for the diagnosis. Extramedullary plasmacytoma has the best prognosis among plasma cell neoplasms, despite the risk for progression to multiple myeloma. Extramedullary plasmacytoma lesions are very sensitive to radiotherapy, and the 10-year survival rate is approximately 70%.10

- Sollecito TP, Greenberg MS. Plasma cell gingivitis: report of two cases. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1992;73:690-693.

- Gargiulo AV, Ladone JA, Ladone PA, et al. Case report: plasma cell gingivitis A. CDS Rev. 1995;88:22-23.

- Abhishek K, Rashmi J. Plasma cell gingivitis associated with inflammatory cheilitis: a report on a rare case. Ethiop J Health Sci. 2013;23:183-187.

- Arduino PG, D'Aiuto F, Cavallito C, et al. Professional oral hygiene as a therapeutic option for pediatric patients with plasma cell gingivitis: preliminary results of a prospective case series. J Periodontol. 2011;82:1670-1675.

- Nayak A, Nayak MT. Multiple myeloma with an unusual oral presentation. J Exp Ther Oncol. 2016;11:199-206.

- Xu HH, Werth VP, Parisi E, et al. Mucous membrane pemphigoid. Dent Clin North Am. 2013;57:611-630.

- Hammers CM, Stanley JR. Mechanisms of disease: pemphigus and bullous pemphigoid. Ann Rev Pathol. 2016;11:75-97.

- Cizenski JD, Michel P, Watson IT, et al. Spectrum of orocutaneous disease associations: immune-mediated conditions. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77:795-806.

- Stoopler ET, Sollecito TP. Recurrent gingival and oral mucosal lesions. JAMA. 2014;312:1794-1795.

- Nair SK, Faizuddin M, Jayanthi D, et al. Extramedullary plasmacytoma of gingiva and soft tissue in neck. J Clin Diagn Res. 2014;8:ZD16-ZD18.

The Diagnosis: Plasma Cell Gingivitis

Microscopic analysis demonstrated an acanthotic stratified squamous epithelium with an edematous fibrous stroma containing dense perivascular infiltrates of plasma cells and lymphocytes (Figure 1). Immunohistochemical analysis with kappa, lambda, and CD79a immunostains indicated a polyclonal proliferation of plasma cells that excluded monoclonal plasma cell neoplasia (Figure 2). Direct immunofluorescence (DIF) was negative. Serum enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for bullous pemphigoid 180 and 230 antibodies as well as desmoglein 1 and 3 antibodies was normal. The cumulative findings were consistent with plasma cell gingivitis (PCG). It was recommended that the patient avoid possible foods (eg, citrus) and oral hygiene products (eg, mint-flavored toothpaste) that could trigger PCG. With patient compliance to an elimination diet for 3 months, the condition resolved (Figure 3).

Plasma cell gingivitis is a rare condition characterized by generalized edema and erythema of the attached gingiva. It was described in the 1960s and classified into 3 types based on etiology: (1) hypersensitivity (most common), (2) neoplastic, and (3) PCG of unknown origin.1,2 Spices, herbs, and flavoring agents are implicated as potential triggers of hypersensitivity PCG, while neoplastic PCG is associated with monoclonal plasma cell neoplasms, such as multiple myeloma and extramedullary plasmacytoma.2,3 Histologically, a diffuse subepithelial infiltrate of a polyclonal mixture of plasma cells typically is observed in hypersensitivity PCG.3 The plasma cell infiltration in hypersensitivity PCG is a benign reactive process without known risk for development of plasma cell malignancy, but the presence of a notable number of plasma cells may require special tissue staining to rule out the possibility of associated neoplasia.2,3 There are no standardized protocols for management of PCG.4 Elimination of potential allergens, including flavored oral hygiene products, may result in resolution of hypersensitivity PCG lesions, as exemplified in our patient.1 Neoplastic PCG responds to treatment of the underlying malignancy.5 Topical, intralesional, and/or systemic steroids may be considered in symptomatic cases of PCG.4

Clinical presentation of PCG can mimic immune-mediated mucocutaneous diseases such as mucous membrane pemphigoid (MMP), pemphigus vulgaris (PV), and oral lichen planus; microscopic analysis is needed to establish the diagnosis.6 Mucous membrane pemphigoid is a chronic autoimmune blistering disease involving the mucous membranes with possible cutaneous involvement. It is characterized by a complement-mediated autoantibody process against one or several antigens in the epithelial basement membrane. The oral mucosa is involved in 85% of MMP patients, and 65% of patients experience complications involving the ocular conjunctiva. Intraorally, MMP typically manifests as painful erosions, ulcerations, desquamative gingivitis, and/or occasionally intact blisters. Ocular complications include conjunctivitis and corneal erosions that often scar, resulting in blindness in approximately 15% of patients with ocular involvement. Microscopic features of MMP classically exhibit subepithelial separation with a mixed inflammatory cell infiltrate on routine analysis and linear deposition of IgG, IgA, or C3 within the basement membrane zone on DIF. Treatment of MMP involves topical or systemic immunosuppressants to control symptoms, minimize complications, and alter disease progression.6

Pemphigus vulgaris is an autoimmune vesiculobullous disease that affects the oral mucosa with or without cutaneous involvement.7 Desmogleins 1 and 3, transmembrane glycoproteins of desmosomes that convene cell-to-cell adhesion, are identified as antigens in PV. Antibodies against these desmoglein proteins result in intraepithelial separation, which leads to blister formation.7 Oral manifestations of PV include mucosal erosions and ulcerations as well as desquamative gingivitis. Bullae rarely are seen in the oral cavity, as they tend to rupture, leaving nonhealing ulcerations.8 Histologically, PV is characterized by acantholysis of the suprabasal cell layers with an intact basement membrane zone on routine examination. The distinctive microscopic feature of PV is the detection of cell surface-bound IgG within the epidermis on DIF.7 Treatment of PV may include topical and/or systemic corticosteroids and other immunosuppressants. Rituximab, a monoclonal antibody, has been successful in the management of PV.8

Oral lichen planus is a T-cell mediated autoimmune condition that leads to subepithelial lymphocytic infiltration and excessive keratinocyte apoptosis.9 Women typically are affected more often than men, and 75% of patients also have cutaneous manifestations of the condition. Desquamation and/or erythema of the gingiva may be the initial manifestation of oral lichen planus.9 Other commonly involved sites include the buccal mucosa, tongue, and palate. Biopsy of affected tissues typically demonstrates degeneration of the basal cell layer with subjacent bandlike lymphocytic infiltration on routine staining. Linear fibrinogen at the basement membrane zone usually is observed on DIF. Topical corticosteroids are considered first-line therapy, but systemic therapy including corticosteroids, steroid-sparing agents, or immunomodulators may be used in severe cases.9